Resolving Food Composition Database Discrepancies: A Roadmap for Harmonized Data in Biomedical Research

This article addresses the critical challenge of discrepancies in Food Composition Databases (FCDBs), which undermine the reliability of nutritional science, public health policies, and the development of functional foods and...

Resolving Food Composition Database Discrepancies: A Roadmap for Harmonized Data in Biomedical Research

Abstract

This article addresses the critical challenge of discrepancies in Food Composition Databases (FCDBs), which undermine the reliability of nutritional science, public health policies, and the development of functional foods and nutraceuticals. We synthesize the current state of FCDBs, highlighting widespread issues of outdated information, incomplete metadata, and poor adherence to FAIR data principles, particularly in low- and middle-income countries. The article provides a structured framework for researchers and drug development professionals, covering foundational causes of data inconsistency, methodological best practices for data compilation and harmonization, troubleshooting strategies for common pitfalls, and validation techniques for ensuring cross-country comparability. By offering actionable solutions for standardizing food composition data, this work aims to empower stakeholders to build more robust, comparable, and reusable datasets, thereby strengthening the evidence base for diet-disease relationships and nutritional interventions.

Understanding the Landscape: The Root Causes of Food Composition Data Discrepancies

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. What are the most common types of inconsistencies found in FCDBs? Researchers will encounter several types of data inconsistencies that can impact their analyses. Key issues include:

- Variability in Scope and Content: The number of foods and components (nutrients, bioactive compounds) in global FCDBs ranges from a few to thousands. This makes cross-database comparisons challenging [1].

- Inadequate Metadata and FAIR Compliance: A core problem is the lack of high-resolution metadata describing the source, preparation, and analysis of foods. While most FCDBs are findable, their aggregate scores for Accessibility, Interoperable, and Reusability are low at 30%, 69%, and 43% respectively. This limits seamless data integration and reuse [1].

- Primary vs. Secondary Data Homogenization: Larger FCDBs often rely on secondary data (e.g., from scientific articles or other databases), which can lead to homogenization and inaccurate representation of local food supplies. In contrast, smaller databases with fewer entries often contain primary analytical data generated in-house [1].

- Infrequent Updates and Regional Biases: Many FCDBs are updated infrequently. Furthermore, they often reflect regional biases, with significant gaps in data for culturally significant, traditional, and biodiverse foods not common in Western diets, such as taro-based poi or edible insects [1].

2. How can I quantitatively assess the quality and coverage of an FCDB for my research? You can evaluate an FCDB by systematically reviewing a set of key quantitative and qualitative attributes. The table below summarizes critical metrics based on a recent global review of 101 FCDBs [1].

Table 1: Key Metrics for Assessing Food Composition Database (FCDB) Quality

| Assessment Attribute | What to Look For | Research Implications |

|---|---|---|

| Number of Foods & Components | Scope ranges from few to thousands; only one-third of FCDBs contain data on >100 components [1]. | Determines if the database covers the foods and nutrients relevant to your study. |

| Data Source (Primary/Secondary) | Checks if data is from direct laboratory analysis (primary) or borrowed from other sources (secondary) [1]. | Primary data is often more accurate for specific contexts; secondary data can introduce homogenization. |

| Update Frequency | Prefer web-based interfaces, which are updated more frequently than static tables [1]. | Ensures you are working with the most current food composition information available. |

| FAIR Compliance | Verify scores for Accessibility, Interoperability, and Reusability, not just Findability [1]. | High FAIR scores indicate the data is easier to access, integrate with other datasets, and reuse correctly. |

| Economic Context of Origin | Databases from high-income countries often have more primary data, web interfaces, and better FAIR adherence [1]. | Provides context for the database's likely strengths and limitations, guiding your confidence in its use. |

3. Our research involves traditional foods not found in major FCDBs. What is the best protocol to handle this? When working with under-represented foods, a rigorous protocol for data gap filling is essential to minimize error.

- Step 1: Exhaustive Search: Before creating new data, search specialized, regional, and ethnobotanical databases and literature for any existing composition data.

- Step 2: Proximate Analogy with Caution: If no data exists, identify a proximate analog from a major FCDB (e.g., USDA FoodData Central). Document all assumptions and the rationale for choosing the analog, noting potential differences in cultivar, growing conditions, and processing [1].

- Step 3: Primary Analysis (Gold Standard): For the most accurate results, commission primary laboratory analysis of the traditional food. The methodology must use validated analytical methods (e.g., AOAC) and record comprehensive, high-resolution metadata [1].

- Step 4: Document and Report: In your research publications, transparently report the source of the composition data, whether it was an analog or from new analysis, and the methods used. This is critical for reproducibility and assessing potential dietary assessment error [1].

4. What is the standard methodology for validating data extracted from multiple FCDBs? To ensure consistency in a merged dataset, implement a harmonization and validation workflow.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for FCDB Analysis

| Research 'Reagent' | Function / Explanation |

|---|---|

| FAIR Data Principles | A framework of guiding principles (Findable, Accessible, Interoperable, Reusable) to make data more discoverable, shareable, and usable [1]. |

| High-Resolution Metadata | Detailed context about a food sample (e.g., cultivar, geographic origin, soil, processing method, analytical technique). It is the key to assessing data quality and comparability [1]. |

| Validated Analytical Methods | Standardized laboratory methods (e.g., from AOAC International) that ensure the accuracy and consistency of nutrient data, allowing for valid comparisons between different studies [1]. |

| Food Data Harmonization Tools | Standardized vocabularies and ontologies (e.g., from INFOODS or EuroFIR) that align different food names, component names, and units across databases, enabling interoperability [1]. |

| USDA FoodData Central | Often used as a primary reference database due to its comprehensive nature and public domain status. It can serve as a benchmark for data comparison and gap-filling [2]. |

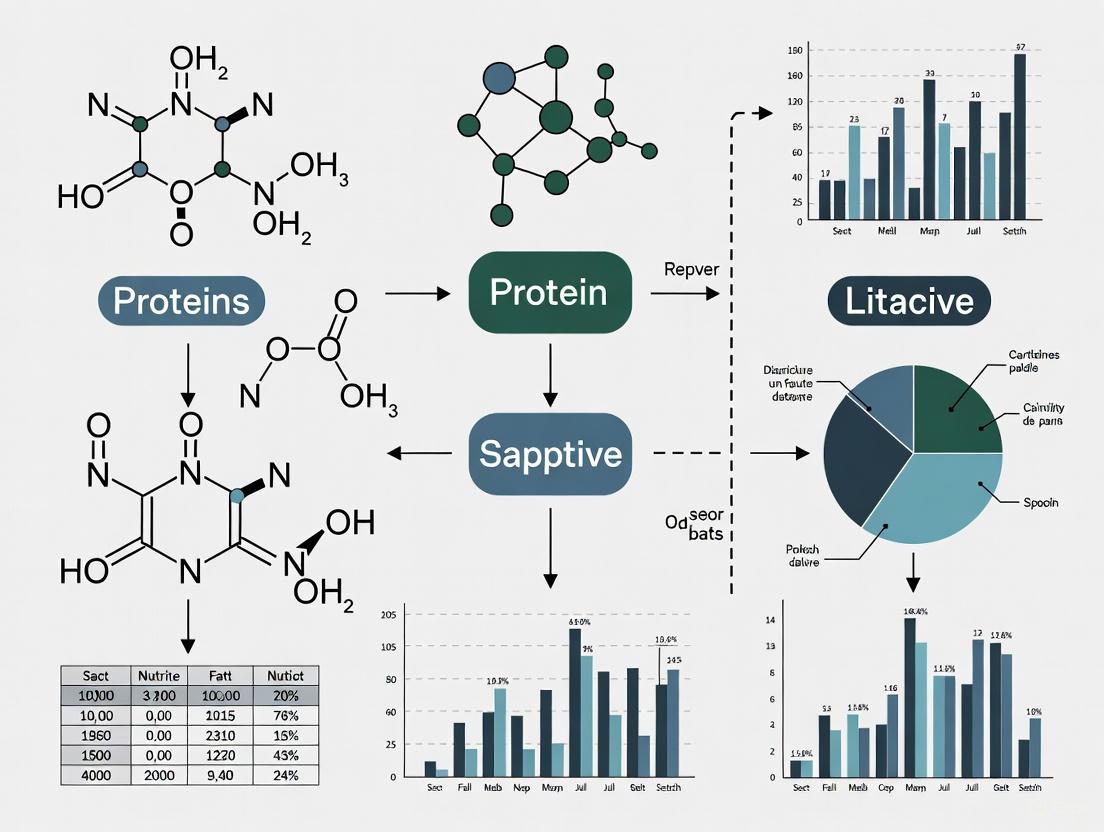

The diagram below outlines a systematic workflow for this process:

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: What are the primary technical sources of discrepancy in food composition database entries? Discrepancies primarily originate from three key areas:

- Analytical Methods: Variation in laboratory techniques, equipment, and data compilation methods. For example, the same food analyzed using different methods (e.g., for fiber or vitamins) can yield different nutrient values [3] [4].

- Environmental Factors: Climate, soil conditions, and agricultural practices (e.g., feed, fertilizer use) can significantly alter the nutrient profile of a food item [5].

- Genetic Diversity (Biodiversity): Nutrient content can vary by up to 1000 times among different varieties, cultivars, or breeds of the same food [5]. Many national databases underrepresent this diversity, especially for local and traditional foods [3].

FAQ 2: How does the source of data (primary vs. secondary) impact database quality? The source of data is a critical factor in quality and scope:

- Primary Data: Generated from direct chemical analysis. Databases with fewer food items and components tend to be based on this high-quality, in-house analytical data [3].

- Secondary Data: Borrowed from scientific literature or other databases. Larger databases (with ≥1,102 food samples and ≥244 components) often rely on secondary data, which can introduce errors if the original analytical context is lost [3] [6].

FAQ 3: What are the common pitfalls in using food composition data for international or multi-regional studies? The main pitfalls include a lack of harmonization and regional bias.

- Lack of Harmonization: There is no unified global system for food naming, nutrient definitions, or analytical methods, making cross-country comparisons difficult [3] [7].

- Regional Bias: Databases from high-income countries are often more comprehensive and regularly updated. Using them for studies in other regions can be inaccurate, as the same food can have a different composition due to environmental or processing factors [3] [5]. Many foods central to local diets are missing from major international databases [3].

FAQ 4: What is the significance of the FAIR data principles in managing food composition data? Adherence to FAIR principles (Findable, Accessible, Interoperable, Reusable) is crucial for data quality and utility. A 2025 review of 101 databases found that while most were Findable, they scored poorly on other principles [3] [8] [7]:

- Accessibility: Only 30% of databases were truly accessible.

- Interoperability: 69% were compatible with other systems.

- Reusability: Only 43% met the standard, often due to inadequate metadata, lack of scientific naming, and unclear reuse permissions [3]. Low reusability limits the long-term value of the data for the research community.

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide 1: Diagnosing and Resolving Discrepancies from Analytical Methods

Problem: Inconsistent nutrient values for the same food item, potentially leading to flawed research conclusions or product formulation errors.

Solution:

- Investigate the Source and Methodology: Trace the data back to its original source. Check for documented information on the specific analytical method used (e.g., AOAC, HPLC). Be aware that updated methods can drastically change values, as seen when HPLC reanalysis halved the estimated β-carotene values in East African foods [4].

- Audit Data Compilation Practices: Ensure the database uses standardized procedures. The Italian Food Composition Database (BDA), for instance, follows certified compilation processes, integrating data from defined sources like other FCDBs, scientific literature, and nutritional labels with a documented hierarchy for data selection [9].

- Verify Handling of Missing Values: Inquire how the database treats missing values, as some systems may default to zero, leading to a significant underestimation of nutrient intake in dietary studies [6].

Guide 2: Correcting for Environmental and Genetic Influences

Problem: Database entries do not reflect the nutritional content of the specific food sample you are working with, due to biodiversity or local growing conditions.

Solution:

- Identify Database Gaps: Compare your food list against the database. Are locally relevant varieties, traditional foods, or specific branded products included? For example, 97 foods commonly consumed in Hawaii are not represented in a major US database [3].

- Prioritize Representative Data: For critical applications, source composition data from databases that are representative of your specific region of study. If such a database does not exist, generating primary analytical data for key local foods may be necessary [4] [5].

- Leverage Advanced Initiatives: For a more comprehensive biochemical profile, consult initiatives like the Periodic Table of Food Initiative (PTFI), which uses advanced mass spectrometry to profile over 30,000 biomolecules in foods from across the globe, specifically targeting under-represented edible biodiversity [3] [7].

Data Presentation

Table 1: FAIR Compliance Scores for Global Food Composition Databases

Data from a 2025 review of 101 databases across 110 countries [3] [8] [7].

| FAIR Principle | Aggregated Score | Common Limitations Leading to Low Scores |

|---|---|---|

| Findability | 100% | Databases are generally well-established and discoverable online. |

| Accessibility | 30% | Data cannot be easily retrieved or used; restrictive access policies. |

| Interoperability | 69% | Inadequate metadata; lack of scientific naming for foods and components. |

| Reusability | 43% | Unclear licensing and data reuse notices; lack of provenance information. |

Table 2: Impact of Database Updates on Nutrient Composition

Comparison of nutrient profiles in the Italian Food Composition Database (BDA) between its 1998 and 2022 versions for cereal products [9].

| Food Sub-Group | Nutrient Components Showing Significant Change | Trend Observed |

|---|---|---|

| Cereals, flours, pasta, bread, crackers, rusks | Available Carbohydrates, Saturated Fatty Acids (SFA), Polyunsaturated Fatty Acids (PUFA) | Increase in calculated/estimated values from labels and recipes. |

| Brioches, cookies, pudding, cakes | Available Carbohydrates, SFA, PUFA | Increase in calculated/estimated values from labels and recipes. |

| Breakfast cereals | Sodium | Decreasing trend. |

| Cereals, flours, pasta, bread, crackers, rusks | Sodium | Decreasing trend. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Standardized Workflow for Updating a Food Composition Database

This protocol is based on the methodology used for the 2022 update of the Italian Food Composition Database (BDA) [9].

1. Objective: To systematically update a food composition database to reflect current food consumption habits and market offerings, ensuring data quality and relevance.

2. Materials and Reagents:

- Source Data: Existing national FCDBs, international FCDBs (e.g., USDA SR), peer-reviewed scientific literature, and nutritional labels from food products.

- Software: A database management system (DBMS) capable of handling large volumes of information and metadata.

- Documentation: Standard Operating Procedures (SOPs) for data compilation, including rules for food description, component identification, and value selection.

3. Procedure: 1. Food Item Selection: Identify and list food items within the target group (e.g., cereals and cereal products) that are representative of current national dietary patterns. 2. Data Sourcing and Hierarchy: Collect data from multiple sources. Adhere to a strict hierarchy: prioritize peer-reviewed analytical data from national sources, then international databases, and finally, use calculation/estimation from recipes or nutritional labels where necessary. 3. Data Compilation: For each food item, compile data for all relevant components. Document the source and type of every value (e.g., analytical, calculated, borrowed). 4. Quality Control: Implement a multi-stage checking process involving different researchers to verify data entry, unit conversions, and adherence to compilation SOPs. 5. Gap Analysis: Calculate the percentage of missing values for the entire food group. Aim to keep this value as low as possible (e.g., 0.99% as achieved in the BDA update) [9]. 6. Publication and Documentation: Publish the updated database, ensuring it is freely accessible online. Provide clear documentation on the compilation methodology and any changes in nutrient profiles from previous versions.

Protocol 2: Assessing the Impact of Genetic Diversity on Food Composition

1. Objective: To evaluate the nutrient variation among different genetic varieties of a single food species.

2. Materials and Reagents:

- Plant/Food Material: Multiple distinct varieties, cultivars, or breeds of the target food (e.g., 10 different varieties of a fruit or grain).

- Analytical Equipment: Access to advanced analytical technologies such as mass spectrometry and metabolomics platforms to profile a wide range of biomolecules beyond basic nutrients [3] [7].

- Data Analysis Tools: Software for statistical analysis and, if applicable, deep learning frameworks for classification and pattern recognition.

3. Procedure: 1. Sample Collection: Acquire or grow the different varieties under controlled or documented conditions to minimize environmental variation. 2. Laboratory Analysis: Using standardized sample preparation, analyze the samples via mass spectrometry-based metabolomics. This allows for the simultaneous quantification of thousands of bioactive compounds, such as polyphenols, sterols, and terpenes [3]. 3. Data Processing: Process the raw spectral data to identify and quantify the detected food components. 4. Statistical Analysis: Perform multivariate statistical analyses to identify which components significantly differ between varieties. The goal is to quantify the extent of variation, which can be substantial [5]. 5. Data Integration: Incorporate the findings into specialized databases like the Periodic Table of Food Initiative (PTFI), which is designed to capture this level of biochemical diversity [7].

Visualization Diagrams

Database Discrepancy Resolution

Food Data Compilation Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Item / Solution | Function in Food Composition Research |

|---|---|

| AOAC International Methods | Provides validated, standardized analytical methods for nutrient analysis (e.g., for fiber, protein), ensuring data consistency and accuracy across different laboratories [3]. |

| High-Pressure Liquid Chromatography (HPLC) | Used for the precise separation, identification, and quantification of specific vitamins and bioactive compounds in food. Its adoption has led to major revisions in vitamin values in food tables [4]. |

| Mass Spectrometry & Metabolomics | Advanced techniques used to profile and quantify thousands of biomolecules in a food sample simultaneously. This is crucial for expanding databases beyond basic nutrients to include specialized metabolites [3] [7]. |

| INFOODS Tagnames | A system of standardized food identifiers developed by the International Network of Food Data Systems to improve interoperability and correct food matching between different databases [3] [4]. |

| EuroFIR Standards | A set of guidelines and quality management systems for the production and compilation of food composition data in Europe, promoting harmonization and data quality [9]. |

Food Composition Databases (FCDBs) are foundational tools across nutrition science, agriculture, and public health policy, providing critical data on the nutritional content of foods [3]. Their reliability directly impacts research quality, from dietary assessment to drug development studies where precise nutrient interactions must be understood. The FAIR Guiding Principles (Findable, Accessible, Interoperable, and Reusable) establish a framework for enhancing data utility by making digital assets optimally discoverable and usable by both humans and computational systems [10]. Achieving FAIR compliance is particularly challenging for FCDBs due to the inherent complexity and variability of food data, creating a significant "FAIRness gap" that researchers must navigate [8].

Recent evaluations of 101 FCDBs from 110 countries reveal substantial variability in FAIR compliance, with particularly low scores in Accessibility (30%), Interoperability (69%), and Reusability (43%), though Findability was universally achieved (100%) [8] [1]. This technical support center provides targeted troubleshooting guidance and experimental protocols to help researchers identify, work around, and ultimately resolve these FAIRness challenges in their food composition research.

FAQs: Understanding the FAIRness Gap in FCDBs

What does each FAIR principle mean specifically for food composition database research?

- Findable: Metadata and data should be easily discoverable by both humans and computers. This is typically achieved through indexing in searchable resources and assigning persistent unique identifiers [10]. For FCDBs, this means complete cataloging in scientific data portals.

- Accessible: Once found, users should clearly understand how to retrieve the data, which may involve authentication or authorization procedures [10]. In practice, this translates to well-documented application programming interfaces (APIs) or download mechanisms rather than static, hard-to-locate tables.

- Interoperable: Data must integrate seamlessly with other datasets and analytical workflows [10]. For FCDBs, this requires using standardized formats, controlled vocabularies (e.g., scientific naming of foods), and consistent units of measurement across different database systems.

- Reusable: The ultimate goal of FAIR is to optimize data reuse through rich descriptions of provenance, licensing, and methodological details [10] [11]. Reusable FCDBs provide comprehensive metadata about analytical methods, sample handling, and clear data reuse policies.

Why does the "FAIRness gap" matter for scientific research reproducibility?

Food composition data underpins numerous research domains, and deficiencies in FAIR compliance directly undermine reproducibility and efficiency. Inadequate metadata, lack of scientific naming, and unclear data reuse notices – all reusability failures – make it difficult to verify findings or combine datasets for robust meta-analyses [8] [1]. Furthermore, FCDBs with infrequent updates and non-machine-readable formats (accessibility and interoperability issues) can lead researchers to use outdated or incompatible data, introducing errors in nutritional assessments, clinical trial formulations, and biomedical research conclusions [3].

Are some FCDBs more FAIR-compliant than others?

Yes, significant disparities exist. Databases from high-income countries generally demonstrate stronger FAIR adherence, featuring more primary data, web-based interfaces, regular updates, and better metadata [8] [1]. Furthermore, FCDBs with the largest numbers of food entries and components often rely heavily on secondary data (compiled from other databases or literature) rather than primary analytical measurements, which can complicate interoperability if source methodologies are inconsistent [8].

Troubleshooting Guides: Addressing Common FAIRness Challenges

Challenge: Inaccessible or Non-Machine-Readable Data

Problem Statement: Researchers cannot reliably retrieve FCDB data through automated means, or data formats require extensive manual manipulation.

Symptoms:

- Data available only in static PDFs or non-standard spreadsheet formats

- No API or programmatic access points

- Broken links to database resources

Solution Protocol:

- Identify Alternative Access Points: Check for web services or APIs mentioned in database documentation. The USDA's FoodData Central, for instance, provides a documented API for programmatic access.

- Implement Web Scraping Ethics: If no API exists, develop respectful scraping scripts with rate limiting to avoid overwhelming servers. Always check

robots.txtand terms of service. - Standardize Data Formats: Convert captured data into standardized formats (e.g., CSV, JSON) using consistent parsing scripts. The R statistical language offers robust packages (

rvest,jsonlite) for such workflows [12]. - Document Extraction Process: Maintain version-controlled scripts and detailed documentation of all data retrieval and transformation steps to ensure reproducibility.

Challenge: Interoperability Barriers Between Databases

Problem Statement: Researchers cannot combine or compare data from multiple FCDBs due to format, unit, or terminology inconsistencies.

Symptoms:

- Incompatible food component nomenclature between databases

- Different units of measurement for the same nutrient

- Missing scientific naming for biological specimens

Solution Protocol:

- Adopt Standardized Vocabularies: Map local food names to scientific binomial nomenclature (e.g., Opuntia ficus-indica instead of just "nopal") and use standardized nutrient identifiers from established systems like INFOODS or EuroFIR [3] [12].

- Create Harmonization Scripts: Develop reusable data transformation scripts, preferably in open-source languages like R or Python, to convert units and align data structures. Example R scripts are available through open science platforms like GitHub [12].

- Implement Quality Checks: Include validation steps in harmonization workflows to flag values outside expected biological ranges, ensuring data integrity during transformation.

- Generate Cross-Reference Tables: Maintain and share mapping tables that connect equivalent foods and components across different database systems.

Challenge: Insufficient Metadata for Reusability

Problem Statement: Retrieved food composition data lacks sufficient methodological context to assess quality or enable replication.

Symptoms:

- Missing analytical method descriptions

- No information on sampling procedures or geographic provenance

- Unclear data ownership or licensing terms

Solution Protocol:

- Develop Metadata Checklists: Create and utilize standardized metadata collection templates based on international standards (e.g., FAO/INFOODS guidelines) to capture essential methodological details [12].

- Provenance Tracking: Implement systems to document data lineage - including original source, any transformations applied, and responsible parties.

- Clear Licensing Statements: Attach explicit usage rights and citation requirements to all shared datasets. Creative Commons licenses provide standardized options for research data.

- Use Metadata Enhancement Tools: Leverage tools like the R-language frameworks developed for reproducible FCT compilation to automatically generate and validate metadata [12].

Experimental Protocols: Methodologies for FAIRness Assessment and Improvement

Protocol: Evaluating FAIR Compliance in FCDBs

Objective: Systematically assess the FAIRness of food composition databases using standardized attributes.

Materials:

- List of target FCDBs

- Data collection form (electronic spreadsheet recommended)

- FAIR assessment rubric

Methodology:

- Database Identification: Compile a comprehensive list of FCDBs through literature search, institutional catalogs (e.g., FAO/INFOODS registry), and expert consultation.

- Attribute Definition: Define evaluation criteria across 35+ data attributes categorized into:

- General Database Information: Origin, maintainer, update frequency, access model

- Foods and Components: Number of foods, number of components, data sources (primary/secondary)

- FAIRness Indicators: Findability mechanisms, accessibility protocols, interoperability features, reusability documentation [8]

- Data Extraction: Systematically examine each database against the defined attributes. Record observations in the standardized collection form.

- Scoring and Analysis: Apply consistent scoring for FAIR principles (0-100% for each dimension). Calculate aggregate scores and identify patterns across economic regions and database types [8].

- Validation: Conduct independent dual extraction for a subset of databases to ensure scoring consistency.

Protocol: Implementing a FAIRification Workflow for FCDBs

Objective: Transform traditional food composition data into FAIR-compliant resources.

Materials:

- Source FCDB data

- Open science computational environment (R Studio recommended)

- Standardized metadata templates

Methodology:

- Data Ingestion: Import source data using reproducible scripts (e.g., R functions specifically developed for FCT processing) [12].

- Standardization: Apply consistent formatting to food names, component identifiers, and units across all records using controlled vocabularies.

- Metadata Enhancement: Enrich datasets with mandatory metadata (analytical methods, sampling procedures, geographic origin) using predefined templates.

- Quality Assurance: Implement computational checks for data integrity, including value range validation, completeness assessment, and internal consistency verification.

- Publication: Package standardized data and rich metadata in multiple accessible formats (CSV, JSON) through persistent digital repositories with assigned DOIs.

- Documentation: Share all processing scripts and workflow descriptions in public repositories (e.g., GitHub) to ensure complete transparency and reproducibility [12].

Visualization: FAIRness Assessment and Improvement Workflow

Diagram Title: FCDB FAIRness Assessment and Improvement Workflow

FAIR Compliance Scores Across Food Composition Databases

Table 1: Aggregate FAIR Compliance Scores for 101 Evaluated FCDBs

| FAIR Principle | Aggregate Score | Key Strengths | Common Deficiencies |

|---|---|---|---|

| Findability | 100% | Universal indexing in searchable resources; Basic metadata present | Limited use of persistent unique identifiers |

| Accessibility | 30% | Human-readable formats typically available | Lack of API access; Restricted data without clear authorization procedures; Static tables |

| Interoperability | 69% | Some use of standardized nutrient identifiers | Inconsistent food nomenclature; Lack of scientific naming; Non-machine-readable formats |

| Reusability | 43% | Basic provenance information often available | Inadequate metadata on analytical methods; Unclear licensing and reuse terms; Insufficient sampling details |

Source: Adapted from Brinkley et al. (2025) assessment of 101 FCDBs from 110 countries [8]

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for FAIR Data Implementation

| Tool Category | Specific Solution | Function in FAIRification | Application Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| Computational Environments | R Statistical Language with custom scripts | Standardizes data harmonization and quality checks | Processing 12 different FCTs into compatible formats [12] |

| Metadata Standards | FAO/INFOODS Guidelines | Provides structured metadata templates | Ensuring capture of essential analytical and sampling metadata |

| Controlled Vocabularies | Scientific Binomial Nomenclature | Enables precise food identification | Distinguishing between Amaranthus species in FCDBs [3] |

| Data Repository Platforms | GitHub with DOI assignment | Ensures findability and persistence | Sharing reproducible FCT compilation scripts [12] |

| Access Protocols | RESTful APIs | Enables programmatic data access | Automated nutrient data retrieval for research applications |

The FAIRness gap in food composition databases presents significant but addressable challenges for the research community. The quantitative assessment revealing particularly low scores in Accessibility (30%) and Reusability (43%) highlights critical areas for technical improvement [8]. By implementing the troubleshooting guides, experimental protocols, and standardization workflows outlined in this technical support resource, researchers can more effectively navigate current limitations while contributing to long-term solutions.

Adopting open science frameworks and computational tools represents the most promising path toward reducing the FAIRness gap [12]. As these practices become more widespread, FCDBs will evolve into more dynamic, integrative resources capable of supporting advanced research applications from precision nutrition to cross-cultural health studies. Through collaborative efforts to enhance data FAIRness, researchers across domains can unlock the full potential of food composition data to address pressing human and planetary health challenges.

Geographical and Economic Disparities in Database Quality and Coverage

A foundational challenge in nutritional research and drug development is the variable quality of the underlying food composition databases (FCDBs). Research outcomes can be significantly influenced by the geographical and economic disparities in the coverage and quality of these databases. This technical support guide helps researchers identify and troubleshoot issues arising from these disparities to ensure robust and comparable results.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: How do economic factors directly impact the quality of a national FCDB? Economic factors are a major determinant of FCDB quality. Evidence shows that databases from high-income countries (HICs) typically feature greater inclusion of primary analytical data, more modern web-based interfaces, more regular updates, and stronger adherence to FAIR data principles (Findable, Accessible, Interoperable, Reusable). In contrast, low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) often rely more heavily on secondary data (borrowed from other databases or scientific literature) and static tables, which can become outdated and are less usable for digital integration [3] [1].

FAQ 2: Why might my analysis of a regional diet be inaccurate even when using a well-known international FCDB? Major international FCDBs, like USDA's FoodData Central, have federal mandates to survey a nation's most widely consumed foods. This can lead to sparse coverage of regionally distinct, traditional, or biodiverse foods. For example, a study identified 97 commonly consumed foods in Hawaii that were not represented in a leading database. This forces researchers to use "closely related food analogs," which can introduce dietary assessment error and disproportionately impact the health outcomes of populations dependent on these foods [3] [1].

FAQ 3: What are the FAIR principles, and how is adherence to them uneven? A 2025 review of 101 FCDBs from 110 countries assessed compliance with FAIR principles. While Findability was universally high, significant gaps were found in other areas, as shown in Table 1 below. These limitations are often due to inadequate metadata, lack of scientific naming conventions for foods, and unclear data reuse licenses, issues more prevalent in databases from LMICs [3] [1].

FAQ 4: What is the difference between primary and secondary data in FCDBs, and why does it matter?

- Primary Data: Refers to food composition data derived from in-house, laboratory analysis specifically conducted for the database compilation. This is generally considered higher quality as the compiling organization controls sampling and analytical procedures [1] [13].

- Secondary Data: Refers to data sourced from other FCDBs, peer-reviewed manuscripts, or other external sources. While facilitating faster compilation, this can lead to data homogenization or inaccurate representations of the local food supply if the borrowed data does not account for local variations in genetics, environment, and agricultural practices [1].

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue 1: Suspected Data Inaccuracy for a Local Food Item

Symptoms: Unusual or inconsistent nutrient values for a specific food; values do not align with local analytical results or scientific literature.

Diagnostic Steps:

- Trace the Data Source: Check the database's documentation to determine if the value is based on primary or secondary data [13].

- Check for Metadata: Look for high-resolution metadata describing the food's source, preparation, and analytical methods used. A lack of metadata reduces confidence and reusability [3] [1].

- Compare with Regional Data: If available, cross-reference the value with a national or regional FCDB from the food's country of origin.

Resolution Protocol:

- Action: If the data is secondary and lacks provenance, prioritize sourcing primary analytical data from local research institutions or the scientific literature.

- Action: For critical research, consider commissioning a dedicated chemical analysis of the food item to generate a reliable data point [14].

Issue 2: Conducting a Multi-Country Comparative Study

Symptoms: Inconsistent or implausible findings when comparing nutrient intake across different countries.

Diagnostic Steps:

- Assess Database Compatibility: Evaluate if the FCDBs from each country use compatible nomenclature, component identifiers, and analytical methods [15] [16].

- Check FAIRness Scores: Refer to studies reviewing database FAIRness to understand the limitations of the datasets you are using, particularly regarding Interoperability and Reusability [3] [1].

- Identify Gaps: Determine if key local foods in one country are missing and being substituted with inaccurate analogs from another country's database [15].

Resolution Protocol:

- Action: Develop a harmonized multi-country FCDB. One established methodology is to use a single, comprehensive database (e.g., USDA) as a base and then modify it with reference to local FCDBs for specific foods [15].

- Action: Implement a food-matching algorithm. For each local food, select the closest match from the primary database based on key nutrients (e.g., energy, macronutrients, minerals) rather than name alone. The table below outlines a protocol from a large international study [15].

Table 1: Protocol for Matching Foods in Cross-Country Studies

| Step | Action | Example from PURE Study |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Define Comparison Nutrients | Select a set of stable, reliably measured nutrients for matching. | For fruits/vegetables: energy, carbs, Ca, P, K, Na. For meats: energy, protein, fat, Fe [15]. |

| 2. Score Matches | Compare 100g of the local food with all entries for that food group in the primary database. Award a matching score of 1 for the closest match for each nutrient. | The food in the primary database with the highest total matching score is selected [15]. |

| 3. Break Ties | Apply a tie-breaking rule based on the most relevant nutrient for that food group. | For fruits/vegetables, use potassium; for dairy and meats, use total fat [15]. |

Issue 3: Evaluating the Reliability of a Specific FCDB

Symptoms: Need to select the most reliable FCDB for a research project or assess the potential bias of a previously used database.

Diagnostic Steps: Evaluate the database against the following quality criteria derived from international standards [13]:

- Data Source: Does it contain primary or secondary data?

- Update Frequency: How often is it updated? Web-based interfaces are typically updated more frequently than static tables [3].

- Scope: Number of foods and components. Only one-third of FCDBs report data on >100 components [3].

- FAIR Compliance: Particularly for Accessibility, Interoperability, and Reusability (see Table 2) [3] [1].

- Metadata & Documentation: Is there clear information on sampling protocols, analytical methods, and food identification? [13]

Table 2: FAIR Principle Compliance in FCDBs (Based on a 2025 Review)

| FAIR Principle | Aggregate Score | Common Deficiencies |

|---|---|---|

| Findable | 100% | All databases met the basic criteria for findability [3] [1]. |

| Accessible | 30% | Lack of clear data access protocols and persistent identifiers [3] [1]. |

| Interoperable | 69% | Inadequate metadata and lack of standardized scientific naming for foods [3] [1]. |

| Reusable | 43% | Unclear data reuse notices and licenses [3] [1]. |

The Scientist's Toolkit

Experimental Workflow for Database Assessment & Harmonization

The following diagram maps the logical workflow for diagnosing and addressing database disparities in a research project.

Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Resources for Addressing FCDB Disparities

| Tool / Resource | Function / Description | Relevance to Disparities |

|---|---|---|

| USDA FoodData Central [2] | A comprehensive, regularly updated FCDB. Often used as a "base" database in international studies. | Serves as a benchmark for quality and scope; its limitations in covering non-U.S. foods highlight coverage gaps [3] [15]. |

| INFOODS (FAO) [3] | International network providing standardized nomenclature, terminology, and guidelines for FCDBs. | A key tool for improving Interoperability between databases from different countries [3] [17]. |

| EuroFIR Standards [18] | European standards and quality schemes for compiling and managing FCDBs. | Provides a model for rigorous database compilation and quality assurance, which can be adopted to improve databases globally [18]. |

| Nutritional Biomarkers [14] | Compounds in the body (e.g., in blood or urine) that indicate intake of specific nutrients. | Provides an objective method to validate dietary intake assessments and bypass biases introduced by unreliable FCDB data and self-reporting [14]. |

| Food Matching Algorithm [15] | A systematic method for selecting the most nutritionally similar food from a reference database. | Mitigates Interoperability issues in cross-country studies by moving beyond simple name-matching [15]. |

The Impact of Outdated Information and Infrequent Updates on Data Integrity

FAQs on Data Integrity in Food Composition Research

Q1: What are the primary consequences of using outdated Food Composition Databases (FCDBs) in research?

Using outdated FCDBs can compromise research integrity and lead to significant downstream costs [4]:

- For Research & Policy: Inaccurate assessment of nutrient intakes can skew population-level studies, leading to flawed public health policies, ineffective nutritional interventions, and misleading dietary guidelines [7] [4]. For example, reanalysis of β-carotene in East African foods showed previous methods had overestimated values by half, dramatically changing the understanding of vitamin A availability [4].

- For Industry: Food manufacturers face higher costs for frequent product analysis and quality control. Reliance on inaccurate public data can lead to non-compliance with regulations or inefficient use of ingredients, increasing production costs and reducing competitive power [4].

- For Data Science: Outdated data hinders the development of reliable predictive models and foodomics approaches, limiting the potential for data-driven solutions in nutrition and health [8] [19].

Q2: How frequently are FCDBs updated, and what is the current state of data quality?

A 2025 global review of 101 FCDBs from 110 countries reveals significant challenges in update frequency and data quality [7] [8]:

- Infrequent Updates: About 39% of databases had not been updated in over five years. Some, like those in Ethiopia and Sri Lanka, had not been updated for more than 50 years [7].

- Limited FAIR Compliance: While most databases are findable, their usability is low. Only 30% were accessible, 69% were interoperable, and just 43% were reusable [7] [8].

- Incomplete Data: Most databases track only a fraction of known food components. Only one-third of FCDBs reported data on more than 100 food components, while modern science shows food contains thousands of biomolecules relevant to health [7] [8].

Q3: What methodologies can researchers employ to identify and compensate for data gaps or outdated values in FCDBs?

Researchers should adopt a critical and proactive approach to data quality [4] [6] [19]:

- Data Provenance Checks: Always review the metadata associated with a food component value. Check the source of the data (e.g., analytical, calculated, borrowed), the date of analysis, and the analytical method used [4] [6].

- Strategic Chemical Analysis: For critical nutrients in key foods, commission new laboratory analyses using modern, validated methods like high-pressure liquid chromatography (HPLC) or mass spectrometry to fill specific data gaps [7] [4].

- Use of Composite Metrics: When precise data is unavailable, use statistical methods to account for uncertainty. Report results with confidence intervals or descriptive explanations of data limitations to ensure transparent interpretation [4].

Q4: Are there global initiatives aimed at improving the quality and standardization of FCDBs?

Yes, several initiatives are working to address these challenges [7] [19]:

- The Periodic Table of Food Initiative (PTFI): A groundbreaking effort that uses advanced metabolomics to profile over 30,000 biomolecules in foods. It is globally focused, includes indigenous and underrepresented foods, and is designed to be 100% FAIR-compliant [7].

- International Networks: Organizations like the International Network of Food Data Systems (INFOODS) and EuroFIR AISBL coordinate experts and compilers to promote data harmonization, standardize food description (e.g., Langual, Eurocode), and share best practices worldwide [4] [19].

Table: Key Challenges and Impacts of Outdated Food Composition Data

| Challenge | Quantitative Measure | Impact on Research & Applications |

|---|---|---|

| Update Frequency | 39% of FCDBs not updated in >5 years [7] | Data does not reflect changes in agriculture, food processing, or market composition [7] [19]. |

| FAIR Compliance | Accessibility: 30%; Reusability: 43% [8] | Limits data sharing, integration, and long-term value for digital innovation [7] [8]. |

| Geographic Disparity | Databases from high-income countries show greater adherence to FAIR principles and more primary data [8] | Perpetuates data inequity, hides richness of local diets, and threatens agricultural biodiversity [7]. |

| Component Coverage | Only 38 components commonly reported; few databases cover >100 components [7] [8] | Misses thousands of bioactive compounds (e.g., phytochemicals), limiting comprehensive diet-health research [7]. |

Troubleshooting Guide: Resolving Data Discrepancies

Problem: Suspected Outdated or Non-Representative Data

Symptoms: Unusual nutrient intake values for a population; inconsistencies between calculated values and biological markers; inability to match a consumed food item in the database.

Solution:

- Verify the Source: Trace the specific food entry back to its original source within the database documentation. Note the year of data generation and the method used (analytical, calculated, borrowed) [6].

- Cross-Reference: Compare the value with a more recently updated database from a comparable region, if available. The USDA Branded Food Products Database is an example of a frequently updated source [6].

- Assess Criticality: Determine if the suspect value is for a key food or nutrient in your study. If the impact is high, consider:

Experimental Protocol: Validating a Food Component Value

Objective: To verify the accuracy of a reported nutrient value in a food composition database using modern analytical techniques.

Materials:

- Food samples (representative of current market variety and processing)

- Liquid Chromatograph with Mass Spectrometry (LC-MS) system or other validated equipment

- Certified reference materials for calibration

- Solvents and reagents of analytical grade

Methodology:

- Sample Preparation: Procure and prepare the food sample according to standard consumption practices (e.g., raw, cooked). Use homogenization to ensure a representative sub-sample for analysis [4] [6].

- Method Selection: Choose an analytical method validated for the specific component of interest (e.g., HPLC for vitamins, mass spectrometry for metabolomic profiling) [7] [4].

- Analysis: Perform the analysis in replicate (minimum n=3) to account for variability and ensure statistical significance.

- Quality Control: Include blanks and certified reference materials in each batch to confirm analytical accuracy and precision.

- Data Reporting: Report the mean value, standard deviation, and method used. This new data can be used to update the FCDB or for direct use in your research [4].

Workflow Diagram: Protocol for Resolving Data Discrepancies

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Reagent / Resource | Function & Application in FCDB Research |

|---|---|

| Liquid Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (LC-MS) | Used for high-resolution identification and quantification of a wide range of food biomolecules, from vitamins to unknown phytochemicals, far beyond basic nutrients [7]. |

| Standardized Food Classification System (e.g., Langual, INFOODS Tagnames) | Provides a universal vocabulary for naming and describing foods, ensuring interoperability and correct matching between different databases and studies [4] [19]. |

| Certified Reference Materials (CRMs) | Essential for calibrating analytical instruments and validating methods, ensuring the accuracy and comparability of new food composition data generated in the lab [4]. |

| FAIR Data Management Platform | A digital system designed to make data Findable, Accessible, Interoperable, and Reusable. Critical for compiling, sharing, and maintaining high-quality FCDBs [7] [8]. |

| Quality Management Framework | A set of documented procedures for evaluating data quality, including checks for sampling plan, analytical performance, and data provenance [19]. |

Building Coherent Systems: Methodologies for Standardized Data Compilation and Harmonization

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: What are the first steps when starting to compile a new national food composition database (FCDB) with limited resources? Begin by utilizing the FAO/INFOODS Compilation Tool, a simple system designed for this purpose. This free Excel-based tool incorporates international standards for food nomenclature (e.g., INFOODS tagnames), component identifiers, and database documentation. It is particularly suited for developing countries and includes functionalities for recipe calculations using yield and nutrient retention factors, providing a standardized starting point for compilation [20] [21].

FAQ 2: Our research involves comparing nutrient intake across European countries. How can we ensure the food composition data from different national databases is comparable? For pan-European research, leverage the resources of EuroFIR, which provides harmonized food composition data from over 26 European countries. Its web tool, FoodEXplorer, allows simultaneous searching across these national databases using standardized vocabularies and the LanguaL food description system. This harmonization is crucial for valid cross-country comparisons, as it minimizes inconsistencies arising from different national compilation practices [22] [23] [24].

FAQ 3: We've found conflicting nutrient values for the same food in different databases. What is the systematic approach to resolving this discrepancy? Resolving discrepancies requires a rigorous, multi-step evaluation of the underlying data quality. The INFOODS/FAO guidelines recommend scrutinizing several key parameters, as outlined in the table below [13].

Table: Key Criteria for Evaluating Conflicting Food Composition Data

| Parameter to Evaluate | Key Scrutiny Questions |

|---|---|

| Food Identity | Is the food (species, variety, part) unequivocally identified? |

| Sampling Protocol | Was the sample representative in terms of geography, season, and number of items? |

| Sample Preparation | Was the edible portion correctly defined? Was the cooking method specified? |

| Analytical Procedure | Was a validated method used? Were quality assurance procedures in place? |

| Data Source | Is the data from analytical work (preferred), a primary publication, or a secondary compilation? |

Prioritize data that is analytical, recently generated, and has comprehensive documentation about its source and methods. The FAO/INFOODS Analytical Food Composition Database (AnFooD2.0) is a useful resource for finding scrutinized analytical data [21] [23] [13].

FAQ 4: A significant portion of our data is borrowed from other countries' databases. How does this impact the accuracy of our dietary intake estimates? Borrowing data is a common practice, but it introduces a potential source of systematic error. The impact depends on how similar the borrowed food item is to the locally consumed food in terms of variety, soil, processing, and recipe formulation. For rarely consumed foods, the impact may be minor. However, for staple foods, borrowed data can lead to significant inaccuracies in intake estimates for specific nutrients. It is critical to document all borrowed data and, where possible, prioritize analytical data for key local foods. Some unified databases have been created with borrowed values comprising 40% to 90% of their content, highlighting the pervasiveness of this practice and its potential effect on epidemiological research [23].

FAQ 5: Beyond basic nutrients, where can we find data on bioactive compounds in plant-based foods and supplements? The EuroFIR network maintains specialized databases for this purpose. eBASIS provides data on bioactive compounds (e.g., polyphenols, phytosterols) in plant foods, while ePlantLIBRA focuses on bioactive compounds in botanicals and plant-food supplements. These databases are sourced from peer-reviewed literature and use standardized quality assurance procedures and descriptions [22] [24].

Troubleshooting Common Experimental & Data Issues

Issue 1: High implausible variability in nutrient intake estimates from dietary surveys.

- Potential Cause: This is often due to measurement errors in the dietary intake data itself, combined with limitations in the FCDB. Errors can be random (e.g., day-to-day intake variation, random misestimation of portions) or systematic (e.g., under-reporting of high-energy foods, social desirability bias) [25] [26].

- Solution:

- For intake data: Use multiple-pass 24-hour recall methods (like the USDA's Automated Multiple-Pass Method) that include probing questions and memory aids to reduce omissions and improve portion size estimation [26].

- For FCDB data: Apply the data scrutiny criteria from FAQ 3. Ensure your database includes fortified and branded foods relevant to your population, as using only generic values can introduce systematic error [23].

Issue 2: Inconsistent results when calculating the nutrient composition of recipes.

- Potential Cause: Different methods of recipe calculation and the application of different sets of nutrient retention and yield factors.

- Solution: Standardize your recipe calculation protocol. The FAO/INFOODS Compilation Tool includes three standardized recipe calculation systems. Ensure you are using appropriate, documented yield and nutrient retention factors that are specific to the food groups and cooking methods in your recipes [20].

Issue 3: Our food composition data is outdated and does not reflect current agricultural or food processing practices.

- Potential Cause: Food composition changes over time due to new varieties, agricultural practices, and reformulations. Many FCDBs contain old data and are not updated regularly [23].

- Solution: Implement a long-term program for updating the FCDB. This should include:

Table: Key Reagents and Resources for Food Composition Database Compilation

| Tool / Resource | Function & Application | Source / Example |

|---|---|---|

| FAO/INFOODS Compilation Tool | A database management system in Excel for standardized compilation, documentation, and recipe calculation. | Free download from INFOODS website [20]. |

| LanguaL Thesaurus | A standardized, multilingual system for describing foods, enabling unambiguous food identification and matching across databases. | EuroFIR / LanguaL [22] [24]. |

| INFOODS Tagnames | A set of unique component identifiers (e.g., "PROT" for protein) to standardize the naming of nutrients in databases. | INFOODS / FAO [20] [27]. |

| FoodEXplorer | A web interface to search and compare harmonized food composition data from multiple European and international databases simultaneously. | EuroFIR (Member access) [22] [24]. |

| eBASIS & ePlantLIBRA | Databases on bioactive compounds in plant foods and food supplements, with data on biological effects and composition. | EuroFIR [22] [24]. |

| Density Database | A tool for converting food volume into weight and vice-versa, crucial for accurate intake assessment. | FAO/INFOODS [21]. |

Experimental Protocol: Systematic Approach to Data Evaluation and Harmonization

Objective: To resolve discrepancies in food composition database entries by evaluating, selecting, and documenting the most appropriate value for a given food component.

Methodology: This protocol is based on international guidelines from FAO/INFOODS and EuroFIR [27] [13].

- Assemble Data Sources: Conduct a rigorous literature search for analytical data, including primary publications, unpublished reports, and existing FCDBs. The INFOODS mailing list and website can be valuable resources [13].

- Archival & Documentation: Record all retrieved information systematically. Use a tool like the FAO/INFOODS Compilation Tool to ensure all mandatory metadata (Food, Component, Value, Reference) is captured [20] [13].

- Data Scrutiny & Evaluation: For each data point, critically evaluate the parameters listed in the table in FAQ 3. Prefer data that is:

- Value Selection & Harmonization:

- Compare all evaluated data for the food-component pair.

- If recent, high-quality analytical data from a representative sample exists, it should be selected.

- If conflicts exist between older and newer data, investigate if changes in the food supply (e.g., new variety, fortification) justify the difference.

- If no representative analytical data exists, borrowing from a similar food or database may be necessary, but this must be thoroughly documented.

- Documentation and Reporting: The final database must include comprehensive documentation for each value, indicating its source, the evaluation process, and any assumptions or conversions made. This is essential for transparency and future updates [20] [13].

The following workflow diagram visualizes this experimental protocol.

Logical Workflow for Food Matching in Dietary Studies

A critical step in estimating nutrient intake is matching the foods consumed to the correct entry in the FCDB. The following diagram outlines a logical workflow to achieve the most appropriate food matching, based on INFOODS guidelines [27].

FAQs: Sourcing and Managing Food Composition Data

What are the primary differences between primary and secondary data in food composition research?

Primary and secondary data differ fundamentally in their origin and characteristics, which directly impact their use in research.

Primary Data: This is data you generate yourself. In food composition, this involves the direct chemical analysis of food samples in a laboratory.

- Characteristics: It is original, collected for a specific purpose, and often provides high-resolution metadata (e.g., details on growing conditions, harvest time, and analytical methods) [3].

- Typical Use: Found in databases with fewer food items and components, where the focus is on specific, often under-represented, foods [3].

Secondary Data: This is data compiled from existing sources, such as scientific literature, other food composition databases (FCDBs), or manufacturer information.

- Characteristics: It is compiled from pre-existing information. The scope is often broader, but metadata about the original source and analysis may be limited [3].

- Typical Use: Found in large national FCDBs, which may contain thousands of foods and components but often rely on aggregated data from various secondary sources [3].

What are the most common discrepancies found in food composition databases (FCDBs)?

Researchers commonly encounter several types of discrepancies that can affect data reliability:

- Data Sourcing Conflicts: Disagreements between values derived from direct chemical analysis (primary data) and those estimated from secondary sources or borrowed from other regions without validation [3].

- Inconsistent Nomenclature: The use of different food names and component definitions across databases, making it difficult to compare or merge datasets [3].

- Missing Metadata: A lack of high-resolution metadata, such as the specific analytical method used, sample preparation, or geographic origin of the food, which is crucial for assessing data quality [3] [7].

- Limited Component Coverage: Many databases report only a small number (e.g., ~38) of common nutrients, omitting thousands of bioactive compounds and specialized metabolites relevant to health [3] [7].

- Outdated Information: A significant number of FCDBs are infrequently updated, with some not updated for over five years, or even decades, failing to reflect changes in food varieties, agricultural practices, or climate effects [7].

How can I validate secondary data when primary analysis isn't feasible?

When direct analysis is not possible, you can employ several strategies to validate secondary data:

- Assess FAIR Compliance: Evaluate the data source against the FAIR principles. Key areas to check are:

- Accessibility: Can the data be easily retrieved and used? (Only 30% of databases meet this well) [7].

- Interoperability: Is the data compatible with other systems through standardized vocabularies and formats? (69% score) [3] [7].

- Reusability: Does the data have a clear license and rich metadata? (43% score) [3] [7].

- Trace the Original Source: Whenever possible, identify the primary study from which the secondary data was derived. Evaluate the analytical methods (e.g., were validated AOAC methods used?) and the context of the original analysis [3].

- Cross-Reference Multiple Databases: Compare values for the same food item across several reputable FCDBs. Significant outliers may indicate unreliable data.

- Implement Data Validation Rules: Apply technical checks to imported data, including [28]:

- Range Validation: Checking if values fall within plausible biological or physical limits.

- Type Validation: Ensuring data matches the expected format (e.g., numeric, text).

- Constraint Validation: Enforcing business rules, such as the uniqueness of sample IDs.

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue: Inconsistent nutrient values for the same food item across different databases.

This is a common problem arising from the use of different data sources, analytical methods, and food definitions.

Resolution Protocol:

- Characterize the Discrepancy: Quantify the difference between the values and determine if it is biologically plausible.

- Investigate Source Lineage: Trace the conflicting values back to their original sources. Determine if they are based on primary analytical data or are imputed/borrowed from other databases [3].

- Compare Metadata: Critically examine the available metadata for each value. Key factors to compare are detailed in the table below.

- Make an Evidence-Based Decision: Weigh the evidence based on the metadata comparison. Data backed by primary analysis and richer metadata should be given higher confidence.

Table: Metadata Checklist for Investigating Data Discrepancies

| Metadata Factor | Questions to Investigate | Impact on Value |

|---|---|---|

| Analytical Method | Was the same method used (e.g., HPLC vs. spectrophotometry)? Are they validated (e.g., AOAC)? | Different methods can yield systematically different results [3]. |

| Sample Description | What was the cultivar, geographic origin, growing conditions, and harvest time? | Soil, climate, and genetics cause natural variation [3]. |

| Food Processing | Was the food raw, cooked, or processed? What was the precise cooking method? | Processing can significantly alter nutrient bioavailability and content. |

| Data Type | Is the value from primary analysis or is it calculated/borrowed from another source? | Primary data is generally more specific and reliable than imputed data [3]. |

| Lab Quality Control | Are there records of calibration standards, recovery rates, and replicate analyses? | Robust QC procedures increase data reliability. |

Issue: Suspected contamination or analytical error in primary composition data.

Errors can occur during sample handling, preparation, or instrumental analysis.

Resolution Protocol:

- Review Raw Instrument Data: Scrutinize chromatograms or spectra for atypical peaks, baseline noise, or shifting retention times that suggest contamination or instrument drift.

- Verify Calibration Curves: Check the linearity (R² value) of calibration curves and the accuracy of quality control (QC) standards analyzed within the sample batch. Values outside acceptable limits (e.g., ±15% of expected value for bioanalytics) indicate potential issues.

- Check Sample Preparation Records: Review logs for errors in weighing, dilution factors, or digestion procedures. Re-prepare and re-analyze the sample if necessary.

- Re-analyze Quality Control Samples: Re-run the QC samples (e.g., certified reference materials, in-house control pools) to confirm the system is performing correctly.

- Repeat the Analysis: If the source of error is confirmed or cannot be identified, repeat the analysis of the affected sample(s) in triplicate.

Diagram: Primary Data Generation and Validation Workflow

This occurs when merging datasets that lack standardized naming conventions and formats.

Resolution Protocol:

- Audit and Standardize Nomenclature: Map all food and component names to a common, controlled vocabulary, such as the INFOODS/FAO thesauri, to ensure interoperability [3].

- Implement Format Validation: Use scripts or data validation tools to check and convert data formats (e.g., dates, units) to a single standard across the merged dataset [28] [29].

- Create a Cross-Reference Dictionary: Build a lookup table that maps synonymous terms from different sources to your standard terms.

- Leverage Modern Data Tools: Utilize AI-powered data validation platforms that can automatically detect inconsistencies, suggest mappings, and standardize formats across large, disparate datasets [29] [30].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table: Essential Resources for Food Composition Data Research

| Resource / Solution | Function | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| INFOODS/FAO Tagnames | Standardized food component nomenclature. | Ensuring interoperability when merging data from different FCDBs by using universal identifiers [3]. |

| USDA FoodData Central | A comprehensive, gold-standard FCDB. | Sourcing secondary data for commonly consumed foods and as a benchmark for method validation [3]. |

| Periodic Table of Food Initiative | A global effort providing extensive compositional data on >30,000 food biomolecules. | Accessing deeply characterized, FAIR-compliant data for a wide array of foods, including underutilized species [3] [7]. |

| AOAC International Methods | Validated, standardized analytical methods. | Providing a benchmark for primary data generation, ensuring accuracy and consistency across labs [3]. |

| National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey | Provides data on dietary intakes and health status. | Informing which food components are of public health concern for over/underconsumption [31]. |

| VISIDA System | An image-voice dietary assessment tool. | Collecting individual-level dietary intake data in populations with low literacy or in field settings [32]. |

Leveraging Advanced Analytical Techniques (Foodomics) for Comprehensive Profiling

Technical Support Center: Troubleshooting Food Composition Database (FCDB) Research

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: My analysis shows significant discrepancies between different Food Composition Databases (FCDBs) for the same food item. What are the primary causes?

Discrepancies arise from multiple sources related to data generation and compilation. Key factors include:

- Data Sources: FCDBs use a mix of primary data (from in-house chemical analysis) and secondary data (borrowed from other databases or scientific literature). The reliance on secondary data can lead to homogenization or inaccuracies if the original data is not representative of your local food supply [1] [5].

- Natural Variation: Nutrient content is influenced by genetics (cultivar/variety), environment (soil, climate), and agricultural practices. Food biodiversity can cause nutrient values to vary up to 1000 times among different varieties of the same food [5].

- Methodological Differences: A lack of standardized analytical methods, definitions for nutrients (e.g., total vs. available carbohydrates), and expressions (e.g., forms of Vitamin A) across different compilations introduces variability [1] [33].

- Database Scope and Update Frequency: Many databases have incomplete coverage, are infrequently updated, and may lack critical metadata, making it difficult to assess data quality and relevance [1] [5].

FAQ 2: How can Foodomics approaches help resolve inconsistencies in FCDB data?

Foodomics, the application of advanced omics technologies in food science, provides powerful tools for data verification and enrichment.

- Metabolomic Profiling: Techniques like Mass Spectrometry (MS) and Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) spectroscopy can comprehensively characterize the metabolome of a food sample. This allows for the identification of unique molecular fingerprints (biomarkers) that can be used to authenticate origin, detect adulteration, and provide a more complete nutritional profile beyond standard nutrients [34] [35].

- Proteomic and Transcriptomic Analysis: These methods can identify species-specific proteins or gene expression patterns, which are crucial for tracing seafood species, verifying the authenticity of dairy products, and ensuring the correct identification of food components [34] [35].

- Data Integration: A multi-omics approach integrates data from metabolomics, proteomics, and transcriptomics to provide a holistic view of the food matrix, helping to explain variations caused by processing, fermentation, or environmental stress [36] [35].

FAQ 3: What are the common limitations when using Foodomics technologies, and how can I overcome them?

While powerful, Foodomics faces several challenges that researchers must navigate.

- High Cost and Complexity: The instrumentation (e.g., LC-MS/MS, NMR) and required consumables are expensive. The data generated is highly complex and requires advanced bioinformatics expertise for analysis [34] [35].

- Variable Food Matrices: The diverse and complex composition of foods can interfere with analysis, making it difficult to extract and quantify all metabolites or proteins effectively [34].

- Lack of Standardization: Protocols for sample preparation, data acquisition, and processing are not yet universally standardized, which can lead to reproducibility concerns [34].

- Mitigation Strategies: Collaborate with experts in bioinformatics and analytical chemistry. Start with targeted omics approaches before moving to untargeted analyses. Actively participate in and promote international efforts to establish standardized guidelines and open-access databases [34] [36].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Nutrient values from an FCDB do not match my own chemical analysis of a complex meal.

Investigation and Resolution Protocol:

- Verify Data Sources: Check the FCDB documentation to determine if the values are primary analytical data, calculated, or imputed from secondary sources. Data sourced from other regions or outdated tables are a likely cause of discrepancy [1] [33].

- Audit Metadata: Examine the available metadata for the food entry, including sampling plan, analytical methods, and culinary preparation (e.g., raw vs. cooked). The lack of high-resolution metadata is a common limitation in FCDBs [1].

- Conformity Check: Ensure your chemical methods align with international standards (e.g., AOAC) used by high-quality FCDBs. Methodological differences directly impact results [1] [33].

- Apply Predictive Models: If systematic bias is confirmed, consider developing linear regression models to adjust FCDB values. A research study successfully used this approach to correct for overestimation of nutrients like Na, vitamin B6, and Ca, providing more reliable estimates based on chemical analysis [33].

Table 1: Common Nutrient Discrepancies Identified in FCDBs vs. Chemical Analysis

| Nutrient | Common Discrepancy | Potential Reason |

|---|---|---|

| Sodium (Na) | Significant overestimation [33] | Use of default values or miscalculation in composite dishes. |

| Vitamin B6 | Significant overestimation [33] | Analytical interference or unstable vitamers in certain food matrices. |

| Calcium (Ca) | Overestimation (varies by database) [33] | Differences in bioavailability assumptions or analytical techniques. |

| Carbohydrates | Overestimation (by calculation) [33] | Use of "by difference" method vs. direct analysis of available carbohydrates. |

Problem: I need to authenticate a food's origin or detect potential adulteration.

Foodomics-Based Resolution Protocol:

- Sample Preparation: Prepare samples using a standardized protocol to ensure reproducibility. For metabolomics, this typically involves metabolite extraction with a solvent like methanol/water [35].

- Data Acquisition (Metabolomic Profiling):

- Instrumentation: Use Liquid Chromatography coupled with Tandem Mass Spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) or NMR spectroscopy.

- Process: Separate the complex food matrix via LC and analyze with MS to obtain precise mass and fragmentation data for metabolite identification [35].

- Data Analysis and Biomarker Discovery:

- Validation: Validate the identified biomarkers using authentic standard compounds and confirm their predictive power with a new set of samples [35].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Foodomics Studies

| Item / Reagent | Function / Application |

|---|---|

| LC-MS/MS Grade Solvents | High-purity solvents for metabolomic and proteomic sample preparation and chromatography to minimize background noise and ion suppression. |

| Stable Isotope-Labeled Standards | Internal standards for precise absolute quantification in proteomics and metabolomics. |

| Trypsin (Proteomic Grade) | Enzyme for digesting proteins into peptides for shotgun proteomics analysis. |

| SILAC Kits / Isobaric Tags | Reagents for multiplexed, quantitative proteomics, enabling comparison of multiple samples in a single MS run. |

| RNA/DNA Stabilization Reagents | Preservation of nucleic acids for transcriptomic analysis of food microbiomes or raw agricultural materials. |

| NMR Solvents | Deuterated solvents for NMR-based metabolomics. |

Experimental Workflows and Data Relationships

The following diagrams illustrate a standardized workflow for food authentication and the relationship between FCDB limitations and Foodomics solutions.

Diagram 1: Food Authentication Workflow

Diagram 2: FCDB Challenges and Foodomics Solutions

A Step-by-Step Framework for Harmonizing National Databases to International Standards

Food Composition Databases (FCDBs) serve as fundamental resources across multiple sectors, including public health nutrition, agricultural policy, and pharmaceutical development for nutraceuticals. However, a comprehensive global review reveals significant challenges in this landscape. An analysis of 101 FCDBs across 110 countries found substantial variability in their scope, content, and quality [37]. These databases exhibit critical gaps in interoperability and reusability, with aggregated FAIR compliance scores showing only 69% for Interoperability and 43% for Reusability, despite 100% Findability [37] [38]. This lack of harmonization creates substantial barriers for researchers and drug development professionals who require reliable, comparable food composition data for epidemiological studies, bioactive compound identification, and understanding diet-health relationships.

The discrepancies between national databases and international standards lead to several methodological challenges. When databases rely on borrowed data from other countries rather than direct analysis of local foods, nutrient composition may not accurately reflect realities due to variations in climate, soil, cooking methods, and crop varieties [37] [38]. Furthermore, the absence of a unified global system for naming foods, defining nutrients, or measuring content creates significant obstacles for cross-national research initiatives and meta-analyses [37]. This technical support center provides a structured framework to address these challenges, offering practical solutions for harmonizing national FCDBs with international standards.

Technical FAQs: Resolving Common Harmonization Challenges

FAQ 1: What are the most critical gaps in current Food Composition Databases that hinder harmonization?

Current FCDBs exhibit several critical gaps that complicate harmonization efforts. The most significant limitation is the inconsistent adoption of FAIR Data Principles. While most databases meet "Findability" standards, only 30% are truly accessible (retrievable and usable), 69% are interoperable, and just 43% meet reusability standards [37] [38]. Additionally, there is a dramatic disparity in database quality between high-income and low-to-middle-income countries, with many regions having outdated or incomplete data - some not updated for over 50 years [38]. The scope of components tracked is another major limitation, with most databases focusing only on approximately 38 basic nutrients and failing to include thousands of bioactive phytochemicals relevant to health research [37] [38].