Single Laboratory Validation (SLV) Fundamentals: A Guide for Reliable Analytical Results

This article provides a comprehensive guide to Single Laboratory Validation (SLV), a critical process for establishing the reliability of analytical methods within one laboratory.

Single Laboratory Validation (SLV) Fundamentals: A Guide for Reliable Analytical Results

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide to Single Laboratory Validation (SLV), a critical process for establishing the reliability of analytical methods within one laboratory. Tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it covers the foundational principles of SLV, a step-by-step methodological approach for implementation, strategies for troubleshooting common pitfalls, and techniques for evaluating method performance against established standards. The content synthesizes current guidelines and best practices to equip laboratories with the knowledge to generate inspection-ready, defensible data that ensures product quality and patient safety.

What is Single Laboratory Validation? Building Your Core Understanding

Single-Laboratory Validation (SLV) represents a critical process in pharmaceutical and clinical laboratories, establishing documented evidence that an analytical method is fit for its intended purpose within a specific laboratory environment. This comprehensive technical guide examines SLV's fundamental role in ensuring data reliability, regulatory compliance, and patient safety throughout the method lifecycle. Framed within the broader context of analytical quality management, SLV serves as the practical implementation bridge between manufacturer validation and routine laboratory application, providing scientists with verified performance characteristics specific to their operational conditions. For researchers and drug development professionals, mastering SLV protocols is essential for generating defensible data that meets both scientific rigor and regulatory standards in pharmaceutical development and clinical diagnostics.

Single-Laboratory Validation (SLV) constitutes a systematic approach for establishing the performance characteristics of an analytical method when implemented within a specific laboratory setting. According to International Vocabulary of Metrology (VIM3) definitions, verification represents "provision of objective evidence that a given item fulfils specified requirements," whereas validation establishes that "the specified requirements are adequate for the intended use" [1]. In practical laboratory applications, SLV occupies the crucial space between comprehensive method validation (primarily a manufacturer's responsibility) and ongoing quality control, ensuring that methods transferred to individual laboratories maintain their reliability despite variations in personnel, equipment, and environmental conditions.

The fundamental distinction between validation and verification lies in their scope and purpose. Method validation comprehensively establishes performance characteristics for a new diagnostic tool, which remains primarily a manufacturer concern. Conversely, method verification constitutes a laboratory-focused process to confirm specified performance characteristics before a test system is implemented for patient testing or product release [1]. This distinction places SLV as a user-centric activity, confirming that pre-validated methods perform as expected within the unique operational context of a single laboratory.

In regulated laboratory environments, SLV provides the foundational evidence required for accreditation under international standards including ISO/IEC 17025 for testing laboratories and ISO 15189 for medical laboratories [1]. The process embodies the practical implementation of quality management systems, directly supporting correct diagnosis, risk assessment, and effective therapeutic monitoring in healthcare, while ensuring reliability in pharmaceutical quality control.

Core Validation Parameters and Acceptance Criteria

SLV protocols investigate multiple analytical performance characteristics to provide comprehensive method assessment. These parameters collectively ensure methods generate reliable, accurate, and precise data under normal operating conditions. The following table summarizes the essential validation parameters, their definitions, and typical acceptance criteria based on international guidelines [2] [3].

Table 1: Essential SLV Parameters and Acceptance Criteria

| Parameter | Definition | Testing Methodology | Acceptance Criteria |

|---|---|---|---|

| Accuracy | Closeness of agreement between accepted reference value and value found | Analysis of known concentrations vs. reference materials; spike recovery studies [3] | Recovery of 95-105% for 9 determinations over 3 concentration levels [2] [3] |

| Precision | Closeness of agreement between independent results under specified conditions | Repeatability (intra-assay) and intermediate precision (different days, analysts, equipment) [3] | %RSD ≤2% for 6 replicates at target concentration [2] |

| Specificity | Ability to measure analyte accurately despite potential interferents | Resolution of closely eluted compounds; peak purity tests using PDA/MS [3] | Resolution ≥1.5 between critical pairs; no interference from matrix [3] |

| Linearity | Ability to obtain results directly proportional to analyte concentration | Minimum of 5 concentration levels across specified range [3] | Correlation coefficient (r²) ≥ 0.99 [2] |

| Range | Interval between upper and lower analyte concentrations with acceptable precision, accuracy, and linearity | Verification across low, medium, and high concentrations | Established based on intended method application [3] |

| LOD | Lowest concentration of analyte that can be detected | Signal-to-noise ratio (3:1) or statistical calculation (3×SD/slope) [3] | Signal-to-noise ratio ≥3:1 [2] [3] |

| LOQ | Lowest concentration of analyte that can be quantified with acceptable precision and accuracy | Signal-to-noise ratio (10:1) or statistical calculation (10×SD/slope) [3] | Signal-to-noise ratio ≥10:1; precision and accuracy within ±20% [2] [3] |

| Robustness | Capacity to remain unaffected by small, deliberate variations in method parameters | Deliberate changes to pH (±0.2), temperature (±5°C), mobile phase composition [2] | No significant impact on accuracy, precision, or specificity [2] |

These parameters form the foundation of SLV protocols, with specific acceptance criteria tailored to the analytical method's intended application. The precision parameter encompasses three distinct measurements: repeatability (intra-assay precision under identical conditions), intermediate precision (within-laboratory variations including different days, analysts, or equipment), and reproducibility (collaborative studies between different laboratories) [3]. For SLV, repeatability and intermediate precision are essential, while reproducibility typically falls outside single-laboratory scope.

The mathematical foundation for these parameters includes rigorous statistical treatment. Random error, representing imprecision, is calculated as the standard error of estimate (Sy/x), which is the standard deviation of points about the regression line [1]. Systematic error, reflecting inaccuracy, is detected through linear regression analysis where the y-intercept indicates constant error and the slope indicates proportional error [1].

SLV Experimental Workflow and Protocol Implementation

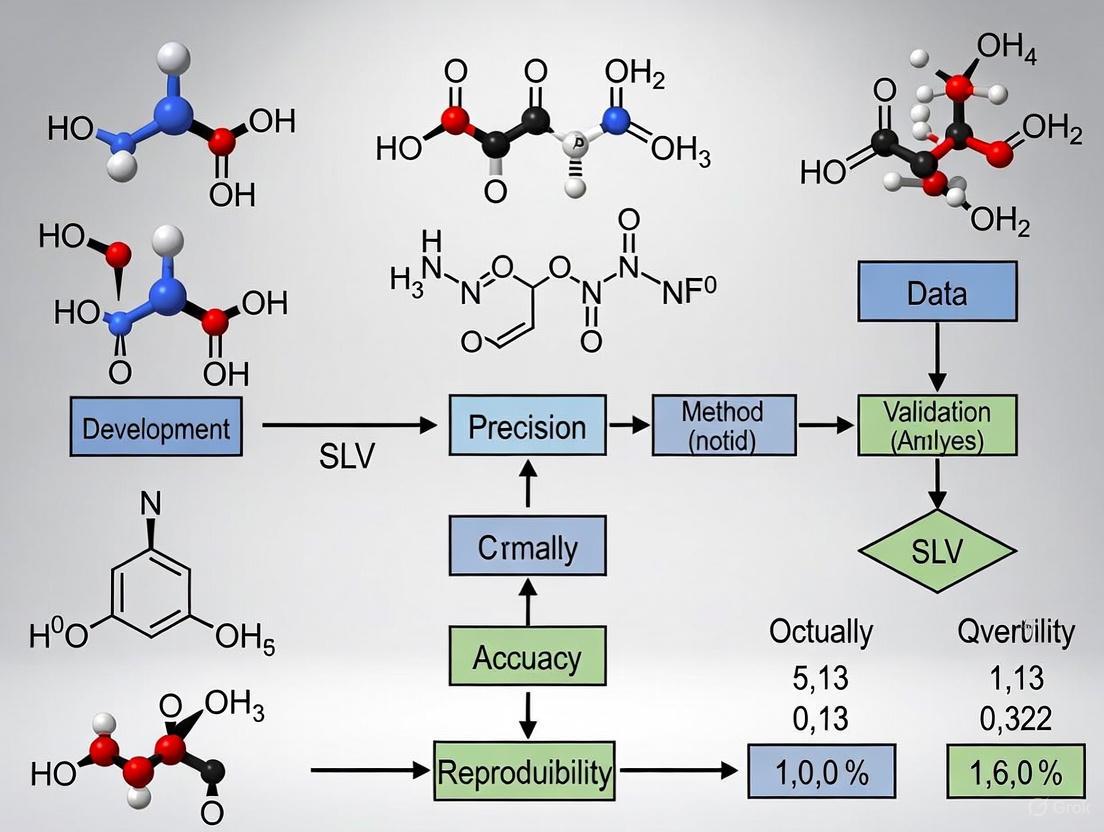

Implementing a robust SLV protocol requires meticulous planning and execution across sequential phases. The following workflow diagram illustrates the comprehensive SLV process from planning through documentation:

Diagram 1: Comprehensive SLV Workflow

Validation Plan Development

The validation plan establishes the strategic foundation for SLV, defining the scope, objectives, and success criteria. This document specifies the method's intended use, analytical performance characteristics to be evaluated, and predefined acceptance criteria based on regulatory guidelines and method requirements [2]. A well-constructed validation plan explicitly defines the experimental design, including sample types, number of replicates, statistical methods, and matrix effect testing protocols to ensure real-world applicability [2]. During this phase, collaboration with quality assurance (QA) and information technology (IT) departments is essential to address data integrity concerns and system access requirements proactively [2].

Experimental Execution

The experimental phase systematically investigates each validation parameter through controlled laboratory studies. Accuracy assessment requires data collection from a minimum of nine determinations across three concentration levels, reporting percent recovery of the known, added amount or the difference between mean and true value with confidence intervals [3]. Precision evaluation encompasses both repeatability (same analyst, same day) through nine determinations covering the specified range and intermediate precision using experimental design that monitors effects of different days, analysts, or equipment [3].

Specificity must be demonstrated through resolution of the two most closely eluted compounds, typically the major component and a closely eluted impurity [3]. Modern specificity verification increasingly incorporates peak purity testing using photodiode-array (PDA) detection or mass spectrometry (MS) to distinguish minute spectral differences not readily observed by simple overlay comparisons [3]. For linearity and range, guidelines specify a minimum of five concentration levels, with data reporting including the equation for the calibration curve line, coefficient of determination (r²), residuals, and the curve itself [3].

Documentation and Reporting

Comprehensive documentation provides the auditable trail demonstrating method validity. The validation report includes an executive summary highlighting key findings, detailed experimental results for each parameter, statistical analysis, and conclusions with formal sign-off by relevant stakeholders (analytical chemist, QA lead, lab manager) [2]. This documentation workflow ensures transparent reporting of any deviations or corrective actions, however minor, maintaining integrity throughout the validation process [2].

Critical Reagents and Research Solutions

Successful SLV implementation requires carefully selected reagents and materials that ensure method reliability. The following table details essential research reagent solutions and their functions within validation protocols:

Table 2: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for SLV

| Reagent/Material | Function in SLV | Critical Quality Attributes |

|---|---|---|

| Certified Reference Materials | Establish accuracy and trueness through comparison to accepted reference values [3] | Certified purity, stated uncertainty, stability documentation |

| System Suitability Standards | Verify chromatographic system performance prior to validation runs [3] | Reproducible retention, peak shape, and resolution characteristics |

| Matrix-Matched Calibrators | Account for matrix effects in biological and pharmaceutical samples [1] | Commutability with patient samples, appropriate analyte-free matrix |

| Quality Control Materials | Monitor precision across validation experiments [1] | Multiple concentration levels, stability, representative matrix |

| Forced Degradation Samples | Demonstrate specificity and stability-indicating capabilities [2] | Controlled degradation under stress conditions (heat, light, pH) |

| Interference Check Solutions | Evaluate analytical specificity against potential interferents [1] | Common interferents (hemoglobin, lipids, bilirubin, concomitant drugs) |

These reagents form the foundation of reliable SLV protocols, with quality attributes directly impacting validation outcomes. Certified reference materials, in particular, require verification of their uncertainty specifications and stability profiles to ensure accuracy measurements are scientifically defensible [3]. Matrix-matched calibrators must demonstrate commutability with actual patient samples to avoid misleading recovery results in clinical method validations [1].

Error Analysis and Measurement Uncertainty

Understanding and quantifying measurement errors represents a fundamental aspect of SLV, with direct implications for method reliability and patient safety. The following diagram illustrates the error classification and quantification framework:

Diagram 2: Error Analysis Framework

The primary purpose of method validation and verification is error assessment—determining the scope of possible errors within laboratory assay results and the extent to which this degree of errors could affect clinical interpretations and patient care [1]. Random error arises from unpredictable variations in repeated measurements and is quantified using standard deviation (SD) and coefficient of variation (CV) [1]. In SLV protocols, random error is calculated as the standard error of estimate (Sy/x), representing the standard deviation of the points about the regression line [1].

Systematic error reflects inaccuracy where control observations shift consistently in one direction from the mean value. Systematic errors manifest as either constant error (affecting all measurements equally) or proportional error (increasing with analyte concentration) [1]. Through linear regression analysis comparing test method results to reference values, the y-intercept indicates constant error while the slope indicates proportional error [1].

Total Error Allowable (TEa) represents the combined random and systematic error permitted by clinical requirements, available analytical methods, and proficiency testing expectations [1]. CLIA 88 has published allowable errors for numerous clinical tests, with recent expansions to include newer assays such as HbA1c and PSA [1]. The error index, calculated as (x-y)/TEa where x and y represent compared methods, provides a standardized approach for assessing method acceptability against established performance standards [1].

Measurement uncertainty expands upon traditional error analysis by providing a quantitative indication of result quality. Uncertainty estimation combines standard uncertainty (Us) from precision data and bias uncertainty (UB) from accuracy studies, resulting in combined standard uncertainty (Uc) and expanded uncertainty (U) using appropriate coverage factors [1]. This comprehensive approach to error quantification ensures methods meet both statistical and clinical performance requirements before implementation.

Advanced SLV Strategies and Lifecycle Management

For experienced professionals, advanced SLV strategies enhance efficiency and provide deeper methodological understanding. Design of Experiments (DoE) methodologies enable simultaneous investigation of multiple variables, efficiently uncovering interactions between factors such as pH and temperature that might be missed in traditional one-factor-at-a-time approaches [2]. DoE creates mathematical models of method behavior, supporting robust operational ranges rather than fixed operating points.

Statistical control charts provide enhanced monitoring beyond basic %RSD thresholds. Implementing X̄–R charts enables detection of subtle methodological drifts before they trigger formal revalidation requirements, supporting proactive method maintenance [2]. These tools transition SLV from a one-time event to continuous method performance verification.

Method transfer protocols establish formal frameworks for moving validated methods between laboratories or instrument platforms. A well-designed transfer plan compares critical parameters across systems, confirming equivalency through parallel testing and statistical analysis [2]. This approach ensures method integrity during technology upgrades or multisite implementations.

SLV represents the beginning, not the conclusion, of methodological quality management. A comprehensive lifecycle approach includes periodic reviews (typically annual or following major instrument service), defined change control procedures specifying revalidation triggers for modifications to critical reagents, software, or procedural steps, and ongoing specificity monitoring through forced-degradation studies to confirm stability-indicating capabilities [2]. This proactive management strategy safeguards against unexpected compliance gaps while maintaining methodological fitness for purpose throughout its operational lifetime.

Single-Laboratory Validation stands as an indispensable discipline within pharmaceutical and clinical laboratories, providing the critical link between manufacturer validation and routine analytical application. Through systematic assessment of accuracy, precision, specificity, and additional performance parameters, SLV delivers documented evidence of method reliability under actual operating conditions. The structured protocols, statistical rigor, and comprehensive documentation requirements detailed in this technical guide establish a foundation for generating scientifically defensible data that supports both regulatory compliance and patient care decisions. As analytical technologies advance and regulatory expectations evolve, the principles of SLV remain constant: ensuring that every method implemented within a laboratory demonstrates proven capability to deliver results fit for their intended purpose, ultimately contributing to medication safety, diagnostic accuracy, and therapeutic efficacy.

Analytical method validation is a foundational pillar in pharmaceutical development and quality control, providing documented evidence that a laboratory procedure is fit for its intended purpose. For scientists conducting single-laboratory validation (SLV) research, understanding the interconnected regulatory landscape is crucial for generating scientifically sound and compliant data. Three principal guidelines form the cornerstone of modern analytical validation: ICH Q2(R1), FDA guidance on analytical procedures, and USP General Chapter <1225>. While these frameworks share common objectives, each possesses distinct emphases and applications that laboratory researchers must navigate to ensure regulatory compliance and methodological rigor.

The validation paradigm has undergone a significant shift from treating validation as a one-time event to managing it as a dynamic lifecycle process. This evolution is embodied in the recent alignment of USP <1225> with ICH Q14 on analytical procedure development and the principles outlined in USP <1220> for the Analytical Procedure Life Cycle (APLC) [4]. For the SLV researcher, this means validation strategies must now extend beyond traditional parameter checks to demonstrate ongoing "fitness for purpose" through the entire method lifespan, from development and validation to routine use and eventual retirement [4].

Core Regulatory Guidelines

ICH Q2(R1): The International Benchmark

ICH Q2(R1), titled "Validation of Analytical Procedures: Text and Methodology," represents the globally recognized standard for validating analytical procedures. This harmonized guideline combines the former Q2A and Q2B documents, providing a unified framework for the validation of analytical methods used in pharmaceutical registration applications [5].

Scope and Application: ICH Q2(R1) establishes the fundamental validation parameters and methodologies required to demonstrate that an analytical procedure is suitable for detecting or quantifying an analyte in a specific matrix. It provides the foundational concepts that have been adopted by regulatory authorities worldwide, creating a streamlined path for international submissions [6] [5].

Key Validation Parameters: The guideline systematically defines the critical characteristics that require validation based on the type of analytical procedure (identification, testing for impurities, assay). These core parameters provide the structural framework for most modern validation protocols [6] [5].

FDA Guidance on Analytical Procedures

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration provides specific guidance for analytical procedures and methods validation that builds upon the ICH foundation while addressing regional regulatory requirements.

Regulatory Framework: The FDA's approach emphasizes method robustness as a critical parameter, requiring demonstration of analytical reliability under varying conditions [6]. The guidance includes detailed recommendations for life-cycle management of analytical methods and specific expectations for revalidation procedures [6].

Application-Specific Guidance: The FDA tailors its validation recommendations to specific product categories. For example, the agency has issued separate guidance documents for tobacco product applications, which recommend how manufacturers can provide validated and verified data for analytical procedures used in premarket submissions [7]. This demonstrates the FDA's risk-based approach to validation requirements across different product types with varying public health impacts.

USP <1225>: Compendial Validation Standards

United States Pharmacopeia General Chapter <1225> "Validation of Compendial Procedures" provides specific guidance for validating analytical methods used in pharmaceutical testing, with particular relevance to methods that may become compendial [8] [6].

Categorical Approach: USP <1225> outlines validation requirements for four categories of analytical procedures: Category I (identification tests), Category II (quantitative tests for impurities), Category III (limit tests), and Category IV (assay procedures) [6]. Each category has specific validation parameter requirements that form the basis for demonstrating method suitability.

Evolving Framework: USP <1225> is currently undergoing significant revision to align with modern validation paradigms. The proposed revision, published in Pharmacopeial Forum PF 51(6), adapts the chapter for validation of both non-compendial and compendial procedures and provides connectivity to related USP chapters, particularly <1220> Analytical Procedure Life Cycle [9] [4]. This revision introduces critical concepts including "Reportable Result" as the definitive output supporting compliance decisions and "Fitness for Purpose" as the overarching goal of validation [9].

Table 1: Comparison of Key Validation Parameters Across Regulatory Guidelines

| Validation Parameter | ICH Q2(R1) | FDA Guidance | USP <1225> |

|---|---|---|---|

| Accuracy | Required | Required | Required |

| Precision | Required | Required | Required |

| Specificity | Required | Required | Required |

| Detection Limit | Required | Required | Required |

| Quantitation Limit | Required | Required | Required |

| Linearity | Required | Required | Required |

| Range | Required | Required | Required |

| Robustness | Recommended | Emphasized | Recommended |

| System Suitability | Not covered | Referenced | Required |

Method Validation Versus Verification

A critical distinction for SLV researchers is understanding the difference between method validation and method verification, as the regulatory requirements and scientific approaches differ significantly.

Method Validation is a comprehensive, documented process that proves an analytical method is acceptable for its intended use. It involves rigorous testing and statistical evaluation of all relevant parameters and is typically required when developing new methods or substantially modifying existing ones [10] [8].

Method Verification confirms that a previously validated method performs as expected under specific laboratory conditions. It involves limited testing to demonstrate the laboratory's ability to execute the method properly and is typically employed when adopting compendial or standardized methods [10] [8].

For USP compendial methods, laboratories typically perform verification rather than full validation, as the method has already been validated by USP [8]. However, for non-compendial or modified compendial methods, full validation is necessary to demonstrate reliability for the specific application [8].

Experimental Protocols for Validation Parameters

Accuracy Assessment Protocol

Accuracy demonstrates the closeness of agreement between the value accepted as a true reference value and the value found through testing [6] [5].

Experimental Methodology: Prepare a minimum of nine determinations across the specified range of the procedure (e.g., three concentrations/three replicates each). For drug assay methods, this typically involves spiking placebo with known quantities of analyte relative to the target concentration (e.g., 80%, 100%, 120%). Compare results against accepted reference values using statistical intervals for evaluation [4] [8].

Data Interpretation: Calculate percent recovery for each concentration and overall mean recovery. Acceptance criteria vary based on method type but typically fall within 98-102% for drug substance assays and 95-105% for impurity determinations at the quantification limit [8].

Precision Evaluation Protocol

Precision validation encompasses repeatability, intermediate precision, and reproducibility [6] [5].

Repeatability (Intra-assay Precision): Perform a minimum of nine determinations covering the specified range (e.g., three concentrations/three replicates) or six replicates at 100% of the test concentration. The replication strategy should reflect the final routine testing procedure that will generate the reportable result [4] [8].

Intermediate Precision: Demonstrate method reliability under variations occurring within a single laboratory over time, including different analysts, equipment, days, and reagent lots. The experimental design should incorporate the same replication strategy used for routine testing to properly capture time-based variability [4].

Statistical Evaluation: Express precision as relative standard deviation (RSD). For assay validation of drug substances, typical acceptance criteria for repeatability is RSD ≤ 1.0% for HPLC methods, while intermediate precision should show RSD ≤ 2.0% [8].

Specificity and Selectivity Protocol

Specificity demonstrates the ability to assess unequivocally the analyte in the presence of components that may be expected to be present, such as impurities, degradation products, and matrix components [6] [5].

For Identification Tests: Demonstrate positive responses for samples containing the target analyte and negative responses for samples without the analyte or with structurally similar compounds.

For Assay and Impurity Tests: Use chromatographic methods to demonstrate baseline separation of analytes from potential interferents. For stability-indicating methods, stress samples (acid, base, oxidative, thermal, photolytic) should demonstrate no co-elution of degradation products with the main analyte [8].

For Chromatographic Methods: Report resolution factors between the analyte and closest eluting potential interferent. Typically, resolution > 2.0 between critical pairs demonstrates adequate specificity [8].

Table 2: Validation Protocol Requirements by Analytical Procedure Category

| Procedure Type | Accuracy | Precision | Specificity | LOD/LOQ | Linearity | Range |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Identification | - | - | Yes | - | - | - |

| Impurity Testing | ||||||

| • Quantitative | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes (LOQ) | Yes | Yes |

| • Limit Test | - | - | Yes | Yes (LOD) | - | - |

| Assay | ||||||

| • Content/Potency | Yes | Yes | Yes | - | Yes | Yes |

| • Dissolution | Yes | Yes | - | - | Yes | Yes |

The Validation Workflow and Lifecycle Approach

The modern validation paradigm has shifted from a one-time exercise to an integrated lifecycle approach, as illustrated below:

This lifecycle approach integrates with the broader quality system through knowledge management, where data generated during method development, platform knowledge from similar methods, and experience with related products constitute legitimate inputs to validation strategy [4].

Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Successful method validation requires carefully selected, well-characterized reagents and materials. The following toolkit represents essential components for pharmaceutical analytical methods:

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Validation Studies

| Reagent/Material | Function in Validation | Critical Quality Attributes |

|---|---|---|

| Reference Standard | Provides the true value for accuracy determination and calibration curve establishment | Certified purity (>98.5%), proper storage conditions, stability documentation |

| Placebo/Blank Matrix | Evaluates specificity/selectivity by detecting potential interference from sample matrix | Represents final formulation without active ingredient, matches composition |

| Chromatographic Columns | Separation component for specificity and selectivity demonstrations | Multiple column lots from different manufacturers, appropriate selectivity |

| Mobile Phase Components | Creates separation environment in chromatographic methods | HPLC-grade or better, specified pH range, organic content, buffer concentration |

| System Suitability Standards | Verifies chromatographic system performance before and during validation experiments | Resolution mixture, tailing factor standards, precision standards |

Current Regulatory Developments and Future Directions

The regulatory landscape for analytical method validation continues to evolve, with several significant developments impacting SLV research:

USP <1225> Revision: The proposed revision of USP <1225>, currently open for comment until January 31, 2026, represents a fundamental shift in validation philosophy [9]. The updated chapter emphasizes "fitness for purpose" as the overarching goal and introduces the "reportable result" as the definitive output supporting compliance decisions [9] [4]. This revision better aligns with ICH Q2(R2) principles and integrates with the analytical procedure lifecycle described in USP <1220> [9].

Enhanced Statistical Approaches: The revised validation frameworks introduce more sophisticated statistical methodologies, including the use of statistical intervals (confidence, prediction, tolerance) as tools for evaluating precision and accuracy in relation to decision risk [9] [4]. Combined evaluation of accuracy and precision is described in more detail than in previous versions, recognizing that what matters for reportable results is the total error combining both bias and variability [4].

Risk-Based Validation Strategies: Modern guidelines increasingly encourage risk-based approaches that match validation effort to analytical criticality and complexity [8]. This represents a shift from the traditional category-based approach that prescribed specific validation parameters based solely on method type rather than method purpose [4].

For single-laboratory validation researchers, staying current with these evolving standards while maintaining robust, defensible validation practices remains essential for generating regulatory-ready data and ensuring product quality and patient safety.

Single-Laboratory Method Validation (SLV) is a critical process that establishes documented evidence, through laboratory studies, that an analytical procedure is fit for its intended purpose within a single laboratory environment [3]. For researchers and drug development professionals, SLV forms the foundational pillar of data integrity, ensuring that the results generated are reliable, consistent, and defensible before a method is transferred to other laboratories or submitted for regulatory approval. The process demonstrates that the performance characteristics of the method meet the requirements for the intended analytical application, providing an assurance of reliability during normal use [3] [11]. In a regulated environment, SLV is not merely good scientific practice but a mandatory compliance requirement for institutions adhering to standards from bodies like the FDA, ICH, and ISO [3] [1].

The core parameters discussed in this guide—Accuracy, Precision, Specificity, Linearity, Range, LOD, LOQ, and Robustness—represent the fundamental analytical performance characteristics that must be investigated during any method validation protocol [3]. These parameters collectively provide a comprehensive picture of a method's capability and limitations. The following workflow outlines the typical stages of analytical method development and validation within a single laboratory context.

Core Validation Parameters: Definitions and Experimental Protocols

This section details the eight core validation parameters, providing their formal definitions, regulatory significance, and detailed experimental methodologies for assessment in a single-laboratory setting.

Accuracy

Accuracy is defined as the closeness of agreement between an accepted reference value and the value found in a sample [3] [12]. It reflects the trueness of measurement and is typically expressed as percent recovery of a known, added amount [3]. Accuracy should be established across the specified range of the method [3].

Experimental Protocol:

- For Drug Substances: Compare results to the analysis of a standard reference material, or to a second, well-characterized method [3].

- For Drug Products: Analyze synthetic mixtures of the drug product spiked with known quantities of components [3].

- For Impurities: Spike the drug substance or product with known amounts of impurities (if available) and determine the recovery [3].

- Data Collection: Collect data from a minimum of nine determinations over a minimum of three concentration levels covering the specified range (e.g., three concentrations, three replicates each) [3]. Recovery is often expected to be within 95–105% for the assay of the drug substance or product [2].

Precision

Precision expresses the closeness of agreement (degree of scatter) among a series of measurements obtained from multiple sampling of the same homogeneous sample under the prescribed conditions [3] [11]. It is commonly broken down into three tiers:

- Repeatability (Intra-assay Precision): Precision under the same operating conditions over a short interval of time [3]. Assessed with a minimum of nine determinations covering the specified range (three concentrations, three repetitions each) or a minimum of six determinations at 100% of the test concentration [3]. Results are reported as %RSD (Relative Standard Deviation), with an aim for ≤2% for assay methods [2].

- Intermediate Precision: Within-laboratory variations due to random events such as different days, different analysts, or different equipment [3] [12]. An experimental design (e.g., two analysts preparing and analyzing replicates on different HPLC systems) is used, and results are compared using statistical tests (e.g., Student's t-test) [3].

- Reproducibility (Between-laboratory): Precision between laboratories, typically assessed during collaborative studies for method standardization [3] [13].

Experimental Protocol for Repeatability:

- Prepare a homogeneous sample at 100% of the test concentration.

- Analyze a minimum of six independent replicates of this sample.

- Calculate the mean, standard deviation (SD), and %RSD of the results.

- Compare the %RSD against pre-defined acceptance criteria.

Specificity

Specificity is the ability to assess unequivocally the analyte in the presence of components that may be expected to be present, such as impurities, degradation products, and matrix components [3] [11]. It ensures that a peak's response is due to a single component.

Experimental Protocol:

- For Chromatographic Methods: Inject blanks, placebo samples, stressed samples (forced degradation), and samples spiked with potential interferents (impurities, excipients) [3].

- Peak Purity Assessment: Use photodiode-array (PDA) detection or mass spectrometry (MS) to demonstrate that the analyte peak is pure and not co-eluting with any other peak [3]. Modern PDA software compares spectra across the peak to determine purity.

- Resolution: Demonstrate resolution between the analyte and the most closely eluting potential interferent. Resolution (Rs) should typically be >1.5 [3].

Linearity

Linearity is the ability of the method to elicit test results that are directly, or by a well-defined mathematical transformation, proportional to the analyte concentration within a given range [3] [12].

Experimental Protocol:

- Prepare a minimum of five (recommended six) standard solutions whose concentrations span the intended range (e.g., 80-120% of the target concentration) [3] [11].

- Analyze each solution in a random order to avoid time-based bias.

- Plot the analyte response against the concentration.

- Perform linear regression analysis to calculate the slope, y-intercept, and coefficient of determination (r²). The correlation coefficient (r) should be ≥ 0.99 [2] [11].

Range

The range of an analytical method is the interval between the upper and lower concentrations (inclusive) of analyte for which it has been demonstrated that the method has a suitable level of precision, accuracy, and linearity [3] [11]. It is derived from the linearity study.

Limit of Detection (LOD) and Limit of Quantitation (LOQ)

- LOD: The lowest concentration of an analyte in a sample that can be detected, but not necessarily quantified, under the stated experimental conditions. It is a limit test [3].

- LOQ: The lowest concentration of an analyte in a sample that can be quantitatively determined with acceptable precision and accuracy [3].

Experimental Protocols:

- Signal-to-Noise Ratio (S/N): Most common for chromatographic methods. The LOD is typically a S/N of 3:1, and the LOQ is a S/N of 10:1 [3] [2].

- Standard Deviation of the Response and Slope: LOD = 3.3σ/S and LOQ = 10σ/S, where σ is the standard deviation of the response (from the blank or low-concentration samples) and S is the slope of the calibration curve [3] [1].

- Visual Evaluation: Determine by analysis of samples with known concentrations of analyte.

Robustness

The robustness of an analytical procedure is a measure of its capacity to remain unaffected by small, deliberate variations in method parameters and provides an indication of its reliability during normal usage [3] [13]. It is typically evaluated during the method development phase.

Experimental Protocol (Screening Design):

- Identify Factors: Select critical method parameters (e.g., mobile phase pH (±0.2), flow rate (±5%), column temperature (±5°C), wavelength) [2] [13].

- Design Experiment: Use a multivariate screening design (e.g., full factorial, fractional factorial, or Plackett-Burman design) to efficiently study multiple factors simultaneously [13].

- Perform Analysis: Execute the experimental runs and monitor critical quality attributes (e.g., retention time, resolution, tailing factor).

- Analyze Data: Use statistical analysis to identify which factors have a significant effect on the method's performance. Establish system suitability test limits based on these findings [13].

The diagram below illustrates the key factors and responses typically evaluated in a robustness study for a chromatographic method.

The table below provides a consolidated summary of the core validation parameters, their definitions, and typical experimental acceptance criteria for a quantitative assay, serving as a quick reference for researchers.

Table 1: Summary of Core Validation Parameters and Typical Acceptance Criteria for a Quantitative Assay

| Parameter | Definition | Typical Experimental Protocol & Acceptance Criteria |

|---|---|---|

| Accuracy [3] | Closeness of agreement between the measured value and a true or accepted reference value. | Protocol: Analyze a minimum of 9 determinations over 3 concentration levels.Criteria: Mean recovery of 95-105% [2]. |

| Precision [3] | Closeness of agreement between a series of measurements from multiple sampling of the same homogeneous sample. | Protocol (Repeatability): 6 replicates at 100% test concentration.Criteria: %RSD ≤ 2.0% for assay [2]. |

| Specificity [3] | Ability to measure the analyte unequivocally in the presence of other components. | Protocol: Inject blank, placebo, and stressed samples. Use PDA or MS for peak purity.Criteria: No interference; resolution >1.5 from closest eluting peak. |

| Linearity [3] [11] | Ability to obtain results directly proportional to analyte concentration. | Protocol: Minimum of 5 concentrations across the specified range (e.g., 80-120%).Criteria: Correlation coefficient r ≥ 0.990 [2] [11]. |

| Range [3] [11] | The interval between the upper and lower concentrations for which linearity, accuracy, and precision are demonstrated. | Derived from the linearity and accuracy studies. Must be specified (e.g., 80-120% of target concentration). |

| LOD [3] | Lowest concentration of analyte that can be detected. | Protocol: Based on S/N ratio or LOD=3.3σ/S.Criteria: S/N ratio ≥ 3:1. |

| LOQ [3] | Lowest concentration of analyte that can be quantified with acceptable precision and accuracy. | Protocol: Based on S/N ratio or LOQ=10σ/S.Criteria: S/N ratio ≥ 10:1; Precision (%RSD) and Accuracy at LOQ should be documented. |

| Robustness [13] | Capacity of the method to remain unaffected by small, deliberate variations in method parameters. | Protocol: Deliberately vary parameters (e.g., pH, flow rate, temperature) in a structured design.Criteria: System suitability criteria are met despite variations. |

Essential Research Reagent Solutions and Materials

The successful execution of validation protocols requires high-quality materials and reagents. The following table lists key items essential for conducting method validation studies.

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions and Materials for Method Validation

| Item | Function in Validation |

|---|---|

| Certified Reference Standards [3] | Used to establish accuracy and linearity. Provides an analyte of known identity and purity to serve as the benchmark for all measurements. |

| High-Purity Solvents & Reagents | Ensure the baseline response (noise) is minimized, critical for LOD/LOQ determinations, and prevent introduction of interfering species affecting specificity. |

| Placebo Matrix | A sample containing all components except the analyte, used in specificity and accuracy (recovery) studies to confirm the absence of interference from excipients or the sample matrix [3]. |

| System Suitability Test Solutions [3] | A reference preparation used to verify that the chromatographic system is adequate for the analysis before and during the validation runs. Typically tests for resolution, tailing factor, and precision. |

| Stressed Samples (Forced Degradation) | Samples exposed to stress conditions (e.g., heat, light, acid/base) to generate degradants, which are used to validate the stability-indicating property and specificity of the method [2]. |

The rigorous assessment of the eight core validation parameters—Accuracy, Precision, Specificity, Linearity, Range, LOD, LOQ, and Robustness—is fundamental to establishing the scientific soundness and regulatory credibility of any analytical method developed within a single laboratory. This guide has provided detailed experimental methodologies and acceptance criteria aligned with international guidelines [3] [14]. A well-executed SLV provides documented evidence that the method is fit for its intended purpose, instills confidence in the generated data, and forms a solid foundation for subsequent method transfer or collaborative studies [11]. As the analytical lifecycle progresses, continuous monitoring and controlled revalidation ensure the method remains in a validated state throughout its operational use [2].

The Critical Link Between SLV, Data Integrity, and Patient Safety

In the development and monitoring of pharmaceuticals, the integrity of data is not merely a regulatory requirement—it is the very bedrock of patient safety. Single-laboratory validation (SLV) serves as the critical scientific foundation upon which this data integrity is built. SLV represents the comprehensive process of establishing, through extensive laboratory studies, that an analytical method is reliable, reproducible, and fit for its intended purpose within a single laboratory environment prior to multilaboratory validation [15]. This rigorous demonstration of methodological robustness is paramount for generating trustworthy data that informs decisions across the entire drug lifecycle, from initial development to post-market surveillance.

The consequences of analytical inadequacy are severe. In the broader healthcare context, poor data quality is not just a technical problem; it is a direct patient safety risk [16]. When professionals doubt the information in front of them, clinical decisions are compromised, highlighting that digital transformation and advanced analytics can only move at the speed of trust. This whitepaper examines the integral relationship between SLV, data integrity, and patient safety, providing researchers and drug development professionals with the technical frameworks necessary to uphold these fundamental standards.

Single-Laboratory Validation: Principles and Protocols

Defining SLV and Its Strategic Importance

Single-laboratory validation is the essential first step in demonstrating that an analytical method meets predefined acceptance criteria for its intended application before transfer to other laboratories. The strategic importance of SLV lies in its ability to provide a controlled, initial assessment of method performance, identifying potential issues early and reducing costs associated with method failure during subsequent collaborative studies [15].

For the pharmaceutical researcher, SLV is particularly crucial when developing methods for novel compounds or complex matrices where standardized methods may not exist. This process ensures that validated methods are essential for regulators, the industry, and basic and clinical researchers alike, creating a foundation of trust in the data generated [15]. By incorporating accurate chemical characterization data in clinical trial reports, there is potential for correlating material content with effectiveness, ultimately leading to more conclusive findings about drug safety and efficacy.

Core Validation Parameters and Experimental Protocols

A robust SLV must systematically evaluate specific performance characteristics to ensure the method is fit for purpose. The experimental protocols for assessing these parameters must be meticulously designed and executed to generate defensible data.

Table 1: Essential SLV Parameters and Experimental Protocols

| Validation Parameter | Experimental Protocol | Acceptance Criteria |

|---|---|---|

| Accuracy/Trueness | Analysis of samples spiked with known quantities of analyte across the validated range; comparison to reference materials or comparison with a validated reference method [15]. | Mean recovery of 70-120% with RSD ≤10% for pharmaceutical applications, though specific criteria may vary based on analyte and matrix. |

| Precision | Repeated analysis (n≥6) of homogeneous samples at multiple concentration levels; includes repeatability (intra-day) and intermediate precision (inter-day, different analysts, different instruments) [15]. | RSD ≤5% for repeatability, ≤10% for intermediate precision, depending on analyte concentration and method complexity. |

| Specificity/Selectivity | Analysis of placebo or blank samples, samples with potentially interfering compounds, and stressed samples (e.g., exposed to light, heat, acid/base degradation) to demonstrate separation from interferents [15]. | No interference at the retention time of the analyte; peak purity confirmation using diode array or mass spectrometric detection. |

| Linearity and Range | Analysis of minimum 5 concentration levels across the claimed range, with each level prepared and analyzed in duplicate; evaluation via linear regression analysis [15]. | Correlation coefficient (r) ≥0.990; residuals randomly distributed around the regression line. |

| Limit of Detection (LOD) & Quantification (LOQ) | LOD: Signal-to-noise ratio of 3:1; LOQ: Signal-to-noise ratio of 10:1 with acceptable accuracy and precision (≤20% RSD) at this level [15]. | LOQ should be at or below the lowest concentration in the calibration curve with acceptable accuracy and precision. |

| Robustness/Ruggedness | Deliberate, small variations in method parameters (e.g., mobile phase pH ±0.2 units, column temperature ±5°C, flow rate ±10%); evaluation of impact on results [15]. | Method remains unaffected by small variations; system suitability criteria still met. |

The experimental workflow for establishing these parameters follows a logical progression from initial method development through to final validation, as illustrated below:

Figure 1: SLV Experimental Workflow - This diagram illustrates the systematic progression of single-laboratory validation from initial development through troubleshooting to final completion.

Data Integrity and Data Validity: The Analytical Framework

Distinguishing Between Data Integrity and Validity

In the context of pharmaceutical analysis, a clear distinction must be drawn between data integrity and data validity, as both represent critical but distinct aspects of data quality:

Data Integrity refers to the maintenance and assurance of the consistency, accuracy, and reliability of data throughout its complete lifecycle [17]. It ensures that data remains unaltered and uncompromised from its original state when created, transmitted, or stored. Data integrity is concerned with the "wholeness" and "trustworthiness" of data, focusing on preventing unauthorized modifications, ensuring completeness, and maintaining accuracy across the data's entire existence [18].

Data Validity refers to the extent to which data is accurate, relevant, and conforms to predefined rules or standards [18]. It ensures that data meets specific criteria or constraints, making it suitable for its intended purpose. Data validity checks if data is properly formatted, within acceptable ranges, and consistent with predefined business rules or scientific requirements.

Table 2: Comparative Analysis: Data Integrity vs. Data Validity

| Aspect | Data Integrity | Data Validity |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Focus | Overall trustworthiness and protection of data throughout its lifecycle [17] | Conformance to predefined rules and fitness for intended purpose [18] |

| Temporal Scope | Entire data lifecycle (creation, modification, storage, transfer, archiving) [17] | Point-in-time assessment against specific criteria |

| Key Measures | Access controls, audit trails, encryption, backup systems, error detection [17] [18] | Validation rules, data entry checks, automated validation, manual review [18] |

| Risk Addressed | Unauthorized alteration, data corruption, incomplete data, fabrication | Incorrect data entry, out-of-range values, improper formatting |

| Impact on Patient Safety | Prevents systematic data corruption that could affect multiple studies or decisions [16] | Prevents individual data points from leading to incorrect conclusions |

Implementing Data Integrity Controls in the Laboratory

The implementation of robust data integrity controls is essential for maintaining trust in analytical data. Key measures include:

- Access Controls: Limit system and data access based on user roles and responsibilities to prevent unauthorized modifications [18]. Implement unique user credentials and regularly review access privileges.

- Audit Trails: Maintain secure, computer-generated, time-stamped electronic audit trails that independently record user activities [18]. These trails must be retained for the entire data lifecycle and regularly reviewed.

- Data Validation and Verification: Implement validation rules during data entry and automated validation checks to verify accuracy and completeness before data storage [18].

- Error Handling Mechanisms: Establish procedures to capture and address data inconsistencies or exceptions promptly, with alerts to notify relevant personnel about potential integrity issues [18].

The Patient Safety Connection: From Laboratory to Clinic

Pharmacovigilance: The Clinical Extension of Analytical Quality

The principles of SLV and data integrity extend directly into clinical practice through pharmacovigilance, defined as "the science and research relating to the detection, assessment, understanding and prevention of adverse effects or any other medicine/vaccine related problem" [19]. Pharmacovigilance represents the clinical manifestation of the quality continuum that begins with analytically sound laboratory data.

Pharmacovigilance has evolved from "a largely recordkeeping function to proactively identifying safety issues ('signals') and taking actions to minimize or mitigate risk to patients" [20]. This progression mirrors the evolution of quality systems in analytical laboratories from simple data recording to proactive quality risk management. The signal management process in pharmacovigilance directly parallels method validation in the laboratory, both systematically assessing potential risks to ensure patient safety.

Consequences of Data Quality Failures in Healthcare

The direct impact of poor data quality on patient safety is increasingly recognized as a critical healthcare challenge. Recent findings indicate that:

- 64% of healthcare professionals believe digital patient data is incomplete, and half report they must double-check its accuracy before acting [16].

- 47% of healthcare professionals have observed patient safety risks arising directly from digital health technologies [16].

- Inaccurate patient tracking lists can lead to patients being overlooked, particularly dangerous when dealing with referral backlogs where patients await initial clinical contact [16].

These data quality issues represent more than mere administrative inefficiencies; they constitute a serious and ongoing patient safety risk that can directly affect clinical decision-making [16]. The relationship between data quality and patient safety forms an interconnected system where failures at any stage can compromise the entire process:

Figure 2: Data Quality Impact Pathway - This diagram illustrates how robust processes create a safety continuum (top), while failures at any stage compromise patient safety (bottom).

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Successful implementation of SLV requires specific materials and reagents tailored to the analytical methodology and matrix. The following toolkit outlines essential solutions for pharmaceutical method validation:

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for SLV

| Reagent/Material | Function in SLV | Application Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Certified Reference Standards | Provide traceable, quality-controlled substances for method calibration and accuracy determination [15]. | Quantification of active pharmaceutical ingredients, impurity profiling, method calibration. |

| Stable Isotope-Labeled Internal Standards | Compensate for matrix effects, extraction efficiency variations, and instrument fluctuations in mass spectrometry [15]. | LC-MS/MS quantification of drugs and metabolites in biological matrices. |

| Matrix-Matched Calibrators | Account for matrix effects by preparing standards in the same matrix as samples (e.g., plasma, urine, tissue homogenates) [15]. | Bioanalytical method validation for pharmacokinetic studies. |

| Quality Control Materials | Monitor method performance over time at defined concentrations (low, medium, high) across the analytical range [15]. | Ongoing method verification, inter-day precision assessment. |

| Sample Preparation Reagents | Enable extraction, purification, and concentration of analytes from complex matrices [15]. | Solid-phase extraction cartridges, protein precipitation solvents, derivatization reagents. |

The critical link between single-laboratory validation, data integrity, and patient safety forms an unbreakable chain connecting laboratory science to clinical outcomes. SLV provides the foundational evidence that analytical methods are capable of generating reliable data, while robust data integrity measures ensure this reliability is maintained throughout the data lifecycle. This analytical rigor directly supports pharmacovigilance activities and clinical decision-making that protects patients from harm.

For researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, upholding these standards is both a scientific imperative and an ethical obligation. As the industry moves toward increasingly sophisticated analytical technologies and data systems, the fundamental principles outlined in this whitepaper remain constant: rigorous method validation, uncompromising data integrity, and an unwavering focus on patient safety must guide all aspects of pharmaceutical development and monitoring. By maintaining this culture of quality, the scientific community can ensure that patients receive medications whose benefits have been accurately characterized and whose risks are properly understood and managed.

Method validation is an essential component of quality assurance in analytical chemistry, ensuring that analytical methods produce reliable data fit for their intended purpose. Within regulated environments, two primary approaches exist for establishing method validity: Single Laboratory Validation (SLV) and Full Validation (often achieved through an interlaboratory collaborative trial). The fundamental distinction lies in their scope and applicability—SLV establishes that a method is suitable for use within a single laboratory, while full validation demonstrates its fitness for purpose across multiple laboratories.

These processes are governed by international standards and guidelines from organizations including ISO, IUPAC, and AOAC INTERNATIONAL. For researchers and drug development professionals, selecting the appropriate validation pathway has significant implications for resource allocation, regulatory compliance, and the reliability of generated data. This guide examines the technical principles, applications, and procedural details of both approaches to inform strategic decision-making in research and development.

Core Principles and Definitions

Single Laboratory Validation (SLV)

Single Laboratory Validation refers to the process where a laboratory conducts studies to demonstrate that an analytical method is fit for its intended purpose within that specific laboratory [21]. SLV determines key performance characteristics of a method—such as accuracy, precision, and selectivity—to prove reliability for a defined analytical system [21]. The results of an SLV are primarily valid only for the laboratory that conducted the study [22].

SLV serves several critical functions: ensuring method viability before committing to a formal collaborative trial, providing evidence of reliability when collaborative trial data is unavailable, and verifying that a laboratory can correctly implement an "off-the-shelf" validated method [21]. In medical laboratories, the SLV approach acts as an assessment of the entire analytical system, incorporating all available information on potential uncertainty influences on the final result [23].

Full Validation

Full Validation typically involves an interlaboratory method performance study (collaborative study/trial) conforming to internationally accepted protocols [21]. This approach establishes method performance characteristics through a structured study across multiple independent laboratories, providing a broader assessment of method robustness across different environments, operators, and equipment.

Full validation represents the most comprehensive approach for methods intended for widespread or regulatory use. The International Harmonised Protocol and ISO standards specify minimum requirements for laboratories and test materials to constitute a full validation [21]. Once fully validated through a collaborative trial, user laboratories need only verify that they can achieve the published performance characteristics, significantly reducing the validation burden on individual laboratories [21] [22].

Comparative Analysis: SLV vs. Full Validation

When to Select Each Approach

The decision between SLV and full validation depends on multiple factors including intended method application, regulatory requirements, available resources, and timeline constraints.

Single Laboratory Validation is appropriate when:

- Assessing method viability before investing in a formal collaborative trial [21]

- Collaborative trial data is unavailable or conducting a formal interlaboratory study is impractical [21]

- The method will be used in only one laboratory for specialized applications [22]

- Dealing with infrequent product manufacturing or small batch production [24]

- Working with products not in their final design or expected to be modified [24]

Full Validation is necessary when:

- The method is intended for widespread use across multiple laboratories [21]

- Regulatory compliance requires fully validated methods (e.g., food testing, pharmaceutical submissions) [21]

- Standardized methods are being developed for publication or regulatory recognition

- The total cost of a collaborative trial is justified by widespread use of the method [21]

Procedural and Resource Requirements

The following table compares key procedural aspects of SLV versus full validation for sterilization dose setting, illustrating typical differences in scope and resource commitment:

Table 1: Comparison of Procedural Requirements for Sterilization Dose Setting

| Test Component | Full Validation | Single Lot Validation |

|---|---|---|

| Bioburden Testing | 30 unirradiated samples (10 from each of 3 production lots) [24] | 10 unirradiated samples from the single lot to be validated [24] |

| Tests of Sterility | 10 samples irradiated at verification dose [24] | 10 samples per lot tested [24] |

| Applicability | Applies to future lots with controlled processes [24] | Applies only to the specific lot tested [24] |

| Time Investment | Longer initial timeline but no delay for future lots [24] | Shorter initial timeline but requires validation for each new lot [24] |

Advantages and Disadvantages

Each validation approach offers distinct advantages and poses specific limitations that must be considered during method development planning.

Table 2: Advantages and Disadvantages of Each Validation Approach

| Validation Type | Advantages | Disadvantages |

|---|---|---|

| Full Validation | • Lowest cost per test for ongoing validations [24] • Least total product used to reach full validation [24] • No delay in use of new lots awaiting test results [24] • Recognized as gold standard for regulatory acceptance | • Requires samples from multiple independent production lots [24] • Higher initial resource investment • Requires periodic dose audits to maintain validation status [24] |

| Single Laboratory Validation | • Ideal for new products with no immediate plans for future production [24] • Lower initial test costs if ongoing production not needed [24] • Costs can be spread over time [24] • No dose audits until full validation achieved [24] | • Results apply only to the specific lot tested [24] • Each new lot requires separate validation before release [24] • Potentially higher total cost if multiple lots produced over time [24] • Limited recognition for regulatory submissions |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Single Laboratory Validation Protocol

SLV requires systematic assessment of multiple method performance characteristics to establish fitness for purpose. The specific characteristics evaluated depend on the method type and intended application, but typically include:

Selectivity/Specificity: Demonstrate the method's ability to measure the analyte accurately in the presence of potential interferents. This involves testing samples with and without interferents and comparing results [21].

Accuracy/Trueness: Assess through spike/recovery experiments using certified reference materials (when available) or by comparison with a reference method. Recovery experiments involve fortifying sample matrix with known analyte quantities and measuring the recovery percentage [21] [23].

Precision: Evaluate through repeatability (same analyst, same equipment, short time interval) and within-laboratory reproducibility (different analysts, equipment, days). Precision is typically expressed as standard deviation or coefficient of variation [23].

Linearity and Range: Establish the analytical range where method response is proportional to analyte concentration. Prepare and analyze calibration standards across the anticipated concentration range [21].

Limit of Detection (LOD) and Quantification (LOQ): Determine the lowest analyte concentration detectable and quantifiable with acceptable precision. Based on signal-to-noise ratio or statistical evaluation of blank samples [21].

Measurement Uncertainty: For medical laboratories, the SLV approach combines random uncertainty (from Internal Quality Control data) and systematic uncertainty (from bias estimation) using the formula: Combined uncertainty = √(random uncertainty² + systematic uncertainty²) [23].

Full Validation Protocol

Full validation through collaborative trials follows internationally standardized protocols:

Method Comparison Study: Initially validates the method against a reference method in one laboratory [22].

Interlaboratory Study: Multiple laboratories (minimum number specified by relevant protocol) analyze identical test materials using the standardized method protocol. ISO 16140-2 specifies separate protocols for qualitative and quantitative microbiological methods [22].

Statistical Analysis: Results from participating laboratories are collected and statistically analyzed to determine method performance characteristics including reproducibility, repeatability, and trueness [21] [22].

Certification Process: Data generated can serve as a basis for certification of alternative methods by independent organizations [22].

For sterilization validation, full validation requires bioburden testing from three different production lots, bioburden recovery efficiency validation, bacteriostasis/fungistasis testing, and sterility tests at the verification dose [24].

Decision Framework for Validation Strategy

The following diagram illustrates the decision-making process for selecting between SLV and full validation:

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Successful method validation requires specific materials and reagents tailored to the analytical methodology. The following table outlines essential categories and their functions:

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Method Validation

| Reagent/Material | Function in Validation | Application Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Certified Reference Materials (CRMs) | Establish trueness through analysis of materials with certified analyte concentrations [21] | Quantifying method bias, establishing measurement traceability |

| Reference Methods | Provide comparator for evaluating accuracy of new or alternative methods [21] [22] | Method comparison studies as required by ISO 16140 series |

| Selective Culture Media | Validate method selectivity and specificity in microbiological analyses [22] | Confirmation procedures, identification methods validation |

| Internal Quality Control (IQC) Materials | Monitor method precision and stability over time [23] | Determining within-laboratory reproducibility, random uncertainty |

| Proficiency Testing Samples | Assess laboratory performance relative to peers and estimate systematic uncertainty [23] | External quality assessment (EQA), bias estimation |

Implementation in Regulated Environments

Regulatory Framework and Standards

Method validation operates within a comprehensive framework of international standards and regulatory requirements:

ISO Standards: The ISO 16140 series provides detailed protocols for microbiological method validation, with Part 2 covering alternative method validation, Part 3 addressing verification in user laboratories, and Part 4 covering single-laboratory validation [22].

IUPAC/AOAC Guidelines: Provide harmonized protocols for method validation across chemical and biological disciplines, including the Statistics Manual of AOAC INTERNATIONAL with guidance on single laboratory studies [21].

ICH Guidelines: Prescribe minimum validation requirements for tests supporting drug approval submissions, particularly for pharmaceutical applications [21].

Verification of Validated Methods

For laboratories implementing previously validated methods, verification demonstrates the laboratory can satisfactorily perform the method. ISO 16140-3 outlines a two-stage process: implementation verification (testing one item from the validation study) and item verification (testing challenging items within the laboratory's scope) [22].

Selecting between Single Laboratory Validation and Full Validation represents a critical strategic decision in method development and implementation. SLV provides a practical approach for methods with limited application scope, offering flexibility and reduced initial resource commitment. Full Validation, while requiring greater initial investment, provides broader recognition and suitability for methods intended for widespread or regulatory use.

The decision framework presented enables researchers and drug development professionals to make informed choices based on method application, regulatory requirements, and available resources. As regulatory expectations continue to evolve, understanding the scope, limitations, and appropriate application of each validation approach remains fundamental to producing reliable analytical data in pharmaceutical research and development.

Executing SLV: A Step-by-Step Protocol for Laboratory Scientists

Single-laboratory validation (SLV) represents a critical process where a laboratory independently establishes, through documented studies, that the performance characteristics of an analytical method are suitable for its intended application. Within a broader thesis on the fundamentals of SLV research, this foundational step ensures that a method provides reliable, accurate, and reproducible data before it is put into routine use or considered for a full inter-laboratory collaborative study. SLV serves as the bedrock of data integrity, providing stakeholders with confidence in the results that drive critical decisions in drug development, quality control, and regulatory submissions [2] [25]. A well-structured SLV protocol, with unambiguous acceptance criteria, is not merely a regulatory formality but a core component of good scientific practice that prevents costly rework and project delays.

The development of a detailed protocol is the most pivotal phase in the SLV process. It transforms the abstract goal of "method validation" into a concrete, executable, and auditable plan. This document precisely defines the scope, objectives, and experimental design, ensuring that all studies are performed consistently and that the resulting data can be evaluated against pre-defined standards of acceptability [2] [26]. In the context of a validation lifecycle, a robust SLV protocol directly supports future method transfers and continuous improvement initiatives, embedding quality at the very foundation of the analytical method [2].

Core Components of an SLV Protocol

A comprehensive SLV protocol is a multi-faceted document that meticulously outlines every aspect of the validation study. Its primary function is to eliminate ambiguity and ensure the study generates data that is both scientifically sound and defensible during audits.

Defining Scope, Objectives, and Applicability

The protocol must begin with a clear statement of purpose. This section defines the analyte of interest, the sample matrices (e.g., active pharmaceutical ingredient, finished drug product, biological fluid), and the intended use of the method (e.g., stability testing, release testing, impurity profiling) [26]. The objectives should be Specific, Measurable, Achievable, Relevant, and Time-bound (SMART). For instance, an objective may be, "To validate a reverse-phase HPLC-UV method for the quantification of Active X in 50 mg tablets over a range of 50% to 150% of the nominal concentration, demonstrating accuracy within 98-102% and precision with an RSD of ≤2.0%."

Detailed Experimental Design

This section is the operational core of the protocol. It provides a step-by-step guide for the experimental work, ensuring consistency and reproducibility. Key elements include:

- Sample Preparation: Detailed procedures for preparing standards, blanks, and quality control (QC) samples at various concentration levels, including the specific solvents, dilution schemes, and stabilization techniques to be used [2].

- Instrumentation and Conditions: A complete description of the analytical instrument (e.g., HPLC, GC) and its configuration, including column type, mobile phase composition, flow rate, temperature, and detection settings [27].

- Number of Replicates and Runs: The protocol must specify the number of replicates for each validation parameter (e.g., a minimum of six replicates at one concentration level for precision) and whether intermediate precision will involve different analysts, instruments, or days [2] [25].

Defining Validation Parameters and Acceptance Criteria

This component explicitly lists the performance characteristics to be evaluated and the quantitative standards for judging their acceptability. These parameters form the basis for the scientific assessment of the method's fitness for purpose. The subsequent section of this guide provides a detailed breakdown of these parameters and their typical acceptance criteria.

Documentation and Data Analysis Procedures

The protocol must specify the format for raw data collection (e.g., electronic lab notebooks, chromatographic data systems) and the statistical methods that will be used to calculate results like mean, standard deviation, %RSD, and regression coefficients [2] [26]. Adherence to ALCOA++ principles (Attributable, Legible, Contemporaneous, Original, Accurate, plus Complete, Consistent, Enduring, and Available) for data integrity is paramount [28].

The following workflow diagram illustrates the logical sequence and key decision points in developing and executing an SLV protocol.

SLV Protocol Development and Execution Workflow

Validation Parameters and Acceptance Criteria

The following table summarizes the core validation parameters, their definitions, common experimental methodologies, and examples of scientifically rigorous acceptance criteria for a pharmaceutical SLV.

Table 1: Core Validation Parameters and Acceptance Criteria for SLV

| Parameter | Definition & Purpose | Recommended Experimental Methodology | Example Acceptance Criteria |

|---|---|---|---|

| Specificity | Ability to unequivocally assess the analyte in the presence of potential interferents (e.g., impurities, matrix). | Compare chromatograms of blank matrix, placebo, standard, and stressed samples (e.g., heat, light, acid/base) [2]. | Baseline separation of analyte peak from all potential interferents; Peak purity index ≥ 990. |

| Accuracy | Closeness of agreement between the measured value and a reference value. | Spike and recovery: Fortify blank matrix with known analyte concentrations (e.g., 3 levels, 3 replicates each) [2]. | Mean recovery of 98–102%; RSD ≤ 2% at each level. |

| Precision | Degree of scatter among a series of measurements. Includes repeatability and intermediate precision. | Analyze multiple preparations (n=6) of a homogeneous sample at 100% concentration. Repeat on different days/analysts [2]. | Repeatability: RSD ≤ 2%. Intermediate Precision: RSD ≤ 2.5% and no significant statistical difference between days/analysts. |

| Linearity | Ability of the method to produce results directly proportional to analyte concentration. | Prepare a minimum of 5 concentration levels across the stated range (e.g., 50%, 75%, 100%, 125%, 150%) [2]. | Correlation coefficient (r) ≥ 0.998; y-intercept not significantly different from zero. |

| Range | The interval between the upper and lower concentration levels for which accuracy, precision, and linearity are established. | Defined by the linearity and accuracy studies. | The range over which linearity, accuracy, and precision meet all acceptance criteria. |

| LOD / LOQ | Limit of Detection (lowest detectable level) and Limit of Quantification (lowest quantifiable level). | Signal-to-Noise ratio of 3:1 for LOD and 10:1 for LOQ, confirmed by experimental analysis [2]. | LOD/LOQ concentrations confirmed by analysis with accuracy of 80-120% and precision of RSD ≤ 10% for LOQ. |

| Robustness | Capacity to remain unaffected by small, deliberate variations in method parameters. | Deliberately alter a single parameter (e.g., flow rate ±0.1 mL/min, temperature ±2°C, pH ±0.1 units) [2]. | System suitability criteria are met for all variations; No significant impact on key results (e.g., retention time, resolution). |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

The reliability of an SLV is contingent on the quality of the materials used. The following table details key reagents and consumables that are essential for executing a robust validation study, particularly in chromatographic analysis.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for SLV