Decoding Dietary Fiber: A Structural and Functional Analysis of Soluble vs. Insoluble Fractions for Biomedical Applications

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of the distinct chemical compositions, structural properties, and physiological functionalities of soluble and insoluble dietary fibers.

Decoding Dietary Fiber: A Structural and Functional Analysis of Soluble vs. Insoluble Fractions for Biomedical Applications

Abstract

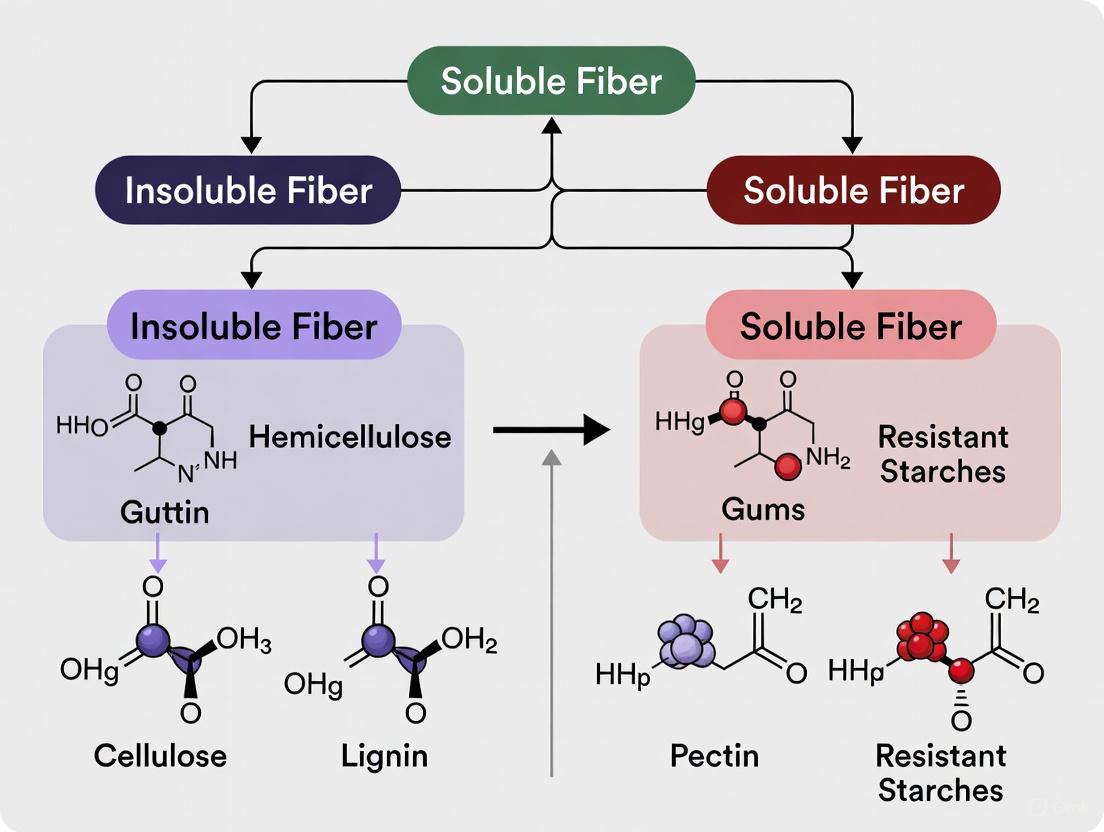

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of the distinct chemical compositions, structural properties, and physiological functionalities of soluble and insoluble dietary fibers. Tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it synthesizes foundational biochemistry with advanced analytical methodologies. The scope spans from defining core components like cellulose, hemicellulose, lignin, and pectin to exploring cutting-edge characterization techniques such as FTIR, NIR, and TGA. It further addresses current challenges in fiber analysis and optimization, including the impact of processing on structure and the evidence-based efficacy of specific fiber types for targeted health benefits, ultimately aiming to inform the development of fiber-based therapeutics and functional foods.

The Molecular Architecture of Dietary Fibers: From Monomers to Complex Polymers

In the study of dietary fiber, the simplistic classification into soluble and insoluble types often obscures the complex chemical architecture that dictates physiological function. The core components of plant cell walls—cellulose, hemicellulose, lignin, and pectin—serve as the fundamental building blocks that determine the solubility, fermentability, and ultimate health impacts of dietary fiber [1] [2]. Understanding their distinct chemical compositions, structural roles, and interactions is crucial for researchers and drug development professionals seeking to leverage specific fiber properties for targeted health outcomes, particularly within the framework of insoluble versus soluble fiber research [3].

This whitepaper provides a technical examination of these four core polymers, detailing their quantitative characteristics, analytical methodologies for their study, and their functional roles within the broader context of fiber research.

Chemical Composition and Structural Properties

The physicochemical diversity of plant cell wall components underpins the varied physiological effects of dietary fibers, from hydration and bulking to fermentation and binding.

Table 1: Core Composition and Characteristics of Dietary Fiber Polymers

| Component | Chemical Structure | Primary Role in Plant | Fiber Solubility Classification | Key Monomeric Units | Glycosidic Linkages |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cellulose | Linear, unbranched polymer | Structural component of cell walls [1] | Insoluble [1] [4] | D-glucose [1] | β-(1→4) [4] |

| Hemicellulose | Branched, heterogeneous polymer [1] | Cell wall polysaccharide; strengthens wall [5] | Mostly Insoluble [1] | Xylose, glucose, mannose, galactose, arabinose [1] [5] | β-(1→4) and others [5] |

| Lignin | Complex, cross-linked phenylpropane polymer [1] | Non-carbohydrate cell wall component; imparts stiffness [1] [6] | Insoluble [1] [4] | Guaiacyl (G), Syringyl (S), p-Hydroxyphenyl (H) units [6] | Carbon-Carbon and ether linkages |

| Pectin | Linear polysaccharide of galacturonic acid [1] [4] | Component of primary cell wall; intercellular cement [1] | Soluble [1] [4] | D-galacturonic acid [1] [4] | α-(1→4) [4] |

Table 2: Physicochemical and Functional Properties Relevant to Physiological Effects

| Component | Fermentability by Gut Microbiota | Viscosity Forming Capacity | Water-Holding Capacity (WHC) | Primary Physiological Effects in Humans |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cellulose | Poorly fermented [4] | Non-viscous [7] | High WHC; provides bulking [8] [4] | Laxative effect; increases stool bulk [8] [4] |

| Hemicellulose | Varies by type and structure [1] | Generally low viscosity | Contributes to bulking | Promotes regularity; bulking effect [7] |

| Lignin | Resists bacterial degradation [1] | Non-viscous | Binds organic materials [1] | Laxative effect; may bind bile acids [1] [4] |

| Pectin | Highly fermentable [1] [4] | Highly viscous; gel-forming [1] [4] | High WHC due to gel formation [1] | Slows gastric emptying; lowers blood cholesterol & glucose [1] [4] |

Advanced Analytical Methodologies for Component Analysis

A detailed understanding of fiber composition requires sophisticated imaging and chemical analysis techniques to probe the complex architecture of plant cell walls.

Imaging and Visualization Techniques

Advanced microscopy allows for the in situ analysis of plant cell wall composition and architecture, providing insights into biomass recalcitrance and digestibility [6].

- Stimulated Raman Scattering (SRS) Microscopy: A label-free technique that utilizes the unique vibrational fingerprints of cellulose, hemicellulose, and lignin to map their distribution in native plant cell walls with high spatial resolution. It is particularly effective for real-time, non-destructive imaging of polymer distributions during conversion processes like enzymatic hydrolysis [6].

- Fluorescence Lifetime Imaging Microscopy (FLIM): Capitalizes on the autofluorescence of lignin to image its distribution. FLIM provides an additional dimension of measurement by resolving the fluorescence decay rate at each pixel, which can be correlated with lignin composition and its interaction with other cell wall polymers [6].

- Atomic Force Microscopy (AFM): Probes the surface topography of cell walls at a nanometer scale. It can be used to characterize the micro- and nanoscale structure of cellulose microfibrils and their assembly, providing information on surface roughness and mechanical properties that influence enzyme accessibility [6].

Chemical and Gravimetric Analysis

Standardized chemical methods remain fundamental for the quantitative isolation and measurement of fiber components.

- Enzymatic-Gravimetric Methods: The most common official methods for total dietary fiber analysis. These involve enzymatic digestion of protein and starch, followed by gravimetric measurement of the undigested residue. Subsequent steps can differentiate soluble and insoluble fractions [1].

- Enzymatic-Chemical Methods: These methods, such as the Uppsala method, go a step further by quantifying specific sugar monomers after hydrolysis of the fiber residue. This allows for a more detailed analysis of the polysaccharide composition of hemicellulose and pectin [1].

- Sequential Extraction and Spectroscopy: Isolating specific components often requires sequential extraction using solvents of varying pH and chelating agents (e.g., for pectin) followed by analysis using Gas Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (GC-MS) or Fourier-Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (FTIR) for structural characterization [1].

Table 3: The Researcher's Toolkit: Key Reagents and Materials for Fiber Analysis

| Research Reagent / Material | Function in Experimental Protocol |

|---|---|

| Cellulase / Hemicellulase Enzymes | Selective hydrolysis of cellulose and hemicellulose to study polymer digestibility and sugar release profiles [6]. |

| Heat-Stable α-Amylase | Digestion of starch in samples prior to dietary fiber analysis to prevent interference [1]. |

| Protease (e.g., Pepsin) | Digestion of protein in food samples to isolate the fiber fraction for gravimetric analysis [1]. |

| Chelating Agents (e.g., CDTA, EDTA) | Sequester calcium ions to solubilize and extract homogalacturonan-rich pectins from plant cell walls [1]. |

| Dilute Acid / Alkali Solutions | Used in sequential extraction to solubilize hemicelluloses and other non-cellulosic polysaccharides [1] [5]. |

| Specific Fluorescent Dyes (e.g., Calcofluor White) | Binding to β-linked polysaccharides like cellulose for visualization under fluorescence microscopy [6]. |

The following workflow diagram illustrates a generalized protocol for the sequential analysis of core fiber components from a plant biomass sample.

Functional Roles in Soluble vs. Insoluble Fiber Context

The binary classification of fiber into soluble and insoluble types is a functional oversimplification, but it provides a valuable framework for understanding the primary physiological contributions of these core polymers.

The Insoluble Fiber Complex: Cellulose, Hemicellulose, and Lignin

The collective action of cellulose, hemicellulose, and lignin forms the insoluble, poorly fermented fiber complex that is integral to the bulking and laxative effects of dietary fiber [1] [4].

- Cellulose: As a primary contributor to this complex, its linear, crystalline structure and resistance to enzymatic digestion allow it to absorb water and increase fecal bulk throughout the gastrointestinal tract, thereby accelerating intestinal transit and preventing constipation [8] [4].

- Hemicellulose: This branched polymer complements cellulose by also holding water and contributing to stool bulk. Its fermentability varies by chemical structure, but it is generally less fermented than soluble fibers, allowing it to retain its hydrating and bulking capacity for longer periods within the colon [1] [7].

- Lignin: This non-carbohydrate polymer is highly resistant to bacterial degradation [1]. Its primary function in the gut is to provide rigidity and structure to the fecal mass. Furthermore, its hydrophobic, cross-linked nature allows it to bind to various organic materials, including bile acids, which may contribute to its observed effect of lowering serum cholesterol [1] [4].

The Soluble Gel-Forming Fiber: Pectin

Pectin is a classic example of a soluble, viscous, and readily fermented fiber whose physiological effects are directly tied to its gel-forming properties and fermentability [1] [4].

- Viscosity and Gel Formation: Upon dissolution in water, pectin forms highly viscous solutions and gels. This viscosity slows the rate of gastric emptying and nutrient absorption in the small intestine, leading to attenuated postprandial blood glucose and insulin responses [1] [4].

- Fermentability and Prebiotic Potential: Pectin is almost completely metabolized by colonic bacteria [1]. This fermentation produces short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs) like acetate, propionate, and butyrate. Propionate is particularly noted for its role in inhibiting cholesterol synthesis in the liver, contributing to the cholesterol-lowering effect of pectin [4]. Butyrate serves as the primary energy source for colonocytes and has anti-inflammatory properties [4].

The following diagram synthesizes the key signaling and metabolic pathways through which soluble, fermentable fibers like pectin exert their systemic health effects.

Cellulose, hemicellulose, lignin, and pectin are not merely structural plant polymers but are bioactive compounds whose distinct chemical properties dictate their functional roles as dietary fibers. A deep understanding of cellulose's crystallinity, hemicellulose's heterogeneity, lignin's recalcitrance, and pectin's gel-forming capacity is fundamental for moving beyond the simplistic soluble/insoluble dichotomy. For researchers and pharmaceutical developers, this knowledge enables the rational design of interventions, whether through the selection of fiber-rich botanicals with specific component profiles or the isolation and modification of individual polymers to target health outcomes such as glycemic control, cholesterol reduction, or improved gastrointestinal function. Future research will continue to elucidate the structure-function relationships of these core components, further refining our ability to harness their full therapeutic potential.

In the study of dietary fibers, the fundamental divergence in chemical composition between insoluble and soluble fractions manifests primarily in their distinct structural architectures. A core structural determinant is the highly ordered, crystalline nature of insoluble dietary fibers (IDF) compared to the disordered, amorphous character of soluble dietary fibers (SDF). This dichotomy in physical structure, arising from differences in molecular composition and bonding, dictates their physicochemical properties, physiological functions, and subsequent applications in food science and pharmaceutical development [9] [10]. Framed within a broader thesis on the chemical composition of fibers, this whitepaper delineates how crystallinity versus amorphousness serves as a primary factor influencing functionality, from gut microbiota modulation to drug delivery system design.

Structural and Chemical Basis

The classification of dietary fibers into soluble and insoluble categories is conventionally based on water solubility, but this property is intrinsically linked to their underlying chemical composition and supra-molecular organization.

- Insoluble Dietary Fibers (IDF): Primarily composed of cellulose, hemicellulose, and lignin, these components intertwine to form dense, rigid network structures [9] [10]. The extensive hydrogen bonding between linear cellulose chains facilitates their tight packing into highly crystalline domains [9]. This crystalline structure is a key reason for IDF's resistance to enzymatic hydrolysis in the human small intestine and its limited fermentability in the colon [9].

- Soluble Dietary Fibers (SDF): These include pectin, gums, inulin, and certain hemicelluloses [9]. Their chemical structures are typically branched and heterogeneous, preventing the orderly molecular packing required for crystallinity. Consequently, SDF exists in an amorphous state, which contributes to their high water solubility and rapid fermentability by gut microbiota [9] [10].

Table 1: Fundamental Composition and Properties of Insoluble vs. Soluble Fibers

| Characteristic | Insoluble Dietary Fiber (IDF) | Soluble Dietary Fiber (SDF) |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Components | Cellulose, hemicellulose, lignin [9] [10] | Pectin, gums, inulin, β-glucan [9] [10] |

| Predominant Structure | Crystalline, ordered regions [9] [11] | Amorphous, disordered matrix [10] |

| Representative Crystallinity Index (CrI) | ~25-40% (Varies by source and processing) [11] | Largely amorphous [10] |

| Water Solubility | Insoluble [9] | Soluble [9] |

| Fermentability by Gut Microbiota | Slow and limited [9] | High and rapid [9] |

Quantitative Structural Analysis

Advanced characterization techniques provide quantitative evidence of the structural differences between fiber types. The Crystallinity Index (CrI), often determined by X-ray diffraction (XRD), is a key metric for comparing the ordered structure of different fiber preparations.

Table 2: Experimental Crystallinity Data from Fiber Research

| Fiber Source & Type | Treatment/Modification | Crystallinity Index (CrI) / Key Finding | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pea Insoluble Dietary Fiber (PIDF) | Ultrafine Grinding (400 min) | CrI significantly decreased from initial state [11] | [11] |

| Date Fruit Insoluble Fiber | Fractionation | Insoluble fiber was crystalline [10] | [10] |

| Date Fruit Soluble Fiber | Fractionation | Soluble fiber was amorphous [10] | [10] |

| Quinoa Insoluble Dietary Fiber (QIDF) | Bound Phenolics Removal | CrI increased after treatment [12] | [12] |

Experimental Methodologies for Characterization

Determining the structural properties of fibers requires a suite of complementary analytical techniques. The following are detailed protocols for key experiments cited in this field.

X-Ray Diffraction (XRD) for Crystallinity Index (CrI)

Application: Quantifying the crystallinity of insoluble dietary fibers like pea IDF [11] and quinoa bran IDF [12]. Procedure:

- Sample Preparation: Compact the dried, powdered fiber sample onto an instrument sample holder.

- Data Acquisition: Use an X-ray diffractometer (e.g., D8 ADVANCE) to scan the sample across a range of diffraction angles (2θ), typically from 5° to 40°.

- Data Analysis: Identify the intensity of the diffraction peak corresponding to the crystalline region (e.g., around 22° for cellulose) and the intensity of the trough for the amorphous region (e.g., around 18°). The Crystallinity Index (CrI) is often calculated using the empirical Segal method:

- Formula:

CrI (%) = [(I_crystalline - I_amorphous) / I_crystalline] × 100[11] whereI_crystallineis the maximum intensity of the principal crystalline peak, andI_amorphousis the intensity of the amorphous background.

- Formula:

Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM) for Morphological Analysis

Application: Visualizing the surface architecture and physical structure of fibers at the micro-scale, such as observing the dense network of PIDF or the loosened structure of QIDF after bound phenolics removal [11] [12]. Procedure:

- Sample Preparation: Adhere dried fiber powder to a metal stub using conductive tape and remove excess powder. Sputter-coat the sample with a thin layer of platinum or gold using an ion sputter (e.g., Hitachi E-1010) for approximately 2 minutes to ensure conductivity.

- Image Acquisition: Transfer the sample to a field-emission scanning electron microscope (e.g., Zeiss Gemini300). Observe the surface morphologies under a high vacuum with an accelerating voltage of 5.0 kV at various magnifications.

Gas Physisorption for Surface Area and Porosity

Application: Measuring the specific surface area (SSA) and pore volume (PV) of fibers, which are critical for understanding adsorption behaviors and are often modified by grinding [11]. Procedure:

- Sample Degassing: Place a known mass of dried fiber sample in a analysis tube and degas under a vacuum to remove contaminants.

- Gas Adsorption/Desorption: Transfer the tube to a surface area analyzer (e.g., Micromeritics Tristar II). Introduce high-purity nitrogen gas at cryogenic temperature and measure the volume of gas adsorbed and desorbed across a range of relative pressures.

- Data Analysis: Calculate the Specific Surface Area (SSA) using the Brunauer-Emmett-Teller (BET) model applied to the adsorption data in the appropriate relative pressure range. Calculate the Pore Volume (PV) and pore-size distribution using the Barrett-Joyner-Halenda (BJH) model applied to the desorption isotherm.

Structural-Functional Relationships and Pathways

The crystalline structure of IDF and the amorphous nature of SDF directly dictate their functional roles in physiological and product applications. The following diagram synthesizes the logical pathway from chemical composition to end-function.

Diagram 1: Logical pathway from chemical composition to function for insoluble and soluble fibers.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents and Materials

This section details essential reagents, materials, and instruments used in the featured experiments for characterizing fiber structure and function.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Fiber Analysis

| Item Name | Type/Description | Primary Function in Research |

|---|---|---|

| α-Amylase & Amyloglucosidase | Enzymes | Sequential enzymatic removal of starch and other digestible components from raw plant material to isolate pure dietary fiber [11]. |

| Alkaline Protease | Enzyme | Degradation and removal of protein contaminants during the dietary fiber extraction process [11]. |

| Nitrogen Gas (High Purity) | Analytical Gas | Adsorbate gas used in physisorption analyzers (BET/BJH method) to determine the specific surface area and pore volume of fiber samples [11]. |

| Phloroglucinol & KMnO₄ | Chemical Stains (Weisner & Mäule) | Histochemical staining for the localization and differentiation of guaiacyl and syringyl lignin units in plant tissue sections [10]. |

| Planetary Ball Mill (e.g., UBE-F2L) | Instrument | Ultrafine grinding equipment used for the physical modification of fibers to reduce particle size and disrupt crystalline structure [11]. |

| X-ray Diffractometer (XRD) | Instrument | Measures the degree of crystallinity (CrI) in fiber samples by analyzing the diffraction pattern of X-rays incident on the material [11]. |

| Surface Area & Porosimetry Analyzer | Instrument (e.g., Micromeritics Tristar II) | Characterizes the specific surface area, pore volume, and pore-size distribution of porous fiber materials via gas adsorption [11]. |

| Field-Emission SEM (e.g., Zeiss Gemini300) | Instrument | Provides high-resolution images of fiber surface morphology and microstructure [11]. |

The structural dichotomy between the crystalline architecture of insoluble fibers and the amorphous matrix of soluble fibers is a fundamental determinant of their chemical and biological behavior. Quantitative characterization through techniques like XRD and gas physisorption provides critical data linking structural parameters like CrI, SSA, and PV to functional outcomes such as glucose adsorption and fermentation kinetics. This understanding is pivotal for the rational design of functional foods and the development of advanced, fiber-based drug delivery systems, where tailoring the structural properties of fibers can lead to precise modulation of their performance and health benefits.

The functional diversity of dietary fibers (DFs), particularly the distinction between insoluble and soluble fractions, is fundamentally governed by their monosaccharide composition and glycosidic linking patterns. These structural parameters determine physicochemical properties such as solubility, viscosity, and fermentability, which in turn dictate physiological impacts including microbiota modulation, short-chain fatty acid (SCFA) production, and chronic disease intervention. This whitepaper synthesizes current research to establish a structure-function framework for DFs, providing researchers and drug development professionals with standardized characterization methodologies, quantitative structural data, and elucidated mechanisms linking chemical composition to health outcomes. Precision in DF structural analysis is critical for developing evidence-based nutritional therapies and functional food ingredients.

Dietary fibers are indigestible carbohydrates with polymerization degrees (DP) generally ≥3, resistant to human digestive enzymes [13]. The classification into soluble dietary fiber (SDF) and insoluble dietary fiber (IDF) is primarily determined by their monosaccharide building blocks and the glycosidic bonds linking them into complex polymers.

SDF, including pectins, β-glucans, and arabinogalactans, typically contains backbone and side-chain monosaccharides that create amorphous, hydratable structures. In contrast, IDF, encompassing cellulose, hemicellulose, and lignin, forms crystalline, tightly packed structures through extensive hydrogen bonding and cross-linking, resisting hydration [10] [14]. These inherent chemical differences directly impact their physiological behavior: SDF increases viscosity, modulates gastric emptying and glucose absorption, and is readily fermented by colonic microbiota to produce SCFAs. IDF primarily affects intestinal transit time, fecal bulk, and provides mechanical stimulation to the gut epithelium [15] [16].

Advancements in analytical techniques have revealed that finer structural details—specific monosaccharide ratios, glycosidic linkage positions (α- or β- configuration, 1→4, 1→3, etc.), degree of branching, and presence of functional group modifications (acetylation, methylation)—further refine these broad categories and create a spectrum of functional diversity [15] [14]. This structural complexity enables the targeted selection or design of DFs for specific research and therapeutic applications.

Structural Determinants of Fiber Function

Monosaccharide Composition and Polymerization Degree

The fundamental monomers constituting DFs directly influence their physical properties and physiological functions.

Table 1: Primary Monosaccharides in Common Dietary Fibers and Their Properties

| Monosaccharide | Common Fiber Sources | Typical Configuration | Key Functional Implications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Glucose | Cellulose, β-Glucans, Resistant Starch | β-(1→4) [Cellulose], Mix of β-(1→3) and β-(1→4) [β-Glucan] | Forms linear, rigid chains (cellulose) or viscous, soluble gels (β-glucans). |

| Galacturonic Acid | Pectin | α-(1→4) | Presence of carboxyl groups allows gel formation via cross-linking with cations; contributes to SDF viscosity. |

| Arabinose | Arabinoxylan, Pectin side chains | α-L-Arabinofuranose | Often found as side-chain substituents; disrupts crystallinity, increases solubility and microbial accessibility. |

| Xylose | Xylans, Arabinoglucuronoxylan | β-(1→4) | Forms a linear backbone; acetylation or substitution with arabinose/glucuronic acid modulates solubility. |

| Mannose | Galactomannans, Glucomannans | β-(1→4) | Forms a backbone with galactose side-chains; contributes to high viscosity and water-binding capacity. |

| Galactose | Galactomannans, Pectin side chains | β-(1→4) in backbone, α-(1→6) in side-chains | Side-chain frequency determines solubility and interaction with water; more branches increase solubility. |

| Lignin | Woody plants, Seed coats | Complex phenolic polymer | Not a carbohydrate; hydrophobic, contributes to IDF structure and fecal bulking capacity. |

The Degree of Polymerization (DP), indicating the number of monomeric units in a polysaccharide chain, is another critical parameter. Generally, lower DP fibers (e.g., oligosaccharides like FOS and XOS) ferment more rapidly in the proximal colon, while higher DP fibers may ferment more slowly and distally [14]. For instance, the molecular weight of SDF from various fruits like citrus and apples can range from 84 to 743 kDa, directly affecting its solubility, viscosity, and gelling properties [14].

Glycosidic Linkage Patterns and Functional Groups

The type, position, and stereochemistry of glycosidic bonds create specific three-dimensional architectures that define a fiber's functional role.

- Linkage Patterns: β-(1→4) linkages in cellulose create straight, rigid chains that form stable, insoluble crystalline microfibrils. In contrast, the mixed β-(1→3) and β-(1→4) linkages in β-glucans introduce kinks in the chain, preventing tight packing and resulting in solubility [14]. The α-(1→4) linked backbone of pectin, rich in galacturonic acid, provides sites for ionic gelation.

- Functional Groups: Hydroxyl groups facilitate hydrogen bonding with water, enhancing solubility. Carboxyl groups (e.g., in galacturonic acid of pectin) can ionize, increasing water binding and allowing gel formation. Acetyl esters (e.g., in acetylated galactoglucomannan from wood) protect against enzymatic degradation and can be cleaved by microbial esterases in the colon, providing a source of acetate [17]. Methyl esters on pectin affect its gelling mechanics.

- Branched vs. Linear Structures: Highly branched polysaccharides, like type II arabinogalactan found in date fruit SDF, are typically amorphous and soluble, while linear polymers tend toward crystallinity and insolubility [10].

Experimental Protocols for Structural Analysis

Accurate characterization of DF structure requires a multi-technique approach. Below are detailed protocols for key analyses.

Monosaccharide Composition Analysis

This protocol determines the qualitative and quantitative monomeric makeup of a DF sample [10].

- Sample Hydrolysis: Precisely weigh 10-20 mg of purified DF. Add 1-2 mL of 2 M trifluoroacetic acid (TFA) in a sealed tube. Heat at 121°C for 1-3 hours to hydrolyze glycosidic bonds.

- Neutralization and Drying: Cool the hydrolysate and neutralize the TFA using a stream of nitrogen gas or by adding a calculated volume of sodium hydroxide.

- Derivatization: Convert the released monosaccharides into volatile derivatives. A common method is conversion to alditol acetates by reduction with sodium borohydride followed by acetylation with acetic anhydride.

- Analysis by Gas Chromatography (GC) or GC-Mass Spectrometry (GC-MS): Inject the derivatized sample. Identify and quantify monosaccharides by comparing retention times and peak areas with authentic standards.

Determination of Glycosidic Linkage Composition

Linkage analysis reveals the bonding pattern between monosaccharides, typically performed via methylation analysis [15].

- Methylation: Suspend 1-5 mg of dry DF sample in anhydrous dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO). Add a methylating agent (e.g., iodomethane) in the presence of a strong base (e.g., sodium hydroxide powder or dimsyl anion) to methylate all free hydroxyl groups.

- Hydrolysis and Reduction: Hydrolyze the permethylated polymer with TFA as in 3.1. Reduce the resulting partially methylated monosaccharides to partially methylated alditol acetates.

- GC-MS Analysis: The unique fragmentation pattern of each partially methylated alditol acetate in the mass spectrometer allows identification of the original linkage type (e.g., a 1,4,5-tri-O-acetyl-2,3,6-tri-O-methyl derivative indicates a 4-linked hexopyranose residue).

Fiber Fractionation and Purification

The AOAC method 991.43 is the standard for separating SDF and IDF [10].

- Enzymatic Digestion: Incubate 1 g of sample (fat-extracted if necessary) with sequential additions of heat-stable α-amylase (95°C, pH 8.2), protease (60°C, pH 7.5), and amyloglucosidase (60°C, pH 4.0-4.5) to remove digestible starch and protein.

- Precipitation of SDF: Add 4 volumes of 95% ethanol (preheated to 60°C) to the filtrate containing soluble fiber. Hold at room temperature for 1 hour to precipitate SDF.

- Filtration and Drying: Filter the mixture through a crucible. The residue on the filter is the SDF fraction (plus protein and ash), while the residue from the initial filtration is the IDF fraction. Wash both residues with 78% ethanol, 95% ethanol, and acetone. Dry and weigh.

- Correction for Protein and Ash: Analyze protein (e.g., by Kjeldahl) and ash content of the residues. Corrected SDF and IDF are calculated by subtracting protein and ash from the respective residues.

Diagram 1: Dietary Fiber Fractionation and Analysis Workflow. This outlines the key steps from raw material to purified fractions ready for structural characterization.

Functional Consequences of Structural Diversity

Impact on Gut Microbiota and SCFA Production

The gut microbiota possesses a vast arsenal of Carbohydrate-Active enZymes (CAZymes) that are highly specific to DF structure. Consequently, monosaccharide composition and linkage patterns dictate which bacterial taxa are selectively promoted.

- Structural Specificity: Bifidobacterium and Lactobacillus are known to utilize β-fructans (inulin, FOS) and α-galactooligosaccharides (α-GOS) [17] [16]. Butyrate-producing bacteria like Faecalibacterium prausnitzii and members of clostridial cluster IX are efficient at fermenting complex xylans and mannans [17]. The presence of acetyl groups on wood-derived hemicelluloses (AcGGM, AcAGX) requires specialized microbial esterases, making these fibers selective for microbes equipped with such enzymes [17].

- SCFA Profile Modulation: The baseline composition of an individual's gut microbiota influences the metabolic outcome of DF fermentation. A microbiota dominated by Bacteroidaceae and Ruminococcaceae tends to produce more butyrate upon DF supplementation, while one dominated by Prevotellaceae and Ruminococcaceae produces more propionate, regardless of the DF type [18]. Specific fibers can skew this further; for instance, acetylated galactoglucomannan (AcGGM) is strongly butyrogenic, while arabinoglucuronoxylan (AcAGX) is more propiogenic [17].

Table 2: Microbiota and SCFA Response to Specific Fiber Structures

| Dietary Fiber Type | Key Structural Features | Microbial Taxa Selectively Promoted | Primary SCFA Output |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fructooligosaccharides (FOS) | β-(2→1) fructose polymers, low DP | Bifidobacterium, Lactobacillus | Acetate |

| Xylooligosaccharides (XOS) | β-(1→4) linked xylose backbone, may be acetylated | Bifidobacterium, Bacteroides | Acetate, Butyrate |

| Galactoglucomannan (AcGGM) | β-(1→4) mannose/glucose backbone, acetylated, galactose side chains | Bifidobacterium, Bacteroides-Prevotella, F. prausnitzii, Clostridial cluster IX | Butyrate |

| Arabinoglucuronoxylan (AcAGX) | β-(1→4) xylose backbone, acetylated, glucuronic acid/arabinose side chains | Bifidobacterium, Bacteroides-Prevotella, F. prausnitzii, Clostridial cluster IX | Propionate |

| Pectin (from fruits) | α-(1→4) galacturonic acid backbone, methyl-esterified, rhammose inserts | Bacteroides, Lachnospiraceae | Acetate, Propionate |

Interactions with Other Dietary Components

DF does not exist in isolation. Its structure influences interactions with other phytochemicals, notably phenolics, forming "antioxidant dietary fiber" [13].

- Covalent and Non-covalent Bonds: Phenolic acids can be ester-linked to DF (e.g., ferulic acid cross-linking arabinoxylans) via covalent bonds. Non-covalent interactions (hydrogen bonding, hydrophobic interactions) can also occur between DF and larger polyphenols.

- Functional Property Changes: These interactions can enhance the stability of phenolics during digestion and transport them to the colon. The bound phenolics can also alter the physicochemical properties of the DF, such as its antioxidant capacity, hydration properties, and fermentability [13].

Diagram 2: Dietary Fiber-Phenolic Interactions and Outcomes. This shows how different binding types lead to complexes with enhanced functional properties.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents and Kits for Dietary Fiber Research

| Research Reagent / Kit | Function / Application | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Enzyme Kits (AOAC 991.43) | Sequential enzymatic digestion for SDF/IDF fractionation. Contains heat-stable α-amylase, protease, and amyloglucosidase. | Quantification of SDF and IDF content in food samples or raw materials [10]. |

| Monosaccharide Standards | High-purity sugars (e.g., L-Rhamnose, L-Arabinose, D-Galactose, etc.) for calibration in GC and HPLC. | Identification and quantification of monosaccharides in DF hydrolysates [10]. |

| Methylation Analysis Reagents | DMSO, Iodomethane, Sodium Hydride, etc., for permethylation of polysaccharides. | Determination of glycosidic linkage patterns in a DF polymer [15]. |

| Inulin/FOS, XOS, GOS Standards | Defined oligosaccharide mixtures for chromatographic calibration and as prebiotic references. | Studying fermentation kinetics of specific DF structures or quality control of prebiotic ingredients [18]. |

| Short-Chain Fatty Acid (SCFA) Standards | Pure acetate, propionate, butyrate, etc., for HPLC or GC calibration. | Quantification of SCFA production in in vitro fermentation models [17] [18]. |

| Polymer Gel Beads (e.g., Gellan Gum) | For immobilizing fecal microbiota in continuous in vitro fermentation systems (e.g., PolyFermS). | Maintaining stable, high-density, and representative gut microbiota for long-term DF intervention studies [18]. |

The functional diversity of dietary fibers is unequivocally rooted in the precise chemical details of their monosaccharide composition and linking patterns. Moving beyond the simplistic soluble vs. insoluble dichotomy to a structure-based understanding is paramount for the rational design of next-generation prebiotics and functional foods.

Future research must prioritize the development of comprehensive standardization guidelines that incorporate monosaccharide composition, DP, and linkage data to ensure product efficacy and reproducibility [15]. Furthermore, increased utilization of advanced continuous in vitro models that maintain complex microbial ecosystems will provide deeper insights into the structure-specific fermentation dynamics and cross-feeding networks. Finally, exploring the synergistic effects of DF-phenolic complexes and the impact of food processing on DF structure will unlock new possibilities for enhancing the health benefits and technological applications of dietary fibers in clinical and consumer settings.

Dietary fiber, a diverse group of carbohydrate polymers and associated compounds, resists digestion by human endogenous enzymes and undergoes varying degrees of fermentation in the large intestine. The classical binary classification system categorizes these compounds based on their solubility in water: soluble dietary fiber (SDF), which includes pectins, β-glucans, and arabinoxylans; and insoluble dietary fiber (IDF), comprising cellulose, hemicellulose, and lignin [19] [3]. This solubility dichotomy fundamentally influences their physicochemical properties and physiological effects, making their distribution in plant sources a critical area of research for understanding their health benefits and potential pharmaceutical applications.

The chemical composition of dietary fibers extends beyond solubility to include structural features such as glycosidic linkages, monomeric composition, molecular weight, and the presence of functional groups. These characteristics determine their functional properties, including water-holding capacity, viscosity, swelling ability, and fermentability [2] [3]. For researchers and drug development professionals, understanding these structural-functional relationships is essential for developing fiber-based interventions targeting specific health outcomes, such as cholesterol reduction, blood glucose regulation, and colorectal health maintenance.

Chemical Composition and Structural Characteristics

Soluble Dietary Fibers (SDF)

Soluble dietary fibers are characterized by their ability to dissolve or swell in water, forming gel-like substances with unique rheological properties. The primary SDF components include:

- Pectins: Complex polysaccharides rich in galacturonic acid with varying degrees of methyl esterification, predominantly found in fruits and vegetables [14]. Their gel-forming capability is instrumental in regulating nutrient absorption rates.

- β-Glucans: Linear polysaccharides of D-glucose monomers with mixed (1→3) and (1→4) linkages, particularly abundant in oats and barley, known for their cholesterol-lowering effects [3].

- Arabinoxylans: Hemicellulose components consisting of xylose backbones with arabinose side chains, prevalent in cereal grains, contributing to viscosity development in the gastrointestinal tract [10].

Advanced structural analysis reveals that SDFs contain various functional groups, including hydroxyl, carboxyl, and methoxyl groups, which facilitate hydrogen bonding with water molecules and cation exchange capacities [14]. Nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) studies of SDF from fruits show chemical shifts in the range of 5.03-5.33 ppm for H1 in the →4)-α-Glcp-(1→ main chain, while →3)-β-Glcp-(1→ residues in β-glucan exhibit H1 chemical shifts between 4.42-4.57 ppm [14].

Insoluble Dietary Fibers (IDF)

Insoluble dietary fibers are characterized by their structural role in plant cell walls and resistance to dissolution in water. Key IDF components include:

- Cellulose: A linear polymer of β(1→4) linked D-glucose units that forms crystalline microfibrils providing structural integrity to plant cells [10] [3].

- Hemicellulose: A heterogeneous polymer of xylose, mannose, galactose, and other sugars with branched structures that cross-link cellulose microfibrils [10].

- Lignin: A complex polyphenolic compound that provides rigidity and resistance to microbial degradation in plants, with guaiacyl and syringyl units identified as primary subunits [10].

The structural complexity of IDF contributes to its higher thermal stability compared to SDF, as demonstrated by thermogravimetric analysis showing greater decomposition resistance in IDF fractions [10]. Crystalline regions within cellulose contribute to this thermal stability, while the amorphous regions of hemicellulose and lignin provide sites for water absorption and microbial adhesion.

Table 1: Comparative Structural and Chemical Properties of Major Dietary Fiber Components

| Fiber Component | Monomeric Units | Glycosidic Linkages | Functional Groups | Structural Features |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pectin (SDF) | Galacturonic acid, arabinose, galactose | α(1→4) | Carboxyl, methoxyl, hydroxyl | Branched, amorphous, gel-forming |

| β-Glucan (SDF) | Glucose | β(1→3), β(1→4) | Hydroxyl | Linear with mixed linkages, viscous |

| Arabinoxylan (SDF) | Xylose, arabinose | β(1→4) | Hydroxyl, ferulic acid | Branched, water-soluble |

| Cellulose (IDF) | Glucose | β(1→4) | Hydroxyl | Linear, crystalline, high tensile strength |

| Hemicellulose (IDF) | Xylose, mannose, glucose, others | β(1→4), various | Hydroxyl, acetyl | Branched, amorphous, heterogeneous |

| Lignin (IDF) | Guaiacyl, syringyl, p-hydroxyphenyl | C-C, C-O-C | Methoxyl, phenolic hydroxyl | Amorphous, three-dimensional network |

Analytical Methodologies for Dietary Fiber Characterization

Fiber Fractionation Protocol

The quantitative separation of soluble and insoluble fiber fractions follows standardized methodologies with specific modifications for different plant matrices. The following protocol, adapted from AOAC Method 991.43 with modifications for date fruit analysis, provides a representative experimental approach [10]:

Materials and Reagents:

- Desugared plant sample (e.g., date fruit powder, ground whole grains)

- Ethanol (78%, 95% v/v)

- Acetone (analytical grade)

- Sodium hydroxide solution

- Enzymes: Heat-stable α-amylase, protease, amyloglucosidase

- Filtration system with crucibles

Experimental Procedure:

- Sample Preparation: Finely grind plant material to 106-250 μm particle size. For fruits high in simple sugars, pre-treat with 80% ethanol (1:10 w/v) six times to remove interfering compounds, followed by drying at 50°C for 18 hours [10].

Enzymatic Digestion: Suspend 1g sample in 40mL phosphate buffer (pH 6.0). Add 50μL heat-stable α-amylase solution, incubate at 95°C for 15 minutes with continuous shaking. Cool to 60°C, add protease solution (100μL), incubate at 60°C for 30 minutes. Adjust pH to 4.5, add amyloglucosidase (200μL), incubate at 60°C for 30 minutes [10].

Soluble/Insoluble Fraction Separation: Transfer digested sample to filtration apparatus with pre-weighed crucible. Wash residue with 78% ethanol (15mL), 95% ethanol (15mL), and acetone (15mL). Retain filtrate for soluble fiber analysis.

Soluble Fiber Precipitation: Combine filtrates, evaporate to approximately 40mL total volume. Add 95% ethanol (80mL, 60°C) to precipitate soluble fiber, stand overnight at 4°C. Recover precipitate by filtration, freeze-dry, and weigh [10].

Protein and Ash Correction: Analyze both fractions for protein (Kjeldahl method, N×6.25 conversion factor) and ash content (550°C for 5 hours). Calculate corrected values:

- SDF = (Soluble fraction weight - protein - ash) / initial sample weight × 100

- IDF = (Insoluble fraction weight - protein - ash) / initial sample weight × 100 [10]

Structural Characterization Techniques

Advanced analytical methods provide detailed structural information about fiber components:

Monosaccharide Composition Analysis:

- Protocol: Hydrolyze fiber samples (1-2mg) with 2M trifluoroacetic acid at 121°C for 1 hour. Derivatize released monosaccharides to alditol acetates or conduct HPAEC-PAD analysis without derivatization. Separate using GC-MS or HPLC systems with appropriate columns (e.g., DB-225 for GC, CarboPac PA20 for HPAEC-PAD) [14].

Lignin Localization and Characterization:

- Mäule Staining: Immerse plant tissue sections in 1% (w/v) potassium permanganate solution for 5 minutes, wash with 3% HCl until color changes from dark brown to light brown, treat with 0.1M ammonia solution. Guaiacyl lignin units appear yellow-brown, syringyl units red-purple [10].

- Weisner Staining: Treat tissue sections with 1% phloroglucinol for 5 minutes, followed by 95% ethanol for 5 minutes. Add concentrated HCl to develop red-purple color specific for guaiacyl units [10].

Molecular Weight Distribution:

- Protocol: Dissolve SDF samples (2-5mg/mL) in appropriate eluent (typically 0.1-0.2M NaNO₃). Perform size-exclusion chromatography with multi-angle light scattering and refractive index detection (SEC-MALS-RI). Use pullulan or dextran standards for calibration [14].

Thermal Analysis:

- Protocol: Subject 5-10mg fiber samples to thermogravimetric analysis (TGA) with temperature ramp of 10°C/min from 25°C to 600°C under nitrogen atmosphere. Determine thermal decomposition profiles and stability parameters [10].

Whole Grains

Whole grains represent a significant source of dietary fiber, with varying ratios of soluble to insoluble components depending on the grain type and anatomical fraction. The bran fraction is particularly rich in insoluble fibers, while the endosperm contains more soluble components [3].

Table 2: Dietary Fiber Composition of Selected Whole Grains (g/100g dry weight)

| Grain Type | Total Dietary Fiber | Soluble Fiber | Insoluble Fiber | SDF:IDF Ratio | Notable Components |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Oats | 60-80 | ~30 | 30-50 | 1:1 to 1:1.7 | High β-glucan (SDF) [3] |

| Barley | 20-30 | 5-10 | 15-20 | 1:2 to 1:3 | Mixed-linkage β-glucan, arabinoxylan [3] |

| Wheat | 9-38 | 1-4 | 8-34 | 1:4 to 1:9 | Arabinoxylan, cellulose, lignin [3] |

| Rye | 14-20 | 2-4 | 12-16 | 1:4 to 1:6 | Arabinoxylan, fructan [3] |

| Corn | 10-15 | 1-2 | 9-13 | 1:6 to 1:8 | Cellulose, heteroxylan [3] |

| Rice | 2-4 | 0.2-0.5 | 1.8-3.5 | 1:7 to 1:9 | Cellulose, arabinoxylan [3] |

| Sorghum | 8-12 | 0.8-1.5 | 7.2-10.5 | 1:7 to 1:9 | Cellulose, heteroxylan [3] |

The structural distribution within grains follows specific patterns. In wheat, the aleurone and starchy endosperm contain high proportions of arabinoxylans (60-70%) and β-glucans (20-30%), while the outer pericarp is rich in cellulose (30%), lignin (12%), and xylans (60%) [3]. Oat bran, comprising 30-50% of the whole grain, contributes significantly to its dietary fiber content, with β-glucan as the primary soluble component [3].

Fruits and Vegetables

Fruits and vegetables exhibit diverse dietary fiber profiles influenced by species, cultivar, maturity, and processing methods. Date fruits (Phoenix dactylifera L.) show total dietary fiber content ranging from 3.2-7.4 g/100g, with over 90% being insoluble fiber composed of crystalline lignin, cellulose, and hemicellulose [10]. The soluble fraction in dates is amorphous and primarily consists of pectin (>50%) with complex branching patterns possibly involving type II arabinogalactan [10].

Structural analyses of fruit SDF reveal diverse monosaccharide profiles. Citrus SDF primarily contains galacturonic acid and glucose, while grapefruits, lemons, pomelos, and citrus peels are rich in galacturonic acid and arabinose [14]. Dragon fruit peel SDF consists mainly of galacturonic acid, mannose, and xylose [14]. The molecular weight of SDF varies significantly by source, with citrus ranging 84-743 kDa, apple 103-485 kDa, and potato 2-1819 kDa [14].

Table 3: Dietary Fiber Content in Selected Fruits and Vegetables

| Plant Source | Total Dietary Fiber (g/100g) | Soluble Fiber (g/100g) | Insoluble Fiber (g/100g) | Notable Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lima beans, cooked | 13.2 | 6.6 | 6.6 | High pectin content [20] |

| Artichoke, cooked | 9.6 | 4.8 | 4.8 | Rich in inulin-type fructans [20] |

| Navy beans, cooked | 9.6 | 4.8 | 4.8 | Balanced SDF/IDF ratio [20] |

| Green peas, cooked | 8.8 | 4.4 | 4.4 | Cellulose, pectin [20] |

| Dates | 3.0 | 0.3 | 2.7 | High lignin content [20] |

| Apple, with skin | 4.8 | ~2.4 | ~2.4 | Pectin in flesh, cellulose in skin [21] |

| Carrots, cooked | 4.8 | ~2.4 | ~2.4 | Pectic polysaccharides [21] |

| Brussels sprouts | 6.4 | ~2.5 | ~3.9 | Cellulose, hemicellulose [20] |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 4: Essential Reagents and Materials for Dietary Fiber Research

| Reagent/Material | Specifications | Research Application | Functional Role |

|---|---|---|---|

| Heat-stable α-amylase | Bacterial source (e.g., Bacillus licheniformis), ≥50 U/mg | Starch digestion in sample preparation | Hydrolyzes α(1→4) glycosidic bonds in starch to eliminate interference [10] |

| Protease | Aspergillus oryzae or Bacillus spp., ≥300 U/mL | Protein digestion in sample preparation | Cleaves peptide bonds to remove protein content from fiber analysis [10] |

| Amyloglucosidase | Aspergillus niger, ≥100 U/mL | Starch digestion completion | Hydrolyzes α(1→6) and α(1→4) linkages in oligosaccharides [10] |

| Phloroglucinol | Analytical grade, ≥99% purity | Weisner staining for lignin detection | Specific colorimetric reaction with guaiacyl lignin units (red-purple) [10] |

| Potassium permanganate | ACS reagent, ≥99% purity | Mäule staining for lignin differentiation | Oxidizes lignin subunits to distinguish guaiacyl (yellow-brown) and syringyl (red-purple) units [10] |

| Standard reference fibers | Citrus pectin, oat β-glucan, wheat arabinoxylan, cellulose | Method validation and calibration | Quality control standards for comparative analysis and quantification [10] [3] |

| Size-exclusion columns | Sepharose, Sephacryl, or equivalent matrices | Molecular weight distribution analysis | Separation of fiber polymers by hydrodynamic volume [14] |

| Monosaccharide standards | L-Arabinose, D-Galactose, D-Glucose, etc., ≥98% purity | Compositional analysis by GC-MS/HPLC | Quantification and identification of hydrolyzed fiber components [10] [14] |

The systematic investigation of dietary fiber sources reveals complex relationships between plant origin, structural characteristics, and functional properties. The distribution of soluble and insoluble fractions across whole grains, fruits, and vegetables demonstrates significant variation, with oats and barley exhibiting higher SDF:IDF ratios (approximately 2:1 to 3:1) due to their richness in β-glucans, while wheat and rice are predominantly rich in IDF with ratios of approximately 1:4 to 1:9 [3]. Fruits such as dates show exceptionally high insoluble fiber content (>90% of TDF), with lignin composition varying significantly between cultivars [10].

The chemical composition of dietary fibers extends beyond the simplistic soluble-insoluble dichotomy to include structural features such as glycosidic linkage patterns, monosaccharide composition, molecular weight distribution, and functional groups that collectively determine their physiological effects. Advanced processing techniques including enzymatic, thermal, and mechanical treatments can modify these structural attributes, potentially enhancing their bioactive properties [14]. For pharmaceutical and nutraceutical development, understanding these structure-function relationships enables targeted selection of fiber sources for specific health applications, such as utilizing high-β-glucan oats for cholesterol management or lignin-rich preparations for prebiotic effects.

Future research directions should focus on elucidating the structure-activity relationships of less-characterized fiber components, developing standardized analytical protocols for novel fiber sources, and exploring synergistic effects between different fiber types in complex food matrices. Such investigations will advance our understanding of dietary fiber chemistry and facilitate the development of evidence-based recommendations for their application in preventive healthcare and therapeutic interventions.

Advanced Analytical Techniques for Fiber Characterization and Functional Assessment

In the field of analytical chemistry, Fourier Transform Infrared (FTIR) and Near-Infrared (NIR) spectroscopy have emerged as powerful techniques for rapid, non-destructive functional group analysis. These vibrational spectroscopic methods provide critical insights into molecular structure and composition without altering the sample, making them indispensable for a wide range of applications. Within the specific context of dietary fiber research—particularly concerning the chemical composition of insoluble versus soluble fiber—these techniques offer unprecedented capabilities for understanding structural-functional relationships that dictate physiological effects. The distinct health benefits of soluble and insoluble dietary fibers, including cholesterol reduction, glycemic control, and digestive regulation, are directly influenced by their molecular architectures and chemical functional groups [2]. This technical guide provides researchers and drug development professionals with a comprehensive framework for applying FTIR and NIR spectroscopy to elucidate these critical structural characteristics, enabling more accurate classification and prediction of fiber functionality beyond the traditional binary soluble-insoluble paradigm.

Fundamental Principles of FTIR and NIR Spectroscopy

Theoretical Foundations

FTIR and NIR spectroscopy both exploit the interactions between matter and infrared light, but they operate in distinct regions of the electromagnetic spectrum and probe different molecular phenomena.

FTIR Spectroscopy operates in the Mid-Infrared (MIR) region, typically covering wavenumbers from 4000 to 400 cm⁻¹ (wavelengths of 2.5 to 25 μm) [22] [23]. This region corresponds to the fundamental vibrational modes of chemical bonds, including stretching, bending, and rotational motions. When infrared radiation interacts with a sample, specific frequencies are absorbed that match the natural vibrational frequencies of molecular bonds within the sample. The resulting absorption spectrum represents a "molecular fingerprint" that is unique to the chemical structure and composition [24] [25]. The Fourier Transform algorithm enables simultaneous measurement of all wavelengths, significantly improving speed and signal-to-noise ratio compared to traditional dispersive infrared instruments.

NIR Spectroscopy utilizes the Near-Infrared region from approximately 750 to 2500 nanometers (13,333 to 4000 cm⁻¹) [22] [23]. This higher-energy region primarily probes overtones and combination bands of fundamental molecular vibrations, particularly those involving hydrogen atoms (O-H, N-H, C-H bonds) [22]. While NIR spectra contain broader, more overlapping bands compared to FTIR, they can be effectively interpreted using advanced multivariate statistical methods to extract quantitative and qualitative information about complex materials.

Molecular Interaction Mechanisms

The fundamental difference in the type of information provided by these techniques stems from their distinct interaction mechanisms with molecular bonds:

Table 1: Fundamental Characteristics of FTIR and NIR Spectroscopy

| Characteristic | FTIR Spectroscopy | NIR Spectroscopy |

|---|---|---|

| Spectral Range | 4000 - 400 cm⁻¹ | 13,333 - 4000 cm⁻¹ |

| Primary Transitions | Fundamental vibrations | Overtones and combination bands |

| Spectral Features | Sharp, well-defined peaks | Broad, overlapping bands |

| Penetration Depth | Shallow (surface analysis) | Deeper tissue penetration |

| Sample Preparation | Often required | Minimal to none |

The functional group sensitivity differs significantly between these techniques. FTIR provides detailed information about specific functional groups including carbonyls (C=O), hydroxyls (O-H), amines (N-H), and various carbon-carbon and carbon-oxygen bonds [24] [25]. NIR, in contrast, is particularly sensitive to molecular vibrations involving hydrogen atoms, making it exceptionally suitable for analyzing organic compounds with O-H, N-H, and C-H bonds [22] [26].

Comparative Analysis: FTIR vs. NIR for Analytical Applications

Technical Capabilities and Limitations

Each technique offers distinct advantages and limitations that must be considered when selecting an appropriate method for specific analytical challenges.

FTIR Strengths and Limitations:

- Structural Elucidation: FTIR excels at identifying unknown materials and characterizing molecular structures through detailed "fingerprint" regions [22] [23].

- Sensitivity: Higher sensitivity for specific chemical bonds and functional groups, providing superior resolution for complex mixtures [23].

- Quantitative Analysis: Suitable for both qualitative identification and quantitative determination of compound concentrations [22].

- Sample Preparation: Often requires more extensive sample preparation, including grinding, pressing, or specific thickness optimization [26] [27].

- Analysis Speed: Generally slower than NIR, making it less suitable for high-throughput applications [22].

NIR Strengths and Limitations:

- Speed and Throughput: Rapid analysis capabilities, with results typically available within seconds [22].

- Non-destructive Nature: Minimal to no sample preparation required, preserving sample integrity for subsequent analyses [22].

- Penetration Capabilities: Deeper sample penetration enables analysis of bulk properties rather than just surface characteristics [26].

- Spectral Interpretation: Broader, overlapping bands require sophisticated chemometric approaches for meaningful interpretation [26] [28].

- Concentration Sensitivity: Generally requires higher analyte concentrations compared to FTIR for reliable detection [23].

Application-Specific Performance

The selection between FTIR and NIR must be guided by the specific analytical requirements and sample characteristics:

Table 2: Application-Based Comparison of FTIR and NIR Spectroscopy

| Application Requirement | Recommended Technique | Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| Structural Identification | FTIR | Superior molecular fingerprinting capabilities |

| High-Throughput Screening | NIR | Rapid analysis (seconds per sample) |

| Quantitative Analysis | Both | FTIR for specific compounds, NIR for bulk composition |

| Intact Sample Analysis | NIR | Minimal sample preparation required |

| Surface Characterization | FTIR | Limited penetration depth ideal for surface analysis |

| Process Monitoring | NIR | Non-contact measurement capability |

Recent comparative studies demonstrate that both techniques can achieve high accuracy in classification tasks. For example, in authentication of food products like hazelnuts, both MIR (FTIR) and NIR achieved ≥93% accuracy in classifying cultivars and geographic origin, with NIR slightly outperforming FTIR for geographic discrimination [29].

Experimental Protocols for Dietary Fiber Analysis

Sample Preparation Methodologies

Proper sample preparation is critical for obtaining reliable and reproducible spectroscopic data in dietary fiber research.

FTIR Sample Preparation Protocols:

- Grinding: Reduce particle size to <500 μm using a laboratory mill to ensure homogeneity and improve spectral reproducibility [26] [28].

- ATR-FTIR Preparation: Place ground sample directly on the ATR crystal and apply consistent pressure (60-75% of maximum) to ensure optimal contact [27].

- Reflectance FTIR Preparation: Position sample on gold-coated reference plate without compression, ideal for delicate or valuable samples [27].

- Transmission FTIR Preparation: Mix finely ground sample with potassium bromide (KBr) and press into pellet form under vacuum.

NIR Sample Preparation Protocols:

- Minimal Preparation: For homogeneous samples, analysis can be performed directly on intact material with minimal processing [26] [28].

- Grinding for Heterogeneous Samples: Reduce particle size to <500 μm to improve spectral consistency and model performance [28] [30].

- Presentation: Place ground or intact samples in appropriate containers with consistent packing density and orientation.

Instrumentation and Data Collection Parameters

Standardized instrument parameters ensure comparable results across different analyses and laboratories:

FTIR Measurement Parameters:

- Spectral Range: 4000-600 cm⁻¹ for comprehensive functional group analysis [27]

- Resolution: 4 cm⁻¹ optimal for balancing detail and signal-to-noise ratio [27]

- Scans: 64-128 accumulations to improve spectral quality [27]

- Detector: Mercury Cadmium Telluride (MCT) for high sensitivity, Deuterated Triglycine Sulfate (DTGS) for routine analysis [27]

NIR Measurement Parameters:

- Spectral Range: 750-2500 nm (13,333-4000 cm⁻¹) for complete overtone coverage [28]

- Resolution: 8-16 cm⁻¹ suitable for most applications

- Scans: 32-64 accumulations typically sufficient due to stronger signal intensity

- Detector: Silicon (Si) for short-wavelength NIR, Indium Gallium Arsenide (InGaAs) for full-range analysis

Data Processing and Chemometric Analysis

Advanced data processing techniques are essential, particularly for NIR spectroscopy where bands are broad and overlapping:

Spectral Preprocessing Methods:

- Scatter Correction: Standard Normal Variate (SNV) and Multiplicative Signal Correction (MSC) to compensate for light scattering effects [27]

- Derivative Techniques: Savitzky-Golay first and second derivatives to enhance spectral resolution and remove baseline effects

- Smoothing: Moving average or Savitzky-Golay filtering to improve signal-to-noise ratio without distorting spectral features

Multivariate Analysis Techniques:

- Principal Component Analysis (PCA): For exploratory data analysis and outlier detection

- Partial Least Squares (PLS) Regression: For developing quantitative models predicting specific fiber components [26] [28]

- Discriminant Analysis: For classification of samples based on soluble/insoluble fiber characteristics [27]

The following workflow diagram illustrates the complete experimental process for spectroscopic analysis of dietary fibers:

Application to Dietary Fiber Research

Analyzing Soluble vs. Insoluble Fiber Composition

The application of FTIR and NIR spectroscopy to dietary fiber research provides unprecedented insights into the structural characteristics that determine physiological functionality. The traditional binary classification of dietary fiber as simply soluble or insoluble fails to capture the complexity of fiber structures and their diverse health effects [2]. A more comprehensive framework that accounts for backbone structure, water-holding capacity, structural charge, fiber matrix, and fermentation rate is necessary to accurately predict physiological outcomes [2].

NIR Applications in Fiber Analysis: Research has demonstrated that NIR spectroscopy can successfully predict insoluble dietary fiber content in diverse cereal products with a standard error of cross validation (SECV) of 1.54% and R² of 0.98 across a concentration range of 0-48.77% [28] [30]. Soluble dietary fiber prediction is less accurate, with SECV of 1.15% and R² of 0.82 (range 0-13.84%), potentially due to limitations in the reference method rather than the spectroscopic technique itself [28]. The expanded model incorporating samples with high fat and sugar content maintained strong performance, demonstrating the robustness of NIR for analyzing complex food matrices [30].

FTIR Applications in Fiber Analysis: FTIR provides detailed molecular-level information about functional groups present in different fiber types. Specific spectral signatures can distinguish between soluble fibers like β-glucans, pectins, and gums, and insoluble fibers such as cellulose, hemicellulose, and lignin [2]. The carbohydrate region (1200-800 cm⁻¹) shows distinct patterns for different structural organizations, while the carbonyl region (1800-1500 cm⁻¹) provides information about esterification and acetylation patterns that influence solubility and fermentability [2].

Advanced Classification Framework

The integration of spectroscopic data with the proposed comprehensive classification framework enables more accurate prediction of health outcomes:

The Researcher's Toolkit: Essential Materials and Reagents

Successful implementation of FTIR and NIR methodologies requires specific materials and analytical tools. The following table summarizes essential components for spectroscopic analysis of dietary fibers:

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Spectroscopic Fiber Analysis

| Item | Specification | Application | Critical Function |

|---|---|---|---|

| Laboratory Mill | Particle size <500 μm | Sample preparation | Homogenization for reproducible spectra |

| KBr Powder | FTIR grade, >99% purity | FTIR pellet preparation | Transparent matrix for transmission measurements |

| ATR Crystal | Diamond, Germanium, or ZnSe | FTIR-ATR measurements | Internal reflection element for surface analysis |

| NIR Reflectance Cup | Rotating or static | NIR measurements | Consistent presentation for powdered samples |

| Reference Materials | Certified fiber standards | Calibration validation | Quality control and method verification |

| Chemometric Software | PLS, PCA capabilities | Data analysis | Multivariate model development and prediction |

FTIR and NIR spectroscopy provide complementary approaches for rapid, non-destructive functional group analysis in dietary fiber research. FTIR excels in detailed molecular characterization and identification of unknown structures, while NIR offers superior speed and minimal sample preparation requirements ideal for high-throughput analysis. The application of these techniques to the complex challenge of dietary fiber classification moves beyond the simplistic soluble-insoluble paradigm toward a comprehensive framework that accurately predicts physiological outcomes based on structural characteristics. For researchers and drug development professionals, the integration of spectroscopic data with advanced chemometric models enables more precise formulation of fiber-enhanced products with targeted health benefits. As spectroscopic technologies continue to advance, particularly in portable instrumentation and machine learning applications, their role in nutritional science and functional food development will expand, offering new opportunities for understanding structure-function relationships in complex biological matrices.

Thermal analysis techniques, particularly Thermogravimetric Analysis (TGA) and Differential Scanning Calorimetry (DSC), serve as critical methodologies for investigating the stability and decomposition kinetics of complex biological materials. Within the context of researching the chemical composition of insoluble versus soluble fibers, these techniques provide fundamental insights into material behavior under thermal stress. TGA measures mass changes in a sample as a function of temperature or time, providing quantitative data on thermal stability and compositional analysis [31]. DSC, conversely, measures heat flows associated with phase transitions and chemical reactions as a function of temperature, enabling characterization of thermal events such as glass transitions, melting, and crystallization [32] [31]. The application of these techniques to dietary fibers—complex carbohydrates resistant to mammalian digestion—allows researchers to decipher the relationship between fiber structure (soluble vs. insoluble) and thermal properties, thereby informing their stability, processing conditions, and potential applications in pharmaceuticals and functional foods.

Theoretical Fundamentals of TGA and DSC

Principles of Thermogravimetric Analysis (TGA)

TGA operates on the fundamental principle of monitoring the mass of a sample as it undergoes a controlled temperature program. The resulting thermogram plots mass (or percentage mass) against temperature or time, revealing steps corresponding to mass loss events such as dehydration, decomposition, and oxidation [31]. In the study of dietary fibers, these mass loss events are directly attributable to the breakdown of specific polymer components. For instance, the thermal decomposition of cellulose, hemicellulose, and lignin—primary constituents of insoluble fibers—occurs at distinct temperature ranges, allowing for their identification and quantification [33] [34]. Modern TGA systems are often hyphenated with gas analyzers such as FTIR or MS, enabling the qualitative identification of volatile decomposition products and providing a deeper understanding of decomposition mechanisms [31].

Principles of Differential Scanning Calorimetry (DSC)

DSC measures the difference in heat flow between a sample and an inert reference as both are subjected to an identical temperature program. Endothermic events (e.g., melting, dehydration) require more heat to maintain the sample at the same temperature as the reference, while exothermic events (e.g., crystallization, oxidation) release heat [31]. This technique is indispensable for characterizing the glass transition temperature (Tg) of amorphous phases in fibrous materials, a critical parameter governing their physical stability, solubility, and bioavailability in pharmaceutical formulations [32] [31]. Furthermore, DSC can detect other thermal events crucial for fiber analysis, including melting points, crystallization behavior, and enthalpic relaxations associated with physical aging.

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Standard TGA Protocol for Fiber Analysis

A robust TGA protocol for characterizing dietary fibers involves several critical steps to ensure reproducible and meaningful data. The following workflow outlines a standard procedure adapted from research on textile fibers and biocomposites [33] [35]:

- Sample Preparation: Gently grind the fiber sample to a consistent powder to ensure uniform heat transfer. For hygroscopic fibers, pre-drying may be necessary to minimize moisture interference.

- Instrument Calibration: Calibrate the TGA balance and temperature sensor using certified reference materials (e.g., nickel or curium) as per the manufacturer's guidelines.

- Experimental Parameters:

- Sample Mass: Load 5-20 mg of sample into an alumina or platinum crucible.

- Atmosphere: Utilize an inert gas purge, such as nitrogen or argon, at a flow rate of 50-100 mL/min to simulate pyrolysis conditions and prevent oxidative degradation [33].

- Temperature Program: Employ a dynamic heating regime, typically between 5 °C/min and 20 °C/min, from ambient temperature to a final temperature of 600-800 °C to ensure complete decomposition [33].

- Data Analysis: Plot the percentage mass loss versus temperature. The derivative of the TGA curve (DTG) is calculated to pinpoint the exact temperatures of maximum decomposition rates for each component.

Standard DSC Protocol for Fiber Analysis

DSC analysis provides complementary information on the thermal transitions of fibers. The standard protocol is as follows [32] [31]:

- Sample Preparation: Precisely weigh 2-10 mg of fiber sample into a hermetically sealed aluminum crucible. An empty, sealed pan serves as the reference.

- Instrument Calibration: Calibrate the DSC cell for temperature and enthalpy using high-purity standards such as indium and zinc.

- Experimental Parameters:

- Atmosphere: Use a nitrogen purge gas (50 mL/min) to maintain an inert environment.

- Temperature Program: Typically, a heat-cool-heat cycle is used. Equilibrate at -50 °C, then heat to a temperature above the expected decomposition (e.g., 300 °C) at a scanning rate of 10 °C/min. Cool rapidly, followed by a second heating cycle to establish a stable baseline and erase thermal history.

- Data Analysis: Analyze the resulting thermogram for thermal events. The glass transition (Tg) is identified as a stepwise change in heat flow, reported as the midpoint of the transition. Melting and crystallization appear as endothermic and exothermic peaks, respectively, with the area under the peak corresponding to the transition enthalpy.

Advanced Hyphenated Techniques

Simultaneous DSC-FTIR microspectroscopy represents a powerful hyphenated technique that combines the quantitative thermal data from DSC with the chemical identification capabilities of FTIR in real-time [32]. This setup allows for one-step screening and qualitative detection of events such as intramolecular condensation, polymorphic transformation, and drug-polymer interactions as they occur, providing unparalleled insight into the stability and solid-state properties of fiber-based formulations [32].

Data Interpretation and Kinetic Analysis

Interpreting TGA and DSC Data for Fibers

The thermal profiles of insoluble and soluble fibers differ significantly due to their distinct chemical structures. Insoluble fibers like cellulose, lignin, and hemicellulose are typically more crystalline and exhibit higher thermal stability. Their TGA curves often show a major, sharp decomposition step at higher temperatures. For example, pure cotton (cellulose) decomposes at approximately 371 °C [33]. In contrast, soluble fibers such as pectins, beta-glucans, and gums often have more amorphous structures and may show broader decomposition profiles at lower temperatures, sometimes preceded by dehydration or melting events detectable by DSC [34] [36].

DSC further differentiates fiber types. Insoluble fibers may display clearer melting transitions due to their crystalline regions, while soluble fibers are more likely to exhibit prominent glass transitions. The Tg is highly sensitive to water content; moisture acts as a plasticizer, significantly lowering the Tg of hydrophilic soluble fibers, which has profound implications for their storage stability and shelf-life in pharmaceutical products [31].

Kinetic Analysis of Decomposition

Kinetic analysis of TGA data quantifies the thermal stability and predicts the material's behavior over time. Model-free isoconversional methods, such as Flynn-Wall-Ozawa (FWO) and Kissinger-Akahira-Sunose (KAS), are preferred for their robustness in analyzing complex reactions like fiber decomposition [33]. These methods calculate the activation energy (Ea) at various extents of conversion (α), revealing multi-step decomposition mechanisms.

For instance, a study on textile fibers found that the activation energy for pure cotton increased from 96.9 kJ/mol (at α = 0.1) to 195.6 kJ/mol (at α = 0.9), indicating a complex, multi-stage decomposition process where the reaction mechanism shifts as the material breaks down [33]. The Coast-Redfern (CR) method can then be applied to identify the most probable reaction model (e.g., nucleation, diffusion), offering a predictive tool for optimizing industrial processes like pyrolysis [33].

Table 1: Kinetic Parameters for Model-Free Analysis of Textile Fibers [33]

| Fiber Type | Conversion (α) | Activation Energy, Ea (kJ/mol) |

|---|---|---|

| Pure Cotton | 0.1 | 96.9 |

| 0.5 | 152.4 | |

| 0.9 | 195.6 | |

| Pure Polyester | 0.1 | 185.2 |

| 0.5 | 212.7 | |

| 0.9 | 238.1 |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Successful thermal analysis requires specific materials and reagents. The following table details key items used in the featured experiments and their critical functions.

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Thermal Analysis of Fibers

| Item / Reagent | Function & Application | Experimental Context |

|---|---|---|

| Nitrogen (N₂) Gas | Creates an inert atmosphere to study pyrolysis and prevent oxidative degradation during TGA/DSC. | Used in TGA of textile fibers at multiple heating rates [33]. |

| Alumina Crucibles | Inert sample pans for TGA that withstand high temperatures without reacting with the sample. | Standard vessel for holding solid powder samples in TGA [31]. |

| Hermetic Aluminum DSC Pans | Sealed containers to prevent solvent (e.g., water) loss during DSC heating, crucial for accurate Tg measurement. | Essential for analyzing hygroscopic materials like soluble fibers [31]. |

| Model-Free Kinetic Software | Software implementing FWO, KAS, and Friedman methods to calculate activation energy from TGA data. | Used to determine complex decomposition kinetics of textile fibers [33]. |

| Phosphonium Salt Catalyst | A catalyst used in epoxy resin systems for composite materials, enhancing curing and final properties. | Used in a novel epoxy resin (EPIDIAN 11) for cryogenic composite fabrication [37]. |

| Sodium Hydroxide (NaOH) | Used for alkaline treatment of natural fibers to improve interfacial bonding in composite materials. | Treatment of sisal fibers to enhance adhesion in epoxy bio-composites [35]. |

Workflow and Data Interpretation Diagrams

Experimental Workflow for Fiber Characterization

The following diagram outlines the logical sequence of experiments from sample preparation to data interpretation for a comprehensive thermal characterization of dietary fibers.

TGA Data Interpretation Pathway

This diagram illustrates the logical process of interpreting a TGA thermogram to extract quantitative and kinetic information about a fiber sample.

Comparative Data Analysis of Fiber Composites

The application of TGA and DSC is critical in developing advanced materials, such as fiber-reinforced composites. The following table summarizes thermal properties from a study on epoxy bio-composites, demonstrating how these techniques quantify the impact of additives like carbon nanotubes (CNTs) on material performance.

Table 3: Thermal Properties of Sisal/CNT Epoxy Bio-Composites [35]

| Composite Type | CNT Content (wt.%) | Onset Degradation Temp. (°C) | Storage Modulus (GPa) | Loss Modulus (MPa) | Damping Factor (tan δ) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | 0.0 | ~250 | Baseline | Baseline | Baseline |

| CNT-Reinforced | 1.0 | ~282 (~13% increase) | +79% | +197% | -56% |