Protocols for Assessing Nutrient Bioavailability: From Foundational Concepts to Advanced Predictive Models

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals on the established and emerging protocols for assessing nutrient bioavailability.

Protocols for Assessing Nutrient Bioavailability: From Foundational Concepts to Advanced Predictive Models

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals on the established and emerging protocols for assessing nutrient bioavailability. It covers the foundational principles defining bioavailability and bioaccessibility, explores the full spectrum of in vivo and in vitro methodologies, and addresses critical troubleshooting factors such as anti-nutrients and food matrix effects. Furthermore, it details the development and validation of predictive algorithms for iron, zinc, and vitamins, enabling a comparative analysis of method efficacy and translation to clinical and biomedical research outcomes.

Defining Bioavailability: Core Principles and Influencing Factors

What is Nutrient Bioavailability? A Review of Key Definitions (Bioavailability vs. Bioaccessibility)

In nutritional science, simply consuming a nutrient does not guarantee its utilization by the body. The concepts of bioaccessibility and bioavailability are critical for understanding the journey of a dietary compound from ingestion to its final physiological use. These terms are foundational for researchers designing experiments, developing functional foods, and formulating drugs or supplements.

The sequential relationship from ingestion to physiological effect can be defined as follows [1] [2]:

- Bioaccessibility refers to the fraction of a compound that is released from its food matrix into the gastrointestinal lumen and thus becomes accessible for intestinal absorption. This process involves digestion in the mouth, stomach, and intestinal lumen, making the nutrient available for uptake by intestinal epithelial cells [1].

- Bioavailability is the proportion of an ingested nutrient that is absorbed, becomes available for physiological functions, and is stored or utilized by the body [3] [4]. From a pharmacological perspective, it can be defined as the rate and extent to an administered drug or bioactive compound that reaches the systemic circulation [1] [5].

It is crucial to distinguish this from bioactivity, which represents the specific biological effect or physiological activity exerted by the absorbed compound or its metabolites at the target tissue [2].

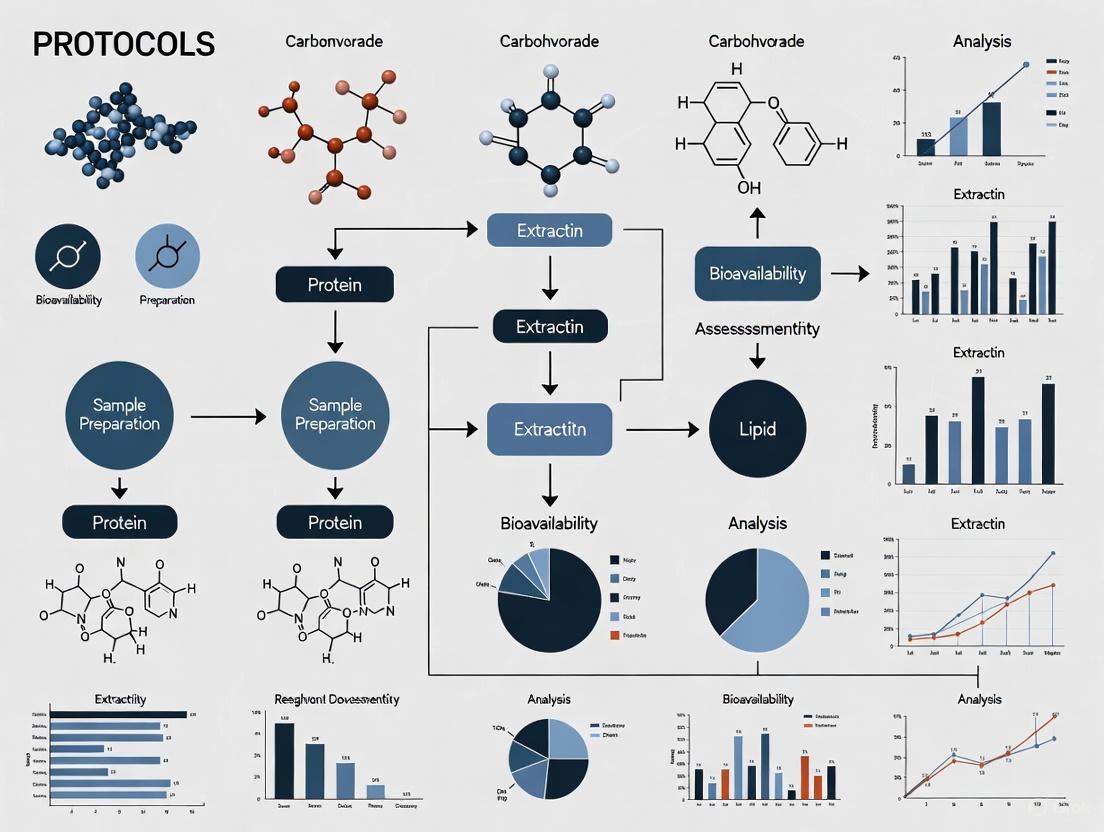

The following diagram illustrates the complete pathway from food ingestion to physiological effect, highlighting the key stages of bioaccessibility and bioavailability.

Quantitative Bioavailability Data for Key Nutrients

The bioavailability of micronutrients varies significantly depending on their food source, chemical form, and interactions with other dietary components. The table below summarizes the bioavailability ranges for selected vitamins and minerals from common food sources, based on in vivo human studies.

Table 1: Bioavailability of Selected Micronutrients from Whole Foods [4] [6]

| Nutrient | Food Source | Bioavailability Range | Key Influencing Factors |

|---|---|---|---|

| Iron (Heme) | Red Meat, Poultry, Fish | 10% - 40% | Iron status of the individual; minimally affected by dietary factors [6]. |

| Iron (Non-Heme) | Plant Foods (e.g., Spinach, Legumes) | 2% - 20% | Strongly inhibited by phytate and polyphenols; enhanced by vitamin C and meat [6]. |

| Calcium | Dairy Products (e.g., Milk, Cheese) | ~40% (varies with age) | Enhanced by vitamin D, casein phosphopeptides, lactose; inhibited by sulfur-containing proteins (increases urinary loss) [4]. |

| Zinc | Cereals, Legumes, Meat | Varies widely | Primarily inhibited by dietary phytate; absorption efficiency is higher from animal sources [6]. |

| Vitamin A (Retinol) | Animal Liver, Dairy, Eggs | 70% - 90% | Efficiently absorbed as pre-formed vitamin A [6]. |

| Vitamin A (Provitamin A Carotenoids) | Orange & Green Vegetables (e.g., Carrots, Spinach) | 10% - 80% | Enhanced by dietary fat; reduced by inefficient bioconversion in the gut [6]. |

| Folate | Leafy Greens, Legumes, Fortified Foods | ~50% (varies with form) | Synthetic folic acid is more bioavailable than natural food folates [6]. |

Methodologies for Assessing Bioaccessibility and Bioavailability

A multi-faceted approach is required to fully evaluate the bioavailability of nutrients, ranging from simulated in vitro digestion to sophisticated in vivo human trials.

In VitroDigestion and Bioaccessibility Models

In vitro models simulate human physiological conditions to predict the bioaccessibility of food components, offering a high-throughput, ethical, and cost-effective alternative to human studies [2]. The INFOGEST network has developed a widely adopted, standardized static protocol that simulates the oral, gastric, and intestinal phases of digestion [2].

- Oral Phase: Food is macerated and mixed with simulated salivary fluid (SSF) containing electrolytes and α-amylase.

- Gastric Phase: The oral bolus is mixed with simulated gastric fluid (SGF) containing pepsin and gastric lipase. The pH is adjusted to 3.0 and incubated at 37°C with shaking.

- Intestinal Phase: The gastric chyme is mixed with simulated intestinal fluid (SIF) containing pancreatic enzymes and bile salts. The pH is adjusted to 7.0 and incubated at 37°C with shaking.

The resulting chyme is centrifuged to obtain the soluble fraction, which represents the bioaccessible component of the nutrient, ready for absorption studies or further chemical analysis [2].

In VivoBioavailability and Absorption Techniques in Humans

While in vitro models are excellent for predicting bioaccessibility, bioavailability determination in humans is considered the "gold standard" [2]. Several sophisticated techniques are employed.

- Plasma Concentration Curves (AUC): This pharmacological method involves measuring the plasma or serum concentration of a nutrient over time after ingestion. The Area Under the Curve (AUC) is calculated and often compared to the AUC after an intravenous dose to determine Absolute Bioavailability [5].

- Use of Isotopic Tracers: The use of stable or radioactive isotopes has greatly improved the accuracy of in vivo nutrient bioavailability studies [4]. The extrinsic tag method, where an isotope is mixed with a food, has been validated against intrinsic tagging (where the food is biosynthetically labeled) for many minerals, showing homogeneous mixing with the native mineral pool in the food [3]. This allows for precise tracking of absorption and utilization.

- Functional Endpoint Measurements: Bioavailability can be estimated by measuring a functional or biochemical endpoint that reflects the absorption and utilization of the nutrient. For example, the change in blood hemoglobin concentration after consumption of an iron source in iron-deficient subjects can serve as a functional measure of iron bioavailability [3].

The following workflow outlines a comprehensive, multi-model research approach for determining nutrient bioavailability, integrating both in vitro and in vivo methods.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Reagents and Materials

Successful experimentation in bioavailability research requires a specific set of reagents and model systems. The following table details essential materials for setting up key experiments, particularly in vitro digestion and absorption studies.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents for Bioavailability Studies

| Reagent / Material | Function / Application | Examples / Specifications |

|---|---|---|

| Simulated Digestive Fluids | To mimic the ionic composition and pH of salivary, gastric, and intestinal secretions. | KCl, KH₂PO₄, NaHCO₃, NaCl, MgCl₂(H₂O)₆, (NH₄)₂CO₃; prepared per INFOGEST protocol [2]. |

| Digestive Enzymes | To catalyze the breakdown of macronutrients (starch, proteins, fats) during in vitro digestion. | α-Amylase (oral), Pepsin (gastric), Pancreatin (intestinal mix), Gastric Lipase [2]. |

| Bile Salts | To emulsify lipids and form mixed micelles, which are crucial for the bioaccessibility of lipophilic compounds. | Porcine bile extracts or synthetic salts like sodium taurocholate [1] [2]. |

| Intestinal Cell Models | To study cellular uptake, metabolism, and transepithelial transport of bioaccessible nutrients. | Caco-2 cell line (human colonic adenocarcinoma), HT-29 (goblet cells), co-cultures, or primary-derived enteroids [2]. |

| Isotopic Tracers | To accurately track and quantify the absorption, distribution, and metabolism of specific nutrients in vivo. | Stable isotopes (e.g., ⁵⁷Fe, ⁶⁷Zn) or radioisotopes (e.g., ⁴⁷Ca, ¹⁴C); used in extrinsic/intrinsic tagging [3] [4]. |

| Transwell Inserts | To create a compartmentalized system (apical and basolateral) for studying transepithelial transport in cell monolayers. | Permeable supports (e.g., polycarbonate, polyester) with a pore size of 0.4–3.0 μm [2]. |

The LADME framework is a foundational pharmacokinetic model that describes the sequential processes a compound undergoes within an organism. Originally developed for pharmaceuticals, this framework is increasingly critical for understanding the fate of bioactive food compounds and nutrients, where it describes the journey from ingestion to elimination [7]. The acronym LADME stands for Liberation, Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism, and Elimination [8]. For nutrition researchers, this framework provides a systematic approach to quantify the bioavailability of nutrients—defined as the proportion of an ingested nutrient that is absorbed, transported, and delivered to target tissues in a form that can be utilized in metabolic functions or stored [9]. Understanding these processes is essential for moving beyond simply measuring the total nutrient content in foods and toward predicting their actual physiological impact, which is a key goal in modern nutritional science [10].

The LADME Process: A Detailed Breakdown for Nutrient Bioavailability

The five components of the LADME framework represent interlinked processes that determine the ultimate bioefficacy of a nutrient.

Liberation: This initial step involves the release of the nutrient from its food matrix. The process is influenced by food structure, processing methods, and mastication. For instance, nutrients entrapped in plant cellular structures or complexed with antagonists like phytates may not be fully liberated during digestion [9] [11]. Techniques such as mechanical processing, fermentation, or enzymatic treatments are often employed in research to enhance nutrient liberation [11].

Absorption: Absorption refers to the movement of nutrients from the gastrointestinal tract into the bloodstream or lymphatic system [8]. This stage is highly dependent on the chemical form of the nutrient (e.g., heme vs. non-heme iron), the presence of other dietary components (enhancers like vitamin C for iron or inhibitors like phytates for minerals), and host factors including gut health and microbiota [9] [12]. The absorption site varies; for example, fat-soluble vitamins are absorbed via the lymphatic system, while most water-soluble vitamins and minerals are absorbed directly into the portal blood [7].

Distribution: Once absorbed, nutrients are distributed via the circulatory system to various tissues and organs. The extent of distribution is influenced by the nutrient's ability to bind to plasma proteins, its lipophilicity, and the body's specific demands at the time. For instance, calcium may be directed to bone tissues, while iron is complexed with transferrin for delivery to the bone marrow and other tissues [7] [9].

Metabolism: Nutrients can undergo metabolic transformations, which can either activate them into more bioactive forms or deactivate them for excretion. A key example is the conversion of provitamin A carotenoids into active retinol or the hydroxylation of vitamin D into its active form, calcifediol [9] [12]. Nutrient metabolism can occur in the liver (first-pass metabolism) or in peripheral tissues and can be influenced by an individual's genetic makeup and nutritional status [7].

Elimination: The final process is the elimination of the nutrient or its metabolites from the body. This primarily occurs via renal (urine) or biliary (feces) excretion [8]. The rate of elimination determines the half-life and residence time of a nutrient in the body, impacting its long-term availability for physiological functions. Balance studies, which measure the difference between ingestion and excretion, are a common method for studying the elimination and overall absorption of nutrients [9].

It is crucial to note that these processes are not discrete sequential events but often occur simultaneously, especially with complex meals or sustained-release formulations [8].

Key Pharmacokinetic Parameters in LADME Studies

The following table summarizes the key quantitative parameters used to evaluate each stage of the LADME framework in nutritional research.

Table 1: Key Quantitative Parameters for Assessing Nutrient Bioavailability via the LADME Framework

| LADME Stage | Key Pharmacokinetic Parameters | Nutritional Application Example |

|---|---|---|

| Liberation | Liberation efficiency, bioaccessibility percentage | Percentage of a carotenoid released from its food matrix during in vitro digestion. |

| Absorption | Fraction absorbed (Famax, Tmax, AUC | Area Under the Curve (AUC) for plasma retinol after consuming β-carotene. |

| Distribution | Apparent Volume of Distribution (Vd), plasma protein binding | Distribution of vitamin E to adipose tissue and cell membranes. |

| Metabolism | Metabolic conversion rate, bioefficacy | Conversion rate of provitamin A carotenoids to retinol [12]. |

| Elimination | Elimination half-life (t1/2), clearance (CL) | Renal clearance of water-soluble B vitamins. |

Experimental Protocols for Assessing LADME Stages

A robust understanding of nutrient bioavailability requires integrated methodologies. The following workflow outlines a multi-technique approach, from simulated digestion to human trials.

Protocol 1: Bioaccessibility and Liberation Assessment

This protocol determines the fraction of a nutrient that is released from the food matrix into the digestive chyme (bioaccessibility), which is the first step toward bioavailability [9].

- Objective: To simulate the gastrointestinal liberation of a target nutrient from a food sample.

- Materials:

- Food Sample: Homogenized test food.

- Simulated Fluids: Simulated salivary fluid (SSF), gastric fluid (SGF), and intestinal fluid (SIF), prepared according to standardized recipes (e.g., INFOGEST).

- Digestive Enzymes: α-amylase, pepsin, pancreatin, and bile extracts.

- Equipment: Water bath or shaking incubator maintaining 37°C, pH meter, centrifuge.

- Methodology:

- Oral Phase: Mix 5 g of food sample with 4 mL of SSF and 1 mL of α-amylase solution. Incubate for 2 minutes at 37°C with constant agitation.

- Gastric Phase: Adjust the pH to 3.0, add 8 mL of SGF and 1 mL of pepsin solution. Incubate for 2 hours at 37°C with agitation.

- Intestinal Phase: Adjust the pH to 7.0, add 8 mL of SIF, 1 mL of pancreatin solution, and 4 mL of bile salts solution. Incubate for 2 hours at 37°C with agitation.

- Centrifugation: Centrifuge the final chyme at high speed (e.g., 10,000 × g, 30 minutes, 4°C) to separate the aqueous micellar phase (containing the liberated nutrient) from the solid residue.

- Analysis: Quantify the target nutrient in the aqueous phase using appropriate analytical techniques (e.g., HPLC for vitamins, ICP-MS for minerals). Calculate bioaccessibility as: (Nutrient in aqueous phase / Total nutrient in food sample) × 100.

Protocol 2: Mineral Absorption Using Stable Isotopes

This method provides a direct and highly accurate measurement of absorption for minerals like iron, zinc, and calcium in human subjects.

- Objective: To determine the true absorption of a mineral by tracking a stable isotope tracer.

- Materials:

- Stable Isotopes: e.g., 57Fe or 70Zn.

- Test Meals: Precisely formulated meals containing the isotope tracer.

- Sample Collection Tubes: For blood and fecal samples.

- Analytical Equipment: Inductively Coupled Plasma Mass Spectrometry (ICP-MS).

- Methodology:

- Administration: Administer a test meal containing a precisely weighed amount of a stable isotope of the mineral (e.g., 57Fe) to a human participant after an overnight fast.

- Sample Collection: Collect complete fecal samples for a period of 8-14 days post-administration to ensure complete excretion of the unabsorbed isotope.

- Sample Preparation: Acid-digest the fecal samples to mineralize all organic matter and bring the mineral into solution.

- Isotopic Analysis: Analyze the isotopic composition of the prepared samples using ICP-MS. The instrument differentiates between the administered stable isotope and the natural isotopes present in the body.

- Calculation: Calculate the fraction of the isotope that was absorbed based on the amount not recovered in the feces: Absorption (%) = [1 - (Isotope recovered in feces / Isotope administered)] × 100.

Protocol 3: Algorithm-Based Bioavailability Estimation for Iron and Zinc

For population-level studies, algorithms that account for dietary enhancers and inhibitors provide a practical estimate of bioavailability [12].

- Objective: To estimate the total absorbed iron and zinc from a whole diet.

- Materials:

- Dietary Intake Data: Detailed food consumption records from participants.

- Comprehensive Food Composition Database: Must include data on the target nutrients, their chemical forms (e.g., heme vs. non-heme iron), and key modulators (phytates, vitamin C, etc.).

- Computational Tool: Software for implementing the algorithms (e.g., R, Python, or Excel).

- Methodology:

- Data Compilation: From the dietary records, calculate the total daily intakes of:

- Apply Algorithm for Non-Heme Iron Absorption:

- Use an algorithm such as: Non-heme Iron Absorption (%) = k × (SF^0.8) × (1 + α × C) × (1 + β × TMF) / ((1 + γ × T) × (1 + δ × P) × (1 + ε × Ca)) [12], where SF is serum ferritin, C is vitamin C, TMF is total meat/fish, T is tea/coffee, P is phytate, and Ca is calcium. Constants (k, α, β, γ, δ, ε) are derived from the literature.

- Apply Algorithm for Zinc Absorption:

- Use the equation: Total Absorbed Zinc (TAZ, mmol) = Total Dietary Zinc (TDZ, mmol) / [1 + (0.5 × Total Dietary Phytates (TDP, mmol))] [12].

- Calculate Total Absorption: For iron, sum the absorbed heme and non-heme iron. The results represent the estimated amount of mineral available for metabolic processes.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Reagents and Materials

Successful execution of bioavailability research requires specific reagents and tools. The following table details essential items for a laboratory focused on nutrient LADME.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Nutrient Bioavailability Studies

| Item Name | Specification / Example | Primary Function in LADME Research |

|---|---|---|

| Simulated Digestive Fluids | INFOGEST standardized SSF, SGF, SIF | To mimic human gastrointestinal conditions for in vitro liberation (L) and absorption (A) studies [9]. |

| Caco-2 Cell Line | Human colon adenocarcinoma cell line | A well-established in vitro model of the intestinal epithelium for studying nutrient transport and absorption (A) [7]. |

| Stable Isotopes | 57Fe, 44Ca, 70Zn | Non-radioactive tracers to precisely track mineral absorption, distribution, and elimination in humans and animals [12]. |

| Phytase Enzymes | From microbial sources (e.g., Aspergillus niger) | Used in processing or in vitro models to hydrolyze phytate, an absorption inhibitor, thereby enhancing mineral bioavailability [9] [11]. |

| Permeation Enhancers | Medium-Chain Triglycerides (MCTs), chitosan | Compounds used in formulations to improve the absorption (A) of poorly absorbed nutrients by increasing intestinal permeability [9]. |

| Encapsulation Materials | Maltodextrin, chitosan, alginate, liposomes | Used for nanoencapsulation to protect sensitive nutrients from metabolism (M) and enhance their stability and absorption [11]. |

Advanced Applications and Current Research Trends

The application of the LADME framework is evolving with new technologies and a deeper understanding of individual variability. Advanced techniques are being deployed to overcome bioavailability challenges.

Table 3: Strategies for Enhancing Nutrient Bioavailability Across the LADME Framework

| LADME Stage | Challenge | Enhancement Strategy | Research Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| Liberation | Nutrient entrapment in plant cell walls. | Mechanical processing (e.g., fine milling), fermentation. | Fermentation by lactic acid bacteria degrades phytates in cereals, liberating bound minerals [11]. |

| Absorption | Low solubility or dietary inhibitors. | Nanoencapsulation, use of absorption enhancers (e.g., vitamin C with iron). | Lipid-based nanoencapsulation improves solubility and absorption of fat-soluble vitamins [9] [11]. |

| Distribution & Metabolism | Rapid metabolism or poor conversion. | Using precursor forms or more bioavailable chemical forms. | Calcifediol (25-hydroxyvitamin D) is more bioavailable than cholecalciferol (vitamin D3) [9]. |

| Overall Bioefficacy | Host-specific factors (genetics, microbiome). | Personalized nutrition based on genotyping and microbiome analysis. | Formulating diets based on individual genetic profiles affecting nutrient metabolism [11]. |

Furthermore, there is a strong push to integrate bioavailability data into public health tools. The International Life Sciences Institute (ILSI) U.S. and Canada recently published a framework for estimating nutrient absorption, aiming to incorporate bioavailability algorithms into nutrient databases, food labels, and dietary assessment tools [10] [13]. This transition from total nutrient content to "usable nutrient intake" represents the ultimate application of LADME research, enabling more accurate dietary recommendations and effective public health interventions.

The assessment of nutrient bioavailability is a critical component of nutritional science and food research. While dietary factors are often emphasized, host-related factors—including genetics, health status, and life stage—fundamentally determine how individuals absorb and utilize nutrients from foods. Understanding these variables is essential for developing accurate research protocols and interpreting experimental outcomes in human studies. This application note provides detailed methodologies for investigating these host-related factors within the context of nutrient bioavailability research, offering researchers a standardized framework to account for intrinsic human variability.

Genetic Factors Influencing Nutrient Absorption

Key Genetic Variants and Mechanisms

Genetic variations introduce significant inter-individual variability in nutrient absorption and metabolism. These differences primarily occur through polymorphisms that affect digestive enzymes, transport proteins, and metabolic pathways.

Table 1: Key Genetic Variants Affecting Nutrient Bioavailability

| Gene | Nutrient Affected | Impact of Variation | Research Implications |

|---|---|---|---|

| TAS2R38 | Phenylthiocarbamide (in brassica vegetables) | Alters taste perception; influences food preference and consumption [14] | Requires dietary preference screening in study participants |

| LCT | Lactose | Determines lactase persistence or non-persistence [14] | Necessitates genotype screening for dairy-based nutrient studies |

| BCO1 | Carotenoids (β-carotene, lutein, zeaxanthin) | SNPs (rs6564851-C, rs6420424-A) significantly impact circulating carotenoid levels [15] | Critical for studies on fat-soluble vitamin bioavailability |

| FLG | Multiple nutrients | Loss-of-function mutations affect skin and gut barriers; alter nutrient absorption [16] | Important for studies on barrier function and nutrient absorption |

| FTO | Lipids | Intronic variant affects IRX3/IRX5 expression; alters adipocyte metabolism [16] | Relevant for lipid metabolism and energy balance studies |

Experimental Protocol: Genotyping for Nutrient Absorption Studies

Objective: To identify and control for genetic variants that significantly impact nutrient bioavailability in human intervention studies.

Materials:

- DNA extraction kit (validated for human biospecimens)

- Pre-designed TaqMan SNP Genotyping Assays or equivalent

- Quantitative PCR system with allelic discrimination capability

- EDTA-treated whole blood or saliva samples

- Laboratory automation equipment for high-throughput processing

Procedure:

- Participant Selection and Stratification:

- Recruit sufficient participants to ensure statistical power for subgroup analysis (typically n≥50 per genotype group)

- Include ancestry and ethnicity matching to control for population-specific allele frequencies [16]

DNA Extraction and Quality Control:

- Extract genomic DNA from whole blood or saliva following manufacturer protocols

- Quantify DNA concentration using spectrophotometry (A260/A280 ratio of 1.8-2.0 acceptable)

- Normalize all samples to working concentration of 5-10 ng/μL

Genotyping Analysis:

- Perform real-time PCR with allele-specific probes

- Include positive controls for all three possible genotypes (homozygous reference, heterozygous, homozygous variant) in each run

- Run duplicate samples to ensure genotype concordance >99%

Data Analysis:

- Cluster plot analysis to assign genotypes

- Calculate Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium p-values for quality control (p>0.05 acceptable)

- Stratify nutrient absorption data by genotype for statistical comparison

Applications: This protocol is particularly valuable for studies investigating carotenoids, lipids, and minerals where known genetic variants explain significant portions of inter-individual variability in response to interventions.

Health Status and Physiological Factors

Impact of Health Conditions on Absorption

Health status significantly modulates nutrient absorption through multiple mechanisms, including alterations in gastrointestinal environment, inflammatory responses, and metabolic demands.

Table 2: Health Status Factors Affecting Nutrient Bioavailability

| Health Factor | Impact on Absorption | Research Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Infections | Decreased food intake, impaired nutrient absorption, nutrient wastage, sequestration [17] | Requires health screening; acute infections may necessitate study postponement |

| Gastric Acid Reduction | Reduced bioavailability of micronutrients, especially iron and B12 [18] | Document medication use (PPIs, H2 blockers); consider age-related decline |

| Inflammatory Bowel Disease | Malabsorption of multiple nutrients due to mucosal damage | Exclusion criterion or separate stratification group |

| Obesity | Altered lipid metabolism, potential micronutrient deficiencies | Record BMI and body composition; may require separate cohort design |

| Helicobacter pylori Infection | Impaired iron and B12 absorption through gastric changes | Screen for infection status in mineral studies |

Experimental Protocol: Assessing Health Status in Bioavailability Studies

Objective: To systematically evaluate and document health status factors that may confound nutrient absorption measurements.

Materials:

- Standardized health screening questionnaire

- Basic metabolic panel reagents

- C-reactive protein (CRP) assay

- Hemoglobin and ferritin measurement systems

- Stool antigen tests for H. pylori (if applicable)

Procedure:

- Comprehensive Health Screening:

- Administer detailed medical history questionnaire covering gastrointestinal conditions, chronic diseases, and surgical history

- Document all prescription and over-the-counter medications, particularly acid-reducing agents and anti-inflammatories

- Record recent (within 2 weeks) symptoms of infection or illness

Biomarker Analysis:

- Collect fasting blood samples for CRP (inflammatory marker), complete blood count, and basic metabolic panel

- For mineral studies, include iron status markers (ferritin, transferrin saturation)

- For fat-soluble nutrient studies, include liver function tests

Statistical Control:

- Include health status covariates in statistical models analyzing nutrient absorption data

- Consider exclusion criteria for values outside normal ranges that may indicate subclinical conditions

- For studies focusing on specific health conditions, recruit homogeneous patient groups with matched controls

Life Stage Considerations

Life Stage Impact on Nutrient Requirements

Physiological changes across the lifespan significantly alter nutrient absorption capacity and requirements. These changes must be accounted for in study design and data interpretation.

Key Life Stage Considerations:

- Aging: Gradual decline in gastric acid production reduces micronutrient bioavailability; older adults show 40% reduction in nutrient absorption efficiency compared to younger individuals [18] [17]

- Pregnancy: Enhanced calcium absorption (approximately 2-fold increase) to support fetal skeletal development; increased zinc absorption tendencies [17]

- Lactation: Altered mineral homeostasis with renal conservation and bone resorption mechanisms [17]

- Infancy/Childhood: Rapidly changing gut maturation and enzyme expression patterns

Experimental Protocol: Life Stage Stratification in Absorption Studies

Objective: To account for physiological differences in nutrient absorption across life stages through appropriate study design and data analysis.

Materials:

- Age-appropriate dosing and sampling protocols

- Pregnancy tests for women of childbearing potential

- Additional safety monitoring for vulnerable populations

Procedure:

- Study Group Design:

- Define specific age ranges for study cohorts (e.g., young adults: 18-35y, older adults: 65-80y)

- For studies including older adults, document medication use that may affect GI function

- For women of childbearing age, conduct pregnancy testing and standardize testing to similar menstrual cycle phases when possible

Protocol Adaptations:

- For elderly participants, consider longer absorption periods to account for slowed GI transit

- For pregnancy studies, carefully time interventions to specific trimesters with obstetric oversight

- For pediatric studies, implement age-appropriate dosing (weight-based) and sampling volumes

Data Interpretation:

- Analyze results stratified by life stage group

- Include age as a continuous variable in regression models examining absorption kinetics

- Compare study populations to reference values for specific age groups

Integrated Experimental Workflow

The investigation of host-related factors in nutrient bioavailability requires a systematic approach that integrates genetic, health, and life stage assessments. The following workflow provides a visual representation of this integrated protocol:

Diagram: Integrated Workflow for Assessing Host Factors in Bioavailability. This workflow systematically integrates assessment of genetic, health, and life stage factors throughout the study design.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Host Factor Analysis

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Research Application | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Genotyping Assays | TaqMan SNP Genotyping Assays, Illumina Infinium arrays | Identification of genetic variants affecting nutrient metabolism [15] [16] | Select population-specific variants; verify assay validation for human genomes |

| DNA Extraction Kits | QIAamp DNA Blood Mini Kit, PureLink Genomic DNA kits | High-quality DNA extraction from blood, saliva, or buccal cells | Assess yield and purity; ensure compatibility with downstream applications |

| Inflammatory Markers | CRP ELISA kits, cytokine panels, leukocyte differentiation kits | Quantification of systemic inflammation affecting nutrient utilization [17] | Establish normal ranges for study population; control for acute inflammation |

| Metabolic Panels | Automated clinical chemistry analyzers, enzyme activity assays | Assessment of organ function and nutrient status [17] | Standardize sampling conditions (fasting, time of day) |

| Nutrient Biomarker Assays | HPLC systems, mass spectrometers, immunoassays | Quantification of nutrient and metabolite concentrations in biological samples [1] | Validate for specific sample matrices; establish detection limits |

| Microbiome Analysis | 16S rRNA sequencing kits, metagenomic sequencing services | Characterization of gut microbiota composition affecting nutrient processing [15] | Standardize sample collection and storage to preserve microbial DNA |

Host-related factors including genetic variation, health status, and life stage constitute fundamental determinants of nutrient bioavailability that must be rigorously controlled in nutritional research. The protocols outlined herein provide researchers with standardized methodologies to account for these variables, thereby enhancing the accuracy, reproducibility, and biological relevance of nutrient absorption studies. By implementing these comprehensive assessment strategies, researchers can advance the development of personalized nutrition approaches and strengthen the scientific basis for dietary recommendations tailored to individual physiological needs.

The food matrix is defined as the integrated physicochemical domain that contains and/or interacts with specific constituents of a food, providing functionalities and behaviors that are different from those exhibited by the components in isolation or a free state [19] [20]. This concept has fundamentally shifted the understanding of nutritional quality, moving beyond simple proximate composition analysis to consider how the complex organization of food components influences nutrient bioavailability—the fraction of an ingested nutrient that becomes available for use and storage in the body [4]. The matrix effect demonstrates that foods are not merely ideal systems with equally distributed components, but rather intricate, multicomponent systems where macro- and microconstituents interact through various molecular forces including hydrogen bonding, coordination forces, electrostatic interactions, π-π stacking, and hydrophobic reactions [20].

Understanding the diet-related factors that enhance or inhibit nutrient bioavailability is crucial for developing effective dietary recommendations, nutritional therapies, and fortified food products [21]. The journey of a nutrient from ingestion to utilization involves multiple biological processes: it must first be released from the food matrix (a concept referred to as bioaccessibility), then absorbed through the gut lining into the bloodstream, and finally utilized by cells [21] [22]. At each of these stages, specific dietary factors can either facilitate or hinder the process, creating a complex network of interactions that ultimately determines the nutritional value of a food. This document provides detailed protocols and application notes for assessing these critical interactions within the context of food bioavailability research.

Key Enhancers and Inhibitors of Nutrient Bioavailability

The following sections provide a detailed overview of the major dietary factors that influence the bioavailability of micronutrients, with specific emphasis on the underlying mechanisms and practical implications for research and food design.

Major Bioavailability Enhancers

Table 1: Key Dietary Bioavailability Enhancers and Their Mechanisms of Action

| Enhancer | Target Nutrient(s) | Mechanism of Action | Food Sources |

|---|---|---|---|

| Vitamin C | Non-heme iron | Reduces ferric iron (Fe³⁺) to more absorbable ferrous (Fe²⁺) form; chelates iron to maintain solubility in intestinal lumen [21] [22]. | Citrus fruits, bell peppers, broccoli, strawberries |

| Milk Proteins (Casein, Whey) | Calcium, Minerals | Phosphopeptides from casein hydrolysis bind calcium, protecting it from precipitation by anions like phosphates; slow release enhances passive diffusion [4]. | Milk, yogurt, cheese |

| Lactose | Calcium | Widens paracellular spaces in enteric cell lining; may function as prebiotic to stimulate calcium absorption in colon [4]. | Milk, dairy products |

| Organic Acids | Various minerals | Acidic environment enhances mineral solubility; chelation effects improve absorption [21]. | Fermented foods, citrus fruits |

| Vitamin D | Calcium | Regulates active transport of calcium at low and moderate intake levels; enhances calcium absorption efficiency [4]. | Fortified dairy, fatty fish, egg yolks |

| Certain Amino Acids | Minerals | L-lysine and L-arginine bind minerals, making them readily released during digestion [4]. | Animal proteins, legumes |

Vitamin C stands as one of the most potent enhancers of non-heme iron absorption, particularly relevant for plant-based diets where iron bioavailability is typically lower [22]. The mechanism involves both chemical reduction of iron to its more absorbable form and chelation to maintain solubility throughout the digestive process. Research indicates that simultaneous consumption of vitamin C-rich foods with iron-rich plant sources can significantly improve iron status, a critical consideration for populations at risk of deficiency [21].

Dairy matrices present a fascinating case of natural enhancement, where multiple components work synergistically to improve calcium bioavailability. The combined action of casein-derived phosphopeptides, whey proteins, lactose, and vitamin D creates a highly efficient calcium delivery system that explains why dairy products remain the most effective source for bone health [4]. This synergistic effect underscores the importance of studying whole foods rather than isolated nutrients, as the net benefit exceeds what would be predicted from individual components alone.

Major Bioavailability Inhibitors

Table 2: Key Dietary Bioavailability Inhibitors and Their Mechanisms of Action

| Inhibitor | Target Nutrient(s) | Mechanism of Action | Food Sources |

|---|---|---|---|

| Phytates (Phytic Acid) | Zinc, Iron, Calcium, Magnesium | Forms insoluble complexes with minerals in the intestinal lumen, preventing absorption [21] [20]. | Whole grains, legumes, nuts, seeds |

| Oxalates | Calcium | Binds calcium to form insoluble calcium oxalate crystals [20]. | Spinach, rhubarb, beets, nuts |

| Polyphenols (Tannins) | Iron, Zinc | Forms insoluble complexes with minerals; inhibits digestive enzymes [22] [20]. | Tea, coffee, red wine, certain legumes |

| Dietary Fiber | Various minerals | Physically traps minerals; increases intestinal transit time; may bind minerals directly [20]. | Whole grains, fruits, vegetables |

| Calcium | Iron, Zinc | Competitive inhibition for transport proteins; particularly affects non-heme iron [4]. | Dairy products, fortified foods |

| Sulfur-containing Proteins | Calcium | Induces hypercalciuria (increased urinary calcium excretion) [4]. | Animal proteins, eggs |

Phytates represent one of the most significant inhibitors of mineral absorption, particularly for zinc and iron. These compounds, which serve as phosphorus storage in seeds and grains, have strong chelating properties that form stable complexes with di- and trivalent minerals, rendering them unavailable for absorption [21]. The negative impact of phytates is particularly pronounced in populations relying heavily on whole grain and legume-based diets, highlighting the importance of food processing techniques such as fermentation, soaking, and germination that can reduce phytate content.

The interaction between different minerals presents another complex inhibitory mechanism. Calcium, for instance, has been shown to inhibit the absorption of both iron and zinc when consumed simultaneously, likely through competition for shared transport mechanisms [4]. This interaction has important implications for meal planning and fortification strategies, as the addition of calcium to iron-fortified products may inadvertently reduce iron bioavailability. Similarly, the presence of multiple inhibitors in the same meal can have cumulative effects, substantially reducing the overall mineral bioavailability from plant-based foods [20].

Diagram 1: Bioavailability Pathway with Key Enhancers and Inhibitors. This workflow illustrates the sequential stages of nutrient bioavailability and points where major enhancers and inhibitors exert their effects.

Experimental Protocols for Assessing Bioavailability

This section provides detailed methodologies for evaluating the impact of diet-related factors on nutrient bioavailability, with specific protocols designed for research applications.

Protocol 1: In Vitro Simulation of Gastrointestinal Digestion

Purpose: To simulate the human digestive process for evaluating nutrient bioaccessibility from complex food matrices under controlled laboratory conditions [4] [20].

Principle: This protocol recreates the sequential physiological conditions of the mouth, stomach, and small intestine to measure the fraction of nutrients released from the food matrix during digestion (bioaccessibility). The method is particularly valuable for rapid screening of multiple food matrix interactions and the effects of processing conditions on nutrient release.

Materials and Reagents:

- Simulated Salivary Fluid (SSF): Contains α-amylase in appropriate buffer

- Simulated Gastric Fluid (SGF): Contains pepsin in acidified saline (pH 3.0)

- Simulated Intestinal Fluid (SIF): Contains pancreatin and bile extracts in neutral buffer

- pH-Stat Titrator: For maintaining precise pH control during intestinal phase

- Water Bath or Incubator: Maintained at 37°C with continuous agitation

- Centrifuge and Ultracentrifuge: For separation of aqueous fraction (micellar phase)

- Dialysis Membranes: Molecular weight cut-off 12-14 kDa for fractionation

- Analytical Equipment: HPLC, ICP-MS, or spectrophotometric systems for nutrient quantification

Procedure:

- Sample Preparation: Homogenize test food material to standardized particle size (typically 2-5 mm). Precisely weigh 5-10 g samples in digestion vessels.

Oral Phase: Add SSF to sample at 1:1 ratio (w/v). Incubate for 2 minutes at 37°C with continuous agitation (100 rpm).

Gastric Phase: Adjust mixture to pH 3.0 using 1M HCl. Add SGF containing pepsin (2000 U/mL final concentration). Incubate for 2 hours at 37°C with continuous agitation.

Intestinal Phase: Adjust mixture to pH 7.0 using 1M NaHCO₃. Add SIF containing pancreatin (100 U/mL trypsin activity) and bile extracts (10 mM final concentration). Incubate for 2 hours at 37°C while maintaining pH at 7.0 using pH-stat titration.

Bioaccessible Fraction Collection: Centrifuge intestinal digest at 5000 × g for 30 minutes at 4°C. Collect supernatant representing the bioaccessible fraction. For additional fractionation, ultracentrifuge at 100,000 × g for 1 hour to isolate the micellar phase.

Analysis: Quantify target nutrients in the bioaccessible fraction using appropriate analytical methods (HPLC for vitamins, ICP-MS for minerals).

Data Interpretation: Calculate bioaccessibility as: (Nutrient content in bioaccessible fraction / Total nutrient content in original sample) × 100. Compare values across different food matrices or processing conditions to determine the impact of enhancers/inhibitors.

Protocol 2: Stable Isotope Studies for Human Bioavailability Assessment

Purpose: To precisely measure the absorption and metabolic utilization of nutrients in human subjects using stable isotope tracers [4].

Principle: This approach uses nutrients labeled with non-radioactive stable isotopes (²H, ¹³C, ¹⁵N, etc.) to trace the fate of specific nutrients from ingestion through absorption, distribution, and excretion. The method provides the most accurate assessment of true bioavailability in humans and is considered the gold standard for bioavailability research.

Materials and Reagents:

- Stable Isotope-Labeled Nutrients: Specifically synthesized with ¹³C, ²H, ⁵⁷Fe, ⁶⁷Zn, etc.

- Medical-Grade Supplement Vehicles: Such as gelatin capsules or sterile solutions

- Blood Collection Equipment: Vacutainer tubes (EDTA, heparin)

- Urine/Stool Collection Containers: Pre-weighed, acid-washed containers

- Mass Spectrometry Equipment: ICP-MS for mineral isotopes, GC-IRMS or LC-IRMS for organic nutrients

- Anthropometric Equipment: For subject screening and monitoring

Procedure:

- Subject Selection and Preparation: Recruit healthy volunteers based on inclusion/exclusion criteria. Provide standardized lead-in diet for 3-7 days before study to normalize nutrient status. Obtain informed consent following institutional ethics committee approval.

Isotope Administration: After an overnight fast, administer precisely weighed stable isotope-labeled nutrient (e.g., ⁵⁷Fe, ²H-folate) with a test meal containing the enhancer/inhibitor of interest. Use cross-over design with washout period when comparing multiple test conditions.

Sample Collection: Collect baseline blood, urine, and stool samples before isotope administration. Continue serial blood sampling at predetermined intervals (30 min, 1, 2, 4, 6, 8, 24 hours). Collect complete urine and stool for 5-7 days post-administration.

Sample Processing: Process blood samples to separate plasma, serum, and erythrocytes. Precisely weigh and homogenize stool samples. Acid-digest samples for mineral analysis or extract for vitamin analysis as appropriate.

Isotope Ratio Analysis: Determine isotope ratios in biological samples using appropriate mass spectrometric techniques:

- ICP-MS: For mineral isotopes (Fe, Zn, Ca, etc.)

- GC-IRMS: For ¹³C-labeled vitamins and organic nutrients

- LC-IRMS: For polar compounds and certain vitamins

Kinetic Modeling: Apply compartmental modeling to isotope appearance curves in blood to calculate absorption parameters. Use fecal monitoring or dual-isotope method to determine total absorption.

Data Interpretation: Calculate bioavailability as the fraction of administered isotope that appears in circulation or is retained in the body. Compare isotopic enrichment patterns between test conditions to quantify the effects of specific enhancers or inhibitors.

Research Reagent Solutions and Essential Materials

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Bioavailability Studies

| Reagent/Material | Specifications | Research Application | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Stable Isotopes | ⁵⁷Fe, ⁶⁷Zn, ⁴⁴Ca, ¹³C-labeled vitamins | Human tracer studies for precise absorption measurement [4] | Purity >98%; chemical form identical to native nutrient; sterile preparation for human use |

| Digestive Enzymes | Porcine or recombinant pepsin, pancreatin, α-amylase | In vitro simulation of gastrointestinal digestion [20] | Activity standardization; lot-to-lot consistency; minimal endogenous nutrient contamination |

| Simulated Gastrointestinal Fluids | SSF, SGF, SIF following standardized recipes | In vitro bioaccessibility assessment [20] | pH stability; ionic composition matching human physiology; sterile filtration |

| Caco-2 Cell Line | Human colon adenocarcinoma cells, passages 30-45 | Intestinal absorption studies and transport mechanisms [20] | Proper differentiation (21 days); TEER measurement for monolayer integrity; mycoplasma testing |

| Dialyzation Membranes | Regenerated cellulose, MWCO 12-14 kDa | Fractionation of bioaccessible nutrients in vitro [20] | Pre-treatment to remove contaminants; compatibility with target analytes; lot consistency |

| Reference Materials | Certified food matrices with known nutrient composition | Method validation and quality control [22] | Matrix-matched to samples; certified values for target nutrients; stability documentation |

The systematic investigation of diet-related factors affecting nutrient bioavailability reveals the profound complexity of food as a biological delivery system rather than merely a collection of individual nutrients. The protocols and application notes provided here offer researchers standardized approaches to quantify these critical interactions, with particular relevance for developing evidence-based dietary recommendations, optimizing food fortification strategies, and designing functional foods targeted to specific population needs.

Future research directions should focus on expanding our understanding of food matrix interactions beyond the traditional vitamin and mineral considerations to include bioactive phytochemicals, the role of the gut microbiome in nutrient utilization, and the development of sophisticated in silico models that can predict bioavailability based on food composition and matrix properties. The integration of these approaches will ultimately enable more personalized nutritional recommendations and the development of food products with optimized nutrient delivery capabilities.

Diagram 2: Comprehensive Research Workflow for Bioavailability Studies. This diagram outlines an integrated approach to investigating enhancers and inhibitors, combining in vitro screening with mechanistic studies and human validation.

A Guide to In Vivo, In Vitro, and In Silico Assessment Methods

The quantitative assessment of nutrient bioavailability in humans requires sophisticated methodologies that can trace metabolic pathways in vivo without disrupting normal physiology. Stable and radioactive isotopes serve as powerful tracers for this purpose, providing the gold standard for understanding the dynamic aspects of human metabolism including nutrient absorption, distribution, and utilization [23]. These tracer techniques allow researchers to move beyond static concentration measurements to kinetic analyses that reveal how nutrients are processed within the human body [23]. The fundamental principle involves administering an isotope-labeled compound and tracking its movement through biological systems, enabling precise measurement of metabolic flux rates, pool sizes, and turnover times [23].

Unlike in vitro methods that merely estimate bio-accessibility, isotopic tracer studies in humans provide direct evidence of bioavailability, defined as the proportion of a nutrient that is absorbed and becomes available for physiological functions [24]. This approach is particularly valuable for assessing nutrients from plant-based foods, where anti-nutrients such as phytic acid and tannins can significantly limit mineral absorption [24]. As plant-based diets gain prominence for health and sustainability reasons, understanding the bioavailability of their nutrients becomes increasingly important for addressing global malnutrition challenges [25].

Fundamental Isotope Concepts for Metabolic Tracers

Stable versus Radioactive Isotopes

Isotopes are variants of a single element that differ in the number of neutrons in their nuclei, resulting in different atomic masses but identical chemical properties [26]. For metabolic research, isotopes are categorized as either stable or radioactive:

- Stable isotopes do not emit radiation, are naturally occurring, and have constant atomic masses over time [27] [26]. Examples include deuterium (²H), carbon-13 (¹³C), nitrogen-15 (¹⁵N), and oxygen-18 (¹⁸O) [23].

- Radioactive isotopes (radioisotopes) spontaneously decay with emission of radiation and have defined half-lives [27] [26]. While useful for certain applications, safety concerns have limited their use in human studies, particularly in vulnerable populations [23].

The selection between stable and radioactive isotopes depends on the research question, target population, and detection capabilities. Gold-197 represents the only stable isotope of gold, while radioactive gold isotopes such as gold-195 (half-life: 186.01 days) and gold-198 (half-life: 2.69 days) exist but are not typically used in nutrient bioavailability studies [28].

Metabolic Tracer Principles

A metabolic isotope tracer is a molecule where one or more atoms have been replaced with an uncommon isotope, making it chemically and functionally identical to the naturally occurring molecule (tracee) but distinguishable by mass or radioactivity [23]. The core requirement is that the tracer must participate in biological processes identically to the tracee while remaining detectable throughout the metabolic pathway of interest.

The tracer-to-tracee ratio (TTR) represents the fundamental measurement in these studies, typically determined using mass spectrometry techniques [23]. For stable isotopes, the natural abundance of heavier isotopes must be accounted for in calculations; for example, approximately 6.6% of naturally occurring glucose contains at least one carbon-13 atom due to its 1.1% natural abundance [23].

Table 1: Stable Isotopes Commonly Used in Bioavailability Research

| Stable Isotope | Natural Abundance | Applications in Nutrition Research |

|---|---|---|

| Carbon-13 (¹³C) | ~1.1% [23] | Breath tests for carbohydrate metabolism, amino acid kinetics, fatty acid metabolism [29] |

| Deuterium (²H) | ~0.015% | Energy expenditure studies, water turnover [29] |

| Nitrogen-15 (¹⁵N) | ~0.4% | Protein turnover, amino acid metabolism [23] |

| Oxygen-18 (¹⁸O) | ~0.2% | Energy expenditure, water turnover (with deuterium) [29] |

| Calcium-42, -44, -46 | Varying abundances | Calcium absorption, bone turnover studies, osteoporosis research [29] |

| Iron-54, -57, -58 | Varying abundances | Iron metabolism, absorption studies, anemia interventions [29] |

Experimental Protocols for Isotope Tracer Studies

General Study Design and Setup

Isotope tracer studies in humans follow standardized protocols to ensure reproducible and interpretable results. The basic design involves administering one or more isotope tracers and collecting biological samples at predetermined time points to track the tracer's appearance, distribution, and disappearance [23].

Subject Preparation: Participants are typically studied after an overnight fast to establish baseline metabolic conditions. For nutrient bioavailability studies, the isotope-labeled nutrient may be administered with a test meal to evaluate absorption under realistic dietary conditions. The tracer dose is carefully calculated based on body weight, natural abundance of the isotope, and detection sensitivity of analytical instruments.

Tracer Administration: Isotope tracers can be administered via multiple routes depending on the research question:

- Intravenous infusion: Provides direct access to systemic circulation for quantifying production, disappearance, and clearance rates [23]

- Oral administration: Essential for assessing absorption and first-pass metabolism of nutrients

- Combined protocols: Simultaneous intravenous and oral tracers (e.g., dual calcium isotopes) can differentiate between absorption and endogenous secretion [29]

Sample Collection: Blood samples are most commonly collected, but urine, breath, saliva, and tissue biopsies may also be obtained depending on the metabolic pathway under investigation. Sampling frequency ranges from minutes to hours or days, determined by the kinetics of the traced metabolite [23].

Protocol for Stable Isotope Tracer Infusion Study

The following protocol outlines a standardized approach for conducting stable isotope tracer infusion studies in human subjects:

- Pre-Study Preparation

- Secure ethical approval and informed consent

- Screen participants for eligibility based on study objectives

- Prepare isotope tracer solutions ensuring pharmaceutical grade purity and sterility

- Calibrate infusion pumps and prepare sampling equipment

- Baseline Sample Collection

- Collect pre-dose blood, urine, or other samples to determine background isotopic enrichment

- Record baseline physiological parameters (weight, height, vital signs)

- Tracer Administration

- For intravenous studies: Insert venous catheter for tracer infusion and a separate catheter for blood sampling to avoid contamination

- Prime the infusion tubing with tracer solution to ensure immediate delivery

- Initiate tracer infusion at a constant rate using a calibrated pump

- For oral administration: Administer the isotope tracer with or without a test meal under standardized conditions

- Sample Collection During Tracer Administration

- Collect biological samples at predetermined time points during the infusion period

- Process samples appropriately for subsequent analysis (e.g., plasma separation, storage at -80°C)

- Record exact sampling times relative to the start of tracer administration

- Sample Analysis

- Extract the analyte of interest from biological samples

- Derivatize if necessary for gas chromatography mass spectrometry (GC/MS) analysis

- Measure isotopic enrichment using GC/MS or liquid chromatography mass spectrometry (LC/MS)

- Calculate tracer-to-tracee ratios (TTR) or mole percent excess (MPE) [23]

- Kinetic Calculations

- Apply appropriate mathematical models to calculate metabolic kinetics based on isotopic enrichment patterns

- Common parameters include rate of appearance (Ra), fractional synthesis rate (FSR), and clearance rate [23]

Figure 1: Experimental workflow for human isotope tracer studies

Specialized Protocol: Dual Isotope Method for Mineral Absorption

The dual isotope method provides a comprehensive approach for assessing mineral bioavailability, particularly useful for minerals like calcium, iron, and zinc:

Isotope Selection: Choose two stable isotopes of the same mineral with different masses (e.g., calcium-42 and calcium-44) [29]

Administration:

- Administer one isotope orally with the test meal

- Simultaneously administer the second isotope intravenously

- Use precise dosing based on participant weight and isotope enrichment

Sample Collection: Collect blood samples at 0, 30, 60, 120, 240, and 360 minutes post-administration, and 24-hour urine collections for several days

Analysis:

- Separate minerals from biological matrices using chemical extraction

- Analyze isotopic ratios using inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry (ICP-MS)

- Correct for natural abundance and spectral interferences

- Calculation:

- Calculate fractional absorption from the ratio of oral and intravenous isotopes in urine or blood

- Determine endogenous excretion and compartmental distribution

Analytical Methodologies for Isotope Detection

Mass Spectrometry Techniques

Mass spectrometry represents the cornerstone technology for detecting stable isotopes in biological samples due to its high sensitivity, specificity, and precision [23]. The two primary approaches are:

Gas Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (GC/MS): This technique combines separation of complex mixtures by gas chromatography with mass detection. Samples must be volatile or chemically derivatized to increase volatility for GC analysis [23]. Within the mass spectrometer, ionization occurs typically through electron impact or chemical impact ionization, followed by separation of ions based on mass-to-charge ratio (m/z) in the mass analyzer [23]. The abundance of specific ions is detected, allowing calculation of isotopic enrichment.

Liquid Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (LC/MS): This approach uses liquid chromatography for separation, making it suitable for compounds that are not easily volatilized. LC/MS has become increasingly popular for analyzing larger molecules, polar compounds, and thermally labile substances without requiring derivatization.

The selection of specific ion fragments for monitoring is critical for accurate enrichment measurements. Ions should be unique to the analyte of interest and contain the atoms that were isotopically labeled [23].

Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) Spectroscopy

While mass spectrometry detects mass differences between isotopes, NMR spectroscopy exploits the magnetic properties of certain nuclei, such as carbon-13. NMR provides complementary structural information about metabolites and can track the position-specific incorporation of isotopes within molecules. This is particularly valuable for understanding metabolic pathways where the position of the labeled atom provides information about specific enzymatic reactions.

Table 2: Comparison of Analytical Techniques for Isotope Detection

| Technique | Principles | Applications in Bioavailability | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| GC/MS | Separation by volatility, detection by mass | Amino acid kinetics, carbohydrate metabolism, fatty acid oxidation | High sensitivity, well-established methods | Requires volatile compounds or derivatization |

| LC/MS | Separation by polarity, detection by mass | Protein turnover, vitamin metabolism, complex lipids | No derivatization needed, handles polar compounds | More complex ionization, potential matrix effects |

| ICP-MS | Ionization in plasma, elemental detection | Mineral absorption studies (Ca, Fe, Zn, Se) | Excellent for elemental analysis, very low detection limits | Does not distinguish molecular forms without separation |

| NMR | Magnetic properties of nuclei | Metabolic pathway mapping, position-specific isotope tracing | Non-destructive, provides structural information | Lower sensitivity than MS, requires higher isotope enrichment |

Applications in Nutrient Bioavailability Research

Mineral Bioavailability Studies

Isotopic tracers have revolutionized our understanding of mineral absorption and metabolism, providing critical data for establishing dietary requirements and developing fortification strategies:

Calcium Metabolism: Stable calcium isotopes (e.g., calcium-42, -44, -46, -48) enable precise measurement of calcium absorption, endogenous excretion, and bone turnover [29]. Using simultaneous oral and intravenous administration of different calcium isotopes, researchers can investigate how various factors such as age, pregnancy, lactation, and dietary composition affect calcium bioavailability [29]. This approach has been particularly valuable in osteoporosis research, revealing how nutritional calcium influences bone remodeling and calcium balance under different physiological conditions [29].

Iron Bioavailability: Stable iron isotopes (iron-54, -57, -58) provide a safe method for studying iron absorption in vulnerable populations, including children and pregnant women [29]. These studies have elucidated how dietary inhibitors (phytic acid, polyphenols) and enhancers (ascorbic acid, meat factors) influence non-heme iron absorption [24]. The double isotope technique, using two different iron isotopes administered with and without a test meal, allows for within-subject comparisons of iron bioavailability from different dietary sources or processing methods.

Zinc and Other Trace Minerals: Similar approaches using stable isotopes have been applied to zinc, copper, selenium, and other essential trace minerals, generating critical data on their absorption kinetics and metabolic utilization [29].

Macronutrient Metabolism

Stable isotopes provide unique insights into the dynamic aspects of macronutrient metabolism:

Protein Turnover: Amino acids labeled with nitrogen-15, carbon-13, or deuterium allow quantification of whole-body protein turnover and tissue-specific protein synthesis and breakdown rates [23]. These techniques have revealed how dietary protein quality, physical activity, aging, and disease states influence protein metabolism. The fundamental approach involves administering a labeled amino acid and measuring its incorporation into body proteins or appearance as oxidation products.

Carbohydrate Metabolism: Glucose labeled with carbon-13 or deuterium enables investigation of glucose production, disposal, and oxidation [23]. These studies have advanced our understanding of metabolic adaptations in conditions such as diabetes, obesity, and intensive exercise. For example, the use of [1-¹³C]glucose in conjunction with NMR spectroscopy can track glycogen synthesis rates in human liver and muscle [29].

Lipid Metabolism: Fatty acids labeled with carbon-13 or deuterium allow tracing of fatty acid oxidation, incorporation into different lipid fractions, and measurement of lipid kinetics. These approaches have elucidated how dietary fatty acids are partitioned between storage and oxidation, and how this partitioning is altered in metabolic disorders.

Figure 2: Metabolic pathways traced using isotope-labeled nutrients

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Successful execution of isotope tracer studies requires specialized reagents and materials designed to maintain isotopic integrity and ensure accurate measurements:

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Isotope Tracer Studies

| Reagent/Material | Specifications | Application in Research |

|---|---|---|

| Stable Isotope Tracers | Pharmaceutical grade, >98% isotopic purity, sterile and pyrogen-free for human administration | Metabolic tracing of specific nutrients [29] |

| Isotope-Labeled Compounds | Position-specific labeling (e.g., [1-¹³C]glucose, 6,6-²H₂-glucose) with known chemical and isotopic purity | Pathway-specific metabolic studies [23] |

| Calibrated Infusion Pumps | Precision pumps with minimal pulsation, calibrated for accurate delivery rates | Controlled administration of isotope tracers [23] |

| Sample Collection Equipment | Evacuated blood collection tubes, catheters, urine containers | Biological sample acquisition without contamination |

| Derivatization Reagents | HPLC or GC grade reagents for sample preparation (e.g., pentaacetate derivative for glucose) | Preparing samples for GC/MS analysis [23] |

| Mass Spectrometry Standards | Certified reference materials with known isotopic composition | Instrument calibration and quality control [23] |

| Solid Phase Extraction Cartridges | Specific chemistries for analyte isolation (C18, ion exchange, mixed mode) | Sample cleanup and concentration before analysis |

| Isotope Ratio Standards | International measurement standards for specific elements | Accurate quantification of isotopic enrichment |

Data Analysis and Kinetic Modeling

The transformation of isotopic enrichment data into meaningful biological parameters requires appropriate mathematical models that describe the system's behavior:

Basic Kinetic Parameters

The fundamental parameters derived from isotope tracer studies include:

- Rate of Appearance (Ra): The entry rate of a substance into the circulation, calculated from the tracer dilution principle during constant tracer infusion [23]

- Fractional Synthesis Rate (FSR): The fraction of a pool that is synthesized per unit time, determined from the incorporation of labeled precursors into products [23]

- Clearance Rate: The volume of plasma completely cleared of a substance per unit time

- Compartmental Masses: The sizes of different metabolic pools within the body

Compartmental Modeling

Compartmental models represent the body as a series of interconnected pools (compartments) between which the traced substance moves. These models range from simple one-compartment systems to complex multi-compartment structures that more accurately represent biological reality. The model structure is determined by the sampling strategy, with more frequent sampling and multiple sampling sites enabling more complex model configurations.

Steady-State versus Non-Steady-State Models

The simplest kinetic analyses assume metabolic steady state, where production rates equal disposal rates, and pool sizes remain constant. However, many nutritional interventions and physiological states involve non-steady-state conditions, requiring more sophisticated modeling approaches that can account for changing pool sizes and flux rates.

Stable and radioactive isotope methodologies represent the gold standard for assessing nutrient bioavailability in human studies, providing unprecedented insights into the dynamic aspects of human metabolism. These techniques enable researchers to move beyond static measurements to kinetic analyses that reveal how nutrients are absorbed, distributed, metabolized, and excreted. The continued refinement of isotopic methods, coupled with advances in analytical technologies and modeling approaches, will further enhance our understanding of nutrient requirements and metabolism across different physiological states and population groups.

As the field progresses, the integration of isotopic tracer methodology with other 'omics' technologies (genomics, proteomics, metabolomics) promises to provide even more comprehensive understanding of the complex relationships between diet, metabolism, and health. These advances will support the development of more personalized nutritional recommendations and targeted interventions to address global malnutrition challenges.

Animal models serve as indispensable tools in bioavailability research, providing complex living systems to study the absorption, distribution, metabolism, and excretion (ADME) of nutrients and bioactive food compounds. Bioavailability represents the fraction of an ingested nutrient that is absorbed and becomes available for physiological functions or storage, while bioaccessibility refers to the amount of an ingested nutrient that is released from the food matrix and becomes potentially available for absorption [1] [30]. These concepts are fundamental to nutritional sciences and drug development, as they determine the efficacy of dietary components and pharmaceuticals.

The selection of appropriate animal models is crucial for generating translatable data in bioavailability studies. Researchers must consider anatomical, physiological, and metabolic similarities between animal species and humans, alongside practical considerations such as cost, lifespan, and ethical justifications [31]. This document provides a comprehensive framework for the application of animal models in bioavailability research, addressing their suitability, methodological protocols, limitations, and ethical considerations within the context of a broader thesis on nutritional assessment protocols.

Suitability of Different Animal Models

The choice of animal model significantly influences the validity and translational potential of bioavailability research findings. Different models offer distinct advantages and limitations based on their physiological resemblance to humans, handling characteristics, and ethical considerations.

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Animal Models in Bioavailability Research

| Animal Model | Key Advantages | Major Limitations | Common Applications in Bioavailability |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mouse (Mus musculus) | Short lifespan enabling generational studies; cost-effective; extensive genomic tools [31] [32] | Small size limits blood and tissue sampling; significant metabolic differences from humans [31] | Preliminary screening of nutrient absorption; genetic studies using transgenic models [33] |

| Rat (Rattus norvegicus) | Larger size than mice for easier sampling; well-established physiological data; cost-effective [31] | Not ideal for inflammation studies; limited genetic diversity in inbred strains [31] | Mineral (iron, zinc, calcium) bioavailability; polyphenol and phytochemical metabolism [31] |

| Guinea Pig (Cavia porcellus) | Similar cholesterol metabolism to humans; suitable for asthma and tuberculosis research [31] | High phenotypic variations; limited infectious disease models for some pathogens [31] | Vitamin C bioavailability studies (as they require dietary Vitamin C like humans) [31] |

| Zebrafish (Danio rerio) | High regenerative capacity; rapid development; transparent embryos for visualization [31] | Less physiological resemblance to humans; small size [31] | Early-stage nutrient uptake studies; genetic screening of metabolic pathways [31] |

| Non-Human Primates | Close phylogenetic relationship to humans; similar genetic, biochemical, and psychological activities [31] | Significant ethical constraints; high cost; long maturity period; specialized housing needs [31] | Critical translational studies for vaccines and complex drug metabolism [31] |

Criteria for Model Selection

Choosing an appropriate animal model requires systematic evaluation of several factors:

- Physiological and Pathophysiological Resemblance: The model should replicate key aspects of human digestion, absorption, and metabolism relevant to the nutrient or compound under investigation [31]. For instance, pigs share remarkable similarities with humans in gastrointestinal anatomy and function, making them valuable for certain bioavailability studies.

- Genetic Considerations: Transgenic animal models, produced by incorporating genetic information directly into embryos via foreign DNA injection or retroviral vectors, enable researchers to study specific metabolic pathways or humanized physiological processes [31] [33].

- Practical Constraints: Factors such as animal availability, size, lifespan, housing requirements, and cost must align with research objectives and resources [31]. Small rodents are often preferred for initial screening due to their cost-effectiveness and short reproductive cycles, while larger animals may be necessary for advanced stages of research.

- Ethical Compliance: The principle of the 3Rs (Replacement, Reduction, Refinement) must guide model selection, prioritizing species with lower neurophysiological capacity when scientifically justified [34] [32] [35].

Limitations and Challenges in Translation

Despite their utility, animal models present significant challenges that can compromise the translatability of research findings to human contexts.

Biological and Methodological Constraints

- Species-Specific Variations: Fundamental differences in genetics, gut microbiota, digestive physiology, and metabolic pathways between animals and humans can lead to divergent outcomes in bioavailability studies [36]. For example, a compound that shows promise in animal models may not be beneficial in humans due to these variations [36].

- Artificial Disease Induction: Many models rely on artificially induced disease states (e.g., chemically induced diabetes or fibrosis) that may not accurately replicate the natural progression or complexity of human conditions [36] [37]. The Streptozotocin (STZ)-induced diabetes model, while producing clinical features resembling human diabetes, faces challenges due to the physiochemical properties and toxicities of STZ that can cause animal mortality [31].

- Genetic Homogeneity: Laboratory animals are often inbred, resulting in genetic uniformity that fails to represent the diversity of human populations [31] [36]. This limitation is particularly relevant for nutritional studies, where inter-individual variability in bioavailability is common due to genetic polymorphisms, gut microbiome composition, and environmental factors [1] [33].

Historical Failures in Translation

Several notable cases highlight the limitations of animal models in predicting human responses:

- Thalidomide: In the 1950s, animal testing failed to predict the severe birth defects caused by thalidomide in humans, as the species used (particularly mice) were less sensitive to the drug's teratogenic effects [36].

- TGN1412 Therapeutic Antibody: A potentially fatal immune response in humans was not predicted by prior testing in non-human primates, despite their close evolutionary relationship to humans [36].

- Monoclonal Antibodies for Cancer: Preclinical trials of monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) in animal models are required for clinical application, yet mAbs are often less adapted to animal studies, creating translational challenges [31].

These cases underscore the critical need for careful interpretation of animal data and the development of more human-relevant models.

Ethical Considerations and Evolving Standards

The use of animals in research involves significant ethical considerations that have evolved into structured frameworks and regulations.

The 3Rs Principle and Ethical Oversight

The foundational framework for ethical animal research is the 3Rs principle:

- Replacement: Use of non-animal alternatives (e.g., in vitro models, computer simulations) whenever scientifically feasible [31] [34] [35]. This includes emerging technologies such as organ-on-a-chip systems and advanced computer modeling [34] [35].

- Reduction: Minimizing the number of animals used while maintaining statistical validity, achieved through improved experimental design, sharing of data and resources, and use of advanced imaging techniques that allow longitudinal studies in the same animals [31] [32] [35].

- Refinement: Modifying procedures to minimize pain, suffering, and distress, and enhancing animal welfare throughout their lifetime [31] [34] [32]. This includes improved housing conditions, better anesthesia and analgesia protocols, and humane endpoints.

All animal research protocols must receive approval from institutional animal care and use committees or ethics committees, which evaluate the justification for animal use and ensure compliance with the 3Rs [34] [32].

Evolving Ethical Standards (2024-2025)