Protein Quality Assessment: From Amino Acid Scores to Advanced Applications in Drug Development

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of the methodologies for determining protein quality, tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals.

Protein Quality Assessment: From Amino Acid Scores to Advanced Applications in Drug Development

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of the methodologies for determining protein quality, tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals. It covers the foundational principles of indispensable amino acids (IAAs) and digestibility, explores established scoring systems like PDCAAS and the newer DIAAS, and details advanced techniques such as stable isotope tracers for measuring muscle protein synthesis. The content addresses key challenges including the impact of food processing, choice of reference patterns, and digestibility measurement. Furthermore, it examines the role of high-quality protein data in multi-omics research, biomarker discovery, and the development of targeted therapies, offering a roadmap for integrating these metrics into biomedical innovation.

The Building Blocks of Protein Quality: Principles and Physiological Significance

Dietary protein quality is defined as the capacity of a food protein to meet human metabolic demands for indispensable (essential) amino acids (IAAs) and nitrogen [1]. This concept is critical for addressing protein malnutrition in low- and middle-income countries and remains highly relevant in high-income countries where optimizing IAA intake can support health and physiological function across the lifespan [1]. The fundamental determinants of protein quality are the IAA composition of the food protein and the bioavailability of these amino acids following digestion and absorption [2]. Accurate assessment of protein quality is therefore essential for developing nutritional guidelines, formulating therapeutic diets, and advancing clinical nutrition strategies.

The evaluation of protein quality has evolved significantly, moving from biological assays in rats to chemical scoring methods based on human amino acid requirements. The current gold standard, the Digestible Indispensable Amino Acid Score (DIAAS), was recommended in 2013 by the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) to replace the previous Protein Digestibility-Corrected Amino Acid Score (PDCAAS) [3]. This shift reflects advances in our understanding of protein digestion and metabolism, particularly the importance of ileal digestibility over fecal digestibility measurements [4] [5]. For researchers and drug development professionals, understanding these methodologies is crucial for evaluating protein sources for nutritional support, therapeutic formulations, and public health interventions.

Critical Components of Protein Quality Assessment

Indispensable Amino Acids (IAAs) and Metabolic Needs

IAAs are amino acids that cannot be synthesized de novo by the human body and must be obtained from the diet. The nine IAAs—histidine, isoleucine, leucine, lysine, methionine, phenylalanine, threonine, tryptophan, and valine—serve as the foundational building blocks for protein synthesis and play critical roles as precursors to key metabolic regulators [1]. A "high-quality" protein source is characterized by its IAA density (percentage of IAAs per calorie), digestibility, bioavailability, and capacity to stimulate protein synthesis [1] [2].

The metabolic requirement for IAAs forms the basis for all protein quality assessment methods. The reference pattern for evaluating protein quality is based on the IAA requirements of preschool-age children (1-3 years), considered the most nutritionally demanding age group [4]. This pattern, as established by the FAO, is detailed in Table 1.

Table 1: Reference Pattern for Indispensable Amino Acid Requirements for Preschool-Age Children

| Amino Acid | mg per g Crude Protein |

|---|---|

| Isoleucine | 25 |

| Leucine | 55 |

| Lysine | 51 |

| Methionine + Cysteine | 25 |

| Phenylalanine + Tyrosine | 47 |

| Threonine | 27 |

| Tryptophan | 7 |

| Valine | 32 |

| Histidine | 18 |

| Total | 287 |

Digestibility and Bioavailability

Digestibility refers to the proportion of dietary protein and its constituent IAAs that is absorbed from the gastrointestinal tract. The shift from PDCAAS to DIAAS represented a critical methodological advancement by prioritizing true ileal digestibility over fecal digestibility [3].

Fecal digestibility measurements, used in PDCAAS, can overestimate protein quality because they fail to account for: (1) microbial metabolism of amino acids in the large intestine, and (2) the presence of antinutritional factors in many plant-based proteins that interfere with absorption in the small intestine [4] [5]. In contrast, ileal digestibility—measured at the end of the small intestine—provides a more accurate assessment of amino acid absorption and availability for protein synthesis in the body [3].

Bioavailability encompasses not only digestibility but also the metabolic utilization of absorbed amino acids for protein synthesis and other physiological functions. Factors affecting bioavailability include food processing methods, presence of antinutritional factors, food matrix structure, and individual physiological factors such as age and health status [1].

Methodologies for Protein Quality Assessment

Evolution from PDCAAS to DIAAS

The Protein Digestibility-Corrected Amino Acid Score (PDCAAS) method, adopted as the preferred method by FAO/WHO in 1993, calculates protein quality based on the IAA composition of a protein corrected by its fecal digestibility [4]. The PDCAAS formula is:

PDCAAS = True Fecal Protein Digestibility × Amino Acid Score

Where Amino Acid Score = (mg of limiting IAA in 1 g test protein) / (mg of same IAA in 1 g reference protein) [4].

Despite its widespread adoption, PDCAAS has several documented limitations:

- Fecal vs. Ileal Digestibility: Fecal measurements do not account for microbial metabolism in the colon [5] [3].

- Truncation Issue: Values exceeding 100% are truncated, limiting discriminatory power between high-quality proteins [4].

- Antinutritional Factors: Fecal digestibility may overestimate quality for proteins containing antinutritional factors [4].

- Lysine Availability: Does not specifically account for reduced lysine bioavailability in processed foods due to Maillard reactions [3].

The Digestible Indispensable Amino Acid Score (DIAAS) was developed to address these limitations:

DIAAS (%) = [mg of digestible dietary IAA in 1 g test protein / mg of the same IAA in 1 g reference protein] × 100 [3]

Key advantages of DIAAS include:

- Use of true ileal digestibility for each IAA

- No truncation of values above 100%

- Specific assessment of reactive lysine bioavailability in processed foods

- More accurate prediction of IAA absorption and utilization [3]

Table 2: Comparison of PDCAAS and DIAAS Methodologies

| Characteristic | PDCAAS | DIAAS |

|---|---|---|

| Digestibility Site | Fecal | Ileal |

| Digestibility Type | Crude protein | Individual amino acids |

| Score Truncation | Values >100% truncated to 100% | No truncation |

| Lysine Assessment | Total lysine | Reactive (bioavailable) lysine |

| Theoretical Range | 0-100% | 0->100% |

| Basis for Requirements | Preschool child pattern | Updated reference patterns |

Experimental Protocols for DIAAS Determination

Animal Model Protocol (Growing Pig)

The growing pig is considered a validated model for human protein digestion due to similarities in gastrointestinal physiology [3].

Materials and Equipment:

- Growing pigs (15-25 kg body weight)

- Test diet containing protein source of interest

- Protein-free diet for determining endogenous losses

- Chromic oxide or titanium dioxide as digestibility marker

- Euthanasia equipment and surgical supplies

- Freeze-drying equipment

- High-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) system for amino acid analysis

Procedure:

- Diet Formulation: Formulate test diets to contain the protein source as the sole protein source. Include 0.2-0.3% of an indigestible marker (e.g., chromic oxide) for digestibility calculation.

- Feeding Period: Feed experimental diets to growing pigs (n=6-8) for a 7-14 day adaptation period followed by a 3-5 day collection period.

- Sample Collection: Euthanize animals at the end of the feeding period. Collect digesta from the distal ileum (last 1/3 of small intestine).

- Sample Processing: Freeze-dry ileal digesta and diet samples. Grind to a fine powder for analysis.

- Chemical Analysis:

- Determine amino acid composition using acid hydrolysis followed by HPLC.

- Determine marker concentration for digestibility calculations.

- For processed foods, assess reactive lysine content using specific methods (e.g., guanidination).

- Calculations:

- True IAA digestibility (%) = [1 - ((AAdigesta × Markerdiet) / (AAdiet × Markerdigesta) - (AAendogenous / AAdiet))] × 100

- Where AAendogenous is determined from pigs fed a protein-free diet.

- DIAAS Calculation: Calculate for each IAA using true ileal digestibility values and identify the first limiting IAA for the final score.

Human Dual-Isotope Protocol

A non-invasive method has been developed for determining IAA digestibility in humans, applicable across different physiological states [3].

Materials and Equipment:

- Stable isotopically labeled test protein (e.g., ^13C, ^2H, ^15N)

- Oral and intravenous tracers

- Mass spectrometry equipment

- Breath collection apparatus

- Blood collection supplies

Procedure:

- Tracer Preparation: Label test protein with stable isotopes using biological incorporation (e.g., in plants or animals) or chemical synthesis.

- Study Design: Administer a single test meal containing the labeled protein to human subjects (n=6-10) after an overnight fast.

- Dual Tracer Administration:

- Provide oral tracer (labeled test protein)

- Simultaneously administer intravenous tracer of the same amino acid

- Sample Collection:

- Collect blood samples at regular intervals (0, 2, 4, 6, 8 hours)

- Collect breath samples for ^13CO2 analysis (if using ^13C-labeled proteins)

- Collect urine over 24-48 hours

- Sample Analysis: Analyze tracer concentrations in plasma, breath, and urine using mass spectrometry.

- Calculations:

- IAA digestibility = (Oral tracer appearance in circulation / Intravenous tracer) × 100

- Correct for endogenous losses and first-pass metabolism

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Protein Quality Assessment

| Reagent/Equipment | Function in Protein Quality Research |

|---|---|

| Stable Isotope Tracers (^13C, ^15N, ^2H) | Metabolic tracing of amino acid absorption and utilization in human studies |

| Amino Acid Standards | Quantification of amino acids in food and digesta via HPLC calibration |

| Indigestible Markers (Chromium Oxide, Titanium Dioxide) | Determination of digestibility coefficients in animal models |

| HPLC-Mass Spectrometry | Precise quantification of amino acids and isotopically labeled tracers |

| Enzyme Assays (for Trypsin Inhibitors, etc.) | Measurement of antinutritional factors affecting protein digestibility |

| Growing Pig Model | Validated animal model for ileal digestibility studies |

| Reactive Lysine Assay Kits | Assessment of lysine bioavailability in processed foods |

Advanced Considerations in Protein Quality Research

Methodological Challenges and Research Gaps

Despite advances in protein quality assessment, several methodological challenges remain:

Ideal Amino Acid Reference Pattern: Current reference patterns are based on limited studies of IAA requirements in preschool children. Further research is needed to validate and potentially update these requirements, and to establish patterns for different age groups and physiological states [5] [3].

Rapid In Vitro Digestibility Assays: The gold standard in vivo digestibility assays are time-consuming and expensive. Development of validated in vitro methods that correlate strongly with in vivo ileal digestibility would significantly advance research capabilities [3].

Conditionally Indispensable Amino Acids: Current scoring methods focus primarily on IAAs, but conditionally indispensable amino acids (e.g., arginine, glutamine) under specific physiological states also contribute to protein quality [5].

Food Matrix Effects: The physical structure of food and interactions with other dietary components influence protein digestibility and IAA bioavailability. Standardized methods for accounting for these effects in protein quality assessment are needed [1].

Applications in Dietary Planning and Public Health

Accurate protein quality assessment has significant implications for dietary recommendations and public health policy:

Plant-Based Diets: Diets high in whole food plant-derived proteins typically have lower protein quality scores due to lower IAA density and digestibility. These diets may require greater total protein and energy intakes to compensate, or strategic combination of complementary protein sources [1] [2].

Aging Populations: Older adults have unique protein quality considerations, including potential need for higher IAA density, increased leucine intake to maximize muscle protein synthesis, and attention to food particle size related to chewing efficiency [1].

Global Nutrition Policy: In low-income countries, reliance on single plant-based protein sources with low protein quality contributes to protein-energy malnutrition. Accurate protein quality assessment is essential for effective food fortification programs and nutritional interventions [3].

Table 4: DIAAS Values for Common Protein Sources

| Protein Source | DIAAS (%) | First Limiting IAA | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pork Meat | >100 | - | Among highest quality proteins |

| Egg | >100 | - | Reference quality protein |

| Casein | >100 | - | High IAA density |

| Potato Protein | >100 | - | High quality plant source |

| Whey Protein | <100 | - | Slightly below 100% |

| Soy Protein | <100 | - | High quality plant source |

| Pea Protein | Variable | Methionine + Cysteine | Quality varies with processing |

| Rice Protein | Low | Lysine | Typically low DIAAS |

| Corn Protein | Low | Tryptophan | Typically low DIAAS |

The assessment of dietary protein quality has evolved significantly with our understanding of protein digestion and metabolism. The critical roles of indispensable amino acids and digestibility are now appropriately captured in the DIAAS methodology, which represents the current gold standard for protein quality evaluation. For researchers and drug development professionals, accurate assessment of protein quality is essential for developing effective nutritional interventions, formulating therapeutic diets, and advancing public health strategies.

Future research directions should focus on validating rapid in vitro digestibility assays, establishing protein quality requirements for specialized populations, and exploring the relationship between protein quality and long-term health outcomes. As the FAO's first overarching recommendation from 2011 suggests, treating each IAA as an individual nutrient may provide the most nuanced approach to protein quality assessment, potentially revolutionizing how we evaluate proteins in research and clinical practice [3].

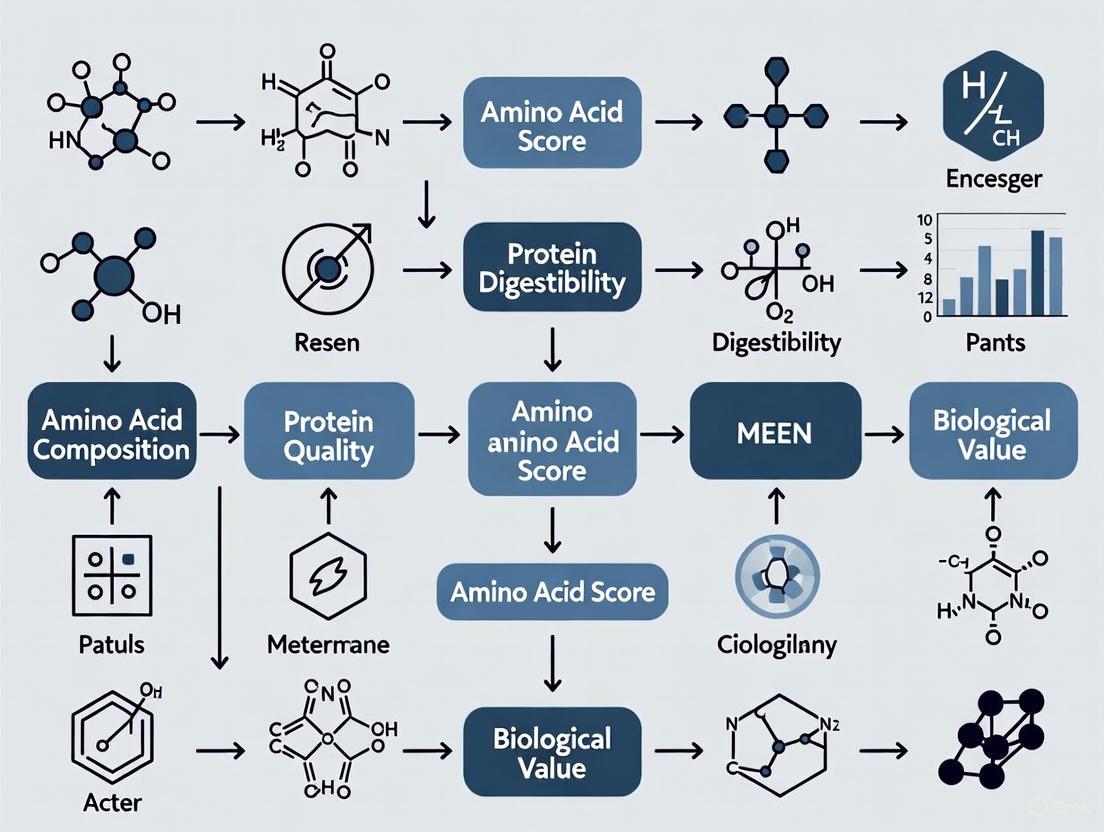

Diagram 1: Protein Quality Assessment Framework. This diagram illustrates the relationships between critical protein quality components, assessment methodologies, experimental approaches, and influencing factors.

Amino acids are fundamental not only as the monomeric units of proteins but also as crucial regulators of metabolic pathways and signaling networks. While their role in protein synthesis is well-established, emerging research highlights their function as metabolic switches that influence anabolic and catabolic processes, immune responses, and cellular energy status [6] [7]. This application note details experimental methodologies for investigating the regulatory functions of amino acids, with particular emphasis on their roles in protein synthesis and metabolic signaling pathways. The content is structured to provide researchers with reproducible protocols and analytical frameworks that bridge fundamental biochemistry with applied protein quality research, enabling comprehensive characterization of amino acid functionality in health and disease.

Analytical Protocols for Amino Acid Profiling

HPLC-Based Amino Acid Analysis

Principle: This method enables quantitative determination of amino acid composition in protein hydrolysates and biological samples using high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) with fluorescence detection after pre-column derivatization with orthophthaldialdehyde (OPA) [8].

Sample Preparation:

- Protein Hydrolysis: Weigh 5-10 mg of protein sample into hydrolysis tubes. For most amino acids, add 1 mL of 6N HCl and perform acid hydrolysis at 110°C for 24 hours under oxygen-free conditions by flushing with nitrogen or argon [9].

- Oxidized Hydrolysis for Sulfur-Containing Amino Acids: For methionine and cystine determination, oxidize protein samples with performic acid (0.08-1.3 mL/mg crude protein) for 16 hours at 0°C before acid hydrolysis [9].

- Alkaline Hydrolysis for Tryptophan: For tryptophan analysis, hydrolyze samples with 4.2N NaOH containing 1% thioglycolic acid at 110°C for 20 hours [9].

- Derivatization: Transfer 100 μL of hydrolysate to an autosampler vial, add 100 μL sodium borate buffer (pH 9.5, 0.14 M) and 50 μL OPA/3-mercaptopropionic acid (MPA) reagent in methanol. After 1 minute, add 25 μL HCl 0.7M to stop the reaction [8].

Chromatographic Conditions:

- Column: Reversed-phase ODS column (250 mm × 4 mm)

- Mobile Phase: Eluent A: methanol-sodium phosphate (pH 6.5, 12.5 mM) (10:90, v/v); Eluent B: methanol-tetrahydrofuran (97:3, v/v)

- Gradient Program:

- 15-20% B in 5 minutes

- 20-32% B in 12 minutes

- 32-60% B in 10 minutes

- 60-90% B in 3 minutes

- 90-15% B in 2 minutes

- Flow Rate: 1.0 mL/min

- Detection: Fluorescence detection with excitation/emission at 330/450 nm [8]

- Injection Volume: 20 μL

Quantification: Prepare calibration curves using amino acid standard solutions. Correct for hydrolytic losses of threonine, serine, valine, and isoleucine using laboratory-specific factors determined through time-hydrolysis studies [9].

Amino Acid Scoring Pattern

Amino acid profiles should be evaluated against the FAO/WHO/UNU reference pattern for preschool children (2-5 years), which is recommended for assessing dietary protein quality for all age groups except infants [9].

Table 1: FAO/WHO/UNU Amino Acid Scoring Pattern

| Amino Acid | Requirement (mg/g crude protein) |

|---|---|

| Histidine | 19 |

| Isoleucine | 28 |

| Leucine | 66 |

| Lysine | 58 |

| Methionine + Cystine | 25 |

| Phenylalanine + Tyrosine | 63 |

| Threonine | 34 |

| Tryptophan | 11 |

| Valine | 35 |

Protein Quality Assessment: PDCAAS Protocol

Protein Digestibility Corrected Amino Acid Score Determination

The PDCAAS method evaluates protein quality based on amino acid composition and digestibility, providing a standardized approach for nutritional assessment [9] [10].

Procedure:

- Proximate Analysis: Determine total nitrogen content using approved methods (e.g., AOAC methods). Calculate protein content using appropriate nitrogen-to-protein conversion factors (typically 6.25) [9].

- Amino Acid Analysis: Determine the concentration of the eleven amino acids that constitute the scoring pattern (nine essential amino acids plus cysteine and tyrosine) using the HPLC method described in Section 2.1 [9].

- Amino Acid Score Calculation: Calculate amino acid ratios for each essential amino acid using the formula: [ \text{Amino Acid Ratio} = \frac{\text{mg of amino acid in 1g test protein}}{\text{mg of same amino acid in reference pattern}} ] Identify the lowest ratio as the amino acid score [9].

- Digestibility Determination: Determine true protein digestibility using the rat fecal-balance method (AOAC Official Method 991.29) or pig nitrogen balance method [9].

- PDCAAS Calculation: Multiply the amino acid score by the true protein digestibility: [ \text{PDCAAS} = \text{Amino Acid Score} \times \text{True Protein Digestibility} ] Truncate scores above 1.00 to 1.00 [9].

Table 2: PDCAAS Values of Common Dietary Proteins

| Protein Source | PDCAAS |

|---|---|

| Eggs | 1.00 |

| Milk | 1.00 |

| Whey Protein | 1.00 |

| Soy Protein | 1.00 |

| Beef | 0.92 |

| Pea Protein | 0.82 |

| Chickpeas | 0.78 |

| Peanuts | 0.52 |

| Lentils | 0.52 |

| Wheat Protein | 0.42 |

| Rice | 0.47 |

Investigating Amino Acid-Regulated Signaling Pathways

mTORC1 Signaling Activation Assay

Principle: The mechanistic target of rapamycin complex 1 (mTORC1) serves as a central regulator of protein synthesis in response to amino acid availability, particularly branched-chain amino acids like leucine [6] [11].

Cell Culture Treatment:

- Culture cells (e.g., C2C12 myotubes, HEK293) in appropriate medium.

- Deprive cells of amino acids for 2 hours using amino acid-free medium.

- Stimulate with complete medium or specific amino acids (e.g., 2 mM leucine) for 15-60 minutes.

- Include control groups with mTOR inhibitors (e.g., 100 nM rapamycin) for specificity validation.

Western Blot Analysis:

- Lyse cells in RIPA buffer containing protease and phosphatase inhibitors.

- Separate 20-40 μg protein by SDS-PAGE and transfer to PVDF membranes.

- Probe with primary antibodies against:

- Phospho-mTOR (Ser2448)

- Phospho-p70S6K (Thr389)

- Phospho-4E-BP1 (Thr37/46)

- Total proteins for normalization

- Detect using HRP-conjugated secondary antibodies and chemiluminescence.

- Quantify band intensity using densitometry software.

Interpretation: Increased phosphorylation of mTOR, p70S6K, and 4E-BP1 indicates pathway activation. Leucine specifically activates mTORC1 by binding to Sestrin2, which relieves inhibition of GATOR2 and allows mTORC1 activation [7].

Integrated Nutrient Signaling Pathway

The mTORC1 pathway integrates signals from amino acids, growth factors, and cellular energy status to regulate protein synthesis and cell growth [11].

Amino Acid Response Pathway Under Starvation

During amino acid deprivation, cells activate protective pathways that suppress translation and promote conservation of resources [12] [11].

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Tools for Amino Acid Metabolism Studies

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Research Application |

|---|---|---|

| Chromatography Standards | Amino acid standard solutions (Sigma), PITC derivatization kit | HPLC quantification of amino acid profiles [8] |

| Cell Culture Reagents | Amino acid-free media, Dialyzed FBS, L-Leucine (2-5 mM) | Controlled amino acid stimulation studies [11] |

| Signaling Pathway Antibodies | Phospho-mTOR (Ser2448), Phospho-p70S6K (Thr389), Phospho-4E-BP1 | Western blot analysis of pathway activation [11] |

| Metabolic Inhibitors/Activators | Rapamycin (mTOR inhibitor), AICAR (AMPK activator) | Pathway modulation and control experiments [6] |

| Animal Models | Rat models (SD, Wistar), C57BL/6 mice | In vivo protein digestibility and metabolism studies [9] |

Advanced Applications: Immunometabolism and Therapeutic Targeting

Amino Acids in Immune Cell Regulation

Protocol: T-cell Activation and Amino Acid Dependency

- Isolate primary human T-cells using density gradient centrifugation.

- Activate cells with anti-CD3/anti-CD28 antibodies in complete RPMI.

- Deplete specific amino acids (Arg, Trp, Leu) using customized media.

- Assess proliferation via CFSE dilution or EdU incorporation.

- Analyze metabolic profiling using Seahorse Analyzer or LC-MS.

Key Findings: Arg and Trp depletion inhibits T-cell proliferation by arresting cells in G0-G1 phase. Arg catabolism by arginase 1 (Arg1) in macrophages produces immunosuppressive polyamines that modulate inflammation [12]. Similarly, indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase (IDO1)-mediated Trp catabolism generates kynurenines with immunoregulatory activities [12].

Amino Acid Restriction as Therapeutic Strategy

Principle: Selective amino acid restriction targets specific metabolic vulnerabilities in cancer cells while sparing normal tissues [7].

Methionine Restriction Protocol:

- Culture cancer cells (e.g., PDAC, NSCLC) in methionine-free medium.

- Supplement with dialyzed FBS and titrated methionine (0-100 μM).

- Assess viability via MTT or resazurin assays at 24-72 hours.

- Analyze cell cycle progression by flow cytometry.

- Evaluate viral replication in infected cells (where applicable).

Mechanistic Insight: Methionine restriction inhibits SARS-CoV-2 RNA cap methylation and replication by limiting S-adenosylmethionine (SAM) production [12]. Tumor cells with high methionine dependency show reduced proliferation under restriction.

The methodologies detailed in this application note provide a comprehensive toolkit for investigating the dual roles of amino acids as both metabolic substrates and regulatory molecules. The integration of analytical chemistry techniques with functional cell signaling assays enables researchers to quantitatively assess protein quality while simultaneously elucidating the molecular mechanisms through which amino acids govern metabolic pathways. These protocols establish standardized approaches for nutritional biochemistry and metabolic research, with particular relevance for developing targeted nutritional interventions and therapeutic strategies based on amino acid manipulation.

The accurate determination of dietary protein quality is fundamental to human nutrition, impacting public health guidelines, clinical nutrition, and food regulatory policies. At its core, protein quality assessment evaluates the capacity of food protein to meet human metabolic requirements for indispensable amino acids (IAAs) and nitrogen [1]. This evaluation bridges the gap between physiological requirements and the chemical composition of foods, creating a critical interface between nutritional science and public health application. The foundation of modern protein quality assessment rests on establishing accurate Estimated Average Requirements (EARs) for protein and translating these into specific IAA reference profiles across different life stages. These reference profiles serve as the benchmark against which all dietary proteins are evaluated, making their accurate determination a cornerstone of nutritional science [13] [14].

The evolution from protein EAR to specific IAA profiles represents a significant advancement in nutritional biochemistry, recognizing that proteins are not simply nitrogen sources but complex assemblies of specific amino acids with distinct metabolic roles. This Application Note details the established protocols and methodologies for determining these fundamental requirements and applying them in protein quality assessment, providing researchers with standardized approaches for evaluating protein sources within the context of a broader thesis on protein quality and amino acid score research.

Theoretical Framework: From Protein EAR to IAA Reference Patterns

Establishing the Protein Estimated Average Requirement (EAR)

The Protein EAR represents the daily intake level sufficient to meet the protein requirements of half the healthy individuals in a particular life stage and gender group. The current international consensus, established by FAO/WHO/UNU experts, sets the EAR for healthy adults at 0.66 grams of protein per kilogram of body weight per day [13] [3]. This value is derived from nitrogen balance studies, which measure the equilibrium between nitrogen intake and excretion, indicating when protein intake is sufficient to replace obligatory losses without depleting body reserves.

For researchers, it is crucial to recognize that the EAR serves as the normalization factor for converting absolute IAA requirements (in mg/kg body weight/day) into the IAA reference pattern (in mg/g protein). This normalization allows for the direct comparison between the amino acid profile of a test protein and the human requirement pattern, forming the mathematical basis for amino acid scoring methods [13].

Determining Indispensable Amino Acid (IAA) Requirements

The methodological evolution for determining IAA requirements has significantly advanced in recent decades. The traditional nitrogen balance method has been largely superseded by more accurate stable isotope tracer techniques, which provide a more precise quantification of individual IAA needs at the metabolic level [14].

Key Methodological Approaches for IAA Requirement Determination:

Direct Amino Acid Oxidation (DAAO): This method involves administering graded levels of a test IAA while infusing a stable isotope-labeled tracer of the same amino acid. The oxidation of the labeled amino acid to 13CO2 is measured in breath samples. The requirement is identified as the intake level at which a breakpoint occurs in the oxidation curve, indicating that the requirement for that amino acid has been met [14].

Indicator Amino Acid Oxidation (IAAO): This technique uses the oxidation of a single indicator amino acid (typically L-[1-13C]phenylalanine) to reflect the adequacy of another dietary IAA. As the intake of the test IAA increases, the oxidation of the indicator amino acid decreases until the test IAA requirement is met, creating a discernible breakpoint [1].

These tracer methods have revealed that IAA requirements for adults are substantially higher (up to three-fold for some IAAs) than previous estimates based on nitrogen balance studies, highlighting the importance of methodological precision in establishing reference values [14].

Constructing IAA Reference Patterns Across Life Stages

IAA reference patterns are created by dividing each IAA requirement (in mg/kg/day) by the protein EAR (in g/kg/day), resulting in a profile expressed in mg of each IAA per gram of dietary protein. The Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) has established distinct reference patterns for different age groups to reflect their unique physiological demands [4] [14].

Table 1: IAA Reference Patterns (mg/g protein) Across Life Stages

| Indispensable Amino Acid | Infants (0-6 mos) | Children (0.5-3 yrs) | Older Children, Adolescents & Adults (>3 yrs) | Historical FAO 1991 Pattern (Preschool Children) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Histidine | 20 | 18 | 16 | 19 |

| Isoleucine | 32 | 31 | 30 | 28 |

| Leucine | 66 | 63 | 61 | 66 |

| Lysine | 57 | 52 | 48 | 58 |

| Methionine + Cysteine | 28 | 26 | 23 | 25 |

| Phenylalanine + Tyrosine | 52 | 46 | 41 | 63 |

| Threonine | 31 | 27 | 25 | 34 |

| Tryptophan | 8.5 | 7.4 | 6.6 | 11 |

| Valine | 43 | 42 | 40 | 35 |

Source: Adapted from FAO 2013 Report and Comparative Analysis [4] [14]

The selection of an appropriate reference pattern is a critical decision in protein quality assessment. For regulatory purposes, the preschool child pattern (FAO 1991) has historically been used as it represents the most demanding requirement pattern. However, the FAO 2013 recommends using age-specific patterns for greater physiological accuracy [4] [14]. Research by Sa et al. demonstrated that using the adult pattern versus the preschool child pattern could change the identification of the limiting amino acid in lentils, significantly affecting the calculated chemical score [14].

Diagram 1: From Protein EAR to IAA Reference Patterns. This workflow illustrates the conceptual process of deriving age-specific IAA reference patterns from fundamental requirement data.

Methodological Approaches for Protein Quality Assessment

Digestible Indispensable Amino Acid Score (DIAAS) Protocol

The DIAAS is currently recommended by the FAO as the preferred method for assessing protein quality. The DIAAS calculation is based on the following formula [13] [3]:

DIAAS (%) = 100 × (mg of digestible dietary IAA in 1 g of the dietary test protein) / (mg of the same IAA in 1 g of the reference protein)

The DIAAS is determined by the most limiting IAA in the test protein in relation to its corresponding content in the reference protein. A key advantage of DIAAS over previous methods is that values are not truncated at 100%, allowing for discrimination between high-quality protein sources [13].

Step-by-Step DIAAS Determination Protocol:

Amino Acid Composition Analysis:

- Principle: Determine the complete IAA profile of the test protein source.

- Procedure: Perform acid hydrolysis (typically 6N HCl at 110°C for 24 hours under vacuum) to liberate individual amino acids from the protein chain. Specific analyses are required for sulfur-containing amino acids (perform performic acid oxidation prior to acid hydrolysis) and tryptophan (use alkaline hydrolysis).

- Analysis: Separate and quantify amino acids using high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) or amino acid analyzers with post-column ninhydrin detection or pre-column derivatization.

- Calculation: Express results as mg of each IAA per gram of crude protein.

True Ileal Amino Acid Digestibility Determination:

- Principle: Measure the disappearance of each IAA from the gastrointestinal tract at the end of the ileum, providing a more accurate assessment of absorption than fecal digestibility.

- Preferred Model: The growing pig is the validated and recommended model, as its gastrointestinal physiology closely resembles that of humans [3].

- Procedure: Fit animals with an ileal T-cannula to collect digesta. Feed the test protein as the sole protein source in a balanced diet. Include an indigestible marker (e.g., titanium dioxide, chromic oxide) to calculate digestibility coefficients. Collect ileal digesta continuously over a standardized period (e.g., 8-12 hours).

- Calculation:

- True IAA Digestibility (%) = [IAA ingested - (IAA in digesta - Endogenous IAA losses)] / IAA ingested × 100

- Endogenous IAA losses are determined using a protein-free diet or the peptide alimentation technique.

- Alternative Human Assay: A dual-isotope method has been developed for non-invasive true ileal amino acid digestibility measurement in humans, applicable across different physiological states [3].

Reactive Lysine Analysis for Processed Foods:

- Principle: For foods that have undergone thermal processing, measure reactive lysine bioavailability to account for Maillard reaction products that reduce lysine utilization.

- Procedure: Use the guanidination reaction with O-methylisourea, which reacts only with the ε-amino group of reactive lysine, allowing for quantification of bioavailable lysine [3].

DIAAS Calculation:

- Procedure: For each IAA, calculate the digestible content (IAA content × true ileal digestibility coefficient). Calculate the reference ratio (digestible IAA content in test protein / corresponding IAA content in reference protein). The lowest reference ratio among all IAAs is the DIAAS, expressed as a percentage.

Diagram 2: DIAAS Determination Workflow. The protocol integrates chemical analysis with biological digestibility assessment, with special consideration for processed foods.

Comparative Analysis: DIAAS vs. PDCAAS

The Protein Digestibility-Corrected Amino Acid Score (PDCAAS) was the previously recommended method for protein quality assessment. Understanding the methodological differences between PDCAAS and DIAAS is crucial for interpreting historical data and transitioning to the newer standard [4].

Table 2: Methodological Comparison: PDCAAS vs. DIAAS

| Parameter | PDCAAS | DIAAS |

|---|---|---|

| Digestibility Site | Fecal | Ileal |

| Digestibility Type | Single value for crude protein | Individual values for each IAA |

| Lysine Assessment | Total lysine | Reactive (bioavailable) lysine for processed foods |

| Scoring | Truncated at 1.0 (100%) | Not truncated |

| Reference Pattern | Originally based on FAO 1991 preschool child pattern | Based on FAO 2013 age-specific patterns |

| Primary Model | Rat fecal digestibility | Pig ileal digestibility |

| Theoretical Basis | Amino acid composition × fecal protein digestibility | Digestible IAA content relative to requirements |

Source: Adapted from FAO Reports and Comparative Analyses [13] [4] [3]

The shift from fecal to ileal digestibility is physiologically significant because amino acids that move beyond the terminal ileum are less likely to be absorbed for protein synthesis and may be utilized by gut bacteria or excreted [4]. The non-truncation of DIAAS values is particularly important for distinguishing between high-quality proteins and for formulating complementary protein mixtures, as the ability of protein sources to provide excess amino acids can be acknowledged [13] [3].

Practical Applications and Research Considerations

Protein Quality in Dietary Planning and Regulation

The application of protein quality assessment extends beyond basic research to practical dietary planning and food regulation. Diet modeling studies demonstrate that essential amino acid (EAA) density and protein quality are typically higher in omnivorous and lacto-ovo-vegetarian diets compared to diets high in whole food plant-derived proteins [1]. Consequently, diets based primarily on plant proteins may require greater total protein and energy intakes to compensate for lower protein quality, a critical consideration in populations with limited food access.

For incomplete plant-derived proteins, consuming complementary proteins that provide offsetting amino acid profiles can be beneficial. The DIAAS methodology, with its non-truncated scores, is particularly valuable for formulating such complementary mixtures as it accurately reflects the potential for excess amino acids in one protein to compensate for deficiencies in another [1] [3].

Special consideration for dietary protein quality in older adults includes addressing factors such as chewing efficiency, food particle size, and the need for higher EAA density with particular emphasis on leucine intake to maximize the muscle protein synthetic response [1].

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Protein Quality Assessment

| Research Reagent/Resource | Application | Technical Function |

|---|---|---|

| Stable Isotope-Labeled Amino Acids (L-[1-13C]Leucine, L-[1-13C]Phenylalanine) | IAAO/DAAO requirement studies | Metabolic tracer for determining IAA requirements and bioavailability |

| Reference Proteins (Casein, Egg White) | Method validation | Standardized proteins for assay calibration and quality control |

| Amino Acid Standard Mixtures | HPLC calibration | Quantitative analysis of amino acid composition |

| Indigestible Markers (Titanium Dioxide, Chromic Oxide) | Digestibility assays | Fecal/ileal flow markers for digestibility calculation |

| O-Methylisourea | Reactive lysine analysis | Guanidination reagent for assessing lysine bioavailability in processed foods |

| Standardized Laboratory Animal Diets (Protein-free, Casein-based) | Digestibility studies | Determination of endogenous losses and baseline measurements |

| Public Protein Databases (UniProt, PRIDE, Peptide Atlas) | Sequence and composition data | Reference data for protein identification and characterization |

Source: Compiled from Methodological References [13] [15] [3]

The establishment of accurate protein and IAA requirements, and their translation into standardized reference patterns, provides the essential foundation for protein quality assessment. The evolution from PDCAAS to DIAAS represents a significant advancement in methodology, with improved physiological relevance through the use of ileal (versus fecal) digestibility coefficients and non-truncated scores.

For researchers in protein quality and amino acid score research, adherence to standardized protocols for IAA requirement determination, amino acid composition analysis, and digestibility assessment is critical for generating comparable and meaningful data. The continuing development of innovative methodologies, such as the dual-isotope technique for human ileal digestibility measurement and refined stable isotope approaches for requirement determination, promises further refinement of protein quality assessment in the future.

The recommendation from the 2011 FAO Consultation to treat each indispensable amino acid as an individual nutrient, with provision of food label information on digestible contents of specific IAAs, remains an important direction for future research and application, potentially transforming how protein quality is conceptualized in dietary planning and public health nutrition [3].

Application Note: Assessing Protein Quality in Plant-Based Food Systems

The global shift toward plant-based diets, driven by health, environmental, and ethical considerations, has intensified the need for precise assessment of protein quality in sustainable food systems. While plant-based diets offer potential benefits, the nutritional quality of plant proteins may be inferior to animal proteins in several respects, including essential amino acid (EAA) profile, digestibility, and bioavailability [16]. This application note provides researchers with standardized methodologies for evaluating protein quality, recognizing it as a multifaceted, modifiable metric essential for improving dietary recommendations and public health outcomes [17]. Protein quality is defined as the capacity of a food to meet human metabolic needs for EAAs and nitrogen, requiring consideration of amino acid composition, digestibility, and bioavailability [18].

Quantitative Comparison of Protein Quality Metrics

Table 1: Protein Quality Scores for Selected Protein Sources

| Protein Source | PDCAAS | DIAAS | Limiting Amino Acid(s) | True Fecal Protein Digestibility |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Milk | 1.00 | 1.08 | None | 0.96 [16] |

| Whey | 1.00 | 0.90 | Histidine | 0.96 [16] |

| Soy | 1.00 | 0.92 | Sulfur Amino Acids | 0.97 [16] |

| Pea | 0.78-0.91 | 0.66 | Sulfur Amino Acids*, Tryptophan | 0.97 [16] |

| Chickpea | 0.71-0.85 | 0.69 | Leucine, Lysine, Sulfur Amino Acids* | 0.85 [16] |

| Lentils | 0.68-0.80 | 0.75 | Leucine, Sulfur Amino Acids*, Threonine, Tryptophan, Valine | Not specified |

Table 2: Essential Amino Acid Requirements Across Age Groups (mg/g protein)

| Amino Acid | 0.5-3 Years | >3 Years (Adults) |

|---|---|---|

| Histidine | 20 | 16 |

| Isoleucine | 32 | 30 |

| Leucine | 66 | 61 |

| Lysine | 57 | 48 |

| SAA (Methionine + Cysteine) | 27 | 23 |

| AAA (Phenylalanine + Tyrosine) | 52 | 41 |

| Threonine | 31 | 25 |

| Tryptophan | 8.5 | 6.6 |

| Valine | 43 | 40 |

Experimental Protocols for Protein Quality Assessment

Protocol 1: Protein Digestibility-Corrected Amino Acid Score (PDCAAS)

Principle

The PDCAAS method evaluates protein quality based on the amino acid requirements of humans and corrects for fecal digestibility. It compares the amino acid profile of a test protein to a reference pattern and applies a digestibility correction [16].

Materials and Equipment

- Test protein material

- Nitrogen analysis apparatus (e.g., Kjeldahl or Dumas combustion method)

- Amino acid analyzer (HPLC with fluorescence or UV detection)

- Animal metabolic cages (for rat assays)

- Protein-free diet

- Laboratory rodents (typically growing rats)

Procedure

Amino Acid Analysis:

- Perform acid hydrolysis of test protein (6N HCl, 110°C, 24 hours) for most amino acids.

- Perform alkaline hydrolysis for tryptophan determination.

- Analyze amino acid content using HPLC with post-column derivatization or pre-column derivatization followed by UV or fluorescence detection.

- Calculate amino acid content in mg/g protein.

Chemical Score Calculation:

- For each indispensable amino acid (IAA), calculate the ratio:

Amino Acid Score (AAS) = (mg of IAA in 1g test protein) / (mg of same IAA in 1g reference protein) - Identify the most limiting amino acid (lowest ratio).

- For each indispensable amino acid (IAA), calculate the ratio:

Digestibility Determination:

- Feed rats (n=5-6) a diet containing test protein as the sole protein source.

- Collect feces over a 5-10 day period after an adaptation period.

- Analyze fecal nitrogen content.

- Calculate true protein digestibility:

Digestibility = (Nitrogen intake - (Fecal nitrogen - Fecal nitrogen on protein-free diet)) / Nitrogen intake

PDCAAS Calculation:

- Multiply the chemical score of the most limiting amino acid by the true protein digestibility.

- Truncate values exceeding 1.00 to 1.00 [16].

Protocol 2: Digestible Indispensable Amino Acid Score (DIAAS)

Principle

DIAAS represents the FAO-recommended updated method that uses ileal digestibility of individual amino acids rather than fecal digestibility of protein, providing a more accurate assessment of amino acid bioavailability [16].

Materials and Equipment

- Test protein material

- Amino acid analyzer

- Ileal cannulation surgery equipment (for human or animal studies)

- Or ileostomized human volunteers

- Enzyme mixtures for in vitro simulations

Procedure

Amino Acid Analysis:

- Perform as described in PDCAAS Protocol (Section 2.1.3, Step 1).

Ileal Digestibility Determination:

- Option A (Human Studies): Use ileostomized volunteers who have intact digestion but bypassed colonic fermentation. Collect ileal effluents after consumption of test protein.

- Option B (Animal Studies): Use growing pigs or rats fitted with ileal T-cannulas for digesta collection.

- Option C (In Vitro Methods): Use validated in vitro digestion models simulating gastric and small intestinal phases.

- Analyze amino acid content in ileal digesta.

- Calculate true ileal digestibility for each indispensable amino acid:

Digestibility (%) = [(Amino acid ingested - Amino acid in ileal digesta) / Amino acid ingested] × 100

DIAAS Calculation:

- For each indispensable amino acid:

DIAAS (%) = [(mg of digestible dietary IAA in 1g test protein) / (mg of the same IAA in 1g reference protein)] × 100 - The final DIAAS is the lowest value among the nine indispensable amino acids.

- Note: Unlike PDCAAS, DIAAS is not truncated and can exceed 100% [16].

- For each indispensable amino acid:

Protocol 3: Complementary Protein Assessment

Principle

This protocol evaluates the protein quality of plant protein blends designed to achieve complementary amino acid profiles, where the limiting amino acids in one protein source are compensated by another [19].

Procedure

Identify Limiting Amino Acids:

- Determine the limiting amino acids for individual plant proteins using chemical scores (see Protocol 1, Step 2).

Formulate Complementary Blends:

- Combine proteins with complementary amino acid profiles (e.g., legumes rich in lysine but limited in sulfur amino acids with cereals limited in lysine but rich in sulfur amino acids).

- Test various proportions to optimize the amino acid score.

Quality Assessment:

- Assess the blended protein using either PDCAAS or DIAAS methodology.

- Note: Complementary effects are only considered valid at the meal level, not across the entire diet consumed over multiple days [19].

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Protein Quality Assessment

| Reagent/Equipment | Function/Application | Example Use Cases |

|---|---|---|

| Amino Acid Standard Mixtures | Calibration and quantification of amino acids in test proteins and biological samples. | HPLC analysis for chemical score determination. |

| Enzyme Mixtures (Pepsin, Trypsin, Pancreatin) | Simulation of human gastrointestinal digestion for in vitro digestibility assays. | In vitro DIAAS determination. |

| Nitrogen-Free Diet | Baseline measurement for endogenous nitrogen losses in digestibility studies. | True fecal protein digestibility determination in rats. |

| Ileal Cannulation Equipment | Surgical access to the terminal ileum for direct collection of digesta in digestibility studies. | True ileal amino acid digestibility measurements. |

| Stable Isotope Tracers (¹³C, ¹⁵N) | Metabolic studies of amino acid utilization, including Indicator Amino Acid Oxidation (IAAO) method. | Determination of amino acid requirements. |

| Protein Reference Standards | Certified reference materials for method validation and quality control. | Inter-laboratory method standardization. |

Methodological Workflow and Decision Pathway

Applications in Sustainable Diet Development

Special Considerations for Vulnerable Populations

For older adults, protein quality considerations must address age-related anabolic resistance through higher EAA density and leucine intake to maximize muscle protein synthesis [17]. Research indicates that aging populations following vegan diets may face particular challenges in meeting protein requirements due to lower protein quality and reduced anabolic potential of plant proteins [20]. Studies show that higher-quality protein benefits muscle protein synthesis at rest and following resistance exercise in both older and young adults [18].

Environmental and Nutritional Trade-offs

When designing sustainable diets, protein quality metrics must be integrated with environmental impact assessments. While plant proteins generally have lower greenhouse gas emissions, expressing environmental impact per unit of protein quality (e.g., per gram of digestible essential amino acids) rather than per gram of protein provides a more nuanced perspective [21]. This approach reveals that some animal-derived proteins may have similar environmental footprints to plant proteins when corrected for protein quality [21].

Processing and Preparation Effects

Protein quality can be modified through processing methods that reduce antinutrients, denature proteins, and reduce food particle size. Conversely, protein quality decreases with prolonged storage, heat sterilization, and exposure to high surface temperatures [17]. These factors must be considered when evaluating the protein quality of plant-based foods in sustainable diets.

Methodologies in Practice: From Classic Scoring Systems to Cutting-Edge Proteomics

The Protein Digestibility-Corrected Amino Acid Score (PDCAAS) is the primary method for evaluating dietary protein quality, officially adopted by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and recognized globally by organizations including the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations and the World Health Organization (FAO/WHO) [22] [4]. This framework addresses a fundamental challenge in nutritional science: that proteins from different sources vary significantly in their capacity to meet human metabolic needs due to differences in both amino acid composition and digestibility [1] [23]. The PDCAAS method was recommended by the FAO/WHO in 1989 and formally adopted by the U.S. FDA in 1993 as the preferred method for determining protein quality, replacing earlier models like the Protein Efficiency Ratio (PER) which was based on amino acid requirements of growing rats rather than humans [4].

Within research and regulatory environments, PDCAAS provides a critical tool for standardizing protein quality assessment, enabling direct comparison between diverse protein sources, substantiating protein content claims on food labels, and guiding product development in the food and pharmaceutical industries [22] [10]. The methodology represents a significant advancement by integrating both the amino acid requirements of humans and their ability to digest dietary protein into a single metric, thereby offering a more accurate prediction of a protein's nutritional value than previous systems [4].

Calculation Methodology

The PDCAAS calculation integrates two fundamental components of protein quality: amino acid composition and digestibility. The resulting score ranges from 0 to 1.0, with 1.0 representing a protein that, when digested, provides 100% or more of the indispensable amino acids required per unit of protein [22] [4].

Amino Acid Score (AAS) Determination

The first component calculates the Amino Acid Score (AAS) by comparing the amino acid profile of the test protein against a reference pattern based on human requirements:

AAS = (mg of limiting amino acid in 1 g of test protein) / (mg of same amino acid in 1 g of reference protein) [4]

The reference pattern is derived from the essential amino acid requirements for preschool-aged children (1-3 years), considered the most nutritionally demanding age group [4]. The following table presents the current FAO/WHO reference pattern:

Table 1: Essential Amino Acid Requirements Reference Pattern (mg per g of protein)

| Amino Acid | Requirement (mg/g protein) |

|---|---|

| Histidine | 18 |

| Isoleucine | 25 |

| Leucine | 55 |

| Lysine | 51 |

| Methionine + Cysteine | 25 |

| Phenylalanine + Tyrosine | 47 |

| Threonine | 27 |

| Tryptophan | 7 |

| Valine | 32 |

| Total | 287 |

The "limiting amino acid" is identified as the essential amino acid with the lowest ratio when compared to this reference pattern [23]. For many plant proteins, common limiting amino acids include lysine (in grains and cereals), sulfur amino acids methionine and cysteine (in pulses), and tryptophan (in pulses) [23].

Protein Digestibility Assessment

The second component measures True Fecal Protein Digestibility (TFPD%) using a rodent bioassay, with the following calculation:

TFPD = [Protein Intake (PI) - (Fecal Protein (FP) - Metabolic Fecal Protein (MFP))] / Protein Intake (PI) [4]

Where Metabolic Fecal Protein represents the amount of protein in feces when the subject is on a protein-free diet [4]. This measurement aims to determine what percentage of the ingested protein is actually absorbed by the body.

Final PDCAAS Calculation

The final PDCAAS value is obtained by multiplying these two components:

PDCAAS = AAS × TFPD [22]

According to regulatory guidelines, values exceeding 1.0 are typically truncated to 1.0, as scores above this threshold indicate the protein contains essential amino acids in excess of human requirements [4] [23].

The following workflow diagram illustrates the complete PDCAAS determination process:

Diagram 1: PDCAAS Determination Workflow

Experimental Protocols

Amino Acid Profiling Using Chromatography Methods

Accurate amino acid profiling is fundamental to PDCAAS calculation and requires sophisticated analytical techniques. The primary methodologies employed in research settings include:

High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC): The most commonly used method for amino acid separation and quantification. The protocol involves: (1) protein hydrolysis using 6M HCl at 110°C for 24 hours to liberate individual amino acids; (2) derivatization of amino acids with reagents such as phenylisothiocyanate (PITC) or o-phthaldialdehyde (OPA) to enable UV or fluorescence detection; (3) separation on a reverse-phase C18 column using a gradient elution system; and (4) quantification against known amino acid standards [22].

Ion-Exchange Chromatography: The traditional method for amino acid analysis that separates amino acids based on their charge characteristics. The protocol involves: (1) sample preparation through acid hydrolysis; (2) separation on a sulfonated polystyrene column using buffer solutions of increasing pH and ionic strength; (3) post-column derivatization with ninhydrin; and (4) detection at 570nm (440nm for proline) [22].

Gas Chromatography (GC): Used as an alternative to HPLC, particularly for volatile amino acids. The methodology requires derivatization to create volatile derivatives before separation on a capillary GC column with flame ionization or mass spectrometric detection [22].

Protein Digestibility Assay

The standard protocol for determining true fecal protein digestibility utilizes a rodent bioassay with the following steps [4] [23]:

- Experimental Design: Utilize weanling rats (typically 8-10 animals per test protein) housed in metabolic cages allowing for separate collection of urine and feces.

- Acclimation Period: Provide a protein-free diet for 3-5 days to determine baseline metabolic fecal protein (MFP) and endogenous urinary nitrogen.

- Testing Period: Feed rats a diet containing the test protein as the sole protein source at a level providing 10% protein for 5-7 days, with precise measurement of food intake and complete collection of feces and urine.

- Sample Analysis: Determine nitrogen content in diet, feces, and urine using the Kjeldahl method or Dumas combustion.

- Calculation: Compute True Fecal Protein Digestibility using the formula: TFPD = [PI - (FP - MFP)] / PI, where PI is protein intake, FP is fecal protein, and MFP is metabolic fecal protein determined during the protein-free period.

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents for PDCAAS Determination

| Reagent/Equipment | Function in PDCAAS Analysis |

|---|---|

| Amino Acid Standards | Quantitative reference for calibrating chromatographic systems and identifying retention times. |

| Hydrochloric Acid (6M) | Protein hydrolysis to liberate individual amino acids for composition analysis. |

| Derivatization Reagents (PITC, OPA, Ninhydrin) | Enable detection of amino acids by adding chromophores or fluorophores. |

| Chromatography Systems (HPLC, IC, GC) | Separation and quantification of individual amino acids in protein hydrolysates. |

| Metabolic Cages | Housing for rodent digestibility studies allowing separate collection of feces and urine. |

| Kjeldahl/Dumas Apparatus | Determination of nitrogen content in food, feces, and urine samples. |

| Reference Protein (Casein) | Control material for validating analytical methods and bioassays. |

Applications and Regulatory Framework

Protein Quality Assessment in Food Products

The PDCAAS framework enables systematic comparison of protein quality across diverse food sources. The following table presents PDCAAS values for common dietary proteins:

Table 3: PDCAAS Values of Common Protein Sources

| Protein Source | PDCAAS Value | Limiting Amino Acid(s) |

|---|---|---|

| Casein | 1.00 | None |

| Whey Protein | 1.00 | None |

| Egg White | 1.00 | None |

| Soy Protein Isolate | 1.00 | None |

| Milk | 1.00 | None |

| Beef | 0.92 | None (score pre-truncation) |

| Pea Protein Concentrate | 0.89 | Sulfur amino acids |

| Chickpeas | 0.78 | Sulfur amino acids |

| Black Beans | 0.75 | Sulfur amino acids |

| Rice | 0.50 | Lysine |

| Peanuts | 0.52 | Lysine, Methionine |

| Wheat Gluten | 0.24 | Lysine |

These values demonstrate a clear pattern: animal-based proteins and soy protein isolate typically achieve the highest scores (1.0), while many plant-based proteins show lower scores due to specific limiting amino acids and/or reduced digestibility [22] [4] [10]. The practical implication is significant - a product containing 10g of wheat protein (PDCAAS 0.24) provides only 2.4g of usable protein, compared to 10g of usable protein from 10g of whey protein (PDCAAS 1.0) [22].

Regulatory Compliance and Protein Claims

The PDCAAS framework is integral to food labeling regulations in the United States. The FDA mandates specific thresholds for protein content claims that must be adjusted based on PDCAAS [22] [23]:

- "Good Source of Protein" Claim: Requires at least 5 grams of PDCAAS-corrected protein per serving (10% of Daily Value)

- "Excellent Source of Protein" Claim: Requires at least 10 grams of PDCAAS-corrected protein per serving (20% of Daily Value)

The corrected protein amount is calculated as: Total protein (g) × PDCAAS [22]. This adjustment is critical for regulatory compliance, as failure to use PDCAAS-corrected values has resulted in recent class-action lawsuits against food manufacturers for overstating protein content, particularly in plant-based products [24].

Food Product Development and Formulation

In product development, PDCAAS guides protein source selection and blending strategies to optimize protein quality cost-effectively. A key application is complementary protein blending, where sources with different limiting amino acids are combined to create a more balanced amino acid profile [23] [25]. For example, blending pea protein (limiting in methionine but high in lysine) with rice protein (limiting in lysine but high in methionine) can achieve a combined PDCAAS approaching 1.0 [25]. This strategy is particularly valuable for developing plant-based products that match the protein quality of animal-derived counterparts.

Limitations and Future Directions

Despite its widespread adoption, the PDCAAS framework has recognized limitations that impact its accuracy and utility in certain applications.

Methodological Limitations

Digestibility Measurement Concerns: PDCAAS relies on fecal digestibility measurements, which may overestimate true protein utilization because amino acids that move beyond the terminal ileum are less likely to be absorbed for protein synthesis but may still be metabolized by gut bacteria, thus appearing to have been digested [4]. This is particularly problematic for proteins containing antinutritional factors (e.g., trypsin inhibitors in legumes), which can interfere with protein absorption in the small intestine but may still be broken down by colonic bacteria [4].

Truncation Artifact: The practice of truncating scores at 1.0 limits the framework's discriminatory power for high-quality proteins. Four different proteins (casein, whey, egg, and soy isolate) all receive identical scores of 1.0 despite potentially different metabolic efficiencies in the human body [4]. This capping prevents differentiation between proteins that may have varying biological effects despite all being classified as "high quality" [4].

Age-Specific Reference Pattern: The use of preschool-age children (2-5 years) as the reference population, while representing the most demanding requirements, may not optimally reflect the needs of other demographic groups, particularly older adults who may have different amino acid requirements and digestive efficiencies [26].

Emerging Alternatives and Framework Evolution

The Digestible Indispensable Amino Acid Score (DIAAS) has been proposed by FAO as a potential successor to PDCAAS, offering several theoretical improvements [1] [23] [17]:

- Uses ileal digestibility measurements (at the end of the small intestine) rather than fecal digestibility, providing a more accurate assessment of amino acid absorption

- Does not truncate values at 1.0, allowing differentiation between high-quality proteins

- Employs updated amino acid reference patterns

However, DIAAS has not yet been officially adopted by any major regulatory jurisdiction and faces practical challenges, including continued reliance on animal bioassays and limited availability of ileal digestibility data for various protein sources [23].

Other emerging frameworks include the Essential Amino Acid 9 (EAA-9) score, which treats individual amino acids as unique nutrients and offers advantages for precision nutrition applications through its additive nature and capacity for personalization based on age or metabolic conditions [26].

Table 4: Comparison of Protein Quality Assessment Methods

| Characteristic | PDCAAS | DIAAS | EAA-9 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Basis | Human amino acid requirements | Human amino acid requirements | Individual EAA requirements |

| Digestibility Measurement | Fecal | Ileal | Variable (method-dependent) |

| Score Capping | Yes (at 1.0) | No | No |

| Additive | No | No | Yes |

| Regulatory Status | FDA-approved | Proposed, not adopted | Research framework |

| Personalization Capacity | Limited | Limited | High |

The PDCAAS framework remains the established regulatory standard for protein quality assessment despite its recognized limitations. Its strength lies in integrating both amino acid composition and digestibility into a single metric that reflects protein utilization in humans rather than animal models. For researchers and product developers, understanding the calculation methodology, applications, and constraints of PDCAAS is essential for designing nutritionally optimized products and conducting compliant regulatory assessments. While emerging methods like DIAAS and EAA-9 offer theoretical advantages for specific applications, PDCAAS continues to serve as the practical benchmark for protein quality evaluation in food and pharmaceutical development. Future evolution of protein quality assessment will likely incorporate elements of precision nutrition, recognizing dietary protein quality as a multifaceted, modifiable metric essential for advancing dietary recommendations and public health outcomes [1] [26].

The Digestible Indispensable Amino Acid Score (DIAAS) has been established by the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) as the recommended method for evaluating protein quality in human nutrition, replacing the previous Protein Digestibility-Corrected Amino Acid Score (PDCAAS) [3] [27]. This paradigm shift is grounded in a more physiologically accurate assessment of how digestible amino acids are absorbed and utilized by the body. DIAAS represents a critical advancement for researchers and drug development professionals who require precise metrics for protein quality in nutritional formulations, therapeutic diets, and clinical nutrition products. The core innovation of DIAAS lies in its focus on true ileal amino acid digestibility, measuring amino acid absorption at the end of the small intestine, and its non-truncated scoring system that allows for values above 100%, thereby providing a more accurate differentiation between high-quality protein sources [3] [28] [27]. This article details the principles, methodologies, and applications of DIAAS within the broader context of protein quality assessment research.

Principles and Conceptual Advancements of DIAAS

Fundamental Shifts from PDCAAS to DIAAS

The transition from PDCAAS to DIAAS is founded on several key physiological and methodological improvements that address significant limitations of the former system. The conceptual framework of this evolution is outlined in the diagram below.

The DIAAS methodology introduces four critical advancements over PDCAAS. First, it utilizes ileal digestibility measured at the end of the small intestine rather than fecal digestibility, which is more physiologically relevant as amino acids are primarily absorbed in the small intestine, and microbial fermentation in the large intestine can alter fecal amino acid content [28] [27]. Second, DIAAS calculates individual amino acid digestibility for each indispensable amino acid, unlike PDCAAS, which applies a single fecal crude protein digestibility value to all amino acids [3] [28]. Third, DIAAS employs a non-truncated scoring system that allows values to exceed 100%, providing a more accurate representation of a protein's ability to exceed amino acid requirements and its potential to complement other proteins in a mixed diet [3] [27]. Finally, DIAAS recommends the use of the growing pig model or direct human assays, as the pig's digestive system is more analogous to humans than the rat model used in PDCAAS determination [28] [27].

Calculation of DIAAS

The DIAAS is calculated using the following formula [3] [27]:

DIAAS (%) = 100 × [(mg of digestible dietary indispensable amino acid in 1 g of dietary protein) / (mg of the same dietary indispensable amino acid in 1 g of reference protein)]

The calculation involves determining the true ileal digestibility of each indispensable amino acid (IAA) in the test protein. The "score" is based on the IAA that is most limiting relative to the reference pattern requirement for a specific age group [3]. The reference protein patterns based on human amino acid requirements are provided in the table below.

Table 1: FAO Reference Amino Acid Requirements for DIAAS Calculation (mg/g protein) [27]

| Amino Acid | 0-6 months | 6 mo-3 years | Over 3 years |

|---|---|---|---|

| Histidine | 21 | 20 | 16 |

| Isoleucine | 55 | 32 | 30 |

| Leucine | 96 | 66 | 61 |

| Lysine | 69 | 57 | 48 |

| SAA (Methionine + Cysteine) | 33 | 27 | 23 |

| AAA (Phenylalanine + Tyrosine) | 94 | 52 | 41 |

| Threonine | 44 | 31 | 25 |

| Tryptophan | 17 | 8.5 | 6.6 |

| Valine | 55 | 43 | 40 |

Experimental Protocols for DIAAS Determination

In Vivo Ileal Digestibility Assay Using the Porcine Model

The growing pig is the recognized model for determining standardized ileal digestibility (SID) of amino acids for DIAAS calculation when direct human measurement is not feasible [28] [29]. The workflow for this protocol is illustrated below.

PROTOCOL: Standardized Ileal Digestibility (SID) in Pigs for DIAAS [30] [28] [29]

Objective: To determine the standardized ileal digestibility of amino acids in a test protein source for subsequent DIAAS calculation.

Animals and Surgical Procedure:

- Animals: Use growing barrows (e.g., initial body weight 25-30 kg). A sample size of 6-12 pigs is typical, allowing for a Latin square design.

- Cannulation: Equip pigs with a T-cannula at the distal ileum under general anesthesia. The cannula barrel length is typically 5 cm with an inner diameter of 1.3-1.5 cm.

- Recovery: Allow a 7-12 day recovery period post-surgery with free access to water and gradual reintroduction to feed.

Dietary Treatments and Experimental Design:

- Test Diets: Formulate diets containing the test ingredient as the sole source of amino acids. For concentrated proteins (e.g., isolates), inclusion rates of 20-50% are used; for grains (e.g., rice, wheat), inclusion rates can exceed 95% [29].

- Nitrogen-Free Diet: Include a nitrogen-free diet to determine the basal endogenous losses of amino acids.

- Marker: Incorporate an indigestible marker (e.g., 0.4% chromic oxide or 0.5% titanium dioxide) in all diets.

- Experimental Design: Employ a repeated Latin square design (e.g., 6×6 or 9×9). Each period typically lasts 7 days, with 5 days for diet adaptation and 2 days for digesta collection.

Feeding and Sample Collection:

- Feeding: Provide daily feed allowance in two equal meals (e.g., at 08:00 and 17:00). The total daily feed is typically provided at 4% of body weight, adjusted at the start of each period.

- Ileal Digesta Collection: On collection days, attach a plastic collection bag to the cannula. Collect digesta continuously for 9 hours on each collection day. Replace bags as they fill, or at minimum every 30 minutes. Immediately freeze collected digesta at -20°C to halt microbial activity.

Chemical Analysis and Calculations:

- Analysis: Analyze test diets and freeze-dried, homogenized digesta for:

- Amino Acid concentration using amino acid analysis (hydrolysis with 6N HCl for 24h at 110°C; perform separate analysis for sulfur-containing amino acids and tryptophan).

- Crude Protein (N × 6.25) via Kjeldahl or Dumas method.

- Indigestible Marker (e.g., chromic oxide) via atomic absorption spectroscopy.

- Standardized Ileal Digestibility (SID):

- AID (%) = [1 - ((AAdiet / AAdigesta) × (Markerdigesta / Markerdiet))] × 100

- SID (%) = AID + [ (BELaa / AAdiet) × 100 ]

- Where AID is Apparent Ileal Digestibility, BELaa is the basal endogenous loss of the amino acid (determined from the N-free diet), AAdiet is the amino acid concentration in the diet, and AAdigesta is the amino acid concentration in the digesta.

- DIAAS Calculation:

- Digestible IAA content (mg/g protein) = (IAA content in 1g test protein × SID of that IAA) / 100

- Reference Ratio = (Digestible IAA content) / (Reference IAA requirement from Table 1)

- DIAAS = 100 × (Lowest Reference Ratio among all IAAs)

Dual-Isotope Tracer Method for Human Studies

For direct measurement in humans, a minimally invasive dual-isotope tracer method has been developed to determine the true ileal digestibility of multiple amino acids simultaneously [3] [31].

PROTOCOL: Dual-Isotope Tracer Method for True Ileal Amino Acid Digestibility in Humans [3] [31]

Objective: To measure the true ileal digestibility of multiple indispensable amino acids in a test protein using a minimally invasive approach suitable for different physiological states, including vulnerable populations.

Principle: The method involves the simultaneous intravenous administration of an isotope-labeled amino acid (e.g., [¹³C]-amino acid) and oral administration of the same test protein intrinsically labeled with a different isotope (e.g., [²H]-amino acid). The ratio of the oral to intravenous tracer appearance in plasma allows for the calculation of digestibility.

Procedure:

- Protein Labeling: Produce an intrinsically labeled test protein by growing plants (e.g., wheat, soy) or administering labeled amino acids to animals (e.g., chickens for eggs, cows for milk) in a controlled environment with stable isotopes (e.g., ²H, ¹³C, ¹⁵N).

- Subject Preparation: After an overnight fast, participants are admitted to a clinical research unit. Intravenous catheters are placed in both arms (one for tracer infusion, one for blood sampling).

- Tracer Administration:

- Intravenous Tracer: A primed, continuous infusion of [¹³C]-labeled amino acid (e.g., [1-¹³C]-leucine) is started (t = -2 h) and maintained throughout the study.

- Oral Tracer: A single test meal containing the intrinsically labeled protein (e.g., [²H]-labeled protein) is consumed at t = 0 h.

- Blood Sampling: Serial blood samples are collected before and at regular intervals after the test meal (e.g., hourly for 8 hours) to measure the enrichment of both isotopic tracers in plasma.

- Analysis:

- Plasma samples are analyzed for amino acid isotopic enrichment using mass spectrometry.

- The true ileal digestibility (TAAD) is calculated using the formula: TAAD (%) = (Δ Oral Tracer Enrichment / Δ IV Tracer Enrichment) × 100 Where Δ Enrichment represents the incremental area under the curve for the respective tracer.

Advantages: This method is minimally invasive compared to naso-ileal intubation or fistulation, allows for simultaneous measurement of multiple amino acids, and can be applied across various physiological states and age groups.

Research Reagent Solutions and Essential Materials

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for DIAAS Determination

| Item | Specification/Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| Growing Pigs | Landrace × Yorkshire crossbred, initial BW 25-30 kg, ileal T-cannula. | In vivo SID assay [30] [29]. |

| T-Cannula | Medical-grade plastic or silicone, ~5 cm barrel, 1.3-1.5 cm inner diameter. | Surgically implanted at distal ileum for digesta collection [29]. |

| Nitrogen-Free Diet | Contains corn starch, sucrose, dextrose, cellulose, vitamin/mineral premix. | Determines basal endogenous amino acid losses for SID calculation [28] [29]. |

| Indigestible Marker | Chromic oxide (0.4-0.5%) or Titanium dioxide. | Non-absorbable reference point for digestibility calculations [28] [29]. |

| Pepsin | From porcine gastric mucosa (e.g., P7000, Sigma-Aldrich), 250 units/mg solid. | In vitro protein digestion simulation (stomach phase) [29]. |

| Pancreatin | From porcine pancreas (e.g., P1750, Sigma-Aldrich), 4 USP. | In vitro protein digestion simulation (small intestinal phase) [29]. |

| Stable Isotopes | ¹³C, ²H, ¹⁵N-labeled amino acids (e.g., [1-¹³C]-Leucine) and intrinsically labeled proteins. | Dual-isotope tracer method for human ileal digestibility [31]. |

| DaisyII Incubator | Multi-sample simultaneous in vitro digestion system (ANKOM Technology). | High-throughput in vitro ileal disappearance assays [29]. |

| Amino Acid Analyzer | HPLC system with post-column ninhydrin detection or UPLC-MS/MS. | Quantification of amino acids in diets and digesta [28] [29]. |

Application Data and Comparative Protein Quality Assessment

The implementation of DIAAS has provided a more accurate and differentiated understanding of protein quality across various sources. The following table consolidates DIAAS values from recent research, demonstrating its application in evaluating both single ingredients and combined meals.

Table 3: Experimentally Determined DIAAS Values for Various Protein Sources [30] [28] [29]

| Protein Source | DIAAS (0.5-3 yr) | DIAAS (>3 yr) | First-Limiting Amino Acid | Notes / Processing Method |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Whey Protein Isolate | 109 | >100 | Valine | High-quality reference protein [27] |

| Milk Protein Concentrate | 118 | >100 | SAA | Values not truncated; excellent quality [27] |

| Skim Milk Powder | 112-116 | 131 | SAA | Consistent high quality across studies [29] [27] |

| Soy Protein Isolate | 75-90 | 87 | SAA | Highly refined plant protein [28] [29] [27] |