Validation Protocols in Food Chemistry: A Comprehensive Guide from Foundations to Foodomics

This article provides a comprehensive guide to the validation of analytical methods in food chemistry, tailored for researchers, scientists, and professionals in drug and food development.

Validation Protocols in Food Chemistry: A Comprehensive Guide from Foundations to Foodomics

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide to the validation of analytical methods in food chemistry, tailored for researchers, scientists, and professionals in drug and food development. It covers the foundational principles and regulatory frameworks established by international bodies like FDA, Eurachem, and ISO. The scope extends to practical methodological applications for analyzing contaminants, nutrients, and bioactive compounds, alongside troubleshooting for common challenges. A critical comparison of validation approaches for chemical, microbiological, and advanced omics methods is presented, synthesizing key performance criteria and current trends to ensure food safety, quality, and authenticity.

Foundations of Food Method Validation: Principles, Regulations, and Core Concepts

Method validation is the cornerstone of generating reliable and defensible analytical data in food chemistry research. It is a formal, systematic process that proves an analytical method is scientifically sound and fit for its intended purpose [1]. For researchers and scientists in drug development and food safety, this process provides the confidence that results quantifying a vitamin, detecting a pathogen, or identifying an adulterant are accurate, precise, and reproducible.

The core purpose of validation is to demonstrate that a method's performance characteristics meet predefined acceptance criteria, which are aligned with the analytical problem and regulatory requirements [2] [1]. In the context of global food supply chains and stringent regulatory frameworks like the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) Food Safety Modernization Act (FSMA), method validation transitions from a best practice to a legal necessity for ensuring consumer safety and product compliance [3] [4].

Distinguishing Validation from Verification

A critical concept in analytical quality assurance is understanding the distinction between method validation and method verification. These are sequential stages in establishing method reliability.

Method Validation is the comprehensive study undertaken to demonstrate that a new method is scientifically suitable for a specific purpose [5]. It is a process of "proving a method's suitability" and is required when a laboratory develops a method in-house or adopts a method for a new matrix or analyte [5] [6].

Method Verification is the process whereby a laboratory demonstrates that it can satisfactorily perform a pre-validated or standardized method—such as one from a pharmacopoeia (e.g., USP) or a standard method (e.g., ISO)—within its own environment using its own personnel and equipment [5] [6] [7]. It is the process of "confirming the accuracy of an already proven method under laboratory conditions" [5].

The global standard ISO 16140 series clearly outlines that both stages are needed before a method is used routinely: first, the method itself must be validated, and second, any user laboratory must verify its competence to perform it [6].

The Regulatory and Scientific Framework

Method validation is mandated by international standards and regulatory bodies worldwide. It is a fundamental requirement for laboratory accreditation under ISO/IEC 17025 [5]. The regulatory landscape is shaped by several key organizations and their guidelines:

- International Council for Harmonisation (ICH): The ICH guidelines, particularly ICH Q2(R2) on "Validation of Analytical Procedures," provide the globally recognized gold standard for validation parameters. The FDA, as a member of ICH, adopts these guidelines, making compliance with ICH Q2(R2) a direct path to meeting FDA requirements for regulatory submissions [2].

- U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA): The FDA rigorously enforces method validation, with recent inspections showing a "significant increase" in requests for product-specific validation and verification reports, especially for over-the-counter (OTC) and prescription products [7].

- USDA-FSIS: Establishments under USDA-FSIS regulation are required to validate their HACCP plans, particularly critical control points (CCPs), with supporting scientific and technical documentation [4].

- ISO: The ISO 16140 series provides specific protocols for the validation and verification of microbiological methods in the food chain, while standards like ISO 17468 set rules for reference methods [6].

The recent modernization of ICH Q2(R2) and the introduction of ICH Q14 on "Analytical Procedure Development" mark a significant shift from a prescriptive, "check-the-box" approach to a more scientific, lifecycle-based model [2]. This new paradigm emphasizes building quality into the method from the beginning, using tools like the Analytical Target Profile (ATP)—a prospective summary of the method's intended purpose and desired performance characteristics [2].

Key Validation Parameters and Performance Criteria

A method is validated through the evaluation of a set of fundamental performance characteristics. The specific parameters tested depend on the method's intended use (e.g., identification vs. quantitative assay), but the core concepts are universal [2] [1].

Table 1: Core Validation Parameters and Their Definitions

| Parameter | Definition | Typical Acceptance Criteria |

|---|---|---|

| Accuracy | The closeness of agreement between the measured value and a known reference or true value [2] [1]. | Recovery studies: 70-120% (varies by analyte and concentration). |

| Precision | The degree of agreement among individual test results when the procedure is applied repeatedly to multiple samplings of a homogeneous sample. Includes repeatability (same day, same analyst) and intermediate precision (different days, different analysts) [2]. | Relative Standard Deviation (RSD) < 5-15% (varies by analyte and concentration). |

| Specificity | The ability to assess the analyte unequivocally in the presence of other components like impurities, degradation products, or matrix components [2]. | No interference from blank or matrix observed. |

| Linearity | The ability of the method to obtain test results that are directly proportional to the concentration of the analyte [2]. | Correlation coefficient (R²) > 0.995. |

| Range | The interval between the upper and lower concentrations of analyte for which suitable levels of linearity, accuracy, and precision have been demonstrated [2]. | Established from linearity and precision data. |

| Limit of Detection (LOD) | The lowest amount of analyte in a sample that can be detected, but not necessarily quantitated [2]. | Signal-to-Noise ratio ≥ 3:1. |

| Limit of Quantitation (LOQ) | The lowest amount of analyte in a sample that can be quantitatively determined with suitable precision and accuracy [2]. | Signal-to-Noise ratio ≥ 10:1; Precision RSD < 20%. |

| Robustness | A measure of the method's capacity to remain unaffected by small, deliberate variations in method parameters (e.g., pH, temperature, flow rate) [2]. | System suitability criteria are met despite variations. |

Beyond these core parameters, the concept of measurement uncertainty is increasingly important. It is a statistical parameter that quantifies the doubt associated with a measurement result, providing a confidence interval for the reported value [5] [1].

Experimental Protocols for Key Validation Parameters

The following protocols provide detailed methodologies for establishing critical validation parameters in a food chemistry context.

Protocol for Determining Accuracy and Precision

This experiment is designed to evaluate the accuracy and precision of a quantitative HPLC method for determining caffeine in soft drinks.

1. Principle: Accuracy is determined by comparing the measured concentration of a known standard to its true value via a recovery study. Precision is assessed by analyzing multiple replicates of the same sample and calculating the relative standard deviation (RSD).

2. Research Reagent Solutions: Table 2: Essential Reagents and Materials for Caffeine Analysis

| Item | Function / Specification |

|---|---|

| Caffeine Certified Reference Material (CRM) | Primary standard for calibration and recovery studies; ensures traceability and accuracy. |

| HPLC-grade Methanol and Water | Mobile phase components; high purity minimizes baseline noise and ghost peaks. |

| Phosphoric Acid | Mobile phase modifier; improves chromatographic peak shape for acidic/basic analytes. |

| Syringe Filters (0.45 µm, Nylon) | Clarifies sample extracts prior to HPLC injection to protect the column from particulates. |

3. Procedure:

1. Preparation of Standard Solutions: Prepare a stock solution of caffeine CRM. Dilute to create calibration standards covering the expected range (e.g., 1-100 µg/mL).

2. Sample Preparation: Spike blank (caffeine-free) soft drink matrix with known quantities of caffeine at three concentration levels (low, mid, high) covering the analytical range. Prepare six replicates at each level.

3. Analysis: Inject each calibration standard and spiked sample replicate in a randomized sequence.

4. Data Analysis:

- Accuracy: Calculate percent recovery for each spike level: (Measured Concentration / Spiked Concentration) * 100. Report mean recovery for each level.

- Precision: Calculate the mean, standard deviation, and RSD of the measured concentrations for the six replicates at each spike level.

Protocol for Establishing Specificity

This experiment verifies that the method can distinguish caffeine from other common soft drink components like benzoic acid and aspartame.

1. Principle: Specificity is demonstrated by analyzing the sample matrix and potential interferences individually to show that the analyte peak is free from co-elution.

2. Procedure: 1. Chromatographic Analysis: - Inject a solvent blank. - Inject standards of pure caffeine, benzoic acid, and aspartame. - Inject a blank soft drink matrix. - Inject the soft drink matrix spiked with caffeine. 2. Data Analysis: Compare the chromatograms. The caffeine peak in the spiked sample should be resolved from any matrix peaks (e.g., Resolution Factor Rs > 1.5). There should be no peak at the retention time of caffeine in the blank matrix.

Protocol for Robustness Testing

This experiment assesses the impact of small, deliberate variations in HPLC method conditions.

1. Principle: Key method parameters are varied within a small, realistic range to evaluate their influence on method performance.

2. Procedure: 1. Experimental Design: Using a standard solution of caffeine, perform the analysis while varying one parameter at a time: - Mobile Phase pH: ± 0.1 units - Column Temperature: ± 2°C - Flow Rate: ± 0.1 mL/min 2. Analysis: For each varied condition, inject the standard and record the retention time, peak area, tailing factor, and theoretical plates. 3. Data Analysis: Compare the system suitability parameters (e.g., %RSD of retention time, peak area) across all variations. The method is considered robust if all system suitability criteria are met under all tested conditions.

The Method Validation Lifecycle and Workflow

The contemporary approach, reinforced by ICH Q2(R2) and Q14, views validation as a continuous lifecycle rather than a one-time event [2]. The process begins with defining the ATP and continues through development, validation, and ongoing monitoring and improvement during routine use.

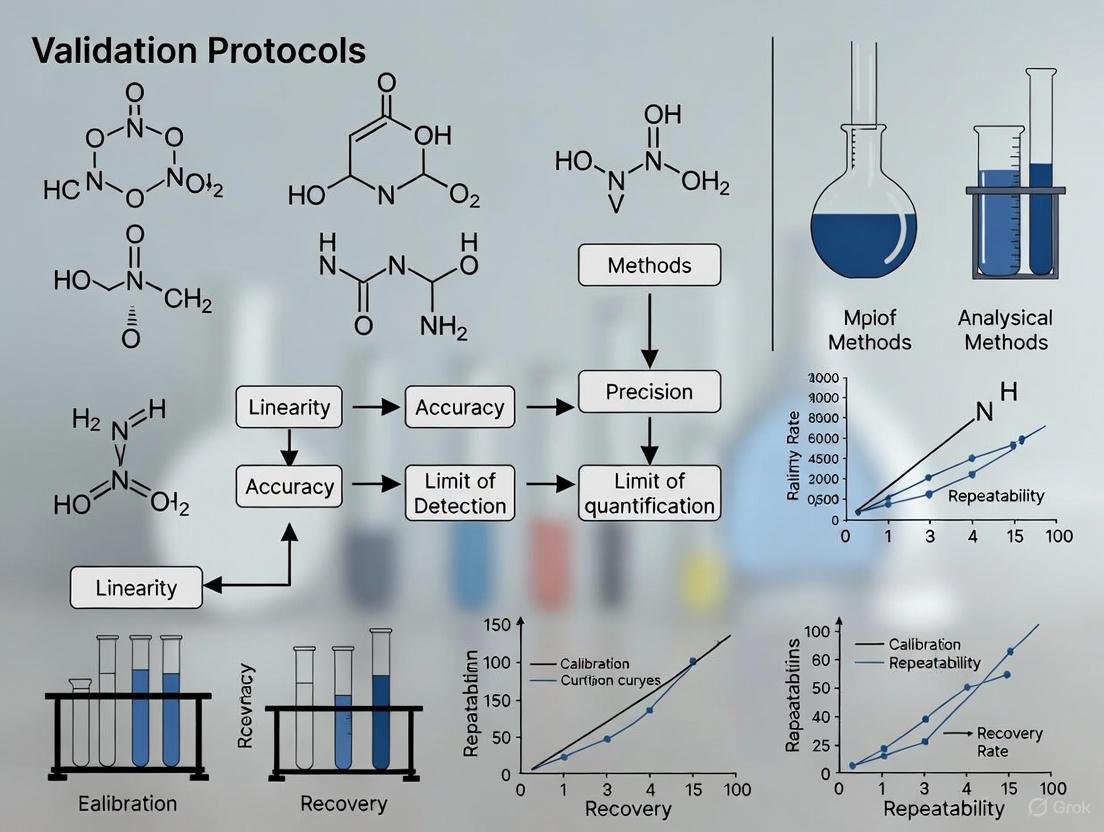

Diagram 1: Method validation lifecycle workflow.

Implementing a Validation Program: A Step-by-Step Guide

For a research laboratory implementing a validation program, the following steps provide a structured roadmap [3] [2]:

- Define Objectives and ATP: Before development, define the purpose of the method, the analyte, matrix, and required performance levels (e.g., LOQ, precision) in an ATP.

- Conduct Risk Assessment: Use a quality risk management approach (ICH Q9) to identify potential sources of variability that could impact method performance.

- Develop a Validation Protocol: Create a detailed, pre-approved plan outlining the experiments, acceptance criteria, and statistical methods for evaluation.

- Execute Protocol and Document: Perform the experiments as per the protocol, ensuring all data is recorded in a traceable and auditable manner.

- Analyze Data and Report: Compile a final report summarizing the data, comparing it against acceptance criteria, and stating a conclusion on the method's validity.

- Manage the Method Lifecycle: Once validated, maintain the method's validated state through a robust change control system, periodic reviews, and verification checks.

Method validation is an indispensable, legally-required discipline that provides the scientific foundation for data integrity in food safety and quality. It is a rigorous process that moves beyond simple compliance to a science-driven, lifecycle-based framework. By systematically demonstrating that an analytical procedure is fit-for-purpose through established parameters like accuracy, precision, and specificity, researchers and scientists can generate data that protects consumers, ensures regulatory compliance, and drives innovation in food chemistry and drug development. The adoption of modern guidelines like ICH Q2(R2) and the use of a structured protocol are critical for establishing reliable, robust, and future-proof analytical methods.

The validation of analytical methods in food chemistry research is a critical process governed by a complex framework of international regulatory bodies and standards organizations. These entities establish the guidelines and requirements that ensure chemical analyses are scientifically sound, reproducible, and fit for their intended purpose. For researchers developing validation protocols, understanding the roles and requirements of the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA), Eurachem, the International Organization for Standardization (ISO), and the International Council for Harmonisation (ICH) is fundamental to producing compliant and reliable results. The FDA protects consumers from harmful exposure to chemicals in foods through a comprehensive, science-driven approach that includes both pre-market and post-market safety evaluations [8]. Complementary to these regulatory requirements, organizations like Eurachem provide detailed technical guidance on method validation, emphasizing that the primary objective is to demonstrate that an analytical method is "fit for purpose" [9]. This application note delineates the specific roles of these key bodies and provides detailed experimental protocols for validating analytical methods within this regulatory context, specifically framed for food chemistry research.

U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA)

The FDA's role in food chemical safety is multifaceted, encompassing the regulation of both intentionally added substances and chemical contaminants. Its authority stems from the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act (FD&C Act) and is executed through several key mechanisms and divisions, including the Office of Food Chemical Safety, Dietary Supplements & Innovation [8].

- Pre-market Review: For food additives, color additives, and food contact substances, the FDA typically requires pre-market review and authorization. Manufacturers must submit data demonstrating that the chemical is safe at its intended level of use. This process involves a petition leading to a regulation or, for food contact substances, a notification that becomes effective upon FDA's safety determination [8].

- Generally Recognized as Safe (GRAS): Substances whose use is generally recognized as safe by qualified experts are exempt from the formal food additive approval process. The FDA manages a voluntary GRAS notification program to help industry meet its responsibility for ensuring safety, though the ultimate legal responsibility rests with the manufacturer [8].

- Post-market Monitoring and Assessment: The FDA continuously monitors the food supply for chemical contaminants and reassesses the safety of authorized substances as new scientific information emerges. Key activities include monitoring contaminant levels, enforcing pesticide tolerances (set by the EPA), and conducting research on contaminants like PFAS and heavy metals. When new data indicates a safety concern, the FDA can revoke authorizations, work with industry on recalls, or issue public alerts [8].

A notable example of the FDA's evolving post-market assessment is its public listing of select chemicals under review, which includes food ingredients, food contact substances, and contaminants. As of August 2025, this list has been updated to include substances such as BHA, BHT, several synthetic food colors (FD&C Blue No. 1, Red No. 40, etc.), and opiate alkaloids on poppy seeds [10] [11]. This initiative provides transparency into the agency's ongoing safety reviews and prioritization of chemicals that may present significant public health concerns.

Eurachem

Eurachem is a network of organizations in Europe with the focus on analytical quality and the validity of chemical measurement. It is a leading provider of guidance on method validation and related topics, with its flagship document being "The Fitness for Purpose of Analytical Methods."

- Fitness for Purpose Principle: The central tenet of Eurachem's guidance is that an analytical method must be validated to be sufficient for its intended use. The level of validation required is commensurate with the application [9].

- Method Validation Guidance: The Eurachem guide provides comprehensive instruction on all aspects of method validation, including the various validation parameters (e.g., selectivity, accuracy, precision, measurement uncertainty), how to perform validation studies, and how to document the process. The 2025 third edition includes new sections on sampling and sample handling, reflecting their importance in the overall validity of the measurement procedure [9].

- Supplementary Guides: Eurachem also publishes specialized guides that are highly relevant to food chemistry, such as:

- Validation of Measurement Procedures that Include Sampling (VaMPIS): This guide extends validation to include the sampling step, which is often the largest source of error in chemical analysis [12].

- Assessment of Performance and Uncertainty in Qualitative Chemical Analysis: This provides metrics and approaches for ensuring the reliability of qualitative analyses, such as identifying contaminants or adulterants [12].

- Use of Uncertainty Information in Compliance Assessment: This guide details how measurement uncertainty should be taken into account when assessing compliance with a regulatory limit, a critical step in food safety enforcement [12].

International Council for Harmonisation (ICH)

While the ICH guidelines (Q-series) were developed primarily for the pharmaceutical industry, their principles of Quality by Design (QbD), risk management, and robust quality systems are increasingly being adopted in other regulated sectors, including food chemistry, especially for high-stakes applications or novel food ingredient development.

- ICH Q8 (Pharmaceutical Development): Promotes the Quality by Design (QbD) approach, which emphasizes a systematic, science-based process for product development. This involves defining a Quality Target Product Profile (QTPP), identifying Critical Quality Attributes (CQAs), and linking material attributes and process parameters to the CQAs. For food chemistry, this translates to a more structured and defensible method development process [13].

- ICH Q9 (Quality Risk Management): Provides a systematic process for assessing, controlling, communicating, and reviewing risks to product quality. The two core principles are that risk assessment should be science-based and linked to patient (or consumer) protection, and the level of effort should be proportional to the risk. This framework is directly applicable for prioritizing validation activities in food chemical analysis [13].

- ICH Q10 (Pharmaceutical Quality System): Describes a comprehensive model for an effective quality management system that encompasses the entire product lifecycle. Its four key elements are: Process Performance and Product Quality Monitoring, Corrective and Preventive Action (CAPA), Change Management, and Management Review [13]. Adopting these principles in a research setting ensures continuous improvement and operational excellence.

International Organization for Standardization (ISO)

ISO develops and publishes international standards that cover a vast range of activities, including testing and calibration. The most directly relevant standard for analytical laboratories is ISO/IEC 17025:2017, "General requirements for the competence of testing and calibration laboratories."

- ISO/IEC 17025: This standard specifies the general requirements for a laboratory's competence to carry out tests and calibrations, including sampling. It covers all aspects of laboratory operations, including structure, resource requirements (personnel, facilities, equipment), processes (handling of test items, method validation, measurement uncertainty), and management system requirements. Accreditation to ISO/IEC 17025 by a recognized body provides independent confirmation of a laboratory's technical competence [12].

- Method Validation and Verification: ISO/IEC 17025 requires laboratories to validate non-standard methods, laboratory-designed/developed methods, and standard methods used outside their intended scope. It also requires that standard methods be verified to confirm that the laboratory can properly perform them [12].

Table 1: Summary of Key Regulatory and Standards Bodies and Their Primary Functions

| Body | Primary Focus & Jurisdiction | Key Documents/Guidelines | Relevance to Food Chemistry Method Validation |

|---|---|---|---|

| U.S. FDA | Regulatory enforcement for food and food contact substances in the United States. | Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act; Various Guidance Documents; "List of Select Chemicals...Under FDA Review" [11]. | Sets legal safety standards; defines data requirements for pre-market approval; monitors contaminants; provides action levels for unavoidable contaminants. |

| Eurachem | Technical guidance on analytical chemistry best practices, globally influential. | "The Fitness for Purpose of Analytical Methods" (2025) [9]; Guides on sampling, uncertainty, and qualitative analysis [12]. | Provides the definitive technical framework and practical protocols for designing and executing method validation studies. |

| ICH | Harmonizing technical requirements for pharmaceutical human drugs (principles applicable to food). | ICH Q8 (Pharmaceutical Development), Q9 (Quality Risk Management), Q10 (Pharmaceutical Quality System) [13]. | Provides structured frameworks for QbD, risk assessment, and quality systems that can enhance the robustness of food analytical method development. |

| ISO | International standardization across industries, including laboratory competence. | ISO/IEC 17025:2017 (General requirements for laboratory competence) [12]. | Defines the management and technical requirements for laboratory quality systems and accreditation. |

Experimental Protocol: Comprehensive Validation of an Analytical Method for Chemical Contaminants in Food

This protocol integrates requirements and guidance from the FDA, Eurachem, ICH Q9, and ISO/IEC 17025 to validate a quantitative analytical method for determining a chemical contaminant (e.g., lead or cadmium) in a food matrix.

Scope and Application

This protocol is designed to validate a method for the quantification of heavy metals in infant formula powder using Inductively Coupled Plasma Mass Spectrometry (ICP-MS). The validated method will be used to assess compliance with FDA action levels, such as those outlined in the agency's "Closer to Zero" initiative [8] [11].

Pre-Validation Requirements (Quality by Design & Risk Assessment)

- Step 1: Define the Analytical Target Profile (ATP). The ATP is a pre-defined objective that summarizes the method's performance requirements. Example: "The method must be capable of quantifying lead and cadmium in infant formula powder with an accuracy of 80-110% and a precision (RSD) of ≤15% at the FDA's proposed action level of 10 ppb for lead and 5 ppb for cadmium."

- Step 2: Apply ICH Q9 Quality Risk Management. Conduct a risk assessment to identify potential variables that could impact method performance.

- Risk Identification: Use a Fishbone (Ishikawa) diagram to brainstorm potential sources of variation (Man, Machine, Material, Method, Measurement, Environment).

- Risk Analysis: Evaluate the severity of failure and the probability of occurrence for each identified risk.

- Risk Evaluation & Control: High-risk factors become the focus of the method development and validation experiments. For example, sample digestion efficiency and spectral interferences are high-risk factors for ICP-MS analysis of complex food matrices.

Reagent and Material Solutions

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for ICP-MS Analysis of Heavy Metals

| Reagent/Material | Specification/Purity | Function in Protocol | Critical Quality Attribute |

|---|---|---|---|

| High-Purity Nitric Acid | Trace metal grade, ≥69% | Primary digestion acid for dissolving organic matrix and extracting metals. | Low and documented blank levels for target analytes. |

| Hydrogen Peroxide | ACS reagent grade, 30% | Oxidizing agent to aid in the complete digestion of organic matter. | Low metal contamination. |

| Single-Element Stock Standards | Certified Reference Material (CRM), 1000 µg/mL | Used for preparation of calibration standards and quality control samples. | NIST-traceable certification and uncertainty. |

| Internal Standard Mix | CRM of Sc, Ge, Rh, In, Tb, Lu | Added to all samples and standards to correct for instrument drift and matrix suppression/enhancement. | Elements not present in samples and that cover the mass range of analytes. |

| Tuning Solution | Contains Li, Y, Ce, Tl | Used to optimize instrument performance for sensitivity, stability, and oxide formation. | Consistent performance against manufacturer's specifications. |

| Certified Reference Material | CRM of infant formula (e.g., NIST SRM 1849a) | Used for method verification and establishing accuracy. | Certified values with defined uncertainty for target analytes. |

Detailed Validation Methodology

The following experiments will be performed to establish the method's validation parameters as per Eurachem and FDA data quality objectives [9] [8].

1. Specificity/Selectivity

- Procedure: Analyze a minimum of six independent lots of blank infant formula matrix. Check for any spectral or matrix interference at the mass-to-charge (m/z) ratios of the target analytes (e.g., 208 for Pb, 111 for Cd).

- Acceptance Criterion: The response in the blank at the analyte retention time (or m/z) must be less than 30% of the response of the analyte at the action level concentration.

2. Linearity and Range

- Procedure: Prepare a minimum of five calibration standards in the matrix-matched solvent, covering a range from the Limit of Quantification (LOQ) to 150% of the expected action level (e.g., 1 ppb to 15 ppb). Analyze each standard in triplicate.

- Acceptance Criterion: The correlation coefficient (r) must be ≥0.995. The back-calculated concentration of each standard should be within ±15% of the nominal value.

3. Accuracy (Recovery)

- Procedure: Prepare and analyze replicate samples (n=6) of the blank matrix fortified with the target analytes at three concentration levels: low (near LOQ), medium (at the action level), and high (near the top of the range).

- Acceptance Criterion: Mean recovery should be within 80-110% for each level, with an RSD of ≤15%.

4. Precision

- Repeatability (Intra-day): Analyze the six replicates at the action level concentration (from the accuracy experiment) in a single analytical run. Calculate the %RSD. Acceptance: RSD ≤15%.

- Intermediate Precision (Inter-day): Repeat the accuracy and precision experiment on a different day, using a different analyst and a different instrument of the same model, if possible. Calculate the overall %RSD from the pooled data. Acceptance: RSD ≤20%.

5. Limit of Quantification (LOQ)

- Procedure: The LOQ is established based on the lowest point on the calibration curve that can be measured with an accuracy of 80-120% and a precision of ≤20% RSD. This is confirmed by analyzing replicate (n=6) samples at that concentration.

- Acceptance Criterion: The signal-to-noise ratio at the LOQ should be ≥10:1, and the above accuracy and precision criteria must be met.

6. Measurement Uncertainty (MU)

- Procedure: Following Eurachem guidance, estimate the MU by identifying and quantifying the significant uncertainty sources. A practical approach is to use the data from the validation study. The combined standard uncertainty (uc) can be estimated from the intermediate precision data (as the standard deviation, s) and the uncertainty of the reference standard (ustd).

- Calculation:

u_c = √(s² + u_std²). The expanded uncertainty (U) is calculated asU = k * u_c, where k is a coverage factor (typically 2 for approximately 95% confidence).

Data Analysis and Reporting

All data must be documented in a structured validation report. The report should include a summary table of all validation parameters against their acceptance criteria, representative chromatograms/spectra, raw data, and a statement on the fitness for purpose. The report must be approved by the study director and quality assurance.

Integrated Workflow for Method Validation and Regulatory Compliance

The following diagram illustrates the integrated workflow for developing and validating an analytical method, incorporating principles from all discussed regulatory and standards bodies to ensure both technical rigor and regulatory compliance.

Navigating the landscape of regulatory and standards bodies is essential for developing robust validation protocols in food chemistry research. The FDA provides the enforceable regulatory framework and safety standards, while Eurachem offers the definitive technical guidance on achieving and demonstrating fitness for purpose. The ICH guidelines, though pharmaceutical in origin, provide powerful systematic frameworks for Quality by Design and Risk Management that enhance method development. Finally, ISO/IEC 17025 sets the benchmark for overall laboratory quality and competence. By integrating the requirements and recommendations from all these bodies, as detailed in the provided application note and protocols, researchers can ensure their analytical methods are not only scientifically valid but also positioned to meet the stringent demands of global regulatory compliance.

Analytical method validation is a critical, systematic process required to confirm that an analytical procedure is suitable for its intended purpose and consistently produces reliable and credible results [14]. This process is indispensable in regulated environments such as food chemistry research and pharmaceutical development, where data integrity is paramount. Validation provides documented evidence that a method consistently meets the pre-defined acceptance criteria for its key performance characteristics, thereby bolstering the credibility of scientific findings and ensuring product safety and quality [15] [14].

The foundational principles of method validation are governed by international guidelines from bodies like the International Council for Harmonisation (ICH) and the World Health Organization (WHO) [16] [14]. Furthermore, specific programs, such as the FDA's Foods Program, operate under detailed Methods Development, Validation, and Implementation Program (MDVIP) Standard Operating Procedures, which mandate the use of properly validated methods to support their regulatory mission [17]. The core objective of validation is to mitigate risks associated with incorrect analytical results, which could lead to severe consequences in product quality and public health [15]. This article delineates the essential performance criteria, provides detailed experimental protocols, and frames the discussion within the context of a rigorous research thesis.

The Six Key Validation Performance Characteristics

A robust analytical method validation protocol must demonstrate acceptable performance across six key characteristics. A useful mnemonic to remember them is: "Silly - Analysts - Produce - Simply - Lame - Results", which corresponds to Specificity, Accuracy, Precision, Sensitivity, Linearity, and Robustness [15]. The following table summarizes these core parameters:

Table 1: Core Analytical Method Validation Parameters

| Parameter | Definition | Core Question |

|---|---|---|

| Specificity | The ability to assess the analyte unequivocally in the presence of other components like impurities, degradants, or matrix. | Can the method distinguish and measure only the target analyte without interference? [15] |

| Accuracy | The closeness of agreement between the value found and a conventional true value or an accepted reference value (also known as trueness). | How close are my measured results to the true value? [15] [14] |

| Precision | The closeness of agreement (degree of scatter) between a series of measurements from multiple sampling of the same homogeneous sample. | How reproducible are my results when the same sample is measured repeatedly? [15] [14] |

| Sensitivity | The ability to detect or quantify the analyte at low levels, defined by the Detection Limit (DL) and Quantitation Limit (QL). | What is the lowest amount of analyte that can be reliably detected or quantified? [15] [14] |

| Linearity | The ability of the method to obtain test results that are directly proportional to the concentration of analyte in the sample within a given range. | Does the instrument response change proportionally with the analyte's concentration? [15] [14] |

| Robustness | A measure of the method's capacity to remain unaffected by small, deliberate variations in method parameters. | Will small, intentional changes in method parameters affect the analytical results? [15] |

These characteristics are interlinked, as visualized in the following workflow that outlines the validation lifecycle from initial specificity testing to ongoing robustness assurance:

Specificity and Selectivity

Specificity is the ability to assess the analyte unequivocally in the presence of components that may be expected to be present, such as impurities, degradants, and matrix components [15] [14]. In chromatography, this is demonstrated by the resolution factor between the analyte peak and the closest eluting potential interferent [14]. A specific method yields results for the target analyte only, free from any interference.

Experimental Protocol for Specificity

- Sample Preparation: Prepare a minimum of three sets of samples:

- Blank Matrix: The sample matrix (e.g., food homogenate) without the target analyte.

- Spiked Matrix: The blank matrix fortified with the target analyte at a known concentration (e.g., at the specification limit).

- Stressed Sample (Forced Degradation): The analyte sample subjected to stress conditions (e.g., heat, light, acid/base, oxidation) to generate degradants.

- Analysis and Evaluation: Analyze all samples using the proposed method. Compare the chromatograms or spectra to demonstrate:

- No interfering peaks are present at the retention time/position of the analyte in the blank matrix.

- The analyte peak is pure and well-resolved from any degradant peaks in the stressed sample (e.g., using Diode Array Detector (DAD) or Mass Spectrometry (MS) for peak purity assessment).

Accuracy and Precision

Accuracy (trueness) and Precision are distinct but related concepts, famously illustrated by the dartboard analogy. In this analogy, the bullseye represents the true value. A method is accurate if the darts (results) are close to the bullseye, and precise if the darts are clustered closely together, regardless of their location relative to the bullseye [14]. An ideal method is both accurate and precise.

Experimental Protocol for Accuracy

- Design: Prepare a minimum of 9 determinations across 3 concentration levels (low, medium, high) covering the specified range, with 3 replicates at each level [14]. Use a certified reference material or a sample spiked with a known quantity of the pure analyte.

- Calculation: For each concentration, calculate the percent recovery.

- Recovery (%) = (Measured Concentration / Known Concentration) × 100

- Acceptance Criteria: The mean recovery should be within a pre-defined range (e.g., 98-102% for an API assay) with a low relative standard deviation [14].

Experimental Protocol for Precision

Precision is evaluated at three tiers, with their relationships and sources of variation illustrated below:

- Repeatability: Perform a minimum of 6 determinations at 100% of the test concentration or 9 determinations covering the entire range (e.g., 3 concentrations x 3 replicates). Analyze under the same operating conditions over a short time interval [14].

- Intermediate Precision (Ruggedness): Incorporate variations such as different analysts, different days, and different equipment within the same laboratory. The experimental design should include a combination of these factors [14].

- Reproducibility: This represents the precision between collaborative laboratories, typically assessed during inter-laboratory comparison studies or method standardization for pharmacopoeias [14].

- Calculation: For each tier, precision is expressed as Standard Deviation (SD) and Relative Standard Deviation (RSD) or Coefficient of Variation (CV).

- RSD (%) = (Standard Deviation / Mean) × 100

Linearity and Range

Linearity is the ability of a method to produce results that are directly proportional to analyte concentration within a given range [15] [14]. The range is the interval between the upper and lower concentrations for which suitable levels of precision, accuracy, and linearity have been demonstrated [14].

Experimental Protocol for Linearity and Range

- Design: Prepare a minimum of 5 concentration levels appropriately distributed across the intended range [14]. For an assay of a drug substance or product, a typical range is 80-120% of the test concentration [14].

- Analysis and Evaluation: Analyze each concentration level, preferably in triplicate. Plot the instrumental response against the analyte concentration and perform a linear regression analysis using the least squares method.

- Key Outputs:

- Correlation Coefficient (R): Should typically be >0.99 for chromatographic assays.

- Coefficient of Determination (R²): A value >0.95 is often used as a minimum acceptance criterion, but >0.99 is expected for precise methods [14].

- Y-Intercept: Should not be significantly different from zero.

- Slope: Represents the sensitivity of the method.

Table 2: Typical Validation Ranges for Different Analytical Procedures

| Analytical Procedure | Typical Validation Range |

|---|---|

| Drug Substance/Product Assay | 80% to 120% of the test concentration [14] |

| Content Uniformity | 70% to 130% of the test concentration [14] |

| Dissolution Testing | ±20% over the entire specification range (e.g., from 0% to 110% of the labeled claim) [14] |

| Impurity Assay | From the reporting level (Quantitation Limit) to 120% of the impurity specification [14] |

Sensitivity: Detection and Quantitation Limits

Sensitivity defines the lowest levels of analyte that can be reliably detected or quantified. The Detection Limit (DL) is the lowest amount that can be detected but not necessarily quantified, while the Quantitation Limit (QL) is the lowest amount that can be quantified with acceptable accuracy and precision [14].

Experimental Protocol for DL and QL

Two common approaches are:

- Signal-to-Noise Ratio (S/N): Applicable for techniques with a baseline signal, like chromatography. The DL is estimated with an S/N of 3:1, and the QL with an S/N of 10:1 [14].

- Standard Deviation of the Response and Slope:

- DL = (3.3 × σ) / S

- QL = (10 × σ) / S

- Where σ is the standard deviation of the response (y-intercept or residual SD) and S is the slope of the calibration curve [14].

Robustness and Ruggedness

Robustness evaluates the method's reliability during normal use by measuring its capacity to remain unaffected by small, deliberate variations in method parameters, such as pH, mobile phase composition, temperature, or flow rate in HPLC [15]. Ruggedness, often considered part of intermediate precision, refers to the degree of reproducibility of test results under a variety of normal conditions, like different analysts or instruments [14].

Experimental Protocol for Robustness

- Design: Use an experimental design (e.g., a Plackett-Burman or fractional factorial design) to systematically vary key method parameters within a realistic range (e.g., pH ±0.2 units, organic composition in mobile phase ±2%).

- Analysis: Analyze a system suitability test sample or a reference material under each varied condition.

- Evaluation: Monitor the effect on critical performance attributes, such as resolution, tailing factor, efficiency (theoretical plates), and assay results. The method is considered robust if these attributes remain within specified acceptance criteria under all tested conditions.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details key reagents and materials essential for executing the validation protocols described, particularly in chromatographic analyses of food and drug matrices.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Method Validation

| Reagent/Material | Function in Validation | Critical Quality Attributes |

|---|---|---|

| Certified Reference Material (CRM) | Serves as the primary standard for establishing accuracy and calibrating the method. Provides the "true value" for recovery studies. | High purity (>99.5%), well-characterized identity and purity, traceable certification. |

| Chromatographic Mobile Phase Solvents | The liquid medium that carries the sample through the chromatographic system. Critical for retention, resolution, and peak shape. | HPLC-grade or better, low UV absorbance, low particulate matter, controlled pH and buffering capacity. |

| Sample Matrix Simulants | A synthetic mixture mimicking the sample (e.g., food product without analyte) used to prepare spiked samples for accuracy, specificity, and QL/DL studies. | Must accurately represent the complexity of the real sample matrix to properly assess matrix effects. |

| Stable Isotope-Labeled Internal Standard | Added in equal amount to all calibration standards and samples to correct for losses during sample preparation and instrument variability. | Structurally analogous to the analyte, chromatographically resolved, must not be present in the original sample. |

The rigorous validation of analytical methods, grounded in the systematic assessment of specificity, accuracy, precision, linearity, sensitivity, and robustness, is a non-negotiable pillar of scientific integrity in food chemistry and pharmaceutical research. Adherence to established protocols and acceptance criteria, as outlined in ICH, WHO, and FDA guidelines, ensures that generated data is reliable, reproducible, and fit-for-purpose [17] [16] [14]. This structured approach to validation forms the bedrock of a research thesis, providing a defensible foundation upon which credible conclusions about product safety, quality, and efficacy can be built. As methods and regulations evolve, the principles of validation remain constant, demanding ongoing verification to ensure methods remain in a state of control throughout their lifecycle [16].

In the field of food chemistry research, the reliability of analytical data forms the bedrock of quality control, regulatory submissions, and ultimately, public health protection [2]. Analytical method validation provides objective evidence that a method is fit for its intended purpose, a process governed by stringent international guidelines from bodies like the International Council for Harmonisation (ICH) and implemented by regulatory agencies such as the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) [2] [17]. The validation process occurs across a spectrum of increasing rigor and collaborative effort, progressing from single-laboratory validation through intermediate tiers to full multi-laboratory collaborative trials.

The FDA Foods Program emphasizes that properly validated methods are essential for supporting its regulatory mission, advocating for multi-laboratory validation (MLV) where feasible to ensure robust and reproducible results [17]. This tiered approach ensures that methods transferred between laboratories or used for regulatory decision-making possess demonstrated accuracy, precision, and reliability across different instruments, operators, and environments. For researchers and drug development professionals, understanding these validation tiers is critical for designing appropriate validation protocols that meet both scientific and regulatory requirements.

Core Validation Parameters Across Tiers

Regardless of the validation tier, certain core performance characteristics must be evaluated to demonstrate a method is fit for purpose. ICH Q2(R2) outlines these fundamental parameters, which form the basis of method validation across pharmaceutical, food, and clinical chemistry disciplines [2] [18].

Table 1: Core Analytical Method Validation Parameters

| Parameter | Definition | Typical Assessment Method |

|---|---|---|

| Accuracy | Closeness of test results to the true value [2] | Analysis of standards with known concentrations; spike recovery studies [2] [18] |

| Precision | Degree of agreement among individual test results from repeated samplings [2] | Measurement of repeatability (intra-assay) and intermediate precision (inter-day, inter-analyst) [2] [18] |

| Specificity | Ability to assess the analyte unequivocally in the presence of potential interferents [2] | Analysis of samples with and without potential interferents like impurities or matrix components [2] |

| Linearity & Range | The interval between upper and lower analyte concentrations where suitable linearity, accuracy, and precision are demonstrated [2] | Analysis of samples at multiple concentrations across the claimed range [2] |

| Detection Limits | Lowest amount of analyte that can be detected (LOD) or quantified (LOQ) with acceptable accuracy and precision [2] [18] | Signal-to-noise ratio or based on standard deviation of the response and slope of the calibration curve [18] |

These parameters are assessed with increasing stringency and statistical power as methods progress through the validation tiers from single-laboratory verification to multi-laboratory collaborative trials.

Single-Laboratory Validation

Purpose and Scope

Single-laboratory validation, often termed "verification," represents the foundational tier where a laboratory establishes that a method performs adequately within its specific environment and with its personnel [18]. According to clinical chemistry guidelines, verification is defined as "provision of objective evidence that a given item fulfils specified requirements," whereas validation establishes that requirements are adequate for the intended use [18]. This distinction is crucial: verification confirms a method works as claimed in a user's laboratory, while validation typically occurs during method development.

For food chemistry researchers, single-laboratory validation is appropriate for methods developed in-house or adopted from literature for internal use, particularly when the method will not be used for regulatory submissions requiring multi-laboratory validation. The FDA Foods Program acknowledges that not all methods require full multi-laboratory validation, but emphasizes that all methods must be properly validated according to their intended use [17].

Experimental Protocol

The following protocol outlines the key experiments for single-laboratory validation:

Step 1: Define Performance Requirements

- Establish the Analytical Target Profile (ATP) - a prospective summary of the method's intended purpose and required performance criteria [2]. The ATP should define acceptable ranges for accuracy, precision, detection limits, and working range based on the method's intended application.

Step 2: Assess Precision

- Conduct repeatability testing: Analyze a minimum of 5 replicates of a homogeneous sample within a single analytical run [18].

- Calculate standard deviation (SD) and coefficient of variation (CV) using the formula for repeatability:

S_r = √[Σ(X_di - X̄_d)² / D(n-1)]where Sr = repeatability, D = total days, n = replicates per day, Xdi = replicate results per day, X̄_d = average of all results for day d [18]. - Conduct intermediate precision: Analyze the same sample over different days, by different analysts, or using different instruments. Calculate between-day variation using:

S_b = √[Σ(X_d - X̄)² / (D-1)]where Sb = between-day standard deviation, Xd = average of all results for day d, X̄ = average of all results [18].

Step 3: Assess Accuracy/Trueness

- Perform spike recovery studies: Fortify blank matrix with known concentrations of analyte (low, medium, high levels across the working range).

- Calculate percent recovery: (Measured concentration / Theoretical concentration) × 100.

- Compare results to certified reference materials when available.

- For trueness verification, calculate the verification interval:

X ± 2.821√(Sx² + Sa²)where X = mean of tested reference material, Sx = standard deviation of tested reference material, Sa = uncertainty of assigned reference material [18].

Step 4: Establish Detection and Quantitation Limits

- Based on signal-to-noise ratio: LOD = concentration giving signal 3.3× noise; LOQ = concentration giving signal 10× noise.

- Based on standard deviation: LOD = 3.3σ/slope; LOQ = 10σ/slope, where σ = standard deviation of response at low concentrations, slope = slope of the calibration curve [18].

Step 5: Demonstrate Linearity and Range

- Prepare and analyze a minimum of 5 concentrations across the claimed working range.

- Plot response against concentration and perform linear regression analysis.

- The method is linear if the correlation coefficient (r) ≥ 0.99 and visual inspection shows random scatter around the regression line.

Step 6: Evaluate Robustness

- Deliberately introduce small, deliberate variations in method parameters (e.g., pH ± 0.2 units, temperature ± 2°C, mobile phase composition ± 2%).

- Measure the impact on method performance to identify critical parameters requiring control.

Intermediate Collaborative Validation

Purpose and Scope

Intermediate collaborative validation represents a crucial bridging tier between single-laboratory work and full collaborative trials. This approach involves a limited number of laboratories (typically 2-4) working collaboratively to validate a method before wider implementation [17]. The FDA Foods Program's Method Validation Subcommittees (MVS) play a role in approving validation plans and evaluating validation results for such collaborative efforts [17].

This tier is particularly valuable for methods intended for use within a limited network of laboratories, such as those within a multi-site organization or a specific research consortium. It provides greater confidence than single-laboratory validation while being more resource-efficient than full collaborative trials. The recent ICH Q2(R2) and Q14 guidelines emphasize a lifecycle approach to analytical procedures, encouraging earlier collaboration and more science-based validation approaches [2].

Experimental Protocol

Step 1: Establish Collaborative Network

- Select 2-4 laboratories with relevant expertise and appropriate equipment.

- Appoint a coordinating laboratory to manage sample distribution, data collection, and statistical analysis.

- Develop a detailed validation protocol specifying responsibilities, timelines, and acceptance criteria.

Step 2: Harmonize Practices Across Laboratories

- Conduct training sessions to ensure consistent sample preparation, instrumentation operation, and data interpretation.

- Distribute standardized reagents and reference materials to all participating laboratories.

- Establish common data reporting formats and quality control procedures.

Step 3: Execute Parallel Validation Studies

- Each laboratory performs the full single-laboratory validation protocol as described in Section 3.2.

- Additionally, all laboratories analyze a common set of blinded samples representing the full analytical range.

- The number of replicates and samples should be sufficient for robust statistical analysis of between-laboratory variation.

Step 4: Statistical Analysis of Collaborative Data

- Calculate reproducibility standard deviation:

S_R = √(S_b² + S_w²)where Sb² = between-lab variance, Sw² = within-lab variance. - Determine Horwitz ratio (HorRat): (Found relative standard deviation / Predicted relative standard deviation).

- Acceptable HorRat values are typically 0.5-2.0, indicating the between-laboratory precision is consistent with that expected based on the analyte concentration.

Step 5: Refine Method Protocol

- Identify sources of variation between laboratories and refine the method protocol to address them.

- Update the method documentation to include troubleshooting guidance and critical control points.

- Establish ongoing quality control monitoring requirements for implementation.

Multi-Laboratory Collaborative Trials

Purpose and Scope

Multi-laboratory collaborative trials represent the most rigorous validation tier, providing definitive evidence of a method's reliability across multiple independent laboratories [17]. These trials are essential for methods intended for regulatory use, standard methods, or widespread adoption across the food chemistry community. The FDA Foods Program specifically prioritizes methods that have undergone multi-laboratory validation where feasible, recognizing their superior reliability for regulatory applications [17].

Successful multi-laboratory collaborations require careful planning and coordination to overcome significant logistical hurdles, including sample transportation, standardized protocols, and harmonized data management across participating sites [19]. These challenges can be addressed through robust project management and clear communication channels, as demonstrated by large-scale collaborative initiatives like The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) Project and the Global Alliance for Genomics and Health (GA4GH) [19].

Experimental Protocol

Step 1: Trial Design and Organization

- Select 8-12 qualified laboratories representing different geographical regions and equipment types.

- Establish a steering committee with representatives from participating laboratories.

- Develop a comprehensive trial protocol including detailed method instructions, data reporting forms, and statistical analysis plan.

- Prepare homogeneous, stable test samples with independently established analyte concentrations.

Step 2: Sample Distribution and Analysis

- Distribute blinded samples to all participants in randomized order.

- Include duplicates at different concentration levels and blank samples to assess specificity.

- Implement a realistic timeline that allows all laboratories to perform analyses under typical working conditions without excessive time pressure.

Step 3: Data Collection and Statistical Analysis

- Collect raw data and calculated results from all participants using standardized reporting formats.

- Apply Cochran and Grubbs tests to identify statistical outliers before calculating method performance parameters.

- Calculate method performance characteristics according to internationally recognized standards (e.g., AOAC, ISO):

Table 2: Statistical Parameters for Multi-Laboratory Collaborative Trials

| Parameter | Calculation Method | Acceptance Criteria |

|---|---|---|

| Repeatability Standard Deviation (S_r) | Standard deviation of results within each laboratory | CVr < 1/2 CVR |

| Reproducibility Standard Deviation (S_R) | Standard deviation of results between laboratories | Method and matrix dependent |

| Repeatability Relative Standard Deviation (RSD_r) | (S_r / overall mean) × 100 | Compared to Horwitz equation prediction |

| Reproducibility Relative Standard Deviation (RSD_R) | (S_R / overall mean) × 100 | HorRat value 0.5-2.0 |

| Method Bias | Difference between overall mean and reference value | < 2 S_R |

Step 4: Documentation and Method Approval

- Prepare a comprehensive collaborative study report including participant laboratories, materials used, individual results, statistical analysis, and conclusions.

- Submit the method and validation data to appropriate standards organizations (e.g., AOAC INTERNATIONAL, ISO) for approval as a standard method.

- Publish results in peer-reviewed literature to facilitate method adoption.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials for Validation Studies

| Reagent/Material | Function in Validation | Critical Quality Attributes |

|---|---|---|

| Certified Reference Materials | Establish accuracy and traceability; used in trueness studies [18] | Certified purity with documented uncertainty; stability appropriate for study duration |

| High-Purity Analytical Standards | Prepare calibration curves; determine linearity and range [18] | Purity ≥ 95%; verified identity and purity; appropriate stability |

| Matrix-Matched Materials | Evaluate specificity and assess matrix effects [2] | Representative of actual samples; demonstrated commutability |

| Stable Isotope-Labeled Internal Standards | Correct for recovery variations in mass spectrometry-based methods | Isotopic purity; chemical stability; co-elution with target analytes |

| Quality Control Materials | Monitor precision over time; establish statistical control [18] | Homogeneous; stable; concentrations at critical decision levels |

The tiered approach to method validation—progressing from single-laboratory verification through intermediate collaboration to full multi-laboratory trials—provides a scientifically sound framework for establishing the reliability of analytical methods in food chemistry research. Each tier serves distinct purposes and provides different levels of evidence, with the appropriate choice depending on the method's intended application and regulatory requirements. The modernized ICH Q2(R2) and Q14 guidelines emphasize a science- and risk-based approach to validation, encouraging researchers to consider the entire method lifecycle from development through post-approval changes [2]. By implementing these structured validation protocols, researchers and drug development professionals can generate high-quality, reliable data that meets both scientific and regulatory standards, ultimately contributing to improved food safety and public health protection.

The Integral Role of Measurement Uncertainty in Food Analysis

In the field of food chemistry, the reliability of analytical data is paramount for ensuring food safety, quality, and regulatory compliance. Measurement uncertainty (MU) is a fundamental metrological parameter that quantifies the doubt associated with an analytical result. According to the Codex Alimentarius Commission, MU is defined as a "parameter associated with the result of a measurement that characterizes the dispersion of the values that could reasonably be attributed to the measurand" [20]. In practical terms, it provides a range within which the true value of a measured quantity is expected to lie with a defined level of confidence.

The importance of MU has been increasingly recognized in food analysis, with some experts considering a result useless or invalid unless accompanied by an uncertainty statement [21]. For instance, in chromatographic analysis of contaminants like aflatoxin B1 in nuts, results of 3.0 ± 0.5 ppb and 2.7 ± 0.4 ppb from different laboratories can be statistically compared for compatibility, whereas results without uncertainty statements provide no information on their comparability [21]. Similarly, in anti-doping laboratories, decision limits for banned substances must incorporate measurement uncertainty to make legally defensible determinations [21].

This article explores the integral role of measurement uncertainty within the broader context of validation protocols for analytical methods in food chemistry research, providing detailed guidance on estimation approaches and practical applications for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals.

Theoretical Foundations and Regulatory Framework

The Relationship Between Method Validation and Measurement Uncertainty

Method validation and measurement uncertainty estimation are interdependent processes in analytical chemistry. Method validation generates performance data that can be directly utilized for uncertainty estimation, creating a circular relationship where validation provides input for uncertainty quantification, which in turn confirms the method's fitness for purpose [21] [22].

The fitness for purpose of an analytical method is demonstrated through proper validation, which assesses performance characteristics including accuracy, precision, specificity, detection limits, and robustness [23]. The recently updated Eurachem Guide "The Fitness for Purpose of Analytical Methods" (2025) emphasizes that sampling and sample handling must be considered as part of the measurement process when estimating uncertainty, reflecting requirements in ISO/IEC 17025:2017 [24] [25].

International standards now explicitly require uncertainty estimation. ISO 17025 mandates that accredited laboratories determine measurement uncertainty when it is relevant to the validity of results or when required by the customer [20]. The Codex Alimentarius Commission has recently unveiled updated guidelines on measurement uncertainty to enhance consistency and readability, incorporating new scientific developments [20].

Key Guidelines and Standards for Measurement Uncertainty

| Guideline/Standard | Issuing Body | Key Focus Areas | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Codex Guideline on Measurement Uncertainty | Codex Alimentarius Commission | Standardized approach for food safety applications | [20] |

| The Fitness for Purpose of Analytical Methods (3rd ed., 2025) | Eurachem | Method validation and uncertainty estimation | [24] [25] |

| SANTE Guideline | European Commission | Pesticide residue analysis in food | [26] |

| ISO/IEC 17025:2017 | International Organization for Standardization | General requirements for laboratory competence | [20] |

| ICH Q2(R1) | International Council for Harmonisation | Validation of analytical procedures (pharmaceuticals) | [23] |

Approaches to Estimating Measurement Uncertainty

The Bottom-Up and Top-Down Approaches

Two primary approaches exist for estimating measurement uncertainty in food analysis: the bottom-up (component-by-component) approach and the top-down (global) approach.

The bottom-up approach, also known as the error-budget approach, involves identifying, quantifying, and combining all individual sources of uncertainty [21]. This method uses cause-and-effect diagrams to structure the list of uncertainty sources, covering aspects such as sampling, sample preparation, instrumental analysis, and calibration [21]. While comprehensive, this approach can be complex and time-consuming when many sources of variability exist.

The top-down approach utilizes data generated during method validation studies, internal quality control procedures, and proficiency testing schemes to estimate uncertainty globally [21]. This approach is generally more practical for testing laboratories as it leverages existing data and reflects the overall method performance under realistic conditions. The main disadvantage is that it provides limited information on individual sources of variability, making it difficult to identify specific areas for method improvement [21].

Practical Implementation Using the Top-Down Approach

A typical top-down approach to uncertainty estimation combines precision and trueness data from method validation. The expanded uncertainty (U) can be calculated using the formula:

U = k × c × √(u²rel,proc + u²rel,trueness + u²rel,pret + u²rel,other)

Where:

- k is the coverage factor (typically 2 for 95% confidence)

- c is the measured concentration

- u_rel,proc is the relative uncertainty of the analytical procedure

- u_rel,trueness is the relative uncertainty of trueness assessment

- u_rel,pret is the relative uncertainty from pre-treatment steps

- u_rel,other covers other uncertainty sources [21]

The uncertainty of the analytical procedure (u_rel,proc) typically represents the method's intermediate precision, obtained under within-laboratory reproducibility conditions varying factors like day, operator, and instrument [21]. For methods applied across wide concentration ranges, precision should be determined at multiple levels (low, medium, high), with relative standard deviations pooled if precision is proportional to concentration [21].

The uncertainty of trueness (u_rel,trueness) accounts for potential method bias, ideally assessed using certified reference materials (CRMs) when available [21]. When CRMs are unavailable—a common situation in food analysis—trueness is typically evaluated through recovery studies using spiked samples [21]. If the recovery does not differ significantly from 100%, its uncertainty can be calculated as:

u_rel,trueness = √(RSD₂² + (1-R)²/n)

Where R is the mean recovery and RSDR is the relative standard deviation of recovery [21].

Experimental Protocols for Uncertainty Estimation

Protocol for Pesticide Residue Analysis in Food Matrices

The following detailed protocol outlines the procedure for validating an analytical method and estimating measurement uncertainty for pesticide residues in food matrices, based on recent studies in tomatoes and okra [26] [22].

Materials and Reagents:

- Pesticide reference standards of high purity (>95%)

- HPLC-grade acetonitrile, methanol, formic acid, ammonium formate

- Anhydrous magnesium sulfate (MgSO₄) and sodium chloride (NaCl) for extraction

- Primary secondary amine (PSA) and other sorbents for clean-up

- Appropriate food matrix (tomato, okra, etc.) free from target pesticides

Equipment:

- Liquid chromatography system coupled to tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) or gas chromatography system (GC) with appropriate detector

- Centrifuge capable of at least 5000 rpm

- Vortex mixer

- Analytical balance with calibration traceable to national standards

- pH meter

Sample Preparation and Extraction (QuEChERS Method):

- Homogenize representative food sample using a food processor

- Weigh 10.0 ± 0.1 g of homogenized sample into a 50-mL centrifuge tube

- Add 10 mL of acetonitrile (with 1% acetic acid for acidic pesticides)

- Vortex vigorously for 1-2 minutes to ensure proper mixing

- Add extraction salt mixture (4 g MgSO₄, 1 g NaCl, 1 g sodium citrate, 0.5 g disodium hydrogen citrate)

- Shake immediately and vigorously for 1 minute

- Centrifuge at ≥5000 rpm for 5 minutes

- Transfer 1 mL of upper acetonitrile layer to a d-SPE tube containing 150 mg PSA and 900 mg MgSO₄

- Vortex for 30 seconds and centrifuge at 4000 rpm for 2 minutes

- Dilute the final extract with water in a 1:3 ratio before instrumental analysis [26]

LC-MS/MS Analysis:

- Separate pesticides using a reversed-phase C18 column (e.g., Poroshell 120 EC-C18, 3.0 × 50 mm, 2.7 μm)

- Use gradient elution with mobile phase A (0.1% formic acid and 5 mM ammonium formate in water) and mobile phase B (0.1% formic acid and 5 mM ammonium formate in methanol)

- Set flow rate to 0.5 mL/min and column temperature to 40°C

- Use positive electrospray ionization (ESI+) with multiple reaction monitoring (MRM)

- Optimize mass parameters for each pesticide (precursor ion, product ions, fragmentor voltage, collision energy) [26]

Method Validation and Uncertainty Estimation:

- Establish calibration curves with at least five concentration levels in solvent and matrix-matched solutions

- Determine specificity by analyzing blank samples to check for interferences at retention times of target pesticides

- Assess precision (repeatability and within-laboratory reproducibility) through replicate analyses (n ≥ 6) at multiple concentration levels

- Evaluate accuracy/trueness through recovery studies at multiple fortification levels (e.g., 0.01, 0.05, 0.10 mg/kg) with n ≥ 5 replicates per level

- Determine limit of detection (LOD) and limit of quantification (LOQ) based on signal-to-noise ratios of 3:1 and 10:1, respectively

- Estimate measurement uncertainty using a top-down approach based on validation data, particularly precision and recovery data [26] [22]

Research Reagent Solutions for Food Analysis

| Reagent/Material | Function in Analysis | Application Example | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Secondary Amine (PSA) | Removes fatty acids, sugars, and other polar organic acids from extracts | Clean-up in QuEChERS method for pesticide residues | [26] [22] |

| Anhydrous MgSO₄ | Removes residual water from organic extracts through binding | Phase separation in QuEChERS extraction | [26] [22] |

| C18 Sorbent | Removes non-polar interferences like lipids and sterols | Clean-up for fatty food matrices | [26] |

| Graphitized Carbon Black (GCB) | Removes pigments (chlorophyll, carotenoids) and sterols | Clean-up for green vegetables and pigmented foods | [26] |

| Certified Reference Materials (CRMs) | Provides traceable matrix-matched reference values | Quality control and trueness assessment | [21] |

Data Analysis and Interpretation

Performance Characteristics in Method Validation

Table 3 summarizes typical performance characteristics for analytical methods in food chemistry, based on validation studies for pesticide residues in food matrices [26] [22].

Table 3: Typical Method Performance Characteristics for Food Analysis

| Performance Characteristic | Acceptance Criteria | Experimental Approach | Role in MU Estimation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Accuracy/Trueness | Recovery 70-120% (for pesticides at LOQ) | Analysis of spiked samples or CRMs | Provides bias component for MU |

| Precision | RSD ≤ 20% (for pesticides at LOQ) | Replicate analyses under intermediate precision conditions | Major contributor to MU budget |

| Linearity | r² ≥ 0.99 | Calibration curves at 5+ concentration levels | Affects uncertainty at different concentrations |

| Limit of Quantification (LOQ) | S/N ≥ 10; recovery and precision acceptable at this level | Analysis of progressively diluted standards | Defines lower limit for reliable quantification |

| Specificity | No interference ≥ 20% of LOQ | Analysis of blank samples and potentially interfering compounds | Contributes to uncertainty if not adequately addressed |

| Matrix Effect | ±20% suppression/enhancement | Comparison of solvent and matrix-matched calibration slopes | Significant contributor to MU in LC-MS/MS |

Case Study: Uncertainty Estimation in Pesticide Residue Analysis

A 2024 study on pesticide residues in tomatoes provides a practical example of measurement uncertainty estimation [26]. The researchers validated an LC-MS/MS method for 26 different pesticides belonging to various chemical classes. The method demonstrated excellent linearity (r² > 0.99), acceptable matrix effects (within ±20%), and satisfactory recovery (>70% with RSD <20% at 5 μg/kg for most compounds) [26].

Measurement uncertainties were estimated using a top-down approach based on the validation data, with all values falling below the default limit of 50% [26]. The study applied the validated method to 52 tomato samples from local markets, finding that only four pesticides were detected, all below the maximum residue limits established by the Codex Alimentarius Commission and national regulations [26].

Similarly, a 2025 study on pesticide residues in okra validated methods for thiamethoxam, ethion, and lambda-cyhalothrin [22]. The method validation demonstrated linearity (r² > 0.99), minimal matrix effects (±20%), and recoveries >70% with RSD <20% at the LOQ of 0.30 mg/kg [22]. Measurement uncertainties based on these validation data were also below the 50% default limit, confirming the method's suitability for monitoring these pesticides in okra [22].

Measurement uncertainty is an integral component of analytical quality assurance in food chemistry, providing crucial information about the reliability of results used for food safety decisions, regulatory compliance, and quality control. As international standards and guidelines continue to evolve, the estimation of measurement uncertainty has become an essential requirement for analytical laboratories.

The top-down approach to uncertainty estimation, utilizing data generated during method validation, provides a practical and efficient means of quantifying measurement reliability. By integrating uncertainty estimation into routine analytical practice, food chemists can provide more meaningful results that support informed decision-making in food safety and quality management. As the field advances, continued harmonization of approaches and increased adoption of uncertainty estimation across all sectors of food analysis will further enhance the reliability and global comparability of food analytical data.

Applied Validation Protocols: From Contaminant Analysis to Foodomics

In food chemistry research, the reliability of data pertaining to contaminant analysis is paramount for ensuring public health and regulatory compliance. The process of analytical method validation provides the evidence that a method is fit for its intended purpose, delivering results with defined levels of accuracy and reliability [2]. Within the context of a broader thesis on validation protocols, this document outlines detailed application notes and experimental protocols for validating chemical methods targeting three critical classes of food contaminants: mycotoxins, pesticides, and heavy metals. The guidance is structured around international harmonized principles, notably the ICH Q2(R2) guideline, which describes a science- and risk-based approach to validation, transitioning from a one-time event to a continuous lifecycle management process [2].

Regulatory Framework and Core Validation Parameters

The International Council for Harmonisation (ICH) guidelines, particularly ICH Q2(R2) on the validation of analytical procedures and ICH Q14 on analytical procedure development, provide the foundational framework for method validation [2]. These guidelines, adopted by regulatory bodies like the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA), promote global consistency. The core validation parameters, as defined by ICH Q2(R2), must be evaluated to demonstrate a method is fit-for-purpose.

- Accuracy: The closeness of agreement between the measured value and a true or accepted reference value. It is typically assessed by spiking a blank matrix with known analyte concentrations and determining recovery percentages [2].

- Precision: The degree of agreement among individual test results when the method is applied repeatedly to multiple samplings of a homogeneous sample. This includes repeatability (intra-assay) and intermediate precision (inter-day, inter-analyst) [2].

- Specificity: The ability to unequivocally assess the analyte in the presence of other components, such as impurities, degradation products, or matrix components, that are expected to be present [2].

- Linearity and Range: The linearity of an analytical procedure is its ability to elicit test results that are directly proportional to analyte concentration. The range is the interval between the upper and lower concentrations for which linearity, accuracy, and precision have been demonstrated [2].

- Limit of Detection (LOD) and Limit of Quantitation (LOQ): The LOD is the lowest amount of analyte that can be detected, but not necessarily quantified. The LOQ is the lowest amount that can be quantified with acceptable accuracy and precision [2].

- Robustness: A measure of the method's capacity to remain unaffected by small, deliberate variations in method parameters (e.g., pH, mobile phase composition, temperature) and provides an indication of its reliability during normal usage [2].

The following workflow outlines the strategic process for developing and validating an analytical method, from defining its purpose to ongoing lifecycle management.

Contaminant-Specific Analytical Methods and Validation Data

The complexity of food matrices necessitates tailored analytical approaches for different contaminant classes. The table below summarizes key analytical techniques and reported validation data for mycotoxins, pesticides, and heavy metals from recent studies.