Validating Macronutrient Intake: A Comprehensive Guide to Dietary Assessment Methods for Research and Drug Development

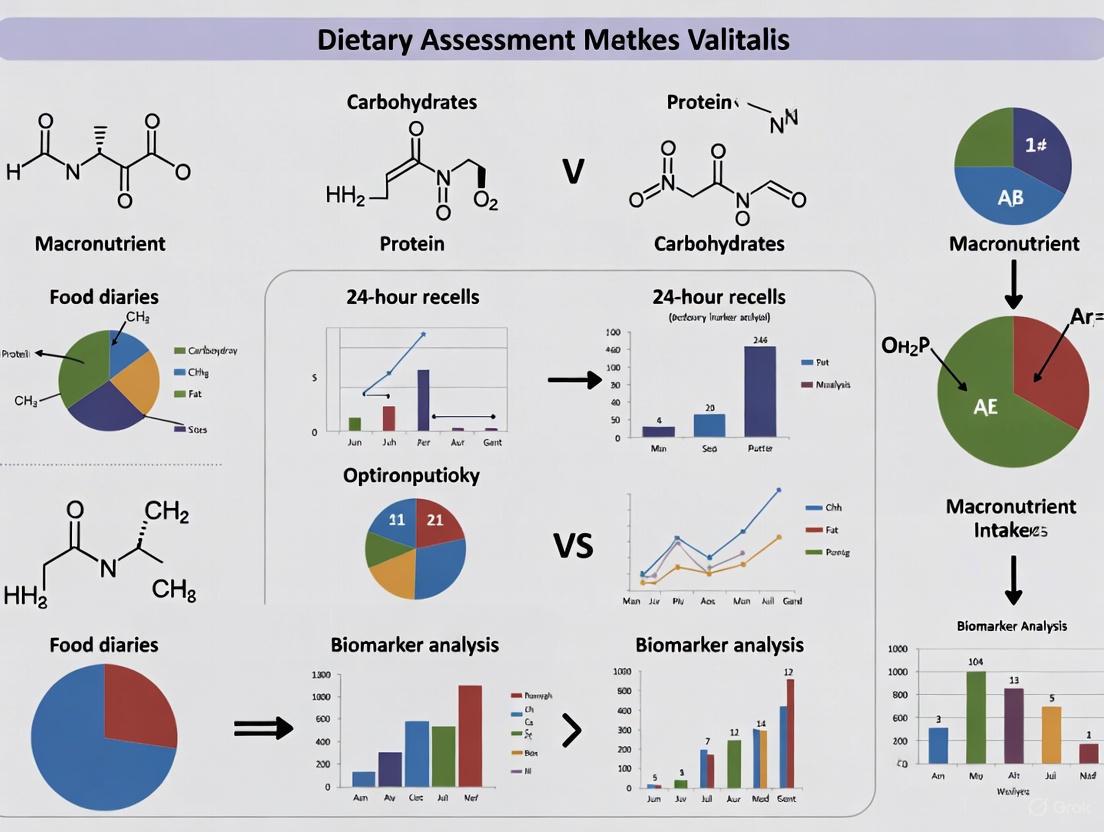

This article provides a systematic review of contemporary dietary assessment methodologies for validating macronutrient intake, tailored for researchers and drug development professionals.

Validating Macronutrient Intake: A Comprehensive Guide to Dietary Assessment Methods for Research and Drug Development

Abstract

This article provides a systematic review of contemporary dietary assessment methodologies for validating macronutrient intake, tailored for researchers and drug development professionals. It explores the evolution from traditional, error-prone methods to advanced artificial intelligence and biomarker-based approaches. The content covers foundational principles, practical applications of novel technologies, strategies to overcome common validation challenges, and comparative analyses of method accuracy. By synthesizing recent evidence from validation studies and meta-analyses, this guide aims to equip professionals with the knowledge to select appropriate methodologies, interpret validation data critically, and implement robust dietary assessment protocols in clinical and research settings to enhance data reliability in nutrition-related studies and pharmaceutical development.

Foundations of Dietary Assessment: Understanding Traditional Methods and Their Limitations in Macronutrient Validation

The Critical Role of Accurate Macronutrient Data in Clinical Research and Drug Development

Accurate macronutrient data serves as the cornerstone of high-quality clinical research, particularly in studies investigating the links between diet, health outcomes, and therapeutic efficacy. In the context of drug development, precise quantification of carbohydrate, protein, and fat intake is essential for understanding how nutritional status influences drug metabolism, patient responsiveness, and treatment outcomes. The integrity of this data directly impacts the validity of research findings and subsequent public health recommendations. Despite technological advancements, significant challenges persist in dietary assessment methodology, with studies consistently revealing systematic underestimation of energy and macronutrient intake across various assessment tools [1]. Recent research demonstrates that even when following identical dietary guidelines, the degree of food processing significantly impacts weight loss and body composition outcomes, underscoring the critical importance of data quality beyond basic macronutrient matching [2]. This application note provides a comprehensive framework for validating macronutrient data in clinical research settings, featuring structured protocols, analytical tools, and evidence-based methodologies to enhance data integrity across study designs.

Quantitative Landscape: Current Evidence on Macronutrient Assessment Accuracy

Table 1: Validation Metrics for Dietary Assessment Methods from Recent Evidence

| Assessment Method | Energy Validation (vs. Reference) | Macronutrient Correlation | Key Limitations | Context of Validation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AI-Based Methods | Correlation >0.7 in 6/13 studies [3] | Correlation >0.7 for macronutrients in 6/13 studies [3] | Moderate risk of bias in 61.5% of studies; mostly preclinical settings [3] | Systematic review of 13 studies (2017-2024) [3] |

| Dietary Record Apps | Pooled effect: -202 kcal/d (95% CI: -319, -85) [1] | Carbohydrates: -18.8 g/d; Fat: -12.7 g/d; Protein: -12.2 g/d [1] | High heterogeneity (I²=72%); learning effects not controlled [1] | Meta-analysis of 11-14 studies (2013-2019) [1] |

| Standardized Diet Histories | Moderate-good agreement for specific nutrients (kappa K=0.48-0.68) [4] | Varies by nutrient and population | Recall bias, social desirability bias, interviewer effects [4] | Eating disorder outpatient clinic (n=13) [4] |

| Controlled Feeding Trials | Direct measurement via provided diets [2] | Direct control and manipulation | High resource burden; limited generalizability | RCT comparing UPF vs. MPF diets (n=55) [2] |

Impact of Data Quality on Clinical Outcomes

The UPDATE randomized controlled trial provides compelling evidence about how data quality and food characterization beyond basic macronutrients significantly impact clinical outcomes. When diets were matched according to the UK Eatwell Guide standards, the minimally processed food (MPF) diet resulted in significantly greater weight loss (-2.06% vs. -1.05%, P=0.024) and superior improvements in body composition compared to the ultra-processed food (UPF) diet, despite nearly identical macronutrient profiles [2]. This finding has profound implications for drug development trials where weight changes might confound assessment of therapeutic efficacy. Additionally, the MPF diet led to significantly greater reductions in fat mass (-0.98 kg, P=0.004), body fat percentage (-0.76%, P=0.010), and triglycerides (-0.25 mmol l⁻¹, P=0.004) compared to the UPF diet [2]. These outcomes demonstrate that conventional macronutrient tracking alone is insufficient for predicting metabolic responses and that the quality and processing characteristics of food must be incorporated into high-quality nutritional assessment.

Methodological Framework: Protocols for Macronutrient Validation

Protocol 1: Controlled Feeding Trial Design for Macronutrient Validation

Objective: To establish causal relationships between precisely controlled macronutrient interventions and clinical outcomes while minimizing participant reporting bias.

Experimental Workflow:

Procedural Details:

- Participant Selection: Recruit adults with BMI ≥25 to <40 kg/m² and habitual ultra-processed food intake ≥50% of calories to ensure relevance to target populations [2]

- Dietary Protocol Development: Formulate both experimental and control diets to adhere to national dietary guidelines (e.g., UK Eatwell Guide) with careful matching of presented energy density, macronutrients, and fiber while varying only the degree of food processing [2]

- Blinding and Compliance: Implement single-blinding where participants are unaware of the primary outcome being measured; use dietitian consultations to enhance adherence and monitor compliance through regular check-ins [5]

- Outcome Assessment: Measure primary outcome (percent weight change) and secondary outcomes (body composition, cardiometabolic biomarkers, appetite measures) at baseline and 8-week endpoints using standardized protocols and calibrated equipment [2]

Key Quality Controls:

- Use identical nutrient analysis software/databases for both diet development and assessment

- Maintain diet consistency through centralized food preparation or detailed provision protocols

- Implement quality control checks for anthropometric measurements across all study timepoints

Protocol 2: AI-Assisted Dietary Assessment Validation Framework

Objective: To validate artificial intelligence-based dietary intake assessment (AI-DIA) methods against traditional dietary assessment and biomarker reference standards.

Experimental Workflow:

Procedural Details:

- Technology Selection: Choose AI-DIA methods incorporating deep learning (46.2% of validated methods) or machine learning (15.3%) approaches for food recognition, portion size estimation, and nutrient analysis [3]

- Reference Standards: Employ multiple reference standards including weighed food records, 24-hour recalls, and biomarkers (doubly labeled water for energy, urinary nitrogen for protein) to address different types of measurement error [1]

- Study Settings: Conduct validation in both preclinical (controlled) and clinical (free-living) settings to assess performance across different conditions; 61.5% of current evidence comes from preclinical settings [3]

- Statistical Analysis: Calculate correlation coefficients (target >0.7 for macronutrients), mean differences, error decomposition, and appropriate agreement statistics (ICC, kappa) based on the reference standard used [3] [1]

Key Quality Controls:

- Control for order effects by randomizing the sequence of assessment methods

- Account for learning effects with adequate training and practice sessions

- Ensure identical nutrient databases between compared methods when evaluating technology performance alone

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Macronutrient Validation Research

| Category | Specific Tool/Solution | Function in Macronutrient Research | Evidence Base |

|---|---|---|---|

| AI-Based Dietary Assessment | Food Recognition Assistance and Nudging Insights [3] | Automated food identification and portion size estimation from images | Validation studies showing correlation >0.7 for energy and macronutrients [3] |

| Controlled Diet Formulation | Eatwell Guide-Compliant Diet Patterns [2] | Standardized reference diets for intervention studies | RCT demonstrating significant clinical differences between MPF and UPF versions [2] |

| Biomarker Reference Methods | Doubly Labeled Water (DLW) [1] | Objective measure of total energy expenditure for energy intake validation | Recommended as reference standard in validation studies [1] |

| Body Composition Analysis | Bioelectrical Impedance Analysis [2] | Tracking changes in fat mass, muscle mass, and body water in response to interventions | Detected significant differences between diet groups in RCT [2] |

| Nutrient Database Management | Standardized Food Composition Tables [1] | Consistent nutrient calculation across assessment methods | Reduces heterogeneity in validation studies (I² from 72% to 0%) [1] |

| Dietary Intake Software | GB HealthWatch, mediPIATTO [3] | Traditional dietary assessment with comprehensive nutrient analysis | Used as comparators in AI-DIA validation studies [3] |

Advanced Applications: Integrating Precision Nutrition into Clinical Trials

Protocol 3: Personalized Nutrition Approach for Clinical Trial Stratification

Objective: To implement nutrigenomic and metabolomic profiling for participant stratification in clinical trials, enhancing detection of intervention effects through reduced inter-individual variability.

Methodological Framework:

Procedural Details:

- Participant Characterization: Collect genomic data (nutrient-related polymorphisms), pre-intervention metabolomic profiles, gut microbiome composition, and baseline response tests (postprandial glucose and triglyceride measurements) [6]

- Stratification Algorithm: Apply machine learning algorithms to identify clusters of participants with similar metabolic characteristics and predicted nutritional responses based on the PREDICT-1 study methodology (achieving r=0.77 for glycemic response prediction) [6]

- Trial Design: Incorporate stratified randomization to ensure balanced representation of different nutritional response phenotypes across study arms, or intentionally enrich for specific subgroups most likely to respond to the nutritional intervention

- Outcome Analysis: Conduct both intention-to-treat analyses and pre-specified subgroup analyses based on nutritional phenotypes to identify heterogeneous treatment effects

Implementation Considerations:

- The heritability of postprandial blood glucose responses is approximately 48%, highlighting the significant influence of genetic factors on nutritional responses [6]

- Integrate continuous glucose monitors and other wearable sensors for real-time response monitoring in free-living participants

- Plan for sufficient sample size to power subgroup analyses, as nutritional response clusters may represent smaller proportions of the general population

The critical role of accurate macronutrient data in clinical research and drug development demands rigorous validation frameworks, appropriate technology selection, and careful attention to methodological details. Evidence from controlled feeding trials demonstrates that even with matched macronutrient profiles, food processing characteristics significantly influence clinical outcomes including weight loss, body composition, and cardiometabolic risk factors [2]. Emerging technologies such as AI-based dietary assessment show promise with correlation coefficients exceeding 0.7 for energy and macronutrients in nearly half of validation studies, though concerns about bias and predominance of preclinical evidence remain [3]. Traditional dietary apps consistently demonstrate underestimation of energy (-202 kcal/d) and macronutrient intake, highlighting the need for improved assessment methods [1]. The integration of precision nutrition approaches—incorporating genetic, metabolic, and microbiome profiling—offers exciting opportunities to reduce variability and enhance signal detection in nutrition-focused clinical trials [6]. By implementing the structured protocols, validation methodologies, and analytical frameworks presented in this application note, researchers can significantly strengthen the quality and impact of macronutrient data in clinical research and drug development programs.

Accurate assessment of dietary intake is fundamental to nutritional epidemiology, clinical nutrition, and public health policy. The validity of data linking diet to health outcomes and the effectiveness of dietary interventions hinges on the precision of the methods used to measure nutritional exposure [7]. Among the most established dietary assessment tools are the traditional methods: food records, 24-hour dietary recalls (24HR), and food frequency questionnaires (FFQs). Each method possesses distinct strengths, limitations, and optimal applications, particularly in the context of macronutrient intake validation research [7] [8].

This systematic review synthesizes current evidence on these three cornerstone methodologies. It provides a comparative analysis of their utility in measuring energy and macronutrient intake, detailed experimental protocols for their application, and visual workflows to guide researchers in selecting and implementing the most appropriate method for their specific scientific inquiries in drug development and nutritional validation research.

Comparative Analysis of Traditional Dietary Assessment Methods

The choice of a dietary assessment method is critical and depends on the research question, study design, sample characteristics, and required precision [7]. Table 1 summarizes the core characteristics, while Table 2 provides a quantitative summary of method performance from validation studies.

Table 1: Core Characteristics of Traditional Dietary Assessment Methods

| Feature | 24-Hour Dietary Recall (24HR) | Food Record | Food Frequency Questionnaire (FFQ) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Purpose | Detailed intake for a specific past day [9] | Comprehensive recording of current intake [7] | Assessment of habitual intake over a long period (months to a year) [7] [10] |

| Time Frame | Short-term (previous 24 hours) [7] | Short-term (typically 3-4 days) [7] | Long-term (habitual intake) [7] [10] |

| Data Collection | Interviewer-administered or automated self-administered [7] [9] | Self-administered by participant [7] | Typically self-administered, can be interviewer-administered [7] [10] |

| Memory Reliance | Specific memory [9] | No memory requirement (prospective) [9] | Generic memory [9] |

| Participant Burden | Moderate (30-60 min per recall) [9] | High (requires literacy and motivation) [7] | Low to Moderate (once completed) [7] |

| Researcher Burden | High (training, interview, coding) [7] | Low to Moderate (data checking and coding) | Low (data processing only) [7] |

| Major Error Type | Random (day-to-day variation) [7] [9] | Random and Systematic (reactivity) [7] | Systematic (measurement error) [7] [9] |

| Reactivity Potential | Low (unannounced) [9] | High (may alter diet for ease of recording) [7] | Low [7] [9] |

Table 2: Quantitative Performance in Macronutrient Validation Studies

| Method | Comparison Standard | Energy Correlation/ Difference | Macronutrient Correlation/ Difference | Key Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Food Record | Doubly Labeled Water (DLW) | Significant under-reporting common [8] | Variable under-reporting | Considered less biased than FFQ but prone to reactivity [7] [8] |

| 24-Hour Recall | Doubly Labeled Water (DLW) | Least biased estimator; under-reporting still occurs [7] [8] | Macronutrients more stable than vitamins/minerals [7] | Multiple non-consecutive recalls required to estimate usual intake [7] [9] |

| FFQ | Multiple 24HRs | Correlations ~0.57-0.63 for energy [10] | Correlations: Protein (0.56-0.62), Lipids (0.51-0.55), Carbs (0.42-0.51) [10] | Effective for ranking individuals by intake rather than measuring absolute intake [7] [10] |

| Digital Food Record Apps | Traditional Food Records | Pooled mean difference: -202 kcal/day (underestimation) [1] | Underestimation: Carbs (-18.8 g/d), Fat (-12.7 g/d), Protein (-12.2 g/d) [1] | Heterogeneity decreases when using consistent food composition databases [1] |

Detailed Methodological Protocols

The 24-Hour Dietary Recall (24HR) Protocol

The 24HR is a structured interview designed to capture detailed information about all foods and beverages consumed by a respondent in the previous 24-hour period [9].

Application Note: The 24HR is ideal for obtaining detailed, quantitative data on recent intake at the group or population level. It is well-suited for cross-sectional studies like the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) and for use as a reference instrument to validate other dietary tools like FFQs [7] [9]. Its open-ended nature allows it to capture a wide variety of foods.

Step-by-Step Protocol:

- Recruitment & Scheduling: Recruit participants and schedule the interview. Unannounced recalls are preferred to minimize reactivity and changes to usual diet [9].

- Initial Briefing: Obtain informed consent. Explain the purpose is to collect a detailed list of all foods and drinks consumed from midnight to midnight the previous day.

- The Interview - Automated Multiple-Pass Method (AMPM): This method uses multiple passes to enhance completeness and accuracy [9].

- Pass 1 - Quick List: The respondent lists all foods and beverages consumed the previous day without interruption.

- Pass 2 - Forgotten Foods: The interviewer uses specific probes to cue memories for commonly forgotten items (e.g., sweets, beverages, snacks, condiments).

- Pass 3 - Time and Occasion: For each item, the interviewer collects the time of consumption and the name of the eating occasion.

- Pass 4 - Detail Cycle: The interviewer probes for detailed descriptions of each food (e.g., preparation method, brand names, additions like fats and sugar) and precise portion sizes using visual aids like food models, pictures, or household measures.

- Pass 5 - Final Review: The interviewer summarizes the entire recall for the respondent to verify completeness and accuracy.

- Data Management: Audio-record the interview (with permission) for quality control. Code the data using a linked nutrient composition database (e.g., Food Patterns Equivalents Database - FPED) and food composition database. Automated systems like ASA24 can handle most coding [9].

- Repeat Administration: To account for day-to-day variation and estimate usual intake, collect multiple 24HRs (at least two) on non-consecutive, random days for each participant [7] [9].

The following workflow visualizes the standardized 5-pass protocol:

The Food Record Protocol

The food record, or diet diary, is a prospective method where the participant records all foods, beverages, and supplements consumed as they are consumed [7].

Application Note: Food records provide highly quantitative data and are considered a strong reference method, though they are subject to reactivity. They require a literate, cooperative, and motivated population. Typically, 3-4 days of recording (including both weekdays and weekend days) are used to account for daily variation without overburdening participants [7].

Step-by-Step Protocol:

- Participant Training: Conduct a comprehensive training session. Train participants to:

- Record items immediately before or after consumption.

- Describe foods in detail (brands, cooking methods, recipes).

- Estimate portion sizes accurately using provided tools (digital scales, measuring cups, spoons, or photographic aids). Weighed records are the gold standard.

- Record time of day and eating occasion.

- Note any leftovers or forgotten items.

- Recording Period: Provide a structured diary (paper or digital) and portion size estimation tools. Define the recording period (e.g., 3-4 consecutive days).

- Real-Time Data Entry: Participants record all dietary intake in real-time throughout the designated period.

- Diary Review and Clarification: Upon completion, a researcher reviews the diary with the participant to clarify entries, resolve ambiguities, and fill in any missing details.

- Data Processing: Code the dietary data using a suitable nutrient composition database. Recipe ingredients must be disaggregated.

- Participant Training: Conduct a comprehensive training session. Train participants to:

The Food Frequency Questionnaire (FFQ) Protocol

An FFQ is designed to capture an individual's usual intake over a long period by asking about the frequency of consumption from a fixed list of food items [7] [10].

Application Note: FFQs are cost-effective for large-scale epidemiological studies where the goal is to rank individuals by their intake rather than measure absolute intake. They can be semi-quantitative (including portion sizes) or qualitative (using assumed portion sizes) [7]. Their validity is highly dependent on being tailored to the specific population's diet [10] [11].

Step-by-Step Protocol:

- Questionnaire Selection/Development: Select or develop an FFQ with a food list that reflects the dietary habits of the target population and includes major sources of the macronutrients of interest [10] [11]. For the PERSIAN Cohort, a 113-item semi-quantitative FFQ was developed and validated [10].

- Administration: The FFQ can be self-administered or interviewer-administered. Provide clear instructions at the beginning.

- Frequency Response: For each food item, the participant indicates their usual frequency of consumption over the reference period (e.g., the past year) using categories such as "never," "1-3 times per month," "once a week," "2-4 times per week," "daily," etc. [10].

- Portion Size Estimation: For semi-quantitative FFQs, the participant selects a usual portion size from predefined options (e.g., small, medium, large) often accompanied by photographs or common household measures [10] [11].

- Data Processing: FFQ responses are converted to daily intake amounts for each food item. These are then linked to a nutrient database to compute average daily nutrient intakes.

The high-level decision process for selecting the appropriate traditional method is summarized below:

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Reagents & Materials

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Tools for Dietary Assessment Validation

| Item | Function & Application | Examples & Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Nutrient Composition Database | Converts reported food consumption into estimated nutrient intakes. Critical for all methods. | USDA FoodData Central; country-specific databases (e.g., Palestinian Food Atlas [12]). Must be compatible with the dietary assessment tool. |

| Food Patterns Equivalents Database (FPED) | Converts foods into guidance-based food groups (e.g., cups of fruit, tsp of added sugars). | Used with USDA dietary data to assess adherence to dietary guidelines [9]. |

| Visual Portion Size Aids | Standardizes the estimation of food amounts by participants and interviewees. | Food models, photographs, atlases, or household utensils (cups, spoons). Essential for 24HR and food records [10] [12]. |

| Automated 24HR System | Standardizes the interview process, reduces interviewer burden, and automates data coding. | ASA24 (Automated Self-Administered 24-hour recall) [7] [9]. |

| Validated FFQ | A population-specific questionnaire to assess habitual diet. | Must be developed and validated for the target population (e.g., PERSIAN Cohort FFQ [10], DIGIKOST-FFQ [13]). |

| Recovery Biomarkers | Objective, non-self-report measures to validate energy and specific nutrient intake. | Doubly Labeled Water (DLW) for energy; urinary nitrogen for protein; urinary sodium/potassium [7] [8]. Considered the gold standard for validation. |

Food records, 24-hour recalls, and FFQs each provide a unique lens through which to view dietary intake, and the choice among them should be a deliberate one dictated by the research question and constraints. The 24HR generally offers the least biased estimate for group-level energy and macronutrient intake, the food record provides high detail at the cost of high participant burden, and the FFQ enables efficient ranking of individuals by habitual intake in large-scale studies. The ongoing integration of technology, such as automated self-administered tools and image-based methods, promises to reduce burden and error, further refining the accuracy of macronutrient validation research [1] [12]. A critical best practice is to always use a method validated for the specific population under study and to account for the pervasive issue of under-reporting, particularly for energy intake.

Accurate dietary assessment is fundamental to validating macronutrient intake in clinical and research settings. However, self-reported dietary data are compromised by inherent methodological limitations including recall bias, measurement errors, and significant participant burden [14]. These challenges persist across diverse populations, from athletes to adolescents, and despite advancements in technology-assisted methods [15] [16]. Understanding the nature, magnitude, and mitigation strategies for these limitations is crucial for researchers and drug development professionals interpreting dietary data or designing nutritional intervention studies. The reliability of macronutrient validation research directly depends on recognizing how these factors influence data quality and subsequent health outcome associations.

Quantitative Evidence of Assessment Limitations

Empirical studies consistently demonstrate systematic errors across various dietary assessment methods. The following tables summarize key quantitative findings on reliability, validity, and misreporting from recent research.

Table 1: Validity and Reliability of Digital Dietary Assessment Tools in Specific Populations

| Tool/Population | Nutrients with Poor Validity | Nutrients with Good Validity | Reliability Findings | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MyFitnessPal (Canadian Endurance Athletes) | Total energy, carbohydrates, protein, cholesterol, sugar, fibre [15] | Not applicable | Low inter-rater reliability for sodium and sugar; differences driven by gender [15] | [15] |

| Cronometer (Canadian Endurance Athletes) | Fibre, Vitamins A & D [15] | All other nutrients assessed [15] | Good to excellent inter-rater reliability for all nutrients [15] | [15] |

| myfood24 (Healthy Danish Adults) | Energy (ρ=0.38 vs. TEE), Protein (ρ=0.45), Potassium (ρ=0.42) [17] | Folate (ρ=0.62 with serum folate) [17] | Strong reproducibility (ρ ≥ 0.50) for most nutrients; lower for fish (ρ=0.30) and Vitamin D (ρ=0.26) [17] | [17] |

Table 2: Common Sources and Magnitude of Dietary Assessment Errors

| Error Type | Primary Sources | Impact on Data Quality | Evidence |

|---|---|---|---|

| Systematic Misreporting | Social desirability bias, memory-related bias, reactivity bias [16] | Underestimation of energy intake; macronutrient skewing [16] | 87% of adults classified as "acceptable reporters" via Goldberg cut-off; indicates 13% significant misreporting [17] |

| Database Errors | Use of non-verified user entries (e.g., MFP), varying fortification practices, brand differences [15] | Inaccurate micronutrient and macronutrient profiling [15] | CRO's use of verified databases (CNF, USDA) resulted in superior validity vs. MFP's user-uploaded entries [15] |

| Recall & Memory Bias | Long recall windows (e.g., 24-hr), complex meals, irregular eating patterns in adolescents [16] | Incomplete food item recall, inaccurate portion size estimation [14] [16] | Shorter recall windows (2-hr, 4-hr) proposed to reduce memory reliance in ecological momentary assessment [16] |

| Participant Burden | Weighed food records, prolonged recording periods, complex tracking interfaces [18] [16] | Low compliance rates, reactivity (altered diet during assessment) [16] | High burden methods (e.g., weighed records) require high participant motivation; leads to dropout or non-representative intake [16] |

Experimental Protocols for Mitigation and Validation

To counteract these limitations, researchers have developed robust protocols that integrate technology and methodological rigor. The following sections detail specific experimental approaches.

Protocol for Evaluating a Digital Dietary Assessment Tool

This protocol, adapted from a study evaluating the Traqq app among adolescents, provides a framework for validating digital tools against reference methods [16].

Objective: To quantitatively evaluate the accuracy, usability, and user perspectives of a digital dietary assessment app using repeated short recalls in a specific population.

Study Design: A mixed-methods approach spanning multiple phases.

- Phase 1 (Quantitative Evaluation): Participants download the target app and complete a demographic questionnaire. Dietary intake is assessed via the app on multiple random, non-consecutive days, employing varying recall windows (e.g., 2-hour and 4-hour recalls). Reference methods, such as interviewer-administered 24-hour recalls and a Food Frequency Questionnaire (FFQ), are conducted in parallel. Usability is evaluated using standardized scales (e.g., System Usability Scale) and an experience questionnaire.

- Phase 2 (Qualitative Evaluation): Semi-structured interviews are conducted within a subsample of participants to explore user experiences in depth.

- Phase 3 (Co-creation): Based on the analyzed data, co-creation sessions are held with participants to inform app customization and improve suitability for the target population.

Key Methodological Considerations:

- Recruitment: Target sample size of ~100 participants, stratified by age or other relevant demographics.

- Reference Methods: Use multiple methods (e.g., 24-hour recalls, FFQ, biomarkers) to triangulate validity.

- Blinding: Raters inputting food records into different tools should be blinded to each other's inputs to minimize bias [15].

- Data Analysis: Compare estimated intakes from the target app with reference methods using correlation analyses, Bland-Altman plots for assessing bias, and statistical tests for agreement.

Protocol for Validation Against Dietary Biomarkers

This protocol uses objective biomarkers to assess the validity and reproducibility of a dietary assessment tool, minimizing reliance on self-report [17].

Objective: To assess the validity and reproducibility of a dietary assessment tool against dietary intake biomarkers in a healthy adult population.

Study Design: A repeated cross-sectional study.

- Visits: The study includes an information meeting, a screening visit, and two main study visits (V1 at baseline, V2 at week 5).

- Dietary Assessment: Participants complete a 7-day weighed food record (WFR) using the target tool (e.g., myfood24) before both V1 and V2.

- Biomarker Collection: On the final day of each WFR, participants collect a 24-hour urine sample (for biomarkers like urea and potassium). At V1 and V2, fasting blood samples are drawn (e.g., for serum folate), and resting energy expenditure is measured via indirect calorimetry.

- Anthropometrics: Body weight and height are measured to ensure weight stability (e.g., deviation <2.5% between visits), confirming adherence to habitual diet.

Key Methodological Considerations:

- Biomarker Selection: Choose biomarkers with established relationships to dietary intake (e.g., urinary nitrogen for protein, serum folate for fruit/vegetable intake) [17].

- Standardization: Provide kitchen scales and detailed instructions for weighed food records and urine collection.

- Reproducibility Analysis: Assess tool reliability by comparing nutrient intakes from the first and second WFRs using correlation analyses.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents and Materials

Essential materials and methodological components for conducting rigorous dietary assessment validation studies are listed below.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Dietary Validation Studies

| Item | Specification/Example | Primary Function in Research |

|---|---|---|

| Validated Digital Tool | Cronometer, myfood24, Traqq | Automated nutrient calculation from food intake records; reduces manual entry error and processing time [15] [16] [17]. |

| Reference Database | Canadian Nutrient File (CNF), USDA FNDDS, ESHA Food Processor | Provides verified, standardized nutrient profiles for foods; serves as the gold standard for validity testing [15] [19]. |

| Biomarker Assays | 24-hour Urinary Nitrogen/Potassium, Serum Folate, Doubly Labeled Water | Offers objective measures of intake for specific nutrients, independent of self-report errors [14] [17]. |

| Portion Control Aids | Kitchen Scales (Digital), Photographic Atlas, Standardized Utensils | Improves accuracy of portion size estimation, a major source of measurement error in self-reports [17]. |

| Energy Expenditure Device | Indirect Calorimetry System | Measures resting energy expenditure (REE) to apply Goldberg cut-offs for identifying misreporters of energy intake [17]. |

| Structured Questionnaires | System Usability Scale (SUS), Demographic Forms, Food Frequency Questionnaire (FFQ) | Quantifies user experience, characterizes the study population, and assesses habitual diet as a reference method [16]. |

The inherent limitations of dietary assessment are pervasive but can be managed through rigorous study design. Key strategic recommendations for researchers include:

- Tool Selection: Prioritize tools that use verified, context-specific food composition databases over those reliant on unvetted user-generated content [15].

- Method Triangulation: Combine multiple assessment methods (e.g., short recalls, biomarkers, FFQs) to counteract the weaknesses of any single approach [16] [17].

- Participant-Centric Design: Employ user-centered design and co-creation, especially for challenging populations like adolescents, to reduce burden and improve compliance and accuracy [16].

Dietary assessment is a cornerstone of nutritional science, essential for validating macronutrient intake in research and clinical practice. The field is undergoing a profound transformation, moving from subjective, memory-dependent methods toward objective, technology-enhanced approaches [20] [21]. This evolution aims to overcome long-standing limitations of traditional techniques, including recall bias, portion size misestimation, and high participant burden [22] [21]. Artificial intelligence (AI) technologies are now reshaping the dietary assessment landscape, offering unprecedented capabilities for precise food recognition, nutrient estimation, and personalized nutrition planning [23] [20]. For researchers and drug development professionals, understanding this methodological shift is crucial for designing robust studies that generate reliable, quantitative macronutrient data for clinical validation research.

Traditional Dietary Assessment Methods: Foundations and Limitations

Traditional dietary assessment methods have provided the foundation for nutritional epidemiology and clinical research for decades. These approaches rely heavily on participant memory and honesty, making them susceptible to systematic errors that can compromise data quality in validation studies [21].

Table 1: Comparison of Traditional Dietary Assessment Methods

| Method | Data Collection Approach | Key Advantages | Key Limitations | Best Use Cases |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 24-Hour Dietary Recall | Trained interviewer collects detailed information about all foods/beverages consumed in previous 24 hours [24] | Minimal participant burden; does not alter eating behavior; appropriate for diverse populations [21] | Relies heavily on memory; underreporting common; single day not representative of usual intake [21] | Population-level intake estimates; large epidemiological studies |

| Food Frequency Questionnaire (FFQ) | Self-reported frequency of consumption for specific food items over extended period (months/year) [24] | Captures long-term dietary patterns; cost-effective for large studies; automated analysis available [25] | Memory dependent; limited accuracy for absolute nutrient intake; portion size estimation challenging [25] | Ranking individuals by intake levels; studying diet-disease relationships |

| Food Records/Diaries | Detailed documentation of all foods/beverages as consumed, typically for 3-7 days [21] | Minimizes memory bias; provides quantitative data; can capture seasonal variation | High participant burden; may alter normal eating patterns; requires literacy and motivation [21] | Metabolic studies; clinical trials requiring detailed intake data |

| Diet History Interview | Comprehensive interview assessing habitual intake, food preferences, and eating patterns [22] | Provides context for dietary habits; captures complex eating behaviors | Time-intensive; requires skilled interviewer; susceptible to social desirability bias [22] | Clinical nutrition assessment; eating disorder evaluation |

The limitations of these traditional methods are particularly pronounced in validation research. Studies comparing dietary intake data against nutritional biomarkers reveal significant discrepancies. For example, research in eating disorder populations found only moderate agreement between diet history interviews and biochemical markers, with correlations varying substantially by nutrient [22]. Energy and protein intake often show systematic underreporting, especially in specific populations [21]. These measurement errors present substantial challenges for macronutrient validation studies where precision is paramount.

The Rise of Technology-Enhanced Dietary Assessment

Image-Assisted Dietary Assessment (IADA)

Image-assisted dietary assessment represents a paradigm shift from memory-based recall to visual documentation. Early systems required trained staff to analyze food images, but recent advancements have integrated artificial intelligence to automate the process [21]. The fundamental premise involves capturing images of meals before and after consumption, then using computer vision algorithms to identify foods and estimate portion sizes.

The technological evolution of IADA has progressed through distinct phases. Before 2015, systems relied on handcrafted machine learning algorithms that processed images through sequential steps: food segmentation, item identification, volume estimation, and nutrient calculation [21]. Since 2015, deep learning algorithms have dominated the field, substantially improving accuracy through convolutional neural networks. The most recent innovation involves end-to-end deep learning and multi-task learning approaches that simultaneously handle multiple aspects of dietary assessment within a single network architecture [21].

Artificial Intelligence and Machine Learning Applications

AI is revolutionizing dietary assessment across multiple dimensions, from automated food recognition to personalized nutrition recommendations. Machine learning algorithms can identify complex, non-linear relationships between dietary patterns and health outcomes that might elude traditional statistical methods [20]. These capabilities are particularly valuable for precision nutrition approaches that integrate genetic, metabolic, and behavioral data to develop individualized dietary recommendations [23].

Several AI-powered platforms demonstrate the potential of these technologies:

- goFOOD: A smartphone-based system utilizing deep learning to estimate micronutrient and energy content from food images, including support for stereo image pairs from dual-camera smartphones [20]

- VBDA (Vision-Based Dietary Assessment): Employs computer vision to automatically detect dietary details from meal images, with recent implementations using multi-task learning for comprehensive nutrient assessment [20]

- AI-Enhanced Chatbots: Provide personalized dietary guidance and tracking support, improving adherence to nutritional interventions [20]

Table 2: Technology-Enhanced Dietary Assessment Tools

| Tool/Platform | Core Technology | Output Metrics | Validation Status | Research Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| goFOOD/goFOODLITE | Deep Learning, Computer Vision | Energy, Micronutrients, Food identification | Pilot testing (n=42); 69% user satisfaction with logging features [20] | Real-time dietary tracking; nutritional epidemiology |

| VBDA Systems | Multi-task Learning, Computer Vision | Food categories, portion sizes, nutrient estimates | Laboratory validation; accuracy improvements over traditional methods [20] [21] | Food environment research; portion size estimation studies |

| Wearable Sensors | Continuous Monitoring, Bio-sensors | Glucose responses, eating episodes, energy expenditure | Varies by device; some CGM systems clinically validated | Metabolic research; personalized nutrition interventions |

| AI-Based Classification | Machine Learning, Natural Language Processing | Food processing level, diet quality scores | NHANES validation against HEI-2020 [26] | Food policy research; diet-disease association studies |

Experimental Protocols for Dietary Assessment Validation

Protocol 1: Validation of Image-Based Assessment Tools

Purpose: To validate the accuracy of AI-powered dietary assessment tools against traditional methods and direct observation.

Materials:

- Smartphone with camera or dedicated dietary assessment device

- Standardized placemats for scale reference

- Food scale (digital, precision ±1g)

- Nutrition analysis software (e.g., FNDDS, USDA database)

- AI-based dietary assessment application (e.g., goFOOD prototype)

Procedure:

- Study Setup: Recruit participants representing target population demographics. Obtain informed consent and institutional review board approval.

- Food Preparation: Prepare standardized meals with varying complexity (single foods, mixed dishes, multi-component meals).

- Image Acquisition: Capture images of each meal from multiple angles (45°, 90°) under consistent lighting conditions before consumption.

- Direct Measurement: Weigh each food component using digital scales; record exact weights and brands.

- AI Analysis: Process images through the AI dietary assessment system to generate food identification and portion size estimates.

- Traditional Assessment: Conduct 24-hour dietary recalls by trained interviewers blinded to direct measurement results.

- Data Analysis: Compare nutrient estimates from AI system and 24-hour recall against direct measurement values (ground truth).

Validation Metrics:

- Food identification accuracy (% correctly identified items)

- Portion size estimation error (mean absolute percentage error)

- Nutrient calculation accuracy (intraclass correlation coefficients)

- Systematic bias assessment (Bland-Altman analysis)

Protocol 2: Biomarker Validation of Dietary Intake

Purpose: To validate self-reported dietary intake against nutritional biomarkers in clinical populations.

Materials:

- Standardized diet history protocol [22]

- Blood collection equipment (vacutainers, centrifuge, storage tubes)

- Automated biochemical analyzer

- Nutritional biomarkers (cholesterol, triglycerides, protein, albumin, iron, hemoglobin, ferritin, TIBC, red cell folate) [22]

Procedure:

- Participant Screening: Recruit participants meeting inclusion criteria (specific clinical populations, age ranges). Exclude those with conditions affecting biomarker metabolism.

- Dietary Assessment: Administer standardized diet history by trained dietitian within 7 days of biomarker collection [22].

- Biomarker Collection: Collect fasting blood samples following standard phlebotomy procedures.

- Sample Processing: Centrifuge blood samples, aliquot serum/plasma, and store at -80°C until analysis.

- Laboratory Analysis: Process samples using validated laboratory methods for targeted nutritional biomarkers.

- Data Analysis:

- Calculate energy-adjusted nutrient intakes

- Perform Spearman's rank correlation between dietary estimates and biomarkers

- Compute kappa statistics for agreement between dietary and biomarker measures

- Conduct Bland-Altman analysis to assess systematic bias

Interpretation:

- Moderate to good agreement: kappa > 0.4 [22]

- Significant correlation: p < 0.05

- Consider confounding factors (supplement use, metabolic disorders, inflammation)

Classification Systems for Food Quality Assessment

Beyond nutrient quantification, classifying foods by quality and processing level is increasingly important in nutritional epidemiology. Several validated systems enable standardized assessment:

NOVA Classification: Categorizes foods into four groups based on processing extent: unprocessed/minimally processed, processed culinary ingredients, processed foods, and ultra-processed foods [26] [27]. While widely used, NOVA has limitations including subjective application and poor adaptation to certain cultural contexts [27].

Moderation Food Classification: A novel nutrient-based method identifying foods high in added sugars, saturated fat, refined grains, and sodium using thresholds aligned with Dietary Guidelines for Americans [26]. This system demonstrates strong validity, with moderation food intake showing high inverse correlation with Healthy Eating Index-2020 scores (r = -0.72) [26].

GR-UPFAST: A culture-specific tool developed for assessing ultra-processed food consumption in Greek populations, demonstrating good internal consistency (Cronbach's α = 0.766) and significant correlation with body weight (rho = 0.140, p = 0.039) [27].

Diagram 1: Evolution of dietary assessment methods showing transition from traditional approaches with inherent limitations to technology-enhanced solutions and future directions. The color progression indicates methodological advancement over time.

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Dietary Assessment Validation

| Resource | Type | Key Features | Application in Research |

|---|---|---|---|

| ASA24 (Automated Self-Administered 24-hour Recall) | Software Tool | Free, web-based, automated 24-hour dietary recall system [24] | Population studies; validation comparator; high-throughput data collection |

| Food and Nutrient Database for Dietary Studies (FNDDS) | Database | Comprehensive nutrient values for ~7,000 foods; linked to NHANES [19] | Nutrient calculation standardization; epidemiological research; diet-disease association studies |

| Register of Validated Short Dietary Assessment Instruments | Toolkit | Repository of validated short dietary screeners with methodological details [25] [24] | Tool selection for specific populations; validation study design; cross-study comparability |

| USDA Food Patterns Equivalents Database (FPED) | Database | Converts foods to 37 USDA Food Patterns components [19] | Diet quality assessment; adherence to dietary guidelines; policy-relevant research |

| Nutritional Biomarkers | Biochemical Assays | Objective measures of nutrient intake (cholesterol, triglycerides, iron, folate, etc.) [22] | Validation of self-reported intake; assessment of nutritional status; metabolic studies |

| Image-Assisted Dietary Assessment (IADA) | Technology Platform | AI-powered food recognition and portion estimation from images [21] | Reduced burden dietary assessment; real-time monitoring; validation of traditional methods |

The evolution of dietary assessment from memory-dependent to technology-enhanced methods represents a fundamental shift in nutritional science research methodology. While traditional tools like 24-hour recalls and food frequency questionnaires remain valuable for specific applications, AI-powered technologies offer unprecedented opportunities to improve accuracy, reduce participant burden, and capture the complexity of dietary intake [20] [21]. For researchers conducting macronutrient validation studies, the integration of multiple assessment approaches—including image-based analysis, sensor technologies, and nutritional biomarkers—provides a robust framework for generating high-quality, validated dietary data. Future advancements will likely focus on standardizing these emerging technologies, improving their accessibility across diverse populations, and further integrating multi-omics data for comprehensive nutritional assessment [23]. This methodological evolution promises to enhance the precision and reliability of nutrition research, ultimately strengthening the evidence base for dietary recommendations and clinical practice.

Accurate dietary assessment is fundamental for understanding diet-disease relationships, informing public health policy, and developing nutritional interventions [28] [7]. However, self-reported dietary intake data are notoriously subject to both random and systematic measurement errors, complicating the interpretation of research findings [7] [8]. Consequently, rigorous validation of dietary assessment methods is essential. Within the context of macronutrient intake validation research, three key methodological approaches have emerged as standard for evaluating validity: correlation coefficients to measure association strength, Bland-Altman analysis to assess agreement, and biomarker comparison for objective verification [22] [8] [29]. This document outlines the application, interpretation, and integration of these core validation metrics, providing structured protocols and benchmarks for researchers conducting validation studies of dietary assessment methods.

Core Validation Metrics: Principles and Interpretation

The validation of dietary assessment methods relies on a suite of statistical tools that evaluate different aspects of measurement performance. The table below summarizes the purpose, interpretation guidelines, and key considerations for the three primary metrics discussed in this document.

Table 1: Key Validation Metrics for Dietary Assessment Methods

| Metric | Primary Purpose | Interpretation Guidelines | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Correlation Coefficients | Quantifies the strength and direction of the association between two methods [22] [30]. | - Spearman's rho ≥ 0.5: Good to strong correlation [30].- ~0.3: Considered meaningful for validity [29].- Kappa (K) > 0.4: Moderate agreement; > 0.6 Good agreement [22]. | Does not measure agreement; sensitive to the range of intakes in the study population [22]. |

| Bland-Altman Analysis | Evaluates the agreement between two methods by analyzing the differences between them across the range of intakes [22] [30]. | - Mean Difference (Bias): Systematic over- or under-reporting.- Limits of Agreement (LoA): (Mean Difference ± 1.96SD) defines the range where 95% of differences lie.- A plot visually reveals bias, trends, and outliers. | High agreement is indicated by a mean difference near zero and narrow LoA. Plots can identify proportional bias [30]. |

| Biomarker Comparison | Provides an objective, non-self-report reference to quantify measurement error [8] [29]. | - Doubly Labeled Water (DLW): Gold standard for total energy expenditure (validation of energy intake) [8] [29].- Urinary Nitrogen: Objective measure of protein intake [29].- Poor correlation suggests method inaccuracy or physiological confounders [31]. | Considered the most rigorous validation approach but is costly, invasive, and limited to specific nutrients [7] [8]. |

Experimental Protocols for Validation Studies

Protocol for a Comprehensive Biomarker Validation Study

The following protocol, adapted from a state-of-the-art validation study, integrates all three key metrics against objective biomarkers [29].

Aim: To validate a novel dietary assessment method (e.g., Experience Sampling-based Dietary Assessment Method - ESDAM) for energy, macronutrient, and food group intake.

Design: A prospective observational study over four weeks.

Participants:

- Sample Size: Minimum of 100 participants to detect a correlation of 0.3 with 80% power and a 5% alpha error [29].

- Eligibility: Healthy adults (18-65 years), stable body weight, not pregnant/lactating, no medically prescribed diets.

Methods and Timeline:

- Weeks 1-2 (Baseline):

- Weeks 3-4 (Intervention & Biomarker Assessment):

- Participants use the novel dietary assessment method (e.g., ESDAM) for the entire period.

- Biomarker Data Collection:

- Doubly Labeled Water (DLW): Administer an oral dose of DLW. Collect urine samples on days 1, 2, 8, and 9 (or over 14 days) to measure total energy expenditure [8] [29].

- Urinary Nitrogen: Collect 24-hour urine samples (e.g., on two separate days) to estimate protein intake [29].

- Blood Samples: Collect fasting blood samples to analyze:

- Compliance Monitoring: Use blinded continuous glucose monitoring to identify eating episodes and cross-verify participant compliance with the dietary app [29].

Validation Analysis:

- Correlation Analysis: Calculate Spearman's rank correlation coefficients between nutrient intakes from the novel method and those from the 24-HDRs and biomarker values [22] [29].

- Bland-Altman Analysis: Plot the differences between the novel method and the reference methods (24-HDRs and biomarkers) against their means to assess bias and limits of agreement [22] [30].

- Method of Triads: Use this statistical technique to quantify the correlation between each of the three measurements (novel method, 24-HDR, and biomarker) and the unknown "true" intake, thereby quantifying the measurement error of each method [29].

Protocol for a Comparative Validity Study Using Biochemical Indicators

This protocol is suited for validating a Food Frequency Questionnaire (FFQ) or diet history against biochemical status indicators [22] [31].

Aim: To examine the relationship between nutrient intake assessed by a dietary tool and corresponding nutritional biomarkers in a specific clinical population.

Design: Cross-sectional secondary data analysis.

Participants:

- A targeted sample (e.g., n=100 [31] or n=13 for a pilot study [22]) of a specific population (e.g., patients with peripheral arterial disease [31] or an eating disorder [22]).

Methods:

- Dietary Assessment: Administer the FFQ or diet history to participants.

- Biomarker Measurement: Collect fasting blood samples within a close timeframe (e.g., 7 days) of the dietary assessment. Analyze for specific biomarkers (e.g., vitamins A, C, D, E, zinc, iron, iron-binding capacity, triglycerides) [22] [31].

- Data Processing: Adjust nutrient intakes for total energy intake to account for confounding by total consumption [22].

Statistical Analysis:

- Correlation: Calculate Spearman's rank correlation coefficients between energy-adjusted nutrient intakes and their corresponding serum biomarker levels [22] [31].

- Agreement Statistics: Compute simple and weighted kappa statistics to assess the agreement in quartile classification between the dietary method and biomarker [22].

- Bland-Altman Analysis: Apply the Bland-Altman method to visually and quantitatively assess the agreement between the two measures across the range of intakes [22].

Workflow and Logical Diagrams

The following diagram illustrates the logical sequence of applying validation metrics in a dietary assessment validation study.

Figure 1: A logical workflow for validating dietary assessment methods, integrating the three key validation metrics.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

The following table lists key materials and tools required for conducting rigorous dietary validation studies.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions for Dietary Validation

| Item | Function/Application | Specification Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Doubly Labeled Water (DLW) | Gold-standard biomarker for measuring total energy expenditure (TEE) to validate reported energy intake [8] [29]. | Requires precise dosing based on body weight and collection of multiple urine samples over 7-14 days. |

| Urinary Nitrogen Analysis Kits | Objective recovery biomarker for validating protein intake estimates from dietary tools [29]. | Typically requires 24-hour urine collections from participants on multiple days. |

| Serum Carotenoid Assays | Concentration biomarker used as an objective indicator for fruit and vegetable consumption [29]. | Analyzed from fasting blood samples; reflects intake over preceding weeks. |

| Erythrocyte Membrane Fatty Acid Profiling | Biomarker for assessing long-term intake of specific fatty acids (e.g., omega-3, omega-6 PUFAs) [29]. | Provides a longer-term reflection of dietary fat intake compared to plasma. |

| Validated 24-Hour Dietary Recall (24-HR) | A standard self-reported reference method for detailed, short-term dietary intake [7] [29]. | Can be interviewer-administered or automated (e.g., ASA-24). Multiple non-consecutive recalls, including weekend days, are needed [28]. |

| Statistical Software (e.g., STATA, R) | For performing correlation, kappa statistics, Bland-Altman analysis, and the method of triads [22] [29]. | Custom scripts for Bland-Altman plots and method of triads are often required. |

Advanced Methodologies in Practice: Implementing AI, Biomarkers, and Digital Tools for Macronutrient Assessment

Accurate dietary assessment is a cornerstone of nutritional epidemiology and clinical research, essential for validating macronutrient intake and understanding its link to health outcomes. Traditional methods, such as 24-hour recalls and food diaries, are often hampered by recall bias, measurement errors, and high participant burden [3] [32]. Artificial Intelligence (AI), particularly deep learning (DL) and machine learning (ML), is transforming this field by introducing automated, objective, and scalable tools for dietary assessment. These technologies enhance the precision of data collection and open new avenues for real-time monitoring and personalized nutrition research, offering powerful solutions for macronutrient intake validation studies [33] [34].

Performance Benchmarks of AI Dietary Assessment Tools

The following tables summarize the performance metrics of various AI approaches as reported in recent validation studies, providing researchers with benchmarks for tool selection.

Table 1: Performance of Image-Based Dietary Assessment AI Systems

| System / Model Name | Primary AI Technique | Key Nutrients Assessed | Reported Performance Metrics |

|---|---|---|---|

| DietAI24 [35] | Multimodal LLM with RAG | 65 nutrients & components (Macro & Micronutrients) | 63% reduction in Mean Absolute Error (MAE) for food weight & 4 key nutrients vs. baselines |

| goFOOD 2.0 [33] | Computer Vision, Deep Learning | Energy (Caloric) Intake | Moderate agreement with dietitians in real-world validation [33] |

| RGB-D Fusion Network [32] | Deep Learning (Convolutional Neural Network) | Caloric Intake | Mean Absolute Error (MAE): 15% |

| Keenoa App [3] | Not Specified | Energy, Macronutrients | Correlation >0.7 for energy and macronutrients vs. traditional methods |

| General AI-DIA Methods [3] | Deep Learning, Machine Learning | Energy, Macro- and Micronutrients | 61.5% of studies reported correlation >0.7 for energy and macronutrients |

Table 2: Performance of Non-Image-Based and Specialized AI Models

| System / Model Type | Input Data | Application / Nutrient Focus | Reported Performance Metrics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sound & Jaw Motion Model [32] | Wearable Sensor Data (Sound, Jaw Motion) | Food Intake Detection | Classification Accuracy: Up to 94% |

| ML Prediction Models [36] | Food Composition Data | Predicting Micronutrients after Cooking | 31% lower average error vs. retention-factor baseline method |

| AI Nutrition Recommender (AINR) [37] | User Profiles, Expert Rules, Meal DB | Personalized Meal Plan Accuracy | High accuracy in caloric/macronutrient suggestions, ensures diversity |

| Intelligent Diet Recommendation System [38] | Body Composition Data, ML | Personalized Diet Plans | Error rate < 3% for personalized plan recommendations |

Application Notes & Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Validation of Image-Based AI Dietary Assessment Tools

This protocol outlines the methodology for validating the accuracy of an image-based AI system (e.g., goFOOD, DietAI24) for macronutrient intake estimation against traditional dietary assessment methods [33] [3].

1. Objective: To determine the relative validity and accuracy of an AI-based dietary intake assessment (AI-DIA) tool in estimating energy and macronutrient intake compared to weighed food records or dietitian-led 24-hour recalls.

2. Materials and Reagents:

- AI-DIA Tool: A smartphone application with integrated AI for food recognition and nutrient estimation (e.g., DietAI24 [35]).

- Reference Method Materials: Digital food scales, standardized food composition database (e.g., FNDDS [35]), and data recording forms.

- Participants: A cohort of free-living adults. Sample sizes in recent studies range from 36 to 136 participants [3].

3. Experimental Procedure:

- Step 1: Study Design. A cross-sectional or randomized controlled trial design is employed where participants concurrently use the AI-DIA tool and complete the reference method for a set period (e.g., 3-7 days) [3] [37].

- Step 2: Data Collection.

- AI-DIA Method: Participants are trained to capture images of all meals and snacks before and after consumption using the smartphone app. The AI system automatically processes images for food identification, portion size estimation, and nutrient analysis [33] [35].

- Reference Method: Participants weigh and record all food and drink items consumed using provided digital scales and logs. Alternatively, a dietitian conducts a 24-hour recall using a multiple-pass method [3].

- Step 3: Data Processing. Nutrient intake data (energy, protein, fat, carbohydrates) from the AI-DIA tool and the reference method are extracted and compiled for statistical analysis.

4. Data Analysis:

- Correlation Analysis: Calculate Pearson or Spearman correlation coefficients to assess the strength of the relationship between nutrient estimates from the two methods. A correlation >0.7 is considered strong [3].

- Bland-Altman Analysis: Plot the mean differences between the two methods against their averages to evaluate bias and limits of agreement [3].

- Error Metrics: Compute Mean Absolute Error (MAE) and Root Mean Square Error (RMSE) to quantify the average magnitude of estimation errors [35].

Protocol: Development of a Personalized Nutrition Recommendation System

This protocol describes the workflow for building and validating an AI-based system that generates personalized weekly meal plans, suitable for intervention studies [37] [39].

1. Objective: To develop and technically validate an AI-based nutrition recommender (AINR) that generates balanced, personalized weekly meal plans tailored to user profiles and nutritional requirements.

2. Materials and Reagents:

- Expert-Validated Meal Database: A structured database of meals with detailed nutritional information, ideally culturally specific (e.g., Mediterranean database [37]).

- User Profile Data: Demographic information, anthropometrics (height, weight), physical activity level (PAL), health goals, allergies, and cultural preferences [37] [38].

- AI Models: A combination of knowledge-based rules (from nutritional guidelines) and machine learning or generative models (e.g., Variational Autoencoders, LLMs) [37] [39].

3. System Workflow and Validation Procedure:

- Step 1: User Profiling. The system calculates the user's Daily Energy Requirement (DER) and macronutrient targets based on entered profile data using established equations (e.g., Mifflin-St Jeor) and expert rules [37].

- Step 2: Meal Filtering and Retrieval. The system filters the meal database based on user constraints (allergies, cuisine preference) and seasonality [37].

- Step 3: Meal Plan Synthesis. An algorithm (e.g., generative model, optimizer) synthesizes daily and weekly meal plans from the filtered pool of meals. It ensures adherence to DER, macronutrient balance, food group variety, and diversity [37] [39].

- Step 4: Validation. The system's performance is evaluated on thousands of generated user profiles. Key metrics include:

- Filtering Accuracy: Percentage of meal plans that correctly exclude allergens or unwanted foods.

- Nutritional Accuracy: Difference between the total recommended energy/macronutrients in the plan and the user's calculated DER/targets. High accuracy is demonstrated by error rates <3% [38].

- Diversity and Balance: Assessment of meal repetition and adherence to food-based dietary guidelines [37].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Components for AI-Driven Dietary Assessment Research

| Component / Tool | Function / Description | Example(s) from Literature |

|---|---|---|

| Standardized Food Database | Provides authoritative, structured nutritional data for food items, essential for training AI models and converting food identifications into nutrient values. | Food and Nutrient Database for Dietary Studies (FNDDS) [35] |

| Expert-Validated Meal Database | A curated collection of meals with precise nutritional information and attributes, used for developing and testing recommendation systems. | Mediterranean Meals Database (Spanish & Turkish cuisines) [37] |

| Multimodal Large Language Model (MLLM) | An AI model that can process and understand both images and text. Used for advanced food recognition and description from meal photos. | GPT-4V (Vision) or similar models integrated via API [35] |

| Retrieval-Augmented Generation (RAG) | A technique that grounds an LLM's responses in external, authoritative databases (like FNDDS) to improve accuracy and reduce factual hallucinations. | DietAI24 Framework [35] |

| Wearable Sensors | Devices that capture passive data related to eating behaviors, such as jaw motion, wrist movement, and swallowing sounds, for objective intake monitoring. | Smartwatches, e-arbuds, or specialized wearable devices [32] [34] |

| Computer Vision Models | Deep learning models (e.g., CNNs) specifically designed for image analysis tasks, including food detection, classification, and portion size estimation. | Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) like NutriNet [3] |

| Generative AI Model | A deep learning model used to create new data instances, such as generating novel but nutritionally-sound meal combinations for personalized plans. | Variational Autoencoder (VAE) [39] |

Accurate dietary assessment is a cornerstone of nutritional epidemiology and is vital for understanding the link between dietary intake and health outcomes [3]. Traditional methods, including food records, 24-hour recalls, and food frequency questionnaires (FFQs), are susceptible to measurement errors, recall bias, and place a significant burden on participants [40] [3]. The emergence of image-based and image-assisted dietary assessment methods, powered by artificial intelligence (AI), offers a promising solution to these challenges by enhancing objectivity, simplifying the data collection process, and improving accuracy [41] [42]. This document outlines the application notes and experimental protocols for these methods within the context of macronutrient intake validation research, providing researchers and drug development professionals with the tools to implement and validate these technologies.

Image-based food recognition systems (IBFRS) typically involve several phases: food detection and segmentation in an image, classification of food items, and estimation of volume, calories, and nutrients [42]. Deep learning, particularly Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs), has become the dominant approach, often outperforming other methods, especially when trained on large, diverse datasets [43] [42].

The tables below summarize key performance metrics from recent validation studies, providing a benchmark for researchers evaluating such systems.

Table 1: Performance Metrics of Automated Food Recognition Technologies

| Technology / Study | Core Method | Identification/Classification Accuracy | Key Performance Findings |

|---|---|---|---|

| Automatic Image Recognition (AIR) App [41] | CNN-based automatic image recognition | 86% (189/220 dishes) correctly identified | Significantly higher accuracy and time efficiency compared to voice input reporting (VIR) [41]. |

| EfficientNetB7 with Lion Optimizer [43] | Deep learning model on a 32-class food dataset | 99% accuracy (32-class) | Mean Absolute Error (MAE): 0.0079; Mean Squared Error (MSE): 0.035; Root Mean Squared Error (RMSE): 0.18 [43]. |

| Photo-Assisted Dietary (PAD) Intake Assessment [40] | Image-assisted with standardized food atlas | N/A | Demonstrated significantly higher consistency with weighed food records than 24-hour recall for cereals, vegetables, and meats (P < 0.05) [40]. |

Table 2: Correlation of AI-Based Methods with Traditional Assessment for Nutrient Estimation

| Nutrient Type | Number of Studies with Correlation >0.7 | Example Traditional Reference Method |

|---|---|---|

| Calories | 6 out of 13 studies [3] | 3-day food diary, weighed food records [3] |

| Macronutrients | 6 out of 13 studies [3] | 3-day food diary, weighed food records [3] |

| Micronutrients | 4 out of 13 studies [3] | 3-day food diary, weighed food records [3] |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Validation of an Automatic Image Recognition (AIR) App

This protocol is adapted from a randomized controlled trial evaluating an AIR app against a voice-input control in a young adult population [41].

- Objective: To assess the reporting accuracy, time efficiency, and user perception of an AIR mobile application compared to a voice input reporting (VIR) application under authentic dining conditions.

- Materials:

- Smartphones (standardized model and operating system, e.g., Android).

- AIR and VIR applications installed on the devices.

- A predefined menu (e.g., 17 dishes) representing a typical meal (one staple, one main course, three side dishes).

- Data collection server for image processing.

- Participant Recruitment:

- Recruit a cohort (e.g., n=42) from the target population (e.g., young adults aged 20-25).

- Randomly assign participants to the AIR (n=22) and VIR (n=20) groups.

- Procedure:

- Provide all participants with the same type of smartphone with the assigned app installed.

- Present each participant with the standardized test meal.

- Instruct participants to use their assigned app to report all dishes in the meal.

- For the AIR group: Participants capture a single image of the entire meal. The app automatically recognizes dishes, and users select the correct name from suggestions or use voice input for unrecognized items. They then confirm and input portion sizes and cooking methods.

- For the VIR group: Participants capture an image of the meal and then use voice input to report food names, portion sizes, and cooking methods for each dish sequentially.

- Record the time taken to complete the reporting for each participant.

- Data Analysis:

- Accuracy: Calculate the percentage of dishes correctly identified and reported in each group. Compare groups using statistical tests (e.g., t-test, P < 0.05).

- Time Efficiency: Compare the mean time to complete reporting between groups using statistical tests.

- User Perception: Administer the System Usability Scale (SUS) to both groups and compare scores.

Protocol 2: Implementing a Photo-Assisted Dietary (PAD) Intake Assessment

This protocol is based on a study validating a PAD method against the gold-standard weighing method in a cafeteria setting [40].

- Objective: To validate the accuracy and feasibility of a PAD method for estimating food weight in a free-living population.

- Materials:

- Standardized set of bowls with known dimensions (e.g., base area 120 cm², varying heights for different food types).

- A pre-developed food atlas containing images of ~70 food items in the standardized bowls from multiple angles (top, 45°).

- Participants' smartphones with a communication app (e.g., WeChat).

- Digital food scales (for validation phase).

- Participant Recruitment:

- Recruit participants from the target populations (e.g., college students, n=76; elderly individuals, n=121) to assess feasibility across groups.

- Procedure for Validation Study:

- In a controlled cafeteria setting, provide participants with a buffet-style dinner served in the standardized bowls.

- Instruct participants to capture photos of their food before and after consumption.

- Weigh each food item served to and leftover by each participant using digital scales (weighing method).

- The following day, conduct a 24-hour recall with the participants for comparison.

- Trained dietary assessors, blinded to the weighed data, use the food atlas to estimate the volume and then the mass of each food item from the photos.

- Data Analysis:

- Accuracy: Compare the food mass estimated via PAD and 24-hour recall to the mass from the weighing method. Calculate absolute and relative differences (D%). Use Bland-Altman analysis to assess limits of agreement.

- Feasibility: Report the proportion of participants who successfully completed the PAD recording and analyze feedback from questionnaires.

Protocol 3: Enhancing Adherence with Tailored Prompting

This protocol provides a methodology for improving user adherence in image-based dietary records, a critical factor for data quality [44].

- Objective: To evaluate the effect of tailored text message prompts on adherence to an image-based dietary record.

- Materials:

- Image-based dietary recording app (e.g., Easy Diet Diary).

- Text messaging system for sending prompts.

- Participant Recruitment:

- Recruit participants (e.g., n=37) meeting inclusion criteria (adults with smartphone and internet access).

- Procedure:

- Baseline: Participants complete a 3-day text-based dietary record to establish habitual meal times.

- Randomization: Participants are randomized to one of six study sequences, each with a unique order of three prompt conditions:

- Control: No prompts.

- Standard: Prompts sent at fixed times (e.g., 7:15 AM, 11:15 AM, 5:15 PM).

- Tailored: Prompts sent 15 minutes before each participant's individual habitual meal times, derived from the baseline record.

- Intervention: Participants complete multiple 3-day image-based dietary records, each separated by a 7-day washout period. They receive prompts according to the condition for that period.

- Data Collection: The number of images captured per participant per day is automatically logged.

- Data Analysis:

- Use linear mixed-effects models to analyze the effect of prompt setting on the image capture rate (images/day), accounting for participant effects and study order.

Workflow Diagrams

Adherence Study Workflow with Tailored Prompting

Automated Image Recognition (AIR) App User Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials and Tools for Image-Based Dietary Assessment Research

| Item | Function/Description | Example/Specification |

|---|---|---|

| Standardized Serveware | Provides visual cues for portion size estimation via a food atlas. Critical for volume-to-mass conversion. | Bowls with identical base area (e.g., 120 cm²) but varying heights for different food types (e.g., staples, meats) [40]. |

| Pre-Developed Food Atlas | A reference image library used by trained assessors to identify foods and estimate volumes from participant photos. | Contains ~150 images of 70+ food items, photographed from multiple angles (overhead, 45°) in standardized serveware [40]. |

| Deep Learning Model Architectures | The core AI engine for automatic food detection and classification from images. | Architectures such as ResNet50, EfficientNetB5-B7, and CNN-based models, often pre-trained on large datasets like ImageNet [41] [43] [42]. |

| Publicly Available Food Datasets (PAFDs) | Used for training and validating food recognition algorithms. Requires diversity and scale. | Datasets with tens of thousands of images across dozens or hundreds of food classes, often including mixed dishes [43] [42]. |

| Data Augmentation Pipeline | A software process to artificially expand training datasets, improving model robustness and reducing overfitting. | Includes image transformations: rotation (±10-15°), translation, shearing, zooming, and brightness/contrast adjustment [43]. |