Protein vs. DNA: A Comparative Analysis of Food Allergen Detection Methods for Biomedical Research

This article provides a comprehensive comparative analysis of protein-based and DNA-based methods for food allergen detection, a critical area for food safety and public health.

Protein vs. DNA: A Comparative Analysis of Food Allergen Detection Methods for Biomedical Research

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive comparative analysis of protein-based and DNA-based methods for food allergen detection, a critical area for food safety and public health. Tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it explores the fundamental principles, advantages, and limitations of immunological assays (e.g., ELISA, lateral flow) and mass spectrometry versus nucleic acid techniques (e.g., PCR, LAMP, real-time PCR). The scope extends to methodological applications, troubleshooting for complex food matrices, optimization strategies to overcome technological limitations, and a rigorous validation framework for method selection. The analysis synthesizes current research trends, including biosensors and high-throughput technologies, to guide future innovations in allergen detection and clinical diagnostics.

Core Principles and the Evolving Landscape of Food Allergen Detection

Food allergy has emerged as a critical public health challenge worldwide, with documented prevalence increases across multiple continents. In China, infant food allergy incidence rose from 7.7% in 2009 to 11.1% in 2019, while similar upward trends are observed in the United States, United Kingdom, and Europe [1] [2]. This rising prevalence, coupled with the potential severity of allergic reactions including life-threatening anaphylaxis, has intensified the focus on reliable allergen detection methods for protective public health measures [1] [3].

With no specific treatment currently available for food allergies, strict avoidance of allergenic foods remains the primary preventive strategy [1]. This approach depends entirely on accurate food labeling, which in turn relies on robust detection methodologies to verify allergen presence [4]. Regulatory frameworks globally have responded by implementing mandatory allergen labeling requirements for major allergens, with the European Union's regulation (EU) No 1169/2011 expanding its list to 14 key allergenic foods including celery, sesame, mustard, lupin, and mollusks alongside traditional allergens [5].

This article provides a comparative analysis of two fundamental allergen detection approaches: protein-based methods (including ELISA and mass spectrometry) and DNA-based methods (primarily PCR-based techniques), examining their performance characteristics, limitations, and appropriate applications within the context of rising public health demands and regulatory compliance needs.

Methodological Approaches: Fundamental Principles and Techniques

Protein-Based Detection Methods

Protein-based methods directly target the allergenic proteins themselves and represent the current mainstream approach for food allergen detection [1]. These techniques include:

Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay (ELISA): This immunological method uses antibodies specific to allergenic proteins and is characterized by high sensitivity, strong specificity, and multi-detection capability [1]. ELISA is recognized as the gold standard for routine allergen screening due to its cost-effectiveness and reliability across various food matrices [4]. The Codex Alimentarius Commission has adopted ELISA as the official test for gluten allergens, setting a threshold of 20 mg/kg for gluten in foods [1].

Mass Spectrometry (MS): LC-MS/MS methods detect and quantify specific allergen proteins by targeting proteotypic peptides unique to each allergen, offering high specificity and the ability to detect multiple allergens simultaneously (multiplexing) [6]. Mass spectrometry is particularly valuable for complex matrices and provides new levels of precision compared to other methods [6].

DNA-Based Detection Methods

DNA-based methods, primarily polymerase chain reaction (PCR) techniques, target allergen-encoding genes rather than the proteins themselves [1]. These methods offer particular advantages for detecting allergens in highly processed foods where proteins may be denatured but DNA remains stable [5]. Key DNA-based approaches include:

Quantitative PCR (qPCR): Enables quantification of allergen DNA through real-time amplification monitoring, with detection sensitivity down to 1 ppm of spiked protein in various food matrices [5].

Loop-Mediated Isothermal Amplification (LAMP): Provides rapid detection without requiring thermal cycling equipment, making it suitable for field applications [1].

Digital PCR and Saltatory Rolling Circle Amplification: Emerging techniques offering enhanced sensitivity and specificity for challenging applications [1].

Comparative Performance Analysis: Experimental Data and Validation

Sensitivity and Detection Limits

Table 1: Sensitivity Comparison Between Protein-Based and DNA-Based Methods

| Method | Detection Limit | Representative Allergens Detected | Experimental Matrix |

|---|---|---|---|

| ELISA | Parts per million (ppm) levels | Gluten, milk, egg, peanut, soy [4] | Processed foods, raw ingredients [4] |

| Mass Spectrometry | As low as 0.01 ng/mL [6] | Peanut (Ara h 3, Ara h 6), milk (Bos d 5), egg (Gal d 1, Gal d 2) [6] | Complex food matrices [6] |

| qPCR | 1 ppm spiked protein [5] | Celery, wheat, maize [5] [7] | Five AOAC food matrix groups [5] |

| Novel PCR Methods | Detection after 220°C/60min baking [7] | Wheat HMW-GS, LMW-GS, maize Zea m 14, Zea m 8, zein [7] | Baked goods, processed foods [7] |

Matrix Effects and Processing Impacts

Food matrix composition significantly influences method performance. A 2024 comparative study of DNA-based celery detection kits found a clear matrix effect across five product groups ((plant-based) meat products, snacks, sauces, dried herbs and spices, and smoothies), despite all kits performing according to specifications [5]. Quantitative performance proved challenging in all food product groups using DNA-based quantification methods [5].

Processing conditions, particularly thermal treatment, dramatically affect detection capability. Protein-based methods may fail when allergenic proteins are denatured by high temperatures, while DNA-based methods face challenges from DNA fragmentation. Research demonstrates that DNA integrity decreases with increasing processing temperature and time, with optimal PCR amplification requiring shorter amplicons (∼200–300 bp) in processed foods [7].

Table 2: Impact of Food Processing on Allergen Detection Methods

| Processing Condition | Effect on Protein-Based Methods | Effect on DNA-Based Methods | Experimental Evidence |

|---|---|---|---|

| Thermal Processing (Baking 180-220°C) | Protein denaturation reduces antibody recognition [5] | DNA degradation requires shorter amplicons (200-300 bp) [7] | Wheat/maize DNA detectable after 60min at 220°C with optimized primers [7] |

| Highly Processed Matrices | Potential epitope destruction limits antibody binding [5] | Higher DNA stability maintains detectability [5] | DNA methods effective for thermally processed foods where proteins denatured [5] |

| Complex Matrices (Sauces, Spices) | Component interference with antibody binding [5] | PCR inhibitors affect amplification efficiency [5] | Clear matrix effect observed in celery detection across 5 product groups [5] |

Quantitative Performance and Regulatory Application

Quantification represents a particular challenge for DNA-based methods. The 2024 celery detection study noted that conversion of DNA results leads to overestimation of the amount of celery, indicating that DNA-based quantification requires optimization for reliable risk management decisions [5]. This limitation is significant in regulatory contexts where precise threshold adherence is mandatory.

Protein-based methods, particularly ELISA, are widely adopted in regulatory frameworks due to their reliable quantification capabilities. Japan recognizes both ELISA and PCR as official testing methods with a defined food allergen threshold of 10 μg/g, while the Codex Alimentarius specifies 20 mg/kg for gluten based on ELISA testing [1].

Method Selection Framework: Technical Considerations

Experimental Workflows

The fundamental methodological differences between protein-based and DNA-based approaches necessitate distinct experimental workflows:

Decision Framework for Method Selection

The choice between protein-based and DNA-based methods depends on multiple experimental factors:

Research Reagent Solutions: Essential Materials and Tools

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Allergen Detection Methods

| Reagent/Material | Function | Application Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Allergen-Specific Antibodies | Binds specifically to target allergenic proteins for detection | ELISA for gluten, peanut, milk proteins [4] |

| CTAB Buffer | Cell lysis and DNA stabilization during extraction | DNA extraction from celery, wheat, maize [5] [7] |

| Proteinase K | Protein digestion for DNA purification or protein analysis | Sample preparation in DNA extraction and MS analysis [5] |

| TaqMan Probes & Primers | Sequence-specific DNA detection in qPCR | Celery detection with Cel-MDH primers/probe [5] |

| Trypsin | Protein digestion for mass spectrometric analysis | Generation of proteotypic peptides for LC-MS/MS [6] |

| Reference Allergen Standards | Quantification and method calibration | Certified reference materials for allergen quantification [5] |

Emerging technologies are poised to transform the allergen detection landscape. Biosensors showing promise for rapid, on-site detection are being developed with high sensitivity and specificity [1]. AI-enhanced methods including hyperspectral imaging and FTIR spectroscopy enable non-destructive, real-time allergen detection without compromising food integrity [6]. Additionally, multiplexed platforms capable of simultaneously detecting multiple allergens address the growing need for comprehensive screening approaches [6].

The future of allergen detection lies in integrating complementary methodologies to leverage their respective strengths while mitigating limitations. As detection technologies evolve alongside increasing regulatory scrutiny and public health demands, the development of accurate, reliable, and accessible allergen detection platforms remains crucial for protecting susceptible populations worldwide.

For researchers and food safety professionals, selecting the optimal allergen detection method is critical for accurate risk assessment and regulatory compliance. The core challenge lies in choosing between two fundamental approaches: protein-based methods, which directly detect the allergenic molecules themselves, and DNA-based methods, which identify the genetic material encoding these proteins. Protein-based techniques, including Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay (ELISA) and mass spectrometry, are the established standard for directly measuring allergenic proteins, the very compounds that trigger immune responses in sensitive individuals [1] [8]. However, the evolving complexity of food matrices and processing techniques demands a thorough comparative analysis to guide methodological selection. This guide provides an objective, data-driven comparison of protein-based detection with DNA-based alternatives, focusing on performance characteristics, experimental protocols, and suitability for different research and quality control scenarios.

Performance Comparison: Protein-Based vs. DNA-Based Methods

The choice between protein-based and DNA-based detection methods involves a careful trade-off between directness, sensitivity, and robustness to food processing. The table below summarizes the core characteristics of each approach.

Table 1: Core Characteristics of Allergen Detection Methodologies

| Feature | Protein-Based Methods | DNA-Based Methods |

|---|---|---|

| Target Analyte | Allergenic proteins (e.g., Gly m 5 in soybean, Tri a 19 in wheat) [9] | DNA sequences encoding allergenic proteins or species-specific genes [1] [9] |

| Directness | Directly measures the causative agent of the allergic reaction [8] | Indirect; infers allergen presence via genetic material [8] |

| Key Advantage | High biological relevance; can correlate with allergenic potential [8] | Superior stability of DNA in processed foods; high sensitivity and specificity [10] [1] |

| Key Limitation | Susceptible to protein denaturation and epitope masking from processing, leading to potential false negatives [9] [8] | Does not directly quantify the allergenic protein; results can be influenced by gene copy number variation [8] |

Beyond these fundamental differences, the practical performance of these methods varies significantly in terms of sensitivity, throughput, and operational requirements.

Table 2: Performance and Operational Comparison

| Performance Metric | Protein-Based Methods | DNA-Based Methods |

|---|---|---|

| Typical Sensitivity | ppm (mg/kg) to low ppb (μg/kg) levels [1] [11] | Can detect down to 1-10 pg/μL of genomic DNA or 0.1% (w/w) of allergenic material [12] [13] [11] |

| Multiplexing Capability | Possible with advanced techniques like multiplex immunoassays or mass spectrometry [8] | Possible with real-time PCR arrays or isothermal amplification, but often requires multiple parallel reactions [9] |

| Throughput | High for ELISA; lower for MS-based methods | High for PCR and isothermal amplification |

| Cost & Expertise | ELISA is relatively low-cost; MS requires expensive instrumentation and specialized expertise [9] | Requires thermocyclers (for PCR) or precise heating blocks; expertise in molecular biology needed |

| Standardization | Well-established as official methods (e.g., ELISA for gluten by Codex Alimentarius) [1] | Recognized as official methods in several countries (e.g., Germany, Japan) [1] |

Experimental Data and Validation

Quantitative Data from Comparative Studies

Independent studies and proficiency testing schemes provide critical insights into the real-world performance of these methods. For instance, a comparative assessment of commercial DNA test kits for celery allergen detection highlighted that while they performed according to specifications, a clear matrix effect was observed across different food product groups, and quantitative performance remained challenging [12]. This underscores that claimed sensitivity can be significantly impacted by the food matrix.

The UK Food Standards Agency's extensive literature review on allergen testing methodologies further confirms that the performance of commercial ELISA and PCR kits can vary, with limits of detection (LOD) and quantitation (LOQ) being periodically updated by manufacturers. This makes direct, time-independent kit-to-kit comparisons difficult [11].

Impact of Food Processing

Food processing is a major factor influencing method selection. Thermal and non-thermal processing can induce protein denaturation, aggregation, and chemical modification (e.g., Maillard reaction), which can mask or destroy antibody-binding epitopes [8]. This can lead to false negatives in protein-based assays like ELISA [9].

In contrast, DNA is generally more stable during processing. However, it is not immune to degradation. A study on wheat and maize demonstrated that while genomic DNA degrades with high-temperature baking (e.g., 220°C for 60 minutes), PCR detection remains possible by targeting short, stable DNA fragments (∼200–300 bp) [10]. This principle is leveraged in novel isothermal amplification methods. For example, the duplex Proofman-LMTIA method developed for soybean and wheat allergen detection achieved a sensitivity of 10 pg/μL genomic DNA and was effective in processed commercial products, whereas a standard LAMP method produced false positives [9].

Experimental Protocols in Practice

Key Workflows

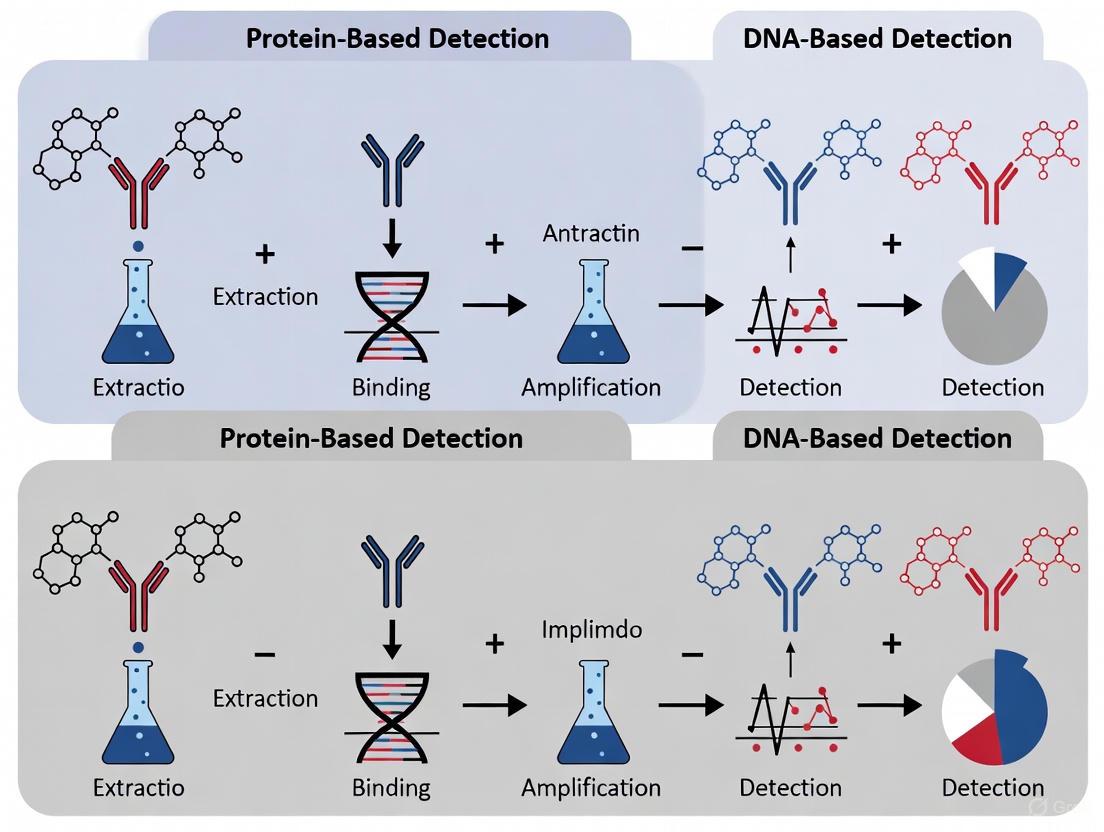

The fundamental workflows for protein-based and DNA-based detection differ significantly, from sample preparation to final analysis. The following diagram outlines the key steps for the primary methodologies in each category.

Detailed Methodological Protocols

Protein-Based Protocol: ELISA for Allergen Quantification

The ELISA is a cornerstone protein-based method. A typical sandwich ELISA protocol involves:

- Coating: A multi-well plate is coated with a capture antibody specific to the target allergen.

- Blocking: The plate is blocked with a protein buffer (e.g., BSA or casein) to prevent non-specific binding.

- Incubation with Sample: The extracted food sample and a series of allergen standards of known concentration are added to separate wells.

- Incubation with Detection Antibody: A second antibody, specific to a different epitope on the same allergen and conjugated to an enzyme (e.g., Horseradish Peroxidase, HRP), is added.

- Signal Development: A substrate solution is added, which the enzyme converts to a colored product.

- Quantification: The reaction is stopped, and the absorbance is measured. The allergen concentration in the sample is determined by interpolation from the standard curve [1].

DNA-Based Protocol: PCR Detection in Processed Foods

For detecting allergens in processed foods, a robust DNA extraction and amplification protocol is critical. A representative protocol from a study on wheat and maize is as follows [10]:

DNA Extraction:

- Sample Preparation: 100 mg of processed sample (e.g., baked dough ground to a flour-like consistency) is used.

- Lysis: The sample is incubated with CTAB buffer and proteinase K at 65°C.

- Purification: Treatment with RNase A, followed by chloroform extraction.

- Precipitation: DNA is precipitated with a CTAB solution, re-dissolved in NaCl, and re-extracted with chloroform.

- Final Precipitation & Dissolution: DNA is precipitated with isopropanol, washed with 70% ethanol, air-dried, and finally dissolved in 100 μL sterile deionized water.

- Quality Control: DNA concentration and purity are assessed using a UV-Vis spectrophotometer (A260/A280 ratio).

PCR Amplification:

- Primer Design: Primers are designed to target short, stable fragments (~200-300 bp) of the allergen-encoding genes (e.g., HMW-glutenin for wheat, Zea m 14 for maize).

- Reaction Setup: The PCR mixture includes the extracted DNA template, specific primers, dNTPs, and a DNA polymerase.

- Amplification: The reaction is run in a thermal cycler with optimized cycles of denaturation, annealing, and extension.

- Analysis: PCR products are analyzed via agarose gel electrophoresis to confirm the presence and size of the amplicon.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Successful allergen detection relies on a suite of specialized reagents and tools. The following table details key items used in the featured experiments and their critical functions.

Table 3: Essential Reagents and Materials for Allergen Detection Research

| Reagent / Material | Function | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| CTAB (Cetyltrimethyl ammonium bromide) Buffer | A detergent-based lysis buffer for efficient plant cell wall breakdown and DNA extraction, particularly from complex, polysaccharide-rich matrices. [10] | DNA extraction from wheat and maize flour and baked goods. [10] |

| Bst DNA Polymerase | An enzyme with strong strand displacement activity, essential for isothermal amplification methods like LAMP and LMTIA. It operates at a constant temperature, negating the need for a thermal cycler. [9] | Used in Proofman-LMTIA for rapid, on-site detection of soybean and wheat allergens. [9] |

| Proteinase K | A broad-spectrum serine protease that degrades proteins and inactivates nucleases during DNA extraction, thereby protecting the target DNA from degradation. [10] | Sample incubation step in CTAB-based DNA extraction protocols. [10] |

| Specific Primers & Probes | Short, single-stranded DNA sequences designed to bind complementarily to a unique segment of the target allergen gene, ensuring high detection specificity. [10] [9] | Targeting the Lectin gene for soybean and the GAG56D gene for wheat in duplex Proofman-LMTIA. [9] |

| Hydroxynaphthol Blue (HNB) / Cresol Red (CR) | Metalochromic and pH-sensitive dyes, respectively, used for visual, colorimetric detection of LAMP amplicons without needing to open the reaction tube, reducing contamination risk. [13] | Pre-added to LAMP reactions; a color change (e.g., purple-to-blue for HNB) indicates a positive amplification. [13] |

| Capture & Detection Antibodies (ELISA) | The core components of an ELISA kit. The capture antibody immobilizes the target allergen, while the enzyme-conjugated detection antibody generates a measurable signal, enabling highly specific protein quantification. [1] | Commercial ELISA kits for gluten detection, officially adopted by the Codex Alimentarius. [1] |

The comparative analysis clearly indicates that there is no single superior method for all allergen detection scenarios. The choice between protein-based and DNA-based detection is context-dependent. Protein-based methods like ELISA are indispensable when the goal is direct quantification of the allergenic protein, providing the most biologically relevant data for risk assessment, especially in raw or minimally processed foods. However, for highly processed foods where proteins may be denatured, DNA-based methods (PCR, LAMP, LMTIA) offer a more robust and sensitive alternative due to the greater stability of DNA. Emerging technologies like multiplex allergen microarrays [8] and isothermal amplification with visual detection [13] [9] are pushing the boundaries of multiplexing, speed, and ease of use. The optimal strategy for researchers and industry professionals often involves a complementary use of both techniques, leveraging the strengths of each to ensure the highest level of accuracy and consumer protection in allergen management.

Food allergy has become a significant global public health issue, with increasing prevalence worldwide and no specific treatment available beyond strict avoidance of allergenic foods [1]. This reality places critical importance on accurate food allergen detection for effective regulatory compliance and consumer protection. Within this landscape, two primary analytical approaches have emerged: protein-based methods that directly detect allergenic proteins, and DNA-based methods that take an indirect approach by targeting species-specific genetic markers [1]. While protein-based methods like ELISA (Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay) detect the actual allergenic molecules, DNA-based techniques identify the genetic blueprint that signals the potential presence of these allergens, making them particularly valuable when proteins have been denatured during food processing [1] [5].

The fundamental distinction between these approaches lies in their analytical targets. Protein-based methods detect the causative agents of allergic reactions but face challenges when protein structures are altered during food processing. In contrast, DNA-based methods exploit the greater stability of DNA molecules under harsh processing conditions, providing an indirect but highly reliable indicator of allergenic ingredient presence [5]. This article provides a comprehensive comparative analysis of DNA-based detection methodologies, their operational principles, and their performance relative to protein-based approaches in food allergen analysis.

Fundamental Principles of DNA-Based Detection

Genetic Markers as Detection Targets

DNA-based allergen detection operates on the principle of identifying unique, species-specific genetic sequences that serve as markers for the presence of allergenic ingredients. Unlike protein-based methods that target the allergenic molecules themselves, DNA-based approaches detect the genetic material from the allergenic source, providing an indirect confirmation of potential allergen presence [1] [14].

The core advantage of this strategy lies in the inherent stability of DNA molecules. DNA typically retains its molecular integrity better than proteins through various food processing treatments, including high-temperature operations [1] [5]. This stability makes DNA-based detection particularly effective for analyzing highly processed foods where protein structures may have been denatured or altered, compromising antibody recognition in immunoassays [1].

Key Genetic Marker Technologies

Several DNA marker technologies have been adapted for food allergen detection, each with distinct characteristics and applications:

PCR-Based Methods: Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR), particularly quantitative PCR (qPCR), represents the most widely utilized DNA-based approach for allergen detection. These methods amplify and detect specific DNA sequences unique to allergenic sources, providing both qualitative identification and quantitative assessment [1] [5]. qPCR has been adopted as an official analytical tool for food allergen detection in several countries, including Germany and Japan [1].

DNA Biosensors: Emerging DNA-based biosensors incorporate functional DNA strands (such as aptamers), DNA hybridization systems, or DNA templates as recognition elements. These platforms offer advantages including rapid detection, high sensitivity, and potential for on-site analysis when combined with technologies like microfluidics [1] [15] [14].

Isothermal Amplification Methods: Techniques like loop-mediated isothermal amplification (LAMP) and closed-tube saltatory rolling circle amplification provide alternatives to traditional PCR, enabling rapid detection without complex thermal cycling equipment [1]. These methods are particularly suited for point-of-care testing scenarios.

The following workflow illustrates the typical process for DNA-based allergen detection:

Comparative Analysis: DNA-Based vs. Protein-Based Methods

Performance Characteristics Across Methodologies

The selection between DNA-based and protein-based allergen detection methods depends on multiple factors including the food matrix, processing methods, required sensitivity, and regulatory context. The table below summarizes the key characteristics of each approach:

Table 1: Comparison of Food Allergen Detection Methods

| Parameter | DNA-Based Methods (PCR) | Protein-Based Methods (ELISA) | Biosensors (Emerging) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Target | Species-specific DNA sequences | Allergenic protein structures | Varies (DNA, protein, or both) |

| Detection Principle | Nucleic acid amplification and detection | Antigen-antibody interaction | Signal transduction from biorecognition event |

| Sensitivity | High (capable of detecting trace DNA) | High (capable of detecting trace proteins) | Variable (potentially very high) |

| Effect of Food Processing | More stable to thermal processing | Protein denaturation may affect detection | Depends on recognition element |

| Quantification | Indirect correlation with allergen amount | Direct measurement of protein | Variable depending on design |

| Specificity | High species specificity | Potential cross-reactivity with related proteins | Can be highly specific |

| Detection Time | 2-4 hours (including DNA extraction) | 1-2 hours | Minutes to hours |

| Throughput | Moderate to high | High | Potentially high |

| Cost | Moderate | Moderate | Varies widely |

| Regulatory Acceptance | Official method in some countries (e.g., Germany, Japan) | Widely accepted (reference method for some allergens) | Emerging validation |

Detection Limits and Matrix Effects

Comparative studies have demonstrated that the performance of DNA-based methods varies significantly across different food matrices and allergen sources. Research on celery detection using commercial DNA-based test kits revealed that while these kits could detect celery DNA down to 1 ppm spiked protein in five different product groups, a clear matrix effect was observed across different food types [5]. The study evaluated products representing different segments of the AOAC food-matrix triangle, including meat products, snacks, sauces, dried herbs and spices, and smoothies.

Notably, quantification of celery content proved challenging across all food product groups using DNA-based quantification methods, with converted DNA results frequently leading to overestimation of the actual celery amount [5]. This highlights a significant limitation of DNA-based approaches: the variable relationship between DNA content and allergenic protein content in different tissues and processing scenarios.

In comparison studies of detection limits, lateral flow immunoassays (LFI) often showed superior sensitivity for specific allergens, but DNA-based methods like the ATP+ADP+AMP (A3) test provided valuable alternatives for detecting food debris where specific LFIs are not commercially available [16]. The A3 test demonstrated preferable or comparable detection limits to LFIs for crustacean shellfish and for processed grains (with exceptions of wheat flour and buckwheat) [16].

Experimental Protocols in DNA-Based Allergen Detection

Standardized qPCR Protocol for Celery Detection

The following protocol, adapted from comparative kit assessment studies, outlines the standard methodology for DNA-based celery detection [5]:

Sample Preparation and DNA Extraction:

- Homogenize 30 mg of food sample in a 2 mL tube

- Add 1 mL of CTAB buffer, 40 μL of proteinase K (20 mg/mL), and 5 μL of RNase (100 mg/mL)

- Incubate for 90 minutes at 65°C to lyse cells and degrade proteins and RNA

- Centrifuge for 10 minutes at 16,000×g

- Transfer 300 μL of supernatant to a Maxwell cartridge

- Purify DNA using Maxwell RSC 48 instrument with PureFood GMO and authentication method

- Elute DNA in 100 μL elution buffer

- Quantify DNA concentration using spectrophotometry (e.g., Nanodrop 1000)

qPCR Amplification and Detection:

- Prepare reaction mix containing Taqman Universal Master Mix

- Add primers and probe targeting celery-specific markers (e.g., Cel-MDH sequences)

- Use final primer and probe concentrations of 300 nM and 200 nM, respectively

- Add 5 μL of diluted DNA sample (10 ng/μL) to 20 μL reaction mix

- Perform amplification with the following thermal profile:

- Initial steps: 2 minutes at 50°C, 10 minutes at 95°C

- 45 cycles of: 15 seconds at 95°C, 1 minute at 60°C

- Analyze amplification curves and determine Cq values

Data Interpretation:

- Compare Cq values to standard curve from known celery concentrations

- Account for matrix effects through appropriate controls

- Consider potential overestimation when converting DNA results to protein equivalents

Emerging DNA Biosensor Protocol

Advanced DNA-based biosensors are incorporating innovative materials and approaches:

Aptamer-Based Electrochemical Sensor Development:

- Immobilize thiol-modified DNA aptamers on gold electrode surfaces

- Alternatively, adsorb single-stranded DNA aptamers on graphene oxide (GO) surfaces through π-π stacking

- Functionalize aptamers with reporter molecules (methylene blue, ferrocene)

- Upon target binding, monitor conformational changes in aptamers through electrochemical impedance

- Detect signal changes proportional to target concentration [15]

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Table 2: Key Research Reagents for DNA-Based Allergen Detection

| Reagent/Material | Function | Examples/Specifications |

|---|---|---|

| CTAB Buffer | Lysis buffer for DNA extraction, helps remove polysaccharides and polyphenols | Contains cetyltrimethylammonium bromide, often with EDTA and sorbitol |

| Proteinase K | Proteolytic enzyme that degrades proteins and nucleases | Typically used at 20 mg/mL concentration |

| RNase A | Ribonuclease that removes contaminating RNA | Typically used at 100 mg/mL concentration |

| DNA Purification Kits | Isolation of high-quality DNA from complex matrices | Maxwell RSC PureFood GMO and Authentication Kit |

| Taq Polymerase | Enzyme for PCR amplification | Thermostable DNA polymerase with buffer system |

| qPCR Master Mix | Optimized mixture for quantitative PCR | Contains Taq polymerase, dNTPs, buffer, often with UDG prevention |

| Sequence-Specific Primers/Probes | Target recognition and amplification | Celery: Cel-MDH-iF/R/probe; Must be validated for specificity |

| DNA Molecular Markers | Size standards for electrophoresis | Typically 50-1000 bp range for fragment analysis |

| Reference Materials | Quality control and quantification | Certified reference materials with known allergen content |

Technological Advances and Future Perspectives

Emerging Trends in DNA-Based Detection

The field of DNA-based allergen detection continues to evolve with several promising technological developments:

Miniaturization and Microfluidics: Integration of DNA-based detection with microfluidic platforms enables assay miniaturization, reducing reagent consumption and analysis time while potentially enabling point-of-care testing [17]. These systems concentrate target molecules into small volumes or regions, enhancing signal strength and improving detection sensitivity [17].

Enhanced Signal Amplification: Novel nucleic acid amplification strategies including hybridization chain reaction (HCR) and catalytic hairpin assembly (CHA) provide enzyme-free signal amplification, improving sensitivity without requiring protein enzymes [15]. These methods enable exponential signal amplification through controlled, autonomous hybridization events.

DNA Nanotechnology: Programmable DNA nanostructures such as DNA tetrahedra and DNA origami provide precise spatial organization for recognition elements, improving binding efficiency and assay performance [15]. These structures offer remarkable addressability and adjustable rigidity for enhanced biosensing applications.

Multiplexing Capabilities: Advanced DNA-based platforms increasingly enable simultaneous detection of multiple allergens in a single reaction, addressing the complex nature of food matrices and potential cross-contamination scenarios [1] [14].

Integration Approaches and Method Selection

The future of food allergen detection likely lies in integrated approaches that leverage the complementary strengths of both DNA-based and protein-based methods. DNA-based techniques excel at specific identification of allergenic sources, particularly in processed foods, while protein-based methods directly quantify the allergenic molecules themselves [1] [3].

The following decision framework illustrates the method selection process:

For researchers and food safety professionals, method selection should consider the specific application context, with DNA-based methods providing critical advantages for specific scenarios but requiring careful interpretation in quantitative applications. As DNA-based technologies continue to advance, particularly in biosensing and miniaturization, their role in comprehensive allergen detection strategies is likely to expand significantly, offering enhanced capabilities for protecting allergic consumers through accurate food labeling and safety assurance.

Current Market Trends and the Dominance of Established Methodologies

The increasing global prevalence of food allergies has positioned food allergen testing as a critical component of modern food safety protocols, with the global market value projected to grow significantly from USD 970.3 million in 2025 to USD 2,062.6 million by 2035 [18]. Within this expanding landscape, a clear dichotomy exists between protein-based and DNA-based detection methodologies. Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay (ELISA) and Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR) have emerged as the dominant technologies, accounting for substantial market shares [19] [18]. This guide provides a comparative analysis of these established methodologies, examining their technical principles, performance under experimental conditions, and respective roles in current market trends. Designed for researchers and drug development professionals, it offers a detailed examination of the protocols and reagent solutions that underpin reliable allergen detection.

The food allergen testing market is characterized by steady growth, driven by rising allergy prevalence, stringent regulatory requirements, and increasing consumer demand for safe, accurately labeled food products [20] [18]. Within this framework, established methodologies maintain their dominance through proven reliability and continuous innovation.

Market Size and Growth Trajectory

- United States Market: Projected to reach US$ 451.58 million by 2033, growing at a CAGR of 7.00% from 2024 [20].

- Global Market: Expected to expand from USD 970.3 million in 2025 to USD 2,062.6 million by 2035, reflecting a CAGR of 7.8% [18].

- Technology Leadership: PCR-based testing leads the technology segment with a 35.4% market share in 2025, while immunoassay-based methods like ELISA remain the gold standard for routine screening [18] [4].

Dominant Testing Methodologies

The market is segmented by technology, with key methods including:

- PCR (Polymerase Chain Reaction): Valued for its high specificity in detecting allergen-specific DNA sequences.

- ELISA (Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay): Recognized as the gold standard for protein detection, known for high sensitivity and specificity.

- Lateral Flow Devices (LFD): Used for rapid, on-site screening.

- Mass Spectrometry (e.g., LC-MS/MS): Gaining traction for its high precision in quantifying specific allergenic proteins [6] [3].

Table 1: Market Position of Major Allergen Testing Technologies

| Technology | Market Share (2025) | Primary Detection Target | Key Strength |

|---|---|---|---|

| PCR | 35.4% [18] | DNA (Allergen-specific genes) | High specificity, effective for processed foods [19] [7] |

| ELISA/Immunoassays | Dominant position [4] | Proteins (Allergenic proteins) | High sensitivity and specificity, cost-effective [19] [4] |

| Lateral Flow Devices | Reported | Proteins | Rapid, on-site results |

| Mass Spectrometry | Emerging | Proteins (Specific protein markers) | High precision and multiplexing capability [6] |

Comparative Methodological Analysis

A nuanced understanding of the performance characteristics of protein-based (e.g., ELISA) and DNA-based (e.g., PCR) methods is essential for selecting the appropriate analytical tool for a given food matrix and regulatory purpose.

Performance Characteristics and Experimental Data

Direct comparative studies and market analyses reveal distinct performance profiles for each methodology.

Table 2: Experimental Performance Comparison of ELISA vs. PCR

| Performance Parameter | ELISA (Protein-Based) | PCR (DNA-Based) |

|---|---|---|

| Detection Limit | Parts per million (ppm) levels [4] | As low as 0.01 ng/mL for some targets [6] |

| Effect of Food Processing | Proteins can be denatured, leading to potential false negatives [4] | DNA is more stable; effective in processed foods (e.g., baked at 220°C) [7] |

| Specificity | High, but can cross-react with related proteins [4] | Very high, based on specific DNA sequences [7] |

| Quantification | Direct quantification of protein levels | Quantifies DNA, which is a proxy for allergen presence |

| Time to Result | Relatively fast (hours) [20] | Can be slower due to DNA extraction and amplification (hours to days) [20] |

| Cost-Effectiveness | More economical for routine screening [4] | Higher cost due to equipment and consumables [19] [20] |

Detailed Experimental Protocol: PCR Detection of Allergens

A 2025 study on detecting wheat and maize allergens provides a robust experimental model for DNA-based method validation [7].

Experimental Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the key steps in the PCR-based detection of allergens in processed foods.

- Sample Preparation: Wheat and maize dough samples were baked at 180°C and 220°C for 10 to 60 minutes to simulate processing.

- DNA Extraction: The CTAB (cetyltrimethyl ammonium bromide) method was used to isolate genomic DNA from 100 mg of each sample. DNA concentration and purity were assessed via spectrophotometry (NanoDrop One).

- PCR Amplification: Novel primers were designed to target major allergen genes:

- Wheat: High-molecular-weight (HMW) and low-molecular-weight (LMW) glutenin subunits.

- Maize: Zea m 14, Zea m 8, and zein.

- Analysis: PCR products were analyzed using agarose gel electrophoresis.

- Key Findings:

- DNA degradation correlated with increased baking temperature and time.

- The optimal primers successfully detected allergen genes even after baking at 220°C for 40-60 minutes.

- PCR sensitivity was positively influenced by DNA extractability and gene copy number but decreased with longer amplicon length and more intense processing.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Successful experimentation in allergen detection relies on a suite of specialized reagents and instruments.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Allergen Testing

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application | Example in Context |

|---|---|---|

| CTAB Buffer | DNA extraction from complex food matrices; helps in separating DNA from polysaccharides and proteins. | Used in the protocol for isolating DNA from baked wheat/maize dough [7]. |

| Proteinase K & RNase A | Enzymes that degrade contaminating proteins and RNA during DNA extraction, purifying the target DNA. | Part of the CTAB-based DNA extraction protocol to obtain high-quality genomic DNA [7]. |

| ELISA Kits | Ready-to-use kits containing antibodies specific to allergenic proteins (e.g., casein, Ara h 2) for quantitative detection. | Used for routine screening of allergens like gluten, milk, egg, and peanut in various food products [4]. |

| PCR Primers | Short, single-stranded DNA sequences designed to bind to and amplify specific allergen genes. | Primers for wheat HMW-glutenin and maize zein genes were critical for specific detection [7]. |

| Taq DNA Polymerase | Enzyme that synthesizes new DNA strands during PCR, essential for amplifying the target DNA sequence. | A core component of any PCR master mix for allergen gene amplification. |

| Antibodies (for ELISA) | Proteins that bind specifically to target allergenic proteins, enabling their detection and quantification. | Monoclonal antibodies are used in kits like the SENSIStrip Gluten PowerLine to reduce false negatives [20]. |

Underlying Mechanism of IgE-Mediated Food Allergy

Understanding the biological mechanism that allergen detection methods are designed to guard against is crucial for contextualizing their application. The following pathway delineates the immunologic process of an IgE-mediated allergic reaction, which is the primary mechanism for the food allergies detected by these methodologies [2].

Pathway Explanation: The process begins with Allergen Exposure and initial Sensitization Phase, where the allergen is presented by Antigen-Presenting Cells (APCs), leading to T-helper 2 (Th2) cell activation. This prompts B cells to produce allergen-specific Immunoglobulin E (IgE) antibodies, which then bind to Fcε receptors on mast cells and basophils [2]. Upon Re-exposure to the same allergen, the Effector Phase is triggered: the allergen cross-links the IgE antibodies on the mast cell surface, causing degranulation and the release of inflammatory mediators like histamine and leukotrienes, which ultimately produce the clinical symptoms of an allergic reaction [2].

Discussion and Future Outlook

The comparative analysis confirms that the dominance of established methodologies like ELISA and PCR is not a matter of stagnation but a reflection of their complementary and validated roles in a complex market. ELISA remains the uncontested leader for routine, high-throughput protein detection due to its cost-effectiveness and direct measurement of the allergenic moiety [4]. In contrast, PCR provides an indispensable tool for scenarios where protein-based methods falter, such as in highly processed foods where proteins are denatured but DNA remains amplifiable [7] [4].

The future evolution of this field will be shaped by several key trends. Multiplexed assays that can detect multiple allergens simultaneously are gaining prominence, improving efficiency and reducing costs [6] [18]. Furthermore, the integration of artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning is poised to enhance data analysis, improve prediction models, and potentially reduce interpretation errors [19] [6]. There is also a growing demand for portable, rapid on-site testing devices that provide results in real-time, empowering manufacturers with immediate quality control data [18]. Finally, advanced proteomic techniques like mass spectrometry are establishing a new benchmark for precision, capable of simultaneously quantifying specific allergenic proteins with high accuracy, thus complementing the existing methodological toolkit [6] [3].

In conclusion, the current market trends do not indicate a wholesale replacement of one established methodology by another, but rather a strategic coexistence and integration. The choice between protein-based and DNA-based methods is, and will remain, contingent on the specific analytical question, the nature of the food matrix, regulatory requirements, and the necessary balance between cost, speed, and accuracy.

Methodologies in Practice: From ELISA and LC-MS/MS to PCR and Isothermal Amplification

Food allergies represent a significant and growing global public health concern, compelling the need for reliable detection methods to ensure food safety and comply with labelling regulations [3]. The accurate detection of food allergens relies on two primary analytical approaches: protein-based methods, which directly target the allergenic proteins themselves, and DNA-based methods, which detect allergen-specific DNA sequences as an indirect marker [1]. Within the sphere of protein-based detection, immunoassays are paramount due to their specificity, sensitivity, and adaptability. This guide provides a comparative analysis of three key immunoassay formats—the Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay (ELISA), Lateral Flow Devices (LFDs), and emerging Immunosensors—framed within the broader context of protein-based versus DNA-based detection strategies. Aimed at researchers and scientists, this article offers an objective comparison of performance characteristics, detailed experimental protocols, and essential reagent toolkits.

Performance Comparison at a Glance

The following tables summarize the core characteristics and quantitative performance data of the discussed methods, allowing for a quick, objective comparison.

Table 1: Overall Method Comparison for Allergen Detection

| Feature | ELISA | Lateral Flow Devices (LFDs) | Immunosensors | DNA-based Methods (qPCR) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Detection Principle | Immunological, colorimetric | Immunological, visual/reader | Electrochemical, optical | Nucleic acid amplification |

| Detection Target | Proteins | Proteins | Proteins | DNA |

| Throughput | High | Low to Moderate | Moderate | High |

| Assay Time | Several hours | 10-30 minutes | Minutes to an hour | Several hours |

| Ease of Use | Requires training | Simple, minimal training | Varies; can be complex | Requires specialized training |

| Quantification | Excellent | Semi-quantitative / Qualitative | Excellent | Quantitative (indirect) |

| Portability | No | Yes | Yes (many formats) | No |

| Best Use Case | Regulatory compliance, high-sensitivity quantitation | Rapid screening, point-of-use testing | Rapid, sensitive quantitation, multiplexing | Detection of thermally processed allergens where proteins may degrade [1] |

Table 2: Experimental Performance Data from Comparative Studies

| Method / Assay Type | Target | Reported Sensitivity | Reported Specificity | Key Findings / Context |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ELISA (IgG) | SARS-CoV-2 Antibody | 81.5% | 100% | Used as a benchmark in a clinical study [21]. |

| ELISA (IgA) | SARS-CoV-2 Antibody | 93.1% | 80.6% | Demonstrated higher sensitivity but lower specificity than IgG ELISA in the same study [21]. |

| Lateral Flow (LFI) | SARS-CoV-2 Antibody | Variable: 61.2% - 91.8% | Variable: 61.7% - 80.2% | Performance is highly dependent on the commercial brand and design [21] [22]. |

| Electrochemiluminescence (CLIA) | SARS-CoV-2 Antibody | 91.8% | 80.2% | Showed superior sensitivity compared to ELISA and LFDs in a head-to-head study [22]. |

| DNA-based Kits (qPCR) | Celery Allergen | Detects down to 1 ppm spiked protein | High, but affected by matrix | Successful detection, but quantitative performance was challenging across different food matrices [5]. |

Detailed Methodologies and Experimental Protocols

Protein-Based Detection: Immunoassays

Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay (ELISA)

ELISA is a foundational, plate-based immunological technique renowned for its high sensitivity and robust quantification capabilities. The following outlines a standard sandwich ELISA protocol, commonly used for allergen detection [1].

Protocol: Sandwich ELISA for Allergen Detection

- Plate Coating: A microplate is coated with a capture antibody specific to the target allergen. The plate is then incubated overnight, typically at 4°C, to allow passive adsorption.

- Blocking: After washing to remove unbound antibody, the plate is blocked with a protein-based solution (e.g., Bovine Serum Albumin or casein) to cover any remaining protein-binding sites on the plastic surface, preventing non-specific binding in later steps.

- Sample Incubation: The food sample extract, appropriately diluted in buffer, is added to the well. If the target allergen is present, it binds to the immobilized capture antibody. The plate is incubated (e.g., 1-2 hours at 37°C) and then washed.

- Detection Antibody Incubation: A second enzyme-conjugated detection antibody, specific to a different epitope on the same allergen, is added. This forms an antibody-allergen-antibody "sandwich." Another incubation and wash step follows.

- Signal Development: A colorless enzyme substrate is added. The conjugated enzyme (e.g., Horseradish Peroxidase) converts the substrate into a colored product.

- Signal Measurement & Quantification: The enzymatic reaction is stopped, and the color intensity (Absorbance) is measured with a plate reader. The concentration of the allergen in the sample is determined by interpolation from a standard curve run concurrently.

The workflow of this sandwich ELISA procedure is systematized in the diagram below.

Lateral Flow Devices (LFDs)

Lateral Flow Devices are rapid, single-use tests designed for qualitative or semi-quantitative analysis. Their operation is based on the capillary flow of a liquid sample across a strip containing immobilized reagents [23].

Protocol: Lateral Flow Immunoassay Operation

- Sample Application: The liquid sample (e.g., food extract) is applied to the sample pad. The pad may contain buffers to adjust the sample pH and ensure optimal flow and binding conditions.

- Conjugate Release: As the sample migrates, it rehydrates and mobilizes conjugated detector particles (e.g., colloidal gold or colored latex beads) stored in the conjugate pad. These conjugates are antibodies specific to the target allergen, bound to the reporter particle.

- Formation of Complexes: If the target allergen is present in the sample, it binds to the mobilized conjugated antibodies, forming an analyte-detector complex.

- Capture at Test Line: The complex continues to flow along the nitrocellulose membrane until it reaches the test line. This line is striped with a second, immobilized capture antibody specific to the target allergen. The complex is trapped, accumulating the colored particles and producing a visible line.

- Capture at Control Line: The remaining fluid and any excess conjugate continue to the control line, which contains an antibody that captures the detector particles regardless of the presence of the allergen (e.g., an anti-species antibody). This line must always appear to validate the test.

- Result Interpretation: The appearance of both the control and test lines indicates a positive result. Only the control line indicates a negative result. If the control line fails to appear, the test is invalid.

The components and process flow of a typical sandwich-format LFD are illustrated below.

Immunosensors

Immunosensors are analytical devices that integrate an immunological recognition element (antibody) with a physicochemical transducer to produce a digital electronic signal. Biosensors are regarded as a promising detection method due to their rapidity, high sensitivity, and potential for on-site use [1].

Protocol: Electrochemical Immunosensor Operation

While designs vary, a general protocol for an electrochemical immunosensor is as follows:

- Bio-recognition Layer Preparation: The surface of the electrode is modified with a capture antibody specific to the target allergen. This can be achieved through various chemical immobilization techniques to ensure stable and oriented antibody attachment.

- Blocking: The electrode surface is blocked with a non-reactive protein (e.g., BSA) to minimize non-specific adsorption of other proteins from the sample matrix.

- Sample Incubation: The prepared food extract is applied to the sensor surface. The target allergen, if present, binds to the capture antibodies. The sensor is then washed.

- Signal Transduction: The binding event is measured by the transducer. In a common electrochemical format, an enzyme-labeled secondary antibody is added. Upon adding an electrochemical substrate, the enzyme catalyzes a reaction that produces an electrical current (amperometry) or changes the electrical potential/impedance (potentiometry/electrochemical impedance spectroscopy). The magnitude of this change is proportional to the allergen concentration.

- Data Analysis: The signal is processed by associated electronics and software, providing a quantitative readout of the allergen concentration.

DNA-Based Allergen Detection

For comparison, DNA-based methods like quantitative Polymerase Chain Reaction (qPCR) provide an indirect approach to detecting the presence of an allergenic ingredient.

Protocol: qPCR for Allergen Detection (e.g., Celery)

- DNA Extraction: DNA is isolated from the food matrix using a commercial kit, such as the Maxwell RSC PureFood GMO and Authentication Kit, which may involve CTAB buffer, proteinase K, and RNase incubation [5].

- DNA Quantification and Quality Assessment: The concentration and purity of the extracted DNA are determined using a spectrophotometer (e.g., Nanodrop) [5].

- qPCR Setup: The reaction mix is prepared containing a DNA polymerase (e.g., Taqman Universal Master Mix), sequence-specific primers, and a fluorescently-labeled probe (e.g., FAM-BBQ) designed to bind a unique gene sequence of the allergenic source (e.g., celery) [5].

- Amplification and Detection: The plate is run in a real-time PCR instrument. The thermal cycling process amplifies the target DNA. The probe is cleaved during amplification, releasing a fluorescent signal monitored in real-time.

- Quantification: The cycle threshold (Ct), at which the fluorescence crosses a background threshold, is determined. The Ct value is inversely proportional to the amount of target DNA in the sample. Quantification is achieved by comparison to a standard curve from known concentrations of the target DNA [5].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Successful development and execution of these assays depend on critical reagents. The table below details essential materials and their functions.

Table 3: Essential Reagents for Immunoassay Development

| Reagent / Material | Function | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Capture & Detection Antibodies | Specific recognition and binding of the target analyte (allergen). | Affinity & Specificity are paramount to avoid false positives/negatives [23]. Clonality: Monoclonal antibodies offer consistency; Polyclonal antibodies can increase sensitivity through multi-epitope recognition [23]. Supply: Must be scalable for commercial production [23]. |

| Reporter Molecules | Generate a detectable signal indicating analyte presence. | Colloidal Gold: Intense color, easy conjugation, visual readout [23]. Latex Beads: Can be colored or fluorescent, allow for multiplexing [23]. Enzymes (e.g., HRP): Used in ELISA for signal amplification via substrate conversion [1]. Fluorescent Dyes: Enable high-sensitivity quantification, require readers [23]. |

| Microplates & Membranes | Solid support for assay construction. | ELISA Plates: High protein-binding capacity polystyrene. LFD Membranes: Nitrocellulose is standard; its flow rate and protein-binding capacity are critical [23]. |

| Sample Pads & Conjugate Pads | LFD components for sample application and reagent release. | Sample Pad: Must efficiently absorb and filter the sample matrix [23]. Conjugate Pad: Must stably store and efficiently release the labeled antibody conjugate [23]. |

| Blocking Agents | Prevent non-specific binding to surfaces. | Proteins like Bovine Serum Albumin (BSA), casein, or synthetic polymers are used to coat unused binding sites on plates and membranes [23]. |

| Control Reagents | Validate the correct performance of the test. | Typically, an antibody that binds the labeled detector antibody irrespective of the analyte (e.g., an anti-species antibody) is striped as a control line [23]. |

The choice between ELISA, LFDs, and immunosensors for food allergen detection is dictated by the specific application requirements. ELISA remains the gold standard for high-sensitivity, quantitative analysis in a laboratory setting, while LFDs offer unparalleled speed and simplicity for rapid screening. Immunosensors represent the cutting edge, promising to combine the sensitivity of laboratory methods with the speed and portability of point-of-use tests. When contextualized within the protein-based vs. DNA-based debate, immunoassays provide a direct measure of the allergenic protein, making them highly relevant for risk assessment. However, as with any method, careful validation for each specific food matrix is essential to ensure accurate and reliable results [21] [5]. The ongoing innovation in reagents, materials, and detection technologies will continue to enhance the performance and accessibility of these critical food safety tools.

Food allergies are a significant and growing public health concern worldwide, affecting an estimated 1-8% of the population depending on geographic region and age group [3]. For allergic individuals, strict avoidance of allergenic foods remains the primary management strategy, making accurate food labeling and detection of unintended cross-contamination critical for consumer safety [24] [25]. This comparative analysis focuses on two principal technological approaches for allergen detection in food products: protein-based methods (specifically targeted mass spectrometry) and DNA-based methods (primarily PCR-based techniques). The fundamental distinction between these approaches lies in their analytical targets: mass spectrometry (MS) directly detects and quantifies the allergenic proteins themselves, while DNA-based methods detect genetic markers associated with allergenic foods [26] [1] [27].

The "Big 8" allergens—comprising milk, eggs, fish, crustacean shellfish, tree nuts, peanuts, wheat, and soybeans—are responsible for the majority of significant allergic reactions and are subject to mandatory labeling in many countries [24] [25]. Accurately quantifying these allergens in complex food matrices presents substantial analytical challenges, particularly at the low concentrations (parts-per-million to parts-per-billion) that can still trigger reactions in sensitive individuals. This guide provides a comprehensive comparison of targeted proteomics and DNA-based methods, examining their respective technical capabilities, limitations, and appropriate applications within food safety testing protocols.

Fundamental Principles and Methodological Comparison

Protein-Based Detection: Targeted Mass Spectrometry

Targeted proteomics using mass spectrometry, specifically Multiple Reaction Monitoring (MRM) also known as Selected Reaction Monitoring (SRM), represents a sophisticated approach for the direct quantification of allergenic proteins [24] [25]. This methodology employs triple quadrupole mass spectrometers, where the first and third quadrupoles act as mass filters for specific precursor and product ions, respectively, while the second quadrupole functions as a collision cell [25]. The core principle involves quantifying proteotypic peptides—unique peptide sequences that reliably indicate the presence of a specific allergenic protein—through their mass-to-charge ratio (m/z) and fragmentation patterns [25].

The critical innovation in quantitative targeted proteomics is the use of stable isotope-labeled internal standards (AQUA peptides), which are chemically identical to the target peptides but differ in mass [24]. These standards are added at known concentrations during sample preparation, enabling precise absolute quantification of the target allergenic proteins by comparing the mass spectrometric response of the native peptide to its labeled counterpart. This approach allows for multiplexed allergen quantification, where multiple allergenic proteins from different food sources can be detected and quantified simultaneously in a single analysis [24] [6].

DNA-Based Detection: PCR Methods

DNA-based detection methods, primarily polymerase chain reaction (PCR) and its variants (e.g., real-time PCR), represent an indirect approach to allergen detection that targets species-specific DNA sequences rather than the allergenic proteins themselves [26] [1] [27]. The fundamental principle involves extracting DNA from food samples, amplifying target sequences using sequence-specific primers, and detecting the amplified products. In real-time PCR, the accumulation of amplified DNA is monitored throughout the reaction using fluorescent dyes or probes, allowing for both detection and quantification of the target DNA [1].

While DNA-based methods do not directly measure the allergenic proteins, they provide an effective surrogate marker for the presence of allergenic ingredients, particularly in complex matrices where protein integrity may be compromised [26]. The technique capitalizes on the greater stability of DNA compared to proteins, especially in processed foods where proteins may be denatured or structurally altered, potentially affecting antibody recognition in immunoassays [1] [27].

Comparative Workflow Analysis

The following diagram illustrates the core procedural differences between mass spectrometry-based and DNA-based allergen detection workflows:

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Targeted Mass Spectrometry Workflow for Allergen Quantification

Sample Preparation and Protein Extraction

The initial step involves extracting proteins from the food matrix using appropriate extraction buffers. The composition of these buffers is critical and often needs to be optimized for different food matrices (e.g., baked goods, dairy, meat products) to ensure efficient protein recovery while minimizing interference from carbohydrates, lipids, and other food components [24] [25]. For complex matrices, additional cleanup steps such as precipitation or immunoaffinity depletion may be employed to reduce background interference and enhance sensitivity [25].

Protein Digestion and Peptide Standardization

Extracted proteins are denatured, reduced, and alkylated before enzymatic digestion. Trypsin is the most commonly used protease due to its high specificity for cleaving C-terminal to lysine and arginine residues, generating peptides of optimal length for LC-MS analysis [25]. Stable isotope-labeled internal standard peptides (AQUA peptides) are added at this stage at known concentrations, which correct for variations in sample preparation and ionization efficiency during MS analysis [24].

Liquid Chromatography and Mass Spectrometric Analysis

The complex peptide mixture is separated by reversed-phase liquid chromatography, typically using nano-flow or capillary LC systems to enhance sensitivity [24] [25]. Eluting peptides are ionized via electrospray ionization (ESI) and introduced into the mass spectrometer. In the MRM/SRM workflow, the triple quadrupole mass spectrometer is programmed to monitor specific precursor ion → product ion transitions for each target peptide, typically 3-5 transitions per peptide [25]. The mass filters are set to these predefined m/z values, and detection occurs only during retention time windows specific to each peptide, significantly enhancing sensitivity and specificity compared to full-scan methods [25].

Data Analysis and Quantification

Peak areas for the target peptides and their corresponding isotope-labeled standards are integrated using specialized software. Protein quantification is achieved by comparing the peak area ratio of the native peptide to the internal standard against a calibration curve generated from standards of known concentration [24] [25]. Data analysis includes verification of transition peak area ratios and co-elution to ensure proper peptide identification and minimize false positives [25].

DNA-Based Detection Workflow

DNA Extraction and Purification

DNA is extracted from food samples using commercial kits or established protocols, with careful consideration to break down the food matrix and remove inhibitors that could affect downstream PCR amplification [1] [27]. The quality and quantity of extracted DNA are assessed, and additional purification steps may be required for complex matrices.

PCR Amplification and Detection

Species-specific primers are designed to target conserved or unique genomic sequences of the allergenic food source [1]. In real-time PCR, amplification is monitored using intercalating dyes (e.g., SYBR Green) or sequence-specific fluorescent probes (e.g., TaqMan). The cycle threshold (Ct) value, representing the PCR cycle at which fluorescence exceeds background levels, is used for quantification relative to standard curves [1].

Performance Comparison and Experimental Data

Quantitative Comparison of Detection Methods

Table 1: Comparative Performance Characteristics of Allergen Detection Methods

| Parameter | Targeted Mass Spectrometry | DNA-Based Methods (PCR) | ELISA (Reference) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Detection Limit | 0.1-5 mg/kg (ppm) [25] | Varies by target; generally similar sensitivity [1] | 0.1-5 mg/kg (ppm) [25] |

| Target Analyte | Proteins/peptides (direct detection of allergens) [25] | DNA (indirect marker) [26] [1] | Proteins (antibody recognition) [1] [25] |

| Multiplexing Capacity | High (dozens of allergens simultaneously) [24] [6] | Moderate (typically single or few targets per reaction) [1] | Low (typically single allergen per test) [25] |

| Impact of Food Processing | Moderate (proteotypic peptides often survive processing) [25] | Low (DNA more stable than proteins) [1] [27] | High (epitopes may be denatured) [25] |

| Quantification Approach | Absolute quantification with isotope standards [24] | Relative quantification to standard curves [1] | Interpolation from standard curves [25] |

| Specificity Challenges | Minimal with proper peptide selection [25] | Cross-reactivity with related species [1] | Antibody cross-reactivity [25] |

Applicability Across Food Allergen Types

Table 2: Method Performance Across Major Allergen Categories

| Allergen Category | Targeted MS Applications | DNA-Based Detection Applications | Notable Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Peanut | Quantification of Ara h 1, Ara h 2, Ara h 3 [25] | Detection of peanut-specific DNA sequences [1] | MS provides protein-specific profile; DNA confirms peanut presence |

| Milk | Independent quantification of casein and whey proteins [25] | Detection of bovine DNA [1] | MS can distinguish different milk protein fractions |

| Egg | Quantification of Gal d 1 (ovalbumin) and Gal d 2 (ovomucoid) [6] | Detection of chicken DNA [1] | Egg-specific proteins vs. general poultry detection |

| Seafood | Detection of parvalbumin (fish) and tropomyosin (shellfish) [27] | Species-specific fish/shellfish DNA detection [27] | MS targets conserved allergen proteins; DNA identifies species |

| Tree Nuts | Detection of specific allergenic proteins in walnut, hazelnut, etc. [25] | Detection of species-specific DNA [1] | Complex matrix effects for both methods |

The Researcher's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Core Reagents and Instrumentation

Table 3: Essential Research Tools for Allergen Detection Methods

| Category | Specific Reagents/Equipment | Function/Purpose |

|---|---|---|

| Mass Spectrometry | Triple quadrupole mass spectrometer (QQQ) | MRM/SRM analysis for targeted quantification [25] |

| Nano/Capillary LC system | High-sensitivity peptide separation [24] | |

| Stable isotope-labeled peptides (AQUA) | Internal standards for absolute quantification [24] | |

| Trypsin (sequencing grade) | Protein digestion to generate measurable peptides [25] | |

| DNA-Based Methods | Real-time PCR instrument | DNA amplification and detection [1] |

| Species-specific primers and probes | Target amplification with specificity [1] | |

| DNA extraction/purification kits | Isolation of amplifiable DNA from food matrices [1] | |

| Inhibition-resistant polymerase | Reliable amplification from complex food matrices [1] | |

| Data Analysis | BatMass [28] | Mass spectrometry data visualization |

| vMS-Share [29] | Public MS repository and data mining | |

| Allergen Peptide Browser [25] | Resource for proteotypic peptide selection |

Critical Analysis and Future Perspectives

Targeted mass spectrometry offers significant advantages for allergen detection, particularly its ability to directly quantify specific allergenic proteins with high specificity and multiplexing capability [24] [25]. The technology demonstrates robustness across various food matrices and can be more resistant to the effects of food processing compared to antibody-based methods, as it targets peptide sequences rather than conformational epitopes [25]. Furthermore, MS methods can be adapted to monitor specific protein modifications (oxidation, deamidation, glycation) that may occur during processing, providing insights into how these modifications affect allergenicity [25].

DNA-based methods excel in scenarios where protein integrity is compromised but DNA remains detectable, particularly in highly processed foods [1] [27]. They also offer advantages in cost and accessibility for routine testing of single allergens. However, they cannot directly quantify the specific proteins responsible for allergic reactions and may detect DNA from allergenic sources that don't contain problematic levels of proteins [26].

The emerging field of biosensors and rapid detection technologies shows promise for future allergen detection, potentially combining the specificity of immunological recognition with the sensitivity of advanced signal detection systems [6] [1]. Additionally, computational approaches and bioinformatics resources such as the Allergen Peptide Browser are enhancing the selection of optimal proteotypic peptides for MS assays, facilitating method development and standardization across laboratories [25].

In conclusion, both targeted mass spectrometry and DNA-based methods provide valuable capabilities for allergen detection, with their respective advantages making them complementary rather than competing technologies. The selection of an appropriate method depends on the specific analytical requirements, including the need for direct protein quantification, the complexity of the food matrix, the degree of food processing, and the required throughput and multiplexing capability. As both technologies continue to evolve, they will collectively enhance our ability to protect consumers through accurate allergen detection and quantification.

Within food safety and public health, accurate food allergen detection is paramount for protecting sensitive individuals. The detection methodologies primarily fall into two categories: protein-based methods (e.g., ELISA, mass spectrometry), which detect the allergenic proteins themselves, and DNA-based methods, which detect the DNA sequences encoding these proteins [1] [3]. DNA-based detection, primarily using Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR) techniques, offers a powerful alternative, particularly for processed foods where proteins may be denatured but DNA remains amplifiable [1] [7]. This guide provides a comparative analysis of three foundational PCR techniques—Endpoint, Real-Time, and Multiplex PCR—within the context of food allergen detection research. It objectively compares their performance, supported by experimental data, and details protocols relevant to scientists and drug development professionals engaged in food safety analysis.

Core Principles and Comparative Analysis of PCR Techniques

The fundamental principle of PCR is to enzymatically amplify a specific DNA target, making it detectable and quantifiable. The techniques discussed here apply this principle in different ways, each with distinct advantages for allergen detection.

Endpoint PCR: This is the traditional form of PCR. After amplifying the target DNA over a set number of cycles, the total accumulated product is analyzed via agarose gel electrophoresis. Measurement occurs in the plateau phase of the PCR reaction, where reagents have become depleted and the amplification rate is no longer consistent [30]. This makes it inherently less suitable for reliable quantification.

Real-Time PCR (qPCR): Also known as quantitative PCR (qPCR), this method monitors the amplification of DNA in real-time as the reaction occurs. Fluorescent dyes or probes report the amount of PCR product after each cycle. By collecting data during the exponential phase of amplification, where the reaction is most consistent and reproducible, qPCR allows for precise quantification of the initial DNA template [31] [30]. The key output is the Cycle threshold (Ct), the cycle number at which the fluorescence crosses a predefined threshold, which is inversely correlated to the starting amount of target DNA [32].

Multiplex PCR: This variant allows for the simultaneous amplification of multiple different DNA targets in a single reaction tube by incorporating multiple pairs of specific primers [33]. This is highly valuable for efficiently screening a food product for several potential allergens at once, saving time, reagents, and sample material.

Table 1: Comparative Performance of Endpoint, Real-Time, and Multiplex PCR for Food Allergen Detection.

| Feature | Endpoint PCR | Real-Time PCR (qPCR) | Multiplex PCR |

|---|---|---|---|

| Quantification Capability | Semi-quantitative or qualitative | Fully quantitative | Typically qualitative or semi-quantitative |

| Sensitivity | Lower | 100-fold more sensitive than endpoint PCR [31] | High, comparable to endpoint or qPCR depending on detection method |

| Dynamic Range | ~2 orders of magnitude [31] | >4 orders of magnitude [31] | Dependent on the number of targets and detection system |

| Precision (CV) | ~6.8% (fluorescence intensity) [31] | ~0.14% (Ct value) [31] | Varies with optimization |

| Key Advantage | Simplicity, low cost | Accuracy, wide dynamic range, high throughput | Multi-target analysis, high efficiency |

| Primary Limitation | Low resolution, low throughput | Higher cost, complex data analysis | Requires extensive optimization, primer competition [33] |

| Best for Allergen Detection | Qualitative presence/absence checks | Precise quantification and high-sensitivity detection [1] | Screening for multiple allergens simultaneously [33] |

Experimental Data in Food Allergen Detection

Sensitivity and Specificity in Practice

The superior sensitivity of real-time PCR is a critical factor in allergen detection, where trace amounts can trigger reactions. A comparative study demonstrated that a real-time PCR system was 100-fold more sensitive than an end-point PCR system when using a single mouse liver cDNA standard [31]. Furthermore, the precision of real-time PCR, with a percentage standard error of the mean of 0.14% for the Ct value across 30 replicates, far exceeded the 6.8% observed for end-point fluorescence intensity [31]. This high precision is crucial for generating reliable and reproducible data in quantitative food safety assessments.

The extreme sensitivity of qPCR, however, requires careful interpretation in a diagnostic context. A clinical study on Pneumocystis pneumonia found that real-time PCR had a significantly higher false-positive rate (35%) compared to endpoint PCR (10%), likely due to its enhanced ability to detect low-level colonization that does not constitute active disease [34]. This underscores the importance of interpreting qPCR results for allergens within the context of known thresholds for eliciting an allergic reaction [3].

Impact of Food Processing on Detection