Food Allergen Thresholds and Detection Limits: A Scientific Framework for Risk Assessment and Method Selection

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of food allergen thresholds and the analytical methods used for their detection, tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals.

Food Allergen Thresholds and Detection Limits: A Scientific Framework for Risk Assessment and Method Selection

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of food allergen thresholds and the analytical methods used for their detection, tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals. It explores the foundational concepts of individual and population thresholds, including the establishment of reference doses by international bodies. The review critically assesses current and emerging detection technologies—from ELISA and PCR to mass spectrometry and AI-enhanced diagnostics—highlighting their operational principles, capabilities, and limitations. A significant focus is placed on troubleshooting common analytical challenges, such as matrix effects and protein degradation in processed foods, and on the critical importance of method validation and comparative performance for ensuring accurate risk assessment and protecting public health.

Defining the Landscape: From Clinical Thresholds to Global Regulatory Standards

In both toxicology and food allergy research, the concept of a "threshold" is fundamental to understanding the relationship between dose and biological effect. A threshold dose is formally defined as the minimum dose of a substance that produces a minimal detectable biological effect in an organism [1]. At doses below this threshold, biological responses are typically absent, and increasing the dose above this level induces a corresponding increase in the percentage or severity of biological responses [1]. This principle forms the cornerstone of modern risk assessment for chemicals, pharmaceuticals, and food allergens, though its application differs significantly between individual susceptibility and population-level protection.

The establishment of these thresholds enables researchers and regulators to define safety standards, set acceptable exposure limits, and protect public health. In the specific context of food allergy research, which frames this technical guide, understanding these concepts is crucial for determining the levels of allergenic proteins that may trigger reactions in sensitive individuals and establishing protective labeling thresholds for the broader population [2] [3]. This whitepaper explores the core concepts of NOAEL, LOAEL, and ED, their methodological establishment, and their critical application in food safety and pharmaceutical development.

Core Threshold Concepts and Definitions

Fundamental Dose Descriptors

Toxicology and pharmacology rely on standardized dose descriptors to quantify the relationship between exposure and effect. The most critical of these are summarized in the table below.

Table 1: Fundamental Toxicological Dose Descriptors

| Acronym | Full Name | Definition | Common Units |

|---|---|---|---|

| NOAEL | No-Observed-Adverse-Effect Level | The highest exposure level at which there are no biologically significant increases in adverse effects [1] [4]. | mg/kg body-weight/day, ppm |

| LOAEL | Lowest-Observed-Adverse-Effect Level | The lowest exposure level that produces biologically significant increases in adverse effects [1] [4]. | mg/kg body-weight/day, ppm |

| NOEL | No-Observed-Effect Level | The maximum dose with no observable effect of any kind (adverse or non-adverse) [1]. | mg/kg body-weight/day, ppm |

| LD₅₀ | Median Lethal Dose | A statistically derived dose that kills 50% of test animals [1] [4]. | mg/kg body weight |

| EC₅₀ | Median Effective Concentration | The concentration that produces 50% of the maximal biological effect [1]. | mg/L, mol/L |

| EDI | Estimated Daily Intake | The measured or estimated amount of a substance consumed daily [5]. | mg/kg body-weight/day |

Population vs. Individual Thresholds

A critical distinction exists between thresholds applicable to populations and those relevant to individuals. Population thresholds like NOAEL and LOAEL are derived from group data and designed to protect the entire population, including sensitive subgroups. These are established through systematic testing in animal or human studies and incorporate safety factors to account for inter-species and inter-individual variability [1] [5].

In contrast, individual thresholds represent the dose at which a specific person exhibits a biological response. In food allergy, this is known as the eliciting dose (ED), which varies significantly between individuals based on their sensitivity [3]. For instance, the ED05 represents the dose of an allergen that elicits a reaction in 5% of the allergic population [3]. This individual variability means that while population thresholds establish generally safe exposure levels, they cannot guarantee protection for every single individual, particularly the most highly sensitive members of the population.

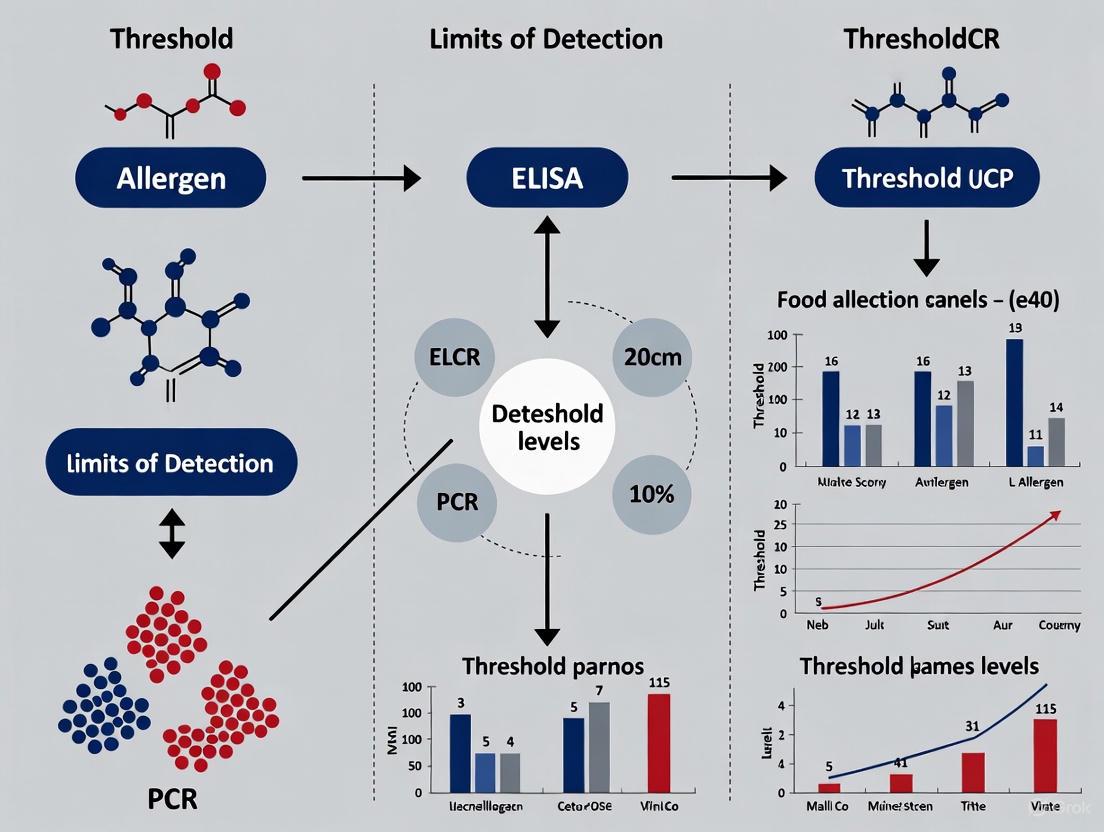

The relationship between these concepts and their progression from experimental data to public health protection is illustrated below.

Methodological Framework for Establishing Thresholds

Experimental Protocols for NOAEL/LOAEL Determination

The establishment of NOAEL and LOAEL values follows rigorous experimental protocols, primarily through repeated dose toxicity studies [1] [4]. The standard methodology involves:

1. Study Design:

- Population: Test species (typically rodents) divided into four groups: control (placebo), low dose, mid-dose, and high dose [1].

- Dosing Regimen: Each group receives the same daily dose for a specified period (28 days, 90 days, or chronic) via appropriate administration routes (oral, dermal, inhalation) [1].

- Parameters Monitored: Comprehensive biological parameters including clinical observations, body weight, food consumption, clinical pathology (hematology, clinical chemistry), organ weights, and histopathology [1].

2. Data Collection and Analysis:

- Necropsy and Tissue Sampling: Conducted at study completion to identify morphological changes [1].

- Statistical Analysis: Comparison of all measured parameters between treated and control groups using appropriate statistical tests to identify biologically significant differences [1].

- Dose-Response Assessment: Establishment of relationship between dose levels and observed effects [1].

3. Threshold Identification:

- NOAEL: The highest dose level without statistically or biologically significant adverse effects [1] [4].

- LOAEL: The lowest dose level with statistically or biologically significant adverse effects [1] [4].

Table 2: Example NOAEL and LOAEL Values from Experimental Studies

| Substance | Test System | NOAEL | LOAEL | Effect Type |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Oxydemeton-methyl | Rat | 0.5 mg/kg/day | 2.3 mg/kg/day | Systemic toxicity [1] |

| Boron | Rat | 55 mg/kg/day | 76 mg/kg/day | Developmental effects [1] |

| Acetaminophen | Human | 25 mg/kg/day | 75 mg/kg/day | Hepatotoxicity [1] |

| Barium | Rat | 0.21 mg/kg/day | 0.51 mg/kg/day | Renal effects [1] |

Food Allergen Threshold Methodologies

For food allergens, threshold determination employs distinct clinical approaches centered on individual patient responses:

1. Controlled Oral Food Challenges (OFC):

- Design: Progressive administration of increasing amounts of the allergenic food under medical supervision [3].

- Dosing: Typically uses a logarithmic dosing scheme (e.g., 1mg, 3mg, 10mg, 30mg, 100mg, 300mg, 1000mg of protein) [3].

- Endpoint: Identification of the lowest dose that elicits objective allergic symptoms (the individual's eliciting dose) [3].

2. Population Threshold Estimation:

- Data Aggregation: Collection of individual eliciting doses from multiple patients [3].

- Statistical Modeling: Application of statistical models (such as log-normal or log-logistic) to individual data to estimate population thresholds like ED05 [3].

- Quality of Life Assessment: Studies show that knowledge of individual thresholds improves quality of life regardless of challenge outcome [3].

The following diagram illustrates the clinical workflow for establishing individual allergen thresholds and their application to population protection.

Statistical Considerations in Threshold Determination

Biomarker Evaluation and Cut Point Analysis

The evaluation of continuous biomarkers presents significant statistical challenges, particularly in the context of cut point selection for diagnostic or prognostic applications [6]. Key considerations include:

1. Information Loss through Discretization:

- Categorizing continuous biomarkers into discrete groups (e.g., "high" vs. "low") results in significant information loss [6].

- This practice assumes an abrupt change in risk at the cut point, which rarely reflects the true biological relationship [6].

- Arbitrary dichotomization using percentiles (e.g., median splits) can distort true dose-response relationships and reduce statistical power [6].

2. Minimal P-value Approach and Instability:

- A common but problematic method involves testing multiple potential cut points and selecting the one with the smallest P-value [6].

- This approach produces highly unstable cut points, inflates false discovery rates, and generates biased effect size estimates [6].

- The instability of such empirically-derived cut points hinders reproducibility across studies and clinical settings [6].

3. Proper Statistical Modeling:

- Continuous biomarkers should ideally be modeled as continuous variables using non-linear terms (splines, polynomials) when appropriate [6].

- When categorization is clinically necessary, pre-specified, biologically relevant cut points should be used whenever possible [6].

- Internal validation techniques (bootstrapping, cross-validation) and external validation in independent datasets are essential for verifying cut point stability [6].

Uncertainty Factors and Risk Assessment

The transition from experimentally observed thresholds to protective human exposure limits requires the application of uncertainty factors (UFs) to account for various sources of variability and uncertainty [1] [5]:

Reference Dose (RfD) = NOAEL ÷ (UFinter × UFintra) [1]

Where:

- UFinter (typically 10x): Accounts for interspecies differences between test animals and humans [1] [5].

- UFintra (typically 10x): Accounts for variability within the human population, including sensitive subgroups [1] [5].

When only LOAEL is available, additional uncertainty factors may be applied, resulting in more conservative (lower) reference doses [4].

Applications in Food Allergen Safety and Drug Development

Food Allergen Thresholds in Practice

The application of threshold concepts in food allergy management has evolved significantly, with several practical applications:

1. Precautionary Allergen Labeling (PAL):

- Informs consumers about potential unintended allergen presence [2].

- Threshold data help establish scientifically justified labeling levels rather than arbitrary thresholds [3].

2. Immunotherapy Guidance:

- Knowledge of individual thresholds helps tailor oral immunotherapy (OIT) starting doses and progression [3].

- Patients with higher baseline thresholds may respond more favorably to specific treatment protocols [3].

3. Risk Communication and Shared Decision-Making:

- Understanding individual thresholds empowers patients to make informed dietary choices [3].

- Clinicians act as risk management consultants, helping frame food allergy risks within the broader context of daily life risks [3].

4. Regulatory Frameworks:

- The FDA identifies nine major food allergens but has not established regulatory thresholds for any allergens [2].

- The Food Allergen Labeling and Consumer Protection Act (FALCPA) requires clear labeling of major food allergens [2].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Materials

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Materials for Threshold Studies

| Reagent/Material | Function in Threshold Research | Application Examples |

|---|---|---|

| ELISA Kits | Quantification of specific proteins or antibodies | Allergen detection in foods; specific IgE measurement [7] |

| Mass Spectrometry Systems | High-precision quantification of proteotypic peptides | Detection of specific allergen markers in complex food matrices [7] |

| Animal Models (Rodents) | In vivo toxicity and efficacy testing | NOAEL/LOAEL determination for chemicals and drugs [1] |

| Cell Culture Systems | In vitro assessment of biological effects | Mechanism of action studies; high-throughput screening [8] |

| Hyperspectral Imaging (HSI) | Non-destructive allergen detection | Food manufacturing quality control; real-time monitoring [7] |

| ATP Meters | Sanitation verification | Allergen control monitoring in production facilities [7] |

Emerging Innovations and Future Directions

The field of threshold determination continues to evolve with several promising technological and methodological advances:

1. Advanced Detection Technologies:

- AI-enhanced testing with hyperspectral imaging and Fourier Transform Infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy enables non-destructive, real-time allergen detection without altering food integrity [7].

- Mass spectrometry can simultaneously quantify specific allergenic proteins (e.g., Ara h 3 in peanut, Bos d 5 in milk) with detection limits as low as 0.01 ng/mL [7].

- Multiplexed immunoassays allow simultaneous detection of multiple allergens, improving efficiency and comprehensiveness [7].

2. Computational and Analytical Advances:

- Novel transcriptomic tools like THRESHOLD analyze gene expression consistency across patient populations, identifying co-regulation patterns critical for understanding disease mechanisms [9].

- Cloud-based platforms integrate multiple data streams (ATP readings, microbial counts, allergen detection) to provide visualized heat maps and trend analysis for predictive risk management [7].

3. Biomarker Development:

- Statistical frameworks for establishing "predictive biomarker" status require parameter stability across populations and limited within-person variability [10].

- Biomarkers that can be expressed as actual intake plus independent error can substitute for actual intake in disease association analyses [10].

- In immunotherapy development, biomarkers play key roles in demonstrating mechanism of action, dose optimization, and predicting adverse reactions [8].

These innovations are poised to transform threshold determination from primarily reactive to increasingly predictive, enabling more personalized approaches to safety assessment and clinical management.

The concepts of NOAEL, LOAEL, and ED provide a critical framework for understanding the relationship between exposure dose and biological effect across toxicology, immunology, and pharmaceutical development. The distinction between individual thresholds (such as eliciting doses for food allergens) and population thresholds (such as NOAEL-derived reference doses) is fundamental to developing effective public health protections while recognizing individual variability. As methodological innovations continue to emerge in detection technologies, computational analysis, and biomarker development, the precision and personalization of threshold-based safety determinations will continue to improve. This progression promises enhanced protection for sensitive individuals while potentially reducing unnecessary restrictions for the broader population, ultimately supporting the dual goals of safety and food freedom articulated in modern food allergy management [3].

The Joint FAO/WHO Expert Consultation on Risk Assessment of Food Allergens has pioneered a transformative approach to managing global food allergy risks through science-based thresholds. Food allergies affect approximately 220 million people worldwide, constituting a critical public health concern that demands international standardization [11] [12]. The FAO/WHO initiative, conducted through a series of expert meetings beginning in 2020, represents a comprehensive effort to establish quantitative risk assessment frameworks for priority food allergens [13] [11]. This systematic approach addresses the fundamental challenge in food allergen management: determining the level of exposure that protects sensitive individuals while facilitating practical food safety guidelines and evidence-based precautionary labeling.

The establishment of reference doses (RfDs) marks a paradigm shift from qualitative to quantitative food allergen management. These health-based guidance values specify the amount of protein from an allergenic source that the vast majority of allergic individuals can consume without experiencing an adverse reaction [14] [12]. This whitepaper examines the complete scientific framework underlying these international standards, detailing the methodological approaches, experimental foundations, and practical implementations of reference doses within global food safety systems. The FAO/WHO recommendations provide the scientific basis for updating the Codex Alimentarius, the collection of internationally recognized food standards and guidelines, thereby facilitating harmonized global trade while protecting public health [11] [12].

Global Priority Allergen List: Identification and Criteria

Hazard Prioritization Methodology

The FAO/WHO expert committee employed a structured, evidence-based framework to identify global priority allergens through systematic evaluation of three primary criteria: prevalence, potency, and severity [12]. This transparent, quantitative methodology enables consistent identification and prioritization of allergenic foods posing significant public health risks across diverse populations and geographic regions. The prevalence criterion evaluates the proportion of populations experiencing immune-mediated adverse reactions to specific foods, drawing from epidemiological studies across multiple geographic regions to establish global significance [12]. The potency criterion assesses the dose-response relationship, examining the minimal protein doses required to elicit allergic reactions in sensitive populations through controlled clinical studies [14] [12]. The severity criterion evaluates the potential of specific food allergens to cause severe reactions, including anaphylaxis, with a threshold of responsibility for at least 5% of all anaphylaxis cases reported to emergency services in three or more geographic regions [12].

This risk assessment framework was deliberately designed to be transparent and repeatable, allowing for re-evaluation as new epidemiological and clinical data emerges. The systematic application of these criteria ensures that prioritization decisions are based on scientific evidence rather than historical precedent or regional perceptions alone, creating a robust foundation for global food safety policy [12].

Globally Recognized Priority Allergens

Based on the comprehensive risk assessment, the FAO/WHO established a global priority allergen list comprising foods consistently associated with significant allergic reactions across multiple regions [12]. This list provides the foundation for international standardization and includes:

- Cereals containing gluten (wheat, rye, barley, and their hybridized strains)

- Crustacea (shrimp, crab, lobster)

- Eggs

- Fish

- Milk

- Peanut

- Sesame

- Tree nuts (almond, hazelnut, walnut, cashew, pistachio, pecan)

The inclusion of these allergens in the priority list reflects their demonstrated global public health significance based on the prevalence, potency, and severity criteria [12]. The list serves as the scientific basis for the Codex Alimentarius standards regarding mandatory allergen declaration on packaged foods, helping to ensure consistent protection for allergic consumers worldwide [11] [12].

Regionally Significant Allergens

The FAO/WHO framework acknowledges that some allergens, while not meeting the criteria for global priority status, may pose significant regional risks due to local consumption patterns or genetic predispositions in specific populations [12]. These regionally important allergens include:

- Soy

- Specific tree nuts (Brazil nuts, macadamia nuts, pine nuts)

- Celery

- Buckwheat

- Lupin

- Mustard

- Oats

The recognition of regionally important allergens allows individual countries or regions to implement targeted management strategies for foods that pose local risks while maintaining a consistent global framework. This flexible approach acknowledges the diverse dietary patterns and allergy profiles across different populations while working toward international harmonization [12].

FAO/WHO Recommended Reference Doses

Quantitative Reference Dose Values

The FAO/WHO expert committee established science-based reference doses (RfDs) for priority allergens, expressed in milligrams of total protein from the allergenic source [14]. These values represent the amount of allergenic protein that can be safely consumed by the vast majority of allergic individuals without triggering a reaction. The recommended reference doses are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1: FAO/WHO Recommended Reference Doses for Priority Allergens

| Allergen | RfD Recommendation (mg total protein) | Special Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Walnut | 1.0 | Includes pecan |

| Pecan | 1.0 | Included with walnut |

| Cashew | 1.0 | Includes pistachio |

| Pistachio | 1.0 | Included with cashew |

| Almond | 1.0 | Provisional recommendation |

| Peanut | 2.0 | - |

| Egg | 2.0 | - |

| Milk | 2.0 | Finalized April 2022 |

| Sesame | 2.0 | Finalized April 2022 |

| Hazelnut | 3.0 | - |

| Wheat | 5.0 | - |

| Fish | 5.0 | - |

| Shrimp | 200.0 | - |

The establishment of these reference doses enables a transition from zero-tolerance policies to risk-based approaches that reflect the actual sensitivity of allergic populations [14]. The substantial variation in reference doses across different allergen categories (ranging from 1.0 mg for several tree nuts to 200.0 mg for shrimp) reflects the differential potency of these allergenic foods, with lower values indicating greater allergenic potency [14].

Scientific Basis for Dose Determination

Methodological Approaches

The FAO/WHO committee evaluated four distinct methodological approaches for establishing allergen thresholds before selecting the most appropriate frameworks [14]:

- Analytical-based approach: Relies on detection capabilities of analytical methods

- No Observed Adverse Effect Level (NOAEL) + Uncertainty Factor approach: Applies safety factors to established no-effect levels

- Benchmark Dose (BMD) with or without Margin of Exposure (MOE): Utilizes statistical modeling of dose-distribution relationships

- Probabilistic Hazard Assessment approach: Integrates population sensitivity and exposure data

The committee determined that the Benchmark Dose (BMD) approach and Probabilistic Hazard Assessment were most aligned with their charge and provided the most scientifically robust foundation for establishing reference doses [14]. The BMD approach specifically refers to a statistical modeling technique that identifies the dose that produces a predetermined response level (benchmark response) in a population, typically ranging from 1-10% for allergenic responses [14].

Clinical Data Integration

The reference dose values were derived through systematic evaluation of clinical data from controlled oral food challenges conducted with allergic individuals [14] [12]. These studies measure the minimal eliciting doses that provoke objective allergic symptoms in sensitized populations, establishing dose-response relationships for each priority allergen. The expert committee analyzed population-based threshold distributions to identify doses that would protect the vast majority (typically 90-99%) of allergic individuals [14].

The resulting reference doses incorporate comprehensive safety margins to account for uncertainties in the data and protect highly sensitive subpopulations. The values represent the total amount of allergenic protein that can be consumed in a single eating occasion while providing adequate protection for allergic consumers [14] [12].

Methodological Framework for Threshold Determination

Risk Assessment Protocol

The FAO/WHO established a systematic protocol for determining reference doses that integrates clinical evidence with population-based risk assessment approaches. The methodological framework consists of sequential phases that transform clinical data into actionable risk management tools, as visualized in Figure 1.

Figure 1: Risk Assessment Workflow for Allergen Threshold Determination

Clinical Challenge Study Methodology

Controlled oral food challenges represent the gold standard for generating data on minimal eliciting doses for food allergens. The experimental protocols for these studies require rigorous standardization to ensure reliability and comparability of results [14] [12].

Participant Selection Criteria

- Confirmed IgE-mediated allergy: Participants must have documented sensitization through positive skin prick tests (wheal diameter ≥3mm larger than negative control) and/or detectable allergen-specific IgE (≥0.35 kU/L) [15]

- Clinical history consistent with food allergy: Self-reported or physician-documented reactions to the challenge food

- Absence of exclusionary conditions: No history of severe anaphylaxis requiring ICU admission, unstable asthma, cardiovascular disease, or pregnancy

- Appropriate age representation: Inclusion of both pediatric and adult populations where applicable

- Medication washout periods: Antihistamines discontinued for 3-5 half-lives prior to challenge

Challenge Protocol Design

- Randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind design: To eliminate bias and ensure scientific validity

- Graduated dosing regimen: Sequential administration of increasing doses (e.g., 0.1mg, 1mg, 10mg, 100mg, 1g, 3g, 10g of allergenic protein) at 15-30 minute intervals

- Dose preparation standardization: Use of defatted nut flours, spray-dried egg white, or purified protein isolates to ensure accurate protein quantification

- Objective symptom monitoring: Standardized assessment tools for evaluating cutaneous, respiratory, gastrointestinal, and cardiovascular symptoms

- Stopping criteria: Predefined symptom thresholds requiring termination of challenge (e.g., widespread urticaria, respiratory distress, 20% decrease in blood pressure)

- Emergency preparedness: Immediate access to epinephrine, antihistamines, corticosteroids, and resuscitation equipment

Statistical Analysis Framework

The dose-distribution modeling approach forms the statistical foundation for reference dose determination. This methodology applies statistical distributions to describe the variation in minimal eliciting doses across allergic populations [14].

Benchmark Dose (BMD) Modeling

- Data fitting: Experimental dose-response data is fitted to appropriate statistical distributions (log-normal, log-logistic, Weibull)

- Benchmark response selection: Typically set at 1-10% of the responding population, representing a tolerable level of response

- BMD calculation: The dose associated with the selected benchmark response is calculated from the fitted distribution

- Uncertainty analysis: Confidence intervals around the BMD estimate are derived using parametric bootstrap or Bayesian methods

Probabilistic Risk Assessment

- Population threshold distribution: Characterizes the variation in individual threshold doses across the allergic population

- Exposure assessment: Integrates data on the distribution of allergen concentrations in food products

- Risk characterization: Combines threshold and exposure distributions to estimate the probability of allergic reactions across the population

- Sensitivity analysis: Evaluates the impact of uncertainty in model parameters on risk estimates

Implementation in Food Safety Systems

Precautionary Allergen Labelling (PAL) Framework

The FAO/WHO recommended implementation of a risk-based precautionary allergen labelling system utilizing the established reference doses [11] [14]. This system provides consistent, evidence-based guidance for indicating the potential presence of unintended allergens in food products. The logical decision process for applying PAL is illustrated in Figure 2.

Figure 2: Decision Framework for Precautionary Allergen Labelling

The PAL system enables quantitative risk management by comparing the estimated exposure to allergenic protein (calculated as concentration multiplied by serving size) with the established reference dose [14]. This represents a significant advancement over previous qualitative approaches that lacked scientific basis and often led to overuse of precautionary labels, diminishing their value for consumers [11] [14].

Global Harmonization Efforts

The FAO/WHO reference doses provide the scientific foundation for international standardization of food allergen management through the Codex Alimentarius Commission [11] [12]. The alignment of global food safety standards offers significant benefits:

- Consistent protection for allergic consumers regardless of geographic location

- Reduced trade barriers through harmonized regulatory requirements

- Improved risk communication with standardized labeling approaches

- Efficient allocation of food industry resources for allergen control measures

- Stimulated innovation in analytical detection methods and food processing technologies

The FAO/WHO recommendations have been presented to the Codex Committee on Food Labelling (CCFL) and the Codex Committee on Food Hygiene (CCFH) to support the development of internationally agreed food safety standards [11]. This represents a critical step toward global implementation of evidence-based allergen management practices.

Regional Implementation Considerations

While the FAO/WHO reference doses provide a scientific foundation for global standards, implementation may vary based on regional factors and regulatory frameworks [14]. In the United States, for example, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has historically maintained a zero-tolerance approach for certain allergens, particularly peanuts, though the agency established a threshold of 20 ppm for gluten-free labeling in 2013 [14]. This suggests that regulatory adoption of the FAO/WHO reference doses may proceed gradually, with initial resistance to moving away from established zero-tolerance positions [14].

Regional differences in priority allergens also necessitate flexible implementation approaches. For example, while the FAO/WHO recognizes sesame as a global priority allergen (with a reference dose of 2.0 mg protein), the United States only added sesame as a major food allergen with the 2021 passage of the FASTER Act [14]. Similarly, regionally important allergens such as lupin, buckwheat, or specific tree nuts may require tailored management strategies in areas where they represent significant allergic risks [12].

Research Reagents and Methodological Tools

Essential Research Materials

The experimental protocols underlying food allergen threshold research require specialized reagents and analytical tools. Table 2 summarizes the key research solutions essential for generating the scientific evidence supporting reference dose establishment.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Methodological Tools

| Research Reagent/Solution | Function/Application | Technical Specifications |

|---|---|---|

| Defatted Allergen Extracts | Oral challenge material preparation | Protein content standardized to 1-100 mg/g |

| Allergen-specific IgE Assays | Participant screening and characterization | ImmunoCAP Phadia systems; threshold ≥0.35 kU/L [16] [15] |

| Skin Prick Test (SPT) Solutions | IgE-mediated sensitivity confirmation | Glycerinated extracts (1:10-1:20 w/v); histamine control (10 mg/mL) [15] |

| Protein Reference Standards | Analytical method calibration | Certified reference materials (NIST, IRMM) |

| Mass Spectrometry Reagents | Allergen detection and quantification | Trypsin for protein digestion, iTRAQ/TMT tags for multiplexing |

| ELISA Kits | Food matrix protein quantification | Sandwich format with monoclonal/polyclonal antibody pairs |

| Molecular Allergen Components | Component-resolved diagnostics | Recombinant or natural purified allergens (rBet v 1, rAra h 2, etc.) [15] |

Analytical Method Requirements

The accurate quantification of allergenic proteins in food matrices represents a critical methodological challenge in implementing reference dose-based management systems. Analytical techniques must demonstrate sufficient sensitivity, specificity, and reproducibility to support risk-based decision making [14].

Method Performance Criteria

- Detection sensitivity: Lower limit of detection sufficient to quantify proteins at levels corresponding to reference doses (typically 0.1-10 ppm protein)

- Quantification accuracy: Recovery rates of 50-150% across relevant food matrices

- Matrix tolerance: Reliable performance in complex processed food systems

- Specificity: No cross-reactivity with non-target proteins or food components

- Precision: Inter- and intra-assay coefficient of variation <15-20%

Method Validation Protocols

- Collaborative trials: Ring tests across multiple laboratories to establish reproducibility

- Reference material characterization: Certification of calibrants for method standardization

- Matrix-specific validation: Performance verification in representative food categories

- Proficiency testing: Ongoing assessment of laboratory performance through blinded samples

Future Directions and Research Needs

The establishment of FAO/WHO reference doses represents a foundational achievement in food allergen risk assessment, but several areas require continued research and methodology development. Future efforts should focus on advancing the scientific basis for allergen management through targeted investigations.

Evidence Gaps and Research Priorities

- Population-level threshold variation: Expanded clinical challenge studies across diverse geographic and demographic groups

- Impact of food processing: Systematic evaluation of how thermal processing, fermentation, and other technologies alter allergen potency

- Co-factor effects: Controlled studies examining how exercise, alcohol, medications, and physiological states affect individual thresholds

- Pediatric-specific sensitivity: Age-stratified threshold data to address the unique needs of children with food allergies

- Longitudinal threshold stability: Prospective studies examining how individual thresholds change over time

Methodological Innovations

- Advanced protein quantification: Mass spectrometry-based methods for specific allergen target peptides

- Biomarker development: Correlates of reaction severity to supplement threshold data

- In vitro correlational models: Cell-based assays that predict clinical reactivity

- Data integration platforms: Harmonized databases combining threshold, prevalence, and severity information

The FAO/WHO initiative has established a robust scientific framework for global management of food allergens through evidence-based reference doses. Ongoing research and international collaboration will further refine these standards, enhancing protection for allergic consumers while supporting innovation in the global food industry.

The Role of Thresholds in Risk Assessment and Shared Clinical Decision-Making

In the field of food allergy, a threshold of reactivity is defined as the amount of allergen that an allergic individual can consume without experiencing an adverse reaction. Quantifying these thresholds has become fundamental to modern risk assessment and clinical management, shifting practice from universal avoidance to more personalized approaches. Food allergy affects approximately 1 in 10 adults and 1 in 13 children, creating a significant public health burden that extends beyond physical health to encompass nutrition, psychology, and quality of life [3]. The establishment of evidence-based thresholds enables clinicians, regulators, and patients to move beyond precautionary principles toward scientifically-grounded risk management strategies.

Historically, food allergy management universally treated all patients as being at risk for anaphylaxis and mandated strict avoidance of allergenic foods in all forms and amounts [17]. However, research over the past two decades has demonstrated that many patients tolerate small amounts of allergen without reaction [17]. This discovery laid the foundation for threshold-based approaches that now inform everything from regulatory policy to individual treatment decisions. The evolving science of thresholds represents a paradigm shift in food allergy management, allowing for more nuanced clinical decision-making through shared decision-making processes that actively engage patients in their care [3].

Quantitative Threshold Data for Major Allergens

International research consortia have systematically collected and analyzed threshold data from controlled oral food challenges to establish population-based reference doses for major allergens. These eliciting doses (ED) describe the amount of allergen protein that will produce a reaction in a given percentage of the allergic population. The ED05 and ED10 values represent the doses at which 5% and 10% of allergic individuals would react, respectively [17].

Table 1: Eliciting Doses for Major Food Allergens

| Food | Discrete ED05 (mg) | Cumulative ED05 (mg) | Discrete ED10 (mg) | Cumulative ED10 (mg) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Peanut | 2.1 | 3.9 | 7.1 | 9.0 |

| Egg | 2.3 | 2.4 | 6.3 | 7.4 |

| Milk | 2.4 | 3.1 | 7.1 | 9.6 |

| Cashew | 0.8 | 1.6 | 3.4 | 6.2 |

| Shrimp | 280 | 429 | 723 | 1265 |

| Sesame | 2.7 | 4.2 | 10.3 | 16.1 |

Source: Adapted from Hourihane et al. [17]

The Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) and World Health Organization (WHO) have established reference doses based on the ED05 for global priority allergens to guide regulatory decisions and precautionary allergen labeling [18]. These values represent the level of exposure without appreciable health risks for most allergic consumers.

Table 2: FAO/WHO Recommended Reference Doses for Global Priority Allergens

| Global Priority Allergens | Recommended Reference Doses (mg Total Protein from Allergen Source) |

|---|---|

| Tree nuts (walnut, pecan, cashew, pistachio, almond) | 1.0 |

| Milk | 2.0 |

| Peanut | 2.0 |

| Egg | 2.0 |

| Sesame | 2.0 |

| Hazelnut | 3.0 |

| Wheat | 5.0 |

| Fish | 5.0 |

| Shrimp | 200 |

Source: FAO/WHO Expert Consultation [18]

Methodological Approaches to Threshold Determination

Experimental Protocols for Threshold Assessment

The gold standard for determining individual thresholds is the double-blind, placebo-controlled food challenge (DBPCFC), conducted using internationally standardized protocols. An expert consensus established in 2004 and refined in 2014 provides detailed methodology for challenge-based threshold determination [17]. The experimental workflow follows a rigorous, stepwise approach to ensure patient safety and data reliability.

Figure 1: Experimental workflow for determining allergen thresholds through controlled food challenges. LOAEL: Lowest Observed Adverse Effect Level; NOAEL: No Observed Adverse Effect Level.

Key Methodological Considerations

The DBPCFC protocol incorporates several critical safety and scientific elements. Challenges begin with minimal doses (typically 0.1-1mg of allergen protein) that are unlikely to provoke severe reactions, with dose escalation following predetermined intervals (15-30 minutes) based on the allergen and patient history [17]. The dosing matrix must effectively mask the allergen while maintaining protein integrity and accurate concentration. Active and placebo challenges are conducted on separate days in randomized order to maintain blinding.

Throughout the challenge, patients undergo continuous symptom monitoring using standardized scoring systems such as the PRACTALL criteria or similar validated tools. The challenge endpoint is determined by either the development of objective clinical symptoms or administration of the complete predetermined dose sequence. The lowest dose that produces objective symptoms is recorded as the Lowest Observed Adverse Effect Level (LOAEL), while the preceding dose is designated the No Observed Adverse Effect Level (NOAEL) [17].

Statistical analysis of population threshold data utilizes interval-censoring survival analysis to account for the range between NOAEL and LOAEL values for each individual. This approach enables modeling of the dose-response relationship across the population and calculation of eliciting doses (EDx) for specific percentiles of the allergic population [17].

Threshold Applications in Risk Assessment and Clinical Management

Regulatory and Public Health Applications

Threshold data provides the scientific foundation for evidence-based precautionary allergen labeling (PAL) policies. The VITAL (Voluntary Incidental Trace Allergen Labelling) program utilizes reference doses to establish action levels for food products, determining when precautionary "may contain" labeling is appropriate [18]. This scientifically-grounded approach addresses the problematic variability in current PAL practices, which often leads to consumer confusion and disregard for warnings [18].

Internationally, the Codex Alimentarius Commission has adopted a Code of Practice on Food Allergen Management (CXC 80-2020) based on threshold concepts, promoting global harmonization of allergen management and labeling requirements [18]. Regulatory bodies including the U.S. FDA and European Food Safety Authority (EFSA) utilize threshold data in evaluating the public health importance of food allergens and establishing labeling frameworks [2] [19].

Clinical Implementation and Shared Decision-Making

In clinical practice, knowledge of individual thresholds facilitates personalized management strategies through shared decision-making processes [3]. Threshold information guides multiple aspects of clinical care:

Oral Immunotherapy (OIT) Dosing: Baseline thresholds inform OIT initiation protocols, with higher threshold patients potentially beginning at more advanced dosing stages or utilizing accelerated protocols [17] [3]. A 2017 study by Garvey et al. demonstrated successful home-based OIT induction in children with high peanut thresholds (mild reactions at >1 peanut), with 50% achieving sustained unresponsiveness [3].

Precautionary Label Interpretation: Patients with thresholds above population reference doses may be advised they can safely consume products with precautionary labeling for their allergen, significantly expanding food choices [3]. Clinical surveys indicate 57% of allergists allow ingestion to specified amounts when thresholds are known [3].

Quality of Life Enhancement: Single-dose low-dose challenges (e.g., 1.5mg peanut protein) have demonstrated significant improvements in food allergy-related quality of life regardless of challenge outcome, providing empowerment through knowledge [17] [3]. This approach has proven highly cost-effective (>$19 million per life-year saved) [3].

Analytical Methods Supporting Threshold Implementation

Accurate allergen detection and quantification are essential for implementing threshold-based approaches. Method selection depends on the specific application, with each technology offering distinct advantages and limitations.

Table 3: Analytical Methods for Allergen Detection and Quantification

| Method Category | Specific Technologies | Detection Capabilities | Applications | Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Immunoassays | ELISA, Lateral Flow, Multiplex Microarray Immunoassay | Intact proteins or large fragments (>15 amino acids); typically 1-10 ppm | Routine testing, regulatory compliance | Gold standard; may detect non-reactive proteins; commercial availability |

| Molecular Biology | PCR, Real-time PCR | Allergen DNA; species-specific sequences | Difficult-to-measure allergens, processed foods | High sensitivity; correlates with protein; detects potential, not actual, allergenicity |

| Mass Spectrometry | LC-MS/MS, MRM | Proteotypic peptides; 0.01 ng/mL sensitivity | Complex matrices, hydrolyzed proteins, method validation | High specificity; absolute quantification; requires specialized expertise |

| Emerging Technologies | Hyperspectral Imaging, Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy, Biosensors | Non-destructive, real-time detection | Processing facilities, rapid screening | Non-destructive; requires validation; limited commercial availability |

Source: Adapted from food allergen analysis literature [7] [18] [20]

A reference measurement system using the mass fraction of total protein from the allergenic ingredient as the primary reference quantity has been proposed to improve comparability across methods and laboratories [20]. This metrology-based approach establishes metrological traceability through primary reference measurement methods, certified reference materials, and reference laboratories, as demonstrated for milk protein in cookies [20].

Variability and Stability of Thresholds

Thresholds demonstrate both inter-individual variability (differences between people) and intra-individual variability (changes within the same person over time). Short-term threshold variation can reach up to 3 logs, though 71.2% of individuals show limited variation within half-log [3]. Multiple factors contribute to this variability:

Cofactors: Exercise and sleep deprivation independently reduce peanut reactivity thresholds by approximately 45%, with sleep deprivation also increasing reaction severity by 48% [3]. Other cofactors include illness, temperature extremes, medications (NSAIDs, beta-blockers), alcohol consumption, and menstruation [3].

Immunologic Status: Underlying mast cell disorders, high-affinity specific IgE concentrations, intestinal permeability, and active immunomodulatory treatments (OIT, omalizumab) influence individual thresholds [3].

Phenotype Considerations: Food allergies demonstrate varying persistence patterns—egg and milk allergies often resolve while peanut, tree nut, and seafood allergies typically persist [3]. These phenotypic differences inform long-term threshold expectations and management strategies.

Despite these variations, thresholds tend toward stability in the short-term, providing a reasonable basis for clinical decision-making when considered alongside individual patient factors [3].

Research Reagents and Materials

The following essential research reagents and materials form the foundation of threshold research and clinical application:

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents for Threshold Studies

| Reagent/Material | Specifications | Research Application | Critical Functions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Food Allergen Reference Materials | Certified reference materials (CRMs) with specified protein content; e.g., NIST peanut butter SRM 2387 | Method calibration, quality control | Provides metrological traceability, ensures analytical accuracy and comparability |

| Allergen-Specific Immunoassays | Validated ELISA kits for major allergens; e.g., RIDASCREEN, Veratox | Food testing, environmental monitoring | Quantifies allergen concentrations in food and environmental samples |

| Mass Spectrometry Standards | Stable isotope-labeled peptide standards for major allergen targets (Ara h 1-6, Bos d 5, Gal d 1-2) | Reference method development, method validation | Enables absolute quantification of specific allergenic proteins via LC-MS/MS |

| Food Challenge Materials | Pharmaceutical-grade allergen powders (e.g., peanut flour) or characterized food sources | Controlled oral food challenges | Provides precise, reproducible dosing for threshold determination |

| Biological Reference Materials | Human serum pools with characterized IgE specificity and concentration | Immunoassay calibration, basophil activation tests | Standardizes IgE detection across platforms and laboratories |

| DNA Extraction and PCR Kits | Validated for complex processed food matrices | Species identification in allergenic foods | Detects allergen sources in difficult matrices where protein detection may fail |

Source: Compiled from analytical methodology literature [18] [20]

Threshold-based approaches have fundamentally transformed food allergy risk assessment and clinical management, replacing universal precaution with evidence-based, personalized strategies. The continued refinement of threshold data, analytical methods, and clinical implementation frameworks supports increasingly precise risk assessment and shared clinical decision-making. Future directions include expanding threshold data for less common allergens, refining understanding of threshold modifiers, developing rapid point-of-care threshold assessment tools, and further harmonizing international regulatory approaches based on population reference doses. As threshold science continues to evolve, it promises to further enhance food safety and quality of life for allergic consumers through increasingly sophisticated risk management frameworks.

The Food Allergen Labeling and Consumer Protection Act of 2004 (FALCPA) represents a cornerstone of U.S. food safety policy, enacted to address the serious public health challenge posed by food allergies [21]. By establishing a standardized framework for declaring major allergens, FALCPA aimed to protect the millions of Americans affected by food allergies by ensuring clear, consistent labeling that enables avoidance of trigger foods. The regulatory landscape continues to evolve, as demonstrated by the recent Food Allergy Safety, Treatment, Education, and Research (FASTER) Act of 2021, which expanded mandatory labeling to include sesame as the ninth major food allergen effective January 1, 2023 [2] [22]. These regulatory developments occur alongside significant advances in the scientific understanding of food allergen thresholds and detection methodologies, creating dynamic interplay between policy, analytical science, and public health protection.

This whitepaper examines the core provisions of FALCPA and the FASTER Act, analyzes recent updates to interpretive guidance, and explores the critical relationship between regulatory frameworks and the scientific research on allergen thresholds and detection limits. For researchers and drug development professionals, understanding these evolving requirements is essential for designing studies, developing analytical methods, and contributing to evidence-based policy refinements that protect allergic consumers while supporting innovation.

Core Legislative Frameworks: FALCPA to FASTER Act

FALCPA: The Foundational Mandate

FALCPA was enacted in response to findings that approximately 2% of adults and 5% of infants and young children in the United States suffered from food allergies, with eight foods or food groups accounting for 90% of all food allergies [21]. The law identified eight "major food allergens": milk, eggs, fish, Crustacean shellfish, tree nuts, peanuts, wheat, and soybeans [2]. FALCPA mandated two primary labeling approaches for declaring these allergens:

- Parenthetical declaration within the ingredient list (e.g., "lecithin (soy)")

- Separate "Contains" statement immediately following the ingredient list (e.g., "Contains wheat, milk, and soy") [2]

The law specifically required that the type of tree nut (e.g., almonds, pecans, walnuts), the species of fish, and the species of Crustacean shellfish be declared, recognizing the variable allergenic potential within these categories [2]. FALCPA's requirements extended to ingredients derived from major food allergens, with limited exceptions such as highly refined oils [21].

The FASTER Act: Expanding Protection to Sesame

The FASTER Act of 2021 marked the first expansion of U.S. food allergen labeling requirements since FALCPA's implementation. Driven by advocacy efforts and evidence that over 1.5 million people in the U.S. are allergic to sesame, with reactions that can be severe or fatal, the law added sesame as the ninth major food allergen [22]. Effective January 1, 2023, sesame must be labeled in the same manner as the original eight major allergens [2] [23].

The FASTER Act also mandated that the Secretary of Health and Human Services report to Congress on food allergy prevalence, severity, and management, establishing a process for considering future modifications to the major allergen list based on emerging science [22]. This provision creates a pathway for potentially adding other emerging allergens as scientific evidence of their public health significance accumulates.

Table 1: Major Food Allergens Under U.S. Law

| Allergen Category | Specific Examples Required | Effective Date |

|---|---|---|

| Milk | Cow, goat, sheep (as of 2025 guidance) | January 1, 2006 |

| Egg | Chicken, duck, quail (as of 2025 guidance) | January 1, 2006 |

| Fish | Bass, flounder, cod (species required) | January 1, 2006 |

| Crustacean Shellfish | Crab, lobster, shrimp (species required) | January 1, 2006 |

| Tree Nuts | Almond, walnut, etc. (12 types as of 2025) | January 1, 2006 |

| Peanuts | January 1, 2006 | |

| Wheat | January 1, 2006 | |

| Soybeans | January 1, 2006 | |

| Sesame | January 1, 2023 |

Recent Regulatory Updates and Refinements

FDA's 2025 Guidance: Revised Tree Nut List and Expanded Definitions

In January 2025, the FDA published the fifth edition of its guidance "Questions and Answers Regarding Food Allergens," implementing significant changes based on stakeholder input and scientific review [24] [25]. These updates reflect the evolving understanding of allergen prevalence and potency:

- Reduced Tree Nut List: The list of tree nuts requiring mandatory allergen labeling was reduced from 23 to 12 types based on a "robust body of scientific evidence" [24] [25]. Coconut, previously a source of confusion for consumers and industry, is no longer considered a major food allergen under the revised guidance [24].

- Expanded "Milk" Definition: The definition now includes milk from domesticated ruminant animals beyond cows, including goats and sheep [24] [25].

- Expanded "Egg" Definition: The definition now includes eggs from various domesticated birds beyond chickens, including ducks, geese, and quail [24] [25].

Table 2: FDA's 2025 Revised Tree Nut List

| Tree Nuts Requiring Labeling | Tree Nuts No Longer Requiring Labeling |

|---|---|

| Almond | Beech nut |

| Black walnut | Butternut |

| Brazil nut | Chestnut |

| California walnut | Chinquapin |

| Cashew | Coconut |

| Filbert (hazelnut) | Ginkgo nut |

| Heartnut (Japanese walnut) | Hickory nut |

| Macadamia nut | Palm nut |

| Pecan | Pili nut |

| Pine nut | Shea nut |

| Pistachio | Cola (kola) nut |

| English and Persian walnut |

Alcohol Beverage Labeling Proposal

In January 2025, the Alcohol and Tobacco Tax and Trade Bureau (TTB) proposed requiring mandatory allergen labeling for wines, distilled spirits, and malt beverages [26]. This proposal would close a long-standing regulatory gap, as these products were previously exempt from FALCPA's mandatory allergen labeling requirements. The proposed compliance date is five years from publication of a final rule [26].

Food Allergen Thresholds and Analytical Detection Methods

The Science of Thresholds and Reactivity

Food allergy thresholds represent the minimum dose of an allergenic protein required to elicit an objective clinical reaction in sensitive individuals. Understanding these thresholds is critical for risk assessment and management. Key research findings include:

- Thresholds and reaction severity are distinct constructs, with only approximately 4.5% of patients reacting to 5 mg of peanut protein experiencing anaphylaxis [3].

- Thresholds demonstrate short-term stability within a half-log variation in 71.2% of individuals, but can be influenced by co-factors such as exercise, sleep deprivation, illness, and medications [3].

- The eliciting dose for 5% of the peanut-allergic population (ED05) has been established at 1.5 mg of peanut protein (approximately 6 mg of whole peanut), providing a scientifically-derived reference point for risk management decisions [3].

Figure 1: Factors Influencing Food Allergen Thresholds and Outcomes

Analytical Methods for Allergen Detection

Validated analytical methods are essential for verifying compliance with allergen labeling requirements and conducting threshold research. The field is evolving from traditional immunoassays toward increasingly sophisticated multiplexed platforms:

- Traditional Methods: Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays (ELISA) and polymerase chain reaction (PCR) have been widely used but have limitations in scope, specificity, and the ability to detect multiple allergens simultaneously [7].

- Mass Spectrometry: Emerging as a powerful tool for simultaneously quantifying specific proteins (e.g., Ara h 3 and Ara h 6 for peanut; Bos d 5 for milk) with high sensitivity and specificity, even in complex food matrices [7].

- AI-Enhanced Platforms: Hyperspectral imaging (HSI), Fourier Transform Infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy, and computer vision combined with machine learning enable non-destructive, real-time allergen detection without altering food integrity [7].

- Integrated Control Systems: Cloud-based platforms that incorporate adenosine triphosphate (ATP) readings with allergen data provide sanitation verification and predictive risk management through centralized dashboards [7].

Table 3: Analytical Methods for Allergen Detection and Characterization

| Method Category | Specific Technologies | Key Applications in Threshold Research |

|---|---|---|

| Immunoassays | ELISA, Lateral Flow Devices | Quantification of specific allergenic proteins; rapid screening |

| Molecular Biology | PCR, Real-time PCR | Detection of allergen-encoding DNA sequences; species identification |

| Mass Spectrometry | LC-MS/MS, Multiple Reaction Monitoring | Multiplexed protein quantification; detection of proteotypic peptides |

| Spectroscopy | HSI, FTIR, Computer Vision | Non-destructive screening; real-time monitoring in processing facilities |

| Integrated Systems | Cloud-based ATP + Allergen Monitoring | Sanitation verification; predictive risk management |

Research Gaps and Future Directions

The evolving regulatory landscape highlights several critical research needs that represent opportunities for scientific advancement:

- Threshold Standardization: Developing standardized approaches for establishing population thresholds for all major allergens, moving beyond peanut to include tree nuts, sesame, and other emerging allergens [3].

- Matrix Effects: Understanding how food matrices alter allergen bioavailability and reactivity, and incorporating these findings into risk assessment models [3].

- Clinical- Analytical Correlation: Strengthening the relationship between clinically relevant thresholds and analytical detection capabilities to ensure public health protection [7].

- Cofactor Impact: Quantifying the effects of exercise, sleep deprivation, and other cofactors on individual thresholds to improve personalized risk assessment [3].

Figure 2: Research-to-Policy Pipeline for Food Allergen Management

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 4: Essential Reagents and Materials for Food Allergen Threshold Research

| Research Tool Category | Specific Examples | Research Application |

|---|---|---|

| Reference Materials | Purified native proteins (Ara h 2, Cor a 9, Ses i 1), Certified reference materials | Method calibration, quality control, challenge meal preparation |

| Immunoassay Reagents | Monoclonal/polyclonal antibodies, ELISA kits, Lateral flow devices | Protein quantification, rapid screening, method comparison |

| Mass Spec Standards | Stable isotope-labeled peptides, Tryptic digest standards | Targeted protein quantification, method validation |

| Molecular Biology | Primer/probe sets, DNA extraction kits, Positive control DNA | Allergen source identification, GMO detection |

| Cell-Based Assays | Basophil activation test reagents, Histamine release assay components | Assessment of biological activity, cross-reactivity studies |

The regulatory frameworks established by FALCPA and the FASTER Act have created a dynamic ecosystem where policy evolves in response to scientific advances and public health needs. The 2025 FDA guidance revisions demonstrate this iterative process, refining definitions based on emerging evidence. For researchers and drug development professionals, understanding these frameworks is essential for designing clinically relevant studies and developing detection methods that align with regulatory priorities.

The future of food allergen management lies in strengthening the connection between clinical threshold research, advanced analytical detection capabilities, and evidence-based policy. By addressing critical research gaps in threshold standardization, matrix effects, and cofactor impacts, the scientific community can contribute to more precise, personalized approaches to allergen management that enhance both consumer protection and quality of life for allergic individuals.

Analytical Toolkit: Principles, Workflows, and Applications of Detection Methodologies

The Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay (ELISA) represents a cornerstone immunological technique for the specific detection and quantification of proteins, playing an indispensable role in food safety and allergen detection research. This plate-based assay leverages the specificity of antigen-antibody interactions, coupled with an enzymatic reaction to generate a measurable signal [27] [28]. Within the context of food allergen research, ELISA provides the foundational analytical sensitivity required to establish thresholds and limits of detection (LOD), which are critical for protecting sensitive individuals while enabling informed risk management [2] [3]. The technique's ability to accurately quantify trace amounts of specific allergenic proteins (e.g., from peanut, milk, or walnut) in complex food matrices makes it a gold standard for compliance with labeling regulations and for the development of evidence-based food safety policies [2] [29].

This guide provides an in-depth examination of ELISA methodologies, from core principles to advanced applications, with a specific focus on their role in quantifying food allergens and determining human eliciting doses. We detail standard and next-generation protocols, data analysis methods for robust quantification, and the direct application of these techniques in setting public health standards for allergen management.

Core Principles and Common ELISA Protocols

Fundamental Mechanism

At its core, ELISA detects the presence of a target molecule (antigen or antibody) by immobilizing it on a solid phase (typically a polystyrene microplate) and then using an enzyme-linked antibody that produces a colorimetric, fluorescent, or chemiluminescent signal upon reaction with a substrate [27] [28]. The key components of any ELISA system include:

- Solid Phase: 96- or 384-well microplates that passively bind proteins [27] [28].

- Capture Molecule: An antibody or antigen coated onto the plate to specifically bind the target.

- Detection Molecule: An enzyme-conjugated antibody that provides the signal.

- Signal Generation System: An enzyme (e.g., Horseradish Peroxidase (HRP) or Alkaline Phosphatase (AP)) and its corresponding substrate (e.g., TMB for HRP) [27].

The relationship between the signal generated (Optical Density, OD) and the target concentration can be positive (in sandwich and indirect ELISA) or negative (in competitive ELISA), depending on the assay format [30].

Common ELISA Formats and Experimental Protocols

The choice of ELISA format depends on the nature of the target analyte and the research objective. The most prevalent formats are detailed below.

Sandwich ELISA

Sandwich ELISA is the most sensitive and specific format for quantifying proteins and is widely used for detecting food allergens [30] [28]. Its protocol is as follows:

Workflow Diagram for Sandwich ELISA

Step-by-Step Protocol:

- Coating: Dilute the specific capture antibody in a carbonate-bicarbonate buffer (pH 9.4) or phosphate-buffered saline (PBS, pH 7.4) to a concentration typically between 2–10 μg/mL. Add 100 μL per well to a 96-well microplate and incubate for several hours to overnight at 4–37°C [28].

- Washing and Blocking: Remove the coating solution and wash the plate 2-3 times with a wash buffer (e.g., PBS with 0.05% Tween 20, PBST). Add 200-300 μL of a blocking buffer (e.g., 1-5% BSA or non-fat dry milk in PBST) to each well to cover all unsaturated binding sites. Incubate for 1-2 hours at room temperature [28].

- Sample and Standard Incubation: Wash the plate. Add 100 μL of the test samples (e.g., food extract) and a serial dilution of the standard antigen (e.g., purified peanut protein) to designated wells. Incubate for 1-2 hours at room temperature to allow the target antigen to be captured [30] [27].

- Detection Antibody Incubation: Wash the plate to remove unbound antigen. Add 100 μL of the enzyme-conjugated detection antibody (specific to a different epitope on the antigen) to each well. Incubate for 1-2 hours at room temperature [30].

- Signal Development: Wash the plate thoroughly to remove unbound detection antibody. Add 100 μL of the enzyme substrate (e.g., TMB for HRP). Incubate in the dark for 15-30 minutes to allow color development [27].

- Signal Measurement: Stop the reaction by adding 50 μL of a stop solution (e.g., 1M H₂SO₄ for TMB). Read the optical density (OD) immediately using a microplate reader at the appropriate wavelength (e.g., 450 nm for TMB) [30] [27].

Competitive ELISA

This format is often used for detecting small molecules, such as certain hormones or chemical contaminants, which may have only a single antibody binding site [30] [28].

Workflow Diagram for Competitive ELISA

Step-by-Step Protocol: The initial coating and blocking steps are similar. The key difference is in step 3: the sample (containing the unknown amount of antigen) is mixed with a fixed, limited concentration of the enzyme-linked antibody before adding it to the antigen-coated plate. The target antigen in the sample and the immobilized antigen on the plate compete for binding to the antibody. After incubation and washing, the subsequent substrate addition and signal detection steps are the same. A higher concentration of antigen in the sample results in less antibody binding to the plate and, therefore, a lower final signal [30] [28].

Indirect ELISA

Indirect ELISA is primarily used for detecting antibodies in a sample, for instance, in serological studies to determine immune response [27].

Protocol: The plate is coated with a specific antigen. After blocking, the test sample (e.g., serum) is added. If present, specific antibodies will bind to the antigen. A secondary, enzyme-conjugated antibody (e.g., anti-human IgG) is then added to detect the bound primary antibody. The signal is developed and measured as described previously [27].

Quantitative Analysis and Data Interpretation

Accurate quantification is a primary strength of ELISA, making it essential for determining allergen thresholds.

Standard Curve and Curve Fitting

Quantification relies on a standard curve generated from known concentrations of a reference standard [30].

- Serial Dilution: Prepare a series of 2-fold to 5-fold dilutions from a high-concentration stock of the purified standard (e.g., peanut protein) in the same matrix as the sample to minimize matrix effects [30].

- Replicates: Run each standard and sample in duplicate or triplicate to ensure consistency and identify pipetting errors [30].

- Background Subtraction: Subtract the average OD value of the blank (zero standard) wells from all other standard and sample readings [30].

- Curve Fitting: Plot the mean adjusted OD (y-axis) against the standard concentration (x-axis, typically log-transformed). The 4-parameter logistic (4PL) model is the most widely used and accurate for fitting the sigmoidal standard curve of an ELISA [30].

The 4-parameter logistic (4PL) equation is: Y = D + (A - D) / (1 + (X / C)^B) Where:

- A = minimum asymptote (background signal)

- D = maximum asymptote (saturation signal)

- C = inflection point (EC50)

- B = slope factor [30]

Calculating Sample Concentrations and Quality Control

- Interpolation: Use the fitted standard curve equation to interpolate the concentration of unknown samples from their adjusted OD values. Ensure sample ODs fall within the range of the standard curve; if not, the sample must be diluted and re-run [30].

- Dilution Factor Correction: Multiply the interpolated concentration by the sample's dilution factor to obtain the original concentration [30].

- Quality Control:

Quantitative Data in Food Allergy Thresholds

ELISA-derived quantitative data on allergen levels in food directly supports clinical research into allergen thresholds. The following table summarizes key quantitative concepts and their relevance.

Table 1: Key Quantitative Concepts in ELISA and Allergen Threshold Research

| Concept | Description | Role in Allergen Threshold Research |

|---|---|---|

| Limit of Detection (LOD) | The lowest concentration of an analyte that can be reliably distinguished from zero [30]. | Determines the lowest level of allergen contamination a method can identify, crucial for detecting trace amounts. |

| Dynamic Range | The concentration interval over which the assay provides accurate quantitative results [30]. | Defines the span of allergen concentrations that can be measured without sample dilution. |

| Eliciting Dose (ED) | The dose of allergenic protein that provokes an allergic reaction in a defined percentage of the population (e.g., ED01, ED05) [29]. | Informs the establishment of reference doses and action levels for precautionary allergen labeling. |

| Coefficient of Variation (CV%) | A measure of assay precision and reproducibility [30]. | Ensures that data on allergen levels in foods are reliable and reproducible across different labs and tests. |

The clinical relevance is clear: studies using oral food challenges have established that, for example, the estimated eliciting doses for walnut protein are 0.8 mg (ED01) and 3.8 mg (ED05) [29]. ELISA is the key laboratory tool that allows regulators and food producers to monitor and ensure that allergen levels in products are below these public health-based thresholds.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Setting up a robust ELISA laboratory requires specific materials and reagents. The following table details the essential components.

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for ELISA

| Item | Function | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Microplates | Solid phase for immobilizing antigens/antibodies [27] [28]. | Use high-protein-binding polystyrene plates (not tissue culture treated). Clear for colorimetry, black/white for fluorescence/chemiluminescence [28]. |

| Capture & Detection Antibodies | Provide specificity for the target analyte. | For sandwich ELISA, a matched antibody pair against different, non-overlapping epitopes is critical [28]. |

| Enzyme Conjugates | Signal generation. Horseradish Peroxidase (HRP) and Alkaline Phosphatase (AP) are most common [27] [28]. | Conjugated to the detection antibody (direct) or a secondary antibody (indirect). |

| Chromogenic/ECL Substrates | React with the enzyme to produce a measurable signal (color or light) [27]. | TMB is a common chromogen for HRP. Chemiluminescent substrates offer higher sensitivity [28]. |

| Blocking Buffer | Covers unsaturated binding sites on the plate to prevent non-specific adsorption of proteins [28]. | Typically 1-5% BSA or non-fat dry milk in a buffer like PBS. |

| Wash Buffer | Removes unbound reagents between steps to reduce background noise [27]. | Typically PBS or Tris buffer with a detergent like Tween-20 (e.g., PBST). |

| Standard Antigen | Pure form of the target analyte used to generate the standard curve [30]. | Must be highly purified and accurately quantified. Critical for absolute quantification of unknowns. |

| Microplate Reader | Instrument to measure the signal (absorbance, fluorescence, or luminescence) from the plate [27]. | Must be compatible with the plate format and detection method (e.g., 450 nm filter for TMB). |

Advancements and Future Directions in ELISA Technology

While traditional ELISA remains a workhorse, several advanced platforms have emerged to address its limitations, such as moderate sensitivity and single-plexing capability.

- Next-Generation ELISA (ELISA 2.0): These platforms incorporate technologies like digital detection, single-molecule sensing, and nanomaterials to achieve ultra-high sensitivity and multiplexing [31]. The market for these advanced assays is growing at a CAGR of 9.6%, reflecting rapid adoption [31].

- Digital ELISA: This method uses femtoliter-sized chambers to isolate individual enzyme-labeled immunocomplexes on beads, allowing for single-molecule counting. It can improve sensitivity by up to 10,000-fold compared to conventional ELISA, achieving detection limits in the attomolar (aM) range [32].

- Multiplexed Assays (e.g., MSD): Platforms like Meso Scale Discovery (MSD) use electrochemiluminescence to simultaneously detect multiple analytes from a single sample. This provides superior sensitivity and a broader dynamic range than traditional colorimetric ELISA, while also saving time, sample volume, and cost [33].

- Novel Detection Probes: Research continues into innovative probes, such as temperature-responsive liposomes containing fluorescent dyes. These can act as powerful signal amplifiers, with one study demonstrating a limit of detection for PSA as low as 0.97 aM [32].

These advancements are particularly relevant for food allergen research, as they promise even more sensitive detection of trace allergens and the ability to profile multiple allergenic proteins simultaneously in a single, efficient assay.

ELISA stands as a powerful, versatile, and robust technique that is central to the field of food allergen research. Its well-established workflows, combined with rigorous quantitative analysis, generate the reliable data necessary to define allergen thresholds and guide evidence-based food safety regulations. As the field moves forward, the integration of next-generation immunoassay technologies will further enhance our ability to detect and quantify food allergens with unparalleled sensitivity and efficiency, ultimately contributing to improved public health outcomes and a better quality of life for food-allergic individuals.

Quantitative PCR (qPCR) and related DNA amplification techniques represent a cornerstone of modern analytical methods for detecting specific biological targets. Within food safety research, particularly in the context of food allergen thresholds and limits of detection, these techniques provide the sensitivity and specificity required to trace minute amounts of allergen-derived genetic material [34]. Food allergies impact a significant portion of the population, with reactions ranging from mild symptoms to life-threatening anaphylaxis [2]. While the immune response is triggered by proteins, DNA-based detection methods offer a powerful indirect approach for identifying the presence of allergenic foods, as they can detect the genetic signature of an allergenic ingredient even when the protein itself is present in trace amounts [3]. This technical guide explores the core PCR workflows, assesses their applicability for quantifying allergenic proteins indirectly, and details their inherent limitations, providing a framework for their use in advanced food allergen research.

Core Principles of PCR and Quantitative Workflows

Fundamental PCR Technologies

The polymerase chain reaction (PCR) is a laboratory technique for amplifying specific DNA fragments from a small initial sample through repeated cycles of denaturation, annealing, and extension [35]. Quantitative PCR (qPCR), also known as real-time PCR, builds upon this foundation by enabling the monitoring of DNA amplification as it occurs, which allows for the quantification of the initial amount of target DNA [34]. When the target analytes are proteins, such as food allergens, an initial conversion step is required. Reverse Transcription Quantitative PCR (RT-qPCR) is used for RNA targets and involves generating complementary DNA (cDNA) from RNA via reverse transcriptase before proceeding with qPCR amplification [34]. This is particularly useful for studying gene expression, which can be correlated with protein production.