Lipid Oxidation and Food Rancidity: Mechanisms, Analytical Methods, and Health Implications for Scientific Research

This article provides a comprehensive review of the chemical mechanisms of lipid oxidation and food rancidity, tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals.

Lipid Oxidation and Food Rancidity: Mechanisms, Analytical Methods, and Health Implications for Scientific Research

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive review of the chemical mechanisms of lipid oxidation and food rancidity, tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals. It explores the foundational science of autoxidation, photo-oxidation, and hydrolytic rancidity, detailing the formation of primary and secondary oxidation products. The scope extends to advanced and traditional analytical methodologies for assessing lipid oxidation and antioxidant efficacy. Furthermore, the article examines strategies to control oxidation in complex food matrices and discusses the implications of lipid oxidation products on human health, including inflammation, carcinogenesis, and atherosclerosis, providing a critical link to biomedical research.

Deconstructing Rancidity: Fundamental Pathways and Chemical Mechanisms of Lipid Oxidation

Rancidity is a critical form of food spoilage involving the chemical degradation of fats and oils, leading to undesirable sensory properties and nutritional losses. Within the broader context of lipid oxidation and food rancidity research, understanding these degradation pathways is essential for developing effective preservation strategies across food and pharmaceutical industries. Rancidity occurs through three primary mechanisms: oxidative, hydrolytic, and microbial pathways [1] [2]. Each mechanism generates distinct breakdown compounds that contribute to off-flavors, off-odors, and potential health concerns.

This technical guide examines these rancidity pathways at a molecular level, providing researchers and drug development professionals with comprehensive mechanistic insights, analytical methodologies, and stabilization approaches. The complex interplay between these pathways significantly impacts product shelf life, nutritional quality, and safety, making their understanding crucial for both fundamental research and industrial applications.

Oxidative Rancidity

Mechanism of Oxidative Rancidity

Oxidative rancidity, primarily affecting unsaturated fatty acids, occurs via a free-radical chain reaction known as autoxidation when lipids encounter oxygen from air, light, or heat [3] [4]. This process unfolds in three distinct phases:

Initiation: Free radicals form as hydrogen atoms are abstracted from fatty acid chains, creating alkyl radicals (R•). This initiation is catalyzed by heat, light, or metal ions [5] [6]: RH + O₂ → R• + •OOH or RH → R• + •H

Propagation: Alkyl radicals rapidly react with atmospheric oxygen to form peroxyl radicals (ROO•), which subsequently abstract hydrogen from other fatty acids to form hydroperoxides (ROOH) and new alkyl radicals, propagating the chain reaction [3] [6]: R• + O₂ → ROO• ROO• + RH → ROOH + R•

Termination: The reaction cycle concludes when free radicals combine to form non-radical products [3] [6]: R• + R• → R-R ROO• + R• → ROOR

Hydroperoxides themselves are relatively tasteless and odorless, but their secondary decomposition yields volatile compounds—including aldehydes, ketones, alcohols, and hydrocarbons—responsible for the characteristic rancid odors and flavors [3] [4]. The rate of oxidation increases with the number of double bonds in fatty acids; thus, polyunsaturated fats are most vulnerable [7].

Factors Influencing Oxidative Rancidity

Multiple factors accelerate oxidative rancidity:

- Oxygen availability: Higher oxygen concentrations increase oxidation rates [1]

- Light exposure: Photo-oxidation occurs when light, especially UV, catalyzes radical formation [3]

- Temperature: Elevated temperatures exponentially accelerate oxidation rates [1]

- Metal catalysts: Trace amounts of iron, copper, and other transition metals catalyze initiation [1]

- Water activity: Moderate moisture levels can promote metal ion mobility and catalytic activity [1]

- Fatty acid composition: Higher unsaturated fat content increases susceptibility [1] [8]

Table 1: Primary Oxidation Products and Detection Methods

| Oxidation Stage | Key Compounds | Characteristic Effects | Detection Methods |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary | Hydroperoxides, Peroxides | Minimal flavor impact, nutrient degradation | Peroxide Value (PV), Conjugated Dienes [5] [4] |

| Secondary | Aldehydes (hexanal, nonanal), Ketones, Alcohols | Rancid odors, off-flavors | p-Anisidine Value (p-AV), TBARS, Gas Chromatography [5] [7] |

| Tertiary | Polymers, Short-chain fatty acids | Texture changes, nutritional loss | Size-exclusion Chromatography, Viscosity measurements [5] |

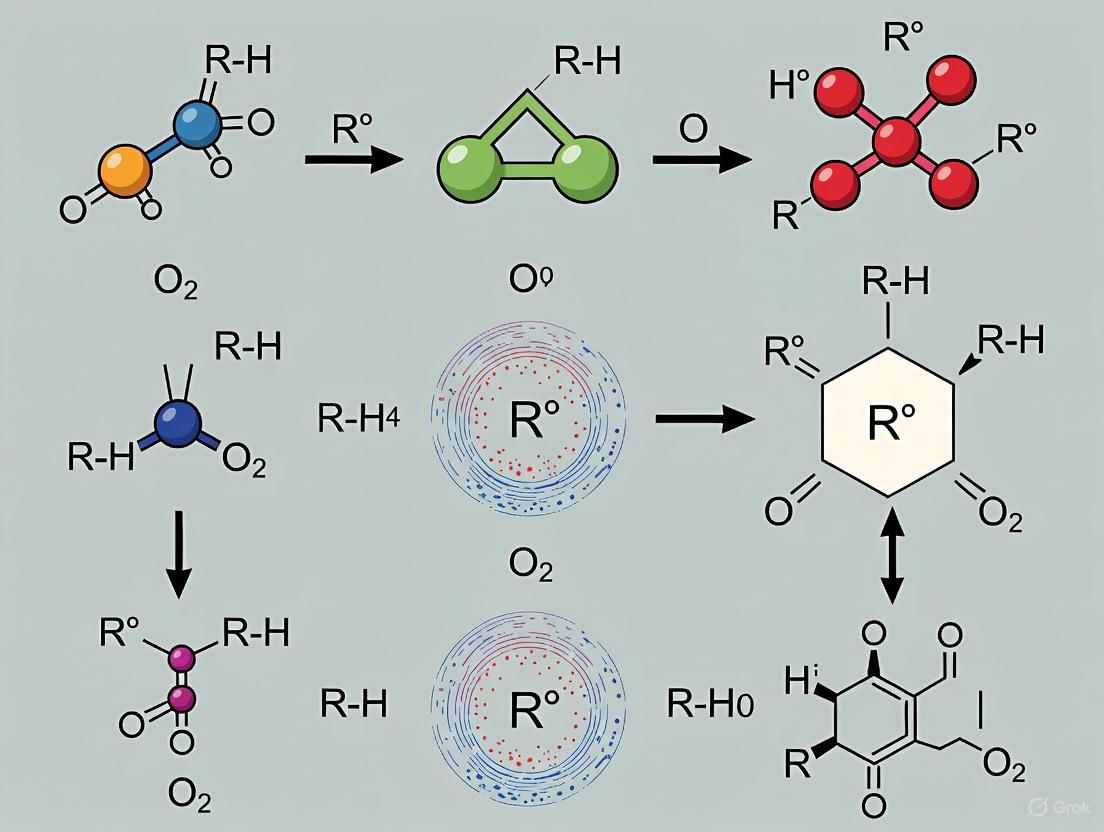

Figure 1: Oxidative Rancidity Free Radical Chain Reaction

Hydrolytic Rancidity

Mechanism of Hydrolytic Rancidity

Hydrolytic rancidity involves the cleavage of ester bonds in triglycerides, releasing free fatty acids (FFAs) from the glycerol backbone [1] [9]. This process occurs through hydrolysis facilitated by either moisture, heat, or enzymatic activity:

Triglyceride + Water → Free Fatty Acids + Di/Monoglycerides + Glycerol

Short-chain free fatty acids (with ≤12 carbon atoms), particularly butyric acid (C4), caproic acid (C6), caprylic acid (C8), and capric acid (C10), are primarily responsible for the sharp, unpleasant, "goaty" odors associated with hydrolytic rancidity [1]. Butyric acid, for instance, contributes positively to flavor profiles in small quantities (as in cheese) but becomes offensive at higher concentrations—it is the primary odor compound in human vomit and used in stink bombs [1].

Enzymatic Hydrolysis

Lipases present naturally in foods or produced by microorganisms catalyze hydrolytic rancidity at ambient temperatures [9] [10]. In pearl millet, high lipase activity combined with substantial lipid content (~5-6%) accelerates hydrolytic rancidity, significantly limiting shelf-life despite its nutritional benefits [9]. Rice bran similarly contains active lipases that rapidly hydrolyze lipids upon milling, severely restricting its food applications [10].

Table 2: Short-Chain Free Fatty Acids in Hydrolytic Rancidity

| Free Fatty Acid | Carbon Atoms | Sensory Characteristics | Common Sources |

|---|---|---|---|

| Butyric acid | 4 | Rancid, cheesy, vomit-like | Butter, milk products [1] |

| Caproic acid | 6 | Pungent, sweaty | Goat milk, cheese [1] |

| Caprylic acid | 8 | Rancid, waxy | Coconut oil, palm oil [1] |

| Capric acid | 10 | Sour, unpleasant | Dairy fats, tropical oils [1] |

Figure 2: Hydrolytic Rancidity Pathway

Microbial Rancidity

Mechanism of Microbial Rancidity

Microbial rancidity results from microorganisms (bacteria, yeasts, molds) producing extracellular enzymes, particularly lipases and phospholipases, that hydrolyze fats into free fatty acids [2]. These liberated fatty acids can undergo further microbial transformation through β-oxidation, generating additional off-flavor compounds.

While microbial rancidity shares similarities with hydrolytic rancidity in its initial steps, the microbial origin introduces additional complexity. Different microbial species produce distinct enzymatic profiles, leading to diverse spoilage patterns. Furthermore, microbial activity is influenced by environmental factors including temperature, pH, water activity, and nutrient availability [2].

Context-Dependent Nature of Microbial Rancidity

The same enzymatic processes that cause spoilage in some foods are deliberately employed in cheese production to develop characteristic flavors [1]. For example, Penicillium roquefortii in Roquefort cheese and lipases from rennet paste in Fiore Sardo and Pecorino cheeses generate short-chain free fatty acids that create desirable spicy and peppery notes [1]. This demonstrates that rancidity is partly defined by cultural and sensory expectations rather than purely chemical processes.

Analytical Methods for Rancidity Assessment

Chemical and Instrumental Methods

Comprehensive rancidity assessment requires monitoring multiple indicators across different degradation stages:

- Peroxide Value (PV): Measures hydroperoxides (primary oxidation products) via iodometric titration; values <5 mEq/kg generally indicate fresh oils [5] [4]

- p-Anisidine Value (p-AV): Quantifies secondary oxidation products (aldehydes) through colorimetric reaction; higher values indicate advanced oxidation [5] [7]

- Thiobarbituric Acid Reactive Substances (TBARS): Detects malondialdehyde and related carbonyls as secondary oxidation markers; particularly useful for meat and low-fat products [5] [4]

- Free Fatty Acids (FFA): Measures hydrolytic rancidity via titration of liberated fatty acids [5]

- Gas Chromatography (GC): Identifies and quantifies specific volatile compounds responsible for off-flavors [5] [7]

- Oxidative Stability Index (OSI): Accelerates oxidation (typically at 60-110°C with air bubbling) to predict shelf-life and antioxidant efficacy [5]

Sensory Evaluation

Sensory analysis remains crucial despite advances in instrumental methods, as human perception ultimately defines acceptability [5] [2]. Trained panels evaluate visual characteristics, odors, and flavors using standardized scales. Sensory testing is particularly important for correlating chemical measurements with actual product quality.

Table 3: Standard Analytical Methods for Rancidity Assessment

| Method | Target Compounds | Application Scope | Advantages/Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Peroxide Value (PV) | Hydroperoxides | Early-stage oxidation | Simple, sensitive to initial oxidation; Peroxides decompose over time [5] |

| p-Anisidine Value (p-AV) | Aldehydes, Ketones | Secondary oxidation | Specific to carbonyls; Limited for dark samples [5] [7] |

| TBARS | Malondialdehyde, Carbonyls | Meat, fish, low-fat foods | Sensitive for specific products; Not comprehensive for all volatiles [5] [4] |

| Free Fatty Acids (FFA) | Liberated fatty acids | Hydrolytic rancidity | Direct measure of hydrolysis; Requires factor adjustment for different fats [5] |

| Gas Chromatography | Volatile compounds | All food types | Identifies specific compounds; Expensive, requires expertise [5] [7] |

| Conjugated Dienes | Diene formation | Early oxidation of PUFAs | Rapid, inexpensive; Limited to early stages [4] |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Peroxide Value Determination

Principle: Peroxides and hydroperoxides in the sample oxidize iodide to iodine, which is quantified by titration with thiosulfate [5] [4].

Reagents:

- Solvent mixture: Glacial acetic acid/chloroform (3:2 v/v)

- Saturated potassium iodide (KI) solution

- Sodium thiosulfate (Na₂S₂O₃) titrant (0.01 N standardized)

- Starch indicator solution (1%)

Procedure:

- Accurately weigh 5.00 g of oil or fat sample into a 250 mL glass-stoppered flask

- Add 30 mL of acetic acid/chloroform solvent mixture and swirl to dissolve

- Add 0.5 mL of saturated KI solution, stopper, and swirl for 60 seconds

- Place in dark for exactly 5 minutes, then add 30 mL of distilled water

- Titrate with 0.01 N sodium thiosulfate until yellow color almost disappears

- Add 0.5 mL starch indicator and continue titration until blue color disappears

- Run blank determination simultaneously

Calculation: PV (meq O₂/kg) = [(S - B) × N × 1000] / sample weight (g) Where: S = sample titrant volume (mL), B = blank titrant volume (mL), N = thiosulfate normality

Protocol: Accelerated Storage Studies

Principle: The Schaal Oven Test accelerates oxidation by storing samples at elevated temperatures (typically 60°C) while monitoring oxidation indicators over time [7].

Procedure:

- Portion uniform samples (50 g) into open glass containers or permeable packaging

- Place in forced-air oven maintained at 60 ± 1°C

- Randomize container positions daily to ensure uniform heating

- Sample at predetermined intervals (0, 3, 6, 9, 12, 16, 20 days)

- Analyze samples for PV, p-AV, FFA, and/or specific volatiles via GC-MS

- Store sampled portions at -20°C in dark if not analyzed immediately

Data Interpretation: Plot oxidation parameters versus time to determine induction period and oxidation rate. Correlation with actual shelf-life requires validation studies.

Protocol: Lipase Activity Assay

Principle: Lipase activity is determined by measuring free fatty acids released from a triglyceride substrate under controlled conditions [9].

Reagents:

- Substrate: 1% tributyrin or olive oil emulsion in 50 mM Tris buffer (pH 7.0-8.0)

- Stopping solution: Acetone/ethanol (1:1)

- Titrant: 0.02 N NaOH with phenolphthalein indicator

Procedure:

- Incubate 1 mL enzyme extract with 5 mL substrate at 37°C for 30 minutes

- Stop reaction by adding 10 mL acetone/ethanol mixture

- Titrate immediately with 0.02 N NaOH to faint pink endpoint

- Run appropriate blank and control reactions

Calculation: One unit of lipase activity = 1 μmol FFA released per minute under assay conditions

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents for Rancidity Studies

| Reagent/Chemical | Technical Function | Application Examples |

|---|---|---|

| tert-Butylhydroquinone (TBHQ) | Synthetic antioxidant, free radical scavenger | Fish oil stabilization, delaying oxidation initiation [7] [6] |

| Propyl Gallate (PG) | Synthetic phenolic antioxidant | Inhibits propagation phase in oils and fats [7] |

| Butylated Hydroxyanisole (BHA) | Antioxidant, donates hydrogen atoms | Preserves rendered products, functional in baking [1] [5] |

| Butylated Hydroxytoluene (BHT) | Chain-breaking antioxidant | Extends shelf-life of oils, animal feeds [1] [5] |

| Thiobarbituric Acid (TBA) | Reacts with malondialdehyde | TBARS assay for secondary oxidation products [5] [4] |

| p-Anisidine | Reacts with aldehydes | p-Anisidine value determination [5] [7] |

| Sodium Thiosulfate | Reductant for iodine titration | Peroxide value determination [5] [4] |

| Lipase from microbial sources | Hydrolyzes triglycerides | Model studies of enzymatic rancidity [9] |

Oxidative, hydrolytic, and microbial rancidity represent distinct but interconnected pathways of lipid degradation, each with characteristic mechanisms, compounds, and analytical approaches. Understanding these pathways at molecular level provides crucial insights for developing effective stabilization strategies across food and pharmaceutical industries. Contemporary research employs increasingly sophisticated methodologies including lipidomics and flavoromics to elucidate complex oxidation pathways and antioxidant mechanisms [7]. Future directions include developing natural antioxidant systems, optimizing delivery mechanisms, and establishing more accurate predictive models for shelf-life determination.

Autoxidation is a spontaneous, free-radical chain reaction between organic compounds and molecular oxygen at normal temperatures, which plays a critical role in the deterioration of fats and oils, leading to food rancidity [11]. This process represents a significant challenge in food science and nutrition research, as it directly impacts food quality, shelf-life, and sensory properties. The free radical-mediated mechanism of autoxidation is responsible for the gradual degradation of unsaturated lipids in various food matrices, generating off-flavors, unpleasant odors, and potentially toxic compounds that compromise nutritional value and consumer safety [9]. Understanding the fundamental principles of the free radical chain reaction—initiation, propagation, and termination—provides researchers with the theoretical foundation necessary to develop effective strategies for mitigating oxidative deterioration in food systems.

The particular susceptibility of polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs) to autoxidation poses a substantial problem for nutrient-dense foods. For instance, pearl millet, recognized as a "nutricereal" due to its high nutritional value, contains 50-55% polyunsaturated fatty acids, primarily linoleic acid, which significantly contributes to its rapid quality deterioration post-milling [9]. This chemical instability necessitates comprehensive research into the mechanistic pathways of lipid oxidation to preserve the health benefits of such nutritionally superior foods. The study of autoxidation mechanisms thus represents an essential intersection of food chemistry, nutritional science, and material stability, with direct implications for food security, waste reduction, and public health.

The Free Radical Chain Reaction Mechanism

The autoxidation process follows a well-established free radical chain mechanism, originally characterized in rubber oxidation but universally applicable to lipid systems [11]. This mechanism consists of three distinct stages: initiation, propagation, and termination, each with characteristic reactions and radical species. The chain reaction nature of autoxidation explains its autocatalytic behavior, where the rate of oxidation accelerates progressively after an initial induction period, as reaction products themselves participate in generating additional radicals [12].

Initiation Phase

The initiation phase encompasses the initial generation of free radicals from non-radical precursor compounds. This step requires energy input, typically from heat, light, or metal catalysts, to break relatively weak chemical bonds [13] [11]. In lipid systems, initiation commonly occurs through the homolytic cleavage of hydroperoxides (ROOH), which may be present as trace impurities or formed through previous oxidation, or through direct hydrogen abstraction from unsaturated fatty acids by reactive oxygen species [14].

Table 1: Common Initiation Reactions in Lipid Autoxidation

| Initiator Type | Representative Reaction | Resulting Radicals | Comment |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hydroperoxides | ROOH → RO• + •OH | Alkoxy, hydroxyl | Thermal or photolytic cleavage |

| Metal Ions | ROOH + Mⁿ⁺ → RO• + M⁽ⁿ⁺¹⁾⁺ + OH⁻ | Alkoxy | Redox cycling |

| Singlet Oxygen | ¹O₂ + RH → ROO• | Peroxyl | Photooxygenation |

| Azo Compounds | R-N=N-R → 2R• + N₂ | Carbon-centered | Intentional initiator |

The initiation step is characterized by a net increase in the number of free radicals in the system, transitioning from zero radicals to two or more radical species [13] [12]. This phase typically demonstrates an induction period where little oxidative activity is observed, followed by progressively accelerating oxygen uptake as the reaction transitions to the propagation phase [11].

Propagation Phase

The propagation phase maintains the radical chain reaction through sequences where radicals react with non-radical substrates to generate new radical species, with no net change in the number of free radicals [13] [12]. This phase consists of two critical steps that cycle repeatedly, allowing a single initiation event to facilitate numerous oxidation cycles before termination.

The primary propagation sequence begins when a carbon-centered radical (R•) reacts rapidly with molecular oxygen to form a peroxyl radical (ROO•). The peroxyl radical then abstracts a hydrogen atom from another unsaturated lipid molecule (RH), generating a hydroperoxide (ROOH) and a new carbon-centered radical (R•) that continues the chain reaction [11]. The hydrogen abstraction step is rate-determining and depends significantly on the bond dissociation energy of the C-H bond involved, with allylic and bis-allylic hydrogens in polyunsaturated fatty acids being particularly susceptible to abstraction due to their relatively low bond dissociation energies [12].

Table 2: Key Propagation Reactions in Lipid Autoxidation

| Reaction Step | Chemical Equation | Radical Count (Reactants → Products) | Role in Chain Reaction |

|---|---|---|---|

| Oxygen addition | R• + O₂ → ROO• | 1 → 1 | Forms peroxyl radical |

| Hydrogen abstraction | ROO• + RH → ROOH + R• | 1 → 1 | Regroups chain carrier radical |

| Hydroperoxide decomposition | ROOH → RO• + •OH | 0 → 2 | Chain branching |

A single initiation event can propagate through thousands of these cycles before termination occurs, with estimates suggesting up to 10⁴ or more cycles per initiation event in some systems [13]. This amplification effect explains why even trace initiator concentrations can drive significant oxidative deterioration in lipid-containing foods.

Termination Phase

The termination phase encompasses reactions where two radical species combine to form non-radical products, resulting in a net decrease in the number of free radicals [13] [12]. These bimolecular reactions between radicals effectively halt the propagation cycle by removing radical species from the system.

Common termination reactions include combinations of peroxyl radicals (ROO•), alkoxyl radicals (RO•), and carbon-centered radicals (R•) to form stable, non-radical products such as alcohols, ketones, aldehydes, and dimeric or cross-linked species [11]. While termination reactions occur throughout the autoxidation process, they become increasingly significant as radical concentrations increase, eventually leading to reaction deceleration when radical generation can no longer keep pace with termination events.

The specific termination pathways operative in a given system depend on factors including radical mobility, concentration, and stability. In viscous or polymeric systems, termination may be limited by diffusion, leading to extended kinetic chains and more extensive oxidation. The cross-linking reactions during termination can lead to macromolecular aggregation and altered physical properties in oxidized lipids and food matrices [11].

Quantitative Analysis of Autoxidation Parameters

Understanding the kinetic and thermodynamic parameters of autoxidation provides researchers with predictive capabilities for lipid stability and enables targeted intervention strategies. Quantitative analysis of these parameters facilitates comparison between different lipid systems and assessment of antioxidant efficacy.

Table 3: Quantitative Parameters in Lipid Autoxidation

| Parameter | Typical Range | Significance | Analytical Methods |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bond Dissociation Energy (C-H) | ~80-100 kcal/mol | Determines H-abstraction susceptibility | Computational chemistry |

| Propagation Rate Constant (kₚ) | 10-10⁴ M⁻¹s⁻¹ | Measures chain carrying efficiency | Competitive kinetics |

| Oxygen uptake | Variable with unsaturation | Direct measure of oxidation extent | Oxygen electrode, manometry |

| Peroxide Value (PV) | 0->20 meq/kg | Early oxidation indicator | Titration, spectrophotometry |

| Induction period | Hours to months | Oxidative stability measure | Rancimat, OSI |

The rate of autoxidation depends significantly on the structure of the lipid substrate, with relative oxidation rates increasing exponentially with the degree of unsaturation. For example, the relative oxidation rates for fatty acids with 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, and 6 double bonds are approximately 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, and 6, respectively, though actual values vary depending on measurement conditions and specific molecular arrangements [11]. This structure-reactivity relationship explains why foods rich in polyunsaturated fats, such as pearl millet (containing 50-55% PUFAs), demonstrate particular susceptibility to rancidity development [9].

Experimental Protocols for Studying Autoxidation

Biomimetic Model Systems for Radical Reactions

Chemical biology approaches utilizing biomimetic models provide controlled environments for studying free radical processes under biologically relevant conditions. These systems enable detailed mechanistic studies without the complexity of intact biological matrices, facilitating the identification of reaction pathways and products [15].

Protocol: UV-Induced Isomerization of Cholesteryl Esters

- Sample Preparation: Dissolve cholesteryl esters (linoleate or arachidonate) in 2-propanol (15 mM concentration). Sonicicate for 15 minutes under argon to ensure complete solubilization.

- Radical Initiation: Transfer the solution to a quartz photochemical reactor. Add 2-mercaptoethanol in 2-propanol to reach 7 mM concentration (from a 2 M stock solution). Flush the reaction mixture with argon for 20 minutes to eliminate oxygen.

- UV Irradiation: Irradiate the reaction mixture using a 5.5W low-pressure mercury lamp at 22±2°C for 4 minutes. Monitor reaction progress by analytical silver-thin layer chromatography (Ag-TLC) to detect formation of mono-trans cholesteryl esters.

- Product Isolation: Quench the reaction at early stages to recover starting material for subsequent isomerization rounds. Purify mono-trans isomers of cholesteryl esters by preparative Ag-TLC using hexane-diethyl ether (9:1 v/v) as eluent for cholesteryl linoleate isomers, or hexane-diethyl ether-acetic acid (9:1:0.1 v/v) for cholesteryl arachidonate isomers [15].

This protocol generates reference compounds for detecting radical-mediated transformations in biological samples, enabling biomarker development for oxidation in complex food systems.

Accelerated Shelf-Life Testing for Food Rancidity

Accelerated storage studies simulate natural post-processing degradation under controlled conditions that promote oxidative reactions, enabling rapid assessment of rancidity development.

Protocol: Pearl Millet Flour Rancidity Induction

- Sample Preparation: Manually clean freshly harvested pearl millet grains to remove debris and non-viable seeds. Mill grains using a standardized grain mill under controlled conditions to ensure uniform flour particle size.

- Storage Conditions: Transfer freshly milled flour into translucent polypropylene bottles with perforated caps to permit controlled aeration. Store samples under ambient laboratory light conditions at constant temperature of 35±1°C to accelerate oxidative and hydrolytic deterioration.

- Sampling Time Points: Collect samples at designated intervals: M0 (immediately after milling, as fresh control), M1 (after 30 days storage, designated rancid flour), and M2 (after 60 days storage, designated severely rancid flour).

- Analysis: Subject samples to metabolomic profiling, enzymatic assays (lipase, lipoxygenase, peroxidase, polyphenol oxidase), and chemical rancidity indices (acid value, peroxide value, free fatty acid content) [9].

This protocol activates native enzymes and promotes oxidation of polyunsaturated fatty acids, effectively simulating flour storage conditions while enabling precise monitoring of rancidity progression.

Analytical Techniques for Oxidation Product Characterization

Comprehensive characterization of autoxidation products requires multidisciplinary analytical approaches spanning chromatographic, spectroscopic, and computational methods.

Protocol: Metabolomic Profiling of Oxidized Lipids

- Metabolite Extraction: Accurately weigh flour samples (50 mg) into pre-chilled microcentrifuge tubes. Spike with internal standard solution (10 μL containing 2-chlorophenylalanine and D₄-glutamic acid). Extract with 400 μL ice-cold 80% methanol in water.

- Homogenization: Vortex vigorously for 30 seconds followed by agitation using a bead mill homogenizer at 30 Hz for two cycles of 30 seconds, with 5-second rest intervals between cycles, maintaining samples on ice.

- Centrifugation and Extraction: Centrifuge at 14,000 × g for 10 minutes at 4°C. Transfer supernatant (polar extract). To remaining pellet, add 400 μL ice-cold chloroform, repeat vortexing, agitation, and centrifugation.

- LC-MS Analysis: Reconstitute dried extracts in acetonitrile:isopropanol:water (65:30:5, v/v/v) containing 0.1% formic acid. Perform metabolome profiling using UHPLC system coupled to Orbitrap mass spectrometer with C18 column separation and gradient elution with 0.1% formic acid in water (solvent A) and 0.1% formic acid in acetonitrile (solvent B) [9].

This protocol enables identification and quantification of a wide range of lipid oxidation products, facilitating development of molecular libraries for biomarker discovery in rancid food products.

Research Reagent Solutions for Autoxidation Studies

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents for Autoxidation Studies

| Reagent/Chemical | Function in Research | Application Example |

|---|---|---|

| 2-Mercaptoethanol | Radical initiator/scavenger | Biomimetic models of radical reactions [15] |

| Cholesteryl esters | Lipid substrate model | Studying radical-induced isomerization [15] |

| Lipoxygenase | Enzyme catalyst | Studying enzymatic oxidation pathways [9] |

| Internal standards (2-chlorophenylalanine, D₄-glutamic acid) | Metabolomic quantification | LC-MS normalization and quantification [9] |

| Acyl peroxides | Chemical initiator | Thermal generation of radical species [12] |

| Silver-TLC plates | Separation of geometric isomers | Analysis of trans lipid isomers [15] |

| Free fatty acids | Rancidity indicators | Acid value determination [9] |

Visualization of Autoxidation Mechanisms and Workflows

Free Radical Chain Reaction Mechanism in Autoxidation

Experimental Workflow for Rancidity Characterization

The free radical chain reaction mechanism of autoxidation, with its distinct initiation, propagation, and termination phases, provides the fundamental chemical framework for understanding lipid oxidation and food rancidity development. This mechanistic understanding enables researchers to identify critical control points for intervention strategies aimed at preserving food quality and extending shelf-life. The experimental protocols and analytical approaches outlined in this work provide researchers with robust methodologies for investigating autoxidation processes in diverse food systems, from model biomimetic environments to complex food matrices like pearl millet flour.

The implications of this research extend beyond fundamental chemical mechanisms to practical applications in food science, nutrition, and public health. By identifying specific metabolic biomarkers associated with rancidity progression, such as the 25 metabolites identified in pearl millet (including phytol, ethanolamine, chlorophyllide b, and glucoside derivatives), researchers can develop rapid assessment tools and targeted preservation technologies [9]. This integrated approach—connecting fundamental chemical mechanisms with practical food stability challenges—represents the future of lipid oxidation research, with significant potential for reducing food waste, enhancing nutritional quality, and improving global food security.

Lipid oxidation significantly impacts food quality, nutritional value, and safety. This technical guide delineates the distinct mechanistic pathways of auto-oxidation and photo-oxidation, emphasizing how each process generates characteristic hydroperoxide isomer profiles. Through detailed experimental protocols and analytical methodologies, we provide researchers with tools to differentiate these oxidation pathways. The findings are contextualized within food rancidity research, offering critical insights for developing effective stabilization strategies to preserve lipid-containing products.

Lipid oxidation is a paramount cause of food spoilage, leading to rancidity, degradation of nutritional quality, and generation of potentially harmful compounds [4]. Unsaturated fatty acids in fats and oils are particularly susceptible to oxidative deterioration. This review focuses on two primary oxidation pathways: auto-oxidation, a spontaneous free-radical chain reaction, and photo-oxidation, a light-induced process that can proceed via distinct mechanisms [16] [17]. Understanding the nuanced differences between these pathways is crucial for food scientists and product developers. The type of oxidation dictates the specific hydroperoxide isomers formed during the initial stages, which subsequently decompose into various volatile and non-volatile secondary products responsible for off-flavors, odors, and diminished shelf life [4] [18]. By identifying the dominant oxidation pathway through its isomer signature, targeted antioxidant strategies can be implemented to mitigate rancidity and maintain product integrity.

Fundamental Mechanisms

The initiation and propagation of lipid oxidation follow fundamentally different pathways depending on the presence of light and photosensitizers.

Auto-Oxidation: A Radical Chain Reaction

Auto-oxidation is a self-sustaining, free-radical chain reaction primarily initiated by heat, trace metals, or other pro-oxidants, rather than light [4] [18]. It proceeds through three classical stages:

- Initiation: The reaction begins with the abstraction of a hydrogen atom from a bis-allylic methylene group (e.g., in linoleic acid) of an unsaturated fatty acid (RH), forming a carbon-centered lipid radical (R•). This step requires an initial radical source.

- Propagation: The lipid radical (R•) rapidly reacts with molecular oxygen (³O₂) to form a lipid peroxyl radical (ROO•). This highly reactive species can then abstract a hydrogen from an adjacent lipid molecule (RH), generating a lipid hydroperoxide (ROOH) and a new carbon-centered radical (R•), thereby propagating the chain reaction.

- Termination: The reaction chain concludes when two radicals combine to form non-radical products [4].

A key characteristic of auto-oxidation is that the radical intermediates are resonance-stabilized. For instance, in linoleic acid, abstraction of a bis-allylic hydrogen leads to a pentadienyl radical that delocalizes, resulting in the formation of specific conjugated diene hydroperoxide isomers [4].

Photo-Oxidation: Pathways Involving Light

Photo-oxidation requires light absorption by a photosensitizer (e.g., chlorophyll, riboflavin, or synthetic dyes), which becomes excited and then engages in one of two primary pathways [16] [19] [17]:

- Type I (Contact-Dependent Pathway): The excited triplet-state photosensitizer (³Sen) reacts directly with a substrate (e.g., the lipid) via electron or hydrogen atom transfer, generating lipid radicals. These radicals then initiate a free-radical chain reaction analogous to auto-oxidation.

- Type II (Contact-Independent Pathway): The excited triplet-state photosensitizer (³Sen) transfers its energy directly to ground-state molecular oxygen (³O₂), generating singlet oxygen (¹O₂) [16] [19]. Singlet oxygen is an electrophilic excited state that reacts rapidly with the double bonds of unsaturated lipids via a concerted "ene" reaction.

This "ene" reaction is non-radical in nature and does not involve hydrogen abstraction. It leads to a shift of the double bond and the formation of hydroperoxides with the hydroperoxyl group on one of the allylic carbons. Crucially, because the reaction proceeds through a different mechanism, photo-oxidation can produce a wider array of hydroperoxide isomers compared to auto-oxidation, including isomers that are not formed during the radical-mediated auto-oxidation process [20].

The following diagram illustrates the core mechanistic differences between these pathways:

Characteristic Hydroperoxide Isomers

The distinct mechanisms of auto-oxidation and photo-oxidation directly dictate the isomeric profile of the resulting hydroperoxides, providing a chemical fingerprint to identify the dominant degradation pathway.

Isomer Profiles from Different Pathways

Docosahexaenoic acid (DHA) serves as an excellent model to illustrate these differences, as it is highly unsaturated and prone to oxidation. The table below summarizes the characteristic DHA hydroperoxide (DHA;OOH) isomers formed via each pathway.

Table 1: Characteristic DHA Hydroperoxide Isomers Formed via Auto-Oxidation and Photo-Oxidation [20]

| Oxidation Mechanism | Reactive Species | Characteristic DHA;OOH Isomers |

|---|---|---|

| Auto-Oxidation | Radicals (ROO•) | Formed via abstraction of bis-allylic hydrogen: 4-, 7-, 8-, 10-, 11-, 13-, 14-, 16-, 17-, 20-OOH |

| Photo-Oxidation (Type II) | Singlet Oxygen (¹O₂) | Includes all auto-oxidation isomers PLUS isomers unique to the 'ene' reaction with double bonds: 5-OOH and 19-OOH |

The presence of 5-OOH and 19-OOH isomers is a definitive marker for singlet oxygen-mediated photo-oxidation, as these specific isomers are not generated through the radical-based auto-oxidation pathway [20]. Similar principles apply to other unsaturated fatty acids; for example, singlet oxygen oxidation of oleic acid yields a mixture of 9-, 10-, and other positional isomers, some of which are non-conjugated, unlike the specific conjugated isomers formed from auto-oxidation.

Comparative Analysis of Isomer Formation

The following diagram visualizes the formation of these diagnostic isomers in DHA, highlighting the carbon atoms attacked by each mechanism:

Experimental Protocols for Isomer Analysis

Direct analysis of hydroperoxide isomers is essential for identifying oxidation pathways. Liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) provides the requisite sensitivity and selectivity.

Sample Preparation and Oxidation Induction

This protocol outlines the procedure for analyzing esterified lipids in complex matrices like mackerel [20].

- Lipid Extraction: Homogenize the food sample (e.g., 300 mg mackerel). Extract total lipids using a modified Folch method (chloroform:methanol, 2:1 v/v). Separate neutral lipids (triacylglycerols, TGs) and phospholipids (PLs) using solid-phase extraction on an aminopropyl cartridge. Elute neutral lipids with chloroform/2-propanol (2:1, v/v) and phospholipids with methanol. Dry fractions under a stream of N₂ gas and reconstitute in appropriate solvents for storage at -80 °C under N₂ [20].

- Induction of Photo-oxidation: Dissolve the purified lipid of interest (e.g., PC 16:0/22:6) in methanol. Add a photosensitizer like Rose Bengal (final concentration ~7.5 µg/mL). Place the solution on ice to mitigate thermal side reactions. Irradiate with a white LED light source (e.g., 6000 lux) for a defined period (e.g., 2 hours) to generate photo-oxidation products [20].

- Induction of Auto-oxidation (Thermal Oxidation): Incubate the purified lipid in the dark at elevated temperatures (e.g., 37-60 °C) for a defined period. This thermal energy promotes the radical chain reaction of auto-oxidation without light-induced pathways [21].

LC-MS/MS Analysis and Isomer Discrimination

The following workflow and table detail the critical analytical steps and reagents.

- Chromatography: Use a reversed-phase C18 column. For phospholipids like PC-DHA;OOH, employ isocratic elution with methanol/water (95:5, v/v). For neutral lipids like TG-DHA;OOH, use a binary gradient with methanol and 2-propanol [20].

- Mass Spectrometry Detection: Operate the mass spectrometer in positive ion mode. Detect lipids as sodium adducts ([M+Na]⁺) by post-column infusion of a sodium acetate solution. For isomer identification, use Multiple Reaction Monitoring (MRM) based on characteristic fragmentation patterns. Monitor specific α-cleavage fragments relative to the hydroperoxide group, which provides a unique fingerprint for each isomer's position, enabling direct discrimination [20].

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for Hydroperoxide Isomer Analysis [20]

| Reagent / Instrument | Function / Application |

|---|---|

| Rose Bengal | Photosensitizer dye used to induce Type II photo-oxidation via singlet oxygen generation. |

| Chloroform:MeOH (2:1 v/v) | Solvent system for the modified Folch method, used for total lipid extraction from food matrices. |

| Aminopropyl Cartridge | Solid-phase extraction column for fractionating total lipids into neutral lipids and phospholipids. |

| Sodium Acetate Solution | Post-column infusion reagent to promote the formation of sodium adducts ([M+Na]⁺) for sensitive MS detection. |

| C18 LC Column | Reversed-phase chromatography column for separating lipid hydroperoxide isomers prior to MS analysis. |

| Tandem Mass Spectrometer | Core instrument for identifying and quantifying isomeric hydroperoxides via MRM and characteristic α-cleavage fragments. |

The experimental workflow from sample to result is summarized below:

Implications for Food Rancidity Research

The differentiation of oxidation pathways has profound implications for assessing food quality and developing preservation strategies.

Different hydroperoxide isomers have varying stabilities and decomposition pathways, leading to different profiles of secondary oxidation products (aldehydes, ketones) that define the sensory attributes of rancidity [4]. Identifying the dominant pathway allows for the rational selection of antioxidants. For example, if photo-oxidation is the primary issue, singlet oxygen quenchers (e.g., carotenoids) or light-blocking packaging are optimal. If auto-oxidation dominates, radical scavengers (e.g., tocopherols, BHT, BHA) are more effective [5] [18]. Research on milk triacylglycerols has demonstrated that light exposure generates a distinct hydroperoxide isomer profile compared to thermal treatment, directly impacting flavor stability [21]. Similarly, in DHA-rich mackerel, radical oxidation was found to progress even under refrigeration, highlighting the need for effective stabilization beyond just light protection [20].

Auto-oxidation and photo-oxidation are distinct chemical processes that generate unique hydroperoxide isomer fingerprints. Auto-oxidation, a radical-mediated chain reaction, produces a specific set of isomers derived from bis-allylic hydrogen abstraction. In contrast, photo-oxidation, particularly the Type II singlet oxygen pathway, produces a broader isomeric profile, including isomers that serve as definitive biomarkers for light-induced damage. Modern LC-MS/MS methodologies enable researchers to differentiate these isomers directly in complex food matrices. This precise mechanistic understanding is fundamental for diagnosing the root cause of rancidity, enabling targeted antioxidant strategies, and ultimately preserving the sensory and nutritional quality of lipid-containing foods.

Lipid oxidation is a fundamental chemical process that represents the most significant chemical threat to food shelf life, quality, safety, and wholesomeness [22]. This complex series of reactions begins when unsaturated lipids in foods become degraded through exposure to oxygen, light, and heat, leading to the formation of undesirable flavors, aromas, and potentially toxic compounds [5] [23]. The process not only causes depreciation of organoleptic quality and shelf life but also directly contributes to increased food waste and economic losses [23]. For researchers and drug development professionals, understanding the precise pathways and products of lipid oxidation is crucial for developing effective stabilization strategies and assessing potential health implications.

The oxidation of lipids progresses via free-radical propagated chain reactions that are typically autocatalytic in nature [4] [24]. These reactions are initiated when unsaturated fatty acids react with molecular oxygen in the presence of initiators such as light, heat, or metal ions [23]. The susceptibility of fatty acids to oxidation increases with their degree of unsaturation due to progressively lower bond dissociation energies of methylene-interrupted carbons [23]. This makes polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs), increasingly promoted in contemporary foods for health reasons, particularly vulnerable to oxidative degradation [22].

Within the context of food rancidity research, the transformation of hydroperoxides to aldehydes and ketones represents a critical pathway that directly impacts food quality and safety. This technical guide examines the key oxidation products formed during lipid degradation, with particular focus on their formation pathways, analytical detection methods, and significance in evaluating food stability and quality.

Mechanisms of Lipid Oxidation and Key Product Formation

The Three-Phase Oxidation Process

Lipid oxidation occurs through a well-characterized three-step process comprising initiation, propagation, and termination phases [5]. Each phase generates distinct products that serve as markers for assessing the extent and progression of oxidation:

Initiation Phase: The formation of free radicals begins and accelerates through hydrogen abstraction from lipid molecules, particularly at bis-allylic positions in polyunsaturated fatty acids [5]. This initial phase produces lipid radicals (L•) that react rapidly with molecular oxygen.

Propagation Phase: A chain reaction of high-energy molecules, including variations of free radicals and oxygen, propagates exponentially if not controlled [5]. During this phase, the rate of peroxide radical formation reaches equilibrium with the rate of decomposition, forming a characteristic bell-shaped curve when measured over time.

Termination Phase: The starting material becomes consumed, and peroxide radicals decompose into secondary oxidation by-products including esters, short-chain fatty acids, polymers, alcohols, ketones, and aldehydes [5]. It is these secondary oxidation by-products, particularly the aldehydes and ketones, that negatively affect food quality and sensory properties.

Formation Pathways of Primary Oxidation Products

Hydroperoxides (LOOHs) represent the main primary products of lipid auto-oxidation [4]. Their formation mechanism varies depending on the specific fatty acid substrate:

Oleic acid oxidation generates two allylic radicals through hydrogen abstraction at C8 and C11 positions, leading to the formation of 8-, 9-, 10-, and 11-allyl hydroperoxides [4] [3].

Linoleic acid auto-oxidation involves doubly reactive penta-dienyl radicals formed by abstraction from the allylic groups of C11, producing conjugated 9- and 13-diene hydroperoxides [4] [3].

Linolenic acid forms two penta-dienyl radicals by abstracting hydrogen on the C11 and C14 methylene groups [4] [3].

The degradation pathways of these hydroperoxides are highly dependent on temperature, pressure, and oxygen concentration [4]. Hydroperoxide cleavage generates alkoxy and hydroxyl radicals through homogeneous cleavage of the O-O bond, with the alkoxy radicals subsequently undergoing cleavage on the C-C bond to form aldehydes and vinyl radicals or unsaturated aldehydes and alkyl radicals [4] [3]. Among the volatile organic compounds generated through these pathways, aldehydes represent the essential critical aroma substances responsible for the characteristic odors associated with rancid fats and oils [4].

Figure 1: Lipid Oxidation Pathway from Initiation to Secondary Products. This diagram illustrates the free radical chain reaction mechanism of lipid oxidation, showing the progression from unsaturated lipids through hydroperoxide formation to aldehyde and ketone generation.

Critical Transition: From Hydroperoxides to Carbonyl Compounds

The transition from hydroperoxides to aldehydes and ketones represents a critical juncture in lipid oxidation that significantly impacts food quality. Recent research has identified the existence of a critical hydroperoxide concentration (CCLOOH) between 38-50 mmol/kg in food emulsions such as mayonnaise, at which point a rapid acceleration of aldehyde generation occurs [24]. This concentration threshold triggers enhanced secondary oxidation mechanisms, making the rapid acceleration of aldehydes imminent.

The specific aldehydes formed depend on the parent fatty acid and degradation pathway:

- Malondialdehyde (MDA) originates from fatty acids containing three or more double bonds [4]

- Hexanal derives predominantly from n-6 fatty acids [24]

- 4-Hydroxy-2-hexenal and 4-Hydroxy-2-nonenal form through more complex degradation pathways [25]

These carbonyl compounds are chemically reactive and can participate in further reactions with proteins and other food components, leading to protein aggregation, changes in food texture, loss of nutritional value, and formation of potentially harmful compounds [4] [23].

Analytical Methods for Detection and Quantification

Assessment of Primary Oxidation Products

The analytical techniques for detecting lipid oxidation products correspond to measuring specific oxidation products and their consequences [4]. For primary oxidation products, the following methods are commonly employed:

Peroxide Value (PV) is the most widely used method for determining peroxide content in foods, particularly meat products [4]. The iodometric and ferric thiocyanate methods directly measure the degree of hydroperoxides formed by oxidation [4]. While the iodometric assay is highly sensitive and accurate, it requires stringent precautions to minimize oxygen in the reaction solution and prevent substances that may induce hydroperoxide decomposition or react with iodine [4].

Conjugated Diene Analysis measured at 233 nm is suitable for polyunsaturated fatty acid-containing foods [4]. This method provides actual values of low-density lipoprotein oxidation during the early stages and offers convenience and low cost, though it depends on lipoprotein composition and size and may struggle to detect small conjugated dienes [4].

High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC) methods, particularly when coupled with chemiluminescence detection (CL-HPLC), enable sensitive determination of lipid hydroperoxides with specificity to hydroperoxide groups [26]. This system can detect as low as 7 nmol of phosphatidylcholine hydroperoxide and has revealed the presence of 28-431 pmol/ml of PCOOH in healthy human plasma [26].

Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) spectroscopy has emerged as a powerful technique for simultaneously quantifying both primary and secondary lipid oxidation products [24]. ¹H NMR methods provide rapid and accurate quantification of the bulk of hydroperoxides and non-volatile aldehydes, enabling comprehensive tracking of oxidation progression [24].

Assessment of Secondary Oxidation Products

Secondary oxidation products, particularly aldehydes and ketones, are typically measured using different approaches:

p-Anisidine Value (p-AV) determines the amount of reactive aldehydes and ketones in the lipid portion of a sample [5]. The compound p-anisidine reacts readily with aldehydes and ketones, and the reaction product is measured using a colorimeter [5]. This method is particularly useful for detecting non-volatile carbonyl compounds that remain in the oil after heating.

Thiobarbituric Acid Reactive Substances (TBARS) assay measures aldehydes (primarily malondialdehyde) created during lipid oxidation [4] [5]. This analysis is primarily useful for low-fat samples, as the whole sample can be analyzed rather than just the extracted lipids [5]. The production of MDA-TBA adducts is detected at 532 nm [4].

Gas Chromatography (GC) methods effectively detect volatile compounds that indicate rancidity, including hexanal and other low-molecular-weight aldehydes and ketones [5] [24]. These methods offer high sensitivity and specificity for profiling the volatile compounds responsible for off-flavors and odors.

Electrochemical Methods represent emerging approaches for rapid assessment of oil quality. Recent studies have demonstrated that cyclic voltammetry, electrochemical impedance spectroscopy, and differential pulse voltammetry parameters show strong correlations with traditional chemical indicators, such as the DPV peak current at +0.2 V with p-anisidine value (r = 0.94, p < 0.001) [27].

Table 1: Analytical Methods for Key Oxidation Products

| Target Compound | Analytical Method | Principle | Detection Range/Limit | Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hydroperoxides | Peroxide Value (PV) | Titration of peroxides | Varies by method; iodometric highly sensitive | Meat, edible oils, oil-based products |

| Hydroperoxides | Conjugated Diene Analysis | UV absorption at 233-234 nm | Convenient for early stage oxidation | PUFA-containing foods |

| Hydroperoxides | CL-HPLC | Chemiluminescence detection post-separation | 7 nmol for PCOOH | Biological samples, quantitative mechanism studies |

| Aldehydes | p-Anisidine Value (p-AV) | Colorimetric reaction with aldehydes | Suitable for objectionable flavors at low levels | Oils, fats, dark samples not ideal |

| Malondialdehyde | TBARS | Colorimetric reaction with TBA | 532 nm detection | Low-fat samples, meat products, fish |

| Volatile Aldehydes/Ketones | Gas Chromatography (GC) | Separation and detection of volatiles | High sensitivity and specificity | Profile volatile off-flavors, hexanal detection |

Advanced and Integrated Approaches

Contemporary research employs integrated analytical approaches to gain comprehensive understanding of lipid oxidation processes:

Total Oxidation (TOTOX) Value combines both primary and secondary oxidation measurements using the formula: TOTOX = 2 × PV + AV [25]. This integrated value provides a more complete picture of the overall oxidation state.

Machine Learning Applications have recently been applied to predict oxidation parameters. Random Forest models trained on electrochemical data have accurately predicted TOTOX values, achieving R² of 0.96 and RMSE of 2.18 for test sets [27]. Feature importance analysis revealed charge transfer resistance and DPV peak currents as the most influential predictors [27].

Accelerated Shelf-Life Testing (ASLT) is widely used in the food industry to assess oxidative stability of different formulations [24]. By storing products under elevated temperatures (e.g., 50°C), oxidation reactions are stimulated to enable faster assessment of stability and shelf-life [24].

Figure 2: Analytical Workflow for Lipid Oxidation Assessment. This diagram outlines the comprehensive approach to analyzing lipid oxidation products, from sample preparation through primary and secondary product analysis to advanced integrated methods and data interpretation.

Experimental Protocols for Key Analyses

Hydroperoxide Quantification by CL-HPLC

The CL-HPLC system enables sensitive determination of lipid hydroperoxides with specificity to hydroperoxide groups, using a chemiluminescence reaction selective for lipid hydroperoxides as the detection part of HPLC [26].

Reagents and Materials:

- Luminol-cytochrome c solution as hydroperoxide-specific luminescent reagent

- High-purity lipid hydroperoxide standards (e.g., phosphatidylcholine hydroperoxide)

- Normal phase HPLC system

- Single photon counting detector

Procedure:

- Extract lipids from samples using appropriate solvents (chloroform:methanol)

- Separate lipid classes by normal phase HPLC

- Post-column mixing with luminol-cytochrome c reagent

- Detect chemiluminescence using single photon counter

- Quantify based on standard curves of authentic hydroperoxides

Critical Notes:

- Detection limit: approximately 7 nmol of phosphatidylcholine hydroperoxide (PCOOH)

- Enables detection of 28-431 pmol/ml of PCOOH in healthy human plasma

- The chemiluminescence reaction is based on the oxidation of luminol by reaction with lipid hydroperoxides and cytochrome c, generating singlet oxygen that oxidizes luminol to produce light emission at 430 nm [26]

Accelerated Shelf-Life Testing with Predictive Modeling

This protocol enables prediction of aldehyde onset based on early hydroperoxide formation kinetics, significantly reducing assessment time from weeks to days [24].

Reagents and Materials:

- Food emulsion samples (e.g., mayonnaise)

- CDCl₃, DMSO-d6 with 4Å molsieves for NMR

- 600 MHz NMR spectrometer

- Temperature-controlled storage chambers

Procedure:

- Prepare emulsion samples with varying antioxidant formulations

- Store aliquots in sealed containers at accelerated conditions (50°C)

- Collect samples at regular intervals (e.g., daily for first week, then weekly)

- Separate oil phase by freeze-thaw and centrifugation (5 min at 17,000 × g)

- Dissolve oil phase (150 μL) in 450 μL 5:1 CDCl₃:DMSO-d6 solvent

- Acquire ¹H NMR spectra using single pulse and band selective experiments

- Quantify hydroperoxides and aldehydes based on characteristic signals

- Fit hydroperoxide concentration vs. time data to Foubert model: [ C(t) = \frac{C{\text{max}}}{1 + e^{-k(t - t{\text{mid}})}} ] where (C{\text{max}}) is maximum LOOH, (k) is rate constant, and (t{\text{mid}}) is midpoint time

- Determine critical LOOH concentration (CCLOOH, typically 38-50 mmol/kg)

- Predict aldehyde onset time as time when LOOH concentration reaches CCLOOH

Critical Notes:

- Foubert function better describes LOOH curvature than Gompertz function

- Model parameters can recognize antioxidant mechanisms at play

- Enables accurate prediction of aldehyde onset within several days rather than weeks

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for Lipid Oxidation Analysis

| Reagent/Instrument | Function | Application Examples | Technical Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Luminol-Cytochrome c | Chemiluminescence detection of hydroperoxides | CL-HPLC for lipid hydroperoxide quantification | Specific for hydroperoxide groups; enables sensitive detection |

| p-Anisidine Reagent | Colorimetric detection of aldehydes | p-Anisidine value for secondary oxidation | Reacts with α,β-unsaturated aldehydes; not suitable for dark samples |

| Thiobarbituric Acid (TBA) | Colorimetric detection of malondialdehyde | TBARS assay for lipid peroxidation extent | Measures primarily MDA; useful for low-fat samples |

| Deuterated Solvents (CDCl₃, DMSO-d6) | NMR analysis without hydrogen interference | ¹H NMR quantification of hydroperoxides and aldehydes | Enables simultaneous detection of multiple oxidation products |

| Fatty Acid Standards | Calibration and identification | GC analysis of fatty acid composition | Essential for quantitative analysis; purity critical |

| Antioxidants (Tocopherols, EDTA, Gallic Acid) | Oxidation inhibition studies | Mechanism studies and antioxidant efficacy | Concentrations typically 10-1000 ppm depending on antioxidant |

Implications for Food Quality and Research Applications

Impact on Food Systems

The progression from hydroperoxides to aldehydes and ketones has profound implications for food quality:

Sensory Deterioration: Aldehydes and ketones generated during lipid oxidation are responsible for the characteristic rancid odors and flavors that render foods unacceptable to consumers [5] [23]. Hexanal, in particular, is linked to the perceived off-taste and off-flavor of oxidized products [24].

Nutritional Quality: Lipid oxidation destroys critical nutrients, including essential fatty acids and fat-soluble vitamins [22]. The resulting products may also reduce protein digestibility and bioavailability through formation of protein aggregates [4].

Physical Properties: In food emulsions such as mayonnaise, lipid oxidation products can affect stability and texture [24]. Protein oxidation induced by lipid oxidation products can lead to protein aggregation, significantly affecting protein physicochemical characteristics and biological functions [4].

Health and Safety Considerations

Beyond quality implications, lipid oxidation products raise important health and safety concerns:

Toxic Products: Oxidation products accumulating to a certain extent could be detrimental to consumer health [4]. Some oxidation products, including certain epoxides and aldehydes, are known to be toxic and potentially mutagenic [22].

Cellular Effects: Studies have shown that oral ingestion of oxidized oil causes severe damage to immune tissues in animal models, with necrosis observed in lymphocytes located in the thymus, and significant decreases in thymus weight, spleen weight, and blood leucocytes number [26].

Chronic Disease Links: There is ample evidence showing that free radical oxidation plays an important role in many pathological situations, including many types of cancer, atherosclerosis, coronary heart disease, rheumatoid arthritis, and other degenerative diseases [23].

Research Significance and Future Directions

Understanding the pathways from hydroperoxides to aldehydes and ketones provides critical insights for:

Food Stabilization Strategies: Traditional practices of adding synthetic antioxidants are insufficient for contemporary foods reformulated with high polyunsaturated fatty acids for health, largely because oxidation in complex food systems involves more molecules than just lipids [22]. Understanding these pathways enables development of more effective stabilization approaches.

Analytical Method Development: Nearly all analyses in industry or research concentrate on how fast a food oxidizes while ignoring how it oxidizes and what types of damage results [22]. Current analyses miss key lipid oxidation products and do not account for broadcasting oxidation to other molecules, particularly proteins [22].

Predictive Modeling: The identification of critical hydroperoxide concentrations that trigger rapid aldehyde formation enables development of predictive models that can significantly reduce the time required for shelf-life assessment [24]. Machine learning approaches applied to electrochemical data show particular promise for rapid quality assessment [27].

The comprehensive understanding of key oxidation products from hydroperoxides to aldehydes and ketones remains essential for advancing food stability, quality, and safety while potentially providing insights relevant to oxidative processes in biological systems and disease pathogenesis.

Lipid oxidation represents a paramount challenge in food science, serving as the primary driver of quality deterioration in lipid-containing food matrices. This complex chemical process not only compromises the lipids themselves but also initiates a cascade of destructive events that negatively impact proteins, sensory attributes, and nutritional value. Within food systems, unsaturated fatty acids react with oxygen through various pathways to form highly reactive free radicals and lipid hydroperoxides, which subsequently decompose into a wide range of secondary products [4] [28]. These reactive intermediates propagate oxidative damage throughout the food matrix, leading to the development of off-flavors, degradation of color and texture, loss of essential nutrients, and formation of potentially toxic compounds [28].

The significance of lipid oxidation extends beyond mere food spoilage, as the process is intimately involved in co-oxidation reactions with proteins, fundamentally altering their structure and functionality [4]. Research interest in this field has grown substantially, with publications on lipid and protein oxidation increasing markedly over the past two decades, reflecting heightened recognition of its implications for food quality and human health [3]. Understanding these complex reaction mechanisms provides the foundational knowledge necessary for developing effective strategies to mitigate oxidative damage in food products, thereby extending shelf life, maintaining sensory appeal, and preserving nutritional integrity within the broader context of food rancidity research.

Fundamental Mechanisms of Lipid Oxidation

Lipid oxidation progresses through a well-defined series of chemical reactions that collectively contribute to the degradation of food matrices. The process typically occurs via three interconnected pathways—auto-oxidation, photo-oxidation, and enzymatic oxidation—with auto-oxidation representing the predominant free-radical chain reaction in most food systems [4].

The Free Radical Chain Reaction

Auto-oxidation proceeds through three distinct phases that collectively drive the oxidative deterioration of food matrices:

- Initiation: This initial phase involves the formation of free lipid radicals (L•) through the abstraction of a hydrogen atom from unsaturated fatty acid molecules (LH), typically catalyzed by factors such as heat, light, or metal ions [4]. The reaction begins as follows: LH → L• + H•.

- Propagation: During this phase, lipid radicals (L•) rapidly react with molecular oxygen (O₂) to form lipid peroxyl radicals (LOO•). These highly reactive intermediates then abstract hydrogen atoms from adjacent unsaturated fatty acids, generating lipid hydroperoxides (LOOH) and new lipid radicals (L•), thereby propagating the chain reaction [4]. The propagation reactions are represented as: L• + O₂ → LOO• and LOO• + LH → LOOH + L•.

- Termination: The chain reaction concludes when free radicals combine with one another to form non-radical products, effectively terminating the oxidative process [4]. Termination reactions include: LOO• + LOO• → LOOL + O₂, L• + L• → LL, and LOO• + L• → LOOL.

Table 1: Primary Lipid Oxidation Products Formed During Different Fatty Acid Oxidation

| Fatty Acid | Type | Primary Oxidation Products | Characteristic Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| Oleic Acid | Monounsaturated | 8-, 9-, 10-, and 11-allyl hydroperoxides | Formation of two allylic radicals with electrons delocalized at three carbon atoms [4] |

| Linoleic Acid | Polyunsaturated | Conjugated 9- and 13-diene hydroperoxides | Formation of penta-dienyl radicals with electrons delocalized at five carbon atoms [4] |

| Linolenic Acid | Polyunsaturated | Multiple hydroperoxide isomers | Formation of two penta-dienyl radicals by abstracting hydrogen on C11 and C14 methylene groups [4] |

Formation of Secondary Oxidation Products

Lipid hydroperoxides (LOOH), the primary products of lipid oxidation, are inherently unstable and decompose readily under the influence of heat, light, or metal catalysts. This decomposition generates alkoxy (LO•) and hydroxyl (HO•) radicals through homolytic cleavage of the peroxide bond [4]. These radicals subsequently undergo carbon-carbon bond cleavage, yielding volatile compounds including aldehydes, alkenes, alcohols, and ketones [4]. Among these secondary oxidation products, aldehydes such as malondialdehyde, 4-hydroxy-trans-2-nonenal, and hexenal are particularly significant due to their low odor thresholds and profound impact on sensory properties [4]. These carbonyl compounds are responsible for the characteristic rancid aromas and flavors associated with oxidized foods, and they also participate in further chemical interactions with proteins, pigments, and other food components, leading to co-oxidation phenomena [4].

Impact on Sensory Quality

The sensory degradation of food matrices resulting from lipid oxidation manifests through distinct changes in flavor, aroma, color, and texture. These alterations significantly reduce consumer acceptance and marketability of affected products.

Flavor and Aroma Deterioration

The development of undesirable flavors and aromas constitutes the most readily perceptible indicator of lipid oxidation. As polyunsaturated fatty acids undergo oxidation, they generate volatile compounds that impart characteristic off-flavors even at minute concentrations [28]. The decomposition of lipid hydroperoxides yields aldehydes, ketones, alcohols, and hydrocarbons that collectively create the sensory experience described as rancidity [4]. Specific volatile compounds produce distinct off-notes: omega-3 fatty acid oxidation generates fishy aromas, while omega-6 fatty acid oxidation produces grassy or painty odors [28]. In meat products, aldehydes derived from lipid oxidation contribute significantly to flavor deterioration and are closely associated with the development of warmed-over flavor [4]. The interaction between lipid oxidation products and Maillard reaction pathways further complicates flavor development, particularly in thermally processed foods [29].

Color and Texture Modifications

Lipid oxidation indirectly affects food color through co-oxidation of pigments and direct interaction with protein structures. Free radicals generated during lipid oxidation readily attack conjugated double bonds in color pigments such as carotenoids and myoglobin, leading to bleaching or discoloration [28]. In muscle foods, lipid oxidation products facilitate the oxidation of oxymyoglobin to metmyoglobin, resulting in an undesirable brownish-gray discoloration [4] [3]. Secondary lipid oxidation products, particularly unsaturated aldehydes, react with primary amino groups in proteins, potentially forming brown Maillard-type pigments that further alter food appearance [28].

Textural changes in oxidized food matrices primarily result from protein co-oxidation induced by lipid-derived free radicals and secondary carbonyl compounds. These interactions promote protein aggregation through covalent cross-linking, including the formation of disulfide bonds and carbonyl-amine bridges [4]. In meat systems, oxidative damage to myofibrillar proteins, especially myosin, leads to diminished water-holding capacity, increased toughness, and reduced juiciness [4] [29]. The structural alterations in proteins subsequently affect functional properties such as emulsification capacity, foam stability, and gelation, further compromising product quality and performance in complex food matrices [4].

Table 2: Sensory Impact of Specific Lipid Oxidation Products

| Oxidation Product | Class | Sensory Impact | Food Systems Where Commonly Found |

|---|---|---|---|

| Malondialdehyde | Aldehyde | Rancid, pungent odor | Meat, fish, edible oils [4] |

| 4-Hydroxy-trans-2-Nonenal | Aldehyde | Strong, disagreeable odor | Vegetable oils, meat products [28] |

| Hexanal | Aldehyde | Green, grassy odor | Vegetable oils, nuts, grains [4] |

| Acrolein | Aldehyde | Acrid, burning aroma | Heated oils, fried foods [28] |

| Crotonaldehyde | Aldehyde | Pungent, suffocating odor | Fried chips, fish, meat [28] |

Nutritional Loss and Health Implications

Lipid oxidation profoundly impacts the nutritional quality of food matrices through multiple mechanisms that extend beyond mere sensory deterioration. The process diminishes nutritional value by degrading essential fatty acids, fat-soluble vitamins, and protein quality, while simultaneously generating potentially harmful compounds.

Degradation of Essential Nutrients

The oxidative process preferentially targets polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs), particularly nutritionally essential omega-3 and omega-6 fatty acids, thereby reducing their bioavailability and biological efficacy [28]. The destruction of these essential lipids represents a significant nutritional loss, as they play crucial roles in human physiology, including inflammatory regulation, neurological function, and cardiovascular health. Concurrently, lipid oxidation accelerates the degradation of fat-soluble vitamins (A, D, E, and K) and carotenoids, which are highly susceptible to radical-mediated degradation [28]. The oxidation of proteins by lipid-derived reactive species diminishes their nutritional value by reducing the bioavailability of essential amino acids, particularly lysine, methionine, cysteine, and histidine [4]. This oxidative modification compromises protein digestibility and alters amino acid profiles, thereby diminishing the protein quality score of affected foods [4].

Formation of Potentially Toxic Compounds

The secondary oxidation products generated during lipid oxidation include various aldehydes that demonstrate potential toxicological effects in biological systems. Among these, α,β-unsaturated aldehydes such as acrolein, crotonaldehyde, 4-hydroxy-trans-2-nonenal (HNE), and 4-hydroxy-trans-2-hexenal (HHE) exhibit particularly concerning biological activities [28]. These reactive carbonyl species can form covalent adducts with cellular proteins, DNA, and phospholipids, potentially disrupting normal physiological functions [28]. Acrolein, produced through linoleic acid oxidation, has been associated with myocardial oxidative stress, cardiomyopathy, and vascular dysfunction in animal studies [28]. Crotonaldehyde, detected in various fried and processed foods, has demonstrated hepatocarcinogenic potential in rodent models through the formation of DNA adducts [28]. HNE and HHE, derived from omega-6 and omega-3 fatty acid oxidation respectively, have shown cytotoxic effects and the ability to induce thymic necrosis in experimental animals [28].

The human health implications of dietary lipid oxidation products remain an area of active investigation, as biological systems possess sophisticated antioxidant defenses and repair mechanisms. However, evidence suggests that consumed oxidation products can be absorbed through the gastrointestinal tract, with unsaturated aldehydes demonstrating greater bioavailability than lipid hydroperoxides [28]. Recent research indicates that lipid oxidation products may adversely affect gut health by altering microbiota composition and promoting colonic inflammation, potentially increasing susceptibility to conditions such as colorectal cancer [28].

Protein Co-oxidation: Mechanisms and Consequences

The interplay between lipid and protein oxidation represents a critical dimension of food matrix deterioration, with lipid-derived reactive species initiating and propagating protein oxidation through various mechanistic pathways.

Mechanisms of Protein Co-oxidation

Protein co-oxidation occurs when reactive intermediates generated during lipid oxidation attack and modify protein structures. Free radicals, including lipid peroxyl (LOO•) and alkoxyl (LO•) radicals, abstract hydrogen atoms from susceptible amino acid side chains, generating protein-centered radicals that subsequently undergo further reactions [4]. These protein radicals can cross-link with other protein molecules or with lipid radicals, forming complex aggregates that alter protein functionality. Simultaneously, secondary lipid oxidation products, particularly reactive aldehydes such as malondialdehyde (MDA), 4-hydroxy-2-nonenal (HNE), and hexenal, form covalent adducts with nucleophilic amino acid residues (e.g., lysine, cysteine, histidine) through Michael addition and Schiff base reactions [4]. These modifications lead to the formation of protein carbonyl groups, loss of sulfhydryl groups, and the generation of advanced lipoxidation end products (ALEs) that parallel advanced glycation end products in their complexity and stability [4].

The initial process of lipid oxidation generates free radicals that subsequently initiate protein oxidation through several interconnected pathways as illustrated below:

Structural and Functional Consequences

Protein oxidation induced by lipid-derived reactive species profoundly affects protein structure at primary, secondary, and tertiary levels, subsequently altering functional properties critical to food quality. Key structural modifications include:

- Carbonyl Formation: Introduction of carbonyl groups on amino acid side chains serves as a hallmark of protein oxidation and correlates with loss of protein functionality [4].

- Sulfhydryl Loss: Oxidation of cysteine residues results in disulfide bond formation, both intra- and intermolecularly, leading to protein aggregation [4].

- Amino Group Modification: Lysine residues react with lipid-derived aldehydes, diminishing protein nutritional quality and creating protein cross-links [4].

- Protein Aggregation: Covalent cross-linking through disulfide bonds, tyrosine dimerization, and aldehyde-mediated bridges generates high molecular weight aggregates with reduced solubility [4].

These structural alterations manifest in significant functional changes that impact food quality. Oxidized proteins typically demonstrate reduced digestibility due to enzyme-resistant cross-links and aggregation, diminishing their nutritional value [4]. Technological functionalities such as emulsification capacity, foam stability, water-holding capacity, and gelation properties are often impaired, compromising performance in processed food applications [4]. In muscle foods, protein oxidation contributes to texture deterioration, including increased toughness and reduced juiciness, while in cereal systems it affects dough handling properties and final product texture [4].

Analytical Methods and Assessment Protocols

Comprehensive evaluation of lipid oxidation and its impact on food matrices requires a multifaceted analytical approach targeting various oxidation products and their effects on coexisting food components.

Assessment of Lipid Oxidation

The complex nature of lipid oxidation necessitates multiple analytical methods to capture the full scope of oxidative deterioration throughout the process. The following workflow outlines a comprehensive analytical strategy for monitoring lipid oxidation:

Table 3: Analytical Methods for Assessing Lipid Oxidation in Food Matrices

| Analysis Target | Method | Principle | Applications | Advantages/Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Products | Peroxide Value (PV) | Titration-based measurement of hydroperoxide content [4] | Oils, meat, fish, edible insects | Highly sensitive and accurate for early oxidation; requires oxygen-free conditions [4] |

| Primary Products | Conjugated Dienes | UV absorption at 233 nm [4] | Polyunsaturated fatty acid-containing foods | Convenient and low-cost; limited sensitivity for small dienes [4] |

| Secondary Products | Thiobarbituric Acid Reactive Substances (TBARS) | Measurement of malondialdehyde-thiobarbituric acid complex at 532 nm [4] | Meat, fish, edible insects | Well-established; may lack specificity due to interference [4] |

| Secondary Products | p-Anisidine Value | Colorimetric determination of aldehydes [5] | Oils and oil-based products | Simple calculation; problematic for dark samples and omega-3-rich oils [4] |