Advanced Analytical Methods for Food Authenticity and Geographic Origin Verification: A Comprehensive Guide for Researchers

This article provides a comprehensive overview of the scientific methods and technologies used to verify food authenticity and geographic origin, crucial for ensuring food safety, regulatory compliance, and consumer trust.

Advanced Analytical Methods for Food Authenticity and Geographic Origin Verification: A Comprehensive Guide for Researchers

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of the scientific methods and technologies used to verify food authenticity and geographic origin, crucial for ensuring food safety, regulatory compliance, and consumer trust. Aimed at researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it explores foundational concepts, detailed methodologies, optimization strategies, and comparative validation of techniques including DNA-based analysis, spectroscopy, isotope ratio mass spectrometry, and multi-omics approaches. The content synthesizes current research trends, addresses practical challenges in method implementation, and examines the implications of food authentication technologies for biomedical and clinical research, particularly in understanding the biological impact of food composition and origin.

The Science Behind Food Fraud: Understanding Authenticity Challenges and Fundamental Principles

Food authenticity represents the accurate and truthful representation of food and its ingredients to consumers and supply chain partners. A food product is considered authentic when its contents and condition precisely match the information declared on its label [1]. The global food authenticity market, valued between USD 8.02 billion (2024) and USD 10.2 billion (2025), is projected to grow at a compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of 6.4% to 9.0%, reaching USD 11.99 billion to USD 17.9 billion by 2029-2034 [1] [2]. This expansion is driven by escalating consumer concerns about food fraud, stringent regulatory requirements, and the increasing complexity of globalized food supply chains that elevate the risk of adulteration and misrepresentation [1] [2].

The core challenge in food authenticity stems from economic incentives for fraud, which occurs whenever a price premium exists between similar products or when there is downward pressure on prices [3]. The UK's regulatory approach adopts a zero-tolerance stance toward any mis-selling, recognizing that even economically motivated adulteration with no direct health risk often correlates with other food safety violations [3]. Food fraud encompasses multiple forms, including adulteration, deliberate substitution, dilution, simulation, counterfeiting, misrepresentation of food ingredients or packaging, and false or misleading statements made for economic gain [3].

Table 1: Global Food Authenticity Market Projections

| Market Aspect | 2024/2025 Value | 2034/2029 Projection | CAGR | Sources |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Market Size (2024) | USD 8.02 billion | USD 11.99 billion (2029) | 9.0% | [1] |

| Market Size (2025) | USD 10.2 billion | USD 17.9 billion (2034) | 6.4% | [2] |

| Testing Services (2025) | USD 6.62 billion | USD 11.31 billion (2035) | 5.5% | [4] |

Analytical Frameworks for Food Authenticity

Strategic Approaches to Authenticity Testing

Analytical testing serves as a crucial component within a comprehensive food fraud defense strategy, though it cannot independently identify every type of food fraud [3]. The Institute of Food Science & Technology (IFST) emphasizes that robust supply chain defense policies, short and transparent supply chains, financial audits, mass balance checks, and effective whistleblower procedures constitute the primary safeguards against fraud, with analytical testing serving as verification rather than a standalone control system [3].

Food manufacturers typically employ risk-based prioritization to conduct unannounced analytical spot checks on raw materials to verify their identity and provenance [3]. However, unlike chemical contaminant testing, food authenticity results often contain inherent ambiguity and uncertainty, requiring manufacturers to establish clear procedures for acting upon suggestive but inconclusive findings [3]. The interpretation of authenticity tests frequently relies on probabilistic assessment rather than definitive binary outcomes, necessitating expert judgment when analytical results inform further investigation through audits or mass balance checks [3].

Fundamental Analytical Classifications

Food authenticity methods can be fundamentally classified through three primary dimensions: analytical approach, specificity, and testing location. Each classification offers distinct advantages and limitations for different authentication scenarios [3].

Targeted vs. Untargeted Analysis: Targeted analysis involves predefined measurement of specific analytes, adulterants, or markers known to be associated with particular fraud types. Examples include testing for melamine in milk powder, chicory in soluble coffee, or using specific DNA primers to amplify genetic material from a particular meat species [3]. This approach offers high sensitivity through optimized instrumentation but remains inherently reactive, as it can only detect issues that are specifically sought [3].

Untargeted analysis employs comprehensive profiling without a predefined target list, measuring multiple data points to generate characteristic patterns or fingerprints. Examples include measuring complex protein, metabolite, or genetic patterns without necessarily identifying individual components, often referred to as "-omics" techniques (genomics, proteomics, metabolomics) [3]. Other examples encompass nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopy of alcoholic beverages or mass spectrometry of dried herbs, followed by multivariate analysis to compare against extensive reference databases [3].

Specific Analyte vs. Multi-Variate Analysis (MVA): This classification distinguishes between methods that measure specific known compounds versus those that analyze multiple variables simultaneously to identify patterns characteristic of authentic or fraudulent products [3].

Laboratory vs. Point-of-Use Testing: The testing environment ranges from sophisticated central laboratories with advanced instrumentation to portable devices deployed at supply chain nodes for rapid on-site decision-making [3]. The growing adoption of portable technologies represents a significant trend, with devices such as handheld PCR systems and portable NIR spectrometers enabling authentication at farms, ports, and distribution centers [4].

Table 2: Analytical Technique Classification and Applications

| Analytical Classification | Technology Examples | Primary Applications | Strengths | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Targeted Analysis | PCR, qPCR, ELISA, LC-MS/MS | Species identification, allergen detection, specific adulterant testing | High sensitivity, quantitative capability, regulatory acceptance | Reactive approach, limited to known targets |

| Untargeted Analysis | NMR, NIR, MS-based metabolomics, proteomics | Geographic origin, production method, variety authentication | Comprehensive profiling, discovery capability | Complex data interpretation, extensive reference databases needed |

| Laboratory-Based | Isotope Ratio MS, NGS, 4D-DIA proteomics | Reference methods, complex authentication, legal cases | Highest accuracy and sensitivity, definitive results | Time-consuming, expensive, requires specialized expertise |

| Point-of-Use | Portable PCR, handheld NIR, LAMP assays | Supply chain screening, rapid checks, field testing | Rapid results, cost-effective, deterrent effect | Limited multiplexing, higher detection limits |

Experimental Protocols for Geographic Origin Authentication

4D-DIA Quantitative Proteomics for Lamb Origin Authentication

Introduction: This advanced protocol implements four-dimensional data-independent acquisition (4D-DIA) quantitative proteomics combined with interpretable machine learning to authenticate the geographical origin of lamb, addressing critical gaps in conventional methodologies that are often limited by short-term dietary influences on analytical results [5]. The method leverages the stability and complexity of muscle proteins as superior biomarkers compared to more volatile lipids and metabolites [5].

Principle: Geographical origin differences induce subtle variations in protein expression patterns in muscle tissue due to environmental factors, feeding practices, and genetic adaptations. By incorporating ion mobility separation as a fourth dimension alongside retention time and mass-to-charge ratio, 4D-DIA proteomics achieves unprecedented resolution and quantitative accuracy for detecting these protein biomarkers [5].

Materials and Equipment:

- Liquid chromatography system with ultra-high performance capabilities

- TimeTOF mass spectrometer with ion mobility capability

- Protein extraction and digestion reagents (surfactants, reducing agents, alkylating agents, proteolytic enzymes)

- Chromatography columns (C18 reversed-phase)

- Data processing software (Spectronaut, DIA-NN, or similar)

- Machine learning environment (Python with scikit-learn, SHAP)

Sample Preparation Protocol:

- Sample Collection: Collect 24 lamb samples (6-month-old males; n=8 per region) from three major production regions separated by significant distance (e.g., Gansu [GTS], Inner Mongolia [ITS], and Ningxia [NTS] for Tan sheep) [5].

- Protein Extraction: Homogenize 100 mg of longissimus dorsi muscle tissue in appropriate extraction buffer containing surfactant and protease inhibitors. Centrifuge at 14,000 × g for 20 minutes at 4°C to collect supernatant [5].

- Protein Digestion: Quantify protein concentration using bicinchoninic acid (BCA) assay. Reduce disulfide bonds with dithiothreitol (10 mM, 30 minutes, 37°C), alkylate with iodoacetamide (20 mM, 30 minutes, dark), and digest with trypsin (enzyme-to-substrate ratio 1:50, 37°C, 12-16 hours) [5].

- Peptide Desalting: Purify digested peptides using C18 solid-phase extraction cartridges, followed by lyophilization and reconstitution in appropriate mobile phase for LC-MS analysis [5].

4D-DIA Proteomic Analysis:

- Chromatographic Separation: Inject peptide samples onto a reversed-phase C18 column (75 μm × 250 mm, 1.6 μm particle size) with a 120-minute linear gradient from 2% to 35% mobile phase B (0.1% formic acid in acetonitrile) at a flow rate of 300 nL/min [5].

- Mass Spectrometry Acquisition: Operate timeTOF mass spectrometer in DIA mode with ion mobility separation. Set acquisition parameters: mass range 100-1700 m/z, ion mobility range 0.6-1.4 Vs/cm², 32 variable windows covering the entire m/z range [5].

- Quality Control: Include quality control samples (pooled from all samples) at regular intervals throughout the acquisition sequence to monitor instrument stability [5].

Data Processing and Statistical Analysis:

- Protein Identification and Quantification: Process raw data using specialized software (Spectronaut or DIA-NN) against appropriate species-specific protein sequence databases. Apply false discovery rate (FDR) threshold of 1% at both peptide and protein levels [5].

- Biomarker Discovery: Apply LASSO (Least Absolute Shrinkage and Selection Operator) regression analysis to identify the minimal set of protein biomarkers that optimally discriminate geographical origins [5].

- Model Building and Validation: Compare multiple machine learning classifiers (logistic regression, random forest, support vector machines, etc.) using cross-validation. Apply SHAP (SHapley Additive exPlanations) analysis to the best-performing model to interpret feature importance and decision processes [5].

Research Reagent Solutions for Proteomic Authentication

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Proteomic Origin Authentication

| Reagent/Material | Specification | Function in Protocol | Technical Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Trypsin | Sequencing grade, modified | Proteolytic digestion of proteins into peptides | Enzyme-to-substrate ratio 1:50; 37°C incubation for 12-16 hours |

| Dithiothreitol (DTT) | Molecular biology grade (10 mM) | Reduction of disulfide bonds | 30-minute incubation at 37°C |

| Iodoacetamide | Molecular biology grade (20 mM) | Alkylation of cysteine residues | 30-minute incubation in dark conditions |

| C18 Solid-Phase Extraction Cartridges | 100 mg sorbent bed | Peptide cleanup and desalting | Condition with acetonitrile and equilibrate with aqueous buffer prior to use |

| LC-MS Mobile Phase A | 0.1% formic acid in water | Aqueous chromatographic solvent | Ultra-pure water and LC-MS grade formic acid |

| LC-MS Mobile Phase B | 0.1% formic acid in acetonitrile | Organic chromatographic solvent | LC-MS grade acetonitrile; linear gradient from 2% to 35% |

| Surfactant | RapiGest or similar | Protein extraction and solubilization | Compatible with MS analysis; remove by acidification |

| Protein Sequence Database | Species-specific (Ovis aries) | Protein identification and quantification | Swiss-Prot or NCBI databases; include common contaminants |

Advanced Technological Applications

Market Adoption of Authentication Technologies

The food authenticity testing landscape demonstrates distinct technology adoption patterns across market segments. Polymerase chain reaction (PCR)-based testing dominates the technology segment with approximately 35% market share in 2025, valued at USD 6.62 billion and projected to reach USD 11.31 billion by 2035 [4]. This supremacy stems from PCR's precision, speed, and adaptability across diverse food matrices, with real-time quantitative PCR (qPCR) preferred for absolute quantification of contaminant DNA and digital PCR (dPCR) emerging for ultra-sensitive detection of genetically modified organisms and trace allergens [4].

Chromatography-based techniques, particularly liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (LC-MS), secure a substantial 28% share of the technology mix, supported by investments in both portable and benchtop systems [4]. LC-MS protocols have been refined to quantify specific adulterants like melamine and Sudan dyes, while GC-MS methods excel in volatile-compound profiling for spices, oils, and flavorings [4].

In the target-testing category, adulteration analysis leads with 32% market share, reflecting heightened regulatory scrutiny and consumer intolerance for hidden contaminants [4]. The meat and meat products segment represents the largest food category with 30% market share, necessitating vigilant verification due to frequent species substitution and undeclared fillers in global supply chains [4].

Table 4: Food Authenticity Market Segmentation and Technology Adoption

| Market Segment | Leading Category | Market Share (2025) | Key Technologies | Growth Drivers |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Technology | PCR-Based Testing | 35% | qPCR, dPCR, multiplex assays | Precision, speed, adaptability across matrices |

| Technology | Chromatography-MS | 28% | LC-MS, GC-MS, portable systems | adulterant quantification, volatile compound profiling |

| Target Testing | Adulteration Analysis | 32% | Chemical analysis, microbiological testing | Regulatory scrutiny, consumer intolerance to contaminants |

| Food Tested | Meat & Meat Products | 30% | DNA multiplex PCR, NGS, portable PCR kits | Species substitution, undeclared fillers, religious requirements |

| Region | North America | Largest share (2024) | DNA-based assays, blockchain tracing | Stringent FDA/USDA guidelines, advanced technology adoption |

| Region | Asia-Pacific | Fastest growing (6.0% CAGR) | Laboratory infrastructure expansion | Growing exports, government scrutiny, investment |

Emerging Innovations and Future Directions

The food authenticity field is experiencing rapid technological evolution, with several emerging innovations reshaping testing capabilities and applications. Artificial intelligence and machine learning integration represent transformative trends, enhancing data analysis and predictive capabilities for faster and more accurate fraud detection [2]. The development of interpretable machine learning techniques, such as SHAP (SHapley Additive Explanations), addresses critical limitations of traditional "black box" approaches by revealing salient features and decision processes, thereby increasing model credibility and scientific value in biomarker discovery [5].

Portable and rapid testing solutions constitute another significant innovation trajectory, with devices such as handheld PCR systems, portable NIR spectrometers, and Loop-Mediated Isothermal Amplification (LAMP) assays enabling on-site authentication at various supply chain nodes [4] [2]. These technologies reduce transportation delays and sample degradation while supporting rapid decision-making at farms, ports, and distribution centers [4].

Blockchain technology is establishing itself as a powerful traceability solution, providing transparent and immutable records across the food supply chain to enhance consumer trust [2]. When integrated with analytical testing, blockchain creates comprehensive authenticity verification systems that combine physical product verification with digital chain-of-custody documentation.

The emerging frontier of 4D-DIA proteomics demonstrates how advanced analytical technologies continue to push authentication capabilities. By incorporating ion mobility as a fourth dimension alongside traditional LC-MS parameters, this approach achieves unprecedented resolution and quantitative accuracy for geographic origin determination [5]. In one implementation, this method identified 26,442 peptides and 3,790 proteins across lamb samples, with LASSO regression refining these to 16 candidate protein markers and ultimately 14 proteins that enabled 100% classification accuracy between geographical origins [5].

The convergence of these technological streams—advanced analytical instrumentation, portable testing platforms, AI-powered data interpretation, and blockchain-enabled traceability—creates a powerful ecosystem for comprehensive food authenticity verification that addresses both current fraud patterns and emerging challenges in an increasingly complex global food system.

Economic and Health Impacts of Food Fraud in Global Supply Chains

Food fraud, defined as the deliberate and intentional alteration, misrepresentation, or adulteration of food products for economic gain, presents a critical challenge to global supply chains [6]. This malicious practice encompasses diverse activities including adulteration, mislabeling, substitution, counterfeiting, and tampering [6]. The complexity of modern food supply chains, combined with economic pressures and global instability, has created unprecedented opportunities for fraudulent activities to flourish [7] [8]. Understanding the multidimensional impacts of food fraud is essential for researchers, regulatory bodies, and industry professionals working to protect public health and economic stability.

The global scale of this problem is staggering, with food fraud estimated to cost the world economy approximately $40 billion annually [6] [9]. Beyond financial losses, food fraud poses significant and direct threats to human health, from allergen exposure to poisoning from hazardous substances [8] [9]. This application note examines these impacts within the broader context of food authenticity research, providing structured data analysis and experimental protocols for geographic origin determination and authenticity verification.

Quantitative Analysis of Global Food Fraud

Economic Impact Assessment

The economic ramifications of food fraud extend across multiple stakeholders, including consumers, legitimate producers, and national economies. Fraud artificially inflates market prices while delivering inferior products, effectively defrauding consumers and undermining legitimate businesses [9]. The sheer diversity of affected product categories demonstrates the pervasive nature of this problem throughout the global food system.

Table 1: Global Economic Impact of Food Fraud

| Impact Category | Scale/Magnitude | Primary Affected Stakeholders |

|---|---|---|

| Annual Global Cost | $40 billion [6] [9] | Global economy, legitimate businesses |

| Supply Chain Impact | 1% of global food supply affected [9] | Producers, distributors, retailers |

| Consumer Impact | Financial deception through price inflation for inferior products [9] | Consumers, especially health-conscious buyers |

| Industry Losses | Profit loss from unfair competition, brand reputation damage [6] | Legitimate food manufacturers and brands |

Product Vulnerability Analysis

Recent data indicates significant shifts in food fraud patterns across product categories. While certain high-value products historically targeted by fraudsters continue to be vulnerable, emerging trends reveal new areas of concern requiring research and regulatory attention.

Table 2: Forecasted Trends in Food Fraud Incidents by Product Category (2025) [6]

| Product Category | Forecasted Change (%) | Common Fraud Types |

|---|---|---|

| Nuts, Nut Products & Seeds | +358% | Adulteration, substitution, undeclared allergens |

| Eggs | +150% | Mislabeling of origin, production method |

| Dairy | +80% | Adulteration, mislabeling |

| Fish & Seafood | +74% | Species substitution, origin mislabeling |

| Cocoa | +66% | Origin fraud, adulteration |

| Herbs & Spices | +25% | Adulteration with fillers, illegal dyes |

| Cereals & Bakery Products | +23% | Mislabeling, quality falsification |

| Non-Alcoholic Beverages | +16% | Ingredient substitution, false claims |

| Coffee | -100% | (Improvement due to increased testing) |

| Honey | -24% | (Improvement due to increased testing) |

| Juices | -26% | (Improvement due to increased testing) |

Health and Safety Implications

Food fraud presents direct and indirect threats to public health, with consequences ranging from acute poisoning to chronic health conditions. These risks emerge primarily through three pathways: (1) introduction of hazardous substances; (2) undeclared allergens through substitution; and (3) nutritional deception through quality manipulation.

Documented Health Incidents

Several high-profile cases demonstrate the severe health consequences of food fraud:

- Lead-Contaminated Cinnamon (2024): Cinnamon imported from Ecuador and used in fruit purée pouches was intentionally adulterated with lead chromate to enhance color and weight, resulting in lead poisoning in hundreds of children across the United States [8].

- Melamine Milk Scandal (2008): Infant formula in China was adulterated with melamine to artificially inflate protein content measurements, resulting in at least 300,000 illnesses and six infant deaths [9].

- Toxic Onions (2025): Philippine authorities seized over 4 million onions smuggled from China that were heavily contaminated with heavy metals and Salmonella, posing risks of cancer, organ damage, and serious food poisoning [8].

- Olive Oil Adulteration (2024-2025): European authorities uncovered a major operation selling low-quality cooking oils mislabeled as virgin or extra virgin olive oil, potentially containing unauthorized additives [8].

Allergen and Dietary Risks

Beyond direct poisoning, fraudulent practices create hidden health risks:

- Species substitution in fish and meat products can introduce undeclared allergens [7] [10].

- Mislabelling of organic, non-GMO, or religiously compliant foods (e.g., halal, kosher) deceives consumers with specific dietary requirements or ethical preferences [7] [9].

Advanced Methodologies for Food Authenticity Testing

Experimental Protocol: Non-Targeted Metabolomics for Geographic Origin Determination

Principle: This method uses liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (LC-MS) to generate comprehensive metabolic profiles followed by multivariate statistical analysis to distinguish products based on geographical origin without prior knowledge of specific markers [11] [12].

Equipment and Reagents:

- Ultra-high-performance liquid chromatography system coupled to high-resolution mass spectrometer (UHPLC-HRMS)

- Mass spectrometry-grade solvents: methanol, acetonitrile, water

- Formic acid or ammonium formate for mobile phase modification

- Reference standards for instrument calibration

- Authentic reference samples of verified origin for model training

Procedure:

- Sample Preparation: Homogenize 1.0 g of sample with 10 mL of 80% methanol-water solution. Centrifuge at 14,000 × g for 15 minutes at 4°C. Filter supernatant through 0.22 μm membrane prior to analysis.

- LC-MS Analysis:

- Column: C18 reversed-phase (100 mm × 2.1 mm, 1.7 μm)

- Mobile Phase: A) 0.1% formic acid in water; B) 0.1% formic acid in acetonitrile

- Gradient: 5% B to 100% B over 25 minutes, hold 5 minutes

- Flow Rate: 0.3 mL/min

- Injection Volume: 5 μL

- MS Detection: Full scan mode m/z 50-1500 in both positive and negative ionization modes

- Data Processing:

- Perform peak picking, alignment, and normalization using XCMS software or equivalent

- Create a data matrix of sample ID × peak intensity × m/z-retention time pairs

- Statistical Analysis:

- Import data into SIMCA-P+ or R software

- Perform unsupervised Principal Component Analysis (PCA) to observe natural clustering

- Apply supervised Orthogonal Projections to Latent Structures-Discriminant Analysis (OPLS-DA) to maximize separation between predefined classes (geographic origins)

- Validate model using cross-validation and external test sets

Data Interpretation: Samples of unknown origin are projected into the validated model. Their classification is based on proximity to established origin clusters in the multivariate space. Model reliability is assessed through permutation testing and cross-validation accuracy metrics.

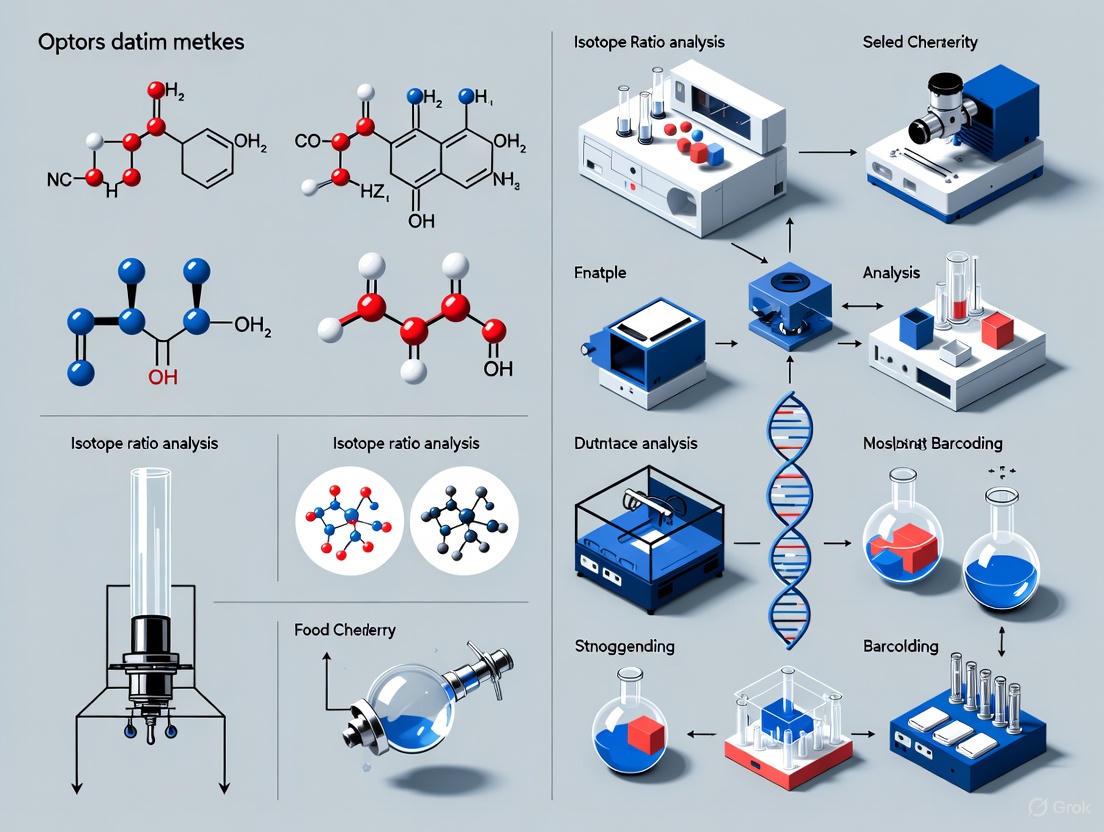

Figure 1: Experimental workflow for non-targeted metabolomics in geographic origin determination

Experimental Protocol: Stable Isotope Ratio Analysis for Authenticity Verification

Principle: This technique measures natural variations in stable isotope ratios (δ¹³C, δ¹⁵N, δ²H, δ¹⁸O) that reflect geographical origin, agricultural practices, and biological processes, making it particularly effective for verifying claims of organic production or specific geographic origins [10] [12].

Equipment and Reagents:

- Isotope Ratio Mass Spectrometer (IRMS) coupled to elemental analyzer or gas chromatography

- High-purity gases: helium, oxygen, carbon dioxide reference gas

- Certified isotope reference materials for calibration

- Tin or silver capsules for solid sample combustion

- Elemental analyzer for sample combustion and purification

Procedure:

- Sample Preparation:

- For solid foods: freeze-dry and homogenize to fine powder

- For liquids: remove water by freeze-drying or analyze directly using specific interfaces

- Precisely weigh 0.5-1.0 mg samples into tin capsules for δ¹³C and δ¹⁵N analysis

- For δ²H and δ¹⁸O analysis, use specialized preparation systems to avoid hydrogen exchange

- Instrumental Analysis:

- For δ¹³C and δ¹⁵N: Use Elemental Analyzer-IRMS system

- Combustion temperature: 1020°C

- Chromatographic column: 2m molecular sieve 5Å at 90°C

- Reference gas: CO₂ of known isotopic composition

- For δ²H and δ¹⁸O: Use Thermal Conversion/Elemental Analyzer-IRMS system

- Pyrolysis temperature: 1400°C

- GC column: 2m molecular sieve 5Å at 90°C

- For δ¹³C and δ¹⁵N: Use Elemental Analyzer-IRMS system

- Calibration and Normalization:

- Analyze certified reference materials with known isotopic composition

- Normalize raw data to international scales (VPDB for δ¹³C, AIR for δ¹⁵N, VSMOW for δ²H and δ¹⁸O)

- Express results in standard δ notation in units per mil (‰)

- Data Interpretation:

- Compare isotopic signatures of unknown samples to established databases of authentic products

- Use discriminant analysis to classify samples based on multiple isotopic parameters

- Establish threshold values for different product categories and origins

Quality Control: Include quality control samples with known isotopic composition in every batch. Monitor analytical precision through repeated analysis of secondary reference materials. Participate in inter-laboratory comparison programs to ensure data comparability.

Experimental Protocol: DNA-Traceable Barcodes for Supply Chain Integrity

Principle: This innovative approach uses synthetic DNA sequences containing encrypted product information (geographical origin, authenticity data) that are encapsulated in silica particles and applied to products, enabling verification through PCR and sequencing [13] [14].

Equipment and Reagents:

- Synthetic DNA fragments containing encrypted product information

- PMD19-T vector or equivalent cloning vector

- Escherichia coli DH5α competent cells

- Silica precursors for encapsulation: tetraethyl orthosilicate (TEOS)

- PCR reagents: primers, dNTPs, Taq polymerase

- DNA sequencing equipment

- Buffered oxide etch (BOE) for DNA release

Procedure:

- DNA-Traceable Barcode Design:

- Convert geographical information to digital code (e.g., postal codes)

- Encode digital information into DNA sequence using conversion table

- Design synthetic DNA fragment containing:

- Identification region (18 bp)

- Traceability information (20 bp)

- Unique species identifier (20 bp, e.g., from Citrus sinensis gene)

- Add primer binding sites for amplification

- Vector Construction:

- Synthesize DNA fragment using phosphoramidite method

- Clone into PMD19-T vector

- Transform into E. coli DH5α cells

- Verify sequence through Sanger sequencing

- Encapsulation Process:

- Suspend DNA-traceable barcode vectors in Tris-EDTA buffer

- Add 0.02% cetyltrimethylammonium bromide (CTAB)

- Mix with tetraethyl orthosilicate (TEOS) and incubate for silica formation

- Recover silica-encapsulated DNA particles by centrifugation

- Application and Recovery:

- Apply encapsulated DNA barcodes to product packaging or directly to food

- For verification: recover particles, dissolve silica with BOE solution

- Purify released DNA using commercial purification kits

- Authentication:

- Amplify DNA barcode using specific primers

- Analyze by PCR-capillary electrophoresis for rapid verification

- Perform DNA sequencing for complete information readout

Data Interpretation: Successful amplification indicates presence of authentic DNA barcode. Sequencing provides complete information about product origin and authenticity. Comparison with database confirms product legitimacy.

Figure 2: DNA-traceable barcode implementation workflow for supply chain integrity

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Food Authenticity Analysis

| Reagent/Material | Application | Function | Example Specifications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Certified Reference Materials | Method calibration & validation | Provides traceable standards for quantitative analysis | NIST standard reference materials, ISO-guided production |

| Stable Isotope Standards | Isotope ratio analysis | Calibration of IRMS instruments to international scales | Vienna Pee Dee Belemnite (VPDB) for δ¹³C, Vienna Standard Mean Ocean Water (VSMOW) for δ²H and δ¹⁸O |

| DNA Extraction Kits | Genomic analysis | High-quality DNA extraction from complex matrices | Silica-membrane technology, optimized for processed foods |

| PCR Master Mixes | DNA amplification | Enzymatic amplification of target sequences | Hot-start Taq polymerase, dNTPs, optimized buffer |

| LC-MS Grade Solvents | Metabolomic profiling | High-purity mobile phases for mass spectrometry | ≥99.9% purity, low UV absorbance, minimal particle content |

| Synthetic DNA Fragments | DNA barcode development | Custom sequences for traceability applications | Phosphoramidite synthesis, HPLC purification, sequence verification |

| Silica Encapsulation Reagents | DNA barcode protection | Nano-encapsulation for environmental protection | Tetraethyl orthosilicate (TEOS), cetyltrimethylammonium bromide (CTAB) |

Food fraud represents a significant multidisciplinary challenge with far-reaching economic and health consequences. The globalized nature of modern food supply chains creates vulnerabilities that fraudulent actors exploit, necessitating sophisticated analytical approaches for detection and prevention. This application note has detailed the substantial economic impacts, documented the serious health consequences, and provided robust methodological frameworks for authenticity testing.

The experimental protocols presented—non-targeted metabolomics, stable isotope analysis, and DNA-traceable barcodes—represent cutting-edge approaches in the field of food authenticity research. When implemented as part of a comprehensive food defense strategy, these methodologies provide researchers and industry professionals with powerful tools to verify claims of geographic origin, detect adulteration, and ensure supply chain integrity. As fraudulent practices evolve in sophistication, continued advancement in analytical technologies and collaborative efforts between researchers, industry, and regulators will be essential to protect both economic interests and public health.

Food authenticity and geographic origin research has become a critical frontier in food science, driven by increasing consumer demand for transparency, stringent regulatory requirements, and the global economic impact of food fraud. Verification of food authenticity ensures that products are genuine, accurately labeled, and free from adulteration, substitution, or false labeling practices. The global food authenticity market, valued at USD 10.2 billion in 2025 and projected to reach USD 17.9 billion by 2034, reflects the growing importance of this field [2]. At the core of modern authenticity research lie three principal analytical approaches: genetic markers for biological identification, elemental composition for geographical fingerprinting, and isotopic signatures for provenance verification. These marker systems, whether used independently or in integrated approaches, provide the scientific foundation for verifying claims related to geographical indications, production methods, and botanical or zoological origin, thereby protecting both consumers and legitimate producers while ensuring supply chain integrity.

Genetic Markers

Genetic markers form the cornerstone of biological identification in food authenticity research, enabling precise differentiation of species, varieties, and breeds based on unique DNA sequences. These markers leverage the fundamental biological differences between organisms to detect substitution, adulteration, and mislabeling in food products.

Fundamental Principles and Applications

Genetic authentication primarily targets specific DNA sequences that exhibit polymorphism between species or varieties. The approach is based on the premise that every biological material carries unique genetic information that remains stable regardless of processing, although DNA degradation in heavily processed foods presents analytical challenges. DNA-based testing, particularly polymerase chain reaction (PCR) based methods and next-generation sequencing, has become prevalent for precise identification of species and geographical origins [2]. These techniques target specific genetic regions such as single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs), microsatellites, or specific genes that display sufficient variation to distinguish between authentic and non-authentic materials.

The application of genetic markers spans numerous food commodities. For meat and meat products, DNA markers verify species origin and detect adulteration with lower-value species [15]. In cereals and grains, DNA authentication protects premium varieties such as Basmati rice, where specific genetic markers can distinguish authentic varieties from other global economically relevant rice varieties and evaluate their genetic background [16]. Similarly, methods have been developed for traditional cattle and pig breeds using SNP DNA markers, protecting valuable geographical indications and traditional production systems [15].

Advanced Methodologies and Protocols

Next-generation sequencing technologies have revolutionized genetic authentication by enabling non-targeted approaches that can detect multiple species simultaneously without prior knowledge of potential adulterants. Metagenomic methods for determination of origin represent cutting-edge developments in this field [15]. These approaches are particularly valuable for complex products where multiple ingredients may be present or where unexpected adulterants might be introduced.

For quantitative authentication, real-time PCR approaches have been developed and validated for the quantitation of specific DNA, such as horse DNA in food samples, enabling not just detection but also quantification of adulteration [15]. The development of isothermal amplification methods like Loop Mediated Isothermal Amplification (LAMP) facilitates point-of-contact DNA testing, bringing authentication capabilities out of central laboratories and into field settings [15].

Table 1: Genetic Marker Applications in Food Authentication

| Application Area | Technology Platform | Key Metrics | Food Matrix Examples |

|---|---|---|---|

| Species Identification | Real-time PCR, DNA sequencing | Detection limit, quantification accuracy | Meat species in processed products, fish speciation |

| Variety Authentication | KASP assays, SNP genotyping | Genetic distance, population structure | Basmati rice, traditional cattle and pig breeds |

| Adulteration Detection | Metagenomics, next-generation sequencing | Number of species detected, read depth | Herbal products, spice mixtures, processed meats |

| Point-of-Contact Testing | LAMP, portable DNA sequencers | Time-to-result, equipment portability | Field testing of agricultural products, supply chain checkpoints |

Experimental Protocol: DNA-Based Basmati Rice Authentication

Principle: Authenticate Basmati rice varieties using Kompetitive Allele Specific PCR (KASP) assays to distinguish them from other global rice varieties based on specific single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) [15].

Materials and Reagents:

- DNA extraction kit (CTAB-based or commercial kit for plant tissues)

- KASP assay mix (containing allele-specific fluorescent primers)

- Universal fluorescent reporter system

- Real-time PCR instrument with capability for fluorescence detection

- Certified reference materials for Basmati and non-Basmati varieties

Procedure:

- Sample Preparation: Grind rice grains to a fine powder using a laboratory mill. For processed rice products, ensure representative sampling.

- DNA Extraction: Extract genomic DNA using CTAB method or commercial kit. Quantify DNA concentration using spectrophotometry and adjust to working concentration of 10-20 ng/μL.

- KASP Reaction Setup:

- Prepare reaction mix containing: 5 μL of DNA template (50-100 ng total), 5 μL of KASP master mix, 0.14 μL of KASP assay mix.

- Include negative controls (no template) and positive controls (authentic Basmati and non-Basmati references).

- Thermocycling Conditions:

- Step 1: 94°C for 15 minutes (hot-start Taq activation)

- Step 2: 10 cycles of 94°C for 20 seconds (denaturation); 61°C for 60 seconds (annealing/extension; touchdown -0.6°C per cycle)

- Step 3: 26 cycles of 94°C for 20 seconds; 55°C for 60 seconds

- Endpoint Genotyping: Read fluorescence signals at room temperature. Analyze using specialized software for allele calling.

- Data Interpretation: Confirm Basmati authenticity by verifying the presence of characteristic SNP profiles. Perform cluster analysis (UPGMA) or principal coordinate analysis to visualize genetic relationships [16].

Quality Control: Validate assays with certified reference materials. Establish threshold values for allele calls. Participate in interlaboratory proficiency testing.

Elemental Markers

Elemental fingerprinting represents a powerful approach for geographical origin determination based on the comprehensive elemental composition of food materials, which reflects the growth environment including soil, water, and agricultural practices.

Fundamental Principles of Elemental Metabolomics

Elemental metabolomics involves the quantification and characterization of the total concentration of elements in biological samples and monitoring of their changes [17]. This approach encompasses not only macro elements (e.g., calcium, potassium) and trace elements (e.g., copper, zinc) but also ultra-trace elements such as rare earth elements (REEs) and precious metals [17]. The elemental fingerprint of a food product is determined by multiple environmental factors including local geology, soil composition, water sources, agricultural practices (fertilization, irrigation), and atmospheric deposition.

The fundamental premise is that plants and animals incorporate elements from their environment into their tissues, creating a distinctive elemental signature that can be traced back to the geographical region of origin. For plant-based products, the link between soil elemental fingerprint and the plant is relatively direct, although modified by factors such as element bioavailability, which depends on the chemical form of the element and the genetic characteristics of the plant species [17]. For animal products, the relationship is more complex as feeds may be imported from different locations, though animals raised on local forage and water typically acquire a local elemental fingerprint [17].

Analytical Techniques and Data Interpretation

High-resolution elemental mass spectrometry (HREMS) has revolutionized elemental fingerprinting by enabling determination of more than 270 elemental isotopes [17]. Inductively Coupled Plasma Optical Emission Spectroscopy (ICP-OES) and ICP Mass Spectrometry (ICP-MS) are the principal techniques employed, each offering different advantages in terms of detection limits, dynamic range, and multi-element capability.

The data generated from elemental analysis requires sophisticated statistical treatment and chemometric tools for meaningful interpretation. Techniques such as Principal Component Analysis (PCA), Orthogonal Projections to Latent Structures-Discriminant Analysis (OPLS-DA), and various machine learning algorithms are employed to identify patterns in the multi-dimensional data and build classification models for geographical origin discrimination [18]. The robustness of these models depends heavily on appropriate sample size, with studies often requiring hundreds of samples to establish statistically valid differentiation [17].

Table 2: Key Elemental Markers for Geographical Origin Determination

| Element Category | Specific Elements | Relationship to Geography | Analytical Techniques |

|---|---|---|---|

| Macro Elements | Ca, K, Mg, P, Na | Soil geology, fertilization practices | ICP-OES, FAAS |

| Trace Elements | Cu, Zn, Fe, Mn, Se, Co | Soil composition, agricultural inputs | ICP-MS, ICP-OES |

| Ultra-Trace Elements | Rare Earth Elements (La, Ce, Nd) | Geological bedrock characteristics | High-resolution ICP-MS |

| Toxic Elements | As, Cd, Pb, Hg | Environmental pollution, natural deposits | ICP-MS (collision/reaction cell) |

Experimental Protocol: Multi-Element Analysis for Potato Geographical Origin

Principle: Verify geographical origin of potatoes using elemental profiling combined with chemometric analysis, as demonstrated for Cypriot potatoes [18].

Materials and Reagents:

- Freeze dryer (e.g., Telstar LyoQuest—55 Plus Eco)

- Analytical balance (±0.0001 g)

- Mortar and pestle (agate or similar contamination-free)

- Microwave digestion system

- ICP-OES or ICP-MS instrument

- Certified reference materials (NIST SRM 1568a Rice Flour, NIST SRM 1573a Tomato Leaves)

- High-purity nitric acid (69%, trace metal grade)

- Hydrogen peroxide (30%, trace metal grade)

Procedure:

- Sample Preparation:

- Peel and slice potato tubers. Homogenize using a commercial blender.

- Weigh approximately 10 g of homogenate into pre-cleaned freeze-drying jars.

- Lyophilize at 0.2 mBar and -50°C condenser temperature until constant weight (typically 24-48 hours).

- Grind lyophilized material to fine powder using mortar and pestle.

- Store in sealed plastic containers at room temperature.

Sample Digestion:

- Accurately weigh 0.5 g of dried sample into microwave digestion vessels.

- Add 6 mL nitric acid and 2 mL hydrogen peroxide.

- Run microwave digestion program: ramp to 180°C over 20 minutes, hold at 180°C for 15 minutes, cool to room temperature.

- Transfer digestate to 50 mL volumetric flask and dilute to volume with ultrapure water (18.2 MΩ·cm).

- Include method blanks and certified reference materials with each digestion batch.

Instrumental Analysis:

- ICP-OES Analysis: Analyze appropriate elemental wavelengths with background correction. Use yttrium or scandium as internal standard.

- ICP-MS Analysis: Use rhodium or iridium as internal standards. Employ collision/reaction cell for interference removal when necessary.

- Calibrate using multi-element standard solutions covering expected concentration range.

Data Processing:

- Calculate elemental concentrations in mg/kg dry weight.

- Apply quality control criteria: recovery in CRMs 85-115%, RSD < 10% for replicates.

- Perform data normalization if necessary.

Chemometric Analysis:

- Apply OPLS-DA to identify most discriminative elements (e.g., Cu in Cypriot potato study [18]).

- Validate model using cross-validation and external validation samples.

- Establish classification rules based on discriminant functions.

Quality Control: Analyze certified reference materials with each batch. Participate in interlaboratory comparisons. Monitor long-term precision and accuracy using control charts.

Isotopic Signatures

Stable isotope ratio analysis has emerged as a powerful tool for geographical authentication, leveraging natural variations in isotope abundances that result from environmental processes and biogeochemical fractionation.

Principles of Isotopic Fractionation and Geographical Discrimination

Stable isotope ratios in food products are influenced by fractionation processes linked to local climate, geology, and soil characteristics [19]. The distribution of stable isotopes of light elements - carbon (12C/13C), nitrogen (14N/15N), sulfur (32S/34S), hydrogen (1H/2H), and oxygen (16O/18O) - varies geographically due to factors such as latitude, altitude, distance from the sea, precipitation levels, and evapotranspiration [19]. These isotopic signatures are transferred from natural sources (water, soil, atmosphere) to plant and animal tissues, creating a record of the geographical origin.

The "isoscapes" concept - isotopic landscapes that map spatial variations in isotope ratios - forms the theoretical foundation for geographical provenance verification [19]. For example, the isotope ratios in water (2H/1H and 18O/16O) provide critical information about local precipitation patterns, while carbon isotope ratios reflect photosynthetic pathways (C3 vs C4 plants) and nitrogen isotopes indicate fertilization practices and soil processes.

Methodological Approaches and Applications

Isotope Ratio Mass Spectrometry (IRMS) is the gold standard for precise measurement of stable isotope ratios in food authentication. Complementary techniques include Site-specific Natural Isotope Fractionation studied by Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (SNIF-NMR), which measures deuterium-to-hydrogen (D/H) ratios at specific molecular positions, providing additional discrimination power [18].

Isotopic analysis has been successfully applied to diverse food commodities including wines, dairy products, meats, fruits, and vegetables. The European Wine DataBank, maintained for over 20 years, represents a pioneering application of isotopic methods for regulatory control [19]. Similarly, stable isotope databases support authentication of protected designations of origin such as Parma ham, Grana Padano cheese, and Parmigiano Reggiano in Italy [19].

The integration of multiple isotopic systems (e.g., δ13C, δ15N, δ18O, δ2H) significantly enhances discrimination power compared to single-isotope approaches. Furthermore, combining isotopic with elemental data creates even more robust authentication models, as demonstrated in the Cypriot potato study where parameters of (D/H)II, δ18O, R and Cu provided the best discrimination markers with 94.07% correct classification [18].

Experimental Protocol: Multi-Isotope Analysis for Geographical Authentication

Principle: Develop unique isotopic fingerprint for food samples using combination of SNIF-NMR and IRMS techniques, as applied to potato authentication [18].

Materials and Reagents:

- Isotope Ratio Mass Spectrometer (e.g., Elementar Isoprime Precision)

- NMR Spectrometer (e.g., 400 MHz Bruker Avance III)

- Freeze dryer

- High-purity α-amylase enzyme

- Saccharomyces cerevisiae dried yeast

- N,N-tetramethylurea (TMU) of known isotopic composition

- Certified reference materials (CRM-123, BCR-660)

- Fluorine lock solution

- High-yield automated distillation system (e.g., Cadiot columns)

Procedure:

- Sample Preparation for SNIF-NMR:

- Alcoholic Fermentation: Homogenize 800 g sample. Add α-amylase (1 mL/100 g sample) and incubate at 90°C for 30 minutes to hydrolyze starch. Cool to 25°C. Add Saccharomyces cerevisiae (3.5 g/600 g sample). Ferment at 25°C for 5-7 days using monitoring system.

- Distillation: Centrifuge fermented mixture and filter supernatant. Distill using automated system with Cadiot columns. Collect ethanol fraction at azeotropic point (78°C). Verify alcohol content >85% v/v using density meter.

SNIF-NMR Analysis:

- Prepare sample solution: 1.3 mL TMU + 3.2 mL ethanol sample + 0.15 mL fluorine lock solution.

- Filter into NMR tubes (0.45 μm).

- Measure (D/H) ratios at methyl-(D/H)I and methylene-(D/H)II positions using 400 MHz NMR spectrometer.

- Acquire 10 spectra per sample. Process using EUROSPEC and TOPSPIN software.

- Validate against CRMs (CRM-123). Ensure precision <0.5 ppm for (D/H)CH3.

IRMS Analysis:

- δ18O Analysis: Place raw sample in glass vials. Purge headspace with He–CO2 mixture. Equilibrate ≥7 hours. Analyze headspace using IRMS.

- δ13C Analysis: Analyze both distilled ethanol and lyophilized sample using elemental analyzer coupled to IRMS.

- δ15N Analysis: Analyze lyophilized sample using elemental analyzer-IRMS.

- Report results in standard δ notation (‰) relative to international standards.

- Ensure accuracy using CRM/BCR 656 (δ13C = -26.91‰).

Data Integration and Chemometrics:

- Combine all isotopic parameters ((D/H)I, (D/H)II, δ13C, δ15N, δ18O) with elemental data.

- Apply OPLS-DA to identify most discriminative markers.

- Validate model using cross-validation and independent sample sets.

Quality Control: Use certified reference materials for both NMR and IRMS measurements. Participate in interlaboratory comparisons. Monitor long-term instrument stability.

Integrated Approaches and Data Management

The convergence of genetic, elemental, and isotopic analyses with advanced data science represents the cutting edge of food authenticity research, enabling more robust and comprehensive authentication systems.

Multi-Marker Integration and Chemometric Modeling

Integrating multiple analytical approaches significantly enhances authentication power compared to single-method strategies. For example, while isotopic methods excel at geographical discrimination and DNA methods at biological identification, their combination can simultaneously verify both geographical origin and varietal authenticity. The emerging trend of "non-targeted" or "untargeted" testing utilizes machine learning to analyze thousands of parameters without prior knowledge of specific markers, then builds classification models based on statistical differences between authentic and non-authentic sample sets [11].

These integrated approaches require sophisticated chemometric tools for data fusion and pattern recognition. Techniques such as Orthogonal Projections to Latent Structures-Discriminant Analysis (OPLS-DA) have demonstrated remarkable classification accuracy, as evidenced by the 94.07% correct classification rate achieved for Cypriot potatoes using combined isotopic and elemental markers [18]. However, the development of robust models requires careful attention to potential pitfalls including seasonal variation, sample representativeness, and unintended bias in training datasets [11].

Database Infrastructure and Quality Assurance

The effectiveness of authentication systems depends critically on comprehensive reference databases of authentic materials. Specialized databases such as IsoFoodTrack provide structured platforms for managing isotopic and elemental composition data for various food commodities, incorporating rich metadata including geographical, production, and methodological details [19]. These databases support statistical, chemometric and machine learning approaches to identify and classify food origin, and facilitate the development of isotope mapping (isoscapes) for spatially continuous predictions [19].

Quality assurance remains paramount throughout authentication workflows. This includes rigorous sample collection protocols to ensure authenticity of reference materials, standardized analytical procedures, participation in interlaboratory proficiency testing, and continuous method validation [19] [15]. For non-targeted methods, particular attention must be paid to model validation using independent sample sets that account for seasonal, annual, and production practice variations [11].

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Food Authenticity Analysis

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function in Analysis | Quality Requirements |

|---|---|---|---|

| Certified Reference Materials | CRM-123, BCR-660, NIST SRMs | Method validation, quality control, instrument calibration | Certified isotope ratios or elemental concentrations |

| Isotopic Standards | V-SMOW, SLAP, NBS references | Scale normalization for isotope ratio measurements | Internationally recognized reference materials |

| DNA Extraction Kits | CTAB-based protocols, commercial kits | High-quality DNA isolation from diverse food matrices | High purity, removal of PCR inhibitors |

| Enzymes for Sample Preparation | α-Amylase, proteases | Targeted breakdown of specific components for analysis | High specificity, minimal isotopic fractionation |

| ICP Calibration Standards | Multi-element standard solutions | Quantification of elemental concentrations | Traceable to primary standards, appropriate acid matrix |

Genetic, elemental, and isotopic markers provide complementary approaches for food authenticity verification, each with distinct strengths and applications. Genetic markers offer unparalleled specificity for biological identification, elemental profiling captures geographical fingerprints through environmental transfer, and isotopic signatures record biogeochemical processes specific to regions. The convergence of these approaches with advanced data science and comprehensive reference databases represents the future of food authentication, enabling robust protection against fraud while supporting regulatory compliance and consumer confidence. As the field evolves, integration of portable technologies, blockchain-enabled traceability systems, and international data sharing will further enhance our ability to verify food authenticity across global supply chains.

Regulatory Framework and Quality Standards for Food Authentication

Food authenticity has emerged as a critical field at the intersection of food science, regulatory policy, and analytical chemistry. The global food authenticity market is projected to grow from USD 10.2 billion in 2025 to USD 17.9 billion by 2034, reflecting increasing concerns about food fraud, mislabeling, and economic adulteration [2]. This growth is driven by consumer demand for transparency, stricter regulatory requirements, and the globalization of food supply chains that increase vulnerability to fraudulent practices [2]. Food authentication encompasses verification of geographical origin, composition, processing methods, and label claims, requiring sophisticated analytical techniques and robust regulatory frameworks. This article examines current regulations, analytical methodologies, and standardized protocols within the broader context of determining food authenticity and geographic origin.

Regulatory Frameworks for Food Authentication

Evolving Standards of Identity

Standards of Identity (SOI) were first established in the United States in 1939 to promote "honesty and fair dealing" by ensuring food characteristics matched consumer expectations [20]. These standards define required and optional ingredients, composition, and sometimes production methods for specific food products. Recently, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration has undertaken significant deregulatory initiatives to eliminate obsolete standards that may stifle innovation while maintaining core protections.

Table 1: Recent FDA Actions on Standards of Identity (2025)

| Action Type | Products Affected | Key Rationale | Status |

|---|---|---|---|

| Direct Final Rule | 11 types of canned fruits and vegetables | Products no longer sold in U.S. grocery stores; some contain obsolete artificial sweeteners | Effective September 2025 [21] |

| Proposed Rule | 18 dairy products | Advancements in food science and additional consumer protections make standards unnecessary | Comment period open [21] |

| Proposed Rule | 23 food products (bakery, macaroni, juices, fish, dressings) | Obsolete standards that no longer promote honesty and fair dealing in interest of consumers | Comment period until September 15, 2025 [22] |

The FDA is shifting from rigid "recipe standards" toward a more flexible approach that prioritizes accurate labeling while allowing innovation. Simultaneously, the agency is updating SOIs to facilitate healthier formulations, such as permitting salt substitutes in standardized foods and removing partially hydrogenated oils as optional ingredients [20].

International Geographical Indications Systems

Geographical Indications (GIs) represent a crucial aspect of food authentication, protecting products whose qualities are specifically linked to their place of origin. Different jurisdictions have established varying approaches to GI protection:

- European Union Model: Features Protected Designation of Origin (PDO) and Protected Geographical Indication (PGI) systems. PDO requires the entire production process occur in the specific region, while PGI requires at least one production stage in the area [23].

- U.S. Approach: Protects GIs primarily through the trademark system, with GIs indicating a good originates from a particular WTO member region possessing specific qualities or reputation [23].

- China-EU GI Agreement: Implemented in 2021, this agreement provides mutual recognition of 275 GI products between these major markets, creating a framework for authentication and protection [24].

Regulatory frameworks continue to evolve in response to new challenges. The EU Regulation 1760/2000 requires declaration of geographical origin for foods containing more than 20% meat, highlighting the importance of origin verification for both economic and safety reasons [23]. In the U.S., emerging state-level legislation like Texas's Senate Bill 25 will require warning labels on foods containing certain additives by 2027, creating new motivations for authentication [25].

Analytical Techniques for Food Authentication

Core Analytical Technologies

Modern food authentication employs a diverse array of analytical techniques, ranging from established laboratory methods to emerging rapid screening technologies.

Table 2: Major Analytical Techniques in Food Authentication

| Technique Category | Specific Methods | Primary Applications | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Genomic | PCR-based methods, Next-Generation Sequencing | Meat speciation, species identification, GMO detection | Requires reference databases; may not identify origin |

| Spectroscopic | NIR, FTIR, Raman, Mass Spectrometry | Geographical origin, composition analysis, rapid screening | Complex data requiring chemometrics |

| Isotopic | Stable Isotope Ratio Mass Spectrometry | Geographic origin verification, adulteration detection | Specialized equipment; reference databases needed |

| Elemental | Inductively Coupled Plasma-MS | Mineral fingerprinting for geographic origin | Affected by environmental variables |

| Separation | Liquid/Gas Chromatography, HPLC | Fatty acid profiles, composition analysis | Sample preparation intensive |

| Hyperspectral Imaging | Combined spectroscopy/imaging | Non-destructive origin verification | Data complexity; emerging technology |

Advanced Geographic Origin Verification

Determining geographical origin represents one of the most challenging aspects of food authentication, requiring techniques that can link products to their production regions through intrinsic chemical signatures.

Stable Isotope Analysis measures ratios of naturally occurring isotopes (e.g., ^2^H/^1^H, ^13^C/^12^C, ^15^N/^14^N, ^18^O/^16^O) that vary geographically due to environmental factors like climate, geology, and agricultural practices. These ratios create distinctive "isotopic fingerprints" in food products [24]. Isotopes of strontium (Sr) are particularly valuable geographical indicators as they originate from geological features rather than being influenced by feed or water sources [23].

Elemental Profiling utilizes the fact that plants incorporate trace elements (Zn, Se, Cu, Mn) from local soils and water, creating distinctive mineral fingerprints. However, limitations exist as supplementary animal feed can introduce elements from different regions, complicating origin verification for conventional meat products [23].

Fatty Acid-Based Authentication represents an emerging approach where specific fatty acid profiles correlate with geographical and climatic conditions. Recent research has developed two novel metrics: the Geographical Differentiation Index (GDI) quantifies spatial variation in fatty acids, while the Environmental Heritability Index (EHI) assesses the relative contributions of environmental conditions versus intrinsic variations [26]. Studies demonstrate that fatty acid distributions follow elevation- and latitude-dependent patterns, with key fatty acids like stearic acid (C18:0) and linoleic acid (C18:2) showing significant correlation with geographic factors globally [26].

Near-Infrared Spectroscopy (NIRS) has gained prominence as a rapid, non-destructive method for origin determination. NIRS measures how meat absorbs and reflects specific wavelengths of light to detect its unique chemical composition influenced by regional factors like soil, water, and feed [23]. Portable NIRS devices enable real-time authentication throughout the supply chain, with studies demonstrating over 80% accuracy in classifying lamb from different Chinese regions and 98-99% accuracy for tilapia fillets [23].

Experimental Protocols for Geographic Origin Authentication

Protocol 1: Fatty Acid Profiling for Oil Crop Authentication

This protocol outlines the procedure for determining geographical origin of oil-rich crops (olive, camellia, walnut, peony seed) through fatty acid analysis using the GDI/EHI framework [26].

Principle: Fatty acid composition is influenced by geographical and climatic conditions through effects on enzyme kinetics and metabolic processes. Specific fatty acids serve as biochemical markers for origin authentication.

Materials and Reagents:

- Gas Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry system

- Fatty acid methyl ester standards

- n-Hexane (HPLC grade)

- Methanolic sodium methoxide solution

- Anhydrous sodium sulfate

- Nitrogen evaporation system

Procedure:

- Sample Preparation: Grind seeds to uniform particle size. Accurately weigh 100mg of sample into a screw-cap test tube.

- Lipid Extraction: Add 3mL of n-hexane and vortex for 30 seconds. Add 200μL of methanolic sodium methoxide, vortex for 30 seconds, and incubate at 50°C for 10 minutes.

- Derivatization: Add 100μL of deionized water and vortex for 30 seconds. Centrifuge at 3000rpm for 5 minutes. Transfer the upper hexane layer containing FAMEs to a new tube containing anhydrous sodium sulfate.

- GC-MS Analysis: Inject 1μL of FAME extract into GC-MS system using a DB-23 capillary column. Use temperature programming from 150°C to 230°C at 3°C/min.

- Data Analysis: Identify fatty acids by comparing retention times with authentic standards. Quantify using peak area normalization.

- Geographical Discrimination: Calculate GDI and EHI indices to identify origin-specific fatty acid markers.

Figure 1: Fatty Acid Authentication Workflow

Protocol 2: Multi-Element Isotope Analysis for Meat Authentication

This protocol details the use of stable isotope and elemental analysis for verifying geographical origin of meat products.

Principle: The "meat fingerprint" is influenced by regional water, soil, and feed, incorporating distinct elemental and isotopic signatures that can be traced to specific geographical origins [23].

Materials and Reagents:

- Isotope Ratio Mass Spectrometer

- Inductively Coupled Plasma Mass Spectrometer

- Ultrapure nitric acid

- Hydrogen peroxide

- Certified reference materials

- Cryogenic mill

Procedure:

- Sample Homogenization: Freeze meat samples in liquid nitrogen and homogenize using cryogenic mill to prevent compositional changes.

- Isotope Analysis:

- For δ^13^C and δ^15^N: Weigh 0.5mg of dried sample into tin capsules. Analyze using IRMS coupled with elemental analyzer.

- For δ^2^H and δ^18^O: Use thermal conversion/elemental analyzer interfaced with IRMS.

- Elemental Analysis:

- Digest 0.5g sample with 8mL HNO~3~ and 2mL H~2~O~2~ in microwave system.

- Dilute to 50mL with deionized water and analyze by ICP-MS.

- Quantify elements using external calibration with internal standards.

- Data Integration:

- Combine isotopic and elemental data using multivariate statistical analysis.

- Develop classification models using Linear Discriminant Analysis.

- Validate models with certified reference materials and blind samples.

Figure 2: Meat Origin Authentication Pathway

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Food Authentication

| Reagent/Material | Application | Function | Technical Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| DNA Extraction Kits | Meat speciation, species identification | Isolation of high-quality DNA for PCR and sequencing | Choose based on sample matrix; inhibitor removal critical |

| Stable Isotope Standards | Isotope ratio analysis | Calibration and quality control for IRMS | Use internationally certified reference materials |

| Fatty Acid Methyl Ester Mix | Fatty acid profiling | GC-MS calibration and quantification | Should cover C8-C24 range for comprehensive analysis |

| Certified Reference Materials | Method validation | Quality assurance and accuracy verification | Matrix-matched materials preferred |

| Multi-element Standard Solutions | Elemental profiling | ICP-MS calibration | Include relevant elements for geographical discrimination |

| Derivatization Reagents | GC sample preparation | Conversion of compounds to volatile derivatives | MSTFA, BSTFA commonly used |

| Solid Phase Extraction Columns | Sample clean-up | Removal of interfering compounds | Select sorbent based on target analytes |

| Mobile Phase Solvents | Chromatography | Separation medium for HPLC/LC-MS | HPLC grade; use appropriate modifiers |

Emerging Trends and Future Directions

Food authentication is rapidly evolving with several significant trends shaping its future. Artificial intelligence and machine learning are being integrated for advanced data analysis, enabling predictive modeling and faster detection of adulteration [2]. Portable testing devices based on technologies like NIR spectroscopy allow on-site authenticity checks and real-time fraud detection throughout the supply chain [2] [23]. Blockchain technology is being implemented for end-to-end traceability, providing transparent and immutable records of the food supply chain [2].

Regulatory developments continue to influence authentication requirements. The FDA's forthcoming definition of "ultraprocessed foods" and new front-of-pack labeling requirements like the U.S. "TRUTH in Labelling Act" will create additional motivations for authentication to verify health-related claims [25]. Simultaneously, analytical techniques are advancing toward non-targeted approaches that can detect unexpected adulterants without prior knowledge of their identity [27].

The emergence of novel food sources, including plant-based alternatives and cultivated meats, presents new authentication challenges and opportunities. The recent FDA approval of Wildtype's cultivated salmon highlights how regulatory frameworks must adapt to authenticate these innovative products [25]. International harmonization of standards and authentication methods will be crucial for combating cross-border food fraud as supply chains become increasingly globalized [2].

As food authentication continues to evolve, the integration of sophisticated analytical techniques with robust regulatory frameworks and digital traceability systems will be essential for ensuring food integrity, protecting consumers, and promoting fair trade practices in the global food system.

Foodomics has emerged as a powerful, data-driven approach that utilizes omics technologies to comprehensively characterize food composition, addressing critical challenges in food authenticity and geographic origin traceability [28]. Defined as the application of omics technologies to characterize and quantify biomolecules to improve wellbeing, foodomics provides a transformative framework for tackling the global issue of food fraud, which affects approximately 95% of published food authentication cases [29] [30]. By integrating multiple "omes" – including the genome, transcriptome, proteome, metabolome, and microbiome – foodomics enables researchers to map the complete molecular profile of foods and their interactions with biological systems, moving beyond traditional single-parameter analyses that provide only fragmented insights [29].

The growing economic and regulatory importance of Protected Designation of Origin (PDO), Protected Geographical Indication (PGI), and traditional specialty guaranteed (TSG) products has intensified the need for robust authentication methods [30] [31]. Foodomics meets this need by offering sophisticated analytical capabilities to verify claims of geographical origin, production methods, and species variety, thereby protecting both consumers from fraudulent practices and producers from unfair competition [32]. This integrated approach is particularly valuable for addressing the technical challenges in food composition evaluation, including reproducibility issues, inadequate representation of food biodiversity, and limited accessibility of comprehensive data [28].

Multi-Omics Analytical Techniques in Foodomics

Foodomics leverages a suite of advanced analytical techniques that provide complementary data for comprehensive food profiling. Each omics layer contributes unique insights that, when integrated, create a powerful system for authentication and origin verification.

Table 1: Core Analytical Techniques in Foodomics for Authentication

| Omics Domain | Key Analytical Techniques | Measurable Parameters | Application in Authentication |

|---|---|---|---|

| Genomics | Long-read sequencing, PCR, DNA-based assays | Genetic sequences, SNPs, gene clusters | Species identification, botanical origin, GMO detection [29] [30] |

| Proteomics | SWATH-MS, MALDI-MSI, HPLC-MS | Protein sequences, post-translational modifications, bioactive peptides | Species authentication, processing verification, allergen detection [29] |

| Metabolomics | UHPLC-QTOF-MS, GC-MS, NMR | Small molecules, metabolites, lipids | Geographic origin discrimination, adulteration detection [29] [32] |

| Elemental & Isotopic | IRMS, MC-ICP-MS, TIMS | Elemental composition, stable isotope ratios (C, H, O, N, S, Sr) | Geographic origin verification, production method authentication [30] [31] |

| Spectroscopic | FTIR, NIR, MIR, LIBS | Molecular vibrations, spectral fingerprints | Rapid screening, classification by origin or variety [30] [31] |

Elemental and Isotopic Analysis Techniques

Stable isotope ratio analysis and elemental profiling have become cornerstone techniques for geographical origin authentication. Isotope-ratio mass spectrometry (IRMS) measures the ratios of stable isotopes of bio-elements (C, H, N, O, S), which vary based on geographical conditions, climate, and agricultural practices [30]. These isotopic signatures serve as unique "fingerprints" that can differentiate products from different regions. For example, the δ13C values in animal tissues reflect the composition of the animal's diet, while δ2H and δ18O values are influenced by regional water sources and can determine geographical location, especially across large scales [31].

Elemental analysis using techniques such as inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry (ICP-MS) provides complementary data by measuring the trace element and rare earth element composition of food products. The distribution of macroelements (Ca, K, Mg, Na) and microelements (Cu, Fe, Zn, Se) in food correlates with the elemental composition of the production environment, which remains relatively stable from harvest to analysis [30] [31]. This stability makes elemental profiles reliable indicators of geographical origin.

Molecular Profiling Techniques

Genomic approaches utilize DNA sequencing and PCR-based methods to identify species-specific genetic markers that can detect adulteration or mislabeling [30]. Proteomic techniques profile protein expression patterns and identify bioactive peptides that serve as authentication biomarkers [29]. Metabolomic approaches using high-resolution mass spectrometry provide the most comprehensive chemical characterization, identifying thousands of small molecules that vary based on genetics, growing conditions, and processing methods [29] [28].

Experimental Protocols for Food Authentication

Protocol: Multi-Omics Workflow for Geographical Origin Authentication

Principle: This integrated protocol combines stable isotope ratio analysis, elemental profiling, and metabolomic fingerprinting to verify the geographical origin of agricultural products.

Materials:

- Cryogenic mill for sample homogenization

- Freeze dryer for sample preservation

- Analytical balance (±0.0001 g precision)

- Solvent extraction system

- Isotope Ratio Mass Spectrometer (IRMS) with elemental analyzer

- Inductively Coupled Plasma Mass Spectrometer (ICP-MS)

- UHPLC-QTOF-MS system

- Certified reference materials for quality control

Procedure:

Sample Preparation:

- Homogenize 100 g of sample using a cryogenic mill to prevent degradation of heat-sensitive compounds.

- Divide the homogenized material into three aliquots for isotopic, elemental, and metabolomic analyses.

- Freeze-dry aliquots for 24 hours at -50°C and 0.001 mbar to remove water without altering isotopic ratios or chemical composition.

Stable Isotope Analysis:

- Weigh 1.0±0.1 mg of dried sample into tin capsules for δ13C, δ15N, and δ34S analysis.

- For δ2H and δ18O analysis, use 0.5±0.05 mg of sample in silver capsules.

- Analyze samples using IRMS coupled with an elemental analyzer.

- Include laboratory reference standards every 10 samples to ensure measurement precision.

- Express results in δ notation relative to international standards (VPDB for carbon, AIR for nitrogen, VSMOW for hydrogen and oxygen).

Elemental Profiling:

- Digest 0.5 g of dried sample with 8 mL concentrated HNO3 and 2 mL H2O2 using microwave-assisted digestion at 180°C for 20 minutes.

- Dilute the digest to 50 mL with ultrapure water and analyze by ICP-MS.

- Quantify a panel of 25 elements including macroelements (Ca, K, Mg, Na) and trace elements (As, Cd, Cr, Cu, Fe, Hg, Mn, Mo, Ni, Se, Zn).

- Use multi-element certified reference materials (NIST 1547 Peach Leaves) for quality assurance.

Metabolomic Fingerprinting:

- Extract metabolites from 100 mg of dried sample using 1 mL of methanol:water (80:20, v/v) with sonication for 30 minutes at 4°C.

- Centrifuge at 14,000 × g for 15 minutes and collect supernatant for analysis.

- Analyze using UHPLC-QTOF-MS with a C18 column (100 × 2.1 mm, 1.7 μm) maintained at 40°C.

- Employ a gradient elution with 0.1% formic acid in water (mobile phase A) and 0.1% formic acid in acetonitrile (mobile phase B).