Comparative Assessment of Nutrient Bioavailability: From Foundational Principles to Advanced Applications in Biomedical Research

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of nutrient bioavailability, a critical determinant of nutritional efficacy defined as the fraction of an ingested nutrient that is absorbed and utilized for normal...

Comparative Assessment of Nutrient Bioavailability: From Foundational Principles to Advanced Applications in Biomedical Research

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of nutrient bioavailability, a critical determinant of nutritional efficacy defined as the fraction of an ingested nutrient that is absorbed and utilized for normal body functions. Tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, the content explores the fundamental principles governing bioavailability, including the LADME framework (Liberation, Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism, Elimination). It details state-of-the-art in vivo and in vitro methodological approaches for assessment, examines key challenges and optimization strategies influenced by diet-host interactions and food matrix effects, and presents comparative analyses of nutrients from diverse food sources and supplements. The synthesis of these areas provides a robust scientific foundation for enhancing clinical nutrition, formulating functional foods, and informing drug-nutrient interaction studies.

Defining Bioavailability: Core Concepts, Physiological Frameworks, and Influencing Factors

The concept of nutrient bioavailability extends far beyond the simple quantity of a nutrient present in a food substance. It encompasses the complex journey that a nutrient undergoes from ingestion to ultimate utilization or elimination within the human body. Current nutrient intake recommendations, nutritional assessments, and food labeling primarily rely on the estimated total nutrient content in foods and dietary supplements [1]. However, the true nutritional adequacy of any consumed substance depends not only on the total amount ingested but critically on the fraction that is absorbed and subsequently utilized by the body [2]. This fundamental distinction highlights a significant gap in conventional nutritional science, one that the structured LADME framework is designed to address.

The LADME framework provides a systematic approach for analyzing the pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic processes governing nutrient and bioactive compound disposition. Liberation refers to the release of the nutrient from its food matrix. Absorption denotes its passage across the intestinal membrane into systemic circulation. Distribution involves its transport to various tissues and organs. Metabolism covers the biotransformation processes that alter the nutrient's structure and activity. Finally, Elimination represents the excretion of the nutrient and its metabolites from the body [2]. Understanding this cascade is paramount for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals engaged in the comparative assessment of nutrient sources, as it moves the focus from mere content to functional bioavailability.

The LADME Framework: A Comparative Lens for Nutrient Bioavailability

The application of the LADME framework enables a mechanistic comparison of how different foods and supplements influence the journey of a nutrient. This is particularly relevant for addressing global nutrient shortfalls, where a failure to account for bioavailability can lead to significant overestimation of the effective nutrient supply from certain foods [2].

Liberation: The Critical First Step

Liberation is the process by which a nutrient is freed from its food matrix during mastication and digestion, becoming accessible for absorption—a state often termed bioaccessible [2]. The physical form and composition of the food, along with processing methods like cooking, grinding, or fermentation, dramatically impact this step.

- Plant vs. Animal Sources: The rigid cell walls of plant tissues can trap minerals like iron and zinc, requiring more extensive mechanical and enzymatic breakdown for liberation. In contrast, the heme iron in animal muscle tissues is already incorporated into organic complexes, facilitating its release.

- Food Processing Effects: Thermal processing (cooking) can denature proteins and break down cell walls, enhancing the liberation of bound nutrients. For instance, heat breaks down the lectins and phytates in legumes that would otherwise bind to minerals, thereby improving mineral bioaccessibility.

Absorption: Crossing the Intestinal Barrier

Absorption is defined as the movement of a liberated nutrient across the intestinal membrane into the systemic circulation [2]. This step is influenced by a multitude of dietary and host factors.

- Competitive Inhibition: The presence of other dietary components in the gut lumen can inhibit absorption. A classic example is calcium inhibiting non-heme iron absorption by competing for shared divalent metal ion transporters (DMT1).

- Absorption Enhancers: Certain food components can facilitate absorption. Vitamin C (ascorbic acid) significantly enhances the absorption of non-heme iron by reducing ferric iron (Fe³⁺) to the more soluble ferrous (Fe²⁺) form and forming a soluble complex that prevents precipitation in the alkaline duodenum.

- Supplement Formulation: The chemical form of a nutrient in a supplement (e.g., zinc gluconate vs. zinc oxide) and the use of technologies like enteric coatings or microencapsulation directly influence the site and efficiency of its absorption [2].

Distribution, Metabolism, and Elimination: Post-Absorption Dynamics

Once absorbed, a nutrient's journey is far from complete. Its efficacy is further modulated by distribution, metabolism, and elimination.

- Distribution: The transport of a nutrient via the bloodstream to its target tissues can be influenced by carrier proteins and the body's nutritional status.

- Metabolism and Bioefficacy: Bioefficacy refers to the proportion of an absorbed nutrient or bioactive that is converted to an active form in the body [2]. For example, the plant-derived carotenoid beta-carotene must be cleaved to form active vitamin A (retinol), a conversion that varies based on genetic factors and the overall composition of the diet.

- Elimination: The rate at which a nutrient and its metabolites are excreted (e.g., via urine or bile) also contributes to its net retention and functional bioavailability within the body.

Table 1: Key Process Definitions in the LADME Framework

| Term | Definition |

|---|---|

| Bioaccessible | The amount of a nutrient freed from the food matrix for absorption [2]. |

| Absorption | The movement of a nutrient into systemic circulation [2]. |

| Bioavailability | The fraction of an ingested nutrient that reaches systemic circulation unchanged [2]. |

| Bioefficacy | The proportion of an absorbed nutrient that is converted to an active form in the body [2]. |

A Framework for Predictive Bioavailability Equations

To systematically apply the LADME principles for comparative assessments, a structured methodology for developing prediction equations is essential. A 2025 framework outlines a 4-step process for creating such equations to estimate nutrient absorption and bioavailability, moving away from reliance on total nutrient content alone [1] [2].

The 4-Step Predictive Framework

This framework is designed to guide researchers in developing robust, data-driven algorithms.

- Identify Key Influencing Factors: The first step involves a systematic identification of all extrinsic factors that influence the nutrient's bioavailability, as detailed in the LADME framework. This includes the food matrix, chemical form, and the presence of enhancers or inhibitors, deliberately excluding host-specific factors like age or health status to ensure broad applicability [1] [2].

- Conduct a Comprehensive Literature Review: This step involves a rigorous review of high-quality human studies that investigate the absorption of the target nutrient. The goal is to gather empirical data that quantifies the impact of the factors identified in Step 1 [1] [2].

- Construct the Predictive Equation: Using the insights from the literature, a mathematical equation or algorithm is built. This model predicts the relative bioavailability of the nutrient from a given food or supplement, often in comparison to a standard reference material [1] [2].

- Validate the Equation: The final, crucial step is to validate the predictive model, where feasible, against independent data sets or through new experimental studies. This ensures the equation's accuracy and reliability and facilitates its translation into practical applications [1] [2].

This framework aims to enhance the precision of bioavailability estimates, highlight data limitations, and inform future research and policy regarding nutrients and bioactive compounds [1].

Experimental Protocols for Bioavailability Assessment

The development of predictive equations relies on data generated from specific, rigorous experimental protocols. Key methodologies include:

- Stable Isotope Studies: This is considered a gold-standard technique for many minerals and vitamins. Subjects are fed a test food containing a stable isotope tracer (e.g., ⁵⁷Fe or ⁶⁷Zn). The appearance and kinetics of this tracer in the blood, or its excretion, are then measured using mass spectrometry, allowing for precise quantification of absorption without the confounding factors of whole-body homeostasis [2].

- Caco-2 Cell Model: This in vitro protocol uses a human intestinal epithelial cell line to simulate nutrient absorption. Digested food samples are applied to the apical side of the cell monolayer, and the transport of the nutrient to the basolateral side is measured. This model is particularly useful for high-throughput screening of the bioaccessibility and absorption of various food matrices and for studying the effects of enhancers/inhibitors.

- Balance Studies: In this classic approach, subjects are fed a controlled diet, and all intake and excretion (urine and feces) of a specific nutrient are meticulously measured over a period. The difference between intake and excretion is assumed to be the amount absorbed and retained by the body. While powerful, these studies are complex and require highly controlled conditions.

Table 2: Comparison of Key Experimental Models for Assessing Nutrient Bioavailability

| Model | Key Measurement | Applications | Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Stable Isotope Tracers | Fractional absorption of the tracer into circulation [2]. | Minerals (Fe, Zn, Ca), Vitamins (A, carotenoids). | Considered the most accurate for human in vivo studies; expensive and technically complex. |

| Caco-2 Cell Model | Transport efficiency of the nutrient across the cell monolayer. | High-throughput screening; mechanism studies of absorption. | An in vitro model that does not fully replicate in vivo complexity; cost-effective. |

| Balance Studies | Net retention (Intake - Excretion) of the nutrient. | Minerals, Nitrogen/Protein. | Provides data on net retention, not just absorption; requires metabolic ward control. |

Comparative Bioavailability in Key Nutrients

Applying the LADME framework and predictive modeling reveals stark contrasts in the bioavailability of the same nutrient from different dietary sources.

Iron: Heme vs. Non-Heme

Iron bioavailability is a prime example of the framework's utility. The DELTA model has projected ongoing global shortfalls in iron intake, which are exacerbated when bioavailability is considered [2].

- Heme Iron (from animal flesh): Typically exhibits absorption rates of 15-35%. It is absorbed as an intact porphyrin complex via a specific pathway that is less influenced by other dietary factors.

- Non-Heme Iron (from plants and fortified foods): Has a much wider and generally lower absorption range of 2-20%. Its absorption is highly sensitive to the meal's composition. Phytates (in whole grains and legumes) and polyphenols (in tea and coffee) can strongly inhibit its absorption, while vitamin C can enhance it significantly.

Calcium: The Influence of Solubility

Calcium absorption is highly dependent on its liberation into a soluble, ionized form in the intestine.

- Dairy vs. Plant Sources: Calcium from dairy products like milk is generally well-absorbed (~30%). In contrast, calcium from plant sources like spinach is poorly absorbed (<5%) due to the presence of inhibitors like oxalic acid, which binds calcium to form insoluble complexes [2].

- Relative Bioavailability: Prediction equations have been developed for calcium that express its absorption from various foods relative to a reference, such as calcium from milk, allowing for direct comparisons independent of host factors [2].

Protein: Amino Acid Profile and Digestibility

The bioavailability of protein is a function of its amino acid composition and its digestibility, encompassing both liberation (digestion) and absorption.

- Animal vs. Plant Proteins: Animal proteins (whey, casein, egg) are typically considered "complete" with an optimal amino acid profile and have high digestibility (>95%). Many plant proteins (from pulses, cereals) are "incomplete," often limiting in lysine or methionine, and may have lower digestibility (70-90%) due to antinutritional factors like trypsin inhibitors, which affect the liberation and absorption of amino acids.

Table 3: Comparative Bioavailability of Key Nutrients from Different Food Sources

| Nutrient | High Bioavailability Source | Estimated Absorption | Low Bioavailability Source | Estimated Absorption | Key Influencing Factor |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Iron | Heme Iron (Beef) | 15-35% | Non-Heme Iron (Spinach) | 2-20% (context-dependent) | Chemical Form, Vitamin C, Phytates |

| Calcium | Milk | ~30% | Spinach | <5% | Oxalic Acid, Solubility [2] |

| Zinc | Oysters, Red Meat | 20-40% | Whole Grains, Legumes | 10-20% | Phytate Content [2] |

| Vitamin A | Retinol (Liver, Eggs) | 70-90% | Beta-Carotene (Carrots, Sweet Potato) | 10-50% (varies by conversion) | Conversion Efficiency (Bioefficacy) [2] |

| Protein | Whey Protein | >95% | Cooked Lentils | ~80% | Amino Acid Profile, Antinutritional Factors |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details key reagents and materials essential for conducting research in nutrient bioavailability, drawing from the experimental protocols discussed.

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Bioavailability Studies

| Item | Function/Application |

|---|---|

| Stable Isotope Tracers | Used as metabolic labels in human studies to precisely track the absorption, distribution, and elimination of a specific nutrient without radioactive hazard [2]. |

| Caco-2 Cell Line | A human colon adenocarcinoma cell line that, upon differentiation, exhibits small intestinal epithelial properties. It is a standard in vitro model for studying intestinal absorption and transport mechanisms. |

| Simulated Gastrointestinal Fluids | Standardized enzymatic and pH-controlled solutions (e.g., pepsin in HCl for gastric phase, pancreatin in bile salts for intestinal phase) used in in vitro digestion models to mimic human digestion and assess bioaccessibility. |

| Mass Spectrometry | An analytical technique essential for detecting and quantifying stable isotope tracers and specific nutrients or their metabolites in complex biological samples like blood, urine, and feces. |

| Transwell/Permeability Supports | Physical inserts used in cell culture to grow Caco-2 cells as a polarized monolayer, allowing for the separate application of test compounds to the apical side and measurement of transport to the basolateral side. |

| Phytate & Oxalate Assay Kits | Commercial kits for the quantitative measurement of potent dietary inhibitors (phytate, oxalic acid) in food samples, enabling the correlation of inhibitor levels with reduced mineral bioavailability. |

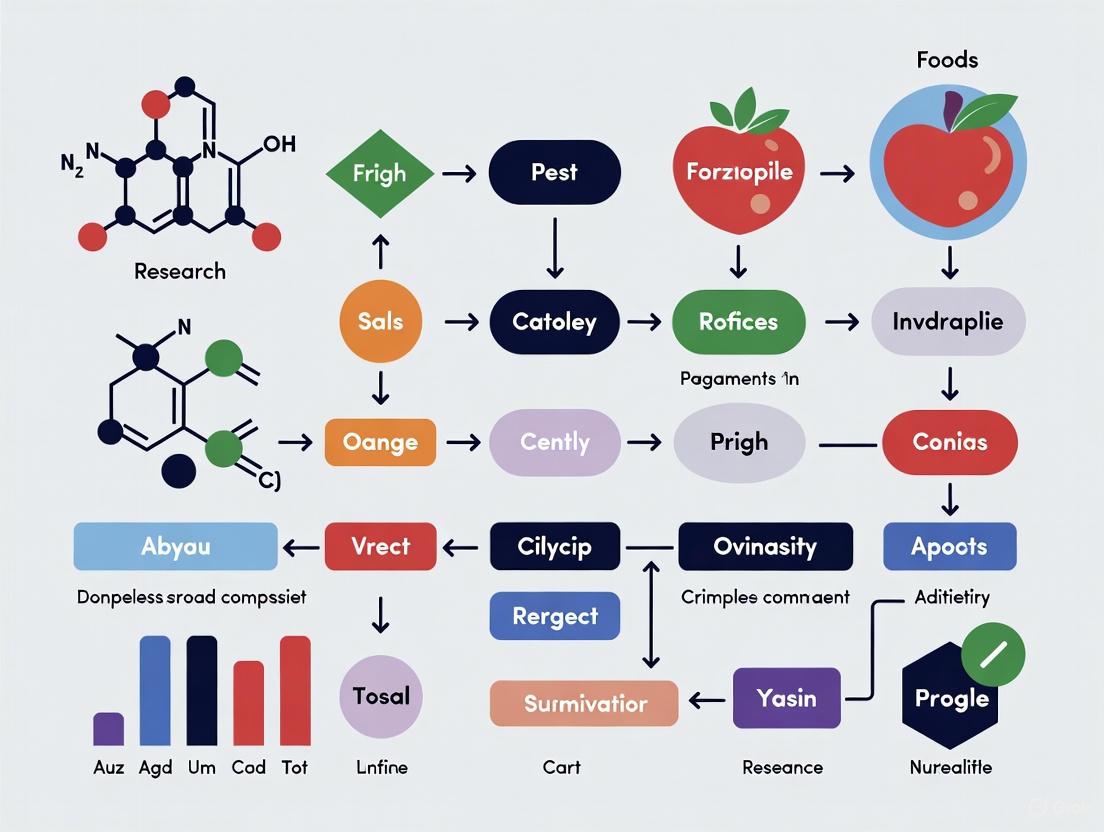

Visualizing the LADME Framework and Predictive Workflow

The following diagrams, created using Graphviz and adhering to the specified color and contrast guidelines, illustrate the core concepts and methodologies discussed in this article.

The LADME Process

Diagram 1: The sequential LADME process from food intake to nutrient utilization.

Bioavailability Prediction Workflow

Diagram 2: The four-step framework for developing predictive bioavailability equations.

The LADME framework provides an indispensable, systematic structure for the comparative assessment of nutrient bioavailability, moving the field beyond simplistic measurements of total nutrient content. By dissecting the journey of a nutrient through the body into discrete, analyzable phases—Liberation, Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism, and Elimination—researchers and product developers can gain a mechanistic understanding of why the same nutrient from different sources exhibits vastly different biological efficacy. The integration of this framework with the emerging methodology for developing predictive bioavailability equations [1] [2] represents a significant advancement. This combined approach holds the promise of transforming areas from the formulation of more effective functional foods and supplements to the refinement of global nutrient intake recommendations and public health policies, ensuring they are based on the nutrient that is truly available for the body to use.

In nutritional science and drug development, accurately predicting the physiological impact of a compound requires moving beyond its mere presence in a food or supplement. The concepts of bioaccessibility, bioavailability, and bioefficacy form a critical sequential pathway that determines the ultimate success of a bioactive compound in eliciting a desired health effect [3] [4]. For researchers and scientists, a precise understanding of these terms and their interrelationships is foundational for designing effective nutritional interventions, formulating drugs, and interpreting clinical outcomes. This guide provides a comparative assessment of these key parameters, underpinned by experimental data and methodologies relevant to the comparative assessment of nutrient bioavailability.

Defining the Core Concepts

The journey of a bioactive compound from ingestion to its final physiological action can be broken down into three distinct phases, each defined by a specific parameter.

Table 1: Core Definitions and Key Characteristics

| Term | Core Definition | Scope & Primary Focus | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bioaccessibility | The fraction of a compound released from its food matrix into the gastrointestinal lumen, making it accessible for intestinal absorption [3] [5]. | Gastrointestinal Lumen | Focuses on digestion and liberation from the food matrix. Involves processes like mastication and enzymatic breakdown [3]. Pre-requisite for absorption. |

| Bioavailability | The proportion of an ingested compound that is absorbed, metabolized, and reaches systemic circulation or the site of physiological action [3] [5] [4]. | Whole Organism (LADME process) | Encompasses Liberation, Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism, and Elimination (LADME) [3]. The key step for ensuring bioefficacy [3] [5]. |

| Bioefficacy | The effectiveness of a compound, once bioavailable, to elicit a specific biological response or therapeutic effect in the target tissue [5] [4]. | Target Tissue & Cellular Level | Reflects the ultimate functional or health outcome. Influenced by the compound's specific activity and the physiological state of the target tissue. |

The relationship between these concepts is sequential and multiplicative. Bioavailability depends on bioaccessibility, and bioefficacy, in turn, depends on bioavailability. One framework quantifies overall bioavailability (F) as the product of three coefficients: the bioaccessibility coefficient (FB), the transport coefficient across the intestinal epithelium (FT), and the fraction that reaches circulation without being metabolized (FM): F = FB × FT × FM [5].

Quantitative Framework and Experimental Data

The theoretical relationship between bioaccessibility, bioavailability, and bioefficacy is demonstrated and validated through experimental studies. The following table compiles data from research on different bioactive compounds, illustrating how their delivery systems impact these key parameters.

Table 2: Experimental Data on Bioaccessibility and Bioavailability of Bioactive Compounds

| Bioactive Compound | Delivery System/Matrix | Experimental Model | Key Finding | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Curcumin | Free (Unformulated) | In Vivo (Rat) | ~75% excreted in feces; only trace amounts in urine, indicating very low bioavailability. | [6] |

| Curcumin | W1/Og/W2 Multiple Emulsion | In Vitro Dynamic (SimuGIT) | Final bioavailability: ~20.2%; 2.5x greater than free curcumin. | [6] |

| Curcumin | Oleogel | In Vitro Dynamic (SimuGIT) | 41.8% of the bioaccessible fraction was bioavailable, highest efficiency post-release. | [6] |

| Ferulic Acid | Wheat (Bound to Fibre) | Human Study | Bioaccessibility < 1% due to high binding affinity to polysaccharides. | [3] |

| Ferulic Acid | Free form added to flour | Human Study | Bioaccessibility ~60%. | [3] |

| Ferulic Acid | Fermented Wheat | Human Study | Fermentation broke ester links, releasing ferulic acid and improving bioavailability. | [3] |

| β-Carotene | Nanoemulsion (Long Chain Triglycerides, LCT) | In Vitro | Bioaccessibility ~66%. | [5] |

| β-Carotene | Nanoemulsion (Medium Chain Triglycerides, MCT) | In Vitro | Bioaccessibility ~2%. | [5] |

| Lycopene | Nanoemulsion (69 nm droplet size) | In Vitro | Bioaccessibility 0.77%, significantly higher than larger emulsions or unemulsified forms. | [5] |

Methodologies for Assessment

A critical task for researchers is selecting the appropriate experimental model to assess these parameters. The choice between in vitro and in vivo approaches depends on the research question, stage of development, and required level of physiological relevance.

Table 3: Key Methodologies for Assessing Bioaccessibility and Bioavailability

| Methodology | Core Principle | Key Applications | Advantages & Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Static In Vitro Digestion Models | Simulates gastrointestinal digestion (mouth, stomach, small intestine) using fixed conditions and enzyme solutions [6]. | Initial screening of bioaccessibility; studying food matrix effects [6]. | Advantages: High-throughput, cost-effective, avoids ethical concerns.Limitations: Oversimplified; does not simulate dynamic physiological changes [6]. |

| Dynamic In Vitro Digestion Models | Simulates GI tract with real-time changes in pH, secretion rates, and gastric emptying [6]. | Rational design of delivery systems; more accurate prediction of in vivo behavior [6]. | Advantages: More physiologically relevant than static models.Limitations: Technically complex and expensive. |

| Cell Culture Models (e.g., Caco-2) | Uses human colon adenocarcinoma cell lines to model the intestinal epithelium and study absorption/transport [7]. | Mechanism-specific transport studies; nutrient-drug interactions. | Advantages: Provides insights into absorption mechanisms.Limitations: Does not fully represent complex in vivo environment. |

| Balance Studies | Measures the difference between nutrient intake and excretion (fecal or ileal) [8]. | Determining apparent absorption of minerals and other nutrients. | Advantages: Direct measure in humans or animals.Limitations: Does not account for internal metabolic utilization. |

| Stable Isotope Studies | Uses non-radioactive isotopic tracers to track the absorption, distribution, and excretion of nutrients [1]. | considered the "gold standard" for measuring mineral bioavailability in humans. | Advantages: Highly accurate, allows for precise tracking.Limitations: Expensive and requires sophisticated instrumentation. |

The following diagram illustrates a generalized experimental workflow that integrates these methodologies, providing a logical pathway from compound testing to efficacy determination.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Successful experimentation in this field relies on a suite of specialized reagents and materials that simulate biological environments or enable precise analysis.

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

| Reagent/Material | Function in Experimental Protocols | Specific Application Example |

|---|---|---|

| Simulated Gastrointestinal Fluids | Mimic the ionic composition and pH of salivary, gastric, and intestinal fluids [6]. | Standardized in vitro digestion protocols (e.g., INFOGEST). |

| Digestive Enzymes | Catalyze the breakdown of macronutrients to liberate bioactive compounds from the food matrix [6]. | Pepsin (gastric phase), Pancreatin & Lipase (intestinal phase) [6]. |

| Bile Salts | Emulsify lipids and form mixed micelles, crucial for the bioaccessibility of lipophilic compounds [5] [6]. | Solubilizing lipids and fat-soluble vitamins in the small intestine phase. |

| Caco-2 Cell Line | A human colon adenocarcinoma cell line that differentiates to form a monolayer with properties of small intestinal enterocytes [7]. | Studying intestinal absorption and transport mechanisms of bioactive compounds. |

| Dialyzation Membranes | Separate the bioaccessible fraction (solubilized in gut lumen) from the non-bioaccessible residue during in vitro studies [7]. | Estimating bioaccessibility and prepared samples for absorption studies. |

| Stable Isotopes | Non-radioactive tracers that allow precise tracking of nutrient absorption, distribution, and metabolism in humans [1]. | Gold-standard human studies for mineral bioavailability (e.g., Zn, Fe). |

The distinct yet interconnected concepts of bioaccessibility, bioavailability, and bioefficacy form a critical framework for research. As demonstrated by experimental data, factors like food matrix, delivery system, and an individual's physiological state can dramatically influence each step, ultimately determining the success of a nutritional or therapeutic intervention. A deep understanding of these definitions and the application of robust, context-appropriate methodologies are therefore indispensable for scientists engaged in the rational development of functional foods, supplements, and pharmaceuticals. Emerging strategies, such as the use of encapsulation technologies and the development of predictive algorithms, continue to advance the field by providing novel means to enhance bioavailability and achieve desired bioefficacy [1] [4] [9].

Nutrient bioavailability—the proportion of an ingested nutrient that is absorbed, becomes available for use, and is stored in the body—is a critical determinant of nutritional efficacy [8]. This bioavailability is not solely dictated by the absolute amount of a nutrient consumed but is profoundly influenced by diet-related factors [8]. The chemical form of a nutrient (e.g., methylfolate vs. folic acid), its encapsulation within a food matrix (the physical and chemical structure of food), and the presence of dietary inhibitors or enhancers collectively govern the nutrient's release, absorption, and ultimate physiological utility [10] [8] [11]. A comparative assessment of these determinants is essential for researchers and drug development professionals to understand the fundamental disparities in nutrient bioavailability from different foods and to design effective nutritional interventions and fortified products.

Comparative Analysis of Key Determinants

The interplay between nutrient chemical form, food matrix, and other dietary components creates a complex landscape that determines the nutritional value of food. The table below provides a comparative overview of these core determinants.

Table 1: Key Diet-Related Determinants of Nutrient Bioavailability

| Determinant | Key Concepts | Impact on Bioavailability | Representative Nutrients Affected |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nutrient Chemical Form | The specific molecular structure of a nutrient [8]. | Different forms have varying absorption efficiencies and metabolic pathways [8]. | Vitamin D (Calcifediol vs. Cholecalciferol) [8]; Folate (Methylfolate vs. Folic Acid) [8]; Carotenoids ((Z)-isomers vs. (all-E)-isomers) [12]. |

| Food Matrix | The physical microstructure and macro-composition (e.g., proteins, carbohydrates) that entrap or bind nutrients [10] [11]. | Intact plant cell walls and certain components can significantly reduce release and absorption [10] [11]. | Carotenoids in raw vegetables [10] [11]; Minerals and flavonoids in whole grains [8] [13]. |

| Inhibitors | Dietary compounds that interfere with nutrient absorption or function [8]. | Can reduce bioavailability by binding nutrients or inhibiting digestive enzymes [8]. | Phytate (minerals) [8]; Fiber (minerals, carotenoids) [10] [8]; Certain proteins and divalent minerals (carotenoids) [10]. |

| Enhancers | Dietary compounds that facilitate nutrient absorption or utilization [8]. | Can significantly improve bioavailability by promoting solubilization, transport, or micellization [8]. | Dietary lipids (fat-soluble vitamins, carotenoids) [10] [8]; Vitamin C (non-heme iron) [8]; Other supportive vitamins (iron) [8]. |

The following diagram illustrates the sequential journey of a nutrient, particularly a lipophilic compound like a carotenoid, through digestion and absorption, highlighting how the key determinants influence its bioavailability.

Figure 1: The Pathway of Nutrient Bioavailability and Influencing Factors. This workflow outlines the key stages from ingestion to utilization, showing where core determinants exert their influence.

The Role of Nutrient Chemical Form

The specific molecular structure of a nutrient is a primary determinant of its absorption efficiency and metabolic fate. This is exemplified by the significant differences in bioavailability between synthetic and natural forms of certain vitamins, as well as between isomers of carotenoids.

Table 2: Impact of Nutrient Chemical Form on Bioavailability

| Nutrient | Chemical Form Comparison | Reported Bioavailability Difference | Underlying Mechanism |

|---|---|---|---|

| Vitamin D | Cholecalciferol (D3) vs. Calcifediol (25-hydroxyvitamin D3) | Calcifediol is significantly more bioavailable than cholecalciferol [8]. | Calcifediol bypasses the initial hydroxylation step in the liver required by cholecalciferol, allowing for more efficient absorption and raising serum 25(OH)D levels more directly [8]. |

| Folate | Folic Acid (synthetic) vs. Methylfolate (5-MTHF, natural) | Methylfolate is more bioavailable than folic acid [8]. | Methylfolate is the active form that does not require conversion by the MTHFR enzyme, making it readily usable, especially in individuals with MTHFR polymorphisms [8]. |

| Carotenoids | (Z)-isomers (e.g., of Lycopene, Astaxanthin) vs. (all-E)-isomers | (Z)-isomers demonstrate greater bioavailability than their (all-E)-counterparts [12]. | (Z)-isomers are more soluble in bile acid micelles and may be preferentially incorporated into mixed micelles, facilitating intestinal absorption. They are also less prone to crystallization [12]. |

The Influence of Food Matrix

The food matrix constitutes a physical and compositional barrier that governs the release of nutrients during digestion. Plant-based foods, in particular, present significant challenges for nutrient bioaccessibility.

Microstructural Barriers

In plant tissues, nutrients like carotenoids are often sequestered within chloroplasts or chromoplasts and surrounded by indigestible cell walls composed of polysaccharides like cellulose, hemicellulose, and pectin [10]. This microstructure acts as a physical barrier, preventing digestive enzymes and bile salts from accessing the nutrients during gastrointestinal transit [10]. For instance, the bioavailability of carotenoids from raw carrots is notably low because the rigid cell walls remain largely intact during digestion, trapping the carotenoids inside [11].

Macro-Compositional Interactions

The major components of the food matrix—proteins, carbohydrates, and lipids—interact with nutrients in complex ways that can either inhibit or enhance their bioavailability.

- Proteins and Dietary Fiber: These components generally exert an inhibitory effect. Proteins can form complexes with polyphenols, reducing their absorption [13]. Dietary fiber, especially viscous fibers like pectin, can impede bioaccessibility by increasing the viscosity of the digestive chyme, which slows diffusion and hinders the activity of digestive enzymes and the formation of mixed micelles [10].

- Lipids: The presence of dietary lipids is one of the most critical enhancers for lipophilic nutrients. Co-consumption with fats stimulates the secretion of bile salts and pancreatic lipases, which are essential for the solubilization of carotenoids and fat-soluble vitamins (A, D, E, K) into mixed micelles [10] [8]. This process is a prerequisite for their absorption by intestinal enterocytes.

Table 3: Impact of Food Matrix Components on Carotenoid Bioaccessibility

| Matrix Component | General Effect on Carotenoid Bioaccessibility | Proposed Mechanism of Action |

|---|---|---|

| Lipids | Enhancer [10] | Stimulate bile secretion and form lipid droplets, facilitating carotenoid incorporation into mixed micelles [10]. |

| Proteins | Variable (Positive and/or Negative) [10] | Can inhibit digestive enzyme activity or form complexes; some processed proteins may improve micellar incorporation [10]. |

| Dietary Fiber (e.g., Pectin) | Inhibitor [10] | Increases viscosity of gut content, impairing enzyme activity and micellization; may bind bile acids [10]. |

| Flavonoids | Enhancer [10] | May improve stability or interact positively with micelle formation [10]. |

| Divalent Minerals (e.g., Ca²⁺, Mg²⁺) | Inhibitor [10] | Can precipitate bile salts or form insoluble soaps with fatty acids, disrupting micelle formation and lipid absorption [10]. |

Experimental Protocols for Assessing Bioavailability

Robust experimental models are required to dissect the individual and combined effects of these diet-related determinants. The following protocols are standard in the field.

In Vitro Simulated Gastrointestinal Digestion

This protocol is widely used for a rapid, cost-effective screening of bioaccessibility.

- Oral Phase: The food sample is comminuted and mixed with simulated salivary fluid (containing electrolytes and α-amylase) at a specific pH (e.g., 6.8-7.0). Incubation is typically for 2-5 minutes at 37°C under constant agitation [8].

- Gastric Phase: Simulated gastric fluid (containing electrolytes and pepsin) is added, and the pH is adjusted to 2.0-3.0. The mixture is incubated for 1-2 hours at 37°C to simulate stomach digestion [10] [8].

- Intestinal Phase: The chyme is neutralized to pH 6.5-7.0 using a NaHCO₃ solution. Simulated intestinal fluid (containing electrolytes, pancreatin, and bile salts) is added. The mixture is incubated for a further 2 hours at 37°C [10] [14].

- Bioaccessible Fraction Collection: The resulting digesta is centrifuged at high speed (e.g., 5,000-10,000 × g) to separate the aqueous micellar phase (containing the bioaccessible nutrient) from the pellet (undigested residue). The nutrient content in the micellar phase is quantified via HPLC or spectrophotometry and expressed as a percentage of the original amount [14].

Ileal Digestibility and Balance Studies in Humans

This method provides a direct measure of apparent absorption in humans and is considered a gold standard.

- Subject Preparation: Participants are placed on a controlled diet for a lead-in period. For ileal digestibility, subjects have a naso-ileal tube placed, or in some cases, are ileostomists [8].

- Dosing and Sample Collection: A test meal containing the nutrient of interest is consumed. In balance studies, total feces are collected for a specific period (e.g., 3-7 days). For ileal digestibility, ileal effluents are collected continuously via the tube over a set period post-consumption [8].

- Sample Analysis: The nutrient content in the collected ileal effluents or fecal matter is analyzed.

- Calculation: Apparent absorption is calculated as: (Intake - Output in Ileal/Fecal content) / Intake × 100% [8].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents and Materials

The following table details essential materials and reagents used in bioavailability research, particularly for the protocols described above.

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents for Bioavailability Studies

| Reagent/Material | Function in Experimentation | Example Application |

|---|---|---|

| Simulated Gastrointestinal Fluids | To mimic the ionic composition and pH of salivary, gastric, and intestinal secretions in vitro [8]. | Standardized in vitro digestion models (e.g., INFOGEST) [8]. |

| Digestive Enzymes (Pepsin, Pancreatin, α-Amylase) | To catalyze the breakdown of proteins, carbohydrates, and lipids, simulating human digestion [10] [8]. | Releasing nutrients from the food matrix during in vitro digestion [10]. |

| Bile Salts (e.g., Sodium Taurocholate) | To emulsify lipids and form mixed micelles with lipolytic products and lipophilic nutrients [10] [14]. | Essential for studying the bioaccessibility of carotenoids and fat-soluble vitamins [10] [14]. |

| Permeation Enhancers | Compounds that temporarily increase intestinal permeability to facilitate nutrient absorption [8]. | Used in formulation studies to improve bioavailability of poorly absorbed drugs/nutrients. |

| Lipid-Based Formulations | To encapsulate and solubilize lipophilic nutrients, enhancing their dispersion and micellarization [8] [14]. | Nanoemulsions, liposomes, and self-emulsifying drug delivery systems (SEDDS) for carotenoids [14]. |

| Phytase Enzyme | To hydrolyze phytic acid (phytate), an antinutrient that chelates minerals, thereby freeing them for absorption [8]. | Improving the bioavailability of iron, zinc, and calcium from plant-based foods and feeds [8]. |

The journey of a nutrient from ingestion to physiological utilization is a complex process governed by an interplay of intrinsic and extrinsic factors. The chemical form of the nutrient dictates its fundamental absorption efficiency, while the food matrix can act as either a formidable barrier or a facilitator of its release. Furthermore, the overall dietary context, defined by the presence of inhibitors or enhancers, can dramatically modulate the final bioavailability. A deep understanding of these determinants is not merely academic; it is foundational for food scientists and drug development professionals aiming to design effective functional foods, nutritional supplements, and therapeutic agents. Overcoming the limitations imposed by a robust food matrix or a poorly absorbed chemical form—through strategies like targeted processing, encapsulation, or the use of bioavailability enhancers—is key to closing nutritional gaps and improving human health outcomes on a population scale.

Nutrient bioavailability is defined as the proportion of an ingested nutrient that is absorbed, transported to target tissues, and utilized in normal physiological functions or stored for future use [15] [16]. While dietary factors such as nutrient form and food matrix significantly influence bioavailability, a growing body of evidence demonstrates that host-related factors—including nutritional status, genetics, gut microbiota composition, and specific health conditions—exert equally powerful effects on nutrient absorption and utilization [15] [17]. Understanding these host factors is critical for researchers and drug development professionals seeking to develop targeted nutritional interventions, personalized nutrition strategies, and therapeutic agents that optimize nutrient delivery and efficacy.

The traditional approach in nutritional sciences has focused primarily on dietary intake levels, but this fails to account for the profound interindividual variation in nutrient absorption and metabolism mediated by host physiology [17]. Host factors can be classified as intestinal factors (influencing luminal and mucosal digestion and absorption) or systemic factors (affecting transport, tissue distribution, and utilization) [17]. This comparative assessment examines the experimental evidence elucidating how specific host characteristics modulate nutrient bioavailability from different foods, providing a foundation for more precise nutritional recommendations and therapeutic development.

Comparative Impact of Key Host Factors on Nutrient Bioavailability

Table 1: Comparative Impact of Host-Related Factors on Nutrient Bioavailability

| Host Factor | Affected Nutrients | Direction of Effect | Proposed Mechanism | Experimental Evidence |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Genetic Variation (LCT locus) | Calcium, Vitamin D | ↑ Bioavailability with dairy intake | Lactase persistence enables lactose digestion, enhancing calcium absorption via paracellular pathway [16] | GWAS of 5,959 individuals: LCT genotype interacted with dairy intake to modulate Bifidobacterium abundance [18] |

| Gut Microbiota Composition | B vitamins, Vitamin K, Iron | ↑ Production/↑ Absorption | Microbial synthesis of vitamins; fermentation of fiber to SCFAs that lower pH and enhance mineral solubility [15] [17] | 16-week crossover trial: Exercise modified gut microbiome more significantly than diet shift, altering metabolic potential [19] |

| Hypochlorhydria/Atrophic Gastritis | Iron, Calcium, Folate, Vitamin B12 | ↓ Absorption | Reduced acid-mediated release of protein-bound nutrients; bacterial overgrowth competing for vitamin B12 [17] | Balance studies showing impaired iron and calcium absorption in individuals with medically induced hypochlorhydria [17] |

| Life Stage (Elderly) | Vitamin D, Calcium, Vitamin B12 | ↓ Absorption | Age-related reduction in gastric acid, intestinal absorptive surface, and synthesis of vitamin D [15] | Meta-analyses showing higher nutrient requirements or fortified foods needed to maintain status in elderly [15] |

| Life Stage (Pregnancy/Lactation) | Iron, Calcium, Folate | ↑ Absorption | Hormonally upregulated absorption pathways to meet increased physiological demands [15] [17] | Isotopic tracer studies demonstrating enhanced fractional absorption of iron and calcium during pregnancy [17] |

| Health Conditions (Environmental Enteric Dysfunction) | Multiple micronutrients | ↓ Absorption | Villus atrophy and intestinal inflammation reducing absorptive surface area [17] | Malabsorption tests and biomarker studies in endemic populations [17] |

Experimental Approaches and Methodologies for Assessing Host Factors

Genomic Association Studies

Protocol for Genome-Wide Microbiome Association Studies: Large-scale population cohorts (e.g., 5,959 individuals in the FINRISK study) with matched genotyping, gut metagenomic sequencing, and dietary records enable identification of host genetic variants associated with microbial abundances and their interactions with diet [18]. The standard methodology involves: (1) Collection of fecal samples for metagenomic sequencing using standardized protocols; (2) Genotyping of participants using microarray technology; (3) Quality control and normalization of microbiome data; (4) Testing for association between genetic variants and microbial taxa abundances while adjusting for covariates including age, sex, and BMI; (5) Testing for gene-diet interactions by including dietary intake as a modifier in models [18]. This approach identified 567 independent SNP-taxon associations, including variants at the LCT locus that associated with Bifidobacterium abundance differently depending on dairy intake [18].

Stable Isotope Studies for Mineral Bioavailability

Protocol for Iron and Zinc Absorption Studies: The use of stable isotopes provides the most accurate measurement of mineral absorption in humans [17]. The standard methodology includes: (1) Administration of stable isotopically labeled test meals; (2) Precise collection of blood samples at defined time points post-consumption; (3) Analysis of isotope ratios in blood or fecal samples using inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry; (4) Calculation of absorption based on isotope appearance in circulation or disappearance from the gut [17]. These studies have been instrumental in developing algorithms that predict iron and zinc bioavailability based on both dietary factors and host iron status [17].

Controlled Intervention Trials

Protocol for Diet-Microbiome-Exercise Interventions: The comparative study of diet shift versus exercise effects on gut microbiome followed a 12-week, randomized, parallel, controlled clinical trial design [19]. Methodology included: (1) Recruitment of 75 volunteers aged 30-50 years; (2) Randomization to three groups: diet shift (DS) from meat-based to vegetarian diet, physical exercise (EX) regimen without dietary change, or control group; (3) Strict monitoring of adherence to interventions; (4) Collection of fecal samples at baseline and 12 weeks for 16S rRNA sequencing; (5) Bioinformatic analysis using mothur pipeline and EzTaxon-e database for taxonomic assignment; (6) α-diversity and β-diversity analyses to assess microbiome changes [19]. This design revealed that exercise modulated gut microbiome composition more significantly than dietary shift, indicating potent host physiological influences on microbiota [19].

Signaling Pathways and Mechanistic Relationships

Diagram 1: Host Factor Pathways Influencing Nutrient Bioavailability: This diagram illustrates the complex interplay between host-related factors and biological processes that collectively determine nutrient bioavailability, including specific gene-nutrient interactions such as the LCT locus with dairy intake.

Research Reagent Solutions for Host Factor Studies

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents for Host Factor Bioavailability Studies

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Research Application | Key Function in Experimental Protocols |

|---|---|---|---|

| Stable Isotopes | ⁵⁸Fe, ⁶⁷Zn, ¹³C-labeled compounds | Mineral absorption studies [17] | Metabolic tracing of nutrient absorption, distribution, and utilization without radioactivity |

| DNA Extraction Kits | MoBio PowerSoil DNA Isolation Kit [19] | Microbiome studies | Standardized microbial DNA extraction from fecal samples for metagenomic sequencing |

| 16S rRNA Primers | V1-9F: 5'-X-AC-GAGTTTGATCMTGGCTCAG-3' and V3-541R: 5'-X-AC-WTTACCGCGGCTGCTGG-3' [19] | Microbiome profiling | Amplification of hypervariable regions of bacterial 16S rRNA gene for taxonomic identification |

| Bioinformatic Tools | mothur pipeline [19], EzTaxon-e database [19] | Microbiome data analysis | Processing of sequencing reads, OTU clustering, and taxonomic classification against reference databases |

| Genotyping Arrays | Illumina Global Screening Array | Genome-wide association studies | High-throughput genotyping of single nucleotide polymorphisms for host genetic analyses |

| Cell Culture Models | Caco-2 human intestinal epithelial cells | Nutrient transport studies | In vitro model of human intestinal barrier for studying nutrient absorption mechanisms |

| Metagenomic Databases | GTDB (Genome Taxonomy Database) [18], CAZy (Carbohydrate-Active Enzymes Database) [18] | Functional microbiome analysis | Reference databases for taxonomic classification and functional annotation of metagenomic data |

The experimental evidence comprehensively demonstrates that host-related factors—including genetics, gut microbiota, physiological state, and health conditions—systematically influence nutrient bioavailability through multiple mechanistic pathways. The comparative data reveals that these host factors can modulate nutrient absorption to a similar or greater extent than dietary composition itself, as exemplified by the finding that exercise-induced physiological changes altered gut microbiome composition more significantly than a major dietary shift from meat-based to vegetarian diet [19]. Furthermore, gene-nutrient interactions, such as the association between LCT genotype and Bifidobacterium abundance that is modified by dairy intake, highlight the complex interplay between host genetics and diet [18].

For researchers and drug development professionals, these findings underscore the critical importance of considering host factors in the design of nutritional interventions, therapeutic agents, and clinical trials. The methodologies and reagents outlined provide a toolkit for investigating these relationships in greater depth, enabling more personalized approaches to nutrition that account for genetic predisposition, microbiota composition, and physiological status. Future research should focus on developing integrated models that simultaneously consider multiple host factors and their interactions, ultimately leading to more effective nutritional strategies tailored to individual host characteristics.

The Absorption Equals Bioavailability Paradigm and Key Exceptions (e.g., Selenium)

The conventional paradigm in nutritional science often equates the absorption of a nutrient with its bioavailability. This framework posits that once a nutrient passes the intestinal barrier and enters systemic circulation, it becomes fully available for physiological utilization. However, a critical examination of essential trace elements, particularly selenium (Se), reveals significant limitations in this oversimplified approach. Bioavailability is more accurately defined as the proportion of an ingested nutrient that is absorbed, becomes available for physiological functions, and is ultimately stored in target tissues [20]. For selenium, this complex process encompasses not only intestinal absorption but also hepatic metabolism, tissue-specific distribution, incorporation into functional selenoproteins, and the often-overlooked role of the gut microbiota in selenium transformation and utilization [20] [21].

The distinction between absorption and bioavailability becomes particularly evident when comparing different chemical forms of selenium and their metabolic fates. While most dietary selenium is absorbed efficiently, retention and functional utilization of organic forms is typically higher than that of inorganic forms [22]. This discrepancy highlights why merely measuring selenium concentration in the bloodstream provides an incomplete picture of its true nutritional status. A more comprehensive assessment requires understanding how different selenium species are metabolized, transported, and incorporated into biologically active selenoproteins that execute critical physiological functions including antioxidant defense, immune regulation, and thyroid hormone metabolism [20] [23]. This article examines the exceptions to the absorption-equals-bioavailability paradigm through the lens of selenium metabolism, presenting experimental data and methodological approaches essential for researchers investigating nutrient bioavailability.

Selenium Bioavailability: Beyond Intestinal Absorption

Chemical Speciation and Metabolic Fate

Selenium bioavailability exhibits remarkable dependence on its chemical form, both in terms of absorption efficiency and post-absorptive utilization. The metabolism of selenium involves a complex network of pathways that vary significantly between different chemical species, ultimately influencing how effectively this trace element is incorporated into biologically active selenoproteins.

Table 1: Comparative Bioavailability of Selenium Forms from Experimental Studies

| Selenium Form | Absorption Mechanism | Relative Bioavailability Range | Key Functional Biomarkers |

|---|---|---|---|

| Selenomethionine (SeMet) | Active transport via amino acid carriers [20] | 22–330% [20] | Plasma Se levels (+25–413%), GPx activity (+29–174%) [20] |

| Selenite | Passive diffusion [20] | 55.5–100% [20] | Plasma Se levels (+19–530%), GPx activity (+16–300%) [20] |

| Selenate | Sulfate co-transporters [20] | 34.7–94% [20] | Plasma Se levels (+58–275%), GPx activity (+30–200%) [20] |

| Se-methylselenocysteine | Not specified | Higher than SeMet for GPX3 and SELENOP synthesis [20] | GPX3 and SELENOP levels [20] |

| Selenocyanate | Not specified | Higher than SeMet for GPX3 and SELENOP synthesis [20] | GPX3 and SELENOP levels [20] |

The absorption mechanisms for selenium compounds vary significantly based on their chemical nature. Inorganic selenate utilizes sulfate co-transporters, while selenite enters enterocytes via passive diffusion. In contrast, organic selenium compounds such as selenomethionine and selenocysteine are transported by the same amino acid transporters as their sulfur-containing counterparts [20]. Following absorption, selenium metabolism converges toward a common pathway. The liver serves as the primary metabolic organ, converting various selenium forms to selenide, a universal intermediate that facilitates the biosynthesis of selenocysteine and its incorporation into specialized selenoproteins [20]. The liver produces selenoprotein P (SELENOP), which functions as a transport protein that distributes selenium to various tissues via the bloodstream [20] [23].

The table reveals exceptionally wide ranges in bioavailability estimates, particularly for selenomethionine, which can reach up to 330% relative bioavailability. This apparent super-bioavailability occurs because selenomethionine can be non-specifically incorporated into general body proteins in place of methionine, creating a reservoir of selenium that is not immediately available for selenoprotein synthesis but contributes to long-term selenium status [23]. This pathway represents a crucial exception to the absorption-equals-bioavailability paradigm, as absorbed selenium may be sequestered in non-functional storage pools rather than being immediately available for physiological functions.

The Critical Role of Gut Microbiota in Selenium Bioavailability

Emerging research has fundamentally expanded our understanding of selenium bioavailability by revealing the gastrointestinal tract as a site of extensive selenium metabolism rather than merely an absorption barrier. The gut microbiota actively participates in selenium metabolism by transforming dietary selenium into various metabolites and even competing with the host for this essential nutrient [20] [21]. This microbial transformation creates a crucial layer of complexity that challenges traditional bioavailability assessment methods.

Table 2: Selenium Transformations by Gut Microbiota

| Selenium Substrate | Microbial Metabolites | Experimental Model | Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Selenate/Selenite | Elemental selenium nanoparticles [20] | In vivo (rats) [20] | Reduces bioavailability but may produce beneficial metabolites |

| Selenium Nanoparticles | Short-chain fatty acids [20] | In vivo (rats) [20] | May produce bioactive metabolites with health benefits |

| Semethylselenocysteine | Selenomethionine [20] | In vivo (rats) [20] | Alters selenium speciation and absorption potential |

| Selenocyanate | Selenomethionine [20] | In vivo (rats) [20] | Converts to more bioavailable form |

| Various Forms | Dimethyl diselenide, Selenosugars [20] | In vitro fermentation [20] | Affects excretion pathways and retention |

The gut microbiota functions as a significant biotransformation system that modifies selenium bioavailability through multiple mechanisms. Certain microbial communities can reduce inorganic selenite and selenate to elemental selenium, potentially decreasing absorption efficiency but simultaneously generating selenium nanoparticles with unique bioactive properties [20]. Conversely, some bacteria convert various selenium compounds into selenomethionine, potentially enhancing its absorption and utilization [20]. Additionally, gut microbes metabolize selenium into volatile compounds like dimethyl selenide, which is excreted via respiration, and transform it into selenosugars that are eliminated in urine [20]. These microbial transformations represent a significant diversion of selenium that would traditionally be considered "absorbed" but is actually lost for functional selenoprotein synthesis.

The composition of the gut microbiota itself is influenced by dietary selenium intake, creating a dynamic interplay that further complicates bioavailability predictions. Selenium deficiency or supplementation can alter the gut microbial community structure, which in turn affects how subsequent selenium intake is metabolized [20]. This bidirectional relationship necessitates a redefinition of selenium bioavailability to include not only the fraction that enters systemic circulation but also the portion metabolized by gut microbiota into bioactive compounds that may indirectly benefit the host [20].

Diagram 1: Selenium Bioavailability Pathway: From Ingestion to Functional Utilization. This diagram illustrates the complex journey of selenium from dietary intake to functional utilization, highlighting the critical role of gut microbiota in transforming selenium compounds and creating exceptions to the simple absorption-equals-bioavailability paradigm.

Methodological Approaches for Assessing Selenium Bioavailability

In Vivo Models and Functional Biomarkers

Accurate assessment of selenium bioavailability requires sophisticated methodological approaches that can capture the complexity of its metabolism. In vivo studies conducted in human subjects or animal models provide the most physiologically relevant data, as they maintain the biological integrity of absorption, distribution, metabolism, and excretion processes. These studies typically employ two primary classes of biomarkers to evaluate selenium status and bioavailability: concentration biomarkers and functional biomarkers [22].

Concentration biomarkers include direct measurements of selenium levels in plasma, serum, or whole blood, as well as quantification of specific selenium species such as selenoprotein P (SELENOP). Functional biomarkers measure the activity of selenium-dependent enzymes, particularly various forms of glutathione peroxidase (GPx) and thioredoxin reductase [22]. The choice of biomarker significantly influences bioavailability estimates, as different biomarkers respond variably to various selenium compounds. For instance, selenomethionine supplementation typically produces greater increases in plasma selenium concentration compared to selenite, but this difference may be less pronounced when measuring GPx activity [22].

The most robust in vivo studies utilize stable isotope tracers to precisely track the absorption, distribution, and elimination of different selenium forms. These methodologies allow researchers to conduct pharmacokinetic analyses and determine the relative bioavailability of different selenium compounds under controlled conditions. However, significant challenges remain in standardizing protocols across laboratories and accounting for inter-individual variations in selenium metabolism due to genetic polymorphisms, health status, and baseline selenium levels [22].

In Vitro and Ex Vivo Models

In vitro systems provide valuable alternatives to in vivo studies, offering greater experimental control, reduced costs, and the ability to investigate specific mechanisms of selenium absorption and metabolism. The most widely utilized in vitro approaches include artificial gastrointestinal digestion systems, cellular absorption models employing Caco-2 cell monolayers, and laboratory-based simulations of colonic fermentation processes [20].

Artificial gastrointestinal digestion systems simulate the chemical conditions of the stomach and small intestine to measure bioaccessibility—the fraction of selenium released from the food matrix during digestion and potentially available for absorption [20]. These systems typically involve sequential incubation with enzymes and pH adjustments to mimic physiological conditions. Following gastrointestinal digestion, Caco-2 cell models (human colon adenocarcinoma cell line that differentiates into enterocyte-like cells) are employed to assess intestinal absorption. Studies using this model have demonstrated that selenium bioavailability varies significantly by form, with one investigation showing selenium bioaccessibility following the order: SeMet > MeSeCys > Se(VI) > Se(IV) [20].

More recently, researchers have developed in vitro colonic fermentation models to investigate the role of gut microbiota in selenium metabolism. These systems incorporate fecal inoculums from human donors to simulate the microbial transformations that occur in the large intestine. Such models have demonstrated that gut microbiota can convert various selenium forms into multiple metabolites, including selenomethionine, short-chain fatty acids, dimethyl diselenide, and nano-sized selenium particles [20]. While in vitro models cannot fully recapitulate the complexity of whole-organism physiology, they provide valuable screening tools and mechanistic insights that complement in vivo findings.

Table 3: Experimental Protocols for Assessing Selenium Bioavailability

| Methodology | Key Procedures | Measured Endpoints | Advantages/Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| In Vivo Supplementation Trials | Administration of specific Se forms to human subjects or animal models; Blood/tissue collection at timed intervals [20] | Plasma/serum Se levels; SELENOP concentration; GPx activity in erythrocytes/tissues [22] [20] | Physiologically relevant; Accounts for whole-body metabolism; Expensive and time-consuming [20] |

| Stable Isotope Tracers | Administration of isotopically labeled Se compounds (e.g., ^74Se); Sequential blood/urine collection; ICP-MS analysis [22] | Isotopic enrichment in biological samples; Kinetic modeling of Se metabolism [22] | Precise tracking of specific Se forms; Requires sophisticated instrumentation [22] |

| In Vitro Digestion (Bioaccessibility) | Sequential incubation with pepsin-HCl (gastric phase) and pancreatin-bile (intestinal phase) with pH control [20] [24] | Soluble Se fraction after gastrointestinal digestion; Often coupled with dialysis membranes to simulate absorption [20] [24] | Rapid screening; Low cost; Does not include microbial or tissue metabolism [20] |

| Caco-2 Cell Absorption Models | Culture of differentiated Caco-2 monolayers; Application of digested samples to apical side; Measurement of Se transport to basolateral compartment [20] | Se content in basolateral medium; Trans-epithelial electrical resistance (TEER); Cellular uptake of Se [20] | Models intestinal absorption; Includes cellular transport mechanisms; Lacks endocrine and microbial influences [20] |

| Microbial Fermentation Models | Incubation of Se compounds with fecal inoculum in anaerobic chambers; Sampling at timed intervals [20] | Se speciation changes (HPLC-ICP-MS); Microbial community analysis (16S rRNA sequencing) [20] | Investigates microbial transformation; Can identify specific metabolites; Simplified microbial community [20] |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Methodologies

Research on selenium bioavailability requires specialized reagents, reference materials, and analytical capabilities to accurately quantify selenium species and their biological activity. The following toolkit outlines essential resources for investigating selenium bioavailability.

Table 4: Research Reagent Solutions for Selenium Bioavailability Studies

| Category | Specific Items | Research Application | Technical Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Selenium Standards | Selenomethionine (SeMet), Selenocysteine (SeCys), Sodium Selenite, Sodium Selenate, Se-methylselenocysteine [20] | Method calibration; Reference compounds for speciation analysis; Preparation of fortified samples | Purity verification essential; Differentiate D/L forms of SeMet; Stability varies among compounds |

| Cell Culture Models | Caco-2 cell line (HTB-37), Appropriate culture media, Transwell inserts, Fetal bovine serum [20] | Intestinal absorption studies; Transport mechanism investigation; Drug-nutrient interaction screens | Require 21-day differentiation; Monitor TEER for integrity; Test for mycoplasma contamination |

| Enzymes for Digestion Models | Pepsin from porcine gastric mucosa, Pancreatin from porcine pancreas, Bile extracts [20] [24] | Simulated gastrointestinal digestion; Bioaccessibility assessment | Standardize enzyme activities; Consider food-grade preparations for food matrix studies |

| Analytical Standards | Certified reference materials (SRM 3149, BCR-637), Isotopically labeled selenium compounds (^74Se, ^77Se) [22] | Quality control; Method validation; Isotope dilution analysis | Verify certification values; Monitor for spectral interferences in ICP-MS |

| Microbial Culture | Fecal sampling kits, Anaerobic culture systems, Specific selenium-transforming strains [20] | Gut microbiota transformation studies; Production of microbial metabolites | Maintain strict anaerobic conditions; Preserve samples immediately after collection |

| Antibodies & ELISA Kits | Anti-SELENOP antibodies, GPx activity assays, SELENOP ELISA kits [22] | Functional biomarker assessment; High-throughput screening | Validate species cross-reactivity; Compare multiple lots for consistency |

| Speciation Columns | Hamilton PRP-X100, Ion-exchange chromatography columns, Size-exclusion columns [20] | Separation of selenium species prior to detection | Match column chemistry to target species; Use guard columns for biological samples |

The investigation of selenium bioavailability reveals fundamental limitations in the absorption-equals-bioavailability paradigm that has traditionally guided nutritional recommendations. The complex metabolism of selenium, particularly the significant role of gut microbiota in transforming selenium compounds and competing with the host for this essential nutrient, demonstrates that bioavailability encompasses far more than mere intestinal absorption [20] [21]. The chemical speciation of selenium dramatically influences its metabolic fate, with organic forms typically exhibiting higher retention and functional utilization compared to inorganic forms, despite similar absorption efficiencies [22].

These findings have profound implications for establishing dietary recommendations, designing functional foods, and interpreting epidemiological studies linking selenium intake to health outcomes. The substantial variations in selenium bioavailability between different chemical forms and food matrices necessitate a more sophisticated approach to nutritional guidance that considers not only total selenium intake but also its chemical form and the food context in which it is consumed [22] [20]. Future research should prioritize the development of standardized bioavailability assessment protocols, the identification of robust functional biomarkers that respond consistently to different selenium forms, and the elucidation of genetic factors that influence individual responses to selenium intake [22].

The exceptional case of selenium bioavailability provides a template for reevaluating the bioavailability of other nutrients with complex metabolism. As nutritional science advances toward more personalized recommendations, understanding the intricate relationships between nutrient chemical forms, food matrices, gut microbiota, and host genetics will be essential for developing targeted nutritional strategies that optimize health outcomes based on individual physiological needs and metabolic characteristics.

Advanced Methodologies for Assessing Nutrient Bioavailability: From Animal Models to Human Studies

The comparative assessment of nutrient bioavailability from different foods is a critical endeavor in nutritional science and drug development. Understanding the extent to which ingested nutrients are absorbed, utilized, and retained by the body requires sophisticated in vivo techniques that can accurately trace metabolic fates. The three cornerstone methodologies for these investigations are animal models, isotopic tracers (with its central dichotomy of intrinsic versus extrinsic tagging), and balance studies. Each approach offers distinct advantages and limitations, providing researchers with a versatile toolkit for probing nutrient metabolism. Animal models enable controlled interventional studies and detailed tissue analysis that would be impractical or unethical in humans. Isotopic tracers, particularly stable isotopes, allow for the precise tracking of nutrients through complex metabolic pathways without radiation exposure. Balance studies provide a holistic view of nutrient retention and loss at the whole-organism level. This guide objectively compares the performance of these methodologies and presents supporting experimental data to inform researchers' selection of appropriate techniques for specific bioavailability questions.

The fundamental principles, applications, and key differences between the three core techniques are summarized in the table below.

Table 1: Comparison of Core In Vivo Techniques for Bioavailability Assessment

| Technique | Fundamental Principle | Primary Applications | Key Measurable Parameters |

|---|---|---|---|

| Animal Models | Use of controlled organisms to simulate human physiological and metabolic responses [16] [25]. | - Screening bioavailability of multiple food matrices- Studying tissue-specific nutrient deposition- Investigating mechanisms of absorption and metabolism [16] [25]. | - Nutrient concentration in target tissues (e.g., liver, bone)- Expression of relevant genes and proteins- Whole-body growth and mineral status [25]. |

| Isotopic Tracers | Tracking of isotopes (stable or radioactive) through biological systems to trace the metabolic fate of nutrients [26] [27]. | - Precisely quantifying absorption and metabolic flux- Studying nutrient kinetics and pool sizes- Mapping pathway utilization (e.g., MFA) [26] [28] [27]. | - Fractional absorption- Isotope enrichment in biological samples- Metabolic flux rates [27]. |

| Balance Studies | Calculation of nutrient retention as the difference between intake and excretion [25]. | - Determining apparent absorption of minerals- Assessing overall nutrient retention- Evaluating the effect of dietary interventions on nutrient status [8] [25]. | - Apparent absorption (%)- Fecal and urinary excretion- Net retention [25]. |

The Critical Distinction: Intrinsic vs. Extrinsic Isotopic Labeling

Within isotopic tracing, the method of introducing the label is paramount. Intrinsic labeling involves biosynthetically incorporating the isotope into the food during its growth (e.g., growing plants in a nutrient solution containing a stable iron isotope), ensuring the tracer is integrated into the natural food matrix [29]. In contrast, extrinsic labeling involves adding the isotopic tracer to the food just before consumption, relying on the tracer to exchange with the native nutrient pools during digestion [29].

The validity of extrinsic labeling has been confirmed for several minerals. A study on zinc absorption in women compared extrinsic ⁶⁴Zn and intrinsic ⁷⁰Zn labels from a milk-based diet, finding that fractional absorption values (0.282 ± 0.086 vs. 0.267 ± 0.092, respectively) were highly correlated and not significantly different [29]. This demonstrates that for some nutrients and food matrices, the simpler extrinsic method is a valid proxy for intrinsic labeling.

Experimental Protocols and Data Output

Protocol for Stable Iron Isotope Absorption Studies

The erythrocyte iron incorporation method is a gold standard for measuring human iron bioavailability [27].

- Dosing: After a baseline blood draw, an oral dose of a stable iron isotope (e.g., ⁵⁷Fe) is administered. For absolute absorption calculation, an intravenous dose of a different isotope (e.g., ⁵⁸Fe) is often given simultaneously [27].

- Equilibration: A 14-day period allows for the incorporation of the absorbed oral iron into circulating erythrocytes [27].

- Sample Collection: A second blood sample is collected after 14 days.

- Analysis: Erythrocytes are processed, and iron is extracted and purified. Isotope ratios (e.g., ⁵⁷Fe/⁵⁶Fe and ⁵⁸Fe/⁵⁶Fe) are measured by Inductively Coupled Plasma Mass Spectrometry (ICP-MS) [27].

- Calculation: Fractional iron absorption is calculated based on the shift in isotope ratios in the erythrocytes, corrected for the intravenous dose [27].

Table 2: Exemplary Data from a Stable Iron Isotope Study

| Subject Group | Iron Source | Extrinsic Isotope Label | Fractional Absorption (%) (Mean ± SD) | Key Finding |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Young Women [29] | Milk-based Diet (Zinc) | ⁶⁴Zn (Extrinsic) | 28.2 ± 8.6 | Extrinsic and intrinsic labels yielded statistically equivalent absorption values, validating the extrinsic method for zinc in this matrix. |

| ⁷⁰Zn (Intrinsic) | 26.7 ± 9.2 |

Protocol for Animal Model (Tissue Indicator) Studies

Animal studies are used to measure the functional bioavailability of a nutrient, often by assessing its deposition in target tissues [25].

- Study Design: Animals (e.g., rodents, pigs) are divided into test groups, each assigned a specific dietary intervention (e.g., different food sources of a mineral).

- Feeding Period: After an adaptation period, subjects consume the experimental diets for a predefined duration, which can range from several weeks to months [25].

- Sample Collection: At the endpoint, target tissues (e.g., liver for iron, bone for calcium) are collected.

- Analysis: Tissue mineral concentration is quantified using techniques like Atomic Absorption Spectroscopy (AAS) or ICP-MS [25].

- Calculation: Bioavailability is inferred from the relative increase in mineral concentration in the target tissue of the test group compared to a control.

Workflow for a Metabolic Balance Study

This traditional method assesses apparent nutrient absorption [25].

- Dietary Control: Subjects consume a controlled diet with a fixed nutrient content for the study period.

- Sample Collection: All food intake is precisely recorded. Complete collections of feces and urine are made throughout the study, often for 7-10 days [25].

- Analysis: The nutrient content of the diet, feces, and urine is analyzed.

- Calculation: Apparent absorption is calculated as: (Nutrient Intake - Fecal Nutrient Output) / Nutrient Intake [25].

Advanced Applications: Stable Isotopes in Metabolic Flux Analysis

Beyond simple absorption, stable isotope tracing is powerful for Metabolic Flux Analysis (MFA), which quantifies the flow of metabolites through biochemical pathways [26] [28]. In this technique, a stable isotope-labeled nutrient (e.g., U-¹³C-glucose) is introduced into a biological system. As the nutrient is metabolized, the label is incorporated into downstream metabolites. The resulting labeling patterns in metabolic intermediates, detected by Mass Spectrometry (MS) or Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR), are used with stoichiometric models to calculate intracellular flux rates [26] [28]. This approach has been pivotal in revealing the metabolic reprogramming of tumors, such as heterogeneous TCA cycle activity in human lung cancers [30] [28].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Research Reagents for Bioavailability Studies

| Reagent / Material | Function and Application | Technical Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Stable Isotope Tracers (e.g., ⁵⁷Fe, ⁷⁰Zn, U-¹³C-Glucose) [30] [27] | Serve as metabolic labels to track the fate of nutrients without radioactivity. | For human infusions, Clinical Trial Material (CTM) or Microbiological and Pyrogen-Tested (MPT) grade is often required [30]. |

| Mass Spectrometry Instruments (ICP-MS, LC-MS/MS, GC-MS) [31] [26] [27] | Detect and quantify isotopic enrichment in biological samples with high sensitivity. | LC-MS/MS and GC-MS are used for organic molecules; ICP-MS is ideal for mineral analysis [26] [27]. |

| Animal Models (Rodents, Pigs) [16] [25] | Provide a controlled system for tissue-level analysis and screening. | Species selection depends on the research question; pigs are often preferred for gastrointestinal studies due to physiological similarities to humans [25]. |

| Standard Reference Materials (Certified diets, tissue homogenates) | Ensure analytical accuracy and precision by calibrating instruments and validating methods. | Critical for generating reliable and reproducible quantitative data across studies. |

| Cell Culture Media for Labeling (e.g., ¹³C-labeled amino acids) [26] | Enable in vitro metabolic flux experiments in controlled cell systems. | Allows for the study of specific cell types in isolation before moving to complex in vivo models. |

Evaluating how nutrients are released from food and absorbed by the body is fundamental to nutritional science, food development, and safety assessment. Bioavailability—the proportion of a nutrient that is absorbed, transported, and utilized in normal physiological processes—varies significantly across different foods and is influenced by multiple factors including food matrix, digestive conditions, and individual physiology [15]. Traditional in vivo studies, while valuable, face limitations regarding cost, complexity, and ethical constraints [32]. Consequently, in vitro simulated digestion models and in silico predictive algorithms have emerged as complementary approaches that provide reproducible, controlled, and mechanistic insights into digestive processes [32] [33].

This guide provides a comparative assessment of these methodologies, detailing their experimental protocols, applications, and integration strategies. The framework aligns with growing regulatory acceptance of New Approach Methodologies (NAMs) and addresses the critical need for accurate nutrient bioavailability assessment in developing novel foods and personalized nutrition strategies [33] [9].