The Secret Life of Salt

How the Solvay Process Turns Limestone and Brine into Baking Soda

The Chemistry We Breathe

Every time you bake cookies, wash clothes, or glance through a window, you're interacting with the hidden legacy of a 160-year-old chemical revolution.

The Solvay process—invented by Belgian chemist Ernest Solvay in 1861—quietly produces sodium bicarbonate (baking soda) and its cousin sodium carbonate (washing soda) from three humble ingredients: saltwater, limestone, and ammonia 1 2 . This ingenious method birthed 95% of the world's soda ash by 1900 and remains a cornerstone of modern industry 3 . Yet today, it faces a reinvention to tackle its environmental footprint. Join us as we unravel how a chemical dance in towering reactors transforms brine into baking soda—and how scientists are making it greener.

The Solvay process produces about 42 million tons of soda ash annually - that's more than 6 kg for every person on Earth 1 .

The Chemical Ballet: Core Principles of the Solvay Process

At its heart, the Solvay process is a masterclass in atom economy and recycling. Unlike earlier methods that released toxic byproducts, Solvay's system recovers and reuses ammonia—a costly catalyst—across multiple steps 1 5 .

The Four-Act Reaction Sequence:

1. Ammoniation

Brine (NaCl solution) absorbs ammonia gas, forming ammoniated brine—a key reactant 2 5 .

2. Carbonation

CO₂ (from limestone calcination) bubbles through ammoniated brine, precipitating sodium bicarbonate:

3. Calcination

Baking soda is heated into dense soda ash (washing soda):

4. Ammonia Recovery

The byproduct ammonium chloride reacts with lime to regenerate ammonia:

Spotlight Experiment: Carbon Capture in the Solvay Process

The Challenge:

Traditional Solvay plants emit 350,000+ tons of CO₂ annually—primarily from limestone calcination and ammonia regeneration. With the EU pushing for industrial decarbonization, researchers sought to trap CO₂ before it exits smokestacks.

Methodology: A Two-Tower Solution

1. Gas Capture

Post-carbonation tail gas (rich in CO₂) is routed to an absorption column.

2. Ammonia Scrubbing

The gas meets an ammonia-water solution, triggering reactions:

3. Solution Regeneration

The CO₂-loaded solution is heated in a distillation column, releasing pure CO₂ for reuse in carbonation 6 .

Results and Analysis

The Polish pilot achieved 70% CO₂ capture efficiency from tail gases. Crucially, it used existing plant infrastructure (e.g., ammonia recovery columns), slashing costs. By recycling captured CO₂, the system reduced limestone consumption by 2.27 kg per kg of CO₂ saved—proving circular chemistry works 6 .

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Reagents in Solvay Chemistry

| Reagent | Function | Source |

|---|---|---|

| Ammoniated brine | Delivers Na⁺ and NH₃ for bicarbonate formation | Brine + NH₃ gas 2 |

| Quicklime (CaO) | Regenerates ammonia from NH₄Cl | Limestone calcination 1 |

| Carbon dioxide | Reacts with ammoniated brine to form NaHCO₃ | Coke-fired limestone kilns 8 |

| Calcium hydroxide | Converts NH₄Cl back to NH₃ | Quicklime + water 5 |

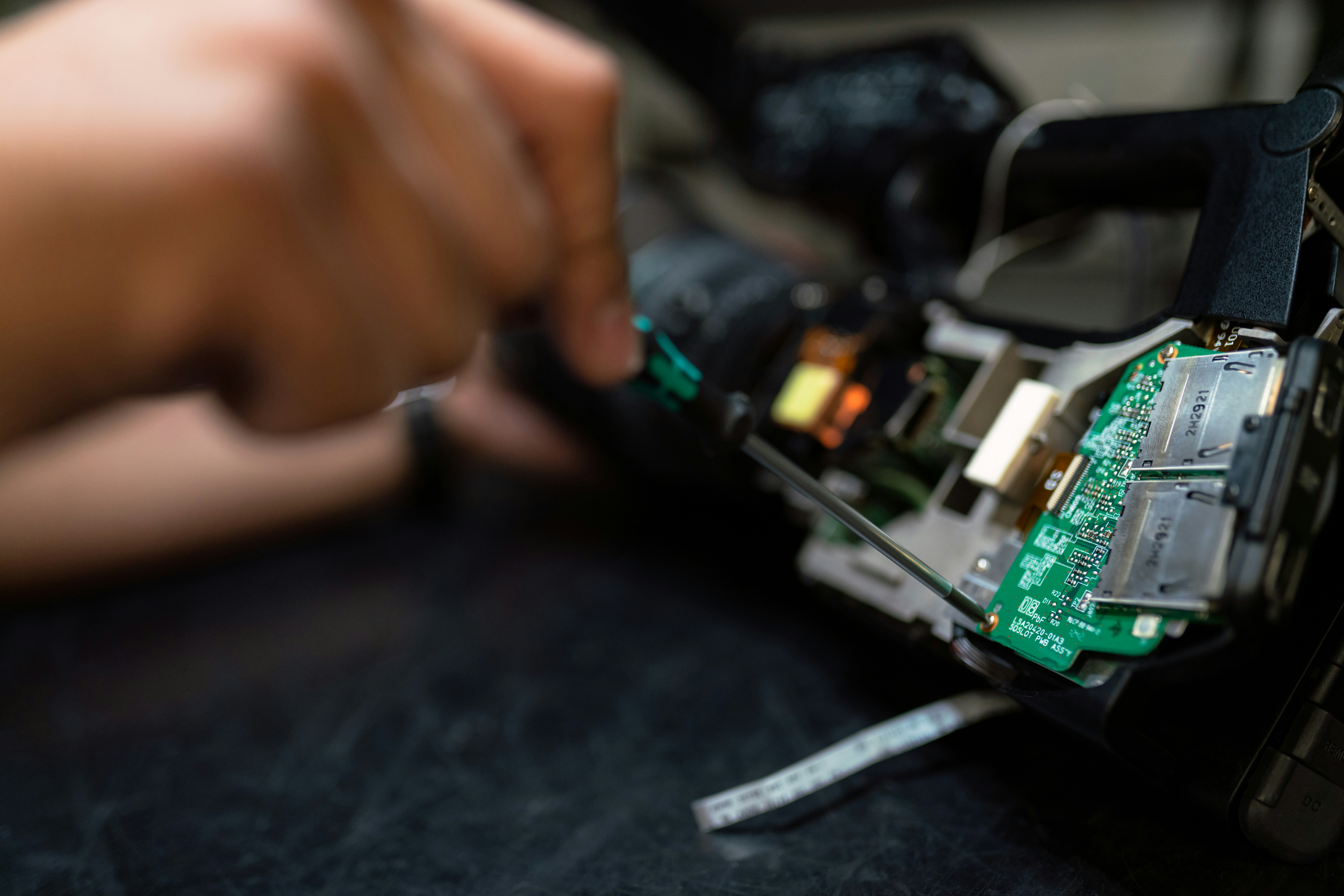

Modern Solvay Plant

Aerial view of a contemporary Solvay process facility showing the complex network of reactors and towers.

Chemical Reactions

Visualization of the key chemical transformations in the Solvay process.

The Green Reinvention: From Solvay to e.Solvay

While efficient, the classic process has a dirty secret: calcium chloride waste. For every ton of soda ash, plants generate 1.5 tons of CaCl₂ slurry, historically dumped in "waste beds" that poisoned waterways like New York's Onondaga Lake 1 3 . Two innovations aim to fix this:

Chinese chemist Hou Debang eliminated CaCl₂ by precipitating ammonium chloride (NH₄Cl) instead—a valuable fertilizer 1 .

Solvay's new electrochemical method slashes CO₂ emissions by 50% and limestone use by 30%. By replacing lime kilns with renewable-powered reactors, it recaptures ammonia without CO₂. A pilot plant in Dombasle, France, tests this tech for global rollout by 2050 3 .

| Parameter | Traditional Solvay | e.Solvay | Advantage |

|---|---|---|---|

| CO₂ emissions | High (from kilns) | 50% lower | Climate impact reduction |

| Limestone consumption | 100% baseline | 30% less | Less mining damage 3 |

| Water use | High | 20% reduction | Conserves freshwater |

Why This Matters: Bread, Glass, and Our Planet

Sodium bicarbonate isn't just for baking—it softens water, makes glass (50% of soda ash use), and even captures sulfur from smokestacks 3 8 . But as climate pressures mount, the Solvay process exemplifies industrial chemistry's evolution: maximizing output while minimizing harm. The shift from waste beds to carbon capture and electrochemical reactors shows sustainability is possible—one molecule at a time.

"I am proud Solvay is perpetuating our founder's legacy of innovation as we lead our industry toward a sustainable future."

From Ernest Solvay's 1861 tower to today's e.Solvay electrolyzers, the quest continues: turning salt and stone into society's building blocks—without baking our planet.