Advanced Strategies for Improving Method Sensitivity in Trace Contaminant Detection

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals seeking to enhance the sensitivity of methods for detecting trace contaminants.

Advanced Strategies for Improving Method Sensitivity in Trace Contaminant Detection

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals seeking to enhance the sensitivity of methods for detecting trace contaminants. It explores the foundational principles of sensitivity, specificity, and accuracy, details cutting-edge methodological advances from automation to novel biosensors, offers practical troubleshooting for common laboratory contamination issues, and establishes a framework for rigorous method validation and comparative analysis to ensure regulatory compliance and data integrity.

Understanding the Pillars of Sensitivity and Accuracy in Trace Analysis

This guide provides troubleshooting and foundational knowledge on the key metrics of sensitivity, specificity, reproducibility, and correctness. These concepts are paramount in trace contaminant detection research, where the accurate identification of minute quantities of material can directly impact diagnostic outcomes, drug safety, and research validity. The following FAQs and guides are designed to help you navigate the challenges of optimizing these metrics in your experimental workflows.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. What is the practical difference between sensitivity and specificity?

- Sensitivity is the ability of your test to correctly identify the presence of a trace contaminant. A highly sensitive test will minimize false negatives, meaning it rarely misses a contaminant that is actually present. This is crucial when failing to detect a contaminant has serious consequences [1] [2] [3].

- Specificity is the ability of your test to correctly confirm the absence of a contaminant. A highly specific test will minimize false positives, meaning it rarely incorrectly flags a clean sample as contaminated. This is important to avoid unnecessary costs, delays, and investigations based on erroneous results [1] [2] [3].

In practice, there is often a trade-off; increasing sensitivity can sometimes reduce specificity, and vice versa [1] [2].

2. My assay has high sensitivity and specificity, but my results are not reproducible. What could be wrong?

High sensitivity and specificity in a single experiment do not guarantee reproducibility, which is the ability to achieve consistent results across repeated experiments. Common culprits for poor reproducibility include:

- Manual Liquid Handling: Variability in pipetting is a major source of error, leading to batch-to-batch inconsistencies [4]. Implementing automated liquid handling can dramatically improve precision [4].

- Uncontrolled Environmental Factors: Inconsistencies in incubation times, temperatures, or humidity (e.g., "edge effects" in plate-based assays) can cause well-to-well variation [4].

- Reagent and Sample Quality: Contamination or degradation of reagents and samples between runs will lead to irreproducible results. Using clean equipment and decontaminating work areas is essential [4].

3. How does the limit of detection relate to sensitivity?

The Limit of Detection (LoD) is a quantitative expression of your method's sensitivity. It is the lowest amount or concentration of a contaminant that your test can reliably detect. A method with a lower LoD has higher sensitivity. For example, deep UV fluorescence detection can achieve a LoD of under 1 nanogram per square cm for organic surface contaminants, indicating exceptionally high sensitivity [5].

4. Why are my test's predictive values different when I use it in a different population?

Unlike sensitivity and specificity, Positive Predictive Value (PPV) and Negative Predictive Value (NPV) are highly dependent on the prevalence of the contaminant or condition in your population [1] [6].

- When testing in a population with a high prevalence of contamination, the PPV increases (positive results are more likely to be correct).

- When testing in a population with a low prevalence, the NPV increases (negative results are more likely to be correct). Therefore, predictive values from one study should not be directly applied to a different setting without considering the local prevalence [6].

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide 1: Improving Sensitivity for Trace Contaminant Detection

Problem: Your method is failing to detect known trace contaminants (low sensitivity, high false-negative rate).

| Step | Action | Rationale & Technical Detail |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Confirm Low Sensitivity | Calculate your method's sensitivity: Sensitivity = True Positives / (True Positives + False Negatives) [1]. A low value confirms the issue. |

| 2 | Optimize Signal Detection | Increase the signal from your target contaminant. For optical methods like fluorescence, this could involve using a brighter dye or a more powerful excitation source like a deep UV laser [5]. In PCR, ensure efficient primer binding and amplification [4]. |

| 3 | Reduce Background Noise | Identify and minimize technical noise. In fMRI for small brainstem structures, this involves advanced physiological noise correction (e.g., aCompCor) to isolate the true signal [7]. For surface contamination, ensure the substrate itself does not auto-fluoresce [5]. |

| 4 | Validate with Calibrated Samples | Use calibrated samples with known, low concentrations of the contaminant (e.g., generated via a ChemCal system) to create a standard curve and verify your improved LoD [5]. |

Guide 2: Improving Specificity to Reduce False Positives

Problem: Your method is generating too many false alarms by incorrectly identifying non-target substances as the target contaminant (low specificity, high false-positive rate).

| Step | Action | Rationale & Technical Detail |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Confirm Low Specificity | Calculate your method's specificity: Specificity = True Negatives / (True Negatives + False Positives) [1]. A low value confirms the issue. |

| 2 | Increase Assay Selectivity | Ensure your detection method is specific for your target. Use higher affinity capture agents (e.g., antibodies in ELISA) or more specific chemical probes. For RNA-seq, improved computational filters and factor analysis can remove confounding signals, reducing empirical False Discovery Rates [8]. |

| 3 | Rigorous Contamination Control | False positives often arise from cross-contamination. Physically separate pre- and post-amplification areas in PCR, use clean equipment, and employ nuclease-free reagents [4]. |

| 4 | Adjust the Detection Threshold | If possible, raise the threshold for a positive call. In a graphical analysis, this is equivalent to moving the cut-off line to require a stronger signal, which can exclude weaker, non-specific signals [2]. |

Guide 3: Establishing Reproducibility in Quantitative Measurements

Problem: Your experimental results vary unacceptably when the assay is repeated (low reproducibility).

| Step | Action | Rationale & Technical Detail |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Automate Liquid Handling | Replace manual pipetting with automated, non-contact dispensers (e.g., I.DOT liquid handler). This eliminates intra- and inter-operator variability, conserves reagents, and ensures precise, equal volumes across all wells [4]. |

| 2 | Standardize Protocols | Strictly control and document all variables: reagent concentrations, incubation times (e.g., for ELISA), temperatures, and cell passage numbers [4]. |

| 3 | Implement Quality Controls | Include positive and negative controls in every experimental run. Use standardized reference samples to monitor performance across different days and operators [8]. |

| 4 | Use High-Fidelity Reagents | Utilize high-quality, low-retention tubes and tips to ensure complete reagent delivery. For cell-based assays, maintain aseptic technique to prevent microbial contamination [4] [3]. |

Quantitative Data and Metrics

The following tables summarize the core formulas for diagnostic accuracy and their interpretation.

Table 1: Core Definitions and Calculations for Diagnostic Metrics [1] [6]

| Metric | Formula | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|

| Sensitivity | True Positives (TP) / [TP + False Negatives (FN)] | Probability the test is positive when the contaminant IS present. |

| Specificity | True Negatives (TN) / [TN + False Positives (FP)] | Probability the test is negative when the contaminant is NOT present. |

| Positive Predictive Value (PPV) | TP / (TP + FP) | Probability the contaminant IS present given a positive test result. |

| Negative Predictive Value (NPV) | TN / (TN + FN) | Probability the contaminant is NOT present given a negative test result. |

| Positive Likelihood Ratio (LR+) | Sensitivity / (1 - Specificity) | How much more likely a positive test is in a contaminated vs. clean sample. Values >10 are significant [6]. |

| Negative Likelihood Ratio (LR-) | (1 - Sensitivity) / Specificity | How much more likely a negative test is in a contaminated vs. clean sample. Values <0.1 are significant [6]. |

Table 2: Worked Example of Metric Calculations from a Validation Study [1]

| Category | Test Result Positive | Test Result Negative | Total | Metric | Calculation | Result |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Actually Contaminated | 369 (TP) | 15 (FN) | 384 | Sensitivity | 369 / 384 | 96.1% |

| Actually Clean | 58 (FP) | 558 (TN) | 616 | Specificity | 558 / 616 | 90.6% |

| Total | 427 | 573 | 1000 | PPV | 369 / 427 | 86.4% |

| NPV | 558 / 573 | 97.4% |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Calibrating a Deep UV Fluorescence Detector for Quantitative Trace Contamination Measurement

Purpose: To generate a calibration curve that converts fluorescence signal intensity into a quantitative measurement of surface contaminant concentration (e.g., oil, grease) with high sensitivity and specificity [5].

Materials:

- Deep UV fluorescence detector (e.g.,

TUCS 1000,TraC) [5]. ChemCalsystem or method for producing calibrated test samples [5].- Surfaces/substrates identical to those used in your manufacturing process.

- Known contaminant(s) for calibration.

Method:

- Preparation of Calibrated Samples: Using the

ChemCalsystem, deposit a series of known, low concentrations of the target contaminant (e.g., from sub-nanogram to 100 ng/cm²) onto the clean substrate surfaces. These will be your calibration standards [5]. - Instrument Setup: Configure the fluorescence detector according to the manufacturer's instructions. Select the appropriate excitation wavelength and emission detection bands for your specific contaminant[s citation:4].

- Data Acquisition: Scan each calibrated sample with the detector, ensuring a consistent working distance and angle. Record the average fluorescence intensity signal for each known concentration [5].

- Curve Fitting: Plot the recorded fluorescence intensity (y-axis) against the known contaminant concentration (x-axis). Use statistical software to fit a curve (e.g., linear, logarithmic) to the data points. The

R²value indicates the goodness of fit. - Validation: Scan independent validation samples with known concentrations to verify the accuracy of your calibration curve.

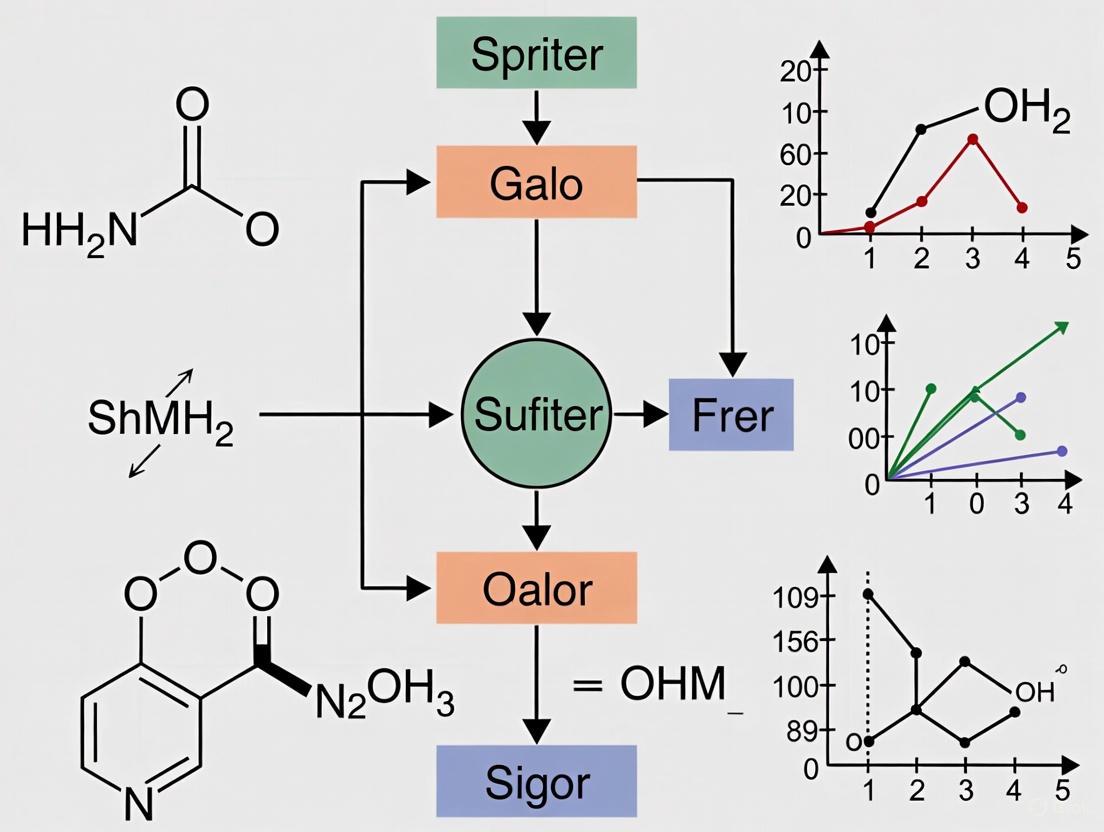

Diagram: Trace Contaminant Detection and Quantification Workflow

Protocol: Optimizing an ELISA for Enhanced Reproducibility

Purpose: To minimize well-to-well and plate-to-plate variation in an ELISA, ensuring reproducible quantitative results.

Materials:

- Automated non-contact liquid handler (e.g.,

I.DOT) [4]. - ELISA kits and reagents.

- Multi-well plates.

- Microplate reader.

Method:

- Automate Reagent Dispensing: Program the liquid handler to dispense all reagents (samples, antibodies, substrates) instead of manual pipetting. The

I.DOTcan dispense 10 nL across a 96-well plate in ~10 seconds, ensuring equal volumes in every well [4]. - Control Environmental Conditions: To prevent "edge effects," perform incubations in a thermally uniform incubator or plate shaker that maintains consistent temperature and humidity across the entire plate [4].

- Standardize Timings: Use a timer to standardize all incubation and reaction development steps precisely.

- Include Controls: On every plate, include a full standard curve, positive controls, and negative controls to allow for inter-plate normalization and quality control.

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Tools for Sensitive and Reproducible Research

| Item | Function/Benefit | Example Use-Case |

|---|---|---|

| Automated Liquid Handler (Non-contact) | Precisely dispenses picoliter to microliter volumes. Eliminates human pipetting error, reduces reagent waste, and enables high-throughput workflows [4]. | ELISA setup, PCR master mix preparation, cell-based assay reagent dispensing. |

| Deep UV Fluorescence Detector | Provides extreme sensitivity for detecting organic contaminants on surfaces, with a limit of detection under 1 ng/cm² and capability for stand-off detection [5]. | In-line verification of component cleanliness before bonding or coating. |

| NGS Automated Clean-Up System | Automates bead-based clean-up steps, which are tedious and prone to manual error during Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS) library prep [4]. | Ensures reproducibility and quality in RNA-Seq or DNA-Seq workflows. |

Calibrated Sample Generator (ChemCal) |

Produces samples with a known amount of contaminant, enabling the creation of a quantitative calibration curve for a detector [5]. | Translating a fluorescence signal from a detector into a precise concentration measurement. |

| Low-Retention Tubes and Tips | Minimizes adhesion of precious samples and reagents to plastic surfaces, ensuring complete liquid transfer and accurate concentrations [4]. | PCR setup with low volumes and concentrations. |

The Impact of Ultralow Detection Limits on Product Safety and Public Health

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue 1: Inconsistent or Falsely Elevated Results in Low-Biomass Samples This is a common problem when detecting trace contaminants or microbes in low-biomass samples, where contaminating DNA can be mistaken for a true signal [9].

- Potential Cause 1: Contaminated Laboratory Tools and Reagents. Reusable homogenizer probes or impure reagents can introduce contaminating analytes [10] [9].

- Solution: For sample homogenization, switch to disposable plastic probes to eliminate cross-contamination between samples. If using stainless steel probes, validate your cleaning protocol by running a blank solution after cleaning to ensure no residual analytes are present [10]. Use reagents that are certified DNA-free, especially for DNA-based assays like PCR [9].

- Potential Cause 2: Cross-Contamination During Sample Handling.

- Solution: Aerosols or splashes can cause well-to-well contamination in 96-well plates. Always spin down sealed plates before removal and remove seals slowly and carefully [10]. Decontaminate work surfaces with solutions like 80% ethanol followed by a nucleic acid-degrading solution (e.g., bleach or commercial products like DNA Away) [9].

- Potential Cause 3: Contamination from Personnel.

- Solution: Researchers should wear appropriate personal protective equipment (PPE) including gloves, masks, and clean lab coats. Gloves should be decontaminated and not touch any surfaces before sample handling [9].

Issue 2: Achieving Ultra-Low Detection Limits in Complex Food Matrices Complex food samples can interfere with assay sensitivity, making it difficult to detect contaminants at ultralow levels [11].

- Potential Cause 1: Insufficient Signal Strength from Labels.

- Solution: Replace conventional gold nanoparticle (Au NP) labels with advanced functional nanomaterials. Fluorescent nanoparticles (e.g., quantum dots) or magnetic nanoparticles can provide significant signal amplification and reduce background noise from the sample matrix [11].

- Potential Cause 2: Non-Specific Binding.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What are the practical benefits of achieving an ultralow detection limit in real-world monitoring? Ultralow detection limits are critical for proactive public health protection. They enable the identification of contaminants at their incipient stages, long before they accumulate to dangerous levels. This allows for timely interventions, prevents the distribution of contaminated products, and helps curb the spread of antibiotic resistance by detecting low-level antibiotic residues in food [11].

Q2: My current method (e.g., HPLC) is sensitive but slow and lab-bound. What are suitable rapid, on-site alternatives? Lateral Flow Assays (LFAs) and miniaturized optical biosensors are excellent for rapid, on-site testing. Modern LFAs, especially those enhanced with fluorescent or magnetic nanomaterials, have closed the sensitivity gap with traditional methods. They are portable, provide results in 5–30 minutes, and are cost-effective (as low as ∼1 RMB per test), making them ideal for field use by food safety inspectors [11] [12].

Q3: How crucial are negative controls when working at the limit of detection? Negative controls are essential. In low-biomass and trace-analysis work, contaminants from reagents, equipment, or the environment can easily produce false positives. Running multiple negative controls—such as empty collection vessels, aliquots of pure solvent, or swabs of the sampling environment—allows you to identify and subtract this background contaminant signal, ensuring your results are reliable [9].

Q4: Our lab is developing a new sensor. What key factors, besides the label, should we optimize for maximum sensitivity? Beyond the detection label, focus on:

- The Biorecognition Element: Use high-affinity antibodies or aptamers. Aptamers, in particular, can be selected for specific binding and stability [11].

- Surface Chemistry: Proper immobilization of the recognition molecule on the sensor surface is crucial to maintain its activity and prevent non-specific binding [12].

- Signal Transduction: Explore advanced methods like Surface-Enhanced Raman Scattering (SERS) or smartphone-based quantification, which can detect minute signal changes with high precision [11] [12].

Performance Data of Advanced Detection Platforms

The table below summarizes key performance metrics of various detection platforms, highlighting how innovative materials and methods achieve ultralow detection limits.

| Detection Platform | Key Material/Technology | Reported Detection Limit | Analysis Time | Key Advantage |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Next-Gen Lateral Flow Assay (LFA) [11] | Fluorescent Nanomaterials, Magnetic Nanoparticles | Dramatically lower than conventional Au NPs | 5–30 minutes | High sensitivity with portability for on-site use |

| Hydrogel Electronic Sensor [13] | PVA-EBPD Hydrogel with dynamic bonds | 0.005% strain | Real-time, instantaneous | Ultra-low detection of physical deformations for medical diagnostics |

| Optical Biosensors (SPR, SERS) [12] | Gold nanoparticles, Quantum Dots | Trace levels of pathogens/toxins | Real-time / Minutes | Label-free, high-sensitivity detection in complex matrices |

| Conventional Methods (HPLC, LC-MS/MS) [11] | N/A | High accuracy | Hours to days | High accuracy; used as lab-based reference standard |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Constructing a Nanomaterial-Enhanced Lateral Flow Assay (LFA) for Antibiotic Residues

This protocol outlines the key steps for creating a high-sensitivity LFA, moving beyond traditional gold nanoparticles [11].

Conjugate Pad Preparation:

- Probe Synthesis: Dilute the functional nanomaterial (e.g., fluorescent quantum dots or carboxylated magnetic nanoparticles) in a suitable buffer (e.g., 2 mM borate buffer, pH 8.0).

- Bioconjugation: Add the specific antibiotic antibody (e.g., anti-sulfonamide IgG) to the nanoparticle solution at an optimized molar ratio.

- Incubation and Blocking: Incubate the mixture for 1 hour at room temperature with gentle shaking. Add a blocking agent (e.g., 1% BSA) to cover unused nanoparticle surfaces and prevent non-specific binding. Incubate for another 30 minutes.

- Purification: Centrifuge the conjugate to remove unbound antibodies and re-suspend it in a preservation buffer containing sucrose and stabilizers.

- Application: Spray the conjugate onto the glass fiber conjugate pad and dry it thoroughly in a desiccator.

Membrane Preparation:

- Test and Control Line Dispensing: Using a precision dispenser, stripe the nitrocellulose membrane with two lines:

- Test Line (T): A solution of the target antibiotic conjugated to a carrier protein (e.g., BSA).

- Control Line (C): A secondary antibody specific to the host species of the detection antibody (e.g., goat anti-mouse IgG).

- Drying: Dry the membrane at 37°C for 12 hours.

- Test and Control Line Dispensing: Using a precision dispenser, stripe the nitrocellulose membrane with two lines:

Assembly and Lamination:

- Assemble the LFA strip by attaching the sample pad, conjugate pad, nitrocellulose membrane, and absorbent pad to a PVC backing card in overlapping sequence.

- Laminate the card to ensure good contact between all components.

Testing and Signal Readout:

- Apply the liquid sample to the sample pad.

- For quantitative results, place the strip in a portable fluorescent or magnetic reader after 15 minutes. For qualitative results, visually inspect the lines.

Protocol 2: Preparing an Ultra-Sensitive PVA-EBPD Hydrogel Sensor

This protocol describes the synthesis of a hydrogel with an ultralow detection limit for strain, useful for biomedical sensing applications [13].

Solution Preparation:

- Prepare a 0.25 M sodium tetrahydroxyborate (NaB(OH)₄) solution in ultrapure water.

- Prepare a 0.15 g/mL aqueous solution of polyvinyl alcohol (PVA).

Synthesis:

- Dissolve 6 mg of (E)-4,4′-(1,2-ethenediyl) bis(1,2-phenylene diol) (EBPD) powder in 200 µL of the 0.25 M NaB(OH)₄ solution. Ultrasonicate until the solution is clear.

- In a separate vial, take 1 mL of the PVA aqueous solution.

- Thoroughly mix the clarified EBPD solution with the PVA solution to form the PVA-EBPD hydrogel via dynamic boron ester bonds. The hydrogel forms without the need for heating, following green chemistry principles.

Diagram: Pathway to Ultralow Detection

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

| Reagent / Material | Function / Explanation |

|---|---|

| High-Affinity Aptamers | Synthetic single-stranded DNA/RNA molecules that bind targets with high specificity and stability; can be selected for antibiotics or toxins where antibodies are limited [11]. |

| Functional Nanomaterials (QDs, Magnetic NPs) | Quantum Dots (QDs) provide intense, stable fluorescence for signal amplification. Magnetic NPs allow for concentration and separation of target analytes from complex matrices, reducing interference [11]. |

| DNA-Free Reagents & Kits | Specially treated reagents and extraction kits that are certified free of microbial DNA. Essential for low-biomass microbiome studies to prevent false positives from reagent contaminants [9]. |

| Dynamic Covalent Hydrogels (e.g., PVA-EBPD) | Polymers cross-linked with reversible bonds (e.g., boron ester bonds). They enable rapid self-recovery and high sensitivity to minute strain, ideal for physical and biochemical sensing [13]. |

| Portable Signal Readers (e.g., Smartphone-based) | Devices that convert visual signals (color, fluorescence) on a test strip into quantitative data. They enhance objectivity, enable data processing, and facilitate point-of-care testing [11] [12]. |

Trace contaminants in pharmaceutical and biomedical research can originate from multiple sources, including raw materials, manufacturing processes, packaging, and the laboratory environment itself. Their presence can critically impact experimental results, product safety, and method sensitivity.

The table below summarizes the primary types and sources of trace contaminants encountered in these settings.

| Contaminant Category | Specific Examples | Common Sources | Potential Impact on Research/Products |

|---|---|---|---|

| Metal Contaminants | Nickel, Chromium, Stainless Steel, Aluminum [14] | Friction or wear from manufacturing equipment; human error in equipment assembly [14] | Introduction of particulate matter; potential toxicological effects [14]. |

| Process-Related Impurities | Genotoxic impurities (e.g., Nitrosamines, Ethyl Methanesulfonate) [14] | Unexpected reaction byproducts; changes in manufacturing reactants; poor cleaning practices [14] | Carcinogenic risk; compromises product safety and necessitates recalls [14]. |

| Microbial Contaminants | Burkholderia cepacia, Vesivirus 2117 [14] | Contaminated water-based routes; animal sera; human plasma components [14] | Can cause widespread and serious infections; leads to drug shortages [14]. |

| Packaging-Related Contaminants | Glass flakes, rubber particles, plasticizers (e.g., phthalates), polymer additives (e.g., Irganox 1010) [14] | Leaching from incompatible packaging materials (e.g., glass vials, rubber stoppers); poor storage conditions [14] | Vascular occlusion from particles; reproductive toxicity and hormonal imbalance from leachates [14]. |

| Drug Cross-Contamination | Potent APIs (e.g., Hydrochlorothiazide, anticancer drugs) [14] | Use of shared manufacturing equipment with improper cleaning; human error and mix-ups [14] | False positive doping tests; unintended pharmacological effects in patients [14]. |

| Emerging Contaminants (ECs) | Pharmaceuticals, Personal Care Products (PPCPs), Per- and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances (PFAS) [15] | Environmental background; contaminated water or reagents [15] | Endocrine disruption; antibiotic resistance; interference with biological assays [15]. |

Troubleshooting Guides for Common Scenarios

FAQ: How can I identify and mitigate metallic particle contamination in my injectable product formulation?

Issue: Visible metallic specks ("black specks") are observed in a liquid formulation during quality control checks.

- Potential Source 1: Wear and tear of manufacturing equipment.

- Investigation: Check for increased friction between metal parts in filling or mixing machinery. Review equipment maintenance and calibration logs [14].

- Solution: Implement more frequent preventative maintenance and equipment inspection schedules. Validate cleaning procedures specifically for metallic particulates.

- Potential Source 2: Incorrect assembly of manufacturing equipment.

- Investigation: Audit equipment assembly procedures. A specific case was traced to a technician misjudging a 1 mm gap between components, leading to friction [14].

- Solution: Enhance technician training and implement automated checks or jigs to ensure correct assembly.

- Preventive Action: Incorporate sensitive metallic particle screening (e.g., elemental analysis) into quality control protocols, as visible specks may indicate a larger underlying issue [14].

Issue: High and variable blanks, signal instability, and poor detection limits during trace metal analysis by ICP-MS.

- Potential Source 1: Contaminated reagents or labware.

- Investigation: Analyze procedural blanks. Check the certificate of analysis for acids and water for elemental contamination levels. Visually inspect labware [16].

- Solution: Use high-purity (e.g., ICP-MS grade) acids and ASTM Type I water [16]. Prefer fluorinated ethylene propylene (FEP) or quartz over borosilicate glass, which can leach boron, silicon, and sodium [16]. Implement automated cleaning for pipettes instead of manual washing [16].

- Potential Source 2: Laboratory environment and personnel.

- Investigation: Sample preparation conducted in a non-clean environment.

- Solution: Perform sample preparation under a HEPA-filtered hood or in a clean room [16]. Enforce a strict policy of powder-free gloves and no jewelry, cosmetics, or lotions in the lab, as these are significant sources of Zn, Al, and other metals [16].

- Potential Source 3: Sample tubing.

- Investigation: Review the path of the sample and the types of tubing used.

- Solution: Avoid silicone tubing, especially with nitric acid, as it leaches silicon, aluminum, iron, and magnesium. Neoprene tubing can contaminate with zinc. Select high-purity alternative polymers [16].

FAQ: We suspect cross-contamination with another drug substance in our shared facility. How can we investigate this?

Issue: Chromatographic or biological assays indicate the presence of an unexpected Active Pharmaceutical Ingredient (API).

- Potential Source 1: Inadequate cleaning of shared manufacturing equipment.

- Potential Source 2: Human error and material flow issues.

- Investigation: Audit the material and personnel flow in the production area. Check for potential for mix-ups during material weighing, dispensing, or line clearance [14].

- Solution: Improve facility design to physically separate production lines. Enhance training and implement real-time document control to prevent mix-ups [14].

Detailed Methodologies for Key Experiments

Standard Operating Procedure (SOP): Determination of Trace Elements by ICP-MS

This protocol is adapted for challenging matrices like biological fluids or process streams with variable salinity and pH [17].

1. Principle: Liquid samples are nebulized into an argon plasma where elements are atomized and ionized. The ions are separated by a mass spectrometer and quantified based on their mass-to-charge ratio [17].

2. Critical Reagents and Materials:

- Water: ASTM Type I ultrapure water (Resistivity >18 MΩ·cm) [16].

- Acids: High-purity (e.g., ICP-MS grade) nitric acid is preferred. Check the certificate of analysis for contaminant levels [16].

- Labware: Use FEP or quartz vials and containers. Avoid colored plastics and borosilicate glass for trace analysis of B, Si, Na, Cu, Fe, Zn, Cd, and Sb [17] [16].

- Calibration Standards: Certified Reference Materials (CRMs) with a current expiration date, matrix-matched to samples when possible [16].

3. Instrumentation and Workflow:

4. Key Operational Considerations:

- Matrix Effects: For high-salinity samples (>3% NaCl), careful dilution is required to prevent signal instability and nebulizer blockage. A 50% dilution of seawater (1.5% NaCl final) is often a safe starting point [17].

- Spectral Interferences: Use a collision/reaction cell (e.g., pressurized with Helium) to reduce polyatomic interferences (e.g., 35Cl16O+ on 51V+) [17].

- Contamination Control: Rinse the outside of CRM containers with deionized water before opening. Recap CRMs quickly. Prepare dilutions in plastic or FEP [16].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents for Trace Contaminant Analysis

| Research Reagent / Material | Function / Purpose | Critical Quality Parameters |

|---|---|---|

| ASTM Type I Water [16] | Primary diluent for standards and samples; rinsing labware. | Resistivity >18 MΩ·cm; total organic carbon (TOC) < 50 ppb. |

| High-Purity Acids (e.g., HNO₃) [16] | Sample digestion, preservation, and dilution. | "ICP-MS grade"; low and documented levels of elemental contaminants (e.g., <10 ppt for key metals). |

| Certified Reference Materials (CRMs) [16] | Instrument calibration and quality control; verifying method accuracy. | Current expiration date; certificate with uncertainty and traceability to SI units. |

| Fluoropolymer Labware (FEP/PFA) [16] | Storing and preparing samples and standards. | Low leachability of trace elements; resistant to strong acids. |

| Helium (He) Gas [17] | Collision gas in ICP-MS to remove polyatomic spectral interferences. | High purity (e.g., >99.995%) to minimize background noise. |

Advanced Techniques and Future Trends

Emerging Trend: Integrated Detection and Remediation for PFAS

Per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) are persistent environmental contaminants that can infiltrate the supply chain. A key future direction involves integrating sensitive detection with effective remediation [18].

- Detection Challenge: Regulatory limits for PFAS (e.g., 4 ppt for PFOA/PFOS in US drinking water) demand extremely sensitive methods like LC-MS/MS, which are lab-bound [18].

- Emerging Solution: Development of portable electrochemical and optical sensors for on-site monitoring, potentially integrated with AI for data analysis [18].

- Integrated Remediation: Electrochemical degradation is a promising destructive technology. It uses electricity to mineralize PFAS to HF and CO₂, avoiding secondary waste. Integrating real-time sensors with such reactors allows for immediate adjustment of treatment processes [18].

FAQs: Understanding False Positives and Contamination

What are the most common sources of false positives in trace metal analysis? The most prevalent sources stem from the environmental ubiquity of metals and improper lab practices. Common culprits include:

- Laboratory Materials: Glassware and low-purity quartz can leach metal ions like zinc, iron, chromium, and nickel into samples [19] [20]. Pipettes with external stainless-steel tip ejectors are also a known source [20].

- Reagents and Solvents: Acids and solvents stored in glass or purchased in insufficient purity can introduce significant metal contaminants [20].

- Airborne Particulates: Dust in laboratory air can settle on samples and surfaces, introducing contaminants [20].

- Improper Handling: Contact between gloves or fingers and the inside of sample tubes, caps, or pipette tips is a direct route for contamination from skin or environmental dust [20].

How can inorganic sample preparation differ from organic sample preparation in terms of contamination risk? The key difference lies in the ubiquity of the analytes. For organic analytes like nicotine, it can often be assumed that laboratory surfaces and materials are free of these specific compounds. This assumption is not valid for trace metal analysis, as metals are present in most common laboratory materials, including glass, filter paper, and hood surfaces. Consequently, the skillset and ancillary materials required for inorganic analysis are fundamentally different and must avoid materials like glass that are otherwise suitable for organic analysis [20].

What is the role of zinc and other metal impurities in false positives for biochemical assays? Metal impurities such as zinc have been identified as promiscuous inhibitors that can cause false-positive signals in high-throughput screening (HTS) campaigns for drug discovery. These inorganic impurities can interfere with a variety of targets and readout systems, including biochemical and biosensor assays. A recommended counter-screen to rule out zinc-caused inhibition is the use of the chelator TPEN [19].

Beyond metals, what other contaminants can lead to false results in sensitive biological experiments? Other significant contaminants include:

- Microbial Contamination: Bacteria, yeast, mold, and mycoplasma in cell cultures can alter experimental conditions and outcomes. For example, bacterial contamination often turns the culture medium yellow, while mycoplasma contamination may only show as slow cell growth and abnormal morphology under a microscope [21].

- DNA Contamination: In PCR, the most potent source of false positives is product carryover from previous amplifications (amplicons). Even a single aerosol particle can contaminate a new reaction, making spatial separation of pre- and post-PCR activities a critical preventative measure [22].

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide 1: Troubleshooting False Positives in Trace Metal Analysis by ICP-MS

Problem: Elevated or variable blanks, high method detection limits, and false positive results for trace metals.

Action Plan:

- Confirm the Contamination: Consistently high analyte levels in your procedural blanks indicate a systemic contamination issue, not a one-off event.

- Isolate the Source Systematically: Set up a series of tests where you replace one component at a time with a verified, high-purity alternative.

- Start with the water, as it is used in the largest volume. Replace with a fresh, unopened aliquot of PCR-grade or ultra-high purity water [22] [20].

- Check all master mix components (acids, buffers) by replacing them with new, high-purity aliquots.

- Examine consumables, including pipette tips and sample tubes. Use polypropylene or fluoropolymer tips instead of glass [20].

- Inspect Labware and Equipment:

- Avoid Glass: Use high-purity fluoropolymer (PFA, FEP) or plastic (polypropylene) labware for all steps [20].

- Check Pipettes: Ensure pipettes do not have external stainless-steel tip ejectors. If they do, remove the ejectors and remove tips manually to prevent contamination [20]. Never turn a pipet with liquid in the tip sideways, as acid can corrode the internal piston.

- The "Full Reset" Option: If the source cannot be pinpointed, perform a full-scale cleanup. Discard all suspect reagents and aliquots. Thoroughly decontaminate workspaces and equipment with 10% bleach and/or UV irradiation (for DNA). Open fresh, certified reagents and consumables [22] [20].

Prevention Checklist:

- Use powder-free nitrile gloves and change them frequently.

- Never handle sample tubes or caps in a way that allows contact with the interior surface.

- Use acids that are double-distilled in fluoropolymer or high-purity quartz stills and sold in PFA or FEP bottles [20].

- Work in a clean environment, such as a laminar flow hood with HEPA-filtered air, to minimize airborne particulate contamination [20].

Guide 2: Troubleshooting General Laboratory Contamination

Problem: Unverified experimental results or unexplained signals across various assay types.

Action Plan: This generalized workflow provides a logical sequence for investigating the source of laboratory contamination.

The table below summarizes key quantitative thresholds and contamination data from research.

Table 1: Quantitative Data on Contamination and Detection Limits

| Analyte / Context | Key Quantitative Value | Significance / Source |

|---|---|---|

| Zinc & Metal Impurities | Causes false positives in HTS [19] | Identified as a promiscuous inhibitor in biochemical assays; use of chelator TPEN is a recommended counter-screen [19]. |

| PFAS Detection (PFOA/PFOS) | EPA Limit: 4 parts per trillion (ppt) [23] | The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency's proposed enforceable limit for these "forever chemicals" in drinking water [23]. |

| PFAS Detection Method | Sensor Detection Limit: 250 parts per quadrillion (ppq) [23] | Demonstrates the extreme sensitivity required for modern trace analysis, equivalent to one grain of sand in an Olympic-sized swimming pool [23]. |

| Electrochemical N₂ to NH₃ (NRR) | Minimum Plausible Yield: 0.1 nmol s⁻¹ cm⁻² [24] | Studies reporting yields below this threshold are considered ambiguous and too low to be convincing of genuine catalytic activity, often masked by contamination [24]. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Counter-Screen for Zinc-Induced False Positives in HTS

Purpose: To confirm whether an observed inhibitory signal in a high-throughput screen is caused by the target compound or by zinc contamination.

Methodology:

- Prepare Test Solutions: Set up duplicate reactions of your hit compound(s) at the concentration that generated the positive signal.

- Apply Chelator: To the test group, add the zinc-specific chelator TPEN (N,N,N′,N′-Tetrakis(2-pyridylmethyl)ethylenediamine) at a standard concentration (e.g., 10-100 µM). The control group should receive an equivalent volume of buffer.

- Run Assay: Conduct the biochemical or biosensor assay under the same conditions as the original HTS campaign.

- Interpret Results:

- Signal Abolished/Lowered with TPEN: The original positive signal was likely caused by zinc contamination present in the sample [19].

- Signal Unchanged with TPEN: The inhibitory activity is likely genuine and specific to the target compound.

Protocol 2: Establishing a Contamination-Control Baseline for Trace Metal Analysis

Purpose: To quantify and minimize the contribution of environmental contamination to procedural blanks, thereby lowering method detection limits and preventing false positives.

Methodology:

- Material Selection: Use only high-purity polymer materials (e.g., PFA, FEP, polypropylene). Avoid glassware entirely, with the rare exception of analyses for mercury alone [20].

- Reagent Preparation: Use ultra-high purity acids (double-distilled in fluoropolymer/quartz) sold in fluoropolymer bottles. Aliquot all reagents into small, single-use volumes to avoid contaminating stock solutions [20].

- Sample Processing:

- Work in a clean, HEPA-filtered environment if possible.

- Use pipettes without external metal tip ejectors and use aerosol-resistant filter tips [20].

- Wear powder-free nitrile gloves and avoid any contact with the interior of containers and caps.

- Run Procedural Blanks: Process a blank sample (e.g., ultra-pure acidified water) through the entire sample preparation and analysis sequence alongside your actual samples.

- Analysis and Acceptance Criteria: Analyze the blanks using ICP-MS. The analyte levels in the procedural blank define your method's background. The method detection limit (MDL) is calculated based on the standard deviation of these blank measurements. A high or variable blank invalidates the run and necessitates troubleshooting using the guide above.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

Table 2: Key Reagents and Materials for Contamination Control

| Item Name | Function / Purpose | Key Consideration |

|---|---|---|

| TPEN Chelator | A zinc-specific chelator used to identify false positives caused by zinc contamination in biochemical assays [19]. | A straightforward counter-screen to rule out metal-based assay interference [19]. |

| High-Purity Acids (PFA/FEP bottles) | Double-distilled acids for sample preparation/digestion in trace metal analysis [20]. | Essential for low procedural blanks. Must be purchased in or transferred to fluoropolymer bottles, never glass [20]. |

| Fluoropolymer Labware (PFA, FEP) | Beakers, bottles, and vials for sample collection, preparation, and storage [20]. | Leach far fewer metal impurities compared to glass or low-purity quartz. The material of choice for inorganic trace analysis [20]. |

| Polypropylene Pipette Tips (Filtered) | For accurate and contamination-free liquid transfer. | The filter prevents aerosol carryover and protects the pipette shaft. Avoids contamination from external metal ejectors [20]. |

| Uracil-DNA Glycosylase (UDG/UNG) | An enzyme used to prevent PCR false positives from amplicon carryover [22]. | Used in a pre-PCR step to degrade any uracil-containing DNA from previous PCR products, leaving the natural template DNA intact [22]. |

| Mycoplasma Detection Kit | For regularly testing cell cultures for mycoplasma contamination [21]. | Essential for maintaining healthy cell lines and ensuring the validity of biological experiments. Testing every 1-2 months is recommended [21]. |

Leveraging Advanced Instrumentation and Automated Workflows for Superior Sensitivity

In the field of trace contaminant detection research, achieving ultimate sensitivity is a paramount goal. The coupling of separation techniques with mass spectrometry, known as hyphenated techniques, provides powerful tools for identifying and quantifying trace-level analytes in complex matrices. For researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, mastering these techniques—specifically GC-MS/MS, LC-MS/MS, and ICP-MS—is essential for advancing analytical capabilities in areas ranging from environmental monitoring to pharmaceutical development. This technical support center addresses the specific challenges and troubleshooting scenarios encountered when working with these sophisticated instruments to maximize method sensitivity.

Technique Selection and Comparative Capabilities

Selecting the appropriate hyphenated technique is the critical first step in any analytical method development for trace analysis. Each technique offers distinct advantages and is suited to specific types of analytes and applications.

Table 1: Comparison of Key Hyphenated Techniques for Trace Analysis

| Technique | Optimal Analyte Types | Ionization Methods | Typical Applications | Key Strengths |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| GC-MS/MS | Volatile, thermally stable, non-polar/low-polar compounds [25] | EI, CI [25] | Environmental monitoring, forensic analysis, metabolomics [26] [25] | Excellent separation efficiency, extensive EI spectral libraries [27] |

| LC-MS/MS | Polar, thermally labile, non-volatile compounds [25] | ESI, APCI, APPI [25] | Pharmaceutical analysis, biomolecule detection, complex matrices [25] | Broad applicability for non-volatile compounds, high selectivity [25] |

| ICP-MS | Elemental analysis, metals, heteroatoms (S, P, Se) [28] | Inductively Coupled Plasma [28] [25] | Electronic gas analysis, metal speciation, environmental contaminants [28] [26] | Exceptional sensitivity (ppt levels), wide linear dynamic range, tolerance to matrix gases [28] |

The publication rates for these techniques reflect their adoption in scientific research. From 1995-2023, PubMed recorded an almost linear yearly publication rate of approximately 3,042 articles for GC-MS and 3,908 for LC-MS, with LC-MS/MS used in about 60% of LC-MS studies compared to only 5% for GC-MS/MS in GC-MS studies [26]. ICP-MS, while less prevalent with 14,000 total articles, fills the critical analytical gap for metal ion analysis [26].

Troubleshooting Guides

GC-MS/MS Troubleshooting

Problem: Decreasing Sensitivity Over Time

- Potential Cause: Active sites in the injection port or column causing adsorption and decomposition.

- Solution: Replace the injection liner, trim 10-15 cm from the column inlet, and use deactivated retention gaps. Regularly maintain the ion source by cleaning to remove contamination.

Problem: Poor Peak Shape for Polar Compounds

- Potential Cause: Insufficient derivatization or column activity.

- Solution: Ensure complete derivatization using appropriate silylating agents. Use inert flow path components and confirm the GC column is properly conditioned.

LC-MS/MS Troubleshooting

Problem: Signal Suppression or Enhancement

- Potential Cause: Matrix effects from co-eluting compounds affecting ionization efficiency.

- Solution: Improve sample cleanup, optimize chromatographic separation to shift elution times, use alternative ionization methods (APCI instead of ESI), and employ stable isotope-labeled internal standards for accurate quantification [26].

Problem: High Background Noise in Mass Spectra

- Potential Cause: Contamination from previous samples, mobile phase impurities, or solvent memory effects.

- Solution: Implement thorough needle wash procedures, use high-purity MS-grade solvents and additives, and regularly clean the ion source and sampling cones.

ICP-MS Troubleshooting

Problem: Nebulizer Clogging with High-Salt Matrices

- Potential Cause: Precipitation of dissolved solids in the nebulizer.

- Solution: Use an argon humidifier for the nebulizer flow gas to prevent salting out, dilute samples appropriately, filter samples prior to introduction, and consider using specialized nebulizers designed to prevent clogging [29].

Problem: Poor Precision in First Reading

- Potential Cause: Insufficient stabilization time for the sample to reach the plasma.

- Solution: Increase stabilization time to allow the signal to equilibrate before data acquisition. Consistently low first readings typically resolve with this adjustment [29].

Problem: Drifting Calibration Curves

- Potential Cause: Contaminated blank solutions or incorrect background correction.

- Solution: Ensure blank is free from analyte contaminants, check peak centering, verify background correction points, and examine raw intensities to fine-tune calibration curves with appropriate statistical weighting [29].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q: Can LC-MS completely replace GC-MS in analytical laboratories? A: No. While LC-MS has broader applicability for polar and thermally unstable compounds, GC-MS remains superior for volatile, thermally stable compounds and benefits from extensive, reproducible electron ionization spectral libraries. The techniques are complementary rather than interchangeable [25].

Q: What is the advantage of using ICP-MS over other elemental analysis techniques? A: ICP-MS offers exceptional sensitivity for elemental analysis, capable of detecting certain elements like germane down to 5 ppt levels [28]. It also provides wide linear dynamic range, high matrix tolerance, and the ability to perform indirect calibration for species without available gas standards using wet-plasma conditions [28].

Q: How can I improve detection limits for sulfur compounds using GC-ICP-MS? A: Utilize collision cell technology with oxygen addition to convert the measurement from the interfered mass 32 (OO+) to mass 48 (SO+), significantly improving sensitivity and specificity for sulfur detection [28].

Q: What is the best approach for analyzing both aqueous and organic samples on the same ICP instrument? A: Maintain separate sample introduction systems, including different autosampler probes, nebulizers, spray chambers, and torches dedicated to each matrix type. Use pump tubing material resistant to organic solvents when analyzing organic matrices [29].

Q: Why is my first reading consistently lower than subsequent readings in ICP-MS analysis? A: This pattern typically indicates insufficient stabilization time. Increase the stabilization delay to allow the sample to fully reach the plasma and for the signal to equilibrate before beginning data acquisition [29].

Enhanced Sensitivity Protocols

GC-ICP-MS for Ultra-trace Gas Analysis

This protocol demonstrates the exceptional sensitivity achievable for detecting trace impurities in electronic gases, with germane detection down to 5 ppt [28].

- Instrumentation: Thermo Electron X-Series ICP-MS coupled with Thermo Electron Focus gas chromatograph.

- Chromatographic Conditions:

- Column: 0.53 μm i.d. capillary GC column

- Temperature: Isothermal, 35°C to 70°C

- Sample Introduction: 400 μL sample loop via switching valve

- ICP-MS Interface:

- Heated transfer line maintained 10°C above column temperature

- Column effluent mixed with heated argon make-up gas

- Optional vacuum application to remove matrix peaks

- ICP-MS Parameters:

- Nebulizer flow: 0.68 L/min

- Auxiliary gas: 0.70 L/min

- Cool gas: 13.5 L/min

- Standard wet plasma tune conditions

- Detection:

- Single ion monitoring for P (m/z 31), Si (m/z 28), As (m/z 75), S (m/z 48), Ge (m/z 74), Se (m/z 78)

- Key Application: Analysis of trace impurities in arsine, including silane, carbonyl sulfide, hydrogen sulfide, germane, and hydrogen selenide.

Cross-Calibration Strategy for Unavailable Gas Standards

ICP-MS operated in wet plasma mode enables indirect calibration when gas standards are unavailable [28].

- Procedure:

- Introduce known aqueous standards of a reference element (e.g., bromine) and the target element (e.g., mercury) via the nebulizer.

- Calculate the relative response factor (RRF) between the elements based on their ICP-MS response per μmol/μL.

- Analyze a known concentration of a volatile compound containing the reference element (e.g., brominated hydrocarbon) via the GC interface.

- Apply the RRF to determine the unknown concentration of the target element in the gas phase.

- Accuracy: Within 50%, which is acceptable for standards unavailable at ppt/ppb levels.

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for Enhanced Sensitivity

| Reagent/Component | Function | Application Example |

|---|---|---|

| Trimethylsilyl Derivatization Reagents | Increases volatility of polar compounds for GC-MS analysis [27] | Analysis of metabolites, carbohydrates, amino acids |

| Stable Isotope-Labeled Internal Standards | Corrects for matrix effects and recovery losses; enables highly accurate quantification [26] | Pharmaceutical quantification, metabolic studies |

| High-Purity Tuning Solution | Optimizes instrument response for specific mass ranges | Daily performance verification of MS systems |

| Custom Matrix-Matched Standards | Compensates for matrix effects in complex samples; improves accuracy [29] | Soil analysis (Mehlich-3 extracts), alloy digestion |

| Collision Cell Gases | Eliminates polyatomic interferences through chemical reactions | Sulfur analysis by converting OO+ interference to SO+ [28] |

| Argon Humidifier | Prevents salt precipitation in nebulizer; reduces clogging with high-TDS samples [29] | Analysis of saline matrices, biological fluids |

Advanced Method Development Insights

Matrix Tolerance Considerations

ICP-MS demonstrates remarkable tolerance to various gas matrices. In hydrocarbon gas analysis, the propane-propylene matrix shows only minimal baseline depression without affecting analyte response, enabling sulfur speciation at low ppb levels [28]. Similarly, when measuring arsine impurities in propylene, the matrix exhibits virtually no signal, providing detection limits approximately 10 times better than GC-AED [28].

Wet vs. Dry Plasma Operation in GC-ICP-MS

The choice between wet and dry plasma operation impacts method robustness and calibration flexibility:

- Wet Plasma: Incorporates a wet aerosol from the nebulization system merged with GC effluent before plasma entry. Advantages include more robust plasma operation and ability for indirect calibration using aqueous standards [28].

- Dry Plasma: Connects GC column effluent directly to the torch with make-up gas. Optimization is accomplished using xenon or other dopants in the make-up gas.

Complementary Technique Approach

For comprehensive analysis of emerging contaminants—which include pharmaceuticals, personal care products, endocrine disruptors, and industrial chemicals—employing multiple hyphenated techniques provides the most complete assessment [15]. The integration of GC-MS/MS, LC-MS/MS, and ICP-MS covers a broad spectrum of contaminant properties from volatility to polarity to elemental composition.

The Role of Automation and Robotics in Streamlining Sample Preparation

Troubleshooting Guides and FAQs

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: How does automation improve method sensitivity for trace contaminant analysis? Automation enhances sensitivity by minimizing human error and variability in sample preparation, which is critical for trace-level detection. Techniques like automated micro-Solid Phase Extraction (µSPE) and Solid Phase Microextraction (SPME) allow for efficient sample clean-up and analyte enrichment, significantly reducing background noise and improving signal-to-noise ratios in subsequent LC/MS or GC/MS analysis [30]. Automated systems also enable the use of minimal sample volumes, which can concentrate analytes and lower detection limits.

Q2: What are the common causes of sample carry-over in automated liquid handling systems, and how can it be minimized? Sample carry-over is often caused by residual analytes in the syringe, needle, or associated tubing. To minimize it:

- Ensure Proper Cleaning Cycles: Program and verify robust washing steps using appropriate solvents between samples.

- Inspect Components: Regularly check the syringe and needle for wear or damage that could trap residues.

- Use Optimal Solvents: Employ wash solvents that are compatible with and effectively dissolve the target analytes to remove them completely [30].

Q3: My robotic system is consistently dropping samples or failing to pick them up. What should I check? This is a common failure mode often related to the End-of-Arm Tooling (EOAT). A systematic check should include:

- Vacuum and Grippers: Verify that vacuum pressure is at the correct level on all lines. Inspect vacuum hoses for holes, ensure they are not longer than necessary, and check that grippers are positioned correctly and not firing prematurely [31].

- Cups and Shafts: Inspect suction cups for wear, tears, or a "sloppy" fit on the shaft. For spring-loaded shafts, check for galling or sticking [31].

- Setup and Programming: Confirm the correct program is loaded and that the EOAT is firmly mounted and positioned correctly. Verify that robot and clamp speeds and timers are synchronized, and consider adding a brief delay to allow vacuum to stabilize [31].

Q4: Can I automate sample preparation for neutral PFAS compounds, which are challenging for LC-MS? Yes, automation is particularly beneficial for neutral PFAS. Automated headspace techniques like Dynamic Headspace (DHS) and SPME can be integrated with GC-MS/MS, bypassing complex solvent extraction steps. You can simply place the sample in a vial, and the automated system handles the extraction and introduction, simplifying the workflow and improving safety by reducing solvent exposure [32].

Troubleshooting Guide: Common Robotic System Failures

The table below outlines specific issues, their potential causes, and corrective actions based on failures in automated sample preparation systems.

| Symptom | Potential Cause | Corrective Action |

|---|---|---|

| Inaccurate Liquid Volume Delivery | - Worn or damaged syringe- Incorrect method parameters- Air bubbles in liquid lines | - Perform syringe calibration and inspection [33]- Verify method settings (aspirate/dispense speed, wait times)- Prime lines thoroughly before operation |

| Failed Pickup / Dropped Samples | - Loss of vacuum- Misaligned EOAT (End of Arm Tooling)- Worn or damaged grippers/suction cups | - Check vacuum pressure and inspect hoses for leaks [31]- Recalibrate robot arm and EOAT position [31]- Replace worn grippers or cups [31] |

| High Background Noise / Contamination in Analysis | - Sample carry-over- Reagent contamination- Cross-contamination between samples | - Execute and validate cleaning protocols [30]- Use high-purity reagents- Utilize system's automatic cleaning between samples [33] |

| Poor Reproducibility Between Runs | - Environmental temperature fluctuations- System not properly calibrated- Inconsistent sample mixing | - Maintain a stable lab environment- Adhere to a strict periodic calibration schedule [33]- Ensure automated mixing (vortex, agitation) is consistent in time and speed |

| System Software or Communication Error | - Loose cable connections- Software bug or glitch- Incorrect driver installation | - Power cycle and check all physical connections- Restart software and re-load method- Reinstall drivers per manufacturer's instructions |

Quantitative Performance Data of Automated Systems

The following table summarizes key quantitative benefits observed from implementing automation in sample preparation, directly impacting method sensitivity and throughput.

| Performance Metric | Manual Preparation | Automated Preparation | Key Source of Improvement |

|---|---|---|---|

| Volume Accuracy Error | ~5% (variable) | As low as ±1% [33] | High-precision injection pumps [33] |

| Sample Throughput | Limited by technician capacity | High-throughput; capable of running >180 samples per batch unattended [33] | Parallel processing (4-12 channels) and large-capacity trays [33] |

| Sample Preparation Time | Several hours for extraction [32] | Minimal; direct vial placement for headspace techniques [32] | Elimination of extraction steps via SPME/DHS [32] |

| Solvent Consumption | High (tens to hundreds of mL) | Significantly Reduced [30] | Miniaturized techniques like µSPE and solvent-free SPME [30] |

Experimental Protocols for Key Workflows

Protocol 1: Automated µSPE for Trace Pesticide Analysis in Food Samples

This protocol is designed for the clean-up of complex food matrices prior to multi-residue pesticide analysis by GC-MS/MS or LC-MS/MS, improving sensitivity by reducing matrix effects.

1. Principle: Micro-Solid Phase Extraction (µSPE) is a miniaturized, automated form of SPE that uses a small amount of sorbent to selectively retain and concentrate target analytes from a sample extract, followed by a wash step to remove interferents and an elution step to collect the purified analytes [30].

2. Reagents and Materials:

- Sample Extract: QuEChERS (Quick, Easy, Cheap, Effective, Rugged, and Safe) extract in acetonitrile.

- µSPE Cartridges: Typically containing sorbents like C18, PSA (Primary Secondary Amine), or graphitized carbon black (GCB).

- Elution Solvent: Acetonitrile or methanol, LC-MS grade.

- Automated System: Robotic liquid handler (e.g., PAL System or RT-Auto Series) equipped for µSPE.

3. Step-by-Step Procedure: 1. Conditioning: The robotic system automatically conditions the µSPE cartridge with a small volume of elution solvent (e.g., 200 µL of acetonitrile), followed by an equilibrium volume of sample solvent. 2. Loading: An aliquot of the QuEChERS sample extract is precisely transferred and passed through the conditioned µSPE cartridge. Analytes and interferents are retained on the sorbent. 3. Washing: A wash solvent (often the same as the sample solvent) is applied to the cartridge to remove weakly retained matrix interferents without eluting the target pesticides. 4. Elution: The target analytes are eluted from the µSPE cartridge using a small volume of a strong solvent (e.g., 100-200 µL of acetonitrile) into a clean MS-compatible vial. 5. Injection: The eluate is directly injected into the GC-MS/MS or LC-MS/MS system for analysis.

4. Key Advantages for Sensitivity:

- Analyte Enrichment: The small elution volume concentrates the analytes, lowering the detection limit.

- Matrix Clean-up: Removes co-extractives like organic acids and pigments that can suppress or enhance ionization in the MS, leading to more accurate and sensitive quantification [30].

Protocol 2: Automated Dynamic Headspace (DHS) for Neutral PFAS in Seafood

This protocol details an automated, solvent-free approach for extracting volatile neutral PFAS precursors, which are poorly suited for LC-MS, and analyzing them via GC-MS/MS.

1. Principle: Dynamic Headspace (DHS) is an automated technique where an inert gas purges the heated sample vial, transferring volatile and semi-volatile analytes from the sample matrix into the headspace. The volatilized compounds are then trapped and concentrated on a sorbent trap, which is subsequently thermally desorbed into the GC-MS/MS for highly sensitive analysis [32].

2. Reagents and Materials:

- Homogenized Seafood Sample.

- Internal Standards: Deuterated or carbon-13 labeled neutral PFAS standards.

- Purge Gas: High-purity helium or nitrogen.

- Sorbent Trap: Containing Tenax TA or a similar material.

- Automated DHS System coupled to a GC-MS/MS.

3. Step-by-Step Procedure: 1. Weighing and Spiking: A weighed amount of homogenized seafood sample is placed in a DHS vial. Internal standards are added to correct for procedural losses. 2. Heating and Purging: The automated system heats the sample vial to a defined temperature (e.g., 80°C) and purges it with a controlled flow of inert gas for a set time (e.g., 10-15 minutes). Volatile neutral PFAS (e.g., FTOHs) are transferred to the headspace and carried to the trap. 3. Trap Conditioning/Analyte Focusing: The sorbent trap is held at a low temperature during the purge to effectively adsorb the target compounds. 4. Thermal Desorption: After the purge, the trap is rapidly heated to desorb the concentrated analytes, which are then transferred via a heated transfer line into the GC injector. 5. GC-MS/MS Analysis: The analytes are separated on the GC column and detected with high specificity and sensitivity by the tandem mass spectrometer.

4. Key Advantages for Sensitivity:

- Total Transfer of Analyte: Nearly 100% of the volatile analyte can be extracted from the sample and transferred to the instrument, maximizing detection capability.

- No Solvent Interference: Being solvent-free, it eliminates the large solvent peak that can obscure early-eluting compounds in GC, allowing for detection of very trace levels [32].

Workflow Visualization

Automated Sample Preparation Workflow

Robotic Troubleshooting Logic

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details key reagents and consumables critical for successful and sensitive automated sample preparation in trace contaminant analysis.

| Item | Function in Automated Preparation |

|---|---|

| µSPE Cartridges | Miniaturized solid-phase extraction units for efficient, high-throughput sample clean-up and analyte concentration with minimal solvent [30]. |

| SPME Arrows/Fibers | A solvent-free extraction device coated with a stationary phase for extracting and concentrating volatile/semi-volatile compounds from sample headspace; the Arrow design offers greater robustness and sensitivity [30]. |

| QuEChERS Extraction Kits | Pre-packaged salts and sorbents for the rapid preparation of sample extracts from complex matrices (e.g., food) in a format amenable to automated handling [30]. |

| High-Purity, MS-Grade Solvents | Essential for minimizing background noise and ion suppression in mass spectrometry; critical for achieving low detection limits. |

| Stable Isotope-Labeled Internal Standards | Added to samples to correct for analyte loss during automated preparation steps and matrix effects during analysis, ensuring quantitative accuracy [30]. |

| Certified Reference Materials (CRMs) | Used for method validation and ongoing quality control to ensure the accuracy and precision of automated workflows. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. Why is the coupling between my microfluidic device and the mass spectrometer so challenging? Coupling is challenging due to the difficulty in sampling picoliter to microliter volumes from the device and interfacing it with the macro-scale MS system. Achieving a stable, low-dead-volume connection that maintains the integrity of the separation or reaction performed on-chip is complex [34].

2. What are the most common types of baseline problems in my LC-MS setup, and what causes them? Common baseline issues include drift and noise. Frequent causes are mobile phase impurities (which can accumulate on-column or contribute to a high baseline), detector response to a major mobile phase component, inconsistent mobile phase composition due to pump problems, and temperature effects on the detector [35].

3. I see no peaks in my MS data. What should I check first? First, verify that your sample is reaching the detector. Check the auto-sampler and syringe for proper operation, ensure the sample is prepared correctly, and inspect the column for cracks. Then, confirm the MS detector is functioning correctly, for instance, by checking that the flame is lit (if applicable) and that gases are flowing properly [36].

4. How can I prevent or troubleshoot leaks in my microfluidic setup? Leaks are a common failure mode in microfluidics due to high operating pressures and the use of multiple connectors. To troubleshoot, ensure all fittings are properly tightened (typically with 1-2 threads visible). Use pressure decay tests or visual inspection to identify leak locations. For complex systems, established standards like ASTM F2391-05 (using helium as a tracer gas) can be adapted for sensitive leak detection [37].

5. My microfluidic device is clogged. What is the best way to unplug it? For devices with integrated reaction chambers, a common method is to disassemble the chamber, reverse the flow direction, and attempt to flush the obstruction out. For persistent clogs, sonicating the component in a bath (e.g., with denatured alcohol) can help. Having a spare reaction chamber is recommended to maintain productivity during cleaning [38].

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide 1: Troubleshooting Microfluidic-MS Connection and Spray Stability

This guide addresses issues specifically related to the interface between your microfluidic device and the mass spectrometer.

| Problem | Possible Cause | Solution | Preventive Measure |

|---|---|---|---|

| Unstable or no electrospray | Incorrect spray voltage application; Unsuitable surface properties at the emitter. | Apply voltage via a dedicated sheath channel intersecting near the channel outlet. Use a hydrophobic coating on the emitter tip to stabilize the Taylor cone [34]. | Design devices with integrated, sharpened emitters to limit sample spreading on the chip edge [34]. |

| Loss of sensitivity | Leaks in the connection between the chip and MS; Contamination. | Check all fittings and interconnects for leaks. Clean the ESI source and connections. For integrated emitters, verify the alignment with the MS orifice [34] [36]. | Implement a regular leak-check procedure using a pressure decay test or a leak detector [37]. |

| Broad peaks and reduced separation efficiency | Significant dead volume at the chip-MS junction. | Use integrated emitters fabricated directly within the device during fabrication to minimize dead volume [34]. | Optimize the chip design so the separation channel extends to a sharp, integrated emitter at the device's edge [34]. |

Guide 2: Troubleshooting LC-MS Baseline and Signal Issues

This guide helps diagnose problems observed in the chromatographic baseline and MS signal, which are critical for detecting trace contaminants.

| Problem | Possible Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| "Ghost peaks" in blank runs | Impurities in the mobile phase solvents or additives. | Use high-purity, LC-MS grade solvents from different manufacturers. Add a similar concentration of additive to both the A and B solvents of the gradient to create a flat baseline [35]. |

| High baseline in blank runs, particularly with MS detection | Contaminated solvents or a contaminated flow path. | Replace the mobile phase with fresh, high-purity solvents from a different supplier. Flush the entire system, including the LC flow path and MS ion source [35] [39]. |

| Saw-tooth or cyclic baseline pattern during a gradient | Inconsistent mobile phase composition due to a failing pump. | Check for sticky check valves or trapped air bubbles in the pump heads of the binary pumping system [35]. |

| High signal in blank runs or inaccurate mass values | Carryover from previous samples or system contamination; Incorrect mass calibration. | Perform intensive system washing and cleaning. Run a calibration using the appropriate standard to recalibrate the mass axis [39]. |

Standardized Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Coupling a Microfluidic Device via an Integrated ESI Emitter

This protocol is adapted from methods used to achieve highly efficient separations coupled online to MS [34].

Objective: To interface a glass-based microfluidic separation device with a mass spectrometer using an integrated electrospray emitter for sensitive analysis of trace contaminants.

Materials:

- Fabricated glass microfluidic device with separation channel.

- Chemical vapor deposition (CVD) system or facilities for wet chemistry.

- (3-aminopropyl)di-isopropylethoxysilane (APDIPES) or (3-aminopropyl)triethoxysilane (APTES) for surface coating.

- MS-compatible separation buffer (e.g., acidic buffer for positive ion mode MS).

- Syringe pump with appropriate tubing.

- High-voltage power supply.

Methodology:

- Device Coating: To generate a stable, positively charged surface that supports anodic electroosmotic flow (EOF) in acidic buffers, coat the glass microchannels using a CVD system. APDIPES is recommended as it has been shown to produce near diffusion-limited separations (theoretical plates >600,000 for peptides) [34].

- Emitter Preparation: Design the device so the separation channel extends to a sharp corner or point. This limits the surface area for liquid spreading and stabilizes the electrospray.

- Electrical Connection: Fabricate a secondary "sheath" channel that intersects the separation channel just before its terminus. Use this channel to apply the electrospray voltage (e.g., 3.6 kV) and/or to introduce a makeup sheath liquid to aid spray stability.

- Alignment: Precisely align the sharpened emitter corner of the chip with the orifice of the mass spectrometer.

- Operation: Drive the separation using EOF or pressure. The separated analytes will be ionized directly from the chip's edge and sampled into the MS.

Protocol 2: Pressure Decay Test for Microfluidic Device Leakage

This non-destructive test is critical for ensuring device integrity before running precious samples for trace analysis [37].

Objective: To quantitatively assess the mechanical integrity and leak-tightness of a sealed microfluidic device.

Materials:

- Device Under Test (DUT).

- Pressure source (regulated air or nitrogen).

- Pressure sensor/transducer with high sensitivity.

- Data acquisition system.

- Sealing fixtures and tubing.

Methodology:

- Setup: Seal all fluidic ports of the DUT except one, which is connected to the pressure source and sensor.

- Pressurization: Pressurize the DUT to a specified test pressure (e.g., 1.5x the expected operating pressure).

- Isolation: Quickly isolate the DUT from the pressure source by closing a valve. The internal pressure will now be contained within the DUT.

- Monitoring: Monitor the pressure inside the DUT over a defined period (e.g., 2-5 minutes) using the high-sensitivity sensor.

- Analysis: Calculate the pressure decay rate. A significant pressure drop over time indicates a leak. The acceptable decay rate should be defined based on the application's sensitivity requirements. This method can be adapted from standards like ASTM F2338-09 (Vacuum Decay Method) [37].

Visual Workflows and Diagrams

Microfluidic-MS Integration and Troubleshooting Workflow

This diagram outlines the key steps for integrating a microfluidic device with MS and the primary troubleshooting pathways for associated issues.

Key Research Reagent Solutions

This table details essential materials and their functions for experiments involving microfluidic devices coupled with mass spectrometry, particularly for trace analysis.

| Reagent/Material | Function in the Experiment |

|---|---|

| Polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) | A biocompatible, transparent, and gas-permeable polymer used for rapid prototyping of microfluidic devices via soft lithography. Ideal for live-cell imaging and cultivation prior to MS analysis [40]. |

| APDIPES/APTES Silane | Used for chemical vapor deposition (CVD) coating of glass microchannels. Creates a stable, positively charged surface that facilitates anodic electroosmotic flow in acidic buffers compatible with positive-ion mode ESI-MS [34]. |

| LC-MS Grade Solvents | High-purity solvents (water, acetonitrile, isopropanol) with minimal ionic and organic impurities. Critical for reducing chemical background noise and "ghost peaks" to achieve high sensitivity in trace contaminant detection [35]. |

| Hydroxypropyl-β-Cyclodextrin | A chiral selector added to the separation buffer in microfluidic electrophoresis to enable separation of enantiomeric compounds (e.g., reaction products) before MS detection [34]. |

Technical Troubleshooting Guide: Frequently Asked Questions

FAQ 1: How can I improve the sensitivity and limit of detection of my electrochemical aptasensor?

- Problem: Low sensitivity can stem from inefficient electron transfer, suboptimal probe density, or non-specific binding.

- Solution:

- Nanomaterial Enhancement: Integrate nanostructures like highly porous gold, polyaniline with platinum nanoparticles, or graphene into your electrode. These materials increase the active surface area and enhance electrical conductivity, which can significantly boost signal strength [41] [42].

- Probe Orientation: Ensure proper orientation of your aptamer or antibody capture probes on the sensor surface. Using a well-designed self-assembled monolayer (SAM) and controlled immobilization chemistry (e.g., EDC/NHS coupling) can improve target accessibility [41].

- Signal Amplification: Employ enzymatic labels (e.g., horseradish peroxidase) or nanolabels (e.g., gold nanoparticles) that catalyze a reaction to produce a multitude of detectable molecules for a single binding event [43].

FAQ 2: My biosensor has a narrow dynamic range. How can I extend its operational window?

- Problem: The sensor signal saturates at relatively low target concentrations, limiting its usefulness for real samples.

- Solution:

- Tune Bioreceptor Affinity: For synthetic biology elements like transcription factors, use directed evolution or rational protein engineering to modify the ligand-binding domain and adjust the affinity constant (

Kd) [44]. - Optimize Surface Chemistry: Vary the density of immobilized bioreceptors (e.g., aptamers, antibodies). A very high density can lead to steric hindrance and reduce the effective operating range [44].

- Employ a Dual-Sensor System: Combine two bioreceptors with different affinities for the same target on a single platform. The high-affinity sensor captures low concentrations, while the low-affinity sensor extends the range to higher concentrations [44].