Optimizing DNA Extraction for Enhanced Allergen Detection in Processed Foods: A Guide for Researchers and Developers

This article provides a comprehensive resource for researchers and drug development professionals focused on overcoming the significant challenge of DNA degradation and the presence of PCR inhibitors during the extraction...

Optimizing DNA Extraction for Enhanced Allergen Detection in Processed Foods: A Guide for Researchers and Developers

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive resource for researchers and drug development professionals focused on overcoming the significant challenge of DNA degradation and the presence of PCR inhibitors during the extraction of genetic material from processed foods for allergen detection. It explores the foundational impact of food processing on DNA integrity, details current and emerging methodological approaches for efficient DNA recovery, outlines targeted optimization and troubleshooting strategies for complex matrices, and discusses the critical role of validation and comparative analysis in ensuring method reliability. By synthesizing recent scientific advances, this review aims to guide the development of robust, sensitive, and accurate DNA-based assays, ultimately contributing to improved food safety and the protection of allergic consumers.

The DNA Extraction Challenge: How Food Processing Impacts Allergen Detectability

The Growing Public Health Concern of Food Allergies and Need for Accurate Detection

FAQs: Troubleshooting DNA-Based Allergen Detection

Q1: Why is my PCR detection failing for highly processed foods like baked goods? DNA degradation during high-temperature processing is a primary cause. As processing intensity increases, genomic DNA breaks down, making amplification of long DNA fragments difficult. For reliable detection in processed foods, target short, specific allergen gene fragments of approximately 200-300 base pairs [1]. Using shorter amplicons significantly improves the success rate for samples exposed to high heat.

Q2: How does food processing impact my choice between protein-based and DNA-based detection methods? DNA-based PCR methods are often more reliable for processed foods because DNA is more stable than proteins under harsh conditions like high heat. Protein structures can be damaged, altering their epitopes and making them undetectable by immunological methods like ELISA. However, the extraction of intact DNA must also be optimized for the specific food matrix [2].

Q3: What are the critical factors for optimizing DNA extraction from complex, challenging matrices? The key is the extraction buffer composition. Factors such as buffer pH, high salt concentration (e.g., 1 M NaCl), and the addition of additives like fish gelatine (to prevent non-specific binding) and Polyvinylpyrrolidone (PVP, to bind and remove polyphenols) are crucial for efficient DNA recovery from complex foods like chocolate or baked biscuits [3]. A 1:10 sample-to-buffer ratio is a common starting point [3].

Q4: My allergen recovery is low from chocolate-based matrices. How can I improve it? Chocolate is a notoriously challenging matrix due to interfering compounds like polyphenols and high fat content. To optimize recovery, use an extraction buffer containing additives such as 1% PVP to bind polyphenols and 10% fish gelatine. Even with optimized buffers, recovery from chocolate matrices may be lower than from other foods, so method validation is essential [3].

Experimental Protocol: DNA Extraction and PCR Detection for Processed Foods

This protocol is adapted from published research for detecting wheat and maize allergens in baked goods [1].

1. Sample Preparation and DNA Extraction (CTAB-based method)

- Sample Homogenization: Grind 100 mg of the processed food sample (e.g., baked crispbread) to a flour-like consistency using an electric grinder [1].

- Cell Lysis: Incubate the sample with CTAB buffer and proteinase K at 65°C [1].

- RNA Removal: Treat the lysate with RNase A [1].

- Purification: Perform chloroform extraction to separate proteins and other contaminants from the DNA [1].

- DNA Precipitation: Precipitate DNA using isopropanol, wash the pellet with 70% ethanol, air-dry, and finally re-suspend in 100 μL sterile deionized water [1].

- Quality Control: Assess DNA concentration and purity using a UV-Vis spectrophotometer (e.g., NanoDrop). Check DNA integrity via 1% agarose gel electrophoresis [1].

2. PCR Amplification of Allergen Genes

- Primer Design: Design primers to target short, specific fragments (~200-300 bp) of the allergen genes of interest. For example:

- Wheat: High-molecular-weight glutenin subunit (HMW-GS) and low-molecular-weight glutenin subunit (LMW-GS) genes.

- Maize: Zea m 14, Zea m 8, and zein genes [1].

- PCR Setup: Use standard PCR reagents and a thermal cycler. The cycling conditions will depend on the primer design and polymerase used.

- Analysis: Analyze PCR products using agarose gel electrophoresis to confirm successful amplification of the target fragments [1].

Data Presentation: Impact of Processing on DNA Detection

Table 1: Detectability of Allergen Genes in Wheat and Maize After Baking [1]

| Allergen Source | Target Gene | Baking Temperature | Maximum Detectable Baking Time |

|---|---|---|---|

| Wheat | HMW-GS / LMW-GS | 220°C | 60 minutes |

| Maize | Zea m 14, Zea m 8, Zein | 220°C | 40 minutes |

Table 2: Optimized Extraction Buffer Compositions for Challenging Food Matrices [3]

| Buffer Component | Function | Example Composition 1 | Example Composition 2 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Buffer Base | pH control, protein stability | 50 mM Carbonate Bicarbonate | PBS |

| Salt (NaCl) | Increases ionic strength, disrupts matrix interactions | - | 1 M |

| Detergent (Tween) | Aids in solubilizing fats and proteins | - | 2% |

| Fish Gelatine | Blocks non-specific binding | 10% | 10% |

| PVP | Binds and removes polyphenols (e.g., in chocolate) | - | 1% |

| Recommended For | - | General allergen recovery | Complex matrices (chocolate, baked) |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents for Allergen DNA Extraction and Detection

| Reagent / Material | Function in the Protocol |

|---|---|

| CTAB (Cetyltrimethyl ammonium bromide) | A detergent used in the lysis buffer to disrupt cell membranes and facilitate DNA release [1]. |

| Proteinase K | An enzyme that degrades proteins and nucleases, helping to purify DNA [1]. |

| Chloroform | Used for liquid-phase separation to remove proteins and other contaminants from the DNA solution [1]. |

| Isopropanol | A solvent used to precipitate DNA from the aqueous solution [1]. |

| RNase A | An enzyme that degrades RNA, preventing it from contaminating the final DNA extract [1]. |

| Fish Gelatine | A protein-based additive in extraction buffers that blocks non-specific binding sites, improving allergen recovery in immunoassays; likely aids in DNA extraction from complex matrices by similar mechanism [3]. |

| Polyvinylpyrrolidone (PVP) | A compound that binds to polyphenols (common in chocolate, fruits), preventing them from interfering with DNA and co-purifying [3]. |

| Allergen-Specific PCR Primers | Short, custom-designed DNA sequences that bind to and allow amplification of a specific allergen gene fragment (e.g., for HMW-GS, Zea m 14) [1]. |

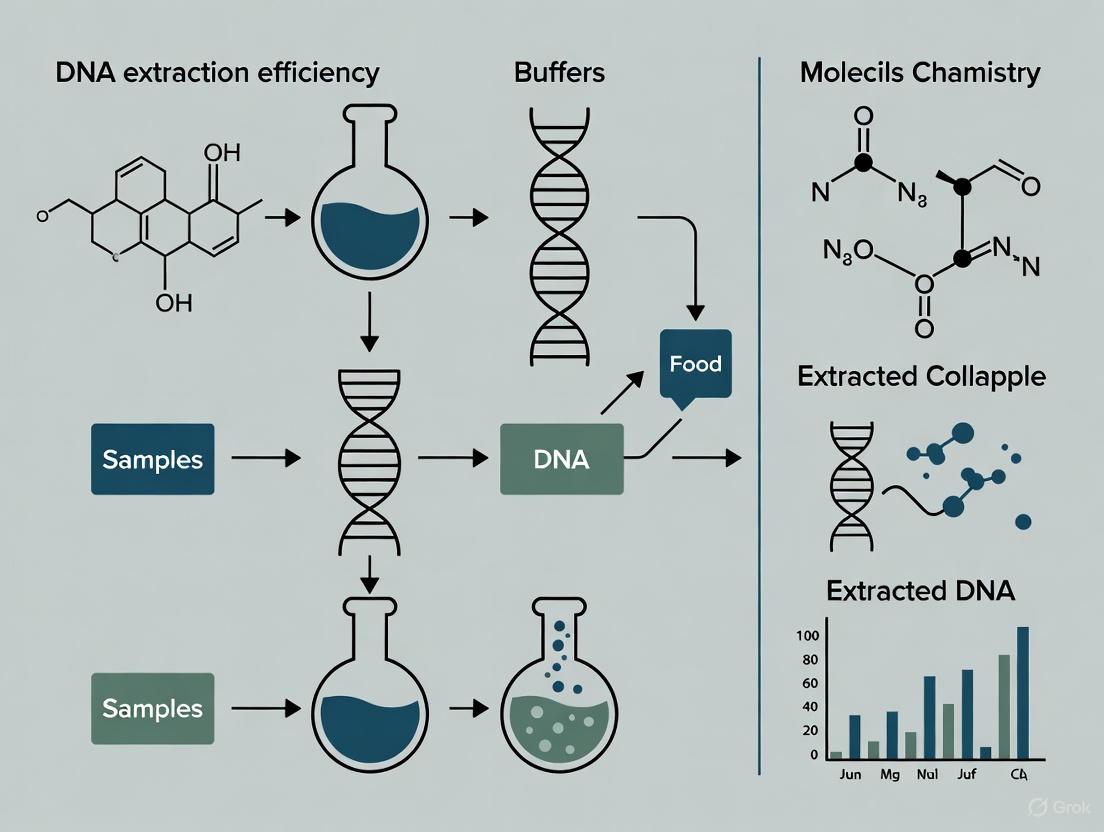

Experimental Workflow and Signaling Pathways

DNA Extraction and PCR Detection Workflow

IgE-Mediated Food Allergy Pathway

FAQ: How does thermal processing damage DNA and affect its detection?

Answer: Thermal processing damages DNA through several mechanisms that directly impact its integrity and your ability to amplify it. The primary damage types are:

- Strand Breaks and Fragmentation: Heat causes the cleavage of the phosphodiester bonds in the DNA backbone. This physically breaks the long DNA strands into smaller fragments. The intensity and duration of heating correlate with the degree of fragmentation [4].

- Depurination: High temperatures can cause the loss of purine bases (adenine and guanine) from the DNA backbone. This creates apurinic sites that are unstable and can lead to subsequent strand breakage [5].

- Deamination: Heat can induce the hydrolytic deamination of cytosine to uracil. This results in a change of the base identity (from a C-G base pair to a T-A base pair), potentially introducing errors during PCR amplification [6].

The direct consequence for your experiments is that the longer the DNA target you are trying to amplify (amplicon), the more likely it is that one of these damage events has occurred within that stretch of DNA, preventing successful PCR.

FAQ: My PCR is failing for a heat-processed food sample. What is the first parameter I should check?

Answer: The first and most critical parameter to check is the amplicon size of your PCR assay. Thermal processing fragments DNA, making long target sequences unrecoverable.

- Solution: Re-design your PCR assays to target shorter DNA sequences, ideally below 200 base pairs (bp), and for highly processed foods, below 100 bp is often necessary [4] [2]. Ensure that both the transgenic/allergen-specific target and the endogenous reference gene target have similar, short amplicon lengths. This ensures they degrade in parallel, allowing for reliable relative quantification [4].

FAQ: Can I still accurately quantify DNA from a heavily processed sample?

Answer: Yes, reliable relative quantification is possible if your assay is properly designed. Research shows that although absolute DNA recovery decreases significantly with intense processing (e.g., autoclaving, UV irradiation), the measured ratio between a transgenic or allergen target and an endogenous reference gene remains accurate [4]. This is because both sequences degrade at a similar rate. The key, as noted above, is using short, similarly-sized amplicons for both targets.

FAQ: Besides amplicon length, what other PCR conditions can I optimize for damaged DNA?

Answer: Optimizing your thermal cycling protocol can improve the sensitivity of detecting degraded DNA.

- Annealing Temperature: Use stringent annealing temperatures (generally 55–72°C), as they enhance discrimination against incorrectly annealed primers, which is more common with fragmented DNA templates [7].

- Polymerase and Extension Time: For short amplicons (e.g., < 2 kb), an extension time of one minute at 72°C is typically sufficient. The rate of nucleotide incorporation can vary from 35 to 100 nucleotides per second depending on buffer conditions [7].

- Denaturation: Avoid excessively long or hot denaturation steps (e.g., >95°C for long periods), as this can unnecessarily degrade the enzyme and further damage the already-fragile DNA template [7].

Table 1: Impact of Different Processing Treatments on DNA Recovery

| Processing Treatment | Impact on DNA Recovery | Key Experimental Finding |

|---|---|---|

| Autoclaving | Severe degradation, least DNA recovery | Profound fragmentation; requires very short amplicons for detection [4]. |

| UV Irradiation | Severe degradation, least DNA recovery | Causes significant DNA damage, similar to autoclaving [4]. |

| Baking / Dry Heat | Moderate to severe degradation | DNA recovery decreases with increasing temperature and duration [4]. |

| Microwaving | Moderate degradation | Can cause significant fragmentation depending on power and time [4]. |

Table 2: Key Reagent Solutions for DNA Analysis in Processed Foods

| Research Reagent | Function / Explanation | Application Note |

|---|---|---|

| Squish Buffer (with high salt) | Lysis buffer for bulk DNA extraction; high salt concentration (e.g., 125 mM NaCl) improves DNA yield and purity from complex samples [8]. | Essential for efficient extraction from difficult matrices like insect parts or processed food. |

| RNase A | Enzyme that degrades RNA. | Used during DNA extraction to remove RNA, reducing sample viscosity and potential PCR interference, leading to cleaner DNA and lower Cq values [8]. |

| Caffeine | Additive in DNA extraction buffers. | Improves DNA yield in real-time PCR applications when added to the squish buffer [8]. |

| Paramagnetic Beads | Used for post-lysis DNA purification. | Binds DNA, allowing impurities to be washed away. Can significantly increase end Relative Fluorescent Units (RFUs) in real-time PCR but adds cost and time [8]. |

| Taq DNA Polymerase | Thermostable enzyme for PCR amplification. | Active over a broad temperature range; its concentration can become critical with rapid cycling protocols [7] [9]. |

Experimental Protocol: Assessing DNA Degradation from Thermal Processing

Title: Protocol for Quantifying DNA Degradation in a Processed Food Model Using Real-Time PCR.

Background: This protocol simulates the effect of various food processing treatments on a dual-target plasmid to systematically evaluate DNA degradation and its impact on the quantitative detection of a specific gene sequence, such as an allergen marker.

Materials:

- Model System: Dual-target plasmid (e.g., pRSETMON-02) harboring two sequences in tandem (e.g., a 359 bp allergen-specific fragment and a 200 bp endogenous reference gene) in a 1:1 ratio [4].

- Equipment: Thermal cycler for real-time PCR, nanodrop or Qubit for DNA quantification, equipment for processing treatments (autoclave, microwave, UV cross-linker, dry bath).

- Reagents: Real-time PCR master mix (e.g., iTaq Universal Probes Supermix), specific primers and probes for short (e.g., 64 bp, 84 bp) and long (e.g., 356 bp) amplicons within the plasmid insert [4].

Methodology:

- Processing Treatments: Subject aliquots of the pure plasmid DNA to various processing treatments:

- Thermal: Autoclaving (e.g., 121°C for 20 min), baking (e.g., 95°C for 30 min), microwaving.

- Radiation: UV irradiation at a defined energy level [4].

- Include an untreated plasmid control.

- DNA Analysis: Dilute all processed and control DNA samples to the same concentration.

- Real-Time PCR Quantification:

- Perform real-time PCR on all samples using primer/probe sets for the short and long amplicons for both the allergen and reference gene targets.

- Run reactions in triplicate.

- Data Analysis:

- Record the quantification cycle (Cq) for each reaction. A higher Cq indicates greater DNA degradation of that specific target.

- Calculate the mean DNA copy number ratio (allergen gene / reference gene) for each processing condition.

- Compare the ratios and absolute Cq values of processed samples to the untreated control.

Expected Outcome: The recovery of longer amplicons (356 bp) will be significantly reduced compared to shorter amplicons (64/84 bp) in processed samples. However, the calculated mean DNA copy number ratio between the allergen and reference gene should remain consistent with the expected 1:1 ratio, demonstrating that accurate relative quantification is possible despite degradation [4].

Visualizing the Concepts

Diagram 1: DNA Degradation and Solution Pathway

Diagram 2: Reliable DNA Detection Workflow

For researchers focused on allergen detection in processed foods, obtaining high-quality DNA is a foundational step. The stability of DNA makes it a superior target for detecting allergenic ingredients like peanuts, soy, or shellfish in complex food matrices. However, food processing techniques—both thermal and non-thermal—can severely degrade DNA, compromising the sensitivity and accuracy of downstream molecular assays such as PCR and DNA barcoding. This technical support center provides targeted troubleshooting guides and FAQs to help you navigate the challenges of extracting analyzable DNA from processed foods, thereby enhancing the efficiency and reliability of your research.

Troubleshooting Guides

Common Problems and Solutions in DNA Extraction from Processed Foods

Problem: Low DNA Yield

| PROBLEM | CAUSE | SOLUTION |

|---|---|---|

| Low DNA Yield | Degradation from extensive mechanical/thermal processing [10] | Optimize sample input; use larger starting material if DNA is highly fragmented [10]. |

| Polysaccharide/polyphenol co-precipitation inhibiting extraction [10] | Use extraction buffers with additives like CTAB or PVP to bind and remove contaminants [10] [11]. | |

| Silica membrane clogged by indigestible tissue fibers [12] | Centrifuge lysate at max speed for 3 min before column loading to pellet fibers [12]. | |

| DNA Degradation | Sample not stored properly post-processing [12] | Flash-freeze samples in liquid nitrogen and store at -80°C; use stabilizing reagents [12]. |

| Activity of endogenous nucleases in raw material [12] | Process samples quickly on ice; use lysis buffers with chelating agents [12]. | |

| Acid-catalyzed hydrolytic destruction during processing [10] | Neutralize acidic samples with appropriate buffers early in the extraction protocol [10]. | |

| Protein Contamination | Incomplete digestion of the sample [12] | Extend Proteinase K digestion time by 30 mins to 3 hours after tissue dissolves [12]. |

| Membrane clogged with tissue fibers [12] | Centrifuge lysate to remove fibers; reduce input material for fibrous tissues [12]. | |

| PCR Inhibition | Carry-over of PCR inhibitors (polysaccharides, polyphenols, salts) [10] | Include additional wash steps; use silica-column based purification over traditional methods [10] [13]. |

| Inadequate purification post-extraction [10] | Perform a pre-wash of the sample or use a kit designed for complex matrices [11]. |

Problem: DNA Degradation

Problem: Protein Contamination

Problem: PCR Inhibition

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. Why is DNA quality from processed foods so variable, and what are the main processing factors that affect it? DNA quality is highly variable because it is affected by a combination of processing steps. Thermal processing (e.g., baking, retorting) causes strand breakage and depurination [10]. Chemical processing, such as exposure to acidic conditions in fruit juices, leads to hydrolytic DNA destruction [10]. Mechanical processing (e.g., blending, homogenization) shears DNA into smaller fragments. The cumulative effect of these processes determines the final fragment size and purity of the DNA, which directly impacts the success of PCR amplification [10].

2. For a highly processed product like Chestnut rose juice, which DNA extraction method is most effective? A comparative study on Chestnut rose juices and beverages found that a combination method, often involving aspects of both CTAB and silica-column purification, showed the greatest performance despite being more time-consuming and costly. This method outperformed a non-commercial modified CTAB method (which had high yield but poor purity) and other commercial kits in terms of DNA quality and amplifiability in qPCR [10].

3. My downstream PCR assay for a peanut allergen is failing. Should I switch to a protein-based method like ELISA? Not necessarily. While food processing also affects proteins, DNA-based methods retain significant advantages. DNA is more stable than proteins during food processing and extraction [14]. Furthermore, DNA-based methods like PCR can be highly sensitive and specific, and are not as strongly misled by cross-reactivity with other nuts as some immunoassays can be [14]. The solution often lies in optimizing the DNA extraction and purification to remove PCR inhibitors, rather than abandoning the DNA-based approach.

4. We work with novel feed ingredients like insect hydrolysates. Are standard DNA extraction kits sufficient? Novel ingredients often require validated protocols. A study on processed animal by-products (including hydrolysates) found that the conventional CTAB-based method and the commercial kits Invisorb Spin Tissue Mini and NucleoSpin Food demonstrated superior extraction efficiency and DNA quality ratios. Commercial kits generally enable faster processing, but the CTAB method can be optimized for specific, complex matrices [11].

5. How can I quickly assess the quality and extent of degradation of my extracted DNA? Beyond spectrophotometric measurements (A260/A280), you can use gel electrophoresis to visually check for DNA smearing (indicating degradation) versus distinct high-molecular-weight bands. A more quantitative approach is to use TaqMan real-time PCR with primers that generate amplicons of different sizes. A significant drop in amplification efficiency with longer amplicons is a clear indicator of DNA fragmentation, helping you assess the utility of the DNA for your intended assay [10].

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Combined CTAB and Silica-Column Method for Processed Plant-Based Foods (e.g., Juices, Jams)

This protocol, adapted from research on Chestnut rose juices, is designed for challenging, polysaccharide-rich matrices [10].

- Sample Preparation: Homogenize 100-200 mg of the sample (or 1-2 mL for liquids after centrifugation) using a sterile pestle.

- Lysis: Add 1 mL of pre-warmed CTAB extraction buffer (2% CTAB, 100 mM Tris-HCl pH 8.0, 20 mM EDTA, 1.4 M NaCl, 0.2% β-mercaptoethanol added fresh) and 20 µL of Proteinase K (20 mg/mL). Mix by vortexing and incubate at 65°C for 60-120 minutes with occasional gentle mixing.

- Decontamination: Add an equal volume of Chloroform:Isoamyl Alcohol (24:1). Mix thoroughly by inversion for 10 minutes. Centrifuge at 12,000 x g for 15 minutes at room temperature.

- DNA Precipitation: Carefully transfer the upper aqueous phase to a new tube. Add 0.7 volumes of isopropanol, mix by inversion, and incubate at -20°C for 30 minutes. Centrifuge at 12,000 x g for 15 minutes to pellet the DNA.

- Wash and Resuspend: Wash the pellet with 1 mL of 70% ethanol. Centrifuge again, carefully discard the ethanol, and air-dry the pellet. Resuspend the DNA in 50-100 µL of TE buffer or nuclease-free water.

- Further Purification (Combination Step): Apply the resuspended DNA to a silica-column from a commercial kit (e.g., NucleoSpin Food). Follow the manufacturer's protocol for binding, washing, and elution. This step helps remove any remaining PCR inhibitors [10] [11].

Protocol 2: Commercial Kit-Based Extraction for Highly Processed Animal By-Products

This protocol is validated for novel ingredients like animal meals and hydrolysates [11].

- Sample Input: Use 60-200 mg of the processed sample.

- Recommended Kits: Invisorb Spin Tissue Mini Kit or NucleoSpin Food Kit.

- Procedure: Follow the manufacturer's instructions precisely. For difficult-to-lyse samples, the protocol can be modified by:

- Extending Lysis Time: Increase the incubation time with lysis buffer and Proteinase K.

- Initial Homogenization: For solid samples, an initial homogenization step with liquid nitrogen may improve yield [11].

- Elution: Elute the purified DNA in a small volume (e.g., 50-100 µL) to increase the final DNA concentration.

Workflow Visualization

The following diagram illustrates the critical decision-making process for selecting and optimizing a DNA extraction method based on the sample's processing history.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Reagent / Kit | Function / Application |

|---|---|

| CTAB (Cetyltrimethylammonium bromide) | A cationic detergent effective in lysing cells and precipitating polysaccharides while co-precipitating DNA. Crucial for plant-based and polysaccharide-rich processed foods [10] [11]. |

| Proteinase K | A broad-spectrum serine protease used to digest proteins and degrade nucleases that could otherwise degrade DNA during extraction. Essential for all sample types, especially tissues [12]. |

| Silica-based Spin Columns (e.g., from NucleoSpin Food kit) | The core of many commercial kits; DNA binds to the silica membrane in the presence of high salt, allowing impurities to be washed away, resulting in high-purity DNA [11] [13]. |

| Polyvinylpyrrolidone (PVP) | Used to bind and remove polyphenols during extraction, preventing them from co-purifying with DNA and inhibiting downstream PCR. Important for plant and juice samples [10]. |

| RNase A | An enzyme that degrades RNA, preventing RNA contamination from affecting DNA quantification and downstream applications [12]. |

| Chelex-100 Resin | A chelating resin that binds metal ions, inhibiting nucleases. Used in rapid, low-cost boiling methods, though with lower purity than column-based methods [13]. |

The reliable detection of food allergens in processed foods is critically dependent on the efficiency of DNA extraction and the subsequent performance of the polymerase chain reaction (PCR). Complex food matrices often contain inherent compounds that potently inhibit enzymatic reactions, leading to false-negative results and compromising food safety assessments. Among these, polyphenols and polysaccharides represent two of the most pervasive and challenging classes of PCR inhibitors. These compounds can co-purify with DNA during extraction, interfering directly with DNA polymerase activity and preventing the amplification of target allergen genes [15] [16]. This guide provides targeted troubleshooting strategies to help researchers overcome these barriers, thereby improving the accuracy and sensitivity of DNA-based allergen detection methods.

Understanding the Inhibitors

To effectively troubleshoot, it is essential to understand the nature and source of common inhibitors.

- Polyphenols: These compounds are abundant in plant tissues and are readily oxidized during cell lysis, often forming complexes with nucleic acids. This binding can render DNA insoluble or inhibit polymerase enzymes directly. Contamination with polyphenols can often be identified by a brownish discoloration in the purified DNA sample [15] [16].

- Polysaccharides: Acidic polysaccharides are particularly problematic as they are structurally similar to nucleic acids and thus co-precipitate during isolation. They are among the strongest PCR inhibitors and can impart a sticky, gelatinous texture to the DNA extract, affecting downstream applications like restriction digestion and PCR [15].

Table 1: Common PCR Inhibitors in Food Matrices

| Inhibitor Class | Common Sources | Impact on PCR | Visible Clues in DNA Extract |

|---|---|---|---|

| Polyphenols | Grape, birch (Betula), chocolate, woody plants, medicinal plants [15] [16] | Bind to nucleic acids and enzymes; inhibit polymerase activity [15] [16] | Brownish color [15] |

| Polysaccharides | Grape, birch, maize, processed cereals [15] | Co-purify with DNA; interfere with polymerases, ligases, and restriction enzymes [15] | Sticky, gelatinous consistency; brown color [15] |

| Proteins | Various food matrices (e.g., milk, eggs) | Can co-purify and inhibit enzyme active sites [15] | - |

| Chaotropic Salts | Carryover from silica-based purification kits [16] | Inhibit polymerase activity [16] | - |

Troubleshooting Guide: Common Issues and Solutions

This section addresses specific experimental problems related to inhibitor carryover.

Issue 1: No Amplification or Low Yield

Possible Causes:

- Carryover of PCR inhibitors like polyphenols or polysaccharides in the DNA template [17] [18].

- Degraded or insufficient DNA template quantity [17].

- Suboptimal PCR reaction conditions.

Recommendations:

- Re-purify DNA: Precipitate and wash the DNA with 70% ethanol to remove residual salts and inhibitors [17].

- Use Inhibitor-Robust Enzymes: Select DNA polymerases with high processivity and tolerance to inhibitors commonly found in plant tissues and processed foods [17].

- Apply PCR Additives: Incorporate additives like * Bovine Serum Albumin (BSA)* or betaine into the PCR mix. BSA can bind to inhibitors, reducing their impact on the polymerase, while betaine can help denature GC-rich templates and stabilize the reaction [18].

- Validate Template: Check DNA concentration and integrity using gel electrophoresis to rule out degradation [17].

Issue 2: Non-Specific Amplification or Primer-Dimer Formation

Possible Causes:

- PCR conditions are not stringent enough, often due to low annealing temperatures or excess magnesium [17] [18].

- High primer concentration [18].

- Use of a non-hot-start DNA polymerase, allowing activity at room temperature [17] [18].

Recommendations:

- Optimize Annealing Temperature: Increase the annealing temperature stepwise in 1–2°C increments. Use a gradient thermal cycler to determine the optimal temperature, which is typically 3–5°C below the primer's Tm [17] [18].

- Optimize Mg²⁺ Concentration: Review and lower the Mg²⁺ concentration to prevent nonspecific products [17] [18].

- Use Hot-Start Polymerases: Employ hot-start DNA polymerases that remain inactive until a high-temperature activation step, preventing nonspecific priming and primer-dimer formation at lower temperatures [17] [18].

Issue 3: Smeared Bands on Agarose Gel

Possible Causes:

- Degraded DNA template [17] [18].

- Contamination from previous PCR amplifications ("carryover contamination") [18].

- Excessively long extension times or low annealing temperatures [18].

Recommendations:

- Assess DNA Integrity: Evaluate the template DNA by gel electrophoresis before PCR. Use intact, high-quality DNA [17].

- Prevent Contamination: Implement strict laboratory practices, including physical separation of pre- and post-PCR areas and using dedicated equipment and reagents [18].

- Optimize Cycling Conditions: Shorten the extension time and/or increase the annealing temperature [18].

Table 2: Summary of Troubleshooting Solutions

| Problem | Solution Category | Specific Action |

|---|---|---|

| No/Low Yield | DNA Template | Re-purify DNA (ethanol precipitation); use inhibitor-tolerant polymerases [17] |

| PCR Additives | Add BSA or betaine to the reaction mix [18] | |

| Non-Specific Bands | Reaction Conditions | Increase annealing temperature; optimize Mg²⁺ concentration [17] [18] |

| Enzyme Choice | Switch to a hot-start DNA polymerase [17] [18] | |

| Primer-Dimer | Primer Design & Concentration | Re-design primers to avoid 3'-end complementarity; optimize primer concentration [18] |

| Smeared Bands | Laboratory Practice | Decontaminate workspace; use physical separation of pre- and post-PCR areas [18] |

| Template & Conditions | Use intact DNA template; optimize cycling conditions [17] [18] |

Optimized Experimental Protocols

CTAB-Based DNA Extraction Protocol for Recalcitrant Plant Tissues

This protocol is specifically designed to remove polyphenols and polysaccharides and has been successfully applied to difficult samples like birch and grape [15].

Buffers:

- Buffer 1: 200 mM Tris-HCl, 1.4 M NaCl, 0.5% (v/v) Triton X-100, 3% (w/v) CTAB, 0.1% (w/v) PVP (add PVP just before use).

- Buffer 2: 50 mM Tris-HCl, 2 M guanidine thiocyanate, 0.2% (v/v) mercaptoethanol (add before use), 0.2 mg/mL Proteinase K (add before use).

Procedure:

- Homogenization: Grind 50 mg of leaf or root tissue in a 2 mL tube.

- Initial Lysis: Add 400 µL of Buffer 1, vortex for 20 seconds, and incubate at 60°C for 30 minutes.

- De-proteinization: Add 400 µL chloroform-isoamyl alcohol (24:1, v/v), shake vigorously for 2 minutes, and centrifuge at 10,000 rpm for 15 minutes.

- Supernatant Transfer: Transfer 300 µL of the upper aqueous phase to a fresh 2 mL tube.

- Enzymatic Digestion: Add 150 µL (1/2 volume) of Buffer 2 and incubate at 40°C for 15 minutes.

- Polysaccharide Precipitation: Add 1/2 volume of 4 M NaCl, shake, and place the tube on ice for 5 minutes.

- DNA Precipitation: Add 2 volumes of cold isopropanol and leave at room temperature for 2 minutes. Centrifuge at 8,000 rpm for 15 minutes to pellet the DNA.

- Wash: Discard the supernatant. Gently wash the pellet with 75% (v/v) ethanol, wait 2 minutes, and centrifuge at 8,000 rpm for 2 minutes.

- Dissolution: Dry the pellet and dissolve the DNA in 100 µL TE buffer. Incubate at 70°C for 10 minutes to ensure complete dissolution [15].

Workflow for DNA Extraction and Allergen Detection in Processed Foods

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow from sample preparation to detection, highlighting key steps for overcoming inhibition.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Selecting the right reagents is fundamental to successfully extracting inhibitor-free DNA and achieving robust PCR amplification.

Table 3: Key Reagent Solutions for Overcoming PCR Inhibition

| Reagent / Tool | Function / Purpose | Specific Examples / Notes |

|---|---|---|

| CTAB (Cetyltrimethylammonium bromide) | A cationic detergent that facilitates cell lysis and forms complexes with polysaccharides to prevent their solubilization [15] [1]. | Used in high-salt extraction buffers (e.g., 1.4 M NaCl) [15]. |

| PVP (Polyvinylpyrrolidone) | Binds to and neutralizes polyphenols, preventing their oxidation and complexation with DNA [15] [3]. | Often added to extraction buffers at 0.1-1% concentration [15] [3]. |

| Proteinase K | Broad-spectrum serine protease that degrades contaminating enzymes and other proteins [15]. | Used to remove nucleases and other proteins [15]. |

| High-Salt Solutions | Prevents the co-solubilization of acidic polysaccharides with DNA [15]. | 1.4 M NaCl in lysis buffer; 4 M NaCl for post-lysis precipitation [15]. |

| Inhibitor-Tolerant DNA Polymerases | Engineered enzymes with high affinity for DNA templates, resistant to common plant and food-derived inhibitors [17] [16]. | KOD One Master Mix; polymerases marketed for high processivity and tolerance [17] [16]. |

| PCR Additives | Compounds that counteract inhibitors or improve amplification efficiency of difficult targets. | BSA: Binds to inhibitors [18]. Betaine: Destabilizes secondary structures [17] [18]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: My DNA extract from chocolate is brown. What does this mean, and what should I do? A brown color strongly suggests contamination with polyphenols, which are abundant in cocoa [3]. You should re-extract the DNA using a protocol that includes PVP in the lysis buffer to bind these compounds. Additionally, consider using a silica-column based purification kit designed for complex matrices, as these can be more effective than CTAB alone for certain samples [16].

Q2: How does food processing affect DNA-based allergen detection? Food processing, especially thermal treatments like baking, boiling, and autoclaving, causes DNA fragmentation and degradation [19] [1]. This degradation limits the size of the DNA target that can be amplified. To ensure detection in processed foods, design your PCR assays to amplify short target sequences (100-200 bp) [1]. Chloroplast DNA targets can sometimes offer an advantage due to their multiple copies per cell [19].

Q3: I've followed an optimized protocol, but my PCR still fails. What are my next steps? First, systematically verify each component:

- Test DNA Quality: Run a fresh aliquot of your DNA on a gel to confirm it is not degraded.

- Check Reagents: Prepare fresh working stocks of PCR reagents, particularly dNTPs and primers.

- Use a Control Template: Perform a PCR with a known, control DNA template and a separate set of validated primers. If this control works, the issue lies with your sample DNA or the allergen-specific primers. If it fails, the problem is likely in your PCR master mix or cycling conditions [18].

- Consider Advanced Methods: For absolute quantification and superior tolerance to inhibitors, explore digital PCR (dPCR), which has been shown to improve sensitivity for allergenic foods like sesame by an order of magnitude compared to real-time PCR [20].

Core Concepts: Proteins, Genes, and Detection

What is the fundamental relationship between an allergenic protein and its encoding gene?

An allergenic protein is a specific molecule, typically a protein, that triggers an abnormal immune response in sensitized individuals. The genetic information for producing this protein is contained within a specific gene—a sequence of DNA. The gene is transcribed into messenger RNA (mRNA), which is then translated into the amino acid sequence that forms the allergenic protein. Therefore, detecting the gene provides an indirect, yet highly reliable, method for identifying the potential presence of the allergenic protein itself [21].

Why target DNA for allergen detection in processed foods?

Targeting DNA is particularly advantageous for detecting allergens in processed foods. While the structure and detectability of allergenic proteins can be damaged or altered by factors such as heat, pressure, or chemical treatments during food processing, DNA is often more stable and retains its molecular integrity under these conditions [2]. In such cases, DNA-based detection provides an effective and reliable alternative when protein-based immunological assays may fail [2].

What are the major allergenic foods, and what are some key allergen examples?

Certain foods are responsible for the majority of allergic reactions. A foundational group, often referred to as the 'Big 8', includes peanuts, eggs, milk, soy, wheat/cereals containing gluten, crustaceans, fish, and tree nuts [21]. Key allergen genes and their proteins have been extensively studied for many of these. For example:

- Peanuts: Ara h 2 and Ara h 6 are two of the most potent allergens, belonging to the prolamin superfamily (2S albumin family) [22]. Their genes have been explored across various Arachis species, revealing natural mutations that can reduce allergenicity [22].

- Wheat & Gluten: Celiac disease is triggered by an autoimmune response to gluten proteins, which is distinct from a wheat allergy, though both involve specific protein fractions and their encoding genes [21].

Methodologies & Data Comparison

The following table summarizes the primary methods used for allergen detection, highlighting the role of DNA-based techniques [2] [21].

Table 1: Comparison of Major Allergen Detection Methods

| Method Type | Principle | Target | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Protein-Based (e.g., ELISA, Lateral Flow) | Immunological binding of antibodies to specific protein epitopes [21]. | Allergenic Protein | Directly detects the causative agent; high sensitivity and specificity; well-standardized [2]. | Protein structure can be denatured during processing, leading to false negatives [2]. |

| DNA-Based (e.g., PCR) | Amplification of specific DNA sequences unique to the allergenic source [21]. | Allergen-Encoding Gene | DNA is more stable in processed foods; highly specific and sensitive [2]. | Does not directly quantify the protein; results may not always correlate with protein amount [2]. |

| Biosensors | Biological recognition element (e.g., antibody, aptamer) coupled to a signal transducer [2]. | Protein or Gene | Potential for rapid, on-site, and high-throughput analysis [2]. | Still emerging technology; can be complex to develop and validate [2]. |

Detailed Protocol: Real-Time PCR for Allergen Detection

This protocol is adapted from methods described for detecting allergenic foods such as lobster, fish, and nuts [2].

Principle: Real-time PCR (Polymerase Chain Reaction) allows for the detection and quantification of specific DNA sequences. It monitors the amplification of a target gene in real time using a fluorescent reporter, allowing researchers to determine the presence and quantity of an allergen-encoding gene in a sample.

Workflow:

The following diagram illustrates the key steps in the DNA-based detection workflow, from sample preparation to final analysis.

Materials & Reagents:

- Sample: Processed food product (e.g., chocolate, cookie, sauce).

- Lysis Buffer: For breaking down cells and releasing DNA.

- DNA Purification Kit: For isolating high-quality DNA from the complex food matrix.

- Primers and Probes: Sequence-specific oligonucleotides designed to bind to a unique region of the target allergen gene (e.g., Ara h 2 or a fish parvalbumin gene). These are the core reagents that define the assay's specificity.

- Real-Time PCR Master Mix: Contains DNA polymerase, dNTPs, buffer, and salts necessary for the amplification reaction. Often includes a fluorescent dye (e.g., SYBR Green) or is compatible with dual-labeled probes (TaqMan).

- Real-Time PCR Instrument: The equipment used to perform thermal cycling and fluorescence detection.

Procedure:

- DNA Extraction: Homogenize the food sample. Extract genomic DNA using a validated purification method, ensuring the removal of inhibitors (e.g., polyphenols, fats) that can affect PCR efficiency. Quantify and assess the purity of the extracted DNA.

- Reaction Setup: Prepare reactions in a 96-well plate or strips. A typical reaction mix includes:

- Real-Time PCR Master Mix: 10 µL

- Forward Primer (specific to target gene): 0.5 µL

- Reverse Primer (specific to target gene): 0.5 µL

- Probe (if using a TaqMan assay): 0.5 µL

- Template DNA (extracted sample): 2-5 µL

- Nuclease-Free Water: to a final volume of 20 µL

- Include appropriate controls: no-template control (NTC), positive control (DNA from known allergenic source), and potentially an internal amplification control.

- Thermal Cycling: Place the plate in the real-time PCR instrument and run a program similar to:

- Initial Denaturation: 95°C for 2-5 minutes.

- 40-50 Cycles of:

- Denaturation: 95°C for 15-30 seconds.

- Annealing/Extension: 60°C for 30-60 seconds (acquire fluorescence at this step).

- Data Analysis: Analyze the amplification curves. The cycle threshold (Ct) value, at which the fluorescence exceeds a background threshold, is used for qualitative detection or quantitative estimation of the target DNA concentration.

Troubleshooting FAQs

Q: We are getting inconsistent results between our DNA-based and protein-based allergen tests on the same processed food sample. What could be the cause?

A: This is a common challenge. The most likely cause is the differential impact of food processing on the targets.

- Scenario 1 (Positive DNA / Negative Protein): The food has been subjected to high heat or harsh chemicals, which denatured the allergenic protein so that antibodies can no longer bind to it. However, the DNA, while potentially fragmented, remains amplifiable for a detectable target sequence. This suggests the allergenic ingredient was present, but the protein's immunoreactivity has been destroyed [2].

- Scenario 2 (Unexpected Quantification Discrepancy): The number of gene copies in the raw material may not always directly correlate with the concentration of the expressed protein. Furthermore, DNA degradation can occur with extreme processing, potentially leading to an underestimation. Always ensure your DNA extraction method is optimized for your specific food matrix to recover sufficient, amplifiable DNA.

Q: Our PCR assays are failing, showing no amplification even in positive controls. What are the first steps in troubleshooting?

A: A systematic approach is key.

- Check Reagent Integrity: Ensure primers and master mix have been stored correctly and are not expired. Prepare fresh aliquots if necessary.

- Verify DNA Quality: Re-evaluate the extracted DNA. Is the concentration sufficient? Is it degraded (check on a gel)? Are there contaminants (assess A260/A280 ratio)? Re-purify the DNA if needed.

- Inspect Thermal Cycler Protocol: Confirm the correct thermal cycling program was selected and executed. Ensure the instrument is calibrated.

- Test Components Systematically: Run a gel electrophoresis on your PCR product to confirm a lack of amplification. Set up a new reaction with a known, high-quality control DNA template to isolate the problem to either the sample DNA or the PCR reagents themselves.

Q: What is the difference between LOD and LOQ, and why are they critical for my DNA-based allergen assay?

A: Understanding these parameters is fundamental for validating your method.

- LOD (Limit of Detection): The lowest amount of the target allergen gene that can be detected by your assay, but not necessarily quantified precisely. It answers the question: "Is it there?"

- LOQ (Limit of Quantification): The lowest amount of the target allergen gene that can be measured with acceptable accuracy and precision. It answers the question: "How much is there?" For allergen management, the LOD is often the most critical parameter for ensuring that even trace amounts of an allergenic food can be detected to prevent cross-contact. However, for quantitative risk assessment, a robust LOQ is essential [21].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents

Table 2: Essential Reagents for DNA-Based Allergen Detection

| Reagent / Material | Function | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Sequence-Specific Primers & Probes | Binds to and enables amplification/detection of a unique sequence within the allergen-encoding gene. | Specificity is paramount; must be designed to avoid cross-reactivity with non-target species. |

| DNA Polymerase (e.g., Taq) | Enzyme that synthesizes new DNA strands during PCR. | Should be robust and efficient for amplifying DNA from complex, potentially inhibitor-rich food matrices. |

| DNA Purification Kit | Isolates and purifies DNA from the food sample, removing proteins, fats, and PCR inhibitors. | Extraction efficiency is critical; the kit must be validated for the specific food type being tested. |

| dNTPs (Deoxynucleotide Triphosphates) | The building blocks (A, T, C, G) for synthesizing new DNA. | Quality and concentration must be consistent to ensure efficient and accurate amplification. |

| Real-Time PCR Master Mix | A pre-mixed, optimized solution containing buffer, salts, dNTPs, polymerase, and fluorescent dye. | Simplifies assay setup and improves reproducibility. Choose a mix suited to your detection chemistry (e.g., SYBR Green, TaqMan). |

| Positive Control DNA | Genomic DNA from a known source of the allergen (e.g., peanut, shrimp). | Essential for validating that the entire assay, from extraction to detection, is functioning correctly. |

Advanced DNA Extraction Protocols and Techniques for Complex Food Matrices

The selection of an appropriate DNA extraction method is a critical first step in the reliable detection of food allergens via PCR-based techniques. The efficiency of this process directly influences the sensitivity, accuracy, and reproducibility of the entire analytical workflow. This guide provides a comparative analysis of traditional CTAB, commercial kits, and emerging rapid protocols, focusing on their application within research and development for allergen detection in complex food matrices.

Table 1: Overall Comparison of DNA Extraction Method Characteristics

| Method | Typical Protocol Duration | Relative Cost per Sample | Best Suited For | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CTAB | 3-4 hours [23] | Low | High-quality DNA for demanding applications (e.g., NGS) [24]; high polysaccharide samples [23] | Time-consuming; multiple steps increase contamination risk; requires hazardous chemicals [25] [23] |

| Commercial Kits (e.g., Qiagen, Mericon, Promega) | ~1 - 1.5 hours [23] [26] | High | Routine, high-throughput analysis; consistent quality; processed foods [23] [26] | Higher cost; potential for low yield if column is overloaded [27] [23] |

| Rapid Protocols (e.g., HSD, Nucleic Acid Releasers) | 4 - 60 minutes [25] [28] | Medium | On-site screening; rapid quality control; simple allergen presence/absence tests [25] [28] | May be less effective with highly complex or inhibitory matrices; not always suitable for quantification |

Table 2: Quantitative Performance in Allergen Detection

| Method | Reported Limit of Detection (LOD) in Food | Key Allergens Successfully Detected | Impact of Food Processing |

|---|---|---|---|

| CTAB | 0.01% walnut (0.01%, LOQ 0.05%) [29] | Walnut [29], Soybean [25], Maize [23] | DNA quality and amplification reduced by autoclaving; HHP has minimal effect [29] |

| Commercial Kits | 1 ppm (mg/kg) celery protein in five product groups [26] | Celery [26], Soybean [25] | Clear matrix effect observed; quantification can be challenging [26] |

| Rapid Protocols | 10 mg/kg soybean in processed food [25]; 0.0001% shrimp in meat [28] | Soybean [25], Shrimp [28] | Designed for robustness in processed foods; performance may vary by matrix [25] |

Detailed Methodologies & Experimental Protocols

Traditional CTAB Protocol with Modifications

The CTAB (cetyltrimethylammonium bromide) method is a well-established, customisable protocol for plant-based materials. It is particularly effective for precipitating DNA while removing polysaccharides and other contaminants common in cereal grains and allergenic foods [23].

Key Reagents:

- CTAB Buffer: 20 g/L CTAB, 2.56 M NaCl, 0.1 M Tris-HCl, 20 mM EDTA, pH 8.0 [23]. Sometimes supplemented with 1-2% PVP (polyvinylpyrrolidone) to bind phenolics [23].

- Proteinase K: For enzymatic digestion of proteins.

- RNase A: For digesting RNA.

- Chloroform:Isoamyl Alcohol (24:1): For denaturing and separating proteins.

- Isopropanol and Ethanol (70%): For precipitating and washing DNA.

Validated Protocol for Cereal Grains (e.g., Maize): [23]

- Tissue Disruption: Grind 100 mg of grain to a fine powder using liquid nitrogen.

- Lysis: Incubate the powder with 500 µL CTAB buffer, 300 µL sterile water, and 20 µL Proteinase K (20 mg/mL) at 65°C for 1.5 hours.

- RNA Removal: Add 20 µL RNase A (10 mg/mL) and incubate at 65°C for 10 minutes.

- Centrifugation: Centrifuge at 16,000×g for 10 minutes. Transfer the supernatant to a new tube.

- Chloroform Extraction: Add 500 µL chloroform, mix thoroughly, centrifuge at 16,000×g for 10 minutes, and transfer the upper aqueous phase to a new tube. Repeat this step twice.

- DNA Precipitation: Mix the supernatant with 2 volumes of CTAB precipitation solution (5 g/L CTAB, 0.04 M NaCl). Incubate at room temperature for 1 hour.

- Centrifugation & Dissolution: Centrifuge at 16,000×g for 5 minutes, discard the supernatant, and dissolve the pellet in 350 µL of 1.2 M NaCl.

- Final Precipitation: Add 0.6 volumes of isopropanol to precipitate the DNA. Centrifuge at 16,000×g for 10 minutes.

- Wash & Elute: Wash the pellet with 500 µL of 70% ethanol, dry, and resuspend in 100 µL sterile water or TE buffer.

Commercial Kit Workflow (e.g., Mericon, SureFood PREP)

Commercial kits provide standardized, user-friendly protocols that minimize hands-on time and improve reproducibility.

Validated Protocol for Soybean in Processed Foods: [25]

- Homogenization: Weigh 100 ± 2 mg of homogenized food sample.

- Rapid Lysis: Add the sample to a tube containing 580 µL of proprietary lysis buffer (from SureFood PREP Advanced kit), 20 µL Proteinase K, a lysis matrix bead, and ~1.5 mg sea sand.

- Mechanical Disruption: Process using a high-speed benchtop homogenizer (e.g., FastPrep-24) at 6.5 m/s for 60 seconds at room temperature.

- Purification: Follow the manufacturer's instructions for the subsequent purification steps, which typically involve binding DNA to a silica membrane, washing with ethanol-based buffers, and eluting in a low-salt buffer [25].

Emerging Rapid Protocol (Nucleic Acid Releaser)

This protocol represents the frontier in speed, designed for near-on-site detection.

Validated Protocol for Shrimp Allergen Detection: [28]

- Rapid Nucleic Acid Release: Add the new nucleic acid releaser reagent directly to the food sample.

- Incubation: A brief incubation step of only 4 minutes is sufficient to release DNA, bypassing lengthy lysis and purification.

- Direct Amplification: The released DNA is used directly in a fast qPCR assay without further purification. The entire process from sample to result is completed in approximately 30 minutes [28].

Technical Support Center: Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs

Troubleshooting Common DNA Extraction Problems

PROBLEM: Low DNA Yield

| Cause | Solution |

|---|---|

| Incomplete tissue homogenization | Grind tissue to the smallest possible pieces with liquid nitrogen. For fibrous tissues, centrifuge the lysate to remove fibers before binding [27]. |

| Overloaded DNA binding column | Do not exceed the recommended input amount of tissue, especially for DNA-rich organs (e.g., liver, spleen) [27]. |

| DNA pellet overdried | Limit drying time after ethanol wash to less than 5 minutes. Overdried DNA is difficult to resuspend [30]. |

| Incorrect handling of cell pellets | Thaw frozen cell pellets slowly on ice and resuspend gently in cold PBS to avoid clumping [27]. |

PROBLEM: DNA Degradation

| Cause | Solution |

|---|---|

| Improper sample storage | Flash-freeze samples in liquid nitrogen and store at -80°C. Avoid long-term storage at 4°C or -20°C [27]. |

| High nuclease activity in tissues (e.g., liver, pancreas) | Process samples quickly, keep frozen, and maintain on ice during preparation. Ensure rapid contact with lysis buffer [27]. |

| Old or thawed blood samples | Use fresh whole blood (less than one week old). For frozen blood, add lysis buffer and Proteinase K directly to the frozen sample to inhibit DNases [27]. |

PROBLEM: Contaminants in DNA Eluate

| Cause | Solution |

|---|---|

| Carryover of guanidine salts from binding buffer | Avoid pipetting lysate onto the upper column wall. Ensure wash buffers contain the correct ethanol concentration and are thoroughly removed [27]. |

| Protein contamination (low A260/A280) | Extend Proteinase K digestion time. For fibrous tissues, ensure centrifugation to remove indigestible fibers [27]. |

| Polysaccharide or phenolic contamination | The CTAB method is specifically designed to remove polysaccharides. Adding PVP to the CTAB buffer can help remove phenolic compounds [23]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: Which DNA extraction method is most suitable for highly processed foods? DNA in highly processed foods can be fragmented and damaged. Studies show that while autoclaving (thermal treatment with pressure) reduces DNA quality and amplifiability, high hydrostatic pressure (HHP) processing has minimal effect [29]. In such cases, commercial kits optimized for processed foods (like the SureFood PREP Advanced kit) or rapid protocols that employ robust mechanical lysis (e.g., with lysing matrix beads) have demonstrated high sensitivity, detecting down to 10 mg/kg of soybean in complex matrices like sausage and chocolate [25].

Q2: Why is my DNA concentration good according to the spectrophotometer, but my PCR fails? A good concentration with PCR failure often indicates the presence of PCR inhibitors. Common inhibitors include polysaccharides, polyphenols, or carryover salts from the extraction process [31]. To overcome this:

- Check the A260/A230 and A260/A280 ratios. A low A260/A230 ratio suggests salt or organic solvent contamination.

- Dilute the DNA template to reduce the concentration of the inhibitor.

- Use a more thorough purification method, such as an additional chloroform extraction for CTAB preps or a second wash step for column-based kits [30].

- Incorporate a blocker protein like BSA into your PCR mix, which can bind to and neutralize some inhibitors.

Q3: Can I use these methods to extract DNA from refined oils for allergen detection? Yes, but it is challenging. DNA is present in crude and refined oils in very low amounts and is often co-extracted with PCR inhibitors. A study comparing CTAB, a commercial MBST kit, and a manual hexane-based method found that the manual hexane-based method provided DNA of sufficient quality and quantity for successful PCR amplification. The key is effectively separating the DNA from the lipid and inhibitory components [31].

Q4: How does the choice of extraction method impact quantitative allergen detection (qPCR)? The extraction method is critical for reliable quantification. Inconsistent DNA yield or purity between samples will lead to inaccurate results. A study on celery detection found that while commercial DNA kits could detect celery at low levels, quantification was challenging across different food matrices due to matrix effects. This highlights that for quantitative work, the extraction method must be thoroughly validated for the specific food product being tested [26].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 4: Key Reagents and Their Functions in DNA Extraction

| Reagent / Kit | Primary Function | Application Note |

|---|---|---|

| CTAB Buffer | Surfactant that dissociates and precipitates DNA from histone proteins; effective at removing polysaccharides [23]. | The classic, customizable workhorse for difficult plant tissues. |

| Proteinase K | Serine protease that digests proteins and inactivates nucleases. | Essential for efficient lysis; concentration and incubation time may need optimization for different tissues [27]. |

| Silica Membrane Columns | Bind DNA in high-salt conditions; impurities are washed away, and pure DNA is eluted in low-salt buffer. | The core of most commercial kits; provides a good balance of speed, yield, and purity [25] [23]. |

| Lysing Matrix Beads | Mechanically disrupt cell walls through high-speed shaking. | Crucial for efficient lysis of tough food matrices in rapid protocols [25]. |

| Nucleic Acid Releaser | A proprietary reagent that rapidly disrupts cells and releases DNA in a PCR-compatible form. | Enables ultra-fast (<5 min) extraction, ideal for on-site screening, but may be less pure [28]. |

| PVP (Polyvinylpyrrolidone) | Binds to and removes polyphenolic compounds that can co-precipitate with DNA and inhibit enzymes. | A valuable additive to CTAB buffer for polyphenol-rich plant species [23]. |

Workflow & Decision-Making Visualizations

Diagram 1: DNA Extraction Method Selection Workflow

Diagram 2: Method Performance Radar Chart Analogy

For researchers in food safety and allergen detection, obtaining high-quality genomic DNA from processed foods is a significant hurdle. Complex food matrices often contain potent PCR inhibitors like polysaccharides, polyphenols, and fats, which compromise detection sensitivity. The HotShot Vitis protocol, a method derived from plant pathology research for detecting grapevine pathogens, presents an innovative model for addressing these challenges. This case study explores how this rapid, cost-effective DNA extraction technique can be adapted to improve detection efficiency for allergen traces in processed foods, enabling more reliable monitoring and safeguarding public health.

The HotShot Vitis (HSV) method is a modified Hot Sodium Hydroxide and Tris (HotSHOT) protocol specifically optimized for difficult plant tissues [32]. Its core principle involves a two-step chemical process: an alkaline lysis step to release and denature DNA, followed by a neutralization step that renders the DNA suitable for PCR [33] [34].

Key Characteristics and Advantages

- Speed: The HSV method reduces DNA extraction time to approximately 30 minutes, a significant improvement over traditional CTAB methods (2 hours) and comparable commercial kits (40 minutes) [32].

- Cost-Effectiveness: It avoids expensive commercial silica columns and specialized enzymes, relying on common laboratory chemicals [32].

- Effectiveness: Despite its simplicity, the protocol efficiently extracts DNA suitable for amplifying target genes and detecting low-abundance targets, performing comparably to lengthier methods in phytoplasma detection [32].

- Scalability: The basic HotSHOT method is easily scaled to 96-well plates, facilitating high-throughput processing essential for large-scale food monitoring [35].

Experimental Protocol: Adapted HotShot Vitis for Food Matrices

The following methodology is adapted from the research conducted on grapevine tissues and can be tailored for processed food samples [32].

Reagent Preparation

| Solution | Composition | Preparation Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Alkaline Lysis Buffer (pH ~12) | 25 mM NaOH, 0.2 mM Disodium EDTA, 1% (w/v) PVP-40, 0.1% (w/v) SDS, 0.5% (w/v) Sodium Metabisulfite [32] | Add PVP-40 to combat polyphenols. SDS and Sodium Metabisulfite aid in breaking down complex food matrices. Solution is stable for 1-2 months at room temperature [33] [36]. |

| Neutralization Buffer (pH ~5) | 40 mM Tris-HCl [32] [33] | Stable at room temperature for long periods (months to years) [36]. |

Step-by-Step Workflow

- Homogenization: Place up to 500 mg of homogenized processed food sample in a tube with 3 mL of Alkaline Lysis Buffer [32]. For very dense or fatty foods, a pre-wash or defatting step may be necessary.

- Incubation: Transfer a 500 µL aliquot of the homogenate to a microcentrifuge tube. Incubate at 95°C for 10 minutes with mild shaking (e.g., 300 rpm in a thermo-mixer) [32]. This step lyses cells and denatures DNA.

- Cooling: Cool the samples on ice for 3 minutes [32].

- Neutralization: Add an equal volume (500 µL) of Neutralization Buffer. Mix gently and centrifuge at 10,000 × g for 5 minutes at 12°C [32].

- Recovery: Carefully transfer the supernatant to a new tube, avoiding disturbance of the pelleted debris [32].

- Storage: Store DNA extracts at 4°C for immediate use (within a week) or at -20°C for long-term preservation [32].

The following diagram illustrates the streamlined workflow of the adapted HotShot Vitis protocol:

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

The effectiveness of the HotShot Vitis protocol relies on a carefully formulated set of reagents, each serving a specific purpose to counteract inhibitors and ensure DNA quality.

Key Reagents and Their Functions

| Reagent | Function in Protocol | Consideration for Food Analysis |

|---|---|---|

| Sodium Hydroxide (NaOH) | Alkaline agent for cell lysis and DNA release [32] [33]. | Concentration is critical; too high can damage DNA, too low reduces yield. |

| Tris-HCl | Neutralizes the alkaline lysate, creating a pH-stable environment for PCR [32] [33]. | pH must be ~5 to effectively neutralize the lysate (pH ~12) to a PCR-compatible range [36]. |

| Polyvinylpyrrolidone (PVP-40) | Binds polyphenols, preventing them from co-purifying and inhibiting PCR [32]. | Essential for chocolate, spice, or plant-based ingredients high in polyphenols. |

| Sodium Dodecyl Sulfate (SDS) | Ionic detergent that disrupts lipid membranes and solubilizes proteins [32]. | Crucial for breaking down fat-containing and emulsified processed foods. |

| Sodium Metabisulfite (Na₂S₂O₅) | Antioxidant that helps prevent oxidation of phenolic compounds [32]. | Enhances DNA quality from samples prone to oxidative browning. |

| Disodium EDTA | Chelates divalent cations (Mg²⁺), inhibiting DNase activity [32] [33]. | Note: This may require increasing MgCl₂ concentration in the subsequent PCR master mix [33]. |

Technical Support Center

Troubleshooting Guide

This guide addresses common problems encountered when adapting the HotShot Vitis protocol for complex food samples.

| Problem | Possible Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Low DNA Yield | Sample too large for buffer volume [33] [34]. | Ensure sample mass to buffer volume ratio is optimal (e.g., 500 mg per 3 mL buffer [32]). For dense foods, reduce sample input. |

| Incomplete homogenization or lysis. | Increase homogenization time/effort. For tough matrices, extend the 95°C incubation in 5-minute increments (max 15-20 min) [36]. | |

| Excessive fat or fiber content. | Centrifuge homogenate after lysis step to pellet fats/fibers before neutralization [37]. | |

| PCR Inhibition | Polyphenols or polysaccharides carried over. | Increase PVP concentration (1-2% w/v) [32]. Dilute the DNA template 1:5 or 1:10 in the PCR reaction. |

| High fat content. | Perform a defatting step (e.g., with hexane or ether) on the food sample prior to homogenization. | |

| DNA Degradation | Sample contained active nucleases. | Ensure samples are kept on ice during preparation. Add Sodium Metabisulfite to the lysis buffer as per the HSV protocol [32]. |

| Food processing (e.g., high heat, hydrolysis) fragmented DNA. | Target shorter amplicons (<150 bp) in your PCR assays, as they are more likely to be preserved in processed foods. | |

| Inconsistent Results | Incomplete neutralization. | Verify the pH of the final extract; it should be close to neutral. Ensure neutralization buffer is at correct pH (~5) and is added in exact equal volume [36]. |

| Pipetting errors or uneven heating. | Ensure precise pipetting and that all samples are fully submerged in the thermo-mixer during incubation [32]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: Can the HotShot Vitis protocol be used for quantitative PCR (qPCR) applications in allergen detection? Yes. The original study validated the HSV method for FDp detection using two qPCR assays [32]. While the buffer composition may preclude accurate spectrophotometric quantification (e.g., Nanodrop), the DNA is of sufficient quality and purity for reliable qPCR amplification. For quantification, use a fluorescent dye-based method (e.g., Qubit) and standard curves from known allergen concentrations.

Q2: How does this method compare to commercial DNA extraction kits for processed foods? The HotShot Vitis protocol offers a compelling balance of speed (≈30 min), low cost, and high yield. While commercial kits provide high purity, they often give lower DNA yields from difficult samples and are more expensive, which is a constraint for large-scale screening [32]. HotShot Vitis is a robust, cost-effective alternative, though it may require more optimization for novel food matrices.

Q3: What is the most common cause of complete PCR failure with this method? Using too much starting tissue relative to the volume of alkaline lysis reagent is a frequently cited cause of failure [33] [36]. The liquid volume must be sufficient to fully submerge the tissue. If you encounter failure, first try significantly reducing the amount of food sample.

Q4: Can this protocol be automated for high-throughput labs? Absolutely. The original HotSHOT method is "easily scaled up to 96-well plates" [35]. The simple, few-step workflow involving homogenization, heating, and neutralization is ideally suited for automation using liquid handling robots, dramatically increasing throughput for food safety monitoring.

The HotShot Vitis protocol stands as a powerful model for revolutionizing DNA extraction in processed food allergen detection. Its core advantages of speed, cost-efficiency, and effectiveness with inhibitor-rich matrices directly address the critical needs of modern food safety laboratories. By leveraging this adaptable protocol and its associated troubleshooting framework, researchers can enhance the sensitivity and reliability of allergen detection, contributing to safer food supplies and improved public health outcomes.

Troubleshooting Guide: Common Issues in DNA Extraction from Complex Food Matrices

This guide addresses frequent challenges researchers face when extracting DNA for allergen detection from processed foods.

Problem: Low DNA Yield

| Potential Cause | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|

| Incomplete cell lysis due to complex, processed matrix [25]. | • Use a high-speed benchtop homogenizer (e.g., 6.5 m/s for 60 s) with lysing matrix beads and sea sand [25].• For fibrous tissues, extend lysis time or use a more aggressive lysing matrix [38] [39]. |

| Carryover of inhibitors (polysaccharides, polyphenols) from plant material [40]. | • Add Polyvinylpyrrolidone (PVP) to the lysis buffer to adsorb polyphenols [40] [3].• Use a chloroform-isoamyl alcohol purification step post-lysis [25].• Employ high-salt concentration (e.g., 1.4M NaCl) in the CTAB buffer to inhibit polysaccharide co-precipitation [40]. |

| Sample is too old or degraded [38] [39]. | • Use fresh or properly frozen samples. For blood, use unfrozen samples within a week [39].• Flash-freeze plant/animal tissues in liquid nitrogen and store at -80°C [38]. |

Problem: DNA Degradation

| Potential Cause | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|

| Endogenous nuclease activity, common in organ tissues (e.g., liver, pancreas) [38]. | • Process samples rapidly and keep them on ice during preparation [38].• Ensure samples are flash-frozen in liquid nitrogen immediately after collection [38]. |

| Tissue pieces are too large, allowing nucleases to degrade DNA before lysis [38]. | • Cut starting material into the smallest possible pieces or grind under liquid nitrogen before lysis [38]. |

Problem: Co-extraction of PCR Inhibitors

| Potential Cause | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|

| Co-purification of contaminants like salts or heme [38] [39]. | • For salt carryover, avoid touching the upper column area during pipetting and close caps gently to prevent splashing [38].• For hemoglobin precipitates in blood, reduce Proteinase K lysis time or centrifuge to pellet precipitates before purification [38] [39]. |

| Polysaccharide contamination from plant-based foods [40]. | • Use the CTAB extraction method, which is specifically designed to remove polysaccharides [40] [25].• Consider a PEG precipitation step to selectively precipitate DNA while leaving sugars in the supernatant [40]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the most critical step in preparing plant material for efficient DNA extraction? The most critical step is the complete and rapid disruption of the rigid plant cell wall while simultaneously inactivating nucleases and sequestering secondary metabolites like polyphenols and polysaccharides. This is often achieved by grinding the material to a fine powder in liquid nitrogen and immediately using a buffer system like CTAB, which contains additives like β-mercaptoethanol to inhibit oxidation [40].

Q2: How does food processing impact my choice of pre-treatment strategy? Food processing, especially thermal treatment (e.g., baking), can cross-link proteins and DNA with other matrix components (e.g., fats, sugars), making them more difficult to extract [3]. For these challenging matrices, you may need to:

- Increase the extraction temperature (e.g., incubate at 60°C [3]).

- Use a denaturing or high-salt buffer to disrupt interactions. Buffers containing 1M NaCl or fish gelatine have been shown to improve recovery [3].

- Combine physical lysis (bead beating) with aggressive chemical lysis [25].

Q3: Are there any universal pre-treatment strategies for different food matrices? While a single universal method remains elusive, research indicates that a combination of physical homogenization and chemical treatment with a buffer containing additives offers the broadest utility. For multiplex allergen detection, two buffers have shown promising recovery for many allergens across matrices: 50 mM carbonate bicarbonate with 10% fish gelatine, and PBS with 2% Tween, 1 M NaCl, 10% fish gelatine, and 1% PVP [3].

Q4: How can I quickly assess the success of my DNA extraction? The most rapid assessment is to use spectrophotometry (e.g., Nanodrop) to check the concentration (A260) and purity via the A260/A280 and A260/A230 ratios. A low A260/A230 ratio may indicate carryover of salts or organic compounds [38]. For a visual check of DNA integrity, agarose gel electrophoresis can confirm the presence of high-molecular-weight DNA and the absence of degradation [39].

Experimental Protocol: Rapid DNA Extraction for Allergen Detection

This optimized protocol for detecting soybean allergen in processed foods significantly reduces extraction time from overnight to minutes [25].

Method: FastPrep Homogenization and Silica Column Purification

Reagents and Equipment:

- High-speed benchtop homogenizer (e.g., FastPrep-24, MP Biomedicals)

- Lysing Matrix A tubes (MP Biomedicals)

- Commercial silica-based DNA purification kit (e.g., SureFood PREP Advanced, R-Biopharm)

- Proteinase K

- Sea sand (approx. 1.5 mg per sample)

Step-by-Step Procedure:

- Homogenization: Weigh 100 ± 2 mg of homogenized sample material into a Lysing Matrix A tube.

- Lysis: Add 580 µL of the kit's lysis buffer, 20 µL of Proteinase K, one lysis matrix bead, and approximately 1.5 mg of sea sand.

- Mechanical Disruption: Process the sample in the homogenizer at a speed of 6.5 m/s for 60 seconds at ambient temperature.

- Purification: Centrifuge the lysate and transfer the supernatant to a new tube. Complete the DNA purification following the manufacturer's instructions for the silica column kit (e.g., binding, washing, and elution) [25].

Workflow: Pre-treatment for Optimal DNA Extraction

The diagram below outlines the logical decision process for selecting and applying pre-treatment methods.

Research Reagent Solutions

This table details key reagents used in the featured protocols and their specific functions in overcoming extraction challenges.

| Reagent/Chemical | Function in Pre-treatment & Extraction |

|---|---|

| CTAB (Cetyltrimethylammonium bromide) | A cationic detergent effective in lysing plant cells and precipitating polysaccharides while keeping nucleic acids in solution [40]. |

| Polyvinylpyrrolidone (PVP) | Binds to and removes polyphenolic compounds that can co-purify with DNA and inhibit downstream PCR reactions [40] [3]. |

| β-mercaptoethanol | A reducing agent added to CTAB buffer to break disulfide bonds in proteins and inhibit polyphenol oxidation by tannins [40]. |

| Proteinase K | A broad-spectrum serine protease that degrades nucleases and other cellular proteins, facilitating the release of intact DNA [38] [25]. |

| Fish Gelatine | Used as a proteinaceous additive in extraction buffers to compete for binding sites on the matrix, improving the recovery and solubility of allergens [3]. |

| Silica Columns/Magnetic Beads | Solid-phase matrices that bind DNA in high-salt conditions, allowing for efficient washing to remove salts, proteins, and other impurities [40] [25]. |

For researchers in food safety and drug development, the efficient extraction of biomolecules is a critical first step in accurately detecting allergens in processed foods. Complex food matrices, particularly those that are chocolate-based or have undergone thermal processing, present significant challenges. They can trap allergens or introduce interfering compounds that lead to false negatives in immunoassays. The strategic use of buffer additives such as Polyvinylpyrrolidone (PVP), Fish Gelatine (FG), and Sodium Dodecyl Sulfate (SDS) is paramount to overcoming these obstacles. This guide provides targeted troubleshooting and methodologies to optimize your extraction protocols, enhancing the accuracy and reliability of your results for both DNA and protein-based allergen detection.

Core Additives and Their Functions

The following table summarizes the key additives used to optimize extraction buffers for challenging food samples.

Table 1: Key Additives for Optimizing Allergen Extraction Buffers

| Additive | Primary Function | Common Use Cases | Key Mechanism |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fish Gelatine (FG) | Protein-blocking agent; reduces non-specific binding [3] [41]. | Complex, processed matrices; immunoassay quantification [3] [41]. | Saturates binding sites on surfaces and sample components, preventing analyte loss [3] [41]. |

| Polyvinylpyrrolidone (PVP) | Binds and removes polyphenols and other secondary metabolites [40] [42]. | Matrices rich in polyphenols (e.g., cocoa, tea, grapes) [40] [42]. | Prevents oxidation and co-precipitation of polyphenols with DNA/proteins, which can inhibit downstream assays [40] [42]. |

| SDS | Ionic detergent; disrupts lipid membranes and denatures proteins [42]. | General cell lysis; component of Edwards-based DNA extraction method [42]. | Solubilizes membranes and proteins by breaking hydrophobic interactions, releasing cellular contents [42]. |

| NaCl (Sodium Chloride) | Increases ionic strength [3] [42]. | CTAB-based DNA extraction; immunoassay extraction buffers [3] [42]. | Neutralizes charges on molecules like polysaccharides, preventing co-precipitation with DNA and disrupting matrix interactions [3] [42]. |

| BSA & NFDM | Protein-blocking agents [43]. | Reducing non-specific binding (NSB) in ELISA [43]. | Like FG, they saturate hydrophobic surfaces on microplates and sample components to minimize background noise [43]. |

Optimized Experimental Protocols for Allergen Extraction

Protocol 1: Optimized Buffer Formulations for Multiplex Allergen Immunoassay

This protocol is derived from a recent study that successfully recovered 14 specific allergens from challenging incurred food matrices like chocolate dessert and baked biscuits [3] [41].

1. Buffer Preparation: Prepare one of the two optimized buffers identified for broad-spectrum recovery [3] [41]:

- Buffer D (Alkaline Buffer): 50 mM sodium carbonate/sodium bicarbonate with 10% fish gelatine, pH 9.6 [41].

- Buffer J (Neutral Salt Buffer): PBS with 2% Tween-20, 1 M NaCl, 10% fish gelatine, and 1% PVP, pH 7.4 [41].

2. Extraction Procedure:

- Sample-to-Buffer Ratio: Use a 1:10 ratio (e.g., 1 g sample to 10 mL extraction buffer) [3] [41].

- Homogenization: Vortex the mixture for 30 seconds to ensure thorough mixing [3] [41].

- Incubation: Incubate for 15 minutes in an orbital shaker at 60°C and 175 rpm [3] [41].

- Clarification: Centrifuge at 1,250 rcf for 20 minutes at 4°C [3] [41].