Protein Denaturation and Nutritional Impact: Mechanisms, Methods, and Clinical Implications for Biomedical Research

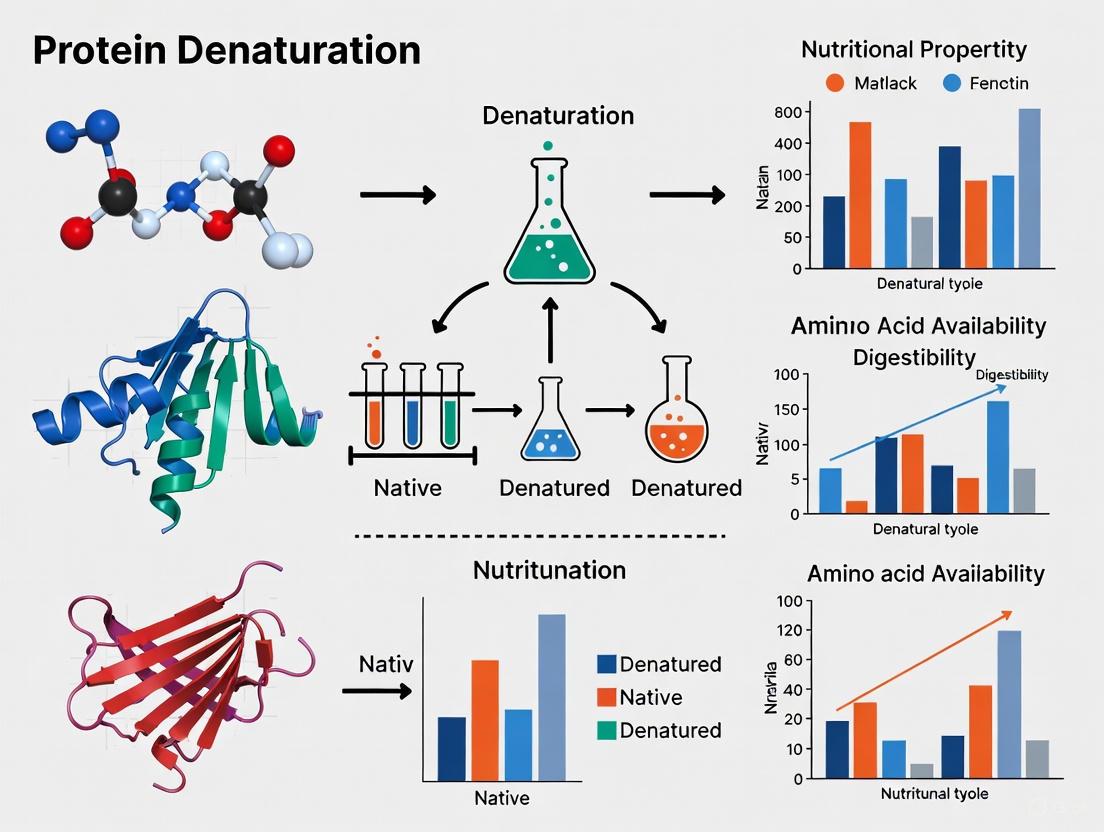

This comprehensive review examines protein denaturation processes and their significant effects on nutritional and functional properties, with specific relevance to drug development and therapeutic protein design.

Protein Denaturation and Nutritional Impact: Mechanisms, Methods, and Clinical Implications for Biomedical Research

Abstract

This comprehensive review examines protein denaturation processes and their significant effects on nutritional and functional properties, with specific relevance to drug development and therapeutic protein design. The article explores fundamental denaturation mechanisms across structural hierarchies, analyzes traditional and emerging denaturation methodologies, addresses stability challenges in therapeutic formulations, and presents comparative validation approaches for assessing protein quality. By synthesizing current research on structural modifications and their nutritional consequences, this work provides critical insights for researchers and scientists developing protein-based therapeutics, with particular emphasis on optimizing stability, bioavailability, and functional performance in clinical applications.

Protein Structure Fundamentals and Denaturation Mechanisms: From Molecular Organization to Functional Consequences

Proteins are fundamental macromolecules that perform a vast array of functions in biological systems, from catalyzing metabolic reactions to providing structural support. The function of a protein is intrinsically linked to its three-dimensional structure, which is organized into four hierarchical levels: primary, secondary, tertiary, and quaternary. Understanding these structural levels is essential for research on protein denaturation—the process by which proteins lose their native structure—and its implications for nutritional properties, drug development, and biotechnology. This whitepaper provides an in-depth technical guide to these structural levels, framed within the context of modern denaturation research, to serve scientists and drug development professionals.

The Hierarchical Levels of Protein Structure

Primary Structure

The primary structure of a protein is the unique, linear sequence of amino acids in a polypeptide chain, held together by covalent peptide bonds [1]. This sequence is genetically determined and encodes all the information necessary for the protein to fold into its functional three-dimensional conformation. The primary structure provides the fundamental nutritional value of a protein, as it contains the essential and non-essential amino acids required for human health [2]. During protein denaturation, the primary structure remains intact since the robust covalent peptide bonds are not disrupted by typical denaturation conditions [3].

Secondary Structure

The secondary structure refers to local, regularly repeating folding patterns within the polypeptide chain, stabilized primarily by hydrogen bonds between the backbone carbonyl oxygen and amide hydrogen atoms of amino acids near each other in the sequence [1]. The most common secondary structures are the α-helix, a right-handed coiled strand, and the β-pleated sheet, formed by extended strands connected side-by-side [1]. α-helices are characterized by 3.6 amino acid residues per turn, with hydrogen bonds forming between the oxygen of residue i and the hydrogen of residue i+4 [1]. In β-sheets, hydrogen bonds form between adjacent strands, which can run in the same (parallel) or opposite (antiparallel) directions. Denaturation disrupts the hydrogen bonds maintaining these secondary structures, causing proteins to lose their regular repeating patterns and often adopt a random coil configuration [3].

Tertiary Structure

The tertiary structure represents the overall three-dimensional folding of a single polypeptide chain, achieved by packing secondary structural elements together into a specific globular or fibrous shape [1]. This level is stabilized by various interactions between amino acid side chains (R groups), including disulfide bridges between cysteine residues, hydrogen bonds, ionic interactions between charged groups, van der Waals forces, and hydrophobic interactions that bury nonpolar residues in the protein's interior [1]. The tertiary structure creates specific binding sites and catalytic centers essential for protein function. Denaturation at this level involves the disruption of these stabilizing interactions—particularly disulfide bridges and van der Waals interactions between side chains—leading to the loss of the protein's native three-dimensional shape and, consequently, its biological activity [3].

Quaternary Structure

The quaternary structure exists in proteins composed of multiple polypeptide chains (subunits) and refers to the spatial arrangement and interactions between these subunits [1]. These complexes are held together by the same non-covalent interactions that stabilize tertiary structure, and sometimes by disulfide bonds. Well-known examples include hemoglobin (comprising two α and two β globin chains) and antibodies [1]. Denaturation at the quaternary level leads to the dissociation of protein subunits and the disruption of their spatial arrangement, effectively dismantling the functional multimeric protein [3].

Table 1: Summary of the Four Levels of Protein Structure and Their Susceptibility to Denaturation

| Structural Level | Definition | Stabilizing Forces/Bonds | Effect of Denaturation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Structure | Linear sequence of amino acids [1] | Covalent peptide bonds [2] | No change; bonds remain intact [3] |

| Secondary Structure | Local folding patterns (α-helix, β-sheet) [1] | Hydrogen bonds (backbone) [1] | Loss of regular patterns; transition to random coil [3] |

| Tertiary Structure | Overall 3D folding of a single chain [1] | Disulfide bridges, hydrophobic interactions, van der Waals forces, ionic bonds [1] | Disruption of interactions and loss of 3D shape/function [3] |

| Quaternary Structure | Assembly of multiple polypeptide chains [1] | Non-covalent interactions between subunits [1] | Subunit dissociation and disruption of spatial arrangement [3] |

Denaturation and Its Impact on Structure and Nutrition

Mechanisms of Protein Denaturation

Protein denaturation is the process by which proteins lose their native three-dimensional structure due to the disruption of weak, non-covalent chemical bonds and interactions, while the primary amino acid sequence remains intact [2]. This process can be triggered by various physical and chemical factors, as summarized in Table 2.

Table 2: Common Protein Denaturation Triggers and Their Mechanisms

| Denaturation Factor | Mechanism of Action | Common Examples in Research/Industry |

|---|---|---|

| Heat | Disrupts hydrogen bonds and hydrophobic interactions [2] | Cooking, pasteurization, ultra-high temperature (UHT) processing [2] |

| Acid/Base | Alters ionic bonds and charge distribution [2] | Stomach acid, food processing (e.g., cheese, yogurt) [2] |

| Chemical Denaturants | Direct interaction with protein backbone and side chains [4] | Urea, guanidinium chloride in laboratory studies [4] |

| Physical Force | Causes mechanical unfolding [2] | Blending, high-pressure processing (HPP) [2] [5] |

| Emerging Technologies | Varied mechanisms (e.g., electrical, acoustic, plasma) [6] | Ohmic heating, ultrasound, cold plasma, pulsed electric fields (PEF) [6] |

Denaturation and Nutritional Properties: A Research Perspective

A critical consideration in nutritional science is whether denaturation destroys the nutritional value of proteins. Research consistently demonstrates that denaturation does not eliminate amino acid content, meaning the fundamental nutritional value for muscle building, recovery, and health is retained [2]. The primary structure, which supplies the amino acids, remains unchanged.

Furthermore, moderate denaturation often enhances protein digestibility by unfolding tightly packed native structures, thereby exposing peptide bonds to digestive enzymes like pepsin and trypsin [2]. A 2025 study on sardines and sprats demonstrated that thermal treatments (frying, steaming, baking) substantially improved protein digestibility compared to raw samples [2]. A 2023 review similarly concluded that methods including heat, ultrasound, and high pressure improve the digestion rate of meat proteins, particularly for older adults [2].

It is crucial to distinguish between biological activity and nutritional value. Denaturation typically eliminates specific biological functions, such as enzymatic activity or antibody binding. However, for nutritional purposes focused on amino acid provision, denatured proteins are equally effective, and often superior, due to improved digestibility [2].

Table 3: Impact of Novel Food Processing Technologies on Food Proteins

| Processing Method | Key Structural/Functional Impacts on Proteins | Potential Nutritional/Product Implications |

|---|---|---|

| Ohmic Heating | Affects particle size, secondary structure, coagulation; can enhance water/oil holding capacity, emulsifying/foaming properties [6] | Can improve bioactivity (e.g., release of bioactive peptides in sheep milk) [6] |

| High-Pressure Processing (HPP) | Primarily affects particle size, secondary structure, and coagulation properties [6] | Can alter texture and improve digestibility [6] |

| Pulsed Electric Fields (PEF) | Enhances protein solubility and can modify protein structure [6] | May improve accessibility for enzymatic breakdown [6] |

| Enzymatic Hydrolysis | Breaks proteins into smaller peptides, improving texture, degree of hydrolysis, and solubility [6] | Directly enhances digestibility and can reduce allergenicity [6] |

| Cold Plasma / Plasma-Activated Water | Can modify protein structure and improve gelation properties [6] | Improves appearance, color, and taste of products like cheese [6] |

Experimental Analysis of Protein Structure and Denaturation

Key Experimental Protocols

4.1.1 Probing Denaturation with Solutes and Temperature A foundational protocol for studying folding/unfolding kinetics involves monitoring the effects of denaturants (urea, guanidinium chloride) and temperature on protein stability [4]. Denaturant thermodynamic m-values (the derivative of the folding free energy with respect to denaturant concentration) and activation heat capacity changes serve as probes for changes in solvent-accessible surface area (ASA) during folding and unfolding [4]. This allows researchers to quantify the amount of hydrocarbon and amide surface buried in the transition state and folding intermediates, providing mechanistic insights.

Table 4: Research Reagent Solutions for Protein Folding/Unfolding Studies

| Research Reagent | Function/Application | Mechanistic Insight Provided |

|---|---|---|

| Urea | Chemical denaturant | Preferentially interacts with amide and hydrocarbon surface; used to determine surface area changes in folding transitions [4] |

| Guanidinium Chloride (GuHCl) | Chemical denaturant | Strong preferential interaction with amide surface; kinetic m-values primarily report on changes in amide surface area [4] |

| Dithiothreitol (DTT) / β-Mercaptoethanol | Reducing agents | Disrupt disulfide bonds to study their role in stabilizing tertiary and quaternary structure [7] |

| Model Compound Systems (e.g., cyclic dipeptides) | Reference systems | Quantify denaturant interaction potentials (α-values) with protein functional groups for mechanistic interpretation [4] |

4.1.2 Electrospinning to Study Denatured Protein Behavior Electrospinning is an advanced technique to study the properties of denatured proteins and create protein-based nanofibers [5]. The protocol involves preparing a protein-polymer solution (e.g., soy protein isolate with PVA or PEO), applying denaturation pre-treatments (e.g., pH adjustment, high hydrostatic pressure, microwave), and then ejecting the solution through a syringe pump under high DC voltage to form fibers collected on a grounded collector [5]. This method is highly sensitive to changes in protein conformation, aggregation, and intermolecular interactions induced by denaturation, making it a powerful tool for characterizing denatured protein behavior.

Visualization and Analysis Tools for the Modern Scientist

Understanding protein structure requires sophisticated visualization software. Key tools used by researchers include:

- ChimeraX: A next-generation system for analysis and presentation graphics, offering high performance on large data and a virtual reality interface [8] [9].

- PyMOL: A widely used, scriptable open-source system for producing publication-quality imagery and animations [8] [9].

- AlphaFold Database: Provides open access to over 200 million AI-predicted protein structures, dramatically accelerating structural research [10].

The four-level hierarchical model of protein structure provides an essential framework for understanding protein function, stability, and interactions. Within the context of denaturation research, it is clear that while the disruption of secondary, tertiary, and quaternary structures alters functionality and biological activity, the nutritional value derived from the primary sequence is preserved and often enhanced through improved digestibility. Emerging non-thermal processing technologies offer precise tools for manipulating protein structure to achieve desired functional and nutritional outcomes in food science and pharmaceutical development. For researchers and drug development professionals, a deep understanding of these structural principles, combined with advanced experimental and computational tools, is fundamental to innovating in fields ranging from nutritional biochemistry to therapeutic design.

Protein denaturation, the process by which proteins lose their native three-dimensional structure, represents a critical phenomenon with profound implications across biochemical, pharmaceutical, and nutritional sciences. This technical review examines the molecular mechanisms underlying protein denaturation, with particular focus on the disruption of weak chemical bonds and alterations in hydration layers that stabilize native protein conformations. We synthesize recent experimental findings that elucidate how denaturing agents—including heat, pH extremes, chemical denaturants, and inorganic salts—destabilize protein structure through distinct yet potentially complementary pathways. The review further explores how these molecular-level events connect to macroscopic functional and nutritional properties, providing researchers with a comprehensive mechanistic framework for manipulating protein behavior in therapeutic and nutritional applications. Advanced analytical techniques, including terahertz spectroscopy, calorimetry, and spectroscopic methods, have revealed previously unappreciated complexities in protein-solvent interactions during denaturation, opening new avenues for controlled protein engineering and processing.

Proteins fulfill their diverse biological functions through precisely defined three-dimensional structures maintained by a delicate balance of weak chemical forces and solvent interactions [11] [12]. Protein denaturation describes the process wherein these native structures unravel, resulting in loss of biological activity while maintaining the primary amino acid sequence [2] [12]. Understanding denaturation mechanisms is fundamental to numerous scientific and industrial applications, from rational drug design to optimizing protein nutritional quality.

The stability of the native protein structure depends on a network of weak non-covalent interactions—including hydrogen bonds, hydrophobic interactions, ionic bonds, and van der Waals forces—that collectively maintain secondary, tertiary, and quaternary structures [11] [13]. Disruption of this network, whether through thermal energy, chemical agents, or mechanical stress, initiates denaturation. Contemporary research has increasingly highlighted the crucial role of hydration layers—organized water molecules surrounding protein surfaces—in modulating protein stability and denaturation kinetics [14].

This review integrates current understanding of how denaturation processes simultaneously target intramolecular protein interactions and surrounding hydration layers. We examine experimental evidence elucidating these mechanisms and their consequences for protein function and nutritional value, with particular relevance to pharmaceutical development and nutritional science research.

Molecular Mechanisms of Denaturation

Disruption of Weak Chemical Bonds

The native conformation of proteins is stabilized by several types of weak chemical bonds that are individually susceptible to environmental perturbations but collectively provide substantial structural stability.

Hydrogen Bonds: Hydrogen bonding between backbone amides and side chain donors/acceptors creates regular secondary structures like α-helices and β-sheets. Denaturing agents compete for these bonding partners; for instance, urea forms hydrogen bonds with protein backbone atoms, while heat increases molecular motion enough to overcome hydrogen bonding energy (typically 2-5 kcal/mol) [12] [13].

Hydrophobic Interactions: The sequestration of nonpolar side chains in the protein interior, driven by the hydrophobic effect, represents a major stabilizing force in tertiary structure. Elevated temperatures reduce the free energy penalty of exposing hydrophobic groups to water, while organic solvents directly disrupt hydrophobic interactions by lowering the dielectric constant of the solution [11] [15].

Electrostatic (Ionic) Interactions: Salt bridges between positively and negatively charged side chains contribute to protein stability, particularly in extreme environments. pH changes alter side chain ionization states, disrupting these interactions, while high salt concentrations shield charged groups and can screen electrostatic attractions [11] [12].

van der Waals Forces: These short-range interactions between electron clouds of adjacent atoms, though individually weak, collectively stabilize compact native folds. Denaturation separates tightly packed groups, eliminating these stabilizing contacts [11].

Disulfide Bridges: Though technically covalent bonds, disulfide linkages between cysteine residues are often disrupted during denaturation through reduction to sulfhydryl groups, particularly in the presence of reducing agents like dithiothreitol (DTT) [12] [15].

Table 1: Weak Chemical Bonds in Protein Structure and Their Disruption by Denaturing Conditions

| Bond Type | Energy Range (kcal/mol) | Location in Structure | Primary Denaturation Mechanisms |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hydrogen bonds | 2-5 | Secondary structures (α-helix, β-sheet) | Heat, urea, guanidinium chloride, extreme pH |

| Hydrophobic interactions | 1-3 | Protein core (tertiary structure) | Heat, detergents, organic solvents |

| Electrostatic interactions | 3-7 | Surface salt bridges | Extreme pH, high salt concentrations |

| van der Waals forces | 0.5-1 | Throughout protein structure | Heat, pressure |

| Disulfide bridges | ~50 | Stabilizing tertiary structure | Reducing agents (DTT, β-mercaptoethanol) |

Alterations in Hydration Layers

The protein-solvent interface plays an active role in maintaining protein stability, with recent research revealing dramatic reorganization of hydration layers during denaturation.

Strongly vs. Weakly Bound Hydration Water

The hydration shell surrounding proteins consists of dynamically distinct water populations. Strongly bound hydration water molecules directly interact with protein surface polar groups, primarily in the first hydration shell, exhibiting restricted mobility. Weakly bound hydration water resides mainly in the second hydration shell, where it experiences moderate perturbation of hydrogen-bonding networks [14].

Terahertz spectroscopy studies of bovine serum albumin (BSA) reveal that denaturation produces contrasting changes in these populations: the number of strongly bound water molecules decreases while weakly bound hydration water increases [14]. This redistribution reflects fundamental changes in protein-water interactions as hydrophobic groups become exposed and hydrophilic groups become entangled during unfolding.

Hydration Layer Changes During Denaturation

In the native state, proteins maintain a well-defined hydration layer with specific strongly and weakly bound water populations. Upon denaturation, exposure of hydrophobic groups to water and entanglement of hydrophilic groups triggers reorganization of this hydration shell [14]. The strengthening of hydrogen bonds between water molecules in the second hydration shell represents a key microscopic mechanism for native state destabilization, as this reduces the energetic penalty for exposing hydrophobic surface area.

Table 2: Changes in Hydration Water Properties Upon Protein Denaturation

| Hydration Parameter | Native State | Denatured State | Experimental Detection Method |

|---|---|---|---|

| Strongly bound water | Higher number of molecules | Decreased number | Terahertz spectroscopy, thermal measurements |

| Weakly bound water | Lower number of molecules | Increased number | Terahertz spectroscopy |

| Hydrogen bond strength | Weaker in second shell | Strengthened between water molecules | Terahertz spectroscopy, infrared spectroscopy |

| Hydration shell extent | Limited to first/second shell | More extended hydration layer | Terahertz spectroscopy, neutron scattering |

| Water mobility | Restricted near protein surface | Increased mobility | NMR spectroscopy, dielectric relaxation |

Experimental Methodologies for Studying Denaturation

Terahertz Time-Domain Spectroscopy (THz-TDS)

Principle: Terahertz spectroscopy probes collective hydrogen-bonding networks and water dynamics in the 0.1-10 THz range, providing unique insight into hydration layer changes during denaturation [14].

Protocol for Protein Denaturation Studies:

- Prepare protein solution (e.g., 13 wt% BSA in ultrapure water) and matched buffer blank

- Utilize attenuated total reflection (ATR) setup with silicon Dove prism to enhance detection sensitivity

- Acquire THz time-domain waveforms for sample and reference

- Apply Fourier transformation to extract complex dielectric function

- Monitor temperature-induced denaturation by collecting spectra at controlled temperature increments

- Analyze hydration water populations through dielectric relaxation parameters

Data Interpretation: Increased absorption in specific THz frequencies indicates strengthened water-water hydrogen bonding in second hydration shell, characteristic of hydrophobic hydration upon denaturation [14].

Differential Scanning Calorimetry (DSC)

Principle: DSC directly measures heat flow associated with thermal denaturation, providing thermodynamic parameters (transition temperature Td, enthalpy ΔH) [11].

Protocol:

- Dialyze protein sample against appropriate buffer to eliminate confounding ions

- Load matched protein and reference solutions into calorimeter cells

- Scan temperature at controlled rate (e.g., 1°C/min) through denaturation transition

- Analyze endothermic peak to determine Td (peak maximum) and ΔH (peak area)

- For complex systems like soy proteins, deconvolute multiple transitions (e.g., conglycinin and glycinin denaturation peaks) [11]

Circular Dichroism (CD) Spectroscopy

Principle: CD measures differential absorption of left- and right-circularly polarized light, sensitive to protein secondary structure [16].

Protocol for Thermal Denaturation:

- Record far-UV (190-260 nm) CD spectrum of native protein at low temperature

- Monitor CD signal at specific wavelength (e.g., 222 nm for α-helix) while ramping temperature

- Fit temperature dependence to two-state or multi-state model to determine Tm

- Analyze post-denaturation spectra for residual structure

- Utilize algorithms like BeStSel for detailed secondary structure quantification, including parallel β-sheets and twisted β-sheets [16]

Analysis of Salt-Induced Denaturation

Principle: Concentrated ions denature proteins through mechanisms distinct from classical denaturants [15].

Protocol for Lithium Bromide Denaturation:

- Prepare concentrated salt solutions (e.g., 8 M LiBr) with reducing agent (DTT) for disulfide-rich proteins

- Incubate protein source (wool, feathers) in salt solution at elevated temperature (e.g., 65°C) with agitation

- Cool solution to permit spontaneous gel formation

- Separate condensed protein gel by centrifugation

- Characterize denaturation extent by FTIR (secondary structure), turbidity measurements (aggregation), and SEM (morphological changes) [15]

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents for Protein Denaturation Studies

| Reagent/Chemical | Function in Denaturation Studies | Typical Working Concentration | Key Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Urea | Disrupts hydrogen bonding network | 6-8 M | Chemical denaturation studies, folding/unfolding experiments |

| Guanidinium chloride | Competes for protein hydrogen bonds | 4-6 M | Equilibrium unfolding, stability measurements |

| Dithiothreitol (DTT) | Reduces disulfide bonds to sulfhydryls | 1-5 mM | Studying disulfide-stabilized proteins (e.g., keratins) |

| Lithium bromide (LiBr) | Disrupts water network structure | 8 M | Alternative denaturation mechanism studies, keratin extraction |

| SDS | Binds protein backbone, disrupts hydrophobic interactions | 0.1-1% | Electrophoresis, membrane protein studies |

| Tris buffers | pH control during denaturation | 10-100 mM | Maintaining specific pH conditions for pH-denaturation studies |

Denaturation Mechanisms and Nutritional Implications

The molecular events of denaturation have direct consequences for protein nutritional properties, particularly digestibility and bioavailability.

Structural Basis for Enhanced Digestibility

Denaturation unfolds compact native structures, exposing peptide bonds to proteolytic enzymes. The loss of tertiary and secondary structure eliminates steric hindrance that limits enzyme access in native proteins [2] [12]. Studies comparing native and denatured proteins consistently demonstrate 20-30% improvements in digestibility for moderately denatured proteins compared to their native counterparts [2].

Infrared and Raman spectroscopic analyses reveal that structural changes during denaturation increase the accessibility of trypsin-cleavable peptide bonds, with the most significant digestibility improvements observed in proteins with tightly packed globular native structures [12].

Amino Acid Bioavailability

While denaturation preserves the primary amino acid sequence, structural changes influence the bioavailability of essential amino acids. Research indicates that properly controlled denaturation enhances amino acid absorption by 10-15% compared to native proteins, though excessive processing can promote Maillard reactions or oxidation that reduce bioavailability [2] [17].

Plant proteins often benefit most from moderate denaturation due to their complex native structures and frequent association with protease inhibitors that are inactivated during thermal denaturation [17].

The molecular mechanisms of protein denaturation involve complex interplay between disruption of weak intramolecular bonds and reorganization of hydration layers. While classical models emphasized direct protein-denaturant interactions, contemporary research reveals significant roles for solvent-mediated effects, particularly with inorganic denaturants like LiBr that operate through entropy-driven mechanisms by disrupting water structure rather than directly binding proteins.

These molecular insights have profound implications for nutritional science, explaining how controlled denaturation can enhance protein digestibility and amino acid bioavailability while preserving nutritional value. Future research integrating high-resolution structural techniques with advanced solvent dynamics measurements will further elucidate the precise sequence of events during denaturation, enabling more precise manipulation of protein functionality for pharmaceutical and nutritional applications.

Visualizations

Diagram 1: Hydration Layer Changes During Protein Denaturation. This schematic illustrates the reorganization of hydration water during the transition from native to denatured protein states, showing decreased strongly bound water and increased weakly bound water populations.

Diagram 2: Weak Bond Disruption in Protein Denaturation. This diagram illustrates how different denaturing mechanisms specifically target various types of weak chemical bonds that stabilize native protein structure.

Protein denaturation, the process by which proteins lose their native three-dimensional structure, is a fundamental phenomenon with profound implications across biochemical research, therapeutic development, and nutritional sciences. The distinction between reversible denaturation, where proteins can refold to their native state, and irreversible denaturation, where they cannot, represents a critical frontier in understanding protein behavior under stress conditions. Within nutritional research, controlling denaturation pathways enables optimization of protein digestibility and functionality in food products and supplements. This review provides a comprehensive analysis of the thermodynamic principles and kinetic parameters governing these processes, equipping researchers with the conceptual frameworks and methodological tools needed to probe denaturation mechanisms in both fundamental and applied contexts.

The native structure of a protein is stabilized by a delicate balance of weak non-covalent interactions—including hydrogen bonds, hydrophobic interactions, and van der Waals forces—as well as disulfide covalent bonds [18]. When subjected to external stresses such as temperature extremes, pH shifts, chemical denaturants, or mechanical agitation, this delicate balance can be disrupted, resulting in unfolding and loss of biological function [18]. While the primary amino acid sequence remains intact during denaturation [2], the loss of higher-order structure (secondary, tertiary, and quaternary) fundamentally alters protein properties, with significant consequences for both biological activity and nutritional quality.

Thermodynamic Fundamentals of Protein Denaturation

The Protein Stability Curve

The thermodynamic behavior of proteins during denaturation is best described by the stability curve, which plots the Gibbs free energy change (ΔG) between the native (N) and unfolded (U) states as a function of temperature. This relationship follows a parabolic shape described by the equation:

ΔG(T) = ΔHm(1 - T/Tm) - ΔCp[(Tm - T) + T ln(T/Tm)]

Where ΔHm is the enthalpy change at the denaturation temperature Tm, and ΔCp is the heat capacity change upon unfolding [19]. The positive ΔCp universally observed in protein denaturation reflects the exposure of hydrophobic groups to water upon unfolding [19]. This fundamental relationship gives rise to several key thermodynamic features:

- Temperature of Maximal Stability (T*) : The point where ΔG reaches its maximum value, typically around 283K (10°C) for many globular, water-soluble proteins, largely independent of Tm [19].

- Cold Denaturation : The phenomenon where proteins unfold at low temperatures due to the weakening of hydrophobic interactions, representing the second zero-crossing point of the stability curve [19].

- Heat Denaturation : The familiar unfolding at elevated temperatures where ΔG becomes negative.

For hyperthermostable proteins with denaturation temperatures exceeding 100°C, research indicates that thermostability is achieved primarily through elevation of the entire stability curve rather than shifting T* to higher temperatures or broadening the curve [20]. Analysis of CutA1 mutant proteins demonstrates that an increase in maximal stability of approximately 0.008 kJ/mol per residue is associated with each 1°C increase in Tm [19].

Driving Forces: Enthalpy versus Entropy

The balance between enthalpy (ΔH) and entropy (ΔS) contributions determines the pathway and reversibility of denaturation:

- Entropy-Driven Denaturation : Recent research on concentrated inorganic ion pairs like LiBr reveals an alternative denaturation mechanism where disruption of the water network structure, rather than direct protein-solute interactions, drives unfolding through entropic gains [15]. This mechanism enables unique protein material regeneration with rapid gel-solid transitions.

- Enthalpy-Driven Stabilization : Hydrophobic mutants of CutA1 exhibit stabilization through accumulation of denaturation enthalpy (ΔH) with minimal entropic gain from hydrophobic solvation around 100°C [20]. In contrast, stabilization from salt bridges in hyperthermostable mutants results from both increased ΔH from ion-ion interactions and entropic effects of electrostatic solvation above 113°C [20].

Table 1: Thermodynamic Parameters for Representative Proteins

| Protein | Tm (K) | ΔHm (kJ/mol) | ΔCp (kJ/mol·K) | ΔG(T*)/N (kJ/mol·res) | T* (K) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1LYS (Lysozyme) | 333 | 427 | 6.3 | 0.32 | 272 |

| 1UBQ (Ubiquitin) | 363 | 308 | 3.3 | 0.48 | 281 |

| 5BPI (BPTI) | 377 | 317 | 2.0 | 1.00 | 248 |

| PFRD1 (Ferredoxin) | 450 | 481 | 3.4 | 1.42 | 333 |

Kinetic Traps and Irreversibility

Pathways to Irreversibility

While the folded state of a protein typically has lower free energy than the unfolded state under native conditions, kinetic barriers often prevent refolding, leading to irreversible denaturation [18]. Several molecular mechanisms contribute to this kinetic irreversibility:

- Aggregation and Precipitation : exposed hydrophobic surfaces on unfolded protein molecules interact to form insoluble aggregates with high kinetic stability [21]. Studies on hen egg white lysozyme (HEWL) at pH 9.0 and high concentrations (≥100 mg/mL) demonstrate irreversible denaturation coupled with aggregation and precipitation, observable as exothermic heat effects following endothermic denaturation peaks in DSC scans [21].

- Chemical Degradation : at elevated temperatures (>80°C), processes such as disulfide bond scrambling, deamidation of asparagine and glutamine residues, and oxidation of cysteine, methionine, and tryptophan side chains create non-native covalent modifications that prevent proper refolding [20].

- Complex Folding Landscapes : proteins with complex domain architectures or cofactor requirements may populate misfolded intermediates that slowly convert to stable, non-native structures.

The irreversibility of thermal denaturation is strongly influenced by hydration status. Research on lysozyme demonstrates three distinct unfolding behaviors dependent on water content: below 37 wt% water, unfolding is irreversible; above 60 wt%, the process is reversible; and in the intermediate range (37-60 wt%), the system phase separates and denaturation involves both crystal melting and molecular unfolding [22].

Experimental Analysis of Irreversible Denaturation

Under irreversible conditions, classical equilibrium thermodynamics does not apply, and kinetic analysis becomes essential. Isothermal calorimetry provides a powerful approach for directly measuring the kinetics of irreversible denaturation and aggregation at physiologically relevant conditions [21]. For example, the rate of irreversible denaturation and aggregation of HEWL at temperatures 12°C below the DSC-measured Tm can be determined through continuous monitoring of heat flow over extended periods (days) [21].

Table 2: Kinetic Parameters for Irreversible Denaturation of Hen Egg White Lysozyme at pH 9.0

| Protein Concentration (mg/mL) | Temperature (°C) | Rate Constant (day⁻¹) | Half-life (days) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 25 | 57 | 0.45 | 1.54 |

| 50 | 58 | 0.62 | 1.12 |

| 100 | 59 | 0.89 | 0.78 |

Methodologies for Denaturation Analysis

Thermodynamic Characterization Techniques

Differential Scanning Calorimetry (DSC) : DSC measures the heat capacity change during thermal denaturation, providing direct access to Tm, ΔH, and, for reversible systems, ΔCp. For irreversible systems, the apparent Tm remains useful for comparative stability assessments under identical scan conditions [21]. Sample preparation typically involves protein concentrations of 0.2-1.5 mg/mL in appropriate buffers, with scan rates of 1°C/min commonly employed to approach equilibrium conditions [21].

Isothermal Titration Calorimetry (ITC) : While primarily used for binding studies, ITC can characterize denaturation by measuring heat changes during chemical denaturant titrations, providing both thermodynamic and kinetic information.

Spectroscopic Techniques :

- Circular Dichroism (CD) spectroscopy monitors changes in secondary structure (far-UV, 190-250 nm) and tertiary structure (near-UV, 250-320 nm) during denaturation.

- Fluorescence spectroscopy, particularly intrinsic tryptophan fluorescence, detects alterations in the local environment of aromatic residues as the protein unfolds.

- Fourier-Transform Infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy identifies changes in secondary structure composition through the amide I band (1600-1700 cm⁻¹) [15].

Kinetic Characterization Methods

Isothermal Chemical Denaturation : This technique employs chemical denaturants (guanidine hydrochloride or urea) at fixed concentrations while monitoring unfolding over time using fluorescence or CD spectroscopy. It is particularly valuable for characterizing slow unfolding processes and identifying transient intermediates.

Isothermal Calorimetry : Specialized isothermal calorimeters can measure very slow denaturation and aggregation processes (rate constants ~1 day⁻¹) at high protein concentrations (>100 mg/mL) by monitoring heat flow over extended periods (days to weeks) [21]. This approach is especially relevant for biologics formulation development.

Stopped-Flow Kinetics : For very rapid unfolding events (milliseconds to seconds), stopped-flow instruments rapidly mix protein with denaturant while monitoring spectroscopic signals, enabling resolution of early unfolding events.

Research Reagent Solutions Toolkit

Table 3: Essential Reagents and Materials for Denaturation Studies

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Guanidine HCl (GdnHCl) | Chemical denaturant for reversible unfolding studies | High purity (>99%); prepare fresh solutions; concentration typically 0-8 M |

| Urea | Chemical denaturant for reversible unfolding | Fresh preparation critical to avoid cyanate formation; concentration typically 0-10 M |

| Lithium Bromide (LiBr) | Ionic denaturant for entropy-driven unfolding [15] | High concentrations (8 M) effective for fibrous proteins; enables unique regeneration pathways |

| Dithiothreitol (DTT) | Reducing agent for disulfide bond disruption | Critical for proteins with cysteine residues; concentration typically 1-5 mM |

| Differential Scanning Calorimeter (DSC) | Direct measurement of thermal denaturation thermodynamics | Requires degassed samples; appropriate scan rates (0.5-2°C/min) |

| Isothermal Calorimeter | Measurement of slow denaturation/aggregation kinetics | Enables studies at high protein concentrations (>100 mg/mL); long measurement times (days) |

| Fluorescence-Compatible Chemical Denaturation System | Automated determination of unfolding curves | Enables high-throughput screening of denaturation conditions |

Denaturation Pathways and Experimental Workflows

Diagram 1: Protein Denaturation Pathways and Analysis

Implications for Nutritional Properties Research

The reversibility of protein denaturation has profound implications for nutritional quality and functionality in food systems. While denaturation generally preserves amino acid content and often improves digestibility by exposing cleavage sites for proteolytic enzymes [2], the extent and pathway of denaturation significantly impact functional properties:

Controlled Denaturation in Prepared Foods : Research on prepared chicken breast demonstrates that mild pre-heating (quantified using a Cooked Value scale based on protein denaturation kinetics) reduces water loss, suppresses protein aggregation during recooking, and yields superior texture compared to full pre-heating [23]. This controlled denaturation approach minimizes excessive protein oxidation while maintaining quality through freezing and reheating cycles.

Emerging Processing Technologies : Novel non-thermal technologies (high hydrostatic pressure, microwave, ultrasound, ozone) enable precise control over denaturation pathways, enhancing protein solubility and functionality while preserving bioactivity [5]. For example:

- High hydrostatic pressure (HHP) pretreatment improves characteristics of soy protein isolate-polyvinyl alcohol electrospinning solutions by increasing viscosity and promoting tangled structures [5].

- pH-shifting treatments generate stronger effects on solution viscosity and fiber morphology than temperature treatments in electrospinning applications [5].

- Ohmic heating modifies protein structure to enhance water and oil holding capacity, emulsifying properties, and foaming characteristics [6].

Digestibility Considerations : Moderate denaturation typically enhances protein digestibility by unfolding tightly packed structures and exposing peptide bonds to digestive enzymes [2]. However, excessive processing under extreme conditions can promote formation of indigestible aggregates or damage amino acids, reducing nutritional value [2].

The dichotomy between reversible and irreversible protein denaturation represents a fundamental principle with far-reaching consequences in biochemical research, therapeutic development, and nutritional science. Thermodynamic analysis reveals that protein stability follows characteristic patterns describable by stability curves, with reversible transitions governed by equilibrium principles and irreversible processes dominated by kinetic traps. Emerging methodologies, particularly isothermal calorimetry and advanced spectroscopic techniques, now enable detailed characterization of both pathways under physiologically relevant conditions.

In nutritional contexts, controlled denaturation strategies—whether through traditional thermal processing or emerging non-thermal technologies—offer pathways to enhance protein functionality and digestibility while preserving nutritional value. The growing understanding of denaturation mechanisms at the molecular level provides a robust foundation for innovative applications across the food and pharmaceutical industries, enabling the rational design of processes that optimize protein behavior for specific nutritional and technological outcomes. Future research will likely focus on leveraging these principles to develop sustainable protein resources and precision nutrition solutions tailored to diverse physiological needs.

Protein denaturation is a fundamental biochemical process defined as the disruption of a protein's native three-dimensional structure, leading to a loss of its biological function [24] [25]. This process involves the destabilization of the non-covalent interactions—including hydrogen bonds, ionic bonds, hydrophobic interactions, and Van der Waals forces—that maintain the secondary, tertiary, and quaternary structures of proteins [24] [12]. Crucially, denaturation typically leaves the primary structure (the amino acid sequence) intact, as peptide bonds are not directly broken by common denaturing agents [12] [25].

The integrity of a protein's native structure is essential for its physiological activity, whether acting as an enzyme, hormone, antibody, or structural component. The process of denaturation unfolds the polypeptide chain, often exposing hydrophobic regions and reactive groups that are normally buried within the protein's core [24] [12]. This unfolding can result in decreased solubility, increased susceptibility to proteolytic digestion, and the loss of specific biological activity [12] [25]. Within the context of nutritional science, understanding and controlling denaturation is critical, as it directly influences protein digestibility, bioavailability, and functionality in food products [26].

Mechanisms and Effects of Common Denaturation Triggers

Denaturation can be induced by a variety of physical and chemical triggers. The following sections detail the mechanisms and effects of the most common ones.

Heat

Heat is one of the most prevalent and effective denaturing agents. Elevated temperatures increase the vibrational energy within protein molecules, which can overcome the weak non-covalent interactions stabilizing the folded conformation [25]. This leads to the unfolding of the polypeptide chain. A classic example is the thermal denaturation of egg white proteins, which transforms a transparent liquid into an opaque solid [12] [25]. The temperature at which denaturation occurs varies significantly between proteins; for instance, while many proteins denature at temperatures around 40-70°C, some, like ribonuclease, are extremely stable and can withstand temperatures up to 90°C for short periods without significant denaturation [12].

pH Changes

Extreme pH levels, both acidic and alkaline, can cause protein denaturation by altering the ionization state of amino acid side chains [25]. This disrupts the pattern of ionic bonds and hydrogen bonding that is critical for maintaining the protein's specific three-dimensional structure [12] [25]. In food processing, this principle is exploited in protein purification and in the production of certain protein-rich foods, where proteins may precipitate out of solution due to denaturation induced by pH shifts [25].

Chemical Agents

A wide range of chemicals can induce denaturation through different mechanisms:

- Urea and Guanidinium Chloride: These agents have a high affinity for peptide bonds and disrupt hydrogen bonds and salt bridges, effectively abolishing the protein's tertiary structure [12].

- Reducing Agents: Agents that reduce disulfide bonds (e.g., conversion of -S-S- to -SH groups) can disrupt the covalent cross-links that stabilize a protein's structure. While reoxidation can sometimes regenerate the native protein, it often results in incorrect pairings and a different, non-functional protein [12].

- Organic Solvents: Solvents like ethanol or acetone interfere with the mutual attraction of nonpolar groups, disrupting the hydrophobic interactions that are crucial for protein folding [12].

- Detergents: Detergents can denature proteins by disrupting hydrophobic interactions and solubilizing proteins, which is a key mechanism in many cleaning processes [25].

Physical Forces

Physical forces such as mechanical agitation (e.g., whipping or shaking), radiation, and high pressure can also denature proteins. These forces mechanically disrupt the weak interactions holding the protein in its native conformation. Repeated freezing can also be a denaturing physical force, as ice crystal formation can disrupt protein structure [24].

Table 1: Summary of Common Protein Denaturation Triggers and Their Mechanisms

| Trigger | Mechanism of Action | Common Examples | Key Effects on Protein |

|---|---|---|---|

| Heat | Increases kinetic energy, breaking weak non-covalent bonds [25]. | Boiling an egg [12]. | Unfolding, aggregation, loss of activity [24]. |

| pH Changes | Alters ionization of side chains, disrupting ionic & H-bonds [25]. | Acid/alkali treatment in food processing [25]. | Altered solubility, precipitation [25]. |

| Chemical Agents | |||

| ∙ Urea/Guanidine HCl | Disrupts hydrogen bonds and salt bridges [12]. | Laboratory protein unfolding [12]. | Unfolding, loss of tertiary structure [12]. |

| ∙ Reducing Agents | Breaks disulfide bridges between cysteine residues [12]. | Beta-mercaptoethanol, DTT. | Loss of structural integrity, potential misfolding [12]. |

| ∙ Organic Solvents | Interferes with hydrophobic interactions [12]. | Ethanol, acetone [12]. | Altered solubility, unfolding of hydrophobic core [12]. |

| Physical Forces | Mechanical shearing or disruption of bonds [24]. | Whipping, high pressure, radiation [24]. | Unfolding, potential fragmentation [24]. |

Analytical Techniques for Studying Denaturation

Monitoring protein denaturation is crucial for both fundamental research and industrial applications. Several spectroscopic techniques are commonly employed to study changes in protein secondary structure and stability.

Spectroscopic Methods

- Circular Dichroism (CD) Spectroscopy: CD spectroscopy in the far-UV region is a valuable tool for estimating the secondary structure composition of proteins (e.g., alpha-helix and beta-sheet content) and for monitoring conformational changes. The BeStSel method is a modern analysis tool for CD spectra that provides detailed information on eight secondary structure components and can also predict protein folds. Furthermore, CD spectroscopy is an excellent technique for determining protein stability from thermal denaturation profiles [16].

- Infrared (IR) and Raman Spectroscopy: These vibrational spectroscopic techniques, particularly when combined with Partial Least Squares (PLS) regression analysis, have been shown to provide excellent results for the quantitative estimation of α-helix and β-sheet secondary structures [27].

- Polarimetry: This technique, which measures the rotation of polarized light, can also be used for protein analysis and has been shown to give good results for determining α-helix content [27].

Table 2: Key Research Reagents and Tools for Denaturation Studies

| Reagent / Tool | Function in Research | Specific Application Example |

|---|---|---|

| Urea & Guanidinium Chloride | Chemical denaturants that disrupt H-bonds and salt bridges [12]. | Unfolding studies to probe protein stability and folding pathways [12]. |

| Chemical Protein Stability Assay (CPSA) | Measures drug-target engagement by quantifying protein stability shift in lysates [28]. | Cellular target engagement screening in drug discovery [28]. |

| BeStSel Web Server | Analyzes CD spectra to determine secondary structure and protein fold [16]. | Verifying correct folding of recombinant proteins; studying mutation effects [16]. |

| Proteases (e.g., S53 family) | Enzymes that hydrolyze peptide bonds to break down proteins [26]. | Assessing/enhancing protein digestibility (e.g., for plant-based proteins) [26]. |

| Differential Scanning Calorimetry (DSC) | Measures heat change associated with thermal denaturation. | Determining melting temperature (Tm) and stability of protein therapeutics. |

Experimental Protocols for Denaturation Studies

Thermal Denaturation Monitored by CD Spectroscopy

Objective: To determine the thermal stability of a protein and its melting temperature (Tm) by observing the loss of secondary structure as a function of temperature.

Methodology:

- Sample Preparation: Prepare a purified protein solution in a suitable buffer. The protein concentration and buffer conditions (pH, ionic strength) should be optimized for the specific protein and the CD instrument.

- Data Collection:

- Place the sample in a quartz cuvette with a path length appropriate for far-UV CD measurements (typically 0.1 cm or 1 mm).

- Set the CD spectrophotometer to monitor the signal at a wavelength characteristic of secondary structure (e.g., 222 nm for α-helices).

- Increase the temperature gradually according to a defined ramp rate (e.g., 1°C per minute) while continuously recording the CD signal.

- Data Analysis:

- Plot the CD signal (or the fraction of folded protein) versus temperature.

- Fit the resulting sigmoidal curve to a model to determine the Tm, which is the temperature at which half of the protein is unfolded.

- The BeStSel web server provides a module specifically for calculating protein stability from such thermal denaturation profiles followed by CD [16].

Chemical Denaturation via CPSA for Target Engagement

Objective: To directly measure drug-target interactions in a cellular context using a Chemical Protein Stability Assay (CPSA), which exploits the stabilization of a protein against chemical denaturation upon ligand binding [28].

Methodology:

- Lysate Preparation: Generate lysates from cells, which can be native or engineered to overexpress a tagged target protein (e.g., HiBiT-tagged) [28].

- Compound Treatment: Expose the lysates to the drug compounds of interest.

- Denaturation: Treat the lysate with a predetermined concentration and type of chemical denaturant (e.g., urea, guanidinium chloride). The optimal denaturant and its concentration must be determined empirically for each target protein [28].

- Detection:

- The proportion of the protein that remains folded versus denatured is assessed.

- Denatured proteins disrupt detection mechanisms. This can be measured using various technologies such as AlphaLISA, HiBiT lytic detection systems, or Western blot [28].

- Data Analysis:

- If the compound has bound to the target, the protein will be more stable, shifting the denaturant concentration response curve compared to a control (e.g., DMSO).

- This shift indicates target engagement and allows for the determination of binding potency (e.g., pXC50) [28].

The following diagram illustrates the core principle of the CPSA assay:

CPSA Assay Principle

Denaturation in Nutritional and Therapeutic Research

The controlled application of denaturation triggers is a powerful tool in both nutritional science and drug discovery.

Enhancing Nutritional Properties

In food science, denaturation is intentionally induced to improve the digestibility, functionality, and safety of proteins.

- Enzymatic Hydrolysis: Proteases are used to break down complex polypeptides into smaller peptides and free amino acids. For example, acid-active bacterial proteases (S53 family) have been shown to increase the digestibility of various plant- and animal-based proteins during simulated gastric and intestinal phases, thereby enhancing their nutritional quality [26].

- Thermal Treatment: Heat denaturation can alter the functional properties of proteins. For instance, thermal denaturation of whey protein isolates, when combined with chitosan, can form composite particles that stabilize Pickering emulsions, potentially improving the bioavailability of encapsulated nutrients like curcumin [26]. Cooking, a form of thermal denaturation, also enhances the digestibility of many dietary proteins and transforms their texture, as seen in the conversion of collagen in meat to gelatin [25].

Applications in Drug Discovery

In pharmaceutical research, denaturation-based assays are critical for identifying and characterizing potential drug candidates.

- Target Engagement: The CPSA technology is a prime example. It is a plate-based, cost-effective assay that measures a compound's binding to its cellular target by quantifying the stabilization of the protein against chemical denaturation. This method is scalable for high-throughput screening and provides valuable data on a compound's mechanism of action and efficacy early in the drug discovery pipeline [28]. Its performance is comparable to thermal denaturation assays, with significant correlation observed in EC50 values for target engagement [28].

The workflow for this key drug discovery application is detailed below:

CPSA Experimental Workflow

Protein denaturation, triggered by heat, pH, chemicals, and physical forces, is a critical phenomenon with far-reaching implications. A deep understanding of its mechanisms allows researchers to harness this process for beneficial purposes. In nutritional science, controlled denaturation is a key strategy for improving the digestibility and functionality of proteins, particularly as the industry explores sustainable plant-based sources. In therapeutics, denaturation-based assays like the CPSA provide powerful, contextually relevant tools for accelerating drug discovery by directly measuring target engagement in a cellular environment. Mastering these triggers and their effects is therefore not only fundamental to biochemistry but also instrumental in advancing applied research in health, food, and medicine.

Protein denaturation, a process defined by the loss of a protein's native three-dimensional structure, represents a critical juncture with divergent biological and nutritional outcomes. This technical review examines the fundamental dichotomy wherein denaturation abolishes biological function—a paramount concern in therapeutic protein and biomarker development—while largely preserving amino acid content, which underpins nutritional value. Within the context of food processing and metabolic health, this analysis delineates the mechanisms by which structural unfolding disrupts protein activity yet can enhance digestibility and amino acid bioavailability. The article synthesizes current research to provide a framework for researchers and drug development professionals to navigate these consequences across biomedical and nutritional applications.

Proteins are sophisticated macromolecules whose function is intrinsically tied to a specific three-dimensional conformation, hierarchically organized into primary (linear amino acid sequence), secondary (α-helices, β-sheets), tertiary (overall 3D folding), and quaternary (multi-subunit assembly) structures [2]. Protein denaturation is the process whereby these intricate structures, particularly the tertiary and quaternary, are disrupted and unfolded, leading to a loss of biological activity without breaking the covalent peptide bonds that constitute the primary structure [2] [11] [12].

This structural disruption creates a fundamental divergence in consequences: the loss of biological function versus the preservation of amino acid content. For researchers in drug development, the irreversible denaturation of a therapeutic protein or a disease biomarker renders it biologically inert, complicating production, storage, and diagnostic measurement [29]. Conversely, from a nutritional standpoint, the amino acids that serve as the foundational monomers for protein synthesis in the body remain intact, and the unfolding process can even make them more accessible to digestive enzymes [2] [30]. This review dissects these parallel outcomes, providing a scientific basis for evaluating protein integrity in both clinical and nutritional contexts.

Fundamental Mechanisms and Triggers of Denaturation

The native state of a protein is stabilized by a delicate balance of weak non-covalent forces, including hydrogen bonds, hydrophobic interactions, ionic bonds, and van der Waals forces. Denaturation occurs when external stresses overwhelm these stabilizing forces, causing the protein to unfold [2] [11].

The table below summarizes common denaturing agents and their mechanisms of action.

Table 1: Common Triggers of Protein Denaturation and Their Mechanisms

| Denaturation Trigger | Mechanism of Action | Common Examples & Research Context |

|---|---|---|

| Heat | Disrupts hydrogen bonds and hydrophobic interactions; provides kinetic energy to overcome weak forces [2] [12]. | Cooking, pasteurization, heat sterilization of therapeutics [2] [30]. |

| Extremes of pH | Alters the charge state of amino acid side chains, disrupting ionic bonds and causing electrostatic repulsion [2] [11]. | Stomach acid, acidic/basic extraction in protein isolation [2] [31]. |

| Organic Solvents | Interferes with hydrophobic interactions and hydrogen bonding; displaces water molecules from the protein surface [12]. | Ethanol, acetone used in precipitation and purification [12]. |

| Chaotropic Agents | Has a high affinity for peptide bonds, disrupting hydrogen bonding networks within the protein core [12]. | Urea, guanidinium chloride used in protein unfolding studies [12]. |

| Reducing Agents | Breaks disulfide bridges (―S―S―) by reducing them to sulfhydryl groups (―SH), compromising structural integrity [11] [12]. | Dithiothreitol (DTT), β-mercaptoethanol in biochemistry protocols. |

| Physical Force | Causes mechanical shearing and unfolding of the polypeptide chain [2]. | High-pressure processing, blending, ultrasound [2] [6]. |

A key concept is the distinction between reversible and irreversible denaturation. In some cases, particularly with smaller proteins, removing the denaturing condition allows the protein to spontaneously refold into its native, functional conformation—a process known as renaturation [12]. However, in many practical scenarios, particularly with complex proteins or harsh conditions, denaturation is irreversible, often leading to protein aggregation and precipitation, as exemplified by the hardening of egg albumin upon boiling [12].

The Biological Consequence: Loss of Function

The loss of biological activity is the most significant consequence of denaturation in a therapeutic or diagnostic context. Function is exquisitely dependent on the precise three-dimensional shape of the protein, which creates specific binding pockets for enzymes, interaction surfaces for receptors, and defined structures for structural proteins.

Impact on Therapeutic and Diagnostic Proteins

For drug development professionals, denaturation poses a substantial challenge. The efficacy of biologic drugs, such as monoclonal antibodies, enzymes, and peptide hormones, is contingent upon their structural integrity.

- Therapeutic Inactivation: Denaturation renders these molecules biologically inert, nullifying their therapeutic potential [12].

- Biomarker Instability: In diagnostics, denaturation of protein biomarkers in blood or other biofluids can alter their immunoreactivity, leading to inaccurate measurements in assays like ELISA and potentially misguiding diagnosis or prognosis assessment [32]. Pre-analytical variables such as sample collection, handling, and storage are critical to prevent artifactual denaturation.

Underlying Mechanisms of Functional Loss

The unfolding process disrupts function through several mechanisms:

- Loss of Active Site Integrity: The specific atomic arrangement required for catalytic activity in enzymes is destroyed.

- Disruption of Binding Interfaces: Surfaces required for protein-protein, protein-DNA, or receptor-ligand interactions are deformed.

- Exposure of Proteolytic Sites: The unfolding of the native structure can expose peptide bonds that are otherwise shielded, making the protein more susceptible to proteolytic degradation by enzymes like trypsin, thereby shortening its functional half-life [12].

The following diagram illustrates the conceptual relationship between protein structure, denaturation, and its divergent biological versus nutritional consequences.

The Nutritional Consequence: Preservation of Amino Acid Content

In stark contrast to the loss of biological function, the nutritional value of a protein, defined by its capacity to provide essential amino acids (EAAs) for human metabolic needs, is largely retained upon denaturation [2] [30].

Preservation of Primary Structure

The core nutritional value resides in the protein's primary structure—its linear sequence of amino acids. Denaturation agents do not break the strong covalent peptide bonds that link amino acids together [2]. Consequently, all essential and non-essential amino acids remain present and are, in principle, fully available for absorption and utilization after digestion [2]. For instance, 25 grams of denatured whey protein provides an identical amino acid profile, including the critical muscle-building amino acid leucine, as 25 grams of its native counterpart [2].

Enhancement of Digestibility and Bioavailability

Paradoxically, controlled denaturation often improves rather than diminishes protein nutritional value by enhancing digestibility. The unfolding of the tightly packed native structure exposes peptide bonds to proteolytic enzymes (e.g., trypsin, pepsin) in the gastrointestinal tract [2] [12].

Table 2: Comparative Protein Digestibility and Nutritional Value

| Protein State | Digestibility Rate | Amino Acid Absorption | Muscle Building Potential |

|---|---|---|---|

| Native | 85-90% | Good | High |

| Moderately Denatured | 90-95% | Excellent | High |

| Properly Processed | 88-93% | Excellent | High |

| Over-processed | 70-80% | Variable | Moderate |

Data derived from nutritional studies indicates that moderate denaturation through cooking or standard processing often improves amino acid absorption compared to raw proteins [2]. This principle is leveraged in food processing, where methods like ohmic heating and high-pressure processing are used to modify protein structure for improved functionality and digestibility [6].

Experimental Protocols for Analysis

Robust experimental workflows are essential for researchers to characterize both the structural and nutritional consequences of protein denaturation.

Protocol for Assessing Loss of Function (Enzymatic Activity Assay)

This protocol measures the functional impact of denaturation on an enzyme.

- Sample Preparation: Divide the purified enzyme solution into aliquots. Treat one with a denaturant (e.g., heat at 80°C for 15 minutes, or 6M urea for 1 hour). Keep a native aliquot on ice as control.

- Activity Assay Setup: In a spectrophotometric cuvette, add the appropriate buffer and substrate for the specific enzyme. The substrate should yield a detectable product (e.g., a chromophore).

- Reaction Initiation & Measurement: Add a fixed volume of native or denatured enzyme to the cuvette. Immediately monitor the change in absorbance (or other relevant signal) over time (e.g., 2-5 minutes).

- Data Analysis: Calculate the initial reaction velocity (V₀) for both samples from the linear portion of the curve. The percentage activity loss is given by:

[1 - (V₀_denatured / V₀_native)] × 100%.

Protocol for Quantifying Amino Acid Preservation (Simulated Gastrointestinal Digestion)

This protocol assesses the nutritional availability of amino acids post-denaturation.

- In Vitro Gastric Phase: Suspend the native and denatured protein samples in a simulated gastric fluid (e.g., 0.1M HCl, pH 2.0, containing pepsin). Incubate at 37°C with continuous shaking for 1-2 hours.

- In Vitro Intestinal Phase: Neutralize the gastric digestate and add simulated intestinal fluid (e.g., phosphate buffer, pH 7.0, containing pancreatin and bile salts). Incubate further at 37°C for 2-4 hours.

- Termination & Analysis: Stop the reaction by heating or adding a protease inhibitor. Centrifuge to collect the supernatant. The amino acid content and composition in the digest can be analyzed using techniques like High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC) or Amino Acid Analyzers to compare the profiles between native and denatured samples [30].

The following workflow diagram outlines the key steps in a parallel investigation of biological function and nutritional content.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents and Materials

The following table details essential reagents and equipment for investigating protein denaturation.

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Protein Denaturation Studies

| Reagent / Material | Function in Research | Specific Application Example |

|---|---|---|

| Urea & Guanidinium Chloride | Chaotropic agents that disrupt hydrogen bonding, effectively unfolding proteins without breaking peptide bonds [12]. | Used to create denaturation curves and study protein folding intermediates. |

| Dithiothreitol (DTT) | A reducing agent that breaks disulfide bonds, critical for studying proteins stabilized by cysteine cross-links [11]. | Sample preparation for SDS-PAGE to ensure complete unfolding. |

| Differential Scanning Calorimeter (DSC) | Instrument that measures the heat change associated with protein unfolding, providing the denaturation temperature (Td) and enthalpy (ΔH) [11]. | Determining the thermal stability of therapeutic protein formulations. |

| Spectrofluorometer | Measures the intrinsic fluorescence of tryptophan residues; the emission spectrum shifts as the protein unfolds and the Trp environment changes. | Monitoring real-time unfolding kinetics in response to denaturants. |

| Simulated Gastric/Intestinal Fluids | Standardized digestive enzyme cocktails and buffers that mimic the human GI tract in vitro [30]. | Assessing the bioaccessibility of amino acids from processed food proteins. |

| Proteolysis-Targeting Chimeras (PROTACs) | Bifunctional small molecules that hijack the cell's ubiquitin-proteasome system to induce targeted degradation of specific pathogenic proteins [29]. | A therapeutic application that deliberately induces "functional denaturation" and degradation in drug discovery. |

Discussion and Future Perspectives

The dichotomy between the loss of biological function and the preservation of nutritional value is a central tenet in protein science. However, the boundaries are not absolute. Extreme processing conditions—such as prolonged exposure to very high temperatures in the presence of carbohydrates (leading to Maillard reactions) or severe alkaline treatments—can damage amino acids like lysine, methionine, and tryptophan, thereby reducing protein quality [2] [30]. This underscores the importance of optimized processing in the food industry to balance safety, functionality, and nutrient retention.

Future research directions are poised to deepen our understanding of this field. The application of novel food processing technologies (e.g., high-pressure processing, pulsed electric fields, cold plasma) offers pathways to achieve desired functional properties, such as improved gelation or emulsification, with minimal negative impact on protein structure and nutritional quality [6]. In biomedicine, the field of Targeted Protein Degradation (TPD), including technologies like PROTACs, represents a deliberate harnessing of the "loss of function" principle. These therapeutic agents are designed to selectively induce the denaturation and degradation of disease-causing proteins, opening new avenues for treating cancer and neurodegenerative disorders [29].

The process of protein denaturation unequivocally severs the link between a protein's structure and its innate biological activity, a critical consideration for the stability of therapeutics and the accuracy of diagnostic biomarkers. Simultaneously, the resilience of the primary amino acid sequence ensures that the fundamental nutritional value of proteins as a source of essential amino acids is maintained, and is often enhanced through improved digestibility. A precise understanding of this duality—the irreversible loss of specific function versus the robust preservation of nutritional building blocks—is indispensable for advancing fields as diverse as biopharmaceutical development, clinical diagnostics, and sustainable food innovation.

Advanced Denaturation Methodologies: Techniques, Applications, and Biomedical Implications

Protein denaturation, the process by which proteins lose their native three-dimensional structure while their primary amino acid sequence remains intact, is a fundamental phenomenon in both food science and pharmaceutical development [33]. Traditional methods to induce denaturation—including thermal processing, pH adjustment, and solvent effects—serve as critical tools for manipulating protein functionality, digestibility, and stability [5] [34]. For researchers and drug development professionals, understanding these processes is essential for designing protein-based therapeutics, optimizing drug delivery systems, and controlling the nutritional and functional properties of protein ingredients. This technical guide provides an in-depth examination of these core denaturation approaches, focusing on underlying mechanisms, experimental methodologies, and implications for nutritional and pharmaceutical applications.

Thermal Processing

Mechanisms and Impact on Protein Structure

Thermal processing induces denaturation by disrupting the weak chemical bonds that stabilize protein secondary, tertiary, and quaternary structures. Heat provides kinetic energy that overcomes the stabilizing energy of hydrogen bonds, hydrophobic interactions, and van der Waals forces, leading to protein unfolding and aggregation [33]. The extent of denaturation depends on both temperature and duration of exposure.

The thermal stability of proteins varies significantly. For instance, whey proteins begin to denature at temperatures above 65°C, while casein exhibits higher thermal stability, with denaturation commencing at approximately 120°C [35]. These differences profoundly impact their functional behavior in complex systems.

Effects on Nutritional and Functional Properties

Controlled thermal denaturation often enhances protein digestibility by unfolding tightly packed native structures, thereby increasing the accessibility of cleavage sites for proteolytic enzymes [33] [36]. A 2025 study on beef demonstrated that different thermal processing methods (steaming, boiling, roasting) at optimal core temperatures (S85: steaming at 85°C, B80: boiling at 80°C, R80: roasting at 80°C) significantly increased protein digestibility and released a greater diversity of bioactive peptides [36].

However, excessive heat treatment can reduce nutritional quality by promoting the formation of protein aggregates and potentially damaging amino acids under extreme conditions [33]. The table below summarizes key quantitative findings on thermal processing effects from recent research:

Table 1: Quantitative Effects of Thermal Processing on Protein Properties

| Protein Source | Processing Conditions | Key Structural Changes | Impact on Digestibility/Functionality |

|---|---|---|---|

| Beef [36] | Steaming at 85°C | Decreased intrinsic fluorescence; α-helix to β-sheet transition; increased surface hydrophobicity | Highest increase in digestibility; release of more peptide species |

| Pork Loin [37] | Sous vide at 55-65°C | Muscle fiber contraction; collagen solubilization; partial protease activation | Improved tenderness, reduced cooking loss, enhanced juiciness |

| Milk Proteins [35] | 140°C for >40 min (casein); 78°C for 30 min (whey) | κ-casein dissociation; whey protein aggregation | Reduced stability in acidified milk beverages |

| Sesame Protein Isolate [6] | Ohmic heating | Increased particle size and turbidity | Enhanced water/oil holding capacity, emulsifying and foaming properties |

Experimental Protocol: Evaluating Thermal Denaturation by Differential Scanning Calorimetry (DSC)

Principle: DSC measures heat flow associated with protein thermal transitions as a function of temperature, providing information on denaturation temperatures and enthalpies [37].

Materials:

- Differential Scanning Calorimeter

- Hermetic pans

- Protein solution (1-10 mg/mL in appropriate buffer)

- Reference buffer

Methodology:

- Dialyze protein solution extensively against desired buffer.

- Load sample and reference solutions into sealed DSC pans.

- Run temperature scan (typically 20-120°C) at constant heating rate (e.g., 1-10°C/min).

- Analyze thermogram for endothermic peak temperature (Td) and enthalpy (ΔH).

Data Interpretation: The denaturation temperature indicates thermal stability, while enthalpy reflects the energy required for unfolding, proportional to the amount of ordered structure [37]. As demonstrated in pork loin studies, distinct endothermic peaks correspond to the denaturation of different protein fractions (myosin ~54°C, sarcoplasmic/connective tissue proteins ~63°C, actin ~77°C) [37].

pH Adjustment

Mechanisms of pH-Induced Denaturation

pH shifting alters protein structure by modifying the ionization states of amino acid side chains, thereby disrupting electrostatic interactions and hydrogen bonding networks that maintain native structure [34]. Under extreme acidic conditions (pH < 3), protonation of carboxyl groups reduces negative charges, while in alkaline environments (pH > 10), deprotonation of amino groups diminishes positive charges [34]. Both scenarios increase electrostatic repulsion between similarly charged regions, leading to protein unfolding.

This approach is particularly valuable for its ability to induce the "molten globule" state—a partially unfolded conformation with retained secondary structure but disrupted tertiary structure—which often exhibits enhanced functional properties [34].

Effects on Functional and Nutritional Properties

pH-shift processing significantly improves protein solubility, emulsification, foaming, and gelation properties [38] [34]. The technique can also reduce allergenicity by altering epitope structures. A 2025 study on egg proteins demonstrated that pH-shift processing modified protein structure, leading to varied techno-functional properties including enhanced foam stability and emulsion stability index [38].

The combination of pH shifting with physical processing methods creates synergistic effects that allow for milder processing conditions while achieving significant functional improvements [34]. This hybrid approach represents an emerging trend in protein modification strategies.

Table 2: Functional Properties Modified by pH-Shift Processing

| Functional Property | Mechanism of Enhancement | Application Example |

|---|---|---|

| Solubility [34] | Increased surface charge and electrostatic repulsion | Plant protein extraction |