Validating Geographical Origin Tracing Methods: Analytical Techniques, Machine Learning, and Future Directions for Food Authenticity

This article provides a comprehensive overview of modern analytical methods for validating the geographical origin of foods, a critical concern for researchers, scientists, and professionals combating food fraud.

Validating Geographical Origin Tracing Methods: Analytical Techniques, Machine Learning, and Future Directions for Food Authenticity

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of modern analytical methods for validating the geographical origin of foods, a critical concern for researchers, scientists, and professionals combating food fraud. It explores the foundational principles of geographical indications (GIs) and the urgent need for robust traceability. The scope encompasses a detailed examination of established and emerging techniques—including elemental profiling, stable isotope analysis, DNA-based methods, and spectroscopy—and their integration with advanced chemometrics and machine learning for data analysis. Further, it addresses key challenges in method implementation and optimization, and provides a framework for the systematic validation and comparison of different analytical approaches, ultimately aiming to enhance food safety, ensure regulatory compliance, and protect consumer trust.

The Foundation of Food Traceability: Understanding Geographical Indications and the Imperative for Origin Validation

A Geographical Indication is a sign used on products that possess a specific geographical origin and embody qualities, reputation, or characteristics inherently attributable to that place of origin [1]. The fundamental principle underpinning GIs is the intrinsic link between the product and its terroir—a combination of natural factors (e.g., soil, climate) and human factors (e.g., traditional knowledge, manufacturing skills) [2]. This connection ensures that the product's unique attributes cannot be replicated outside its designated geographical area. GIs function as a form of intellectual property right that enables producers who conform to established standards to prevent third parties from using the indication for non-conforming products [1]. While traditionally applied to agricultural products, foodstuffs, wines, and spirits, their use has expanded to include handicrafts and industrial products [1] [2].

The protection of GIs provides a legal framework that benefits both producers and consumers. For producers, it safeguards their traditional knowledge and adds commercial value to their products. For consumers, it acts as a certification of origin and quality, guaranteeing that the product they purchase is authentic and produced according to specific standards [3]. The World Trade Organization's TRIPS Agreement (Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights) formally defines geographical indications as "indications which identify a good as originating in the territory of a Member, or a region or locality in that territory, where a given quality, reputation or other characteristic of the good is essentially attributable to its geographical origin" [4].

Regulatory Frameworks and Quality Schemes

Various international and regional systems exist for protecting Geographical Indications, with the European Union's framework being one of the most developed. The EU's quality policy aims to protect product names to promote their unique characteristics while helping producers market their products more effectively and enabling consumers to trust and distinguish quality products [3]. The EU system provides three primary forms of protection for geographical indications, each with distinct requirements and legal implications, as detailed in Table 1.

Table 1: EU Quality Schemes for Geographical Indications

| Scheme | Full Name | Products Covered | Key Specifications | Example |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PDO | Protected Designation of Origin | Food, agricultural products, wines | Every part of production, processing, and preparation must occur in the specific region. | Kalamata olive oil PDO (Greece) [3] |

| PGI | Protected Geographical Indication | Food, agricultural products, wines | At least one production stage must occur in the region; strong reputation link to origin required. | Westfälischer Knochenschinken PGI ham (Germany) [3] |

| GI | Geographical Indication | Spirit drinks | At least one stage of distillation/preparation must occur in the region; reputation linked to origin. | Irish Whiskey GI [3] |

Beyond these main schemes, the EU also recognizes Traditional Speciality Guaranteed (TSG), which highlights traditional production methods or composition without being linked to a specific geographical area [3]. A new EU regulation entered into force in May 2024, strengthening the GI system by introducing a single legal framework, recognizing sustainable practices, increasing online protection, and empowering producer groups [3].

Globally, GIs can be protected through different legal approaches, including:

- Sui generis systems (special regimes of protection)

- Collective or certification marks

- Administrative product approval schemes

- Laws against unfair competition [1]

The Lisbon System, administered by the World Intellectual Property Organization (WIPO), facilitates international protection of appellations of origin through a single registration procedure [1].

Analytical Techniques for Geographical Origin Authentication

The Need for Authentication Methods

The protection of geographical indications requires robust scientific methods to verify product origin and prevent fraudulent practices. As highlighted in systematic literature reviews, the most common type of food fraud (appearing in 95% of publications) involves component substitution with cheaper alternatives, which is difficult for consumers to recognize and requires sophisticated analytical techniques to detect [5]. The expansion of global markets has increased risks of food adulteration, where inferior products are marketed as premium GI products, necessitating reliable authentication systems [5].

Elemental and Isotopic Analysis Techniques

Modern analytical techniques for geographical origin authentication leverage advanced instrumentation to identify chemical fingerprints that are unique to products from specific regions. Isotope Ratio Mass Spectrometry (IRMS) has emerged as a particularly powerful technique, measuring stable isotope ratios of bio-elements (C, H, N, O, S) that reflect environmental conditions and agricultural practices of the production area [5]. Inductively Coupled Plasma Mass Spectrometry (ICP-MS) enables precise measurement of trace elements and rare earth elements whose composition in agricultural products reflects the geological conditions of the growth environment [5]. These techniques, along with other spectroscopic and chromatographic methods, provide complementary data for multivariate statistical analysis to confirm geographical origin.

Table 2: Analytical Techniques for Geographical Origin Authentication

| Technique Category | Specific Techniques | Measured Parameters | Application Examples |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mass Spectrometry | IRMS, ICP-MS, MC-ICP-MS, TIMS | Isotope ratios (C, H, N, O, S, Sr, Pb); Elemental composition | Wine, oils, honey, meat, dairy products [5] |

| Spectroscopy | FTIR, NIR, MIR, NMR, ESR, LIBS | Molecular vibrations; Energy transitions; Elemental emission | Cereals, honey, dairy products [5] |

| Chromatography | GC-MS, HPLC | Volatile compounds; Organic acids; Pigments | Fruit juices, spices, alcoholic beverages [5] |

| Molecular Biology | PCR, DNA-based techniques | Genetic markers; Species identification | Meat, fish, cereals, herbal products [5] |

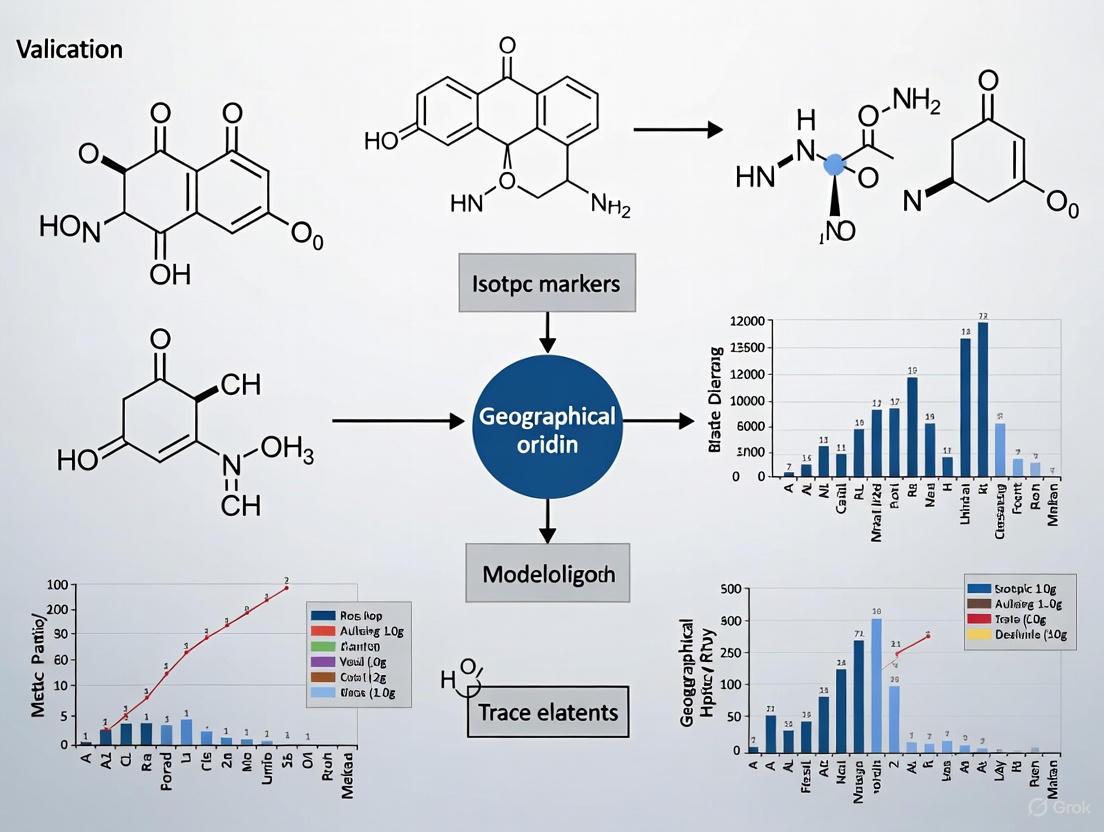

Figure 1: Experimental workflow for geographical origin authentication of GI products

Multi-Technique Approach and Data Analysis

Successful geographical certification typically requires a multimethod approach that combines several analytical techniques to measure multiple independent parameters [5]. This comprehensive data collection enables statistical processing to identify key tracers that differentiate products from various geographical regions. The establishment of reference databases containing authentic samples is crucial for comparing test samples and verifying their authenticity [5]. Statistical tools such as principal component analysis (PCA), linear discriminant analysis (LDA), and cluster analysis are employed to identify patterns and classify products based on their geographical origin.

Research Reagent Solutions for GI Authentication

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Geographical Origin Analysis

| Reagent/Material | Function | Application Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Certified Reference Materials | Quality control; Instrument calibration; Method validation | Elemental and isotopic analysis [5] |

| Isotopic Standards | Reference for delta value calculations; Quality assurance | IRMS analysis of bio-elements [5] |

| Ultrapure Acids & Reagents | Sample digestion; Extraction; Minimal contamination | Trace element analysis by ICP-MS [5] |

| Solid Phase Extraction Cartridges | Sample cleanup; Analyte pre-concentration; Matrix removal | Chromatographic analysis of organic compounds [5] |

| DNA Extraction Kits | Isolation of genetic material for species and origin identification | PCR-based authentication methods [5] |

| Derivatization Reagents | Chemical modification for volatility; Detection enhancement | GC-MS analysis of non-volatile compounds [5] |

Global Perspectives and Economic Implications

The protection and authentication of Geographical Indications have significant economic and rural development implications. GI products typically command premium prices (often 20-25% higher) due to their perceived quality and uniqueness [2]. This added value can contribute to rural development by strengthening local economies, preserving traditional production methods, and promoting sustainable agricultural practices [2]. The economic benefits depend on effective enforcement of GI rights and robust authentication systems to prevent free-riding by illegitimate producers [2].

International agreements play a crucial role in the global protection of GIs. The China-EU Geographical Indications Agreement, implemented in 2021, represents a significant development in bilateral GI protection, facilitating trade by ensuring mutual recognition and protection of GI products between these major markets [6]. Comparative studies between China and the EU highlight differences in their GI protection systems regarding institutional frameworks, operational systems, and implementation status [6]. Such agreements and comparative analyses help identify best practices and enhance international cooperation in GI protection.

The future of GI protection will likely involve increasingly sophisticated authentication technologies, harmonization of international standards, and greater emphasis on sustainability aspects. The integration of advanced analytical techniques with digital traceability systems offers promising approaches for ensuring the integrity of GI products throughout the supply chain. As research in this field advances, the link between product, place, and quality will continue to be strengthened through scientifically validated methods for geographical origin authentication.

The global food system is currently facing an unprecedented challenge from economically motivated adulteration, a threat that compromises both economic stability and public health. Recent data reveals that food fraud cases have risen tenfold over the past four years, costing the global economy an estimated $40 billion annually [7]. This surge in fraudulent activity is exploiting increasingly complex supply chains and global disruptions, including climate change, pandemics, and geopolitical conflicts, which collectively drive up food prices and create opportunities for deception [7]. For researchers and regulatory professionals, the stakes have never been higher, as fraudulent practices evolve in sophistication and scale.

The verification of geographical origin has emerged as a critical frontier in combating food fraud. Beyond economic deception, origin misrepresentation can conceal serious health risks, including undisclosed allergens, heavy metal contamination, and toxic additives [8] [9]. With international legislation such as the EU's Regulation on Deforestation Free Products (EUDR) mandating exact geolocation verification for imported commodities, the development of robust, scientifically validated origin tracing methods has become both a scientific and regulatory imperative [10] [11]. This review comprehensively compares the current analytical toolkit for origin verification, providing researchers with experimental protocols and performance data to strengthen food integrity programs.

The Evolving Landscape of Food Fraud: Key Targets and Trends

Current High-Risk Commodities

The food fraud landscape is shifting rapidly, with certain product categories experiencing dramatic increases in fraudulent activity. According to the FOODAKAI Global Food Fraud Index for Q1 2025, several categories show alarming trends [7] [12]:

Table 1: Forecasted Trends in Global Food Fraud Incidents for 2025

| Commodity Category | Forecasted Change | Primary Fraud Types |

|---|---|---|

| Nuts, Nut Products & Seeds | +358% | Species substitution, origin mislabeling, undeclared allergens |

| Eggs | +150% | Not specified in search results |

| Dairy | +80% | Dilution, counterfeit labeling, non-declared additives |

| Fish & Seafood | +74% | Species substitution, antibiotic use, origin mislabeling |

| Cocoa | +66% | Not specified in search results |

| Herbs & Spices | +25% | Bulking with non-spice material, artificial coloring |

| Cereals & Bakery Products | +23% | Unauthorized additives, mislabeled gluten content |

| Non-Alcoholic Beverages | +16% | Dilution, false "natural" claims, undeclared sweeteners |

The dramatic 358% projected increase in fraud for nuts, seeds, and nut products represents a particularly serious concern due to the allergenicity of these commodities, especially in powdered forms where adulteration is difficult to detect [12]. Professor Chris Elliott from Queen's University Belfast notes that "market shortage and price rises of some varieties such as walnuts, almonds and pistachios" has created ideal conditions for fraudsters [12].

Meanwhile, fish and seafood remain persistently problematic categories, with species substitution remaining rampant and new concerns emerging about "illegal types" of antibiotics being used in aquaculture systems, particularly for shrimps and prawns [12]. Dairy fraud has evolved with reports of 'fake butter' in Russia and generally higher milk prices creating economic incentives for adulteration [12].

Emerging and Declining Risk Categories

While some categories are experiencing surges, others show decreasing fraud trends. Coffee is projected to see a significant decline (-100%), though it remains a historically high-risk commodity, with major brands like Starbucks facing lawsuits over misleading ethical sourcing claims [7]. Juices (-26%), honey (-24%), and meat and poultry (-12%) also show improving trends, though these commodities require continued vigilance [7].

Perhaps most concerning are the newly emerging fraud targets. Garlic appeared in fraud reports for the first time in Q1 2025, with concerns about "its country (region) of production and adulteration with low cost bulking agents" [12]. Non-alcoholic beverages have also emerged as an unexpected area of concern, with steady fraud activity forecasted to increase [12].

Analytical Methodologies for Origin Verification: A Comparative Analysis

Established Techniques and Their Applications

The verification of geographical origin relies on a multifaceted analytical approach, with different techniques offering complementary strengths for various commodity types. No single method serves as a "silver bullet" for origin determination; rather, a combination of techniques provides the most reliable verification [10].

Table 2: Analytical Methods for Origin Verification of Key Commodities

| Commodity | Most Promising Techniques | Methodology Maturity | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cereals | Trace element analysis + Stable Isotope Ratio Analysis (SIRA) | Established | Requires extensive databases, seasonal variation |

| Cocoa | Near infra-red (NIR) spectroscopy + AI, Sensory techniques with AI | Emerging | Limited geographical scope |

| Coffee | SIRA + Trace element analysis | Established | Database quality critical |

| Fish & Shellfish | Trace elements + NIR + REIMS (lipid markers) | Developing | High variability due to aquatic environment mobility |

| Honey | Pollen analysis + SIRA + Trace elements + Metabolomics + Genomics + Blockchain | Multi-method | floral type differentiation challenging |

| Meat | SIRA + Trace element analysis + Fatty acid profiling + RFID | Established | Animal movement tracking complementary |

| Olive Oil | SIRA + NMR + Phenolic compounds profiling + FTIR | Established | Complex chemical profiling required |

| Rice | SIRA + Trace element analysis | Established | Limited to verification, not identification |

| Wine | SIRA + SNIF-NMR + Trace element analysis | Highly Established | Database dependent |

Stable Isotope Ratio Analysis (SIRA) combined with trace element profiling forms the cornerstone of most origin verification systems. These methods leverage geographical variations in elemental composition and isotopic signatures that become incorporated into food matrices through local water, soil, and environmental conditions [10]. The technique has proven particularly effective for verifying the origin of wines, meats, and cereals.

Spectroscopic techniques such as Near Infra-Red (NIR) and Fourier Transform Infra-Red (FTIR) spectroscopy offer rapid, non-destructive analysis that can screen for inconsistencies in product composition. These methods are increasingly being combined with artificial intelligence to improve pattern recognition and classification accuracy [10].

Advanced and Emerging Methodologies

Recent advances in analytical chemistry have introduced more sophisticated techniques for challenging verification scenarios. Inductively Coupled Plasma Mass Spectrometry (ICP-MS) has emerged as a powerful tool for multi-element analysis, with detection capabilities ranging from macro-elements (K, Ca, Mg) to trace metals (As, Pb, Cd, Cu) at concentrations as low as 0.0004 mg·kg⁻¹ in some nut varieties [13]. When combined with multivariate statistical methods like Principal Component Analysis (PCA), ICP-MS can effectively discriminate geographical origins by reducing complex elemental data to meaningful patterns [13].

Genomic approaches are revolutionizing origin verification for biological materials. A 2025 study on illegal timber tracing in Central Africa demonstrated that combining genetic markers (238 plastid Single Nucleotide Polymorphisms) with stable isotopes and multi-element analysis achieved unprecedented 94% accuracy in identifying samples within 100 km of their origin, significantly outperforming individual methods (50-80% accuracy) [11]. This methodological complementarity shows particular promise for high-value commodities where precise geographical discrimination is required.

Speciation analysis represents another frontier in analytical capability, particularly for safety-related verification. For chromium contamination in foods, distinguishing between relatively harmless trivalent chromium (Cr(III)) and carcinogenic hexavalent chromium (Cr(VI)) requires specialized speciation methods, which have seen recent advances through species-specific isotope dilution mass spectrometry [14].

Experimental Protocols for Origin Verification

ICP-MS with Multivariate Analysis for Plant-Based Foods

Protocol Overview: This method utilizes inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry (ICP-MS) for multi-element analysis combined with principal component analysis (PCA) for geographical discrimination of plant-based foods [13].

Sample Preparation:

- Representative samples are homogenized using industrial-grade blenders or grinders

- Precisely weigh 0.5 g of homogenized material into digestion vessels

- Add 5 mL of high-purity nitric acid (HNO₃, 65-67%) and 1 mL of hydrogen peroxide (H₂O₂, 30%)

- Perform microwave-assisted digestion using a standardized program (e.g., 15 min ramp to 180°C, hold for 20 min)

- Cool samples, transfer to volumetric flasks, and dilute to 50 mL with ultra-pure water (18.2 MΩ·cm)

ICP-MS Analysis:

- Instrument: ICP-MS system with collision/reaction cell technology

- Calibration: Prepare multi-element standard solutions covering mass range 7Li to 238U

- Use internal standards (e.g., 45Sc, 89Y, 159Tb, 209Bi) to correct for matrix effects and instrumental drift

- Operating parameters: RF power 1.5 kW, plasma gas flow 15 L·min⁻¹, carrier gas flow 0.8 L·min⁻¹, peristaltic pump speed 0.3 rps

- Acquire data in triplicate for each sample

Data Processing with PCA:

- Compile element concentration data into a matrix (samples × elements)

- Autoscale data to give each variable equal weight

- Perform PCA to reduce dimensionality while preserving geographic discrimination patterns

- Visualize results in 2D or 3D score plots to identify geographical clustering

- Establish confidence ellipses for known origin reference samples

- Compare unknown samples against established clusters for origin verification

Validation:

- Analyze certified reference materials (CRMs) with each batch to ensure accuracy

- Participate in inter-laboratory comparisons to verify reproducibility

- Maintain and regularly update database with new samples to account for seasonal variations

Multi-Method Authentication for High-Risk Spices (Cinnamon)

Protocol Overview: A holistic approach combining multiple analytical techniques to detect substitution, adulteration, and safety issues in cinnamon [9].

Sample Collection:

- Collect 104 commercial samples from retailers across multiple EU countries

- Document labeling information including claimed botanical and geographical origin

- Grind solid samples to consistent particle size using laboratory mills

Multi-Technique Analysis:

Energy Dispersive X-Ray Fluorescence (EDXRF):

- Preparation: Pelletize powdered samples using hydraulic press

- Analysis: Measure elemental composition including Pb, Cr, S with quantification limits sufficient for regulatory compliance (Pb: 2.0 mg·kg⁻¹)

- Purpose: Detect heavy metal contamination non-compliant with EU Regulation 2023/915

Head Space-Gas Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (HS-GC-MS):

- Parameters: Equilibrium headspace at 80°C for 30 min, inject 1 mL to GC-MS with DB-5MS column

- Temperature program: 40°C (2 min), ramp to 250°C at 10°C/min, hold 5 min

- Purpose: Quantify coumarin content to distinguish Ceylon from Cassia cinnamon and identify potential toxicological risks

Thermogravimetric Analysis (TGA):

- Parameters: Heat 10 mg sample from ambient to 800°C at 10°C/min under nitrogen atmosphere

- Measure weight loss steps to determine total ash content

- Purpose: Assess quality compliance with ISO 6539 (Ceylon) and ISO 6538 (Cassia) standards

Quantitative Polymerase Chain Reaction (q-PCR):

- DNA extraction: CTAB method with silica-based purification

- Primer design: Species-specific markers for C. zeylanicum vs. Cassia species

- Amplification: Standard q-PCR conditions with SYBR Green detection

- Purpose: Verify botanical origin and detect species substitution

Results Interpretation:

- 66.3% of commercial samples showed quality, safety, or fraud issues [9]

- 20.7% of samples with adequate labeling failed quality criteria

- 9.6% exceeded regulatory limits for lead contamination

- Multiple authentication techniques required to cover full spectrum of fraud types

Visualizing Analytical Approaches: Method Selection Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the decision pathway for selecting appropriate analytical methods based on the verification scenario and available resources:

Figure 1: Method Selection for Origin Verification

The Researcher's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Origin Verification Studies

| Category | Specific Reagents/Materials | Research Function | Application Examples |

|---|---|---|---|

| ICP-MS Analysis | High-purity nitric acid (HNO₃, 65-67%), Hydrogen peroxide (H₂O₂, 30%), Multi-element calibration standards, Certified Reference Materials (CRMs) | Quantitative elemental analysis for geographical discrimination | Plant foods, meat, dairy, cereals [13] |

| Stable Isotope Analysis | Laboratory gases (He, CO₂), International reference materials (VSMOW, VPDB), Elemental analyzers, High-precision isotope ratio mass spectrometers | Determine isotopic signatures (δ¹⁸O, δ²H, δ¹³C, δ¹⁵N) related to geographical origin | Wine, honey, olive oil, meat [10] |

| Genomic Analysis | DNA extraction kits (CTAB method), Species-specific primers, PCR reagents, DNA sequencing kits, Gel electrophoresis materials | Species identification and genetic origin verification | Fish species, timber, botanical ingredients [11] [9] |

| Chromatography | HPLC/MS-grade solvents, Certified standard compounds, Solid-phase extraction cartridges, GC columns | Detection of authenticity markers, contaminant analysis | Cinnamon (coumarin), olive oil (phenolics), juice authenticity [9] |

| Spectroscopy | NIR calibration standards, FTIR crystals, Sample pellets for EDXRF | Rapid screening and classification | Cereals, cocoa, edible oils [10] |

The escalating threat of food fraud demands increasingly sophisticated approaches to geographical origin verification. While individual analytical methods provide valuable data, the future lies in integrated multi-method approaches that leverage the complementary strengths of different techniques. The successful timber tracing model achieving 94% accuracy through combined genetic, isotopic, and elemental analysis demonstrates the power of this approach [11].

For researchers and regulatory scientists, several critical priorities emerge. First, the development of comprehensive, curated databases that span global geographies and account for seasonal and annual variations is essential. Second, harmonized analytical protocols and regular inter-laboratory comparisons ensure data reproducibility and reliability. Third, the integration of emerging technologies like blockchain with analytical verification creates a robust "weight-of-evidence" approach to supply chain transparency [10].

As food fraud continues to evolve in response to global disruptions and economic pressures, the scientific community must remain proactive in developing, validating, and implementing origin verification methods. Only through continued methodological innovation and collaborative data sharing can researchers provide the tools needed to protect global food integrity, consumer safety, and economic fairness in food systems.

For researchers and professionals in food science and drug development, verifying the geographical origin of agricultural products is a critical challenge with implications for quality, safety, and economic value. At the heart of modern traceability techniques lies a fundamental principle: the unique interplay of environmental factors at a specific location imprints a natural, chemical signature on the organisms that grow there. This signature, or "chemical fingerprint," arises from the immutable influence of local soil composition, climate patterns, and water sources on a plant's biochemical and elemental profile. This article explores the core mechanisms through which these environmental factors create traceable markers, objectively comparing the efficacy of different analytical methodologies and presenting the experimental data that validates this approach within the broader thesis of geographical origin authentication.

The Environmental Basis of Chemical Fingerprints

The traceability of agricultural products hinges on the transfer of environmental signals from the growth environment into the plant's tissue. This process creates a unique, measurable profile that serves as a natural barcode for its origin.

- Soil and Geology: The elemental composition of soil, derived from underlying bedrock and modified by local pedogenesis, provides a primary source of trace elements that are absorbed by plant root systems [15]. Elements such as strontium (Sr) are particularly powerful tracers because their isotopic ratios (e.g., ⁸⁷Sr/⁸⁶Sr) directly reflect the geology of the area and are transferred from soil to plant with minimal fractionation [16]. The uptake of these elements is further modulated by soil properties, including pH, organic matter content, and microbial activity [15] [17].

- Climate and Atmosphere: Climatic conditions—including temperature, humidity, rainfall, and solar radiation—directly influence plant physiology and leave distinct isotopic imprints. The ratios of stable hydrogen (δ²H) and oxygen (δ¹⁸O) in plant tissue are strongly correlated with the isotopic composition of local precipitation, which varies systematically with latitude, altitude, and distance from the coast [15] [18]. Furthermore, the carbon isotope ratio (δ¹³C) is fractionated during photosynthesis and is influenced by water availability, light intensity, and altitude [19] [18].

- Water Sources: The hydrogen and oxygen isotopic composition of a plant's water source is faithfully recorded in its tissues. Plants incorporate water from precipitation and soil water without significant isotopic fractionation, making δ²H and δ¹⁸O powerful proxies for the hydrological conditions of the production region [15] [20].

The following diagram illustrates the fundamental pathway through which environmental factors create a traceable chemical fingerprint in a plant.

Comparative Efficacy of Analytical Techniques for Fingerprint Detection

A variety of analytical techniques are employed to detect and measure the chemical fingerprints imparted by the environment. The choice of technique depends on the type of marker being analyzed and the required sensitivity and specificity.

Table 1: Comparison of Key Analytical Techniques for Geographical Origin Traceability

| Analytical Technique | Targeted Markers | Principle | Representative Application | Key Differentiating Factors |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Inductively Coupled Plasma Mass Spectrometry (ICP-MS) | Multi-elemental composition (Macro, trace, and rare earth elements) | Ionizes sample atoms and separates them based on mass-to-charge ratio [15] [16]. | Discrimination of Romanian potatoes using Sr, and Euryales Semen using Na, V, Ba [16] [19]. | High sensitivity, multi-element capability, requires sample digestion. |

| Isotope Ratio Mass Spectrometry (IRMS) | Stable isotope ratios (δ²H, δ¹⁸O, δ¹³C, δ¹⁵N, δ³⁴S) | Precisely measures the relative abundance of stable isotopes in a sample [15] [16] [20]. | Tracing grape origin via δ²H/δ¹⁸O [15]; authenticating virgin olive oil [21]. | High-precision isotope measurement; requires specialized sample preparation. |

| Fourier Transform Near-Infrared (FT-NIR) Spectroscopy | Molecular overtone and combination vibrations (C-H, O-H, N-H bonds) | Measures absorption of near-infrared light to create a chemical profile [22]. | Rapid discrimination of kimchi geographical origin [22]. | Fast, non-destructive, no reagents; but a secondary technique reliant on chemometrics. |

| Hyperspectral Imaging (HSI) | Spatial and spectral information | Combines spectroscopy with imaging to map chemical composition [23]. | Non-destructive origin traceability of Salvia miltiorrhiza [23]. | Provides visual and chemical data; powerful with deep learning models. |

Experimental Protocols and Data

Detailed Methodologies for Key Analytical Approaches

Protocol 1: Multi-Elemental and Isotopic Analysis of Potatoes for Origin Discrimination [16]

- Sample Preparation: 100 potato samples were collected. Water was extracted from the tubers via cryogenic distillation under vacuum. The dried solid material was then divided; one portion was used for elemental analysis and the other for δ¹³C analysis.

- Elemental Analysis (ICP-MS): 0.1 g of the dried sample was digested with 3 mL of concentrated nitric acid using a microwave oven (200°C for 12 min). The digest was diluted to 50 mL with ultrapure water and analyzed via ICP-MS (Perkin Elmer ELAN DRC(e)). A semi-quantitative "Total Quant" method was used for initial fingerprinting.

- Isotopic Analysis (IRMS): The δ²H and δ¹⁸O values of the extracted water were measured. The δ¹³C value of the bulk dried material was also determined via IRMS.

- Data Analysis: Linear Discriminant Analysis (LDA) was applied to the combined elemental and isotopic dataset to build a classification model. The most significant markers for Romanian potatoes were identified as δ¹³C, δ²H of the tissue water, and Sr.

Protocol 2: Stable Isotope Analysis in Pu-erh Tea Processing [18]

- Experimental Design: Fresh tea leaves were collected from three distinct regions (Jinggu, Linxiang, Ning'er). The leaves were processed into ripe Pu-erh tea according to local methods, which included fixation, rolling, drying, and a distinctive post-fermentation stage known as ‘Wo Dui’.

- Isotope Measurement: The stable isotope ratios (δ¹³C, δ¹⁵N, δ²H, δ¹⁸O) were measured in both the bulk tea material and in extracted caffeine at different processing stages using IRMS.

- Statistical Analysis: One-way ANOVA and Orthogonal Partial Least Squares Discriminant Analysis (OPLS-DA) were used to assess the significance of regional differences and the impact of processing on the isotopic fingerprints.

Quantitative Data from Traceability Studies

The following table consolidates experimental findings from various studies, demonstrating how specific markers are linked to geographical origin.

Table 2: Key Chemical Markers and Their Correlation with Geographical Origin

| Agricultural Product | Key Discriminatory Markers | Observed Variation / Correlation | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ecolly Grapes (China) | δ²H, δ¹⁸O, Mineral Elements | δ²H values ranged from -41.37‰ to -3.70‰ across three regions, showing significant differences (P < 0.001) [15]. | [15] |

| Potatoes (Romania vs. Imports) | δ¹³C, δ²H (tissue water), Sr | Identified as the most significant markers for distinguishing Romanian potatoes from other European origins using LDA [16]. | [16] |

| Euryales Semen (China) | Na, V, Ba, Sb, Cu, Ti, Mn, %N, Amylose | SHAP analysis identified these as the top 10 significant variables (SHAP value >1.0) for a LightGBM model with 97.67% accuracy [19]. | [19] |

| Oil-Rich Crops (Global) | Stearic Acid (C18:0), Linoleic Acid (C18:2) | Fatty acid profiles showed strong, significant correlations with latitude and altitude on a global scale [17]. | [17] |

| Kimchi (Domestic vs. Imported) | FT-NIR Spectral Profiles | k-Nearest Neighbors model achieved accurate classification based on spectral differences in C-H, O-H, and N-H bond regions [22]. | [22] |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Successful implementation of geographical origin traceability requires specific, high-quality reagents and materials. The following table details essential items for setting up these analyses.

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions and Essential Materials

| Item | Function / Application | Specific Example / Note |

|---|---|---|

| Certified Reference Materials (CRMs) | Validation and quality control for elemental and isotopic analysis. | CRM NCS ZC85006 (tomato) and IAEA-359 (cabbage) were used for method validation in potato analysis [16]. |

| Ultrapure Acids & Solvents | Sample digestion and extraction for ICP-MS and IRMS. | Use of ultrapure nitric acid (HNO₃, Merck) for microwave-assisted digestion of potato samples [16]. |

| Isotopic Reference Waters | Calibration of IRMS for hydrogen and oxygen isotope analysis. | Use of Vienna Standard Mean Ocean Water (VSMOW) as an international standard [20]. |

| Deuterium Oxide (D₂O) & H₂¹⁸O | Experimental preparation of waters with known isotopic abundance for processing studies. | Used to create cooking waters with δ²H from -160‰ to +50‰ and δ¹⁸O from -22.9‰ to +99.9‰ for noodle boiling experiments [20]. |

| Solid Phase Microextraction (SPME) Fibers | Extraction of volatile compounds for GC-MS analysis. | DVB/CAR/PDMS fiber used for sesquiterpene fingerprinting of virgin olive oil [21]. |

The scientific validation of geographical origin rests on the robust foundation that environmental factors—soil, climate, and water—create a persistent and measurable chemical fingerprint in agricultural products. As demonstrated by the experimental data and protocols, techniques such as ICP-MS and IRMS can detect these fingerprints with high precision, while FT-NIR and HSI offer rapid, non-destructive alternatives. The growing integration of these analytical datasets with advanced machine learning models, including LightGBM and interpretable AI, is pushing the boundaries of traceability accuracy and providing deeper insights into the key variables for discrimination. For researchers in food science and drug development, where the provenance of natural ingredients is paramount, these core principles and methodologies provide a powerful toolkit for ensuring authenticity, quality, and safety in a globalized market.

The authentication of geographical origin has become a cornerstone of food safety and quality assurance, serving as a critical mechanism for protecting high-value products from economically motivated adulteration. The global food fraud cost is estimated at approximately 49 billion US dollars annually, driving the need for robust analytical verification methods [24]. For products like rice, Angelica sinensis (a traditional medicinal herb), and spirits, the quality, reputation, and specific characteristics are intrinsically linked to their geographical provenance [25] [26]. This guide compares the performance of modern analytical techniques used to verify geographical origin, providing researchers with experimental data and protocols essential for method selection and development.

Geographical Indication (GI) frameworks, including Protected Geographical Indication (PGI) and Protected Designations of Origin (PDO), have been established globally to protect products with specific terroir-linked qualities [25]. However, certification alone often proves insufficient against sophisticated fraud. For instance, counterfeit Yangcheng hairy crabs reportedly reach 10 times the market volume of genuine products [26]. Similarly, a 2010 scandal revealed that ten times more Wuchang rice was sold than produced [27]. Such incidents demonstrate the critical need for analytical verification to complement documentary traceability systems.

Comparative Performance of Authentication Technologies

The table below summarizes the performance of different analytical approaches applied to rice, Angelica sinensis, and spirits, providing a direct comparison of their capabilities.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Origin Authentication Methods

| Analytical Technique | Product | Key Discriminatory Markers | Classification Accuracy | Multivariate Analysis Method |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Elemental Profiling (ICP-MS) + Machine Learning [27] | Chinese GI Rice | Al, B, Rb, Na | 100% | Support Vector Machine (SVM), Random Forest (RF) |

| Fluorescence Spectroscopy + Machine Learning [28] | Jilin Province Rice | NADPH, Riboflavin (B2), Starch, Protein | 99.5% | Support Vector Machine (SVM) |

| Multi-Element + Stable Isotope Analysis [29] [30] | Angelica sinensis | K, Ca/Al, δ13C, δ15N, δ18O | 84% | PLS-DA, Linear Discriminant Analysis (LDA) |

| Elemental Profiling (ICP-MS/OES) [31] | Whisky | Mn, K, P, S | Effective discrimination achieved | Principal Component Analysis (PCA) |

Key Insights from Comparative Data

- Machine Learning Enhances Accuracy: The integration of machine learning algorithms (SVM, RF) with elemental or spectroscopic data has achieved exceptional classification accuracy, surpassing 99% for rice authentication [28] [27]. These models handle complex, non-linear relationships in data more effectively than traditional chemometrics.

- Multi-Technique Approach for Complex Products: For botanicals like Angelica sinensis, combining multiple analytical techniques—such as elemental analysis with stable isotope analysis—improves discriminatory power by capturing different aspects of the product's chemical fingerprint influenced by geography [29].

- Marker Elements Reveal Production History: The elements identified as discriminatory markers often provide insights into environmental conditions and production processes. For example, in whisky, the lower concentrations of Mn, K, and P in fake samples indicate a lack of proper barrel aging, as these elements migrate from wood to spirit over time [31].

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Elemental Profiling with ICP-MS for Rice Authentication

This protocol, adapted from studies on Chinese GI rice, uses inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry (ICP-MS) to create a unique elemental fingerprint [27].

Sample Preparation:

- Collect rice samples directly from processing factories to ensure origin authenticity.

- Dehusk and mill rice grains, then pulverize using a high-speed pulverizer.

- Pass the powdered sample through a 100-mesh sieve for uniform particle size.

- Use a standardized mass (e.g., 0.5 g) for microwave-assisted acid digestion with nitric acid and hydrogen peroxide.

Instrumental Analysis:

- Technique: Inductively Coupled Plasma Mass Spectrometry (ICP-MS).

- Calibration: Use a series of multi-element standard solutions for calibration.

- Quality Control: Include Standard Reference Material (SRM) 1568b (rice flour) to verify analytical accuracy. Acceptable recovery rates should range between 80.8% and 102.3%.

Data Processing:

- Perform feature selection using algorithms like Relief to identify the most significant elemental markers (e.g., Al, B, Rb, Na).

- Build classification models using machine learning algorithms such as Support Vector Machine (SVM) or Random Forest (RF).

- Validate models using a separate testing set not used in model training.

Figure 1: ICP-MS Workflow for Rice Authentication

Protocol 2: Multi-Element and Stable Isotope Analysis for Angelica Sinensis

This protocol validates the geographical origin of Angelica sinensis using a combination of elemental and stable isotope analysis [29] [30].

Sample Collection and Preparation:

- Collect root samples from defined geographical locations, recording GPS coordinates.

- Clean roots thoroughly with deionized water to remove surface soil.

- Dry samples in a constant temperature oven at 70°C until constant weight is achieved.

- Grind dried roots to a fine powder using a high-speed pulverizer and pass through a 100-mesh sieve.

Elemental Analysis:

- Technique: Inductively Coupled Plasma Mass Spectrometry (ICP-MS).

- Analytes: Measure 8 mineral elements (K, Mg, Ca, Zn, Cu, Mn, Cr, Al).

Stable Isotope Analysis:

- Technique: Isotope Ratio Mass Spectrometry (IRMS).

- Analytes: Measure three stable isotopes (δ13C, δ15N, δ18O).

Statistical Analysis:

- Use both unsupervised (Principal Component Analysis - PCA) and supervised (Partial Least Squares Discriminant Analysis - PLS-DA, Linear Discriminant Analysis - LDA) methods.

- Perform cross-validation to assess model performance and avoid overfitting.

Figure 2: Multi-Analyte Authentication Workflow for Angelica Sinensis

Protocol 3: Elemental Fingerprinting for Whisky Authentication

This protocol focuses on detecting whisky adulteration, particularly through insufficient aging, by analyzing elemental profiles [31].

Sample Preparation:

- Analyze whisky samples directly without digestion for elements soluble in the alcohol matrix.

- For total elemental analysis, perform digestion with nitric acid to break down organic components.

Multi-Technique Elemental Analysis:

- ICP-MS: Measure trace elements at very low concentrations.

- ICP-OES: Measure major and minor elements.

- CV-AAS: Specifically measure mercury using Cold Vapor Atomic Absorption Spectrometry.

Additional Measurements:

- Measure pH using a calibrated pH-meter.

- Determine isotopic ratios (88Sr/86Sr, 84Sr/86Sr, 87Sr/86Sr, 63Cu/65Cu) using ICP-MS.

Data Analysis:

- Use Principal Component Analysis to visualize natural clustering of authentic vs. fake samples.

- Identify key marker elements (Mn, K, P, S) whose concentrations differ significantly between authentic and fake products.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 2: Essential Research Materials for Origin Authentication Studies

| Material/Reagent | Specification/Function | Application Example |

|---|---|---|

| ICP-MS Calibration Standards | Multi-element mixed standard solutions for quantitative analysis. | Quantifying Al, B, Rb, Na in rice samples [27]. |

| Certified Reference Material (CRM) | SRM 1568b (rice flour) for method validation and quality control. | Verifying analytical accuracy and precision in ICP-MS analysis [27]. |

| Isotope Reference Materials | Certified isotope standards for calibrating IRMS instruments. | Accurate measurement of δ13C, δ15N, δ18O ratios in Angelica sinensis [29]. |

| Sample Preparation Consumables | 100-mesh sieves for particle size uniformity; high-purity acids for digestion. | Ensuring representative sampling and minimizing contamination during sample preparation [29] [27]. |

| Solid Phase Microextraction (SPME) Fibers | Extracting volatile organic compounds for chromatographic analysis. | Creating aroma profiles for spirit authentication (e.g., whisky) [25]. |

The comparative analysis demonstrates that while all featured techniques provide effective geographical origin authentication, methods combining elemental profiling with advanced machine learning currently achieve the highest classification accuracy, reaching up to 100% for rice authentication [27]. The optimal choice of technique depends on the specific product matrix, available instrumentation, and required discrimination power.

Future research should focus on developing more integrated methodologies that combine multiple analytical approaches to create comprehensive product fingerprints. Additionally, making these techniques more accessible and cost-effective for routine use by regulatory bodies and industry represents a critical challenge. As food fraud methods become more sophisticated, the continued advancement and validation of these analytical techniques remain essential for protecting consumers, ensuring fair trade, and safeguarding the reputation of high-value geographical indication products.

Analytical Arsenal: A Deep Dive into Techniques for Geographical Origin Authentication

Verifying the geographical origin of food has become a critical frontier in food forensics, driven by the need to combat economically motivated fraud and protect consumers. The fundamental premise of this analytical approach is that the multi-elemental composition of an agricultural product is a direct reflection of the geochemistry of the soil in which it was grown. Elements present in the bedrock and soil are absorbed by plants through their root systems, creating a distinct elemental fingerprint that is characteristic of a specific geographical location [32] [33]. Inductively Coupled Plasma Mass Spectrometry (ICP-MS) has emerged as a dominant technique for reading these fingerprints due to its exceptional sensitivity, capable of detecting trace and ultra-trace elements at parts per trillion (ppt) levels, and its ability to perform multi-element analysis for a wide range of elements simultaneously [32] [34]. This guide provides an objective comparison of ICP-MS against other analytical techniques and details the experimental protocols required for its application in validating the geographical origin of foods.

Technique Comparison: ICP-MS versus Alternative Methods

Selecting the appropriate analytical technique is crucial for a geographical traceability study. The choice depends on the required detection limits, sample throughput, need for quantitative precision, and available resources. The table below provides a structured comparison of ICP-MS with other common elemental analysis techniques.

Table 1: Comparison of Analytical Techniques for Elemental Profiling in Geographical Origin Studies

| Technique | Typical Detection Limits | Analytical Throughput | Sample Preparation | Key Advantages | Major Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ICP-MS | Parts per trillion (ppt) [35] [34] | High (after digestion) | Complex; requires full acid digestion [34] | Exceptional sensitivity and multi-element capability [32] [34] | High instrument cost; skilled operation required; time-consuming sample prep [34] |

| ICP-OES | Parts per million (ppm) [35] | High (after digestion) | Complex; requires full acid digestion | Good for higher concentration elements; robust | Higher detection limits than ICP-MS [35] |

| XRF | Parts per million (ppm) [34] | Very High | Minimal; often non-destructive [34] | Rapid, non-destructive analysis; ideal for screening [34] | Higher detection limits; can be less accurate for heterogeneous samples [34] |

| LA-ICP-MS | Parts per billion (ppb) to ppt [36] | Moderate to High | Minimal; no digestion required [36] | Spatially resolved analysis; reduced sample prep and chemical use [36] | Challenges with quantification precision [37] |

A 2025 comparative study of soil analysis highlighted that while techniques like XRF are invaluable for rapid screening, statistical analyses can reveal significant differences in results for elements like Ni, Cr, V, and As compared to ICP-MS. This underscores the importance of ICP-MS when high accuracy and sensitivity for trace elements are paramount [34].

Experimental Protocols for ICP-MS Analysis

A rigorous and standardized protocol is essential for generating reliable and reproducible elemental profiling data. The following workflow and detailed methodology are compiled from established research in the field.

Figure 1: ICP-MS Geographical Origin Analysis Workflow

Sample Collection and Preparation

Sampling: Soil and plant samples must be collected following a strict protocol to ensure representativeness. For soil, samples are often taken from a depth of about 20 cm after discarding the surface layer, targeting the root zone [38]. Plant materials (e.g., grapes, hazelnuts, leaves) should be collected from multiple plants across the sampling site to account for individual variations [38]. All samples must be sealed in pre-cleaned containers to avoid contamination [38].

Sample Pre-Treatment: Plant samples are typically washed with ultrapure water to remove dust and pesticide residues, then freeze-dried (lyophilized) to preserve their composition and facilitate grinding [38] [36]. The dried samples are pulverized into a homogeneous powder using a mill, sometimes cooled with liquid nitrogen to prevent heat degradation [38]. Soil samples are air-dried, ground with an agate mortar, and sieved (e.g., to 125 μm) to obtain a consistent particle size [38].

Microwave-Assisted Acid Digestion

This is a critical step to convert solid samples into a liquid form suitable for nebulization in the ICP-MS.

- Reagents: High-purity nitric acid (HNO₃, 65-70%) is standard, often supplemented with hydrogen peroxide (H₂O₂, 30%) for more complete organic matter decomposition [38] [36].

- Process: A precisely weighed amount of sample (e.g., 100-250 mg) is combined with acids (e.g., 4 mL HNO₃ and 1 mL H₂O₂) in sealed Teflon vessels.

- Digestion: The vessels are heated in a microwave digestor using a controlled temperature ramp. This sealed-vessel approach minimizes contamination, allows for higher temperatures, and prevents the loss of volatile elements [37].

- Post-processing: After digestion and cooling, the resulting digestate is filtered, diluted to a known volume with ultrapure water (e.g., 18.2 MΩ cm resistivity), and is then ready for analysis [32].

ICP-MS Instrumental Analysis and Quality Control

The diluted sample solutions are introduced into the ICP-MS instrument.

- Operation: The liquid sample is pumped into a nebulizer, creating an aerosol that is transported into the argon plasma. The plasma, at temperatures of ~6000-10000 K, effectively atomizes and ionizes the elements. The resulting ions are separated by a mass spectrometer based on their mass-to-charge ratio and detected [32] [33].

- Quantification: Analysis is performed against external multi-element calibration standards. Internal standards (e.g., Germanium (Ge), Indium (In)) are added to all samples and standards to correct for instrumental drift and matrix effects [38].

- Quality Assurance: The method's accuracy is validated using certified reference materials (CRMs) with known element concentrations. Precision is determined through replicate analyses, and method detection limits are established by analyzing procedural blanks [37].

Applications in Food Origin Authentication

The combination of ICP-MS elemental profiling and multivariate statistics has been successfully applied to authenticate the origin of a wide variety of food products.

Table 2: Selected Experimental Data from Food Origin Authentication Studies Using ICP-MS

| Food Product | Key Discriminatory Elements Identified | Geographical Origins Differentiated | Statistical Method Used | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hazelnuts | B, Ca, Ti, Cr, Mn, Fe, Co, Ni, Cu, Zn, Ga, Rb, Sr, Mo, Cd, Ba, La [36] | France, Georgia, Germany, Italy, Türkiye | PCA, LDA, SVM, Random Forest [36] | Müller et al., 2024 |

| Sangiovese Grapes & Leaves | Rare Earth Elements (REEs) and transition metals [38] | Sub-regions within Chianti, Italy (10-20 km range) | PCA & LDA [38] | PMC 2024 |

| Various Plant Foods | Macro-elements (K, Ca, Mg); Micro-elements (Co, Cu, Rb, Sr) [13] | Varies by study (e.g., peppers, tomatoes, rice, cocoa) | Principal Component Analysis (PCA) [13] | Foods 2023 |

These studies demonstrate the power of this approach. For instance, research on hazelnuts analyzed 244 samples and identified 17 significant elements for origin discrimination, achieving a 95% correct classification rate using Linear Discriminant Analysis (LDA) [36]. Another study on Sangiovese grapes successfully discriminated origins within the Chianti area at a high-resolution range of just 10-20 km, highlighting the remarkable sensitivity of the method [38].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

The following table details key consumables and reagents required for conducting ICP-MS-based geographical origin studies.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for ICP-MS Analysis

| Item | Function / Application | Technical Notes |

|---|---|---|

| High-Purity Nitric Acid (HNO₃) | Primary digesting acid for soil and plant matrices. | Must be "redistilled" or "trace metal grade" (e.g., >99.999% purity) to minimize blank contamination [38]. |

| Hydrogen Peroxide (H₂O₂, 30%) | Oxidizing agent added to improve digestion of organic matter. | Use "Suprapur" or similar high-purity grade [38] [36]. |

| Multi-Element Standard Solutions | Used for external calibration of the ICP-MS instrument. | Certified reference solutions with known concentrations of a wide range of elements [38]. |

| Internal Standard Solution | Corrects for instrumental drift and matrix effects during analysis. | Typically contains elements not found in the sample (e.g., Ge, In, Rh) added to all samples and standards [38]. |

| Certified Reference Materials (CRMs) | Validates the accuracy and precision of the entire analytical method. | Should be matrix-matched (e.g., soil, plant leaves) with certified values for elements of interest [37]. |

| Ultrapure Water | Dilution of digested samples and preparation of standards. | Resistivity of 18.2 MΩ·cm, produced by systems like Millipore Direct-Q [38] [36]. |

| Teflon Digestion Vessels | Containers for microwave-assisted acid digestion. | Withstand high temperature and pressure; sealed to prevent cross-contamination and loss of volatiles [37]. |

ICP-MS stands as a powerful and sensitive technique for authenticating the geographical origin of foods through elemental profiling. Its superior detection limits and multi-element capability make it a gold standard for precise traceability studies, especially when differentiating between closely located regions. While techniques like XRF offer advantages for rapid, non-destructive screening, and LA-ICP-MS presents a greener alternative with minimal sample preparation, the quantitative power and sensitivity of solution-based ICP-MS are unmatched for definitive analysis. The effectiveness of the method is maximized when rigorous experimental protocols for sample preparation, digestion, and instrumental analysis are followed, and when the complex elemental data is interpreted using robust multivariate statistical models. This comprehensive approach provides a reliable scientific foundation for fighting food fraud and protecting valued geographical indications.

Stable Isotope Ratio Mass Spectrometry (IRMS) has emerged as a powerful analytical technique for geographical origin authentication of agri-food products, providing unique isotopic "fingerprints" that serve as reliable tracers for product verification. This technology enables researchers to measure minute variations in the natural abundance of stable isotopes of light elements—particularly carbon (δ13C), nitrogen (δ15N), and oxygen (δ18O)—with exceptional precision. The fundamental principle underpinning IRMS authentication is that the isotopic composition of agricultural products reflects the environmental conditions and agricultural practices of their geographic origin, including climate, soil composition, water sources, and fertilization methods [5]. These isotopic signatures remain stable through food processing and storage, making them ideal markers for traceability systems and authentication protocols in the face of increasing global food fraud incidents.

The application of IRMS has gained substantial traction in response to growing consumer concern about food authenticity and the economic need to protect high-quality regional products with Protected Designation of Origin (PDO) or Protected Geographical Indication (PGI) status [5]. As analytical technologies have advanced, IRMS has evolved from a specialized geochemical tool to an essential technique in food authentication, capable of discriminating between products from different regions—even those in close geographical proximity—based on their intrinsic isotopic patterns. This comparison guide examines the current state of IRMS technology, its performance relative to alternative authentication methods, and the experimental protocols that enable researchers to reliably track δ13C, δ15N, and δ18O signatures for geographical origin verification.

IRMS Technology and Instrumentation Comparison

Fundamental Principles of IRMS

Isotope Ratio Mass Spectrometry operates on the principle of measuring relative differences in the natural abundance of stable isotopes in organic and inorganic materials. Unlike conventional mass spectrometry that identifies molecular structures, IRMS precisely quantifies the ratios of minor to major isotopes (e.g., 13C/12C, 15N/14N, 18O/16O) in purified gases derived from sample combustion or pyrolysis. These ratios are expressed in delta (δ) notation in units per mil (‰) relative to international standards, calculated as δX = [(Rsample/Rstandard) - 1] × 1000, where X is the heavy isotope and R is the isotope ratio [39]. The exceptional precision of IRMS—capable of detecting differences as small as 0.1‰ for δ13C—enables discrimination of geographical origins based on subtle natural variations in isotopic fractionation that occur during biogeochemical processes, including photosynthesis, nitrogen fixation, and water uptake [40] [5].

Modern IRMS systems incorporate several critical technological advancements that enhance their analytical performance. These include improved ionization efficiency, with current instruments achieving approximately 1,100 molecules of CO2 per ion in continuous flow mode; enhanced mass resolution of 110 m/Δm (at 10% valley separation); and simultaneous measurement capabilities for up to 10 ion beams across a ±25% mass range [41]. The development of continuous flow interfaces using elemental analyzers has significantly streamlined analytical workflows, allowing direct coupling of combustion/pyrolysis systems with IRMS and enabling high-throughput analysis of diverse sample types without requiring offline sample preparation [41] [39]. Furthermore, automated dilution, switching, and standby modes in contemporary systems like the isoprime precisION have improved analytical efficiency and stability for laboratories conducting large-scale geographical authentication studies [41].

Comparative Instrumentation Analysis

Table 1: Comparison of Modern IRMS Instrumentation and Features

| Instrument Model | Key Technological Features | Analytical Performance | Geographical Application Suitability |

|---|---|---|---|

| isoprime precisION (Elementar) | Novel Inlet Control Module; centrION Continuous Flow Interface; lyticOS Software Suite with Method Workflow Designer | Ionization efficiency: 1,100 molecules/ion (CO2); Mass resolution: 110 m/Δm; Simultaneous measurement of up to 10 ion beams | High flexibility for diverse sample types; Suitable for research requiring method development for novel applications |

| Thermo Scientific DELTA Q | Advanced continuous flow interface; Temperature-controlled ion source; ConFlo IV universal interface | High sensitivity for small samples; Wide dynamic range; Precision: ≤0.1‰ for δ13C | Ideal for high-precision bulk analysis; Appropriate for established authentication protocols |

| Sercon 20-22 | Continuous flow and dual inlet configurations; Integrated peripheral automation; High stability detection system | Enhanced reliability for routine analysis; Comprehensive data management | Well-suited for quality control laboratories handling large sample volumes |

| Neoma MC-ICP-MS (Thermo Fisher) | Inductively coupled plasma source; Multi-collection system; MS/MS capability for interference removal | Analysis of broader element range; Capable of measuring non-traditional metal isotopes | Complementary technique for when light elements require supplementation with metal isotope data |

The selection of appropriate IRMS instrumentation depends heavily on the specific requirements of geographical authentication studies. For laboratories focusing primarily on light element isotopes (C, N, O, H, S) in bulk materials, dedicated IRMS systems like the isoprime precisION and DELTA Q provide optimal performance with streamlined workflows [41] [42]. These systems offer the high precision necessary for detecting the subtle isotopic variations that differentiate geographical origins. In contrast, multi-collector inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry (MC-ICP-MS) instruments like the Neoma expand analytical capabilities to include metal isotopes (e.g., Sr, Pb) that can provide complementary geographical information, particularly for mineral-rich products or when tracing water sources via strontium isotopes [42]. However, MC-ICP-MS requires more complex sample preparation and must account for polyatomic and isobaric interferences during analysis [40].

The integration of automated peripheral systems has significantly enhanced the application of IRMS for geographical authentication. Modern configurations commonly include elemental analyzers for solid and liquid samples (EA-IRMS), gas chromatography interfaces for compound-specific isotope analysis (GC-IRMS), and specialized preparation systems for specific sample types (e.g., carbonates, water) [41] [39]. These automated interfaces improve analytical reproducibility—a critical factor for building reliable geographical origin databases—while increasing sample throughput to 50-100 analyses per day depending on the specific configuration and analytical requirements [39].

Experimental Data and Performance Comparison

IRMS Applications in Food Authentication

The performance of IRMS for geographical origin discrimination is well-documented across diverse agri-food products. Recent research demonstrates that multi-isotope approaches analyzing δ13C, δ15N, and δ34S or δ18O provide the highest discrimination power, capturing different aspects of geographical variation including climate, agricultural practices, and geological background [39] [5]. A 2025 study on rice authentication achieved 91.9% accuracy in discriminating between three Greek regions (Agrinio, Serres, and Chalastra) using δ13C, δ15N, and δ34S values analyzed with a decision tree algorithm [39]. The isotopic ranges observed demonstrated clear geographical patterns, with δ15N values lowest in Agrinio (4.64‰) and highest in Chalastra (5.90‰), while δ13C values showed distinct clustering with Serres rice displaying less negative values (-26.1‰) compared to Chalastra (-28.0‰) [39].

Similar discriminatory power has been demonstrated in other food matrices. Research on virgin olive oil authentication has combined traditional stable isotope ratios with emerging sesquiterpene fingerprinting, achieving enhanced geographical discrimination through chemometric analysis [21]. Pharmaceutical authentication studies using δ2H, δ13C, and δ18O measurements have successfully identified unique isotopic signatures in ibuprofen drug products from different manufacturers and countries, with batch-to-batch variation (δ13C = -22.11 ± 0.46‰) significantly lower than variation across different manufacturers, enabling detection of substandard and falsified products [40]. These applications highlight the versatility of IRMS across different sample types and its robustness for both food and pharmaceutical authentication.

Table 2: Representative Isotopic Ranges for Geographical Discrimination of Agricultural Products

| Product Type | δ13C Range (‰) | δ15N Range (‰) | δ18O Range (‰) | Key Geographical Discriminators | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rice (Greek) | -28.0 to -26.1 | 4.64 to 5.90 | N/A | δ15N and δ34S most significant; Regional differentiation possible | [39] |

| Ibuprofen Pharmaceuticals | -22.11 ± 0.46 | N/A | 34.18 ± 1.73 | Manufacturing origin; Batch consistency verification | [40] |

| Virgin Olive Oil | Not specified | Not specified | Not specified | Combined with sesquiterpene profiles; Multi-variate analysis | [21] |

| Plant-Derived Excipients | -34 to -10 (C3 vs C4 plants) | Variable | Variable | Photosynthetic pathway discrimination; Natural vs synthetic origin | [40] |

Comparative Performance Against Alternative Techniques

IRMS occupies a distinctive niche in the analytical toolkit for geographical authentication, offering advantages and limitations compared to alternative techniques. When evaluated against spectroscopic methods like NIR, MIR, and Raman spectroscopy, IRMS provides more fundamental chemical information based on atomic properties rather than molecular vibrations, making it less susceptible to variations caused by processing or storage conditions [5]. Compared to elemental analysis techniques like ICP-MS, IRMS focuses on the natural variation of isotope ratios rather than elemental concentrations, providing complementary information that often has stronger links to specific environmental conditions and biogeochemical processes [5].

The principal advantage of IRMS lies in its exceptional precision for isotope ratio measurements and the direct connection between light element isotopic compositions and geographical factors. Carbon isotopes (δ13C) primarily reflect photosynthetic pathways (C3, C4, CAM plants) and water-use efficiency, nitrogen isotopes (δ15N) indicate soil management practices and fertilizer sources, while oxygen (δ18O) and hydrogen (δ2H) isotopes correlate strongly with regional water sources and climate patterns [40] [5]. This direct environmental linkage makes IRMS particularly valuable for constructing traceability systems based on fundamental geographical characteristics rather than potentially variable chemical compositions.

However, IRMS does have limitations that can be addressed through complementary techniques. The method requires representative reference databases for geographical assignment, and its discrimination power can decrease for regions with similar environmental conditions. Combining IRMS with complementary techniques like elemental analysis, spectroscopy, or DNA-based methods typically enhances authentication accuracy [5]. For example, a ground-breaking comparison study on virgin olive oil demonstrated that combining traditional stable isotope ratios with emerging sesquiterpene fingerprinting improved geographical discrimination through chemometric analysis [21]. Similarly, pharmaceutical authentication benefits from combining δ2H, δ13C, and δ18O measurements with additional analytical data to account for complex formulation factors [40].

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Sample Preparation Protocols

Proper sample preparation is critical for obtaining reliable IRMS data for geographical authentication. Protocols vary depending on sample matrix and the target isotopes, but all share common principles of representativeness, homogeneity, and contamination prevention. For agricultural products like rice, the documented protocol involves unhusking samples using a semi-industrial machine, grinding to a fine powder in a mill (e.g., pulverisette 11, Fritsch GmbH), and oven-drying at 60°C for 48 hours to remove residual moisture that could affect hydrogen and oxygen isotope measurements [39]. The homogenized samples are then stored in desiccators to prevent atmospheric moisture absorption until analysis [39].

For pharmaceutical applications, sample preparation protocols for ibuprofen tablets involve homogenizing the entire drug product by ball milling without separation of active pharmaceutical ingredients (APIs) and excipients, followed by careful portioning for analysis [40]. This approach preserves the complete isotopic signature of the formulated product, which reflects both the API origin and the excipient characteristics. Approximately 150 μg of sample material is encapsulated in tin or silver capsules (typically 4 × 4 × 11 mm) for elemental analysis, with careful attention to avoid atmospheric contamination during weighing [40] [39]. Sample sizes typically range from 0.1 to 5 mg depending on the element concentration and analytical requirements, with replicates (usually n=3-5) essential for assessing measurement precision [40] [39].

Specialized preparation techniques are required for specific sample types and isotopes. Carbonate-containing samples may require acid treatment to remove inorganic carbon, while water samples need specific equilibration or conversion techniques for oxygen and hydrogen isotope analysis. For compound-specific isotope analysis, extensive sample extraction and purification is necessary before GC-IRMS analysis. Throughout all preparation protocols, consistency is paramount for geographical authentication studies, as variations in preparation methods can introduce isotopic fractionation that compromises data comparability.

IRMS Analytical Methodologies

The core IRMS analytical methodology involves quantitative conversion of sample elements into simple gases followed by precise isotope ratio measurement. For δ13C and δ15N analysis via elemental analyzer-IRMS (EA-IRMS), samples are combusted in an oxygen-enriched environment at approximately 1150°C, converting carbon to CO2 and nitrogen to N2, with subsequent reduction of nitrogen oxides to N2 in a copper reduction tube at 850°C [39]. The resulting gases are separated by chromatography and introduced into the IRMS for isotope ratio determination [39].

For δ18O and δ2H analysis, thermal conversion/elemental analyzer (TC/EA) systems pyrolyze samples at high temperatures (typically >1350°C) to convert oxygen to CO and hydrogen to H2, which are then analyzed by IRMS [40]. These analyses require particularly careful handling to avoid isotopic exchange with atmospheric moisture, often employing zero-blank autosamplers that purge inert He gas over samples to eliminate reactions with external factors [40].

Table 3: Standard IRMS Analytical Conditions for Geographical Authentication

| Analysis Type | Sample Weight | Combustion/Pyrolysis Temperature | Reference Materials | Quality Control Measures |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| δ13C and δ15N (EA-IRMS) | 0.5-5 mg | 1150°C combustion; 850°C reduction | USP/PhEur certified reference materials; IAEA standards | System suitability tests; Continuous calibration verification; Blank corrections |

| δ18O and δ2H (TC/EA-IRMS) | 0.1-0.5 mg | >1350°C pyrolysis | IAEA-602 benzoic acid; USGS water standards | Memory effect assessment; Reaction efficiency monitoring; Humidity control |

| Bulk δ34S (EA-IRMS) | 3-10 mg | 1150°C combustion; 850°C reduction | IAEA-S-1, IAEA-S-2, IAEA-S-3 | SO2 yield verification; Silver wool trap maintenance |

| Compound-Specific δ13C (GC-IRMS) | Extract equivalent to 10-100 mg original sample | 940°C combustion after GC separation | n-Alkane standards; In-house reference compounds | Linearity checks; Co-elution assessment; Peak identification verification |

Quality assurance protocols are integral to IRMS analysis for geographical authentication. These include regular calibration using certified reference materials with internationally recognized isotopic compositions, system suitability tests to verify analytical performance, continuous calibration verification during analytical sequences, blank corrections, and participation in proficiency testing schemes [40] [39]. Data quality assessment typically involves evaluating measurement precision through replicate analyses, accuracy through reference materials, and uncertainty estimation using established metrological approaches. For geographical authentication studies, the long-term reproducibility of measurements is particularly important, with studies demonstrating high data reproducibility over consecutive weeks of analysis [40].

Visualization of IRMS Workflows

Geographical Authentication Workflow

Multi-Isotope Data Interpretation Pathway

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for IRMS Geographical Authentication

| Category | Specific Items | Function/Application | Technical Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Reference Materials | IAEA-602 Benzoic Acid; USGS40, USGS41; NBS-18, NBS-19; IAEA-S-1, IAEA-S-2, IAEA-S-3 | Calibration and quality control; Ensuring measurement traceability to international standards | Must cover expected δ-range of samples; Should be matrix-matched when possible |

| Sample Containers | Tin Capsules (4×4×11 mm); Silver Capsules; Exetainer Vials (12 mL); Septa | Sample encapsulation and storage; Preventing isotopic exchange with atmosphere | Tin for C,N,S analysis; Silver for O,H analysis; Proper sealing critical |

| Consumables | High-Purity Oxygen (≥99.995%); High-Purity Helium (≥99.999%); Liquid Nitrogen; Copper Oxide; Reduced Copper Wire | Combustion/pyrolysis reagents; Carrier gas; Cryogenic focusing | Impurities affect analytical accuracy; Regular replacement required |

| Standards | Laboratory Working Standards; In-House Reference Materials; Process Blanks | Daily calibration verification; Monitoring instrumental drift | Should be isotopically homogeneous; Stable over long-term storage |

| Sample Preparation | Ball Mill with Agate Jars; Freeze Dryer; Microbalance (±0.001 mg); Desiccators | Homogenization; Moisture removal; Precise weighing; Dry storage | Avoid contamination during grinding; Control humidity during weighing |

The selection of appropriate research reagents and materials is critical for obtaining reliable IRMS data for geographical authentication. High-purity gases are essential, as impurities can cause incomplete combustion/pyrolysis or interfere with isotope ratio measurements. Certified reference materials with internationally recognized isotopic compositions provide the foundation for measurement traceability, allowing comparison of data across different laboratories and over time [40] [39]. Sample encapsulation materials must be selected based on the target isotopes—tin capsules for carbon, nitrogen, and sulfur analysis due to their exothermic reaction during combustion, and silver capsules for oxygen and hydrogen analysis because of their higher thermal conductivity and lower blank contributions [39].