Advanced Spectroscopy for Protein Structure: Transforming Nutritional Research and Clinical Applications

This article provides a comprehensive overview of advanced spectroscopy techniques—including Vibrational Spectroscopy (FTIR, NIR, Raman), Mass Spectrometry (H/D Exchange, ESI), and NMR—for characterizing protein structure and dynamics in nutrition research.

Advanced Spectroscopy for Protein Structure: Transforming Nutritional Research and Clinical Applications

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of advanced spectroscopy techniques—including Vibrational Spectroscopy (FTIR, NIR, Raman), Mass Spectrometry (H/D Exchange, ESI), and NMR—for characterizing protein structure and dynamics in nutrition research. It explores the foundational principles, methodological applications for protein quantification and structural analysis, and strategies for overcoming challenges in complex food matrices. The content critically compares these techniques with traditional methods, highlighting their role in validating nutritional quality, understanding protein digestibility, and guiding the development of personalized nutrition and therapeutic strategies. Tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, this review synthesizes current trends and future directions, emphasizing the integration of spectroscopy with chemometrics and artificial intelligence to drive innovations in biomedical and clinical research.

Protein Structures and Nutritional Impact: Why Spectroscopy is a Game-Changer

The Critical Link Between Protein Structure and Nutritional Functionality

In nutritional science, the functional quality of a protein—encompassing its digestibility, bioavailability, and bioactivity—is intrinsically governed by its three-dimensional structure. Structural elements, from the primary amino acid sequence to complex secondary and tertiary folds, dictate how a protein interacts within the human gastrointestinal tract and influences physiological responses [1]. The rising global emphasis on sustainable plant-based proteins has intensified the need for precise analytical techniques that can characterize these structure-function relationships. Spectroscopy provides a powerful, non-destructive toolkit for researchers to probe these structural features, enabling the rational development of enhanced nutritional ingredients and formulations [1]. This document outlines practical protocols and applications of key spectroscopic methods in nutrition research.

Spectroscopic Techniques for Protein Analysis

The following table summarizes the primary spectroscopic techniques used for probing protein structure and their relevance to nutritional functionality.

Table 1: Key Spectroscopic Techniques in Protein Nutrition Research

| Technique | Structural Information Provided | Key Nutritional Correlations | Sample Preparation Complexity |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fourier-Transform Infrared (FTIR) Spectroscopy | Secondary structure (β-sheet, α-helix, random coil) [1] | Solubility, digestibility, gelling, and emulsifying capacity [1] | Low to Moderate |

| Near-Infrared (NIR) Spectroscopy | Bulk protein content, moisture, fat [1] | Rapid nutritional content analysis, quality control | Low |

| Raman Spectroscopy | Secondary structure; complementary to FTIR [1] | Structural changes due to processing (e.g., extrusion, heating) | Low |

| Intrinsic Fluorescence Spectroscopy | Tertiary structure, conformational changes, ligand binding [2] | Bioavailability of bioactive compounds, protein-ligand interactions | Moderate |

| Circular Dichroism (CD) Spectroscopy | Secondary structure composition and stability [3] | Protein stability under different pH/temperature conditions relevant to processing | Moderate |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Analyzing Protein Secondary Structure using FTIR Spectroscopy

This protocol is ideal for determining the secondary structure of plant-based protein isolates and monitoring structural changes induced by processing.

- Principle: FTIR measures the vibrational energy of chemical bonds. The Amide I band (1600-1700 cm⁻¹) is highly sensitive to protein backbone conformation and is used for secondary structure quantification [1].

- Materials & Reagents:

- Plant protein isolate (e.g., soy, pea, kidney bean protein)

- Potassium bromide (KBr) or Calcium Fluoride (CaF₂) cells

- FTIR Spectrometer

- Lyophilizer

- Hydraulic press (if using KBr pellets)

- Procedure:

- Sample Preparation: Lyophilize the protein sample to remove interfering water signals. Gently grind into a fine, homogeneous powder.

- Pellet Preparation (KBr Method): Mix 1-2 mg of protein powder with 200 mg of dry KBr. Press the mixture under vacuum into a clear pellet.

- Data Acquisition: Place the pellet in the FTIR spectrometer. Collect spectra in the mid-IR range (4000-400 cm⁻¹) with a resolution of 4 cm⁻¹. Accumulate 64-128 scans to improve the signal-to-noise ratio.

- Spectral Processing: Subtract the background spectrum. Perform atmospheric compensation (for CO₂ and water vapor). Apply second-derivative transformation and deconvolute the Amide I region to identify underlying peaks.

- Data Analysis: Fit the deconvoluted Amide I band using Gaussian curve fitting. Assign secondary structures to the resolved peaks: 1615-1637 cm⁻¹ (β-sheet), 1645-1655 cm⁻¹ (random coil), 1658-1665 cm⁻¹ (α-helix), and 1670-1690 cm⁻¹ (β-turns). Quantify by calculating the relative area of each assigned peak [1].

Protocol 2: Probing Tertiary Structure with Intrinsic Fluorescence Spectroscopy

This protocol is used to monitor changes in the tertiary structure and micro-environment of tryptophan residues, which is crucial for understanding functional properties.

- Principle: Intrinsic fluorophores (tryptophan, tyrosine, phenylalanine) exhibit changes in fluorescence intensity and emission wavelength maximum (λmax) when their local environment is altered by unfolding, aggregation, or ligand binding [3] [2].

- Materials & Reagents:

- Protein solution (0.1-0.5 mg/mL in suitable buffer, e.g., phosphate-buffered saline)

- Fluorescence Spectrophotometer

- Centrifugal filters (for clarification and buffer exchange)

- Procedure:

- Sample Preparation: Clarify the protein solution by centrifugation or filtration to remove particulate matter that causes light scattering.

- Instrument Setup: Set the spectrophotometer's excitation wavelength to 295 nm (to selectively excite tryptophan residues). Set the emission scan range from 300 to 400 nm.

- Data Acquisition: Place the protein solution in a quartz cuvette. Record the fluorescence emission spectrum. Perform all measurements at a constant, controlled temperature.

- Data Analysis: Identify the emission λmax. A shift towards longer wavelengths (red-shift) indicates the movement of tryptophan residues to a more hydrophilic, solvent-exposed environment, characteristic of protein unfolding. A shift towards shorter wavelengths (blue-shift) suggests a more hydrophobic, buried environment. Changes in fluorescence intensity can also reflect quenching or conformational rearrangements [2].

Diagram 1: Intrinsic fluorescence spectroscopy workflow for analyzing protein tertiary structure.

Application in Nutrition Research: A Case Study

Ultrasound-Assisted Glycosylation of Kidney Bean Protein Antioxidant Peptides

Recent research on British red kidney bean protein antioxidant peptides (BHPs) provides a compelling case study on how spectroscopy elucidates structure-function relationships. A 2025 study investigated how ultrasound-assisted glycosylation (US-GR) with glucose enhances antioxidant activity and functional properties [3].

- Objective: To characterize the structural changes and functional improvements in BHPs following ultrasound-assisted glycosylation with glucose.

- Experimental Groups: The study compared four treatments: native peptides (BHPs), ultrasound-only (US), glycosylation-only (GR), and the combined ultrasound-glycosylation (US-GR) [3].

- Key Spectroscopic & Analytical Findings:

- FTIR Spectroscopy: Confirmed successful glycosylation by showing new absorption bands, indicating covalent bonding between peptide amino groups and sugar carbonyls [3].

- Circular Dichroism (CD): Revealed a decrease in β-sheet content and an increase in random coils in the US-GR group, suggesting a more flexible and open structure [3].

- Intrinsic Fluorescence & Surface Hydrophobicity: showed decreased fluorescence intensity and surface hydrophobicity in US-GR, indicating that sugar molecules were shielding hydrophobic regions on the peptides [3].

- Atomic Force Microscopy (AFM): showed a more uniform and smaller 3D size distribution, indicating reduced aggregation [3].

Table 2: Correlation Between Structural Changes and Enhanced functionality in Glycosylated Peptides

| Measured Parameter | Change in US-GR Group | Implied Structural Change | Resulting Functional Improvement |

|---|---|---|---|

| Grafting Degree | Increased by 36.16% [3] | Covalent attachment of glucose to peptides | Improved stability and bioactivity |

| Free Amino Group Content | Decreased by 33.58% [3] | Confirmation of glycosylation bond formation | Masked bitterness, improved flavor |

| Surface Hydrophobicity | Decreased [3] | Shielding of hydrophobic patches by glucose | Enhanced solubility and dispersibility |

| Secondary Structure (β-sheet / Random coil) | Decreased / Increased [3] | Unfolding and increased structural flexibility | Improved emulsifying and foaming properties |

| In Vitro Antioxidant Activity | Significantly enhanced (e.g., Reducing power increased by 105.38%) [3] | Increased exposure of electron-donating groups | Enhanced free radical scavenging capacity |

Diagram 2: Relationship between ultrasound treatment, structural changes, glycosylation, and functional improvements in peptides.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Spectroscopic Protein Analysis

| Reagent / Material | Function / Application | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Potassium Bromide (KBr) | Infrared-transparent matrix for preparing solid pellets for FTIR analysis. | Creating homogeneous pellets for high-quality FTIR spectral acquisition of protein powders [1]. |

| o-Phthaldialdehyde (OPA) Reagent | Derivatization agent that reacts with primary amines to form fluorescent adducts. | Quantifying the loss of free amino groups to monitor the degree of glycosylation in modified peptides [3]. |

| DTNB (Ellman's Reagent) | Compound that reacts with sulfhydryl groups to produce a yellow chromophore. | Determining the total and free sulfhydryl group content in proteins, indicating changes in tertiary structure and oxidation state [3]. |

| TNBS (Trinitrobenzenesulfonic Acid) | Reagent that reacts with primary amines to form a colored product measurable at 335 nm. | Directly measuring the grafting degree in glycosylation experiments by tracking the consumption of free amino groups [3]. |

| Alkaline Protease | Enzyme used to hydrolyze proteins and generate bioactive peptide fractions from parent proteins. | Production of antioxidant peptide fractions from British red kidney bean protein for subsequent modification and study [3]. |

Fundamental Principles of Light-Molecule Interactions in Spectroscopy

In nutrition research, the detailed characterization of protein structures is paramount for understanding their functional properties, nutritional quality, and behavior in food products. Spectroscopy provides a powerful suite of tools for this purpose, as the interaction between light and protein molecules yields detailed information about secondary and tertiary structure, stability, and composition. The fundamental principle underpinning these techniques is that the way a molecule interacts with specific wavelengths of light is dictated by its unique chemical structure and environment. This application note details the core principles of light-molecule interactions, provides protocols for protein structure characterization, and contextualizes the data within nutrition research, offering a resource for scientists and drug development professionals.

Fundamental Physics of Light-Matter Interaction

The Dual Nature of Light

Light, or electromagnetic radiation, exhibits both wave-like and particle-like properties. As a wave, light is characterized by its wavelength—the distance between successive peaks—which determines its color and place in the electromagnetic spectrum, from gamma rays to radio waves [4]. As a particle, light consists of photons, discrete packets of energy where the energy of a single photon is inversely proportional to its wavelength [4]. This relationship is critical for spectroscopy, as a photon's energy must precisely match the energy gap of a molecular transition for absorption to occur.

Atomic and Molecular Structure

Matter is composed of atoms, which contain a nucleus surrounded by electrons that occupy specific energy levels or orbitals [4] [5]. Molecules, being collections of atoms, possess more complex energy states, including electronic, vibrational, and rotational levels. A fundamental rule of quantum mechanics is that electrons can "jump" to higher energy levels or "drop" to lower ones, but they cannot exist between these discrete states [4].

Key Interaction Mechanisms

When light encounters a molecule, several key interactions can occur, each providing different structural insights:

- Absorption: A photon is absorbed by the molecule, and its energy promotes an electron to a higher energy state or increases the vibrational/rotational energy of the molecule [4] [6]. This is the primary interaction measured in many spectroscopic techniques.

- Reflection: Light bounces off the material's surface without being absorbed.

- Transmission: Light passes through the material without being absorbed [4].

At the molecular scale, the oscillating electric field of the light wave rhythmically pushes the positive and negative charges within a molecule in opposite directions, causing polarization [6]. When the frequency of the light matches a resonant frequency of the molecular component, energy is efficiently absorbed.

The Transition Dipole Moment and Selection Rules

The probability of a spectroscopic transition is governed by the transition dipole moment, μfi [5]. This is a quantum mechanical integral expressed as: μfi = ⟨Ψf | ˆμ | Ψi⟩ where Ψi and Ψf are the wavefunctions of the initial and final states, and ˆμ is the electric dipole moment operator [5]. The square of this probability amplitude gives the transition probability. For this integral to be non-zero, the product of the symmetries of the initial state, the operator, and the final state must contain the totally symmetric irreducible representation. This requirement leads to selection rules that dictate which transitions are allowed, such as the rule for atomic electronic transitions where Δl = ±1 [5].

Spectroscopic Techniques for Protein Characterization

The following table summarizes the primary spectroscopic techniques used in protein analysis, their fundamental principles, and key applications in nutrition research.

Table 1: Spectroscopic Techniques for Protein Structure Characterization

| Technique | Principle of Light-Matter Interaction | Primary Structural Information | Typical Application in Nutrition Research |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mass Spectrometry (MS) | Analyzes molecular weight by ionizing molecules and measuring their mass-to-charge ratio [7]. | Primary structure, amino acid sequence, post-translational modifications [8]. | Protein identification and quantification in complex food matrices [9]. |

| Fourier Transform Infrared (FTIR) | Measures absorption of infrared light, exciting vibrational modes of molecular bonds [8]. | Secondary structure (α-helix, β-sheet) via amide I and II bands [8]. | Monitoring heat-induced structural changes in proteins (e.g., whey protein denaturation) [9]. |

| Circular Dichroism (CD) | Measures the difference in absorption of left-handed and right-handed circularly polarized light by chiral molecules [8]. | Secondary structure and protein folding stability [8]. | Assessing structural stability of novel protein isolates under different pH conditions [9]. |

| Microfluidic Modulation Spectroscopy (MMS) | Combines IR absorption with microfluidic technology and a high-intensity laser for superior signal-to-noise [8]. | Quantifies secondary structure with high sensitivity and without buffer interference [8]. | Detecting subtle structural changes in protein biologics and formulations [8]. |

| UV-Vis Spectroscopy | Measures electronic transitions in conjugated systems, such as aromatic amino acid side chains. | Protein concentration, aggregation, and ligand binding. | Measuring lycopene and chlorophyll content in plant-based foods [6]. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Protein Secondary Structure Analysis via FTIR

Principle: This protocol determines the secondary structure of a protein sample by analyzing the amide I band (1600-1700 cm⁻¹), which arises primarily from C=O stretching vibrations of the peptide backbone and is highly sensitive to hydrogen bonding patterns [8].

Materials:

- Purified protein sample (e.g., hazelnut kernel protein isolate [10])

- FTIR Spectrometer

- Lyophilizer

- ATR (Attenuated Total Reflectance) accessory

Procedure:

- Sample Preparation: Dialyze the protein solution against a volatile buffer (e.g., ammonium bicarbonate) and lyophilize to create a dry powder [8].

- Instrument Setup: Purge the FTIR spectrometer with dry nitrogen to minimize interference from atmospheric water vapor. Set the spectral resolution to 4 cm⁻¹ and accumulate 256 scans.

- Data Acquisition: Place a small amount of the lyophilized protein powder on the ATR crystal and ensure good contact. Acquire the infrared spectrum in the range of 4000 to 1000 cm⁻¹.

- Data Analysis:

- Subtract the background spectrum.

- Focus on the amide I region (1700-1600 cm⁻¹).

- Perform Fourier self-deconvolution or second derivative analysis to resolve overlapping bands.

- Use curve-fitting procedures to assign components: ~1650 cm⁻¹ (α-helix), ~1630 cm⁻¹ (β-sheet), ~1670 cm⁻¹ (β-turns) [8].

Protocol: Assessing Nutritional Quality via Amino Acid Analysis

Principle: This protocol quantifies the amino acid composition of a food protein to evaluate its nutritional value by comparing it to FAO/WHO standards [10].

Materials:

- Defatted food protein sample (e.g., Corylus mandshurica Maxim kernel flour [10])

- Hydrolysis tubes

- 6M HCl

- Amino Acid Analyzer

Procedure:

- Sample Hydrolysis: Weigh approximately 10 mg of defatted protein into a hydrolysis tube. Add 10 mL of 6M HCl. Seal the tube under vacuum and hydrolyze at 110°C for 24 hours.

- Sample Analysis: Filter the hydrolysate and dilute with an appropriate buffer. Load the sample into an automatic amino acid analyzer, which separates amino acids by ion-exchange chromatography and detects them post-column with ninhydrin [10].

- Data Analysis & Nutritional Indices:

Table 2: Amino Acid Profile and Nutritional Indices of Corylus mandshurica Maxim Kernel Proteins [10]

| Parameter | Water-Soluble Protein | Protein Isolate | FAO/WHO Adult Requirement |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total EAA (mg/g protein) | 324.52 | 249.58 | - |

| EAAI | 72.19 | 58.59 | - |

| Biological Value (BV) | 66.99 | 52.16 | - |

| Nutritional Index (NI) | 55.78 | 41.68 | - |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Protein Spectroscopy

| Item | Function/Application |

|---|---|

| Defatted Protein Flour | Starting material for protein extraction and analysis; removal of lipids minimizes interference in spectral measurements [10]. |

| Volatile Buffers (e.g., Ammonium Bicarbonate) | Used for protein dialysis and lyophilization prior to FTIR; they sublime easily, leaving no interfering residue in the spectrum [8]. |

| Microfluidic Flow Cell | Central to MMS, it modulates between sample and buffer for real-time background subtraction, eliminating signal interference from excipients [8]. |

| Quantum Cascade Laser (QCL) | The high-intensity IR light source in MMS, providing at least 1000x greater intensity than conventional sources for ultra-high sensitivity [8]. |

| Reference Protein Library | A curated database of known protein structures used with analytical software (e.g., in MMS) to accurately quantify secondary structure in unknown samples [8]. |

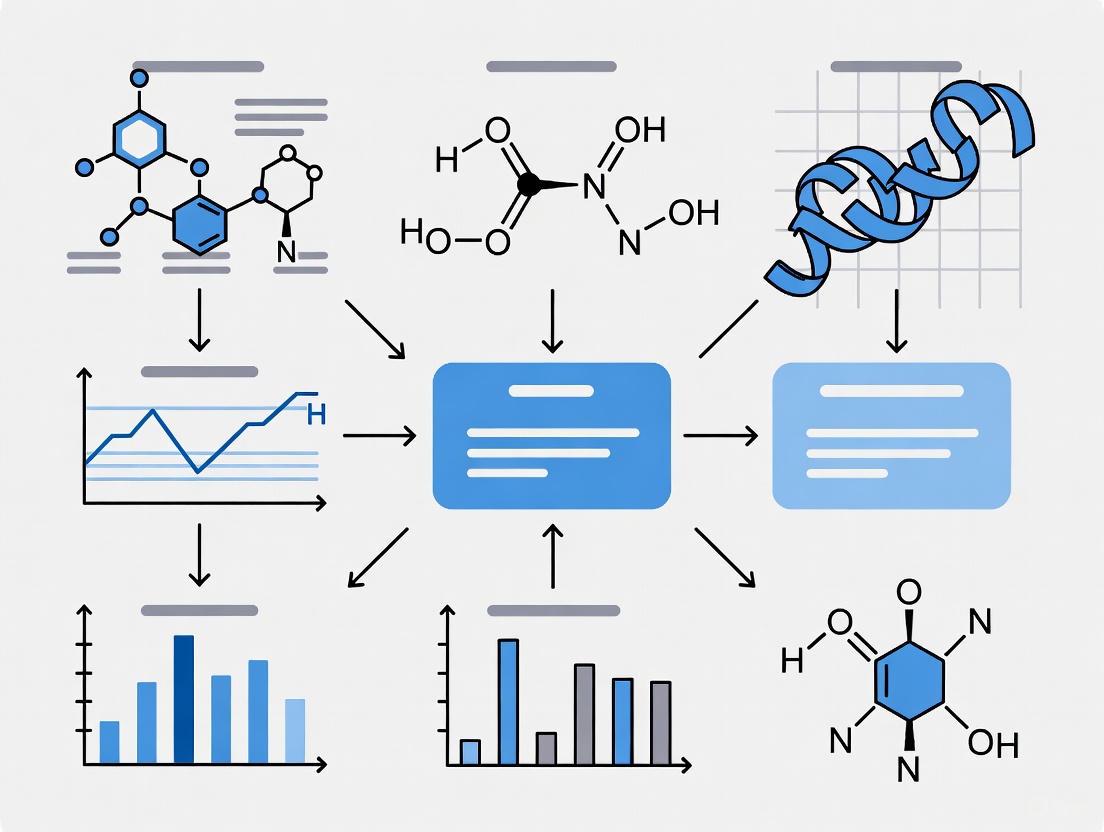

Workflow and Signaling Pathways

The following diagram illustrates the core workflow of a spectroscopic experiment, from the initial light-matter interaction to the final structural interpretation for proteins.

Spectroscopy Workflow for Protein Analysis

The fundamental signaling pathway of the light-molecule interaction itself, leading to specific spectroscopic outputs, can be summarized as follows:

Pathway of Light-Molecule Interaction

The comprehensive analysis of protein structure is fundamental to advancing research in nutrition, drug development, and biotechnology. Proteins are highly complex macromolecules whose biological function is directly related to their three-dimensional structure [11]. Even minor alterations in protein conformation can significantly impact their physicochemical and functional properties [12]. Spectroscopic techniques provide powerful, and often non-destructive, tools for probing these structural characteristics across different complexity levels—from primary amino acid sequence to quaternary assembly.

This article provides a detailed overview of five key spectroscopic techniques—Fourier-Transform Infrared (FTIR), Near-Infrared (NIR), Raman, Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR), and Mass Spectrometry (MS)—framed within the context of protein structure characterization for nutritional research. We present standardized application notes and experimental protocols to enable researchers to effectively select and implement these methods, complete with comparative data tables, workflow visualizations, and essential reagent solutions.

The following table summarizes the core characteristics, applications, and structural insights provided by each spectroscopic technique discussed in this article.

Table 1: Comparative Overview of Key Spectroscopic Techniques for Protein Analysis

| Technique | Principle of Operation | Structural Information Obtained | Typical Sample Form | Key Advantages |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| FTIR Spectroscopy | Measures absorption of IR light by molecular bond vibrations [11]. | Secondary structure (e.g., α-helix, β-sheet) [11]. | Solid, liquid, lyophilized powder [11]. | Rapid analysis; well-established for secondary structure. |

| NIR Spectroscopy | Measures overtone and combination vibrations of C-H, O-H, and N-H bonds [13]. | Secondary structure; protein content quantification [13] [14]. | Solid, liquid, aqueous solutions [13]. | Non-destructive; high-throughput; minimal sample prep. |

| Raman Spectroscopy | Measures inelastic light scattering from molecular bond vibrations [15]. | Secondary structure; side-chain environments; disulfide bonds [16] [17]. | Solid, liquid, gels [14]. | Minimal water interference; suitable for aqueous solutions. |

| NMR Spectroscopy | Detects absorption of radio waves by atomic nuclei in a magnetic field [18]. | Full 3D structure; atomic-level dynamics; interactions [18] [12]. | Liquid (solution), solid-state [18]. | Atomic-resolution structure; studies dynamics in solution. |

| Mass Spectrometry (MS) | Measures mass-to-charge ratio ((m/z)) of ionized molecules [19]. | Primary structure; molecular weight; post-translational modifications [19] [12]. | Liquid, solid (vaporized) [19]. | High sensitivity; identifies and quantifies proteins. |

Detailed Techniques: Applications and Protocols

Fourier-Transform Infrared (FTIR) Spectroscopy

Application Note: FTIR spectroscopy is a fundamental technique for characterizing protein secondary structure, both in solution and in the solid state [11]. It is particularly valuable for monitoring conformational stability during processes like lyophilization (freeze-drying) used in pharmaceutical and food powder production [11]. The technique probes the vibrational modes of the protein's amide bonds, with the amide I band (around 1650 cm⁻¹) being most commonly used for secondary structure analysis as it originates mainly from the C=O stretching vibration of the peptide backbone [11].

Experimental Protocol:

- Sample Preparation:

- Solid Samples: For lyophilized proteins, mix ~1-2 mg of protein powder with ~100 mg of potassium bromide (KBr). Grind thoroughly to a fine powder using a mortar and pestle and press into a transparent pellet using a hydraulic press.

- Liquid Samples: Place a small volume of protein solution (e.g., 20 mg·mL⁻¹ or higher) between two infrared-transparent windows (e.g., CaF₂ or BaF₂) separated by a thin spacer (e.g., 6-50 μm pathlength) to minimize strong water absorption [15].

- Data Collection:

- Acquire spectra in transmission or Attenuated Total Reflectance (ATR) mode. ATR is advantageous for aqueous samples as it minimizes path length issues [15].

- Set spectral resolution to 4 cm⁻¹ and accumulate 64-128 scans to achieve a good signal-to-noise ratio.

- Collect a background spectrum under identical conditions (e.g., empty cell or clean ATR crystal).

- Data Analysis:

- Subtract the background spectrum from the sample spectrum.

- Apply a second derivative function to the spectrum in the amide I region (1600-1700 cm⁻¹) to narrow the bands and enhance resolution [11].

- Use Fourier self-deconvolution or curve-fitting (Gaussian/Lorentzian bands) to estimate the relative areas of component bands assigned to specific secondary structures:

- α-Helix: 1650-1660 cm⁻¹

- β-Sheet: 1620-1640 cm⁻¹

- β-Turns: 1660-1680 cm⁻¹

- Random coil: 1640-1650 cm⁻¹

Near-Infrared (NIR) Spectroscopy

Application Note: NIR spectroscopy is a rapid, non-destructive tool ideal for high-throughput quantification of protein content and the analysis of secondary structure in bulk food materials and solid formulations [14]. It probes overtone and combination vibrations of C-H, O-H, and N-H bonds in the combination (4000-5000 cm⁻¹) and first overtone (5600-6600 cm⁻¹) regions [13]. It is highly suited for in-line monitoring in manufacturing settings to ensure product consistency [14].

Experimental Protocol:

- Sample Preparation:

- Samples can be analyzed in their native state (powders, pastes, liquids) with minimal preparation. Ensure sample presentation is consistent (e.g., uniform particle size for powders, consistent pathlength for liquids).

- Data Collection:

- For solid powders, use a diffuse reflection accessory. For liquids, use a transmission cell with a pathlength of 0.5 mm to 2 mm.

- Acquire spectra at a resolution of 8-16 cm⁻¹ with 32-64 scans per spectrum.

- Data Analysis:

- Preprocess raw spectra using standard normal variate (SNV) or multiplicative scatter correction (MSC) to reduce scattering effects.

- Calculate the second derivative of the spectra to resolve overlapping bands [13].

- Identify key bands associated with protein structure, such as those around 4090 cm⁻¹ (α-helix) and 4865 cm⁻¹ (β-sheet) [13].

- Develop a calibration model using multivariate regression techniques (e.g., PLS) by correlating NIR spectra with reference data (e.g., protein content from Kjeldahl method, secondary structure from FTIR).

Raman Spectroscopy

Application Note: Raman spectroscopy provides complementary information to FTIR and is highly effective for studying protein secondary structure, side-chain environments, and disulfide bond conformations [16] [17]. Its major advantage is the minimal interference from water, making it exceptionally suitable for analyzing proteins in aqueous solutions [15] [14]. The technique is sensitive to the polarizability of molecular bonds, making it particularly strong for probing aromatic amino acids and S-S bridges [16].

Experimental Protocol:

- Sample Preparation:

- Protein solutions can be analyzed as-is in glass capillaries, quartz cuvettes, or multi-well plates. Typical concentrations range from 1-50 mg/mL. Solid powders can be analyzed in a similar fashion to FTIR.

- Data Collection:

- Focus the laser beam (common wavelengths: 532 nm, 785 nm) onto the sample. A 785 nm laser minimizes fluorescence from certain samples.

- Use a microscope objective to collect the scattered light.

- Set acquisition time to 10-60 seconds and accumulate 2-10 scans to build up signal.

- Data Analysis:

- Identify key Raman bands indicative of protein structure:

- Amide I: ~1660-1680 cm⁻¹ (α-helix), ~1665-1680 cm⁻¹ (β-sheet)

- Amide III: 1230-1310 cm⁻¹ (useful for α-helix/β-sheet distinction)

- S-S Stretch: 500-550 cm⁻¹ (gauche-gauche-gauche ~510 cm⁻¹, gauche-gauche-trans ~525 cm⁻¹) [16]

- Phenylalanine Ring Breath: ~1000 cm⁻¹

- Analyze the amide I and III regions via band fitting to quantify secondary structure elements.

- Identify key Raman bands indicative of protein structure:

Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) Spectroscopy

Application Note: Protein NMR is a powerful technique for determining the three-dimensional structure of proteins at atomic resolution in a solution environment that mimics physiological conditions [18]. It is also uniquely capable of probing protein dynamics and interactions with other molecules, such as ligands, DNA, or other proteins [18]. For larger proteins, isotopic labeling with ¹⁵N and ¹³C is essential [18].

Experimental Protocol:

- Sample Preparation:

- Prepare a highly purified protein sample (>95% purity) in a suitable buffer (e.g., phosphate buffer, 20-50 mM). The sample volume is typically 300-600 μL with a protein concentration of 0.5-1.0 mM.

- Add 5-10% D₂O to provide a lock signal for the spectrometer.

- For structural studies, the protein must be uniformly labeled with ¹⁵N and/or ¹³C isotopes, expressed in E. coli grown on isotopically enriched media.

- Data Collection:

- Start with a 1H 1D spectrum to assess sample quality.

- Acquire a 2D ¹H-¹⁵N HSQC (Heteronuclear Single Quantum Coherence) spectrum. Each peak in this "fingerprint" spectrum typically corresponds to one backbone amide group in the protein [18].

- For full structure determination, collect a suite of 3D experiments (e.g., HNCA, HNCACB, CBCA(CO)NH, HNCO) to assign backbone and side-chain chemical shifts [18].

- Acquire 3D NOESY spectra to obtain distance restraints between protons that are close in space.

- Data Analysis:

- Assign all ¹H, ¹⁵N, and ¹³C chemical shifts using triple-resonance experiments.

- Assign NOE (Nuclear Overhauser Effect) cross-peaks to generate a list of inter-proton distance restraints.

- Calculate a bundle of 3D structures using computational programs (e.g., CYANA, XPLOR-NIH) that satisfy the experimental restraints.

- Validate the final structure bundle for stereochemical quality.

Mass Spectrometry (MS)

Application Note: Mass spectrometry is an indispensable tool for characterizing the primary structure of proteins, including their molecular weight, amino acid sequence, and post-translational modifications (PTMs) such as phosphorylation and glycosylation [19]. Tandem MS (MS/MS) enables high-throughput identification and quantification of proteins from complex mixtures, forming the backbone of modern proteomics [19].

Experimental Protocol:

- Sample Preparation:

- Denature the protein (e.g., with 8 M urea or guanidine-HCl), reduce disulfide bonds (e.g., with dithiothreitol, DTT), and alkylate cysteine residues (e.g., with iodoacetamide).

- Digest the protein into peptides using a sequence-specific protease, most commonly trypsin, overnight at 37°C.

- Desalt the resulting peptides using a C18 solid-phase extraction tip or column.

- Data Collection (LC-MS/MS):

- Separate the peptides using nano-flow liquid chromatography (nanoLC) with a C18 reversed-phase column.

- Ionize the eluting peptides using electrospray ionization (ESI) and introduce them into the mass spectrometer.

- Operate the instrument in data-dependent acquisition (DDA) mode:

- MS1 Survey Scan: Acquire a full MS scan to measure the (m/z) of intact peptide ions.

- MS2 Fragmentation Scan: Select the most intense peptide ions from the MS1 scan for fragmentation (typically using Higher-energy C-trap dissociation, HCD) and acquire their MS/MS spectra.

- Data Analysis:

- Search the MS/MS spectra against a protein sequence database using software tools (e.g., MaxQuant, Proteome Discoverer, Mascot).

- Identify proteins based on the match between experimental MS/MS spectra and theoretical spectra generated from the database.

- For PTM analysis, include variable modifications (e.g., phosphorylation on serine/threonine/tyrosine, oxidation on methionine) in the database search parameters.

Workflow Visualization

The following diagram illustrates the general decision-making workflow for selecting an appropriate spectroscopic technique based on the primary structural information required.

Research Reagent Solutions

The following table lists essential reagents and materials commonly required for the experimental protocols described in this article.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents for Protein Spectroscopy

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application | Technique(s) |

|---|---|---|

| Potassium Bromide (KBr) | Matrix for preparing solid pellets for transmission FTIR. | FTIR |

| Infrared-Transparent Windows (CaF₂, BaF₂) | Cells for holding liquid samples during FTIR analysis. | FTIR |

| Deuterium Oxide (D₂O) | Provides a lock signal for the NMR spectrometer; used for solvent suppression. | NMR |

| Isotopically Labeled Nutrients (¹⁵NH₄Cl, ¹³C-Glucose) | For producing uniformly ¹⁵N- and/or ¹³C-labeled proteins for multidimensional NMR. | NMR |

| Trypsin (Protease) | Enzymatically cleaves proteins into peptides for bottom-up MS analysis. | MS |

| Dithiothreitol (DTT) / Tris(2-carboxyethyl)phosphine (TCEP) | Reduces disulfide bonds to denature proteins for MS and other analyses. | MS, General |

| Iodoacetamide | Alkylates cysteine residues to prevent reformation of disulfide bonds. | MS, General |

| C18 Solid-Phase Extraction Tips | Desalts and concentrates peptide mixtures prior to LC-MS/MS. | MS |

| Buffers (e.g., Phosphate, Tris) | Maintains protein stability and pH during analysis. | All |

| Stable Isotope Tags (e.g., TMT, SILAC) | Labels proteins/peptides for multiplexed relative quantification in MS. | MS |

In the field of nutrition research, the accurate characterization of protein structure—encompassing secondary, tertiary, and quaternary conformations—is fundamental to understanding their nutritional quality, functional properties in food matrices, and digestibility [1]. Traditional methods for protein analysis, including Kjeldahl and Dumas combustion for content quantification, and chromatography, circular dichroism (CD), and nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) for structural elucidation, are often time-consuming, require extensive sample preparation, and are destructive in nature [1] [20]. These processes can be laborious and provide only retrospective results, limiting their utility for rapid quality control or real-time monitoring in food production and drug development pipelines.

Vibrational spectroscopy techniques, namely Fourier-Transform Infrared (FTIR), Near-Infrared (NIR), and Raman spectroscopy, have emerged as powerful alternatives that directly address these limitations. Their core advantages reside in their exceptional speed, non-destructive character, and capacity for in-situ analysis, allowing researchers to probe protein structure within complex, native environments without the need for chemical reagents or lengthy extractions [1] [21]. This application note details the experimental protocols and presents quantitative data demonstrating how these spectroscopic methods are revolutionizing protein characterization within the context of modern nutrition science and biopharmaceutical development.

Comparative Advantages of Spectroscopic Techniques

The following table summarizes the key advantages of FTIR, NIR, and Raman spectroscopy over traditional protein analysis methods across critical parameters for research and industry.

Table 1: Advantages of Spectroscopic Techniques over Traditional Protein Analysis Methods

| Analytical Parameter | Traditional Methods (e.g., Kjeldahl, CD, HPLC) | Vibrational Spectroscopy (FTIR, NIR, Raman) | Practical Implication for Research & Industry |

|---|---|---|---|

| Analysis Speed | Hours to days [1] | Seconds to minutes [1] [22] | Enables high-throughput screening and real-time process control. |

| Sample Preparation | Extensive; often involves extraction, digestion, or derivatization [1] | Minimal to none; analysis of solids, liquids, and complex matrices [1] | Reduces labor, cost, and analyst error; preserves sample integrity. |

| Sample Destructiveness | Destructive; sample consumed or altered [1] | Non-destructive or micro-destructive; sample can be retained for further analysis [1] [23] | Allows longitudinal studies on precious samples and multiple analyses on the same specimen. |

| In-Situ Capability | Generally requires lab-based, off-line analysis | High potential for in-situ and on-line monitoring [24] | Facilitates at-line and in-line quality control in manufacturing and field analysis. |

| Chemical Consumption | Often requires solvents and reagents | Solvent-free and reagentless [25] | Supports green chemistry initiatives; reduces operational costs and waste. |

| Structural Information | Varies by technique; some are limited to solution state. | Direct assessment of secondary structure (e.g., via Amide I band) in various physical states [1] [20] | Provides insights into structure-function relationships in native-like environments. |

Experimental Protocols for Protein Characterization

The following protocols are generalized for analyzing plant-based protein powders and isolates, which are of significant interest in nutritional and pharmaceutical sciences.

Protocol for Protein Secondary Structure Analysis using FTIR Spectroscopy

FTIR spectroscopy is a highly sensitive technique for probing the secondary structure of proteins (α-helices, β-sheets, turns, random coils) through the analysis of the Amide I band.

Table 2: Key Research Reagents and Solutions for FTIR Analysis

| Item/Material | Function/Description |

|---|---|

| FTIR Spectrometer | Equipped with a DTGS (deuterated triglycine sulfate) or MCT (mercury-cadmium-telluride) detector for high sensitivity. |

| ATR (Attenuated Total Reflectance) Accessory | Diamond or ZnSe crystal. Allows direct analysis of solid and liquid samples with minimal preparation. |

| Potassium Bromide (KBr) | Optional; for preparing traditional pellets if ATR is not available. |

| Deuterated Buffer (e.g., D₂O) | For studying proteins in solution; reduces strong water absorption in the mid-IR region. |

Step-by-Step Procedure:

- Sample Preparation (Solid): For plant protein powders, ensure the sample is finely ground and homogeneous. Place a small amount directly onto the ATR crystal.

- Sample Preparation (Solution): For protein solutions, a drop is placed on the ATR crystal. Using deuterated buffer (D₂O) is advantageous for shifting the H₂O band and better exposing the Amide I region.

- Data Acquisition: Apply consistent pressure to the sample to ensure good contact with the crystal. Collect the spectrum in the mid-IR range (e.g., 4000-400 cm⁻¹) with a resolution of 4 cm⁻¹. Acquire 64-128 scans to achieve a high signal-to-noise ratio. A background spectrum of the clean crystal must be collected immediately before the sample measurement.

- Spectral Processing: Subtract the background spectrum from the sample spectrum. Perform essential preprocessing steps: atmospheric compensation (for CO₂ and water vapor), baseline correction, and smoothing.

- Data Analysis (Critical Step): Focus on the Amide I band (1600-1700 cm⁻¹), which is primarily C=O stretching and is highly sensitive to secondary structure.

- Second Derivative Analysis: Calculate the second derivative of the spectrum to enhance the resolution of overlapping bands.

- Curve Fitting/Deconvolution: Deconvolute the Amide I band using Gaussian or Lorentzian functions. The number, position, and area of the sub-bands correspond to different secondary structures:

- 1650-1658 cm⁻¹: α-Helix

- 1620-1640 cm⁻¹: β-Sheet

- 1660-1680 cm⁻¹: β-Turns

- 1640-1650 cm⁻¹: Random Coil

Protocol for Rapid Protein Content Quantification using NIR Spectroscopy

NIR spectroscopy excels at the rapid, non-destructive quantification of bulk protein content in complex food matrices, making it ideal for quality control.

Step-by-Step Procedure:

- Calibration Model Development (Prerequisite): This is the most critical step for NIR analysis. A robust model requires a large and diverse set of samples (n > 100) covering the expected variation in protein content and matrix composition.

- Reference Analysis: Precisely determine the protein content of all calibration samples using a primary reference method (e.g., Dumas combustion).

- Spectral Acquisition: Collect NIR spectra (e.g., 780-2500 nm) for all calibration samples using a benchtop or portable spectrometer.

- Chemometric Modeling: Use multivariate calibration algorithms to correlate the spectral data (X-matrix) with the reference protein data (Y-matrix).

- Algorithm: Partial Least Squares Regression (PLSR) is the most common and effective algorithm for this purpose.

- Preprocessing: Apply spectral preprocessing techniques like Standard Normal Variate (SNV), Multiplicative Scatter Correction (MSC), and derivatives (1st, 2nd) to minimize light scattering and enhance spectral features.

- Model Validation: Rigorously validate the model using an independent set of samples not included in the calibration. Key figures of merit include:

- Coefficient of Determination (R²)

- Root Mean Square Error of Prediction (RMSEP)

- Ratio of Performance to Deviation (RPD)

- Routine Analysis: Once a validated model is deployed, protein content in unknown samples can be predicted in seconds by simply acquiring their NIR spectrum.

Data Presentation and Analysis

Quantitative Performance of Spectroscopy

The following table compiles representative quantitative data from research applications, demonstrating the performance of vibrational spectroscopy in protein analysis.

Table 3: Quantitative Performance of Spectroscopic Methods in Protein Analysis

| Application | Technique | Chemometric Method | Performance | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Protein Content in Milk Powder | NIR Spectroscopy | PLSR | R² = 0.88-0.90 for bulk density, insolubility index | [22] |

| Protein Content in Plant Proteins | NIR / FTIR / Raman | PLSR, SVR, Deep Learning | High predictive accuracy for pea protein, lentils | [1] |

| Dietary Fatty Acids in Liquid Milk | NIR Spectroscopy + Aquaphotomics | PLSR | R² > 0.75, RPD > 1.5 for multiple fatty acids | [22] |

| Discrimination of Fracture-Related Infection (Clinical) | FTIR Spectroscopy on Plasma | Multivariate Analysis | AUROC ≈ 0.803, Sensitivity ≈ 0.755, Specificity ≈ 0.677 | [26] |

Integration with Industry 4.0 and Advanced Data Analysis

The true potential of spectroscopy is unlocked through integration with modern data science and industrial digitalization, moving analysis from the lab to the production line.

- AI and Chemometrics: The complex, overlapping spectral signals are deciphered using advanced algorithms like support vector regression (SVR) and deep learning, which improve the accuracy and robustness of quantification models [1].

- Real-Time Monitoring: Spectroscopy-based sensors, when combined with Internet of Things (IoT) and cloud computing, enable real-time quality and safety monitoring across the food and pharmaceutical supply chains, providing a non-destructive alternative to retrospective lab analyses [24].

- Data Fusion: Integrating data from multiple spectroscopic techniques (e.g., NIR, FTIR, Raman) provides a more comprehensive characterization of the protein system, overcoming the limitations of any single technique [1].

The transition from traditional, destructive wet-chemistry methods to rapid, non-destructive, and in-situ vibrational spectroscopy represents a paradigm shift in protein characterization for nutrition and pharmaceutical research. The documented advantages in speed, minimal sample preparation, and the ability to analyze proteins within their natural matrices directly address the needs of modern scientists and drug development professionals for efficiency and precision. As advancements in AI-driven chemometrics, portable instrumentation, and Industry 4.0 integration continue, spectroscopic techniques are poised to become the cornerstone of quality-by-design and real-time release in the development of high-quality, sustainable protein sources and biopharmaceuticals.

A Practical Guide to Spectroscopic Techniques for Protein Analysis

Vibrational Spectroscopy for Rapid Quantification and Secondary Structure

In the fields of nutritional research and drug development, the precise characterization of protein content and structure is paramount for understanding functionality, nutritional quality, and safety. Traditional methods for protein analysis, such as the Kjeldahl and Dumas methods, while effective, are labor-intensive, require extensive sample preparation, and are not suited for rapid, high-throughput analysis [14]. Vibrational spectroscopy techniques have emerged as powerful, rapid, and non-destructive alternatives that are increasingly essential for modern analytical workflows. These methods provide simultaneous insights into both the quantitative content and secondary structure of proteins, which are critical for evaluating the quality of plant-based proteins, studying biopharmaceuticals, and supporting the transition to more sustainable protein sources [14] [1]. This document outlines detailed application notes and protocols for using these techniques, framed within the context of protein characterization for nutrition research.

Core Techniques and Principles

Vibrational spectroscopy encompasses several techniques that probe molecular vibrations to reveal chemical information. The primary methods for protein analysis are Fourier-Transform Infrared (FTIR), Near-Infrared (NIR), and Raman spectroscopy.

- FTIR Spectroscopy measures the absorption of infrared light, primarily exciting vibrations that involve a change in the dipole moment. The amide I band (approximately 1600-1700 cm⁻¹), which arises mainly from C=O stretching vibrations of the peptide backbone, is highly sensitive to protein secondary structure and is the most critical region for conformational analysis [27] [28].

- Raman Spectroscopy relies on the inelastic scattering of light and is sensitive to vibrations that involve a change in polarizability. It provides complementary information to FTIR and is particularly effective for detecting non-polar functional groups. A significant advantage is its relative insensitivity to water, allowing for the analysis of proteins in their native aqueous solutions [14] [1].

- NIR Spectroscopy probes overtones and combination bands of fundamental molecular vibrations (e.g., C-H, N-H, O-H) in the range of 780-2500 nm. It is ideally suited for the rapid quantification of bulk protein content in complex matrices with minimal sample preparation [1].

The integration of chemometrics and artificial intelligence (AI) is crucial for interpreting the complex spectral data generated by these techniques. Multivariate statistical methods, such as Partial Least Squares Regression (PLSR), are employed to build calibration models that correlate spectral data to protein content or structure [1] [29].

Application Notes: Data and Quantification

Quantitative Analysis of Protein Content

Vibrational spectroscopy offers a rapid and non-destructive means for quantifying protein content in various sample types, from raw ingredients to finished products. NIR spectroscopy, in particular, is widely adopted in industrial settings for high-throughput analysis.

Table 1: Performance of Vibrational Spectroscopy Techniques for Protein Quantification

| Technique | Typical Spectral Range | Key Analytical Use | Representative Performance (R²/Precision) | Reference Model |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| NIR Spectroscopy | 780-2500 nm | Bulk protein content in powders, grains, and ingredients | R² > 0.98 for pea protein isolate [1] | PLSR, Support Vector Regression (SVR) |

| FTIR Spectroscopy | 4000-400 cm⁻¹ | Protein content and secondary structure in isolated proteins | Excellent results vs. traditional methods [28] | PLSR |

| Raman Spectroscopy | 4000-50 cm⁻¹ | Protein content in complex matrices with water interference | High precision in aqueous solutions [1] | PLSR, Deep Learning Models |

Secondary Structure Determination

The secondary structure of a protein (α-helix, β-sheet, turns, random coil) directly influences its functional properties, such as solubility, gelation, and emulsification capacity. FTIR and Raman spectroscopy are the primary techniques for this analysis.

The amide I band in FTIR spectra is deconvoluted to determine the relative proportions of different secondary structures. The characteristic absorption ranges for key structures are as follows [27]:

Table 2: Characteristic Amide I Band Positions for Protein Secondary Structures in H₂O

| Secondary Structure | Band Position (cm⁻¹) |

|---|---|

| β-sheet | 1623 - 1641 |

| Random coil | 1642 - 1657 |

| α-helix | 1648 - 1657 |

| Turns | 1662 - 1686 |

Recent advances combine these spectroscopic methods with machine learning to accelerate analysis. For instance, neural network models can use data from just seven discrete infrared frequencies to accurately predict secondary structure components, reducing data acquisition time nearly six-fold and analysis time by over 3000 times compared to conventional spectral fitting [30].

Experimental Protocols

General Workflow for Protein Analysis

The following diagram illustrates the overarching experimental workflow for protein characterization using vibrational spectroscopy, integrating sample preparation, data acquisition, and data analysis.

Protocol 1: FTIR Analysis of Protein Secondary Structure

Objective: To determine the secondary structure composition of a purified plant-based protein isolate (e.g., from soy or pea).

Materials and Reagents:

- Purified protein sample

- FTIR spectrometer with a deuterated triglycine sulfate (DTGS) detector

- Attenuated Total Reflectance (ATR) accessory (e.g., diamond crystal)

- Hydraulic press (optional, for solid powders)

- Lab wash bottle with distilled water and lint-free wipes for cleaning

Procedure:

- System Initialization: Power on the FTIR spectrometer and the associated computer. Allow the instrument to initialize for at least 15 minutes.

- Background Collection: Clean the ATR crystal thoroughly with ethanol and distilled water. Dry it with a lint-free wipe. Collect a background spectrum (typically 32-64 scans) at a resolution of 4 cm⁻¹.

- Sample Preparation: For solid protein powders, place a small amount of sample directly onto the ATR crystal. Use a hydraulic press to ensure uniform and firm contact between the sample and the crystal, if applicable. For liquid samples, deposit a few microliters directly on the crystal.

- Spectral Acquisition: Collect the sample spectrum over the mid-IR range (e.g., 4000-600 cm⁻¹) using the same scan parameters as the background (e.g., 64 scans at 4 cm⁻¹ resolution).

- Post-measurement Cleaning: Carefully remove the sample and clean the ATR crystal thoroughly to prevent cross-contamination.

- Data Pre-processing: Process the raw absorbance spectrum. Apply a linear baseline correction to the amide I region (approximately 1700-1600 cm⁻¹). Use second-derivative spectroscopy or Fourier self-deconvolution to resolve overlapping component bands.

- Curve Fitting: Perform a curve-fitting procedure (e.g., Gaussian or Lorentzian functions) on the amide I band. The number, position, and width of the component bands should be guided by the second-derivative spectrum.

- Quantification: Integrate the area under each fitted component band. The relative area of each band, corresponding to a specific secondary structure (see Table 2), is reported as the percentage of that structure in the protein.

Protocol 2: NIR Analysis for Bulk Protein Content

Objective: To rapidly quantify the protein content in a powdered plant-based protein sample using a calibration model.

Materials and Reagents:

- Powdered samples of known protein content (for calibration)

- Unknown sample for prediction

- NIR spectrometer equipped with a reflectance cup

- Sample cup or vial compatible with the spectrometer

Procedure:

- Calibration Set: Assemble a set of 50-100 samples that represent the expected variation in protein content and matrix composition. The reference protein values for these samples must be determined using a primary method (e.g., Dumas combustion).

- Spectral Acquisition: Fill the sample cup consistently and uniformly to ensure reproducible packing. Collect the NIR reflectance spectra (e.g., 10000-4000 cm⁻¹) for each calibration sample. Take multiple scans per sample and average them to improve the signal-to-noise ratio.

- Model Development: Pre-process the spectra using Standard Normal Variate (SNV) and detrending to remove light scatter effects. Use a chemometric software package to develop a PLSR model that correlates the pre-processed spectral data to the known protein content.

- Model Validation: Validate the performance of the PLSR model using an independent set of validation samples not included in the calibration set. Key performance metrics include the Coefficient of Determination (R²), Root Mean Square Error of Prediction (RMSEP), and Residual Predictive Deviation (RPD).

- Routine Analysis: For unknown samples, acquire their NIR spectra under identical conditions. Input the pre-processed spectra into the validated PLSR model to obtain a predicted protein content value.

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions and Materials

| Item | Function/Application | Technical Notes |

|---|---|---|

| ATR-FTIR Accessory | Enables direct analysis of solids, liquids, and powders without extensive preparation. | Diamond crystal offers durability; ensure consistent pressure application for reproducible results. |

| PLSR Software | Multivariate data analysis for building quantitative calibration models from spectral data. | Open-source (e.g., R packages) and commercial options (e.g., Unscrambler, SIMCA) are available. |

| Hyperspectral Imaging | Combines spectroscopy with spatial imaging for visualizing protein distribution in a sample. | Useful for heterogeneous samples like plant tissues or food products [14]. |

| Portable NIR Spectrometer | Allows for on-site, rapid quality control at various points in the supply chain. | Ideal for testing raw material ingredients upon delivery at a processing facility. |

| Isotope-Labelled Proteins | (¹³C, ¹⁵N) Enable site-specific probing of protein structure and dynamics in FTIR/Raman studies [27]. | Used in advanced research, particularly for studying protein aggregation mechanisms. |

Integrated Data Analysis and Pathway

The analytical process, from raw spectral data to biochemical insight, relies on a structured data analysis pathway. The following diagram outlines this critical process, highlighting the role of computational methods.

Vibrational spectroscopy provides a robust, rapid, and non-destructive suite of tools for the dual analysis of protein content and secondary structure. As the demand for plant-based proteins and precise biopharmaceutical characterization grows, these techniques are becoming indispensable in research and industrial quality control. The integration of advanced data analytics, such as AI and machine learning, is pushing the boundaries of speed and accuracy, enabling real-time, data-driven decision-making in nutrition research and drug development [14] [30]. The protocols outlined herein offer a foundation for the rigorous application of these powerful analytical methods.

Mass Spectrometry for Protein Folding, Dynamics, and Non-Covalent Interactions

Within nutritional research, understanding the intricate relationship between a protein's structure and its biological function is paramount. The folding, dynamics, and interaction profiles of dietary proteins and receptors for bioactive compounds directly influence their nutritional efficacy and health outcomes. Mass spectrometry (MS) has evolved beyond a simple analytical tool for mass determination into a powerful platform for interrogating protein higher-order structure, dynamics, and non-covalent complexes directly from solution conditions relevant to physiological and nutritional environments [19] [31]. This Application Note details key MS-based protocols for characterizing protein conformational stability, folding intermediates, and functional assemblies, providing a critical toolkit for nutrition scientists.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

The following table catalogues essential materials and reagents required for the mass spectrometric analysis of protein structure and interactions.

Table 1: Key Research Reagent Solutions for MS-Based Protein Analysis

| Item | Function/Application |

|---|---|

| Ammonium Acetate (Volatile Buffer) | Prepares protein samples under native, MS-compatible conditions for the preservation of non-covalent interactions and folded structures [32]. |

| Deuterium Oxide (D₂O) | Serves as the labeling agent in Hydrogen/Deuterium Exchange (HDX) experiments to probe protein dynamics and solvent accessibility [31]. |

| Urea (High-Purity) | Chaotropic agent used in denaturation studies to probe protein folding stability and populate unfolding intermediates [32]. |

| Nano-Electrospray Ionization (nESI) Emitters | Small-diameter emitters (≈1 µm) enabling direct analysis from solutions containing high concentrations of non-volatile additives like urea and salts [32]. |

| Pepsin | Acid-active protease used for on-line digestion in HDX-MS workflows to generate peptides for localized analysis of deuterium uptake [31]. |

| Chemical Crosslinkers (e.g., BS3, DSS) | Bifunctional reagents that covalently link spatially proximate amino acid residues, providing constraints for modeling protein topology and interactions [31]. |

Application Notes & Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Monitoring Urea-Induced Protein Denaturation by nESI-MS

Objective: To directly monitor protein unfolding and detect folding intermediates by tracking changes in electrospray charge state distributions from solutions containing molar concentrations of urea [32].

Background: Protein conformational stability, a key parameter in understanding the function of bioactive proteins and enzymes, is traditionally probed by urea-induced denaturation monitored with optical spectroscopy. This protocol leverages advanced nESI emitter design to overcome historical incompatibilities between MS and high urea concentrations, allowing for the direct detection of co-populated states within a conformational ensemble.

Table 2: Key Parameters for Urea Denaturation Monitored by nESI-MS

| Parameter | Typical Setting or Observation |

|---|---|

| Urea Concentration Range | 0 M to 8 M |

| Compatible Protein Buffer | 200 mM ammonium acetate, pH 6.8 |

| nESI Emitter Inner Diameter | ≈1 µm |

| Key Analytical Readout | Shift in Charge State Distribution (CSD) towards higher charge states; loss of non-covalently bound ligands (e.g., heme) [32]. |

| Observed Folding Intermediate | For Myoglobin: Co-existence of holo (folded, heme-bound) and apo (unfolded, heme-free) forms at intermediate urea concentrations [32]. |

Step-by-Step Procedure:

- Sample Preparation: Prepare a series of identical protein samples (e.g., 5 µM myoglobin) in 200 mM ammonium acetate (pH 6.8) with urea concentrations ranging from 0 M to 8 M.

- Instrument Setup: Load the sample into a pulled glass nESI emitter with an inner diameter of approximately 1 µm.

- Utilize a mass spectrometer (e.g., Synapt G2-S IMS-MS or Q Exactive UHMR) with instrument conditions tuned to minimize gas-phase unfolding and activation [32].

- For on-axis ESI sources, a slight lateral offset of the needle relative to the inlet can improve spray stability and reduce urea intake.

- Data Acquisition: Acquire mass spectra for each sample condition. Ensure spray stability and signal quality are maintained across the entire urea concentration series.

- Data Analysis:

- Charge State Distribution (CSD): Plot the relative intensity of different charge states versus urea concentration. A shift from low (e.g., +8 for native myoglobin) to high charge states indicates a loss of compact tertiary structure.

- Ligand Binding: Monitor the relative intensity of the holo (ligand-bound) and apo (ligand-free) protein forms. A decrease in the holo form signifies disruption of the native binding pocket.

- Ion Mobility (Optional): Analyze the arrival time distribution for individual charge states across urea concentrations. Minimal changes suggest the CSD shift primarily reflects solution-phase, not gas-phase, unfolding [32].

Protocol 2: Investigating Protein Dynamics with Hydrogen/Deuterium Exchange MS (HDX-MS)

Objective: To characterize protein conformational dynamics and map solvent-accessible regions by measuring the exchange rate of backbone amide hydrogens with deuterium present in the solvent [31].

Background: The rate of HDX is slowed by hydrogen bonding (e.g., in secondary structure) and burial from solvent. Thus, HDX kinetics provide a sensitive measure of local protein dynamics, folding, and regions involved in binding events, which is crucial for understanding how food processing or digestion alters protein structure.

Step-by-Step Procedure:

- Labeling Reaction: Initiate exchange by diluting the protein of interest (e.g., from a concentrated stock in H₂O buffer) into a deuterated buffer (e.g., 200 mM ammonium acetate in D₂O, pD 7.0). Perform labeling for a series of time points (e.g., 10 seconds, 1 minute, 10 minutes, 1 hour) at a controlled temperature (e.g., 25°C).

- Quenching: At each time point, withdraw an aliquot and quench the exchange reaction by rapidly lowering the pH to ~2.5 and the temperature to 0°C (e.g., using a quench solution of cold glycine-HCl or formic acid).

- Proteolysis and Separation: Immediately inject the quenched sample into an on-line system for digestion by an immobilized acid-active protease (e.g., pepsin) and subsequent separation of the resulting peptides by liquid chromatography (UPLC) at 0°C.

- Mass Analysis: Elute peptides directly into the mass spectrometer for mass analysis. The increase in mass of each peptide (+1 Da per incorporated deuteron) is measured.

- Data Processing:

- Identify the peptide sequence based on its mass (using non-deuterated controls) and potentially MS/MS fragmentation.

- For each peptide at each time point, calculate the deuterium uptake: D = (m - m₀) / (m₁₀₀% - m₀), where m is the centroid mass of the deuterated peptide, m₀ is the centroid mass of the non-deuterated peptide, and m₁₀₀% is the theoretical mass of the fully deuterated peptide.

- Plot deuterium uptake versus time for each peptide to determine exchange kinetics.

Protocol 3: Characterizing Non-Covalent Assemblies by Native MS and MALDI-MS

Objective: To determine the stoichiometry, stability, and structural properties of non-covalent protein-protein complexes under native-like conditions [33].

Background: The function of many protein assemblies in nutrition (e.g., oligomeric enzymes, receptor-ligand complexes) depends on their quaternary structure. Native MS, using soft ionization techniques like nESI and MALDI, can transfer these fragile complexes from solution into the gas phase for direct analysis.

Step-by-Step Procedure: A. Native Electrospray MS

- Buffer Exchange: Desalt the protein complex into a volatile ammonium acetate solution (e.g., 100-200 mM, pH 6.8-7.5) using size-exclusion chromatography or centrifugal filters.

- nESI-MS Analysis: Introduce the sample via nESI emitters using instrument conditions optimized for non-covalent complexes (low collision energies, elevated pressure regions).

- Data Interpretation: Identify the mass of the intact complex from the m/z spectrum. The stoichiometry is derived from the mass, and the width of charge state peaks can inform on structural homogeneity.

B. MALDI-MS for Non-Covalent Complexes

- Matrix Selection and Preparation: Use a "cool" matrix like sinapinic acid. Prepare the matrix in a solvent that does not fully disrupt the complex (e.g., mild acidity, no strong organic solvents).

- Sample Preparation: Mix the protein complex solution directly with the matrix solution on the MALDI target and allow it to crystallize under gentle conditions (e.g., room temperature, no vacuum).

- Data Acquisition: Use low laser fluence, just above the detection threshold, to minimize gas-phase dissociation of the complex.

- Data Interpretation: Identify signals corresponding to the intact complex. Control experiments with denaturing conditions are essential to confirm the non-covalent nature of the assembly [33].

Table 3: Comparison of MS Techniques for Protein Assemblies

| Feature | Native ESI-MS | MALDI-MS for Complexes |

|---|---|---|

| Typical Buffer | Volatile buffers (Ammonium Acetate) | Limited buffer compatibility |

| Ionization Process | Gentle desolvation from droplets | Rapid desorption/ionization by laser |

| Key Application | Determining stoichiometry & relative binding affinity | Detection of stable non-covalent complexes |

| Challenge | Maintaining complex stability during transfer | Finding conditions that preserve interactions in the solid matrix [33] |

The protocols outlined herein provide a robust framework for integrating mass spectrometry into nutrition research focused on protein structure. The ability of MS to detect co-existing conformational states, quantify dynamics with residue-level precision, and characterize intact functional assemblies offers a multidimensional perspective that complements traditional biophysical and spectroscopic methods. Applying these techniques to dietary proteins, enzymes, and receptors will yield deeper insights into the molecular mechanisms underpinning their nutritional and physiological functions.

NMR Spectroscopy for Atomic-Resolution Structure and Molecular Interactions

Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) spectroscopy stands as a powerful technique in structural biology, capable of elucidating the three-dimensional structures of proteins and their complex interaction networks at atomic resolution under near-physiological conditions. For nutrition research, understanding the structure-function relationship of dietary proteins, enzymes involved in metabolic pathways, and receptors for nutritional compounds is paramount. NMR provides unique insights into protein dynamics, folding, and molecular interactions that are central to nutrient metabolism, bioavailability, and the mechanistic action of bioactive food components, offering a foundation for rational design of nutritional interventions and nutraceuticals.

Key NMR Methodologies for Characterizing Protein Complexes

Protein-protein interactions are critical in numerous cellular events, including signal transduction pathways relevant to nutrient sensing and metabolic regulation [34]. NMR spectroscopy offers a suite of methods for extracting atomic-resolution information on binding interfaces, intermolecular affinity, and binding-induced conformational changes.

Interface and Affinity of Binding

Targeting specific protein-protein interactions offers a viable way to control and manipulate selective pathways, which in nutrition research could translate to modulating metabolic pathways or nutrient-sensing mechanisms.

Chemical Shift Perturbation (CSP)

CSP analysis is among the most informative and widely applicable NMR methods for investigating binding interactions [34]. The chemical shift of NMR-active nuclei is exquisitely sensitive to their local electronic environment, which is perturbed by binding events.

In a typical CSP experiment, a reference 2D-heteronuclear single quantum coherence (HSQC) spectrum of a 15N- or 13C-labeled protein is acquired in the absence of its binding partner. This is followed by a series of HSQC spectra measured at increasing concentrations of an unlabeled ligand [34]. These titration methods are ideally suited for weak binding interactions (affinity in the µM-mM range) that exchange rapidly on the NMR timescale (exchange rate ≥ µs⁻¹). For such fast-exchange regimes, the observed chemical shifts represent a population-weighted average of the chemical shifts of the free and complexed protein [34]. A plot of the chemical shift change as a function of the binding partner's concentration produces a binding isotherm that can be fitted to obtain the dissociation constant (KD) for the complex.

Table 1: Key Features of Chemical Shift Perturbation (CSP) Experiments

| Aspect | Description |

|---|---|

| Primary Application | Identification of binding interfaces and determination of binding affinity (KD). |

| Ideal Affinity Range | Weak binding (µM-mM range). |

| Exchange Regime | Fast exchange on the NMR timescale. |

| Observable | Change in chemical shift of nucleus (e.g., 1H-15N) upon binding. |

| Titration Data | Binding isotherm from which KD is derived. |

| Key Limitation | Sensitive to allosteric effects, which can ambiguate direct binding interface identification. |

Solvent Paramagnetic Relaxation Enhancement (Solvent-PRE)

Solvent-PRE effects arise from the magnetic dipolar coupling between an NMR-active nucleus on the protein and unpaired electrons located on a paramagnetic molecule added to the solution as a solvent accessibility probe [34]. This coupling enhances the longitudinal and transverse nuclear spin relaxation rates (R1 and R2, respectively) by an amount proportional to the local concentration of the paramagnetic molecule.

Solvent-PREs are measured by taking the difference between the 1H-R2 rate measured with a paramagnetic probe and the rate measured in a diamagnetic reference sample [34]. In a folded globular protein, solvent-PREs decrease with increasing distance from the molecular surface. To identify a protein-protein binding interface, solvent PREs are compared for the free and complexed forms. A reduction in PRE (positive ΔPRE) at specific residues indicates that those residues are shielded from the solvent paramagnetic probe due to their involvement in the binding interface, providing a more unambiguous definition of the interface than CSP alone [34].

Table 2: Key Features of Solvent Paramagnetic Relaxation Enhancement (PRE) Experiments

| Aspect | Description |

|---|---|

| Primary Application | Mapping protein-protein binding interfaces and protein surface accessibility. |

| Measured Parameter | Enhancement of nuclear spin relaxation rates (R1, R2). |

| Probe Mechanism | Paramagnetic molecule (e.g., Gd(DTPA-BMA)) in solution interacts with solvent-exposed nuclei. |

| Interface Identification | Residues with reduced PRE (positive ΔPRE) in the complex are part of the binding interface. |

| Key Advantage | Less sensitive to allosteric conformational changes compared to CSP, providing a more direct map of the interface. |

Advanced Structural Constraints

For full structural characterization of a protein-protein complex, NMR provides methods to obtain precise distance and orientation constraints.

- Intermolecular Nuclear Overhauser Effect (NOE): The NOE provides information about the distances between atoms (typically <5 Å). Intermolecular NOEs between two interacting proteins are the most direct source of structural constraints for defining the atomic details of a binding interface [34].

- Residual Dipolar Couplings (RDCs): RDCs are measured when proteins are partially aligned in a dilute liquid crystalline medium. They provide information on the orientation of bond vectors relative to a common molecular frame and are exceptionally valuable for determining the relative orientation of protein domains or proteins within a complex [34].

Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Binding Interface Mapping via CSP and Solvent-PRE

This protocol outlines the steps for identifying a protein-protein binding interface and estimating binding affinity using CSP and Solvent-PRE.

Sample Requirements:

- Protein A: Uniformly labeled with 15N (for 1H-15N HSQC-based experiments). Concentration ~0.1-0.5 mM in a suitable buffer.

- Protein B: Unlabeled binding partner. Prepare a concentrated stock solution.

Step-by-Step Procedure:

Prepare NMR Samples:

- Reference Sample: A single sample containing only 15N-labeled Protein A.

- Titration Series: Prepare a series of samples with a constant concentration of 15N-labeled Protein A and increasing molar equivalents of unlabeled Protein B (e.g., 0.5:1, 1:1, 2:1, 4:1 Protein B:Protein A ratios).

- Solvent-PRE Samples: Prepare four samples:

- (i) 15N-labeled Protein A only.

- (ii) 15N-labeled Protein A + 4 mM paramagnetic probe (e.g., Gd(DTPA-BMA)).

- (iii) 15N-labeled Protein A + unlabeled Protein B (at saturating concentration).

- (iv) 15N-labeled Protein A + unlabeled Protein B + 4 mM paramagnetic probe.

NMR Data Collection:

- For all samples, acquire 2D 1H-15N HSQC spectra.

- For Solvent-PRE samples (i-iv), additionally measure the 1H transverse relaxation rate (R2) for each residue, or estimate it from the line-broadening of cross-peaks in the HSQC.

CSP Data Analysis:

- For each residue in the titration series, track the chemical shift changes of the cross-peaks. The combined chemical shift change (Δδ) is often calculated as Δδ = √((ΔδH)2 + (αΔδN)2), where α is a scaling factor (typically ~0.2).

- Plot Δδ vs. the concentration (or ratio) of Protein B. Fit the data for a single residue or an average of significantly perturbed residues to a binding isotherm to obtain the KD.

- Map the Δδ values at saturating concentration of Protein B onto the 3D structure of Protein A to visualize the putative binding interface.

Solvent-PRE Data Analysis:

- Calculate the PRE (Γ2) for each residue in the free and bound states: Γ2 = R2(paramagnetic) - R2(diamagnetic).

- Calculate the difference in PRE (ΔPRE) for each residue: ΔPRE = Γ2(free) - Γ2(bound).

- Residues showing significant positive ΔPRE values are shielded from the solvent paramagnet upon complex formation and are interpreted as being part of the binding interface. Map these residues onto the protein structure.

Protocol: In-Cell NMR for Studying Proteins in Human Cells

Recent advancements enable the study of protein structure and interactions directly within living human cells, providing physiological context that is absent in purified systems [35]. This is particularly relevant for nutrition research to understand how the intracellular environment affects nutrient-related proteins.

Workflow for In-Cell NMR in Synchronized Cells:

The following diagram illustrates the protocol for obtaining atomically-resolved NMR data from proteins in human cells synchronized in specific cell cycle phases, a key development in the field [35].

Step-by-Step Procedure:

Generate Stable Inducible Cell Line: Insert the gene of the target protein (e.g., human superoxide dismutase 1, hSOD1) into an inducible vector system, such as the PiggyBac Cumate Switch or a Tetracycline (Tet)-inducible system [35]. Generate a stable polyclonal cell line (e.g., HEK293-TRex). Isolate a single clone (monoclonal cell line) based on a fluorescent reporter (e.g., GFP) to ensure uniform and high-level expression of the target protein, which is crucial for sensitive in-cell NMR detection [35].

Protein Expression and Cell Synchronization: Induce protein overexpression in the monoclonal cell line by adding tetracycline for approximately 48 hours. To study cell cycle-specific effects, subject the culture to synchronization agents during induction [35]:

- For G1/S-phase synchronization: Treat with mM Mimosine for 14-24 hours.

- For G2/M-phase synchronization: Treat with µM RO3306 followed by µg/mL Nocodazole.

NMR Sample Preparation and Data Acquisition: Harvest the synchronized cells and prepare them for NMR analysis. Pack the cells into an NMR tube. To maintain cell viability and synchronization during prolonged data acquisition (which can take over 24 hours), use an NMR bioreactor to continuously supply fresh medium supplemented with the synchronization agents [35]. Acquire 2D 1H-15N SOFAST-HMQC spectra, which are optimized for rapid acquisition and are well-suited for in-cell applications [35].