Advanced Methods for Detecting Food Allergens and Contaminants: A 2025 Guide for Research and Development

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of the current landscape and future directions in food allergen and contaminant detection, tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals.

Advanced Methods for Detecting Food Allergens and Contaminants: A 2025 Guide for Research and Development

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of the current landscape and future directions in food allergen and contaminant detection, tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals. It covers foundational knowledge on key biological, chemical, and physical hazards, explores the principles and real-world applications of both conventional and emerging analytical methodologies, addresses critical challenges in method optimization and regulatory compliance, and offers a comparative evaluation of technology performance. The synthesis of these core intents aims to inform R&D strategy, facilitate the adoption of innovative portable and green analytical techniques, and highlight the growing convergence of food safety with clinical and biomedical research, particularly in understanding allergenicity and mitigating health risks.

Understanding the Landscape: A Primer on Food Allergens and Contaminants for Researchers

The integrity of the global food supply is continuously challenged by a spectrum of chemical threats that pose significant risks to public health and economic stability. For researchers and drug development professionals, a precise understanding of these hazards—food allergens, environmental chemical contaminants, and economically motivated adulterants—is fundamental to developing effective detection and mitigation strategies. These three categories represent distinct challenges: allergens involve specific proteins that trigger immune responses in sensitized individuals; environmental contaminants persist from pollution or natural sources into the food chain; and adulterants are deliberately introduced for economic gain [1] [2] [3]. Framed within a broader thesis on detection methodologies, this document provides detailed application notes and experimental protocols to support advanced research into identifying and quantifying these hazards. The subsequent sections will delineate the defining characteristics of each threat, summarize current and emerging analytical techniques in a structured format, and provide granular laboratory protocols for the most pivotal detection methods.

Threat Characterization and Definitions

The "threat spectrum" in food safety encompasses diverse agents with unique origins, motivations, and health impacts. A clear taxonomic distinction is essential for directing appropriate analytical and regulatory responses.

Food Allergens: These are naturally occurring proteins that can provoke an immunoglobulin E (IgE)-mediated immune response in sensitive individuals. The reactions can range from mild hives to life-threatening anaphylaxis [4]. In the United States, the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act identifies nine "major" food allergens: milk, eggs, fish, Crustacean shellfish, tree nuts, peanuts, wheat, soybeans, and sesame, with the latter being added by the FASTER Act in 2023 [4] [5]. The primary concern in manufacturing is cross-contact, where allergens are inadvertently transferred to products not intended to contain them, making reliable detection critical for accurate labeling and consumer protection [4].

Environmental Chemical Contaminants: This category includes substances that enter the food supply unintentionally from environmental sources or from certain agricultural and industrial processes. They are not added deliberately. The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) monitors a range of such contaminants, with a particular focus on toxic elements like arsenic, lead, cadmium, and mercury through its "Closer to Zero" initiative, which aims to reduce exposure in vulnerable populations [1]. Other environmental contaminants include perchlorate, radionuclides, dioxins, and per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) [1]. Exposure to these elements, especially during active brain development, is associated with potential neurological harm and other systemic toxicities [1].

Economically Motivated Adulterants (EMA): Also termed "food fraud," EMA occurs when substances are intentionally omitted, substituted, or added to a food to increase its apparent value or reduce its cost of production, for economic gain [2] [3]. This practice is particularly insidious as the adulterants can be non-traditional and chosen specifically to evade routine quality control checks. Examples include the substitution of high-value fish species with lower-cost varieties, the dilution of olive oil with cheaper oils, and the infamous 2007 and 2013 incidents involving melamine in milk and horsemeat in beef products, respectively [2] [6]. The health consequences can be severe, including cancer, liver, kidney, and cardiovascular diseases [2].

Table 1: Characterization of the Food Threat Spectrum

| Threat Category | Definition & Origin | Primary Motivation | Common Examples | Key Health Concerns |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Food Allergens | Naturally occurring proteins causing immune response [4] | Unintentional cross-contact during processing [4] | Milk, Egg, Peanut, Tree Nuts, Soy, Wheat, Shellfish, Fish, Sesame [5] | Allergic reactions (hives, anaphylaxis) [4] |

| Environmental Contaminants | Substances from environment/pollution entering food [1] | Unintentional contamination | Arsenic, Lead, Cadmium, Mercury, Dioxins, PFAS [1] | Neurological damage, cancer, organ failure [1] |

| Economically Motivated Adulterants | Deliberate substitution, addition or dilution for profit [2] [3] | Economic gain | Melamine in milk, horsemeat in beef, Sudan Red dye in spices [2] | Organ failure, cancer, decreased immunity [2] |

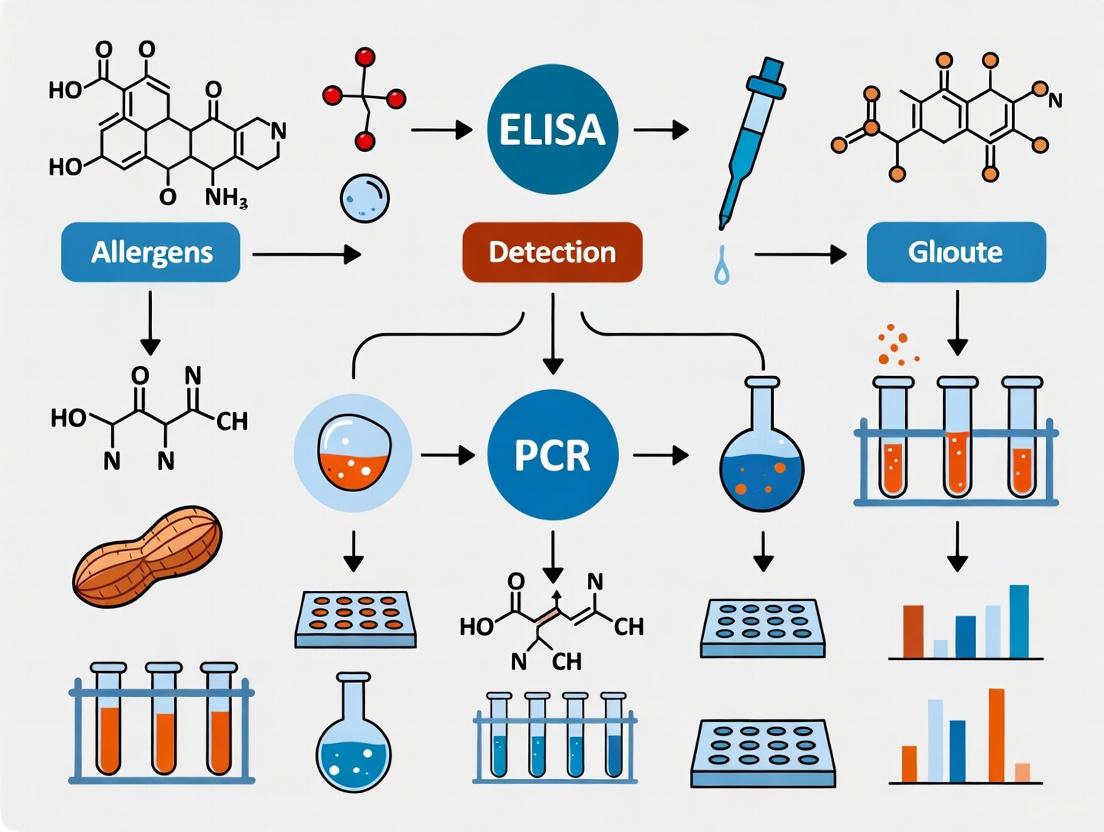

Analytical Methodologies for Detection

The detection of food threats relies on a diverse array of analytical techniques, selected based on the nature of the target analyte (e.g., protein, DNA, or specific chemical molecule), the food matrix, and the required sensitivity. The following section and corresponding table summarize the core methodologies.

Protein-Based Detection (Allergens): The workhorse for allergen detection is the Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay (ELISA), which uses antibodies to specifically target and quantify allergenic proteins. This method is clinically relevant as it directly measures the molecule responsible for the allergic reaction [7]. A key limitation is that food processing (e.g., heating) can denature proteins, altering their structure and potentially leading to false negatives if the antibody cannot recognize the deformed protein [7]. Liquid Chromatography-Tandem Mass Spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) is an emerging, highly sensitive technique that detects signature peptides from allergenic proteins. While powerful, it currently lacks standardized methods and is more costly than ELISA [7].

DNA-Based Detection (Adulteration & Allergens): The Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR) is a highly specific technique that amplifies unique DNA sequences to identify the biological source of an allergen or an adulterant (e.g., a specific meat species) [2] [7]. It is particularly useful when protein-based methods fail due to extreme processing conditions. However, since it detects DNA and not the allergenic protein itself, a positive PCR result does not always correlate with the presence of the protein at a level that would cause an allergic reaction [7].

Chromatography & Spectroscopy (Contaminants & Adulterants): These techniques form the backbone of chemical analysis. Gas Chromatography (GC) and Liquid Chromatography (LC), often coupled with mass spectrometry (MS), are used to separate, identify, and quantify a vast range of chemical contaminants and adulterants, from pesticide residues and mycotoxins to melamine and unauthorized dyes [2] [8] [6]. Mass Spectrometry platforms like MALDI-TOF MS (Matrix-Assisted Laser Desorption/Ionization – Time of Flight Mass Spectrometry) are gaining traction for their ability to rapidly generate unique protein or peptide "fingerprints" that can authenticate food species and detect adulteration in a high-throughput manner [6].

Table 2: Summary of Key Analytical Methods for Food Threat Detection

| Method | Principle | Primary Applications | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ELISA [7] | Antibody-antigen binding for protein detection | Allergen testing, specific protein quantification | Quantitative, high throughput, clinically relevant (targets protein) | Protein denaturation from processing can cause false negatives |

| PCR [2] [7] | Amplification of species-specific DNA sequences | Species adulteration, allergen source identification | Highly specific, works on highly processed foods | Qualitative/semi-quantitative; detects DNA, not allergenic protein |

| LC-MS/MS [8] [7] | Separation by LC, identification by tandem MS | Allergen peptides, chemical contaminants, mycotoxins | Highly sensitive and specific, multi-target capability | High cost, complex data analysis, no standardized allergen methods |

| GC-MS [2] [6] | Separation by GC, identification by MS | Volatile organic compounds, pesticides, fatty acids | Excellent separation power, robust compound libraries | Requires volatile or derivatized samples |

| MALDI-TOF MS [6] | Ionized molecule "fingerprinting" based on mass/charge | Microbial ID, food speciation, protein profiling | High-speed, high-throughput, minimal sample prep | Semi-quantitative, requires robust reference databases |

Integrated Workflow for Threat Detection

The following diagram outlines a generalized decision-making workflow for selecting an appropriate detection method based on the suspected hazard and food matrix, a critical first step in analytical protocol design.

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Detection of Allergenic Proteins via ELISA

This protocol describes the quantitative detection of a specific allergenic protein (e.g., from peanut or milk) in a solid food matrix using a commercial sandwich ELISA kit [7].

4.1.1 Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents for Allergen ELISA

| Reagent/Material | Function | Notes for Researchers |

|---|---|---|

| Commercial ELISA Kit | Provides pre-coated plates, antibodies, standards, and buffers. | Select a kit validated for your target allergen (e.g., peanut, egg). |

| Sample Diluent Buffer | Extracts protein from the food matrix and provides a compatible medium for the assay. | Composition is often proprietary; use the kit-provided buffer. |

| Blocking Buffer | Typically 1-5% BSA or non-fat dry milk in PBS. | Prevents non-specific binding of antibodies to the plate or sample components. |

| Wash Buffer | Usually PBS or Tris-based with a detergent (e.g., Tween-20). | Removes unbound reagents and reduces background signal. |

| Enzyme Substrate | Tetramethylbenzidine (TMB) is common. | Produces a colorimetric signal proportional to the amount of captured allergen. |

| Stop Solution | 1-2 M Sulfuric Acid or HCl. | Halts the enzyme-substrate reaction, stabilizing the signal for measurement. |

4.1.2 Step-by-Step Procedure

- Sample Preparation: Homogenize 1 g of the solid food sample with 10 mL of the provided extraction buffer. Vortex vigorously for 2 minutes and then centrifuge at 4,500 x g for 10 minutes at room temperature. Collect the supernatant for analysis. For complex matrices, filtration or defatting may be required.

- Standard Curve Preparation: Reconstitute the protein standard and prepare a serial dilution in the provided diluent to create a concentration series covering the kit's dynamic range (e.g., 0, 1, 5, 10, 25, 50 ng/mL).

- Assay Incubation: Add 50-100 µL of standards, prepared samples, and controls to the antibody-coated microwells. Incubate for a specified time (e.g., 60 minutes at room temperature) to allow the allergenic protein to bind.

- Washing: Decant the liquid from the wells and wash 3-5 times with 300 µL of wash buffer, ensuring complete removal of liquid between washes.

- Detection Antibody Incubation: Add the enzyme-conjugated detection antibody to each well. Incubate for a specified time (e.g., 60 minutes at room temperature). Wash again as in Step 4.

- Signal Development: Add the enzyme substrate solution (e.g., TMB) to each well. Incubate in the dark for 10-20 minutes until color develops.

- Reaction Stopping & Reading: Add the stop solution to each well. The blue color will turn yellow. Read the absorbance immediately at 450 nm using a microplate reader.

- Data Analysis: Generate a standard curve by plotting the mean absorbance of each standard against its concentration. Use the curve to interpolate the concentration of the allergenic protein in the test samples.

4.1.3 Validation Notes

- Spike Recovery: To validate the method for a new matrix, perform a spike recovery test. Add a known amount of the pure allergen to a blank sample, process it through the entire protocol, and calculate the percentage of the allergen recovered. Recovery of 80-120% is typically acceptable [7].

- Cross-Reactivity: Be aware of potential cross-reactivity. For example, a walnut test might cross-react with pecan due to biological similarity. The kit manufacturer's information should be consulted [7].

Protocol: Detection of Meat Speciation Adulteration via PCR

This protocol is designed to detect the adulteration of a declared meat (e.g., beef) with an undeclared species (e.g., horse or pork) using DNA extraction and species-specific PCR [2] [6].

4.2.1 Research Reagent Solutions

Table 4: Essential Reagents for Meat Speciation PCR

| Reagent/Material | Function | Notes for Researchers |

|---|---|---|

| DNA Extraction Kit | Isolates high-quality genomic DNA from the meat matrix. | Silica-membrane based kits are common. |

| Species-Specific Primers | Short DNA sequences that bind to and amplify a unique region of the target species' DNA. | Must be designed for high specificity (e.g., targeting mitochondrial cytochrome b gene). |

| PCR Master Mix | Contains Taq DNA polymerase, dNTPs, MgCl₂, and reaction buffer. | Provides all components necessary for the DNA amplification reaction. |

| Agarose | Polysaccharide used to create a gel for electrophoresis. | Typically used at 1.5-2.0% in TAE buffer. |

| Gel Stain | Ethidium bromide or safer alternatives (e.g., SYBR Safe). | Intercalates with DNA, allowing visualization under UV light. |

| DNA Molecular Weight Ladder | A mix of DNA fragments of known sizes. | Essential for confirming the size of the amplified PCR product. |

4.2.2 Step-by-Step Procedure

- DNA Extraction: Following the manufacturer's protocol for the DNA extraction kit, isolate genomic DNA from approximately 25 mg of the raw or cooked meat sample. Quantify the DNA purity and concentration using a spectrophotometer (A260/A280 ratio ~1.8 is ideal).

- PCR Reaction Setup: Prepare a 25 µL reaction mixture containing:

- 12.5 µL of PCR Master Mix

- 1.0 µL each of forward and reverse species-specific primers (10 µM stock)

- 50-100 ng of template DNA

- Nuclease-free water to 25 µL.

- Thermal Cycling: Place the tubes in a thermal cycler and run a program such as:

- Initial Denaturation: 95°C for 5 minutes.

- 35-40 Cycles of:

- Denaturation: 95°C for 30 seconds.

- Annealing: (Primer-specific temperature, e.g., 60°C) for 30 seconds.

- Extension: 72°C for 1 minute.

- Final Extension: 72°C for 7 minutes.

- Hold: 4°C.

- Gel Electrophoresis: Prepare a 1.5% agarose gel in 1x TAE buffer with a fluorescent nucleic acid stain. Mix 5-10 µL of each PCR product with a loading dye and load into the gel wells alongside a DNA ladder. Run the gel at 100-120 V for 30-40 minutes.

- Visualization & Analysis: Visualize the gel under UV light. The presence of a band at the expected molecular weight (e.g., 200 base pairs) confirms the presence of the target species. The absence of a band indicates the species is not present above the detection limit of the assay.

Protocol: Analysis of Chemical Contaminants via LC-MS/MS

This protocol provides a generalized framework for the sensitive detection and quantification of chemical contaminants, such as pesticide residues or mycotoxins, using Liquid Chromatography-Tandem Mass Spectrometry [8].

4.3.1 Research Reagent Solutions

Table 5: Essential Reagents for LC-MS/MS Analysis of Contaminants

| Reagent/Material | Function | Notes for Researchers |

|---|---|---|

| Extraction Solvents | Acetonitrile, Methanol, Acidified Acetonitrile. | Extracts the target analyte from the food matrix. Solvent choice is analyte-dependent. |

| QuEChERS Extraction Salts | MgSO₄, NaCl, buffering salts. | Used in a quick, easy, cheap, effective, rugged, and safe (QuEChERS) sample prep to induce partitioning. |

| Dispersive SPE Sorbents | PSA, C18, GCB. | Removes co-extracted matrix interferents like fatty acids, sugars, and pigments during clean-up. |

| LC Mobile Phases | Water and Methanol/Acetonitrile, often with modifiers (e.g., Formic Acid, Ammonium Acetate). | Carries the sample through the chromatographic column, separating analytes. |

| Analytical Standards | Pure certified reference standards of the target analytes. | Essential for creating a calibration curve and for positive identification based on retention time and mass spectra. |

4.3.2 Step-by-Step Procedure

- Sample Preparation & Extraction: Homogenize the food sample. Weigh 10 g into a 50 mL centrifuge tube. Add 10 mL of acetonitrile (1% formic acid) and shake vigorously for 1 minute. Add a pre-packaged QuEChERS salt mixture (e.g., containing 4 g MgSO₄, 1 g NaCl), shake immediately and vigorously for another minute, and then centrifuge.

- Extract Clean-up (dSPE): Transfer 1 mL of the upper acetonitrile layer to a 2 mL dSPE tube containing sorbents (e.g., 150 mg MgSO₄, 25 mg PSA). Vortex for 30 seconds and centrifuge. The clean extract is then transferred to an autosampler vial, potentially after dilution or concentration.

- Liquid Chromatography (LC): Inject an aliquot (e.g., 5 µL) of the cleaned extract onto the LC system. Use a reversed-phase C18 column and a gradient elution program. A typical gradient might run from 95% water/5% methanol to 5% water/95% methanol over 10-15 minutes, effectively separating the analytes.

- Tandem Mass Spectrometry (MS/MS) Detection: The eluting analytes are ionized (typically using Electrospray Ionization - ESI) and enter the mass spectrometer. The instrument is operated in Multiple Reaction Monitoring (MRM) mode, where a specific precursor ion for each analyte is selected and fragmented, and a specific product ion is monitored. This provides high selectivity and sensitivity.

- Data Analysis: Using the instrument software, integrate the peak areas for each analyte and its corresponding internal standard. Generate a calibration curve using the analyzed standards. Quantify the contaminants in the samples by interpolating from this curve. Positive identification requires the sample peak to have the same retention time and MRM transition ratio as the standard.

The Scientist's Toolkit

A robust research program requires a suite of reliable reagents, standards, and analytical instruments. The following table details key solutions for the featured experiments.

Table 6: Research Reagent Solutions for Food Threat Detection

| Tool Category | Specific Examples | Research Function |

|---|---|---|

| Immunoassay Reagents | Commercial ELISA Kits, Anti-peanut/Anti-milk monoclonal antibodies, Protein standards (e.g., β-lactoglobulin, Ara h1) | Target-specific protein quantification for allergen detection and risk assessment [7]. |

| Molecular Biology Kits | DNA Extraction Kits (silica-membrane), Taq DNA Polymerase, dNTPs, Species-specific Primer/Probe Sets | Genetic material isolation and amplification for species identification and adulteration detection [2] [7]. |

| Chromatography Standards | Certified Pesticide/Mycotoxin Reference Standards, Stable Isotope-Labeled Internal Standards (e.g., ¹³C-labeled), Fatty Acid Methyl Esters (FAMEs) | Calibration, precise quantification, and quality control in chromatographic methods like GC-MS and LC-MS/MS [8]. |

| Sample Preparation | QuEChERS Extraction Kits, Solid-Phase Extraction (SPE) Cartridges (C18, Florisil, NH₂), Solvents (HPLC/MS-grade Acetonitrile, Methanol) | Efficient extraction and clean-up of analytes from complex food matrices to reduce interference and protect instrumentation [8]. |

| Mass Spectrometry | MALDI Matrices (e.g., α-Cyano-4-hydroxycinnamic acid), LC-MS/MS and GC-MS Systems, High-Resolution Mass Spectrometers (HRMS) | Provides definitive analyte identification and characterization through accurate mass measurement and structural elucidation [8] [6]. |

Navigating the complex threat spectrum of food allergens, chemical contaminants, and adulterants demands a sophisticated, multi-pronged analytical approach. As detailed in these application notes, the researcher's arsenal ranges from the antibody-based specificity of ELISA and the genetic precision of PCR to the separation power and definitive identification offered by chromatographic and mass spectrometric techniques. The choice of method is critically dependent on the nature of the threat and the food matrix, a decision-making process that is greatly aided by the workflows and protocols provided. The ongoing development of these methodologies, including the refinement of high-throughput techniques like MALDI-TOF MS and the establishment of standardized LC-MS/MS protocols for allergens, represents the forefront of food safety research. By implementing and validating these detailed protocols, scientists and drug development professionals can contribute significantly to the protection of public health and the assurance of food authenticity.

In 2025, global food safety regulatory bodies are implementing significant updates that directly impact research and development in food allergen and contaminant detection. The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA), European Food Safety Authority (EFSA), and Codex Alimentarius Commission have aligned their priorities toward enhancing pre-market safety evaluations, strengthening post-market surveillance, and addressing emerging chemical risks. These developments reflect a concerted global effort to integrate advanced scientific methodologies, including New Approach Methodologies (NAMs) and artificial intelligence, into regulatory frameworks. For researchers focused on detection methods, understanding these evolving priorities is crucial for developing compliant, effective, and innovative analytical solutions.

Major Regulatory Bodies and Their 2025 Focus Areas

Table 1: Key Regulatory Priorities for 2025

| Regulatory Body | Primary 2025 Focus Areas | Key Updates & Deadlines |

|---|---|---|

| U.S. FDA (Human Foods Program) | Food Chemical Safety, Allergen Labeling, Microbiological Safety, Nutrition | Final guidance on food allergen thresholds (Sep 2025); Post-market assessment framework update; Closer to Zero action levels for contaminants [4] [9]. |

| European Food Safety Authority (EFSA) | Novel Food Applications, Food Allergen Assessment | Updated Novel Food guidance effective February 2025; Enhanced data requirements for novel food safety assessments [10] [11]. |

| Codex Alimentarius (FAO/WHO) | Food Additives, Contaminant Limits, Food Hygiene | New standards for lead in spices (2.5 mg/kg) and culinary herbs (2.0 mg/kg); Revised code of practice for aflatoxins in peanuts [12] [13]. |

Detailed Analysis of 2025 Regulatory Priorities

U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA)

The FDA's Human Foods Program has been reorganized to centralize risk management, with food chemical safety representing a cornerstone of its 2025 deliverables [9]. A critical initiative is the advancement of the "Closer to Zero" action levels for environmental contaminants like lead, cadmium, and arsenic in foods intended for infants and young children [9]. This includes targeting the issuance of final guidance on action levels for lead, which will establish enforceable thresholds and drive the need for more sensitive detection methodologies in infant formula and baby food [9].

Regarding allergens, the FDA is prioritizing the evaluation of non-listed food allergens (those beyond the nine major allergens) based on a structured assessment framework finalized in January 2025 [4] [14]. This guidance outlines the scientific factors for evaluating the public health importance of emerging allergens, which will inform future labeling and manufacturing requirements [14]. Furthermore, the FDA is actively developing AI-driven tools like the Warp Intelligent Learning Engine (WILEE) for post-market signal detection and surveillance of the food supply, representing a significant shift toward data-driven risk prioritization [9].

European Food Safety Authority (EFSA)

EFSA's updated guidance on Novel Food applications, effective February 2025, mandates more detailed scientific requirements for market authorization [10]. Applicants must now provide comprehensive data on the novel food's composition, production process, stability, and anticipated intake, with heightened emphasis on allergenicity potential and nutritional safety [10]. This reflects EFSA's commitment to a precautionary principle, ensuring that innovative foods entering the EU market are not nutritionally disadvantageous and are safe for consumption, including for sensitive individuals [10].

The guidance also strongly encourages the use of validated alternative methods to minimize animal testing, in alignment with the EU's broader strategic goal to phase out in-vivo studies [10]. This directive challenges researchers to develop robust in-vitro or in-silico models for predicting protein allergenicity, a rapidly evolving field in food safety science.

Codex Alimentarius Commission

The Codex Alimentarius Commission, at its 48th session in November 2025, adopted several standards with direct implications for contaminant monitoring and control [12]. Notably, it set Maximum Levels (MLs) for lead in dried cinnamon (2.5 mg/kg) and dried culinary herbs (2.0 mg/kg), addressing the neurotoxic effects of lead exposure [12]. These internationally recognized standards are critical for harmonizing global trade and protecting consumer health, providing a benchmark for national regulatory frameworks.

Additionally, the Commission revised the Code of Practice (CXC 55-2004) for preventing aflatoxin contamination in peanuts, integrating new scientific information on optimal harvesting stages and the effect of roasting processes in reducing aflatoxin levels [12]. This provides a critical framework for managing these potent carcinogens throughout the supply chain.

Emerging Detection Technologies and Methodologies

The regulatory focus on lower contaminant thresholds and unlisted allergens is accelerating the adoption of highly sensitive and multiplexed detection technologies.

Table 2: Emerging Technologies in Allergen and Contaminant Detection

| Technology | Principle | Key Applications | Sensitivity/LOD |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mass Spectrometry (MS) | Detection of proteotypic peptides via multiple reaction monitoring (MRM) | Simultaneous quantification of specific allergenic proteins (e.g., Ara h 3/6 in peanut, Bos d 5 in milk) [15] | High sensitivity and specificity across complex food matrices [15] |

| AI-Enhanced Hyperspectral Imaging (HSI) | Computer vision and machine learning analysis of spectral signatures | Non-destructive, real-time allergen detection without altering food integrity [15] | Varies by analyte and model training |

| Multiplexed Immunoassays | Simultaneous binding of multiple antibodies to specific protein targets | High-throughput screening for multiple allergens in a single sample run [15] | As low as 0.01 ng/mL for specific allergens [15] |

| ATP-based Sanitation Verification | Cloud-based integration of adenosine triphosphate readings with allergen data | Real-time sanitation verification and predictive risk management in production facilities [15] | Provides indirect monitoring of hygiene control |

Experimental Protocol: Multiplex Mass Spectrometry for Allergen Detection

This protocol details the simultaneous detection and quantification of key allergenic proteins from peanut, milk, and egg in a baked goods matrix using liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) [15].

1. Sample Preparation:

- Homogenization: Precisely weigh 2 g of the ground food sample into a 50 mL centrifuge tube.

- Protein Extraction: Add 10 mL of extraction buffer (50 mM ammonium bicarbonate, pH 8.0) and 10 µL of 1 M dithiothreitol (DTT). Vortex vigorously for 1 minute and incubate at 60°C for 30 minutes with shaking.

- Alkylation: Cool to room temperature. Add 40 µL of 1 M iodoacetamide (IAA), vortex, and incubate in the dark for 30 minutes.

- Digestion: Add 100 µL of 0.1 µg/µL trypsin solution. Incubate at 37°C for 4 hours with continuous shaking.

- Clean-up: Acidify the digest with 1% formic acid and purify using a C18 solid-phase extraction (SPE) cartridge. Elute peptides with 60% acetonitrile/0.1% formic acid and dry under a gentle nitrogen stream.

2. LC-MS/MS Analysis:

- Chromatography: Reconstitute the dried peptides in 100 µL of 2% acetonitrile/0.1% formic acid. Inject 10 µL onto a reverse-phase C18 column (2.1 mm x 150 mm, 1.7 µm particle size). Use a gradient of 2% to 40% solvent B (0.1% formic acid in acetonitrile) over 25 minutes.

- Mass Spectrometry: Operate the mass spectrometer in positive electrospray ionization (ESI+) mode with scheduled Multiple Reaction Monitoring (MRM). Monitor specific precursor ion > product ion transitions for proteotypic peptides of Ara h 3 (peptide: LDNLNQNLR; transition: 530.3 -> 801.4), Bos d 5 (peptide: VLVLDTDYK; transition: 539.8 -> 853.4), and Gal d 1 (peptide: GGLEPINFQTAADQAR; transition: 886.4 -> 1135.6).

3. Data Quantification:

- Prepare a calibration curve using certified reference materials of the purified allergenic proteins.

- Use stable isotope-labeled versions of the target peptides as internal standards.

- Quantify based on the ratio of the analyte peak area to the internal standard peak area, interpolated from the linear calibration curve.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents for Advanced Food Safety Research

| Research Reagent / Material | Function & Application | Justification for Use |

|---|---|---|

| Certified Reference Materials (CRMs) | Calibration and validation of analytical methods for contaminants and allergens [15]. | Essential for meeting the traceability and accuracy demands of new regulatory thresholds (e.g., Codex lead MLs) [12]. |

| Stable Isotope-Labeled Peptides | Internal standards for multiplex MS-based allergen quantification [15]. | Correct for matrix effects and ionization efficiency variations, ensuring precise and reproducible results. |

| Proteotypic Peptide Standards | Target enrichment for specific allergenic proteins (e.g., Ara h 3, Bos d 5) [15]. | Enable highly specific detection and avoid cross-reactivity, crucial for monitoring undeclared allergens. |

| Monoclonal Antibody Panels | Development of immunoassays for emerging and major food allergens. | Provide the specificity required for detecting individual allergenic proteins in complex food matrices. |

| PFAS Analytical Standards | Quantifying per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances in food [9]. | Critical for FDA's research initiative to better understand PFAS exposure from food [9]. |

Regulatory Workflow and Research Integration

Navigating the updated regulatory landscape requires a systematic approach from method development to compliance. The following diagram outlines the integrated workflow for validating a new detection method against 2025 regulatory criteria, from initial risk assessment to final application.

The 2025 regulatory priorities of the FDA, EFSA, and Codex Alimentarius present both challenges and opportunities for researchers in food allergen and contaminant detection. The overarching trends point toward stricter contaminant limits, a broader scope of regulated allergens, and an increased reliance on sophisticated, non-targeted analytical techniques. Success in this evolving landscape will depend on the widespread adoption of advanced technologies like multiplex mass spectrometry and AI-enhanced imaging, coupled with robust, validated experimental protocols. By aligning research and development with these global regulatory directions, scientists can actively contribute to a safer, more transparent, and innovative food supply.

The Rising Burden of Food Allergies and Its Implications for Public Health Research

Food allergy is a significant and growing public health problem, estimated to affect at least 1 in 10 adults and 1 in 13 children in developed nations [16]. This pathological immune system reaction, triggered by the ingestion of allergenic proteins, has far-reaching effects on individual well-being, family dynamics, and healthcare systems. The global food supply chain's complexity, coupled with the potential for severe and sometimes life-threatening reactions, necessitates advanced research into reliable detection methodologies [17] [18]. The burden of foodborne diseases, including those caused by allergens, is substantial, with unsafe food causing an estimated 600 million illnesses and 420,000 deaths annually worldwide [18]. This application note frames the rising burden of food allergies within the critical context of detecting food allergens and contaminants, providing structured data, detailed experimental protocols, and visual workflows to support public health research and safety initiatives.

The Public Health and Economic Burden

The impact of food allergies extends beyond immediate health reactions, creating significant nutritional, psychological, and economic challenges. Children with food allergy are at risk for inadequate nutrient intake, poor growth, feeding difficulties, and anxiety [16]. The financial burden is considerable, with one systematic review reporting mean household-level out-of-pocket costs of $3,339 and opportunity costs of $4,881 [17]. At a societal level, the total productivity loss associated with foodborne diseases in low- and middle-income countries is estimated at US$ 95.2 billion per year, with an annual cost of treating these illnesses estimated at US$ 15 billion [18].

Table 1: Major Food Allergens and Their Prevalence Characteristics

| Allergen Category | Examples | Persistence Profile | Key Regulatory Status |

|---|---|---|---|

| Peanut | - | Typically persistent [16] | Major allergen (FALCPA) [4] |

| Tree Nuts | Almonds, Pecans, Walnuts [4] | Typically persistent [16] | Major allergen (FALCPA) [4] |

| Seafood | Fish, Crustacean shellfish (e.g., Crab, Lobster) [4] | Typically persistent [16] | Major allergen (FALCPA) [4] |

| Milk | Casein, Beta-lactoglobulin [19] | Often transient [16] | Major allergen (FALCPA) [4] |

| Egg | - | Often transient [16] | Major allergen (FALCPA) [4] |

| Sesame | - | - | 9th major allergen (FASTER Act, 2023) [4] |

Analytical Frameworks for Allergen Detection

Effective management and prevention of food-allergic reactions rely on the accurate detection and quantification of allergenic proteins in food products. However, several factors complicate this analysis, including the composition of food extracts, the impact of food processing on proteins, and the inherent variability of immunological responses [17]. To ensure consistency, Health Canada's Allergen Methods Committee (AMC) recommends using the Bicinchoninic Acid Assay (BCA test) with Bovine Serum Albumin (BSA) as a common reference for quantifying protein content in calibrators, despite variations in allergen protein behavior [19].

Table 2: Comparison of Major Allergen Detection Methodologies

| Methodology | Principle | Key Advantages | Key Limitations | Best Suited For |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Immunoassays (ELISA) | Antigen-antibody binding detected enzymatically [20]. | High specificity and sensitivity; commercially available kits [17]. | May detect denatured proteins; affected by food matrix [17]. | Routine detection of specific, preselected allergens [17] [19]. |

| DNA-Based Methods (PCR) | Amplification of species-specific DNA sequences [20]. | High specificity; useful for processed foods where protein is denatured [17]. | Indirect (DNA presence ≠ protein presence); not for all foods [17]. | Detecting preselected species contamination (e.g., speciation) [17]. |

| Mass Spectrometry | Separation and identification based on mass-to-charge ratio [21] [20]. | High specificity and multiplexing capability; can detect multiple allergens [17]. | Expensive equipment; complex data analysis; requires expertise [17]. | Confirmatory analysis and untargeted discovery of allergens [17]. |

| Multiplex Allergen Microarray | IgE-binding inhibition on a biochip with many allergens [17]. | Multiplexed; identifies many known/unknown IgE-binding proteins in one test [17]. | Relatively new; limited widespread use and validation [17]. | Comprehensive allergen profiling and discovery [17]. |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Multiplex Allergen Microarray-Based Inhibition Assay (SPHIAa)

This protocol is adapted for identifying and profiling IgE-binding proteins in a food sample using a multiplex biochip [17].

1. Reagent and Sample Preparation

- Food Extract Preparation: Homogenize the food sample. Extract proteins using a high-salt or high-pH buffer to improve the recovery of allergenic proteins [17]. Determine protein concentration using a standardized method like the BCA assay [19].

- Control Solutions: Prepare a positive control (e.g., a known allergenic food extract) and a negative control (extraction buffer alone).

2. Inhibition Assay Setup

- Incubation: In a tube, pre-incubate a constant volume of a pooled human serum sample (from individuals allergic to the target food) with serial dilutions of the prepared food extract for 30-60 minutes at room temperature. This allows allergens from the food sample to bind to serum IgE.

- Biochip Application: Apply the pre-incubated mixture onto the multiplex allergen microarray biochip (e.g., ISAC, FABER), which contains immobilized allergenic proteins.

- Binding and Washing: Incubate the biochip according to manufacturer specifications. Any free, unbound IgE from the serum that recognizes the immobilized allergens on the chip will bind. Wash the biochip thoroughly to remove unbound materials.

3. Detection and Analysis

- Labeling: Add a fluorescently labelled anti-human IgE antibody to the biochip and incubate.

- Signal Detection: Wash the biochip again and scan it with a microarray scanner to detect fluorescence signals.

- Data Interpretation: A reduced fluorescence signal at a specific spot on the biochip indicates that the food extract contained the corresponding allergen, which inhibited the binding of serum IgE to the immobilized allergen. The signal reduction is proportional to the allergen's concentration in the food sample.

Protocol: Validation of Allergen Detection Methods as per Health Canada AMC Guidelines

This protocol outlines the evaluation process for quantitative allergen detection methods intended for compliance activities [19].

1. Define Evaluation Parameters

- Reference Material: Select a well-characterized, representative material for the allergenic food commodity (e.g., defatted hazelnut flour).

- Matrices: Select appropriate food matrices for evaluation based on common allergen presence.

- Fortification Levels: Prepare samples at three key levels: a blank (no added allergen), 2x the method's Limit of Quantification (LOQ), and 5x LOQ.

2. Inter-laboratory Testing

- Laboratory Participation: A minimum of three AMC-affiliated laboratories, plus the method developer's laboratory, should participate in a full evaluation.

- Sample Analysis: Each laboratory analyzes the fortified and blank samples with a predefined number of replicates. The results, expressed in µg of protein per gram of commodity, are reported centrally.

3. Performance Assessment

- Data Analysis: Calculate key performance metrics including repeatability, reproducibility, recovery, and linearity.

- Compendium Reporting: The generated data is compiled into a report for the web-based Compendium of Methodologies, allowing users to assess the method's suitability for their needs without implying regulatory endorsement.

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents and Materials for Allergen Research

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application | Example/Note |

|---|---|---|

| Reference Materials | Serves as a common ground for method evaluation and calibration; essential for quantitative accuracy [19]. | Defatted hazelnut flour; well-characterized and reproducible [19]. |

| Protein Standard (BSA) | Reference standard for quantifying total protein content in allergen extracts using the BCA assay [19]. | Bovine Serum Albumin (BSA) [19]. |

| High-Salt/High-pH Buffers | Extraction buffers to improve the solubility and recovery of allergenic proteins from complex food matrices [17]. | Phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) with high salt concentration [17]. |

| Pooled Allergic Human Sera | Critical reagent for immunoassays and inhibition studies to detect IgE-binding proteins [17]. | Sera from multiple individuals with confirmed allergy to the target food [17]. |

| Multiplex Allergen Biochip | Solid-phase support for simultaneous detection of numerous IgE reactivities in a single sample [17]. | ISAC or FABER test chips [17]. |

| Fluorescent Anti-IgE Antibody | Detection antibody for visualizing IgE binding in microarray and other fluorescent immunoassays [17]. | Fluorescein or Cy3-labeled antibody [17]. |

Visualization of Workflows

Food Allergen Detection Research Pathway

Multiplex Microarray Inhibition Assay Workflow

The rising global burden of food allergies demands robust, sensitive, and multifaceted research approaches to protect public health. Accurate detection of food allergens is complicated by variable thresholds, the effects of food processing, and complex matrices. This application note has detailed the public health context, presented comparative analytical data, and provided detailed protocols for advanced methods like the multiplex allergen microarray. The ongoing development of international standards, reference materials, and validated methods, as coordinated by bodies like the Allergen Methods Committee, is crucial for harmonizing global efforts [19]. Future research must continue to refine these detection methodologies, explore the impact of cofactors on reactivity, and integrate new technologies like biosensors and artificial intelligence to enhance food safety and improve the quality of life for allergic individuals [16] [20].

Food allergen detection presents significant challenges that are profoundly influenced by the composition and processing of the food matrix itself. Complex matrices can interfere with analytical techniques, leading to potential false negatives that pose serious risks to consumer safety. For researchers and scientists in drug development and food safety, understanding these matrix effects is crucial for developing accurate detection methodologies. This application note details the primary food matrices of concern, provides optimized experimental protocols for allergen extraction, and outlines advanced analytical techniques for detecting allergens and contaminants in these challenging systems. The protocols are framed within the context of a broader research thesis on advancing detection methods for food allergens and contaminants, addressing current gaps in standardization and recovery rates.

Key Challenging Food Matrices in Allergen Analysis

The structural complexity and compositional variability of certain food matrices significantly complicate allergen detection and quantification. The table below summarizes the primary challenging matrices, their key interferents, and the associated analytical complications.

Table 1: Key Food Matrices of Concern in Allergen Detection

| Food Matrix Category | Specific Examples | Key Interfering Compounds/Properties | Impact on Allergen Detection |

|---|---|---|---|

| Plant-Based Alternative Proteins | Plant-based meats, dairy alternatives, insect proteins, fungal proteins | Protein cross-reactivity, high polyphenol content, novel protein structures | Masks target allergens, creates false positives in immunoassays, requires new reference materials and methods [22]. |

| Thermally Processed Foods | Baked biscuits, roasted nuts, pasteurized dairy, ultra-processed foods | Protein denaturation, Maillard reaction products, protein aggregation | Alters antibody-binding epitopes, reduces extractability, lowers analytical recovery [23]. |

| High-Fat/High- Polyphenol Matrices | Chocolate desserts, nut spreads, dark cocoa products | Fats, tannins, polyphenols from cocoa | Binds to and precipitates allergenic proteins, quenches assay signals, necessitates specialized extraction buffers [23]. |

| Complex Multi-Ingredient Systems | Bakery products, confectionery items, sauces, dressings | Multiple allergen sources (e.g., wheat, eggs, milk, nuts, soy), emulsifiers, stabilizers | Creates high risk of cross-contact, introduces multiple interferents, complicates method development and validation [22]. |

The rise of alternative proteins, including plant-based, insect, and fermentation-derived ingredients, introduces novel allergenic proteins and potential cross-reactivity with known allergens, demanding specialized testing beyond standard immunoassays [22]. Furthermore, food processing methods such as heat treatment, enzymatic hydrolysis, and fermentation can modify protein structures, affecting their detectability by conventional antibody-based tests [22].

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Optimized Allergen Extraction from Challenging Matrices

Efficient and reproducible extraction of allergenic proteins is the most critical step for accurate detection, particularly from complex, processed matrices. The following protocol is optimized for simultaneous extraction of multiple clinically relevant allergens.

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Reagents for Allergen Extraction Optimization

| Reagent/Solution | Function/Principle | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Extraction Buffer D(50 mM Carbonate-Bicarbonate, 10% Fish Gelatine, pH 9.6) | Alkaline pH and fish gelatine help solubilize proteins and minimize binding to matrix components, improving recovery from baked and complex matrices [23]. | Ideal for general use across multiple allergen types. Fish gelatine is preferred over mammalian gelatine to avoid cross-reactivity. |

| Extraction Buffer J(PBS, 2% Tween-20, 1 M NaCl, 10% Fish Gelatine, 1% PVP, pH 7.4) | Detergent (Tween), high salt, and PVP are critical for disrupting hydrophobic interactions and binding polyphenols in chocolate and high-fat matrices [23]. | Superior for challenging matrices rich in polyphenols (e.g., chocolate, certain spices). |

| Fish Gelatine | Acts as a protein blocking agent, reducing non-specific binding of allergens to tube walls and food particulates [23]. | Reduces surface adsorption, a significant source of protein loss. |

| Polyvinylpyrrolidone (PVP) | Binds and precipitates polyphenols and tannins, preventing them from interfering with proteins and assay antibodies [23]. | Essential for recovering allergens from cocoa, berries, and other polyphenol-rich foods. |

| Sodium Dodecyl Sulfate (SDS) | Ionic detergent that denatures proteins and disrupts strong protein-lipid and protein-protein interactions [23]. | Use with caution as it may denature epitopes recognized by some antibodies. |

Sample Preparation and Extraction Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the complete workflow for preparing and analyzing incurred food samples for allergen content.

Materials and Equipment:

- Prepared incurred food matrices (e.g., chocolate dessert, biscuit dough)

- Selected extraction buffers (D and J from Table 1)

- Analytical balance

- Vortex mixer

- Orbital incubator (e.g., Stuart SI500)

- Centrifuge capable of maintaining 4°C

- Micropipettes and sterile tips

Procedure:

- Sample Homogenization: Begin with a finely ground and well-mixed sample to ensure representativeness.

- Weighing: Precisely weigh 1.0 ± 0.05 g of the homogenized sample into a 15 mL centrifuge tube.

- Buffer Addition: Add 10 mL of the pre-warmed (60°C) selected extraction buffer, ensuring a 1:10 sample-to-buffer ratio.

- Initial Mixing: Vortex the mixture vigorously for 30 seconds to ensure complete suspension of the sample.

- Incubation: Incubate the sample in an orbital incubator at 60°C for 15 minutes with shaking set to 175 rpm. This elevated temperature aids in protein solubilization.

- Clarification: Centrifuge the samples at 1250 rcf for 20 minutes at 4°C to pellet insoluble debris.

- Supernatant Collection: Carefully collect the clarified supernatant from the middle of the tube, avoiding the surface lipid layer and the bottom pellet. Proceed immediately to analysis or store at -20°C.

Validation Notes: This optimized protocol typically achieves recoveries of 50-150% for 14 major food allergens from most matrices. However, matrices containing chocolate or subjected to intense thermal processing may still yield lower recoveries, necessitating method-specific validation [23].

Advanced Analytical Detection Techniques

Following extraction, selecting an appropriate detection method is vital. The choice depends on the required sensitivity, specificity, and the need for multiplexing.

Allergen-Specific Multiplex Immunoassay (e.g., MARIA)

Multiplex arrays allow for the simultaneous quantification of multiple specific allergens in a single sample, saving time and sample volume.

Procedure:

- Bead Coupling: Covalently couple allergen-specific monoclonal antibodies to distinct magnetic bead regions.

- Assay Setup: Mix the bead set with sample extracts and allergen standards in a microplate well.

- Incubation: Incubate with shaking to allow the formation of bead-allergen complexes.

- Detection: Add a biotinylated detection antibody followed by streptavidin-phycoerythrin.

- Analysis: Analyze the plate using a multiplex reader (e.g., Luminex). The median fluorescence intensity is proportional to the allergen concentration, calculated against a standard curve.

Advantages: This method provides high-throughput, multiplexed analysis with improved standardization and reporting clarity by targeting clinically relevant proteins like Ara h 3/6 (peanut) and Bos d 5 (milk) [15] [23].

Liquid Chromatography with Tandem Mass Spectrometry (LC-MS/MS)

LC-MS/MS offers high specificity and is particularly useful for detecting allergens in processed foods where proteins are denatured or for confirming results from immunoassays.

Procedure:

- Protein Digestion: Digest the extracted protein sample with trypsin to generate peptide fragments.

- Chromatographic Separation: Inject the peptides onto a reverse-phase UHPLC column for separation.

- Mass Spectrometry Analysis: Analyze eluting peptides using a triple-quadrupole mass spectrometer in Multiple Reaction Monitoring (MRM) mode.

- Quantification: Monitor specific proteotypic peptide ions unique to the target allergen. Quantify by comparing the peak areas of the target peptides to those of a stable isotope-labeled internal standard.

Advantages: LC-MS/MS can achieve detection limits as low as 0.01 ng/mL, provides high specificity by targeting marker peptides, and is less susceptible to antibody cross-reactivity issues [15] [22]. It is the preferred method for quantifying specific proteins in complex matrices where antibody-based methods may fail.

Emerging Technologies and Future Directions

The field of food allergen detection is rapidly evolving with the integration of artificial intelligence and novel biosensing technologies.

- AI-Enhanced Testing: Machine learning models are being developed to predict the allergenicity of new ingredients before they enter the supply chain. Furthermore, AI is combined with non-destructive techniques like Hyperspectral Imaging (HSI) and Fourier Transform Infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy for real-time, in-line allergen detection without altering food integrity [15].

- Biosensors and Portable Kits: Advanced biosensor technologies using gold nanoparticles and graphene-based transducers are achieving femtomolar detection limits. These platforms are paving the way for point-of-use testing solutions, including smartphone-integrated devices, which could enable monitoring at various points in the supply chain [22].

- Regulatory Shifts: The FDA's recent activities, including a virtual public meeting on food allergen thresholds and the issuance of Edition 5 guidance on allergen labeling, signal a move towards more standardized, science-based regulatory frameworks [4] [24]. The "Make America Healthy Again" (MAHA) strategy also highlights increased scrutiny on food additives and chemicals, which may influence allergen management practices [24].

Accurate detection of food allergens in challenging matrices such as plant-based alternatives and processed foods requires a meticulous, multi-faceted approach. The optimized extraction protocols detailed herein, utilizing specialized buffers containing fish gelatine and PVP, are critical for achieving reliable recovery rates. Subsequent analysis by allergen-specific multiplex immunoassays or confirmatory LC-MS/MS provides the sensitivity and specificity required for both research and regulatory compliance. As the food landscape continues to evolve with novel ingredients and processing technologies, so too must the analytical methods, with a clear trend towards the integration of AI, biosensors, and harmonized international standards to ensure public safety.

From Bench to Batch: Analytical Techniques for Allergen and Contaminant Detection

In the ongoing effort to ensure global food safety, the precise detection of allergens and contaminants remains a paramount challenge for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals. Food allergies, which are adverse immune responses to specific food proteins, affect millions of individuals worldwide, with prevalence rates rising annually [25]. The accurate detection and quantification of biological and chemical contaminants in complex food matrices are critical for protecting public health, ensuring regulatory compliance, and maintaining consumer trust. This document details the established, conventional methodologies that form the backbone of modern food safety analysis: chromatography, enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA), and polymerase chain reaction (PCR)-based methods. These techniques provide the sensitivity, specificity, and robustness required for definitive identification and measurement of target analytes, from pathogenic bacteria and mycotoxins to undeclared allergenic proteins [7] [26] [27].

Each of the three conventional workhorses offers distinct advantages based on the analyte of interest and the specific requirements of the analysis. ELISA is a quantitative immunological method that leverages the specificity of antibody-antigen interactions, typically targeting specific allergenic proteins, which are the molecules that directly cause adverse reactions in sensitized individuals [7]. PCR-based methods, in contrast, are molecular techniques that target the DNA of the organism containing the allergenic protein, providing indirect evidence of its potential presence [7]. Chromatography, particularly when coupled with mass spectrometry (e.g., LC-MS/MS), is a powerful analytical chemistry technique that separates complex mixtures and can identify and quantify specific proteins or peptides based on their mass, offering high specificity and the ability to analyze multiple allergens simultaneously [26] [28].

The table below provides a quantitative comparison of these core techniques.

Table 1: Quantitative Comparison of Conventional Food Allergen and Contaminant Detection Methods

| Method | Typical Analytes | Principle | Detection Limit | Throughput | Quantitative Ability | Key Advantage |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ELISA | Specific proteins (e.g., casein, tropomyosin) [7] | Antibody-antigen binding with enzymatic signal generation [26] | Variable; specific kits can reach ppm/ppb levels [26] | Moderate to High | Quantitative results expressed in protein [7] | High clinical relevance as it targets the reactive protein [7] |

| PCR-Based | Species-specific DNA sequences [7] | Amplification of target DNA sequences [28] | High (e.g., dPCR for low-level contaminants) [28] | High (esp. multiplex qPCR) [28] | Qualitative or Quantitative (qPCR, dPCR) [28] | High sensitivity and specificity for DNA; resistant to food matrix effects in some cases [7] |

| Chromatography (LC-MS/MS) | Proteins, peptides, chemical contaminants [26] | Physical separation followed by mass-based detection [28] | High (e.g., trace levels below ppb) [28] | Moderate | Quantitative | Can analyze multiple allergens/contaminants at once (multiplexing) [26] |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol for Allergen Detection via Sandwich ELISA

Sandwich ELISA is a highly specific and quantitative method widely used for detecting proteins like β-lactoglobulin in milk or tropomyosin in shellfish [26]. The following protocol outlines the key steps.

Workflow Overview: Sandwich ELISA

Materials:

- Microtiter Plates: Coated with a capture antibody specific to the target allergen (e.g., mouse antiglycinin monoclonal antibody for soy) [26].

- Blocking Buffer: Typically a protein-based solution like Bovine Serum Albumin (BSA) or non-fat dry milk to prevent non-specific binding [26].

- Allergen Standards: A series of known concentrations of the purified allergen for generating a standard curve.

- Test Samples: Food extracts prepared in an appropriate extraction buffer.

- Detection Antibody: An antibody specific to a different epitope on the target allergen, conjugated to an enzyme (e.g., Horseradish Peroxidase - HRP) [26].

- Enzyme Substrate: A chromogenic substrate (e.g., TMB for HRP) that produces a color change upon reaction with the enzyme.

- Stop Solution: An acid (e.g., sulfuric acid) to terminate the enzyme-substrate reaction.

- Microplate Reader: An instrument capable of measuring the absorbance of the solution in each well.

Procedure:

- Coating and Blocking: The wells of a microtiter plate are pre-coated with the capture antibody. Any remaining protein-binding sites are then blocked with a blocking buffer to minimize non-specific background signal [26].

- Incubation with Sample: Add the prepared test samples and allergen standards to the respective wells. Incubate to allow the target allergen (antigen) to bind to the immobilized capture antibody, forming an antigen-antibody complex.

- Detection Antibody Binding: After washing to remove unbound materials, add the enzyme-conjugated detection antibody. This antibody binds to the captured allergen, forming a "sandwich" [26].

- Signal Development and Detection: Following another wash step to remove unbound detection antibody, add the enzyme substrate. The enzyme catalyzes a reaction that produces a colored product. The reaction is stopped after a fixed time, and the absorbance is measured with a microplate reader [26].

- Quantification: The absorbance of the standards is used to generate a standard curve. The concentration of the allergen in the test samples is interpolated from this curve.

Protocol for Pathogen Detection via Quantitative PCR (qPCR)

qPCR allows for the simultaneous amplification and quantification of specific DNA sequences, making it ideal for detecting and quantifying foodborne pathogens like Salmonella or Listeria [28].

Workflow Overview: Quantitative PCR (qPCR)

Materials:

- DNA Extraction Kit: For isolating and purifying genomic DNA from the food matrix.

- Species-Specific Primers and Probes: Short, synthetic oligonucleotides designed to bind exclusively to a unique DNA sequence of the target organism. Probes are typically labeled with a fluorophore and a quencher.

- qPCR Master Mix: A pre-mixed solution containing heat-stable DNA polymerase, dNTPs, MgCl₂, and reaction buffers.

- qPCR Instrument: A thermal cycler equipped with a optical detection system to monitor fluorescence in real-time.

Procedure:

- DNA Extraction: Extract and purify total DNA from the food sample. The efficiency of this step is critical for the final quantitative result [28].

- Reaction Setup: Prepare the qPCR reaction mix by combining the extracted DNA, master mix, and species-specific primers and probes.

- Amplification and Real-Time Detection: Load the reaction plates into the qPCR instrument. The instrument runs a series of temperature cycles (denaturation, annealing, extension). During each cycle, the probe is cleaved, separating the fluorophore from the quencher and generating a fluorescent signal proportional to the amount of amplified DNA [28].

- Data Analysis: The instrument software plots fluorescence against cycle number. The cycle threshold (Ct) is determined for each sample, which is the cycle number at which fluorescence exceeds a background level. The Ct value is inversely proportional to the starting quantity of the target DNA. Quantification is achieved by comparing the Ct values of unknown samples to a standard curve generated from samples with known DNA concentrations [28].

Protocol for Multi-Allergen Detection via LC-MS/MS

Liquid Chromatography-Tandem Mass Spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) is a confirmatory technique that is gaining acceptance for the quantitative detection of multiple allergens in complex food samples [26].

Workflow Overview: LC-MS/MS for Allergen Detection

Materials:

- Extraction Buffer: A solution to efficiently solubilize proteins from the food matrix.

- Digestion Enzyme: Typically trypsin, which cleaves proteins at specific amino acid residues to generate peptides.

- Signature Peptides: Unique peptide sequences that serve as markers for the specific allergenic protein [26].

- Liquid Chromatography System: For separating the complex peptide mixture based on hydrophobicity.

- Tandem Mass Spectrometer: Equipped with an electrospray ionization (ESI) source and a triple quadrupole mass analyzer for highly selective and sensitive detection.

Procedure:

- Protein Extraction and Digestion: Proteins are extracted from the food sample. The extracted proteins are then digested with trypsin to generate a mixture of peptides [26].

- Chromatographic Separation: The peptide mixture is injected into the LC system, where peptides are separated based on their chemical properties as they pass through a chromatographic column.

- Ionization and Mass Analysis: The eluting peptides are ionized via electrospray ionization and enter the first quadrupole (Q1) of the mass spectrometer, which selects ions of a specific mass-to-charge ratio (m/z) corresponding to a target signature peptide. These selected precursor ions are then fragmented in a collision cell (second quadrupole), and the resulting product ions are analyzed in the third quadrupole (Q2) [28].

- Identification and Quantification: The unique pattern of fragment ions (transition ions) serves as a definitive "fingerprint" for the target peptide and its parent protein. Quantification is achieved by comparing the signal intensity of the transition ions in the sample to that of a calibration curve prepared from known concentrations of the signature peptide or protein standard [26].

Research Reagent Solutions

The successful application of these conventional methods relies on a suite of specific, high-quality reagents. The following table details essential materials and their functions.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents for Food Allergen and Contaminant Analysis

| Reagent / Material | Function | Application Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Capture & Detection Antibodies | Bind specifically to target allergenic proteins (antigens) with high affinity [26]. | Monoclonal mouse anti-glycinin for soy detection; polyclonal rabbit anti-tropomyosin for shellfish [26]. |

| Species-Specific Primers & Probes | Initiate and report the amplification of a unique DNA sequence from a target organism via PCR [28]. | Primers for Salmonella virulence genes; TaqMan probes for peanut DNA (Ara h 1-6) [28]. |

| Signature Peptides | Unique peptide sequences that serve as analytical markers for specific allergenic proteins in LC-MS/MS [26]. | Peptides from Ara h 3 and Ara h 6 for peanut; peptides from casein for milk [26]. |

| Chromatography Columns | Stationary phases for separating complex mixtures of peptides or chemicals before detection [28]. | C18 reversed-phase columns for peptide separation in LC-MS/MS [28]. |

| Enzyme-Substrate Systems | Generate a measurable signal (e.g., color, fluorescence) proportional to the amount of detected analyte in ELISA [26]. | Horseradish Peroxidase (HRP) with TMB substrate; Alkaline Phosphatase (AP) with pNPP substrate [26]. |

Chromatography, ELISA, and PCR-based methods collectively provide a powerful and complementary toolkit for addressing the complex challenges of food allergen and contaminant analysis. While emerging technologies promise future advancements in speed and data integration, these conventional workhorses remain indispensable for their proven reliability, quantitative rigor, and well-understood protocols. The choice of method depends critically on the analytical question: ELISA for direct, clinically relevant protein quantification; PCR for highly sensitive and specific detection of biological sources; and LC-MS/MS for definitive, multi-analyte confirmation. A thorough understanding of the principles, applications, and detailed methodologies of these techniques, as outlined in this document, is fundamental for researchers and scientists dedicated to ensuring food safety and protecting public health.

The global food system faces mounting challenges in ensuring food safety, driven by increasing allergic sensitivities among consumers and the persistent threat of microbial contamination. The precision of food safety management directly impacts public health, regulatory compliance, and economic stability through reduced recall incidents. This application note details three transformative technological paradigms—biosensors, CRISPR-based systems, and Whole Genome Sequencing (WGS)—that are redefining detection capabilities for food allergens and contaminants. These methodologies enable unprecedented sensitivity, specificity, and operational speed, moving food safety analysis from reactive testing to proactive risk management. The content is structured to provide researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals with actionable technical protocols, comparative performance data, and implementation frameworks applicable to both industrial and research settings.

Advanced Biosensor Platforms for Allergen Detection

Biosensor technology represents a frontier in rapid, on-site food allergen detection. These systems translate molecular recognition events into quantifiable electrical or optical signals, facilitating real-time monitoring.

Electrochemical biosensors, the current vanguard in this category, function by detecting changes in electrical properties upon allergen-antibody or allergen-aptamer binding. The iEAT2 (integrated Exogenous Allergen Test 2) system exemplifies this technology. It is a compact, electrochemical sensing platform designed for the simultaneous detection of multiple allergens [29]. Its operation hinges on immunoreactions occurring on the surface of electrode chips, where binding events alter the interfacial electron transfer, generating a measurable current signal proportional to allergen concentration.

A distinct class of AI-enhanced non-destructive diagnostics, including Hyperspectral Imaging (HSI) and Fourier Transform Infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy, leverages machine learning to identify allergen signatures without altering food integrity [15]. These systems capture spectral data from food samples, which AI models then analyze against trained libraries to detect and quantify contaminating allergens.

Performance Metrics and Applications

The table below summarizes the quantified performance of emerging biosensor platforms as reported in recent literature.

Table 1: Performance Metrics of Advanced Biosensor Platforms for Allergen Detection

| Technology | Detection Principle | Key Allergens Detected | Reported Sensitivity | Assay Time | Key Advantage |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| iEAT2 Sensor | Electrochemical | Gliadin, Ara h 1, Ovalbumin | Below established allergic reaction thresholds [29] | < 15 minutes [29] | Multiplexing & portability |

| AI-Enhanced HSI/FTIR | Spectral Imaging & Machine Learning | Not Specified (Model Dependent) | Not Specified | Real-time [15] | Non-destructive analysis |

| Mass Spectrometry | Detection of Proteotypic Peptides | Peanut (Ara h 3, Ara h 6), Milk (Bos d 5), Egg (Gal d 1, Gal d 2) [15] | As low as 0.01 ng/mL [15] | Varies with sample prep | High specificity for protein markers |

Experimental Protocol: Multiplexed Allergen Detection with an Electrochemical Biosensor

Application: Simultaneous on-site detection of gliadin, Ara h 1, and ovalbumin in processed food products.

Workflow Overview: The following diagram illustrates the key steps in the biosensor protocol.

Materials:

- iEAT2 Device: Compact potentiostat with a multi-electrode array chip [29].

- Reagent Kit: Includes extraction buffers, antibody-conjugated magnetic beads, and washing solutions.

- Torsion Grinder: For uniform homogenization of solid food samples [29].

- Positive Controls: Purified standards of gliadin, Ara h 1, and ovalbumin.

Procedure:

- Sample Preparation: Weigh 1 g of homogenized food sample. Add 10 mL of proprietary extraction buffer and mix thoroughly for 2 minutes using a vortex mixer. Centrifuge at 5,000 x g for 5 minutes to pellet debris. Collect the supernatant [29].

- Sample Loading: Pipette 100 µL of the extracted supernatant into the designated well of the iEAT2 electrode chip.

- Incubation and Binding: Allow the chip to incubate at room temperature for 10 minutes. During this period, target allergenic proteins bind specifically to capture antibodies immobilized on the electrode surfaces.

- Washing: Automatically rinse the electrode array with a wash buffer to remove unbound materials and reduce non-specific signal.

- Electrochemical Measurement: The device applies a voltage sweep and measures the resulting current (e.g., via amperometry) at each of the 16 independent electrodes. The current signal is directly correlated with the concentration of the captured allergen [29].

- Data Analysis: The device's software converts the electrical signals into allergen concentrations (e.g., ppm) using an internal calibration curve and displays the results for all three allergens simultaneously.

CRISPR/Cas Systems for Pathogen and Contaminant Detection

The CRISPR (Clustered Regularly Interspaced Short Palindromic Repeats) and associated Cas proteins system has been repurposed from a gene-editing tool into a powerful diagnostic platform for nucleic acid detection, offering exceptional specificity and single-base resolution [30].

The core mechanism relies on a Cas enzyme (e.g., Cas12, Cas13) programmed by a guide RNA (crRNA) to find a specific DNA or RNA sequence from a pathogen. Upon target recognition, the Cas enzyme becomes activated and unleashes a "collateral cleavage" or "trans-cleavage" activity, non-specifically cutting nearby reporter molecules [30] [31]. This collateral activity amplifies the detection signal.

- Cas12a: Targets DNA and exhibits collateral cleavage of single-stranded DNA (ssDNA) reporters [31].

- Cas13a: Targets RNA and exhibits collateral cleavage of single-stranded RNA (ssRNA) reporters [31].

This system can be coupled with Functional Nucleic Acids (FNAs) like aptamers to detect non-nucleic acid targets, such as small molecules or toxins. The aptamer undergoes a structural change upon binding its target, which can then trigger the release of a short DNA activator that initiates the CRISPR/Cas reaction [30].

Experimental Protocol: DetectingSalmonella entericavia CRISPR-Cas12a

Application: Sensitive and specific detection of Salmonella enterica in food homogenates.

Workflow Overview: The following diagram illustrates the multi-stage amplification and detection process.

Materials:

- Cas12a Enzyme: Recombinant protein.

- Custom crRNA: Designed against a unique sequence in the Salmonella invA gene.

- ssDNA Reporter Probe: Quenched fluorescent oligonucleotide (e.g., FAM-TTATT-BHQ1).

- Isothermal Amplification Kit: Recombinase Polymerase Amplification (RPA) kit.

- Fluorometer or Lateral Flow Dipstick: For endpoint or real-time signal detection.

Procedure:

- Sample Preparation and DNA Extraction: Enrich the food sample in buffered peptone water. Extract genomic DNA from 1 mL of enriched culture using a commercial bacterial DNA extraction kit. Elute in 50 µL of nuclease-free water.

- Target Pre-amplification (RPA): Prepare a 50 µL RPA reaction mix according to the manufacturer's instructions. Use primers targeting a ~200 bp region of the Salmonella invA gene. Incubate the reaction at 39°C for 15-20 minutes to amplify the target DNA.

- CRISPR/Cas12a Detection:

- Prepare a 20 µL reaction mix containing: 100 nM Cas12a, 50 nM crRNA, 500 nM of ssDNA reporter probe, and 1x reaction buffer.

- Add 5 µL of the RPA amplification product to the CRISPR reaction mix.

- Incubate at 37°C for 10-15 minutes.

- Signal Visualization:

- Fluorometric Method: Measure fluorescence in real-time or at endpoint. A significant increase in fluorescence over a negative control indicates the presence of Salmonella.

- Lateral Flow Method:

Research Reagent Solutions for CRISPR-Based Detection

Table 2: Essential Reagents for CRISPR/Cas Food Safety Assays

| Reagent / Material | Function | Example / Note |

|---|---|---|

| Cas Enzyme | Core nuclease for target recognition and signal generation. | Cas12a for DNA targets (e.g., bacteria), Cas13a for RNA targets (e.g., viruses) [30] [31]. |

| crRNA | Guides Cas enzyme to the specific target sequence. | Must be designed against a conserved and unique region of the pathogen's genome [31]. |

| Reporter Probe | Molecule cleaved to generate a detectable signal. | Fluorescent ssDNA for Cas12a (FAM-TTATT-BHQ1); Fluorescent ssRNA for Cas13a [31]. |

| Isothermal Amplification Kit | Pre-amplifies target nucleic acids to enhance sensitivity. | Recombinase Polymerase Amplification (RPA) or LAMP kits [30]. |

| Lateral Flow Dipstick | For simple, equipment-free visual readout. | Interprets results as visible bands, ideal for field use [30]. |

Whole Genome Sequencing (WGS) for Outbreak Investigation and Surveillance

WGS is a high-resolution molecular typing method that determines the complete DNA sequence of a pathogen's genome. It has become the gold standard for foodborne outbreak investigation and microbial surveillance [32] [33].

Unlike traditional methods that may only examine a few genetic markers, WGS provides the full genetic blueprint of a microorganism. Bioinformatic tools then compare single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) across the genomes of bacterial isolates from sick patients, food products, and production environments. Isolates with highly similar or indistinguishable genomes are considered part of the same outbreak cluster, enabling precise source attribution [32]. Furthermore, WGS can simultaneously identify virulence genes and predict antimicrobial resistance (AMR) profiles, offering a comprehensive risk assessment from a single test [32] [33].

Experimental Protocol: WGS for Source Tracking ofListeria monocytogenes

Application: High-resolution genetic comparison of Listeria monocytogenes isolates to confirm or refute their relatedness in a suspected outbreak.

Materials:

- Bacterial Isolates: Pure cultures from patient clinical samples, food, and environmental swabs.

- DNA Extraction Kit: For high-molecular-weight, high-purity genomic DNA.

- Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS) Platform: e.g., Illumina NovaSeq.

- Bioinformatics Software: Tools for genome assembly (e.g., SPAdes), phylogenetic analysis (e.g., RAxML), and gene finding (e.g., ABRicate).

Procedure:

- Isolate Culturing and DNA Extraction: Sub-culture pure isolates on appropriate agar plates. Extract genomic DNA, quantifying it via fluorometry and ensuring high purity (A260/A280 ~1.8-2.0).

- Library Preparation and Sequencing: Fragment the genomic DNA to a target size. Attach sequencing adapters and barcodes (unique for each sample) to create sequencing libraries. Pool libraries and perform shotgun sequencing on an NGS platform to generate high-coverage (>50x) whole genome data.

- Bioinformatic Analysis:

- Quality Control & Assembly: Filter raw sequencing reads for quality and adapter content. Assemble the cleaned reads into contiguous sequences (contigs) to reconstruct the genome.