ELISA vs PCR for Allergen Detection in Processed Foods: A Scientific Comparison for Researchers

This article provides a comprehensive comparison of ELISA (Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay) and PCR (Polymerase Chain Reaction) methodologies for allergen detection in processed food matrices.

ELISA vs PCR for Allergen Detection in Processed Foods: A Scientific Comparison for Researchers

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive comparison of ELISA (Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay) and PCR (Polymerase Chain Reaction) methodologies for allergen detection in processed food matrices. Tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it explores the foundational principles, optimal applications, and limitations of each technique. The content covers methodological considerations for complex and processed foods, troubleshooting for common challenges, and validation strategies through comparative data. By synthesizing current research and technological advances, this review serves as a strategic guide for selecting and optimizing allergen detection methods to ensure food safety and regulatory compliance.

Core Principles: Understanding ELISA and PCR Technologies in Allergen Science

This guide provides an in-depth examination of the enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) fundamental mechanism, focusing on its core principle of antigen-antibody interaction for protein detection. Within the broader context of analytical techniques for food allergen detection, we objectively compare ELISA's performance with polymerase chain reaction (PCR)-based methods, presenting experimental data on sensitivity, specificity, and applicability across various food matrices. For researchers and drug development professionals, this analysis delineates the specific technological niches where each method excels, supported by recent comparative studies and standardized protocols.

The enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) is a plate-based technique designed for detecting and quantifying soluble substances such as peptides, proteins, antibodies, and hormones [1]. The method was originally described by Engvall and Perlmann in 1971 and relies on the highly specific interaction between an antibody and its target antigen to analyze protein samples immobilized in microplate wells [1]. This interaction forms the foundational basis for ELISA's application across diverse fields, including clinical diagnostics, therapeutic development, and food safety analysis.

In food allergen detection, the accurate identification and quantification of specific allergenic proteins is crucial for public health protection. Food allergies constitute a significant global health concern, and since avoidance is the primary preventive measure, sensitive and accurate detection methods are essential [2] [3]. ELISA has emerged as a cornerstone technology in this domain, offering the sensitivity and specificity required for regulatory compliance and quality control [4] [5]. The Codex Alimentarius Commission has formally adopted ELISA as the official test for gluten allergens, specifying that gluten levels in food must not exceed 20 mg/kg [3].

Fundamental Mechanism of ELISA

The fundamental mechanism of ELISA centers on the specific binding between an antigen and an antibody, with the detection achieved through an enzyme-mediated colorimetric reaction. All ELISA variants share a common fundamental workflow consisting of four core steps: coating/capture, plate blocking, probing/detection, and signal measurement [1]. The critical element ensuring assay specificity is the antibody-antigen interaction, while sensitivity is achieved through enzyme-mediated signal amplification.

Core Steps in ELISA Protocol

The ELISA procedure follows a sequential process that ensures specific antigen capture and sensitive detection:

- Coating/Capture: Direct or indirect immobilization of antigens to the surface of polystyrene microplate wells [1]. This is typically achieved through passive adsorption via hydrophobic interactions between the plastic and non-polar protein residues [1].

- Plate Blocking: Addition of an irrelevant protein (e.g., bovine serum albumin) or other molecule to cover all unsaturated surface-binding sites of the microplate wells, thereby reducing non-specific binding [6] [7].

- Probing/Detection: Incubation with antigen-specific antibodies that affinity-bind to the target antigens [1]. This may involve primary and secondary antibody systems depending on the ELISA format.

- Signal Measurement: Detection of the signal generated via an enzyme-linked conjugate and its substrate [1]. Common enzyme labels include horseradish peroxidase (HRP) and alkaline phosphatase (AP), with substrates selected for colorimetric, fluorescent, or chemiluminescent detection [1].

Key ELISA Formats and Their Mechanisms

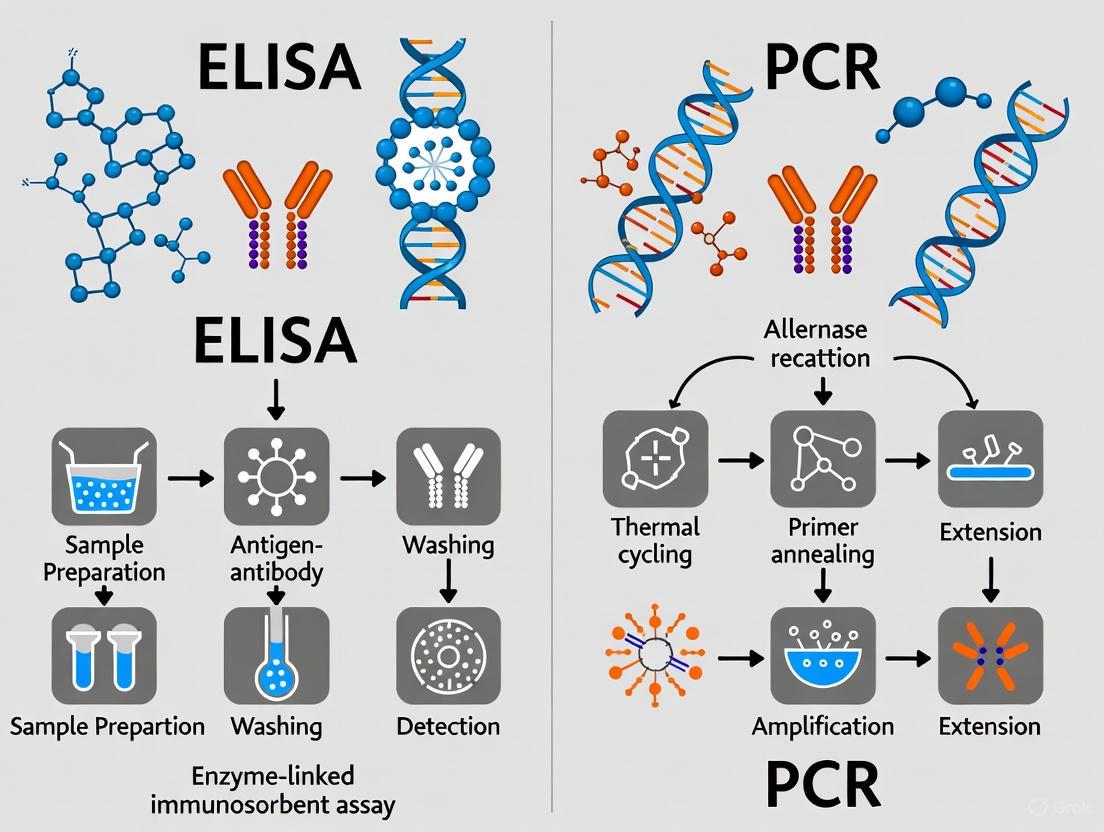

Among several ELISA formats, the sandwich ELISA is predominant for allergen detection due to its high specificity and sensitivity [4]. The diagram below illustrates the fundamental mechanism and procedural workflow of a sandwich ELISA.

Diagram 1: ELISA Mechanism and Workflow. This illustrates the sequential steps of a sandwich ELISA and the molecular interactions at each stage, culminating in signal generation.

The sandwich ELISA format, which "sandwiches" the target antigen between two specific antibodies, provides exceptional specificity because it requires simultaneous recognition by two different antibodies [1] [4]. This dual-antibody recognition minimizes false positives, making it particularly valuable for detecting specific allergenic proteins in complex food matrices [4]. For low-molecular-weight targets that cannot accommodate two antibodies, competitive ELISA formats are employed, where the antigen in the sample competes with a labeled reference for binding to a limited amount of antibody [1] [6].

Comparative Performance: ELISA vs. PCR in Food Allergen Detection

When selecting an appropriate method for allergen detection in processed foods, researchers must consider the fundamental differences in what each technique detects: ELISA targets specific allergenic proteins, while PCR detects species-specific DNA sequences. The table below summarizes the core characteristics of each method.

Table 1: Fundamental Comparison of ELISA and PCR Methodologies

| Parameter | ELISA (Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay) | PCR (Polymerase Chain Reaction) |

|---|---|---|

| Detection Target | Allergenic proteins (the actual allergens) [4] [5] | DNA from allergenic ingredients [4] [5] |

| Principle | Antigen-antibody interaction and enzyme-mediated color development [1] [6] | Amplification of species-specific DNA sequences [4] |

| Sensitivity | High (sensitive to low protein levels) [4] | Very high (detects trace DNA) [4] |

| Quantification | Quantitative (measures allergen concentration) [4] [5] | Generally qualitative or semi-quantitative [4] |

| Time to Result | ~2-3 days [4] | ~4-5 days [4] |

Experimental Data from Comparative Studies

Direct comparative studies reveal how these fundamental differences translate into practical performance for detecting allergens in various food matrices. The following table compiles experimental findings from recent research.

Table 2: Experimental Performance Data for Allergen Detection

| Study Focus & Matrix | Method | Key Performance Findings | Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| Crustacean Allergens (Manhattan clam chowder, fish sauce) | Real-time PCR | Broader dynamic range (0.1–10⁶ mg/kg); no significant matrix interference observed. | [2] |

| ELISA | Narrower dynamic range (200–4000 mg/kg); exhibited matrix interference. | [2] | |

| Beef & Pork Detection (Processed meat products) | Real-time PCR | Detected pork at 0.10% and beef at 0.50% in binary mixtures. | [8] |

| ELISA | Detected pork at 10.0% and beef at 1.00% in binary mixtures. | [8] | |

| General Allergen Detection (Various foods) | PCR | Preferred for highly processed foods, complex matrices, and when target is celery/fish. More stable DNA survives heat/pressure/pH changes. | [4] [5] |

| ELISA | Standard method for gluten; preferred for egg, milk, and when quantitative results are required. Proteins may degrade with processing. | [4] [5] |

The data indicate that real-time PCR often demonstrates higher sensitivity and a broader dynamic range in complex matrices, as it is less susceptible to matrix interference than ELISA [2] [8]. However, a significant limitation of PCR is its indirect nature; it detects DNA, not the allergenic protein itself, which can lead to false positives if the DNA is present from a non-allergenic source or if the allergenic protein has been removed [3]. Conversely, ELISA's direct measurement of the protein allergen can be compromised by food processing that denatures the protein's structure, altering antibody-binding epitopes and potentially leading to false negatives [3].

Detailed Experimental Protocols

To ensure reproducibility and reliability in research applications, standardized protocols for both ELISA and PCR are essential. The following sections detail the core methodologies.

Detailed Protocol: Sandwich ELISA for Allergen Detection

The following protocol is adapted from established methodologies for food allergen analysis [7]:

- Plate Coating: Dilute the capture antibody in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS, pH 7.4) or carbonate-bicarbonate buffer (pH 9.4) to a concentration of 2–10 μg/mL. Add 100 μL per well to a 96-well polystyrene microplate. Seal the plate to prevent evaporation and incubate at 4°C for 15-18 hours to immobilize the antibody via hydrophobic interactions [1] [7].

- Washing: Remove the coating solution. Wash the plate three times with washing solution (e.g., PBS containing 0.05% Tween 20) to remove unbound antibody [7].

- Blocking: Add 200-300 μL of blocking buffer (e.g., 1% BSA or 5% non-fat dry milk in PBS) to each well. Incubate at 37°C for 1 hour to cover any remaining protein-binding sites [7].

- Washing: Remove the blocking buffer and wash the plate three times with washing solution [7].

- Sample Addition: Dilute the food sample extract in an appropriate sample dilution buffer. Add 100 μL of the diluted sample or antigen standard (for the calibration curve) to each well. Incubate at 37°C for 1 hour to allow the target antigen to bind to the capture antibody [7].

- Washing: Remove the sample and wash the plate five times with washing solution to remove unbound material [7].

- Detection Antibody Incubation: Dilute the specific, biotinylated or enzyme-labeled detection antibody in sample dilution buffer. Add 100 μL to each well and incubate at 37°C for 1 hour. This antibody must recognize a different epitope on the target antigen than the capture antibody [7].

- Washing: Remove the detection antibody and wash the plate five times with washing solution [7].

- Enzyme Conjugate Incubation (if needed): For indirect detection, add an enzyme-conjugated secondary antibody (e.g., HRP-labeled anti-species IgG) and incubate for 1 hour at 37°C, followed by another five washes [7].

- Signal Development: Add 100 μL of enzyme substrate solution (e.g., TMB for HRP) to each well. Incubate at room temperature in the dark for 15-30 minutes to allow color development [6] [7].

- Reaction Stopping: Add 100 μL of stop solution (e.g., 1M sulfuric acid for TMB) to each well to terminate the enzyme reaction [7].

- Absorbance Measurement: Immediately measure the absorbance of each well at the appropriate wavelength (e.g., 450 nm for TMB) using a microplate reader. The antigen concentration in the sample is determined by interpolation from the standard curve [6] [7].

While a full protocol is beyond this guide's scope, the core workflow for PCR-based allergen detection includes [4]:

- DNA Extraction: Isolate total DNA from the food sample using a commercial kit suitable for the specific matrix.

- Primer/Probe Design: Design oligonucleotide primers and probes (e.g., TaqMan) that target a species-specific DNA sequence (e.g., mitochondrial 12S rRNA, cytochrome b gene) [2] [8].

- Amplification Reaction: Prepare a reaction mix containing the extracted DNA, primers, probes, nucleotides, and a DNA polymerase with hot-start capability. Run the reaction in a real-time PCR instrument with a defined thermal cycling profile (e.g., initial denaturation at 95°C, followed by 40 cycles of denaturation, annealing, and extension) [8].

- Data Analysis: Determine the cycle threshold (Ct) value. The presence of the target allergen is confirmed by a Ct value below a validated cutoff. Quantification, if applied, is achieved by comparison to a standard curve from serial dilutions of known target DNA [4].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Successful implementation of ELISA requires specific, high-quality reagents and equipment. The following table details essential components for establishing a robust sandwich ELISA.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Sandwich ELISA

| Item | Function/Description | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Microplate | 96-well or 384-well polystyrene plate for immobilizing biomolecules [1]. | Choose clear for colorimetric, black/white for fluorescent/chemiluminescent signals; ensure high protein-binding capacity and low well-to-well variation [1]. |

| Capture Antibody | The primary antibody immobilized on the plate to specifically bind the target antigen [1]. | Must be highly specific and recognize a different epitope than the detection antibody; often a monoclonal antibody for consistency. |

| Blocking Buffer | A solution of irrelevant protein (e.g., BSA, casein) used to cover unsaturated binding sites [6]. | Prevents non-specific binding of other assay components to the plate; critical for reducing background noise. |

| Detection Antibody | The antibody that binds to a different epitope of the captured antigen [1]. | Often conjugated directly to an enzyme (e.g., HRP) or a tag (e.g., biotin) for subsequent detection. |

| Enzyme-Conjugate | An enzyme-linked secondary antibody or streptavidin used for signal generation [1]. | Must be specific to the detection antibody; common enzymes are Horseradish Peroxidase (HRP) and Alkaline Phosphatase (AP) [6]. |

| Substrate | The molecule converted by the enzyme to a detectable product [1]. | Choice depends on the enzyme and detection method (colorimetric, chemiluminescent, fluorescent); TMB is a common colorimetric substrate for HRP [6]. |

| Wash Buffer | Typically a buffered solution with a mild detergent (e.g., PBS with 0.05% Tween 20) [6]. | Used to remove unbound reagents between steps; critical for achieving a high signal-to-noise ratio. |

| Microplate Reader | Instrument to measure the absorbance, fluorescence, or luminescence of the plate wells [1]. | Must be compatible with the plate format and the chosen detection method (e.g., spectrophotometer for colorimetric signals) [1]. |

The fundamental mechanism of ELISA, rooted in specific antigen-antibody interaction and enzymatic signal amplification, makes it a powerful tool for the direct quantification of protein allergens. Its strengths are particularly evident in quantitative analysis of specific proteins like gluten and in matrices where protein integrity is maintained. However, as the comparative data show, PCR provides a complementary and sometimes superior approach for detecting allergens in highly processed foods or complex ingredients, owing to the stability of DNA. The choice between ELISA and PCR is not a matter of which technology is universally better, but which is more fit-for-purpose given the specific sample matrix, the target molecule, and the required information (qualitative vs. quantitative). For a comprehensive food allergen control program, leveraging the strengths of both methods often provides the most robust strategy for ensuring product safety and regulatory compliance.

The Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR) is a foundational technique in molecular biology that allows for the exponential amplification of specific DNA sequences in vitro [9]. Since its introduction by Kary Mullis in 1985, for which he was later awarded the Nobel Prize in Chemistry, PCR has revolutionized genetic analysis and become an indispensable tool in biomedical research, clinical diagnostics, and food safety testing [9] [10]. In the specific context of allergen detection in processed foods, PCR offers a powerful DNA-based method to identify the presence of allergenic ingredients, such as crustacean shellfish, by targeting and amplifying species-specific genetic markers, even in complex food matrices [2] [5]. This technique is particularly valuable for verifying allergen-free claims and detecting allergens in processed foods where protein structures may be altered, as DNA is often more stable than proteins through various food processing conditions [5].

This guide will objectively compare the performance of PCR with the protein-based Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay (ELISA) for allergen detection, providing supporting experimental data to highlight the strengths, limitations, and optimal applications of each technology.

Fundamental Mechanism of PCR

The core principle of PCR is the enzymatic amplification of a specific DNA fragment, defined by two short oligonucleotide primers, through repeated cycles of heating and cooling. The process relies on a thermostable DNA polymerase, typically Taq polymerase isolated from the thermophilic bacterium Thermus aquaticus, which remains active despite repeated exposure to high temperatures [9] [11].

The PCR Cycle

A standard PCR amplification involves three fundamental steps per cycle, repeated 30-40 times [9] [12]:

- Denaturation: The double-stranded DNA template is heated to 94–95°C for 15 seconds to 2 minutes. This high temperature disrupts the hydrogen bonds between complementary base pairs, resulting in two single-stranded DNA molecules [9] [12].

- Annealing: The reaction temperature is lowered to 40–60°C (typically 55–72°C) for 15–60 seconds. This allows the forward and reverse primers to bind (anneal) to their complementary sequences on the single-stranded DNA templates, providing a starting point for DNA synthesis [9] [12].

- Extension: The temperature is raised to the optimum for the DNA polymerase, usually 70–74°C, for 1–2 minutes. Taq polymerase synthesizes a new DNA strand by adding deoxynucleotide triphosphates (dNTPs) to the 3' end of the primers, elongating the DNA sequence complementary to the template strand [9] [12].

Each cycle theoretically doubles the amount of the target DNA fragment, or amplicon, leading to an exponential amplification that can generate billions of copies from a single target sequence in a matter of hours [10] [12].

Key Variations: Real-Time PCR and RT-PCR

For allergen detection, two advanced forms of PCR are particularly relevant:

- Real-Time PCR (qPCR): This method allows for the simultaneous amplification and quantification of target DNA. It uses fluorescent dyes or probes that emit signals proportional to the amount of amplified DNA, enabling real-time monitoring of the reaction. This eliminates the need for post-PCR processing and provides quantitative data [9] [5].

- Reverse Transcription PCR (RT-PCR): When the target is RNA, RT-PCR is used. It first employs a reverse transcriptase enzyme to convert RNA into complementary DNA (cDNA), which is then amplified by standard PCR. This was the primary method for detecting SARS-CoV-2 RNA during the COVID-19 pandemic [9] [12].

Comparative Performance Data: PCR vs. ELISA

The choice between PCR and ELISA for allergen detection depends on the specific application, as each method has distinct performance characteristics. The table below summarizes key comparative data from experimental studies.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of PCR and ELISA for Allergen Detection

| Parameter | PCR (DNA-Based) | ELISA (Protein-Based) | Experimental Context & Data Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| Target Molecule | Species-specific DNA sequences [5] | Allergenic proteins (e.g., tropomyosin) [5] [13] | Fundamental difference in detection principle [5]. |

| Dynamic Range | 0.1 – 106 mg/kg [2] | 200 – 4000 mg/kg [2] | Comparison for crustacean shellfish allergens in food matrices [2]. |

| Sensitivity | High (can detect trace DNA) [5] | High (can detect trace proteins) [6] [13] | Both are highly sensitive, but to different molecular targets [5]. |

| Matrix Interference | Less susceptible in studied models [2] | Observed in complex matrices (e.g., chowder, fish sauce) [2] | Side-by-side comparison in Manhattan clam chowder and fish sauce [2]. |

| Quantification | Preferred for qualitative analysis; qPCR enables quantification [5] | Gold standard for quantitative protein analysis [6] [5] | ELISA is the standard for gluten quantification per Codex Alimentarius [5]. |

| Effect of Food Processing | More reliable for highly processed foods (DNA is stable) [5] | Protein denaturation in processing can affect detection [5] | PCR is preferred for hydrolyzed and fermented samples [5]. |

| Specific Allergen Suitability | Celery, fish, and for species differentiation [5] | Egg, milk, gluten; targets the allergenic protein directly [5] | Celery is low-protein; no common fish antigen for ELISA [5]. |

Experimental Protocols for Allergen Detection

To ensure reproducibility in research, detailed methodologies for both PCR and ELISA are provided below.

Protocol for Real-Time PCR Detection of Allergens

This protocol is adapted from methodologies used for detecting crustacean shellfish allergens [2] [5].

- DNA Extraction: Extract genomic DNA from the food sample using a commercial kit suitable for the specific matrix (e.g., baked goods, sauces). The quality and purity of the DNA are critical for amplification efficiency [5].

- Primer Design: Select primers that target a species-specific gene sequence. Common targets include mitochondrial genes (e.g., 12S rRNA for shrimp, crab, lobster) or the nuclear tropomyosin gene [2] [5].

- Reaction Setup: Prepare the qPCR reaction mix containing:

- Thermal Cycling: Run the reaction in a real-time thermal cycler with a program such as:

- Data Analysis: Determine the quantification cycle (Cq). The presence of the target allergen is confirmed by a Cq value below a predetermined threshold. A standard curve can be used for relative quantification [9].

Protocol for Sandwich ELISA Detection of Allergens

This protocol, based on standard sandwich ELISA procedures, is used for quantifying specific allergenic proteins like tropomyosin [6] [5].

- Coating: Coat a 96-well microplate with a capture antibody specific to the target allergen (e.g., anti-tropomyosin). Incubate overnight at 4°C [6].

- Blocking: Wash the plate with PBS-T (phosphate-buffered saline with Tween-20) to remove unbound antibody. Block remaining protein-binding sites with a blocking agent like bovine serum albumin (BSA) or synthetic block buffer for 1-2 hours at room temperature [6].

- Sample Incubation: Prepare the food sample by extracting proteins in a suitable buffer, often at high temperatures. Add the sample extract or standard to the wells and incubate for 1-2 hours at 37°C. The target allergen binds to the capture antibody [5] [13].

- Detection Antibody Incubation: Wash the plate and add an enzyme-linked detection antibody (conjugated with HRP or AP) specific to a different epitope on the allergen. Incubate for 1-2 hours at room temperature [6].

- Signal Development and Measurement: Wash the plate to remove unbound detection antibody. Add an enzyme substrate (e.g., TMB for HRP). The enzyme catalyzes a reaction that produces a color change. Stop the reaction with an acid (e.g., sulfuric acid) and measure the absorbance of the solution with a spectrophotometer [6] [14]. The color intensity is proportional to the concentration of the allergen in the sample.

Decision Workflow: Selecting the Appropriate Method

The following diagram outlines a logical workflow to guide researchers in selecting the most appropriate method based on their experimental goal and sample characteristics.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Successful implementation of PCR and ELISA requires specific, high-quality reagents. The following table details the essential components for each method.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents for PCR and ELISA

| Method | Reagent/Material | Function | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| PCR | Taq DNA Polymerase | Thermostable enzyme that synthesizes new DNA strands [9] [10]. | Thermostability is critical for repeated heating cycles. |

| Primers | Short, single-stranded DNA sequences that define the start and end of the target DNA region to be amplified [9]. | Must be specific to the target allergen's DNA sequence; design is critical for specificity. | |

| dNTPs | Deoxynucleotide triphosphates (dATP, dCTP, dGTP, dTTP); the building blocks for new DNA strands [12]. | Quality and concentration affect amplification efficiency and fidelity. | |

| Thermal Cycler | Instrument that automates the temperature cycles required for PCR [9] [10]. | Must provide precise temperature control and rapid transitions. | |

| Fluorescent Probes/Dyes | Molecules that fluoresce when bound to double-stranded DNA, enabling real-time detection in qPCR [9]. | Allows for quantification of the amplified product. | |

| ELISA | Microplate | 96-well polystyrene plate that serves as the solid phase for the immunoassay [6]. | Must have high protein-binding capacity. |

| Capture & Detection Antibodies | Antibodies that bind specifically to the target allergenic protein [6] [13]. | Specificity is paramount; "matched pairs" are needed for sandwich ELISA. | |

| Enzyme Conjugate | Detection antibody linked to an enzyme (e.g., Horseradish Peroxidase - HRP). | Catalyzes the signal-generating reaction [6]. | |

| Enzyme Substrate | Compound (e.g., TMB) converted by the enzyme to a colored product [6]. | Signal intensity is proportional to allergen concentration. | |

| Blocking Buffer | (e.g., BSA) used to coat unused protein-binding sites on the microplate. | Reduces nonspecific binding, minimizing background noise [6]. |

Both PCR and ELISA are powerful techniques for allergen detection in processed foods, yet they operate on fundamentally different principles. PCR excels in sensitivity and specificity for DNA-based identification, proving particularly robust for detecting allergens in highly processed foods and for species differentiation. Conversely, ELISA directly quantifies the allergenic protein itself and remains the gold standard for compliance testing where regulatory thresholds are defined in protein concentration.

The choice between these methods is not a matter of superiority but of context. Researchers and food safety professionals must base their selection on the specific experimental or monitoring goal, considering the nature of the allergen, the complexity of the food matrix, and the required output (qualitative vs. quantitative). As demonstrated in comparative studies, an integrated approach using both methods can often provide the most comprehensive and reliable assurance of food safety, leveraging the complementary strengths of DNA and protein analysis to protect consumers effectively.

In the field of food allergen detection, two methodologies dominate research and routine analysis: the enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) and the polymerase chain reaction (PCR). These techniques are fundamentally distinct in their analytical targets. ELISA is a protein-based immunochemical method that directly detects the allergenic proteins themselves, which are the actual molecules that trigger immune responses in sensitized individuals [15] [5]. In contrast, PCR is a DNA-based molecular biology technique that detects specific DNA sequences unique to the allergenic source (e.g., peanut, crustacean, wheat) [16] [4]. This core distinction—direct protein detection versus indirect genetic marker detection—dictates their respective performance characteristics, advantages, and limitations, particularly when applied to processed food matrices where both proteins and DNA can undergo significant structural alteration.

The choice between ELISA and PCR is not merely a matter of preference but a strategic decision based on the research question, the nature of the food matrix, and the processing history of the sample. This guide provides an objective, data-driven comparison of these two cornerstone technologies to inform researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals in selecting the optimal method for their specific application.

Performance Comparison: Sensitivity, Specificity, and Limitations

Extensive comparative studies have quantified the performance differences between ELISA and PCR across various food allergens and matrices. The following table summarizes key experimental findings from direct comparison studies.

Table 1: Experimental Performance Data from Direct Method Comparisons

| Study Focus | Method | Reported Sensitivity (LOD/LOQ) | Dynamic Range | Key Finding | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Crustacean Shellfish (Shrimp, Crab, Lobster) | Real-time PCR | Broader dynamic range | 0.1 - 100,000 mg/kg | No significant matrix interference observed in tested matrices. | [2] |

| ELISA (Total Crustacean) | More limited dynamic range | 200 - 4,000 mg/kg | Showed matrix interference in some samples. | [2] | |

| Beef in Meat Products | Real-time PCR | Consistent detection at 0.50% (w/w) | N/R | Greater sensitivity and agreement among duplicates. | [8] |

| ELISA | Consistent detection at 1.00% (w/w) | N/R | Less time-consuming and easier to perform. | [8] | |

| Pork in Meat Products | Real-time PCR | Consistent detection at 0.10% (w/w) | N/R | Optimal for low detection limits in processed products. | [8] |

| ELISA | Consistent detection at 10.0% (w/w) | N/R | 100% specificity, but significantly less sensitive for pork. | [8] | |

| Peanut in Processed Foods | Real-time PCR | <10 ppm | N/R | Detected one more positive sample than ELISA in market survey. | [17] |

| Sandwich ELISA | <10 ppm | N/R | Results correlated well with PCR; a reliable tool for hidden allergens. | [17] |

Abbreviations: LOD (Limit of Detection), LOQ (Limit of Quantification), N/R (Not Reported in the context of the study).

A critical limitation of ELISA is its susceptibility to producing false-negative results in processed foods. Heat treatment, fermentation, and hydrolysis can denature proteins, altering the conformational epitopes recognized by the antibodies used in ELISA kits [18]. If the antibody cannot bind to the denatured protein, the allergen will not be detected, even if it retains its allergenic potential [15]. PCR can circumvent this issue, as DNA is generally more stable than proteins under such conditions [16] [5]. However, a positive PCR signal indicates the presence of the source organism's DNA, not necessarily the intact, harmful allergen, which can lead to false positives from non-allergenic contaminating material [15] [4].

Table 2: Inherent Advantages and Limitations of ELISA and PCR

| Aspect | ELISA (Protein-Based) | PCR (DNA-Based) |

|---|---|---|

| Analytical Target | Allergenic proteins (the hazard itself) | Species-specific DNA sequences (a marker for the hazard) |

| Quantitative Capability | Strong; directly quantitative [5] | Generally qualitative or semi-quantitative [4] |

| Effect of Food Processing | Proteins may be denatured or altered, leading to potential false negatives [15] [18] | DNA may be fragmented, but short targets are stable; less affected by processing [16] [5] |

| Risk of False Positives | Possible cross-reactivity with similar proteins from non-target sources [4] | Detects DNA from any tissue of the species, which may not correlate with allergenic protein presence [15] |

| Best Suited For | Quantification of allergenic protein, verification of "free-from" claims, regulatory compliance (e.g., gluten) [3] [19] | Detection in highly processed, fermented, or hydrolyzed foods; complex matrices with potential protein interference [3] [5] |

Experimental Workflows and Protocols

ELISA Methodology: Sandwich Assay for Allergen Detection

The sandwich ELISA is the predominant format for allergen detection due to its high specificity and robust quantitative performance [4]. The workflow relies on two antibodies that bind to different epitopes on the same target protein.

Diagram 1: Sandwich ELISA Workflow

Detailed Protocol:

- Protein Extraction: The food sample is homogenized in an appropriate extraction buffer. The buffer composition is critical; high-salt or high-pH buffers are often employed to improve the recovery of proteins that may interact with the food matrix [15] [18]. Optimization of this step is essential for reliable detection, especially in processed foods.

- Capture: The extracted protein solution is added to the wells of a microplate that have been pre-coated with a capture antibody specific to the target allergen (e.g., anti-Ara h 1 for peanut) [5] [4]. Incubation allows the allergen protein to bind to the capture antibody.

- Detection: After washing to remove unbound material, a second enzyme-conjugated antibody (detection antibody), specific to a different epitope on the same allergen, is added. This forms an "antibody-allergen-antibody" sandwich complex [4].

- Signal Development: A colorless enzyme substrate is added. The enzyme (e.g., Horseradish Peroxidase) converts the substrate into a colored product.

- Quantification: The intensity of the color, measured spectrophotometrically, is directly proportional to the concentration of the target allergen in the sample. This is compared against a standard curve prepared with known concentrations of the purified allergen [5].

PCR Methodology: Real-Time PCR for Allergen Source Detection

Real-time PCR (qPCR) detects and amplifies a short, species-specific DNA sequence. The process is monitored in real-time, allowing for the detection of trace amounts of DNA.

Diagram 2: Real-Time PCR Workflow

Detailed Protocol:

- DNA Extraction: DNA is purified from the food sample. The cetyltrimethyl ammonium bromide (CTAB) method is a common and effective approach for plant-based and complex matrices [16]. The goal is to obtain DNA of sufficient purity and length, while inhibiting compounds must be removed.

- Reaction Setup: The extracted DNA is combined with a reaction mix containing primers and a fluorescently labeled probe. The primers are short, single-stranded DNA sequences designed to hybridize specifically to the target gene (e.g., a segment of the Ara h 2 gene for peanut or a glutenin gene for wheat) [16] [17]. The TaqMan probe with a minor groove binder (MGB) provides high specificity [8].

- Amplification & Detection: The mixture undergoes repeated thermal cycles in a real-time PCR instrument:

- Denaturation: High temperature (∼95°C) separates the double-stranded DNA.

- Annealing: Lower temperature (∼60°C) allows primers and probe to bind to the target sequence.

- Extension: The DNA polymerase extends the primers. During this phase, the probe is cleaved, releasing a fluorescent signal. The fluorescence increases with each cycle in proportion to the amount of amplified PCR product [5].

- Analysis: The cycle threshold (Ct), the cycle number at which fluorescence exceeds a background level, is determined. A lower Ct value indicates a higher initial concentration of the target DNA. The result is typically qualitative (presence/absence) or semi-quantitative when compared to reference standards [4].

Research Reagent Solutions and Essential Materials

Successful implementation of ELISA and PCR requires specific, high-quality reagents. The following table catalogues the essential components for each method.

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Materials for Allergen Detection

| Method | Reagent/Material | Function and Critical Features |

|---|---|---|

| ELISA | Capture & Detection Antibodies | High-affinity, specific antibodies (often monoclonal) that recognize distinct, stable epitopes on the native or denatured allergenic protein. Critical for assay specificity and sensitivity [4]. |

| Protein Extraction Buffers | Optimized buffers (e.g., high-salt, high-pH) to efficiently solubilize allergenic proteins from complex or processed food matrices while preserving epitope integrity [15] [18]. | |

| Enzyme-Substrate System | Conjugated enzyme (e.g., HRP) and its corresponding chromogenic or chemiluminescent substrate. Determines the signal-to-noise ratio and dynamic range of the assay. | |

| Allergen Protein Standards | Purified, quantified allergenic proteins (e.g., Ara h 1, β-lactoglobulin) for generating a standard curve, which is essential for accurate quantification [3]. | |

| PCR | Species-Specific Primers & Probes | Short, synthetic oligonucleotides designed to amplify a unique, short (100-300 bp) sequence from the genome of the allergenic source. Specificity is paramount [8] [16]. |

| DNA Polymerase | Thermostable enzyme (e.g., Taq polymerase) that synthesizes new DNA strands during thermal cycling. Fidelity and processivity affect amplification efficiency. | |

| DNA Extraction Kits/CTAB Reagents | Chemicals and kits for efficient lysis of cells and purification of DNA, free of inhibitors (e.g., polyphenols, polysaccharides) commonly found in food [16]. | |

| dNTPs | Deoxynucleotide triphosphates (dATP, dCTP, dGTP, dTTP), the building blocks for DNA synthesis by the polymerase. | |

| General | Reference Materials | Incurred control samples with known, homogeneously distributed allergen concentrations. Used for method validation to assess recovery and accuracy [4]. |

| Microplates & PCR Plates | Consumables compatible with automated liquid handlers, spectrophotometers, and real-time PCR thermal cyclers. |

The choice between ELISA and PCR is not a question of which method is universally superior, but which is most fit-for-purpose for a specific research or testing scenario. ELISA is the unequivocal choice when the research objective is the direct quantification of specific allergenic proteins, as it measures the causative agent of the allergic reaction itself. It is the established gold standard for compliance with regulatory thresholds, such as for gluten [3] [19]. PCR, however, excels as a highly sensitive detective tool when protein integrity is questionable, such as in highly processed, hydrolyzed, or fermented foods where target epitopes may be destroyed [16] [5]. It is also indispensable for detecting allergens in low-protein matrices like celery or when specific antibodies are unavailable or suffer from cross-reactivity.

For a comprehensive allergen risk assessment, an integrated approach using both methods provides the most robust picture. PCR can serve as a sensitive screening tool to identify the presence of an allergenic source, while ELISA can subsequently quantify the allergenic protein load, offering a complementary strategy that leverages the strengths of both techniques to ensure maximum consumer protection and regulatory compliance [5] [19].

In the field of food allergen detection, the accurate measurement of performance metrics is paramount for method validation and regulatory compliance. Sensitivity, specificity, and limit of detection (LOD) serve as critical benchmarks for evaluating analytical techniques, particularly when comparing established methods like Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay (ELISA) and Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR). These parameters determine the reliability of detection systems in identifying trace amounts of allergens in complex food matrices, directly impacting consumer safety and product labeling accuracy. Within the broader thesis comparing ELISA and PCR for allergen detection in processed foods, understanding these metrics provides a foundation for objective methodological evaluation and appropriate technology selection based on specific analytical requirements.

The fundamental distinction between these metrics lies in their respective roles: sensitivity measures a method's ability to correctly identify true positives, specificity indicates its capacity to avoid false positives by correctly identifying true negatives, and LOD represents the lowest analyte concentration that can be reliably detected. For food allergen analysis, where protection of sensitized consumers is the ultimate goal, the precise determination and interpretation of these parameters directly influence methodological choices in both research and quality control environments.

Theoretical Foundations of Performance Metrics

Conceptual Definitions and Distinctions

The terms sensitivity, specificity, and LOD possess precise technical definitions established by international standards organizations, though their application and interpretation vary between immunological and molecular biological methods. The Clinical Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) defines LOD as "the lowest amount of analyte in a sample that can be detected with stated probability" [20]. This distinguishes it from the limit of quantification (LOQ), defined as "the lowest amount of measurand that can be quantitatively determined with stated acceptable precision and accuracy" [20]. This distinction is crucial, as detection alone does not ensure precise measurement.

In diagnostic contexts, sensitivity represents the proportion of true positives correctly identified by the assay, while specificity indicates the proportion of true negatives correctly identified [21]. The International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry (IUPAC) further defines analytical sensitivity as the slope of the calibration curve, representing the method's ability to distinguish small concentration differences [22]. Understanding these nuanced definitions is essential for proper method evaluation and comparison.

Statistical Determination and Calculation Methods

The statistical determination of LOD follows established protocols that differ between linear immunoassays and logarithmic molecular methods. For immunoassays with linear response curves, LOD is typically calculated as LoB + 1.645 × σ low concentration sample, where LoB (limit of blank) equals mean blank + 1.645 × σ blank [20]. This approach assumes normal distribution of data in linear scale and a 95% confidence level.

For qPCR methods with logarithmic response characteristics, standard linear approaches are inappropriate since negative samples produce no Cq values, preventing standard deviation calculation. Instead, logistic regression models based on binary detection outcomes at various concentrations are employed, with maximum likelihood estimation determining the concentration at which 95% of replicates test positive [20]. This method accommodates the fundamental characteristics of molecular amplification data without violating statistical assumptions.

Methodology Comparison: ELISA versus PCR

Fundamental Principles and Mechanisms

ELISA operates on antigen-antibody interaction principles, where antibodies specifically bind to allergenic proteins. In typical sandwich ELISA formats, captured antigens are detected using enzyme-linked secondary antibodies that generate measurable color signals upon substrate addition [5]. The signal intensity correlates with allergen concentration, enabling quantification. The technique's performance depends heavily on antibody affinity, specificity, and the stability of target epitopes through food processing.

PCR-based methods target species-specific DNA sequences rather than proteins. Through cyclic amplification using sequence-specific primers, trace amounts of DNA are exponentially multiplied to detectable levels [5]. Real-time PCR (qPCR) monitors amplification kinetics, providing both qualitative detection and quantitative capability. The method's effectiveness depends on DNA extractability, primer specificity, and the conservation of target sequences across species.

Experimental Protocols for Allergen Detection

Standard ELISA Protocol:

- Sample Preparation: Food samples are homogenized and proteins extracted using appropriate buffers

- Plate Coating: Microplate wells are coated with allergen-specific capture antibodies

- Incubation: Sample extracts are added and allowed to bind during incubation

- Washing: Unbound materials are removed by washing

- Detection: Enzyme-conjugated detection antibodies are added and bind to captured allergens

- Signal Development: Enzyme substrates are added, generating colorimetric signals

- Measurement: Absorbance is measured spectrophotometrically and compared to standards [5]

Standard PCR Protocol:

- DNA Extraction: Food samples are processed to isolate total DNA

- Primer Design: Species-specific primers target unique allergen-encoding sequences

- Amplification: DNA is mixed with primers in a thermal cycler for repeated heating/cooling cycles

- Detection: Amplified DNA is detected in real-time using fluorescent probes or intercalating dyes

- Analysis: Cq values are determined and compared to standard curves for quantification [5]

Recommended Workflows for Complex Matrices

For comprehensive allergen analysis in processed foods, regulatory authorities recommend integrated workflows rather than reliance on single methods. The UK Food Standards Agency advises initial screening with ELISA, followed by confirmatory testing with alternative methods when negative results are obtained [23]. This approach mitigates limitations inherent in individual technologies.

For egg allergen detection, workflows should incorporate multiple ELISA tests targeting different egg white proteins, with LC-MS/MS confirmation [23]. Similarly, milk allergen analysis should target both casein and β-lactoglobulin via ELISA before considering supplemental methods [23]. These workflows acknowledge that no single method currently addresses all analytical challenges across diverse food matrices.

Performance Data Comparison

Quantitative Performance Metrics

Table 1: Direct Comparison of ELISA and PCR Performance Characteristics for Allergen Detection

| Performance Parameter | ELISA | Real-Time PCR |

|---|---|---|

| Dynamic Range | 200-4000 mg/kg [2] | 0.1-106 mg/kg [2] |

| Typical Sensitivity (LOD) | Picograms to nanograms per milliliter [24] | As low as 1-2 viral copies/μL in clinical models [25] |

| Matrix Interference | Significant in complex matrices [2] | Minimal demonstrated [2] |

| Quantitative Capability | Strong within validated range [5] | Limited to qualitative without proper controls [5] |

| Measurement Target | Proteins (allergens directly) [23] | DNA (indirect marker) [23] |

Table 2: Method Application by Allergen Type and Food Matrix

| Allergen/Matrix Scenario | Recommended Method | Rationale | Performance Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Egg, Milk allergens | ELISA [23] [5] | PCR cannot differentiate sources; targets relevant proteins | Prefer kits detecting multiple proteins (casein, β-lactoglobulin for milk) |

| Highly processed foods | PCR [5] | DNA more stable than protein epitopes | May detect non-allergenic material; clinical relevance uncertain |

| Celery, certain fish | PCR [5] | Lack of common antigen for ELISA; low-protein matrix | Currently the only option despite limitations |

| Incident management | ELISA first, then LC-MS/MS confirmation [23] | Avoid false negatives through orthogonal verification | Requires multiple kits targeting different epitopes |

Specificity Considerations in Complex Matrices

Method specificity presents distinct challenges for each technology. ELISA specificity depends on antibody cross-reactivity profiles, which can produce false positives when related non-target proteins share epitopes [23]. PCR specificity is determined by primer design, with potential cross-reactivity to closely related species sharing conserved DNA sequences [5].

In processed foods, matrix effects significantly impact specificity. ELISA demonstrates superior specificity for directly measuring allergenic proteins, the molecules actually responsible for allergic reactions [23]. PCR's indirect measurement through DNA may detect species presence without correlating to allergen content, particularly concerning for ingredients that may contain DNA but not allergenic proteins due to processing or tissue type.

Advanced Detection Technologies

Emerging Methodologies

While ELISA and PCR dominate current allergen detection, several emerging technologies show promise for overcoming their limitations. Mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) enables highly specific multiplex detection by targeting proteotypic peptides, providing direct measurement of multiple allergenic proteins simultaneously [23] [26]. Although currently less sensitive than ELISA, its specificity advantages warrant inclusion in confirmatory workflows.

Temperature-responsive liposome-linked immunosorbent assay (TLip-LISA) represents an innovative approach combining liposome technology with immunoassay principles. This method incorporates squaraine dye-containing liposomes that exhibit dramatic fluorescence increase at phase transition temperature, achieving extraordinary sensitivity down to 0.97 aM for PSA detection in model systems [27]. While not yet established for food allergens, this technology demonstrates the potential for significant sensitivity improvements beyond conventional ELISA.

Non-Destructive and Rapid Methods

Hyperspectral imaging (HSI) and Fourier Transform Infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy are emerging as non-destructive alternatives for allergen screening [26]. When combined with machine learning algorithms, these techniques enable real-time monitoring without altering food integrity. Similarly, lateral flow assays (LFAs) provide rapid, on-site testing capabilities suitable for manufacturing environments, though primarily as qualitative screening tools [5].

Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Allergen Detection Studies

| Reagent/Material | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Reference Materials (RMs) | Method calibration and validation [23] | Preferably incurred materials; limited CRM availability |

| Allergen-Specific Antibodies | Target capture and detection in ELISA [24] | Monoclonal preferred for consistency; affinity critical for sensitivity |

| Species-Specific Primers/Probes | DNA amplification in PCR [5] | Must target unique sequences; design critical for specificity |

| Protein Extraction Buffers | Allergen extraction from food matrices [23] | Composition critical for efficient extraction, especially in processed foods |

| DNA Extraction Kits | Nucleic acid isolation for PCR [5] | Efficiency varies by matrix; must remove PCR inhibitors |

Experimental Workflows

Diagram 1: Comprehensive allergen detection workflow integrating multiple analytical methods for incident management, based on UK Food Standards Agency recommendations [23]. The sequential approach utilizing orthogonal methods reduces false negative risks.

The comparative analysis of ELISA and PCR for food allergen detection reveals a complex landscape where neither technology universally outperforms the other across all applications. Instead, method selection must align with specific analytical requirements, considering the particular allergen, food matrix, processing history, and required sensitivity level. ELISA maintains advantages for directly quantifying allergenic proteins in many applications, while PCR offers superior sensitivity and resistance to matrix effects in challenging scenarios.

The critical evaluation of performance metrics—sensitivity, specificity, and LOD—must extend beyond numerical comparisons to encompass methodological fitness for purpose. Future methodological developments will likely focus on multiplexed detection platforms with enhanced sensitivity and reduced matrix effects, potentially through hybrid approaches combining the complementary strengths of existing technologies. For researchers and food safety professionals, informed method selection based on comprehensive understanding of these performance metrics remains essential for effective allergen management and consumer protection.

Food allergies represent a significant and growing public health concern worldwide, with strict avoidance of allergenic foods being the primary management strategy for affected individuals. This reality places immense importance on accurate allergen detection and clear food labeling to ensure consumer safety. The global allergen testing market is experiencing substantial growth, driven by increasing allergy prevalence, stringent regulatory requirements, and technological advancements in detection methodologies. Within this landscape, ELISA (Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay) and PCR (Polymerase Chain Reaction) have emerged as two dominant analytical techniques, each with distinct advantages and limitations for detecting allergens in processed foods. This guide provides an objective comparison of these methodologies, focusing on their performance characteristics, applications in complex food matrices, and positioning within the current regulatory framework.

The global food allergen testing market is positioned for significant expansion, with its value projected to increase from USD 970.3 million in 2025 to USD 2,062.6 million by 2035, reflecting a compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of 7.8% [28]. This growth trajectory is mirrored in the broader allergy diagnostics sector, which includes clinical applications and is expected to grow from US$5.8 billion in 2024 to US$10.7 billion by 2030, at a CAGR of 10.8% [29].

Several key factors are propelling this market expansion:

- Rising Allergy Prevalence: Increasing incidence of food allergies worldwide, particularly among children [28]

- Stringent Regulations: Implementation of stricter food safety laws and labeling requirements across regions [19] [28]

- Consumer Awareness: Growing consumer demand for allergen-free products and transparent labeling [29]

- Technological Innovation: Development of more sensitive, rapid, and multiplexed detection platforms [26] [28]

Table 1: Global Food Allergen Testing Market Outlook

| Metric | 2025 Value | 2035 Projected Value | CAGR (2025-2035) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Market Size | USD 970.3 million | USD 2,062.6 million | 7.8% |

| Technology Leader | PCR-based Testing (35.4% share) | ||

| Top Application | Processed Food (28% share) | ||

| Leading Source | Milk (25% share) |

Regionally, North America currently dominates the allergy diagnostics market, holding an estimated 45.4% share in 2024 [29]. However, the Asia-Pacific region is projected to record the fastest growth rate in allergy diagnostics, with a CAGR of 11.8% during 2024-2030, driven by rapid urbanization, increasing pollution, and healthcare infrastructure development [29]. Japan leads growth projections for food allergen testing with a CAGR of 6.5% from 2025 to 2035, followed by the UK (6.2% CAGR) and Germany (6.1% CAGR) [28].

Regulatory Framework

The regulatory landscape for allergen management has evolved significantly to protect consumer health. In the United States, the Food Allergen Labeling and Consumer Protection Act (FALCPA) identifies nine major food allergens: milk, eggs, fish, Crustacean shellfish, tree nuts, peanuts, wheat, soybeans, and sesame [30]. The Food and Drug Administration (FDA) enforces labeling requirements for these allergens in most packaged foods, requiring clear declaration of allergen sources either in the ingredient list or through a "contains" statement [30].

A critical regulatory aspect is that the FDA has not established threshold levels for any allergens, meaning there is no defined value below which allergen presence is considered safe for all allergic individuals [30]. This regulatory stance places additional responsibility on food manufacturers to implement stringent controls and sensitive detection methods to prevent cross-contamination.

Globally, regulatory approaches vary, with regions like the European Union implementing the Food Information for Consumers Regulation, and countries like Japan maintaining strict allergen declaration frameworks with defined thresholds (10 μg/g for certain allergens) [3]. These regulatory differences create compliance complexities for global food manufacturers, necessitating versatile testing approaches that can meet varying regional requirements.

Methodology Comparison: ELISA vs. PCR

Principles and Technologies

ELISA (Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay) is an immunochemical method that detects allergenic proteins through antigen-antibody interactions. The process involves:

- Sample Preparation: Proteins are extracted from food samples using buffer solutions, often at high temperatures to release potential allergens [13]

- Antibody Coating: A microplate is pre-coated with antibodies specific to the target allergen [5] [13]

- Binding Phase: Allergenic proteins in the sample bind to the capture antibodies [5]

- Detection: A second enzyme-linked antibody binds to the captured allergen [5] [13]

- Signal Measurement: Enzyme substrate addition produces a color change measurable via spectrophotometry, with intensity proportional to allergen concentration [5] [13]

PCR (Polymerase Chain Reaction) is a molecular biology technique that amplifies specific DNA sequences associated with allergenic foods. The methodology includes:

- DNA Extraction: Isolation of DNA from food samples using various extraction protocols [16]

- Amplification: Target DNA sequences are amplified using specific primers in a thermal cycler [5]

- Detection: Amplified DNA is detected via real-time PCR, providing measurable signals indicating allergen presence [5] [16]

Experimental Performance Data

Recent studies provide quantitative performance data for both techniques in processed food matrices:

Table 2: Methodological Comparison of ELISA and PCR for Allergen Detection

| Parameter | ELISA | PCR |

|---|---|---|

| Target Molecule | Proteins (direct detection) | DNA (indirect detection) |

| Sensitivity | Parts per million (ppm) levels; High sensitivity for native proteins [19] | High sensitivity for target DNA sequences; Effective even in processed foods [16] |

| Specificity | High; Dependent on antibody quality [19] | High; Primers target unique allergen gene sequences [16] |

| Quantification | Direct quantitative results [5] | Primarily qualitative; Semi-quantitative with standard curves [5] |

| Impact of Processing | Protein denaturation may reduce detectability [3] [19] | DNA stability allows detection in processed foods [3] [16] |

| Detection Time | ~30 minutes to several hours [13] | Several hours including DNA extraction [5] |

| Multiplexing Capability | Limited | High with multiplex PCR [28] |

| Regulatory Status | Gold standard for routine screening [19] | Official method in some countries (e.g., Germany, Japan) [3] |

Research on wheat and maize allergen detection demonstrates PCR's effectiveness in processed foods, where DNA remains amplifiable even after baking at 220°C for 40-60 minutes, though with some degradation [16]. For reliable PCR analysis of processed foods, target amplicons should be limited to approximately 200-300 base pairs to accommodate potential DNA fragmentation [16].

ELISA maintains advantages for certain applications, being the officially recognized method for gluten detection by the Codex Alimentarius, with a defined threshold of 20 mg/kg [3]. The technique's direct measurement of allergenic proteins rather than genetic markers provides more clinically relevant data for allergy risk assessment.

Allergen Detection Method Selection Workflow

Application in Processed Foods

The selection between ELISA and PCR becomes particularly significant when analyzing processed foods, where manufacturing operations can alter the detectability of target molecules. Thermal processing, fermentation, hydrolysis, and high-pressure treatments can denature proteins, potentially affecting antibody recognition in ELISA methods [3] [19]. Conversely, DNA demonstrates greater stability through various food processing conditions, making PCR particularly valuable for detecting allergens in baked goods, extruded snacks, hydrolyzed products, and fermented foods [5] [19].

Research demonstrates that while genomic DNA undergoes degradation during high-temperature processing (e.g., baking at 180-220°C), appropriate primer design targeting shorter DNA fragments (200-300 bp) maintains reliable detection of wheat and maize allergens [16]. This robustness makes PCR particularly suitable for verifying allergen-free claims in complex processed products where protein integrity may be compromised [5].

ELISA maintains advantages for detecting specific allergenic proteins in native or minimally processed matrices, and remains the preferred method when quantitative protein data is required for compliance with specific regulatory standards, such as gluten-free labeling [5] [3]. The direct measurement of allergenic proteins rather than genetic markers provides more clinically relevant information about potential allergenicity.

Emerging Technologies and Future Outlook

The allergen testing landscape is evolving with several promising technologies emerging to address current methodological limitations:

- Mass Spectrometry: Particularly liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (LC-MS), enables highly specific detection and quantification of multiple allergenic proteins simultaneously through identification of proteotypic peptides, offering high precision across complex food matrices [26]

- Biosensors: Various biosensor platforms are under development, leveraging aptamers, antibodies, or cell-based recognition elements coupled with electrochemical, optical, or piezoelectric transducers for rapid, sensitive allergen detection [3]

- AI-Enhanced Platforms: Integration of artificial intelligence with detection technologies like hyperspectral imaging, Fourier Transform Infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy, and computer vision enables non-destructive, real-time allergen monitoring without compromising food integrity [26]

- Digital ELISA and Microfluidics: Advanced immunoassay formats offering improved sensitivity through single-molecule counting and reduced sample/reagent requirements, with recent developments demonstrating 60% reduced sample volumes (20 μL vs. 50 μL) compared to conventional systems [31]

These emerging technologies promise to address current challenges related to detection sensitivity, multiplexing capability, analysis time, and applicability to complex matrices. The integration of cloud-based data management platforms further enhances utility by providing centralized dashboards for compliance documentation and trend analysis [26].

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Successful implementation of allergen testing methodologies requires specific reagent systems and materials:

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Allergen Detection

| Reagent/Material | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Allergen-Specific Antibodies | Recognition and binding to target allergenic proteins | Critical for ELISA specificity; monoclonal antibodies reduce cross-reactivity [13] |

| Protein Extraction Buffers | Solubilize and extract proteins from food matrices | Composition optimized for different food types; may include denaturants or reducing agents [13] |

| DNA Extraction Kits | Isolate DNA from complex food matrices | CTAB-based methods effective for plant-derived foods [16] |

| Species-Specific Primers | Amplify target DNA sequences in PCR | Designed for conserved allergen genes; short amplicons (200-300 bp) for processed foods [16] |

| Microplates and Readout Systems | Solid phase for binding and detection | Spectrophotometers for colorimetric ELISA; thermal cyclers and fluorescence detectors for PCR [5] |

| Reference Materials | Method validation and calibration | Certified reference materials with known allergen content essential for quantification [3] |

The current market and regulatory landscape for allergen testing reflects a dynamic field balancing technological innovation with increasing public health demands. While ELISA remains the gold standard for routine allergen screening due to its direct protein detection, cost-effectiveness, and regulatory acceptance, PCR technology has established a crucial complementary role, particularly for processed foods where protein denaturation may compromise immunoassay effectiveness. The choice between these methodologies depends on multiple factors, including food matrix composition, degree of processing, regulatory requirements, and needed output (quantitative vs. qualitative). Future methodological developments will likely focus on multiplexing capabilities, rapid on-site testing, enhanced sensitivity, and integration with data analytics platforms to address the evolving needs of food manufacturers, regulatory agencies, and allergic consumers.

Strategic Application: Selecting ELISA or PCR Based on Food Matrix and Processing

ELISA as the Gold Standard for Quantitative Protein Analysis in Raw Ingredients

Among the various analytical techniques available for allergen detection, the Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay (ELISA) maintains its position as the gold standard for quantitative protein analysis in raw food ingredients. This comprehensive guide examines the technical foundations, performance parameters, and practical applications of ELISA methodology in comparison with emerging molecular techniques, particularly Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR). Through systematic evaluation of experimental data and validation criteria, we demonstrate why ELISA remains the preferred platform for precise protein quantification in research, quality control, and regulatory compliance contexts within food safety and pharmaceutical development.

Food allergen detection has become increasingly critical in public health and food safety, with undeclared allergens consistently representing the leading cause of food product recalls globally [4]. Accurate detection and quantification of allergenic proteins in raw ingredients establishes the foundation for effective allergen control programs, compliance with labeling regulations, and protection of consumer health. The two predominant analytical approaches for allergen detection target different molecular entities: immunoassays detect allergenic proteins directly, while molecular methods detect species-specific DNA sequences [5] [3].

Within this landscape, ELISA has emerged as the benchmark technique for quantitative protein analysis due to its robust antigen-antibody interaction principle, standardized protocols, and well-characterized validation parameters [32]. The technique's direct measurement of clinically relevant proteins—the molecules that actually trigger allergic responses—provides a significant advantage over indirect DNA-based methods when determining the potential allergenicity of food ingredients [4]. Internationally recognized bodies including the Codex Alimentarius Commission have formally adopted ELISA as the official reference method for detecting specific allergens like gluten in foods [3].

Technical Comparison of ELISA and PCR Methodologies

Fundamental Principles and Workflows

ELISA operates on the principle of specific antigen-antibody recognition, typically employing a sandwich format where the target protein is captured between two antibodies [4]. This double-antibody recognition system provides exceptional specificity, while enzyme-mediated signal amplification enables sensitive quantification of the target protein [5]. The direct measurement of proteins makes ELISA particularly valuable for assessing the actual allergenic risk in food products.

PCR technology amplifies specific DNA sequences unique to allergenic species using thermal cycling and DNA polymerase enzymes [5]. While exceptionally sensitive for detecting species-specific genetic material, PCR does not directly measure the allergenic proteins themselves, potentially leading to discrepancies between detected DNA and actual allergenicity [33].

The experimental workflow for each method differs significantly, as illustrated below:

Comparative Performance Characteristics

The table below summarizes the fundamental operational differences between ELISA and PCR methods:

| Parameter | ELISA | PCR |

|---|---|---|

| Detection Target | Specific allergenic proteins [4] | Species-specific DNA sequences [5] |

| Measurement Output | Quantitative protein concentration [5] [34] | Qualitative or semi-quantitative DNA detection [5] [4] |

| Sensitivity | High (parts per million range) [35] | Very high (detects trace DNA) [4] |

| Specificity | Protein epitope specificity [36] | Species-level DNA specificity [4] |

| Impact of Food Processing | Protein structure may be denatured [5] | DNA is more stable through processing [5] |

| Regulatory Status | Official Codex method for gluten [3] | Official method in Germany and Japan [3] |

Experimental Data and Validation Metrics

ELISA Performance Validation Parameters

Rigorous validation establishes the reliability of quantitative ELISA methods. The following validation parameters demonstrate why ELISA meets gold standard status for protein quantification:

Precision and Reproducibility: Intra-assay precision (within-plate variability) typically shows coefficient of variation (CV) <10%, while inter-assay precision (between-plate variability) also maintains CV <10% across different operators and days [36]. This consistency ensures reproducible results in quality control environments.

Accuracy and Recovery: Spike-and-recovery experiments evaluate accuracy by measuring the detection of known analyte quantities added to sample matrices. Recovery rates of 80-120% indicate minimal matrix interference [36]. For sesame protein detection in incurred foods, recovery rates of 67-81% demonstrate acceptable performance in complex matrices [35].

Sensitivity and Specificity: ELISA methods exhibit exceptional sensitivity with limits of detection (LOD) as low as 0.013 μg/g for sesame proteins [35]. Specificity is ensured through antibodies that recognize target proteins without cross-reactivity to related molecules, validated through comprehensive cross-reactivity panels [36] [32].

The quantitative performance of ELISA is demonstrated in the following validation data:

| Validation Parameter | Typical Performance | Experimental Example |

|---|---|---|

| Intra-Assay Precision | CV <10% [36] | VCAM-1 Human ELISA: CV 4.85-7.68% across samples [36] |

| Inter-Assay Precision | CV <10% [36] | Amyloid beta 42 ELISA: CV 5.32-9.85% across multiple runs [36] |

| Linearity of Dilution | 70-130% of expected [36] | c-Myc Human ELISA: 76-126% across serial dilutions [36] |

| Recovery Rate | 80-120% [36] | Sesame protein ELISA: 67-81% in incurred foods [35] |

| Limit of Detection | Varies by target | Sesame protein ELISA: 0.013 μg/g [35] |

Comparative Method Performance Data

Direct comparison studies reveal contextual advantages for each method. In malaria research, a mitochondrial COX-I PCR method demonstrated higher sensitivity (67-88% detection in abdomen segments) compared to CSP ELISA (single detection) during early infection stages in mosquitoes [33]. However, this superior sensitivity comes with a significant limitation—the PCR method detected all parasite life stages rather than specifically identifying infectious sporozoites [33].

For food allergen applications, ELISA provides direct measurement of clinically relevant proteins at regulated thresholds. The Codex Alimentarius specifies ELISA as the method for gluten detection with a regulatory threshold of 20 mg/kg, while Japan implements both ELISA and PCR with an allergen threshold of 10 μg/g [3].

Method Selection Framework

The decision between ELISA and PCR methods depends on multiple experimental factors, which can be navigated using the following workflow:

Application-Specific Recommendations

ELISA is Recommended For:

- Quantitative analysis of allergenic proteins in raw ingredients [5]

- Regulatory compliance and verification of "free-from" claims [4]

- Process validation where protein detection correlates directly with allergenicity [3]

- Applications requiring precise quantification against established thresholds [35]

PCR is Preferred For:

- Detection of allergenic species in highly processed foods where proteins may be denatured [5]

- Identification of specific biological species in complex matrices [3]

- Situations where DNA stability offers advantage over protein detectability [5]

- Qualitative screening when extreme sensitivity is required [33]

Combined Approaches are particularly powerful in complex scenarios, such as:

- Method verification and confirmatory analysis [5]

- Comprehensive allergen control programs [4]

- Research applications characterizing both presence and potency of allergens [3]

Research Reagent Solutions and Experimental Implementation

Essential Components for ELISA

Successful implementation of quantitative ELISA requires specific reagent systems and laboratory materials:

| Reagent/Material | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Capture Antibodies | Bind target protein to solid phase [32] | High affinity, specific to target epitope; require concentration optimization [32] |

| Detection Antibodies | Recognize different epitope on captured protein [4] | Typically enzyme-conjugated (HRP, AP); enable signal generation [36] |

| Blocking Buffers | Prevent non-specific binding [32] | BSA, non-fat dry milk, or commercial formulations; require optimization [32] |

| Enzyme Substrates | Generate detectable signal [36] | Colorimetric, chemiluminescent, or fluorescent; selection depends on sensitivity needs [36] |

| Reference Standards | Calibrate quantitative measurements [34] | Certified reference materials calibrated to international standards (e.g., NIBSC) [36] |

| Microplate Readers | Measure signal intensity [36] | Spectrophotometers for colorimetric detection; compatible with 96-well format [36] |

Standard ELISA Protocol for Protein Quantification

The following detailed methodology ensures reliable quantification of allergenic proteins in raw ingredients:

Sample Preparation:

- Homogenize representative samples of raw ingredients using appropriate extraction buffers [35]

- Extract proteins using buffers optimized for target allergens and matrix compatibility [32]

- Clarify extracts by centrifugation (10,000 × g for 10 minutes at 4°C)

- Determine optimal sample dilution to fall within assay dynamic range [34]

Assay Procedure:

- Coat microplate wells with capture antibody (typically 1-10 μg/mL in coating buffer) and incubate overnight at 4°C [32]

- Block remaining protein-binding sites with appropriate blocking buffer (1-2 hours at room temperature) [32]

- Add standards and samples to wells in duplicate or triplicate; incubate 1-2 hours at room temperature [34]

- Wash plates thoroughly (3-5 times with wash buffer) to remove unbound proteins [32]

- Add enzyme-conjugated detection antibody; incubate 1-2 hours at room temperature [36]

- Repeat washing step to remove unbound detection antibody [32]

- Add enzyme substrate solution; incubate for precise duration (typically 15-30 minutes) [36]

- Stop reaction (if required) and measure signal intensity using microplate reader [34]

Data Analysis:

- Generate standard curve using reference standards of known concentration [34]

- Apply 4-parameter logistic (4PL) curve fit for optimal quantitative accuracy [34]

- Interpolate sample concentrations from standard curve [34]

- Apply dilution factors to calculate original sample concentration [34]

- Validate assay acceptance criteria (R² > 0.99 for standard curve, CV < 10% for replicates) [36]

ELISA maintains its gold standard status for quantitative protein analysis in raw ingredients through its direct measurement of clinically relevant allergens, robust validation parameters, and regulatory acceptance. While PCR offers advantages in specific scenarios—particularly for detecting allergenic species in highly processed foods—ELISA remains unmatched for precise protein quantification essential for regulatory compliance and consumer protection. The methodological framework presented here enables researchers to implement ELISA methodologies effectively while understanding the complementary role of PCR-based approaches in comprehensive allergen detection strategies. As food safety regulations evolve globally, the quantitative precision of ELISA ensures its continued relevance in protecting allergic consumers through accurate allergen detection and quantification.