Beyond Nutrient Content: How Food Processing Technologies and Formulation Impact Bioavailability for Biomedical Applications

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of the critical relationship between food processing and nutrient bioavailability, tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals.

Beyond Nutrient Content: How Food Processing Technologies and Formulation Impact Bioavailability for Biomedical Applications

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of the critical relationship between food processing and nutrient bioavailability, tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals. It explores the foundational principles defining bioavailability, bioaccessibility, and bioactivity, and details advanced in vitro and in vivo methodologies for its assessment. The scope includes an examination of how both conventional and novel processing technologies—from thermal treatments to cold plasma and high-pressure processing—alter nutrient release and absorption. Furthermore, the review investigates strategies to mitigate anti-nutritional factors and optimize food matrices, compares the efficacy of various processing interventions, and discusses the implications for developing functional foods, personalized nutrition, and nutraceuticals, thereby bridging food science with biomedical research.

Defining the Landscape: Core Concepts of Nutrient Bioavailability and the Food Matrix Effect

In pharmacology and nutritional sciences, accurately predicting the physiological effect of an administered compound—whether a potent drug or an essential nutrient—hinges on understanding its journey within the body. Two fundamental concepts governing this journey are absorption and bioavailability. Although often used interchangeably, they represent distinct physiological processes. Absorption describes the translocation of a substance from its site of administration into the systemic circulation [1] [2]. In contrast, bioavailability is a broader, more clinically relevant parameter defined as the proportion of an administered dose that reaches the systemic circulation in an active form, and is thereby available to exert its therapeutic or physiological effect at the target site of action [3] [4]. The critical distinction is that bioavailability encompasses not only absorption but also subsequent pre-systemic metabolic processes that can inactivate the compound before it ever reaches the bloodstream [1].

This distinction is paramount within the context of food processing research. The techniques used to process foods—ranging from traditional fermentation to modern ultra-processing—fundamentally alter the food matrix. This matrix dictates how nutrients are released during digestion (bioaccessibility), absorbed across the intestinal epithelium, and subsequently metabolized before reaching circulation. Therefore, evaluating the impact of any processing technique requires a clear mechanistic understanding of both absorption and the metabolic fates of nutrients, as together they determine the final bioavailable fraction that the human body can ultimately utilize.

Core Concepts and Definitions

Mechanistic Insights into Absorption

Absorption is the initial, critical step for any orally administered substance. It involves the compound crossing biological barriers, primarily the intestinal epithelium, to enter the bloodstream. Several mechanisms facilitate this transport, each with distinct implications for the rate and extent of absorption [2]:

- Passive Diffusion: The most common pathway, where molecules move from a region of higher concentration (the gut lumen) to a region of lower concentration (the bloodstream) without energy expenditure. This process is driven by the concentration gradient and is favored for lipophilic (fat-soluble) molecules [2].

- Carrier-Mediated Membrane Transport: This involves specialized transporter proteins embedded in the cell membrane.

- Active Transport: Requires energy and can move molecules against their concentration gradient. This system is crucial for absorbing nutrients that mimic natural metabolites, such as 5-fluorouracil [2].

- Facilitated Diffusion: Also uses carrier proteins but does not require energy and cannot move molecules against a concentration gradient. An example is the organic cation transporter 1 (OCT1) that moves metformin [2].

- Paracellular Transport: Passive movement of substances through the spaces between cells, which is more common for small, hydrophilic molecules.

The following diagram illustrates the journey of an oral compound, highlighting the key processes of absorption and pre-systemic metabolism that determine its ultimate bioavailability.

The Comprehensive Nature of Bioavailability

Bioavailability (denoted as F) is a quantitative measure, typically expressed as a percentage, of the total administered dose that reaches the systemic circulation in an active form. An intravenously (IV) administered drug bypasses absorption and pre-systemic metabolism, thus having a bioavailability of 100% [4]. For all other routes, especially oral, F is less than 100%.

The concept of first-pass metabolism is central to understanding reduced oral bioavailability. After absorption from the gut, the compounds travel via the hepatic portal vein to the liver, a primary site of metabolism, where they can be extensively broken down before ever reaching the systemic circulation [3] [4]. Bioavailability is thus calculated by comparing the total exposure to a drug from an oral dose versus an IV dose, measured as the Area Under the plasma Concentration-time curve (AUC):

F = (AUC~oral~ × Dose~IV~) / (AUC~IV~ × Dose~oral~) × 100 [4]

Two key types of bioavailability studies are conducted:

- Absolute Bioavailability: Compares the systemic exposure of an extravascular (e.g., oral) formulation to an IV formulation of the same drug [4].

- Relative Bioavailability: Compares the systemic exposure of two different formulations (e.g., a generic vs. a brand-name drug) administered by the same route to establish bioequivalence [4].

Table 1: Key Factors Influencing Drug Absorption and Bioavailability

| Category | Specific Factor | Impact on Absorption/Bioavailability |

|---|---|---|

| Drug-Specific | Solubility & Permeability | Low water solubility or poor membrane permeability impedes absorption [2]. |

| pKa & pH | Determines the ionized/non-ionized fraction; non-ionized, lipophilic forms are better absorbed [2]. | |

| Dosage Form | Solutions are absorbed faster than tablets; modified-release formulations alter the absorption rate [2] [4]. | |

| Patient-Specific | Gastric Emptying & Intestinal Transit | Faster transit can reduce time for absorption, especially for slow-dissolving drugs [2]. |

| Food Content | Can increase, decrease, or delay absorption (e.g., fatty meals enhance albendazole absorption) [2]. | |

| Age & Disease State | Reduced absorption is common in elderly or critically ill patients with altered GI physiology [2] [3]. | |

| Genetic Phenotype | Inter-individual variation in metabolic enzyme activity (e.g., Cytochrome P450) affects first-pass metabolism [4]. | |

| Other | Drug-Drug/Food Interactions | Can form complexes (tetracycline with metals), inhibit/induce metabolism (grapefruit juice inhibits CYP3A), or compete for transporters [3] [4]. |

The Impact of Food Processing on Nutrient Bioavailability

The principles of bioavailability are directly applicable to nutritional science, where food processing techniques act as a primary determinant of a nutrient's fate in the body. Processing alters the food matrix, which in turn influences the release, transformation, and stability of nutrients and bioactive compounds.

Processing Techniques and Their Biochemical Consequences

Food processing methods can be broadly categorized, and their effects on nutrient bioavailability are complex and often dualistic.

Table 2: Impact of Food Processing Techniques on Nutrient Bioavailability

| Processing Technique | Effects on Food Matrix & Nutrients | Net Effect on Bioavailability |

|---|---|---|

| Thermal Processing (Cooking, Pasteurization) | - Disrupts cell walls, releasing bound nutrients [5].- Degrades heat-sensitive vitamins (e.g., Vitamin C, some B vitamins) [6].- Denatures proteins, potentially improving digestibility.- Can oxidize lipids and degrade certain antioxidants. | Variable. Can enhance bioavailability of carotenoids and some minerals [5]. Often reduces bioavailability of heat-labile vitamins. |

| Fermentation | - Microbes produce enzymes that break down antinutrients (e.g., phytates) [7] [8].- Pre-digests macromolecules like carbohydrates and proteins.- Can synthesize new bioactive compounds (e.g., bioactive peptides). | Mostly Enhances. Significantly improves mineral bioaccessibility by reducing phytate content [7] [8]. |

| Mechanical Processing (Milling, Extrusion) | - Reduces particle size, increasing surface area for enzyme action.- Disrupts the physical barrier of the cell wall.- Can generate heat, causing simultaneous thermal effects. | Enhances. Improves the bioaccessibility of encapsulated nutrients by breaking down the food matrix [8]. |

| Soaking & Germination | - Activates endogenous enzymes (e.g., phytase) that degrade antinutrients [8].- Leaches water-soluble antinutrients like phytates into the soak water. | Enhances. Effective for reducing phytate levels, thereby increasing mineral bioavailability [8]. |

A Research Case Study: Millet Fermentation

Research on traditional Ghanaian fermented foods, koko (a porridge) and zoomkoom (a beverage), provides a quantifiable example of how processing enhances bioavailability. Pearl millet, while nutrient-dense, contains high levels of phytic acid, an antinutrient that chelates minerals like iron, zinc, and calcium, forming insoluble complexes that cannot be absorbed in the gut [7].

The study found that the traditional processing techniques, which included fermentation, caused a 56.7% to 76.76% reduction in phytic acid content in the pearl millet. This degradation led to a direct decrease in the molar ratios of phytate to minerals ([Ca]:[Phy], [Fe]:[Phy], [Phy]:[Zn]). A lower phytate-to-mineral ratio correlates with higher mineral bioaccessibility. Consequently, the iron bioaccessibility in the products was measured within a range of 5-30%, with one koko sample (KP1) reaching 21.8%. Zinc bioaccessibility was even higher, with one zoomkoom sample (ZP1) at 42.2% [7]. This demonstrates clearly how a biotransformation achieved through processing directly improves the bioavailability of essential micronutrients.

Essential Research Methodologies and Tools

Experimental Protocols for Assessing Bioavailability

Determining bioavailability requires a multi-faceted experimental approach, often progressing from in vitro simulations to complex in vivo studies.

1. In Vitro Bioaccessibility Models

- Purpose: To simulate human digestion and estimate the fraction of a nutrient released from the food matrix for potential absorption.

- Protocol: The INFOGEST static in vitro simulation of gastrointestinal digestion is a widely adopted standardized protocol. It involves sequential incubation of the food sample with electrolytes, enzymes (e.g., pepsin in the gastric phase, pancreatin and bile salts in the intestinal phase), and under controlled pH and time conditions that mimic the human GI tract [7].

- Measurement: After centrifugation, the nutrient content in the soluble (digested) fraction is analyzed using techniques like Inductively Coupled Plasma Optical Emission Spectrometry (ICP-OES) for minerals or High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC) for organic compounds. The bioaccessibility percentage is calculated as: (Content in soluble fraction / Total content in food) × 100 [7].

2. In Vivo Pharmacokinetic Studies

- Purpose: To measure the actual absorption and bioavailability of a compound in a living organism.

- Protocol:

- Study Design: A controlled trial, typically crossover, where subjects receive the test compound orally and, on a separate occasion, an intravenous reference standard [4].

- Sample Collection: Serial blood samples are collected at predetermined time points post-administration.

- Bioanalysis: Plasma or serum is separated, and the concentration of the compound (and its metabolites) is quantified using validated analytical methods like LC-MS/MS.

- Data Analysis: The plasma concentration-time data is used to calculate key pharmacokinetic parameters:

The following diagram outlines the key decision points and methodologies in the experimental workflow for determining bioavailability.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Bioavailability Studies

| Reagent / Material | Function / Application |

|---|---|

| Simulated Gastrointestinal Fluids | Standardized mixtures of electrolytes, enzymes (pepsin, pancreatin), and bile salts used in in vitro digestion models to mimic the chemical environment of the human GI tract [7]. |

| Stable Isotope-Labeled Compounds (e.g., ¹³C, ²H) | Used as metabolic tracers in clinical studies. When administered orally or intravenously, they allow researchers to track the absorption, distribution, and metabolism of the compound of interest with high specificity using Mass Spectrometry, enabling precise absolute bioavailability determination without cross-interference [4]. |

| Caco-2 Cell Line | A human colon adenocarcinoma cell line that, upon differentiation, exhibits phenotypes similar to small intestinal enterocytes. It is a standard in vitro model for studying intestinal permeability and active/passive transport mechanisms of compounds [2]. |

| LC-MS/MS (Liquid Chromatography-Tandem Mass Spectrometry) | The cornerstone analytical technology for bioanalysis. It provides high sensitivity, specificity, and throughput for quantifying drugs, nutrients, and their metabolites in complex biological matrices like plasma, serum, and urine [9]. |

| P-Glycoprotein (P-gp) Substrates/Inhibitors | P-gp is a critical efflux transporter that can limit the absorption of many drugs. Using known substrates (e.g., digoxin) and inhibitors (e.g., verapamil) in experiments helps elucidate the role of transporter-mediated flux in a compound's bioavailability [2]. |

The rigorous distinction between absorption—the process of entry into the bloodstream—and bioavailability—the proportion of dose that reaches systemic circulation intact—is foundational for research in pharmacology and nutrition. This distinction provides the necessary framework for understanding how food processing techniques, by modifying the food matrix, can profoundly influence the nutritional value of our food. As research continues to evolve, moving beyond simplistic food classification systems and towards a deeper understanding of the biochemical composition and bioavailability of processed foods [9], these concepts will be crucial. They will guide the development of novel processing technologies and functional foods designed not only for safety and shelf-life but, most importantly, for optimized nutrient delivery and enhanced human health.

The Interplay of Bioaccessibility, Bioavailability, and Bioactivity in Nutrient Delivery

The efficacy of food components, whether nutrients or bioactive compounds, is not solely determined by their quantity in a food product. Instead, their health benefits are dictated by a sequential journey through the human body, conceptualized as bioaccessibility, bioavailability, and bioactivity [10] [11]. Understanding this cascade is paramount in nutritional science, food technology, and drug development, particularly when evaluating the impact of food processing on the ultimate physiological value of what we consume. This tripartite relationship forms a critical pathway that determines whether an ingested compound can exert its intended health-promoting effects. Within the context of a broader thesis on the impact of food processing on nutrient bioavailability research, this guide provides an in-depth technical examination of these concepts, their assessment methodologies, and the factors that influence them.

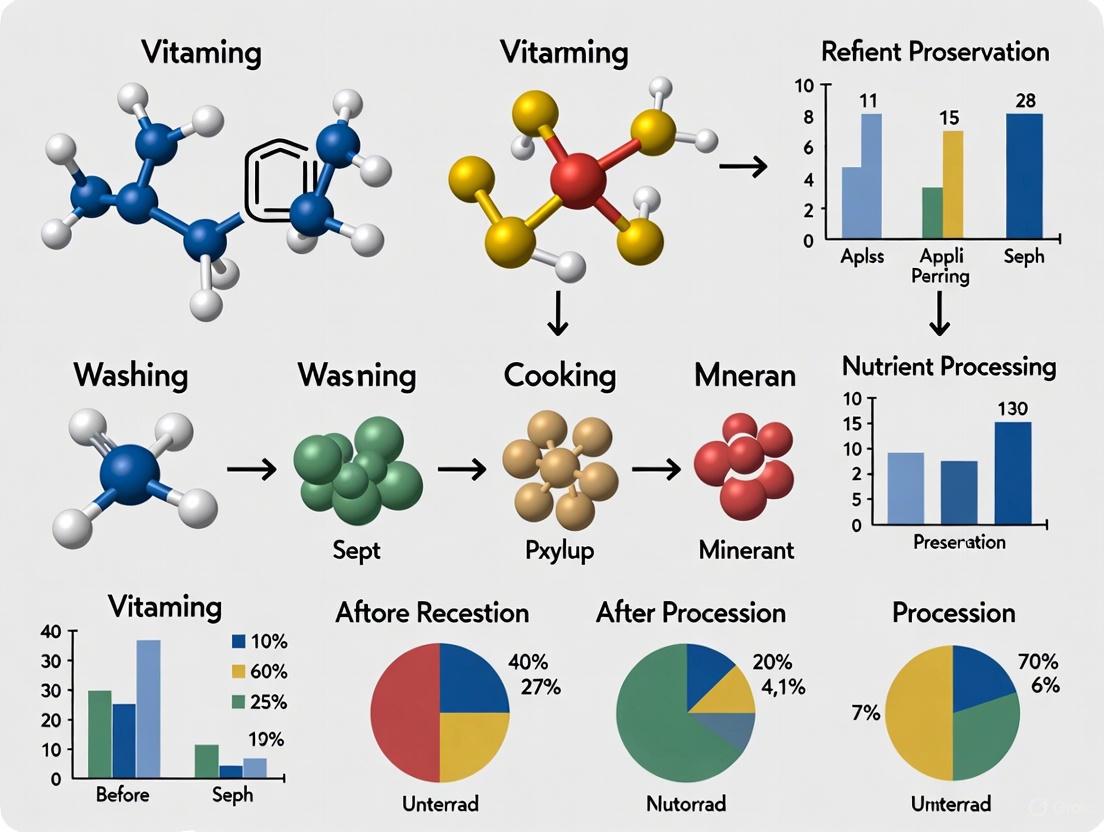

The interplay of these concepts is fundamental for designing functional foods and nutraceuticals. Bioavailability serves as an umbrella term that encompasses the entire fate of a food component, from ingestion to its utilization in physiological functions or storage [10]. Before a compound can become bioavailable, it must first become bioaccessible—released from the food matrix and transformed in the gastrointestinal tract into a form available for absorption [11]. Finally, bioactivity represents the culminating step, describing the specific physiological effects and mechanisms of action that the absorbed compound elicits at its target site [10]. This sequential relationship is visually summarized in Figure 1.

Figure 1. The Sequential Relationship from Ingestion to Physiological Effect. This pathway illustrates the journey of a nutrient or bioactive compound, where each step is a prerequisite for the next.

Defining the Core Concepts

Bioaccessibility

Bioaccessibility refers to the fraction of an ingested compound that is released from its food matrix into the gastrointestinal lumen and thus becomes available for intestinal absorption [12] [11]. It encompasses digestive transformations of foods into material ready for assimilation. This process is dependent on digestion and release from the food matrix, but does not include passage through the intestinal mucosa [12]. In essence, a compound that is not bioaccessible cannot be bioavailable. For instance, a polyphenol trapped within an intact plant cell wall that survives digestion and is excreted in feces was bioaccessible but not bioavailable.

Bioavailability

Bioavailability is a broader and more complex term, defined as the proportion of an ingested nutrient that is absorbed, becomes available for physiological functions, and is stored or utilized by the body [12] [10]. From a nutritional point of view, it refers to the fraction of the nutrient that is stored or available for physiological functions [13]. Bioavailability includes not only bioaccessibility but also absorption by intestinal cells, metabolism, tissue distribution, and bioactivity [10]. It is a key term for nutritional effectiveness, as not all the amounts of bioactive compounds are used effectively by the organism [10].

Bioactivity

Bioactivity describes the specific physiological effects and mechanisms of action exerted by a bioactive compound once it has reached its target tissue or organ [10]. This is the final manifestation of a compound's health-promoting potential. For example, the bioactivity of an antioxidant flavonoid might involve quenching free radicals in vascular endothelial cells, thereby reducing oxidative stress and inflammation. It is crucial to note that some compounds, such as non-digestible prebiotics, may exert bioactivity within the gastrointestinal tract without being absorbed into the systemic circulation [13].

Table 1: Core Concept Definitions and Determinants

| Concept | Definition | Key Determinants | Primary Assessment Methods |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bioaccessibility | The quantity of a compound released from its food matrix in the GI tract, making it available for absorption [11]. | Food matrix structure, digestion efficiency, solubility, interaction with other food components (e.g., fibers, lipids) [12] [14]. | In vitro solubility assays, dialyzability methods, gastrointestinal models (e.g., TIM) [12]. |

| Bioavailability | The fraction of an ingested nutrient that is absorbed and available for physiological functions or storage [12] [10]. | Absorption at enterocytes, presystemic metabolism, transport to systemic circulation, tissue distribution [12] [11]. | In vivo balance studies, tissue concentration assays, Caco-2 cell models for uptake/transport [12] [13]. |

| Bioactivity | The specific physiological effect or mechanism of action of a compound at its target site in the body [10]. | Affinity for cellular receptors, modulation of signaling pathways, enzymatic activity, interaction with gene expression. | Cell culture assays, animal model studies, human clinical trials measuring biomarker changes [5]. |

Methodologies for Assessing Bioaccessibility and Bioavailability

A range of in vitro and in vivo methods have been developed to evaluate bioaccessibility and components of bioavailability. These methods are critical for screening and ranking food formulations without the immediate need for expensive and complex human trials [12].

In Vitro Digestion Models

In vitro methods simulate the human digestive system via a multi-step digestion process that typically includes gastric and intestinal phases [12]. The general workflow is illustrated in Figure 2.

Figure 2. Generalized Workflow for a Two-Step In Vitro Digestion Model. This simulation is foundational for subsequent bioaccessibility measurements.

Following simulated digestion, the bioaccessible fraction is quantified using several principal methods, each with distinct endpoints, advantages, and limitations, as summarized in Table 2.

Table 2: Comparison of Primary In Vitro Methods for Assessing Bioaccessibility and Bioavailability [12]

| Method | Endpoint Measured | Key Advantages | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Solubility | Bioaccessibility | Simple, inexpensive, requires standard laboratory equipment. | Unreliable predictor of bioavailability; cannot assess uptake kinetics or nutrient competition. |

| Dialyzability | Bioaccessibility | Simple, inexpensive; based on equilibrium dialysis to simulate absorption [12]. | Cannot assess rate of uptake/absorption or nutrient competition at absorption site. |

| Gastrointestinal Models (TIM) | Bioaccessibility (can be coupled with cells for bioavailability) | Incorporates realistic parameters (peristalsis, body temperature, pH regulation); allows sampling at any digestive step [12]. | Expensive equipment; limited validation studies. |

| Caco-2 Cell Model | Bioavailability (uptake, transport) | Allows study of nutrient competition and transport mechanisms at the intestinal site [12]. | Requires trained personnel in cell culture; enzymatic digest must be treated to prevent cell degradation [12]. |

The Caco-2 Model for Bioavailability

The Caco-2 cell line, derived from human colon adenocarcinoma, differentiates to exhibit phenotypes similar to small intestinal enterocytes and is a gold standard for in vitro bioavailability studies [12]. These cells are typically grown on permeable Transwell inserts to create a polarized monolayer. The experimental process involves:

- Cell Culture: Caco-2 cells are cultured until they form a confluent, differentiated monolayer with tight junctions, which can take 14-21 days.

- Sample Application: The digested food sample (the bioaccessible fraction) is applied to the apical compartment (simulating the intestinal lumen).

- Uptake and Transport Measurement: After incubation, the amount of the compound that has been (a) taken up into the cells (uptake) or (b) transported to the basolateral compartment (transport) is quantified using techniques like HPLC or mass spectrometry [12].

A critical technical consideration is protecting the cell monolayer from the enzymatic activity of the digestive simulant (pancreatin/bile). This can be achieved by securing a dialysis membrane between the digest and the cells or by heat-treating the digest to inactivate the enzymes, though the latter may denature food components [12].

The Impact of Food Processing on Nutrient Delivery

Food processing is a pivotal factor that can dramatically alter the bioaccessibility and bioavailability of dietary bioactives. Its effects are complex and can be either detrimental or beneficial, depending on the compound, the matrix, and the processing conditions [5].

Processing Techniques and Their Effects

Table 3: Impact of Food Processing Techniques on Bioaccessibility and Bioavailability

| Processing Technique | Impact on Bioaccessibility/Bioavailability | Proposed Mechanism |

|---|---|---|

| Thermal (Cooking, Baking) | Variable: Can increase (e.g., carotenoids in sweetpotato) or decrease (e.g., Vitamin C) bioaccessibility [14] [5]. | Facilitates release from matrix by disrupting cell walls and complexes; can also degrade heat-labile compounds [5]. |

| Mechanical (Milling, Grinding) | Generally increases bioaccessibility. | Reduces particle size, disrupts physical barriers (e.g., cell walls), increasing surface area for digestive enzyme action [14]. |

| Fermentation | Often enhances bioavailability, particularly for minerals. | Reduces levels of anti-nutrients (e.g., phytic acid), improving mineral absorption [15]. |

| High-Pressure Processing (HPP) | Can improve the bioaccessibility of bioactive compounds. | Induces structural changes in the food matrix without significant heat, facilitating the release of compounds while minimizing degradation [16]. |

| Pulsed Electric Field (PEF) | Can enhance the release and bioavailability of bioactives. | Electroporation disrupts cellular membranes, improving the extractability and release of intracellular compounds [14]. |

The Role of the Food Matrix and Interactions

The native food matrix and interactions with other dietary components are dominant factors controlling nutrient delivery. For example, fat enhances the bioavailability of quercetin in meals [10] and is essential for the absorption of lipid-soluble vitamins and carotenoids. Conversely, anti-nutrients such as phytic acid (in cereals and legumes) and tannins can strongly chelate minerals like iron and zinc, forming insoluble complexes that drastically reduce their bioavailability [17]. Processing strategies are often designed to mitigate these negative interactions. Furthermore, the interaction between bioactives and macronutrients (proteins, carbohydrates) can modify chemical structures and either protect the bioactive from degradation or entrap it, preventing release [14].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Reagents and Materials

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Bioaccessibility/Bioavailability Studies

| Reagent / Material | Function in Experimental Protocol |

|---|---|

| Pepsin (from porcine stomach) | Enzyme for the in vitro gastric digestion phase; proteolysis at acidic pH (pH 2) [12]. |

| Pancreatin & Bile Salts | Added in the intestinal phase; pancreatin provides a cocktail of pancreatic enzymes (amylase, lipase, proteases), while bile salts act as emulsifiers [12]. |

| Dialysis Tubing (with specific MWCO) | Used in dialyzability methods to separate low molecular weight, bioaccessible compounds from the digest [12]. |

| Caco-2 cell line (HTB-37) | Human epithelial cell line used as a model of the intestinal barrier for uptake and transport studies [12]. |

| Transwell Inserts | Permeable supports for growing Caco-2 cells as polarized monolayers, allowing separate access to apical and basolateral compartments [12]. |

| Atomic Absorption Spectrophotometry (AAS)/ICP-AES | For quantification of mineral elements in solubility/dialyzability assays [12]. |

| High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC) coupled with Mass Spectrometry (MS) | For separation, identification, and quantification of specific bioactive compounds (e.g., polyphenols, carotenoids) and their metabolites in digests, cell lysates, and basolateral media [14]. |

The journey of a nutrient from the plate to its physiological action is a complex cascade governed by the principles of bioaccessibility, bioavailability, and bioactivity. This interplay is not a linear guarantee but a series of hurdles that can be dramatically influenced by food processing and the intrinsic properties of the food matrix. While in vitro methodologies provide powerful, cost-effective tools for screening and understanding these processes, they cannot fully replicate the complexity of in vivo systems, including host factors like nutrient status, age, and genotype [12]. The future of optimizing nutrient delivery lies in the continued refinement of these models, their validation against human studies, and the intelligent application of novel processing technologies—both thermal and non-thermal—designed to maximize the health-promoting potential of our food. A deep understanding of this interplay is indispensable for researchers and professionals in food science, nutrition, and drug development aiming to create effective functional foods and nutraceuticals.

The Role of Food Microstructure and Cellular Barriers in Nutrient Release

The bioavailability of nutrients is not solely determined by their chemical presence in food. Instead, the physical microstructure of food and the natural cellular barriers within plant and animal tissues play a decisive role in governing how nutrients are released, absorbed, and utilized by the human body [18]. This relationship is critically important within the broader context of food processing research, as processing methods fundamentally alter food microstructure, thereby directly influencing the nutritional value of the final product. A growing body of evidence suggests that the health implications of foods extend beyond their nutrient composition to encompass their structural integrity [9]. This whitepaper provides an in-depth technical analysis of the mechanisms through which food microstructure modulates nutrient release, supported by contemporary research findings and experimental methodologies relevant to researchers and scientists in the field.

Theoretical Framework: Food Matrix and Bioavailability

Defining Bioavailability and Bioaccessibility

In nutritional sciences, bioavailability is comprehensively defined as the proportion of an ingested nutrient that is absorbed, transported to the systemic circulation, and made available for use in physiological functions or for storage [19]. This multifaceted process encompasses several stages: liberation from the food matrix during digestion, absorption across the intestinal epithelium, and subsequent metabolism [19]. Bioaccessibility, a closely related and preceding concept, specifically refers to the fraction of a nutrient that is released from the food matrix and becomes accessible for intestinal absorption [20]. Both concepts are intrinsically linked to the structural properties of food.

The Intestinal Barrier as a Gatekeeper

The intestinal epithelium serves as the primary interface for nutrient absorption and is a sophisticated selective barrier. This barrier function is primarily regulated by tight junctions – protein complexes that seal the paracellular space between epithelial cells and control the passive diffusion of molecules [18] [21]. Key tight junction proteins include claudins, occludin, and zonula occludens (ZO), which anchor the transmembrane proteins to the actin cytoskeleton [18]. Nutrients can cross this barrier via two primary pathways:

- Paracellular Transport: Passive, size-restricted diffusion through tight junction pores, driven by electrochemical or osmotic gradients [18].

- Transcellular Transport: Receptor-mediated or fluid-phase endocytosis of nutrients across the epithelial cell itself [18].

Table 1: Key Components of the Intestinal Barrier and Their Functions

| Component | Type | Primary Function in Nutrient Absorption |

|---|---|---|

| Tight Junctions | Multiprotein Complex | Regulates paracellular permeability of small molecules and ions [18]. |

| Claudins | Transmembrane Protein | Forms the primary seal; determines charge and size selectivity of pores [18]. |

| Occludin | Transmembrane Protein | Contributes to barrier regulation and stability [18]. |

| Zonula Occludens (ZO) | Cytosolic Scaffold Protein | Anchors transmembrane proteins to the actin cytoskeleton [18]. |

| Enterocytes | Epithelial Cell | Mediates transcellular absorption of nutrients via transporters and endocytosis [18]. |

| M Cells | Epithelial Cell | Specialized for antigen and microparticle sampling in Peyer's patches [18]. |

| Secretory IgA (sIgA) | Immunoglobulin | Neutralizes pathogens and dietary antigens within the lumen [18]. |

| Mucus Layer | Glycoprotein | Acts as a physical and chemical barrier preventing direct bacterial adhesion [18]. |

The Impact of Processing on Food Microstructure and Nutrient Release

Food processing techniques, from mechanical grinding to thermal treatments, directly compromise cellular integrity, with significant consequences for nutrient delivery.

The Cellular Entrapment Concept

In whole plant foods, nutrients are naturally encapsulated within cell walls made of indigestible dietary fiber. This cellular structure acts as a physical barrier that must be broken down by digestion or processing to release the contents. A pivotal study demonstrated this principle using chickpea meals with controlled cellular structures [22] [23]. Meals with intact cell structures resulted in a slower, more prolonged release of metabolites further down the gastrointestinal tract, stimulating the distal release of satiety hormones GLP-1 and PYY. In contrast, meals with broken cell structures caused a rapid spike in blood glucose and the upper-GI hormone GIP [22] [23]. This confirms that even with identical chemical compositions, food structure dictates the kinetics of nutrient release and subsequent hormonal responses.

Processing Methods and Structural Alterations

Different processing and preservation methods alter the food matrix in distinct ways, influencing both nutrient retention and bioaccessibility.

Table 2: Effect of Drying Methods on Kiwifruit Quality and Bioaccessibility [20]

| Drying Method | Impact on Microstructure | Nutrient Retention | Effect on Bioaccessibility |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hot Air Drying (HAD) | Severe shrinkage and collapse of porous structure. | Lowest retention of heat-sensitive nutrients (e.g., ascorbic acid, polyphenols). | Can enhance bioaccessibility of some carotenoids by breaking down cellular barriers. |

| Vacuum Freeze Drying (FD) | Preserves a uniform, porous structure via ice sublimation. | Highest retention of total acids, sugars, polyphenols, and ascorbic acid. | High nutrient retention but not always optimal bioaccessibility. |

| Combined MVD-FD | Shows variably compressed pores. | High nutrient retention, similar to FD. | Significantly enhanced bioaccessibility of polyphenols, ascorbic acid, lutein, and zeaxanthin compared to FD. |

Furthermore, advanced manufacturing like 3D food printing (3D-FP) allows for precise structuring of food matrices to control nutrient delivery. The design of the printed matrix, including its porosity and internal structure, can protect sensitive micronutrients during digestion and target their release to specific gut regions [24]. However, the addition of micronutrients can also alter the ink's rheology and the printing process, demonstrating the complex interplay between nutrition and material science [24].

Experimental Approaches and Analytical Techniques

In Vitro Digestion Models

A standard protocol for assessing nutrient bioaccessibility involves simulated gastrointestinal digestion. A typical experiment, as used in the kiwifruit drying study, follows these stages [20]:

- Oral Phase: The sample is mixed with simulated salivary fluid (e.g., α-amylase in pH 6.8-7.0 buffer) and incubated briefly (e.g., 2-5 minutes).

- Gastric Phase: The oral bolus is combined with simulated gastric fluid (e.g., pepsin in pH 2.5-3.0 HCl solution) and incubated for 1-2 hours at 37°C with constant agitation.

- Intestinal Phase: The gastric chyme is neutralized and mixed with simulated intestinal fluid (e.g., pancreatin and bile salts in pH 7.0 buffer) and incubated for 2 hours at 37°C.

- Centrifugation: The final digestate is centrifuged (e.g., 5,000 × g, 30 minutes) to separate the aqueous fraction (containing bioaccessible compounds) from the solid residue.

- Analysis: The bioaccessible fraction in the supernatant is quantified using analytical techniques such as High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC) for vitamins and phenolics, or spectrophotometry for total polyphenols and carotenoids [20].

In Vivo and Clinical Studies

Human studies are essential for validating findings from in vitro models. The chickpea cellular structure study provides a robust protocol for investigating the real-time impact of food structure on metabolic and hormonal responses [22] [23]:

- Participant Preparation: Healthy participants reside as inpatients. For detailed GI sampling, they can be fitted with enteral feeding tubes positioned in the stomach and upper-small intestine.

- Test Meal Design: Meals are formulated to have identical macronutrient and micronutrient profiles but differ in cellular structure (intact vs. broken cells), verified by light microscopy.

- Sample Collection: Following test meal consumption, serial samples are collected over several hours. This includes blood (for hormones like GIP, GLP-1, PYY, insulin, and glucose), intestinal contents aspirated via tubes, and subjective appetite scores using visual analogue scales (VAS).

- Metabolite Profiling: Advanced techniques like LC-MS are used to characterize the metabolite profile of intestinal contents, correlating it with hormonal and glycaemic responses [22].

Diagram 1: Experimental workflow for in vivo food structure studies.

Metabolomics for Biochemical Profiling

Non-targeted metabolomics using Liquid Chromatography coupled with Mass Spectrometry (LC-MS) is a powerful tool for comprehensively assessing how processing alters a food's biochemical profile. This approach was effectively used to analyze 168 plant-based protein-rich foods, revealing that processing-induced changes in phytochemicals (e.g., isoflavonoids in soy) do not align with conventional classification systems like NOVA, highlighting the importance of direct biochemical measurement over arbitrary processing categories [9].

Research Reagent Solutions Toolkit

Table 3: Essential Reagents and Materials for Food Structure and Bioavailability Research

| Reagent / Material | Function / Application | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Simulated Digestive Fluids | Replicate the chemical environment of the human GI tract for in vitro digestion studies. | Contains enzymes (α-amylase, pepsin, pancreatin) and salts at physiologically relevant pH and concentrations [20]. |

| Cell Culture Models (e.g., IPEC-J2, Caco-2) | Model the human intestinal epithelium for transport and barrier function studies. | Used to investigate the effects of dietary components on tight junction protein expression and integrity [21]. |

| Chromatography Standards | Calibration and quantification in HPLC and LC-MS analysis. | Pure compounds (e.g., daidzein, genistein, ascorbic acid, rutin) for identifying and measuring specific nutrients and metabolites [20] [9]. |

| Specific Antibodies | Detect and quantify proteins via Western Blot or Immunofluorescence. | Antibodies against tight junction proteins (Claudin-1, Occludin, ZO-1) to assess intestinal barrier integrity [21]. |

| Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay (ELISA) Kits | Quantify hormones, cytokines, and other biomarkers in biological samples. | Measure gut hormone levels (GLP-1, GIP, PYY) in plasma/serum from clinical studies [22] [23]. |

Implications for Food Design and Future Research

Understanding the role of food microstructure opens avenues for designing foods with tailored physiological effects. The potential to structure foods to promote satiety hormones like GLP-1 offers a dietary strategy to complement the management of obesity and type 2 diabetes [22] [23]. Furthermore, technologies like 3D food printing and microencapsulation allow for the precise engineering of food matrices to protect sensitive micronutrients during processing and storage, and to control their release kinetics during digestion [24].

Future research should focus on:

- Establishing clearer quantitative structure-function relationships in complex food matrices.

- Conducting long-term clinical trials to validate the health benefits of structurally designed foods.

- Developing standardized methodologies for assessing food structure and its nutritional implications.

Diagram 2: Logical pathway from food structure to physiological outcome.

The microstructure of food and the integrity of its cellular barriers are fundamental determinants of nutrient bioavailability and subsequent physiological responses. The evidence is clear that two foods with identical chemical compositions can have vastly different metabolic effects based on their physical structure. This understanding challenges oversimplified food classification systems and emphasizes the need for a more nuanced view of food processing. For researchers and drug development professionals, incorporating food structure analysis into nutritional studies is no longer optional but essential for developing effective, food-based nutritional strategies and interventions for improving public health.

Impact of Anti-Nutritional Factors (ANFs) on Mineral and Protein Digestibility

Abstract Anti-nutritional factors (ANFs) are naturally occurring compounds in plant-based foods that significantly impair the bioavailability of proteins and minerals. By interacting with nutrients through mechanisms such as chelation, complexation, and enzyme inhibition, ANFs reduce the nutritional value of diets, which has profound implications for global health and food security. This whitepaper provides a comprehensive technical review of the primary ANFs, their modes of action, and the efficacy of conventional and novel processing technologies in mitigating their effects. Framed within broader research on nutrient bioavailability, this guide is intended to support scientists and product developers in formulating strategies to enhance the nutritional quality of plant-based food products.

The pursuit of sustainable food systems has intensified the focus on plant-based proteins. However, the nutritional value of these sources is not solely determined by their gross nutrient content but by their bioavailability—the proportion of a nutrient that is digested, absorbed, and utilized in normal physiological processes [19]. A primary constraint on the bioavailability of minerals and proteins from plant matrices is the presence of anti-nutritional factors (ANFs).

ANFs such as phytic acid, tannins, and protease inhibitors can reduce nutrient intake, hinder digestion, and decrease metabolic utilization [25]. Understanding their specific mechanisms and learning to mitigate their effects through targeted processing is a critical frontier in nutritional science and food technology, directly impacting the development of efficacious foods and clinical nutrition products.

Mechanisms of Action: How ANFs Impair Digestibility

ANFs impact nutrient bioavailability through several distinct biochemical pathways, interfering with both the digestive processes and the absorbability of nutrients.

Table 1: Key Anti-Nutritional Factors and Their Primary Mechanisms of Action

| Anti-Nutritional Factor (ANF) | Primary Nutrient(s) Affected | Mechanism of Action |

|---|---|---|

| Phytic Acid (Myo-inositol hexaphosphate) | Minerals (Zn, Fe, Ca, Mg), Protein | Chelates di- and trivalent mineral cations, forming insoluble phytate complexes that are unavailable for absorption. Can also bind to proteins, reducing proteolysis [25] [26]. |

| Tannins (Proanthocyanidins) | Proteins, Minerals | Bind to proline-rich proteins via hydrogen and hydrophobic bonds, precipitating dietary and digestive enzymes (e.g., trypsin, amylase), thereby inhibiting their activity [25]. |

| Trypsin and Chymotrypsin Inhibitors | Proteins | Form stable, inactive complexes with proteolytic enzymes in the gut, directly blocking protein digestion and amino acid absorption [25] [27]. |

| Lectins | Gastrointestinal Function | Bind to carbohydrate receptors on intestinal epithelial cell membranes, disrupting gut barrier integrity and function, which can indirectly impair nutrient absorption [25]. |

| Oxalates | Minerals (Ca) | Form insoluble salts with calcium (e.g., calcium oxalate), preventing its absorption [26]. |

The following diagram illustrates the coordinated impact of these ANFs on the digestive pathway:

Figure 1: Mechanisms of ANF Interference on Nutrient Bioavailability. ANFs act through multiple pathways to reduce the availability of minerals and proteins for absorption.

Quantitative Impact of Processing on ANF Reduction

A primary strategy to counteract ANFs is the application of food processing techniques. The effectiveness of these methods varies significantly, and optimizing processing conditions is crucial for maximizing nutritional outcomes.

Table 2: Efficacy of Processing Interventions on ANF Reduction [25]

| Processing Method | Key ANFs Reduced | Typical Reduction Range | Notes on Mechanism & Application |

|---|---|---|---|

| Soaking | Phytic Acid | 20 - 40% | Leaching of water-soluble ANFs. Effectiveness depends on water pH, temperature, and soak time. |

| Germination | Phytic Acid | 40 - 80% | Activation of endogenous phytase enzymes which hydrolyze phytic acid. |

| Fermentation | Phytic Acid, Tannins | 40 - 80% | Microbial synthesis of phytases and other degradative enzymes. |

| Thermal Processing | Protease Inhibitors, Lectins | > 80% (for TIs under optimized conditions) | Denaturation of heat-labile protein-based ANFs. Excessive heat can damage amino acids. |

| Extrusion Cooking | Tannins, Trypsin Inhibitors | > 80% (under optimized conditions) | Combined effect of high temperature, shear force, and pressure. |

| Enzymatic Treatment | Phytic Acid | Variable (Highly Effective) | Direct application of exogenous enzymes (e.g., phytase, xylanase) to hydrolyze specific ANFs [27]. |

| Cold Plasma | Tannins, Trypsin Inhibitors | > 80% (under optimized conditions) | Reactive species generated by plasma oxidize and degrade ANFs; a non-thermal technology. |

Experimental Protocols for ANF and Digestibility Analysis

Robust and standardized experimental methodologies are essential for quantifying ANFs and assessing their impact on protein quality.

Quantification of Major ANFs

- Phytic Acid: The colorimetric method (Megazyme Assay Kit) is widely used. Phytic acid is extracted from a defatted sample with HCl. The extract is treated with a ferric chloride solution, forming a colored complex that is measured spectrophotometrically. Results are expressed as mg/100g [26].

- Tannins: The Folin-Ciocalteu method for total phenolics and the vanillin-HCl method for condensed tannins (proanthocyanidins) are common. Samples are extracted with methanol, and the absorbance of the reaction product is measured. Results are expressed in mg Catechin Equivalents (CE)/100g [26].

- Trypsin Inhibitor Activity (TIA): The method is based on the sample's ability to inhibit the hydrolysis of a synthetic substrate (BAPA - Nα-Benzoyl-DL-arginine 4-nitroanilide hydrochloride) by trypsin. One Trypsin Inhibitor Unit (TIU) is defined as a decrease of 0.01 in absorbance per 10 mL of extract. Results are expressed as TIU/mg [27].

Assessing Protein Digestibility and Quality

- In Vitro Protein Digestibility (IVPD): The INFOGEST 2.0 simulated gastrointestinal digestion protocol is a standardized international static model [27].

- Gastric Phase: The sample is incubated with a simulated gastric fluid (containing pepsin) at pH 3 for a set time (e.g., 1 hour) at 37°C.

- Intestinal Phase: The gastric chyme is adjusted to pH 7 and incubated with simulated intestinal fluid (containing pancreatin).

- Analysis: The degree of hydrolysis (DH) is determined by the pH-stat method or by quantifying released amino groups using the o-phthaldialdehyde (OPA) assay. Digestibility is calculated as the percentage of protein nitrogen converted into a form soluble in trichloroacetic acid.

- In Vitro Digestibility-Corrected Amino Acid Score (IVDCAAS): This is the gold standard for evaluating protein quality [26].

- Perform an in vitro digestion of the protein source.

- Analyze the amino acid profile of the digest using UHPLC-QQQ-MS/MS for precise quantification [27].

- Compare the concentration of the first limiting amino acid in the digest to its concentration in a reference pattern (e.g., FAO/WHO requirement pattern for a preschool child).

- IVDCAAS = (mg of limiting amino acid in 1g of digested protein / mg of same amino acid in 1g of reference protein) × 100%.

The workflow for a comprehensive protein quality assessment is as follows:

Figure 2: Workflow for Comprehensive Protein Quality Assessment. The protocol integrates ANF quantification with advanced digestibility and amino acid scoring.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Essential Reagents and Kits for ANF and Digestibility Research

| Item | Function/Application | Technical Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Phytic Acid / Phytate Assay Kit | Quantitative analysis of phytic acid content in food samples. | Kits (e.g., from Megazyme) provide standardized reagents and protocols for reliable colorimetric detection. |

| Folin-Ciocalteu Reagent | Quantification of total phenolic compounds, a precursor to tannin analysis. | Requires a standard (e.g., gallic acid) for calibration. Sample extraction is critical. |

| Trypsin from Porcine Pancreas & BAPA Substrate | Determination of Trypsin Inhibitor Activity (TIA). | The enzyme and substrate must be of high purity. Reaction conditions (pH, temperature, time) must be rigorously controlled. |

| Simulated Digestive Fluids | For in vitro digestion studies (INFOGEST protocol). | Includes simulated salivary, gastric, and intestinal fluids with standardized electrolyte and enzyme (e.g., pepsin, pancreatin) compositions. |

| o-Phthaldialdehyde (OPA) Reagent | Spectrophotometric measurement of the degree of protein hydrolysis. | Reacts with primary amines released during proteolysis. A rapid and sensitive method. |

| Amino Acid Standards | Calibration for UHPLC-QQQ-MS/MS analysis of amino acid profiles. | A certified mix of all proteinogenic amino acids is required for accurate quantification. |

| Exogenous Enzymes (Phytase, Proteases) | Research on enzymatic mitigation of ANFs and protein hydrolysis. | Used to pretreat samples and study enhancement of digestibility [27]. Acid-active proteases (e.g., S53 family) can significantly boost gastric-phase digestibility. |

Anti-nutritional factors represent a significant challenge to leveraging the full potential of plant-based proteins for human nutrition. A deep understanding of their mechanisms—from mineral chelation to enzyme inhibition—provides the foundational knowledge required to develop effective countermeasures. As demonstrated, processing technologies, both traditional and novel, can substantially reduce ANF levels, with techniques like enzymatic hydrolysis and fermentation showing particular promise. The future of this field lies in the precise application and optimization of these technologies, guided by robust experimental protocols, to create a new generation of plant-based foods with superior protein and mineral bioavailability, thereby contributing to more secure and healthier food systems.

Advanced Analytical and Modeling Approaches for Assessing Nutrient Bioavailability

In vitro simulated gastrointestinal digestion models are indispensable laboratory tools for predicting the behavior of foods, nutrients, and pharmaceuticals during digestion without the need for human or animal trials [28]. These models serve as valuable instruments for mechanistic investigations and hypothesis testing due to their inherent reproducibility, adaptability in selecting controlled experimental parameters, and the convenient facilitation of sampling [28]. The primary strength of these models lies in their ability to provide insights into complex processes such as nutrient bioaccessibility, structural changes in the food matrix, and the release of active compounds [28] [29].

This guide details the core protocols and applications of these models, framed within the context of research on the impact of food processing on nutrient bioavailability. Understanding the absorption and bioavailability of nutrients from whole foods, and their interaction with other food components, is critical for designing foods, meals, and diets that supply bioavailable nutrients to specific populations [29].

Types of In Vitro Digestion Models

In vitro digestion models vary significantly in their complexity and physiological relevance. They are broadly categorized into static and dynamic systems.

Static Digestion Models

Static models are the most widely used, simulating digestion as a series of sequential steps (oral, gastric, intestinal) in separate vessels with fixed parameters (e.g., pH, digestion time, and enzyme concentrations) [30]. Their key advantage is simplicity, cost-effectiveness, and high reproducibility, making them suitable for high-throughput screening [30]. A significant development in this area is the INFOGEST protocol, an international effort to standardize static models to improve the consistency and cross-comparability of research findings worldwide [28]. However, a major limitation is their inability to mimic dynamic physiological processes like gradual acidification, gastric emptying, or continuous enzyme secretion [30].

Dynamic Digestion Models

Dynamic models are more advanced systems designed to closely mimic the changing conditions of the human gastrointestinal tract. They can simulate processes like gradual acidification in the stomach, controlled secretion of digestive fluids, and peristaltic mixing [28] [30]. Equipment like the TIM-1 (TNO Gastro-Intestinal Model) is considered one of the most sophisticated and physiologically accurate dynamic systems available [30]. While dynamic models provide a more realistic representation of in vivo digestion, they are also characterized by high complexity and cost, limiting their accessibility for many laboratories [28] [30].

Model Selection and Comparison

Table 1: Comparison of In Vitro Digestion Model Types

| Feature | Static Model | Dynamic Model |

|---|---|---|

| Complexity & Cost | Low; cheap to establish and maintain [30] | High; complex equipment, costly [28] [30] |

| Physiological Realism | Low; fixed conditions [30] | High; simulates gradual changes (e.g., pH, secretion) [28] [30] |

| Throughput | High; suitable for screening many samples [30] | Low; typically one sample per run |

| Data Output | Endpoint analysis of digestas | Time-course data on digestion kinetics |

| Primary Application | Standardized digestibility assessment, bioaccessibility screening [28] | Mechanistic studies, formulation testing where kinetics are critical |

Standardized Experimental Protocols

This section provides a detailed methodology for a standardized static in vitro digestion simulation, based on the widely adopted INFOGEST framework.

The INFOGEST Static Protocol Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the generalized workflow for a standardized static digestion simulation, which can be adapted for various food or drug substrates.

Detailed Phase Description and Reagents

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for In Vitro Digestion Models

| Reagent / Enzyme | Typical Source | Primary Function in Simulation | Key Operational Parameters |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pepsin | Porcine gastric mucosa [31] | Gastric protease; hydrolyzes proteins into peptides in the acidic stomach environment. | Activity: e.g., 250 U/mg [31]; pH: 3.0 [28] |

| Trypsin | Porcine pancreas [31] | Pancreatic serine protease; continues protein breakdown in the small intestine. | Activity: e.g., 250 U/mg [31]; pH: 7.0 |

| Pancreatin | Porcine pancreas [31] | A mixture of pancreatic enzymes (amylase, proteases, lipases) simulating pancreatic juice. | Used for comprehensive intestinal digestion [31]. |

| Bile Salts | Porcine bile extract [31] | Emulsifies lipids, facilitating their digestion by lipases; also forms micelles for lipid absorption. | Concentration varies by model (e.g., fasted vs. fed state). |

| α-Amylase | Human saliva or fungal/bacterial | Initiates starch hydrolysis in the oral phase by breaking down α-linkages. | pH: ~7.0; inhibited by low gastric pH. |

Oral Phase: The sample is mixed with a simulated saliva fluid containing electrolytes and α-amylase. The mixture is incubated for a short period (typically 2-5 minutes) at pH 7 to mimic the initial enzymatic breakdown of starch in the mouth [28] [30].

Gastric Phase: The oral bolus is combined with a simulated gastric fluid, the pH is adjusted to 3.0, and pepsin is added. This phase involves incubation (e.g., 1-2 hours) under agitation to simulate the stomach's harsh acidic and proteolytic environment [28] [31].

Intestinal Phase: The gastric chyme is neutralized to pH 7.0 and mixed with a simulated intestinal fluid containing pancreatin (a mixture of enzymes including trypsin and amylase) and bile salts. This phase, which can last several hours, represents digestion in the small intestine, where the majority of nutrient absorption occurs [28] [31].

Following digestion, the sample (digesta) is centrifuged. The resulting supernatant represents the bioaccessible fraction—the compounds released from the food matrix and available for intestinal absorption [28].

Applications in Food and Nutritional Sciences

In vitro models are pivotal for advancing research in food science, nutrition, and pharmaceutical development.

Assessing Nutrient and Bioactive Compound Bioaccessibility

A primary application is evaluating the bioaccessibility of nutrients and bioactive compounds. For instance, a 2025 study on Pyracantha fortuneana fruit pectin (PFP) used a simulated digestion model to demonstrate that the polysaccharide's molecular weight and reducing sugar content remained largely unchanged. This indicated that PFP was resistant to gastrointestinal digestion and could effectively reach the colon to act as a prebiotic [31]. Similarly, these models are used to study the release of micronutrients like vitamins and minerals from complex food matrices, such as dairy products and vegetables, and how this process is influenced by interactions with other food components [29].

Evaluating the Impact of Food Processing and the Food Matrix

These models are essential for investigating how different food processing techniques (e.g., cooking, fermentation, milling) and the physical structure of the food matrix affect nutrient digestibility [30] [32]. For example, research has shown that the hydrolysis patterns of milk protein differ between static and dynamic models, and that the state of the food (liquid, semi-solid, solid) significantly impacts its digestion trajectory, especially in the oral and gastric stages [30]. This information is crucial for designing processed foods with optimized nutritional profiles.

Development of Foods for Specific Populations

In vitro models have been adapted to simulate the unique gastrointestinal conditions of specific demographic groups, such as infants, the elderly, or individuals with specific health conditions like cystic fibrosis [28] [30]. An infant digestion model, for instance, would incorporate lower gastric acid and enzyme concentrations to reflect the immature infant digestive system. This allows for the customized development of infant formulas and weaning foods that are appropriate for their digestive capabilities [30].

Validation and Future Perspectives

While in vitro models are powerful tools, their predictive power for human outcomes must be critically assessed. Correlations between in vitro and in vivo data have been confirmed for some nutrients, but the simplified nature of these models remains a limitation [30] [29]. A key recommendation is that "conclusions and interpretations from such studies should be used with caution" and they cannot fully replace human trials [28].

Future perspectives in the field include:

- Enhanced Personalization: Developing more sophisticated models that mimic the digestion of specific populations (e.g., infants, the elderly) to support personalized nutrition [28].

- Integration with Gut Microbiota: Combining gastrointestinal digestion models with in vitro fecal fermentation models to study the prebiotic effects of non-digestible compounds and their interaction with the gut microbiome, as demonstrated in the PFP study [31].

- Standardization and Harmonization: Continued efforts to standardize protocols, like INFOGEST, to improve the reliability and cross-comparability of research data across different laboratories [28].

Understanding the impact of food processing on nutrient bioavailability requires a multifaceted research approach that spans from controlled laboratory studies to human clinical trials. In vivo methodologies form the cornerstone of this research, providing critical insights into how nutrients are released, absorbed, distributed, and utilized by living organisms. The research continuum begins with animal models that allow for controlled dietary interventions and tissue-specific analyses, and progresses to human isotope tracer studies that provide the most relevant data on nutrient metabolism in people. This technical guide details the core methodologies, experimental protocols, and analytical frameworks used to investigate how food processing techniques alter the bioavailability of micronutrients, enabling researchers to develop enhanced food products that maximize nutrient delivery and health benefits.

The fundamental challenge in nutrient bioavailability research lies in the complex journey of a nutrient from ingestion to utilization. As outlined in recent research, "bioavailability" encompasses the "proportion of an ingested nutrient that is released during digestion, absorbed via the gastrointestinal tract, transported and distributed to target cells and tissues, in a form that is available for utilization in metabolic functions or for storage" [19]. Food processing methods can significantly influence each of these stages by altering food matrix structure, inactivating enzymatic inhibitors, or creating new molecular interactions that affect nutrient release and absorption. Within this context, in vivo models provide the necessary physiological complexity to evaluate these interconnected processes, serving as an indispensable bridge between in vitro screening models and population-level health outcomes.

Animal Models in Nutrient Bioavailability Research

Rationale and Model Selection

Animal models represent a critical first step in evaluating the bioavailability of nutrients from processed foods, allowing researchers to conduct controlled dietary interventions that would be impractical or unethical in human subjects. These models enable investigation into tissue-specific nutrient accumulation, metabolic pathways, and physiological responses to different food processing techniques [33]. The choice of animal model depends on the specific research questions, nutrient of interest, and physiological systems under investigation. Rodent models, particularly rats and mice, are most commonly employed due to their physiological similarity to humans in many metabolic processes, relatively short lifespan, and well-characterized genetics. Additionally, their smaller size allows for controlled feeding studies and precise measurement of nutrient intake and excretion.

Recent advancements have expanded the toolbox for nutrient researchers, with New Approach Methodologies (NAMs) including organoids and induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) providing complementary approaches to traditional animal models [33]. However, as noted in current research resources, "while this field is rapidly evolving, the need for animal models remains since current alternative approaches cannot accurately replicate or model all biological and behavioral aspects of human disease" and complex physiological processes like nutrient absorption [33]. Importantly, animal models serve as vital in vivo controls for the validation and verification of these emerging methodologies, ensuring that findings from reduced systems translate to whole-organism physiology.

Key Methodologies and Experimental Protocols

Balance Studies

The balance study is one of the most fundamental and widely used methods for assessing nutrient bioavailability in animal models. This approach measures the difference between nutrient intake and excretion to determine retention and apparent absorption [19]. The standard protocol involves:

- Acclimation Period: House animals under controlled environmental conditions (temperature, humidity, light-dark cycle) with free access to water and a standard diet for 5-7 days before the experiment.

- Experimental Diet Phase: Randomly assign animals to experimental diets containing the processed food component of interest. Precisely measure daily food intake.

- Sample Collection: Collect total feces and urine separately over a predetermined collection period (typically 5-10 days) using metabolic cages designed to prevent cross-contamination between excretory products.

- Sample Analysis: Homogenize feces and urine samples, then analyze for the nutrient of interest using appropriate analytical methods (HPLC, ICP-MS, etc.).

- Calculation: Calculate apparent absorption using the formula: Apparent Absorption (%) = [(Intake - Fecal Excretion) / Intake] × 100.

Ileal Digestibility Studies

Ileal digestibility measures provide a more precise assessment of nutrient absorption by analyzing digesta collected from the terminal ileum, thereby avoiding potential artifacts introduced by microbial metabolism in the colon [19]. This method is particularly valuable for minerals and certain vitamins that can be modified by colonic microbiota. The key steps include:

- Surgical Preparation: Implant a simple T-cannula in the distal ileum of animals under anesthesia, allowing for representative sampling of ileal digesta.

- Recovery Period: Allow animals to recover for 7-10 days post-surgery with free access to food and water.

- Diet Administration: Provide experimental diets containing the processed food component, often incorporating an indigestible marker (such as titanium dioxide or chromic oxide) to calculate nutrient flow.

- Digesta Collection: Collect ileal digesta continuously over 12-24 hours during the experimental period.

- Analysis: Analyze digesta for the nutrient of interest and recovery marker to calculate true ileal digestibility.

Table 1: Key Methodologies for Assessing Nutrient Bioavailability in Animal Models

| Methodology | Key Measurements | Applications | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Balance Studies | Nutrient intake, fecal & urinary excretion | Mineral absorption, energy availability | Non-invasive, comprehensive | Does not distinguish between absorption and microbial metabolism |

| Ileal Digestibility | Nutrient content in ileal digesta | Protein & amino acid bioavailability | Avoids colonic artifacts, more precise | Requires surgical modification |

| Tissue Accumulation | Nutrient concentration in target tissues (liver, bone, etc.) | Mineral bioavailability, vitamin status | Direct measure of physiological utilization | Invasive terminal procedure |

| Plasma Kinetics | Plasma nutrient concentrations over time | Vitamin absorption, mineral metabolism | Dynamic assessment, repeated measures | May not reflect tissue uptake |

Surgical and Isotopic Tracer Methodologies

For more sophisticated absorption studies, surgical models and isotopic tracers provide enhanced temporal resolution and mechanistic insights. Surgical approaches include in situ intestinal loop preparations that allow direct measurement of nutrient uptake across specific intestinal segments. Stable isotopic tracers (e.g., ^67Zn, ^46Ca, ^2H-labelled vitamins) enable researchers to distinguish between dietary nutrients and endogenous sources, providing more accurate absorption measurements and insights into nutrient turnover and pool sizes.

The experimental workflow for these advanced approaches typically involves intravenous or intragastric administration of isotopically labeled nutrients followed by serial blood sampling and/or tissue collection at predetermined time points. Analysis of isotopic enrichment in these samples using mass spectrometry techniques allows construction of comprehensive kinetic models of nutrient absorption, distribution, and elimination.

Human Isotope Tracer Studies

Study Designs and Applications

Human isotope tracer studies represent the gold standard for determining nutrient bioavailability in people, providing direct evidence of how food processing affects nutrient absorption and metabolism in human physiology. These studies employ stable (non-radioactive) isotopes of minerals and labeled forms of vitamins to track the fate of dietary nutrients without health risks [19]. The major study designs include:

- Single-Meal Absorption Studies: Participants consume a single test meal containing an isotopically labeled nutrient, with serial blood samples collected over several hours to assess absorption kinetics. This design is ideal for comparing bioavailability from different food processing methods.

- Metabolic Balance Studies: Participants reside in a metabolic unit for several days while consuming a controlled diet containing isotopically labeled nutrients, with complete collection of all excreta (feces and urine) to determine retention and utilization.

- Long-Term Tracer Studies: Participants receive repeated doses of isotopic tracers over weeks or months, with periodic blood and tissue samples (e.g., adipose biopsies for fat-soluble vitamins) to assess long-term storage and turnover.

Experimental Protocol for Dual-Isotope Tracer Studies

Dual-isotope tracer methods, which administer different isotopes by oral and intravenous routes, provide the most accurate measurement of true absorption by accounting for endogenous excretion and compartmental distribution. A standardized protocol includes:

- Participant Selection and Preparation: Recruit healthy participants who meet specific inclusion criteria (age, BMI, health status). Provide a standardized lead-in diet low in the nutrient of interest for 3-7 days before the study to standardize nutrient status.

- Tracer Administration: After an overnight fast, administer an oral dose of the test meal containing one isotope (e.g., ^67Zn) and a simultaneous intravenous dose of a different isotope (e.g., ^70Zn). The test meal contains the processed food component of interest.

- Sample Collection: Collect blood samples at baseline, 30min, 1, 2, 4, 6, 8, 10, 12, and 24 hours post-dosing. Collect total urine for 24 hours and feces until the tracer is completely excreted (typically 5-7 days).

- Sample Analysis: Isolate the nutrient of interest from biological samples and determine isotopic ratios using inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry (ICP-MS) or thermal ionization mass spectrometry (TIMS).

- Data Analysis and Modeling: Calculate fractional absorption using the cumulative fecal excretion of the oral isotope or the urinary enrichment ratio method. Compartmental modeling techniques can derive additional kinetic parameters such as distribution volumes, transfer rates, and pool sizes.

Table 2: Comparison of Human Isotope Tracer Methodologies for Bioavailability Assessment

| Method | Tracer Administration | Key Biological Samples | Primary Calculations | Applications in Food Processing Research |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Oral Tracer Only | Single oral dose with test meal | Feces, plasma | Fecal recovery, plasma appearance | Rapid screening of multiple processing methods |

| Dual-Isotope Method | Oral + intravenous tracers | Urine, plasma, feces | Fractional absorption, endogenous losses | Precise absorption measurement for regulatory claims |

| Stable Isotope Labels | ^13C, ^2H-labeled compounds | Breath (for ^13CO₂), plasma, urine | Oxidation rates, metabolic fate | Vitamin and phytochemical metabolism studies |

| Long-Term Tracer Kinetics | Multiple oral or IV doses over time | Plasma, adipose tissue, RBCs | Turnover rates, pool sizes, storage | Fat-soluble vitamin bioavailability from processed foods |

Methodological Visualization and Workflows

Integrated Experimental Approach for Bioavailability Research

The following diagram illustrates the integrated experimental workflow for evaluating the impact of food processing on nutrient bioavailability, combining in vitro screening, animal models, and human studies:

Integrated Workflow for Bioavailability Research

Nutrient Absorption and Metabolic Pathway

The following diagram outlines the key physiological processes involved in nutrient bioavailability from processed foods, highlighting potential sites where food processing can influence outcomes:

Nutrient Absorption and Metabolic Pathway

Research Reagent Solutions for Bioavailability Studies

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Nutrient Bioavailability Studies

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Research Applications | Key Functions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Stable Isotope Tracers | ^67Zn, ^46Ca, ^58Fe, ^13C-labeled vitamins | Human and animal tracer studies | Quantification of absorption, distribution, and kinetics |

| Reference Standards | Certified elemental standards, vitamin isoforms | Analytical method validation | Calibration of instrumentation, quality control |

| Cell Culture Models | Caco-2 cells, HT-29-MTX co-cultures | Intestinal absorption screening | Mechanistic transport studies, rapid formulation screening |

| Enzymatic Kits | Phytase, digestive enzyme mixtures | In vitro digestion models | Simulation of human gastrointestinal conditions |

| Analytical Standards | Isotopically labeled internal standards | Mass spectrometry analysis | Quantification accuracy, recovery calculations |

| Research Diets | Purified ingredient diets, defined nutrient composition | Animal feeding studies | Controlled nutrient delivery, matrix effect studies |

The strategic integration of animal models and human isotope tracer studies provides a powerful methodological framework for investigating how food processing impacts nutrient bioavailability. While animal models offer valuable preliminary data and mechanistic insights under controlled conditions, human isotope studies remain the definitive approach for establishing bioavailability in human populations. The continuing refinement of these methodologies, including the development of more sophisticated tracer techniques and analytical capabilities, will enhance our understanding of the complex relationships between food processing, nutrient delivery, and human health. As food science continues to evolve toward personalized nutrition and precision processing, these in vivo methodologies will play an increasingly critical role in optimizing the health benefits of processed foods while maintaining safety, palatability, and sustainability.

Foodomics, defined as the discipline that studies food and nutrition through the application and integration of omics technologies, represents a transformative approach for unraveling the complex effects of food processing on nutrient bioavailability [34]. This field employs advanced analytical platforms, including mass spectrometry (MS) and nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopy, coupled with multivariate statistical analysis, to obtain a comprehensive molecular perspective of food composition and its biological consequences [35]. In the specific context of nutrient bioavailability research, Foodomics provides the methodological framework to move beyond simple nutrient presence/absence quantification toward understanding how processing-induced changes alter food composition and subsequently influence nutrient release, absorption, and metabolic utilization [34] [36].

The investigation of how food processing affects nutrient bioavailability presents particular challenges due to the immense complexity of both the food matrix and the biological systems involved. Foodomics addresses this by enabling the non-targeted and exhaustive profiling of the vast pool of compounds present in food and biological samples, collectively termed the "Foodome" [34]. Through integrated applications of genomics, transcriptomics, proteomics, and metabolomics, researchers can monitor global molecular changes resulting from processing techniques and correlate these changes with physiological responses measured in interacting biological systems [34] [35]. This systematic approach is essential for developing a mechanistic understanding of how processing modifies food composition and subsequently influences the bioavailability of nutrients and bioactive compounds, ultimately affecting human health outcomes [36].

Core Analytical Platforms in Foodomics

Mass Spectrometry (MS) Technologies

Mass spectrometry stands as a cornerstone analytical platform within the Foodomics toolbox due to its exceptional sensitivity, specificity, and capacity for high-throughput analysis of diverse molecular species. MS technologies enable the comprehensive characterization of proteins, peptides, lipids, and metabolites within complex food matrices, making them indispensable for studying processing-induced molecular changes that impact nutrient bioavailability [35]. The typical MS workflow involves sample extraction, chromatographic or electrophoretic separation, MS detection, and sophisticated data analysis to extract biologically relevant information [35].