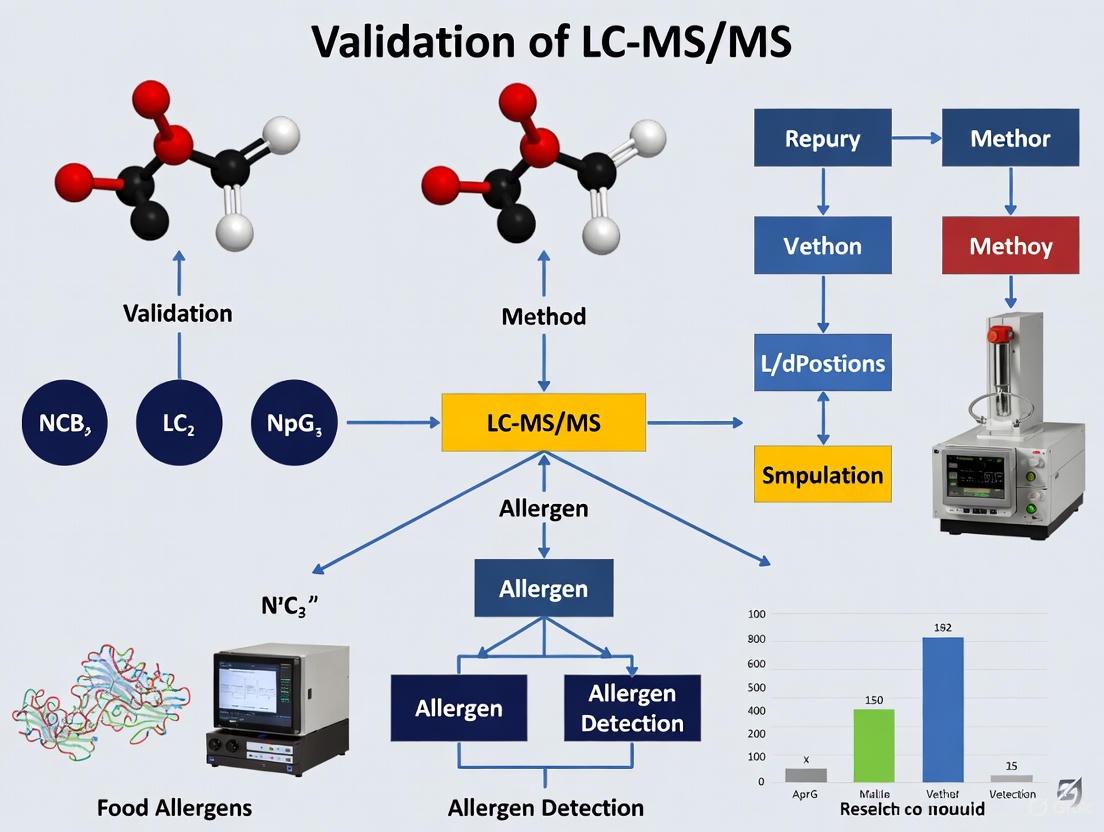

Development and Validation of an LC-MS/MS Method for the Simultaneous Detection of Seven Major Food Allergens in Processed Foods

This article details the development and comprehensive validation of a robust, high-sensitivity liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) method for the simultaneous quantification of seven major food allergens (wheat, buckwheat, milk,...

Development and Validation of an LC-MS/MS Method for the Simultaneous Detection of Seven Major Food Allergens in Processed Foods

Abstract

This article details the development and comprehensive validation of a robust, high-sensitivity liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) method for the simultaneous quantification of seven major food allergens (wheat, buckwheat, milk, egg, crustacean, peanut, and walnut) in complex processed food matrices. Tailored for researchers and analytical scientists, the content explores the foundational need for multiplex allergen detection, outlines a streamlined methodological workflow incorporating S-Trap columns and on-line SPE for rapid analysis, provides strategic troubleshooting for common LC-MS/MS challenges like ion suppression, and presents rigorous validation data demonstrating high precision, recovery rates of 90.4–101.5%, and limits of detection below 1 mg/kg. The method establishes a reliable tool for verifying food allergen labeling and enhancing public health protection.

The Critical Need for Multiplex Allergen Detection: Scope, Regulations, and Analytical Challenges

Global Prevalence and Health Impact of Food Allergies

Food allergy is a significant and growing public health concern, imposing considerable clinical, economic, and quality-of-life burdens on affected individuals and their families worldwide. This immune-mediated condition affects both children and adults, with heterogeneous manifestations and varying prevalence across different regions. Understanding the global epidemiology and health impact of food allergies is crucial for developing effective diagnostic, management, and therapeutic strategies. Recent advances in detection methodologies, particularly liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS), have enhanced our ability to accurately identify and quantify food allergens, thereby improving risk assessment and regulatory decision-making. This article examines the current landscape of food allergy prevalence, its substantial health burden, and the experimental protocols supporting the validation of sophisticated allergen detection methods.

Global Epidemiology of Food Allergies

Prevalence Estimates and Regional Variations

Epidemiological studies reveal a rising prevalence of food allergies globally, with significant differences across geographic regions, age groups, and dietary practices. The perceived prevalence of food allergy often exceeds clinically confirmed cases, highlighting the importance of standardized diagnostic criteria. In a US study, approximately 30% of parents reported that their child had a food allergy, but only one in five medically diagnosed cases was confirmed by oral challenge testing [1].

Table 1: Global Prevalence of Food Allergies Across Different Regions

| Region | Self-Reported Prevalence | Confirmed Prevalence (Oral Challenge) | Most Common Allergens |

|---|---|---|---|

| Europe (Overall) | 6.5%-24.6% (school children) [1] | 0.7%-3.8% (school children) [1] | Hazelnut, peanut, milk, egg [1] |

| North America | ~11% (general population) [2] | 4.0% (IgE-mediated in children) [1] | Peanut (1.9%), egg (0.8%), shellfish (0.6%) [1] |

| Australia | N/A | 11.0% (age 1), 3.8% (age 4) [1] | Peanut, hen's egg, sesame [1] |

| Asia | Varies by country [1] | Data limited | Shellfish, fish [1] |

| Germany | 13.2%-13.9% (parent-reported in children) [1] | 4.2% (confirmed by DBPCFC) [1] | Peanut, apple, carrot, wheat [1] |

Industrialized countries generally report higher food allergy rates, with approximately 8% of children and 10% of adults affected [1]. The EuroPrevall birth cohort study, which included over 12,000 infants from nine European countries, provided valuable insights into the early development of food allergies across different regions [1]. Regional variations in prevalent allergens are notable: peanut and hen's egg allergies dominate in North America and Northern Europe, while shellfish and fish allergies are more common in Asia [1]. In Southern Europe, allergies to lipid transfer proteins (LTP) found in peaches and other foods are prominent and often severe [1].

Temporal Trends and Age-Related Patterns

Food allergy prevalence has demonstrated a concerning upward trajectory over recent decades. Data from the United Kingdom indicates that cases of severe allergies like anaphylaxis increased by almost 400% since 2007 [3]. The natural history of food allergies also varies significantly by allergen type. Childhood allergies to cow's milk, hen's egg, wheat, and soy often resolve before adulthood, whereas peanut, tree nut, and shellfish allergies tend to persist [1]. Australian research from the HealthNuts study illustrates this progression: hen's egg allergy prevalence decreases substantially from 9.5% at age 1 to 0.6% at age 10, while peanut allergy remains more persistent (3.1% at age 6 to 2.9% at age 10) [1].

Clinical Burden and Comorbidities

Reaction Frequency and Severity

Food allergies impose a substantial clinical burden on affected individuals, characterized by frequent allergic reactions and the constant risk of anaphylaxis. Data from the FARE Patient Registry, the largest registry of food allergy patients globally, reveals that 42% of patients experience more than one food-related allergic reaction per year, with 46% experiencing food-induced anaphylaxis [2]. Approximately half of all food-related allergic reactions occur at home, and accidental exposures to food allergens are experienced by 77% of patients [2].

Multiple food allergies significantly increase the clinical burden. Patients with multiple food allergies experience higher rates of annual reactions (57% vs. 41%) and anaphylaxis (48% vs. 37%) compared to those with single food allergies [2]. The most common food allergens among registered patients include peanut (66%), tree nuts (61%), egg (43%), and milk (37%) [2].

Table 2: Clinical Burden of Food Allergies Based on FARE Patient Registry (n=5,587)

| Clinical Characteristic | Single Food Allergy (n=993) | Multiple Food Allergies (n=4,594) | Overall Cohort |

|---|---|---|---|

| >1 reaction per year | 41% | 57% | 42% |

| Experienced anaphylaxis | 37% | 48% | 46% |

| Accidental exposures | Data not specified | Data not specified | 77% |

| Atopic dermatitis | 33% | 52% | 48% |

| Asthma | 32% | 49% | 46% |

| Allergic rhinitis | 28% | 42% | 39% |

| Diagnosed <6 years | 68% | 74% | 73% |

Allergic Comorbidities and Psychological Impact

Food allergies frequently coexist with other allergic conditions, creating a multifactorial disease burden. According to the FARE Registry, the most common allergic comorbidities reported by patients with food allergies are atopic dermatitis (48%), asthma (46%), and allergic rhinitis (39%) [2]. These comorbidities are significantly more prevalent in patients with multiple food allergies compared to those with single food allergies.

The psychosocial burden of food allergies is profound for both patients and caregivers. Anxiety (54%) and panic (32%) are the most common emotions patients report following allergic reactions [4]. Approximately 62% of patients report mental health concerns related to food allergies, including anxiety after an allergic reaction, anxiety about living with food allergies, and concerns about food avoidance [4]. Caregivers also experience significant psychological distress, including fear for their children's safety, with many seeking mental health care to cope with worry related to caring for patients with food allergies [4].

Socioeconomic Burden of Food Allergy

The economic impact of food allergies extends to both affected households and the healthcare system. For families, food allergy costs are primarily driven by specialized dietary needs and constant emergency preparedness [5]. These financial burdens have been exacerbated by continuous increases in food prices since 2020 [5]. Research indicates that cost increases vary by household income, with direct cost increases being about double in higher income households compared to lower income households [5].

From a healthcare system perspective, costs include epinephrine auto-injector dispensings and allergy hospitalizations. A Swedish study found that despite the removal of auto-injector co-payments, epinephrine dispensings remained stable from 2018 to 2022, with more dispensings for children ages 5-18 years than adults [5]. Children ages 0-4 years had the lowest dispensings but highest rates of hospitalizations [5].

Food insecurity presents additional challenges for families managing food allergies. Undocumented populations face barriers related to language and digital literacy, complicating access to appropriate resources and support [5]. Supply chain disruptions, such as the 2022 infant formula shortage in the U.S., particularly affected infants with cow's milk protein allergy (CMPA), forcing families to struggle to find alternative safe and affordable formulas [5].

Advances in Allergen Detection Methods

LC-MS/MS Methodologies for Multiple Allergen Detection

Liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) has emerged as a powerful confirmatory tool for the sensitive detection of undeclared allergenic ingredients in food products. Recent methodological advances have focused on developing multiplex assays capable of simultaneously detecting multiple food allergens with high sensitivity and specificity.

Table 3: LC-MS/MS Methods for Food Allergen Detection

| Study Target | Matrices | Sample Preparation | LOD/LOQ | Key Innovations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 6 allergens: cow's milk, hen's egg, peanut, soybean, hazelnut, almond [6] | Chocolate-based matrix | Protein extraction, purification, tryptic digestion | LOD: 0.08-1.2 µgTAFP/g food [6] | Use of conversion factors to report as total allergenic food protein; well-characterized incurred materials |

| 7 allergens: wheat, buckwheat, milk, egg, crustacean, peanut, walnut [7] | Various processed foods | Suspension-trapping (S-Trap) columns, on-line SPE | LOD: <1 mg/kg for all proteins [7] | Simplified pretreatment, rapid analysis suitable for screening |

| 5 meat allergens: beef, lamb, pork, chicken, duck [8] | Food products | Protein extraction, enzymatic digestion, peptide purification | LOD: 2.0-5.0 mg/kg; LOQ: 5.0-10.0 mg/kg [8] | First LC-MS/MS method for quantitative analysis of meat allergens |

A significant challenge in food allergen analysis has been the lack of harmonization in analytical validation, impairing comparability of results across studies [6]. The ThRAll (Thresholds and Reference method for Allergen detection) project addressed this by developing a prototype quantitative reference method for multiple food allergens in complex matrices like chocolate and broth powder [6]. This method incorporated matrix-matched calibration curves using synthetic surrogate peptides and isotopically labeled analogs, achieving excellent sensitivity with detection limits between 0.08 and 1.2 µg of total allergenic food protein per gram of food [6].

Experimental Protocols for Method Validation

Rigorous validation of LC-MS/MS methods for allergen detection follows established guidelines from organizations such as the European Committee for Standardization. Key performance characteristics assessed during validation include:

- Selectivity: Ability to accurately measure the target allergen in the presence of other components [6]

- Linearity: Demonstrated over a two-order of magnitude range, focusing on low concentrations for proper assessment of detection and quantification limits [6]

- Sensitivity: Determined through limits of detection (LOD) and quantification (LOQ) using calibration approaches [6]

- Accuracy and Precision: Evaluated through recovery studies and repeated measurements [8]

The conversion of peptide concentrations to clinically relevant units represents a critical advancement. Recent research has established conversion factors to report results as fractions of total allergenic food protein per mass of food (µgTAFP/gfood), making data applicable to risk assessment plans [6]. This addresses a previous limitation where various reporting units complicated cross-study comparisons.

LC-MS/MS Allergen Detection Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 4: Key Research Reagents for LC-MS/MS Allergen Detection

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function in Experimental Protocol |

|---|---|---|

| Extraction Buffers | Tris HCl buffer (200 mM, pH 8.2), Urea solution [6] | Protein solubilization from complex food matrices |

| Reduction/Alkylation Reagents | Dithiothreitol (DTT), Iodoacetamide (IAA) [6] | Disulfide bond reduction and cysteine alkylation |

| Enzymes | Trypsin (sequencing grade) [6] [8] | Proteolytic digestion to generate marker peptides |

| Purification Materials | PD-10 desalting cartridges, Strata-X polymeric reversed phase [6] | Peptide cleanup and concentration |

| Chromatography | C18 columns, HPLC-grade solvents (acetonitrile, methanol) [6] [8] | Peptide separation prior to mass spectrometry |

| Mass Standards | AQUA synthetic peptides (native and isotopically labeled) [6] | Absolute quantification using internal standards |

Food allergies represent a substantial and growing global health concern with heterogeneous prevalence patterns across different regions and populations. The clinical burden is considerable, encompassing frequent allergic reactions, risk of anaphylaxis, significant comorbidities, and profound psychosocial impacts on patients and caregivers. Advances in detection methodologies, particularly LC-MS/MS technologies, have revolutionized our ability to accurately identify and quantify food allergens in complex matrices. These methodological improvements, coupled with standardized validation approaches and appropriate reference materials, support enhanced risk assessment, regulatory decision-making, and ultimately, improved clinical management of food allergies. Future research directions should focus on further harmonizing detection methods, elucidating environmental and genetic factors driving the increasing prevalence, and developing more effective targeted therapies for this complex immune-mediated condition.

Food allergies represent a significant global public health concern, impacting an estimated 8% of children and 4% of adults worldwide [8]. These conditions trigger abnormal immune responses to specific food proteins, ranging from mild symptoms to life-threatening anaphylaxis [8] [9]. Regulatory frameworks across various jurisdictions mandate specific labeling for major food allergens to protect consumers. In the United States, the Food Allergen Labeling and Consumer Protection Act of 2004 (FALCPA) initially identified eight major allergens, with sesame recently added as the ninth major allergen effective January 1, 2023, under the FASTER Act [9] [10] [11]. These nine allergens, often called the "Big Nine," account for over 90% of all food allergy reactions [10] [11].

Compliance with evolving allergen labeling requirements presents ongoing challenges for the food industry. On January 6, 2025, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) published a revised 5th edition of its Guidance for Industry, incorporating significant changes to allergen definitions and labeling expectations [12] [13]. These updates include an expanded interpretation of "milk" and "egg" allergens and a substantial reduction in the number of "tree nuts" considered major allergens [12]. Simultaneously, advances in analytical detection methods, particularly liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS), are enhancing the ability to validate allergen presence and manage cross-contact risks, supporting both regulatory compliance and public health safety [8] [14].

The "Big Nine" Major Food Allergens

The "Big Nine" major food allergens, as recognized by U.S. law, are milk, egg, peanut, soy, wheat, tree nuts, fish, crustacean shellfish, and sesame [9] [10] [11]. Understanding the specific characteristics and prevalence of each allergen is crucial for effective risk management and regulatory compliance.

Table 1: The "Big Nine" Major Food Allergens and Key Characteristics

| Allergen | Prevalence & Affected Population | Common Sources & Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Milk | Most common in children; 2-3% under age 3 [10] [15]. Distinguish from lactose intolerance [10]. | Cow's milk; now includes milk from goats, sheep, other ruminants [12] [13]. |

| Egg | ~2% of children; 70% outgrow by age 16 [10] [15]. | Chicken eggs; now includes eggs from ducks, geese, quail, other fowl [12] [13]. |

| Peanut | ~2.5% of children; high risk of anaphylaxis [10]. | Legume, not tree nut. Risk of cross-contact with tree nuts [10] [15]. |

| Soy | Common in infants/children; most outgrow [10] [15]. | Soybeans, tofu. Refined soybean oil/lecithin often tolerated [10]. |

| Wheat | Up to 1% of children; 2/3 outgrow by age 12 [10] [15]. | Distinct from celiac disease (autoimmune reaction) [9] [10]. |

| Tree Nuts | ~0.4-0.5% of U.S. population; <10% outgrow [10]. | Almond, cashew, pistachio, walnut, etc. [10] [13]. 12 types now require labeling [13]. |

| Fish | ~1% of Americans; 40% first react as adults [10] [15]. | Salmon, tuna, halibut. Finned fish, not shellfish [10] [15]. |

| Shellfish | ~2% of Americans; most common adult allergy [10] [15]. | Shrimp, crab, lobster (crustaceans). Mollusks often tolerated [10] [15]. |

| Sesame | ~0.23% of Americans; labeling mandatory as of Jan 2023 [10] [15]. | Seeds, tahini. Now must be labeled in plain language [9] [11]. |

Recent Regulatory Updates to Allergen Definitions

The FDA's 2025 guidance introduced critical changes to the definitions of several major allergens, reflecting evolving scientific understanding:

- Expanded "Milk" and "Egg" Definitions: The FDA has expanded its interpretation to include milk from domesticated ruminants beyond cows (e.g., goats, sheep) and eggs from birds beyond chickens (e.g., ducks, geese, quail) [12] [13]. For labeling, ingredients must declare the specific source (e.g., "goat milk," "duck egg") in the ingredient list or a "Contains" statement [12].

- Reduced "Tree Nuts" List: The number of tree nuts classified as major allergens has been reduced from 23 to 12. Nuts no longer requiring allergen labeling include coconut, beech nut, butternut, chestnut, chinquapin, cola nut, ginkgo nut, hickory nut, palm nut, pili nut, and shea nut [12] [13]. While these are no longer subject to FALCPA's major allergen labeling rules, they must still be declared in the ingredient list by their common or usual name when used as ingredients [12].

International Labeling Requirements

While specific allergens may vary, many countries have adopted regulatory frameworks for allergen labeling to protect consumers. The European Union's Regulation (EU) No 1169/2011 mandates the declaration of 14 allergens, including celery, mustard, and lupin, which are not currently major allergens in the U.S. [14]. Internationally, organizations like the Codex Alimentarius, through its Committee on Food Labelling (CCFL), work to harmonize food standards, including those for allergens, to facilitate fair trade and enhance food safety [16].

A significant challenge in global allergen management is the inconsistent use of Precautionary Allergen Labelling (PAL), such as "may contain [allergen]" statements. These labels are voluntary in the U.S. and not uniformly regulated, leading to potential consumer confusion [9] [16]. The FDA's 2025 guidance clarifies that "free-from" claims cannot be used on the same label as a PAL statement for the same allergen, as this would be misleading [12]. International efforts, including the updated VITAL (Voluntary Incidental Trace Allergen Labelling) Program 4.0, aim to provide a more scientific and risk-based approach to PAL decision-making [16].

LC-MS/MS in Allergen Detection: Methodologies and Validation

The detection and quantification of food allergens at trace levels is essential for verifying labeling accuracy, managing cross-contact, and protecting public health. Liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) has become a powerful tool for this purpose, offering high sensitivity, specificity, and the ability to simultaneously detect multiple allergens.

Experimental Protocols for LC-MS/MS Allergen Detection

A robust LC-MS/MS method for quantifying meat allergens (beef, lamb, pork, chicken, duck) was developed and validated, demonstrating the technical workflow [8]:

- Sample Preparation: Protein extraction from food matrices was optimized, followed by enzymatic digestion with trypsin and peptide purification. This step is critical for releasing and preparing the target peptide markers for analysis [8].

- Target Peptide Selection: Using Skyline software, surrogate peptides from myoglobin and myosin light chain were selected as quantitative markers for the five meat allergens. The heat stability and species specificity of these peptides are crucial for reliable detection, especially in processed foods [8].

- Mass Spectrometry Analysis: Multiple reaction monitoring (MRM) parameters were refined on a triple quadrupole (QqQ) mass spectrometer. To achieve high sensitivity and accuracy, matrix effects were minimized using matrix-matched calibration curves and stable isotope-labeled peptides as internal standards [8].

Table 2: Validation Parameters for a Quantitative LC-MS/MS Method for Meat Allergens [8]

| Validation Parameter | Result | Implication for Method Reliability |

|---|---|---|

| Limits of Detection (LOD) | 2.0–5.0 mg/kg | High sensitivity for trace-level detection |

| Limits of Quantification (LOQ) | 5.0–10.0 mg/kg | Confirms reliable quantification at low levels |

| Apparent Recoveries | 80.2%–101.5% | Demonstrates high accuracy and minimal matrix effect |

| Precision (RSD) | < 13.8% | Indicates excellent repeatability |

| Linearity (R²) | > 0.995 | Shows a strong, predictable response across concentrations |

Another study developed an LC-MS/MS method for the qualitative detection of pistachio, a tree nut, in complex matrices like cereals, chocolate, and sauces [14]. The method successfully addressed the challenge of cross-reactivity between pistachio and cashew, a common limitation of ELISA and PCR techniques, achieving a screening detection limit (SDL) of 1 mg/kg [14]. Method validation included assessments of specificity, SDL, β error, precision, and ruggedness, confirming its suitability for official food control [14].

Interlaboratory validation studies further support the reliability of LC-MS/MS methods. One such study using model processed foods (rice porridge and pancake) for nine allergens demonstrated good accuracy and a high level of agreement between laboratories, confirming the method's practicality for simultaneous allergen screening [17].

LC-MS/MS Allergen Detection Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

The development and application of robust LC-MS/MS methods rely on specific reagents and tools.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for LC-MS/MS Allergen Analysis

| Reagent / Tool | Function in Analysis |

|---|---|

| Sequencing-Grade Trypsin | Enzyme for specific protein digestion into measurable peptides [8]. |

| Stable Isotope-Labeled Peptides | Internal standards for precise quantification; correct for matrix effects [8]. |

| Surrogate Peptide Markers | Target analytes (e.g., from myoglobin); selected for stability and specificity [8]. |

| Matrix-Matched Calibrants | Calibration standards in allergen-free matrix; compensate for signal suppression/enhancement [8]. |

| Skyline Software | Open-source tool for MRM assay development, data analysis, and quantification [8]. |

The landscape of major food allergens and their associated labeling requirements is dynamic, as evidenced by recent U.S. regulatory updates that refined the definitions of milk, egg, and tree nuts. Compliance with these regulations is paramount for consumer safety. Concurrently, analytical methods for allergen detection have advanced significantly. LC-MS/MS has emerged as a superior platform for sensitive, specific, and multi-allergen detection, overcoming limitations of traditional techniques like ELISA and PCR. Validated protocols for quantifying meat allergens and discriminating between closely related tree nuts like pistachio and cashew demonstrate the power of this technology. As international efforts continue to harmonize labeling and risk assessment approaches, LC-MS/MS will play an increasingly critical role in ensuring accurate food labeling, effective allergen risk management, and the protection of allergic consumers worldwide.

Food allergies represent a significant and growing public health concern, impacting millions of consumers worldwide and necessitating stringent food safety measures. For affected individuals, the accurate detection and declaration of allergenic substances in food products is not merely a matter of convenience but a critical health imperative. The "Big Eight" allergens—milk, eggs, peanuts, wheat, soy, fish, shellfish, and tree nuts—along with emerging allergens like sesame and certain meats, are responsible for the majority of severe reactions [18] [8]. Regulatory frameworks in many countries, including the United States and the European Union, mandate the clear labeling of these allergens when intentionally used as ingredients [19] [20]. However, unintentional cross-contamination during manufacturing and processing poses a persistent threat, often communicated through Precautionary Allergen Labeling (PAL). The effectiveness of such labeling is entirely dependent on the analytical accuracy of the detection methods used to inform it. For decades, the food industry has largely relied on two principal techniques for allergen monitoring: the Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay (ELISA) and the Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR). While these methods are well-established, they possess inherent limitations—specifically, ELISA's susceptibility to antibody cross-reactivity and PCR's vulnerability to DNA degradation during food processing—that can compromise their reliability for ensuring consumer safety. This review delineates these limitations within the context of advancing analytical science, framing them as the rationale for transitioning to more robust detection platforms, notably liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS).

Fundamental Principles and Limitations of ELISA

The Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay (ELISA) is an immunoassay that leverages the specificity of antigen-antibody binding to detect and quantify protein allergens. In a typical sandwich ELISA, a capture antibody bound to a solid surface immobilizes the target allergen protein, which is then detected by a second enzyme-conjugated antibody. The ensuing enzyme-substrate reaction yields a measurable signal, typically a color change, proportional to the allergen concentration [18]. This method is prized for its high sensitivity, with detection capabilities often reported in the range of 0.1–5 mg/kg, and its relative ease of use, making it suitable for high-throughput screening in quality control laboratories [18].

However, the core strength of ELISA—its dependence on antibody-protein recognition—is also the source of its most significant weakness, particularly in processed foods. A primary limitation is antibody cross-reactivity, where antibodies designed for a specific target allergen may inadvertently bind to structurally similar, but non-target, proteins from other food sources. This can lead to false-positive results, unnecessarily triggering product recalls and narrowing the dietary options for allergic consumers. For instance, the high degree of protein similarity between cashew and pistachio nuts frequently confounds ELISA, making it difficult to distinguish between these two allergenic sources [20]. Cross-reactive epitopes are well-documented in many food groups, including tree nuts, legumes, and seafood, complicating diagnosis and management [21] [22].

Furthermore, the structural integrity of the target protein is paramount for antibody recognition. Food processing techniques—such as thermal treatment (cooking, baking, sterilization), fermentation, and high-pressure processing—can induce profound changes in proteins. These changes include denaturation (unfolding), aggregation, and Maillard reaction-induced chemical modification. Such alterations can destroy or obscure the conformational epitopes that antibodies recognize. Consequently, even if an allergenic protein is present and retains its biological activity, it may become undetectable by ELISA, resulting in a dangerous false negative.

Table 1: Documented Limitations of ELISA in Food Allergen Detection

| Limitation | Underlying Cause | Consequence | Experimental Evidence |

|---|---|---|---|

| Protein Cross-Reactivity | Shared linear or conformational epitopes between unrelated food proteins. | False Positive Results | Cashew and pistachio allergens are frequently indistinguishable due to protein similarity [20]. |

| Altered Protein Extractability | Heat-induced aggregation or embedding of proteins in the food matrix. | False Negative Results | Mustard proteins in brewed sausages showed reduced detectability compared to raw sausages [23]. |

| Epitope Destruction | Denaturation and chemical modification of proteins during thermal processing. | False Negative Results | Allergens in baked bread (milk, egg, soy at 1000 mg/kg) remained undetected by ELISA, while LC-MS/MS identified them [24]. |

Fundamental Principles and Limitations of PCR

Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR) and its quantitative variant, real-time PCR, offer a different approach by targeting the DNA of the allergenic source rather than the protein itself. This technique amplifies specific, species-specific DNA sequences, allowing for the detection of minute traces of an allergenic ingredient. PCR is highly specific and sensitive for raw materials, as the DNA target is often present in multiple copies per cell and is inherently more stable than some proteins [23].

The principal vulnerability of PCR lies in the degradation of DNA during food processing. DNA is a long, fragile polymer that is susceptible to fragmentation when subjected to physical force (e.g., milling, shearing), high temperatures, extreme pH, and enzymatic activity [25] [26]. The success of PCR is contingent on the presence of intact DNA strands that encompass the entire target amplicon region. When DNA is severely fragmented, the probability of the target sequence remaining intact diminishes, leading to a loss of signal and false-negative results. Research has demonstrated that food processing can cause significant DNA fragmentation, directly impacting the reliability of PCR analysis [26]. The degree of fragmentation can be quantified using an indicator value like the DNA Fragmentation Index (DFI), which is calculated from the quantification cycle (Cq) values of real-time PCR assays amplifying targets of varying lengths. A higher DFI indicates more extensive fragmentation and a greater likelihood of analytical failure [26].

Another significant, though less often cited, limitation is the indirect nature of PCR detection. Since PCR detects DNA and not the allergenic protein itself, it cannot directly confirm the presence of the causative agent of an allergic reaction. There can be a disconnect between the presence of DNA and the protein; for example, highly refined oils may contain trace DNA but no protein, while thoroughly processed foods may contain protein fragments (peptides) that remain allergenic even after the DNA has been degraded beyond detection [20]. This fundamental disconnect makes PCR an imperfect proxy for allergen risk assessment.

Table 2: Documented Limitations of PCR in Food Allergen Detection

| Limitation | Underlying Cause | Consequence | Experimental Evidence |

|---|---|---|---|

| DNA Fragmentation | Physical, thermal, and chemical stresses during food manufacturing. | False Negative Results | A real-time PCR method quantified DNA fragmentation, showing its direct impact on the limit of detection in processed foods [26]. |

| Indirect Detection | Detects genetic material, not the allergenic protein itself. | Poor Correlation with Allergenic Risk | A product may test positive for nut DNA but contain no allergenic protein, or vice versa [20]. |

| PCR Inhibition | Co-extraction of compounds from the food matrix that inhibit the polymerase enzyme. | False Negative/Quantification Errors | Complex food matrices (e.g., chocolate, spices) can contain PCR inhibitors that must be controlled for using internal standards [26]. |

LC-MS/MS as a Confirmatory Solution

Liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) has emerged as a powerful confirmatory technique that effectively overcomes the primary limitations of both ELISA and PCR. This method directly detects and quantifies the allergenic proteins themselves, but through analysis of their constituent signature peptides. The workflow involves extracting proteins from the food matrix, digesting them with an enzyme like trypsin to generate a characteristic peptide mixture, separating these peptides via liquid chromatography, and then identifying and quantifying them using a mass spectrometer [20] [8].

The advantages of this approach are manifold. First, it offers high specificity and freedom from cross-reactivity. Since identification is based on the unique mass-to-charge ratio of peptides and their fragmentation patterns, LC-MS/MS can readily distinguish between highly similar allergens, such as cashew and pistachio, that confound ELISA [20]. Second, it is highly resilient to food processing. Thermal processing may denature proteins, but the primary amino acid sequence—which determines the mass of the signature peptides—remains unchanged. This allows LC-MS/MS to detect allergens in baked goods and other processed foods where ELISA and PCR fail [24]. Third, it is inherently multiplexable, enabling the simultaneous detection and quantification of numerous allergens from different food groups in a single analytical run, as demonstrated by methods developed for the simultaneous detection of seven allergens [24] or five meat species [8].

The following diagram illustrates the robust LC-MS/MS workflow, highlighting steps where it overcomes traditional method limitations.

LC-MS/MS Workflow and Advantage Over Traditional Methods

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Reagents for LC-MS/MS Allergen Detection

The development and application of a robust LC-MS/MS method require a specific set of high-quality reagents and materials. The following table details essential research reagent solutions for this technique.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for LC-MS/MS-based Allergen Detection

| Reagent/Material | Function in Workflow | Specific Example & Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| Protein Extraction Buffer | To efficiently solubilize and extract proteins from complex, processed food matrices. | Tris-based buffer containing SDS and sodium sulfite [19]. SDS denatures proteins and aids in solubilizing aggregates formed during processing, ensuring full extraction. |

| Proteolytic Enzyme | To digest extracted proteins into predictable signature peptides for mass spectrometric analysis. | Sequencing-grade trypsin [8]. Provides specific cleavage at lysine and arginine residues, ensuring reproducible and consistent peptide generation. |

| Signature Peptides | To serve as quantitative markers for the unambiguous identification of the target allergen. | Unique, stable peptides from allergen proteins (e.g., from myoglobin for meats [8] or Ses i 6 for sesame [19]). Selected for species-specificity and resistance to processing. |

| Stable Isotope-Labeled Peptides | To act as internal standards for precise and accurate quantification, correcting for matrix effects and preparation losses. | Synthetic peptides identical to signature peptides but containing heavy isotopes (e.g., 13C, 15N) [8]. They co-elute with native peptides but are distinguished by mass. |

| Matrix-Matched Calibrants | To construct calibration curves that account for signal suppression or enhancement caused by the sample matrix. | Allergen standards spiked into a representative allergen-free food matrix [20] [8]. Essential for achieving accurate quantification in complex foods. |

The limitations of traditional ELISA and PCR methods present significant challenges for accurate food allergen risk assessment. ELISA's vulnerability to antibody cross-reactivity and protein denaturation, coupled with PCR's susceptibility to DNA fragmentation and its indirect detection principle, can lead to both false assurances and unnecessary alerts. Within the context of methodological validation for multi-allergen detection, these shortcomings are not merely academic but represent tangible risks to consumer safety and efficient food production. The emergence of LC-MS/MS as a confirmatory technique addresses these core limitations head-on. By directly targeting stable protein markers (signature peptides), LC-MS/MS provides a highly specific, multiplexable, and processing-resistant analytical platform. The experimental data consolidated in this review strongly supports the adoption of LC-MS/MS as a superior tool for the validation of allergen detection methods, ensuring that precautionary labeling and risk management decisions are grounded in the most reliable scientific evidence available.

The accurate detection of food allergens is a critical public health issue, with an estimated over 150 million people worldwide suffering from food allergies [27]. For researchers and food safety professionals, selecting the optimal analytical method is paramount. While traditional techniques like Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay (ELISA) and Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR) have been widely used, Liquid Chromatography-Tandem Mass Spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) has emerged as a powerful orthogonal technology. This guide objectively compares the performance of LC-MS/MS against established methods, framing the discussion within the context of validating a multi-allergen detection strategy. We present experimental data and detailed methodologies that underscore LC-MS/MS's advantages in direct protein detection, unmatched specificity, and robust multiplexing capability.

Methodological Comparison: LC-MS/MS vs. Traditional Techniques

The choice of allergen detection method significantly impacts the reliability, scope, and accuracy of results. The table below provides a systematic comparison of the most prevalent technologies.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Food Allergen Detection Methods

| Method | Target Analyte | Key Advantages | Key Limitations | Multiplexing Capability |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| LC-MS/MS | Protein (Peptide fragments) | Direct detection of allergenic proteins; High specificity and confirmatory power; Minimal cross-reactivity [20] [27] | High-cost equipment; Requires skilled personnel; Complex sample preparation [20] [28] | High (Simultaneous detection of 7+ allergens in a single run) [29] [20] |

| ELISA | Protein (Intact, via antibodies) | Fast; Easy to use; High throughput [27] | Susceptible to cross-reactivity and false positives/negatives; Antibody specificity can be affected by food processing [28] [27] | Low (Typically single-analyte per test) [28] [27] |

| PCR | DNA | High specificity to organism; Effective for nut allergens [27] | Indirect method (does not detect the allergenic protein itself); Unsuitable for egg/milk due to inability to distinguish by-product from tissue proteins; DNA can be destroyed in processing [27] | Moderate (Multiple allergens possible in one sample prep) [27] |

Critical Interpretation of Comparative Data:

- Directness of Detection: LC-MS/MS's direct analysis of allergenic protein peptides is a fundamental advantage over PCR, which detects DNA. The presence of DNA does not guarantee the presence of the allergenic protein, and the two can be separated during food processing [27]. This makes LC-MS/MS more reliable for confirming allergen presence.

- Specificity and Cross-Reactivity: ELISA's reliance on antibody-protein binding makes it vulnerable. For instance, antibodies for a cow's milk allergen (β-lactoglobulin) can cross-react with some egg proteins, complicating result interpretation [27]. LC-MS/MS overcomes this by targeting unique peptide sequences, allowing for selective detection and the ability to discriminate between highly similar allergens, such as pistachio and cashew [20].

- Throughput vs. Information: While ELISA can be faster for a single allergen, LC-MS/MS provides a superior multiplexing advantage. A single LC-MS/MS analysis can replace multiple ELISA kits, saving time and sample material when a broad allergen screen is required [29] [27].

Experimental Validation: The 7-Allergen Screening Model

A foundational study demonstrating the practical multiplexing power of LC-MS/MS developed a method for the simultaneous detection of seven major allergens: milk, egg, soy, hazelnut, peanut, walnut, and almond [29].

Experimental Protocol

The workflow for this multi-allergen screening method is outlined below, detailing the critical steps from sample to analysis.

Figure 1: Workflow for the simultaneous detection of seven food allergens using LC-MS/MS. MRM: Multiple Reaction Monitoring.

Step-by-Step Methodology [29] [27]:

- Protein Extraction: Samples are homogenized, and proteins are extracted using a buffer containing ammonium bicarbonate, urea, and dithiothreitol (DTT). This buffer helps to solubilize proteins and break disulfide bonds.

- Reduction and Alkylation: Extracted proteins are treated with DTT (reduction) and iodoacetamide (alkylation). This step permanently breaks disulfide bonds and prevents their reformation, ensuring complete digestion.

- Enzymatic Digestion: Trypsin is added to digest proteins into peptides. This digestion typically occurs during an overnight incubation. Trypsin cleaves proteins at specific amino acid residues (lysine and arginine), generating a reproducible set of peptides.

- Sample Cleanup: The resulting peptide mixture is purified and concentrated using Solid-Phase Extraction (SPE). This critical step removes interfering matrix components (like sugars and salts) and concentrates the target peptides, which lowers the limit of detection.

- LC-MS/MS Analysis: The purified peptides are separated by liquid chromatography and analyzed by a triple-quadrupole mass spectrometer operating in Multiple Reaction Monitoring (MRM) mode. In MRM, the instrument specifically filters for predefined precursor and fragment ions of the target allergenic peptides, providing high sensitivity and specificity.

Key Research Reagents and Solutions

The following table details the essential reagents and materials used in the aforementioned protocol.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for LC-MS/MS Allergen Detection

| Reagent/Material | Function | Specific Example / Note |

|---|---|---|

| Extraction Buffer | Solubilizes proteins from the complex food matrix; breaks disulfide bonds. | Ammonium bicarbonate, Urea, Dithiothreitol (DTT) [29] [27] |

| Alkylating Agent | Prevents reformation of disulfide bonds after reduction, ensuring linearized proteins for digestion. | Iodoacetamide [29] [27] |

| Protease | Enzymatically digests proteins into smaller, analyzable peptides. | Sequencing-grade modified trypsin [29] |

| Solid-Phase Extraction (SPE) Cartridge | Purifies and concentrates the peptide digest, removing matrix interferents. | Strata-X cartridges (200 mg/6 mL) [27] |

| Chromatography Column | Separates peptides based on hydrophobicity before mass spectrometry analysis. | Reversed-phase C18 column [27] |

| Mass Spectrometer | Detects and quantifies target peptides based on mass-to-charge ratio. | Triple-quadrupole instrument operating in MRM mode [29] [20] |

| Internal Standards | Improves quantification accuracy by correcting for sample preparation and ionization variability. | Isotopically labeled peptide analogs (recommended for quantification) [20] |

Technical Foundations of LC-MS/MS Superiority

The advantages of LC-MS/MS are rooted in its core operational principles and technical flexibility, which can be tailored to different research needs.

Acquisition Modes for Targeted and Untargeted Discovery

LC-MS/MS proteomics can be broadly divided into targeted and non-targeted (global) approaches, each with specific acquisition modes suited for different applications.

Figure 2: A taxonomy of common LC-MS/MS acquisition modes and their primary applications.

Performance of Different LC-MS/MS Modes [30]:

- Targeted Proteomics (SRM/MRM & PRM): These are the gold standards for quantitative analysis of a predefined set of proteins, such as specific allergens.

- SRM/MRM on a triple-quadrupole instrument is renowned for high sensitivity, specificity, and reproducibility, making it the most prevalent technique in quantitative allergen studies [30] [29].

- PRM, performed on high-resolution mass spectrometers (e.g., Orbitrap), offers similar or even higher sensitivity and selectivity than SRM, with the advantage of recording all fragment ions for a precursor, simplifying method development [30] [31].

- Non-Targeted Proteomics (DDA & DIA): These are powerful for discovery-phase research.

- DDA (Data-Dependent Acquisition) is excellent for identifying thousands of proteins in a complex mixture but suffers from lower reproducibility in precursor selection [30].

- DIA (Data-Independent Acquisition) is a newer technology that fragments all ions in sequential mass windows, combining the high proteome coverage of DDA with the quantitative consistency of targeted methods. It shows high correlation with targeted proteomics results and is promising for large-scale multiplex quantification [30].

The Specificity Argument: Peptide Markers and MRM

The core of LC-MS/MS's specificity lies in its two-tiered filtering process. The first stage of mass spectrometry (MS1) isolates the target peptide based on its precise mass-to-charge ratio (m/z). The second stage (MS2) fragments this isolated peptide and monitors for specific, characteristic fragment ions. This Multiple Reaction Monitoring (MRM) transition, from a specific precursor ion to specific product ions, creates a highly selective signature that is extremely resistant to chemical noise and matrix interference, providing confirmatory power that ELISA and PCR cannot match [30] [27].

The validation of LC-MS/MS for the simultaneous detection of multiple food allergens solidifies its position as a superior analytical platform for demanding research applications. While the initial investment in instrumentation and expertise is significant, the return is a method that provides direct, unambiguous detection of the causative agents of allergy—the proteins themselves. Its capacity for highly specific multiplexing in a single analysis run offers unparalleled efficiency and a comprehensive view of allergen contamination. As the food industry and regulatory bodies worldwide move towards more stringent labeling requirements and a deeper understanding of threshold levels, LC-MS/MS stands ready as a confirmatory and discovery-driven technology capable of meeting these challenges with precision and reliability.

A Streamlined LC-MS/MS Workflow: From Sample Preparation to Multiplex Analysis

Selection of Species-Specific Marker Peptides from Allergenic Proteins

Liquid chromatography coupled with tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) has emerged as a powerful confirmatory technique for food allergen detection, offering high specificity, sensitivity, and multi-allergen capability. This methodology enables the direct detection of allergenic proteins via unique peptide markers, overcoming limitations of antibody-based ELISA or DNA-based PCR methods, which often suffer from cross-reactivity and an inability to distinguish between closely related species [14]. The selection of optimal species-specific peptide markers is therefore critical for developing robust analytical methods that can protect allergic consumers through accurate food labeling and allergen control. This guide provides a comparative analysis of peptide marker selection strategies across diverse allergenic foods, supported by experimental data and detailed protocols.

Marker Peptides for Different Allergenic Foods

Peptide Markers for Meat Allergens

Table 1: Species-Specific Peptide Markers for Meat Allergens

| Allergen Source | Protein Origin | Marker Peptide | LOD/LOQ | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Beef | Myoglobin, Myosin Light Chain | VLGFHG | LOD: 2.0-5.0 mg/kg | [8] |

| Pork | Myoglobin, Myosin Light Chain | HPGDFGADAQGAMSK | LOD: 2.0-5.0 mg/kg | [8] [32] |

| Pork | Carbonic Anhydrase III | GGPLTAAYR | LOD: 0.1% (w/w) | [32] |

| Chicken | Myosin Light Chain (Gal d 7) | Peptides not specified | LOD: 2.0-5.0 mg/kg | [8] |

| Lamb | Myoglobin, Myosin Light Chain | Peptides not specified | LOD: 2.0-5.0 mg/kg | [8] |

| Duck | Myoglobin, Myosin Light Chain | Peptides not specified | LOD: 2.0-5.0 mg/kg | [8] |

Meat allergens from livestock and poultry pose significant health risks, with primary allergenic proteins including serum albumin (Bos d 6, Sus s 1, Gal d 5), myoglobin, and myosin light chains (Gal d 7, Bos d 13) [8]. A recently developed LC-MS/MS method for simultaneous quantification of five meat allergens (beef, lamb, pork, chicken, duck) achieved impressive sensitivity with limits of detection (LOD) of 2.0-5.0 mg/kg through careful selection of surrogate peptides from myoglobin and myosin light chain proteins [8]. The method demonstrated excellent precision with relative standard deviations (RSD) below 13.8% and apparent recoveries of 80.2-101.5%, validated through matrix-matched calibration and stable isotope-labeled peptides.

For pork and beef authentication in mixed meat products, researchers have successfully utilized species-specific peptide markers in combination with global markers (peptides widely distributed in muscle tissue). The pork-specific peptide HPGDFGADAQGAMSK and beef-specific peptide VLGFHG, when analyzed alongside global marker LFDLR, provided reliable validation of declared pork/beef compositions across various raw and processed products [32]. This combined approach enables relative quantification and authentication of meat composition without prior knowledge of potential adulterants.

Peptide Markers for Plant-Based Allergens

Table 2: Species-Specific Peptide Markers for Plant-Based Allergens

| Allergen Source | Protein Origin | Marker Peptide | LOD/LOQ | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Flaxseed | Conlinin | WVQQAK | Not specified | [33] |

| Sesame | 11S Globulin | LVYIER | Not specified | [33] |

| Sesame | Allergens (Ses i 1-7) | 92 specific peptides | Not specified | [34] |

| Quinoa | Oleosin | DVGQTIESK | Not specified | [33] |

| Amaranth | Agglutinin-like lectin | CAGVSVIR | Not specified | [33] |

| Hemp seed | Edestin | FLQLSAER | Not specified | [33] |

| Poppy seed | Cupin-like protein | INIVNSQK | Not specified | [33] |

| Pistachio | Allergenic proteins | Peptides not specified | SDL: 1 mg/kg | [14] |

| Multiple Allergens* | Various | 16 peptide markers | LOD: <1 mg/kg | [35] [7] |

*Simultaneous detection of wheat, buckwheat, milk, egg, crustacean, peanut, and walnut [7]

Plant-based allergens, particularly from seeds and tree nuts, present significant authentication challenges due to protein similarities between closely related species. Proteomic analysis of cold-pressed oils identified 92 species-specific peptides from coconut, evening primrose, flax, hemp, milk thistle, nigella, pumpkin, rapeseed, sesame, and sunflower oilseeds [34]. Most specific peptides derived from major seed storage proteins (11S globulins, 2S albumins) and oleosins, confirming the presence of allergenic proteins including pumpkin Cuc ma 5, sunflower Hel a 3, and six sesame allergens (Ses i 1, Ses i 2, Ses i 3, Ses i 4, Ses i 6, Ses i 7) [34].

For "superseed" authentication, targeted proteomics successfully identified species-specific peptide markers for six of eleven superseeds investigated, including conlinins in flaxseed (WVQQAK), 11S globulins in sesame (LVYIER), oleosin in quinoa (DVGQTIESK), agglutinin-like lectins in amaranth (CAGVSVIR), cupin-like proteins in poppy seeds (INIVNSQK), and edestins in hemp seeds (FLQLSAER) [33]. Cross-analysis disqualified the isomeric peptide LTALEPTNR from 11S globulins present in both amaranth and quinoa, highlighting the importance of verifying peptide uniqueness [33].

A multi-allergen LC-MS/MS method developed for simultaneous detection of seven food allergens (wheat, buckwheat, milk, egg, crustacean, peanut, walnut) achieved excellent sensitivity with LOD values below 1 mg/kg across five types of incurred food samples [7]. The method utilized suspension-trapping (S-Trap) columns and on-line automated solid-phase extraction to simplify the traditionally complex pretreatment process for allergen analysis.

Experimental Protocols for Marker Peptide Analysis

Protein Extraction and Digestion Workflow

Diagram 1: Protein Extraction and Digestion Workflow

Protein Extraction Protocols

Three primary extraction methods have been optimized for different sample matrices:

SDS Buffer Extraction: For seed proteins, sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) buffer protocol demonstrated superior performance over ammonium bicarbonate/urea (Ambi/urea) extraction and trichloroacetic acid (TCA) precipitation, providing consistent protein profiles with high reproducibility [33]. The protocol involves homogenizing defatted seed powder with SDS buffer (e.g., 2% SDS, 100 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0) followed by centrifugation to collect soluble proteins.

Acetone Extraction: For cold-pressed oils, acetone extraction effectively recovers proteins from various oil matrices, successfully identifying over 380 proteins and 1050 peptides from 10 cold-pressed oils [34]. The method involves mixing oil with cold acetone, vortexing, incubating at -20°C, and centrifuging to collect the protein precipitate.

Urea/Thiourea Buffer: For meat allergens, extraction with urea/thiourea buffer (e.g., 7 M urea, 2 M thiourea, 40 mM Tris) effectively solubilizes muscle proteins, particularly for myofibrillar protein isolation [36] [32]. Extraction is typically performed at room temperature with continuous shaking, followed by centrifugation to collect the supernatant.

Protein Digestion and Cleanup

Protein digestion follows standard proteomics protocols with modifications for specific matrices:

Reduction and Alkylation: Proteins are reduced with 10 mM dithiothreitol (DTT) at 37°C for 1 hour, followed by alkylation with 25 mM iodoacetamide (IAA) at room temperature in the dark for 30 minutes [8] [35].

Enzymatic Digestion: Sequencing-grade trypsin is the preferred enzyme, typically added at 1:20-1:50 (w/w) enzyme-to-protein ratio and incubated at 37°C for 4-16 hours [8] [35] [7]. For complex matrices, trypsin Gold Mass Spectrometry Grade provides optimal performance [35].

Peptide Purification: Various cleanup methods include:

LC-MS/MS Analysis Parameters

Diagram 2: LC-MS/MS Analysis Workflow

Liquid Chromatography Conditions

Chromatographic separation typically employs reversed-phase C18 columns with the following parameters:

- Column: C18 column (e.g., 2.1 × 100 mm, 1.7 μm or 2.6 μm particle size)

- Mobile Phase: A: 0.1% formic acid in water; B: 0.1% formic acid in acetonitrile

- Gradient: 2-35% B over 15-30 minutes, depending on complexity

- Flow Rate: 0.2-0.4 mL/min

- Column Temperature: 40-50°C [8] [35] [7]

Recent methods have incorporated on-line solid-phase extraction systems to improve sensitivity and reduce matrix effects, particularly for complex food matrices [7].

Mass Spectrometry Parameters

Mass spectrometric detection employs either triple quadrupole (QqQ) or high-resolution instruments with optimized parameters:

- Ionization: Electrospray ionization (ESI) in positive mode

- Spray Voltage: 3.5-4.5 kV

- Source Temperature: 300-350°C

- Nebulizing Gas: 8-12 L/min

- Drying Gas: 10-15 L/min

- Detection Mode: Multiple Reaction Monitoring (MRM) for targeted analysis

- Collision Energy: Optimized for each peptide transition [8] [35] [7]

For high-resolution systems, parallel reaction monitoring (PRM) provides additional specificity through accurate mass measurements [35].

Method Validation and Performance

Table 3: Method Validation Parameters for Allergen Detection

| Validation Parameter | Target Values | Experimental Results | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Specificity | No interference | No cross-reactivity between pistachio and cashew | [14] |

| Linearity (R²) | >0.995 | >0.995 for meat allergens | [8] |

| LOD | <10 mg/kg | 2.0-5.0 mg/kg for meat allergens | [8] |

| LOQ | <10 mg/kg | 5.0-10.0 mg/kg for meat allergens | [8] |

| Recovery (%) | 80-120 | 80.2-101.5% for meat allergens | [8] |

| Precision (RSD%) | <15 | <13.8% for meat allergens | [8] |

| Reproducibility | Consistent across labs | Good interlaboratory agreement for 9 allergens | [17] |

Method validation follows established guidelines to ensure reliability, with interlaboratory studies confirming the robustness of LC-MS/MS methods for simultaneous allergen detection. A recent interlaboratory validation study using model processed foods (rice porridge and pancake) for nine allergens (wheat, egg, milk, peanut, buckwheat, crustaceans, walnut, soybean) demonstrated good accuracy and high agreement between laboratories [17].

For meat allergen quantification, validation confirmed excellent specificity, linearity (R² > 0.995), limits of quantification (LOQ) of 5.0-10.0 mg/kg, apparent recoveries of 80.2-101.5%, and precision (RSD < 13.8%) [8]. The method utilized matrix-matched calibration and stable isotope-labeled peptides to minimize matrix effects, essential for accurate quantification in complex food matrices.

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents for Allergen Peptide Analysis

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function in Workflow | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Extraction Buffers | SDS buffer, Urea/thiourea buffer, Ammonium bicarbonate/urea | Protein solubilization and extraction | [36] [33] |

| Reduction Reagents | Dithiothreitol (DTT), Tributyl phosphate (TBP) | Disruption of protein disulfide bonds | [36] [35] |

| Alkylation Reagents | Iodoacetamide (IAA) | Cysteine residue alkylation | [8] [35] |

| Proteolytic Enzymes | Sequencing-grade trypsin, Trypsin Gold MS Grade | Protein digestion to peptides | [8] [35] |

| Chromatographic Media | C18 cartridges, S-Trap columns, PD-10 desalting cartridges | Peptide cleanup and purification | [35] [7] |

| Internal Standards | Stable isotope-labeled peptides | Quantification and recovery correction | [8] |

| Mobile Phase Additives | Formic acid, Acetonitrile, Methanol | LC-MS/MS chromatographic separation | [8] [35] |

Key reagents must be of high purity to ensure optimal assay performance. LC-MS grade solvents minimize background interference, while sequencing-grade trypsin ensures complete and reproducible protein digestion without autolysis fragments. Stable isotope-labeled peptides serve as internal standards for precise quantification, correcting for sample preparation variability and matrix effects [8].

The selection of species-specific marker peptides from allergenic proteins requires careful consideration of peptide uniqueness, stability, and detectability. LC-MS/MS-based methods have demonstrated exceptional performance for multi-allergen detection across diverse food matrices, with validation data confirming high sensitivity, specificity, and reproducibility. The continued identification of novel peptide markers, coupled with improvements in sample preparation and instrumentation, will further enhance our ability to protect allergic consumers through accurate food allergen detection and labeling. Future work should focus on expanding marker peptide libraries for underrepresented allergenic foods, standardizing analytical protocols across laboratories, and establishing clinically relevant thresholds for allergen quantification.

Optimized Protein Extraction and Digestion Protocols for Complex Matrices

The accuracy of liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) for the simultaneous detection of food allergens is critically dependent on the initial steps of protein extraction and digestion. Within the broader context of validating a multi-allergen detection method, the selection of an appropriate sample preparation protocol directly influences key performance characteristics, including sensitivity, reproducibility, and quantitative accuracy [6] [37]. Inefficient or inconsistent protein recovery from complex food matrices, such as chocolate, baked goods, or processed meats, can lead to false negatives or inaccurate quantification, posing a significant risk to allergic consumers [38]. This guide provides an objective comparison of contemporary extraction and digestion techniques, supported by experimental data, to inform method development for researchers and scientists in food safety and drug development.

Comparative Analysis of Protein Extraction Methods

Protein extraction is the foundational step designed to solubilize target allergenic proteins from a complex food matrix while minimizing co-extraction of interfering compounds like lipids, polyphenols, and tannins [6]. The efficiency of this step is paramount, as it sets the upper limit for detection sensitivity.

Key Extraction Protocols and Performance Data

The following table summarizes the core characteristics and performance of several extraction methods documented in recent literature.

Table 1: Comparison of Protein Extraction Methods for Complex Matrices

| Extraction Method | Key Components | Reported Matrix | Performance Highlights | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tris-HCL Buffer Extraction | 200 mM Tris·HCl buffer (pH 7.4) | Chocolate bar | Optimized for six allergenic ingredients; validated in a pilot-plant-produced matrix. | [6] |

| Multi-Buffer Optimized Extraction | Ammonium bicarbonate, Urea, Dithiothreitol (DTT) | Diverse alternative protein matrices | Achieved ~80% extraction efficiency across several complex food matrices. | [38] |

| Acid-Insoluble Proteome Extraction | Simple acid-based buffers | Archaeological bone (Highly degraded) | Superior performance for highly degraded specimens in palaeoproteomics. | [39] |

| SDS-Based Decellularization | Tris-HCl, SDS, EDTA | Murine organs (Heart, liver, etc.) | Led to the highest matrisome enrichment efficiency in comparative studies. | [40] |

Insights from Comparative Studies

Rigorous comparisons highlight that the optimal extraction method is often matrix-dependent. A study comparing six proteomic extraction methods on Late Pleistocene bone specimens with variable preservation found striking differences in obtained proteome complexity and sequence coverage [39]. Specifically, simple acid-insoluble proteome extraction methods performed better in highly degraded contexts, whereas methods using EDTA demineralization achieved higher identified peptide counts in well-preserved specimens [39]. This underscores the principle that the degree of matrix processing and protein degradation should guide protocol selection.

Furthermore, the direct impact of extraction efficiency on downstream analysis was demonstrated in a study on alternative protein matrices. The research established a direct correlation, finding that higher extraction efficiency improved the reproducibility of identified proteins and resulted in increased abundances of individual allergenic proteins, which is crucial for accurate risk assessment [38].

Comparison of Protein Digestion Techniques

Following extraction, proteins must be digested into peptides for LC-MS/MS analysis. Digestion efficiency and completeness are critical for generating a representative set of target peptides for quantification.

Key Digestion Protocols and Performance Data

The digestion step typically involves protein denaturation, reduction, alkylation, and enzymatic cleavage. Recent studies have compared traditional approaches with newer filter-based techniques.

Table 2: Comparison of Protein Digestion Methods for Proteomics

| Digestion Method | Principle | Key Advantages | Reported Performance | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| In-Solution Digestion | Traditional digestion in a liquid phase. | Methodological simplicity; widely established. | Lower number of identified peptides and proteins compared to S-Trap. | [41] |

| S-Trap Digestion | Spin-column-based; uses SDS and traps proteins on a filter for digestion. | Effective with SDS; high recovery; identifies hydrophobic/membrane proteins. | Highest number of identified peptides and proteins. | [41] |

| Pellet S-Trap Digestion | S-Trap applied to an insoluble pellet after initial buffer extraction. | Accesses proteins from multilayer membranes and extracellular spaces. | Identified more extracellular space proteins. | [41] |

Experimental Data and Workflow

A systematic evaluation of in-solution versus S-Trap digestion methods using SDS buffer revealed clear performance differences. The S-Trap method significantly increased the number of identified proteins, including a greater number of mitochondrial and membrane-related proteins, which are often challenging to analyze [41]. This is particularly relevant for detecting certain allergenic proteins that may be embedded in cellular membranes or are part of insoluble complexes.

The pellet S-Trap variant offers a unique advantage for comprehensive profiling. When applied to the pellet remaining after the removal of buffer-soluble proteins, this method identified a different subset of proteins, notably enriching for extracellular space proteins [41]. This two-pronged approach (soluble + insoluble fraction) can provide a more complete picture of a complex food matrix's proteome.

Integrated Workflow for Allergen Detection

The optimized extraction and digestion protocols are integral components of a larger LC-MS/MS workflow for allergen detection. The following diagram illustrates the logical sequence and key decision points in a robust method for analyzing complex matrices.

Diagram 1: Integrated workflow for allergen detection in complex matrices, highlighting key protocol decision points for extraction and digestion.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

The successful implementation of the protocols described above relies on a set of essential reagents and materials. The following table details key solutions and their functions in the workflow.

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Allergen Proteomics

| Reagent / Solution | Function / Purpose | Typical Composition / Example |

|---|---|---|

| Extraction Buffer | Solubilizes proteins, disrupts matrix interactions, and begins denaturation. | Tris HCl (e.g., 200 mM, pH 7.4) [6]; or Urea (e.g., 4-8 M), CHAPS, DTT [38] [42]. |

| Reducing Agent | Breaks disulfide bonds within and between protein molecules. | Dithiothreitol (DTT) or Tris(2-carboxyethyl)phosphine (TCEP). |

| Alkylating Agent | Modifies cysteine residues to prevent reformation of disulfide bonds. | Iodoacetamide (IAA). |

| Digestion Enzyme | Cleaves proteins into peptides amenable to LC-MS/MS analysis. | Trypsin (Mass Spectrometry Grade) [6]. |

| Solid Phase Extraction (SPE) | Purifies and concentrates peptide digests, removing salts and other interferents. | Reversed-phase cartridges (e.g., Strata-X) [6] [27]. |

| Internal Standards | Corrects for variability in sample preparation and instrument response, enabling accurate quantification. | Stable Isotope-Labeled (SIL) synthetic peptides [6] [8]. |

The selection of protein extraction and digestion protocols is a critical determinant in the success of an LC-MS/MS method for multi-allergen detection. As evidenced by comparative studies, no single method is universally superior; rather, the choice must be tailored to the specific physical and chemical challenges posed by the food matrix. For routine analysis of standard food products, a Tris-HCl buffer extraction followed by a robust digestion method like S-Trap offers a strong balance of performance and practicality. For highly processed, degraded, or particularly challenging matrices, more specialized protocols like acid-insoluble extraction or pellet S-Trap digestion may be necessary to achieve the sensitivity and reproducibility required for reliable allergen detection and quantification. By grounding protocol selection in empirical performance data, researchers can significantly enhance the reliability of their analytical results, thereby strengthening food safety and public health protection.

The reliability of food allergen detection using liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) is critically dependent on the sample preparation stage. Complex food matrices contain numerous interfering components—such as lipids, salts, and pigments—that can impede chromatographic separation, suppress ionization, and ultimately reduce analytical sensitivity. The selection of an appropriate sample clean-up technique is therefore paramount for developing robust, accurate, and sensitive multiplexed allergen detection methods. Among the various strategies available, Suspension-Trapping (S-Trap) columns and on-line Solid-Phase Extraction (SPE) have emerged as two powerful, yet functionally distinct, approaches for purifying and concentrating allergenic proteins and peptides prior to LC-MS/MS analysis. This guide objectively compares the performance, experimental protocols, and applications of these two techniques within the context of validating an LC-MS/MS method for the simultaneous detection of seven major food allergens (wheat, buckwheat, milk, egg, crustacean, peanut, and walnut) [43] [7].

Technology Comparison at a Glance

The following table summarizes the core characteristics, strengths, and limitations of S-Trap columns and on-line SPE to provide a high-level overview of these technologies.

Table 1: Comparative Overview of S-Trap and On-line SPE Techniques

| Feature | S-Trap Columns | On-line SPE |

|---|---|---|

| Core Principle | Spin-column-based protein immobilization, purification, and digestion | Automated cartridge-based extraction coupled directly to LC-MS/MS |

| Primary Role | Protein clean-up and accelerated enzymatic digestion | Automated peptide concentration and desalting |

| Key Strengths | - Effective surfactant (SDS) removal- Rapid digestion (≈1 hour)- Handles complex matrices well | - Full automation- High reproducibility- Minimal sample manipulation- Excellent for high sensitivity |

| Typical Workflow Stage | Off-line, post-protein extraction, pre-digestion | On-line, post-digestion, pre-LC-MS/MS injection |

| Throughput | Medium (manual, batch processing) | High (fully automated) |

| Reported Sensitivity | Limits of detection <1 mg/kg for allergens [43] [7] | Enhances sensitivity of the overall method [43] [44] |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

S-Trap Column Protocol for Food Allergen Detection

The S-Trap method revolutionizes the traditionally lengthy and complex protein preparation process for food samples. The protocol below is adapted from a validated method for the simultaneous detection of seven food allergens [43] [45].

Step-by-Step Workflow:

- Protein Extraction and Denaturation: Homogenize the food sample. Extract proteins using a lysis buffer containing sodium dodecyl sulphate (SDS) and a reducing agent like dithiothreitol (DTT) to denature proteins and break disulfide bonds.

- Alkylation and Acidification: Alkylate the proteins with iodoacetamide to prevent reformation of disulfide bonds. Subsequently, acidify the sample mixture using phosphoric acid.

- Binding and Wash: Load the acidified sample onto the S-Trap column and centrifuge. The proteins are trapped on the filter, while detergents, salts, and other interfering compounds are efficiently removed through a series of wash steps with a specific binding/wash buffer.

- On-Column Digestion: Add a trypsin solution directly to the column and incubate. The unique microstructure of the S-Trap filter allows for highly efficient protease digestion, typically completed within 1 hour—a significant reduction from the conventional 4-24 hour in-solution digestion.

- Peptide Elution: Elute the digested peptides sequentially using appropriate buffers, and combine the eluents for analysis.

On-line SPE Protocol for Food Allergen Detection

On-line SPE automates the purification and concentration of peptides after digestion, directly coupling this step to the LC-MS/MS system. This method is often used following an S-Trap clean-up to achieve maximum sensitivity [43] [44].

Step-by-Step Workflow:

- Sample Loading: The digested and acidified peptide mixture is injected onto the on-line SPE cartridge, which is typically packed with a reversed-phase sorbent (e.g., C18).

- Trapping and Desalting: Peptides are retained and concentrated on the sorbent, while unbound salts and polar contaminants are washed to waste.

- Elution to Analytical Column: Upon valve switching, the trapped peptides are back-flushed from the SPE cartridge onto the analytical LC column using the chromatographic gradient.

- LC-MS/MS Analysis: Peptides are separated on the analytical column and introduced into the mass spectrometer for detection and quantification.

Performance and Application Data

Quantitative Performance in Food Analysis

The combination of S-Trap and on-line SPE has been rigorously validated for food allergen analysis. The table below summarizes key performance metrics from a study detecting seven allergens in processed foods [43] [7].

Table 2: Experimental Performance Data for Combined S-Trap/On-line SPE Method

| Parameter | Performance Result |

|---|---|

| Target Allergens | Wheat, buckwheat, milk, egg, crustacean (shrimp/crab), peanut, walnut |

| Sample Types | Five different incurred processed food samples |

| Limit of Detection (LOD) | <1 mg/kg for each target protein |

| Digestion Time | Approximately 1 hour (using S-Trap) |

| Key Advantage | Simple and rapid measurement; effective screening for a wide range of processed foods |

Advantages Over Traditional Methods

Both S-Trap and on-line SPE offer distinct advantages that address the limitations of traditional allergen detection methods like ELISA (enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay) and PCR (polymerase chain reaction) [43] [37].

- Multiplexing Capability: Unlike single-analyte ELISAs, LC-MS/MS with these clean-up methods can detect numerous allergens simultaneously [37].

- Robustness to Processing: MS detects peptide sequences rather than conformational protein epitopes. This makes it more reliable for analyzing heat-processed foods where epitopes can be denatured, leading to false negatives in ELISA [43] [37].

- High Specificity: The use of marker peptides and MS/MS detection minimizes cross-reactivity, a known issue with antibody-based methods [43].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Successful implementation of these sample clean-up techniques requires specific materials. The following table lists key reagents and their functions in the workflow.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

| Item | Function/Description | Key Feature |

|---|---|---|

| S-Trap Micro or Midi Columns | Spin-column filter for protein trapping, clean-up, and digestion. | Unique filter structure for efficient SDS removal and rapid digestion [45]. |

| Trypsin, Sequencing Grade | Protease for digesting proteins into peptides for MS analysis. | High specificity for cleavage C-terminal to Lys and Arg; high purity reduces autolysis [43] [37]. |

| On-line SPE System | Automated system (e.g., column-switching valve) with SPE cartridges. | Enables automated sample concentration/desalting; reduces manual intervention [43] [44]. |

| SDS (Sodium Dodecyl Sulphate) | Ionic surfactant for efficient protein extraction and denaturation. | Compatible with S-Trap, which is designed for its subsequent removal [43]. |

| DL-Dithiothreitol (DTT) | Reducing agent for breaking protein disulfide bonds. | Essential for protein denaturation prior to alkylation and digestion [43]. |

| Iodoacetamide | Alkylating agent for cysteine residues. | Prevents reformation of disulfide bonds and stabilizes the protein structure for digestion [43]. |

Integrated Workflow and Decision Framework

The synergy between S-Trap and on-line SPE can be leveraged to create a highly efficient and sensitive analytical pipeline for allergen detection. The following diagram illustrates the integrated workflow and its advantages.

Integrated Workflow for Allergen Detection