From Waste to Wellness: Advanced Extraction and Characterization of Bioactive Compounds for Biomedical Applications

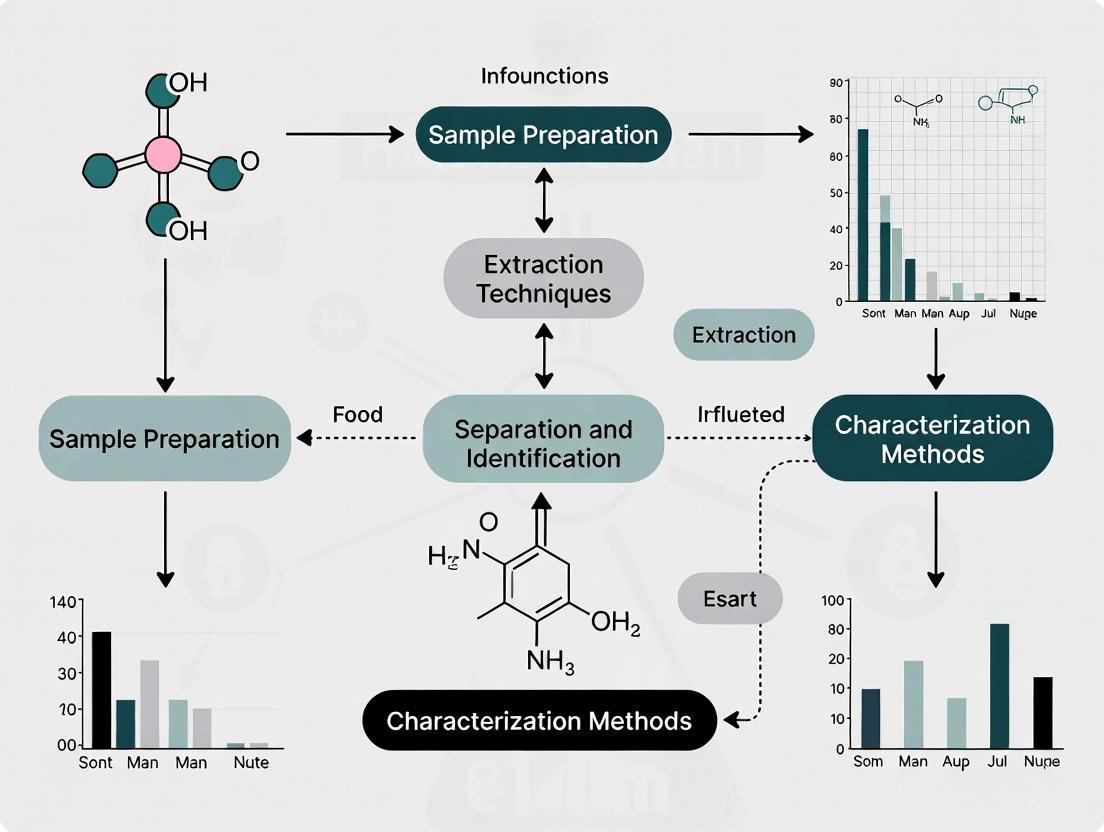

This comprehensive review addresses the critical process of obtaining and analyzing bioactive compounds from food and agri-food waste for drug development and biomedical research.

From Waste to Wellness: Advanced Extraction and Characterization of Bioactive Compounds for Biomedical Applications

Abstract

This comprehensive review addresses the critical process of obtaining and analyzing bioactive compounds from food and agri-food waste for drug development and biomedical research. It explores the foundational science behind these health-promoting compounds, details both traditional and cutting-edge extraction methodologies, and provides strategies to overcome key challenges in scalability and compound bioavailability. The article further covers advanced characterization techniques and comparative analysis of methods, offering researchers and pharmaceutical professionals a validated framework for efficiently translating natural compounds into therapeutic applications, thereby bridging the gap between food science and clinical innovation.

Unlocking Nature's Pharmacy: The Science and Sources of Bioactive Compounds

Bioactive compounds are extra-nutritional, physiologically active components naturally present in small quantities in plants, microalgae, and other biological sources [1] [2]. These compounds have gained substantial attention for their potential health benefits and functional properties, extending beyond basic nutrition to provide therapeutic effects [3] [4]. The growing interest in bioactive compounds stems from epidemiological evidence linking diets rich in these components—such as the Mediterranean diet—with lower incidence of cardiovascular, metabolic, and neurodegenerative diseases, as well as cancer [1].

These compounds demonstrate a broad spectrum of therapeutic activities, including antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, antimicrobial, antithrombotic, cardioprotective, and vasodilatory properties [2]. Well-established sources of bioactive molecules include fruits, vegetables, grains, legumes, herbs, fermented foods, and marine organisms, which are rich in diverse compounds such as flavonoids, phenolic acids, carotenoids, glucosinolates, alkaloids, vitamins, and probiotics [1]. The global agricultural production system also generates substantial agri-food wastes that represent valuable sources of these compounds, promoting sustainability while providing health benefits [5].

Table 1: Major Classes of Bioactive Compounds and Their Characteristics

| Compound Class | Subclasses | Natural Sources | Key Health Benefits |

|---|---|---|---|

| Polyphenols | Flavonoids, Phenolic acids, Lignans, Stilbenes | Berries, apples, green tea, cocoa, coffee, whole grains, flaxseeds, red wine | Cardiovascular protection, anti-inflammatory effects, neuroprotection, antioxidant properties [1] [4] |

| Carotenoids | Beta-carotene, Lutein, Zeaxanthin | Carrots, sweet potatoes, spinach, mangoes, pumpkin, kale, corn, egg yolk | Vision support, immune function, skin health, blue light filtration [4] |

| Bioactive Peptides | Lactoferrin, Casokinins, Lactokinins | Fermented foods, dairy products, animal proteins | Immunomodulatory, antihypertensive, antioxidant, mineral-binding properties [1] [6] |

| Alkaloids | Caffeine, Nicotine, Morphine | Tea, coffee, cacao, medicinal plants | Neuroprotective, anti-inflammatory, analgesic effects [3] [2] |

| Terpenoids | Monoterpenes, Sesquiterpenes, Diterpenes | Herbs, spices, citrus fruits, microalgae | Antimicrobial, anticancer, anti-inflammatory properties [3] [7] |

Extraction Methodologies

Conventional Extraction Techniques

Traditional extraction methods have been widely used for recovering bioactive compounds from biological matrices. These include techniques such as maceration, soxhlet extraction, hydro-distillation, and steam distillation [5] [8]. Solvent extraction relies on organic solvents like ethanol, acetone, and methanol to break down the plant matrix and extract target compounds [5]. The efficiency of these methods depends on several factors including solvent selection, temperature, extraction duration, and solid-to-liquid ratio [5].

Maceration involves soaking plant material in solvent with periodic agitation to facilitate compound dissolution. This technique is particularly suitable for heat-sensitive compounds but requires extended processing times [8]. Soxhlet extraction provides continuous washing of the sample with fresh solvent, improving extraction efficiency but potentially degrading thermolabile compounds due to prolonged heating [5]. Steam distillation is primarily used for extracting volatile compounds, exposing algal or plant biomass to steam at temperatures ranging from 180-240°C followed by rapid depressurization [8].

Table 2: Comparison of Extraction Methods for Bioactive Compounds

| Extraction Method | Principles | Advantages | Limitations | Optimal Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Solvent Extraction | Uses organic solvents to dissolve compounds from matrix | Simple operation, low equipment cost, high capacity | Large solvent consumption, potential toxicity, long extraction time | Wide application for various compound classes [5] |

| Ultrasound-Assisted Extraction (UAE) | Uses ultrasonic waves to generate cavitation bubbles that disrupt cells | Reduced extraction time, lower solvent consumption, higher yields | Possible degradation of compounds, scalability challenges | Polyphenols, flavonoids, carotenoids from plant materials [3] [5] |

| Microwave-Assisted Extraction (MAE) | Uses microwave energy to heat solvents and samples rapidly | Rapid heating, reduced solvent use, high efficiency | Non-uniform heating, safety concerns, equipment cost | Thermostable compounds from various matrices [3] [5] |

| Supercritical Fluid Extraction (SFE) | Uses supercritical fluids (typically CO₂) as extraction solvent | Green technology, tunable selectivity, low environmental impact | High capital cost, high pressure requirements, limited polarity | Lipophilic compounds, essential oils, pigments [3] [5] |

| Enzyme-Assisted Extraction (EAE) | Uses enzymes to degrade cell walls and release compounds | Mild conditions, high specificity, environmentally friendly | High enzyme cost, optimization complexity, longer processing | Heat-sensitive compounds, bound phenolics [5] |

Emerging Extraction Technologies

Modern extraction techniques have been developed to address limitations of conventional methods, offering improved efficiency, sustainability, and compound preservation [3] [5]. Ultrasound-assisted extraction (UAE) utilizes ultrasonic waves to generate cavitation bubbles that implode, creating shock waves that disrupt plant cells and enhance mass transfer [5]. This method has proven effective for extracting polyphenols, flavonoids, and carotenoids with reduced processing time and solvent consumption [5].

Microwave-assisted extraction (MAE) employs microwave energy to rapidly heat solvents and samples, causing instantaneous cell rupture due to internal pressure buildup [3]. MAE significantly reduces extraction time while improving yield and is particularly effective for thermostable compounds [5]. Supercritical fluid extraction (SFE), most commonly using CO₂ as the supercritical fluid, offers tunable selectivity by adjusting pressure and temperature parameters [3]. This method is considered environmentally friendly and is ideal for extracting lipophilic compounds, essential oils, and pigments [5].

Enzyme-assisted extraction (EAE) uses specific enzymes such as cellulases, proteases, and pectinases to degrade cell walls and liberate bound compounds under mild conditions [5]. This method preserves heat-sensitive bioactive compounds and has demonstrated enhanced extraction of phenolic compounds from citrus peel compared to traditional methods [5]. However, EAE faces challenges related to enzyme costs and optimization complexity that may limit industrial applications [5].

Analytical Characterization Techniques

Separation and Identification Methods

Advanced analytical techniques are essential for separating, identifying, and characterizing the complex mixture of bioactive compounds present in natural sources [3] [9]. Chromatographic methods including high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC), ultra-high-performance liquid chromatography (UHPLC), and gas chromatography (GC) are widely employed for compound separation [3] [7]. These techniques are often coupled with various detection systems to provide comprehensive analysis.

The combination of liquid chromatography with mass spectrometry (LC-MS), particularly using quadrupole time-of-flight (QTOF) analyzers, has revolutionized the identification of bioactive compounds [7] [10]. UPLC-QTOF-MS offers high resolution, sensitivity, and mass accuracy, enabling the tentative identification of compounds even without reference standards [7] [10]. This technique was successfully applied to characterize forty constituents in the "ginseng-polygala" drug pair, with twelve compounds accurately identified using reference standards [10].

Spectroscopic techniques including nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR), infrared (IR) spectroscopy, and ultraviolet-visible (UV-Vis) spectroscopy provide complementary structural information [3]. NMR is particularly powerful for complete structural elucidation of unknown compounds, while FT-IR offers functional group information [5]. UV-Vis spectroscopy is commonly used for quantification of specific compound classes like polyphenols and carotenoids [5].

Analytical Workflow for Bioactive Compounds

Quantification and Quality Assessment

Accurate quantification of bioactive compounds is crucial for standardizing extracts and establishing dose-response relationships [7] [10]. High-performance liquid chromatography with various detectors (UV, DAD, ELSD) is routinely used for quantitative analysis [10] [9]. For instance, HPLC quantification of the "ginseng-polygala" drug pair revealed that quercetin-3-O-α-l-rhamnoside and amentoflavone were present at 203.78 and 69.84 mg/g respectively in the crude extract [7].

Recent advances in hyperspectral imaging (HSI) and near-infrared spectroscopy (NIRS) have enabled rapid, non-destructive quality assessment of medicinal plants and functional ingredients [9]. These techniques provide both spatial and spectral information, allowing for the visualization of compound distribution within samples while reducing analysis time and solvent consumption [9].

Table 3: Analytical Techniques for Bioactive Compound Characterization

| Analytical Technique | Principles | Applications | Sensitivity | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HPLC/UPLC | High-pressure liquid separation with various detectors | Quantitative analysis, quality control, purity assessment | High (ng-μg) | Requires standards, method development |

| LC-MS/QTOF-MS | Liquid separation coupled with high-resolution mass spectrometry | Structural identification, metabolite profiling, unknown compound characterization | Very high (pg-ng) | High cost, complex data interpretation |

| GC-MS | Gas separation coupled with mass spectrometry | Volatile compounds, fatty acids, essential oils | High (ng) | Limited to volatile/derivatized compounds |

| NMR Spectroscopy | Magnetic properties of atomic nuclei in magnetic field | Complete structural elucidation, stereochemistry determination | Moderate (μg-mg) | Lower sensitivity, expensive equipment |

| FT-IR Spectroscopy | Molecular vibration measurements using infrared light | Functional group identification, quality screening | Moderate (μg) | Limited structural information |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: UPLC-QTOF-MS Analysis of Flavonoids and Lignans

Objective: To qualitatively analyze major bioactive components in plant extracts using UPLC-QTOF-MS [7].

Materials and Reagents:

- Plant material (e.g., Juniperus chinensis L. leaves)

- Methanol (HPLC grade)

- Formic acid (LC-MS grade)

- Reference standards (isoquercetin, quercetin-3-O-α-l-rhamnoside, amentoflavone, etc.)

- Deionized water (HPLC grade)

Equipment:

- UPLC system with binary pump, autosampler, and column compartment

- Quadrupole time-of-flight mass spectrometer with electrospray ionization (ESI) source

- C18 reversed-phase column (100 × 2.1 mm, 1.7 μm)

- Centrifuge

- Ultrasonic bath

- 0.45 μm nylon membrane filters

Procedure:

- Sample Preparation: Reduce plant material to fine powder using a grinder. Accurately weigh 1.0 g of powder and extract with 10 mL methanol using ultrasonication for 60 minutes. Centrifuge at 10,000 × g for 10 minutes and filter the supernatant through a 0.45 μm nylon membrane [7] [10].

UPLC Conditions:

- Column temperature: 40°C

- Injection volume: 2 μL

- Flow rate: 0.3 mL/min

- Mobile phase A: 0.1% formic acid in water

- Mobile phase B: 0.1% formic acid in acetonitrile

- Gradient program: 5-30% B (0-5 min), 30-60% B (5-10 min), 60-95% B (10-15 min), 95% B (15-17 min), 95-5% B (17-18 min), 5% B (18-20 min) [7]

QTOF-MS Parameters:

Data Analysis: Acquire data using appropriate software. Process raw data by peak picking, alignment, and normalization. Identify compounds by matching accurate mass, isotopic pattern, and fragmentation spectra with databases and reference standards [7].

Troubleshooting Tips:

- If peak resolution is poor, optimize gradient elution program

- If sensitivity is low, check ion source cleanliness and optimize fragmentor voltage

- For complex samples, use molecular networking strategy to cluster related compounds [10]

Protocol 2: HPLC Quantification of Major Bioactive Compounds

Objective: To quantitatively determine specific bioactive compounds in plant extracts using HPLC [10].

Materials and Reagents:

- Standard compounds (purity >98%)

- Acetonitrile (HPLC grade)

- Methanol (HPLC grade)

- Phosphoric acid or formic acid (HPLC grade)

- Deionized water (HPLC grade)

Equipment:

- HPLC system with DAD or UV detector

- C18 column (250 × 4.6 mm, 5 μm)

- Analytical balance

- Ultrasonic bath

- 0.45 μm membrane filters

Procedure:

- Standard Solution Preparation: Precisely weigh 4.00 mg of each reference standard and dissolve in 1.0 mL methanol to prepare stock solutions. Prepare working standards by appropriate dilution with methanol [10].

Sample Preparation: Extract plant material as described in Protocol 1. Filter through 0.45 μm membrane before injection [10].

HPLC Conditions:

- Detection wavelength: 254-360 nm (depending on compounds)

- Column temperature: 30°C

- Injection volume: 10 μL

- Flow rate: 1.0 mL/min

- Mobile phase: Various gradients of water with 0.1% acid and acetonitrile [10]

Calibration Curve: Inject series of standard solutions at different concentrations. Plot peak area against concentration to generate calibration curves. Calculate regression equations and correlation coefficients (R² > 0.999) [10].

Validation: Determine linearity, limit of detection (LOD), limit of quantification (LOQ), precision, and accuracy according to ICH guidelines [10].

Calculation: Compound content (mg/g) = (C × V × D) / W Where: C = concentration from calibration curve (mg/mL), V = volume of extract (mL), D = dilution factor, W = weight of sample (g)

Bioactivity Assessment and Mechanisms of Action

Signaling Pathways and Molecular Mechanisms

Bioactive compounds exert their therapeutic effects through modulation of key cellular signaling pathways [6]. Polyphenols such as flavonoids, catechins, and resveratrol demonstrate antioxidant and anti-inflammatory activities primarily through the p38 MAPK/Nrf2 pathway, which regulates oxidative stress responses and cellular antioxidant defenses [6]. For instance, mulberry leaf flavonoids and carnosic acid complex have been shown to enhance antioxidant capacity in broilers by activating this pathway [6].

Bioactive peptides influence inflammatory processes by modulating the MAPK and NF-κB signaling pathways, thereby reducing the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines and providing a natural alternative to non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) [6]. Catechins from green tea, particularly (-)-Epigallocatechin-3-gallate (EGCG), exhibit neuroprotective effects by attenuating neuroinflammatory processes and oxidative stress mechanisms, showing promise for Alzheimer's and Parkinson's diseases [6].

Cellular Mechanisms of Bioactive Compounds

Bioactivity Screening Methods

In vitro models provide efficient systems for initial bioactivity screening. The PC12 cell line, derived from rat pheochromocytoma, serves as a valuable model for neuroprotective activity assessment [10]. In one study, Aβ₂₅‑₃₅-induced PC12 cells were used as an in vitro injury model to evaluate the effects of the "ginseng-polygala" drug pair on Alzheimer's disease treatment [10]. Results demonstrated that the drug pair significantly increased cell viability and reduced reactive oxygen species and inflammatory factor levels [10].

Antibacterial activity screening against pathogenic bacteria provides valuable information for potential antimicrobial applications. The crude extract of Juniperus chinensis L. leaves exhibited potential antibacterial activity against ten pathogenic bacteria, with the highest activity detected against Bordetella pertussis [7]. Standard methods include disk diffusion, broth microdilution for MIC determination, and time-kill assays.

Antioxidant capacity assays including DPPH, ABTS, FRAP, and ORAC are routinely employed to quantify free radical scavenging activity of bioactive compounds [2]. These assays provide valuable information about potential protective effects against oxidative stress-related diseases.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Bioactive Compound Analysis

| Research Reagent/Material | Specification | Application Function | Example Vendors/ Sources |

|---|---|---|---|

| HPLC Grade Solvents | Methanol, Acetonitrile, Water (≥99.9% purity) | Mobile phase preparation, sample extraction | Sigma-Aldrich, Fisher Scientific, Tedia |

| Reference Standards | Certified purity (>95-98%) | Compound identification, quantification calibration | Chengdu Preferred Biological Technology, Sigma-Aldrich, ChromaDex |

| UHPLC/QTOF-MS System | High-resolution mass accuracy (<5 ppm) | Structural characterization, unknown compound identification | Agilent, AB SCIEX, Waters, Thermo Scientific |

| Chromatography Columns | C18 reversed-phase (1.7-5 μm particle size) | Compound separation based on hydrophobicity | Waters, Phenomenex, Agilent |

| Cell Lines | PC12, Caco-2, RAW 264.7, HEK293 | Bioactivity screening, mechanism studies | ATCC, Boster Biological Technology |

| Bioassay Kits | Antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, cytotoxicity | Quantitative bioactivity assessment | Sigma-Aldrich, Abcam, Cayman Chemical |

| Solid Phase Extraction | C18, silica, ion-exchange cartridges | Sample clean-up, compound enrichment | Waters, Phenomenex, Sigma-Aldrich |

Applications in Functional Foods and Pharmaceuticals

The application of bioactive compounds spans multiple industries including functional foods, nutraceuticals, pharmaceuticals, and cosmeceuticals [3] [4]. In the functional food sector, bioactive compounds are incorporated into diverse matrices including fortified beverages, dairy products, snack items, and dietary supplements [4]. These applications leverage the dual functionality of bioactive compounds, which can improve shelf-life, safety, and sensory qualities of foods while providing health benefits [1].

Modern biotechnological and AI-driven approaches have revolutionized the precision and efficacy of functional food development by enabling high-throughput screening of bioactive compounds, predictive modeling for formulation, and large-scale data mining to identify novel ingredient interactions and health correlations [4]. These technologies help overcome challenges related to stability, bioavailability, and regulatory compliance [4].

Pharmaceutical applications of bioactive compounds include their use as natural anti-inflammatory agents, neuroprotective compounds, and antimicrobial therapies [6]. For instance, ellagic acid supplementation in multiple sclerosis patients has demonstrated significant reduction in inflammatory cytokines and modulation of gene expression related to immune response [6]. Similarly, polyphenolic natural products like curcumin, quercetin, and resveratrol show promise as photosensitizers in antimicrobial photodynamic therapy, offering solutions to rising antibiotic resistance concerns [6].

The growing body of evidence supporting the health benefits of bioactive compounds has led to their incorporation into dietary guidelines and health policies on a global scale [4]. However, regulatory landscapes for functional foods and nutraceuticals vary regionally, requiring collaboration between food scientists, nutritionists, and regulatory agencies to ensure scientific validation, quality control, and appropriate labeling [4].

Agri-Food Waste as a Rich, Untapped Reservoir for Drug Discovery

The valorization of agri-food waste represents a paradigm shift in the approach to drug discovery, aligning with the principles of the circular bioeconomy. Globally, an estimated one-third of all food produced, approximately 1.3 billion tons annually, is lost or wasted [11] [12]. This inefficiency is not only an economic and ethical issue but also represents a monumental misallocation of bioactive compounds with therapeutic potential. Agricultural and food production residues, once considered low-value biomass, are now recognized as rich sources of polyphenols, carotenoids, flavonoids, and other bioactive phytochemicals [13] [14]. This application note details the extraction, characterization, and therapeutic evaluation protocols for bioactives derived from agri-food waste, providing researchers with a framework for transforming waste into valuable pharmacological agents.

Bioactive Compound Diversity in Agri-Food Waste

Agri-food wastes, including peels, seeds, pulp, husks, and leaves, are abundant sources of diverse bioactive compounds. The composition and concentration of these phytochemicals vary significantly based on the waste source, genotype, environmental conditions, and harvest timing [13].

Table 1: Key Bioactive Compounds in Selected Agri-Food Wastes and Their Potential Therapeutic Applications

| Agri-Food Waste Source | Predominant Bioactive Compounds | Reported Bioactivities | Potential Therapeutic Application |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cinnamon Leaves [13] | Cinnamaldehyde, Flavonoids | Neuroprotective, Antioxidant | Parkinson's Disease Therapy |

| Sesame Seed Coat [13] | Phenolic Compounds | Antimicrobial, Antioxidant | Food Preservation, Infectious Disease |

| Almond Shells [13] | Cellulose Nanocrystals (CNCs) | Biocompatibility, Structural | Drug Delivery Scaffolds |

| Wheat Processing Waste [15] | Ferulic Acid, Dihydroferulic Acid | Antioxidant (ABTS: 8.598 mmol Trolox/kg), Biocompatible | Cosmeceuticals, Topical Formulations |

| Fruit Peels & Vegetable Residues [12] [14] | Polyphenols, Carotenoids, Flavonoids | Antioxidant, Anti-inflammatory, Anticarcinogenic | Chronic Disease Prevention & Management |

The intrinsic biological and ecological factors that regulate phytochemical accumulation are critical. Studies have demonstrated that harvest timing and genetic diversity have profound effects on the nutritional properties and composition of different plant species [13]. For instance, seasonal dynamics markedly influence the flavonoid and phenolic profiles in plant species like Rheum officinale, with antioxidant activity peaking at distinct growth stages [13]. This temporal and genetic variation must be considered when sourcing raw materials for reproducible drug discovery efforts.

Protocols for Extraction and Isolation

The recovery of bioactive compounds from agri-food waste requires efficient, selective, and environmentally responsible extraction technologies. Conventional methods are often limited by low efficiency, high energy consumption, and the use of hazardous solvents. The following protocols outline advanced, sustainable extraction techniques.

Microwave-Assisted Extraction (MAE) of Cellulose Nanocrystals

This protocol, adapted from Valdés et al., is designed for the extraction of cellulose nanocrystals (CNCs) from lignocellulosic waste like almond shells [13]. CNCs are promising for creating biodegradable drug delivery systems.

- Objective: To efficiently extract high-purity cellulose nanocrystals from almond shell waste.

- Materials:

- Raw Material: Dried, milled almond shells (Prunus amygdalus).

- Reagents: Sodium hydroxide (NaOH), Acetic acid, Sulfuric acid (H₂SO₄), Distilled water.

- Equipment: Microwave reactor system, Centrifuge, Vacuum filtration unit, Dialysis tubing, Sonicator, Fourier-Transform Infrared (FTIR) Spectrometer, X-Ray Diffractometer (XRD).

- Procedure:

- Pre-treatment: Treat 20g of dried almond shell powder with 500 mL of 4% w/v NaOH solution at 80°C for 2 hours to remove lignin and hemicellulose. Wash the residue to neutrality.

- Bleaching: Treat the pre-treated material with an acidic solution (e.g., acetate buffer) at 80°C for 1 hour to further purify the cellulose. Wash thoroughly.

- Microwave-Assisted Acid Hydrolysis: Suspend the bleached cellulose in 250 mL of 60% w/w H₂SO₄. Subject the mixture to microwave irradiation (e.g., 400W, 70°C) for 30-45 minutes under continuous stirring.

- Quenching & Purification: Dilute the reaction mixture 10-fold with ice-cold distilled water to stop hydrolysis. Centrifuge at 10,000 rpm for 15 minutes. Wash the pellet repeatedly until the supernatant is neutral. Purify the resulting CNCs via dialysis against distilled water for 3 days.

- Dispersion: Sonicate the final CNC suspension in water for 10-15 minutes to ensure a homogeneous dispersion.

- Analysis: The success of extraction is determined by:

- FTIR: To confirm chemical structure and removal of non-cellulosic components.

- XRD: To determine crystallinity index, which MAE enhances compared to traditional methods [13].

Ultrasound-Assisted Extraction (UAE) of Phenolic Compounds

This protocol is effective for recovering heat-sensitive phenolic antioxidants from sources like fruit peels and seed coats [13] [12] [14].

- Objective: To extract antioxidant phenolic compounds from sesame seed coats using ultrasound.

- Materials:

- Raw Material: Dried sesame seed coat powder.

- Reagents: Food-grade ethanol, Folin-Ciocalteu reagent, Gallic acid, Trolox.

- Equipment: Ultrasonic bath or probe sonicator, Centrifuge, Rotary evaporator, Spectrophotometer.

- Procedure:

- Preparation: Mix 5g of sesame seed coat powder with 100 mL of a 50% ethanol/water solution.

- Sonication: Subject the mixture to ultrasound using a probe sonicator at an amplitude of 60% for 10 minutes, maintaining the temperature below 40°C using an ice bath.

- Separation: Centrifuge the sonicated mixture at 5,000 rpm for 10 minutes. Collect the supernatant.

- Concentration: Concentrate the supernatant under reduced pressure at 40°C using a rotary evaporator.

- Lyophilization: Lyophilize the concentrated extract to obtain a dry powder for storage and further use.

- Analysis:

The following workflow visualizes the complete valorization pathway from raw agri-food waste to a characterized drug delivery system.

Agri-Food Waste Valorization Workflow

Protocols for Chemical Characterization and Biological Evaluation

UHPLC-Q-Orbitrap HRMS for Phytochemical Profiling

This high-resolution mass spectrometry technique is essential for identifying and quantifying bioactive compounds in complex waste extracts [13] [15].

- Objective: To characterize the polyphenolic profile of wheat-based solid waste.

- Materials:

- Sample: Polyphenolic extract from solid wheat waste (from Protocol 3.2).

- Reagents: Methanol, Acetonitrile (UHPLC-MS grade), Formic Acid, Water (UHPLC-MS grade), Polyphenol standards (e.g., ferulic acid).

- Equipment: UHPLC system coupled to Q-Exactive Orbitrap mass spectrometer, C18 reversed-phase column (e.g., 2.1 x 100 mm, 1.7 µm).

- Procedure:

- Chromatographic Separation:

- Mobile Phase A: 0.1% Formic acid in water.

- Mobile Phase B: 0.1% Formic acid in acetonitrile.

- Gradient: 5% B to 95% B over 25 minutes.

- Flow Rate: 0.3 mL/min.

- Injection Volume: 2 µL.

- Mass Spectrometric Detection:

- Ionization Mode: Heated Electrospray Ionization (HESI) in negative and positive modes.

- Full Scan Parameters: Resolution: 70,000; Scan Range: m/z 100-1500.

- Data-Dependent MS/MS: Resolution: 17,500; Top 5 most intense ions.

- Chromatographic Separation:

- Data Analysis: Identify compounds by matching accurate mass and MS/MS fragmentation patterns against databases (e.g., mzCloud, HMDB) and confirm by comparison with authentic standards. Quantify predominant compounds like ferulic acid using external calibration curves [15].

In Vitro Neuroprotective Efficacy Screening

This protocol evaluates the neuroprotective potential of bioactive extracts, as demonstrated in studies on cinnamon leaf extracts [13].

- Objective: To assess the neuroprotective effect of a cinnamon leaf extract nanoemulsion in a cellular or animal model of Parkinson's disease.

- Materials:

- Test Substance: Nanoemulsion encapsulated cinnamon leaf extract.

- In Vitro Model: SH-SY5Y neuroblastoma cells.

- Inducing Agent: 1-Methyl-4-phenylpyridinium (MPP⁺) to induce Parkinsonian phenotype.

- Assay Kits: MTT assay kit for cell viability, Caspase-3 activity kit for apoptosis, ELISA kits for oxidative stress markers (e.g., ROS, GSH).

- Procedure:

- Cell Culture & Treatment: Maintain SH-SY5Y cells in standard culture conditions.

- Pre-treatment Group: Incubate cells with the nanoemulsion (e.g., 10-100 µg/mL) for 24 hours.

- Injury Group: Expose cells to MPP⁺ (e.g., 1 mM) for 24 hours to induce damage.

- Therapeutic Group: Pre-treat with nanoemulsion, then co-treat with MPP⁺.

- Viability Assay: Use MTT assay per manufacturer's instructions to measure cell viability after 24 hours of treatment.

- Apoptosis Analysis: Measure Caspase-3 activity in cell lysates as a marker of apoptosis.

- Oxidative Stress Measurement: Quantify intracellular ROS levels and glutathione (GSH) levels using commercially available kits.

- Cell Culture & Treatment: Maintain SH-SY5Y cells in standard culture conditions.

- Analysis: Compare viability, apoptosis, and oxidative stress markers across treatment groups. A significant improvement in the therapeutic group compared to the injury group indicates neuroprotective efficacy. In vivo models can further assess motor function improvements [13].

Advanced Formulation: Nanoencapsulation and 3D Printing

To overcome challenges like poor bioavailability and stability, advanced formulation strategies are crucial.

Nanoemulsion Encapsulation for Antimicrobial Application

This protocol details the encapsulation of sesame seed coat phenolics for antimicrobial use in food preservation and potential topical applications [13].

- Objective: To fabricate a nanoemulsion for the delivery of antimicrobial phenolic compounds.

- Materials: Sesame seed coat phenolic extract, Food-grade surfactant (e.g., Tween 80), Oil phase (e.g., medium-chain triglyceride, MCT), High-speed homogenizer, Ultrasonic processor.

- Procedure:

- Oil Phase: Dissolve the phenolic extract in the MCT oil.

- Aqueous Phase: Dissolve the surfactant in distilled water.

- Pre-emulsification: Slowly add the oil phase to the aqueous phase under high-speed homogenization (10,000 rpm for 5 minutes).

- Nanoemulsification: Further process the coarse emulsion using an ultrasonic processor at 200 W for 10 minutes (pulse mode 5s on/5s off) in an ice bath.

- Characterization: Analyze droplet size, polydispersity index (PDI), and zeta potential using dynamic light scattering. Test antimicrobial efficacy in a model system (e.g., milk preservation) by monitoring microbial load reduction over time [13].

3D Printing of Drug Delivery Systems from Food Waste

This emerging technology uses biopolymers derived from food waste, such as cellulose and lignin, to create customized drug delivery systems [16].

- Objective: To develop a 3D-printed drug delivery system using a bio-ink derived from food waste.

- Materials:

- Biopolymers: Rice husk cellulose, Soy protein, or other waste-derived polymers.

- Bio-ink Preparation Equipment: Mixer, Syringe.

- 3D Printer: Extrusion-based 3D bioprinter.

- Procedure:

- Bio-ink Formulation: Blend the purified food waste biopolymer (e.g., 5% w/v) with a biocompatible crosslinker (e.g., calcium chloride for alginate) and the active pharmaceutical ingredient (API).

- Printing: Load the bio-ink into a syringe and print onto a substrate using pre-designed software models (e.g., a lattice structure for controlled release).

- Post-processing: Crosslink the printed structure by exposing it to a crosslinking vapor or solution.

- Evaluation: Test the mechanical stability, drug release profile in simulated physiological fluids, and biocompatibility in cell cultures [16].

Table 2: Advanced Formulation Technologies for Agri-Waste Bioactives

| Formulation Technology | Core Material/Process | Key Advantages | Application in Drug Discovery |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nanoencapsulation [13] | Formation of oil-in-water nanoemulsions | Enhances solubility, stability, and bioefficacy of sensitive phenolics | Targeted antimicrobial delivery; Improved bioavailability of neuroprotective compounds |

| 3D Printing [16] | Food waste-derived bio-inks (e.g., cellulose, lignin) | Enables patient-specific, customizable geometries for controlled release | Fabrication of tailored drug delivery implants and scaffolds |

| Microbial Electrochemical Systems (METs) [17] | Electroactive bacteria on electrodes | Recovers energy and value-added products from solubilized organic waste | Sustainable production of biochemical precursors for pharmaceuticals |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Agri-Waste Valorization

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application | Example Use in Protocol |

|---|---|---|

| UHPLC-Q-Orbitrap HRMS System | High-resolution separation and identification of bioactive compounds. | Precise quantification of ferulic acid in wheat waste [15]. |

| Microwave Reactor System | Enhanced extraction efficiency with reduced solvent and time. | Extraction of cellulose nanocrystals from almond shells [13]. |

| Ultrasonic Processor | Cell disruption and formation of nanoemulsions. | Creating nanoemulsions of sesame seed phenolics; Ultrasound-assisted extraction [13] [14]. |

| Food-Grade Surfactants (e.g., Tween 80) | Stabilization of nanoemulsions for bioactive delivery. | Formulating antimicrobial nanoemulsions for milk preservation [13]. |

| Supercritical CO₂ Extraction System | Green, non-toxic solvent for extracting heat-sensitive bioactives. | Extraction of polyphenols and carotenoids without solvent residues [12] [14]. |

| 3D Bioprinter (Extrusion-based) | Fabrication of customized drug delivery scaffolds. | Printing patient-specific dosage forms using waste-derived bio-inks [16]. |

Bioactive compounds derived from food sources are increasingly recognized for their critical role in modulating oxidative stress and inflammation, two fundamental pathways in the pathogenesis of chronic diseases. These compounds, including polyphenols, polysaccharides, and fatty acids, interact with cellular signaling pathways to exert antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, and disease-preventing effects [4] [18] [2]. The growing body of research in this field bridges nutritional science with pharmaceutical development, offering promising natural strategies for disease prevention and health promotion. This application note provides a structured framework for researching these mechanisms, featuring standardized protocols, quantitative data comparisons, and visualization tools to support researchers and drug development professionals in the systematic investigation of bioactive compounds from extraction to mechanistic characterization.

Key Bioactive Compounds and Their Health Connections

Table 1: Major Bioactive Compound Classes and Their Health Mechanisms

| Compound Class | Primary Food Sources | Key Antioxidant Mechanisms | Key Anti-inflammatory Mechanisms | Documented Health Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Polyphenols [4] | Berries, apples, green tea, coffee, flaxseeds | Free radical scavenging, metal chelation, upregulation of endogenous antioxidants (SOD, CAT, GSH-Px) [19] | Inhibition of NF-κB signaling, reduction of pro-inflammatory cytokines [20] | Cardiovascular protection, neuroprotection, anti-diabetic [4] [21] |

| Polysaccharides [19] [22] | Fungi (e.g., Suillus bovinus), fruits (e.g., Phyllanthus emblica) | Reactive oxygen species (ROS) scavenging, enhancement of cellular antioxidant defenses [19] | Modulation of gut microbiota, immunomodulation via prebiotic activity [22] | Gut health promotion, immunomodulation, hepatoprotection [19] [22] |

| Carotenoids [4] | Carrots, tomatoes, leafy greens, bell peppers | Quenching of singlet oxygen, free radical neutralization | Reduction of inflammatory markers, immune system modulation | Eye health, skin protection, immune function [4] |

| Omega-3 Fatty Acids [4] | Fish, flaxseeds, walnuts | Reduction of oxidative stress indirectly through anti-inflammatory effects | Precursors to specialized pro-resolving mediators (SPMs), competition with arachidonic acid | Cardiovascular risk reduction, cognitive health, anti-inflammatory effects [4] |

Quantitative Assessment of Bioactive Compound Efficacy

Table 2: Experimentally Determined Bioactivity of Characterized Compounds

| Bioactive Source | Extraction Method & Yield | Assay System | Key Quantitative Results | Positive Control |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Suillus bovinus polysaccharide (Y-1) [19] | BBD-RSM optimized hot water extraction | HepG2 cells induced by t-BHP | 34.73% ± 1.31% reduction in ROS at 50 μg/mL; significantly increased SOD, CAT, GSH-Px; reduced MDA | Vitamin C (50 μg/mL) |

| Phyllanthus emblica polysaccharide (PEP-U) [22] | UMSE (8.09% yield) | In vitro chemical assays | DPPH scavenging: ~85% at 1 mg/mL; ABTS scavenging: ~90% at 1 mg/mL; significant hydroxyl radical scavenging | Not specified |

| Dandelion Seed Oil (DSO) [23] | Petroleum ether extraction (13.46% yield) | In vitro chemical and cell culture | DPPH scavenging: 85.42% at 1 mg/mL; FRAP: 0.81 ± 0.05; antitumor activity against HeLa, TE-1, MCF-7 cells | Vitamin C (FRAP), Cisplatin (antitumor) |

| Musa balbisiana peel extract [24] | MAE-RSM optimized | In vitro chemical assays | TPC: 48.82 mg GAE/g DM; TSC: 57.18 mg/g DM; identified oleanolic acid as major compound | Not specified |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Optimization of Polysaccharide Extraction Using Box-Behnken Design (BBD)

Application: This protocol is adapted from the optimization of Suillus bovinus polysaccharide extraction [19] and can be applied to various fungal or plant materials.

Workflow Overview:

Materials and Reagents:

- DEAE-52 cellulose column (Solarbio) [19]

- Sephadex G-100 chromatography column (Solarbio) [19]

- Phenol-sulfuric acid reagents (Sigma-Aldrich) [19]

- Vacuum freeze-dryer

- Sevag reagent (chloroform/n-butanol, 4:1 v/v) [19]

Procedure:

- Single-Factor Experiments: Conduct preliminary tests to identify key extraction parameters (liquid-to-solid ratio: 10-50 mL/g, temperature: 30-70°C, time: 1-5 h) affecting polysaccharide yield [19].

- BBD Experimental Design: Using Design Expert software (Version 11), create a three-variable, three-level BBD with 17 experimental runs.

- Model Validation: Confirm model adequacy through ANOVA with significance level p < 0.05.

- Optimization: Utilize desirability function to identify optimal extraction parameters.

- Verification: Conduct triplicate experiments at predicted optimal conditions to validate model predictions.

Protocol 2: In Vitro Assessment of Cellular Antioxidant Mechanisms

Application: Protocol for evaluating cellular antioxidant activity using HepG2 cell model, adapted from Y-1 polysaccharide characterization [19].

Workflow Overview:

Materials and Reagents:

- HepG2 cells (ATCC)

- DMEM with 10% FBS (Gibco) [19]

- t-BHP (tert-butyl hydroperoxide) for oxidative stress induction

- DCFH-DA fluorescent probe (Sigma-Aldrich) [19]

- CCK-8 assay kit for cell viability

- Commercial SOD, CAT, GSH-Px, and MDA assay kits

Procedure:

- Cell Culture and Treatment: Seed HepG2 cells at 1 × 10^4 cells/well in 96-well plates. Culture for 24 h, then treat with test compounds (0-50 μg/mL) for 6 h [19].

- Oxidative Stress Induction: Expose cells to 0.4 mM t-BHP for 3 h (viability assay) or 30 min (ROS measurement) [19].

- ROS Measurement: After t-BHP exposure, stain cells with 1 μM DCFH-DA for 40 min. Measure fluorescence at excitation/emission 485/525 nm [19].

- Antioxidant Enzyme Assays: Follow commercial kit protocols for SOD, CAT, and GSH-Px activities in cell lysates.

- Lipid Peroxidation Assessment: Quantify MDA content using thiobarbituric acid reactive substances (TBARS) assay.

Protocol 3: Anti-inflammatory Mechanism Evaluation

Application: Protocol for assessing anti-inflammatory activity of bioactive compounds, adapted from Hibiscus sabdariffa research [20].

Materials and Reagents:

- RAW 264.7 macrophage cell line

- Lipopolysaccharide (LPS) for inflammation induction

- ELISA kits for TNF-α, IL-6, IL-1β

- Western blot reagents for NF-κB pathway proteins

- Protocatechuic acid (PCA) as reference compound [20]

Procedure:

- Cell Culture and Treatment: Culture RAW 264.7 cells and pre-treat with test compounds for 2 h.

- Inflammation Induction: Stimulate cells with LPS (100 ng/mL) for 18-24 h.

- Cytokine Measurement: Collect culture supernatant and quantify TNF-α, IL-6, and IL-1β using ELISA.

- NF-κB Pathway Analysis: Prepare cell lysates for Western blot analysis of NF-κB p65 phosphorylation and nuclear translocation.

- Statistical Analysis: Perform triplicate experiments with ANOVA and post-hoc tests (p < 0.05 significance).

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Bioactive Compound Research

| Reagent/Chemical | Supplier Examples | Primary Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| DEAE-52 Cellulose | Solarbio | Anion-exchange chromatography for polysaccharide purification | Sequential elution with 0-0.7 M NaCl effectively separates acidic and neutral polysaccharides [19] |

| Sephadex G-100 | Solarbio | Size-exclusion chromatography for molecular weight separation | Effective for purifying polysaccharides in molecular weight range 47.34-97.07 kDa [19] |

| DCFH-DA Probe | Sigma-Aldrich | Fluorescent detection of intracellular ROS | Critical for cellular antioxidant assays; requires careful handling due to light sensitivity [19] |

| Folin-Ciocalteu Reagent | Sigma-Aldrich | Total antioxidant/phenolic content quantification | Reacts with various reducing agents, not specific to phenolics [25] [24] |

| CCK-8 Assay Kit | Various suppliers | Cell viability and proliferation assessment | More sensitive and less toxic alternative to MTT assay [19] |

| Sevag Reagent | Laboratory preparation | Protein removal from polysaccharide extracts | Chloroform:n-butanol (4:1 v/v) effectively denatures and removes proteins [19] [22] |

Mechanistic Pathways of Bioactive Compounds

Cellular Signaling Pathways:

The molecular mechanisms illustrated above demonstrate how bioactive compounds interact with key cellular pathways to exert their health-protective effects. Natural compounds from sources like Suillus bovinus and Hibiscus sabdariffa modulate these pathways through multiple interconnected mechanisms: (1) direct free radical scavenging, (2) enhancement of endogenous antioxidant defenses (SOD, CAT, GSH-Px), (3) inhibition of pro-inflammatory transcription factors (NF-κB), and (4) reduction of inflammatory mediators (TNF-α, IL-6) [19] [20]. These coordinated actions at the molecular level translate to observed protective effects against chronic diseases including cardiovascular disorders, neurodegenerative conditions, and metabolic syndrome.

The systematic investigation of bioactive compounds from foods requires integrated approaches combining optimized extraction methodologies, robust analytical techniques, and mechanistic biological assays. The protocols and data presented herein provide a standardized framework for researchers to quantitatively assess the antioxidant and anti-inflammatory potential of food-derived compounds, facilitating the translation of basic research into potential therapeutic applications. As the field advances, the integration of these approaches with emerging technologies such as AI-assisted compound discovery and multi-omics profiling will further accelerate the identification and characterization of novel bioactive compounds with disease-preventing properties [4] [21].

The valorization of agricultural by-products represents a cornerstone of sustainable biotechnology, aligning with circular economy principles by transforming waste into high-value functional ingredients [26]. Fruit processing generates substantial quantities of residues—including peels, seeds, and pomace—which are now recognized as rich repositories of bioactive compounds with nutraceutical potential [26] [27]. These materials contain diverse phytochemicals such as polyphenols, carotenoids, anthocyanins, flavonoids, tannins, and saponins, which demonstrate significant biological activities including antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, antimicrobial, anticancer, and anti-obesity properties [26]. Recent scientific surveillance indicates a 67.6% increase in research activity in this field over the past five years, with particular emphasis on developing advanced extraction technologies and characterizing novel plant materials [26]. This document provides detailed application notes and experimental protocols for the extraction, characterization, and utilization of bioactive compounds from these key sources, specifically designed for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals.

Tropical Fruit By-products

Tropical fruit processing generates significant waste streams with remarkable nutraceutical potential. Mango, pineapple, and avocado by-products contain substantial quantities of polyphenols, carotenoids, and flavonoids with demonstrated therapeutic properties [26]. Research emphasis has grown on green extraction technologies and validating functional potential through in vitro digestion and bioavailability assays [26].

Berry Fruit By-products

Berry processing generates pomace comprising 25-50% of the initial fruit mass, containing skins, seeds, stems, and leaves [28]. These materials are particularly rich in phenolic compounds, with approximately 10% found in pulp, 28-35% in skin, and 60-70% in seeds [28]. The predominant phenolics include flavonoids (flavonols, flavanols, anthocyanins), proanthocyanidins, and phenolic acids. Anthocyanin distribution varies significantly by species, accounting for about 30% of total phenolic content in blackcurrants and 70% in blueberries [28].

Banana Peel (Musa balbisiana)

Musa balbisiana peel, an underutilized by-product, contains valuable polyphenols and saponins [24]. Under optimized microwave-assisted extraction conditions, researchers have reported total polyphenol content of 48.82 mg GAE/gDM and total saponin content of 57.18 mg/gDM [24]. The purified fractions contain oleanolic acid as a major compound, contributing to observed biological activities including hypoglycemic, anti-inflammatory, and enzyme inhibitory effects [24].

Fenugreek Seeds and Bioactives

Fenugreek (Trigonella foenum-graecum) seeds contain valuable bioactive compounds including diosgenin (0.50-0.93%), trigonelline (5.22-13.65 mg g⁻¹), and 4-hydroxyisoleucine (0.41-1.90%) [29]. These concentrations are significantly influenced by genotype, environment, and their interactions, with specific genotypes from Sivas/TR, Amasya/TR, Konya/TR, and Samsun/TR exhibiting higher diosgenin content across all conditions [29].

Table 1: Bioactive Compound Yields from Key Plant By-product Sources

| Source Material | Bioactive Compounds | Extraction Yield | Extraction Method | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Musa balbisiana peel | Total Polyphenols | 48.82 mg GAE/gDM | Microwave-assisted | [24] |

| Musa balbisiana peel | Total Saponins | 57.18 mg/gDM | Microwave-assisted | [24] |

| Fenugreek seeds | Diosgenin | 0.50-0.93% | Pressurized n-propane | [29] [30] |

| Fenugreek seeds | Trigonelline | 5.22-13.65 mg g⁻¹ | Pressurized n-propane | [29] |

| Fenugreek seeds | 4-Hydroxyisoleucine | 0.41-1.90% | Pressurized n-propane | [29] |

| Germinated fenugreek seeds | α-Tocopherol | ~3x increase vs. raw | Pressurized n-propane | [30] |

| Germinated fenugreek seeds | β-Carotene | 55% higher vs. raw | Pressurized n-propane | [30] |

Extraction Methodologies

Modern Extraction Techniques

Conventional extraction methods like maceration and Soxhlet extraction are increasingly replaced by advanced techniques offering improved efficiency, reduced solvent consumption, and better preservation of heat-sensitive compounds [31] [32] [33]. These modern approaches include ultrasound-assisted extraction (UAE), microwave-assisted extraction (MAE), supercritical fluid extraction (SFE), pressurized liquid extraction (PLE), and enzyme-assisted extraction (EAE) [31] [32].

The efficiency of these techniques stems from enhanced cell wall disruption mechanisms: UAE employs acoustic cavitation, MAE uses microwave energy for rapid heating, SFE utilizes supercritical fluids with gas-like diffusion and liquid-like density, while PLE operates at elevated temperatures and pressures to maintain solvents in liquid state [32] [33]. Hybrid approaches combining multiple technologies demonstrate synergistic effects for challenging plant matrices [32].

Table 2: Comparison of Advanced Extraction Techniques for Bioactive Compounds

| Extraction Method | Key Parameters | Advantages | Limitations | Optimal Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Microwave-Assisted Extraction (MAE) | Solvent concentration, microwave power, irradiation time, cycle duration | Reduced processing time, lower solvent consumption, higher efficiency | Potential degradation of thermolabile compounds, non-uniform heating | Polyphenols, saponins from fruit peels and seeds [24] |

| Ultrasound-Assisted Extraction (UAE) | Amplitude, temperature, solvent type, particle size | Enhanced mass transfer, cell wall disruption, lower temperatures | Possible radical formation, limited scale-up for some systems | Flavonoids, antioxidants from berry pomace [32] [28] |

| Supercritical Fluid Extraction (SFE) | Pressure, temperature, cosolvents, flow rate | Solvent-free residues, selective extraction, low environmental impact | High capital cost, pressure limitations for some compounds | Lipophilic compounds, essential oils [31] [33] |

| Pressurized Liquid Extraction (PLE) | Temperature, pressure, solvent, static/dynamic mode | Rapid extraction, reduced solvent use, automation capability | High pressure requirements, equipment cost | Thermally stable compounds from seeds [30] |

| Enzyme-Assisted Extraction (EAE) | Enzyme type, concentration, incubation time/temperature | Selective cell wall degradation, higher release of bound compounds | Additional purification steps, cost of enzymes | Bound phenolics, polysaccharides [32] |

Protocol: Microwave-Assisted Extraction from Musa balbisiana Peel

Application Note: This protocol optimizes the simultaneous extraction of polyphenols and saponins from Musa balbisiana peel using microwave-assisted extraction combined with Response Surface Methodology [24].

Materials and Equipment:

- Dried Musa balbisiana peel powder (particle size <80 mesh)

- Methanol (analytical grade)

- Folin-Ciocalteu reagent

- Gallic acid standard

- Microwave extraction system with power control

- UV-Vis spectrophotometer

- Thermostatic water bath

- Whatman No. 1 filter paper

Experimental Procedure:

Sample Preparation:

- Collect Musa balbisiana peel at 80-85% ripeness

- Clean, slice, and dry at 60°C to moisture content below 10%

- Grind to particle size <80 mesh and store at 4°C in sealed containers [24]

Extraction Process:

- Weigh 1g of dried peel powder (accurate to 0.001g)

- Add methanol solvent at concentration 81.09% (v/v)

- Maintain solid-to-solvent ratio of 1:30 (w/v)

- Set microwave irradiation cycle to 4.39 s/min

- Extract for 44.54 minutes at optimized power [24]

- Transfer samples to 60°C thermostatic bath for 60 minutes incubation

- Filter mixture through Whatman No. 1 filter paper

- Collect filtrate for analysis

Analytical Quantification:

Optimization Approach:

- Employ Response Surface Methodology with Box-Behnken design

- Model using quadratic regression equation: [ \gamma = \beta0 + \sum\limits{i=1}^{k} \betaiXi + \sum\limits{i=1}^{k} \beta{ii}Xi^{2} + \sum\limits{i=1}^{k} \sum\limits{j=i+1}^{k-1} \beta{ij}XiXj ]

- Where Y is predicted response, β₀ is constant, βi is linear coefficient, βii is quadratic coefficient, and βij is interaction coefficient [24]

Protocol: Pressurized n-Propane Extraction from Fenugreek Seeds

Application Note: This procedure describes the extraction of bioactive compounds from raw and germinated fenugreek seeds using pressurized n-propane, enhancing recovery of thermolabile compounds [30].

Materials and Equipment:

- Fenugreek seeds (raw and germinated)

- n-Propane (95% purity)

- Aloe vera gel (for germination elicitor)

- Sodium hypochlorite solution (1%)

- Pressurized fluid extraction system

- Petri dishes

- Drying oven

- Grinding apparatus

Experimental Procedure:

Seed Germination and Elicitation:

- Sterilize raw fenugreek seeds with 1% sodium hypochlorite for 15 minutes

- Rinse thoroughly with deionized water

- Soak seeds in deionized water for 24 hours to break dormancy

- Germinate in two substrates: (1) water, (2) 30% Aloe vera gel solution

- Maintain at 24°C in darkness for 96 hours

- Spray with distilled water or Aloe vera solution every 12 hours as needed

- Dry sprouts at 308K for 8 hours

- Grind and sieve through 0.55 mesh Tyler series [30]

Pressurized n-Propane Extraction:

- Load extraction vessel with ground seed material (raw, germinated, or mixtures)

- Maintain n-propane in subcritical state

- Conduct extractions in duplicate at optimized pressure and temperature

- Use 1:2 and 2:1 ratios for seed mixtures (raw:germinated)

- Collect extracts for analysis [30]

Bioactivity Assessment:

- Antioxidant Activity: Evaluate using ABTS•+ assay with Trolox standard

- Anticancer Activity: Test in vitro against HeLa and SiHa cell lines

- Anti-hyperglycemic Activity: Assess α-glucosidase and α-amylase inhibition [30]

Characterization Techniques

Structural Elucidation of Bioactive Compounds

Advanced analytical techniques are essential for characterizing bioactive compounds from plant materials. Fourier Transform Infrared (FT-IR) and Raman spectroscopy provide information about functional groups and molecular structures [24]. Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) spectroscopy, including ¹H-NMR and ¹³C-NMR, offers detailed structural elucidation [24]. High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC) and Gas Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (GC-MS) enable separation, identification, and quantification of individual compounds in complex mixtures [32].

Protocol: Structural Characterization of M. balbisiana Peel Extracts

Sample Purification:

- Perform liquid-liquid extraction with petroleum ether to remove lipids

- Further separate with n-butanol-water system to eliminate pigments

- Fractionate via silica gel column chromatography with chloroform:methanol or ethyl acetate:n-hexane solvent systems

- Monitor purity by Thin Layer Chromatography (TLC) [24]

FT-IR Analysis:

- Prepare KBr pellet with purified extract

- Record spectrum on Tensor 37 Brucker spectrometer

- Scan range: 400-4000 cm⁻¹

- Identify characteristic functional groups of polyphenols and saponins [24]

Raman Spectroscopy:

- Use Raman Cora 5X00 spectrometer

- Analyze fingerprint region for compound identification

- Confirm presence of specific bioactive compounds [24]

NMR Spectroscopy:

- Dissolve purified sample in D₂O at concentration 20 μg/mL

- Record ¹H-NMR and ¹³C-NMR spectra on Bruker Advance DPX-500 NMR spectrometer

- Operate at 75.5 MHz for ¹³C-NMR

- Maintain temperature at 27°C

- Identify oleanolic acid as major compound in purified fractions [24]

Bioactivity Assessment

Protocol: In Vitro Bioactivity Screening

Antioxidant Activity:

Enzyme Inhibition Assays:

Anticancer Activity:

- Maintain cancer cell lines (HeLa, SiHa) in appropriate media

- Treat with serial dilutions of extracts

- Assess viability using MTT or Alamar Blue assays

- Calculate IC₅₀ values from dose-response curves [30]

Antimicrobial Activity:

- Employ broth microdilution for MIC determination

- Use agar diffusion for preliminary screening

- Test against Gram-positive, Gram-negative bacteria, and fungi [32]

Pathway Visualization: Bioactive Compound Extraction and Characterization

Diagram 1: Comprehensive workflow for bioactive compound extraction and characterization from plant by-products

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Bioactive Compound Analysis

| Reagent/Material | Specification | Application/Function | Example Use |

|---|---|---|---|

| Methanol | Analytical grade, 80-100% concentration | Extraction solvent for polyphenols and saponins | Microwave-assisted extraction from banana peel [24] |

| n-Propane | 95% purity, pressurized | Green solvent for pressurized liquid extraction | Extraction of fenugreek seed bioactives [30] |

| Folin-Ciocalteu Reagent | Commercial standard solution | Quantification of total phenolic content | TPC determination in fruit peel extracts [24] |

| Aloe vera gel | 30% solution in deionized water | Elicitor for seed germination | Enhancement of bioactive compounds in fenugreek [30] |

| ABTS•+ | [2,2-azino-bis-(3-ethylbenzthiazoline-6-sulfonic acid)] | Antioxidant capacity assessment | Radical scavenging activity measurement [30] |

| Trolox | (6-hydroxy-2,5,7,8-tetramethylchroman-2-carboxylic acid) | Standard for antioxidant assays | Calibration standard for TEAC values [30] |

| Deuterated Solvents (D₂O) | NMR grade, 99.9% deuterium | Solvent for NMR spectroscopy | Structural elucidation of purified compounds [24] |

| Silica Gel | 60-120 mesh for column chromatography | Stationary phase for compound separation | Fractionation of banana peel extracts [24] |

| Cell Lines | HeLa, SiHa (cervical cancer) | In vitro anticancer activity assessment | Cytotoxicity testing of plant extracts [30] |

| Enzyme Substrates | p-nitrophenyl glucopyranoside, starch | Enzyme inhibition assays | α-glucosidase and α-amylase inhibition [30] |

Fruit by-products, seeds, peels, and novel plant materials represent valuable, sustainable sources of bioactive compounds with significant potential for pharmaceutical and nutraceutical applications. The integration of advanced extraction technologies—particularly microwave-assisted, pressurized liquid, and supercritical fluid extraction—enables efficient recovery of these compounds while preserving their bioactivity. Comprehensive characterization using spectroscopic and chromatographic techniques, coupled with robust bioactivity assessment, provides the necessary foundation for drug development and functional food formulation. The protocols and application notes presented herein offer researchers standardized methodologies for exploring these promising resources, supporting the transition toward circular bioeconomy models in scientific and industrial practice.

From Lab to Scale: Extraction Techniques and Biomedical Applications

The extraction and characterization of bioactive compounds from foods is a critical research area for discovering new nutraceuticals and therapeutic agents. The efficacy of this research is fundamentally dependent on the initial extraction process, which dictates the yield, composition, and subsequent bioactivity of the isolated compounds [32]. Conventional extraction techniques such as Soxhlet, maceration, and hydro-distillation, despite the advent of modern methods, remain widely used due to their simplicity, robustness, and established protocols [34]. These methods serve as the foundational standard against which newer technologies are often compared. This application note provides detailed protocols and a comparative analysis of these three conventional methods, framed within the context of rigorous scientific research for the extraction of food-based bioactive compounds.

The selection of an appropriate extraction method is pivotal, as it directly influences the phytochemical profile and biofunctional properties of the final extract [35] [32]. The table below summarizes the core characteristics, advantages, and limitations of Soxhlet, maceration, and hydro-distillation.

Table 1: Comparative analysis of Soxhlet, maceration, and hydro-distillation techniques.

| Feature | Soxhlet Extraction | Maceration | Hydro-Distillation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Principle | Continuous solvent reflux and siphoning [34] | Passive diffusion using a solvent at room temperature [36] | Co-distillation of essential oils with boiling water [37] |

| Extraction Process | Automated, cyclic immersion | Static, prolonged soaking | Volatilization, condensation, and separation |

| Typical Duration | 4 to 6 hours [38] or longer [39] | 72 hours [35] to several weeks [40] | Several hours, depending on plant material [37] |

| Temperature | Boiling point of the solvent (e.g., ~78°C for ethanol) [32] | Ambient temperature [36] | 100°C (at atmospheric pressure) [37] |

| Solvent Consumption | Moderate, but solvent is recycled [34] | High, single-use of solvent [34] | Water only; no organic solvents |

| Suitability | Non-polar to semi-polar compounds; thermostable molecules [34] | Wide range, but best for thermolabile compounds [32] | Exclusively for volatile, heat-stable compounds (essential oils) [37] |

| Key Advantages | High efficiency, continuous extraction with fresh solvent, established standard [34] [39] | Simple equipment, preserves thermolabile compounds, easy operation [34] [36] | Solvent-free extracts, simple apparatus, ideal for volatile oils [37] |

| Major Limitations | Long time, potential thermal degradation, high solvent use [34] [32] | Lengthy process, high solvent consumption, low efficiency [34] | High energy input, degradation of thermosensitive and hydrolyzable compounds [37] |

Table 2: Impact of extraction technique on phytochemical yield and bioactivity based on a study of Mentha longifolia L. [35].

| Extraction Method | Solvent | Total Phenolic Content (mg GAE/g) | Total Flavonoid Content (mg QE/g) | Antioxidant & Antimicrobial Activity |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Soxhlet | 70% Ethanol | High | High | Most powerful |

| Maceration | 70% Ethanol | High | High | Most powerful |

| Ultrasound-Assisted | 70% Ethanol | Intermediate | Intermediate | Significant |

| Soxhlet/Maceration | Ethyl Acetate | Lower | Lower | Moderate |

| Soxhlet/Maceration | Water | Lowest | Lowest | Weakest |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol for Soxhlet Extraction

Soxhlet extraction is a continuous, semi-automated method ideal for extracting compounds from solid matrices using relatively pure solvents [34] [39].

Principle: The method operates on the principles of solvent reflux and siphoning. The sample is repeatedly exposed to fresh, warm solvent, which improves mass transfer and extraction efficiency [34].

Procedure:

- Sample Preparation: Approximately 0.5–10 g of the dried food sample (e.g., plant material) is ground to a coarse powder to increase surface area. The powder is then placed inside a cellulose or glass fiber thimble [38] [35].

- Apparatus Setup: The thimble is positioned in the main chamber of the Soxhlet extractor. A suitable solvent (e.g., 90 mL of methanol, ethanol, or hexane) is added to a round-bottom flask, which is attached to the extractor. A condenser is fitted to the top [38].

- Heating and Extraction: The solvent is heated to reflux. The vapor travels up to the condenser, liquefies, and drips onto the sample in the thimble. The chamber slowly fills until the liquid siphons back into the round-bottom flask, carrying the extracted compounds. This cycle is repeated for a set duration, typically 4–6 hours [38] [35].

- Concentration: After extraction, the solvent in the flask, now containing the target analytes, is evaporated under reduced pressure using a rotary evaporator. The concentrated extract is transferred to a volumetric flask, made up to volume with the same solvent, filtered (e.g., through a 0.45 µm membrane), and stored for analysis (e.g., by HPLC) [38] [35].

Protocol for Maceration

Maceration is a simple, low-temperature extraction technique that is gentle on heat-sensitive bioactive compounds [36].

Principle: This method relies on the passive diffusion of soluble compounds from the plant material into the surrounding solvent, driven by a concentration gradient. Agitation can improve the rate of extraction [36].

Procedure:

- Sample Preparation: The dried food sample is cleaned and chopped or ground into small pieces to break cell walls and facilitate solvent penetration. Powdering should be avoided if it complicates subsequent filtration [36] [40].

- Solvent Addition: The prepared sample is placed in an airtight glass container. A solvent is chosen based on the target compounds' polarity (e.g., 70% ethanol for a broad range of phenolics, or a vegetable oil for oil-soluble actives) and added to the container, ensuring the plant material is fully submerged to prevent microbial growth [35] [40].

- Steeping: The container is sealed and stored at room temperature, protected from light, for an extended period—typically 72 hours for research purposes, or up to several weeks for traditional preparations. The mixture should be shaken or stirred daily to enhance extraction [35] [36].

- Separation and Storage: After maceration, the mixture is filtered through filter paper or a cloth to separate the marc (spent plant material) from the extract. The resulting liquid can be concentrated under reduced pressure if an organic solvent was used, or stored directly as an infusion. For stability, adding an antioxidant like Vitamin E (0.5-1%) is recommended for oil-based macerates. The final extract should be stored in a sealed, dark container [40].

Protocol for Hydro-Distillation

Hydro-distillation is a traditional method specifically designed for the isolation of volatile compounds and essential oils from plant materials [37].

Principle: The process involves direct contact between the plant material and boiling water. The steam and volatile oils co-vaporize, travel through a condenser where they return to the liquid state, and are subsequently separated from the water in a receiver based on density differences [37].

Procedure:

- Apparatus Assembly: A hydro-distillation unit, typically comprising a distillation flask, a condenser, and a receiving flask (often with a built-in separator), is set up.

- Loading: The food sample (fresh or dried) is immersed in water inside the distillation flask. The flask is heated, bringing the water to a boil.

- Distillation: The steam, carrying the volatile essential oils, passes into the condenser. The cooled mixture of essential oil and hydrosol (floral water) is collected in the receiver.

- Oil Separation: Due to immiscibility and density differences, the essential oil separates from the water layer. The oil is then decanted or separated using a separating funnel. The process continues until a sufficient quantity of oil is obtained, which can take several hours depending on the plant material's oil content [37].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

Table 3: Key reagents, materials, and equipment for conventional extraction methods.

| Item | Specification/Function |

|---|---|

| Solvents | Methanol, Ethanol (70-100%), Hexane, Ethyl Acetate, Water. Selected based on target compound polarity and solubility [34] [35]. |

| Sample Preparation | Mortar and Pestle, Mechanical Grinder. For particle size reduction to increase surface area for extraction [35]. |

| Extraction Vessels | Cellulose/Glass Fiber Thimbles (Soxhlet), Airtight Glass Jars (Maceration), Clevenger-type Apparatus or Hydro-distillation Unit (Hydro-Distillation) [38] [37] [40]. |

| Heating & Control | Isomantle Heater, Heating Mantle (Soxhlet/Hydro), Thermostatically Controlled Water Bath (for heated maceration). Provides precise temperature control [38]. |

| Solvent Recovery & Concentration | Rotary Evaporator (Rotavapor) with Vacuum Pump. For gentle removal of solvent from the extract under reduced pressure and controlled temperature (e.g., 40°C) [35]. |

| Filtration | Filter Paper (Whatman No. 01), 0.45 µm Syringe Filters. For clarification of the final extract prior to analysis [38] [35]. |

| Chemical Additives | Vitamin E (Tocopherol). Added as an antioxidant (0.5-1%) to oil-based macerates to prevent rancidity [40]. |

| Analytical Instrumentation | High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC). For qualitative and quantitative analysis of the extracted bioactive compounds [38] [35]. |

Workflow and Pathway Diagrams

Soxhlet, maceration, and hydro-distillation are foundational techniques in the extraction and characterization of bioactive compounds from foods. Each method offers distinct advantages: Soxhlet for its efficiency with stable compounds, maceration for its gentleness on thermolabile bioactives, and hydro-distillation for its specialization in volatile oils. The choice of method profoundly impacts the extract's yield, chemical profile, and functional properties, as evidenced by comparative studies [35]. While modern techniques offer improvements in speed and solvent use, these conventional methods remain vital for research standardization, method validation, and specific applications where their particular strengths are required. A critical understanding of their principles, protocols, and limitations is indispensable for researchers in food science, nutraceuticals, and drug development.

The extraction and characterization of bioactive compounds from foods represent a critical frontier in nutritional science, pharmaceutical development, and functional food innovation. Conventional extraction methods, while established, often involve large quantities of organic solvents, prolonged extraction times, and high energy consumption, which can degrade thermolabile compounds and generate hazardous waste [34]. In response to these limitations, a suite of emerging green extraction technologies has been developed, aligning with the principles of green chemistry to minimize environmental impact while enhancing efficiency and selectivity [41]. This article provides detailed application notes and protocols for four key green technologies: Supercritical Fluid Extraction (SFE), Ultrasound-Assisted Extraction (UAE), Microwave-Assisted Extraction (MAE), and Enzyme-Assisted Extraction (EAE). Framed within a thesis on the extraction and characterization of food-derived bioactive compounds, this guide offers researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals with the experimental frameworks necessary to implement these sustainable techniques.

Green extraction techniques leverage innovative mechanisms to disrupt plant cell walls and enhance the mass transfer of bioactive compounds into the solvent. The selection of an appropriate method depends on the target compound's nature, the source material, and the desired yield and purity [34] [42].

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Emerging Green Extraction Technologies

| Technology | Fundamental Principle | Optimal Compound Classes | Key Operational Advantages | Inherent Limitations & Challenges |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Supercritical Fluid Extraction (SFE) | Uses supercritical fluids (e.g., CO₂) whose solvating power is tunable via pressure and temperature [43] [44]. | Lipids, essential oils, fragrances, non-polar pigments (e.g., carotenoids) [43] [45]. | Near-complete solvent removal; preserves thermolabile compounds; high selectivity [43] [44]. | High initial capital investment; limited efficiency for polar molecules without co-solvents [44]. |

| Ultrasound-Assisted Extraction (UAE) | Induces cell wall disruption via ultrasonic cavitation, enhancing solvent penetration [41]. | Polyphenols, antioxidants, flavonoids [41]. | Rapid extraction; reduced solvent consumption; operates at low temperatures [41]. | Potential for free radical formation degrading some compounds; scaling challenges [41]. |

| Microwave-Assisted Extraction (MAE) | Uses microwave energy to rapidly heat the solvent and matrix, creating internal pressure that ruptures cells [46]. | Phenolics, flavonoids, saponins, alkaloids [46]. | Significantly reduced extraction time; high efficiency with small solvent volumes [46] [41]. | Non-uniform heating risk; limited to solvents that absorb microwave energy [46]. |

| Enzyme-Assisted Extraction (EAE) | Employs specific enzymes (e.g., cellulase, pectinase) to hydrolyze cell wall structural polymers [41]. | Polysaccharides, oils, pigments, and bioactive compounds trapped within polysaccharide networks [41]. | High specificity; operates under mild pH and temperature conditions; ideal for heat-sensitive compounds [41]. | Relatively high cost of enzymes; requires precise control of incubation conditions [41]. |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol for Supercritical Fluid Extraction (SFE)

Application Note: SFE is exceptionally suitable for extracting non-polar to moderately polar lipophilic compounds from solid plant matrices. The following protocol outlines a method for extracting bioactive lipids from microalgae, a source of omega-3 fatty acids and carotenoids [45].

Workflow Overview:

Materials:

- Supercritical CO₂ Extraction System: Consisting of a CO₂ pump, a thermostated extraction vessel, a pressure control valve, and a collection vessel.

- Source Material: Dried, powdered microalgae (e.g., Nannochloropsis sp. or Chlorella sp.) [45].

- Extraction Solvent: Food-grade carbon dioxide (CO₂).

- Co-solvent (Optional): Anhydrous ethanol (for enhancing polar compound recovery) [43].

- Analytical Equipment: GC-MS or HPLC for compound analysis.

Step-by-Step Procedure:

- Sample Preparation: The microalgae biomass should be freeze-dried and ground to a uniform particle size (e.g., 40-60 mesh). Accurately weigh a specific mass (e.g., 10-50 g) and load it into the extraction vessel, ensuring even packing to avoid channeling.

- System Pressurization and Heating: Seal the extraction vessel. Pressurize the system with CO₂ and heat it until the supercritical state is achieved. A standard starting condition is 45°C and 300 bar [43] [44].

- Dynamic Extraction: Maintain the supercritical conditions and set the CO₂ flow rate (e.g., 2-5 mL/min). The extraction is typically performed for 60-120 minutes. A co-solvent like ethanol (5-15% of total solvent volume) can be added via a separate pump to improve the yield of polar compounds [43].

- Separation and Collection: The CO₂-rich extract is passed through a pressure reduction valve into a separation chamber maintained at a lower pressure (e.g., 50-60 bar) and temperature. This drop in solvating power causes the extract to precipitate and be collected in the vessel. The CO₂ is either vented or recycled.

- Extract Processing: The collected extract is transferred to a vial. If a co-solvent was used, it may be removed under a gentle stream of nitrogen or by rotary evaporation. The extract should be stored at -20°C and protected from light prior to analysis.

Protocol for Microwave-Assisted Extraction (MAE)

Application Note: MAE is highly effective for the rapid extraction of polar phenolic compounds and antioxidants. This protocol is optimized for extracting polyphenols from stinging nettle (Urtica dioica) leaves [46].

Workflow Overview:

Materials:

- Microwave-Assisted Extractor: Closed-vessel system with temperature and pressure control.

- Source Material: Oven-dried (50±5°C) and powdered stinging nettle leaves, sieved through a 40-mesh screen [46].

- Extraction Solvents: Water, 80% Ethanol, or Natural Deep Eutectic Solvent (NADES) (e.g., Choline Chloride:Lactic acid in a 1:2 molar ratio) [46].