HPLC and GC-MS in Food Analysis: A Comprehensive Guide to Methods, Applications, and Optimization for Researchers

This article provides a comprehensive overview of High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC) and Gas Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (GC-MS) methodologies for the analysis of food components and contaminants.

HPLC and GC-MS in Food Analysis: A Comprehensive Guide to Methods, Applications, and Optimization for Researchers

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC) and Gas Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (GC-MS) methodologies for the analysis of food components and contaminants. Tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it covers the foundational principles of both techniques, explores their specific applications across diverse food matrices—from mycotoxins in grains to PFAS in packaged foods—and offers practical troubleshooting and optimization strategies. The content further delves into method validation protocols and a comparative analysis of HPLC versus GC-MS, empowering professionals to select and implement the most appropriate analytical technique for their specific food safety and quality research objectives.

Core Principles of HPLC and GC-MS: Building a Foundation for Food Analysis

High-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) and gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (GC-MS) represent two cornerstone analytical techniques in modern chemical analysis. HPLC is a broad analytical chemistry technique used to separate, identify, and quantify compounds in a liquid mixture using pressure-driven flow through a column packed with a stationary phase [1]. GC-MS combines two analytical tools—gas chromatography for separating volatile components and mass spectrometry for identification—to provide a powerful system for analyzing complex mixtures [2]. Within food analysis research, these techniques enable scientists to address critical challenges related to food safety, authenticity, quality control, and nutritional profiling, supporting the development of safer and higher-quality food products.

Core Principles and Instrumentation

High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC)

The fundamental principle of HPLC is the distribution of analytes between a mobile phase (liquid solvent) and a stationary phase (packing material within a column) [3]. Separation occurs as different compounds in a sample interact to varying degrees with the stationary phase, leading to different retention times as they are carried by the mobile phase through the system [1]. A typical HPLC instrument consists of four major components: a pump to deliver the mobile phase, an autosampler to inject the sample, a column for separation, and a detector to measure the compounds [1].

Separation Modes: HPLC separations are performed in two primary elution modes [1] [3]:

- Isocratic Elution: Uses a constant mobile phase composition throughout the analysis.

- Gradient Elution: Employs a changing mobile phase composition during the separation, typically by mixing two or more solvents in varying proportions.

Table 1: Key Chromatographic Parameters in HPLC

| Parameter | Symbol | Definition | Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Retention Time | tR | Time between sample injection and maximum peak signal | Compound identification |

| Delay Time | t0 | Time for non-retained compound to reach detector | System dead volume measurement |

| Peak Width | w | Width of the peak at baseline | Measure of separation efficiency |

| Tailing Factor | T | Ratio of trailing to leading peak width at 10% height (T = b/a) | Peak symmetry measurement |

Gas Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (GC-MS)

GC-MS operates by first separating chemical mixtures using gas chromatography, then identifying and quantifying the components with mass spectrometry [2]. In the GC stage, a liquid sample is vaporized and carried by an inert gas through a column where separation occurs based on volatility and polarity [4]. The separated compounds then enter the mass spectrometer, where they are ionized (typically by electron ionization), fragmented, and analyzed based on their mass-to-charge ratios (m/z) [2] [4].

Mass Spectrometry Detection: GC-MS systems employ different mass analyzer configurations [4]:

- Single Quadrupole (GC-MS): Suitable for both targeted and untargeted analysis.

- Triple Quadrupole (GC-MS/MS): Provides higher selectivity and sensitivity for targeted quantification.

- High-Resolution Accurate Mass (HRAM) Systems: Enable comprehensive sample characterization with precise mass measurement.

Comparative Operational Principles

Table 2: Comparison of HPLC and GC-MS Core Characteristics

| Characteristic | HPLC | GC-MS |

|---|---|---|

| Separation Principle | Distribution between liquid mobile phase and solid stationary phase | Partitioning between gaseous mobile phase and liquid stationary phase |

| Mobile Phase | Liquid solvents (water, acetonitrile, methanol) | Inert gas (helium, hydrogen, nitrogen) |

| Sample Requirements | Non-volatile and semi-volatile compounds; liquid samples | Volatile and thermally stable compounds; requires vaporization |

| Common Detectors | UV-Vis, fluorescence, refractive index, mass spectrometry | Mass spectrometer (quadrupole, ion trap, TOF) |

| Primary Applications in Food Analysis | Sugars, organic acids, vitamins, pigments, phenolic compounds, mycotoxins [5] | Pesticides, volatile aromas, fatty acids, environmental contaminants [4] |

Advanced Techniques and Technological Innovations

HPLC Advancements

The field of liquid chromatography continues to evolve with significant advancements in column technology and system capabilities. Recent innovations focus on improving separation efficiency, peak shape, and analytical sensitivity [6]:

- Ultra-High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (UHPLC): Utilizes smaller stationary phase particles (<2 μm) and higher operating pressures (600-1200 bar) for improved resolution, sensitivity, and faster analysis compared to standard HPLC [1].

- Advanced Column Chemistries: New stationary phases including superficially porous particles (e.g., fused-core technology) and specialized ligands (e.g., phenyl-hexyl, biphenyl) provide enhanced selectivity for challenging separations [6].

- Inert Hardware: Columns with passivated or metal-free hardware minimize analyte-surface interactions, improving recovery for metal-sensitive compounds like phosphorylated species and certain PFAS compounds [6].

GC-MS Advancements

Modern GC-MS systems have seen substantial improvements in separation power and detection capabilities:

- Comprehensive Two-Dimensional GC (GC×GC): Enhances separation power by employing two columns with different stationary phases, significantly increasing peak capacity for complex samples [7].

- High-Resolution Mass Spectrometry: Provides accurate mass measurements that enable elemental composition determination and facilitate unknown compound identification [4].

- Low-Pressure GC-MS: Uses shorter mega-bore columns under reduced pressure conditions to achieve faster analysis times while maintaining separation efficiency [7].

Application Protocols in Food Analysis

Protocol: HPLC Analysis of PFAS in Food Samples

Principle: This method describes the determination of per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) in food using reversed-phase HPLC coupled with tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS), based on EPA Method 1633 [8].

Materials and Reagents:

- HPLC System: UHPLC system capable of gradient elution

- Analytical Column: C18 reversed-phase column (e.g., 2.1 × 100 mm, 1.7-2.7 μm particle size)

- Mass Spectrometer: Triple quadrupole MS with electrospray ionization (ESI)

- Solvents: LC-MS grade water, methanol, and acetonitrile

- Ammonium acetate for mobile phase additive

- Reference Standards: Target PFAS compounds (PFOA, PFOS, etc.)

Sample Preparation:

- Extraction: Homogenize food sample and extract using solid-phase extraction (SPE) or QuEChERS methodology.

- Clean-up: Perform dispersive solid-phase extraction (d-SPE) to remove matrix interferents.

- Concentration: Evaporate extract to near dryness under gentle nitrogen stream and reconstitute in injection solvent.

Chromatographic Conditions:

- Mobile Phase A: 2mM ammonium acetate in water

- Mobile Phase B: Methanol or acetonitrile

- Gradient Program: Initial 20% B, increase to 95% B over 10 minutes, hold for 3 minutes, re-equilibrate

- Flow Rate: 0.3-0.5 mL/min

- Column Temperature: 40°C

- Injection Volume: 5-10 μL

Mass Spectrometry Parameters:

- Ionization Mode: Electrospray ionization (ESI) in negative mode

- Detection Mode: Multiple reaction monitoring (MRM)

- Source Temperature: 300°C

- Nebulizer Gas: Nitrogen

Quantification:

- Prepare calibration standards covering expected concentration range (typically 0.1-100 ng/mL).

- Use internal standard calibration with isotopically labeled PFAS analogs.

- Establish retention times and MRM transitions for each target analyte.

Protocol: GC-MS Analysis of Food Aroma Compounds

Principle: This method describes the characterization of volatile aroma compounds in food products using headspace solid-phase microextraction (HS-SPME) coupled with GC-MS, applicable for flavor profiling and authenticity studies [9].

Materials and Reagents:

- GC-MS System: Gas chromatograph with mass spectrometer detector

- GC Column: Mid-polarity stationary phase (e.g., 5% phenyl polysiloxane, 30 m × 0.25 mm × 0.25 μm)

- SPME Fiber: Divinylbenzene/Carboxen/Polydimethylsiloxane (DVB/CAR/PDMS) coating

- Internal Standards: Deuterated compounds or alkylpyrazines for quantification

Sample Preparation:

- Homogenization: Grind solid food samples to uniform consistency.

- Equilibration: Weigh 2-5 g sample into 20 mL headspace vial, add internal standard.

- Extraction: Incubate sample at 40-60°C for 10-15 minutes, then expose SPME fiber to headspace for 30-45 minutes.

GC Conditions:

- Carrier Gas: Helium, constant flow 1.0 mL/min

- Injector Temperature: 250°C, splitless mode

- Oven Program: 40°C (hold 2 min), ramp to 240°C at 5°C/min, final hold 5 min

- Transfer Line Temperature: 250°C

Mass Spectrometry Conditions:

- Ionization Mode: Electron ionization (EI) at 70 eV

- Ion Source Temperature: 230°C

- Scan Range: m/z 35-350

- Solvent Delay: 2-3 minutes

Data Analysis:

- Identify compounds by comparing mass spectra with NIST/Adams libraries.

- Perform semi-quantification using internal standard method.

- Apply multivariate statistical analysis (PCA, PLS-DA) for pattern recognition when comparing multiple samples.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for HPLC and GC-MS Food Analysis

| Item | Function | Application Examples |

|---|---|---|

| C18 Reversed-Phase Columns | Separation of non-polar to moderately polar compounds | PFAS, pesticides, lipids, fat-soluble vitamins [8] [6] |

| HILIC Columns | Separation of polar and hydrophilic compounds | Sugars, organic acids, amino acids, water-soluble vitamins |

| Phenyl-Hexyl and Biphenyl Columns | Alternative selectivity through π-π interactions | Aromatic compounds, isomeric separations [6] |

| Inert Column Hardware | Minimize metal-analyte interactions | Phosphorylated compounds, chelating PFAS, metal-sensitive analytes [6] |

| LC-MS Grade Solvents | High purity mobile phases with minimal background | All LC-MS applications to reduce signal interference |

| SPME Fibers | Extraction and concentration of volatile compounds | Food aroma profiling, contaminant analysis [9] |

| QuEChERS Extraction Kits | Rapid sample preparation for complex matrices | Pesticide residues, veterinary drugs, contaminants [7] |

| Mass Spectrometry Reference Libraries | Compound identification through spectral matching | Unknown compound identification, aroma compound characterization [9] |

| Cefaclor-d5 | Cefaclor-d5, MF:C15H14ClN3O4S, MW:372.8 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Oxolinic Acid-d5 | Oxolinic Acid-d5|CAS 1189890-98-9|Internal Standard | Oxolinic Acid-d5 is a deuterated internal standard for LC/GC-MS analysis of quinolone antibacterials. For research use only. Not for human or veterinary use. |

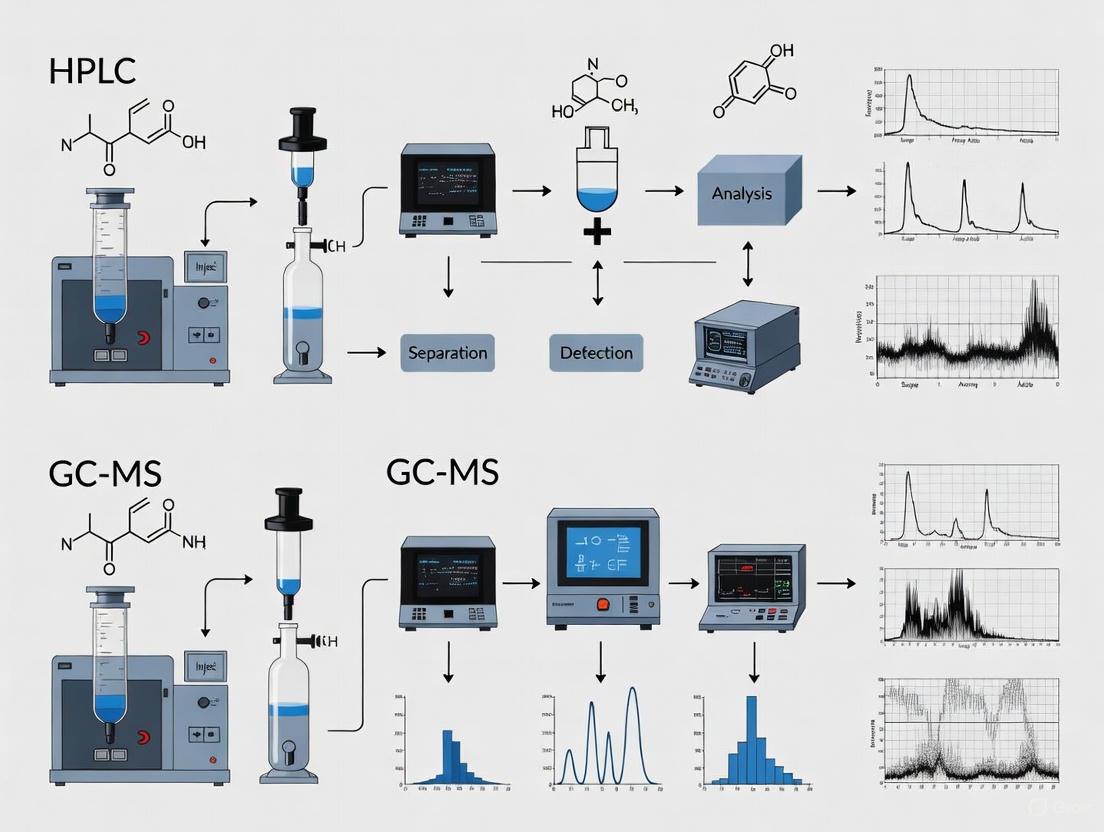

Workflow and Data Integration Diagrams

HPLC Instrumental Workflow

GC-MS Instrumental Workflow

Integrated Food Analysis Strategy

HPLC and GC-MS provide complementary analytical capabilities that form the foundation of modern food component analysis. HPLC excels in separating non-volatile and semi-volatile compounds, while GC-MS offers superior performance for volatile and thermally stable analytes. The continuing advancement of these technologies—including the development of more efficient separation columns, more sensitive detection systems, and improved sample preparation methodologies—ensures their ongoing critical role in food safety, authenticity, and quality research. The integration of these analytical techniques with chemometrics and machine learning approaches represents the cutting edge of food analysis, enabling researchers to extract maximum information from complex food matrices and address increasingly sophisticated analytical challenges.

The selection of an appropriate analytical technique is foundational to the success of any chemical analysis in food research. The fundamental physicochemical properties of the target analytes—specifically, their volatility and thermal stability—directly dictate the choice between High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC) and Gas Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (GC-MS) [10] [11]. Within the context of food component analysis, an erroneous selection can lead to incomplete analysis, degraded compounds, and ultimately, inaccurate data.

This application note provides a structured framework for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals to make an informed choice between HPLC and GC-MS. We detail the core principles, provide a direct comparative analysis, and offer practical experimental protocols for the analysis of food components, ensuring data reliability and method robustness in alignment with the rigorous demands of thesis research.

Core Principles and Comparative Analysis

High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC)

HPLC separates compounds dissolved in a liquid mobile phase using a solid stationary phase under high pressure [12]. Its principal advantage lies in its applicability to a wide range of compounds that are non-volatile, polar, or thermally unstable [10] [11]. Since the separation occurs in a liquid phase at ambient or controlled temperatures, it is ideally suited for analytes that would decompose or not vaporize at the temperatures required for GC-MS. This makes it indispensable for analyzing many pharmaceuticals, biomolecules, and food components like additives and pigments [12] [13].

Gas Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (GC-MS)

GC-MS combines gas chromatography, which separates volatile compounds, with mass spectrometry, which provides definitive identification [14]. In GC, the sample is vaporized and carried by an inert gas through a column. Separation is based on the analyte's volatility and its interaction with the column's stationary phase [10]. The technique is exceptionally powerful for separating and identifying volatile and thermally stable compounds [11]. However, its major limitation is that the analyte must survive the vaporization process without decomposition. For polar or thermally labile compounds, this often necessitates a derivatization step to increase volatility and thermal stability [10] [11].

Technique Selection Guide

The table below summarizes the key characteristics of each technique to guide method selection.

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of HPLC and GC-MS for Food Component Analysis

| Aspect | HPLC | GC-MS |

|---|---|---|

| Analyte Suitability | Non-volatile, thermally unstable, polar, and high-molecular-weight compounds [10] [11] | Volatile and thermally stable compounds; polar compounds often require derivatization [10] [11] |

| Separation Principle | Differential partitioning between liquid mobile phase and solid stationary phase [12] | Partitioning between a gaseous mobile phase and a liquid stationary phase, based on volatility/polarity [14] |

| Typical Food Applications | Additives (e.g., preservatives, sweeteners), vitamins, organic acids, mycotoxins, pigments, antibiotics [13] | Aroma compounds, flavor volatiles, pesticide residues, fatty acids, volatile organic pollutants [10] [15] |

| Key Advantage | Broad applicability without need for volatility; gentle on labile molecules [12] [10] | High resolution and peak capacity for volatile mixtures; powerful identification via MS libraries [10] [14] |

| Primary Limitation | Higher solvent consumption; generally slower than GC; can have lower resolution [12] [10] | Limited to volatile/stable analytes; derivatization adds complexity; high temperatures can degrade samples [10] [11] |

The following decision flowchart provides a systematic approach for selecting the appropriate technique based on the analyte's properties.

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: HPLC Analysis of Non-Volatile Food Additives

This protocol is designed for the simultaneous determination of synthetic sweeteners (e.g., acesulfame, saccharin) and preservatives (e.g., benzoate, sorbate) in a beverage matrix [13].

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Reagents and Materials for HPLC Analysis

| Item | Function | Specification/Note |

|---|---|---|

| HPLC System | Instrumentation | With binary pump, autosampler, and DAD/UV-Vis detector [12] |

| C18 Column | Stationary Phase | 150 mm x 4.6 mm, 5 µm particle size for reversed-phase separation [16] |

| Ammonium Acetate Buffer | Mobile Phase Component | Provides buffered pH for consistent ionization of analytes [16] |

| HPLC-Grade Acetonitrile | Mobile Phase Component | Organic modifier for gradient elution [16] |

| Syringe Filters | Sample Cleanup | 0.22 µm or 0.45 µm, nylon or PVDF, to remove particulates [17] |

Sample Preparation Workflow

The sample preparation and analysis process is outlined below.

Procedure:

- Sample Preparation: Degas the beverage sample by sonication for 5 minutes. Dilute 1 mL of the degassed sample to 10 mL with mobile phase A (20 mM Ammonium Acetate, pH 4.5). Pass the diluted sample through a 0.45 µm syringe filter into an HPLC vial [17] [16].

- Mobile Phase Preparation: Prepare mobile phase A (20 mM Ammonium Acetate in HPLC-grade water, adjust pH to 4.5 with acetic acid) and mobile phase B (HPLC-grade Acetonitrile). Degas both phases by sonication or sparging with an inert gas [18].

- HPLC Method Conditions:

- Column: C18 (150 mm x 4.6 mm, 5 µm)

- Flow Rate: 1.0 mL/min

- Temperature: 30 °C

- Injection Volume: 10 µL

- Detection: UV-Vis Diode Array Detector (DAD), 230 nm

- Gradient Program: | Time (min) | %A | %B | | :--- | :--- | :--- | | 0 | 95 | 5 | | 10 | 80 | 20 | | 15 | 50 | 50 | | 15.1 | 95 | 5 | | 20 | 95 | 5 |

- Data Analysis: Identify compounds by comparing retention times with authentic standards. Quantify using external calibration curves prepared from standard solutions [17].

Protocol 2: GC-MS Analysis of Volatile Flavor Compounds

This protocol is suitable for profiling the volatile organic compounds responsible for the aroma in fruits (e.g., apples, grapes) using Headspace Solid-Phase Microextraction (HS-SPME) [15].

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents and Materials for GC-MS Analysis

| Item | Function | Specification/Note |

|---|---|---|

| GC-MS System | Instrumentation | With split/splitless injector and a mass spectrometer detector [14] |

| Mid-Polarity GC Column | Stationary Phase | e.g., (5%-Phenyl)-methylpolysiloxane, 30 m x 0.25 mm ID, 0.25 µm film [14] |

| SPME Fiber | Sample Extraction | 50/30 µm DVB/CAR/PDMS is common for broad-range volatiles [15] |

| Internal Standard | Quantification Control | e.g., 4-Methyl-2-pentanone or deuterated analogs, corrects for injection variability [19] |

| Helium Carrier Gas | Mobile Phase | High-purity (99.999%) carrier gas for GC [14] |

Sample Preparation and Analysis Workflow

The workflow for analyzing volatile compounds via HS-SPME-GC-MS is as follows.

Procedure:

- Sample Preparation: Homogenize 5.0 g of fresh fruit pulp in a sealed container. Precisely weigh 2.0 g of the homogenate into a 20 mL headspace vial. Add 10 µL of internal standard solution (e.g., 100 ppm 4-Methyl-2-pentanone) and immediately cap the vial [19] [15].

- HS-SPME Extraction: Place the vial in a heated autosampler tray. Condition the SPME fiber (50/30 µm DVB/CAR/PDMS) according to manufacturer instructions. The automated method should include:

- Incubation: 60°C for 10 min with agitation.

- Extraction: Expose the fiber to the vial headspace at 60°C for 30 min.

- Desorption: Inject the fiber into the GC injector port for 5 min at 250°C in splitless mode [15].

- GC-MS Method Conditions:

- Column: (5%-Phenyl)-methylpolysiloxane, 30 m x 0.25 mm ID, 0.25 µm df

- Carrier Gas: Helium, constant flow of 1.0 mL/min

- Oven Program: | Time (min) | Rate (°C/min) | Temperature (°C) | Hold (min) | | :--- | :--- | :--- | :--- | | 0 | - | 40 | 2 | | 5 | 10 | 150 | 0 | | 10 | 25 | 250 | 2 |

- Injector: 250°C, splitless mode

- Mass Spectrometer: Electron Impact (EI) ionization at 70 eV; ion source temperature: 230°C; quadrupole temperature: 150°C; acquisition mode: Scan (m/z 35-350) [14].

- Data Analysis: Identify compounds by searching acquired mass spectra against commercial libraries (e.g., NIST). Use the internal standard for semi-quantification. For precise quantification, employ matrix-matched calibration curves to compensate for matrix effects [19] [15].

Critical Considerations for Robust Method Development

Managing Matrix Effects in Food Analysis

Matrix effects, where co-extracted compounds from the sample interfere with the analysis, are a significant challenge in food analysis, particularly in GC-MS [19]. These effects can cause signal suppression or enhancement, leading to inaccurate quantification.

- GC-MS: Matrix effects often manifest as signal enhancement due to the matrix components blocking active sites in the GC system, thus improving the transfer of the analyte into the column [19]. This is prevalent in complex food matrices.

- HPLC-MS: Matrix effects typically result in ion suppression in the mass spectrometer interface, reducing the signal for the target analyte [17].

Mitigation Strategies:

- Matrix-Matched Calibration: Prepare calibration standards in a blank extract of the same food matrix (e.g., pesticide-free apple extract). This is the most effective and widely recommended approach, especially for GC-MS analysis of pesticides [19].

- Sample Dilution: If the method sensitivity allows, diluting the sample extract can reduce the concentration of interfering matrix components [17].

- Improved Sample Cleanup: Utilize additional or more selective sample preparation steps, such as Solid-Phase Extraction (SPE), to remove specific interfering compounds from the extract [17] [19].

- Stable Isotope-Labeled Internal Standards: For LC-MS and GC-MS, these standards behave identically to the analyte during sample preparation and ionization, correcting for both losses and matrix effects [19].

Ensuring HPLC Retention Time Precision

Precise and reproducible retention times are critical for reliable analyte identification in HPLC. Several factors must be controlled [18]:

- Mobile Phase Composition: Use HPLC-grade solvents, prepare buffers fresh daily, and maintain consistent pH and ionic strength. Always degas the mobile phase to prevent air bubbles from affecting the pump's flow rate [18].

- Temperature Control: Maintain a constant column temperature using a column oven. Fluctuations in ambient lab temperature can directly impact retention times [18].

- Column Health and Maintenance: A column's performance degrades with use. Monitor system pressure and peak shape. Follow a regular column cleaning schedule and replace columns after ~1000-2000 injections or when performance drops [18].

The strategic selection between HPLC and GC-MS, grounded in a clear understanding of analyte volatility and thermal stability, is a critical determinant of success in food component analysis. HPLC serves as the versatile tool for a vast array of non-volatile and labile food compounds, from additives to nutrients. In contrast, GC-MS offers unparalleled separation and identification power for volatile flavor and aroma profiles, as well as for many pesticide residues.

By adhering to the structured protocols for method selection, sample preparation, and instrumental analysis outlined in this document, researchers can develop robust, reliable, and validated methods. Meticulous attention to mitigating matrix effects and controlling chromatographic parameters will ensure the generation of high-quality, reproducible data essential for rigorous scientific research, quality control, and regulatory compliance in the food industry.

Mass spectrometry (MS) has become a cornerstone analytical technique in food component analysis due to its powerful capability to identify and quantify chemical compounds with high specificity and sensitivity. When coupled with separation techniques like Gas Chromatography (GC) and High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC), MS enables researchers to detect a vast array of food components, from lipids and allergens to contaminants and flavor compounds, even within complex matrices. The continuous technological advancements in mass spectrometry are pushing the boundaries of detection, providing researchers and drug development professionals with the precise tools necessary to ensure food safety, quality, and nutritional value. This document outlines specific application notes and detailed protocols that highlight the critical role of MS in modern food analysis.

The field of mass spectrometry is evolving rapidly, with recent innovations focusing on improving resolution, speed, and confidence in compound identification. Key developments directly enhance the specificity and sensitivity required for challenging food matrices.

Next-Generation Orbital Trap Instruments

Thermo Fisher Scientific's recent launch of the Orbitrap Astral Zoom MS demonstrates a significant leap in performance for proteomics and biopharma applications, with metrics that are equally relevant for complex food protein analysis. This instrument delivers a 35% faster scan speed, 40% higher throughput, and a 50% expansion in multiplexing capabilities compared to its predecessor, enabling deeper coverage of protein biomarkers in food products [20].

The Rise of 4D-Metabolomics and Lipidomics

Bruker's novel timsMetabo mass spectrometer introduces a fourth dimension of separation—Trapped Ion Mobility Spectrometry (TIMS)—to liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry. This 4D-LC-TIMS-MS/MS platform provides:

- Unprecedented sensitivity for small molecule analysis.

- Collision Cross Section (CCS) measurements as a stable, reproducible molecular identifier, increasing annotation confidence.

- Enhanced separation of isomers and isobars, which is crucial for accurately profiling sugars, lipids, and other stereosensitive compounds in food. The system generates a "digital metabolome archive" for each sample, facilitating AI and machine learning data analysis [21].

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Advanced Mass Spectrometers

| Instrument/Technology | Key Advancement | Impact on Specificity & Sensitivity | Primary Food Application |

|---|---|---|---|

| Orbitrap Astral Zoom MS [20] | 35% faster scan speed; 40% higher throughput | Deeper proteomic coverage; richer data from limited sample | Protein quantification; allergen detection |

| timsMetabo with TIMS [21] | Adds ion mobility separation (CCS value) | Resolves isomers/isobars; reduces background noise | Metabolomics; lipidomics; flavor profiling |

| GC-MS with ML Integration [9] | Machine learning models for aroma prediction | Decodes complex volatile relationships; predicts sensory outcomes | Food aroma and quality control |

Application Notes in Food Analysis

The following applications demonstrate the practical implementation of MS techniques to solve real-world challenges in food science.

Application Note AN-001: Determination of Fatty Acids in Special Formula Milk Powder using GC-MS

- Objective: To establish a rapid, accurate, and cost-effective GC-MS method for profiling fatty acids in complex food matrices like special formula milk powder [22].

- Background: Foods for Special Medical Purposes (FSMPs) require rigorous quality control. Existing standard methods for fatty acid detection can be time-consuming and costly, creating a need for optimized protocols.

- Experimental Protocol: The detailed methodology is provided in Section 4.1.

- Results and Discussion: The developed method demonstrated excellent performance metrics [22]:

- Linearity: Correlation coefficients ranged from 0.9959 to 0.9997.

- Precision: Relative Standard Deviation (RSD) for precision was between 0.41% and 3.36%.

- Accuracy: The spiked recovery rate was 90.03%–107.76%, confirming high accuracy. Compared to the Chinese national standard GB 5009.168–2016, this method reduced the analysis time by 0.5 hours and was more cost-effective. It also provided a more comprehensive and subdivided fatty acid profile than the international standard AOAC 996.06 [22].

Application Note AN-002: Multi-component Sterol Analysis in Pre-prepared Dishes using GC-MS

- Objective: To develop a sensitive and selective GC-MS method for the simultaneous qualification and quantification of multiple sterols in pre-prepared dishes, which have complex matrices of fats, proteins, and seasonings [23].

- Background: Sterols are key functional components that affect the nutritional value of food. Their detection is hampered by matrix interference, making robust sample preparation critical.

- Experimental Protocol: The detailed methodology is provided in Section 4.2.

- Results and Discussion: The method was successfully validated and applied to real samples [23]:

- The method showed good linearity (correlation coefficients ≥0.99) across a concentration range of 1.0–100.0 μg/mL.

- It exhibited high sensitivity, with Limits of Detection (LODs) and Quantification (LOQs) of 0.05–5.0 mg/100 g and 0.165–16.5 mg/100 g, respectively.

- The average recovery rates were 87.0% to 106% with RSDs of 0.99–9.00%, proving its reliability for complex matrices. Application to actual pre-prepared dishes revealed significant variations in sterol content, dominated by meat ingredients, and successfully identified β-sitosterol, campesterol, and stigmasterol as major components [23].

Application Note AN-003: HPLC-MS/MS Analysis of PFAS in Food

- Objective: To detect and quantify Per- and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances (PFAS) in food and food packaging at parts-per-trillion (ppt) levels using advanced HPLC-MS/MS [8].

- Background: PFAS are persistent environmental contaminants that can migrate into food from packaging. Their analysis is challenging due to low regulatory limits and complex sample matrices.

- Key Technological Features:

- HPLC Advancements: Use of core-shell and monolithic columns for improved separation efficiency and faster analysis.

- Detection: Coupling with tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) is essential for achieving the required sensitivity and specificity at ppt levels, as mandated by the U.S. EPA Method 1633 [8].

- Sample Preparation: Techniques like Solid-Phase Extraction (SPE) and QuEChERS are refined to improve recovery rates and reduce matrix effects.

- Regulatory Context: This application supports compliance with stringent regulations, such as the U.S. EPA's Maximum Contaminant Levels of 4 ppt for PFOA and PFOS in drinking water [8].

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol P-001: GC-MS Analysis of Fatty Acids in Milk Powder

The following workflow details the sample preparation and analysis for determining fatty acids:

Materials and Reagents:

- Special formula milk powder sample

- n-Hexane (HPLC grade)

- Sodium methoxide solution in methanol

- Internal standard solution (e.g., C13-labeled fatty acid)

- Ultrapure water

Procedure:

- Lipid Extraction: Accurately weigh ~1 g of milk powder. Perform ultrasound-assisted lipid extraction in a solution state using n-hexane.

- Derivatization: Transfer the extracted lipids to a reaction vial. Add a defined volume of sodium methoxide in methanol solution to convert (methyl esterify) the fatty acids to their corresponding Fatty Acid Methyl Esters (FAMEs).

- GC-MS Analysis: Inject the derivatized sample into the GC-MS system under the following conditions [22]:

- Injection Mode: Split (10:1 ratio).

- Column: Appropriate fused-silica capillary column (e.g., DB-5MS).

- Temperature Program: A defined gradient from a low initial hold temperature (e.g., 60°C) to a high final temperature (e.g., 300°C).

- Ionization: Electron Impact (EI) at 70 eV.

- Quantification: Identify fatty acids by comparing retention times and mass spectra to certified standards. Quantify using the internal standard method, constructing a calibration curve for each target fatty acid.

Protocol P-002: Sterol Determination in Pre-prepared Dishes

The multi-step sample preparation for sterol analysis is critical for dealing with complex matrices:

Materials and Reagents:

- Homogenized pre-prepared dish sample

- Methanolic KOH solution (for saponification)

- n-Hexane (HPLC grade)

- Derivatization reagent (e.g., BSTFA + TMCS)

- Internal standard (e.g., 5α-cholestane)

- Ultrapure water

Procedure:

- Saponification: Weigh a homogenized sample (~2 g) into a flask. Add methanolic KOH and heat to hydrolyze (saponify) triglycerides and release free sterols.

- Extraction: After cooling, add ultrapure water to assist dispersion. Extract the free sterols with n-hexane. Combine the organic layers.

- Concentration: Evaporate the n-hexane extract to dryness under a gentle stream of nitrogen gas.

- Derivatization: Reconstitute the dry residue in a derivatization reagent (e.g., BSTFA) to convert sterols into more volatile trimethylsilyl (TMS) ether derivatives for improved GC separation and sensitivity [23].

- GC-MS Analysis: Inject the derivatized sample.

- Column: High-resolution capillary column (e.g., DB-5MS).

- Temperature Program: Use a optimized gradient to resolve sterol isomers (e.g., β-sitosterol, campesterol, stigmasterol).

- Detection: Operate MS in Selected Ion Monitoring (SIM) mode for higher sensitivity or full scan mode for untargeted profiling.

- Quantification: Quantify using the internal standard method, with calibration curves for each sterol.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Key Reagents and Materials for MS-Based Food Analysis

| Item Name | Function/Benefit | Example Application |

|---|---|---|

| Sodium Methoxide in Methanol | Catalyst for transesterification of fatty acids to volatile FAMEs. | Fatty acid analysis in milk powder and oils [22]. |

| Saponification Reagent (e.g., Methanolic KOH) | Hydrolyzes triglycerides to release free sterols for analysis. | Sample prep for sterol determination in complex foods [23]. |

| Derivatization Reagents (e.g., BSTFA) | Increases volatility and thermal stability of polar compounds (e.g., sterols) for GC-MS. | Analysis of sterols, sugars, and other non-volatile analytes [23]. |

| Solid-Phase Extraction (SPE) Cartridges | Clean-up and pre-concentration of analytes; reduces matrix effects. | PFAS analysis in complex food matrices [8]. |

| QuEChERS Kits | Quick, Easy, Cheap, Effective, Rugged, Safe; multi-residue extraction. | Pesticide and contaminant analysis in fruits and vegetables. |

| Stable Isotope-Labeled Internal Standards | Corrects for analyte loss during preparation and ion suppression/enhancement during MS. | Essential for accurate quantification in LC-MS/MS and GC-MS [22] [23]. |

| QSee QC Suite & Reference Materials | Automated performance monitoring and long-term system stability for high-quality metabolomics data [21]. | Ensuring data quality and reproducibility in untargeted LC-MS studies. |

| Enrofloxacin-d5 | Enrofloxacin-d5, CAS:1173021-92-5, MF:C19H22FN3O3, MW:364.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Olaquindox-d4 | Olaquindox-d4, CAS:1189487-82-8, MF:C12H13N3O4, MW:267.27 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

The selection of an appropriate detector is a critical step in the development of any chromatographic method, particularly in the field of food analysis where the accurate quantification of diverse components—from nutrients and bioactive compounds to contaminants and adulterants—is essential. Detectors convert the physical or chemical characteristics of analytes separated by High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC) or Gas Chromatography (GC) into measurable signals, defining the sensitivity, selectivity, and overall applicability of the method. This application note provides a detailed overview of four fundamental detectors—UV-Vis, Fluorescence (FLD), Flame Ionization (FID), and Mass Spectrometry (MS)—within the context of a thesis researching HPLC and GC-MS methods for food components. It includes performance comparisons, detailed experimental protocols from recent food safety research, and essential workflows to guide researchers and scientists in method selection and implementation.

Detector Fundamentals and Performance Comparison

Operational Principles

UV-Vis Detectors operate on the principle of the Beer-Lambert law, where analytes absorbing ultraviolet or visible radiation (typically 200-400 nm) in a flow cell cause a reduction in the transmitted light intensity, which is measured by a photodiode [24]. Modern variable wavelength detectors use a diffraction grating to select a specific wavelength, while diode array detectors (DAD) pass white light through the flow cell first, then disperse it onto an array of photodiodes to capture full spectra simultaneously, enabling peak purity assessment and library matching [24].

Fluorescence Detectors (FLD) offer higher specificity and sensitivity than UV-Vis by measuring the light emitted by analytes after they have been excited by a specific wavelength of light. This two-wavelength measurement (excitation and emission) significantly reduces background noise, making FLD ideal for trace analysis of native fluorescent compounds or those that can be derivatized to become fluorescent [25] [26].

Flame Ionization Detectors (FID) are nearly universal for GC. Analytes eluting from the column are combusted in a hydrogen/air flame, generating ions and free electrons from hydrocarbon backbones. An electrode collects these charged particles, generating a current proportional to the number of carbon atoms entering the flame [27]. FID is highly sensitive to most organic compounds but exhibits limited response to inorganic species, water, and permanent gases [27].

Mass Spectrometry Detectors (MS) provide unparalleled selectivity by separating and detecting ions based on their mass-to-charge ratio (m/z). MS can be coupled with either LC or GC (as LC-MS or GC-MS). It functions by ionizing analyte molecules, separating the resulting ions in a mass analyzer (e.g., Quadrupole, Time-of-Flight), and detecting them. MS detectors provide structural information, enable identification of unknown compounds through library matching, and are capable of extremely high sensitivity, especially in selected reaction monitoring (SRM) mode on tandem MS systems [28] [29].

Comparative Performance Metrics

The following table summarizes the key characteristics and food analysis applications of these detectors for easy comparison.

Table 1: Comparative Overview of Common Chromatographic Detectors

| Detector | Principle of Detection | Selectivity | Typical Sensitivity | Linear Dynamic Range | Example Food Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| UV-Vis (DAD) | Absorption of UV/Vis light [24] | Selective for chromophores | Moderate (ng) | ~10³ | Vitamins, mycotoxins, food colorants, polyphenols [24] |

| Fluorescence (FLD) | Emission of light after excitation [25] | Highly selective for fluorophores | High (pg-fg) | ~10â´ | Aflatoxins, Ochratoxin A [25], Bisphenol A [26], Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons |

| Flame Ionization (FID) | Combustion in Hâ‚‚/air flame [27] | Universal for organic C-H bonds | High (pg) | ~10â· | Fatty acids, residual solvents, hydrocarbons, sugars (after derivatization) [27] |

| Mass Spectrometry (MS) | Mass-to-charge ratio (m/z) of ions | Highly Selective and Universal | Very High (fg-ag) | ~10âµ | Pesticide residues, mycotoxins, drug residues, metabolomics, flavor compounds [28] [29] |

Application-Oriented Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: HPLC-FLD for Determination of Ochratoxin A in Mouse Tissues

This validated protocol for monitoring mycotoxin exposure in neurodegeneration research demonstrates the high sensitivity of FLD [25].

3.1.1 Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Reagents and Materials for OTA Analysis

| Item | Function / Specification |

|---|---|

| Ochratoxin A (OTA) Certified Standard | Primary analyte for calibration and quantification. |

| HPLC-Grade Acetonitrile and Methanol | Mobile phase components and extraction solvents. |

| Formic Acid or Acetic Acid | Mobile phase additive to improve chromatographic peak shape. |

| Ultrapure Water (Type I) | Aqueous component of the mobile phase. |

| Solid Phase Extraction (SPE) Cartridges | Clean-up and pre-concentration of samples (e.g., C18 or IAC). |

| Homogenizer (e.g., Polytron) | For homogenizing tissue samples (kidney, liver, brain, intestine). |

3.1.2 Method Conditions and Validation Data

Table 3: Validated HPLC-FLD Method Parameters for OTA [25]

| Parameter | Specification |

|---|---|

| Sample Types | Mouse plasma, kidney, liver, brain, intestine |

| LLOQ (Plasma) | 2.35 ng/mL |

| LLOQ (Tissues) | 9.4 ng/g |

| Linear Range | 2.35–22.83 ng/mL and 22.83–228.33 ng/mL |

| Accuracy (Recovery) | 74.8% (Plasma) to 87.6% (Kidney) |

| Precision (CV%) | < 12% for all matrices |

| Chromatographic Column | C18 column (e.g., 150 x 4.6 mm, 5 µm) |

| Mobile Phase | Aqueous acid (e.g., formic acid) and Acetonitrile (gradient) |

| FLD Detection | Ex: λex ~ 330 nm, λem ~ 460 nm |

3.1.3 Detailed Workflow

- Sample Homogenization: Precisely weigh tissue samples (~100 mg) and homogenize with a suitable volume of acidified aqueous acetonitrile (e.g., 50% ACN, 1% acetic acid).

- Extraction and Clean-up: Centrifuge the homogenate, collect the supernatant, and further purify using an immunoaffinity or reversed-phase SPE column to remove interfering matrix components.

- Evaporation and Reconstitution: Evaporate the eluted solvent to dryness under a gentle stream of nitrogen. Reconstitute the dry residue in a small volume of the HPLC starting mobile phase (e.g., 100-200 µL) to pre-concentrate the analyte.

- HPLC-FLD Analysis: Inject the reconstituted sample onto the HPLC system. Employ a gradient elution to separate OTA from any remaining co-extractives. Quantify OTA by comparing the peak area to a calibration curve of pure standards using fluorescence detection.

Protocol 2: HPLC-FLD for Determination of Bisphenol A in Canned Vegetables

This protocol highlights the application of FLD for monitoring migrant contaminants from food packaging [26].

3.2.1 Research Reagent Solutions

Table 4: Essential Reagents and Materials for BPA Analysis

| Item | Function / Specification |

|---|---|

| Bisphenol A (BPA) Certified Standard | Primary analyte for calibration. |

| HPLC-Grade Acetonitrile | Mobile phase component and solvent for standard preparation. |

| Ultrapure Water (Type I) | Aqueous component of the mobile phase. |

| Syringe Filters (0.22 µm or 0.45 µm, Nylon/PTFE) | For filtration of sample extracts prior to injection. |

| Canned Vegetable Samples | Food simulant or the liquid phase from canned goods. |

3.2.2 Method Conditions

- Chromatographic Column: C18 column (e.g., 250 x 4.6 mm, 5 µm).

- Mobile Phase: Gradient elution with water and acetonitrile.

- FLD Detection: Optimal excitation and emission wavelengths for BPA are typically λex = 230-275 nm and λem = 300-315 nm [26].

- Limit of Quantification (LOQ): 0.01 mg/kg, well below the specific migration limit of 0.05 mg/kg set by the EU [26].

3.2.3 Detailed Workflow

- Sample Collection: Drain the liquid phase from the canned vegetable sample into a clean beaker.

- Sample Preparation: Mix an aliquot of the liquid (e.g., 900 µL) with a small volume of organic solvent (e.g., 100 µL acetonitrile) to ensure compatibility with the HPLC mobile phase.

- Filtration: Pass the mixture through a 0.45 µm syringe filter directly into an HPLC vial.

- HPLC-FLD Analysis: Inject the filtered sample. BPA is quantified by external calibration. For confirmatory analysis, the same extract can be analyzed by LC-MS/MS [26].

Workflow and Technology Selection Diagrams

Detector Selection and Method Development Workflow

The following diagram outlines a logical decision-making process for selecting the most appropriate detector based on the analytical goal and the physicochemical properties of the target analyte.

Operational Principles of Key Detectors

The diagram below illustrates the fundamental components and operational processes of three core detectors.

The choice of detector is a foundational decision in chromatographic method development for food analysis. UV-Vis detectors offer a robust and cost-effective solution for compounds with chromophores, while fluorescence detection provides superior sensitivity and selectivity for targeted analysis of fluorophores. FID remains a stalwart for universal, quantitative GC analysis of organic compounds. However, mass spectrometry stands out for its unmatched versatility, providing the selectivity needed for confirmatory analysis, identification of unknowns, and sensitive quantification of trace-level contaminants in complex food matrices. As food safety and quality demands intensify, the trend is moving towards hyphenated techniques like LC-MS and GC-MS, with ongoing developments in instrumentation—such as miniaturization, improved ionization sources, and AI-driven data analysis—further enhancing their speed, sensitivity, and accessibility [30] [31]. By understanding the principles, capabilities, and applications of these key detectors, researchers can effectively design and implement analytical strategies to address the complex challenges in modern food science.

Chromatographic methods, primarily High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC) and Gas Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (GC-MS), are cornerstone techniques for separating, identifying, and quantifying components in complex food matrices [32]. The journey from a raw food sample to an interpretable chromatogram is a multi-stage process where each step is critical for ensuring the accuracy, reliability, and reproducibility of the final analytical results. This workflow encompasses sample collection, preparation, instrumental analysis, and data interpretation, with the overarching goals of ensuring food safety, verifying quality, and complying with regulations [33] [7]. This application note details a standardized protocol for this entire workflow, contextualized within modern advancements in automation and sustainability for food research and development [34] [35].

Experimental Protocols

Sample Collection and Storage

The integrity of the entire analytical process hinges on proper initial sample handling [32].

Protocol for Solid Foods (e.g., vegetables, grains):

- Collection: Obtain a representative portion from the bulk sample. For heterogeneous materials (e.g., entire apples), multiple sub-samples from different locations should be taken and combined.

- Homogenization: Process the sample using a laboratory blender or grinder to create a consistent and homogeneous mixture.

- Storage: Immediately freeze the homogenized sample at -20 °C or below to inhibit microbial growth and chemical degradation. Store in an inert, airtight container to prevent moisture loss or absorption.

Protocol for Liquid Foods (e.g., juice, milk):

- Collection: Ensure the sample is well-mixed before aliquoting to prevent sedimentation.

- Storage: Refrigerate at 4 °C for short-term storage (hours to a few days). For long-term stability, freeze at -20 °C. Preservatives may be added depending on the analytes of interest.

Sample Preparation and Extraction

This is often the most critical and variable step, aimed at isolating target analytes from the complex food matrix while minimizing interferences [33].

Protocol 1: QuEChERS (Quick, Easy, Cheap, Effective, Rugged, and Safe) for Multi-Pesticide Residues

- Principle: This method combines extraction and clean-up into a streamlined process, ideal for non-polar to semi-polar analytes in a variety of food matrices [33] [36].

- Procedure:

- Weigh 10 ± 0.1 g of homogenized sample into a 50 mL centrifuge tube.

- Add 10 mL of acetonitrile and vortex vigorously for 1 minute.

- Add a pre-packaged salt mixture (typically containing MgSOâ‚„ to remove water and NaOAc as a buffer) and shake immediately and vigorously for 1 minute.

- Centrifuge at >4000 RCF for 5 minutes.

- Transfer an aliquot of the upper acetonitrile layer to a dispersive Solid-Phase Extraction (dSPE) tube containing clean-up sorbents (e.g., PSA to remove organic acids, GCB for pigments, and MgSOâ‚„).

- Vortex and centrifuge. The final supernatant is ready for analysis by GC-MS or LC-MS [33].

Protocol 2: Supported Liquid Extraction (SLE) for Aqueous Matrices

- Principle: A modern alternative to Liquid-Liquid Extraction (LLE), SLE offers high selectivity and eliminates emulsion formation, making it suitable for beverages, juices, and other aqueous samples [33].

- Procedure:

- Dilute the aqueous sample, if necessary, and adjust the pH.

- Load the sample onto the SLE cartridge or plate and allow it to absorb into the diatomaceous earth for 5-10 minutes.

- Elute the target analytes with a water-immiscible organic solvent (e.g., ethyl acetate or dichloromethane) by gravity or low-pressure vacuum.

- Collect the eluent, which can often be directly injected or concentrated for analysis [33].

Protocol 3: Solid-Phase Extraction (SPE) for Selective Clean-up

- Principle: SPE provides highly customizable and selective clean-up by leveraging specific interactions between analytes, the matrix, and a functionalized sorbent [33] [37].

- General Procedure:

- Conditioning: Pass 2-3 column volumes of a strong solvent (e.g., methanol) through the SPE sorbent, followed by 2-3 volumes of a weak solvent (e.g., water or buffer) without letting the bed dry out.

- Loading: Apply the prepared sample extract to the cartridge at a controlled, slow flow rate (<5 mL/min).

- Washing: Pass 2-3 column volumes of a weak wash solvent to remove weakly retained matrix interferences.

- Elution: Elute the tightly bound analytes with a strong solvent (e.g., methanol or acetonitrile, often acidified or basified). This fraction is collected for analysis [33].

Chromatographic Analysis

The choice of chromatographic technique depends on the volatility, stability, and polarity of the target analytes.

HPLC Method for Vitamins in Fortified Foods [37]

- Column: C18 reversed-phase (e.g., Aqua column, 250 mm × 4.6 mm, 5 µm).

- Mobile Phase: Isocratic elution with 70% NaHâ‚‚POâ‚„ buffer (pH 4.95) and 30% methanol.

- Flow Rate: 0.9 mL/min.

- Column Temperature: 40 °C.

- Detection: Diode Array Detector (DAD) for Riboflavin (B2) and Pyridoxine (B6). For Thiamine (B1), a Fluorescence Detector (FLD) is used after a pre-column oxidation step to convert it into a fluorescent thiochrome derivative.

- Injection Volume: 10-20 µL.

GC-MS Method for Pesticides or Flavors [7] [38]

- Column: A standard (e.g., 30 m × 0.25 mm × 0.25 µm) or a fast (e.g., 10 m × 0.53 mm × 1 µm) "5% phenyl" polysiloxane column.

- Carrier Gas: Helium or Hydrogen, with constant flow or pressure.

- Injection: Pulsed Splitless or PTV injection at 250-280 °C.

- Oven Program: Temperature ramp from a low initial hold (e.g., 60 °C) to a high final temperature (e.g., 300 °C) at a defined rate.

- Mass Spectrometer: Operated in Electron Ionization (EI) mode at 70 eV.

- Acquisition Mode: Full scan (for untargeted analysis) or Selected Ion Monitoring (SIM) / Multiple Reaction Monitoring (MRM) for targeted, high-sensitivity quantification [7].

Data Analysis and Interpretation

The final stage involves translating the chromatogram into meaningful qualitative and quantitative information.

- Peak Identification: Analytes are primarily identified by comparing their retention time to that of an authentic standard analyzed under identical conditions. In GC-MS and LC-MS, the mass spectrum provides a definitive identifier by matching against a reference spectral library [7] [32].

- Peak Integration: The chromatographic software calculates the area or height of each peak.

- Quantification: The peak area of the analyte is compared to a calibration curve constructed from standard solutions of known concentration. Results are reported in appropriate units (e.g., mg/kg, µg/L, ppb).

Results and Data Presentation

Performance Metrics of Analytical Methods

The following table summarizes the typical validation parameters for robust chromatographic methods in food analysis, as demonstrated in recent applications.

Table 1: Quantitative Performance Data from Validated Food Analysis Methods

| Method Description | Analytes | Linearity (R²) | Precision (% RSD) | Accuracy (% Recovery) | LOD/LOQ | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HPLC-DAD/FLD for vitamins in gummies & fluids | B1, B2, B6 Vitamins | > 0.999 | < 3.23% | 100 ± 3% | Not specified | [37] |

| GC-MS for cooling agents in aerosols | Menthol, WS-3, WS-23 | ≥ 0.9994 | 1.40% - 4.15% | 91.32% - 113.25% | LOD: 0.137 ng/mL - 0.114 µg/mL | [38] |

| HPLC-UV for Carvedilol & impurities | Carvedilol, Impurity C, N-formyl | > 0.999 | < 2.0% | 96.5% - 101% | Not specified | [39] |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

A successful analysis requires careful selection of reagents and materials tailored to the sample and analytical goals.

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Food Analysis Workflows

| Item | Function/Description | Application Example |

|---|---|---|

| QuEChERS Kits | Pre-packaged salts and dSPE sorbents for streamlined extraction and clean-up. | Multi-residue pesticide analysis in fruits and vegetables [33]. |

| SPE Sorbents (C18, PSA, GCB) | Selectively retain analytes or remove interferences based on polarity, acidity, or molecular shape. | C18 for general clean-up; PSA for removing sugars and acids; GCB for planar pigments [33]. |

| HPLC-Grade Solvents | High-purity solvents (Acetonitrile, Methanol, Water) with minimal UV absorbance and contaminants. | Mobile phase preparation for HPLC to ensure low background noise and stable baselines [39]. |

| Buffers (e.g., Phosphate) | Control pH of the mobile phase to improve peak shape and separation reproducibility. | Separation of ionizable compounds like carvedilol [39] and B-vitamins [37]. |

| Certified Reference Standards | Analytes of known purity and concentration for method development, calibration, and validation. | Essential for accurate peak identification and quantification in both HPLC and GC-MS. |

| Flumequine-13C3 | Flumequine-13C3, MF:C14H12FNO3, MW:264.23 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Sulfameter-d4 | Sulfameter-d4, MF:C11H12N4O3S, MW:284.33 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Workflow Visualization

The following diagram illustrates the complete, integrated workflow for chromatographic food analysis, highlighting critical decision points and the two primary technique paths (HPLC and GC-MS).

Food Analysis Workflow from Sample to Data

Discussion

Advancements in Method Development and Sustainability

The field of food analysis is rapidly evolving with the integration of Artificial Intelligence (AI) and Machine Learning (ML). These tools are now being applied to manage the complex, interdependent parameters of chromatographic method development, significantly accelerating the optimization process, especially for demanding techniques like two-dimensional LC (2D-LC) [34]. Furthermore, there is a strong paradigm shift towards Green Analytical Chemistry (GAC) and Circular Analytical Chemistry (CAC). This involves adapting traditional methods to reduce environmental impact by minimizing solvent and energy consumption, for example, by using automated, miniaturized, and parallel processing techniques [35]. Automation is a key enabler here, not only reducing labor and human error but also aligning with GSP principles by improving throughput and consistency while often reducing reagent consumption [36].

Troubleshooting Common Workflow Challenges

- Poor Recovery in SPE: If analytes are not adequately recovered, systematically check where the analyte is being lost. If it elutes during loading, the sorbent or sample solvent may be incorrect. If it appears in the wash fractions, the wash solvent is too strong. If it is not eluted, a stronger elution solvent is needed [33].

- Matrix Effects in LC-MS/MS: Ion suppression or enhancement is a common issue, particularly in complex food matrices. Using stable isotope-labeled internal standards is the most effective way to compensate for these effects. Efficient sample clean-up (e.g., with SPE or dSPE) and chromatographic separation also help mitigate this problem [33].

- Co-elution in GC-MS: In complex food profiles, peak overlap is frequent. Beyond optimizing the GC temperature program, leveraging the mass spectrometer's capabilities is crucial. Techniques like extracted ion chromatograms, mass spectral deconvolution, or using a high-resolution mass spectrometer can resolve co-eluting peaks based on their unique mass fragments [7].

Targeted Applications: Implementing HPLC and GC-MS Methods in Food Matrices

High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC) represents a fundamental analytical technique that has revolutionized the analysis of non-volatile compounds in complex food matrices [40]. Its versatility in separating, identifying, and quantifying analytes has made it indispensable for assessing nutritional quality and ensuring food safety [13]. Within food and feed laboratories, HPLC serves as a cornerstone technology for implementing regulatory thresholds that establish acceptable levels for individual chemical additives, residues, and contaminants [13]. The technique's principle relies on the differential partition of analytes between a stationary phase and a liquid mobile phase under high pressure, enabling the resolution of complex mixtures into their individual components [40].

This application note details specific HPLC methodologies for four critical classes of non-volatile food components: mycotoxins, vitamins, food additives, and lipids. Each analyte category presents unique analytical challenges that require specialized approaches in sample preparation, chromatographic separation, and detection. The protocols described herein are designed to provide researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals with robust analytical procedures that can be implemented for routine analysis, method development, and research applications within the broader context of food component analysis.

Analytical Targets and Challenges

Target Compounds in Food Analysis

Mycotoxins are toxic secondary metabolites produced by filamentous fungi such as Aspergillus, Fusarium, and Penicillium, including aflatoxins (AFs), ochratoxin A (OTA), fumonisins, and zearalenone (ZEA) [41]. They are considered one of the most dangerous agricultural and food contaminants due to their toxicity and stability, with regulations specifying strict limits in foodstuffs [41]. Approximately 500 mycotoxins are currently known, contaminating nearly 40% of globally produced cereals [41].

Vitamins are complex unrelated compounds present in minute amounts in natural foodstuffs, essential to normal metabolism [13]. They are classified based on solubility characteristics as either lipid-soluble (A, D, E, K) or water-soluble (B-vitamins and C) [42]. Each vitamin can have multiple biologically active forms called vitamers that differ in potency, stability, and chemical structure [42].

Food Additives include compounds such as acidulants, antioxidants, preservatives, and sweeteners that are intentionally added to foods to serve specific technological functions [13]. These compounds must be monitored to ensure compliance with regulatory limits and to verify labeling accuracy.

Lipids serve as major constituents of foods and feeds, providing essential fat-soluble nutrients and serving as a significant source of dietary energy [13]. The primary lipid classes include glycerolipids, glycerophospholipids, and sterol lipids, each comprising numerous molecular species with variations in acyl chain length, double bonds, and regiospecificity [43].

Analytical Challenges

The analysis of these diverse compound classes presents several shared and unique challenges. Mycotoxins often exist at trace levels in complex food matrices, requiring sensitive detection methods and extensive sample clean-up [41]. Vitamins encompass a wide range of chemical structures with differing stability, necessitating careful control of extraction and analysis conditions to prevent degradation [42]. Food additives must be monitored amidst potentially interfering compounds from the food matrix, requiring selective detection methods. Lipids present challenges due to the presence of numerous isomers and isobars, demanding high-resolution separations or specific detection strategies [43].

HPLC Instrumentation and Method Development

Modern HPLC Systems

Contemporary HPLC instrumentation has evolved to provide superior separation efficiency and analytical precision [40]. Key components include:

Solvent Delivery System: Binary and quaternary gradient systems enable sophisticated mobile phase compositions, essential for complex separations [40]. Modern ultra-high-pressure pumps can operate above 15,000 psi, facilitating the use of smaller particle size columns and faster separations [40].

Sample Introduction: Advanced autosamplers offer high-precision injection volumes ranging from sub-microliter to milliliter quantities, with temperature-controlled sample storage and automated sample preparation capabilities [40].

Column Technology: The introduction of sub-2-μm particles has revolutionized separation efficiency and speed [40]. Core-shell particles, combining a solid core with a porous outer layer, offer reduced diffusion paths and improved mass transfer characteristics [40]. Monolithic columns provide high permeability and efficiency, particularly suitable for biological samples [40].

Detection Systems: The coupling of HPLC with various detection systems has significantly enhanced its analytical capabilities [40]. While UV-visible spectrophotometry remains widely used, mass spectrometry has emerged as a powerful complementary technique, providing structural information and improved selectivity in complex sample analysis [40].

Table 1: HPLC Detection Systems for Non-Volatile Food Components

| Detection Type | Detection Limit | Key Features | Primary Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| UV-DAD | ng-μg/mL | Multi-wavelength detection, Spectral analysis | General analysis, Purity assessment |

| Fluorescence | pg-ng/mL | High sensitivity, Selectivity | Trace analysis, Biological compounds |

| Mass Spectrometry | fg-pg/mL | Structural information, High selectivity | Complex mixture analysis, Unknown identification |

| CAD/ELSD | ng-μg/mL | Universal detection, Non-volatile compounds | Lipids, Polymers, Carbohydrates |

| Electrochemical | pg-ng/mL | High sensitivity for electroactive compounds | Neurotransmitters, Oxidizable compounds |

Method Development and Optimization

Method development in HPLC requires careful consideration of multiple parameters to achieve optimal separation [40]. A systematic approach should include:

Mobile Phase Selection: The choice between reversed-phase, normal-phase, or hydrophilic interaction chromatography depends on analyte properties and separation requirements [40]. Buffer selection, pH control, and organic modifier ratios play crucial roles in achieving reproducible separations.

Stationary Phase Considerations: Selection of appropriate stationary phases requires understanding molecular interactions between analytes and column chemistry [40]. Modified silica phases (C18, C8, phenyl) offer different selectivity patterns for various compound classes.

Temperature Effects: Column temperature control represents a critical parameter in method development [40]. Elevated temperatures can reduce mobile phase viscosity, allowing faster flow rates and improved mass transfer.

Gradient Optimization: Proper design of gradient elution profiles is essential for resolving complex mixtures of non-volatile compounds with varying polarities.

Diagram 1: HPLC method development workflow for non-volatile compounds

Application-Specific Protocols

Mycotoxin Analysis by HPLC-FLD and LC-MS/MS

Principle: Mycotoxins are toxic secondary metabolites produced by fungi that contaminate various agricultural products [41]. This protocol describes the determination of aflatoxins (B1, B2, G1, G2) and ochratoxin A in cereal samples using HPLC with fluorescence detection (FLD) with post-column derivatization.

Sample Preparation:

- Extraction: Weigh 25 g of homogenized sample into a blender jar. Add 5 g sodium chloride and 100 mL methanol:water (70:30, v/v). Blend at high speed for 3 minutes.

- Filtration: Filter the extract through Whatman No. 4 filter paper.

- Clean-up: Pass 10 mL filtrate through an immunoaffinity column containing antibodies specific to the target mycotoxins at a flow rate of 1-2 mL/min.

- Elution: Wash column with 10 mL water at 5 mL/min. Elute mycotoxins with 1.5 mL methanol at a flow rate of 1 mL/min. Collect eluate in a glass vial.

- Evaporation: Evaporate eluate to dryness under gentle nitrogen stream at 60°C. Reconstitute in 500 μL mobile phase for analysis.

HPLC Conditions:

- Column: C18, 150 × 4.6 mm, 5 μm

- Mobile Phase: Water:methanol:acetonitrile (57:29:14, v/v/v) with 119 mg potassium bromide and 350 μL 4M nitric acid per liter

- Flow Rate: 1.0 mL/min

- Injection Volume: 50 μL

- Temperature: 30°C

- Detection: FLD for aflatoxins B1 and G1: λex = 365 nm, λem = 435 nm; for aflatoxins B2 and G2: λex = 365 nm, λem = 435 nm; for ochratoxin A: λex = 333 nm, λem = 460 nm

- Post-column Derivatization: Electrochemically generated bromine using Kobra Cell

Table 2: HPLC-FLD Method Performance for Mycotoxin Analysis

| Mycotoxin | LOD (μg/kg) | LOQ (μg/kg) | Recovery (%) | Linearity Range (μg/kg) | RSD (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aflatoxin B1 | 0.05 | 0.15 | 88-95 | 0.15-20 | 3-8 |

| Aflatoxin B2 | 0.02 | 0.06 | 85-92 | 0.06-20 | 4-9 |

| Aflatoxin G1 | 0.05 | 0.15 | 86-94 | 0.15-20 | 3-7 |

| Aflatoxin G2 | 0.02 | 0.06 | 84-91 | 0.06-20 | 4-8 |

| Ochratoxin A | 0.10 | 0.30 | 82-90 | 0.30-50 | 5-10 |

LC-MS/MS Protocol for Multi-Mycotoxin Analysis: For comprehensive analysis of multiple mycotoxin classes, LC-MS/MS provides superior sensitivity and selectivity [44].

Sample Preparation:

- Extraction: Weigh 5 g homogenized sample into a 50 mL centrifuge tube. Add 20 mL acetonitrile:water:acetic acid (79:20:1, v/v/v).

- Shaking: Shake vigorously for 60 minutes on a horizontal shaker.

- Centrifugation: Centrifuge at 4000 × g for 10 minutes.

- Dilution: Transfer 1 mL supernatant to a clean tube and dilute with 1 mL water.

- Filtration: Filter through 0.22 μm PVDF filter prior to LC-MS/MS analysis.

LC-MS/MS Conditions:

- Column: C18, 100 × 2.1 mm, 1.7 μm

- Mobile Phase A: Water with 5 mM ammonium acetate

- Mobile Phase B: Methanol with 5 mM ammonium acetate

- Gradient: 5% B to 100% B over 15 min, hold 3 min

- Flow Rate: 0.3 mL/min

- Temperature: 40°C

- Injection Volume: 5 μL

- Ionization: ESI positive/negative switching

- Detection: MRM mode

Vitamin Analysis by HPLC-UV/DAD

Principle: This method describes the simultaneous determination of fat-soluble vitamins (A, D, E, K) in fortified food products using HPLC with diode array detection (DAD). The protocol utilizes non-aqueous reversed-phase (NARP) chromatography for separating these hydrophobic compounds [42].

Sample Preparation:

- Saponification: Weigh 2 g sample into a screw-cap tube. Add 10 mL ethanol and 1 mL 50% potassium hydroxide solution. Heat at 80°C for 30 minutes with occasional shaking.

- Extraction: Cool under running water. Add 10 mL n-hexane and shake vigorously for 2 minutes. Add 10 mL water and shake for 30 seconds.

- Centrifugation: Centrifuge at 3000 × g for 5 minutes. Transfer hexane layer to a clean tube.

- Washing: Repeat extraction twice with 10 mL n-hexane. Combine hexane layers and wash with 20 mL water.

- Evaporation: Evaporate combined hexane extracts to dryness under nitrogen at 40°C.

- Reconstitution: Dissolve residue in 1 mL methanol:tetrahydrofuran (80:20, v/v). Filter through 0.45 μm PTFE filter.

HPLC Conditions:

- Column: C30, 250 × 4.6 mm, 5 μm

- Mobile Phase A: Methanol

- Mobile Phase B: Methyl tert-butyl ether (MTBE)

- Gradient: 0-20 min: 0-25% B; 20-25 min: 25-100% B; 25-30 min: 100% B

- Flow Rate: 1.0 mL/min

- Temperature: 25°C

- Injection Volume: 20 μL

- Detection: DAD with monitoring at 265 nm (vitamin D), 292 nm (vitamin E), 325 nm (vitamin A), 248 nm (vitamin K)

Table 3: Retention Times and Method Parameters for Fat-Soluble Vitamins

| Vitamin | Retention Time (min) | LOD (μg/g) | LOQ (μg/g) | Recovery (%) | Linear Range (μg/g) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vitamin A (Retinol) | 12.5 | 0.02 | 0.05 | 92-98 | 0.05-50 |

| Vitamin D3 (Cholecalciferol) | 15.8 | 0.05 | 0.15 | 85-95 | 0.15-20 |

| Vitamin E (α-Tocopherol) | 19.2 | 0.10 | 0.30 | 90-102 | 0.30-100 |

| Vitamin K1 (Phylloquinone) | 22.4 | 0.03 | 0.10 | 88-96 | 0.10-25 |

Water-Soluble Vitamin Analysis: For B-complex vitamins and vitamin C, alternative approaches are required:

Sample Preparation for Water-Soluble Vitamins:

- Extraction: Weigh 2 g sample into a 50 mL centrifuge tube. Add 25 mL 0.1N hydrochloric acid containing 1% metaphosphoric acid.

- Homogenization: Homogenize using a probe homogenizer for 1 minute.

- Enzymatic Digestion: For bound vitamins, add 0.5 mL takadiastase solution (10% in water) and incubate at 37°C for 3 hours.

- Centrifugation: Centrifuge at 5000 × g for 10 minutes.

- Filtration: Filter supernatant through 0.45 μm nylon filter.

HPLC Conditions:

- Column: C18, 250 × 4.6 mm, 5 μm

- Mobile Phase A: 50 mM potassium phosphate buffer, pH 3.0

- Mobile Phase B: Acetonitrile

- Gradient: 0-15 min: 2-20% B; 15-20 min: 20-80% B

- Flow Rate: 1.0 mL/min

- Temperature: 30°C

- Detection: DAD with multiple wavelength monitoring

Food Additive Analysis by HPLC-UV

Principle: This protocol describes the simultaneous determination of synthetic antioxidants (BHA, BHT, TBHQ) and preservatives (benzoates, sorbates) in various food matrices using reversed-phase HPLC with UV detection.

Sample Preparation:

- Extraction: Weigh 2 g homogenized sample into a 50 mL centrifuge tube. For fatty foods, add 10 mL hexane, vortex for 2 minutes, and discard hexane layer.

- Add 10 mL acetonitrile, vortex for 2 minutes, and sonicate for 15 minutes.

- Clean-up: Add 2 g anhydrous sodium sulfate and 0.5 g C18 sorbent. Vortex for 1 minute.

- Centrifugation: Centrifuge at 5000 × g for 5 minutes.

- Filtration: Transfer supernatant and filter through 0.45 μm PTFE filter.

HPLC Conditions:

- Column: C18, 250 × 4.6 mm, 5 μm

- Mobile Phase A: Water with 0.1% acetic acid

- Mobile Phase B: Acetonitrile with 0.1% acetic acid

- Gradient: 0-10 min: 40-80% B; 10-12 min: 80-100% B; 12-15 min: 100% B

- Flow Rate: 1.2 mL/min

- Temperature: 35°C

- Injection Volume: 20 μL

- Detection: UV at 280 nm

Table 4: HPLC-UV Method Performance for Food Additives

| Additive | Retention Time (min) | LOD (mg/kg) | LOQ (mg/kg) | Recovery (%) | Regulatory Limit (mg/kg) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BHA | 6.8 | 0.1 | 0.3 | 85-95 | 200 |

| BHT | 9.2 | 0.2 | 0.5 | 82-90 | 100 |

| TBHQ | 7.5 | 0.1 | 0.3 | 88-96 | 200 |

| Potassium Sorbate | 4.3 | 0.5 | 1.5 | 90-102 | 1000-2000 |

| Sodium Benzoate | 5.1 | 0.5 | 1.5 | 92-105 | 1000-1500 |

Lipid Analysis by HPLC-ELSD/CAD

Principle: This method describes the separation and quantification of lipid classes including triacylglycerols (TAG), diacylglycerols (DAG), monoacylglycerols (MAG), and phospholipids using HPLC with evaporative light scattering detection (ELSD) or charged aerosol detection (CAD). These detection techniques provide universal response for non-volatile compounds without requiring chromophores [45].

Sample Preparation:

- Lipid Extraction: Weigh 1 g sample into a glass tube. Add 10 mL chloroform:methanol (2:1, v/v) and vortex for 2 minutes.

- Partitioning: Add 2 mL 0.9% sodium chloride solution, vortex for 1 minute, and centrifuge at 3000 × g for 10 minutes.

- Collection: Collect lower chloroform layer containing lipids.

- Re-extraction: Re-extract aqueous phase with 5 mL chloroform. Combine chloroform layers.

- Drying: Evaporate under nitrogen at 40°C. Reconstitute in 2 mL isopropanol:hexane (80:20, v/v). Filter through 0.45 μm PTFE filter.

HPLC Conditions for Neutral Lipids:

- Column: C18, 250 × 4.6 mm, 5 μm

- Mobile Phase A: Acetonitrile

- Mobile Phase B: Isopropanol:hexane (80:20, v/v)

- Gradient: 0-5 min: 100% A; 5-40 min: 0-100% B; 40-50 min: 100% B

- Flow Rate: 1.0 mL/min

- Temperature: 35°C

- Injection Volume: 10 μL

- Detection: ELSD with drift tube temperature: 50°C, nebulizer gas: 1.0 mL/min (nitrogen), gain: 3 [45]

HPLC Conditions for Phospholipids:

- Column: Silica, 250 × 4.6 mm, 5 μm

- Mobile Phase A: Chloroform:methanol:ammonium hydroxide (80:19.5:0.5, v/v/v)

- Mobile Phase B: Chloroform:methanol:water:ammonium hydroxide (60:34:5.5:0.5, v/v/v/v)

- Gradient: 0-20 min: 0-100% B; 20-25 min: 100% B

- Flow Rate: 1.0 mL/min

- Detection: ELSD with drift tube temperature: 45°C

Table 5: HPLC-ELSD Retention Times and Response Factors for Lipid Classes

| Lipid Class | Retention Time (min) | LOD (μg) | LOQ (μg) | Response Factor | Key Molecular Species |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cholesterol | 8.5 | 0.1 | 0.3 | 1.00 | - |

| DAG | 15.2 | 0.2 | 0.5 | 0.85 | 1,2-DAG; 1,3-DAG |

| MAG | 12.8 | 0.3 | 0.8 | 0.78 | 1-MAG; 2-MAG |

| TAG | 22-35 | 0.5 | 1.5 | 1.12 | Varies by acyl chains |

| PC | 18.5 | 0.2 | 0.6 | 0.95 | Phosphatidylcholine |

| PE | 20.3 | 0.3 | 0.8 | 0.88 | Phosphatidylethanolamine |

| PS | 23.7 | 0.4 | 1.0 | 0.82 | Phosphatidylserine |

Diagram 2: Sample preparation workflow for HPLC analysis of non-volatiles

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 6: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for HPLC Analysis of Non-Volatiles

| Reagent/Material | Function | Application Examples | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Immunoaffinity Columns | Selective clean-up of target analytes using antibody-antigen interactions | Mycotoxin extraction from cereals, nuts, dairy products | High specificity, single-use, various targets available |

| C18 Solid-Phase Extraction Cartridges | Reversed-phase extraction of medium to non-polar compounds | Lipid extraction, vitamin purification, additive isolation | Various sizes (1g, 500mg, 100mg), requires conditioning |

| Molecularly Imprinted Polymers (MIPs) | Synthetic polymer sorbents with specific recognition sites | Selective mycotoxin extraction, additive clean-up | Stable, high specificity, reduces matrix interference [41] |

| Derivatization Reagents | Chemical modification to enhance detection properties | FLD detection of aflatoxins, vitamin analysis | Improves sensitivity and selectivity for certain detectors |

| Matrix-Matched Standards | Calibration standards prepared in blank matrix | Quantification to compensate for matrix effects | Essential for accurate quantification in complex matrices |

| Stable Isotope-Labeled Internal Standards | Internal standards for mass spectrometry | LC-MS/MS analysis of mycotoxins, vitamins, additives | Compensates for extraction and ionization variability |