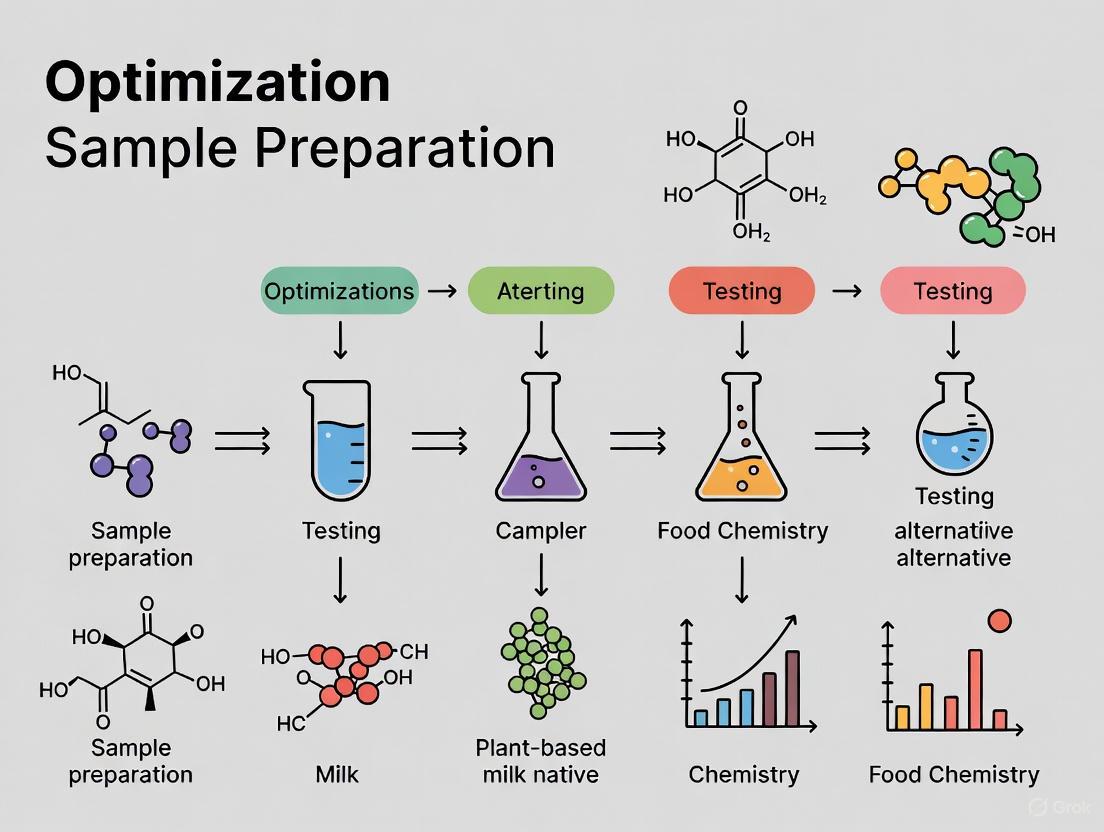

Optimizing Sample Preparation for Plant-Based Milk Alternative Testing: Strategies for Contaminant Detection and Analytical Accuracy

This comprehensive review addresses the critical challenges and methodological innovations in sample preparation for plant-based milk alternative (PBMA) testing.

Optimizing Sample Preparation for Plant-Based Milk Alternative Testing: Strategies for Contaminant Detection and Analytical Accuracy

Abstract

This comprehensive review addresses the critical challenges and methodological innovations in sample preparation for plant-based milk alternative (PBMA) testing. Targeting researchers and laboratory professionals, we explore the complex matrix effects arising from diverse plant sources and processing techniques that complicate contaminant detection. The article systematically evaluates conventional and emerging sample preparation protocols for analyzing biological contaminants, allergens, chemical adulterants, and mycotoxins. We provide practical troubleshooting guidance for overcoming interference from lipids, proteins, and polysaccharides, and present validation frameworks for method comparison. By integrating advanced techniques like green extraction, AI-driven spectroscopy, and biosensor compatibility, this work establishes optimized pathways for enhancing analytical precision, ensuring PBMA safety, and supporting regulatory compliance in a rapidly expanding market.

Understanding PBMA Matrix Complexity: Compositional Challenges in Analytical Sample Preparation

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: Why is sample homogeneity a significant challenge when analyzing different types of Plant-Based Milk Alternatives (PBMAs)?

Sample homogeneity is a major challenge due to the inherent variability in the physical and chemical composition of raw materials (nuts, legumes, grains, seeds) and the different processing methods used. Key factors include:

- Particle Size Variation: PBMAs generally have larger and more variable particle sizes compared to bovine milk. This can lead to sedimentation or creaming, creating a non-uniform sample that affects the reproducibility of analytical measurements [1]. Larger particles are linked to greater sedimentation rates and a gritty mouthfeel, directly indicating heterogeneity [1].

- Divergent Compositions: The fundamental composition (e.g., protein, carbohydrate, and fat content) varies drastically between PBMA types. For instance, soy-based drinks are typically higher in protein, while oat and rice drinks are richer in carbohydrates [2]. This variability means that a single, universal sample preparation method is often insufficient for accurate analysis across different matrices.

FAQ 2: How does the choice of plant source impact the mineral content and potential contaminants in my analytical samples?

The plant source is a primary determinant of the mineral and potential contaminant profile, introducing significant variability that researchers must account for.

- Nutrient Variability: Analytical data shows that mineral content differs substantially across PBMA types. For example, pea PBMAs were found to contain the highest mean amounts of phosphorus, selenium, and zinc, while soy PBMAs were highest in magnesium. Most PBMAs have lower mean mineral amounts than cow's milk [3].

- Contaminant Profile: Certain raw materials are more prone to specific contaminants. For example, rice PBMAs have been observed to contain the highest levels of total arsenic among the types studied [3]. Additionally, the detection of processing contaminants like acrylamide in almond and oat PBMAs further underscores the need for source-specific analytical controls [2].

FAQ 3: What are the key technological hurdles in creating PBMAs with consistent, milk-like properties for comparative studies?

The main technological hurdles in achieving consistent, dairy-like properties are:

- Mimicking Sensory Properties: Replicating the sensory profile of cow's milk is difficult. Off-flavors (e.g., beany notes in soy, cereal notes in oat) and textural differences (e.g., lower creaminess, astringency) are common challenges [1] [4].

- Stability and Mouthfeel: Achieving a stable emulsion with a particle size distribution similar to cow's milk is technically challenging. The larger particle sizes in PBMAs result in lower physical stability and a less desirable mouthfeel [1].

- Nutritional Standardization: Formulating PBMAs to have a consistent and comparable nutritional profile to milk, particularly for protein and micronutrients like vitamin B12, B2, and calcium, requires extensive fortification and blending of different plant sources [4] [5].

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue 1: Inconsistent Results in Elemental Analysis

Problem: Measurements of target minerals (e.g., Mg, P, Se, Zn) and screening for contaminants (e.g., As, Cd, Pb) yield high variability between samples of the same PBMA type or even across different production lots.

Solutions:

- Standardized Sample Pre-Treatment: Ensure all liquid samples are mixed thoroughly immediately before aliquoting to re-suspend settled particles. For solid samples, use cryogenic grinding under liquid nitrogen to achieve a homogeneous powder and prevent segregation of components [3].

- Validate Against Certified Reference Materials (CRMs): Use matrix-matched CRMs to validate your analytical method. For instance, Standard Reference Material (SRM) 1549a (Whole Milk Powder) from the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) can be used for quality control, though it's important to note the potential matrix differences with PBMAs [3].

- Account for Source-Specific Variability: Recognize that mineral content varies significantly by PBMA type. Use the following table as a guide for expected concentration ranges and to select appropriate calibration standards.

Table 1: Mean Mineral Content in Different PBMA Types (mg/100 g) [3]

| PBMA Type | Magnesium (Mg) | Phosphorus (P) | Selenium (Se) | Zinc (Zn) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pea | 12.1 | 80.6 | 0.027 | 0.284 |

| Soy | 15.8 | 66.6 | 0.017 | 0.193 |

| Almond | 5.8 | 38.6 | < LOD* | 0.067 |

| Oat | 8.5 | 59.3 | 0.005 | 0.116 |

| Cow's Milk | 11.6 | 79.8 | 0.019 | 0.536 |

*LOD: Limit of Detection

Issue 2: Inefficient Detection of Allergens and Adulterants

Problem: Low recovery rates or high limits of detection when analyzing for common allergens (e.g., soy, almond) or adulterants in complex PBMA matrices.

Solutions:

- Optimize DNA Extraction for PCR Methods: The efficiency of DNA-based detection methods (e.g., PCR) can be hampered by PCR inhibitors and poor DNA yield from processed PBMAs. Optimize your sample preparation protocol to include steps for the removal of polysaccharides and phenolic compounds, which are common in plant matrices [6].

- Employ Multi-Technique Approaches: No single method is optimal for all contaminants. Integrate multiple techniques to cross-verify results. The following workflow diagram illustrates a recommended multi-technique strategy for ensuring PBMA safety and authenticity.

Issue 3: Uncontrolled Formation of Process Contaminants During Analysis

Problem: Heat treatments or other processing steps during sample preparation can lead to the formation of Maillard reaction products (MRPs) like acrylamide or furans, skewing results.

Solutions:

- Control Heating Steps: If thermal processing is part of your experimental design, carefully control time-temperature parameters. Research indicates that PBMAs can contain higher levels of certain MRPs, such as α-dicarbonyl compounds, compared to UHT cow's milk [2].

- Monitor Key Indicators: Quantify early-stage MRPs like furosine to gauge the intensity of heat treatment the sample has undergone. The correlation between sugar content (high in oat and rice PBMAs) and the formation of advanced glycation end products (AGEs) should be a key consideration in your experimental planning [2].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Reagents and Materials for PBMA Analysis

| Item | Function/Application | Example in Context |

|---|---|---|

| Inductively Coupled Plasma-Mass Spectrometry (ICP-MS) | Quantitative multi-element analysis for minerals (Mg, P, Zn, Se) and contaminants (As, Cd, Pb) with high sensitivity [3]. | Used to determine the low levels of selenium in oat milk and the elevated arsenic in rice-based PBMAs [3]. |

| Gas Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (GC-MS) | Identification and quantification of volatile organic compounds, including off-flavors and process-derived contaminants [1]. | Employed to identify benzaldehyde (almond-like aroma) in almond milk and lactones (creamy notes) in coconut milk [1]. |

| High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC) | Analysis of non-volatile compounds, including amino acids, MRPs (furosine, AGEs), and acrylamide [2]. | Used to profile essential amino acids and quantify advanced glycation end products (AGEs) like CML and CEL in various PBMAs [2]. |

| Electronic Tongue (E-Tongue) | Instrumental sensory analysis to impartially assess taste profiles and compare them to conventional milk [4]. | Effectively confirmed sensory panel evaluations of taste attributes, providing an objective tool for product development [4]. |

| Turbiscan Stability Analyzer | Accelerated physical stability testing of emulsions by measuring light transmission and backscattering to predict sedimentation and creaming [1]. | Quantified the physical instability of rice milk (which had the largest particle size) over a storage period by calculating the Turbiscan Stability Index (TSI) [1]. |

| Standard Reference Material (SRM) 1549a | Certified Reference Material (Whole Milk Powder) from NIST for quality control and method validation in elemental analysis [3]. | Serves as a benchmark for analytical recovery and accuracy, though analysts should note the matrix differences with plant-based samples [3]. |

Troubleshooting Guides and FAQs

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: What are the primary reasons for the complex matrix effects encountered when analyzing plant-based milk alternatives (PBMAs) compared to dairy milk?

Plant-based milk alternatives present a uniquely complex and variable matrix for several reasons. Unlike bovine milk, which has a relatively consistent composition, PBMAs are derived from diverse sources (cereals, legumes, nuts, and seeds), each with distinct intrinsic compositions [7]. This leads to significant variations in the type and quantity of lipids, proteins, and carbohydrates [8]. Furthermore, industrial processing, such as enzymatic hydrolysis used to break down starch in oat milk, fundamentally alters the molecular structure of these components, creating new analytes and potential interferents [9]. The widespread practice of fortification adds another layer of complexity, introducing compounds that may not be native to the original plant material [10]. Finally, the natural presence of antinutrients like phytates in cereals and legumes can bind to proteins and minerals, affecting their quantification and bioavailability [7] [8].

Q2: During lipid analysis via mass spectrometry, I observe significant ion suppression in nut-based PBMAs but not in oat-based ones. What is the likely cause and how can I mitigate this?

The ion suppression you describe is likely due to the diverse and abundant lipid profiles in nut-based PBMAs, particularly triacylglycerides and their varying fatty acid chain lengths [11]. These co-eluting lipids can compete for charge during ionization. To mitigate this, implement rigorous sample preparation protocols. Solid-phase extraction (SPE) is highly effective for pre-analytical purification and concentration of target lipids while removing interfering matrix components [11]. Additionally, consider employing advanced lipidomics approaches that use high-resolution mass spectrometry to better separate and identify individual lipid species, thereby reducing spectral overlap and improving accuracy [11].

Q3: Why is the accurate quantification of protein content and quality in PBMAs particularly challenging, and what methods can address these challenges?

Quantifying protein in PBMAs is challenging due to two main factors: low overall content (with the exception of soya) and the presence of interfering non-protein nitrogen compounds [10] [8]. Traditional spectrophotometric methods like the Bradford or Lowry assay can be skewed by these interferents. More critically, the quality of protein, defined by its essential amino acid profile and digestibility, is a major differentiator from dairy milk [8]. Dairy proteins contain all essential amino acids and have a high Digestible Indispensable Amino Acid Score (DIAAS ~1.45), whereas most PBMAs have inferior DIAAS (e.g., almond milk ~0.39, oat milk ~0.59) [8]. To address this, use a combination of methods. Chromatographic techniques (LC-MS/MS) can precisely separate and quantify individual amino acids [11] [12]. For quality assessment, the protein digestibility-corrected amino acid score (PDCAAS) or the more modern DIAAS should be calculated, which requires information on amino acid composition and their digestibility [8].

Q4: High carbohydrate content, specifically starch, in cereal-based PBMAs causes issues with viscosity and filtration during sample preparation. How can this be resolved?

This is a common issue, particularly in oat milk, where starch constitutes 50-60% of the grain and gelatinizes upon heating, dramatically increasing viscosity and hindering filtration [9]. The most effective solution is enzymatic hydrolysis. Using amylase enzymes (e.g., α-amylase) during the liquefaction process breaks down starch polymers into smaller dextrins and sugars, significantly reducing viscosity and simplifying subsequent filtration and analysis steps [9]. The Box-Behnken response surface methodology has been successfully used to optimize process variables like enzyme concentration, slurry concentration, and liquefaction time to maximize yield and minimize viscosity [9].

Key Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details essential reagents and materials for sample preparation and analysis of PBMAs.

Table 1: Essential Research Reagents for PBMA Analysis

| Reagent/Material | Primary Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Alpha-Amylase | Enzymatic hydrolysis of starch to reduce viscosity and prevent gelatinization. | Critical for sample prep of cereal-based PBMAs (oat, rice). Optimization of concentration and time is required [9]. |

| Solid Phase Extraction (SPE) Cartridges | Pre-analytical purification and concentration of target analytes; removal of lipid, protein, and carbohydrate interferents. | Essential for cleaning up complex matrices prior to chromatographic analysis to mitigate ion suppression in MS [11] [12]. |

| Chloroform-Methanol Mixtures | Solvent system for exhaustive lipid extraction from complex food matrices. | Used in standard methods like Folch and Bligh & Dyer for total lipid extraction [11]. |

| Urea, Thiourea, Detergents (CHAPS) | Protein denaturation and solubilization agents. | Key components of extraction buffers for efficient protein isolation, particularly for hydrophobic proteins [11]. |

| Phytase Enzyme | Hydrolysis of phytic acid (phytate), an antinutrient that binds proteins and minerals. | Used in sample prep to improve mineral bioavailability and accuracy of protein assays by freeing bound analytes [7]. |

| Isotopically Labeled Internal Standards | Internal calibration for mass spectrometry-based quantification. | Crucial for compensating for matrix-induced ion suppression/enhancement in proteomics, lipidomics, and metabolomics [11] [12]. |

Analytical Workflows for Complex Matrices

The following diagrams outline standardized workflows to manage interferents during the analysis of PBMAs.

Sample Preparation Workflow for PBMA Analysis

Troubleshooting Common Matrix Interference Issues

Troubleshooting Guides

Homogenization Issues and Solutions

Homogenization is critical for achieving uniform particle size and product stability in plant-based milk analogues (PBMAs). The table below outlines common problems, their causes, and practical solutions.

Table 1: Common Homogenization Problems and Troubleshooting Guide

| Problem | Root Cause | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Inconsistent Particle Size [13] | Incorrect pressure settings; Worn homogenizer valves and seals [13] | Verify operating pressure matches product specifications; Inspect and replace worn valves and seals regularly [13] |

| Excessive Heat Generation [13] | High pressure and friction during processing [13] | Use a cooling jacket or heat exchanger; Slightly reduce pressure if possible; Schedule short processing intervals for heat-sensitive materials [13] |

| Cavitation Damage [13] | Vapor bubble collapse due to low inlet pressure [13] | Maintain proper inlet pressure to prevent vapor formation; Ensure feed pump delivers a steady flow [13] |

| High Energy Consumption [13] | Overpressure or inefficient pump operation [13] | Optimize pressure settings for the desired particle size; Service pumps and bearings to reduce friction losses [13] |

| Product Foaming [13] | Air trapped in the feed or improper deaeration [13] | Pre-degas the product before homogenization; Maintain proper feed tank design; Use vacuum deaeration [13] |

| Curdling in Acidic Environments (e.g., coffee) [14] | Protein-coated fat droplets lose electrical charge near pH 5, promoting aggregation [14] | Use microelectrophoresis analysis to characterize electrical properties and formulate for stability in target pH range [14] |

Thermal Treatment and Nutrient Stability

Thermal processing like High-Temperature Short-Time (HTST) pasteurization ensures microbial safety but can affect sample integrity and nutrient retention. The following table summarizes the effect of pilot-scale HTST processing on key micronutrients in a fortified almond-based beverage [15].

Table 2: Effect of HTST Processing (up to 116°C for 30s) on Micronutrients in a Fortified Almond-Based Beverage [15]

| Micronutrient | Effect of HTST Processing | Statistical Significance & Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Vitamin A (Palmitate) | No significant change | Stable under tested conditions (p > 0.05) [15] |

| Vitamin D₂ | No significant change | Stable under tested conditions (p > 0.05) [15] |

| Riboflavin (B₂) | No significant change | Stable under tested conditions (p > 0.05) [15] |

| Total Vitamin B₆ | No significant change | Stable under tested conditions (p > 0.05) [15] |

| Thiamin (B₁) | Decreased by 17.9% | Significant degradation at 116°C (p < 0.05) [15] |

| Total Vitamin B₃ | Increased by 35.2% | Significant increase (p < 0.05), potentially due to liberation from matrix [15] |

| Minerals (Mg, P, K, Ca, Zn) | No significant change | All monitored minerals were stable (p > 0.05) [15] |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. Why does my plant-based milk sample curdle or aggregate when added to hot coffee, and how can I prevent this?

This occurs due to protein aggregation when the product is exposed to a combination of heat and low pH (coffee is typically around pH 5). At this pH, protein-coated fat droplets can lose their electrical charge [14]. To prevent this, use microelectrophoresis analysis during development to characterize the electrical properties (zeta potential) of the particles. Formulate or adjust the processing conditions to ensure the particles maintain a strong charge and remain stable across the pH range of your target application [14].

2. My analytical results for the same sample type show high variability. What could be causing this?

Sample integrity in plant-based milk analysis is highly susceptible to processing-dependent variability. Key factors to investigate include [16]:

- Homogenization Efficiency: Inconsistent pressure or worn parts lead to uneven particle size distribution, directly impacting analytical reproducibility [13].

- Thermal History: Variations in time-temperature profiles during heat treatment can alter protein denaturation, nutrient retention, and the product's physicochemical structure [15].

- Ingredient Sourcing: The natural nutritional variation in plant sources (e.g., seasonality, cultivar) can introduce variability if not accounted for [16] [17]. Implementing standardized, well-documented protocols for sample preparation is crucial to minimize this variance [14].

3. What are the most effective methods to standardize the sensory and physicochemical analysis of plant-based milk alternatives?

A combination of instrumental and sensory methods is recommended [14]:

- Particle Analysis: Use Static Light Scattering (SLS) and Dynamic Light Scattering (DLS) to consistently measure particle size distribution, which influences stability and texture [14].

- Flavor Analysis: Employ Gas Chromatography (GC) coupled with Mass Spectrometry (MS) and olfactometry to identify and quantify volatile organic compounds responsible for desirable and undesirable flavors (e.g., "beany," "rancid") [14].

- Structured Sensory Evaluation: Use trained panels for descriptive analysis to quantify sensory attributes, and separate hedonic testing with a sufficient number (~60) of target consumers to assess overall acceptability. Never use the same trained panel for both descriptive and hedonic testing [14].

4. How can I improve the nutritional profile and stability of a plant-based milk formulated from a blend of ingredients?

Using blends of different plant sources (e.g., nuts, seeds, legumes) is an effective strategy to enhance the nutritional profile and functional properties [17]. Research shows that designed blends can improve the content of minerals like iron (Fe) and magnesium (Mg), as well as high-quality lipids [17]. Furthermore, optimization of unit operations like dehulling, peeling, and roasting can significantly enhance the nutritional and sensory quality by reducing anti-nutrients and off-flavors [18].

Experimental Protocols for Key Analyses

Application: Measuring particle size distribution and colloidal stability of plant-based milk emulsions. Methodology:

- Sample Preparation: Dilute the plant-based milk sample appropriately with the continuous phase (e.g., distilled water or its own serum) to avoid multiple scattering effects. A typical dilution factor is 1:100 to 1:1000, which should be determined empirically.

- Dynamic Light Scattering (DLS):

- Use a DLS instrument (also known as Photon Correlation Spectroscopy or PCS).

- Measure the fluctuation in scattered light intensity caused by Brownian motion of particles.

- Analyze the correlation function to determine the hydrodynamic diameter (Z-average) and the polydispersity index (PDI), which indicates the width of the size distribution.

- Static Light Scattering (SLS) (or Laser Diffraction):

- Use a laser diffraction particle size analyzer.

- Measure the angular variation in intensity of scattered light as a laser beam passes through the dispersed sample.

- Apply Mie theory to calculate the particle size distribution, which is reported as volume-based diameters (e.g., D10, D50, D90). Significance: This protocol is essential for optimizing homogenization and stabilization processes, as particle size directly influences product stability, texture, and mouthfeel [14].

Application: Determining the electrical charge (zeta potential) on particles in plant-based milk, which is a key indicator of colloidal stability. Methodology:

- Sample Preparation: Dilute the sample in a suitable electrolyte solution (e.g., 1mM KCl) to ensure the electrical conductivity is within the instrument's optimal range.

- Loading: Inject the diluted sample into a specialized folded capillary cell (or equivalent) with electrodes.

- Measurement:

- Apply an electric field across the cell.

- The instrument uses Laser Doppler Velocimetry to track the velocity of particles moving towards the electrode of opposite charge (electrophoretic mobility).

- The Henry equation is used to convert the measured electrophoretic mobility into the zeta potential (in millivolts, mV).

- Analysis: Measure samples at different pH values to identify the isoelectric point, where the zeta potential is zero and aggregation is most likely. Significance: This method is critical for predicting shelf-life and preventing aggregation in acidic environments like coffee. A high absolute zeta potential (typically > |30| mV) indicates good electrostatic stability [14].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

Table 3: Key Materials and Reagents for Plant-Based Milk Alternative Research

| Item | Function / Application | Example from Literature |

|---|---|---|

| Gellan Gum [15] | A gelling agent and stabilizer used to improve mouthfeel, suspend particles, and enhance the stability of the emulsion. | Used at 0.02% (w/w) in a pilot-scale almond-based beverage formulation [15]. |

| Sunflower Lecithin (De-oiled) [15] | An emulsifier that helps to create a stable oil-in-water emulsion, preventing separation of fat and water phases. | Used at 0.2% (w/w) in a pilot-scale almond-based beverage [15]. |

| Vitamin & Mineral Premix [15] | A blend of micronutrients used to fortify PBMAs to match the nutritional profile of bovine milk. | A premix containing calcium carbonate, zinc gluconate, vitamin A (retinyl palmitate), riboflavin, and vitamin D₂ (ergocalciferol) was used [15]. |

| α-Amylase from Bacillus subtilis [18] | An enzyme used in the enzymatic extraction of milk from grains (e.g., oats) to break down starch, improving yield and sweetness. | Used for enzymatic extraction of rolled oats under optimized conditions (slurry concentration 27.1% w/w; enzyme concentration 2.1% w/w) [18]. |

| Protease Enzyme [18] | An enzyme used in the enzymatic-assisted aqueous extraction technique to improve protein yield from raw materials. | Used to optimize the extraction of cottonseed milk (0.50% enzyme concentration, 30°C, pH 7) [18]. |

| Sodium Bicarbonate (NaHCO₃) [18] | A soaking agent used to reduce anti-nutritional factors and off-flavors in legumes and grains during pre-treatment. | Used for soaking sesame seeds (0.5-1 g/100 mL) and soybeans before extraction [18]. |

Workflow for Sample Preparation and Integrity Control

The following diagram outlines a standardized workflow for preparing plant-based milk analogues, integrating critical control points to manage processing-dependent variability.

This technical support guide is designed to assist researchers in overcoming common challenges in the analysis of plant-based milk alternatives (PBMAs). Effective testing is crucial for ensuring the safety and authenticity of these products, which have experienced remarkable market growth, with sales projected to reach USD 29.5 billion by 2031 [19]. The optimization of sample preparation and analytical methods is a foundational step for accurate detection of key target analytes, including biological contaminants, allergens, mycotoxins, and adulterants. This document provides targeted troubleshooting guides and detailed protocols to support your research within this framework.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) and Troubleshooting

FAQ 1: Why do my mycotoxin detection results show high variability and matrix interference when testing different types of PBMAs?

- Problem: Inconsistent results and matrix effects are common when analyzing diverse PBMA formulations.

- Root Cause: PBMAs are complex, heterogeneous mixtures of proteins, fats, and carbohydrates from various plants (cereals, nuts, legumes). This complexity causes variable matrix interference with analytical techniques like enzyme immunoassays (EIA) and chromatography [20]. For instance, nut-based and legume-based drinks can interfere differently with the same assay.

- Solution:

- Implement Dilution: A minimum 1:8 dilution of the PBMA sample is often necessary to reduce matrix interference in EIA methods [20].

- Validate for Each Matrix: Do not assume a method validated for one PBMA type (e.g., oat) will work for another (e.g., soy or almond). Conduct recovery studies for each matrix.

- Consider Alternative Cleanup: For precise quantification, use immunoaffinity columns (IAC) or QuEChERS (Quick, Easy, Cheap, Effective, Rugged, Safe) extraction for sample cleanup before liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) analysis [21] [20].

FAQ 2: How effective are common cooking processes, like microwave heating, at reducing mycotoxin levels in PBMA ingredients?

- Problem: The effect of consumer-level processing on mycotoxin stability in PBMA matrices is not well understood.

- Root Cause: Mycotoxins are generally heat-stable, but their degradation depends on the specific toxin, temperature, time, and food matrix [21].

- Solution:

- Understand Degradation Patterns: Research shows microwave cooking (e.g., 800 W for 60-90 seconds) can degrade certain mycotoxins, but the effect is highly variable. Fumonisins are more susceptible, while aflatoxins (AFs) are highly stable [21].

- Do Not Rely on Cooking for Decontamination: View cooking as a mitigation step, not a solution. The degradation is often incomplete. For example, one study found that extrusion cooking can reduce fumonisin, aflatoxin, and zearalenone levels by over 83%, but reduction of ochratoxin A and deoxynivalenol was less pronounced (30-55%) [22].

- Monitor for By-products: Document that processing might reduce parent mycotoxin levels but could create potentially toxic transformation products that require monitoring.

FAQ 3: What are the primary microbial risks in PBMAs, given they are heat-treated?

- Problem: Despite thermal processing like Ultra-High Temperature (UHT) treatment, microbial risks persist.

- Root Cause: The UHT process (138–145°C for 1-10 seconds), designed to eradicate spores, can be insufficient for highly heat-resistant endospores from thermophilic spore-forming microorganisms (e.g., Bacillus, Paenibacillus) [19]. Post-processing contamination can also occur.

- Solution:

- Target Testing: Focus on spore-forming spoilage bacteria and pathogens. Studies show that Listeria and Salmonella can grow better in PBMAs compared to bovine milk if post-processing contamination occurs [19].

- Test for Fungi: While most yeast and moulds are eliminated by pasteurization, their heat-resistant spores may persist, and airborne contamination can occur after heat treatment [19].

- Environmental Monitoring: Implement strict sanitation protocols in processing facilities to prevent post-processing contamination by pathogens like Listeria monocytogenes and Staphylococcus aureus [22].

Experimental Protocols for Key Analyses

Protocol: Multi-Mycotoxin Analysis in PBMA Ingredients Using LC-MS/MS After Microwave Processing

This protocol is adapted from a study investigating mycotoxin degradation during microwave cooking [21].

1. Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function |

|---|---|

| Soybeans, Oats, Nuts | Representative raw ingredients for PBMA production. |

| Mycotoxin Standards (AFB1, OTA, ZEA, Fumonisins, etc.) | For calibration, quantification, and quality control. |

| Acetonitrile (ACN) & Methanol | LC-MS grade solvents for extraction and mobile phase. |

| QuEChERS Extraction Kits | Contains salts (MgSO₄, NaCl) and buffers for efficient extraction and partitioning. |

| Primary Secondary Amine (PSA) | Sorbent for clean-up, removes fatty acids and sugars. |

| LC-MS/MS System | For high-sensitivity separation, detection, and quantification of multiple mycotoxins. |

2. Procedure

- Step 1: Sample Preparation. Homogenize the plant ingredients (e.g., soybeans) using a laboratory mixer. For solid ingredients, create a model burger or slurry to simulate a food matrix.

- Step 2: Fortification (for method validation). Artificially contaminate samples with a known concentration of mycotoxin standard solution to establish recovery rates.

- Step 3: Microwave Cooking. Cook 5g samples with 5mL of water in a partially open 50mL Falcon tube. Apply conditions such as 800 W for 60s ("Min") and 90s ("Max"). Measure the temperature immediately after cooking with a calibrated contact thermometer [21].

- Step 4: QuEChERS Extraction.

- Add 10 mL of water and 10 mL of acetonitrile with 2% formic acid to the cooked sample.

- Vortex vigorously for 15 minutes.

- Incubate at -20°C for 15 minutes.

- Add contents of a QuEChERS extraction tube (e.g., 4 g MgSO₄, 1 g NaCl, citrate salts). Shake for 1 minute and centrifuge at 5000 rpm for 10 minutes.

- Step 5: Clean-up.

- Transfer the supernatant to a tube containing a dispersive solid-phase extraction (d-SPE) sorbent like PSA and MgSO₄.

- Shake and centrifuge again.

- Evaporate 3 mL of the clean supernatant to dryness and reconstitute in 600 μL of a 50/50 methanol/water solution for LC-MS/MS analysis [21].

- Step 6: LC-MS/MS Analysis. Inject the sample into the UHPLC system coupled to a tandem mass spectrometer. Use a reversed-phase column (e.g., C18) and a gradient elution with water and methanol/acetonitrile, both containing mobile phase additives like formic acid or ammonium formate.

3. Troubleshooting Notes

- Low Recovery: Ensure the pH is acidic during extraction (using formic acid) to improve the recovery of a broad range of mycotoxins.

- Matrix Effects: Use stable isotopically labelled internal standards (e.g., ¹³C-OTA) for each mycotoxin to correct for signal suppression or enhancement in the mass spectrometer.

- High Background Noise: Optimize the d-SPE clean-up step; increasing the amount of PSA can help remove more co-extractives.

Protocol: Allergen and Adulterant Detection via DNA-Based Methods

This protocol outlines a general approach for detecting undeclared plant species or animal-derived ingredients that may cause allergic reactions or constitute adulteration [19] [6].

1. Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function |

|---|---|

| Proteinase K | Enzyme that degrades proteins and nucleases, facilitating DNA release. |

| CTAB Buffer | Cetyltrimethylammonium bromide buffer; lyses cells and removes polysaccharides and polyphenols. |

| DNA Purification Kits | Silica-based columns for purifying high-quality DNA from complex matrices. |

| Taq DNA Polymerase | Enzyme for the Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR). |

| Species-Specific Primers & Probes | Oligonucleotides designed to uniquely amplify DNA from a target species (e.g., soy, peanut, cow). |

| Real-time PCR System | For quantitative (qPCR) or qualitative detection of amplified DNA. |

2. Procedure

- Step 1: DNA Extraction. This is the most critical step. Use a CTAB-based protocol or a commercial kit designed for difficult plant matrices. The goal is to obtain DNA that is both intact and free of PCR inhibitors.

- Step 2: DNA Quantification and Quality Check. Measure DNA concentration and purity (A260/A280 ratio) using a spectrophotometer. Assess integrity via gel electrophoresis.

- Step 3: PCR Setup. Prepare a reaction mix containing buffer, dNTPs, Taq polymerase, and species-specific primers. For higher specificity and sensitivity, use qPCR with hydrolysis (TaqMan) probes.

- Step 4: Amplification. Run the PCR with a optimized thermal cycling profile (e.g., initial denaturation at 95°C, followed by 35-40 cycles of denaturation, annealing, and extension).

- Step 5: Analysis. For qPCR, analyze the cycle threshold (Ct) values to determine the presence and/or quantity of the target DNA. For conventional PCR, analyze the amplification products using gel electrophoresis.

3. Troubleshooting Notes

- No Amplification: Check DNA quality and the presence of inhibitors. Dilute the DNA template or re-purify it. Verify primer specificity.

- Non-Specific Amplification: Optimize the annealing temperature of the PCR cycle. Use a "hot-start" polymerase enzyme. Consider designing new, more specific primers.

- Poor Efficiency in qPCR: Re-design probes and primers. Ensure the DNA template is of high quality.

The following tables consolidate key data on target analytes and analytical performance from recent research to guide method development and evaluation.

Table 1: Common Mycotoxins in PBMA Ingredients and Analytical Challenges

| Mycotoxin | Primary Producing Fungi | Key Health Risks | Stability During Processing | Key Detection Methods |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aflatoxins (AFs) | Aspergillus spp. | Carcinogenic, hepatotoxic | Highly stable; withstands boiling/baking [21] | LC-MS/MS, HPLC-FLD, EIA |

| Ochratoxin A (OTA) | Aspergillus, Penicillium | Nephrotoxic, carcinogenic | Relatively stable; reduced by 30-55% in extrusion [22] | LC-MS/MS, EIA |

| Fumonisins (FBs) | Fusarium spp. | Carcinogenic, neurotoxic | More susceptible to heat; >83% reduction in extrusion [22] | LC-MS/MS, EIA |

| Zearalenone (ZEA) | Fusarium spp. | Estrogenic, reproductive effects | Relatively stable [21] | LC-MS/MS, EIA |

| Trichothecenes (e.g., T-2, DON) | Fusarium spp. | Immunosuppressive, emetic | Relatively stable [21] | LC-MS/MS, EIA |

Table 2: Performance of Detection Methods for Key Analytes in PBMAs

| Target Analytic | Detection Method | Limit of Detection (LOD) / Notes | Sample Preparation Needs |

|---|---|---|---|

| Multiple Mycotoxins | LC-MS/MS | LODs in low μg/kg range; gold standard for multi-analyte confirmation [21] | Requires extensive cleanup (e.g., QuEChERS, IAC) |

| Mycotoxins (AFB1, OTA, etc.) | Enzyme Immunoassay (EIA) | LODs: AFB1 ~0.4 μg/L, OTA ~0.08 μg/L post 1:8 dilution [20] | Minimal; dilution critical to reduce matrix interference |

| Allergens / Adulterants | PCR / qPCR | High specificity; detects DNA from target species (e.g., soy, peanut, cow) [19] [6] | Critical to obtain high-quality, inhibitor-free DNA |

| Pathogenic Bacteria | Culture-based & Molecular | Confirms viability and identifies species; e.g., Listeria, Salmonella [19] | Enrichment culture often required |

Visual Workflows and Pathways

Mycotoxin Analysis Workflow

Diagram Title: Mycotoxin Analysis Workflow in PBMAs

Method Selection Logic

Diagram Title: Analytical Method Selection Guide

Plant-based milk alternatives (PBMAs) represent one of the fastest-growing segments in the food industry, driven by increasing consumer demand for sustainable and health-conscious products. However, ensuring the safety and quality of these products presents unique challenges for researchers and analytical scientists. This technical support center addresses critical gaps in sample preparation methodologies, focusing specifically on two understudied areas: viral contaminants and processing-induced compounds. The complex matrices of PBMAs—derived from legumes, cereals, nuts, and seeds—require sophisticated sample preparation techniques to accurately detect and quantify these analytes. As the industry moves toward more innovative processing technologies, the need for optimized, matrix-specific preparation protocols becomes increasingly urgent. The following FAQs, troubleshooting guides, and experimental protocols provide structured guidance for addressing these methodological challenges within the broader context of optimizing PBMA testing research.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. Why is viral contaminant detection particularly challenging in PBMA matrices?

Viral detection in PBMAs remains problematic due to several matrix-specific interferences. Plant-based materials contain high levels of polysaccharides, polyphenols, and lipids that can inhibit molecular detection methods like PCR. Additionally, the efficient recovery of viral particles from high-fat and high-protein PBMA matrices is poorly characterized, leading to potential false negatives. Research indicates that "optimizing sample preparation protocols and improving DNA-based methods efficiency" represents a significant challenge in the field [23] [6]. The lack of validated concentration methods for viruses in viscous, particulate-rich PBMA samples further complicates accurate detection and quantification.

2. What processing-related compounds require specialized sample preparation approaches?

Thermal processing of PBMAs generates several compounds that necessitate specialized sample preparation. Maillard reaction products (MRPs) including α-dicarbonyl compounds, furans, and advanced glycation end products (AGEs) have been identified as significant analytes of concern [2]. Recent research found that "PBMAs contained more MRPs than UHT milk, especially α-dicarbonyl compounds," with acrylamide detected specifically in almond and oat PBMAs [2]. Sample preparation for these compounds must account for their varying chemical properties and stability, while also addressing matrix effects that differ significantly between PBMA types (soy versus oat versus almond-based products).

3. What are the key methodological gaps in current PBMA sample preparation protocols?

Three major methodological gaps persist in PBMA sample preparation:

- Lack of standardized extraction protocols for simultaneous analysis of multiple contaminant classes

- Insufficient cleanup procedures for removing matrix interferents without losing target analytes

- Limited validation of pre-analytical concentration methods for low-abundance viral contaminants and processing-induced compounds

These gaps are particularly evident in the detection of viral contaminants and processing-related compounds, where "research gaps exist in detecting viral, and processing-related contaminants" [19] [6]. The absence of reference materials and validated methods for these emerging analytes in PBMA matrices further exacerbates these challenges.

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem 1: Low Viral Recovery from High-Lipid PBMA Matrices

Symptoms: Inconsistent PCR results, low viral yields after extraction, poor reproducibility between samples.

Possible Causes:

- Lipid interference during viral concentration steps

- Non-optimal binding conditions for viral particles during concentration

- Protease or enzyme inhibition by matrix components

Solutions:

- Implement a defatting step using food-grade solvents (e.g., hexane) prior to viral concentration

- Optimize binding buffer pH and ionic strength for specific PBMA matrices

- Include appropriate internal controls to monitor extraction efficiency

- Utilize charged filtration systems that have proven effective in other complex matrices [24]

Problem 2: Inconsistent Quantification of Maillard Reaction Products

Symptoms: High variability in MRP measurements, unstable derivatives, matrix interference in chromatographic analysis.

Possible Causes:

- Incomplete extraction of MRPs from protein-rich matrices

- Degradation of labile intermediates during sample preparation

- Co-extraction of interfering compounds

Solutions:

- Optimize extraction solvent composition (e.g., water-acetonitrile mixtures with acid modifiers)

- Implement stabilization agents for reactive α-dicarbonyl compounds

- Use solid-phase extraction (SPE) with mixed-mode sorbents for improved cleanup

- Employ standard addition methods to account for matrix effects

Problem 3: Poor Detection Sensitivity for Trace-Level Contaminants

Symptoms: Inability to detect contaminants near regulatory limits, high background noise, poor signal-to-noise ratios.

Possible Causes:

- Insufficient sample concentration prior to analysis

- Matrix-induced suppression in mass spectrometric detection

- Inefficient separation of target analytes from interferents

Solutions:

- Implement large-volume injection techniques for liquid chromatography

- Optimize sample concentration factors based on PBMA matrix type

- Utilize matrix-matched calibration standards to correct for suppression effects

- Employ innovative concentration techniques such as immunoaffinity extraction

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Multi-Class Extraction of Processing-Induced Compounds from PBMA Matrices

Principle: This method enables simultaneous extraction and cleanup of MRPs, including α-dicarbonyl compounds, furans, and AGEs, from various PBMA matrices for subsequent LC-MS/MS analysis.

Reagents and Materials:

- PBMA samples (soy, oat, almond-based)

- Deuterated internal standards (d₄-3-deoxyglucosone, d₃-acrylamide, ¹³C₅-N-Ɛ-carboxymethyllysine)

- Extraction solvent: Water:acetonitrile:formic acid (80:19:1, v/v/v)

- Solid-phase extraction cartridges (Mixed-mode cation exchange, 60 mg/3 mL)

- Derivatization reagent: 20 mM o-phenylenediamine in water

Procedure:

- Sample Preparation: Transfer 2 mL of homogenized PBMA sample to a 15 mL centrifuge tube.

- Internal Standard Addition: Add 50 µL of deuterated internal standard mixture.

- Protein Precipitation: Add 4 mL of cold acetonitrile, vortex for 1 minute, and centrifuge at 4,000 × g for 10 minutes.

- Extraction: Transfer supernatant to a new tube and evaporate under nitrogen at 40°C to approximately 1 mL.

- Derivatization: Add 500 µL of o-phenylenediamine solution, incubate at 25°C for 30 minutes in the dark.

- Cleanup: Load onto pre-conditioned SPE cartridge, wash with 2 mL water, elute with 2 mL methanol:ammonium hydroxide (98:2, v/v).

- Reconstitution: Evaporate eluent to dryness and reconstitute in 200 µL mobile phase A for LC-MS/MS analysis.

Critical Parameters:

- Maintain sample temperature below 25°C during extraction to prevent artifactual formation of MRPs

- Control derivatization time precisely to ensure complete reaction without degradation

- Use amber vials to protect light-sensitive analytes throughout the procedure

Protocol 2: Virus Concentration and Nucleic Acid Extraction from PBMA Samples

Principle: This protocol describes an efficient method for concentrating viral particles and extracting viral nucleic acids from complex PBMA matrices for downstream molecular detection.

Reagents and Materials:

- PBMA samples (soy, oat, almond-based)

- PEG 8000 precipitation solution (10% PEG, 0.5 M NaCl)

- Lysis buffer (Guarnidinium thiocyanate-based)

- Nucleic acid binding beads

- Proteinase K solution (20 mg/mL)

- Inhibitor removal columns

Procedure:

- Sample Clarification: Centrifuge 50 mL PBMA at 10,000 × g for 20 minutes at 4°C.

- Virus Concentration: Mix supernatant with ¼ volume PEG solution, incubate overnight at 4°C, pellet at 12,000 × g for 60 minutes.

- Virus Resuspension: Resuspend pellet in 500 µL PBS with 0.1% Tween 80.

- Nucleic Acid Extraction: Add proteinase K to 1 mg/mL, incubate at 56°C for 30 minutes.

- Inhibitor Removal: Process through inhibitor removal column according to manufacturer's instructions.

- Nucleic Acid Purification: Bind nucleic acids to magnetic beads, wash twice with 70% ethanol, elute in 50 µL nuclease-free water.

Critical Parameters:

- Optimize PEG concentration based on PBMA matrix composition

- Include process controls to monitor extraction efficiency

- Use inhibitor removal methods tailored to plant-based matrices

- Validate method with appropriate viral surrogates spiked into PBMA samples

Data Presentation

Table 1: Comparison of Analytical Techniques for Detecting Contaminants in PBMAs

| Analytical Technique | Target Analytes | Limit of Detection | Sample Preparation Requirements | Matrix Effects |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| LC-MS/MS | MRPs, AGEs, acrylamide | 0.1-5 µg/kg | Extensive cleanup, derivatization | High (requires matrix-matched calibration) |

| PCR-based methods | Viral contaminants | 10-100 copies/µL | Concentration, inhibitor removal | Severe (plant compounds inhibit enzymes) |

| Immunoassays | Allergens, mycotoxins | 0.1-1 mg/kg | Minimal dilution | Moderate (cross-reactivity possible) |

| Biosensors | Various contaminants | Varies by target | Minimal to moderate | Variable (requires characterization) |

| Next-generation sequencing | Viral contaminants | Dependent on sequencing depth | Nucleic acid extraction, library prep | Moderate (inhibition during amplification) |

Table 2: Concentrations of Processing-Related Compounds in Commercial PBMAs

| PBMA Type | Furosine (mg/100 g protein) | 3-Deoxyglucosone (µg/L) | Acrylamide (µg/kg) | N-Ɛ-(carboxymethyl)lysine (mg/100 g protein) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Soy-based | 15.8 ± 2.3 | 125.6 ± 15.3 | ND | 3.2 ± 0.4 |

| Oat-based | 22.4 ± 3.1 | 198.7 ± 22.5 | 12.5 ± 1.8 | 4.8 ± 0.6 |

| Almond-based | 8.9 ± 1.2 | 85.4 ± 9.7 | 8.3 ± 1.1 | 2.1 ± 0.3 |

| Rice-based | 18.6 ± 2.5 | 156.2 ± 17.8 | ND | 3.9 ± 0.5 |

| Coconut-based | 5.2 ± 0.8 | 45.3 ± 5.2 | ND | 1.4 ± 0.2 |

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for PBMA Sample Preparation

| Reagent/ Material | Function | Application Examples | Considerations for PBMA Matrices |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mixed-mode SPE sorbents | Simultaneous removal of polar and non-polar interferents | Cleanup for MRP analysis | Requires optimization for different PBMA types |

| Immunoaffinity columns | Selective extraction of target analytes | Mycotoxin, allergen detection | Limited availability for emerging contaminants |

| Molecularly imprinted polymers | Synthetic antibody mimics | Selective concentration of processing markers | Custom synthesis often required |

| Inhibitor removal kits | Elimination of PCR interferents | Viral detection in plant matrices | Efficiency varies with PBMA composition |

| Charged filtration membranes | Virus concentration | Adventitious virus detection | Adaptation from biopharmaceutical applications [24] |

| Derivatization reagents | Enhancement of detection sensitivity | α-dicarbonyl compound analysis | Must not form artifacts with matrix components |

Workflow Diagrams

Addressing the research gaps in PBMA sample preparation requires a multidisciplinary approach that leverages advances in analytical chemistry, molecular biology, and food science. The methodologies presented in this technical support center provide a foundation for developing robust, reproducible sample preparation protocols specifically optimized for the unique challenges posed by PBMA matrices. As the PBMA market continues to expand, the development and validation of these methods will be crucial for ensuring product safety, quality, and regulatory compliance. Future research should focus on establishing standardized reference materials, validating multi-analyte extraction procedures, and developing innovative concentration techniques that can overcome the current limitations in sensitivity and reproducibility. By addressing these critical gaps, researchers will contribute significantly to the continued growth and safety assurance of plant-based milk alternatives.

Advanced Sample Preparation Techniques: From Conventional Extraction to Emerging Methodologies

The accurate analysis of plant-based milk alternatives (PBMAs) presents unique challenges due to their complex and variable matrices, which include proteins, carbohydrates, fats, and a diverse range of phytochemicals. Effective sample preparation is a critical first step to ensure reliable, reproducible, and meaningful analytical results. This guide details established and emerging protocols for the extraction and cleanup of analytes from PBMAs, focusing on the core principles of solvent selection, pH adjustment, and partitioning optimization. These protocols are designed to help researchers navigate the complexities of PBMA matrices—from nut and grain-based beverages to newer ingredients like jackfruit seed and tamarind seed milks—to achieve optimal recovery of target compounds whether they are volatiles, lipids, vitamins, or phytochemicals.

Troubleshooting Guides

Solvent Selection and Performance

Problem: Incomplete or Biased Metabolite Recovery A common issue in untargeted analysis is the failure to capture a broad spectrum of metabolites, leading to a biased snapshot of the sample's composition.

- Cause & Solution: The choice of extraction solvent is the primary factor influencing metabolite coverage. Different solvents have varying affinities for different classes of metabolites.

- Investigation: A study systematically comparing four common single-phase extraction solvents—100% acetonitrile, 100% methanol, 50:50 acetonitrile:methanol, and 50:50 methyl tert-butyl ether (MTBE):methanol—found that each solvent covered a distinct area of the milk metabolome. Their coverage overlapped significantly only for previously annotated compounds [25].

- Recommendation: Solvent systems containing methanol generally provided better metabolite recovery. If the research goal is a comprehensive, untargeted profile, the choice of solvent is crucial. For targeted analysis of known compounds, solvent choice may be less critical [25].

Problem: Poor Chromatographic Performance and Ion Suppression Peak tailing, shifting retention times, and reduced sensitivity can often be traced back to inadequate sample cleanup.

- Cause & Solution: The high lipid and protein content in PBMAs can foul chromatography columns and suppress ionization during mass spectrometric analysis.

- Investigation: A standard protocol for analyzing metabolites from cow's milk involves a defatting step via centrifugation (e.g., 11,627 rcf for 10 min at 4°C) prior to solvent extraction. The subsequent extraction with an organic solvent (e.g., 800 µL solvent added to 200 µL of defatted sample) simultaneously precipitates proteins, which are then removed by a second centrifugation step [25]. This two-step cleanup—defatting and protein precipitation—is essential for obtaining a clean extract.

- Recommendation: Consistently include defatting and protein precipitation steps in your protocol. The specific centrifugal force and solvent-to-sample ratio may require optimization for different PBMA matrices.

Extraction Technique Optimization

Problem: Low Recovery of Specific Vitamin Analytes The quantification of fat-soluble vitamins like Vitamin D3 in PBMAs is difficult due to low natural abundance and matrix interference.

- Cause & Solution: Traditional liquid-liquid extraction (LLE) can be inefficient and require large volumes of toxic solvents.

- Investigation: A Dispersive Liquid-Liquid Micro-Extraction (DLLME) technique was optimized for Vitamin D3 in dairy milk. The optimal protocol used 2 mL of acetonitrile (as disperser and for protein precipitation) and 80 µL of carbon tetrachloride (as extraction solvent) per 1 mL of milk. This formed a cloudy solution, and the extracted analytes were sedimented by centrifugation [26].

- Recommendation: For the extraction of vitamins and other low-abundance compounds, consider modern micro-extraction techniques like DLLME. They offer high recovery rates (86.6–113.3% in the cited study), use minimal solvent, and are environmentally friendly [26].

Problem: Inconsistent Volatile Compound Profiling Flavor analysis is critical for consumer acceptance, but headspace sampling can be inconsistent.

- Cause & Solution: The Headspace-Solid Phase Microextraction (HS-SPME) process is sensitive to several parameters. Suboptimal settings lead to poor sensitivity and non-reproducible results.

- Investigation: An optimized HS-SPME-GC-MS method for nut-based milks determined that the following parameters yielded the best extraction of a wide range of volatile compounds (aldehydes, ketones, alcohols) [27]:

- Fiber Coating: DVB/CAR/PDMS

- Sample Volume: 2 mL in a 15-mL vial

- Extraction Temperature: 60 °C

- Extraction Time: 40 min

- Stirring Speed: 700 rpm

- Salt Addition: None required for the matrices tested

- Recommendation: Use this optimized protocol as a starting point for profiling volatiles in PBMAs. The "one-factor-at-a-time" approach used in the investigation is a reliable method for re-optimizing parameters if a new PBMA matrix is being studied.

- Investigation: An optimized HS-SPME-GC-MS method for nut-based milks determined that the following parameters yielded the best extraction of a wide range of volatile compounds (aldehydes, ketones, alcohols) [27]:

Instrumentation and Chromatography

Problem: Peak Tailing or Shouldering This issue directly impacts the quality of separation and quantification.

- Cause & Solution: A very common cause is a void volume or mixing chamber caused by poorly installed fittings or improperly cut tubing at the column head [28].

- Action: Check all connections before the column. Ensure the tubing is cut cleanly to a planar surface and that fittings from different manufacturers are not mixed, as this can prevent a proper seal.

Problem: Shifting Retention Times Changes in retention time from run to run indicate an instability in the chromatographic system.

- Cause & Solution: For isocratic runs, a decreasing retention time often points to a fault in the aqueous pump (Pump A), while an increasing retention time suggests an issue with the organic pump (Pump B) [28].

- Action: Purge the suspected pump and attempt to clean the check valves. Check for leaks and consider replacing consumables. Note that a run-to-run retention time variation of ±0.02-0.05 min is considered normal [28].

Problem: Jagged or Noisy Peaks This can make integration inaccurate and non-repeatable.

- Cause & Solution: An insufficient data acquisition rate is a likely culprit. The detector is not collecting enough data points to define the peak smoothly [28].

- Action: Increase the detector's data acquisition rate. A good rule of thumb is to strive for at least 10-20 data points across a peak to ensure smooth, symmetric Gaussian peak shapes and reproducible results [28].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the most critical factor in solvent selection for untargeted metabolomics of PBMAs? The extraction solvent is the most critical factor. No single solvent can capture the entire metabolome. Mixtures like 50:50 acetonitrile:methanol or 50:50 MTBE:methanol are often used, with methanol-containing solvents generally providing better recovery. The choice should be guided by the chemical space you wish to cover [25].

Q2: How does pH adjustment factor into sample preparation? pH adjustment is crucial for several reasons. It can:

- Stabilize Analytes: Prevent degradation of pH-sensitive compounds.

- Control Protein-Flavor Interactions: In dairy protein solutions, pH influences the binding of flavor compounds. A higher pH can strengthen interactions, reducing the headspace concentration of volatiles [29].

- Enable Cleanup: It is a fundamental part of techniques like the "pH-shift" for protein precipitation or the differential pH method used in milk freshness biosensing [30].

Q3: My research involves flavor-protein interactions. How can I predict the behavior of a new flavor compound? A predictive model for dairy proteins shows that flavor retention is primarily governed by the flavor compound's hydrophobicity, measured by its octanol-water partition coefficient (log P). A higher log P predicts stronger retention by proteins. For most compounds (esters, alcohols, ketones), non-specific hydrophobic interactions dominate. However, aldehydes exhibit specific chemical interactions with proteins (e.g., Schiff base formation with lysine), leading to even stronger retention [29].

Q4: What are the key parameters to optimize in a HS-SPME method for PBMA volatiles? The key parameters, in order of importance, are: fiber coating, extraction temperature and time, sample volume, and stirring speed. For nut-based milks, a DVB/CAR/PDMS fiber at 60°C for 40 minutes with a 2 mL sample volume and 700 rpm stirring has been shown to be effective [27].

Q5: Are there any green analytical methods emerging for PBMA quality control? Yes, there is a strong trend towards green analytical methods. This includes using solvent-free extraction techniques (like HS-SPME), replacing synthetic chemical dyes with natural pH indicators (e.g., Ruellia simplex flower extract) for freshness monitoring, and developing portable biosensors and sustainable sample preparation techniques [6] [30].

Experimental Protocols & Data Presentation

Standardized Metabolite Extraction for Liquid Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (LC-MS)

This protocol, adapted from a cow's milk metabolomics study, is a robust starting point for untargeted analysis of PBMAs [25].

- Defatting: Centrifuge the PBMA sample (e.g., 11,627 rcf for 10 min at 4°C). Carefully collect the supernatant (skimmed milk).

- Protein Precipitation/Solvent Extraction:

- Aliquot 200 µL of the skimmed PBMA into a microcentrifuge tube.

- Add 800 µL of pre-chilled (4°C) extraction solvent (e.g., 100% MeOH, 100% MeCN, or a 50:50 mixture of both).

- Vortex the mixture vigorously for 1-2 minutes.

- Centrifuge the sample (e.g., 11,337 rcf for 10 min) to pellet the precipitated proteins and other insoluble material.

- Collection: Transfer 100 µL of the clear supernatant to an LC-MS vial for analysis.

- Controls: Prepare process blanks for each solvent using LC-MS grade water in place of the sample.

HS-SPME-GC-MS for Volatile Profiling in Nut-Based Milks

This detailed protocol is optimized for the extraction of volatile compounds from nut-based milk alternatives [27].

- Materials: DVB/CAR/PDMS SPME fiber, 15-mL glass vials, magnetic stirrer.

- Procedure:

- Place 2 mL of the PBMA sample into a 15-mL glass vial.

- Place the vial on a heated stir plate and maintain a temperature of 60°C.

- Introduce the SPME fiber into the vial headspace, ensuring the sample is being stirred at 700 rpm.

- Extract for 40 minutes.

- Retract the fiber and immediately inject it into the GC-MS injection port for thermal desorption (typically 5-10 minutes at 250°C, depending on the analyte).

Quantitative Data: Solvent and Cleanup Method Comparison

Table 1: Comparison of Single-Phase Extraction Solvents for Untargeted Metabolomics

| Extraction Solvent | Key Characteristics | Recommended Use |

|---|---|---|

| 100% Acetonitrile | Strong protein precipitant, less comprehensive metabolite recovery. | Targeted analysis where protein removal is the highest priority. |

| 100% Methanol | Good overall recovery, denatures proteins effectively. | General purpose untargeted profiling; a good starting point. |

| 50:50 Acetonitrile:Methanol | Combines strengths of both solvents, can offer a broader metabolite coverage. | Comprehensive untargeted metabolomics where a wide polarity range is of interest. |

| 50:50 MTBE:Methanol | Good for lipid-soluble compounds, single-phase extraction. | Research focused on lipids and lipophilic metabolites. |

Table 2: Overview of Sample Cleanup and Extraction Techniques

| Technique | Principle | Application in PBMAs | Key Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Centrifugation | Physical separation based on density differential. | Defatting; post-precipitation pellet removal. | [25] [31] |

| Protein Precipitation | Use of organic solvent to denature and isolate proteins. | Clarification of samples for LC-MS; preventing column fouling. | [25] [26] |

| Dispersive Liquid-Liquid Microextraction (DLLME) | High-efficiency extraction using minimal solvent volumes. | Pre-concentration of trace analytes like vitamins. | [26] |

| Headspace-SPME (HS-SPME) | Equilibrium partitioning of volatiles to a fiber coating. | Solvent-free extraction of flavor and aroma compounds for GC-MS. | [27] |

Workflow Visualization

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents and Materials for PBMA Analysis

| Item | Function / Application | Technical Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Methanol (MeOH) & Acetonitrile (MeCN) | Primary solvents for protein precipitation and metabolite extraction. | LC-MS grade purity is recommended. Mixtures (e.g., 50:50) can broaden metabolite coverage [25]. |

| Methyl tert-butyl ether (MTBE) | Solvent for lipid-oriented, single-phase extraction. | Used in mixtures with methanol (e.g., 50:50 MTBE:MeOH) [25]. |

| DVB/CAR/PDMS SPME Fiber | Adsorptive coating for extracting volatile compounds. | The optimized fiber for HS-SPME-GC-MS analysis of volatiles in nut-based milks [27]. |

| Carbon Tetrachloride | Extraction solvent in DLLME. | Used in small volumes (e.g., 80 µL) for pre-concentrating Vitamin D3 [26]. (Note: Handle with care due to toxicity). |

| Hydrophilic Interaction Liquid Chromatography (HILIC) Column | Stationary phase for LC-MS separation. | Provides good retention and separation for a wide range of polar metabolites, often superior to reverse-phase C18 in untargeted studies [25]. |

| Natural pH Indicators (e.g., Ruellia simplex extract) | Non-toxic, biodegradable sensor for freshness/milk quality. | Contains anthocyanins that change color with pH, offering a green alternative to synthetic dyes for quality screening [30]. |

Core Principles and Comparison

This section addresses fundamental questions about the core principles and key differences in sample preparation for LC-MS/MS and GC-MS, two foundational techniques in the analysis of plant-based milk alternatives (PBMAs).

FAQs

1. What is the fundamental objective of sample preparation for chromatography?

The primary goal is to prepare a sample that is compatible with the chromatographic system, free of interferents, and concentrated enough for reliable detection. Effective preparation protects the instrumentation, improves data quality, and is essential for isolating target analytes from complex matrices like plant-based milks, which contain proteins, fats, and carbohydrates [32].

2. What are the most critical differences in preparing a sample for GC-MS versus LC-MS/MS?

The key differences arise from the physical state of the mobile phase and the nature of the analytes each technique can handle. The table below summarizes the major distinctions.

Table: Key Differences in Sample Preparation for GC-MS and LC-MS/MS

| Preparation Factor | GC-MS | LC-MS/MS |

|---|---|---|

| Sample Volatility | Must be volatile; often requires derivatization to increase volatility and thermal stability [33]. | No volatility requirement; suitable for polar, ionic, thermally unstable, and large molecules (e.g., peptides, proteins) [34]. |

| Typical Sample Volume | Higher (e.g., 1-3 mL) due to generally lower sensitivity [33]. | Lower (e.g., 50-200 µL) due to high sensitivity [33]. |

| Solid-Phase Extraction (SPE) | Requires larger sorbent beds and solvent volumes to handle larger sample volumes [33]. | Smaller sorbent beds are often sufficient. |

| Reconstitution Solvent | 100% organic solvent (e.g., ethyl acetate, acetonitrile) [33]. | Solvent often matches the initial LC mobile phase conditions (e.g., a high-aqueous mix) [33]. |

| Ideal Analytes | Small, volatile, and semi-volatile organic compounds. | Non-volatile, polar, ionic, and large molecules [34]. |

Sample Preparation Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the general decision-making workflow for selecting and executing a sample preparation method for PBMA analysis.

Research Reagent Solutions

This table details essential materials and reagents used in sample preparation for chromatographic analysis of PBMAs.

Table: Essential Reagents and Materials for PBMA Sample Preparation

| Reagent/Material | Function | Application Examples |

|---|---|---|

| C-18 (Octadecyl) SPE Sorbents | Silica-based stationary phase for reversed-phase extraction; retains non-polar analytes from aqueous samples [34]. | Extracting pesticides, lipids, and non-polar contaminants from PBMA matrices [34]. |

| Polymer-based SPE Sorbents | Alternative to silica; more stable across a wide pH range, useful for acidic samples [34]. | Extraction of acidic compounds from PBMAs. |

| Methyl-tert-butyl-ether (MTBE) | Organic solvent used in liquid-liquid extraction (LLE) to partition analytes from aqueous samples [34]. | Extraction of compounds like hormones from PBMAs [34]. |

| Methanol, Acetonitrile | High-purity organic solvents used for protein precipitation, mobile phases, and sample reconstitution [34]. | Precipitating proteins from PBMAs; HPLC mobile phase component [34] [32]. |

| Ammonium Acetate, Formic Acid | Buffers and mobile phase additives to control pH and improve ionization efficiency in MS [34]. | Reconstitution solvent for LC-MS/MS analysis of various analytes [34]. |

| Derivatization Reagents | Chemical agents (e.g., MSTFA) that modify analytes to increase volatility and stability for GC-MS [33]. | Analyzing non-volatile compounds like certain sugars or organic acids in PBMAs by GC-MS. |

| Hydrophilic/Lipophilic Balanced (HLB) Sorbents | SPE sorbents designed to capture a broad spectrum of analytes, from polar to non-polar. | Broad-spectrum extraction of multiple contaminant classes from complex PBMA matrices. |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Solid-Phase Extraction (SPE) for LC-MS/MS Analysis of Contaminants

This protocol is adapted for the clean-up and concentration of target analytes like pesticides or mycotoxins from a PBMA sample prior to LC-MS/MS.

- Conditioning: Activate a reversed-phase C-18 SPE cartridge by passing 3-5 mL of methanol through it. Equilibrate the cartridge with 3-5 mL of water or a buffer compatible with your sample. Do not let the sorbent bed run dry [34] [32].

- Sample Loading: Dilute the homogenized PBMA sample appropriately with water to reduce solvent strength. Load the entire sample volume (e.g., 1-10 mL, depending on the method) onto the cartridge at a controlled, slow flow rate (e.g., 1-2 mL/min) to ensure optimal analyte binding [34].

- Washing: Remove weakly retained matrix interferents by passing 2-3 mL of a wash solution. This is typically a mild aqueous buffer (e.g., 5% methanol in water) that does not elute the target analytes [34] [32].

- Elution: Elute the purified target analytes into a clean collection tube using 1-2 mL of a strong organic solvent (e.g., pure methanol or acetonitrile). Ensure the elution solvent is compatible with your subsequent LC-MS/MS analysis [34].

- Reconstitution: Evaporate the eluent to complete dryness under a gentle stream of nitrogen or using a centrifugal evaporator. Reconstitute the dry residue in 100-200 µL of the initial LC mobile phase conditions (e.g., 90:10 water/methanol with 0.1% formic acid). Vortex thoroughly and transfer to an LC vial for analysis [34] [33].

Protocol 2: Protein Precipitation for LC-MS/MS Proteomic Analysis

This method is used to isolate proteins from complex PBMA matrices like soy or pea milk for downstream proteomic characterization.

- Precipitation: Add a volume of ice-cold organic solvent (e.g., acetone or methanol) to the PBMA sample. A typical ratio is 4 volumes of solvent to 1 volume of sample. Vortex vigorously for 1-2 minutes [34].

- Incubation: Incubate the mixture at -20°C for at least 1 hour (or overnight for higher efficiency) to ensure complete protein precipitation.

- Pelletion: Centrifuge the sample at high speed (e.g., 10,000 - 15,000 x g) for 10 minutes. The proteins will form a tight pellet at the bottom of the tube.

- Washing and Reconstitution: Carefully decant the supernatant. Wash the protein pellet once with the same cold organic solvent to remove residual salts and non-protein contaminants. Allow the pellet to air-dry briefly to evaporate residual solvent. Redissolve the protein pellet in a suitable buffer (e.g., mass-spectrometry-compatible digestion buffer) for further processing or analysis [34].

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Issues

FAQs

1. My chromatograms show high background noise. What could be the cause and how can I fix it?

High background noise severely compromises detection and quantification limits. The most common cause is the use of impure solvents, water, or buffers to prepare the mobile phase [34].

- Solution: Always use the highest purity (e.g., LC-MS grade) water, solvents, and additives for preparing both your mobile phases and your samples. Ensure all glassware and consumables are meticulously clean [34].

2. I am seeing poor recovery of my target analytes during SPE. What should I check?

Poor recovery indicates the analyte is not effectively binding to or eluting from the sorbent.

- Solution: Verify the chemistry of your SPE sorbent is appropriate for your analyte's polarity (e.g., C-18 for non-polar, HILIC for polar). Ensure the cartridge is properly conditioned and never allowed to dry before sample loading. Optimize the wash and elution solvent compositions and volumes; the wash should be strong enough to remove impurities but not your analyte, and the elution solvent must be strong enough to completely desorb the analyte [34] [32].

3. My plant-based milk sample consistently clogs the chromatography column. How can I prevent this?

Column clogging is often caused by insufficient removal of particulates or precipitated macromolecules from the sample matrix [32].

- Solution: After extraction, always perform a filtration step using a compatible filter (e.g., 0.22 µm or 0.45 µm PVDF or nylon membrane filter) before injecting the sample into the chromatograph. For protein-rich PBMAs, protein precipitation or enzymatic digestion can help reduce the load of clogging agents [32].

4. When I add my plant-based milk to a hot beverage for a stability test, it curdles. How can the sample prep or analysis help understand this?

This instability is related to the loss of electrical charge on colloidal particles (proteins, fat droplets) near the pH of coffee (~pH 5), causing them to aggregate [14].

- Solution: You can use microelectrophoresis analysis (measuring zeta potential) during R&D to characterize the electrical properties of your PBMA particles. Formulations where particles maintain a high charge (positive or negative) around pH 5 are less likely to aggregate in coffee. This instrumental method helps screen formulations for stability without relying solely on time-consuming sensory tests [14].

The rapid growth of the plant-based milk alternative (PBMA) market necessitates robust safety and authentication measures to ensure product integrity and consumer trust [6]. DNA-based methods, particularly PCR, are the gold standard for detecting contaminants, allergens, and adulterants in these complex matrices [23]. However, the accuracy of these molecular diagnostics is critically dependent on the first upstream step: nucleic acid isolation [35] [36]. Plant-based ingredients like nuts, grains, and legumes contain high levels of polysaccharides, polyphenols, and other secondary metabolites that co-precipitate with nucleic acids and inhibit downstream enzymatic reactions [36] [37]. Efficiently extracting high-quality DNA from PBMAs is therefore a foundational challenge that must be overcome for reliable pathogen detection, GMO testing, and species authentication in food safety laboratories.

Troubleshooting Guides: Overcoming Common Nucleic Acid Isolation Challenges

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: Why is extracting DNA from plant-based milks particularly challenging compared to other matrices? PBMA matrices are complex due to their plant origins, which contain rigid cell walls, high levels of polysaccharides, polyphenols, and other secondary metabolites that act as potent PCR inhibitors. Additionally, processing treatments can fragment DNA and alter cell wall structures, making lysis more difficult [36] [37]. Unlike animal tissues, plant cells require more rigorous disruption methods to break down cellulose and lignin walls before nucleic acids can be released.

Q2: My DNA yields from oat milk are consistently low. What optimization strategies should I consider? Low yields often indicate incomplete cell disruption or inefficient binding. First, ensure thorough mechanical homogenization using bead beating or grinding in liquid nitrogen. Second, optimize your lysis buffer composition by incorporating polyvinylpyrrolidone (PVP) to bind polyphenols and β-mercaptoethanol to neutralize oxidizing compounds [36] [37]. Finally, for silica-based methods, verify that the binding buffer pH is optimized—studies show lower pH (around 4.1) significantly improves DNA binding efficiency to silica surfaces by reducing electrostatic repulsion [38].

Q3: I obtain high DNA concentrations but poor amplification in downstream PCR. What contaminants are likely responsible? This discrepancy suggests carryover of PCR inhibitors such as polysaccharides, polyphenols, or lipids from the PBMA matrix. Polysaccharides often create viscous solutions and reduce amplification efficiency. To address this, implement additional wash steps with ethanol-based buffers, use silica columns specifically designed for plant matrices, or dilute the DNA template in subsequent PCR reactions. Assessing purity via A260/A230 and A260/A280 ratios can help identify specific contaminants [37].

Q4: Are automated extraction systems suitable for high-throughput PBMA testing? Yes, automated magnetic bead-based systems provide excellent solutions for high-throughput laboratories. They offer superior consistency, reduced cross-contamination risk, and faster processing times. When developing automated workflows for challenging samples, factors such as bead mixing mechanics and elution conditions require optimization. "Tip-based" mixing, where the binding mix is aspirated and dispensed repeatedly, has been shown to achieve ~85% DNA binding within 1 minute compared to only ~61% with conventional orbital shaking [39] [38].

Troubleshooting Common DNA Extraction Problems

Table 1: Common Problems and Evidence-Based Solutions in PBMA Nucleic Acid Isolation