Portable vs. Laboratory Allergen Detection: A 2025 Comparative Analysis for Biomedical Research

This article provides a comparative analysis for researchers and drug development professionals on the evolving landscape of food allergen detection.

Portable vs. Laboratory Allergen Detection: A 2025 Comparative Analysis for Biomedical Research

Abstract

This article provides a comparative analysis for researchers and drug development professionals on the evolving landscape of food allergen detection. It explores the foundational principles of both portable devices and established laboratory methods like ELISA and PCR. The analysis covers methodological applications, troubleshooting for complex food matrices, and a critical validation of performance metrics including sensitivity, specificity, and throughput. Synthesizing current market data and technological trends, it concludes with strategic insights on selecting the appropriate method based on research intent and outlines future directions driven by AI, biosensors, and multiplexing technologies.

Understanding the Landscape: Core Technologies in Allergen Detection

Food allergies represent a significant and growing international health problem, affecting approximately 2% of adults and 5-8% of children worldwide [1]. For these individuals, exposure to even trace amounts of allergens can trigger reactions ranging from hives and digestive issues to life-threatening anaphylactic shock [1]. This public health concern is compounded by the economic burden of allergen management, including healthcare costs, product recalls, and regulatory compliance. Accurate allergen detection is therefore a critical component of food safety, serving to protect consumers and manage economic risks.

The field of allergen analysis is currently divided between traditional laboratory-based methods and emerging portable detection technologies. Laboratory methods like ELISA (Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay) and PCR (Polymerase Chain Reaction) have long been the gold standard, offering high sensitivity and reliability for quality control and regulatory purposes [2] [3]. However, these methods are time-consuming, require trained personnel and specialized equipment, and are generally unsuitable for real-time, on-the-spot testing [3] [1].

In response to these limitations, a new generation of portable food allergen sensors is emerging. These devices are designed to provide rapid, on-site detection, empowering consumers to verify the safety of their food instantly [3]. This guide provides an objective comparison of the performance characteristics, methodologies, and appropriate applications of portable allergen detection devices versus established laboratory methods, framed within the context of ongoing research and technological advancement.

Performance Comparison: Portable Sensors vs. Laboratory Methods

The following table summarizes the key performance metrics of traditional laboratory methods versus emerging portable detection technologies.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Allergen Detection Methods

| Feature | Traditional Laboratory Methods | Portable Detection Devices |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Examples | ELISA, PCR, Mass Spectrometry [2] [3] | Smartphone-based assays, Handheld electrochemical sensors [3] [1] |

| Detection Principle | Antibody-Antigen binding (ELISA), DNA amplification (PCR), Protein-specific peptide detection (MS) [2] [3] [1] | Electrochemical, Optical (colorimetry, fluorescence), often with antibodies or aptamers [3] |

| Throughput | High (can process many samples simultaneously) | Low to Medium (single or multiplexed tests) |

| Time to Result | Hours to days [3] | Minutes [3] |

| Sensitivity | Very High (e.g., Mass Spectrometry: as low as 0.01 ng/mL) [2] | Variable; can be high, but often lower than lab methods [3] |

| Quantification | Fully Quantitative | Mostly Semi-Quantitative or Qualitative |

| User Skill Requirement | Requires trained technicians | Designed for consumer or front-line staff use |

| Key Advantage | High accuracy, sensitivity, and reliability for compliance | Speed, portability, and ease of use for point-of-care |

| Key Limitation | Time-consuming, expensive, not portable | Limited multiplexing, sensitivity can be affected by food matrix [3] |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Laboratory-Based Methods

A. Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay (ELISA)

ELISA is a widely used immunochemical method for detecting allergenic proteins. The workflow involves extracting proteins from a food sample and incubating them in wells coated with allergen-specific antibodies. After washing, a second antibody linked to an enzyme is added. A substrate is then introduced, and the enzyme catalyzes a reaction that produces a color change, measured spectrophotometrically, which is proportional to the allergen concentration [3] [1]. While highly sensitive, ELISA can struggle to detect denatured proteins found in cooked foods, and antibody cross-reactivity may lead to false positives [3].

B. Mass Spectrometry (MS)-Based Methods

Liquid Chromatography-Tandem Mass Spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) is a powerful proteomic technique. The protocol involves:

- Extraction and Digestion: Proteins are extracted from the food matrix and digested with an enzyme (e.g., trypsin) to generate specific peptide fragments.

- Chromatographic Separation: The peptide mixture is separated by liquid chromatography.

- Mass Analysis & Quantification: Peptides are ionized and identified by their mass-to-charge ratio. Unique proteotypic peptides (e.g., Ara h 3 and Ara h 6 for peanut, Bos d 5 for milk) serve as biomarkers for absolute quantification of specific allergenic proteins [2] [4]. This method offers high specificity and the ability to multiplex, detecting multiple allergens in a single run [2].

Portable Sensor Technologies

A. Electrochemical Sensor Protocol

Handheld sensors, similar to glucometers, use disposable test strips. The experimental process is:

- Sample Preparation: A small, dissolved food sample is applied to the disposable strip.

- Biorecognition: The strip contains a biorecognition element (e.g., an antibody, aptamer, or Molecularly Imprinted Polymer (MIP)) that binds specifically to the target allergen.

- Signal Transduction: This binding event causes a change in electrical properties (current, potential, or impedance).

- Readout: The handheld reader processes this change and provides a digital output (e.g., ppm) within minutes [3]. MIPs are noted for their durability and resistance to heat and acidity, making them suitable for complex food matrices [3].

B. Smartphone-Based Optical Detection Protocol

This approach leverages a smartphone's camera and processing power:

- Assay Execution: The user performs a lateral flow immunoassay (LFIA) or uses a microfluidic chip, following the device instructions.

- Image Capture: The smartphone camera captures an image of the test strip or chip.

- Data Processing: A dedicated app analyzes color intensity or fluorescence patterns.

- Result Delivery: The app interprets the signal, providing a clear "detected/not detected" result or a semi-quantitative concentration, sometimes with geo-tagging capabilities for data mapping [1].

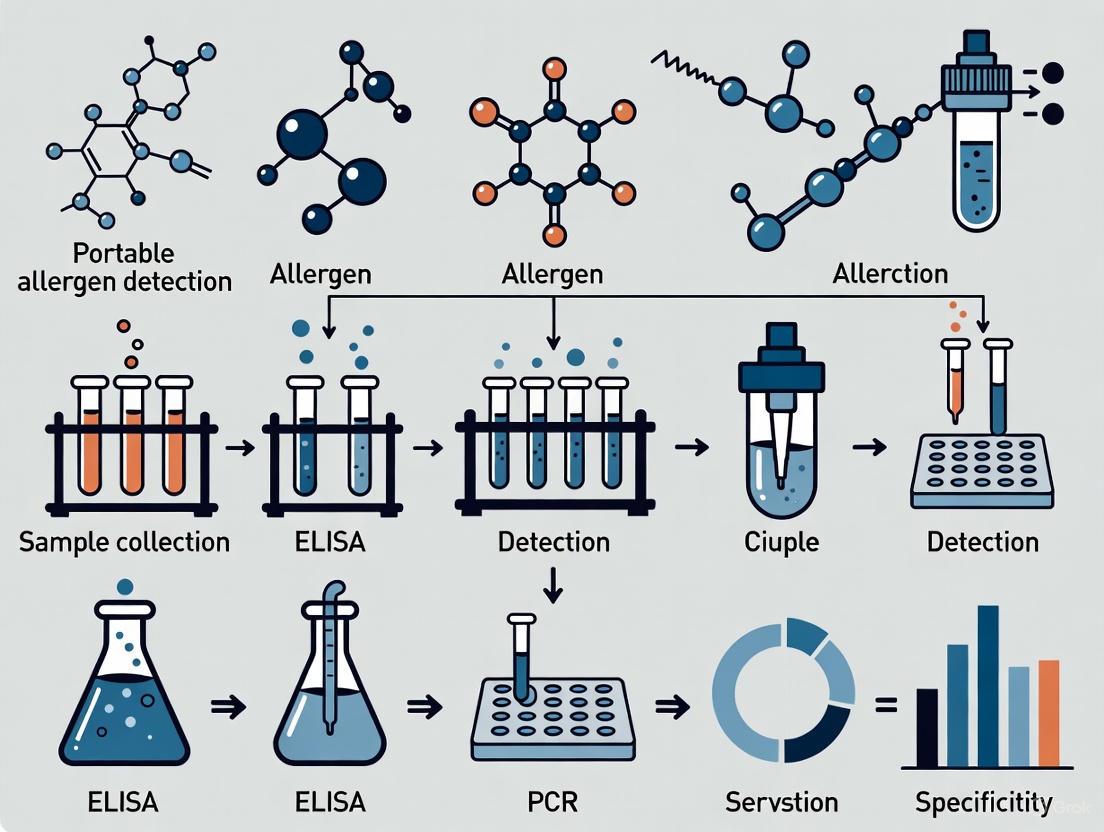

Diagram 1: Method Workflow Comparison

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents & Materials

Successful allergen detection, whether in a lab or a portable format, relies on specific, high-quality reagents. The following table details essential components and their functions.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents for Allergen Detection

| Reagent/Material | Function in Detection | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| Allergen-Specific Antibodies | Biorecognition element that binds specifically to target allergenic proteins (e.g., Ara h 1, Bos d 5). | Core component of ELISA, lateral flow devices, and some biosensors [3] [1]. |

| Aptamers | Synthetic single-stranded DNA or RNA oligonucleotides that bind targets with high specificity and affinity. | Used as more stable, cost-effective alternatives to antibodies in some modern biosensors [3]. |

| Molecularly Imprinted Polymers (MIPs) | Synthetic polymers with cavities tailored to fit specific allergen molecules; robust and stable. | Bioreceptor in electrochemical sensors for challenging environments (e.g., cooked foods) [3]. |

| Proteotypic Peptides | Unique peptide sequences that serve as biomarkers for a specific protein in a mass spectrometry assay. | Essential for the development of targeted, quantitative LC-MS/MS methods for specific allergens [2] [4]. |

| Certified Reference Materials (CRMs) | Materials with certified values for allergen/protein content, used for method validation and calibration. | Critical for ensuring accuracy, traceability, and harmonization of measurements across labs; a key focus of programs like the NIST Food Protein Allergen Program [4]. |

| LOINC/NPU Codes | Standardized codes for identifying laboratory tests and results in a universal, unambiguous way. | Used for data harmonization and interoperability, as seen in the CLSI ILA37 database for allergen-specific IgE testing [5]. |

Discussion and Future Directions

The comparison reveals that portable devices and laboratory methods serve complementary roles. Laboratory methods remain indispensable for regulatory compliance, method validation, and quantitative analysis where ultimate accuracy is required. In contrast, portable devices excel in providing rapid, on-the-spot screening for consumers, restaurants, and manufacturing line checks, putting analytical power directly into the hands of users [3].

Future innovation is focused on overcoming current limitations. Research is advancing towards:

- Multiplexing: Developing portable devices that can simultaneously test for multiple allergens from a single sample [3] [1].

- Enhanced Sensitivity: Incorporating nanomaterials like graphene and gold nanoparticles to improve detection limits [3].

- Improved Bioreceptors: Engineering more stable and cost-effective elements like peptide aptamers and nanobodies [3].

- Data Integration: Leveraging Artificial Intelligence (AI) to improve signal interpretation and using the Internet of Things (IoT) to create real-time allergen exposure maps [2] [3].

Diagram 2: Future Technology Directions

In conclusion, the choice between portable and laboratory methods is not a matter of superiority but of application. Researchers and industry professionals must select the appropriate tool based on the required balance between speed, sensitivity, precision, and context of use. The ongoing convergence of these technologies—driven by advancements in materials science, genomics, and data analytics—promises a future with more transparent, reliable, and accessible allergen management systems.

In the context of increasing global food allergies, reliable detection of allergens is crucial for protecting public health. For researchers developing portable allergen detection devices, a deep understanding of established laboratory gold standards is foundational. These traditional methods—Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay (ELISA), Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR), and Mass Spectrometry (MS)—set the benchmark for sensitivity, specificity, and reliability against which new technologies are measured. This guide provides a detailed, objective comparison of these three core techniques, framing their principles, performance data, and experimental protocols within the needs of modern scientific and development professionals.

Core Principles and Experimental Workflows

The following workflows diagram the standard experimental procedures for each method, highlighting key preparatory and analytical steps.

ELISA Workflow

Diagram Title: ELISA Sandwich Assay Procedure

The Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay (ELISA) is an antibody-based technique that detects target proteins. In the common sandwich format shown above, a capture antibody immobilized on a plate binds the target allergen. A second enzyme-conjugated detection antibody then binds to the captured allergen. A substrate is added, and the enzyme catalyzes a reaction, producing a color change measured via absorbance. The intensity is proportional to the allergen concentration [6] [7].

PCR Workflow

Diagram Title: Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR) Process

The Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR) is a DNA-based method that amplifies specific nucleic acid sequences for detection. The process involves repeated thermal cycles of denaturation, primer annealing, and enzyme-driven extension to exponentially copy a target DNA region. In real-time PCR, fluorescent probes allow for simultaneous amplification and quantification, enabling the detection of allergen-specific DNA from ingredients [8] [9].

Mass Spectrometry Workflow

Diagram Title: LC-MS/MS Protein Analysis Workflow

Mass Spectrometry (MS), particularly Liquid Chromatography-Tandem Mass Spectrometry (LC-MS/MS), identifies and quantifies proteins by analyzing their peptide fragments. Proteins are digested into peptides, separated by liquid chromatography, ionized, and then analyzed based on their mass-to-charge ratio. The first mass analyzer selects specific peptide ions, which are then fragmented, and a second mass analyzer measures the fragments, generating a "fingerprint" for highly specific identification [6] [10].

Performance Comparison and Experimental Data

The following table summarizes the key performance characteristics of ELISA, PCR, and Mass Spectrometry, drawing from direct comparative studies and evaluations of each technology.

| Performance Metric | ELISA | PCR | Mass Spectrometry |

|---|---|---|---|

| Analytical Target | Protein [8] | DNA [8] | Protein/Peptide [6] |

| Sensitivity (Example) | Pork: 10.0% w/w; Beef: 1.00% w/w [8] | Pork: 0.10% w/w; Beef: 0.50% w/w [8] | Detection limits as low as 0.01 ng/mL for specific allergens [2] |

| Specificity | High (Relies on antibody affinity) [7] | High (Determined by primer design) [8] | Very High (Identifies proteotypic peptides) [2] |

| Multiplexing Capability | Low (Typically one protein per assay) [10] | Moderate with specialized design | High (Can detect many proteins simultaneously) [2] |

| Throughput | Medium to High (96-well plate format) [10] | Medium to High (96-well plate format) | Low to Medium (One sample at a time; scale-up possible) [10] |

| Quantification | Relative or Absolute [10] | Relative or Absolute [10] | Relative or Absolute [10] |

| Sample Input Volume | ~100 µL [10] | Varies (Small amount of DNA) | ~150 µL (highly concentrated) [10] |

| Key Advantage | Cost-effective, regulatory approved, high sensitivity for proteins [7] | Excellent sensitivity, works in processed foods where protein is denatured [8] [7] | Unmatched specificity, can detect multiple allergens in one run, high precision [6] [2] |

| Key Limitation | Can be affected by food processing that denatures protein targets [7] | Detects DNA, not the allergenic protein itself; can be inhibited by food matrices [8] | High cost, requires specialized equipment and trained operators [6] [10] |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Sandwich ELISA for Allergen Detection

This protocol is adapted from procedures used for detecting allergens like peanuts or milk proteins [7].

- Coating: Dilute the capture antibody in a coating buffer (e.g., carbonate-bicarbonate buffer, pH 9.6). Add 100 µL per well to a 96-well microplate. Seal the plate and incubate overnight at 4°C.

- Washing: Aspirate the contents of the wells and wash three times with a wash buffer (e.g., PBS containing 0.05% Tween 20). Blot the plate on absorbent paper to remove residual buffer.

- Blocking: Add 200 µL of blocking buffer (e.g., 1-5% BSA or non-fat dry milk in PBS) to each well. Incubate for 1-2 hours at room temperature. Wash as in step 2.

- Sample & Standard Incubation: Prepare a dilution series of the allergen standard. Extract and prepare food samples in an appropriate extraction buffer. Add 100 µL of standards, samples, and controls (blank) to assigned wells. Incubate for 1-2 hours at room temperature. Wash thoroughly.

- Detection Antibody Incubation: Add 100 µL of the enzyme-conjugated detection antibody (e.g., Horseradish Peroxidase conjugate) diluted in assay buffer to each well. Incubate for 1-2 hours at room temperature. Wash thoroughly.

- Signal Development: Add 100 µL of substrate solution (e.g., TMB for HRP) to each well. Incubate in the dark for 15-30 minutes until color develops.

- Reaction Stopping: Add 50 µL of stop solution (e.g., 1M sulfuric acid) to each well. The color will change from blue to yellow.

- Measurement: Measure the absorbance of each well at 450 nm using a microplate reader within 30 minutes. Plot the standard curve and calculate the allergen concentration in the samples.

Protocol: Real-Time PCR for Meat Species Identification

This protocol is based on a comparative study detecting beef and pork in processed meat products [8].

- DNA Extraction: Use a commercial DNA extraction kit suitable for food matrices. From the homogenized sample, extract genomic DNA following the manufacturer's instructions. Quantify the DNA purity and concentration using a spectrophotometer.

- PCR Reaction Setup: Prepare a master mix for each sample containing:

- SensiFAST Probe No-ROX Mix (or equivalent): 10 µL

- Species-Specific Forward Primer (e.g., for pork): 0.7 µL

- Species-Specific Reverse Primer: 0.7 µL

- Species-Specific TaqMan Probe (with a fluorescent dye, e.g., FAM): 0.2 µL

- Nuclease-Free Water: 6.4 µL

- Total Volume: 18 µL per reaction

- Sample Addition: Add 2 µL of template DNA (or non-template control water) to each PCR tube/strip containing the 18 µL master mix, for a final reaction volume of 20 µL.

- Real-Time PCR Amplification: Place the samples in a real-time PCR instrument and run the following program:

- Initial Denaturation: 95°C for 10 minutes (1 cycle)

- Amplification (40 cycles):

- Denaturation: 95°C for 15 seconds

- Annealing/Extension: 60°C for 1 minute (with fluorescence data collection)

- Data Analysis: Set the cycle threshold (Ct) manually or allow the instrument software to set it. A sample is considered positive if it produces a Ct value below a predetermined cutoff (e.g., Ct < 40). The Ct value is inversely proportional to the amount of target DNA in the original sample.

Protocol: LC-MS/MS for Allergen-Specific Peptide Detection

This protocol outlines the core steps for detecting allergenic proteins via their proteotypic peptides, as used in high-precision applications [6] [2].

- Protein Extraction and Digestion: Weigh a homogenized food sample. Extract proteins using an appropriate buffer (e.g., urea or SDS-based). Reduce disulfide bonds with dithiothreitol (DTT) and alkylate with iodoacetamide (IAA). Digest the proteins into peptides using a proteolytic enzyme, most commonly trypsin, overnight at 37°C.

- Peptide Clean-up: Desalt the digested peptide mixture using a solid-phase extraction (SPE) cartridge (e.g., C18 resin) to remove interfering salts and buffers. Elute peptides in a solvent compatible with LC-MS/MS (e.g., acetonitrile with 0.1% formic acid) and dry down in a vacuum concentrator.

- Liquid Chromatography (LC): Reconstitute the dried peptides in a mobile phase (e.g., water with 0.1% formic acid). Inject the sample onto a reverse-phase C18 LC column. Separate the peptides using a gradient of increasing organic solvent (e.g., acetonitrile) over time.

- Tandem Mass Spectrometry (MS/MS):

- Ionization: The eluting peptides are ionized via Electrospray Ionization (ESI).

- MS1 Survey Scan: The mass spectrometer performs a full scan to measure the mass-to-charge (m/z) ratios of all intact peptide ions entering the instrument.

- Selection and Fragmentation: The instrument automatically selects the most abundant peptide ions (precursor ions) from the MS1 scan and fragments them using an inert gas (like nitrogen or argon) in a collision cell—a process known as Collision-Induced Dissociation (CID).

- MS2 Fragment Scan: The mass spectrometer then performs a second scan to measure the m/z ratios of the resulting fragment ions.

- Data Analysis: The MS2 fragmentation spectra are searched against a protein database containing the sequences of known allergenic proteins (e.g., Ara h 1 from peanut, Bos d 5 from milk) using specialized software (e.g., MaxQuant, Skyline). The identification of allergen-specific peptides is confirmed by matching the observed fragment ions to the theoretical fragmentation pattern.

Research Reagent Solutions

The table below lists key reagents and materials essential for implementing the described laboratory methods.

| Reagent/Material | Function | Primary Application |

|---|---|---|

| Capture & Detection Antibodies | Specifically bind to the target allergen protein for immobilization and signal generation. | ELISA |

| Microtiter Plates (96-well) | Solid surface for immobilizing capture antibodies and conducting the assay. | ELISA |

| Enzyme Substrate (e.g., TMB) | Chromogenic compound that produces a measurable color change when catalyzed by the detection enzyme. | ELISA |

| Species-Specific Primers & Probes | Short oligonucleotides that bind to and facilitate the amplification/detection of unique DNA sequences. | PCR |

| Taq DNA Polymerase | Heat-stable enzyme that synthesizes new DNA strands during the PCR amplification process. | PCR |

| dNTPs | Deoxynucleotide triphosphates (A, T, C, G); the building blocks for DNA synthesis. | PCR |

| Trypsin | Proteolytic enzyme that digests proteins into smaller peptides for mass spectrometry analysis. | Mass Spectrometry |

| C18 Solid-Phase Extraction Cartridge | Used to desalt and concentrate peptide mixtures prior to LC-MS/MS analysis. | Mass Spectrometry |

| LC Column (e.g., C18) | Chromatographically separates peptides by hydrophobicity before they enter the mass spectrometer. | Mass Spectrometry |

ELISA, PCR, and Mass Spectrometry each offer distinct advantages as laboratory gold standards for allergen detection. ELISA remains the workhorse for routine, high-throughput protein detection due to its cost-effectiveness and regulatory acceptance. PCR provides exceptional sensitivity for DNA, proving valuable when proteins are denatured or for confirming results. Mass Spectrometry offers unrivalled specificity and multiplexing capabilities by directly identifying protein biomarkers, making it a powerful tool for method validation and complex matrices.

For researchers developing portable devices, this comparison highlights critical trade-offs. The ideal portable technology would combine the simplicity and low cost of ELISA, the high sensitivity of PCR, and the definitive specificity of MS. Understanding the principles and performance boundaries of these established methods is key to innovating the next generation of rapid, on-site allergen tests that meet the rigorous demands of food safety and public health.

The increasing global prevalence of food allergies has intensified the need for reliable, rapid detection methods that can be deployed beyond traditional laboratory settings [6]. While conventional techniques like Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay (ELISA), Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR), and Liquid Chromatography-Tandem Mass Spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) provide highly sensitive and specific results, they require costly equipment, well-trained technicians, and several hours to complete, making them unsuitable for on-site testing [6]. In response, portable biosensors and lateral flow devices have emerged as powerful alternatives that offer rapid, user-friendly, and cost-effective detection of food allergens, enabling point-of-care testing in supply chain settings, restaurants, and even at home [6] [11]. This guide objectively compares the operational principles and performance of these rapid methods against established laboratory techniques, providing researchers and scientists with critical experimental data and protocols for informed methodological selection.

Technology Comparison: Operational Principles and Performance Metrics

Fundamental Principles of Conventional Laboratory Methods

Immunoassays (ELISA): This method relies on the specific binding between an allergen (antigen) and its antibody. The detection is typically achieved through an enzyme-linked antibody that produces a colored product when its substrate is added, with color intensity proportional to the allergen concentration [6]. Nucleic Acid-Based Methods (PCR): PCR amplifies specific DNA sequences unique to allergenic foods, making it highly specific and sensitive. It is particularly useful for detecting allergens in processed foods where protein structures may be denatured [6]. Chromatographic Methods (LC-MS/MS): This technique separates and identifies allergenic proteins based on their mass-to-charge ratio after proteolytic digestion, providing high specificity and the ability to detect multiple allergens simultaneously (multiplexing) [6] [2].

Fundamental Principles of Portable Rapid Methods

Portable Biosensors: These devices consist of a bio-recognition element (e.g., antibody, aptamer, enzyme) that specifically interacts with the target allergen and a transducer that converts this biological interaction into a quantifiable signal [6]. Transduction mechanisms include electrochemical (measuring electrical changes), optical (detecting colorimetric, fluorescent, or SERS signals), and piezoelectric (measuring mass changes) principles [6]. Lateral Flow Devices (LFDs): Also known as lateral flow immunoassays (LFIAs), these paper-based platforms utilize capillary action to move the sample across various zones where the target allergen is captured between labeled and immobilized antibodies, producing a visible test line typically within 5-30 minutes [12] [13]. They can operate in sandwich format (for larger analytes) or competitive format (for small molecules) [14].

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Allergen Detection Technologies

| Technology | Detection Principle | Detection Time | Sensitivity | Multiplexing Capability | Primary Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ELISA | Antibody-antigen interaction with enzyme-mediated color development | 2-4 hours | ppm to ppb range | Low | Laboratory quantification of specific allergens |

| PCR | Amplification of allergen-specific DNA sequences | 3-6 hours | ppb level | Medium | Laboratory detection, especially for processed foods |

| LC-MS/MS | Separation and identification based on mass-to-charge ratio | Several hours | ppt to ppb range | High | Laboratory reference method, multiplex detection |

| Portable Biosensors | Bio-recognition coupled with electrochemical/optical transduction | Minutes | ppb to ppt range | Medium to High | On-site screening, quality control |

| Lateral Flow Devices | Capillary flow with immunochromatographic detection | 5-30 minutes | ppm to ppb range | Low to Medium | Rapid screening, point-of-care testing |

Table 2: Experimental Performance Data for Allergen Detection in Food Matrices

| Allergen Target | Detection Method | Reported LOD | Matrix | Assay Time | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total Hazelnut Protein | Passive Flow-through Immunoassay | 1 ppm | Food matrix | <10 minutes | [11] |

| Total Peanut Protein | Passive Flow-through Immunoassay | 5 ppm | Food matrix | <10 minutes | [11] |

| Total Hazelnut Protein | Active Flow-through Immunoassay | 0.5 ppm | Food matrix | <10 minutes | [11] |

| Total Peanut Protein | Active Flow-through Immunoassay | 1 ppm | Food matrix | <10 minutes | [11] |

| Total Hazelnut Protein | Optimized Lateral Flow Immunoassay | 0.5 ppm | Food matrix | <10 minutes | [11] |

| Total Peanut Protein | Optimized Lateral Flow Immunoassay | 0.5 ppm | Food matrix | <10 minutes | [11] |

| Various Allergens | Electrochemical Biosensing | ppb level | Various foods | Minutes | [6] |

| Various Allergens | SERS Biosensing | ppt to ppb level | Various foods | Minutes | [6] |

Experimental Protocols and Methodological Details

Protocol for Lateral Flow Immunoassay Development

1. Antibody Selection and Characterization: Select high-affinity monoclonal or polyclonal antibodies specific to the target allergen. Characterize binding kinetics using surface plasmon resonance (SPR) to identify antibodies with fast association rates, which is crucial for rapid assays [11]. 2. Conjugate Pad Preparation: Conjugate gold nanoparticles (typically 20-40 nm) or other labels (e.g., latex beads, carbon nanoparticles) to the detection antibody. Optimize the pH and antibody concentration for maximum conjugation efficiency. The conjugate is then sprayed onto the glass fiber pad and dried [11] [12]. 3. Membrane Biofunctionalization: Dispense the capture antibody and control antibody onto the nitrocellulose membrane at the test and control lines, respectively. The membrane's capillary flow rate (typically 120-150 s/4 cm) should be optimized to balance assay speed and sensitivity [11] [12]. 4. Assembly and Cassetting: The sample pad, conjugate pad, nitrocellulose membrane, and absorbent pad are overlapped approximately 2 mm and assembled onto a plastic backing card. The card is then cut into individual strips and housed in plastic cassettes [13].

Protocol for Enhanced Sensitivity Using Electrophoretic LFDs

1. Device Fabrication: Create a portable, 3D-printed electrophoretic device equipped with electrodes and a power source (battery-operated) [15]. 2. Assay Operation: Apply the sample to the LFD strip and initiate an electric field to control fluid movement. The electrophoretic force enables iterative incubation and washing steps directly on the nitrocellulose strip, overcoming mass transport limitations of conventional capillary flow [15]. 3. Signal Detection and Quantification: After optimization of parameters (Joule heating, buffer evaporation, and electroosmotic flow), the accumulated gold nanoparticles at the test line are measured visually or using a portable reader. This approach has demonstrated a 367-fold improvement in sensitivity for human lactate dehydrogenase detection compared to conventional LFIAs [15].

Protocol for Biosensor-Based Allergen Detection

1. Recognition Element Immobilization: Immobilize bio-recognition elements (antibodies, aptamers, or molecularly imprinted polymers) onto the transducer surface. Proper orientation and density are crucial for maintaining binding affinity [6]. 2. Sample Introduction and Incubation: Apply the prepared food sample to the biosensor chamber. Incubation time varies (typically 5-20 minutes) depending on the assay format and desired sensitivity [6]. 3. Signal Transduction and Readout: Measure the signal generated from the allergen-biorecognition element interaction. For electrochemical biosensors, this may involve measuring changes in current (amperometric), potential (potentiometric), or impedance (impedimetric). For optical biosensors, changes in color, fluorescence, or surface plasmon resonance are measured [6]. 4. Data Processing: Convert the signal into allergen concentration using pre-established calibration curves. Smartphone-based readers can facilitate this process for point-of-care applications [6] [11].

Operational Principles and Signaling Pathways: Visual Representations

Lateral Flow Device Operational Workflow

Biosensor Signal Transduction Pathways

Research Reagent Solutions and Essential Materials

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Materials for Portable Allergen Detection Development

| Reagent/Material | Function | Examples/Specifications |

|---|---|---|

| Capture & Detection Antibodies | Specific recognition of target allergens | High-affinity monoclonal/polyclonal antibodies; characterized by SPR for kinetic parameters [11] |

| Gold Nanoparticles | Signal generation in LFDs | 20-40 nm spherical particles; functionalized with antibodies via passive adsorption or covalent binding [12] [13] |

| Nitrocellulose Membranes | Porous matrix for capillary flow & test/control lines | Various pore sizes (5-15 μm) and flow rates (120-150 s/4 cm recommended) [11] [12] |

| Aptamers | Synthetic recognition elements | Single-stranded DNA/RNA molecules with high specificity and stability; alternative to antibodies [6] [12] |

| Sample Pads | Initial sample application and filtration | Glass fiber or cellulose with pretreatment buffers to control flow and pH [12] [13] |

| Nanozymes | Signal amplification | Enzyme-mimicking nanoparticles (e.g., Pt nanoparticles) for catalytic signal enhancement [12] |

| SERS Substrates | Enhanced spectroscopic detection | Noble metal nanoparticles (Au/Ag) with roughened surfaces for plasmonic enhancement [6] [12] |

| Electrochemical Transducers | Signal conversion in biosensors | Screen-printed electrodes (carbon, gold) functionalized with recognition elements [6] |

Portable biosensors and lateral flow devices represent a paradigm shift in food allergen detection, offering rapid, cost-effective, and user-friendly alternatives to conventional laboratory methods. While these rapid methods generally provide slightly lower sensitivity than sophisticated techniques like LC-MS/MS, their performance continues to improve through innovative engineering approaches such as electrophoretic flow control, advanced nanomaterial labels, and signal amplification strategies [6] [15]. The future of portable allergen detection lies in the integration of artificial intelligence for data interpretation, multiplexing capabilities for simultaneous detection of multiple allergens, enhanced connectivity through smartphone integration, and the development of increasingly robust and sensitive platforms that can handle complex food matrices with minimal sample preparation [2] [16] [13]. For researchers and drug development professionals, selecting the appropriate method involves balancing the need for sensitivity, specificity, speed, and practicality based on the specific application requirements.

The increasing global prevalence of food allergies has positioned allergen detection as a critical frontier in food safety and public health. For researchers and drug development professionals, the landscape is divided between highly accurate, established laboratory methods and a new generation of portable devices promising rapid, on-site analysis. This guide provides an objective comparison of these technologies, focusing on their operational principles, performance metrics, and suitability for various research and development applications. Understanding the dynamics between these methods is crucial for navigating a market propelled by stringent regulatory frameworks and growing consumer awareness, which collectively drive innovation and demand for more precise and accessible testing solutions [17] [18].

The United States food allergen testing market is experiencing significant growth, projected to expand from US$ 245.63 million in 2024 to US$ 451.58 million by 2033, with a compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of 7.00%. [17] [18] This expansion is underpinned by several interconnected drivers:

- Stringent Regulatory Frameworks: Agencies like the U.S. FDA are strengthening allergen compliance norms, emphasizing cross-contact prevention, robust supply-chain management, and clear advisory labeling. These regulations compel manufacturers to adopt advanced testing to avoid recalls and legal liabilities. [17] [18]

- Rising Consumer Awareness: Food allergies now affect an estimated 33 million Americans, with one in thirteen children impacted. Heightened public awareness, fueled by advocacy and social media, pressures brands to prioritize transparency and rigorous allergen screening. [17] [18]

- Technological Innovation: Advancements are enhancing the speed, sensitivity, and accuracy of detection methods. For instance, the 2024 launch of the SENSIStrip Gluten PowerLine test exemplifies progress in reducing false negatives and improving reliability across diverse food matrices. [17]

- Shift in Food Consumption Patterns: The growing demand for processed, packaged, and "free-from" foods increases the risk of cross-contamination, making routine allergen testing an essential component of quality assurance. [18]

Comparison of Allergen Detection Methods

The choice between laboratory-based and portable methods depends on the specific requirements of the analysis, such as sensitivity, throughput, and context of use. The table below summarizes the core technologies in the researcher's toolkit.

Table 1: Core Allergen Detection Technologies for Research and Development

| Method Category | Technology | Principle of Detection | Key Performance Attributes | Best Use Cases in R&D |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Laboratory-Based | ELISA (Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay) | Targets specific allergenic proteins using antibodies. [19] | Quantitative; high sensitivity and specificity for target proteins. [19] | Protein-specific quantitation, cleaning validation, clinical relevance studies. [19] |

| Laboratory-Based | PCR (Polymerase Chain Reaction) | Detects unique DNA sequences of the allergenic source. [19] | Qualitative; high species specificity; not directly measures protein. [19] | Identifying allergenic source in complex matrices where protein is denatured. [19] |

| Laboratory-Based | LC-MS/MS (Liquid Chromatography Tandem Mass Spectrometry) | Detects proteotypic peptides after protein digestion. [2] | Highly sensitive and specific; multiplexing capability; quantitative. [2] | High-precision protein quantification, complex matrices, method development. [19] |

| Portable | Smartphone-based iSPR (Imaging Surface Plasmon Resonance) | Measures refractive index changes from allergen-antibody binding. [20] | High sensitivity (LODs ~0.04–0.53 µg/mL for hazelnut); portable; real-time. [20] | On-site screening, rapid prototype testing, field-deployable diagnostics. [20] |

| Portable | Rapid Lateral Flow Devices (RLFD) | Immuno-chromatographic assay with antibody-coated strips. [19] | Semi-quantitative/qualitative; very fast results; ease of use. [19] | Environmental swab verification, rinse water testing, preliminary screening. [19] |

Performance Data and Experimental Comparison

Quantitative Performance Benchmarking

A 2023 study directly compared a portable smartphone-based imaging Surface Plasmon Resonance (iSPR) biosensor against a conventional benchtop SPR system for detecting hazelnut allergen in plant-based milks. [20] The results demonstrate the capabilities of emerging portable technologies.

Table 2: Analytical Performance of Smartphone iSPR vs. Benchtop SPR for Hazelnut Allergen Detection

| Plant-Based Milk Matrix | Smartphone iSPR Limit of Detection (LOD) (µg/mL) | Correlation with Benchtop SPR (R²) |

|---|---|---|

| Soy | 0.53 | 0.950 – 0.991 |

| Oat | 0.16 | 0.950 – 0.991 |

| Rice | 0.14 | 0.950 – 0.991 |

| Coconut | 0.06 | 0.950 – 0.991 |

| Almond | 0.04 | 0.950 – 0.991 |

The smartphone iSPR showed a strong correlation with the conventional system, achieving detection limits for total hazelnut protein as low as 0.04 µg/mL in almond milk, confirming its viability for sensitive, on-site analysis. [20]

Experimental Protocol: Smartphone iSPR for Allergen Detection

The following workflow details the experimental methodology cited from the 2023 Talanta study, which can serve as a prototype for validating portable biosensors. [20]

1. Biosensor Functionalization:

- The gold surface of the microfluidic SPR chip is activated.

- A specific monoclonal or polyclonal antibody against the target allergenic protein (e.g., hazelnut protein) is immobilized onto the chip surface.

2. Sample Preparation:

- Food samples (e.g., plant-based milks) are diluted (e.g., 10x) in an appropriate running buffer to reduce matrix interference.

- Samples are spiked with known concentrations of the target allergen to create a standard curve for quantification.

3. Analysis Setup:

- The functionalized chip is integrated into the 3D-printed portable device.

- The smartphone is positioned to image the SPR reaction in real-time.

4. Measurement and Data Acquisition:

- The sample solution is injected over the chip surface.

- As allergens bind to the immobilized antibodies, the local refractive index changes, causing a shift in the SPR angle.

- The smartphone camera captures these changes in real-time, generating sensorgrams.

5. Data Processing:

- A dedicated smartphone application processes the video or images to quantify the SPR shift.

- The signal is correlated to allergen concentration using the pre-established standard curve.

Diagram 1: Smartphone iSPR experimental workflow.

Critical Considerations for Method Validation

Robust experimental design must account for factors that can compromise result accuracy. Key validation protocols include: [19]

- Spike Recovery Tests: A known allergen quantity is added to a test sample. The measured result versus the known value determines recovery percentage, confirming the method's accuracy in a specific food matrix. [19]

- Cross-Reactivity Checks: The assay is tested against biologically similar substances to ensure it does not generate false positives (e.g., a walnut test should not react with pecans). [19]

- Positive Control Testing: A sample containing the allergen as a deliberate ingredient is analyzed to verify the test can detect the allergen when it is present, guarding against false negatives. This is especially critical for processed allergens, like cooked egg, where protein denaturation can hinder detection by some ELISA kits. [19]

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Successful experimentation in allergen detection requires a suite of specialized reagents and materials. The following table details key components for setting up immunoassays like ELISA or SPR biosensors.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Allergen Detection Immunoassays

| Research Reagent / Material | Function and Importance in Experimental Protocol |

|---|---|

| Specific Antibodies (Monoclonal/Polyclonal) | Core recognition element that binds specifically to the target allergenic protein (e.g., against Ara h 1 in peanuts). Critical for assay specificity. [2] |

| Purified Allergen Standards | Highly characterized native or recombinant allergenic proteins. Essential for creating calibration curves, determining LOD/LOQ, and conducting spike recovery experiments. [21] |

| Microfluidic SPR Chip | The transducer surface in an SPR biosensor. Its functionalization with antibodies is the foundation for label-free, real-time detection of binding events. [20] |

| Blocking Buffers (e.g., BSA) | Solutions used to cover unused binding sites on the sensor or well surfaces after antibody coating. Prevents non-specific binding, which is a major source of false positives. |

| Sensor Chip Coupling Reagents | Chemical agents (e.g., EDC/NHS) that activate carboxylated dextran surfaces on SPR chips to facilitate the covalent immobilization of antibodies. [20] |

Technology Positioning and Future Research Directions

The relative positioning of these technologies within the research and development ecosystem can be visualized based on their operational complexity and analytical information depth.

Diagram 2: Technology positioning map.

Emerging research is focused on integrating artificial intelligence and non-destructive diagnostics. AI models are being developed to predict the allergenicity of new ingredients before they enter the supply chain, while technologies like Hyperspectral Imaging (HSI) and Fourier Transform Infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy, combined with machine learning, allow for non-destructive, real-time allergen detection without altering the food's integrity. [2] Furthermore, mass spectrometry is advancing with its ability to detect proteotypic peptides across complex food matrices, offering unparalleled precision for multi-allergen detection. [2] These innovations point toward a future of smarter, faster, and more integrated allergen detection systems, shaping the next generation of portable and laboratory-based tools.

Methodology in Practice: Deploying Detection Technologies from Lab to Field

In the evolving landscape of diagnostic and food safety research, the demand for high-throughput, accurate detection methods is paramount. For scientists developing portable allergen detection devices, understanding the capabilities and limitations of established laboratory methods provides a crucial performance baseline. Among these, Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay (ELISA) and Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR) represent two foundational technologies. ELISA is renowned for its direct quantification of protein allergens, while PCR offers exceptional sensitivity in detecting allergen-encoding DNA sequences. This guide objectively compares the performance, protocols, and applications of ELISA and PCR within high-throughput screening environments, synthesizing experimental data to inform the development of next-generation portable detection systems. The quantitative data and workflows presented here serve as a reference point for evaluating the performance of emerging field-deployable technologies against established laboratory standards.

Performance Comparison: ELISA vs. PCR

The choice between ELISA and PCR is often dictated by the specific requirements of the detection scenario, including the nature of the sample, the required sensitivity, and whether qualitative or quantitative data is needed. The table below summarizes a direct comparison based on key performance parameters.

Table 1: Direct comparison of ELISA and PCR for detection applications.

| Parameter | ELISA | PCR |

|---|---|---|

| Target Molecule | Proteins (e.g., allergenic proteins) [22] | DNA (from the allergenic species) [22] |

| Throughput | High (can be automated for 96 or 384-well plates) | High, with capabilities for multiplexing (detecting multiple allergens simultaneously) [22] |

| Quantification | Direct and highly accurate quantification of proteins [22] | Primarily qualitative; can be semi-quantitative [22] |

| Sensitivity | High (e.g., detects gluten at 20 mg/kg as per Codex Alimentarius) [23] | Very High (detects trace DNA) [22] |

| Specificity | High, dependent on antibody affinity | High, dependent on primer design [23] |

| Best For | Detecting allergens in raw ingredients and less processed foods where protein structure is intact [22] | Detecting allergens in complex, highly processed foods where proteins may be denatured but DNA remains stable [22] [23] |

| Sample Processing | Protein extraction | DNA extraction [22] |

| Time to Result | Several hours | Several hours (though high-speed microfluidic PCR can reduce this to minutes) [24] |

| Cost-Effectiveness | Established, relatively cost-effective for protein detection | Higher cost for DNA-based detection, but offers high-throughput multiplexing [22] |

Supporting Experimental Data

Independent comparative studies reinforce these characteristics. A 2025 study evaluating an in-house ELISA for SARS-CoV-2 antibody detection demonstrated its substantial agreement with commercial chemiluminescent assays (Elecsys CLIA), with a positive percent agreement (PPA) of 81.7% and a negative percent agreement (NPA) of 80.1%. The overall concordance was 80.8%, with a kappa coefficient of κ=0.61 (95% CI 0.55–0.67), indicating good reliability for serosurveillance [25]. This showcases ELISA's robustness in quantitative protein detection.

Similarly, a 2020 comparison of eight commercial serological assays for SARS-CoV-2 highlighted that while a good correlation exists between different methods, discrepancies can occur, particularly in individuals with low antibody levels. This underscores the importance of understanding the limits of detection and the potential for false negatives in certain populations, a consideration that directly translates to allergen detection research [26].

Method Selection Guide

Selecting the appropriate method is critical for accurate results. The following flowchart provides a logical workflow for deciding between ELISA, PCR, or other methods based on the sample and research question.

Figure 1: A decision workflow for selecting appropriate detection methods based on sample type and requirements. LFA is included as a common portable alternative for context [22].

Experimental Protocols in Practice

To ensure reproducibility and provide a clear understanding of laboratory standards, detailed protocols for ELISA and PCR are outlined below. These methodologies form the benchmark against which portable devices are often validated.

Detailed ELISA Protocol for Protein Detection

The following protocol, adapted from serology and allergen testing research, describes an indirect ELISA for detecting specific antibodies or proteins [25] [23].

Principle: A capture antibody (or antigen) is immobilized on a solid phase. The sample containing the target protein is added. A secondary enzyme-conjugated detection antibody is then used, which produces a measurable signal upon substrate addition [22].

Materials:

- Microtiter Plates: 96-well plates for high-throughput analysis [25].

- Coating Antigen/Antibody: The purified protein (e.g., recombinant RBD of a spike protein) or capture antibody [25].

- Blocking Buffer: 4% skimmed milk in PBS with 0.1% Tween-20 to prevent non-specific binding [25].

- Washing Buffer: Phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) with 0.1% Tween-20 (PBST) [25].

- Detection Antibody: Enzyme-linked (e.g., Horseradish Peroxidase, HRP) antibody specific to the target [25] [27].

- Substrate Solution: TMB (3,3',5,5'-Tetramethylbenzidine) for HRP, which produces a blue color [27].

- Stop Solution: Acidic solution to halt the enzyme reaction [27].

- Plate Reader: Spectrophotometer for measuring absorbance at a specific wavelength (e.g., 450 nm) [22].

Step-by-Step Workflow:

Figure 2: The key steps in an indirect ELISA protocol for detecting a specific protein or antibody [25] [27].

Detailed PCR Protocol for Nucleic Acid Detection

This protocol describes a standard real-time PCR (qPCR) procedure for detecting specific DNA sequences, common in food allergen analysis [22] [23].

Principle: Target DNA sequences are amplified exponentially through thermal cycling. In qPCR, the accumulation of amplified DNA is measured in real-time using fluorescent dyes, allowing for quantification [22].

Materials:

- Thermal Cycler: Instrument for precise temperature cycling, with fluorescence detection for qPCR [24].

- PCR Reagents Mix: Contains DNA polymerase (e.g., Taq polymerase), dNTPs, and MgCl₂ in an appropriate buffer [22].

- Primers: Short, specific nucleotide sequences designed to flank the target DNA region [22].

- Probes/Dye: Fluorescent probe (e.g., TaqMan) or intercalating dye (e.g., SYBR Green) for detection in qPCR [23].

- DNA Template: Extracted and purified DNA from the sample [22].

Step-by-Step Workflow:

Figure 3: The standard workflow for a PCR assay, highlighting the cyclical nature of amplification [22] [23].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Successful implementation of ELISA and PCR workflows relies on a suite of specialized reagents and instruments. The following table details key materials and their functions in these assays.

Table 2: Essential reagents and equipment for ELISA and PCR workflows.

| Category | Item | Primary Function in Assay |

|---|---|---|

| ELISA-Specific | Microtiter Plates | Solid-phase surface for immobilizing the capture molecule [25]. |

| Coating Antigen/Antibody | The initial protein that specifically captures the target from the sample [25]. | |

| Enzyme-Conjugated Antibody | Produces a measurable signal (color, light) upon reacting with its substrate [25] [27]. | |

| TMB Substrate | Chromogenic substrate for HRP enzyme, changes color in presence of the target [27]. | |

| PCR-Specific | Thermostable DNA Polymerase | Enzyme that synthesizes new DNA strands at high temperatures [22]. |

| Primers | Short DNA sequences that define the start and end of the target DNA region to be amplified [22]. | |

| dNTPs | The building blocks (nucleotides) for synthesizing new DNA strands [22]. | |

| Fluorescent Probe/Dye | Allows for real-time detection and quantification of amplified DNA in qPCR [23]. | |

| General/Core | Plate Reader (Spectrophotometer) | Measures the absorbance of the final solution in ELISA wells for quantification [22]. |

| Thermal Cycler | Precisely controls temperature cycles for DNA amplification in PCR [24]. | |

| Blocking Buffer (e.g., BSA, Milk) | Prevents non-specific binding of proteins to the plate in ELISA [25]. |

Future Directions and Integrated Approaches

The future of detection lies in leveraging the strengths of different technologies. Integrated approaches using both ELISA and PCR are increasingly used to overcome the limitations of a single method, especially in complex food matrices or for verifying allergen-free claims [22]. For instance, PCR can first screen for the presence of allergenic species DNA, with ELISA providing subsequent confirmation and quantification of the actual allergenic protein [22].

Emerging technologies are also shaping the field. Biosensors, combined with microfluidics, offer promise for on-site detection with advantages in rapidity and sensitivity [23]. Furthermore, Artificial Intelligence (AI) and machine learning are being integrated into high-throughput screening platforms to analyze massive datasets, optimize assay design, and improve pattern recognition for more accurate diagnostics [28]. The ongoing development of high-speed microfluidic PCR systems, accelerated during the COVID-19 pandemic, aims to reduce analysis time from hours to minutes, blurring the lines between laboratory and point-of-care testing [24]. These advancements provide a exciting roadmap for the evolution of portable allergen detection devices.

The growing global burden of allergic diseases, which now affect over 25% of the population in many developed nations, has intensified the need for accurate, accessible diagnostic tools [29] [30]. Traditional laboratory-based methods for allergen detection, including enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays (ELISAs) and ImmunoCAP systems, have long served as the gold standard for specific IgE detection and allergen quantification in food products [31] [32]. However, these methods require centralized laboratories, specialized equipment, and trained personnel, creating significant barriers to rapid diagnosis and point-of-care testing. In response to these limitations, portable detection platforms combining lateral flow assays (LFAs) with smartphone-based detection have emerged as transformative technologies that bridge the gap between laboratory accuracy and field-deployable testing.

The fundamental appeal of these integrated systems lies in their ability to meet WHO ASSURED criteria (Affordable, Sensitive, Specific, User-friendly, Rapid and Robust, Equipment-free, and Deliverable to end-users) while incorporating advanced digital capabilities [33]. Smartphone integration addresses one of the most significant limitations of conventional LFAs: the subjective interpretation of results. Studies demonstrate that AI algorithms integrated with smartphone readers have reduced interpretation errors by 40% in low-contrast conditions, substantially improving diagnostic reliability [33]. Furthermore, the integration of digital connectivity enables real-time data analysis, geotracking of allergen exposures, and remote consultation capabilities that enhance both clinical diagnostics and public health surveillance.

Performance Comparison: Portable vs. Laboratory Methods

The analytical and clinical performance of smartphone-integrated LFA systems must be rigorously evaluated against established laboratory methods to determine their appropriate applications and limitations. The following tables summarize key performance metrics based on current validation studies and market analyses.

Table 1: Analytical Performance Comparison of Allergen Detection Platforms

| Parameter | Smartphone-LFA Systems | Laboratory ELISA | Laboratory ImmunoCAP |

|---|---|---|---|

| Limit of Detection | 0.01 pg/mL (nanoparticle-enhanced) [33] | 0.1-1 ng/mL [31] | 0.1 kUA/L [32] |

| Assay Time | 5-30 minutes [34] [32] | 2-4 hours [31] | 3-4 hours [32] |

| Multiplexing Capability | Up to 20 allergens simultaneously (15% of new products) [34] [35] | Typically single-plex | Limited multiplexing |

| Sample Volume | 10-100 μL [14] [32] | 50-200 μL | 50-100 μL |

| Quantification | Semi-quantitative with smartphone readers [34] [33] | Fully quantitative | Fully quantitative |

| Cost per Test | $5-25 [34] | $25-100 | $50-150 |

Table 2: Clinical Performance of Representative Portable Allergy Tests

| Test System | Sensitivity | Specificity | Concordance with Lab Methods | Allergens Detected |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| FastCheckPOC 20 | 43.3% overall; 79.8% for grass pollen [32] | 92.1% overall [32] | Variable by allergen class | 20 allergens |

| Smartphone-Nano LFA | 92% (modeled estimate) [33] | 98% (modeled estimate) [33] | 92% with gold-standard assays [33] | Customizable |

| Conventional LFA | 76% (literature report) [32] | 80% (literature report) [32] | 70-85% depending on analyte [34] | Variable |

Performance data reveal that while smartphone-integrated systems approach laboratory-level sensitivity for some applications, significant variability exists between different platforms and allergen targets. The FastCheckPOC 20 device demonstrates notably higher sensitivity for inhalation allergens (79.8% for grass pollen) compared to food allergens, highlighting how protein characteristics impact test performance [32]. Meanwhile, advancements in nanoparticle-enhanced LFAs have achieved detection limits as low as 0.01 pg/mL – a 100-fold improvement over conventional LFAs – suggesting the potential for future platforms to rival laboratory sensitivity [33].

Lateral flow assays operate on capillary action principles, where a liquid sample migrates through a series of porous membranes containing biorecognition elements that generate a visible signal in the presence of target analytes [14] [33]. The two primary LFA formats used in allergen detection are sandwich assays (for larger targets with multiple epitopes) and competitive assays (for small molecules and single-epitope targets) [14]. Understanding these fundamental mechanisms is essential for selecting appropriate platforms for specific allergen targets.

Smartphone Integration and Detection Modalities

Smartphone-integrated LFA systems employ multiple detection modalities that transform simple colorimetric tests into quantitative analytical tools. The primary detection methods include:

- Colorimetric Analysis: Smartphone cameras capture test line intensity, with proprietary algorithms converting pixel density to analyte concentration. This approach has demonstrated 98% specificity in real-world surveillance applications [33].

- Fluorescent Detection: Using quantum dots or fluorescent nanoparticles, these systems provide enhanced sensitivity with detection limits up to 100-fold lower than colorimetric methods, though they require additional illumination components [33].

- Surface-Enhanced Raman Spectroscopy (SERS): Noble metal nanoparticles functionalized with recognition elements provide unique spectral fingerprints for target analytes, enabling highly specific multiplex detection [33].

The integration of artificial intelligence has been particularly transformative, with machine learning algorithms now capable of distinguishing faint test lines in suboptimal lighting conditions and automatically validating control line functionality to reduce invalid results [33]. Furthermore, cloud connectivity enables the aggregation of population-level data, creating opportunities for mapping allergen prevalence and identifying emerging sensitization patterns.

Experimental Protocols: Validation Methodologies for Portable Systems

Robust validation against established laboratory methods is essential when evaluating smartphone-LFA systems. The following protocols outline standardized approaches for performance verification.

Protocol 1: Comparative Sensitivity and Specificity Analysis

This protocol evaluates the clinical performance of a smartphone-LFA system against laboratory reference methods for specific IgE detection [32] [30].

Materials and Reagents:

- Serum samples from characterized allergic and non-allergic donors

- Smartphone-LFA system and associated reagents

- Reference laboratory equipment (e.g., ImmunoCAP, ELISA)

- Standardized allergen extracts

- Data collection forms and statistical analysis software

Procedure:

- Collect serum samples from 150-200 participants representing diverse allergen sensitivities and demographic characteristics [32] [30].

- Divide each sample for parallel testing with the smartphone-LFA system and reference laboratory method.

- Perform all tests according to manufacturer specifications, ensuring blinded analysis.

- For smartphone-LFA systems, capture both visual and algorithm-interpreted results.

- Compare results using statistical measures including sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value, negative predictive value, and overall agreement.

- Conduct subgroup analyses based on allergen class, patient age, and symptom severity [32].

Data Interpretation: Calculate Cohen's kappa coefficient to assess agreement beyond chance. ROC analysis determines optimal cutoff values. For the FastCheckPOC 20 system, this approach revealed 43.3% overall sensitivity and 92.1% specificity compared to ALEX2 microarray testing [32].

Protocol 2: Limit of Detection and Quantification Assessment

This protocol establishes the analytical sensitivity of smartphone-LFA systems for allergen detection in food matrices [31] [36].

Materials and Reagents:

- Purified allergen standards (e.g., Ara h 1 for peanut, Bos d 5 for milk)

- Appropriate food matrices (naturally allergen-free)

- Smartphone-LFA system with calibration standards

- Sample preparation equipment (blenders, centrifuges, filters)

- Reference method (ELISA or mass spectrometry)

Procedure:

- Prepare serial dilutions of purified allergen standards in appropriate matrices covering the expected detection range.

- Spike allergen-free food samples with known allergen concentrations for recovery studies.

- Process samples through the smartphone-LFA system according to established protocols.

- Analyze each concentration in triplicate across multiple lots of test devices.

- Compare results with reference laboratory methods using matched samples.

- Determine limit of detection (LOD) as the lowest concentration detectable above background and limit of quantification (LOQ) as the lowest concentration measurable with ≤20% coefficient of variation.

Data Interpretation: Nanoparticle-enhanced LFAs have achieved LODs as low as 0.01 pg/mL for some targets, representing a 100-fold improvement over conventional LFAs [33]. However, performance varies significantly across food matrices, emphasizing the need for matrix-specific validation.

Research Reagent Solutions and Essential Materials

Successful implementation of smartphone-LFA systems requires specific reagents and materials optimized for portable detection platforms.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Smartphone-Integrated Allergen Detection

| Reagent/Material | Function | Performance Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Nitroc cellulose Membranes | Porous substrate for capillary flow and bioreceptor immobilization | Pore size (5-15 μm) affects flow rate and test line resolution [14] |

| Colloidal Gold Nanoparticles | Colorimetric labels for visual detection | 20-40 nm diameter optimizes color intensity and conjugation efficiency [33] |

| Quantum Dots | Fluorescent labels for enhanced sensitivity | Emission wavelengths should match smartphone camera filters; 5-10 nm diameter [33] |

| Mono clonal Antibodies | Target recognition elements for sandwich assays | Must recognize different epitopes than detection antibodies; high affinity (KD < 10⁻⁸ M) [14] |

| Recombinant Allergens | Positive controls and calibration standards | Should represent immunodominant epitopes; purity >95% [36] |

| Blocking Buffers | Prevent non-specific binding | Typically contain proteins (BSA, casein) and surfactants (Tween-20) [14] |

| Conjugation Buffers | Optimize antibody-nanoparticle coupling | pH 8-9 with minimal salt content preserves antibody binding capacity [14] |

Applications and Implementation Considerations

The implementation of smartphone-integrated LFA systems spans multiple domains, each with distinct requirements and validation criteria.

Clinical Diagnostic Applications

In clinical settings, these systems enable rapid specific IgE testing with 30-minute turnaround times compared to 3-4 hours for laboratory methods [32]. However, performance varies significantly by allergen class, with inhalation allergens typically showing higher sensitivity (79.8% for grass pollen) than food allergens [32]. This variability necessitates careful test selection based on clinical presentation and prevalence of specific allergens in the target population.

Recent studies implementing these systems in primary care settings demonstrate particular utility for ruling out sensitization due to high specificity (92.1% for FCP20), though low overall sensitivity (43.3%) limits their utility as standalone screening tools [32]. The integration of smartphone-based decision support algorithms has shown promise in improving appropriate test utilization and interpretation by non-specialists.

Food Safety and Environmental Monitoring

In food safety applications, smartphone-LFA systems provide rapid detection of allergenic contaminants with sensitivity approaching 0.1 ppm for major allergens like peanut and milk [31] [36]. The ability to perform on-site testing without specialized laboratory facilities enables food manufacturers to conduct frequent environmental monitoring and verify sanitation protocols.

Multiplex systems capable of simultaneously detecting multiple allergens in a single test are particularly valuable for food manufacturing facilities handling multiple allergenic ingredients. Approximately 15% of new LFA products now incorporate multiplexing capabilities, though competitive assay formats remain challenging for multiplex detection due to complex signal interpretation [34] [35].

Smartphone-integrated lateral flow assays represent a significant advancement in portable allergen detection, offering a compelling balance between performance characteristics and practical utility. While these systems have not yet achieved parity with laboratory methods for all performance parameters, their 98% specificity in real-world applications, rapid turnaround time, and connectivity features position them as valuable tools for specific use cases [33].

The future trajectory of this technology points toward enhanced sensitivity through novel nanomaterials, expanded multiplexing capabilities leveraging CRISPR-based detection, and improved connectivity through 5G and cloud-based analytics [33]. Additionally, the emergence of sustainable manufacturing approaches using biodegradable materials addresses environmental concerns while maintaining performance [35]. For researchers and clinicians, these advancements promise increasingly sophisticated portable platforms that may eventually achieve laboratory-level performance while retaining the practical advantages of point-of-care testing.

For the present, optimal implementation requires careful matching of technology capabilities to specific application requirements, with laboratory confirmation remaining essential for cases where portable systems demonstrate limited sensitivity. As validation datasets expand and technology evolves, smartphone-integrated LFA systems are poised to play an increasingly central role in decentralized allergen detection across clinical, food safety, and environmental monitoring applications.

The management of allergens is a critical public health challenge, with accurate detection serving as the cornerstone for protecting susceptible individuals. While traditional laboratory methods like enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) and polymerase chain reaction (PCR) have long been the gold standard, a new generation of portable detection devices is emerging. These technologies promise rapid, on-site analysis, potentially transforming practices in clinical diagnostics, food manufacturing, and food service. This guide provides an objective comparison of these portable technologies against established laboratory methods, framing the analysis within the broader thesis that while field-deployable devices offer significant advantages in speed and convenience, their performance must be carefully evaluated against application-specific requirements.

Performance Comparison of Allergen Detection Methods

The following tables summarize the key operational characteristics and performance data of various detection methods, highlighting the trade-offs between laboratory-based and portable platforms.

Table 1: Comparison of Core Allergen Detection Technologies

| Method | Format | Detection Mechanism | Time-to-Result | Key Advantages | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lateral Flow Device (LFD) [37] | Portable, Immunoassay | Visual colorimetric line | < 20 minutes | Ideal for quick spot-checks; minimal training required | Qualitative/Semi-quantitative (yes/no); lower sensitivity than ELISA |

| Electrochemical Sensor [38] | Portable, Biosensor | Electrochemical signal from MIP | Rapid (specific time not given) | High accuracy in complex foods; consumer-friendly potential | Emerging technology; limited commercial availability |

| ELISA [37] | Laboratory, Immunoassay | Colorimetric readout via plate reader | Several hours | High sensitivity and quantification; robust and established | Requires lab equipment and trained technicians |

| LC-MS/MS [6] | Laboratory, Mass Spectrometry | Mass-to-charge ratio of allergen peptides | Several hours | High selectivity and throughput; detects multiple allergens | Costly equipment; complex sample preparation |

Table 2: Experimental Performance Data of Portable vs. Laboratory Methods

| Technology (Study) | Sensitivity | Specificity | Comparative Laboratory Method | Notes / Context |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| FastCheckPOC (FCP20) [32] | 43.3% (Overall) | 92.1% (Overall) | ALEX2 Multiplex Assay | Utility limited by low overall sensitivity, but useful for exclusion. |

| FastCheckPOC (FCP20) [32] | 79.8% (Grass Pollen) | Not specified | ALEX2 Multiplex Assay | Performance varies significantly by allergen type. |

| Electrochemical Sensor (Allergy Amulet) [38] | Correctly identified presence/absence in 42 foods | Not specified | Commercial LFD & Immunoassay | Effective in diverse, complex food matrices. |

Clinical Point-of-Care Deployment

The deployment of point-of-care (POC) tests in primary care settings aims to streamline the diagnosis of allergic sensitization, providing rapid results that can guide clinical decision-making during a patient's visit.

Experimental Protocol: Evaluating a POC Test

A recent 2025 cross-sectional study evaluated the performance of the FastCheckPOC 20 Atopy (FCP20), a lateral flow POC test, against the laboratory multiplex assay Allergy Explorer 2 (ALEX2) [32].

- Participant Recruitment and Sample Collection: 215 participants were recruited. Venous blood was drawn from each participant, and the sample was left to clot for 15-30 minutes [32].

- Serum Separation: The blood sample was centrifuged at 1,500 × g for 10 minutes. The resulting serum was divided into two aliquots: one for immediate POC testing and one for laboratory analysis [32].

- POC Testing (FCP20): The serum aliquot for the FCP20 test was used immediately. The sample was diluted with a provided diluent, applied to the test cassette, followed by the sequential addition of washing solutions and a buffer solution. The test results were optically evaluated after 30 minutes. A result was classified as positive for levels 2-5, corresponding to CAP class 2 and above [32].

- Laboratory Testing (ALEX2): The second serum aliquot was stored at -20°C. The frozen samples were shipped on dry ice to a central laboratory, where the ALEX2 test was performed according to the manufacturer's instructions. This test provides a comprehensive sensitization profile [32].

- Data Analysis: Results from the FCP20 and ALEX2 were compared. Dichotomous data (positive/negative) were used to calculate the overall sensitivity and specificity of the FCP20, using the ALEX2 as the reference standard [32].

Technology Comparison and Workflow

The diagram below illustrates the procedural differences between conducting a POC test in a clinical setting and sending a sample to a central laboratory.

Food Manufacturing & Dining Safety Deployment

In food safety, the priority is to prevent allergen cross-contact and verify the effectiveness of cleaning protocols to protect consumers and comply with labeling regulations.

Experimental Protocol: Sensor Testing in Complex Foods

A 2021 study demonstrated a rapid electrochemical sensor using molecularly imprinted polymers (MIPs) for detecting a soy allergen tracer (genistein) in complex food products [38].

- Sample Preparation: For solid foods, 1 g of sample was homogenized into a fine powder using a mortar and pestle for 5 minutes. The powder was mixed with 10 mL of buffer solution and stirred for 15 minutes. For liquid foods, 1 g was mixed directly with 10 mL of buffer [38].

- Sensor Preparation: Template-extracted MIP electrodes were equilibrated in a clean buffer solution for 5 minutes before measurement [38].

- Sample Incubation and Measurement: The prepared electrode was incubated with 100 µL of the sample solution for 1 minute. It was then subjected to differential pulse voltammetry (DPV) measurements using a potentiostat. The critical DPV parameters were: scan rate of 50 mV/s, pulse width of 50 ms, and amplitude of 50 mV [38].

- Result Interpretation: A positive response was confirmed by the presence of an oxidation peak at approximately 0.60 V (vs Ag/AgCl reference electrode) and an imprinting factor (MIP signal/NIP signal) above 1.3 [38].

- Confirmatory Analysis: Results were confirmed using a commercial Soy Protein LFD kit, following the manufacturer's protocol, which involved extracting the sample in a specific buffer and incubating in the LFD for 11 minutes [38].

Comparative Analysis of Food Safety Tools

The following diagram outlines the decision-making process for allergen testing in a food production environment, comparing different tools.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents and Materials

The development and validation of novel allergen detection methods rely on a specific set of reagents and materials. The following table details key components used in the featured experiments.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Allergen Detection Development

| Reagent / Material | Function / Role in Research | Example from Literature |

|---|---|---|

| Monoclonal/Polyclonal Antibodies | Bio-recognition element in immunoassays (ELISA, LFD) that specifically binds to target allergenic protein. | Used in commercial LFDs and ELISA kits for allergen detection [37]. |

| Molecularly Imprinted Polymer (MIP) | Synthetic polymer with cavities complementary to a specific allergen molecule; serves as an antibody mimic in biosensors. | Used as the recognition element in an electrochemical sensor for soy allergen detection [38]. |

| Allergen Extracts & purified proteins | Positive controls for assay development and validation; used to determine sensitivity and specificity. | Aerosolized proteins from mites, dander, and pollen used in UV light inactivation studies [39]. |

| Screen-Printed Electrodes (SPE) | Disposable electrochemical cells used for portable biosensor development; enable miniaturization. | Carbon ItalSens IS-C SPEs were used in the development of the soy allergen electrochemical sensor [38]. |

| Sample Diluent / Extraction Buffer | Liquid medium used to extract allergens from complex samples and prepare them for analysis. | 3M extraction buffer used for LFD analysis; PBS buffer used for electrochemical sensor testing [38]. |

The landscape of allergen detection is diversifying, with portable devices now addressing needs that were once the exclusive domain of central laboratories. Lateral Flow Devices offer unparalleled speed for routine monitoring in food production, while emerging electrochemical biosensors show strong potential for accurate, consumer-facing applications. In the clinic, POC tests can aid in initial screening but are currently best suited for ruling out sensitization due to variable sensitivity. The choice between these technologies is not a matter of superiority but of context. Researchers and professionals must base their selection on a clear understanding of the required detection limits, the need for quantification, the complexity of the sample matrix, and the trade-off between the rapidity of a field result and the comprehensive data provided by a laboratory test. Future advancements will likely focus on improving the sensitivity and multiplexing capabilities of portable devices to narrow this performance gap further.