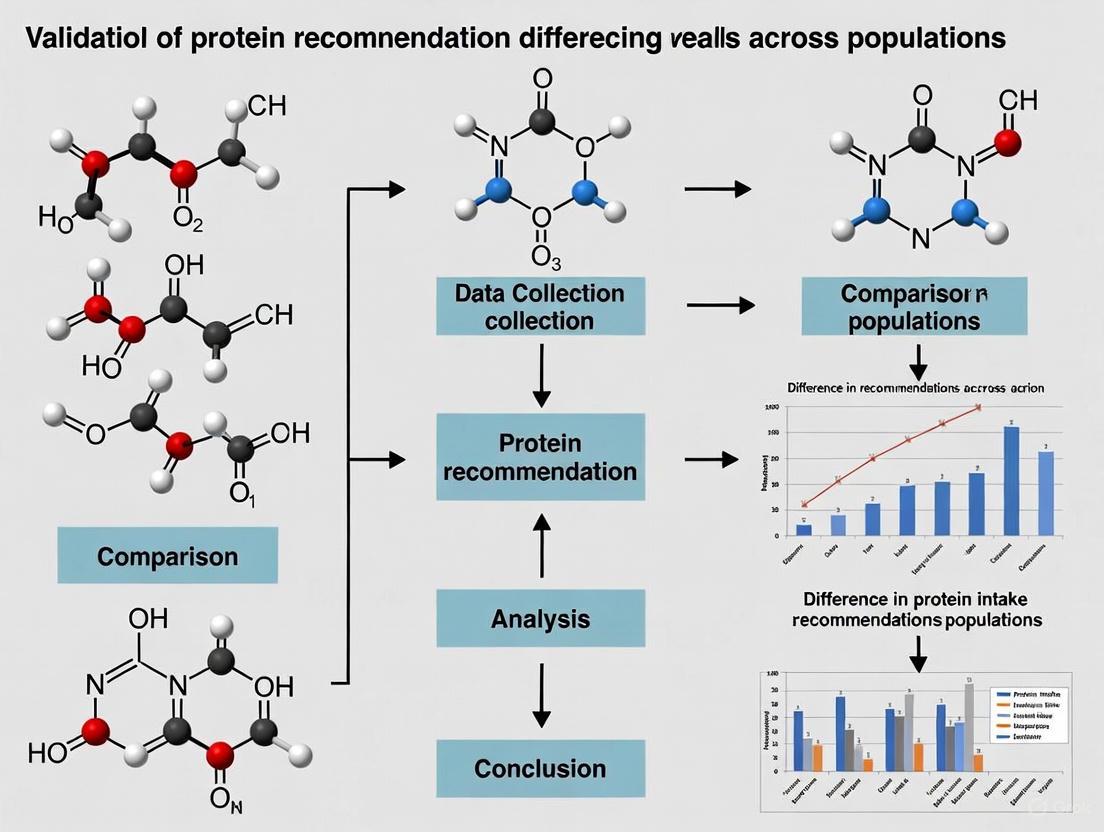

Beyond One-Size-Fits-All: Validating Protein Recommendations for Diverse Populations in Biomedical Research

Current dietary protein recommendations, largely based on outdated nitrogen balance studies, fail to account for the distinct physiological needs of different populations.

Beyond One-Size-Fits-All: Validating Protein Recommendations for Diverse Populations in Biomedical Research

Abstract

Current dietary protein recommendations, largely based on outdated nitrogen balance studies, fail to account for the distinct physiological needs of different populations. This article explores the critical need for validating and modernizing protein intake guidelines for specific demographic and clinical groups, including older adults, athletes, and individuals with metabolic conditions. We examine the limitations of existing recommendation frameworks, evaluate novel methodological approaches for protein requirement assessment, and discuss strategies for optimizing and validating protein intake protocols. By synthesizing evidence from recent meta-analyses, indicator amino acid oxidation studies, and clinical outcomes research, this review provides a roadmap for developing population-specific protein recommendations that support musculoskeletal health, metabolic function, and overall wellness in both research and clinical applications.

The Evolving Science of Protein Requirements: From Historical Benchmarks to Population-Specific Needs

The Recommended Dietary Allowance (RDA) for protein, established at 0.8 grams per kilogram of body weight per day (g/kg/d) for healthy adults, has remained fundamentally unchanged for decades despite significant advancements in nutritional science. This review critically examines the nitrogen balance methodology underpinning this recommendation and evaluates emerging evidence challenging its universal adequacy. We analyze limitations inherent in nitrogen balance studies, including population representativeness, methodological assumptions, and inadequate consideration of protein quality. Comparative data from alternative methodologies and functional outcome studies are synthesized, revealing that protein requirements may be substantially higher for specific populations, including older adults, vegans, and physically active individuals. This analysis concludes that a re-evaluation of current protein recommendations is warranted to reflect contemporary scientific evidence.

The current protein RDA of 0.8 g/kg/d primarily derives from nitrogen balance studies conducted in the mid-20th century, representing the intake sufficient to maintain nitrogen equilibrium in 97.5% of the population [1]. Nitrogen balance methodology calculates the difference between nitrogen ingested (primarily from dietary protein) and nitrogen excreted (in urine, feces, and other routes), with equilibrium achieved when intake matches losses [2]. While this approach has served as the historical gold standard for determining protein requirements, its limitations have become increasingly apparent as nutritional science has evolved.

Recent evidence challenges the universal applicability of the current RDA. Multiple lines of investigation—including re-analyses of original nitrogen balance data, studies employing the indicator amino acid oxidation (IAAO) technique, and research demonstrating functional benefits of higher protein intakes—suggest that the existing recommendations may be insufficient for optimizing health outcomes across diverse populations [3]. This review systematically evaluates the methodological constraints of nitrogen balance studies and synthesizes contemporary evidence supporting a re-evaluation of protein requirements to better reflect physiological needs for muscle maintenance, metabolic function, and overall health throughout the life course.

Foundations of Current Protein Recommendations

The Nitrogen Balance Methodology

Nitrogen balance determination relies on the principle that protein is the primary nitrogen-containing macronutrient, enabling protein status assessment through precise measurement of nitrogen intake and excretion. The fundamental equation is:

Nitrogen Balance (B) = Nitrogen Intake (I) - Nitrogen Losses (U + F + S)

Where U represents urinary nitrogen, F represents fecal nitrogen, and S represents integumental and other miscellaneous losses [2]. In healthy adults, nitrogen equilibrium (balance ≈ 0) indicates that protein intake matches requirements for maintaining body protein pools. The current RDA was derived from the estimated average requirement (EAR) of 0.66 g/kg/d, with the RDA calculated as EAR + 2 standard deviations to cover the needs of 97.5% of the population [4].

The 2002 meta-analysis by Rand et al. [4] of 235 individual subjects from 19 nitrogen balance studies established the foundation for current recommendations. This analysis reported a median EAR of 105 mg N·kg⁻¹·d⁻¹ (0.65 g protein·kg⁻¹·d⁻¹) and an RDA of 132 mg N·kg⁻¹·d⁻¹ (0.83 g protein·kg⁻¹·d⁻¹), rounded to 0.8 g/kg/d. Notably, this analysis concluded no significant differences in requirements based on age, sex, or dietary protein source, though plant-based diets were underrepresented [4].

Key Nitrogen Balance Studies Underpinning the RDA

Table 1: Foundational Nitrogen Balance Studies Informing Current Protein Recommendations

| Study/Reference | Population | Design | Key Findings | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rand et al. (2002) meta-analysis [4] | 235 adults from 19 studies | Nitrogen balance analysis across multiple intakes | EAR: 0.65 g/kg/d; RDA: 0.83 g/kg/d | Limited representation of plant-based diets; narrow population |

| Original FAO/WHO/UNU (1985) | Mixed | Nitrogen balance | Established previous international standards | Methodological limitations in individual studies |

| "Vegetable diet" studies in Rand analysis [2] | Diets with >90% plant protein | Nitrogen balance | Average nitrogen balance: -2.21 mg N·kg⁻¹·d⁻¹ | Contained up to 10% animal protein; not strictly vegan |

Methodological Limitations of Nitrogen Balance Studies

Technical and Measurement Challenges

Nitrogen balance methodology contains systematic biases that tend to overestimate nitrogen retention and consequently underestimate true protein requirements. These technical limitations include:

- Overestimation of Nitrogen Intake: Analytical errors in determining the nitrogen content of diets lead to systematic overestimation of intake [3].

- Underestimation of Nitrogen Losses: Incomplete collection of urinary and fecal nitrogen, coupled with unmeasured integumental (skin, sweat, hair, nails) and other miscellaneous losses (estimated at 5-8 mg N·kg⁻¹·d⁻¹), results in underestimation of total nitrogen excretion [3] [5].

- Adaptation Periods: The relatively short adaptation periods (typically 5-14 days) used in nitrogen balance studies may be insufficient for the body to fully adjust to new protein intake levels, particularly at lower intakes where metabolic adaptation can create a false appearance of equilibrium [3].

These methodological shortcomings collectively bias nitrogen balance toward positivity, suggesting adequate protein intake at levels that may be insufficient for long-term maintenance of body protein pools.

Population Representativeness and Generalizability

The populations studied in foundational nitrogen balance research lack diversity in ways that critically limit the generalizability of the resulting RDA:

- Age Bias: Studies predominantly featured young adults (typically college-aged), despite evidence that protein metabolism and requirements change significantly with aging due to anabolic resistance [5].

- Sex Imbalance: Male participants were overrepresented, with limited investigation of potential sex-based differences in protein requirements [5].

- Health Status: Participants were generally healthy and lean, excluding those with conditions that might alter protein metabolism [5].

- Limited Physical Activity: Studies often used sedentary individuals, failing to account for the increased protein needs of physically active populations [3].

- Underrepresentation of Vegetarian/Vegan Populations: The meta-analysis by Rand et al. included "vegetable diets" but these contained up to 10% animal protein, not reflecting strict vegetarian or vegan patterns [2].

Diagram 1: Methodological Limitations of Nitrogen Balance Studies

Conceptual and Interpretative Flaws

Beyond technical issues, nitrogen balance methodology suffers from fundamental conceptual limitations:

- Linearity Assumption: The relationship between nitrogen intake and balance is inherently curvilinear, with decreasing efficiency of protein utilization as zero balance is approached. Application of linear regression models to this relationship violates this physiological reality and may underestimate requirements [3].

- Adequacy Versus Optimization: Nitrogen balance establishes the minimum protein intake to prevent deficiency but provides no information about optimal intakes for physiological functions beyond equilibrium, such as muscle hypertrophy, immune function, or metabolic health [1] [5].

- Protein Quality Considerations: The RDA assumes consumption of high-quality, highly digestible protein with optimal amino acid composition (e.g., egg, milk). Plant proteins typically have lower digestibility and less optimal amino acid profiles, necessitating higher intakes to achieve equivalent nitrogen balance [2] [6].

Evidence Challenging the Current RDA

Studies in Specific Populations

Vegan and Plant-Based Populations

A 2023 controlled feeding study specifically investigated nitrogen balance in strict vegan men consuming exactly 0.8 g/kg/d of protein from mixed plant sources [2]. Both absolute nitrogen balance (-1.38 ± 1.22 g/d) and relative nitrogen balance (-18.60 ± 16.96 mg/kg/d) were significantly lower than zero (equilibrium), demonstrating that the current RDA is insufficient to maintain nitrogen balance in this population. This contrasts with the original Rand meta-analysis that included diets with up to 10% animal protein and highlights how protein quality affects requirements [2].

Older Adults

Multiple lines of evidence indicate increased protein requirements with aging. Short-term nitrogen balance studies suggest the protein RDA is inadequate for maintaining nitrogen equilibrium in older adults [6]. Retrospective analyses indicate nitrogen equilibrium is achieved at approximately 0.91 g/kg/d—15% higher than the current RDA [6]. Studies using the IAAO technique report increased protein requirements in older adults compared with younger counterparts [6]. This has led to calls from expert groups for protein intake recommendations of 1.2-1.7 g/kg/d for older adults to support muscle mass maintenance and prevent sarcopenia [6].

Physically Active Individuals

Meta-analyses of randomized controlled trials demonstrate that protein intakes greater than the RDA (typically 1.2-1.7 g/kg/d) differentially influence body composition under catabolic or anabolic conditions [7]. Specifically, protein intakes exceeding the RDA attenuate lean mass loss during energy restriction and increase lean mass during resistance training, whereas the RDA appears sufficient only under non-stressed conditions without exercise or calorie restriction [7].

Table 2: Protein Requirements Across Populations Based on Contemporary Evidence

| Population | Current RDA (g/kg/d) | Evidence-Based Suggested Intake (g/kg/d) | Key Evidence |

|---|---|---|---|

| Healthy Young Adults | 0.8 | 0.8-1.2 | RDA sufficient for basic equilibrium in non-stressed state [7] |

| Older Adults | 0.8 | 1.2-1.7 | IAAO studies, muscle preservation trials [6] |

| Strict Vegans | 0.8 | 1.0-1.3 | Negative nitrogen balance at RDA [2] |

| Resistance-Trained | 0.8 | 1.2-1.7 | Enhanced lean mass gains in meta-analyses [7] |

| Dieting/Energy Restricted | 0.8 | 1.6-2.2 | Preservation of lean mass during deficit [7] |

Indicator Amino Acid Oxidation (IAAO) Studies

The IAAO technique has emerged as a validated alternative to nitrogen balance for estimating protein and amino acid requirements. This method measures the oxidation of a labeled indispensable amino acid, with the breakpoint in oxidation indicating the requirement. IAAO studies generally suggest higher protein requirements than nitrogen balance, particularly in older adults and athletes [3]. The latest Dietary Reference Intakes acknowledged IAAO as the gold-standard method for estimating amino acid requirements but did not fully incorporate IAAO-derived values into protein recommendations [3].

Evidence from Functional Outcomes

Studies investigating functional outcomes beyond nitrogen balance provide compelling evidence for re-evaluating the RDA:

- Muscle Mass and Function: Higher protein intakes (≥1.2 g/kg/d) are associated with greater lean mass preservation, reduced risk of sarcopenia, and better physical function in older adults [8].

- Health Status: Observational data from NHANES indicate that older adults not meeting protein recommendations have significantly more functional limitations and lower grip strength [8].

- Metabolic Health: Adequate protein intake supports glucose homeostasis through maintenance of skeletal muscle mass, the primary site of glucose disposal [5].

Experimental Approaches and Methodologies

Nitrogen Balance Protocol

A standardized nitrogen balance study typically involves:

Participants: Recruited based on specific inclusion/exclusion criteria (e.g., healthy, weight-stable, specific age range) [2].

Dietary Control: Participants receive a eucaloric diet with precisely controlled protein content for an adaptation period (typically 5-14 days). Diets are individualized to meet energy needs based on equations like Harris-Benedict with an appropriate activity factor [2].

Nitrogen Intake Assessment: All foods are weighed and analyzed for nitrogen content, typically using the Dumas method, with careful accounting of uneaten portions [2].

Nitrogen Loss Measurement:

- Urinary Nitrogen: 24-hour urine collections with refrigeration and without preservatives. The first morning void is discarded, and all urine collected for 24 hours, including the first void the following morning [2].

- Fecal Nitrogen: Collection throughout the study period or during specific balance periods using fecal markers.

- Miscellaneous Losses: Estimated based on standard values (typically 5-8 mg N·kg⁻¹·d⁻¹) for skin, sweat, hair, and nail losses [3].

Calculation: Nitrogen balance = (Nitrogen intake) - (Urinary nitrogen + Fecal nitrogen + Miscellaneous losses) [2].

Indicator Amino Acid Oxidation (IAAO) Protocol

The IAAO technique represents a more contemporary approach:

Participants: Fed diets with varying levels of the test protein or amino acid.

Tracer Administration: Receives a labeled indispensable amino acid (typically [1-¹³C]phenylalanine).

Measurements: Breath samples collected to measure ¹³CO₂ enrichment, reflecting oxidation of the labeled amino acid.

Analysis: The breakpoint in the oxidation curve indicates the requirement, as oxidation increases once the requirement is exceeded [3].

Diagram 2: Comparison of Methodological Approaches for Determining Protein Requirements

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Materials and Methods for Protein Requirement Studies

| Reagent/Equipment | Specification/Standard | Research Application | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Controlled Diets | Precisely formulated protein content | Provides exact nitrogen intake | Protein quality, amino acid profile, digestibility |

| Urine Collection | 24-hour containers, refrigeration | Quantifies urinary nitrogen losses | Completeness of collection, storage conditions |

| Fecal Markers | Carmine red, blue dye | Marks fecal collection periods | Accurate separation of balance periods |

| Nitrogen Analyzer | Dumas combustion method | Measures nitrogen in food, urine, feces | Calibration, standardization |

| Amino Acid Tracers | [1-¹³C]phenylalanine, L-[1-¹³C]leucine | IAAO studies to determine requirements | Isotopic purity, administration route |

| Isotope Ratio Mass Spectrometer | High-precision ¹³CO₂ measurement | IAAO breath sample analysis | Sensitivity, calibration standards |

| Body Composition Tools | DXA, BIA, ADP | Measures lean mass changes | Validation for population, precision |

The critical analysis presented herein demonstrates significant limitations in the nitrogen balance methodology underpinning current protein RDAs. Methodological biases, narrow population sampling, and conceptual flaws related to the distinction between minimal versus optimal intake collectively challenge the universal applicability of the 0.8 g/kg/d recommendation. Contemporary evidence from controlled studies in specific populations, IAAO methodology, and functional outcome research consistently indicates higher protein requirements for numerous segments of the population, particularly older adults, vegans, and those engaged in regular physical activity.

These findings highlight the urgent need to re-evaluate current protein recommendations using contemporary methodologies and with consideration of diverse populations and functional outcomes. Future dietary guidelines should incorporate evidence beyond nitrogen balance to establish protein recommendations that optimize health outcomes across the lifespan, rather than merely preventing deficiency. The scientific consensus is increasingly converging on population-specific protein recommendations that better reflect modern understanding of protein needs for health preservation and chronic disease prevention.

Dietary protein is indispensable for numerous physiological functions, including the synthesis of muscle tissue, immune cell production, and wound healing. The establishment of a universal protein Recommended Dietary Allowance (RDA) of 0.8 grams per kilogram of body weight per day (g/kg/day) has historically provided a baseline for nutritional guidance [9]. However, a growing body of evidence underscores that this one-size-fits-all recommendation is insufficient for specific demographic groups with heightened anabolic demands or altered metabolic states [10] [11]. The validation of differential protein requirements across populations is a critical endeavor in nutritional science, moving beyond mere nitrogen balance to encompass functional outcomes such as muscle strength, physical capacity, and recovery from illness. This guide objectively compares protein recommendations for aging populations and athletes, synthesizing experimental data and detailing the methodologies that underpin these evidence-based conclusions.

Quantitative Comparison of Protein Recommendations Across Populations

The following table summarizes the evidence-based protein intake recommendations for different populations, highlighting the significant deviations from the standard RDA.

Table 1: Evidence-Based Daily Protein Intake Recommendations by Population

| Population Group | Recommended Intake (g/kg/day) | Key Rationale and Evidence Base |

|---|---|---|

| General Healthy Adults (RDA) | 0.8 [9] | Based on classic nitrogen balance studies to prevent deficiency. |

| Healthy Older Adults | 1.0 - 1.2 [12] [11] | Counters anabolic resistance and age-related muscle loss (sarcopenia) [10]. |

| Older Adults with Acute/Chronic Illness | 1.2 - 1.5 [12] [11] | Supports increased demands for immune function and tissue repair. |

| Recreational Endurance Athletes | ~1.0 [13] | May not differ significantly from sedentary adults if exercise intensity is low. |

| Elite Endurance Athletes | 1.46 - 1.8 [13] | Offsets protein oxidation during prolonged exercise and aids recovery. |

| Strength/Power Athletes | 1.4 - 2.0 [9] [13] | Supports muscle protein synthesis (MPS) and adaptation to resistance training. |

For optimal anabolic stimulation, especially in older adults, research also emphasizes the importance of protein distribution, recommending 25-30 g of high-quality protein per meal to maximize Muscle Protein Synthesis (MPS) rates [12]. Furthermore, the amino acid leucine is identified as a critical trigger for MPS, with some studies suggesting that older adults may benefit from consuming 2.8–3 g of leucine per meal to overcome anabolic resistance [12].

Experimental Protocols for Determining Protein Requirements

The validation of protein recommendations relies on sophisticated metabolic techniques. The following section details the core methodologies cited in the literature.

Nitrogen Balance Technique

This method involves precisely measuring all nitrogen (N) ingested and all nitrogen excreted over a controlled period [9]. Participants consume a diet with varying, known levels of protein (nitrogen intake) for periods of 10-14 days. During the final 3-5 days, total nitrogen losses are measured from urine, feces, skin, and other miscellaneous sources [10]. Nitrogen balance is calculated as: Nitrogen Balance = Nitrogen Intake - Nitrogen Losses.

B. Data Analysis and Requirement Determination

Linear regression is performed on the different nitrogen intake levels and their corresponding balance measures. The Estimated Average Requirement (EAR) is determined by interpolating the intake level that results in zero nitrogen balance (intake = losses). The RDA is set at two standard deviations above the EAR to cover the needs of ~97.5% of the population [10].

C. Limitations

The nitrogen balance technique has recognized shortcomings. It may underestimate protein needs for optimal function, as it does not directly measure outcomes like muscle mass or physical performance [9]. The methodology itself can be prone to errors in the complete collection of nitrogen losses [10].

Indicator Amino Acid Oxidation (IAAO)

The IAAO method is considered a more dynamic and precise alternative [10]. Study participants are fed diets with varying levels of protein intake. One indispensable (essential) amino acid, typically L-[1-¹³C]phenylalanine, is labeled as the "indicator" and administered. When dietary protein is deficient, the body cannot fully utilize the indicator amino acid for protein synthesis, leading to its oxidation.

B. Data Analysis and Requirement Determination

The oxidation rate of the labeled indicator amino acid is measured by analyzing ¹³CO₂ in the breath. As protein intake approaches the individual's requirement, the body utilizes more of the indicator amino acid for synthesis, and its oxidation decreases. The breakpoint in the oxidation curve, where further protein intake no longer reduces oxidation, is identified through biphasic linear regression and represents the average protein requirement [10].

C. Key Findings

Studies using IAAO have reported higher requirements than the RDA, suggesting values of 0.94 g/kg/day for older men and 0.96 g/kg/day for older women, with safe intake levels (analogous to an RDA) of 1.24 g/kg/day and 1.29 g/kg/day, respectively [10].

Molecular Pathways and Experimental Workflows

The cellular mechanism by which protein intake stimulates muscle growth, and the experimental workflow for identifying proteins in complex mixtures, are foundational to this field.

Leucine-Mediated Muscle Protein Synthesis Signaling Pathway

The following diagram illustrates the key molecular pathway through which dietary protein, and specifically the amino acid leucine, stimulates muscle protein synthesis, a process crucial for adapting to exercise and countering age-related anabolic resistance.

Diagram Title: Leucine Activates Muscle Protein Synthesis

Shotgun Proteomics Workflow for Protein Identification

In basic research, proteomics techniques are used to understand protein expression and interactions. The shotgun proteomics workflow is a key method for identifying a wide array of proteins from biological samples.

Diagram Title: Shotgun Proteomics Identification Process

Research Reagent Solutions for Protein Metabolism Studies

The following table details key reagents and materials essential for conducting research in protein metabolism and requirements.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

| Research Reagent / Material | Function and Application in Research |

|---|---|

| L-[1-¹³C]Phenylalanine | A stable isotope-labeled amino acid used as the "indicator" in the IAAO technique to measure whole-body protein metabolism and determine requirements [10]. |

| Stable Isotope-Labeled Amino Acids (e.g., ¹³C-Leucine) | Used in tracer infusion studies to directly measure rates of Muscle Protein Synthesis (MPS) and breakdown in response to dietary or exercise interventions [10]. |

| Reference Protein Sources (e.g., Casein, Whey, Egg) | Highly-characterized proteins used in controlled feeding studies to compare the anabolic properties, digestibility, and amino acid bioavailability of different protein types [14]. |

| Protein Sequence Databases (e.g., UniProt) | Curated databases of protein sequences that are essential for the peptide spectrum matching step in shotgun proteomics workflows [15]. |

| Mass Spectrometer | The core instrument used in proteomics and metabolic studies for precise measurement of peptide masses (m/z) and fragmentation patterns (MS/MS) for identification [15]. |

The evidence compellingly demonstrates that protein requirements are not static but are instead dictated by demographic and physiological imperatives. The validation of increased needs for aging populations and athletes moves beyond the simplistic prevention of deficiency towards the promotion of functional health, performance, and recovery. While the RDA of 0.8 g/kg/day remains a benchmark for sedentary adults, research validates daily intakes of 1.0-1.2 g/kg for healthy older adults, 1.2-1.5 g/kg for those who are ill, and 1.4-2.0 g/kg for athletes [10] [9] [12]. Future research must continue to refine these recommendations using robust methodologies like IAAO and direct measures of MPS, with a focus on long-term functional outcomes as the primary validation metric.

Dietary protein is a critical macronutrient for human health, supporting functions from cellular structure and immune function to muscle maintenance. However, the balance between its consumption and actual physiological requirements varies dramatically across the globe, creating significant public health challenges. This guide provides a comparative analysis of global protein consumption patterns against established recommended intakes, synthesizing current data on disparities, their health implications, and the methodologies underpinning protein research. For researchers and drug development professionals, understanding these patterns is essential for designing targeted nutritional interventions and public health strategies that address both undernutrition and overconsumption. The analysis is framed within the broader context of validating differences in protein recommendations across diverse populations, highlighting that a one-size-fits-all approach is inadequate for global nutritional guidance [6].

Global Protein Consumption Patterns

Global protein consumption is characterized by profound geographical and socioeconomic disparities. In high-income countries, protein intake, particularly from animal sources, significantly exceeds average requirements. Conversely, in many low-income regions, protein intake is insufficient to meet basic physiological needs, contributing to malnutrition and its associated burdens [6] [16].

Table 1: Global and Regional Per Capita Protein Consumption Patterns

| Region/Country | Total Protein Consumption (g/person/day) | Animal Protein Contribution | Plant Protein Contribution | Key Consumption Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Global Average | ~142% of requirement [16] | ~40% of total [6] | ~60% of total [6] | Supply is sufficient if equitably distributed. |

| United States | >50% from animal products [6] | High | Lower | Men consume ~2x RDA; women ~1.5x RDA [17]. |

| United Kingdom | Animal-based dominant [6] | High | Lower | Habitual intake declines with age [6]. |

| Wealthy Regions | >50% above requirement [17] | High | Variable | 42% of global population lives in such countries [16]. |

| Sub-Saharan Africa | Among lowest globally [17] | Lower | Higher | High prevalence of protein-energy malnutrition [6] [16]. |

| Parts of Asia | Variable | Variable | Higher | West/Southern India: high reliance on rice/millet [6]. |

Consumption patterns are also influenced by gender and socioeconomic status. A 2025 cross-sectional study of Italian adults found that men had significantly higher consumption of meat and processed meat, while women consumed more plant-based proteins like soy. These gender differences persisted across socioeconomic levels, with low-income men consuming the most meat and processed meat. These dietary choices were further associated with body composition; high meat consumption correlated with a higher BMI, while soy consumption was associated with a lower BMI [18]. This illustrates that protein consumption is not merely a biological necessity but a complex behavior shaped by cultural norms, economic access, and gender identities [18].

Established Protein Recommendations and Intake Guidelines

Protein recommendations are not universal; they vary by age, physiological status, and activity level. Most national guidelines for healthy adults are based on preventing deficiency rather than optimizing long-term health.

Table 2: Summary of Protein Recommendations for Adults

| Population Group | Recommended Dietary Allowance (RDA) | Elevated/Upper Intake Level | Key Rationale and Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Healthy Adults (Avg.) | 0.8 g/kg/day [19] [17] | 1.0-1.6 g/kg/day for active individuals [19] | Minimum to prevent nitrogen loss; safe upper limit ~2 g/kg/day [19]. |

| Older Adults (>40-50) | 0.75-0.8 g/kg/day (UK/US RDA) [6] | 1.0-1.7 g/kg/day [6] [20] | To counteract sarcopenia (age-related muscle loss) [6] [20]. |

| Regular Exercisers | RDA: 0.8 g/kg/day | 1.1-1.5 g/kg/day [20] | Supports repair and adaptation. |

| Weightlifters/Athletes | RDA: 0.8 g/kg/day | 1.2-1.7 g/kg/day [20] | For muscle building and recovery; >2 g/kg/day is excessive [20]. |

The evidence base for these recommendations is evolving. Recent research using novel stable isotope pulse methods suggests that traditional techniques may have underestimated net protein breakdown, potentially indicating higher requirements. This new concept posits a relationship between habitual protein intake and an individual's requirements, which may be lower in older adults and those with comorbidities [21]. Furthermore, the source and quality of protein are critical. Animal proteins are generally "complete" with all essential amino acids, while most plant proteins are "incomplete." The Digestible Indispensable Amino Acid Score (DIAAS) is the preferred method for evaluating protein quality, accounting for ileal digestibility. Achieving adequate intake with plant-based diets requires consuming a variety of sources to ensure a complementary amino acid profile [6] [17].

Disparities Between Consumption and Recommendations

The gap between actual consumption and recommended intakes presents a dual public health burden of excess and deficiency.

Overnutrition in High-Income Countries: In wealthy nations, average protein consumption far exceeds the RDA. For instance, American men consume about twice the RDA, and women about 1.5 times it [17]. This overconsumption is largely driven by abundant access to animal products. However, despite high total intake, dietary patterns often lack diversity and do not align with recommendations for specific protein subgroups, such as seafood and legumes [17]. This suggests that the focus in these regions should shift from quantity to quality and source of protein.

Undernutrition in Vulnerable Populations: At the other extreme, an estimated 570 million people live in countries where the total digestible protein supply is insufficient to meet the population's average requirements [16]. This is starkly evident in regions like West Africa and Southern India, where diets rely heavily on low-protein staples and childhood protein malnutrition is prevalent [6]. Furthermore, within otherwise well-nourished populations, specific groups are at risk. Older adults, for example, frequently consume less protein than recommended, a concern exacerbated by the fact that they often consume lower-quality proteins, further compromising musculoskeletal health [6].

The Quality and Timing Gap: Disparities extend beyond gross quantity. The consumption of low-quality proteins, which lack essential amino acids or have poor digestibility, can render an apparently adequate intake functionally insufficient [6] [17]. Additionally, the timing of protein consumption is often suboptimal. In many Western populations, protein intake is skewed heavily toward the evening meal, whereas distributing 15-30 grams of high-quality protein evenly across meals is more effective for stimulating muscle protein synthesis throughout the day [20].

Public Health Implications

The disparities in protein consumption have significant consequences for population health and healthcare systems.

Health Risks of Overnutrition: Chronic consumption of protein significantly above requirements, especially from animal sources high in saturated fat, can pose health risks. While a recent 2025 umbrella review found no major association between total, animal, or plant protein intake and the risk of coronary heart disease or stroke, the certainty of evidence was "probable" for CHD and "possible" for stroke [22]. However, high-protein diets can lead to elevated blood lipids if the protein sources are also high in saturated fat, and they may pose a risk to individuals predisposed to kidney disease [20]. Furthermore, any excess calories from protein, like other macronutrients, are stored as body fat [20].

Health Risks of Undernutrition: Protein inadequacy remains a debilitating issue, leading to stunted growth in children, anemia, physical weakness, edema, vascular dysfunction, and impaired immunity [19]. In older adults, insufficient protein intake accelerates sarcopenia, leading to loss of muscle mass, strength, and functional independence, which is a major predictor of mortality [6] [20].

Beyond Protein: The Micronutrient Gap: A critical public health insight is that producing more protein alone will not solve global hunger. An estimated 2.8 billion people suffer from "hidden hunger," or micronutrient deficiencies, and many of these individuals may actually have adequate or even surplus protein and energy intake [16]. Therefore, interventions aimed at closing protein gaps must also consider the delivery of essential micronutrients. For example, supplementing with cereals provides zinc and fiber, dairy provides calcium and riboflavin, and meat provides bioavailable iron and vitamin B12 [16].

Experimental Protocols for Protein Research

Validating protein requirements and understanding metabolic fate relies on sophisticated experimental protocols.

Stable Isotope Tracer Methods

This is the gold standard for measuring whole-body protein metabolism. The protocol involves administering amino acids labeled with non-radioactive stable isotopes (e.g., ^13C-Leucine or ^13C-Phenylalanine) and tracing their appearance in plasma, breath, or other compartments.

- Primed Constant Infusion: A classic method where a loading dose (prime) of a labeled amino acid is followed by a continuous, prolonged intravenous infusion. Plasma samples are taken to measure the dilution of the tracer, which allows calculation of the Rate of Appearance (Ra) of the amino acid in the plasma, representing whole-body protein breakdown [21].

- Pulse Tracer Administration: A newer approach involving a single bolus or short-term infusion. Compartmental modeling of the tracer and product (e.g., labeled tyrosine from phenylalanine) kinetics is used to estimate intracellular amino acid production. This method suggests intracellular protein breakdown is significantly higher than estimates from plasma-based methods, potentially leading to revised, higher protein requirement estimates [21].

Protein Quality Assessment: The DIAAS Method

The Digestible Indispensable Amino Acid Score (DIAAS) is the FAO-recommended method for evaluating protein quality, replacing the older Protein Digestibility-Corrected Amino Acid Score (PDCAAS).

- Analysis: Determine the content of each indispensable (essential) amino acid (IAA) in a gram of the test protein.

- Reference Comparison: Compare this to the content of the same IAA in a gram of a reference protein pattern (based on human requirements).

- Ileal Digestibility: The key differentiator from PDCAAS. Digestibility is calculated based on the amount of each IAA absorbed at the end of the small intestine (ileum), typically measured in animal models (e.g., pigs) or increasingly via in vitro digestion systems. This provides a more accurate measure than fecal digestibility, which is confounded by microbial metabolism in the colon [6].

- Calculation: DIAAS = [(mg of digestible dietary IAA in 1 g of test protein) / (mg of the same IAA in 1 g of reference protein)] × 100. A score ≥100 indicates a high-quality protein that is fully utilized [6].

Research Toolkit: Key Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Protein Metabolism Studies

| Reagent/Material | Function in Research | Example Application |

|---|---|---|

| L-[ring-^13C₆]Phenylalanine | Stable isotope tracer for amino acid kinetics. | Quantifying whole-body protein breakdown and synthesis rates via primed constant or pulse infusion [21]. |

| L-[1-^13C]Leucine | Stable isotope tracer; its oxidation can be measured. | Assessing protein metabolism and amino acid oxidation via breath ^13CO₂ analysis [21]. |

| Bioelectrical Impedance Analyser (BIA) | Measures body composition (fat mass, fat-free mass). | Evaluating the impact of protein interventions on muscle mass in clinical trials [18]. |

| In Vitro Digestion Model | Simulates human gastrointestinal digestion. | Screening protein digestibility and bioaccessibility without invasive in vivo studies [6]. |

| Tanita BC-420 MA BIA | A specific, validated BIA device. | Used in cross-sectional studies to link protein intake to body composition parameters [18]. |

| Alpha-ketoisocaproic acid (KIC) | A metabolite of leucine. | Plasma KIC enrichment is used as a proxy for intracellular leucine enrichment to improve accuracy of leucine tracer studies [21]. |

Visualization of Research Workflows

Protein Assessment Workflow

Health Outcome Pathway

For decades, the assessment of dietary protein quality relied primarily on the Protein Digestibility Corrected Amino Acid Score (PDCAAS). However, in 2013, a Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) Expert Consultation recommended the Digestible Indispensable Amino Acid Score (DIAAS) as a more accurate method for evaluating protein quality, citing several limitations in the PDCAAS approach [23] [24]. This paradigm shift represents a significant advancement in nutritional science, particularly for researchers and drug development professionals who require precise understanding of protein utilization in human physiology. The fundamental difference between these methods lies in their approach to digestibility: PDCAAS uses fecal digestibility estimates, which can be influenced by microbial activity in the large intestine, while DIAAS is based on ileal digestibility measured at the end of the small intestine, providing a more accurate representation of amino acid absorption [25] [24]. This technical improvement allows for better prediction of how efficiently amino acids from various food sources become bioavailable for metabolic processes, tissue repair, and protein synthesis—critical considerations for nutritional interventions and therapeutic formulations.

The DIAAS method addresses several specific limitations of PDCAAS. First, it considers the individual digestibility of each indispensable amino acid rather than applying a single crude protein digestibility value [24]. Second, DIAAS does not truncate values at 100%, allowing for differentiation between high-quality protein sources that exceed requirements [23] [25]. Third, it specifically accounts for lysine bioavailability in processed foods where Maillard reactions may have occurred, using true ileal digestible reactive lysine rather than total lysine [23]. For researchers investigating protein metabolism across different populations, these methodological refinements provide enhanced tools for evaluating protein sources and their potential to meet specific physiological needs.

DIAAS: Methodology and Calculation

Fundamental Principles and Calculation

The Digestible Indispensable Amino Acid Score is calculated based on a food's content of digestible indispensable amino acids relative to a reference amino acid pattern for a specific age group [25]. The calculation involves:

DIAAS (%) = 100 × (mg of digestible dietary indispensable amino acid in 1 g of the dietary protein / mg of the same dietary indispensable amino acid in 1 g of the reference protein) [23]

The score is determined by the first-limiting digestible indispensable amino acid—the amino acid with the lowest ratio when compared to the reference pattern [26]. This calculation requires two key pieces of information for each indispensable amino acid: the concentration in the food protein and its true ileal digestibility coefficient. The FAO has established reference amino acid patterns for three distinct age groups: 0-6 months, 6 months to 3 years, and over 3 years (including adults) [25], acknowledging that amino acid requirements differ across developmental stages—a crucial consideration for research targeting specific populations.

Reference Amino Acid Patterns

The reference patterns used in DIAAS calculations were derived from updated understanding of human amino acid requirements [25]:

Table 1: FAO Reference Amino Acid Patterns for DIAAS Calculation (mg/g protein)

| Amino Acid | 0-6 months | 6 mo-3 years | Over 3 years |

|---|---|---|---|

| Histidine | 21 | 20 | 16 |

| Isoleucine | 55 | 32 | 30 |

| Leucine | 96 | 66 | 61 |

| Lysine | 69 | 57 | 48 |

| Methionine + Cysteine | 33 | 27 | 23 |

| Phenylalanine + Tyrosine | 94 | 52 | 41 |

| Threonine | 44 | 31 | 25 |

| Tryptophan | 17 | 8.5 | 6.6 |

| Valine | 55 | 43 | 40 |

These reference patterns reflect the understanding that infants and young children have higher relative requirements for most indispensable amino acids to support rapid growth and development [25]. For researchers studying specific populations, selection of the appropriate reference pattern is essential for accurate protein quality assessment.

DIAAS vs. PDCAAS: Key Methodological Differences

The transition from PDCAAS to DIAAS represents a significant advancement in protein quality assessment methodology. The key differences between these approaches have important implications for research and product development:

Table 2: Comparison of PDCAAS and DIAAS Methodologies

| Aspect | PDCAAS | DIAAS |

|---|---|---|

| Digestibility Site | Fecal | Ileal (end of small intestine) |

| Digestibility Basis | Single crude protein value | Individual amino acids |

| Score Truncation | Truncated at 100% | Not truncated |

| Experimental Model | Rats | Growing pigs (preferred) |

| Lysine Assessment | Total lysine | Reactive lysine in processed foods |

| Reference Pattern | 2-5 year-old children only | Three age-specific patterns |

The use of ileal digestibility in DIAAS is physiologically superior because it measures amino acid absorption before microbial metabolism in the colon, which can alter the composition and amount of amino acids that actually reach systemic circulation [25] [24]. The avoidance of score truncation enables researchers to distinguish between protein sources that exceed requirements, which is particularly valuable for formulating products targeted at populations with elevated protein needs, such as athletes or older adults [23]. Additionally, the age-specific reference patterns align with our understanding that amino acid requirements differ across life stages, allowing for more precise nutritional planning and product development for specific demographic groups.

Animal vs. Plant-Based Proteins

Substantial research has documented significant variation in DIAAS values across different protein sources, with general patterns showing higher scores for animal-based proteins compared to plant-based sources [26]. However, considerable variation exists within these broad categories, and processing methods can significantly impact protein quality.

Table 3: DIAAS Values for Selected Protein Sources (based on 0.5-3 year reference pattern)

| Protein Source | DIAAS (%) | Limiting Amino Acid(s) | Quality Classification |

|---|---|---|---|

| Animal-Based Sources | |||

| Pork meat | >100 | - | Excellent |

| Whey Protein Isolate | 109 | Valine | Excellent |

| Whole milk | 114 | Sulfur amino acids | Excellent |

| Egg | 113 | Histidine | Excellent |

| Beef | 112 | - | Excellent |

| Casein | >100 | - | Excellent |

| Gelatin | <75 | Tryptophan | No quality claim |

| Plant-Based Sources | |||

| Potato protein | >100 | - | Excellent |

| Soy Protein Isolate | 90 | Sulfur amino acids | High |

| Tofu | 97 | Sulfur amino acids | High |

| Chickpeas | 83 | Sulfur amino acids | High |

| Pea Protein Concentrate | 82 | Sulfur amino acids | High |

| Cooked kidney beans | 59 | - | No quality claim |

| Wheat flour | 40 | Lysine | No quality claim |

| Rice Protein Concentrate | 37 | Lysine | No quality claim |

| Corn-based cereal | 1 | Lysine | No quality claim |

According to FAO recommendations, proteins are classified as: excellent quality (DIAAS ≥100), high quality (DIAAS 75-99), or no quality claim (DIAAS <75) [26]. The data reveal that while many plant-based proteins fall into the "high quality" category, their DIAAS values are typically lower than animal proteins due to limitations in specific indispensable amino acids and/or reduced digestibility [27]. The most common limiting amino acids in plant proteins are lysine in cereals and sulfur-containing amino acids (methionine and cysteine) in legumes [6] [26].

Impact of Food Processing and Matrix Effects

Recent research has highlighted that protein quality is not solely determined by the raw protein source but is significantly influenced by processing methods and food matrix effects. A 2025 study evaluating commercial protein bars found that despite high protein content claims, all tested bars had relatively low DIAAS values (highest was 61), primarily due to the inclusion of lower-quality proteins like collagen and interactions with other ingredients such as carbohydrates and fibers that reduced amino acid bioaccessibility [28]. This demonstrates how food formulation can substantially alter the nutritional quality of protein, an important consideration for product development.

Processing can also improve protein quality in some cases. Heat processing may inactivate anti-nutritional factors present in plant proteins such as trypsin inhibitors and lectins, thereby improving protein digestibility [27]. However, excessive heat treatment can promote Maillard reactions that reduce lysine bioavailability [23]. These competing effects underscore the need for optimized processing conditions to maximize protein nutritional quality.

Methodologies for Determining DIAAS

In Vivo Assessment Methods

The gold standard for DIAAS determination involves measuring true ileal amino acid digestibility in humans or animal models. The growing pig has been validated as the preferred animal model due to similarities in gastrointestinal physiology and digestive processes to humans [23] [26]. For human studies, a dual stable isotope tracer approach has been developed as a non-invasive method to determine true ileal amino acid digestibility across different physiological states [23] [29].

A recent study protocol illustrates the application of this method: older men received primed constant infusions of [1,2-13C2] leucine while consuming protein blends containing universally labeled 13C-spirulina and 2H-cell free amino acid mix [29]. The ratio of 13C:2H enrichment in plasma compared to the test drink was used to determine digestibility, with the free amino acid mixture representing 100% bioavailability [29]. This innovative approach enables researchers to study protein digestibility in vulnerable populations without invasive procedures like naso-ileal intubation.

In Vitro Digestion Models

While in vivo methods provide the most accurate assessment, they are resource-intensive and not always practical for screening multiple protein sources. Consequently, validated in vitro digestion simulation systems have been developed that correlate with in vivo findings [6] [28]. The INFOGEST method, an internationally standardized static in vitro simulation of gastrointestinal digestion, has been specifically validated for determining DIAAS of both animal and plant-based proteins [28].

The INFOGEST protocol involves sequential incubation of food samples with simulated salivary, gastric, and intestinal fluids under controlled pH, time, and electrolyte composition conditions [28]. The digestibility of individual amino acids is then determined by analyzing the bioaccessible fraction after intestinal digestion. This method enables rapid, cost-effective screening of protein digestibility, though it may not fully capture all aspects of the complex human digestive system, particularly microbial interactions and the role of the gut-brain axis in digestion regulation.

Protein Requirements Across Populations: Implications of Protein Quality

Age-Related Variations in Protein Needs

Understanding protein requirements across different populations is essential for contextualizing the importance of protein quality. Current evidence suggests that protein needs may be higher than traditional recommendations, particularly for older adults. A 2025 meta-analysis comparing protein requirements determined by nitrogen balance (NB) and indicator amino acid oxidation (IAAO) methods found that IAAO-derived requirements were approximately 30% higher than NB-based estimates [30]. For non-athletes, the IAAO method yielded a mean requirement of 0.88 g/kg/d compared to 0.64 g/kg/d with the NB method [30].

The anabolic resistance associated with aging, coupled with typically lower food intake, places older adults at particular risk of protein inadequacy [6]. Research indicates that approximately 40% of older adults in North America consume less than the recommended dietary allowance for protein [6]. This insufficiency is compounded by the fact that protein intake tends to decline with age, with adults over 75 years consuming 11-19% less protein than those under 64 years [6]. Furthermore, the relative contribution of animal proteins to overall protein intake is often lower in older individuals with inadequate gross protein intake, potentially exacerbating quality-related deficiencies [6].

Protein Quality in Dietary Patterns

For populations with limited protein intake, either due to low total food consumption or selective consumption patterns (e.g., vegetarian/vegan diets), protein quality becomes a critical factor in maintaining nitrogen balance and muscle protein synthesis. The DIAAS framework helps quantify the potential compensatory intake needed when relying on lower-quality protein sources.

Research demonstrates that complementary protein mixtures can achieve higher DIAAS values than individual components through strategic combination of proteins with different limiting amino acids [26]. For example, blending legumes (limiting in sulfur amino acids but rich in lysine) with cereals (limiting in lysine but adequate in sulfur amino acids) can produce a more balanced amino acid profile [26]. Mathematical modeling of protein mixtures has identified optimal ratios that maximize DIAAS, highlighting the potential of targeted food formulation to enhance protein nutritional quality, particularly in plant-based products [26].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Protein Quality Assessment

| Reagent/Material | Function in Research | Application Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Stable Isotope Tracers | Enable tracking of amino acid absorption and metabolism without radioactivity | [1,2-13C2] leucine for IAAO studies [29] [30] |

| Universally Labeled Proteins | Intrinsically labeled proteins for digestibility studies | U-13C spirulina as reporter protein [29] |

| Simulated Digestive Fluids | Standardized in vitro digestion following INFOGEST protocol | Gastric/intestinal fluid simulations [28] |

| Amino Acid Standards | Reference for HPLC/UPLC-MS quantification of individual amino acids | Establishing calibration curves [26] |

| Reference Proteins | Controls with known DIAAS for method validation | Casein, whey protein isolates [26] [24] |

| Cell-Free Amino Acid Mix | Reference for 100% bioavailability in dual-tracer studies | U-2H labeled AA mix [29] |

The adoption of DIAAS represents a significant advancement in protein quality assessment, providing researchers and product developers with a more accurate tool for evaluating the nutritional value of protein sources. The method's emphasis on ileal digestibility of individual amino acids offers physiological relevance that surpasses previous scoring systems. Evidence to date confirms that protein quality varies substantially across sources, with animal-derived proteins typically demonstrating higher DIAAS values, though strategic formulation of plant protein mixtures can achieve complementary effects that enhance overall protein quality.

Important research gaps remain, including the need for more comprehensive DIAAS data on commonly consumed foods, better understanding of the effects of food processing and matrix interactions on amino acid bioavailability, and development of rapid, cost-effective in vitro methods that strongly correlate with in vivo findings [23]. Additionally, the first overarching recommendation from the 2011 FAO Consultation—to treat each indispensable amino acid as an individual nutrient—has received limited attention, suggesting a need for more research focusing on specific amino acid metabolism rather than protein as a aggregate nutrient [23].

For researchers and drug development professionals, the DIAAS framework provides enhanced capability to design nutritional interventions and therapeutic products targeted to specific population needs, from supporting healthy aging to addressing metabolic disorders. As global protein supply challenges intensify and alternative protein sources emerge, accurate assessment of protein quality becomes increasingly crucial for developing sustainable, nutritionally adequate food systems.

Dietary protein is a critical macronutrient for human health, supporting vital functions from cellular structure to immune response. The establishment of universal protein recommendations, such as the Recommended Dietary Allowance (RDA) of 0.8 g per kg of body weight per day for adults, represents a foundational scientific consensus. However, emerging research reveals that these one-size-fits-all guidelines may be insufficient for specific population subgroups, creating significant evidence gaps that hinder personalized nutritional guidance. This review systematically identifies and evaluates these gaps, focusing on the methodological limitations in establishing protein requirements and the pressing need for population-specific dietary recommendations.

The current protein RDA of 0.8 g/kg/day is primarily derived from nitrogen balance studies focused on preventing deficiency rather than optimizing health across diverse physiological states. As a library, NLM provides access to scientific literature. Inclusion in an NLM database does not imply endorsement of, or agreement with, the contents by NLM or the National Institutes of Health. Learn more: PMC Disclaimer | PMC Copyright Notice [31]. This approach has been challenged by more recent research indicating that protein needs vary substantially based on age, health status, and physiological demands. Furthermore, the assumption of high-quality protein consumption underlying these recommendations fails to account for the varying protein quality in different dietary patterns, particularly those relying heavily on plant-based sources. This analysis compares the evidence supporting current protein recommendations against emerging research needs, providing a framework for future investigation to refine population-specific protein requirements.

Comparative Analysis of Protein Recommendations Across Populations

Table 1: Current Protein Recommendations and Identified Gaps for Different Populations

| Population Group | Current Recommendation | Proposed New Targets | Key Evidence Gaps |

|---|---|---|---|

| Healthy Adults (18+ years) | 0.8 g/kg/day [32] | 0.65-0.83 g/kg/day (based on meta-analysis) [4] | Long-term efficacy studies; optimal intake for chronic disease prevention |

| Adults >65 Years | 0.8 g/kg/day | 1.0-1.2 g/kg/day (healthy); 1.2-1.5 g/kg/day (ill/ malnourished) [31] | Effective strategies to increase intake; impact on functional outcomes |

| Older Adults (40-65 Years) | 0.8 g/kg/day | Limited evidence for increased intake | Optimal intake for preventing sarcopenia onset; per-meal distribution |

| Athletes | 0.8 g/kg/day | 1.4-2.0 g/kg/day [33] | Sport-specific requirements; timing strategies for different training modalities |

| Plant-Based Consumers | 0.8 g/kg/day | Higher intakes suggested to compensate for quality [6] | Accurate protein quality assessment; complementary protein strategies |

Table 2: Protein Intake Patterns and Deficiencies in Older Adults

| Parameter | Adults 51-60 Years | Adults 61-70 Years | Adults >70 Years |

|---|---|---|---|

| Not meeting 0.8 g/kg/day | Up to 46% [8] | Similar deficit patterns | Up to 46% [8] |

| Associated diet quality | Significantly poorer [8] | Significantly poorer [8] | Significantly poorer [8] |

| Functional limitations | Significantly more in low protein consumers [8] | Significantly more in low protein consumers [8] | Significantly more in low protein consumers [8] |

| Grip strength | Not significantly different | Not significantly different | Significantly lower in low protein consumers [8] |

The disparity between current recommendations and physiological needs is particularly pronounced in aging populations. Muscle mass declines gradually from the third decade of life, with a 30-50% decrease reported between ages 40 and 80 [31]. Despite this physiological reality, protein recommendations remain unchanged until age 65, creating a significant evidence gap for adults in the 40-65 age range. Observational data reveals that protein intake actually declines with advancing age while requirements may be increasing, creating a concerning nutritional paradox. In Dutch older adults, approximately 50% consume less than 1.0 g/kg/day [34], and similar patterns are observed across Western countries [6].

Methodological Limitations in Protein Requirement Research

Nitrogen Balance Technique Constraints

The nitrogen balance method, which underpins current protein recommendations, has significant methodological limitations that contribute to ongoing evidence gaps. This approach may be inaccurate due to unaccounted routes of nitrogen input and output [31], potentially underestimating true protein requirements. Furthermore, nitrogen balance studies are typically conducted in controlled clinical environments, limiting assessment to short-term outcomes rather than long-term physiological adaptations [31]. The technique fundamentally establishes minimum requirements to prevent deficiency rather than optimal intakes for health promotion or disease prevention.

Recent meta-analyses of nitrogen balance studies suggest the RDA should be approximately 0.65 g/kg/day for the estimated average requirement and 0.83 g/kg/day for the RDA [4]. These values challenge the current 0.8 g/kg/day RDA and highlight the ongoing debate surrounding methodological approaches to determining protein requirements. The continued reliance on nitrogen balance studies without complementary methodologies represents a significant constraint in advancing the field of protein requirements research.

Emerging Techniques and Their Potential

The indicator amino acid oxidation (IAAO) technique has emerged as a promising alternative methodology, with studies using this approach reporting increased protein requirements in older adults compared with younger counterparts [6]. This method offers several advantages, including reduced subject burden and shorter study durations, potentially facilitating research in more diverse populations and settings.

Other innovative approaches include in vitro digestion modeling systems to screen protein quality from novel sources [6] and improved assessment tools such as the Protein Screener (Pro-MS) that can identify individuals with habitually low protein intake [35]. One study validated a protein intake screening tool for UK adults with an area under the curve of 0.731, indicating reasonable accuracy in identifying individuals consuming ≤1.0 g/kg/day [35]. While these methodologies show promise, they have not yet been widely adopted or validated across diverse populations, representing both an evidence gap and opportunity for future research.

Key Evidence Gaps in Population-Specific Protein Requirements

Aging Population Research Needs

The aging population presents particularly complex evidence gaps regarding protein requirements. While consensus groups recommend 1.0-1.2 g/kg/day for healthy adults over 65 [31], the appropriate intake for adults aged 40-65 years remains poorly defined despite the onset of sarcopenia in this demographic. The loss of muscle mass begins as early as age 40, with an accelerated decline after age 50 [31], yet targeted protein recommendations for this critical prevention window are lacking.

Beyond total daily intake, the distribution pattern of protein consumption throughout the day represents another significant evidence gap. Current evidence suggests that consuming 25-30 g of high-quality protein per meal optimally stimulates muscle protein synthesis [31], but the application of this research to older adults with anabolic resistance requires further investigation. The estimated per-meal threshold for plant proteins is particularly understudied [31], creating practical challenges for clinicians advising patients following plant-based diets.

The assessment of protein quality represents a fundamental evidence gap with implications for dietary recommendations and environmental sustainability. The Digestible Indispensable Amino Acid Score (DIAAS) has replaced the Protein Digestibility Corrected Amino Acid Score (PDCAAS) as the preferred method for evaluating protein quality [6], but application remains limited. Plant proteins generally have lower DIAAS values due to incomplete amino acid profiles and reduced digestibility [6], but the implications for population recommendations when consuming mixed diets requires clarification.

Table 3: Protein Quality Assessment and Research Needs

| Protein Source | Amino Acid Limitations | Digestibility Concerns | Research Priorities |

|---|---|---|---|

| Animal Proteins | Generally complete amino acid profile | High digestibility | Environmental impact; health effects in different life stages |

| Soy Protein | Complete amino acid profile | Moderate to high digestibility | Hormonal effects in specific populations; processing optimization |

| Legume Proteins | Often limited in methionine | Reduced by anti-nutrients (phytates, protease inhibitors) | Effective processing methods; complementary protein strategies |

| Cereal Proteins | Often limited in lysine | Reduced by fiber interactions; compact protein structures | Biofortification approaches; fermentation techniques |

| Novel Proteins | Varies by source (insects, fungi, algae) | Unknown without specific testing | Safety assessment; allergenicity; cultural acceptance |

The environmental implications of protein production necessitate research on sustainable alternatives. Animal protein production requires large areas of dedicated land, water, and energy while generating significant greenhouse gas emissions [31]. Transitioning to more plant-based proteins requires understanding how to maintain protein quality while shifting consumption patterns—a critical evidence gap given that plant-based nutrition may affect appetite and energy intake in older adults at risk of malnutrition [31].

Experimental Approaches and Methodological Frameworks

Nitrogen Balance Protocol

The nitrogen balance technique remains a foundational methodology for determining protein requirements, despite its limitations. The following protocol outlines a standardized approach:

Objective: To determine protein requirements by measuring nitrogen intake and output to establish equilibrium.

Subjects: Healthy adults representing the target population (e.g., older adults, athletes) with controlled physical activity levels.

Dietary Control:

- Provision of controlled diets with varying protein levels (0.1-1.5 g/kg/day)

- Precise measurement of all food intake and composition

- Adaptation period of 5-7 days at each test protein level

Sample Collection:

- Total urine collection for 24-hour periods throughout the study

- Stool collection for nitrogen content analysis

- Assessment of other nitrogen losses (skin, sweat, hair)

Analysis:

- Nitrogen content of diet, urine, and feces using Kjeldahl or Dumas method

- Calculation: Nitrogen Balance = Nitrogen Intake - (Urinary Nitrogen + Fecal Nitrogen + Miscellaneous Losses)

Data Interpretation: Requirement determined as the intake level at which nitrogen equilibrium is maintained.

This protocol was used in the meta-analysis that established requirements of 0.65 g/kg/day for the EAR and 0.83 g/kg/day for the RDA [4]. Recent applications suggest these values may better reflect true requirements than the current RDA of 0.8 g/kg/day.

Indicator Amino Acid Oxidation (IAAO)

The IAAO method represents a more modern approach to determining protein requirements:

Principle: Based on the concept that when one indispensable amino acid is deficient for protein synthesis, all other amino acids including the indicator amino acid will be oxidized.

Subjects: Typically studied in a metabolic research setting with controlled dietary intake.

Dietary Protocol:

- Adaptation to test protein levels for shorter periods than nitrogen balance (1-2 days)

- Provision of diets with varying protein levels but constant energy

- Use of amino acid mixtures to create specific protein quality profiles

Tracer Administration:

- Administration of stable isotope-labeled amino acid (typically [1-13C]phenylalanine)

- Continuous infusion or bolus protocols depending on study design

Sample Collection:

- Breath samples for 13CO2 enrichment measurement

- Blood samples for amino acid concentrations and enrichment

Analysis:

- Measurement of 13CO2 enrichment in breath samples

- Calculation of indicator amino acid oxidation rate

- Identification of breakpoint where oxidation rapidly increases indicating requirement

Advantages: Shorter study duration, less subject burden, applicable to vulnerable populations [6].

This method has demonstrated higher protein requirements in older adults compared to younger individuals, suggesting potential limitations in the current RDA [6].

Diagram 1: Methodological Framework for Protein Requirement Research. This flowchart illustrates the decision process for selecting appropriate methodologies based on research questions and population characteristics.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Methods

Table 4: Essential Research Tools for Protein Requirement Studies

| Tool/Reagent | Application | Specific Examples | Research Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Stable Isotope Tracers | IAAO studies to determine requirements | [1-13C]phenylalanine, [2H3]leucine | Purity verification; appropriate dosing strategies |

| Amino Acid Mixtures | Protein quality studies; controlled diets | Crystalline amino acids patterned after target proteins | Palatability challenges; matching physiological ratios |

| Indirect Calorimetry | Measure energy expenditure and substrate oxidation | Metabolic carts with breath collection | Calibration with standard gases; steady-state conditions |

| Body Composition Tools | Assess muscle mass changes | DEXA, BIA, MRI, CT | Method-specific precision errors; validation in population |

| Dietary Assessment Platforms | Measure habitual intake and compliance | 24-hour recalls, food frequency questionnaires, food diaries | Systematic biases; memory effects; cultural appropriateness |

| Protein Quality Assays | In vitro digestibility assessment | INFOGEST static digestion model | Correlation with in vivo results; anti-nutrient analysis |

| Muscle Biopsy Tools | Acute MPS measurement | Bergström needle with suction | Standardization of processing; analytical variability |

The selection of appropriate research tools depends heavily on the specific research question and population being studied. For example, while nitrogen balance studies require precise collection of all nitrogen outputs, IAAO studies depend on highly specific tracer methodologies and mass spectrometry analysis. Body composition assessment presents particular challenges in older adults, where fluid shifts may affect methods like bioelectrical impedance analysis.

Beyond laboratory methodologies, validated assessment tools for dietary intake and protein-specific screening instruments are essential for population-based research. The development of a protein intake screener for UK adults demonstrates the potential for efficient identification of individuals with low protein intake [35], though such tools require population-specific validation before widespread implementation.

Future Research Directions and Priority Populations

Several key populations merit prioritized investigation for protein requirements research. Older adults (particularly those aged 40-65 years) represent a critical target given the onset of sarcopenia during this life stage and the current absence of evidence-based recommendations. Research should focus not only on total protein intake but also on distribution patterns throughout the day, anabolic resistance mechanisms, and practical interventions to improve protein intake in those with declining appetite or functional limitations.

Individuals following plant-based diets constitute another priority population, as current recommendations assume high-quality protein consumption. Research must establish conversion factors for different protein sources and determine whether protein requirements increase when relying primarily on plant proteins. The complementary effects of different plant proteins and the impact of food processing on protein quality represent additional research priorities.

Athletes and physically active individuals require further sport-specific protein recommendation research, particularly regarding timing, distribution, and optimal protein sources for different training modalities. The efficacy of protein interventions in clinical populations, including those with renal impairment, metabolic conditions, or acute critical illness, represents another significant evidence gap with direct clinical implications.

Diagram 2: Research Priority Framework for Population-Specific Protein Requirements. This diagram illustrates the interconnected relationships between priority populations and research needs, highlighting the multidimensional approach required to address current evidence gaps.

From a methodological perspective, future research should prioritize long-term studies that evaluate functional outcomes rather than relying solely on short-term nitrogen balance or MPS measurements. The development and validation of improved assessment tools, including biomarkers of protein intake and status, would significantly advance the field. Finally, research integrating environmental sustainability with protein requirements would provide valuable guidance for developing recommendations that optimize both human and planetary health.

Significant evidence gaps persist in our understanding of protein requirements across diverse populations, limiting the development of evidence-based, personalized protein recommendations. Current guidelines, based primarily on short-term nitrogen balance studies assuming high-quality protein intake, fail to address the nuanced needs of aging adults, plant-based consumers, and individuals with varying physiological demands. Methodological limitations, including the focus on preventing deficiency rather than promoting optimal health, further constrain our understanding.

Addressing these evidence gaps requires a multidisciplinary approach incorporating validated assessment tools, long-term functional outcomes, and consideration of environmental sustainability. Priority should be given to research in vulnerable populations, including adults aged 40-65 years experiencing early sarcopenia and those following plant-based diets who may be consuming proteins with reduced quality and digestibility. Through targeted investigation of these evidence gaps, the scientific community can develop refined, population-specific protein recommendations that optimize health across the lifespan while promoting sustainable food systems.

Advanced Methodologies for Protein Requirement Assessment and Clinical Application

For decades, the determination of protein requirements has relied predominantly on the nitrogen balance (NB) method, which has formed the basis for dietary reference intakes worldwide. However, significant methodological limitations have prompted the scientific community to seek more robust and accurate alternatives. The indicator amino acid oxidation (IAAO) technique has emerged as a superior methodological approach, offering enhanced precision and reliability for determining protein and amino acid requirements across diverse populations. This paradigm shift is supported by a growing body of evidence demonstrating consistent discrepancies between these two methods, with IAAO-derived requirements consistently exceeding NB-based estimates by approximately 30% across multiple population subgroups.

The fundamental distinction between these methodologies lies in their conceptual foundations: while NB measures a static equilibrium between nitrogen intake and excretion, IAAO dynamically assesses the metabolic utilization of amino acids for protein synthesis at the cellular level. This technical advancement allows researchers to move beyond mere maintenance of body mass to optimization of metabolic function. As global interest in precision nutrition intensifies, particularly for specialized populations including athletes, older adults, and clinical groups, the validation of IAAO as the new gold standard represents a critical evolution in nutritional science with far-reaching implications for research, clinical practice, and public health policy.

Quantitative Comparison: IAAO vs. Nitrogen Balance

Recent meta-analyses have provided compelling quantitative evidence establishing significant differences between protein requirements determined via IAAO versus traditional NB methodology. A comprehensive umbrella review and meta-analysis published in 2025, encompassing 43 NB articles (777 participants) and 17 IAAO articles (186 participants), revealed consistent and statistically significant disparities across population subgroups [30] [36].

Table 1: Protein Requirement Comparison Between NB and IAAO Methods

| Population | NB Method (g/kg/d) | IAAO Method (g/kg/d) | Percentage Difference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Non-athletes | 0.64 (95% CI: 0.61, 0.68) | 0.88 (95% CI: 0.85, 0.90) | 36% higher with IAAO |

| Athletes | 1.27 (95% CI: 1.06, 1.47) | 1.61 (95% CI: 1.44, 1.78) | 27% higher with IAAO |

| Older Adults | 0.64-0.70 (linear regression) | 0.85-0.96 (breakpoint) | 30-37% higher with IAAO |

| Children | 0.76 (EAR) | 1.25-1.30 (breakpoint) | 58-71% higher with IAAO |

The data demonstrate that IAAO-derived protein requirements are substantially higher than NB estimates, with an average difference of approximately 30% across populations [30] [36]. This discrepancy is particularly pronounced in athletic populations, where IAAO suggests protein requirements up to 1.61-2.10 g/kg/d for endurance and resistance-trained athletes, significantly exceeding the NB-based estimates of 1.27 g/kg/d [30] [37]. Similarly, for older adults with sarcopenia, recent IAAO studies indicate requirements of 1.21 g/kg/d for the estimated average requirement (EAR) and 1.54 g/kg/d for recommended nutrient intake (RNI), substantially higher than current recommendations based on NB methodology [38].

Table 2: IAAO-Determined Protein Requirements Across Populations

| Population | EAR (Breakpoint) g/kg/d | RDA/RNI (Upper 95% CI) g/kg/d | Key Studies |

|---|---|---|---|

| General Young Adults | 0.87-0.93 | 1.17-1.29 | Matsumoto et al., 2023 [37] |

| Resistance-Trained Athletes | 1.49-2.00 | - | Bandegan et al., 2017; Mazzulla et al., 2020 [30] |

| Endurance Athletes | 1.65-2.10 | - | Matsumoto et al., 2023 [37] |

| Older Adults | 0.85-0.96 | 1.13-1.95 | Wu et al., 2025; Rafii et al., 2015 [37] [38] |