Troubleshooting Fiber Analysis in Mixed Diets: A Research Guide for Overcoming Methodological Challenges

Analyzing the health effects of mixed dietary fibers presents significant methodological challenges that can obscure their true physiological impact.

Troubleshooting Fiber Analysis in Mixed Diets: A Research Guide for Overcoming Methodological Challenges

Abstract

Analyzing the health effects of mixed dietary fibers presents significant methodological challenges that can obscure their true physiological impact. This article provides a comprehensive framework for researchers and scientists to navigate these complexities, moving beyond the simplistic soluble vs. insoluble classification. We explore the foundational principles of fiber diversity, advanced methodological approaches for accurate assessment, and targeted troubleshooting strategies for common experimental pitfalls. By integrating insights from gut microbiome research, mechanistic studies, and validation techniques, this guide aims to enhance the reliability and interpretability of fiber analysis in complex dietary matrices, ultimately supporting more effective translation into clinical and pharmaceutical applications.

Beyond Soluble vs. Insoluble: Foundational Principles of Dietary Fiber Complexity

Limitations of Traditional Binary Fiber Classification Systems

For decades, dietary fiber (DF) has been broadly categorized into "soluble" and "insoluble" types. This binary classification system, while useful for basic labeling and education, is insufficient for modern nutritional research and the development of targeted therapeutic interventions. The central limitation is that this simplistic division does not predict the physiological functionality of a fiber in the human body [1]. Fibers within the same solubility category can have vastly different effects on health outcomes because their functionality is governed by a complex set of physicochemical properties that solubility alone cannot capture [1]. Relying on this outdated system can lead to inconsistent research results, difficulties in replicating studies, and an inability to establish clear structure-function relationships for specific fibers, particularly in the complex environment of mixed diets [1].

This technical support guide will help researchers troubleshoot common issues arising from the use of traditional binary classification in their experiments and provide methodologies for a more nuanced, property-based analysis.

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Issues

Q1: Why do I get inconsistent physiological results (e.g., appetite suppression, blood glucose response) when using fibers classified under the same "soluble" category?

A: This is a direct consequence of the variability in key functional properties not described by the binary system. Two soluble fibers can have different molecular weights, viscosities, and fermentability rates, leading to different physiologic effects [1].

- Root Cause: The binary system groups together fibers with divergent functional properties. For example, both low-viscosity FOS and high-viscosity beta-glucan are "soluble," but they interact with the digestive system in fundamentally different ways.

- Solution: Characterize and report the specific physicochemical properties of your test fibers. Key properties to measure include [1]:

- Molecular Weight (MW) / Degree of Polymerization: Significantly impacts viscosity and fermentation rate.

- Viscosity: A critical factor for effects on gastric emptying, nutrient absorption, and glycemic response.

- Fermentation Rate & Extent: Determines the production of Short-Chain Fatty Acids (SCFAs) and interactions with the gut microbiota.

- Water-Holding Capacity: Affects stool bulk and intestinal transit time.

Q2: My experiment with a mixed-fiber diet did not produce the expected beneficial outcomes, even though the total fiber content was high. What went wrong?

A: The effects of fiber are not always additive. A mixture may fail to achieve the critical threshold of a specific fiber type required to elicit a physiological response.

- Root Cause: In a mixture, individual fibers are present at lower concentrations. A specific physiologic effect may require a single fiber to be present above a threshold dose to shift specific bacterial populations or generate sufficient viscosity [2].

- Solution: Design experiments that consider both the dose and the type of individual fibers within a mixture. Do not assume that a blend of fibers at a total of 10% will have the same effect as a single fiber at 10%. The research by Shallangwa et al. (2025) demonstrated that 10% pectin or 10% FOS suppressed high-fat diet-induced weight gain in mice, but a 10% mixture of four fibers (each at 2.5%) did not, highlighting the importance of a threshold abundance for specific fibers [2].

Q3: How can I improve the reproducibility of my fiber research for publication and peer review?

A: Inadequate characterization of test materials is a major reason for the inability to replicate studies and weakens the validity of meta-analyses [1].

- Root Cause: Many studies fail to adequately report the source, composition, and properties of the DF used, focusing only on the total amount and perhaps the soluble/insoluble ratio [1].

- Solution: Adopt rigorous reporting standards. The table below outlines the minimum characterization required for a fiber intervention study to be considered well-reported [1].

Table 1: Essential Characterization and Reporting for Dietary Fiber in Research

| Category | Parameters to Report | Importance for Reproducibility & Function |

|---|---|---|

| Source & Identity | Precise botanical/chemical source; supplier and product lot number. | Allows for independent sourcing and replication [1]. |

| Composition & Purity | Total DF content (by analyzed method), associated compounds (e.g., phenolics). | Ensures accurate dosing and identifies potential confounders [1]. |

| Molecular Structure | Molecular Weight (MW) distribution, Degree of Polymerization, monosaccharide composition, specific structural features (e.g., degree of methylation for pectin). | Directly determines physical properties like viscosity and gelation [1]. |

| Physical Properties | Viscosity (under relevant conditions), water-holding capacity, solubility. | Predicts physiological functionality in the gut [1]. |

| Fermentation Profile | Rate and extent of fermentation in vitro; SCFA profile produced. | Predicts interaction with the gut microbiota and metabolic consequences [1]. |

Advanced Methodologies for Fiber Analysis

To overcome the limitations of binary classification, researchers must employ methodologies that characterize the functional properties of fibers.

Experimental Protocol 1: Determining Viscosity of Dietary Fibers

Principle: Viscosity is a key functional property that should be measured in conditions mimicking the food matrix or gastrointestinal environment relevant to the study hypothesis [1].

Materials:

- Research Dietary Fiber (e.g., Pectin, Beta-Glucan, FOS)

- Physiologically Relevant Buffer (e.g., simulated gastric or intestinal fluid)

- Rheometer (controlled stress or strain)

- Analytical Balance

- Temperature-Controlled Water Bath

Procedure:

- Solution Preparation: Precisely prepare a solution of the DF in the chosen buffer at a concentration relevant to the intended dietary dose (e.g., 1-5% w/w).

- Hydration: Allow the solution to hydrate fully with constant stirring for a standardized time (e.g., 24 hours at 4°C) to ensure complete dissolution and polymer swelling.

- Rheometry: Load the hydrated solution into the rheometer. Use a cone-and-plate or coaxial cylinder geometry.

- Shear Sweep: Perform a steady-state shear sweep (e.g., from 0.1 to 100 s⁻¹) at a constant physiological temperature (e.g., 37°C).

- Data Analysis: Record the apparent viscosity at a specific, biologically relevant shear rate (e.g., 10-50 s⁻¹, representative of intestinal peristalsis). Report the viscosity in mPa·s or Pa·s.

Experimental Protocol 2: AssessingIn VitroFermentation

Principle: This protocol estimates the rate and extent of microbial fermentation of a DF and the resulting SCFA production.

Materials:

- Anaerobic Chamber

- Fecal Inoculum (from human or animal donors)

- Fermentation Media (e.g., nutrient-rich, carbohydrate-free)

- Water Bath Shaker

- Gas Chromatography (GC) System

- pH Meter

Procedure:

- Inoculum Preparation: Collect and homogenize fresh fecal samples in an anaerobic phosphate buffer under a constant flow of CO₂.

- Fermentation Setup: Weigh test fibers into fermentation vessels. Add fermentation media and inoculate with the prepared fecal slurry. Include a control vessel with no fiber (blank) and a reference fiber (e.g., cellulose, FOS).

- Incubation: Incubate vessels anaerobically in a shaking water bath at 37°C for up to 48 hours.

- Sampling: At predetermined time points (e.g., 0, 6, 12, 24, 48h), sample the headspace gas for hydrogen/methane and withdraw liquid samples.

- Analysis:

- SCFAs: Analyze liquid samples via GC to quantify acetate, propionate, and butyrate production.

- Substrate Disappearance: Measure the remaining fiber substrate using a suitable chemical method.

- pH: Monitor pH changes throughout the fermentation.

Table 2: The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Reagents for Advanced Fiber Analysis

| Research Reagent | Function in Experimentation |

|---|---|

| Purified Fiber Polymers (e.g., Pectin, Beta-Glucan, Inulin, FOS) | Serve as well-defined test materials to establish clear structure-function relationships, moving beyond crude fiber extracts [2]. |

| Short-Chain Fatty Acid (SCFA) Standards (Acetate, Propionate, Butyrate) | Essential for calibrating Gas Chromatography (GC) systems to quantify the key metabolites of fiber fermentation [2]. |

| Simulated Gastrointestinal Fluids (Gastric & Intestinal) | Provide a physiologically relevant medium for testing fiber functionality, such as viscosity development, under conditions mimicking the human gut [1]. |

| Specific Enzyme Assays (e.g., for amylase, protease) | Used to confirm the resistance of the fiber to digestion by human endogenous enzymes, a key criterion in the definition of dietary fiber [1]. |

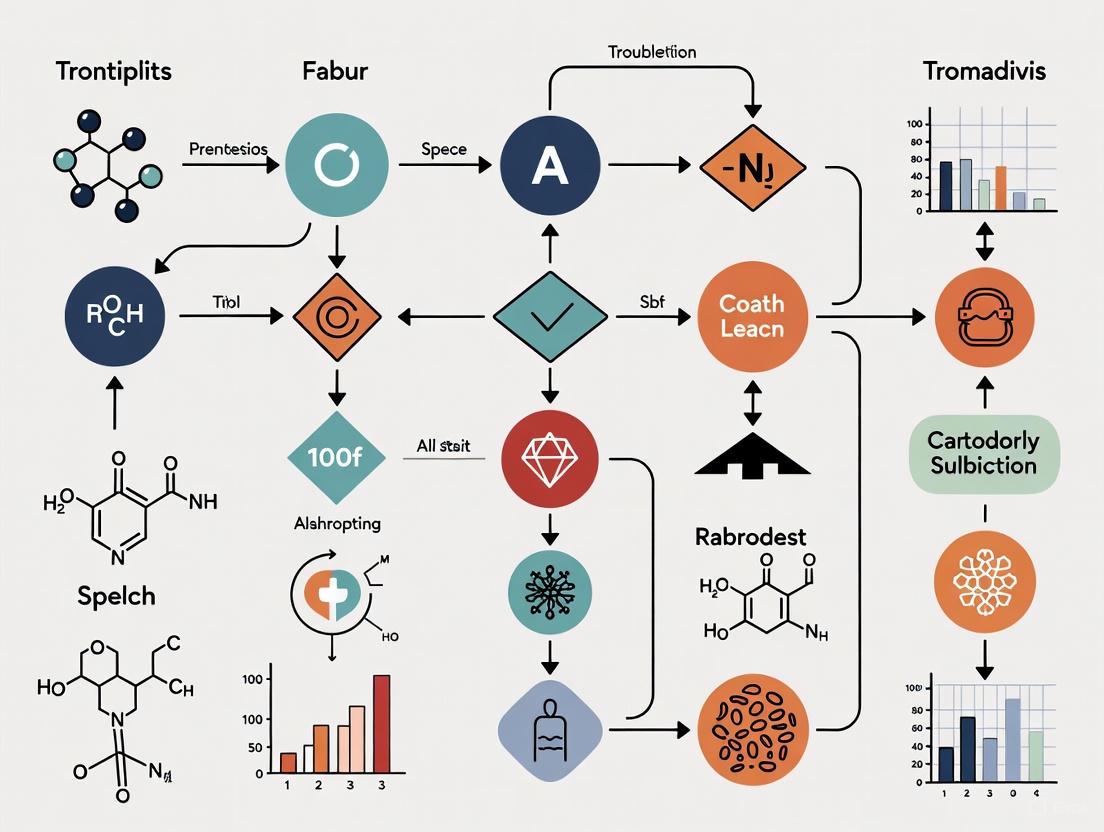

Visualizing the Multi-Parameter Fiber Analysis Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the recommended workflow for moving beyond binary classification to a multi-parameter analysis system.

Multi-Parameter Fiber Analysis Workflow

Visualizing the Troubleshooting Decision Pathway

When experimental results are inconsistent with expectations based on binary classification, follow this logical troubleshooting pathway.

Troubleshooting Pathway for Fiber Experiments

Key Structural and Functional Properties Governing Physiological Effects

FAQ: Troubleshooting Fiber Analysis in Mixed Diets Research

Q1: Why does the traditional "soluble vs. insoluble" classification of dietary fiber fail to predict physiological outcomes in my research?

The soluble vs. insoluble classification is a simplistic binary system that overlooks the structural and functional complexity of diverse fiber types. This limited framework fails to account for critical properties that directly govern physiological effects, such as fermentability, impact on insulin secretion, and cholesterol-lowering capacity. A more holistic classification framework encompassing backbone structure, water-holding capacity, structural charge, fiber matrix, and fermentation rate is required to accurately predict health outcomes [3]. Furthermore, fiber functionality depends on specific subtypes (e.g., β-fructans, β-glucans, pectin), each with distinct molecular structures and functions that are obscured by the traditional binary classification [4].

Q2: My in vivo experiments show inconsistent body weight suppression with mixed fiber diets. What could be the cause?

Research indicates that the ability of dietary fiber to suppress high-fat diet-induced weight gain is dependent on both fiber type and dose. In controlled murine studies, single fibers like 10% pectin and 10% FOS (fructooligosaccharide) effectively suppressed weight gain, whereas mixtures of fibers totaling 2% or 10% did not produce the same effect. This suggests that single fibers at sufficient doses may need to shift specific bacterial abundances above a critical threshold to elicit a metabolic response, an effect that may be diluted in fiber mixtures [2]. Ensure your experimental design considers that mixed fibers may stimulate distinct gut microbiota profiles compared to single fibers.

Q3: How can improper fiber analysis methodology lead to irreproducible results in my feed and digesta samples?

Fiber is a heterogeneous entity, and the method defines what is measured. Inconsistent sample preparation, filtration difficulties in Neutral Detergent Fiber (aNDF) analysis, and inexact adherence to protocol can severely impact repeatability within a lab and reproducibility across labs. Rigorous standardization, such as that achieved with the AOAC Official Method 2002.04 for amylase-treated NDF (aNDF), is critical. Furthermore, accounting for variable aNDF digestibility through improved in vitro ruminal digestibility and gas production procedures is essential for accurate feed evaluation and overall digestibility calculations [5].

Q4: What are the best practices for documenting dietary fibers in my research to ensure reproducibility?

Poor documentation of fiber sources is a significant source of inconsistent evidence. Your manuscripts should consistently report:

- Fiber Type and Subtype: Specify the chemical subtype (e.g., β-glucan, pectin, arabinoxylan) rather than just "soluble fiber" [4].

- Fiber Source: Detail the plant source (e.g., apple pectin, oat β-glucan) [2].

- Growing Conditions & Ripeness: These factors can alter fiber content [4].

- Processing & Cooking: Describe any preparation methods, as soaking and boiling can modify fiber properties [6].

- Analytical Method: State the method used to quantify fiber content (e.g., AOAC 985.29) [6].

Troubleshooting Guide: Common Experimental Issues

| Problem | Potential Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Inconsistent physiological outcomes (e.g., weight, adiposity) | Using mixed fibers vs. single fibers; incorrect dosing. | Test single fibers at multiple doses (e.g., 2% vs. 10%). A specific effect may require a threshold dose of a single fiber type [2]. |

| High variability in fiber analysis results | Poor lab technique; non-standardized methods; inaccurate correction for blanks. | Strictly adhere to reference methods (e.g., AOAC 2002.04). Implement laboratory proficiency programs and use validated in vitro digestibility procedures [5]. |

| Unexpected or absent gut hormone response (PYY, GLP-1) | Fiber type may not effectively stimulate target gut bacteria or SCFA production. | Consider that 10% pectin and FOS elevated PYY, while a mixed fiber diet did not, despite similar total fiber. Verify the gut microbiota profile response to your specific fiber intervention [2]. |

| Poor anti-pathogen effects in vitro | Incorrect fiber type or mechanism of action. | Screen fibers for specific anti-infectious properties. Lentil extract can reduce toxin production, while yeast cell walls can inhibit pathogen adhesion to cells and mucins—effects not universal to all fibers [6]. |

| Inability to correlate structure with function | Over-reliance on "soluble vs. insoluble" classification. | Characterize fibers using a multi-property framework: backbone structure, water-holding capacity, structural charge, fiber matrix, and fermentation rate [3]. |

Experimental Protocols for Key Fiber Analyses

Protocol 1: Single Fiber Pull-Out Test for Fiber Shedding Propensity (In Vitro)

Application: Evaluating the mechanical shedding property of textile pile debridement materials, where shed fibers can impair wound healing [7].

- Sample Preparation: Prepare fabric samples with varying structural designs (pile density, number of ground yarns) and processing parameters (e.g., back-coating repetitions).

- Testing Setup: Employ a mechanical tester configured for single fiber pull-out. A single pile fiber is gripped and pulled from the ground fabric structure.

- Data Collection: Record the force required to pull the fiber out (pull-out force) and the corresponding displacement.

- Analysis: Analyze the load-displacement curve to determine the maximum pull-out force. Identify the failure mode: fiber slippage, coating point rupture, or fiber breakage.

- Interpretation: Higher pull-out force indicates lower fiber shedding propensity. Back-coating significantly increases pull-out force and reduces shedding [7].

Protocol 2: In Vitro Evaluation of Anti-Adhesive Properties Against Enteric Pathogens

Application: Screening dietary fibers for their potential to prevent infection by pathogens like Enterotoxigenic E. coli (ETEC) [6].

- Fiber Preparation: Obtain or extract fiber-containing products (e.g., from lentils, oats, yeast). Analyze fiber content using a standard method like AOAC 985.29. Use at a consistent concentration (e.g., 2 g·L⁻¹) in assays.

- Mucin Bead Adhesion Assay:

- Produce mucin-alginate beads by dropping a mucin/alginate mixture into a CaCl₂ solution.

- Resuspend beads in PBS with or without the fiber product.

- Incubate with ETEC strain H10407 for 30-60 minutes.

- Wash beads thoroughly to remove non-adhered bacteria.

- Crush beads and plate the homogenate to enumerate adhered bacteria.

- Cell Culture Adhesion Assay:

- Culture human intestinal epithelial cells (e.g., Caco-2/HT29-MTX co-culture) to form a differentiated monolayer.

- Pre-incubate bacteria with or without fiber product, then apply to cells.

- After incubation, wash cells and lyse them to release adhered bacteria for enumeration.

- Interpretation: A significant reduction in bacterial count in the fiber-treated groups compared to the control indicates anti-adhesive properties [6].

Research Reagent Solutions Toolkit

| Item | Function in Experiment |

|---|---|

| Amylase-treated NDF (aNDF) | Standardized method for analyzing insoluble fiber in feeds and digesta, crucial for accurate ration formulation [5]. |

| Pectin (e.g., Apple Pectin) | A soluble, highly fermentable fiber used to study suppression of weight gain and stimulation of gut hormones like PYY [2]. |

| Fructooligosaccharide (FOS) | A soluble prebiotic fiber used to study modulation of the gut microbiota and its metabolic consequences [2]. |

| Lentil Extract | A fiber-containing product demonstrated to reduce heat-labile toxin production and inhibit adhesion of ETEC in vitro [6]. |

| Yeast Cell Walls | A fiber source shown to interfere with pathogen adhesion to mucins and intestinal cells, acting as a protective decoy [6]. |

| Polyacrylate Latex | A back-coating agent used in textile pile fabrics to significantly reduce fiber shedding by increasing single fiber pull-out force [7]. |

Experimental Workflow for Fiber Analysis Troubleshooting

The diagram below outlines a logical workflow for diagnosing and resolving common issues in fiber research, based on the principles and data from the search results.

Gut Microbiota as a Central Mediator of Fiber-Specific Responses

Core Concepts: Understanding Fiber-Microbiota Interactions

Frequently Asked Questions

What constitutes "dietary fiber" from a research perspective? Dietary fiber encompasses carbohydrate polymers with ten or more monomeric units that resist hydrolysis by human endogenous enzymes and absorption in the small intestine. This includes three primary types based on physiological properties and polymerization: nonstarch polysaccharides (NSPs) with MU ≥ 10 (e.g., cellulose, hemicellulose, pectin, inulin), resistant starches (RS) with MU ≥ 10, and resistant oligosaccharides (ROS) with MU 3-9 (e.g., fructo-oligosaccharides/FOS, galacto-oligosaccharides/GOS) [8].

Why do individual responses to fiber interventions vary so significantly? Individual responses to fiber interventions vary substantially due to baseline gut microbiota composition. The Prevotella-to-Bacteroides (P/B) ratio has emerged as a key biomarker predicting responsiveness. Individuals with Prevotella-dominated (P-type) microbiota respond differently to specific fibers than those with Bacteroides-dominated (B-type) microbiota, with P-type individuals showing more significant global microbiota shifts and functional changes in response to resistant starch-rich interventions like unripe banana flour [9] [10].

How does soluble versus insoluble fiber classification limit our understanding? The traditional soluble versus insoluble classification overlooks critical functional differences between fiber subtypes. Fiber functionality extends beyond solubility to include molecular structure, monosaccharide composition, chain length, polymerization degree, and glycosidic linkages. Each subtype (β-fructans, β-glucans, pectin, arabinoxylans, etc.) exhibits distinct molecular structures and functions that significantly influence microbial fermentation patterns and host physiological responses [4].

What mechanisms explain how fiber benefits host metabolism through microbiota? Gut microbes ferment dietary fibers to produce short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs), primarily acetate, propionate, and butyrate. These SCFAs serve as energy sources for colonocytes and act as signaling molecules that influence host metabolism through multiple pathways: they activate G-protein coupled receptors (FFAR2/FFAR3), regulate gut hormones (PYY, GLP-1), maintain gut barrier integrity, modulate immune function, and impact systemic metabolic processes [11] [2].

Research Reagent Solutions: Essential Materials for Fiber-Microbiota Research

Table 1: Key Research Reagents for Investigating Fiber-Microbiota Interactions

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Research Application & Function |

|---|---|---|

| Purified Fiber Types | Arabinoxylan (AX), Inulin (INU), Fructo-oligosaccharides (FOS), Pectin, Resistant Starch (RS) | Used in controlled interventions to test specific fiber effects on microbiota composition and SCFA production [9] [2] |

| Microbiota Analysis Tools | 16S rRNA gene sequencing, PICRUSt for functional prediction, Fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH), Quantitative PCR (qPCR) | Enables characterization of microbial community structure, abundance of specific taxa, and prediction of metabolic potential [12] [10] [13] |

| SCFA Measurement | Gas chromatography, Mass spectrometry | Quantifies concentrations of acetate, propionate, butyrate, and branched-chain fatty acids in fecal samples or blood plasma [9] [11] |

| Gut Hormone Assays | ELISA for PYY, GLP-1, CCK | Measures fiber-induced changes in enteroendocrine cell hormone secretion that regulates appetite and metabolism [2] |

| Cell Culture Models | Intestinal organoids, Enteroendocrine cell lines (e.g., STC-1, NCI-H716) | Studies molecular mechanisms of microbial metabolite effects on intestinal epithelial function without animal models [11] |

Experimental Design & Protocol Troubleshooting

Frequently Asked Questions

What are the critical considerations when designing a fiber intervention study? Key considerations include: (1) Fiber dose - threshold effects exist where 10% pectin or FOS suppressed high fat diet-induced weight gain in mice while 2% doses did not [2]; (2) Intervention duration - short-term (4-week) supplementation can significantly improve bowel-related quality of life and modulate microbiota, but longer interventions may be needed for systemic effects [12]; (3) Control selection - appropriate placebo (e.g., maltodextrin) controlling for non-fiber carbohydrate effects is essential [9] [10]; (4) Participant stratification - baseline microbiota assessment allows for P/B ratio stratification to account for responsiveness variability [9] [10].

How can researchers optimize fecal sample processing for SCFA analysis? Proper SCFA analysis requires: immediate freezing of fecal samples at -80°C after collection to prevent continued microbial fermentation; use of acidification to preserve SCFA profiles; standardized extraction protocols; and implementation of internal standards during gas chromatography to ensure quantification accuracy. Plasma SCFA measurement should include both fasting and postprandial assessments to capture dynamic responses [9].

What are the methodological pitfalls in fiber content analysis? Critical pitfalls include: (1) Overreliance on crude fiber analysis which underestimates total fiber content by failing to fully recover hemicellulose and some cellulose components [14]; (2) Inadequate particle size standardization - samples should be homogenized to 1mm particles; (3) Variable detergent concentrations and cooking times that affect fiber extraction efficiency; (4) Inconsistent filtration methods - porosity changes in glass crucibles can increase error rates [14]. The Van Soest method (NDF, ADF, ADL analysis) provides more comprehensive fiber fractionation [14].

Quantitative Data Synthesis: Fiber Effects from Clinical Studies

Table 2: Clinically Observed Effects of Specific Fiber Interventions on Microbiota and Metabolic Parameters

| Fiber Type | Dose/Duration | Microbiota Changes | SCFA & Metabolic Effects | Study Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Arabinoxylan | 15 g/day, 1 week | Increased Fusicatenibacter in B-types; Increased Paraprevotella in P-types | Increased fasting propionate in P-types; Increased postprandial acetate & propionate in B-types | [9] |

| Inulin | 15 g/day, 1 week | Increased Anaerostipes & Bifidobacterium; Reduced Phocaeicola in both P&B types | Reduced branched-chain fatty acids in B-types; No significant SCFA increase | [9] |

| Mixed Fiber Supplement | 8.2 g/day total (6.4 g fermentable), 4 weeks | Increased SCFA-associated genera (Anaerostipes, Bifidobacterium, Fusicatenibacter) | Improved bowel-related quality of life; Limited effects on sleep/skin | [12] |

| Fructans & Galacto-oligosaccharides | Various doses (Meta-analysis) | Significantly increased Bifidobacterium & Lactobacillus spp. | Increased fecal butyrate concentration; No change in other SCFAs | [13] |

| Resistant Starch (UBF) | 3 times/week, 6 weeks | Major global microbiota shifts only in P-type individuals | Functional changes in 533 KEGG orthologs in P-type consumers | [10] |

Methodology & Analysis Troubleshooting

Experimental Protocol: Assessing Fiber Responsiveness by Microbiota Enterotype

Objective: To determine individual responsiveness to specific fiber types based on baseline Prevotella-to-Bacteroides ratio [9] [10].

Materials and Equipment:

- Stool collection kits (DNA stabilizer)

- DNA extraction kit optimized for bacterial DNA

- 16S rRNA gene sequencing primers (V3-V4 region)

- QIIME2 or similar microbiome analysis pipeline

- Purified fiber supplements (arabinoxylan, inulin, resistant starch)

- Placebo (maltodextrin)

- Gas chromatography system for SCFA analysis

- ELISA kits for PYY, GLP-1

Procedure:

- Baseline Microbiota Assessment:

- Collect fecal samples from participants using DNA-stabilizing solution

- Extract bacterial DNA using bead-beating method for cell lysis

- Amplify V3-V4 region of 16S rRNA gene

- Sequence amplicons using Illumina MiSeq platform (2×300 bp)

- Process sequences through QIIME2: denoise with DADA2, assign taxonomy using Silva database

- Calculate Prevotella-to-Bacteroides ratio, classify as P-type (≥10% Prevotella) or B-type (≥10% Bacteroides)

Randomized Crossover Intervention:

- Implement 1-week supplementation periods with 2-week washouts between treatments

- Administer in randomized order: 15 g/day arabinoxylan, 15 g/day inulin, placebo (maltodextrin)

- Maintain dietary records to control for background fiber intake

Outcome Assessment:

- Collect fasting and postprandial plasma samples for SCFA analysis (GC-MS)

- Analyze gut hormones (PYY, GLP-1) via ELISA

- Record gastrointestinal symptoms using validated questionnaires (GSRS)

- Assess microbiota changes after each intervention period

Data Analysis:

- Compare outcomes between P-type and B-type groups for each fiber

- Use repeated-measures ANOVA for metabolic parameters

- Perform PERMANOVA on weighted UniFrac distances for microbiota changes

- Correlate specific bacterial taxa shifts with SCFA production

Frequently Asked Questions

Why do mixed fiber interventions sometimes fail where single fibers succeed? Mixed fiber interventions may fail due to dilution effects - when multiple fibers are combined at lower individual doses, none may reach the threshold required to meaningfully shift specific bacterial populations. In mice, 10% pectin or FOS suppressed high fat diet-induced weight gain, but a 10% mixture of four fibers (each at 2.5%) did not, despite similar total fiber content. Single fibers at sufficient doses shift specific bacteria above threshold abundances required for physiological effects [2].

How can researchers account for inter-individual microbiota variability? Implement stratification by baseline microbiota composition before intervention. Cluster participants based on P/B ratio or other enterotype classifications. Increase sample size to account for expected response variability. Consider crossover designs where participants serve as their own controls. Include detailed dietary monitoring to control for background fiber intake that influences baseline microbiota [9] [10].

What are the limitations of 16S rRNA sequencing for fiber intervention studies? 16S sequencing identifies taxonomic changes but provides limited functional information. It cannot detect: (1) strain-level changes potentially important for fiber metabolism; (2) functional gene expression shifts in response to fibers; (3) actual metabolic activity of microbiota. Complementary techniques like metatranscriptomics, metabolomics, or PICRUSt functional prediction can address some limitations but have their own constraints [10] [13].

Data Interpretation & Validation Troubleshooting

Frequently Asked Questions

How can researchers distinguish direct fiber effects from confounding factors? Use placebo-controlled designs with carefully matched controls (e.g., maltodextrin for energy matching). Implement run-in periods to stabilize background diet. Measure compliance biomarkers like plasma SCFA levels or breath hydrogen. Analyze fiber-specific bacterial taxa changes rather than overall diversity metrics. Perform dose-response studies to establish causality [12] [9].

What constitutes a meaningful versus incidental microbiota change? Meaningful changes are: (1) Consistent across multiple participants within the same enterotype; (2) Dose-dependent and reproducible; (3) Associated with functional outcomes like SCFA production, not just taxonomic shifts; (4) Temporally stable during intervention periods; (5) Linked to physiological endpoints like improved insulin sensitivity, weight management, or inflammation reduction [9] [10] [13].

Why do some fibers increase SCFA-producing bacteria without increasing SCFA levels? Disconnects between bacterial abundance and SCFA production may occur due to: (1) Functional redundancy where different bacteria produce similar SCFAs; (2) Compensatory metabolic pathways activation; (3) Rapid SCFA absorption or utilization by other bacteria; (4) Methodological issues in SCFA measurement stability; (5) Insufficient fermentation time for metabolite accumulation [9] [13].

Signaling Pathway Diagram: SCFA-Mediated Mechanisms

Advanced Technical Considerations

Research Reagent Solutions: Advanced Analytical Tools

Table 3: Advanced Methodologies for Mechanistic Fiber-Microbiota Research

| Methodology | Specific Application | Technical Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Metabolomics | Comprehensive SCFA profiling, Identification of novel microbial metabolites | Requires sophisticated normalization for fecal samples; LC-MS/MS provides broader coverage than GC-MS for unknown metabolites |

| Gnotobiotic Models | Causality establishment between specific microbiota and fiber responses | Technically challenging; allows colonization with defined microbial communities to test fiber effects in controlled systems |

| Intestinal Organoids | Study direct effects of fiber metabolites on intestinal epithelium | Maintains tissue-specific function without animal use; enables human-specific response assessment [11] |

| Multi-omics Integration | Combining metagenomics, metabolomics, transcriptomics | Computational complexity; requires specialized bioinformatics pipelines for data integration |

| Van Soest Fiber Analysis | Comprehensive fiber fractionation beyond crude fiber | Distinguishes NDF, ADF, ADL for precise fiber characterization; more informative than crude fiber analysis [14] |

Frequently Asked Questions

What emerging technologies are advancing fiber-microbiota research? Emerging technologies include: (1) Microbial culturomics enabling functional characterization of fiber-degrading bacteria; (2) Stable isotope probing tracking fiber metabolism by specific taxa; (3) Single-cell metabolomics revealing heterogeneity in microbial responses; (4) Gut-on-a-chip systems modeling human gut microenvironment; (5) Machine learning approaches predicting individual responses to fiber interventions based on baseline features [4] [11].

How can researchers translate mouse fiber studies to human applications? Improve translational relevance by: (1) Using humanized microbiota mice colonized with human gut microbes; (2) Matching fiber doses to human equivalent consumption; (3) Considering physiological differences in gut transit time, anatomy, and bile acid composition; (4) Incorporating human-relevant dietary backgrounds rather than standard chow; (5) Validating promising findings in human pilot studies before large trials [2].

What are the key gaps in current fiber analysis methodologies? Significant gaps include: (1) Inadequate characterization of fiber structures in complex foods; (2) Limited understanding of how food processing affects fiber fermentability; (3) Insufficient standardization across fiber analysis methods between laboratories; (4) Poor quantification of fiber intake in observational studies; (5) Incomplete databases of fiber content in commonly consumed foods [4] [14].

Dose-Response Relationships and Threshold Effects in Fiber Efficacy

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: What is the observed relationship between dietary fiber intake and cognitive function in older adults? Research indicates a non-linear, J-shaped relationship between dietary fiber intake and cognitive function in adults aged 60 and over. Cognitive performance improves with increasing fiber intake up to a specific threshold, after which the benefits plateau or may slightly decrease. For example, processing speed (measured by DSST) plateaus at an intake of approximately 29.65 grams per day, while global cognitive composite scores plateau at about 22.65 grams per day [15].

Q2: How does vitamin E influence the relationship between fiber and cognition? Vitamin E intake is a significant mediator. It was found to mediate 85.0% of the association between dietary fiber and global cognitive scores, and 86.8% of the association with processing speed. This suggests that the cognitive benefits of dietary fiber are largely explained by its correlation with vitamin E intake, possibly due to vitamin E's role in reducing oxidative stress in the brain [15].

Q3: Why is understanding non-linear dose-response relationships important in fiber research? Non-linear relationships are common in nutrient-health research. Assuming a simple linear association can lead to incorrect conclusions about the benefits or risks of a nutrient. Analyzing for threshold effects and curve patterns (like J-shaped or U-shaped) allows for a more accurate depiction of physiological processes, helps identify optimal intake levels, and provides a stronger scientific basis for dietary recommendations [15] [16].

Q4: Can high fiber intake affect the availability of other nutrients? Yes, high dietary fiber intake can decrease the metabolizable energy content and digestibility of mixed diets. Increasing fiber intake has been shown to decrease the apparent digestibility of both fat and protein. Consequently, the metabolizable energy content of the diet decreases as fiber intake increases [17].

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue 1: Inconsistent Cognitive Benefits from Fiber Interventions

Problem: An intervention study increasing fiber intake in older adults fails to show consistent improvement in cognitive test scores.

Potential Causes and Solutions:

- Cause: Inadequate consideration of threshold effects.

- Solution: Analyze your data for non-linear relationships. Do not assume the effect is linear across all intake levels. Use statistical models like Generalized Additive Models (GAM) or two-piecewise linear regression to identify potential inflection points where the effect changes [15].

- Cause: Confounding by other nutrient intakes.

- Solution: Measure and control for key mediating nutrients, particularly vitamin E. Conduct mediation analysis to determine if the effect of fiber is direct or indirect through other dietary components [15].

- Cause: Use of a single cognitive test.

- Solution: Cognitive function is multi-faceted. Use a comprehensive cognitive battery assessing different domains such as memory (e.g., CERAD), executive function (e.g., Animal Fluency Test), and processing speed (e.g., Digit Symbol Substitution Test). A global composite z-score can provide a more robust measure [15].

Issue 2: Difficulty in Precisely Quantifying Fiber Intake

Problem: Inaccurate or imprecise measurement of dietary fiber intake leads to misclassification of exposure and weakens study findings.

Potential Causes and Solutions:

- Cause: Reliance on a single 24-hour dietary recall.

- Solution: Implement multiple 24-hour dietary recalls (e.g., two recalls, one in-person and one via telephone 3-10 days later) to better estimate usual intake. The use of the Automated Multiple-Pass Method can enhance the accuracy and completeness of dietary recall data [15].

- Cause: Not accounting for the impact of fiber on overall energy and nutrient absorption.

- Solution: In studies focused on energy balance or specific nutrient status, be aware that high fiber can reduce the metabolizable energy and digestibility of fat and protein. This should be factored into the study's design and interpretation of results [17].

Table 1: Threshold Effects of Dietary Fiber on Cognitive Performance

| Cognitive Domain | Test Used | Inflection Point (g/day) | Association Below Threshold (β, 95% CI) | Association Above Threshold (β, 95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Processing Speed / Executive Function | Digit Symbol Substitution Test (DSST) | 29.65 | β: 0.18 (CI: 0.01–0.26), P<0.0001 | β: -0.15 (CI: -0.29 to -0.02), P=0.0265 |

| Global Cognition | Composite Z-Score | 22.65 | β: 0.01 (CI: 0.00–0.01), P=0.0004 | β: -0.00 (CI: -0.01–0.00), P=0.9043 (non-significant) |

Source: Analysis of NHANES 2011-2014 data (n=2,713 adults ≥60 years) [15].

Table 2: Key inflammatory Markers and Fiber's Effect in Pediatric Populations

| Inflammatory Marker | Effect of Dietary Fiber Intervention (Mean Difference vs. Control) | Statistical Significance | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| C-Reactive Protein (CRP) | -0.640 (95% CI: -1.075, -0.204) | Significant decrease | Fiber supplementation resulted in greater reductions than fiber-rich foods [18]. |

| Interleukin-6 (IL-6) | No significant effect | Not significant | Findings across studies were inconsistent [18]. |

| Tumor Necrosis Factor-α (TNF-α) | No significant effect | Not significant | Findings across studies were inconsistent [18]. |

Source: Meta-analysis of 25 Randomized Controlled Trials in children and adolescents [18].

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Investigating the Fiber-Cognition Relationship with Mediation Analysis

This protocol is based on a cross-sectional analysis of NHANES data [15].

1. Participant Selection:

- Population: Include adults aged 60 years and older.

- Exclusion Criteria: Participants with incomplete cognitive assessment data or missing dietary fiber intake information.

2. Dietary Assessment:

- Method: Conduct two 24-hour dietary recalls using the Automated Multiple-Pass Method.

- Timing: First recall in-person; second recall via telephone 3-10 days later.

- Nutrient Calculation: Average nutrient intakes (dietary fiber, vitamin E, and other vitamins) from the two recalls using a validated nutrient database.

3. Cognitive Function Assessment:

- Consortium to Establish a Registry for Alzheimer's Disease (CERAD): Assesses verbal learning and memory.

- CERAD Immediate Recall (CERAD.IRT): Sum of correct responses from three consecutive trials of 10 words.

- CERAD Delayed Recall (CERAD.DRT): Recall of the 10 words after 8-10 minutes.

- Animal Fluency Test (AFT): Assesses executive function. Participants name as many animals as possible in 1 minute.

- Digit Symbol Substitution Test (DSST): Assesses processing speed and executive function. Participants match symbols to numbers in 133 boxes in 2 minutes.

- Global Cognition Score: Calculate a composite z-score by averaging the standardized scores (z-scores) of all individual cognitive tests.

4. Covariate Collection:

- Collect data on sociodemographics (age, gender, race, income, education), health status (hypertension, diabetes, depression), anthropometrics (BMI, waist circumference), and lifestyle factors (smoking, alcohol, physical activity).

5. Statistical Analysis:

- Non-Linear Modeling: Use Generalized Additive Models (GAM) to visualize potential non-linear relationships.

- Threshold Analysis: Apply two-piecewise linear regression models to identify inflection points statistically.

- Mediation Analysis: Use a non-parametric percentile bootstrap method to quantify the proportion of the effect of fiber on cognition that is mediated by vitamin E intake.

Protocol 2: Assessing the Anti-inflammatory Impact of Fiber in Youth

This protocol is based on a meta-analysis of RCTs in pediatric populations [18].

1. Study Design:

- Design: Randomized Controlled Trial (RCT).

- Participants: Children and adolescents (≤18 years).

2. Intervention Groups:

- Intervention Group: Receives a dietary fiber intervention. This can be delivered as:

- Fiber supplementation (e.g., prebiotics like FOS/GOS).

- Consumption of fiber-rich foods (e.g., whole grains, fruits, vegetables).

- Dietary advice to increase fiber intake.

- Control Group: Receives a placebo, a control diet, or general dietary advice.

3. Outcome Measurement:

- Primary Outcomes: Changes in serum markers of chronic low-grade inflammation.

- C-Reactive Protein (CRP or hs-CRP)

- Interleukin-6 (IL-6)

- Tumor Necrosis Factor-α (TNF-α)

- Blood Collection: Collect fasting blood samples at baseline and at the end of the intervention period. Analyze serum using standardized, high-sensitivity assays.

4. Data Synthesis (for Meta-Analysis):

- Effect Size Calculation: For each study, calculate the mean difference (MD) and 95% confidence interval (CI) in inflammatory marker levels between the intervention and control groups.

- Statistical Pooling: Pool the MDs across studies using a random-effects meta-analysis model.

- Exploring Heterogeneity: Conduct meta-regression or subgroup analysis to investigate if the effect varies by the type of intervention (supplementation vs. food).

Visualized Workflows and Pathways

Fiber-Cognition Mediation Pathway

Fiber Research Experimental Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Fiber Analysis Studies

| Item | Function / Application |

|---|---|

| 24-Hour Dietary Recall (Automated Multiple-Pass Method) | A standardized interview method to comprehensively assess all foods and beverages consumed in the past 24 hours, minimizing recall bias [15]. |

| NHANES Cognitive Battery (CERAD, AFT, DSST) | A set of validated, standardized neuropsychological tests to assess key cognitive domains including memory, executive function, and processing speed in large-scale epidemiological studies [15]. |

| High-Sensitivity CRP (hs-CRP) Assay | An immunoassay kit to measure low levels of C-reactive protein in serum, a key biomarker for chronic low-grade inflammation [18]. |

| Dietary Fiber Supplements (e.g., FOS, GOS) | Purified fibers used in intervention trials to provide a standardized, controlled dose, isolating the effect of fiber from the food matrix [18]. |

| Statistical Software (R, SAS, Stata) | Software packages capable of running advanced statistical models like Generalized Additive Models (GAM), piecewise regression, and mediation analysis with bootstrapping [15]. |

Inter-fiber Interactions and Matrix Effects in Mixed Formulations

Frequently Asked Questions

Q: Why do my total dietary fiber (TDF) values not match the calculated sum of individual fibers in a mixed formulation? A: This discrepancy is often due to inter-fiber interactions and matrix effects. Soluble fibers like pectin or guar gum can form matrices that trap insoluble fibers, making them inaccessible to the enzymes and chemicals used in the standard AOAC 991.43 method. This can lead to an underestimation of insoluble fiber content. Furthermore, some fiber blends can alter the viscosity of the solution, preventing proper enzymatic digestion of starch and protein, which skews results [19] [3].

Q: How does the solubility of a fiber impact its analysis in a mixture? A: The traditional soluble vs. insoluble classification is insufficient for predicting analytical behavior. A more useful framework considers properties like fermentation rate, water-holding capacity (WHC), and structural charge. For example, a soluble, highly viscous fiber like beta-glucan can increase the WHC of the entire mixture, disrupting the filtration step and co-precipitating with insoluble fibers, leading to measurement inaccuracies [19] [3].

Q: What is the best method to account for resistant starch in mixed fiber analysis? A: Resistant starch (RS) is a significant confounder. The AOAC 991.43 method includes steps to dissolve and then reprecipitate RS. However, in mixed formulations, the presence of other fibers can interfere with this process. Using the AOAC 2002.02 method for RS in conjunction with TDF analysis is recommended. For accurate results, always perform a blank analysis and confirm complete starch removal with an iodine test [19].

Q: Can the food processing method affect my fiber analysis results? A: Yes, significantly. Processes like extrusion, heating, or freezing can alter the fiber matrix. For instance, heat can solubilize some hemicelluloses, increasing the measured soluble fiber fraction, while freezing and thawing can change the water-holding capacity of certain fibers, affecting the extraction and filtration efficiency during analysis [19].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem 1: Inconsistent Replicate Results in TDF Analysis

| Possible Cause | Explanation | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Incomplete Filtration | High-viscosity soluble fibers (e.g., guar gum, pectin) can clog filters, slowing or halting filtration and leading to variable recovery [19]. | • Pre-treat samples with heat-stable α-amylase at a higher temperature (e.g., 95°C for 15 min) to reduce viscosity.• Use larger porosity filter papers or a co-solvent like acetone to reduce gel formation.• Increase the sample preparation time to ensure full hydration and dispersion. |

| Inconsistent Sample Homogenization | Mixed diets often contain particulate matter of varying sizes and densities, leading to sub-sampling error. | • Use a cryogenic mill to grind the entire sample to a uniform particle size (< 0.5 mm).• Ensure the sample is perfectly dry before grinding to prevent clumping. |

Problem 2: Measured Values Lower Than Expected

| Possible Cause | Explanation | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Inter-fiber Matrix Formation | Soluble and insoluble fibers can interact, creating a dense matrix that shields some fiber components from enzymatic and chemical digestion [3]. | • Incorporate a mechanical disruption step (e.g., high-speed blending) after the enzymatic digestion phases.• Use sequential extraction with different buffers (e.g., phosphate buffer at pH 7, then acetate buffer at pH 4.5) to break down the matrix gradually. |

| Enzyme Inhibition | Tannins, phytates, or organic acids present in the mixed diet can inhibit the activity of the amylase, protease, or amyloglucosidase enzymes. | • Increase the enzyme concentration by 50-100%.• Include an internal standard (e.g., pure starch or casein) in a separate run to verify complete enzymatic digestion. |

Problem 3: Overestimation of Fiber Content

| Possible Cause | Explanation | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Incomplete Starch or Protein Removal | High-fiber matrices can physically protect starch and protein, making them resistant to enzymatic digestion, thus being weighed as fiber residue [19]. | • Perform a second, identical enzymatic digestion cycle on the residue.• Verify the absence of starch using an iodine stain test on the residue and of protein via a total nitrogen test (e.g., Kjeldahl method). |

| Co-precipitation of Non-Fiber Components | Dietary components like Maillard reaction products or some lipids can precipitate with the alcohol and be mistakenly weighed as dietary fiber. | • Perform a defatting step with petroleum ether prior to analysis if the sample is high in fat.• Correct for ash and protein content in the final residue by performing ash and nitrogen analysis on the residue. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Standard TDF Analysis with Matrix Disruption Modifications

This protocol is based on the AOAC 991.43 method with enhancements to mitigate inter-fiber interactions.

1. Principle: The sample is digested with heat-stable α-amylase, protease, and amyloglucosidase to remove starch and protein. The insoluble fiber is filtered off, and the soluble fiber is precipitated with ethanol. The residue is then corrected for ash and protein [19].

2. Reagents and Equipment:

- Enzymes: Heat-stable α-amylase, Protease (Type XIV, Bacillus licheniformis), Amyloglucosidase.

- Equipment: Thermostatic water bath, Filtration apparatus, Muffle furnace, Desiccator, Analytical balance.

- Buffers: Phosphate buffer (pH 7.0), Acetate buffer (pH 4.5).

3. Step-by-Step Procedure:

- Step 1: Weigh approximately 1 g of dry, homogenized sample (record exact weight to 0.1 mg) into a screw-cap bottle.

- Step 2: Add 40 mL of phosphate buffer (pH 7.0). Add 50 µL of heat-stable α-amylase. Incubate in a boiling water bath for 30 minutes with vigorous shaking every 5 minutes to disrupt the matrix.

- Step 3: Cool, add 100 µL of protease, and incubate at 60°C for 30 minutes.

- Step 4: Adjust pH to 4.5, add 100 µL of amyloglucosidase, and incubate at 60°C for 30 minutes.

- Step 5: Filter the mixture through a pre-weighed crucible. Wash the residue with water and ethanol.

- Step 6: Dry the crucible overnight at 105°C, cool in a desiccator, and weigh to determine the residue.

- Step 7: Ash the residue in a muffle furnace at 525°C for 5 hours. Cool and weigh. The weight loss on ashing corrects for mineral content.

4. Data Interpretation:

TDF (%) = [(R - A - P) / M] * 100

Where: R = weight of residue, A = weight of ash, P = weight of protein (from nitrogen analysis), and M = weight of sample.

Protocol 2: Sequential Soluble and Insoluble Fiber Extraction for Complex Matrices

This protocol is designed to separately quantify soluble and insoluble fiber while minimizing their interaction.

1. Principle: The sample is sequentially treated with enzymes under conditions that first extract and later precipitate soluble fiber, allowing for separate filtration and quantification of insoluble and soluble fractions [19] [3].

2. Workflow Diagram: The sequential steps for fiber extraction are illustrated below.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function in Fiber Analysis |

|---|---|

| Heat-stable α-amylase | Gelatinizes and hydrolyzes starch into dextrins at high temperatures (95-100°C), preventing starch from interfering with fiber measurement [19]. |

| Amyloglucosidase | Further hydrolyzes dextrins and starch fragments into glucose, ensuring complete removal of starch from the fiber residue. |

| Protease (Type XIV) | Digests and solubilizes protein in the sample, preventing protein from being weighed as part of the fiber residue. |

| Ethanol (78-80%) | Precipitates soluble dietary fiber components (e.g., pectins, beta-glucans, gums) out of the aqueous solution after enzymatic digestion, allowing them to be collected by filtration [19]. |

| Celite | A filtration aid, it acts as an inert filter cake that prevents clogging of the filter crucible by gel-forming soluble fibers, ensuring consistent filtration rates. |

| Phosphate & Acetate Buffers | Maintain the optimal pH for enzymatic activity (pH 7 for protease, pH 4.5 for amyloglucosidase), which is critical for complete and specific digestion. |

Advanced Methodologies for Assessing Fiber Effects in Complex Matrices

Welcome to the Technical Support Center for Fiber Analysis

This resource is designed for researchers and laboratory professionals facing methodological challenges in the assessment of dietary fiber intake, particularly within mixed diets studies. The following guides and FAQs provide targeted, evidence-based support to troubleshoot common experimental issues and standardize your protocols.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. What is the difference between a detailed FFQ and a short fiber screener, and when should I use each?

A detailed Food Frequency Questionnaire (FFQ) aims for a comprehensive assessment of the total diet and provides quantitative intake estimates, but it is time-consuming, often taking 45-60 minutes to complete. In contrast, a short fiber screener, like the 18-item FiberScreen, is designed specifically for rapid dietary screening, typically taking only around 4 minutes. Use an FFQ when you need detailed, quantitative nutrient data for analysis. A validated screener is ideal for efficient subject recruitment, ranking participants based on fiber intake, or for large-scale studies where diet is a secondary variable [20].

2. My research requires classifying fiber types for physiological effect prediction. Is the 'soluble vs. insoluble' model sufficient?

While common, the soluble vs. insoluble classification is often too simplistic and does not accurately predict the full range of physiological effects. A more comprehensive framework that accounts for properties like fermentation rate, water-holding capacity, and structural charge is recommended for studies linking specific fiber types to health outcomes. This refined approach allows for better prediction of effects on serum cholesterol, insulin secretion, and gut fermentation [3].

3. We are seeing high variability in fiber intake data from our screeners. What are the key validation metrics I should check?

When evaluating a fiber screener, key validation metrics to consult include:

- Correlation with a reference method (e.g., an FFQ): A strong correlation (e.g., r = 0.563) indicates good ability to rank subjects correctly [20].

- Mean difference in intake estimate compared to a reference method: A small, non-significant difference suggests good agreement [20].

- Completion time: A shorter time (e.g., ~4 minutes) reduces participant burden and improves compliance [20].

Troubleshooting Guide: Fiber Intake Assessment

Problem: Inaccurate Ranking of Participants' Fiber Intake

Symptoms: Your screening tool fails to correctly identify participants with low vs. high fiber intake, potentially compromising eligibility screening or group stratification.

| Potential Cause & Solution | Evidence & Rationale |

|---|---|

| Cause 1: Overly simplistic questionnaire. Using a screener with too few items that misses key fiber sources. | Solution: Adopt a multi-item questionnaire that specifies food categories. The 18-item FiberScreen, which includes fruits, vegetables, whole grains (specifying types of bread), legumes, and adds nuts, seeds, and dried fruits, showed a strong correlation (r=0.563) with a full FFQ, unlike a simpler 5-item version [20]. |

| Cause 2: Lack of portion size assessment. A screener that only assesses frequency without portion sizes may lack precision. | Solution: Select a tool that includes portion size questions. The National Cancer Institute's (NCI) Dietary Screener Questionnaire (DSQ) is an example of an instrument that has been developed and used in national surveys to assess fiber and whole grain intake with portion size information [21]. |

Problem: Data Inconsistency with Expected Biological Outcomes

Symptoms: Reported fiber intake from your assessment tool does not correlate with expected physiological markers (e.g., stool frequency, serum cholesterol).

| Potential Cause & Solution | Evidence & Rationale |

|---|---|

| Cause 1: Tool does not capture fiber types with relevant physiological properties. The screener may only assess total fiber, overlooking specific fibers with functional effects. | Solution: Ensure your assessment tool captures foods rich in specific fiber types. For example, to study cholesterol-lowering, include items on oats and barley (sources of beta-glucan, a soluble fiber). Understanding a fiber's water-holding capacity and fermentability is key to linking intake to outcomes like stool bulk or short-chain fatty acid production [3] [22]. |

| Cause 2: Misclassification of whole-grain foods. Participants may misreport refined grains as whole grains, skewing fiber intake estimates. | Solution: Use screeners with detailed questions. The optimized FiberScreen asks separately about consumption of white, brown, multigrain, and whole grain bread, leading to a more accurate estimation of actual whole grain and fiber intake [20]. |

Standardized Protocols & Methodologies

Protocol 1: Implementing the 18-Item FiberScreen

Purpose: To rapidly and accurately screen and rank adult participants based on their dietary fiber intake for study recruitment or population assessment [20].

Materials:

- The 18-item FiberScreen questionnaire (includes items on fruit, dried fruit, vegetables, types of bread, other whole grains, pasta/rice/potatoes, legumes, nuts, and seeds).

- A scoring system based on fiber content from a national food composition database.

Methodology:

- Administration: The questionnaire should be self-administered by participants, recalling their intake over the previous 2 weeks.

- Scoring: Calculate a total fiber intake score (in grams) based on the frequency, amount, and type of foods reported, using a predetermined scoring algorithm derived from a relevant food composition database.

- Validation Benchmark: In a validation study, this protocol demonstrated a strong correlation (r=0.563, p<0.001) with a full FFQ, with a mean completion time of 4.2 minutes [20].

Protocol 2: Validation of a Short Fiber Assessment Tool Against a Reference Method

Purpose: To establish the validity of a new or adopted short dietary fiber assessment instrument in a specific population.

Materials:

- The short fiber assessment tool to be validated.

- A validated reference method, such as a FFQ or multiple 24-hour dietary recalls.

- Access to a statistical analysis software package.

Methodology:

- Study Design: Administer both the short tool and the reference method to the same group of participants within a close time frame to minimize changes in actual diet.

- Data Analysis:

- Calculate Pearson's or Spearman's correlation coefficient between the fiber intake estimates from the two instruments. A moderate to strong correlation (e.g., >0.5) is desirable [20].

- Perform a paired t-test to check for significant mean differences between the two methods.

- Use Bland-Altman plots to visually assess the agreement and identify any systematic bias [20].

- Interpretation: The tool is considered valid for ranking individuals if it shows a significant and strong correlation with the reference method without substantial systematic bias.

Experimental Workflow & Decision Pathways

Diagram: Selecting a Fiber Intake Assessment Tool

| Tool or Resource | Function & Application in Research |

|---|---|

| 18-item FiberScreen | A validated short questionnaire to screen and rank fiber intake in adults. Ideal for reducing participant burden during study recruitment [20]. |

| NCI Dietary Screener Questionnaire (DSQ) | A short instrument that assesses multiple dietary constructs, including fiber/whole grains. Provides a standardized tool for use in large population studies [21]. |

| Food Frequency Questionnaire (FFQ) | A comprehensive dietary assessment method used as a reference standard to validate shorter screeners or to obtain detailed nutrient intake data [20]. |

| Food Composition Database | A standardized table of nutrient values (e.g., USDA database) used to assign fiber content to foods reported in questionnaires, enabling the calculation of total intake [20]. |

| Functional Fiber Classification Framework | A modern framework moving beyond soluble/insoluble to classify fibers by properties like fermentation rate and water-holding capacity. Critical for designing studies on specific health outcomes [3] [22]. |

Microbiota Profiling Techniques to Decipher Fiber-Specific Responses

FAQs: Addressing Common Experimental Challenges

FAQ 1: Why do I observe highly variable SCFA production in response to the same fiber supplement across my study cohort?

This is a common challenge rooted in the baseline composition of the gut microbiota. Research shows that an individual's predominant microbial enterotype is a key determinant of their response to fiber.

- Prevotella-dominated (P-type) vs. Bacteroides-dominated (B-type) Responses: A 2025 study demonstrated that individuals with a Prevotella-dominated (P-type) microbiota showed a significant increase in fasting propionate after consuming arabinoxylan, whereas those with a Bacteroides-dominated (B-type) microbiota showed increases in both fasting and postprandial propionate and acetate with the same fiber [9].

- Intervention-Specific Effects: Another 2025 trial found that a resistant starch (RS)-rich intervention significantly modulated the microbiota and its function almost exclusively in Prevotella-rich individuals, while effects on Bacteroides-rich individuals were minimal [23].

- Troubleshooting Recommendation: Instead of treating your cohort as a single group, pre-stratify participants based on baseline microbiota profiling (e.g., P/B ratio) before assessing fiber responses. This can account for a significant portion of the observed variability.

FAQ 2: My 16S rRNA sequencing results for negative controls show microbial signals. How should I handle this in my data analysis?

The detection of microbial signals in negative controls is a clear indicator of contamination, which is a critical concern, especially in low-biomass microbiome studies.

- Sources of Contamination: Contaminants can be introduced from DNA extraction kits, laboratory reagents, sampling equipment, and the researcher themselves [24].

- Best Practices for Control and Reporting:

- Include Multiple Controls: Run negative controls (e.g., blank extraction kits, sterile swabs, DNA-free water) alongside your experimental samples throughout the entire process [24].

- Use In Vitro Diagnostic (IVD)-Certified Tests: Whenever possible, use tests that follow strict quality control measures to improve reproducibility [25].

- Post-Hoc Decontamination: Employ bioinformatic tools (e.g.,

decontamin R) to identify and remove contaminant sequences found in your controls from your experimental dataset [24]. - Report Contamination Workflow: Transparently report the contamination controls used and the steps taken to mitigate their impact in your publications [24].

FAQ 3: The current soluble vs. insoluble fiber classification is insufficient for predicting my experimental outcomes. Is there a better framework?

Yes, the traditional binary classification is increasingly seen as inadequate. A new framework proposes categorizing fibers based on five key properties that more accurately predict their physiological effects [3] [26].

- Proposed Fiber Classification Framework:

- Backbone Structure: The primary chemical composition (e.g., beta-glucan, arabinoxylan).

- Water-Holding Capacity: The ability to absorb and retain water, influencing gut transit time.

- Structural Charge: The presence of ionizable groups affecting interactions with other molecules.

- Fiber Matrix: The physical microstructure and porosity.

- Fermentation Rate: The speed at which the fiber is broken down by gut microbes (fast vs. slow) [3].

- Application: Utilizing this framework allows researchers to select fibers based on specific properties aligned with their desired health outcome, moving beyond the simplistic soluble/insoluble distinction [26].

FAQ 4: Can machine learning help in predicting individual responses to fiber based on gut microbiota?

Yes, machine learning (ML) is an emerging and powerful tool for this purpose. A 2025 study demonstrated that ML algorithms can accurately distinguish between different chronic inflammatory diseases based on gut microbiota patterns and their response to various fibers with up to 95% accuracy [27].

- Implementation: The study successfully used algorithms including Random Forest (RF), Support Vector Machine (SVM), Artificial Neural Networks (ANN), and Convolutional Neural Networks (CNN) on 16S rRNA sequencing data [27].

- Utility: This approach can uncover hidden patterns in high-dimensional microbiome data that are difficult to detect with traditional statistics, paving the way for highly personalized nutritional recommendations.

Experimental Protocols & Workflows

Standardized Protocol for a Fiber Intervention Study with Microbiota Stratification

This protocol is synthesized from recent clinical trials investigating fiber responses in stratified cohorts [9] [23].

1. Participant Recruitment and Baseline Sampling:

- Recruit healthy adults and collect baseline stool samples.

- Sample Collection: Use sterile, DNA-free collection kits. Collect multiple samples if possible to account for temporal variation [25]. Immediately freeze samples at -80°C.

2. Microbiota Profiling and Stratification:

- DNA Extraction: Perform extraction in a dedicated, clean laboratory space using an IVD-certified kit to minimize contamination [25]. Include extraction negative controls.

- 16S rRNA Gene Sequencing: Amplify the V3-V4 or V4 region using primers 341F/806R [27]. Use a standardized platform (e.g., Illumina MiSeq).

- Bioinformatic Analysis: Process sequences using a denoising algorithm like DADA2 (for ASVs) or a clustering algorithm like UPARSE (for OTUs), as these have shown superior performance in recent benchmarking [28].

- Stratification: Classify participants into enterotypes, specifically P-type (Prevotella-dominated) and B-type (Bacteroides-dominated), based on a threshold (e.g., ≥10% relative abundance) [9].

3. Intervention Design:

- Design: A randomized, controlled, crossover study is ideal.

- Interventions: Test at least two different purified fibers (e.g., arabinoxylan (AX) and inulin (INU)) and a placebo (e.g., maltodextrin). A dose of 15 g/day for 1-2 weeks has been used effectively [9].

- Washout Period: Include a sufficient washout period (e.g., 2 weeks) between interventions to allow the microbiota to return to baseline.

4. Outcome Assessment:

- Primary Outcomes: Measure fasting and postprandial plasma Short-Chain Fatty Acids (SCFAs: acetate, propionate, butyrate) and Branched-Chain Fatty Acids (BCFAs) [9].

- Secondary Outcomes:

5. Data Integration and Statistical Analysis:

- Integrate microbiota data with SCFA and clinical metadata.

- Use multivariate statistics (PERMANOVA) to test for global microbiota shifts and repeated-measures ANOVA to test for metabolic changes.

- Apply machine learning models to predict responder status based on baseline features [27].

The following workflow diagram summarizes this multi-stage experimental design.

In Vitro Fecal Fermentation Model for Rapid Fiber Screening

This protocol is adapted from a 2025 study that used in vitro fermentation to model fiber responses across different disease states [27].

1. Sample Preparation:

- Collect fresh stool samples from donors and process within an anaerobic chamber.

- Prepare a phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) solution and pre-reduce it overnight in the anaerobic chamber.

2. Fermentation Setup:

- Add 5 mL of PBS to anaerobic tubes.

- Add the test dietary fiber at a concentration of 1% (w/v).

- Inoculate with 5% (w/v) of a homogenized fecal slurry.

- Seal the tubes and incubate at 37°C for 12 hours.

3. Post-Fermentation Analysis:

- Centrifuge the fermenta at 14,000 g for 5 minutes.

- Pellet: Use for DNA extraction and 16S rRNA sequencing to assess microbial composition changes.

- Supernatant: Analyze for SCFA concentration using gas chromatography (GC) or LC-MS.

Table 1: Differential Fiber Responses by Enterotype in Clinical Trials

| Fiber Type | Prevotella-Dominant (P-type) Response | Bacteroides-Dominant (B-type) Response | Key Microbial Shifts |

|---|---|---|---|

| Arabinoxylan (AX) | - ↑ Fasting propionate [9]- Reduced appetite ratings [9] | - ↑ Fasting & postprandial propionate [9]- ↑ Postprandial acetate [9] | - B-types: ↑ Fusicatenibacter [9]- P-types: ↑ Paraprevotella [9] |

| Inulin (INU) | Modest microbiota modulation [23] | - No significant SCFA increase [9]- ↑ Breath hydrogen variability [9]- ↓ Branched-Chain Fatty Acids (BCFAs) [9] | - ↑ Anaerostipes & Bifidobacterium in both groups [9]- Reduced Phocaeicola [9] |

| Resistant Starch (RS)(e.g., Unripe Banana Flour) | - Significant global microbiota shifts [23]- Major functional changes (533 KEGG orthologs) [23] | Minimal to no significant effects on microbiota structure or function [23] | Not Specified |

Table 2: Benchmarking of 16S rRNA Amplicon Processing Algorithms

| Algorithm | Type | Key Strengths | Key Limitations | Best Use Scenario |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| DADA2 [28] | ASV (Denoising) | - Consistent output- Closest resemblance to intended community (Alpha/Beta diversity) | - Prone to over-splitting (splitting single biological sequences into multiple ASVs) | Studies requiring high resolution and reproducibility across datasets. |

| UPARSE [28] | OTU (Clustering) | - Lower error rates in clusters- Closest resemblance to intended community | - Prone to over-merging (merging distinct biological sequences into one OTU) | Standardized workflows where a 97% identity threshold is acceptable. |

| Deblur [28] | ASV (Denoising) | Consistent output | Suffers from over-splitting | Similar to DADA2, but performance may vary. |

| Opticlust [28] | OTU (Clustering) | Iterative cluster quality evaluation | More over-merging compared to denoising methods | Requires careful parameter tuning. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

| Item | Function & Specification | Example Application in Fiber Research |

|---|---|---|

| Purified Dietary Fibers | Defined chemical structures for controlled interventions. Examples: Arabinoxylan, Inulin, Resistant Starch (e.g., from Unripe Banana Flour), Beta-Glucan. | Used in clinical and in vitro studies to test specific structure-function relationships [9] [23] [27]. |

| DNA/RNA Shield or similar preservative | Preserves microbial DNA/RNA integrity at ambient temperature during stool sample transport and storage. | Crucial for achieving accurate baseline and post-intervention microbiota profiles, especially in multi-center trials [25]. |

| IVD-Certified DNA Extraction Kits | Ensures standardized, high-quality, and reproducible DNA extraction from complex stool samples, minimizing batch effects. | Recommended for clinical studies aiming for diagnostic-level reproducibility [25]. |

| 16S rRNA Primers (341F/806R) | Targets the V3-V4 hypervariable region of the 16S rRNA gene for amplicon sequencing. | Widely used for cost-effective profiling of bacterial community composition [27]. |

| SCFA Standards | High-purity chemical standards (Acetate, Propionate, Butyrate, etc.) for calibration of analytical equipment. | Essential for the quantitative measurement of SCFAs in plasma, feces, or in vitro fermenta supernatants via GC-MS/LC-MS [9]. |

| Anaerobic Chamber | Creates an oxygen-free environment (typically with N₂/CO₂/H₂ mix) for processing samples and setting up in vitro fermentations. | Critical for maintaining the viability of obligate anaerobic gut bacteria during fecal sample processing and in vitro experiments [27]. |

Transcriptomic and Metabolomic Approaches for Mechanistic Insights

Troubleshooting Guides and FAQs

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: My transcriptomic and metabolomic data seem disconnected. How can I better integrate them to find meaningful biological pathways? A1: Successful integration relies on correlating patterns in time and space. Focus on common enriched pathways and use cross-referencing. For instance, in a study of cotton fiber, researchers correlated the expression of genes in pathways like "fatty acid degradation" with corresponding lipids and organic acids identified in the metabolome [29]. When data seem disconnected, ensure your sampling for both analyses is from the same biological material and time point. Using spatial transcriptomics and metabolomics techniques can also precisely align gene expression with metabolite localization [30].

Q2: What is a critical but often-overlooked time point for sampling in developmental studies? A2: 40 days post-anthesis (DPA) was identified as a crucial stage for determining final protein and oil content in cottonseed, as significant differences between varieties emerged only after this point [29]. In fiber studies, the transition stage (around 18-21 DPA) is key, as it involves major cell wall remodeling and is a stable developmental stage [31]. Overlooking these critical windows can cause you to miss pivotal regulatory events.

Q3: How can I manage reactive oxygen species (ROS) in my samples to avoid oxidative stress confounds? A3: ROS are natural signaling molecules in development but can cause damage in excess. Evidence implicates the ascorbate-glutathione cycle as a key manager of ROS. One study found that a 138-fold increase in ascorbate concentration was linked to a enhanced capacity for prolonged fiber elongation and reduced oxidative stress [31]. Ensuring your extraction buffers contain antioxidants like ascorbate or dithiothreitol (DTT) can help preserve sample integrity.

Q4: What are some key metabolites I should monitor in fiber and nutritional quality research? A4: Key metabolite classes include:

- Lipids and Lipid-like Molecules: Central to oil content and cell membrane integrity [29].

- Organic Acids: Often involved in key energy and biosynthesis pathways [29].

- Fatty Acids: Such as linoleic acid and α-linolenic acid, which are implicated in early fiber development [30].

- Polyamines: Spermidine and spermine are also important for early developmental processes [30].

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Issues

Issue 1: High Variability in Metabolite Profiles from Seemingly identical Tissue Samples

- Potential Cause: Incomplete homogenization of tissues with complex cell type composition. The sample may contain a mixture of cell types at different developmental stages.

- Solution: Employ spatial metabolomics techniques like Mass Spectrometry Imaging (MSI) to visualize metabolite distribution within a tissue section [30]. This allows you to determine if variability is technical or biological. If spatial tech is unavailable, improve dissection protocols or use laser-capture microdissection to isolate specific cell populations.

Issue 2: Low RNA Yield or Quality from Fibrous Plant Materials

- Potential Cause: Fibrous tissues are rich in polysaccharides and polyphenols that can co-precipitate with RNA and degrade its quality.

- Solution: Use a commercial kit specifically validated for challenging plant tissues. The protocol from one study involved extracting total RNA with a TransZol kit, followed by quantification with a NanoPhotometer and Qsep400 bioanalyzer to ensure RNA Integrity Number (RIN) > 7 before library preparation [32] [30]. Increasing the concentration of β-mercaptoethanol in the extraction buffer can also help inhibit polyphenol oxidation.

Issue 3: Identifying Causative Genes from a Large List of Differentially Expressed Genes (DEGs)

- Potential Cause: Standard enrichment analysis provides correlation, not causation.