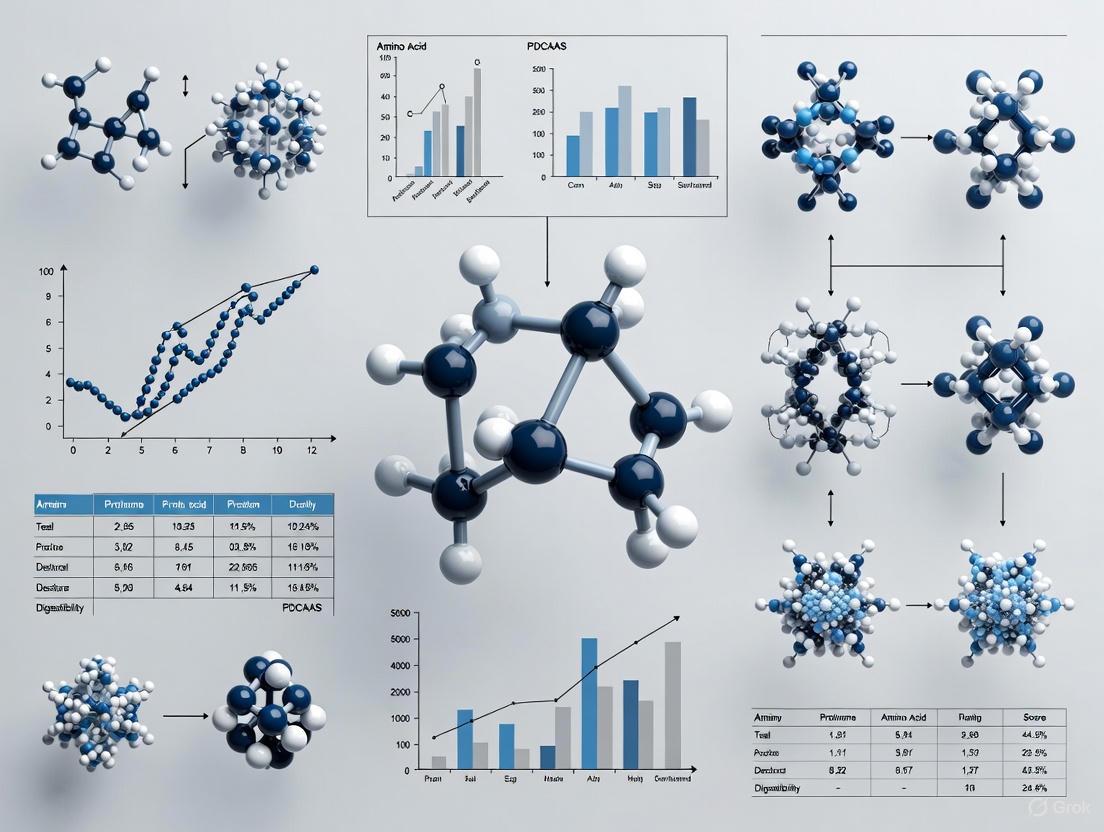

Advancing Protein Quality Assessment: From PDCAAS Limitations to Next-Generation Scoring Methods

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of protein digestibility-corrected amino acid score (PDCAAS) methodology, its well-documented limitations, and the evolving landscape of protein quality assessment for research and pharmaceutical applications.

Advancing Protein Quality Assessment: From PDCAAS Limitations to Next-Generation Scoring Methods

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of protein digestibility-corrected amino acid score (PDCAAS) methodology, its well-documented limitations, and the evolving landscape of protein quality assessment for research and pharmaceutical applications. We explore the scientific foundations of PDCAAS, including its calculation methodology and inherent constraints such as truncation effects and fecal digestibility measurements. The review covers emerging methodologies including the Digestible Indispensable Amino Acid Score (DIAAS) framework, in vitro digestion protocols like INFOGEST, and novel computational approaches for protein quality optimization. We critically examine validation strategies comparing in vitro and in vivo data, discuss troubleshooting analytical challenges, and present future directions including stable isotope methods and personalized nutrition applications that hold significant implications for clinical research and therapeutic development.

The PDCAAS Framework: Foundations, Limitations, and the Case for Methodological Evolution

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. Why did regulatory bodies transition from PER to PDCAAS as the preferred method for evaluating protein quality? The transition was primarily driven by two key factors. First, the Protein Efficiency Ratio (PER) is based on the amino acid requirements and growth patterns of young rats, which differ significantly from those of humans [1]. In contrast, the Protein Digestibility-Corrected Amino Acid Score (PDCAAS) is based directly on human amino acid requirements, making it a more appropriate model for human nutrition [1]. Second, leading international health organizations like the FAO/WHO recommended PDCAAS for regulatory purposes, leading to its adoption by the U.S. FDA in 1993 [1].

2. What are the main methodological limitations of the PER method that PDCAAS sought to address? The PER method has several critical limitations. As a bioassay in growing rats, it credits protein used for growth but does not adequately account for protein used for body maintenance [2]. Furthermore, PER values for protein mixtures cannot be meaningfully derived by averaging the PER values of the constituent proteins, creating significant challenges for evaluating mixed diets [2]. Due to these limitations, Canada remains the only developed nation using PER to validate protein content claims on non-infant foods [2].

3. How does the truncation of PDCAAS values affect the evaluation of high-quality proteins? The PDCAAS method truncates values at 1.0 (or 100%), meaning any score exceeding this threshold is rounded down [3] [1]. Consequently, proteins with different amino acid profiles that all score above the requirement—such as casein, milk, eggs, and soy protein—receive an identical score of 1.0, limiting the method's ability to distinguish their relative quality and their potential to compensate for low levels of dietary essential amino acids in other proteins when used as supplements [1] [4].

4. What is the fundamental difference between fecal and ileal digestibility, and why is this significant? Fecal digestibility, used in PDCAAS, measures nitrogen disappearance at the fecal level, which can overestimate nutritional value because amino acid nitrogen that reaches the colon is lost for protein synthesis in the body [3] [5]. Ileal digestibility, used in the newer DIAAS method, measures absorption at the end of the small intestine (ileum) and is considered a more accurate representation of actual amino acid absorption, as it prevents bacterial metabolism in the colon from skewing the results [2] [5].

5. What key methodological consideration is required when determining the amino acid score for PDCAAS? The calculation must use a specific reference pattern based on the essential amino acid requirements of a defined human age group. Following FDA regulations, the pattern for preschool-aged children (2-5 years) is typically used, as this group is considered the most nutritionally demanding [1] [6]. This pattern is then used to identify the first limiting amino acid in the test protein.

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Issues

Issue 1: Inconsistent PDCAAS values for the same protein source.

- Potential Cause: The use of different reference patterns or nitrogen-to-protein conversion factors can drastically alter the calculated chemical score [7].

- Solution: Ensure methodological consistency. For regulatory purposes, use the FAO/WHO 1991 preschool child amino acid requirement pattern and a standard nitrogen conversion factor of 6.25, unless a specific factor for the protein source is established and justified [6] [7].

Issue 2: Overestimation of protein quality for ingredients containing antinutritional factors.

- Potential Cause: The PDCAAS uses fecal digestibility, which may not capture the negative impact of antinutritional factors (e.g., trypsin inhibitors, lectins) in the upper digestive tract. These factors can heighten endogenous amino acid losses and reduce ileal absorption, even if fecal digestibility appears high [4] [2].

- Solution: For proteins known to contain antinutritional factors (e.g., legumes), consider using ileal digestibility data if available, as this provides a more accurate measure of bioavailable amino acids. Be aware that this is a recognized limitation of the standard PDCAAS protocol [1] [5].

Issue 3: Inability to differentiate between high-quality proteins for research purposes.

- Potential Cause: The standard PDCAAS protocol truncates values at 1.0 [3].

- Solution: For research comparisons, report the untruncated PDCAAS value. This allows for a more nuanced comparison of proteins whose scores exceed the requirement pattern, such as casein (1.21) versus whey (1.09), enabling better evaluation of their potential in dietary formulations [1].

Experimental Protocols & Data

Detailed Methodology: Calculating the PDCAAS

The following workflow outlines the standard experimental and calculation procedures for determining the PDCAAS of a food protein.

Step 1: Amino Acid Analysis

- Objective: Determine the indispensable amino acid (IAA) profile of the test protein.

- Protocol: Use High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC) or Ion-Exchange Chromatography to analyze the hydrolyzed protein sample. The resulting profile is expressed in milligrams of each IAA per gram of crude protein [6].

- Key Reagent: Protein hydrolysate prepared via acid hydrolysis.

Step 2: Calculate the Amino Acid Score (AAS)

- Objective: Identify the first limiting amino acid.

- Protocol:

- Reference Pattern: Use the requirement pattern for preschool-aged children (2-5 years) as defined by FAO/WHO [1]. Requirements are shown in the table below.

Step 3: Determine True Fecal Protein Digestibility (FTPD)

- Objective: Correct the AAS for the proportion of protein that is digested and absorbed.

- Protocol: The standard method uses a rat balance study. The formula for True Fecal Digestibility is [1]:

FTPD = [Protein Intake (PI) - (Fecal Protein (FP) - Metabolic Fecal Protein (MFP))] / PIWhere MFP is the amount of protein in feces when the rat is fed a protein-free diet.

Step 4 & 5: Final Calculation and Truncation

- Objective: Derive the final PDCAAS value.

- Protocol: Multiply the AAS (from Step 2) by the FTPD (from Step 3). If the resulting value is greater than 1.0, it is truncated to 1.0 for regulatory labeling purposes [3] [1].

Reference Pattern for PDCAAS Calculation

This table provides the official reference pattern based on the amino acid requirements of preschool-aged children (2-5 years), which must be used for calculating the PDCAAS [1] [6].

| Amino Acid | Requirement (mg/g of protein) |

|---|---|

| Isoleucine | 25 - 28 |

| Leucine | 55 - 66 |

| Lysine | 51 - 58 |

| Methionine + Cysteine | 25 |

| Phenylalanine + Tyrosine | 47 - 63 |

| Threonine | 27 - 34 |

| Tryptophan | 7 - 11 |

| Valine | 32 - 35 |

| Histidine | 18 |

Note: Ranges reflect slight variations between cited sources. [1] [6]

Comparative Protein Quality Scores (PDCAAS)

This table provides typical PDCAAS values for common protein sources, illustrating the truncation effect for high-quality proteins [1] [6].

| Protein Source | Untruncated PDCAAS | Truncated PDCAAS (Regulatory) |

|---|---|---|

| Casein | 1.31 | 1.0 |

| Whey Protein | 1.09 | 1.0 |

| Egg White | 1.18 | 1.0 |

| Soy Protein Isolate | 1.00 | 1.0 |

| Beef | 0.92 | 0.92 |

| Pea Protein Concentrate | 0.89 | 0.89 |

| Black Beans | 0.75 | 0.75 |

| Rice | 0.50 | 0.50 |

| Wheat Gluten | 0.25 | 0.25 |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents & Materials

| Item | Function in PDCAAS Analysis |

|---|---|

| High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC) System | The primary analytical instrument used for separating, identifying, and quantifying the individual amino acids in a hydrolyzed protein sample [6]. |

| Amino Acid Standard Mixture | A calibrated reference solution containing known concentrations of pure amino acids. It is essential for identifying and quantifying amino acids in the test sample via HPLC [6]. |

| Protein-Free Diet (for Rat Assay) | A specially formulated diet used in the in vivo rat digestibility assay to determine the metabolic fecal protein (MFP) loss, which is necessary to calculate true fecal digestibility [1] [8]. |

| Reference Protein (Casein) | A high-quality, well-characterized protein often used as a positive control in rat digestibility assays to validate experimental conditions and calculations [1]. |

| Nitrogen Analysis Apparatus (e.g., Kjeldahl or Dumas) | Equipment used to determine the total nitrogen content of a sample, which is then converted to crude protein content using a standard factor (often 6.25) [7]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: What is the fundamental difference between the PDCAAS and DIAAS methods?

The primary difference lies in the level at which digestibility is assessed. The Protein Digestibility-Corrected Amino Acid Score (PDCAAS) uses fecal digestibility of total nitrogen/protein as a single correction factor for the overall score [9] [10]. In contrast, the Digestible Indispensable Amino Acid Score (DIAAS) uses ileal digestibility measured at the end of the small intestine for each indispensable amino acid individually [9] [7]. Furthermore, PDCAAS values are truncated at 1.0, while DIAAS values are not capped, allowing for differentiation between high-quality proteins [1] [11].

FAQ 2: Why is the choice of reference pattern critical, and which one should I use?

The reference pattern, derived from human amino acid requirements, is the benchmark for calculating the score [7]. Using an incorrect pattern will invalidate your results. The FAO/WHO recommends different reference patterns for specific age groups [9] [1]. For a standard PDCAAS analysis, the pattern for preschool-aged children (2-5 years) is often used, as it is considered the most demanding [1]. However, the FAO 2013 report provides distinct patterns for three groups: infants (0-6 months), young children (6 months-3 years), and older children/adults (>3 years) [7]. Your research objective and target population should dictate the pattern used.

FAQ 3: What are the major limitations of the PDCAAS method I must account for in my research?

Researchers should be aware of several key limitations:

- Fecal vs. Ileal Digestibility: Fecal digestibility can overestimate protein value because it does not account for nitrogen losses to colonic bacteria, which is lost for protein synthesis [10] [7].

- Truncation of Scores: Rounding scores down to 1.0 obscures the true value of proteins with excess amino acids and prevents meaningful comparison between high-quality proteins [1] [11].

- Antinutritional Factors (ANFs): The presence of ANFs in plant-based proteins (e.g., trypsin inhibitors, tannins) can impair digestibility. The rat-based fecal digestibility method may not fully capture this effect, as gut bacteria can break down these compounds, leading to an overestimation of digestibility [1].

- Aging and ANFs: Older rat models show lower PDCAAS values for protein sources containing ANFs compared to young rats, suggesting age impacts results [1].

FAQ 4: How does the nitrogen-to-protein conversion factor impact my amino acid score results?

The conversion factor (typically 6.25) used to calculate crude protein from measured nitrogen content has a marked impact on the chemical score [7]. The universal factor of 6.25 overestimates the true protein content of most sources because food proteins contain different amounts of non-protein nitrogen. This overestimation of the protein denominator penalizes (lowers) the final amino acid score. Using a specific conversion factor for your protein source (e.g., 5.7 for wheat, 6.38 for milk) is more accurate [7].

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Issues

Problem: High variability in amino acid profiling results.

- Potential Cause: Inconsistencies in sample preparation, particularly during the acid hydrolysis step, which can destroy certain amino acids (e.g., tryptophan) or cause variable losses [7].

- Solution:

- Standardize Hydrolysis: Strictly control hydrolysis time, temperature, and acid concentration.

- Use Internal Standards: Employ amino acid standards that are added to the sample before hydrolysis to correct for analytical losses and improve inter-laboratory reproducibility [7].

- Validate Methodology: Use established methods like High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC) and ensure proper calibration [6].

Problem: Observed protein digestibility is lower than literature values.

- Potential Cause: The presence of antinutritional factors (ANFs) or the impact of food processing and matrix effects (e.g., Maillard reaction products) that are not fully accounted for in the standard rat fecal digestibility assay [1] [7].

- Solution:

- Measure ANFs: Quantify relevant ANFs (e.g., trypsin inhibitors, phytates) in your test material.

- Consider Processing Effects: Document all processing steps (heating, extrusion) applied to the protein source, as these can alter protein structure and digestibility [12].

- Explore Advanced Models: For greater accuracy, consider using an ileal-digestibility model (e.g., in pigs or humans) instead of the rat fecal model, especially for novel or highly processed proteins [1] [7].

Problem: Uncertainty in selecting the correct reference pattern for DIAAS.

- Potential Cause: The FAO 2013 guidelines provide multiple reference patterns, and selecting an inappropriate one for the target demographic compromises the relevance of the DIAAS [9] [7].

- Solution: Align the reference pattern with the intended study population.

- For infant formula research, use the infant (0-6 mo) pattern.

- For general population foods, use the >3 years pattern.

- Justify your choice in the methodology based on the research context [7].

Experimental Protocols & Data Presentation

Reference Patterns for Amino Acid Scoring

The following table compares the essential amino acid requirements (mg/g crude protein) in different FAO reference patterns. The choice of pattern significantly impacts the calculated score [1] [7].

Table 1: FAO Reference Patterns for Amino Acid Scoring

| Amino Acid | Preschool Child (FAO 1991) [1] | Child & Adult (FAO 2013) [7] |

|---|---|---|

| Histidine | 18 | 20 |

| Isoleucine | 25 | 30 |

| Leucine | 55 | 61 |

| Lysine | 51 | 48 |

| Methionine + Cysteine | 25 | 23 |

| Phenylalanine + Tyrosine | 47 | 41 |

| Threonine | 27 | 25 |

| Tryptophan | 7 | 6.6 |

| Valine | 32 | 40 |

Standardized PDCAAS Calculation Protocol

Objective: To determine the Protein Digestibility-Corrected Amino Acid Score for a test protein.

Workflow Overview:

Step-by-Step Methodology:

Amino Acid Profiling:

- Method: Use High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC) or Ion-Exchange Chromatography.

- Procedure: Perform acid hydrolysis on the test protein. Separate, identify, and quantify the individual amino acids. Use internal standards (e.g., norleucine) to correct for hydrolysis losses [6] [7].

- Output: Amino acid profile in mg of each essential amino acid per gram of test protein.

Amino Acid Score (AAS) Calculation:

- Procedure: For each essential amino acid

i, calculate the ratio:(mg of i per g test protein) / (mg of i per g reference protein). - Identify Limiting Amino Acid: The amino acid with the smallest ratio is the "limiting amino acid."

- Calculate AAS: The AAS is the ratio of the limiting amino acid, expressed as a percentage:

AAS = 100% × (T_l / R_l)[9] [1].

- Procedure: For each essential amino acid

True Fecal Digestibility (TD) Assay:

Final PDCAAS Calculation:

Example PDCAAS Values for Common Proteins

This table provides reference values to benchmark your experimental results against established protein sources.

Table 2: Example PDCAAS Values of Selected Foods [1] [13]

| Food Protein | PDCAAS (Truncated) | Limiting Amino Acid(s) | Key Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Whey Protein | 1.0 | None | Reference standard, highly digestible |

| Casein | 1.0 | None | Slow-digesting milk protein |

| Egg | 1.0 | None | Biological reference protein |

| Soy Protein Isolate | 1.0 | None | Highest quality plant protein |

| Beef | 0.92 | - | High-quality animal protein |

| Chicken | 0.95 | - | High-quality animal protein |

| Pea Protein Concentrate | 0.89 | Methionine/Cysteine | Often blended with other plant proteins |

| Mycoprotein (Quorn) | 0.996 | - | Fungal-based protein |

| Black Beans | 0.75 | Methionine/Cysteine | Legume, deficient in sulfur amino acids |

| Chickpeas | 0.78 | Methionine/Cysteine | Legume, deficient in sulfur amino acids |

| Rice | 0.50 | Lysine | Cereal grain, severely limited in lysine |

| Peanuts | 0.52 | Lysine, Methionine | Limited in multiple amino acids |

| Wheat Gluten | 0.25 | Lysine | Severely limited in lysine |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents and Materials for Protein Quality Assessment

| Item | Function/Explanation |

|---|---|

| Amino Acid Standards | Pure solutions of individual amino acids for calibrating chromatographic equipment and quantifying samples. Essential for accurate profiling [6]. |

| Internal Standards (e.g., Norleucine) | Added to the sample before hydrolysis to correct for variable losses during the preparation and analysis process, improving accuracy [7]. |

| Protein-Free Diet | Used in rodent digestibility assays to determine the Metabolic Fecal Protein (MFP) component, which is subtracted to calculate true digestibility [1]. |

| Reference Proteins (e.g., Casein) | Well-characterized proteins with known amino acid profiles and digestibility. Used as positive controls to validate experimental methods [1]. |

| Chromatography Solvents & Buffers | High-purity mobile phases and buffers (e.g., for HPLC) required for the separation and detection of amino acids. |

| Enzymes for In-vitro Assays | Proteolytic enzymes (e.g., pepsin, pancreatin) used in simulated in-vitro digestibility models as an alternative to animal studies [7]. |

FAQs: Addressing Core Methodological Limitations

Q1: What are the specific limitations of the PDCAAS method related to fecal digestibility assumptions?

The primary limitation of the Protein Digestibility-Corrected Amino Acid Score (PDCAAS) is its reliance on fecal digestibility measurements, typically from rat models [14]. This approach does not accurately represent human ileal digestibility, as it includes microbial protein metabolism in the colon, which can overestimate the true availability of amino acids for bodily functions [14]. Furthermore, the PDCAAS method truncates scores at 1.0 (or 100%), meaning it cannot distinguish between protein sources that meet requirements and those that substantially exceed them, limiting its usefulness for protein quality differentiation [14].

Q2: How does the newer DIAAS method address the shortcomings of PDCAAS?

The Digestible Indispensable Amino Acid Score (DIAAS), recommended by the FAO in 2013, addresses these key shortcomings through two major improvements [14]:

- Ileal Digestibility: It uses true ileal digestibility for each indispensable amino acid, measured at the end of the small intestine. This provides a more accurate reflection of the amino acids actually absorbed by the body, before microbial interference in the colon [14].

- No Score Truncation: DIAAS does not truncate scores at 100%. A score greater than 100 indicates the protein source not only meets but can also compensate for deficiencies in other dietary proteins. This allows for better quality discrimination among high-quality proteins [14].

Q3: What experimental challenges are associated with determining true ileal digestibility in humans?

Determining true ileal digestibility in humans is methodologically complex and expensive. It requires access to subjects with ileostomies or the use of invasive intubation techniques to collect digesta from the end of the small intestine. Consequently, human data is scarce, and researchers often rely on data from growing pigs, which have a gastrointestinal physiology closer to humans, or from rat models, though these are less ideal [14].

Q4: In protein truncation studies, how can researchers ensure that a truncated protein is correctly folded and functional?

When creating truncated protein variants, a major risk is that the deletion causes protein misfolding, aggregation, or loss of function unrelated to the removed region's specific role. To mitigate this:

- Structural Alignment: Prior to truncation, the protein's structure should be compared with structurally related proteins (e.g., using VAST) to identify conserved domains and logical boundaries for deletion that are less likely to disrupt the core fold [15].

- Chimeric Protein Approach: As an alternative, consider generating chimeric proteins where a specific region is swapped with the equivalent region from a structurally similar but functionally distinct protein. This preserves the overall protein architecture while testing the function of a specific segment [15].

- Functional Assays: The truncated protein must be tested in appropriate biological activity assays (e.g., receptor activation, enzyme activity). A loss of activity in a properly expressed protein indicates the removed region was functionally critical [15].

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Evaluating Protein Quality Using the DIAAS Framework

This protocol outlines the key steps for calculating the Digestible Indispensable Amino Acid Score for a protein source.

1. Principle: The DIAAS evaluates protein quality based on the content and ileal digestibility of the first limiting indispensable amino acid in a food protein, compared to a reference amino acid pattern for a specific age group [14].

2. Reagents and Equipment:

- Test protein material

- Amino acid analyzer (HPLC)

- Access to ileal digestibility data (from human, pig, or rat models)

- Reference amino acid requirement patterns (FAO/WHO 2007)

3. Procedure:

- Step 1: Amino Acid Composition Analysis Chemically analyze the test protein to determine its content of all indispensable amino acids (mg per gram of protein) [14].

- Step 2: Obtain Ileal Digestibility Values For each indispensable amino acid, obtain its true ileal digestibility (%). This is ideally derived from human studies, or alternatively from validated pig or rat models [14].

- Step 3: Calculate Digestible Amino Acid Content

For each indispensable amino acid, calculate its digestible content:

Digestible AA content (mg/g protein) = AA content (mg/g protein) × (True ileal digestibility of AA / 100) - Step 4: Calculate DIAAS for Each Amino Acid

For each indispensable amino acid, calculate a score:

DIAAS_AA (%) = [Digestible AA content (mg/g protein) / Reference requirement for same AA (mg/g protein)] × 100 - Step 5: Determine the Final DIAAS

The lowest calculated

DIAAS_AAamong all indispensable amino acids is the overall DIAAS for the test protein. According to FAO, a DIAAS < 75% indicates poor protein quality; 75-99% is "Good"; and ≥100% is "Excellent" [14].

4. Data Analysis: The result is a percentage score that is not truncated, allowing high-quality proteins to be ranked. This score more accurately reflects the protein's capacity to meet and supplement human amino acid needs compared to PDCAAS.

Protocol 2: Designing Chimeric Proteins to Investigate Functional Regions

This protocol describes a method to identify functionally critical protein regions by constructing chimeras, an approach relevant to studying truncation effects while minimizing misfolding.

1. Principle: Functionally critical regions of a protein can be identified by swapping domains between a protein of interest (recipient) and a structurally similar but functionally divergent protein (donor). The chimeric protein's activity is then tested [15].

2. Reagents and Equipment:

- cDNA for recipient and donor proteins

- Mammalian expression system

- Site-directed mutagenesis kit or overlapping PCR reagents

- Structural visualization software (e.g., PyMOL)

- Functional assay reagents specific to the protein

3. Procedure:

- Step 1: Select Donor and Recipient Proteins Identify a donor protein that is structurally similar to your recipient protein (e.g., using VAST search on PDB) but has a divergent biological function [15].

- Step 2: Define Protein Regions for Swapping Analyze the 3D structure (from PDB) of both proteins to identify conserved secondary structures (helices, loops). Divide the sequence into logical structural regions that will be swapped [15].

- Step 3: Design Chimeric Constructs Using DNA editing software, design a chimeric gene where a specific region of the recipient protein's sequence is replaced with the equivalent region from the donor protein. Ensure the swap occurs at structurally conserved boundaries to maintain the overall fold [15].

- Step 4: Generate Chimeric Protein via Overlap PCR Use a nested PCR protocol with overlapping primers to assemble and amplify the full chimeric DNA sequence. Clone the resulting product into an appropriate mammalian expression vector to ensure proper folding and post-translational modifications [15].

- Step 5: Express and Test Chimeric Protein Function Express the chimeric protein in the mammalian system. Test its biological activity in a functional readout assay (e.g., receptor binding, signaling activation). A loss or change of function in the chimera indicates the swapped region is critical for the activity [15].

4. Data Analysis: A successful chimera that is expressed but lacks function pinpoints a critical functional region. This region can then be studied in greater detail using site-directed mutagenesis for higher resolution [15].

Data Presentation

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of PDCAAS and DIAAS Protein Quality Evaluation Methods

| Feature | PDCAAS (Protein Digestibility-Corrected Amino Acid Score) | DIAAS (Digestible Indispensable Amino Acid Score) |

|---|---|---|

| Core Principle | Score based on the first limiting amino acid, corrected for fecal digestibility [14]. | Score based on the digestible content of the first limiting amino acid, using ileal digestibility [14]. |

| Digestibility Measurement | Fecal (Total Tract) Digestibility, typically from rat models. Includes microbial metabolism in the colon [14]. | True Ileal Digestibility for each amino acid, measured at the end of the small intestine. More accurate for human absorption [14]. |

| Score Truncation | Scores are truncated at 1.0 (100%). Cannot differentiate between sources that meet vs. exceed requirements [14]. | No truncation. Scores can exceed 100%, allowing quality discrimination among excellent sources [14]. |

| Reference Pattern | Based on FAO/WHO 1985 amino acid requirement pattern for 2-5 year-old children [14]. | Based on updated FAO/WHO 2007 amino acid requirement patterns, with different patterns for various age groups [14]. |

| Key Limitation | Can overestimate protein quality for humans due to fecal digestibility assumption and truncation [14]. | Methodologically complex and costly to obtain human ileal digestibility data [14]. |

| Quality Classification | Not formally classified beyond the score (truncated at 1.0). | <75%: Poor source75-99%: Good source≥100%: Excellent source [14] |

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for Protein Quality and Function Studies

| Reagent / Material | Function in Research |

|---|---|

| Amino Acid Analyzer (HPLC) | Precisely quantifies the amino acid composition of test protein samples, which is the foundational data for both PDCAAS and DIAAS calculations [14]. |

| Mammalian Expression System | Used for expressing chimeric or truncated proteins to ensure native folding and authentic post-translational modifications, which is critical for functional studies [15]. |

| Structural Visualization Software (e.g., PyMOL) | Allows researchers to visualize and analyze protein 3D structures from PDB files, which is essential for identifying logical domains and boundaries for chimera design or truncation without causing misfolding [15]. |

| Overlapping PCR Reagents | Enable the seamless assembly of DNA fragments from different genes to create chimeric protein constructs for functional region mapping [15]. |

| Validated Animal Models (e.g., Growing Pigs) | Provide a source of ileal digestibility data for amino acids when human data is unavailable, as their gastrointestinal physiology is closer to humans than rodents [14]. |

Methodological Workflow and Pathway Visualization

The diagram below outlines the logical workflow for selecting the appropriate strategy to investigate a protein's functional regions, highlighting the advantages of the chimeric approach over simple truncation.

Protein Functional Analysis Workflow

The diagram below illustrates the key steps and decision points in the experimental protocol for determining a protein's DIAAS, emphasizing the critical shift from fecal to ileal digestibility measurement.

DIAAS Determination Protocol

Impact of Antinutritional Factors on Accuracy

Troubleshooting Guide: Common Experimental Challenges in Protein Quality Assessment

Issue 1: Overestimation of Protein Quality by PDCAAS

Problem: Your calculated Protein Digestibility-Corrected Amino Acid Score (PDCAAS) appears significantly higher than biological assays indicate, particularly with certain protein sources.

- Root Cause: The PDCAAS method is known to overestimate the protein quality of sources containing antinutritional factors (ANFs) or those that have undergone specific processing [16]. This occurs because PDCAAS may not fully account for the negative impact of ANFs on protein digestion and amino acid bioavailability.

- Affected Samples: This discrepancy is pronounced with:

- Mustard flour (containing glucosinolates) [16]

- Raw or under-processed legumes like black beans (containing trypsin inhibitors) [16] [17]

- Alkaline or heat-treated proteins (e.g., lactalbumin, soy protein isolate) which may contain compounds like lysinoalanine [16] [18]

- Heated skim milk containing Maillard reaction products [16] [18]

- Poorly digestible proteins like zein, even when supplemented with limiting amino acids [16]

- Solution: Validate PDCAAS results with a biological assay, such as the Protein Efficiency Ratio (PER) or Net Protein Ratio (NPR) in a rat model, especially when analyzing proteins prone to containing ANFs [16].

Issue 2: Low Protein Digestibility in In Vitro Models

Problem: Your in vitro protein digestibility results are consistently low, not aligning with expected values.

- Root Cause: The presence of ANFs such as trypsin inhibitors, tannins, or phytates is interfering with enzymatic digestion [17] [19].

- Investigation Steps:

- Quantify Key ANFs: Determine the levels of protease inhibitors (e.g., trypsin inhibitors), tannins, and phytic acid in your test protein [17] [20].

- Review Processing History: Under-processing fails to inactivate ANFs, while over-processing (excessive heat) can damage amino acids like lysine and create harmful compounds (e.g., lysinoalanine, D-amino acids), reducing digestibility [21] [17].

- Solution: Optimize processing conditions (e.g., precise heat, fermentation, germination) to inactivate ANFs without damaging the protein [22] [19]. Consider adapting your in vitro protocol to include a pre-treatment step that mimics physiological mechanisms for dealing with certain ANFs.

Issue 3: Age-Related Discrepancies in Protein Digestibility

Problem: Protein digestibility values obtained from young animal models do not accurately predict values for older subjects.

- Root Cause: Animal age significantly influences the impact of ANFs on protein digestibility. Older rats exhibit markedly lower digestibility than young rats when fed proteins containing ANFs [18].

- Supporting Data: The following table summarizes the digestibility differences between young (5-week-old) and old (20-month-old) rats fed various protein sources [18].

| Protein Product | ANFs Present | Digestibility in Young Rats | Digestibility in Old Rats | Digestibility Difference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Casein | Properly processed | High | High | Small (up to 3%) |

| Soy Protein Isolate | Properly processed | High | High | Small (up to 5%) |

| Mustard Flour | Glucosinolates | Lower | Much Lower | 7-17% lower in old rats |

| Alkaline-treated SPI | Lysinoalanine | Lower | Much Lower | 7-17% lower in old rats |

| Raw Soybean Meal | Trypsin Inhibitors | Lower | Much Lower | 7-17% lower in old rats |

| Heated Skim Milk | Maillard Compounds | Lower | Much Lower | 7-17% lower in old rats |

- Solution: For research specifically targeting elderly nutrition, determine protein digestibility using aged animal models (e.g., 20-month-old rats) instead of relying solely on data from young animals [18].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What are the most critical antinutritional factors affecting protein quality assessment?

The most critical ANFs that interfere with protein digestibility and amino acid bioavailability include [21] [17] [23]:

- Protease Inhibitors (e.g., Trypsin inhibitors): Reduce protein digestibility by inhibiting key proteolytic enzymes.

- Tannins: Bind to proteins and digestive enzymes, hindering hydrolysis and increasing endogenous protein losses.

- Lectins: Bind to intestinal mucosa, damaging the gut wall and reducing nutrient absorption.

- Phytic Acid: Complexes with minerals and can also bind to proteins, reducing their bioavailability.

- Processing-induced Factors: Such as lysinoalanine (LAL) and Maillard reaction products, which are poorly digestible and can be toxic.

Q2: How do processing methods affect antinutritional factors?

Processing is essential to mitigate ANFs, but requires precise control [21] [22] [19].

| Processing Method | Effect on ANFs | Key Consideration |

|---|---|---|

| Heat Treatment / Autoclaving | Inactivates heat-labile ANFs (trypsin inhibitors, lectins) | Over-heating can reduce amino acid availability (e.g., lysine) and create harmful compounds like LAL [21] [17]. |

| Fermentation / Germination | Reduces tannins and phytic acid through microbial or endogenous enzyme activity | Effective for a broad range of ANFs and can improve overall nutritional profile [22] [19]. |

| Extrusion | Effective against tannins and kafirin in grains like sorghum | Combination of heat and shear pressure disrupts ANF structures [24]. |

| Soaking & Milling | Reduces water-soluble ANFs and removes seed coats rich in tannins | Simple, low-tech method often used in combination with others [19]. |

The PDCAAS method can be unsuitable because it overestimates protein quality for protein sources containing ANFs or those that are poorly digestible [16]. The method relies on fecal digestibility (often measured in young animals) and does not fully capture the negative effects ANFs have on gut absorption, endogenous protein losses, and metabolic utilization. Biological growth methods (PER, NPR) often reveal a much lower protein quality for such ingredients than the PDCAAS predicts [16] [18].

Q4: Are there any novel analytical approaches for studying ANFs?

Yes, omics approaches (e.g., proteomics, metabolomics) are increasingly being used to efficiently explore and characterize ANFs in novel and complex food matrices, such as insects, algae, and microbial biomass [22]. Furthermore, there is a push for developing improved quantitative methods that can distinguish between different forms of ANFs and better determine their biological activity in food systems [22].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Reagent / Material | Function in Experimentation |

|---|---|

| Trypsin/Chymotrypsin/Protease Enzymes | Used for in vitro protein digestibility assays to simulate gastric and intestinal digestion [20]. |

| Amino Acid Standards | Essential for HPLC analysis to quantify amino acid composition and calculate amino acid scores [20]. |

| ELISA Kits (e.g., Gliadin) | To detect and quantify specific antigenic proteins or ANFs in novel protein ingredients [20]. |

| Hemagglutination Kits | Used to detect and measure the activity of lectins in protein samples [20]. |

| Megazyme Kits (e.g., K-ACHDF) | For precise quantification of dietary fiber components, which can interact with ANFs and affect digestibility [20]. |

| Chemicals for ANF Quantification (e.g., Vanillin for saponins; Folin-Ciocalteu reagent for phenolics; KMnO4 for oxalates) | Essential for colorimetric or titration-based quantification of specific ANFs in sample preparation [20]. |

Experimental Workflow & Pathway Diagrams

Diagram 1: Assessing ANF Impact on Protein Quality

This workflow outlines the key experimental steps for evaluating how antinutritional factors affect protein quality, from sample preparation to data interpretation.

Diagram 2: ANF-Protein Digestibility Interference Pathway

This diagram visualizes the biological mechanisms through which common antinutritional factors impair protein digestion and amino acid absorption.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: Why is the amino acid requirement pattern for preschool children used in PDCAAS instead of the adult pattern?

The FAO/WHO expert consultation in 1989 selected the preschool-age child (1-3 years old) as the reference model for the PDCAAS scoring pattern. This age group is considered the most nutritionally demanding population for amino acid requirements. If a protein meets the needs of this demanding group, it will sufficiently meet the needs of older children and adults. The reference pattern is based on the essential amino acid requirements for preschool children, with values such as 51 mg/g for Lysine and 25 mg/g for sulfur amino acids (Methionine + Cysteine) [1].

Q2: What are the specific quantitative differences between the preschool child and adult reference patterns?

While the search results confirm that "adults aged 18+ will have slightly lower requirements" than the preschool-child pattern used in PDCAAS [1], the specific quantitative values for an adult reference pattern were not provided in the search results. Researchers should consult the most recent FAO/WHO reports or authoritative dietary reference intake publications for detailed adult amino acid requirement figures.

Q3: What is a key limitation of using fecal digestibility in the classic PDCAAS method?

A significant limitation is that fecal digestibility can overestimate the nutritional value of a protein. Amino acids that are not absorbed in the small intestine and move into the colon are lost for body protein synthesis. These amino acids may be utilized by gut bacteria or excreted, meaning they were not truly available to the human body. There is strong evidence that ileal digestibility (measuring absorption at the end of the small intestine) is a more accurate parameter for correction [1] [3]. This is one reason the FAO has proposed a shift to the Digestible Indispensable Amino Acid Score (DIAAS), which uses ileal digestibility [1].

Q4: How do antinutritional factors in plant-based proteins affect PDCAAS results?

Plant proteins often contain antinutritional factors (e.g., phytic acid, trypsin inhibitors) that can interfere with protein digestion and absorption [12] [25]. The PDCAAS method, based on rat fecal digestibility, may overestimate protein quality in such cases. The antinutritional factors can prevent protein absorption in the rat's small intestine, but the protein may still be broken down and fermented by bacteria in the rat's gut, making it appear as if it was digested. This is a particular issue for grain legumes like beans and peas, where the true ileal digestibility of amino acids like methionine can be much lower than the fecal digestibility value suggests [1].

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Issues

Problem: Inconsistent PDCAAS results when analyzing plant proteins with antinutritional factors.

- Potential Cause: The standard rat fecal digestibility assay may not accurately reflect human ileal digestibility for certain protein sources due to the presence of antinutritional factors [1] [25].

- Solution: Consider using an in vitro digestion model that simulates human gastrointestinal conditions. These models can be calibrated to estimate ileal digestibility more directly. Furthermore, pre-treat the protein sample with processing methods known to reduce specific antinutritional factors, such as:

- Heat Processing: Can denature protease inhibitors.

- Fermentation: Can break down phytic acid.

- Sonication: Can disrupt cell walls and enhance enzyme accessibility [25].

Problem: The calculated PDCAAS value exceeds 1.0, leading to truncation and loss of comparative data.

- Potential Cause: Truncation is a defined characteristic of the official PDCAAS method. Scores above 1.0 are rounded down to 1.0 because they are considered to supply essential amino acids in excess of human requirements [1] [3].

- Solution: For research purposes where direct comparison between high-quality proteins is necessary, report the uncapped PDCAAS value (the product of fecal true protein digestibility and the amino acid score). This provides a more discriminative metric. Clearly state in your methodology whether you are using the official (truncated) or uncapped value [1].

Problem: Low protein digestibility values from alternative protein sources like insects or algae.

- Potential Cause: These novel proteins may have complex cellular structures (e.g., chitin in insects, cell walls in algae) that are resistant to digestive enzymes [25].

- Solution: Investigate novel processing techniques to disrupt these structures and improve bioavailability. Promising methods include:

- Enzyme Engineering: Using specialized enzyme blends to target specific protein structures.

- Ultrasonic Processing: To break down cell walls.

- High-Pressure Processing: To modify protein structure without excessive heat [25].

Experimental Protocols & Workflows

Protocol 1: Calculating the PDCAAS

This protocol outlines the steps to determine the Protein Digestibility-Corrected Amino Acid Score for a test protein.

1. Determine the Amino Acid Score (AAS):

- Step 1: Perform amino acid analysis on the test protein to obtain its profile (mg amino acid per gram of protein).

- Step 2: Identify the first limiting indispensable amino acid in the test protein by comparing its concentration to the reference pattern.

- Step 3: Calculate the AAS using the formula:

AAS = (mg of limiting amino acid in 1 g test protein) / (mg of same amino acid in 1 g reference protein)[1].

2. Determine the True Fecal Protein Digestibility (FTPD):

- Step 1: Conduct a digestibility trial using a rat model. The standard formula for FTPD is:

FTPD = [PI - (FP - MFP)] / PI- Where:

PI= Protein IntakeFP= Fecal Protein from the test dietMFP= Metabolic Fecal Protein (protein in feces on a protein-free diet) [1].

3. Calculate the PDCAAS:

PDCAAS = FTPD × AAS × 100%[1].- Truncation: According to the official method, any value exceeding 1.0 (or 100%) is truncated to 1.0 [1] [3].

Protocol 2: In Vitro Protein Digestibility Assay

This method provides a rapid, high-throughput alternative to animal studies for estimating protein digestibility.

1. Simulated Gastric Digestion:

- Prepare a simulated gastric fluid (e.g., containing pepsin) and adjust the pH to 2.0.

- Incubate the protein sample in the gastric fluid for a set time (e.g., 30-60 minutes) at 37°C with constant agitation [25].

2. Simulated Intestinal Digestion:

- Raise the pH to ~7.0 and add simulated intestinal fluid (e.g., containing pancreatin).

- Continue incubation for a further set time (e.g., 2-4 hours) at 37°C [25].

3. Analysis:

- Stop the enzymatic reaction (e.g., by heat inactivation).

- The degree of protein digestion can be quantified by methods such as:

- Determining the release of amino acids (e.g., using o-phthaldialdehyde).

- Measuring the nitrogen content in the supernatant after centrifugation.

- Analyzing the molecular weight profile of digested peptides via SDS-PAGE.

Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details key materials and reagents essential for conducting protein quality assessment experiments.

| Reagent / Material | Function in Experiment |

|---|---|

| Reference Protein (e.g., Casein) | A high-quality standard protein against which test proteins are compared for digestibility and amino acid scoring assays [1]. |

| Amino Acid Reference Standard | A calibrated mixture of known amino acids used to quantify the amino acid composition of test proteins via HPLC or amino acid analyzer. |

| Digestive Enzymes (Pepsin, Pancreatin) | Used in in vitro digestibility assays to simulate the proteolytic activity of the human stomach and small intestine [25]. |

| Simulated Gastric & Intestinal Fluids | Buffered solutions formulated to mimic the pH and ionic composition of human digestive environments for in vitro studies [25]. |

| Nitrogen-Free Diet | Used in animal (rat) digestibility studies to determine the Metabolic Fecal Protein (MFP) correction factor [1]. |

Methodological Visualizations

PDCAAS Calculation Workflow

Digestibility Assessment Methods

Q1: What is a nitrogen-to-protein conversion factor and why is it critical in protein analysis?

The nitrogen-to-protein conversion factor is a multiplier used to estimate protein content from the measurement of total nitrogen in a sample. This method is foundational in food and nutritional science because the direct quantification of protein is complex and labor-intensive. The standard Kjeldahl and Dumas methods for determining total nitrogen are relatively simple, fast, and inexpensive. The resulting nitrogen value is then converted to a protein value using a conversion factor, as proteins are the primary nitrogen-containing compounds in many biological materials. The accuracy of this factor is paramount, as an incorrect factor will lead to a systematic over- or under-estimation of the true protein content, impacting nutritional labeling, product valuation, and scientific research [26] [27].

Q2: Why is the universal factor of 6.25 often inappropriate, and what are the consequences of its misuse?

The factor of 6.25 is based on the assumption that proteins contain an average of 16% nitrogen and that all nitrogen in a sample comes from protein. However, both these assumptions are frequently flawed. Many proteins have nitrogen contents that deviate from 16%, and most biological materials contain significant amounts of Non-Protein Nitrogen (NPN). NPN includes nitrogen from compounds like chlorophyll, nucleic acids (DNA/RNA), amino sugars, and chitin [26] [27]. Using 6.25 for materials with high NPN leads to an overestimation of "crude protein." For example, in insects and microalgae, which can have substantial NPN, the use of 6.25 overestimates protein content by approximately 17% on average. This has direct implications for the economic valuation of alternative protein sources and the accuracy of nutritional studies [26] [27].

Troubleshooting Common Analytical Challenges

Q3: My protein values seem inflated compared to functional properties. What could be the issue?

This is a classic symptom of using an inappropriate nitrogen-to-protein conversion factor. The reported protein value, calculated with a factor that doesn't account for your specific sample's composition, is likely overestimated due to NPN. The calculated "protein" includes non-protein compounds that do not contribute to functional properties like gelling or foaming. To resolve this, you should determine and use a specific conversion factor (kp) for your sample type. Furthermore, for protein isolates, the factor kA is more appropriate as it relates specifically to protein nitrogen [27].

Q4: How do I select the correct conversion factor for a novel biological material, such as microalgae or insect biomass?

Selecting the correct factor requires a systematic approach to account for the specific composition of your material. The following workflow outlines the logical decision process for factor selection, from the simplest to the most accurate method.

For novel materials, the most accurate method involves determining a specific factor, kp, which is calculated as the ratio of the true protein content (from amino acid analysis) to the total nitrogen content [26] [27]. The general steps are:

- Amino Acid Analysis: Perform complete amino acid profiling via acid hydrolysis and HPLC to determine the sum of anhydrous amino acid residues (∑Ei). This represents the true protein content [26].

- Total Nitrogen Analysis: Measure the total nitrogen content (%N) of the sample using an elemental analyzer or Kjeldahl method [26] [27].

- Calculation: The specific conversion factor is

kp = ∑Ei / %N[27].

Q5: How does non-protein nitrogen (NPN) affect protein quantification, and how can I account for it?

NPN introduces a positive bias in protein estimation when total nitrogen is used. The extent of this bias depends on the sample type. For instance:

- Microalgae: NPN can account for up to 54% of total nitrogen, causing significant overestimation [26].

- Sugar Beet Leaves: Despite the presence of NPN, a strong correlation between total nitrogen and proteinogenic nitrogen was found, suggesting total nitrogen can still be a reliable indicator for this specific material [28].

- Edible Insects: Chitin in the exoskeleton is a major source of NPN, leading to overestimation when using the 6.25 factor [27].

Accounting for NPN requires moving from the kA factor (which assumes NPN=0) to the kp factor, which incorporates NPN into the calculation, providing a more accurate reflection of the actual protein content in a complex biomass [26].

Q6: What are the best practices for sample preparation to ensure accurate nitrogen and protein measurements?

Proper sample preparation is critical for reproducibility.

- Representative Sampling: For heterogeneous materials like plant leaves, collect a minimum number of individual plants (e.g., ≥25 sugar beet plants) and standardize the leaf position (e.g., middle leaves) to reduce variability [28].

- Handling and Storage: Lyophilize (freeze-dry) samples immediately after collection to prevent degradation. Grind the dried material into a fine, homogeneous powder to ensure analytical consistency [27].

- Moisture Determination: Always measure the residual moisture content of the dried powder to report all results on a consistent dry weight basis [27].

Advanced Applications & Future Methods

Q7: How are nitrogen-to-protein conversion factors applied in the valorization of non-traditional protein sources like microalgae and insects?

The drive to valorize alternative proteins has highlighted the importance of accurate conversion factors. Using the standard 6.25 factor misrepresents the economic and nutritional value of these sources. Studies have established specific, lower factors for these materials, leading to more realistic protein content claims.

Table 1: Experimentally Determined Nitrogen-to-Protein Conversion Factors for Various Organisms

| Organism / Material | Specific Conversion Factor (kp) | Traditional Factor (6.25) | Implications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Microalgae (avg.) | 4.78 [26] | 6.25 | Prevents ~24% overestimation of protein, crucial for techno-economic models. |

| Edible Insects (avg.) | 5.33 [27] | 6.25 | Prevents ~17% overestimation, enabling fair market valuation. |

| Mealworm Larvae | 5.41 [27] | 6.25 | Species-specific factor for accurate labeling. |

| House Crickets | 5.25 [27] | 6.25 | Species-specific factor for accurate labeling. |

| Locusts | 5.33 [27] | 6.25 | Species-specific factor for accurate labeling. |

| Sugar Beet Leaves | 4.32 - 4.95 [28] | 6.25 | Varies with plant age; essential for leaf protein valorization. |

Q8: What high-throughput methods are available for protein content screening in breeding or bioprocessing trials?

Near-Infrared Spectroscopy (NIRs) is a powerful high-throughput phenotyping tool. It can be used to develop predictive models for total nitrogen-based protein content in dried and milled samples, such as plant leaves [28]. Furthermore, NIRs can be calibrated to predict more complex traits like protein extractability, which measures the efficiency of releasing protein from a biomass matrix. This allows for the rapid screening of thousands of samples in breeding programs aimed at improving protein yield [28].

Q9: How does the choice of conversion factor integrate with the Protein Digestibility-Corrected Amino Acid Score (PDCAAS) framework?

Accurate protein content is the first critical step in calculating PDCAAS. The PDCAAS method evaluates protein quality by comparing the limiting amino acid in the test protein to a reference requirement pattern, then correcting for fecal digestibility [29] [10] [1]. If the initial protein content is overestimated due to a poor conversion factor, the subsequent amino acid score and the final PDCAAS will be inaccurate. Therefore, using a specific kp factor is a prerequisite for a reliable PDCAAS calculation. It is also important to note that the PDCAAS method has limitations, including the use of fecal digestibility (which can overestimate quality) and the truncation of scores to 100%, and is being supplemented by the newer Digestible Indispensable Amino Acid Score (DIAAS) [29] [30] [10].

Experimental Protocols & Reagents

Detailed Protocol: Determination of a Specific Nitrogen-to-Protein Conversion Factor (kp)

This protocol is adapted from methodologies used for edible insects and microalgae [26] [27].

Principle: The factor kp is calculated from the ratio of the true protein content, measured as the sum of anhydrous amino acids from a complete amino acid analysis, to the total nitrogen content of the sample.

Workflow Overview:

The experimental pathway for determining the specific conversion factor kp involves parallel tracks for nitrogen analysis and true protein quantification, which are then combined for the final calculation.

Steps:

Sample Preparation:

- Lyophilize the biological material (e.g., insect, algal biomass).

- Grind to a fine, homogeneous powder using a laboratory mill.

- Determine residual moisture content by drying a sub-sample at 100°C to constant weight.

Total Nitrogen Analysis (%N):

- Weigh ~1-2 mg of dried powder into a tin capsule (for Dumas combustion analysis) or a larger sample for Kjeldahl digestion.

- Analyze samples in quadruplicate using an elemental analyzer or Kjeldahl apparatus.

- Calculate the average %N content.

True Protein Analysis (Sum of Anhydrous Amino Acids, ∑Ei):

- Multiple Hydrolyses: Perform multiple acid hydrolyses (up to six) per sample to completely quantify all amino acids. This includes:

- Standard 24 h HCl hydrolysis for most amino acids.

- Separate hydrolyses for sulfur-containing amino acids (Met, Cys).

- Different time points (e.g., 12 h, 48 h) for acids degraded (Ser, Thr) or slowly released.

- Separate analysis for Tryptophan [26].

- HPLC Analysis: Derivatize and analyze the hydrolysates via HPLC against an amino acid standard.

- Calculation of ∑Ei: For each amino acid, subtract the mass of one water molecule (18 Da) to account for the residue mass after polymerization into protein. Sum the masses of all anhydrous amino acid residues to obtain ∑Ei [26].

- Multiple Hydrolyses: Perform multiple acid hydrolyses (up to six) per sample to completely quantify all amino acids. This includes:

Calculation:

- Calculate the specific conversion factor:

kp = ∑Ei / %N[27].

- Calculate the specific conversion factor:

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Materials and Reagents for Protein and Nitrogen Analysis

| Item | Function / Application |

|---|---|

| Elemental Analyzer | Instrument for high-precision determination of total nitrogen content via Dumas combustion [27]. |

| Kjeldahl Apparatus | Traditional setup for nitrogen determination through acid digestion and distillation [27]. |

| Amino Acid Standard | Certified reference mixture for calibration and quantification in HPLC analysis [27]. |

| Hydrochloric Acid (HCl), 6M | Primary reagent for protein hydrolysis in amino acid analysis [26]. |

| Bovine Serum Albumin (BSA) | High-purity protein standard used for method validation and recovery experiments [27]. |

| Phenyl Isothiocyanate (PITC) | Derivatization agent for amino acids to make them detectable by UV in HPLC [27]. |

| Near-Infrared Spectrometer (NIRs) | Instrument for high-throughput, non-destructive prediction of protein and other components [28]. |

Next-Generation Methodologies: DIAAS, In Vitro Systems, and Computational Approaches

The Digestible Indispensable Amino Acid Score (DIAAS) is a method for evaluating protein quality, recommended by the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) of the United Nations in 2013 to replace the previous Protein Digestibility-Corrected Amino Acid Score (PDCAAS) [5] [2]. DIAAS is currently considered the most accurate method for routinely assessing the protein quality of single-source proteins, as it provides a more precise measurement of the digestibility of individual amino acids [5].

The fundamental principle of DIAAS is to evaluate the quality of a protein based on the digestible content of each indispensable amino acid (IAA) and how this profile matches human amino acid requirements [31]. The score is calculated using the following equation [31]:

DIAAS (%) = 100 × [(mg of digestible dietary IAA in 1 g of the dietary test protein) / (mg of the same amino acid in 1 g of the reference protein)]

In practice, the digestible content of each IAA is calculated by multiplying the amino acid content of the protein by their respective true ileal digestibility coefficients. A reference ratio is calculated for each IAA, and the lowest value among them becomes the DIAAS (expressed as a percentage) [31]. Unlike PDCAAS, DIAAS values are not truncated at 100%, allowing for distinction between high-quality protein sources [5] [2].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the primary difference between DIAAS and the older PDCAAS method?

The key differences between DIAAS and PDCAAS are summarized in the table below:

| Feature | PDCAAS | DIAAS |

|---|---|---|

| Digestibility Measurement | Fecal crude protein digestibility [5] | True ileal amino acid digestibility [5] |

| Score Truncation | Values truncated at 100% [2] | Values not truncated (except for mixed diets/sole source foods) [5] |

| Lysine Handling | Does not account for lysine availability in processed foods [5] | Uses true ileal digestible reactive lysine for processed foods [5] |

| Basis of Calculation | Single value for protein digestibility [5] | Individual digestibility coefficients for each amino acid [2] |

| Methodological Foundation | Based on rat studies [2] | Preferred use of human data or growing pig model [5] |

Q2: Why is true ileal digestibility preferred over fecal digestibility for amino acid assessment?

True ileal digestibility is preferred because it measures amino acid disappearance at the end of the small intestine (ileum), which more accurately represents absorption for metabolic use [5]. Fecal digestibility overestimates protein quality because it doesn't account for amino acids that are fermented by colonic bacteria or lost due to antinutritional factors [5] [3]. Bacterial metabolism in the colon can alter the apparent digestibility, making ileal measurements more physiologically relevant [2].

Q3: What are the appropriate reference patterns for calculating DIAAS?

The FAO 2013 report proposed three reference patterns based on different age groups [7]:

- Infants (0-6 months)

- Children (0.5-3 years)

- Individuals older than 3 years

The choice of reference pattern significantly impacts the calculated score, particularly for plant-based proteins that may have different limiting amino acids across age groups [7].

Q4: What are the main challenges in implementing DIAAS in research settings?

Key implementation challenges include:

- Limited data: Insufficient true ileal amino acid digestibility values for commonly consumed foods, especially processed foods and plant-based proteins [32] [33]

- Methodological complexity: Ileal digestibility studies are more invasive and resource-intensive than fecal digestibility studies [5]

- Analytical requirements: Need for precise amino acid analysis and appropriate nitrogen-to-protein conversion factors [7]

- Species-specific considerations: Growing pigs are validated models, but translation to human physiology requires careful interpretation [5] [32]

Experimental Protocols & Methodologies

Determining True Ileal Amino Acid Digestibility

The following workflow outlines the key steps for determining true ileal amino acid digestibility, a fundamental requirement for calculating DIAAS:

Detailed Protocol Description:

Model System Selection:

- Growing Pig Model: Validated as a predictive model for human ileal digestibility studies [5]. Pigs are surgically fitted with ileal T-cannulas or post-valve T-cannulas to allow for digesta collection.

- Human Studies: Use of dual-isotope tracer method, a non-invasive approach applicable across different physiological states [5]. This method involves administering stable isotope-labeled proteins and measuring appearance in blood.

Test Protein Preparation:

Diet Administration and Digesta Collection:

- Employ standardized feeding protocols with appropriate adaptation periods.

- Collect ileal digesta samples over multiple hours postprandially.

- Immediately freeze collected samples to prevent microbial degradation.

Analytical Procedures:

Calculations:

DIAAS Calculation Methodology

The step-by-step procedure for calculating DIAAS is as follows:

Determine Amino Acid Composition: Obtain the content (mg/g protein) of each indispensable amino acid in the test protein [31].

Apply Digestibility Coefficients: Multiply each IAA content by its true ileal digestibility coefficient to obtain digestible IAA content [31].

Select Reference Pattern: Choose the appropriate FAO 2013 reference pattern based on the target population [7].

Calculate Reference Ratio: For each IAA, calculate the ratio: (mg of digestible IAA in 1g test protein) / (mg of same IAA in 1g reference protein) [31].

Identify Limiting Amino Acid: The lowest reference ratio among all IAAs determines the limiting amino acid [31].

Compute DIAAS: Multiply the lowest reference ratio by 100 to obtain the DIAAS percentage [31].

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Challenges

Challenge 1: High Variability in Ileal Digestibility Measurements

- Potential Cause: Insufficient adaptation period to test diets; inappropriate sampling techniques; microbial degradation of samples.

- Solution: Ensure minimum 5-7 day adaptation period; use protease inhibitors during sample collection; maintain strict temperature control during and after collection.

Challenge 2: Discrepancy Between In Vivo and In Vitro Digestibility Values

- Potential Cause: In vitro methods may not fully replicate complex physiological conditions of the gastrointestinal tract.

- Solution: Use in vitro methods for screening but validate key findings with in vivo studies; develop improved in vitro systems that simulate gastric emptying, enzyme secretion, and transit times [5].

Challenge 3: Inaccurate Lysine Bioavailability in Processed Foods

- Potential Cause: Maillard reaction products not detected by conventional amino acid analysis.

- Solution: Implement specific assays for reactive (bioavailable) lysine rather than total lysine [5]; use furosine or other marker compounds to estimate lysine damage.

Challenge 4: Disagreement Between Pig and Human Digestibility Values

- Potential Cause: Physiological differences between species; variations in experimental protocols.

- Solution: Standardize protocols across laboratories; use the dual-isotope method in humans for validation when possible [5]; recognize that the growing pig model has been validated for predicting human ileal digestibility [5].

Essential Research Reagents and Materials

The following table outlines key reagents and materials required for DIAAS determination:

| Category | Specific Items | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Model Systems | Growing pigs (25-50 kg), Human participants for dual-isotope studies | Pigs should be surgically fitted with ileal cannulas; human studies require ethical approval [5] |

| Analytical Standards | Amino acid standards, Stable isotope-labeled amino acids (¹³C, ¹⁵N), Nitrogen standards (EDTA, ammonium sulfate) | Use isotopically labeled amino acids for human studies; certified reference materials for calibration [5] [33] |

| Digestibility Assay Kits | Furosine assay kits, O-phthaldialdehyde (OPA) reagent, Protease enzyme kits | Furosine assay specifically for measuring Maillard reaction damage in processed foods [5] |

| Laboratory Equipment | HPLC systems with fluorescence/UV detection, Amino acid analyzers, Isotope ratio mass spectrometers, Cannulation kits | Ensure appropriate columns for amino acid separation (e.g., C18 reverse phase) [33] |

Advanced Methodological Considerations

Dual-Isotope Method for Human Studies

The dual-isotope method represents a significant advancement for determining ileal amino acid digestibility in humans without invasive procedures [5]. This approach involves:

- Simultaneous administration of two isotopically labeled forms of the same amino acid - one orally and one intravenously.

- Frequent blood sampling to measure the appearance of isotopes in circulation.

- Calculation of digestibility based on the ratio of the two isotopes appearing in the blood.

Future Directions and Research Gaps

Current research priorities for improving DIAAS implementation include [5] [34]:

- Development of rapid, inexpensive in vitro digestibility assays that correlate well with in vivo values

- Better characterization of ideal dietary amino acid balance across different physiological states

- Expanded database of true ileal digestibility values for commonly consumed foods, particularly plant-based proteins

- Investigation of effects of food processing, storage, and preparation on ileal amino acid digestibility

- Exploration of personalized protein quality assessment based on age, health status, and metabolic conditions

Researchers should consider these gaps when designing studies and interpreting DIAAS values, particularly in the context of mixed diets and diverse population groups.

Troubleshooting Guide and FAQs for the INFOGEST Protocol

This technical support center addresses common challenges researchers face when implementing the static INFOGEST in vitro digestion method, with a specific focus on applications in protein digestibility research.

Frequently Asked Questions

FAQ 1: What is the most critical step to ensure consistency in protein hydrolysis across different laboratories? The determination and stabilization of pepsin activity during the gastric phase is widely recognized as a major source of inter-laboratory variability [35]. To ensure consistency:

- Standardize Activity Assays: Use the recommended enzymatic unit definition for pepsin: one unit should produce a ΔA280 of 0.001 per minute at pH 2.0 and 37°C, with hemoglobin as a substrate [36].

- Verify New Batches: Determine the activity of each new enzyme batch upon receipt and after prolonged storage, rather than relying solely on manufacturer specifications [37].

- Stabilize pH: Pay close attention to the pH adjustment to 3.0 at the start of the gastric phase, as pH fluctuations significantly impact pepsin efficacy [38] [35].

FAQ 2: How can I adapt the INFOGEST protocol for subsequent toxicological studies on intestinal cell models? A common challenge is the inherent cytotoxicity of the final digestion product (digesta) on cell lines like Caco-2, often caused by high bile salt concentrations and osmolality [37].

- Problem: The standard intestinal phase uses a 10 mM final bile salt concentration, which can be toxic to cells [37].

- Solution: Research indicates that reducing the final bile salt concentration in the intestinal phase can mitigate cytotoxicity while maintaining the method's validity for specific endpoints. The optimal reduced concentration should be determined empirically for your assay [37].

- Alternative Strategies: Other approaches include inactivating digestive enzymes post-digestion using specific inhibitors (e.g., Pefabloc SC), or physically separating the digested sample from the fluids via centrifugation or filtration [37].

FAQ 3: When should gastric lipase be included in the protocol? The 2019 INFOGEST 2.0 protocol clarifies that gastric lipase is not included by default for several reasons [38]. These include the limited gastric lipolysis due to low pH, and the lack of a widely available, affordable enzyme source with the correct pH and site specificity for humans [38] [36]. The standard protocol focuses on pepsin for proteolysis in the gastric phase.

FAQ 4: How is the oral phase correctly simulated for solid versus liquid foods? The protocol differentiates between solid and liquid foods to reflect physiological relevance [36].

- Solid Foods: Should be subjected to a "chewing" step (e.g., using a mincer) and then mixed with simulated salivary fluid (SSF) containing α-amylase at a 1:1 ratio (v/w) for 2 minutes at 37°C [39] [36].

- Liquid Foods: Can be directly mixed with simulated salivary fluid, bypassing the chewing step, though the addition of α-amylase may still be relevant depending on the research objectives [36].

Connecting INFOGEST to Protein Digestibility and PDCAAS

The INFOGEST protocol provides a standardized in vitro method to study protein digestibility, a core component of the Protein Digestibility Corrected Amino Acid Score (PDCAAS). PDCAAS evaluates protein quality based on both the amino acid requirements of humans and a protein's digestibility [1] [40].

Summary of PDCAAS Values for Common Proteins The table below lists the PDCAAS for various foods, demonstrating how protein quality varies. A score of 1.0 is the highest, indicating excellent amino acid profile and high digestibility [1] [40].

| Food / Protein Source | PDCAAS Score |

|---|---|

| Casein (Milk Protein) | 1.00 |

| Egg | 1.00 |

| Whey Protein | 1.00 |

| Soy Protein | 1.00 |

| Beef | 0.92 |

| Pea Protein Concentrate | 0.82 - 0.89 |

| Chickpeas | 0.78 |

| Cooked Peas | 0.60 |

| Peanuts | 0.52 |

| Wheat | 0.42 |

Limitations of PDCAAS and the Role of INFOGEST:

- Fecal vs. Ileal Digestibility: PDCAAS uses total fecal digestibility, which can overestimate protein absorption at the end of the small intestine (ileal) because it does not account for microbial metabolism in the colon [1]. The INFOGEST protocol models digestion only in the upper GI tract, which can provide data more aligned with ileal digestibility.

- Antinutritional Factors: The presence of antinutritional factors in foods like legumes can lower protein digestibility. The INFOGEST method can be used to study the impact of these factors on protein breakdown under controlled conditions [1].

- Capped Scores: The PDCAAS method truncates scores at 1.0, making it difficult to distinguish between high-quality proteins. In vitro analysis with INFOGEST can provide more granular data on the digestibility kinetics and peptide release profiles of these proteins [1].

Research Reagent Solutions for INFOGEST Digestion

The following table details the key reagents required to execute the standard INFOGEST static digestion protocol [38] [36] [37].

| Reagent / Component | Function in the Protocol |

|---|---|

| Simulated Salivary Fluid (SSF) | Electrolyte solution (KCl, KH₂PO₄, NaHCO₃, etc.) that mimics the ionic composition of saliva [36]. |

| α-Amylase | Digestive enzyme added in the oral phase to initiate starch hydrolysis [39] [36]. |

| Simulated Gastric Fluid (SGF) | Electrolyte solution (KCl, KH₂PO₄, NaHCO₃, NaCl, etc.) that mimics the ionic composition of gastric juice [36]. |

| Pepsin | The primary proteolytic enzyme in the gastric phase, responsible for the breakdown of proteins into peptides [38] [36]. |

| Simulated Intestinal Fluid (SIF) | Electrolyte solution (KCl, KH₂PO₄, NaHCO₃, NaCl, etc.) that mimics the ionic composition of intestinal fluid [36]. |

| Pancreatin | A mixture of pancreatic enzymes (including proteases, lipases, and amylases) that drives digestion in the intestinal phase [39]. |

| Bile Salts | Added in the intestinal phase to emulsify lipids and facilitate the formation of mixed micelles for absorption [38] [37]. |

| Calcium Chloride (CaCl₂) | Added in precise concentrations in each phase to simulate physiological calcium levels, which is critical for enzyme activity [36] [37]. |

Standardized INFOGEST Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the sequential three-phase workflow of the INFOGEST static digestion method, summarizing the key parameters for each stage.

Framing the Research Problem The evaluation of protein quality is pivotal in human nutrition, with the Protein Digestibility-Corrected Amino Acid Score (PDCAAS) established as the preferred method by FAO/WHO. This method measures protein value by comparing the concentration of the first limiting essential amino acid in a test protein to a reference pattern based on the requirements of preschool-age children, subsequently corrected for true fecal digestibility [3]. However, despite its widespread adoption, the PDCAAS method faces significant critiques, including questions about the validity of the amino acid requirement values for preschool-age children, the use of fecal rather than ileal digestibility for correction, and the practice of truncating scores to 100% [3] [10]. These limitations create a compelling research landscape for applying computational optimization techniques to develop more accurate and context-specific models for amino acid balancing and protein quality evaluation.

Linear Programming (LP) represents a powerful mathematical tool to address these challenges. In nutritional science, LP is used to determine the optimal allocation of limited food resources subject to nutritional constraints, thereby identifying dietary patterns that meet specific nutrient requirements at a minimal cost or other defined objectives [41]. Its application is particularly valuable for formulating food-based recommendations (FBRs) and designing complementary foods that fulfill amino acid and micronutrient requirements, especially for vulnerable populations such as stunted children [42]. By integrating the principles of PDCAAS within an optimization framework, researchers can systematically address the limitations of current protein quality evaluation methods and develop superior nutritional solutions.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) & Troubleshooting

Foundational Concepts