From Data to Discovery: How AI and Machine Learning Are Revolutionizing Food Chemistry Analysis

This article explores the transformative impact of Artificial Intelligence (AI) and Machine Learning (ML) on food chemistry data analysis.

From Data to Discovery: How AI and Machine Learning Are Revolutionizing Food Chemistry Analysis

Abstract

This article explores the transformative impact of Artificial Intelligence (AI) and Machine Learning (ML) on food chemistry data analysis. Tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it provides a comprehensive overview of how these technologies are being integrated with traditional analytical methods like spectroscopy, chromatography, and mass spectrometry. The scope ranges from foundational concepts and key food databases to advanced methodological applications in quality control, contaminant detection, and novel ingredient design. It further addresses critical challenges in model optimization and data quality, compares the performance of AI against traditional statistical methods, and synthesizes key takeaways to highlight future implications for biomedical and clinical research, including the role of AI in advancing personalized nutrition.

The New Frontier: Understanding AI's Role in Modern Food Chemistry

Application Notes

The integration of Artificial Intelligence (AI) and Machine Learning (ML) is fundamentally transforming food chemistry research. These technologies are moving beyond traditional statistical methods to address complex challenges in food safety, quality, authenticity, and the development of sustainable products [1]. The following table summarizes key application areas and representative algorithms as identified in current literature.

Table 1: Key Applications of AI and ML in Food Chemistry

| Application Area | Specific Task | Representative AI/ML Techniques | Reported Outcome / Advantage |

|---|---|---|---|

| Food Authenticity & Provenance | Classification of geographical origin, variety, and production method (e.g., apples) [1] | Random Forest with LC-MS data [1] | High classification accuracy for multiple authentication questions from a single analytical run [1]. |

| Bioactivity Prediction | Investigating relationships between food components (e.g., polyphenols, amino acids) and bioactivities (e.g., antioxidant capacity) [1] | Random Forest Regression (as an Explainable AI approach) [1] | Identifies key bioactive compounds and provides interpretable models, moving beyond "black box" predictions [1]. |

| Sensory Property Prediction | Predicting taste properties (e.g., umami) of food-derived compounds and peptides [2] | Graph Neural Networks (GNNs), Deep Forest (gcForest), Consensus Models [1] | Models molecular structure to efficiently predict sensory properties, reducing reliance on time-consuming sensory panels [1]. |

| Rapid Quality Control | Non-destructive determination of food components (e.g., moisture, crude protein) [1] | XGBoost, CNN, ResNet, PLSR, Random Forest Regression with NIR/FTIR data [1] | Enables fast, non-destructive screening for quality parameters in industrial settings [1]. |

| Food Image Recognition | Fine-grained visual classification of foods for dietary monitoring and quality control [1] | Multi-level Attention Feature Fusion Networks, Deep Learning [1] | Addresses challenges of high inter-class similarity and intra-class variability in food products [1]. |

| Novel Food Design | Formulation optimization and prediction of properties for alternative protein products [3] | Generative AI, Optimization Algorithms, Predictive Models [3] | Accelerates the design of nutritious and sustainable foods by screening a massive multimodal parameter space [3]. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Food Authentication Using LC-MS and Random Forest

This protocol details the procedure for classifying food items based on geographical origin, variety, and production method, as demonstrated for apples [1].

1. Sample Preparation and Analysis

- Reagents/Materials: Food samples (e.g., apples of different varieties, from different regions and farming practices), LC-MS grade solvents (water, acetonitrile, methanol), formic acid.

- Instrumentation: UHPLC system coupled to a Quadrupole Time-of-Flight Mass Spectrometer (UHPLC-Q-ToF-MS).

- Procedure:

- Homogenize representative portions of each food sample.

- Perform metabolite extraction using a suitable solvent system (e.g., methanol/water).

- Centrifuge the extracts and filter the supernatant.

- Analyze all samples using the UHPLC-Q-ToF-MS method with consistent chromatographic conditions (column, gradient, flow rate) and MS data acquisition in positive and negative ionization modes.

- Include quality control (QC) samples (a pool of all samples) throughout the run to monitor instrument stability.

2. Data Preprocessing and Feature Extraction

- Use vendor or open-source software (e.g., XCMS, MS-DIAL) for peak picking, alignment, and retention time correction.

- Filter features to remove noise and those with high variance in QC samples.

- Create a data matrix where rows are samples, columns are ion features (m/z and RT pair), and values are peak intensities.

- Perform missing value imputation if necessary.

3. Model Training and Validation with Random Forest

- Software: Python (scikit-learn) or R.

- Data Splitting: Split the preprocessed data into a training set (e.g., 70-80%) and a hold-out test set (e.g., 20-30%).

- Model Training: Train a Random Forest classifier on the training set. The model parameters (e.g., number of trees, maximum depth) should be optimized via cross-validation.

- Model Validation: Use the hold-out test set to evaluate the model's performance. Report metrics such as accuracy, precision, recall, and F1-score.

- Explainability: Perform variable importance analysis provided by the Random Forest algorithm to identify the ion features (potential chemical markers) most critical for classification.

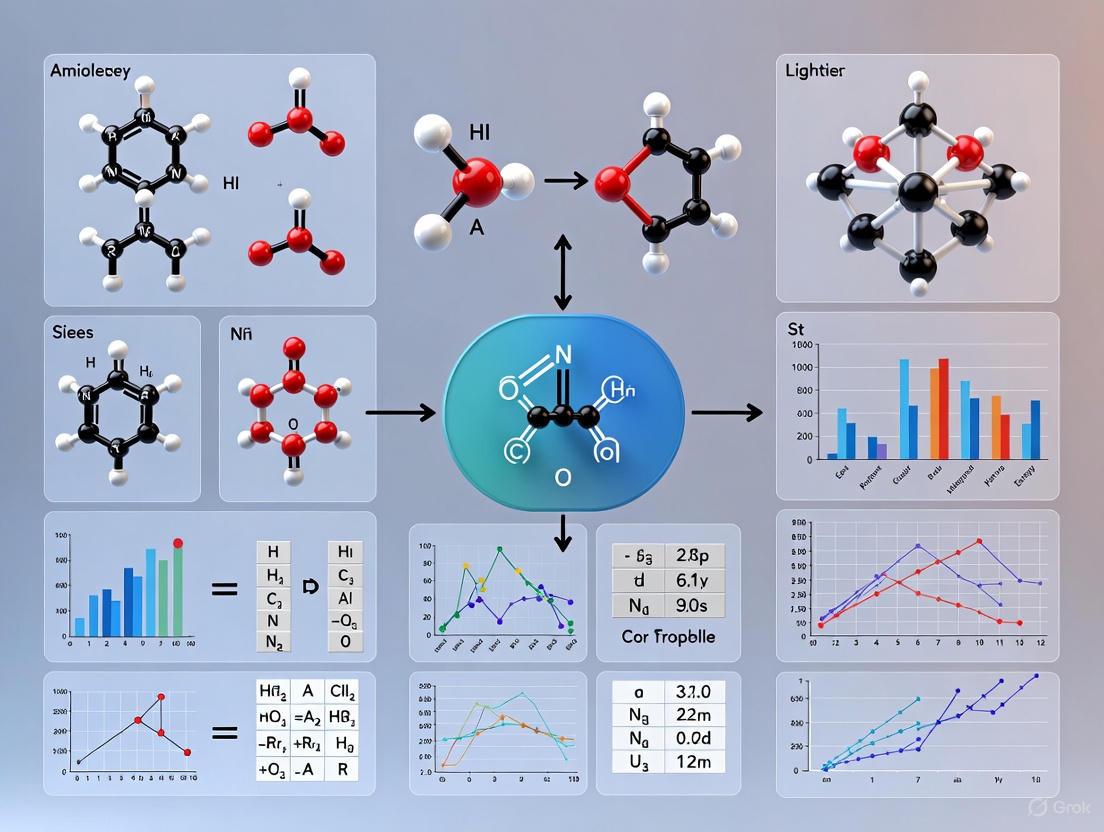

AI-Driven Food Authentication Workflow

Protocol 2: Predicting Bioactive Compound Interactions Using Explainable AI

This protocol uses Random Forest Regression in an Explainable AI (XAI) framework to uncover relationships between food components and their functional properties, as applied to fermented apricot kernels [1].

1. Data Collection on Food Composition and Bioactivity

- Measurements:

- Independent Variables (X): Quantify the concentrations of key chemical classes (e.g., phenolic compounds, amino acids) using standard analytical methods (HPLC, GC-MS).

- Dependent Variable (Y): Measure the relevant bioactivity (e.g., antioxidant activity via ORAC, DPPH, or FRAP assays) for each sample.

- Sample Set: Ensure a sufficient number of samples (n) to build a robust model, ideally following guidelines for multivariate regression.

2. Data Preprocessing and Model Building

- Autoscale or standardize the concentration data (X variables) to ensure all features contribute equally to the model.

- Split the dataset into training and test sets.

- Train a Random Forest Regression model on the training data. Optimize hyperparameters (e.g.,

n_estimators,max_features) using cross-validation to prevent overfitting.

3. Model Interpretation and XAI Analysis

- Performance Assessment: Evaluate the model on the test set by reporting R², Root Mean Square Error (RMSE).

- Feature Importance: Extract and plot the Gini or permutation importance from the trained Random Forest model. This ranks the compounds based on their contribution to predicting the bioactivity.

- Partial Dependence Plots (PDPs): Generate PDPs for the top important features to visualize the relationship between the concentration of a specific compound and the predicted bioactivity, marginalizing over the effects of all other features.

Visualization of Methodologies

AI-Driven Formulation Design Workflow

The process of using AI, particularly generative models, to design novel food products involves a cyclical workflow of generation, prediction, and validation [3].

AI-Driven Food Formulation Design Cycle

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

The following table lists essential reagents, materials, and computational tools used in AI-driven food chemistry research.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Tools for AI-Enabled Food Chemistry

| Category / Item | Function / Application |

|---|---|

| Analytical Chemistry Standards | |

| LC-MS Grade Solvents (Water, Acetonitrile, Methanol) | Essential for high-sensitivity mass spectrometry to minimize background noise and ion suppression [1]. |

| Stable Isotope-Labeled Internal Standards | Used for absolute quantification and correcting for matrix effects and instrument variability in MS-based assays [1]. |

| Chemical Standards (Phenolics, Amino Acids, etc.) | Required for creating calibration curves to identify and quantify specific compounds in food samples [1]. |

| Data Analysis & AI/ML Software | |

| Python Programming Language (Libraries: scikit-learn, TensorFlow, PyTorch, Pandas) | The primary ecosystem for building, training, and deploying machine learning and deep learning models [1] [3]. |

| R Programming Language (Libraries: caret, randomForest, xgboost) | Widely used for statistical analysis, data visualization, and implementing chemometric and ML models [1]. |

| Chemometrics Software (e.g., SIMCA, The Unscrambler) | Commercial software packages offering user-friendly interfaces for traditional multivariate analysis like PCA and PLS [1]. |

| Computational Resources | |

| High-Performance Computing (HPC) Cluster / Cloud GPU | Necessary for training complex deep learning models (e.g., GNNs, CNNs) on large, high-dimensional datasets in a reasonable time [3]. |

For researchers applying artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning (ML) in food chemistry, accessing high-quality, well-structured data is the critical first step in building robust predictive models. Food composition and flavor databases provide the essential training data that powers AI applications, from predicting nutrient profiles to designing novel food compounds. The integration of these data resources enables a new era of data-driven discovery in food chemistry, allowing scientists to move beyond traditional trial-and-error approaches [3]. The utility of these databases is maximized when they adhere to the FAIR Data Principles (Findable, Accessible, Interoperable, and Reusable), which facilitate seamless data integration and machine actionability [4] [5]. Understanding the scope, structure, and optimal application of these databases is fundamental to accelerating AI-powered innovation in food science.

Table 1: Core Food Data Resources for AI and ML Research

| Database Name | Primary Focus | Key Data Types | AI/ML Readiness Indicators |

|---|---|---|---|

| USDA FoodData Central | Macro & micronutrient composition | Food components, nutrients, metadata | Standardized data formats, public domain licensing, regular updates [6] |

| FooDB | Food metabolomics | Chemical compounds, concentrations, food sources | Detailed chemical descriptors, structural information |

| FlavorDB | Flavor chemistry | Flavor molecules, sensory properties, thresholds | Quantitative structure-taste relationships, receptor data |

Database-Specific Application Notes and Protocols

USDA FoodData Central: Protocol for Nutritional Profiling and Predictive Modeling

The USDA FoodData Central serves as a foundational resource for nutritional profiling and predictive modeling in food chemistry research. This database provides analytically validated data on commodity and minimally processed foods, making it particularly suitable for developing regression models that predict nutrient content based on food type, origin, or processing method [6]. The database's structure supports both supervised and unsupervised learning tasks, with standardized nutrient measures serving as ideal target variables for predictive algorithms.

Experimental Protocol 1: Developing a Nutrient Prediction Model

- Data Acquisition: Download the "Foundation Foods" dataset from FoodData Central, which includes high-resolution metadata on food samples, including geographic origin, production method, and analytical techniques [6].

- Feature Engineering: Extract key nutritional features (proteins, fats, carbohydrates, vitamins, minerals) and metadata fields (food category, scientific name) for use as input variables.

- Data Preprocessing: Handle missing values using k-nearest neighbors imputation and normalize nutrient values using z-score standardization to prepare for ML algorithms.

- Model Training: Implement a Random Forest regression model to predict specific nutrient values (e.g., vitamin content) based on other compositional features and metadata, leveraging the ensemble method's ability to handle non-linear relationships.

- Validation: Validate model performance using k-fold cross-validation and compare predicted values against analytically measured values in the test set.

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Food Data Analysis

| Reagent/Material | Function in Experimental Protocol |

|---|---|

| Python Pandas Library | Data wrangling, cleaning, and transformation of bulk database exports |

| Scikit-learn ML Framework | Implementation of regression, classification, and clustering algorithms |

| Jupyter Notebook Environment | Interactive development and visualization of data analysis workflows |

| Scikit-learn Imputation Modules | Handling missing data values in compositional datasets |

| Matplotlib/Seaborn Visualization | Generation of exploratory data analysis plots and model performance charts |

FooDB and FlavorDB: Protocol for Flavor Compound Prediction and Food Pairing

FooDB and FlavorDB provide complementary chemical data that enable AI-driven discovery in flavor science and sensory perception. These databases offer structural information on food compounds and their sensory properties, creating opportunities for quantitative structure-taste relationship (QSTR) modeling [1]. The integration of this chemical data with sensory information facilitates the prediction of novel flavor compounds and optimal food pairings through network analysis and graph neural networks.

Experimental Protocol 2: Predicting Novel Flavor Pairings Using Graph Neural Networks

- Data Integration: Extract chemical compound data from FooDB and cross-reference with sensory profiles from FlavorDB to create a comprehensive flavor-compound network.

- Graph Construction: Represent compounds as nodes and their co-occurrence in foods as edges, with node features encoding molecular descriptors and sensory attributes.

- Model Architecture: Implement a Graph Neural Network (GNN) to learn embeddings for flavor molecules, capturing the complex relationships between chemical structure and sensory perception [1].

- Pairing Prediction: Use the learned embeddings to predict novel flavor combinations by identifying compounds with complementary sensory profiles but low co-occurrence in existing food products.

- Validation: Validate predictions through literature mining and, where possible, empirical sensory evaluation.

Multi-Omics Data Integration: Protocol for Comprehensive Food Profiling

Modern food chemistry research increasingly requires the integration of multiple data types to build comprehensive food profiles. This multi-omics approach combines compositional data from USDA FoodData Central with chemical compound data from FooDB and sensory information from FlavorDB, enabling holistic food characterization that captures nutritional, chemical, and sensory dimensions simultaneously.

Experimental Protocol 3: Multi-Omics Food Profiling Using Data Fusion Techniques

- Data Alignment: Harmonize data from all three databases using standardized food identifiers and chemical compound registries, addressing nomenclature inconsistencies through semantic mapping.

- Feature Extraction: Generate unified feature vectors for each food item, incorporating nutritional composition, chemical diversity, and sensory attributes.

- Data Fusion: Apply multi-block analysis or similar data fusion techniques to integrate the different data types while preserving their unique variance structures [1].

- Pattern Recognition: Use unsupervised learning approaches (e.g., clustering, principal component analysis) to identify natural groupings of foods with similar multi-omics profiles.

- Knowledge Discovery: Interpret the resulting food clusters to identify novel relationships between nutritional composition, chemical signatures, and sensory properties.

AI and Machine Learning Integration in Food Data Analysis

Current Applications and Methodologies

The application of AI and ML in food chemistry data analysis has moved beyond traditional statistical approaches to encompass sophisticated pattern recognition and predictive modeling. Current methodologies leverage the complex, high-dimensional data available from food composition databases to solve challenges in food authentication, quality control, and novel food design [1] [7].

Chemical Compound Classification with Random Forest: For food authentication tasks, Random Forest algorithms have demonstrated exceptional performance in classifying foods based on geographical origin, variety, and production methods using mass spectrometry data [1]. The protocol involves UHPLC-Q-ToF-MS analysis followed by feature extraction and Random Forest classification with rigorous cross-validation, achieving high accuracy in distinguishing subtle compositional differences.

Explainable AI (XAI) for Bioactivity Prediction: The application of Explainable AI approaches, particularly Random Forest Regression with feature importance analysis, enables researchers to understand the relationship between chemical compounds and bioactivities [1]. This methodology has been successfully applied to elucidate how specific phenolic compounds and amino acids in fermented foods influence antioxidant activity, providing interpretable models that bridge AI prediction with fundamental food chemistry principles.

Advanced Workflow for AI-Driven Food Formulation

The integration of multiple food databases enables a sophisticated AI-driven workflow for formulating novel food products with targeted nutritional and sensory properties. This approach moves beyond simple prediction to generative design of food formulations.

Experimental Protocol 4: Generative Formulation Design Using Constrained Optimization

- Constraint Definition: Specify nutritional targets (e.g., protein content, vitamin levels), sensory preferences, and ingredient restrictions (e.g., allergens, sustainability criteria).

- Search Space Definition: Define the universe of possible ingredients and their proportional ranges based on culinary feasibility and functional properties.

- Multi-Objective Optimization: Implement generative AI algorithms to explore the formulation space and identify ingredient combinations that optimally balance the defined constraints and objectives [3].

- Property Prediction: For each candidate formulation, predict nutritional profiles using USDA data and sensory properties using FooDB/FlavorDB relationships.

- Iterative Refinement: Use human feedback or simulated consumer acceptance models to refine the generated formulations through iterative improvement cycles.

Future Perspectives and Challenges

The future of food data resources lies in enhancing their interoperability and machine-readiness to better serve AI and ML applications. Current databases show significant variability in their adherence to FAIR principles, with particular needs for improvement in metadata richness, standardized nomenclature, and reusability [4] [5]. Emerging opportunities include the development of federated learning approaches that can leverage distributed food data without centralization, and the application of transfer learning to adapt models trained on major databases to regional or specialty foods.

A critical challenge remains the representation gap for biodiverse and culturally significant foods in major databases, which can lead to algorithmic biases and limit the global applicability of AI models [4]. Addressing this gap requires concerted effort to expand analytical characterization of traditional and indigenous foods, ensuring that the benefits of AI-driven food innovation are equitably distributed across global food systems. As these databases evolve to become more comprehensive and AI-ready, they will increasingly serve as the foundation for a new era of data-driven food design and personalized nutrition.

The field of food chemistry is undergoing a profound transformation, driven by the integration of artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning (ML). Modern analytical instruments, from chromatography–mass spectrometry to high-resolution hyperspectral imaging, generate vast, complex datasets that are too large and intricate for traditional chemometric methods to handle fully [1]. This application note explores how AI technologies are not replacing these traditional methods but are instead augmenting them, enabling researchers to extract deeper insights, achieve greater predictive accuracy, and unlock new possibilities in food quality, safety, and authenticity analysis. Framed within a broader thesis on the application of AI in food chemistry data analysis, this document provides detailed protocols and illustrative case studies to guide researchers in bridging the gap between classical analytical techniques and modern data-driven discovery.

AI-Enhanced Spectroscopic Analysis

Spectroscopic techniques such as Near-Infrared (NIR), Fourier-Transform Infrared (FTIR), and Raman spectroscopy have long been used for rapid, non-destructive food analysis. The integration of AI has significantly boosted their power for quantitative prediction and qualitative classification.

Key Applications and Workflow

AI-driven spectroscopy is routinely applied to predict chemical composition (e.g., moisture, protein, fat), assess sensory attributes, determine geographic origin, and detect adulteration [8] [1]. The core enhancement lies in ML algorithms' ability to model complex, non-linear relationships within spectral data that traditional linear models like PLSR might miss.

The following workflow delineates the standard procedure for developing an AI-enhanced spectroscopic model, from data acquisition to deployment.

Experimental Protocol: Moisture Content Prediction inPorphyra yezoensisvia NIR

This protocol is adapted from Zhang et al. (2025), which compared multiple ML models for this application [1].

- Objective: To predict the moisture content of the seaweed Porphyra yezoensis using NIR spectroscopy and machine learning models.

- Materials and Equipment:

- NIR spectrometer

- Lab-scale drying oven

- Analytical balance (±0.1 mg)

- Porphyra yezoensis samples

- Procedure:

- Sample Preparation: Prepare a set of 150 Porphyra yezoensis samples with varying moisture levels.

- Reference Analysis: Determine the reference moisture content for each sample using the standard oven-drying method (AOAC 930.15). This creates the ground truth data for model training.

- Spectral Acquisition: Collect NIR spectra from each sample using the spectrometer. Ensure consistent environmental conditions and sample presentation.

- Data Preprocessing: Apply standard preprocessing techniques to the raw spectral data:

- Savitzky–Golay Smoothing: Reduce high-frequency noise.

- Standard Normal Variate (SNV): Correct for scatter effects and path-length differences.

- Detrending: Remove baseline shifts.

- Dataset Splitting: Randomly divide the dataset into a training set (e.g., 70%) for model building and a hold-out test set (e.g., 30%) for final model evaluation.

- Model Training and Validation:

- Train multiple ML models on the preprocessed training set, including:

- XGBoost: A powerful gradient-boosting algorithm.

- 1D-CNN: A convolutional neural network that can learn features directly from spectral curves.

- Optimize model hyperparameters using k-fold cross-validation (e.g., k=5 or k=10) on the training set to prevent overfitting.

- Evaluate the final optimized models on the untouched test set.

- Train multiple ML models on the preprocessed training set, including:

- Results and Analysis: In the referenced study, XGBoost was recommended as the optimal model for industrial application due to its high predictive accuracy and computational efficiency. Gaussian Process Regression was used to assess prediction uncertainty, a critical step for ensuring reliability in real-world applications [1].

Table 1: Performance Comparison of ML Models for Moisture Prediction [1]

| Model | R² (Test Set) | RMSE (Test Set) | Key Advantages |

|---|---|---|---|

| XGBoost | 0.95 | 0.45 | High accuracy, fast training, handles non-linearity well |

| 1D-CNN | 0.93 | 0.52 | Automatic feature extraction, can model complex patterns |

| PLSR (Baseline) | 0.88 | 0.75 | Simple, interpretable, robust for linear relationships |

AI-Enhanced Chromatography and Mass Spectrometry

Liquid and gas chromatography coupled with mass spectrometry (LC-MS, GC-MS) are powerful for separating, identifying, and quantifying complex mixtures of food components. AI revolutionizes the analysis of the rich, high-dimensional data these techniques produce.

Key Applications and Workflow

Primary applications include food authenticity and traceability (e.g., determining geographical origin, variety, production method), biomarker discovery, non-targeted analysis for contaminant detection, and elucidating changes in food composition during processing [8] [1]. AI excels at finding subtle patterns in these complex datasets that are imperceptible to manual analysis.

The workflow for AI-enhanced chromatography/mass spectrometry involves sophisticated data alignment and model interpretation steps.

Experimental Protocol: Authenticity and Origin Classification of Apples via UHPLC-Q-ToF-MS

This protocol is based on the work of Hansen et al. (2025) [1].

- Objective: To classify apple samples based on geographical origin, variety, and production method (conventional vs. organic) using UHPLC-Q-ToF-MS data and a Random Forest model.

- Materials and Equipment:

- UHPLC system coupled to a Q-ToF mass spectrometer.

- Solvents: LC-MS grade methanol, acetonitrile, water.

- Formic acid or ammonium formate for mobile phase modification.

- Apple samples from defined origins, varieties, and farming practices.

- Procedure:

- Sample Extraction: Homogenize apple flesh. Perform a metabolite extraction using a solvent like methanol/water, followed by centrifugation and filtration to obtain a clear extract for analysis.

- Chromatographic Separation: Inject the extract into the UHPLC system. Use a reversed-phase C18 column and a gradient elution with water and acetonitrile (both modified with 0.1% formic acid) to separate the complex mixture of compounds.

- Mass Spectrometry Analysis: Analyze the column effluent using the Q-ToF mass spectrometer in data-dependent acquisition (DDA) mode, collecting high-resolution MS and MS/MS data.

- Data Processing:

- Use software (e.g., XCMS, MS-DIAL) for peak picking, alignment, and integration across all samples.

- Create a data matrix where rows are samples, columns are ion features (m/z-retention time pairs), and values are peak intensities.

- Model Training and Validation:

- Train a Random Forest classifier using the ion feature data as input and the class labels (e.g., "Origin A", "Origin B", "Variety X", "Organic") as the output.

- Use cross-validation and a hold-out test set to evaluate classification accuracy.

- Explainable AI (XAI) and Marker Discovery:

- Apply XAI techniques to the trained Random Forest model. Analyze variable importance measures (e.g., Mean Decrease in Gini index) to identify which ion features are most discriminatory for each classification task (origin, variety, method).

- Tentatively identify the top discriminatory features by matching their accurate mass and MS/MS fragmentation spectra against commercial and public databases (e.g., HMDB, MassBank).

- Results and Analysis: The study demonstrated that a single UHPLC-Q-ToF-MS analysis, when coupled with a versatile AI model like Random Forest, could yield multiple classification models for different authentication questions. The XAI component was crucial for identifying the key chemical markers (e.g., specific polyphenols, sugars) driving the classifications, thereby building trust in the model and providing actionable chemical insights [1].

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for Featured Experiments

| Reagent / Material | Function in Analysis | Example Experiment |

|---|---|---|

| UHPLC-Q-ToF-MS System | High-resolution separation and accurate mass measurement of complex food metabolites. | Apple Authenticity [1] |

| NIR Spectrometer | Rapid, non-destructive collection of molecular vibration data from samples. | Seaweed Moisture Prediction [1] |

| Hyperspectral Imaging (HSI) System | Simultaneous capture of spatial and spectral information for visualizing chemical distribution. | Shrimp Spoilage Monitoring [9] |

| Random Forest Algorithm | Robust, multi-class classification and regression; provides feature importance metrics. | Apple Authenticity, Apricot Kernel Bioactivity [1] |

| Convolutional Neural Network (CNN) | Advanced feature learning from complex data structures like images and spectra. | Shrimp Spoilage, Food Image Recognition [9] [1] |

AI-Enhanced Hyperspectral Imaging (HSI)

Hyperspectral Imaging (HSI) merges spectroscopy with digital imaging, providing a spatial map of spectral information. This is a classic example of a technique that generates data too vast and complex for manual analysis, making it an ideal candidate for AI enhancement.

Key Applications and Workflow

HSI is extensively used for non-destructive quality control, including freshness assessment in meats and seafood, detection of foreign bodies, distribution analysis of specific constituents (e.g., water, fat), and visualization of spoilage or contamination [9].

The following workflow illustrates the process of using HSI and AI to visualize chemical changes in a food sample.

Experimental Protocol: Monitoring Shrimp Flesh Deterioration

This protocol is derived from the comprehensive study by Xi et al. (2025) [9].

- Objective: To quantitatively analyze and visualize the spatial distribution of spoilage indicators (TVB-N and K value) in shrimp flesh during storage using HSI and machine learning.

- Materials and Equipment:

- Vis-NIR hyperspectral imaging system (e.g., 400-1000 nm range).

- Refrigerated storage chambers.

- Laboratory equipment for reference TVB-N (e.g., micro-diffusion apparatus) and K value (HPLC) analysis.

- Procedure:

- Sample Preparation and Storage: Obtain fresh shrimp and store them under controlled refrigerated conditions. At regular time intervals (e.g., 0h, 12h, 24h, 48h), remove a subset of samples for analysis.

- Reference Analysis: For each time point, destructively analyze shrimp samples to measure the reference TVB-N and K values using standard methods.

- Hyperspectral Image Acquisition: For the remaining samples at each time point, capture hyperspectral images. Ensure consistent lighting and camera settings.

- Spectral Data Extraction and Fusion: Extract average spectra from regions of interest (ROI) on the shrimp images. Fuse spectral data from the Visible (Vis) and NIR regions to create a low-level fusion (LLF) data block, which provides a more comprehensive chemical profile.

- Feature Selection: Apply variable selection algorithms like IRIV or VCPA-IRIV on the LLF data to identify the most informative wavelengths for predicting TVB-N and K value, thus simplifying the model and improving robustness.

- Model Building and Visualization:

- Develop ML models (e.g., PLSR, SVM) between the selected spectral features and the reference chemical values.

- Once a robust model is built, apply it to every pixel in the hyperspectral image. This predicts the TVB-N or K value for that specific pixel.

- Generate a visual chemical distribution map by assigning a color scale to the predicted values, allowing for direct observation of spoilage progression across the shrimp surface.

- Results and Analysis: The study demonstrated that models built on LLF data and optimized with feature selection yielded superior predictive performance (e.g., R²p > 0.94 for TVB-N) compared to models using full spectra or single spectral regions. The visualization maps clearly showed heterogeneous spoilage, beginning in specific areas before spreading, providing critical insights that are impossible to obtain with bulk analysis alone [9].

Table 3: Performance of AI-HSI Models for Shrimp Spoilage Indicators [9]

| Spoilage Indicator | Data Type | Optimal Model | R²p | RMSEP | RPD |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TVB-N (mg/100g) | Low-Level Fusion (LLF) | IRIV | 0.9431 | 2.49 | 4.23 |

| K Value (%) | Low-Level Fusion (LLF) | VCPA-IRIV | 0.9815 | 2.17 | 7.40 |

The transition from spectra to predictions is no longer a frontier but a present-day reality in advanced food chemistry laboratories. As demonstrated through these application notes and protocols, AI and ML do not render traditional analytical methods obsolete; instead, they serve as powerful force multipliers. By leveraging algorithms like Random Forest, XGBoost, and CNNs, researchers can extract unprecedented levels of information from spectroscopic, chromatographic, and imaging data. This synergy enables more precise quantitative predictions, robust classification for authenticity, and dynamic visualization of chemical changes, thereby driving innovation in food safety, quality control, and product development. The future of food chemistry data analysis lies in the continued refinement of these hybrid approaches, with a growing emphasis on explainable AI, multi-omics data integration, and the development of standardized validation frameworks for widespread industrial and regulatory adoption.

The integration of artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning (ML) is fundamentally transforming data analysis within food chemistry research. These technologies are becoming indispensable for addressing complex challenges related to food quality, safety, and nutrition [1]. Modern analytical instruments, such as chromatography–mass spectrometry and high-resolution imaging, generate vast, complex datasets that are too large and intricate for traditional methods to handle, creating an unprecedented need for advanced analytical power [1]. This document provides a detailed overview of core AI applications, accompanied by structured experimental protocols and data, to equip researchers with practical methodologies for implementing these technologies in food chemistry research.

Core Application Areas & Performance Data

The following table summarizes the key performance metrics of AI technologies across the primary domains of food analysis.

Table 1: Performance Metrics of AI Technologies in Food Analysis

| Application Domain | Specific AI Technology | Reported Performance | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Food Safety & Authenticity | Machine Learning with Biosensor Networks [10] | >90% sensitivity for Salmonella and Listeria detection [10] | Controlled experimental settings |

| Predictive Analytics for E. coli [10] | Up to 89% forecasting precision [10] | Integrates meteorological, livestock, wastewater data | |

| Random Forest for Food Provenance [1] | High classification accuracy for apple origin, variety, cultivation [1] | UHPLC-Q-ToF-MS data | |

| Food Quality Control | Image-based Machine Vision [10] | Up to 97.6% accuracy for freshness classification [10] | Vegetable soybeans, pilot-scale |

| XGBoost for Moisture Content [1] | High predictive accuracy recommended for industrial use [1] | Near-infrared spectroscopy of Porphyra yezoensis | |

| AI-enabled Spectroscopic Analysis [1] | Rapid, non-destructive quality control for meat and dairy [1] | Spectroscopy data fusion with ML | |

| Personalized Nutrition | Computer Vision for Food Recognition [11] | >85-90% classification accuracy [11] | Automated dietary assessment from images |

| Reinforcement Learning for Glycemic Control [11] | Up to 40% reduction in glycemic excursions [11] | Real-time dietary advice using CGM data | |

| Deep Learning for Food Label Analysis [12] | >97% accuracy in categorizing foods and calculating nutrition scores [12] | Natural Language Processing (NLP) of label data |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol: AI-Driven Food Authentication Using LC-MS and Random Forest

This protocol details the procedure for verifying food geographical origin, variety, and production method, as applied to apple authentication [1].

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for Food Authentication

| Reagent/Material | Function in the Experiment |

|---|---|

| UHPLC-Q-ToF-MS System | High-resolution separation and mass analysis of complex chemical compounds in food samples. |

| Solvent Blends (e.g., Methanol, Acetonitrile) | Extraction of metabolites and chromatographic separation. |

| Reference Standard Compounds | Identification and calibration of metabolites detected in samples. |

| Random Forest Algorithm (e.g., in R or Python) | Multivariate classification model that handles complex, high-dimensional data for authentication. |

| Feature Selection Tool (e.g., CARS) | Identifies and selects the most significant metabolite markers for classification. |

Workflow Diagram Title: Food Authentication via LC-MS and AI

Procedure:

- Sample Preparation: Homogenize food samples (e.g., apples). Perform metabolite extraction using a standardized solvent system (e.g., methanol-water) [1].

- LC-MS Analysis: Inject samples into the UHPLC-Q-ToF-MS system. Use a reverse-phase column and a water-acetonitrile gradient for separation. Acquire data in both positive and negative ionization modes to maximize metabolite coverage [1].

- Data Preprocessing: Process raw data to detect peaks, align features across samples, and perform normalization to correct for run-order variation. Export a peak intensity table (samples × features).

- Feature Selection: Apply a feature selection method like CARS (Competitive Adaptive Reweighted Sampling) to identify the most discriminative mass features (m/z-retention time pairs) for the classification task (e.g., geographical origin) [1].

- Model Training & Validation: Split data into training and test sets. Train a Random Forest classifier on the training set using the selected features. Optimize hyperparameters (e.g., number of trees) via cross-validation. Assess final model performance on the held-out test set using accuracy, precision, and recall.

- Interpretation: Analyze the Random Forest model's output (e.g., feature importance scores) to identify the key metabolites driving the classification, adding explainability to the results [1].

Protocol: Predictive Modeling for Food Safety Contamination

This protocol outlines the use of AI for forecasting microbial contamination risks in the food supply chain [10].

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Predictive Food Safety

| Reagent/Material | Function in the Experiment |

|---|---|

| Historical Outbreak Datasets | Foundational data for training predictive models on contamination events. |

| Meteorological Data | Provides environmental variables (temperature, rainfall) that influence pathogen growth and spread. |

| Livestock Movement Data | Tracks potential sources and pathways of zoonotic pathogens. |

| Wastewater Surveillance Data | Acts as a population-level early warning signal for pathogen presence. |

| Deep Learning Algorithms (e.g., LSTM, CNN) | Models complex, non-linear relationships in multivariate time-series data for forecasting. |

Workflow Diagram Title: Predictive Food Safety Modeling

Procedure:

- Data Aggregation: Compile a multimodal dataset from disparate sources. This includes historical records of foodborne illness outbreaks, gridded meteorological data (temperature, humidity, precipitation), livestock movement and density data, and wastewater surveillance metrics for key pathogens [10].

- Data Integration & Preprocessing: Clean and harmonize all datasets to a common spatio-temporal resolution (e.g., weekly, by region). Handle missing data and normalize features to a common scale.

- Model Architecture & Training: Design a deep learning model, such as a Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) network for temporal forecasting or a Convolutional Neural Network (CNN) for spatial risk mapping. Train the model to predict contamination probability (e.g., for E. coli) using the integrated data [10].

- Validation & Deployment: Validate model precision (reported up to 89% for E. coli [10]) using retrospective hold-out datasets and, if possible, prospective pilot studies. Deploy the model to generate dynamic, spatio-temporal risk maps.

- Actionable Outputs: Integrate model outputs with regulatory or supply chain management systems to enable targeted inspections, early warnings, and preventive interventions.

Protocol: Image-Based Dietary Assessment via Computer Vision

This protocol describes the use of deep learning for automated food recognition and nutrient estimation from images, a key tool for personalized nutrition [11].

Table 4: Research Reagent Solutions for Image-Based Dietary Assessment

| Reagent/Material | Function in the Experiment |

|---|---|

| Curated Food Image Datasets (e.g., CNFOOD-241) | Large-scale, labeled datasets for training and validating robust deep learning models. |

| Convolutional Neural Network (CNN) | The core deep learning architecture for image classification and feature extraction. |

| Attention Mechanisms | Enhances model performance by focusing on discriminative local regions of food images. |

| Food Composition Database | Links recognized food items and estimated portions to their nutritional profiles. |

Workflow Diagram Title: Computer Vision for Diet Assessment

Procedure:

- Data Curation: Utilize a large-scale, annotated food image dataset (e.g., CNFOOD-241) that includes labels for food type and portion size [11].

- Model Selection & Training: Select a base CNN architecture (e.g., ResNet, Vision Transformer) and augment it with attention mechanisms to improve recognition of fine-grained food categories [1] [11]. Train the model on the curated dataset, using techniques like multi-level feature fusion to boost accuracy beyond 90% [11].

- Portion Size Estimation: Implement a model branch or a complementary algorithm (e.g., using reference objects in the image) to estimate the volume or weight of the identified food.

- Nutrient Estimation: Integrate the model outputs with a comprehensive food composition database. By combining the identified food item and its estimated portion, the system can automatically calculate and output the nutritional content of the meal [11].

- Validation: Validate the entire pipeline's accuracy against ground-truth data from weighted food records or doubly labeled water methods in controlled studies.

AI in Action: Machine Learning Workflows and Real-World Applications

The integration of spectroscopic technologies with artificial intelligence (AI) is revolutionizing food chemistry data analysis, enabling rapid, non-destructive, and high-throughput quality control. Spectroscopic classification serves as a critical first step in automated food analysis systems, ensuring that subsequent quality assessment algorithms are correctly applied based on the specific food type [13]. For researchers and drug development professionals, these methodologies offer transferable principles for handling complex, multi-dimensional biochemical data. The robust identification of raw food materials forms the foundation for ensuring food safety, authenticating authenticity, and optimizing industrial processes, with machine learning (ML) models providing the computational framework to decode intricate spectral signatures [14] [13].

This application note details the protocols for building robust ML models tailored for spectroscopic classification of raw foods, framed within the broader context of AI applications in food chemistry. We present a systematic workflow encompassing data acquisition, preprocessing, model selection, and validation, with a focus on practical implementation for research scientists.

Core Spectroscopic Technologies and Data Characteristics

The selection of an appropriate spectroscopic technique is paramount, as each interacts with food matrices in distinct ways, yielding complementary information. The following table summarizes the primary technologies used in raw food identification.

Table 1: Core Spectroscopic Technologies for Raw Food Identification

| Technology | Spectral Range | Information Obtained | Key Advantages | Sample Applications in Food ID |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fourier-Transform Infrared (FTIR) [13] | Mid-infrared (MIR) | Molecular vibration fingerprints | High specificity for functional groups, robust | Multi-class raw food categorization (meat, fish, etc.) |

| Near-Infrared (NIR) Spectroscopy [14] [15] | Near-infrared (NIR) | Overtone/combination vibrations of C-H, O-H, N-H | Rapid, deep penetration, minimal sample prep | Authentication of grains, analysis of protein/moisture |

| Raman Spectroscopy [14] [16] | Varies (Laser-dependent) | Molecular vibration and rotation | Minimal water interference, specific fingerprinting | Detection of foodborne pathogens, sweetener identification |

| Hyperspectral Imaging (HSI) [14] [15] | UV, Visible, NIR | Simultaneous spatial and spectral data | Combines visual & chemical analysis; mapping capability | Spatial distribution of contaminants, defect detection |

Machine Learning Workflow for Spectroscopic Classification

The process of transforming raw spectral data into a reliable classification model involves a sequence of critical steps. The workflow, from sample preparation to model deployment, is designed to ensure robustness and generalizability.

Experimental Protocol: Raw Food Spectroscopic Classification

Objective: To classify seven different types of raw food (e.g., meat, fish, poultry) using FTIR spectroscopy combined with a Support Vector Machine (SVM) classifier [13].

I. Materials and Reagents

- Spectrometer: Fourier-Transform Infrared (FTIR) spectrometer.

- Samples: Diverse batches of raw food samples (e.g., chicken, beef, pork, salmon, cod, shrimp, turkey) [13].

- Storage Materials: Materials for simulating real-world storage conditions (e.g., aerobic and modified atmosphere packaging, temperature-controlled incubators) to introduce natural variability into the dataset [13].

II. Procedure

Step 1: Sample Preparation and Spectral Acquisition

- Prepare food samples in a consistent, reproducible form (e.g., uniform slice thickness and surface area).

- Acquire FTIR spectra from each sample. For robust modeling, collect multiple spectra from different spots on each sample.

- Document storage conditions (time, temperature, packaging) for each sample batch to embed real-world variance into the model [13].

Step 2: Data Preprocessing and Feature Engineering

- Apply Standard Normal Variate (SNV) or its robust variant (RNV) to correct for multiplicative scatter effects and baseline drift [13].

- Utilize Partial Least Squares (PLS) regression as a supervised dimensionality reduction technique. This projects the high-dimensional spectral data into a latent variable space optimized for separating the predefined food classes [13].

- Retain the top PLS components that explain the majority of the variance in the data. These components serve as the engineered features for the subsequent classification model.

Step 3: Model Training and Validation

- Split the preprocessed dataset (features from PLS and class labels) into a training set (e.g., 70-80%) and an independent test set (e.g., 20-30%).

- Train a Support Vector Machine (SVM) classifier with a non-linear kernel (e.g., Radial Basis Function) on the training set. The SVM aims to find the optimal hyperplane that separates the different food classes [13].

- Validate the model's performance using the held-out test set. Evaluate using metrics such as accuracy, precision, recall, and F1-score. A well-executed protocol can achieve accuracy exceeding 95-100% on multi-class raw food identification [13].

Performance of ML Models in Food Spectroscopy

Different machine learning algorithms offer varying advantages depending on the data structure and classification task. The selection often involves a trade-off between model interpretability and predictive power.

Table 2: Performance Comparison of Machine Learning Models for Spectroscopic Classification

| Model | Model Type | Key Principles | Reported Performance | Best Use Cases |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Support Vector Machine (SVM) [13] | Traditional ML | Finds optimal separating hyperplane in high-dim space | 100% accuracy for 7-class raw food ID with FTIR [13] | High-dimensional data, clear margin separation |

| Random Forest (RF) [1] [17] | Ensemble ML | Averages predictions from multiple decision trees | Near-perfect identification of sweeteners with Raman [17] | Robust to outliers, feature importance analysis |

| Partial Least Squares-Discriminant Analysis (PLS-DA) [15] [18] | Linear Projection | Combines dimensionality reduction with classification | ~88% accuracy for pesticide classification on Hami melon [18] | Small-sample scenarios, highly interpretable |

| Convolutional Neural Network (CNN) [16] [18] | Deep Learning | Automatically extracts hierarchical spatial features | 98.4% accuracy for pathogen ID with Raman; 95.8% for pesticide ID with NIR [16] [18] | Large, complex datasets, raw spectral data |

| Dual-Scale CNN [16] | Advanced Deep Learning | Captures both local feature peaks and global spectral patterns | 98.4-99.2% accuracy for pathogen serotypes with Raman [16] | Complex samples with spectral similarities and interference |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Spectroscopic Food Analysis

| Item | Function/Application | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| FTIR Spectrometer [13] | Acquires molecular vibration fingerprints from food surfaces. | Non-destructive classification of raw meat and fish samples. |

| Portable NIR Spectrometer [14] | Enables on-site, rapid analysis with minimal sample preparation. | In-field quality assessment and authentication of grains and staples. |

| Hyperspectral Imaging System [14] [15] | Simultaneously captures spatial and spectral information. | Mapping the distribution of contaminants or defects on fruit surfaces. |

| Standard Normal Variate (SNV) [13] | Preprocessing algorithm to remove scatter and multiplicative interference. | Essential data pretreatment step before model training to enhance signal. |

| Surface-Enhanced Raman Scattering (SERS) Substrates [14] | Enhances Raman signal intensity for trace-level analysis. | Detection of low-concentration contaminants like pesticides or melamine. |

Advanced Applications and Future Directions

The convergence of spectroscopy and AI is pushing the boundaries of food chemistry analysis. Key advanced applications include:

- Pathogen Detection: Raman spectroscopy powered by a dual-scale CNN has been used to identify foodborne pathogen serotypes with 98.4% accuracy, drastically reducing analysis time compared to traditional culturing methods [16].

- Pesticide Residue Analysis: Hyperspectral imaging combined with Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs) has been applied to predict pesticide residue levels in cantaloupe, achieving a high coefficient of determination (R²P = 0.8781) [18].

- Sweetener Identification: The combination of Raman spectroscopy with a Random Forest classifier allows for rapid (5-6 seconds per sample) and accurate identification of sweeteners like sucrose and cyclamate [17].

Future research is directed towards Explainable AI (XAI) to demystify model decisions, multimodal data fusion integrating spectral, omics, and imaging data, and the development of lightweight models for edge computing in portable devices [14] [1]. Standardization and validation frameworks will be crucial for the widespread adoption and regulatory acceptance of these AI-powered methods in the food industry and related fields [1].

The landscape of food safety is being reshaped by the transformative power of data handling tools, including chemometrics, machine learning (ML), and artificial intelligence (AI) [1]. Modern analytical instruments generate vast, complex datasets that are too large and intricate for traditional methods to handle, creating an unprecedented need for advanced analytical power [1]. Predictive microbiology, which involves using mathematical models to forecast the growth and behavior of microorganisms in food products under different environmental conditions, has emerged as a crucial tool for proactive food safety management [19]. This shift represents a move away from reactive, hazard-based approaches toward a preventative, risk-based framework that can anticipate and mitigate food safety hazards before they reach consumers [19].

The integration of AI and ML into predictive modeling addresses significant limitations of conventional methods. While classical chemometric techniques like Principal Component Analysis (PCA) and Partial Least Squares Regression (PLSR) have been instrumental, they often struggle with the sheer volume and dimensionality of data from high-throughput technologies [1]. Machine learning algorithms such as Support Vector Machines, Random Forests, and Artificial Neural Networks are adept at handling large, high-dimensional datasets and uncovering complex, non-linear relationships that traditional methods often miss [1]. This technological evolution is enabling unprecedented capabilities in detecting contaminants and predicting spoilage across the global food supply chain.

Foundational Concepts and Data Considerations

Data Types and Characteristics in Food Safety

Effective predictive modeling begins with an understanding of food safety data fundamentals. Data generated in food safety experiments fall into two main categories: quantitative (continuous) and qualitative (categorical) [20]. Microbial counting, a cornerstone of contaminant detection, produces quantitative data that is typically log-normally distributed and often heteroscedastic [20]. Understanding these distribution characteristics is essential for selecting appropriate statistical analyses and transformation techniques.

Food safety data exhibits several distinctive characteristics that influence analytical approaches:

- Multidimensional data: From chromatography–mass spectrometry detecting hundreds of compounds in a single sample to high-resolution imaging capturing minute textural details [1]

- Spatial-temporal patterns: Geographic and time-based distributions of contamination risks [21]

- Hierarchical structures: Data organized within supply chain relationships [21]

- Associated relations: Complex networks connecting contamination sources, pathways, and endpoints [21]

Diverse data sources feed predictive models in food safety applications:

- Sensors and analytical instruments: Chromatograph-mass spectrometers for pesticide residue detection, RFID sensors for food safety quality traceability, and Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (FTIS) for rapid composition analysis [21] [1]

- Online databases: Risk information from monitoring procedures and alert systems published by authorities like WHO, USFDA, EFSA, and SAMR [21]

- Satellite and meteorological data: Ground and weather data collected by remote sensing satellites and drones for monitoring environmental contamination factors [21]

- Social media platforms: Public sentiment and emerging contamination reports from platforms like Weibo and Twitter [21]

Predictive Modeling Approaches: From Traditional to AI-Enhanced

Traditional Predictive Microbiology Models

Traditional predictive models in food microbiology represent the dynamic interactions between intrinsic and extrinsic food factors as mathematical equations, applying these data to predict shelf life, spoilage, and microbial risk assessment [19]. These tools are increasingly integrated into Hazard Analysis Critical Control Point (HACCP) protocols and food safety objectives [19].

The primary model types include:

- Kinetic models: Describe microbial growth, survival, or inactivation over time under constant conditions

- Probability models: Predict the likelihood of microbial growth or toxin production under specific conditions

- Empirical models: Statistically relate microbial responses to environmental factors without claiming to represent underlying mechanisms

- Mechanistic models: Based on theoretical understanding of microbial behavior and physiological processes

Machine Learning and AI Integration

Machine learning algorithms are becoming integral components of evolving food safety models, offering significant advantages over traditional approaches [19]. ML encompasses several learning paradigms suited to different data characteristics and prediction tasks:

Table 1: Machine Learning Approaches for Food Safety Prediction

| Learning Type | Key Algorithms | Food Safety Applications | Advantages |

|---|---|---|---|

| Supervised Learning | Random Forest, SVM, XGBoost, CNN, ResNet [1] [22] | Classification of geographical origin, variety, production method [1] | High accuracy with labeled data, well-established implementations |

| Unsupervised Learning | PCA, k-means clustering, Hierarchical clustering [22] [23] | Pattern discovery in unlabeled contamination data | Identifies hidden patterns without predefined categories |

| Deep Learning | Artificial Neural Networks, CNN, RNN, GNN [1] [23] | Food image recognition, molecular structure modeling [1] | Excels with complex, high-dimensional data like images |

The following workflow illustrates the integrated process of developing and applying AI-enhanced predictive models in food safety research:

Explainable AI (XAI) for Enhanced Model Trust

A critical advancement in AI for food safety is the development of explainable AI (XAI), which addresses the "black box" nature of many complex models [1]. For regulatory acceptance and practical implementation, stakeholders must understand how models reach specific decisions. Techniques like Random Forest Regression with feature importance analysis not only provide predictions but also identify which variables (e.g., specific amino acids or phenolic compounds) most significantly impact outcomes like antioxidant activity [1]. This transparency builds trust and provides actionable insights for intervention strategies.

Application Notes: Experimental Protocols for Predictive Modeling

Protocol 1: Food Authenticity and Fraud Detection Using LC-MS and Random Forest

This protocol outlines the detection of food fraud and verification of geographical origin using liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (LC-MS) combined with Random Forest classification, as demonstrated in apple authentication [1].

Research Reagent Solutions and Materials

Table 2: Essential Materials for LC-MS Based Authentication

| Item | Specification | Function/Purpose |

|---|---|---|

| UHPLC-Q-ToF-MS System | Ultra-High Performance Liquid Chromatography Quadrupole Time-of-Flight Mass Spectrometry | Separation and detection of chemical compounds for fingerprinting |

| Solvent Systems | HPLC-grade methanol, acetonitrile, water with 0.1% formic acid | Mobile phase for compound separation |

| Reference Standards | Authentic chemical standards for target compounds | Method validation and compound identification |

| Sample Preparation Kit | Centrifuges, filters, solid-phase extraction cartridges | Sample cleanup and concentration |

| Random Forest Algorithm | Implementation in R (randomForest package) or Python (scikit-learn) | Classification model building |

Step-by-Step Methodology

Sample Collection and Preparation:

- Collect representative samples from different geographical origins, varieties, or production methods

- Homogenize and extract using standardized protocol (e.g., 1g sample in 10mL methanol-water mixture, 70:30 v/v)

- Centrifuge at 10,000 × g for 10 minutes and filter through 0.22μm membrane

LC-MS Analysis:

- Inject 5μL of prepared sample into UHPLC system

- Employ reverse-phase C18 column (100 × 2.1mm, 1.7μm) maintained at 40°C

- Use binary gradient elution: (A) water with 0.1% formic acid; (B) acetonitrile with 0.1% formic acid

- Set flow rate to 0.3mL/min with gradient from 5% to 95% B over 20 minutes

- Operate MS in positive/negative electrospray ionization mode with mass range 50-1500m/z

Data Preprocessing:

- Perform peak picking, alignment, and normalization using software (e.g., XCMS, ProteoWizard)

- Create data matrix with samples as rows and detected ion features (m/z-retention time pairs) as columns

- Apply log transformation and Pareto scaling to reduce heteroscedasticity

Model Training and Validation:

- Split data into training (70%) and test sets (30%) with stratified sampling

- Train Random Forest classifier with 1000 trees on training set

- Optimize hyperparameters (mtry, node size) via cross-validation

- Evaluate model performance on test set using accuracy, precision, recall, and F1-score

- Generate variable importance plots to identify most discriminatory compounds

Protocol 2: Spoilage Prediction Using Spectroscopy and Machine Learning

This protocol details the prediction of moisture content in food products using near-infrared (NIR) spectroscopy combined with machine learning models, as demonstrated in Porphyra yezoensis (seaweed) analysis [1].

Research Reagent Solutions and Materials

Table 3: Essential Materials for Spectroscopy-Based Spoilage Prediction

| Item | Specification | Function/Purpose |

|---|---|---|

| NIR Spectrometer | Fourier Transform Near-Infrared Spectrometer with diffuse reflectance accessory | Rapid, non-destructive spectral acquisition |

| Reference Analyzer | Moisture analyzer based on loss-on-drying or Karl Fischer titration | Reference method validation |

| Spectral Standards | White reference tiles, ceramic standards | Instrument calibration and validation |

| Data Analysis Software | Python with scikit-learn, R with caret package, or proprietary chemometrics software | Model development and validation |

Step-by-Step Methodology

Sample Preparation and Spectral Acquisition:

- Prepare samples with varying moisture levels (e.g., through controlled drying)

- Acquire NIR spectra in the range of 800-2500nm at 2nm resolution

- For each sample, collect 32 scans and average to improve signal-to-noise ratio

- Measure reference moisture values using standard method (e.g., AOAC 930.15)

Spectral Preprocessing:

- Apply Savitzky-Golay smoothing (window size 11, polynomial order 2) to reduce noise

- Perform standard normal variate (SNV) transformation to remove scatter effects

- Use first or second derivative (Savitzky-Golay, gap = 5) to enhance spectral features

- Employ adaptive iteratively reweighted Penalized Least Squares (airPLS) for baseline correction [1]

Feature Selection and Model Comparison:

Model Deployment:

- Select best-performing model based on root mean square error of prediction (RMSEP) and R²

- Validate model with independent test set not used in model development

- Implement model in production environment for real-time quality monitoring

The relationship between data preprocessing, model selection, and performance evaluation in spectroscopic analysis follows a systematic pathway:

Data Analysis and Visualization Framework

Statistical Considerations for Microbial Data

Microbiological data presents unique analytical challenges that must be addressed for valid predictions:

- Non-normal distribution: Microbial counts typically follow lognormal distribution, requiring log transformation before analysis [20]

- Left-censored data: Handling non-detectable values through proper statistical methods [20]

- Heteroscedasticity: Variance often increases with mean count, requiring weighting or transformation [20]

Statistical tests should be applied to verify assumptions:

- Shapiro-Wilk test: For small sample sizes (n < 50) to test normality of residuals [20]

- Kolmogorov-Smirnov test: For larger sample sizes to test distributional assumptions [20]

- Breusch-Pagan test: To verify homoscedasticity of variances [20]

Visualization Techniques for Food Safety Data

Effective visualization enhances interpretation of complex food safety data:

Table 4: Visualization Methods for Different Data Types in Food Safety

| Data Characteristic | Visualization Methods | Application Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Multidimensional Data | Parallel coordinates, scatterplot matrix, PCA biplots [21] | Visualizing multiple chemical compounds across samples |

| Spatial-temporal Data | Map-based methods, timeline visualizations, heat maps [21] | Tracking contamination spread across regions over time |

| Associated Relations | Node-link diagrams, network graphs, adjacency matrices [21] | Modeling contamination pathways through supply chain |

| Hierarchical Data | Tree diagrams, sunburst plots, treemaps [21] | Organizing data by food categories and subcategories |

Implementation Challenges and Future Directions

Current Limitations and Barriers

Despite promising advances, several challenges remain in implementing predictive models for food safety:

- Data quality and standardization: Inconsistent data collection protocols and missing values complicate model development [19]

- Model interpretability: Complex deep learning models often function as "black boxes," raising concerns for regulatory acceptance [1]

- Computational requirements: Sophisticated models demand significant processing power and technical expertise [24]

- Validation hurdles: Demonstrating model robustness across diverse food matrices and environmental conditions [19]

Consumer acceptance also presents implementation challenges. A 2025 survey revealed that 70% of consumers who would be unlikely to choose an AI-assisted product cited trust in its ability to maintain food safety as a concern, while 53% of those who would be likely to choose such products believe AI can improve food safety [25]. This highlights the importance of transparency and education in technology adoption.

Emerging Trends and Research Frontiers

Future research directions are focusing on several promising areas:

- Multi-omics integration: Using AI to fuse data from genomics, metabolomics, and proteomics with conventional analytical data for a more holistic understanding of food products [1]

- Explainable AI (XAI): Developing models that are not only accurate but also interpretable, providing clear insights into the underlying chemical and physical properties that drive predictions [1]

- Standardization frameworks: Establishing consensus on best practices, data sharing protocols, and model validation procedures for regulatory acceptance [1]

- Human-in-the-loop visual analytics: Integrating human intelligence with machine capabilities through interactive visual interfaces to support analytical reasoning and decision-making [21]

The integration of whole genome sequencing (WGS) with machine learning represents a particularly promising frontier. WGS technologies generate vast amounts of high-throughput data that serve as invaluable resources for training models to track pathogen transmission and evolution [19].

Predictive models enhanced with AI and machine learning are fundamentally transforming contaminant and spoilage detection in food systems. By shifting from reactive to proactive approaches, these technologies enable earlier detection of food safety risks, more targeted interventions, and ultimately, enhanced public health protection. The protocols outlined in this document provide researchers with practical frameworks for implementing these advanced analytical techniques while highlighting critical considerations for data quality, model validation, and interpretation.

As the field evolves, emphasis on explainable AI, multimodal data integration, and standardized validation frameworks will be essential for building regulatory and consumer confidence in these powerful tools. The ongoing collaboration between food scientists, data analysts, and regulatory bodies will ensure that predictive modeling continues to advance as a reliable cornerstone of modern food safety systems.

Precision nutrition (PN) represents a paradigm shift from generalized dietary advice to tailored interventions that account for individual variability in biology, behavior, and environment [26] [11]. This approach recognizes that dietary responses are markedly influenced by inter-individual metabolic variability, which challenges the one-size-fits-all approach to dietary advice [27]. Artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning (ML) have emerged as transformative technologies enabling the implementation of precision nutrition at scale by analyzing complex multimodal datasets to deliver personalized dietary recommendations [11] [3].

The integration of AI into nutritional science has accelerated rapidly, with approximately 75% of relevant studies published since 2020 [26] [28]. This growth reflects the increasing recognition of AI's potential to address persistent challenges in nutritional assessment, intervention personalization, and outcome monitoring. AI technologies can process diverse data sources including genetic profiles, metabolic markers, dietary patterns, and lifestyle factors to generate actionable insights for individualized nutrition planning [11].

This application note provides detailed methodologies and protocols for implementing AI-assisted dietary assessment and personalized analysis within research and clinical settings. The content is framed within the broader context of applying AI and machine learning in food chemistry data analysis research, with specific consideration for the needs of researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals working at the intersection of nutrition, technology, and health outcomes.

AI-driven precision nutrition employs diverse computational approaches to analyze complex nutritional datasets. Table 1 summarizes the key AI methodologies and their primary applications in the field.

Table 1: AI Methods and Applications in Precision Nutrition

| AI Methodology | Sub-categories | Primary Applications in Precision Nutrition | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Supervised Learning | Random Forest, XGBoost, Support Vector Machines (SVM), Multilayer Perceptrons (MLP) | Predicting postprandial glycemic responses, nutrient deficiency risk assessment, disease status classification (e.g., diabetes, cardiovascular diseases). | [26] [1] [11] |

| Deep Learning | Convolutional Neural Networks (CNN), Recurrent Neural Networks (RNN), Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM), Transformers | Food image recognition and classification, automated dietary assessment from images, time-series analysis of biomarker data. | [1] [11] |

| Unsupervised Learning | k-means Clustering, Principal Component Analysis (PCA) | Identifying population subgroups or phenotypes based on metabolic profiles, dietary patterns, or genetic markers. | [11] [27] |

| Reinforcement Learning | Deep Q-Networks, Policy Gradient Methods | Generating dynamic, adaptive dietary recommendations based on continuous feedback from user data. | [11] |

| Natural Language Processing | Large Language Models (LLMs), Text Mining | Analyzing clinical notes, processing dietary logs, powering conversational agents (chatbots) for patient engagement. | [26] [29] |

The selection of an appropriate AI methodology depends on the research question, data type, and desired outcome. Supervised learning models are particularly valuable for prediction tasks where labeled data exists, while unsupervised approaches can reveal novel patterns in unlabeled data. Deep learning excels at processing complex data structures like images and time-series information, and reinforcement learning offers dynamic adaptation for intervention personalization [26] [11].

Experimental Protocols for AI-Assisted Dietary Assessment

Protocol 1: Image-Based Dietary Intake Assessment Using Convolutional Neural Networks

Purpose: To automatically identify food items and estimate portion sizes from meal images for objective dietary assessment.

Background: Traditional dietary assessment methods like 24-hour recalls and food frequency questionnaires are prone to memory bias and measurement error [30]. Image-based methods offer a more objective and scalable alternative.

Materials and Reagents:

- Digital camera or smartphone with minimum 12MP resolution

- Color calibration card (e.g., X-Rite ColorChecker Classic)

- Standardized placement surface

- Reference object for scale (e.g., a checkerboard pattern of known dimensions)

- Computing hardware: GPU-enabled workstation (minimum 8GB VRAM)

- Software: Python 3.8+, PyTorch or TensorFlow framework, OpenCV

Experimental Workflow:

Image Acquisition and Pre-processing:

- Capture food images from multiple angles (top-down and 45-degree angle recommended) under consistent lighting conditions.

- Include color calibration card and reference object in the initial frame.

- Apply chromatic adaptation transform using the color checker to standardize colors across images.

- Resize images to a standardized resolution (e.g., 512x512 pixels) and normalize pixel values.

Model Training and Validation:

- Utilize a pre-trained CNN architecture (e.g., ResNet-50, EfficientNet) as the backbone.

- Fine-tune the model on a domain-specific food dataset (e.g., Food-101, CNFOOD-241, or a proprietary dataset).

- Implement data augmentation techniques including rotation, flipping, and brightness adjustment to improve model robustness.

- For portion size estimation, train a regression head in parallel with the classification layer, using reference object for scale calibration.

- Validate model performance using hold-out test sets with standard metrics: top-1 accuracy, top-5 accuracy, and mean absolute error for portion estimation.

Nutrient Estimation:

- Link identified food items and estimated portions to standardized food composition databases (e.g., USDA FoodData Central, local composition tables).

- Calculate nutrient intake by matching classified foods and their estimated volumes to database entries.

The workflow for this protocol is visualized in Figure 1.

Figure 1: Workflow for Image-Based Dietary Assessment Using CNN

Protocol 2: Multi-Omic Data Integration for Nutritional Phenotyping

Purpose: To integrate genomic, proteomic, and metabolomic data for comprehensive nutritional phenotyping and stratification of individuals into sub-groups for targeted interventions.

Background: The successful implementation of precision nutrition requires a systems-level understanding of human physiological networks and their variations in response to dietary exposures [27]. Multi-omics platforms enable a holistic characterization of the complex relationships between nutrition and health at the molecular level.

Materials and Reagents:

- Biological samples (whole blood, urine, saliva)

- DNA/RNA extraction kits (e.g., Qiagen DNeasy Blood & Tissue Kit)

- LC-MS/MS system for proteomic and metabolomic analysis

- Next-generation sequencing platform (e.g., Illumina)

- High-performance computing cluster with minimum 32GB RAM

- Bioinformatics software: FastQC, Trimmomatic, STAR aligner, DESeq2, limma

Experimental Workflow:

Sample Collection and Preparation:

- Collect biological samples following standardized protocols (time of collection, fasting status, and processing methods should be consistent).

- Extract DNA/RNA using validated kits, ensuring quality control (A260/A280 ratio >1.8 for DNA, RIN >7 for RNA).

- For proteomics/metabolomics: perform protein precipitation and metabolite extraction using appropriate solvents (e.g., methanol:acetonitrile 1:1).

Data Generation:

- Genomics: Perform whole-genome or targeted sequencing using NGS platforms.

- Transcriptomics: Conduct RNA sequencing with minimum 30 million reads per sample.

- Proteomics: Perform LC-MS/MS analysis in data-dependent acquisition mode.

- Metabolomics: Utilize LC-MS/MS in both positive and negative ionization modes.

Bioinformatic Processing:

- Quality Control: Assess sequence quality (FastQC), filter adapters and low-quality reads (Trimmomatic).

- Alignment and Quantification: Align sequences to reference genome (STAR), perform variant calling (SAMtools), quantify gene/protein expression (DESeq2 for RNA-seq, MaxQuant for proteomics).