Food Matrix Effects: Unlocking Bioavailability and Drug Delivery in Pharmaceutical Sciences

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of the interactions between food components and the resulting matrix effects, with a specific focus on implications for drug development and nutrient bioavailability.

Food Matrix Effects: Unlocking Bioavailability and Drug Delivery in Pharmaceutical Sciences

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of the interactions between food components and the resulting matrix effects, with a specific focus on implications for drug development and nutrient bioavailability. It explores the fundamental mechanisms behind these interactions, reviews advanced methodological approaches for their study, addresses key challenges in predicting and optimizing for matrix effects, and discusses validation strategies for translating in vitro findings to clinical outcomes. Aimed at researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, this review synthesizes current knowledge to guide the design of more effective nutraceuticals and oral drug formulations by harnessing the power of food matrix science.

Deconstructing the Food Matrix: Core Concepts and Interaction Mechanisms

For decades, nutritional science has predominantly operated on a reductionist paradigm, focusing on the health effects of individual nutrients such as saturated fats, specific vitamins, or sodium [1]. While this approach has yielded valuable insights, it increasingly fails to predict the complex physiological responses to whole foods. The concept of the food matrix represents a fundamental shift toward a more holistic understanding. The food matrix is defined as the unique physical and chemical structure of a food, encompassing how its components—including nutrients, water, air, and other bioactive compounds—are organized and interact at molecular, microscopic, and macroscopic levels [2] [3]. This structure is not merely a passive container but a functional domain that actively modulates the digestion, absorption, and bioavailability of its constituents, resulting in health effects that cannot be predicted from composition data alone [3]. This technical guide delineates the core principles, analytical methodologies, and research applications of the food matrix, framing it within the broader context of interactions between food components and matrix effects research for a scientific audience.

Deconstructing the Food Matrix: Structural Hierarchy and Key Components

The food matrix can be conceptualized across multiple structural hierarchies, each contributing to its functional properties.

Levels of Structural Organization

Food matrices operate across three primary levels of organization:

- Molecular Level: This includes the primary, secondary, tertiary, and quaternary structures of proteins; the crystalline or amorphous forms of carbohydrates; and the organization of lipids in emulsions.

- Microscopic Level: This encompasses structures visible under microscopy, such as the protein network in cheese or yogurt, the cellular walls in plant tissues, and the structure of fat globules.

- Macroscopic Level: These are the bulk properties perceived by touch or sight, including texture, hardness, viscosity, and overall food geometry [3].

Table 1: Key Components and Their Functional Roles in the Food Matrix

| Matrix Component | Primary Functional Role | Impact on Nutrient Bioavailability |

|---|---|---|

| Proteins (e.g., β-lactoglobulin, casein) | Forms gel networks; encapsulates nutrients and flavor compounds; interacts with polyphenols and lipids via covalent/non-covalent bonds. | Modulates peptide release kinetics during digestion; can bind to and reduce the bioavailability of certain compounds [4]. |

| Lipids (e.g., Milk Fat Globule Membrane) | Forms emulsion droplets; compartmentalizes fat-soluble vitamins; creates unique interfacial structures. | Slows gastric emptying; influences postprandial lipemia; carries fat-soluble bioactives [2] [3]. |

| Carbohydrates (e.g., dietary fiber, starch, amylose) | Forms viscous gels and intact cell walls; can trap nutrients and other components within its structure. | Reduces glycemic response; physically shields lipids from digestive enzymes, lowering metabolizable energy [3]. |

| Minerals & Bioactive Compounds (e.g., Calcium, Polyphenols) | Cross-links biopolymers (e.g., calcium in protein gels); interacts with and binds to other food components. | Can form indigestible complexes (e.g., calcium with fatty acids); binding can alter the release of flavors and nutrients [2] [4]. |

The Dairy Matrix: A Prime Example of Structural Complexity

Dairy foods serve as a canonical example of a complex food matrix. Milk is a natural emulsion of fat globules suspended in an aqueous phase containing proteins, minerals, and vitamins [3]. The milk fat globule membrane (MFGM), a triple-layer phospholipid membrane encapsulating the fat droplet, is a critical structural component that influences lipid digestion and metabolic responses [2]. Furthermore, processing transforms this initial matrix into diverse structures:

- Cheese: A semi-solid protein gel (casein) entrapping fat and water.

- Yogurt: An acid-induced gel of casein proteins. These structural differences, despite similar nutrient profiles, lead to distinct physiological outcomes. Clinical data show that dairy systems with different macrostructures (liquid milk vs. semi-solid yogurt) with identical caloric content elicit different satiety responses [3]. This underscores that the matrix's physical form is a key determinant of its functional behavior.

Analytical Framework: Methodologies for Quantifying Matrix Effects

A multi-pronged analytical approach is required to deconstruct and quantify food matrix effects, focusing on digestibility, bioaccessibility, and flavor release.

Assessing Nutrient Digestibility and Bioaccessibility

Objective: To determine the efficiency with which an analyte is released from the food matrix during digestion (extractability) and its subsequent availability for absorption (bioaccessibility). Protocol:

- In Vitro Digestion Models: Subject the food sample to a simulated gastrointestinal digestion process (e.g., INFOGEST protocol) involving oral, gastric, and intestinal phases.

- Sample Preparation: Prepare two sets of samples:

- Set C (Pre-extraction spike): Spike the analyte of interest into the food sample before the digestion process.

- Set A (Control): Prepare a standard solution of the analyte in a clean solvent.

- Analysis: Use techniques like High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC) or Gas Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (GC-MS) to quantify the analyte concentration in the digested samples.

- Calculation: Calculate the analyte recovery, which represents extractability, using the formula [5]: Recovery (%) = (Peak Response of Analyte in Set C / Peak Response of Analyte in Set A) × 100

Evaluating Flavor-Matrix Interactions

Objective: To characterize the non-covalent interactions (e.g., hydrophobic, van der Waals, hydrogen bonding) between food matrices (e.g., proteins, carbohydrates) and volatile odorants that modulate aroma perception. Protocol:

- Headspace Analysis: Use Headspace Solid-Phase Microextraction (HS-SPME) coupled with GC-MS to measure the concentration of free volatile compounds in the headspace above a food sample. A decrease in headspace concentration indicates binding to the matrix [4].

- Sensory Evaluation: Conduct sensory analysis (e.g., threshold tests, aroma profiling) to correlate physicochemical data with human perception. The σ-τ plot method can be used to evaluate the impact of compound interactions on aroma perception [4].

- Mechanistic Elucidation: Employ spectroscopic and molecular simulation techniques to unravel interaction mechanisms.

- Spectroscopic Analysis: Use Fluorescence Spectroscopy (FS), Circular Dichroism (CD), and Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) to detect conformational changes in proteins upon binding with ligands.

- Molecular Docking & Dynamics Simulations: Computational methods to model the binding affinity, binding site location, and the stability of the complex formed between a matrix component (e.g., β-lactoglobulin) and an odorant [4].

Quantifying Matrix Effects in Analytical Chemistry

Objective: To determine the impact of co-extracted matrix components from a food sample on the detection and quantitation of a target analyte (e.g., pesticide, contaminant) using LC-MS or GC-MS. Protocol (Post-extraction Addition Method):

- Sample Extraction: Extract a blank (analyte-free) representative food matrix using a standard method (e.g., QuEChERS).

- Standard Preparation: Prepare two sets of calibration standards:

- Set A: Standards prepared in a pure solvent.

- Set B: Standards prepared by spiking the extracted blank matrix (post-extraction).

- Instrumental Analysis: Analyze both sets using LC-MS/MS or GC-MS/MS under identical conditions.

- Calculation: Calculate the Matrix Effect (ME) for each analyte using the formula [5]: ME (%) = [(Slope of Matrix-Matched Calibration Curve (mB) / Slope of Solvent-Based Calibration Curve (mA)) - 1] × 100 An ME > 0 indicates signal enhancement, while an ME < 0 indicates signal suppression. Guidelines (e.g., SANTE/12682/2019) typically recommend action if |ME| > 20% [5].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Food Matrix Analysis

| Reagent / Material | Technical Function in Research |

|---|---|

| β-lactoglobulin (β-lg) | A major whey protein used as a model system to study protein-ligand binding interactions with polyphenols, flavor compounds, and fatty acids via spectroscopic and computational methods [4]. |

| Simulated Gastrointestinal Fluids | Standardized enzymatic and electrolyte solutions (e.g., per INFOGEST protocol) for in vitro simulation of oral, gastric, and intestinal digestion to study nutrient bioaccessibility and matrix disintegration [3]. |

| QuEChERS Extraction Kits | (Quick, Easy, Cheap, Effective, Rugged, Safe) kits for preparing sample extracts for contaminant analysis. Used to evaluate matrix-induced enhancement/suppression effects in LC-MS/GC-MS [5]. |

| HS-SPME Fibers | (Headspace Solid-Phase Microextraction) fibers with varying polymer coatings (e.g., DVB/CAR/PDMS) for trapping volatile organic compounds from the headspace of food samples prior to GC-MS analysis, critical for flavor-release studies [4]. |

| Fluorescence Probes | Small molecules (e.g., 1-Anilinonaphthalene-8-sulfonate, ANS) used to probe conformational changes and surface hydrophobicity of proteins upon binding with other matrix components or under different processing conditions [4]. |

Implications for Research and Public Health

The food matrix concept has profound implications beyond basic science, influencing nutritional policy and public health strategies.

Resolving Discrepancies in Epidemiological Data

The matrix effect provides a plausible explanation for the "dairy paradox": despite containing saturated fats, dairy consumption, particularly fermented products like cheese and yogurt, is often neutrally or inversely associated with cardiovascular disease and type 2 diabetes risk [2] [1] [3]. The matrix modulates the digestibility of fats; for instance, the unique structure of cheese and the presence of calcium can alter lipid metabolism in a manner that is not reflected by its saturated fat content alone [3]. Similarly, the cellular structure of almonds leads to a ~30% lower metabolizable energy than predicted by the Atwater factors, as the cell walls impede lipid bioaccessibility [3].

Informing Evidence-Based Dietary Guidance and Labeling

A reductionist focus on isolated nutrients in front-of-pack (FOP) labeling systems can misclassify nutrient-dense whole foods. For example, the Nutri-Score algorithm, based on negative nutrients, can designate cheese as "less healthy" while assigning a more favorable rating to diet soda [1]. This ignores the integrated health benefits conferred by the dairy matrix, including improved nutrient absorption and associated positive health outcomes. Consequently, there is a growing consensus favoring food-based and dietary pattern recommendations over single-nutrient targets to avoid unintended consequences and consumer confusion [1].

The food matrix is a critical functional domain that dictates the physiological fate of food components. Moving beyond a reductionist view of food as merely the sum of its nutrients to an understanding of its complex structure is paramount for advancing nutritional science, developing functional foods, and formulating effective public health policies. Future research must continue to integrate advanced analytical techniques with clinical and sensory studies to fully elucidate the mechanisms behind matrix effects, ultimately enabling a more precise and personalized approach to nutrition and health.

This whitepaper provides a comprehensive technical guide on the fundamental interaction types—covalent, ionic, and non-covalent forces—that govern the behavior of molecules in complex systems. Focusing on the context of food component and matrix effects research, we detail the chemical principles, relative strengths, and functional consequences of these interactions. The document includes standardized experimental protocols for their investigation, visual workflows for data analysis, and a dedicated toolkit for researchers. Understanding these interactions is paramount for predicting ingredient functionality, nutrient bioavailability, and final product quality in food and pharmaceutical applications.

In both food science and drug development, the biological and functional outcomes of a product are rarely dictated by a single compound in isolation. Instead, they emerge from a complex web of interactions between various components within a matrix. Food and biological systems are multicomponent assemblies where proteins, carbohydrates, lipids, polyphenols, and other molecules continuously interact through distinct chemical forces [6] [7]. These interactions, which occur during processing, storage, and digestion, significantly alter the matrix's macroscopic properties, the stability of active compounds, and their release and absorption profiles [4] [8].

A deep understanding of covalent bonds, ionic interactions, and the diverse family of non-covalent forces is therefore not merely an academic exercise but a practical necessity. It enables the rational design of foods with tailored textures and flavors, improves the stability of fortified nutrients, and enhances the bioavailability of bioactive compounds. Similarly, in pharmaceuticals, it informs drug delivery systems and helps mitigate analytical challenges like matrix effects in bioanalysis [9]. This guide dissects these core interactions, providing a foundational resource for researchers and scientists aiming to master the complexity of composite systems.

Theoretical Foundations and Key Characteristics

Chemical interactions exist on a spectrum, from strong, permanent bonds that create new molecules to weak, reversible forces that govern supramolecular assembly. The following sections delineate their defining principles.

Covalent Bonds

Covalent bonding involves the sharing of electron pairs between atoms. This type of bond is typically the strongest of the chemical interactions and is responsible for forming the fundamental molecular skeleton of organic compounds and biomacromolecules [10].

- Formation and Energy: These bonds form when atoms have similar electronegativities and can share electrons to achieve stable noble gas configurations. Covalent bond energies are high, generally ranging from 150 to 500 kJ/mol, making them stable and permanent under typical biological conditions [10].

- Role in Matrices: In food systems, covalent bonds are crucial for the primary structure of proteins and polysaccharides. They can also form during processing; for example, the Maillard reaction involves covalent interactions between amino acids and reducing sugars, which influences color, flavor, and nutritional value [6] [8].

Ionic Interactions

Ionic bonding results from the complete transfer of electrons from one atom to another, generating positively charged cations and negatively charged anions that attract each other through electrostatic forces [10].

- Formation and Energy: This occurs between atoms with large differences in electronegativity, typically between metals and nonmetals. While the individual electrostatic attraction is strong, the net energy in a solid lattice context is high, but isolated ion-pair interactions in solution are weaker and can be influenced by the surrounding environment [10].

- Role in Matrices: Ionic interactions play a key role in stabilizing the tertiary and quaternary structures of proteins (e.g., salt bridges). They are also critical for the gelation of polysaccharides like pectin, which is controlled by the presence of calcium ions, and can affect the binding of charged aroma compounds to proteins [4].

Non-Covalent Forces

Non-covalent forces are reversible, intermolecular interactions that do not involve electron sharing or transfer. They are individually weak but collectively determine the three-dimensional structure of biomolecules, drive molecular recognition, and control the self-assembly of supramolecular structures [11] [12]. The operational term "non-covalent" has been critiqued, as these interactions, particularly hydrogen bonding, have significant covalent character rooted in quantum mechanical effects [12]. The table below summarizes the primary types.

Table 1: Key Non-Covalent Interaction Types and Properties

| Interaction Type | Strength Range (kJ/mol) | Chemical Basis | Role in Food & Biological Matrices |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hydrogen Bonding | 5 - 100 [11] | Dipole attraction between H (donor) and electronegative atom (acceptor) [11] | Stabilizes protein secondary structure (α-helices, β-sheets); critical for polysaccharide gel networks; binds polyphenols to proteins [6] [4] |

| Electrostatic (Ion-Ion/Dipole) | 1 - 25 [11] | Attraction between permanent charges or between charge and dipole | Protein-protein interactions; binding of ionic flavors; encapsulation efficiency [4] |

| π-π Stacking | 0 - 50 | Attraction between aromatic rings via orbital overlap | Stabilizes tertiary structure of proteins; important for polyphenol self-association and binding [13] |

| van der Waals | 0.5 - 5 | Transient dipole-induced dipole attractions | Dominant in hydrophobic effect; contributes to adhesion and cohesion in colloidal systems [4] [13] |

| Hydrophobic Effect | Entropy-driven | Association of non-polar groups in aqueous media to minimize disruptive interactions with water | Drives protein folding; formation of micelles and lipid bilayers; affects flavor binding [4] |

| Metal-Ligand Coordination | 10 - 400 [11] | Lewis acid-base interaction between metal ion and electron donor | Cross-linking in polysaccharide gels (e.g., Ca²⁺ in pectin); involved in enzyme cofactors; used in supramolecular self-healing materials [11] [13] |

In material science, these non-covalent interactions are exploited to create self-healing materials, where reversible bonds like hydrogen bonding or metal-ligand coordination allow a material to repair damage, effectively extending its lifespan [11]. In food, they are the primary mechanism behind non-covalent complexation, such as that between anthocyanins and cell wall polysaccharides or proteins, which modulates color, taste, and nutrient bioavailability [6] [7].

Experimental Protocols for Investigating Interactions

A multi-technique approach is essential to conclusively identify interaction types and quantify their effects. The workflow below outlines a strategic pathway for this analysis.

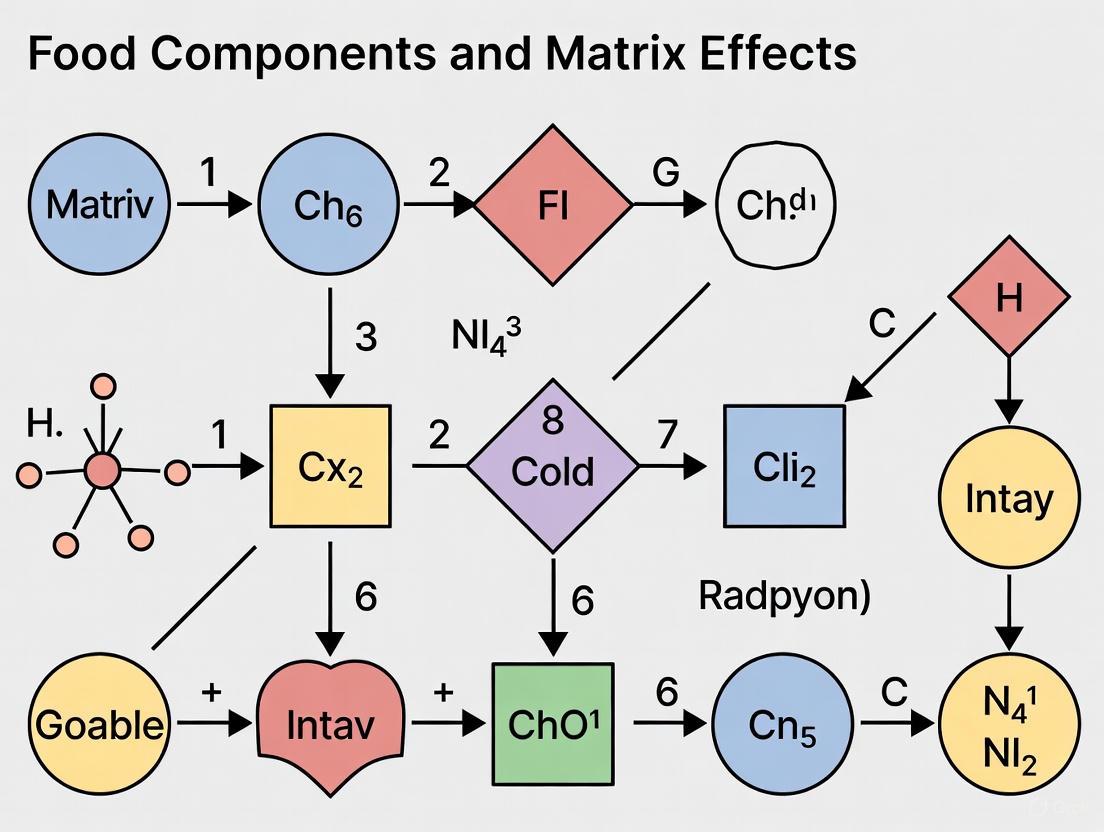

Figure 1: Experimental workflow for analyzing interactions in complex matrices.

Sensory and Volatility Analysis

The process often begins by observing a functional or sensory change.

- Sensory Evaluation: Trained panels or threshold tests (e.g., σ-τ method) assess how a matrix component alters aroma or taste perception, indicating a potential interaction [4].

- Headspace Gas Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (HS-GC-MS): This technique quantitatively measures the release of volatile compounds (e.g., odorants) from a matrix. A decrease in headspace concentration of a volatile in the presence of another component (like a protein or polysaccharide) provides direct evidence of binding or entrapment [4]. Protocol: Prepare the sample in a sealed headspace vial. Equilibrate at a controlled temperature. Use an automated headspace sampler to inject the volatiles into the GC-MS. Compare peak areas of the target analyte in the presence and absence of the suspected binding partner.

Spectroscopic Analysis of Binding

Spectroscopic methods can confirm binding and identify the forces involved.

- Fluorescence Spectroscopy (FS): Intrinsic protein fluorescence (from tryptophan residues) is quenched upon binding with a compound like a polyphenol. The quenching data (Stern-Volmer plot) can determine the binding constant (K) and number of binding sites (n) [4]. Protocol: Titrate a fixed concentration of the protein with increasing concentrations of the ligand. Measure fluorescence emission intensity after each addition. Analyze the quenching data using the Stern-Volmer equation to extract binding parameters.

- Isothermal Titration Calorimetry (ITC): This gold-standard technique directly measures the heat absorbed or released during a binding event. It provides a full thermodynamic profile, including the binding constant (K), enthalpy change (ΔH), entropy change (ΔS), and stoichiometry (n) in a single experiment [4]. Protocol: Load the ligand into the syringe and the macromolecule (e.g., protein) into the sample cell. Perform a series of automatic injections. The integrated heat data is fitted to an appropriate binding model to extract all parameters.

- Fourier-Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (FTIR): Detects changes in the vibrational states of functional groups (e.g., amide I band in proteins) upon interaction, which can reveal structural changes like a shift from α-helix to β-sheet [4].

Computational Modeling

Computational methods provide atom-level insight into interaction mechanisms.

- Molecular Docking: Predicts the preferred orientation (binding pose) of a small molecule (ligand) when bound to a macromolecule (e.g., protein). It identifies potential binding sites and the specific amino acids involved [4]. Protocol: Obtain the 3D structure of the receptor (from PDB or homology modeling). Prepare the ligand and receptor structures (add hydrogens, assign charges). Run the docking simulation using software like AutoDock Vina. Analyze the top poses for key hydrogen bonds, hydrophobic contacts, and electrostatic interactions.

- Molecular Dynamics (MD) Simulations: Models the physical movements of atoms and molecules over time, providing a dynamic view of the stability of a docked complex and the behavior of interactions under simulated physiological conditions [4] [13].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Research into food and biological matrix interactions relies on a set of core reagents and analytical standards.

Table 2: Key Research Reagents and Materials for Interaction Studies

| Reagent/Material | Function and Application | Example Use-Case |

|---|---|---|

| β-Lactoglobulin (β-lg) | Model food protein for studying protein-ligand interactions. | Investigating the binding of polyphenols or flavor compounds in dairy systems [4]. |

| Pectin (High-/Low-Methoxy) | Model anionic polysaccharide for studying ionic and hydrogel formation. | Studying Ca²⁺-mediated gelation (ionic) or sugar-acid gelation (H-bonding) [6]. |

| Procyanidins (e.g., B2) | Model polyphenols for studying non-covalent complexation. | Probing interactions with cell wall material or salivary proteins to understand astringency [6] [7]. |

| Internal Standards (IS) | Critical for quantifying analytes and compensating for matrix effects in LC-MS/MS. | Deuterated analogs of target analytes (e.g., GluCer C22:0-d4) are used to normalize signal suppression/enhancement [9]. |

| Chaotropes & Kosmotropes | Agents that disrupt or strengthen water structure, used to probe the role of the hydrophobic effect. | Urea (chaotrope) can be used to denature proteins, testing the stability of hydrophobic cores. |

| Standard pH Buffers | To systematically control and study the impact of electrostatic interactions. | Studying the pH-dependent binding of a charged flavor compound to a protein [4]. |

Mastering the interplay of covalent bonds, ionic interactions, and non-covalent forces is fundamental to advancing research in food matrix effects and drug development. Covalent bonds provide permanent structure, ionic interactions offer reversible, charge-based control, and the diverse array of non-covalent forces dictate the dynamic, responsive nature of supramolecular assemblies. By employing the integrated experimental strategies and tools outlined in this whitepaper—from initial sensory observation to advanced computational modeling—researchers can systematically decode complex matrix interactions. This knowledge paves the way for the rational design of healthier, more stable, and higher-quality food and pharmaceutical products.

Food matrix effects research has emerged as a critical discipline for understanding the complex interplay between macromolecular components in biological systems. The interactions between proteins-polyphenols, polysaccharides-lipids, and starch-protein complexes fundamentally determine the structural, functional, and nutritional properties of food systems, with significant implications for food science, nutritional biochemistry, and pharmaceutical development [14]. These macromolecular interactions influence everything from basic physicochemical behaviors to bioavailability and therapeutic efficacy of bioactive compounds [15] [16].

For researchers and drug development professionals, understanding these interactions provides a foundation for designing targeted delivery systems, enhancing stability of bioactive compounds, and controlling release profiles in complex matrices. This technical guide synthesizes current knowledge on interaction mechanisms, characterization methodologies, and experimental approaches to enable advanced research in this multidisciplinary field. The systematic investigation of these interactions facilitates the discovery, design, and development of future functional foods and pharmaceutical formulations [14].

Protein-Polyphenol Interactions

Interaction Mechanisms and Binding Forces

Protein-polyphenol interactions occur through two primary mechanisms: covalent bonding and non-covalent complexation. The non-covalent interactions include hydrogen bonding, hydrophobic interactions, ionic bonds, and van der Waals forces [17]. Covalent interactions are irreversible and typically form under specific processing conditions or through enzymatic catalysis, resulting in stronger complexes that significantly alter protein structure and functionality [15].

Table 1: Protein-Polyphenol Interaction Mechanisms and Characteristics

| Interaction Type | Binding Forces | Reversibility | Formation Conditions | Impact on Protein Structure |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Covalent | Quinone-protein adducts, C-N/C-S bonds | Irreversible | Alkaline conditions, enzymatic oxidation, heat treatment | Significant structural modification, altered isoelectric point |

| Non-covalent | Hydrogen bonding, hydrophobic interactions | Reversible | Ambient conditions, pH-dependent | Moderate structural changes, often temporary |

| Hydrogen Bonding | Polyphenol hydroxyl groups with protein carbonyl/amine groups | Reversible | Wide pH range, aqueous environments | Secondary structure stabilization |

| Hydrophobic | Aromatic polyphenol rings with non-polar protein residues | Reversible | Enhanced at higher temperatures | Tertiary structure alterations |

| Electrostatic | Ionic interactions between charged groups | Reversible | pH-dependent, specific ionic strength | Surface charge modification |

Covalent binding initiation occurs primarily through polyphenol oxidation to form quinones or semi-quinone radicals, which subsequently react with nucleophilic amino acid residues including lysine (free amino groups), cysteine (sulfhydryl groups), and tryptophan, proline, methionine, histidine, or tyrosine residues [15]. The electrophilic nature of quinones drives their reaction with these protein functional groups, forming stable covalent adducts that permanently modify protein structure and functionality.

Experimental Protocols for Characterization

Spectroscopic Analysis of Structural Changes

Protocol Objective: Determine structural alterations in proteins following polyphenol interaction using multi-spectroscopic approaches.

Materials and Reagents:

- Purified protein (e.g., β-lactoglobulin, bovine serum albumin)

- Polyphenol standard (e.g., EGCG, quercetin, catechin)

- Buffer solutions (phosphate buffer, Tris-HCl) across pH range (2.5-8.0)

- Fluorescence cuvettes with 1 cm path length

- Spectrofluorometer and UV-Vis spectrophotometer

Methodology:

- Prepare protein solutions (0.1-1.0 mg/mL) in appropriate buffer

- Incubate with polyphenols at varying molar ratios (1:1 to 1:10 protein:polyphenol)

- Fluorescence Quenching Analysis:

- Set excitation wavelength to 280 nm (tryptophan excitation)

- Record emission spectra from 300-400 nm

- Calculate quenching constants using Stern-Volmer equation

- FT-IR Spectroscopy:

- Scan protein-polyphenol complexes in range 4000-400 cm⁻¹

- Analyze amide I (1600-1700 cm⁻¹) and amide II (1480-1575 cm⁻¹) bands

- Deconvolute spectra to quantify secondary structure changes

- Circular Dichroism (CD):

- Record far-UV CD spectra (190-250 nm) for secondary structure

- Record near-UV CD spectra (250-320 nm) for tertiary structure

- Express results as mean residue ellipticity [θ] (deg·cm²·dmol⁻¹)

Data Interpretation: Fluorescence quenching indicates conformational changes and binding affinity. FT-IR and CD spectral changes reveal alterations in α-helix, β-sheet, and random coil content, providing quantitative assessment of structural modifications induced by polyphenol binding [15] [18].

Isothermal Titration Calorimetry (ITC) for Binding Affinity

Protocol Objective: Quantitatively determine binding constants, stoichiometry, and thermodynamic parameters of protein-polyphenol interactions.

Materials and Reagents:

- High-purity protein and polyphenol standards

- Degassed buffer solutions matching experimental conditions

- ITC instrument with 1.8 mL sample cell

Methodology:

- Dialyze protein extensively against chosen buffer

- Prepare polyphenol solution in dialysate to minimize buffer mismatches

- Load protein solution (0.01-0.1 mM) into sample cell

- Fill syringe with polyphenol solution (10x concentrated relative to protein)

- Program instrument with appropriate parameters:

- Number of injections: 15-25

- Injection volume: 2-10 μL

- Duration: 4-20 seconds

- Spacing: 120-300 seconds

- Reference power: 5-10 μcal/sec

- Run control experiment by injecting polyphenol into buffer alone

- Analyze data using appropriate binding models (one-site, two-site, sequential)

Data Interpretation: ITC provides direct measurement of binding constant (Kₐ), enthalpy change (ΔH), entropy change (ΔS), Gibbs free energy (ΔG), and binding stoichiometry (n). These parameters elucidate the driving forces behind the interactions and the spontaneity of complex formation [19].

Impact of Processing Conditions

Processing methods significantly influence protein-polyphenol interactions through structural modifications. Thermal processing (pasteurization, UHT, baking) induces polyphenol autoxidation to quinones while unfolding proteins to expose additional binding sites [15]. Enzymatic processing using polyphenol oxidase in the presence of oxygen catalyzes quinone formation, while proteolysis generates peptides with altered binding capacities [15]. Ultrasonication generates hydroxyl radicals that promote covalent interactions through free radical mechanisms, and alkaline conditions (pH > 8) facilitate polyphenol oxidation and subsequent protein binding [15] [18].

Polysaccharide-Lipid Interactions

Interaction Mechanisms and Metabolic Consequences

Polysaccharide-lipid interactions primarily occur indirectly through modulation of gut microbiota and digestive processes, rather than through direct molecular complexation. These interactions significantly influence lipid metabolism through multiple mechanisms, including viscosity effects, microbiota modulation, and molecular encapsulation.

Table 2: Polysaccharide-Lipid Interaction Mechanisms and Metabolic Effects

| Interaction Mechanism | Biological Consequences | Key Metabolites/Pathways | Research Evidence |

|---|---|---|---|

| Viscosity Modulation | Altered digestion kinetics, reduced enzyme accessibility | Delayed lipid absorption, modified satiety hormones | In vitro digestion models [20] |

| Gut Microbiota Remodeling | SCFA production, intestinal barrier enhancement | Acetate, propionate, butyrate; GLP-1, PYY | 16S rRNA sequencing, metabolite profiling [21] |

| Bile Acid Binding | Modified bile acid circulation, hepatic cholesterol metabolism | TMAO reduction, FXR signaling modulation | Serum biomarkers, hepatic gene expression [21] |

| Nanocarrier Systems | Targeted delivery, improved bioavailability | Enhanced cellular uptake, controlled release | Encapsulation efficiency studies [21] |

| Inflammation Reduction | Improved systemic metabolic parameters | Cytokine modulation, immune cell recruitment | Inflammatory marker assessment [21] |

Polysaccharides with β-linkages (e.g., cellulose, hemicellulose) form rigid, fibrous structures that resist human digestive enzymes but serve as substrates for gut microbiota, producing short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs) that influence lipid metabolism and energy homeostasis [16]. These indigestible polysaccharides increase digesta viscosity, physically impeding interactions between digestive enzymes and their substrates, thereby modulating lipid absorption and postprandial metabolism [20].

Experimental Protocols for Gut Microbiota Studies

Microbiota Analysis and Metabolite Profiling

Protocol Objective: Investigate polysaccharide-induced changes in gut microbiota composition and metabolic output relevant to lipid metabolism.

Materials and Reagents:

- Animal model (mice, rats) or human fecal samples

- DNA extraction kit (e.g., E.Z.N.A. Soil DNA Kit)

- Universal 16S rRNA primers (338F/806R targeting V3-V4 region)

- Illumina MiSeq platform or equivalent

- SCFA standards (acetate, propionate, butyrate)

- Gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (GC-MS) system

Methodology:

- Sample Collection and DNA Extraction:

- Collect fecal samples under anaerobic conditions

- Extract genomic DNA using standardized kit protocol

- Assess DNA quality/purity (A260/A280 ratio ~1.8-2.0)

- 16S rRNA Amplification and Sequencing:

- Amplify target region with barcoded primers

- Purify PCR products and quantify

- Pool samples in equimolar ratios for sequencing

- Sequence on Illumina MiSeq platform (2×300 bp)

- Bioinformatic Analysis:

- Quality filter raw sequences (Q-score >20, length >150 bp)

- Remove chimeras using USEARCH with ChimeraSlayer database

- Cluster sequences into OTUs at 97% similarity threshold

- Assign taxonomy using reference databases (Greengenes, SILVA)

- SCFA Analysis:

- Derivatize fecal or cecal samples

- Separate and quantify SCFAs using GC-MS

- Compare concentrations across experimental groups

Data Interpretation: Taxonomic analysis reveals polysaccharide-induced shifts in microbial community structure (e.g., Bacteroidetes/Firmicutes ratio). SCFA quantification provides functional readout of microbial metabolic activity, with butyrate particularly relevant for gut barrier function and lipid metabolism regulation [21] [22].

Starch-Protein Complexes

Interaction Mechanisms and Structural Effects

Starch-protein interactions significantly impact the structural, physicochemical, and nutritional properties of starch-based systems. These interactions occur through various forces, including covalent bonds, hydrogen bonding, hydrophobic interactions, electrostatic interactions, and size exclusion effects [23].

Table 3: Starch-Protein Interaction Forces and Functional Consequences

| Interaction Force | Molecular Basis | Impact on Starch Properties | Food System Examples |

|---|---|---|---|

| Covalent Bonds | Maillard reaction, disulfide bridges | Reduced swelling power, modified gelatinization | Baked products, extruded foods |

| Hydrogen Bonding | OH/NH groups with starch hydroxyls | Altered hydration, modified viscosity | Protein-fortified starches |

| Hydrophobic Interactions | Non-polar amino acids with lipid chains | Starch digestibility reduction, gel texture modification | Starch-whey protein complexes |

| Electrostatic Interactions | Charged amino acids with phosphate groups | pH-dependent pasting behavior, ionic strength effects | Starch-soy protein systems |

| Size Exclusion | Phase separation, molecular crowding | Retarded starch retrogradation, modified rheology | Dough systems, protein-enriched foods |

Starch granule-associated proteins (SGAPs) tightly bind to starch surfaces or internal channels through hydrogen bonding, hydrophobic interactions, and electrostatic forces, significantly inhibiting starch swelling and gelatinization [23]. In contrast, storage proteins primarily interact through hydrogen bonding alone, with less dramatic effects on starch functionality. These differential interaction patterns explain why protein removal significantly enhances starch swelling capacity, water absorption, and digestibility [23].

Experimental Protocols for Starch-Protein Characterization

Starch Digestibility Assessment

Protocol Objective: Evaluate the impact of protein interactions on starch digestion kinetics and enzymatic accessibility.

Materials and Reagents:

- Starch-protein composite samples

- Pancreatic α-amylase (≥10 U/mg)

- Amyloglucosidase (≥70 U/mg)

- Glucose oxidase-peroxidase (GOPOD) assay kit

- Phosphate buffer (pH 6.9 with 6.7 mM NaCl)

- Water bath with shaking capability

Methodology:

- Sample Preparation:

- Prepare starch-protein mixtures at defined ratios (e.g., 10:1 to 1:1)

- Cook samples under standardized conditions (e.g., 95°C, 30 min)

- Cool to 37°C before digestion assay

- In Vitro Digestion:

- Add enzyme solution (pancreatic α-amylase + amyloglucosidase)

- Incubate at 37°C with continuous shaking

- Collect aliquots at defined timepoints (0, 20, 60, 90, 120, 180 min)

- Immediately heat-inactivate enzymes (95°C, 5 min)

- Glucose Quantification:

- Centrifuge aliquots to remove precipitates

- Analyze supernatant using GOPOD assay

- Measure absorbance at 510 nm

- Calculate glucose equivalents from standard curve

- Kinetic Analysis:

- Calculate percentage hydrolysis at each timepoint

- Plot digestion kinetics curve

- Calculate rapidly digestible starch (RDS), slowly digestible starch (SDS), and resistant starch (RS) fractions

Data Interpretation: Protein interactions typically reduce starch digestibility by physically blocking enzyme access to starch granules and through molecular interactions that modify starch structure. This results in increased SDS and RS fractions, with implications for glycemic response and nutritional functionality [23].

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents for Macromolecular Interaction Studies

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Research Application | Technical Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Polyphenol Standards | EGCG, quercetin, catechin, resveratrol | Protein binding studies, antioxidant assays | Stability varies; requires protection from light, oxygen |

| Enzyme Preparations | Polyphenol oxidase, trypsin, α-amylase | Simulated processing, digestibility studies | Activity units must be standardized; storage conditions critical |

| Protein Isolates | β-lactoglobulin, soy protein, gliadin | Interaction mechanism studies | Purity level affects reproducibility; consider genetic variants |

| Polysaccharide Types | Pectin, β-glucan, cellulose, starch | Viscosity studies, microbiota modulation | Molecular weight, branching degree impact functionality |

| Analytical Standards | SCFA mixtures, bile acids, glucose | Metabolite quantification, digestion analysis | Calibration curve range must encompass expected concentrations |

| Chromatography Media | Size exclusion, affinity columns | Complex separation, binding partner isolation | Buffer compatibility, pressure limits, binding capacity |

Visualization of Interaction Networks and Experimental Workflows

Protein-Polyphenol Interaction Pathways

Macromolecular Interaction Characterization Workflow

The systematic investigation of macromolecular interactions between proteins-polyphenols, polysaccharides-lipids, and starch-protein complexes provides critical insights for advancing food matrix effects research. Understanding these interactions at molecular, structural, and functional levels enables researchers and pharmaceutical developers to design optimized systems with tailored properties for specific applications.

The experimental methodologies and characterization techniques outlined in this technical guide provide a comprehensive toolkit for investigating these complex interactions. As research in this field advances, integrating multi-omics approaches with high-resolution structural analysis will further elucidate the intricate relationship between macromolecular interactions and their biological consequences, facilitating the development of next-generation functional foods and targeted delivery systems.

The food matrix is defined as the intricate physical and chemical structure of food, encompassing how components like proteins, carbohydrates, lipids, and micronutrients are organized and interact within the food structure [24]. This matrix is not a mere vessel for nutrients; it plays a critical functional role in determining the bioaccessibility of nutrients, the stability of bioactive compounds, and the overall sensory and textural properties of food. Research into matrix effects is fundamentally shifting nutritional science from a reductionist focus on single nutrients to a holistic understanding of how the entire food structure influences health outcomes [2]. For instance, the dairy matrix demonstrates that the complex interaction of nutrients and bioactive components within cheese and yogurt can influence health outcomes differently than isolated nutrients, explaining phenomena like the observed reduced risks of mortality and heart disease from cheese consumption despite its saturated fat and sodium content [2].

The integrity of this matrix is highly susceptible to modification by various processing technologies. Both thermal and non-thermal interventions, along with mechanical disruption, can alter the micro- and macro-structure of foods, thereby modulating the functional properties of food components. Understanding these changes is paramount for researchers and product developers aiming to design foods with tailored nutritional profiles, enhanced sensory attributes, and improved safety. This guide provides a technical examination of how different processing methodologies impact food matrix integrity, complete with experimental data, protocols, and analytical tools for rigorous investigation.

Thermal Processing and Its Impact on Matrix Components

Thermal processing remains a cornerstone of food preservation, primarily aimed at inactivating pathogens and spoilage microorganisms. However, the application of heat induces significant, often irreversible, changes to the food matrix.

Fundamental Principles and Matrix Alterations

Thermal technologies disrupt microbial cellular structures and metabolic functions primarily through protein denaturation, cell membrane disruption, and interference with nucleic acid synthesis [25]. While effective for safety, this thermodynamic disruption also affects the food itself. Key alterations include:

- Protein Denaturation: The unfolding of protein structures, leading to aggregation and loss of functionality, which can alter texture and nutrient availability [25].

- Starch Gelatinization: The disruption of starch granule structure, leading to swelling and hydration, which profoundly impacts viscosity and digestibility [26].

- Nutrient Degradation: Heat-sensitive nutrients, such as vitamins (e.g., Vitamin C) and polyphenols, can be destroyed, reducing the overall nutritional value [25].

- Maillard Reaction: The reaction between reducing sugars and amino acids produces desirable flavors and colors but can also reduce protein quality and generate undesirable compounds [25].

A primary engineering challenge is the non-uniformity of heating, particularly in conventional thermal processes. This can result in uneven microbial inactivation and variable matrix degradation, with some areas being over-processed while others are under-processed, posing significant quality and safety risks [25].

Quantitative Analysis of Thermal Effects on Starch Digestibility

The impact of thermal processing is highly dependent on the cereal type and its physical form (whole grain vs. flour). The following table summarizes key findings from a study on cereal-based infant purees autoclaved at 121 °C for 30 minutes, illustrating the variable matrix effects [26].

Table 1: Impact of Autoclaving (121°C, 30 min) on Starch Digestibility in Cereal-Based Infant Purees

| Cereal Type | Sample Form | Total Hydrolyzed Starch (THS) (g/100 g starch) | Change in THS vs. Control | Key Matrix Change |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wheat | Whole Grain (WG) | 27.8 | Significant Reduction | Preserved cellular structure |

| Whole Grain Flour (WGF) | ~29% Increase | 29% Increase | Disrupted cellular integrity | |

| Flour Suspension (FS) | 57.4 | 57.4 g/100g (Significant Increase) | Complete gelatinization | |

| Maize | Whole Grain (WG) | 11.3 | Significant Reduction | Preserved cellular structure |

| Whole Grain Flour (WGF) | ~92% Increase | 92% Increase | Disrupted cellular integrity | |

| Flour Suspension (FS) | 45.4 | 45.4 g/100g (Significant Increase) | Complete gelatinization | |

| Rice | Whole Grain Flour (WGF) | ~70% Increase | 70% Increase | Disrupted cellular integrity |

| Flour Suspension (FS) | 39.3 | 39.3 g/100g (Significant Increase) | Complete gelatinization |

Experimental Protocol: Assessing Thermal Impact on Starch

Objective: To evaluate the effect of autoclave thermal treatment on the starch digestibility of cereal matrices.

Materials:

- Cereal grains (e.g., durum wheat, brown rice, white maize).

- Porcine pancreatic α-amylase (A3176, Sigma-Aldrich), pepsin (P7000, Sigma-Aldrich), pancreatin (P7545, Sigma-Aldrich).

- Differential Scanning Calorimeter (DSC, e.g., DSC 823, Mettler-Toledo).

- Rapid Visco-Analyzer (RVA, e.g., RVA-4500, Perten Instruments).

- Freeze dryer.

Methodology:

- Sample Preparation: Prepare three sample types from each cereal:

- Whole Grains (WG): Clean, intact grains.

- Whole Grain Flour (WGF): Mill grains using a cyclonic mill (e.g., Cyclotec CT193, Foss) to 0.5 mm.

- Flour Suspension (FS): Mix 100 g WGF with 500 mL water (1:5 ratio) [26].

- Thermal Treatment: Autoclave samples at 121 °C for 30 min at 0.11 MPa. Freeze-dry FS samples post-treatment [26].

- Microstructural Analysis: Examine milled samples using polarized light microscopy (e.g., Leica DM5000B microscope) to observe loss of amyloplast birefringence, indicating gelatinization [26].

- Pasting Properties: Analyze using RVA. Suspend samples (3.5 g dry basis) in 28 mL distilled water. Use standard pasting method to determine peak viscosity, breakdown, and final viscosity [26].

- Thermal Properties: Analyze using DSC. Weigh 5 mg (db) sample into aluminum pans with 10 μL water. Hermetically seal, equilibrate 24h, and heat from 20°C to 120°C at 10°C/min. Record gelatinization peak temperature (Tp) and enthalpy (ΔH) [26].

- In Vitro Digestion: Simulate infant gastrointestinal conditions. Subject samples to digestion using pepsin, pancreatin, and α-amylase. Quantify Total Hydrolyzed Starch (THS) to assess digestibility [26].

Diagram 1: Experimental workflow for analyzing thermal impact on starch.

Non-Thermal Interventions and Matrix Stability

Non-thermal technologies have emerged as alternatives to minimize the adverse effects of heat on nutritional and sensory quality while effectively controlling pathogens.

These technologies aim to inactivate microorganisms and alter matrix functionality through mechanisms other than heat.

- High Pressure Processing (HPP): Subjects packaged food to isostatic pressure (300-600 MPa), uniformly disrupting non-covalent bonds in microbial cells, leading to inactivation. It preserves nutritional and organoleptic profiles well but may alter textures of delicate foods and is less effective against spores [25].

- Pulsed Electric Field (PEF): Applies high-voltage pulses to food, causing electroporation—the formation of pores in cell membranes. This disrupts vital cell functions and can enhance the extraction of intracellular compounds or reduce microbial load [27] [25].

- Cold Atmospheric Plasma: Utilizes ionized gas containing reactive species that can oxidize microbial cell membranes and components, leading to inactivation, with minimal thermal effects on the food matrix [27].

- Ultrasound: Employs high-frequency sound waves to generate cavitation bubbles in a liquid medium. The implosion of these bubbles creates localized high pressure and temperature, disrupting cell walls and enhancing mass transfer [27].

Comparative Analysis of Preservation Technologies

The table below provides a technical comparison of the mechanisms and matrix impacts of various preservation technologies.

Table 2: Comparative Analysis of Food Preservation Technologies on Matrix Integrity

| Technology | Primary Mechanism | Key Matrix Impacts | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Thermal Processing | Protein denaturation, cell membrane disruption via heat [25] | Nutrient loss, texture alteration, Maillard reactions, starch gelatinization [25] [26] | Highly effective, well-established | High nutrient/quality degradation, non-uniform heating [25] |

| High Pressure Processing (HPP) | Disruption of non-covalent bonds under isostatic pressure [25] | Minimal effect on small molecules (vitamins), can alter protein structure and texture [25] | Excellent freshness retention, volumetric treatment | High cost, variable effect on textures, limited efficacy vs. spores [25] |

| Pulsed Electric Field (PEF) | Electroporation of cell membranes [25] | Selective disruption of cellular tissues, enhanced extractability [27] [25] | Low thermal load, preserves heat-sensitive compounds | Primarily for pumpable foods, homogeneity challenges [25] |

| Microwave (MW) Heating | Volumetric dielectric heating [25] | Rapid, internal heating; risk of non-uniform "hot spots" [25] | Faster than conventional heating | Non-uniform heating, potential for runaway effects [25] |

| Ohmic Heating (OH) | Volumetric Joule heating [25] | Rapid and relatively uniform heating if electrical properties are consistent [25] | Uniform for homogeneous matrices | Challenging for heterogeneous foods [25] |

Mechanical Disruption and the Food Matrix

Mechanical forces, from grinding and blending to high-shear homogenization, represent a significant form of matrix disruption, often used in conjunction with other processes.

The Role of Particle Size and Structural Breakdown

The reduction of particle size through milling or homogenization increases the surface area of food components, which can dramatically enhance their susceptibility to enzymatic and chemical reactions. This is critically evident in the difference between whole grains and flours. As demonstrated in Table 1, the digestibility of starch is significantly higher in flours and flour suspensions compared to whole grains after identical thermal processing. This is because milling mechanically breaks down the cell walls that would otherwise encapsulate starch granules, making them more accessible to digestive enzymes [26]. This principle underscores that mechanical disruption is a primary determinant of subsequent matrix interactions during processing.

Case Study: Beetroot Incorporation in Bakery Products

The physical form of an ingredient—a result of mechanical processing—significantly influences its integration into a new food matrix. A study on incorporating beetroot into cupcakes compared powder and paste forms at various concentrations (10%-50% w/w) [28].

- Matrix Interaction: Paste formulations consistently yielded better textural properties (higher springiness and cohesiveness), color development, and sensory acceptability than powder at equivalent concentrations. This is attributed to the more uniform distribution and superior water-holding capacity of the paste, which integrated more harmoniously into the cupcake's protein-starch matrix [28].

- Quantitative Impact: At 50% substitution, beetroot powder increased hardness by 72.5% and decreased volume by 20.3%, whereas paste increased hardness by only 54.3% and decreased volume by 22.4%. Furthermore, the optimal sensory acceptance level was 20% for powder and 30% for paste, indicating that the paste form was less disruptive to the matrix at higher inclusion levels [28].

This case highlights that the pre-processing mechanical treatment of an ingredient (into powder vs. paste) is a critical variable controlling its functional performance and the ultimate integrity of the composite food matrix.

Advanced Analytical and Modeling Approaches

The complexity of food matrices and their interactions with processing demands sophisticated analytical and computational tools for prediction and optimization.

Foodomics and Advanced Analytics

Foodomics—the application of omics technologies in food science—utilizes advanced tools like high-resolution mass spectrometry (HRMS), NMR, and multivariate statistical analysis to decrypt the food matrix [29]. For example:

- Meat Authentication: HRMS coupled with multivariate statistics like Hierarchical Clustering Analysis (HCA) can rapidly screen for species-specific peptide biomarkers in processed meat products, ensuring authenticity even after complex processing has denatured proteins [30].

- Aptamer Stability in Complex Matrices: Studies on tetrodotoxin (TTX) detection in seafood use aptamer-based sensors. Research shows that the structural stability of aptamers (single-stranded DNA/RNA) is highly sensitive to the food matrix, particularly cationic strength and matrix proteins, which can cause conformational changes and reduce sensor accuracy. This highlights the direct interference a complex matrix can have on analytical methods themselves [31].

Numerical Simulation and AI Integration

Empirical data alone is often insufficient for optimizing novel food processes. Numerical simulation provides a digital model to represent the system comprehensively.

- Process Characterization: Simulations are crucial for characterizing volumetric technologies like PEF, OH, and MW. They help model fluid dynamics, electric field distribution, and temperature profiles to identify and mitigate non-uniform treatment zones, thereby preventing under- or over-processing [25].

- AI-Enhanced Optimization: The integration of Artificial Intelligence (AI) and Machine Learning (ML) with numerical simulations can drastically reduce computational hours, simplify complex models, and enable the computer-assisted optimization of processing parameters for safety, quality, and energy efficiency [25] [32]. ML also provides a pathway to achieving food data integrity, establishing robust connections between data, algorithms, and practical applications throughout the food lifecycle [32].

Diagram 2: AI-enhanced simulation for process optimization.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

This section details key reagents, materials, and equipment essential for conducting research on food matrix integrity, as cited in the studies discussed.

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Matrix Integrity Studies

| Reagent / Material | Specification / Catalog Number | Primary Function in Research |

|---|---|---|

| Trypsin | BioReagent, from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA) [30] | Proteolytic enzyme for protein digestion in proteomics and peptide biomarker studies. |

| Porcine Pancreatic α-Amylase | A3176, Sigma-Aldrich [26] | Enzyme for in vitro starch digestion studies simulating human digestion. |

| Pepsin | P7000, Sigma-Aldrich [26] | Gastric protease for simulating the gastric phase of in vitro digestion. |

| Pancreatin | P7545, Sigma-Aldrich [26] | Enzyme mixture for simulating the intestinal phase of in vitro digestion. |

| Dithiothreitol (DTT) | From Sigma-Aldrich [30] | Reducing agent for breaking disulfide bonds in proteins during extraction and digestion. |

| Iodoacetamide (IAA) | From Sigma-Aldrich [30] | Alkylating agent for cysteine residues, preventing reformation of disulfide bonds. |

| C18 Solid-Phase Extraction Column | 60 mg, 3 mL, from Waters Corporation [30] | Purification and desalting of peptide mixtures prior to mass spectrometry analysis. |

| DNA Oligonucleotides (Aptamers) | Custom synthesis, e.g., Sangon Biotech [31] | Recognition molecules in biosensors for studying target binding in complex matrices. |

| Urea & Thiourea | Analytical Grade, Sinopharm Chemical Reagent [30] | Chaotropic agents in extraction buffers to denature proteins and enhance solubility. |

| Tris-HCl Buffer | Analytical Grade, Sinopharm Chemical Reagent [30] | Common buffer for maintaining stable pH during protein extraction and digestion. |

The matrix effect is a fundamental phenomenon where the physical and chemical structure of a substance—the matrix—directly governs the release, bioavailability, and ultimate efficacy of its active components. This principle is critically important across scientific disciplines, from the design of controlled-release pharmaceuticals to understanding the nutritional impact of whole foods. A matrix is more than a simple carrier; it is a dynamic structure that can modulate how an active compound is liberated and absorbed. In pharmacology, this often involves a polymeric network designed to control drug diffusion [33]. In nutrition, it refers to the natural organization of nutrients within a food's physical architecture [24] [2]. Despite the different contexts, the core principle is identical: the matrix dictates the rate and extent of release. Research demonstrates that ignoring these effects can lead to unreliable analytical results in drug development [34], suboptimal therapeutic outcomes from pharmaceuticals [33], and an incomplete understanding of a food's health impacts [2]. This guide explores the mechanisms and implications of matrix effects, providing researchers with the methodologies and tools to effectively study and harness this powerful phenomenon.

Matrix Effects in Pharmaceutical Science

In pharmaceutical science, matrix effects primarily refer to two interconnected concepts: the ability of a drug's formulation to control its release profile, and interferences in analytical techniques used for drug quantification.

Polymeric Matrices for Controlled Drug Release

Controlled-release matrix tablets are a cornerstone of modern drug delivery, designed to release an active pharmaceutical ingredient (API) over an extended period. These systems offer significant advantages, including reduced dosing frequency, lower incidence of adverse effects, and improved patient adherence [33]. The release kinetics are predominantly governed by the choice of polymer.

Table 1: Key Polymers Used in Controlled-Release Matrix Tablets

| Polymer | Polymer Type | Key Mechanism of Drug Release | Typical Performance Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hydroxypropyl Methylcellulose (HPMC) | Hydrophilic/Soluble | Hydration, gel layer formation, diffusion/erosion [33] | Superior compactability (T~max~ = 4.61 MPa), sustained release (85.4% at 12 h) [33] |

| Polyethylene Oxide (PEO) | Hydrophilic/Soluble | Swelling, gradual erosion [33] | Consistent delivery (88.7% at 12 h) [33] |

| Ethylcellulose (EC) | Hydrophobic/Insoluble | Diffusion through pores, intact matrix [33] | Often shows high cohesiveness but poor matrix integrity, can lead to premature release (76.6% at 1 h) [33] |

The performance of these polymers is critically influenced by their granulometric and mechanical properties, which affect flowability, compaction behavior, and the final integrity of the tablet [33].

Analytical Matrix Effects in Bioanalysis

In the context of bioanalytical chemistry, particularly when using Liquid Chromatography-Tandem Mass Spectrometry (LC/MS/MS), the term "matrix effect" describes the ion suppression or enhancement caused by co-eluting substances from the biological sample [34]. This is a significant challenge for accurate quantification.

- Mechanism: In electrospray ionization (ESI), co-eluting endogenous compounds (e.g., phospholipids) or other analytes compete for charge and access to the droplet surface, leading to suppressed or enhanced signal for the target analyte [34].

- Impact: This effect can result in unreliable data, poor sensitivity, and a prolonged method development process. Electrospray ionization (ESI) is noted as being more prone to this issue than Atmospheric Pressure Chemical Ionization (APCI) [34].

- Solution: A common practice of using simple protein precipitation for high-throughput analysis can exacerbate this problem, as it does not provide very clean final extracts. Therefore, chromatographic separation cannot be entirely minimized despite the specificity of MS/MS detection [34].

Diagram 1: Two key aspects of pharmaceutical matrix effects: drug delivery and analytical interference.

The Food Matrix Concept in Nutrition

The food matrix is defined as the intricate physical and chemical structure of a food, which governs how its nutrients are digested, absorbed, and metabolized [24] [2]. This concept challenges the reductionist approach of focusing solely on individual nutrients and emphasizes a more holistic understanding of food and health.

- Concept: The food matrix encompasses the organization of macronutrients (fats, proteins, carbohydrates), micronutrients, and bioactive compounds, as well as factors like texture and particle size [2]. This structure influences the bioaccessibility of nutrients, meaning the fraction released from the food that is available for intestinal absorption.

- The Dairy Matrix Example: Dairy products provide a compelling case study. Despite containing saturated fat and sodium, cheese consumption is associated with a reduced risk of mortality and heart disease [2]. This effect is attributed not to isolated nutrients, but to the complex interactions within the cheese matrix—including the presence of protein, calcium, phosphorus, magnesium, and unique microstructures like the milk fat globule membrane (MFGM). Similarly, the fermented matrix of yogurt, containing probiotics and nutrients, is linked to a lower risk of type 2 diabetes and improved cardiovascular health, likely due to a slower digestion process and support of gut health [2].

- Implications: The food matrix concept underscores that "foods are more than the sum of their nutrients." Processing methods that disrupt the native food matrix can significantly alter its physiological effects, which helps explain the observed health differences between whole and ultra-processed foods [24] [2].

Experimental Protocols for Matrix Analysis

Robust experimental design is essential for characterizing matrix effects. Below are detailed methodologies for evaluating pharmaceutical and food matrices.

Protocol for Controlled-Release Matrix Tablet Formulation and Evaluation

This protocol is adapted from preformulation studies of galantamine matrix tablets [33].

1. Materials Preparation:

- APIs and Polymers: Galantamine HBr, HPMC (METHOCEL K15M), PEO (POLYOX WSR N12K), EC (ETHOCEL Standard 10 FP).

- Excipients: Diluents (e.g., Spray-dried lactose monohydrate, Partially Pregelatinized Maize Starch), lubricants (e.g., Colloidal silicon dioxide - Aerosil 200), glidants (e.g., Magnesium stearate) [33].

- Sieving: Sieve all powders using appropriate mesh sizes (e.g., No. 60 for polymers, No. 30 for API) to ensure uniform particle size.

2. Powder Blending:

- Weigh all components according to the formulation design (e.g., 31.52% w/w polymer, 4.44% w/w GAL, and balanced diluents and lubricants) [33].

- Mix in a multi-directional powder blender for a fixed time and speed (e.g., 5 min at 20 rpm) to achieve a homogeneous blend.

3. Preformulation Compatibility Studies:

- FT-IR Spectroscopy: Record spectra of pure ingredients and drug-polymer binary mixtures (1:10) in the range of 4000 to 400 cm⁻¹ to identify any potential incompatibilities [33].

- Differential Scanning Calorimetry (DSC): Perform modulated heating-cooling cycles from 25°C to 400°C at a rate of 5.0 °C/min under nitrogen flow. Analyze thermograms for shifts in melting points or appearance/disappearance of peaks that indicate interactions [33].

4. Granulometric and Mechanical Analysis:

- Evaluate powder flowability, cohesion, and aeration.

- Apply compressibility models (Kawakita, Heckel, Leuenberger) during compaction to characterize deformation mechanisms (e.g., plasticity, fragmentation) [33].

5. Tablet Compaction and Drug Release:

- Compact powders into tablets under controlled pressure.

- Perform in vitro drug release studies using a USP dissolution apparatus (e.g., paddle method) in a suitable buffer (e.g., phosphate buffer, pH 6.8) over 12 hours.

- Calculate the Dissolution Efficiency (DE%) at specific time points to compare formulations quantitatively [33].

Protocol for Investigating Analytical Matrix Effects in LC/MS/MS

This protocol outlines the process for identifying and mitigating matrix effects in bioanalytical methods [34].

1. Post-Column Infusion Experiment:

- Infuse a solution of the analyte directly into the mobile post-column effluent entering the mass spectrometer.

- Inject a blank, extracted biological sample (e.g., plasma) onto the LC column.

- Monitor the signal of the infused analyte. A dip in the signal at the retention time of co-eluting matrix components indicates ion suppression.

2. Monitoring Phospholipids:

- Use specific multiple reaction monitoring (MRM) transitions to detect endogenous phospholipids that are known to cause ion suppression.

- Develop LC conditions (gradient, column) to separate these phospholipids from the analytes of interest, thereby minimizing their co-elution and the resultant matrix effect [34].

3. Modification of LC Conditions:

- If matrix effect is identified, optimize the chromatographic method. This may involve:

- Increasing the run time to improve peak separation.

- Adjusting the mobile phase gradient to shift the retention times of the analyte away from the region of high matrix interference.

- Changing the column chemistry [34].

Diagram 2: General experimental workflow for developing and evaluating a controlled-release matrix tablet.

Quantitative Data and Comparison

The quantitative evaluation of matrix systems is critical for comparing performance. The following tables summarize key data from a pharmaceutical preformulation study and contrast the core aspects of matrix effects in different fields.

Table 2: Quantitative Performance of Galantamine in Different Polymer Matrices [33]

| Formulation Parameter | HPMC Matrix | PEO Matrix | EC Matrix |

|---|---|---|---|

| Tensile Strength (T~max~) | 4.61 MPa | Data Not Provided | Data Not Provided |

| Drug Release at 1 hour | Data Not Provided | Data Not Provided | 76.6% |

| Drug Release at 12 hours | 85.4% | 88.7% | Not Applicable |

| Dissolution Efficiency (DE%) | 62.2% | 57.5% | 73.7% |

| USP Criteria Met | Yes | Yes | No |

Table 3: Cross-Disciplinary Comparison of Matrix Effects

| Aspect | Pharmaceutical Drug Delivery Matrix | Analytical Matrix Effect (LC/MS/MS) | Food Matrix |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Function | Control API release rate and profile [33] | Interfere with accurate analyte quantification [34] | Modulate nutrient digestion and bioavailability [2] |

| Key Components | Synthetic/Economical Polymers (HPMC, PEO, EC) [33] | Endogenous plasma components (e.g., phospholipids), co-eluting analytes [34] | Natural macronutrient structures (e.g., MFGM), fiber, protein networks |

| Desired Outcome | Sustained, predictable drug release | Elimination of ion suppression/enhancement | Targeted health benefits (e.g., reduced cardiometabolic risk) |

| Common Analysis Methods | Dissolution testing, DSC, FT-IR, compaction models [33] | Post-column infusion, matrix factor calculation, MRM monitoring [34] | Human intervention studies, metabolomics, digestion models |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 4: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Matrix Effect Studies

| Reagent/Material | Function and Application | Example from Literature |

|---|---|---|

| Hydroxypropyl Methylcellulose (HPMC) | Hydrophilic matrix polymer for sustained drug release via gel formation [33]. | METHOCEL K15M used in galantamine controlled-release tablets [33]. |

| Polyethylene Oxide (PEO) | High-molecular-weight polymer enabling drug release through swelling and erosion mechanisms [33]. | POLYOX WSR N12K LEO used in galantamine formulations [33]. |

| Ethylcellulose (EC) | Insoluble, hydrophobic polymer used for forming inert matrix systems for drug release [33]. | ETHOCEL Standard 10 FP evaluated in galantamine study [33]. |

| Phospholipid Standards | Used to identify and characterize regions of ion suppression in LC/MS/MS method development [34]. | Monitoring phospholipids via MRM to troubleshoot matrix effects in clinical bioanalysis [34]. |

| Stable Isotope-Labeled IS | Internal Standards (e.g., Deuterated) used to correct for matrix effects and variability in mass spectrometry [34]. | 2H5-Piperacillin used as an internal standard for antibiotic analysis in plasma [34]. |

| LC/MS/MS System | Analytical platform for quantifying analytes in complex matrices; prone to matrix effects requiring mitigation [34]. | API4000 triple quadrupole mass spectrometer with TurboIonSpray probe used in pharmacokinetic studies [34]. |

Advanced Methodologies for Analyzing and Applying Matrix Effects

Understanding the complex journey of food through the human gastrointestinal (GI) tract is fundamental to advancing nutritional science, food development, and therapeutic delivery. In vitro digestion models have emerged as indispensable laboratory systems that simulate food breakdown in the human digestive system, providing valuable insights without the ethical concerns and practical limitations of human or animal studies [35]. These models serve as crucial tools for investigating the liberation of nutrients, bioavailability of active ingredients, and effects of digestion, particularly within the context of food component and matrix effects research [35] [36].

The growing interest in understanding how dietary intake impacts human health has positioned in vitro techniques as essential complements to human nutritional research, offering advantages in expediency, affordability, reduced labor intensity, and ethical flexibility [35]. These models enable controlled mechanistic investigations and hypothesis testing through their inherent reproducibility, adaptability in selecting experimental parameters, and convenient sampling capabilities at locations of interest throughout the simulated digestive tract [35]. As research increasingly focuses on how food composition and structure influence nutrient release and bioavailability, in vitro models provide the standardized, controlled environments necessary to unravel the complex interactions between food components and their digestive fates.

Classification of In Vitro Digestion Models: From Static to Dynamic Systems

In vitro digestion models can be broadly categorized into static and dynamic systems, each with distinct characteristics, advantages, and limitations suited to different research objectives.

Static Digestion Models

Static models represent the simplest approach to simulating digestion, where food is sequentially exposed to simulated digestive fluids in different compartments (mouth, stomach, intestine) under fixed conditions [36]. In a typical static digestion protocol, a sample is mixed with simulated salivary fluid at pH 7 for 2 minutes at 37°C, followed by addition of simulated gastric fluid and pepsin with pH adjustment to 3.0, then incubation for 120 minutes before adjusting pH back to 7 and adding simulated intestinal fluid containing pancreatin and bile salts for a final 120-minute incubation [36].

The primary advantage of static models lies in their simplicity, reproducibility, and suitability for screening large sample sets or building hypotheses [35] [36]. They have been widely employed to evaluate the effect of food processing on nutrient bioaccessibility, bioavailability, and allergenic potential [36]. However, a significant limitation is their inability to mimic the complex, evolving processes of in vivo digestion, particularly the instantaneous pH changes between different digestion phases and the dynamic nature of gastrointestinal physiology [36].

Dynamic Digestion Models

Dynamic in vitro models more accurately reproduce the gradual transit of ingested compounds through the gastrointestinal tract using multicompartment computer-controlled systems [37]. These systems, such as TIM-1, DIDGI, and ESIN, incorporate features such as gradual gastric acidification, controlled secretions, and regulated emptying patterns that more closely mimic physiological conditions [36] [38].

For instance, the DIDGI system, a two-compartment digestion system, maintains anaerobic conditions, controls flows of ingesta and digestive reagents via peristaltic pumps, and uses mathematical equations to regulate transit times through each compartment [37]. Parameters can be fixed based on human physiological data, with gastric pH gradually decreasing from 6.4 to 1.7 over 12 hours while intestinal pH remains constant at 6.5, with continuous addition of pancreatin, pancreatic lipase, and bile salts [37].

While dynamic models provide more physiologically relevant data, they require sophisticated equipment and are more resource-intensive than static systems [35]. The choice between model types depends on research objectives, with static models suitable for high-throughput screening and dynamic models preferred when closer approximation to in vivo conditions is necessary.

Table 1: Comparison of Static vs. Dynamic In Vitro Digestion Models

| Characteristic | Static Models | Dynamic Models |

|---|---|---|

| Complexity | Single-compartment, simple setup | Multi-compartment, sophisticated equipment |

| pH Control | Instant changes between phases | Gradual adjustment mimicking physiology |

| Transit | No gradual emptying | Controlled transit between compartments |

| Secretions | Bolus addition | Continuous, controlled addition |

| Cost | Low | High |

| Throughput | High | Low to moderate |

| Physiological Relevance | Limited | Higher |

| Primary Applications | Screening, comparative studies | Mechanistic studies, bioaccessibility prediction |

Standardized Protocols and Key Parameters: The INFOGEST Framework

The lack of standardized protocols historically made cross-comparison of research findings challenging, with different authors adopting slightly but critically varied methodologies [36]. In response, the international INFOGEST network established a harmonized in vitro digestion protocol simulating adult human digestion, which has become the gold standard for food digestion studies [35] [36].

The INFOGEST method standardizes crucial parameters including pH levels, enzyme concentrations, and digestion times for each stage of digestion [35]. This harmonization enables researchers worldwide to replicate studies and compare results systematically, significantly enhancing the reliability and predictive power of in vitro digestion research [35]. The protocol specifies the use of simulated salivary, gastric, and intestinal fluids with carefully defined electrolyte compositions, along with standardized enzyme activities from porcine sources (pepsin for gastric phase; pancreatin, trypsin, and lipase for intestinal phase) and bile salt concentrations [36] [39].