Biosensors vs. Conventional Methods: A Performance Evaluation for Next-Generation Allergen Detection

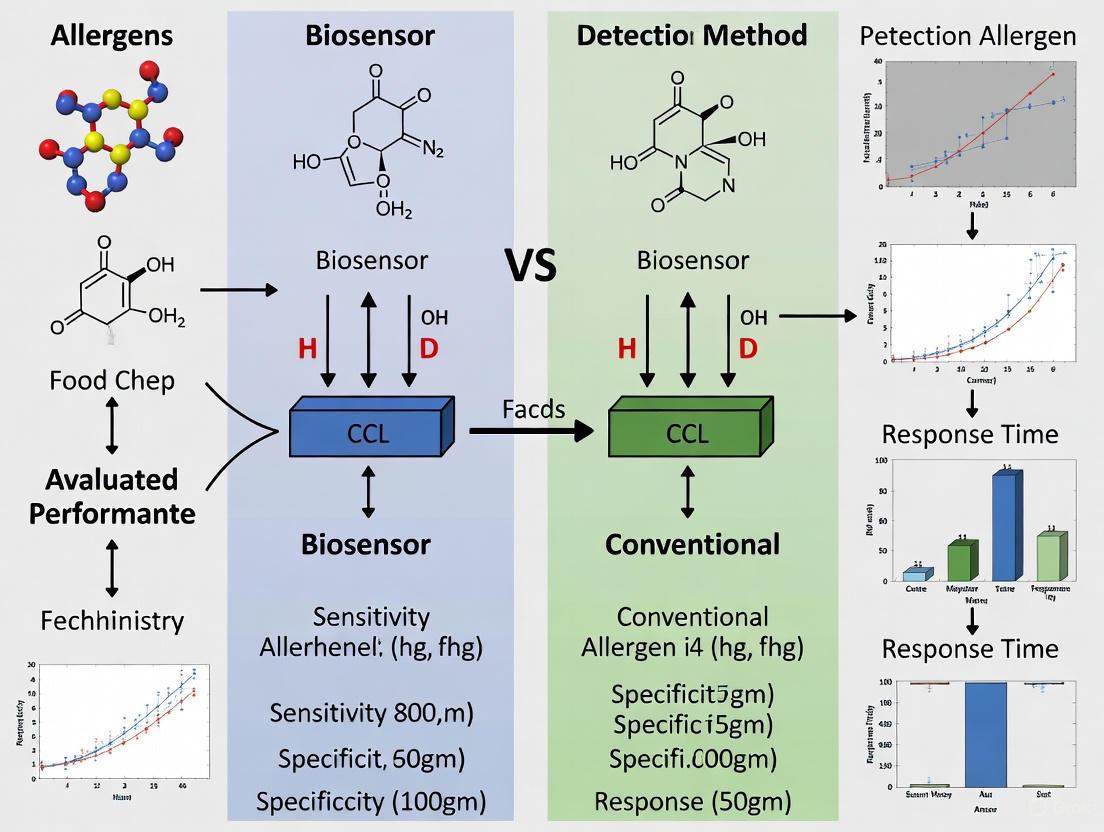

This article provides a comprehensive evaluation of emerging biosensing technologies against established conventional methods for allergen detection.

Biosensors vs. Conventional Methods: A Performance Evaluation for Next-Generation Allergen Detection

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive evaluation of emerging biosensing technologies against established conventional methods for allergen detection. Aimed at researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it explores the foundational principles of colorimetric, fluorescent, electrochemical, SERS, and SPR biosensors, alongside portable platforms like lateral flow assays and microfluidic devices. The scope extends to methodological applications, critical troubleshooting of performance parameters such as sensitivity and dynamic range, and a direct comparative analysis of analytical capabilities. By synthesizing validation data and future prospects, this review serves as a strategic guide for selecting, optimizing, and advancing detection technologies to enhance food safety, clinical diagnostics, and biomanufacturing processes.

The Analytical Landscape: Foundational Principles of Allergen Detection Technologies

The Growing Public Health Imperative for Accurate Allergen Detection

Food allergy has emerged as a significant global public health concern, with increasing prevalence affecting individuals of all ages in both developed and developing countries [1]. According to recent studies, the incidence of food allergies in infants in China has risen from 7.7% in 2009 to 11.1% in 2019, reflecting a worrying worldwide trend [2]. In the United States alone, peanut allergies affect approximately 6.2 million individuals, posing a serious public health risk due to the potential for accidental exposure and life-threatening anaphylaxis [3]. Since the only effective prevention for affected individuals remains strict avoidance of allergenic foods, accurate detection and labeling become critical components of public health protection [2] [1].

This escalating health burden has prompted regulatory bodies worldwide to establish labeling requirements for major allergens. The European Union mandates declaration of 14 allergenic foods, while the United States focuses on the "big eight" allergens responsible for 90% of all food allergies [4]. Japan has implemented one of the most specific regulatory thresholds, requiring labeling at 10 μg allergen protein per gram of food and establishing official analytical methods for validation [2] [4]. Despite these regulatory frameworks, accidental exposure continues to occur, with more than half of food allergy reactions in restaurants happening even after staff are notified of a customer's allergy [3]. This reality underscores the critical need for reliable, sensitive, and accessible allergen detection methods that can protect susceptible populations while supporting food manufacturers in regulatory compliance.

Conventional Allergen Detection Methods: Foundations and Limitations

Traditional allergen detection methodologies have primarily relied on immunochemical and DNA-based techniques, each with distinct advantages and limitations for specific application scenarios.

Immunoassays and DNA-Based Methods

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) represents the gold standard in food allergen detection, offering high sensitivity, specificity, and relatively easy operation [2]. The Codex Alimentarius Commission has adopted ELISA as the official test for gluten allergens, specifying that gluten levels in food should not exceed 20 mg/kg [2]. Commercial ELISA kits are widely available for a broad selection of food allergens, with detection limits typically ranging from 1-25 ppm, making them suitable for most regulatory compliance testing [4]. However, ELISA presents several limitations: it is time-consuming (requiring up to 3.5 hours per analysis), relatively expensive for small sample batches, prone to cross-reactivity interference, and difficult to miniaturize for portable applications [4].

Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) methods provide an alternative approach that detects allergen-coding genes rather than the proteins themselves [2] [4]. These methods are particularly valuable for detecting highly processed allergenic foods where proteins may be denatured but DNA remains intact [2]. Germany has employed PCR as an official analytical tool for food allergen detection, and Japan recognizes both ELISA and PCR as official testing methods [2]. The primary advantage of PCR lies in the greater stability of DNA fragments compared to proteins, especially in processed foods. However, PCR is considered an indirect detection method and may be less suitable for food allergens containing high protein but low DNA content, such as eggs [4].

Mass Spectrometry and Emerging Conventional Techniques

Liquid chromatography with tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) has gained traction for its ability to detect proteotypic peptides across complex food matrices, offering new levels of precision compared to immunochemical methods [5]. Mass spectrometry can simultaneously quantify specific proteins responsible for allergic responses, such as Ara h 3 and Ara h 6 in peanuts, Bos d 5 in milk, Gal d 1 and Gal d 2 in eggs, and tropomyosin in shellfish [5]. With detection limits as low as 0.01 ng/mL, mass spectrometry offers high sensitivity and specificity, with scalability across all key allergens featured in labeling regulations worldwide [5]. The technique is particularly valuable for multiplexed analysis and provides unambiguous identification of allergens, though it requires sophisticated instrumentation and specialized expertise [5].

Table 1: Comparison of Conventional Allergen Detection Methods

| Method | Detection Principle | Sensitivity | Analysis Time | Key Applications | Major Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ELISA | Antigen-antibody binding | 1-25 ppm [4] | Up to 3.5 hours [4] | Regulatory compliance testing [2] | Cross-reactivity, difficult miniaturization [4] |

| PCR | DNA amplification | Varies by target | 2-4 hours | Processed foods, official testing [2] | Indirect detection, not suitable for low-DNA allergens [4] |

| Lateral Flow Immunoassay | Antigen-antibody binding | Moderate | 10-15 minutes | Rapid screening, qualitative testing [4] | Semi-quantitative, lower sensitivity [4] |

| Mass Spectrometry | Protein mass analysis | 0.01 ng/mL [5] | 1-2 hours | Multiplex detection, complex matrices [5] | Expensive equipment, requires expertise [5] |

Biosensing Technologies: Next-Generation Approaches

Biosensors represent a transformative approach to allergen detection, integrating biological recognition elements with transducers to convert molecular interactions into measurable signals [6]. These systems offer the potential for rapid, sensitive, and on-site detection, addressing critical limitations of conventional methods.

Electrochemical Biosensors

Electrochemical biosensors have shown significant promise for food allergen detection due to their high sensitivity, portability, and potential for miniaturization [4]. These sensors employ various recognition elements, including antibodies, nucleic acids, cells, and molecularly imprinted polymers, with nanomaterials playing a crucial role in enhancing signal transduction [4]. Recent innovations have demonstrated remarkable performance characteristics. For instance, an electrochemical immunosensor utilizing a nanocomposite of gold nanoparticles, molybdenum disulfide, and chitosan achieved a detection limit of 0.04 ng/mL for the BRCA-1 protein, though applied in cancer diagnostics, this showcases the sensitivity potential for allergen detection [7]. Similarly, enzyme-based solid-phase electrochemiluminescence sensors have been developed with wide linear ranges from 10 μM to 7.0 mM and limits of detection of 1 μM for targets like glucose, demonstrating principles applicable to allergen sensing [7].

The advantages of electrochemical biosensors include their compatibility with complex food matrices, minimal sample preparation requirements, and rapid analysis times. Additionally, their electrical readout system facilitates integration with digital technologies and point-of-care platforms, making them suitable for field-deployable applications in food manufacturing facilities, restaurants, and even home use [4].

CRISPR-Based Biosensing Platforms

CRISPR-based biosensors represent a revolutionary approach to nucleic acid detection, offering unprecedented specificity and sensitivity. The DETECTR system, which combines recombinase polymerase amplification with CRISPR-Cas12a, has been applied to peanut allergen detection targeting the Ara h1 DNA sequence [3]. This system operates under isothermal conditions, eliminating the need for thermal cycling equipment and enabling rapid, cost-effective detection suitable for point-of-use applications [3].

The CRISPR-Cas12a mechanism involves collateral cleavage of single-stranded DNA reporters upon recognition of a target sequence, producing a visible color change when linked to chromoproteins like amilCP [3]. Studies on DETECTR-based systems have reported sensitivity down to 10 aM (attomolar) and specificity above 95% for target DNA recognition [3]. When integrated into lateral flow biosensors, these systems create user-friendly, portable tests that can significantly reduce accidental exposures and improve food safety for individuals with peanut allergies [3].

Optical and Microfluidic Biosensors

Optical biosensors, including those based on surface plasmon resonance, fluorescence, and colorimetric detection, offer alternative transduction mechanisms for allergen detection. Recent advances include graphene-quantum dot hybrid biosensors that achieve femtomolar sensitivity through charge transfer-based quenching and recovery mechanisms [7]. These platforms have been validated for biotin-streptavidin and IgG-anti-IgG interactions, achieving limits of detection down to 0.1 fM, establishing a robust framework for next-generation biosensors [7].

Microfluidic biosensors integrate sample processing and detection within miniaturized channels, enabling precise fluid control with volumes as small as 10^(-6) to 10^(-15) mL [6]. These systems offer multiple advantages, including simultaneous detection of multiple parallel samples, high throughput, reduced reagent consumption, and shortened analysis times [6]. When combined with paper-based microfluidic analytical devices (μPADs), these systems eliminate the need for external power supplies through capillary action, further enhancing their field-deployability [6].

Table 2: Emerging Biosensing Platforms for Allergen Detection

| Technology | Detection Principle | Sensitivity | Analysis Time | Portability | Development Status |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Electrochemical Biosensors | Electrochemical impedance, amperometry | 0.04 ng/mL [7] | Minutes | High [4] | Research with some commercial applications |

| CRISPR-DETECTR | CRISPR-Cas12a collateral cleavage | 10 aM [3] | <1 hour | High [3] | Proof-of-concept demonstrated |

| Microfluidic Biosensors | Lab-on-a-chip fluidics with various detectors | Varies by detection method | <30 minutes | High [6] | Active research and development |

| Optical Biosensors | Surface plasmon resonance, fluorescence | 0.1 fM [7] | Minutes to hours | Moderate | Research phase |

Experimental Protocols: Methodologies for Performance Validation

CRISPR-DETECTR for Peanut Allergen Detection

The CRISPR-DETECTR platform for peanut allergen detection employs a streamlined protocol that can be divided into three core stages: DNA extraction, amplification, and CRISPR-based detection [3].

Sample Preparation and DNA Extraction:

- Food Sample Homogenization: Grind food samples to a fine consistency using a manual grinder, motorized mini-blender, or rolling press to enhance protein/DNA extraction efficiency.

- DNA Extraction: Extract DNA using commercial food DNA extraction kits, following manufacturer protocols. Quantify DNA concentration using spectrophotometry.

- Target Selection: Focus on the Ara h1 gene, selecting conserved, stable regions that remain detectable after food processing and heating.

Recombinase Polymerase Amplification (RPA):

- Prepare RPA Master Mix: Combine the following components in a sterile microcentrifuge tube:

- 50-100 ng extracted DNA sample

- Forward and reverse primers specific to Ara h1 (0.4 μM each)

- Rehydration buffer (14.5 μL provided with RPA kit)

- Recombinase enzyme

- Single-stranded binding protein

- Strand-displacing DNA polymerase

- ATP and necessary cofactors

- Amplification Protocol: Incubate the reaction mixture at 37°C for 15-20 minutes for isothermal amplification.

CRISPR-Cas12a Detection:

- Prepare CRISPR Reaction Mix: To the amplified RPA product, add:

- Cas12a enzyme (50-100 nM)

- crRNA designed for Ara h1 target sequence (50-100 nM)

- Single-stranded DNA reporter labeled with fluorophore-quencher pair (100-200 nM)

- Incubation and Signal Detection: Incubate at 37°C for 10-15 minutes. Cas12a recognizes the target sequence, activates collateral cleavage activity, and separates fluorophore from quencher, generating a detectable signal.

- Lateral Flow Readout: Alternatively, use a chromoprotein-quencher system (e.g., amilCP) producing a strong blue color visible to the naked eye, and integrate with lateral flow strips for visual detection.

Validation and Quality Control:

- Include positive controls (known peanut-contaminated foods) and negative controls (peanut-free foods).

- Compare results against commercial peanut test kits to measure accuracy.

- Test different sample preparation methods to determine optimal protein extraction efficiency.

Electrochemical Immunosensor for Protein Allergens

Electrochemical biosensors for direct protein allergen detection follow a different approach, focusing on immunochemical recognition rather than DNA detection.

Electrode Modification and Sensor Fabrication:

- Electrode Preparation: Clean and polish working electrode (e.g., glassy carbon, gold, or screen-printed carbon electrodes) according to standard electrochemical protocols.

- Nanomaterial Modification: Deposit nanocomposite materials to enhance surface area and electron transfer. For example:

- Prepare graphene oxide solution and reduce on electrode surface

- Drop-cast gold nanoparticles (10-20 nm diameter) suspended in aqueous solution

- Apply molybdenum disulfide nanosheets functionalized with chitosan

- Antibody Immobilization: Immobilize capture antibodies specific to target allergen (e.g., anti-Ara h2 for peanut) through:

- Physical adsorption: Incubate with antibody solution (10-100 μg/mL) for 2 hours at 4°C

- Covalent attachment: Use EDC/NHS chemistry to form amide bonds with carboxyl-functionalized surfaces

- Affinity-based immobilization: Utilize protein A/G or streptavidin-biotin systems

Electrochemical Measurement Protocol:

- Blocking: Treat modified electrode with blocking buffer (e.g., 1% BSA, casein, or synthetic blockers) for 1 hour to minimize nonspecific binding.

- Sample Incubation: Incubate electrode with extracted food sample or standard solutions for 20-30 minutes with gentle agitation.

- Washing: Rinse electrode thoroughly with PBS or appropriate buffer to remove unbound materials.

- Detection Antibody Application: For sandwich assays, incubate with detection antibody labeled with electroactive tag (e.g., horseradish peroxidase, alkaline phosphatase) or directly with redox labels.

- Electrochemical Measurement: Perform measurement using suitable technique:

- Amperometry: Apply fixed potential and measure current over time

- Electrochemical Impedance Spectroscopy: Scan frequency range from 0.1 Hz to 100 kHz with 10 mV amplitude

- Square Wave Voltammetry: Scan from -0.5V to +0.5V with optimized pulse parameters

Data Analysis and Quantification:

- Calibration Curve: Measure standard solutions with known allergen concentrations to establish calibration curve.

- Signal Processing: Apply background subtraction and signal smoothing algorithms as needed.

- Quantitative Analysis: Calculate unknown concentrations from linear regression of calibration data.

- Validation: Compare results with reference methods (ELISA, MS) to verify accuracy.

Comparative Performance Analysis: Biosensors Versus Conventional Methods

The transition from conventional methods to biosensing platforms represents a paradigm shift in allergen detection capabilities, with each approach offering distinct advantages for specific application scenarios.

Sensitivity and Detection Limits

Modern biosensing platforms have achieved remarkable sensitivity levels that rival or exceed conventional methods. CRISPR-DETECTR systems demonstrate sensitivities down to 10 aM for target DNA sequences, while advanced electrochemical biosensors can detect protein targets at concentrations as low as 0.04 ng/mL [3] [7]. These sensitivity levels approach or surpass those of traditional ELISA (1-25 ppm) and mass spectrometry (0.01 ng/mL) [5] [4]. For context, the threshold for allergic reactions can be as low as 0.2 mg of peanut protein for highly sensitive individuals, necessitating detection capabilities in the parts-per-million range or lower [1]. Both biosensors and conventional methods can meet these sensitivity requirements, though biosensors often achieve them with simpler instrumentation and faster analysis times.

Analysis Time and Throughput

Analysis time represents one of the most significant advantages of biosensing platforms over conventional methods. While traditional ELISA requires up to 3.5 hours and PCR methods need 2-4 hours, biosensors can deliver results in minutes to under one hour [3] [4]. This accelerated timeline enables more rapid decision-making in food production environments and allows for more extensive testing regimes. Lateral flow biosensors, in particular, can provide results in 10-15 minutes, making them suitable for point-of-use applications where time is critical [4]. Microfluidic biosensors further enhance throughput capabilities through parallel processing of multiple samples, automating labor-intensive steps, and reducing hands-on time [6].

Portability and Point-of-Need Applications

Perhaps the most transformative advantage of biosensors is their compatibility with portable, point-of-need applications. Unlike conventional methods that require sophisticated laboratory infrastructure, biosensors can be engineered into compact, user-friendly devices suitable for field use [3] [4] [6]. The integration of biosensors with microfluidic platforms and lateral flow strips creates systems that require minimal technical expertise, enabling deployment in restaurants, homes, and food production facilities [3] [6]. This addresses a critical gap in food safety monitoring, as more than half of food allergy reactions occur in restaurant settings despite staff notification of allergies [3].

Table 3: Comprehensive Method Comparison for Allergen Detection

| Performance Characteristic | ELISA | PCR | Mass Spectrometry | Biosensors |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sensitivity | 1-25 ppm [4] | Varies by target | 0.01 ng/mL [5] | 0.04 ng/mL - 10 aM [3] [7] |

| Analysis Time | Up to 3.5 hours [4] | 2-4 hours | 1-2 hours | Minutes to 1 hour [3] |

| Quantitative Capability | Excellent | Good to excellent | Excellent | Good to excellent |

| Multiplexing Capacity | Limited | Moderate | High | Moderate to high |

| Equipment Cost | Moderate | Moderate | High | Low to moderate |

| Portability | Low | Low | Low | High [3] [6] |

| Ease of Use | Moderate training required | Specialized training required | Extensive training required | Simple to moderate [3] |

| Approval Status | Widely accepted and validated | Accepted in some jurisdictions [2] | Gaining acceptance | Emerging validation |

Technology Integration and Pathway Analysis

The evolution of allergen detection technologies follows a clear trajectory toward integration, miniaturization, and intelligence. The signaling pathways and technological relationships in advanced biosensing platforms can be visualized through the following workflow:

This integration pathway highlights the convergence of multiple technological approaches, from sample processing to detection output, enabling the development of comprehensive allergen detection systems that address the limitations of conventional methods.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

The development and implementation of advanced allergen detection methods require specialized reagents and materials optimized for specific technological platforms.

Table 4: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Allergen Detection Development

| Reagent/Material | Function | Application Examples | Technical Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Recombinase Polymerase Amplification (RPA) Kits | Isothermal nucleic acid amplification | CRISPR-DETECTR platforms [3] | Maintain at recommended storage temperatures; optimize primer design for target sequences |

| CRISPR-Cas12a Enzymes | Target-specific recognition and collateral cleavage | Nucleic acid-based allergen detection [3] | Requires specific crRNA design; activity varies by buffer conditions |

| Chromoprotein-Quencher Systems (amilCP) | Visual signal generation | Lateral flow biosensors [3] | Provides color change visible to naked eye; consider colorblind accessibility |

| Gold Nanoparticles | Signal amplification, electrode modification | Electrochemical and optical biosensors [7] [4] | Control size distribution (10-20 nm optimal); functionalize surface for biomolecule conjugation |

| Graphene-Based Nanomaterials | Enhanced electron transfer, high surface area | Electrochemical sensor substrates [7] | Quality varies by synthesis method; optimize oxidation level for specific applications |

| Monoclonal/Polyclonal Antibodies | Specific allergen recognition | Immunoassays, immunosensors [2] [4] | Validate specificity for target epitopes; consider cross-reactivity with related proteins |

| Aptamers | Nucleic acid-based recognition elements | Alternative to antibodies in biosensors [4] | SELEX selection required; offers better stability than antibodies |

| Microfluidic Chip Substrates (PDMS, PMMA, Paper) | Miniaturized fluidic pathways | Microfluidic biosensors [6] | PDMS: optical transparency but protein adsorption; Paper: low cost but limited complexity |

The evolving landscape of allergen detection reflects a clear transition from conventional laboratory-based methods to advanced biosensing platforms that offer enhanced sensitivity, rapid analysis, and point-of-need capabilities. While traditional techniques like ELISA and PCR remain foundational for reference analysis and regulatory compliance, biosensors address critical gaps in the food safety ecosystem, particularly for rapid screening and field-deployable applications [2] [4].

Future developments in allergen detection will likely focus on several key areas. AI-enhanced testing and non-destructive diagnostics are reshaping allergen detection through methods such as hyperspectral imaging, Fourier Transform Infrared spectroscopy, and computer vision [5]. When combined with machine learning, these approaches allow non-destructive, real-time allergen detection without altering food integrity [5]. Multiplexed platforms capable of simultaneously detecting multiple allergens will address the growing need for comprehensive food safety assessment, particularly for products with complex ingredient profiles [5] [6]. Integration with cloud-based systems and Internet of Things technologies will enable real-time monitoring, data visualization, and predictive risk management across food production facilities [5].

The convergence of these technological advances with regulatory standards and public health priorities creates a compelling imperative for continued innovation in allergen detection. As these technologies mature, they will enable faster decision-making, enhance consumer safety, improve regulatory compliance, and ultimately reduce the public health burden of food allergies through more effective prevention and management strategies [5].

In the field of diagnostic science, certain conventional methods have established themselves as "gold standards" for the accurate detection and quantification of analytes due to their proven reliability, sensitivity, and specificity. Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay (ELISA), Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR), and Liquid Chromatography-Tandem Mass Spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) represent three pillars of analytical techniques widely used in clinical, research, and environmental settings [8] [9]. These methods provide the benchmark against which emerging technologies, such as novel biosensors, are evaluated [10]. This guide provides a comprehensive comparison of these established techniques, detailing their fundamental principles, experimental protocols, and analytical performance to serve as a reference for researchers and developers validating new diagnostic platforms.

Table 1: Core Principles and Applications of Gold Standard Methods

| Method | Fundamental Principle | Primary Target | Common Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| ELISA | Antibody-antigen interaction with enzyme-mediated colorimetric detection [11] | Proteins, Antigens [10] | Clinical biomarkers (e.g., ferritin, cardiac markers), hormone detection, food allergens [8] [10] |

| PCR | Enzymatic amplification of specific DNA/RNA sequences | Nucleic Acids (DNA, RNA) [8] | Pathogen detection (e.g., SARS-CoV-2 [12]), food allergen detection from genetically modified organisms [8] |

| LC-MS/MS | Physical separation by liquid chromatography followed by mass-to-charge ratio analysis [9] | Small molecules, metabolites, proteins [13] [9] | Metabolomics, therapeutic drug monitoring, biomarker discovery and validation [13] [9] |

Principles and Experimental Protocols

Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay (ELISA)

The core principle of ELISA is the specific binding between an antibody and its target antigen, with detection achieved via an enzyme-linked conjugate that produces a measurable signal, typically a color change [11]. A common format is the sandwich ELISA, which is renowned for its high sensitivity [10].

Detailed Protocol for a Sandwich ELISA [10]:

- Coating: A capture antibody is immobilized onto the surface of a microplate well.

- Blocking: The well is treated with a blocking buffer (e.g., bovine serum albumin) to cover any remaining protein-binding sites, thereby minimizing non-specific binding.

- Sample Incubation: The sample containing the target antigen is added. If the antigen is present, it binds to the capture antibody.

- Detection Antibody Incubation: A second, enzyme-conjugated detection antibody is added, which binds to a different epitope on the captured antigen, forming a "sandwich."

- Washing: Between each step, the well is thoroughly washed to remove unbound components.

- Signal Development: A substrate solution is added. The enzyme conjugated to the detection antibody catalyzes a reaction that converts the substrate into a colored product.

- Signal Measurement & Quantification: The reaction is stopped, and the intensity of the color is measured spectrophotometrically. The signal intensity is proportional to the amount of antigen present in the sample, and quantification is achieved by comparison to a standard curve.

Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR)

PCR is a molecular technique that amplifies a specific region of DNA (or RNA, via reverse transcription) through repetitive thermal cycling, enabling the detection of trace amounts of nucleic acids [8]. Real-time PCR (qPCR) allows for the quantification of the amplified DNA by monitoring the fluorescence signal at each cycle.

Detailed Protocol for Real-Time PCR [12]:

- Nucleic Acid Extraction: The target DNA or RNA is purified from the sample matrix (e.g., nasopharyngeal swab, food sample).

- Reverse Transcription (if targeting RNA): For RNA viruses like SARS-CoV-2, the RNA is first transcribed into complementary DNA (cDNA) using a reverse transcriptase enzyme [12].

- Reaction Setup: The extracted DNA (or cDNA) is mixed with a master mix containing:

- Primers: Short, specific DNA sequences that flank the target region.

- Nucleotides: The building blocks (dNTPs) for new DNA strands.

- DNA Polymerase: A thermostable enzyme that synthesizes new DNA.

- Probe: A sequence-specific oligonucleotide with a fluorescent reporter and quencher (e.g., TaqMan probe).

- Amplification & Detection: The mixture is placed in a thermal cycler and subjected to repeated cycles of:

- Denaturation: High temperature (~95°C) separates the double-stranded DNA.

- Annealing: Lower temperature allows primers to bind to their specific target sequences.

- Extension: The DNA polymerase extends the primers, synthesizing new DNA strands. During this step, the probe is cleaved, separating the reporter from the quencher and generating a fluorescent signal.

- Quantification: The instrument measures the fluorescence in real-time. The cycle threshold (Ct), the point at which the fluorescence crosses a predetermined background level, is used for quantification. A lower Ct value indicates a higher initial concentration of the target [12].

Liquid Chromatography-Tandem Mass Spectrometry (LC-MS/MS)

LC-MS/MS combines the physical separation capabilities of liquid chromatography with the highly specific and sensitive detection of tandem mass spectrometry [9]. It is particularly valued for its ability to accurately quantify a wide range of analytes in complex biological matrices.

Detailed Protocol for a Quantitative LC-MS/MS Assay [14]:

- Sample Preparation: The sample (e.g., serum, tissue, sewage sludge) undergoes processing, which may include protein precipitation, solid-phase extraction (SPE), or other cleanup methods to remove interfering matrix components [14].

- Internal Standard Addition: A known amount of an isotopically labeled internal standard (e.g., erythromycin-13C2) is added to the sample. This standard corrects for analyte loss during preparation and matrix effects during ionization [9] [14].

- Liquid Chromatography (LC): The sample extract is injected into the LC system, where analytes are separated based on their chemical properties (e.g., hydrophobicity) as they pass through a chromatographic column.

- Ionization: The eluted analytes are ionized, typically using Electrospray Ionization (ESI), to form gas-phase ions.

- Mass Analysis (Tandem MS): The ions are first analyzed in the first mass analyzer (MS1) to select the precursor ion of the target analyte. The selected ions are then fragmented in a collision cell, and the resulting product ions are analyzed in the second mass analyzer (MS2).

- Detection & Quantification: The detector records a signal for a specific precursor-product ion transition for each analyte. The peak area of the analyte is compared to the peak area of the internal standard. Quantification is achieved by referencing a calibration curve prepared with known concentrations of the authentic standard [14].

Figure 1: LC-MS/MS Analytical Workflow. The process involves sample preparation, chromatographic separation, ionization, and two stages of mass spectrometric analysis for highly specific detection and quantification [9] [14].

Performance Comparison and Experimental Data

The choice among ELISA, PCR, and LC-MS/MS is dictated by the specific analytical requirements. The following table and experimental data highlight their comparative performance.

Table 2: Analytical Performance Comparison of ELISA, PCR, and LC-MS/MS

| Performance Metric | ELISA | PCR | LC-MS/MS |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sensitivity | High (immunoassay-based) [10] | Extremely High (can detect few copies) [12] | Very High (zeptomole range for HRP) [15] |

| Specificity | High (antibody-dependent) [11] | Very High (primer/probe sequence-dependent) | Very High (mass resolution-dependent) [9] |

| Multiplexing Capability | Low to Moderate [8] | Moderate to High (multiplex panels) | High (can analyze 1000s of features) [9] |

| Throughput | High (96-well plate format) | High | Moderate to High [9] |

| Analysis Time | Few hours [8] | Few hours [8] | Longer (includes separation time) |

| Quantification Accuracy | Good (can be affected by cross-reactivity) | Excellent (based on Ct value) [12] | Excellent (with isotope dilution) [9] [14] |

Experimental Data from Validation Studies

ELISA vs. Photonic Crystal Biosensor: A method comparison study for ferritin detection demonstrated that while a novel photonic crystal (PC) biosensor showed promise, its total calculated error (TEcalc) exceeded the total allowable error (TEa) when certified ELISAs were used as the reference method. This underscores the reliability of ELISA as a benchmark, while also indicating areas for optimization in newer platforms [10].

PCR vs. Rapid Antigen Test (RAT): The performance of the Standard Q COVID-19 RAT was evaluated against rRT-PCR. The study found that while the RAT had 100% specificity, its clinical sensitivity was highly dependent on the viral load. For samples with an RdRp Ct value ≤ 23.37 (high viral load), the RAT's sensitivity was 81.4%. However, for all specimens, the overall sensitivity dropped to 28.7%, highlighting the superior sensitivity of PCR for low-level detection [12].

LC-MS/MS Quantification Methods: A systematic study on antibiotic quantification in biosolids revealed that the choice of quantification method in LC-MS/MS significantly impacts results. Using external calibration alone led to substantial over- or under-estimation (e.g., 110–450% overestimation for erythromycin). The most accurate results were achieved using isotope dilution with an authentic target analog, which effectively compensates for matrix effects and analyte loss, showcasing a key advantage of LC-MS/MS for precise quantification in complex matrices [14].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

The successful application of these gold standard methods relies on a set of critical reagents, each with a specific function.

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions and Their Functions

| Reagent / Material | Function | Associated Method |

|---|---|---|

| Capture & Detection Antibodies | Biological recognition elements that provide specificity by binding to the target antigen. | ELISA [11] [10] |

| Primers and Probes | Short nucleic acid sequences that dictate the specificity of the amplification by binding to complementary target DNA/RNA. | PCR [12] |

| Isotopically Labeled Internal Standards | Chemically identical analogs of the analyte with heavy isotopes; used for precise normalization and compensation of matrix effects. | LC-MS/MS [9] [14] |

| Horseradish Peroxidase (HRP) | A common enzyme used in conjugates to catalyze a colorimetric, chemiluminescent, or fluorescent reaction for signal generation. | ELISA, Biosensors [11] [15] |

| Functionalized Iron-Oxide Nanoparticles (fAb-IONs) | Magnetic nanoparticles conjugated with antibodies; used for efficient extraction and purification of target antigens from complex samples like serum. | ELISA, PC Biosensor [10] |

ELISA, PCR, and LC-MS/MS each possess distinct strengths that solidify their status as gold standard methods. ELISA offers robust, high-throughput protein detection. PCR provides unparalleled sensitivity and specificity for nucleic acid amplification. LC-MS/MS delivers exceptional versatility, multiplexing capability, and quantification accuracy for a broad spectrum of molecules. The choice of method depends fundamentally on the analyte of interest and the required analytical performance. These established techniques provide the essential benchmark for validation and performance comparison of emerging analytical technologies, including modern biosensors.

The field of biosensing is revolutionizing diagnostic and monitoring capabilities across healthcare, food safety, and environmental protection. Biosensors are analytical devices that integrate a biological recognition element with a physicochemical transducer to produce a measurable signal proportional to the concentration of a target analyte [16]. This technological rise represents a paradigm shift from conventional laboratory-based detection methods, offering the potential for rapid, sensitive, and on-site analysis.

The core of any biosensor lies in two fundamental processes: bio-recognition, where a specific biological element selectively interacts with the target, and signal transduction, where this interaction is converted into a quantifiable output [16]. This guide provides a comparative evaluation of biosensor performance against traditional allergen detection methods, presenting structured experimental data and protocols to inform researchers and drug development professionals. We focus specifically on food allergen detection as a key application area where biosensors demonstrate significant advantages in sensitivity, speed, and portability [8].

Performance Comparison: Biosensors vs. Conventional Allergen Detection Methods

Traditional techniques for food allergen detection, such as enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA), polymerase chain reaction (PCR), and liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS), have been the cornerstone of analytical testing. However, emerging biosensing technologies increasingly challenge their dominance, particularly for applications requiring rapid, on-site analysis [8].

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Allergen Detection Technologies

| Technology | Detection Principle | Typical LOD | Analysis Time | Multiplexing Capability | Portability | Key Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ELISA | Antibody-Antigen Binding | Moderate (ng-mcg/mL) | Hours | Low | Low | Laboratory confirmation |

| PCR | Nucleic Acid Amplification | High (pg-ng/mL) | 2-4 hours | Moderate | Low | Official analysis (Germany, Japan) |

| LC-MS/MS | Mass Spectrometry | High (pg-ng/mL) | Hours | High | Low | High-throughput lab testing |

| Electrochemical Biosensors | Electron Transfer | High (fM-nM) [17] | Minutes | Developing | High | Point-of-care, on-site screening |

| Optical Biosensors | Refractive Index/Luminescence | High (fM-nM) | Minutes | High | Moderate | Clinical diagnostics, food safety |

Table 2: Quantitative Performance Data for Emerging Biosensing Technologies in Food Allergen Detection

| Biosensing Technology | Target Allergen | Recognition Element | Linear Range | Limit of Detection (LOD) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Colorimetric LFA | Peanut | Antibody | 0.5–50 ng/mL | 0.5 ng/mL | [8] |

| Electrochemical Immunosensor | Tropomyosin | Antibody | 1–100 ng/mL | 0.3 ng/mL | [8] |

| Fluorescent Aptasensor | Major peanut allergen (Ara h 1) | Aptamer | 0.5–1000 ng/mL | 0.16 ng/mL | [8] |

| SERS Biosensing | Milk allergen (β-lactoglobulin) | Antibody | 0.01–100 ng/mL | 0.008 ng/mL | [8] |

The comparative data reveals that emerging biosensors consistently match or surpass the sensitivity of traditional methods like ELISA while offering significantly reduced analysis times. Furthermore, biosensors integrated into portable platforms such as lateral flow assays (LFAs) and microfluidic devices enable on-site detection capabilities that are simply not feasible with conventional techniques [8]. This addresses critical needs in food safety management, allowing for rapid screening throughout the production chain rather than relying solely on end-product laboratory testing.

Experimental Protocols for Biosensor Development and Validation

To ensure reliable and reproducible results, researchers follow standardized experimental protocols for biosensor development. The following sections detail key methodologies cited in recent literature.

Aptamer Characterization via Fluorescence Titration and Isothermal Titration Calorimetry (ITC)

Objective: To discover and characterize DNA aptamers for specific targets (e.g., bilirubin and biliverdin) by determining binding affinity and thermodynamic parameters.

Materials:

- Synthesized DNA aptamer candidates

- Target analytes (e.g., biliverdin, bilirubin)

- Thioflavin T (ThT) dye

- Binding buffer (appropriate pH and ionic strength)

- Fluorescence spectrophotometer

- Isothermal Titration Calorimeter

Procedure:

- Aptamer Preparation: Dilute the DNA aptamer in binding buffer and anneal by heating to 95°C for 5 minutes, followed by gradual cooling to room temperature.

- Fluorescence Titration:

- Prepare a solution containing the aptamer and ThT dye.

- Titrate with increasing concentrations of the target analyte.

- Measure fluorescence emission intensity at each addition.

- Plot fluorescence intensity versus analyte concentration to generate binding curves and calculate dissociation constant (Kd).

- Isothermal Titration Calorimetry:

- Load the aptamer solution into the sample cell and the target analyte into the syringe.

- Perform sequential injections of the analyte into the aptamer solution.

- Measure the heat absorbed or released with each injection.

- Integrate heat data and fit to an appropriate binding model to determine Kd, enthalpy change (ΔH), and entropy change (ΔS).

Validation: This protocol enabled the identification of a biliverdin aptamer with a Kd of 6 nM and LOD of 0.7 nM, and a bilirubin aptamer with a Kd of 203 nM and LOD of 47 nM, confirmed through orthogonal techniques [18].

Development of Electrochemical Immunosensors Using Nanomaterial-Modified Electrodes

Objective: To construct an ultrasensitive electrochemical immunosensor for biomarker detection (e.g., BRCA-1) using nanocomposite-modified electrodes.

Materials:

- Disposable pencil graphite electrodes

- Gold nanoparticles (AuNPs)

- Molybdenum disulfide (MoS₂)

- Chitosan (CS)

- Monoclonal anti-BRCA-1 antibodies

- BRCA-1 antigen standards

- Electrochemical workstation with potentiostat

Procedure:

- Electrode Modification:

- Prepare a nanocomposite suspension of AuNPs, MoS₂, and CS.

- Drop-cast the nanocomposite onto the surface of pre-polished pencil graphite electrodes and dry.

- Antibody Immobilization:

- Incubate the modified electrode with anti-BRCA-1 antibody solution.

- Wash to remove unbound antibodies.

- Electrochemical Measurement:

- Incubate the immunosensor with BRCA-1 antigen standards or samples.

- Perform electrochemical detection using differential pulse voltammetry (DPV) or electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS).

- Measure current or impedance changes correlated with antigen concentration.

Validation: The constructed immunosensor demonstrated a linear detection range of 0.05–20 ng/mL for BRCA-1 with an LOD of 0.04 ng/mL, high reproducibility (RSD 3.59%), and maintained 98 ± 3% recovery in spiked serum samples [7].

Signaling Pathways and Experimental Workflows in Biosensing

The following diagrams illustrate core signaling pathways and experimental workflows fundamental to biosensor operation, based on transduction mechanisms described in the research literature.

Electrochemical Biosensor Signal Transduction Pathway

Workflow for Aptamer Characterization and Biosensor Development

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

The development and implementation of high-performance biosensors rely on specialized reagents and materials. The following table details key components essential for biosensor research and development.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Biosensor Development

| Reagent/Material | Function | Example Applications |

|---|---|---|

| Nucleic Acid Aptamers | Synthetic recognition elements obtained via SELEX; offer high stability and specificity for targets | Bilirubin/biliverdin sensing [18], detection of small molecules, proteins |

| Monoclonal Antibodies | High-specificity biorecognition elements for antigen binding | Food allergen detection (e.g., tropomyosin) [8], cancer biomarkers (e.g., BRCA-1) [7] |

| Gold Nanoparticles (AuNPs) | Enhance electron transfer in electrochemical sensors; provide plasmonic effects in optical sensors | Electrode modification for immunosensors [7], SERS platforms [19] |

| Graphene & MoS₂ | 2D nanomaterials with high surface area and excellent electrical properties | Field-effect transistors (FETs), composite electrodes for improved sensitivity [7] |

| Thioflavin T (ThT) | Fluorescent dye that exhibits enhanced fluorescence upon binding to specific aptamer structures | Aptamer characterization via fluorescence titration [18] |

| Silver Nanoparticles (AgNPs) | Signal amplification in optical and electrochemical biosensors; drug delivery carriers | Plasmonic biosensors, monitoring drug release [20] |

| Molecularly Imprinted Polymers (MIPs) | Artificial receptors with tailor-made binding sites for specific molecules | Synthetic recognition elements as antibody alternatives [16] |

The comparative analysis presented in this guide demonstrates that biosensing technologies offer significant advantages over conventional detection methods, particularly in applications requiring rapid, sensitive, and on-site analysis such as food allergen monitoring. The core mechanisms of bio-recognition and signal transduction have evolved to provide detection capabilities that match or exceed traditional laboratory-based techniques while offering unprecedented portability and speed.

Future developments in biosensing will likely focus on integrating artificial intelligence for data interpretation, creating wearable biosensing systems, and developing IoT-connected platforms for real-time monitoring [17]. Furthermore, standardization of biosensor evaluation criteria, particularly concerning dynamic performance parameters such as response time and signal-to-noise ratio, will be critical for broader adoption in clinical and industrial settings [21]. As these technologies continue to mature, they hold the potential to transform diagnostic paradigms across healthcare, food safety, and environmental monitoring.

In the fields of food safety, clinical diagnostics, and pharmaceutical development, the reliability of analytical methods hinges on rigorously defined performance metrics. Sensitivity, specificity, and limit of detection (LOD) form the fundamental triad that determines whether a detection method can be trusted for critical decision-making. These parameters take on heightened importance when evaluating emerging biosensing technologies against established conventional methods, particularly in applications with significant public health implications such as allergen detection in foods [2] [22].

The global rise in food allergy prevalence has intensified the need for highly accurate detection methods, as avoidance remains the primary preventive strategy for susceptible individuals [2]. This comparative guide objectively examines how modern biosensors perform against traditional techniques like enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) and polymerase chain reaction (PCR), providing researchers with a structured framework for method selection and validation. By synthesizing current experimental data and standardized protocols, this analysis offers evidence-based insights into the evolving landscape of allergen detection technologies.

Defining the Core Performance Metrics

Limit of Detection (LOD)

The limit of detection represents the lowest concentration of an analyte that can be reliably distinguished from its absence. Formally defined as the minimum analyte concentration that produces a signal significantly different from the blank (typically with a signal-to-noise ratio of 3:1), LOD establishes the fundamental detection capability of an analytical method [22] [23]. While a lower LOD is often pursued as a marker of technological advancement, its practical importance varies significantly across applications. In food allergen detection, LOD values must be evaluated against clinically relevant thresholds established by regulatory bodies, which typically range from 0.1 to 20 mg/kg depending on the specific allergen and jurisdiction [2] [24].

Sensitivity

In analytical chemistry, sensitivity refers to the ability of a method to detect minute differences in analyte concentration, quantitatively expressed as the change in instrument response per unit change in analyte concentration [22]. Method sensitivity directly impacts the precision of quantitative measurements and determines whether a technique can monitor concentration changes within biologically or toxicologically relevant ranges. For biosensors, sensitivity is often enhanced through material engineering approaches that increase the available electrochemical interface, such as three-dimensional porous nanostructures that allow dense immobilization of bioreceptors [22].

Specificity

Specificity describes a method's capacity to detect only the target analyte without cross-reactivity to similar compounds or matrix interferences [25]. In immunochemical methods, specificity is determined by the molecular recognition properties of antibodies toward specific epitopes, while nucleic acid-based methods achieve specificity through complementary base pairing. High specificity is particularly challenging in complex food matrices where non-target components may resemble the analyte structurally or produce similar signals. Biosensors address this challenge through sophisticated surface chemistry and biorecognition elements that minimize nonspecific binding while maintaining affinity for the intended target [25] [26].

Comparative Performance Analysis: Biosensors vs. Conventional Methods

Table 1: Performance comparison of major allergen detection methodologies

| Method Type | Representative LOD | Key Strengths | Key Limitations | Detection Time | Multiplexing Capability |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Immunoassays (ELISA) | 0.1-5 mg/kg [2] | High specificity, standardized protocols | Protein structure dependency, antibody cross-reactivity | 2-4 hours | Low to moderate |

| PCR Methods | 1-10 mg/kg [2] | Effective for processed foods, high specificity | Indirect detection, does not detect proteins directly | 1-3 hours | Moderate |

| Mass Spectrometry | 0.01-1 mg/kg [5] | High specificity and sensitivity, multiplexing | Expensive instrumentation, complex sample prep | 30 min - 2 hours | High |

| Biosensors | 0.01-0.1 mg/kg [5] [27] | Rapid response, portability, high sensitivity | Matrix effects, limited commercialization | 1 second - 30 minutes | Variable |

Table 2: Experimental performance data for specific detection platforms

| Technology Platform | Target Analyte | Reported LOD | Linear Range | Specificity Assessment | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PCB Biosensor | HER2/CA15-3 biomarkers | 10⁻¹⁵ g/mL [27] | Not specified | Clinical validation with 29 saliva samples | [27] |

| Photonic Ring Resonator | IL-17A, CRP | Not specified | Clinically relevant ranges | Reference subtraction for nonspecific binding | [25] |

| Lateral Flow Immunoassay | Gluten | 20 mg/kg (CAC standard) [2] | Not specified | Visual detection, suitable for on-site use | [2] |

| Real-time PCR | Fish parvalbumin gene | Single copy detection [2] | 5 orders of magnitude | Species-specific detection | [2] |

| Electrochemical Biosensor | Tropomyosin | 0.01 ng/mL [5] | Not specified | Aptamer-based recognition | [2] |

Performance Trade-offs and Method Selection Considerations

The comparative data reveal significant trade-offs between conventional methods and emerging biosensor technologies. While ELISA offers well-established protocols and regulatory acceptance, its susceptibility to protein denaturation during food processing represents a substantial limitation [2]. PCR methods circumvent this issue by targeting more stable DNA markers but provide only indirect evidence of allergen presence since the problematic molecules are proteins, not nucleic acids [2].

Biosensors demonstrate remarkable improvements in detection speed and sensitivity, with some platforms achieving results within seconds and detecting attomolar concentrations [27]. However, these advanced systems face challenges related to matrix effects, nonspecific binding, and limited commercial availability [25] [23]. The optimal method selection depends heavily on the application context—while clinical settings may prioritize specificity and regulatory compliance, manufacturing environments often value speed and portability for rapid decision-making.

Experimental Protocols for Method Validation

Protocol 1: Validation of Biosensor Specificity Using Reference Probes

Background: Specificity validation is particularly challenging for label-free biosensors due to nonspecific binding (NSB) of matrix constituents in complex samples like serum or food extracts. A systematic framework inspired by FDA guidelines provides a standardized approach for control probe selection [25].

Materials:

- Photonic microring resonator (PhRR) sensors or comparable biosensor platform

- Target capture antibodies (e.g., anti-IL-17A, anti-CRP)

- Panel of negative control proteins (BSA, isotype-matched antibodies, cytochrome c, anti-FITC)

- Complex sample matrix (serum, food extract)

- Microfluidic packaging system with pressure-sensitive adhesive and PDMS gaskets

- Sterile PBS and assay diluents

Procedure:

- Functionalize sensor chips with capture antibodies and control probes in a multiplexed layout

- Package sensors in microfluidic devices using layer-by-layer assembly of PSA and PDMS

- Introduce sample matrices containing target analytes at clinically relevant concentrations

- Measure wavelength shifts for both specific capture and reference probes

- Calculate specific binding by subtracting reference signals from capture signals

- Evaluate control probe performance based on linearity, accuracy, and selectivity parameters

Validation Metrics: The optimal reference control varies by analyte. Experimental data indicate that while isotype-matching is conceptually appealing, the best-performing reference differs between targets—BSA scored highest (83%) for IL-17A detection, while a rat IgG1 isotype control performed best (95%) for CRP assays [25].

Protocol 2: LOD and Sensitivity Determination for Electrochemical Biosensors

Background: This protocol outlines the characterization of key analytical parameters for electrochemical biosensors, using allergen detection as an application example.

Materials:

- Glucose test strips (bare carbon electrode structure without enzymes)

- Ozone cleaner and ammonium hydroxide solution

- 3-Mercaptopropanyl-N-hydroxysuccinimide ester (NHS ester) in ethanol

- Target-specific antibodies (e.g., anti-tropomyosin, anti-Bos d 5)

- Ethanolamine blocking solution

- Electrochemical workstation with Bluetooth capability for data transmission

- Standard solutions of target allergen at varying concentrations

Procedure:

- Perform surface cleaning via ozone treatment (15 minutes) followed by ammonium hydroxide wash

- Functionalize electrode surface with NHS ester solution (2-hour immersion)

- Immobilize specific antibodies (20 μg/mL) by introducing to microfluidic channels

- Seal strips and refrigerate at 4°C for 18 hours

- Deactivate unreacted groups with ethanolamine

- Introduce standard solutions across clinically relevant concentration range

- Measure electrical signals (current-voltage characteristics, capacitance)

- Plot calibration curve of signal response versus analyte concentration

- Calculate LOD as mean blank signal plus three standard deviations

- Determine sensitivity as slope of the linear portion of the calibration curve

Validation Metrics: This approach has demonstrated exceptional sensitivity, with reported LOD values as low as 10⁻¹⁵ g/mL for protein biomarkers—4-5 orders of magnitude more sensitive than conventional ELISA [27].

Visualizing Biosensor Performance Evaluation

Diagram 1: A systematic framework for evaluating biosensor performance against conventional methods, emphasizing the interconnected relationship between core metrics and experimental validation.

Diagram 2: Experimental workflow for biosensor specificity validation using reference controls to account for nonspecific binding in complex sample matrices.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key research reagents and materials for biosensor development and validation

| Reagent/Material | Function | Application Examples | Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| NHS Ester Chemistry | Bioconjugation agent for immobilizing amine-containing biomolecules | Antibody attachment to sensor surfaces | Provides reactive sites for stable biorecognition element attachment [27] |

| Photonic Ring Resonators | Label-free detection via refractive index changes | Molecular binding kinetics studies | Enables reference subtraction for nonspecific binding [25] |

| Isotype-Matched Control Antibodies | Negative controls for specificity validation | Assessing nonspecific binding in immunoassays | Performance varies by target; requires empirical optimization [25] |

| Carbon Electrode Test Strips | Disposable sensing platforms | Electrochemical biosensors | Enable reusable PCB systems with disposable sensing elements [27] |

| Microfluidic Packaging Systems | Sample handling and delivery | Integrated biosensor systems | Incorporate PDMS gaskets and pressure-sensitive adhesives [25] |

| Phage Display Libraries | Source of novel binding elements | Aptamer and affinity reagent development | Alternative to traditional antibodies for recognition elements |

| Three-Dimensional Nanomaterials | Signal amplification | Enhancing sensor sensitivity | High surface-to-volume ratio improves signal magnitude [22] |

The comparative analysis of performance metrics reveals a nuanced landscape where no single detection technology universally outperforms all others across all parameters. Instead, method selection requires careful consideration of application-specific requirements, particularly the clinically or regulatory relevant concentration ranges for the target analyte [23].

Traditional methods like ELISA and PCR maintain important advantages in standardization, regulatory acceptance, and established performance characteristics [2] [24]. However, emerging biosensor technologies offer compelling benefits in detection speed, sensitivity, and potential for portability that make them increasingly suitable for point-of-need applications [5] [27]. The experimental data indicate that biosensors can achieve remarkable detection limits, with some platforms demonstrating up to 10⁻¹⁵ g/mL sensitivity for protein biomarkers—significantly surpassing conventional ELISA [27].

Future developments in biosensor technology will likely focus on balancing the pursuit of ultra-low LODs with practical utility, addressing challenges related to matrix effects, reproducibility, and commercial scalability [22] [23]. For researchers and drug development professionals, this evolving landscape presents opportunities to implement detection strategies that align technical capabilities with real-world application requirements, ultimately enhancing food safety, diagnostic accuracy, and public health protection.

Biosensing in Action: Methodological Advances and Integrated Platforms

Biosensors are analytical devices that combine a biological recognition element with a physicochemical transducer to detect target analytes. The integration of biological specificity with sensitive signal transduction has established biosensors as powerful tools in clinical diagnostics, food safety, and environmental monitoring. The performance of any biosensing platform is fundamentally determined by its transduction mechanism, which directly influences sensitivity, selectivity, and practical applicability.

This guide provides a systematic comparison of three principal biosensing modalities: electrochemical, optical, and Surface-Enhanced Raman Spectroscopy (SERS)-based systems. Framed within the context of detecting food allergens—an area where conventional methods like Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay (ELISA) and Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR) face limitations in cost, speed, and portability—this analysis evaluates emerging biosensor technologies against traditional benchmarks. For researchers and drug development professionals, understanding the operational principles, performance parameters, and experimental requirements of each modality is crucial for selecting the appropriate technology for specific applications.

Performance Comparison of Biosensing Modalities

The quantitative performance of electrochemical, optical, and SERS-based biosensors varies significantly across key metrics, influencing their suitability for different research or diagnostic applications. Table 1 summarizes the typical performance characteristics and comparative advantages of each modality.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Biosensing Modalities

| Modality | Typical Limit of Detection (LOD) | Key Advantages | Common Bioreceptors | Representative Application |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Electrochemical | Picomolar to femtomolar range [28] | High sensitivity, portability, low cost, miniaturization, works in turbid samples [29] | Enzymes, Antibodies, Aptamers, Cells [29] | Glucose monitoring, Food allergen detection (e.g., Ovalbumin) [30] [28] |

| Optical (General) | Varies by technique (e.g., SPR: ng/mL) [28] | Label-free detection, real-time monitoring, high specificity [31] | Antibodies, Nucleic acids [31] | Biomolecular interaction analysis, Body fat estimation [32] |

| SERS | Single-molecule level (in ideal conditions) [33] | Multiplexing capability, fingerprint identification, resistance to photobleaching [33] | Antibodies, Aptamers [19] [33] | Cancer biomarker detection (e.g., α-Fetoprotein) [19] |

Electrochemical biosensors transduce a biological recognition event into an electronic signal (current, potential, or impedance change). They are renowned for their exceptional sensitivity, often achieving detection limits in the picomolar to femtomolar range for food allergens [28]. A key advantage is their compatibility with miniaturized, portable, and low-cost point-of-care devices, as they are less affected by turbid samples or optically absorbing compounds compared to optical methods [29].

Optical biosensors, such as those based on Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR), detect changes in the optical properties of a sensor surface. SPR measures the change in the refractive index upon analyte binding, enabling real-time, label-free monitoring of biomolecular interactions [31]. While some optical sensors for egg white allergens report limits of detection in the ng/mL range [28], advanced configurations can achieve higher sensitivity. For instance, a fiber-optic SPR sensor using CdSe-ZnCdS quantum dots demonstrated a sensitivity of 3540 nm/RIU for body fat estimation [32].

SERS-based biosensors leverage the enormous enhancement of Raman scattering signals from molecules adsorbed on or near nanostructured metallic surfaces, typically gold or silver [33]. This plasmonic enhancement can boost signals by factors of 10⁶ to 10⁸, enabling detection down to the single-molecule level under ideal conditions [33]. SERS provides a unique "fingerprint" identification of molecules and allows for multiplexed detection using a single wavelength excitation source [33]. Recent developments include the use of spiky Au-Ag nanostars to create powerful SERS platforms for detecting cancer biomarkers like α-fetoprotein [19].

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

The reliability and performance of a biosensor are directly tied to the rigor of its experimental design and fabrication. Below are detailed protocols representative of each modality.

Electrochemical Immunosensor for Biomarker Detection

The development of a electrochemical immunosensor for the cancer biomarker BRCA-1 illustrates a common protocol involving nanomaterial-enhanced electrodes [7].

Workflow Overview:

- Electrode Modification: A pencil graphite electrode (PGE) is sequentially modified with chitosan (CS), molybdenum disulfide (MoS₂), and gold nanoparticles (AuNPs). Chitosan provides a biocompatible film, MoS₂ offers a high surface area and catalytic activity, and AuNPs facilitate electron transfer and antibody immobilization.

- Antibody Immobilization: Anti-BRCA-1 antibodies are immobilized onto the AuNP-modified surface, typically through covalent coupling or physical adsorption.

- Blocking: The remaining active sites on the electrode are blocked with a non-reactive protein (e.g., Bovine Serum Albumin) to prevent non-specific binding.

- Detection and Measurement: The immunosensor is incubated with the sample containing BRCA-1. The formation of the antigen-antibody complex hinders electron transfer at the electrode surface. The detection is performed using electrochemical techniques like differential pulse voltammetry (DPV) or electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS) in a solution containing a redox probe like [Fe(CN)₆]³⁻/⁴⁻. The change in current or impedance is proportional to the analyte concentration.

This sensor achieved a linear detection range of 0.05–20 ng/mL and an LOD of 0.04 ng/mL, showcasing the high sensitivity attainable with electrochemical platforms [7].

SERS-Based Immunoassay for Protein Detection

A protocol for a SERS-based immunoassay for α-fetoprotein (AFP) utilizes the intense plasmonic properties of metallic nanostructures [19].

Workflow Overview:

- Substrate Fabrication: Spiky Au-Ag nanostars are synthesized as the SERS-active substrate. Their sharp tips act as "hotspots" generating intense electromagnetic fields for signal enhancement.

- Functionalization: The nanostars are functionalized with a capture antibody specific to the target protein (AFP).

- Immunocomplex Formation: The sample is introduced, and the target analyte binds to the capture antibody.

- Signal Generation with Raman Reporter: A secondary antibody, labeled with a Raman reporter molecule (e.g., malachite green), is added to form a sandwich immunocomplex. The reporter molecule provides a characteristic SERS signal upon laser excitation.

- Measurement and Analysis: The substrate is irradiated with a laser, and the SERS spectrum is collected. The intensity of the Raman reporter's characteristic peak is quantified and correlated with the analyte concentration.

This liquid-phase SERS platform addresses limitations in cancer biomarker detection by offering high sensitivity and specificity [19].

Fiber-Optic SPR Sensor with Quantum Dots

A protocol for a quantum dot-enhanced SPR sensor demonstrates the fusion of optical sensing with advanced nanomaterials for body fat estimation [32].

Workflow Overview:

- Fiber Preparation: A germanium dioxide (GeO₂) core optical fiber with sodium fluoride (NaF) cladding is used.

- Metal Deposition: An optimized thin layer of silver is deposited on the fiber core.

- Quantum Dot Coating: The silver layer is coated with CdSe-ZnCdS core-shell quantum dots (QDs). The QDs enhance the evanescent field and modify the refractive index properties, boosting sensitivity.

- Interrogation and Sensing: Light is launched through the fiber. The resonance condition (the specific wavelength at which surface plasmons are excited) is monitored via wavelength interrogation. Changes in the resonance wavelength are directly related to changes in the refractive index of the surrounding medium (e.g., due to the adhesion of fat tissue). The sensor achieved a maximum sensitivity of 3540 nm/RIU [32].

Signaling Pathways and Experimental Workflows

The following diagrams illustrate the core enhancement mechanism of SERS and a generalized experimental workflow for electrochemical biosensing.

SERS Enhancement Mechanism

SERS enhancement arises from two primary mechanisms: the electromagnetic effect from plasmonic nanoparticles and the chemical effect from charge transfer [33].

Diagram 1: SERS enhancement mechanism involves electromagnetic and chemical effects.

Electrochemical Biosensor Workflow

The fabrication and operation of a typical nanomaterial-modified electrochemical immunosensor involves a sequence of critical steps [34] [7].

Diagram 2: Electrochemical biosensor development and detection workflow.

Research Reagent Solutions

The performance of modern biosensors is heavily dependent on the selection of nanomaterials and biological recognition elements. Table 2 details key reagents and their functions in biosensor development.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents for Biosensor Development

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function in Biosensor | Relevant Modality |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nanomaterials | Gold Nanoparticles (AuNPs) [33] [7], Graphene/Reduced Graphene Oxide (RGO) [34], Quantum Dots (CdSe-ZnCdS) [32], MXene Quantum Dots [31] | Enhance electron transfer, increase surface area, provide plasmonic enhancement, enable immobilization. | Electrochemical, Optical, SERS |

| Bioreceptors | Antibodies [19] [7], Aptamers [19] [28], Enzymes (Glucose Oxidase) [7] | Provide specific recognition and binding to the target analyte. | All |

| Electrode Materials | Gold [34], Indium Tin Oxide (ITO) [7], Pencil Graphite [7] | Serve as the transduction platform. Gold offers stability and easy functionalization. | Electrochemical |

| Signal Reporters | Raman Dyes (Malachite Green) [7], Enzymes (Horseradish Peroxidase), Redox Probes ([Fe(CN)₆]³⁻/⁴⁻) [34] | Generate a measurable signal (optical, electrochemical) upon analyte binding. | SERS, Electrochemical |

Electrochemical, optical, and SERS-based biosensing modalities each present a unique set of capabilities. Electrochemical sensors lead in miniaturization and cost-effectiveness for point-of-care testing, optical sensors like SPR excel in providing real-time, label-free interaction kinetics, and SERS offers unparalleled specificity and multiplexing potential.

The choice of biosensing modality depends on the specific application requirements, including the required sensitivity, need for portability, sample matrix, and available budget. The ongoing integration of novel nanomaterials like graphene, MXenes, and quantum dots is pushing the performance boundaries of all these platforms. For researchers in drug development and diagnostics, this comparative analysis provides a framework for selecting and optimizing the appropriate biosensing technology, ultimately contributing to advancements in healthcare, food safety, and personalized medicine. Future perspectives point toward the development of multi-modal sensors and the increased use of artificial intelligence for data analysis to further improve the accuracy and utility of biosensing systems.

The field of diagnostic testing is undergoing a revolutionary shift from centralized laboratory analyses toward decentralized, point-of-care (POC) testing. This transformation is largely driven by the development and refinement of lateral flow assays (LFAs) and paper-based microfluidic devices, which combine the principles of microfluidics with the practicality of paper substrates to create affordable, user-friendly, and rapid diagnostic platforms [35] [36]. These devices leverage capillary action to transport fluids through porous membranes without requiring external power sources, making them particularly valuable for resource-limited settings [36]. The COVID-19 pandemic dramatically accelerated the adoption and visibility of these technologies, with LFAs becoming household items for SARS-CoV-2 antigen detection [37] [38]. Beyond infectious disease diagnostics, these portable platforms have found significant applications in food safety monitoring, environmental surveillance, and clinical diagnostics, offering a compelling alternative to conventional methods such as enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays (ELISA), polymerase chain reaction (PCR), and liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) [39] [8].

This review objectively compares the performance of LFA and paper-based microfluidic biosensors against conventional allergen detection methods, focusing on analytical performance parameters including sensitivity, specificity, assay time, and operational requirements. We provide structured experimental data and detailed methodologies to enable researchers to evaluate the current capabilities and limitations of these portable platforms within the broader context of biosensor performance evaluation.

Lateral Flow Immunoassays (LFIs)

LFAs are membrane-based diagnostic tests that operate on capillary action to transport samples across various zones containing recognition elements. A typical LFA strip consists of four overlapping membranes: a sample pad for application, a conjugate pad containing labeled bioreceptors, a detection membrane (usually nitrocellulose) with immobilized capture lines, and an absorbent pad to maintain flow [40]. These components are often mounted on a backing card for structural support. The fundamental principle involves the migration of the liquid sample, which resuspends the labeled conjugates, allowing the formation of complexes that are captured at specific test lines to generate a detectable signal, typically within 5-20 minutes [39] [40].

LFAs primarily operate in two formats: sandwich and competitive immunoassays. Sandwich assays are used for larger analytes with multiple epitopes (e.g., proteins), where the intensity of the test line increases proportionally with target concentration [40]. In contrast, competitive formats are employed for small molecules or single-epitope targets, where the test line intensity decreases as analyte concentration increases—an inverse relationship that can be less intuitive for users [40]. Competitive assays offer the advantage of requiring only one bioreceptor and being insensitive to the "hook effect," a phenomenon where extremely high analyte concentrations can cause false-negative results in sandwich assays [39] [40].

Paper-Based Microfluidic Devices

Paper-based microfluidics, or "lab on paper," represents a significant evolution beyond simple lateral flow strips. These devices create precisely defined hydrophilic-hydrophobic channels on paper substrates to guide liquid flow in controlled pathways for complex analytical procedures [36]. The technology was pioneered by the Whitesides Group at Harvard University, though earlier work by Müller in 1949 on paraffin-patterned paper channels represents its rudimentary beginning [36].

Multiple fabrication techniques have been developed for creating microfluidic channels on paper, including wax printing, inkjet printing, photolithography, and laser treatment [36]. The fundamental principle across these techniques is patterning hydrophilic-hydrophobic contrasts on paper to create micron-scale capillary channels. More advanced devices incorporate passive fluidic circuits with functional elements such as multi-bi-material cantilever (B-MaC) assemblies, delay channels, and buffer zones to enable sequential reagent delivery for complex assays like paper-based ELISA (p-ELISA) [41].

A particularly innovative application is the microfluidic paper-based analytical device (μPAD) for quantitative p-ELISA, which seamlessly executes conventional ELISA steps in a paper-based format. This device utilizes a passive fluidic circuit that autonomously sequences the loading of wash solutions, substrates, and stop solutions onto the detection zone, completing assays in under 30 minutes with minimal reagent requirements and equipment needs [41].

Table 1: Comparison of LFA and Paper-Based Microfluidic Platforms

| Feature | Lateral Flow Assays | Paper-Based Microfluidic Devices |

|---|---|---|

| Principle | Capillary flow through sequential zones | Controlled capillary flow through patterned channels |

| Complexity | Relatively simple | Can accommodate complex multi-step assays |

| Assay Types | Primarily immunoassays | Immunoassays, chemical assays, enzymatic assays |

| Multiplexing Capability | Limited | Enhanced through multi-channel designs |

| Fabrication | Membrane stacking and lamination | Patterning techniques (wax printing, photolithography, etc.) |

| Quantification | Semi-quantitative (visual) | Quantitative with reader systems |

| Fluid Control | Limited control | Advanced control (delay channels, valves, buffers) |

| Typical Assay Time | 1-20 minutes | 10-30 minutes |

Detection Mechanisms and Signal Enhancement

Multiple detection mechanisms are employed in these platforms, ranging from simple colorimetric tests read by the naked eye to more sophisticated systems requiring dedicated readers. Colorimetric detection using gold nanoparticles (AuNPs) remains the most common approach due to its simplicity and low cost [41]. However, recent advancements have incorporated fluorescent, electrochemical, and surface-enhanced Raman spectroscopy (SERS) detection methods to improve sensitivity [8]. For instance, gold-platinum nanoflowers (AuPt NFs) in LFIAs have demonstrated a 100-fold improvement in detection limits compared to conventional AuNP-based LFIAs [41].