Controlling Lipid Oxidation in Fatty Foods: Mechanisms, Analytical Methods, and Innovative Preservation Strategies

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of lipid oxidation control in fatty food products, tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals.

Controlling Lipid Oxidation in Fatty Foods: Mechanisms, Analytical Methods, and Innovative Preservation Strategies

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of lipid oxidation control in fatty food products, tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals. It explores the fundamental free radical chain reaction mechanisms and the complex roles of pro-oxidants like heme pigments and transition metals. The content details advanced analytical methodologies for assessing primary and secondary oxidation products, evaluates the efficacy of natural antioxidant sources and active packaging technologies, and compares predictive computational models for shelf-life stability. By synthesizing foundational science with applied innovations and validation frameworks, this review aims to bridge knowledge gaps and inspire interdisciplinary strategies for enhancing oxidative stability in food and related biomedical applications.

The Mechanisms of Lipid Oxidation: From Basic Pathways to Complex Food Matrices

FAQs: Core Concepts and Mechanisms

Q1: What are the fundamental stages of the lipid oxidation chain reaction? The lipid oxidation chain reaction occurs in three distinct stages [1] [2]:

- Initiation: A reactive oxygen species (ROS), most commonly a hydroxyl radical (HO•), abstracts a hydrogen atom from an allylic carbon in a polyunsaturated fatty acid (PUFA). This forms a lipid radical (L•) and water (H₂O) [1].

- Propagation: The lipid radical (L•) rapidly reacts with molecular oxygen (O₂) to form a lipid peroxyl radical (LOO•). This peroxyl radical can then abstract a hydrogen atom from a new PUFA molecule, generating a lipid hydroperoxide (LOOH) and a new lipid radical (L•), which propagates the chain reaction [1] [2].

- Termination: The chain reaction ends when two radicals combine to form stable, non-radical products. This can occur through the interaction of two peroxyl radicals (LOO•) or when a radical is neutralized by an antioxidant [1] [2].

Q2: Why are Polyunsaturated Fatty Acids (PUFAs) particularly susceptible to oxidation? PUFAs are primary targets for lipid oxidation because their carbon chains contain multiple double bonds. The carbon-hydrogen bonds on the methylene groups (-CHâ‚‚-) between these double bonds (allylic carbons) are exceptionally weak, requiring less energy for hydrogen abstraction by initiating radicals. This low bond dissociation energy makes PUFAs the preferred starting material for the initiation phase of the chain reaction [1].

Q3: What are the primary and secondary oxidation products, and how do they affect food quality?

- Primary Products: Lipid hydroperoxides (LOOH) are the main primary products. They are initially flavorless and odorless but are highly unstable [2] [3].

- Secondary Products: Hydroperoxides decompose into a complex mixture of volatile compounds, including aldehydes (like malondialdehyde (MDA), hexanal), ketones, and alcohols. It is these secondary products that are directly responsible for the offensive rancid flavors and odors (e.g., painty, grassy, metallic) that significantly degrade the sensory quality, nutritional value, and safety of fatty foods [1] [3].

Q4: In food research, what are the key factors that accelerate lipid oxidation? Several intrinsic and extrinsic factors can accelerate the chain reaction [4] [3]:

- Pro-oxidant Metals: Trace amounts of iron (Fe²âº/Fe³âº) and copper (Cuâº/Cu²âº) ions catalyze the decomposition of lipid hydroperoxides into new radicals, dramatically speeding up the propagation phase via Fenton and Haber-Weiss reactions [1].

- Heat and Light: Elevated temperatures increase reaction kinetics, while light (especially UV) can provide the energy required for radical initiation.

- Oxygen Concentration: The propagation phase directly consumes oxygen. Higher partial pressures of oxygen increase the rate of oxidation.

- Surface Area: A larger surface area exposed to air (e.g., in emulsified foods) facilitates oxygen transfer.

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Challenges

Q1: Our peroxide value (PV) data is inconsistent across replicates when testing high-fat powders. What could be the issue? This is a common challenge often related to sampling and homogeneity. High-fat powdered foods, such as milk powder or protein powders, are prone to segregation and localized "hot spots" of oxidation.

- Solution: Ensure the entire batch of powder is thoroughly blended before sampling. For fine powders, consider using a riffle splitter to obtain a representative sample. Analyze samples immediately after opening containers to prevent further oxygen exposure, and standardize the sampling depth and location if using a powder sampler.

Q2: We are using antioxidants, but they are ineffective in preventing rancidity in our model emulsion system. Why might this be? The efficacy of an antioxidant is highly dependent on its partitioning behavior and the site of radical generation.

- Solution: Analyze the polarity of your antioxidant and the phases of your emulsion.

- Non-polar antioxidants (e.g., BHA, BHT, tocopherols) are more effective in the oil phase.

- Polar antioxidants (e.g., Ascorbic Acid) are more effective in the aqueous phase.

- For complex systems, consider using a combination of polar and non-polar antioxidants or employing chelating agents (e.g., EDTA, Citric Acid) in the aqueous phase to sequester pro-oxidant metal ions, which is often a more effective strategy in emulsions [3].

Q3: The TBARS assay for malondialdehyde (MDA) gives unexpectedly high values even in fresh meat samples. How can we improve accuracy? The TBARS test is notoriously non-specific and can react with other compounds like sugars and amino acids [1].

- Solution:

- Sample Preparation: Incorporate a distillation step or solid-phase extraction to purify the sample before the TBA reaction, removing interfering substances.

- Analytical Technique: Move beyond the simple spectrophotometric TBARS assay. Use more specific and sensitive techniques like HPLC (High-Performance Liquid Chromatography) or GC-MS (Gas Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry) to separate and quantify MDA directly, which provides a more accurate measurement [1].

Experimental Protocols for Key Analyses

Protocol 1: Determination of Peroxide Value (PV) to Measure Primary Oxidation

The Peroxide Value quantifies the concentration of hydroperoxides, indicating the extent of primary lipid oxidation [3].

1. Principle: Lipids are dissolved in a chloroform-acetic acid mixture. Iodide ions (Iâ») from potassium iodide (KI) reduce the hydroperoxides (LOOH), producing iodine (Iâ‚‚). The liberated Iâ‚‚ is then titrated with a standardized sodium thiosulfate (Naâ‚‚Sâ‚‚O₃) solution using a starch indicator. 2. Reagents:

- Chloroform, Glacial Acetic Acid, Potassium Iodide (KI), Sodium Thiosulfate (Na₂S₂O₃), Starch Indicator.

3. Procedure:

- Weigh 5.00 g of melted oil/fat into a clean glass-stoppered flask.

- Add 30 mL of the chloroform-acetic acid (3:2 v/v) solvent mixture and swirl to dissolve.

- Add 0.5 mL of a saturated KI solution.

- Stopper the flask, swirl, and let it stand in the dark for exactly 1 minute.

- Immediately add 30 mL of distilled water and 0.5 mL of starch indicator solution.

- Titrate immediately with standardized 0.01 N Na₂S₂O₃ solution with continuous shaking until the blue/purple color just disappears.

- Run a blank titration simultaneously.

4. Calculation:

PV (meq O₂/kg oil) = [(S - B) × N × 1000] / WWhere: S = sample titrant volume (mL), B = blank titrant volume (mL), N = normality of Na₂S₂O₃, W = sample weight (g).

Protocol 2: TBARS Assay for Secondary Oxidation Products

The Thiobarbituric Acid Reactive Substances (TBARS) assay measures malondialdehyde (MDA) and related compounds as an indicator of secondary lipid oxidation [1].

1. Principle: Malondialdehyde (MDA), a secondary breakdown product of lipid hydroperoxides, reacts with thiobarbituric acid (TBA) under acidic conditions and heat to form a pink chromogen with a maximum absorbance at 530-535 nm. 2. Reagents:

- Thiobarbituric Acid (TBA) solution, Trichloroacetic Acid (TCA) solution, 1,1,3,3-Tetraethoxypropane (TEP) for standard curve.

3. Procedure:

- Sample Preparation: Homogenize 1 g of food sample with 10 mL of a TCA/BHT solution to extract MDA and prevent further oxidation.

- Filtration/Centrifugation: Filter or centrifuge the homogenate to obtain a clear supernatant.

- Reaction: Mix 2 mL of supernatant with 2 mL of TBA solution in a test tube. Heat the mixture in a boiling water bath for 35 minutes.

- Cooling & Measurement: Cool the tubes in cold water. Measure the absorbance of the solution at 532 nm against a blank prepared with distilled water.

- Standard Curve: Prepare a series of MDA standards from TEP and plot absorbance vs. concentration. 4. Calculation: Determine the MDA concentration of the sample from the standard curve and express the result as mg MDA equivalents per kg of sample.

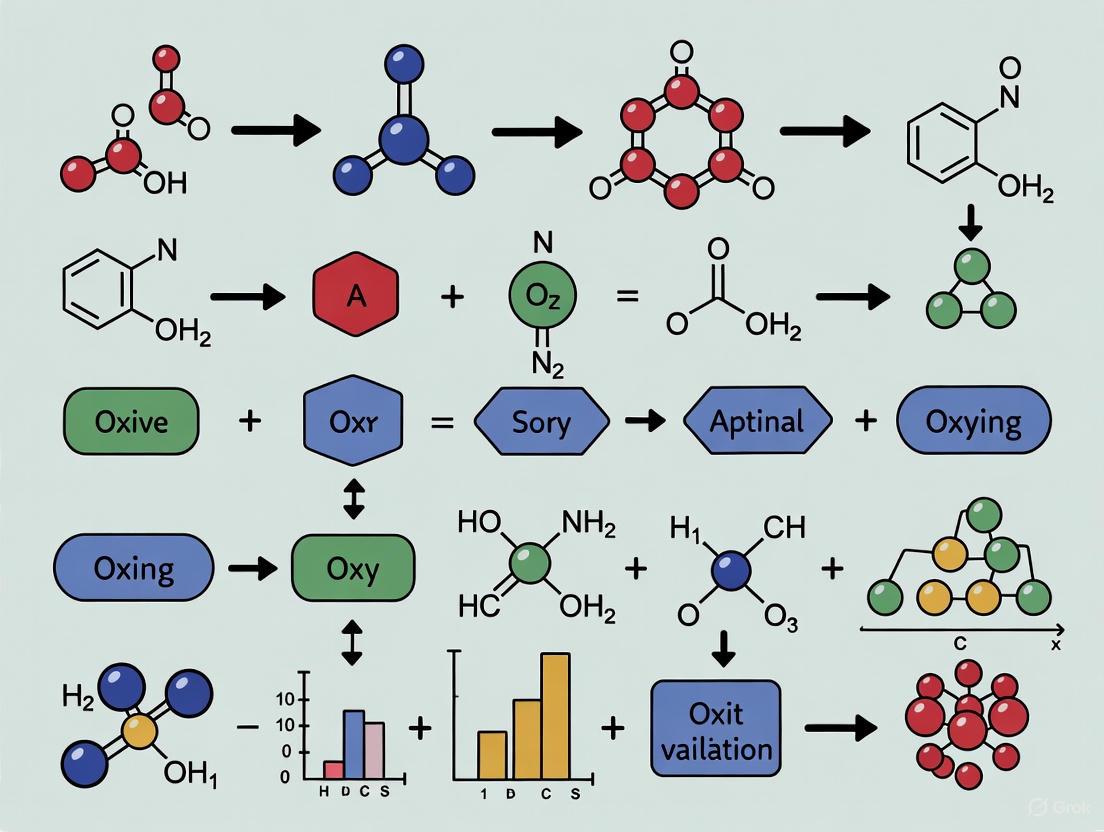

Lipid Oxidation Chain Reaction Mechanism

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 1: Key Reagents for Studying and Controlling Lipid Oxidation

| Reagent/Chemical | Function in Research | Key Mechanism of Action |

|---|---|---|

| Butylated Hydroxyanisole (BHA) | Synthetic Antioxidant | Donates a hydrogen atom to lipid peroxyl radicals (LOO•), forming a stable radical and terminating the chain propagation [3]. |

| Tocopherols (Vitamin E) | Natural Antioxidant | Primary chain-breaking antioxidant that scavenges peroxyl radicals in the lipid phase; donates a phenolic hydrogen to LOO• [1] [3]. |

| Ascorbic Acid (Vitamin C) | Antioxidant / Synergist | Can act as an oxygen scavenger and reduce tocopherol radicals, regenerating active tocopherol. Effective in aqueous phases [2] [3]. |

| Ethylenediaminetetraacetic Acid (EDTA) | Chelating Agent | Binds pro-oxidant metal ions (Fe²âº, Cuâº) in a stable complex, preventing them from catalyzing hydroperoxide decomposition and radical initiation [3]. |

| Citric Acid | Chelating Agent / Synergist | Chelates metal ions and can also act synergistically with primary antioxidants to enhance their effectiveness [3]. |

| Thiobarbituric Acid (TBA) | Analytical Reagent | Reacts with malondialdehyde (MDA) to form a pink chromogen for spectrophotometric quantification of secondary lipid oxidation [1]. |

| 1,1,3,3-Tetraethoxypropane (TEP) | Analytical Standard | Stable precursor of MDA; hydrolyzed to produce MDA for constructing a standard curve in the TBARS assay [1]. |

Advanced Pathway and Experimental Workflow

Integrated Lipid Oxidation Pathway in Food Systems

This diagram integrates the biochemical chain reaction with its real-world consequences in food products.

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Challenges

FAQ: Our meat samples develop rancid odors and discoloration rapidly during storage experiments, despite controlling temperature. What are the primary pro-oxidants we should investigate?

The rapid onset of rancidity and color loss you describe is characteristic of accelerated lipid oxidation, most frequently initiated by three interconnected pro-oxidant factors in muscle foods.

- Heme Pigments (Myoglobin and Hemoglobin): These are your most likely culprits. During processing (grinding, cooking) or storage, the iron within myoglobin and hemoglobin can be released from its porphyrin ring or become hypervalent (e.g., ferryl species), dramatically increasing its reactivity [5] [6]. This "activated" heme iron efficiently decomposes pre-existing lipid hydroperoxides into free radicals, propagating a chain reaction. In meat, heme pigments are considered a major prooxidant [7].

- Transition Metals (Free Iron and Copper): Even at low concentrations, free iron and copper are potent prooxidants. They catalyze the decomposition of lipid hydroperoxides (LOOH) and hydrogen peroxide (Hâ‚‚Oâ‚‚) into alkoxyl (LO•) and hydroxyl (HO•) radicals via Fenton and Haber-Weiss reactions [5] [8]. The prooxidant activity is significantly higher in their reduced states (Fe²âº, Cuâº) [7].

- Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS): Superoxide anion (O₂•â»), hydrogen peroxide (Hâ‚‚Oâ‚‚), and hydroxyl radicals (HO•) are constantly formed in biological systems. The hydroxyl radical is particularly destructive and can be generated from Hâ‚‚Oâ‚‚ via Fenton reactions catalyzed by heme iron or free transition metals [9].

Experimental Protocol: Isolating Pro-Oxidant Factors To identify the dominant pro-oxidant in your system, follow this isolation protocol:

- Sample Preparation: Prepare homogeneous meat samples (e.g., ground muscle tissue) and divide into equal portions.

- Inhibitor Treatment:

- Group A (Heme Inhibitor): Add sodium nitrite (100 ppm) or specific heme-chelating agents. Nitrite stabilizes heme pigments and can inhibit their pro-oxidant activity [6].

- Group B (Transition Metal Chelator): Add EDTA (Ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid) or citrate (250-500 µM). These chelators bind free iron and copper, rendering them catalytically inactive [5] [10].

- Group C (ROS Scavenger): Add a combination of antioxidants, such as ascorbate (Vitamin C, 500 µM) to scavenge free radicals and superoxide dismutase (SOD) to eliminate superoxide anions.

- Group D (Control): No additives.

- Incubation: Incubate all samples under controlled conditions (e.g., 4°C, in the dark) that accelerate oxidation.

- Analysis: Monitor lipid oxidation over time by measuring Thiobarbituric Acid-Reactive Substances (TBARS) for secondary oxidation products (like malondialdehyde) and peroxide value (PV) for primary hydroperoxides [11].

- Interpretation: The treatment group that shows the greatest suppression of lipid oxidation indicates the primary pro-oxidant pathway in your specific sample.

FAQ: When we cook our meat or fish samples, lipid oxidation accelerates significantly. Why does heating exacerbate the problem, and how can we control it in experiments?

Cooking is a major pro-oxidative processing step due to several simultaneous events [7]:

- Release of Bound Iron: Heat denatures proteins, releasing protein-bound iron and heme from myoglobin, making them more accessible to lipids [7].

- Inactivation of Antioxidant Enzymes: Endogenous antioxidant defense systems (e.g., catalase, glutathione peroxidase) are thermally inactivated [5].

- Membrane Disruption: Heating disrupts cellular membranes, bringing unsaturated phospholipids into closer contact with pro-oxidants [7].

- Heme Pigment Activation: Heating promotes the conversion of oxymyoglobin to metmyoglobin, a process that generates hydrogen peroxide (Hâ‚‚Oâ‚‚) as a by-product, which can then participate in radical-generating reactions [7].

Experimental Protocol: Minimizing Oxidation During Thermal Processing To control oxidation during cooking in research settings:

- Antioxidant Incorporation: Pre-treat raw meat samples with a solution of natural antioxidants (e.g., rosemary extract, tocopherols) or chelators (e.g., EDTA, if permitted) before cooking. This provides a protective matrix before pro-oxidants are activated [12].

- Optimized Cooking Method: Use precise, controlled thermal processing (e.g., water bath) instead of high-heat grilling. Studies suggest that low-temperature, long-time heating may release less catalytic iron compared to high-temperature searing [7].

- Rapid Cooling: Immediately after reaching the target internal temperature, rapidly chill samples in an ice bath to slow down propagation reactions.

- Packaging: Perform cooking in an oxygen-free environment (e.g., vacuum-sealed bags) if possible, or flush the sample container with nitrogen to limit oxygen availability [5].

Quantitative Data on Pro-Oxidant Factors

Table 1: Key Pro-Oxidants in Muscle Foods and Their Catalytic Mechanisms

| Pro-Oxidant Factor | Common Sources in Food | Primary Catalytic Mechanism | Key Reaction |

|---|---|---|---|

| Heme Iron | Myoglobin, Hemoglobin | Decomposes peroxides to free radicals; can release free iron [6] [7]. | Heme-Fe(III) + LOOH → Heme-Fe(IV)=O + LO•Heme-Fe(IV)=O + LOOH → Heme-Fe(III) + LOO• + H₂O |

| Free Iron (Fe²âº) | Released from ferritin, heme proteins; contamination. | Fenton reaction: generates hydroxyl radicals from Hâ‚‚Oâ‚‚ [5] [7]. | Fe²⺠+ Hâ‚‚Oâ‚‚ → Fe³⺠+ HO• + OHâ» |

| Free Copper (Cuâº) | Contamination from equipment, water. | Fenton-like reaction; faster peroxide decomposition than iron [7]. | Cu⺠+ Hâ‚‚Oâ‚‚ → Cu²⺠+ HO• + OHâ» |

| Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS) | Metabolic by-products, auto-oxidation, irradiation. | Direct attack on fatty acids; feeds metal-catalyzed reactions [5] [9]. | HO• + LH → L• + H₂O |

Table 2: Relative Importance of Pro-Oxidants in Different Food Matrices

| Food Matrix | Primary Pro-Oxidant | Secondary Pro-Oxidant | Notes & Experimental Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Raw Red Meat | Heme Pigments (Myoglobin) [7] | Free Iron | In raw meat homogenates, heme pigments may show little prooxidant effect until systems are cooked or washed [5]. |

| Cooked Meat | Heme Pigments & Released Iron [7] | Free Iron | Cooking releases protein-bound iron and activates heme pigments, making both highly prooxidative [7]. |

| Fish Muscle | Released Hematin [7] | Heme Pigments | Hematin has lower affinity for myoglobin in fish, making free hematin a more significant prooxidant [7]. |

| Oil-in-Water Emulsions | Free Iron, Copper [12] | Heme Pigments | In model systems like emulsions and washed muscle, heme pigments are strong prooxidants [5]. |

Pro-Oxidant Pathways and Interactions

The following diagram illustrates the core pathways and interactions between the key pro-oxidant factors that drive lipid oxidation.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents

Table 3: Essential Reagents for Investigating Pro-Oxidant Factors

| Reagent / Material | Function in Experiment | Key Mechanism / Note |

|---|---|---|

| EDTA (Ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid) | Transition Metal Chelator | Binds free iron and copper ions, forming inert complexes and preventing Fenton reactions [10]. |

| Sodium Nitrite | Heme Pigment Stabilizer | Reacts with heme pigments to form nitrosylmyoglobin, which can inhibit heme's catalytic activity [6]. |

| Sodium Chloride (NaCl) | Pro-Oxidant at specific concentrations | At ~2% concentration, can act as a prooxidant by releasing protein-bound iron; at 3%, this effect may not be observed [7]. |

| Desferrioxamine | Specific Iron Chelator | A potent and specific chelator for iron, used to confirm iron-mediated oxidation pathways [8]. |

| Trolox or BHT | Synthetic Radical Scavenger | Water-soluble (Trolox) or lipid-soluble (BHT) chain-breaking antioxidants that donate electrons to lipid radicals [12] [11]. |

| Superoxide Dismutase (SOD) | Enzymatic ROS Scavenger | Catalyzes the dismutation of superoxide anion (O₂•â») into hydrogen peroxide and oxygen [9]. |

| Catalase | Enzymatic ROS Scavenger | Converts hydrogen peroxide (Hâ‚‚Oâ‚‚) into water and oxygen, removing a key substrate for Fenton chemistry [9]. |

| 2,2'-Azobis(2-amidinopropane) dihydrochloride (AAPH) | Chemical Radical Initiator | A water-soluble azo compound that generates peroxyl radicals at a constant rate upon thermal decomposition, used to induce and study oxidation under controlled conditions [11]. |

| DL-Glyceraldehyde-2-13C | DL-Glyceraldehyde-2-13C, MF:C3H6O3, MW:91.07 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| 2,8-Thianthrenedicarboxylic acid | 2,8-Thianthrenedicarboxylic Acid|High-Purity RUO | 2,8-Thianthrenedicarboxylic acid is a high-purity reagent for research use only (RUO). It is a key building block for synthesizing macrocyclic compounds and functional materials. Not for human or veterinary use. |

Lipid oxidation is a major cause of quality deterioration in fatty food products, leading to undesirable flavors, loss of nutritional value, and potential generation of harmful compounds. The rate and pathway of lipid oxidation are profoundly influenced by the food matrix structure and composition. Understanding these matrix-specific effects is crucial for developing effective strategies to control oxidation in various food products, from emulsions and bulk oils to complex muscle foods.

Fundamental Mechanisms of Lipid Oxidation

Chemical Pathways

Lipid oxidation proceeds through a free radical chain reaction mechanism comprising three main stages:

- Initiation: The reaction begins with the abstraction of a hydrogen atom from an unsaturated fatty acid (LH), forming a lipid alkyl radical (L•). This initiation can be triggered by heat, light, metal catalysts, or other radicals [13] [14].

- Propagation: The lipid alkyl radical (L•) reacts with oxygen to form a lipid peroxyl radical (LOO•), which can then abstract a hydrogen atom from another unsaturated fatty acid, forming a lipid hydroperoxide (LOOH) and a new alkyl radical, thus propagating the chain reaction [14].

- Termination: The reaction chain ends when two radicals combine to form non-radical products [14].

The following diagram illustrates the cyclical nature of this process:

Primary and Secondary Oxidation Products

- Primary products: Hydroperoxides (LOOH) are the main initial products of lipid oxidation. They are relatively unstable and decompose to form secondary oxidation products [15].

- Secondary products: Aldehydes, ketones, alcohols, and hydrocarbons are formed through the decomposition of hydroperoxides. These compounds are responsible for the rancid odors and flavors associated with oxidized foods [15] [10].

Food Matrix-Specific Oxidation Mechanisms

Oil-in-Water Emulsions

In oil-in-water (O/W) emulsions, lipid oxidation occurs primarily at the oil-water interface, where lipids come into contact with water-soluble pro-oxidants from the aqueous phase [16] [17]. The physical structure of emulsions significantly influences oxidation rates through several mechanisms:

Droplet Size Effect: Smaller oil droplets have a larger specific interfacial area (m² interface/m³ oil), increasing contact between lipids and pro-oxidants. Monodisperse emulsions with controlled droplet sizes demonstrate that lipid oxidation increases with decreasing droplet size [17].

Interfacial Composition: The type and concentration of emulsifiers at the oil-water interface can either promote or inhibit oxidation. Emulsifiers can affect the accessibility of lipid substrates to pro-oxidants and antioxidants [16].

Table 1: Effect of Droplet Size on Lipid Oxidation in O/W Emulsions

| Droplet Size (µm) | Specific Interfacial Area | Relative Oxidation Rate | Key Observations |

|---|---|---|---|

| 4.7 | Large | High | Rapid hydroperoxide formation; fastest oxygen consumption |

| 9.1 | Medium | Medium | Moderate oxidation rate |

| 26.0 | Small | Low | Slowest hydroperoxide formation and oxygen consumption |

Bulk Oils

Unlike emulsions, lipid oxidation in bulk oils occurs throughout the continuous lipid phase, with specific implications:

Reverse Micelle Formation: Bulk oils contain surface-active compounds (diacylglycerols, free fatty acids, phospholipids) that form reverse micelles in the presence of trace water. These structures create unique environments where hydroperoxides accumulate and interact with metal catalysts [18].

Polar Antioxidant Partitioning: Polar antioxidants tend to accumulate at the interfaces of reverse micelles, enhancing their effectiveness by positioning them where oxidation is initiated [18].

Muscle Foods

Muscle foods represent complex matrices where lipids and proteins coexist, leading to interconnected oxidation pathways:

Lipid-Protein Co-oxidation: Secondary lipid oxidation products (particularly aldehydes) react with amino groups in proteins, causing protein oxidation and aggregation. This affects protein functionality, digestibility, and nutritional value [19] [15].

Heme Protein Catalysis: Myoglobin and hemoglobin in muscle foods can undergo redox cycling, generating reactive oxygen species that initiate and propagate lipid oxidation [14].

Membrane Phospholipid Susceptibility: Phospholipids in cellular membranes are particularly susceptible to oxidation due to their high unsaturated fatty acid content and association with pro-oxidants [14].

The diagram below illustrates the complex co-oxidation relationships in muscle foods:

Troubleshooting Guide: Common Experimental Challenges

Emulsion Stability and Oxidation

Problem: Inconsistent oxidation rates between emulsion batches.

- Potential Cause: Variations in droplet size distribution and polydispersity.

- Solution: Use microfluidic emulsification to produce monodisperse emulsions with highly controlled droplet sizes. Standardize emulsification procedures to minimize batch-to-batch variation [17].

Problem: Accelerated oxidation in O/W emulsions compared to bulk oils.

- Potential Cause: Increased specific interfacial area providing more sites for oxidation initiation.

- Solution: Optimize interfacial composition using emulsifiers that form thick, protective layers. Consider incorporating interfacial antioxidants [16].

Bulk Oil Oxidation Issues

Problem: Variable induction periods in bulk oil oxidation studies.

- Potential Cause: Inconsistent reverse micelle formation due to variations in polar compound content and water activity.

- Solution: Standardize oil purification methods. Control water activity and consider the impact of minor components on oxidation kinetics [18].

Muscle Food Oxidation Challenges

Problem: Rapid quality deterioration in muscle foods during storage.

- Potential Cause: Interconnected lipid-protein oxidation cycles.

- Solution: Target antioxidants to both lipid and protein phases. Consider the use of metal chelators to inhibit heme protein catalysis [19] [14].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: Why do smaller oil droplets in emulsions generally oxidize faster than larger droplets?

- A: Smaller droplets have a larger specific interfacial area (interface area per unit volume of oil), increasing contact between lipid substrates and pro-oxidants dissolved in the aqueous phase. Monodisperse emulsions with 4.7 µm droplets showed significantly faster hydroperoxide formation and oxygen consumption compared to 26 µm droplets [17].

Q2: How does the food matrix affect antioxidant effectiveness?

- A: Antioxidant effectiveness depends on their partitioning behavior and location within the food matrix. In bulk oils, polar antioxidants accumulate at reverse micelle interfaces where oxidation initiates. In emulsions, surface-active antioxidants that concentrate at the oil-water interface are more effective [18].

Q3: What are the key differences between oxidation in bulk oils versus emulsions?

- A: The main difference lies in the oxidation initiation site. In bulk oils, oxidation occurs throughout the continuous lipid phase, primarily within reverse micelles. In O/W emulsions, oxidation initiates predominantly at the oil-water interface where lipids contact aqueous pro-oxidants [16] [18].

Q4: Why are muscle foods particularly susceptible to oxidation?

- A: Muscle foods contain multiple pro-oxidants including heme proteins, transition metals, and phospholipid-rich membranes. The proximity of unsaturated lipids to these pro-oxidants in cellular structures facilitates oxidation initiation. Additionally, co-oxidation between lipids and proteins creates self-propagating cycles of quality deterioration [19] [14].

Experimental Protocols for Matrix-Specific Oxidation Studies

Protocol for Emulsion Oxidation Studies

Materials:

- Polyglycerol polyricinoleate (PGPR) emulsifier [16]

- Purified canola or sunflower oil [16] [18]

- Aqueous phase with controlled ionic composition [16]

Method:

- Prepare oil phase by dissolving PGPR (4-10 wt%) in purified oil at 45°C for 10 min [16].

- Prepare aqueous phase with desired NaCl concentration (10-300 mM) [16].

- Gradually add aqueous phase (30-80% v/v) to oil phase while applying shear using Ultra-Turrax homogenizer [16].

- Standardize mixing conditions: 2 min at 5000 rpm, then 5 min at 7000 rpm [16].

- Protect emulsions from light during preparation and storage using tinfoil wrapping [16].

- Assess physical stability using LUMiSizer stability analyzer [16].

Protocol for Bulk Oil Oxidation Studies with Natural Antioxidants

Materials:

Method:

- Purify sunflower oil using adsorption chromatography to remove endogenous antioxidants [18].

- Dissect phycocyanin in acetone and incorporate into purified oil at concentrations of 0.02-0.08% (w/w) [18].

- For samples with lecithin, dissolve 0.05% (w/w) lecithin in ethyl acetate, stir for 60 min at 45°C, then gradually add purified oil [18].

- Remove solvent under vacuum [18].

- Monitor oxidation using peroxide value and thiobarbituric acid reactive substances (TBARS) assays [16] [18].

Protocol for Assessing Lipid-Protein Co-oxidation in Muscle Foods

Materials:

- Fresh muscle tissue (beef, pork, poultry, or fish) [14]

- Antioxidant solutions (e.g., plant extracts, synthetic antioxidants) [13]

Method:

- Homogenize muscle tissue under controlled conditions to minimize premature oxidation.

- Apply antioxidant treatments by mixing with homogenized tissue.

- Store samples under controlled temperature and atmospheric conditions.

- Monitor lipid oxidation using TBARS assay and conjugated diene analysis [15].

- Assess protein oxidation by measuring protein carbonyl content and sulfhydryl group loss [15].

- Evaluate protein aggregation using SDS-PAGE and size exclusion chromatography [15].

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Key Reagents for Lipid Oxidation Research

| Reagent | Function | Application Examples | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| PGPR (Polyglycerol Polyricinoleate) | Lipophilic emulsifier | Stabilization of W/O and W/O HIPEs [16] | Use at 4-10 wt%; higher concentrations may cause off-flavors |

| Phycocyanin | Natural antioxidant protein | Bulk oil and emulsion stabilization [18] | Water-soluble; effective at 0.02-0.08% (w/w); shows synergy with lecithin |

| Lecithin | Amphiphilic surfactant; antioxidant synergist | Reverse micelle formation in bulk oils [18] | Enhances antioxidant activity by improving interfacial positioning |

| Iron-EDTA complex | Pro-oxidant initiator | Controlled initiation of oxidation in emulsion studies [17] | Provides consistent oxidation initiation; concentration must be standardized |

| Tween 20 | Non-ionic surfactant | O/W emulsion stabilization [17] | May oxidize itself, contributing to oxygen consumption |

Analytical Methods for Oxidation Assessment

Table 3: Common Methods for Monitoring Lipid Oxidation

| Method | Target | Application | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Peroxide Value (PV) | Hydroperoxides (primary products) | Bulk oils, emulsions, muscle foods [15] | Direct measurement of primary oxidation products | Hydroperoxides may decompose during analysis |

| Thiobarbituric Acid Reactive Substances (TBARS) | Malondialdehyde and other secondary products | Muscle foods, emulsions [16] | Sensitive measure of secondary oxidation | Not specific to lipid oxidation; can interact with other food components |

| Conjugated Diene Analysis | Conjugated dienes from PUFA oxidation | Oils, emulsions [15] | Simple, rapid; useful for early oxidation detection | Limited to early oxidation stages; interference from other UV-absorbing compounds |

| Gas Chromatography (GC) | Volatile secondary oxidation products | All matrices [15] | Specific identification and quantification of volatile compounds | Complex sample preparation; requires specialized equipment |

| Oxygen Consumption | Oxygen uptake during oxidation | Emulsions, bulk oils [17] | Direct measure of oxidation extent | Requires specialized equipment; may not distinguish between different oxidation pathways |

The food matrix profoundly influences lipid oxidation pathways and kinetics. Emulsions, bulk oils, and muscle foods each present unique challenges and opportunities for oxidation control. Understanding these matrix-specific effects enables researchers to design more effective strategies for maintaining food quality and safety. Key considerations include the role of interfacial phenomena in emulsions, reverse micelle formation in bulk oils, and complex co-oxidation networks in muscle foods. This knowledge provides a foundation for developing targeted approaches to inhibit oxidation in diverse food products.

Lipid oxidation is a primary cause of quality deterioration in fatty food products, leading to rancidity, nutrient loss, and the formation of potentially harmful compounds. While the classic three-stage chain reaction of autoxidation (initiation, propagation, termination) is well-known, other pathways, namely photo-oxidation and enzyme-catalyzed oxidation, present significant and distinct challenges in research and product development. Understanding these pathways is critical for developing effective stabilization strategies for foods rich in polyunsaturated fats. This guide provides troubleshooting and methodological support for researchers investigating these complex oxidative processes.

FAQs and Troubleshooting Guides

Photo-oxidation

Q1: Our accelerated shelf-life study for a new omega-3 enriched beverage showed rapid off-flavor development, but standard oxidation markers (PV, TBARS) at room temperature were low. What could be the cause?

This discrepancy strongly suggests uncontrolled photo-oxidation is occurring during your testing. Unlike autoxidation, photo-oxidation is initiated by light and can proceed at much faster rates, even at lower temperatures.

- Root Cause: Exposure to light, particularly in the UV to visible blue spectrum, can sensitize molecules like riboflavin in your beverage. These sensitizers transfer energy to atmospheric oxygen, generating highly reactive singlet oxygen (

¹O₂), which directly attacks double bonds in unsaturated lipids [20] [21]. This bypasses the slow initiation phase of autoxidation. - Troubleshooting Steps:

- Review Storage Conditions: Ensure all samples in the accelerated study are stored in complete darkness or using amber glass/opaque packaging.

- Analyze for Specific Markers: Test for primary products of photo-oxidation. While conjugated dienes form in both autoxidation and photo-oxidation, photo-oxidation can produce a different profile of hydroperoxides.

- Employ Real-Time Monitoring: Use specialized methods like differential photocalorimetry (DPC) to directly study the oxidation kinetics under controlled light exposure [22].

- Reformulate with Quenchers: Incorporate singlet oxygen quenchers such as carotenoids (e.g., beta-carotene) into your formulation. These compounds deactivate singlet oxygen, converting its energy to heat [23].

Q2: We are studying the health impact of oxidized lipids. How can we create a reliably photo-oxized model food for our in-vivo experiments?

Creating a reproducible model requires precise control over the light exposure parameters.

- Experimental Protocol for Photo-oxidized Milk/Milk Fat:

- Sample Preparation: Dispense the liquid sample (e.g., milk, oil-in-water emulsion) into shallow, transparent containers to ensure uniform light penetration.

- Light Exposure: Expose samples to a consistent, controlled light source. Studies often use cool white fluorescent lamps with an intensity of 2000–3000 lux for a defined period (e.g., 24-72 hours) [24]. Including a UV component can accelerate the process.

- Temperature Control: Maintain a constant, low temperature (e.g., 4-10°C) during illumination to minimize concurrent thermal autoxidation.

- Validation of Oxidation: Confirm the degree of oxidation using a panel of analytical methods. As demonstrated in a 2024 mouse model study, successful photo-oxidation was validated by tracking specific metabolites like lumichrome and all-trans-retinal in the liver, and observing significant disruption in glycerophospholipid metabolism and the PPAR signaling pathway [24].

Enzyme-Catalyzed Oxidation

Q3: We suspect lipoxygenase (LOX) activity is causing rapid off-flavors in our plant-based meat analog during processing. How can we confirm this and identify the critical control point?

Enzyme-catalyzed oxidation via LOX can cause quality defects in milliseconds, making it crucial to identify and deactivate the enzyme.

- Root Cause: Lipoxygenases are enzymes that directly catalyze the oxidation of polyunsaturated fatty acids, forming specific hydroperoxide products.

- Troubleshooting Steps:

- Heat Inactivation Test: Take a raw material slurry and divide it. Blanch or heat-treat one portion to a temperature known to inactivate LOX (typically 80-90°C for several minutes). Process both treated and untreated samples identically and compare oxidation markers (e.g., hexanal) immediately after processing. A significant reduction in oxidation in the heat-treated sample confirms LOX activity.

- pH Adjustment: LOX has an optimal pH range (often near pH 6.5 for plant LOX). Adjusting the slurry's pH away from this optimum can suppress activity.

- Use of Specific Inhibitors: In research settings, adding a known LOX inhibitor (e.g., nordihydroguaiaretic acid or esculetin) can help confirm the pathway.

- Critical Control Point: The key is to inactivate LOX at the earliest possible stage, ideally immediately after crushing or milling the raw materials, before it can act on the liberated lipids.

Q4: What are the key differences in the oxidation products from autoxidation versus enzyme-catalyzed pathways, and how can we analytically distinguish them?

The primary difference lies in the specificity of the reaction, which is reflected in the product profile.

- Autoxidation: A non-enzymatic, free-radical process that produces a complex mixture of hydroperoxide isomers. The reaction is not stereo- or regio-specific.

- Enzyme-Catalyzed Oxidation (e.g., via Lipoxygenase): Enzymes are highly specific. LOX typically produces a limited set of hydroperoxide isomers with high stereochemical (optical) purity. For example, soybean LOX converts linoleic acid predominantly to the 13(S)-hydroperoxy-9(Z),11(E)-octadecadienoic acid isomer.

The following table summarizes the core differences between these oxidation pathways.

| Feature | Autoxidation | Photo-oxidation | Enzyme-Catalyzed Oxidation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Initiator | Heat, metal ions, radicals [25] | Light (via sensitizers) [20] [21] | Enzymes (e.g., Lipoxygenase) [26] |

| Reactive Species | Alkyl radicals (L•), peroxyl radicals (LOO•) | Singlet Oxygen (¹O₂) |

Enzyme-substrate complex |

| Primary Products | Complex mixture of hydroperoxide isomers | Specific hydroperoxide isomers (e.g., from ¹O₂ addition) |

Specific, stereospecific hydroperoxide isomers [26] |

| Key Analytical Method to Distinguish | General PV, CD; GC-MS for volatile profile | DPC, specific volatile profile | Chiral-phase HPLC to identify specific stereoisomers [27] |

| Optimal Prevention Strategy | Radical-scavenging antioxidants (e.g., BHT, Tocopherols) [23] | Light-blocking packaging, singlet oxygen quenchers (e.g., carotenoids) [23] | Thermal inactivation, pH control, specific enzyme inhibitors |

Experimental Protocols & Data Interpretation

Protocol 1: Monitoring Photo-oxidation Kinetics via Differential Photocalorimetry (DPC)

DPC is an advanced method that directly measures heat flow from a sample undergoing photo-oxidation, allowing for real-time kinetic studies [22].

Methodology:

- Sample Preparation: Place the lipid sample (ca. 10-50 mg) in a transparent DPC pan. For solid foods, a homogeneous paste is recommended.

- Instrument Calibration: Calibrate the DPC cell for heat flow and temperature using standard references.

- Analysis: Expose the sample to a controlled, intense light source within the instrument while maintaining a constant temperature (e.g., 25°C to 60°C). Isothermal mode is used for stability studies, while temperature-ramping mode can determine onset temperatures.

- Data Collection: Monitor the heat flow signal over time. The induction period (IP), which indicates resistance to oxidation, is determined as the time to a sharp onset of the exothermic signal.

Data Interpretation:

- A longer IP signifies greater oxidative stability.

- The maximum heat flow rate is proportional to the oxidation rate.

- This method is ideal for rapidly screening the efficacy of antioxidants like tocopherols or carotenoids under light stress [22].

Protocol 2: Accelerated Stability Testing with the Oxitest Reactor

For quality control and shelf-life prediction, accelerated stability tests are invaluable. The Oxitest reactor is an official method (AOCS Cd 12c-16) that accelerates oxidation by using elevated temperature and oxygen pressure [28].

Methodology:

- Sample Preparation: A key advantage is the ability to use whole samples (solid, liquid, paste) without lipid extraction, which is more representative of real-world conditions [28].

- Analysis: The sample is placed in sealed chambers, which are charged with pure oxygen (typically 6 bar) and heated to an elevated temperature (e.g., 90°C).

- Data Collection: The instrument automatically monitors the pressure drop in the chambers as oxygen is consumed by the sample. The software records the pressure over time and calculates the Induction Period (IP).

Data Interpretation:

- The IP is the point where the oxygen uptake accelerates markedly. A longer IP means the product is more stable.

- By testing at different temperatures, you can construct an Arrhenius plot to predict shelf-life at ambient storage conditions [28].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

The following table lists key reagents, inhibitors, and analytical standards essential for researching alternative lipid oxidation pathways.

| Item | Function/Application | Key Consideration |

|---|---|---|

| 2,2'-Azobis(2-amidinopropane) dihydrochloride (AAPH) | Water-soluble radical generator; used to induce autoxidation in model systems [11]. | Useful for studying water-soluble antioxidant mechanisms in emulsions. |

| Diphenyl-1-pyrenylphosphine (DPPP) | Fluorescent probe that specifically reacts with lipid hydroperoxides (LOOH) to form the fluorescent DPPPO [11]. | Allows highly sensitive detection and quantification of primary oxidation products. |

| Nordihydroguaiaretic Acid (NDGA) | A potent lipoxygenase (LOX) enzyme inhibitor [26]. | Used in model systems to confirm and quantify the contribution of enzymatic oxidation pathways. |

| Chiral-Phase HPLC Columns | Chromatographic columns designed to separate enantiomers (mirror-image isomers). | Critical for distinguishing non-specific hydroperoxides from the stereospecific hydroperoxides produced by LOX [27]. |

| β-Carotene | A natural carotenoid that acts as a singlet oxygen (¹O₂) quencher [23]. |

Used to study and mitigate photo-oxidation pathways in light-exposed products. |

| 13(S)-HPODE | Chiral hydroperoxide standard (13(S)-Hydroperoxy-9Z,11E-octadecadienoic acid). | An analytical standard for identifying and quantifying the specific product of linoleic acid oxidation by common lipoxygenases. |

| Celecoxib-d7 | Celecoxib-d7, CAS:544686-21-7, MF:C17H14F3N3O2S, MW:388.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| 1-(4-Bromo-2,5-dimethoxybenzyl)piperazine | 1-(4-Bromo-2,5-dimethoxybenzyl)piperazine, CAS:1094424-37-9, MF:C13H19BrN2O2, MW:315.211 | Chemical Reagent |

Visualizing Oxidation Pathways and Experimental Workflows

Diagram 1: Parallel Lipid Oxidation Pathways

This diagram illustrates the key initiation mechanisms for autoxidation, photo-oxidation, and enzyme-catalyzed oxidation, highlighting their distinct entry points into the propagation phase.

Diagram 2: Systematic Workflow for Pathway Investigation

This flowchart outlines a structured experimental approach to diagnose the dominant oxidation pathway in a product and select appropriate mitigation strategies.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What are the Polar Paradox and Cut-Off Effect, and why are they important for my research on fatty foods?

The Polar Paradox is a theory describing the paradoxical relationship between antioxidant polarity and its effectiveness in different food systems. It observes that polar antioxidants (e.g., ascorbic acid) are generally more effective in non-polar, bulk oil systems, while non-polar antioxidants (e.g., α-tocopherol) are more effective in more polar, oil-in-water emulsion systems [29] [30]. This is largely explained by the location of oxidation reactions and where the antioxidant is most needed.

The Cut-Off Effect refines this theory, stating that antioxidant effectiveness does not increase infinitely with the lengthening of an antioxidant's alkyl chain. Instead, efficacy increases up to a certain chain length, after which it sharply decreases. This is attributed to changes in the molecule's orientation and ability to participate in interfacial reactions [30].

For researchers, these concepts are crucial for selecting the right antioxidant for a specific food matrix (like bulk oil versus emulsified products) to effectively control lipid oxidation, extend shelf life, and maintain product quality.

Q2: My experimental results in a bulk oil system contradict the Polar Paradox. What could be the reason?

Recent research indicates the classic Polar Paradox does not always hold. Your contradictory results could stem from several factors:

- Association Colloids: Bulk oils are not homogeneous. Trace amphiphilic components (like phospholipids, free fatty acids, and monoacylglycerols) self-assemble into reverse micelles or other association colloids, creating oil-water interfaces within the bulk oil. Lipid oxidation primarily occurs at these interfaces [30]. An antioxidant's effectiveness depends on its ability to incorporate into these structures, not just its overall polarity [29] [30].

- Antioxidant Solubility: A 2024 study hypothesized that the Polar Paradox might hold for water-soluble antioxidants but not for those with low water solubility [29]. The specific molecular structure and interaction with the oxidation site are more critical than polarity alone.

- Oxidation Assay Used: The theory's applicability may depend on the measurement method. One study found the Polar Paradox might explain oxidation at the air-oil interface but could be less appropriate for other assays [29].

Q3: What are the most critical factors to consider when designing an experiment to test antioxidant efficacy?

When designing your experiment, control and characterize these key factors:

- System Composition: Precisely define your model system. For bulk oils, use stripped oil to remove native minor components, allowing you to build a defined system [29]. Be aware that the presence and type of endogenous surfactants (e.g., diacylglycerols, phospholipids) will significantly influence oxidation rates and antioxidant action by forming association colloids [30].

- Antioxidant Properties: Consider the antioxidant's molecular structure, partitioning behavior, and surface activity. For homolog series, test a range of alkyl chain lengths to identify the "cut-off" point for maximum efficacy [30].

- Environmental Conditions: Strictly control temperature, oxygen content, and light exposure, as these are major drivers of lipid oxidation [10].

Q4: Which analytical methods are best for tracking lipid oxidation and antioxidant performance?

A combination of methods tracking primary and secondary oxidation products is recommended. The table below summarizes key techniques.

Table 1: Key Analytical Methods for Assessing Lipid Oxidation and Antioxidant Efficacy

| Analysis Target | Method Name | What It Measures | Key Insights Provided |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Oxidation Products | Peroxide Value (PV) [15] | Lipid hydroperoxides | Early-stage oxidation; useful for monitoring the propagation phase. |

| Conjugated Dienes (CDA) [29] [15] | Diene bonds formed in fatty acids during oxidation | Early-stage oxidation; convenient and low-cost [15]. | |

| Secondary Oxidation Products | p-Anisidine Value (p-AV) [29] [15] | Secondary aldehydes (especially non-volatile) | Later-stage oxidation; indicates degradation of hydroperoxides. |

| Thiobarbituric Acid Reactive Substances (TBARS) [15] | Malondialdehyde (MDA) and other carbonyls | Later-stage oxidation; widely used for meat, fish, and edible insects. | |

| Hexanal Analysis (SPME-GC-MS) [29] | Specific volatile aldehydes (e.g., hexanal) | Highly sensitive and specific marker for oxidation of omega-6 PUFAs. | |

| Oxidation Stability | Rancimat / Oil Stability Index (OSI) [29] [15] | Time until rapid oxidation under accelerated conditions | Provides a single value for comparative stability testing. |

| Oxidant Atmosphere | Headspace Oxygen Content [29] | Oxygen consumption in a sealed system | Directly measures the rate of oxygen uptake due to oxidation. |

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Inconsistent or Irreproducible Oxidation Results in Bulk Oil Studies

| Potential Cause | Solution |

|---|---|

| Variable Oil Composition | Use stripped oils as your starting material. This removes native tocopherols, phospholipids, and other variable minor components that can act as pro-oxidants or antioxidants, providing a consistent baseline [29]. |

| Uncontrolled Initial Quality | Always measure the initial peroxide value and other oxidation markers of your oil before beginning the experiment. Discard or purify oils with high initial oxidation. |

| Oxygen Exposure | Conduct all sample preparation under a nitrogen blanket or in an oxygen-free chamber to prevent initiation of oxidation before the test begins [29]. Use sealed vessels for incubation. |

| Insufficient or Inappropriate Sampling Frequency | Lipid oxidation follows a sigmoidal kinetic model (lag, propagation, termination phases). Sample frequently enough to accurately capture the curve, especially during the lag and early propagation phases [30]. |

Problem: An Antioxidant is Ineffective or Acts as a Pro-Oxidant

| Potential Cause | Solution |

|---|---|

| Incorrect Polarity for the System | Re-evaluate the antioxidant's polarity relative to your food matrix. In bulk oil, consider more polar antioxidants or those with an optimal alkyl chain length for incorporation into association colloids [30]. |

| Concentration is Too High | Antioxidants can become pro-oxidants at high concentrations. Conduct a dose-response study to identify the optimal concentration for your specific system. |

| Interactions with Other Components | The antioxidant may chelate metals or interact with other proteins and surfactants in complex ways. Review the literature for known interactions in similar systems and check for the presence of metal contaminants. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Reagents for Studying Antioxidant Efficacy in Lipid Oxidation

| Reagent / Material | Function in Research |

|---|---|

| Stripped Corn/Soybean Oil | A defined, simplified model system for bulk oil studies, allowing for the controlled addition of specific components [29]. |

| Ascorbyl Palmitate (AP) | A lipophilic derivative of ascorbic acid; a model compound for testing the Polar Paradox and Cut-Off Effect in bulk oils [29]. |

| α-Tocopherol (TO) | A natural, lipophilic antioxidant (Vitamin E); serves as a benchmark for comparing the efficacy of novel antioxidants [29]. |

| Trolox (TR) | A water-soluble analog of Vitamin E; used as a standard in antioxidant capacity assays (e.g., ABTS, ORAC) and to study polarity effects [29]. |

| Gallic Acid (GA) & Alkyl Gallates | A phenolic acid and its lipophilic esters (e.g., hexadecyl gallate). This homolog series is ideal for experimentally demonstrating the Cut-Off Effect [29] [30]. |

| Silicic Acid & Activated Charcoal | Used in combination for the purification and stripping of commercial oils to remove polar minor components [29]. |

| Novozyme 435 | A commercial immobilized lipase (Candida antarctica Lipase B). Used in the enzymatic synthesis of lipophilized antioxidant derivatives (e.g., resveratryl palmitate) [29]. |

| Cyclocurcumin | Cyclocurcumin|Bioactive Natural Compound|RUO |

| Ondansetron-d3 | Ondansetron-d3, MF:C18H19N3O, MW:296.4 g/mol |

Experimental Protocol: Evaluating Antioxidants in a Bulk Oil System

This protocol is adapted from recent research to test the efficacy of different antioxidants in stripped bulk oil [29].

Objective: To compare the efficacy of polar and non-polar antioxidants in delaying lipid oxidation in a bulk oil system.

Materials:

- Stripped corn oil

- Antioxidants: e.g., Ascorbic acid (AA, polar), Ascorbyl palmitate (AP, less polar), Trolox (TR, polar), α-Tocopherol (TO, non-polar)

- Ethanol (for dissolving antioxidants)

- Brown glass vials

- Nitrogen gas tank

- Oven set to 60°C (for accelerated storage)

Method:

- Sample Preparation:

- Dissolve each antioxidant in ethanol to prepare a stock solution (e.g., 100 mM).

- Accurately weigh 1 g of stripped corn oil into separate brown glass vials.

- Add a calculated volume of the antioxidant stock solution to the oil to achieve the desired final concentration (e.g., 100 μM). For the control sample, add an equivalent volume of pure ethanol.

- Crucially, purge the headspace of each vial with a stream of nitrogen gas for 30-60 seconds before sealing to remove oxygen [29].

- Accelerated Oxidation:

- Place all sealed vials in an oven set to 60°C for 8 days [29].

- In a real experiment, you would also include samples stored at lower temperatures for more realistic kinetics.

- Sampling and Analysis:

- Remove samples in triplicate from the oven on days 0, 2, 4, 6, and 8.

- Analyze the samples using the methods listed in Table 1. For a comprehensive view, it is recommended to use at least one primary method (e.g., PV or CDA) and one secondary method (e.g., p-AV or hexanal).

- Data Interpretation:

- Plot the results (e.g., PV over time) for the control and each antioxidant.

- Determine the lag phase length and the rate of oxidation during the propagation phase.

- Compare the performance of polar vs. non-polar antioxidants in your bulk oil system and evaluate the results against the Polar Paradox and your initial hypothesis.

Conceptual Diagrams

Antioxidant Efficacy Paradoxes

Lipid Oxidation in Bulk Oil

Analytical Techniques and Antioxidant Strategies for Oxidation Control

In research focused on controlling lipid oxidation in fatty food products, the accurate determination of primary oxidation products is fundamental for assessing initial oxidative deterioration. Lipid oxidation is a major cause of quality degradation in foods, leading to rancidity, loss of nutritional value, and formation of potentially harmful compounds [25] [31] [32]. The process occurs through autoxidation, photo-oxidation, or enzymatic-catalyzed oxidation, with autoxidation being the most common pathway in foods [25] [32].

This technical support center provides detailed methodologies and troubleshooting guides for two essential techniques in lipid oxidation research: Peroxide Value (PV) and Conjugated Diene (CD) analysis. These methods target the early-stage products of lipid oxidation—hydroperoxides and conjugated dienes—serving as sensitive indicators of oxidative stability [25] [15]. Their proper application enables researchers to evaluate the effectiveness of antioxidants, optimize processing conditions, and predict product shelf-life with greater accuracy.

Experimental Protocols & Methodologies

Peroxide Value (PV) Determination via Iodometric Titration

The Peroxide Value measures the concentration of peroxides and hydroperoxides formed in fats and oils during the initial stages of oxidation [33] [34]. The standard iodometric titration method is based on the oxidation of iodide ions by hydroperoxides, with subsequent titration of the liberated iodine.

Detailed Protocol:

Principle: Peroxides in the oil sample oxidize iodide ions (Iâ») to iodine (Iâ‚‚) in an acidic environment. The liberated iodine is then titrated with a standardized sodium thiosulfate (Naâ‚‚Sâ‚‚O₃) solution [33] [35]. The reactions are as follows:

Materials and Reagents:

- Oil or fat sample

- Chloroform-glacial acetic acid mixture (2:3 v/v)

- Saturated potassium iodide (KI) solution

- Sodium thiosulfate (Na₂S₂O₃) titrant, 0.01 N standardized

- Starch indicator solution (1%)

- Burette, conical flasks, volumetric pipettes

Procedure:

- Weigh 1-5 g of oil sample (accurately recorded) into a 250 mL clean, dry conical flask [33].

- Add 10 mL of the chloroform-acetic acid mixture and swirl to dissolve the sample completely.

- Pipette 0.5 mL of saturated KI solution into the flask, stopper it, and swirl for 10-20 seconds.

- Allow the mixture to stand in a dark place for exactly 5 minutes to complete the reaction.

- Add 15 mL of distilled water and titrate immediately with 0.01 N sodium thiosulfate solution. Swirl continuously until the yellow color of iodine almost disappears.

- Add 0.5 mL of starch indicator solution (blue color appears) and continue titration until the blue color just disappears, indicating the endpoint.

- Conduct a blank determination simultaneously using the same reagents but without the oil sample.

Calculation: Calculate the Peroxide Value (PV) using the following formula, typically expressed in milliequivalents of peroxide oxygen per kilogram of fat (meq Oâ‚‚/kg) [33]:

PV (meq/kg) = [(S - B) × N × 1000] / Sample Weight (g)- S = Volume of Na₂S₂O₃ used for the sample (mL)

- B = Volume of Na₂S₂O₃ used for the blank (mL)

- N = Normality of the Na₂S₂O₃ solution

Conjugated Diene (CD) Analysis via UV Spectrophotometry

Conjugated Diene analysis quantifies the formation of conjugated diene structures in polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs), which are early intermediates in the lipid autoxidation chain reaction [25] [36].

Detailed Protocol:

Principle: During the initiation stage of autoxidation, the rearrangement of double bonds in PUFAs forms conjugated dienes, which have a characteristic strong UV absorption maximum at 233 nm [25] [36]. The increase in absorbance at this wavelength is directly proportional to the concentration of these primary oxidation products.

Materials and Reagents:

- Oil sample or lipid extract

- High-grade, UV-transparent cyclohexane or isooctane solvent

- UV-Vis spectrophotometer with quartz cuvettes

- Volumetric flasks, pipettes

Procedure:

- Accurately weigh a small quantity of oil (5-20 mg, recorded precisely) into a volumetric flask (e.g., 25 mL or 50 mL capacity) [36].

- Dilute to the mark with the solvent (cyclohexane or isooctane) and mix thoroughly to obtain a clear solution.

- Transfer the solution to a quartz cuvette and measure the absorbance against a pure solvent blank at a wavelength of 233 nm.

- Ensure the absorbance reading falls within the linear range of the instrument (preferably between 0.1 and 1.0). If the absorbance is too high, prepare a more dilute solution.

Calculation: The results are often expressed as the Conjugated Diene Value (CD Value) or simply as the absorbance value per unit concentration.

CD Value = (A × V) / (c × l)- A = Measured Absorbance at 233 nm

- V = Final Volume of the solution (mL)

- c = Sample Weight (g)

- l = Pathlength of the cuvette (cm, typically 1 cm)

Note: The CD Value is a unitless measure of the concentration of conjugated dienes. Some methodologies report it as the absorbance of a 1% solution in a 1 cm cuvette (A¹%â‚cm).

Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: When should I use the PV method over the CD method, and vice versa? A: Both methods target the early stages of oxidation, but their applications can differ. The PV method is the most widely accepted standard for quantifying hydroperoxides in a variety of oils and fats [33] [34]. The CD method is particularly suitable for pure oils and model systems rich in PUFAs, as it is a rapid, low-cost technique that requires no chemical reagents [25] [36]. For a comprehensive analysis, they can be used complementarily.

Q2: My PV results are inconsistent. What could be the reason? A: Inconsistent PV results are often due to:

- Oxygen Interference: Molecular oxygen in the air can oxidize iodide, leading to falsely high values. Ensure the titration is performed promptly after adding KI and use degassed solvents if necessary [25].

- Light and Heat Exposure: Hydroperoxides are unstable and can decompose under light or heat. Perform the analysis quickly and store samples/reagents appropriately [33].

- Endpoint Determination: The starch endpoint can be subtle and subjective. Ensure consistent lighting and practice endpoint recognition. Using potentiometric titration can eliminate this subjectivity.

Q3: Why is my CD analysis absorbance reading off the scale, even with a dilute sample? A: This indicates an advanced state of oxidation in your sample. The conjugated dienes have accumulated to a very high concentration. You need to further dilute your sample in solvent until the absorbance at 233 nm falls within the linear range of your spectrophotometer (typically 0.1-1.0 AU). Re-prepare the solution from the beginning with a smaller sample mass or a larger final dilution volume.

Q4: Are there limitations to these primary oxidation methods? A: Yes. The primary limitation is that hydroperoxides are unstable intermediates. They decompose into secondary oxidation products (aldehydes, ketones). Therefore, in highly oxidized samples or during long-term storage, PV may decrease while secondary products increase, giving a false impression of stability [25] [15]. For a complete picture, combine PV or CD with a secondary product analysis like p-anisidine value or TBARS [15] [32].

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Issues

| Problem | Potential Causes | Solutions & Preventive Actions |

|---|---|---|

| Low or erratic PV results | • Decomposition of hydroperoxides during storage/analysis.• Presence of oxygen scavengers or antioxidants in the sample.• Incomplete reaction (too short standing time).• Incorrect normality of thiosulfate titrant. | • Analyze samples immediately after extraction. Minimize light and heat exposure [25].• Verify the accuracy of standardized thiosulfate solution.• Ensure consistent reaction time (5 min in the dark) [33]. |

| Fading endpoint in PV titration | • Slow reaction kinetics in saturated or less oxidized fats.• Acid concentration too low. | • Titrate slowly with vigorous swirling. Confirm the composition of the acetic acid-chloroform solvent mixture is correct. |

| High blank titration value | • Contaminated reagents (especially KI).• Exposure of reagents to light, causing photo-oxidation. | • Prepare fresh KI solution. Use high-purity reagents.• Store reagents in dark bottles and keep them in the dark during the assay [25]. |

| No absorbance peak at 233 nm in CD analysis | • Sample is not oxidized or is saturated fat.• Solvent impurity absorbing in the UV range.• Incorrect wavelength calibration. | • Use UV-grade solvent. Verify spectrophotometer calibration with a standard. Ensure the sample contains PUFAs. |

| Obscure or noisy CD spectrum | • Contaminants in the lipid extract or solvent.• Sample solution is too concentrated or turbid. | • Re-purify the solvent. Ensure the final solution is clear. Filter the sample solution if necessary. Use a high-purity solvent for dilution. |

Research Reagent Solutions & Essential Materials

The following table details key reagents and materials required for these experiments, along with their critical functions.

Table: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application | Key Considerations for Use |

|---|---|---|

| Sodium Thiosulfate (Na₂S₂O₃) | Standardized titrant for quantifying liberated iodine in PV analysis [33] [35]. | Standardize frequently against potassium iodate (KIO₃). Store in a dark, cool place to prevent decomposition. |

| Potassium Iodide (KI) | Reducing agent that reacts with hydroperoxides to release iodine [33] [35]. | Prepare a saturated solution fresh regularly. A yellow color indicates decomposition; discard if present. Keep in dark bottles. |

| Chloroform & Glacial Acetic Acid | Solvent system for PV analysis; dissolves lipids and provides an acidic environment for the reaction [33]. | Use high-purity grades. Chloroform is toxic; handle in a fume hood with appropriate PPE. |

| Cyclohexane or Isooctane | UV-transparent solvent for CD analysis to prepare sample solutions [36]. | Must be "UV-grade" or "spectrophotometric grade" to ensure low background absorbance at 233 nm. |

| Starch Indicator | Forms a blue complex with iodine, providing a visual endpoint for PV titration [33] [35]. | Prepare fresh (or use stabilized solution). Add only after the titration has reduced the iodine color to pale yellow. |

| Quartz Cuvettes | Hold samples for UV spectrophotometry in CD analysis. | Must be used for UV range measurements (below 350 nm). Plastic or glass cuvettes are not suitable. |

Workflow and Pathway Visualizations

Lipid Oxidation Pathway and Analysis Points

Figure 1: This diagram illustrates the autoxidation pathway of lipids, highlighting the formation of primary products (conjugated dienes and hydroperoxides) and the subsequent decomposition to secondary products. The dashed lines indicate the specific analytical targets for the Conjugated Diene (CD) and Peroxide Value (PV) methods within this pathway [25] [32].

Peroxide Value Titration Workflow

Figure 2: This flowchart details the step-by-step workflow for determining the Peroxide Value using the standard iodometric titration method, highlighting critical steps such as the dark incubation and visual endpoint detection [33] [35].

Core Concepts: Understanding Secondary Lipid Oxidation

What is the TBARS Assay Measuring? The Thiobarbituric Acid Reactive Substances (TBARS) assay is a widely used method to estimate lipid peroxidation in biological and food samples by measuring malondialdehyde (MDA), a prevalent secondary oxidation product [37]. The assay is not entirely specific for MDA, as its name implies; it detects a range of thiobarbituric acid-reactive substances. However, MDA is generally considered to account for almost all the color development in the reaction, forming an MDA-TBA2 adduct that absorbs light at 532 nm [37].

How Does Chromatographic Analysis Complement the TBARS Assay? While the TBARS assay provides a general, cost-effective estimate of lipid oxidation, chromatographic techniques like Gas Chromatography (GC) offer higher specificity and sensitivity for identifying and quantifying individual volatile carbonyl compounds and other secondary oxidation products [15]. Using these methods together provides a more comprehensive picture of the oxidation state—TBARS for a rapid assessment and chromatography for detailed profiling of specific aldehydes and aromas contributing to food rancidity [15].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q: Can the TBARS assay be used for any sample type? A: The TBARS assay is not species-specific and can be used with samples from any species [38]. However, sample matrix can significantly interfere. For instance, samples with high hemoglobin content (like blood, liver tissue) or plant samples containing anthocyanins require a butanol extraction step to remove interfering pigments that cause false positives [38]. The assay is compatible with liver and plant samples provided this extraction is performed [38].

Q: Is the butanol extraction step always necessary? A: No, the butanol extraction is an optional step but is highly recommended for serum samples or any other samples with high hemoglobin levels [38]. Hemoglobin absorbs light at a wavelength very close to the MDA-TBA adduct (540 nm vs. 532 nm). The extraction removes hemoglobin to the aqueous phase, while the MDA-TBA adduct moves to the upper butanol phase, allowing for accurate measurement [38].

Q: Why do my sample storage conditions matter? A: MDA modification is not very stable and can begin to degrade after about one month of storage, even at -80°C [38]. For samples stored for longer periods (e.g., over a year), it is advisable to consider more stable oxidative stress markers, such as 8-OHdG in DNA or protein carbonyls [38].

Q: What is the purpose of adding BHT to samples? A: BHT is an antioxidant that helps prevent samples from undergoing further oxidation during the assay procedure. Its omission is not recommended, as it safeguards against artificial inflation of oxidation values due to the assay process itself [38].

Q: How does an MDA ELISA compare to the TBARS assay? A: An MDA Adduct Competitive ELISA Kit is typically more sensitive and specific than the TBARS assay [38]. The key difference is that the ELISA measures only MDA-protein adducts, while the TBARS assay measures total MDA, including free MDA and MDA adducts. This often results in higher measured values with the TBARS assay. The ELISA is also less susceptible to interference from hemoglobin [38].

Troubleshooting Guides

TBARS Assay Troubleshooting

| Symptom | Possible Cause | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Erroneous High Readings/False Positives | Hemoglobin interference (in blood, liver samples); Anthocyanins (in plant samples) [38]. | Perform the optional butanol extraction to remove interfering pigments [38]. |

| Skewed Baseline & Poor Data | Sample matrix complexities causing a nonlinear, elevated baseline [37]. | Apply corrective data analysis: subtract absorbance at 572 nm or perform derivative analysis on full spectral scan data (400-700 nm) [37]. |

| Low MDA Detection | Sample degradation from prolonged storage [38]. | Use fresh samples (less than 1 month old at -80°C) or switch to a more stable marker (e.g., protein carbonyls) for older samples [38]. |

| Inconsistent Results | Ongoing oxidation during the assay [38]. | Ensure BHT is added to the sample and reaction mixture to minimize artifact oxidation [38] [37]. |

Chromatographic Analysis Troubleshooting

This guide addresses common issues in headspace sampling for Gas Chromatography (GC) analysis of volatiles [39].

| Symptom | Possible Cause | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Poor Repeatability | Incomplete equilibrium; Inconsistent temperature; Poor vial sealing [39]. | Extend incubation time (15-30 min); Use automated systems; Regularly replace septa [39]. |

| Low Peak Area/Sensitivity | Low volatility; System leakage; Low incubation temperature [39]. | Check for leaks; Increase incubation temperature; Use "salting-out" (e.g., add NaCl) [39]. |

| High Background/ Ghost Peaks | Contamination in needle, valves, or vials [39]. | Run blank samples; Clean injection system regularly; Use clean/disposable vials [39]. |

| Retention Time Drift | Unstable temperature; Vial leakage; Carrier gas fluctuations [39]. | Calibrate temperature controllers; Check for leaks; Use pressure/flow control systems [39]. |

| Target Compounds Not Detected | Low volatility; Strong matrix binding; Inadequate headspace conditions [39]. | Increase incubation temperature/time; Adjust pH; Consider switching to SPME for higher sensitivity [39]. |

Methodological Protocols

Detailed Protocol: TBARS Assay with Butanol Extraction

Key Research Reagent Solutions

- BHT (Butylated Hydroxytoluene): An antioxidant added to samples and the reaction mixture to prevent further oxidation during the assay, minimizing artifacts [38] [37].

- TBA (Thiobarbituric Acid) Reactant: The core reagent that reacts with malondialdehyde (MDA) and other secondary oxidation products to form a pink chromophore [37].

- MDA Standard: Used to generate a calibration curve for quantifying MDA concentration in unknown samples.

- n-Butanol Solvent: Used in the extraction step to separate the MDA-TBA adduct (into the organic phase) from interfering substances like hemoglobin and anthocyanins (which remain in the aqueous phase) [38].

Workflow Overview

Step-by-Step Instructions:

- Sample Preparation: Homogenize tissue or prepare serum/plasma samples. It is critical to include the antioxidant BHT in the homogenization buffer to prevent ex vivo oxidation [38] [37].

- TBA Reaction: Add TBA reagent to the sample and heat in a 95°C water bath for 45-60 minutes. This forms the pink MDA-TBA adduct.

- Cooling: Cool the reaction tubes to room temperature to stop the reaction.

- Butanol Extraction: Add n-butanol to the cooled mixture, vortex vigorously for 30-60 seconds, and centrifuge to separate the phases.

- Phase Separation: Carefully transfer the upper organic layer (n-butanol), which contains the MDA-TBA adduct, to a clean cuvette. The lower aqueous phase contains interfering substances like proteins and hemoglobin [38].

- Spectrophotometry: Measure the absorbance of the butanol phase at 532 nm. For complex samples, also record absorbance at 572 nm for baseline correction or perform a full wavelength scan from 400-700 nm [37].

- Data Analysis: Calculate MDA equivalents using a standard curve. For accurate results, apply a baseline correction (e.g., A532 - A572) or use derivative analysis on scan data to account for matrix-induced baseline shifts [37].

Detailed Protocol: Headspace GC Analysis of Volatile Carbonyls

Workflow Overview

Step-by-Step Instructions:

- Sample Preparation: Precisely weigh a homogeneous food sample into a headspace vial. For solid samples, a powdered or finely minced state is ideal.

- Additives: Add a known amount of internal standard for quantification. To enhance the volatility of target analytes (the "salting-out" effect), add an inorganic salt like sodium chloride (NaCl) [39].

- Sealing: Immediately seal the vial with a crimp cap containing a fresh PTFE/silicone septum. Worn septa are a common source of leaks and poor repeatability [39].

- Equilibration: Place the vial in the headspace autosampler and incubate at a defined temperature (e.g., 60-90°C) for a sufficient time (15-30 minutes) to allow volatiles to partition into the headspace. Time and temperature must be optimized and held constant for reproducibility [39].

- Injection: The autosampler needle pressurizes the vial and injects a precise volume of the headspace gas into the GC inlet.

- Chromatography: The volatile compounds are separated on the GC column using an optimized temperature program and detected by a Mass Spectrometer (MS) or Flame Ionization Detector (FID).

- Data Analysis: Identify compounds by comparing retention times and mass spectra to standards. Quantify concentrations using calibration curves, normalized to the internal standard response.

Research Reagent Solutions

| Reagent / Material | Function in the Experiment |

|---|---|

| BHT (Butylated Hydroxytoluene) | An antioxidant added to samples to prevent further, artificial oxidation during the assay procedure, ensuring measured values reflect the sample's true state [38] [37]. |

| Thiobarbituric Acid (TBA) | The core reactive compound that binds with malondialdehyde (MDA) to form a pink-colored complex measurable by spectrophotometry [37]. |

| n-Butanol | An organic solvent used for extraction to separate the MDA-TBA adduct from interfering substances like hemoglobin in complex sample matrices [38]. |

| MDA Standard | A purified standard of malondialdehyde used to create a calibration curve for quantifying the concentration of MDA in unknown samples. |

| Headspace Vials & Septa | Specially designed sealed vials that maintain pressure and integrity during heating and injection, preventing leaks and loss of volatile analytes [39]. |

| Internal Standard (for GC) | A known compound added to the sample at a constant concentration before GC analysis to correct for variability in injection volume and sample preparation [39]. |

| Inorganic Salts (e.g., NaCl) | Used in headspace GC to increase the ionic strength of the solution, which improves the partitioning of volatile analytes into the headspace gas, thereby increasing sensitivity (salting-out effect) [39]. |

Antioxidant Source Compendium

This section provides a quantitative overview of potent natural antioxidant sources, focusing on their key bioactive compounds and antioxidant capacity metrics relevant for stabilizing lipid-rich food products.

Table 1: Key Natural Antioxidant Sources and Their Bioactive Compounds

| Source | Key Bioactive Phenolic Compounds | Total Phenolic Content (Examples) | Reported Antioxidant Capacity (Assay Examples) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Clove | Eugenol, Gallic acid, Caffeic acid, Quercetin [40] [41] | Among the highest among spices [40] | High free radical scavenging activity [40] |

| Oregano | Thymol, Rosmarinic acid, Caffeic acid derivatives, Vanillic acid [40] [41] | High concentration [40] | Strong antioxidant and antimicrobial activity [40] |