Validation of Rapid Methods vs. Reference Techniques: A Strategic Guide for Drug Development

This article provides a comprehensive framework for researchers and scientists in drug development to validate rapid analytical methods against traditional reference techniques.

Validation of Rapid Methods vs. Reference Techniques: A Strategic Guide for Drug Development

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive framework for researchers and scientists in drug development to validate rapid analytical methods against traditional reference techniques. It covers the foundational principles of analytical validation, explores a spectrum of rapid methodologies from nucleic-acid based assays to biosensors, and addresses common troubleshooting and optimization challenges. A core focus is placed on the strategic, step-by-step process for conducting rigorous comparative studies, ensuring that new methods meet regulatory standards for accuracy, precision, and reliability to accelerate timelines without compromising quality.

The Critical Need for Speed: Why Rapid Method Validation is Essential in Modern Pharma

In the pharmaceutical industry, compendial methods—those detailed in official compendia such as the United States Pharmacopeia (USP)—have long been the gold standard for quality control testing. These methods, which include traditional culture-based techniques for microbiological quality control, provide the legal standards for assessing pharmaceutical products according to Section 501 of the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act [1]. However, the evolving demands of modern drug development and manufacturing are increasingly exposing significant limitations in these traditional approaches. This guide objectively compares the performance of traditional compendial methods with emerging rapid microbiological methods (RMMs), focusing on the critical constraints of time, labor, and analytical sensitivity. The validation of these rapid methods against established compendial standards, guided by frameworks such as USP <1223>, ensures their reliability and suitability for intended use while addressing the pressing needs of contemporary pharmaceutical quality control [2].

Experimental Protocols for Comparative Evaluation

Protocol 1: Water System Monitoring for Microbial Contamination

This protocol compares the traditional heterotrophic plate count method with an ATP bioluminescence-based rapid method for monitoring microbial quality in pharmaceutical water systems [3].

- Sample Collection: Water samples are aseptically collected from various points in the water production and distribution loops.

- Traditional Compendial Method (Heterotrophic Plate Count): Each sample is filtered through a 0.45µm membrane. The membrane is placed onto R2A agar in duplicate and incubated at 30°C for 5 days. After incubation, developed colonies are counted manually [3].

- Rapid Method (ATP Bioluminescence - Pallchek System): The sample is filtered, and the membrane is placed in a test plate. For direct measurement, reagents are added to lyse microbial cells and release intracellular ATP. A luciferin-luciferase enzyme reagent is then added, producing light measured as Relative Light Units (RLU) by a luminometer. For a lower detection limit, an indirect method incorporates an enrichment step where the filtered sample is incubated in liquid culture media for 24 hours before ATP measurement [3].

- Data Analysis: Results from the rapid method (available in minutes or 24 hours) are compared against the 5-day plate count for equivalence, determining correlation factors between RLU and colony-forming units (cfu).

Protocol 2: Rapid GC-MS Screening for Seized Drugs

This protocol, while from a forensic context, illustrates the principles of method acceleration and was validated according to rigorous standards [4].

- Sample Preparation: Solid samples are ground and extracted with methanol via sonication and centrifugation. Trace samples are collected with methanol-moistened swabs, which are then vortexed in methanol for extraction [4].

- Conventional GC-MS Method: The extract is analyzed using a 30-m DB-5 ms column with a temperature program that results in a total run time of approximately 30 minutes [4].

- Rapid GC-MS Method: The same sample extract is analyzed using an optimized method on the same instrument type. The method employs a drastically accelerated temperature ramp and adjusted carrier gas flow, reducing the total analysis time to 10 minutes [4].

- Validation and Comparison: The rapid method is validated for parameters including detection limit, repeatability, reproducibility, and carryover. Its performance is directly compared to the conventional method using the same set of samples, and the results are confirmed with mass spectral library matching [4].

Comparative Performance Data: Traditional vs. Rapid Methods

Table 1: Quantitative Comparison of Method Performance Characteristics

| Performance Characteristic | Traditional Heterotrophic Plate Count (Water) | Rapid ATP Bioluminescence (Direct) | Rapid ATP Bioluminescence (Indirect) | Conventional GC-MS (Drugs) | Rapid GC-MS (Drugs) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Time to Result | 5 days [3] | ~1 minute [3] | ~24 hours [3] | ~30 minutes [4] | ~10 minutes [4] |

| Detection Limit | 1 cfu/sample (theoretical) | 100-1000 cfu [3] | 1 cfu [3] | Cocaine: 2.5 µg/mL [4] | Cocaine: 1.0 µg/mL [4] |

| Labor Intensity | High (manual plating, counting) | Low (automated reading) | Moderate (enrichment handling) | High (long run times) | Low (fast run times) |

| Sensitivity to Stressed Cells | Poor (may not grow) [3] | Good (detects cellular ATP) | Excellent (after growth) | N/A | N/A |

| Precision (Repeatability) | Dependent on analyst skill | RSD < 0.25% for stable compounds [4] | RSD < 0.25% for stable compounds [4] | Dependent on method | Excellent (RSD < 0.25%) [4] |

Table 2: Impact on Operational and Decision-Making Processes

| Operational Aspect | Impact of Traditional Methods | Impact of Rapid Methods |

|---|---|---|

| Corrective Action Delay | Up to 5 days for water OOS results, risking underestimation of contamination and ineffective action [3] | Same-day or real-time results enable immediate corrective actions [3] |

| Process Monitoring | Retrospective analysis only | Near real-time data allows for proactive process control and adjustment (PAT) [3] |

| Laboratory Efficiency | Low throughput; analyst time consumed by manual tasks [3] | High throughput; automation frees analyst time for other tasks [2] |

| Inventory Management | Finished products held until microbiological results are available | Potential for significantly reduced quarantine times for finished products [2] |

Visualizing the Method Workflows

Traditional vs. Rapid Microbial Method Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details key reagents, materials, and instruments critical for implementing the rapid methods discussed in this guide.

Table 3: Key Reagents and Instruments for Rapid Method Implementation

| Item | Function/Description | Application in Featured Experiments |

|---|---|---|

| ATP Bioluminescence Reagents | Cell lysis reagent releases intracellular ATP; luciferin-luciferase enzyme produces light proportional to ATP concentration [3]. | Used in the Pallchek Rapid Microbiology System for rapid detection of microbial contamination in water samples [3]. |

| R2A Agar | Low-nutrient culture medium designed to support the growth of stressed and chlorine-injured microorganisms commonly found in water systems. | The standard medium used in the traditional heterotrophic plate count method for water system monitoring [3]. |

| DB-5 ms GC Column (30 m × 0.25 mm × 0.25 µm) | A (5%-phenyl)-methylpolysiloxane capillary column widely used for the separation of semi-volatile organic compounds. | Used in both the conventional and optimized rapid GC-MS methods for drug screening, enabling the accelerated analysis [4]. |

| Reference Standards & Materials | Analyte samples of known purity and concentration, crucial for method calibration, qualification, and ensuring accuracy [1] [5]. | Used in USP compendial assays and for establishing correlation curves (e.g., RLU vs. cfu, RLU vs. ATP) during RMM validation [3] [1]. |

| High-Sensitivity Luminometer | Instrument containing a photomultiplier tube to detect and amplify photon signals, converting them to Relative Light Units (RLU) [3]. | Core component of the Pallchek system for measuring the bioluminescence signal generated by the ATP reaction [3]. |

The limitations of traditional compendial methods in time, labor, and sensitivity are no longer theoretical concerns but demonstrable realities that impact pharmaceutical quality control and operational efficiency. As the presented experimental data and workflows illustrate, rapid methods such as ATP bioluminescence and accelerated GC-MS offer transformative advantages. They provide critical quality results in minutes or hours instead of days, reduce manual labor through automation, and can offer superior or equivalent analytical performance. The robust validation frameworks established by USP <1223> and other regulatory guidelines provide the necessary pathway for laboratories to confidently adopt these technologies. For researchers and drug development professionals, the objective evidence strongly supports the integration of validated rapid methods as a means to enhance product safety, streamline manufacturing processes, and advance modern quality control paradigms.

In the competitive and highly regulated field of drug development, the adoption of Rapid Microbiological Methods (RMMs) represents a significant shift from traditional, culture-based techniques. This guide objectively compares these rapid methods against reference analytical techniques, framing the discussion within the critical context of method validation as required by leading regulatory bodies such as the United States Pharmacopeia (USP) and the European Pharmacopoeia (Ph. Eur.) [6].

Core Principles of Rapid Methods

Rapid Methods are defined by their ability to provide faster detection, quantification, or identification of microorganisms compared to traditional plate-based or culture methods, which can take days or weeks to yield results [6]. The core principles that underpin their drive for efficiency include:

- Speed and Timeliness: Delivering results in hours rather than days, enabling faster decision-making and product release [6].

- Automation and Efficiency: Utilizing technologies that reduce manual intervention and streamline workflows [6].

- Accuracy and Precision: Ensuring results are both correct and reproducible [6].

- Robustness and Reliability: Performing consistently under varied but realistic operating conditions [6].

These principles are operationalized through a rigorous validation process, which is paramount to ensuring that RMMs are not just faster, but also equivalent or superior in performance to the compendial methods they are intended to replace [6].

Comparative Analysis: RMMs vs. Traditional Methods

The following table summarizes a quantitative comparison of key performance indicators between Rapid Microbiological Methods and traditional, culture-based techniques.

| Performance Indicator | Rapid Microbiological Methods (RMMs) | Traditional Culture-Based Methods |

|---|---|---|

| Time to Result | Hours to a maximum of 2-3 days [6] | 5 to 7 days, or longer for slow-growing organisms [6] |

| Level of Automation | High (e.g., automated detection systems) [6] | Low (primarily manual processes) |

| Potential for Real-Time Data | Yes (e.g., ATP bioluminescence) [6] | No |

| Key Validation Parameter: Accuracy | Measured against known concentrations of microorganisms; must demonstrate equivalence to compendial method [6] | Established as the reference standard |

| Key Validation Parameter: Precision | Evaluates reproducibility (repeatability & intermediate precision) [6] | Inherently variable due to manual techniques |

| Key Validation Parameter: Specificity | Must detect target organisms without matrix interference [6] | Generally high, but can be affected by sample matrix |

Experimental Protocols for Validation

For a rapid method to be accepted for use in a regulated environment like pharmaceutical manufacturing, it must undergo a formal validation. The following workflow, based on USP <1223> and Ph. Eur. 5.1.6 guidelines, details the key phases and activities in this process [6].

Detailed Methodology of Key Experiments

The validation parameters listed in Phase 3 are assessed through specific experimental protocols:

- Accuracy: The RMM is used to test samples spiked with a known concentration of a specific microorganism (e.g., E. coli). The results are compared to the true value and the result from the compendial method. The percentage recovery is calculated to demonstrate closeness to the true value [6].

- Precision: The same homogeneous sample is tested multiple times under identical conditions (repeatability) and by different analysts or on different days using the same instrument (intermediate precision). The standard deviation and coefficient of variation of the results are calculated to confirm reproducibility [6].

- Specificity and Matrix Interference: The product sample (e.g., a cream or solution) is spiked with a low level of a target organism. The RMM's ability to detect the organism in the presence of the product matrix is compared to its detection in a neutral control. This demonstrates that the product does not cause inhibitory (false negative) or enhancing (false positive) effects [6].

- Limit of Detection (LOD) and Quantification (LOQ): Samples are spiked with serial dilutions of a microorganism to determine the lowest level that can be reliably detected (LOD) and the lowest level that can be quantified with acceptable precision and accuracy (LOQ) [6].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

The successful validation and implementation of an RMM rely on a set of essential materials and reagents.

| Item | Function in Validation |

|---|---|

| Reference Microorganism Strains | Certified cultures used to spike samples for accuracy, precision, and LOD/LOQ studies. They provide a known, standardized baseline for all tests [6]. |

| Product-Specific Matrix | The actual drug product or a placebo used to conduct interference studies. It is critical for proving the method works in the real sample, not just in ideal lab conditions [6]. |

| Compendial Method Materials | The components of the traditional method (e.g., agar plates, broths, membrane filters) used for parallel testing to demonstrate equivalency [6]. |

| Calibration Standards | For quantitative RMMs, these standards are used to ensure the instrument's readings are accurate across the intended measurement range [6]. |

| Neutralizing Agents | Used in sample preparation to inactivate antimicrobial properties of the product, ensuring any microorganisms present can be detected by the RMM [6]. |

The drive for efficiency in drug development, fueled by the need for faster product release and enhanced contamination control, makes Rapid Microbiological Methods an indispensable tool. The foundational principle, however, remains that speed must not come at the cost of reliability. A rigorous, structured validation framework—as outlined in USP <1223> and Ph. Eur. 5.1.6—ensures that these rapid methods provide accurate, precise, and defensible data. For researchers and scientists, mastering this validation process is not just a regulatory hurdle but a critical competency that enables the adoption of innovative technologies, ultimately contributing to a more agile and quality-focused pharmaceutical industry [6].

In the pharmaceutical sciences, the validation of analytical methods is a critical prerequisite for ensuring the quality, safety, and efficacy of drug substances and products. This process provides documented evidence that an analytical procedure is suitable for its intended use [7]. Within the broader research context of comparing rapid microbiological and analytical methods against traditional reference techniques, the evaluation of key performance parameters becomes paramount [6] [8]. Regulatory guidelines from the International Council for Harmonisation (ICH), United States Pharmacopeia (USP), and other bodies mandate the assessment of specific characteristics to demonstrate method reliability [9] [7].

This guide focuses on four fundamental validation parameters—Accuracy, Precision, Specificity, and Robustness—objectively comparing their performance in rapid methods versus compendial reference techniques. The shift towards rapid methods, such as those for sterility testing or pesticide residue analysis, is driven by the need for faster results, improved efficiency, and enhanced contamination control [6] [10] [11]. However, these innovative methods must undergo rigorous validation to prove they are at least equivalent to, or superior than, established traditional methods before they can be adopted for product release decisions [6] [8].

Defining the Key Parameters

Accuracy

Accuracy measures the closeness of agreement between the value found by the analytical method and the true value or an accepted reference value [9] [7] [12]. It is typically expressed as the percentage recovery of a known amount of analyte spiked into the sample matrix [9] [7]. For instance, in the validation of a method for pesticide residues in okra, accuracy was demonstrated by spiking samples with known concentrations of pesticides and achieving average recoveries of more than 70%, which fell within acceptable validation criteria [10].

Precision

Precision describes the closeness of agreement between a series of measurements obtained from multiple sampling of the same homogeneous sample under the prescribed conditions [7]. It is usually expressed as standard deviation or relative standard deviation (RSD) and is considered at three levels:

- Repeatability: Precision under the same operating conditions over a short interval of time (e.g., same analyst, same equipment) [13] [7].

- Intermediate Precision (Ruggedness): Precision within the same laboratory but with variations like different days, different analysts, or different equipment [7].

- Reproducibility: Precision between different laboratories, often assessed in collaborative studies [7].

It is crucial to remember that a method can be precise without being accurate, for example, if consistent results are obtained but are all biased away from the true value due to a systematic error [13] [12] [14].

Specificity

Specificity is the ability of the method to assess the analyte unequivocally in the presence of other components that may be expected to be present in the sample matrix, such as impurities, degradation products, or excipients [6] [7]. For chromatographic methods, this is often demonstrated by showing that the analyte peak is well-resolved from other peaks and that the response is not interfered with by the blank matrix [10]. In microbiological methods like sterility testing, specificity is demonstrated through the method's ability to detect a range of relevant microorganisms in the presence of the product [6] [11].

Robustness

Robustness evaluates the capacity of a method to remain unaffected by small, deliberate variations in method parameters, such as temperature, pH, mobile phase composition, or reagent concentration [6] [7]. A robust method is reliable during normal usage and is less likely to fail when transferred between laboratories or when minor operational fluctuations occur [6].

Comparative Experimental Data: Rapid Methods vs. Reference Techniques

The following tables summarize experimental data from published studies comparing rapid methods with traditional reference techniques across different application fields.

Table 1: Comparison of Sterility Testing Methods [11]

| Parameter | Pharmacopoeial Sterility Test (Reference) | BacT/Alert 3D System (Rapid Method) |

|---|---|---|

| Principle | Turbidity (visual inspection) | Colorimetric CO₂ detection (automated) |

| Incubation Time | 14 days | ≤ 7 days (most detections in 1-3 days) |

| Culture Media | FTM and SCDM | SA, SN, FA, FN, iAST, iNST, iLYM |

| Specificity (Ability to detect challenge microorganisms) | Detected all challenge microorganisms | Equivalent detection of all challenge microorganisms with no significant difference |

| Key Advantage | Compendial standard; well-established | Rapid detection; automated monitoring; reduced labor |

Table 2: Comparison of Analytical Methods for Pesticide Residues in Okra [10]

| Parameter | Traditional Validation (Reference Expectations) | Validated Rapid HPLC/GC Method with QuEChERS |

|---|---|---|

| Analytical Technique | Various | HPLC/GC |

| Sample Preparation | Varies, often complex | Modified QuEChERS (rapid, simple) |

| Linearity (r²) | > 0.99 | > 0.99 for all three pesticides |

| Accuracy (Average Recovery) | Acceptable range (e.g., 70-120%) | > 70% at 0.30 mg/kg |

| Precision (RSD) | < 20% | < 20% |

| Matrix Effect | Should be minimal | Within ±20% |

Table 3: General Comparison of Method Validation vs. Verification [8]

| Comparison Factor | Method Validation (for new methods) | Method Verification (for compendial methods) |

|---|---|---|

| Scope | Comprehensive, all parameters assessed | Limited, focused on critical parameters |

| Accuracy & Precision | Fully characterized and documented | Confirmed for the lab's specific conditions |

| Specificity | Demonstrated for analyte in matrix | Typically inferred from validation data |

| Robustness | Often evaluated | Not typically re-evaluated |

| Regulatory Suitability | Required for new drug applications | Acceptable for standard methods |

| Implementation Time | Weeks or months | Days |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol for Validating a Rapid Microbiological Method (RMM)

This protocol aligns with the requirements of USP <1223> and Ph. Eur. 5.1.6 for demonstrating equivalency to a compendial sterility test [6] [11].

- Define Purpose and Scope: Clearly state the intended use of the RMM, e.g., for sterility testing of an injectable product.

- Method Equivalency Study:

- Sample Inoculation: Use a statistically appropriate number of test samples. Artificially contaminate some samples with a low level (e.g., < 100 CFU) of suitable challenge microorganisms (Staphylococcus aureus, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Bacillus subtilis, Clostridium sporogenes, Candida albicans, Aspergillus brasiliensis).

- Parallel Testing: Test each sample simultaneously using both the RMM (e.g., BacT/Alert culture bottles) and the pharmacopoeial method (FTM and SCDM media).

- Culturing and Detection: Incubate the compendial method for 14 days with visual inspection for turbidity. Incubate the RMM according to the manufacturer's instructions (e.g., in the BacT/Alert 3D system, which monitors continuously for ~7 days).

- Data Collection: Record the time to detection for each positive sample in the RMM and the final positive/negative results for both methods after the full incubation periods.

- Data Analysis: Compare the results using statistical methods (e.g., Chi-square) to demonstrate that there is no statistically significant difference in the ability of the two methods to detect microbial contamination. The RMM should detect the same positives as the reference method, often in a significantly shorter time [11].

Protocol for Assessing Accuracy and Precision in a Chemical Assay

This protocol is based on ICH Q2(R1) guidelines and is applicable for quantifying an active ingredient in a drug product [7].

- Accuracy by Recovery:

- Sample Preparation: Prepare a synthetic mixture of the drug product excipients without the active ingredient (placebo). If this is not possible, use a test sample with a known background level of the analyte.

- Spiking: Spike the placebo or test sample with known amounts of the analyte of known purity at three concentration levels (e.g., 80%, 100%, and 120% of the target test concentration). Prepare each level in triplicate.

- Analysis: Analyze the spiked samples using the complete analytical procedure.

- Calculation: Calculate the recovery (%) for each sample using the formula:

Recovery (%) = (Measured Concentration / Theoretical Concentration) * 100. Report the mean recovery and confidence intervals for each level.

- Precision (Repeatability):

- Analysis: Analyze a minimum of 6 determinations at 100% of the test concentration, or a minimum of 9 determinations covering the reportable range (e.g., 3 concentrations x 3 replicates).

- Calculation: Calculate the standard deviation and relative standard deviation (RSD) for the set of measurements.

Visualization of Validation Workflows and Relationships

Rapid Method Validation Workflow

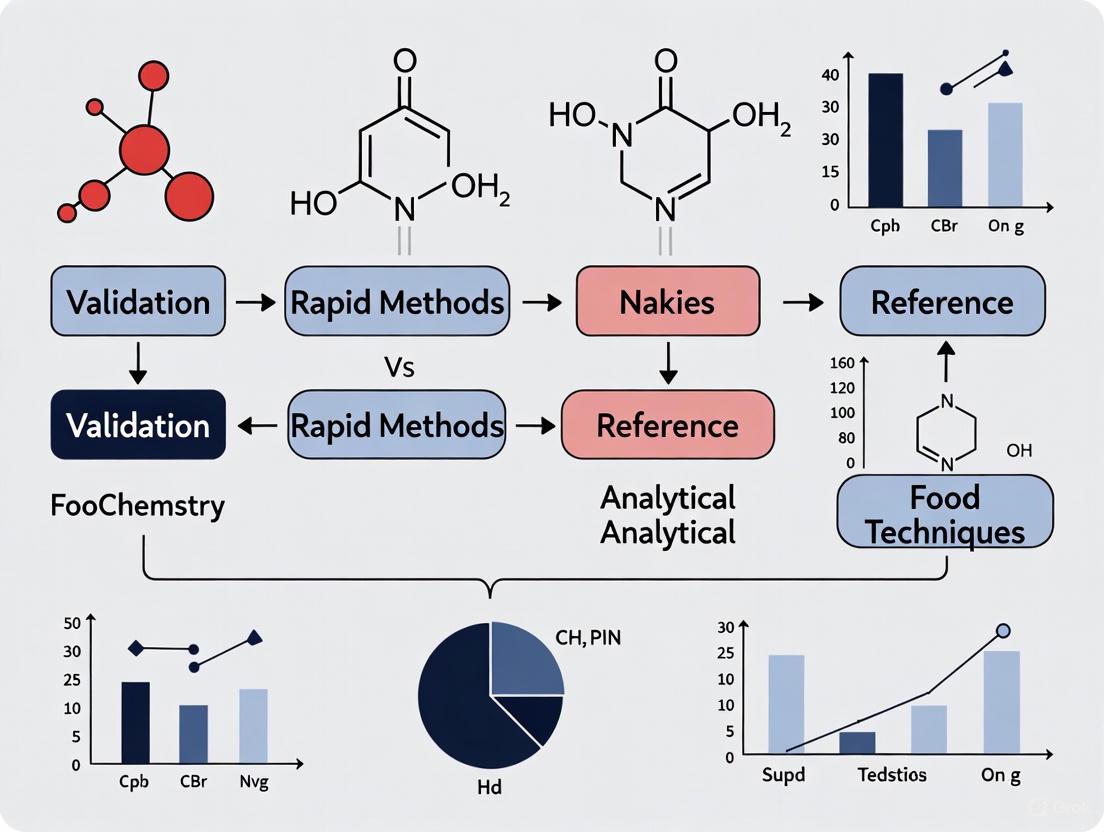

The following diagram illustrates the key stages in validating a rapid method against a reference technique.

Diagram Title: Rapid Method Validation Workflow

Relationship Between Accuracy and Precision

This diagram clarifies the conceptual relationship between accuracy and precision, a fundamental concept in method validation.

Diagram Title: Accuracy and Precision Relationship

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 4: Key Reagents and Materials for Validation Experiments

| Item | Function in Validation | Example Applications |

|---|---|---|

| Reference Standards | Certified materials of known purity and identity used to prepare calibration curves and assess accuracy [9]. | Quantification of drug substance; accuracy recovery studies. |

| Challenge Microorganisms | Defined strains of bacteria, yeast, and mold used to demonstrate that a method can detect specific contaminants [6] [11]. | Specificity and limit of detection studies for sterility tests or environmental monitoring methods. |

| Culture Media | Nutrient formulations designed to support microbial growth. Both compendial (FTM, SCDM) and proprietary (e.g., BacT/Alert SA/SN) media are used [11]. | Growth promotion testing; equivalency studies between rapid and traditional methods. |

| Chromatographic Columns and Phases | The heart of separation techniques (HPLC/GC); different selectivities are used to achieve separation of the analyte from interfering components [10]. | Demonstrating specificity and robustness of chromatographic methods. |

| Sample Preparation Kits | Standardized kits (e.g., QuEChERS) for efficient extraction and clean-up of analytes from complex matrices [10]. | Ensuring accurate and precise results by minimizing matrix effects. |

| Certified Reference Materials (CRMs) | Real-world samples with certified values for one or more properties, used as a benchmark for method validation [9]. | Ultimate test for accuracy when available for a specific matrix and analyte. |

For researchers and drug development professionals, navigating the regulatory ecosystem is fundamental to bringing safe and effective products to market. The landscape is built upon a foundation of Good Manufacturing Practices (GMP), which provide the minimum standards for production and control. These principles are enforced in the United States by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and are harmonized internationally through the efforts of the International Council for Harmonisation (ICH). A core tenet of modern quality systems, as outlined in ICH Q9, is Quality Risk Management (QRM), which provides a systematic approach to assessing, controlling, and communicating risks across the product lifecycle [15]. Simultaneously, the Process Analytical Technology (PAT) initiative encourages the adoption of innovative, real-time monitoring methods to ensure quality control [16]. Together, these frameworks guide the development, validation, and implementation of new analytical techniques, including rapid microbiological methods (RMMs), which offer significant advantages over traditional compendial methods.

Core Regulatory Bodies and Guidelines

Understanding the distinct yet interconnected roles of key regulatory bodies and their guidelines is the first step toward successful compliance and product development.

Table 1: Key Regulatory Bodies and Their Primary Guidelines

| Regulatory Body | Acronym | Primary Focus & Guidelines | Key Concepts |

|---|---|---|---|

| International Council for Harmonisation | ICH | Harmonizes technical requirements for pharmaceuticals across the US, EU, and Japan. Key guidelines include: |

- ICH Q7: GMP for Active Pharmaceutical Ingredients (APIs) [15].

- ICH Q8 (R2): Pharmaceutical Development and Quality by Design (QbD) [15].

- ICH Q9 (R1): Quality Risk Management (QRM) [15]. | Quality by Design (QbD), Quality Risk Management (QRM), Design Space, Critical Quality Attributes (CQAs) | | U.S. Food and Drug Administration | FDA | Ensures the safety and efficacy of drugs in the US market. Key regulations include:

- 21 CFR Parts 210 & 211: cGMP for finished pharmaceuticals [17].

- 21 CFR Part 820: Quality System Regulation for medical devices [17].

- PAT Initiative: A framework for innovative manufacturing and quality assurance [16]. | Current Good Manufacturing Practice (cGMP), Process Analytical Technology (PAT), Data Integrity | | European Medicines Agency | EMA | Oversees medicinal products for the European Union.

- EudraLex Volume 4: The EU's GMP guidelines, including Annex 1 for sterile products [18]. | EU GMP, Advanced Therapy Medicinal Products (ATMPs) |

The Role of ICH Guidelines

The ICH guidelines provide a harmonized, science-based foundation for pharmaceutical quality. ICH Q7 establishes GMP standards specifically for Active Pharmaceutical Ingredients (APIs), mandating an independent Quality Unit and increasing the stringency of controls as the API manufacturing process progresses from early steps to final purification and packaging [15]. ICH Q8 (R2) introduces the concept of Quality by Design (QbD), a systematic approach to development that begins with predefined objectives and emphasizes product and process understanding and control. This is achieved by defining a Quality Target Product Profile (QTPP), identifying Critical Quality Attributes (CQAs), and establishing a design space and control strategy [15]. ICH Q9 provides the practical tools for implementing a QbD approach by formalizing Quality Risk Management (QRM). It offers a systematic process and tools (e.g., FMEA, HACCP, risk matrices) to identify, assess, and control potential quality risks throughout the product lifecycle [15].

FDA cGMP and the PAT Initiative

The FDA's current Good Manufacturing Practice (cGMP) regulations require that manufacturers use modern, validated systems and technologies. The "c" in cGMP stands for "current," reinforcing the expectation that methods and equipment are updated to reflect the most recent advancements [17]. A key driver for innovation is the Process Analytical Technology (PAT) initiative. The FDA defines PAT as "systems for analysis and control of manufacturing processes based on timely measurements... to assure acceptable end product quality" [16]. This framework explicitly encourages the use of alternative methods, including rapid microbiological methods, that can provide real-time or near-real-time data for better process control, moving beyond traditional end-product testing [16].

Validation of Rapid Methods vs. Reference Techniques

The adoption of any new analytical method, particularly Rapid Microbiological Methods (RMMs), requires a rigorous validation process to demonstrate it is fit-for-purpose and equivalent or superior to the reference compendial method.

Regulatory Framework for Method Validation

Regulatory authorities provide a clear pathway for implementing alternative methods. The FDA's guidance on aseptic processing states that "Other suitable microbiological test methods (e.g., rapid test methods) can be considered... after it is demonstrated that the methods are equivalent or better than traditional methods (e.g., USP)" [16]. Internationally, the ISO 16140 series provides a standardized protocol for the validation of alternative microbiological methods, which involves two key stages [19]:

- Method Validation: This initial stage proves the method is fit-for-purpose, typically through a method comparison study against a reference method and an interlaboratory study.

- Method Verification: This second stage demonstrates that a user laboratory can satisfactorily perform the validated method.

Industry consortia like BioPhorum have further streamlined this process by proposing a structured nine-step framework for the evaluation, validation, and implementation of RMMs to overcome perceived barriers to adoption [20].

Experimental Protocols for Method Comparison

A standard validation protocol for an RMM involves a head-to-head comparison with the compendial method, such as the one described in the United States Pharmacopoeia (USP) Chapter <71> or 21 CFR 610.12 for sterility testing. A typical methodology is outlined below.

Table 2: Example Experimental Protocol for Sterility Test Method Comparison

| Protocol Element | Description | Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Test Organisms | A panel of microorganisms representing Gram-negative/-positive bacteria, aerobic/anaerobic bacteria, yeast, and fungi (e.g., Staphylococcus aureus, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Bacillus subtilis, Clostridium sporogenes, Candida albicans, Aspergillus brasiliensis). | Select organisms relevant to the product manufacturing environment and patient use. |

| Inoculum Preparation | Prepare serial dilutions of each organism in a neutral fluid (e.g., Fluid A) or the product matrix to contain approximately 0.1, 1, 10, and 100 colony forming units (CFU) in an inoculum of 10 mL [21]. | Low-level inoculation challenges the method's limit of detection. |

| Test Methods | Inoculate samples into both the compendial method media (Fluid Thioglycollate Medium and Tryptic Soy Broth) and the RMM system (e.g., ATP bioluminescence, CO2 monitoring) [21]. | The compendial method is the benchmark for comparison. |

| Data Analysis | Compare the sensitivity (ability to detect low CFUs) and time to detection for each microorganism across both methods. Statistical analysis (e.g., t-test) should be used to determine significant differences (p < 0.05) [21]. | The RMM must demonstrate non-inferiority or superiority. |

| Matrix Interference | Repeat testing in the presence of the actual product formulation, including preservatives (e.g., 0.01% thimerosal) or adjuvants (e.g., aluminum hydroxide), to assess interference [21]. | Critical for ensuring the method works with the product. |

Comparative Performance Data: RMM vs. Compendial Methods

Experimental data consistently demonstrates the advantages of validated RMMs over traditional growth-based methods.

Table 3: Quantitative Comparison of Rapid Microbiological Methods vs. Compendial Sterility Test

| Performance Metric | Compendial Method (USP <71>) | ATP Bioluminescence (Rapid Milliflex) | CO2 Monitoring (BacT/Alert) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total Test Duration | 14 days [21] | 5 days [21] | Faster than compendial for most organisms [21] |

| Sensitivity at 0.1 CFU | Baseline | Significantly more sensitive (p < 0.05) [21] | Less sensitive than the compendial membrane filtration method (p < 0.05) [21] |

| Compatibility with 0.01% Thimerosal | Not applicable (baseline) | Compatible (detected all test microorganisms) [21] | Not consistently compatible (did not detect all microorganisms) [21] |

| Key Advantage | Established regulatory acceptance | Speed, sensitivity, and compatibility with challenging matrices [21] | Automation and reduced time-to-result for products without preservatives [21] |

The data shows that the ATP bioluminescence method was not only significantly faster but also more sensitive in detecting low levels of microorganisms compared to the compendial method. Furthermore, its compatibility with products containing preservatives like thimerosal makes it a robust alternative for specific applications [21].

A Risk-Based Approach to Selecting and Implementing Rapid Methods

The Selection Framework

Selecting the right RMM requires a structured evaluation beyond technical performance. The following workflow outlines a risk-based decision process, integrating business needs and regulatory strategy.

Diagram 1: RMM Selection and Implementation Workflow.

When evaluating technologies, consider the following ten attributes to guide decision-making [22]:

- Accuracy for the intended purpose and reduction in human error.

- Speed in time-to-result and productivity.

- Overall cost, including equipment and per-test cost.

- Regulatory acceptability and precedent of use.

- Simplicity of operation and training requirements.

- Vendor reputation and technical support.

- Utility and space requirements.

- Automation and connectivity to LIMS.

- Detection capability for viable but non-culturable organisms.

- Validation pathway and required resources.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

The successful execution of a method validation study requires specific reagents and materials. The following table details key solutions used in the featured sterility testing experiment [21].

Table 4: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Sterility Method Validation

| Reagent/Material | Function in the Experiment | Example from Protocol |

|---|---|---|

| Fluid Thioglycollate Medium (FTM) | A growth medium used in the compendial method to support the growth of aerobic and anaerobic bacteria. | Served as one of the two reference compendial media for detecting microbial growth via turbidity [21]. |

| Tryptic Soy Broth (TSB) | A general-purpose, liquid growth medium used in the compendial method to support the growth of a wide range of bacteria and fungi. | Served as the second reference compendial media for the direct inoculation sterility test [21]. |

| Sabouraud Dextrose Agar (SDA) | A solid growth medium selective for fungi, particularly yeasts and molds. | Used as one of the solid culture media in the ATP bioluminescence (RMDS) rapid method system [21]. |

| Schaedler Blood Agar (SBA) | A rich, supplemented medium used for the cultivation of fastidious and anaerobic bacteria. | Utilized in the ATP bioluminescence (RMDS) system and proved effective for detecting all test microorganisms, even in the presence of thimerosal [21]. |

| iAST / iNST Culture Media | Specialized, liquid culture media used in the BacT/Alert system for the automated detection of microbial growth in aerobic and anaerobic conditions, respectively. | The growth of microorganisms produces CO2, which is detected by a sensor in the bottle [21]. |

| Neutralizing Fluid (e.g., Fluid A) | Used to suspend and dilute microorganisms without causing stress or death, ensuring accurate inoculum preparation. | Used to prepare microbial aliquots for inoculation, ensuring the test itself does not inhibit growth [21]. |

Navigating the regulatory landscape for pharmaceutical manufacturing requires a solid understanding of the interconnected roles of FDA regulations, ICH quality guidelines, and GMP principles. The framework provided by ICH Q8 (QbD) and ICH Q9 (QRM) empowers scientists to make science-based decisions, while initiatives like PAT from the FDA encourage the adoption of innovative technologies. As demonstrated by the experimental data, validated Rapid Microbiological Methods offer significant advantages over traditional compendial techniques, including reduced time-to-result, improved sensitivity, and enhanced robustness. By following a structured, risk-based approach to selection, validation, and implementation—in alignment with regulatory guidance from the FDA, ISO, and industry consortia—researchers and drug development professionals can successfully integrate these advanced methods, ultimately enhancing product quality and patient safety.

A Toolkit of Rapid Methods: From Pathogen Detection to AI-Driven Design

The validation of rapid, specific detection methods against reference analytical techniques is a cornerstone of molecular biology research and diagnostics. This guide provides an objective comparison of four foundational nucleic acid-based methods—PCR, qPCR, LAMP, and Microarrays—focusing on their performance characteristics, supported by experimental data. Understanding the sensitivity, specificity, speed, and operational requirements of each technique is essential for researchers and drug development professionals to select the optimal method for their specific application, whether it's for gene expression studies, pathogen detection, or biomarker discovery [23].

The following table provides a systematic comparison of the key performance metrics and characteristics of the four nucleic acid detection methods.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Nucleic Acid-Based Detection Methods

| Feature | Conventional PCR | Quantitative PCR (qPCR) | Loop-Mediated Isothermal Amplification (LAMP) | Microarrays |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Key Principle | End-point amplification via thermal cycling [24] | Real-time fluorescence monitoring during thermal cycling [24] | Isothermal amplification with 4-6 primers [25] | Hybridization of labeled nucleic acids to immobilized probes [23] |

| Detection Method | Gel electrophoresis (post-amplification) [24] | Fluorescent dyes/probes (real-time) [24] | Turbidity, fluorescence, or visual color change [25] | Fluorescence scanning [23] |

| Typical Sensitivity | ~100 pg (in a given study) [25] | 100 fg (in a given study) [25] | ~1 pg (in a given study) [25] | Lower than qPCR for miRNA [26] |

| Relative Sensitivity | 1x (as baseline) | 1000x more sensitive than PCR [24] | 10x more sensitive than conventional PCR [25] | Varies by platform and target |

| Assay Speed | Several hours (includes gel analysis) [24] | Faster than PCR (no post-processing) [24] | <60 minutes [25] | Long hybridization and analysis times [23] |

| Throughput | Low to medium | High (384- or 1536-well plates) [24] | Medium | Very high (whole genome) [23] |

| Quantification | No (semi-quantitative) | Yes (absolute or relative) [24] | Yes | Yes (relative) [23] |

| Ease of Use | Requires post-processing | Complex data analysis [24] | Simple, minimal equipment [25] | Complex data analysis and bioinformatics [23] |

| Cost | Low | High (equipment and reagents) [24] | Low | High |

Experimental Data and Performance Validation

Sensitivity Analysis in Pathogen Detection

A direct comparison of four methods for detecting the fungal pathogen Alternaria solani demonstrated clear sensitivity differences. The study, based on the histidine kinase gene (HK1), highlights the importance of method selection based on detection needs [25]:

- qPCR was the most sensitive, detecting down to 100 fg of genomic DNA.

- Nested PCR was 10-fold less sensitive than qPCR but 1000-fold more sensitive than conventional PCR, detecting down to 1 pg.

- LAMP showed intermediate sensitivity, 10-fold higher than conventional PCR but 10-fold lower than nested PCR, detecting down to 10 pg.

- Conventional PCR was the least sensitive, requiring at least 100 pg of DNA for detection [25].

This data underscores qPCR as the reference method for maximum sensitivity, while LAMP offers a compelling balance of speed and sensitivity for field-deployable diagnostics.

Reproducibility and False Positive Rates

A study comparing miRNA profiling techniques revealed significant operational differences between qPCR arrays and microarrays:

- qPCR arrays demonstrated high reproducibility with minimal variation between different reverse transcription reactions and assays performed on different days [26].

- Microarrays exhibited a higher false-positive rate for differential miRNA expression and showed greater variation between replicates, especially for low-abundance targets [26].

- The correlation between the two platforms was low (r = -0.443), indicating considerable variability between the assay technologies [26].

This evidence positions qPCR as a more reliable method for validation purposes, particularly for low-expression targets.

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol: qPCR Validation of Microarray Data

Validating microarray results with qPCR is a standard practice. However, when RNA is limited, using the amplified amino allyl labeled RNA (AA-aRNA) leftover from the microarray process is an efficient alternative. The following workflow diagram outlines an optimized protocol to overcome the inhibition of qPCR by amplification and labeling compounds [27] [28].

Workflow Title: Optimized RT Protocol for Microarray Validation via qPCR

Key Steps and Rationale: [27] [28]

- Input Material: Begin with amplified amino allyl labeled RNA (AA-aRNA). Using AA-aRNA is particularly valuable when the original RNA quantity is limited.

- Denaturation: A denaturation step is added to unfold secondary structures in the AA-aRNA.

- Primer Annealing: A 2-minute incubation at room temperature is introduced to improve the annealing of random primers to the template.

- Transcription Initiation: This step enhances the efficiency of the reverse transcription reaction itself.

- Reverse Transcription: performed using SuperScript II.

- RNase H Treatment: This post-RT step degrades any remaining RNA, reducing potential interference in the subsequent qPCR. Outcome: This optimized protocol was shown to provide a significant gain in Cq values (2.7-3.4 cycles on average) and increased qPCR efficiency, allowing for the detection of low-abundance genes that were previously undetectable with the standard protocol [27] [28].

Protocol: LAMP Assay for Rapid Pathogen Detection

The LAMP protocol offers a rapid, isothermal alternative for specific detection, suitable for resource-limited settings. The following workflow details the steps for detecting Alternaria solani [25].

Workflow Title: LAMP Assay Workflow for Direct Detection

Key Steps and Rationale: [25]

- Template Preparation: DNA can be extracted using simple methods, as LAMP is notably tolerant to inhibitors present in biological samples, sometimes even allowing for the use of diluted pure culture without extensive DNA purification.

- Reaction Setup: The reaction mix includes strand-displacing Bst DNA polymerase and a set of four to six primers (F3, B3, FIP, BIP) specifically designed to recognize distinct regions of the target gene (e.g., the HK1 gene for A. solani). This multi-primer system is the source of the technique's high specificity.

- Amplification: The reaction is incubated at a constant temperature of 63°C for 60 minutes. The isothermal nature eliminates the need for a thermal cycler.

- Detection: Amplification can be detected by several methods:

- Gel electrophoresis for traditional analysis.

- Real-time turbidity measurement due to the precipitation of magnesium pyrophosphate.

- Visual inspection after adding fluorescent intercalating dyes (e.g., SYBR Green), enabling naked-eye detection.

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

The following table catalogues key reagents and their functions that are critical for successfully implementing the discussed nucleic acid detection methods.

Table 2: Key Reagents and Their Functions in Nucleic Acid Detection

| Reagent / Solution | Function | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Bst DNA Polymerase | Enzyme for LAMP amplification; has strand-displacement activity [25]. | Isothermal; does not require a thermal cycler. |

| Taq DNA Polymerase | Thermostable enzyme for PCR, qPCR amplification [24]. | Requires thermal cycling. |

| SYBR Green / BRYT Dye | Fluorescent dsDNA-binding dye for qPCR and LAMP detection [25] [29]. | Binds non-specifically to dsDNA; cost-effective for qPCR. |

| TaqMan Probes | Sequence-specific fluorescent probes for qPCR [29]. | Higher specificity than DNA-binding dyes. |

| Amino Allyl UTP (AA-UTP) | Modified nucleotide for labeling RNA in microarray target preparation [27]. | Serves as an arm for fluorescent dye coupling. |

| Megaplex RT/Preamplification Primers | Primer pools for reverse transcription and pre-amplification in large-scale qPCR arrays [26]. | Enables profiling of hundreds of targets from minimal RNA. |

| SuperScript II Reverse Transcriptase | Enzyme for synthesizing cDNA from RNA templates [27]. | Used in qPCR and microarray sample prep. |

| Master Mix | Optimized, ready-to-use mixture of enzymes, dNTPs, and buffers for qPCR [29]. | Ensures reproducibility and efficiency; required for high-sensitivity qPCR. |

The choice among PCR, qPCR, LAMP, and microarrays is dictated by the specific requirements of the experiment. qPCR stands out as the sensitive, quantitative reference method for validation and precise quantification. LAMP is a superior choice for rapid, field-deployable diagnostics due to its speed, simplicity, and robustness. Microarrays provide an excellent discovery tool for genome-wide screening, though their results often require confirmation by a more sensitive technique like qPCR. Finally, conventional PCR remains a viable, low-cost option for simple, non-quantitative detection. By understanding the performance characteristics and operational workflows of each method, researchers can make informed decisions to ensure the accuracy and reliability of their nucleic acid detection experiments.

Biosensors are analytical devices that combine a biological recognition element with a physicochemical detector to analyze a wide range of substances, providing real-time data with high sensitivity and specificity [30]. The fundamental principle of these devices involves the molecular recognition between biological elements (such as enzymes, antibodies, or nucleic acids) and target analytes, followed by transformation into measurable physical or chemical signals through various transduction mechanisms [31]. For researchers and drug development professionals, validating these rapid analytical methods against established reference techniques is paramount to ensuring data reliability, regulatory compliance, and successful translation from research to clinical applications.

The validation of analytical methods, including biosensors, follows established guidelines such as ICH Q2 to demonstrate that a method is suitable for its intended purpose [32]. Key validation parameters include specificity, accuracy, precision, linearity, and range, which collectively ensure that results are consistent, reproducible, and reliable [32]. Within this framework, optical, electrochemical, and mass-based biosensors each offer distinct advantages and limitations for specific applications in pharmaceutical development, clinical diagnostics, and environmental monitoring. This guide provides a comprehensive comparison of these technologies, supported by experimental data and detailed methodologies to inform selection and implementation decisions.

Technology Comparison and Performance Data

Fundamental Operating Principles

Optical Biosensors: These devices detect changes in light properties (intensity, wavelength, or phase) resulting from biological interactions [30]. Major types include surface plasmon resonance (SPR), fluorescence, and interferometry [30]. For instance, fluorescent biosensors often utilize Förster resonance energy transfer (FRET) between donor and acceptor molecules, where energy transfer efficiency changes in response to analyte binding [33].

Electrochemical Biosensors: These operate by detecting electrical signal changes (voltage, current, or impedance) during biological reactions [30]. They are categorized into amperometric (measuring current), potentiometric (measuring potential), and impedimetric (measuring impedance) sensors [30]. Their operation relies on the production or consumption of ions or electrons during biological recognition events.

Mass-Based Biosensors: These systems, including piezoelectric and quartz crystal microbalance (QCM) devices, detect mass changes occurring from the binding of target analytes to the sensor surface [31]. The fundamental principle involves measuring frequency changes of a crystal oscillator when mass is added or removed from its surface.

Comparative Performance Analysis

Table 1: Comprehensive comparison of biosensor technologies

| Performance Parameter | Optical Biosensors | Electrochemical Biosensors | Mass-Based Biosensors |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sensitivity | Superior sensitivity; FRET biosensors achieve near-quantitative (>95%) efficiency [33] | High sensitivity for specific analytes (e.g., glucose) [30] | Generally high for mass-changing interactions [31] |

| Detection Limit | Capable of detecting minute quantities; femtogram-per-mL range for protein detection [34] | May require specific conditions to maintain accuracy in complex samples [30] | Suitable for detecting larger biomolecules and whole cells [31] |

| Dynamic Range | Unprecedented dynamic ranges with engineered FRET pairs [33] | Moderate dynamic range, often optimized for specific concentration windows [30] | Limited by mass loading capacity of sensor surface [31] |

| Analysis Time | Real-time monitoring capabilities [30] | Rapid results, suitable for point-of-care testing [30] | Real-time monitoring of binding events [31] |

| Multiplexing Capability | High; multicolor FRET sensors enable simultaneous monitoring of different analytes [33] | Moderate; requires multiple electrode arrays [30] | Limited; typically single-analyte detection [31] |

| Cost & Accessibility | Higher cost due to sophisticated equipment [30] | More affordable, accessible for mass-market applications [30] | Moderate cost, specialized equipment required [31] |

| Portability | Generally less portable, complex setups [30] | Excellent portability; compact, user-friendly designs [30] | Variable; benchtop systems common [31] |

Table 2: Application-focused comparison across industry sectors

| Application Sector | Optical Biosensors | Electrochemical Biosensors | Mass-Based Biosensors |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pharmaceutical R&D | High-precision target engagement studies, intracellular metabolite monitoring [33] | Drug screening, toxicity assessment [30] | Ligand-binding studies, affinity characterization [31] |

| Clinical Diagnostics | Protein biomarker detection, high-sensitivity immunoassays [34] | Glucose monitoring, point-of-care infectious disease tests [30] | Pathogen detection (e.g., Bacillus anthracis) [31] |

| Environmental Monitoring | Potential for multiplexed contaminant detection [33] | Heavy metal detection, water quality monitoring [30] | Bacterial spore detection in environmental samples [31] |

| Food Safety | Limited due to complexity and cost [30] | Pesticide residue detection, spoilage indicators [30] | Pathogen screening (e.g., whole-cell detection) [31] |

Validation Against Reference Methods

When validating biosensor technologies against reference analytical methods, researchers must establish correlation across key parameters. For optical biosensors, validation often involves comparison with enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) or mass spectrometry for analyte quantification [31] [32]. Electrochemical biosensors are frequently validated against chromatographic methods or standardized clinical chemistry analyzers [30] [32]. Mass-based biosensors typically require correlation with culture-based microbiological methods or other reference techniques for microbial detection [31].

The validation process must demonstrate that the rapid biosensor method provides equivalent or superior performance to the reference method for the intended application, with particular attention to specificity, accuracy, and precision under actual use conditions [32]. For example, a study comparing a microwave resonator biosensor for cell cytotoxicity against the established CCK-8 colorimetric method showed strong linear correlation, validating its use for high-throughput drug screening [34].

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Development of FRET-Based Optical Biosensors

Protocol Objective: Create highly sensitive FRET biosensors with large dynamic ranges for intracellular metabolite monitoring [33].

Key Reagents and Materials:

- Plasmid vectors encoding fluorescent proteins (e.g., eGFP, mCerulean3, Venus, mScarlet)

- HaloTag7 (HT7) construct

- Silicon rhodamine (SiR) or tetramethylrhodamine (TMR) fluorophore substrates

- Cell culture reagents (appropriate cell lines, media, transfection reagents)

- Microplate reader or fluorescence microscopy setup

Methodology:

- FRET Pair Engineering: Fuse selected fluorescent protein (FP) to N-terminus of HT7 using molecular cloning techniques. The construct eGFP-HT7 (termed ChemoG1) serves as starting point [33].

- Interface Optimization: Introduce stabilizing mutations at FP-HT7 interface (e.g., eGFP: A206K, T225R; HT7: E143R, E147R, L271E) to enhance FRET efficiency through stepwise mutagenesis [33].

- Fluorophore Labeling: Incubate expressed constructs with cell-permeable rhodamine-based fluorophores (e.g., SiR, JF525, JF669) to label HaloTag moiety [33].

- FRET Efficiency Quantification: Measure fluorescence emission spectra following donor excitation. Calculate FRET efficiency using formula:

E = 1 - (FDA/FD), where FDA is donor emission in presence of acceptor, and FD is donor emission alone [33]. - Sensor Validation in Cellular Systems: Express optimized biosensors in relevant cell lines (e.g., U-2 OS cells). Confirm subcellular localization and dynamic range following stimulation (e.g., genotoxic stress for NAD+ sensors) [33].

Validation Parameters:

- FRET efficiency (near-quantitative ≥94% for optimized constructs)

- Dynamic range (fold-change in emission ratio between analyte-bound and unbound states)

- pH and salt stability (minimal effect on FRET efficiency within physiological ranges)

- Spectral characteristics across FP and acceptor combinations [33]

Electrochemical Immunosensor for Pathogen Detection

Protocol Objective: Develop electrochemical immunosensor for detection of Bacillus anthracis spores as model pathogen [31].

Key Reagents and Materials:

- Capture antibodies specific to target pathogen surface antigens

- Electrode systems (gold, carbon, or indium tin oxide electrodes)

- Redox mediators (e.g., ferricyanide, ferrocene derivatives)

- Blocking agents (bovine serum albumin, casein)

- Potentiostat/galvanostat for electrochemical measurements

Methodology:

- Electrode Modification: Clean and functionalize electrode surface to enable antibody immobilization through covalent coupling or physical adsorption [31] [30].

- Antibody Immobilization: Incubate functionalized electrode with capture antibody solution. Optimize concentration and incubation time to maximize surface coverage while maintaining activity [31].

- Blocking: Treat modified electrode with blocking solution to minimize non-specific binding on sensor surface [31].

- Sample Incubation: Expose functionalized electrode to sample containing target analyte for predetermined time [31].

- Electrochemical Measurement: Perform electrochemical measurement (amperometric, potentiometric, or impedimetric) in presence of redox mediator:

- Amperometric: Apply fixed potential and measure current change

- Impedimetric: Apply AC potential across frequency range and measure impedance spectra [30]

- Signal Correlation: Relate electrical signal to analyte concentration through calibration curve [31].

Validation Parameters:

- Limit of detection (LOD) and quantification (LOQ) in relevant matrices

- Specificity against related species or common interferents

- Accuracy (percentage recovery of spiked samples)

- Precision (intra-assay and inter-assay variability)

- Correlation with reference methods (e.g., culture, PCR) [31] [32]

Mass-Based Immunosensor Implementation

Protocol Objective: Implement piezoelectric mass-based immunosensor for detection of bacterial pathogens [31].

Key Reagents and Materials:

- Quartz crystal microbalance (QCM) with flow injection system

- Antibodies specific to target analytes

- Reference crystals for background subtraction

- Buffer solutions for stable biorecognition element immobilization

Methodology:

- Crystal Functionalization: Modify gold electrode surface of quartz crystal to enable antibody immobilization using self-assembled monolayers or polymer coatings [31].

- Antibody Immobilization: Incubate functionalized crystal with antibody solution under optimized conditions [31].

- Baseline Establishment: Flow buffer solution across crystal surface until stable frequency baseline is achieved [31].

- Sample Introduction: Introduce sample containing target analyte through flow system [31].

- Frequency Monitoring: Continuously monitor resonance frequency shift during association and dissociation phases [31].

- Data Analysis: Calculate mass change using Sauerbrey equation:

Δm = -C·Δf/n, where C is sensitivity constant, Δf is frequency change, and n is overtone number [31].

Validation Parameters:

- Binding kinetics (association/dissociation rates)

- Mass detection limit

- Reusability/regeneration capability

- Specificity in complex samples

- Correlation with reference microbiological methods [31]

Signaling Pathways and Experimental Workflows

Biosensor Development Pathway

FRET Biosensor Mechanism

Biosensor Validation Workflow

Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key research reagents for biosensor development and validation

| Reagent/Material | Function | Example Applications |

|---|---|---|

| Fluorescent Proteins (eGFP, mCerulean3, Venus) | FRET donors in optical biosensors | Intracellular metabolite monitoring [33] |

| HaloTag7 with Rhodamine Substrates | Chemogenetic FRET acceptor system | Engineered biosensors with large dynamic ranges [33] |

| Capture Antibodies | Biorecognition elements for specific analyte binding | Pathogen detection immunosensors [31] |

| Functionalized Electrodes (Gold, Carbon) | Transducer surfaces for electrochemical detection | Amperometric and impedimetric biosensors [30] |

| Quartz Crystal Microbalances | Mass-sensitive transducer platforms | Piezoelectric immunosensors [31] |

| Redox Mediators (Ferricyanide) | Electron transfer facilitators in electrochemical sensors | Amplifying electrochemical signals [30] |

| Blocking Agents (BSA, Casein) | Minimize non-specific binding | Improving assay specificity across platforms [31] |

| Reference Analytical Standards | Method validation and calibration | Establishing accuracy against reference methods [32] |

The comparative analysis of optical, electrochemical, and mass-based biosensor technologies reveals distinctive performance profiles that dictate their suitability for specific applications in pharmaceutical research and drug development. Optical biosensors, particularly advanced FRET-based systems, offer exceptional sensitivity and dynamic range for intracellular monitoring and high-precision applications, albeit with higher complexity and cost [33]. Electrochemical biosensors provide an optimal balance of performance, cost-effectiveness, and portability, making them ideal for point-of-care diagnostics and high-throughput screening [30]. Mass-based biosensors deliver valuable capabilities for direct detection of larger biomolecules and pathogens, though with more limited multiplexing capabilities [31].

From a method validation perspective, the selection of appropriate biosensor technology must be guided by intended use requirements and alignment with validation parameters outlined in regulatory guidelines [32]. As the field advances, integration with complementary metal-oxide-semiconductor (CMOS) technology, microfluidics, and artificial intelligence is poised to enhance the performance, scalability, and accessibility of biosensor platforms [34]. Future developments will likely focus on overcoming existing limitations in multiplexing, environmental interference, and complexity while maintaining the rigorous validation standards required for adoption in regulated pharmaceutical and clinical environments.

Serological assays, which detect the presence of antibodies or antigens in biological samples, serve as fundamental tools in clinical diagnostics, epidemiological studies, and therapeutic development. Among these techniques, Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay (ELISA) and Lateral Flow Immunoassay (LFA) represent two widely utilized platforms with distinct operational characteristics and application domains. Within the context of method validation research, comparing established reference techniques like ELISA with rapid alternatives such as LFA is crucial for determining their appropriate implementation in various settings. ELISA has long been considered a reference analytical technique in clinical microbiology and serological testing due to its robustness, sensitivity, and quantitative capabilities [35] [36]. In contrast, lateral flow immunoassays have emerged as rapid, point-of-care alternatives that sacrifice some analytical performance for speed and operational simplicity [35].

The COVID-19 pandemic has provided a recent real-world context for comparing these methodologies, with numerous studies evaluating their respective performances in detecting SARS-CoV-2 antibodies. This comparison guide objectively examines the technical specifications, performance characteristics, and experimental validation data for ELISA and LFA, providing researchers and drug development professionals with evidence-based insights for selecting appropriate assay platforms based on their specific requirements. The framework for this comparison centers on validation parameters established for immunoassays, including sensitivity, specificity, precision, and robustness [37].

Fundamental Principles and Methodologies

Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay (ELISA)

ELISA is a plate-based technique that utilizes the specific binding between antigen and antibody, with detection enabled by an enzyme-linked conjugate that produces a measurable signal, typically colorimetric, fluorescent, or chemiluminescent [35] [36]. The fundamental principle involves immobilizing either an antigen or antibody onto a solid surface (typically a polystyrene microtiter plate) and then detecting the target analyte through a series of binding and washing steps. The most common ELISA formats include direct, indirect, and sandwich assays, each with specific advantages for different applications.

In the direct ELISA format, antigens are immobilized in the well of a microtiter plate, and an enzyme-conjugated antibody specific for the antigen is added. After washing to remove unbound antibodies, a colorless substrate (chromogen) is added, and the presence of the enzyme converts the substrate into a colored end product [35]. The indirect ELISA begins with attaching known antigen to the bottom of the microtiter plate wells. After blocking, patient serum is added; if antibodies are present, they will bind the antigen. After washing, a secondary antibody with conjugated enzyme is added, directed against the primary antibody [35]. The sandwich ELISA uses a capture antibody coated onto the plate to detect specific antigen present in a solution. The primary antibody captures the antigen, and after washing, a secondary antibody conjugated to an enzyme is added [35].

The optimization of ELISA requires careful attention to multiple parameters, including antigen coating concentration, blocking conditions, sample preparation methods, and detection system optimization [36]. Coating wells with antigen or capturing antibodies typically uses protein solutions in PBS or carbonate buffer applied to microtiter plates with modified surfaces that have high affinity for molecules with polar or hydrophilic groups [36]. Blocking free binding sites is critical to prevent nonspecific binding and improve the signal-to-noise ratio and specificity, with various blocking buffers available including BSA, nonfat-dried milk, casein, or whole serum [36].

Lateral Flow Immunoassays (LFA)

Lateral flow immunoassays, commonly known as lateral flow tests or strip tests, are simple devices designed to detect the presence or absence of a target analyte in a liquid sample without the need for specialized equipment [35]. These assays operate on the principle of immunochromatography, where the sample migrates along a strip of porous material (typically nitrocellulose) through capillary action, encountering various zones containing biological reagents that produce a visual signal when the target analyte is present.

The basic components of a lateral flow strip include a sample pad, conjugate pad, nitrocellulose membrane, and absorbent pad. The sample pad acts as a filter to remove particles and ensure smooth flow. The conjugate pad contains labeled antibodies (typically with gold nanoparticles, latex beads, or fluorescent tags) that recognize the target analyte. The nitrocellulose membrane contains test and control lines where capture molecules are immobilized [35]. When a fluid sample is applied to the absorbent pad, it flows by capillary action and moves through a stripe of beads with antibodies attached to their surfaces. The fluid hydrates the reagents, which are present in a dried state in the stripe [35].

In the detection mechanism, antibody-coated beads made of latex or tiny gold particles bind antigens in the test fluid. The antibody-antigen complexes then flow over a second stripe that has immobilized antibody against the antigen; this stripe retains the beads that have bound antigen [35]. A third control stripe binds any beads, serving as an internal control to validate the test procedure. A red color (from gold particles) or blue (from latex beads) developing at the test line indicates a positive test, while color development only at the control line indicates a negative result [35].

Like ELISA techniques, lateral flow tests take advantage of antibody sandwiches, providing sensitivity and specificity, though they are generally not as quantitative as ELISA [35]. The primary advantages of LFA include speed, simplicity, low cost, and independence from special equipment, making them suitable for point-of-care use or in-home testing [35].

Comparative Workflow Visualization

The following diagram illustrates the fundamental workflows and key differences between ELISA and LFA procedures:

Performance Comparison: Experimental Data

Diagnostic Performance in SARS-CoV-2 Detection

Multiple comparative studies conducted during the COVID-19 pandemic have provided robust experimental data on the performance characteristics of ELISA and LFA in detecting SARS-CoV-2 antibodies. The table below summarizes key findings from these studies:

Table 1: Comparative Performance of ELISA and LFA in SARS-CoV-2 Antibody Detection

| Study Reference | Assay Type | Specific Test | Sensitivity (%) | Specificity (%) | Time Post-Symptom Onset | Sample Size |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ong et al. [38] | LFA | Orient Gene Biotech IgG/IgM | 43 (34-53) | 98 (95-100) | All patients | 99 positive, 129 negative |

| Ong et al. [38] | LFA | Orient Gene Biotech IgG/IgM | 60 (46-73) | - | ≥7 days | 52 positive |

| Ong et al. [38] | ELISA | Wantai SARS-CoV-2 Ab | 62 (52-72) | 98 (95-100) | All patients | 95 positive, 128 negative |

| Ong et al. [38] | ELISA | Wantai SARS-CoV-2 Ab | 79 (68-91) | - | ≥7 days | 48 positive |

| Frontiers Study [39] | ELISA | EUROIMMUN IgG | 71.0 | 100 | >10 days | 40 positive, 10 negative |

| Frontiers Study [39] | LFA | T-Tek IgG/IgM | 35.5 | 100 | >10 days | 40 positive, 10 negative |

| Egyptian Study [40] | In-house ELISA | Anti-nucleocapsid IgG/IgM | 86.0 | 92.0 | Not specified | Not specified |

| Egyptian Study [40] | In-house LFA | Anti-nucleocapsid IgG/IgM | 96.5 | 93.75 | Not specified | Not specified |

The data reveals considerable variability in performance between different commercial assays and between studies. Overall, ELISA demonstrates higher sensitivity compared to LFA in most direct comparisons, particularly in early infection stages. The sensitivity of both techniques improves with longer duration since symptom onset, as antibody levels increase over time [38]. The specificity remains consistently high for both platforms when properly optimized.

The heterogeneity in LFA performance is particularly notable. One study evaluating six different LFAs found sensitivity characteristics ranging from 10% (95% CI 0%-23%) to 55% (95% CI 33%-77%) on the same patient samples [38]. This variability highlights the importance of rigorous validation before implementing rapid tests in clinical or research settings.

Methodological Comparison and Operational Characteristics

Beyond diagnostic performance, ELISA and LFA differ significantly in their operational parameters, infrastructure requirements, and implementation considerations:

Table 2: Operational Characteristics of ELISA versus Lateral Flow Assays

| Parameter | ELISA | Lateral Flow Immunoassay |

|---|---|---|

| Time to Result | 2-5 hours [35] | 15-30 minutes [35] |

| Equipment Requirements | Plate washer, plate reader, incubator [35] | None required [35] |

| Sample Throughput | High (96-well format) | Low to moderate (individual tests) |

| Quantitative Capability | Fully quantitative [35] | Qualitative or semi-quantitative [35] |

| Personnel Skill Requirements | Technical expertise needed | Minimal training required |

| Cost per Test | Moderate to high | Low |

| Storage Requirements | Typically refrigerated | Often stable at room temperature |

| Quality Control | Internal and external controls possible | Built-in control line |

| Applications | Reference testing, batch analysis, research | Point-of-care, rapid screening, field use |

The operational differences make these technologies complementary rather than directly competitive. ELISA serves as an ideal platform for high-throughput laboratory settings where quantitative results, high sensitivity, and batch processing are prioritized. In contrast, LFA provides a practical solution for rapid screening, point-of-care testing, and resource-limited settings where speed, simplicity, and low cost are paramount.

Validation Frameworks and Experimental Protocols

Method Validation Parameters

For researchers implementing these assays, particularly for regulatory purposes or method transfer, understanding validation requirements is essential. The following validation parameters should be assessed based on the intended use of the method:

Table 3: Key Validation Parameters for Immunoassays

| Validation Parameter | Definition | Application to ELISA | Application to LFA |

|---|---|---|---|

| Precision | Closeness of agreement between independent test results [37] | Assessed within-run, between-run, and between-laboratory | Typically assessed between different lots and readers |

| Trueness | Closeness of agreement between average value and accepted reference value [37] | Comparison with reference method or standard | Comparison with reference method (often ELISA) |

| Robustness | Ability to remain unaffected by small variations in method parameters [37] | Testing variations in incubation time, temperature, reagent lots | Testing variations in sample volume, environmental conditions |

| Limits of Quantification | Highest and lowest concentrations measurable with acceptable precision and accuracy [37] | Established through dilution series | Typically not applicable (qualitative tests) |

| Selectivity | Ability to measure and differentiate analytes in presence of potential interferents [37] | Testing cross-reactivity with related antigens | Testing cross-reactivity and sample matrix effects |

| Sample Stability | Chemical stability of analyte under specific conditions [37] | Evaluation of storage conditions and freeze-thaw cycles | Evaluation of storage conditions, particularly test strips |

For laboratory-developed tests or in-house assays, full validation is required, while for commercial assays, partial validation may suffice to verify performance claims under local conditions [37]. The extent of validation should be determined based on the intended application, with diagnostic applications requiring more rigorous validation than research use.

Experimental Protocol for Comparative Validation

Researchers conducting comparative assessments of ELISA and LFA should implement standardized protocols to ensure meaningful results:

Sample Selection and Preparation:

- Include well-characterized positive and negative samples, preferably confirmed by reference methods

- Ensure appropriate sample size for statistical power (typically ≥50 positive and ≥50 negative samples)

- Store samples appropriately (-80°C for long-term storage, avoid repeated freeze-thaw cycles)

- Include samples with varying analyte concentrations and from different demographic groups

Testing Procedure:

- Perform ELISA and LFA testing according to manufacturer instructions

- Ensure technicians are blinded to sample status and other test results

- Include appropriate controls in each run (positive, negative, calibrators if quantitative)

- For quantitative assays, establish standard curves using reference materials

Data Analysis:

- Calculate sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value, and negative predictive value