Ensuring Food Safety and Integrity: A Guide to Analytical Method Validation in Food Chemistry

This article provides a comprehensive guide to the principles of analytical method validation for researchers, scientists, and professionals in food chemistry and related fields.

Ensuring Food Safety and Integrity: A Guide to Analytical Method Validation in Food Chemistry

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide to the principles of analytical method validation for researchers, scientists, and professionals in food chemistry and related fields. It explores the foundational guidelines from international regulatory bodies like ICH and FDA, detailing core validation parameters such as accuracy, precision, and specificity. The content covers the practical application of these principles across various food matrices, from cereals to processed foods, and addresses common troubleshooting and optimization challenges. Furthermore, it clarifies the critical distinction between method validation and verification, empowering laboratories to implement robust, compliant, and fit-for-purpose analytical procedures that ensure food safety, authenticity, and quality.

The Foundation of Trust: Core Principles and Regulatory Frameworks for Food Method Validation

In the field of food chemistry research, the integrity of analytical data forms the foundation upon which scientific conclusions, regulatory decisions, and ultimately, public health safety are built. Analytical method validation is the systematic process that ensures these data are reliable, reproducible, and fit for their intended purpose. It provides the scientific evidence that an analytical method consistently produces results that accurately characterize the composition, safety, and quality of food products [1]. For researchers and drug development professionals working at the intersection of food and health, understanding validation principles is not merely a technical requirement but a fundamental scientific responsibility.

The consequences of using unvalidated methods can be severe, potentially leading to inaccurate nutrient labeling, undetected contaminant presence, or faulty dietary exposure assessments. In pharmaceutical development, where food-drug interactions or nutraceutical products are concerned, invalidated methods could compromise dosage recommendations or efficacy evaluations [1]. Method validation thus serves as a critical risk mitigation strategy, protecting both consumer health and the credibility of scientific research.

Foundational Principles and Regulatory Framework

The International Harmonization of Validation Guidelines

Globally, method validation practices are harmonized through guidelines established by the International Council for Harmonisation (ICH) and adopted by regulatory bodies like the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) [2]. The simultaneous release of ICH Q2(R2) "Validation of Analytical Procedures" and ICH Q14 "Analytical Procedure Development" represents a significant modernization in analytical science, shifting from a prescriptive approach to a scientific, risk-based lifecycle model [2].

For food analysis specifically, the FDA Foods Program operates under the Methods Development, Validation, and Implementation Program (MDVIP) Standard Operating Procedures, which ensure that FDA laboratories use properly validated methods, with multi-laboratory validation employed where feasible [3]. These frameworks provide the structural foundation for validation protocols across diverse analytical applications in food chemistry.

The Analytical Method Lifecycle: A Modern Paradigm

Contemporary validation guidance emphasizes that analytical procedure validation is not a one-time event but a continuous process throughout the method's entire lifecycle [2]. This lifecycle approach begins with defining the Analytical Target Profile (ATP) – a prospective summary of the method's intended purpose and desired performance characteristics [2]. The ATP establishes target criteria for validation parameters before method development begins, ensuring the resulting method is fit-for-purpose from the outset.

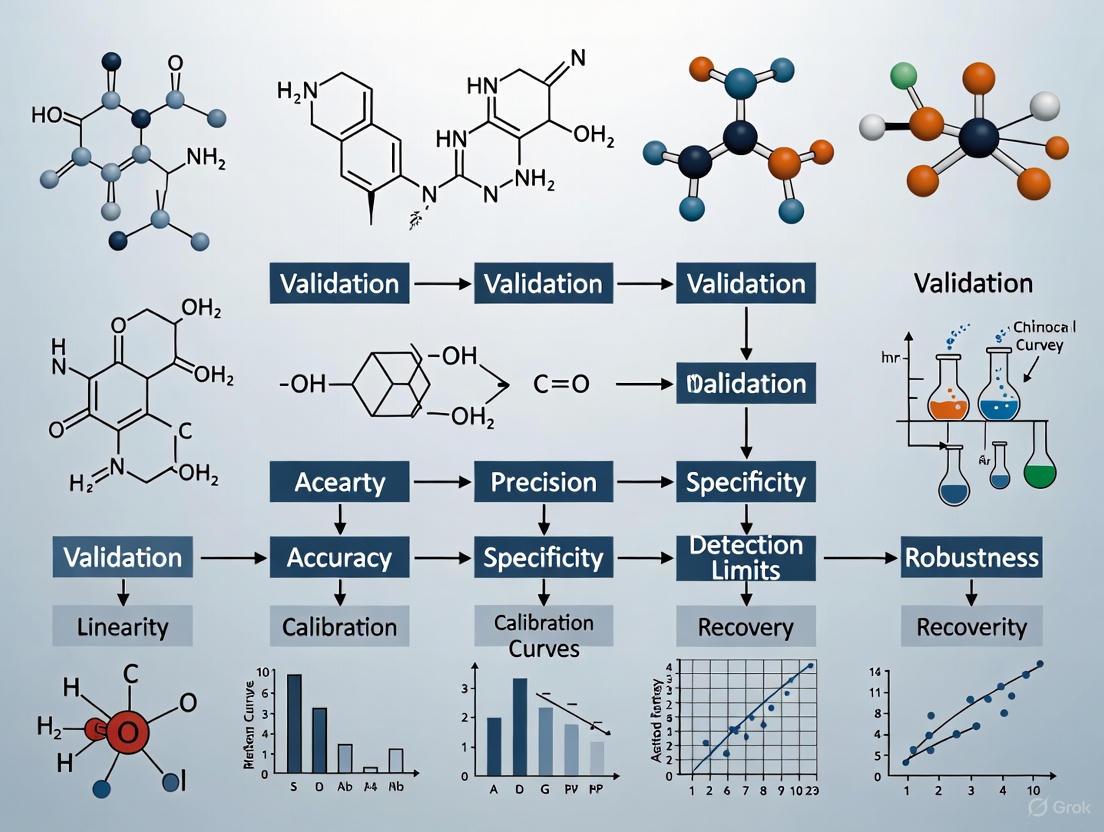

The following diagram illustrates this comprehensive lifecycle approach to analytical method validation:

Core Validation Parameters: Definitions and Experimental Protocols

Method validation requires rigorous assessment of multiple performance characteristics that collectively demonstrate a method's reliability. The specific parameters evaluated depend on the method's intended use, but core validation elements remain consistent across analytical applications.

Essential Validation Characteristics and Protocols

Table 1: Core Validation Parameters and Assessment Methodologies

| Parameter | Definition | Experimental Protocol | Acceptance Criteria |

|---|---|---|---|

| Accuracy | Closeness of test results to true value [2] [1] | Analyze samples with known concentrations (e.g., spiked placebo); compare measured vs. actual values [2] | Recovery rates typically 70-120% depending on analyte and matrix [4] |

| Precision | Degree of agreement among individual test results [2] [1] | Repeat analysis of homogeneous samples multiple times; calculate standard deviation/RSD [2] [1] | RSD <20% for precision; stricter criteria for repeatability [4] [2] |

| Specificity | Ability to measure analyte unequivocally in presence of potential interferents [2] | Analyze samples with and without interferents; demonstrate resolution from similar compounds | No significant interference from matrix components at analyte retention time |

| Linearity | Ability to obtain results proportional to analyte concentration [2] [1] | Analyze samples at 5+ concentrations across specified range; plot response vs. concentration | Correlation coefficient (r) typically ≥0.99 [4] |

| Range | Interval between upper and lower analyte concentrations with suitable precision, accuracy, and linearity [2] | Establish from linearity studies where validation parameters meet acceptance criteria | Demonstrated across the entire working range of the method |

| LOD/LOQ | Lowest concentration that can be detected (LOD) or quantified (LOQ) with accuracy and precision [2] | Signal-to-noise approach (typically 3:1 for LOD, 10:1 for LOQ) or based on standard deviation of response [4] | LOQs as low as 0.003 ng/g achievable in food matrices [4] |

| Robustness | Capacity to remain unaffected by small, deliberate variations in method parameters [2] [1] | Deliberately vary parameters (pH, temperature, mobile phase composition); monitor impact on results | Method performance remains within acceptance criteria despite variations |

Experimental Design for Validation Studies

A properly designed validation study begins with a comprehensive protocol that specifies all experimental conditions, acceptance criteria, and statistical approaches. For example, in validating a method for fungicide analysis in plant-based foods, researchers employed a quaternary solvent system and triple quadrupole mass spectrometer to achieve the necessary sensitivity and specificity [4]. The study incorporated three isotopically labelled internal standards to correct for matrix effects and variations in sample preparation, demonstrating the level of experimental rigor required for robust method validation [4].

Statistical methods are indispensable throughout validation. Standard deviation, confidence intervals, and regression analysis provide quantitative assessment of validation parameters [1]. For precision studies, both repeatability (intra-assay precision) and intermediate precision (inter-day, inter-analyst variability) must be evaluated, often requiring a multi-day experimental design with different analysts [2].

Case Study: Validation of SDHI Fungicide Analysis in Foods

A recent study exemplifies comprehensive method validation in food analysis: the development of a highly sensitive procedure for analyzing succinate dehydrogenase inhibitor (SDHI) fungicides and their metabolites in plant-based foods and beverages [4]. The method simultaneously quantifies 12 SDHIs and 7 metabolites across diverse matrices including fruits, vegetables, fruit juices, wine, and water [4].

The analytical approach combined QuEChERS (Quick, Easy, Cheap, Effective, Rugged, and Safe) sample preparation with UHPLC-MS/MS (Ultra-High Performance Liquid Chromatography coupled with Tandem Mass Spectrometry). This combination provided the necessary selectivity, sensitivity, and high-throughput capability required for monitoring these pesticide residues at trace levels [4].

Experimental Workflow and Reagent Solutions

The following diagram illustrates the complete analytical workflow, from sample preparation to final quantification:

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for SDHI Fungicide Analysis

| Reagent/Material | Function in Analysis | Specific Application in SDHI Method |

|---|---|---|

| QuEChERS Extraction Salts | Promotes partitioning between organic and aqueous phases | Magnesium sulfate for water removal, sodium chloride for phase separation |

| Isotopically Labelled Internal Standards | Corrects for matrix effects and preparation losses | Three deuterated SDHI analogs for quantification accuracy [4] |

| UHPLC Mobile Phases | Carries analytes through chromatographic separation | Quaternary solvent system for optimal separation of 19 analytes [4] |

| Mass Spectrometry Reference Standards | Enables compound identification and quantification | Pure SDHI fungicide and metabolite standards for calibration [4] |

| Dispersive SPE Sorbents | Removes matrix interferents during clean-up | Primary secondary amine (PSA) for pigment and fatty acid removal |

Validation Results and Performance

The method demonstrated exceptional performance characteristics during validation, meeting stringent acceptance criteria across all parameters:

Table 3: Validation Performance Data for SDHI Fungicide Method

| Validation Parameter | Performance Result | Matrix Variations |

|---|---|---|

| Linearity Range | >3 orders of magnitude | Consistent across all studied matrices |

| Precision (RSD) | <20% for all compounds | Meeting acceptance criteria in all validations [4] |

| Accuracy (Recovery) | 70-120% for all analytes | Demonstrated in water, wine, juices, fruits, vegetables [4] |

| Limit of Quantification | 0.003-0.3 ng/g | Varies by analyte and matrix complexity [4] |

| Application to Real Samples | 28 representative samples analyzed | Successful quantification in fruits, vegetables, juices, wine [4] |

The method's robustness was confirmed through application to 28 random samples of various matrices, illustrating its reliability for routine monitoring of SDHI fungicides across diverse food commodities [4]. The achieved limits of quantification were sufficient to enforce maximum residue limits and conduct proper dietary exposure assessments.

Advanced Topics: Specialized Validation Approaches

Validation of Multivariate Classification Methods

Food authenticity and traceability often employ multivariate classification methods based on analytical fingerprints. Unlike conventional univariate methods, these approaches require specialized validation protocols that address their inherent complexity [5]. A proposed framework for validating such methods includes:

- Qualitative validation of sample set composition and adequateness

- Probabilistic performance assessment using class probability scores rather than binary classification

- Combined cross-validation and external validation to predict future performance

- Permutation testing to establish statistical significance

In a case study on organic feed classification, this approach yielded an expected accuracy of 96% for recognizing organic versus conventional laying hen feed based on fatty acid profiling [5].

Statistical Methods for Food Composition Database Analysis

Statistical analysis of food composition databases presents unique validation challenges due to the compositional nature of nutrient data, where components are inherently correlated [6]. Appropriate statistical approaches identified for food composition database analysis include:

- Clustering techniques (agglomerative hierarchical clustering, k-means) for grouping similar food items

- Dimension reduction methods (principal component analysis) for nutrient pattern identification

- Correlation analysis (Spearman's rank correlation) for determining nutrient co-occurrence

- Regression methods for associating nutrient content with food characteristics

These methods must account for the data structure, including correlated components, natural groupings, and compositional constraints [6].

Analytical method validation remains the indispensable foundation of reliable food analysis, providing the scientific assurance that analytical data accurately represent the composition, safety, and quality of food products. The evolution from a check-the-box exercise to a science- and risk-based lifecycle approach represents significant progress in analytical science, encouraging deeper method understanding and more flexible control strategies [2].

For researchers and drug development professionals, embracing this modern validation paradigm means building quality into methods from their inception through the Analytical Target Profile, implementing robust statistical assessment throughout validation, and maintaining vigilance through continuous monitoring during routine use. As analytical technologies advance and regulatory scrutiny intensifies, the principles of method validation will continue to ensure that scientific conclusions about our food supply remain trustworthy, reproducible, and protective of public health.

In the modern scientific landscape, the harmonization of global regulatory standards is crucial for ensuring product safety, efficacy, and quality while facilitating international trade and innovation. The International Council for Harmonisation (ICH) plays a pivotal role in this ecosystem by bringing together regulatory authorities and pharmaceutical industry experts to discuss scientific and technical aspects of product registration. Established in 1990, ICH's mission is to ensure that safe, effective, high-quality medicines are developed and registered efficiently through consensus-based guidelines [7]. While ICH guidelines originated primarily for human pharmaceuticals, their principles of quality, safety, and efficacy have influenced regulatory approaches in adjacent fields, including aspects of food chemical safety and analytical method validation.

Regulatory bodies such as the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) actively participate in and adopt ICH standards, creating a coordinated global framework. In September 2025, the FDA adopted the ICH E6(R3) Good Clinical Practice guideline without altering its scientific content, instead making only presentational changes to align with U.S. regulatory frameworks [7]. This adoption exemplifies the trend toward international regulatory convergence while maintaining jurisdictional specificity. For researchers and scientists, understanding the interplay between overarching ICH guidelines and specific FDA implementations is essential for navigating compliance requirements across different regions and regulatory domains, including the complex field of food chemistry research.

Core ICH Guidelines and FDA Equivalents

Foundational Principles and Recent Updates

The ICH regulatory framework is structured around quality, efficacy, safety, and multidisciplinary guidelines that collectively govern pharmaceutical development and regulation. Recent updates to these guidelines emphasize risk-based approaches, quality-by-design (QbD), and analytical procedure lifecycle management, reflecting the industry's evolution toward more flexible, scientifically grounded standards [8] [9]. These principles are increasingly relevant to food chemistry researchers developing analytical methods for chemical safety assessment.

A significant development in the efficacy domain is the ICH E6(R3) Good Clinical Practice guideline, which introduces flexible, risk-based approaches and embraces modern innovations in trial design, conduct, and technology [10]. The FDA's adoption of this guideline in September 2025 demonstrates regulatory harmonization in practice. Although focused on clinical trials, its principles of risk proportionality and quality-by-design parallel similar approaches in analytical method validation [8]. For the quality domain, the recently implemented ICH Q2(R2) and ICH Q14 guidelines provide a harmonized framework for analytical method validation and development, emphasizing that methods should be "fit-for-purpose" throughout their lifecycle [9].

Comparative Analysis: ICH Versus FDA Implementation

When ICH guidelines are adopted by regulatory agencies like the FDA, the scientific content typically remains identical, though presentational and contextual differences exist to align with national regulatory frameworks. The table below illustrates key differences observed in the FDA's adoption of ICH E6(R3), which exemplify the general pattern of implementation across various guidelines:

Table: Comparison of ICH E6(R3) and FDA E6(R3) Implementation

| Category | ICH E6(R3) | FDA E6(R3) | Impact Level |

|---|---|---|---|

| Document Title | ICH E6(R3) Good Clinical Practice | E6(R3) Good Clinical Practice: Guidance for Industry | Minimal |

| Legal Status Disclaimer | Not present | "Contains Nonbinding Recommendations" appears on most pages | Notable |

| Regulatory Context | International harmonization focus | U.S. regulatory framework with references to 21 CFR and 42 USC | Notable |

| Alternative Approaches | Not explicitly addressed | Clarifies that alternative approaches may be used if they satisfy statutes | Notable |

| Scientific Content | Complete GCP guidelines | Identical - no technical or scientific changes | Identical |

| Core Principles | Risk-based quality management, flexibility, technology adoption | Identical principles and requirements | Identical |

As evidenced in the comparison, while the FDA does not alter technical or scientific content from ICH guidelines, it adds important contextual clarifications regarding the document's non-binding nature and flexibility in approach [7]. This pattern holds true across many ICH guideline implementations, including those relevant to analytical method validation. For researchers, this means that mastery of ICH guidelines provides a solid foundation for global compliance, while awareness of specific national implementations ensures adherence to regional regulatory expectations.

Analytical Method Validation: Principles and Protocols

ICH Q2(R2) and Q14 Framework

Analytical method validation represents a critical component of pharmaceutical development and food chemical safety assessment, ensuring that analytical procedures yield reliable, reproducible, and scientifically sound data. The updated ICH Q2(R2) guideline, effective since June 2024, provides a harmonized international approach to validating analytical procedures, defining the necessary studies, performance characteristics, and acceptance criteria to demonstrate a method is fit for its intended purpose [9]. This guideline expands upon its predecessor to cover modern analytical technologies, including spectroscopic and multivariate methods, reflecting the industry's technological evolution.

Complementing ICH Q2(R2), the ICH Q14 guideline introduces a structured approach to analytical procedure development, emphasizing science- and risk-based methodologies [9]. Together, these documents form a comprehensive framework for the entire analytical procedure lifecycle, from development through validation and routine use. Key concepts introduced in these guidelines include the Analytical Target Profile (ATP) – a predefined objective that defines the required quality of the analytical results – and enhanced approaches for method development, control strategy, and lifecycle management. For food chemistry researchers, these principles provide a structured foundation for developing robust analytical methods to assess chemical safety, detect contaminants, and quantify additives in food products, even as the guidelines themselves originate from the pharmaceutical sector.

Core Validation Parameters and Acceptance Criteria

According to ICH Q2(R2), analytical method validation requires assessment of multiple performance characteristics to ensure the method's suitability for its intended purpose. The specific parameters evaluated depend on the type of analytical procedure (identification, testing for impurities, assay), but typically include the following core elements:

Table: Core Validation Parameters and Typical Acceptance Criteria

| Validation Parameter | Definition | Typical Acceptance Criteria | Application in Food Chemistry |

|---|---|---|---|

| Specificity | Ability to measure analyte accurately in presence of other components | No interference from blank; baseline separation | Detect additives/contaminants in complex food matrices |

| Accuracy | Closeness of results to true value | Recovery 98-102% for APIs; ±10% for impurities | Quantify chemical concentrations in food samples |

| Precision | Degree of scatter among repeated measurements | %RSD ≤ 2% for assay; ≤ 5-10% for impurities | Ensure reproducible results across laboratories |

| Linearity | Direct proportionality of response to analyte concentration | Correlation coefficient R² > 0.998 | Establish quantitative range for food chemicals |

| Range | Interval between upper and lower analyte concentrations | Dependent on intended application with justification | Cover expected concentrations in food products |

| LOD/LOQ | Lowest detectable/quantifiable analyte amount | Signal-to-noise ratio 3:1 for LOD; 10:1 for LOQ | Detect trace contaminants in food supply |

The validation protocol should document method description and intended use, justification for method selection, experimental design, predefined acceptance criteria, and statistical evaluation of results [9]. This systematic approach ensures alignment with both ICH Q2(R2) expectations and FDA guidance for industry analytical method validation, providing a solid foundation for generating reliable data in food chemistry research.

Experimental Protocols for Analytical Method Validation

Workflow for Method Validation

The validation of analytical methods follows a structured workflow to ensure all critical parameters are thoroughly assessed. The diagram below illustrates this comprehensive validation process:

Detailed Methodologies for Key Experiments

Specificity and Selectivity Assessment

Purpose: To demonstrate that the analytical method can unequivocally identify and quantify the target analyte in the presence of other potentially interfering components that may be present in the sample matrix.

Protocol:

- Sample Preparation: Prepare a minimum of six independent samples of the analyte at appropriate concentrations in the presence of all expected matrix components, including impurities, degradants, and excipients.

- Forced Degradation Studies: For stability-indicating methods, subject the sample to forced degradation conditions (acid/base hydrolysis, oxidation, thermal stress, photolysis) to generate degradants.

- Chromatographic Separation: For HPLC methods, demonstrate baseline separation between the analyte peak and all potential interfering peaks, with resolution > 2.0 between the closest eluting peaks.

- Peak Purity Assessment: Use diode array detector (DAD) or mass spectrometry (MS) to verify peak homogeneity and confirm the absence of co-eluting substances.

- Acceptance Criteria: The method should show no interference from blank matrix components, and the analyte response should be unaffected by the presence of other sample constituents.

Accuracy and Precision Evaluation

Purpose: To establish the closeness of agreement between the measured value and the true value (accuracy) and the degree of scatter between series of measurements (precision).

Protocol:

- Sample Preparation: Prepare a minimum of nine determinations across the specified range of the procedure (e.g., three concentrations with three replicates each).

- Accuracy Determination: Compare measured values to known reference values, expressed as percent recovery. For drug substance analysis, typical recovery should be 98-102%; for impurities, ±10% of the accepted reference value.

- Precision Assessment:

- Repeatability: Perform at least six determinations at 100% of the test concentration, calculating percent relative standard deviation (%RSD).

- Intermediate Precision: Have a second analyst repeat the study on a different day using different equipment, evaluating the combined data for %RSD.

- Statistical Analysis: Calculate mean, standard deviation, and %RSD for all measurements. For validated methods, %RSD should typically be ≤ 2% for assay methods and ≤ 5-10% for impurity methods, depending on level.

Linearity and Range Determination

Purpose: To demonstrate that the analytical procedure produces results that are directly proportional to the concentration of the analyte in the sample within a specified range.

Protocol:

- Sample Preparation: Prepare a minimum of five concentration levels across the operating range, with appropriate spacing (e.g., 50%, 75%, 100%, 125%, 150% of target concentration).

- Instrument Analysis: Analyze each concentration level in triplicate, using the proposed analytical procedure.

- Statistical Analysis: Plot mean response against concentration and perform linear regression analysis.

- Acceptance Criteria: The correlation coefficient (R²) should typically be > 0.998 for the working range. The y-intercept should not be significantly different from zero, and the residuals should be randomly distributed.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Successful analytical method development and validation requires specific reagents, reference materials, and instrumentation to ensure accurate, reproducible results. The following table details key research reagent solutions essential for implementing ICH-compliant analytical methods in food chemistry research:

Table: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Analytical Method Validation

| Reagent/Material | Function/Purpose | Application Examples | Quality Requirements |

|---|---|---|---|

| Certified Reference Standards | Quantification and method calibration | Primary standard for analyte identification and purity assessment | Certified purity with Certificate of Analysis (CoA) |

| Chromatography Columns | Stationary phase for compound separation | HPLC/UHPLC separation of food chemicals/contaminants | Column efficiency (theoretical plates) verification |

| MS-Grade Mobile Phase Additives | Enhance ionization in LC-MS methods | Formic acid, ammonium acetate for pesticide residue analysis | Low UV absorbance; minimal particle content |

| Sample Preparation Sorbents | Extract and clean up samples | Solid-phase extraction (SPE) for mycotoxin analysis | Lot-to-lot reproducibility with performance testing |

| Stable Isotope-Labeled Internal Standards | Correct for matrix effects and recovery | Quantitative analysis of PFAS, phthalates in foods | Isotopic purity > 99%; chemical stability |

| System Suitability Standards | Verify chromatographic system performance | USP resolution mixtures; tailing factor standards | Compatible with method parameters |

These reagents form the foundation of robust analytical methods compliant with ICH Q2(R2) requirements. Their proper selection, qualification, and documentation are essential for generating reliable data that meets regulatory standards for both pharmaceuticals and food chemical safety assessment.

Application in Food Chemistry Research

Interface Between Pharmaceutical Guidelines and Food Safety

While ICH guidelines originated in the pharmaceutical sector, their principles of analytical method validation have significant applicability to food chemistry research, particularly in the assessment of chemical safety in food. The FDA's increasing focus on systematic post-market assessment of food chemicals further underscores the need for robust, validated analytical methods in this domain [11] [12]. The Multi-Criteria Decision Analysis (MCDA) approach recently proposed by the FDA for ranking chemicals in the food supply relies on high-quality analytical data generated through validated methods similar to those described in ICH Q2(R2) [11] [13].

Food chemistry researchers face unique challenges not always encountered in pharmaceutical analysis, including more complex and variable matrices, lower analyte concentrations, and diverse sample types. Nevertheless, the core principles of specificity, accuracy, precision, and robustness outlined in ICH guidelines provide a solid foundation for developing reliable analytical methods to detect and quantify chemicals in food. As regulatory scrutiny of food chemicals intensifies – with high-profile additives such as butylated hydroxytoluene (BHT), butylated hydroxyanisole (BHA), and phthalates undergoing expedited review – the implementation of ICH-aligned validation approaches becomes increasingly critical for generating defensible scientific data [12].

Case Study: HPLC Method for Chemical Analysis in Food

Background: The development and validation of a stability-indicating HPLC method for the quantification of synthetic dyes in candy products demonstrates the practical application of ICH guidelines in food chemistry research.

Methodology:

- Chromatographic Conditions: C18 column (250 × 4.6 mm, 5 μm) maintained at 30°C, with gradient elution using methanol and ammonium acetate buffer as mobile phase.

- Sample Preparation: Candy samples dissolved in water, extracted via solid-phase extraction, and filtered before injection.

- Validation Parameters Assessed:

- Specificity: No interference from candy matrix components or co-eluting dyes.

- Linearity: R² > 0.999 over concentration range 1-100 μg/mL.

- Accuracy: Mean recovery 97.5-102.3% across three spike levels.

- Precision: Intra-day and inter-day RSD < 2%.

- Robustness: Deliberate variations in column temperature (±2°C), mobile phase pH (±0.2 units), and flow rate (±0.1 mL/min) demonstrated method robustness.

Results and Discussion: The validated method successfully addressed the complex candy matrix while providing the necessary sensitivity to quantify dyes at levels relevant to regulatory thresholds. The method demonstrated the applicability of ICH Q2(R2) principles to food analysis, particularly regarding specificity in complex matrices and accuracy in recovery studies. This case study illustrates how pharmaceutical guidelines can be adapted to food chemistry contexts while maintaining scientific rigor and regulatory alignment.

The harmonization of global regulatory standards through ICH guidelines and their adoption by regulatory agencies like the FDA creates a consistent framework for analytical method validation across sectors. While these guidelines originated in the pharmaceutical industry, their core principles of specificity, accuracy, precision, and robustness are universally applicable to food chemistry research, particularly as regulatory scrutiny of food chemicals intensifies. The recent FDA initiatives on chemical ranking and post-market assessment further emphasize the need for robust, validated analytical methods in the food sector [11] [12] [13].

For researchers and scientists, understanding the nuanced relationship between ICH guidelines and FDA implementations provides a strategic advantage in navigating global regulatory expectations. By adopting a science- and risk-based approach to analytical method validation – as outlined in ICH Q2(R2) and Q14 – food chemistry professionals can generate reliable, defensible data that supports chemical safety assessments and regulatory decision-making. As the analytical science continues to evolve with new technologies and complex challenges, these foundational principles and structured validation approaches will remain essential for ensuring both food safety and regulatory compliance in an increasingly globalized marketplace.

In food chemistry research, the reliability of analytical data is paramount for ensuring product safety, authenticity, and compliance with global regulations. The analytical method lifecycle encompasses the entire journey of a testing procedure, from its initial development and validation through its routine use and eventual retirement or improvement. This holistic approach moves beyond treating validation as a single event, instead framing it as a continuous process of quality assurance. Within the framework of a broader thesis on validation principles, this guide details the core stages and technical requirements for managing methods that accurately detect and quantify chemical constituents, contaminants, and residues in complex food matrices. Adherence to this lifecycle is critical for supporting food safety management systems, verifying nutritional labels, and preventing economic fraud, thereby protecting public health and maintaining consumer trust [14] [15].

The Stages of the Analytical Method Lifecycle

The analytical method lifecycle can be systematically divided into three primary phases: the initial development of the method, its formal validation, and its ongoing management during routine use. Each phase contains critical sub-steps that ensure the method remains fit-for-purpose throughout its operational existence.

Phase One: Method Development and Feasibility

The lifecycle begins with method development, a research-intensive stage where the analytical technique (e.g., HPLC, GC-MS) is selected and optimized for the specific analyte and food matrix [15]. Key parameters investigated include the selection of sample preparation techniques, chromatography conditions, and detection systems. This stage aims to establish a foundational protocol that demonstrates potential for achieving the required specificity, sensitivity, and robustness.

Following development, a feasibility assessment acts as a trial run. This step determines if the developed method can work with the specific product or matrix and identifies potential interferences from other ingredients [16]. For instance, when measuring a compound like salicylic acid in a cream, feasibility testing would check for signal interference from excipients like oils or emulsifiers [16]. The outcome is a prototype method that is ready for formal validation.

Phase Two: Formal Method Validation

This phase provides documented evidence that the method is suitable for its intended use [17]. It is a rigorous process where the method's performance characteristics are tested against predefined acceptance criteria, as per international guidelines like ICH Q2(R2) [16]. The following table summarizes the core validation parameters and their definitions:

Table 1: Key Performance Characteristics for Analytical Method Validation

| Validation Parameter | Definition | Typical Acceptance Criteria |

|---|---|---|

| Specificity/Selectivity | The ability to measure the analyte accurately despite other components [17] [15]. | No interference from the sample matrix; resolution of closely eluting peaks [17]. |

| Accuracy | The closeness between a measured value and a true or accepted reference value [17] [15]. | Expressed as percent recovery of a known, spiked amount; minimum of 9 determinations over 3 levels [17] [16]. |

| Precision | The closeness of agreement among individual test results from repeated analyses [17]. | Reported as %RSD for repeatability (intra-assay) and intermediate precision (different days, analysts) [17]. |

| Linearity & Range | The ability to produce results proportional to analyte concentration within a specified interval [17]. | Minimum of 5 concentration levels; correlation coefficient (R²) often ≥ 0.99 [17] [16]. |

| Limit of Detection (LOD) | The lowest concentration that can be detected, but not necessarily quantified [17] [15]. | Typically a signal-to-noise ratio of 3:1 [17]. |

| Limit of Quantitation (LOQ) | The lowest concentration that can be quantified with acceptable accuracy and precision [17] [15]. | Typically a signal-to-noise ratio of 10:1 [17]. |

| Robustness | A measure of the method's reliability when small, deliberate changes are made to operational parameters [17] [16]. | Method remains accurate and precise with slight variations in flow rate, temperature, or pH [16]. |

Phase Three: Ongoing Method Management and Verification

A validated method enters the routine use phase, where it is deployed for daily testing under a strict quality management system. This involves following standard operating procedures (SOPs), using qualified instruments, and maintaining comprehensive documentation for traceability and regulatory compliance (e.g., FDA cGMP, ISO 17025) [15].

Method Verification is required when a validated method is transferred to a new laboratory or applied to a new, similar matrix. Verification confirms that the method performs as validated in the new environment or application, typically by testing a subset of validation parameters like accuracy and specificity [16].

Finally, the lifecycle includes ongoing monitoring and continuous improvement. This involves tracking system suitability tests, investigating discrepancies, and periodically reviewing method performance. As technology and regulations evolve, methods may be updated or retired, thus re-initiating the development and validation cycle [15].

Experimental Protocols for Key Validation Parameters

This section provides detailed methodologies for conducting critical experiments during the formal validation phase.

Protocol for Determining Accuracy

Accuracy is measured as the percent recovery of the analyte from the sample matrix [17].

- Sample Preparation: Prepare a minimum of nine samples spiked with the analyte at three distinct concentration levels (low, medium, high) covering the specified range of the method. Each concentration level should be prepared in triplicate [17] [16].

- Analysis: Analyze the spiked samples using the validated method.

- Calculation: Calculate the recovery for each sample using the formula:

% Recovery = (Measured Concentration / Spiked Concentration) * 100. - Reporting: Report the mean recovery and confidence interval (e.g., ±1 standard deviation) for each concentration level. The recovery percentages should fall within predefined acceptance criteria to demonstrate accuracy [17].

Protocol for Assessing Precision

Precision is evaluated at multiple levels: repeatability and intermediate precision [17].

- Repeatability (Intra-assay):

- Analyze a minimum of six determinations at 100% of the test concentration, or nine determinations covering the specified range (three levels, three replicates each) [17].

- Perform all analyses under identical conditions (same analyst, same instrument, short time interval).

- Calculate the relative standard deviation (%RSD) of the results [17].

- Intermediate Precision:

- Design an experiment to incorporate variations found within a single laboratory, such as different days, different analysts, or different equipment [17].

- Have a second analyst prepare and analyze replicate sample preparations using their own standards and a different HPLC system.

- The %-difference in the mean values between the two analysts' results is calculated and subjected to statistical testing (e.g., Student's t-test) [17].

Protocol for Establishing Specificity

Specificity ensures the method can distinguish the analyte from other components.

- For Assay and Impurity Tests: Inject samples containing the analyte and likely interferences (excipients, impurities, degradation products). The resolution between the analyte peak and the most closely eluting potential interferent must meet acceptance criteria [17].

- Peak Purity Assessment: Use advanced detection techniques to confirm the analyte peak is pure. Modern practices recommend using Photodiode-Array (PDA) detection to compare spectra across the peak or Mass Spectrometry (MS) for unequivocal confirmation of purity and identity [17].

Visualizing the Lifecycle and Validation Parameters

The following diagrams provide a visual summary of the key concepts and workflows described in this guide.

Diagram 1: Analytical Method Lifecycle Overview

Diagram 2: Core Method Validation Parameters

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

The development and validation of robust analytical methods rely on a suite of essential materials and reagents. The following table details key components of the research toolkit for a food chemistry laboratory focused on chromatographic analyses.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Analytical Food Chemistry

| Tool/Reagent | Function/Explanation |

|---|---|

| LC-HRMS Instrumentation | Liquid Chromatography-High Resolution Mass Spectrometry provides high accuracy mass measurements for identifying and quantifying non-volatile food contact chemicals and contaminants, even in complex matrices [18]. |

| Eco-friendly Solvents | Safer solvent alternatives (e.g., ethanol, ethyl acetate) that reduce toxicity and environmental impact, aligning with Green Analytical Chemistry (GAC) principles for sustainable food analysis [14]. |

| Certified Reference Materials | Standards with a certified purity or concentration, used to establish method accuracy by comparing test results to a known reference value during validation [17] [15]. |

| Sample Preparation Kits | Kits for procedures like solid-phase extraction (SPE) used to isolate, clean up, and concentrate analytes from complex food samples, improving sensitivity and reducing matrix effects [15]. |

| System Suitability Standards | Standard mixtures used to verify that the entire chromatographic system (instrument, column, conditions) is performing adequately before sample analysis is conducted [17]. |

The rigorous management of the analytical method lifecycle is a cornerstone of reliable food chemistry research. By systematically progressing from development through validation to ongoing monitoring, laboratories can ensure their data is accurate, precise, and defensible, thereby upholding the highest standards of food safety and quality. Furthermore, the field is increasingly aligned with the principles of Green Analytical Chemistry, which encourages the use of eco-friendly solvents, miniaturized systems, and waste reduction strategies to create more sustainable laboratory practices [14] [19]. Tools like the AGREE metric are now available to help scientists quantitatively assess and improve the environmental footprint of their methods [14]. Ultimately, embracing the complete method lifecycle fosters a culture of continuous improvement, operational excellence, and environmental responsibility, which is essential for tackling the evolving challenges in global food supply chains.

In the landscape of food chemistry research and pharmaceutical development, the integrity of analytical data forms the bedrock of product quality, safety, and regulatory compliance. Traditional approaches to method development often followed a linear, trial-and-error path, where parameters were adjusted sequentially until satisfactory results were obtained. This reactive methodology proved to be time-consuming, resource-intensive, and potentially lacking in robustness [20]. In response to these challenges, a transformative framework has emerged: the Analytical Target Profile (ATP).

The ATP represents a proactive, systematic blueprint that fundamentally reorients the method development process. It is defined as a prospective summary of the performance requirements for an analytical procedure, stating what the method is intended to measure and the necessary performance characteristics to ensure it is fit for its intended purpose [2] [9]. Within modern quality frameworks like Analytical Quality by Design (AQbD), the ATP establishes the target from the very outset, guiding the entire development process and ensuring the resulting method is robust, reliable, and meets all regulatory and scientific needs [20]. This guide explores the core principles, development methodology, and practical implementation of the ATP, specifically contextualized within food chemistry research.

The What and Why of the Analytical Target Profile

Core Definition and Components

The Analytical Target Profile serves as the formalized link between the analytical needs of a research project and the technical development of the method itself. It outlines the purpose of the measurement and the required performance criteria the method must achieve [2]. By defining these elements before any experimental work begins, the ATP ensures the development process remains focused and efficient.

Key components of a well-constructed ATP include:

- Analyte and Matrix: A clear description of the target analyte (e.g., a specific pesticide, nutrient, bioactive compound) and the food matrix in which it will be measured (e.g., dairy, cereal, botanical supplement).

- Analytical Technique: The primary technology or platform (e.g., HPLC, GC-MS, ELISA) intended for use, selected based on the analyte's properties and the required performance level.

- Performance Criteria: Quantitative targets for critical parameters such as accuracy, precision, specificity, and range, tailored to the method's intended use [21] [9].

The Strategic Importance of the ATP

Adopting an ATP-driven approach yields significant strategic advantages throughout the method lifecycle.

2.2.1 Ensuring Regulatory Compliance Global regulatory bodies increasingly emphasize science- and risk-based approaches. The ICH Q14 guideline, which complements ICH Q2(R2) on analytical procedure development, formally introduces concepts like the ATP, encouraging a more structured development process [2] [9]. For food chemistry, journals like Food Chemistry recommend following internationally recognized validation guidelines, the principles of which are embedded within the ATP concept [22]. A pre-defined ATP demonstrates a proactive quality culture and facilitates smoother regulatory submissions.

2.2.2 Enhancing Method Robustness and Reliability Methods developed with a clear ATP are inherently more robust. By defining the acceptable performance boundaries upfront, scientists can systematically design experiments to optimize critical method parameters, thereby reducing the number of out-of-trend (OOT) and out-of-specification (OOS) results during routine use [20]. This robustness is crucial for complex food matrices where interferences are common.

2.2.3 Facilitating Efficient Lifecycle Management The ATP establishes a benchmark for the method's entire lifecycle. If changes are needed post-approval—such as adapting a method to a new food matrix or implementing a new technology—the ATP provides a clear reference point. This allows for a science-based assessment of the change's impact, often reducing the regulatory burden and supporting continuous improvement [2] [20].

Table 1: Comparison of Traditional vs. ATP-Driven Method Development

| Aspect | Traditional Approach | ATP-Driven Approach |

|---|---|---|

| Philosophy | Reactive, sequential optimization | Proactive, systematic design |

| Starting Point | Trial-based experiments | Defined performance requirements (ATP) |

| Development Focus | Achieving a "working" method | Understanding method operation within a Design Space |

| Regulatory Flexibility | Limited, often requires prior approval for changes | Enhanced, due to established scientific understanding |

| Lifecycle Management | Reactive to failures | Continuous verification against the ATP |

Developing an Effective ATP: A Step-by-Step Methodology

Creating a actionable ATP is a multi-stage process that requires collaboration among chemists, quality professionals, and stakeholders.

Defining the Analytical Need and Performance Criteria

The first step involves a precise definition of the method's purpose.

- Identify the Analyte and Matrix: The ATP must clearly state the specific analyte (e.g., "furan in jarred baby food") and the complete description of the sample matrix. For complex foods, this includes considering all major components that could interfere.

- Establish Performance Requirements: Based on the method's intent, quantitative targets for key validation parameters must be set [21]. For instance:

- Accuracy: May be required as ±10% of the true value for a nutrient, but ±15% for an impurity.

- Precision: Repeatability precision (Relative Standard Deviation, RSD) of ≤2% for an active ingredient assay.

- Specificity: Must be able to resolve the target analyte from all potential interferents present in the food matrix.

- Range: The interval between the upper and lower analyte concentration (including accuracy and precision), such as 50-150% of the label claim for a dosage form.

These criteria should be aligned with the intended use of the method, guided by regulatory standards and the principles of fitness for purpose.

Tool 1: The ATP Specification Table

A well-structured table is the most effective way to present the ATP, ensuring all requirements are clear, unambiguous, and measurable.

Table 2: Example ATP Specification Table for a Hypothetical Bioactive Compound in a Green Tea Extract

| ATP Component | Specification | Justification / Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| Analyte | Epigallocatechin gallate (EGCG) | Primary bioactive marker compound |

| Matrix | Green tea (Camellia sinensis) extract | Finished product specification requirement |

| Intended Purpose | Quantitative release testing | To ensure product quality and label claim compliance |

| Analytical Technique | Reversed-Phase HPLC with UV detection | Technique capable of achieving required specificity and precision |

| Accuracy | Mean recovery of 98–102% | To ensure accurate quantification for label claim |

| Precision (Repeatability) | RSD ≤ 2.0% | To ensure consistent results within a single laboratory run |

| Specificity | Baseline resolution (R > 2.0) from all other catechins and known impurities | To accurately quantify EGCG without interference |

| Linearity | R² ≥ 0.999 over a range of 50-150% of target concentration | To demonstrate proportional response across the range |

| Range | 50–150% of the target concentration (50 mg/mL) | Covers from well below to above the expected release specification |

Tool 2: The ATP Development Workflow

The process of defining the ATP is iterative and should be visualized as a logical workflow. The following diagram maps the key decision points and activities involved in creating a comprehensive ATP.

The ATP within the Broader AQbD and Validation Framework

The ATP is the foundational first step within the broader Analytical Quality by Design (AQbD) paradigm and connects directly to subsequent method validation.

The Role of ATP in Analytical Quality by Design (AQbD)

AQbD is a systematic approach to analytical development that emphasizes building quality into the method from the beginning, rather than testing it in at the end [20]. The ATP is the cornerstone of this framework.

- Link to Critical Quality Attributes (CQAs): The performance requirements defined in the ATP (e.g., accuracy, precision) become the CQAs for the analytical procedure. These are the measurable attributes that must be controlled to ensure the method meets its intended purpose [20].

- Informing Risk Assessment: Once the ATP/CQAs are set, a risk assessment is conducted to identify method parameters (e.g., mobile phase pH, column temperature, sample preparation time) that can significantly impact the CQAs. Tools like Ishikawa (fishbone) diagrams and Failure Mode Effects Analysis (FMEA) are used for this purpose [20].

- Defining the Design Space: Through structured experimentation (Design of Experiments, DoE), the relationship between critical method parameters and the CQAs is modeled. This leads to the establishment of a Method Operable Design Region (MODR), a multidimensional combination of parameter ranges within which the method performs as specified by the ATP without requiring re-validation [20].

Connecting the ATP to Method Validation

Method validation provides the experimental proof that the developed method consistently meets the criteria laid out in the ATP. The validation parameters tested directly correspond to the performance requirements defined in the ATP.

Table 3: Relationship Between Common ATP Requirements and ICH Validation Parameters

| ATP Performance Requirement | Corresponding ICH Q2(R2) Validation Parameter | Typical Experimental Approach |

|---|---|---|

| "Measure analyte accurately" | Accuracy | Spiking known amounts of analyte into the matrix and calculating % recovery. |

| "Produce consistent results" | Precision (Repeatability, Intermediate Precision) | Analyzing multiple preparations of the same sample under specified conditions. |

| "Measure analyte without interference" | Specificity | Analyzing blank matrix, placebo, and samples spiked with potential interferents. |

| "Quantify over a defined concentration span" | Linearity and Range | Analyzing samples at a minimum of 5 concentration levels across the claimed range. |

| "Detect trace-level analytes" | Limit of Detection (LOD) / Quantitation (LOQ) | Signal-to-noise ratio or based on the standard deviation of the response and the slope. |

| "Withstand minor operational variations" | Robustness | Deliberately varying parameters (e.g., flow rate ±0.1 mL/min, temperature ±2°C). |

The Analytical Lifecycle: From ATP to Control Strategy

The following diagram illustrates how the ATP integrates into the complete analytical procedure lifecycle, from initial development through routine use and continuous improvement.

Essential Research Reagent Solutions for ATP Implementation

Successfully developing and validating a method against a stringent ATP requires high-quality materials and reagents. The following table details key solutions and their functions in the context of food chemistry research.

Table 4: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Method Development and Validation

| Reagent / Material | Function in Development/Validation | Critical Considerations for ATP Compliance |

|---|---|---|

| Certified Reference Standards | Provides the known quantity of pure analyte for calibration, accuracy (recovery) studies, and specificity testing. | Purity and certification traceability are paramount for demonstrating accuracy against ATP targets. |

| Chromatography Columns | The stationary phase for separation (HPLC, GC, SFC). Critical for achieving specificity (resolution) and robustness. | Different selectivities (C18, HILIC, chiral) may be screened to meet the ATP's specificity requirements. |

| High-Purity Solvents & Mobile Phase Additives | Forms the mobile phase for chromatographic elution. Impacts retention, peak shape, and detection. | Low UV absorbance, minimal impurities, and lot-to-lot consistency are vital for robustness and low LOD/LOQ. |

| Sample Preparation Materials (e.g., SPE cartridges, filtration devices) | Isolates and purifies the analyte from the complex food matrix, reducing interferences. | Selectivity and recovery efficiency for the target analyte directly impact method accuracy, precision, and specificity. |

| Stable Isotope-Labeled Internal Standards | Added to samples to correct for losses during preparation and variability during analysis. | Essential for achieving the high precision and accuracy required by the ATP, especially in complex matrices like food. |

The Analytical Target Profile is far more than a procedural document; it is the strategic blueprint that ensures analytical methods are developed with a clear purpose, robust performance, and long-term viability. By shifting the paradigm from reactive troubleshooting to proactive, science-based design, the ATP framework empowers food chemistry researchers and drug development professionals to build quality into their methods from the very beginning. In an era of increasing regulatory scrutiny and analytical complexity, embracing the ATP and the associated AQbD principles is not just a best practice—it is an essential strategy for ensuring data integrity, regulatory compliance, and ultimately, the safety and quality of the global food and drug supply.

In the pharmaceutical, food, and life sciences industries, the integrity and reliability of analytical data are the bedrock of quality control, regulatory submissions, and ultimately, consumer safety [2]. Analytical method validation is the process of providing documented evidence that a method does what it is intended to do, establishing through laboratory studies that its performance characteristics meet the requirements for the intended analytical application [17]. For food chemistry researchers, this process is paramount for ensuring the accuracy of data regarding nutritional content, the detection of potentially toxic elements, and the authentication of food products to combat fraud [23] [24].

Regulatory bodies worldwide, including the International Council for Harmonisation (ICH) and the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA), have provided harmonized guidelines to ensure global consistency. Complying with standards such as ICH Q2(R2) for validation and the newer ICH Q14 for analytical procedure development is a direct path to meeting regulatory requirements [2]. This guide details the core validation parameters—Accuracy, Precision, Specificity, Linearity, and Range—providing a foundational framework for researchers and scientists to ensure their methods are fit-for-purpose.

Core Validation Parameters

Accuracy

Accuracy is defined as the closeness of agreement between a test result and an accepted reference value, or the true value [17] [25] [26]. It is a measure of exactness, answering the fundamental question: "How close is my measurement to the true amount?"

- Experimental Protocol: The most common technique for determining accuracy in the analysis of complex food matrices is the spike recovery method [25]. This involves:

- Preparing a sample of a known matrix that either does not contain the analyte or where the native amount has been precisely determined.

- Adding ("spiking") a known amount of a pure reference standard of the analyte into the sample.

- Subjecting the spiked sample to the entire analytical procedure, from preparation to final measurement.

- Calculating the percentage recovery using the formula:

Recovery (%) = (Measured Concentration / Theoretical Concentration) × 100[25].

- Data Interpretation: The FDA guidance suggests that accuracy should be assessed using a minimum of nine determinations over a minimum of three concentration levels (e.g., 80%, 100%, and 120% of the target concentration) covering the specified range [2] [25]. This ensures the method's accuracy is consistent across expected analyte levels.

Table 1: Experimental Design for Assessing Accuracy

| Concentration Level | Number of Replicates | Theoretical Amount | Acceptance Criteria for Recovery (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 80% of target | 3 | Known | Varies by method and analyte |

| 100% of target | 3 | Known | Varies by method and analyte |

| 120% of target | 3 | Known | Varies by method and analyte |

Precision

Precision describes the closeness of agreement between a series of measurements obtained from multiple sampling of the same homogeneous sample under prescribed conditions [17] [26]. It is a measure of method reproducibility, independent of its accuracy. A method can be precise (giving consistent results) without being accurate (all results are consistently wrong). Precision is evaluated at three levels:

- Repeatability (Intra-assay Precision): This assesses precision under the same operating conditions over a short interval of time [2] [17]. The guidelines recommend a minimum of nine determinations across the specified range (e.g., three concentrations/three replicates each) or a minimum of six determinations at 100% of the test concentration [17]. Results are typically reported as the % Relative Standard Deviation (%RSD).

- Intermediate Precision: This expresses within-laboratory variations, such as different days, different analysts, or different equipment [2] [26]. An experimental design where two analysts prepare and analyze replicates using different HPLC systems and different days is typical. The results are compared using statistical tests (e.g., Student's t-test) to check for significant differences [17].

- Reproducibility: This represents the precision between different laboratories, typically assessed through collaborative studies [17]. It is critical for methods that will be used across multiple sites.

Table 2: Hierarchy of Precision Measurements

| Precision Type | Conditions | Typical Output | Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Repeatability | Same analyst, same day, same instrument | %RSD | Measures the basic reliability of the method. |

| Intermediate Precision | Different days, different analysts, different instruments | %RSD and statistical comparison of means (e.g., t-test) | Assesses the method's robustness to normal laboratory variations. |

| Reproducibility | Different laboratories | %RSD and confidence intervals | Ensures the method can be transferred successfully. |

Specificity

Specificity is the ability of the method to assess unequivocally the analyte in the presence of other components that may be expected to be present in the sample matrix [2] [17]. These components can include impurities, degradation products, excipients, or other matrix interferences. In chromatography, specificity is demonstrated by the resolution of the two most closely eluted compounds, typically the analyte and a potential interferent [17].

- Experimental Protocol:

- Chromatographic Separation: Inject a standard of the analyte alone and note its retention time and peak shape.

- Analysis of Blank: Inject a blank sample (the matrix without the analyte) to demonstrate the absence of interfering peaks at the retention time of the analyte [27].

- Forced Degradation/Interference Study: Stress the sample (e.g., with heat, light, or acid/base) to generate degradants, or spike the sample with likely interferences. Analyze these samples to show that the analyte peak is pure and unaffected, and that degradant peaks are resolved [17].

- Peak Purity Assessment: Modern techniques use photodiode-array (PDA) detection or mass spectrometry (MS) to confirm that a chromatographic peak represents a single, pure compound by comparing spectra across the peak [17]. MS is particularly powerful for providing unequivocal peak purity and structural information.

Linearity and Range

Linearity and Range are interrelated parameters. Linearity is the ability of the method to obtain test results that are directly proportional to the concentration of the analyte in the sample within a given range [2] [26]. The Range is the interval between the upper and lower concentrations of the analyte for which the method has demonstrated suitable levels of linearity, accuracy, and precision [2].

- Experimental Protocol:

- Prepare a series of standard solutions at a minimum of five concentration levels spanning the expected range of the method [2] [17] [27].

- Analyze each concentration level, plotting the instrumental response (e.g., peak area) against the concentration.

- Perform linear regression analysis on the data to obtain the calibration curve. The key outputs are the slope, y-intercept, and the coefficient of determination (r²).

- Data Interpretation: A linear relationship is typically confirmed by a high r² value (e.g., >0.998), though this alone is not sufficient. Analysis of residuals (the difference between the experimental and calculated values) is also important to detect bias [17].

Table 3: Example Minimum Ranges for Different Method Types as per Guidelines [17]

| Method Type | Example Minimum Range |

|---|---|

| Assay of Drug Product | 80% to 120% of the target concentration |

| Content Uniformity | 70% to 130% of the target concentration |

| Impurity Testing | Reporting level to 120% of the impurity specification |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

The following table lists key reagents and materials critical for successfully executing method validation experiments.

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Method Validation

| Item | Function in Validation |

|---|---|

| Certified Reference Material | A substance with a known, certified purity and concentration. Serves as the primary standard for establishing accuracy and creating calibration curves [25]. |

| Matrix-Matched Blank | A sample of the actual sample matrix (e.g., food tissue) that is confirmed to be free of the target analyte. Used to assess specificity by checking for interferences and to prepare spiked samples for accuracy/recovery studies [27]. |

| Reagent Blank | Composed of all reagents used in the sample preparation procedure without the sample matrix. Used to identify and correct for any background signal contributed by the reagents or solvents [27]. |

| Spiked Solutions | Samples (or matrix blanks) to which a known concentration of the analyte has been added. Fundamental for determining method accuracy via recovery experiments and for testing specificity in the presence of the matrix [25] [27]. |

| System Suitability Standards | A reference solution used to verify that the chromatographic system (or other instrument) is performing adequately with respect to resolution, reproducibility, and efficiency before and during the analysis of unknowns [17] [27]. |

Advanced Considerations: The Modern Validation Lifecycle

The field of analytical method validation is evolving. The recent simultaneous introduction of ICH Q2(R2) and ICH Q14 marks a shift from a one-time, prescriptive validation event to a more scientific, lifecycle-based approach [2].

A key modern concept is the Analytical Target Profile (ATP). The ATP is a prospective summary of the intended purpose of an analytical procedure and its required performance criteria [2]. By defining the ATP at the beginning of method development—for instance, "the method must quantify analyte X in food matrix Y with an accuracy of 98-102% and a precision of ≤2% RSD"—the entire development and validation process is strategically designed to meet these predefined objectives. This proactive, risk-based approach ensures methods are robust and fit-for-purpose from their inception.

Furthermore, technological advancements are shaping the future of validation. The use of artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning (ML) is being explored to optimize methods, interpret complex data sets, and even assist in the validation process itself by efficiently extracting performance data from scientific literature [28]. The rise of non-targeted methods (NTMs), which use high-resolution analytical instruments combined with chemometrics to create a "fingerprint" of a sample, also presents new validation challenges and opportunities, particularly in food authenticity and fraud detection [23].

A rigorous understanding and application of the core validation parameters—Accuracy, Precision, Specificity, Linearity, and Range—are non-negotiable for generating reliable and defensible analytical data in food chemistry research. These parameters form an interconnected framework that collectively demonstrates a method's fitness for purpose. By adhering to detailed experimental protocols and embracing the modern, lifecycle-oriented approach outlined in the latest ICH guidelines, researchers can ensure their analytical methods not only meet regulatory compliance but also produce data of the highest integrity, thereby safeguarding public health and advancing scientific knowledge.

Within the rigorous framework of analytical method validation, the establishment of performance limits at low analyte concentrations is paramount to ensuring data reliability. For food chemistry researchers and drug development professionals, understanding the capabilities of an analytical procedure is critical for accurate monitoring of contaminants, nutrients, active pharmaceutical ingredients, and impurities. The Limit of Detection (LOD) and Limit of Quantification (LOQ) are two fundamental figures of merit that describe the smallest concentrations of an analyte that can be reliably detected and quantified, respectively [29] [30]. These parameters are essential for determining the sensitivity and applicability of a method to its intended purpose, whether for ensuring food safety, enforcing regulatory compliance, or guaranteeing pharmaceutical quality [31] [32]. This guide provides an in-depth examination of the core principles, calculation methodologies, and practical protocols for establishing LOD and LOQ, framed within the broader context of analytical method validation.

Defining the Fundamental Limits

The terms LOD and LOQ, along with the related concept of the Limit of Blank (LOB), have distinct statistical and practical definitions. Confusion between these terms can lead to the misapplication of an analytical method.

Limit of Blank (LOB): The LOB is defined as the highest apparent analyte concentration expected to be found when replicates of a blank sample (containing no analyte) are tested. It characterizes the background noise of the method [29] [33]. Statistically, the LOB is calculated as the mean blank signal plus 1.645 times its standard deviation (assuming a one-sided 95% confidence interval for a Gaussian distribution) [29]. This means that only 5% of blank measurements will exceed the LOB due to random noise, creating a false positive (Type I error).

Limit of Detection (LOD): The LOD is the lowest analyte concentration that can be reliably distinguished from the LOB. Detection is feasible at this level, but without guaranteed precision or accuracy for quantification [29] [30]. The LOD must be greater than the LOB to account for the distribution of signals from very low concentration samples. It is determined using both the LOB and test replicates of a sample containing a low concentration of analyte [29]. A traditional formula is LOD = LOB + 1.645(SD low concentration sample), ensuring that 95% of measurements at the LOD exceed the LOB [29]. Other common approaches use a signal-to-noise ratio of 3:1 or the formula LOD = 3.3σ/S, where σ is the standard deviation of the response and S is the slope of the calibration curve [34] [35].

Limit of Quantification (LOQ): The LOQ is the lowest concentration at which the analyte can not only be reliably detected but also quantified with acceptable accuracy and precision [29] [30]. Predefined goals for bias and imprecision must be met at the LOQ [29]. In many guidelines, the LOQ is defined as the concentration that yields a signal-to-noise ratio of 10:1 [34] [33]. It can also be calculated as LOQ = 10σ/S [34] [35]. The LOQ is typically higher than the LOD and represents the lower boundary of the method's quantitative range.

The conceptual relationship between these three parameters is illustrated below.

Methodologies for Determining LOD and LOQ

Several approaches are recognized by guidelines such as ICH Q2(R1) for determining LOD and LOQ. The choice of method depends on the nature of the analytical procedure [34] [33].

Statistical Calculation Methods

1. Based on Standard Deviation of the Blank and the Calibration Curve Slope

This method is applicable to instrumental techniques and is one of the most scientifically satisfying approaches [35] [33]. It uses the standard deviation of the response (σ) and the slope (S) of the calibration curve.

- Formulas:

- Determining σ (Standard Deviation of the Response): The estimate of σ can be derived in different ways:

- Example Calculation: Using calibration data with a standard error (σ) of 0.4328 and a slope (S) of 1.9303, the calculations would be [35]:

- ( \text{LOD} = 3.3 \times 0.4328 / 1.9303 = 0.74 ) ng/mL

- ( \text{LOQ} = 10 \times 0.4328 / 1.9303 = 2.24 ) ng/mL

2. Based on Limit of Blank (LOB)

This clinical laboratory-focused approach, defined in CLSI EP17, explicitly accounts for the distribution of both blank and low-concentration sample results [29].

- Procedure:

- Measure a sufficient number of blank samples (n ≥ 60 for establishment, n ≥ 20 for verification) to calculate the mean and standard deviation (SD) [29].

- Calculate ( \text{LOB} = \text{mean}{blank} + 1.645(\text{SD}{blank}) ) [29].

- Measure replicates of a low-concentration sample (n ≥ 60 for establishment, n ≥ 20 for verification).

- Calculate ( \text{LOD} = \text{LOB} + 1.645(\text{SD}_{low concentration sample}) ) [29].

Signal-to-Noise Ratio

This method is common for chromatographic techniques where a baseline noise is present and measurable [34] [33].

- Principle: The LOD is the concentration that gives a signal-to-noise ratio (S/N) of 3:1. The LOQ is the concentration that gives a S/N of 10:1 [34] [33].

- Application: The signal is measured from a sample with low analyte concentration, and the noise is estimated from the baseline of a blank sample [34].

Visual Evaluation

This non-instrumental approach is suitable for methods like titration or visual colorimetric tests [34] [33].

- Principle: The LOD or LOQ is determined by analyzing samples with known concentrations of analyte and establishing the minimum level at which the analyte can be reliably detected (for LOD) or quantified (for LOQ) by a human analyst or instrument [34].

- Data Analysis: Results from multiple analysts and determinations are often analyzed using logistic regression to find the concentration with a 95-99% probability of detection or quantification [33].

Table 1: Comparison of LOD and LOQ Determination Methods

| Method | Principle | Typical Applications | Key Advantages | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Standard Deviation & Slope | Uses variability (σ) and sensitivity (S) of the calibration curve. | HPLC, UV-Vis, other instrumental methods with linear response. | Scientifically rigorous; uses standard regression output [35]. | Requires homoscedasticity; relies on linearity at low levels [36]. |

| Limit of Blank (LOB) | Statistically models distributions of blank and low-concentration samples. | Clinical diagnostics, highly sensitive immunoassays. | Explicitly handles error rates (α and β) for blank and low samples [29]. | Experimentally intensive; requires large number of replicates [29]. |

| Signal-to-Noise (S/N) | Compares analyte signal magnitude to baseline noise. | Chromatography (HPLC, GC), electrophoresis. | Simple, intuitive, and widely used for chromatographic methods [34]. | Subjective noise measurement; instrument-dependent [32]. |

| Visual Evaluation | Determines the lowest concentration perceptible to an analyst. | Titration, lateral flow assays, colorimetric tests. | Directly applicable to non-instrumental, qualitative methods [34]. | Subjective; requires multiple analysts and replicates for statistical power [33]. |

Experimental Protocols and Validation

Establishing LOD and LOQ is not merely a calculation but an experimental process that requires careful design and validation.

General Experimental Workflow

The following workflow outlines the key steps in a robust determination of LOD and LOQ.

Detailed Protocol: Calibration Curve Method

This protocol is based on the ICH Q2(R1) approach using the standard deviation of the response and the slope of the calibration curve [35].

- Sample Preparation:

- Prepare a blank sample (containing all components except the analyte).

- Prepare a minimum of five standard solutions at concentrations expected to be in the range of the LOD/LOQ. A minimum of six replicate measurements per concentration is recommended to capture method variability robustly [33].

- Instrumental Analysis:

- Analyze all samples in a randomized sequence to minimize drift effects.

- The analysis should be performed on two or more instruments and with different reagent lots to capture expected performance of the typical population of analyzers [29].

- Data Analysis and Calculation:

- Perform linear regression analysis on the calibration standards (concentration vs. response).

- From the regression output, record the slope (S) and the standard error (SE) of the regression, which serves as the estimate for σ.

- Apply the formulas:

- ( \text{LOD} = 3.3 \times \frac{\sigma}{S} )

- ( \text{LOQ} = 10 \times \frac{\sigma}{S} )

- Experimental Verification (Mandatory):

- Prepare and analyze a sufficient number of independent samples (e.g., n = 6-20) at the calculated LOD and LOQ concentrations [29] [35].

- For LOD Verification: At the LOD concentration, the analyte should be detected in approximately 95% of the replicates. A signal-to-noise ratio of ≥3:1 can serve as a confirmatory check [35].

- For LOQ Verification: At the LOQ concentration, the method should demonstrate an acceptable precision (e.g., %CV ≤ 20%) and accuracy (e.g., bias within ±20%) [32]. If the predefined goals for bias and imprecision are not met, the LOQ must be re-estimated at a higher concentration [29].

Case Study: Iron Detection in Foodstuffs

A recent study developed a paper-based colorimetric test strip for Fe²⁺ detection in food, providing an excellent example of LOD/LOQ determination in food chemistry [31].