Advanced Strategies for Acrylamide Mitigation in Processed Foods: From Molecular Mechanisms to Industrial Application

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of evidence-based strategies for reducing acrylamide, a Group 2A probable human carcinogen, in thermally processed foods.

Advanced Strategies for Acrylamide Mitigation in Processed Foods: From Molecular Mechanisms to Industrial Application

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of evidence-based strategies for reducing acrylamide, a Group 2A probable human carcinogen, in thermally processed foods. Tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, the content explores the molecular foundations of acrylamide formation via the Maillard reaction, details cutting-edge mitigation methodologies including enzymatic and novel technological interventions, addresses critical challenges in industrial implementation and sensory optimization, and evaluates analytical and comparative frameworks for validation. By synthesizing current research and regulatory landscapes, this review aims to bridge the gap between laboratory findings and scalable food safety applications, offering a scientific basis for future biomedical research and toxicity risk management.

Understanding Acrylamide: Formation Pathways, Toxicity, and Regulatory Landscape

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Challenges

FAQ: Why does my asparaginase treatment yield inconsistent acrylamide reduction despite controlled temperature and pH?

Inconsistent results with asparaginase treatment often stem from insufficient enzyme-substrate contact or the presence of inhibitory compounds in the complex food matrix. The enzyme must adequately access free asparagine before thermal processing to achieve effective mitigation [1]. Solutions include:

- Increase treatment time or enzyme concentration: Extend incubation time or optimize dosage to ensure complete precursor conversion [2].

- Improve substrate accessibility: For solid foods, consider injecting enzyme solutions or creating purees to enhance penetration [3].

- Matrix purification: Remove fats and proteins that may hinder enzyme activity using Carrez solution or acetonitrile extraction [4].

- Uniform application: Ensure homogeneous distribution of the enzyme solution throughout the food sample [1].

FAQ: My acrylamide quantification shows high variability between replicate samples. What analytical factors should I verify?

High variability often originates from incomplete extraction or matrix interference during analysis. Address this by:

- Optimize extraction parameters: Use acidified acetonitrile as your solvent, maintain a consistent solvent-to-sample ratio (typically 5:1 to 10:1), and ensure adequate homogenization [4].

- Implement defatting: For fatty matrices, include a defatting step with non-polar solvents before acrylamide extraction [4].

- Control thermal degradation: Avoid generating additional acrylamide during extraction by keeping temperatures below 60°C during solvent removal [4].

- Use internal standards: Incorporate deuterated acrylamide (acrylamide-d3) as an internal standard to correct for recovery variations [4].

FAQ: How can I effectively balance acrylamide reduction with maintaining desirable sensory properties in my product?

The Maillard reaction creates both acrylamide and desirable flavor compounds, creating a significant challenge [1]. Strategies include:

- Targeted precursor reduction: Use asparaginase to specifically convert asparagine to aspartic acid, which doesn't form acrylamide but still participates in flavor development [1] [2].

- Combination approaches: Employ multiple mild interventions (e.g., slight pH reduction, blanching, and lower-temperature vacuum processing) rather than a single aggressive method [2] [3].

- Antioxidant incorporation: Add natural antioxidants like rosemary extract or green tea polyphenols, which can inhibit acrylamide formation while potentially enhancing flavor complexity [2] [5].

- Optimize thermal input: Use just enough heat to achieve target sensory attributes, as acrylamide formation increases exponentially with temperature [5].

Experimental Protocols & Methodologies

Asparaginase Treatment Protocol for Cereal-Based Products

This protocol details the application of asparaginase to dough systems for acrylamide mitigation in baked goods, achieving 50-90% reduction when optimized [2] [3].

Materials Required:

- L-asparaginase enzyme (commercial food-grade)

- Wheat flour (or other cereal flour)

- Buffer solutions (pH 4-7)

- Incubator or water bath

- Mixing equipment

Procedure:

- Enzyme Solution Preparation: Prepare asparaginase solution in appropriate buffer. Optimal activity typically occurs between pH 4-7 and 30-50°C [3].

- Dough Formation: Incorporate enzyme solution during dough mixing. Ensure uniform distribution.

- Incubation: Incubate dough at 30-40°C for 30-60 minutes to allow asparagine conversion.

- Termination: Proceed directly to baking; enzyme activity ceases above 60°C.

- Control Preparation: Prepare identical dough without enzyme treatment for comparison.

Critical Parameters:

- Maintain dough temperature below 40°C during incubation to prevent premature Maillard reaction

- Optimal enzyme dosage typically ranges from 100-300 ASNU/kg flour [3]

- Adjust water content in formulation to account for added enzyme solution

LC-MS/MS Acrylamide Quantification Method

This method enables precise acrylamide detection at trace levels (μg/kg range) in complex food matrices [4].

Materials Required:

- Liquid chromatography system coupled to tandem mass spectrometer

- Acrylamide standard (and acrylamide-d3 internal standard)

- Extraction solvents (water, acetonitrile, acidified acetonitrile)

- Solid-phase extraction cartridges (if needed)

- Centrifuge and homogenization equipment

Procedure:

- Sample Preparation: Homogenize sample to fine powder. For high-fat matrices, defat with hexane prior to extraction.

- Extraction: Weigh 1g sample into centrifuge tube, add 5mL acidified acetonitrile and internal standard. Shake vigorously for 1 minute.

- Centrifugation: Centrifuge at 4000×g for 10 minutes. Collect supernatant.

- Clean-up (if needed): Pass extract through solid-phase extraction cartridge for complex matrices.

- Concentration: Evaporate extract to near-dryness under gentle nitrogen stream at <50°C.

- Reconstitution: Reconstitute in mobile phase for LC-MS/MS analysis.

- Chromatography: Use reverse-phase C18 column with water/methanol mobile phase.

- MS Detection: Employ multiple reaction monitoring (MRM) with transitions m/z 72→55 and 72→44 for acrylamide.

Quality Control:

- Include method blanks to monitor contamination

- Use matrix-matched calibration standards

- Maintain recovery rates of 85-115% with internal standard correction

Quantitative Data Comparison

Table 1: Efficacy Comparison of Acrylamide Mitigation Strategies in Cereal-Based Products

| Mitigation Strategy | Reduction Efficiency | Key Parameters | Impact on Sensory Properties |

|---|---|---|---|

| Asparaginase Treatment | 50-90% [2] [3] | pH 4-7, 30-50°C, 30-60min incubation | Minimal impact when optimized; maintains Maillard-derived flavors [1] |

| Glucose Oxidase | 30-70% [2] | pH 5-7, 30-45°C | May affect browning and sweetness due to glucose depletion [2] |

| Natural Antioxidants | 20-60% [2] [5] | 0.1-0.5% concentration in dough | Can introduce distinctive flavors; rosemary extract may impart herbal notes [2] |

| Vacuum Baking | 40-80% [2] [3] | 50-200 mbar, 15-30°C lower temperature | Alters texture and crust formation; may require process adjustment [3] |

| Fermentation | 30-70% [3] | 18-48 hours, LAB cultures | Develops characteristic sourdough flavors; affects volume and texture [3] |

Table 2: Typical Acrylamide Levels in Common Food Categories

| Food Category | Acrylamide Range (mcg/kg) | Primary Factors Influencing Formation |

|---|---|---|

| Bread Products | 10-1500 [2] | Flour type, fermentation time, baking temperature, surface browning |

| Biscuits & Cookies | 20-1000 [2] | Recipe (sugar type), thickness, baking temperature and time |

| Breakfast Cereals | 10-1000 [2] | Cereal type, extrusion parameters, toasting degree |

| Potato Products | 200-3700 (estimated from studies) | Potato variety, storage conditions, cutting style, frying temperature/time [6] |

| Coffee | Varies with roast degree | Bean type, roasting temperature and profile, degree of roast [5] |

Pathway Visualizations

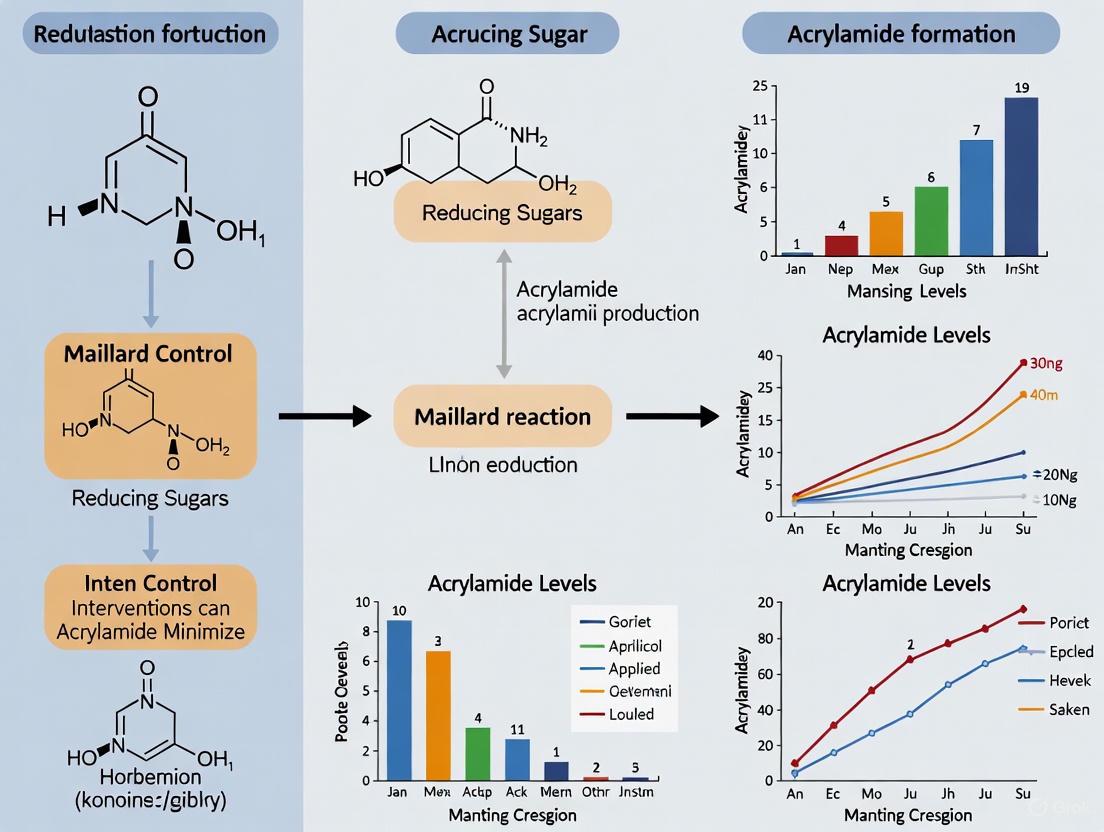

Figure 1: Primary Acrylamide Formation Pathway

Figure 2: Enzymatic Acrylamide Mitigation Pathways

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Acrylamide Mitigation Studies

| Reagent / Material | Function / Application | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| L-Asparaginase | Converts asparagine to aspartic acid, removing key acrylamide precursor [1] [3] | Select food-grade versions; optimize pH (4-7) and temperature (30-50°C) for specific matrices |

| Glucose Oxidase | Reduces glucose content, limiting Maillard reaction substrates [2] | May require oxygen cofactor; affects product sweetness and browning potential |

| Natural Antioxidants (Rosemary extract, green tea polyphenols) | Inhibit Maillard reaction and scavenge free radicals [2] [5] | Can impart flavor/color; effective at 0.1-0.5% concentrations; consider synergistic effects |

| Lactic Acid Bacteria | Utilizes asparagine and reducing sugars during fermentation [3] | Select strains with high asparagine utilization; 18-48 hour fermentation typically required |

| LC-MS/MS System | Gold-standard acrylamide quantification at trace levels [4] | Requires internal standards (acrylamide-d3); method detection limits of 1-10 μg/kg achievable |

| Solid-Phase Extraction Cartridges | Matrix clean-up prior to analysis [4] | Improve method accuracy for complex matrices; select appropriate sorbent chemistry |

Acrylamide (ACR) is a chemical contaminant that forms naturally in carbohydrate-rich foods during high-temperature processing methods such as frying, roasting, and baking. It was first identified in food in 2002, drawing significant scientific and regulatory attention due to its concerning toxicological profile [5]. Acrylamide primarily forms via the Maillard reaction between the amino acid asparagine and reducing sugars like glucose and fructose at temperatures exceeding 120°C [5] [4]. Common dietary sources include fried potato products, baked cereals, bread, coffee, and various snack foods [5]. This technical resource addresses the key toxicological risks of acrylamide exposure—neurotoxicity, carcinogenicity, and reproductive toxicity—within the context of research aimed at reducing its formation in processed foods. It provides troubleshooting guidance and methodological support for scientists investigating these health impacts and developing mitigation strategies.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) on Acrylamide Toxicity

Q1: What are the primary metabolic pathways of acrylamide in biological systems? Acrylamide is a small, water-soluble molecule that undergoes rapid absorption and distribution throughout the body [7] [8]. Its metabolism proceeds via two main competing pathways:

- Detoxification via Glutathione Conjugation: Acrylamide can conjugate with glutathione, a process catalyzed by glutathione S-transferases. This reaction forms N-acetyl-S-cysteine, which is further metabolized into mercapturic acids and excreted in urine. This pathway represents a primary detoxification route [4] [8].

- Bioactivation via Cytochrome P450: Alternatively, acrylamide can be transformed by the cytochrome P450 enzyme system (specifically CYP2E1) into a highly reactive epoxide metabolite, glycidamide (GA) [4] [8]. Glycidamide exhibits a greater ability to form adducts with DNA and proteins (such as hemoglobin) than its parent compound, which is a key mechanism underlying its genotoxic and carcinogenic potential [7] [8].

Q2: What is the molecular basis for acrylamide-induced neurotoxicity? Neurotoxicity is the most well-documented effect of acrylamide in humans [8]. The mechanisms are multifaceted, involving:

- Nerve Terminal Damage: ACR can form covalent adducts with nucleophilic cysteine residues on presynaptic proteins. This deactivates neurons and disrupts neurotransmitter release, leading to nerve terminal degeneration in both the central and peripheral nervous systems [4] [8].

- Oxidative Stress: The conjugation of ACR with glutathione depletes antioxidant reserves, leading to an accumulation of reactive oxygen species. This oxidative stress contributes significantly to neuronal damage [9] [4] [8].

- Inflammatory Response and Apoptosis: ACR exposure can trigger neuroinflammation, including the activation of microglial cells and astrocytes. It can also induce programmed cell death (apoptosis) in nerve cells [8]. Emerging research also suggests a role for gut-brain axis disruption in ACR neurotoxicity [8].

Q3: Why is acrylamide classified as a probable human carcinogen? The International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) classifies acrylamide as a Group 2A carcinogen, meaning it is "probably carcinogenic to humans" [8]. This classification is based on "sufficient evidence" of carcinogenicity in animal studies [7]. The primary mechanism involves its metabolite, glycidamide. Glycidamide can bind to purine bases in DNA, forming DNA adducts that can lead to mutations and initiate cancer development [7] [4] [8]. While epidemiological studies in humans have provided limited and sometimes inconsistent evidence, the robust animal data warrant this precautionary classification [7].

Q4: How does acrylamide affect reproductive health and development? Acrylamide has demonstrated adverse effects on reproduction and development in animal models:

- Reproductive Toxicity: It causes dominant lethal mutations, sperm-head abnormalities, and degeneration of testicular epithelial tissue [7].

- Developmental Toxicity: ACR can cross the placental barrier and reach the developing fetus. Studies indicate it can produce direct developmental and post-natal effects, with neurotoxicity observed in neonates even at exposure levels not overtly toxic to the mother [7].

Q5: What are the primary sources of human exposure to acrylamide? Exposure occurs through three main routes:

- Dietary Exposure: This is the most significant source for the general population. Foods like French fries, potato chips, bread, biscuits, breakfast cereals, and coffee are major contributors [5] [8].

- Occupational Exposure: Workers in industries involving the production of acrylamide polymers, grouting, paper manufacturing, and wastewater treatment may be exposed through inhalation or dermal contact [8].

- Environmental Exposure: Lower-level exposure can occur through drinking water (where polyacrylamide is used as a flocculant), cigarette smoke, and cosmetics [8].

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Challenges

Challenge 1: Inconsistent Acrylamide Formation in Food Models

- Problem: Difficulty in achieving reproducible levels of acrylamide in lab-scale food models, leading to highly variable experimental data.

- Solution:

- Standardize Precursor Levels: Select and characterize raw materials (e.g., potato variety, flour type) for consistent levels of asparagine and reducing sugars [5].

- Control Processing Parameters Precisely: Use ovens and fryers with accurate temperature control and monitoring. Key parameters include:

- Monitor Food pH: The pH of the food matrix affects acrylamide formation, which is favored in neutral to slightly alkaline conditions [5].

Challenge 2: Low Recovery Rates During Acrylamide Extraction and Analysis

- Problem: Poor extraction efficiency and low recovery of acrylamide from complex food matrices.

- Solution:

- Optimize Sample Preparation: Ensure thorough homogenization and consider a defatting step for fatty foods using non-polar solvents [4].

- Select an Appropriate Extraction Solvent: Acetonitrile, particularly acidified acetonitrile, has demonstrated high efficacy in extracting acrylamide while precipitating proteins and reducing co-extraction of non-polar interferents [4].

- Implement Purification Techniques: Use solid-phase extraction (SPE) or Carrez clarification to remove impurities and reduce matrix effects before instrumental analysis [4].

Challenge 3: Differentiating the Effects of Acrylamide vs. Glycidamide

- Problem: Difficulty in attributing observed toxicological effects specifically to acrylamide or its metabolite, glycidamide.

- Solution:

- Biomarker Analysis: Measure specific hemoglobin (Hb) adducts. Hb adducts of both acrylamide and glycidamide serve as reliable biomarkers of internal exposure and metabolic activation [4] [8].

- Use of Metabolic Inhibitors: In in vitro or in vivo models, employ selective inhibitors of the CYP2E1 enzyme (e.g., disulfiram) to block the conversion of ACR to GA. Comparing outcomes with and without inhibition can help delineate their respective roles [8].

- Direct Metabolite Quantification: Quantify urinary metabolites, including mercapturic acids of both ACR and GA, to assess metabolic pathway activity [4] [8].

Experimental Protocols for Toxicity Assessment

Protocol for In Vitro Assessment of Neurotoxicity

Objective: To evaluate acrylamide-induced cytotoxicity and oxidative stress in neuronal cell lines (e.g., SH-SY5Y or PC12 cells).

Methodology:

- Cell Culture: Maintain cells in appropriate medium and passage regularly.

- ACR Exposure: Seed cells in multi-well plates and treat with a range of ACR concentrations (typical range 0.1-5 mM) for 24-72 hours. Include a vehicle control (e.g., DMSO <0.1%) [8].

- Viability Assay: Perform an MTT or Alamar Blue assay to measure cell viability and determine the IC₅₀ value.

- Oxidative Stress Measurement:

- ROS Detection: Use a fluorescent probe like DCFH-DA to measure intracellular reactive oxygen species.

- Antioxidant Status: Measure the level of reduced glutathione (GSH) using a commercial kit.

- Apoptosis Assay: Detect apoptotic cells via Annexin V-FITC/PI staining followed by flow cytometry.

Troubleshooting Tip: If the cytotoxic effect is too rapid, consider using a shorter exposure time or lower concentration range. Ensure ACR solutions are prepared fresh in aqueous buffer to avoid degradation.

Protocol for Analyzing Acrylamide and its Metabolites

Objective: To quantify acrylamide levels in food samples and corresponding biomarkers in biological samples.

Methodology:

- Sample Preparation (Food):

- Homogenization: Freeze the food sample with liquid nitrogen and grind to a fine powder.

- Extraction: Weigh ~1 g of sample, add 10 mL of acidified acetonitrile, and vortex/shake vigorously for 20 minutes [4].

- Clean-up: Centrifuge, collect the supernatant, and pass it through a SPE cartridge (e.g., C18 or mixed-mode). Evaporate the eluent to dryness under a gentle nitrogen stream and reconstitute in a mobile phase for analysis [4].

- Instrumental Analysis:

- Technique: Liquid Chromatography coupled with Tandem Mass Spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) is the gold standard due to its high sensitivity and selectivity [4].

- Chromatography: Use a reverse-phase C18 column. A water/methanol or water/acetonitrile gradient is typical.

- Mass Spectrometry: Operate in Multiple Reaction Monitoring (MRM) mode. Key transitions for ACR are m/z 72 → 55 and 72 → 27 [4].

- Biomarker Analysis (Hb Adducts):

- Isolate hemoglobin from blood samples.

- Hydrolyze the adducts to release modified amino acids (e.g., for GA, it releases hydroxy-hydroxypropylvaline).

- Derivatize and analyze using GC-MS or LC-MS/MS [8].

Troubleshooting Tip: Matrix effects can suppress or enhance the MS signal. Use isotope-labeled internal standards (e.g., ¹³C₃-acrylamide) to correct for recovery losses and matrix effects.

Data Presentation: Toxicity Reference Tables

Table 1: Summary of Acrylamide's Toxicological Effects and Key Evidence

| Toxicity Endpoint | Key Mechanistic Insights | Experimental Evidence | Observed Effects in Models |

|---|---|---|---|

| Neurotoxicity | Covalent binding to presynaptic proteins; Oxidative stress; Neuroinflammation; Axonal degeneration [4] [8]. | Human occupational exposure; Animal models (rats, mice) at 5-50 mg/kg/day [8]. | Gait abnormalities, weakness, weight loss, nerve terminal damage, glial cell activation [8]. |

| Carcinogenicity | Metabolic activation to glycidamide (GA); Formation of DNA adducts leading to mutations [7] [4] [8]. | Animal studies (rodents) showing tumors at multiple sites [7]. | Classified as Group 2A ("probable human carcinogen") by IARC [8]. |

| Reproductive & Developmental Toxicity | Transplacental transfer; Direct toxicity to germinal and testicular cells [7]. | Animal studies (rodents) [7]. | Dominant lethal mutations, sperm abnormalities, testicular atrophy, developmental neurotoxicity in offspring [7]. |

Table 2: Acrylamide Content in Common Food Sources and Regulatory Benchmarks

| Food Category | Typical Acrylamide Levels (μg/kg) | EU Benchmark Levels (μg/kg) [5] [8] |

|---|---|---|

| French Fries (ready-to-eat) | Up to 1000+ [5] | 500 |

| Potato Crisps | Varies widely, can be high [5] | 750 |

| Bread & Bakery Products | Moderate [5] | Varies by product (e.g., 50-300 for soft bread) |

| Roasted Coffee | Up to 4500 [8] | 400 |

| Instant Coffee | - | 850 |

| Breakfast Cereals | Moderate [5] | Varies by cereal (e.g., 150-300) |

Signaling Pathways and Experimental Workflows

Acrylamide Metabolism and Neurotoxicity Pathways

Diagram 1: ACR Metabolic Pathways and Toxicity

Workflow for Food Acrylamide Analysis and Mitigation

Diagram 2: Food ACR Analysis Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Essential Reagents and Materials for Acrylamide Research

| Item/Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application in Research |

|---|---|---|

| Analytical Standards | Acrylamide (¹²C₃), Isotope-Labeled Acrylamide (¹³C₃) | Quantification by LC-MS/MS; used as internal standard to ensure analytical accuracy and correct for matrix effects [4]. |

| Enzymes for Mitigation | L-Asparaginase (from Aspergillus or E. coli) | Pre-treatment of raw materials to hydrolyze the primary precursor, asparagine, thereby reducing acrylamide formation [5] [10]. |

| Cell Culture Models | SH-SY5Y, PC12, primary neuronal cultures | In vitro models for studying mechanisms of neurotoxicity, oxidative stress, and apoptosis [8]. |

| Metabolic Probes CYP2E1 Inhibitors (e.g., Disulfiram), Glutathione Depletors (e.g., BSO) | To investigate metabolic pathways; inhibiting CYP2E1 blocks formation of glycidamide, allowing differentiation of ACR vs. GA effects [8]. | |

| Antioxidants & Phytochemicals | Polyphenols (e.g., from tea, rosemary), Vitamins | Used in mitigation studies to counteract oxidative stress induced by ACR and potentially reduce its formation in food [9] [10]. |

| Chromatography Consumables | C18 SPE Cartridges, Reverse-Phase LC Columns (C18), HPLC-grade solvents (Acetonitrile, Methanol) | Sample clean-up and purification; essential components for the separation and analysis of acrylamide in complex food and biological matrices [4]. |

Dietary Exposure and Public Health Concerns for Vulnerable Populations

FREQUENTLY ASKED QUESTIONS (FAQs)

FAQ 1: What are the primary metabolic pathways of acrylamide in humans, and why is this significant for risk assessment?

Acrylamide is metabolized via two primary pathways. The major detoxification route involves direct conjugation with glutathione, facilitated by glutathione-S-transferases (GSTs), leading to the excretion of mercapturic acid derivatives. The primary activation pathway is CYP2E1 (cytochrome P450 2E1)-dependent epoxidation, which converts acrylamide into its genotoxic metabolite, glycidamide (GA). Glycidamide can form adducts with DNA and proteins, which is considered the main pathway responsible for the carcinogenic effects observed in animal studies. The balance between these activation and detoxification pathways, influenced by genetic polymorphisms in enzymes like CYP2E1, GSTs, and EPHX1, is a critical determinant of individual susceptibility and is essential for precise risk characterization [11].

FAQ 2: Beyond potatoes and cereals, what are some less obvious dietary sources of acrylamide that researchers should consider in exposure models?

While potato products, cereals, and coffee are well-known sources, certain cooking practices for other foods can contribute significantly to exposure. Studies, particularly in Asian populations, have identified vegetables cooked at high temperatures (e.g., stir-frying, roasting) as notable contributors. Additionally, canned black olives, prune juice, and certain teas have been reported to contain acrylamide. The trend of "snackification" means that foods consumed outside main meals, such as potato-based crackers, chips, and even some roasted vegetable snacks, can have high concentrations and contribute nearly as much to total exposure as main meals, highlighting the need for comprehensive dietary surveys [12] [13].

FAQ 3: What is the biochemical rationale for using asparaginase as a mitigation strategy, and what are its limitations?

Asparaginase is an enzyme that catalyzes the hydrolysis of the amino acid asparagine into aspartic acid and ammonia. Since free asparagine is the primary precursor for acrylamide formation in the Maillard reaction, reducing its availability in the raw food matrix directly limits the potential for acrylamide generation during subsequent thermal processing. This intervention targets the root cause of the problem in starchy foods. Its limitations include potential cost implications, the need for optimization for different food matrices to ensure effectiveness, and the necessity to ensure that its application does not adversely affect the final product's taste, texture, or other organoleptic properties [14] [15].

TROUBLESHOOTING GUIDES

Issue 1: Inconsistent Acrylamide Measurement in Bakery Product Replicates

Problem: High variability in acrylamide levels when testing multiple batches of the same bakery product formula.

Solution: Investigate and control key variables in the experimental protocol.

- Potential Cause 1: Inconsistent fermentation conditions.

- Corrective Action: Strictly control yeast percentage, fermentation temperature, and time. Studies show that extending fermentation time to 10-12 hours can significantly reduce acrylamide in the final product by allowing yeast to consume more free sugars and asparagine [14].

- Potential Cause 2: Fluctuating oven temperature and hot spots.

- Corrective Action: Calibrate the oven thermometer and use data loggers to map the temperature profile. Optimize baking to the lowest possible temperature and time that ensures product safety and quality. For instance, reducing biscuit baking temperature from 200°C to 180°C can cut acrylamide formation by over 50% [14].

- Potential Cause 3: Variable raw material composition.

Issue 2: Failure to Reduce Acrylamide in Fried Potato Prototypes

Problem: Mitigation strategies applied to potato products (e.g., fries, chips) are not yielding the expected reduction in acrylamide.

Solution: Focus on pre-processing steps and cooking parameters.

- Potential Cause 1: Incorrect potato storage.

- Potential Cause 2: Inadequate pre-treatment.

- Potential Cause 3: Overly aggressive frying.

- Corrective Action: Aim for a final product color of golden yellow rather than dark brown. Avoid burning. The end-point color is a direct visual indicator of the extent of the Maillard reaction and acrylamide formation [18].

DATA TABLES

Table 1: Benchmark Levels and Reported Acrylamide Concentrations in Select Cereal-Based Foods

This table compiles regulatory benchmarks and occurrence data to help researchers set target levels for their mitigation studies.

| Food Category | EU Benchmark Level (μg/kg) [14] | Mean Reported Level (μg/kg) [14] | 95th Percentile Reported Level (μg/kg) [14] |

|---|---|---|---|

| Soft Bread (Wheat) | 50 | 38 | 120 |

| Breakfast Cereals (Maize, Oats) | 150 | 102 | 403 |

| Biscuits and Wafers | 350 | 201 | 810 |

| Crackers | 400 | 231 | 590 |

| Gingerbread | 800 | 407 | 1600 |

| Baby Foods (Processed Cereal) | 40 | 89 | 60 |

Table 2: Estimated Dietary Acrylamide Exposure in Different Populations

This table summarizes exposure assessments from various regions, which is crucial for understanding public health impact and prioritizing research.

| Population / Country | Mean Exposure (μg/kg bw/day) | High Consumer Exposure (95th Percentile, μg/kg bw/day) | Main Dietary Contributors |

|---|---|---|---|

| Singapore [13] | 0.165 | 0.392 | Potato crackers/chips, vegetables cooked at high temps |

| United States [12] | 0.36 - 0.44 | - | French fries, breakfast cereals, cookies, potato chips |

| Europe (EFSA) [13] | 0.4 - 1.9 | 0.6 - 3.4 | Fried potatoes, coffee, bakery products |

| China [13] | 0.175 | - | Potato samples, cooked vegetables |

| Hong Kong [13] | 0.213 | 0.538 | Snack foods, cooked vegetables |

EXPERIMENTAL PROTOCOLS

Protocol 1: Determining the Impact of Fermentation Time on Acrylamide in Wheat Bread

1. Objective: To quantify the reduction of acrylamide in wheat bread as a function of yeast fermentation time.

2. Materials:

- Standard bread-making ingredients: wheat flour, water, yeast, salt.

- Laboratory-scale bakery equipment (mixer, proofer, oven).

- Liquid Chromatography with Tandem Mass Spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) system for acrylamide analysis [13].

3. Methodology:

- Step 1: Dough Preparation. Prepare a standardized dough formula. Divide into equal portions.

- Step 2: Controlled Fermentation. Subject each dough portion to a fixed proofing temperature (e.g., 30°C) but vary the fermentation time (e.g., 2, 4, 6, 8, 10, and 12 hours).

- Step 3: Baking. Bake all samples under identical conditions (temperature and time) until a standardized, light golden-brown color is achieved.

- Step 4: Sample Analysis. Homogenize the baked bread crust and crumb. Extract and analyze acrylamide content using a validated LC-MS/MS method. The use of an internal standard like acrylamide-2,3,3-d3 is recommended for quantification accuracy [13].

4. Expected Outcome: A significant, non-linear decrease in acrylamide content is expected with increased fermentation time, as observed in previous studies where extension to 10-12 hours showed a strong mitigating effect [14].

Protocol 2: Evaluating the Efficacy of Asparaginase in a Cookie Model System

1. Objective: To assess the reduction of acrylamide in cookies treated with the enzyme asparaginase prior to baking.

2. Materials:

- Cookie ingredients: wheat flour, sugar, fat, water.

- Food-grade asparaginase preparation.

- Dough sheeter, cookie cutters, laboratory oven.

- LC-MS/MS system for acrylamide analysis.

3. Methodology:

- Step 1: Dough Preparation & Treatment. Prepare a uniform cookie dough. Divide into two batches.

- Control Batch: No enzyme added.

- Treated Batch: Incorporate asparaginase according to the manufacturer's specifications. Allow sufficient incubation time and temperature for the enzyme to react with free asparagine in the dough.

- Step 2: Baking. Bake both batches under identical conditions (e.g., 180°C vs 200°C) to a similar light color.

- Step 3: Analysis. Measure and compare the acrylamide levels in the control and treated cookies.

4. Expected Outcome: The asparaginase-treated batch is expected to show a significant reduction (e.g., >50%) in acrylamide compared to the control, confirming the removal of the key precursor, as demonstrated in model systems [15].

DIAGRAMS

Acrylamide Metabolism Pathways

Acrylamide Formation in Food

THE SCIENTIST'S TOOLKIT

Key Research Reagent Solutions

| Reagent / Material | Function in Acrylamide Research |

|---|---|

| Asparaginase | Enzyme used to hydrolyze free asparagine in food matrices, reducing the primary precursor for acrylamide formation [14]. |

| Deuterated Internal Standards (e.g., Acrylamide-2,3,3-d3) | Used in LC-MS/MS analysis for highly accurate and precise quantification of acrylamide, correcting for matrix effects and recovery losses [13]. |

| Glutathione (GSH) | Key tripeptide for studying the detoxification pathway of both acrylamide and glycidamide via conjugation, catalyzed by Glutathione-S-Transferases (GSTs) [11]. |

| Specific CYP2E1 Inhibitors (e.g., diethyldithiocarbamate) | Pharmacological tools used in in vitro and in vivo models to inhibit the metabolic activation of acrylamide to glycidamide, helping to elucidate its role in toxicity [11]. |

| Antibodies for GA-DNA/Protein Adducts | Essential reagents for immunoassays or immunohistochemistry to detect and quantify the formation of glycidamide-derived adducts, biomarkers of genotoxic exposure [11]. |

Troubleshooting Guide: Acrylamide Analysis and Mitigation

FAQ 1: My food product samples consistently exceed acrylamide benchmarks despite process adjustments. What are the key precursors I should be analyzing in my raw materials?

The primary precursors for acrylamide formation are free asparagine (an amino acid) and reducing sugars (e.g., glucose, fructose) [17]. Your experimental protocol should prioritize the quantification of these compounds in raw ingredients.

Detailed Methodology for Precursor Analysis:

- Sampling: Obtain a representative sample of your raw material (e.g., potato flour, wheat flour). For potatoes, note the cultivar and storage conditions, as these significantly impact sugar levels [20].

- Extraction: Use a solvent like water or methanol-water solution to extract free amino acids and sugars from the homogenized sample.

- Analysis: Employ High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC) coupled with a Mass Spectrometer (MS) or a UV detector. Specific settings will depend on the target analytes, but the method should be validated for quantifying asparagine and reducing sugars.

- Data Interpretation: Correlate high precursor levels with acrylamide concentrations in the final cooked product. Research indicates that the use of potato varieties with low reducing sugar content or the partial replacement of wheat flour with rice flour are effective mitigation strategies rooted in reducing these precursors [20].

Research Reagent Solutions:

Research Reagent Function in Experiment L-Asparagine Standard Serves as a reference standard for calibrating the HPLC/MS instrument to quantify asparagine concentration in samples. Reducing Sugar Standards A mix of glucose, fructose, and maltose used to calibrate the analytical instrument for accurate sugar quantification. Asparaginase Enzyme A processing aid that converts the amino acid asparagine into aspartic acid, thereby preventing it from forming acrylamide during heating [21]. Solvents (e.g., Methanol, Water) Used for the extraction of free amino acids and reducing sugars from solid food matrices during sample preparation.

FAQ 2: When validating a new mitigation technique like asparaginase application, what is the critical experimental workflow to ensure it does not adversely affect product quality?

A rigorous validation workflow must assess both acrylamide reduction and the final product's sensory properties, as mitigation should not adversely impact consumer acceptance [21].

- Experimental Protocol for Mitigation Validation:

- Sample Preparation: Divide your food product batter or dough into two batches: a control group and a test group where asparaginase is applied according to the manufacturer's specifications (e.g., dosage, incubation time/temperature).

- Processing: Cook both batches using your standard process (e.g., frying, baking) under strictly controlled time-temperature conditions.

- Analysis:

- Acrylamide Quantification: Use GC-MS or LC-MS/MS to measure acrylamide levels in both the control and test samples. Calculate the percentage reduction.

- Quality Assessment: Conduct a paired comparison test using a trained sensory panel. Evaluate key attributes like color (using a colorimeter), texture, taste, and aroma [21].

- Data Interpretation: The mitigation is successful if a significant reduction in acrylamide is achieved (ideally below the relevant benchmark level) with no statistically significant negative impact on the sensory profile.

The following workflow diagrams the logical relationship between regulatory goals, mitigation strategies, and necessary validation steps.

Acrylamide Formation and Regulatory Context

A clear understanding of the acrylamide formation pathway is fundamental for researchers developing mitigation strategies. The following diagram details the primary chemical pathway.

FAQ 3: What are the current benchmark levels for acrylamide in major food categories, and how is the ALARA principle applied in a regulatory context?

There are currently no internationally mandated maximum limits for acrylamide in food [20]. Instead, regulatory bodies like the Codex Alimentarius Commission and the European Union have established benchmark levels to guide the implementation of the ALARA (As Low As Reasonably Achievable) principle [20] [21]. This means manufacturers are expected to reduce acrylamide levels as much as possible without adversely affecting the food supply, product safety, or consumer acceptance.

The following table summarizes the quantitative regulatory context. Note that these are benchmarks for mitigation measures, not strict legal limits.

| Food Category | Regulatory Context & Key Levels |

|---|---|

| French Fries & Potato Crisps | The EU sets benchmark levels. Mitigation includes selecting potato cultivars with low reducing sugars and controlling storage temperatures to prevent "cold sweetening" [20] [21]. |

| Bread, Biscuits, Cereals | The EU sets benchmark levels. The Code of Practice recommends replacing part of wheat flour with rice flour and avoiding reducing sugars and ammonium-based raising agents in recipes [20]. |

| Coffee & Coffee Substitutes | The EU sets benchmark levels. Acrylamide forms during roasting, with levels peaking early and declining in longer roasts; instant coffee may contain higher levels [19] [21]. |

| Baby Foods | The EU sets stringent benchmark levels. The ALARA principle is strictly applied due to infants' higher vulnerability and lower body weight [21] [22]. |

FAQ 4: Our color analysis shows a strong correlation between surface browning and acrylamide concentration. What is a reliable quantitative method to establish this for a new product?

The Maillard Reaction is responsible for both desirable browning/flavor and the formation of acrylamide [17]. You can establish a quantitative model to predict acrylamide levels based on color.

- Experimental Protocol for Color-Acrylamide Correlation:

- Sample Preparation: Create a series of samples (e.g., potato chips, toast) cooked to varying degrees of browning, from light to dark.

- Color Measurement: Use a colorimeter to measure the Lab* color space for each sample. The L* value (lightness) is often the most critical parameter, with a lower L* value indicating darker coloring.

- Acrylamide Quantification: Using the same samples, perform precise acrylamide quantification via LC-MS/MS (Liquid Chromatography with Tandem Mass Spectrometry), which is considered the gold standard due to its high sensitivity and specificity.

- Statistical Analysis: Perform a linear or non-linear regression analysis to establish a correlation between the colorimeter readings (e.g., L* value) and the chemically analyzed acrylamide concentration. This model can then be used for rapid, non-destructive screening of future batches.

Intervention Strategies: From Agricultural Selection to Processing Innovations

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: Why is selecting low-asparagine potato cultivars a primary strategy for reducing acrylamide in processed foods?

The formation of acrylamide in high-temperature processed foods primarily occurs through the Maillard reaction, which involves the amino acid asparagine and reducing sugars. In potato tubers, asparagine is the most abundant free amino acid, sometimes constituting over 50% of the total free amino acid pool. This makes it the major precursor for acrylamide formation during frying, baking, or roasting. By selecting cultivars that inherently accumulate lower levels of asparagine, the availability of this key precursor is reduced at the source, thereby limiting the potential for acrylamide formation during subsequent processing stages. This is considered a foundational and highly effective mitigation strategy [6] [23].

FAQ 2: Besides precursor content, what other raw material factors should we consider when selecting potatoes for low-acrylamide potential?

While low asparagine is crucial, a comprehensive selection criteria should include:

- Reducing Sugar Content: The concentration of reducing sugars (e.g., glucose, fructose) is equally critical, as it is the second reactant in acrylamide formation. Cultivars with low levels of both asparagine and reducing sugars are ideal.

- Cold Storage Response: Potatoes stored at low temperatures (below 6-8°C) can undergo "cold-induced sweetening," where starch breaks down into sugars, drastically increasing reducing sugar content. Selecting cultivars that are less susceptible to cold-induced sweetening is vital for maintaining low-acrylamide potential post-storage [24].

- Dry Matter/Solid Content: Cultivars with higher solid content tend to absorb less oil during frying and may have different heat transfer properties, which can indirectly influence acrylamide formation.

FAQ 3: What are the key methodological steps for screening and validating new potato cultivars for low acrylamide potential?

A robust experimental protocol involves a multi-step process, from raw material analysis to finished product testing, as visualized below.

FAQ 4: How do genetic approaches like CRISPR contribute to the development of low-asparagine cultivars?

Conventional breeding can be time-consuming and may not always combine low precursors with other desirable agronomic traits. Genetic engineering offers a more targeted approach. CRISPR-Cas9 technology enables precise gene editing to knock out specific genes responsible for metabolic pathways. For instance, research has shown that inactivating a single gene responsible for sugar accumulation during cold storage can significantly reduce cold-induced sweetening, thereby maintaining low reducing sugar levels. Similarly, genes in the asparagine biosynthesis pathway can be targeted to lower the free asparagine content in the tuber, creating next-generation cultivars with intrinsically low acrylamide-forming potential [6] [25].

FAQ 5: Are there any trade-offs in sensory or quality attributes when using low-asparagine/low-sugar cultivars?

This is a critical consideration for industry adoption. Cultivars with very low sugar levels may produce products with a lighter color because the Maillard reaction is also responsible for the desirable golden-brown color and roasted flavors. While this is positive from an acrylamide perspective, it may require adjustments to meet consumer expectations for color. Furthermore, flavor profiles might be altered. The key is to find a cultivar that achieves a balance – providing sufficiently low precursors to meet regulatory and safety benchmarks while still delivering acceptable sensory characteristics through optimized processing conditions [25].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: High Acrylamide Despite Using a Promising Low-Precursor Cultivar

| Symptom | Possible Cause | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| High acrylamide in final product. | Potatoes were stored at incorrect temperatures, leading to cold-induced sweetening. | Implement strict cold chain management. Store potatoes at recommended temperatures (typically above 8°C) and avoid prolonged cold storage. Monitor sugar levels upon receipt and before processing [24]. |

| Inconsistent acrylamide levels between batches of the same cultivar. | High natural variability in raw material. Inconsistent growing conditions, soil fertility, or harvest maturity. | Work with growers to ensure consistent agricultural practices. Implement robust incoming raw material inspection and sorting. Blend raw material from different lots to average out precursor levels. |

| Cultivar performs well in lab tests but not at industrial scale. | Industrial processing parameters (e.g., frying temperature/time, equipment type) are not optimized for the new cultivar. | Re-calibrate and optimize processing conditions (temperature, time) specifically for the new cultivar. Pilot-scale trials are essential before full-scale implementation. |

Problem: Challenges in Precursor Analysis and Cultivar Screening

| Symptom | Possible Cause | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Inaccurate quantification of asparagine or reducing sugars. | Sample preparation errors or interference from other compounds in the complex food matrix. | Use internal standards during HPLC analysis. Validate the analytical method for potato matrices. Ensure proper extraction and purification of analytes prior to injection. |

| Poor correlation between precursor levels in raw tubers and acrylamide in finished product. | Sampling method is not representative, or the processing conditions are not standardized during screening. | Use a standardized, controlled cooking protocol (e.g., fixed time/temperature) for all cultivar samples. Ensure a homogeneous and representative sample of the tuber is taken for both precursor and acrylamide analysis. |

Quantitative Data on Acrylamide in Foods

The following table summarizes the acrylamide levels found in various food categories, highlighting the high levels in potato products and the critical need for mitigation strategies like cultivar selection.

Table 1: Acrylamide Content in Various Food Products [24]

| Food Category | Specific Food Product | Acrylamide Content (μg/kg) |

|---|---|---|

| Potato Chips | Various Brands | Up to 3,000 |

| Potato Chips | Brand A (BBQ Flavor) | >1,000 |

| French Fries | Fast Food Chain | 890 |

| Biscuits & Crackers | Fish-shaped Crackers | 2,100 |

| Breakfast Cereals | Wheat Bran Cereal | 460 |

| Root Vegetable Chips | Terra Taro Chips | 470 |

| Banana Chips | Lightly Sweetened | 190 |

| Rice Crackers | Cheese Flavor | 39 |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents & Materials

Table 2: Essential Reagents and Kits for Low-Asparagine Cultivar Research

| Research Reagent / Material | Function in Experimental Protocol |

|---|---|

| L-Asparagine Standard | Used as a calibration standard in High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC) for the quantitative analysis of free asparagine content in potato tuber samples [23]. |

| D-Glucose/D-Fructose Standard | Serves as a calibration standard for the enzymatic or HPLC analysis of reducing sugars, which are co-precursors in acrylamide formation [23]. |

| Acrylamide Analytical Standard | Essential for creating a calibration curve using Liquid Chromatography-Tandem Mass Spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) to accurately quantify trace levels of acrylamide in processed food samples [24]. |

| Enzymatic Assay Kits (e.g., for sugars) | Provide a ready-to-use, validated method for the colorimetric or fluorometric determination of reducing sugars (glucose, fructose) in complex plant extracts, offering an alternative to HPLC. |

| Asparaginase Enzyme | Used in intervention studies as a comparative control. It reduces acrylamide by pre-hydrolyzing asparagine in food formulations before heating, serving as a benchmark against the efficacy of low-asparagine cultivars [23] [25]. |

Acrylamide (AA, C₃H₅NO) is a process contaminant that forms naturally in carbohydrate-rich foods during high-temperature processing (e.g., frying, baking, roasting) above 120°C [16] [26]. It is classified as a Group 2A probable human carcinogen by the International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) due to concerns about its neurotoxicity, carcinogenicity, and reproductive toxicity [16] [26]. Acrylamide primarily forms via the Maillard reaction between the amino acid asparagine and reducing sugars (e.g., glucose, fructose) [16] [27].

Pre-processing treatments are crucial first-line strategies for reducing acrylamide precursors in raw materials before thermal processing. Soaking, blanching, and fermentation directly target the key reactants—asparagine and reducing sugars—offering effective mitigation without significantly altering final product quality. These methods are particularly effective for plant-based foods like potatoes and cereals, which are major dietary sources of acrylamide [26] [27]. This guide provides technical protocols and troubleshooting for researchers implementing these strategies.

Fundamental Mechanisms of Acrylamide Formation

The Maillard Reaction Pathway

The primary pathway for acrylamide formation begins with a condensation reaction between the amino group of free asparagine and the carbonyl group of a reducing sugar, forming a Schiff base. This unstable compound undergoes decarboxylation to form a decarboxylated Schiff base, which then decomposes to yield acrylamide [16]. The reaction is favored at temperatures above 120°C and in low-moisture conditions [27].

Key Factors Influencing Acrylamide Formation

Understanding these factors is essential for developing effective mitigation strategies:

- Precursor Concentration: Foods with high levels of free asparagine and reducing sugars (e.g., potatoes, cereals) are particularly prone to acrylamide formation [16] [27].

- Processing Temperature and Time: Acrylamide formation increases with temperature up to a point, with maximum formation typically occurring between 160°C and 180°C. Longer heating times also increase yields [28] [16].

- pH: The Maillard reaction proceeds more readily under alkaline conditions. Lowering pH can significantly inhibit acrylamide formation [29].

- Water Activity: Low-moisture environments favor acrylamide formation, while boiling (100°C) does not produce significant amounts [16] [26].

- Surface Area to Volume Ratio: Foods with larger surface areas (e.g., thin chips) form more acrylamide due to greater exposure to heat [16] [29].

Experimental Protocols for Pre-Processing Treatments

Soaking and Blanching Protocols

Objective: To reduce water-soluble acrylamide precursors (asparagine and reducing sugars) from potato tissues before frying or baking.

Materials:

- Fresh potato tubers

- Distilled water

- Thermostatic water bath

- Food slicer (for consistent thickness)

- Refractometer (for measuring sugar content)

- Containers for soaking

Method A: Soaking Protocol

- Sample Preparation: Peel and slice potatoes to uniform thickness (e.g., 1-2 cm thick sticks or 2-3 mm slices for chips).

- Soaking Treatment: Immerse slices in distilled water at ambient temperature (approx. 20°C). Use a sample-to-water ratio of at least 1:5.

- Duration: Soak for 30-60 minutes, with occasional gentle agitation.

- Rinsing and Drying: Remove slices, rinse briefly with distilled water, and pat dry with paper towels to remove surface moisture.

- Control: Process a separate batch of untreated slices alongside the treated samples.

Method B: Blanching Protocol

- Sample Preparation: Prepare potatoes as in Step 1 of Method A.

- Blanching Treatment: Immerse slices in hot distilled water maintained at 70-85°C for 3-10 minutes in a thermostatic water bath.

- Cooling: Immediately transfer blanched slices to an ice-water bath to stop the cooking process.

- Drying: Drain and thoroughly pat dry before further processing.

- Control: Process a separate batch of untreated slices alongside the treated samples.

Expected Efficacy: Soaking and blanching can reduce acrylamide formation in subsequent frying by 20-40% by leaching out precursors [26]. Blanching is typically more effective than soaking alone.

Fermentation Protocols

Objective: To utilize microbial metabolism to degrade acrylamide precursors, primarily asparagine, in cereal and potato-based matrices.

Materials:

- Cereal flour (e.g., wheat, rye) or potato puree

- Lactic acid bacteria (LAB) strains (e.g., Lactobacillus spp., Pediococcus pentosaceus) or yeast (Saccharomyces cerevisiae)

- Microbial incubator

- Fermentation vessels

- pH meter

Method C: Lactic Acid Bacteria (LAB) Fermentation for Dough

- Starter Culture Preparation: Inoculate LAB strains into MRS broth and incubate at 37°C for 18-24 hours to achieve active growth.

- Dough Formulation: Mix cereal flour with water (hydration levels depending on flour type) and inoculate with 5-10% (v/w) active LAB culture.

- Fermentation: Incubate dough at 30-37°C for 12-24 hours. Monitor pH drop to 4.0-4.5.

- Control: Prepare a non-fermented dough or a dough fermented with commercial baker's yeast only.

Method D: Yeast-LAB Synergistic Fermentation (Sourdough)

- Sourdough Starter: Maintain a stable culture containing both LAB and wild yeast.

- Dough Inoculation: Mix cereal flour and water, and inoculate with 20% (w/w) mature sourdough starter.

- Fermentation: Incubate at 25-30°C for 12-20 hours until the dough is well-leavened and has a distinct acidic aroma.

- Control: Prepare a control dough using only commercial baker's yeast and no extended fermentation.

Expected Efficacy: LAB fermentation can reduce acrylamide in final products by 30-50%, while sourdough fermentation with LAB-yeast synergy has demonstrated reductions of up to 79.6% in rye crispbread [27].

Table 1: Comparative Efficacy of Pre-Processing Treatments on Acrylamide Reduction

| Treatment Method | Food Matrix | Key Process Parameters | Reduction in Acrylamide | Key Mechanism of Action |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Soaking | Potato slices | 30-60 min, 20°C, Water | 20-40% [26] | Leaching of reducing sugars and asparagine |

| Blanching | Potato slices | 70-85°C, 3-10 min, Water | 20-40% [26] | Enhanced leaching and enzyme inactivation |

| LAB Fermentation | Wheat/Rye dough | 30-37°C, 12-24 hrs, pH 4.0-4.5 | 30-50% [28] [27] | Microbial consumption of asparagine; pH reduction inhibiting Maillard reaction |

| Sourdough Fermentation | Whole wheat bread | 25-30°C, 12-20 hrs, 20% starter | Up to 79.6% [27] | Synergistic action of yeast and LAB on precursor depletion |

| Use of Lemon/Rosemary Juice | Whole wheat bread | Added during dough mixing, extended fermentation | Significant reduction [28] | Acidification (lowering pH) and antioxidant activity |

Table 2: Impact of Fermentation Microorganisms on Acrylamide Mitigation

| Microorganism Type | Example Strains | Primary Mode of Action | Optimal Fermentation Time | Compatible Food Matrices |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lactic Acid Bacteria (LAB) | Lactobacillus spp., Pediococcus pentosaceus [28] [27] | Lowers pH, consumes asparagine and sugars [27] | 12-24 hours [27] | Bread, crackers, vegetable-based products [27] |

| Yeast | Saccharomyces cerevisiae | Consumes asparagine and sugars for biomass production | 1-2 hours (standard baking) | Bread, baked goods |

| Probiotic Cultures | Lactobacillus plantarum, Bifidobacterium spp. [27] | Degrades asparagine in plant-based substrates [27] | 12-24 hours [27] | Soy drinks, cereal-based functional foods [27] |

Troubleshooting Guides and FAQs

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: Why did my blanched potato samples result in higher acrylamide levels than untreated controls? A1: This can occur if the blanching treatment was too severe (excessive time/temperature), causing gelatinization of starch. Gelatinized starch more readily releases sugars that participate in the Maillard reaction during subsequent frying. Ensure blanching parameters (70-85°C for 3-10 min) are strictly controlled and that samples are thoroughly dried post-treatment, as surface moisture can lower oil temperature and extend frying time, paradoxically increasing acrylamide formation [26].

Q2: Our fermented dough shows a significant pH drop, but acrylamide reduction is minimal. What is the cause? A2: While pH reduction is important, it is not the sole mechanism. The primary mechanism for acrylamide reduction in fermentation is the depletion of free asparagine by microbial metabolism. This issue may arise from:

- Strain Selection: The selected LAB strain may have low asparaginase activity. Screen for strains known to efficiently metabolize asparagine [27].

- Fermentation Time: The duration might be insufficient for significant precursor depletion. Extend fermentation time and monitor asparagine levels directly via HPLC if possible [27].

- Nutrient Availability: Other readily available nitrogen sources in the dough might be preferred by the microbes, sparing asparagine.

Q3: How can we accurately measure the success of a soaking pre-treatment in the lab? A3: Beyond measuring final acrylamide after cooking, you can directly quantify the treatment's effectiveness by:

- Measuring Leachate: Analyze the soaking water for glucose and fructose content using a refractometer or HPLC.

- Analyzing Treated Tissue: Measure the residual sugar and free asparagine content in the raw, treated potato slices compared to untreated controls. A significant decrease in these precursors correlates with reduced acrylamide formation potential [29].

Q4: Are there any negative sensory impacts of these pre-treatments, and how can they be managed? A4: Yes, potential impacts must be managed:

- Soaking/Blanching: Can lead to loss of flavor compounds, vitamins, and minerals. It can also affect texture, making potatoes less crisp. Using mild conditions and optimizing time/temperature can minimize this.

- Fermentation: Produces acidic compounds (lactic, acetic acid) which impart a sour taste. This is desirable in products like sourdough but may be undesirable in others. The level of sourness can be controlled by the fermentation time, temperature, and starter culture composition [27].

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Problems

- Problem: Inconsistent acrylamide reduction in replicate fermentation experiments.

- Solution: Standardize the vitality and cell count of the starter culture. Use a controlled incubator to maintain a stable, precise temperature throughout fermentation.

- Problem: Soaked potato slices absorbing too much oil during frying.

- Solution: Ensure slices are thoroughly dried after soaking. Surface moisture causes violent steam release during frying, which draws oil into the product. Use paper towels and/or air drying.

- Problem: Fermentation process is too slow.

- Solution: Check the viability of the starter culture. Ensure the fermentation temperature is within the optimal range for the specific microorganism. Provide necessary nutrients if the matrix is deficient.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents and Materials for Acrylamide Mitigation Research

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application | Example Use Case | Technical Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lactic Acid Bacteria (LAB) Strains | Microbial consumption of asparagine; acidification of matrix [27] | Fermentation of dough for bread/crackers | Select strains with high asparaginase activity (e.g., Lactobacillus spp., Pediococcus pentosaceus) [28] [27] |

| Sourdough Starter Cultures | Synergistic reduction of precursors via yeast-LAB consortium [27] | Production of low-acrylamide rye or whole wheat bread | A 20% inoculation rate with extended fermentation (12-20 hrs) shows high efficacy [27] |

| Asparaginase Enzymes | Direct hydrolysis of asparagine to aspartic acid, preventing its reaction [28] | Treatment of dough or potato slurry before processing | Commercial preparations (e.g., Acrylerase) are available; effective in coffee and beverages [28] |

| Natural Acidulants (Citric Acid, Lemon Juice, Vinegar) | Lowering system pH to inhibit Maillard reaction [28] [29] | Adding to blanching water or dough formulation | A small pH reduction can have a significant effect; impacts flavor profile [29] |

| Phytic Acid & Calcium Salts | Chelation and independent reduction mechanisms in potato models [29] | Addition to blanching or soaking solutions | Studies show effects are independent of, but can complement, pH reduction [29] |

| Plant Extracts (Rosemary, Ginger) | Antioxidant activity; potential mitigation of acrylamide formation [28] | Incorporation into coatings or directly into formulations | Shown to reduce acrylamide in fried potato models without affecting sensory properties [28] |

Workflow and Mechanism Visualization

Acrylamide is a food-borne toxicant classified as a probable human carcinogen and neurotoxin, forming primarily in starch-rich foods during high-temperature processing via the Maillard reaction between the amino acid L-asparagine and reducing sugars [30] [31]. Enzymatic mitigation presents a targeted approach to reduce acrylamide formation by degrading its precursors before heat treatment occurs. The two primary enzymes employed are L-asparaginase (EC 3.5.1.1) and glucose oxidase (EC 1.1.3.4). L-Asparaginase catalyzes the hydrolysis of L-asparagine to L-aspartic acid and ammonia, thereby depleting the primary amino acid precursor required for acrylamide formation [32] [2]. Glucose oxidase mitigates acrylamide by reducing the availability of reducing sugars, converting β-D-glucose into D-glucono-δ-lactone and hydrogen peroxide [2]. These enzymes offer industry-compatible solutions with minimal impact on the sensory and rheological properties of the final food products, making them particularly suitable for applications in products like potato chips, French fries, bread, and biscuits [30] [2].

Mechanisms of Action

L-Asparaginase Mechanism

L-Asparaginase suppresses acrylamide formation by specifically targeting its key precursor, free L-asparagine. The enzyme catalyzes the hydrolytic deamination of the amide group on the side chain of asparagine, converting it into L-aspartic acid and ammonia [32] [2]. The resulting aspartic acid cannot participate in the Maillard reaction to form acrylamide, as it lacks the necessary reactive amide group. Studies indicate that pre-treating food materials like potato slices or dough with L-asparaginase can reduce acrylamide content in the final cooked product by 40% to over 97%, depending on the application method and dosage [33] [34]. The enzyme, particularly the type II form from microbial sources such as E. coli and Bacillus subtilis, has a high affinity for L-asparagine and functions optimally at neutral to slightly alkaline pH ranges and temperatures around 37°C [32].

Glucose Oxidase Mechanism

Glucose oxidase (GOX) reduces acrylamide formation by decreasing the concentration of reducing sugars, which are carbonyl sources essential for the Maillard reaction. GOX employs a tightly bound flavin adenine dinucleotide (FAD) as a redox cofactor to catalyze the oxidation of β-D-glucose. This reaction consumes oxygen and produces D-glucono-δ-lactone and hydrogen peroxide [2]. The lactone subsequently hydrolyzes spontaneously into gluconic acid. By enzymatically lowering the available glucose in the food matrix, the potential for acrylamide formation is substantially diminished. The use of GOX is especially beneficial in cereal-based products where glucose content is a significant limiting factor for acrylamide formation [2].

The following diagram illustrates the sequential biochemical pathways through which L-Asparaginase and Glucose Oxidase prevent acrylamide formation:

Troubleshooting Guides and FAQs

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: Why is my L-asparaginase treatment not achieving the expected acrylamide reduction (>80%) in my potato chip samples? A: Suboptimal reduction is often due to insufficient enzyme penetration into the food matrix. The intact cellular structure of raw potatoes can limit enzyme access to L-asparagine. Implement a pre-treatment step such as blanching, freeze-thawing, or vacuum infusion to disrupt cell membranes. One study achieved approximately 90% L-asparagine hydrolysis by combining freeze-thaw and vacuum treatment prior to applying Bacillus subtilis L-asparaginase (4 U/g potato) [33]. Ensure the enzyme solution is uniformly applied to all surfaces.

Q2: How can I prevent the undesirable sensory changes (color, taste) in my baked product when using glucose oxidase? A: Glucose oxidase can sometimes lead to over-oxidation, affecting product quality. To mitigate this:

- Optimize enzyme dosage: Conduct a dose-response curve to find the minimal effective dose. Overdosing can lead to excessive acid production, altering pH and taste.

- Control reaction time: Limit the incubation time with the enzyme before baking to prevent complete sugar depletion, which is necessary for desired browning and flavor development via the Maillard reaction.

- Combine with other methods: Consider using glucose oxidase in combination with low levels of asparaginase to target both precursors without fully depleting either [2].

Q3: My immobilized enzyme system shows a rapid decline in activity after a few reuse cycles. What could be the cause? A: A sharp decline in activity is typically attributed to enzyme leaching, carrier fouling, or structural degradation of the support.

- Check immobilization efficiency: Ensure stable covalent binding between the enzyme and the carrier. Using carriers like agarose activated with N-hydroxysuccinimide (NHS) esters can create stable, food-safe linkages. One study reported 93.21% activity retention after 6 cycles and 72.25% after 28 days of storage with an agarose-immobilized system [35].

- Assess carrier compatibility: The food matrix may contain lipids or proteins that foul the carrier surface. Implement a regular cleaning-in-place (CIP) protocol with a mild buffer or salt solution between cycles.

- Verify operational stability: Ensure the enzyme is not exposed to pH or temperature extremes beyond its stability range during processing.

Q4: What is the best way to quantify the efficacy of my enzymatic mitigation experiment? A: Efficacy should be measured by quantifying the reduction in both the precursor (L-asparagine or reducing sugars) and the final acrylamide content.

- Precursor Analysis: Measure free L-asparagine content in treated vs. untreated samples using HPLC after enzyme treatment but before heating [33].

- Acrylamide Analysis: Quantify acrylamide in the final cooked product using highly sensitive techniques like LC-MS/MS (Liquid Chromatography-Tandem Mass Spectrometry) or GC-MS (Gas Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry), which can detect trace levels (mcg/kg) even in complex food matrices [4].

- Process Indicators: Monitor by-products like ammonia or gluconic acid to confirm enzymatic activity.

Advanced Troubleshooting: Common Experimental Issues

| Problem | Possible Cause | Suggested Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Low enzyme activity recovery after immobilization | Unstable covalent binding; harsh activation chemistry. | Use a food-safe, mild activator like NHS ester. Optimize ligand density on the carrier (e.g., by controlling epichlorohydrin ratio between 1/90 to 1/3 (v/v)) [35]. |

| Inconsistent acrylamide reduction across product batches | Variability in raw material precursor content. | Source raw materials from a consistent supplier and batch. Pre-screen raw materials (e.g., potato varieties, flour types) for L-asparagine and reducing sugar levels before processing [2]. |

| Enzyme is ineffective in dough systems | Limited diffusion; suboptimal water activity. | Increase mixing time to ensure homogeneous distribution. Add the enzyme during the water-mixing phase. Optimize dough resting time and temperature to allow sufficient reaction time (e.g., 30-60 min at 37°C) [34]. |

| High operational cost of enzyme application | Non-recyclable free enzyme; low stability. | Transition to an immobilized enzyme system in a packed-bed reactor for continuous processing and enzyme reuse [35]. Explore solid-state fermentation to produce the enzyme cost-effectively using agricultural residues [36]. |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Acrylamide Mitigation in Potato Chips Using L-Asparaginase

This protocol is adapted from a study using Bacillus subtilis L-asparaginase (BAsnase), which achieved up to 80-90% acrylamide reduction in fried potato chips [33].

Objective: To significantly reduce the acrylamide content in fried potato chips through a pre-treatment with L-asparaginase.

Materials:

- Fresh potatoes

- Purified L-asparaginase (e.g., BAsnase, specific activity ~45 U/mg)

- Potassium phosphate buffer (pH 8.0)

- Corn oil for frying

- Freezer, dryer, vacuum chamber

Methodology:

- Sample Preparation: Wash, peel, and slice potatoes into uniform pieces (e.g., 1.5 mm thickness).

- Pre-treatment (Crucial Step): To enhance enzyme penetration, subject slices to a combination of:

- Freeze-thaw: Freeze at -20°C for 20 min, then thaw at room temperature.

- Drying: Dry at 90°C for 20 min.

- Vacuum Infusion: Place slices under reduced pressure (3.2 × 10⁻³ – 1.6 × 10⁻³ MPa) for 10 min.

- Enzymatic Treatment: Evenly apply L-asparaginase solution (4 U per gram of potato) onto the pre-treated slices. Incubate at 60°C for 10 minutes.

- Frying and Analysis: Fry the treated slices in corn oil at 170°C for 90 seconds. Let cool, then analyze acrylamide content via LC-MS/MS or HPLC.

Key Parameters:

- Enzyme Dosage: 4 U/g of potato [33].

- Optimal Pre-treatment: Combined freeze-thaw, drying, and vacuum [33].

- Control: Always run a parallel batch without enzyme treatment for comparison.

Protocol 2: Mitigating Acrylamide in Sweet Bread with L-Asparaginase

This protocol, based on a study using Cladosporium sp. L-asparaginase, demonstrated a 97% reduction of acrylamide in the crust of sweet bread [34].

Objective: To integrate L-asparaginase into a bread-making process to reduce acrylamide formation during baking.

Materials:

- Wheat flour and other standard bread ingredients (yeast, sugar, salt, water)

- L-Asparaginase (e.g., from Cladosporium sp.)

Methodology:

- Dough Preparation: Prepare a standard sweet bread dough according to your recipe.

- Enzyme Incorporation: During the mixing stage, add L-asparaginase solution directly to the dough. The study used doses ranging from 50 to 300 U per batch of dough to achieve a dose-dependent reduction [34].

- Fermentation and Baking: Proceed with standard fermentation, proofing, and baking protocols.

- Analysis: After baking, separately analyze the crust and crumb for acrylamide content, sugars (e.g., glucose), L-asparagine, and indicators of the Maillard reaction like hydroxymethylfurfural (HMF) and color.

Key Parameters:

- Enzyme Dosage: 300 U for maximum reduction (97% in crust) [34].

- No Negative Impact: The study confirmed no changes in the rheological properties of the wheat flour or the physico-sensory characteristics of the final bread [34].

Efficacy of Enzymatic Mitigation Strategies in Various Food Matrices

The following table consolidates key quantitative findings on the efficacy of asparaginase and glucose oxidase from the cited research.

| Food Matrix | Enzyme Used | Dosage & Conditions | Reduction in Acrylamide | Key Findings | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fried Potato Chips | Bacillus subtilis L-ASNase | 4 U/g potato; Pre-treatment: freeze-thaw, drying, vacuum | >80% (to below 20% of untreated) | Pre-treatment is critical for ~90% L-asparagine hydrolysis. | [33] |

| Sweet Bread | Cladosporium sp. L-ASNase | 300 U per dough batch | 97% (crust), 73% (crumb) | No negative effects on sensory or rheological properties. HMF also decreased. | [34] |

| Bread & Biscuits | L-ASNase (general) | 10 U/g flour | ~90% | Effective integration into existing baking processes. | [35] |

| Fluid Food Model | Agarose-Immobilized L-ASNase | Packed-bed reactor, continuous flow | ~89% | Enzyme retained 72.25% activity after 28 days of storage. | [35] |

| Cereal-Based Foods | Glucose Oxidase | Varies by matrix; depletes glucose | Substantial reduction (specific % not stated) | Effective when reducing sugar content is the limiting factor. | [2] |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details essential reagents, materials, and tools for conducting research on the enzymatic mitigation of acrylamide.

| Item/Category | Function/Description | Example & Notes |

|---|---|---|

| L-Asparaginase | Hydrolyzes L-asparagine to L-aspartic acid and ammonia, removing the key nitrogen precursor for acrylamide. | Available from microbial sources (e.g., E. coli, Bacillus subtilis). For food use, consider enzymes from GRAS (Generally Recognized as Safe) organisms like Aspergillus oryzae [32] [33]. |

| Glucose Oxidase | Oxidizes glucose to gluconic acid and hydrogen peroxide, depleting the carbonyl precursor for the Maillard reaction. | Often used in cereal-based products. Purity and source (e.g., Aspergillus niger) can affect performance [2] [37]. |

| Immobilization Carriers | Solid supports for enzyme binding, enabling reuse, improved stability, and continuous processing. | Agarose microspheres activated with NHS esters are a food-safe option [35]. Other carriers include chitosan, dextran, and magnetic nanoparticles. |

| Activity Assay Kits | Quantify enzyme activity by measuring reaction by-products. | Nessler's reagent can be used to measure ammonia production from L-asparaginase activity [33] [35]. Commercial glucose oxidase kits often measure H₂O₂ production. |

| Analytical Standards | Essential for accurate quantification of target analytes. | L-Asparagine, L-Aspartic Acid, Acrylamide, Glucose of high purity (HPLC grade) for calibration curves [33] [4]. |

| Chromatography Systems | For separation and sensitive detection of acrylamide, precursors, and by-products. | LC-MS/MS or GC-MS are gold standards for trace-level acrylamide quantification in complex food matrices [4]. HPLC with UV/VIS or fluorescence detection is also commonly used. |

This technical support center provides targeted guidance for researchers and scientists working to mitigate acrylamide formation in processed foods. Acrylamide, a processing contaminant classified as a probable human carcinogen, forms primarily via the Maillard reaction between the amino acid asparagine and reducing sugars at temperatures above 120°C [26] [16]. The following troubleshooting guides, FAQs, and experimental protocols are framed within the broader thesis that strategic formulation engineering—using additives, amino acids, and organic acids—offers a potent, industry-compatible approach to significantly reduce acrylamide levels without compromising product quality or safety.

Mechanisms and Pathways

Understanding the chemical foundation of acrylamide formation is crucial for developing effective mitigation strategies. The primary route is the Maillard reaction, with key pathways and intervention points outlined below.

Diagram: Key Pathways for Acrylamide Formation and Mitigation. Strategic interventions target precursors (asparagine, sugars) or alter reaction conditions to inhibit acrylamide formation.

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide 1: Inconsistent Acrylamide Reduction with Additives

Problem: Despite adding anti-acrylamide additives, the reduction in final product acrylamide content is inconsistent or below expectations.

Investigation Steps:

- Verify Precursor Levels: Quantify free asparagine and reducing sugar concentrations in your raw materials. High inherent variability in agricultural commodities can lead to inconsistent results [2]. Use LC-MS or HPLC for accurate measurement.

- Check Additive Incorporation: Ensure the additive is uniformly distributed within the food matrix. Poor mixing can create localized "hot spots" of high acrylamide formation.

- Review Processing Parameters: Re-examine time-temperature profiles. Even with additives, excessively high temperatures or prolonged heating can overwhelm the mitigation effect [28] [14]. Lowering baking temperature from 200°C to 180°C can reduce acrylamide in biscuits by over 50% [28].

- Assess Additive-Patrix Interaction: Evaluate if the additive is being bound by other food components (e.g., proteins, fibers), reducing its effective concentration at the reaction site.

Solutions:

- Pre-treatment of Raw Materials: For potato-based products, implement blanching or soaking in water or additive solutions to leach out precursors before thermal processing [26] [38].

- Optimize Additive Combination: Use a synergistic combination of additives. For example, combine an amino acid like glycine with an organic acid like citric acid. Glycine competes with asparagine in the Maillard reaction, while citric acid lowers the pH, making the reaction less favorable [14] [38].

- Adjust Additive Concentration: Systematically test higher concentrations of the additive, ensuring it remains within legal limits and does not adversely affect sensory properties.

Guide 2: Undesirable Sensory Changes Post-Mitigation