Next-Generation Biosensors for Rapid On-Site Allergen Detection: From Nanozymes to AI-Driven Platforms

The global surge in food allergies necessitates the development of rapid, sensitive, and on-site detection systems to ensure food safety and protect consumers.

Next-Generation Biosensors for Rapid On-Site Allergen Detection: From Nanozymes to AI-Driven Platforms

Abstract

The global surge in food allergies necessitates the development of rapid, sensitive, and on-site detection systems to ensure food safety and protect consumers. This article explores the implementation of advanced biosensor systems for allergen detection, moving beyond traditional techniques like ELISA and PCR. We cover the foundational principles of biosensor mechanisms, including electrochemical, optical, and piezoelectric transducers. The review details cutting-edge methodological advances such as nanozyme-based signal amplification, isothermal amplification techniques (e.g., LAMP), and multiplexed platforms for simultaneous detection of key allergens (e.g., Ara h proteins in peanut, Bos d 5 in milk). Furthermore, it addresses critical troubleshooting and optimization strategies, focusing on interfacial chemistry, surface functionalization, and the mitigation of nonspecific binding in complex food matrices. Finally, we provide a comparative analysis of emerging technologies, including AI-enhanced biosensor design and hyperspectral imaging, against conventional methods, evaluating their validation pathways, limits of detection, and scalability for point-of-care use. This comprehensive overview is tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals working at the intersection of food safety, biosensing, and clinical diagnostics.

The Urgent Need and Fundamental Principles of Allergen-Detecting Biosensors

Food allergy has emerged as a critical global public health issue, affecting millions of individuals worldwide and presenting complex challenges for healthcare systems, food industries, and allergic individuals themselves [1]. The condition represents an immune-mediated reaction to specific food proteins, ranging from mild discomfort to life-threatening anaphylaxis [2]. With no curative treatments currently available, the cornerstone of management remains strict avoidance of allergenic foods, making accurate detection and labeling paramount for patient safety [3] [4].

Recent epidemiological data reveals a disturbing upward trend in food allergy prevalence across many regions, compounding the urgency of addressing current diagnostic limitations [5] [1]. Conventional allergen detection methods, while valuable, often require centralized laboratory facilities, trained personnel, and considerable time—creating significant gaps between exposure and risk identification [4] [6]. These challenges are particularly acute in everyday dining settings and food manufacturing facilities where cross-contamination risks persist.

The emergence of biosensor technologies represents a promising frontier in bridging these diagnostic gaps. These systems offer the potential for rapid, sensitive, on-site detection that can empower both consumers and food industry stakeholders to make informed safety decisions [3] [7]. This application note explores the current landscape of food allergy diagnostics within the context of implementing advanced biosensor systems, with particular focus on technical methodologies, reagent solutions, and experimental protocols that can enhance detection capabilities.

Global Epidemiology and Current Diagnostic Landscape

The Rising Global Burden

Food allergy prevalence demonstrates significant geographical variation, with recent studies indicating concerning rates across multiple countries. A comprehensive investigation of 46,572 children and 44,835 adults published by Elsevier in 2023 revealed particularly high rates in China, where 8.71% of children and 8.14% of adults report food allergies [5]. Similar patterns emerge in North America, with Canada reporting 7.35% prevalence in children and the United States at 4.32% in children (though 6.3% in adults) [5]. Globally, approximately 4.3% of the population is affected, with regional variations ranging from 7.6% in US children to 0.61% in Brazil [1].

The most prevalent allergens include peanuts, milk, eggs, fish, shellfish, wheat, soy, and sesame, with peanut and tree nut allergies often persisting into adulthood [1]. Interestingly, allergen patterns vary by region, with shrimp representing the most prevalent allergen in China compared to peanuts, milk, and eggs in other countries [5]. This epidemiological landscape underscores the need for versatile detection systems capable of identifying multiple allergen targets across diverse food matrices.

Table 1: Global Food Allergy Prevalence Data

| Country | Food Allergy Prevalence in Children (%) | Food Allergy Prevalence in Adults (%) | Most Prevalent Allergens |

|---|---|---|---|

| China | 8.71 | 8.14 | Shrimp |

| Canada | 7.35 | 5.36 | Peanuts, milk, eggs |

| Spain | 5.23 | 4.65 | Peanuts, milk, eggs |

| United States | 4.32 | 6.30 | Peanuts, milk, eggs |

| United Kingdom | 4.27 | 4.63 | Peanuts, milk, eggs |

| Japan | 3.90 | 2.10 | Peanuts, milk, eggs |

| France | 3.61 | 2.98 | Peanuts, milk, eggs |

| Italy | 3.04 | 6.59 | Peanuts, milk, eggs |

| Germany | 2.35 | 2.40 | Peanuts, milk, eggs |

Conventional Detection Methods and Limitations

Current allergen detection methodologies primarily encompass protein-based immunoassays, nucleic acid-based techniques, and emerging biosensor platforms [4]. Each approach presents distinct advantages and limitations for various application scenarios:

Table 2: Comparison of Food Allergen Detection Methods

| Method Type | Examples | Detection Limit | Time Required | Key Advantages | Major Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Immunoassays | ELISA, Lateral Flow Immunoassay (LFIA) | ~0.1-5 ppm | 1-3 hours | High sensitivity and specificity; standardized protocols | Susceptible to protein denaturation from processing; requires specific antibodies |

| Nucleic Acid-Based | PCR, Real-time PCR, LAMP | ~1-10 ppm | 1-2 hours | Effective for processed foods; DNA more stable than proteins | Indirect detection; does not correlate directly with allergenicity |

| Mass Spectrometry | LC-MS/MS | ~1-10 ppm | Several hours | High specificity and multiplexing capability | Expensive equipment; requires skilled operators |

| Biosensors | Electrochemical, Optical, Nanomaterial-based | ~0.1-1 ppm | 15-30 minutes | Rapid; potential for on-site use; high sensitivity | Still evolving; standardization challenges |

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) remains the gold standard for quantitative allergen detection due to its high sensitivity, specificity, and potential for standardization [4]. The Codex Alimentarius Commission has formally adopted ELISA for gluten detection, establishing a threshold of 20 mg/kg for "gluten-free" labeling [4]. Similarly, polymerase chain reaction (PCR) methods are valued for detecting allergens in highly processed foods where DNA remains stable despite protein structural denaturation [4]. Germany and Japan have incorporated PCR into official testing methodologies, with Japan setting an allergen threshold of 10 μg/g [4].

However, these conventional methods face significant limitations for on-site application. ELISA requires specialized laboratory equipment, trained personnel, and considerable time (up to 3.5 hours), creating delays in obtaining results [6]. Similarly, PCR demands DNA extraction, amplification, and detection instrumentation ill-suited for field deployment [4]. These limitations highlight the critical need for rapid, portable, and user-friendly detection systems that can provide accurate results in real-world settings.

Biosensing Technologies: Principles and Implementation

Electrochemical Biosensing Systems

Electrochemical biosensors represent a promising technological approach for allergen detection, leveraging signal amplification through redox-active reporters to achieve high sensitivity in compact, low-power devices [3]. The iEAT2 (integrated Exogenous Allergen Test 2) system exemplifies recent advancements in this category, featuring technical breakthroughs including a complete sample processing kit and a novel strategy for multi-electrode measurements enabling simultaneous detection of multiple allergens [3] [7].

This system employs an immunomagnetic approach for allergen retrieval, streamlining sample handling. The assay workflow begins with food matrix disruption in allergen-extraction buffer, followed by mixing with immunomagnetic beads that capture target allergens [3]. Beads are collected via permanent magnet and incubated with detection antibodies conjugated with horseradish peroxidase (HRP), after which an electrochemical readout occurs using a redox-active reporter [3]. The entire protocol completes within 15 minutes—significantly faster than conventional ELISA—and detects allergens at concentrations below established allergic reaction thresholds [3].

A key innovation in the iEAT2 system is its parallel array of two-terminal electrochemical cells, each functioning as an independent current source [3]. This design significantly simplifies electronics and electrical connections compared to conventional three-electrode schemes, enabling scalable multiplexed detection in a compact form factor. Experimental validation confirmed independent electrochemical measurements during simultaneous operation, demonstrating robust performance for detecting gliadin (wheat), Ara h1 (peanut), and ovalbumin (egg white) in real-world food samples [3].

Optical and Microfluidic Platforms

Optical biosensors based on absorption, fluorescence, and surface plasmon resonance (SPR) have emerged as powerful alternatives for food allergen analysis [6]. SPR technology detects binding events between immobilized antibodies and allergens in samples through changes in the refractive index at the sensor chip surface [6]. While SPR systems offer advantages including real-time results, automation, and high surface sensitivity, their implementation has been limited by relatively high costs associated with sophisticated optical components and sensor chips [6].

Microfluidics technology integrated with biosensing platforms addresses several limitations of conventional systems by enabling faster reaction times, reduced sample consumption (5-10 μL versus hundreds in commercial ELISA kits), and enhanced sensitivity through short diffusion distances and high surface tension [6]. A microfluidic ELISA platform combined with a custom optical sensor demonstrated quantitative analysis of wheat gluten and Ara h 1 with assay times reduced to 15-20 minutes compared to 3.5 hours for conventional ELISA [6]. This substantial reduction in analysis time, coupled with minimal reagent requirements, positions microfluidic systems as promising platforms for decentralized allergen testing.

Research Reagent Solutions for Allergen Detection

Successful implementation of biosensor systems for allergen detection requires carefully selected research reagents and materials tailored to specific detection methodologies. The following table outlines essential components for developing and deploying these detection platforms:

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Allergen Biosensing

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function in Detection System | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Immunomagnetic Beads | Dynabeads M-270 Epoxy | Capture and concentrate target allergens from food matrices | Enable sample purification and concentration; 6.7×10^7 beads/mg capacity [3] |

| Detection Antibodies | HRP-conjugated anti-gliadin, biotinylated 2F7 for Ara h 1 | Specific recognition and binding to target allergens | Require validation for specificity and cross-reactivity; conjugation with enzymes for signal generation [3] [6] |

| ELISA Components | Anti-gliadin 14D5, monoclonal 2C12, TMB substrate | Conventional reference method; component in biosensor systems | TMB substrate provides colorimetric/electrochemical signal upon enzymatic reaction [6] |

| Extraction Buffers | Food allergen ELISA kit extraction buffer | Efficient recovery of allergens from complex food matrices | Composition critical for maintaining protein structure and epitope recognition [3] |

| Blocking Agents | Bovine Serum Albumin (BSA) | Reduce non-specific binding in immunoassays | Improve signal-to-noise ratio; concentration optimization required [3] |

| Microfluidic Materials | PDMS (Polydimethylsiloxane) | Fabrication of microfluidic channels and reaction chambers | Biocompatible; gas permeable; suitable for soft lithography [6] |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol for iEAT2 Electrochemical Detection

Principle: This protocol describes the simultaneous detection of multiple food allergens (gliadin, Ara h 1, ovalbumin) using the iEAT2 electrochemical sensing system based on an immunomagnetic detection approach [3].

Materials Required:

- iEAT2 device with 16-electrode array

- Torsion device for food grinding

- Immunomagnetic beads (Dynabeads M-270 Epoxy)

- Allergen-specific detection antibodies (HRP-conjugated)

- Extraction buffer (Food allergen ELISA kit, Morinaga Institute)

- TMB substrate solution

- Permanent magnet for bead collection

- Ultrapure water

Procedure:

- Sample Preparation:

- Grind 0.5 g food sample using torsion device

- Add 9.5 mL extraction buffer and vortex for 30 seconds

- Incubate in boiling water bath for 10 minutes, then cool under running water

- Centrifuge at 3000× g for 20 minutes at room temperature

- Filter supernatant through 0.2 μm membrane syringe filter

Immunomagnetic Capture:

- Mix 100 μL food extract with 50 μL immunomagnetic beads

- Incubate with agitation for 5 minutes at room temperature

- Collect beads using permanent magnet, discard supernatant

- Wash beads twice with 200 μL PBS-Tween buffer

Detection Antibody Incubation:

- Resuspend beads in 50 μL HRP-conjugated detection antibody solution

- Incubate for 5 minutes with agitation

- Collect beads with magnet, discard supernatant

- Wash three times with 200 μL PBS-Tween buffer

Electrochemical Measurement:

- Transfer beads to iEAT2 electrode array

- Add 50 μL TMB substrate solution

- Apply potential and measure current simultaneously across all 16 electrodes

- Record electrochemical signals at 2-minute intervals for 10 minutes

Data Analysis:

- Plot current versus time for each electrode

- Calculate allergen concentration from standard curves

- Apply correction factors for matrix effects when necessary

Validation:

- System detects allergens below established allergic reaction thresholds

- Complete protocol time: 15 minutes from extraction to detection

- Effective identification of cross-contamination in real-world samples [3]

Protocol for Microfluidic ELISA-Based Optical Detection

Principle: This protocol describes the quantitative detection of gluten and Ara h 1 allergens using a microfluidic ELISA platform integrated with an optical sensor, reducing assay time and reagent consumption compared to conventional ELISA [6].

Materials Required:

- PDMS microfluidic chip with four inlets and one outlet

- Gluten (Gliadin) ELISA Kit or Ara h 1 ELISA Kit

- Anti-gliadin antibody 14D5 (for gluten detection)

- HRP-conjugated rabbit anti-gliadin polyclonal antibody

- Monoclonal antibody 2C12 and biotinylated antibody 2F7 (for Ara h 1 detection)

- TMB substrate

- Microfluidic syringe pump or manual dispensing system

- Custom optical sensor setup

Procedure:

- Chip Preparation:

- Fabricate microfluidic chip using standard photolithography and soft lithography

- Create master mold with 80 μm UV-cured SU-8 2025 negative photoresist

- Prepare PDMS chips from master mold

- Functionalize detection chambers with capture antibodies (1 μg/mL in PBS, overnight at 4°C)

Sample Preparation:

- Follow sample preparation steps as in Section 5.1, steps 1-2

- Prepare serial dilutions of extracted samples in PBS

On-Chip Immunoassay:

- Load 5 μL sample solution through inlet port

- Incubate for 5 minutes to allow allergen-antibody binding

- Wash with 10 μL PBS buffer

- Load 5 μL HRP-conjugated detection antibody solution

- Incubate for 5 minutes

- Wash with 10 μL PBS buffer

- Load 5 μL TMB substrate solution

Optical Detection:

- Monitor color development using custom optical sensor

- Measure absorbance at 650 nm at 30-second intervals

- Generate standard curves using known allergen concentrations

- Calculate unknown concentrations from standard curve

Chip Regeneration:

- Flush with glycine-HCl buffer (pH 2.5) to remove bound complexes

- Re-equilibrate with PBS buffer before next use

Validation:

- Assay time: 15-20 minutes (versus 3.5 hours for conventional ELISA)

- Sample/reagent consumption: 5-10 μL (versus hundreds of μL in commercial kits)

- Sensitivity comparable to conventional ELISA with quantitative capability [6]

Future Perspectives and Research Directions

The field of allergen detection continues to evolve rapidly, with several promising research directions emerging. Molecular allergen component testing represents a significant advancement, enabling clinicians to identify specific allergen components and enhance diagnostic precision for personalized immunotherapy approaches [8]. Similarly, the integration of automation and artificial intelligence is revolutionizing allergy diagnostics workflows through automated immunoassay analyzers and AI-assisted data interpretation that reduce manual errors and enhance laboratory productivity [8].

Critical research gaps identified by EFSA's Panel on Genetically Modified Organisms include the need to update in silico tools with targeted databases, better integrate and standardize test materials, and clarify the weight-of-evidence approach for protein safety assessment [9]. Future biosensor development must also address clinical relevance determination through fit-for-purpose databases where allergens are ranked according to clinical significance [9]. Additionally, the influence of food processing on allergen detection requires greater consideration, as industrial processes may denature proteins, generate new antigenic epitopes, or affect antibody recognition [9] [4].

The growing focus on pediatric allergy management underscores the need for diagnostic systems capable of early detection and prevention strategies [8]. Future biosensor platforms should incorporate pediatric-focused testing panels and child-specific allergens to address this vulnerable population's needs. Furthermore, the development of standardized reference materials and validation protocols will be essential for ensuring reliability and comparability across different detection platforms and geographical regions.

As biosensor technologies mature, their integration into food safety management systems will become increasingly seamless, enabling real-time monitoring of production lines and rapid response to contamination events. The convergence of biosensing with digital health platforms may further empower consumers through connected detection systems that provide immediate feedback and documentation of allergen safety. These advancements collectively promise to transform the management of food allergies from reactive avoidance to proactive risk mitigation, ultimately reducing the global burden of this significant public health challenge.

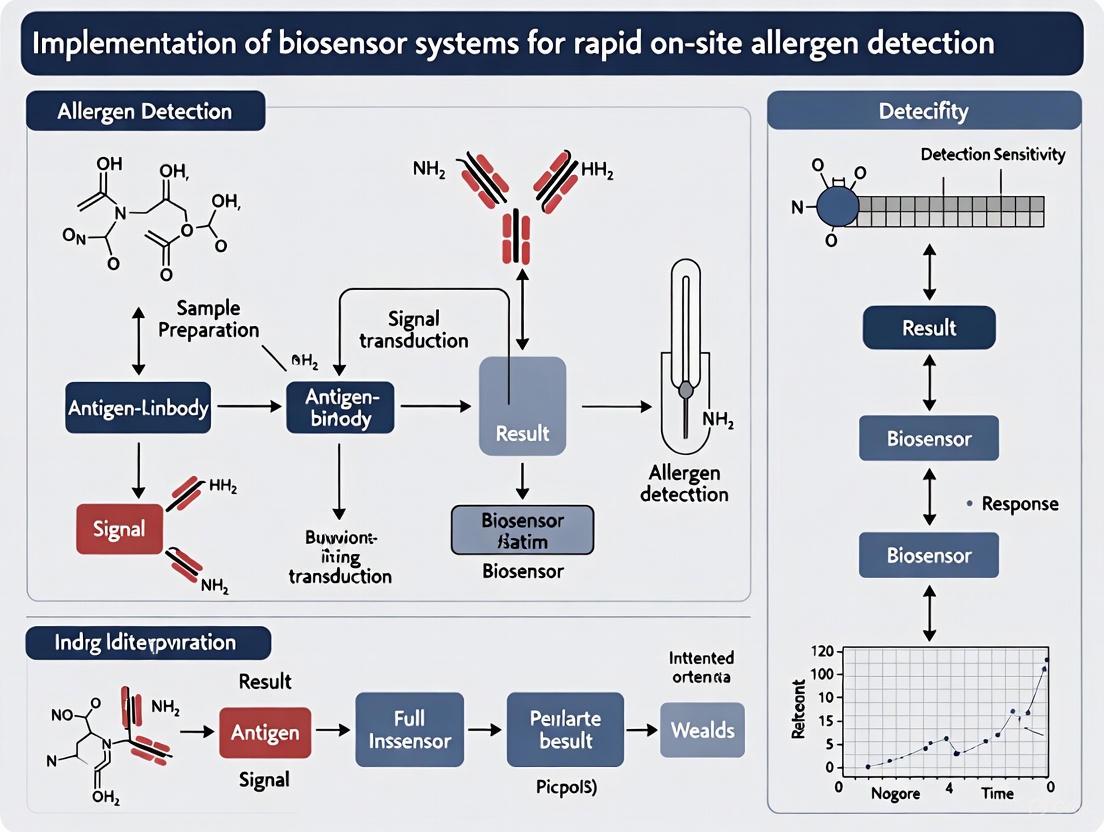

A biosensor is an analytical device that combines a biological recognition element with a transducer to produce a measurable signal proportional to the concentration of a specific analyte [10] [11]. In the context of rapid on-site allergen detection, biosensors offer the exceptional selectivity, sensitivity, and portability required for real-world food safety applications [3] [12]. The fundamental operation involves a bio-recognition event, where a bioreceptor selectively interacts with the target allergen, followed by signal transduction, where this biological interaction is converted into a quantifiable output [10] [13]. The efficient collaboration of these components enables researchers and developers to create powerful diagnostic tools that can be deployed at the point-of-care.

Core Components of a Biosensor

The analytical power of a biosensor stems from the integrated function of its three core components: the bioreceptor, the transducer, and the readout system. The sequential operation of these components transforms a specific biological binding event into an interpretable result.

Bioreceptors: The Molecular Recognition Elements

Bioreceptors are the source of a biosensor's selectivity. They are biological or biomimetic molecules immobilized on the sensor surface that specifically bind to the target analyte [10] [11]. The choice of bioreceptor is paramount, as it determines the specificity and robustness of the detection system, especially critical for distinguishing specific allergenic proteins in complex food matrices [14].

- Antibodies: These proteins generated by the immune system bind to specific epitopes on a target antigen with high affinity. Immunosensors utilize this very specific binding for detection [11]. For instance, a biosensor for the egg allergen ovomucoid (OVM) or peanut allergen Ara h1 would employ anti-OVM or anti-Ara h1 antibodies, respectively [3] [12].

- Enzymes: Enzyme-based biosensors rely on the catalytic activity of enzymes to convert a substrate into a detectable product. The analyte (e.g., an allergen) can be the enzyme's substrate, an inhibitor, or a modulator of its activity [14] [11]. The consumption of a reactant or generation of a product during the reaction is what gets measured.

- Nucleic Acids (Aptamers): Aptamers are single-stranded DNA or RNA oligonucleotides that fold into specific three-dimensional structures capable of binding to a target molecule (e.g., a protein allergen) with high affinity and specificity, similar to antibodies. Their synthetic nature and stability make them attractive alternatives to antibodies in biosensing [11].

- Whole Cells and Tissues: Living microorganisms, organelles, or plant/animal tissues can serve as bioreceptors. They are often used to monitor global parameters like toxicity or stress conditions [11].

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow of a biosensor, from sample introduction to final readout, highlighting the role of each core component.

Transducers: Converting Biological Events into Signals

The transducer is the component that converts the biological recognition event into a measurable signal [10] [13]. The nature of this signal defines the primary classification of biosensors and is a key determinant of their sensitivity and suitability for on-site applications.

- Electrochemical Transducers: These are among the most common and successfully commercialized transducers [13]. They detect electrical changes arising from the bio-recognition event.

- Amperometric: Measures current generated by a redox reaction at a constant applied voltage [10] [3]. The iEAT2 system for allergen detection is a prominent example, where an immunomagnetic assay generates an enzymatic product that is electrochemically oxidized, producing a current [3].

- Potentiometric: Measures the change in potential (voltage) at an electrode surface when the bioreaction occurs [10].

- Impedimetric: Measures the change in electrical impedance (resistance to current flow) of the sensor surface, often used for label-free detection of bacterial cells or proteins [15].

- Optical Transducers: These transducers monitor changes in the properties of light.

- Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR): Detects changes in the refractive index on a sensor surface, which occurs when molecules bind, allowing for real-time, label-free monitoring [10].

- Colorimetric: Detects visible color changes, often enhanced by nanoparticles. The plasmonic biosensor for ovomucoid uses silver nanodome arrays that exhibit visible color shifts upon target binding, enabling spectrometer-free detection [12].

- Fluorometric: Measures the emission of light from fluorescent labels or quantum dots upon excitation. Fluorescence-based biosensors are prized for their high sensitivity [16].

- Mass-Sensitive Transducers: These include piezoelectric devices like quartz crystal microbalances (QCM), which detect the change in resonant frequency of a crystal when mass is adsorbed onto its surface [10] [14].

Table 1: Comparison of Common Biosensor Transducer Types

| Transducer Type | Measured Quantity | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Amperometric | Electric Current | High sensitivity, well-established, portable | Often requires labels or mediators |

| Potentiometric | Potential (Voltage) | Simple instrumentation, wide detection range | Slower response, susceptible to ionic interference |

| Impedimetric | Impedance | Label-free, real-time monitoring, studies binding kinetics | Complex data interpretation, can be non-specific |

| SPR | Refractive Index | Label-free, real-time, high sensitivity | Expensive instrumentation, bulkier systems |

| Colorimetric | Light Absorbance/Color | Simple, low-cost, visible readout (e.g., smartphone) | Can be less sensitive, susceptible to sample turbidity |

| Fluorometric | Fluorescence Intensity | Extremely high sensitivity, multiplexing capability | Requires fluorescent labels, photobleaching possible |

Electronics and Readout: The User Interface

The electronics and display unit form the final component of the biosensor, processing the transduced signal and presenting it in a user-friendly format [10]. This stage involves complex electronic circuitry that performs signal conditioning—such as amplification, filtering, and conversion from analog to digital form [10] [13]. The final readout can be numeric, graphic, or tabular, displayed on a screen, printed, or transmitted wirelessly [10]. For on-site allergen detectors like the iEAT2, the readout is a compact, portable device that quantifies the allergen concentration, often within minutes [3].

Advanced Topic: Experimental Design for Biosensor Optimization

Developing a high-performance biosensor requires systematic optimization of numerous parameters, such as bioreceptor immobilization density, incubation times, and transducer surface chemistry. The traditional "one-variable-at-a-time" approach is inefficient and can miss interactions between variables. Design of Experiments (DoE) is a powerful chemometric tool that addresses this challenge by systematically exploring the entire experimental domain with a minimal number of runs [17].

DoE involves identifying key factors (e.g., pH, temperature, concentration), defining their experimental ranges, and conducting a predetermined set of experiments. The data is then used to build a mathematical model that relates the experimental conditions (inputs) to the sensor's performance (output, e.g., signal intensity). This model can identify not only the individual effect of each factor but also their interaction effects, which are often crucial but overlooked in univariate optimization [17]. For instance, a 2k factorial design is an efficient first-order design to screen for significant factors, while a central composite design can be used to model curvature and find a true optimum [17]. Applying DoE accelerates the development of robust and reliable biosensors for clinical and point-of-care diagnostics.

Application Note: Protocol for Rapid Electrochemical Allergen Detection

This protocol is adapted from the iEAT2 system and related biosensing literature for the simultaneous detection of major food allergens (e.g., gliadin from wheat, Ara h1 from peanut, ovalbumin from egg) [3] [12].

Principle: Target allergens are extracted from a food sample and captured by antibody-conjugated magnetic beads. The bead-allergen complex is then incubated with a secondary antibody conjugated to the enzyme Horseradish Peroxidase (HRP). Upon addition of an electrochemical substrate (e.g., TMB), HRP catalyzes a redox reaction. The resulting current, measured amperometrically, is proportional to the allergen concentration.

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Reagents for Electrochemical Allergen Immunoassay

| Reagent / Material | Function / Role in the Assay |

|---|---|

| Immunomagnetic Beads | Solid support for immobilizing capture antibodies; enable magnetic separation and concentration of the target allergen from the food matrix. |

| Allergen-Specific Antibodies | Bioreceptors that provide high specificity for the target allergen (e.g., anti-gliadin, anti-Ara h1). |

| HRP-Conjugated Detection Antibodies | Generate the measurable signal; bind to the captured allergen and catalyze the electrochemical reaction. |

| Tetramethylbenzidine (TMB) Substrate | An enzymatic substrate for HRP; its oxidized form is electrochemically active and produces a measurable current. |

| Allergen Extraction Buffer | A solution designed to efficiently release allergenic proteins from various food matrices while maintaining their immunoreactivity. |

| Blocking Buffer (e.g., BSA) | Blocks non-specific binding sites on the sensor surface or magnetic beads to reduce background noise and improve signal-to-noise ratio. |

Step-by-Step Workflow

The following diagram outlines the detailed experimental workflow for the electrochemical detection of allergens.

Procedure:

- Sample Preparation: Weigh 1 g of homogenized food sample. Add 10 mL of extraction buffer and vortex vigorously for 5 minutes. Centrifuge at 5,000 g for 5 min to pellet debris. Collect the supernatant containing the soluble allergens [3].

- Immunomagnetic Capture: Incubate 1 mL of the food extract with 100 µL of antibody-conjugated magnetic beads for 10 minutes with constant agitation. This allows the target allergens to bind specifically to the beads.

- Magnetic Separation and Washing: Place the tube on a magnetic rack for 2 minutes to separate the beads from the solution. Carefully aspirate and discard the supernatant. Wash the bead complex twice with 1 mL of wash buffer (e.g., PBS with 0.05% Tween 20) to remove unbound substances.

- Enzyme Labeling: Incubate the washed beads with 100 µL of HRP-conjugated detection antibody for 5 minutes. Perform another magnetic separation and two wash steps to remove unbound detection antibodies.

- Electrochemical Measurement: Resuspend the final bead complex in 200 µL of electrochemical measurement cell containing TMB substrate. Immediately place the cell into the potentiostat and apply a defined reducing potential (e.g., -0.1 V vs. Ag/AgCl). Measure the resulting current.

- Data Analysis: The measured current is proportional to the allergen concentration. Quantify the allergen content by comparing the signal to a standard curve generated with known concentrations of purified allergen.

Performance Metrics

The iEAT2 prototype demonstrated a complete testing protocol within 15 minutes, from allergen extraction to detection, with sensitivities below established allergic reaction thresholds [3]. The system utilized a 16-electrode array for simultaneous detection of multiple allergens, showcasing the scalability of this electrochemical approach.

The deconstruction of a biosensor into its fundamental components—bioreceptor, transducer, and readout—provides a clear framework for research and development in the field of rapid on-site diagnostics. The strategic selection and integration of these elements are critical for achieving the high sensitivity, specificity, and portability required for applications like food allergen detection. As transducer technologies advance and bioreceptor engineering becomes more sophisticated, the potential for developing even more powerful, multi-analyte, and user-friendly biosensing systems becomes immense, promising significant advancements in food safety, clinical diagnostics, and environmental monitoring.

The increasing global prevalence of food allergies represents a critical public health challenge, with current management strategies relying almost exclusively on the avoidance of allergenic foods [18]. This approach creates an urgent need for reliable, sensitive, and specific food allergen detection methods to ensure accurate food labeling and protect consumer safety [4]. For decades, enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) and polymerase chain reaction (PCR) have served as the cornerstone techniques for allergen analysis, forming the basis of many regulatory standards worldwide [4]. However, the evolving complexity of food matrices, advancements in food processing technologies, and increasingly stringent regulatory requirements have exposed significant limitations in these traditional methods [19] [20]. This application note systematically examines the technical constraints of ELISA and PCR platforms within modern allergen analysis workflows. Furthermore, it provides detailed experimental protocols for their implementation and contextualizes the imperative for novel biosensor systems that enable rapid, on-site allergen detection to address these methodological gaps. The transition toward innovative detection platforms is essential for advancing public health goals, improving regulatory compliance, and fostering the development of safer food products for sensitized populations.

Limitations of Traditional Methods

Technical Constraints of ELISA

The ELISA platform, despite its status as a gold standard in protein detection, faces several inherent technical limitations that impact its reliability and applicability in modern allergen analysis. A primary constraint is its narrow dynamic range compared to advanced immunoassays, which can restrict accurate quantification across varying allergen concentrations found in complex food products [19]. Performance is highly dependent on antibody quality, and developing a new ELISA assay can be both costly and time-consuming [19]. Additionally, the technique demonstrates particular vulnerability to matrix effects, especially in challenging samples like urine, but extending to complex food matrices where interfering components can lead to false-positive or false-negative results [19] [20]. This is compounded when food undergoes processing, as the structure of allergenic proteins can be damaged, altering antibody-binding epitopes and reducing detection accuracy [4]. While the CAC has adopted ELISA for gluten detection with a threshold of 20 mg/kg, the method's limitations necessitate careful consideration of its appropriate application [4].

Inherent Shortcomings of PCR

PCR, as a widely used nucleic acid-based method, provides an indirect approach to allergen detection by targeting allergen-encoding DNA sequences. Although it is particularly suitable for detecting highly processed allergenic foods where protein integrity may be compromised but DNA remains stable, this very principle constitutes a significant drawback [4]. The fundamental limitation is that PCR does not detect the allergenic protein itself, which is the actual molecule responsible for eliciting allergic reactions [4]. This disconnection between the marker (DNA) and the hazard (protein) can lead to discrepancies in risk assessment. Furthermore, PCR is not suitable for identifying allergen proteins with unascertained genes, which limits its scope of application [20]. The technique also typically requires stringent sample preparation, a larger sample volume, and longer analysis times, resulting in higher operational costs [20].

Comparative Analysis: ELISA vs. PCR

Table 1: Comparative analysis of ELISA and PCR for allergen detection.

| Parameter | ELISA (Protein-Based) | PCR (DNA-Based) |

|---|---|---|

| Target Molecule | Allergenic proteins (direct detection) | DNA encoding allergenic proteins (indirect detection) |

| Effect of Food Processing | Protein structure damage causes reduced detection [4] | DNA stability allows detection in processed foods [4] |

| Specificity | High, but dependent on antibody quality [19] [20] | High for specific DNA sequences [20] |

| Sensitivity | High (e.g., CAC gluten threshold: 20 mg/kg) [4] | High (e.g., Japan's threshold: 10 µg/g for some allergens) [4] |

| Key Limitation | Susceptible to epitope denaturation; matrix effects [19] [20] [4] | Does not detect the pathogenic protein; limited to known genes [20] [4] |

| Cost per Analysis | Higher cost (e.g., ~$61.53 for 4 inflammatory biomarkers) [19] | Generally high due to instrumentation and reagents [20] |

Economic and Operational Constraints

Beyond technical limitations, both ELISA and PCR present significant economic and operational challenges in routine analytical settings. Measuring a panel of four inflammatory biomarkers (IL-1β, IL-6, TNF-α, and IFN-γ) using individual ELISAs costs approximately $61.53 per sample [19]. In contrast, employing a multiplexed assay like Meso Scale Discovery (MSD) reduces the cost to $19.20 per sample, yielding a substantial saving of $42.33 per sample and highlighting the economic inefficiency of traditional single-plex approaches [19]. Furthermore, both techniques generally require centralized laboratory settings, sophisticated instrumentation, and trained personnel, rendering them unsuitable for rapid, on-site decision-making in production facilities or supply chain checkpoints [20] [21]. This lack of portability and lengthy turnaround times creates critical bottlenecks in quality control and hazard analysis, ultimately impacting consumer safety and regulatory compliance.

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Sandwich ELISA for Allergen Quantification

Principle: This protocol describes the quantification of a specific allergenic protein (e.g., β-lactoglobulin from milk) using a sandwich ELISA. The method relies on two specific antibodies: a capture antibody immobilized on a microplate and a detection antibody conjugated to an enzyme (e.g., Horseradish Peroxidase, HRP). The target allergen is sandwiched between them, and the enzyme catalyzes a colorimetric reaction proportional to the allergen concentration [4].

- Workflow Diagram: Sandwich ELISA Protocol

Materials:

- Microplate: 96-well plate, high protein-binding capacity.

- Antibodies: Monoclonal or polyclonal capture antibody specific to the target allergen (e.g., β-lactoglobulin), detection antibody specific to a different epitope of the target allergen, conjugated to HRP.

- Allergen Standard: Purified, quantified target allergen for standard curve generation.

- Buffers: Coating buffer (e.g., carbonate-bicarbonate, pH 9.6), Phosphate-Buffered Saline with Tween (PBST) for washing, blocking buffer (e.g., 1-5% BSA or non-fat dry milk in PBST).

- Substrate: TMB (3,3',5,5'-Tetramethylbenzidine) or other HRP-compatible chromogenic substrate.

- Stop Solution: 1-2 M Sulfuric acid (H₂SO₄).

- Equipment: Microplate reader capable of measuring absorbance at 450 nm, microplate washer (optional), analytical software.

Procedure:

- Coating: Dilute the capture antibody in coating buffer to a predetermined optimal concentration (typically 1-10 µg/mL). Add 100 µL per well to the microplate. Seal the plate and incubate overnight at 4°C.

- Washing: Aspirate the coating solution and wash the plate three times with ~300 µL of PBST per well. Blot the plate on absorbent paper to remove residual liquid.

- Blocking: Add 200 µL of blocking buffer to each well. Incubate for 1-2 hours at room temperature (or 37°C). Repeat the washing step as in (2).

- Sample & Standard Addition: Prepare a serial dilution of the allergen standard in an appropriate buffer. Dilute food sample extracts in the same buffer. Add 100 µL of each standard, sample, and blank (buffer only) to designated wells in duplicate. Incubate for 1-2 hours at room temperature. Wash the plate three times.

- Detection Antibody Addition: Dilute the HRP-conjugated detection antibody to the recommended concentration in blocking buffer. Add 100 µL to each well. Incubate for 1-2 hours at room temperature. Wash the plate three times.

- Signal Development: Add 100 µL of TMB substrate solution to each well. Incubate in the dark for 15-30 minutes at room temperature, monitoring for color development.

- Reaction Stopping: Add 50 µL of stop solution to each well. The blue color will turn yellow.

- Measurement & Analysis: Measure the absorbance at 450 nm within 30 minutes using a microplate reader. Generate a standard curve (absorbance vs. log concentration) and calculate the allergen concentration in the unknown samples.

Protocol 2: Real-Time PCR for Allergen Gene Detection

Principle: This protocol detects and quantifies the presence of DNA sequences specific to an allergenic food (e.g., peanut, hazelnut). Real-time PCR (qPCR) utilizes sequence-specific primers and a fluorescent probe (or DNA-binding dye) to amplify and monitor the accumulation of the target DNA in real-time. The cycle threshold (Ct) value is used for qualitative or quantitative analysis [22] [4].

- Workflow Diagram: qPCR Protocol

Materials:

- DNA Extraction Kit: Commercial kit suitable for complex food matrices.

- qPCR Reagents: Master mix containing DNA polymerase, dNTPs, and buffer. MgCl₂ may be required separately.

- Oligonucleotides: Forward and reverse primers specific to the target allergen gene (e.g., Ara h 2 for peanut). A fluorescently labeled probe (e.g., TaqMan) is recommended for superior specificity.

- DNA Standards: Genomic DNA from the pure allergenic food for creating a standard curve (for quantitative analysis).

- Equipment: Real-time PCR instrument, microcentrifuge, thermal cycler, spectrophotometer or fluorometer for DNA quantification.

Procedure:

- DNA Extraction: Extract genomic DNA from the test food sample and a positive control (known allergenic food) using a commercial kit. Follow the manufacturer's instructions, which typically involve cell lysis, binding of DNA to a column, washing, and elution. Quantify the DNA concentration and assess purity (A260/A280 ratio).

- qPCR Reaction Setup: Prepare a master mix on ice. For a 20 µL reaction: 10 µL of 2x qPCR master mix, 0.5 µL each of forward and reverse primer (10 µM), 0.5 µL of probe (10 µM), and nuclease-free water to bring the volume to 18 µL per reaction. Mix gently. Aliquot 18 µL of the master mix into each well of a qPCR plate. Add 2 µL of template DNA (sample, standard, or no-template control - NTC) to each respective well. Seal the plate with an optical adhesive film and centrifuge briefly.

- qPCR Run Program: Place the plate in the real-time PCR instrument. Set the thermal cycling conditions as follows:

- Initial Denaturation: 95°C for 10 minutes (for polymerase activation).

- Amplification (40-45 cycles):

- Denature: 95°C for 15 seconds.

- Anneal/Extend: 60°C for 1 minute (acquire fluorescence at this step).

- Data Analysis:

- Qualitative Analysis: Set a fluorescence threshold within the exponential phase of amplification. A sample is considered positive if its Ct value is less than a predefined limit (e.g., 35-40) and the NTC shows no amplification.

- Quantitative Analysis: Use the serial dilutions of the standard DNA to generate a standard curve (Ct vs. log DNA quantity). The instrument's software will interpolate the quantity of target DNA in the unknown samples from this curve.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Successful implementation of traditional and next-generation allergen detection methods relies on a suite of specialized reagents and tools. The following table details key components essential for research in this field.

Table 2: Key research reagents and materials for allergen analysis.

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|

| Monoclonal/Polyclonal Antibodies | Core recognition element in immunoassays like ELISA [4]. | High specificity and affinity for a single (monoclonal) or multiple (polyclonal) epitopes on the target allergen. |

| Nucleic Acid Aptamers | Synthetic oligonucleotide recognition probes in biosensors [20] [23]. | High stability, facile synthesis/modification, and target versatility (proteins, small molecules). |

| TMB (3,3',5,5'-Tetramethylbenzidine) | Chromogenic enzyme substrate for HRP in ELISA [4]. | Yields a measurable color change (blue to yellow upon stopping) proportional to the target concentration. |

| PCR Primers & Probes | Amplify and detect specific DNA sequences from allergenic sources [4]. | Sequence-specificity is critical for accurate detection; often target multi-copy genes for sensitivity. |

| U-PLEX Multiplex Assay Plates | Simultaneous measurement of multiple protein biomarkers [19]. | Customizable panels enhance efficiency and reduce sample volume requirements compared to ELISAs. |

| Magnetic Beads (Functionalized) | Solid support for immunocapture or aptamer immobilization in automated systems [4]. | Enable separation and concentration of targets from complex matrices, improving sensitivity. |

The Pathway Forward: Bridging to Biosensors

The documented limitations of ELISA and PCR create a compelling case for the development and adoption of alternative technologies. Aptamer-based biosensors represent a promising avenue, offering the specificity of molecular recognition with the potential for rapid, on-site deployment. Aptamers, single-stranded DNA or RNA oligonucleotides selected for high-affinity binding to specific targets, present advantages over antibodies, including superior stability, easier modification, and lower production costs [20]. When coupled with transducers like electrochemical, optical (fluorescence), or SERS (Surface-Enhanced Raman Scattering) platforms, these biosensors can achieve high sensitivity and specificity. A meta-analysis of aptamer-based biosensors for SARS-CoV-2 detection, for instance, demonstrated that a SERS platform achieved a sensitivity of 0.97 and a specificity of 0.98, highlighting the potential diagnostic accuracy of such technologies for allergen detection [23].

The future of allergen analysis lies in the integration of these novel biosensing platforms with microfluidics for sample handling, connectivity for data transfer, and artificial intelligence for data interpretation and risk prediction [21]. These innovations are poised to transition allergen detection from a centralized, slow process to a decentralized, rapid, and data-rich practice, ultimately enhancing food safety and quality of life for allergic consumers.

The accurate and rapid detection of specific allergenic proteins in food products is a critical component of public health strategies to prevent severe allergic reactions. For individuals with food allergies, the only effective management strategy remains strict avoidance of the offending allergens, making reliable food labeling essential [24]. This document frames the detection of three major allergen targets—Ara h 1 (peanut), Gal d 3 (egg), and Tropomyosin (shellfish)—within the broader context of implementing advanced biosensor systems for rapid on-site analysis. The protocols herein are designed for researchers and scientists developing next-generation diagnostic tools that offer advantages in speed, sensitivity, and portability over conventional methods like ELISA [25].

Key Allergen Targets and Biosensor Performance

The "Big Eight" allergenic foods account for the majority of significant allergic reactions worldwide. Among these, peanut, egg, and crustacean shellfish are notably prevalent and are associated with severe, potentially life-threatening anaphylaxis [24]. The following table summarizes the primary allergen targets discussed in this document and the performance of biosensors developed for their detection.

Table 1: Key Allergen Targets and Analytical Performance of Biosensing Platforms

| Allergen Target | Source Food | Biosensor Platform | Linear Detection Range | Limit of Detection (LOD) | Assay Time | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ara h 1 | Peanut | Voltammetric Immunosensor (CdSe@ZnS QDs) | 25 – 1000 ng·mL⁻¹ | 3.5 ng·mL⁻¹ | 1 hour | [26] |

| Ara h 1 | Peanut | Electrochemical Immunosensor (PrNbO₄/f-CNF) | 0.0062 – 620 fg·mL⁻¹ | 0.0029 fg·mL⁻¹ | Information Missing | [27] |

| Tropomyosin | Shrimp/Crab | Electrochemical Immunosensor (ALP/3-IP/AgNO₃) | 2.5 – 20 ng·mL⁻¹ | 1.7 ng·mL⁻¹ | 2 hours 50 min | [28] |

| Tropomyosin | Shrimp/Crab | Colorimetric Aptasensor (AuNPs) | 10 – 200 nmol/L | 40 nmol/L (in buffer) | Information Missing | [29] |

| Gal d 3 (Ovotransferrin) | Hen's Egg | Amperometric Immunosensor (HRP/TMB) | 55 – 1000 ng·mL⁻¹ | 16 ng·mL⁻¹ | 30 min | [30] |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Voltammetric Immunosensor for Peanut Allergen Ara h 1

This protocol details the construction of a sandwich-type electrochemical immunosensor for Ara h 1 using quantum dots as an electroactive label, achieving detection in a one-hour assay [26].

Workflow Diagram: Ara h 1 QD Immunosensor

Materials and Reagents

- Transducer: Bare Screen-Printed Carbon Electrodes (SPCEs), DRP-110 [26].

- Capture & Detection Antibodies: Monoclonal anti-Ara h 1 antibodies (clone 2C12 for capture; biotinylated clone 2F7 for detection) [26].

- Electroactive Label: Core/shell CdSe@ZnS Quantum Dots conjugated with streptavidin (e.g., Qdot 655) [26].

- Buffers:

- 0.1 M Tris-HCl buffer, pH 7.4 (for biomolecule preparation).

- Tris-Tween 20 wash buffer, pH 7.4.

- 0.1 M Acetate buffer, pH 4.5, containing 1.0 mg·L⁻¹ Bi(III) for stripping analysis.

- Chemical Reagents: Hydrochloric acid (HCl) for QD dissolution.

Step-by-Step Procedure

- SPCE Biomodification: Physically adsorb 10 µL of monoclonal capture antibody onto the SPCE's working electrode. Incubate overnight at 4°C in a humidified chamber [26].

- Surface Blocking: Wash the electrode with Tris buffer. Apply 40 µL of a 2% (m/V) Bovine Serum Albumin (BSA) solution and incubate for 30 minutes at room temperature to block non-specific binding sites. Wash again [26].

- Target Capture and Detection: Pre-mix the sample/standard solution containing Ara h 1 with the biotinylated detection antibody for 10 minutes. Apply 40 µL of this mixture to the SPCE and incubate for 60 minutes. Wash to remove unbound material [26].

- Quantum Dot Labeling: Incubate the SPCE with streptavidin-coated CdSe@ZnS QDs for a specified time to allow binding to the biotinylated detection antibody. Perform a final wash step [26] [24].

- Electrochemical Detection:

- Dissolve the QD labels by adding a drop of HCl to release Cd²⁺ ions.

- Transfer the SPCE to the acetate buffer containing Bi(III).

- Perform Differential Pulse Anodic Stripping Voltammetry (DPASV):

- Preconcentration/Deposition: Apply a negative potential to reduce Cd²⁺ to metallic Cd(0) onto the SPCE surface, forming a Bi-Cd alloy.

- Stripping Step: Apply a positive potential scan. The anodic stripping current peak at approximately -0.9 V is proportional to the Ara h 1 concentration [26].

Protocol 2: Colorimetric Aptasensor for Shrimp Tropomyosin

This protocol describes a label-free aptasensor using gold nanoparticles (AuNPs) and a tropomyosin-binding aptamer for visual detection of the shrimp allergen, ideal for point-of-need testing [29].

Workflow Diagram: AuNP Aptasensor for Tropomyosin

Materials and Reagents

- Gold Nanoparticles (AuNPs): Citrate-capped AuNPs, ~13 nm diameter [29].

- Aptamer: Tropomyosin-binding aptamer, a single-stranded DNA (ssDNA) sequence [29].

- Salt Solution: Sodium Chloride (NaCl) at a concentration sufficient to induce aggregation in unprotected AuNPs.

- Buffers: Appropriate buffer for reconstituting the aptamer and diluting the TM standard/sample.

Step-by-Step Procedure

- Aptamer-AuNP Complex Formation: Incubate the tropomyosin-binding aptamer with the colloidal AuNPs solution. The ssDNA adsorbs onto the AuNP surface, protecting them from salt-induced aggregation [29].

- Sample Incubation: Add the sample or standard containing Tropomyosin to the Aptamer-AuNP complex. If TM is present, the aptamer binds to its target, folding into a specific tertiary structure and desorbing from the AuNP surface [29].

- Salt-Induced Aggregation and Readout: Add a predetermined concentration of NaCl to the mixture and allow it to incubate briefly.

- Positive Result (TM present): The AuNPs are less stabilized due to aptamer desorption. They aggregate in the salt solution, causing a color change from wine-red to purple or blue. This can be monitored visually or by a shift in the UV-Vis absorption peak from 520 nm [29].

- Negative Result (TM absent): The aptamer remains adsorbed on the AuNPs, stabilizing them against aggregation. The solution remains red [29].

Protocol 3: Amperometric Immunosensor for Egg Allergen Gal d 3

This protocol outlines a rapid, sandwich-type amperometric immunosensor for the detection of ovotransferrin (Gal d 3) in food products, with a total assay time of 30 minutes [30].

Workflow Diagram: Gal d 3 Amperometric Immunosensor

Materials and Reagents

- Transducer: Screen-Printed Carbon Electrodes (SPCEs, DRP-110) [30].

- Antibodies: Rabbit anti-Gal d 3 polyclonal antibody (unconjugated, for capture). Peroxidase-conjugated rabbit anti-Gal d 3 polyclonal antibody (for detection, DAb-HRP) [30].

- Enzymatic Substrate: 3,3',5,5'-Tetramethylbenzidine (TMB) with hydrogen peroxide (H₂O₂) [30].

- Buffers:

- Phosphate-Buffered Saline (PBS), pH 7.4, for biosensor construction.

- PBS with 0.5% (m/V) BSA for preparing allergen and detection antibody working solutions.

Step-by-Step Procedure

- Immunosensor Construction: Drop-cast 10 µL of the capture antibody onto the working electrode of the SPCE. Incubate overnight at 4°C in a humid chamber. Wash with PBS and block with a BSA solution [30].

- Allergen Incubation: Apply 40 µL of the standard or sample extract to the SPCE. Incubate for 15 minutes to allow Gal d 3 to bind to the capture antibody. Wash thoroughly with PBS [30].

- Enzyme-Labelled Detection: Apply 40 µL of the HRP-conjugated detection antibody to the SPCE. Incubate for 15 minutes to form the sandwich complex. Wash to remove excess, unbound DAb-HRP [30].

- Amperometric Measurement:

- Place the SPCE in an electrochemical cell containing the potentiostat.

- Add 40 µL of the TMB/H₂O₂ substrate solution.

- Apply a constant potential of -0.1 V versus the integrated silver pseudoreference electrode.

- Measure the reduction current generated by the electrochemical reduction of the enzymatically oxidized TMB product. The steady-state current is directly proportional to the concentration of Gal d 3 in the sample [30].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

The development and implementation of these biosensing platforms rely on a core set of reagents and materials. The following table lists key solutions and their critical functions in allergen detection assays.

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Allergen Biosensor Development

| Reagent / Material | Function / Application | Example from Protocols |

|---|---|---|

| Screen-Printed Electrodes (SPCE/SPGE) | Low-cost, disposable, portable transducer platform for electrochemical detection. | Carbon (SPCE) or Gold (SPGE) working electrodes form the base of most electrochemical immunosensors [26] [30] [27]. |

| Monoclonal & Polyclonal Antibodies | Provide high specificity and affinity as capture and detection elements in immunoassays. | Anti-Ara h 1 monoclonal antibodies [26]; anti-Gal d 3 polyclonal antibodies [30]. |

| Aptamers | Single-stranded DNA/RNA recognition elements; offer stability and cost-efficiency as antibody alternatives. | Tropomyosin-binding aptamer (TMBA) for AuNP-based colorimetric sensing [29]. |

| Enzymatic Labels (HRP, ALP) | Catalyze substrate conversion to generate measurable (e.g., electrochemical, colorimetric) signals. | Horseradish Peroxidase (HRP) for TMB reaction in Gal d 3 sensor [30]; Alkaline Phosphatase (ALP) for silver deposition in TPM sensor [28]. |

| Nanomaterial Labels (QDs, AuNPs) | Signal amplification; QDs provide electroactive metals for stripping voltammetry, AuNPs enable colorimetric readout. | CdSe@ZnS QDs for DPASV detection of Ara h 1 [26]; AuNPs for salt-induced aggregation assay for TPM [29]. |

| Electrode Modifiers | Enhance conductivity, surface area, and biocompatibility to improve sensor sensitivity. | Praseodymium niobate-functionalized Carbon Nanofibers (PrNbO₄/f-CNF) for ultrasensitive Ara h 1 detection [27]. |

| Blocking Agents (BSA, Casein) | Prevent non-specific adsorption of proteins to the sensor surface, reducing background signal. | 2% BSA solution used in all immunosensor protocols to block unmodified SPCE surfaces [26] [28] [30]. |

Cutting-Edge Methodologies: From Nanozymes to Point-of-Care Platforms

Nanozymes are nanomaterials with intrinsic enzyme-like characteristics that have emerged as powerful tools in biosensing, particularly for applications requiring high stability and sensitivity [31]. Their significance is especially pronounced in the field of rapid on-site allergen detection, where traditional natural enzymes often face limitations due to their sensitivity to environmental conditions, complex production processes, and high cost [32] [31]. Nanozymes address these challenges by offering exceptional storage stability, facile engineering, and reusability while maintaining catalytic efficiency comparable to their natural counterparts [32].

The fundamental advantage of nanozymes lies in their robust performance in harsh conditions where natural enzymes would denature. This makes them ideal candidates for developing portable, field-deployable biosensor systems for food allergen monitoring [32] [33]. Furthermore, their catalytic properties can be precisely tuned through rational engineering approaches, enabling the development of highly sensitive detection systems capable of identifying trace-level allergens in complex food matrices [32].

Fundamental Advantages Over Natural Enzymes

The transition from natural enzymes to nanozymes in biosensor development is driven by several distinct advantages that address critical limitations in real-world detection scenarios.

Table 1: Comparison Between Natural Enzymes and Nanozymes for Allergen Detection

| Property | Natural Enzymes | Nanozymes |

|---|---|---|

| Storage Stability | Limited; often require cold chain storage | Exceptional; often stable at room temperature for extended periods [34] |

| Environmental Tolerance | Sensitive to pH, temperature, and organic solvents | Robust performance under extreme conditions [32] [35] |

| Production Cost | High (complex extraction/purification) | Low-cost, scalable synthesis [33] |

| Engineering Flexibility | Limited to genetic/immobilization techniques | Highly tunable activity via size, morphology, and composition control [31] |

| Reusability | Often limited | Good reusability potential [32] |

The operational stability of nanozymes is a paramount advantage for on-site detection. For instance, Cu({2-x})Se@Bi(2)MoO(_6) nanocomposites developed for walnut allergen detection demonstrated suitability for room-temperature storage, eliminating the need for refrigeration and significantly simplifying logistics for field use [34]. This characteristic is invaluable for deploying biosensors in resource-limited settings or for industrial quality control across distributed facilities.

Additionally, nanozymes exhibit resistance to harsh conditions including extreme pH levels and high temperatures, which might be encountered during sample processing or in certain food matrices [32] [35]. This robustness ensures consistent catalytic performance and reliable detection outcomes across varied real-world conditions, a critical factor for standardizing allergen detection protocols.

Engineering and Design Strategies

The rational design of nanozymes focuses on enhancing their catalytic activity, selectivity, and integration capabilities within biosensing platforms. Several advanced material systems have been successfully engineered for this purpose.

Material Composition and Structure

Nanozymes can be constructed from diverse nanomaterials including metal-based nanoparticles (e.g., gold, silver), metal oxides (e.g., Fe(3)O(4), CeO(_2)), carbon-based materials (e.g., graphene, carbon nanotubes), and metal-organic frameworks (MOFs) [33] [31] [35]. Each material system offers distinct advantages:

- MOF-based nanozymes provide exceptionally high surface areas and tunable porosity, enabling enhanced bioreceptor immobilization and mass transport [33].

- Carbon-based nanozymes such as graphene quantum dots offer excellent electron transfer capabilities and facile functionalization through surface oxygen-containing groups [35].

- Hybrid nanozymes like Cu({2-x})Se@Bi(2)MoO(_6) nanocomposites combine the advantages of different materials, often resulting in synergistic enhancements of catalytic activity [34].

Surface Functionalization and Bioconjugation

Effective integration of nanozymes into biosensors requires strategic surface functionalization to interface with biological recognition elements. Common approaches include:

- Electrostatic adsorption for antibody attachment, as demonstrated in the development of immunoassays for walnut allergen detection [34].

- Covalent conjugation using crosslinkers to immobilize enzymes, aptamers, or antibodies while maintaining their biological activity.

- Molecular imprinting to create synthetic recognition sites complementary to specific allergen epitopes [33].

These functionalization strategies enable nanozymes to serve as highly sensitive signal probes in various immunoassay formats, translating molecular recognition events into detectable signals with amplification capabilities surpassing those of conventional enzyme labels [34].

Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Developing a Nanozyme-Based Competitive Immunoassay for Food Allergen Detection

This protocol outlines the procedure for developing a direct competitive immunoassay for walnut allergen (Jug r 4) detection using Cu({2-x})Se@Bi(2)MoO(_6) nanozymes, adaptable to other food allergens [34].

Materials and Equipment

- Synthesized Cu({2-x})Se@Bi(2)MoO(_6) nanozymes

- Walnut monoclonal antibody (mAb)

- Food samples (bread, biscuits, milk)

- Microplate reader

- 3,3',5,5'-Tetramethylbenzidine (TMB) substrate

- Hydrogen peroxide (H(2)O(2))

- Buffer solutions (phosphate buffer, coating buffer)

- Blocking solution (e.g., BSA or skim milk)

Procedure

Nanozyme-Antibody Probe Preparation

- Incubate Cu({2-x})Se@Bi(2)MoO(_6) nanozymes with walnut mAb at optimal ratio (determined via checkerboard titration) in phosphate buffer (pH 7.4) for 2 hours at room temperature with gentle shaking.

- Centrifuge at 12,000 × g for 15 minutes to remove unbound antibodies.

- Resuspend the nanozyme-mAb conjugate in storage buffer containing stabilizers.

Competitive Immunoassay Procedure

- Coat microplate wells with purified walnut protein antigen (1-10 μg/mL in carbonate buffer, pH 9.6) overnight at 4°C.

- Block nonspecific sites with 1% BSA in PBS for 2 hours at 37°C.

- Prepare standard solutions of walnut allergen (0-3500 μg/L) in appropriate food matrix extracts.

- Incubate fixed concentration of nanozyme-mAb probe with varying concentrations of walnut allergen standard or sample extract for 1 hour at 37°C.

- Transfer the mixture to antigen-coated wells and incubate for 45 minutes at 37°C.

- Wash wells thoroughly to remove unbound nanozyme-mAb probes.

- Add TMB/H(2)O(2) substrate solution and incubate for 15-30 minutes for color development.

- Stop the reaction with sulfuric acid and measure absorbance at 450 nm.

Data Analysis

- Plot standard curve of absorbance versus allergen concentration.

- Calculate allergen concentration in unknown samples using the standard curve.

- Validate method recovery by spiking known allergen concentrations into control matrices.

Protocol: Evaluating Nanozyme Peroxidase-like Activity

This standardized protocol assesses the peroxidase-mimicking activity of nanozymes, a crucial parameter for biosensor development [34] [35].

Materials

- Nanozyme suspension (appropriately diluted)

- TMB substrate solution (0.4 mg/mL)

- Hydrogen peroxide (10 mM)

- Buffer solutions (various pH)

- Spectrophotometer or microplate reader

Procedure

Prepare reaction mixture containing:

- 100 μL nanozyme suspension

- 50 μL TMB solution

- 50 μL H(2)O(2) solution

- 800 μL buffer (optimal pH)

Incubate at desired temperature (typically 25-37°C) for 10-30 minutes.

Measure absorbance at 652 nm (TMB oxidation product).

Calculate enzymatic activity parameters (Michaelis-Menten constant, catalytic efficiency) by varying substrate concentrations.

Compare catalytic efficiency with natural horseradish peroxidase as reference.

Performance Data and Applications

Nanozyme-based biosensors have demonstrated exceptional performance in detecting various allergens and contaminants, as summarized in the table below.

Table 2: Performance Metrics of Nanozyme-Based Detection Systems

| Nanozyme Type | Target Analyte | Detection Mechanism | Linear Range | Limit of Detection (LOD) | Application Matrix |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cu({2-x})Se@Bi(2)MoO(_6) | Walnut allergen (Jug r 4) | Colorimetric immunoassay | 137.35 ± 0.14 to 3526.0 ± 4.53 μg/L | 81.63 ± 0.89 μg/L | Bread, biscuits, milk [34] |

| Graphene Quantum Dots (GQDs) | Dichlorvos (pesticide) | Fluorescence quenching | Not specified | 0.778 μM | Food samples [35] |

| Various X-based nanozymes | Pesticide residues | Multimodal sensing | Varies by design | 2-3 orders magnitude improvement vs conventional | Agricultural products [35] |

The data demonstrate that nanozyme-based detection systems achieve excellent sensitivity with detection limits suitable for monitoring allergens and contaminants at regulated levels. The broad linear range enables accurate quantification across concentration ranges relevant to food safety monitoring. Furthermore, the implementation of multimodal sensing approaches (colorimetric/fluorescence, fluorescence/photothermal, photothermal/colorimetric) provides mutual verification of multiple signals, significantly enhancing detection reliability [35].

Beyond allergen detection, nanozymes have shown remarkable utility in environmental monitoring, particularly for pesticide detection in food. The integration of nanozymes with microfluidic chips or paper-based technologies has enabled the development of portable detection devices that increase detection sensitivity by 2-3 orders of magnitude while reducing costs by approximately 80% compared to conventional methods [35].

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Nanozyme Biosensor Development

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|

| Cu({2-x})Se@Bi(2)MoO(_6) Nanozyme | Peroxidase-mimic signal probe in immunoassays | High catalytic activity, room temperature stable, cost-effective synthesis [34] |

| TMB (3,3',5,5'-Tetramethylbenzidine) | Chromogenic substrate for peroxidase-like activity | Colorless-to-blue conversion, measurable at 652 nm [34] |

| Graphene Quantum Dots (GQDs) | Fluorescent nanozymes for sensing applications | Peroxidase-like activity, tunable surface chemistry [35] |

| Metal-Organic Frameworks (MOFs) | High-surface-area nanozyme scaffolds | Exceptional loading capacity, tunable porosity [33] |

| Molecularly Imprinted Polymers (MIPs) | Synthetic bioreceptors for target recognition | Enhanced selectivity, stability, catalytic activity when hybridized [33] |

| Acetylcholinesterase (AChE) Enzyme | Biological recognition element in pesticide sensors | Inhibition-based detection mechanism [35] |

Signaling Pathways and Workflow Visualization

The following diagram illustrates the signaling mechanism and experimental workflow for a nanozyme-based competitive immunoassay for allergen detection:

Diagram 1: Nanozyme-Based Competitive Immunoassay Workflow - This visualization illustrates the competitive binding mechanism between free allergen and immobilized allergen for nanozyme-antibody probes, culminating in catalytic signal generation inversely proportional to allergen concentration.

Implementation Considerations

Integration with Emerging Technologies

The future development of nanozyme-based biosensors for allergen detection is closely tied to integration with advanced technologies:

Artificial Intelligence (AI): Machine learning algorithms can guide the rational design of nanozymes with tailored catalytic properties and selectivity for specific allergen targets [35]. AI can also optimize detection parameters and analyze complex signal patterns in multimodal sensing approaches.

Multimodal Sensing: Combining multiple detection modalities (colorimetric/fluorescence/photothermal) enhances reliability through signal verification and provides complementary information about the target analyte [35].

Portable Platforms: Integration with microfluidic chips and paper-based devices enables the development of point-of-care biosensors suitable for field use in food production facilities and regulatory inspections [35].

Validation and Standardization

For successful implementation in food safety monitoring programs, nanozyme-based biosensors require:

- Cross-validation with reference methods such as ELISA or LC-MS/MS to establish correlation and accuracy [36].

- Robustness testing across different food matrices to evaluate matrix effects and develop appropriate sample preparation protocols.

- Inter-laboratory validation to establish reproducibility and reliability of the detection method.

- Standardization of nanozyme characterization including catalytic activity metrics, stability profiles, and batch-to-batch consistency.

The exceptional properties of nanozymes—including their stability, tunable catalytic activity, and cost-effectiveness—position them as transformative tools for developing next-generation biosensing systems that can effectively address the critical need for rapid, sensitive, and on-site allergen detection in food products.

Food allergies represent a significant global health challenge, affecting millions of individuals and necessitating strict avoidance of allergenic foods. Currently, the most effective strategy for food allergy management remains the stringent avoidance of offending allergens [37]. Unlike some other major food allergens, substances like soy are uniquely challenging to avoid due to their prevalence and insidiousness in a wide variety of food products, including infant formulas [37]. In response to this challenge, biosensor technology has emerged as a promising solution for rapid, sensitive, and on-site detection of food allergens.

Biosensors are defined as self-contained integrated devices capable of offering specific quantitative or semi-quantitative analytical information using a biological recognition element directly interfaced with a transducer [38]. These devices have shown tremendous potential for transforming food safety monitoring by enabling real-time, accurate detection of allergenic proteins in complex food matrices. The critical importance of such technology stems from the fact that even trace amounts of allergens can trigger severe, life-threatening reactions in sensitive individuals [3].

This application note focuses on three principal signal transduction techniques—electrochemical, colorimetric, and fluorescent—that form the foundation of modern biosensing platforms for allergen detection. Each technique offers distinct advantages and operational characteristics that make them suitable for various application scenarios, from laboratory testing to point-of-care monitoring in food production facilities and even consumer-level use. The continuous improvement of material science and nanotechnology has significantly enhanced the performance of these biosensors, enabling unprecedented sensitivity and specificity in detecting trace-level allergens in complex food matrices [39].

Technical Comparison of Biosensing Modalities

The selection of an appropriate biosensing technique depends on multiple factors, including the required sensitivity, specificity, cost constraints, and the intended application environment. The table below provides a systematic comparison of the three primary biosensing modalities discussed in this document.

Table 1: Comparative analysis of biosensor transduction techniques for allergen detection

| Parameter | Electrochemical | Colorimetric | Fluorescent |

|---|---|---|---|

| Detection Principle | Measures changes in electrical properties (current, voltage, impedance) due to redox reactions [39] | Monitors color changes from nanoparticle aggregation or catalytic reactions [40] [41] | Detects fluorescence emission changes from quantum dots, carbon dots, or organic dyes [40] [42] |

| Sensitivity | High (picomolar to attomolar levels) [38] [39] | Moderate to high (micromolar range) [41] | Very high (able to detect single molecules in optimized systems) [42] |

| Detection Time | Rapid (<15 minutes for complete protocols) [3] | Very rapid (<1 minute in some cases) [41] | Moderate to rapid (minutes to hours) [42] |

| Equipment Needs | Portable potentiostats, screen-printed electrodes [37] [3] | Minimal (often visual inspection), sometimes with smartphone integration [40] | Fluorometers, UV lamps, or smartphone-based detectors [40] [42] |

| Multiplexing Capability | High (e.g., 16 simultaneous reactions in iEAT2) [3] | Limited to moderate | Moderate to high |

| Cost Considerations | Low to moderate (disposable electrodes, portable readers) [39] | Very low (paper-based platforms) [41] | Moderate (light sources, detectors required) |

| Key Advantages | High sensitivity, miniaturization potential, suitable for turbid samples [39] | Simplicity, visual readout, no instrumentation needed for qualitative assessment [41] | Exceptional sensitivity, multiplexing capability, tunable probes [42] |

| Limitations | Electrode fouling, requires reference electrode systems | Limited sensitivity in complex matrices, subjective interpretation | Photobleaching, interference from autofluorescence in food samples [39] [42] |

Electrochemical Biosensing

Principles and Mechanisms

Electrochemical biosensors function by detecting changes in electrical properties—including current, voltage, and impedance—that arise when allergenic molecules attach to designated receptors immobilized on the sensor surface [38]. The fundamental mechanism involves redox reactions between target analytes and the electrode surface, which are modulated through nanostructure-engineered interfaces [39]. When analytes such as allergenic proteins interact with recognition elements (aptamers, antibodies, or molecularly imprinted polymers) immobilized on sensing interfaces, electron transfer kinetics are altered, generating measurable electrical signals.

The signal output in electrochemical biosensors can originate from multiple sources. The analytes themselves, if possessing intrinsic redox activity, can be directly detected to obtain electrochemical signals [39]. More commonly, signal probes based on enzymes such as horseradish peroxidase (HRP) are leveraged to detect analytes by coupling catalytic reactions [3] [39]. Additionally, nanostructures with enzyme-like properties (nanozymes) and redox mediators like ferrocene derivatives or methylene blue are exploited as signal probes for generating current responses [39].

Experimental Protocol: Molecularly Imprinted Polymer-Based Soy Allergen Detection

Objective: Rapid and accurate detection of soy allergenic tracers in complex food matrices using molecularly imprinted polymer (MIP)-based electrochemical sensors [37].

Materials and Reagents:

- Screen-printed carbon electrodes (ItalSens IS-C) [37]

- Ortho-phenylenediamine (o-PD) and genistein (soy allergen marker) [37]

- Phosphate-buffered saline (PBS, pH 7.4) and sodium acetate buffer [37]

- Food samples and allergen extraction buffer [37]

Procedure:

- Sensor Preparation: Prepare MIP electrodes by electropolymerization of o-PD in the presence of genistein template molecules, followed by template extraction to create specific binding cavities [37].

- Sample Preparation: Homogenize 1 g of solid food using a mortar and pestle until a fine powder is obtained. Mix with 10 mL of extraction buffer and stir for 15 minutes. For liquid foods, directly mix 1 g with 10 mL of buffer solution [37].

- Electrochemical Measurement:

- Insert template-extracted MIP electrodes into 10 mL of buffer solution and equilibrate for 5 minutes.

- Incubate electrodes with 100 µL of sample solution for 1 minute.

- Perform differential pulse voltammetry (DPV) measurements with parameters: scan rate 50 mV/s, pulse width 50 ms, amplitude 50 mV [37].

- Data Analysis: Identify a positive response when the sensor shows an oxidation peak at approximately 0.60 V vs Ag/AgCl and an imprinting factor above 1.3, corresponding to oxidative redox transformations of genistein [37].

Experimental Protocol: iEAT2 System for Multiplexed Allergen Detection

Objective: Simultaneous detection of multiple food allergens (gliadin, Ara h1, ovalbumin) using an advanced electrochemical sensing system [3] [7].

Materials and Reagents: