Advanced Strategies for Preventing Enzymatic Browning in Fruits and Vegetables: Mechanisms, Applications, and Future Directions for Research and Development

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of enzymatic browning, a major cause of postharvest quality and nutritional loss in fruits and vegetables, responsible for significant economic waste.

Advanced Strategies for Preventing Enzymatic Browning in Fruits and Vegetables: Mechanisms, Applications, and Future Directions for Research and Development

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of enzymatic browning, a major cause of postharvest quality and nutritional loss in fruits and vegetables, responsible for significant economic waste. Tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, we explore the foundational biochemistry of polyphenol oxidases (PPOs) and the critical role of cell membrane integrity from a multi-omics perspective. The scope extends to evaluating traditional and novel intervention methods, including natural extracts, chemical inhibitors, physical treatments, and emerging genome-editing techniques. We further detail optimization strategies for complex food matrices and provide a rigorous comparative analysis of method efficacy, supported by proteomic and transcriptomic validation. The review concludes by synthesizing key takeaways and highlighting the translational potential of these strategies for biomedical research, particularly in the stabilization of plant-based therapeutics and nutraceuticals.

Deconstructing Enzymatic Browning: From PPO Biochemistry to Cellular Compartmentalization

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What are the core structural components and cofactors of PPO? PPO is a type-3 copper-containing enzyme. Its active site contains two copper ions, known as CuA and CuB, each coordinated by three histidine residues [1] [2]. The enzyme is generally synthesized as a zymogen in an inactive state and is located within the plastids of plant cells, such as chloroplasts [2]. Its structure includes three key domains: an N-terminal domain with a plastid transit peptide, a highly conserved central type-III copper center for catalysis, and a C-terminal domain that is involved in maintaining the enzyme's latent state [2].

Q2: What is the fundamental reaction mechanism PPO catalyzes? PPO catalyzes two primary reactions in the enzymatic browning pathway [3] [4]:

- Cresolase activity (Monophenolase, EC 1.14.18.1): The hydroxylation of monophenols to o-diphenols.

- Catecholase activity (Diphenolase, EC 1.10.3.1): The oxidation of o-diphenols to o-quinones. The o-quinones produced are highly reactive and undergo subsequent non-enzymatic polymerization, eventually forming the brown melanin pigments responsible for the browning of fruits and vegetables [1] [5].

Q3: Why does tissue damage in fresh produce trigger rapid browning? In intact plant cells, PPO enzymes are compartmentalized within the plastids, while their phenolic substrates are stored separately in the vacuoles [6] [7]. Physical damage from cutting, bruising, or compression breaks down these cellular compartments, allowing the enzyme, substrate, and oxygen to come into contact, thereby initiating the enzymatic browning reaction [3] [5].

Q4: How does pH affect PPO activity in experimental assays? PPO exhibits optimal activity within a specific pH range, typically between 5.0 and 7.0, though this can vary based on the plant source and substrate [2] [8]. The enzyme's activity follows a parabolic pattern, with catalytic efficiency declining in more acidic or alkaline conditions. Acidifying agents below pH 3.0 can effectively inhibit PPO activity, which is a common strategy for controlling browning [8] [5].

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Issues

Problem 1: Inconsistent PPO Activity Readings in Spectrophotometric Assays

| Potential Cause | Solution |

|---|---|

| Enzyme Latency | The enzyme may be in a latent state. Activate it by incubating with a protease like trypsin or a surfactant such as SDS [2]. |

| Substrate Specificity | The chosen substrate may not be optimal for your plant PPO. Test a range of common diphenols like catechol, 4-methylcatechol, or chlorogenic acid to identify the one with the highest affinity [1] [4]. |

| Improper Extraction pH | The extraction buffer pH may be denaturing the enzyme. Ensure the pH of your extraction and assay buffers is optimized for your specific plant material (typically pH 6-8) [4]. |

Problem 2: High Background Browning in Enzyme Extraction

| Potential Cause | Solution |

|---|---|

| Phenolic Oxidation During Homogenization | Include polyvinylpolypyrrolidone (PVPP) in your extraction buffer to bind and precipitate phenolic compounds [4]. |

| Co-factor Interference | Add a chelating agent like EDTA to your extraction buffer to sequester metal ions that might promote oxidation [4]. |

| Proteolytic Degradation | Incorporate protease inhibitors such as phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride (PMSF) into the extraction buffer to protect the enzyme from degradation [4]. |

Quantitative Data for Experimental Design

Table 1: Kinetic Parameters of PPO from Various Fruit Sources. Data obtained with catechol as a substrate under optimal pH and temperature conditions [1].

| Fruit Source | V~max~ (U mL⁻¹ min⁻¹) | K~m~ (mM) | k~cat~/K~m~ (s⁻¹ mM⁻¹) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Marula Fruit | 122.0 | 4.99 | - |

| Jackfruit | 109.9 | 8.2 | - |

| Apricot (cv. Bulida) | 210 | 5.3 | - |

| Guankou Grape | 2617.60 | 30.22 | 86.46 |

| Blueberry | 187.90 | 6.55 | 182.72 |

Table 2: Efficacy of Common Chemical PPO Inhibitors [9] [8].

| Inhibitor | Primary Mode of Action | Example Concentration | Target Product |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ascorbic Acid | Antioxidant/Reducing Agent | 5 mM | Apple juice [8] |

| Citric Acid | Acidulant & Copper Chelator | - | General use [5] |

| L-Cysteine | Reducing Agent & Quinone Binder | 1% | Fruit salad [8] |

| Oxalic Acid | Competitive Inhibitor & Copper Chelator | 1.1 mM (I₅₀) | Catechol-PPO model [9] |

| 4-Hexylresorcinol | PPO Inactivator | 1.8 μM | Pear, Apple [8] |

Core Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Standard Spectrophotometric Assay for PPO Activity [4]

This method measures the rate of quinone formation, typically monitored by an increase in absorbance.

Workflow Description:

- Homogenization: Grind the plant tissue in a suitable cold buffer (e.g., phosphate buffer, pH 6.5-7.0) containing insoluble PVPP, EDTA, and PMSF to inhibit proteases and prevent oxidation [4].

- Clarification: Centrifuge the homogenate at high speed (e.g., 10,000-15,000 × g) for 15-30 minutes at 4°C. Collect the supernatant, which contains the soluble PPO enzyme [4].

- Reaction Setup: Prepare a reaction mixture containing buffer and an appropriate substrate (e.g., 25-50 mM catechol).

- Kinetic Measurement: Add the enzyme extract to the reaction mixture and immediately measure the increase in absorbance at a wavelength between 410 nm and 550 nm (depending on the substrate and the resulting quinone) for approximately 3 minutes [4]. One unit of PPO activity is often defined as the change in absorbance per minute per gram of tissue or milligram of protein.

Protocol 2: Evaluating Anti-browning Treatments on Fresh-Cut Produce

This practical protocol assesses the effectiveness of potential PPO inhibitors.

Procedure:

- Sample Preparation: Cut the fruit or vegetable (e.g., apple, potato) into uniform slices or discs.

- Treatment: Immerse the samples in the test inhibitor solution (e.g., 0.5% ascorbic acid, 1% citric acid, or a natural extract) for a set time (e.g., 2-5 minutes). Use a water dip as a negative control.

- Drying and Storage: Gently blot the treated samples dry and place them in a controlled environment (e.g., room temperature, high humidity).

- Browning Assessment: Monitor browning at regular intervals (e.g., 0, 1, 2, 4, 6, 24 hours). Assessment can be visual (using a standardized browning index scale) or instrumental by measuring color parameters (L, a, b) with a colorimeter, where a decrease in L (lightness) and an increase in a* (red-green value) indicate browning [4].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents

Table 3: Essential Reagents for PPO Research.

| Reagent | Function in PPO Research | Example Application |

|---|---|---|

| Catechol | Common substrate for catechol oxidase activity | Determining kinetic parameters (K~m~, V~max~) [4]. |

| 4-Methylcatechol | Synthetic substrate with often higher affinity | Assaying PPO activity where natural substrates are less effective [1]. |

| Chlorogenic Acid | Natural phenolic substrate | Mimicking in-vivo browning reactions in apples, artichokes [1] [7]. |

| Polyvinylpolypyrrolidone (PVPP) | Phenolic compound binder | Preventing oxidation and background browning during enzyme extraction [4]. |

| Sodium Dodecyl Sulfate (SDS) | Surfactant / Activator | Activating latent forms of PPO in experimental assays [2]. |

| Diethyldithiocarbamate (DDC) | Copper chelator | Specific inhibition of PPO by removing the essential copper cofactor from the active site [3]. |

Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs

FAQ: Core Concepts

Q1: What is the fundamental biochemical principle behind enzymatic browning that our research aims to prevent? A1: Enzymatic browning is primarily catalyzed by polyphenol oxidase (PPO). In intact cells, PPO is sequestered in the plastids, while its phenolic substrates are located in the vacuole. Cellular compartmentalization prevents their interaction. Damage to membrane integrity, through mechanical stress, senescence, or pathological conditions, disrupts this compartmentalization, allowing PPO to contact phenolics and molecular oxygen, leading to the production of brown melanin pigments.

Q2: Why is assessing membrane integrity critical in our anti-browning research? A2: The loss of membrane integrity is the initiating event for browning. Quantifying this loss allows researchers to:

- Correlate the extent of physical damage with the rate of browning.

- Evaluate the efficacy of postharvest treatments (e.g., calcium dips, heat treatments, edible coatings) in preserving membrane structure.

- Identify the precise stage at which an intervention is most effective.

Q3: Which cellular membranes are most critical to monitor? A3: The tonoplast (vacuolar membrane) and the plasma membrane are the most critical. The tonoplast separates phenolics from PPO, and the plasma membrane regulates the influx of extracellular oxygen, a key substrate for the browning reaction.

Troubleshooting Guide: Experimental Pitfalls

Q4: Issue: Inconsistent browning measurements across sample replicates.

- Potential Cause 1: Non-uniform tissue damage during sample preparation.

- Solution: Use a sharp, consistent coring tool or biopsy punch. Standardize the cutting speed and pressure.

- Potential Cause 2: Variations in sample incubation conditions (temperature, humidity, atmospheric composition).

- Solution: Use a calibrated incubator or water bath. For ambient conditions, use a data logger to monitor and report temperature and humidity. Consider using sealed containers with controlled atmosphere.

Q5: Issue: High background signal in membrane integrity assays (e.g., Electrolyte Leakage).

- Potential Cause: Contamination from ions released during the initial cutting of the tissue.

- Solution: Perform a quick rinse of the samples with deionized water after cutting and before the initial incubation. Ensure the rinse is consistent and brief across all samples.

Q6: Issue: No detectable browning despite confirmed membrane leakage.

- Potential Cause 1: Depletion of endogenous phenolic substrates or PPO co-factors (e.g., copper).

- Solution: Include a positive control by homogenizing a sample to forcibly mix all compartments. If browning occurs in the homogenate but not the intact tissue, the assay is valid, and the result suggests other regulatory factors are at play.

- Potential Cause 2: The experimental buffer may have an incorrect pH. PPO has a pH optimum typically between 5.0 and 7.0.

- Solution: Verify and adjust the pH of your incubation medium.

Table 1: Efficacy of Membrane-Stabilizing Treatments on Browning and Leakage in Apple Discs

| Treatment | Concentration | Incubation Time (hr) | Browning Index (a.u.)* | Electrolyte Leakage (%)* | Relative PPO Activity (%)* |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control (H₂O) | - | 4 | 85.5 ± 4.2 | 78.3 ± 5.1 | 100.0 ± 3.5 |

| Calcium Chloride | 2% (w/v) | 4 | 25.1 ± 3.1 | 35.2 ± 3.8 | 28.5 ± 2.9 |

| Ascorbic Acid | 1% (w/v) | 4 | 15.8 ± 2.5 | 72.1 ± 4.5 | 10.2 ± 1.8 |

| Heat Shock | 45°C, 10 min | 4 | 32.4 ± 3.8 | 41.5 ± 4.1 | 45.1 ± 3.2 |

| Chitosan Coating | 1.5% (w/v) | 4 | 48.9 ± 4.0 | 58.9 ± 4.7 | 65.3 ± 4.1 |

*Data presented as mean ± standard deviation (n=6). a.u. = arbitrary units.

Table 2: Correlation Between Membrane Leakage Metrics and Visual Browning

| Membrane Assay | Correlation with Browning Index (R²) | Typical Measurement Timepoint |

|---|---|---|

| Electrolyte Leakage | 0.89 - 0.95 | 30-60 minutes post-injury |

| Malondialdehyde (MDA) Content | 0.82 - 0.90 | 2-4 hours post-injury |

| Lipid Hydroperoxides | 0.78 - 0.87 | 2-4 hours post-injury |

| Evans Blue Uptake | 0.85 - 0.92 | 1-2 hours post-injury |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Standardized Electrolyte Leakage Assay for Membrane Integrity

Principle: Measures the efflux of ions from damaged tissues, directly proportional to loss of plasma membrane integrity.

Materials:

- Fruit/vegetable tissue discs (e.g., 10mm diameter, 2mm thick)

- Deionized water

- Conductivity meter

- Vacuum desiccator or benchtop shaker

- 50ml conical tubes

Procedure:

- Prepare uniform tissue discs and rinse briefly with deionized water.

- Place 10 discs into a 50ml tube containing 30ml of deionized water.

- Place tubes under a light vacuum (25 inHg) for 15 minutes to infiltrate intercellular spaces. Release vacuum slowly.

- Shake tubes gently on an orbital shaker (100 rpm) for 30 minutes.

- Measure initial conductivity (C_initial) of the solution.

- Boil the samples for 20 minutes to release all ions, cool to room temperature.

- Measure final conductivity (C_final).

- Calculate electrolyte leakage as: (Cinitial / Cfinal) * 100%.

Protocol 2: Spectrophotometric Quantification of Enzymatic Browning

Principle: Quantifies the formation of brown pigments (melanins) which absorb light at 420-450 nm.

Materials:

- Tissue samples (identical to those used in leakage assay)

- Liquid Nitrogen

- 0.1 M Sodium Phosphate Buffer (pH 6.5)

- Centrifuge and microcentrifuge tubes

- Spectrophotometer and cuvettes

Procedure:

- After the desired incubation period, flash-freeze tissue samples in liquid nitrogen.

- Homogenize the frozen tissue in 1.0 ml of cold phosphate buffer.

- Centrifuge the homogenate at 12,000 x g for 15 minutes at 4°C.

- Collect the supernatant and dilute 1:5 with phosphate buffer if necessary.

- Measure the absorbance of the supernatant at 420 nm against a buffer blank.

- Report as Browning Index in arbitrary units (a.u.) or normalize to tissue fresh weight.

Visualizations

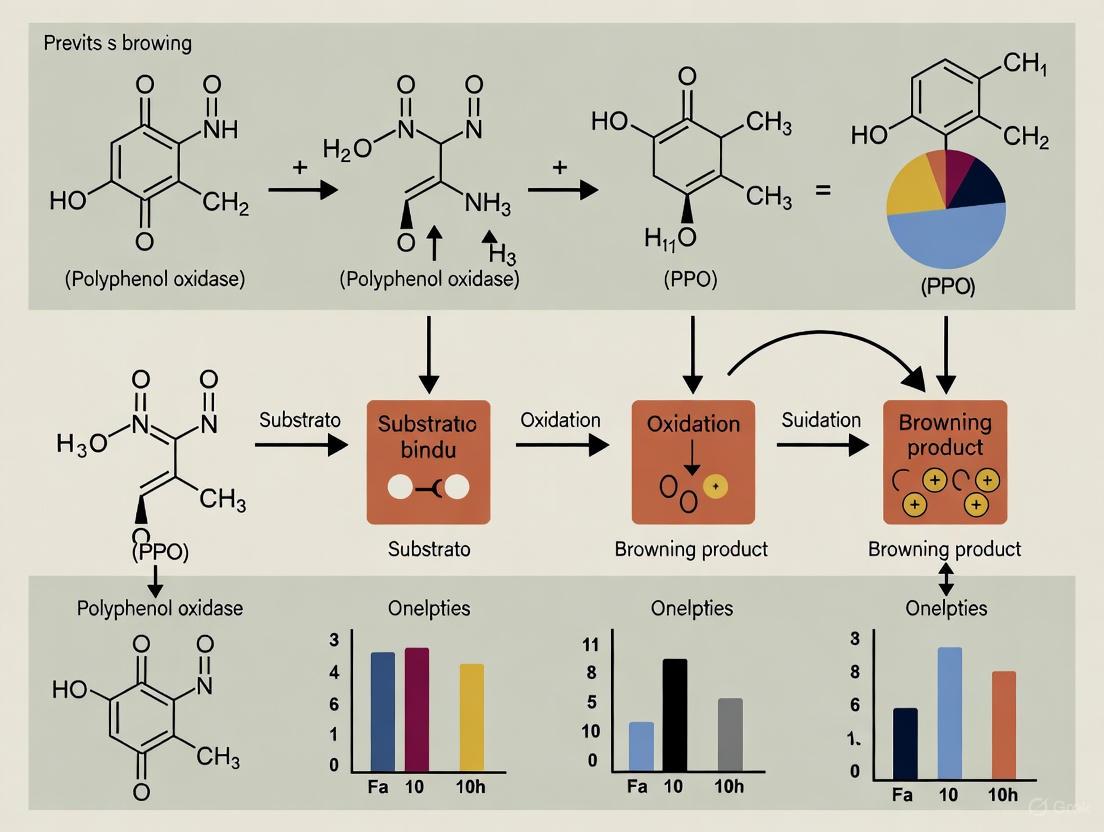

Diagram Title: Enzymatic Browning Pathway Initiation

Diagram Title: Experimental Workflow for Anti-Browning

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Browning Studies

| Reagent / Material | Function / Rationale |

|---|---|

| Calcium Chloride (CaCl₂) | Cross-links pectins in the cell wall and stabilizes membranes by bridging phospholipids, reducing permeability. |

| Ascorbic Acid | A reducing agent that chemically reduces o-quinones back to colorless diphenols before they can polymerize. |

| Cysteine | Thiol-containing compound that forms colorless adducts with o-quinones, competitively inhibiting melanin formation. |

| Chitosan | A biopolymer coating that forms a semi-permeable film, modifying internal atmosphere (O₂/CO₂) and providing a physical barrier. |

| Polyvinylpolypyrrolidone (PVPP) | Insoluble polymer used to bind and precipitate phenolic compounds during PPO enzyme extraction, preventing artifactual browning. |

| Triton X-100 | Non-ionic detergent used to solubilize membrane-bound PPO isoforms for total enzyme activity assays. |

| Thiobarbituric Acid (TBA) | Reacts with malondialdehyde (MDA), a secondary end-product of lipid peroxidation, to quantify membrane oxidative damage. |

| Evans Blue Dye | A non-permeating, water-soluble dye used to visually assess loss of plasma membrane integrity; viable cells exclude it. |

Enzymatic browning is a natural oxidation reaction that occurs in many fruits and vegetables, leading to the formation of brown pigments. This process initiates when fresh produce is bruised, cut, peeled, or exposed to abnormal conditions, causing rapid darkening upon air exposure. The reaction is primarily catalyzed by the enzyme polyphenol oxidase (PPO), which oxidizes phenolic compounds present in plant tissues. While this process is desirable for products like tea, coffee, and cocoa, it causes significant quality deterioration in most fresh fruits and vegetables, affecting their color, flavor, texture, and nutritional value. This browning phenomenon contributes substantially to food waste throughout the supply chain, with estimates suggesting over 50% of susceptible produce is lost due to enzymatic browning [1] [6] [5].

The Biochemical Mechanism: From Phenolics to Melanin

FAQ: What is the core chemical process behind enzymatic browning?

The enzymatic browning cascade involves a sequential biochemical pathway where phenolic compounds are enzymatically converted to brown melanin polymers through several intermediate steps [1] [10] [5]:

- Enzymatic Oxidation: PPO catalyzes the oxidation of phenolic compounds (o-diphenols) to o-quinones

- Polymerization: Quinones undergo subsequent non-enzymatic reactions and polymerization

- Pigment Formation: Brown, high molecular weight melanins are formed

This reaction requires three key components: PPO enzymes, phenolic substrates, and oxygen. In intact plant cells, these components are separated by compartmentalization, but when tissues are damaged, they come into contact, initiating the browning process [10] [5].

The Browning Pathway Visualization

The following diagram illustrates the complete enzymatic browning cascade from phenolic compounds to melanin formation:

Key Enzymes and Substrates

Polyphenol Oxidase (PPO) is a copper-containing enzyme that exists in multiple forms with differing activities. Catechol oxidase (EC 1.10.3.1) specifically catalyzes the oxidation of o-diphenols to o-quinones, while tyrosinase (EC 1.14.18.1) can additionally hydroxylate monophenols to diphenols. Plant PPOs primarily exhibit catechol oxidase activity, though some display both activities at different rates [1] [11].

The substrate specificity of PPO varies significantly across plant sources. Common phenolic substrates include chlorogenic acid, catechin, catechol, caffeic acid, and 4-methylcatechol. The table below summarizes kinetic parameters for PPO from various food sources:

Table 1: Polyphenol Oxidase Enzyme Kinetics from Various Plant Sources

| Source | Substrate | Vmax (U mL⁻¹ min) | Km (mM) | Vmax/Km (U min⁻¹ mM⁻¹) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Apricot fruit | Chlorogenic acid | 1400 | 2.7 | 500 |

| 4-methylcatechol | 700 | 2.0 | 340 | |

| Marula fruit | 4-methylcatechol | 69.5 | 1.45 | 47.9 |

| Catechol | 122.0 | 4.99 | 24.2 | |

| Guankou grape | Caffeic acid | 1035.63 | 0.31 | 3505.88 |

| Catechinic acid | 3557.76 | 4.89 | 727.39 | |

| Kirmizi Kismis grape | 4-methylcatechol | 2000 | 4.8 | 416.66 |

| Blueberry | Catechol | 187.90 | 6.55 | 182.72 |

| Chlorogenic acid | 42.21 | 6.30 | 42.67 |

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Challenges

FAQ: Why do my browning inhibition results vary between apple cultivars?

Different apple cultivars contain varying concentrations and compositions of phenolic compounds, which significantly affects browning susceptibility. Research has identified at least 24 different phenolic compounds in apples, with concentrations varying by cultivar, tissue type, and growing conditions. The peel typically contains higher phenolic concentrations than the flesh. Cultivars with higher phenolic content, particularly low molecular weight phenolics like catechin, chlorogenic acid, and caffeic acid, show greater browning susceptibility as these serve as more effective PPO substrates [12].

Table 2: Key Phenolic Compounds in Apples and Their Role in Browning

| Phenolic Compound | Concentration Variation Factors | Role as PPO Substrate |

|---|---|---|

| Chlorogenic acid | Cultivar, rootstock, altitude | Highly effective substrate |

| Catechin | Fruit age, storage conditions | Highly effective substrate |

| Caffeic acid | Cultivar, growing conditions | Effective substrate |

| p-Coumaric acid | Tissue type (peel vs. flesh) | Moderately effective |

| Phloridzin | Developmental stage, cultivar | Less effective |

| Quercetin glycosides | Light exposure, altitude | Variable effectiveness |

FAQ: How can I accurately quantify browning intensity in my experiments?

Researchers employ multiple methods to objectively assess browning intensity:

Colorimetric Measurements: Use spectrophotometers or colorimeters to measure L* (lightness), a* (red-green), and b* (yellow-blue) values. The most sensitive parameter is typically the decrease in L* value, which correlates with darkening.

PPO Activity Assays: Directly measure enzyme activity using spectrophotometric methods with specific substrates like catechol or 4-methylcatechol, monitoring quinone formation at 420 nm.

Polymer Quantification: Measure melanin formation through extraction and spectrophotometric analysis.

Oxygen Consumption: Monitor oxygen depletion during the oxidation reaction using oxygen electrodes.

For consistent results, standardize your measurement protocol across all samples and include appropriate controls to account for non-enzymatic browning [10] [5].

FAQ: Why does my extracted PPO show different substrate specificity than reported in literature?

PPO substrate specificity is influenced by several factors:

- Source Variation: PPO from different plant species exhibits distinct substrate preferences

- Isoenzyme Composition: Multiple PPO isoenzymes with different substrate affinities may be present

- Extraction Method: Extraction conditions can selectively recover certain isoenzymes

- Cellular Localization: Membrane-bound vs. soluble PPO fractions may have different activities

To address this, characterize your specific enzyme preparation against multiple substrates and compare kinetic parameters (Km, Vmax) with literature values for your specific plant source [1] [11].

Research Reagent Solutions for Browning Studies

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Enzymatic Browning Studies

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Mechanism of Action | Effective Concentration Range |

|---|---|---|---|

| Acidulants | Citric acid, Ascorbic acid | Lowers pH below PPO optimum (pH 3-4), reduces quinones | 0.1-2.0% |

| Reducing Agents | L-cysteine, Glutathione, N-acetyl cysteine | Reduces quinones back to diphenols, competitive inhibition | 0.5-25 mM |

| Chelating Agents | EDTA, Kojic acid, Citric acid | Chelates copper cofactor in PPO active site | 0.1-5 mM |

| Natural Extracts | Green tea, Pineapple, Onion extracts | Mixed mechanisms: antioxidant, chelating, enzyme inhibition | Varies by extract |

| Enzyme Inhibitors | 4-Hexylresorcinol, Sulfites | Specific PPO active site interaction | 1.8 μM-5 mM |

| Oxygen Scavengers | Ascorbic acid, Erythorbic acid | Competes for available oxygen, reduces oxidation | 5-50 mM |

Experimental Protocols for Key Methodologies

Protocol: Standardized PPO Activity Assay

Purpose: To quantitatively measure PPO enzyme activity from fruit and vegetable samples.

Materials:

- Extraction buffer (0.1 M phosphate buffer, pH 6.5, containing 1% PVPP)

- Substrate solution (0.1 M catechol in distilled water)

- Spectrophotometer with temperature control

- Centrifuge

Procedure:

- Homogenize 5 g of tissue in 20 mL cold extraction buffer

- Centrifuge at 15,000 × g for 20 minutes at 4°C

- Collect the supernatant as crude enzyme extract

- Prepare reaction mixture: 2.8 mL phosphate buffer (0.1 M, pH 6.5) + 0.1 mL enzyme extract

- Initiate reaction by adding 0.1 mL substrate solution

- Monitor absorbance increase at 420 nm for 3 minutes

- Calculate activity: One unit of PPO activity = ΔA₄₂₀/min × reaction volume / (extinction coefficient × enzyme volume) [1] [12]

Protocol: Evaluating Anti-browning Agents

Purpose: To systematically screen potential browning inhibitors.

Materials:

- Fresh-cut fruit/vegetable slices (standardize size and thickness)

- Treatment solutions (anti-browning agents in distilled water)

- Colorimeter

- Storage containers

Procedure:

- Prepare uniform slices (5-10 mm thickness) using sharp cutter

- Treat by dipping slices in test solutions for 2-5 minutes

- Drain excess solution and place slices on trays

- Store at controlled temperature (typically 4°C for refrigeration studies)

- Measure color at regular intervals (0, 24, 48, 72 hours)

- Analyze PPO activity and phenolic content from parallel samples

- Calculate browning index: BI = [100(x - 0.31)]/0.17 where x = (a + 1.75L)/(5.645L + a* - 3.012b*) [8] [13]

Experimental Workflow for Browning Prevention Studies

The following diagram outlines a systematic research approach for evaluating browning prevention strategies:

Advanced Research Methodologies

Molecular Approaches for Browning Control

Gene Editing Technologies:

- CRISPR/Cas9 systems to silence PPO genes

- RNA interference to reduce PPO expression

- Promoter manipulation to regulate PPO transcription

The Arctic apple represents a successful application of genetic engineering for browning control, where PPO expression was silenced through gene splicing technology. This approach has demonstrated successful reduction of browning without affecting other quality parameters [6] [5] [12].

Transcriptome Analysis: Advanced studies now examine expression patterns of browning-related genes (PPO, PAL, POD) to understand the molecular basis of browning susceptibility. Research shows significantly elevated expression levels of PPO and peroxidase genes in browning-sensitive cultivars compared to resistant varieties [12].

Emerging Natural Inhibitors from Food By-products

Recent research focuses on sustainable natural extracts from food processing by-products with anti-browning properties:

- Rice bran protein hydrolysates: Contain copper-chelating peptides

- Citrus hydrosols: By-products from essential oil production

- Onion and garlic extracts: Rich in sulfur compounds

- Fennel seed extracts: Potent antioxidant activity

These natural inhibitors typically function through multiple mechanisms including antioxidant activity, copper chelation, and enzyme inhibition, making them promising alternatives to synthetic inhibitors [6] [13].

The browning cascade from phenolic oxidation to melanin formation involves complex biochemical pathways that can be controlled through multiple intervention strategies. Successful inhibition requires understanding the specific PPO characteristics, phenolic composition, and environmental factors affecting the target commodity. Future research directions include developing multi-targeted inhibition approaches, utilizing food-grade natural extracts from sustainable sources, and applying advanced gene editing technologies to develop naturally browning-resistant varieties. Standardization of assessment methodologies across studies will enhance comparability and accelerate progress in this critical area of postharvest research.

Core Mechanisms of Enzymatic Browning: A Multi-Omics Perspective

What is the fundamental mechanism of enzymatic browning revealed by multi-omics studies? Multi-omics research has elucidated that enzymatic browning is primarily a consequence of loss of cellular compartmentalization. In intact plant cells, polyphenol oxidase (PPO) enzymes and their phenolic substrates are physically separated by membranes—PPO is often located in plastids, while phenolics are stored in vacuoles. Mechanical damage from fresh-cutting disrupts membrane integrity, allowing these components to mix and initiate browning reactions that produce brown melanin pigments [14] [15] [16]. Transcriptomic and proteomic analyses consistently show that this membrane degradation is actively driven by upregulated lipid metabolism enzymes following injury.

How do reactive oxygen species (ROS) contribute to the browning cascade? ROS function as critical signaling molecules and damaging agents in the browning pathway. Multi-omics studies demonstrate that fresh-cutting triggers a burst of ROS including hydrogen peroxide (H₂O₂) and superoxide anions (O₂⁻), which directly oxidize membrane lipids, further compromising membrane integrity and accelerating cellular disintegration [15] [16]. This creates a destructive feedback cycle: membrane damage facilitates enzyme-substrate mixing for browning, while simultaneously generating more ROS that exacerbate additional membrane damage.

Table 1: Key Molecular Players in Enzymatic Browning Identified Through Multi-Omics Approaches

| Molecular Component | Function in Browning | Multi-Omics Evidence |

|---|---|---|

| Polyphenol Oxidase (PPO) | Oxidizes phenolic compounds to quinones | Genomics: PPO gene families identified (e.g., 10 in banana) [14] |

| Peroxidase (POD) | Oxidizes various substrates using H₂O₂ | Proteomics: Increased abundance during browning [14] |

| Lipoxygenase (LOX) | Initiates membrane lipid peroxidation | Transcriptomics: Gene induction correlates with browning [14] |

| Phenylalanine Ammonia-Lyase (PAL) | Key enzyme in phenolic compound biosynthesis | Multi-omics: Coordinated upregulation in transcriptome and metabolome [17] |

| Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS) | Signaling molecules that induce oxidative stress | Metabolomics: H₂O₂ accumulation precedes browning [15] |

Troubleshooting Common Multi-Omics Experimental Challenges

Why don't my transcriptomics and proteomics data show perfect correlation when studying browning pathways? Discordance between transcriptomic and proteomic data is expected and stems from fundamental biological and technical factors:

- Post-transcriptional Regulation: mRNA levels don't always predict protein abundance due to regulatory mechanisms [18]

- Protein Turnover Rates: Proteins have varying half-lives independent of mRNA stability [18]

- Post-translational Modifications: Protein activity can be modulated without changes in abundance [18]

- Technical Limitations: Proteomics has lower sensitivity than transcriptomics, potentially missing low-abundance proteins [18]

Solution: Implement pathway-level integration rather than expecting gene-by-gene correlation. Combine datasets to identify activated pathways where multiple components show coordinated changes [18] [19].

How can I improve proteomic coverage from small tissue samples typical of browning experiments? Limited sample size is a common challenge in fresh-cut produce research. These strategies can enhance coverage:

- Microproteomics Optimization: Use specialized sample processing for low cell numbers (<1000 cells) [18]

- Pathway Expansion Analysis: Employ computational methods to infer missing proteome components based on enriched pathways [18]

- Multi-omics Integration: Leverage transcriptomic data to prioritize proteins for targeted proteomics detection [18]

- Canonical Pathway Mapping: Identify proteins through known pathway associations when direct detection fails [18]

Experimental Protocols & Methodologies

Transcriptomics Workflow for Browning Time-Series Analysis

Protocol for Time-Course Transcriptome Analysis of Fresh-Cut Browning [20]

Sample Preparation:

- Select uniform fruits/vegetables at commercial maturity

- Process using standardized cutting dimensions (e.g., 1cm thick slices)

- Flash-freeze tissue in liquid N₂ at multiple time points (0, 30, 60 minutes post-cutting)

- Maintain minimum three biological replicates per time point

RNA Extraction & Sequencing:

- Use polysaccharide-rich extraction protocols for plant tissues

- Quality check: RIN >7.0 for all samples

- Library preparation: Strand-specific mRNA-seq

- Sequencing depth: ≥30 million reads per sample, paired-end

Bioinformatic Analysis:

- Alignment to reference genome (where available) or de novo assembly

- Differential expression analysis: DESeq2 or edgeR

- Weighted Gene Co-expression Network Analysis (WGCNA) to identify browning-associated modules

- Pathway enrichment: KEGG and GO term analysis

Simultaneous Metabolite and RNA Extraction from the Same Tissue Sample:

Sample Homogenization:

- Grind frozen tissue under liquid nitrogen

- Split powder for parallel metabolomics and transcriptomics

Metabolite Profiling:

- Extraction: 80% methanol with internal standards

- Analysis: UPLC-QTOF-MS in both positive and negative ionization modes

- Identification: Compare to authentic standards and databases

Integrated Data Analysis:

- Map differentially expressed genes and accumulated metabolites to KEGG pathways

- Identify key regulatory genes upstream of metabolite changes

- Construct metabolite-gene correlation networks

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents for Multi-Omics Browning Studies

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Research Application |

|---|---|---|

| PPO Activity Assays | Catechol, L-tyrosine, 4-methylcatechol | Enzyme kinetics and inhibitor screening [8] |

| Membrane Integrity Indicators | Thiobarbituric acid reactive substances (TBARS), electrolyte leakage measurements | Quantifying membrane lipid peroxidation [14] |

| ROS Detection Kits | DAB staining (H₂O₂), NBT staining (O₂⁻) | Histochemical localization and quantification of ROS [15] |

| Natural Anti-browning Agents | Mangrove extracts, green tea polyphenols, thyme essential oils | Natural PPO inhibition studies [6] |

| RNA-seq Library Preps | Illumina TruSeq Stranded mRNA, SMARTer Ultra Low Input | Transcriptome profiling from minimal tissue [20] |

Pathway Visualization & Data Integration

Enzymatic Browning Pathway Integration

Multi-Omics Experimental Workflow

Advanced Applications & Emerging Technologies

How is genome editing being applied to prevent enzymatic browning based on multi-omics findings? Multi-omics has enabled precision breeding by identifying key genetic targets:

- PPO Gene Knockouts: CRISPR/Cas9 has successfully targeted multiple PPO genes in eggplant (SmelPPO4, SmelPPO5, SmelPPO6), reducing browning by ~70% [6]

- Non-browning Commercial Varieties: Arctic Apples were developed through RNA silencing of PPO genes [6]

- Regulatory Network Engineering: Transcriptomics reveals transcription factors (WRKY, ERF families) that coordinate browning responses as potential targets [20]

What novel anti-browning strategies have multi-omics approaches revealed beyond traditional methods? Integrated omics has uncovered several innovative intervention points:

- Membrane Stabilization: Treatments that maintain membrane integrity (e.g., melatonin, hydrogen gas) delay browning by preventing enzyme-substrate mixing [14] [17]

- ROS Scavenging Enhancement: Upregulating antioxidant enzymes (SOD, APX, CAT) through priming treatments [15]

- Phenylpropanoid Pathway Modulation: Targeted inhibition of key enzymes (PAL, 4CL) to reduce phenolic substrate accumulation [17]

- Hydrogen Gas Treatments: H₂ fumigation alters expression of browning-related genes in Lanzhou lily, reducing browning by ~40% [17]

Enzymatic browning remains a significant challenge in postharvest biology, causing substantial economic losses and quality deterioration in fruits and vegetables. This technical guide focuses on three key initiating factors: mechanical damage, reactive oxygen species (ROS) accumulation, and lipid peroxidation. These factors operate through interconnected biochemical pathways that activate polyphenol oxidase (PPO) and peroxidase (POD), the primary enzymes responsible for browning reactions [21] [16]. Understanding these triggers is essential for developing effective anti-browning strategies that preserve the sensory, nutritional, and marketable qualities of fresh produce [6] [8].

The enzymatic browning process begins when cellular compartmentalization is compromised, allowing previously separated enzymes and substrates to interact. PPO, a copper-containing oxidoreductase, catalyzes the oxidation of phenolic compounds to quinones in the presence of oxygen [21] [5]. These quinones subsequently polymerize into brown melanins, negatively affecting food quality [21] [16]. Recent research has revealed that mechanical injury serves as the primary physical initiator, while ROS accumulation and membrane lipid peroxidation constitute critical biochemical amplifiers that accelerate and intensify the browning process [22] [16].

Troubleshooting Guides: Identifying and Resolving Browning Initiators

FAQ: Mechanical Damage-Induced Browning

Q1: How does minimal processing like cutting or slicing trigger such rapid browning in apple and potato tissues?

A1: Mechanical damage from cutting disrupts cellular compartmentalization, allowing PPO enzymes normally segregated in the cytoplasm to contact phenolic substrates stored in plastids [16]. This disruption initiates a three-stage browning cascade:

- Membrane Integrity Loss: Physical trauma compromises plasma membrane and organelle integrity [16].

- Enzyme-Substrate Mixing: PPO and phenolics mix with oxygen, initiating oxidation [23] [5].

- Melanin Formation: Quinones polymerize into brown melanins [21] [16].

The rate of browning correlates directly with the extent of membrane disruption and the PPO activity level in specific cultivars [21] [23].

Q2: Why do some apple varieties brown almost immediately after cutting while others resist browning?

A2: Browning susceptibility varies due to several intrinsic factors:

- PPO Content and Isoforms: Varieties with higher PPO content and specific PPO isoforms brown more rapidly [21].

- Phenolic Profile: Cultivars rich in ortho-dihydroxyphenolic compounds (substrates with adjacent hydroxyl groups) show accelerated browning [16].

- Membrane Stability: Natural variations in membrane lipid composition affect resilience to mechanical stress [16].

- Genetic Factors: Genetically modified varieties like Arctic apples have silenced PPO expression, dramatically reducing browning [5].

Q3: What are the most effective physical methods to minimize browning from mechanical damage?

A3: The most effective physical approaches include:

- Temperature Manipulation: Blanching (heat treatment) denatures PPO enzymes but is unsuitable for fresh consumption [8] [5]. Cold storage slows enzyme activity but must be optimized to avoid chilling injury [5].

- Oxygen Exclusion: Modified atmosphere packaging (N₂ or CO₂), vacuum packaging, and edible coatings create physical barriers to oxygen [8] [5].

- Barrier Methods: Impermeable films and edible coatings prevent oxygen contact while reducing moisture loss [5].

FAQ: Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS)-Mediated Browning

Q1: What specific ROS types are most implicated in promoting browning reactions?

A1: The primary ROS involved in browning initiation include:

- Superoxide anion (O₂⁻): The initial ROS formed in oxidative stress [16].

- Hydrogen peroxide (H₂O₂): Serves as both a signaling molecule and oxidative agent [16].

- Hydroxyl radicals (OH·): Highly reactive radicals causing severe cellular damage [16].

- Singlet oxygen (¹O₂): Promotes oxidation of phenolic compounds [16].

At low concentrations, ROS function as signaling molecules, but at high concentrations, they induce oxidative stress, membrane damage, and accelerate browning [16].

Q2: How does ROS accumulation lead to increased PPO activity?

A2: ROS promotes browning through multiple interconnected mechanisms:

- Enzyme Activation: Oxidative stress conditions can activate latent PPO forms or enhance their catalytic activity [16].

- Membrane Peroxidation: ROS attacks polyunsaturated fatty acids in membranes, increasing permeability and facilitating enzyme-substrate contact [22] [16].

- Cellular Compartmentalization Loss: ROS-induced membrane damage destroys the physical separation between PPO and phenolic compounds [16].

- Stress Signaling: ROS triggers stress-responsive pathways that may upregulate browning-related enzymes [16].

Q3: What experimental approaches can effectively control ROS-induced browning?

A3: Effective ROS control strategies include:

- Antioxidant Application: Natural extracts rich in antioxidants (e.g., green tea, roselle, thyme) scavenge ROS and reduce oxidative stress [6].

- Enhancing Native Antioxidant Systems: Treatments like γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA) upregulate SOD, APX, and CAT activities, strengthening the plant's inherent ROS-scavenging capacity [22] [16].

- Controlled Atmospheres: Reducing oxygen concentration in storage environments limits ROS generation [8].

Table 1: Key Enzymes in ROS Metabolism and Their Roles in Browning Prevention

| Enzyme | EC Number | Function in ROS Scavenging | Effect on Browning |

|---|---|---|---|

| Superoxide Dismutase (SOD) | EC 1.15.1.1 | Catalyzes dismutation of O₂⁻ to H₂O₂ and O₂ [16] | Reduces superoxide levels, decreases oxidative stress [16] |

| Catalase (CAT) | EC 1.11.1.6 | Converts H₂O₂ to H₂O and O₂ [16] | Detoxifies H₂O₂, protects membrane integrity [16] |

| Ascorbate Peroxidase (APX) | EC 1.11.1.11 | Reduces H₂O₂ to H₂O using ascorbate [16] | Crucial for H₂O₂ removal in cellular compartments [16] |

FAQ: Lipid Peroxidation-Triggered Browning

Q1: What is the relationship between membrane lipid metabolism and enzymatic browning?

A1: Membrane lipid metabolism is fundamentally linked to browning through compartmentalization maintenance. The enzymatic browning reaction requires the mixing of PPO (cytoplasmic) and phenolic compounds (plastid), which are normally separated by intact membranes [16]. Lipid peroxidation disrupts this critical separation. When membranes are compromised through peroxidation, cellular contents mix, initiating the browning cascade [22] [16]. The integrity of the plasma membrane and organelle membranes is therefore a primary determinant of browning susceptibility.

Q2: What are the key indicators of lipid peroxidation in stored fresh-cut produce?

A2: The most reliable indicators include:

- Malondialdehyde (MDA) Content: A primary secondary product of lipid peroxidation; increased MDA correlates strongly with browning intensity [22].

- Electrolyte Leakage: Measures membrane integrity and permeability; higher leakage indicates severe membrane damage [22].

- Lipoxygenase (LOX) Activity: Elevated LOX activity accelerates peroxidation of unsaturated fatty acids [22].

- Fatty Acid Composition Changes: Decreases in polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs) indicate peroxidation [22].

Q3: How do treatments like GABA inhibit lipid peroxidation and subsequent browning?

A3: GABA treatment demonstrates multiple protective mechanisms:

- Membrane Metabolism Regulation: GABA downregulates key enzymes (PLD, lipase) in membrane lipid degradation, preserving membrane structure [22].

- ROS Scavenging Enhancement: GABA boosts activities of SOD, CAT, and APX, reducing the ROS that initiate lipid peroxidation [22].

- Peroxidation Product Reduction: GABA-treated tissues show significantly lower MDA content and reduced electrolyte leakage [22].

- Gene Expression Modulation: GABA downregulates genes involved in membrane degradation and ROS production [22].

Table 2: Analytical Measures of Lipid Peroxidation and Membrane Integrity in Fresh-Cut Stem Lettuce Treated with GABA

| Parameter | Control Group | GABA-Treated Group | Biological Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Browning Degree | High | Significantly Delayed [22] | Visual quality preservation |

| Malondialdehyde (MDA) Content | High | Significantly Decreased [22] | Reduced lipid peroxidation |

| Electrolyte Leakage | High | Significantly Reduced [22] | Improved membrane integrity |

| PPO Activity | High | Suppressed [22] | Direct browning control |

| Microbial Propagation | Higher | Slower [22] | Extended shelf-life |

Experimental Protocols for Browning Factor Analysis

Protocol 1: Assessing Mechanical Damage Severity

Objective: To quantify the relationship between mechanical injury extent and browning development.

Materials:

- Fresh produce (apples, potatoes, or lettuce)

- Sharp knife and cork borer

- Spectrophotometer

- Extraction buffer (phosphate buffer, pH 6.5)

- Catechol or other phenolic substrates

Methodology:

- Sample Preparation: Create varying damage levels (intact, sliced, crushed).

- PPO Extraction: Homogenize samples in cold buffer, centrifuge, and collect supernatant.

- Enzyme Assay: Mix supernatant with catechol, measure absorbance at 420 nm.

- Browning Index: Quantify melanin formation at damage sites using colorimetry.

- Membrane Integrity: Measure electrolyte leakage with a conductivity meter [22].

Expected Outcomes: Higher mechanical damage increases PPO activity, electrolyte leakage, and browning index [23] [16].

Protocol 2: Monitoring ROS Accumulation and Scavenging

Objective: To measure ROS production and antioxidant enzyme responses during storage.

Materials:

- Fresh-cut samples

- Hydrogen peroxide assay kit

- NBT staining solution (for O₂⁻ detection)

- Reagents for SOD, CAT, APX assays

- GABA or other anti-browning treatments [22]

Methodology:

- Treatment Application: Apply GABA (e.g., 5 mM) or other anti-browning agents by immersion [22].

- ROS Detection: Quantify H₂O₂ and O₂⁻ using chemical assays or staining.

- Antioxidant Enzyme Assays:

- SOD: Measures inhibition of photochemical reduction of NBT.

- CAT: Tracks H₂O₂ decomposition at 240 nm.

- APX: Monitors ascorbate oxidation at 290 nm [16].

- Correlation Analysis: Relate ROS levels and enzyme activities to browning development.

Expected Outcomes: Effective treatments (like GABA) reduce ROS accumulation and enhance antioxidant enzyme activities, consequently delaying browning [22] [16].

Protocol 3: Evaluating Lipid Peroxidation and Membrane Stability

Objective: To analyze membrane lipid metabolism under different browning conditions.

Materials:

- Tissue samples from different browning stages

- Thiobarbituric acid (TBA) for MDA quantification

- Conductivity meter

- GC-MS for fatty acid analysis

- RT-PCR reagents for gene expression

Methodology:

- MDA Measurement: React TBA with tissue homogenate, measure absorbance at 532, 600, and 450 nm [22].

- Electrolyte Leakage: Measure conductivity of immersion water after incubation [22].

- Gene Expression: Analyze expression levels of PLD, lipase, SOD, CAT, and APX genes using RT-PCR [22].

- Statistical Analysis: Correlate MDA content and electrolyte leakage with browning scores.

Expected Outcomes: Effective anti-browning treatments maintain lower MDA levels, reduced electrolyte leakage, and downregulate membrane degradation genes [22].

Pathway Visualization: The Interconnected Browning Initiation Network

Diagram 1: Interconnected Browning Initiation Pathways. This diagram illustrates how mechanical damage, ROS accumulation, and lipid peroxidation interact to trigger the enzymatic browning cascade, ultimately leading to melanin formation.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Research Reagents for Studying Browning Initiating Factors

| Reagent / Material | Function / Application | Specific Examples & Notes |

|---|---|---|

| γ-Aminobutyric Acid (GABA) | A natural signaling molecule used to study the regulation of ROS and membrane lipid metabolism. Applied via immersion to fresh-cut produce [22]. | Effectively reduces browning in stem lettuce by enhancing antioxidant enzymes (SOD, CAT, APX) and inhibiting membrane degradation genes [22]. |

| Natural Anti-browning Extracts | Plant-based extracts used as alternatives to synthetic inhibitors. Serve as sources of antioxidants, acidulants, and/or chelating agents [6] [8]. | Include extracts from mangrove, green tea, roselle, thyme, pineapple, and onion. Function by inhibiting PPO activity, scavenging ROS, or chelating copper [6] [5]. |

| Chemical Inhibitors (Reference Standards) | Well-characterized inhibitors used as positive controls to benchmark the efficacy of new treatments [21] [8]. | Ascorbic Acid: Antioxidant/reducing agent [8]. \nCitric Acid: Acidulant & copper chelator [8] [5]. \n4-Hexylresorcinol: Synthetic PPO inhibitor [21] [8]. \nL-Cysteine: Reducing agent & quinone scavenger [21] [8]. |

| Assay Kits | Essential for quantifying key biochemical markers. | MDA Assay Kit: Measures lipid peroxidation extent [22]. \nH₂O₂ / ROS Assay Kits: Quantify oxidative stress levels [16]. \nPPO/POD Activity Kits: Directly measure enzyme activity [21]. |

| Gene Expression Analysis Tools | Used to investigate the molecular mechanisms of anti-browning treatments at the transcriptional level. | RT-PCR / qPCR: To measure expression levels of genes like LsPPO, SOD, CAT, APX, and membrane metabolism genes (PLD, Lipase) [22]. |

Intervention Arsenal: From Natural Extracts to Physical and Genetic Control Methods

FAQs: Mechanisms and Efficacy of Natural Anti-browning Agents

Q1: What are the primary mechanisms by which natural agents inhibit enzymatic browning? Natural anti-browning agents inhibit enzymatic browning through several targeted mechanisms aimed at the polyphenol oxidase (PPO) enzyme and the browning reaction pathway. The primary modes of action include:

- Direct Enzyme Inhibition: Many active constituents, such as flavonoids and phenolic acids, can bind to PPO at various sites. This binding occurs through hydrogen bonds, van der Waals forces, π-sigma/π-π stack interactions, and electrostatic or hydrophobic forces, which deforms the enzyme's active site and renders it inactive [13].

- Chelation of Copper Cofactors: PPO is a copper-containing enzyme. Compounds with chelating properties, such as carboxylic acids and specific peptides, can sequester the copper ions at the enzyme's active site, directly inhibiting its catalytic activity [8] [13] [21].

- Antioxidant/Reducing Activity: Agents like thiol-containing compounds (e.g., glutathione) or antioxidants (e.g., ascorbic acid derivatives) can reduce the initial quinones—the primary products of PPO oxidation—back to their colorless phenolic precursors. This breaks the chain reaction that leads to melanin formation [8] [5].

- Acidification: PPO exhibits optimal activity in a pH range of 5 to 7. Natural acidulants, such as citric acid in lemon juice, lower the pH of the food surface below 3, creating an unfavorable environment that significantly suppresses PPO activity [8] [5] [23].

- Oxygen Scavenging: Some compounds act as oxygen scavengers, reducing the amount of oxygen available for the initial oxidation reaction catalyzed by PPO [8].

Q2: How does the efficacy of natural plant extracts compare to traditional synthetic agents like sulfites? Natural plant extracts are promising alternatives to synthetic agents, but their efficacy is often context-dependent. While synthetic agents like sulfites are powerful, broad-spectrum inhibitors, their use in fresh fruits and vegetables is prohibited in many regions due to potential health risks, such as allergic reactions [6] [8]. Research shows that certain natural extracts can achieve comparable or even superior anti-browning effects to ascorbic acid, a common traditional agent [24]. For instance, a study on fresh-cut Fuji apples found that N-acetylcysteine at a 1% concentration was more effective at maintaining color over 14 days than ascorbic acid [24]. However, a common challenge is that natural extracts may exhibit high variability and sometimes lower overall effectiveness than synthetic counterparts, and they may impart unwanted colors or odors [13].

Q3: What are the key challenges in applying essential oils and honey as anti-browning agents on fresh-cut produce? The application of these natural agents faces several technical hurdles:

- Essential Oils: Their strong aromatic odor can alter the natural aroma and flavor of the treated produce. They also have limited solubility in water, are volatile, and can require emulsification for even application [13].

- Honey and Plant Extracts: These can vary significantly in their active compound composition based on their botanical source, geographical origin, and processing methods, leading to inconsistent anti-browning performance. Furthermore, they may introduce their own color to the product or have a lower potency, requiring higher application concentrations that might affect sensory qualities [13].

Q4: Can agro-food by-products be a sustainable source for anti-browning extracts? Yes, the utilization of agro-food by-products is an emerging and sustainable strategy for obtaining potent anti-browning compounds. Research has identified that by-products such as rice bran, fruit peels, and seeds are rich sources of bioactive components like phenolic compounds and peptides. These components have demonstrated significant antioxidant and copper-chelating activities, which are key mechanisms for inhibiting PPO [8]. For example, hydrolyzed rice-bran-derived albumin has been shown to contain peptides that inhibit tyrosinase by chelating copper [13]. This approach not only helps in controlling browning but also adds value to food waste, contributing to a more sustainable food system [8].

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Issues

Problem: Inconsistent anti-browning results when using a plant extract.

- Potential Cause 1: Natural variation in the bioactive compound content of the plant material.

- Solution: Standardize the extract by quantifying key active constituents (e.g., total phenolic content via Folin-Ciocalteu assay) and use a consistent, documented source for raw materials.

- Potential Cause 2: Degradation of active compounds during extraction or storage.

- Solution: Optimize extraction parameters (e.g., temperature, solvent) and store extracts in dark, cool conditions, possibly under an inert atmosphere.

Problem: The natural agent imparts an undesirable color or odor to the food product.

- Potential Cause: The extract itself is highly pigmented or aromatic.

- Solution: Consider using purified or semi-purified fractions of the extract enriched for the active anti-browning compounds but with less pigment/odor. Alternatively, explore different application methods like encapsulation or edible coatings to control release.

Problem: The anti-browning effect is temporary, and browning occurs after prolonged storage.

- Potential Cause: The agent may be getting depleted (e.g., antioxidants are fully oxidized) or the coating is deteriorating.

- Solution: Use a combination of agents with different mechanisms (e.g., an antioxidant with a chelator). Re-formulate the application medium, for example, by using an edible coating that acts as a barrier to oxygen and a carrier for the active compounds.

Experimental Protocols: Evaluating Anti-browning Agents

Protocol 1: Standard In Vitro PPO Inhibition Assay

This protocol is used to directly quantify the ability of a natural agent to inhibit the PPO enzyme before application on a food product.

- Enzyme Extraction: Homogenize a known weight of the plant material (e.g., potato or mushroom) in an cold extraction buffer (e.g., 0.1 M phosphate buffer, pH 6.5). Centrifuge the homogenate and collect the supernatant as the crude enzyme source [21].

- Reagent Preparation: Prepare a substrate solution (e.g., 0.01 M catechol in the same buffer) and serial dilutions of the natural anti-browning agent (e.g., plant extract, essential oil emulsion, or honey solution).

- Reaction Mixture: In a cuvette, mix:

- Buffer (to a final volume of 3 mL)

- Crude Enzyme Extract (e.g., 0.5 mL)

- Anti-browning Agent (e.g., 0.5 mL of a specific concentration)

- Initiation and Measurement: Start the reaction by adding the substrate solution (e.g., 0.5 mL). Immediately measure the increase in absorbance at 420 nm every 30 seconds for 3 minutes.

- Controls: Run a control without the inhibitor (replace with buffer) and a blank without the enzyme.

- Calculation: Calculate the percentage inhibition of PPO activity using the formula:

- Inhibition (%) = [(ΔAcontrol - ΔAsample) / ΔA_control] × 100 where ΔA is the change in absorbance per minute.

Protocol 2: Anti-browning Efficacy on Fresh-Cut Produce

This protocol assesses the performance of a natural agent on a real food system.

- Sample Preparation: Peel and cut the target fruit or vegetable (e.g., apple, potato) into uniform slices or cubes.

- Treatment: Divide samples randomly into groups. Immerse each group in a treatment solution for a fixed time (e.g., 2-3 minutes) with gentle agitation. Treatment groups should include:

- Test Group: Solution of the natural anti-browning agent.

- Positive Control: A known inhibitor (e.g., 0.5% ascorbic acid).

- Negative Control: Distilled water.

- Drain and Store: Drain the treated samples and allow them to dry superficially. Place them in sterile Petri dishes or packaging and store at refrigerated temperature (e.g., 4°C).

- Evaluation: At regular intervals (e.g., 0, 1, 3, 5, 7 days), evaluate the samples for:

- Color: Using a colorimeter (measure L, a, b* values) or subjective scoring.

- Browning Degree: Visually score on a scale (e.g., 1 = no browning to 5 = severe browning).

- PPO Activity: Can be extracted and measured from the treated tissue using Protocol 1.

Quantitative Data on Natural Anti-browning Agents

Table 1: Efficacy of Selected Natural Anti-browning Agents on Various Food Products

| Natural Agent | Active Constituents | Tested Product | Effective Concentration | Key Findings | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N-Acetyl Cysteine (NAC) | Thiol compound | Fresh-cut Fuji apple | 1% (w/v) | Effectively maintained color over 14 days; better than ascorbic acid. | [24] |

| Green Tea Extract | Polyphenols (e.g., EGCG) | Cloudy apple juice | 200 - 400 mg/L | Significantly inhibited browning and reduced PPO activity. | [13] |

| Citrus Hydrosols | Organic acids, volatile compounds | In vitro Tyrosinase assay | Not Specified | Showed tyrosinase inhibition due to acidity and bioactive compounds. | [13] |

| Onion Extract | Sulfur compounds, Flavonoids | Not Specified | Not Specified | Exhibited potent PPO inhibitory activity. | [5] |

| Pineapple Juice | Bromelain (enzyme), Acids | Apples and Bananas | Not Specified | Demonstrated anti-browning effect. | [5] |

| Rice Bran Albumin Hydrolysate | Bioactive Peptides | Potato puree | 0.1 - 0.5% (w/v) | Inhibited enzymatic browning via copper chelation. | [13] |

Table 2: Mechanisms of Action of Different Classes of Natural Anti-browning Agents

| Class of Agent | Example Agents | Primary Mechanism of Action | Additional Effects |

|---|---|---|---|

| Plant Extracts | Green tea, fennel seed, roselle | Direct PPO inhibition, Antioxidant, Chelating | May suppress substrate synthesis, promote membrane integrity. |

| Essential Oils | Clove, Cinnamon, Thyme | Direct PPO inhibition, Chelating, Antimicrobial | Creates a barrier, scavenges oxygen. |

| Honey | Palo Fierro honey | Antioxidant, Acidulant | Chelating agent, reduces o-quinones. |

| Thiol Compounds | N-Acetyl Cysteine, Glutathione | Reducing agent, Competitive PPO inhibition | Scavenges reactive oxygen species. |

Mechanism and Workflow Diagrams

Diagram Title: Mechanisms of Natural Agents in Inhibiting Enzymatic Browning

Diagram Title: Workflow for Evaluating Natural Anti-browning Agents

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Essential Reagents and Materials for Anti-browning Research

| Item | Function/Application in Research |

|---|---|

| Polyphenol Oxidase (PPO) | Crude enzyme extract from potato, mushroom, or apple for in vitro inhibition assays. Serves as the primary target for anti-browning agents. |

| Spectrophotometer | Essential instrument for measuring PPO activity by tracking the formation of quinones (absorbance at ~420 nm) in real-time. |

| Colorimeter | Used to objectively quantify the color changes (L, a, b* values) of treated and control fruit/vegetable samples over storage time. |

| Common Substrates | Catechol, tyrosine, or dopamine. Used in in vitro assays as the phenolic compound that PPO oxidizes to initiate the browning reaction. |

| Buffer Solutions (Phosphate, etc.) | Used to maintain a stable pH during enzyme extraction and in vitro assays, ensuring consistent and reproducible reaction conditions. |

| Synthetic Inhibitors (Ascorbic Acid, etc.) | Used as positive controls (e.g., 0.5% ascorbic acid) to benchmark the performance of novel natural anti-browning agents. |

| Edible Coating Polymers (Chitosan, Alginate) | Used as a matrix or carrier to deliver and control the release of natural anti-browning agents (e.g., essential oils) on the food surface. |

Enzymatic browning, primarily catalyzed by the enzyme polyphenol oxidase (PPO), is a significant cause of quality deterioration in fresh and fresh-cut fruits and vegetables, leading to substantial economic losses and food waste [8] [6]. This oxidative process, which initiates when phenolic compounds are converted to quinones and subsequently polymerize into brown melanins, compromises the color, flavor, nutritional value, and shelf-life of produce [8] [1]. Controlling this reaction is therefore a critical focus in postharvest research and industrial applications. The inhibition of PPO is a key strategy, and chemical inhibitors represent a primary line of defense [8] [25]. These inhibitors can be systematically categorized based on their mechanism of action, principally falling into the groups of acidulants, reducing agents, and chelating agents [8] [25]. This technical resource center elaborates on the mechanisms of these chemical inhibitors, provides detailed experimental protocols for their evaluation, and offers troubleshooting guidance for researchers and scientists in the field.

Core Mechanisms of Chemical Inhibitors

Polyphenol oxidase (PPO) is a copper-containing enzyme that requires specific conditions for optimal activity, including a pH between 5 and 7 and the presence of its copper cofactor [8] [10]. Chemical inhibitors target these requirements and the reaction pathway at distinct points. The following table summarizes the mechanisms, representative examples, and key considerations for each category.

Table 1: Classification and Mechanisms of Common Chemical Anti-Browning Agents

| Inhibitor Category | Mechanism of Action | Representative Compounds | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Acidulants | Lowers the environmental pH below the optimal range for PPO activity (typically below pH 3.0), causing enzyme conformational changes and loss of activity [8] [10]. | Citric acid, Ascorbic acid, Phosphoric acid, Malic acid [8] [10] [5]. | The effect is often pH-dependent and reversible; efficacy can be limited in high-buffering capacity systems [8]. |

| Reducing Agents | Acts as an antioxidant or oxygen scavenger. Reduces colored o-quinones back to colorless o-diphenols, thereby interrupting the polymerization chain leading to melanin [8] [10] [5]. | Ascorbic acid, Erythorbic acid, L-Cysteine, N-Acetyl Cysteine (NAC), Glutathione, 4-Hexylresorcinol [8] [5]. | The protection is often temporary, as the agent is consumed over time in the reaction, allowing browning to proceed once depleted [8]. |

| Chelating Agents | Binds to the essential copper ion at the active site of PPO, rendering the enzyme inactive by removing its catalytic core [8] [5] [26]. | Citric acid, EDTA, Kojic acid, Polyphosphates, Sodium Chlorite [8] [5] [26]. | Efficacy depends on the chelator's affinity for copper and its ability to access the enzyme's active site. Some, like citric acid, exhibit mixed mechanisms (acidulant & chelator) [8]. |

The following diagram illustrates how these different inhibitor types interrupt the enzymatic browning pathway at specific stages.

Figure 1: Inhibition Points in the Enzymatic Browning Pathway. Chemical inhibitors disrupt this pathway at key points: Chelators inactivate the PPO enzyme, Reducing Agents reduce o-quinones back to colorless compounds, and Acidulants create an unfavorable environment for the initial enzymatic reaction.

Quantitative Comparison of Inhibitor Efficacy

The effectiveness of anti-browning agents can vary significantly based on the specific PPO source, substrate, and environmental conditions. The following table consolidates quantitative data from various studies to aid in the selection of appropriate agents and concentrations.

Table 2: Quantitative Efficacy of Selected Anti-Browning Agents

| Compound | Concentration | System / Product | Observed Effect | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ascorbic Acid | 5 mM | Apple juice | Reduced o-quinones to diphenols | [8] |

| Ascorbic Acid | 0.1 % | Fruit-based beverages | Inhibited browning | [10] |

| N-Acetyl Cysteine (NAC) | 0.75 % (≈47 mM) | Fresh-cut pear | Efficiently blocked browning for 28 days at 4°C | [8] |

| 4-Hexylresorcinol | 1.8 μM | Pear & Apple | PPO inactivation; synergistic with ascorbic acid and NAC | [8] |

| Sodium Chlorite | 1.0 mM | Model system (PPO + Chlorogenic Acid) | Significantly inhibited the browning reaction | [26] |

| Sodium Chlorite | 3.0 mM | Model system (PPO) | Inactivated two identified PPO isoforms | [26] |

| Citric Acid | - | General | PPO inhibition below pH 3.0 | [8] [10] |

Experimental Protocols for Evaluating Inhibitors

Standard Protocol for Assessing PPO Activity and Inhibition In Vitro

This methodology provides a foundational assay to quantify PPO activity and screen the efficacy of potential inhibitors in a controlled, cell-free system [27] [1].

Research Reagent Solutions:

- PPO Enzyme Extract: Crude extract from plant tissue (e.g., potato, apple). Homogenize tissue in cold phosphate or acetate buffer (pH 6.5-7.0), centrifuge, and use the supernatant.

- Substrate Solution: A defined phenolic compound dissolved in the same buffer. Common substrates include catechol (0.1 M), pyrocatechol (0.5 M in 0.1 M sodium acetate buffer, pH 6.5), or chlorogenic acid (concentration varies) [27] [1].

- Inhibitor Stock Solutions: Prepare stock solutions of the test inhibitors (acidulants, reducing agents, chelators) in buffer or an appropriate solvent. Filter-sterilize if necessary.

- Sodium Acetate/Phosphate Buffer (0.1 M, pH 6.5): To maintain optimal pH for PPO activity in the control.

Detailed Workflow:

- Experimental Setup: Prepare reaction mixtures in spectrophotometer cuvettes with a final volume of 1-3 mL. A standard setup includes:

- Test: Buffer + Substrate + Inhibitor + Enzyme Extract.

- Control: Buffer + Substrate + Enzyme Extract (no inhibitor).

- Blank: Buffer + Substrate + Inhibitor (no enzyme).

- Reaction Initiation: Start the reaction by adding the enzyme extract. Mix immediately and thoroughly.

- Kinetic Measurement: Immediately place the cuvette in a UV-Vis spectrophotometer pre-heated to the assay temperature (typically 25°C). Monitor the change in absorbance at the appropriate wavelength (e.g., 420 nm for catechol/quinone products) for 1-5 minutes [27].

- Data Analysis: Calculate the enzyme activity from the slope of the linear portion of the reaction curve (change in absorbance per minute). The percentage inhibition is calculated as:

- % Inhibition = [1 - (Activity{test} / Activity{control})] × 100

The workflow for this protocol is systematized in the following diagram.

Figure 2: In Vitro PPO Inhibition Assay Workflow. A standardized protocol for screening and quantifying the efficacy of anti-browning agents.

Protocol for Anti-Browning Treatment on Fresh-Cut Produce

This protocol evaluates the practical efficacy of inhibitors on real food matrices, simulating industrial applications for fresh-cut products [8] [10].

Research Reagent Solutions:

- Produce: Uniform, fresh fruits or vegetables (e.g., apple, potato, pear).

- Treatment Solutions: Aqueous solutions of the test inhibitors. These can be used individually or in combination. Common examples include citric acid (1-2%), ascorbic acid (0.5-2%), and cysteine (0.5-1%) [8].

- Distilled Water: For control treatment.

Detailed Workflow:

- Sample Preparation: Peel (if necessary) and cut the produce into uniform shapes (e.g., slices, cubes). Use a sharp blade to ensure minimal cell damage.

- Treatment Application: Immerse the fresh-cut samples in the treatment solutions for a predetermined time (e.g., 2-5 minutes) with gentle agitation. Immerse a control batch in distilled water.

- Draining and Storage: Drain the samples and allow them to air-dry. Package the samples in sterile containers or trays and store them at refrigerated temperature (e.g., 4°C).

- Evaluation:

- Color Measurement: Use a colorimeter (e.g., Hunter Lab) to measure L* (lightness), a* (red-green), and b* (yellow-blue) values at regular intervals during storage. A decrease in L* value indicates darkening [27].

- Visual Assessment: Use a standardized browning scale to score the samples visually.

- PPO Extraction and Assay: Periodically, homogenize samples from each treatment to extract PPO and measure residual activity using the in vitro protocol above.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Reagents for Enzymatic Browning Research

| Reagent / Material | Function / Role in Research |

|---|---|

| Catechol | A classic, high-activity substrate for PPO used to standardize enzyme activity assays [27] [1]. |

| Chlorogenic Acid | A natural phenolic substrate found in many fruits (e.g., apples, peaches); used for more physiologically relevant studies [1] [26]. |

| L-Cysteine / N-Acetyl Cysteine | Potent reducing agent and nucleophile that reacts with quinones; commonly used in anti-browning research and some commercial applications [8] [5]. |

| Citric Acid | A multi-functional agent serving as both an acidulant and a weak copper chelator; a benchmark for comparison [8] [10]. |

| EDTA (Ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid) | A strong, non-specific chelating agent used to confirm the copper-dependency of PPO activity and as a chelation benchmark [5]. |

| 4-Hexylresorcinol | A synthetic anti-browning agent that acts as a competitive PPO inhibitor and is particularly effective in preventing melanosis in shellfish [8] [5]. |

| Spectrophotometer with Kinetics Capability | Essential equipment for measuring the rate of quinone formation in real-time during in vitro PPO activity assays [27]. |

| Colorimeter | Used to objectively quantify color changes (e.g., L, a, b* values) in treated and untreated fresh-cut produce during storage studies [27]. |

Troubleshooting Guide & FAQs

FAQ 1: Why is the browning inhibition in my fresh-cut apple samples only temporary, even with a high concentration of ascorbic acid?

- Answer: Ascorbic acid is a reducing agent, not a permanent PPO inactivator. It functions by reducing o-quinones back to o-diphenols, thereby breaking the polymerization chain. This reaction consumes ascorbic acid. Once the ascorbic acid in the system is fully oxidized, the browning reaction will proceed unchecked [8]. For longer-term protection, consider using a combination of ascorbic acid with an acidulant (like citric acid) to lower the pH and slow PPO activity, or with a chelator (like EDTA) that permanently inactivates the enzyme.

FAQ 2: My in vitro results show excellent PPO inhibition, but when I apply the inhibitor to a real food system, the effect is minimal. What could be the cause?

- Answer: This is a common challenge due to the complexity of food matrices. Potential causes include:

- Buffering Capacity: The food tissue may have a high buffering capacity, preventing acidulants from effectively lowering the internal pH to inhibitory levels [8].

- Cellular Compartmentalization: The inhibitor may not be penetrating the cells effectively to reach the PPO enzyme, which is often bound to organelles [10] [1].

- Alternative Substrates or Enzymes: Other oxidative enzymes, like peroxidase (POD), or non-PPO mediated oxidation pathways may be contributing to browning in the complex food system [27] [10].

- Interaction with Food Components: The inhibitor might be binding to proteins, starches, or other food constituents, reducing its available concentration.

FAQ 3: How can I determine if an inhibitor is acting as a chelator versus an acidulant?

- Answer: To deconvolute the mechanism, conduct a pH-stat experiment.

- Prepare a PPO solution and adjust its pH to the optimal level (e.g., 6.5).

- Add the inhibitor and monitor PPO activity without letting the pH change (use a pH-stat apparatus or manually add small amounts of acid/base to maintain pH).

- If the inhibitor reduces PPO activity while the pH is held constant, it is likely acting through a mechanism other than acidification, such as chelation (if it is known to bind metals) or direct enzyme inhibition [8]. Conversely, if it only shows efficacy in an un-buffered system where the pH drops, its primary mechanism is acidulation.

FAQ 4: Sodium chlorite shows strong anti-browning effects. What is its proposed mechanism?

- Answer: Research indicates that sodium chlorite has a dual mechanism of action. It not only directly inactivates the PPO enzyme but also promotes the oxidative degradation of its phenolic substrates (e.g., chlorogenic acid), breaking them down into non-reactive compounds like quinic acid and caffeic acid. This two-pronged attack on both the enzyme and the substrate makes it a highly effective inhibitor [26].

Enzymatic browning is a primary cause of quality deterioration in fresh-cut fruits and vegetables (FV). This process is catalyzed by the enzyme polyphenol oxidase (PPO), a copper-containing oxidoreductase. When FV tissues are damaged during processing (e.g., cutting, slicing), PPO becomes exposed to oxygen and phenolic compounds, initiating a reaction that oxidizes phenols to quinones. These quinones subsequently polymerize, forming dark brown pigments known as melanins, which degrade the product's sensory and nutritional quality [8].

Physical intervention strategies aim to prevent this chain reaction by targeting its essential components: the PPO enzyme, available oxygen, or the phenolic substrates. The core mechanisms of the strategies discussed in this technical center are:

- Blanching: Uses thermal energy to denature and inactivate the PPO enzyme.

- Modified Atmosphere Packaging (MAP): Creates a physical barrier that alters the internal gas composition, primarily by reducing oxygen concentration, to suppress the oxidation reaction.

- Non-Thermal Processing: Employs alternative physical means (e.g., high pressure, electric fields) to inactivate microorganisms and enzymes while minimizing damage to heat-sensitive nutrients.

Troubleshooting Guides

Troubleshooting Blanching for Enzymatic Browning Control

Objective: To achieve complete PPO inactivation without excessive softening, loss of color, or nutrient leaching.

| Problem Symptom | Potential Root Cause | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Browning occurs after storage. | Incomplete enzyme inactivation due to insufficient time/temperature. | Increase blanching time in 15-30 second increments; Verify temperature uniformity with a calibrated thermometer. |

| Product is overly soft or mushy. | Excessive thermal degradation due to over-blanching. | Reduce blanching time; Consider high-temperature/short-time (HTST) methods if equipment allows. |

| Leaching of water-soluble vitamins and pigments. | Cell rupture and diffusion into the blanch water. | Use steam blanching instead of water blanching; Reduce blanch water volume; Consider recycling blanch water. |

| Surface pitting or discoloration. | Too rapid heating/cooling causing tissue damage. | Implement slower come-up time or pre-warming; Ensure cooling water is not excessively cold. |

Troubleshooting Modified Atmosphere Packaging (MAP)

Objective: To establish and maintain a gas atmosphere that suppresses enzymatic browning and microbial growth throughout the product's shelf life.

| Problem Symptom | Potential Root Cause | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|