Dietary Triglycerides and Phospholipids: Molecular Structures, Metabolic Pathways, and Clinical Implications

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of the distinct chemical structures of dietary triglycerides and phospholipids and their profound influence on metabolism, health, and disease.

Dietary Triglycerides and Phospholipids: Molecular Structures, Metabolic Pathways, and Clinical Implications

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of the distinct chemical structures of dietary triglycerides and phospholipids and their profound influence on metabolism, health, and disease. Tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it synthesizes foundational biochemistry with contemporary research. The scope spans from structural biology and analytical methodologies to the optimization of lipid-based formulations and a comparative review of their roles in cardiometabolic health, neurological function, and pharmaceutical applications. The content is structured to bridge basic science with translational research, highlighting opportunities for therapeutic innovation.

Deconstructing Lipid Architectures: From Glycerol Backbones to Functional Assemblies

The glycerol backbone, a simple three-carbon polyol, serves as a fundamental architectural platform for an immense diversity of biological lipids. This universal core, when esterified with various fatty acid chains and head groups, gives rise to both triglycerides—the primary energy storage molecules in diets—and phospholipids—the essential structural components of cellular membranes. The specific chemical modifications at each carbon position on the glycerol scaffold dictate the ultimate physicochemical properties, metabolic fate, and biological functions of the resulting lipid species. This whitepaper delves into the structural principles governing this diversity, summarizes quantitative data on lipid composition, outlines key experimental methodologies for their study, and visualizes critical metabolic pathways, providing a technical resource for researchers and drug development professionals.

The glycerol backbone, chemically defined as propane-1,2,3-triol, is the central structural component of most lipids in living organisms [1] [2]. Its significance stems from a simple yet versatile architecture: a three-carbon chain where each carbon bears a hydroxyl group, enabling it to form ester linkages with a wide array of fatty acids and other functional groups [3]. This capacity for regioselective substitution transforms this simple molecule into a platform for an astonishing array of complex lipids with vastly different biological roles.

In biological systems, the glycerol backbone is found in two primary enantiomeric forms, which have profound implications for membrane biochemistry and evolution. Eukaryotes and bacteria utilize sn-glycerol-3-phosphate, whereas archaea utilize sn-glycerol-1-phosphate as the backbone for their membrane lipids [1]. This review will focus on the roles of the glycerol backbone in the context of dietary triglycerides and physiological phospholipids, exploring how minimal alterations to its substituents create lipids tailored for functions ranging from long-term energy storage to the formation of dynamic cellular membranes and sophisticated signaling cascades.

Structural Classes of Glycerolipids

The glycerol backbone gives rise to several major classes of lipids, primarily classified based on the nature of the groups attached to the three carbon positions. The table below summarizes the core structures and primary functions of the main glycerolipid classes.

Table 1: Major Classes of Glycerolipids and Their Core Characteristics

| Lipid Class | Backbone Substitutions | Core Structure | Primary Functions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Triacylglycerols (TAGs) [3] | Three fatty acids | Glycerol + 3 Fatty Acyl Chains | Energy storage, thermal insulation [3] |

| Phosphatidylcholine (PC) [4] | Two fatty acids, Phosphate-Choline | Glycerol + 2 Fatty Acyl Chains + Phosphate + Choline | Major eukaryotic membrane lipid; membrane structure and fluidity [3] [5] |

| Phosphatidylethanolamine (PE) [4] | Two fatty acids, Phosphate-Ethanolamine | Glycerol + 2 Fatty Acyl Chains + Phosphate + Ethanolamine | Inner leaflet of plasma membrane; membrane curvature [3] [5] |

| Phosphatidylserine (PS) [4] | Two fatty acids, Phosphate-Serine | Glycerol + 2 Fatty Acyl Chains + Phosphate + Serine | Apoptosis signaling, cell recognition [3] |

| Phosphatidylinositol (PI) [4] | Two fatty acids, Phosphate-Inositol | Glycerol + 2 Fatty Acyl Chains + Phosphate + Inositol | Precursor for intracellular signaling molecules [3] |

| Phosphatidylglycerol (PG) [4] | Two fatty acids, Phosphate-Glycerol | Glycerol + 2 Fatty Acyl Chains + Phosphate + Glycerol | Plant and bacterial membranes; precursor to Cardiolipin [6] |

| Cardiolipin (CL) [3] | Four fatty acids, Two Phosphates | Two Glycerol Backbones + 4 Fatty Acyl Chains + 2 Phosphates | Inner mitochondrial membrane function, apoptosis regulation [3] |

| Monogalactosyldiacylglycerol (MGDG) [6] | Two fatty acids, Monogalactose | Glycerol + 2 Fatty Acyl Chains + Galactose | Main lipid of thylakoid membranes in photosynthesis [7] [6] |

Triglycerides: Dietary Energy Reservoirs

Triacylglycerols (TAGs), or triglycerides, consist of a glycerol backbone esterified with three fatty acid molecules [3]. This structure makes them highly hydrophobic and inert, ideal for compact energy storage in lipid droplets within adipose tissue [3]. The fatty acid composition of dietary TAGs—namely, the chain length, degree of saturation, and precise position (sn-1, sn-2, or sn-3) on the glycerol backbone—directly influences their nutritional value, physical properties (like melting point), and metabolic processing in the body [8]. The hydrolysis of TAGs by lipases releases free fatty acids and glycerol, which can then be utilized for energy production or gluconeogenesis [1].

Phospholipids: Architects of the Cellular Membranes

Glycerophospholipids (or phospholipids) are amphipathic molecules in which the glycerol backbone's sn-1 and sn-2 positions are esterified with fatty acids, and the sn-3 position is linked to a phosphate group. This phosphate group is, in turn, often esterified to a polar head group such as choline, ethanolamine, serine, or inositol [4] [3]. This structure creates a molecule with a hydrophobic tail (the fatty acids) and a hydrophilic head, enabling the spontaneous formation of the lipid bilayer that constitutes all cellular membranes [2]. Phospholipids are not merely structural; they are functional molecules involved in signal transduction, membrane trafficking, and the regulation of membrane-protein interactions [9] [5].

Glycolipids and Specialized Glycerolipids

Glycolipids, such as the monogalactosyldiacylglycerol (MGDG) prevalent in plant chloroplast membranes, feature a sugar moiety attached directly to the glycerol backbone [7] [6]. Other complex glycerolipids include cardiolipin, a unique dimeric phospholipid essential for the function of mitochondrial respiratory complexes [3], and glycero-glycophospholipids like phosphatidylglucoside (PtdGlc), which contain both a phosphate and a sugar in their head group and are involved in cell differentiation and signaling [7].

Quantitative Composition and Physical Properties

The composition of fatty acids attached to the glycerol backbone is highly regulated and varies significantly between different lipid classes, tissues, and organellar membranes. This variation directly impacts membrane physical properties such as fluidity and rigidity.

Table 2: Representative Fatty Acid Compositions of Membrane Glycerophospholipids

| Fatty Acid Notation | Common Name | Typical Role in Membrane Properties | Prevalence in Phospholipids |

|---|---|---|---|

| C16:0 | Palmitic Acid | Saturated; increases membrane rigidity and order | Major component in PC, PE, PG [4] |

| C18:0 | Stearic Acid | Saturated; contributes to membrane packing and stability | Found in PC, PE, PS [4] |

| C18:1 | Oleic Acid | Monounsaturated; introduces kinks, enhances fluidity | Common in most phospholipid classes [4] |

| C18:2 | Linoleic Acid | Polyunsaturated; significantly increases fluidity | Found in various phospholipids, levels can vary with diet [4] |

| C18:3 (α) | α-Linolenic Acid (ALA) | Polyunsaturated; precursor for longer omega-3 fatty acids | Found in various phospholipids, levels can vary with diet [4] |

| C20:4 | Arachidonic Acid (AA) | Polyunsaturated; precursor for eicosanoid signaling molecules | Enriched in certain PI and PS pools for signaling [4] |

Table 3: Glycerolipid Distribution in Cellular Membranes (Mol % of Total Lipids)

| Lipid Class | Representative Cell (Plasma Membrane) | Neuron | Astrocyte | Mitochondrial Membrane (Inner) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Phosphatidylcholine (PC) | 45-55% [5] | ~40% [5] | ~40% [5] | ~40% [5] |

| Phosphatidylethanolamine (PE) | 15-25% [5] | ~15% [5] | ~20% [5] | ~35% [5] |

| Phosphatidylinositol (PI) | 10-15% [5] | ~2% [5] | ~5% [5] | <5% |

| Phosphatidylserine (PS) | 5-10% [5] | ~2% [5] | ~8% [5] | <5% |

| Cardiolipin (CL) | 2-5% [5] | <1% [5] | <1% [5] | ~15% [5] |

| Sphingolipids | 5-15% [5] | ~2% [5] | ~10% [5] | Low |

| Sterol Lipids | 10-20% [5] | ~40% [5] | ~25% [5] | Low |

Experimental Methodologies for Analysis

X-Ray Scattering for Nanostructural Analysis

Principle: X-ray scattering is an invaluable tool for investigating the nanostructural properties of crystalline triglycerides and the lamellar structures of phospholipid bilayers. Small-angle X-ray scattering (SAXS) provides information on long-range ordering, such as lamellar repeat distances, while wide-angle X-ray scattering (WAXS) reveals short-range ordering, including polymorphic forms and hydrocarbon chain packing [8].

Detailed Protocol for Triglyceride Polymorphism Analysis:

- Sample Preparation: Pure triglycerides or complex fat systems are melted and then crystallized under controlled temperature and cooling rates to promote the formation of a specific polymorph.

- Data Collection: Simultaneous SAXS and WAXS data are collected, typically using a synchrotron radiation source for high intensity and resolution. The scattering vector range of 0.05 < q < 7 nm⁻¹ is used for SAXS, and 7 < q < 20 nm⁻¹ for WAXS [8].

- Data Analysis:

- Lamellar Stacking: SAXS peaks are analyzed using Bragg's law to determine the long spacing, which corresponds to the distance between crystal lamellae.

- Polymorphic Identification: The short spacings from WAXS patterns are characteristic of the chain packing subcell (e.g., α, β', β) and are used to identify the polymorphic form [8].

- Electron Density Profile (EDP): SAXS data can be used to calculate the EDP, decomposing the lamellar repeat distance into bilayer and monolayer contributions.

- Crystallite Size: The Scherrer equation is applied to the full-width at half maximum (FWHM) of diffraction peaks to estimate the crystallite size and lattice strain [8].

- Chain Tilt and Area: The chain tilt angle within the bilayer and the area per hydrocarbon chain can be estimated by combining information from SAXS and WAXS data [8].

Enzymatic Synthesis of Complex Phospholipids

Principle: Phospholipase D (PLD) catalyzes the transphosphatidylation reaction, enabling the head group exchange of natural phospholipids to synthesize rare or complex phospholipid species in a sustainable and regioselective manner [10].

Detailed Protocol for Synthesis of Hemi-BMPs/BDPs:

- Reaction Setup: A phospholipid substrate (e.g., phosphatidylcholine from soy or egg) is dissolved in an appropriate buffer with a high concentration of an alcohol donor, such as a specific monoacylglycerol (MAG) or diacylglycerol (DAG) regioisomer.

- Enzymatic Catalysis: PLD from Streptomyces sp. is added to the mixture. The enzyme shows broad substrate promiscuity towards both phospholipids and alcohol donors.

- Reaction Monitoring: The reaction is typically carried out for about 2 hours and monitored by thin-layer chromatography (TLC) to track the consumption of the starting material and the formation of the target phospholipid, such as Hemi-bis(monoacylglycero)phosphate (Hemi-BMP) or bis(diacylglycero)phosphate (BDP).

- Product Isolation: The reaction is stopped, and the products are extracted using organic solvents (e.g., chloroform/methanol). The target complex phospholipid is purified using successive column chromatography techniques, yielding a pure product as confirmed by NMR and mass spectrometry [7] [10].

Mass Spectrometry-Based Lipidomics

Principle: Modern mass spectrometry (MS), particularly coupled with liquid chromatography (LC), allows for the comprehensive identification and quantification of thousands of individual lipid species from complex biological extracts. This is crucial for profiling alterations in glycerolipid metabolism in disease states like Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis (ALS) [5].

Detailed Workflow:

- Lipid Extraction: Lipids are extracted from tissues, cells, or biofluids using a validated method like Bligh and Dyer, ensuring the recovery of a broad range of glycerolipid classes.

- Chromatographic Separation: The extract is subjected to LC separation, often using reverse-phase columns, to reduce sample complexity and ion suppression before MS analysis.

- Mass Spectrometry Analysis: The eluting lipids are analyzed using high-resolution mass spectrometers. Data-Dependent Acquisition (DDA) or Data-Independent Acquisition (DIA) modes can be used to fragment ions and obtain structural information.

- Data Processing and Integration: Specialized software is used to align peaks, identify lipid species based on their mass-to-charge ratio and fragmentation patterns, and perform relative or absolute quantification. The data is often integrated into resources like the Neurolipid Atlas for cross-study comparison [5].

Pathways and Workflows: A Visual Guide

Glycerophospholipid Biosynthesis Pathway

Diagram Title: Glycerophospholipid Biosynthesis Network

Lipidomics Experimental Workflow

Diagram Title: Lipidomics Analysis Pipeline

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 4: Key Reagents and Materials for Glycerolipid Research

| Reagent/Material | Function in Research | Specific Application Example |

|---|---|---|

| Phospholipase D (PLD) | Catalyzes transphosphatidylation for headgroup exchange | Sustainable synthesis of complex phospholipids like Hemi-BMPs from natural PC [10] |

| Synchrotron X-ray Source | Provides high-intensity, tunable X-ray radiation | High-resolution SAXS/WAXS for analyzing triglyceride polymorphic structures and transitions [8] |

| Deuterated Solvents (e.g., CDCl₃) | NMR-active solvents for structural analysis | Determining the structure and stereochemistry of novel glycerolipids like phosphatidylglucoside (PtdGlc) [7] |

| Silica Gel Stationary Phase | Medium for chromatographic separation | Purification of specific glycerolipid classes (e.g., PC, PE) or individual molecular species from complex extracts [7] [4] |

| High-Purity Acyl-CoA Donors | Activated fatty acid donors for enzymatic acylation | Substrates for in vitro studies of glycerol-3-phosphate acyltransferases (GPATs) in phosphatidic acid synthesis [5] |

| Specific Antibodies | Immunodetection of rare lipids | Identification and localization of trace glycero-glycophospholipids like PtdGlc in tissue sections [7] |

The glycerol backbone is a testament to evolutionary parsimony, where a simple molecular scaffold has been leveraged to generate an extensive library of complex lipids through regioselective biochemical decoration. The structural diversity arising from this platform directly underpins the functional dichotomy between triglycerides as energy reservoirs and phospholipids as membrane architects and signaling mediators. A deep understanding of the chemical principles governing this diversity—including fatty acid chain geometry, head group identity, and biosynthetic pathways—is fundamental for research fields ranging from nutritional science and membrane biophysics to drug delivery and the study of neurodegenerative diseases. Continued advancements in analytical techniques like X-ray scattering and lipidomics, coupled with enzymatic synthesis methods, promise to further unravel the complexities of glycerolipid function and their roles in health and disease.

A triglyceride, also known as triacylglycerol (TAG), is a central chemical entity in lipid science, defined as an ester derived from the alcohol glycerol and three fatty acid molecules [11]. This structure serves as the main constituent of body fat in humans, other vertebrates, and vegetable fat [11]. Within the context of dietary lipids and phospholipids research, the triglyceride structure represents the primary form of energy storage and dietary lipid intake, contrasting with the bilayer-forming, structural role of phospholipids [12] [13]. The compositional specificity and structural differences between triglycerides and structural polar lipids, such as the complete "inversion" of fatty acid distribution observed in tissues like pig kidney, point to distinct biosynthetic pathways and functional roles within organisms [13]. A precise understanding of the triglyceride molecule—its isomeric forms, polymorphic crystal behavior, and structure-function relationships—is foundational for research aimed at developing therapeutics for conditions like hypertriglyceridemia, a significant risk factor for cardiovascular and metabolic diseases [14] [15] [16].

Structural Composition and Molecular Geometry

The fundamental architecture of a triglyceride consists of a glycerol backbone serving as a three-carbon hub, with each of its hydroxyl groups esterified to a fatty acid carboxyl group [11] [17]. The three fatty acid substituents can be identical, forming a simple triglyceride (e.g., tristearin), but are most often different, resulting in a mixed triglyceride [11] [12]. The specific positions of these fatty acids on the glycerol molecule are designated using stereospecific numbering (sn) as sn-1, sn-2, and sn-3 [11].

- Glycerol Backbone: A triol (three hydroxyl groups) that forms the structural core of the molecule [18].

- Fatty Acids: Long-chain carboxylic acids with varying lengths (typically 16, 18, or 20 carbon atoms) and degrees of saturation [11] [19]. The chain length and saturation determine the physical and metabolic properties of the triglyceride.

- Ester Bonds: The chemical linkage formed from the reaction between each glycerol hydroxyl group and a fatty acid carboxyl group, releasing a water molecule per esterification [11] [17].

The chain lengths of the fatty acids and their placement on the glycerol backbone are not random. In many natural fats, the distribution is regiospecific. For instance, in most vegetable oils, the saturated palmitic (C16:0) and stearic (C18:0) acid residues are typically attached to positions sn-1 and sn-3, whereas the middle position (sn-2) is usually occupied by an unsaturated fatty acid, such as oleic (C18:1, ω–9) or linoleic (C18:2, ω–6) [11]. This regiochemistry has profound implications for the triglyceride's physical behavior, its digestion by lipases, and its biological effects [12].

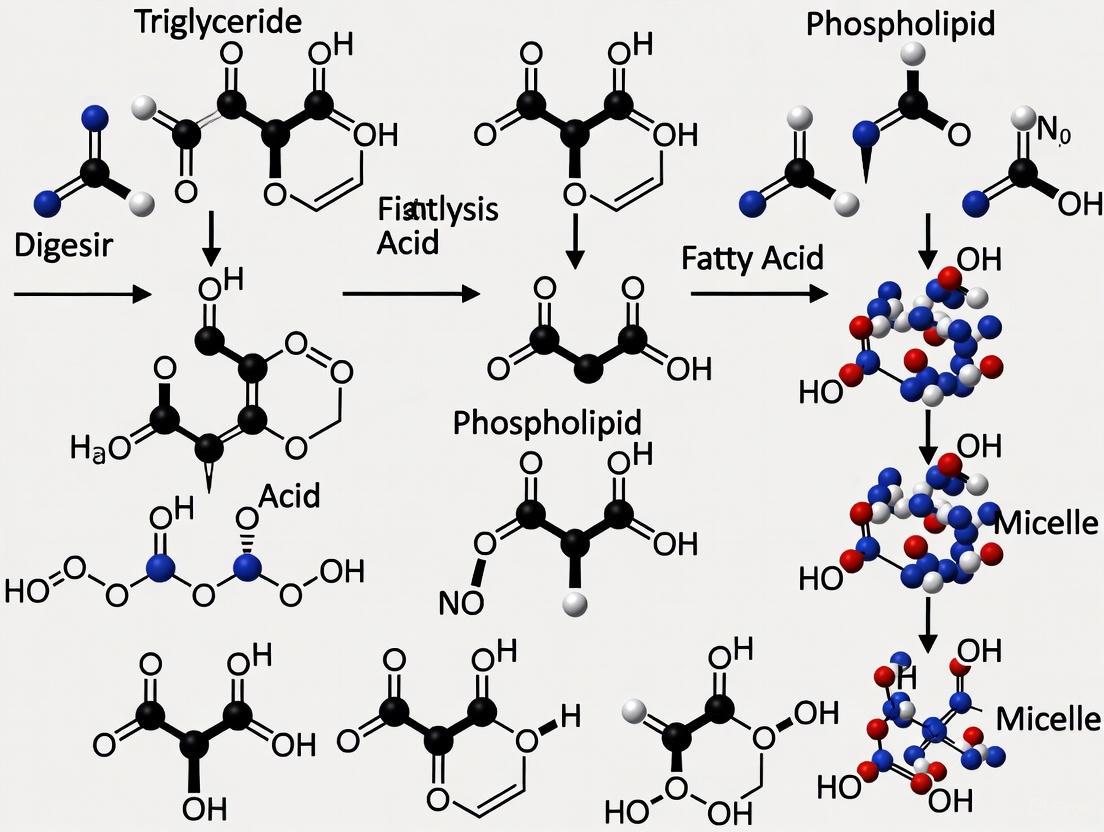

Visualizing Triglyceride Structure and Biosynthesis

The following diagram illustrates the esterification reaction that forms a triglyceride and highlights the stereospecific numbering of the glycerol backbone.

Classification and Physical Properties

Triglycerides are classified based on the chemical nature of their constituent fatty acids, which directly dictates their physical state and metabolic fate.

- Saturated Triglycerides: Composed of triglycerides where all fatty acids contain no carbon-carbon double bonds (C=C groups). The carbon chains are "saturated" with hydrogen atoms, allowing them to pack tightly. This results in a higher melting point, making them solids (fats) at room temperature (e.g., stearin from animal tallow) [11] [19].

- Unsaturated Triglycerides: Contain one or more fatty acids with at least one double bond. This introduces "kinks" (cis configuration) in the hydrocarbon chain, preventing tight packing and leading to a lower melting point. They are often liquids (oils) at room temperature (e.g., triolein in olive oil) [11] [19].

- Monounsaturated (MUFA): One double bond in the fatty acid chains.

- Polyunsaturated (PUFA): Two or more double bonds in the fatty acid chains.

The physical properties of triglycerides, such as melting point and density, are heavily influenced by their molecular structure. Saturated fats have higher melting points than unsaturated analogs with the same molecular weight [11]. Furthermore, even a single triglyceride species can exist in multiple crystalline forms known as polymorphs (α, β, and β'), which differ in their melting points and packing geometries [11] [8]. This polymorphic behavior is critical in food science (e.g., chocolate tempering) and pharmaceutical development.

Quantitative Data: Fatty Acid Chain Length and Melting Behavior

The table below summarizes the classification of triglycerides based on fatty acid chain length and provides examples with their typical physical states.

Table 1: Classification of Triglycerides by Fatty Acid Chain Length and Saturation

| Classification | Chain Length (Carbons) | Example | Physical State at Room Temp | Common Sources |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Long-Chain | 16, 18, 20 | Tristearin (C18:0) | Solid | Animal fats (tallow, lard), cocoa butter [11] |

| Medium-Chain | Shorter than C16 | Triacylglycerols with C8-C12 | Liquid/Semi-solid | Coconut oil, palm kernel oil [11] |

| Saturated | Varies (no C=C bonds) | Tristearin | Solid | Butter, cheese, lard [11] [18] |

| Monounsaturated | Varies (one C=C bond) | Triolein | Liquid | Olive oil, canola oil, peanuts [11] [19] |

| Polyunsaturated | Varies (≥ two C=C bonds) | Linoleic/Linolenic acids | Liquid | Soybean oil, corn oil, fatty fish [11] [19] |

Analytical and Experimental Protocols

Understanding triglyceride structure and function requires robust analytical methods. Enzymatic assays are standard for concentration measurement, while X-ray scattering techniques provide deep insights into crystalline nanostructure.

Standard Enzymatic Assay for Triglyceride Quantification

This protocol is widely used in clinical and research settings to determine triglyceride concentrations in biological samples like serum [15].

Principle: Triglycerides are hydrolyzed to glycerol and free fatty acids. The glycerol is then enzymatically quantified through a series of coupled reactions that produce a colored chromogen, the intensity of which is proportional to the original triglyceride concentration [15].

Detailed Workflow:

Hydrolysis:

Triglyceride + H₂O → Lipoprotein Lipase → Glycerol + 3 Fatty Acids[15]Phosphorylation:

Glycerol + ATP → Glycerol Kinase → Glycerol-3-phosphate[15]Oxidation:

Glycerol-3-phosphate + O₂ → Glycerol-3-phosphate Oxidase → Dihydroxyacetone Phosphate + H₂O₂[15]Chromogen Formation (Color Reaction):

H₂O₂ + 4-Aminoantipyrine (4-AAP) + 4-Chlorophenol → Peroxidase → Quinoneimine Dye (Red) + H₂O[15]

Materials and Reagents [15]:

- Working Reagent: Contains lipoprotein lipase, ATP, glycerol kinase, glycerol-3-phosphate oxidase, peroxidase, 4-AAP/4-aminophenazone, and 4-chlorophenol.

- Triglyceride Standard (200 mg/dL).

- Sample: Serum or heparinized plasma.

- Equipment: Spectrophotometer, test tubes, pipettes.

Procedure [15]:

- Pipette into labeled test tubes (Blank, Standard, Test):

- Blank: 0.01 mL Water + 1 mL Working Reagent

- Standard: 0.01 mL Triglyceride Standard + 1 mL Working Reagent

- Test: 0.01 mL Sample + 1 mL Working Reagent

- Mix and incubate for 10 minutes at room temperature.

- Measure absorbance of Standard (ODS) and Test (ODT) against the Blank at 505 nm.

Calculation [15]: Triglyceride Concentration (mg/dL) = [(ODT – ODB) / (ODS – ODB)] × Concentration of Standard (200 mg/dL)

X-Ray Scattering for Polymorph and Nanostructure Analysis

X-ray scattering is an invaluable tool for characterizing the nanostructural aspects of pure triglycerides and complex fat systems, providing data on polymorphic states, phase transitions, and crystallite size [8].

Key Techniques:

- Small-Angle X-Ray Scattering (SAXS): Reveals information about lamellar stacking and long-range ordering (repeat distances ~0.05 < q < 7 nm⁻¹) [8].

- Wide-Angle X-Ray Scattering (WAXS): Provides details about the polymorphic state and chain packing density within the crystal lattice (q ~7 < 20 nm⁻¹) [8].

Experimental Data Analysis Workflow [8]:

- Data Collection: Perform SAXS/WAXS on triglyceride samples under controlled temperature conditions to monitor crystallization and melting.

- Electron Density Profile (EDP) Calculation: Decomposes the lamellar repeat distance (from SAXS) into bilayer and monolayer contributions.

- Chain Tilt Angle Estimation: Determines the inclination of hydrocarbon chains within the crystal structure.

- Crystallite Size and Strain Analysis: Uses peak broadening (e.g., Scherrer equation) to estimate the size of ordered crystalline domains.

- Area Per Hydrocarbon Chain Calculation: Provides insights into packing geometry and density.

Visualizing the Enzymatic Assay Workflow

The following diagram outlines the sequential reactions in the standard enzymatic assay for triglyceride quantification.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents and Materials

This section details essential reagents, compounds, and materials used in triglyceride research, from basic analysis to advanced drug development.

Table 2: Essential Reagents and Materials for Triglyceride Research

| Reagent/Material | Function/Description | Research Application |

|---|---|---|

| Lipoprotein Lipase (LPL) | Key enzyme hydrolyzing triglycerides in lipoprotein particles [15]. | Triglyceride clearance studies; enzymatic assay reagent [15]. |

| Olezarsen (IONIS-APOCIII-LRx) | An investigational antisense oligonucleotide targeting apolipoprotein C-III mRNA [16]. | Phase III clinical trial drug for lowering triglycerides in high-risk patients [16]. |

| SEFA-1024 (NorthSea Therapeutics) | An oral, semi-synthetic eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA) derivative [14]. | Phase II investigational drug for severe hypertriglyceridemia (sHTG) [14]. |

| 4-Aminoantipyrine (4-AAP) | Chromogenic substrate that forms a red quinoneimine dye with H₂O₂ [15]. | Colorimetric detection in enzymatic triglyceride quantification assays [15]. |

| GC304 (Genecradle Therapeutics) | A recombinant adeno-associated virus (AAV) vector carrying the LPL gene [14]. | Phase I gene therapy for severe hypertriglyceridemia via long-term LPL expression [14]. |

| Working Reagent (Enzymatic Kit) | Pre-mixed solution containing all necessary enzymes (lipase, GK, GPO), co-factors (ATP), and chromogens [15]. | Standardized high-throughput measurement of serum/plasma triglyceride levels [15]. |

Research and Clinical Implications

The detailed understanding of triglyceride structure directly informs drug discovery and clinical management of dyslipidemias. Elevated triglycerides (hypertriglyceridemia) are an independent risk factor for atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD) and pancreatitis [15] [16]. Modern therapeutic strategies are moving beyond general lipid-lowering to target specific pathways involved in triglyceride metabolism.

A prominent example is Olezarsen, an apolipoprotein C-III (apoC-III) targeting drug. Apolipoprotein C-III inhibits the activity of lipoprotein lipase (LPL), the enzyme responsible for hydrolyzing triglycerides in circulating lipoproteins [16]. By reducing apoC-III production, Olezarsen enhances triglyceride clearance. In the recent ESSENCE-TIMI 73b Phase III trial, monthly subcutaneous Olezarsen injections in patients with moderate hypertriglyceridemia and high cardiovascular risk resulted in an approximate 60% reduction in triglyceride levels at 6 months compared to placebo, with over 80% of patients achieving normal triglyceride levels (<150 mg/dL) [16]. This demonstrates how targeting a specific regulatory protein, rooted in a deep understanding of triglyceride metabolism, can yield potent therapeutic effects.

Other innovative approaches in the pipeline include:

- Gene Therapy: GC304, an AAV vector carrying the beneficial LPLS447X gene variant, aims to provide long-term enzymatic activity to degrade triglycerides [14].

- Multi-Agonists: DR10624 is a first-in-class long-acting tri-agonist targeting FGF21R, GLP-1R, and GCGR, showing promise in reducing body weight and triglycerides in preclinical studies [14].

These advancements underscore the critical role of fundamental structural biology in driving translational research and developing next-generation therapeutics for metabolic diseases.

Phospholipids represent a critically important class of lipids that serve as the fundamental architectural components of all biological membranes. These amphipathic molecules possess a unique molecular structure that enables the formation of lipid bilayers—the primary matrix of cellular membranes that separates intracellular components from the extracellular environment while facilitating selective transport and cellular communication [20] [21]. The defining characteristic of phospholipids is their amphipathic nature, which arises from a molecular structure consisting of a hydrophilic, phosphate-containing head group and two hydrophobic fatty acid tails [21] [22]. This structural duality allows phospholipids to spontaneously organize into complex supramolecular structures in aqueous environments, making them indispensable for cellular life and increasingly valuable in pharmaceutical applications.

Within the broader context of research on the chemical structure of dietary triglycerides and phospholipids, understanding phospholipid structure is paramount. While triglycerides serve primarily as energy storage molecules with three fatty acid chains attached to a glycerol backbone, phospholipids exhibit a more complex structural arrangement with distinct polar and non-polar regions that confer membrane-forming capabilities [23] [21]. This review provides a comprehensive technical examination of phospholipid structure, experimental characterization methodologies, and emerging applications in pharmaceutical research, with particular emphasis on the relationship between molecular structure and biological function.

Molecular Architecture of Phospholipids

Fundamental Structural Components

The molecular architecture of phospholipids consists of four principal components that together create the amphipathic character essential for their biological function. These components include a glycerol backbone that serves as the structural foundation, two hydrophobic fatty acid tails that provide the hydrophobic barrier function, a phosphate group that introduces negative charge and polarity, and a variable alcohol-derived head group that determines the specific chemical identity and properties of the phospholipid [20] [21] [22].

The glycerol backbone forms the central core of the phospholipid molecule, with three carbon atoms typically designated as sn-1, sn-2, and sn-3 according to stereospecific numbering convention. The sn-1 and sn-2 positions are esterified with fatty acid chains, while the sn-3 position is linked to a phosphate group [22]. This arrangement creates the fundamental platform upon which the amphipathic character of the molecule is built. The fatty acid tails attached to the glycerol backbone are long hydrocarbon chains typically consisting of 14-24 carbon atoms that may be either saturated (containing no double bonds) or unsaturated (containing one or more double bonds) [20] [22]. The degree of saturation and chain length significantly influences the packing efficiency and fluidity of the membranes formed by phospholipids, with unsaturated chains introducing kinks that prevent tight packing and increase membrane fluidity.

The phosphate group connected to the sn-3 position of the glycerol backbone consists of a phosphorus atom bonded to four oxygen atoms in a tetrahedral arrangement, with one oxygen atom forming a phosphoester bond with glycerol [21]. This group carries a negative charge under physiological pH conditions, contributing significantly to the hydrophilic nature of the phospholipid head region. The head group is attached to the phosphate group through a phosphoester bond and determines the specific class and chemical properties of the phospholipid [20] [22]. Common naturally occurring head groups include choline (forming phosphatidylcholine), ethanolamine (forming phosphatidylethanolamine), serine (forming phosphatidylserine), inositol (forming phosphatidylinositol), and glycerol (forming phosphatidylglycerol). The chemical diversity of these head groups imparts distinct biophysical properties, charge characteristics, and biological functionalities to different phospholipid classes.

Classification and Structural Variants

Phospholipids are classified based on the nature of their head group, backbone structure, and fatty acid composition. The major classes of glycerophospholipids include phosphatidylcholine (PC), phosphatidylethanolamine (PE), phosphatidylserine (PS), phosphatidylinositol (PI), phosphatidylglycerol (PG), and phosphatidic acid (PA) [20]. Each class exhibits distinct charge characteristics, hydrogen-bonding capabilities, and membrane properties that influence biological function. For instance, phosphatidylcholine and phosphatidylethanolamine are zwitterionic under physiological conditions, while phosphatidylserine carries a net negative charge and phosphatidylinositol can be phosphorylated at multiple positions to create signaling molecules such as PIP₂ (phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate) [20].

The structural notation for phospholipids follows a standardized convention that specifies the head group type and the fatty acid composition. For example, PC(16:0/18:1) denotes a phosphatidylcholine molecule with a palmitic acid (16:0, saturated) at the sn-1 position and an oleic acid (18:1, monounsaturated) at the sn-2 position [22]. This notation provides precise information about the molecular structure that correlates with physical properties such as phase transition temperature, membrane curvature, and lateral organization.

Table 1: Major Phospholipid Classes and Their Structural Characteristics

| Phospholipid Class | Head Group | Charge at pH 7.4 | Abundance in Mammalian Membranes | Key Structural Features |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Phosphatidylcholine (PC) | Choline | Zwitterionic | 40-50% | Cylindrical shape; promotes bilayer formation |

| Phosphatidylethanolamine (PE) | Ethanolamine | Zwitterionic | 20-25% | Conical shape; promotes hexagonal phases |

| Phosphatidylserine (PS) | Serine | Negative | 5-10% | Localized to inner leaflet; apoptosis marker |

| Phosphatidylinositol (PI) | Inositol | Negative | 5-10% | Signaling precursor; can be phosphorylated |

| Phosphatidylglycerol (PG) | Glycerol | Negative | 1-2% | Mitochondrial membrane component |

| Phosphatidic Acid (PA) | Hydrogen | Negative | <1% | Signaling lipid; small head group |

Sphingophospholipids represent another important category of phospholipids that utilize sphingosine rather than glycerol as their backbone. The most prominent member of this class is sphingomyelin, which contains a phosphocholine head group attached to a ceramide unit [20]. Sphingomyelin is particularly abundant in the myelin sheath of nerve cells and forms lipid rafts—specific membrane microdomains involved in cellular signaling. The structural diversity of phospholipids extends to ether-linked variants such as plasmalogens, which contain a vinyl ether linkage at the sn-1 position and are particularly enriched in neural and cardiac tissues.

Amphipathic Nature and Self-Assembly Behavior

The Amphipathic Design Principle

The amphipathic character of phospholipids represents their most defining structural feature, with clear spatial segregation between hydrophilic and hydrophobic regions. The hydrophilic component encompasses the phosphate group and its associated head group, which exhibit polarity and hydrogen-bonding capacity that favors interactions with aqueous environments [21]. In contrast, the hydrophobic component consists of the fatty acid tails, which are nonpolar and exclusively interact with other hydrophobic moieties through van der Waals interactions [21]. This molecular duality drives the spontaneous self-assembly of phospholipids into complex supramolecular structures when dispersed in aqueous solutions.

The amphipathic nature of phospholipids can be visualized through their molecular representation, which shows distinct spatial regions with different solubility parameters. The hydrophilic head orients toward aqueous phases, while the hydrophobic tails minimize contact with water by associating with other hydrophobic chains. This molecular organization arises from the thermodynamic driving force to maximize favorable interactions (head-water and tail-tail) while minimizing unfavorable ones (tail-water). The resulting reduction in free energy provides the impetus for self-assembly processes that create biologically essential structures [21].

Supramolecular Assemblies and Phase Behavior

Depending on concentration, temperature, and molecular structure, phospholipids can form various lyotropic liquid crystalline phases including micelles, bilayers, and hexagonal phases. The critical packing parameter (CPP), defined as CPP = v/(a₀·l), where v is the hydrocarbon chain volume, a₀ is the optimal head group area, and l is the chain length, predicts the preferred supramolecular arrangement [24]. Phospholipids with relatively large head groups and single-chain tails typically form spherical or cylindrical micelles, while those with two hydrocarbon chains and moderate head group sizes preferentially assemble into bilayers [21].

The lipid bilayer represents the most biologically significant supramolecular structure formed by phospholipids. In this arrangement, two monolayers of phospholipids associate tail-to-tail to form a planar sheet approximately 5 nm thick, with the hydrophilic head groups facing the aqueous environment on both sides and the hydrophobic tails forming a continuous internal hydrocarbon core [21]. This configuration effectively separates two aqueous compartments while providing a two-dimensional fluid matrix for membrane proteins. The bilayer structure forms the fundamental architecture of all cellular membranes, including the plasma membrane and various organellar membranes.

Table 2: Phospholipid Self-Assembly Structures and Their Characteristics

| Assembly Structure | Molecular Shape | Critical Packing Parameter | Typical Phospholipids | Biological Relevance |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Micelle | Cone-shaped | < 1/3 | Lysophospholipids | Lipid digestion, bile acids |

| Bilayer | Cylindrical | ~1 | Phosphatidylcholine | Cellular membranes |

| Hexagonal II (HII) | Inverted cone | > 1 | Phosphatidylethanolamine | Membrane fusion, protein function |

| Cubic Phase | Complex | ~1 | Mixtures | Membrane organization, protein crystallization |

The phase behavior of phospholipids is strongly influenced by temperature, hydration, and molecular structure. Phospholipids undergo thermotropic phase transitions between ordered gel phases and disordered fluid phases at characteristic temperatures known as transition temperatures (Tₘ) [24]. Below Tₘ, the hydrocarbon chains exist in an extended, all-trans conformation and exhibit limited lateral mobility. Above Tₘ, the chains contain gauche conformers that introduce kinks, increasing free volume and enabling lateral diffusion of membrane components. This phase behavior is critically important for membrane function, as biological membranes must maintain fluidity for proper functionality while providing sufficient structural integrity.

Experimental Characterization of Phospholipid Structure

Physicochemical Analysis Techniques

The structural characterization of phospholipids employs a diverse array of biophysical techniques that provide complementary information about molecular organization, phase behavior, and dynamic properties. Differential scanning calorimetry (DSC) measures the heat capacity changes associated with phase transitions, providing quantitative data on transition temperatures, enthalpies, and cooperativity [24]. Isothermal titration calorimetry (ITC) characterizes the thermodynamics of phospholipid interactions with other molecules, including drugs, proteins, and membrane-active compounds.

X-ray scattering (XRD) techniques, including small-angle X-ray scattering (SAXS) and wide-angle X-ray scattering (WAXS), provide detailed structural information about phospholipid assemblies [8] [24]. SAXS measures long-range organization such as lamellar repeat distances in multilamellar vesicles, while WAXS characterizes short-range molecular packing including chain-chain distances and tilt angles. Fourier-transform infrared (FT-IR) spectroscopy probes vibrational modes that are sensitive to conformational order, hydration status, and inter-molecular interactions, particularly in the hydrocarbon chain region [24].

Nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopy, especially ³¹P-NMR and ²H-NMR, provides insights into head group orientation and chain dynamics, respectively [20] [24]. ³¹P-NMR is particularly valuable for characterizing phospholipid head group conformation and phase identification, while ²H-NMR using deuterated chains reveals order parameters that quantify the degree of orientational constraint along the fatty acid chains. Fluorescence spectroscopy utilizing environment-sensitive fluorophores provides information about membrane fluidity, lateral organization, and phase separation in phospholipid membranes [24].

Analytical Methodologies for Structural Elucidation

The comprehensive structural analysis of phospholipid mixtures requires sophisticated analytical separation and detection methods. High-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) coupled with evaporative light scattering detection (ELSD) enables separation and relative quantification of different phospholipid classes based on their polar head groups [20]. Mass spectrometry, particularly electrospray ionization mass spectrometry (ESI-MS) and matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization (MALDI-MS), provides detailed information about molecular mass, fatty acyl composition, and regiospecific distribution [22].

Mass spectrometric analysis of phospholipids involves multiple stages, beginning with lipid extraction using organic solvents such as chloroform-methanol mixtures. The extracted lipids are then separated by normal-phase HPLC according to head group polarity or by reversed-phase HPLC based on fatty acyl chain characteristics [22]. Tandem mass spectrometry (MS/MS) with collision-induced dissociation generates characteristic fragment patterns that enable structural identification, including determination of fatty acyl regiospecificity (sn-1 versus sn-2 position) [22]. This analytical approach has been instrumental in establishing lipidomics as a comprehensive methodology for quantifying and characterizing complete phospholipid profiles in biological systems.

Diagram 1: Experimental workflow for comprehensive phospholipid analysis showing the integration of multiple analytical techniques for structural characterization.

Research Reagent Solutions for Phospholipid Studies

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Phospholipid Structural Analysis

| Research Reagent | Composition/Type | Experimental Function | Key Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Synthetic Phospholipids | DPPC, DOPC, DSPC, POPC | Defined model membranes | Phase behavior studies, membrane protein research |

| Natural Phospholipid Extracts | Soy PC, Egg PC, Liver PI | Biologically relevant mixtures | Membrane biophysics, lipidomics |

| Fluorescent Probes | DPH, NBD-PE, Laurdan | Membrane environment sensors | Fluidity measurements, lipid domain visualization |

| Deuterated Lipids | DMPC-d₅₄, DPPC-d₆₂ | NMR spectroscopy standards | Molecular dynamics, order parameter determination |

| Spin-Labeled Lipids | DOXYL, TEMPO derivatives | EPR spectroscopy | Membrane dynamics, oxygen permeability |

| Lipid Standards | Odd-chain, deuterated | Mass spectrometry | Quantitative lipidomics, identification |

Structural Determinants of Membrane Organization

Lipid Bilayer Formation and Properties

The spontaneous formation of phospholipid bilayers represents the structural foundation of biological membranes. When phospholipids are dispersed in aqueous solution, they spontaneously self-assemble into closed bilayered vesicles known as liposomes [21]. These structures typically range from 50 nm to several micrometers in diameter and encapsulate an aqueous interior, providing a model system for studying membrane properties and functions. The driving force for bilayer formation is the hydrophobic effect, which promotes the sequestration of hydrocarbon chains from water while maintaining favorable interactions between hydrophilic head groups and the aqueous environment [21].

The fluid mosaic model describes the biological membrane as a two-dimensional fluid matrix in which phospholipids can diffuse laterally while proteins and other components are embedded [20]. This model emphasizes the dynamic nature of membranes, with phospholipid molecules exhibiting rapid lateral diffusion (approximately 10⁻⁸ cm²/s) and slower transbilayer movement (flip-flop). Membrane fluidity is modulated by several structural factors including fatty acyl chain length, degree of unsaturation, cholesterol content, and temperature. Shorter chains and cis-unsaturated bonds increase fluidity by reducing packing efficiency, while longer saturated chains and cholesterol decrease fluidity [21].

Asymmetric Distribution and Lateral Organization

Biological membranes exhibit asymmetric distribution of phospholipid classes between the inner and outer leaflets. In eukaryotic plasma membranes, phosphatidylcholine and sphingomyelin are predominantly located in the outer leaflet, while phosphatidylethanolamine, phosphatidylserine, and phosphatidylinositol are concentrated in the inner leaflet [20]. This asymmetry is generated and maintained by ATP-dependent lipid transporters such as flippases, floppases, and scramblases. Phospholipid asymmetry has functional consequences for membrane properties, protein recruitment, and cellular signaling, with the exposure of phosphatidylserine in the outer leaflet serving as an important signal for apoptosis.

In addition to transverse asymmetry, biological membranes exhibit lateral heterogeneity with the formation of specialized microdomains known as lipid rafts. These nanoscale domains are enriched in sphingolipids, cholesterol, and specific membrane proteins, and function as organizing centers for cellular signaling [20]. The structural basis for raft formation lies in the preferential packing between saturated sphingolipids and cholesterol, which creates liquid-ordered phases that coexist with the more disordered bulk membrane environment. This lateral organization enables the spatial segregation of signaling components and contributes to the regulation of cellular processes.

Advanced Structural Applications in Pharmaceutical Research

Phospholipids in Drug Delivery Systems

The amphipathic nature and self-assembly properties of phospholipids make them invaluable excipients in pharmaceutical formulations, particularly for advanced drug delivery systems. Liposomes—spherical vesicles consisting of one or more phospholipid bilayers—represent the most extensively developed phospholipid-based delivery platform [20] [25]. These nanostructures can encapsulate hydrophilic drugs within their aqueous interior or incorporate hydrophobic drugs within the lipid bilayer, providing protection from degradation, modifying biodistribution, and enabling controlled release kinetics.

The structural properties of component phospholipids determine critical characteristics of liposomal formulations including size, surface charge, membrane fluidity, and stability. Saturated phospholipids with high phase transition temperatures (e.g., DSPC) form rigid, less permeable bilayers that extend drug retention, while unsaturated phospholipids (e.g., DOPC) create more fluid membranes that enhance release rates [20]. Surface modification with polyethylene glycol (PEG)-conjugated phospholipids creates steric stabilization that reduces opsonization and extends circulation half-life—a key advancement known as PEGylation [25].

Recent innovations in phospholipid-based delivery systems include lipid nanoparticles (LNPs) for nucleic acid delivery, ethosomal systems for enhanced transdermal penetration, and targeted liposomes functionalized with ligands for specific cell types [20] [25]. The successful deployment of LNPs for mRNA COVID-19 vaccines highlights the pharmaceutical importance of phospholipid-based delivery systems, where ionizable phospholipids form complex structures that protect nucleic acid payloads and facilitate cellular uptake [25].

Structural Considerations in Formulation Development

The rational design of phospholipid-based drug delivery systems requires comprehensive understanding of structure-function relationships. Key structural parameters include head group chemistry, fatty acyl chain length and saturation, and regiospecific distribution of fatty acids. For instance, the molecular shape of phospholipids—determined by the relative cross-sectional areas of the head group and acyl chains—influences membrane curvature and fusogenicity [26]. Cone-shaped lipids such as phosphatidylethanolamine promote negative curvature and facilitate membrane fusion, while inverted cone-shaped lysophospholipids induce positive curvature.

The positional distribution of fatty acids on the glycerol backbone significantly impacts biological activity and metabolic fate. Phospholipids with docosahexaenoic acid (DHA) at the sn-2 position adopt a hairpin conformation that facilitates enzymatic recognition and membrane integration, while sn-1 DHA creates U-shaped configurations that profoundly influence membrane fluidity and protein interactions [26]. These structural nuances determine the pharmacological performance of phospholipid-based formulations including their stability, biodistribution, cellular uptake, and intracellular trafficking.

Diagram 2: Structure-function relationships in phospholipid-based drug delivery systems showing how molecular features influence pharmacological performance.

Emerging Research and Future Perspectives

Current Frontiers in Phospholipid Research

Recent advances in phospholipid research have revealed increasingly sophisticated structure-function relationships with important implications for pharmaceutical science. The 8th International Symposium on Phospholipids in Pharmaceutical Research (2024) highlighted several emerging areas including anisotropic lipid nanoparticles, tetraether lipids for enhanced stability, and multifunctional lipopeptides [25]. These developments leverage the unique structural properties of phospholipids to create increasingly sophisticated delivery platforms with enhanced targeting capabilities and improved pharmacokinetic profiles.

Structural phospholipidomics has emerged as a powerful approach for comprehensively characterizing phospholipid molecular species and their biological roles [26]. Advanced mass spectrometry techniques now enable detailed analysis of phospholipid regioisomers and stereoisomers, revealing previously unappreciated structural diversity. The position-specific effects of polyunsaturated fatty acids such as DHA are particularly significant, with sn-1 versus sn-2 localization dictating membrane biophysical properties and metabolic processing [26]. These insights are driving the development of structurally optimized phospholipids with tailored properties for specific therapeutic applications.

Future Directions and Applications

The evolving understanding of phospholipid structure continues to enable innovative applications in pharmaceutical technology and medicine. Current research directions include the design of stimuli-responsive phospholipids that undergo structural changes in response to specific triggers such as pH, enzymes, or light, enabling spatially and temporally controlled drug release [25]. Additionally, the integration of phospholipids with biomaterials and tissue engineering scaffolds creates biomimetic interfaces that modulate cellular responses and promote regeneration.

The development of synthetic phospholipids with non-natural head groups or tailored acyl chains represents another promising frontier [20]. These designer phospholipids can be engineered to exhibit specific properties such as enhanced stability, reduced immunogenicity, or selective enzymatic cleavage. Furthermore, the convergence of phospholipid research with gene therapy and RNA medicine is creating new opportunities for advanced delivery systems, as evidenced by the critical role of ionizable phospholipids in mRNA-LNP formulations [25]. As structural characterization techniques continue to advance, particularly with improvements in cryo-electron microscopy and molecular dynamics simulations, our understanding of phospholipid structure and function will continue to deepen, enabling increasingly sophisticated pharmaceutical applications.

The amphipathic structure of phospholipids, characterized by a phosphate-containing head group and hydrophobic fatty acid tails, represents a remarkable example of molecular design that enables fundamental biological processes and advanced pharmaceutical applications. The structural principles governing phospholipid self-assembly, membrane organization, and molecular interactions provide the foundation for understanding their diverse roles in biological systems and exploiting their properties for therapeutic benefit. Ongoing research continues to reveal new dimensions of phospholipid structural complexity, from position-specific effects of fatty acids to the sophisticated behavior of mixed lipid systems. These advances underscore the enduring importance of phospholipid structure as a rich area of scientific inquiry with significant implications for drug development and human health.

Lipids are a diverse group of hydrophobic or amphiphilic molecules that serve crucial structural and metabolic roles in biological systems. The fundamental classes of lipids include triglycerides, phospholipids, sterols, and waxes [27] [28]. While triglycerides, composed of a glycerol backbone esterified with three fatty acids, constitute more than 95% of dietary lipids and serve primarily as energy storage molecules, phospholipids represent a structurally and functionally distinct class [27] [19]. Phospholipids are amphiphilic molecules, featuring a glycerol backbone attached to two hydrophobic fatty acid "tails" and a hydrophilic phosphate-containing "head" group [27] [28]. This unique structure enables them to form the fundamental architectural matrix of all biological membranes and act as critical signaling molecules [27] [29] [30]. This whitepaper provides an in-depth technical examination of the four major classes of dietary phospholipids—phosphatidylcholine, phosphatidylethanolamine, phosphatidylserine, and sphingomyelin—framed within the broader context of chemical structure-function relationships in lipid research.

Structural Foundations: Glycerophospholipids vs. Sphingophospholipids

Dietary phospholipids are categorized based on their backbone structure into glycerophospholipids (phosphatidylcholine, phosphatidylethanolamine, phosphatidylserine) and sphingophospholipids (sphingomyelin).

Glycerophospholipids share a common structural blueprint: a glycerol backbone, where the sn-1 and sn-2 positions are esterified to fatty acids of varying chain lengths and saturation, and the sn-3 position is linked to a phosphate group. The identity of the phospholipid is determined by the specific alcohol moiety (e.g., choline, ethanolamine, serine) attached to this phosphate [27] [29] [30]. The fatty acid composition is highly variable, influencing the molecule's physical properties, such as membrane fluidity and melting point [19].

Sphingomyelin is distinct as a sphingophospholipid. Its backbone is sphingosine, an amino alcohol, rather than glycerol. A fatty acid is attached via an amide bond to the sphingosine, forming a ceramide. The primary hydroxyl group of ceramide is then esterified to phosphocholine, giving it a head group identical to phosphatidylcholine [31].

The following diagram illustrates this structural classification and biosynthesis pathway.

Detailed Analysis of Major Phospholipid Classes

Phosphatidylcholine (PC)

Chemical Structure: Phosphatidylcholine consists of a glycerol backbone esterified to two fatty acids and a phosphate group linked to a choline molecule [29]. It is a zwitterionic phospholipid at physiological pH due to the positive quaternary ammonium on choline and the negative phosphate group.

Biosynthesis: The primary pathway for PC synthesis in eukaryotes is the Kennedy pathway, which involves the condensation of diacylglycerol (DAG) with CDP-choline, catalyzed by diacylglycerol cholinephosphotransferase [29]. An alternative pathway in the liver involves the methylation of phosphatidylethanolamine using S-adenosyl methionine (SAM) as the methyl donor [29].

Dietary Sources and Commercial Production: PC is a major component of the lecithin group of substances. Commercial PC is often derived from soybean and egg yolk [29]. As a food emulsifier, it is commonly labeled as "lecithin."

Biological Functions:

- Membrane Integrity: PC is a fundamental building block of all biological membranes, predominantly located in the outer leaflet of the plasma membrane [29].

- Surfactant Function: Dipalmitoylphosphatidylcholine is a critical component of pulmonary surfactant, essential for reducing surface tension in the lungs [29].

- Signal Transduction: PC serves as a substrate for phospholipases, generating lipid second messengers, and is involved in membrane-mediated cell signaling [29].

Phosphatidylethanolamine (PE)

Chemical Structure: PE shares the glycerol backbone with two fatty acids but is esterified to an ethanolamine head group [30]. Its smaller head group creates a molecular cone shape, promoting membrane curvature.

Biosynthesis: PE can be synthesized via the CDP-ethanolamine pathway or by the decarboxylation of phosphatidylserine by phosphatidylserine decarboxylase in the mitochondrial membrane [30].

Dietary Sources: PE is abundant in nervous tissue, soy lecithin, and egg yolk [30].

Biological Functions:

- Membrane Curvature and Fusion: PE's molecular shape is crucial for facilitating membrane fusion and fission events, such as those in cell division and vesicle trafficking [30].

- Cellular Process Support: In bacteria, the principal phospholipid is PE, where it supports the proper folding and function of membrane transport proteins like lactose permease [30].

- Precursor Role: PE is a precursor for the synthesis of phosphatidylcholine (via methylation) and the endocannabinoid anandamide [30].

Phosphatidylserine (PS)

Chemical Structure: PS features a serine amino acid linked to the phosphate group on the glycerol backbone [32]. This gives it a net negative charge at physiological pH.

Biosynthesis: In mammals, PS is synthesized from pre-existing PC or PE via a Ca²⁺-dependent head-group exchange reaction catalyzed by phosphatidylserine synthase 1 or 2 in the endoplasmic reticulum [32].

Dietary Sources: PS is found in meat, fish, and offal. Soy lecithin is a notable plant source, containing about 3% PS of total phospholipids [32].

Biological Functions:

- Apoptotic Signal: A critical function of PS is its role in apoptosis. In healthy cells, PS is almost exclusively confined to the inner leaflet of the plasma membrane. During programmed cell death, PS rapidly translocates to the outer leaflet, acting as an "eat-me" signal for phagocytic cells to clear the dying cell [32].

- Signaling Cofactor: PS located in the cytoplasmic leaflet of the plasma membrane serves as a cofactor for several key signaling proteins, including Akt and Protein Kinase C (PKC), thereby stimulating processes like neuronal survival and growth [32].

Sphingomyelin (SM)

Chemical Structure: SM is built on a ceramide backbone (sphingosine plus a fatty acid) with a phosphocholine head group [31]. Its fatty acids tend to be longer and more saturated than those of glycerophospholipids.

Biosynthesis: SM is synthesized in the Golgi apparatus by the transfer of a phosphocholine group from PC to a ceramide, a reaction catalyzed by sphingomyelin synthase, which also produces diacylglycerol as a byproduct [31].

Dietary Sources: SM is found in animal cell membranes, with particularly high concentrations in the myelin sheath surrounding nerve cells, milk, and egg yolks [31].

Biological Functions:

- Myelin Formation: SM is a major constituent of the myelin sheath, providing insulation and facilitating rapid nerve conduction [31].

- Lipid Raft Formation: Due to its high transition temperature and strong interactions with cholesterol, SM is a key component of lipid rafts—ordered membrane microdomains involved in signal transduction and membrane trafficking [31].

- Signal Transduction: The hydrolysis of SM by sphingomyelinases generates ceramide, a potent lipid second messenger deeply involved in stress response, apoptosis, and cell senescence [31].

Table 1: Comparative Summary of Major Dietary Phospholipid Classes

| Feature | Phosphatidylcholine (PC) | Phosphatidylethanolamine (PE) | Phosphatidylserine (PS) | Sphingomyelin (SM) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Backbone Structure | Glycerol | Glycerol | Glycerol | Sphingosine (Ceramide) |

| Polar Head Group | Choline | Ethanolamine | Serine | Phosphocholine |

| Net Charge (pH 7) | Zwitterionic | Zwitterionic | Negative (-1) | Zwitterionic |

| Primary Location in Membrane | Outer & Inner Leaflet (more in outer) | Inner Leaflet (mainly) | Inner Leaflet (exclusively in viable cells) | Outer Leaflet (primarily) |

| Key Biological Functions | Membrane structure, pulmonary surfactant, signaling precursor | Membrane fusion, curvature, chaperone for membrane proteins | Apoptotic signaling, cofactor for PKC/Akt signaling | Myelin formation, lipid rafts, source of ceramide |

| Rich Dietary Sources | Egg yolk, soy lecithin, meat | Nervous tissue, soy lecithin, eggs | Offal (liver, kidney), mackerel, soy lecithin | Animal meats, milk, egg yolk, myelin-rich tissues |

Experimental Protocols in Phospholipid Research

Lipidomics Workflow for Analyzing Dietary Phospholipid Effects

Modern phospholipid research relies heavily on lipidomics to comprehensively analyze lipid compositions and their changes in response to dietary interventions. The following diagram outlines a standard lipidomics workflow based on a cited dietary intervention study [33].

Detailed Protocol Description:

Dietary Intervention Design: A controlled feeding trial is implemented. For example, the DIVAS trial was a 16-week randomized controlled trial (RCT) where an isoenergetic diet high in saturated fatty acids (SFA; 17% total energy) was compared to a diet where 8% of SFA was replaced with unsaturated fatty acids (UFA; primarily from plants) [33]. This design isolates the effect of dietary fat quality on the lipidome.

Sample Collection and Lipid Extraction: Blood samples are collected from fasting participants before and after the intervention. Plasma or serum is separated. Lipids are then extracted using methods like liquid-liquid extraction (e.g., Folch or Bligh & Dyer methods) to isolate the total lipid fraction from proteins and other polar contaminants [33].

Lipidomics Profiling via Mass Spectrometry: The extracted lipids are analyzed using liquid chromatography coupled to tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS). This platform can separate and quantify hundreds to thousands of individual lipid molecular species, including the major phospholipid classes (PC, PE, PS, SM) and their constituent fatty acids. The DIVAS trial profiled 987 molecular lipid species [33].

Data Processing and Statistical Analysis: Raw MS data are processed for peak identification, alignment, and absolute or relative quantification. Statistical analysis identifies lipids significantly altered by the intervention. In the DIVAS trial, 45 class-specific fatty acid concentrations were significantly changed after false discovery rate (FDR) correction. These changes are often summarized into a Multi-Lipid Score (MLS) to capture the overall lipidomic response to the dietary intervention [33].

Health Outcome Correlation: The derived MLS or individual lipid changes are then tested for association with health outcomes, such as incident cardiovascular disease (CVD) or type 2 diabetes (T2D), in large prospective cohorts to validate their biological and clinical relevance [33].

Analysis of Phospholipid-Derived Flavor Compounds

Objective: To investigate how dietary phospholipids influence the volatile flavor compound profiles in muscle tissue, as demonstrated in abalone [34].

Methodology:

- Feeding Trial: Conduct a long-term feeding trial (e.g., 106 days) with graded levels of dietary phospholipids (e.g., 0.10% to 2.48%) [34].

- Flavor Compound Analysis: Analyze muscle tissue using Gas Chromatograph-Ion Mobility Spectrometry (GC-IMS). This technique separates and identifies volatile organic compounds based on their retention time and drift time, creating a fingerprint of the flavor profile [34].

- Lipidomics Analysis: Perform comprehensive lipidomic analysis on the same tissue to identify changes in lipid composition.

- Data Integration: Use multivariate statistical methods like Partial Least Squares Regression (PLS-R) to correlate specific lipid species (e.g., PC and PE) with the abundance of specific volatile flavor compounds [34].

Key Findings: The study found that dietary phospholipid levels significantly altered the volatile flavor profile, increasing compounds with pleasant aromas at higher inclusion levels. Lipidomics revealed that phosphatidylcholines (PCs) and phosphatidylethanolamines (PEs) were the main differential lipids, and PLS-R analysis confirmed a strong relationship between changes in these phospholipids and the formation of flavor compounds [34].

Table 2: Key Reagent Solutions for Phospholipid Research

| Research Reagent / Material | Function / Application in Protocol |

|---|---|

| Soybean or Egg Yolk Lecithin | A natural, commercially available source of mixed phospholipids (PC, PE, PI, PS) used in dietary intervention studies and as a standard for analysis [29] [30]. |

| Lipid Standards (e.g., dipalmitoyl-PC, palmitoyl-oleoyl-PE) | Isotopically labeled or unlabeled pure chemical standards used for mass spectrometry calibration, peak identification, and quantitative analysis [33]. |

| LC-MS/MS Grade Solvents (e.g., Chloroform, Methanol, Isopropanol) | High-purity solvents used for lipid extraction from biological samples (e.g., plasma, tissue) and for the mobile phase in liquid chromatography to prevent background interference [33]. |

| Solid Phase Extraction (SPE) Cartridges (e.g., Silica, C18) | Used for pre-analytical clean-up and fractionation of complex lipid extracts to isolate specific phospholipid classes before mass spectrometry analysis. |

| Sphingomyelinase Enzyme | A specific type-C phospholipase used experimentally to hydrolyze sphingomyelin to ceramide and phosphocholine, enabling the study of SM's role in signaling pathways like apoptosis [31]. |

| Gas Chromatograph-Ion Mobility Spectrometry (GC-IMS) | An analytical platform used to separate, detect, and identify volatile organic compounds, applied in research linking phospholipid composition to flavor and aroma profiles in foods [34]. |

Health, Disease, and Nutritional Implications

Phospholipids in Metabolic Health and Disease

Lipidomics studies reveal that dietary fat quality significantly influences the plasma phospholipid profile, which is intimately linked to cardiometabolic health. Replacing saturated fats (SFA) with unsaturated fats (UFA) in the diet induces a specific lipidomic signature characterized by reductions in specific ceramides and other lipid species, a pattern associated with a substantially lower risk of cardiovascular disease (-32%) and type 2 diabetes (-26%) [33]. This highlights the role of specific phospholipids and their metabolites as mediators between diet and disease.

Furthermore, individual phospholipid classes are implicated in specific pathologies:

- Sphingomyelin and Atherosclerosis: The metabolism of SM generates ceramide, a pro-apoptotic and pro-inflammatory signaling molecule. High SM intake or aberrant SM metabolism may contribute to insulin resistance and atherosclerosis through ceramide-mediated pathways [31].

- Phosphatidylserine and Cognitive Function: While some studies suggest PS supplementation may support cognitive function, authoritative bodies like the European Food Safety Authority (EFSA) have found the evidence inconclusive, noting that source (soy vs. bovine brain) may significantly influence biological activity [32].

- Phosphatidylethanolamine and Prion Diseases: PE has been shown to play a unique role in facilitating the propagation of infectious prions in the absence of nucleic acids, highlighting its significance in neurodegenerative diseases [30].

Nutritional Significance and Dietary Recommendations

Phospholipids, though comprising a smaller fraction of dietary lipids compared to triglycerides, are essential for health. They are integral components of cell membranes and contribute to cellular signaling. While the body can synthesize most phospholipids, dietary intake contributes to the body's pools.

Key Nutritional Considerations:

- Essential Fatty Acid Carrier: Phospholipids are important carriers of essential fatty acids like eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA) and docosahexaenoic acid (DHA). Studies show that increasing dietary phospholipids elevates the EPA and DHA content in tissues [34].

- Flavor and Texture: As natural emulsifiers, phospholipids like lecithin (rich in PC) are critical in food processing for creating smooth textures, preventing separation, and enhancing mouthfeel. They also influence the generation of desirable flavor compounds during food processing and cooking [34] [27].

- Safety and Supplements: Phospholipid supplements, particularly PS and PC, are marketed for cognitive and liver health. Initial PS supplements derived from bovine brain cortex were replaced by soy-based sources due to concerns about transmissible spongiform encephalopathies [32]. Generally, phospholipid supplementation is considered safe at recommended doses.

Table 3: Phospholipid Content in Select Foods (mg/100 g) [32]

| Food Source | Phosphatidylserine (PS) | Food Source | Phospholipid Association |

|---|---|---|---|

| Soy Lecithin | ~1,650 mg | Egg Yolk | Rich in PC and PE [29] [30] |

| Atlantic Mackerel | ~480 mg | Bovine Brain | Historically a key source of PS and SM [31] [32] |

| Chicken Heart | ~414 mg | Dairy Milk | Contains SM and PC [31] |

| Chicken Liver | ~123 mg | Meat and Poultry | Contains all major classes (PC, PE, PS, SM) |

| White Beans | ~107 mg | Fish Roe | Exceptionally high in PC and other phospholipids |

| Beef | ~69 mg |

Within the realm of lipid biochemistry, triglycerides and phospholipids represent two fundamental classes of molecules with distinct biological roles and structural manifestations. Triglycerides (TAGs) serve as the primary storage form of metabolic energy in intracellular lipid droplets, characterized by a unique core-shell architecture where a neutral lipid core is surrounded by a phospholipid monolayer [35]. In contrast, phospholipids spontaneously form the phospholipid bilayer that constitutes the primary structural matrix of all cellular membranes, creating stable barriers between aqueous compartments [36] [37]. This whitepaper provides an in-depth technical examination of the spatial arrangements and self-assembly phenomena governing these structures, with particular focus on triglyceride crystalline polymorphs and their relationship to the phospholipid bilayer. Framed within research on dietary triglycerides and phospholipids, this analysis aims to equip researchers and drug development professionals with advanced methodological frameworks for investigating these crucial nanoscale assemblies.

The molecular structure of triglycerides consists of a glycerol backbone esterified to three fatty acid chains, which can vary in length, degree of saturation, and positional distribution on the glycerol molecule [8]. These structural variations directly influence the packing efficiency and polymorphic behavior of triglyceride crystals. Phospholipids, featuring a glycerol backbone with two fatty acid chains and a hydrophilic phosphate-containing headgroup, are amphipathic molecules that spontaneously self-assemble into bilayers in aqueous environments through the hydrophobic effect [36]. This fundamental difference in molecular architecture dictates their divergent biological functions: triglycerides as energy-dense storage depots and phospholipids as structural membrane components.

Structural Principles and Molecular Organization

The Phospholipid Bilayer: A Foundation for Cellular Compartmentalization

The phospholipid bilayer forms the fundamental permeability barrier of cell membranes, with a typical thickness of 5-6 nm [36]. This nanostructure emerges from the amphipathic nature of phospholipid molecules, which drives their self-assembly into two-dimensional sheets with hydrophobic cores facing inward and hydrophilic headgroups interfacing with aqueous environments. According to the fluid mosaic model proposed by Singer and Nicolson, biological membranes function as two-dimensional fluids wherein proteins are embedded within the lipid bilayer matrix [37]. Several critical features define bilayer organization:

Molecular asymmetry: The inner and outer leaflets differ in phospholipid composition, with phosphatidylcholine and sphingomyelin predominantly in the outer leaflet, and phosphatidylethanolamine, phosphatidylserine, and phosphatidylinositol concentrated in the inner leaflet [36] [37]. This asymmetry is maintained by ATP-dependent flippases and scramblases and has functional consequences for membrane signaling and apoptosis.

Phase behavior: Bilayers undergo thermotropic phase transitions from gel to fluid states, influenced by fatty acid chain length, unsaturation, and cholesterol content [36]. The introduction of double bonds creates kinks in hydrocarbon chains that disrupt packing and increase fluidity.

Lateral heterogeneity: Membrane domains known as "lipid rafts" enriched in cholesterol and sphingolipids form platforms for protein assembly and signaling [37].

Table 1: Major Phospholipid Classes in Mammalian Cell Membranes and Their Properties

| Phospholipid Class | Primary Location | Charge at pH 7 | Approximate Percentage of Total Lipid | Functional Significance |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Phosphatidylcholine (PC) | Outer leaflet | Zwitterionic | ~50% | Structural backbone of membrane |

| Phosphatidylethanolamine (PE) | Inner leaflet | Zwitterionic | ~20-25% | Membrane fusion, curvature |

| Phosphatidylserine (PS) | Inner leaflet | Negative | ~5-10% | Apoptosis signal, signaling scaffold |

| Phosphatidylinositol (PI) | Inner leaflet | Negative | <5% | Intracellular signaling |

| Sphingomyelin | Outer leaflet | Zwitterionic | ~10-15% | Lipid rafts, signaling |

Triglyceride Crystalline Polymorphs: Structural Complexity in Energy Storage

Triglycerides exhibit complex polymorphic behavior, crystallizing in multiple distinct forms with different thermodynamic stabilities and physical properties. This polymorphism arises from variations in molecular packing and chain alignment, which are influenced by processing conditions and thermal history [8]. The primary polymorphic forms include:

α form: The least stable polymorph characterized by hexagonal hydrocarbon chain packing with minimal rotational order. This form has the lowest density and melting point.

β' form: An intermediate metastable polymorph with orthorhombic perpendicular chain packing. This form is important in food applications for its desirable texture properties.

β form: The most stable and densely packed polymorph with triclinic parallel chain stacking. This form has the highest melting point and thermodynamic stability.

The specific polymorph that forms depends on the homologous structure of the triglyceride, including fatty acid chain length, saturation patterns, and positional distribution on the glycerol backbone [8]. For example, symmetrical monounsaturated triglycerides like POP (palmitic-oleic-palmitic) exhibit different polymorphic tendencies than asymmetrical or fully saturated analogues.

Table 2: Characteristics of Primary Triglyceride Polymorphic Forms

| Polymorph | Chain Packing Structure | Subcell Type | Relative Stability | Melting Temperature | Density |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| α | Hexagonal | H | Lowest | Lowest | Lowest |

| β' | Orthorhombic perpendicular | O⟂ | Intermediate | Intermediate | Intermediate |

| β | Triclinic parallel | T∕∕ | Highest | Highest | Highest |

Experimental Methodologies for Structural Analysis

X-ray Scattering Techniques for Nanostructural Characterization