Non-Targeted Metabolomics for Food Authentication: A Comprehensive Guide for Researchers and Scientists

This article provides a comprehensive overview of the application of non-targeted metabolomics in food authentication, a critical field for ensuring food safety, quality, and traceability.

Non-Targeted Metabolomics for Food Authentication: A Comprehensive Guide for Researchers and Scientists

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of the application of non-targeted metabolomics in food authentication, a critical field for ensuring food safety, quality, and traceability. Aimed at researchers, scientists, and professionals in drug development and food science, it covers the foundational principles of using metabolic fingerprints to combat food fraud, including origin misrepresentation, species substitution, and adulteration. The scope extends from core concepts and analytical methodologies—highlighting advances in mass spectrometry (MS) and nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR)—to the application of machine learning for data analysis. It further addresses the critical challenges of method validation, harmonization, and quality assurance, while comparing metabolomics with other omics technologies. The goal is to equip professionals with the knowledge to develop, optimize, and implement robust, non-targeted methods for authenticating food in complex global supply chains.

The Principles and Scope of Food Metabolomics in Authenticity

Defining Food Authentication and Its Global Challenges

Food authentication represents a critical frontier in analytical chemistry and food science, employing advanced analytical techniques to verify food product integrity, composition, and origin within increasingly complex global supply chains. This application note examines the foundational principles, methodological approaches, and significant challenges in food authentication, with particular emphasis on the emerging role of non-targeted metabolomics. We provide detailed experimental protocols for metabolite profiling, comprehensive data analysis workflows, and specialized reagent solutions to support implementation in research settings. The escalating economic and public health impacts of food fraud—estimated at $10-15 billion annually—underscore the urgent need for robust, high-throughput authentication technologies that can detect sophisticated adulteration practices and mislabeling across diverse food matrices [1].

Food authentication encompasses the analytical procedures and regulatory frameworks designed to verify that food products conform to their label descriptions regarding composition, origin, processing methods, and quality attributes. It addresses deliberate misrepresentation for economic gain, commonly termed "food fraud," which includes practices such as adulteration (adding unauthorized substances), substitution (replacing valuable ingredients with inferior alternatives), and mislabeling (providing false geographic, species, or quality information) [2] [1]. The fundamental objective of authentication is to protect consumers from health risks, ensure fair trade practices, and maintain trust in food supply chains.

The global significance of food authentication has intensified due to several converging factors: the expansion and complexity of international food supply networks, increasing consumer awareness and demand for premium products with specific attributes (e.g., organic, geographic origin, traditional production), and the escalating economic incentives for fraudulent activities [2] [3]. High-value products such as extra-virgin olive oil, manuka honey, wine, and seafood consistently rank among the most frequently adulterated commodities, with fraudulent practices becoming increasingly sophisticated and difficult to detect through conventional analytical methods [2] [1]. For instance, global sales of manuka honey reportedly reach 10,000 tonnes annually despite only 1,700 tonnes being produced in New Zealand, indicating widespread misrepresentation in the marketplace [1].

Global Challenges in Food Authentication

Economic and Public Health Impact

Food fraud inflicts substantial economic damage and poses serious public health risks worldwide. The economic burden is staggering, with estimates indicating annual global losses between $10-15 billion across the food industry [1]. Beyond financial impacts, adulteration incidents have led to severe health crises, most notably the 2008 melamine contamination of infant formula in China that resulted in 54,000 hospitalizations and 6 infant deaths [1]. These incidents highlight the critical intersection between economic fraud and food safety emergencies, necessitating robust detection and prevention systems.

Table 1: Documented Food Fraud Incidents and Impacts

| Product Category | Type of Fraud | Economic/Health Impact |

|---|---|---|

| Infant Formula | Melamine adulteration | 54,000 hospitalizations, 6 deaths [1] |

| Manuka Honey | Mislabeling as premium product | 10,000 tonnes sold globally vs. 1,700 tonnes produced [1] |

| Olive Oil | Adulteration with cheaper oils | 9 of 20 Italian brands failed quality verification [1] |

| Meat Products | Horsemeat in beef products | €300 million market value drop for Tesco [1] |

| Dried Oregano | Adulteration with other leaves | 19 of 78 samples contained 30-70% foreign matter [1] |

Technical and Regulatory Complexities

The technical landscape of food authentication presents multifaceted challenges. Food matrices exhibit tremendous chemical complexity, with composition variations arising from natural biological diversity, environmental conditions, and processing methods. This complexity is compounded by the globalization of supply chains, where ingredients may traverse multiple countries and processing stages before reaching consumers, significantly complicating origin verification and traceability efforts [2] [4]. Regulatory frameworks struggle to maintain pace with evolving fraudulent practices, often lagging behind emerging threats due to lengthy policy development and implementation cycles [2]. The absence of uniform international standards and enforcement mechanisms further creates vulnerabilities, particularly for products involving numerous jurisdictions with varying regulatory rigor [2] [4].

Non-Targeted Metabolomics in Food Authentication

Theoretical Foundations

Non-targeted metabolomics has emerged as a powerful approach for food authentication by comprehensively analyzing the small molecule metabolites (typically <1500 Da) present in biological samples. Unlike targeted methods that quantify predefined analytes, non-targeted strategies aim to capture global biochemical profiles, enabling detection of unexpected alterations resulting from adulteration, substitution, or misrepresentation [5] [6]. This methodology is particularly well-suited to authentication because the metabolome provides a sensitive record of a food's biological history, reflecting factors such as geographic origin, botanical variety, agricultural practices, and processing methods [5] [3].

The conceptual framework for applying non-targeted metabolomics to food authentication centers on identifying distinctive chemical patterns or "fingerprints" that are characteristic of authentic products. These patterns may derive from environmentally influenced metabolic pathways (the "terroir" effect), species-specific biochemical processes, or production method signatures [5]. By establishing reference metabolomic profiles for authentic materials, researchers can develop classification models capable of detecting deviations indicative of fraud. This approach has demonstrated particular utility for verifying geographic origin—the most prevalent focus in food authentication research—with successful applications across diverse commodities including wine, rice, olive oil, spices, and honey [5].

Analytical Platforms and Workflows

Liquid chromatography coupled with high-resolution mass spectrometry (LC-HRMS) represents the predominant analytical platform for non-targeted metabolomics in food authentication due to its sensitivity, broad dynamic range, and capability to detect diverse chemical classes without derivatization [6] [7]. Common instrumental configurations include Q-TOF (quadrupole time-of-flight) and Orbitrap mass analyzers, which provide the mass accuracy and resolution necessary for confident compound annotation [6] [7]. Effective non-targeted workflows typically incorporate complementary separation techniques, most frequently combining reversed-phase chromatography (for lipophilic compounds) with hydrophilic interaction liquid chromatography (HILIC) for polar metabolites, thereby expanding metabolome coverage [6].

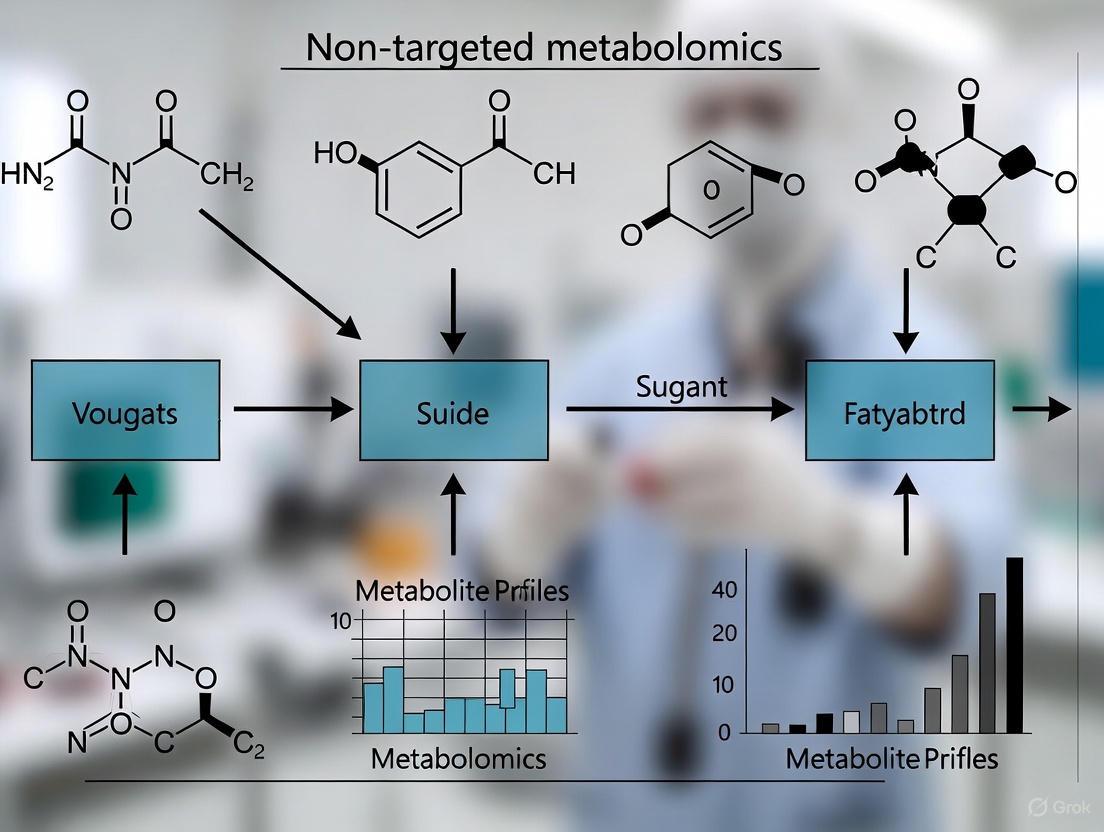

Figure 1: Non-Targeted Metabolomics Workflow for Food Authentication

Experimental Protocols for Non-Targeted Metabolomics

Sample Preparation and Metabolite Extraction

Principle: Effective metabolite extraction is critical for comprehensive metabolome coverage, requiring optimization to capture chemically diverse compounds while minimizing bias and degradation.

Reagents and Materials:

- LC/MS-grade water, acetonitrile, and methanol

- LC/MS-grade formic acid (99.0+%)

- Ammonium formate

- Stable isotope-labeled internal standards (e.g., l-Phenylalanine-d8, l-Valine-d8)

- Analytical balance (precision 0.1 mg)

- Vortex mixer and ultrasonic bath

- Refrigerated centrifuge

- 1.5 mL microcentrifuge tubes

Procedure:

- Weigh 50 mg (±5 mg) of homogenized food sample into a 1.5 mL microcentrifuge tube.

- Add 800 μL of ice-cold extraction solvent (acetonitrile:methanol:formic acid, 74.9:24.9:0.2, v/v/v) containing internal standards (0.1 μg/mL l-Phenylalanine-d8 and 0.2 μg/mL l-Valine-d8).

- Vortex vigorously for 60 seconds until completely mixed.

- Sonicate for 15 minutes in an ice-cold water bath.

- Centrifuge at 14,000 × g for 10 minutes at 4°C.

- Transfer 600 μL of supernatant to a new LC-MS vial.

- Evaporate to dryness under a gentle nitrogen stream at 30°C.

- Reconstitute in 100 μL of starting mobile phase (for HILIC: 90% acetonitrile with 0.1% formic acid; for RP-LC: 95% water with 0.1% formic acid).

- Centrifuge again at 14,000 × g for 5 minutes before LC-MS analysis [6].

LC-HRMS Analysis for Food Authentication

Principle: This protocol describes HILIC-MS analysis optimized for polar metabolites relevant to food authentication, particularly useful for geographic origin discrimination.

Chromatographic Conditions:

- Column: Waters Atlantis HILIC Silica (150 × 2.1 mm, 3 μm)

- Mobile Phase A: 10 mM ammonium formate with 0.1% formic acid in water

- Mobile Phase B: 0.1% formic acid in acetonitrile

- Gradient Program: 0-2 min: 90% B; 2-15 min: 90%→30% B; 15-18 min: 30% B; 18-18.1 min: 30%→90% B; 18.1-23 min: 90% B (re-equilibration)

- Flow Rate: 0.3 mL/min

- Injection Volume: 5 μL

- Column Temperature: 30°C

Mass Spectrometry Conditions (Orbitrap):

- Ionization Mode: Electrospray ionization (ESI) positive and negative modes

- Spray Voltage: +3.5 kV (positive), -2.8 kV (negative)

- Capillary Temperature: 320°C

- Sheath Gas: 40 arbitrary units

- Auxiliary Gas: 15 arbitrary units

- Scan Range: m/z 70-1050

- Resolution: 70,000 (at m/z 200)

- Data Acquisition: Full MS with fragmentation (data-dependent MS/MS) [6] [7]

Data Processing and Chemometric Analysis

Principle: Transforming raw LC-HRMS data into meaningful authentication models requires specialized computational workflows for feature detection, multivariate statistics, and classification.

Software Tools:

- Feature Detection: Compound Discoverer, XCMS, MS-DIAL

- Statistical Analysis: SIMCA-P, MetaboAnalyst, R packages

- Machine Learning: Python scikit-learn, KNIME

Procedure:

- Convert raw files to open formats (mzML, mzXML) using vendor converters or ProteoWizard.

- Perform peak picking and alignment across all samples with retention time correction.

- Annotate metabolites using accurate mass (±5 ppm), isotopic patterns, and MS/MS fragmentation against databases (HMDB, FoodDB, KEGG).

- Normalize data using internal standards and quality control samples.

- Apply Pareto scaling or unit variance scaling to reduce dominance of high-abundance metabolites.

- Conduct unsupervised pattern recognition using Principal Component Analysis (PCA) to identify natural clustering and outliers.

- Apply supervised methods such as Partial Least Squares-Discriminant Analysis (PLS-DA) or machine learning algorithms (random forests, support vector machines) to build classification models.

- Validate model performance through cross-validation (7-fold) and external validation with independent sample sets [6] [7].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Food Metabolomics

| Reagent/Material | Function in Protocol | Application Example |

|---|---|---|

| HILIC Silica Column | Separation of polar metabolites | Geographic origin discrimination of black tea [7] |

| Stable Isotope-Labeled Internal Standards | Quality control & quantification | l-Phenylalanine-d8 for extraction efficiency monitoring [6] |

| Ammonium Formate | Mobile phase additive for improved ionization | HILIC-MS analysis of honey carbohydrates [6] |

| Formic Acid | Mobile phase modifier for protonation | LC-MS analysis of olive oil phenolics [6] |

| Acetonitrile: Methanol Extraction Solvent | Comprehensive metabolite extraction | Polar metabolite profiling from diverse food matrices [6] |

| C18 Reversed-Phase Column | Separation of non-polar metabolites | Lipid profiling for oil authentication [3] |

Application Case Study: Black Tea Geographic Origin Authentication

A recent investigation demonstrated the power of non-targeted metabolomics for authenticating black tea geographical origins. Researchers analyzed 302 black tea samples from 9 distinct geographical indication regions using LC-QToF mass spectrometry. The workflow identified 229-145 metabolite biomarkers that enabled perfect discrimination (100% accuracy) between origins through internal 7-fold cross-validation and external validation [7]. This case exemplifies how non-targeted fingerprinting, coupled with machine learning, can address one of the most challenging authentication problems—multi-class geographical origin discrimination in complex plant-based products.

Figure 2: Black Tea Geographical Origin Authentication Workflow

Non-targeted metabolomics represents a transformative approach to food authentication, offering unprecedented capabilities for detecting sophisticated fraudulent practices across global supply chains. The methodologies and protocols detailed in this application note provide researchers with robust frameworks for implementing these powerful analytical strategies. As food fraud continues to evolve in complexity and scale, further advancements in high-resolution mass spectrometry, computational metabolomics, and multi-omics integration will be essential for developing increasingly sensitive, rapid, and accessible authentication platforms. These technological innovations, coupled with enhanced international collaboration and data sharing, will play a pivotal role in safeguarding food integrity and protecting consumers worldwide.

Metabolomics, defined as the comprehensive analysis of small molecule metabolites in a biological system, has emerged as a powerful tool in food science. In the context of food authentication, it provides a snapshot of the chemical fingerprint of a food product, which is influenced by its geographical origin, production method, and processing techniques [8] [3]. This approach is technically implemented to ensure consumer protection through the strict inspection and enforcement of food labeling, detecting adulterants or ingredients that are added deliberately to compromise the authenticity or quality of food products [8]. The two primary methodological paradigms in this field are untargeted and targeted metabolomics, each with distinct purposes, workflows, and applications.

Foodomics integrates metabolomics with other omics technologies like proteomics and genomics, using advanced biostatistics and bioinformatics to address complex challenges in food authenticity and safety from field to table [3]. The stability and complexity of the metabolome make it an ideal target for distinguishing authentic high-value foods from fraudulent substitutes.

Core Principles and Comparative Analysis

Untargeted Metabolomics

The untargeted approach is a hypothesis-generating methodology that aims to comprehensively analyze all detectable analytes in a sample without prior knowledge of which metabolites will be found [8] [9]. It is considered a "soft" authentication technique because it can detect both known and unknown forms of food fraud without targeting a specific adulterant, making it particularly valuable for detecting emerging and unpredictable fraudulent practices [9]. A key challenge is the immense amount of raw data generated, which requires sophisticated chemometric analysis for interpretation [8].

Targeted Metabolomics

In contrast, targeted metabolomics is a hypothesis-driven approach where the chemical attributes of the metabolites to be analyzed are known before data acquisition begins [8]. Analytical methods are specifically designed and validated to provide high precision, selectivity, and reliability for these predefined compounds [8]. This method leverages established knowledge of metabolic enzymes, their kinetics, and biochemical pathways, allowing for a focused investigation of specific metabolites or pathways of interest [8].

Table 1: Fundamental Characteristics of Untargeted and Targeted Metabolomics

| Feature | Untargeted Metabolomics | Targeted Metabolomics |

|---|---|---|

| Objective | Hypothesis generation, comprehensive profiling, discovery of novel markers [8] | Hypothesis testing, precise quantification of predefined metabolites [8] |

| Scope | Global analysis of all detectable metabolites [8] [9] | Analysis of a predefined set of metabolites [8] |

| Nature | Non-targeted, "soft" authentication method [9] | Targeted, focused analysis |

| Data Complexity | High, requires advanced chemometrics [8] | Lower, focused data analysis |

| Identification Level | Unknowns and knowns, with challenges in annotation [10] [8] | Known metabolites, based on authentic standards |

Table 2: Analytical and Practical Considerations for Metabolomics Approaches

| Consideration | Untargeted Metabolomics | Targeted Metabolomics |

|---|---|---|

| Throughput | High-throughput for screening [11] | Lower throughput, focused analysis |

| Data Processing | Time-consuming; requires advanced tools (e.g., MS-DIAL, Compound Discoverer) [10] [8] | Streamlined, immediate biological interpretation [8] |

| Standardization | Challenging due to comprehensive nature [8] | Easier to standardize and validate |

| Ideal Application | Geographical discrimination, detection of unknown adulterants [10] [3] | Verification of specific adulteration, compliance testing [8] |

Workflow and Experimental Design

The general workflow for metabolomics in food authentication involves several key stages, from sample preparation to data interpretation. The specific requirements, however, diverge significantly between untargeted and targeted strategies.

Figure 1: Comparative Workflows for Untargeted and Targeted Metabolomics

Sample Preparation Protocols

A. Generic Protocol for Untargeted Analysis of Plant Materials (e.g., Herbs and Spices) This protocol is adapted from studies on the geographical discrimination of thyme and other herbs [10].

- Homogenization: Weigh 200.00 ± 0.01 mg of the sample. For solid materials like dried thyme, grind to a fine powder (e.g., 0.2 mm particle size) using an ultra-centrifugal mill to ensure homogeneity [10].

- Extraction: Add 4 mL of chilled, GC-MS grade ethyl acetate to the sample in a 15 mL polypropylene tube.

- Sonication: Place the sample in an ultrasonic bath for 30 minutes at 37 kHz and room temperature to facilitate metabolite extraction [10].

- Centrifugation: Centrifuge the extract at 4400 × g (5500 rpm) for 10 minutes to pellet insoluble debris.

- Filtration: Filter the supernatant through a 0.45 µm nylon filter to remove any remaining particulates.

- Storage: Store the final extract at -21 °C until analysis to preserve metabolite stability.

B. Protocol for Animal Tissues (e.g., Liver or Muscle) This protocol is derived from toxicology and meat quality studies [12] [13].

- Quenching and Homogenization: Snap-freeze approximately 100 mg of tissue in liquid nitrogen and homogenize it to a fine powder using a mortar and pestle, kept cold with liquid nitrogen.

- Protein Precipitation: Resuspend the homogenized powder in 1 mL of pre-chilled 80% methanol. Vortex the mixture thoroughly.

- Incubation: Incubate the homogenate on ice for 5 minutes.

- Centrifugation: Centrifuge at 15,000 × g for 20 minutes at 4 °C to pellet proteins and other macromolecules.

- Dilution: Dilute a portion of the supernatant with LC-MS grade water to a final methanol concentration of 53% [12].

- Second Centrifugation: Centrifuge again at 15,000 × g for 20 minutes at 4 °C.

- Collection: Collect the final supernatant for LC-MS/MS analysis.

Instrumental Analysis and Data Acquisition

The choice of analytical platform is critical and depends on the chosen metabolomics approach.

Untargeted Analysis typically employs High-Resolution Mass Spectrometry (HRMS) coupled with chromatography (LC or GC) to achieve broad metabolite coverage.

GC-Orbitrap-HRMS Protocol for Herbs [10]:

- Instrument: Trace 1310 GC coupled to Q-Exactive Orbitrap mass analyzer.

- Column: Standard capillary GC column.

- Sample Injection: Follows established chromatographic methods for volatile compounds.

- Data Acquisition: Full-scan mode with high mass accuracy (< 5 ppm) to record all detectable ions.

LC-MS/MS Protocol for Animal Tissues [12] [14]:

- Instrument: Vanquish UHPLC system coupled with an Orbitrap Q Exactive HF or HF-X mass spectrometer.

- Column: Hypersil Gold column (100 × 2.1 mm, 1.9 μm).

- Flow Rate: 0.2 mL/min with a 12-minute linear gradient.

- Mobile Phases:

- Positive ion mode: (A) 0.1% formic acid in water, (B) methanol.

- Negative ion mode: (A) 5 mM ammonium acetate (pH 9.0), (B) methanol.

- Ionization: Electrospray Ionization (ESI) in both positive and negative modes.

Targeted Analysis often uses triple quadrupole (QQQ) mass spectrometers operating in Selected Reaction Monitoring (SRM) or Multiple Reaction Monitoring (MRM) mode for high sensitivity and specific quantification of pre-defined metabolite panels.

Data Processing and Analysis

Untargeted Data Processing

The processing of untargeted HRMS data is a key and time-consuming challenge [10]. The workflow involves:

- Feature Extraction: Detecting all ion signals (features) from the raw data, comprising a mass-to-charge ratio (m/z), retention time, and intensity. Software tools like the open-source MS-DIAL and commercial Compound Discoverer are widely used for this purpose [10]. The performance of these tools can vary, leading to different subsets of detected features from the same dataset [10].

- Metabolite Annotation: Assigning a putative identity to features using accurate mass and fragmentation spectra (MS/MS) by querying metabolic databases such as the Human Metabolome Database (HMDB), FoodDB (www.foodb.ca), and MassBank [8] [15]. Confidence levels for identification should be reported (e.g., Level 1: confirmed with standard, Level 2: putative annotation) [10].

- Multivariate Statistical Analysis: Using techniques like Principal Component Analysis (PCA) and Orthogonal Projections to Latent Structures-Discriminant Analysis (OPLS-DA) to identify patterns and metabolites that differentiate sample groups (e.g., different geographical origins) [10] [13].

- Pathway Analysis: Enriching the biological interpretation by mapping differentially abundant metabolites to biochemical pathways using databases like KEGG (Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes) [12] [13].

Targeted Data Processing

Targeted data processing is more straightforward, focusing on:

- Peak Integration: Quantifying the area under the chromatographic peak for each targeted metabolite.

- Quantification: Calculating concentrations by comparing peak areas to a calibration curve created from authentic standards.

- Statistical Validation: Using univariate statistics (e.g., t-tests, ANOVA) to validate hypotheses about specific metabolite changes.

Figure 2: Pathway and Biomarker Analysis Workflow

Application in Food Authentication: A Case Study

Case Study: Geographical Discrimination of Thyme using GC-Orbitrap-HRMS [10]

- Objective: To differentiate thyme samples from Spain (Castilla-La Mancha) and Poland (Lublin) and identify marker metabolites.

- Approach: Untargeted metabolomics.

- Sample Preparation: Ultrasound-assisted extraction with ethyl acetate, as detailed in Section 3.1.A.

- Analysis: GC-Orbitrap-HRMS.

- Data Processing: Both MS-DIAL and Compound Discoverer software were compared for feature extraction and annotation.

- Results:

- The data processing approach significantly influenced the results. Compound Discoverer putatively annotated 52 compounds, while MS-DIAL annotated 115 compounds (both at Level 2 confidence) [10].

- Multivariate data analysis of the data from both software tools successfully identified differential compounds that served as markers for geographical discrimination [10].

- This study highlights that the putative identification of markers in untargeted analysis heavily depends on the data processing parameters and the databases used [10].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Metabolomics in Food Authentication

| Reagent / Material | Function | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| GC-MS Grade Solvents (e.g., Ethyl Acetate) | High-purity extraction solvent for volatile and semi-volatile metabolites, minimizing background interference [10]. | Ultrasound-assisted extraction of herbs and spices (e.g., thyme) [10]. |

| LC-MS Grade Solvents & Additives (Methanol, Water, Formic Acid) | High-purity mobile phase components for LC-MS, essential for stable retention times and high sensitivity [12] [14]. | Metabolite extraction and UHPLC separation of liver or muscle tissue [12] [13]. |

| Authentic Chemical Standards | Unambiguous identification and absolute quantification of metabolites in targeted analyses [8]. | Validation and quantification of potential biomarker molecules. |

| Alkane Standard Mixture (C7-C40) | Calculation of Kovats Retention Indices (KI) in GC-MS, aiding in the identification of metabolites [10]. | Reliable annotation of volatile compounds in herb profiling [10]. |

| Stable Isotope-Labeled Internal Standards (e.g., 13C, 15N) | Correction for matrix effects and losses during sample preparation, improving quantification accuracy [8]. | Used in both targeted and untargeted workflows for data normalization. |

| Protein Precipitation Solvents (e.g., 80% Methanol) | Efficiently deproteinate complex biological samples like tissue or serum, releasing metabolites for analysis [12]. | Preparation of liver tissue extracts for metabolomic profiling [12]. |

Food authentication is a critical scientific frontier in protecting public health, ensuring economic fairness, and combating food fraud, which costs the global economy an estimated $40 billion annually [16]. In an era of increasingly complex and globalized supply chains, verifying key product attributes—geographic origin, production system, and absence of adulteration—is paramount. Non-targeted metabolomics has emerged as a powerful tool for this purpose, capable of detecting unexpected deviations by comprehensively profiling the small-molecule composition of a food sample. This document provides detailed application notes and protocols for using non-targeted metabolomics to address these three primary authentication targets within a research framework.

Non-Targeted Metabolomics Workflow for Food Authentication

The standard non-targeted metabolomics workflow involves a sequence of steps from experimental design through data interpretation. The following diagram illustrates this integrated workflow, highlighting the key stages and decision points.

Figure 1: A generalized workflow for non-targeted metabolomics in food authentication, from sample preparation to model deployment.

Targeted Application Notes and Protocols

Authentication of Geographic Origin

3.1.1 Application Note Geographic origin is one of the most challenging authenticity targets due to the complex "terroir" effect—the interaction of genotype, environment, and agricultural practice that creates a unique biochemical fingerprint in a food product [5]. Non-targeted metabolomics can capture this fingerprint by analyzing a wide range of metabolites. A seminal study on 302 black tea samples from 9 geographical regions successfully used LC-QToF-based non-targeted fingerprinting combined with machine learning to discriminate origins with 100% accuracy in both internal and external validation [7]. This demonstrates the power of the approach to manage complex, multi-class discrimination problems.

3.1.2 Detailed Experimental Protocol

Sample Preparation:

- Materials: Lyophilizer, cryomill, analytical balance, methanol, water, methyl tert-butyl ether (MTBE).

- Procedure:

- Freeze-dry the samples (e.g., tea leaves) to a constant weight.

- Homogenize into a fine powder using a cryomill.

- Precisely weigh 50 mg of powdered sample into a 2 mL microcentrifuge tube.

- Add 1 mL of a pre-cooled methanol/MTBE/water mixture (1.5:5:1.94, v/v/v).

- Vortex vigorously for 1 minute, then sonicate in an ice-water bath for 30 minutes.

- Centrifuge at 14,000 × g for 15 minutes at 4°C.

- Collect the supernatant and filter through a 0.22 µm PVDF syringe filter into an LC-MS vial for analysis.

LC-QToF Analysis:

- Instrumentation: Agilent 1290 Infinity II LC system coupled to an Agilent 6546 QToF mass spectrometer.

- Chromatography:

- Column: ZORBAX Eclipse Plus C18 (2.1 × 100 mm, 1.8 µm).

- Mobile Phase A: Water with 0.1% formic acid.

- Mobile Phase B: Acetonitrile with 0.1% formic acid.

- Gradient: 0-2 min, 5% B; 2-15 min, 5-95% B; 15-18 min, 95% B; 18-18.1 min, 95-5% B; 18.1-20 min, 5% B for re-equilibration.

- Flow Rate: 0.3 mL/min.

- Column Temperature: 40°C.

- Injection Volume: 2 µL.

- Mass Spectrometry:

- Ionization: Dual AJS ESI, positive and negative ion modes.

- Data Acquisition: Full scan mode (m/z 50-1700) and data-dependent MS/MS (Top 10) for biomarker identification.

- Source Parameters: Drying gas temperature 325°C, flow 8 L/min, nebulizer 35 psi, sheath gas temperature 350°C, flow 11 L/min, VCap 3500 V.

Data Processing and Analysis:

- Convert raw data to open formats (e.g., mzML) using tools like ThermoRawFileParser [17].

- Process using software like Metabox 2.0 or XCMS Online for peak picking, alignment, and integration [18].

- For studies requiring high quantitative fidelity, apply the CCMN normalization method followed by square root transformation to best approximate absolute quantitative data [18].

- Export the final peak intensity table for statistical analysis.

Verification of Production System

3.2.1 Application Note The production system (e.g., organic vs. conventional, free-range vs. caged) directly influences a food's metabolite profile due to differences in fertilizer use, animal feed, and overall management practices. Non-targeted metabolomics can detect markers associated with these inputs and stresses. For instance, it can identify the unauthorized use of synthetic fertilizers in products labeled as "organic" or distinguish between different farming practices [19].

3.2.2 Detailed Experimental Protocol

Experimental Design:

- Crucial: Collect paired samples from well-documented organic and conventional production systems, controlling for other variables like geographic location, cultivar, and harvest time.

- Include a sufficient number of biological replicates (recommended n > 10 per group) to ensure statistical power.

Metabolite Profiling:

- The sample preparation and LC-QToF analysis can follow the protocol outlined in Section 3.1.2.

- Focus on specific metabolite classes: The analytical method can be tuned to target specific classes known to be affected by production systems, such as polyphenols, alkaloids, or specific lipids.

Statistical Analysis:

- Perform unsupervised analysis (Principal Component Analysis - PCA) to observe natural clustering and identify potential outliers.

- Use supervised methods like Orthogonal Projections to Latent Structures-Discriminant Analysis (OPLS-DA) to maximize the separation between organic and conventional groups and identify discriminant features.

- Apply false discovery rate (FDR) correction to p-values to account for multiple testing.

- Select features with a Variable Importance in Projection (VIP) score > 1.5 and a p-value (FDR-corrected) < 0.05 as potential biomarkers.

Detection of Adulteration and Substitution

3.2.1 Application Note Adulteration involves the addition of undeclared, inferior, or cheaper substances to a product. Common examples include adding cassava starch to sweet potato vermicelli [20], diluting olive oil with cheaper vegetable oils [16], or misrepresenting the species in meat and seafood products. Non-targeted metabolomics is highly effective here because it does not require a priori knowledge of the adulterant; it can detect unexpected compositional changes.

3.2.2 Detailed Experimental Protocol & Reverse Metabolomics

A powerful emerging strategy for adulteration detection is "reverse metabolomics" [17]. This approach leverages public data repositories to discover adulteration-relevant biomarkers, flipping the traditional workflow.

Figure 2: A comparison of the traditional and reverse metabolomics workflows. Reverse metabolomics begins with known spectra to discover biological or, in this context, adulteration-related associations from public data [17].

- Protocol for Reverse Metabolomics in Adulteration Detection:

- Obtain MS/MS Spectra of Interest: Start with the MS/MS spectrum of a known marker for an authentic product or a suspected adulterant. This can come from in-house libraries or public databases like MassBank or GNPS [17]. Assign a Universal Spectrum Identifier (USI) if possible.

- Mass Spectrometry Search Tool (MASST) Search: Use the MASST tool (or its domain-specific versions like foodMASST) to query public metabolomics data repositories (e.g., MetaboLights, GNPS) for datasets containing the same MS/MS spectrum [17].

- Link Files with Metadata: Use frameworks like the Reanalysis Data User Interface (ReDU) to link the MASST search results (positive data files) with their associated sample metadata (e.g., sample type, disease state, geographic origin, or processing method) [17].

- Validation: Statistically validate the association between the metabolite and a specific sample type (e.g., authentic vs. adulterated) found in the public data by conducting controlled, targeted experiments in the lab.

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 1: Essential Reagents, Materials, and Software for Non-Targeted Metabolomics

| Category | Item | Function / Application |

|---|---|---|

| Chemicals & Solvents | LC-MS Grade Methanol, Acetonitrile, Water | Mobile phase preparation, ensuring minimal background noise and ion suppression. |

| Methyl tert-butyl ether (MTBE) | For lipid-rich sample extraction in biphasic systems. | |

| Formic Acid / Ammonium Acetate | Mobile phase additives to promote protonation/deprotonation in positive/negative ESI mode. | |

| Internal Standards (e.g., Heptanoic methyl ester) | Used for data normalization (e.g., CCMN method) to correct for technical variation [18]. | |

| Consumables | Syringe Filters (PVDF, 0.22 µm) | Filtering sample extracts prior to LC-MS injection to remove particulates. |

| LC Vials and Caps | Safe holding of samples in the autosampler. | |

| Solid Phase Extraction (SPE) Cartridges (C18) | Clean-up of complex samples to reduce matrix effects. | |

| Software & Databases | Metabox 2.0 / XCMS | Data processing pipeline: peak picking, alignment, normalization, and statistical analysis [18]. |

| GNPS (Global Natural Products Social Molecular Networking) | Platform for MS/MS spectral library matching, molecular networking, and performing MASST searches [17]. | |

| FoodMASST | A specialized MASST tool for searching metabolomics data against foods and beverages [17]. | |

| PubChem / HMDB | Chemical databases for metabolite annotation and structural information. |

Data Analysis and Biomarker Workflow

The journey from raw data to robust authentication biomarkers involves a critical feature selection and validation process, as visualized below.

Figure 3: The biomarker selection and validation workflow, which refines thousands of metabolic features into a concise, validated panel for model building [7].

Table 2: Summary of Quantitative Performance from a Non-Targeted Metabolomics Study on Black Tea [7]

| Parameter | Result / Value |

|---|---|

| Sample Size | 302 black tea samples |

| Number of Geographical Origins | 9 regions |

| Metabolites Detected (Features) | 229 - 145 selected as biomarkers |

| Model Validation | 7-fold cross-validation & external validation |

| Reported Discrimination Accuracy | 100% |

Non-targeted metabolomics, supported by robust protocols for geographic origin, production system, and adulteration analysis, provides a comprehensive solution for modern food authentication challenges. The integration of advanced instrumentation, rigorous data processing techniques like CCMN normalization [18], and innovative discovery frameworks like reverse metabolomics [17] creates a powerful toolkit for researchers. As public metabolomics data repositories continue to grow, the potential for developing highly accurate, standardized, and globally applicable authentication models will only increase, ultimately leading to greater transparency and security in the global food supply chain.

The concept of terroir, traditionally associated with wine, refers to the unique combination of environmental factors that give an agricultural product its distinctive character. Scientifically, terroir encompasses the interactive ecosystem of a given place, including climate, soil, topography, and the associated biological communities such as the plant microbiome [21]. Modern metabolomics technologies now allow researchers to move beyond subjective tasting notes and objectively characterize the biochemical signatures imparted by terroir. This is particularly relevant for food authentication research, where non-targeted metabolomics serves as a powerful tool to verify geographical origin and combat fraud by detecting the unique metabolic fingerprints that arise from specific growing conditions [22] [21].

Metabolomics, the large-scale systematic study of small molecules or metabolites, is ideally suited to this task as it provides a snapshot of the physiological state of an organism, bridging the gap between genotype and phenotype [23] [24]. The metabolome is highly dynamic and can be perturbed by biology, phenotype, chemicals, or the environment, making it a sensitive marker for terroir-induced variation [24]. By employing non-targeted approaches, which comprehensively analyze a sample's metabolite profile without prior hypothesis, researchers can uncover the complex ways in which environment shapes food chemistry, thus providing a scientific basis for the terroir concept [25].

Key Metabolomic Findings on Terroir

Metabolic Pathways Influenced by Terroir

Research has consistently shown that specific metabolic pathways are particularly plastic and responsive to environmental conditions. The table below summarizes key pathways and metabolites affected by terroir in various agricultural products, as identified through non-targeted metabolomics studies.

Table 1: Key Metabolic Pathways and Metabolites Influenced by Terroir

| Agricultural Product | Key Metabolic Pathways Affected | Specific Metabolites of Interest |

|---|---|---|

| Grape (Wine) | Phenylpropanoid pathway, Resveratrol biosynthesis, Tricarboxylic Acid (TCA) cycle, Fatty acid metabolism | Anthocyanins, Flavonoids, Tannins, Stilbenes, Organic acids (tartaric, malic) [22] |

| Coffee | Not specified in search results; requires non-targeted profiling | Aromas (Jasmine, Tangerine, Bergamot) linked to volatile organic compounds (VOCs) [21] |

| General Plant Products | Amino acid metabolism, Lipid metabolism, Carbohydrate metabolism | Amino acids (proline, arginine), Sugars (glucose, fructose), Fatty acids, Phenolic acids [22] |

Studies on a single clone of the Corvina grape variety cultivated across different vineyards revealed that the phenylpropanoid pathway, especially resveratrol biosynthesis, was one of the most environmentally-dependent metabolic components [22]. This demonstrates that even without genetic variation, the environment can profoundly shape the phytochemical profile of a crop. Furthermore, environmental stress, such as limited nitrogen or high altitude, can trigger the accumulation of specific compounds like sugars, phenolics, anthocyanins, and tannins, which directly impact product quality and sensory characteristics [21].

The Role of the Plant Microbiome

A critical and often overlooked component of terroir is the plant microbiome. The collective communities of bacteria, fungi, and other microorganisms associated with plant organs (the rhizosphere, endosphere, and phyllosphere) form a holobiont with the host plant [21]. This microbiome contributes to terroir by:

- Altering Host Metabolism: Microbes can increase the nutrients absorbed by roots, which are then deposited in leaves, seeds, and fruits [21].

- Modifying the Metabolome: They can consume plant molecules, thereby removing them, or contribute their own metabolites, which directly add to the smells and flavors of the final product [21].

Advanced metagenomics and metabolomics have made it possible to correlate the diversity of a plant's microbiome with the chemical variation in its derived products, solidifying the microbiome's role as a key contributor to agricultural terroir [21].

Experimental Protocols for Non-Targeted Metabolomics in Terroir Research

This section details a standardized protocol for non-targeted metabolomics, adapted for characterizing the terroir of food products.

Sample Preparation and Metabolite Extraction

Principle: To reproducibly isolate a wide range of small molecules from solid food matrices (e.g., berries, beans, leaves) while minimizing degradation.

Protocol (Based on Grape Berry Metabolomics) [22]:

- Sampling: Collect plant material (e.g., 30 clusters from different positions along vine rows) at the desired physiological stage (e.g., véraison, mid-ripening, full maturity). Avoid damaged or infected tissues.

- Freezing and Grinding: Immediately freeze the selected samples in liquid nitrogen. Prior to extraction, crush and finely grind the frozen material (seeds removed) to a homogeneous powder using a pre-chilled mortar and pestle or a laboratory mill.

- Metabolite Extraction: Extract metabolites at room temperature using a methanol-based solvent.

- Add three volumes (w/v) of methanol acidified with 0.1% (v/v) formic acid to the powdered tissue.

- Sonicate in an ultrasonic bath at 40 kHz for 15 minutes.

- Centrifuge the extract twice for 10 minutes at 16,000 × g at 4°C.

- Dilute the supernatant 1:2 (v/v) with milliQ water.

- Filter the diluted extract through a 0.2-μm syringe filter before instrumental analysis.

Standardized Approach (PTFI Platform) [25]: For greater cross-study comparability, the Partnership for Food Metabolomics Innovation (PTFI) platform uses a standardized protocol involving solid phase extraction (SPE) to isolate small molecules. A key feature is the incorporation of a unique internal retention standard reagent containing 33 compounds not found endogenously in food, which allows for data harmonization across different laboratories.

Instrumental Analysis: LC-HRMS

Principle: To separate, detect, and accurately mass-measure the vast array of metabolites in a complex extract.

- Chromatography: Use Reverse-Phase Liquid Chromatography (RP-LC).

- Column: An analytical C18 column (e.g., 150 × 2.1 mm, 3 μm particle size).

- Mobile Phase: Solvent A (5% acetonitrile, 0.5% formic acid in water) and Solvent B (100% acetonitrile).

- Gradient: Employ a linear gradient, for example: 0-10% B in 5 min, 10-20% B in 20 min, 20-25% B in 5 min, and 25-70% B in 15 min, at a constant flow rate of 0.2 mL/min.

- Mass Spectrometry: Use High-Resolution Mass Spectrometry (HRMS) such as an Orbitrap or FT-MS instrument.

- Ionization: Electrospray Ionization (ESI), alternating between positive and negative ion modes.

- Scanning: Full scan mode in the range of 50-1500 m/z.

- Data-Dependent Acquisition (optional): For metabolite identification, trigger MS/MS or MSn scans for the most intense ions with a defined fragmentation amplitude.

The following workflow diagram summarizes the key steps from sample to data, highlighting the parallel paths for MS1 and MS/MS data, which are crucial for identification in non-targeted studies.

Data Processing and Functional Analysis

Principle: To convert raw spectral data into meaningful biological insights about pathway activity.

- Data Preprocessing: Use software like XCMS, MZmine, or MetaboAnalyst to perform:

- Noise filtering and peak detection.

- Retention time alignment and correction.

- Peak integration and deconvolution.

- Creation of a data matrix (samples × metabolic features with intensities).

- Quality Control: Use Quality Control (QC) samples to monitor and correct for technical variance. Features with high variance in QCs are typically removed.

- Compound Identification & Functional Analysis:

- For MS1 peak lists: Upload a table containing m/z, p-values, and/or t-scores/fold-changes into a tool like MetaboAnalyst. Use algorithms like mummichog to predict pathway activity directly from the m/z features, bypassing the need for complete metabolite identification [26].

- For MS/MS data: Use spectral matching against reference libraries (e.g., MassBank, GNPS) to achieve a higher level of identification confidence (e.g., Level 2 or higher per the Metabolomics Standards Initiative) [23].

Computational Analysis & Data Integration

Non-targeted metabolomics generates complex, high-dimensional data. Effective analysis requires specialized statistical and bioinformatics tools.

- Multivariate Statistics: Techniques like Principal Component Analysis (PCA) and Orthogonal Projections to Latent Structures-Discriminant Analysis (OPLS-DA) are essential for visualizing clustering patterns and identifying the metabolic features that most contribute to the differentiation between terroirs [24] [27].

- Pathway Analysis: Tools like mummichog (in MetaboAnalyst) use a priori knowledge of metabolic pathways to infer biological activity from significant m/z features, providing a functional interpretation of the terroir effect [26].

- Data Integration: Integrating metabolomics data with other omics data (transcriptomics, proteomics) and metadata (soil composition, climate data) is recommended to obtain an exhaustive description of the biological processes underlying terroir [23]. This requires specialized integration algorithms and software.

The diagram below illustrates the logical flow of computational analysis, from raw data to biological interpretation, showcasing how different data types are integrated.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Successful non-targeted metabolomics relies on a suite of reliable reagents and materials. The table below lists essential items for a terroir study based on LC-HRMS.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Non-Targeted Metabolomics

| Item | Function / Purpose | Example / Specification |

|---|---|---|

| LC-MS Grade Solvents | To minimize background noise and ion suppression during MS analysis; essential for high-sensitivity detection. | Acetonitrile, Methanol, Water, Formic Acid (all LC-MS grade) [22] |

| Solid Phase Extraction (SPE) Cartridges | To clean up samples and pre-concentrate metabolites, reducing matrix effects and improving data quality. | Reverse-phase C18 cartridges [25] |

| Internal Standard Mixture | To correct for retention time shifts and enable data harmonization across multiple batches and labs. | PTFI's mixture of 33 nonendogenous compounds [25] |

| Authenticated Chemical Standards | For confident metabolite identification (Level 1 according to MSI) by matching retention time and MS/MS spectrum. | Commercial standards for key metabolites (e.g., resveratrol, malic acid) [23] |

| Quality Control (QC) Pool Sample | To monitor instrument stability, balance analytical bias, and correct for technical noise throughout a run. | A pool created by combining small aliquots of all experimental samples [23] |

| Chromatography Column | To separate a complex metabolite mixture based on chemical polarity, reducing MS complexity and increasing ID confidence. | Reverse-phase C18 column (e.g., 150 x 2.1 mm, 3 μm) [22] |

Non-targeted metabolomics has emerged as a powerful analytical strategy for food authentication, offering a comprehensive snapshot of the complex metabolite profiles in food commodities. This approach is particularly vital for combating economically motivated adulteration in high-value products such as wine, olive oil, honey, spices, and cereals. Unlike targeted methods that focus on predefined compounds, non-targeted metabolomics enables the detection of unexpected adulterants and emerging fraud patterns by analyzing the entire metabolome [28] [29]. This application note provides detailed protocols and data analysis workflows for authenticating these top five commodities of concern, supporting researchers in implementing robust food integrity programs.

Experimental Protocols

Sample Preparation Standards

Universal Metabolite Extraction Protocol:

- Homogenization: Cryogenically grind solid samples (grains, spices) using liquid nitrogen, mortar, and pestle to preserve labile metabolites [30] [31].

- Weighing: Accurately weigh 100±5 mg of homogeneous sample into extraction tubes.

- Extraction: Add 1 mL of cold extraction solvent (80:20 methanol:water with 0.1% formic acid) per 100 mg sample [32] [33].

- Spiking: Introduce internal standards (e.g., creatine-D3, leucine-D3, L-tryptophan-D3) at 0.5 ng/μL final concentration [32] [33].

- Mixing: Vortex vigorously for 60 seconds, then shake for 15 minutes at room temperature.

- Centrifugation: Spin at 18,000× g for 10 minutes at 4°C [32].

- Collection: Transfer 500 μL of supernatant to LC-MS vial for analysis.

Note: For oily matrices (olive oil), prior liquid-liquid extraction with hexane may be required to remove lipids that interfere with analysis [28].

LC-HRMS Non-Targeted Analysis

Chromatographic Conditions:

- Column: HILIC or C18 (e.g., DB-5, 30 m × 0.25 mm × 0.25 μm) [30] [33]

- Mobile Phase A: LC-MS grade water with 0.1% formic acid

- Mobile Phase B: Acetonitrile with 0.1% formic acid

- Gradient: 5-95% B over 25 minutes, hold at 95% B for 5 minutes

- Flow Rate: 0.3 mL/min

- Injection Volume: 5 μL [32] [34]

Mass Spectrometry Parameters:

- Instrument: UPLC-QTOF or UPLC-Orbitrap

- Ionization: ESI positive/negative mode switching

- Mass Range: m/z 50-1000

- Resolution: >30,000

- Collision Energy: 10-40 eV ramp for MS/MS

- Source Temperature: 300°C

- Drying Gas: 8 L/min [32] [34] [33]

Data Processing Workflow

- Raw Data Conversion: Convert vendor files to .mzXML or .netCDF format

- Peak Detection: Use AMDIS or MS-DIAL for peak picking and deconvolution

- Alignment: Correct retention time drift across samples

- Normalization: Apply internal standard and quality control-based correction

- Metabolite Annotation: Query databases (HMDB, MassBank, mzCloud) with mass accuracy <5 ppm [30] [33]

Commodity-Specific Authentication Data

Table 1: Quality Indices and Adulteration Markers in Olive Oil

| Parameter | EVOO Standard | Adulterated/Low Quality | Analytical Method |

|---|---|---|---|

| Free Fatty Acids | ≤0.8% oleic acid | >0.8% oleic acid | Titration (AOCS Ca 5a-40) [28] |

| Peroxide Value | ≤20 meq O₂/kg | >20 meq O₂/kg | Titration (AOCS Cd 8-53) [28] |

| Pyropheophytins | ≤17% | >17% | HPLC-DAD (ISO 29841:2009) [28] |

| Phenolic Compounds | Specific profile | Altered profile | LC-QTOF-MS [35] |

| Fatty Acid Profile | Specific composition | Deviations | GC-FID [28] |

Table 2: Metabolomic Profiling of Cereal Phenolics (μg/g)

| Phenolic Compound | Barley | Corn | Oats | Rice | Rye | Wheat |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Catechin | 1.31-2.38 | 7.36 | 0.56±0.05 | 0-1.39 | + | 0.83-1.79 [31] |

| Quercetin | 0.0004-18.41 | 0.09-1.58 | 10.18±0.06 | 0-1.87 | + | 1.96-10.48 [31] |

| Cyanidin | 0.86-23.93 | 0.6-260.1 | npr | 0-302.22 | 0.29 | 0-7.1 [31] |

| Apigenin | + | + | npr | 1.44-2.85 | 0-1.52 | 20.0-36.5 [31] |

| Ferulic Acid | High | Medium | Medium | High | Medium | High [31] |

+ = present but not quantified; npr = no published results

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

| Reagent/Material | Function | Example Applications |

|---|---|---|

| HILIC Chromatography Column | Polar metabolite separation | Cereal sugars, wine acids [33] |

| C18 Reverse Phase Column | Non-polar metabolite separation | Olive oil phenolics, spice oils [30] [35] |

| Stable Isotope Standards | Quantification & normalization | Absolute metabolite quantification [33] |

| Divinylbenzene/CAR/PDMS Fiber | SPME for volatile capture | Spice aroma profiling [30] |

| Methanol:Water (80:20) | Metabolite extraction | Universal metabolite extraction [32] [33] |

| Quality Control Pool | System performance monitoring | All non-targeted experiments [33] |

Data Analysis and Chemometric Modeling

Statistical Workflow for Authentication

Step 1: Data Preprocessing

- Apply quality control-based robust LOESS signal correction

- Use Pareto or Unit Variance scaling for normalization

- Implement missing value imputation (KNN or minimum value)

Step 2: Exploratory Analysis

- Perform Principal Component Analysis (PCA) to identify outliers and natural clustering

- Generate hierarchical clustering to visualize sample relationships

Step 3: Supervised Modeling

- Develop Partial Least Squares-Discriminant Analysis (PLS-DA) models to maximize class separation

- Apply Orthogonal PLS-DA (OPLS-DA) to separate predictive and non-predictive variation

- Validate models using cross-validation and permutation testing (n>100) [28] [34] [35]

Step 4: Marker Selection

- Calculate Variable Importance in Projection (VIP) scores

- Perform ANOVA with false discovery rate correction

- Assess fold-change thresholds (typically >1.5 or <0.67) [35]

Case Study: Wine Clone Discrimination

Non-targeted UPLC-FT-ICR-MS successfully distinguished wines from three different Vitis vinifera cv. Pinot noir clones grown under identical conditions. The sensory analysis panel detected significant differences in astringency, bitterness, and acidity that correlated with specific non-volatile metabolite profiles. The OPLS-DA model demonstrated excellent separation (R2Y=0.95, Q2=0.87) with 25 molecular features contributing most to discrimination [34].

Case Study: Honey Adulteration Detection

LC-HRMS non-targeted metabolomics identified a specific marker for sugar syrup adulteration in honey that was present in beet, corn, and wheat syrups but absent in authentic honeys. The method demonstrated a limit of quantification of approximately 5% fortification, showing a linear trend in intentionally adulterated samples [32].

Non-targeted metabolomics provides an powerful framework for authenticating high-risk food commodities. The protocols and data analysis workflows presented here enable researchers to implement comprehensive food authentication programs that can detect both known and emerging adulteration practices. Through integration of advanced analytical techniques with robust chemometric modeling, these methods offer the sensitivity, specificity, and breadth needed to address evolving challenges in food fraud prevention.

Analytical Platforms and Data Analysis Strategies

Non-targeted metabolomics has emerged as a powerful analytical strategy for food authentication, enabling the comprehensive detection and identification of metabolites without prior hypothesis [36] [37]. This approach is particularly valuable for addressing food fraud challenges, including mislabeling of geographical origin, species substitution, and detection of undeclared adulterants [3] [37]. The analytical workflow encompasses multiple critical stages, from initial sample collection through to data acquisition and processing, each requiring meticulous execution to ensure data quality and biological relevance. This protocol outlines a standardized workflow specifically tailored for food authentication studies, incorporating recent methodological advances to enhance cross-laboratory reproducibility and data reliability [38].

Experimental Protocols

Sample Preparation and Extraction

Principle: The objective of sample preparation is to extract a comprehensive range of metabolites while maintaining sample integrity and minimizing analytical bias. Proper sample handling is crucial for obtaining metabolomic profiles that accurately represent the food sample's biochemical composition [37].

Protocol Steps:

- Homogenization: For solid food matrices (meat, grains, cheese), rapidly freeze samples in liquid nitrogen and pulverize using a laboratory mill until a fine, homogeneous powder is achieved. For liquid matrices (oil, milk, juice), vortex thoroughly for 30-60 seconds to ensure uniformity [37].

- Metabolite Extraction: Weigh 100 ± 5 mg of homogenized solid sample or aliquot 1 mL of liquid sample into a 2 mL microcentrifuge tube.

- Add 1 mL of pre-chilled extraction solvent (typically methanol:water:chloroform in a 2:1:1 ratio) to simultaneously extract both polar and non-polar metabolites [37].

- Vortex vigorously for 60 seconds, then sonicate in an ice-water bath for 15 minutes.

- Precipitation and Recovery: Centrifuge at 14,000 × g for 15 minutes at 4°C to pellet proteins and insoluble debris. Carefully transfer the supernatant (containing the metabolites) to a new vial.

- Concentration and Reconstitution: Evaporate the solvent to dryness under a gentle stream of nitrogen gas. Reconstitute the dried metabolite extract in 100 µL of solvent compatible with the subsequent analytical method (e.g., water:acetonitrile, 95:5 for LC-MS). Vortex for 30 seconds to ensure complete dissolution.

- Quality Control (QC): Pool equal aliquots from all samples to create a quality control sample. This QC sample is analyzed repeatedly throughout the analytical sequence to monitor instrument performance and stability [38].

Data Acquisition via Liquid Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (LC-MS)

Principle: LC-MS combines chromatographic separation with high-sensitivity mass spectrometric detection, making it the cornerstone platform for non-targeted metabolomics due to its broad coverage of metabolites [39] [36]. The choice between Data-Dependent Acquisition (DDA) and Data-Independent Acquisition (DIA) is a key consideration, as performance is dependent on sample complexity [39].

Protocol Steps:

- Chromatographic Separation:

- Column: Utilize a reversed-phase C18 column (e.g., 2.1 × 100 mm, 1.7 µm) maintained at 40°C.

- Mobile Phase: A) Water with 0.1% formic acid and B) Acetonitrile with 0.1% formic acid.

- Gradient: Employ a linear gradient from 2% to 98% B over 20 minutes, followed by a 5-minute wash at 98% B and a 7-minute re-equilibration at 2% B.

- Flow Rate: 0.3 mL/min.

- Injection Volume: 5 µL.

- Mass Spectrometric Detection:

- Ion Source: Electrospray Ionization (ESI), operated in both positive and negative ionization modes to maximize metabolite coverage.

- Source Parameters: Capillary voltage: 3.0 kV (ESI+), 2.5 kV (ESI-); Source temperature: 150°C; Desolvation temperature: 350°C.

- Mass Analyzer: Time-of-Flight (TOF) mass analyzer for high-resolution and accurate mass measurement.

- Acquisition Mode: Operate in full-scan mode over a mass range of m/z 50-1200 for MS¹ profiling. The decision to use DDA or DIA should be guided by sample complexity. DIA (e.g., MSE, SWATH) fragments all ions within sequential isolation windows, providing comprehensive fragmentation data and is superior when few compounds elute simultaneously. DDA selects the most abundant ions from the MS¹ scan for fragmentation, which can be more effective as ion overlap increases in complex samples [39].

Data Processing and Statistical Analysis

Principle: Raw LC-MS data must be processed to extract meaningful metabolic features, which are then subjected to statistical analysis to identify metabolites that differentiate authentic from adulterated food samples [40] [37].

Protocol Steps:

- Spectral Processing and Feature Detection: Process raw data files using software platforms (e.g., MZmine, XCMS, or the Global Natural Products Social Molecular Networking (GNPS) pipeline). Key steps include:

- Peak picking and deconvolution.

- Retention time alignment and correction using an Internal Retention Time Standard (IRTS) mixture of compounds non-endogenous to food to enable robust cross-laboratory data alignment [38].

- Isotope and adduct annotation.

- Generation of a feature table containing m/z, retention time, and intensity for all detected peaks.

- Multivariate Statistical Analysis: Import the normalized feature table into statistical software (R, Python, or SIMCA-P).

- Unsupervised Analysis: Perform Principal Component Analysis (PCA) to visualize natural clustering and identify outliers.

- Supervised Analysis: Apply Orthogonal Projections to Latent Structures-Discriminant Analysis (OPLS-DA) to maximize separation between pre-defined sample classes (e.g., authentic vs. adulterated) and identify candidate biomarker ions.

- Metabolite Identification and Validation: Query the accurate mass and fragmentation spectra (MS/MS) of significant features against metabolomic databases such as HMDB, METLIN, and FoodDB [36] [37]. Confirm putative identifications by comparing retention times and fragmentation patterns with authentic chemical standards, when available.

Workflow Visualization

The following diagram summarizes the complete analytical workflow for non-targeted metabolomics in food authentication.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

The following table details key reagents, solvents, and materials essential for executing the non-targeted metabolomics workflow for food authentication.

Table 1: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Non-Targeted Metabolomics

| Item | Function/Application in Workflow |

|---|---|

| Internal Retention Time Standard (IRTS) | A proprietary mixture of compounds non-endogenous to food; enables robust chromatographic alignment and cross-laboratory comparison of data [38]. |

| Methanol, Acetonitrile, Chloroform (HPLC/MS Grade) | High-purity solvents used for metabolite extraction and as mobile phases in LC-MS to minimize background noise and ion suppression. |

| Formic Acid (Optima LC/MS Grade) | Mobile phase additive (0.1%) used to promote protonation of analytes in positive ESI mode, improving ionization efficiency and chromatographic peak shape. |

| Water (HPLC/MS Grade) | Used for sample reconstitution and as a mobile phase component; high purity is critical to reduce chemical noise. |

| Reversed-Phase C18 LC Column | The core separation media (e.g., 2.1 x 100 mm, 1.7 µm) for resolving a wide range of metabolites based on hydrophobicity prior to mass spectrometry. |

| Quality Control (QC) Sample | A pooled sample from all test samples used to condition the instrument and injected at regular intervals throughout the run to monitor system stability and performance. |

| Mass Calibration Standard | A reference standard (e.g., sodium formate) used to calibrate the mass axis of the mass spectrometer, ensuring high mass accuracy for metabolite identification. |

Data Presentation: Key Analytical Parameters

The table below summarizes the core quantitative parameters and specifications for the major stages of the LC-MS-based non-targeted metabolomics workflow.

Table 2: Key Parameters for LC-MS-Based Non-Targeted Metabolomics Workflow

| Workflow Stage | Parameter | Specification / Value | Purpose / Rationale |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sample Preparation | Sample Amount | 100 mg (solid); 1 mL (liquid) | Provides sufficient material for comprehensive metabolite extraction. |

| Extraction Solvent | Methanol:Water:Chloroform (2:1:1) | Simultaneous extraction of polar and non-polar metabolites. | |

| LC Separation | Column Type | Reversed-Phase C18 (e.g., 1.7 µm) | High-resolution separation of complex metabolite mixtures. |

| Run Time | ~32 minutes (incl. equilibration) | Balances throughput with sufficient chromatographic resolution. | |

| Mobile Phase | Water/Acetonitrile + 0.1% Formic Acid | Facilitates efficient separation and ionization in ESI-MS. | |

| MS Detection | Mass Analyzer | Time-of-Flight (TOF) | Provides high-resolution and accurate mass data for metabolite identification. |

| Mass Range | m/z 50 - 1200 | Covers a broad range of small molecule metabolites. | |

| Ionization Mode | ESI+ and ESI- | Maximizes coverage of ionizable metabolites. | |

| Data Processing | IRTS | Included in all samples | Enables cross-laboratory chromatographic alignment [38]. |

| Software | MZmine, XCMS, GNPS | For feature detection, alignment, and statistical analysis [40]. |

This application note provides a detailed protocol for an analytical workflow in non-targeted metabolomics, specifically contextualized for food authentication research. The standardized method—from rigorous sample preparation through to advanced data acquisition and processing strategies—ensures the generation of high-quality, reproducible data. The integration of internal standards for cross-laboratory alignment and clear guidelines for handling complex food matrices makes this workflow a robust tool for combating food fraud. By adhering to this structured approach, researchers can reliably identify metabolite markers that are essential for verifying food authenticity, ensuring safety, and protecting consumer interests.

Mass spectrometry (MS) platforms are indispensable tools in modern food authentication research, enabling the precise detection and identification of metabolites that serve as chemical fingerprints for food origin, quality, and authenticity. Non-targeted metabolomics has emerged as a powerful hypothesis-generating approach that comprehensively analyzes small molecule metabolites to distinguish food products based on geographical origin, variety, and production methods [41]. The versatility of MS platforms allows researchers to address complex food fraud challenges through detailed chemical profiling.

The fundamental strength of mass spectrometry lies in its ability to provide both qualitative and quantitative information on a wide range of compounds in complex food matrices. When hyphenated with separation techniques like gas chromatography (GC) and liquid chromatography (LC), MS becomes exceptionally powerful for resolving complex mixtures encountered in food analysis [42] [41]. The continuous advancements in high-resolution mass spectrometry (HRMS) have significantly enhanced these capabilities, providing greater confidence in metabolite identification through accurate mass measurement [43].

This article explores the principal MS platforms used in food authentication research, with a specific focus on their application in non-targeted metabolomics for addressing food integrity challenges. We will examine the complementary strengths of GC-MS and LC-MS systems, the transformative role of high-resolution techniques, and provide detailed application notes and protocols for implementing these methodologies in food authentication research.

The selection of an appropriate MS platform represents a critical decision point in designing food authentication studies. Each platform offers distinct advantages and limitations that must be aligned with research objectives, sample characteristics, and target metabolome coverage.

GC-MS systems excel in separating and analyzing volatile and semi-volatile compounds, making them ideal for aroma profiling and primary metabolite analysis [42]. The technique provides high chromatographic resolution and excellent reproducibility, with electron ionization (EI) generating consistent, library-searchable fragmentation patterns. A key limitation, however, is the requirement for volatile analytes, often necessitating chemical derivatization for non-volatile compounds like sugars, organic acids, and amino acids [44] [45]. This additional sample preparation step can introduce variability but enables coverage of central carbon metabolism intermediates.

LC-MS platforms, particularly those coupled to high-resolution mass spectrometers, offer complementary capabilities for analyzing non-volatile, thermally labile, and high molecular weight compounds without derivatization [46]. This includes important biomarker classes like polyphenols, lipids, and carotenoids that are intractable to GC-MS analysis. The soft ionization techniques employed in LC-MS (electrospray ionization (ESI) and atmospheric pressure chemical ionization (APCI)) primarily generate molecular ion information, with structural characterization achieved through tandem MS experiments [41].

High-resolution mass spectrometry represents a significant advancement, with Orbitrap and time-of-flight (TOF) analyzers providing accurate mass measurements (<5 ppm mass accuracy) that enable confident elemental composition assignment and facilitate the identification of unknown metabolites [43] [41]. The high resolving power (>25,000) allows separation of isobaric compounds that would co-elute on lower resolution instruments, while full-scan data acquisition enables retrospective data mining without re-injection [42].

Table 1: Comparison of Mass Spectrometry Platforms for Food Authentication

| Platform | Mass Analyzer | Resolving Power | Mass Accuracy | Key Applications in Food Authentication | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GC-MS | Quadrupole, TOF | Unit resolution (Quadrupole), >5,000 (TOF) | >100 ppm | Geographical origin discrimination, variety differentiation, volatile profiling | Requires volatility/derivatization, limited to lower molecular weight compounds |

| LC-MS/MS | QqQ, Ion Trap | Unit resolution | >100 ppm | Targeted analysis of specific biomarker classes, adulterant detection | Limited compound identification in untargeted mode |

| GC-Orbitrap | Orbitrap | 25,000-120,000 | <3 ppm | Untargeted analysis for geographical discrimination, marker identification [47] | Higher instrument cost, requires derivatization |

| LC-Orbitrap | Orbitrap | 25,000-240,000 | <3 ppm | Comprehensive lipidomics, polyphenol profiling, food intake biomarker discovery [48] | Higher instrument cost, matrix effects in ESI |

| LC-TOF | TOF | 20,000-60,000 | <5 ppm | Food contaminant screening, metabolite fingerprinting [41] | Requires frequent mass calibration |

The choice between these platforms should be guided by the specific research question. For volatile profiling or central metabolite analysis, GC-MS provides robust, reproducible data. For comprehensive analysis of secondary metabolites and complex lipids, LC-HRMS is indispensable. Many advanced laboratories now employ complementary platforms to maximize metabolome coverage, as the combined data provides a more complete chemical signature for authentication purposes [41].

Detailed Experimental Protocols

GC-Orbitrap-HRMS for Geographical Discrimination of Herbs

This protocol details the application of GC-Orbitrap-HRMS for geographical discrimination of thyme, based on a published case study that demonstrated successful differentiation of Spanish and Polish origins [47].

Sample Preparation:

- Weigh 200.0 ± 0.1 mg of homogenized thyme sample (particle size 0.2 mm) into a 15 mL polypropylene tube.

- Add 4 mL of GC-MS grade ethyl acetate (≥99.5% purity).

- Perform ultrasound-assisted extraction for 30 minutes at 37 kHz and room temperature.

- Centrifuge at 5,500 rpm (4,400 × g) for 10 minutes.

- Filter supernatant through 0.45 μm nylon filters.

- Store extracts at -21°C until analysis.

- Prepare procedure blanks to identify background signals.

Instrumental Analysis:

- System: Thermo Scientific Trace 1310 GC coupled to Q-Exactive Orbitrap mass analyzer.

- Column: BP5MS capillary column (30 m × 0.25 mm i.d., 0.25 μm film thickness).

- Injection: 1 μL with split/splitless injector.

- Carrier Gas: Helium, constant flow.

- Oven Program: Initial temperature 60°C (hold 1 min), ramp to 300°C at 10°C/min, final hold 5 min.

- Transfer Line Temperature: 280°C.

- Ionization: Electron ionization (EI) at 70 eV.

- Mass Resolution: 60,000 at m/z 200.

- Mass Range: m/z 50-500.

- Quality Control: Inject pooled quality control (QC) samples throughout the sequence to monitor system performance.

Data Processing:

- Process raw data using either commercial (Compound Discoverer) or open-source (MS-DIAL) software.

- Perform peak picking, deconvolution, and alignment.

- Annotate metabolites using authentic standards (Level 1 identification) or spectral libraries (Level 2 identification) [47].

- Apply multivariate statistical analysis (PCA, PLS-DA) to identify discriminatory features.

Figure 1: GC-Orbitrap-HRMS Workflow for Food Authentication

LC-HRMS Metabolomic Profiling for Dietary Biomarker Discovery

This protocol describes an untargeted LC-MS/MS approach for discovering biomarkers of dietary patterns, specifically applied to identify plasma biomarkers of Mediterranean diet adherence [48] [49].

Sample Preparation:

- Thaw plasma samples slowly on ice for 30 minutes.

- Aliquot 100 μL of plasma into a clean microcentrifuge tube.

- Add 300 μL of ice-cold methanol for protein precipitation.

- Mix for 10 minutes at 700 rpm.

- Centrifuge at 13,000 × g for 15 minutes at 4°C.

- Filter supernatant through 0.22 μm centrifugal filters at 8,000 × g for 5 minutes.

- Transfer to maximum recovery vials for LC-MS analysis.

LC-MS Analysis:

- System: Dionex Ultimate 3000 UHPLC coupled to LTQ Orbitrap Elite mass spectrometer.

- Column: C18 column (e.g., 150 × 2.1 mm, 1.9 μm).

- Mobile Phase: A) water with 0.1% formic acid; B) acetonitrile with 0.1% formic acid.

- Gradient: 5-95% B over 25 minutes.

- Flow Rate: 0.3 mL/min.

- Column Temperature: 40°C.

- Injection Volume: 5-10 μL.

- Ionization: Heated electrospray ionization (H-ESI) in positive and negative modes.

- Mass Resolution: 60,000-120,000.

- Mass Range: m/z 100-1500.

- Fragmentation: Data-dependent MS/MS for top 10 ions.

Data Processing and Biomarker Panel Development:

- Process raw data using XCMS Online or similar software for peak detection, alignment, and normalization.

- Perform statistical analysis using multivariate methods (PCA, OPLS-DA) to identify differentially abundant features.

- Validate model quality with cross-validation and permutation tests (R2 > Q2).

- Annotate significant features using accurate mass, isotopic patterns, and MS/MS fragmentation.

- Develop biomarker panel through stepwise elimination, selecting 3-5 highly discriminatory metabolites.

- Build logistic regression model to classify dietary adherence and evaluate using ROC curve analysis (AUC >0.8 indicates good performance) [48].

GC-MS Metabolomics for Rice Variety Differentiation

This protocol describes a non-targeted GC-MS approach for discriminating rice varieties based on their seed metabolic profiles [44] [45].

Sample Preparation and Derivatization:

- Grind brown rice seeds to fine powder using a mixer mill.

- Weigh 50 mg into a 2 mL microcentrifuge tube.

- Add 0.5 mL of methanol:chloroform (3:1, v/v) and 10 μL of ribitol (2 mg/mL in water) as internal standard.

- Vortex for 30 seconds, then grind at 45 Hz for 4 minutes.

- Incubate in ice bath for 5 minutes.

- Repeat steps 4-5 three times for complete extraction.

- Centrifuge at 12,000 rpm for 15 minutes.

- Collect 300 μL of polar (upper) phase.

- Dry completely in a centrifugal concentrator for 3 hours.

- Add 60 μL of methoxyamine hydrochloride (20 mg/mL in pyridine) and incubate at 80°C for 30 minutes for methoximation.