Analytical Specificity in Food Analysis: From Foundational Concepts to Advanced Applications for Researchers

This article provides a comprehensive examination of specificity in food analytical methods, addressing the critical needs of researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals.

Analytical Specificity in Food Analysis: From Foundational Concepts to Advanced Applications for Researchers

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive examination of specificity in food analytical methods, addressing the critical needs of researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals. It explores foundational principles of method specificity and its role in ensuring food safety, quality, and authenticity. The content covers advanced methodological applications across various analytical platforms, practical troubleshooting and optimization strategies, and rigorous validation frameworks. By synthesizing current technological advancements and regulatory standards, this review serves as an essential resource for professionals developing and implementing precise analytical methods in complex food matrices for both food and pharmaceutical applications.

The Fundamentals of Analytical Specificity in Complex Food Matrices

Defining Specificity and Selectivity in Food Analytical Chemistry

In food analytical chemistry, the accurate detection and quantification of target analytes within complex food matrices are fundamental to ensuring safety, quality, and authenticity. Specificity and Selectivity are two pivotal analytical performance parameters that underpin this reliability. These concepts, while often used interchangeably, possess distinct meanings. Specificity refers to the ability of a method to measure unequivocally the analyte in the presence of components that may be expected to be present, such as impurities, degradants, or matrix components. It represents the highest degree of selectivity, which is the ability of the method to distinguish the analyte from other substances in the sample [1] [2].

The precise determination of these parameters is not merely an academic exercise; it is a critical component of method validation, directly impacting public health and economic stability. With food fraud estimated to cost the global industry US$30–40 billion annually and foodborne illnesses affecting millions, the role of robust analytical methods has never been more crucial [3]. This guide provides an in-depth examination of specificity and selectivity within the context of modern food analysis, offering a detailed framework for their assessment and application.

Fundamental Concepts and Definitions

Specificity vs. Selectivity: A Critical Distinction

Although both terms describe a method's capacity to distinguish the target analyte from interferences, a nuanced difference exists:

- Specificity is the ideal, implying that the method responds only to the target analyte and is completely unaffected by the sample matrix or other components. It is often considered an absolute term.

- Selectivity is a more practical and graduated parameter, indicating the extent to which a method can determine a particular analyte in a mixture or matrix without interference from other analytes or matrix components. A method can be highly selective without being completely specific [1].

In chromatographic terms, specificity would be demonstrated by a single peak for the analyte with no co-eluting peaks, while selectivity ensures that the peaks for the analyte and potential interferents are sufficiently resolved to allow for accurate quantification.

The Impact of Matrix Effects

Food matrices are inherently complex, comprising proteins, carbohydrates, lipids, minerals, and water. This complexity poses a significant challenge, as these components can suppress or enhance the analytical signal, a phenomenon known as the matrix effect. These effects are a primary focus when assessing selectivity, as they can lead to false positives or inaccurate quantification [4]. The intricate nature of food samples means that a method perfectly selective in a pure solvent may suffer from severe interferences when applied to a real food sample, such as cola, garlic, or spices [5].

Experimental Assessment and Protocols

Establishing the specificity and selectivity of an analytical method is a systematic process that involves a series of experiments designed to challenge the method with potential interferents.

Core Assessment Protocol

The following workflow provides a general procedure for determining method selectivity. This should be adapted based on the specific technique (e.g., HPLC, GC-MS, ELISA) and analyte.

Protocol: Assessment of Method Selectivity

- Objective: To demonstrate that the method is unaffected by the presence of other components in the sample matrix.

Materials:

- Target analyte reference standard (high purity)

- Blank matrix (e.g., the food sample without the analyte)

- Potential interferents (e.g., structurally similar compounds, degradation products, common matrix components)

- Appropriate solvents and reagents for sample preparation

- Analytical instrument (HPLC-MS, GC-MS, etc.) calibrated according to manufacturer guidelines

Procedure:

- Prepare Solutions:

- Solution A (Analyte): Prepare the target analyte in an appropriate solvent at a concentration within the method's working range.

- Solution B (Blank Matrix): Prepare the sample matrix without the analyte, using the same sample preparation procedure.

- Solution C (Fortified Matrix): Fortify the blank matrix with the target analyte at a known concentration.

- Solution D (Interference Challenge): Fortify the blank matrix with the target analyte and potential interferents at concentrations expected to be encountered.

- Analyze Solutions: Inject or analyze each solution (A, B, C, D) in triplicate using the developed analytical method.

- Chromatographic/Data Analysis:

- Compare the chromatogram or output from Solution B (blank) with that from Solution C (fortified) to confirm the absence of co-eluting peaks from the matrix at the retention time of the analyte.

- In Solution D, verify that the signal for the analyte is unchanged compared to Solution C and that no new peaks from the interferents co-elute with the analyte.

- Quantitative Assessment: Calculate the recovery of the analyte from the fortified matrix (Solution C) and the interference-challenged matrix (Solution D). The recovery should be within acceptable limits (e.g., 90-110%) and consistent between Solutions C and D.

- Prepare Solutions:

Critical Parameters:

- The blank matrix must be truly free of the analyte.

- The concentrations of potential interferents should be realistic and sufficiently high to provide a meaningful challenge to the method.

- The experiment should be conducted over multiple batches or days to establish intermediate precision.

Advanced Techniques for Enhanced Selectivity

When standard methods face limitations, advanced techniques can be employed to improve selectivity and sensitivity.

Cryogen-free Trap Focusing in GC-MS: This technique addresses challenges like poor peak shape and co-elution in complex food analyses (e.g., flavor profiling in cola or garlic, fumigant analysis in spices). Analytes from a headspace or SPME extraction are focused on a cool trap before being rapidly thermally desorbed as a sharp band into the GC column. This process improves chromatographic resolution, thereby enhancing the selectivity of detection by separating compounds that might otherwise co-elute [5].

Molecularly Imprinted Polymers (MIPs): MIPs are synthetic polymers with tailor-made recognition sites for a specific target molecule (template). During synthesis, the template is surrounded by functional monomers and cross-linkers. After polymerization and template removal, cavities complementary in size, shape, and functional groups to the analyte remain. These "plastic antibodies" can be integrated into sensors or solid-phase extraction cartridges to selectively bind the target analyte from a complex food matrix, effectively filtering out interferents [1].

Table 1: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Selectivity Enhancement

| Reagent/Material | Function in Experimental Protocol | Application Example |

|---|---|---|

| Molecularly Imprinted Polymer (MIP) | Synthetic receptor for selective extraction and pre-concentration of a target analyte from a complex matrix. | Selective solid-phase extraction of pesticides, mycotoxins, or antibiotics from food samples prior to LC-MS analysis [1]. |

| SPME Arrow Fiber (PDMS/CWR/DVB) | A sorptive extraction device for sampling volatile and semi-volatile compounds from headspace; concentrates analytes and reduces solvent use. | Extraction of aroma-active compounds from cola or sulfur compounds from garlic for GC-MS analysis [5]. |

| Cryogen-free Focusing Trap | A packed tube for re-focusing analytes post-extraction, leading to sharper injection bands into the GC and improved peak resolution. | Essential for the trap-focused GC-MS workflow to separate and detect early-eluting compounds in complex food matrices [5]. |

| Deep Eutectic Solvents (DES) | A class of green, biodegradable solvents used in sample preparation to selectively extract target compounds based on hydrogen bonding. | Extraction of phenolic compounds or other polar analytes from food samples, replacing traditional toxic organic solvents [6]. |

| Certified Reference Material (CRM) | A material with certified property values, used to validate the accuracy and selectivity of an analytical method. | Used to verify method performance for authenticating food origin or quantifying specific contaminants/adulterants [3]. |

Methodologies and Instrumentation for Selective Analysis

The choice of analytical technique is critical in achieving the required level of selectivity for a given application.

Table 2: Selectivity of Common Analytical Techniques in Food Chemistry

| Analytical Technique | Principle | Demonstrated Selectivity For | Key Applications in Food Analysis |

|---|---|---|---|

| LC-MS / MS (Triple Quad) | Liquid chromatography separation coupled to tandem mass spectrometry; uses unique mass fragments for identification. | High selectivity for non-volatile, thermally labile compounds. | Multi-residue screening of pesticides, veterinary drugs, mycotoxins [7]. |

| GC-MS / MS (Triple Quad) | Gas chromatography separation coupled to tandem mass spectrometry; uses unique mass fragments for identification. | High selectivity for volatile and semi-volatile compounds. | Pesticide residue analysis, flavor profiling, environmental contaminants [7]. |

| High-Resolution MS (HRMS) | Measures the exact mass of ions with very high mass accuracy (e.g., Orbitrap, TOF). | Exceptional selectivity; enables non-targeted screening and identification of unknown compounds. | Fraud detection, discovery of novel contaminants, adulterant identification [7]. |

| Immunoassays (e.g., ELISA) | Uses antibody-antigen binding for detection. | High selectivity for specific proteins or complex molecules. | Rapid detection of food allergens, specific toxins (e.g., aflatoxin), hormones [7]. |

| ICP-MS | Ionizes sample in plasma and separates ions by mass-to-charge ratio. | Highly selective for elemental composition and isotopes. | Trace-level analysis of heavy metals (Pb, Cd, As, Hg) [7]. |

Validation and Quality Assurance Frameworks

The assessment of specificity and selectivity is an integral part of formal method validation, guided by international standards.

Integration into Validation Guidelines

According to ICH Q2(R1) and other guidelines, specificity is a required validation parameter. The experiments described in Section 3.1 form the core evidence for demonstrating specificity/selectivity in a validation dossier [2]. The use of Reference Materials (RMs) and Certified Reference Materials (CRMs) is crucial in this process. These materials, with their metrologically traceable property values, are used for method validation, calibration, and quality control, ensuring the comparability and reliability of testing results across different laboratories and over time [3].

The Red Analytical Performance Index (RAPI)

The White Analytical Chemistry (WAC) concept proposes that an ideal method balances analytical performance (Red), ecological impact (Green), and practicality/economy (Blue). The Red Analytical Performance Index (RAPI) is a recently developed tool that provides a quantitative and visual assessment of a method's "red" criteria, including specificity and selectivity [8].

RAPI uses open-source software to score ten key analytical performance parameters on a scale of 0-10. The results are displayed in a star-like pictogram, providing an immediate, holistic view of a method's analytical robustness. This tool allows researchers to systematically compare methods and identify potential weaknesses in performance, including selectivity, before they are deployed in routine analysis [8].

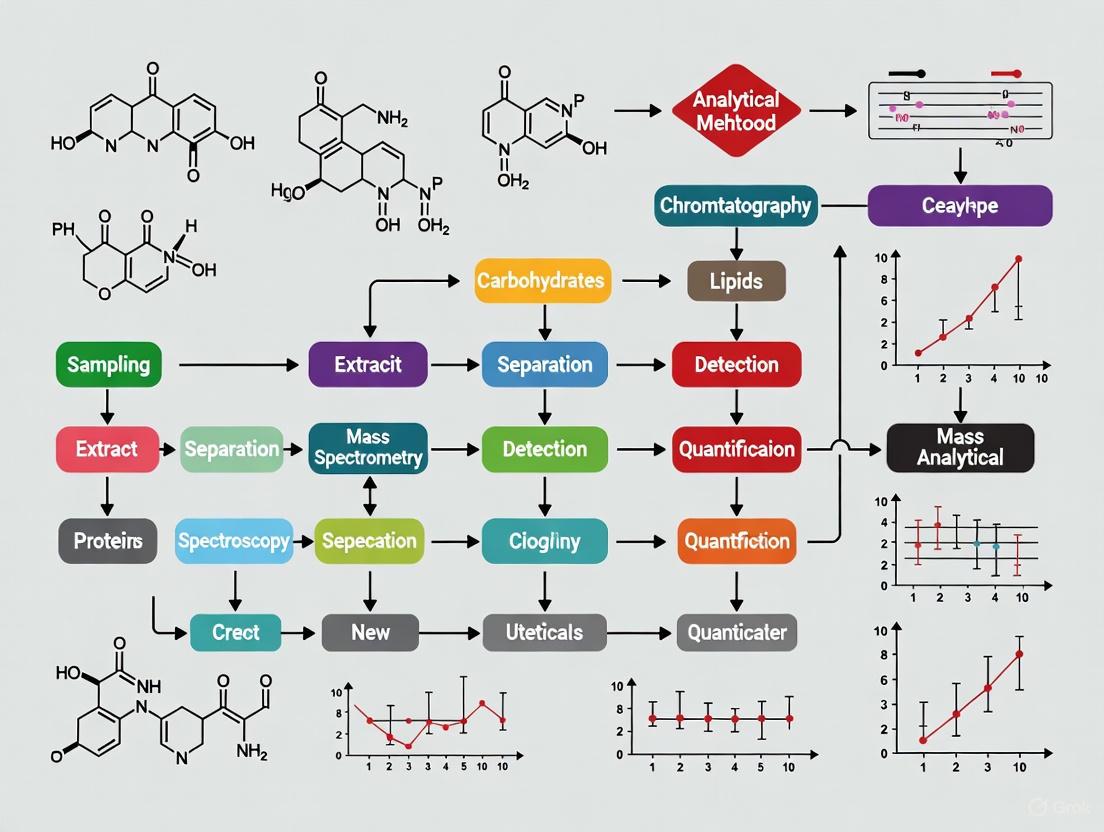

Visualizing the Workflow for Assessing Selectivity

The following diagram illustrates the logical sequence and decision points in the experimental assessment of method selectivity.

In the demanding field of food analytical chemistry, a deep and practical understanding of specificity and selectivity is non-negotiable. These parameters are the bedrock upon which reliable, reproducible, and legally defensible analytical results are built. From fundamental protocols using CRMs to advanced techniques like MIPs and HRMS, the tools available to the scientist for demonstrating selectivity are powerful and diverse. The integration of these concepts into formal validation frameworks and modern assessment tools like RAPI ensures that methods are not only scientifically sound but also fit for their intended purpose in protecting consumer health and ensuring fair trade practices in the global food supply.

The Critical Role of Specificity in Food Safety, Quality, and Authenticity

In the contemporary food industry, the concepts of food safety, quality, and authenticity represent interconnected pillars essential for consumer protection, regulatory compliance, and market transparency. Specificity in analytical methodologies serves as the foundational element that distinguishes between these pillars, enabling accurate detection, identification, and quantification of target analytes amidst complex food matrices. This technical guide examines the critical role of methodological specificity across diverse applications, from pathogen detection to authenticity verification, providing researchers with advanced frameworks for analytical development and implementation.

The globalization of food supply chains has introduced unprecedented challenges in monitoring and controlling food integrity. Food authenticity, encompassing origin, processing techniques, and label compliance, has emerged as a scientific discipline in its own right, necessitating sophisticated analytical solutions [9]. Simultaneously, persistent concerns regarding foodborne pathogens and chemical contaminants demand methods capable of precise identification to mitigate public health risks. Within this context, specificity transcends mere analytical performance characteristic to become an indispensable attribute for effective food governance, economic fairness, and consumer trust.

Specificity Fundamentals in Food Analytics

Defining Analytical Specificity

In food analytical methods, specificity refers to the ability to unequivocally identify and measure the target analyte in the presence of interfering components that may be expected to be present in the sample matrix. This distinguishes it from selectivity, which describes the method's capacity to distinguish between the target analyte and other closely related substances. High specificity ensures that analytical signals originate exclusively from the intended analyte, minimizing false positives and negatives that could compromise food safety determinations or authenticity verification.

The fundamental challenge in achieving specificity stems from the inherent complexity of food matrices, which may contain numerous compounds with similar physical or chemical properties to target analytes. For instance, distinguishing specific meat species in heavily processed products requires techniques capable of identifying minimal genetic or protein signatures despite extensive degradation and denaturation during processing [10]. Similarly, detecting specific pesticide residues at regulatory limits demands methods that can differentiate these compounds from naturally occurring phytochemicals with similar structural characteristics.

Technical Approaches to Ensure Specificity

Multiple technological approaches have been developed to address specificity challenges in food analysis:

Molecular recognition techniques utilize biological recognition elements (antibodies, nucleic acid probes, enzymes) with inherent binding specificity for target analytes. These form the basis for immunoassays and DNA-based methods that can identify specific pathogens, allergens, or genetically modified ingredients amid complex food backgrounds [11].

Separation-based techniques employ chromatographic or electrophoretic separation to physically isolate target analytes from potential interferents before detection. High-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) with UV detection, when combined with chemometrics, has demonstrated excellent specificity for meat authentication based on metabolomic fingerprints [12].

Spectroscopic and spectrometric techniques leverage unique molecular fingerprints for identification. Mass spectrometry, particularly when coupled with separation techniques (GC-MS, LC-MS), provides highly specific detection through accurate mass measurement and fragmentation patterns, enabling definitive confirmation of chemical contaminants and authenticity markers [9].

Multivariate statistical approaches enhance method specificity through mathematical resolution of complex signals. Chemometric analysis of spectroscopic or chromatographic data can extract specific patterns corresponding to target attributes even when individual markers cannot be isolated, facilitating geographical origin verification and fraud detection [12].

Specificity in Food Safety Applications

Pathogen Detection

The specific detection of pathogenic microorganisms represents a critical application where analytical specificity directly impacts public health outcomes. Traditional culture-based methods, while specific, are time-consuming and labor-intensive. Modern rapid methods have embraced nucleic acid-based techniques and immunoassays that offer superior specificity through molecular recognition mechanisms.

Loop-mediated isothermal amplification (LAMP) has emerged as a highly specific detection platform for foodborne pathogens. This technique employs four to six specially designed primers that recognize six to eight distinct regions on the target gene, ensuring exceptional specificity. A study on Anisakis parasite detection in fish demonstrated 100% sensitivity and no cross-reactivity with similar genera (Contracaecum, Pseudoterranova, or Hysterothylacium), highlighting the method's superior specificity compared to traditional morphological identification [11].

For Listeria monocytogenes outbreak investigations, specific real-time PCR screening assays have been developed that can quickly distinguish outbreak-related strains from background strains. This specific identification enables rapid implementation of control measures, minimizing the scale and impact of foodborne illness outbreaks [11].

Chemical Hazard Identification

Specific identification of chemical hazards—including pesticides, veterinary drug residues, environmental contaminants, and naturally occurring toxins—requires methods capable of distinguishing structurally similar compounds at trace levels.

Advanced separation techniques coupled with selective detection systems have significantly enhanced specificity in chemical hazard analysis. Liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) provides exceptional specificity through multiple reaction monitoring (MRM), where precursor-to-product ion transitions serve as highly specific identifiers for target compounds. This approach has been successfully applied to detect pesticide residues, mycotoxins, and other chemical contaminants in complex food matrices with minimal sample cleanup [11].

The development of nanomaterial-based sensors has introduced novel pathways for specific chemical detection. Gold nanoparticles functionalized with specific receptors have been employed for histamine detection in fish, with specificity achieved through molecular imprinting or biomimetic recognition elements. These systems provide specific detection even in the presence of structurally similar biogenic amines that commonly coexist in spoiled fish products [11].

Table 1: Specificity Performance of Rapid Food Safety Methods

| Analytical Technique | Target Analyte | Specificity Measure | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| LAMP assay | Anisakis spp. parasites | 100% sensitivity, no cross-reactivity with similar genera | [11] |

| Real-time PCR screening | Listeria monocytogenes outbreak strains | Specific identification of outbreak-related strains from background population | [11] |

| Au-NP based sensor | Histamine in fish | Selective detection despite presence of similar biogenic amines | [11] |

| FT-NIR with chemometrics | Sugar and acid content in grapes | Specific correlation with sensory properties despite matrix complexity | [11] |

| Immunosensor with carbon nanotubes | Aflatoxin B1 in olive oil | Specific detection at 0.01 ng/mL levels below regulatory limits | [12] |

Specificity in Food Authenticity and Traceability

Meat Speciation and Authenticity

Meat products represent one of the most vulnerable categories for fraudulent substitution and mislabeling. Specific identification of species origin, particularly in processed products where morphological characteristics are destroyed, requires highly specific analytical approaches.

DNA-based methods leveraging polymerase chain reaction (PCR) techniques provide exceptional specificity for meat speciation. The stability of DNA molecules through processing conditions enables specific identification even in thermally treated products. Single Nucleotide Polymorphism (SNP) markers have been developed for verifying meat from traditional cattle and pig breeds, allowing specific authentication of premium products [10]. DNA barcoding employing specific mitochondrial gene sequences (e.g., cytochrome b, COX1) enables discrimination of even closely related species with high genetic similarity, such as wild boar versus domestic pig [9].

Proteomics approaches utilizing mass spectrometry have emerged for specific meat speciation in heavily processed foodstuffs where DNA may be extensively degraded. Specific peptide markers unique to each species enable definitive identification, with methods developed for various meat species and applications including halal and kosher authentication [10].

Geographical Origin Verification

Specific verification of geographical origin represents a challenging analytical problem requiring techniques that can detect subtle compositional differences imparted by environmental and production factors.

Stable isotope ratio analysis provides specific fingerprints related to geographical origin through natural abundance variations of light elements (H, C, N, O, S) that reflect local environmental conditions. This approach has been successfully applied to develop "isoscapes" for verifying the provenance of high-value products including chicken, pork, and beef [10].

Metabolomic fingerprinting using HPLC-UV combined with multivariate statistics has demonstrated remarkable specificity for geographical origin authentication. A comprehensive study on meat authentication achieved sensitivity and specificity values exceeding 99.3% for classifying meat species and origin, with classification errors below 0.4% [12]. The specificity stems from detecting unique pattern combinations of multiple metabolites rather than relying on single markers.

Table 2: Specificity in Food Authenticity Methods

| Analytical Approach | Application | Specificity Mechanism | Performance | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| DNA-based SNP markers | Traditional breed verification | Specific single nucleotide polymorphisms | Breed-specific authentication | [10] |

| Proteomics mass spectrometry | Meat speciation in processed foods | Specific peptide markers | Identification in heavily processed matrices | [10] |

| Stable isotope analysis | Geographical origin verification | Element-specific isotopic ratios reflecting geography | Construction of origin "isoscapes" | [10] |

| HPLC-UV metabolomic fingerprinting | Meat species and origin | Multivariate pattern recognition | >99.3% specificity, <0.4% classification error | [12] |

| DNA barcoding | Seafood species identification | Specific mitochondrial gene sequences | Species identification regardless of processing | [9] |

Advanced Specificity Enhancement Strategies

Multi-Omics Approaches

The integration of multiple analytical platforms through multi-omics strategies represents a paradigm shift in enhancing analytical specificity for complex authentication challenges. Foodomics—the integration of proteomics, metabolomics, lipidomics, genomics, and transcriptomics with advanced bioinformatics—provides multidimensional data that collectively offer specificity unattainable through single-platform approaches [9].

In fermented foods, where complex microbial interactions create challenging matrices, multi-omics approaches have surmounted the limitations of single-omics analysis. The combined application of proteomics, genomics, and metabolomics has enabled specific identification of functional microbiota and their metabolic activities, leading to improved fermentation control and quality assurance [9]. Similarly, for dairy safety, proteomics and genomics integration has enabled specific quantitative risk assessment for pathogenic microorganisms [9].

The major challenge in implementing multi-omics approaches lies in managing data heterogeneity across platforms. Advanced chemometric tools and machine learning algorithms are required to extract specific patterns from these complex datasets and translate them into actionable authentication criteria.

Microfluidic Integration

Microfluidic technology presents innovative pathways to enhance specificity through controlled fluid manipulation at microscale dimensions. The integration of multiple processing steps within miniaturized systems reduces manual intervention and associated variability while improving reaction efficiency and detection specificity.

A novel integrated aflatoxin B1 extraction and detection system demonstrated how microfluidic technology enhances specificity through efficient sample preparation and detection integration. The system employed a poly(dimethylsiloxane) microfluidic mixer for rapid extraction followed by a paper-based immunosensor with carbon nanotubes for specific detection at 0.01 nanogram levels—well below regulatory requirements [12]. The confined microfluidic environment minimizes nonspecific interactions and enhances target binding efficiency, directly improving method specificity.

Data Mining and Artificial Intelligence

Advanced data analysis techniques, including association rule mining and graph neural networks (GNNs), are emerging as powerful tools for enhancing analytical specificity in complex food systems. These approaches identify subtle relationships between multiple factors that collectively contribute to specific identification of safety risks or authenticity parameters.

A targeted sampling decision-making method based on association rule mining and GNNs demonstrated how pattern recognition in historical sampling data could specifically identify high-risk combinations of food type, sampling time, and regional attributes [13]. The improved frequent pattern growth algorithm with constraints mined specific association rules between decision-making factors, enabling precise risk prediction and resource allocation for food safety monitoring [13].

Experimental Protocols for Specificity Assessment

Protocol for Molecular Detection Specificity

Objective: Validate specificity of DNA-based detection method for meat species identification.

Materials:

- DNA extraction kit (e.g., DNeasy Mericon Food Kit)

- Species-specific primers and probes

- Real-time PCR instrument

- Reference DNA from target and non-target species

- Authentic food samples

Procedure:

- Extract DNA from reference materials and test samples using standardized protocol [9]

- Perform real-time PCR amplification with species-specific primers/probes

- Include cross-reactivity panel containing DNA from related species (e.g., for beef detection, include pork, lamb, chicken, horse)

- Assess amplification efficiency and cycle threshold values for target versus non-target species

- Determine specificity as percentage of correct identifications in blinded sample panel

Specificity Validation: Method should demonstrate 100% specific identification of target species with no cross-reactivity with non-target species, even at DNA concentrations 10-fold higher than target [10].

Protocol for Chromatographic Method Specificity

Objective: Establish specificity of HPLC-UV metabolomic fingerprinting for meat authentication.

Materials:

- HPLC system with UV-Vis detector

- C18 reverse-phase column

- Methanol, acetonitrile, water (HPLC grade)

- Formic acid

- Meat samples from different species and origins

Procedure:

- Prepare aqueous extracts from meat samples (1:5 w/v ratio)

- Centrifuge at 10,000 × g for 15 minutes and filter supernatant

- Inject 20 μL onto HPLC column maintained at 30°C

- Apply gradient elution: 5-95% organic phase over 45 minutes

- Acquire UV spectra at multiple wavelengths (210, 254, 280 nm)

- Process chromatographic data using chemometric software (PCA, PLS-DA)

Specificity Validation: Method should achieve >99.3% specificity in distinguishing meat species and >91.2% specificity for geographical origin and production method (organic, halal, kosher) with classification errors below 6.9% [12].

Visualization of Analytical Specificity Frameworks

The following diagrams illustrate key workflows and relationships that ensure specificity in food analytical methods.

Multi-Omics Specificity Enhancement Framework

Microfluidic Pathogen Detection Specificity

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Specific Food Analytical Methods

| Reagent/Material | Specific Function | Application Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Species-specific primers and probes | Target unique DNA sequences for specific identification | Meat speciation, GMO detection, allergen identification |

| Monoclonal antibodies | Bind specific epitopes with high specificity | Immunoassays for pathogens, toxins, protein markers |

| Molecularly imprinted polymers | Synthetic receptors with specific binding cavities | Chemical contaminant detection, small molecule analysis |

| Stable isotope standards | Internal standards for specific quantification | LC-MS/MS analysis of contaminants, nutrient analysis |

| Carbon nanotubes | Enhance sensor surface area and electron transfer | Biosensors for mycotoxins, pathogens, histamine |

| Gold nanoparticles | Signal amplification and colorimetric detection | Rapid tests for pesticides, antibiotics, spoilage indicators |

| DNA extraction kits | Isolate high-quality DNA from complex matrices | PCR-based authentication, pathogen detection |

| QuEChERS kits | Rapid sample preparation for chemical analysis | Pesticide residue analysis, contaminant testing |

Specificity stands as the cornerstone of reliable food analytical methods, underpinning accurate safety assessments, quality verifications, and authenticity determinations. As food supply chains grow increasingly complex and sophisticated fraud emerges, continuous advancement in specific detection methodologies becomes imperative. The future trajectory points toward integrated multi-omics platforms, microfluidic automation, and AI-enhanced data analysis that will collectively elevate specificity to unprecedented levels. For researchers and food development professionals, maintaining rigorous specificity validation across all analytical applications remains essential for upholding the integrity of the global food system and protecting consumer interests.

Evolution from Targeted Analysis to Comprehensive 'Foodomics' Approaches

The field of food science is undergoing a significant transformation, evolving from traditional targeted analysis towards comprehensive 'Foodomics' approaches. This paradigm shift represents a move from analyzing a limited set of known compounds to employing untargeted, holistic strategies that can capture the complete molecular profile of food matrices. Foodomics is defined as an emerging multidisciplinary field that applies omics technologies such as genomics, proteomics, metabolomics, transcriptomics, and nutrigenomics to improve the understanding of food composition, quality, safety, and traceability [14]. This evolution is driven by the recognition that food is a complex biological system, and understanding its impact on human health requires more than just quantifying a few predetermined nutrients or contaminants. The integration of these advanced analytical techniques with sophisticated data analysis tools is enabling researchers to address global food challenges, including microbiological resistance, climate change impacts, and the need for improved food safety and quality [14]. Within precision nutrition research, this comprehensive approach is particularly valuable for understanding complex relationships, such as how polyphenols influence the gut microbiome, where unexplained inconsistencies in findings may be attributed to previously unmeasured variations in food composition [15].

Comparative Analysis: Targeted vs. Foodomics Approaches

The distinction between traditional targeted methods and comprehensive Foodomics approaches extends beyond the number of compounds analyzed to encompass fundamental differences in philosophy, methodology, and application as shown in Table 1.

Table 1: Comparison between Targeted Analysis and Foodomics Approaches

| Feature | Targeted Analysis | Foodomics Approaches |

|---|---|---|

| Analytical Scope | Focused on known, predefined compounds (e.g., specific nutrients, contaminants) [16] | Holistic, aiming to capture a wide range of known and unknown molecules [15] [14] |

| Primary Objective | Quantification and validation of specific analytes [16] | Discovery, fingerprinting, and comprehensive profiling of food matrices [16] |

| Common Techniques | HPLC-DAD, GC-MS, ICP-OES for specific compound classes [16] | NMR, MS-based untargeted platforms, integrated multi-omics [15] [14] |

| Data Output | Quantitative data on specific compounds | High-throughput, complex datasets requiring advanced bioinformatics [14] |

| Key Advantage | High sensitivity and accuracy for target compounds | Ability to discover novel compounds and understand system-wide interactions [15] |

A recent review of dietary intervention clinical trials from 2014 to 2024 highlights this technological gap. The study found that while targeted methods were commonly used for food composition analysis (18 of 38 studies) and clinical samples (24 of 38 studies), none of the studies employed untargeted omics approaches for food composition analysis, and only 5 of the 38 used untargeted omics for clinical sample analysis [15]. This demonstrates that while the field recognizes the value of comprehensive approaches, their implementation in practice is still limited.

Detailed Foodomics Methodologies and Workflows

Core Analytical Techniques in Foodomics

Foodomics relies on a suite of advanced analytical platforms that enable the comprehensive characterization of food components:

Mass Spectrometry (MS)-Based Platforms: These are cornerstone technologies for metabolomic, proteomic, and lipidomic analyses. They can be coupled with separation techniques like gas chromatography (GC) or liquid chromatography (LC) to handle complex food matrices. MS-based methods can be deployed in either targeted mode, to quantify specific known metabolites, or untargeted mode, to profile all detectable metabolites for novel discovery [16]. For instance, GC-MS was effectively used to analyze fatty acids in probiotic cheese enriched with microalgae [16].

Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) Spectroscopy: NMR provides a complementary approach to MS, offering advantages in quantitative analysis and structural elucidation without requiring extensive sample preparation. It is particularly useful for profiling primary metabolites in food samples [16].

Chromatography Techniques: High-Pressure Liquid Chromatography with a diode array detector (HPLC-DAD) is utilized for compounds like amino acids, organic acids, and vitamins (A and E), while Inductively Coupled Plasma-Optical Emission Spectrometry (ICP-OES) is employed for mineral analysis [16].

Experimental Protocol: A Representative Foodomics Workflow

The following detailed protocol, adapted from a study on probiotic cheese enriched with microalgae, illustrates a integrated Foodomics approach [16]:

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Foodomics Analysis

| Reagent/Material | Function in the Protocol | Technical Specification |

|---|---|---|

| Lactobacillus acidophilus LA-5 | Probiotic functional ingredient | Chr. Hansen strain, viable culture |

| Chlorella vulgaris & Arthrospira platensis | Microalgae enrichment | Freeze-dried biomass |

| Microbial Rennet | Milk coagulation agent | From Rhizomucor miehei fermentation |

| HPLC-DAD System | Analysis of amino acids, organic acids, vitamins (A, E) | Standard analytical configuration |

| GC-MS System | Fatty acid profiling and identification | Standard analytical configuration |

| ICP-OES System | Multi-element mineral analysis | Standard analytical configuration |

Sample Preparation and Design:

- Formulation: Develop experimental cheese batches: control (C1), with L. acidophilus LA-5 (C2), with LA-5 and C. vulgaris (C3), and with LA-5 and A. platensis (C4).

- Processing: Inoculate raw cow milk with the respective probiotic and microalgae. Add microbial rennet for coagulation.

- Ripening and Sampling: Brine the cheese and allow it to ripen for 90 days. Collect samples at predetermined time points (e.g., day 1, 30, 60, 90) for analysis.

Microbiological and Compositional Analysis:

- Enumerate total mesophilic aerobic bacteria (TMAB), non-starter lactic acid bacteria (NSLAB), and L. acidophilus LA-5 counts using standard plate counts.

- Analyze basic composition: moisture, fat, protein, salt, pH, and titratable acidity.

Metabolomic Characterization:

- Amino Acids, Organic Acids, Vitamins: Extract metabolites and analyze using HPLC-DAD.

- Fatty Acids: Extract lipids, derive fatty acids to methyl esters (FAMEs), and analyze using GC-MS.

- Minerals: Digest samples and perform multi-element analysis using ICP-OES.

Data Integration and Chemometric Analysis:

- Compile all high-throughput data from microbiological, compositional, and metabolomic analyses.

- Calculate nutritional quality indices based on the metabolomic profiles (e.g., Essential Amino Acid Index (EAAI), Atherogenicity Index (AI), Thrombogenicity Index (TI)).

- Perform multivariate statistical analysis, including Hierarchical Cluster Analysis (HCA) and Principal Component Analysis (PCA), to visualize variance and relationships between samples and their attributes.

The workflow for this comprehensive analysis is visualized in the following diagram:

Data Analysis and Interpretation in Foodomics

The high-throughput data generated from Foodomics analyses require robust chemometric and bioinformatic tools for interpretation. Multivariate statistical analysis is fundamental, with Principal Component Analysis (PCA) and Hierarchical Cluster Analysis (HCA) being widely used to identify patterns, group samples, and highlight the most significant variables contributing to variance [16]. Furthermore, the calculation of nutritional quality indices based on the comprehensive metabolomic data bridges the gap between molecular composition and health impact. These indices, such as the Essential Amino Acid Index (EAAI), Atherogenicity Index (AI), and Thrombogenicity Index (TI), transform complex chemical data into meaningful nutritional metrics [16]. The integration of these datasets enables a systems biology approach, revealing interactions between ingredients, the food matrix, and the resulting nutritional and functional properties.

Applications, Challenges, and Future Directions

Transformative Applications of Foodomics

The application of Foodomics is revolutionizing various domains within food science and nutrition:

- Precision Nutrition and Gut Microbiome Research: Foodomics provides the tools to understand inter-individual variations in response to diet. By comprehensively characterizing food composition and correlating it with individual microbiome and metabolomic profiles, it enables the development of personalized dietary recommendations [15].

- Food Authenticity, Traceability, and Quality Control: Foodomics is critical for verifying food authenticity and preventing fraud. Case studies demonstrate the use of metabolomics for authenticating horse milk adulteration, proteomic profiling for tracing seafood species and dairy product origins, and transcriptomic approaches for monitoring flavonoid biosynthesis in seeds and stress responses in plants [14].

- Safety and Contaminant Analysis: The non-targeted capability of Foodomics allows for the simultaneous monitoring of known and unknown contaminants, pathogens, toxins, and allergens in the food chain, thereby enhancing food safety [16] [17].

Current Challenges and Limitations

Despite its promise, the widespread adoption of Foodomics faces several significant hurdles:

- High Costs and Technical Complexity: The acquisition and maintenance of advanced instrumentation like high-resolution mass spectrometers, coupled with the need for specialized technical expertise, represent major financial and operational barriers, particularly for developing countries [14].

- Data Complexity and Bioinformatics Bottleneck: The immense volume and complexity of data generated require advanced bioinformatics skills and computational resources for processing, storage, and interpretation. A lack of standardized protocols and data sharing frameworks further complicates this issue [14].

- Reproducibility and Metrological Rigor: Ensuring the reliability, comparability, and metrological traceability of data from non-targeted analyses remains a challenge. Establishing robust validation protocols and reference materials is an ongoing focus for the community [17].

Future Perspectives

The future of Foodomics lies in the integration of technologies and collaborative frameworks to overcome existing challenges:

- Integration with Advanced Data Science: The coupling of Foodomics with machine learning and artificial intelligence will be crucial for predictive modeling, extracting hidden patterns from complex datasets, and automating data analysis [14].

- Portable and Affordable Platforms: Advancements in portable, affordable sensors and analytical devices will be essential for decentralizing Foodomics analyses, enabling applications in field settings, supply chain monitoring, and broader geographical implementation [14].

- Enhanced Supply Chain Transparency: Combining Foodomics data with technologies like blockchain can create immutable records of food composition and provenance, significantly enhancing supply chain transparency and consumer trust [14].

- Collaborative and Standardization Efforts: Future progress depends on strong collaboration among researchers, industry, and regulators to establish clear regulatory frameworks, standardize protocols, and promote data sharing through initiatives like METROFOOD-RI, which focuses on high-level metrology services in food and nutrition [14] [17].

The evolution from targeted analysis to comprehensive Foodomics represents a fundamental shift in how we study food. This transition, from a reductionist to a holistic perspective, is pivotal for addressing the complexity of food matrices and their interactions with human physiology. While challenges related to cost, data complexity, and standardization persist, the integration of Foodomics with emerging technologies like AI and portable sensors, along with strong collaborative efforts, is poised to unlock its full potential. This will ultimately lead to significant advancements in personalized nutrition, food safety, quality control, and public health outcomes, providing a deeper, systems-level understanding of food.

In food analytical methods research, achieving absolute specificity is a fundamental yet challenging goal. The accurate identification and quantification of target analytes are consistently challenged by the complex chemical background of food matrices. These challenges—matrix effects (ME), the presence of interfering compounds, and structural analyte similarity—directly impact the reliability, accuracy, and precision of analytical results. Within the context of a broader thesis on understanding specificity, this technical guide examines the core analytical challenges that complicate the path to unambiguous measurement. The phenomenon of matrix effects, where co-extracted matrix components alter the analytical signal, is particularly pervasive in techniques like liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (LC-MS), where it can unpredictably compromise accuracy and precision [18]. Simultaneously, the structural similarity of isomeric compounds and the sheer number of potential chemical interferents demand increasingly sophisticated instrumental solutions. Addressing these interconnected challenges is critical for advancing food safety, ensuring authenticity, and enabling accurate risk assessment in the exposome era, where characterizing complex chemical mixtures in food becomes paramount [19].

Matrix Effects in Mass Spectrometry

Mechanisms and Impact

Matrix effects refer to the influence of all non-analyte components within a sample on the quantification of target compounds, a phenomenon particularly acute in mass spectrometric detection [18]. In LC-MS with electrospray ionization (ESI), MEs primarily manifest as ion suppression or enhancement, where co-eluting matrix components hinder or facilitate the ionization of the target analyte [20]. The mechanisms are diverse, including competition for available charge during the droplet evaporation process and the impact of non-volatile or surface-active compounds on ionization efficiency [21]. These effects can severely compromise quantitative analysis at trace levels, affecting detection capability, precision, and accuracy [21]. The extent of ME is highly variable and depends on a complex interplay of factors including the matrix species, the specific analyte, the sample preparation protocol, and the ion source design of the mass spectrometer itself [22].

Quantitative Assessment of Matrix Effects

The calibration-graph method and the concentration-based method are two established approaches for assessing ME. Research has demonstrated that the concentration-based method, which evaluates ME at each concentration level, provides a more precise understanding, revealing that lower analyte levels are often more significantly affected by ME than higher levels [18]. This finding is critical for trace analysis.

The following table summarizes quantitative ME data from a study on 74 pesticides in various fruits, illustrating the variability of this phenomenon [18].

Table 1: Matrix Effect (ME) on Pesticide Analysis in Fruits by UPLC-MS/MS

| Fruit Matrix | Number of Pesticides Studied | Key Findings on Matrix Effect | Correlation Strength (Spearman Test) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Golden Gooseberry (GG) | 74 | Similar pesticide response found with Purple Passion Fruit. | Stronger positive correlation for GG-PPF pair. |

| Purple Passion Fruit (PPF) | 74 | Similar pesticide response found with Golden Gooseberry. | Stronger positive correlation for GG-PPF pair. |

| Hass Avocado (HA) | 74 | Significant differences in pesticide response compared to GG and PPF. | Weaker correlation for GG-HA and PPF-HA pairs. |

Experimental Protocol: Evaluating Matrix Effect via the Calibration-Graph Method

Principle: This method evaluates ME by comparing the slope of the calibration curve in a matrix to the slope of the calibration curve in a pure solvent.

Procedure:

- Standard Solution Preparation: Prepare a series of standard solutions of the target analytes in a pure, matrix-free solvent (e.g., methanol/acetonitrile) at a minimum of five concentration levels.

- Matrix-Matched Standard Preparation: For each matrix under investigation (e.g., avocado, gooseberry), prepare a corresponding set of matrix-matched standard solutions at the same concentration levels. This requires extracting a blank matrix and using the final extract to reconstitute or dilute the standards.

- Instrumental Analysis: Analyze both the solvent-based and matrix-matched calibration standards using the validated LC-MS/MS or GC-MS method.

- Calculation of Matrix Effect (ME): Calculate the ME for each analyte using the formula: *ME (%) = [(Slope of matrix-matched calibration curve / Slope of solvent calibration curve) - 1] × 100%

- Interpretation: An ME value around 0% indicates no matrix effect. Negative values indicate ion suppression, and positive values indicate ion enhancement. Typically, |ME| < 20% is considered negligible, while |ME| > 20% is considered significant and requires mitigation [21].

Strategies for Mitigating Matrix Effects

Sample Preparation and Cleanup

A primary strategy for managing ME involves reducing the concentration of interfering compounds introduced into the instrument.

- The QuEChERS Approach: The Quick, Easy, Cheap, Effective, Rugged, and Safe (QuEChERS) method is widely used for multi-residue analysis. It employs different sorbents (e.g., primary secondary amine (PSA) for removing fatty acids, C18 for lipophilic compounds, graphitized carbon black (GCB) for pigments) for sample clean-up [19]. An advanced version, QuEChERSER, has been developed to extend analyte coverage, enabling the complementary determination of a broader scope of 245 chemicals, including pesticides, PCBs, and PAHs, across various food commodities [19].

- Sample Dilution: Diluting the sample extract is a simple and effective method to reduce the concentration of interfering compounds, thereby diminishing MEs. A study demonstrated that a dilution factor of 15 was sufficient to eliminate most matrix effects in the analysis of 53 pesticides in orange, tomato, and leek, allowing for quantification with solvent-based standards in most cases [21]. The obvious trade-off is a reduction in sensitivity, which must be compensated for by highly sensitive instrumentation.

- Advanced Extraction Solvents: The use of Natural Deep Eutectic Solvents (NADES) is a promising, sustainable trend. NADES are biodegradable, non-toxic, and offer tunable extraction properties, providing an efficient and environmentally friendly alternative for sample preparation that can be optimized to reduce co-extraction of interferents [19].

Instrumental and Calibration Approaches

When MEs cannot be fully eliminated, compensation through calibration techniques is essential.

- Matrix-Matched Calibration: This is the most common compensation technique, where the calibration standards are prepared in the same blank matrix as the samples, thereby matching the ME between standards and samples [21]. However, this approach requires access to blank matrices and can be labor-intensive.

- Stable Isotope-Labelled Internal Standards (SIL-IS): This is considered the gold standard for compensation. A SIL-IS is an isotopically labeled version of the target analyte that has nearly identical chemical properties and chromatographic retention, and therefore experiences the same ME. By using the response ratio of the analyte to the SIL-IS for quantification, the ME is effectively corrected [21]. Their high cost and limited availability for all analytes are the main drawbacks.

- High-Resolution Mass Spectrometry (HRMS): Instrumental advances also offer solutions. Comparing multiple reaction monitoring (MRM) on tandem mass spectrometry (MS/MS) with the information-dependent acquisition (IDA) mode on quadrupole time-of-flight (QTOF) MS has shown that the latter can simultaneously weaken MEs for multiple pesticides across diverse matrices, suggesting HRMS can provide a inherent advantage in mitigating ME-related issues [22].

The following workflow diagram summarizes the decision process for assessing and mitigating matrix effects.

The Challenge of Interfering Compounds and Analyte Similarity

Structural Isomers and In-Source Fragmentation

Beyond broad matrix effects, a more targeted challenge is posed by structurally isomeric compounds. These analytes share the same elemental composition and nominal mass, making them indistinguishable by first-generation mass spectrometers, even those with high resolving power [23]. When these isomers co-elute chromatographically, they can cause significant misidentification and inaccurate quantification.

Experimental Protocol: Differentiating Isomers by Tandem Mass Spectrometry

Principle: Isomeric compounds, despite having the same precursor ion, often undergo characteristic fragmentation pathways, producing unique product ion spectra.

Procedure:

- Chromatographic Separation: Optimize the LC method to achieve the best possible separation of the isomeric pairs. Even partial separation reduces the likelihood of simultaneous introduction into the ion source.

- MS/MS Analysis: For each isomeric standard, acquire MS/MS spectra at multiple collision energies.

- Fragment Ion Identification: Identify and record the relative abundances of characteristic fragment ions for each isomer.

- Method Development for Quantification: Select one or more unique fragment ions (or a unique ratio of fragment ions) for each isomer to use as a quantitative transition in a scheduled MRM method.

- Validation: Validate the method to ensure that there is no cross-talk between the MRM channels of the isomers and that quantification is accurate. This approach has been successfully used for the spectral discrimination of isomeric food pollutants, differentiating them based on their distinct fragmentation pathways [23].

The Research Reagent Toolkit

Successfully navigating the challenges of matrix effects and interference requires a suite of specialized reagents and materials.

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Managing Matrix Effects and Interference

| Reagent / Material | Function / Purpose | Example Application |

|---|---|---|

| QuEChERS Kits | A standardized, multi-step sample preparation protocol for extraction and clean-up. | Removal of organic acids, pigments, and sugars from fruit and vegetable extracts prior to pesticide analysis [19] [22]. |

| Zirconium Dioxide Sorbents | Selective removal of phospholipids and other matrix components during clean-up. | Efficient clean-up of complex, phospholipid-rich matrices like avocado and dairy products [19]. |

| Stable Isotope-Labelled Internal Standards | Internal standards used to correct for matrix-induced signal suppression/enhancement and losses during sample preparation. | Quantification of pesticides in complex spices like ginger and Sichuan pepper where matrix effects are strong [21] [22]. |

| Natural Deep Eutectic Solvents | Green, tunable solvents for efficient and selective extraction of analytes. | Sustainable extraction of a wide range of contaminants from diverse food matrices, minimizing co-extraction of interferents [19]. |

The challenges of matrix effects, interfering compounds, and analyte similarity represent significant hurdles in the pursuit of analytical specificity. As this guide has detailed, these are not isolated issues but are deeply interconnected, often requiring a holistic and integrated mitigation strategy. The persistence of these challenges underscores a critical thesis in food analytical methods research: that the choice of methodology is a series of compromises, and the "perfect" method is an ideal that guides continuous improvement rather than a final destination. The future of overcoming these specificity challenges lies in the development of integrated, multi-platform approaches that leverage advanced instrumentation like LC-HRMS and GC-HRMS with ion mobility spectrometry, coupled with intelligent, green sample preparation [19] [24]. Furthermore, the adoption of data analysis strategies from fields like metabolomics to handle the multi-dimensional data generated by ME studies points to a more sophisticated, informatics-driven future for food analysis [22]. By systematically addressing these core challenges, the field moves closer to ensuring the accuracy and reliability required for protecting public health and guaranteeing food integrity.

Regulatory Frameworks and Standards Governing Analytical Specificity

Analytical specificity is a fundamental method validation parameter that confirms an analytical procedure's ability to measure the analyte unequivocally in the presence of other components, including impurities, degradation products, and matrix constituents. Within food analytical methods research, establishing specificity is crucial for ensuring the accuracy, reliability, and legal defensibility of data used for regulatory compliance, safety assessments, and nutritional labeling. The increasing complexity of global food supply chains and the proliferation of novel food ingredients demand rigorous specificity validation to prevent mislabeling, adulteration, and potential health risks. This guide examines the regulatory frameworks and standards governing this critical attribute, providing researchers with the experimental protocols and tools necessary for robust method development.

Global Regulatory Landscape

Food analytical methods operate within a multi-layered regulatory environment, where standards are set by international bodies, national agencies, and regional economic communities. Understanding the interplay between these frameworks is essential for researchers developing methods for global markets.

International Standards and Guidelines

The Codex Alimentarius Commission, established by the UN Food and Agriculture Organization and the World Health Organization, develops international food standards and guidelines. While Codex does not prescribe specific analytical methods, its texts, such as the Principles for the Establishment of Codex Methods of Analysis, mandate that methods be characterized for performance criteria including specificity, accuracy, and precision. Codex methods often serve as a basis for national standards, promoting global harmonization [25].

National Regulatory Frameworks

- United States (U.S. Food and Drug Administration): The FDA's authority derives from the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act. For chemical hazards, the FDA's Human Foods Program is enhancing its post-market assessment framework, which relies on specific analytical methods to ensure chemical safety [26] [27]. The Food Safety Modernization Act mandates science-based approaches to prevention, implicitly requiring specific methods for verifying preventive controls and traceability [28]. The FDA's compliance programs, such as its updated food labeling program, detail the agency's approach to verifying compliance through sample analysis, necessitating methods with proven specificity for regulated allergens and nutritional components [29].

- European Union (EU): The EU operates a centralized system for food safety through the European Food Safety Authority, with regulations such as the Official Controls Regulation setting rules for analytical method validation. Methods used for official controls must demonstrate specificity, among other performance criteria, and are often referenced in standardized methods published by the European Committee for Standardization.

- India (Food Safety and Standards Authority of India - FSSAI): The FSSAI recently amended its import regulations to allow the use of validated methods from internationally recognized bodies like AOAC, ISO, and Codex when a specific method is not available in its own manuals. This shift underscores the critical importance of validated specificity in internationally accepted methods for clearing imported foods [30].

- Other Key Regions: Countries including Japan, South Korea, Thailand, and China maintain their own specifications and standards for food additives and contaminants, each with associated analytical requirements. Updates to these regulations, such as Japan's amendments to its food additive specifications, frequently occur and necessitate ongoing validation of method specificity for market access [25].

Table 1: Key Global Regulatory Bodies and Their Relevant Guidance on Analytical Specificity

| Regulatory Body | Region/Country | Key Document/Guidance | Primary Focus Related to Specificity |

|---|---|---|---|

| Codex Alimentarius | International | Principles for the Establishment of Codex Methods of Analysis | Establishes foundational performance criteria for methods used in international trade. |

| U.S. FDA | United States | Food Safety Modernization Act (FSMA) Rules; Compliance Program Guidance Manuals | Ensures methods can accurately identify and quantify chemical, microbiological, and allergenic hazards in a complex food supply [26] [28]. |

| European Commission | European Union | Commission Regulation (EC) No 333/2007 (on methods of sampling and analysis for official control) | Lays down specific performance criteria for methods used to detect regulated contaminants. |

| FSSAI | India | Food Safety and Standards (Import) Regulations | Mandates the use of FSSAI methods or other internationally validated methods, requiring demonstrated specificity [30]. |

| Health Canada | Canada | Food and Drug Regulations | Specifies methods for assessing compliance with standards for ingredients, contaminants, and nutrients. |

Core Principles of Analytical Specificity

Specificity in food analysis demonstrates that a method can distinguish the target analyte from all other substances present in the sample matrix. This is distinct from selectivity, which refers to the degree to which a method can determine a particular analyte in mixtures without interference from other components; in practice, the terms are often used interchangeably. Key challenges requiring rigorous specificity assessment include:

- Matrix Effects: Co-extractives from diverse food matrices (e.g., fats, proteins, pigments) can suppress or enhance analyte signal in chromatographic or mass spectrometric methods.

- Structural Analogs: Compounds with similar chemical structures (e.g., different mycotoxins, drug metabolites, or isobaric compounds in mass spectrometry) can co-elute and interfere with detection.

- Degradation Products: In stability studies or processed foods, the ability to differentiate the intact analyte from its breakdown products is critical.

Experimental Protocols for Establishing Specificity

A comprehensive specificity assessment is a multi-faceted experimental process. The following protocols outline the core methodologies for chromatographic and microbiological/immunoassay-based techniques, which are prevalent in food analysis.

Protocol 1: Specificity Assessment for Chromatographic Methods (e.g., HPLC, UPLC, GC)

This protocol is designed to validate methods for analyzing chemical contaminants, such as pesticides, mycotoxins, or unauthorized additives.

1. Hypothesis: The chromatographic method can resolve the target analyte from closely related chemical compounds and matrix interferences, providing an accurate and unambiguous measurement.

2. Materials and Reagents:

- Standard Solutions: High-purity certified reference materials of the target analyte and potential interferents.

- Blank Matrix Samples: Representative food samples confirmed to be free of the target analyte.

- Mobile Phase Solvents: HPLC or GC grade.

- Sample Preparation Reagents: Extraction solvents, solid-phase extraction cartridges, derivatization agents.

3. Experimental Workflow: The following diagram outlines the key experimental steps for assessing specificity in chromatographic methods.

4. Procedure: 1. Analyte Standard Analysis: Inject the pure analyte standard and record the retention time and peak characteristics (shape, symmetry). 2. Blank Matrix Analysis: Inject a prepared sample of the blank food matrix. The chromatogram should show no peaks co-eluting at the retention time of the analyte. 3. Forced Degradation/Interferent Analysis: Inject a mixture containing the target analyte and known potential interferents (e.g., structural analogs, degradation products, or key matrix components). Observe baseline resolution between the analyte peak and all interferent peaks. 4. Spiked Matrix Analysis: Fortify the blank matrix with a known concentration of the analyte and process through the entire method. The recovery of the analyte and the cleanliness of the chromatogram in the region of interest demonstrate specificity in the presence of the matrix.

5. Data Analysis and Acceptance Criteria:

- Resolution Factor (Rs): For chromatographic peaks, Rs > 1.5 between the analyte and the closest eluting potential interferent.

- Peak Purity: For diode array detectors, spectral homogeneity across the peak should be confirmed. For mass spectrometers, the absence of co-eluting isobars is confirmed via unique mass fragments.

- Absence of Interference: The response of the blank matrix at the analyte's retention time should be less than a defined threshold (e.g., 20% of the response for the analyte at the limit of quantification).

Protocol 2: Specificity Assessment for Microbiological and Immunoassay Methods

This protocol applies to methods detecting pathogens, allergens, or other biological analytes via antibody-antigen interactions or microbial growth.

1. Hypothesis: The assay's biological recognition element (antibody, culture media) is specific for the target organism or protein and does not cross-react with non-target organisms or food matrix components.

2. Materials and Reagents:

- Target Strain/Allergen: Certified reference strain of the pathogen or purified allergen protein.

- Non-Target Strains/Proteins: A panel of genetically or structurally related non-target organisms or proteins (e.g., different Salmonella serovars for a S. Enteritidis assay, or milk caseins for a beta-lactoglobulin ELISA).

- Cross-Reactive Food Matrices: Samples known to contain substances that may cause cross-reactivity (e.g., high-fat matrices, fermented products).

- Growth Media or Assay Buffer: As specified by the method.

3. Experimental Workflow: The logical flow for assessing biological assay specificity is shown below.

4. Procedure: 1. Positive Control Test: Analyze a sample containing the target organism/allergen at a defined level. The result must be unequivocally positive. 2. Cross-Reactivity Panel Test: Individually analyze samples containing each non-target organism or protein from the panel at a high concentration (typically 100-1000x the limit of detection of the target). The results for all non-targets must be negative. 3. Matrix Interference Test: Analyze a blank matrix and a matrix spiked with a low level of the target analyte. The blank must test negative, and the spiked sample must test positive with recovery within acceptable limits (e.g., 70-120%).

5. Data Analysis and Acceptance Criteria:

- Cross-Reactivity: For immunoassays, cross-reactivity is calculated as

(Concentration of target giving 50% response / Concentration of interferent giving 50% response) * 100%. Cross-reactivity with non-targets should be< 1%. - False Positives/Negatives: For microbiological methods, no growth or positive signal should occur for the non-target panel (0% false positives), and the target must be correctly identified (0% false negatives for the pure culture).

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

The following reagents and materials are fundamental for conducting the specificity experiments described above.

Table 2: Essential Reagents and Materials for Specificity Validation

| Item/Category | Function in Specificity Assessment | Key Considerations for Selection |

|---|---|---|

| Certified Reference Materials (CRMs) | Serves as the definitive standard for the target analyte and potential interferents; used to establish retention time, spectral identity, and assay response. | Purity, stability, and traceability to a national metrology institute are critical. Must be representative of the analyte form in the food. |

| Characterized Blank Matrices | Provides the baseline for assessing matrix interference; used in blank and spiked recovery experiments. | Must be verified as analyte-free. Should represent the diversity of matrices to which the method will be applied (e.g., high-fat, high-protein, high-carbohydrate). |

| Chromatographic Columns | The stationary phase is a primary determinant of chromatographic resolution and peak shape, directly impacting specificity. | Selectivity (e.g., C18, phenyl-hexyl, HILIC) should be chosen based on analyte and interferent polarity and structure. |

| Specific Antibodies (for Immunoassays) | The biological recognition element that confers specificity by binding to a unique epitope on the target allergen or protein. | Monoclonal antibodies offer higher specificity than polyclonal. Must be validated for lack of cross-reactivity with related proteins. |

| Selective Culture Media (for Microbiology) | Promotes the growth of the target microorganism while suppressing the growth of non-target background flora. | Selectivity agents (e.g., antibiotics, chemicals) must be optimized to avoid inhibiting target strains. |

| Mass Spectrometry Standards (IS, SS) | Isotopically labeled internal standards correct for matrix effects and confirm analyte identity, enhancing specificity. | The ideal internal standard is a stable isotope-labeled version of the analyte itself, which co-elutes and has nearly identical chemical behavior. |

Emerging Trends and Future Directions

The regulatory and technological landscape for analytical specificity is rapidly evolving. Key trends include:

- Advanced Mass Spectrometry: The use of high-resolution accurate mass spectrometry is becoming the gold standard for confirmatory analysis, providing unparalleled specificity via exact mass measurement and isotope ratio confirmation.

- Data Science and AI: Regulatory agencies are developing AI tools, such as the FDA's Warp Intelligent Learning Engine, for horizon-scanning and signal detection. This may lead to a more dynamic identification of new potential interferents that require specificity testing [26].

- Global Harmonization: Initiatives like the FSSAI's acceptance of internationally validated methods point toward a growing recognition of the need for global alignment on validation standards, which could simplify compliance for multinational food companies [30].

- Novel Foods and Ingredients: The regulatory approval of new products, such as cultivated salmon, and the revocation of outdated standards of identity for various foods, create new analytical challenges, requiring the development of highly specific methods to distinguish novel products from traditional ones and verify compliance with modernized standards [31] [29].

Advanced Analytical Platforms and Their Specificity Applications

Chromatographic techniques, particularly High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC) and Gas Chromatography (GC), serve as foundational pillars in modern analytical science, especially within food analysis research. When these separation techniques are coupled with spectroscopic detection methods—creating hyphenated systems—they provide unparalleled capabilities for identifying and quantifying chemical compounds in complex matrices [32] [33]. The specificity achieved through these methods forms the critical linkage between analytical protocol and meaningful scientific interpretation in food analytical methods research.

This technical guide examines the fundamental principles, operational parameters, and practical implementation of HPLC, GC, and their hyphenated configurations. Within the context of food analysis, where samples present exceptional complexity and diversity, the precise characterization of individual components demands sophisticated approaches that combine physical separation with chemical identification [34]. The integration of chromatography with mass spectrometry, infrared spectroscopy, and nuclear magnetic resonance has revolutionized how researchers address challenges in food safety, quality control, authenticity verification, and nutritional assessment [33] [35].

Fundamental Principles and Instrumentation

Core Chromatographic Concepts

Both HPLC and GC operate on the same fundamental principle: the distribution of analytes between stationary and mobile phases to achieve separation based on differential partitioning [36]. The efficiency of both HPLC and GC columns is expressed in terms of Height Equivalent to Theoretical Plate (HETP), a standardized metric for evaluating column performance over its operational lifespan [36]. Band broadening, described by the Van Deemter equation, represents a universal challenge in both techniques, contributing to resolution loss through diffusion, mass transfer, and flow velocity effects [36].

Chromatograms generated by both systems display peak-shaped responses with compound concentration proportional to either peak height or area [36]. Quantitative analysis employs identical methodologies across both techniques, including normalization of peak areas, internal standard, external standard, and standard addition methods [36]. Both systems require validated reference standards traceable to certified materials for reliable quantification, with regular verification of retention times under specified operational conditions [36].

High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC)

HPLC employs liquid mobile phases under high pressure to achieve rapid separation of non-volatile or thermally labile compounds. Modern HPLC systems for food analysis typically incorporate:

- High-pressure pumping systems capable of generating precise, pulse-free gradients

- Injection valves with fixed-volume loops for reproducible sample introduction

- Thermostatically controlled column compartments for retention time stability

- Specialized detectors including Diode Array Detectors (DAD), Fluorescence Detectors, and Refractive Index Detectors [37] [38]

Reverse-phase chromatography with C18 bonded phases represents the most prevalent configuration for food compound analysis, utilizing hydrophobic interactions for separation [37] [38]. The mobile phase typically consists of water blended with organic modifiers such as acetonitrile or methanol, sometimes with modifiers like formic acid to enhance chromatographic performance [37].

Gas Chromatography (GC)

GC utilizes inert gaseous mobile phases (helium, hydrogen, or nitrogen) to transport vaporized samples through thermally controlled columns containing liquid stationary phases [39] [33]. System components include:

- Heated injection ports for sample vaporization (split/splitless modes)

- Capillary columns with coated stationary phases

- Precisely controlled oven for temperature programming

- Detection systems including Flame Ionization (FID), Electron Capture (ECD), and Mass Spectrometric detectors [39] [33]

GC applications primarily target volatile compounds, though semi-volatile analytes can be analyzed through derivatization techniques that enhance volatility and thermal stability [33]. The trimethylsilyl derivatization represents the most common approach for polar compounds containing multiple hydroxyl groups [33].

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of HPLC and GC Systems

| Parameter | HPLC | GC |

|---|---|---|

| Mobile Phase | Liquid (water, methanol, acetonitrile) | Gas (helium, hydrogen, nitrogen) |

| Sample Compatibility | Non-volatile, thermally labile compounds | Volatile and semi-volatile compounds |

| Separation Mechanism | Polarity, size, ion-exchange, hydrophobic interaction | Volatility and polarity |

| Common Detectors | UV-Vis/DAD, Fluorescence, MS | FID, ECD, MS |

| Typical Applications in Food Analysis | Phenolics, flavonoids, amino acids, vitamins, pigments | Fatty acids, pesticides, flavor compounds, essential oils |

| Derivatization Requirement | Occasionally for detection enhancement | Frequently for volatility enhancement |

Hyphenated Techniques: Integration of Separation and Detection

Conceptual Framework and Historical Development