Advanced Extraction Techniques for Bioactive Compounds: A Comprehensive Guide for Pharmaceutical Research

This article provides a critical analysis of modern extraction methodologies for isolating bioactive compounds from natural sources, tailored for researchers and drug development professionals.

Advanced Extraction Techniques for Bioactive Compounds: A Comprehensive Guide for Pharmaceutical Research

Abstract

This article provides a critical analysis of modern extraction methodologies for isolating bioactive compounds from natural sources, tailored for researchers and drug development professionals. It explores the foundational principles of bioactive compounds and the challenges of plant metabolome coverage, detailing advanced techniques like Ultrasound-Assisted Extraction (UAE), Microwave-Assisted Extraction (MAE), and Supercritical Fluid Extraction (SFE). The content delves into practical optimization strategies, including parameter tuning and the integration of Artificial Intelligence (AI) for process control. A comparative evaluation of techniques based on yield, bioactivity, and scalability is presented, alongside modern validation protocols using UHPLC-HRMS and bioautography to ensure compound purity and efficacy for biomedical applications.

Understanding Bioactive Compounds and Extraction Fundamentals

Bioactive compounds, the naturally occurring chemicals with therapeutic potential, are at the forefront of modern pharmaceutical, cosmetic, and functional food development. These compounds, which include phenolics, flavonoids, carotenoids, and alkaloids, exhibit diverse health-promoting effects such as antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, antimicrobial, and neuroprotective activities [1] [2]. The efficient extraction of these valuable molecules from natural sources—ranging from medicinal plants to marine macroalgae—represents a critical challenge for researchers and drug development professionals. Extraction serves as the crucial first step in the analysis of medicinal plants, as it is necessary to extract the desired chemical components from plant materials for further separation and characterization [2]. The selection of appropriate extraction techniques directly influences the yield, purity, and biological activity of the resulting extracts, ultimately determining their suitability for therapeutic applications. With advancements in extraction technology, yields have increased and extracted ingredients have become richer, yet no universal extraction technology exists [3]. This guide provides an objective comparison of contemporary extraction methodologies, supported by experimental data, to inform strategic decisions in bioactive compound research.

Extraction Fundamentals: Principles and Objectives

The fundamental objective of extraction is to efficiently separate bioactive compounds from their native biological matrices while preserving their chemical integrity and biological activity. The process relies on mass transfer principles, where solvents penetrate plant tissues, dissolve target compounds, and diffuse out of the matrix. Key parameters influencing this process include solvent selection, temperature, pressure, extraction time, solvent-to-solid ratio, and the physical characteristics of the source material [1] [2]. The choice of solvent system largely depends on the specific nature of the bioactive compound being targeted, with polar solvents like methanol, ethanol, or ethyl-acetate used for hydrophilic compounds, and dichloromethane or hexane for more lipophilic compounds [2].

Traditional extraction methods, including maceration, percolation, reflux, and Soxhlet extraction, have historically dominated laboratory and industrial practice. These methods are characterized by their operational simplicity and minimal equipment requirements [3]. However, they often suffer from significant limitations, including long extraction times (ranging from several hours to days), high organic solvent consumption, potential thermal degradation of sensitive compounds, and relatively low extraction efficiency [1] [3]. The limitations of traditional solvents, such as lengthy extraction times, high energy consumption, and high toxicity, have prompted the development of more efficient and environmentally friendly alternatives [3].

Modern extraction technologies have emerged to address these limitations, offering improved efficiency, reduced environmental impact, and enhanced selectivity. These advanced techniques, including ultrasound-assisted extraction (UAE), microwave-assisted extraction (MAE), accelerated solvent extraction (ASE), and supercritical fluid extraction (SFE), utilize physical phenomena such as cavitation, dielectric heating, and pressurized solvents to accelerate mass transfer processes [1] [3]. The development of efficient, rapid, and environmentally friendly techniques aligns with the principles of green chemistry, resulting in innovation through the selection of renewable resources, reduced solvent consumption, and lower energy consumption [1].

Comparative Analysis of Extraction Techniques

Performance Metrics and Experimental Data

Different extraction techniques yield significantly different outcomes in terms of bioactive compound recovery. The table below summarizes comparative experimental data from recent studies, highlighting the performance variations across methods and source materials.

Table 1: Comparative Extraction Efficiency for Various Bioactive Compounds

| Source Material | Target Compound | Extraction Method | Optimal Conditions | Yield/Efficiency | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cinnamomum zeylanicum (Cinnamon) | Total Phenolic Content (TPC) | Accelerated Solvent Extraction (ASE) | 50% Ethanol | 6.83 ± 0.31 mg GAE/g | [4] |

| Cinnamomum zeylanicum (Cinnamon) | Cinnamaldehyde | Accelerated Solvent Extraction (ASE) | 50% Ethanol | 19.33 ± 0.002 mg/g | [4] |

| Cinnamomum zeylanicum (Cinnamon) | Total Phenolic Content (TPC) | Ultrasonic-Assisted Extraction (UAE) | 50% Ethanol | Lower than ASE | [4] |

| Lemon Peel (Citrus limon L.) | Hesperidin | Modified QuEChERS | Not specified | 48.7% higher yield vs. UAE, 75% shorter time | [5] |

| Oregano Processing Waste | Total Phenolic Content (TPC) | Optimized UAE | >58 min, Ethanol/Water ~1:1 | Maximized TPC | [6] |

| Cecropia Species Leaves | Total Flavonoids (TF), Chlorogenic Acid (CA), Flavonolignans (FL) | Optimized UAE | 70-75% Methanol, 30 min, 1:50 ratio | Maximized TF, CA, and FL yields | [7] |

Technical Parameters and Operational Characteristics

The selection of an extraction technique involves balancing multiple operational parameters, including time, solvent consumption, temperature, and scalability. The following table compares the key characteristics of major extraction methods.

Table 2: Technical Comparison of Extraction Methods for Bioactive Compounds

| Extraction Method | Principle | Operational Temperature | Extraction Time | Solvent Consumption | Key Advantages | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Maceration | Passive diffusion through soaking | Ambient or controlled | 3-4 days | High | Simple equipment, low energy requirement | Time-consuming, low efficiency, high solvent use [2] [3] |

| Soxhlet Extraction | Continuous reflux and siphoning | Solvent boiling point | 3-18 hours | Moderate to High | High throughput, no filtration needed | Long time, thermal degradation, high solvent use [2] [3] |

| Ultrasound-Assisted Extraction (UAE) | Acoustic cavitation disrupting cells | Ambient to moderate | 1-60 minutes | Low to Moderate | Reduced time, lower temperature, improved efficiency | Potential free radical formation, optimization needed [4] [1] [6] |

| Microwave-Assisted Extraction (MAE) | Dielectric heating causing internal pressure buildup | Elevated | Seconds to minutes | Low | Rapid heating, reduced time, high efficiency | Non-uniform heating, limited penetration depth [1] [8] |

| Accelerated Solvent Extraction (ASE) | Pressurized liquid at elevated temperatures | Elevated (50-200°C) | 12-20 minutes per cycle | Low | Automated, fast, reduced solvent, high yield | High equipment cost, limited for thermolabile compounds [4] [1] |

| Supercritical Fluid Extraction (SFE) | Solvation power of supercritical fluids (e.g., CO₂) | Near-ambient to elevated | Moderate | Very Low | Tunable selectivity, no solvent residues, high purity | High capital cost, high pressure operation [1] [3] |

Detailed Methodologies and Workflows

Optimized Ultrasound-Assisted Extraction (UAE) Protocol

UAE has demonstrated significant efficiency improvements for various plant materials. The following workflow illustrates a generalized optimization approach for polyphenol extraction:

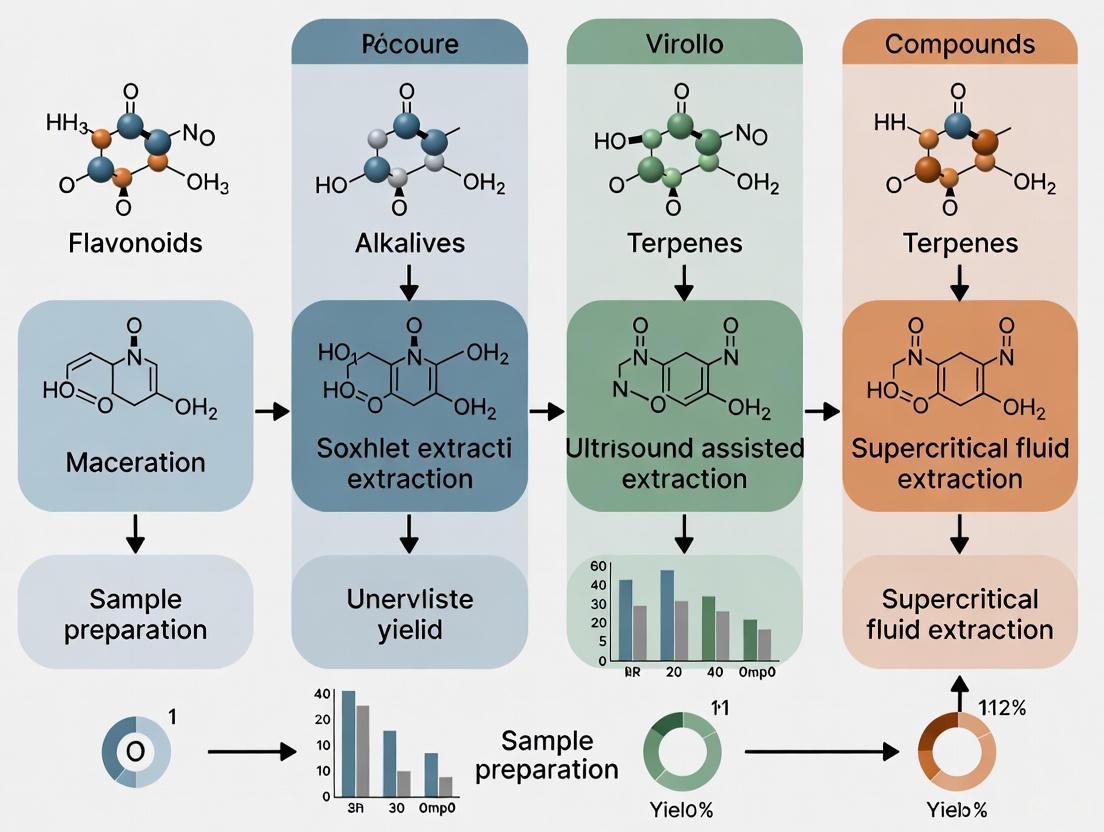

Diagram 1: UAE Optimization Workflow. Optimization of UAE requires systematic parameter adjustment to maximize yield [6] [7].

For oregano waste valorization, researchers optimized UAE using a central composite design, maximizing total phenolic content at conditions exceeding 58 minutes extraction time, sample/solvent ratio between 0.058 and 0.078, and ethanol/water ratio approximately 1:1 [6]. The extraction employed an ultrasonic bath system, with the resulting extracts subsequently filtered and dried either by spray drying or freeze drying for stability assessment.

For Cecropia species leaves, researchers implemented a fractional factorial design (FFD) followed by a central composite design (CCD) to optimize the extraction of total flavonoids (TF), chlorogenic acid (CA), and flavonolignans (FL) [7]. The optimized parameters included:

- Methanol fraction: 70-75% (v/v) for TF, 55-72% for CA, and 70-80% for FL

- Extraction temperature: Significant positive effect on all compounds

- Mass/solvent ratio: 1:50 (m/v)

- Particle size: ≤125 µm

- Extraction time: 30 minutes

- Number of extractions: Three with methanol, one with acetone

This systematic optimization approach enabled the development of an appropriate extraction process with time-efficient execution of experiments, with experimental values agreeing with those predicted [7].

Accelerated Solvent Extraction (ASE) Protocol

ASE, also known as pressurized liquid extraction (PLE), utilizes high pressure to maintain solvents in liquid state at temperatures above their normal boiling points, enhancing extraction efficiency.

Table 3: Accelerated Solvent Extraction Protocol for Cinnamomum zeylanicum [4]

| Parameter | Specification |

|---|---|

| Extraction System | Accelerated Solvent Extractor |

| Solvent | 50% Ethanol in Water |

| Temperature | Elevated (specific value not reported) |

| Pressure | High (specific value not reported) |

| Cell Size | Not specified |

| Cycle Configuration | Not specified |

| Total Extraction Time | Not specified |

| Yield Analysis | HPLC for target compounds (cinnamaldehyde, eugenol, cinnamic acid) |

ASE with 50% ethanol yielded the highest total phenolic content (6.83 ± 0.31 mg GAE/g), total flavonoid content (0.50 ± 0.01 mg QE/g), cinnamaldehyde (19.33 ± 0.002 mg/g), eugenol (10.57 ± 0.03 mg/g), and cinnamic acid (0.18 ± 0.004 mg/g), making it superior to UAE for these specific compounds from Cinnamomum zeylanicum [4]. The method demonstrated a strong correlation (R = 0.81) between total phenolic content and total flavonoid content in ASE extracts, indicating that flavonoids are major contributors to the phenolic content.

Modified QuEChERS Protocol for Citrus Compounds

The modified QuEChERS (Quick, Easy, Cheap, Effective, Rugged, and Safe) method has demonstrated superior performance for specific compound classes compared to conventional techniques:

Diagram 2: Modified QuEChERS Extraction Workflow. This method significantly reduces processing time while improving yields for specific compounds [5].

The modified QuEChERS method resulted in the highest extraction efficiency for hesperidin from lemon peel while significantly reducing processing time by 75% compared to ultrasound-assisted extraction [5]. The validated method demonstrated excellent sensitivity (LOQ: 10.0 µg/mL), high accuracy (recovery >93%), and good precision (RSD <3.4%), making it a reliable and cost-effective approach for routine hesperidin analysis in citrus peel.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Successful extraction and analysis of bioactive compounds requires carefully selected reagents and materials. The following table details key solutions and their applications in extraction protocols.

Table 4: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Bioactive Compound Extraction

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application | Extraction Method Compatibility | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ethanol-Water Mixtures | Extraction of medium-polarity phenolics and flavonoids | UAE, ASE, Maceration, Percolation | Green solvent, food/pharmaceutical safe [4] [6] |

| Methanol-Water Mixtures | High-efficiency extraction of polar compounds | UAE, Soxhlet, Maceration | Higher toxicity, limited for consumables [1] [7] |

| Acetone | Extraction of medium-polarity compounds | UAE, Conventional methods | Moderate toxicity, good extraction efficiency [7] |

| Natural Deep Eutectic Solvents (NADES) | Green alternative to organic solvents | Gas-expanded liquid extraction, UAE, MAE | Tunable properties, biodegradable, biocompatible [1] [9] |

| Dispersive SPE Sorbents | Matrix clean-up and purification | Modified QuEChERS | PSA (primary secondary amine) for polar impurities, C18 for lipophilic compounds [5] |

| Maltodextrin | Encapsulant and stabilizer for extracts | Spray drying, Freeze drying | Protects thermo-labile compounds, improves shelf life [6] |

| Activated Charcoal | Purification and removal of contaminants | Post-extraction clean-up | Effective for pigment removal, may adsorb target compounds [9] |

| HPLC-DAD Systems | Quantification of target bioactive compounds | All extraction methods | Enables simultaneous quantification of multiple compound classes [5] [7] |

Analytical Validation and Quality Assessment

Robust analytical methods are essential for accurate quantification of extracted bioactive compounds. High-performance liquid chromatography with diode array detection (HPLC-DAD) has proven particularly valuable for routine analysis of natural products, offering reliable and reproducible performance with the possibility of online collection of UV spectra [7]. For example, a validated HPLC-DAD method for Cecropia species demonstrated excellent selectivity, linearity, precision (repeatability and intermediate precision below 2% and 5%, respectively), and accuracy (98-102%) for the quantification of chlorogenic acid, total flavonoids, and flavonolignans [7].

Validation parameters for analytical methods should follow international guidelines such as ICH M10, assessing linearity, precision, accuracy, limit of detection (LOD), limit of quantification (LOQ), and robustness [8] [7]. For instance, the modified QuEChERS method for hesperidin quantification demonstrated excellent sensitivity (LOQ: 10.0 µg/mL), high accuracy (recovery >93%), and good precision (RSD <3.4%) [5].

The comparative analysis presented in this guide demonstrates that extraction technique selection must be guided by multiple factors, including target compound characteristics, source material properties, required throughput, and sustainability considerations. While traditional methods like maceration and Soxhlet extraction offer operational simplicity, advanced techniques including UAE, ASE, and modified QuEChERS provide significant advantages in efficiency, yield, and environmental impact. The growing emphasis on green extraction technologies has driven adoption of methods that reduce organic solvent consumption, decrease processing time, and improve sustainability [1] [10]. Furthermore, the integration of phytochemical extraction with biorefinery concepts showcases the potential for circular economy approaches and zero-waste valorization of plant biomass [10]. As research continues, the strategic selection and optimization of extraction methodologies will remain fundamental to unlocking the full therapeutic potential of bioactive compounds from natural sources.

Efficient extraction is a foundational step in natural product-based drug discovery, serving as the critical gateway that transforms raw biological material into the pure compounds needed for pharmaceutical development. The choice of extraction technique directly influences the yield, chemical diversity, and biological activity of isolated compounds, thereby determining the success of downstream discovery pipelines. This guide provides a comparative analysis of modern extraction methodologies, offering scientists a data-driven framework for selecting techniques aligned with specific research objectives.

The Analytical Challenge: A Comparative Framework for Extraction Techniques

The journey from natural source to drug candidate begins with the effective liberation of bioactive compounds from their complex biological matrices. Inefficient extraction can lead to the irreversible loss of valuable chemistries, creating a bottleneck that hampers the entire discovery process. The optimal technique balances extraction efficiency, compound selectivity, operational practicality, and environmental impact [11] [12].

Advanced approaches are increasingly moving beyond single-method paradigms toward hybrid strategies that integrate the robustness of traditional bioassay-guided isolation with the broad analytical power of modern metabolomics [13]. This integrated framework accelerates the identification of novel bioactive entities while ensuring their functional relevance is confirmed through biological testing.

Experimental Protocol for Comparative Extraction Analysis

To generate comparable data on extraction efficiency, a standardized experimental protocol is essential. The following methodology, adapted from studies on grape pomace and cinnamon, provides a replicable framework [11] [4].

- Raw Material Preparation: Biological material (e.g., grape pomace, plant bark) should be dried and ground to a consistent particle size (e.g., 20-40 mesh). Uniform preparation ensures reproducible solvent contact and extraction kinetics [11].

- Solvent Selection: Green solvents like ethanol are prioritized. Ethanol is Generally Recognized as Safe (GRAS), biodegradable, and effective for a broad range of mid-to-low polarity bioactives. Studies often use absolute (anhydrous) ethanol for better penetration and to avoid hydrolytic degradation [11].

- Extraction Techniques: Compared techniques typically include:

- Soxhlet (SOX): Exhaustive heat-reflux extraction.

- Maceration (MAC): Passive room-temperature soaking.

- Ultrasound-Assisted (UAE): Cavitation-enhanced disruption.

- Microwave-Assisted (MAE): Dielectric heating.

- Pressurized Liquid (PLE): High-pressure/temperature extraction.

- Analysis of Extracts: Key performance metrics are quantified:

Performance Comparison of Extraction Techniques

Systematic comparisons under standardized conditions reveal that no single technique excels across all performance metrics. The choice becomes strategic, depending on whether the objective is maximizing yield, enriching specific bioactives, or preserving functional activity.

The table below summarizes quantitative data from direct comparisons of extraction methods for recovering bioactives from grape pomace and cinnamon [11] [4].

Table 1: Quantitative Comparison of Extraction Technique Performance

| Extraction Technique | Extraction Yield (%) | Total Phenolic Content (mg GAE/g) | Antioxidant Activity (IC50, μg/mL) | Key Compounds Identified |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Soxhlet (SOX) | 13.93 ± 0.19 [11] | Not the highest [11] | 0.13 ± 0.01 (DPPH) [11] | Fatty acids, esters, phytosterols [11] |

| Ultrasound-Assisted (UAE) | Lower than SOX [11] | 87.48 ± 1.05 [11] | 3.26 (ABTS) [4] | Phenolic compounds [11] |

| Microwave-Assisted (MAE) | Moderate [11] | Moderate [11] | Moderate [11] | Varies with source material |

| Pressurized Liquid (PLE) | Moderate [11] | High [4] | Data not available | Cinnamaldehyde, Eugenol [4] |

| Accelerated Solvent (ASE)* | Data not available | 6.83 ± 0.31 [4] | No significant difference to UAE [4] | Cinnamaldehyde (19.33 ± 0.002 mg/g) [4] |

*ASE is considered a type of PLE under controlled conditions.

Interpreting the Data: Trade-offs and Strategic Selection

- Soxhlet Extraction remains the benchmark for exhaustive recovery and maximum yield, as its continuous solvent cycling efficiently exhausts the raw material. Interestingly, while its phenolic content may be lower than UAE, it can demonstrate superior antioxidant activity, indicating that the specific compounds it extracts are highly potent or that non-phenolic antioxidants are being recovered [11].

- Ultrasound-Assisted Extraction excels at liberating phenolic compounds, achieving the highest TPC values. This makes UAE ideal for projects targeting this major class of antioxidants. The mechanical effects of acoustic cavitation effectively break cell walls, enhancing release of intracellular compounds [11].

- Modern Techniques (MAE, PLE/ASE) offer an excellent balance of speed, efficiency, and green credentials. ASE with 50% ethanol has been shown to optimally recover specific bioactive markers like cinnamaldehyde and eugenol from cinnamon, demonstrating high selectivity and efficiency [4].

Table 2: Strategic Selection Guide for Extraction Techniques

| Research Objective | Recommended Technique | Rationale | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Maximize Crude Extract Yield | Soxhlet (SOX) | Exhaustive nature provides highest mass recovery [11] | High temperature can degrade thermolabile compounds; high solvent consumption |

| Maximize Polyphenol Recovery | Ultrasound-Assisted (UAE) | Cavitation effectively ruptures plant cells rich in phenolics [11] | May be less effective for non-polar compounds; scaling challenges |

| Target Specific Bioactive Markers | Accelerated Solvent (ASE) | High pressure and temperature enable efficient and selective recovery [4] | Equipment cost; potential for thermal degradation if not optimized |

| Rapid, Low-Volume Screening | μ-SPEed | High-throughput, minimal solvent use, ideal for small samples [14] | Limited capacity for bulk processing |

| Minimize Environmental Impact | Pressurized Liquid (PLE) | Reduced solvent consumption; often uses green solvents like ethanol [11] | Capital investment; optimization complexity |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

The following reagents and materials are fundamental for implementing the extraction protocols discussed in this guide.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Bioactive Extraction

| Item | Function/Application | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Absolute Ethanol | Green, GRAS-certified solvent for mid-to-low polarity bioactives [11] | Primary extraction solvent for grape pomace phenolics [11] |

| Hydrophilic-Lipophilic Balance (HLB) Sorbent | Solid-phase extraction for purifying complex extracts [15] | Purification of phosphopeptides from tissue digests [15] |

| C18-Bonded Silica Sorbent | Non-polar stationary phase for reversed-phase SPE [16] [15] | Clean-up and concentration of phenolic compounds prior to LC-MS |

| Silica Gel 60 UV254 Plates | Stationary phase for TLC/HPTLC analysis [16] | Monitoring extraction progress and preliminary compound identification |

| Folin-Ciocalteu Reagent | Quantification of total phenolic content (TPC) [11] [4] | Standard assay for evaluating extraction efficiency of antioxidants |

| DPPH/ABTS Radicals | Evaluation of antioxidant activity in extracts [11] [4] | Functional bioactivity screening of extracts |

Workflow Visualization: From Raw Material to Drug Candidate

The following diagram illustrates the integrated, decision-based workflow for applying extraction techniques within a modern natural product drug discovery pipeline.

The imperative for efficient extraction in drug discovery is clear: the initial choice of technique fundamentally shapes the chemical landscape available for screening. As the data demonstrates, strategic selection is paramount. Researchers must align their method with the project's primary goal—be it maximizing yield with Soxhlet, enriching phenolics with UAE, or targeting specific markers with ASE. Looking forward, the future lies not in a single superior technique, but in the intelligent integration of methods and data. Hybrid approaches that couple the functional validation of bioassay-guided isolation with the comprehensive chemical profiling of metabolomics represent the most powerful path forward [13]. By adopting this strategic, data-driven mindset, scientists can transform the extraction phase from a potential bottleneck into a powerful engine for accelerating natural product drug discovery.

Plant metabolomics faces the fundamental challenge of capturing an immense chemical diversity, comprising both primary metabolites essential for growth and development and a vast array of secondary metabolites with species-specific functions. This complexity is compounded by the broad dynamic range of metabolite concentrations and their varying physicochemical properties, from highly polar sugars to non-polar lipids. No single extraction or analytical technique can comprehensively cover the entire plant metabolome, making the choice of methodology a critical determinant of experimental outcomes [17] [18].

The extraction technique employed significantly influences the resulting metabolic profile by selectively recovering certain compound classes while excluding others. This selection bias directly impacts the biological interpretations and conclusions drawn from metabolomic studies. Understanding the strengths, limitations, and applications of different extraction methods is therefore essential for designing experiments that effectively address specific research questions in plant science, drug discovery, and bioactive compound research [3] [18].

Comparative Analysis of Extraction Techniques

Conventional Extraction Methods

Traditional extraction techniques, while historically important, present significant limitations for comprehensive metabolome coverage. Maceration involves soaking plant material in solvents for extended periods, offering simple operation but requiring large solvent volumes and prolonged extraction times. Percolation provides continuous solvent flow through plant material, improving efficiency but further increasing solvent consumption. Reflux extraction uses heated solvents in a closed system to prevent solvent loss, but thermal degradation can compromise heat-sensitive compounds. Soxhlet extraction enables continuous extraction with solvent recycling but subjects compounds to prolonged high temperatures, potentially degrading thermolabile metabolites [3].

These conventional methods share common drawbacks, including high solvent consumption, long processing times, and potential degradation of sensitive compounds like flavonoids and polyphenols due to excessive heat exposure. While these techniques may be suitable for targeting specific, abundant metabolites, their limited efficiency and potential to alter native metabolic profiles render them suboptimal for untargeted metabolomics aiming for comprehensive coverage [3] [18].

Advanced Green Extraction Technologies

Advanced extraction technologies have emerged to address the limitations of conventional methods, offering improved efficiency, selectivity, and preservation of bioactive compounds.

Microwave-Assisted Extraction (MAE): Utilizes microwave energy to rapidly heat plant material internally, enhancing cell disruption and compound release. MAE significantly reduces extraction time and solvent consumption while improving yields for various metabolite classes [3] [18].

Ultrasound-Assisted Extraction (UAE): Employs acoustic cavitation to disrupt cell walls and enhance mass transfer. UAE operates at lower temperatures, better preserving heat-sensitive compounds while increasing extraction efficiency and reducing processing time [3] [18].

Supercritical Fluid Extraction (SFE): Typically uses supercritical CO₂ as a tunable extraction medium. By adjusting temperature and pressure, SFE can selectively target different compound classes without solvent residues. This method is particularly valuable for lipophilic compounds and for applications requiring high-purity extracts [3].

Pressurized Liquid Extraction (PLE): Uses solvents at elevated temperatures and pressures to enhance extraction efficiency while reducing time and solvent volume. The controlled conditions improve reproducibility compared to conventional methods [3].

Performance Comparison of Extraction Techniques

Table 1: Comparison of Extraction Techniques for Plant Metabolome Coverage

| Extraction Method | Mechanism | Target Metabolites | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Maceration | Passive diffusion in solvent | Broad spectrum, polarity-dependent | Simple equipment, low cost | Long extraction time, high solvent use |

| Soxhlet | Continuous solvent cycling | Medium-nonpolar compounds | High efficiency, no filtration needed | Thermal degradation, long process |

| Microwave-Assisted (MAE) | Microwave-induced cell disruption | Polar to medium-polar compounds | Rapid, reduced solvent, high yield | Potential hotspot formation |

| Ultrasound-Assisted (UAE) | Cavitation-induced cell rupture | Broad spectrum, especially thermolabile | Low temperature, improved kinetics | Limited scale-up potential |

| Supercritical Fluid (SFE) | Solvation with supercritical CO₂ | Lipophilic compounds | Tunable selectivity, no solvent residue | High equipment cost, limited polarity |

| Enzyme-Assisted (EAE) | Cell wall degradation | Bound metabolites, glycosides | Mild conditions, high selectivity | Enzyme cost, optimized parameters needed |

Table 2: Impact of Extraction Methods on Bioactive Compound Recovery and Application

| Extraction Method | Antioxidant Compound Yield | Anti-inflammatory Compound Preservation | Antimicrobial Compound Recovery | Recommended Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Solvent-based | Moderate to high (depends on solvent polarity) | Moderate (thermal degradation possible) | Moderate to high | Initial screening, cost-sensitive applications |

| Ultrasound-Assisted | High (especially flavonoids) | High (preserves thermolabile phenolics) | High (efficient cell disruption) | Thermosensitive compound extraction |

| Microwave-Assisted | High (reduced degradation) | Moderate to high | High | Rapid extraction of stable compounds |

| Supercritical Fluid | Selective for lipophilic antioxidants | High for terpenoids | Selective | Pharmaceutical/nutraceutical applications |

| Enzyme-Assisted | High for bound phenolics | High for glycosylated compounds | Specific to substrate | Release of bound bioactive compounds |

Methodological Considerations for Optimal Metabolome Coverage

Solvent Selection Strategies

Solvent polarity is a primary determinant of metabolite recovery in extraction protocols. Polar solvents (e.g., methanol, ethanol, water) effectively extract hydrophilic compounds like phenolics, flavonoids, and sugars, while non-polar solvents (e.g., hexane, chloroform) target lipophilic metabolites including terpenoids, carotenoids, and chlorophyll. Binary solvent systems often provide broader metabolome coverage by extracting compounds across a wider polarity range [18].

Recent advances in green alternative solvents address toxicity concerns associated with traditional organic solvents. Bio-based solvents, ionic liquids, and deep eutectic solvents offer improved environmental profiles while maintaining extraction efficiency. These alternatives are particularly valuable for pharmaceutical and nutraceutical applications where solvent residues pose safety concerns [3].

Integration and Hybrid Approaches

Hybrid extraction strategies that combine multiple techniques often yield superior metabolome coverage compared to single-method approaches. For instance, enzyme-assisted extraction followed by ultrasound or microwave processing can enhance the release of cell wall-bound metabolites while improving overall extraction efficiency [18].

The sequential application of extraction methods with complementary selectivity represents another powerful strategy. Initial non-polar solvent extraction can target lipophilic compounds, followed by polar solvent extraction for hydrophilic metabolites. This approach effectively "fractionates" the metabolome, reducing complexity in individual analytical runs and improving detection of low-abundance metabolites [18].

Experimental Protocols for Method Comparison

Standardized Workflow for Method Evaluation

To ensure meaningful comparison between extraction techniques, researchers should implement a standardized workflow:

Sample Preparation: Use identical plant source material with controlled genetic background, growth conditions, and developmental stage. Lyophilize samples and homogenize to consistent particle size (e.g., 0.5-1.0 mm) to minimize variability [18].

Extraction Conditions: Maintain consistent sample-to-solvent ratio (e.g., 1:10 to 1:20) and extraction duration across methods when comparable. Adjust method-specific parameters (e.g., temperature, power settings) according to established protocols for each technique.

Post-Extraction Processing: Employ standardized filtration, concentration, and storage conditions to prevent technical artifacts.

Quality Controls: Include internal standards added prior to extraction to monitor recovery and analytical performance [19].

Protocol for Solvent-Based Extraction Comparison

Materials: Plant material powder, methanol, ethanol, acetonitrile, hexane, ethyl acetate, water, internal standards mixture.

Procedure:

- Accurately weigh 100 mg of homogeneous plant powder into separate extraction vessels.

- Add 2 mL of each test solvent plus internal standards mixture.

- Perform extraction with shaking (200 rpm) at 25°C for 60 minutes.

- Centrifuge at 14,000 × g for 10 minutes.

- Collect supernatant and evaporate under nitrogen stream.

- Reconstitute in 100 μL methanol:water (1:1, v/v) for analysis.

- Analyze all extracts using identical LC-MS/GC-MS conditions [19].

Protocol for Ultrasound-Assisted Extraction

Materials: Plant material powder, methanol, ultrasonic probe or bath, temperature control system.

Procedure:

- Weigh 100 mg plant powder into extraction vessel.

- Add 2 mL methanol and suspend homogenously.

- Subject to ultrasonic treatment (e.g., 40 kHz, 300 W) for 5-15 minutes with temperature maintained below 40°C.

- Centrifuge at 14,000 × g for 10 minutes.

- Collect supernatant for analysis [3] [18].

Solid-Phase Extraction Cleanup Protocol

Materials: Methanol extracts, Phree phospholipid removal tubes or equivalent C18 SPE cartridges, vacuum manifold.

Procedure:

- Condition SPE sorbent with appropriate solvent.

- Load methanol extract onto cartridge.

- Wash with water or mild solvent to remove polar interferences.

- Elute metabolites with progressively stronger solvents.

- Evaporate and reconstitute for analysis [20] [19].

Analytical Considerations for Comprehensive Coverage

Complementary Analytical Platforms

Comprehensive plant metabolome coverage typically requires multiple analytical platforms due to the diverse physicochemical properties of metabolites:

GC-MS: Ideal for volatile compounds and derivatized polar metabolites (e.g., organic acids, sugars, amino acids). Provides excellent separation efficiency and reproducible fragmentation patterns for compound identification [21] [22].

LC-MS: Suitable for semi-polar and non-polar compounds, including secondary metabolites (e.g., flavonoids, alkaloids). Reversed-phase chromatography separates compounds by hydrophobicity, while HILIC mode targets polar metabolites [23].

LC-Nano-ESI-MS: Offers enhanced sensitivity for detecting low-abundance metabolites through improved ionization efficiency. Particularly valuable for limited samples or trace compound analysis [23].

Method Validation Parameters

Rigorous method validation should assess multiple performance characteristics:

- Extraction Efficiency: Calculate using internal standards and comparison to established methods.

- Repeatability: Determine through intra- and inter-day precision measurements (%RSD).

- Linearity: Evaluate across relevant concentration ranges.

- Matrix Effects: Assess by comparing standards in solvent versus matrix.

- Metabolite Coverage: Quantify by number of detected features with confident annotations [19].

Research Reagent Solutions for Plant Metabolomics

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Plant Metabolome Extraction and Analysis

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function in Metabolomics Workflow |

|---|---|---|

| Extraction Solvents | Methanol, Acetonitrile, Ethanol, Water, Hexane, Chloroform | Primary extraction media with selective polarity for metabolite classes |

| Derivatization Reagents | N-Methyl-N-(trimethylsilyl)trifluoroacetamide (MSTFA), N,O-Bis(trimethylsilyl)trifluoroacetamide (BSTFA) | Increase volatility of polar metabolites for GC-MS analysis |

| Internal Standards | Succinic acid-2,3-13C2, L-tyrosine-(phenyl-3,5-d2), D-glucose-13C6 | Monitor extraction efficiency, instrument performance, and quantify metabolites |

| Solid-Phase Extraction Sorbents | C18, Phree phospholipid removal tubes, Mixed-mode phases | Remove interfering compounds (e.g., phospholipids) and fractionate metabolite classes |

| Mobile Phase Additives | Formic acid, Ammonium acetate, Ammonium formate | Enhance chromatographic separation and ionization efficiency in LC-MS |

| Isotopically Labeled Standards | 13C, 15N, or 2H labeled amino acids, organic acids, sugars | Absolute quantification in targeted metabolomics |

Workflow Visualization

Comprehensive Plant Metabolomics Workflow

Navigating the chemical complexity of plant metabolomes requires careful consideration of extraction methodologies and their impact on metabolite coverage. While advanced techniques like UAE, MAE, and SFE offer significant improvements in efficiency and compound preservation, the optimal approach often involves integrated strategies that leverage the complementary strengths of multiple methods.

The growing emphasis on green chemistry principles and standardized protocols will enhance reproducibility and comparability across studies. Future methodological developments will likely focus on miniaturized extraction systems, automated workflows, and integrated multi-omics approaches that provide more comprehensive insights into plant metabolic networks. By strategically selecting and combining extraction techniques based on specific research objectives, scientists can more effectively navigate the challenges of plant metabolome coverage and unlock the full potential of plant-derived bioactive compounds for pharmaceutical and nutraceutical applications.

The efficacy of extracting bioactive compounds from natural sources is critically dependent on the selection of an appropriate solvent. The process is governed by the principle of "like dissolves like," where solvents with polarity values similar to the target solute generally achieve higher extraction efficiency [24]. This selection process requires a careful balance between maximizing the yield of desired phytochemicals and adhering to safety and environmental sustainability principles. Solvent choice directly influences not only the quantity of the extracted compounds but also their biological activity, which is paramount for applications in pharmaceutical development, functional foods, and nutraceuticals [25] [26]. Researchers must navigate a complex interplay of factors including solvent polarity, toxicity, cost, and environmental impact, while also considering how the solvent interacts with the plant matrix and the specific extraction methodology employed [26] [24].

The growing demand for natural products across various industries has accelerated research into optimizing extraction processes. Modern solvent selection extends beyond mere efficiency to encompass the principles of green chemistry, which emphasize the use of safer, bio-based, and environmentally benign solvents [25] [27]. This comprehensive guide examines the fundamental principles of solvent selection, supported by experimental data from recent studies, to provide researchers with evidence-based strategies for optimizing the extraction of bioactive compounds while balancing polarity, toxicity, and efficiency considerations.

Fundamental Principles of Solvent Polarity

The "Like Dissolves Like" Rule and Solvent Classification

The cornerstone of solvent selection is the principle of "like dissolves like," which posits that solvents are most effective at dissolving compounds with similar polarity characteristics [24]. Polarity refers to the distribution of electrical charge across a molecule; polar solvents have uneven charge distribution and are typically characterized by the presence of functional groups such as hydroxyls or carbonyls, while non-polar solvents have more even charge distribution [28]. This polarity matching is crucial because it determines the solute-solvent interactions that drive the dissolution process.

Solvents can be broadly categorized based on their polarity and dielectric constants. Polar protic solvents (e.g., water, methanol, ethanol) can form hydrogen bonds and are particularly effective for extracting polar compounds like phenolic acids and flavonoid glycosides. Polar aprotic solvents (e.g., acetone, ethyl acetate) possess dipole moments but lack acidic hydrogen and are suitable for medium-polarity compounds. Non-polar solvents (e.g., hexane, chloroform, dichloromethane) are ideal for extracting lipophilic substances such as oils, waxes, and less polar terpenoids [29] [25]. The polarity of solvents directly affects the extraction yield and composition of bioactive compounds, as demonstrated in studies where different solvents yielded extracts with distinct phytochemical profiles and biological activities [30] [29].

Beyond Pure Solvents: The Advantage of Binary Mixtures

While pure solvents are effective for specific compound classes, binary solvent systems often demonstrate superior extraction efficiency for complex plant matrices containing compounds of varying polarities. The strategic combination of water with organic solvents such as ethanol, methanol, or acetone creates a mixed-polarity environment that can simultaneously extract both polar and mid-polarity compounds [28] [26]. The addition of water to organic solvents enhances the overall extraction efficiency by swelling the plant matrix and increasing the diffusivity of the solvent into the cellular structures, thereby facilitating the release of intracellular compounds [26].

Recent research on Sideritis species demonstrated that 70% ethanol was more effective for extracting various phytochemical classes, including flavonoids, phenylethanoid glycosides, and terpenoids, compared to pure organic solvents or pure water [26]. Similarly, a study optimizing extraction from pitaya cultivars found that ternary mixtures, particularly F5 (25% ethanol, 25% methanol, and 50% water), outperformed pure solvents in extracting antioxidant compounds, phenolics, and betalains, with increases of up to 25.8% in antioxidant activity compared to the least effective solvents [28]. This synergistic effect stems from the complementary polarities of the solvent components, which collectively cover a broader polarity range and enhance mass transfer processes.

Comparative Experimental Data on Solvent Performance

Extraction Efficiency Across Different Plant Matrices

Table 1: Comparison of solvent performance across different plant matrices and target compounds

| Plant Material | Target Compounds | Most Effective Solvent(s) | Extraction Yield/Bioactive Content | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Matthiola ovatifolia (Aerial parts) | Total phenolics, flavonoids, tannins, alkaloids, saponins | Ethanol (MAE method) | Total phenolics: 69.6 mg GAE/g DW; Flavonoids: 44.5 mg QE/g DW; Tannins: 45.3 mg catechin/g DW; Alkaloids: 71.6 mg AE/g DW; Saponins: 285.6 mg EE/g DW | [30] |

| Sideritis raeseri and S. scardica | Flavonoids, phenylethanoid glycosides, phenolic acids | 70% Ethanol (UAE, MAE, HP) | ~3x higher overall metabolite recovery vs. conventional extraction; High antioxidant activity | [26] |

| Olea europaea (Olive leaf) | Antimicrobial compounds | Ethanol, Acetone | Strongest antimicrobial activity against S. aureus and E. coli | [29] |

| Acacia dealbata (Mimosa leaf) | Antimicrobial compounds | Ethanol, Acetone | Strongest antimicrobial activity against S. aureus and E. coli | [29] |

| Pitaya cultivars | Antioxidants, phenolics, betalains | F5 (25% Ethanol, 25% Methanol, 50% Water) | 25.8% ↑ antioxidant activity, 23.5% ↑ total phenolics, 22.7% ↑ betacyanins, 27.0% ↑ betaxanthins vs. least effective solvents | [28] |

| Microalgae | Lipids (for biodiesel) | Hexane, Chloroform | Lipid yield: 100.01 mg/g (Hexane), 94.33 mg/g (Chloroform) vs. 40.12 mg/g (Methanol), 86.91 mg/g (Acetone) | [31] |

Influence of Solvent on Bioactivity of Extracts

The choice of extraction solvent not only affects the quantitative yield of phytochemicals but also qualitatively influences the bioactivity profile of the resulting extracts. Different solvents possess varying selectivity for specific compound classes, leading to extracts with distinct biological properties. For instance, in a study on Olea europaea and Acacia dealbata, ethanol and acetone were identified as the most effective solvents for extracting compounds with antimicrobial activity, regardless of the extraction method employed [29]. This suggests that these solvents preferentially dissolve antimicrobial principles from the plant matrix.

Similarly, the polarity of solvents significantly influenced the fatty acid methyl esters (FAMEs) composition and biodiesel properties of microalgal lipids. Chloroform extraction yielded lipids with higher saturated fatty acids content (61.53%) compared to methanol extraction (38.85%), which consequently affected fuel properties such as cetane number and oxidative stability [31]. These findings underscore how solvent selection can be strategically used to tailor extract composition for specific applications, whether for pharmaceutical, nutraceutical, or industrial purposes.

Toxicity and Environmental Considerations

Green Solvent Alternatives in Modern Extraction

The growing emphasis on sustainable laboratory practices has accelerated the development and adoption of green solvents that reduce environmental impact while maintaining extraction efficiency. Traditional organic solvents such as chloroform, dichloromethane, and hexane face increasing regulatory restrictions due to their toxicity, environmental persistence, and potential health hazards [25] [27]. Green solvents are characterized by favorable safety profiles, low toxicity, biodegradability, and preferably, derivation from renewable resources [27].

Promising green solvent classes include:

- Bio-based alcohols (ethanol, isopropanol): Ethanol is particularly valuable as it is relatively non-toxic, biodegradable, and can be derived from renewable resources, making it suitable for food and pharmaceutical applications [26].

- Ethyl lactate: Derived from lactic acid and ethanol, both from renewable resources, it offers low toxicity and high biodegradability.

- Natural deep eutectic solvents (NADES): These are mixtures of natural compounds such as choline chloride combined with sugars, alcohols, or organic acids that form liquids with favorable extraction properties for various bioactive compounds [9].

- Supercritical fluids: Particularly supercritical CO₂, which is non-flammable, non-toxic, and easily removed from extracts, though it requires specialized equipment [26].

Recent research on citrus biomass extraction demonstrated that gas-expanded NADES could effectively extract bioactive compounds while maintaining the potential for solvent recovery and reuse, highlighting the circular economy approach in extraction technology [9].

Solvent Selection Guides and Miscibility Considerations

To assist researchers in solvent selection, several pharmaceutical companies and consortia have developed solvent selection guides that rank solvents based on their environmental, health, and safety profiles. The CHEM21 solvent selection guide, for instance, categorizes solvents as "recommended," "problematic," "hazardous," or "highly hazardous" based on comprehensive assessment criteria [27]. These guides promote the substitution of hazardous solvents with greener alternatives while considering technical performance.

Miscibility between solvents is another critical practical consideration, particularly for processes involving liquid-liquid extraction, chromatography, or multi-solvent systems. Traditional miscibility tables have recently been updated to include emerging green solvents, providing researchers with valuable data for designing extraction and purification workflows [27]. For example, the miscibility of 28 green solvents was systematically evaluated to facilitate the replacement of hazardous solvents in various chemical processes, including natural product extraction [27].

Integration with Extraction Techniques

Synergistic Effects Between Solvents and Extraction Methods

The efficiency of solvent extraction is profoundly influenced by the extraction technique employed, with different methods leveraging distinct mechanisms to enhance compound recovery. Modern assisted extraction techniques can significantly improve solvent performance by facilitating better matrix penetration and compound dissolution.

Table 2: Performance of solvent-extraction technique combinations for bioactive compound recovery

| Extraction Method | Mechanism of Action | Optimal Solvent Characteristics | Reported Advantages | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Microwave-Assisted Extraction (MAE) | Volumetric heating, cell rupture by internal pressure | Medium dielectric constant for microwave absorption | Highest phytochemical yield from M. ovatifolia; Reduced processing time and solvent consumption | [30] |

| Ultrasound-Assisted Extraction (UAE) | Cavitation, cell wall disruption | Moderate viscosity for cavitation propagation | Improved extraction yield for Sideritis spp.; Shorter extraction time; Preservation of thermolabile compounds | [30] [26] |

| Ultrasound-Microwave-Assisted Extraction (UMAE) | Combined cavitation and volumetric heating | Balanced dielectric constant and viscosity | Synergistic cell disruption; Enhanced recovery efficiency | [30] |

| Conventional Solvent Extraction (CSE) | Diffusion, osmosis | Wide range depending on target compounds | Simple setup; Familiar methodology; Lower equipment cost | [30] |

| Pressurized Liquid Extraction (PLE) | Enhanced penetration at high pressure | Thermal stability | High metabolite recovery from Sideritis spp.; Similar recovery in <20 min vs. 2 h boiling | [26] |

Methodological Protocols for Optimal Extraction

Based on the reviewed literature, the following protocols represent optimized methodologies for bioactive compound extraction:

Protocol 1: Microwave-Assisted Extraction (MAE) for Phytochemical-Rich Extracts

- Plant Preparation: Lyophilize aerial parts and grind to fine powder [30].

- Solvent System: Ethanol demonstrates superior performance for comprehensive phytochemical recovery [30].

- Parameters: Solid-to-liquid ratio of 1:30 (g/mL), microwave power of 550W, extraction time of 165 seconds [30].

- Procedure: Combine plant material with solvent in MAE vessel. Extract under specified parameters. Centrifuge at 10,000×g for 10 minutes at 4°C. Collect supernatant and concentrate at 40°C using rotary evaporation [30].

- Applications: Optimal for simultaneous extraction of multiple phytochemical classes (phenolics, flavonoids, alkaloids, saponins) with enhanced biological activities [30].

Protocol 2: Ultrasound-Assisted Extraction (UAE) for Thermolabile Compounds

- Plant Preparation: Lyophilize and grind plant material to increase surface area [30] [26].

- Solvent System: 70% ethanol for balanced polarity or binary mixtures tailored to target compounds [26].

- Parameters: Solid-to-liquid ratio of 1:30 (g/mL), ultrasonic power of 250W, extraction time of 15 minutes [30].

- Procedure: Mix plant material with solvent in ultrasound bath. Sonicate for specified time. Centrifuge at 10,000×g for 10 minutes at 4°C. Collect supernatant and concentrate [30].

- Applications: Ideal for thermolabile compounds; improves overall metabolite recovery approximately 3-fold compared to conventional extraction [26].

Protocol 3: Solvent Mixture Optimization for Complex Matrices

- Approach: Test binary and ternary mixtures of water with ethanol, methanol, and/or acetone [28].

- Optimization: Evaluate different proportions to identify optimal synergy for target compounds.

- Procedure: Prepare solvent mixtures according to experimental design. Perform extraction using preferred method (UAE, MAE, or conventional). Compare extraction efficiency using spectrophotometric and chromatographic analyses [28].

- Applications: Particularly effective for plants with diverse bioactive compounds spanning a range of polarities, such as pitaya with its antioxidants, phenolics, and betalains [28].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Essential research reagents and materials for solvent extraction of bioactive compounds

| Item | Function/Application | Examples/Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Ethanol (especially 70-100%) | Extraction of broad-spectrum phytochemicals; Green alternative | Effective for phenolics, flavonoids, saponins; Preferred for food/pharma applications [30] [26] |

| Acetone | Extraction of antimicrobial compounds and medium-polarity molecules | Effective for antimicrobial principles from olive and mimosa leaves [29] |

| Methanol | High-efficiency extraction of phenolics | Often highest extraction yield but toxicity concerns for some applications [29] |

| Water | Green solvent for polar compounds; Component of binary mixtures | Enhances solvent diffusivity in matrix; Swells plant material [26] |

| Binary Solvent Mixtures | Enhanced extraction of complex phytochemical profiles | Water-ethanol, water-acetone, water-methanol combinations [28] [26] |

| NADES | Green alternative with tunable properties | Choline chloride-based mixtures for specialized applications [9] |

| Folinciocalteu Reagent | Quantification of total phenolic content | Spectrophotometric analysis at 765nm [30] |

| ABTS/DPPH Reagents | Assessment of antioxidant capacity | Standardized assays for radical scavenging activity [29] |

| Aluminum Chloride | Flavonoid content determination | Complexation with flavonoids for spectrophotometric quantification [30] |

| Rotary Evaporator | Solvent removal from extracts | Gentle concentration at controlled temperatures (e.g., 40°C) [30] |

Decision Framework and Future Perspectives

Integrated Workflow for Solvent Selection

The following workflow diagram illustrates a systematic approach to solvent selection for bioactive compound extraction:

Emerging Trends and Future Directions

The field of solvent extraction for bioactive compounds continues to evolve, with several promising trends emerging. Natural deep eutectic solvents (NADES) represent a particularly innovative approach, offering tunable physicochemical properties and high biodegradability [9]. Research on citrus biomass has demonstrated the feasibility of combining NADES with gas-expanded technology, followed by effective solvent removal using activated charcoal or antisolvent methods to obtain NADES-free bioactive extracts [9].

The integration of machine learning and computational modeling in solvent selection processes shows significant potential for accelerating method development. These approaches can predict solvent behavior, miscibility, and extraction efficiency, reducing the need for extensive experimental screening [32]. Additionally, continuous flow extraction technologies are gaining attention for their potential to reduce solvent consumption and improve process control, though they present unique challenges in solvent management, particularly regarding solubility maintenance and prevention of system clogging [32].

Future research directions likely include the development of more sophisticated solvent recycling systems, the design of switchable solvents whose properties can be modulated during the extraction process, and increased emphasis on life cycle assessment (LCA) to comprehensively evaluate the environmental impact of extraction processes from cradle to grave [27] [32]. As these technologies mature, they will further enable researchers to balance the critical factors of polarity, toxicity, and efficiency in solvent selection for bioactive compound extraction.

A Practical Guide to Advanced Extraction Technologies

Microwave-Assisted Extraction (MAE) has emerged as a prominent green extraction technology, revolutionizing the process of obtaining bioactive compounds from natural sources. This technique utilizes microwave energy to rapidly heat solvents in contact with a sample matrix, facilitating efficient partitioning of analytes from the solid matrix into the solvent [33] [34]. The fundamental advantage of MAE lies in its ability to significantly reduce extraction times—typically to just 15-30 minutes—while simultaneously decreasing solvent consumption by approximately tenfold compared to conventional techniques like Soxhlet extraction [34]. These attributes, combined with enhanced extraction efficiency and improved reproducibility, have established MAE as a cornerstone technology in sustainable extraction methodologies for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals [35].

The global shift toward environmentally friendly industrial practices has accelerated MAE adoption across food, pharmaceutical, and cosmetic industries. As a sustainable alternative to conventional methods, MAE leverages volumetric heating to achieve rapid, efficient, and selective recovery of natural compounds while preserving their bioactivity [35]. This technical overview examines MAE's fundamental principles, mechanisms, and operational parameters, providing a scientific foundation for its application in bioactive compound research.

Fundamental Principles and Mechanisms

Theoretical Foundations of Microwave Heating

MAE operates based on the interaction between microwave electromagnetic energy and materials. Microwaves occupy the electromagnetic spectrum between 300 MHz and 300 GHz, with 2.45 GHz being the standard frequency for laboratory equipment due to its effective penetration depth and heating characteristics [36] [37]. This frequency corresponds to a wavelength of approximately 12.2 cm, which optimally interacts with molecular dipoles in the extraction system.

The heating mechanism in MAE fundamentally differs from conventional conduction-based heating. While traditional methods rely on thermal gradients that gradually transfer heat from the outside inward, microwave energy generates heat volumetrically through direct interaction with the sample and solvent molecules [37]. This direct energy transfer eliminates thermal latency and enables simultaneous heating throughout the material, leading to dramatically reduced extraction times.

Working Mechanism of MAE

The MAE process involves a synergistic combination of heat and mass transfer working in the same direction, unlike conventional methods where mass transfer occurs from inside to outside while heat transfer proceeds in the opposite direction [37]. The extraction mechanism follows a sequence of distinct phenomenological events:

- Selective Heating: Microwave energy directly targets polar molecules and ionic species within the plant matrix, particularly residual water present in plant cells [33].

- Rapid Temperature Rise: The intense, localized heating causes a swift temperature increase, transforming liquid water into vapor [37].

- Pressure Buildup: The vaporized solvents create enormous internal pressure within plant cells [38].

- Cell Wall Rupture: The accumulated pressure exceeds the cell wall's structural integrity, leading to cell disruption and rupture [37].

- Compound Release: The compromised cellular structure enables efficient leaching of bioactive compounds into the surrounding solvent [37].

This mechanism is visually summarized in the following diagram:

The exceptional efficiency of MAE stems from this direct cellular disruption, which creates efficient passageways for solute transfer from the plant matrix to the solvent while minimizing thermal degradation through reduced processing times [39].

Critical Operational Parameters

MAE efficiency depends on several interconnected parameters that require optimization for each specific application and plant matrix. Understanding these factors enables researchers to design efficient extraction protocols tailored to their target compounds.

Solvent Selection and Properties

Solvent choice profoundly influences MAE efficiency due to varying microwave absorption capacities. Solvents with high dielectric constants (ε) and dielectric losses absorb microwave energy more effectively [37]. The table below summarizes dielectric properties of common MAE solvents:

Table 1: Dielectric Properties of Common MAE Solvents

| Solvent | Dielectric Constant | Dielectric Loss | Loss Tangent | Microwave Absorption |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Water | 80.4 | 12.3 | 9.889 | Excellent |

| Ethanol | 24.3 | 22.866 | 0.941 | Excellent |

| Ethylene Glycol | 37.0 | 49.950 | 1.350 | Excellent |

| Dimethyl Sulfoxide | 45.0 | 37.125 | 0.825 | Excellent |

| Dimethylformamide | 37.7 | 6.079 | 0.161 | Moderate |

| Chloroform | 4.8 | 0.437 | 0.091 | Poor |

| Toluene | 2.4 | 0.096 | 0.040 | Poor |

| Hexane | 1.9 | 0.038 | 0.020 | Poor |

Ethanol-water mixtures are particularly effective for extracting phenolic compounds and other bioactive molecules, offering an optimal balance between microwave absorption and compound solubility [40]. The addition of small water quantities to polar solvents enhances diffusion into cell matrices, improving heating efficiency and mass transfer rates [37]. Recent advancements have also introduced Natural Deep Eutectic Solvents (NADES) as sustainable alternatives with customizable properties for specific compound classes [41].

Microwave Parameters

Power and Temperature: Microwave power directly influences extraction temperature and kinetics. Higher power levels generate rapid heating, which can enhance extraction rates but risk degrading thermolabile compounds. Optimal power settings are matrix-dependent and must be determined experimentally [39]. Modern MAE systems offer precise temperature control to maintain compounds below their degradation thresholds [33].

Extraction Time: MAE typically achieves complete extraction within 5-25 minutes, significantly shorter than conventional methods requiring hours or days [34] [38]. Prolonged exposure to microwave energy can degrade heat-sensitive compounds, necessitating time optimization for each application [33].

Matrix Characteristics and Solvent Ratio

Plant Matrix Properties: Sample characteristics—including particle size, moisture content, and morphological structure—significantly impact MAE efficiency. Smaller particle sizes increase surface area for solvent interaction, while residual moisture enhances microwave absorption through its exceptional dielectric properties [39]. The water content within plant cells facilitates selective heating and subsequent cell rupture, making MAE particularly effective for fresh or rehydrated materials [33].

Solvent-to-Feed Ratio: The solvent volume relative to sample mass affects extraction efficiency and process economics. Typical MAE solvent-to-feed ratios range from 10:1 to 20:1 (mL/g) [37]. Insufficient solvent volumes may limit complete compound extraction, while excessive volumes reduce concentration efficiency and increase waste [39].

MAE in Comparative Context

Performance Comparison with Alternative Techniques

When evaluated against other extraction methodologies, MAE demonstrates distinct advantages in specific performance categories. The following table summarizes comparative experimental data from recent studies:

Table 2: Comparative Performance of Extraction Techniques for Bioactive Compounds

| Extraction Method | Time Requirements | Solvent Consumption | Temperature | Typical TPC Yield | Key Advantages | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MAE | 5-25 min [38] | Low [34] | Moderate-High [33] | 227.63 mg GAE/g [40] | Rapid heating, high efficiency, good selectivity | Potential thermal degradation, equipment cost |

| Ultrasound-Assisted Extraction (UAE) | 5-45 min [38] | Low [36] | Low-Moderate [40] | 92.99 mg GAE/g [40] | Low temperature, simple operation | Lower efficiency for some matrices |

| Pressurized Liquid Extraction (PLE) | 10-60 min [40] | Medium [40] | High [40] | 173.65 mg GAE/g [40] | Automated, efficient | High pressure requirements, equipment cost |

| Supercritical Fluid Extraction (SFE) | 30-120 min [40] | Very Low (CO₂) [36] | Low (40°C) [40] | 37 mg GAE/g [40] | Solvent-free, selective | High equipment cost, limited polarity range |

| Soxhlet (Conventional) | 6-24 hours [39] | High [34] | High [39] | 48.6-71 mg GAE/g [40] | Simple, established | Long duration, thermal degradation |

Application-Specific Performance

Recent comparative studies demonstrate MAE's effectiveness across various plant matrices:

Camellia japonica Flowers: MAE achieved maximum extraction yields of 80% using high temperature (180°C) and short time (5 minutes), significantly outperforming UAE's maximum yield of 56% under optimal conditions (62% amplitude, 8 minutes) [38].

Hemp Seeds and Wheat Bran: MAE and UMAE (ultrasound-microwave assisted extraction) produced extracts with the highest polyphenol and flavonoid content, alongside superior antioxidant activities compared to maceration and standalone UAE [42].

Piper betel L. Leaves: Optimized MAE conditions (239.6 W, 1.58 minutes, 1:22 solid-to-solvent ratio) yielded extracts with TPC of 77.98 mg GAE/g and TFC of 38.99 mg QUE/g, demonstrating MAE's efficiency for thermolabile compounds [39].

Experimental Optimization and Protocols

Standard MAE Experimental Methodology

A typical MAE protocol for bioactive compound extraction involves the following steps:

- Sample Preparation: Plant material is dried (typically at 40°C), ground to a uniform particle size (150-500 μm), and stored in airtight containers to prevent moisture variation [39].

- Solvent Selection: Based on target compound polarity, appropriate solvents (ethanol-water mixtures are common for phenolics) are prepared [40] [39].

- Extraction Vessel Loading: The sample-solvent mixture is placed in sealed microwave-transparent vessels, ensuring proper headspace for pressure management [33].

- Microwave Treatment: Vessels are subjected to controlled microwave irradiation under optimized power, time, and temperature parameters [39].

- Post-Extraction Processing: The extract is cooled, centrifuged (e.g., 5000 rpm for 10 minutes), filtered, and concentrated under reduced pressure at moderate temperatures (≤40°C) [39] [41].

Optimization Approaches

Response Surface Methodology (RSM) with Box-Behnken or Central Composite Designs is widely employed to optimize MAE parameters [39] [41]. These statistical approaches efficiently model parameter interactions and identify optimal conditions while minimizing experimental runs. For example, MAE optimization for nettle leaves employed RSM with microwave power (300-600 W), time (10-20 minutes), and solvent-to-slurry ratio (1:10-1:20) as independent variables [41].

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for MAE Protocols

| Reagent/Equipment | Specification | Research Function | Application Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| Microwave Reactor | Closed-vessel system with temperature and pressure control | Provides controlled microwave energy under safe conditions | Ethos Milestone system for nettle leaf extraction [41] |

| Polar Solvents | Ethanol (95-100%), methanol, water | Microwave absorption and compound dissolution | Ethanol-water for phenolic compound extraction [40] |

| NADES | Choline chloride: lactic acid (1:2) | Green solvent with tunable properties | NADES-based MAE for antioxidant compounds [41] |

| Folin-Ciocalteu Reagent | Commercial solution | Quantification of total phenolic content | TPC measurement in betel leaf extracts [39] |

| DPPH | 2,2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl | Free radical for antioxidant activity assessment | Antioxidant capacity of hemp seed extracts [42] |

| Analytical Standards | Gallic acid, quercetin, etc. | Calibration and quantification references | HPLC quantification of phenolic compounds [38] |

Recent Advancements and Future Perspectives

MAE technology continues evolving through several innovative approaches:

Synergistic Hybrid Techniques: Combining MAE with other technologies enhances extraction efficiency. Ultrasound-Microwave Assisted Extraction (UMAE) integrates cavitation effects with microwave heating, improving cell wall disruption and compound release [33] [42]. Enzyme-Assisted Ultrasonic-Microwave Synergistic Extraction (EAUMSE) further increases yields by enzymatically degrading structural components before microwave treatment [33].

Green Solvent Applications: Natural Deep Eutectic Solvents (NADES) represent a promising green alternative to conventional organic solvents. These designer solvents offer tunable properties for specific compound classes while maintaining low toxicity and environmental impact [41].

Process Modeling and AI: Advanced computational approaches, including artificial intelligence and machine learning, are increasingly applied to model, predict, and optimize MAE processes. These technologies enable more efficient parameter optimization and scale-up predictions [35].

Selective Extraction Strategies: MAE's selective heating properties are being exploited for targeted compound recovery through careful manipulation of solvent dielectric properties and matrix characteristics [35].

Microwave-Assisted Extraction represents a sophisticated, efficient, and sustainable technology for recovering bioactive compounds from plant matrices. Its unique mechanism—combining direct volumetric heating with internal pressure-induced cell disruption—provides distinct advantages over conventional extraction methods, including dramatically reduced processing times, lower solvent consumption, and enhanced extraction efficiency. While equipment costs and potential thermal degradation require consideration, MAE's overall performance profile positions it as a valuable tool for researchers and pharmaceutical developers seeking efficient, scalable extraction methodologies. Continuing advancements in synergistic hybrid techniques, green solvent systems, and AI-assisted optimization promise to further expand MAE applications in bioactive compound research and development.

The efficient extraction of bioactive compounds from natural sources is a critical step in pharmaceutical, nutraceutical, and cosmetic research and development. Bioactive components such as polyphenols, flavonoids, carotenoids, and alkaloids possess diverse health-promoting properties but are often entrapped within rigid cellular structures, making their extraction challenging [43]. Traditional extraction methods like maceration, Soxhlet extraction, and reflux extraction have been widely used for decades but present significant limitations including longer extraction times, higher solvent consumption, reduced extraction efficiency, and potential degradation of thermolabile compounds due to high temperatures [44] [10]. These drawbacks have prompted the development of innovative, non-thermal extraction technologies that can improve yield while minimizing environmental impact [45].

Among emerging green extraction technologies, ultrasound-assisted extraction (UAE) has gained significant traction as an efficient, environmentally friendly alternative to conventional methods [46]. UAE utilizes acoustic energy to disrupt cellular walls and enhance mass transfer, facilitating the release of intracellular compounds into the extraction solvent [43]. This technology aligns with the principles of green extraction by reducing solvent consumption, minimizing energy requirements, and preserving heat-sensitive bioactive compounds [46]. The growing interest in UAE stems from its potential to overcome the limitations of traditional methods while providing higher yields of bioactive compounds in shorter time frames under mild temperature conditions [47]. This article provides a comprehensive comparison of UAE with other extraction technologies, focusing on its mechanism, efficiency, and practical applications in research settings.

Fundamental Principles of Ultrasound-Assisted Extraction

The Cavitation Phenomenon

The core mechanism underlying ultrasound-assisted extraction is acoustic cavitation, a physical process that generates, grows, and collapses microbubbles within a liquid medium [45] [47]. When high-frequency sound waves (typically >20 kHz) propagate through a liquid medium, they create alternating compression and rarefaction (expansion) cycles. During the rarefaction phase, the negative pressure exceeds the attractive forces between liquid molecules, creating microscopic vapor-filled cavities [47]. These cavities grow over successive cycles through coalescence and eventually implode violently during the compression phase, generating localized extreme conditions with temperatures reaching approximately 5,000 K and pressures up to 1,000 atmospheres [47].

This cavitation phenomenon occurs in close proximity to solid surfaces such as plant cell walls, leading to asymmetric bubble collapse that produces powerful microjets directed toward the solid surface [45]. These microjets, with velocities estimated at up to 100 m/s, create intense shear forces that erode and fragment the cellular matrix, facilitating the release of intracellular compounds [45]. Additionally, the collapse of cavitation bubbles generates powerful shockwaves that further disrupt cellular structures and enhance mass transfer by reducing particle size and increasing the surface area available for solvent contact [47].

Cellular Disruption Mechanisms

The physical forces generated during acoustic cavitation induce multiple cellular disruption mechanisms that collectively enhance extraction efficiency. These include:

- Fragmentation: The violent collapse of cavitation bubbles near cell walls generates shockwaves that break down cellular structures into smaller particles, increasing the surface area for solvent contact [47].

- Erosion: Asymmetric bubble collapse produces microjets that locally erode the solid surface, creating channels for improved solvent penetration into the cellular matrix [45].

- Sonoporation: The formation of transient pores in cell membranes during cavitation facilitates the release of intracellular compounds without complete cell destruction [45] [47].

- Shear Forces: Turbulence and microstreaming within the fluid create shear forces that disrupt cellular walls and enhance the diffusion of solutes from the cellular interior to the surrounding solvent [47].

The combination of these mechanisms significantly improves solvent penetration into plant tissues and enhances the mass transfer of bioactive compounds from cells to the extraction medium [46]. The cumulative effect is a substantial reduction in extraction time and increase in yield compared to conventional extraction methods.

Comparative Analysis of Extraction Technologies

Methodology for Comparison

To objectively evaluate the performance of ultrasound-assisted extraction against other techniques, we analyzed comparative studies from recent scientific literature (2018-2025) focusing on yield, time, solvent consumption, and temperature parameters. The comparison includes both conventional methods (maceration, Soxhlet, reflux) and emerging green technologies (microwave-assisted extraction, supercritical fluid extraction, pressurized liquid extraction). Extraction efficiency was normalized across studies where possible, with particular attention to the recovery of thermolabile bioactive compounds that are susceptible to degradation under high-temperature conditions. The data presented represents average values from multiple studies to provide a comprehensive overview of each technology's performance characteristics.

Performance Comparison Table

Table 1: Comparative analysis of extraction technologies for bioactive compounds

| Extraction Method | Extraction Time | Temperature (°C) | Solvent Consumption | Relative Yield | Energy Consumption | Applicability to Thermolabile Compounds |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ultrasound-Assisted Extraction (UAE) | 5-40 min [47] | 25-60 [45] | Low | High | Moderate | Excellent [48] |

| Maceration | 120-4320 min [46] | 25-40 | High | Low | Low | Good |

| Soxhlet Extraction | 180-360 min [46] | 60-200 | High | Moderate | High | Poor |

| Microwave-Assisted Extraction | 5-20 min | 60-120 | Low | High | Moderate | Moderate |

| Supercritical Fluid Extraction | 30-120 min | 31-80 [44] | Very Low | High | High | Excellent |