ICH Q2(R1) Analytical Method Validation: The Definitive Guide for Pharmaceutical Professionals

This guide provides a comprehensive overview of ICH Q2(R1) analytical method validation, a critical process for ensuring the quality, safety, and efficacy of pharmaceuticals.

ICH Q2(R1) Analytical Method Validation: The Definitive Guide for Pharmaceutical Professionals

Abstract

This guide provides a comprehensive overview of ICH Q2(R1) analytical method validation, a critical process for ensuring the quality, safety, and efficacy of pharmaceuticals. Tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it covers the foundational principles, methodological application of key validation parameters, and practical troubleshooting strategies. The content also addresses the evolving regulatory landscape, comparing ICH Q2(R1) with the modernized Q2(R2) and Q14 guidelines to offer a complete perspective on analytical procedure lifecycle management for both chemical and biological drugs.

Understanding ICH Q2(R1): The Foundation of Analytical Method Validation

Historical Development of ICH Q2(R1)

The International Council for Harmonisation (ICH) Q2(R1) guideline, titled "Validation of Analytical Procedures: Text and Methodology," represents a cornerstone of global pharmaceutical regulation. Its development began in the 1990s to address conflicting technical requirements for pharmaceutical registration across major regions [1]. The guideline originated as two separate documents: ICH Q2A ("Text on Validation of Analytical Procedures"), finalized in October 1994, and ICH Q2B ("Validation of Analytical Procedures: Methodology"), finalized in 1996 [1] [2].

In November 2005, these two documents were unified into a single, comprehensive guideline renamed ICH Q2(R1) without changes to their original technical content [3] [2]. This harmonized document was subsequently adopted by regulatory authorities worldwide, including the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA), the European Commission (EC), and Japan's Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare (MHLW/PMDA) [4]. In September 2021, the FDA reissued the combined Q2(R1) guidance, confirming its ongoing regulatory status while the scientific community anticipates the finalization of its successor, ICH Q2(R2) [5].

Harmonization Objectives and Regulatory Impact

The primary harmonization goal of ICH Q2(R1) was to establish a uniform framework for validating analytical procedures used in pharmaceutical development and quality control [4]. Before its implementation, pharmaceutical companies faced significant challenges in meeting divergent regulatory expectations from different regions, leading to redundant testing, increased costs, and delays in product approvals [1].

ICH Q2(R1) successfully created a common language and standardized set of requirements for analytical procedure validation that regulatory authorities in the United States, European Union, Japan, and other adopting regions (such as Canada) would accept [4] [1]. This harmonization eliminated the need for companies to conduct multiple validations for the same product in different jurisdictions, streamlining the drug registration process and facilitating global market access [6].

The guideline achieved this by providing clear recommendations on the validation characteristics that must be evaluated for different types of analytical procedures, along with the specific data that should be presented in registration applications [4]. This ensured that analytical methods used to assess drug substances and products would generate reliable, reproducible results that accurately reflected product quality, safety, and efficacy, regardless of where the testing was performed [7].

Core Principles and Validation Parameters

Scope and Application

ICH Q2(R1) applies to the four most common types of analytical procedures used in pharmaceutical analysis [2]:

- Identification Tests: Methods intended to ensure the identity of an analyte in a sample, typically through comparison to a reference standard [2].

- Quantitative Tests for Impurities' Content: Procedures to measure the amount of impurities present in a sample [2].

- Limit Tests for the Control of Impurities: Methods to determine whether impurities exceed a specified limit [2].

- Quantitative Tests of the Active Moisty: Assays to measure the active component in drug substance or drug product samples [2].

Key Validation Characteristics

The guideline defines specific validation characteristics that must be demonstrated based on the type of analytical procedure. The table below summarizes these requirements:

Table 1: Validation Characteristics for Different Analytical Procedures per ICH Q2(R1)

| Validation Characteristic | Identification | Testing for Impurities | Assay | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Quantitative | Limit | |||

| Accuracy | - | Yes | - | Yes |

| Precision | - | Yes | - | Yes |

| Specificity | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Detection Limit | - | - | Yes | - |

| Quantitation Limit | - | Yes | - | - |

| Linearity | - | Yes | - | Yes |

| Range | - | Yes | - | Yes |

| Robustness | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

Source: Adapted from ICH Q2(R1) guidance [2]

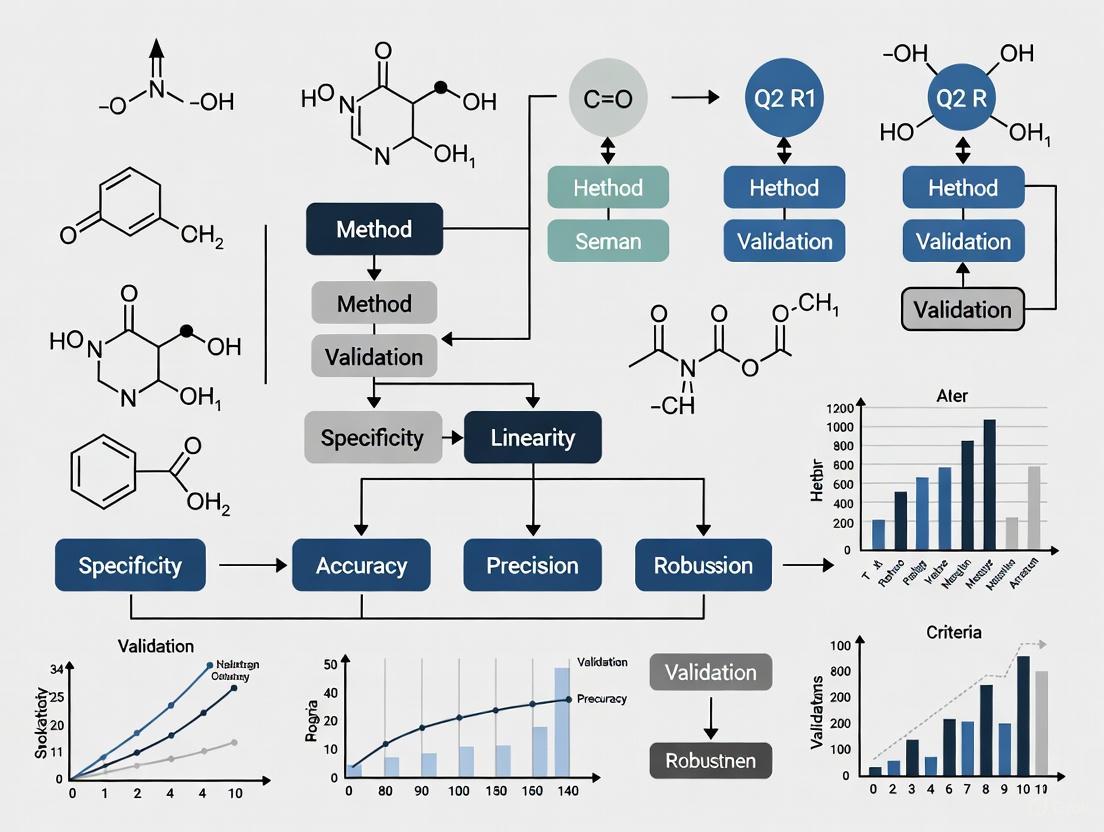

The following diagram illustrates the logical relationship between the analytical procedure lifecycle and its core validation components as conceptualized under ICH Q2(R1):

Detailed Methodologies for Core Validation Parameters

Accuracy

Accuracy demonstrates the closeness of agreement between the measured value and a reference value [2]. Recommended methodologies include:

- Spiked Recovery Studies: For drug substance analysis, compare measured values against known amounts of reference standards. For drug products, use the placebo formulation spiked with known quantities of the analyte [2].

- Comparison to Reference Method: Evaluate results against those obtained from a well-characterized independent procedure [2].

- Acceptance Criteria: Typically requires minimum of 9 determinations across a minimum of 3 concentration levels covering the specified range [2].

Precision

Precision expresses the closeness of agreement between a series of measurements from multiple sampling under prescribed conditions [2]. It should be investigated at three levels:

- Repeatability (Intra-assay Precision): Assess precision under the same operating conditions over a short time interval using at least 9 determinations covering the specified range or 6 determinations at 100% of the test concentration [2].

- Intermediate Precision: Evaluate within-laboratory variations due to different days, different analysts, different equipment, etc. [2].

- Reproducibility: Assess precision between laboratories, typically applied during technology transfer or standardization of methodology [2].

Specificity

Specificity is the ability to assess unequivocally the analyte in the presence of components that may be expected to be present [2]. Methodology includes:

- For Identification: Ensure identity of an analyte through comparison with reference standard using techniques like spectroscopy or chromatographic behavior [2].

- For Assay and Impurity Tests: Demonstrate complete separation of analyte from impurities, degradation products, or matrix components using chromatographic peak purity tests or orthogonal methods [2].

Detection Limit (DL) and Quantitation Limit (QL)

Detection Limit Methodologies:

- Visual Evaluation: Determine lowest concentration detectable by instrumental or visual examination [2].

- Signal-to-Noise Approach: Apply signal-to-noise ratio between 3:1 or 2:1 [2].

- Standard Deviation Method: Calculate based on standard deviation of response and slope of calibration curve: DL = 3.3σ/S [2].

Quantitation Limit Methodologies:

Linearity and Range

- Linearity: Demonstrate ability to obtain test results directly proportional to analyte concentration within a given range. Typically requires minimum of 5 concentrations with correlation coefficients, y-intercept, and slope of regression line reported [2].

- Range: Establish interval between upper and lower concentrations demonstrating suitable level of accuracy, precision, and linearity. Specific ranges depend on application (e.g., for assay of drug substance/drug product: 80-120% of test concentration) [2].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for ICH Q2(R1) Validation

| Item | Function in Validation | Critical Quality Attributes |

|---|---|---|

| Reference Standards | Serves as primary benchmark for identity, purity, and potency assessments [2]. | Well-characterized identity, certified purity, documented stability, traceable source [2]. |

| High-Purity Reagents | Used in mobile phases, sample preparation, and system suitability testing [2]. | Appropriate grade (HPLC, ACS), low impurity levels, minimal interference background [2]. |

| Placebo Formulation | Evaluates specificity by confirming absence of interference with analyte detection [2]. | Representative of final product composition without active ingredient, consistent with manufacturing process [2]. |

| System Suitability Solutions | Verifies chromatographic system resolution, efficiency, and reproducibility before validation runs [2]. | Stable composition, produces characteristic retention times and peak shapes, sensitive to system variations [2]. |

Evolution Beyond ICH Q2(R1) and Current Status

While ICH Q2(R1) remains the current implemented standard, the ICH has recognized limitations in addressing modern analytical techniques such as Near-IR, Raman spectroscopy, and multivariate models [1] [8]. This has led to the development of revised guidelines:

- ICH Q2(R2): Expands validation guidance to include modern analytical procedures and provides more detailed methodology with specific annexes for techniques like quantitative LC/MS and binding assays [6] [8].

- ICH Q14: Introduces a systematic approach to analytical procedure development, incorporating Quality by Design (QbD) principles and the Analytical Procedure Lifecycle concept [6].

These new guidelines promote a more holistic approach where validation begins with clear definition of the Analytical Target Profile (ATP) and continues through ongoing performance verification, representing a significant evolution beyond the foundation established by ICH Q2(R1) [6].

Defining Analytical Procedure Validation and Its Critical Importance

In the pharmaceutical industry, analytical procedure validation is the formal, documented process of demonstrating that an analytical method is suitable for its intended purpose, providing a high degree of assurance that it will consistently yield reliable and accurate results [7]. This process establishes, through laboratory studies, that the method's performance characteristics meet the requirements for its specific analytical application, ensuring reliability during normal use [9]. Validation serves as definitive evidence that the analytical procedure attains the necessary levels of precision, accuracy, and reliability required for assessing the identity, strength, quality, purity, and potency of drug substances and products [10].

The International Council for Harmonisation (ICH) guideline Q2(R1), titled "Validation of Analytical Procedures: Text and Methodology," serves as the primary global standard for this activity [5] [3]. First finalized and later harmonized in 2005, ICH Q2(R1) combines the principles of two earlier documents (Q2A and Q2B) to provide a comprehensive framework for the validation of analytical methods used in regulatory submissions [5] [2]. For pharmaceutical manufacturers, validation is not merely a regulatory formality but a fundamental requirement for compliance with Good Laboratory Practices (GLP) and Current Good Manufacturing Practices (cGMP) [7]. It is a critical component of the overall validation process that ensures the safety and efficacy of pharmaceutical products reaching patients [10].

The Regulatory Framework: ICH Q2(R1)

Scope and Objective

The ICH Q2(R1) guideline provides a harmonized framework for validating analytical procedures, with its core objective being to demonstrate that a procedure is suitable for its intended purpose [2]. This guideline primarily addresses the validation of the four most common types of analytical procedures encountered in pharmaceutical analysis:

- Identification Tests: Methods intended to ensure the identity of an analyte in a sample, typically achieved by comparing a property of the sample (such as spectrum, chromatographic behavior, or chemical reactivity) to that of a reference standard [2].

- Quantitative Tests for Impurities: Procedures designed to accurately measure the content of impurities in a sample, reflecting the purity characteristics of the material [2].

- Limit Tests for Impurities: Methods that determine whether an impurity is above or below a specified limit, without necessarily providing an exact quantitative value [2].

- Assay Procedures: Quantitative measurements of the major component(s) in a drug substance or drug product, which also apply to assays for the active moiety or other selected components in the final product [2].

The guidance outlines the fundamental validation parameters that must be evaluated for each type of procedure, recognizing that different parameters may be applicable depending on the method's intended use [2].

The Validation Lifecycle and Recent Evolution

While ICH Q2(R1) has served as the cornerstone for analytical method validation for nearly two decades, the regulatory landscape is evolving. Recent updates have introduced a more comprehensive lifecycle approach to analytical procedures [6]. The simultaneous introduction of ICH Q2(R2) and the new ICH Q14 guideline represents a significant modernization, shifting from a prescriptive, "check-the-box" approach to a more scientific, risk-based model [6] [11].

This evolution addresses the increasing complexity of biopharmaceutical products and the need for more flexible, science-based approaches to method validation [6]. The new guidelines emphasize that analytical procedure validation is not a one-time event but a continuous process that begins with method development and continues throughout the method's entire operational life [6] [11]. This shift requires organizations to implement systems for ongoing method evaluation and improvement, integrating quality control and method optimization as continuous activities [6].

Core Validation Parameters and Methodologies

The validation process involves the systematic evaluation of specific performance characteristics as defined in ICH Q2(R1). The following parameters are considered fundamental to demonstrating a method's suitability.

Specificity

Specificity is the ability of a method to assess the analyte unequivocally in the presence of other components that may be expected to be present, such as impurities, degradation products, or matrix components [7] [2]. This parameter ensures that the analytical procedure can accurately measure the analyte without interference from other substances.

- Methodology for Identification: Specificity is demonstrated by the ability to discriminate between compounds in the sample or by comparison to known reference materials [9].

- Methodology for Assay and Impurity Tests: Specificity can be shown by resolving the two most closely eluted compounds, typically the major component and a closely eluted impurity [9]. For chromatographic methods, peak purity assessment using photodiode-array (PDA) detection or mass spectrometry (MS) is recommended to demonstrate that a peak's response is due to a single component with no co-elutions [9].

Accuracy

Accuracy expresses the closeness of agreement between the value accepted as a conventional true value or an accepted reference value and the value found [2]. It is sometimes termed "trueness" and measures the exactness of the analytical method.

- Methodology for Drug Substance: Accuracy is typically assessed by comparison with a standard reference material or by comparison to a second, well-characterized method [9].

- Methodology for Drug Product: Accuracy is evaluated by analyzing synthetic mixtures spiked with known quantities of components [9]. For impurity quantification, accuracy is determined by analyzing samples spiked with known amounts of impurities [9].

- Recommended Data: The guidelines recommend collecting data from a minimum of nine determinations over at least three concentration levels covering the specified range (e.g., three concentrations, three replicates each) [9]. Results should be reported as the percentage recovery of the known, added amount, or as the difference between the mean and true value with confidence intervals [9].

Precision

Precision expresses the closeness of agreement between a series of measurements obtained from multiple sampling of the same homogeneous sample under the prescribed conditions [2]. Precision should be considered at three levels, as outlined in the table below.

Table 1: Levels of Precision Evaluation in Analytical Method Validation

| Precision Level | Description | Experimental Approach | Data Reporting |

|---|---|---|---|

| Repeatability | Precision under the same operating conditions over a short time interval (intra-assay precision) [2]. | A minimum of nine determinations covering the specified range (three concentrations, three repetitions) or at least six determinations at 100% of test concentration [9]. | Typically reported as % RSD (Relative Standard Deviation) [9]. |

| Intermediate Precision | Within-laboratory variations: different days, analysts, equipment, etc. [2]. | Experimental design where effects of individual variables (e.g., different analysts, instruments, days) are monitored [9]. | % RSD and statistical comparison (e.g., Student's t-test) of results under varied conditions [9]. |

| Reproducibility | Precision between laboratories (collaborative studies) [2]. | Analysis of the same samples by multiple laboratories, often for technology transfer or compendial method standardization [9]. | Standard deviation, % RSD, and confidence intervals between laboratories [9]. |

Detection Limit (LOD) and Quantitation Limit (LOQ)

- Detection Limit (LOD): The lowest amount of analyte in a sample that can be detected but not necessarily quantitated as an exact value [2].

- Quantitation Limit (LOQ): The lowest amount of analyte in a sample that can be quantitatively determined with suitable precision and accuracy [2]. This parameter is particularly critical for determining impurities and degradation products.

Methodologies for Determination:

- Visual Evaluation: Can be used for non-instrumental and instrumental methods [2].

- Signal-to-Noise Ratio: Typically 3:1 for LOD and 10:1 for LOQ in chromatographic methods [9].

- Standard Deviation of Response and Slope: Based on the formula: LOD = 3.3(SD/S) and LOQ = 10(SD/S), where SD is the standard deviation of response and S is the slope of the calibration curve [9].

Linearity and Range

- Linearity: The ability of the method to obtain test results that are directly proportional to the concentration (amount) of analyte in the sample within a given range [2].

- Range: The interval between the upper and lower concentrations of analyte (inclusive) that have been demonstrated to be determined with acceptable precision, accuracy, and linearity using the method as written [9].

Methodology: Linearity is typically demonstrated using a minimum of five concentration levels across the specified range [9]. Data should be reported with the equation for the calibration curve line, the coefficient of determination (r²), residuals, and the calibration curve itself [9].

Robustness

Robustness measures the capacity of a method to remain unaffected by small, deliberate variations in method parameters (e.g., pH, mobile phase composition, temperature, flow rate) and provides an indication of its reliability during normal usage [9] [11].

Methodology: Robustness is evaluated by deliberately introducing small changes to method parameters and monitoring the resulting effect on the method's performance [9]. The experimental design should identify critical parameters that may require tight control in the method instructions to ensure reproducibility [9].

The following workflow diagram illustrates the strategic process and key decision points in analytical method validation according to regulatory standards:

Experimental Protocols for Key Validation Parameters

Protocol for Accuracy Assessment

Objective: To demonstrate that the analytical method provides results that are close to the true value.

Materials and Reagents:

- Reference standard of known purity

- Placebo formulation (excluding active ingredient)

- Appropriate solvents and reagents as per method

Procedure:

- Prepare a minimum of nine samples over three concentration levels (e.g., 80%, 100%, 120% of target concentration) with three replicates at each level.

- For drug substance, compare results against a certified reference standard.

- For drug product, prepare samples by spiking placebo with known quantities of the active ingredient.

- Analyze all samples using the analytical method under validation.

- Calculate the percentage recovery for each sample using the formula: Recovery (%) = (Measured Concentration / Theoretical Concentration) × 100.

Acceptance Criteria: The mean recovery should be within specified limits (e.g., 98-102% for drug substance, 97-103% for drug product) with appropriate precision (%RSD) [9].

Protocol for Precision Evaluation

Objective: To demonstrate the degree of scatter in results under prescribed conditions.

Materials and Reagents:

- Homogeneous sample of drug substance or product

- Reference standard

- Appropriate solvents and reagents

Procedure for Repeatability:

- Prepare six independent sample preparations at 100% of test concentration.

- Analyze all six preparations under the same operating conditions.

- Calculate the mean, standard deviation, and %RSD of the results.

Procedure for Intermediate Precision:

- Perform the analysis on different days, with different analysts, or using different instruments.

- Follow the same procedure as for repeatability but under varied conditions.

- Analyze a minimum of three concentration levels with three replicates each.

- Compare results from both sets of data using statistical tests (e.g., Student's t-test).

Acceptance Criteria: %RSD for repeatability should typically be ≤ 2% for assay of drug substance, and ≤ 3% for drug product. Results from intermediate precision should show no significant difference between operators or instruments [9].

Protocol for Linearity and Range Determination

Objective: To establish that the method provides results proportional to analyte concentration.

Materials and Reagents:

- Reference standard

- Appropriate solvents and reagents

Procedure:

- Prepare a minimum of five standard solutions covering the specified range (e.g., 50%, 75%, 100%, 125%, 150% of target concentration).

- Analyze each concentration in triplicate.

- Plot the mean response against concentration.

- Perform linear regression analysis to calculate the correlation coefficient, y-intercept, and slope of the line.

Acceptance Criteria: The correlation coefficient (r) should typically be ≥ 0.999 for assay methods. The y-intercept should not be significantly different from zero, and the residuals should be randomly distributed [9].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Materials and Reagents

Successful analytical method validation requires specific, high-quality materials and reagents. The following table details essential components of the validation toolkit.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagent Solutions and Materials for Analytical Method Validation

| Material/Reagent | Function and Importance in Validation | Key Quality Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Reference Standards | Certified reference materials of known purity and identity serve as the benchmark for accuracy determination [9]. | Must be of certified purity and properly characterized; traceable to national or international standards. |

| Chromatographic Columns | Essential for separation-based methods (HPLC, GC); critical for achieving specificity and resolution [10]. | Multiple columns from different lots should be tested to demonstrate robustness and column-to-column reproducibility. |

| High-Purity Solvents & Reagents | Used for preparation of mobile phases, standard and sample solutions; impurities can interfere with analysis [10]. | HPLC or LC-MS grade solvents minimize background noise and interference, especially important for LOD/LOQ determination. |

| Mass Spectrometry Reference Compounds | For mass-dependent detectors; used for calibration and ensuring accurate mass measurement [9]. | Should be appropriate for the mass range being analyzed and compatible with the ionization technique used. |

| System Suitability Standards | Specific test mixtures used to verify that the total analytical system is adequate for the intended analysis [9]. | Must contain components that test critical method parameters (resolution, efficiency, tailing). |

| Placebo Formulation | For drug product methods; used in accuracy studies to assess interference from excipients [9]. | Should contain all formulation components except the active ingredient, representing the complete sample matrix. |

Critical Importance in Pharmaceutical Development

Analytical procedure validation plays an indispensable role in ensuring pharmaceutical product quality, safety, and efficacy through several critical dimensions:

Ensuring Regulatory Compliance and Product Quality

Validation is a mandatory requirement for regulatory submissions such as New Drug Applications (NDAs) and Abbreviated New Drug Applications (ANDAs) [11]. Regulatory bodies including the FDA, European Medicines Agency (EMA), and other global authorities require comprehensive validation data to support the identity, potency, quality, and purity of pharmaceutical substances and products [10] [11]. Without proper validation, regulatory submissions face substantial delays or rejection, potentially preventing products from reaching the market [10].

The process provides documented evidence that analytical methods can consistently generate reliable data for critical quality decisions, including batch release, stability studies, and shelf-life determination [7] [9]. This documented evidence is essential during regulatory inspections and audits, demonstrating a commitment to quality and compliance [6].

Protecting Patient Safety

Perhaps the most crucial aspect of analytical procedure validation is its role in safeguarding patient health [10]. Validated methods ensure that:

- Drugs contain the correct amount of active ingredient, ensuring proper dosing and therapeutic efficacy [7].

- Impurities and degradation products are properly identified and controlled within safe limits [2].

- Products maintain their identity, purity, and quality throughout their shelf life [7].

The thorough assessment of specificity, accuracy, and precision provides assurance that analytical results truly reflect the quality attributes of the product, preventing the release of substandard or potentially harmful medications to the market [10].

Supporting Robust Quality Control Systems

Well-validated analytical methods form the foundation of effective quality control systems in pharmaceutical manufacturing [10]. They provide the necessary tools for:

- Raw Material Testing: Ensuring the quality of incoming materials before they enter the manufacturing process [7].

- In-Process Controls: Monitoring critical parameters during manufacturing to ensure process consistency [7].

- Finished Product Testing: Verifying that the final product meets all established specifications before release [7].

- Stability Studies: Monitoring product quality over time to establish appropriate storage conditions and expiration dates [12].

The robustness evaluation within validation ensures that methods remain reliable despite minor variations in laboratory conditions, equipment, or analysts, contributing to the overall robustness of the quality control system [9].

Analytical procedure validation stands as a cornerstone practice in pharmaceutical development and manufacturing, providing the critical evidence that analytical methods are fit for their intended purpose. The ICH Q2(R1) guideline, while recently complemented by updated standards, continues to provide the fundamental framework for demonstrating method suitability through the assessment of specificity, accuracy, precision, and other key parameters.

The critical importance of validation extends far beyond mere regulatory compliance, serving as an essential safeguard for patient safety and a fundamental component of effective pharmaceutical quality systems. As the industry continues to evolve with increasingly complex molecules and advanced analytical technologies, the principles of method validation remain constant in their purpose: to ensure that analytical data driving critical quality decisions are reliable, accurate, and reproducible.

The ongoing evolution toward a lifecycle approach with ICH Q2(R2) and Q14 further strengthens this foundation, emphasizing that method quality is built through systematic development, thorough validation, and continuous monitoring throughout the method's operational life. For researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, understanding and implementing these validation principles remains non-negotiable for ensuring product quality and, ultimately, patient safety.

In the pharmaceutical industry, the validation of analytical procedures is a fundamental regulatory requirement to ensure the quality, safety, and efficacy of drug substances and products. The International Council for Harmonisation (ICH) Q2(R1) guideline, titled "Validation of Analytical Procedures: Text and Methodology," serves as the primary global standard for this critical activity [11]. It provides a harmonized framework for validating analytical methods, ensuring that data generated are reliable and reproducible for regulatory submissions and quality control [3] [7].

Analytical method validation provides documented evidence that a specific analytical procedure is suitable for its intended use, consistently producing results that accurately reflect the quality of the material being tested [13] [7]. According to ICH Q2(R1), analytical procedures are predominantly categorized into three major types, each addressing a fundamental aspect of pharmaceutical quality as defined by the identity, purity, and content of a medicinal product [14]. This article provides an in-depth technical guide to these three core types—identification tests, impurity tests, and assays—detailing their purposes, validation requirements, and practical methodologies within the framework of ICH Q2(R1).

The Three Primary Analytical Procedure Categories

The three categories of analytical procedures directly correspond to the core tenets of pharmaceutical quality as outlined in the definition of the German Medicines Act (AMG) and other international regulations: identity, purity, and content [14]. Simply put, they answer the following critical questions:

- Does it contain what is declared? (Identity)

- Does it exclusively contain what is declared? (Purity)

- Does it contain as much as is declared? (Content) [14]

The table below summarizes the key characteristics of these analytical procedure categories.

Table 1: Overview of Primary Analytical Procedure Categories per ICH Q2(R1)

| Procedure Category | Primary Objective | Key Validation Parameters* | Example Techniques |

|---|---|---|---|

| Identification Tests | To verify the identity of an analyte in a sample [14]. | Specificity [14] [13] | Color reactions, FTIR, Peptide Mapping, PCR [14] |

| Impurity Tests | To detect and quantify or limit impurities and degradation products [14]. | Specificity, Accuracy, Precision (Quantitative); Specificity, LOD, LOQ (Limit Test) [13] | HPLC, GC, Limit tests for arsenic or residual solvents [14] [13] |

| Assays | To quantify the analyte or measure its potency in a sample [14]. | Specificity, Linearity, Accuracy, Precision [14] [13] | HPLC/UV-Vis Assay, Bioassays, Potency Tests [14] |

*Note: This list includes the most critical parameters; other parameters may be required based on the specific procedure [13].

Identification Tests

Purpose and Principle

Identification tests are performed to confirm the identity of an active pharmaceutical ingredient (API) or other analyte in a given sample [14]. This is a fundamental regulatory requirement to prove that a drug product contains the correct substance claimed to have healing properties [14]. The core principle involves comparing a property of the analyte in the sample to that of a authenticated reference standard [14].

Key Validation Parameter: Specificity

The paramount validation parameter for an identification test is specificity (sometimes referred to as selectivity) [14] [13]. The method must demonstrate its ability to unequivocally discriminate between the analyte of interest and other closely related substances that might be present, such as impurities, degradation products, or excipients [14] [13]. A non-specific method can lead to false positives or negatives, compromising patient safety and product efficacy.

Experimental Protocols and Techniques

The choice of technique depends on the complexity of the molecule and the required level of discrimination.

- For Small Molecules: Techniques like color reactions (as listed in pharmacopoeias), Fourier-Transform Infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy, or melting point determination are commonly used due to their simplicity and speed [14].

- For Biologics: More sophisticated techniques are necessary. Peptide mapping provides a unique "fingerprint" for a protein based on its specific cleavage pattern [14]. Capillary isoelectric focusing (cIEF) can identify a known monoclonal antibody charge variant among a pool of others [14]. Techniques like Western Blotting or immunofluorescence use specific antibodies to bind and identify target proteins or viruses [14]. Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR) is a highly specific identity test for nucleic acid-containing pharmaceuticals, as specific primers amplify only a defined gene sequence unique to the target [14].

Impurity Tests

Purpose and Principle

Impurity tests are designed to establish the purity profile of a drug substance or product by detecting, and often quantifying, impurities and degradation products [14]. The objective is to demonstrate that all impurities are controlled below levels considered safe for the patient [14]. These procedures can be either quantitative, providing a precise measurement of impurity content, or limit tests, which simply demonstrate that an impurity is below a specified acceptable threshold [14].

Key Validation Parameters

The validation parameters required depend on whether the test is quantitative or a limit test.

- For Quantitative Impurity Tests: Key parameters include specificity (to ensure separation from the main analyte and other impurities), accuracy (to ensure the measured value is close to the true amount), precision, LOQ (the lowest level that can be accurately quantified), and linearity across the expected range [14] [13].

- For Limit Tests: The focus is on specificity and the LOD (the lowest level at which the impurity can be detected) [14] [13].

Experimental Protocols and Techniques

- Quantitative Tests: Chromatographic techniques like High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC) are the gold standard for quantifying impurities. The method is validated to ensure it can resolve and accurately measure known and potential unknown impurities.

- Limit Tests: These are often used for common, potentially toxic contaminants. Examples include colorimetric or photometric methods that show a visible color change when the impurity concentration exceeds the limit [14]. Pharmacopoeias such as the European Pharmacopoeia (Ph. Eur.) include limit tests for substances like methanol, formaldehyde, and arsenic [14].

Assays

Purpose and Principle

Assays are analytical procedures used for the quantification of the major analyte in a sample [14]. This category can be divided into two main aspects:

- Content Determination: Measures the amount of the active pharmaceutical ingredient present in the drug product [14].

- Potency Testing: Measures the biological or functional activity of the API, which is critical for complex molecules like biologics where the amount does not directly correlate with therapeutic effect [14].

Key Validation Parameters

For a typical content assay, the key validation parameters as per ICH Q2(R1) include specificity, linearity, accuracy, and precision [14] [13]. The method must be proven to accurately and reproducibly measure the analyte across the specified range without interference.

Experimental Protocols and Techniques

- Content Assays: Techniques like HPLC with UV-Vis detection are widely used for small molecules [14]. For proteins, a simple UV absorption measurement at 280 nm is often sufficient for content determination [14].

- Potency Assays (Bioassays): These are essential for biologics. They are often cell-based or biochemical assays that measure a specific biological response. An example is a clot lysis assay for tissue plasminogen activator (tPA), which directly measures the enzyme's functional activity [14]. For live viral vaccines, a plaque-forming unit (PFU) virus titration is used, which quantifies the amount of infectious virus, thereby reflecting its potency [14].

It is important to note that a single method may lack full specificity. The ICH Q2(R2) guideline notes that a lack of specificity in one procedure (e.g., a PFU assay that cannot distinguish between virus strains) can be compensated by other supporting procedures (e.g., a specific identification test using antibodies) [14].

The Method Validation Lifecycle and Experimental Protocols

The following diagram illustrates the interconnected stages of the analytical procedure lifecycle, from initial design through to ongoing performance verification, as informed by modern regulatory thinking [15].

Core Validation Parameters and Protocols

The validation process involves conducting specific experiments to demonstrate that the analytical procedure meets predefined acceptance criteria for a set of core performance characteristics [11] [13]. The parameters required depend on the type of analytical procedure, as summarized in the table below.

Table 2: Validation Parameters for Different Analytical Procedure Types (based on ICH Q2(R1))

| Validation Parameter | Definition | Identification | Impurity Test (Quantitative) | Assay (Content) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Accuracy | Closeness of results to the true value [13]. | - | Yes [13] | Yes [13] |

| Precision (Repeatability, Intermediate Precision) | Closeness of repeated individual measurements [13]. | - | Yes [13] | Yes [13] |

| Specificity | Ability to assess analyte unequivocally in the presence of potential interferents [13]. | Yes [14] [13] | Yes [13] | Yes [13] |

| Linearity | Ability to obtain results proportional to analyte concentration [13]. | - | Yes [13] | Yes [13] |

| Range | Interval between upper and lower analyte levels demonstrating suitability [13]. | - | Yes [13] | Yes [13] |

| LOD | Lowest amount of analyte that can be detected [13]. | - | Yes [13] | - |

| LOQ | Lowest amount of analyte that can be quantified [13]. | - | Yes [13] | - |

Accuracy

- Protocol: Accuracy is typically established by analyzing a sample of known concentration (e.g., a reference standard) and calculating the percent recovery of the measured value. Alternatively, the method of standard addition ("spiking") is used, where a placebo is spiked with a known, precise amount of the analyte, and the recovery is calculated [13]. This should be performed across the specified range of the procedure, often at a minimum of three concentration levels with multiple replicates each [13].

Precision

Precision has three tiers:

- Repeatability (Intra-assay Precision): Assesses precision under the same operating conditions over a short time interval. Protocol: A minimum of nine determinations covering the specified range (e.g., three concentrations/three replicates each) or a minimum of six determinations at 100% of the test concentration [13].

- Intermediate Precision: Expresses within-laboratory variations (e.g., different days, different analysts, different equipment) [13].

- Reproducibility: Expresses precision between laboratories, often assessed during method transfer [13]. Precision is measured by the scatter of individual results and expressed as the relative standard deviation (RSD) [13].

Specificity

- Protocol: For chromatographic assays, specificity is demonstrated by injecting samples containing potential interferents (impurities, degradation products forced through stress studies, excipients) and showing that the analyte peak is pure and unaffected (e.g., with peak purity tools) and that interferents are baseline separated [13].

Linearity and Range

- Protocol: Linearity is assessed by preparing a series of samples where the analyte concentration spans the claimed range of the procedure. A minimum of five concentrations is recommended [13]. The data is evaluated by appropriate statistical methods, such as linear regression analysis, and the correlation coefficient, y-intercept, and slope of the regression line are reported [13]. The range is derived from these linearity studies [13].

Essential Research Reagents and Materials

The integrity of analytical method validation is contingent upon the quality of the materials used. The following table details key reagent solutions and their critical functions.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Analytical Method Validation

| Reagent / Material | Function and Importance in Validation |

|---|---|

| Reference Standard | An authenticated substance of known purity and identity used as a benchmark for all quantitative and qualitative measurements (e.g., for calibration, identification, potency tests) [14]. |

| Placebo Formulation | A mixture of all excipients without the active ingredient. Critical for specificity testing and for accuracy studies via the standard addition (spiking) method [13]. |

| System Suitability Test (SST) Solutions | Specific mixtures containing the analyte and key impurities used to verify that the chromatographic system (or other instrumentation) is performing adequately at the time of the test [13]. |

| Forced Degradation Samples | Samples of the drug substance and product that have been intentionally stressed under various conditions (e.g., heat, light, acid, base, oxidation). Used to demonstrate the stability-indicating properties and specificity of the method [13]. |

| Certified Mobile Phases and Reagents | High-purity solvents, buffers, and other chemical reagents are essential for achieving the required specificity, sensitivity (LOD/LOQ), and robustness, as variations can significantly impact method performance [13]. |

Within the rigorous framework of ICH Q2(R1), the categorization of analytical procedures into identification, impurity testing, and assays forms the bedrock of pharmaceutical quality control. Each category serves a distinct and vital purpose in verifying the identity, purity, and strength of a drug product, thereby directly ensuring patient safety and product efficacy. A thorough understanding of the specific validation parameters required for each procedure type, coupled with the execution of robust experimental protocols, is non-negotiable for regulatory compliance. As the industry evolves, the principles outlined in ICH Q2(R1) continue to provide a stable foundation, even as newer guidelines like ICH Q2(R2) and ICH Q14 introduce enhanced, lifecycle-based approaches for analytical procedures [11] [6]. For researchers and drug development professionals, mastering these core analytical procedure types is an essential competency for successfully bringing safe and effective medicines to market.

In the highly regulated pharmaceutical landscape, demonstrating that an analytical method is suitable for its intended purpose is not merely a best practice—it is a fundamental regulatory requirement. This process, formally known as analytical method validation, provides documented evidence that the method consistently produces reliable, accurate, and reproducible results that are fit for their intended use in supporting the identity, strength, quality, purity, and potency of drug substances and products [16] [17]. The International Council for Harmonisation (ICH) guideline Q2(R1), "Validation of Analytical Procedures," serves as the internationally recognized standard for this critical activity, outlining the scientific framework and specific performance parameters that must be evaluated [6] [18]. Validation confirms that a method's performance characteristics meet the requirements for its analytical application, thereby providing assurance of reliability during normal use and forming the foundation of quality in the analytical laboratory [17].

The importance of this demonstration cannot be overstated. A flawed or unsuitable analytical method can lead to questionable results, potentially compromising patient safety, leading to costly product recalls, and causing significant delays in regulatory approval [16]. For researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, a thorough understanding and execution of method validation according to ICH Q2(R1) is therefore indispensable. It is the crucial link between raw laboratory data and evidence-based, regulatory-ready decisions, ensuring that every test result generated can be trusted to reflect the true quality of the pharmaceutical product.

Core Principles of ICH Q2(R1) Method Validation

The ICH Q2(R1) guideline establishes a comprehensive framework for validating analytical methods. Its core principle is that the validation effort must be commensurate with the method's purpose and the stage of product development [16]. The guideline systematically categorizes the validation requirements based on the type of analytical procedure (e.g., identification, impurity testing, or assay), and defines the key performance parameters that must be evaluated to prove a method's suitability [18].

Distinguishing Validation from Verification and Qualification

A critical first step is understanding the distinction between validation, verification, and qualification, as these terms are often misused. Each serves a distinct purpose within the pharmaceutical quality system:

- Validation: A formal, comprehensive process that demonstrates a method's suitability for its intended use through extensive laboratory studies. It is typically required for methods used in the routine quality control testing of drug substances, raw materials, or finished products for release and stability testing [16].

- Verification: A more limited process performed to confirm that a previously validated method works as expected in a new laboratory setting, with its specific analysts, equipment, and environmental conditions. This is often applicable when adopting a compendial method (e.g., from the USP) [16].

- Qualification: An early-stage evaluation of an analytical method's performance, often used during early development phases (preclinical or Phase I). It provides preliminary data showing the method is likely reliable before committing to a full validation [16].

For the purposes of this guide, the focus is on the full validation required for methods supporting commercial products and critical decision-making.

The Validation Lifecycle and Regulatory Context

Method validation is not an isolated event but part of a broader validation lifecycle. This lifecycle begins with qualified instrumentation and validated software, proceeds through method development and validation, and is maintained through system suitability tests and ongoing performance verification [17]. Regulatory authorities, including the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and the European Medicines Agency (EMA), require full validation for methods that support decision-making for the finished product, and they expect compliance with guidelines such as ICH Q2(R1) [16] [6]. Furthermore, the recent introduction of ICH Q14 on Analytical Procedure Development and the update of ICH Q2(R1) to Q2(R2) emphasize a more structured, lifecycle approach, incorporating Quality by Design (QbD) principles and continuous validation processes [6].

Key Validation Parameters and Experimental Protocols

The demonstration of method suitability is achieved through the experimental assessment of specific performance characteristics. The following sections detail the key validation parameters outlined in ICH Q2(R1), their definitions, and the standard experimental protocols for their determination.

Specificity

Definition: Specificity is the ability of the method to assess the analyte unequivocally in the presence of components that may be expected to be present, such as impurities, degradation products, and matrix components [18].

Experimental Protocol:

- Analyze Blank and Placebo: Inject the sample matrix or formulation placebo without the analyte to demonstrate the absence of interfering signals at the retention time of the analyte and other critical peaks.

- Analyze Spiked Samples: Spike the placebo or matrix with the analyte at the target concentration to confirm that the response is due solely to the analyte.

- Stress Testing (Forced Degradation): Subject the sample to stress conditions (e.g., acid/base, oxidative, thermal, photolytic) to generate degradation products. Analyze the stressed sample to demonstrate that the analyte peak is pure and resolved from degradation peaks, and that the method can detect the degradants. This is often assessed using a diode array detector (DAD) to check for peak purity [18].

Accuracy

Definition: Accuracy expresses the closeness of agreement between the value found and the value accepted as a true or reference value. It is typically reported as percent recovery [18].

Experimental Protocol:

- Prepare a reference standard of the analyte with known, high purity.

- Spike the placebo or matrix with the analyte at a minimum of three concentration levels covering the specified range (e.g., 80%, 100%, 120% of the target concentration).

- Perform a minimum of nine determinations (e.g., three replicates at each of the three levels).

- Calculate the percent recovery for each measurement and determine the mean recovery across all levels. Acceptance criteria are typically 98-102% for assay methods [18].

Precision

Definition: Precision expresses the closeness of agreement between a series of measurements obtained from multiple sampling of the same homogeneous sample under prescribed conditions. It is considered at three levels: repeatability, intermediate precision, and reproducibility [18].

Experimental Protocol:

- Repeatability (Intra-assay Precision):

- Assay a minimum of six independent preparations of a homogeneous sample at 100% of the test concentration.

- Calculate the relative standard deviation (RSD). Acceptance criteria for assay methods are typically an RSD of less than 2% [18].

- Intermediate Precision:

- Demonstrate the method's reliability under variations within the same laboratory.

- Perform the analysis on different days, with different analysts, and using different equipment.

- Compare the results from both sets of data; no significant variation should be observed.

- Reproducibility: Reproducibility is assessed when method transfer occurs between laboratories, such as during a collaborative study [18].

Detection Limit (LOD) and Quantitation Limit (LOQ)

Definitions:

- LOD: The lowest concentration of an analyte that can be detected, but not necessarily quantified, under the stated experimental conditions.

- LOQ: The lowest concentration of an analyte that can be quantified with acceptable accuracy and precision [18].

Experimental Protocol (Calculation Methods):

- Signal-to-Noise Ratio: Typically applied to chromatographic methods. A ratio of 3:1 is generally accepted for LOD, and 10:1 for LOQ [18].

- Standard Deviation of the Response and Slope:

- LOD can be calculated as (3.3 \times \sigma / S), where (\sigma) is the standard deviation of the response (y-intercept) and (S) is the slope of the calibration curve.

- LOQ can be calculated as (10 \times \sigma / S) [18].

Linearity and Range

Definitions:

- Linearity: The ability of the method to obtain test results that are directly proportional to the concentration of the analyte within a given range.

- Range: The interval between the upper and lower concentrations of analyte for which it has been demonstrated that the method has suitable levels of accuracy, precision, and linearity [18].

Experimental Protocol:

- Prepare a minimum of five concentrations spanning the intended range (e.g., 50%, 75%, 100%, 125%, 150%).

- Analyze each concentration in triplicate.

- Plot the response versus the concentration and perform linear regression analysis.

- The correlation coefficient (r) should be not less than 0.995. The y-intercept should be not significantly different from zero, and the residuals should be randomly scattered [18].

Robustness

Definition: The robustness of a method is a measure of its capacity to remain unaffected by small, deliberate variations in method parameters, and provides an indication of its reliability during normal usage [18].

Experimental Protocol:

- Deliberately introduce small changes to critical method parameters. For an HPLC method, this could include:

- Variations in mobile phase pH (±0.2 units)

- Variations in column temperature (±5°C)

- Variations in flow rate (±10%)

- Different columns (from different lots or suppliers)

- Analyze a standard and a sample under each varied condition.

- Evaluate the impact on critical results such as resolution, tailing factor, and assay value. The method should perform acceptably under all tested conditions.

The table below summarizes the key validation parameters, their experimental objectives, and typical acceptance criteria for a quantitative assay method, providing a clear overview for protocol design and reporting.

Table 1: Summary of Key ICH Q2(R1) Validation Parameters and Criteria

| Validation Parameter | Objective | Typical Experimental Approach | Typical Acceptance Criteria (for Assay) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Specificity | To prove the method measures only the analyte. | Compare blank, placebo, and analyte; perform forced degradation studies. | No interference from placebo, impurities, or degradants at the analyte retention time. Peak purity confirmed. |

| Accuracy | To determine the closeness to the true value. | Spike and recover analyte from placebo/matrix at 3 levels with 9 determinations. | Mean recovery of 98–102% [18]. |

| Precision | To determine the degree of scatter in the data. | Analyze 6 samples at 100% test concentration. | RSD < 2% for repeatability [18]. |

| Linearity | To demonstrate proportional response to concentration. | Analyze a minimum of 5 concentrations across the range. | Correlation coefficient (r) ≥ 0.995 [18]. |

| Range | To confirm accuracy, precision, and linearity across the operating range. | The interval from the LOQ to 120% of the test concentration for assay. | Meets accuracy and precision criteria across the specified range [18]. |

| LOD | To determine the lowest detectable amount. | Signal-to-Noise ratio or based on standard deviation of the response and the slope. | Signal-to-Noise ratio ~ 3:1 [18]. |

| LOQ | To determine the lowest quantifiable amount with accuracy and precision. | Signal-to-Noise ratio or based on standard deviation of the response and the slope. | Signal-to-Noise ratio ~ 10:1. At LOQ, accuracy and precision should be demonstrated [18]. |

| Robustness | To assess the method's resistance to deliberate parameter changes. | Vary critical parameters (pH, temperature, flow rate, column). | System suitability criteria are met; no significant impact on results. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

The successful execution of validation protocols relies on the use of high-quality, well-characterized materials. The following table details key reagents and their critical functions in ensuring the integrity of the validation study.

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Method Validation

| Reagent / Material | Function in Validation |

|---|---|

| Reference Standard | A substance of established quality, purity, and identity used as a benchmark for assessing the performance of the analytical method and for quantifying the analyte [18]. |

| High-Purity Solvents | Used for preparation of mobile phases, sample solutions, and standards. Purity is critical to prevent baseline noise, ghost peaks, or unintended chemical interactions. |

| Placebo / Blank Matrix | The formulation or biological matrix without the active analyte. It is essential for demonstrating specificity by proving the absence of interfering signals and for conducting accuracy (recovery) studies [18]. |

| Characterized Impurities and Degradation Products | Isolated and identified impurities and forced degradation products are used to challenge the method's specificity, ensuring it can separate and resolve the analyte from other related substances. |

| System Suitability Test Solutions | A stable, well-characterized mixture of the analyte and critical impurities, or a standard, used to verify that the chromatographic system is adequate for the intended analysis before and during the validation runs [17] [18]. |

Method Validation Workflow and Relationship Diagram

The following diagram illustrates the logical sequence and relationships between the core activities in the analytical method validation lifecycle, from initial preparation through to ongoing verification.

Analytical Method Validation Workflow

Demonstrating that an analytical method is suitable for its intended purpose through rigorous validation, as dictated by the core principles of ICH Q2(R1), is a non-negotiable pillar of pharmaceutical development and quality control. It is a deliberate, science-based process that transforms a laboratory procedure from a theoretical concept into a trusted tool for critical decision-making. By systematically evaluating the parameters of specificity, accuracy, precision, and the others outlined herein, scientists generate the documented evidence required by regulators and, more importantly, build the confidence that their methods will reliably safeguard patient health. As the industry evolves with the adoption of ICH Q14 and Q2(R2), the principles of a structured, lifecycle approach and enhanced method development will further strengthen this foundation, ensuring that analytical methods continue to meet the challenges of modern, complex therapeutics [6].

In the global pharmaceutical industry, the validation of analytical methods is a regulatory imperative to ensure the safety, quality, and efficacy of drug products. The International Council for Harmonisation (ICH) Q2(R1) guideline, titled "Validation of Analytical Procedures: Text and Methodology," provides the foundational scientific framework for this process. Its adoption and interpretation by regulatory agencies worldwide, particularly the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA), form a complex landscape that researchers and drug development professionals must navigate. This guide examines the precise relationship between the ICH Q2(R1) standard and FDA regulations, detailing how this global guideline is implemented under U.S. regulatory oversight and providing explicit experimental protocols for compliance.

The ICH Q2(R1) and FDA Regulatory Nexus

The ICH Q2(R1) guideline establishes the core validation parameters and methodologies accepted by its member regions, including the United States, the European Union, and Japan. The FDA integrates this guideline directly into its regulatory expectations for drug applications. While ICH Q2(R1) provides the scientific and methodological basis, the FDA enforces it through its own guidance documents and inspectional activities. A critical understanding for any applicant is that the FDA views method validation not as a one-time event but as an activity spanning the entire method lifecycle, from initial development and validation to ongoing verification and monitoring during the product's market life [19] [20].

For instance, the FDA's own guidance documents, such as those for specific product categories like tobacco products, reinforce the need for fully validated and verified analytical test methods in application submissions, which is fully consistent with the principles of ICH Q2(R1) [21]. The selection of the appropriate validation guideline is not arbitrary; it is determined by the product's target market. Using a guideline misaligned with the regulatory region, such as submitting data based solely on EMA expectations to the FDA, can result in rejected applications, costly revalidation, and significant product launch delays [19].

Table 1: Core Regulatory Bodies and Their Guidance Alignment with ICH Q2(R1)

| Regulatory Body | Regional Focus | Primary Guidance | Key Emphasis in Validation |

|---|---|---|---|

| FDA | United States | ICH Q2(R1) and supporting FDA-specific guidances | Lifecycle validation, risk management, data integrity for regulatory submissions [21] [19]. |

| EMA | European Union | ICH Q2(R1) | Scientific rigor, compliance with EU regulatory directives. |

| PMDA | Japan | ICH Q2(R1) | Alignment with Japanese Pharmacopoeia and national standards. |

The following diagram illustrates the interconnected regulatory and scientific workflow for method validation, from foundational guidelines to ongoing process control.

Structured Comparison of Validation Parameters

Adherence to ICH Q2(R1) requires the systematic testing of specific analytical performance parameters. The following tables provide a structured overview of these core parameters and the standard experimental protocols for assessing them, offering a clear, comparable format essential for laboratory execution and regulatory documentation.

Table 2: Core Validation Parameters as Defined by ICH Q2(R1) and Regulatory Expectations

| Validation Parameter | ICH Q2(R1) Definition | Regulatory Purpose & Objective |

|---|---|---|

| Accuracy | The closeness of agreement between a conventionally accepted true value and the value found. | To demonstrate that the method provides results that are unbiased and reflect the true value of the analyte, crucial for patient safety and dosing. |

| Precision (Repeatability & Intermediate Precision) | The closeness of agreement between a series of measurements. | To ensure the method produces consistent results under normal operating conditions, across different days, analysts, and equipment. |

| Specificity | The ability to assess the analyte unequivocally in the presence of components that may be expected to be present. | To prove the method can distinguish and quantify the analyte from impurities, degradants, or matrix components. |

| Linearity | The ability of the method to obtain test results proportional to the concentration of the analyte. | To establish that the method's response is directly proportional to analyte concentration across a specified range. |

| Range | The interval between the upper and lower concentrations of analyte for which it has been demonstrated that the method has suitable precision, accuracy, and linearity. | To define the concentrations over which the method is fit for purpose, ensuring it covers all intended applications. |

| Robustness | A measure of the method's capacity to remain unaffected by small, deliberate variations in method parameters. | To identify critical method parameters and ensure reliability during routine use, such as in different laboratories. |

Table 3: Standard Experimental Protocols for Key Validation Parameters

| Parameter | Recommended Experimental Methodology | Typical Acceptance Criteria |

|---|---|---|

| Accuracy | Analyze a minimum of 9 determinations across a minimum of 3 concentration levels (e.g., 80%, 100%, 120% of target) in the presence of the sample matrix. Report % recovery of the known added amount or comparison to a reference method. | Mean Recovery: 98.0% - 102.0% RSD < 2.0% |

| Precision (Repeatability) | Perform a minimum of 6 independent preparations at 100% of the test concentration and analyze under the same operating conditions over a short interval of time. | RSD ≤ 1.0% for drug substance; RSD ≤ 2.0% for drug product (varies by product) |

| Linearity | Prepare and analyze a minimum of 5 concentration levels (e.g., 50%, 75%, 100%, 125%, 150% of target). Plot response vs. concentration and calculate regression statistics (slope, intercept, correlation coefficient). | Correlation Coefficient (r) ≥ 0.999 |

| Robustness | Deliberately vary method parameters (e.g., column temperature ±2°C, flow rate ±10%, mobile phase pH ±0.2 units) in a systematic, pre-planned design (e.g., Design of Experiments). Evaluate impact on system suitability criteria. | All results meet system suitability requirements; resolution of critical pairs > 2.0. |

Advanced Monitoring: Statistical Process Control (SPC) in the Method Lifecycle

The FDA's lifecycle approach to method validation necessitates robust ongoing monitoring strategies post-approval. Statistical Process Control (SPC) is a powerful methodology for this purpose, enabling scientists to monitor a method's performance over time and distinguish between inherent, common-cause variation and assignable, special-cause variation that requires investigation [22] [20].

SPC is most effectively implemented using control charts, which are graphical tools that plot process data (e.g., results from system suitability tests or quality control standards) against statistically derived control limits. The most common charts for continuous data in the laboratory are the Individual Moving Range (I-MR) chart and the X-bar & R chart [20]. Decision rules, such as the Western Electric Rules, are applied to these charts to detect non-random patterns that indicate a process may be going out of control. These rules include a single point outside the 3-sigma control limits, or two out of three consecutive points beyond the 2-sigma warning limits [20].

Table 4: Essential Research Reagent Solutions and Materials for Method Validation

| Item / Reagent Solution | Critical Function in Validation Experiments |

|---|---|

| Reference Standard (High-Purity) | Serves as the benchmark for quantifying the analyte; its certified purity and stability are foundational for accuracy, linearity, and specificity studies. |

| System Suitability Test (SST) Solutions | A mixture of key analytes and potential interferents used to verify that the chromatographic or analytical system is performing adequately at the start of, during, and at the end of a sequence. |

| Placebo/Blank Matrix | The drug product formulation without the active ingredient; critical for demonstrating specificity by proving the absence of interference at the retention time of the analyte. |

| Forced Degradation Samples | Samples of the drug substance or product subjected to stress conditions (heat, light, acid, base, oxidation); used to validate the method's ability to separate and quantify the analyte from its degradation products (Specificity). |

| Mobile Phase/Buffer Components | High-purity solvents and salts used to create the eluent system; their quality and precise preparation are vital for robustness, reproducibility, and consistent retention times. |

The integration of SPC within a modern quality management system is visualized in the following diagram, highlighting its role in maintaining a state of control.

The ICH Q2(R1) guideline provides the indispensable technical and scientific foundation for analytical method validation. Its adoption by the FDA and other major regulatory bodies creates a harmonized, though not identical, global standard. For researchers and drug development professionals, success hinges on a dual understanding: a deep mastery of the experimental protocols defined by ICH Q2(R1) and a strategic awareness of how these protocols are applied and monitored within the FDA's rigorous, lifecycle-oriented regulatory framework. By integrating robust initial validation with data-driven monitoring tools like SPC, organizations can ensure both compliance and continuous quality assurance throughout a product's market life.

Implementing Q2(R1): A Step-by-Step Guide to Validation Parameters

Within the framework of the ICH Q2(R2) guideline on analytical procedure validation, specificity stands as a foundational parameter, critical for ensuring the reliability of identity, assay, and impurity tests methods [23]. It is the quality that demonstrates that an analytical procedure can unambiguously assess the analyte of interest when other components are present in the sample matrix. In the context of drug development, this means proving that a method can accurately measure the active pharmaceutical ingredient (API) and distinguish it from excipients, impurities, degradation products, or other potential interferents. A specific method provides confidence that the reported result is truly representative of the analyte and is not biased by the presence of other substances, thereby forming the bedrock of product quality, safety, and efficacy assessments.

This technical guide provides an in-depth exploration of specificity, detailing its regulatory context, experimental methodologies, and data interpretation strategies to equip scientists with the knowledge to robustly validate their analytical procedures.

Core Definition and Regulatory Significance

Specificity is defined as the ability to assess unequivocally the analyte in the presence of components that may be expected to be present, such as impurities, degradation products, and matrix components [9]. It takes into account the degree of interference from other active ingredients, excipients, impurities, and degradation products. For a chromatographic method, this ensures that a peak's response is due to a single component, with no peak co-elutions [9].

The significance of specificity is directly tied to the purpose of the analytical procedure:

- For Identification: Specificity must be able to discriminate between compounds of closely related structures which are likely to be present.

- For Purity Tests: The method must demonstrate that it can separate and accurately quantify all specified impurities and degradation products from the API and from each other.

- For Assay (Content/Potency): The method must be shown to be unaffected by the presence of impurities, excipients, or other matrix components.

The International Council for Harmonisation (ICH) guideline Q2(R2), which came into effect in 2023, provides the harmonized framework for validating analytical procedures for the pharmaceutical industry [23]. Compliance with this guideline is essential for regulatory submissions within ICH member regions, including the European Medicines Agency (EMA).

Experimental Design for Specificity Assessment

A well-designed specificity experiment challenges the analytical method with samples containing all potential interferents to prove its discriminatory power.

Sample Types for Specificity Challenges

To conclusively demonstrate specificity, a set of deliberately challenged samples must be analyzed and compared to a reference standard of the pure analyte.

Key Experimental Protocols

Forced Degradation Studies

Forced degradation (or stress testing) is a critical part of specificity validation for stability-indicating methods. The goal is to generate representative samples containing degradation products.

- Protocol: Separate portions of the drug substance or product are subjected to various stress conditions.

- Acidic/Basic Hydrolysis: Treat with a defined concentration (e.g., 0.1-1 M) of HCl or NaOH for a specified time and temperature (e.g., at 60°C for several hours or days).

- Oxidative Degradation: Treat with an oxidizing agent (e.g., 0.1-3% hydrogen peroxide) under controlled conditions.

- Thermal Degradation: Expose the solid drug substance or product to elevated temperatures (e.g., 70-105°C).

- Photolytic Degradation: Expose to UV and visible light as per ICH Q1B conditions.

- Analysis: The stressed samples are analyzed, and the chromatograms are examined for the formation of degradation products. The method should successfully resolve the main analyte peak from all degradation peaks. Peak purity testing (discussed in Section 4) is essential for these samples.

Resolution of Critical Pair

This test directly challenges the method's ability to separate the most difficult-to-separate components.

- Protocol: Prepare a mixture containing the analyte and a closely eluting impurity or degradation product. Alternatively, a mixture of the drug product with all known impurities can be used. The analysis should demonstrate baseline separation (Resolution, Rs > 1.5) between the analyte and this critical pair [9].

Analytical Techniques and Peak Purity Assessment

While traditional chromatography parameters are necessary, modern guidance emphasizes advanced techniques for unequivocal specificity demonstration.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Technologies

Table 1: Key Technologies for Specificity Assessment

| Technology / Reagent | Primary Function in Specificity Assessment |

|---|---|

| High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC) | The primary separation platform for resolving analytes from interferents. |

| Photodiode-Array (PDA) Detector | Collects full spectra across a peak; the primary tool for confirming peak homogeneity/purity by spectral comparison [9]. |

| Mass Spectrometry (MS) Detector | Provides unequivocal peak purity information, exact mass, and structural data; highly effective for identifying unknown degradants [9]. |

| Chemical Reference Standards | Pure substances of the analyte and known impurities used to confirm identity and retention time. |

| Stressed/Degraded Samples | Artificially generated samples containing potential interferents to challenge the method's discriminatory power. |

Peak Purity Assessment

This is a definitive test to prove that a chromatographic peak corresponds to a single chemical entity, with no hidden co-eluting compounds.

- Using a PDA Detector: Modern PDA detectors collect spectra across a range of wavelengths at every point during a peak's elution. Software algorithms then compare these spectra. A pure peak will show a high degree of spectral similarity throughout, while a peak with a co-eluting impurity will show spectral variations [9].

- Using Mass Spectrometry: MS detection is a more powerful technique for peak purity. It can detect co-eluting compounds based on differences in mass-to-charge ratio, even if they have identical UV spectra. The combination of both PDA and MS on a single instrument provides valuable orthogonal information for a comprehensive specificity assessment [9].

It is important to note the limitations of PDA-based purity testing, including a lack of UV response from potential interferents and limitations in distinguishing compounds with very similar spectra, especially at low relative concentrations [9].

Data Analysis, Acceptance Criteria, and Comparison of Methods

Key Parameters and Acceptance Criteria

The data generated from specificity experiments must be evaluated against predefined, scientifically justified acceptance criteria.

Table 2: Specificity Parameters and Typical Acceptance Criteria

| Analytical Procedure | Parameter | Typical Acceptance Criteria |

|---|---|---|

| All Procedures | Peak Purity | The peak is determined to be pure by PDA or MS (i.e., no co-elution detected) [9]. |

| Chromatographic Assay/Impurity Test | Resolution (Rs) | Baseline separation between analyte and closest eluting peak; Rs ≥ 1.5 [9]. |

| Assay (Drug Product) | Interference from Placebo | No interference (peak area < reporting threshold) from placebo at the retention time of the analyte peak. |

| Impurity Test | Separation of Impurities | All specified impurities are resolved from each other and from the main analyte. |

Comparison of Methods for Comprehensive Validation

The ICH Q2(R2) guideline emphasizes that validation should be a structured process, with specificity being one critical component among others. As outlined in the Comparison of Methods Experiment, assessing the systematic error or inaccuracy of a method is another key validation activity [24]. While specificity ensures the signal is correct, a comparison of methods (often against a well-characterized reference method) quantifies the overall systematic error.

- Purpose: To estimate inaccuracy by analyzing patient samples (or representative test samples) by both the new (test) method and a comparative method [24].