Macronutrient Malabsorption in Research Populations: Mechanisms, Assessment, and Translational Applications

This article provides a comprehensive resource for researchers and drug development professionals navigating the complexities of macronutrient malabsorption.

Macronutrient Malabsorption in Research Populations: Mechanisms, Assessment, and Translational Applications

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive resource for researchers and drug development professionals navigating the complexities of macronutrient malabsorption. It synthesizes current evidence on the pathophysiology of impaired digestion and absorption of fats, proteins, and carbohydrates across diverse research populations, including those with environmental enteropathy, inflammatory bowel disease, and pancreatic insufficiency. We detail a battery of established and emerging functional tests—from breath analyses to direct invasive procedures—evaluating their applicability, limitations, and standardization in research settings. The scope extends to troubleshooting common methodological pitfalls, optimizing nutritional status in study cohorts, and validating novel biomarkers against histological and clinical endpoints. Finally, we present a framework for the comparative analysis of malabsorption syndromes to inform the development of targeted nutritional and pharmacologic interventions, aiming to bridge the gap between basic science and clinical application.

Deconstructing Macronutrient Malabsorption: Pathophysiological Mechanisms and Research Populations

Technical Support Center

Welcome to the technical support center for research on macronutrient malabsorption. This resource provides troubleshooting guidance for experiments based on the Three-Phase Model of Nutrient Assimilation, designed to help you pinpoint the phase of disruption.

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide 1: Investigating Luminal Phase Disruption

- Q: We are observing inconsistent digestion of a lipid emulsion in our in vitro gut model. What could be the cause?

- A: Inconsistent luminal digestion often stems from variable enzyme activity or suboptimal physicochemical conditions.

- Checkpoints:

- Enzyme Activity: Assay the activity of your pancreatic lipase and colipase preparation. Ensure it is fresh and has not been subjected to freeze-thaw cycles that degrade activity.

- pH & Bile Salts: Verify the pH of your simulated intestinal fluid is consistently maintained at 6.5-7.0. Confirm the critical micellar concentration (CMC) of your bile salt mixture is being achieved and that the composition (e.g., taurocholate vs. glycocholate ratio) is physiologically relevant.

- Substrate Preparation: Ensure the lipid emulsion is homogenous and stable. Sonication time and power should be standardized.

Guide 2: Investigating Mucosal Phase Disruption

- Q: Our Caco-2 cell monolayer assays show high transepithelial electrical resistance (TEER) but unexpectedly low uptake of a glucose analog. What should we investigate?

- A: High TEER confirms barrier integrity, so the issue is likely with specific transport mechanisms, not paracellular leakage.

- Checkpoints:

- Transporter Expression: Confirm the expression and membrane localization of key transporters (e.g., SGLT1 for glucose) via Western blot or immunofluorescence. Passage number can affect differentiation and transporter profile.

- Competitive Inhibition: Check your assay buffer for compounds that might competitively inhibit your target transporter (e.g., phlorizin for SGLT1).

- Cellular Viability & Metabolism: Use an MTT or similar assay to rule out general cytotoxicity from your test compound that may be impairing active transport processes non-specifically.

Guide 3: Investigating Post-Absorptive Phase Disruption

- Q: In our rodent model, we detect nutrients in the portal blood but see no corresponding change in peripheral tissue (e.g., muscle) biomarkers of anabolism. Where is the blockage?

- A: The nutrient is absorbed but not utilized, indicating a post-absorptive defect.

- Checkpoints:

- Hepatic First-Pass Metabolism: The liver may be sequestering or metabolizing the nutrient before it reaches systemic circulation. Measure arterial vs. portal nutrient concentrations.

- Signaling Pathways: Analyze key anabolic signaling pathways in the target tissue (e.g., the Insulin/IGF-1 → PI3K/Akt pathway for protein synthesis). Phospho-specific antibodies can detect activation status.

- Systemic Hormones: Measure plasma levels of insulin, glucagon, and incretins (e.g., GLP-1). Dysregulation here can prevent nutrient partitioning to tissues.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q: What is the best biomarker to confirm a luminal phase defect for proteins?

- A: Fecal nitrogen or specific undigested protein fragments (measured via mass spectrometry) are direct markers. A rise in breath hydrogen after a protein meal can also indicate bacterial fermentation of undigested protein in the colon.

Q: How can we differentiate between a mucosal and a post-absorptive defect for carbohydrates?

- A: A combined oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT) with serum insulin measurement is key. A flat blood glucose curve with low insulin suggests a mucosal defect (impaired absorption). A rising blood glucose curve with low or absent insulin suggests a post-absorptive defect (pancreatic beta-cell dysfunction).

Q: Our drug candidate is intended to enhance fat absorption. Which phase-specific assays are most relevant for preclinical validation?

- A:

- Luminal: In vitro lipolysis model measuring fatty acid release over time.

- Mucosal: Caco-2 cell uptake assay for bile acid-micellized fatty acids.

- Post-Absorptive: In vivo study measuring post-prandial plasma triglycerides, chylomicron levels, and tissue-specific fatty acid uptake.

- A:

Experimental Data & Protocols

Table 1: Key Biomarkers for Phase-Specific Disruption in Macronutrient Malabsorption

| Phase | Macronutrient | Key Biomarkers of Disruption | Normal Range (Exemplary) | Disrupted Range |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Luminal | Lipids | Fecal Fat Excretion | <7 g/24h | >7 g/24h |

| Proteins | Fecal Nitrogen | <2.0 g/24h | >2.5 g/24h | |

| Carbohydrates | Breath H2 | <20 ppm rise from baseline | >20 ppm rise | |

| Mucosal | All | D-Xylose Blood Test (5h) | >20 mg/dL | <20 mg/dL |

| Lipids | Serum Beta-Carotene | 50-250 µg/dL | Low | |

| Post-Absorptive | Proteins | Plasma Amino Acid Ratio (Val/Gly) | Stable Post-Prandial Rise | Blunted Response |

| Carbohydrates | Oral GTT (2h Glucose) | <140 mg/dL | Impaired |

Protocol 1: In Vitro Lipolysis Model to Assess Luminal Phase

- Prepare Simulated Intestinal Fluid (SIF): 150 mM NaCl, 5 mM Tris, 1.4 mM CaCl2, 3 mM NaTDC, 0.75 mM PC, pH 7.5.

- Add Substrate: Introduce your lipid formulation (e.g., 5 mg triglyceride) to the SIF.

- Initiate Digestion: Add pancreatic lipase/colipase solution (e.g., 1000 U/mL) to the mixture.

- Maintain pH: Use a pH-stat titrator to automatically add NaOH, maintaining pH 7.5. The volume of NaOH consumed is proportional to fatty acids released.

- Sample & Analyze: Take samples at timed intervals. Stop the reaction and quantify liberated fatty acids via gas chromatography or a colorimetric assay.

Protocol 2: Differentiated Caco-2 Cell Monolayer Uptake Assay

- Culture: Seed Caco-2 cells on Transwell inserts at high density. Culture for 21 days, changing media every 2-3 days. Monitor TEER until >500 Ω·cm².

- Prepare Uptake Buffer: Hank's Balanced Salt Solution (HBSS) with 10 mM HEPES, pH 7.4.

- Uptake Experiment: Aspirate culture media. Wash cells with uptake buffer. Add the test compound (e.g., C13-glucose) in buffer to the apical chamber.

- Incubate: Incubate at 37°C for a defined time (e.g., 15-60 min).

- Terminate & Quantify: Remove the apical solution and wash the monolayer with ice-cold buffer. Lyse the cells and analyze the lysate for transported compound using LC-MS/MS or a scintillation counter for radiolabeled compounds.

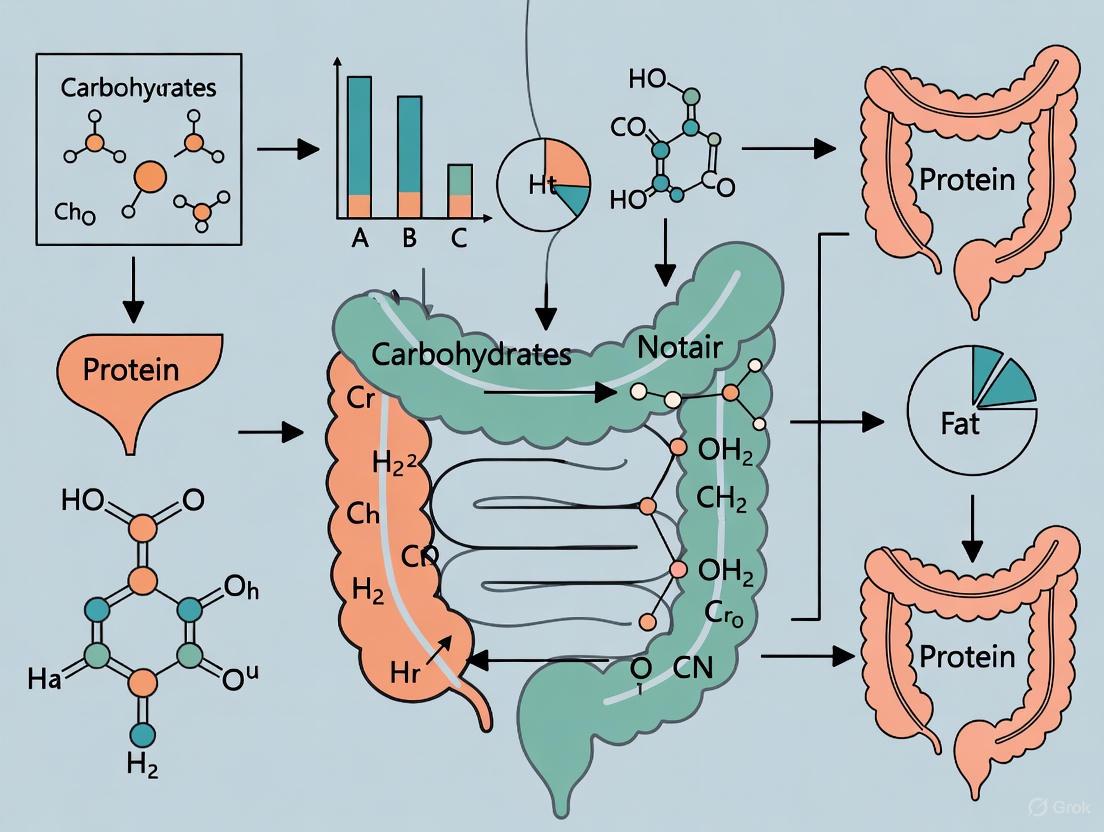

Pathway and Workflow Visualizations

Diagram: Luminal Digestion & Disruption

Diagram: Mucosal Uptake & Disruption

Diagram: Post-Absorptive Processing & Disruption

Diagram: Phase Disruption Diagnostic Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for Macronutrient Absorption Studies

| Reagent / Material | Function / Application |

|---|---|

| Porcine Pancreatin | A crude extract containing lipases, proteases, and amylases for simulating luminal digestion in in vitro models. |

| Taurocholic Acid Sodium Salt | A primary bile salt used to achieve physiologically relevant micelle formation for lipid solubilization. |

| Caco-2 Cell Line | A human colon adenocarcinoma cell line that spontaneously differentiates into enterocyte-like cells, forming a polarized monolayer for mucosal uptake and transport studies. |

| Transwell Permeable Supports | Inserts with a porous membrane used to culture Caco-2 cells, allowing separate access to apical and basolateral compartments. |

| D-[U-¹⁴C] Glucose | Radiolabeled glucose tracer used to quantitatively track carbohydrate uptake and transport in cellular and tissue models. |

| Electric Cell-Substrate Impedance Sensing (ECIS) | A real-time, label-free method to monitor cell barrier integrity (TEER) and cell behavior in culture. |

| Phospho-Akt (Ser473) Antibody | A key reagent for assessing activation of the PI3K/Akt pathway, a central regulator of post-absorptive nutrient utilization and anabolism. |

| Luminex Multiplex Assay Panels | For simultaneous measurement of multiple hormones (insulin, GLP-1, glucagon) from small volume plasma/serum samples to assess systemic post-absorptive signaling. |

FAQs: Core Concepts and Phenotype Differentiation

Q1: What is the fundamental difference between global and selective malabsorption in a research context?

A1: Global malabsorption involves the impaired absorption of almost all nutrients across multiple classes (fats, proteins, carbohydrates, vitamins, and minerals), typically resulting from conditions causing widespread mucosal damage or a significant reduction in absorptive surface area. In contrast, selective malabsorption is the isolated or specific malabsorption of a single nutrient or a limited array of nutrients, often due to a defect in a specific transporter, enzyme, or receptor [1] [2]. For example, celiac disease often presents as global malabsorption, while lactose intolerance, caused by lactase deficiency, is a classic example of selective carbohydrate malabsorption [3] [1].

Q2: What are the primary pathophysiological mechanisms a researcher should consider when modeling these phenotypes?

A2: Malabsorption can be categorized based on the disruption of one of the three phases of nutrient assimilation [3] [4] [5]:

- Luminal Phase (Maldigestion): Defective hydrolysis of nutrients. Causes include exocrine pancreatic insufficiency (e.g., chronic pancreatitis, cystic fibrosis), insufficient bile salt synthesis or secretion, and small intestinal bacterial overgrowth (SIBO) which deconjugates bile salts [3] [5] [6].

- Mucosal Phase (Malabsorption): Defects at the brush border membrane or within the enterocyte. This includes disorders like celiac disease and other enteropathies that damage the mucosa, congenital deficiencies of brush border enzymes (e.g., lactase), and specific defects in nutrient transporters [7] [3] [6].

- Post-Absorptive (Transport) Phase: Impairment in the delivery of absorbed nutrients via the lymphatic system or circulation. Conditions include intestinal lymphangiectasia, lymphoma, and abetalipoproteinemia [3] [6].

Q3: Which non-invasive functional tests are most suitable for phenotyping research populations, particularly in pediatric or field settings?

A3: Breath tests are increasingly favored for their non-invasive nature. Key examples include [7] [8]:

- Hydrogen Breath Tests: Used to diagnose specific carbohydrate intolerances (e.g., lactose, fructose) and Small Intestinal Bacterial Overgrowth (SIBO).

- ¹³C-Labeled Substrate Breath Tests: Can measure the absorption of carbohydrates (e.g., ¹³C-starch, ¹³C-sucrose), fats (e.g., ¹³C-mixed triglyceride), and proteins (using labeled dipeptides like benzoyl-L-tyrosyl-L-1-¹³C-alanine). These tests show promise for detecting subclinical malabsorption in conditions like environmental enteric dysfunction [8].

Troubleshooting Guides for Experimental Challenges

Challenge 1: Differentiating between pancreatic and mucosal causes of fat malabsorption in an animal model.

- Step 1 - Confirm Fat Malabsorption: Quantify fecal fat using a 72-hour stool collection while the subject is on a controlled diet (≥100 g fat/day). Fecal fat excretion >7 g/day confirms steatorrhea [4].

- Step 2 - Functional Testing:

- Direct Pancreatic Function: Measure fecal levels of pancreatic enzymes. Low fecal elastase or chymotrypsin is indicative of exocrine pancreatic insufficiency [4].

- Assess Mucosal Integrity/Absorption: The D-xylose absorption test can be used. Normal D-xylose absorption in the presence of steatorrhea points toward a pancreatic cause, whereas an abnormal result suggests mucosal disease [4].

- Step 3 - Histological Confirmation: A small intestinal biopsy remains the gold standard for identifying mucosal abnormalities such as villous atrophy, intraepithelial lymphocytes, or other enteropathies [7] [4].

Challenge 2: Inconsistent results from breath tests in a longitudinal cohort study.

- Potential Cause 1: Lack of standardized test protocols and subject preparation.

- Solution: Strictly control pre-test conditions: overnight fasting, avoidance of antibiotics and prokinetics before testing, use of standardized test meals, and consistent physical activity during the test [8].

- Potential Cause 2: Variable gastric emptying or small intestinal transit time.

- Solution: Consider dual-label isotope tests that can account for transit time or use study designs that allow each subject to serve as their own control.

- Potential Cause 3: Establishing appropriate, population-specific normative cut-off values.

- Solution: Conduct pilot studies to establish baseline values for your specific research population rather than relying on published values from different demographic or health groups [8].

Table 1: Characteristics of Global vs. Selective Malabsorption Phenotypes

| Feature | Global Malabsorption | Selective Malabsorption |

|---|---|---|

| Definition | Impaired absorption of multiple nutrients [1] | Impaired absorption of a single or limited nutrients [1] |

| Common Causes | Celiac disease, Crohn's disease, extensive mucosal damage, Short Bowel Syndrome [7] [3] [2] | Lactose intolerance (lactase deficiency), Pernicious anemia (B12), Abetalipoproteinemia [3] [1] [2] |

| Key Lab Findings | Steatorrhea, weight loss, deficiencies in iron (microcytic anemia), B12/folate (macrocytic anemia), vitamins A, D, E, K, hypoalbuminemia, hypocalcemia [4] [9] [2] | Findings specific to the deficient nutrient (e.g., iron deficiency anemia; osteoporosis from vitamin D malabsorption) [4] [2] |

| Primary Research Focus | Restoring mucosal integrity, nutritional support, managing underlying inflammatory disease [7] | Enzyme replacement, dietary modification, targeted nutrient delivery [9] |

Table 2: Key Functional Tests for Macronutrient Malabsorption Assessment

| Nutrient | Test Method | Experimental Protocol Summary | Interpretation & Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fat | 72-hour Fecal Fat Measurement [4] | 1. Subject consumes a controlled diet with 100g fat/day for 3 days.2. Collect all stool for 72 hours.3. Analyze total stool fat content. | Abnormal: >7g fat/24h. Gold standard but cumbersome. High values (≥40g/day) suggest pancreatic or severe mucosal disease. |

| Fat | ¹³C-Mixed Triglyceride Breath Test [8] | 1. Administer a test meal containing ¹³C-labeled mixed triglyceride.2. Collect breath samples at baseline and at regular intervals for up to 6 hours.3. Measure ¹³CO₂ enrichment. | Non-invasive proxy for pancreatic lipase activity. Requires standardization and population-specific cut-offs. |

| Carbohydrate | Hydrogen/Methane Breath Test [8] [9] | 1. After an overnight fast, administer a load of the specific carbohydrate (e.g., 25-50g lactose).2. Measure breath H₂/CH₄ at baseline and every 15-30 minutes for 2-5 hours. | A rise in H₂ ≥20 ppm from baseline indicates malabsorption. False negatives occur in non-H₂ producers; assess with lactulose. |

| Protein | Fecal Nitrogen [4] | Measure nitrogen content in a 72-hour stool collection. | Technically difficult and rarely used in clinical practice; research tool. |

| Protein | ¹³C-Dipeptide Breath Test [8] | Administer a labeled dipeptide (e.g., Benzoyl-L-tyrosyl-L-1-¹³C-alanine) and measure ¹³CO₂ in breath over time. | Non-invasive research method to assess peptide absorption and mucosal function. |

Experimental Protocols for Key Assessments

Protocol 1: D-Xylose Absorption Test for Mucosal Integrity Principle: D-xylose is a pentose sugar absorbed via passive diffusion that does not require pancreatic enzymes for digestion. Its absorption serves as a marker of proximal small intestinal mucosal integrity [4]. Procedure:

- The subject fasts overnight.

- A 25g dose of D-xylose is dissolved in 250-500 mL of water and administered orally.

- Blood is drawn at 1 hour post-administration. Alternatively, all urine is collected over a 5-hour period.

- Serum D-xylose or total urinary D-xylose excretion is measured. Interpretation:

- Abnormal: 1-hour serum level <20 mg/dL (1.33 mmol/L) or 5-hour urinary excretion <4 g [4].

- A normal result in the presence of steatorrhea suggests pancreatic insufficiency, while an abnormal result indicates mucosal disease or SIBO (as bacteria metabolize the D-xylose) [4].

Protocol 2: Serum Biomarkers for Nutritional Deficiencies in Malabsorption Research Principle: Widespread or specific nutrient malabsorption leads to measurable deficiencies in blood, serving as surrogate markers for the condition's severity and scope [4] [2]. Procedure:

- Collect a fasting blood sample from research subjects.

- Analyze for the following key biomarkers:

- Complete Blood Count (CBC) with indices: To detect microcytic (iron deficiency) or macrocytic (B12/folate deficiency) anemia [4] [2].

- Iron Studies (Ferritin), Vitamin B12, Folate: To confirm and specify deficiencies.

- Fat-Soluble Vitamins (A, D, E): Commonly low in fat malabsorption.

- Albumin, Prealbumin: Markers of protein-calorie nutrition and chronic deficiency.

- Calcium, Magnesium, Phosphate: May be low due to malabsorption or vitamin D deficiency.

- Prothrombin Time (PT): Prolonged in vitamin K deficiency [4] [9].

Diagnostic Pathway and Research Reagent Solutions

Diagram Title: Research Diagnostic Pathway for Malabsorption Phenotypes

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Malabsorption Studies

| Reagent / Material | Primary Function in Research |

|---|---|

| ¹³C-Labeled Substrates (e.g., Mixed Triglyceride, Sucrose, Dipeptides) | Non-invasive probes for assessing the digestive and absorptive capacity of specific macronutrients via breath tests [8]. |

| D-Xylose | A carbohydrate probe used to assess the integrity of the small intestinal mucosa independently of pancreatic function [4]. |

| Hydrogen/Methane Breath Test Kits (Lactulose, Lactose, Fructose) | Diagnostic kits for detecting carbohydrate malabsorption and small intestinal bacterial overgrowth (SIBO) by measuring bacterial fermentation gases [8] [9]. |

| Fecal Fat Analysis Kits (Acid Steatocrit, Near-Infrared Reflectance Analysis - NIRA) | Quantitative and semi-quantitative methods for confirming steatorrhea in study subjects, with varying levels of practicality and precision [4]. |

| ELISA/Kits for Serological Markers (Anti-tTG, Anti-EMA for Celiac Disease) | Essential for screening and identifying specific etiologies of mucosal damage within study cohorts [7] [2]. |

| Endoscopy & Biopsy Forceps | Tools for obtaining gold-standard histopathological samples from the small intestinal mucosa to confirm and classify enteropathies [7] [4]. |

Pathophysiology and Key Etiologies of Fat Malabsorption

Fat malabsorption, or steatorrhea, occurs when the digestive system fails to properly process and absorb dietary fats. Normal fat absorption is a complex process that can be disrupted at several key stages: the luminal phase (digestion), the mucosal phase (absorption), and the post-absorptive phase (transport) [3] [4].

The table below summarizes the primary etiologies of fat malabsorption, categorized by the physiological phase they disrupt.

Table 1: Major Etiologies of Fat Malabsorption

| Physiological Phase | Underlying Mechanism | Specific Conditions |

|---|---|---|

| Luminal Phase (Digestion) [3] [10] | Impaired hydrolysis of triglycerides due to insufficient pancreatic enzyme activity or an unfavorable luminal environment. | Exocrine Pancreatic Insufficiency (EPI) from Chronic Pancreatitis, Cystic Fibrosis, Pancreatic Tumors, or Pancreatic Resection [3] [11] [10]. |

| Reduced bile acid synthesis or secretion, critical for micelle formation [3]. | Cholestatic Liver Disease, Cirrhosis, Small Intestinal Bacterial Overgrowth (SIBO) causing bile acid deconjugation [3] [4]. | |

| Mucosal Phase (Absorption) [3] | Damage to the intestinal mucosa, reducing the functional surface area for absorption. | Celiac Disease, Crohn's Disease, Environmental Enteropathy [3] [12]. |

| Post-Absorptive Phase (Transport) [3] | Defective packaging or transport of absorbed lipids via the lymphatic system. | Abetalipoproteinemia, Intestinal Lymphangiectasia [3]. |

Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs

Guide 1: Investigating Suspected Fat Malabsorption in a Pre-Clinical Model

Problem: An animal model presents with weight loss and diarrhea following a surgical procedure or dietary challenge. You suspect fat malabsorption.

Objective: Systematically identify the phase of fat absorption that is impaired.

Table 2: Troubleshooting Workflow for Fat Malabsorption

| Step | Investigation | Methodology / Assay | Interpretation of Key Results |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Confirm Steatorrhea | Quantitative Fecal Fat Analysis [4] | 72-hour stool collection while subject is on a controlled, high-fat diet (≥100 g/day). Measure total fecal fat. | Fecal fat >7 g/day confirms steatorrhea [4]. |

| 2. Localize the Defect | Differentiate Pancreatic vs. Mucosal Cause [4] | Fecal Elastase-1 (FE-1) Test [11] [13]. | Low FE-1 suggests Exocrine Pancreatic Insufficiency (EPI). Normal FE-1 points toward a mucosal or post-absorptive defect [4]. |

| 3. Identify Specific Etiology | Evaluate Mucosal Integrity & Function | Serum Blood Tests: Vitamin B12, Folate, Ferritin, Albumin [4]. | Microcytic anemia (iron deficiency) suggests proximal mucosal disease (e.g., Celiac). Low B12 can indicate terminal ileal disease or SIBO [4]. |

| Small Bowel Biopsy [4] | Histology can reveal villous atrophy (Celiac), lymphangiectasia, or other mucosal pathologies [3]. | ||

| Test for Carbohydrate Malabsorption | 13C-Substrate Breath Tests (e.g., 13C-Sucrose) [12]. | Abnormal results indicate generalized mucosal dysfunction, as seen in Environmental Enteropathy [12]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: What are the most reliable non-invasive tests to differentiate pancreatic from intestinal causes of fat malabsorption in human studies?

The Fecal Elastase-1 (FE-1) test is the most widely used and reliable non-invasive test for this purpose. It is a simple, single-stool sample test that does not require discontinuation of pancreatic enzyme replacement therapy (PERT). A concentration of <200 μg/g is indicative of Exocrine Pancreatic Insufficiency (EPI), while a value of <15 μg/g demonstrates high sensitivity and specificity for severe EPI. A normal FE-1 value in the presence of steatorrhea strongly suggests a mucosal or post-absorptive etiology [11] [4] [13].

FAQ 2: Beyond classic pancreatic diseases, what other conditions should researchers consider as potential causes of EPI?

EPI can result from both pancreatic and non-pancreatic disorders. Key non-pancreatic causes include:

- Diabetes Mellitus

- Celiac Disease

- Inflammatory Bowel Disease (IBD)

- Post-Gastrointestinal Surgery (e.g., Gastrectomy): Disrupts neurohormonal signaling and causes pancreaticocibal asynchrony [11] [13].

- Advanced Age [11].

FAQ 3: In the context of environmental enteropathy (EE), which macronutrients are most likely to be malabsorbed, and what tests are suitable for field studies?

Available evidence suggests that lactose and fat malabsorption are more likely to occur in EE [12]. For field studies in pediatric populations, non-invasive 13C-breath tests are particularly suitable. These include the 13C-mixed triglyceride breath test for fat malabsorption and the 13C-sucrose or 13C-lactose breath tests for carbohydrate malabsorption. These tests are well-tolerated and provide a functional readout of digestive and absorptive capacity [12].

Experimental Protocols & The Scientist's Toolkit

Detailed Protocol: Fecal Fat Quantification (72-Hour Collection)

Principle: This is the gold-standard method to objectively confirm steatorrhea by directly measuring the amount of fat excreted in stool over a precise period while the subject consumes a standardized high-fat diet [4].

Materials:

- Pre-weighed, sealed, and labeled stool collection containers.

- Metabolic cage or dedicated collection system.

- Controlled diet with precisely measured fat content (≥100 g/day).

- Solvents and laboratory equipment for fat extraction (e.g., gravimetric analysis or near-infrared reflectance analysis).

Procedure:

- Diet Standardization: For 3 days prior to and throughout the 72-hour collection period, provide the subject with a controlled diet containing exactly 100 grams of fat per day.

- Stool Collection: Collect all stool produced over a continuous 72-hour period. Ensure immediate storage of collected samples at -20°C to prevent fat degradation and water loss.

- Homogenization and Analysis: Pool and thoroughly homogenize the entire 72-hour stool sample. Take a representative aliquot for fat analysis.

- Fat Extraction & Calculation: Perform fat extraction using a standard method (e.g., van de Kamer method). Calculate total fat content and express the result as grams of fat excreted per 24 hours.

- Interpretation: Fat excretion of >7 grams/24 hours is diagnostic of steatorrhea. Severe malabsorption (≥40 g/day) is often seen in pancreatic insufficiency or severe mucosal disease [4].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents & Materials

Table 3: Essential Reagents for Investigating Fat Malabsorption

| Reagent / Material | Primary Function in Research | Specific Application Example |

|---|---|---|

| Fecal Elastase-1 (FE-1) ELISA Kit | To quantitatively measure pancreatic elastase levels in stool samples as a marker of exocrine pancreatic function [11] [13]. | Diagnosing and stratifying the severity of Exocrine Pancreatic Insufficiency (EPI) in animal models or human subjects. |

| 13C-Labeled Substrates (Mixed Triglyceride, Sucrose, Lactose) | To act as tracer molecules for non-invasive breath tests that assess digestive and absorptive function [12]. | Evaluating fat (13C-MTG) or carbohydrate (13C-sucrose) malabsorption in functional studies, especially in pediatric or field research settings. |

| D-Xylose | To assess the integrity of the small intestinal mucosa independently of pancreatic function [4]. | Differentiating between mucosal disease (abnormal D-xylose absorption) and pancreatic disease (normal D-xylose absorption) in the presence of steatorrhea. |

| Pancreatic Enzyme Replacement Therapy (PERT) | To provide exogenous digestive enzymes (lipase, protease, amylase) and rescue fat malabsorption in experimental models [11]. | Conducting therapeutic intervention studies to confirm an EPI diagnosis and evaluate the efficacy of new treatments. |

Diagnostic and Pathophysiological Visualizations

Diagram 1: Diagnostic decision tree for fat malabsorption.

Diagram 2: Key pathophysiological phases of fat absorption.

FAQs and Troubleshooting Guide

Q1: Why do my hydrogen breath test results show high hydrogen levels, yet the volunteer reports no gastrointestinal symptoms?

A: This is a common finding and underscores the crucial difference between malabsorption and intolerance [14]. Malabsorption is a biochemical phenomenon confirmed by diagnostic tests, while intolerance is the clinical manifestation of symptoms [14]. A significant proportion of individuals (up to 50% for fructose and sorbitol) are asymptomatic "malabsorbers" [14]. Symptom development depends on factors beyond bacterial gas production, including:

- Colonic Microbiome Composition: The specific bacterial species present and their metabolic pathways (e.g., hydrogen vs. methane production) influence symptoms [14].

- Visceral Hypersensitivity: Some individuals have a heightened sensitivity to gut distension from gas and osmotic load [14].

- Intestinal Motility: Rapid transit may exacerbate diarrhea, while slower transit could increase fermentation time and gas-related symptoms [3].

Q2: How can I distinguish between SIBO and a primary enzyme deficiency as the cause of carbohydrate malabsorption in my study participants?

A: Differentiation is critical for directing appropriate therapy. The clinical presentation can overlap, but key diagnostic features can help distinguish them [3]:

- Pattern on Hydrogen Breath Test: SIBO often produces an early peak (e.g., within 60-90 minutes) in hydrogen concentration as the substrate is fermented prematurely in the small intestine. A primary deficiency typically shows a later peak as the carbohydrate reaches the colon [3].

- Response to a Lactulose Breath Test: Lactulose is not absorbed in the small intestine. A double peak (small intestinal and colonic) on the lactulose test is suggestive of SIBO [3].

- Underlying Risk Factors: A history of abdominal surgery, motility disorders, or proton pump inhibitor use supports a SIBO diagnosis [3].

- Broad Symptom Profile: SIBO can cause fat malabsorption (steatorrhea) and vitamin B12 deficiency due to bacterial consumption, which is not typical of isolated enzyme deficiencies [3].

Q3: What are the primary limitations of the hydrogen breath test, and how can I mitigate them in my research protocol?

A: The hydrogen breath test, while non-invasive, has several limitations that must be controlled for in rigorous research [14] [15]:

- Non-Hydrogen Producers: An estimated 2-20% of the population has a microbiome that produces little to no hydrogen, leading to false-negative results. Mitigation: Include a concomitant lactulose challenge to confirm the presence of hydrogen-producing bacteria. Consider measuring methane (CH4) in addition to hydrogen, as some individuals are methanogenic producers [14].

- False-Positive Results: These can occur due to small intestinal bacterial overgrowth (SIBO) or orocecal transit time that is excessively rapid or slow. Mitigation: A standardized pre-test diet (low-fermentable carbohydrates for 24 hours) and an overnight fast are essential to reduce baseline hydrogen levels [15].

- Lack of Standardization: Test dose, formulation, and duration can vary. Mitigation: Adhere to published consensus guidelines (e.g., Rome Consensus Conference) for dosage (e.g., 25g fructose, 50g lactose) and test duration (typically 3-4 hours) [15].

Q4: Our dietary intervention for fructose malabsorption is failing. Could other FODMAPs be influencing the results?

A: Absolutely. A common pitfall in dietary intervention studies is focusing on a single sugar in isolation. The gut absorbs and ferments multiple carbohydrates simultaneously, and they interact [14] [16]. For example, the presence of glucose enhances fructose absorption via the GLUT2 transporter, while sorbitol competitively inhibits the GLUT5 transporter, thereby exacerbating fructose malabsorption [14]. A successful dietary intervention must account for the total "fermentable load" and consider a comprehensive low-FODMAP approach, at least initially, to establish a baseline response.

Key Experimental Protocol: Hydrogen/Methane Breath Test

The hydrogen breath test is the primary non-invasive method for detecting carbohydrate malabsorption [14] [15].

Detailed Methodology:

Pre-Test Preparation:

- Volunteers must fast for a minimum of 12 hours prior to testing (water is permitted) [15].

- Avoid antibiotics, probiotics, and laxatives for at least 4 weeks before the test [14].

- No smoking or vigorous exercise on the test day, as this can affect gut motility and hydrogen production.

- A low-fermentable carbohydrate dinner is recommended the night before.

Baseline Breath Sample:

- Collect a baseline (time 0) end-expiratory breath sample using a standardized breath bag or hand-held analyzer to measure fasting hydrogen and methane levels.

Test Substrate Administration:

- Administer the test sugar dissolved in 250 mL of water. Common research doses are:

- Note: For fructose malabsorption testing, simultaneous measurement of blood glucose is recommended to rule out hereditary fructose intolerance, which can cause dangerous hypoglycemia [14].

Post-Ingestion Sampling:

- Collect subsequent breath samples every 15-30 minutes for a period of 3 to 4 hours [15].

- Volunteers should record the onset of any symptoms (bloating, pain, diarrhea) and their severity on a standardized scale at each time point.

Interpretation of Results:

- Positive for Malabsorption: An increase in hydrogen of > 20 parts per million (ppm) over the baseline value at any time point is considered diagnostic of malabsorption [15].

- Methane Production: An increase in methane of > 10 ppm over baseline is also considered significant [14].

- Clinical Correlation: A positive test must be correlated with the volunteer's symptom log to diagnose carbohydrate intolerance.

Quantitative Data on Carbohydrate Malabsorption

The prevalence of carbohydrate malabsorption varies significantly by type of sugar, dose, and population ethnicity [14].

Table 1: Prevalence of Carbohydrate Malabsorption in Response to Test Doses

| Sugar | Test Dose | Prevalence of Malabsorption | Key Population Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lactose | 50 g | 70% - 100% in parts of Asia, Africa, Southern Europe [14] | Prevalence follows a north-south gradient in Europe; <10% in Scandinavia [14]. |

| Fructose | 25 g in 250 mL water | ~40% [14] | Dose-dependent; rate increases with higher doses [14]. |

| 50 g in 250 mL water | 60% - 70% [14] | ||

| Sorbitol | 10 g | Up to 100% [14] | Poorly absorbed by passive diffusion in most individuals [14]. |

Table 2: Comparison of Primary Carbohydrate Malabsorption Disorders

| Disorder | Defective Mechanism | Primary Site of Dysfunction | Key Diagnostic Method |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lactose Intolerance | Deficiency of lactase enzyme (LPH) [15] | Small intestinal brush border [3] | Hydrogen breath test, Lactose tolerance test [15] |

| Fructose Malabsorption | Deficiency/ dysfunction of GLUT5 transporter [14] | Small intestinal enterocyte membrane [3] | Hydrogen breath test with concurrent blood glucose measurement [14] |

| Sucrase-Isomaltase Deficiency | Deficiency of sucrase-isomaltase (SI) complex [3] | Small intestinal brush border [3] | Breath test or enzymatic assay from intestinal biopsy [3] |

Pathway and Workflow Visualizations

Carbohydrate Digestion & Malabsorption Pathway

Diagnostic Workflow for Malabsorption

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents and Materials for Carbohydrate Malabsorption Research

| Research Reagent / Material | Function / Application in Research |

|---|---|

| Lactulose | A non-absorbable disaccharide used as a positive control in breath testing to confirm the presence of hydrogen-producing colonic bacteria and to assess orocecal transit time [14]. |

| 13C-Labeled Substrates (e.g., 13C-lactose, 13C-sucrose) | Stable isotope-labeled compounds used in 13C-breath tests. The measurement of 13CO2 in breath provides an alternative, non-radioactive method to assess carbohydrate digestion and absorption [8]. |

| Test Carbohydrates (Pharmaceutical Grade) | High-purity lactose, fructose, sorbitol, and glucose are essential for standardized oral challenges and hydrogen breath tests to ensure consistent and reproducible dosing [14] [15]. |

| Hydrogen & Methane Breath Analyzer | A gas chromatograph or specialized handheld device for the quantitative, high-frequency measurement of hydrogen (H2) and methane (CH4) concentrations in end-expiratory breath samples [14]. |

| Standardized Symptom Questionnaires | Validated instruments (e.g., visual analogue scales, Likert scales) for the quantitative and systematic recording of abdominal pain, bloating, flatulence, and stool consistency during challenge tests to correlate with biochemical findings [15]. |

| Modular Diet Components | Pre-defined, chemically controlled meals or formula diets (e.g., low-FODMAP, lactose-free, fructose-restricted) for conducting controlled dietary intervention studies to assess the efficacy of elimination diets [14]. |

Protein Malabsorption and Amino Acid Transport Dysfunction

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What are the primary clinical signs that suggest a patient or research model is experiencing protein malabsorption?

Initial signs often resemble general indigestion, including abdominal bloating, gas, and diarrhea [9]. Over time, symptoms progress to those of protein undernutrition and amino acid deficiency, such as unintentional weight loss, muscle wasting (sarcopenia), edema (swelling due to fluid), and easy bruising [9]. Laboratory findings may include hypoalbuminemia (low serum albumin) and generalized malnutrition [17] [18].

Q2: What are the main mechanisms that lead to protein malabsorption?

The causes can be organized by the phase of digestion and absorption they disrupt:

- Luminal Phase (Impaired Digestion): Defects in the initial breakdown of proteins. Causes include Exocrine Pancreatic Insufficiency (EPI) (deficiency of proteases like trypsin) from chronic pancreatitis, cystic fibrosis, or pancreatic resection [3] [18]. Inactivation of pancreatic enzymes from gastric hypersecretion (e.g., Zollinger-Ellison syndrome) is another cause [18].

- Mucosal Phase (Impaired Absorption): Defects at the level of the small intestinal lining. This includes damage to the mucosal surface from celiac disease, Crohn's disease, or infectious enteropathies, which reduces the absorptive surface area [9] [3]. It also encompasses specific defects in amino acid transporter systems themselves [19] [18].

- Post-Absorptive Phase (Impaired Transport): Obstruction of the lymphatic system (e.g., intestinal lymphangiectasia, lymphoma) can impair the transport of absorbed nutrients, leading to protein-losing enteropathy [3] [18].

Q3: What are some specific genetic disorders of amino acid transport, and which transporters do they affect?

Several inherited disorders are linked to specific amino acid transporter defects. The table below summarizes key examples [19].

Table 1: Inherited Disorders of Amino Acid Transport

| Disorder Name | Gene / Transporter | SLC Family | Main Clinical Manifestations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lysinuric Protein Intolerance | SLC7A7 (y+LAT-1) | SLC7 | Inability to digest proteins, diarrhea, vomiting, hyperammonemia after meals. |

| Hartnup Disorder | SLC6A19 (B⁰AT1) | SLC6 | Pellagra-like photosensitive rash, cerebellar ataxia, aminoaciduria. |

| Cystinuria | SLC3A1 (rBAT) & SLC7A9 (b⁰⁺AT) | SLC3 / SLC7 | Formation of cystine stones in the kidneys. |

| Iminoglycinuria | SLC6A20 (SIT1) or SLC36A2 (PAT2) | SLC6 / SLC36 | Typically benign, excessive glycine and proline in urine. |

Q4: How is amino acid transport across the Blood-Brain Barrier (BBB) relevant to neurological disorders?

The BBB tightly regulates the brain's environment. Amino acid transporters at the BBB are essential for providing precursors for neurotransmitters and antioxidants. Dysfunction of these transporters is linked to abnormalities in amino acid levels, which have been implicated in the pathophysiology of conditions like schizophrenia, autism spectrum disorder, and Huntington's disease. For instance, a deficiency in L-Cysteine transport can limit the production of the critical antioxidant glutathione, leading to oxidative stress in the central nervous system [20].

Q5: What is the role of SLC7 transporters in metabolic disease and diabetes pathophysiology?

The SLC7 family, particularly LAT1 (SLC7A5), transports large neutral amino acids (LNAAs) like branched-chain amino acids (BCAAs). Alterations in the expression or function of these transporters are implicated in insulin resistance and Type 2 Diabetes (T2D). Elevated plasma BCAA levels, a common finding in T2D, are thought to arise from and contribute to dysregulated mTOR signaling, a key pathway in insulin action [21]. This can lead to impaired glucose uptake in skeletal muscle cells [21].

Experimental Protocols & Methodologies

Protocol for Diagnosing Protein Malabsorption in a Clinical Research Setting

Aim: To systematically identify and confirm protein malabsorption and differentiate its causes in a study population.

Methodology:

- Initial Screening:

- Blood Tests:

- Stool Tests:

- Fecal Fat Content (72-hour collection): Since fat malabsorption frequently accompanies protein malabsorption, this is a key test. Healthy individuals excrete <7g fat per day on a 100g fat diet [17].

- Fecal Elastase or Chymotrypsin: Low levels indicate Exocrine Pancreatic Insufficiency (EPI) as a likely cause [17].

Functional and Mucosal Integrity Tests:

- D-Xylose Test: This test assesses mucosal integrity. Abnormal absorption suggests a mucosal problem rather than a pancreatic one [17].

- Breath Tests:

- Hydrogen Breath Test: Used to diagnose carbohydrate malabsorption (e.g., lactose intolerance) and small intestinal bacterial overgrowth (SIBO), which can contribute to general malabsorption [9] [17].

- ¹³C-Di-peptide Breath Test: An emerging, non-invasive method to directly assess protein/peptide absorption. The test uses a synthetic dipeptide labeled with ¹³C (e.g., Benzoyl-L-tyrosyl-L-1-¹³C-alanine). Upon absorption and metabolism, ¹³CO₂ is exhaled and measured, with lower levels indicating malabsorption [8].

Definitive Diagnosis:

- Upper Endoscopy with Duodenal Biopsy: The gold standard for diagnosing mucosal diseases. Histologic examination of biopsied tissue can confirm celiac disease, tropical sprue, Whipple's disease, and other infiltrative or inflammatory conditions [17].

The following workflow diagram illustrates the diagnostic pathway for protein malabsorption.

Protocol for Investigating Amino Acid Transporter Function in Cell Models

Aim: To characterize the function and kinetics of a specific amino acid transporter in a cultured cell line.

Methodology:

- Cell Culture: Use an appropriate cell model (e.g., Caco-2 for intestinal transport, HEK293 for heterologous expression). Culture cells to confluence on multi-well plates or permeable filter supports (for transepithelial transport studies).

- Uptake Assay:

- Prepare an uptake buffer containing a radiolabeled (e.g., ¹⁴C, ³H) or stable isotope-labeled amino acid of interest.

- Wash cells with a pre-warmed buffer.

- Initiate uptake by adding the labeled amino acid solution to the cells for a defined time (e.g., 1-10 minutes). Incubate at 37°C.

- Include control conditions with an excess of unlabeled amino acid to measure non-specific transport and determine carrier-mediated uptake.

- Terminate the reaction by rapid removal of the uptake solution and washing with an ice-cold buffer.

- Quantification:

- For radiolabeled amino acids, lyse the cells and measure the accumulated radioactivity using a scintillation counter.

- For stable isotopes, use mass spectrometry to quantify the accumulated label.

- Kinetic Analysis: Repeat the uptake assay with a range of amino acid concentrations. Plot the uptake rate (V) against substrate concentration ([S]) and fit the data to the Michaelis-Menten equation (V = Vₘₐₓ * [S] / (Kₘ + [S])) to determine the transporter's affinity (Kₘ) and maximum transport capacity (Vₘₐₓ).

Research Reagent Solutions

This table lists key reagents and tools used in the study of amino acid transporters and protein absorption.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents for Amino Acid Transport Studies

| Reagent / Material | Function / Application | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Stable Isotope-Labeled Amino Acids (e.g., ¹³C, ¹⁵N) | Tracing amino acid uptake, metabolism, and flux in vitro and in vivo. | ¹³C-dipeptide breath test in human subjects [8]; kinetic uptake assays in cell culture. |

| Radiolabeled Amino Acids (e.g., ³H, ¹⁴C) | High-sensitivity detection for quantitative measurement of transporter kinetics. | Classic cell-based uptake assays to determine Kₘ and Vₘₐₓ. |

| Specific Transporter Inhibitors | Pharmacologically blocking specific transporter systems to elucidate function. | Using BCH (2-aminobicyclo[2.2.1]heptane-2-carboxylic acid) to inhibit System L (LAT1/SLC7A5) transport. |

| cDNA Plasmids for SLC Transporters | Heterologous expression of transporters in model cell lines (e.g., HEK293, Xenopus oocytes). | Functional characterization of a wild-type vs. mutant transporter gene [19]. |

| Anti-SLC Transporter Antibodies | Detecting protein expression, localization, and quantification via Western Blot, Immunofluorescence. | Confirming plasma membrane localization of LAT1 in cancer cell lines. |

| Permeable Filter Supports (e.g., Transwell) | Modeling polarized epithelial transport and barrier function. | Measuring transepithelial flux of amino acids across a Caco-2 cell monolayer. |

Signaling Pathways & Metabolic Context

Amino acid transporters are not just conduits for nutrients; they are critical signaling nodes. The SLC7 family, particularly the SLC3A2-SLC7A5 heterodimer (LAT1), transports branched-chain amino acids (BCAAs) like leucine, which activate the mTORC1 signaling pathway. This pathway is a central regulator of cell growth, proliferation, and metabolism. The following diagram illustrates this key signaling relationship and its implication in insulin resistance.

Troubleshooting Guides and FAQs

Q: What are the key differences in intestinal permeability assessment methods between EE, IBD, and celiac disease models?

A: Intestinal permeability assessment requires method optimization for each condition:

Lactulose-Mannitol Test Issues:

- False positives in EE: Address by controlling for tropical enteropathy confounding factors

- IBD variability: Time testing relative to flare activity

- Celiac specificity: Combine with gluten challenge protocols

Ussing Chamber Technical Problems:

- Tissue viability maintenance during transport

- Mounting orientation consistency

- Solution osmolarity calibration

Q: How do I optimize organoid cultures from different disease biopsies?

A: Disease-specific optimization is critical:

Environmental Enteropathy:

- Problem: Poor crypt survival from malnourished tissue

- Solution: Pre-condition with lipid-enriched media for 48 hours

IBD-derived Organoids:

- Problem: Inflammatory cytokine interference

- Solution: Add TNF-α inhibitors during initial establishment

Post-surgical Tissue:

- Problem: Fibrotic tissue contamination

- Solution: Implement longer collagenase digestion (90 minutes)

Table 1: Macronutrient Absorption Markers in Disease Populations

| Disease State | Fecal Fat (g/24h) | D-Xylose Absorption (g/5h) | Serum Albumin (g/dL) | Citrulline (μmol/L) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Healthy Controls | <7 | >4.5 | 3.5-5.0 | 30-45 |

| Environmental Enteropathy | 8-15 | 2.5-4.0 | 2.8-3.5 | 15-28 |

| Active IBD | 10-25 | 1.8-3.5 | 2.5-3.8 | 10-25 |

| Celiac Disease (Untreated) | 9-18 | 2.0-3.8 | 2.9-3.9 | 18-30 |

| Post-Surgical (Short Bowel) | 15-40 | 1.0-2.5 | 2.2-3.2 | 8-20 |

Table 2: Barrier Function Parameters Across Conditions

| Parameter | Normal Range | EE | IBD | Celiac | Post-Surgical |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TEER (Ω·cm²) | >50 | 25-40 | 20-35 | 30-45 | 15-30 |

| FITC-Dextran Flux (μg/ml) | <0.5 | 0.8-2.5 | 1.2-4.0 | 0.9-2.8 | 1.5-5.0 |

| Zonulin (ng/ml) | <50 | 65-120 | 80-200 | 70-150 | 60-110 |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Dual-Sugar Absorption Test for Field Studies

Purpose: Assess intestinal permeability in resource-limited settings Materials:

- Lactulose and mannitol solutions

- Urine collection containers

- HPLC system with refractive index detector

Procedure:

- Administer oral dose (5g lactulose + 2g mannitol in 100ml water)

- Collect urine over 5-hour period

- Preserve with thymol crystals

- Analyze sugar concentrations via HPLC

- Calculate L:M ratio (normal <0.03)

Troubleshooting:

- Incomplete urine collection: Use para-aminobenzoic acid as recovery marker

- Bacterial degradation: Add chlorhexidine to collection containers

Protocol 2: Ex Vivo Mucosal Healing Assay

Purpose: Quantify epithelial repair mechanisms Materials:

- IBD patient-derived colonoids

- Electric cell-substrate impedance sensing (ECIS) system

- Wounding electrodes

Procedure:

- Seed colonoids in ECIS arrays (20,000 cells/well)

- Grow to confluence (TER >1000 Ω)

- Apply wounding pulse (30 seconds, 3000 μA)

- Monitor resistance recovery every 5 minutes for 48 hours

- Calculate healing rate from recovery curve slope

Pathway Diagrams

Title: Nutrient Absorption Disruption Pathway

Title: Tight Junction Regulation Pathway

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents

| Reagent | Function | Application |

|---|---|---|

| FITC-dextran 4kDa | Paracellular permeability tracer | Barrier function assays |

| Human zonulin ELISA | Tight junction regulator quantification | EE and celiac research |

| Citrulline assay kit | Enterocyte mass marker | Absorption capacity assessment |

| Ussing chamber system | Electrophysiology measurement | Transepithelial resistance |

| Organoid culture matrix | 3D growth support | Patient-derived models |

| Cytokine multiplex panel | Inflammatory profile | IBD mechanism studies |

| Stable isotope nutrients | Metabolic trafficking | Absorption pathway mapping |

Troubleshooting Common SIBO Research Challenges

FAQ 1: How can I distinguish between SIBO and other malabsorption syndromes in a research setting?

SIBO presents a diagnostic challenge due to symptom overlap with other malabsorption syndromes. The key is to identify the unique etiological factors and diagnostic patterns of SIBO. Table 1 outlines the primary diagnostic approaches and their research considerations [22] [23].

Table 1: Diagnostic Methods for SIBO in Research Populations

| Method | Procedure | Research Advantages | Research Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Jejunal Aspirate & Culture | Endoscopic collection of small intestinal fluid with quantitative culture (>10³ CFU/mL diagnostic) | Considered historical gold standard; allows bacterial identification | Invasive, expensive, risk of oropharyngeal contamination, poorly reproducible [22] |

| Glucose Breath Test | Oral administration of 50-75g glucose solution with breath hydrogen/methane measurement | High specificity (less colonic fermentation) | May miss distal SIBO (false negatives); sensitivity 20-93%, specificity 45-86% [22] [24] |

| Lactulose Breath Test | Oral administration of 10g lactulose solution with breath hydrogen/methane measurement | Identifies SIBO throughout entire small intestine | Potential for false positives from rapid transit; sensitivity 17-68%, specificity 44-86% [22] [24] |

| Supportive Laboratory Findings | Measurement of B12, folate, fat-soluble vitamins, nutritional markers | Non-invasive, indicates functional consequences | Non-specific; can be normal in early disease [22] [25] |

FAQ 2: What are the most common confounding variables in SIBO comorbidity research, and how can they be controlled?

Several confounding variables can complicate SIBO research. Motility disorders (diabetes, scleroderma), anatomical abnormalities (small intestinal diverticula, surgical blind loops), and medications (PPIs, narcotics) strongly associate with SIBO [22] [25] [26]. Control strategies include: (1) Detailed participant stratification based on comorbid conditions; (2) Standardized medication documentation and analysis; (3) Pre-study fasting and dietary controls to minimize test variability [24].

FAQ 3: Why might SIBO treatment protocols fail in research populations with significant comorbidities?

Treatment failure often stems from unaddressed underlying mechanisms. Key reasons include: (1) Persistent dysmotility not managed with prokinetics; (2) Anatomical defects requiring surgical intervention; (3) Biofilm formation requiring sequential or combination therapies; (4) Methane-dominant SIBO (IMO) requiring different antibiotic regimens [22]. Complex comorbidities like scleroderma, Crohn's disease, and immunodeficiency disorders often require simultaneous management of the underlying condition for successful SIBO eradication [22] [25].

Essential Experimental Protocols for SIBO Research

Hydrogen/Methane Breath Testing Protocol

Principle: Bacterial fermentation of carbohydrates produces hydrogen and methane gases, which are absorbed and exhaled [24].

Materials: Breath test kit (collection tubes, labels), substrate (lactulose or glucose), timing device, breath analyzer.

Procedure:

- Pre-Test Preparation (4 weeks prior): Complete any antibiotic courses [24].

- One Week Pre-Test: Discontinue prokinetics and laxatives if tolerated (consult physician) [24].

- 24-Hour Prep Diet: Avoid complex carbohydrates and fermentable foods. Consume only plain meat, fish, eggs, white rice, clear fluids [24] [27].

- 12-Hour Fast: Overnight fast with only water permitted [24] [27].

- Test Day: Avoid smoking and physical activity [24].

- Baseline Sample: Collect initial breath sample.

- Substrate Ingestion: Drink sugar solution (10g lactulose or 50-75g glucose).

- Timed Sampling: Collect breath samples every 20 minutes for 3 hours (total 10 samples) [27].

- Sample Analysis: Measure hydrogen and methane concentrations.

Interpretation: Positive test defined as (1) Rise in hydrogen ≥20 ppm from baseline within 90 minutes, OR (2) Methane level ≥10 ppm at any point [22].

Jejunal Aspirate Culture Protocol

Principle: Direct quantification of bacterial load in small intestinal contents [22].

Materials: Sterile endoscope, protected specimen brush or aspiration catheter, anaerobic and aerobic transport media, culture plates.

Procedure:

- Pre-Procedure: Overnight fast with clear liquids only.

- Endoscopic Collection: Advance endoscope to distal duodenum/proximal jejunum.

- Aspiration: Use sterile catheter to collect 2-3mL of intestinal fluid.

- Transport: Immediately place sample in anaerobic transport media.

- Processing: Serial dilutions and culture on selective media.

- Quantification: Count colony-forming units after 48-72 hours incubation.

Interpretation: >10³ CFU/mL indicates SIBO. >10⁵ CFU/mL confirms diagnosis [22] [26].

SIBO and Systemic Inflammation: Pathophysiological Pathways

The relationship between SIBO and systemic inflammation involves multiple interconnected pathways that contribute to macronutrient malabsorption. The following diagram illustrates these key mechanisms:

Key Pathophysiological Mechanisms:

Direct Mucosal Injury: Bacterial endotoxins and metabolites damage epithelial tight junctions, increasing intestinal permeability and allowing bacterial translocation into systemic circulation [22] [26].

Nutrient Competition and Malabsorption: Bacteria compete for nutrients, particularly vitamin B12, iron, and thiamine, leading to deficiencies despite adequate intake [22] [28].

Metabolic Consequences: Bacterial deconjugation of bile salts impairs micelle formation, causing fat malabsorption and steatorrhea. Carbohydrate fermentation produces excess gas and osmotic diarrhea [22] [25].

Inflammatory Cascade Activation: Bacterial translocation triggers immune responses with increased pro-inflammatory cytokines (TNF-α, IL-6, IL-8), contributing to systemic inflammation [26].

Research Reagent Solutions for SIBO Investigation

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents for SIBO and Malabsorption Studies

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Research Application | Considerations for Comorbid Populations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Breath Test Substrates | Lactulose, Glucose | Non-invasive SIBO diagnosis | Lactulose detects distal SIBO; glucose has higher specificity but may miss distal SIBO [24] |

| Culture Media | MacConkey agar, Blood agar, Selective anaerobic media | Bacterial quantification from aspirates | Essential for antibiotic sensitivity testing; anaerobic culture crucial [22] |

| Antibiotic Agents | Rifaximin, Neomycin, Metronidazole, Ciprofloxacin | SIBO eradication studies | Rifaximin (1650mg/day) for hydrogen; combo therapy for methane; consider resistance patterns [22] |

| Nutritional Assays | Vitamin B12, folate, fat-soluble vitamins (A,D,E,K), iron studies | Assessment of malabsorption | SIBO typically shows low B12 but elevated folate; multiple deficiencies indicate severity [22] [25] |

| Inflammatory Markers | Cytokine panels (TNF-α, IL-6, IL-8), fecal calprotectin, intestinal fatty-acid binding protein (I-FABP) | Quantification of systemic inflammation | Limited evidence for fecal calprotectin in SIBO; novel biomarkers needed [23] |

| Motility Assessment | Lactulose hydrogen breath test for orocecal transit time, SmartPill | Evaluation of underlying dysmotility | Critical for comorbid conditions like diabetes and scleroderma [22] [26] |

Advanced Research Considerations for Complex Comorbidities

FAQ 4: How do SIBO research approaches differ between hydrogen-dominant and methane-dominant variants?

Methane-dominant SIBO (also termed Intestinal Methanogen Overgrowth) represents a distinct research entity with different treatment responses and clinical implications [22]. Table 3 highlights these critical differences.

Table 3: Comparative Analysis of SIBO Variants in Research Populations

| Characteristic | Hydrogen-Dominant SIBO | Methane-Dominant SIBO |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Gas | Hydrogen (H₂) | Methane (CH₄) |

| Microbial Origin | Facultative anaerobes (E. coli, Klebsiella) | Archaea (Methanobrevibacter smithii) |

| Breath Test Threshold | ≥20 ppm H₂ rise from baseline | ≥10 ppm CH₄ at any time point [22] |

| Dominant Symptoms | Diarrhea, abdominal pain, bloating | Constipation, bloating, gas retention |

| First-Line Treatment | Rifaximin 1650mg/day for 14 days | Rifaximin 1650mg/day + Neomycin 1000mg/day for 14 days [22] |

| Research Implications | More responsive to single antibiotic therapy | Requires combination therapy; higher relapse rates |

FAQ 5: What specialized methodologies are needed for SIBO research in populations with neuropsychiatric comorbidities?

Emerging research indicates complex gut-brain axis interactions in SIBO. Patients with psychiatric disorders show altered tryptophan metabolism through the kynurenine pathway, potentially contributing to neurological symptoms [29]. Essential methodologies include: (1) Mass spectrometry for tryptophan metabolite quantification; (2) Intestinal permeability assessment (lactulose-mannitol test); (3) Fecal microbiome analysis with 16S rRNA sequencing; (4) Standardized neuropsychiatric assessments integrated with GI evaluation [29].

The intricate relationship between thyroid disorders and SIBO further complicates research in this area, as hypothyroidism can impair motility while SIBO may affect thyroid hormone conversion, creating a bidirectional relationship that requires careful stratification in study design [29].

A Researcher's Toolkit: Functional Tests for Assessing Macronutrient Digestion and Absorption

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) for Researchers

Q1: What is the specific clinical and research utility of the 72-hour fecal fat test?

The 72-hour quantitative fecal fat test is historically considered a gold standard for objectively confirming the presence of steatorrhea (excess fat in stool) in a research setting [30] [31]. It provides a quantitative measure of fat malabsorption. However, leading guidelines strongly caution against its use for differential diagnosis, such as distinguishing between pancreatic and intestinal causes of malabsorption [30] [32]. Its role in modern research is often limited to validating the efficacy of new therapeutic interventions, such as pancreatic enzyme replacement therapies, or as a benchmark for validating newer, less invasive diagnostic methods [32].

Q2: What are the primary limitations that affect its reliability in clinical studies?

The test's reliability is compromised by several significant challenges:

- Stringent Pre-Analytical Requirements: The test is highly sensitive to dietary fat intake (typically requiring 100-150 grams per day), complete stool collection, and avoidance of interfering substances [30] [33]. Even minor deviations can invalidate results.

- Patient Burden and Compliance: The 72-hour collection period is cumbersome for participants, leading to potential non-compliance and incomplete collections, which skews results [30] [34].

- Lack of Etiological Specificity: A positive test confirms malabsorption but does not provide information on the underlying mechanism or disease cause [30] [31].

Q3: What are the recommended alternative or complementary assays for investigating macronutrient malabsorption?

Given the challenges of the 72-hour collection, researchers are exploring several alternative techniques, particularly for studies in vulnerable populations like children [12] [8]. The table below summarizes key investigational methods.

Table 1: Investigational Assays for Macronutrient Malabsorption

| Macronutrient | Investigation Method | Function Tested | Key Advantages & Status |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fat | ¹³C-Mixed Triglyceride Breath Test | Global fat digestion and absorption [12] [8] | Non-invasive; potential for use in pediatric studies [12] [8]. |

| Carbohydrates | ¹³C-Starch/Sucrose/Lactose Breath Tests | Carbohydrate digestion and absorption [12] [8] | Non-invasive; can probe specific digestive pathways [12] [8]. |

| Protein | Benzoyl-L-tyrosyl-L-1-¹³C-alanine Breath Test | Dipeptide absorption [12] [8] | Non-invasive; assesses functional peptide transport [12] [8]. |

| Pancreatic Function | Fecal Elastase-1 | Pancreatic exocrine output [30] | Single stool sample; high negative predictive value for pancreatic insufficiency [30]. |

Q4: How should fecal fat results be interpreted in a pediatric research population?

Interpretation in pediatric populations requires special consideration. Reference values for timed collections are not firmly established for patients under 18 years of age [33] [32]. For random stool samples, results are often reported as a percentage of fat, with a typical reference value of 0-19% for all ages [32]. Furthermore, results may be reported as a Coefficient of Fat Absorption (CFA), which calculates the percentage of ingested fat that was absorbed, providing a more normalized metric for inter-individual comparison [32].

Experimental Protocol: 72-Hour Quantitative Fecal Fat Collection

This protocol outlines the standardized methodology for the 72-hour fecal fat test, based on guidelines from major reference laboratories [33] [32].

Pre-Collection Phase (Patient Preparation)

- Duration: 3 days prior to and throughout the 72-hour stool collection period.

- Controlled Diet: Participants must consume a fat-controlled diet of 100-150 grams of fat per day [33] [32]. Dietary intake records are crucial for accurate interpretation [30].

- Prohibited Substances:

- Laxatives, particularly mineral oil and castor oil [33] [32].

- Synthetic fat substitutes (e.g., Olestra) or fat-blocking nutritional supplements (e.g., Orlistat) [30] [33].

- Diaper rash ointments or creams, which can falsely elevate results [34] [33]. Petroleum jelly or cornstarch are acceptable alternatives [34].

- Other Considerations: Discontinue pancreatic enzyme replacement therapy if applicable (under medical supervision) [30]. A 48-hour waiting period is required after procedures using barium contrast [33].

Collection Phase

- Duration: A full, continuous 72-hour period.

- Supplies: Use approved, single-use stool collection containers provided by the laboratory. These are often designed to comply with shipping safety regulations [33].

- Procedure:

- Collect all stool passed during the 72-hour window.

- Use a wooden tongue depressor or plastic spoon to transfer stool to the container.

- Avoid contamination with urine, toilet water, or toilet paper [34] [31].

- Close the lid tightly after each use. If multiple containers are needed, label them sequentially (e.g., "1 of 3").

- Storage: Keep the specimen container refrigerated or on ice in a cooler during the collection period [34] [32].

- Specimen Submission: The entire collection must be submitted to the lab. The total weight of the collection must be documented.

Analytical Phase

- Methodology: The preferred method at many core laboratories is Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) Spectroscopy [32].

- Process: The homogenized stool sample is weighed, dried, and analyzed by NMR to determine the percentage of fat. This value is converted to grams of fat excreted per 24-hour period [32].

Data Interpretation and Troubleshooting

Reference Values and Interpretation

Table 2: Reference Values for 72-Hour Fecal Fat Test

| Population | Specimen Type | Reference Range | Interpretation of Abnormal Result |

|---|---|---|---|

| Adults (≥18 years) | 72-hour Timed | < 7 g fat/24 hours [32] | >7 g/24h is suggestive of malabsorption, provided dietary compliance [30] [32]. |

| Pediatrics (& All Ages) | Random | 0-19% fat [32] | >19% fat is abnormal. A timed collection should be performed for confirmation. |

Common Experimental Pitfalls and Solutions

Table 3: Troubleshooting Guide for the 72-Hour Fecal Fat Test

| Problem | Potential Impact on Results | Corrective Action / Prevention |

|---|---|---|

| Inadequate Dietary Fat Intake | Falsely low result; failure to challenge absorptive capacity [30]. | Provide participants with detailed dietary instructions and a food diary to ensure consistent 100-150 g/day intake. |

| Incomplete Stool Collection | Falsely low result; underestimation of total fat excretion [30]. | Provide clear verbal and written collection instructions. Emphasize the need to collect every stool. |

| Use of Prohibited Medications/Ointments | Falsely elevated results [30] [33]. | Provide a comprehensive list of prohibited substances and verify compliance during the collection period. |

| Specimen Contamination (Urine, Water) | Analytically interference; invalid results [34] [31]. | Instruct on proper use of collection devices like a "toilet hat" or plastic wrap. |

The Researcher's Toolkit: Essential Materials

Table 4: Key Research Reagent Solutions for 72-Hour Fecal Fat Testing

| Item | Function / Utility in the Experiment |

|---|---|

| Stool Collection Kit (72-Hour) | A specialized container, often provided by reference labs (e.g., Mayo T291), is required for safe specimen containment and shipping [33]. |

| Fat-Controlled Diet Protocol | Standardized dietary guidelines and recording sheets are critical to ensure a consistent fat challenge, which is fundamental to test validity [30] [32]. |

| Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) Spectrometer | The analytical instrument used for quantitative fat measurement in homogenized stool samples at reference laboratories [32]. |

| Proprietary Stool Stabilizers | Some specialized collection kits may include stabilizers to preserve specimen integrity during storage and transport. |

Experimental and Diagnostic Pathways

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow for a researcher or clinician investigating malabsorption, highlighting the role of the 72-hour fecal fat test alongside modern alternatives.

Malabsorption Diagnostic Workflow

Technical Support Center

FAQs & Troubleshooting Guides

General Breath Test Principles

- Q: What is the fundamental principle behind a 13C-breath test?

- A: A 13C-labeled substrate (carbohydrate, fat, or protein) is orally administered. If the substrate is properly digested, absorbed, and metabolized, the 13C-isotope is ultimately oxidized in the liver, producing 13CO2. This 13CO2 is excreted via the lungs and can be measured in breath samples over time. A reduced or delayed 13CO2 recovery indicates malabsorption or impaired metabolic function.

Substrate-Specific Issues

Carbohydrates (e.g., 13C-Spirulina platensis, 13C-Starch)

- Q: We are observing low 13CO2 recovery with a 13C-starch test. What could be the cause?

- A: Low recovery suggests carbohydrate malabsorption. Key troubleshooting steps:

- Confirm Pancreatic Function: Rule out pancreatic exocrine insufficiency (PEI) as a cause of inadequate amylase secretion. Correlate with a 13C-mixed triglyceride breath test.

- Check for Small Intestinal Bacterial Overgrowth (SIBO): SIBO can cause premature fermentation of carbohydrates in the small intestine, diverting the 13C from oxidative metabolism and reducing 13CO2 recovery. A positive hydrogen/methane breath test can confirm this.

- Verify Substrate Preparation: Ensure the substrate was prepared and administered correctly, as per the experimental protocol.

- A: Low recovery suggests carbohydrate malabsorption. Key troubleshooting steps:

Lipids (e.g., 13C-Mixed Triglyceride (MTG), 13C-Octanoic Acid)

- Q: Our 13C-MTG breath test results are highly variable between subjects. How can we improve consistency?

- A: Variability often stems from the test meal composition.

- Standardize the Test Meal: Use a high-fat, standardized meal (see Experimental Protocols below) to ensure consistent stimulation of pancreatic lipase and biliary secretion.

- Control Gastric Emptying: The 13C-MTG test is influenced by gastric emptying rates. Consider co-administering a 13C-octanoic acid capsule (a marker for gastric emptying) in a separate test to normalize results.

- Subject Preparation: Ensure subjects fasted for the recommended 12 hours and abstained from alcohol and strenuous exercise prior to testing.

- A: Variability often stems from the test meal composition.

Proteins (e.g., 13C-Leucine, 13C-Lysine)

- Q: What does a delayed peak in 13CO2 excretion during a 13C-leucine breath test indicate?

- A: A delayed time to peak (Tmax) typically indicates impaired gastric emptying, as the substrate must reach the small intestine for absorption. A reduced cumulative recovery (%CD) suggests impaired protein digestion (e.g., pepsin or pancreatic protease deficiency) or impaired hepatic metabolism (e.g., liver dysfunction).

Analytical Troubleshooting

- Q: The Isotope Ratio Mass Spectrometer (IRMS) is giving unstable baseline readings. What should we check?

- A:

- Gas Purity: Ensure the reference CO2 gas supply is pure and not depleted.

- Leak Check: Perform a full system leak check, including the breath sample inlet system.

- Contamination: Clean the sample introduction needle and check for contaminants in the breath collection bags or tubes.

- A:

Quantitative Data Summary

Table 1: Common 13C-Labeled Substrates for Macronutrient Absorption Studies

| Macronutrient | Exemplary Substrate | Targeted Dysfunction | Key Pharmacokinetic Parameter | Normal Range (Example) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Carbohydrate | 13C-Spirulina platensis | Generalized Malabsorption | Cumulative % Dose Recovered (CDR) | > 14% (over 6 hours) |

| Lipid | 13C-Mixed Triglyceride | Pancreatic Exocrine Insufficiency (PEI) | Cumulative % Dose Recovered (CDR) | > 29% (over 6 hours) |

| Protein | 13C-Leucine | Gastric Emptying / Metabolic Rate | Time to Peak (Tmax) / %CD | Tmax: 60-120 mins |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: 13C-Mixed Triglyceride (MTG) Breath Test for Pancreatic Exocrine Insufficiency

- Subject Preparation: Overnight fast (12 hours). No smoking or strenuous exercise on test day.

- Test Meal: Administer a standardized test meal (e.g., 60g white bread, 20g butter, 200mL whole milk) containing 250mg of 13C-MTG.

- Baseline Breath Sample: Collect a baseline breath sample in a suitable container (e.g., Exetainer tube) before substrate administration.

- Post-Dose Sampling: Collect breath samples at 30, 60, 90, 120, 150, 180, 240, 300, and 360 minutes after the test meal.

- Sample Analysis: Analyze breath samples via Isotope Ratio Mass Spectrometry (IRMS) to determine the 13CO2/12CO2 ratio.

- Data Calculation: Calculate the percentage of 13C dose recovered per hour (%DR/h) and the cumulative recovery (%CDR) over 6 hours.

Protocol 2: 13C-Spirulina platensis Breath Test for Carbohydrate Malabsorption

- Subject Preparation: As per Protocol 1.

- Substrate Administration: Administer 100mg of 13C-Spirulina platensis (or equivalent 13C-labeled carbohydrate) with 150mL of water.

- Breath Sampling: Collect baseline and post-dose breath samples at 30, 60, 90, 120, 150, 180, 210, 240, 300, and 360 minutes.

- Sample Analysis: Analyze via IRMS.

- Data Calculation: Calculate the cumulative %CDR over 6 hours. A lower value indicates malabsorption.

Visualizations

13C Breath Test Workflow

13C-MTG Metabolic Pathway

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 2: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function / Application |

|---|---|

| 13C-Labeled Substrates | The core tracer for the breath test (e.g., 13C-MTG for fat, 13C-Spirulina for carbs). |

| Standardized Test Meal | Ensures consistent and physiological stimulation of digestive processes (e.g., for lipid tests). |

| Breath Collection Bags/Tubes | Vacuum-evacuated containers (e.g., Exetainer) for stable, long-term storage of breath samples. |

| Isotope Ratio Mass Spectrometer (IRMS) | The gold-standard analytical instrument for high-precision measurement of 13CO2/12CO2 ratios. |

| Reference CO2 Gas | A calibrated, high-purity CO2 standard gas required for accurate IRMS calibration. |

| Software for Kinetic Analysis | Used to calculate key parameters like Cumulative % Dose Recovered (CDR) and Time to Peak (Tmax). |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

What is the primary clinical and research application of the secretin-stimulated ePFT? The secretin-stimulated ePFT is considered the definitive method for assessing exocrine pancreatic function. Its primary application is the diagnosis of early chronic pancreatitis, especially in cases where imaging tests are normal, and for determining a pancreatic cause for unexplained chronic diarrhea [35]. It is a sensitive tool for detecting functional deficiencies before structural damage becomes apparent.

How does ePFT compare to other diagnostic tests for Exocrine Pancreatic Insufficiency (EPI)? ePFT is considered the most accurate test for assessing pancreatic exocrine function but is limited to specialized centers [36]. In clinical practice, less invasive tests are often used first. The fecal elastase test is commonly recommended as an initial test, though it may be less sensitive for mild EPI [37] [38]. The 72-hour fecal fat test quantitatively measures fat malabsorption but is cumbersome for patients [38] [36].

What are the common technical challenges when collecting pancreatic secretions? A key challenge is ensuring proper tube placement in the duodenum to allow for uncontaminated, sequential collection of pancreatic juice. Secretions are typically collected at set intervals (e.g., every 15 minutes for 60 minutes) following secretin injection [35]. Fluid collection must be meticulous to avoid loss of sample, which can compromise the bicarbonate measurement.

What does an abnormal bicarbonate concentration indicate? The bicarbonate concentration in the collected pancreatic secretions is the primary outcome measure. An adequate production and secretion of bicarbonate implies intact pancreatic function. A low bicarbonate output, particularly when progressively lower concentrations are seen over the collection period, is indicative of impaired exocrine function and supports a diagnosis of chronic pancreatitis [35].

Troubleshooting Guide for Direct Pancreatic Function Testing

| Problem Area | Specific Issue | Potential Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|---|