Developing Advanced Analytical Methods for Food Contaminants: A Comprehensive Guide from Foundation to Validation

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and scientists on developing robust analytical methods for detecting chemical and microbial food contaminants.

Developing Advanced Analytical Methods for Food Contaminants: A Comprehensive Guide from Foundation to Validation

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and scientists on developing robust analytical methods for detecting chemical and microbial food contaminants. It covers the entire workflow from foundational principles and regulatory requirements to the application of advanced techniques like LC-MS/MS, GC-MS/MS, biosensors, and CRISPR-based assays. The content addresses critical challenges in method optimization, troubleshooting complex food matrices, and navigating the stringent validation protocols required for regulatory acceptance and accreditation. By integrating scientific innovation with practical application, this guide serves as an essential resource for professionals aiming to enhance food safety and respond to emerging contaminants.

Understanding the Landscape of Food Contaminants and Regulatory Frameworks

Food contaminants represent a diverse group of undesirable substances that unintentionally enter the food supply, posing significant risks to public health and global food safety. These substances can be introduced at any stage of the food production chain—from agricultural practices and environmental conditions to processing, packaging, and transportation. The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) defines chemical contaminants as a broad range of chemicals that may be present in food and have the potential to cause harm, emphasizing that manufacturers must implement preventive controls to significantly minimize or prevent these chemical hazards [1]. Within the regulatory framework of the European Commission (No. 315/93), food contaminants are specifically characterized as "substances that are unintentionally added to food and may be present in food as a result of various stages of its production, processing, or transport," while also acknowledging their potential origin from environmental contamination [2].

The systematic categorization of food contaminants is fundamental to developing effective analytical methods and mitigation strategies. Contemporary research classifies these hazardous agents into three primary categories: biological, chemical, and physical contaminants [3]. Biological contaminants encompass pathogenic microorganisms (bacteria, viruses, fungi) and their toxic metabolites. Chemical contaminants include a wide spectrum of substances ranging from environmental heavy metals and pesticide residues to process-induced toxins. Physical contaminants involve extraneous matter that may pose choking hazards or introduce microbial risks. Understanding this classification framework provides the necessary foundation for researchers to develop targeted analytical approaches that address the unique properties and behaviors of each contaminant category within different food matrices.

Categorization and Health Impacts of Food Contaminants

Chemical Contaminants

Chemical contaminants constitute a major concern in food safety due to their pervasive nature and potential for chronic health effects. The FDA monitors these substances extensively, categorizing them into environmental contaminants, process contaminants, and toxins based on their origin and formation pathways [1].

Environmental Contaminants: These substances enter the food chain from contaminated soil, water, or air where food is grown or cultivated. Significant environmental contaminants include:

- Heavy metals such as arsenic, lead, mercury, and cadmium that occur naturally in the environment but often appear at higher levels from past industrial uses and pollution. These contaminants have been prioritized due to their potential for harm during critical periods of brain development—from in utero stages through early childhood [1].

- Perchlorate which is manufactured for industrial applications but can also occur naturally.

- Radionuclides (radioactive elements) that may occur naturally or be present when radioactive materials are discharged into the environment.

- Human-made chemicals including benzene, dioxins, PCBs, and Per- and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances (PFAS) formed from or used in manufacturing industrial and consumer products [1].

Process Contaminants: These compounds form when heating or processing food, though the specific types were not elaborated in the search results [1].

Pesticide Residues: Pesticides applied by growers to protect crops from insects, weeds, fungi, and other pests can leave residues on food. The FDA enforces tolerances established by the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) for the amounts of pesticide residues that may legally remain on food [1].

At the molecular level, these chemical contaminants exert toxic effects through diverse mechanisms. Heavy metals trigger oxidative stress, mitochondrial dysfunction, and DNA damage [4]. Aflatoxins form DNA adducts that drive carcinogenesis, while organophosphate pesticide residues inhibit cholinesterase activity, disrupting neurological function [4]. The cumulative scientific evidence indicates that chronic exposure to food contaminants contributes to serious health conditions including cancer, endocrine disorders, and neurodegenerative diseases [4].

Biological Contaminants

Biological contaminants include pathogenic microorganisms and the toxins they produce. The FDA's Bacteriological Analytical Manual (BAM) contains the agency's preferred laboratory procedures for microbiological analyses of foods, highlighting the importance of monitoring these hazards [5]. Major biological contaminants of concern include:

- Salmonella species: A leading cause of foodborne illness worldwide, frequently associated with eggs, poultry, and produce.

- Listeria species: Particularly concerning for ready-to-eat foods, with thousands of listeriosis cases recorded annually in Europe alone [6].

- Escherichia coli: Certain strains can cause severe gastrointestinal illness and complications.

- Bacillus species: Some strains produce toxins that cause food poisoning.

- Mycotoxins: Toxic metabolites produced by fungi, with aflatoxins and ochratoxin A being particularly significant due to their potent toxicity and carcinogenicity [4].

These microbial contaminants pose the most immediate health risk, as the presence of bacteria or pathogens in food may cause severe disease within hours of consumption [7]. Dairy, seafood, meat, and ready-to-eat meals present particularly high risks when hygiene or temperature control is inadequate during preparation or storage processes [7].

Regulatory Limits for Key Contaminants

Regulatory agencies worldwide, including the WHO, FDA, EFSA, and the European Commission, establish strict limits for contaminants in food based on rigorous risk assessments. These limits account for factors such as toxicity, exposure levels, and vulnerable population groups [4]. The following table summarizes key regulatory limits for major contaminants:

Table 1: Regulatory Limits for Major Food Contaminants

| Contaminant | Food Matrix | Regulatory Limit | Basis/Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cadmium | Wheat | 100 ppb | EU limit [4] |

| Lead | Candy | 0.1 ppm | Protection for children [4] |

| Arsenic | Apple juice | 10 ppb | FDA action level [4] |

| Aflatoxins | Various foods | Extremely low tolerance | EU has particularly strict limits [7] |

| Pesticide residues | Food crops | EPA-established tolerances | Varies by specific pesticide and crop [1] |

These regulatory standards are dynamic, with the European Commission's new regulation (No. 915/2023) establishing maximum levels in both animal and plant-based foods for mycotoxins, vegetable toxins, metals, halogenated persistent organic pollutants, and process contaminants, among others [2]. The continuously evolving landscape of regulatory standards necessitates that analytical methods remain adaptable to ensure food compliance with current regulations.

Analytical Methodologies for Contaminant Detection

Chromatographic Techniques

Chromatographic techniques represent powerful analytical tools extensively utilized in food contaminant analysis due to their exceptional separation capabilities and sensitivity.

Gas Chromatography (GC) applications in food analysis are diverse, encompassing:

- Pesticide residue testing through techniques such as solid phase microextraction (SPME) or headspace analysis for the extraction and quantification of residues [8].

- Nutritional analysis to determine levels of vitamins, proteins, preservatives, additives, and fats, providing crucial information for regulatory-compliant labeling [8].

- Quality control through analysis of volatile compounds that contribute to aroma and flavor, facilitating assessment of food quality, authenticity, and sensory characteristics [8].

- Flavor profiling by identifying and quantifying volatile compounds that offer valuable insights for flavor development and assessment [8].

Liquid Chromatography (LC) plays an equally significant role, particularly in residue analysis:

- High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC) is invaluable for identifying and quantifying specific target analytes, enabling monitoring of pesticide levels in food products to ensure regulatory compliance [8].

- Antibiotic residue analysis in animal-derived products represents a critical application domain where HPLC is indispensable for effective detection and measurement [8].

- Liquid Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (LC-MS) enables precise monitoring of contaminants at trace levels, with applications spanning pesticide residues, mycotoxins, and veterinary drug residues [4].

Spectrometric and Elemental Analysis Techniques

Inductively Coupled Plasma Mass Spectrometry (ICP-MS) has become the technique of choice for elemental analysis in food safety, offering high sensitivity with low detection limits for heavy metals across diverse food sample types [7]. FDA laboratories perform these sample analyses using sound analytical practices documented in the Elemental Analysis Manual for Food and Related Products (EAM) [5].

Mass Spectrometry hyphenated techniques provide exceptional selectivity and sensitivity for contaminant identification and quantification:

- LC-MS/MS and GC-MS/MS are widely used systems for multi-residue screening of dozens of pesticide compounds within a single testing cycle [7].

- These tandem mass spectrometry approaches provide the confirmatory data required for regulatory compliance, offering structural information that enables definitive contaminant identification.

Emerging and Rapid Detection Technologies

The field of food contaminant detection is experiencing rapid technological transformation, driven by evolving contamination threats and regulatory requirements.

Biosensor Technologies represent a groundbreaking advancement:

- Molecularly imprinted polymer-based sensors can collapse traditional detection timelines from days to minutes. For instance, Sensip-dx's sensor technology detects bacterial pathogens in just 15 minutes compared to traditional methods requiring up to three days [6].

- These sensors use synthetic materials engineered with molecular binding sites for specific bacteria combined with thermal resistance measurements to identify pathogenic presence in real time [6].

- The manufacturing process involves stopping polymer curing mid-process and pressing living bacteria into the half-cured material, creating both physical imprints and chemical bonds that resume after polymerization completion, leaving precisely shaped binding sites that recognize matching pathogens [6].

AI-Powered Computer Vision Systems are revolutionizing quality control:

- These systems now recognize food inconsistencies faster and more accurately than humans, achieving 97% accuracy in defect detection [6].

- Unlike traditional vision systems that flag acceptable natural variations as defects, AI-powered systems learn to distinguish genuine quality issues from inherent variability in organic products [6].

- Machine learning models can predict quality factors such as water content, soluble solids, and color changes while eliminating subjective human assessments [6].

Advanced Detection Platforms highlighted in recent scientific literature include:

- Spectroscopy, hyperspectral imaging, NMR, MALDI-TOF, RT-PCR, and various biosensor platforms [9].

- Emerging trends incorporating nanotechnology, artificial intelligence (AI), machine learning (ML), 3D printing, neural networks, and enzyme engineering [9].

Table 2: Analytical Techniques for Major Food Contaminant Classes

| Contaminant Class | Primary Analytical Techniques | Key Applications | Detection Capabilities |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pesticide Residues | LC-MS/MS, GC-MS/MS | Multi-residue screening, regulatory compliance | Wide range of compounds in single analysis [7] |

| Heavy Metals | ICP-MS | Grains, pulses, spices, nutritional products | High sensitivity, low detection limits, speciation capability [7] |

| Mycotoxins | HPLC, LC-MS | Grains, nuts, spices | Trace-level quantification of aflatoxins B1, B2, G1, G2 [7] |

| Microbial Pathogens | Traditional culture, rapid kits, biosensors | Meat, dairy, ready-to-eat foods | Cultural confirmation vs. rapid screening (15 minutes) [6] [7] |

| Antibiotic Residues | LC-MS/MS, microbiological inhibition | Meat, milk, egg products | Trace-level confirmation for regulatory filing [7] |

Experimental Workflow for Contaminant Analysis

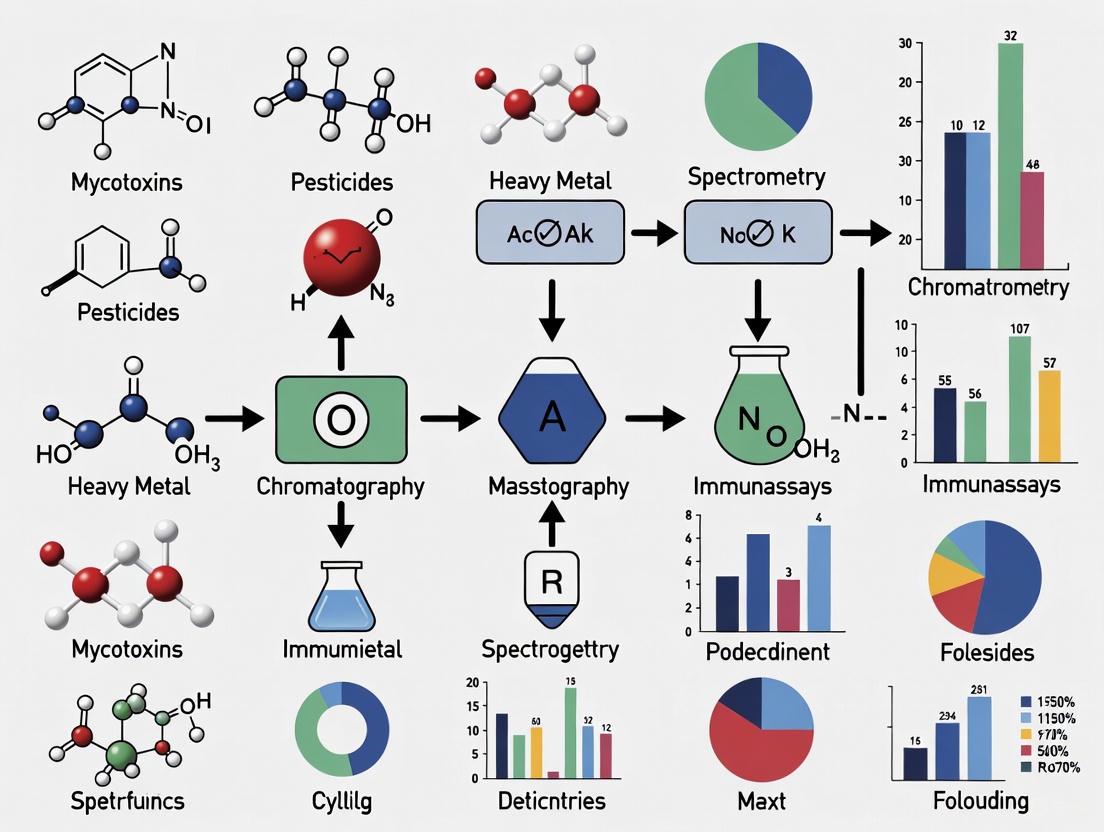

A standardized approach to contaminant analysis ensures reliable, reproducible results. The following diagram illustrates the comprehensive workflow for food contaminant analysis from sample preparation to final determination:

Analytical Workflow for Food Contaminants

This workflow emphasizes the complementary nature of screening and confirmatory methods, with rapid technologies enabling immediate production decisions while sophisticated instrumentation provides definitive identification and quantification for regulatory compliance.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Successful analysis of food contaminants requires carefully selected reagents, reference materials, and specialized equipment. The following table details essential components of the modern food safety researcher's toolkit:

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Food Contaminant Analysis

| Category/Item | Specification/Properties | Primary Function | Application Examples |

|---|---|---|---|

| Molecularly Imprinted Polymers | Synthetic materials with engineered molecular binding sites | Selective capture of target contaminants | Pathogen sensors; Sample clean-up [6] |

| Certified Reference Materials | Matrix-matched with certified contaminant concentrations | Method validation; Quality assurance; Calibration | All quantitative analyses [5] |

| Solid Phase Extraction (SPE) Cartridges | Various sorbent chemistries (C18, ion-exchange, etc.) | Sample clean-up; Analyte concentration | Pesticide residue analysis; Mycotoxin detection |

| Chromatography Columns | UHPLC, HPLC, GC columns with specific stationary phases | Compound separation | Residue analysis; Metabolite profiling [8] |

| Mass Spectrometry Tuning Solutions | Standardized mixtures of known ions | Instrument calibration; Performance verification | LC-MS/MS; GC-MS/MS method setup [5] |

| Microbial Culture Media | Selective and differential formulations | Pathogen enrichment and isolation | Traditional microbiological methods [5] [7] |

| ELISA Kits & Rapid Test Strips | Antibody-based detection systems | High-throughput screening; Field testing | Pesticide screening; Mycotoxin detection |

| Enzyme Inhibitors | Specific to target enzymes (e.g., cholinesterase) | Mechanism-based detection | Organophosphate pesticide biosensors [4] |

| Stable Isotope-Labeled Internal Standards | Deuterated or 13C-labeled analogs of target analytes | Quantification accuracy; Matrix effect compensation | LC-MS/MS quantitative methods [5] |

| Preservation Solutions | Antioxidants, antimicrobials, stabilizers | Sample integrity maintenance during storage | Field sampling; Biobanking [6] |

The FDA Foods Program Compendium of Analytical Laboratory Methods serves as a critical resource, containing chemical methods that have been validated using the FDA Foods Program Guidelines for the Validation of Chemical Methods [5]. These validated methods represent essential tools for researchers developing new analytical approaches, providing benchmark protocols against which novel methods can be compared.

Method Validation and Quality Assurance

Regulatory Method Validation Frameworks

The development of robust analytical methods for food contaminant detection requires rigorous validation to ensure reliability, accuracy, and reproducibility. The FDA has established comprehensive guidelines through its Method Development, Validation, and Implementation Program (MDVIP) [5]. All methods developed for the FDA Foods Program must be validated according to these established guidelines and appendices, which define parameters for chemical, microbiological, and DNA-based methods [5]. Successfully validated methods are added to the FDA Foods Program Compendium of Analytical Methods, providing researchers with benchmark protocols.

Method validation encompasses multiple performance characteristics including:

- Specificity/SELECTIVITY: The ability to distinguish target analytes from interfering substances in complex food matrices.

- Accuracy: The closeness of agreement between measured values and true reference values.

- Precision: The degree of agreement among individual test results when the method is applied repeatedly to multiple samplings.

- Limit of Detection (LOD) and Limit of Quantification (LOQ): The lowest concentrations of an analyte that can be reliably detected and quantified.

- Linearity and Range: The method's ability to produce results directly proportional to analyte concentration within a given range.

- Robustness: The capacity of the method to remain unaffected by small, deliberate variations in method parameters.

Quality Management Systems

Effective laboratory quality management is fundamental to generating reliable contaminant data. The CFSAN Laboratory Quality Assurance Manual (LQM), 4th Edition (2019) contains policies and instructions related to laboratory quality assurance, serving as a central resource for understanding CFSAN's quality system [5]. Similarly, the ORA Laboratory Manual provides FDA personnel with information on internal procedures for testing consumer products, training laboratory staff, report writing, safety, research, review of private laboratory reports, and court testimony [5].

These quality systems implement principles including:

- Documentation Control: Ensuring all methods, procedures, and records are properly maintained and version-controlled.

- Personnel Competency: Establishing training requirements and competency assessments for analytical staff.

- Equipment Qualification: Verifying that instruments are properly installed, operational, and calibrated.

- Proficiency Testing: Regular participation in inter-laboratory comparison programs to verify analytical performance.

- Audit Procedures: Internal and external assessments to identify areas for improvement in the quality system.

Future Directions in Food Contaminant Analysis

The field of food contaminant analysis is undergoing rapid transformation, driven by technological advancements and evolving regulatory requirements. Several key trends are shaping the future landscape of food safety research:

Artificial Intelligence and Machine Learning integration is accelerating, with the global AI in food safety and quality control market projected to grow from $2.7 billion in 2024 to $13.7 billion by 2030, representing a compound annual growth rate of 30.9% [10]. AI applications include:

- Predictive analytics for contamination risks and spoilage patterns [10].

- Computer vision systems with 97% accuracy in defect detection, surpassing human capabilities [6].

- Automated compliance monitoring against evolving regulatory standards across global markets [10].

Advanced Preservation Technologies are emerging to complement detection methods:

- Electrostatic freezing applications that apply controlled electromagnetic fields during freezing to prevent large ice crystal formation, protecting both texture and flavor while reducing surface bacteria [6].

- Liquid nitrogen freezing alternatives that address quality degradation without chemical interventions [6].

Regulatory Evolution continues to drive methodological advancements:

- The FDA's Food Traceability Rule compliance deadline extension to July 2028 provides additional implementation time for enhanced traceability systems [6].

- International regulatory divergence necessitates market-specific testing approaches, as standards increasingly vary between regions [7].

- The FDA's recent funding opportunity (RFA-FD-25-024) for a pilot study on contaminants in school meals demonstrates the ongoing emphasis on protecting vulnerable populations [1].

The convergence of these technological and regulatory trends points toward a future where food contaminant analysis becomes increasingly automated, predictive, and integrated across the entire food supply chain. Researchers developing analytical methods must therefore consider not only current detection capabilities but also the evolving landscape of food production, processing, and regulation that will define tomorrow's food safety challenges and solutions.

The global framework for food safety is continuously evolving, demanding increasingly sophisticated and responsive analytical methods from researchers and scientists. The regulatory environment is characterized by a shift towards preventive risk management, stricter contaminant limits, and the integration of advanced technologies for safety assessment. For professionals developing analytical methods for food contaminants, understanding these regulatory drivers is not merely about compliance; it is about pioneering the scientific tools that will define the next generation of food safety protection. This guide provides a detailed technical analysis of three pivotal regulatory forces: the United States Food and Drug Administration's (FDA) Human Foods Program (HFP) priorities, the European Union's Regulation (EU) 2023/915 on contaminant maximum levels, and the international food safety management standard, ISO 22000. By framing these drivers within the context of analytical method development, this document aims to equip researchers with the knowledge to create robust, forward-looking, and regulatory-relevant experimental protocols.

FDA Human Foods Program (HFP): Strategic Priorities for FY 2025

Established as part of a major FDA reorganization in October 2024, the Human Foods Program (HFP) consolidates all agency activities related to food safety and nutrition under the leadership of a single Deputy Commissioner [11] [12]. Its mission is to protect public health through science-based approaches to prevent foodborne illness, reduce diet-related chronic disease, and ensure the safety of chemicals in food [11]. The program is structured around three core risk management areas, each with specific FY 2025 deliverables that signal key research and development priorities for the analytical science community [11] [13].

Microbiological Food Safety

The HFP focuses on preventing pathogen-related foodborne illnesses through a regulatory framework based on prevention, scientific rigor, and partnerships [11]. Key deliverables that influence analytical method development include:

- Advancing Traceability: Implementing the FDA Food Traceability Final Rule requires tools to rapidly identify and remove contaminated products from the marketplace [11]. This creates a need for methods that can quickly link pathogen strains from food samples to clinical isolates.

- Genomic Surveillance: A major initiative involves integrating GenomeTrakr data from food and facility inspections into the CDC's new outbreak surveillance platform, PN 2.0 [11]. This underscores the critical role of Whole-Genome Sequencing (WGS) for pathogen identification and outbreak response.

- Environmental Studies: A new study in Southwest Indiana will investigate the ecology of human pathogens in the environment following multiple Salmonella outbreaks [11]. Research into environmental sampling and culture-independent detection methods for pathogens in agricultural settings is directly relevant.

Food Chemical Safety

This area focuses on ensuring the safety of exposure to chemicals, including additives and contaminants, in food [11]. Key research-oriented deliverables include:

- Post-Market Assessment: The HFP is updating its assessment framework for chemicals in food and will publish a list of substances prioritized for re-assessment [11]. This highlights a growing need for robust, high-throughput analytical methods for post-market surveillance of emerging contaminants.

- "Closer to Zero" Initiative: The program will advance action levels for environmental contaminants like lead in foods intended for infants and young children [11]. This drives demand for highly sensitive and accurate methods for elemental analysis at very low (ppb) concentrations.

- New Approach Methods (NAMs): The HFP is completing the external review and validation of the Expanded Decision Tree (EDT), a tool that uses structure-based questions to classify chemicals by toxic potential [11]. This signifies regulatory acceptance of in silico and alternative methods, creating opportunities in computational toxicology.

- Artificial Intelligence for Signal Detection: The implementation of the Warp Intelligent Learning Engine (WILEE), an AI-powered horizon-scanning tool, will enhance post-market assessment [11]. Research into integrating AI with analytical data from techniques like LC-HRMS for automated contaminant identification is aligned with this priority.

- PFAS Exposure Assessment: The program is expanding the use of new methods to understand exposure to Per- and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances (PFAS) [11]. This reinforces the need for advanced LC-MS/MS methods capable of quantifying a broad panel of PFAS compounds in diverse food matrices.

Nutrition

While focused on chronic disease and health equity, the Nutrition center of excellence also ensures the nutritional adequacy and safety of infant formula [12], which intersects with contaminant analysis for this vulnerable population.

Table 1: Key FDA HFP FY2025 Deliverables and Implications for Analytical Method Development

| HFP Focus Area | Specific FY2025 Deliverable | Implication for Analytical Method Development |

|---|---|---|

| Microbiological Safety | Integration of GenomeTrakr & PN 2.0 [11] | Standardized WGS protocols, bioinformatics pipelines for pathogen phylogenetics. |

| Microbiological Safety | Focused engagement on Listeria control strategies [11] | Validation of rapid detection and strain-typing methods for L. monocytogenes in facilities. |

| Chemical Safety | "Closer to Zero" action levels for lead [11] | High-sensitivity ICP-MS/MS methods for heavy metals in complex baby food matrices. |

| Chemical Safety | Post-market signal detection using AI (WILEE) [11] | HRMS data acquisition for non-targeted analysis and retrospective data mining. |

| Chemical Safety | Understanding PFAS exposure [11] | LC-MS/MS and LC-HRMS methods for diverse PFAS compounds in food. |

| Chemical Safety | Validation of the Expanded Decision Tree (NAM) [11] | Development of in vitro and in silico assays for toxic potential of uncharacterized chemicals. |

EU Regulation 2023/915: Maximum Levels for Contaminants in Food

Commission Regulation (EU) 2023/915, which repealed and replaced Regulation (EC) No 1881/2006, sets legally binding maximum levels for specific contaminants in foodstuffs across the European Union [14] [15]. It embodies the "As Low As Reasonably Achievable" (ALARA) principle, requiring that contaminant levels be minimized through good agricultural, fishery, and manufacturing practices [14]. For analytical scientists, this regulation is a primary source for compliance testing requirements and benchmark levels.

Core Principles and Updates

The regulation includes several key updates and clarifications critical for method development:

- Explicit Scope: It explicitly forbids the placement on the market of food exceeding maximum levels, including its use as a food ingredient or in mixed food products [14] [15].

- Processing Factors: For dried, diluted, processed, and compound foods, food business operators must provide concentration, dilution, and processing factors to competent authorities, supported by experimental data [14] [15]. This necessitates validated methods to accurately determine these factors.

- Analytical Clarity: The regulation clarifies that for the sum of multiple compounds, lower bound concentrations should be used unless specified otherwise [14] [15]. This has direct implications for the calculation and reporting of results, particularly for contaminants like certain mycotoxins and PAHs.

- Prohibition of Chemical Detoxification: The treatment of food with chemicals to detoxify contaminants is prohibited, emphasizing the need for control measures earlier in the supply chain [14] [15].

Specific Contaminant Updates and New Regulations

Regulation (EU) 2023/915 consolidates and updates maximum levels for a wide range of contaminants. Furthermore, subsequent amendments, such as the introduction of maximum levels for nickel, demonstrate the dynamic nature of this regulation.

- Nickel: For the first time, maximum levels for nickel in various foodstuffs will come into force on 1 July 2025 [16]. The European Food Safety Authority (EFSA) has derived a Tolerable Daily Intake (TDI) of 13 μg/kg body weight per day [16]. The highest levels are found in cocoa powder (11.1 mg/kg) and cashew nuts (5.4 mg/kg) [16].

- Cadmium: The exemption from maximum levels has been extended to all cereals used for beer or distillate production, as cadmium remains in the cereal residue [14] [15].

- Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons (PAHs): Instant/soluble coffee is excluded from the maximum levels for powdered plant-based foods for beverages due to negligible PAH content [14] [15]. Maximum levels for infant formulae are clarified to refer to the product ready for use [14] [15].

- Melamine: The regulation incorporates the Codex Alimentarius maximum level for liquid infant formula in addition to powdered formula [14] [15].

Table 2: Selected Maximum Levels from EU Regulation 2023/915 and Related Amendments

| Contaminant | Food Product Category | Maximum Level | Notes & Effective Date |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nickel (Ni) | Cocoa powder | 11.1 mg/kg (typical level) | New ML: 1 July 2025 [16] |

| Nickel (Ni) | Cashew nuts | 5.4 mg/kg (typical level) | New ML: 1 July 2025 [16] |

| Nickel (Ni) | Cereals and cereal-based products | To be defined | New ML: 1 July 2026 [16] |

| Lead (Pb) | Infant formulae, follow-on formulae | 0.01 mg/kg wet weight | Ready-to-use product [14] |

| Cadmium (Cd) | Beer | Exempted | Applies if cereal residue not marketed as food [14] [15] |

| Melamine | Liquid infant formula | 0.15 mg/kg | Incorporated from Codex Alimentarius [15] |

| Dioxins, DL-PCBs, NDL-PCBs | Fish from Baltic region | Higher levels permitted | Derogation for Latvia, Finland, Sweden with consumer information [14] [15] |

ISO 22000: Global Food Safety Management Systems

ISO 22000 is an international standard that specifies the requirements for a Food Safety Management System (FSMS) [17] [18]. It integrates the Hazard Analysis and Critical Control Point (HACCP) principles developed by the Codex Alimentarius Commission with prerequisite programs and core management system elements [18]. For researchers, ISO 22000 provides the overarching framework within which analytical data is generated, validated, and used for decision-making.

Key Components and Relevance to Research

The standard is designed to be applicable to all organizations in the food chain, regardless of size [18]. Its key components directly impact laboratory operations and method validation:

- Interactive Communication: Ensures that information about food safety issues, including new and emerging hazards, is communicated throughout the food chain [18]. This necessitates that analytical labs stay abreast of evolving regulatory and scientific knowledge.

- System Management: Adopts the Plan-Do-Check-Act (PDCA) cycle and High-Level Structure (HLS), making it compatible with other management standards like ISO 9001 (quality) and ISO 17025 (testing and calibration laboratories) [18] [19].

- Prerequisite Programs (PRPs): Includes basic conditions and activities necessary to maintain a hygienic environment throughout the food chain [18].

- HACCP Principles: The systematic identification and control of significant food safety hazards is central to the standard [18]. Analytical data is the foundation for validating control measures and verifying the effectiveness of the HACCP plan.

Certification to ISO 22000, while not a requirement of the standard, provides global recognition of an organization's commitment to food safety and can be a prerequisite for market access [19].

Developing Analytical Methods in a Regulatory Context

The convergence of regulatory drivers from the FDA, EU, and international standards creates a clear roadmap for the development of next-generation analytical methods. The following workflows and toolkits are designed to guide researchers in this endeavor.

Method Development Workflow for Regulatory Compliance

This workflow outlines a systematic approach for developing and validating analytical methods that meet the demands of modern food safety regulations, incorporating elements from FDA priorities (e.g., NAMs, AI) and EU maximum level enforcement.

Diagram: A systematic workflow for developing analytical methods that meet regulatory demands, from scoping to continuous improvement.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

This toolkit details the essential reagents, materials, and technological solutions required for developing methods that address the key regulatory drivers discussed in this guide.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Tools for Modern Food Contaminant Analysis

| Tool/Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function & Application |

|---|---|---|

| Mass Spectrometry | LC-MS/MS, Q-TOF, Orbitrap, ICP-MS | Target quantification (EU MLs), non-target screening (FDA AI/ML), elemental analysis (Closer to Zero). |

| Genomic Surveillance | Whole-Genome Sequencing Kits, Bioinformatic Pipelines | Pathogen strain identification and outbreak tracing (FDA GenomeTrakr). |

| Certified Reference Materials | CRM for heavy metals, mycotoxins, PAHs, PFAS | Method validation and ongoing accuracy verification for compliance with EU MLs. |

| Sample Preparation | SPE Cartridges, QuEChERS Kits, Enzymes, Isotopically Labeled Internal Standards | Matrix cleanup, analyte extraction, and quantification accuracy. |

| New Approach Methods | In vitro assay kits, Computational (QSAR) Software | Preliminary toxicological assessment (FDA EDT), prioritization of chemicals for testing. |

| Data Science & AI | Python/R scripts, Cloud Computing, WILEE-like platforms | HRMS data processing, pattern recognition, and predictive signal detection. |

The regulatory landscape for food contaminants is defined by a clear and convergent trajectory: the FDA HFP emphasizes proactive, science-based prevention and the integration of advanced tools like genomics and AI; the EU's Regulation 2023/915 sets stringent, legally-binding maximum levels under the ALARA principle; and ISO 22000 provides the systematic management framework to ensure consistent application. For researchers and scientists, success lies in developing analytical methods that are not only sensitive and accurate but also fast, scalable, and intelligent. The future of food safety research depends on the ability to merge traditional analytical chemistry and microbiology with cutting-edge computational and genomic tools. By aligning experimental design and method validation with these key regulatory drivers, the scientific community can directly contribute to a more predictive, preventive, and protective global food safety system.

In food contaminants research, establishing a robust analytical rationale is fundamental to safeguarding public health, ensuring economic fairness, and complying with a dynamic global regulatory landscape. This rationale rests on three interdependent pillars: safety (protecting consumers from biological, chemical, and physical hazards), authenticity (verifying product identity and preventing fraud), and compliance (adhering to legal and standards frameworks) [20] [21]. The drive for this rationale is fueled by sobering statistics, including an estimated 600 million annual cases of foodborne illness globally [20] and the persistent economic and safety threats posed by adulteration and contamination [21].

The process of developing analytical methods for food contaminants is not performed in isolation. It is a targeted activity, framed by a risk-based approach that prioritizes resources according to the severity and likelihood of harm [22]. This guide delves into the core technical considerations, current methodologies, and experimental protocols that underpin the development of rigorous, fit-for-purpose analytical methods in modern food safety research.

Foundational Principles of Method Development

The Analytical Development Workflow

The journey from a recognized contaminant to a validated analytical method follows a structured, iterative pathway. The diagram below outlines the key stages in this workflow.

Hazard Identification and Risk Assessment

The initial stage involves a precise definition of the analytical problem. This begins with Hazard Identification, which determines the specific analyte of concern (e.g., a pathogen, pesticide, or heavy metal) and its known health impacts [22]. Subsequently, a Risk Assessment is conducted to evaluate the likelihood and severity of the hazard occurring in a specific food matrix. This risk-based rationale dictates the required sensitivity and specificity of the analytical method [23] [21]. For instance, the near-zero tolerance for pathogens like Listeria monocytogenes in ready-to-eat foods demands methods with exceptionally low detection limits [23].

Defining Analytical Performance Characteristics

Once the analyte and matrix are defined, the target performance characteristics for the method must be established. These characteristics are non-negotiable for ensuring data reliability.

- Accuracy and Precision: Accuracy refers to the closeness of a measured value to the true value, while precision describes the repeatability of measurements [21].

- Limit of Detection (LOD) and Limit of Quantification (LOQ): The LOD is the lowest concentration of an analyte that can be detected, while the LOQ is the lowest concentration that can be quantified with acceptable precision and accuracy [22]. The required levels are determined by the risk assessment and regulatory limits.

- Specificity and Selectivity: Specificity is the ability to detect the target analyte in the presence of other components, while selectivity is the ability to distinguish the analyte from interferences [24] [25].

- Robustness and Ruggedness: Robustness is the method's resilience to small, deliberate variations in operational parameters, while ruggedness refers to its reproducibility under different conditions, such as between laboratories or analysts [26].

Table 1: Key Performance Characteristics for Analytical Methods

| Characteristic | Definition | Considerations in Method Development |

|---|---|---|

| Accuracy | Closeness of the measured value to the true value. | Assessed using certified reference materials (CRMs); affected by matrix effects and sample preparation. |

| Precision | The repeatability and reproducibility of measurements. | Evaluated through repeated analyses; can be reported as relative standard deviation (RSD). |

| Limit of Detection (LOD) | The lowest concentration that can be detected. | Must be low enough to ensure safety and compliance, often driven by regulatory standards. |

| Limit of Quantification (LOQ) | The lowest concentration that can be quantified with precision and accuracy. | Typically 3 to 10 times higher than the LOD. |

| Specificity/Selectivity | Ability to measure the analyte accurately in the presence of interferences. | Critical in complex food matrices; enhanced by chromatographic separation or specific detectors. |

| Robustness | Insensitivity of the method to small, deliberate procedural changes. | Tested during method development to define strict operational parameters. |

Current Analytical Technologies and Workflows

Separation and Detection Techniques

The core of chemical contaminant analysis often involves coupling a separation technique with a sensitive detector.

- Liquid Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (LC-MS/MS): Triple quadrupole mass spectrometers (GC-MS/MS or LC-MS/MS) are the workhorses for targeted analysis of pesticides, veterinary drug residues, and mycotoxins due to their high sensitivity and selectivity in complex matrices [20]. The trend is towards high-throughput and rapid screening, with techniques like direct analysis in real time (DART) coupled to triple quadrupole MS reducing analysis times from minutes to seconds [27].

- Gas Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (GC-MS/MS): This is ideal for volatile and semi-volatile organic compounds, such as certain pesticides, ethylene oxide, and environmental contaminants [20].

- Inductively Coupled Plasma-Mass Spectrometry (ICP-MS): This is the premier technique for elemental analysis and quantifying toxic heavy metals (e.g., lead, cadmium, arsenic, mercury) at ultra-trace levels with high accuracy [22] [20].

Microbiological and Molecular Detection

Pathogen analysis has evolved significantly from traditional culture-based methods.

- Cultural Methods: These traditional methods, detailed in manuals like the FDA's Bacteriological Analytical Manual (BAM), remain the "gold standard" for viability and confirmation but are time-consuming, taking days to yield results [22] [21].

- Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR) and Real-Time PCR: These molecular techniques detect pathogen-specific DNA sequences, offering rapid results (hours instead of days) and high specificity. They are widely used for screening pathogens like Salmonella, L. monocytogenes, and E. coli O157:H7 [22] [20]. Reverse Transcription PCR (RT-PCR) is also critical for GMO detection [20].

- Immunoassays (e.g., ELISA): Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays (ELISA) use antibodies to detect microbial antigens or toxins. They offer a good balance of speed, sensitivity, and ease of use for high-volume screening [22].

The following diagram illustrates a typical workflow for pathogen detection, highlighting the integration of rapid and traditional methods.

Emerging and Non-Destructive Technologies

The field is rapidly advancing with new technologies that promise faster, cheaper, and in-line analysis.

- Hyperspectral Imaging (HSI) and Infrared Spectroscopy: These non-destructive technologies provide both spatial and chemical information, allowing for the detection of foreign objects, contaminants, and quality attributes without destroying the sample [24].

- Surface-Enhanced Raman Scattering (SERS): SERS offers high sensitivity and molecular fingerprinting capability for detecting chemical contaminants and adulterants at very low concentrations [24].

- Biosensors and Portable Devices: The development of handheld biosensors and other portable devices enables real-time monitoring and testing at various points in the supply chain, moving analysis out of the central laboratory [22] [24].

- Non-Targeted Analysis (NTA) and Suspect Screening: Using high-resolution mass spectrometry, these workflows allow for the comprehensive detection of known and unknown contaminants without a pre-defined list of targets, which is crucial for identifying emerging contaminants and food fraud [28].

Experimental Protocols and Data Interpretation

Case Study: Quantitative Microbial Risk Assessment (QMRA) forListeria monocytogenes

A powerful example of an integrated analytical rationale is the application of QMRA for L. monocytogenes in ready-to-eat (RTE) foods. A 2025 study on pre-packaged, non-vacuum, refrigerated RTE meat products in Chengdu, China, provides a clear protocol [23].

- 1. Hazard Identification: Listeria monocytogenes was identified as the hazard, a pathogen causing severe illness (listeriosis) with high mortality rates, particularly in vulnerable populations [23].

- 2. Exposure Assessment:

- Sampling: 145 samples were collected from retail points.

- Analysis: Qualitative and quantitative detection was performed according to GB 4789.30-2016 (a national standard method analogous to ISO 11290).

- Data Integration: Initial contamination levels and prevalence data were combined with predictive growth models for L. monocytogenes. Key variables included retail storage temperature and time, transport temperature and time, and home storage duration. These parameters were modeled using probability distributions (e.g., Pert distributions) to account for variability [23].

- Software Simulation: The integrated data was processed using @Risk software, running 10,000 Monte Carlo simulations to model the potential growth of the pathogen from retail to consumption and estimate the final exposure level at the point of consumption [23].

- 3. Hazard Characterization: A dose-response model was applied to estimate the probability of illness based on the estimated exposure level for different population groups (general population, elderly, pregnant women) [23].

- 4. Risk Characterization: The model output quantified the annual cases of listeriosis per million people for each group. Sensitivity analysis (a Pearson correlation coefficient) identified that the initial contamination level at retail was the most critical factor influencing the final risk, followed by retail temperature [23].

Table 2: Key Parameters and Outcomes from a QMRA for L. monocytogenes in RTE Meats [23]

| Parameter / Outcome | Details | Quantitative Value / Finding | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sample Size | Pre-packaged, non-vacuum, refrigerated RTE meats | 145 samples | |

| Prevalence | Percentage of positive samples | 20.0% | |

| Initial Contamination | Level in positive samples | 31.03% of positives had ≥ 110 MPN/g | |

| Risk Output (Annual cases/million) | General population (5-65 yrs) | 0.01 | |

| Elderly (65+ yrs) | 0.22 | ||

| Pregnant Women | 2.88 | ||

| Sensitivity Analysis (Factor | Correlation Coefficient R) | Initial Contamination Level | R=0.25 |

| Retail Temperature | R=0.08 | ||

| Retail Duration | R=0.07 | ||

| Consumption Amount | R=0.07 |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

The execution of these protocols relies on a suite of essential reagents and materials.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Contaminant Analysis

| Item | Function and Importance |

|---|---|

| Certified Reference Materials (CRMs) | Provides a matrix-matched material with a certified analyte concentration. Essential for method validation, calibration, and ensuring accuracy and traceability to international standards [26] [21]. |

| Selective Enrichment Broths & Agar Media | Used in microbiological analysis to selectively promote the growth of target pathogens while inhibiting background flora. Critical for improving the detection limit of cultural and molecular methods [22] [21]. |

| Molecular Grade Reagents & Primers/Probes | High-purity reagents (e.g., for PCR) free of nucleases and inhibitors are vital for the sensitivity and specificity of DNA-based detection and identification methods [28] [20]. |

| Immunoassay Kits (e.g., ELISA) | Self-contained kits with antibodies specific to a target antigen (e.g., a mycotoxin or pathogen). Enable high-throughput, rapid screening with standardized protocols [22]. |

| Solid-Phase Extraction (SPE) Sorbents | Used for sample clean-up and pre-concentration of analytes from complex food matrices. Reduces matrix effects and improves the sensitivity and reliability of chromatographic analysis [25]. |

| Stable Isotope-Labeled Internal Standards | Added to samples at the beginning of extraction. They correct for analyte loss during sample preparation and matrix effects during MS analysis, significantly improving quantitative accuracy in LC-MS/MS and GC-MS/MS [27]. |

Establishing a robust analytical rationale is a multifaceted process that extends beyond operating sophisticated instruments. It requires a foundational understanding of the "why" – the safety, authenticity, and compliance drivers – which informs the "how" – the selection, development, and validation of appropriate methods. The integration of advanced techniques like non-targeted screening and real-time sensors, supported by AI and data analytics, represents the future of proactive food safety [24] [28]. However, these innovations must be built upon the timeless principles of rigorous method validation, quality assurance, and a clear, defensible scientific rationale that ensures the integrity of the global food supply.

The continuous evolution of the global food supply chain has been paralleled by the emergence and identification of complex chemical contaminants, presenting unprecedented challenges to food safety and public health. Among these, per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS), mycotoxins, and microplastics have garnered significant scientific and regulatory attention due to their persistent nature, biological potency, and ubiquity in food systems. The development of robust, sensitive, and reliable analytical methods is fundamental to understanding the occurrence, exposure risks, and mitigation strategies for these contaminants. This technical guide provides a comprehensive overview of the current analytical landscape for PFAS, mycotoxins, and microplastics in food, framed within the broader context of analytical method development for food safety research. It synthesizes advanced detection techniques, validated experimental protocols, and comparative data to support researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals in advancing contaminant monitoring and ensuring food safety.

PFAS Analytical Methods

Compound Characteristics and Analytical Challenges

Per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) comprise a vast group of anthropogenic compounds characterized by fully or partially fluorinated carbon chains. The absence of a universally accepted PFAS definition directly impacts analytical methodologies, particularly screening methods designed to determine total fluorinated compounds [29]. PFAS are broadly divided into polymeric and non-polymeric substances, with well-known compounds like perfluorooctanoic acid (PFOA) and perfluorooctane sulfonic acid (PFOS) falling into the non-polymeric perfluoroalkyl category [29]. The major analytical challenge lies in their diverse chemical structures and presence at ultra-trace levels in complex food matrices, necessitating highly sensitive and selective methods.

Established Regulatory Methods and Advanced Approaches

U.S. federal agencies have established several validated methods for PFAS analysis in environmental and food matrices. The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) has promulgated methods including EPA 533, EPA 537.1, and EPA 1633 for water, solids, biosolids, and tissue samples, all based on solid-phase extraction (SPE) and liquid chromatography with tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) [29]. For food analysis, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has refined methods since 2012 to measure low PFAS levels, particularly in foods from areas with known environmental contamination [30].

Recent research advances focus on expanding the scope of target analytes and improving efficiency. A 2025 study developed and validated a method for 74 PFAS analytes across 15 different groups—including legacy PFAS, short-chain alternatives, precursors, and breakdown products—in various foods of animal origin (beef, chicken, pork, catfish, eggs) using a modified QuEChERSER (Quick, Easy, Cheap, Effective, Rugged, Safe, Efficient, and Robust) approach with LC-MS/MS [31]. This method achieved recoveries of 72–93% with reagent-only calibration and 84–97% with matrix-matched calibration, demonstrating performance comparable or superior to existing FDA and USDA methods [31].

Detailed Experimental Protocol: QuEChERSER Method for PFAS in Foods of Animal Origin

The following protocol outlines the comprehensive method for analyzing 74 PFAS in various food matrices [31]:

- Sample Preparation: Homogenize 2 ± 0.1 g of sample (beef, chicken, pork, catfish, or egg). For liquid eggs, use 2 g directly. For powdered eggs, reconstitute with 2 mL of water.

- Extraction: Add 10 mL of acetonitrile containing 1% acetic acid and internal standards. Shake vigorously for 1 minute. Add a salt mixture (4 g MgSO4, 1 g NaCl, 1 g trisodium citrate dihydrate, 0.5 g disodium hydrogen citrate sesquihydrate). Shake for another minute and centrifuge at 4000 rpm for 5 minutes.

- Cleanup: Transfer 6 mL of the supernatant to a dispersive SPE tube containing 150 mg MgSO4, 50 mg C18, and 50 mg of a weak anion exchange (WAX) sorbent. Shake for 1 minute and centrifuge at 4000 rpm for 5 minutes.

- Concentration: Transfer 4 mL of the cleaned extract and evaporate to near dryness under a gentle nitrogen stream at 40°C. Reconstitute the residue in 500 µL of methanol/water (50:50, v/v) and filter through a 0.2 µm PTFE syringe filter.

- Instrumental Analysis: Analyze using LC-MS/MS with a C18 column (100 × 2.1 mm, 2.6 µm) maintained at 40°C. The mobile phase consists of (A) 2 mM ammonium acetate in water and (B) 2 mM ammonium acetate in methanol. Use a gradient elution from 10% B to 100% B over 14 minutes. Employ electrospray ionization in negative mode with multiple reaction monitoring (MRM).

- Validation: Validate the method using matrix-matched calibration curves, with limits of quantification (LOQs) ranging from 0.020 to 2.24 ng/g wet weight. Verify accuracy using NIST Standard Reference Materials 1946 and 1947, achieving accuracies of 71–112%.

Complementary Analytical Techniques

Beyond targeted LC-MS/MS methods, additional techniques provide complementary data:

- Total Fluorine Methods: Including particle-induced gamma-ray emission (PIGE) and combustion ion chromatography (CIC) to measure total organic fluorine (TOF) as a screening tool [29].

- Precursor Oxidizer Assay: Uses hydroxyl radical oxidation to convert precursor compounds into measurable perfluoroalkyl acids [29].

- Non-Targeted Analysis: Employing high-resolution mass spectrometry (HRMS) to identify novel PFAS compounds not included in targeted methods [29].

Mycotoxins Analytical Methods

Contamination Challenges and Health Impacts

Mycotoxins are toxic secondary metabolites produced by filamentous fungi that contaminate up to 60–80% of global crops, with Fusarium mycotoxins being most dominant in temperate climates [32]. These compounds pose severe health risks, including carcinogenicity, nephrotoxicity, immunotoxicity, and endocrine disruption. Aflatoxin B1 (AFB1) is classified as a Group 1 human carcinogen by IARC, while ochratoxin A and fumonisin B1 are considered Group 2B carcinogens [33]. Climate change is exacerbating contamination patterns by altering the geographical distribution of mycotoxigenic fungi and creating new plant-pathogen interactions [32].

Advanced Detection Techniques and Nanomaterial Applications

Traditional methods for mycotoxin analysis include high-performance liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (HPLC-MS/MS) and immunoassays, which offer high sensitivity but often require complex sample preparation and sophisticated instrumentation [33]. Recent advances have focused on integrating nanomaterials to improve detection performance through enhanced enrichment capabilities, signal amplification, and sensing platform development.

Nanomaterials serve multiple functions in mycotoxin analysis:

- As Adsorbents: Porous nanomaterials like covalent organic frameworks (COFs), metal-organic frameworks (MOFs), and molecularly imprinted polymers (MIPs) provide high-surface-area materials for efficient extraction and clean-up. COFs achieve 10–100 times greater enrichment efficiencies than traditional adsorbents like silica gel through precise pore design and surface modification enabling specific interactions (hydrogen bonding, π-π stacking) [33].

- As Signal Amplifiers: Gold nanoparticles (AuNPs) and other plasmonic materials enhance sensor sensitivity through localized surface plasmon resonance (LSPR), achieving sub-picogram per milliliter detection limits [33].

- As Sensing Platforms: Graphene and carbon nanotubes serve as signal transduction units in electrochemical sensors, enabling ultrasensitive instant detection when coupled with aptamer recognition elements [33].

Detailed Experimental Protocol: Nanomaterial-Enhanced Mycotoxin Detection

A representative protocol utilizing functionalized nanomaterials for aflatoxin B1 detection [33]:

- Nanomaterial Synthesis: Prepare COF nanoparticles via solvothermal synthesis using 1,3,5-triformylphloroglucinol and benzidine in a mixture of mesitylene/1,4-dioxane/acetic acid at 120°C for 72 hours. Functionalize with aptamers through EDC/NHS chemistry.

- Sample Preparation: Grind representative sample to fine powder. Extract 5 g of sample with 20 mL of methanol/water (70:30, v/v) by shaking for 30 minutes. Centrifuge at 8000 rpm for 10 minutes and collect supernatant.

- Extraction and Cleanup: Dilute extract with 30 mL of phosphate buffer (10 mM, pH 7.4). Add 10 mg of aptamer-functionalized COF nanoparticles and incubate with shaking for 15 minutes. Separate nanoparticles by centrifugation at 10000 rpm for 5 minutes.

- Elution: Elute bound mycotoxins with 2 mL of methanol/acetic acid (98:2, v/v) by vortexing for 2 minutes. Centrifuge and collect eluent. Evaporate to dryness under nitrogen stream and reconstitute in 200 µL of mobile phase.

- HPLC-MS/MS Analysis: Analyze using HPLC system coupled with triple quadrupole mass spectrometer. Use C18 column (100 × 2.1 mm, 1.8 µm) with mobile phase of (A) water with 0.1% formic acid and (B) methanol with 0.1% formic acid. Gradient: 20% B to 95% B over 10 minutes. MS detection using electrospray ionization in positive mode with MRM.

- Method Validation: Validate according to EU regulations, achieving LOQs of 0.1 µg/kg for aflatoxins, significantly below the EU regulatory limit of 0.1–12 µg/kg for total aflatoxins in various food commodities [32].

Table 1: Maximum Regulatory Limits for Selected Mycotoxins in Food

| Mycotoxin | Commodity Group | EU Threshold (µg/kg) | US FDA Threshold (µg/kg) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Aflatoxin B1 | Dried fruits, nuts, cereals | 2.0–12.0 | 20.0 (total aflatoxins) |

| Aflatoxin M1 | Raw milk, heat-treated milk | 0.05 | 0.5 |

| Ochratoxin A | Cereals, dried fruits, wine | 2.0–80.0 | Not specified |

| Deoxynivalenol | Unprocessed cereals, bakery products | 250–1750 | 1000 |

| Zearalenone | Unprocessed cereals, milling products | 50–400 | Not specified |

| Fumonisins (B1+B2) | Unprocessed maize, maize products | 800–4000 | 2000–4000 (B1+B2+B3) |

| Patulin | Fruit juices, cider | 25–50 | 50 |

Emerging Sensing Platforms and Multi-Toxin Analysis

Advanced biosensing platforms integrate nanomaterials with various transduction mechanisms:

- Electrochemical Aptasensors: Use gold nanoparticles modified with aptamers for signal amplification, achieving detection limits of 0.01 pg/mL for ochratoxin A in coffee samples [33].

- Fluorescence Immunosensors: Employ quantum dots or upconversion nanoparticles with antibody functionalization for multiplexed detection of aflatoxins and zearalenone in cereals [33].

- Surface-Enhanced Raman Scattering (SERS): Utilize plasmonic nanostructures for highly sensitive detection with characteristic fingerprint spectra, enabling simultaneous detection of multiple mycotoxins [33].

Microplastics Analytical Methods

Microplastics—plastic particles smaller than 5 mm—have emerged as a significant food contaminant, primarily migrating from food packaging materials during use [34]. Their analysis presents unique challenges due to the diverse polymer compositions, size variations, and complex food matrices that interfere with detection and quantification. The lack of standardized methods remains a significant bottleneck in exposure assessment and risk evaluation [35].

Comprehensive Analytical Approaches

Current analytical workflows for microplastics in food involve multiple complementary techniques:

- Sample Preparation: Requires specialized digestion protocols to remove organic matter without degrading plastic polymers. Common approaches include enzymatic digestion, alkaline hydrolysis (KOH or NaOH), and oxidative treatments (H2O2) [34] [35].

- Separation and Identification: Combines spectroscopic, thermal, and mass spectrometric techniques:

- Vibrational Spectroscopy: Fourier-Transform Infrared (FTIR) and Raman spectroscopy provide polymer identification through characteristic vibrational fingerprints, with microscopy enabling size and shape characterization [34] [35].

- Thermal Analysis: Pyrolysis-Gas Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (Py-GC/MS) enables polymer identification and quantification through thermal decomposition products, offering excellent sensitivity but requiring destructive analysis [34].

- Liquid Chromatography: Size-exclusion chromatography coupled with high-resolution mass spectrometry can identify dissolved polymer fractions and additives [34].

Detailed Experimental Protocol: Microplastics Analysis in Food Packaging

A comprehensive protocol for analyzing microplastics released from food packaging materials [34] [35]:

- Migration Assay: Cut food packaging material into standardized surface areas (e.g., 1 dm²). Expose to food simulants (e.g., 10% ethanol for aqueous foods, 50% ethanol for dairy products, olive oil for fatty foods) at appropriate temperatures and times based on intended use. For accelerated testing, use 70°C for 2 hours or 40°C for 10 days.

- Sample Preparation: Filter simulant through gold-coated membrane filters (pore size 0.8–1.2 µm) to collect particulate matter. For complex food matrices, digest organic material with 10% KOH at 60°C for 24 hours or enzymatic treatments with proteinase K and cellulase. Centrifuge and filter digestate.

- Microscopic Characterization: Examine filters under stereomicroscope to count and categorize particles by size, shape, and color. Use fluorescence microscopy with Nile Red staining for enhanced visualization.

- Polymer Identification:

- FTIR Microscopy: Analyze individual particles in transmission or reflection mode. Collect spectra in range 4000–600 cm⁻¹ with 4 cm⁻¹ resolution. Compare to polymer reference libraries.

- Raman Spectroscopy: Use 785 nm or 532 nm laser excitation. Apply cosmic ray correction and baseline correction. Match spectra to reference databases.

- Py-GC/MS: Transfer particles to pyrolysis cups. Use pyrolysis temperature of 600–800°C. Separate degradation products using GC with DB-5ms column and identify with MS detection.

- Quantification and Quality Control: Include procedural blanks, positive controls (known polymer standards), and matrix spikes. Report particles per surface area or per volume simulant. Implement strict contamination control measures including cotton lab coats, air filtration, and glassware instead of plastics [35].

Table 2: Analytical Techniques for Microplastics Characterization

| Technique | Principle | Key Applications | Limitations | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| FTIR Microscopy | Molecular vibration absorption | Polymer identification, particle counting | Size limit ~10-20 µm, time-consuming | |

| Raman Spectroscopy | Inelastic light scattering | Polymer ID, additives detection, <1 µm particles | Fluorescence interference | |

| Py-GC/MS | Thermal decomposition & separation | Polymer quantification, additive analysis | Destructive, no particle information | |

| - | Liquid Chromatography | Hydrodynamic volume separation | Dissolved polymer fractions | Limited to soluble polymers |

| SEM-EDS | Electron imaging & elemental analysis | Surface morphology, elemental composition | No polymer identification |

Quality Assurance and Emerging Directions

Critical considerations for microplastics analysis include:

- Contamination Control: Implement rigorous protocols including air filtration, glass fiber filters in ventilation, cotton lab coats, and procedural blanks to account for background contamination [35].

- Standardization Needs: Current inter-laboratory comparisons show significant variability, highlighting the need for standardized protocols, reference materials, and harmonized reporting units [35].

- Advanced Techniques: Emerging approaches include focal plane array-FTIR for high-throughput analysis, TED-GC/MS for larger sample sizes, and machine learning algorithms for automated particle classification [34].

Comparative Analysis and Method Selection

Analytical Method Performance Comparison

Each contaminant class presents distinct analytical challenges requiring specialized approaches. PFAS analysis achieves exceptional sensitivity through advanced LC-MS/MS techniques, with LOQs reaching 0.020 ng/g [31]. Mycotoxin methods balance regulatory compliance with rapid screening needs through nanomaterial-enhanced platforms [33]. Microplastics analysis remains qualitatively oriented, focusing on polymer identification and particle characterization rather than ultra-trace quantification [34].

Table 3: Comparative Analytical Performance Across Contaminant Classes

| Parameter | PFAS | Mycotoxins | Microplastics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Technique | LC-MS/MS | HPLC-MS/MS, Immunoassays | FTIR, Raman, Py-GC/MS |

| Typical LOQ | 0.02-2.24 ng/g [31] | 0.1-50 µg/kg [33] | Visual: ~1 µm, Spectroscopy: ~10 µm |

| Key Challenge | Comprehensive analyte coverage | Matrix complexity, rapid detection | Standardization, particle identification |

| Sample Preparation | QuEChERS, SPE [31] | Immunoaffinity, DLLME, nano-adsorbents [33] | Digestion, filtration, density separation |

| Regulatory Framework | Evolving, few established limits [30] | Well-established limits [32] | Emerging, no standardized methods |

Method Development Considerations

Developing analytical methods for emerging contaminants requires addressing several cross-cutting considerations:

- Matrix Complexity: Food matrices introduce significant interference challenges, necessitating efficient extraction and clean-up strategies specific to each contaminant group [31] [33] [36].

- Sensitivity Requirements: Regulatory limits continue to decrease, demanding increasingly sensitive methods capable of detecting contaminants at parts-per-trillion levels [31] [36].

- Multi-Residue Capability: The diversity within each contaminant class drives development of methods that can simultaneously analyze dozens to hundreds of analytes [31].

- Throughput and Efficiency: Balancing analytical rigor with practical throughput requirements through streamlined sample preparation and rapid detection techniques [33].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 4: Key Research Reagents for Emerging Contaminant Analysis

| Reagent/Material | Application | Function | Example Use |

|---|---|---|---|

| Weak Anion Exchange (WAX) Sorbent | PFAS Analysis | Selective retention of anionic PFAS during clean-up | QuEChERSER method for 74 PFAS in foods [31] |

| Isotopically Labeled Internal Standards | PFAS & Mycotoxin Analysis | Quantification correction for matrix effects & recovery | 13C-labeled PFAS in LC-MS/MS analysis [31] |

| Covalent Organic Frameworks (COFs) | Mycotoxin Analysis | High-efficiency extraction with tailored porosity | AFB1 enrichment with 10-100× efficiency vs. silica [33] |

| Molecularly Imprinted Polymers (MIPs) | Mycotoxin Analysis | Biomimetic recognition for selective extraction | OTA clean-up in coffee and wine samples [33] |

| Gold Nanoparticles (AuNPs) | Mycotoxin Biosensing | Signal amplification in optical & electrochemical sensors | LSPR enhancement for ochratoxin A detection [33] |

| Aptamers | Mycotoxin & PFAS Sensing | Synthetic recognition elements for biosensors | AFB1 detection in electrochemical aptasensors [33] |

| Food Simulants | Microplastics Migration | Simulating chemical migration under use conditions | 10% ethanol, 50% ethanol, olive oil [34] |

| Gold-Coated Membrane Filters | Microplastics Analysis | Minimizing background interference in spectroscopy | FTIR analysis of particles from food simulants [35] |

The analytical landscape for emerging food contaminants is evolving rapidly to address the complex challenges posed by PFAS, mycotoxins, and microplastics. While each contaminant class requires specialized approaches, common themes include the need for enhanced sensitivity, expanded analyte coverage, efficient sample preparation, and method standardization. Advanced mass spectrometry continues to set the standard for PFAS and mycotoxin quantification, while nanomaterial-enhanced sensing platforms offer promising avenues for rapid screening. Microplastics analysis, though less mature in its methodological development, is progressing through complementary spectroscopic and thermal techniques. The continued development of robust, sensitive, and standardized analytical methods remains crucial for accurate exposure assessment, regulatory compliance, and ultimately, the protection of public health from emerging contaminants in the food supply. Future directions will likely focus on high-throughput methods, non-targeted analysis for unknown compounds, and integrated approaches for assessing mixture effects.

Selecting and Implementing Advanced Analytical Techniques

The development of robust analytical methods for identifying and quantifying chemical contaminants in food is a cornerstone of modern food safety research. This technical guide provides an in-depth examination of three pivotal techniques—Liquid Chromatography-Tandem Mass Spectrometry (LC-MS/MS), Gas Chromatography-Tandem Mass Spectrometry (GC-MS/MS), and Inductively Coupled Plasma Mass Spectrometry (ICP-MS). These methodologies form the analytical foundation for detecting a diverse range of chemical hazards, from pesticide residues and environmental contaminants to toxic elements, at increasingly stringent regulatory levels. With the global chromatography food testing market projected to grow from USD 24.27 billion in 2025 to USD 41.70 billion by 2034, driven by stricter food safety regulations and technological advancements, proficiency in these techniques is essential for researchers and method development scientists [37]. This whitepaper details the core principles, application-specific methodologies, and performance characteristics of each technique, providing a structured framework for their application in food contaminant research.

Technique Fundamentals and Application Scope

The selection of an appropriate analytical technique is dictated by the physicochemical properties of the target analytes and the complexity of the food matrix. LC-MS/MS, GC-MS/MS, and ICP-MS offer complementary capabilities that cover the vast majority of chemical contaminants of concern.

Liquid Chromatography-Tandem Mass Spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) is particularly suited for the analysis of thermolabile, polar, and non-volatile compounds. Its primary applications in food safety include the determination of polar pesticide residues, veterinary drug residues (e.g., antimicrobials), mycotoxins, and other organic contaminants [38] [39]. The technique's versatility allows for the analysis of a wide scope of compounds, with modern high-resolution accurate mass spectrometry (HRMS) expanding its capabilities for non-targeted screening and the identification of unknown contaminants [40].

Gas Chromatography-Tandem Mass Spectrometry (GC-MS/MS) is the technique of choice for volatile and semi-volatile compounds that are thermally stable. It is extensively used for the analysis of numerous pesticide residues (e.g., organochlorine and organophosphorus pesticides), persistent organic pollutants (POPs), and aroma compounds [38] [41]. GC-MS/MS and LC-MS/MS are highly complementary; the former is ideal for GC-amenable pesticides, while the latter covers thermolabile and polar compounds [38].

Inductively Coupled Plasma Mass Spectrometry (ICP-MS) is a powerful elemental analysis technique dedicated to the detection of essential and toxic trace elements. Its key applications in food testing include the quantification of toxic elements like arsenic (As), cadmium (Cd), lead (Pb), and mercury (Hg), as well as essential nutrients [42] [43]. ICP-MS offers exceptionally low detection limits, multi-element detection capabilities, and a wide linear dynamic range, making it indispensable for monitoring compliance with regulatory thresholds for metals and other elements in food [42].

Table 1: Scope of Application for Major Analytical Techniques in Food Contaminant Analysis

| Technique | Primary Analyte Classes | Example Contaminants | Common Food Matrices |

|---|---|---|---|

| LC-MS/MS | Polar pesticides, veterinary drugs, mycotoxins, bioactive compounds | Polar pesticides, oxytetracycline, enrofloxacin, phytochemicals | Lettuce, fruits, vegetables, honey, beef [44] [39] |

| GC-MS/MS | Organochlorine & organophosphorus pesticides, volatile organic compounds | p,p'-DDT, γ-lindane, isofenphos, aroma volatiles | Meat, spices, fruits, vegetables, roasted coffee, tea [38] [41] |

| ICP-MS | Toxic and essential trace elements | Arsenic (As), Cadmium (Cd), Lead (Pb), Mercury (Hg) | Rice flour, fish protein, mussel tissues, aromatic spices [42] [43] |

Core Analytical Methodologies

Liquid Chromatography-Tandem Mass Spectrometry (LC-MS/MS)

LC-MS/MS has become a workhorse in food contaminant analysis due to its high sensitivity and specificity. A key application is the monitoring of polar pesticides using established methods like the Quick Polar Pesticides (QuPPe) method [44].

Experimental Protocol: Determination of Anionic Polar Pesticides

- Sample Preparation: The QuPPe method involves a generic extraction of foodstuffs (e.g., cucumber, wheat flour) with acidified methanol. The extract is then directly analyzed without a clean-up step, demonstrating the method's ruggedness for multi-residue analysis [44].

- Instrumental Analysis: Analysis is performed using a UHPLC system coupled to a tandem quadrupole mass spectrometer operating in negative electrospray ionization (ESI) mode. The use of a photomultiplier detector can enhance sensitivity for challenging negative ionizing compounds [44].

- Chromatography: A reverse-phase column (e.g., C18) is typically used with a mobile phase gradient of water and methanol or acetonitrile, often modified with buffers to aid separation and ionization.

- Mass Spectrometry: Detection and quantification are carried out using Multiple Reaction Monitoring (MRM), where specific transitions from precursor ion to product ion are monitored for each analyte, providing high selectivity in complex matrices.

- Quantitation: Calibration standards are prepared in the blank matrix to compensate for matrix effects. For cucumber, the limit of quantification (LOQ) can be achieved at 0.5 μg/kg for most anionic polar pesticides, while for drier matrices like wheat flour, the LOQ is typically 2 μg/kg [44].

Gas Chromatography-Tandem Mass Spectrometry (GC-MS/MS)

GC-MS/MS is renowned for its high resolution and sensitivity for volatile analytes. Its effectiveness relies heavily on robust sample preparation to handle complex food matrices.

Experimental Protocol: Multi-residue Pesticide Analysis in Complex Matrices

- Sample Preparation: The QuEChERS (Quick, Easy, Cheap, Effective, Rugged, and Safe) method is widely adopted. It involves an extraction with acetonitrile followed by a salting-out step and a clean-up using dispersive Solid-Phase Extraction (d-SPE). For complex, dry matrices like spices and herbs, the sample intake may be reduced, and the d-SPE clean-up optimized with different adsorbent combinations [38].

- Instrumental Analysis: The extract is analyzed using a GC system coupled to a triple quadrupole mass spectrometer.

- Chromatography: Separation is achieved using a fused-silica capillary column with a stationary phase suitable for the target analytes.

- Mass Spectrometry: The MS/MS operates in MRM mode. The careful selection of precursor and product ions is critical to avoid matrix interferences and achieve lower limits of quantification [38].