Molecular Architecture of Macronutrients: From Chemical Structure to Clinical Application in Drug Development

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of the chemical composition and structure of dietary macronutrients—proteins, carbohydrates, and lipids—for a specialized audience of researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals.

Molecular Architecture of Macronutrients: From Chemical Structure to Clinical Application in Drug Development

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of the chemical composition and structure of dietary macronutrients—proteins, carbohydrates, and lipids—for a specialized audience of researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals. It explores the foundational biochemistry governing macronutrient structure and function, examines analytical methodologies for characterization, addresses stability challenges in formulation, and validates structural insights through biomedical applications. The synthesis of this knowledge underscores the critical role of macronutrient chemistry in advancing nutraceuticals, drug delivery systems, and targeted therapies.

The Biochemical Blueprint: Atomic Structure and Classification of Food Macronutrients

Within nutritional biochemistry, macronutrients are defined as chemical substances required by the body in large quantities to sustain physiological functions, provide energy, and serve as building blocks for structural components [1] [2]. The classification of macronutrients into essential and non-essential categories is fundamental to understanding their roles in human metabolism and nutritional requirements. Essential macronutrients are those that the body cannot synthesize in sufficient quantities and must be obtained from the diet, whereas non-essential macronutrients can be endogenously produced from other dietary components [3] [4]. This distinction is particularly critical in research focused on dietary formulation, metabolic studies, and pharmaceutical development related to nutritional interventions.

The chemical composition and structure of macronutrients directly determine their metabolic fate, bioavailability, and functional properties in biological systems. This technical guide provides a comprehensive analysis of the molecular architecture of macronutrients, their essential components, and experimental approaches for their quantification and characterization in food research.

Macronutrient Classification and Chemical Architecture

Definitive Framework of Macronutrients

Table 1: Fundamental Classification of Macronutrients and Their Components

| Macronutrient Category | Essential Components | Non-Essential Components | Basic Chemical Units |

|---|---|---|---|

| Proteins | Essential amino acids: Histidine, Isoleucine, Leucine, Lysine, Methionine, Phenylalanine, Threonine, Tryptophan, Valine [3] [4] | Non-essential amino acids: Alanine, Arginine, Asparagine, Aspartic acid, Cysteine, Glutamic acid, Glutamine, Glycine, Proline, Serine, Tyrosine [3] | Amino acids linked by peptide bonds; composed of carbon, hydrogen, oxygen, and nitrogen [5] [3] |

| Lipids | Essential fatty acids: Alpha-linolenic acid (omega-3), Linoleic acid (omega-6) [5] [1] | Saturated fats, Monounsaturated fats, Cholesterol [5] [4] | Fatty acids, Glycerol; composed primarily of carbon and hydrogen with some oxygen [5] |

| Carbohydrates | Glucose (as required for brain function) [6] | Fructose, Galactose, Starch (can be synthesized via gluconeogenesis) [1] [4] | Monosaccharides (simple sugars); composed of carbon, hydrogen, and oxygen [1] |

Asterisk () indicates conditionally essential amino acids that may become essential under certain physiological conditions such as stress, illness, or premature infancy [3].

The fundamental distinction between essential and non-essential components lies in the body's biosynthetic capabilities. Essential nutrients contain specific molecular structures that human metabolic pathways cannot synthesize, necessitating dietary intake. For instance, the nine essential amino acids feature specific carbon skeleton configurations and nitrogen placement that cannot be replicated through transamination reactions [3] [4]. Similarly, essential fatty acids possess double bonds at specific positions (n-3 and n-6) that mammalian desaturase enzymes cannot introduce [5].

Energy Yield and Molecular Composition

Table 2: Quantitative Energy Yield and Elemental Composition of Macronutrients

| Macronutrient | Energy Density (kcal/g) | Primary Elements | Characteristic Structural Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| Carbohydrates | 4 [5] [1] [4] | Carbon, Hydrogen, Oxygen (typically in 1:2:1 ratio) [1] [6] | Hydroxyl groups, Aldehyde or ketone functionality, Glycosidic bonds linking monosaccharide units [1] |

| Proteins | 4 [5] [1] [4] | Carbon, Hydrogen, Oxygen, Nitrogen, Sulfur (in some amino acids) [5] [3] | Amino group, Carboxyl group, Variable side chains, Peptide bonds forming primary structure [3] |

| Lipids | 9 [5] [1] [4] | Carbon, Hydrogen, Oxygen (fewer oxygen atoms relative to carbohydrates) [5] | Hydrocarbon chains, Ester linkages, Variable degrees of unsaturation, Amphipathic properties [5] |

The nitrogen content represents a crucial distinguishing feature of proteins, as neither carbohydrates nor lipids contain nitrogen in their fundamental structures [3]. This nitrogen content is critically important for maintaining nitrogen balance in the body and serves as a key parameter in nutritional assessment [5].

Methodological Approaches in Macronutrient Research

Analytical Framework for Macronutrient Quantification

Research on macronutrient composition requires precise methodological approaches to ensure accurate characterization of food components and their metabolic effects.

Dietary Assessment Methodologies:

- 24-Hour Dietary Recall (24HR): A structured interview method to quantify all foods and beverages consumed in the previous 24-hour period using standardized protocols, often employing multiple-pass techniques to enhance accuracy [7]. This method requires conversion of household measures to metric units using standardized references, photographic aids, and food atlases.

- Food Composition Analysis: Utilizes centesimal composition tables, chemical analysis, or food label information to determine nutrient profiles [7]. For mixed dishes, ingredients are dissected according to preparation technical sheets to determine individual component contributions.

Classification Systems:

- NOVA Classification: Categorizes foods based on the extent and purpose of industrial processing into four groups: (1) unprocessed or minimally processed foods, (2) culinary ingredients, (3) processed foods, and (4) ultra-processed foods [7]. This system is particularly valuable for investigating relationships between food processing, nutrient composition, and health outcomes.

Body Composition Assessment:

- Bioelectrical Impedance Analysis (BIA): A non-invasive method that measures the resistance of body tissues to small electrical currents to estimate body composition parameters including fat mass, fat-free mass, and hydration status [8]. Validated devices such as the TANITA Body Composition Analyzer series provide standardized measurements for research applications.

- Anthropometric Measurements: Include body mass index (BMI), waist circumference (WC), and waist-to-hip ratio (WHR), which serve as proxies for adiposity distribution and metabolic health risk assessment [8].

Experimental Design Considerations

Intervention Studies: Recent research has employed various dietary intervention models to examine the effects of macronutrient composition on health outcomes [8]. These include:

- Caloric Restriction Models: Including low-energy diets (LED: 800-1,200 kcal/day) and very low-energy diets (VLED: 400-800 kcal/day) with varying macronutrient distributions [8].

- Isocaloric Models: Diets with identical caloric content but different macronutrient distributions, including low-carbohydrate diets (LCD), ketogenic diets (KD), high-protein diets (HPD), and time-restricted eating (TRE) protocols [8].

Standardized monitoring in these interventions typically includes baseline, intermediate (e.g., 6-week), and final (e.g., 12-week) assessments of anthropometric parameters, body composition, and biochemical markers [8].

Research Reagent Solutions for Macronutrient Analysis

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Macronutrient Investigation

| Reagent/Material | Research Application | Technical Function |

|---|---|---|

| Nitrogen Analysis Reagents | Protein quantification [5] | Determination of nitrogen content for protein calculation using Kjeldahl or Dumas methods |

| Fat Extraction Solvents | Lipid isolation and quantification [9] | Solvent-based extraction of fats from food matrices (e.g., using chloroform-methanol mixtures) |

| Enzyme Assays | Carbohydrate characterization [1] | Specific enzymatic digestion for quantification of starch, fiber, and sugar components |

| Amino Acid Standards | Protein quality assessment [3] [4] | HPLC reference standards for identification and quantification of essential and non-essential amino acids |

| Fatty Acid Methyl Esters | Lipid profiling [5] | GC-MS standards for characterization of saturated, monounsaturated, and polyunsaturated fatty acids |

| DNA/RNA Extraction Kits | Nutrigenomics studies [8] | Isolation of genetic material for investigation of nutrient-gene interactions |

| Immunoassay Reagents | Hormone and cytokine measurement [8] | Quantification of metabolic biomarkers affected by macronutrient intake (e.g., insulin, leptin) |

Structural and Functional Relationships

The chemical structure of macronutrients directly determines their physiological functions and metabolic processing. Proteins exhibit the most structural diversity due to variations in amino acid sequence, side chain properties, and three-dimensional folding [3]. This structural complexity enables proteins to serve diverse functions including enzymatic catalysis, structural support, mechanical movement, and immune defense [5] [3].

Carbohydrates range from simple monosaccharides to complex polysaccharides with varying glycosidic linkages that determine their digestibility and functional properties [1]. The presence of beta-linkages in dietary fiber creates bonds resistant to human digestive enzymes, resulting in their classification as non-digestible carbohydrates that nonetheless provide important physiological benefits [5] [1].

Lipids are characterized by their hydrophobic properties derived from predominantly non-polar carbon-hydrogen bonds [5]. The degree of saturation and chain length of fatty acids significantly influences their physical properties, metabolic behavior, and physiological effects [5] [4].

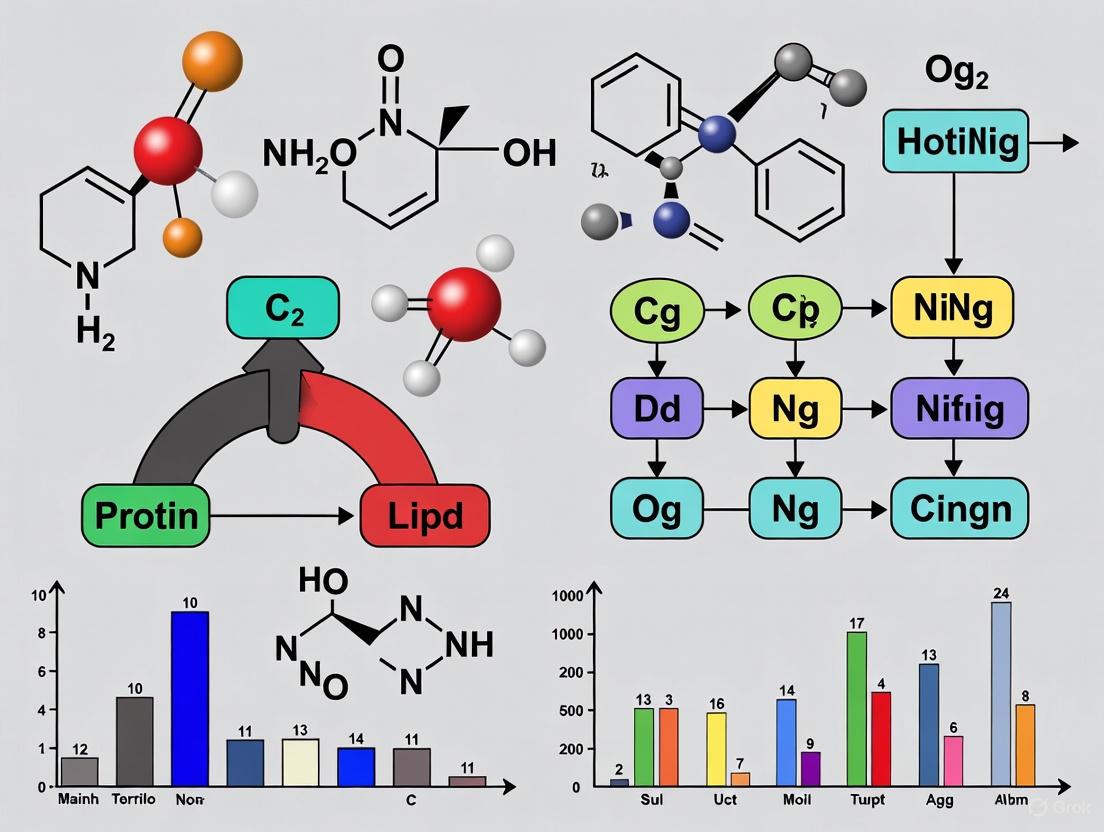

Figure 1: Macronutrient Classification and Research Methodology Framework. This diagram illustrates the hierarchical classification of macronutrients into essential (red) and non-essential (green) components, alongside the methodological approaches used in nutritional research to investigate their composition and metabolic effects.

Implications for Research and Development

The precise understanding of essential versus non-essential macronutrient components has significant implications for multiple research domains:

Nutritional Formulation and Clinical Applications

Understanding essential amino acid requirements is critical for developing protein sources with optimal biological value, particularly in formulations for clinical nutrition, athletic performance, and specialized populations [3] [4]. The protein digestibility-corrected amino acid score (PDCAAS) represents a key methodology for evaluating protein quality based on essential amino acid composition and digestibility [4].

Research indicates that essential fatty acid requirements extend beyond mere deficiency prevention to include optimal ratios of n-6 to n-3 fatty acids for inflammatory modulation and chronic disease risk reduction [5]. The typical Western diet often exhibits an imbalanced ratio (high n-6:n-3), which has stimulated research on targeted lipid formulations [5].

Public Health and Dietary Guidelines

Evidence from systematic reviews indicates that dietary patterns emphasizing nutrient-dense sources of macronutrients—including lean proteins, unsaturated fats, and fiber-rich carbohydrates—are associated with more favorable health outcomes compared to patterns characterized by ultra-processed foods [10] [7]. Longitudinal cohort studies demonstrate that high consumption of ultra-processed foods correlates with excessive intake of refined carbohydrates, saturated fats, and trans fats, while providing insufficient protein, fiber, and essential micronutrients [7].

Current nutritional epidemiology employs sophisticated methodologies to investigate relationships between macronutrient sources, processing levels, and health outcomes, providing the evidence base for dietary recommendations [10]. These findings inform the development of public health strategies aimed at optimizing macronutrient intake patterns at the population level.

The rigorous differentiation between essential and non-essential macronutrient components provides a critical foundation for advancing nutritional science, food technology, and clinical practice. The chemical architecture of these nutrients—particularly the specific molecular features that render certain amino acids and fatty acids essential—represents a fundamental determinant of their biological functions and nutritional requirements. Contemporary research methodologies continue to refine our understanding of macronutrient metabolism, enabling more precise dietary recommendations and targeted nutritional interventions for diverse populations and physiological conditions. Future research directions will likely focus on personalized nutrition approaches that account for genetic variation in nutrient metabolism and utilization, further enhancing the translation of basic nutritional biochemistry into practical health applications.

Proteins are fundamental biological macromolecules that perform a vast array of functions in living organisms, serving as structural components, enzymes, transporters, and signaling molecules. As a primary macronutrient in food, proteins provide essential amino acids and contribute to the structural and sensory properties of food matrices. The biological functionality of proteins is directly determined by their three-dimensional architecture, which is encoded in their amino acid sequence and achieved through specific folding pathways. This whitepaper examines the hierarchical organization of proteins from their primary chemical structure to their complex tertiary and quaternary arrangements, with emphasis on the folding process, stabilizing forces, and experimental approaches for structural analysis. Understanding protein architecture provides critical insights for research in nutritional sciences, drug development, and food technology, enabling the manipulation of protein functionality for specific applications.

Hierarchical Structure of Proteins

Protein structure is organized through four distinct hierarchical levels, each contributing to the overall conformation and functionality of the molecule [11]. This hierarchical organization enables the conversion of one-dimensional genetic information into complex three-dimensional structures capable of diverse biological functions.

Primary Structure: The Amino Acid Foundation

The primary structure comprises the linear sequence of amino acids joined by covalent peptide bonds, forming the polypeptide backbone [12] [13]. This sequence is genetically determined and contains all information necessary for the protein to fold into its native conformation.

Each amino acid features a central alpha carbon atom bonded to an amino group (-NH₂), a carboxyl group (-COOH), a hydrogen atom, and a variable side chain (R-group) that determines the amino acid's chemical properties [12] [14]. Under physiological conditions, amino acids exist as zwitterions with protonated amino groups (-NH₃⁺) and deprotonated carboxyl groups (-COO⁻) [14].

Amino acids are classified according to their side chain properties:

- Non-polar aliphatic: Glycine, Alanine, Valine, Leucine, Isoleucine, Methionine, Proline

- Non-polar aromatic: Phenylalanine, Tryptophan, Tyrosine

- Polar uncharged: Serine, Threonine, Cysteine, Asparagine, Glutamine

- Polar acidic: Aspartic acid, Glutamic acid

- Polar basic: Lysine, Arginine, Histidine

Table 1: Amino Acid Classification by Side Chain Properties

| Category | Representative Amino Acids | Key Structural Features |

|---|---|---|

| Non-polar aliphatic | Valine, Leucine, Isoleucine | Hydrocarbon chains, hydrophobic |

| Non-polar aromatic | Phenylalanine, Tryptophan | Aromatic rings, hydrophobic |

| Polar uncharged | Serine, Threonine, Cysteine | Contain -OH or -SH groups, form hydrogen bonds |

| Polar acidic | Aspartic acid, Glutamic acid | Contain carboxyl groups, negatively charged at pH 7.4 |

| Polar basic | Lysine, Arginine, Histidine | Contain amino groups, positively charged at pH 7.4 |

Peptide bonds form through a condensation reaction between the carboxyl group of one amino acid and the amino group of another, releasing a water molecule [13]. The peptide bond exhibits partial double-bond character due to resonance, creating a rigid planar structure that restricts rotation [13] [15]. This planar arrangement influences the possible conformations of the polypeptide backbone.

The primary structure also includes disulfide bonds formed between cysteine residues through oxidation of their thiol groups [13]. These covalent linkages can connect different parts of a single polypeptide chain or different polypeptide chains, significantly contributing to structural stability.

Secondary Structure: Local Folding Patterns

Secondary structures arise from regular, repeating patterns of hydrogen bonding between the backbone carbonyl oxygen and amide hydrogen atoms [11] [15]. The two most common secondary structures are alpha-helices and beta-sheets, which form rapidly during the folding process and provide structural framework.

Alpha-helices are right-handed coiled structures stabilized by intramolecular hydrogen bonds parallel to the helix axis, with hydrogen bonds forming between the carbonyl oxygen of residue n and the amide hydrogen of residue n+4 [11] [15]. The side chains extend outward from the helical core, minimizing steric hindrance. Alpha-helices contain approximately 3.6 amino acid residues per turn and are common in transmembrane domains and structural proteins.

Beta-sheets consist of extended beta-strands connected by hydrogen bonds between backbone atoms of adjacent strands [11] [15]. These sheets can be parallel (adjacent strands run in the same direction) or antiparallel (adjacent strands run in opposite directions). Antiparallel beta-sheets typically form more stable hydrogen bonds with ideal 180-degree alignment compared to the slanted hydrogen bonds in parallel arrangements [15].

Table 2: Characteristics of Major Secondary Structure Elements

| Feature | Alpha-Helix | Beta-Sheet |

|---|---|---|

| Hydrogen bonding | Intra-chain, parallel to helix axis | Inter-strand, between adjacent strands |

| Residues per turn | 3.6 | Extended conformation |

| Side chain orientation | Outward from helix core | Alternating above and below sheet plane |

| Stability factors | Optimal main-chain hydrogen bonding, side-chain packing | Extended conformation, strand alignment |

| Common occurrences | Transmembrane domains, DNA-binding motifs | Protein cores, silk fibroin |

Certain amino acids possess special structural properties. Glycine and proline often disrupt alpha-helical structures due to their unique properties: glycine provides excessive conformational flexibility, while proline introduces structural kinks due to its cyclic side chain [14]. Additionally, serine, threonine, and tyrosine are frequent phosphorylation targets, with their hydroxyl groups serving as sites for regulatory modifications [14].

Tertiary Structure: Global Three-Dimensional Organization

Tertiary structure refers to the overall three-dimensional arrangement of a single polypeptide chain, formed by the packing of secondary structural elements and connecting loops into a compact globular fold [11]. This level of organization is stabilized by various interactions between amino acid side chains, including hydrophobic interactions, hydrogen bonds, ionic interactions (salt bridges), and disulfide bonds [12] [15].

The hydrophobic effect represents a major driving force in tertiary structure formation [15]. Nonpolar side chains tend to cluster in the protein's interior to minimize contact with aqueous solvent, while hydrophilic residues typically occupy the surface [12]. This arrangement maximizes entropy by reducing the ordered water cages around hydrophobic groups.

Hydrogen bonds between polar side chains and salt bridges between oppositely charged residues (e.g., aspartic acid and lysine) further stabilize the tertiary structure [12] [14]. Disulfide bonds between cysteine residues provide covalent stabilization, particularly in extracellular proteins and harsh environments [13].

Tertiary structures often comprise multiple domains—independently folding compact units that may perform distinct functions within a single polypeptide chain. Protein folds can be classified according to databases such as CATH (Class, Architecture, Topology, Homologous superfamily) and SCOP (Structural Classification of Proteins), which categorize proteins based on structural and evolutionary relationships [11].

Quaternary Structure: Multi-Subunit Assemblies

Many functional proteins consist of multiple polypeptide chains (subunits) associated into a specific quaternary structure [11] [15]. These multi-subunit complexes may contain identical subunits (homo-oligomers) or different subunits (hetero-oligomers). The quaternary structure is stabilized by the same non-covalent interactions that stabilize tertiary structure, with precise interfaces ensuring proper subunit assembly.

Quaternary organization provides functional advantages including enhanced stability, cooperative effects in allosteric regulation, and the ability to form complex molecular machines. For example, the sliding clamp protein (PDB ID 6gis) forms a ring-shaped trimeric structure that encircles DNA and maintains polymerase attachment during replication [11].

Protein Folding Pathways and Mechanisms

Protein folding is the physical process by which a newly synthesized polypeptide chain assumes its biologically functional three-dimensional conformation [15]. This process occurs spontaneously based on the information contained within the amino acid sequence, though cellular factors often assist in vivo.

Thermodynamic Driving Forces

Protein folding is thermodynamically favorable under physiological conditions, with folded states typically exhibiting negative Gibbs free energy values [15]. The primary driving forces include:

- Hydrophobic effect: The sequestration of nonpolar side chains away from water, which increases system entropy by releasing ordered water molecules [15]

- Hydrogen bonding: The formation of optimal intra-molecular hydrogen bonds that compensate for broken protein-water hydrogen bonds

- van der Waals interactions: Weak attractive forces between closely packed atoms in the protein core

- Electrostatic interactions: Salt bridges between oppositely charged residues and other charge-dipole interactions

The folded native state represents the global minimum of free energy for the system, balancing favorable enthalpy changes from bond formation with the typically unfavorable entropy change associated with transitioning from a disordered to ordered state [15].

Folding Pathways and the Energy Landscape

Protein folding often proceeds through a hierarchical pathway rather than a random search of all possible conformations [16]. The "building block folding model" proposes that proteins fold through a top-down process where local elements form first, followed by combinatorial assembly of these folding units [16].

Small single-domain proteins may fold in a single cooperative step on microsecond to millisecond timescales, while larger multi-domain proteins typically fold through intermediate states with structured regions and disordered loops [15]. The folding process can be visualized as navigation across a funnel-shaped energy landscape, where the protein progressively samples lower-energy conformations en route to the native state.

Figure 1: Protein Folding Energy Landscape and Chaperone Assistance

Molecular Chaperones and Folding Catalysts

In cellular environments, protein folding is assisted by molecular chaperones—specialized proteins that prevent inappropriate interactions and aggregation but do not become part of the final structure [12] [15]. Chaperones operate by binding to and stabilizing unstable folding intermediates, providing a more efficient pathway to the native state without increasing the rate of individual folding steps [15].

Major chaperone systems include:

- Hsp70 family: Bind to hydrophobic regions of nascent chains and unfolded proteins

- Chaperonins (GroEL/GroES in bacteria): Form barrel-shaped complexes that provide isolated folding chambers for individual proteins [12]

- Hsp90 family: Assist in the maturation of specific regulatory proteins

Folding catalysts, including protein disulfide isomerases (which catalyze disulfide bond formation and rearrangement) and peptidyl-prolyl isomerases (which accelerate cis-trans isomerization of proline peptide bonds), facilitate slow steps in the folding pathway [15].

Experimental and Computational Approaches

Understanding protein architecture requires sophisticated experimental and computational methods for structure determination and folding analysis.

Structural Determination Methods

X-ray crystallography remains the most common method for high-resolution protein structure determination [12]. This technique involves analyzing the diffraction patterns produced when X-rays pass through protein crystals, enabling calculation of electron density maps and atomic positions.

Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) spectroscopy can determine protein structures in solution, providing information about dynamics and folding intermediates. Cryo-Electron Microscopy (cryo-EM) has emerged as a powerful technique for visualizing large protein complexes that are difficult to crystallize.

Computational Structure Prediction

Recent advances in deep learning have revolutionized protein structure prediction. AlphaFold2 and RoseTTAFold demonstrate remarkable accuracy in predicting three-dimensional structures from amino acid sequences alone [11]. These methods employ neural networks trained on known protein structures to model spatial relationships and physical constraints.

Computational approaches also enable the study of folding pathways through molecular dynamics simulations, which model atomic movements over time to observe folding events and intermediate states [16].

Research Reagents and Methodologies

Protein architecture research requires specialized reagents and methodologies for structural analysis and manipulation.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Protein Architecture Studies

| Reagent/Method | Function/Application | Technical Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| X-ray Crystallography | High-resolution structure determination | Requires high-quality crystals; provides atomic-resolution data |

| NMR Spectroscopy | Solution-state structure and dynamics | Limited to smaller proteins; provides dynamic information |

| Circular Dichroism (CD) | Secondary structure content assessment | Rapid analysis of folding states; requires purified protein |

| Differential Scanning Calorimetry (DSC) | Thermal stability measurements | Determines melting temperature (Tm) and folding thermodynamics |

| Size Exclusion Chromatography | Oligomeric state analysis | Estimates molecular size and detects aggregation |

| Proteinase K | Limited proteolysis for folding unit identification | Cleaves unstructured regions; reveals protected folding domains [16] |

| Urea/Guanidine HCl | Chemical denaturation studies | Unfolds proteins for folding thermodynamics measurements |

| DTT/TCEP | Disulfide bond reduction | Controls redox state for folding studies |

| Molecular Chaperones | In vitro folding assistance | Improves yield of properly folded proteins |

| Isotope-labeled Amino Acids | NMR spectroscopy | Enables structural studies of large proteins |

Experimental Protocol: Limited Proteolysis for Folding Unit Identification

Purpose: To identify stable protein folding units and domains [16].

Methodology:

- Prepare protein sample at 0.5-1 mg/mL in appropriate buffer

- Add Proteinase K at enzyme:substrate ratio of 1:100 (w/w)

- Incubate at 25°C for varying time intervals (0-60 minutes)

- Stop reaction by adding PMSF (phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride) to 1 mM final concentration

- Analyze proteolytic fragments by SDS-PAGE and mass spectrometry

- Compare fragment boundaries to computational predictions of folding units

Expected Outcomes: Proteolysis occurs preferentially in unstructured regions, generating stable fragments that correspond to autonomous folding units. Comparison with computationally predicted building blocks validates folding models [16].

Experimental Protocol: Equilibrium Unfolding Studies

Purpose: To determine protein stability and folding thermodynamics.

Methodology:

- Prepare protein samples at constant concentration in series of denaturant solutions (e.g., 0-8 M urea)

- Equilibrate samples for sufficient time to reach equilibrium (typically 4-12 hours)

- Measure spectroscopic signal (fluorescence or CD) sensitive to folding state

- Fit data to two-state or multi-state unfolding models to extract free energy of unfolding (ΔG°)

- Analyze dependence of ΔG° on denaturant concentration to obtain m-value (cooperativity parameter)

Applications: Quantifying mutational effects on stability, comparing homologous proteins, and evaluating ligand binding effects on folding stability.

Implications for Food and Nutritional Sciences

Protein architecture fundamentally influences the nutritional and functional properties of dietary proteins. The hierarchical structure determines digestibility, bioavailability of amino acids, and potential allergenicity. For instance, tightly folded globular proteins may resist proteolytic digestion, potentially limiting amino acid absorption, while misfolded proteins can form aggregates associated with certain pathological conditions [15].

From a food science perspective, understanding protein folding and stability enables the optimization of processing conditions to preserve nutritional quality while achieving desired functional properties such as gelation, emulsification, and foaming. The structural organization of food proteins directly impacts texture, mouthfeel, and sensory characteristics of protein-rich foods.

Protein requirements for humans reflect both the quantity and quality of dietary protein, with the current RDA set at 0.8 g/kg body weight as a minimum to prevent deficiency [5]. However, emerging evidence suggests potential benefits of higher protein intake (1.2 g/kg or more) for mitigating age-related muscle loss [5]. Protein quality depends not only on amino acid composition but also on digestibility, which is influenced by protein structure and food processing methods.

Protein architecture represents a sophisticated hierarchical system in which linear amino acid sequences encode complex three-dimensional structures through specific folding pathways. The four levels of protein structure—primary, secondary, tertiary, and quaternary—provide increasing organizational complexity that enables diverse biological functions. Protein folding is driven primarily by the hydrophobic effect and stabilized by various covalent and non-covalent interactions, with molecular chaperones assisting in cellular environments.

Advanced experimental and computational methods continue to enhance our understanding of protein structure-function relationships, with significant implications for nutritional science, drug development, and food technology. As research progresses, the integration of structural information with nutritional science will facilitate the development of improved protein sources and processing methods that optimize both health outcomes and food quality.

Carbohydrates constitute one of the major classes of biomolecules and represent the most abundant biomolecules on Earth, playing indispensable roles in both structural integrity and energy metabolism across biological systems [17] [18] [19]. From a chemical perspective, carbohydrates are primarily combinations of carbon and water, with many having the empirical formula (CH₂O)ₙ, where n is the number of carbon atoms in the molecule [20] [21] [19]. This empirical formula leads to the term "carbohydrate," meaning "hydrated carbon." Carbohydrates perform numerous essential functions in living organisms: they serve as critical energy sources, provide structural support to cell walls in plants and fungi, contribute to cellular identity and recognition through cell-surface glycans, and form the backbone of genetic molecules like RNA and DNA [17] [18]. Within the context of food macronutrient research, understanding carbohydrate complexity is fundamental to elucidating their nutritional bioavailability, physiological effects, and technological applications in food systems and therapeutic development.

Structural Hierarchy of Carbohydrates

Carbohydrates are systematically classified based on their degree of polymerization (DP) into monosaccharides, disaccharides, oligosaccharides, and polysaccharides [17] [18]. This structural hierarchy directly influences their chemical behavior, nutritional functionality, and physiological impact.

Monosaccharides: The Fundamental Units

Monosaccharides are the simplest carbohydrate forms, often called simple sugars, and serve as the basic building blocks for more complex carbohydrates [20] [21]. They cannot be hydrolyzed into smaller carbohydrate units [18]. Monosaccharides are classified according to two primary criteria: the number of carbon atoms in the chain and the type of carbonyl functional group they contain.

Table 1: Classification of Representative Monosaccharides

| Carbon Count | Classification | Aldose Example | Ketose Example | Biological Significance |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3 | Triose | Glyceraldehyde | Dihydroxyacetone | Metabolic intermediates in glycolysis |

| 5 | Pentose | Ribose | Ribulose | Component of RNA, DNA, and coenzymes |

| 6 | Hexose | Glucose, Galactose | Fructose | Primary energy source; component of lactose and sucrose |

Monosaccharides containing an aldehyde group (R-CHO) are classified as aldoses, while those containing a ketone group (RC(=O)R') are ketoses [20] [21]. Although glucose, galactose, and fructose share the same chemical formula (C₆H₁₂O₆), they are structural isomers with distinct arrangements of functional groups around asymmetric carbon atoms, leading to different chemical properties and biological activities [21]. In aqueous solutions, monosaccharides with five or more carbons predominantly exist as cyclic ring structures, which form through a chemical reaction between the carbonyl group and a hydroxyl group on the sugar molecule [19]. This cyclization creates an anomeric carbon, which can have the hydroxyl group positioned either below (alpha (α) position) or above (beta (β) position) the ring plane, a distinction critical for the properties of subsequent glycosidic linkages [21].

Disaccharides and Oligosaccharides: The Emergence of Complexity

Disaccharides consist of two monosaccharide units linked covalently via a glycosidic bond [21] [19]. This bond forms through a dehydration synthesis (condensation) reaction, where a hydroxyl group of one monosaccharide combines with the hydrogen of another, releasing a water molecule [21]. Oligosaccharides are carbohydrates containing three to ten monosaccharide units connected by glycosidic bonds [17]. They are often found conjugated to proteins or lipids on cell surfaces, where they play crucial roles in cell-cell recognition and signaling [22].

Table 2: Common Disaccharides in Nutrition and Food Science

| Disaccharide | Monosaccharide Components | Glycosidic Bond | Dietary Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sucrose | Glucose + Fructose | α-1,2 | Table sugar, sugarcane, sugar beets |

| Lactose | Galactose + Glucose | β-1,4 | Milk and dairy products |

| Maltose | Glucose + Glucose | α-1,4 | Hydrolyzed starch, malt products |

Polysaccharides: Macromolecular Architecture

Polysaccharides (glycans) are large polymers composed of long chains of monosaccharides linked by glycosidic bonds, typically exceeding ten monomeric units and often reaching molecular weights of 100,000 daltons or more [17] [21]. These macromolecules can be linear or highly branched and may consist of a single type of monosaccharide (homopolysaccharides) or multiple different monosaccharides (heteropolysaccharides) [21]. The primary functions of polysaccharides are energy storage and structural support.

Table 3: Characteristics of Major Polysaccharides

| Polysaccharide | Monomeric Unit | Glycosidic Linkage | Primary Function | Organism/Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Starch | Glucose | α-1,4 and α-1,6 (branch points) | Energy storage | Plants |

| Glycogen | Glucose | α-1,4 and α-1,6 (more branched than starch) | Energy storage | Animals and bacteria |

| Cellulose | Glucose | β-1,4 | Structural support | Plant cell walls |

| Chitin | N-acetyl-β-d-glucosamine | β-1,4 | Structural support | Fungal cell walls, arthropod exoskeletons |

The spatial orientation of glycosidic bonds fundamentally differentiates the properties of these macromolecules. Starch and glycogen feature α-glycosidic linkages, which create helical structures that are readily accessible to digestive enzymes [21]. In contrast, cellulose possesses β-1,4 linkages that result in linear chains capable of forming tight, parallel bundles stabilized by extensive hydrogen bonding, yielding a rigid structure resistant to hydrolysis [21]. Most vertebrates, including humans, lack the enzymes (cellulases) necessary to cleave β-1,4 linkages, rendering cellulose indigestible but valuable as dietary fiber [21].

The Glycosidic Bond: Structure, Function, and Synthesis

Chemical Nature of Glycosidic Linkages

A glycosidic bond is a type of covalent ether bond that joins a carbohydrate molecule to another group, which may be another carbohydrate or a non-sugar molecule (aglycone) [23]. This bond forms between the hemiacetal or hemiketal group (the anomeric carbon) of a saccharide and the hydroxyl group of another compound [23]. When the anomeric center is involved in the glycosidic bond, the linkage can be classified as either α- or β-, determined by the relative stereochemistry of the anomeric position and the stereocenter furthest from C1 in the saccharide [23].

The most common glycosidic bonds are O-glycosidic bonds, where oxygen serves as the bridging atom [23]. However, other types exist, including S-glycosidic bonds (sulfur bridge), N-glycosidic bonds (nitrogen bridge, found in nucleotides and glycoproteins), and C-glycosidic bonds (carbon bridge), each with different susceptibility to hydrolysis [23]. N-glycosidic bonds are particularly crucial in DNA, where they covalently link the anomeric carbon of deoxyribose to the nitrogen atom of nucleobases; lesions in these bonds are repaired by DNA glycosylases that catalyze their hydrolysis [23].

Experimental Protocols for Glycosidic Bond Synthesis and Analysis

Stereoselective Glycosylation via Directed S_N2 Reaction

Controlling the stereochemistry (α or β) during glycosidic bond formation represents a central challenge in synthetic carbohydrate chemistry. A recent groundbreaking methodology developed by researchers at UC Santa Barbara and the Max Planck Institute employs a directed S_N2 (bimolecular nucleophilic substitution) mechanism to achieve precise stereocontrol [22].

Detailed Methodology:

- Reaction Setup: The reaction is conducted under conditions that are neither strongly acidic nor basic, either in solution or on a solid support for automated synthesis [22].

- Directed Leaving Group: A directing molecule is added to the leaving group (typically at the anomeric carbon of the donor sugar). This director promotes nucleophilic attack by the incoming sugar (acceptor) before the leaving group departs, ensuring a concerted S_N2 mechanism [22].

- S_N2 Mechanism: In this one-step process, the incoming nucleophile (hydroxyl group of the acceptor sugar) attacks the anomeric carbon from the side opposite the leaving group. This backside attack results in a Walden inversion, reliably producing the desired stereochemistry at the anomeric center [22].

- Solid-Phase Synthesis: For automated synthesis, the growing oligosaccharide chain is anchored to a polymer support. After each glycosylation cycle, the apparatus is washed, removing all byproducts while the desired product remains attached, enabling iterative chain elongation without intermediate purification [22].

Significance: This method provides a broadly applicable approach to control bonding orientation across various sugar-sugar connections and is compatible with automated solid-phase synthesis, dramatically accelerating the production of complex oligosaccharides for biomedical research [22].

Analysis of Glycosidic Bond Type in Polysaccharides

Determining the specific type of glycosidic linkage in an unknown polysaccharide sample is fundamental to characterizing its structure and predicting its functional properties.

Detailed Methodology:

- Sample Preparation: The polysaccharide sample is purified using precipitation or chromatographic techniques to remove contaminants [24].

- Enzymatic Hydrolysis: Specific glycoside hydrolases are employed to cleave particular linkages:

- Cellulase (containing endo-1,4-β-D-glucanase, exo-1,4-β-D-glucanase, and β-glucosidase) targets β-1,4 linkages in cellulose [24].

- Amylase enzymes target α-1,4 and α-1,6 linkages in starch and glycogen [21].

- The hydrolysis reaction is typically performed in buffered solutions at the enzyme's optimal temperature and pH [24].

- Product Analysis: The hydrolysis products (monosaccharides, disaccharides) are analyzed using techniques such as:

- Thin-Layer Chromatography (TLC) for preliminary separation and identification.

- High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC) for quantitative analysis of the hydrolysis products [24].

- Mass Spectrometry (MS) for precise determination of the molecular weights of the fragments.

- Linkage Determination: The specific glycosidic linkages present in the original polysaccharide are inferred from the identity of the enzymatic cleavage products and the known specificity of the glycosidases used.

Carbohydrate Complexity in Therapeutics and Biomedical Applications

Carbohydrates have gained a central role in therapeutic applications, with more than 200 carbohydrate-based drugs approved worldwide in recent decades [25] [26]. These molecules play crucial roles in various diseases, including lysosomal storage diseases, diabetes (iminosugars), cancers, Alzheimer's disease, autoimmune diseases, and bacterial and infectious diseases [25] [26]. Several key areas highlight the importance of carbohydrate complexity in biomedical research:

Glycoconjugates in Cell Signaling and Recognition

Oligosaccharides are often found on cell surfaces as glycoconjugates (glycoproteins, proteoglycans, and glycolipids), where they play critical roles in intercellular communication, viral and bacterial infection, immune system modulation, and developmental processes [22] [18]. The enormous structural diversity of oligosaccharides—with variations in their components, connecting locations, and the handedness of connecting bonds—enables them to encode substantial biological information; scientists estimate there can be more than 100 million kinds of five-unit oligosaccharides [22]. This complexity makes them ideal for specific biological recognition events, such as pathogen binding and immune recognition.

Carbohydrate-Based Drug Design and Delivery

Advanced carbohydrate-based therapeutic platforms are being developed for various applications:

- Smart Theranostic Platforms: Carbohydrate-based hydrogels serve as intelligent biomedical systems for biosensing and therapeutic drug delivery, offering intrinsic biocompatibility, structural versatility, and capacity for functional modification [26].

- Vaccine Development: Glycoconjugate vaccines against bacterial and fungal infections represent a promising application, with researchers developing complex carbohydrate synthesis methodologies to produce antigenic oligosaccharides [22] [26].

- Antiviral Therapeutics: Polysaccharides from brown seaweeds (e.g., Padina boergesenii and Sargassum euryphyllum) have demonstrated promising inhibitory activity against SARS-CoV-2, potentially preventing viral entry through multiple mechanisms [26].

Research Reagent Solutions for Carbohydrate Studies

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents for Carbohydrate Analysis and Synthesis

| Reagent/Category | Function/Application | Specific Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Glycosyltransferases | Enzymatic synthesis of specific glycosidic bonds; transfer sugar units from activated donors to acceptor molecules | Sialyltransferases, fucosyltransferases [23] |

| Glycoside Hydrolases | Selective cleavage of specific glycosidic linkages for structural analysis; some used in reverse synthesis | Cellulase, amylase, β-glucosidase, glucosidase [23] [24] |

| Activated Sugar Donors | Serve as substrates for glycosyltransferases in enzymatic synthesis; "activate" monosaccharides for incorporation | UDP-glucose, GDP-mannose, CMP-sialic acid [23] |

| Chiral Stationary Phases (CSPs) | Enantioseparation of chiral carbohydrate derivatives; analysis of optical purity | Derivatized cellulose- or amylose-based CSPs [24] |

| Directed SN2 Glycosylation Kit | Stereoselective formation of glycosidic bonds using directed leaving group technology | Anomeric donors with directing groups, solid supports [22] |

The structural progression from simple monosaccharides to complex polysaccharides interconnected by specific glycosidic linkages constitutes a fundamental dimension of carbohydrate complexity with far-reaching implications for food macronutrient research and therapeutic development. The precise arrangement of monosaccharide units, the stereochemistry of their connections, and the three-dimensional architecture of the resulting polymers directly determine their biological function, nutritional value, and metabolic fate. Recent methodological advances in the stereoselective synthesis of glycosidic bonds, particularly automated solid-phase oligosaccharide synthesis, are now providing researchers with unprecedented access to these complex molecules [22]. This progress promises to accelerate discovery in carbohydrate-based therapeutics, including novel vaccines, targeted drug delivery systems, and advanced diagnostic tools [25] [26]. As research continues to unravel the intricate relationship between carbohydrate structure and function, the strategic manipulation of glycosidic linkages will remain central to exploiting the full potential of these versatile biomolecules in both nutritional science and biomedical applications.

Lipids represent a fundamental class of food macronutrients characterized by exceptional chemical diversity and functional complexity. In the context of food science research, lipids are defined as hydrophobic or amphipathic molecules that serve as critical structural elements of cell membranes, energy storage compounds, and precursors for bioactive molecules essential for human health [27] [28]. The structural heterogeneity of lipids arises from variations in their backbone architectures, fatty acyl chain compositions, and polar head groups, which collectively determine their physicochemical properties, metabolic fates, and nutritional functionalities [27].

The comprehensive analysis of lipid structures is paramount for understanding their roles in food quality, bioavailability, and impact on human physiology. Advanced analytical techniques including lipidomics now enable researchers to characterize lipid compositional patterns and their interactions with other dietary components, offering unprecedented insights for developing personalized nutrition strategies and functional foods [27] [28]. This technical guide provides a systematic examination of the core lipid classes, their structural characteristics, analytical methodologies, and experimental approaches relevant to food chemistry research and development.

Structural Classification and Chemical Properties

Lipids are systematically categorized based on their core chemical structures and functional groups. The eight main categories of lipids, along with their representative examples and key structural features, are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1: Comprehensive Classification of Lipid Categories and Representative Structures

| Lipid Category | Core Structure | Representative Examples | Key Structural Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fatty Acyls | Carboxylic acids with hydrocarbon chains | Palmitic acid, Arachidonic acid, Eicosanoids | Hydrocarbon chain length, degree of unsaturation, presence of oxygenated functional groups |

| Glycerolipids | Glycerol backbone with fatty acyl chains | Mono-, Di-, and Triacylglycerols (TAGs) | Number of esterified fatty acids, carbon chain length and saturation of acyl chains |

| Glycerophospholipids | Glycerol backbone with phosphate and head group | Phosphatidylcholines (PCs), Phosphatidylethanolamines (PEs), Lysophosphatidylcholines (LPCs) | Polar head group (choline, ethanolamine, etc.), fatty acyl composition at sn-1 and sn-2 positions |

| Sphingolipids | Sphingoid base backbone | Ceramides (Cers), Sphingomyelins (SMs), Glycosphingolipids | Sphingosine backbone, amide-linked fatty acid, variable head groups |

| Sterol Lipids | Cyclopentanoperhydrophenanthrene ring system | Cholesterol esters (CEs), Phytosterols (β-sitosterol, Campesterol) | Sterol ring system, side chain modifications, esterification sites |

| Prenol Lipids | Isoprene units | Ubiquinone (Coenzyme Q), Dolichol | Polymerized isoprene units, various degrees of saturation and functional groups |

| Saccharolipids | Fatty acids linked to sugar backbones | Lipid A (component of bacterial lipopolysaccharide) | Glycosidic linkage between fatty acids and carbohydrate moieties |

| Polyketides | Polymerized acetyl and propionyl subunits | Erythromycin, Tetracycline (antibiotic polyketides) | Complex structures derived from polyketide synthase enzymes |

The structural diversity within each category profoundly influences their nutritional functionality and technological applications in food systems. For instance, in glycerophospholipids, the composition of polar head groups and the unsaturation degree of fatty acyl chains determine their behavior as emulsifiers and their susceptibility to oxidation, which directly impacts food flavor quality and shelf life [29]. Similarly, the carbon chain length and saturation pattern of triacylglycerols significantly affect their digestibility and absorption kinetics, which is particularly relevant in infant nutrition and clinical nutritional products [30].

Quantitative Compositional Analysis in Food Matrices

The quantitative analysis of lipid components across different food matrices reveals substantial variation in composition, which directly influences nutritional quality and technological functionality. Table 2 presents comparative compositional data for key lipid classes across selected food systems relevant to nutritional research.

Table 2: Quantitative Composition of Lipid Classes in Selected Food Matrices

| Food Matrix | Lipid Class | Specific Component | Concentration Range | Analytical Method | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tiger Nut Oil | Phospholipids | Hydratable Phospholipids (HP) | 0.5-8.0 g/kg (added to STNO) | Column Chromatography, NMR | [31] |

| Antioxidants | Tocopherols | 142-348 mg/kg | HPLC | [31] | |

| Sterols | Phytosterols | 1714-6856 mg/kg | GC-MS | [31] | |

| Sturgeon Caviar | Phospholipids | Phosphatidylcholine (PC) | 58.2-82.3% | ³¹P NMR, Lipidomics | [29] |

| Phospholipids | Phosphatidylethanolamine (PE) | 5.8-10.4% | ³¹P NMR, Lipidomics | [29] | |

| Fatty Acids | C22:6, C20:5, C20:4, C18:2 | Key precursors for flavor | GC-MS, Correlation Analysis | [29] | |

| Pre-prepared Dishes | Sterols | Cholesterol | Variable by meat content | GC-MS | [32] |

| Sterols | β-sitosterol, Campesterol, Stigmasterol | Major components | GC-MS | [32] | |

| Sterols | Ergosterol | Not detected | GC-MS | [32] | |

| Infant Formula Emulsions | Triglycerides | Medium-chain (Coconut oil) | 3.5% in emulsion | Gas Chromatography | [30] |

| Triglycerides | Long-chain (OPO) | 3.5% in emulsion | Gas Chromatography | [30] | |

| Triglycerides | Ultra-long-chain (DHA Algae oil) | 3.5% in emulsion | Gas Chromatography | [30] |

The compositional data highlights several structurally significant relationships. In sturgeon caviar, the relative proportions of PC and PE decrease significantly during storage (from 82.3% to 58.2% for PC and from 10.4% to 5.8% for PE), indicating selective degradation of specific phospholipid classes that directly impacts flavor quality through the release of volatile compounds [29]. In tiger nut oil, the presence of hydratable phospholipids (0.5-8.0 g/kg) significantly enhances oxidative stability, demonstrating a dose-dependent effect that surpasses the contribution of sterols alone [31].

Experimental Methodologies for Structural Analysis

Phospholipid Structural Dynamics Monitoring

Objective: To systematically investigate oxidation-induced structural and compositional changes in phospholipids and establish their relationship with flavor formation in sturgeon caviar during storage [29].

Sample Preparation: Fresh hybrid sturgeon caviar was stored at 4°C for six weeks, with weekly sampling. Phospholipids were extracted using a modified Folch method with chloroform-methanol (2:1 v/v) solution. The extract was washed with 0.88% KCl solution and the lower chloroform phase containing lipids was collected and concentrated under nitrogen [29].

Structural Analysis Techniques:

- ³¹P and ¹H Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR): Samples were dissolved in CDCl₃-MeOH-D₂O (50:50:15, v/v/v) for ³¹P NMR analysis. Spectra were acquired to quantify phospholipid classes and monitor structural changes in polar head groups and fatty acyl chains.

- Electron Spin Resonance (ESR): Spin trapping techniques were employed using α-(4-pyridyl-1-oxide)-N-tert-butylnitrone (POBN) to detect and quantify free radical formation during lipid oxidation.

- Raman Spectroscopy: Spectra were collected in the range of 500-2000 cm⁻¹ with excitation at 785 nm. Specific bands at 970 cm⁻¹ and 1080 cm⁻¹ were monitored to assess changes in unsaturation degree due to phospholipid oxidation.

- Lipidomics Analysis: LC-MS-based non-targeted lipidomics was performed using UPLC-Q-Exactive HF-X Mass Spectrometer to identify and quantify individual phospholipid species, focusing on PC and PE containing C22:6, C20:5, C20:4, and C18:2 fatty acyl chains.

Key Findings: The application of this multi-technique approach revealed a significant decrease in unsaturated acyl groups in PLs during storage, with free radical signals showing an initial increase followed by decrease. Correlation analysis identified 10 specific PC and PE species associated with 8 flavor substances, establishing these phospholipid subsets as key precursors for flavor development in caviar [29].

Multi-component Sterol Determination in Complex Matrices

Objective: To develop a sensitive and selective GC-MS method for simultaneous qualitative and quantitative analysis of multi-component sterols in pre-prepared dishes with complex matrices [32].

Sample Preparation: A 2.0 g sample (accurate to 0.1 mg) was weighed into a 50 mL polypropylene centrifuge tube. 50 μL internal standard working solution (cholestane, 1 mg/mL) and 15 mL absolute ethanol were added. The mixture was vortex-mixed, then supplemented with 5 mL 60% (w/w) potassium hydroxide solution. Saponification was performed in a constant-temperature oscillating water bath at 80°C for 45 minutes with shaking at 200 rpm. After cooling, 10 mL of ultrapure water was added, and sterols were extracted with 3 × 10 mL n-hexane by vortex mixing and centrifugation. The combined n-hexane extracts were evaporated to dryness under nitrogen at 40°C [32].

Derivatization and GC-MS Analysis:

- Derivatization: The dried extract was reconstituted in 200 μL of BSTFA (containing 1% TMCS) and 100 μL of pyridine, then heated at 80°C for 40 minutes.

- GC Conditions: DB-5MS capillary column (30 m × 250 μm × 0.25 μm); temperature program: initial 100°C (1 min hold), ramp at 20°C/min to 220°C, then at 5°C/min to 270°C (5 min hold), followed by 2°C/min to 290°C (5 min final hold); total run time 37 min; injector temperature 290°C; helium carrier gas at 1.0 mL/min; split ratio 10:1; injection volume 1.0 μL.

- MS Conditions: Electron ionization (EI) source at 70 eV; ion source temperature 230°C; interface temperature 280°C; acquisition in selected ion monitoring (SIM) mode.

Method Validation: The method demonstrated good linearity (R² ≥ 0.99) within 1.0-100.0 μg/mL range, with LODs of 0.05-5.0 mg/100 g and LOQs of 0.165-16.5 mg/100 g. Average recoveries ranged from 87.0 to 106% with RSDs of 0.99-9.00% [32].

Emulsion Interface Engineering for Digestibility Studies

Objective: To investigate the combined effects of triglyceride carbon chain length and emulsifier content on the physicochemical properties and digestive characteristics of emulsions, with application to infant formula development [30].

Emulsion Preparation: Emulsions were prepared using three oil types: coconut oil (medium-chain), OPO (long-chain), and DHA algae oil (ultra-long-chain) at 3.5% concentration. Emulsifier systems included MFGM, whey protein isolate (WPI), and sodium caseinate (SCN) in varying ratios as detailed in Table 1 of the source material [30].

Physicochemical Characterization:

- Particle Size Analysis: Dynamic light scattering was employed to measure average particle size and distribution of emulsion droplets.

- Interfacial Properties: Surface tension and viscosity measurements were performed to characterize the emulsion interface structure.

- Stability Assessment: Centrifugal stability tests and storage stability at different temperatures were conducted.

In Vitro Digestion Model:

- Gastric Phase: Emulsions were mixed with simulated gastric fluid containing pepsin at pH 3.0 and incubated at 37°C for 1 hour with continuous shaking.

- Intestinal Phase: The gastric chyme was mixed with simulated intestinal fluid containing pancreatin and bile salts at pH 7.0 and incubated at 37°C for 2 hours.

- Lipolysis Monitoring: Samples were collected at regular intervals, and free fatty acid release was quantified by titration or GC analysis of FAME derivatives.

Key Findings: Emulsions prepared with OPO exhibited the largest average particle size and greater stability. When whey protein and casein were added in a 6:4 ratio, the effect of fatty acid carbon chain length on average particle size and emulsification characteristics was significantly reduced. Emulsions with short-chain fatty acids or low surface protein content showed higher lipolysis rates [30].

Structural Relationships and Functional Pathways

The structural diversity of lipids directly determines their functional roles in food systems and biological activities. The relationship between lipid structures and their nutritional functionalities can be visualized through the following conceptual pathway:

Diagram 1: Structure-Function Relationships in Nutritional Lipids

The oxidation pathway of phospholipids and their role in flavor formation represents another critical structural-functional relationship, particularly in marine-based food products:

Diagram 2: Phospholipid Oxidation and Flavor Formation Pathway

Research Reagent Solutions for Lipid Analysis

The experimental methodologies described require specialized reagents and materials optimized for lipid research. Table 3 compiles key research reagent solutions essential for investigating lipid diversity in food matrices.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Lipid Structural Analysis

| Reagent Category | Specific Reagents | Research Application | Functional Role |

|---|---|---|---|

| Chromatography Standards | Stigmasterol, β-sitosterol, Ergosterol, Campesterol, Brassicasterol, Cholestane (IS) | Sterol quantification by GC-MS [32] | Quantitative calibration, internal standardization, method validation |

| Derivatization Reagents | N,O-bis(trimethylsilyl)trifluoroacetamide (BSTFA) with 1% TMCS, Pyridine | GC-MS analysis of sterols and other lipids [32] | Hydroxyl group silylation for enhanced volatility and detection |

| Lipid Extraction Solvents | Chloroform, Methanol, n-hexane, Isopropanol, Dichloromethane | Lipid extraction from food matrices [29] [32] [31] | Selective solubility for lipid classes, matrix separation |

| NMR Solvents | Deuterated chloroform (CDCl₃), CDCl₃-MeOH-D₂O (50:50:15) | Phospholipid structural analysis [29] | Isotopic labeling for spectroscopic detection, sample solubilization |

| Saponification Reagents | Potassium hydroxide, Ethanol, Citric acid solution | Sterol liberation from esterified forms [32] [31] | Hydrolysis of ester bonds, removal of glyceride backbone |

| Antioxidant Standards | α-Tocopherol, β-Tocopherol, γ-Tocopherol | Antioxidant activity assessment [31] | Reference compounds for antioxidant capacity quantification |

| Phospholipid Standards | Phosphatidylcholine, Phosphatidylethanolamine | Phospholipid quantification [29] | Class-specific calibration, identification confirmation |

| Enzymatic Reagents | Lipoxygenase (LOX), Phospholipase A₂, Trypsin, Pancreatin | In vitro digestion models [29] [30] | Simulation of biological digestion, specific lipid modification |

The structural diversity of lipids represents a fundamental dimension in food macronutrient research with far-reaching implications for nutritional science, food technology, and clinical applications. The intricate relationships between lipid structures and their functional properties—from the digestibility kinetics governed by fatty acid chain length to the flavor profiles determined by phospholipid oxidation pathways—underscore the importance of comprehensive structural characterization in food research [29] [30].

Advanced analytical methodologies, particularly the integration of multiple techniques such as NMR, ESR, Raman spectroscopy, and lipidomics, provide powerful tools for deciphering these structure-function relationships in complex food matrices [29]. The continued refinement of these methods, coupled with the development of standardized experimental protocols and reference materials, will enable researchers to more precisely elucidate the mechanisms through which lipid diversity influences food quality, nutritional value, and health outcomes.

Future research directions should focus on expanding lipidomic databases for diverse food commodities, establishing quantitative structure-activity relationship (QSAR) models for predicting lipid functionality, and developing targeted lipid-based interventions for specific population groups. Such advances will ultimately enhance our ability to harness lipid diversity for optimizing human health through evidence-based nutritional strategies.

The chemical composition and structural organization of food macronutrients are fundamental to their nutritional functionality and physiological impact. This whitepaper examines the core molecular forces—hydrogen bonding, hydrophobic interactions, and van der Waals forces—that govern macronutrient conformation, stability, and behavior within food systems and biological environments. Understanding these non-covalent interactions provides critical insights for researchers and drug development professionals seeking to manipulate macronutrient properties for enhanced nutritional outcomes, targeted delivery systems, and therapeutic applications. The intricate balance of these forces dictates everything from protein folding and lipid membrane integrity to carbohydrate solubility and enzymatic accessibility, forming the foundational physics underlying food chemistry and nutrition science.

Recent advances in analytical technologies, particularly molecular dynamics simulations and quantum chemical calculations, have revolutionized our ability to probe these interactions with unprecedented precision [33]. This review synthesizes current understanding of these molecular mechanisms, providing both quantitative analysis and practical methodological guidance for investigating the supramolecular architecture of macronutrients. The principles discussed herein have significant implications for designing novel foods with precise nutritional functionality and developing nutraceutical interventions based on molecular-level interactions.

Fundamental Molecular Forces in Macronutrient Systems

Hydrogen Bonding

Hydrogen bonding represents a particularly strong dipole-dipole interaction occurring between a hydrogen atom covalently bonded to an electronegative atom (O, N, F) and another electronegative atom bearing a lone pair of electrons. In macronutrient systems, these interactions are critical for maintaining secondary and tertiary structures, particularly in proteins and carbohydrates.

In protein chemistry, hydrogen bonding primarily occurs through backbone amide groups and side chain functionalities, stabilizing α-helices and β-sheets in secondary structures [34]. The Badger-Bauer rule establishes a correlation between the strength of hydrogen bonds and shifts in spectroscopic measurements, particularly infrared spectroscopy, enabling quantitative assessment of these interactions [35]. Research demonstrates that hydrogen bonding between sugars and proteins inhibits dehydration-induced protein unfolding through direct molecular interactions rather than water entrapment mechanisms [34]. The protective effect of disaccharides like trehalose in lyophilization processes stems specifically from their capacity to form extensive hydrogen-bonding networks with protein surfaces, substituting for water molecules normally involved in hydration shells.

In carbohydrate systems, hydrogen bonding governs solubility, crystallization behavior, and interactions with other food components. The extensive hydroxyl groups on sugar molecules create multiple hydrogen-bonding sites that determine their physicochemical properties and biological recognition. Recent studies employing Fourier Transform Infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy have quantified the relationship between hydrogen bonding strength and thermodynamic parameters including fusion enthalpies, revealing how these interactions contribute to structural stability in both simple and complex carbohydrate systems [35].

Hydrophobic Interactions

Hydrophobic interactions describe the thermodynamic driving force that causes nonpolar substances to aggregate in aqueous solutions, minimizing their unfavorable contacts with water molecules. These interactions are not true bonds but rather emergent properties of water's hydrogen-bonding network reorganizing to maximize entropy. In macronutrient systems, hydrophobic interactions are paramount for protein folding, lipid membrane formation, and emulsification properties.

In proteins, hydrophobic amino acids typically cluster together in the protein's interior, away from surrounding water, creating a stable core that drives the folding process and maintains three-dimensional structure [36]. The mechanical stability provided by hydrophobic interactions varies significantly from their contribution to thermodynamic stability. Steered molecular dynamics simulations reveal that hydrophobic interactions contribute approximately 20-33% of the total force resisting mechanical unfolding, with hydrogen bonds providing the predominant mechanical resistance [37]. This distinction highlights the context-dependent nature of molecular forces in macronutrient systems.

In food processing applications, hydrophobic interactions significantly impact functional properties including solubility, texture, and emulsification. When proteins undergo thermal processing or mechanical forces, their hydrophobic regions become exposed, enabling them to stabilize oil-water interfaces in emulsion systems [36]. Recent research on myofibrillar protein emulsion gels demonstrates that strategic modulation of hydrophobic interactions can improve gel properties at high temperatures (95°C), with hydrophobic interactions primarily enhancing the gel matrix rather than interfacial films [38].

Van der Waals Forces

Van der Waals forces encompass distance-dependent interactions between atoms or molecules arising from correlations in the fluctuating polarizations of nearby particles. These forces include London dispersion forces between "instantaneously induced dipoles," Debye forces between permanent dipoles and induced dipoles, and Keesom forces between permanent molecular dipoles [39]. Unlike covalent or ionic bonds, van der Waals forces are comparatively weak and susceptible to disturbance, yet they collectively contribute significantly to molecular organization in macronutrient systems.

In molecular physics, van der Waals forces quickly vanish at longer distances between interacting molecules (approximately following a r⁻⁷ relationship) and become repulsive at very short distances due to electron cloud overlap [39]. The strength of van der Waals interactions increases with the polarizability of the participating atoms, explaining why larger atoms with more diffuse electron clouds exhibit stronger interactions. For example, the pairwise van der Waals interaction energy between oxygen atoms in different O₂ molecules equals 0.44 kJ/mol, while the same interaction between more polarizable sulfur atoms in H₂S exceeds 1 kJ/mol [39].

In macronutrient systems, van der Waals forces play crucial roles in molecular recognition, starch-lipid complexation, and the structural integrity of molecular assemblies. Recent research has quantified the relationship between van der Waals contributions to fusion enthalpies and molecular sphericity parameters, enabling researchers to deconvolute the relative contributions of specific interactions and dispersion forces to thermodynamic properties [35]. In low molecular weight alcohols, hydrogen-bonding properties dominate weaker van der Waals interactions, whereas in higher molecular weight alcohols, the properties of nonpolar hydrocarbon chains dominate due to the cumulative effect of numerous van der Waals contacts [39].

Quantitative Analysis of Molecular Forces

Table 1: Relative Strength and Characteristics of Molecular Forces in Macronutrient Systems

| Force Type | Energy Range (kJ/mol) | Distance Dependence | Directionality | Primary Role in Macronutrients |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hydrogen Bonds | 4-60 (~13-30 in biological systems) | ~r⁻³ to r⁻⁴ | Highly directional | Protein secondary structure, carbohydrate solubility, molecular recognition |

| Hydrophobic Interactions | Not applicable (entropic driving force) | Dependent on solvent reorganization | Non-directional | Protein folding, membrane formation, emulsion stabilization |

| Van der Waals Forces | 0.06-2 (pairwise), up to 32 in aggregates | ~r⁻⁷ | Non-directional | Molecular packing, starch-lipid complexes, supramolecular assembly |

| London Dispersion | 0.06-2.35 (pairwise between atoms) | ~r⁻⁶ to r⁻⁷ | Non-directional | Dominant van der Waals component for nonpolar molecules, carbohydrate crystallization |

Table 2: Contribution of Molecular Forces to Protein Stability Parameters

| Force Type | Contribution to Thermodynamic Stability | Contribution to Mechanical Stability | Temperature Dependence |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hydrogen Bonds | Moderate (can be stabilizing or destabilizing) | High (60-80% of unfolding force) | Dependent (weaken with increasing T) |

| Hydrophobic Interactions | High (major folding driving force) | Moderate (20-33% of unfolding force) | Strengthen with increasing T (to a point) |

| Van der Waals Forces | Moderate (packing efficiency) | Low (background interactions) | Minimal (except for Keesom force) |

The quantitative contribution of hydrogen bonding to fusion enthalpies can be separated from van der Waals contributions by analyzing the relationship between fusion enthalpies and volume changes during melting processes. Recent research demonstrates that the ratio of enthalpy-to-volume change correlates with molecular sphericity parameters, enabling this deconvolution [35]. For associated molecular substances like alcohols, phenols, and carboxylic acids, the hydrogen bonding contribution to fusion enthalpies can be quantified using the Badger-Bauer rule, with independent estimates agreeing within 1.1 kJ mol⁻¹ on average [35].

Hydrophobic interactions contribute variably to protein mechanical stability, with steered molecular dynamics simulations revealing they account for between one-fifth and one-third of the total force resisting mechanical extension, while hydrogen bonds provide the majority of mechanical resistance [37]. This represents a significant inversion of their relative importance to thermodynamic stability, where hydrophobic interactions typically dominate. The differential contribution stems from the steeper free energy dependence of hydrogen bonds on the relative positions of interacting atoms compared to the more gradual energy landscape of hydrophobic interactions [37].

Experimental Methodologies for Investigating Molecular Forces

Spectroscopic Techniques

Spectroscopic methods provide powerful approaches for characterizing molecular interactions in macronutrient systems. Fourier Transform Infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy detects hydrogen bonding through shifts in absorption frequencies, particularly in the amide I region (1600-1700 cm⁻¹) for proteins and the hydroxyl stretching region (3000-3600 cm⁻¹) for carbohydrates [34] [33]. The relationship between sample moisture content measured by coulometric Karl Fischer titration and the apparent moisture content predicted by the area of the protein side chain carboxylate band at approximately 1580 cm⁻¹ in infrared spectra enables researchers to distinguish between direct sugar-protein hydrogen bonding and water entrapment mechanisms [34].

Raman spectroscopy complements FTIR by providing information about molecular vibrations with minimal water interference, making it particularly valuable for studying hydrophobic regions and lipid assemblies [33]. Fluorescence spectroscopy, particularly intrinsic fluorescence from tryptophan residues or extrinsic probes, sensitively reports on local environmental changes resulting from molecular interactions, enabling quantification of binding constants and conformational changes [33].

Molecular Simulation Approaches

Molecular dynamics (MD) simulations computationally model the physical movements of atoms and molecules over time, providing atomic-level insights into molecular interactions and conformational dynamics [33]. Steered molecular dynamics simulations with constant-velocity pulling can generate force-extension curves of protein domains and monitor hydrophobic surface unravelling upon extension, enabling quantitative analysis of mechanical stability contributions [37].

Molecular docking predicts the preferred orientation of one molecule relative to a second when bound to each other, elucidating binding mechanisms between nutrients and biological targets [33]. Quantum chemical calculations (QCC) provide even more precise descriptions of electronic structures and interaction energies, though they require significant computational resources [33]. These computational approaches have revealed that hydrophobic force peaks shift toward larger protein extensions compared to hydrogen bond force peaks during mechanical unfolding processes [37].

Calorimetric and Volumetric Methods

Isothermal titration calorimetry (ITC) directly measures heat changes during molecular interactions, providing complete thermodynamic profiles (ΔG, ΔH, ΔS, Kₐ) of binding events. Differential scanning calorimetry (DSC) monitors heat capacity changes during thermal denaturation, revealing information about cooperative unfolding and stability contributions from various molecular forces.

The relationship between fusion enthalpies and volume changes during melting provides particularly valuable insights into the balance between hydrogen bonding and van der Waals forces [35]. Analyzing the enthalpy-to-volume ratio relative to molecular sphericity parameters enables researchers to separate the total fusion enthalpy into van der Waals and specific interaction contributions [35].

Research Reagent Solutions for Molecular Force Analysis

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Investigating Molecular Forces

| Reagent/Chemical | Primary Function in Research | Molecular Force Studied |

|---|---|---|

| Octenyl Succinic Anhydride (OSA) | Modulates hydrophobic interactions in protein systems | Hydrophobic Interactions |