Decoding Flavor: Molecular Mechanisms, Advanced Analytics, and Clinical Applications in Sensory Perception

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of the molecular basis of food sensory perception and flavor, tailored for researchers and drug development professionals.

Decoding Flavor: Molecular Mechanisms, Advanced Analytics, and Clinical Applications in Sensory Perception

Abstract

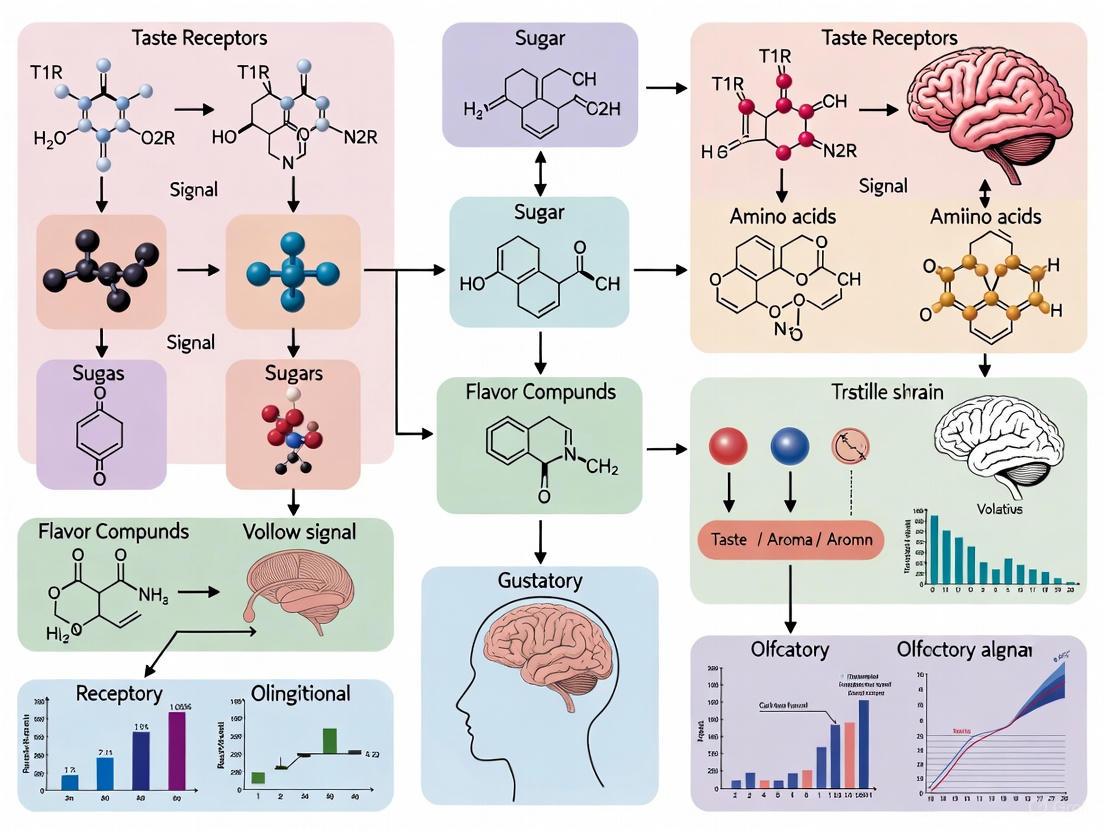

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of the molecular basis of food sensory perception and flavor, tailored for researchers and drug development professionals. It explores the fundamental biological pathways of taste and smell, from receptor-level interactions to complex neural processing. The scope encompasses modern flavoromics approaches that integrate advanced analytical techniques like GC-MS, LC-HRMS, and NMR with sensory evaluation. The content addresses methodological challenges in flavor analysis, compares traditional and novel sensory assessment tools, and examines applications in medicinal taste masking and personalized nutrition. By synthesizing current research from chemistry, biology, and sensory science, this review aims to bridge fundamental discovery with translational applications in pharmaceuticals and clinical research.

From Molecules to Sensation: Unraveling the Biological Pathways of Flavor Perception

The perception of taste is a fundamental biological process that enables organisms to assess the nutritional value and potential toxicity of food. For decades, taste was categorized into four primary qualities: sweet, sour, salty, and bitter. The discovery of umami, the savory taste of glutamate, established it as the fifth basic taste [1]. Research into the molecular basis of taste perception has revealed complex receptor systems and signal transduction pathways that convert chemical stimuli into neural signals. This whitepaper examines the receptor-level mechanisms and signal transduction processes for each of the five basic tastes, providing a technical resource for researchers investigating the molecular foundations of sensory perception. Understanding these mechanisms is crucial for advancing fields ranging from food science to neuropharmacology, particularly in the context of a broader thesis on the molecular basis of food sensory perception and flavor research.

Taste Receptor Families and Signal Transduction Mechanisms

The human gustatory system employs distinct receptor families and signaling mechanisms to detect the five basic tastes. Table 1 summarizes the receptor types, key molecular components, and cellular responses for each taste quality.

Table 1: Receptor Mechanisms and Signal Transduction Pathways for the Five Basic Tastes

| Taste Quality | Receptor Type/Channel | Key Molecular Components | Signal Transduction Mechanism | Taste Cell Type | Primary Signal Output |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sweet | Class C GPCR (heterodimer) | T1R2, T1R3, Gα-gustducin, PLCβ2, IP₃R, TRPM5 [2] | G protein activation → PLCβ2 → IP₃ → Ca²⁺ release → TRPM5 opening → depolarization [2] | Type II | ATP release [3] |

| Umami | Class C GPCR (heterodimer & others) | T1R1, T1R3, mGluR4 (truncated), Gα-gustducin, PLCβ2, IP₃R, TRPM5 [2] [4] | G protein activation → PLCβ2 → IP₃ → Ca²⁺ release → TRPM5 opening → depolarization [2] [4] | Type II | ATP release [3] |

| Bitter | Class A GPCR (family) | ~25 T2Rs, Gα-gustducin, PLCβ2, IP₃R, TRPM5 [3] | G protein activation → PLCβ2 → IP₃ → Ca²⁺ release → TRPM5 opening → depolarization [3] | Type II | ATP release [3] |

| Salty | Ion Channel | ENaC (low [Na⁺]), other channels (high [Na⁺]) [3] | Na⁺ influx through cation channels → direct depolarization [3] | Type III | Serotonin release [3] |

| Sour | Ion Channel | OTOP1, PKD2L1 [3] | H⁺ influx → channel blockade or direct gating → depolarization [3] | Type III | Serotonin release [3] |

Diagram: Common Signal Transduction Pathway for Sweet, Umami, and Bitter Tastes

The following diagram illustrates the shared G-protein coupled receptor pathway used by sweet, umami, and bitter tastes.

Detailed Mechanisms by Taste Quality

Sweet Taste

Sweet taste is primarily mediated by the T1R2/T1R3 heterodimer, a Class C G-protein coupled receptor (GPCR) [2]. This receptor responds to a diverse range of sweet-tasting compounds, including sugars, artificial sweeteners, and sweet proteins [2]. The Venus flytrap domain in the large N-terminal region of the T1R subunits contains the primary binding site for most natural sugars, while other sweeteners may bind to the transmembrane domain or cysteine-rich region [2].

Key experimental approaches for studying sweet taste include:

- Calcium imaging in heterologous systems: HEK-293 cells transfected with T1R2 and T1R3 genes show intracellular Ca²⁺ increases when stimulated with sweet compounds, confirming receptor functionality [2].

- Knockout mouse models: Mice lacking the Tas1r3 or Tas1r2 genes show markedly diminished behavioral and nerve responses to sweet substances [2].

- Electrophysiological recordings: Chorda tympani nerve recordings measure integrated responses from taste buds to sweet stimuli [2].

Umami Taste

Umami taste represents a complex case of taste coding, with multiple receptors potentially contributing to the perception of L-glutamate and ribonucleotides. The primary receptor is believed to be the T1R1/T1R3 heterodimer, which displays synergistic enhancement when glutamate is combined with 5'-ribonucleotides such as inosine monophosphate (IMP) or guanosine monophosphate (GMP) [2] [4]. However, evidence suggests additional receptors may be involved, including truncated forms of metabotropic glutamate receptors (mGluR4 and mGluR1) [4].

Unlike the truncated mGluR4 receptor, which responds specifically to glutamate, the T1R1/T1R3 receptor exhibits a broader amino acid sensitivity and shows pronounced synergy with nucleotides [4]. This synergism is a hallmark of umami taste, where the presence of IMP or GMP can enhance the perceived intensity of glutamate by up to 20-fold [2].

Critical experimental findings on umami taste include:

- Knockout studies show partial responses: Mice lacking the Tas1r1 or Tas1r3 genes show depressed but not eliminated neural and behavioral responses to umami stimuli, suggesting multiple receptor mechanisms [4].

- mGluR4 knockout increases preference: Mice lacking mGluR4 show significantly increased preference for MSG, indicating this receptor may normally exert an inhibitory influence on umami responses [4].

- L-AP4 taste similarity: In conditioned taste aversion assays, rats generalize the tastes of glutamate and L-AP4 (an mGluR4 agonist), supporting its role as a functional umami receptor [4].

Bitter Taste

Bitterness is detected by a family of approximately 25 T2R receptors (in humans) belonging to the Class A GPCR family [3]. This receptor diversity enables the detection of a wide range of structurally diverse bitter compounds, which often signal potential toxins in food [3]. Individual taste receptor cells typically express multiple T2R receptors, allowing for a broad response spectrum to various bitter compounds [3].

The signal transduction pathway for bitter taste shares the same downstream components (Gα-gustducin, PLCβ2, IP₃R, TRPM5) as sweet and umami tastes [3]. This convergence explains why these three qualitatively distinct tastes share a common output pathway from Type II taste cells.

Sour Taste

Sour taste detection mechanisms have been more elusive, but recent research has identified OTOP1 as a proton channel that is essential for sour perception [3]. This ion channel is gated by extracellular protons (H⁺), allowing cation influx that leads to membrane depolarization in Type III taste cells [3].

Earlier candidates for sour receptors included:

- PKD2L1: Expressed in Type III taste cells and implicated in sour responses [3].

- Other channels: ASIC, HCN, KCNK, and KIR2.1 channels have been proposed to contribute to acid sensing [3].

Salty Taste

Salty taste transduction mechanisms are the least well-characterized among the basic tastes. Low concentrations of sodium chloride are thought to be detected primarily by the epithelial sodium channel (ENaC), which allows Na⁺ influx leading to direct depolarization [3]. The mechanisms for detecting high salt concentrations and the specific cell types involved remain areas of active investigation [3].

The following diagram provides an integrated overview of how different taste qualities are detected and transmitted.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents and Methods

Table 2 provides a comprehensive list of essential research tools, reagents, and their applications for studying taste mechanisms.

Table 2: Key Research Reagents and Methodologies for Taste Research

| Reagent/Method | Category | Specific Application | Key Function in Research |

|---|---|---|---|

| HEK-293T Cells | Cellular Model | Heterologous expression system | Express cloned taste receptors for deorphanization and screening assays [2] |

| Calcium-Sensitive Dyes (e.g., Fura-2) | Fluorescent Indicator | Live-cell calcium imaging | Measure intracellular Ca²⁺ changes in response to taste stimuli in vitro or in taste buds [2] |

| T1R3-Knockout Mice | Animal Model | Sweet and umami taste studies | Determine necessity of T1R3 for sweet/umami responses; reveal alternate pathways [4] |

| Gustducin Antibodies | Immunological Reagent | Tissue localization | Identify taste receptor cells (Type II) in taste buds via immunohistochemistry [4] |

| L-AP4 (mGluR4 Agonist) | Pharmacological Tool | Umami receptor studies | Probe the role of mGluR4 in umami taste in behavioral and neural assays [4] |

| Lactisole | TASTE RECEPTOR ANTAGONIST | Sweet and umami taste studies | Inhibits human T1R3, used to dissect T1R-dependent vs. T1R-independent pathways [2] |

| Chorda Tympani Nerve Recording | Electrophysiology | Integrated taste response measurement | Record whole-nerve activity in response to taste stimuli in vivo [4] |

| Two-Bottle Preference Test | Behavioral Assay | Taste perception and preference | Measure relative preference for a taste solution vs. water in rodents [4] |

| Conditioned Taste Aversion | Behavioral Assay | Taste quality assessment | Test if animals generalize a conditioned aversion between stimuli to determine perceptual similarity [4] |

| Electronic Tongue (E-tongue) | Analytical Instrument | Taste compound screening | Objectively measure and predict taste profiles of chemical compounds or food samples [5] |

Advanced Research Applications and Future Directions

Research on basic taste mechanisms continues to evolve with implications for food science, nutrition, and medicine. Artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning are now being applied to predict sensory qualities from chemical data, creating digital models of taste perception [5]. Electronic tongues (E-tongues) equipped with multisensor arrays can detect taste substances and, when combined with AI, predict human sensory perceptions with increasing accuracy [5] [6].

The discovery of extra-oral taste receptors in the gastrointestinal tract, respiratory system, and other tissues suggests broader physiological roles for taste receptors beyond conscious perception, including nutrient sensing and regulation of metabolic processes [3]. Furthermore, understanding taste receptor mechanisms has significant clinical implications, as evidenced by research on taste disorders (dysgeusia), which can arise from various causes including viral infections such as SARS-CoV-2 [3].

The molecular dissection of taste perception continues to provide insights not only into gustatory processing but also into broader principles of sensory coding and receptor function, offering multiple avenues for future scientific exploration and therapeutic development.

The perception of flavor, a cornerstone of food sensory science, is a multisensory experience heavily dependent on the olfactory system's ability to detect and decode a vast array of volatile organic compounds (VOCs). These VOCs, released from food, constitute the chemical basis of aroma and are detected by a large family of specialized proteins known as odorant receptors (ORs) [7] [8]. This complex interaction between volatiles and receptors is the molecular foundation of smell, which, when integrated with taste and other senses, creates the unified perception of flavor [7]. Understanding the mechanisms of volatile detection and the nature of OR families is therefore critical for advancing research in food chemistry, sensory evaluation, and the development of novel flavors and aroma-based products. This whitepaper provides an in-depth technical guide to the core components of olfactory detection, focusing on the properties of volatile compounds, the structure and function of odorant receptor families, and the experimental methodologies driving this field forward.

Volatile Organic Compounds: The Chemical Landscape of Smell

Volatile organic compounds are low molecular weight organic chemicals that readily evaporate at ambient temperatures, allowing them to travel through the air and reach the olfactory system [9]. In the context of food, VOCs are paramount to aroma and flavor perception. The terrestrial vegetation, which includes most food sources, produces an amazing diversity of VOCs derived from several key metabolic pathways, including the mevalonic acid (MVA) and methylerythritol phosphate (MEP) pathways for isoprenoids, the lipoxygenase (LOX) pathway for fatty acid derivatives, and the shikimic acid pathway for benzenoids and phenylpropanoids [9].

The specific profile of VOCs emitted is highly dynamic and depends on the plant species, tissue type, and environmental conditions, such as stress or herbivory [9]. For example, in sweet basil (Ocimum basilicum L.), distinct sensory profiles are chemically characterized by different volatile compounds. The anise aroma and flavor are closely associated with methyl chavicol, while a clove aroma is linked to eugenol [10]. Advanced analytical techniques like gas chromatography coupled with mass spectrometry (GC-MS) and electronic noses (E-Nose) are essential tools for identifying and quantifying these compounds in complex food matrices [8].

Table 1: Key Classes of Volatile Organic Compounds in Food and Their Sensory Attributes

| Compound Class | Example Compounds | Common Food Sources | Sensory Attributes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Terpenes | Limonene, Pinene, Caryophyllene [8] [9] | Citrus fruits, herbs, spices [9] | Citrus, pine, floral, woody |

| Benzenoids/Phenylpropanoids | Eugenol, Methyl chavicol [10] [9] | Basil, cloves, anise [10] | Clove, anise, spicy |

| Fatty Acid Derivatives | (E)-2-Hexenal, Hexanal [11] [9] | Green leaves, cut grass [9] | Green, grassy |

| Amino Acid Derivatives | Sulfur compounds, Indole [8] [9] | Passion fruit wine, fermented foods [8] | Tropical fruit, sulfurous |

Odorant Receptor Families: Molecular Gatekeepers of Olfaction

Odorant receptors are G protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs) that serve as the primary molecular gatekeepers of the olfactory system [12] [13]. They are located on the cilia of olfactory sensory neurons (OSNs) within the olfactory epithelium. The OR gene family is the largest in the animal genome, comprising approximately 1000 genes in mice and rats, which represents about 1% of the genome [12] [13]. In humans, the family includes roughly 400 functional receptors [14].

A foundational principle of olfactory coding is combinatorial reception. A single odorant molecule can bind to multiple ORs, and a single OR can be activated by multiple odorants [12]. The identity of an odor is thus encoded by a unique combination of activated ORs, creating a combinatorial code that allows a limited number of receptors to discern a vast universe of smells.

The origin of the OR gene family in insects has been a subject of significant research. Evidence indicates that ORs were present in the ancestor of all insects but are absent from non-insect hexapod lineages, suggesting that the origin of this gene family coincided with the evolution of insects, possibly as an adaptation to terrestriality [15]. A key innovation in insect olfaction was the evolution of a universal, highly conserved co-receptor (Orco). All ORs form a heteromeric complex with Orco, which is essential for the receptor's function and trafficking to the cell membrane [15]. The OR/Orco system is found in most insects, with the exception of some ancestrally wingless lineages like Archaeognatha (bristletails) [15].

Table 2: Key Features of Vertebrate and Insect Odorant Receptor Families

| Feature | Vertebrates | Insects |

|---|---|---|

| Receptor Type | G Protein-Coupled Receptors (GPCRs) [13] | GPCRs (divergent from vertebrates) [15] |

| Gene Family Size | ~1000 in mouse/rat; ~400 in humans [14] [12] | Varies by species (e.g., 43 in Thermobia domestica) [15] |

| Co-receptor | Not applicable | Orco (universal co-receptor) [15] |

| Expression Pattern | One receptor per neuron (typically) [12] | One receptor per neuron (typically) [12] |

| Signal Transduction | Golf protein, cAMP pathway [16] | Orco-dependent, non-selective cation channel [15] |

A major resource for researchers is GPCRdb, which in its 2024/2025 release has incorporated all approximately 400 human odorant receptors and their orthologs in major model organisms [14]. This database provides reference data, analysis, and visualization tools for these receptors, allowing scientists to study their sequences, genetic relationships, and structural models. GPCRdb also includes updated inactive- and active-state models of human GPCRs, including ORs, built using advanced computational methods like AlphaFold-Multistate and RoseTTAFold, which are invaluable for structure-based research and ligand screening [14].

From Odorant Binding to Neural Perception

The journey from a volatile compound in the environment to a perceived smell involves a sophisticated signal transduction pathway and subsequent neural processing. The following diagram illustrates the core signaling pathway from odorant binding to initial signal transmission to the brain.

Diagram 1: Olfactory Signal Transduction Pathway. This diagram outlines the key steps in the vertebrate olfactory pathway, from odorant binding to the generation of an action potential that is transmitted to the olfactory bulb for further processing [16] [12].

The process begins when an odorant molecule enters the nasal cavity and binds to a specific OR on the cilia of an OSN [16]. This binding event activates the OR, which in turn activates a G protein (Golf). The activated G protein stimulates adenylyl cyclase to produce the second messenger cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP). The rise in cAMP levels opens cyclic nucleotide-gated (CNG) ion channels, allowing an influx of calcium and sodium ions into the cell. This influx depolarizes the neuron, generating an action potential that travels along the axon of the OSN to the olfactory bulb [16] [12].

In the olfactory bulb, axons from OSNs expressing the same OR converge onto discrete structures called glomeruli [12]. This creates a spatial map of olfactory information, where each glomerulus corresponds to a specific odorant receptor type. The signal is then processed by mitral and tufted cells, the primary output neurons of the olfactory bulb, which project directly to higher olfactory areas like the piriform cortex, forming the perception of smell [16]. The olfactory cortex is integral to pattern recognition and associating smells with memories and emotions [16].

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Surface Plasmon Resonance Imaging (SPRi) for VOC Detection

Objective: To develop highly sensitive olfactory biosensors for the detection and quantification of volatile organic compounds (VOCs) using immobilized odorant binding proteins (OBPs) and SPRi technology [11].

Detailed Protocol:

Sensor Chip Functionalization:

- Prepare a gold-coated glass chip for chemical modification.

- Immobilize three customized derivatives of rat OBP3 (odorant binding protein 3) as sensing elements onto the chip surface. Ensure immobilization conditions are optimized to preserve the binding properties of the proteins [11].

Sample Introduction and Binding Analysis:

- Use a microfluidic system to flow solutions containing target VOCs (e.g., β-ionone, hexanal) over the functionalized sensor chip.

- The SPRi instrument directs a polarized light beam at the chip surface, generating surface plasmon waves. As VOCs bind to the OBPs, the local refractive index at the chip surface changes [11].

Real-Time Monitoring and Data Acquisition:

- Monitor changes in the reflected light angle or intensity in real-time using a CCD camera. This change is directly proportional to the mass of molecules bound to the sensor surface, allowing for the quantification of binding events [11].

Regeneration and Reusability:

- After each measurement cycle, apply an optimized regeneration solution (e.g., a mild acid or buffer) to dissociate the bound VOC from the OBP without denaturing the protein. This step is critical for achieving repeatable measurements and extending the biosensor's lifespan, which can be up to two months [11].

Key Performance Metrics from this Protocol [11]:

- Limit of Detection (LOD): 200 pM for β-ionone.

- Molecular Weight Range: Capable of detecting VOCs with molecular weights as low as 100 g/mol (e.g., hexanal).

- Selectivity: High selectivity, especially at low VOC concentrations.

- Repeatability: Excellent measurement-to-measurement and chip-to-chip repeatability.

Gas Chromatography-Olfactometry (GC-O) for Aroma Compound Identification

Objective: To separate the volatile compounds of a food sample and directly evaluate their sensory impact by a human assessor, identifying the key odor-active compounds [8].

Detailed Protocol:

Sample Preparation and Volatile Extraction:

- Extract VOCs from the food matrix using techniques such as Headspace-Solid Phase Microextraction (HS-SPME), which concentrates volatiles onto a fused silica fiber [8].

Compound Separation:

- Inject the extracted volatiles into a Gas Chromatograph (GC). The compounds are separated as they travel through the GC column based on their differential partitioning between a mobile gas phase and a stationary liquid phase [8].

Splitting and Simultaneous Detection:

- At the end of the GC column, the effluent is split into two streams.

- One stream is directed to a physical detector (e.g., a Mass Spectrometer, MS) for chemical identification of each separated compound.

- The second stream is directed to an "olfactometry port," a heated outlet where a trained human assessor sniffs the effluent [8].

Sensory Evaluation and Data Correlation:

- The assessor records the perceived aroma, its intensity, and duration for each eluting compound.

- The data from the MS detector (chemical identity) and the assessor's notes (sensory attribute) are correlated to determine which chemicals are responsible for specific aroma notes in the food sample [8].

The following diagram illustrates the workflow of a combined GC-O and GC-MS system.

Diagram 2: GC-Olfactometry Workflow. This diagram shows the parallel chemical and sensory analysis used to identify key aroma-active compounds in a sample [8].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Olfactory Studies

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Odorant Binding Proteins (OBPs) | Sensing element in biosensors; binds specific VOCs with high affinity [11]. | Immobilized on SPRi chips for highly sensitive VOC detection [11]. |

| Heterologous Cell Systems (e.g., HEK293) | Cell lines used to functionally express odorant receptors for in vitro ligand screening [12]. | Co-expressing an OR and Orco to test activation by candidate odorants [12]. |

| SPRi Sensor Chips (Gold-coated) | Platform for immobilizing biological sensing elements (e.g., OBPs, ORs) and monitoring biomolecular interactions in real-time [11]. | Developing olfactory biosensors for trace detection of VOCs in solution [11]. |

| Solid-Phase Microextraction (SPME) Fibers | Extracts and concentrates volatile compounds from liquid or headspace samples for analytical analysis [8]. | Pre-concentrating volatiles from a wine sample prior to GC-MS analysis [8]. |

| GC-MS and GC-Orbitrap-MS Systems | High-resolution analytical instruments for separating, identifying, and quantifying volatile compounds in complex mixtures [8]. | Characterizing the full volatile profile of a food product like passion fruit wine [8]. |

| GPCRdb Database | Online resource providing curated data, structures, and analysis tools for G protein-coupled receptors, including odorant receptors [14]. | Retrieving sequence alignments, phylogenetic trees, and AlphaFold models for a specific human OR [14]. |

The intricate interplay between volatile organic compounds and odorant receptor families forms the basis of olfactory perception, a critical component of flavor. The advancements in analytical techniques, such as SPRi-based biosensors and GC-O, coupled with the expansion of genomic and structural databases like GPCRdb, have dramatically enhanced our ability to dissect this complexity at a molecular level. A deep understanding of these mechanisms provides a powerful framework for researchers in food science, flavor chemistry, and neurobiology to objectively decode sensory perception, paving the way for innovative applications in product development, quality control, and a fundamental understanding of sensory experience.

While taste and smell dominate the sensory evaluation of food, the somatosensory system provides the critical physical and chemical context that completes the flavor experience. This whitepaper details the molecular mechanisms of somatosensation and chemesthesis—the tactile, thermal, and chemical-irritant sensations mediated primarily by Transient Receptor Potential (TRP) and Acid-Sensing Ion Channels (ASICs). We provide a technical framework for researchers investigating the neural basis of flavor, including standardized experimental protocols for assessing trigeminal sensitivity, quantitative data on stimulus-response relationships, and visualization of key signaling pathways. The integration of these chemosensory signals offers novel targets for modulating flavor perception in food design and therapeutic interventions.

Flavor perception represents a complex synthesis of gustatory, olfactory, and somatosensory inputs. Somatosensation encompasses the physical sensations of texture, temperature, and touch mediated by mechanoreceptors and thermoreceptors. Chemesthesis refers to the chemical sensitivity of mucosal surfaces and skin, producing sensations such as the burn of capsaicin, the coolness of menthol, or the tingle of carbonation [17]. These signals converge primarily through the trigeminal nerve (Cranial Nerve V), which innervates the oral, nasal, and ocular surfaces.

Understanding the molecular basis of these systems is paramount for:

- Food Science: Designing controlled flavor release profiles and novel sensory experiences.

- Pharmaceutical Development: Optimizing drug palatability and creating non-opioid analgesics that target peripheral sensory pathways.

- Basic Research: Decoding the integrated neural circuits that translate chemical stimuli into conscious perception.

Molecular Mechanisms and Signaling Pathways

The perception of chemesthetic and somatosensory stimuli is mediated by a suite of ion channels expressed on sensory neurons.

Key Receptor Families

| Receptor Family | Primary Agonists | Resultant Sensation | Cellular Location |

|---|---|---|---|

| TRPV1 | Capsaicin, Heat (>43°C), Acids | Burning, Pain | C-fibers, Aδ-fibers |

| TRPM8 | Menthol, Icilin, Cold (<28°C) | Cooling | C-fibers |

| TRPA1 | Allyl Isothiocyanate (Mustard), Cinnamaldehyde, Cold (<17°C) | Pungency, Stinging | C-fibers |

| ASICs | Protons (Low pH) | Sourness, Sharpness | Sensory Neuron Terminals |

Integrated Signaling Pathway

The following diagram illustrates the core signaling pathway from stimulus application to neural signaling and perceived sensation.

Quantitative Data and Psychophysical Relationships

Effective experimental design requires an understanding of the quantitative relationships between stimulus concentration and perceived intensity. The following table summarizes threshold and saturation data for common chemesthetic agents.

Table 2: Psychophysical Parameters of Common Chemesthetic Stimuli

| Stimulus | Target Receptor | Detection Threshold (Human, Oral) | Half-Maximal Efficacy (EC₅₀) | Perceptual Quality |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Capsaicin | TRPV1 | 0.1 - 1.0 µM | ~0.3 µM | Burning, Pungent |

| Menthol | TRPM8 | 10 - 50 µM | ~60 µM | Cooling |

| Allyl Isothiocyanate | TRPA1 | 1 - 5 µM | ~8 µM | Sharp, Pungent |

| Carbonation | ASICs/Carbonic Anhydrase | 1.5 - 2.0 atm CO₂ | N/A | Tingling, Sharp |

| Ethanol | TRPV1/TRPA1 | 2-5% v/v | N/A | Burning, Warmth |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Robust experimentation requires standardized protocols to ensure reproducibility and valid cross-study comparisons.

Cell-Based Calcium Imaging for Receptor Activation

This protocol is used to characterize receptor responses and screen for agonists/antagonists.

Workflow Diagram:

Detailed Procedure:

- Cell Preparation: Culture HEK293T cells or dissociate trigeminal ganglion neurons from animal models (e.g., mouse, rat).

- Receptor Expression: For HEK293T cells, transiently transfect with plasmid DNA encoding the target human receptor (e.g., TRPV1) using a standard method like lipofection.

- Dye Loading: Incubate cells with 1-5 µM cell-permeant calcium indicator (e.g., Fluo-4 AM) in a physiological buffer (e.g., HBSS) for 30-60 minutes at 37°C. Protect from light.

- Baseline Acquisition: Wash cells and place in a clear, isotonic solution. Using a fluorescent microscope or plate reader, acquire baseline fluorescence (F₀) for 1-2 minutes.

- Stimulus Application: Apply the chemesthetic agent (e.g., capsaicin) in a series of increasing concentrations. Include a positive control (e.g., ionomycin) and vehicle control.

- Signal Capture: Continuously monitor fluorescence (F) for 3-5 minutes post-application. Calculate the relative fluorescence change (ΔF/F₀ = (F - F₀)/F₀).

- Data Analysis: Plot ΔF/F₀ against time and agonist concentration. Fit the concentration-response data with a sigmoidal curve (e.g., using a four-parameter logistic equation) to determine EC₅₀ values.

Human Psychophysical Evaluation: Two-Alternative Forced Choice (2-AFC)

This sensory test determines detection thresholds in human participants.

Detailed Procedure:

- Solution Preparation: Prepare a series of solutions with the target stimulus (e.g., capsaicin) in a neutral vehicle (e.g., mineral oil, water with 5% ethanol) using a logarithmic concentration scale.

- Trial Structure: In each trial, present the participant with two samples: one containing the stimulus and one vehicle control. The order is randomized.

- Participant Task: Instruct the participant to identify which sample contains the stimulus.

- Threshold Calculation: Use a staircase or ascending forced-choice method. The detection threshold is defined as the concentration at which the participant correctly identifies the stimulus at a statistically significant level (e.g., 75% correct), corrected for chance.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Successful research in this field relies on a specific set of high-quality reagents and tools.

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function & Utility | Example Specification |

|---|---|---|

| TRP Channel Agonists/Antagonists | Pharmacological tools to activate or block specific receptors for mechanism studies. | Capsaicin (TRPV1 agonist, >98% purity), AMG-517 (TRPV1 antagonist) |

| Calcium-Sensitive Fluorescent Dyes | To visually quantify receptor activation and cellular signaling in real-time. | Fluo-4 AM (cell-permeant), Fura-2 (rationetric) |

| Cell Lines for Heterologous Expression | A controlled system for studying recombinant human receptors without endogenous background. | HEK293T (high transfection efficiency), CHO-K1 |

| Primary Sensory Neurons | For physiologically relevant studies in native cells expressing the full complement of receptors. | Isolated rat or mouse Trigeminal Ganglion (TG) neurons |

| Animal Models | In vivo studies of behavior, neural coding, and genetics of chemesthesis. | Wild-type C57BL/6 mice; TRPV1-KO, TRPM8-KO strains |

| Psychophysical Testing Equipment | To deliver precise stimuli and collect human sensory data. | Glass sniff bottles, filter paper strips for taste strips, olfactometers |

The molecular dissection of somatosensation and chemesthesis has transformed our understanding of flavor from a simple combination of taste and smell to a complex, integrated sensory experience mediated by specific ion channels. The experimental frameworks and data presented here provide a foundation for advancing research in this field. Future efforts should focus on:

- Elucidating the complex interactions and cross-desensitization between different TRP channels.

- Exploring the genetic polymorphisms in these receptors that underlie individual differences in flavor perception and food preference.

- Developing high-throughput screening assays to discover novel flavor modulators and analgesics from natural and synthetic libraries.

Mastering this "third pathway" of flavor opens new frontiers for creating tailored food experiences and targeted therapeutic agents that operate at the fundamental interface between chemistry and sensation.

Flavor perception is a quintessentially multisensory experience, constructed by the brain's integration of distinct sensory cues from gustatory (taste), retronasal olfactory (smell), and somatosensory (texture, temperature) systems [18] [19]. Contrary to popular belief, what we perceive as "taste" is largely a synthesis of these separate inputs. Cognitive neuroscience has revealed that the brain does not process these signals in isolation; instead, it employs sophisticated neural mechanisms to bind them into a unified flavor percept [20]. This integration is not a simple summation but a complex, reliability-dependent computation performed primarily within the gustatory cortex (GC) and involving a network of other brain regions [18]. Understanding these processes at a molecular and systems level is critical for advancing fundamental knowledge in sensory neuroscience and has direct applications in the development of novel foods, flavor enhancers, and therapeutic strategies for sensory impairments.

Core Neural Mechanisms and Computations

The brain's integration of multisensory flavor signals follows specific computational principles, with the gustatory cortex acting as a central hub.

Reliability-Dependent Integration in the Gustatory Cortex

Recent research establishes that GC neurons perform a weighted integration of taste and smell inputs, where the weight assigned to each modality is dynamically calibrated based on its reliability [18]. Reliability in this context is defined by the noisiness or variability of the sensory input. A more reliable sensory signal—characterized by less variable neural responses—contributes more strongly to the final neural representation of the flavor mixture.

The underlying computation can be conceptualized as a weighted average, where the hedonic judgment (palatability) of a taste-smell mixture is determined by the formula: Judgmentmixture = (Weighttaste × Judgmenttaste) + (Weightsmell × Judgmentsmell). The weights are not fixed but are a function of the relative reliability of each component [18]. This reliability-dependent weighting allows the brain to form a robust and accurate percept of a food's flavor value, even when individual sensory channels are noisy.

The Neural Correlates of Flavor Binding

The mechanistic basis for this computation is observed in the electrophysiological properties of GC neurons. Extracellular recordings of single-neuron spiking and local field potential (LFP) activity in animal models reveal two key neural correlates:

- Response Variability: Unreliable sensory inputs are associated with more variable neural responses, quantified by a higher Fano factor (a measure of trial-to-trial variability in spike counts) [18].

- Network Synchronization: Reliable inputs correlate with stronger network-level synchronization in the gamma band of LFP activity [18]. Gamma synchronization is thought to facilitate effective communication between neuronal groups, thereby allowing a more reliable signal to exert a greater influence on the network's output.

This neural code ensures that the most trustworthy sensory information dominates the percept that guides feeding behavior.

A Distributed Flavor Network

While the GC is a critical site for integration, flavor perception involves a distributed network. Neuroimaging studies in humans show that the insula and orbitofrontal cortex (OFC) are deeply involved [19] [20]. The insula is a primary taste cortex, receiving direct taste inputs, while the OFC is heavily implicated in encoding the hedonic value (liking/disliking) of flavors [20]. The ventromedial prefrontal cortex has also been shown to correlate with behavioral preferences for familiar drinks, highlighting the role of higher-order cognitive and reward areas [19]. This network processes not only the sensory-discriminative aspects of flavor ("what" it is) but also the affective-motivational aspects ("how much" it is liked) [19].

Quantitative Experimental Data

Key findings from recent studies provide quantitative evidence for the neural principles of flavor integration. The following table summarizes data from an investigation into reliability-dependent integration in the gustatory cortex [18].

Table 1: Quantitative Summary of Key Neural and Behavioral Findings from Gustatory Cortex Studies

| Parameter | Experimental Finding | Experimental Method | Implication for Flavor Perception |

|---|---|---|---|

| Behavioral Hedonic Judgment | A weighted average of component judgments; weights shifted with manipulated reliability. | Two-bottle preference test (rats) | Hedonic assessment of flavor is a flexible computation, not a fixed property. |

| Neural Decoding Accuracy | GC population activity more accurately decoded flavor identity when inputs were integrated based on reliability. | Extracellular recording & decoding analysis | Reliability-dependent integration enhances the discriminability of flavors in the neural code. |

| Response Variability (Fano Factor) | Less reliable inputs elicited higher Fano factor (more variable spiking) in GC neurons. | Single-neuron spiking analysis | Input reliability is neurally encoded as response variability at the single-cell level. |

| Gamma Synchronization | More reliable sensory inputs were associated with stronger gamma-band LFP synchronization. | Local field potential (LFP) analysis | Network-level oscillations provide a mechanism for weighting sensory inputs. |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

To investigate the neural integration of flavor, researchers employ rigorous protocols combining behavioral assays with state-of-the-art neurophysiological techniques.

Protocol 1: Behavioral Assay for Hedonic Flavor Judgments

This protocol assesses how animals form hedonic judgments of multisensory flavor stimuli based on cue reliability [18].

- Objective: To determine if hedonic judgments of taste-smell mixtures follow a reliability-dependent weighted average model.

- Materials:

- Subjects: Rodent models (e.g., rats).

- Stimuli: Aqueous solutions of pure tastants (e.g., sucrose, quinine), odorants, and their mixtures.

- Apparatus: Two-bottle testing chamber, automated lick detectors.

- Procedure:

- Pre-training: Habituate animals to the testing chamber and establish baseline preference for unmixed taste and smell solutions.

- Reliability Manipulation: Alter the perceptual reliability of a taste or smell cue. This can be achieved by presenting a diluted (less intense) version of a stimulus, making it a less reliable indicator of identity or value.

- Two-Bottle Preference Test: For each trial, present the animal with two bottles: one containing a taste-smell mixture and the other containing a control solution (e.g., water). The relative position of the bottles is switched randomly.

- Data Collection: Record the number of licks and the time spent drinking from each bottle over a set period (e.g., 10 minutes). The preference ratio (licks to mixture / total licks) serves as the quantitative measure of hedonic judgment.

- Analysis: Fit the behavioral preference data to a weighted average model to determine the relative weights assigned to the taste and smell components under different reliability conditions.

Protocol 2: Neurophysiological Recording in the Gustatory Cortex

This protocol characterizes the neural activity in GC during the presentation of multisensory flavor stimuli [18].

- Objective: To identify neural correlates of reliability-dependent integration in the gustatory cortex.

- Materials:

- Subjects: Rodent models implanted with chronic recording electrodes.

- Stimuli: As in Protocol 1.

- Apparatus: Stereotaxic apparatus for electrode implantation, multichannel extracellular recording system, microinfusion pump for precise stimulus delivery to the tongue.

- Procedure:

- Surgery: Implant a multielectrode array or bundle of tetrodes into the gustatory cortex under anesthesia using stereotaxic coordinates.

- Stimulus Presentation: Awake, head-fixed animals receive controlled intra-oral infusions of taste, smell, and mixture stimuli while neural activity is recorded.

- Neural Data Acquisition: Simultaneously record:

- Single-Unit Activity: Action potentials from individual neurons.

- Local Field Potential (LFP): Low-frequency population signals from the electrode.

- Analysis:

- Spike Sorting: Isolate single-neuron spike waveforms from the recorded signals.

- Fano Factor Calculation: Compute the Fano factor (variance/mean of spike counts) across trials for each neuron and stimulus condition.

- Spectral Analysis of LFP: Perform a time-frequency analysis (e.g., wavelet transform) on the LFP to quantify power in the gamma band (e.g., 30-100 Hz).

- Population Decoding: Use machine learning classifiers (e.g., linear discriminant analysis) to decode stimulus identity from the population neural activity and assess decoding accuracy.

Signaling Pathways and Experimental Workflows

The following diagrams, generated using Graphviz, illustrate the core concepts of neural flavor integration and the experimental workflow used to study it.

Neural Pathway of Multisensory Flavor Integration

Experimental Workflow for Flavor Neuroscience

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents & Materials

Research in the molecular basis of multisensory flavor perception relies on a specific toolkit of reagents, technologies, and analytical methods.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Technologies for Flavor Neuroscience

| Tool/Reagent | Function/Application | Specific Examples & Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Multichannel Electrophysiology Systems | Record single-neuron and population (LFP) activity from the brain in awake, behaving animals. | Chronic implant microdrives/electrode arrays (e.g., tetrodes) targeting the Gustatory Cortex, Insula, or OFC [18]. |

| Controlled Stimulus Delivery Devices | Precisely administer taste and smell stimuli with accurate timing and concentration. | Gustometers for intra-oral fluid delivery; Olfactometers for retronasal odorant delivery [21]. |

| Pure Chemical Tastants & Odorants | Serve as standardized sensory stimuli to probe specific receptor pathways and neural responses. | Tastants: Sucrose (sweet), Quinine HCl (bitter), Sodium Chloride (salty). Odorants: Ethyl butyrate (fruity), Hexanal (green) [18] [22]. |

| Data Analysis Software | Process and model complex neurophysiological and behavioral datasets. | Custom scripts (Python, MATLAB) for spike sorting, LFP spectral analysis, and machine learning-based decoding [18]. |

| Electronic Nose (E-nose) | Objectively analyze volatile flavor profiles, correlating chemical signatures with sensory data. | Sensor arrays that detect key volatiles (e.g., aldehydes, sulfides); used with machine learning for classification [23] [22]. |

| Gas Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (GC-MS) | Identify and quantify specific volatile organic compounds that contribute to a food's aroma and flavor. | Used to pinpoint key flavor compounds (e.g., dimethyl trisulfide in ham) and validate E-nose findings [23] [22]. |

| Functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging (fMRI) | Non-invasively map brain activity in humans during flavor perception to identify involved networks. | Locates active regions (e.g., OFC, insula) in response to flavor stimuli, linking perception to neural structures [23] [19]. |

Sensory receptors function as the primary interface between an organism and its chemical environment, playing a critical role in detecting nutrients, avoiding toxins, and guiding food preferences [24]. The study of genetic variations in these receptors provides a mechanistic understanding of why individuals experience the sensory world differently, particularly in the context of food perception and flavor evaluation. Genetic polymorphisms in sensory receptor genes contribute substantially to individualized sensory systems, affecting receptor function, expression levels, and ultimately, perceptual experiences [25] [26]. These variations are not random; they are shaped by evolutionary forces that reflect species adaptations to their chemical environments and feeding ecology [24]. For researchers in food science and pharmaceutical development, understanding these genetic determinants offers pathways to personalized nutrition and sensory-targeted product design.

The mechanisms through which genetic variation influences sensory perception are multifaceted. Nonsynonymous single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) can alter receptor protein structure, changing its binding affinity for specific ligands [27]. Promoter region variations can affect the level of receptor gene expression, ultimately influencing the abundance of specific sensory neuron subtypes [25]. Furthermore, gene duplications and deletions can expand or contract entire receptor families, creating population-level differences in sensory capabilities [24] [28]. This technical guide explores the key genetic variations in chemosensory receptors, their functional consequences, and the methodological approaches for their investigation within the context of food sensory perception and flavor research.

Genetic Variation in Taste Receptors

Taste Receptor Families and Their Functions

The human taste system detects five basic qualities—sweet, umami, bitter, salty, and sour—through specialized receptors and transduction pathways. Sweet, umami, and bitter tastes are mediated by G protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs), while salty and sour tastes are transduced primarily through ion channels [26]. The T1R family of taste receptors includes three members: T1R1, T1R2, and T1R3, which function as heterodimers. The T1R2+T1R3 heterodimer acts as the sweet receptor, responding to sugars, artificial sweeteners, and sweet-tasting proteins, while the T1R1+T1R3 heterodimer functions as the umami receptor, responding to L-amino acids such as glutamate [24]. In contrast, the T2R family comprises approximately 25 functionally diverse bitter receptors that detect a wide array of toxic and aversive compounds [26].

Table 1: Major Taste Receptor Families and Their Genetic Attributes

| Receptor Family | Taste Quality | Gene Symbols | Number of Genes | Chromosomal Location | Key Genetic Variations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| T1R | Sweet, Umami | TAS1R1, TAS1R2, TAS1R3 | 3 in humans | 1p36 | Multiple SNPs in coding and non-coding regions affecting sweet and umami perception [26] |

| T2R | Bitter | TAS2Rs | >25 in humans | 7p21, 12p13 | Extensive polymorphisms; TAS2R38 PAV/AVI haplotypes strongly linked to PTC/PROP bitterness [27] [26] |

| ENaC | Salty | SCNN family | Multiple subunits | Multiple locations | Less influenced by genetic variation; strongly affected by environmental factors [26] |

Documented Functional polymorphisms in Taste Receptors

Genetic variation in taste receptor genes contributes significantly to individual differences in taste sensitivity and food preferences. The TAS2R38 gene represents one of the most thoroughly studied examples, with three common haplotypes defined by SNPs at positions 49, 262, and 296: PAV (proline-alanine-valine) and AVI (alanine-valine-isoleucine) being the most frequent [27]. Functional expression studies demonstrate that these haplotypes code for operatively distinct receptors, with the PAV haplotype conferring high sensitivity to the bitter compounds phenylthiocarbamide (PTC) and propylthiouracil (PROP), while the AVI haplotype produces an insensate receptor [27]. This polymorphism divides populations into "supertasters," "medium tasters," and "nontasters" of these thiourea compounds, which has implications for the perception of bitter foods like brassica vegetables, green tea, and soya [26].

Variation in sweet and umami perception is linked to polymorphisms in the TAS1R gene family. The TAS1R3 subunit, common to both sweet and umami receptors, contains non-coding SNPs that affect promoter activity and contribute to individual variability in sucrose perception [26]. Recent studies have identified associations between SNPs in sweet, fat, umami, and salt taste receptor genes and psychophysical measures of taste detection threshold, suprathreshold sensitivity, and preference [29]. These genetically determined differences in taste perception may influence dietary choices and nutrient intake patterns, potentially contributing to long-term health outcomes.

Genetic Variation in Olfactory Receptors

Olfactory Receptor Diversity and Regulation

The olfactory system exhibits remarkable diversity, with humans possessing approximately 400 functional olfactory receptor (OR) genes. Each olfactory sensory neuron (OSN) expresses typically a single OR gene in a monoallelic fashion, creating a highly heterogeneous neuronal repertoire [25]. The distribution of OSN subtypes is stereotyped in genetically identical individuals but varies extensively between different strains, with cis-acting genetic variation representing the greatest component influencing OSN composition [25]. This variation is independent of OR protein function and occurs primarily within regulatory elements of OR genes.

Recent research has demonstrated that olfactory stimulation with specific odorants can modulate the abundance of dozens of OSN subtypes in a subtle but reproducible, specific, and time-dependent manner [25]. This environmental modulation interacts with genetic predispositions to generate a highly individualized olfactory sensory system. One well-characterized example involves the OR7D4 receptor, where genotypic variation (specifically the RT versus WM variants) predicts sensitivity to androstenone and influences the sensory perception of cooked pork containing this compound [30]. Individuals with two copies of the functional OR7D4 RT variant are more sensitive to androstenone and tend to rate androstenone-tainted meat less favorably than those carrying the non-functional WM variant [30].

Orthonasal vs. Retronasal Olfaction in Flavor Perception

In the context of food flavor research, it is crucial to distinguish between orthonasal (sniffing) and retronasal (mouth-level) olfaction. While both processes involve the same olfactory receptors, they provide distinct perceptual experiences and are differentially affected by genetic variation. Retronasal olfaction, which combines with taste and texture to create flavor perception, is particularly relevant to food science. Genetic variations in odorant receptors like OR7D4 can directly impact flavor perception and food preferences by altering the intensity and hedonics of food aromas [30].

Evolutionary Perspectives on Sensory Receptor Variation

Sensory receptors exhibit distinct evolutionary patterns across animal taxa. Mechanoreceptors, thermoreceptors, and photoreceptors often constitute part of the ancestral sensory toolkit of animals, frequently predating the evolution of multicellularity and nervous systems [28]. In contrast, chemoreceptors display a dynamic history of lineage-specific expansions and contractions correlated with the disparate complexity of chemical environments [28]. The T2R bitter receptor family, for instance, has undergone significant species-specific diversification, reflecting adaptations to different dietary niches and toxin exposures [24] [26].

Evolutionary analyses reveal that sensory receptors serve as hotspots for adaptive evolution. Polymorphisms in sensory receptors are maintained through balancing selection in some cases, while in others, directional selection drives the fixation of alleles advantageous in specific ecological contexts [24]. The high degree of polymorphism in bitter receptor genes compared to most other genes suggests ongoing evolutionary arms races between plants producing defensive compounds and animals evolving detection mechanisms [26]. Understanding these evolutionary dynamics provides valuable context for interpreting functional genetic studies and developing evolutionary-informed hypotheses in sensory research.

Experimental Approaches and Methodologies

Genotyping and Phenotyping Protocols

TAS2R38 Haplotyping and Phenotyping: The determination of TAS2R38 genotype status represents a well-established protocol in sensory genetics research. The methodology involves:

- DNA Extraction: Collect buccal cells or blood samples using standard DNA extraction kits.

- Genotype Analysis: Amplify the TAS2R38 gene region containing the SNP positions 49, 262, and 296 using PCR with specific primers: Forward: 5'-GCACTTCATAATCGCAGTCC-3', Reverse: 5'-CAGGGCAAGAGAATGGAAGA-3'.

- Haplotype Determination: Perform restriction fragment length polymorphism (RFLP) analysis or direct sequencing to identify the three key SNPs that define the major haplotypes (PAV, AVI).

- Phenotype Verification: Conduct psychophysical testing using filter paper strips impregnated with 0.0001 mol/L PROP solution or prepared PTC solutions. Participants rate intensity on a generalized Labeled Magnitude Scale (gLMS) to classify them as nontasters, medium tasters, or supertasters [27].

Olfactory Receptor Functional Assays: For olfactory receptors like OR7D4, functional characterization involves:

- In vitro Receptor Activation Assay: Clone variant OR7D4 alleles into expression vectors and transfect into HEK-293 cells.

- Calcium Imaging: Load cells with calcium-sensitive dyes and measure fluorescence changes upon stimulation with androstenone solutions (typically 1-100 µM).

- Dose-Response Analysis: Calculate EC50 values for each receptor variant to determine functional differences between genotypes [30].

- Sensory Evaluation: Conduct controlled sensory tests using cooked meat samples with varying androstenone concentrations (0.1-1.0 ppm). Participants rate intensity and pleasantness using visual analog scales while controlling for environmental variables [30].

Quantitative Assessment of Neuronal Populations

Advanced RNA-sequencing techniques enable comprehensive mapping of olfactory sensory neuron diversity:

- Tissue Collection: Dissect main olfactory epithelium from model organisms immediately after euthanasia.

- RNA Extraction and Library Preparation: Use standardized kits to extract high-quality RNA and prepare sequencing libraries.

- Sequencing and Analysis: Perform high-throughput sequencing (minimum 30 million reads per sample) and map reads to extended olfactory receptor gene annotations.

- Validation: Verify RNAseq findings with in situ hybridization for selected receptors to confirm correlation between mRNA levels and actual OSN counts [25].

Genetic Variation to Behavior Pathway

Research Reagent Solutions Toolkit

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents for Sensory Genetics Studies

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Research Application | Function/Purpose |

|---|---|---|---|

| Genetic Analysis Kits | DNA extraction kits (e.g., Qiagen DNeasy), TaqMan SNP Genotyping Assays, PCR reagents | Genotyping of TAS2R38, TAS1R, and OR gene variants | DNA isolation and specific polymorphism detection for candidate gene studies [27] [29] |

| Psychophysical Testing Stimuli | PROP (propylthiouracil) solutions (0.0001-0.0032 M), PTC papers, gLMS scales | Phenotypic assessment of taste sensitivity | Determination of taster status and intensity ratings for correlation with genotype [26] |

| Cell-Based Assay Systems | HEK-293T cells, calcium-sensitive dyes (e.g., Fluo-4), expression vectors | In vitro functional characterization of receptor variants | Assessment of receptor activation and dose-response relationships for variant receptors [30] |

| RNA Sequencing Tools | RNA extraction kits, library preparation kits, sequencing platforms | Comprehensive analysis of olfactory receptor expression | Quantification of OSN subtype abundance and repertoire composition [25] |

| Odorant/Tastant Stimuli | Androstenone, monosodium glutamate, nicotine, bitter compounds (PTC/PROP) | Controlled sensory evaluation studies | Standardized stimuli for psychophysical testing and correlation with genetic variation [30] [31] |

Implications for Food Science and Pharmaceutical Development

Understanding genetic variation in sensory receptors has profound implications for product development in both food and pharmaceutical industries. Bitter receptor polymorphisms significantly influence medication compliance, as genetic variation in TAS2R38 affects the perception of bitter-tasting pharmaceuticals [27]. Pharmacogenetic approaches that account for this variation can guide the development of better-tasting oral medications or bitter blockers to improve patient acceptance [24] [31].

In food science, genetic variation in taste and smell receptors explains why individuals differ in their preferences for specific foods, including vegetables, sweet substances, and fatty foods [26] [29]. This knowledge enables the development of personalized nutrition strategies and products tailored to different genetic profiles. Furthermore, identifying enhancers of sweet and umami taste through receptor-based screening can facilitate the creation of healthier products with reduced sugar and sodium content without sacrificing palatability [24].

Taste Signal Transduction Pathway

Genetic variation in sensory receptors represents a fundamental biological factor underlying individual differences in sensory perception, with far-reaching implications for food preference, dietary behavior, and pharmaceutical acceptance. The functional polymorphisms identified in taste and olfactory receptor genes demonstrate how sequence variations translate to perceptual differences through effects on receptor function and neuronal representation. For researchers in sensory science, flavor chemistry, and product development, incorporating genetic perspectives offers a more comprehensive understanding of consumer variability and creates opportunities for personalized approaches. Future research directions should focus on elucidating gene-environment interactions, developing high-throughput screening methods for receptor variants, and translating basic genetic findings into practical applications for tailored nutrition and medicine.

Flavor represents a critical multisensory attribute of food, resulting from the complex integration of taste, aroma, and texture perceptions. The sensation of flavor occurs through simultaneous stimulation of our chemical senses, primarily triggered by volatile and non-volatile chemicals present in or generated during food processing [32]. From a physiological perspective, flavor perception initiates when signals from taste buds, olfactory receptors, and somatosensory cells converge in the brain's gustatory cortex and orbitofrontal cortex for integration into a unified experience [32]. The molecular mechanisms underlying odor-taste interactions that collectively form flavor perception remain an active area of scientific investigation, though it is established that flavor compounds interact with specific receptors triggering neural responses that are interpreted as distinctive flavor profiles [32].

The field of flavor research has evolved significantly from traditional sensory-guided techniques to comprehensive flavoromics approaches. Flavoromics combines advanced analytical chemistry, sensory evaluation, and data science to systematically understand relationships between chemical composition and flavor characteristics in food [33]. This interdisciplinary field employs untargeted chemical analysis using instruments including gas chromatography–mass spectrometry (GC–MS) and liquid chromatography–high-resolution mass spectrometry (LC–HRMS) to characterize a broad spectrum of compounds, including previously unknown molecules that influence flavor formation and regulation [33]. This review examines key flavor compounds across the spectrum from natural products to processed foods, with emphasis on their chemical properties, analytical methodologies, and industrial applications within the theoretical framework of food sensory perception.

Key Flavor Compounds in Natural Products

Aromatic Volatile Compounds in Essential Oils

Aromatic volatile compounds of essential oils (ACEO) constitute a significant bioactive fraction derived from various plant species, primarily comprising monoterpenes, sesquiterpenes, and aromatic compounds [34]. These compounds are defined as the principal odorous components responsible for the characteristic scents of aromatic plants. From a structural perspective, aromatic volatile compounds are classified based on their chemical structures and reactive functional groups, dividing them into hydrocarbons, oxygenated hydrocarbons, acids, esters, and sulfur/nitrogen-containing compounds [34].

Table 1: Key Aromatic Volatile Compounds in Essential Oils and Their Sources

| Aromatic Compound | Primary Natural Source | Plant Organ | Concentration | Characteristic Aroma |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Eugenol | Clove (Syzygium aromaticum) | Flower buds | 60-90% [34] | Spicy, clove-like |

| Thymol | Thyme (Thymus vulgaris) | Herb | Up to 39.5% [34] | Medicinal, herbal |

| Methyl salicylate | Wintergreen (Gaultheria procumbens) | Leaves | Major constituent [34] | Sweet, wintergreen |

| Anethole | Anise (Pimpinella anisum) | Seeds | Major constituent [34] | Sweet, licorice-like |

| Myristicin | Nutmeg (Myristica fragrans) | Seeds | Varies [34] | Spicy, warm |

These aromatic compounds are distributed across specific plant families including Lamiaceae, Myrtaceae, and Apiaceae [34]. Their proportional distribution in aromatic plants is generally lower compared to aliphatic constituents, though they play a crucial role in the odorant properties of these plants. In certain species, single aromatic compounds dominate the essential oil profile; for example, methyl salicylate comprises the majority of American wintergreen oil, while eugenol can constitute 60-90% of clove oil [34]. Beyond their sensory properties, these compounds exhibit significant biological activities, with traditional and modern applications leveraging their antimicrobial, anti-inflammatory, and therapeutic properties [34].

Flavor Compounds in Fruits and Agricultural Commodities

In fresh fruits, flavor development involves complex biochemical pathways producing both volatile aroma compounds and non-volatile taste components. Sugars and organic acids represent significant chemical components contributing to balanced sweetness and sourness in fruits [33]. The ratio of total soluble solids to titratable acidity (TSS/TA) serves as a common indicator for assessing flavor quality and ripeness, though recent research emphasizes measuring individual sugars and organic acids due to their different taste activity values [33].

Advanced analytical approaches have identified numerous key flavor compounds in fruits:

Strawberries: Recent research unexpectedly identified ethyl vanillin in strawberries, marking the first observation of this compound in a natural food source [33]. The presence was confirmed through multiple analytical techniques including GC–MS/MS, LC–HRMS, and LC–MS/MS with isotope-labeled ethyl vanillin.

Cherries: Studies on Prunus pseudocerasus identified glucose, fructose, and maltose as key indicators of cherry flavor, leading to proposed new grading criteria based on these specific sugar profiles [33].

Pears: Widely targeted metabolomics approaches have annotated nearly 1000 metabolites in pears, with statistical correlation network analysis revealing relationships between metabolites and sensory attributes [33].

The flavor profile development in fruits involves metabolic pathways converting precursors into characteristic volatile compounds. In peppers, for instance, specific fatty acids and amino acids highly correlate with the formation of characteristic aroma volatiles [33]. Understanding these precursor relationships and biosynthetic pathways represents a crucial aspect of flavor chemistry research in natural products.

Analytical Methodologies in Flavor Research

Experimental Workflows and Instrumental Techniques

Flavor research employs sophisticated analytical workflows to identify and quantify compounds responsible for sensory properties. The field has evolved from sensory-guided techniques targeting individual compounds to comprehensive flavoromics approaches that examine the complete chemical profile [35]. Traditional methods focus on identifying character-impact compounds through techniques such as gas chromatography-olfactometry (GC-O) and aroma extract dilution analysis (AEDA) [35]. These approaches have successfully identified hundreds of aroma-active compounds from the over 12,000 volatile compounds detected in foods to date.

Table 2: Key Analytical Techniques in Flavor Compound Identification

| Analytical Technique | Application in Flavor Research | Key Advantages | Representative Examples |

|---|---|---|---|

| GC-MS (Gas Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry) | Volatile compound separation and identification | High sensitivity, compound identification capability | Aroma profiling in roasted beef [33] |

| LC-HRMS (Liquid Chromatography-High Resolution Mass Spectrometry) | Non-volatile compound analysis | High resolution, accurate mass measurement | Identification of bitter-masking compounds in allspice [33] |

| GC-IMS (Gas Chromatography-Ion Mobility Spectrometry) | Rapid volatile compound detection | Fast analysis, high sensitivity | Characterization of steamed beef with rice flour [36] |

| Electronic Nose/Tongue | Overall flavor profile assessment | Rapid screening, pattern recognition | Quality assessment of honeys [36] |

| NMR (Nuclear Magnetic Resonance) | Structural elucidation of unknown compounds | Detailed structural information | Compound identification in novel flavor molecules [33] |

Modern flavoromics employs untargeted analysis using GC×GC–QTOF–MS (two-dimensional gas chromatography coupled to quadrupole-time-of-flight mass spectrometry) to comprehensively characterize odorants. For example, a recent study of Chinese black teas identified 190 volatiles, with 23 confirmed as key odorants contributing to regional distinctions [33]. This approach enables researchers to address challenges including distinguishing similar food products and ensuring authenticity through chemical fingerprinting [36].

Experimental Protocol: Flavor Compound Analysis in Food Matrices

Protocol Title: Comprehensive Flavor Profiling of Natural Products Using Gas Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry and Sensory Evaluation

Principle: This protocol describes the simultaneous application of instrumental analysis and sensory evaluation to characterize key flavor compounds in natural products, enabling correlation of chemical data with sensory attributes.

Materials and Reagents:

- Sample Material: Fresh or processed food product (e.g., fruits, spices, processed foods)

- Extraction Solvents: Dichloromethane, diethyl ether, pentane-ethyl acetate mixture (high purity grade)

- Internal Standards: Deuterated compounds (e.g., d₃-2-acetyl-1-pyrroline for aromas)

- Derivatization Agents: MSTFA (N-Methyl-N-(trimethylsilyl)trifluoroacetamide) for polar compounds

- Solid Phase Microextraction (SPME) Fibers: Divinylbenzene/Carboxen/Polydimethylsiloxane (DVB/CAR/PDMS) for volatile collection

Equipment:

- Gas Chromatograph coupled with Mass Spectrometer (GC-MS) with electron impact (EI) source

- GC-Olfactometry (GC-O) port with humidified air supply

- Solid Phase Microextraction (SPME) injector

- Electronic nose and electronic tongue instruments

- Sensory evaluation facilities with standardized testing booths

Procedure:

- Sample Preparation:

- Homogenize representative sample under controlled conditions (temperature, time)

- For volatile analysis: Weigh 2g sample into 20mL SPME vial, add internal standards

- For non-volatile taste compounds: Extract with appropriate solvent (methanol/water), concentrate under nitrogen

Volatile Compound Extraction:

- Condition SPME fiber according to manufacturer specifications

- Incubate sample at 40°C for 10min, then expose fiber to headspace for 30min at same temperature

- Desorb fiber in GC injector at 250°C for 5min in splitless mode

GC-MS Analysis:

- Use capillary column (e.g., DB-5MS, 30m × 0.25mm × 0.25μm)

- Employ temperature program: 40°C (hold 2min), ramp 5°C/min to 240°C (hold 10min)

- Set MS transfer line temperature to 250°C, ion source to 230°C

- Acquire mass spectra in full scan mode (m/z 35-350)

GC-Olfactometry:

- Split column effluent between MS detector and olfactory port (typically 1:1 ratio)

- Train sensory panelists to detect and describe odors at specific retention times

- Use aroma extract dilution analysis (AEDA) to determine potency of odorants

Data Analysis:

- Identify compounds by comparing mass spectra with databases (NIST, Wiley) and linear retention indices

- Quantify using internal standard method and calibration curves

- Correlate compound concentrations with sensory evaluation results

Safety Considerations: Perform all extractions with appropriate ventilation; handle organic solvents with chemical-resistant gloves; follow electrical safety guidelines for instrumentation.

This methodology enables comprehensive characterization of flavor compounds, from volatile aromas to non-volatile taste components, facilitating understanding of the molecular basis of food sensory perception.

Figure 1: Experimental workflow for comprehensive flavor analysis, integrating instrumental techniques and sensory evaluation to identify key flavor compounds.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Flavor Analysis

| Reagent/Material | Function in Flavor Research | Application Examples |

|---|---|---|

| SPME Fibers (DVB/CAR/PDMS) | Adsorption and concentration of volatile compounds | Headspace sampling of fruits, spices, and processed foods [33] |

| Deuterated Internal Standards | Quantification reference for mass spectrometry | d₃-2-acetyl-1-pyrroline for aroma compound quantification [35] |

| MSTFA Derivatization Agent | Enhancement of volatility for polar compounds | Analysis of sugars, organic acids in fruits [33] |

| Reference Aroma Compounds | Sensory calibration and identification | Linalool, hexanal, vanillin for GC-O training [35] |

| Stable Isotope Labeled Compounds | Validation of novel compound identification | Isotope-labeled ethyl vanillin in strawberry study [33] |

Flavor Compounds in Processed Foods

Flavor Transformation During Processing

Food processing induces complex chemical reactions that dramatically alter flavor profiles through thermal degradation, Maillard reactions, and lipid oxidation [33]. These transformations generate numerous volatile and non-volatile compounds that define the sensory characteristics of processed foods. Recent research has extensively characterized these changes across various food matrices:

In meat products, thermal processing generates characteristic aroma compounds through Maillard reactions and lipid degradation. Studies on marinated and stewed beef have identified key odorants associated with warmed-over flavor development after refrigeration and reheating, using sensomics approaches combining sensory evaluation with GC–IMS/MS analysis [33]. The application of gas chromatography-ion mobility spectrometry (GC-IMS) combined with electronic nose and tongue has provided valuable insights into industrial-scale production and flavor regulation of products like steamed beef with rice flour [36].

In fermented foods, microbial activity profoundly influences flavor development. Research on fermented sausages demonstrates that starter cultures (e.g., L. plantarum with S. simulans) enhance flavor by generating high levels of umami taste-related compounds [33]. Similarly, studies on sauerkraut have tracked dynamic changes in flavor compounds throughout the fermentation process [33].

The development of plant-based alternatives represents a growing application area for flavor chemistry. Research has utilized soybean by-products as additives for plant-based patties, resulting in improved texture profiles and reduced levels of undesirable flavor volatiles including benzaldehyde, nonanal, and 2-heptanone compared to control patties [33].

Market Applications and Industrial Perspectives

The global flavor compounds market reflects the commercial significance of these ingredients, projected to grow from USD 29.7 billion in 2025 to USD 52.7 billion by 2035, representing a compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of 5.9% [37]. Flavor compounds constitute approximately 18% of the overall food additives market, underscoring their essential role in processed food formulation [37].

Market segmentation reveals distinctive application patterns:

- The salty flavor segment dominates with approximately 28.5% market share, driven by snack manufacturing and processed foods where salt-based compounds enhance palatability [37].

- The protein bars segment leads application categories with 37.2% share, propelled by global health and wellness trends where flavor compounds mask the natural bitterness of protein ingredients [37].

Regionally, China and India exhibit the strongest growth at 8.0% and 7.4% CAGRs respectively, reflecting expanding manufacturing capabilities and rising consumer demand [37]. Developed markets including Germany (6.8%) and the United States (5.0%) maintain steady utilization under stringent food safety standards [37].

Future Perspectives and Research Directions

The field of flavor research continues to evolve with emerging trends shaping future investigations. Clean-label and natural formulations represent a significant consumer-driven trend, with demand moving toward naturally functional ingredients rather than artificially fortified products [38]. This aligns with findings that 72% of consumers are more likely to purchase products mentioning health benefits on packaging, rising to 87% among those aged 18-24 [38].

Technological innovations are expanding flavor research capabilities. Microencapsulation and novel extraction methods offer promising tools to improve flavor stability and sensory acceptance, addressing challenges such as low bioavailability of certain natural flavor compounds [32]. Advanced extraction techniques including supercritical fluid extraction (SFE), microwave-assisted extraction (MAE), and ultrasonic-assisted extraction (UAE) demonstrate higher yields compared to conventional methods while aligning with sustainability principles through reduced energy consumption and organic solvent use [39].

The growing field of personalized nutrition presents new research directions, with 79% of consumers believing their genetic makeup affects nutritional needs [38]. Flavoromics integrated with genomics could enable tailored dietary recommendations based on individual genetic profiles and flavor preferences [36]. Research suggests potential applications in medicine for improving medication palatability and developing functional foods targeting specific health conditions [36].

Regulatory science faces ongoing challenges in flavor compound oversight. Current frameworks relying on voluntary GRAS (Generally Recognized As Safe) designation raise concerns about transparency and comprehensive safety evaluation [40]. Future regulatory developments may address emerging scientific concerns about chronic exposure to complex flavor mixtures and cumulative effects of multiple food additives [40].

As flavor research advances, interdisciplinary approaches combining analytical chemistry, sensory science, molecular biology, and data science will continue to unravel the complex relationships between chemical composition and sensory perception, ultimately enhancing food quality, safety, and consumer satisfaction across the global food system.

Advanced Analytical Techniques and Flavoromics in Research and Development