A Practical Guide to HPLC Method Validation for Food Analysis: Protocols, Applications, and ICH Compliance

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and scientists on validating High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC) methods for food analysis.

A Practical Guide to HPLC Method Validation for Food Analysis: Protocols, Applications, and ICH Compliance

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and scientists on validating High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC) methods for food analysis. Covering the entire process from foundational principles to advanced applications, it details the core validation parameters as per the latest ICH Q2(R2) and FDA guidelines. The content explores method development strategies, troubleshooting for complex food matrices, and comparative detector selection. With practical examples from recent studies on analyzing compounds like carvedilol, xylitol, and thiabendazole in various foods, this guide serves as an essential resource for ensuring data reliability, regulatory compliance, and robust quality control in food testing laboratories.

Foundations of HPLC Validation: Understanding ICH Guidelines and Core Principles for Food Labs

The International Council for Harmonisation (ICH) and the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) provide the foundational global framework for ensuring the reliability and quality of analytical data in pharmaceuticals and related fields [1]. The ICH Q2(R2) guideline, titled "Validation of Analytical Procedures," serves as the primary global standard for validating analytical methods, with the FDA adopting and implementing these harmonized guidelines in the United States [2] [1]. A significant modernization occurred in March 2024 with the finalization of the updated ICH Q2(R2) guideline, which replaces the previous Q2(R1) version [2] [3]. This revision was released simultaneously with the new ICH Q14 guideline on Analytical Procedure Development, representing a strategic shift from a prescriptive approach to a more scientific, risk-based, and lifecycle-oriented model for analytical procedures [1] [3].

For researchers developing HPLC method validation protocols for food analysis, these guidelines provide a rigorous, transferable foundation. The principles, though designed for drug substances and products, are equally applicable to ensuring the reliability, accuracy, and precision of methods used to analyze food constituents and contaminants [4]. The core objective is to build quality into the analytical method from its initial development and demonstrate through validation that it is fit-for-purpose for its intended use, whether for release testing, stability studies, or authenticity assessment of food products [4] [1].

Core Principles of ICH Q2(R2) and FDA Guidelines

The Modernized Lifecycle Approach

The concurrent issuance of ICH Q2(R2) and ICH Q14 signifies a critical evolution in regulatory philosophy. The new framework emphasizes that analytical procedure validation is not a one-time event but a continuous process that begins with method development and continues throughout the method's entire lifecycle [1]. This lifecycle management is supported by two pivotal concepts:

- Analytical Target Profile (ATP): Introduced in ICH Q14, the ATP is a prospective summary that describes the intended purpose of an analytical procedure and its required performance characteristics [1]. Defining the ATP at the start of development ensures the method is designed to be fit-for-purpose from the outset, guiding both development and validation.

- Science- and Risk-Based Decisions: The modernized approach encourages a deeper understanding of the method and its potential variables. This scientific understanding, combined with quality risk management (ICH Q9), facilitates a more flexible post-approval change management process, allowing for justified changes without extensive regulatory filings when supported by sound data [1] [3].

Scope and Application to Food Analysis

While ICH Q2(R2) primarily applies to new or revised analytical procedures used for release and stability testing of commercial drug substances and products, the guideline also states it "can be applied to other analytical procedures used as part of a control strategy following a risk-based approach" [4]. This extension makes it directly relevant to food research, particularly for:

- Quality control of bioactive compounds (e.g., trigonelline in fenugreek) [5]

- Authenticity assessment and fraud detection (e.g., artificial colorants in açaí pulp) [6]

- Safety monitoring of contaminants (e.g., alkylphenols migrating from plastic packaging into milk) [7]

The guideline encompasses the most common analytical procedure purposes, including assay/potency, purity, impurities, identity, and other quantitative or qualitative measurements [4].

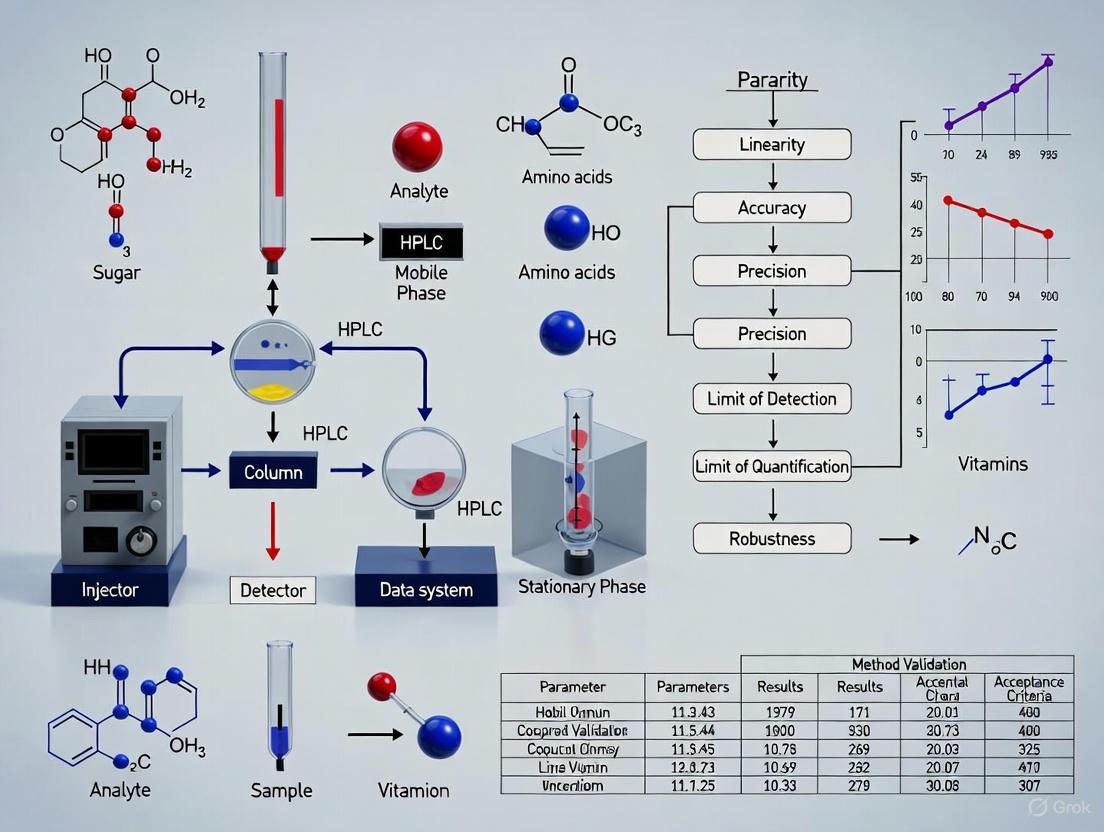

Core Validation Parameters

ICH Q2(R2) outlines specific performance characteristics that must be evaluated to demonstrate a method is fit for its intended purpose [1]. The validation parameters required depend on the type of method (e.g., identification, testing for impurities, or assay). The table below summarizes the core validation parameters for quantitative impurity and assay methods.

Table 1: Core Validation Parameters for Quantitative HPLC Methods Based on ICH Q2(R2)

| Parameter | Definition | Typical Acceptance Criteria for HPLC Assay | Application in Food Analysis |

|---|---|---|---|

| Accuracy | Closeness of test results to the true value [1] | Recovery: 95-105% [5] | Demonstrated by spiking a known amount of analyte into the food matrix and measuring recovery [6] [7] |

| Precision (Repeatability) | Degree of agreement under the same operating conditions over a short time [1] | RSD < 2% [5] | Measured by multiple preparations of a homogeneous food sample [7] |

| Specificity | Ability to assess the analyte unequivocally in the presence of other components [1] | No interference from blank, placebo, or known impurities [8] | Critical in complex food matrices to distinguish target analytes from interfering compounds [6] |

| Linearity | Ability to obtain results proportional to analyte concentration [1] | R² > 0.999 [5] | Established using a series of standard solutions across the specified range [5] |

| Range | Interval between upper and lower analyte concentrations with suitable precision, accuracy, and linearity [1] | Dependent on the method purpose (e.g., 80-120% of test concentration for assay) [1] | Defined based on the expected concentrations in the food product [6] |

| Limit of Detection (LOD) | Lowest amount of analyte that can be detected [1] | Signal-to-noise ratio ≥ 3 [6] | For monitoring contaminants or impurities at trace levels [7] |

| Limit of Quantitation (LOQ) | Lowest amount of analyte that can be quantified with acceptable accuracy and precision [1] | Signal-to-noise ratio ≥ 10; RSD < 5% for precision at LOQ [6] | Essential for setting specification limits for undesirable compounds [7] |

| Robustness | Capacity to remain unaffected by small, deliberate variations in method parameters [1] | System suitability criteria are met despite variations [8] | Evaluated by varying parameters like pH, flow rate, or column temperature [8] |

Experimental Protocols for HPLC Method Validation

This section provides detailed methodologies for key experiments in validating an HPLC method, framed within the context of food analysis research.

Protocol for Determining Accuracy and Precision

The following workflow illustrates the experimental process for determining accuracy and precision, fundamental parameters in method validation:

Title: Accuracy and Precision Workflow

Detailed Procedure:

- Sample Preparation: For a food matrix, prepare a blank sample (free of the target analyte) or use a certified reference material. Spike the blank matrix with known quantities of the analyte standard at a minimum of three concentration levels (e.g., 80%, 100%, and 120% of the target test concentration) [1].

- Replicate Analysis: Prepare and analyze a minimum of six replicates at each concentration level. For intermediate precision, repeat the analysis on a different day, with a different analyst, or using a different instrument, as applicable [1].

- Calculation of Accuracy: Calculate the recovery percentage for each spike level using the formula: Recovery (%) = (Measured Concentration / Spiked Concentration) × 100 The mean recovery should be within the predefined acceptance criteria (e.g., 95-105%) [5].

- Calculation of Precision: Calculate the relative standard deviation (RSD) of the measured concentrations for the replicates at each level. The RSD is calculated as: RSD (%) = (Standard Deviation / Mean) × 100 For repeatability, the RSD should typically be less than 2% for an assay [5]. In the alkylphenols in milk study, precision was evaluated at each concentration level for both intra-day and inter-day measurements, with errors maintained within pre-established acceptability limits (±10%) [7].

Protocol for Specificity and Linearity

Specificity Procedure:

- Inject Blanks: Analyze the sample diluent or solvent to identify any interfering peaks at the retention time of the target analyte [8].

- Analyze Placebo/Matrix: If available, analyze a placebo formulation (for drugs) or a blank food matrix (e.g., milk without alkylphenols, açaí pulp without colorants) to ensure no matrix components co-elute with the analyte [6] [7].

- Stress Samples: For stability-indicating methods, analyze samples that have been subjected to stress conditions (e.g., heat, light, acid/base hydrolysis) to demonstrate that the analyte peak is pure and free from interfering degradation products [8].

- Peak Purity Assessment: When using a Diode Array Detector (DAD), use peak purity algorithms to confirm that the analyte peak is homogeneous and not contaminated with co-eluting compounds [8].

Linearity and Range Procedure:

- Standard Preparation: Prepare a series of standard solutions at a minimum of five concentration levels, ideally spanning the entire working range of the method (e.g., from LOQ to 120-150% of the target concentration) [1].

- Analysis and Plotting: Analyze each standard solution in triplicate. Plot the mean peak response (area or height) against the corresponding analyte concentration.

- Statistical Analysis: Perform linear regression analysis on the data to determine the correlation coefficient (R²), slope, and y-intercept. An excellent linear relationship is typically indicated by R² > 0.999 [5]. The residual plot should be random, confirming the model's appropriateness.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Successful development and validation of an HPLC method for food analysis requires carefully selected reagents and materials. The following table details key solutions and their critical functions in the analytical process.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for HPLC Method Validation

| Reagent/Material | Function & Importance | Application Example from Research |

|---|---|---|

| HPLC-Grade Solvents (Acetonitrile, Methanol) | Mobile phase components; high purity minimizes UV absorbance background noise and prevents system damage [8]. | Used as the organic modifier in the mobile phase for trigonelline analysis [5] and alkylphenols detection [7]. |

| HPLC-Grade Water (Purified, filtered) | Aqueous component of the mobile phase and sample diluent; must be free of particles and organics [8]. | Used in mobile phase and diluent preparation for all cited studies [5] [6] [7]. |

| Buffer Salts & Additives (e.g., Ammonium formate, Formic acid) | Control pH and ionic strength of the mobile phase to optimize peak shape, retention, and selectivity [8]. | 20 mM ammonium formate buffer, pH 3.7, used for the alkylphenols method to control ionization [7]. |

| Certified Reference Standards | Provide the primary calibrator for quantifying the analyte and confirming identity; purity and traceability are critical [8]. | G-1234 reference standard used for potency and identity in drug analysis [8]; alkylphenol standards with certified purity used for quantification in milk [7]. |

| Column Equivalents (Specified and alternative columns) | Ensures method portability; testing an equivalent column from a different vendor is part of robustness evaluation [8]. | The trigonelline method specified a Dalian Elite Hypersil NH2 column (250 mm × 4.6 mm, 5 µm) [5]. |

| Sample Preparation Sorbents (e.g., SLE, SPE cartridges) | Remove matrix interferents (proteins, lipids) to enhance sensitivity and specificity, and protect the HPLC column [7]. | Chem Elut SLE cartridges used to remove lipids and proteins from milk samples prior to alkylphenols analysis [7]. Carrez I and II reagents used for protein precipitation in açaí pulp analysis [6]. |

Application in Food Analysis: Case Studies

The principles of ICH Q2(R2) are directly applicable to food analysis, as demonstrated by recent research where method validation ensures reliable monitoring of food quality, safety, and authenticity.

Case Study 1: Quantification of Bioactive Compounds

A 2024 study developed and validated an HPLC method for the quantitative analysis of trigonelline, an alkaloid with anti-diabetic and antioxidant effects found in fenugreek seeds [5]. The method was rigorously validated, demonstrating:

- Linearity: An excellent linear range with R² > 0.9999.

- Precision: High precision with RSD < 2%.

- Accuracy: A recovery rate between 95% and 105%. This validated method provides robust technical support for the quality evaluation of trigonelline and related pharmaceutical or nutraceutical products [5].

Case Study 2: Food Authenticity and Adulteration Control

A 2025 study addressed food fraud by developing an HPLC-DAD method to detect eight artificial colorants in açaí pulp, where their use is prohibited by Brazilian regulations [6]. The method was validated according to regulatory guidelines, showing:

- Selectivity: Baseline separation of all eight dyes in a 14-minute gradient.

- Sensitivity: Low detection limits (1.5-6.25 mg.kg⁻¹).

- Accuracy: Acceptable recovery of 92-105%. This application highlights the role of validated methods in regulatory monitoring and food authenticity assessment [6].

Case Study 3: Contaminant and Migrant Analysis

A 2025 study developed a validated HPLC-DAD method to determine alkylphenols in milk, which are endocrine-disrupting chemicals that can migrate from plastic packaging [7]. The method utilized a novel cleanup process and was validated using the strategy of accuracy profiling, which calculates the method's total error (encompassing bias and standard deviation) and uses β-expectation tolerance intervals [7]. The method met pre-established acceptability limits (±10%), proving its suitability for routine monitoring of these contaminants in a complex, fatty food matrix [7].

The ICH Q2(R2) and FDA guidelines provide a comprehensive, modern, and science-based framework for analytical method validation. The integration of ICH Q14's Analytical Target Profile and the emphasis on a lifecycle approach encourage deeper method understanding and more flexible, risk-based management. For scientists developing HPLC validation protocols for food analysis research, adhering to these principles ensures the generation of reliable, accurate, and reproducible data. This is critical not only for regulatory compliance but also for advancing food science, ensuring product quality, protecting consumer safety, and combating food fraud.

The Analytical Target Profile (ATP) represents a fundamental shift in the approach to analytical science, moving from a traditional, prescriptive method to a systematic, risk-based framework. Within food analysis, the ATP serves as a formalized statement that outlines the intended purpose of an analytical procedure and defines the criteria for its required performance. This application note details the integration of the ATP within the Analytical Procedure Lifecycle Management (APLM) framework, specifically for developing and validating High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC) methods. By defining the ATP at the outset, laboratories can ensure methods are fit-for-purpose, robust, and capable of meeting the rigorous demands of food authenticity, safety, and quality control.

The Analytical Target Profile: A Foundational Concept

The Analytical Target Profile (ATP) is a prospective summary of the intended purpose of an analytical procedure and its required performance characteristics [1]. It is the cornerstone of the modern lifecycle approach to analytical procedures, as championed by new guidelines such as ICH Q14 for Analytical Procedure Development and the draft USP <1220> on Analytical Procedure Lifecycle Management [1] [9].

The traditional view of method validation, guided by ICH Q2(R1), often involved a ritualistic, "check-the-box" approach that could lead to situations where methods were validated for parameters irrelevant to their actual use, such as determining Limits of Detection (LOD) for an assay intended to measure an active component at 90-110% of label claim [9]. The ATP framework eliminates this inefficiency by forcing a critical assessment of the method's purpose from the very beginning.

In essence, the ATP shifts the paradigm from a one-time validation event to a continuous lifecycle management process, ensuring that the analytical method remains fit-for-purpose throughout its operational use [1]. This is particularly critical in food analysis, where methods are used to combat food fraud, ensure regulatory compliance, and guarantee product safety.

The ATP within the Analytical Procedure Lifecycle

The lifecycle of an analytical procedure, as advocated by USP <1220>, consists of three interconnected stages, with the ATP informing every step [9].

Figure 1. The Analytical Procedure Lifecycle. The ATP defines the target for the entire process, with continuous feedback enabling method improvement [9].

Stage 1: Procedure Design and Development

This stage translates the ATP into a working analytical method. Method development activities are planned and executed based on the performance requirements defined in the ATP. A risk assessment is conducted to identify factors that could significantly impact method performance, guiding systematic optimization [10]. For instance, an HPLC method for quantifying artificial colorants in açaí pulp would be developed to achieve the specificity, accuracy, and sensitivity mandated by its ATP [6].

Stage 2: Procedure Performance Qualification

This stage corresponds to the traditional method validation but is now driven by the ATP. The validation parameters tested and the acceptance criteria are directly derived from the ATP's performance requirements [1]. This ensures that the validation demonstrates the method is truly fit-for-purpose.

Stage 3: Procedure Performance Verification

Once the method is in routine use, its performance is continuously monitored through quality control samples and system suitability tests [9]. This ongoing verification ensures the method remains in a state of control and alerts analysts to any performance drift, triggering corrective action or method improvement.

Constructing an ATP for Food Analysis: Core Components

A well-defined ATP is a concise, factual statement that specifies "what" the method must achieve, not "how" it will be achieved. The key components of an ATP for an HPLC method in food analysis are detailed in the table below.

Table 1: Core Components of an Analytical Target Profile for Food Analysis

| ATP Component | Description | Example: HPLC Method for Quantifying Artificial Colorants [6] |

|---|---|---|

| Analyte & Matrix | Clearly defines the target substance(s) and the food matrix in which it will be measured. | Eight artificial dyes (Tartrazine, Bordeaux Red, etc.) in açaí pulp, juçara pulps, and açaí-based sorbets. |

| Analytical Technique | Specifies the primary technique used, allowing for flexibility in the specific instrumentation. | Reversed-Phase High-Performance Liquid Chromatography with Diode Array Detection (RP-HPLC-DAD). |

| Reportable Value | Defines the form and units of the final result. | Concentration in mg/kg (mg.kg⁻¹). |

| Performance Criteria | Quantifies the required method performance, including the following key parameters: | |

| • Target Range | The interval between the upper and lower analyte concentrations for which the method is required to perform suitably. | From the Limit of Quantitation (LOQ) to 200% of the expected maximum level from adulteration. |

| • Accuracy | The closeness of agreement between the accepted reference value and the value found. | Recovery of 92-105%. |

| • Precision | The degree of agreement among individual test results. Expressed as Repeatability and Intermediate Precision (%RSD). | RSD < 2%. |

| • Specificity | The ability to assess the analyte unequivocally in the presence of other components. | Baseline separation of all eight dyes from each other and from matrix interferences in a 14-minute gradient. |

| • Sensitivity (LOQ) | The lowest amount of analyte that can be quantified with acceptable accuracy and precision. | LOQ between 1.5 and 6.25 mg.kg⁻¹ for the different dyes. |

Experimental Protocol: From ATP to Validated HPLC Method

The following protocol outlines the key steps for developing and validating an HPLC method for food analysis, guided by an ATP.

Protocol: ATP-Driven HPLC Method Development and Validation

Objective: To develop and validate a specific, accurate, and robust HPLC method for the quantification of [Insert Target Analyte, e.g., Artificial Colorants] in [Insert Food Matrix, e.g., Açaí Pulp] as defined by a pre-established ATP.

Principle: The method will utilize Reversed-Phase HPLC (RP-HPLC) with optimal chromatographic conditions determined via a risk-based experimental design. The method will be validated per ICH Q2(R2) and ICH Q14 principles to confirm it meets all ATP performance criteria [1] [6].

I. Materials and Reagents

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions and Essential Materials

| Item | Function / Explanation |

|---|---|

| HPLC System | A system with a quaternary pump, autosampler, column thermostat, and Diode Array Detector (DAD). The DAD is crucial for confirming peak purity and selecting optimal detection wavelengths [6]. |

| Chromatographic Column | The separation engine. A C18 column (e.g., 250 mm x 4.6 mm, 5 µm) is typical for RP-HPLC. Column type is a high-risk factor and should be studied during development [10]. |

| Mobile Phase Components | Acetonitrile/Methanol: Organic modifiers. Buffer Salts (e.g., Disodium hydrogen phosphate): To control pH and improve peak shape. The buffer pH and ratio with organic solvent are critical method parameters [10]. |

| Analytical Standards | High-purity reference standards of the target analytes for calibration, identification, and determining accuracy. |

| Sample Preparation Solvents & Reagents | Carrez I & II reagents: Used for protein precipitation and clarification in complex food matrices like fruit pulps [6]. Dichloromethane: For liquid-liquid extraction to remove lipids. |

II. Procedure

Step 1: Method Scouting and Risk Assessment

- Define the ATP for the method (refer to Table 1 for components).

- Based on the ATP, identify Critical Method Parameters (CMPs) through risk assessment. These typically include column type (X1), mobile phase ratio (X2), and buffer pH (X3) [10].

- Use an experimental design (e.g., d-optimal design) to systematically study the impact of these CMPs on Critical Method Attributes (CMAs) such as retention time (Y1), peak area (Y2), tailing factor (Y3), and theoretical plates (Y4) [10].

Step 2: Method Optimization and MODR Establishment

- Analyze the experimental design data to understand the relationship between CMPs and CMAs.

- Employ software (e.g., MODDE Pro) and Monte Carlo simulations to establish a Method Operable Design Region (MODR). The MODR defines the multidimensional combination of CMPs within which the method meets ATP criteria, ensuring robustness [10].

- Select the final, robust set point from within the MODR.

Step 3: Final Chromatographic Conditions

- The following conditions are illustrative from a published AQbD study [10]:

- Column: Inertsil ODS-3 C18 (250 mm, 4.6 mm, 5 µm).

- Mobile Phase: Acetonitrile: 20 mM disodium hydrogen phosphate buffer, pH 3.1 (18:82, v/v).

- Flow Rate: 1.0 mL/min.

- Temperature: 30 °C.

- Detection: DAD, 323 nm (wavelength to be adjusted for specific analytes).

- Injection Volume: 10 µL.

- Elution Mode: Isocratic.

Step 4: Sample Preparation

- Optimize extraction using a design like a simplex-centroid mixture design [6].

- For complex matrices like açaí pulp, a protocol may include:

Step 5: Method Validation Execute the following validation experiments, with acceptance criteria defined by the ATP.

Table 3: Method Validation Parameters and Protocols [11] [1]

| Validation Parameter | Experimental Protocol | Acceptance Criterion (Example) |

|---|---|---|

| Specificity | Inject blank matrix, standard, and sample. Subject the sample to stress conditions (acid, base, oxidation, heat, light) to demonstrate separation of the analyte from interferents and degradation products. Check peak purity using a DAD. | No interference at the analyte retention time. Resolution > 1.5 between analyte and closest eluting peak. Peak purity index > 990. |

| Linearity & Range | Prepare and analyze a minimum of 5 calibration standards, from LOQ to 200% of the target concentration. Each concentration should be injected once. | Correlation coefficient (r) > 0.999. |

| Accuracy | Analyze replicate samples (n=3) at three concentration levels (80%, 100%, 120%) within the range. Calculate recovery of the spiked amount. | Mean recovery between 98-102%, RSD < 2%. |

| Precision(Repeatability) | Analyze six independent test preparations from a single homogeneous sample batch by the same analyst on the same day. | RSD of content < 2%. |

| Precision(Intermediate Precision) | Repeat the precision study on a different day, with a different analyst, and using a different instrument. Combine all results (n=12). | RSD of all 12 results < 2%. |

| Limit of Quantification (LOQ) | Determine the concentration that yields a signal-to-noise ratio (S/N) of 10:1. Confirm by injecting six preparations at this concentration. | S/N ≥ 10. RSD of the peak area of six injections < 5%. |

| Robustness | Deliberately vary method parameters (e.g., flow rate ±10%, mobile phase ratio ±2%, column temperature ±2°C, columns from different brands). Analyze two sample and two reference solutions at each condition. | RSD of assay results across all variations (n=6 per variation) < 2%. System suitability criteria are met in all conditions. |

The following diagram summarizes the experimental workflow from ATP to a validated method.

Figure 2. ATP-Driven Method Development Workflow. CMPs: Critical Method Parameters; CMAs: Critical Method Attributes; MODR: Method Operable Design Region.

The Analytical Target Profile is more than a document; it is the strategic foundation for modern, robust, and compliant analytical methods in food analysis. By defining the purpose and required performance at the outset, the ATP ensures that subsequent development, validation, and operational use of HPLC methods are efficient, science-based, and fully aligned with their intended use. Adopting this lifecycle approach, as outlined in ICH Q14 and USP <1220>, empowers laboratories to move beyond mere regulatory compliance and toward a paradigm of continuous improvement, ultimately enhancing the reliability of data used to ensure food safety and authenticity.

In high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) for food analysis, demonstrating that an analytical method is reliable and fit for purpose is a fundamental requirement for research and quality control. Method validation provides objective evidence that a method consistently meets predefined performance standards, ensuring the accuracy and reliability of data used in food safety assessments, nutritional labeling, and regulatory submissions [12] [13]. The International Council for Harmonisation (ICH) guideline Q2(R1) and other regulatory bodies provide a framework for this process, outlining key validation characteristics [12] [14].

This application note details the core validation parameters—Accuracy, Precision, Specificity, and Linearity—within the context of developing an HPLC method for food analysis. Using a practical example of quantifying organic acids in processed foods, we will define each parameter, describe its experimental protocol, and present acceptance criteria, providing a clear roadmap for researchers to validate their analytical methods effectively [15].

Core Parameters and Experimental Protocols

The following parameters form the foundation of HPLC method validation, confirming that the method produces truthful, reproducible, and selective measurements over a defined range.

Accuracy

Accuracy refers to the closeness of agreement between the value found by the analytical method and the value accepted as either a conventional true value or an accepted reference value. It indicates the method's freedom from systematic error (bias) and is typically expressed as percent recovery [12] [13].

Experimental Protocol for Food Analysis (Spike and Recovery): This standard approach evaluates accuracy by spiking a known amount of the pure analyte into the sample matrix.

- Sample Preparation: Obtain or prepare a representative sample of the food matrix (e.g., a homogenized barley grain or beverage sample) known to be free of the target analyte or with a known background level.

- Spiking: Spike the sample matrix with the analyte (e.g., tocopherols or organic acids) at a minimum of three concentration levels covering the specified range (e.g., 80%, 100%, and 120% of the target concentration) [13]. Each level should be prepared and analyzed in triplicate (n=3), leading to a minimum of nine determinations [12] [13].

- Analysis and Calculation: Analyze the spiked samples and calculate the concentration found using the HPLC method. The percent recovery is calculated as:

- Recovery (%) = (Measured Concentration / Spiked Concentration) × 100

- Interpretation: The mean recovery value at each level should fall within predefined acceptance criteria. For food analysis, recoveries of 80-110% are often considered acceptable, though tighter ranges (e.g., 98-102%) are expected for major components at high concentrations [16] [17] [15].

Precision

Precision expresses the closeness of agreement (degree of scatter) between a series of measurements obtained from multiple sampling of the same homogeneous sample under prescribed conditions. It is a measure of random error and is usually expressed as relative standard deviation (RSD) or coefficient of variation (CV) [12] [13]. Precision has three tiers:

- Repeatability: Precision under the same operating conditions over a short interval (intra-day).

- Intermediate Precision: Precision within the same laboratory on different days, with different analysts, or different equipment.

- Reproducibility: Precision between different laboratories (often assessed during method transfer).

Experimental Protocol for Repeatability (Intra-day Precision):

- Sample Preparation: Prepare a minimum of six independent test samples from a single, homogeneous batch of the food product at 100% of the target concentration [12] [13].

- Analysis: Analyze all six preparations using the same HPLC method, same analyst, and same instrument within one day.

- Calculation: For each injection, calculate the analyte concentration. From the six results, calculate the mean, standard deviation (SD), and relative standard deviation (RSD).

- RSD (%) = (Standard Deviation / Mean) × 100

- Interpretation: The %RSD for assay of the active ingredient should typically be not more than 2.0% [13]. For impurities at lower concentrations, a higher RSD may be acceptable.

Specificity and Selectivity

Specificity is the ability to assess unequivocally the analyte in the presence of components that may be expected to be present, such as impurities, degradation products, and matrix components [12] [13]. In chromatography, specificity is typically demonstrated by the baseline resolution of the analyte peak from all other potential peaks.

Experimental Protocol for Specificity in Food Matrix Analysis:

- Chromatogram Comparison: Inject and analyze the following solutions:

- Blank: The solvent or solution used to prepare the sample.

- Placebo/Matrix Blank: A mock sample containing all excipients or the food matrix without the active ingredient(s).

- Standard Solution: A solution of the reference standard of the target analyte.

- Test Sample: The actual food sample containing the analyte.

- Forced Degradation (Stability-Indicating Property): Stress the sample (e.g., with heat, light, acid, base, oxidation) to generate degradation products. Analyze the stressed sample to demonstrate that the analyte peak is unaffected and that all degradation products are separated from the main peak [14] [13].

- Assessment: The method is specific if there is no interference from the blank or matrix at the retention time of the analyte, and the peak purity of the analyte is confirmed (e.g., using a diode array detector or mass spectrometry) [13].

Linearity and Range

Linearity is the ability of the method to elicit test results that are directly, or through a well-defined mathematical transformation, proportional to the concentration of analyte in samples within a given range. The range is the interval between the upper and lower concentrations of analyte for which it has been demonstrated that the method has suitable levels of accuracy, precision, and linearity [12] [14].

Experimental Protocol for Linearity:

- Standard Preparation: Prepare a series of standard solutions at a minimum of five to six concentration levels over the intended range (e.g., from 50% to 150% of the target concentration) [12] [14]. A linearity study for organic acids, for instance, might use concentrations from 0.05 to 200 mg/L [15].

- Analysis: Analyze each concentration level in triplicate.

- Calibration Curve: Plot the mean peak area (or height) against the corresponding concentration of the standard. Perform linear regression analysis on the data to obtain the correlation coefficient (r), coefficient of determination (R²), y-intercept, and slope of the regression line.

- Interpretation: A correlation coefficient (r) of ≥ 0.999 is generally expected for the assay of active ingredients [12] [14]. The y-intercept should be statistically indistinguishable from zero.

The following table summarizes typical acceptance criteria for the core validation parameters in the context of food analysis, drawing from examples in the search results.

Table 1: Typical Acceptance Criteria for Core HPLC Validation Parameters in Food Analysis

| Parameter | Experimental Approach | Typical Acceptance Criteria | Example from Food Analysis Research |

|---|---|---|---|

| Accuracy | Recovery study using spiked matrix at 3 levels (n=3 each). | Recovery of 98–102% for assay; 80–110% for impurities, depending on level [13]. | Recovery of 89.02–99.30% for quercitrin in pepper extract [16]. Recovery of 85.1–100.8% for organic acids in processed foods [15]. |

| Precision (Repeatability) | Analysis of six individual sample preparations. | RSD ≤ 2.0% for assay; higher for impurities [13]. | RSD of 0.50–5.95% for quercitrin recovery [16]. RSD of 0.62–4.87% for organic acids [15]. |

| Specificity | Chromatographic comparison of blank, standard, and sample. Baseline separation of analyte from closest eluting peak. | No interference at analyte retention time. Resolution (Rs) > 2.0 between critical pairs [14]. | Peak purity confirmed for organic acids with no interference from food matrix [15]. |

| Linearity | Minimum of 5 concentrations analyzed. | Correlation coefficient (r) ≥ 0.998 (R² ≥ 0.996) [14]. | R² > 0.9997 for quercitrin in the range of 2.5–15.0 μg/mL [16]. R² > 0.999 for organic acids in the range of 0.05–200 mg/L [15]. |

Experimental Workflow and Relationship of Parameters

The validation process is a logical sequence of experiments designed to comprehensively characterize method performance. The following workflow diagram illustrates the key steps and how the core parameters interrelate.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Successful method development and validation rely on high-quality materials and reagents. The following table lists key items required for the experiments described in this note.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for HPLC Method Validation

| Item | Function/Application | Example from Literature |

|---|---|---|

| High-Purity Analytical Standards | Used to prepare calibration solutions for linearity and as a reference for accuracy studies. Purity should be certified and traceable. | Quercitrin standard (≥98%) for quantifying flavonoid in peppers [16]. Organic acid standards (≥95%) for food additive analysis [15]. |

| Chromatography Column (C18) | The stationary phase where chemical separation occurs. Its selectivity and efficiency are critical for achieving specificity. | CAPCELL PAK C18 UG120 column [16]; Eclipse XDB C18 column [17]; C18 column for organic acid separation [15]. |

| HPLC-Grade Solvents & Reagents | Used for mobile phase and sample preparation. High purity is essential to minimize baseline noise and prevent system damage. | Methanol, water, and formic acid used for pepper extract analysis [16]. Methanol, water, and phosphoric acid for organic acid analysis [15]. |

| Sample Preparation Materials | For consistent and reproducible processing of food matrices. Includes items for extraction, filtration, and dilution. | Ultrasonicator for extracting quercitrin [16]. Matrix Solid-Phase Dispersion (MSPD) with alumina for extracting tocols from barley [17]. 0.45-μm membrane filters [16]. |

Rigorous validation of Accuracy, Precision, Specificity, and Linearity is non-negotiable for establishing reliable HPLC methods in food analysis research. By adhering to the structured experimental protocols and acceptance criteria outlined in this application note, scientists can generate defensible data that meets stringent quality standards. This foundational work ensures that analytical results are trustworthy, supporting critical decisions in food safety, quality control, and regulatory compliance.

Establishing Method Range, LOD, and LOQ for Diverse Food Matrices

High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC) method validation is a critical process in food analysis research, ensuring that analytical methods produce reliable and accurate results for quality control, authenticity assessment, and regulatory compliance. The establishment of method range, limit of detection (LOD), and limit of quantification (LOQ) represents fundamental parameters that characterize the performance and capability of an analytical method, particularly when dealing with complex and varied food matrices. These parameters define the boundaries within which a method can accurately detect and quantify analytes, from the lowest concentrations traceable with statistical confidence to the upper limits of quantitative measurement. In food analysis, where compounds of interest may be present at vastly different concentration levels across diverse sample types—from major components to trace-level contaminants or adulterants—properly establishing these parameters is essential for generating scientifically defensible data. This application note provides detailed protocols and current methodologies for determining range, LOD, and LOQ specifically tailored to the challenges of food matrix analysis, framed within the comprehensive context of HPLC method validation for food research.

Theoretical Foundations and Regulatory Framework

Definitions and Significance in Food Analysis

In analytical chemistry applied to food matrices, the method range (or linear range) refers to the interval between the upper and lower concentration levels of an analyte for which the method has suitable levels of accuracy, precision, and linearity. This range must encompass the expected concentrations of the analyte in actual samples, from trace amounts to maximum expected levels. The limit of detection (LOD) represents the lowest concentration of an analyte that can be reliably detected but not necessarily quantified under the stated experimental conditions. Conversely, the limit of quantification (LOQ) is the lowest concentration that can be quantitatively determined with acceptable precision and accuracy. These parameters are particularly challenging to establish in food analysis due to matrix complexity, which can significantly influence analytical signals and method performance [18].

The mathematical relationship for LOD and LOQ based on the calibration curve approach follows the formulas recommended by ICH Q2(R1), where LOD = 3.3 × σ/S and LOQ = 10 × σ/S, with σ representing the standard deviation of the response and S being the slope of the calibration curve [19]. This approach leverages the statistical properties of the calibration model to estimate the lowest detectable and quantifiable concentrations.

Regulatory Guidelines and Recommendations

Several international guidelines provide frameworks for determining these crucial method validation parameters, though with varying calculation approaches:

Table 1: Comparison of LOD and LOQ Calculation Methods Across Guidelines

| Guideline/Organization | LOD Calculation | LOQ Calculation | Food Analysis Applicability |

|---|---|---|---|

| IUPAC | Based on blank signal variability | Typically 3.3 × LOD | Well-suited for simple matrices |

| USEPA | Signal-to-noise ratio (3:1) | Signal-to-noise ratio (10:1) | Broad environmental and food applications |

| EURACHEM | Based on calibration curve statistics | Based on calibration curve statistics | Emphasizes measurement uncertainty |

| AOAC | Collaborative study data | Collaborative study data | Food-specific method validation |

| ICH Q2(R1) | 3.3 × σ/S | 10 × σ/S | Pharmaceuticals, adaptable to food |

| European Commission 2002/657/EC | CCα (decision limit) | CCβ (detection capability) | Regulatory focus, contaminants in food |

The calculation of LOD and LOQ constitutes a crucial task during the validation of a method, yet significant discrepancies can occur depending on the selected approach [18]. For food analysis applications, the AOAC guidelines and European Commission protocols often provide the most relevant frameworks, though ICH guidelines offer well-established statistical approaches that can be adapted to food matrices.

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Establishing the Method Range

The method range should be established using a minimum of six concentration levels prepared in triplicate, covering the expected concentration range encountered in actual samples. For food analysis, it is essential that calibration standards are prepared in a matrix-matched blank to account for matrix effects [20] [6].

Protocol for Range Establishment:

- Preparation of Matrix-Matched Standards: Identify or create an appropriate blank matrix free of the target analyte. For endogenous compounds where a genuine analyte-free matrix does not exist, use the standard addition method or minimal baseline level samples [18].

- Concentration Levels: Prepare calibration standards at concentrations spanning from below the expected LOQ to above the maximum expected concentration. A typical series includes 25%, 50%, 75%, 100%, 125%, and 150% of the target concentration [20].

- Analysis and Evaluation: Analyze each concentration level in triplicate using the optimized HPLC conditions. Evaluate linearity using correlation coefficient (R²), which should be >0.99 for quantitative methods, and visual inspection of residual plots.

- Accuracy and Precision Verification: For each concentration level, verify that accuracy (expressed as recovery percentage) and precision (relative standard deviation, RSD) meet acceptance criteria, typically 80-120% recovery with RSD <5% for the lower range and <2% for the upper range of the method [13].

For complex food matrices, the range may need to be verified across different sample types (e.g., high-fat vs. high-carbohydrate foods) to ensure consistent performance.

Determining LOD and LOQ

Multiple approaches exist for determining LOD and LOQ, each with specific applications and limitations for food analysis:

3.2.1 Signal-to-Noise Ratio (S/N) Approach This practical approach is particularly useful for chromatographic methods with baseline noise.

- Procedure: Inject a series of low-concentration standards and measure the signal height of the analyte peak compared to the baseline noise height.

- Calculation: LOD is the concentration giving S/N ≥ 3:1; LOQ is the concentration giving S/N ≥ 10:1.

- Application: Best suited for methods with consistent, measurable baseline noise. Particularly appropriate for initial estimation before applying more rigorous statistical approaches [18].

3.2.2 Calibration Curve Approach This statistical approach uses the properties of the calibration curve in the low concentration range.

Protocol for Calibration Curve Approach:

- Prepare calibration standards in the low concentration range, ideally not more than 10 times the presumed detection limit as the highest concentration [19].

- Use a minimum of 5 concentration levels with multiple replicates (at least 3) at each level [19].

- Analyze the standards using the optimized HPLC method.

- Perform regression analysis to determine the slope (S) and the standard deviation of the response (σ).

- Calculate LOD and LOQ using the formulas: LOD = 3.3 × σ/S and LOQ = 10 × σ/S.

The standard deviation (σ) can be determined as either:

- The residual standard deviation of the regression line (SD~Residuals~)

- The standard deviation of the y-intercepts of regression lines (SD~Y-intercept~) [19]

Table 2: Example LOD Calculation Using Calibration Curve Approach

| Experiment | Slope (m) | SD~Y-intercept~ | SD~Residuals~ | LOD (µg/mL) using SD~Y-intercept~ | LOD (µg/mL) using SD~Residuals~ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 15878 | 2943 | 3443 | 0.61 | 0.72 |

| 2 | 15814 | 2849 | 3333 | 0.59 | 0.70 |

| 3 | 16562 | 1429 | 1672 | 0.28 | 0.33 |

| 4 | 15844 | 2937 | 3436 | 0.61 | 0.72 |

Note: This constructed example shows how LOD results can vary depending on the standard deviation parameter selected for the calculation [19].

3.2.3 Blank Sample Method This approach uses the standard deviation of blank measurements but requires careful consideration in food analysis.

- Procedure: Analyze multiple replicates (at least 10) of a blank matrix sample and calculate the standard deviation of the response.

- Calculation: LOD = 3.3 × SD~blank~ / S and LOQ = 10 × SD~blank~ / S, where S is the slope of the calibration curve.

- Challenge in Food Analysis: Obtaining a true blank matrix can be difficult, particularly for endogenous compounds. For exogenous compounds (e.g., contaminants, adulterants), a blank matrix may be available or can be simulated [18].

Comprehensive Workflow for Parameter Estimation

The following workflow diagram illustrates a systematic approach for establishing range, LOD, and LOQ in food analysis methods:

Case Studies in Food Matrix Analysis

Analysis of Trigonelline in Fenugreek Seeds

A recent study developed and validated an HPLC method for quantification of trigonelline in fenugreek seeds. The method employed a Dalian Elite Hypersil NH2 chromatographic column (250 mm × 4.6 mm, 5 µm) with a mobile phase of acetonitrile:water (70:30, v/v) at a flow rate of 1.0 mL/min. The column temperature was maintained at 35°C with detection at 264 nm. Sample preparation involved ultrasonic extraction with methanol for 30 minutes. Method validation demonstrated excellent linearity (R² > 0.9999) with high precision (RSD < 2%) and recovery rates between 95% and 105%, meeting quality standards for trigonelline analysis [5].

Determination of Artificial Colorants in Açaí Pulp

Another relevant application involved the development and validation of an HPLC-DAD method for simultaneous determination of eight artificial dyes in açaí pulp and commercial products. The method addressed significant challenges in sample preparation, including lipid removal using liquid-liquid extraction with dichloromethane and protein precipitation using Carrez I and II reagents. Chromatographic conditions were optimized to ensure baseline separation under a 14-minute gradient. Validation according to regulatory guidelines showed suitable selectivity, linearity (R² > 0.98 for most analytes), low detection limits (1.5-6.25 mg·kg⁻¹), and acceptable recovery (92-105%). This method provides a robust tool for regulatory monitoring and authenticity assessment of açaí-based products, demonstrating effective approaches to complex food matrices [6].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for HPLC Method Validation in Food Analysis

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application | Considerations for Food Matrices |

|---|---|---|

| Matrix-Matched Blank | Serves as analyte-free base for calibration standards | Critical for accurate quantification; for endogenous compounds, use standard addition method |

| Carrez I & II Reagents | Protein precipitation and clarification in sample preparation | Essential for high-protein food matrices like dairy products and legume extracts [6] |

| Dichloromethane | Lipid removal in sample preparation | Important for high-fat food matrices; enables cleaner extracts and reduces matrix effects [6] |

| Reference Standards | Calibration and method qualification | Should be of high purity; matrix-matched calibration recommended for complex food samples |

| HPLC-Grade Solvents | Mobile phase preparation and sample extraction | Essential for reproducible retention times and minimal background noise |

| SPE Cartridges | Sample clean-up and concentration | Select sorbent chemistry based on target analyte properties and matrix composition |

Recommendations for Complex Food Matrices

Food matrices present unique challenges for method validation, particularly regarding matrix effects, interfering compounds, and availability of true blank samples. The following recommendations address these specific concerns:

Matrix Effects Evaluation: Validate methods using representative food matrices that cover the expected sample types. For multi-matrix methods, verify LOD, LOQ, and range in each major matrix category (e.g., high-fat, high-protein, high-carbohydrate) [6].

Blank Sample Generation: For exogenous compounds (e.g., contaminants, adulterants), use naturally free matrices or simulated blanks. For endogenous compounds, the standard addition method may be necessary, or use of a minimally incurred material [18].

Handling of Background Levels: For analytes naturally present in food matrices (endogenous compounds), report the method detection limit (MDL) rather than the instrument detection limit, and clearly distinguish between the two in reporting.

Uncertainty Estimation: Include measurement uncertainty in LOD/LOQ reporting, particularly for regulatory applications where these parameters may inform compliance decisions.

Transparent Reporting: Clearly specify the calculation method used for LOD and LOQ determination, as results can vary significantly between approaches. Document all experimental parameters including number of replicates, concentration levels, and matrix used for calibration [18] [19].

Establishing method range, LOD, and LOQ for diverse food matrices requires careful consideration of matrix effects, appropriate calibration designs, and statistical approaches. The protocols outlined in this application note provide a framework for developing scientifically sound HPLC methods that generate reliable data for food analysis applications. As demonstrated in the case studies, proper validation of these parameters ensures methods are fit-for-purpose in quality control, authenticity assessment, and regulatory monitoring of food products. By adhering to systematic validation protocols and selecting appropriate calculation methods based on the specific analytical requirements and matrix complexities, researchers can generate defensible data that supports food safety, quality, and authenticity initiatives.

The International Council for Harmonisation (ICH) Q14 guideline, officially adopted in November 2023, represents a fundamental shift in analytical science by establishing a systematic, science-based and risk-based framework for analytical procedure development [21] [22] [23]. This guideline encourages the application of Quality by Design (QbD) principles to the analytical method lifecycle, moving beyond the traditional, empirical approach to a more structured paradigm that emphasizes proactive development and robust control strategies [21] [24]. This application note explores the core principles of ICH Q14 and provides detailed protocols for its implementation within the context of developing High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC) methods for food analysis. By integrating these principles, researchers can achieve more reliable, reproducible, and adaptable methods, facilitating smoother regulatory evaluations and more flexible post-approval change management [23].

The introduction of ICH Q14 marks a significant evolution in regulatory expectations for analytical procedures. It provides harmonized guidance for developing and maintaining methods suitable for assessing the quality of both drug substances and products, a framework that can be directly extrapolated to food components and contaminants [22] [23]. The guideline formally recognizes two approaches: the traditional "minimal" approach and the more systematic "enhanced" approach [21]. The enhanced approach, the focus of this document, is characterized by a structured methodology for developing analytical procedures and a robust framework for Analytical Procedure Lifecycle Management (APLM) [21] [24].

APLM, extrapolated from the concepts in ICH Q12, ensures that analytical methods remain fit-for-purpose throughout their entire operational life, from initial development through commercial use [21]. This is crucial for food analysis, where raw material variations and complex matrices can challenge method performance over time. The lifecycle approach treats method validation not as a one-time event, but as an ongoing process of verification and continuous improvement [21] [13]. This proactive management, supported by established conditions (ECs) and a strong control strategy, minimizes the risk of method failure and enhances the reliability of data used for quality decisions in food research and production [21].

Core Principles of ICH Q14 for Method Development

The Analytical Target Profile (ATP)

The ATP is the cornerstone of the ICH Q14 enhanced approach. It is a predefined objective that summarizes the intended purpose of the analytical procedure [21] [24]. Essentially, the ATP outlines what the method needs to achieve, specifying the analyte(s) to be measured and the required performance criteria the method must meet against specific Critical Quality Attributes (CQAs) [21].

For a food analysis HPLC method targeting a nutritional component or contaminant, the ATP would explicitly define:

- Analyte of Interest: e.g., a specific sugar, vitamin, or mycotoxin.

- Sample Matrix: e.g., herbal extract, dairy product, or grain.

- Required Performance Characteristics: such as the target precision (e.g., %RSD), accuracy (e.g., %Recovery), range, and specific limits of detection (LOD) and quantification (LOQ) suitable for the intended use [25] [13] [24]. The ATP provides a clear target for development and a benchmark for validation, ensuring the final method is scientifically sound and fit-for-purpose [21].

Critical Method Parameters and Design of Experiments (DoE)

A fundamental shift under QbD principles is moving from a univariate (One-Factor-At-a-time) approach to a systematic, multivariate one using Design of Experiments (DoE) [21] [26]. Critical Method Parameters (CMPs)—such as mobile phase composition, column temperature, flow rate, and gradient profile—are identified and their interactive effects on Critical Method Attributes (CMAs)—such as resolution, peak symmetry, and analysis time—are rigorously studied [26].

A case study on developing an HPLC-ELSD method for sugar analysis in botanical extracts exemplifies this approach. Researchers used a fractional factorial design to screen eight potential CMPs, including initial and final mobile phase composition, flow rate, and column temperature, to determine their impact on CMAs like retention time and signal-to-noise ratio [26]. This efficient experimental strategy allows for the establishment of a Method Operable Design Region (MODR), which is the multidimensional combination of CMP ranges within which method performance remains consistent [21]. Operating within the MODR ensures method robustness.

Analytical Control Strategy and Established Conditions

The analytical control strategy is a planned set of controls, derived from current product and process understanding, that ensures method performance [21]. A key component is system suitability testing (SST), which verifies that the analytical system is functioning correctly at the time of testing [21] [13]. SST parameters are directly linked to the ATP and are set to ensure the method meets its required performance criteria for each analysis [13].

Under ICH Q14, Established Conditions (ECs) are the legally binding, validated parameters that are considered critical to assuring product quality [21]. For an HPLC method, ECs may include the principle of the technique (e.g., Reversed-Phase HPLC), performance characteristics, system suitability criteria, and set points or ranges for critical procedure parameters [21]. A major advantage of the enhanced approach is that if a PAR or MODR has been established and approved for an EC, changes within that range may only require notification to regulatory authorities rather than prior approval, granting laboratories greater operational flexibility [21].

Experimental Design and Protocols

Protocol: Defining the Analytical Target Profile (ATP)

Objective: To create a formal ATP document that guides the development and validation of an HPLC method for quantifying a target analyte in a complex food matrix.

Procedure:

- Define the Purpose: Clearly state the method's goal (e.g., "To quantify sucrose content in Astragali Radix extract with precision and accuracy suitable for quality control release").

- Identify the Analyte and Matrix: Specify the analyte(s) (e.g., D-fructose, D-glucose, sucrose) and the specific sample matrix (e.g., herbal extract, fruit juice).

- Select the Analytical Technique: Justify the choice of technique (e.g., HPLC-ELSD for non-chromophoric sugars).

- Establish Performance Requirements: Define the minimum acceptable criteria for each performance characteristic based on regulatory guidelines and product needs [13]. An example for a sugar assay is provided in Table 1.

Table 1: Example ATP Performance Criteria for a Sugar Assay in Herbal Extracts

| Performance Characteristic | Target Requirement | Reference / Justification |

|---|---|---|

| Accuracy (Recovery) | 95–105% | ICH Q2(R1); [13] |

| Precision (Repeatability) | RSD ≤ 2.0% | ICH Q2(R1); [13] |

| Linearity | R² ≥ 0.999 | ICH Q2(R1); [25] |

| Range | 50%–150% of target concentration | ICH Q2(R1); [13] |

| Specificity | Baseline resolution (Resolution ≥ 2.0) from all known impurities and degradants | ICH Q2(R1); [13] |

| LOQ | Sufficient to quantify at reporting threshold (e.g., 0.1 μg/mL) | ICH Q2(R1); [25] |

Protocol: Implementing AQbD using DoE

Objective: To identify CMPs and model their relationship with CMAs to establish a robust MODR for an HPLC-ELSD method for sugar analysis.

Materials and Reagents:

- The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Reagents for HPLC-ELSD Sugar Analysis [26]:

- HPLC-grade acetonitrile and water: Mobile phase components for optimal separation and ELSD compatibility.

- Triethylamine (TEA): Additive to modify mobile phase pH and suppress silanol activity, improving peak shape.

- Reference standards (D-fructose, D-glucose, sucrose): For system calibration and peak identification.

- Astragali Radix and Codonopsis Radix extracts: Representative sample matrices.

- Waters XBridge Amide column (4.6×250 mm, 5 μm): Stationary phase for polar compound separation.

Experimental Workflow:

- Risk Assessment & Parameter Screening: Use an Ishikawa (fishbone) diagram to brainstorm potential factors affecting method performance. Select the most likely CMPs for initial screening (e.g., X1: initial %B, X2: final %B, X3: flow rate, X4: column temperature) [26].

- Screening Design: Execute a two-level fractional factorial design (e.g., Resolution IV) with center points to identify the most significant CMPs impacting key CMAs (e.g., resolution between critical pairs, analysis time, S/N ratio) [26].

- Optimization & Modeling: For the significant CMPs, perform a response surface methodology (RSM) design, such as a Box-Behnken Design, to model the quantitative relationships between CMPs and CMAs.

- Define the MODR: Using statistical software and Monte-Carlo simulations, calculate the probability-based design space—the combination of CMP ranges where the probability of meeting all CMA criteria is acceptably high (e.g., ≥ 95%) [26].

- Verify the MODR: Experimentally verify method performance at multiple points within the MODR, including the edges, to confirm robustness.

Protocol: Method Validation per ICH Q2(R2) and Lifecycle Management

Objective: To validate the HPLC method according to ICH Q2(R2) principles and establish a plan for ongoing lifecycle management [23].

Procedure:

- Specificity: Inject blank (mobile phase), placebo (if applicable), standard, and sample solutions. For stability-indicating methods, analyze stressed samples (e.g., acid/base, thermal, oxidative degradation) to demonstrate separation of the analyte from degradants. Use peak purity tools (PDA or MS) to confirm analyte homogeneity [13].

- Linearity and Range: Prepare a minimum of 5 concentrations spanning the defined range (e.g., from LOQ to 150% of specification). Inject each level in triplicate. Plot mean response versus concentration and perform linear regression. A correlation coefficient (R²) of ≥ 0.999 is typically expected for assays [25] [13].

- Accuracy: Spike the target analyte into the sample matrix at three levels (e.g., 50%, 100%, 150%) with a minimum of three replicates per level. Calculate the percent recovery of the known, added amount. Acceptance criteria are typically 95–105% recovery for the assay of APIs [13].

- Precision:

- Repeatability: Analyze six independent sample preparations at 100% of the test concentration. The RSD of the results should be ≤ 2.0% for the assay [13].

- Intermediate Precision: Have a second analyst repeat the repeatability study on a different day using a different instrument. The combined RSD from both analysts should meet predefined criteria.

- LOQ and LOD: Determine based on signal-to-noise ratio (e.g., S/N ≥ 10 for LOQ and ≥ 3 for LOD) or using the standard deviation of the response and the slope of the calibration curve [25].

- Lifecycle Management: Implement a procedure for continuous monitoring of system suitability test results and method performance indicators over time. Use this data for periodic method reviews. Any proposed changes to ECs must be assessed via a risk-based change management process, potentially using a Post-Approval Change Management Protocol (PACMP) [21].

Workflow and Strategy Visualization

Analytical Procedure Lifecycle Management (APLM) Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the continuous lifecycle of an analytical procedure under ICH Q14, from initial development through post-approval management.

A high-level overview of the Analytical Procedure Lifecycle, showing the interconnected stages from defining requirements to managing post-approval changes.

Analytical Quality by Design (AQbD) Implementation Logic

This diagram details the logical flow and key decision points for implementing the AQbD approach during the method development phase.

The structured process of Analytical Quality by Design, from initial risk assessment to defining a control strategy based on the established design space.

The ICH Q14 guideline provides a powerful, forward-looking framework that elevates analytical procedure development from a minimally documented exercise to a systematic, knowledge-driven endeavor. For researchers in food analysis, adopting the enhanced approach—centered on a clear ATP, QbD principles, DoE, and a proactive control strategy—facilitates the development of more robust, reliable, and adaptable HPLC methods. While the initial investment in resources and expertise may be greater, the long-term benefits of reduced method failures, greater operational flexibility, and enhanced product quality and safety are substantial [21]. Embracing the analytical procedure lifecycle management concept ensures that methods remain fit-for-purpose, supporting the consistent delivery of high-quality and safe food products.

From Theory to Practice: Developing and Applying Robust HPLC Methods in Food Analysis

High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC) is a pivotal analytical technique in food analysis research, enabling the precise separation, identification, and quantification of components in complex matrices [27]. The reliability of analytical results hinges entirely on a robust method development and validation protocol [28]. This application note provides a detailed, systematic roadmap for developing and executing a validated HPLC method tailored for food research, ensuring data integrity and regulatory compliance.

HPLC Method Development: A Step-by-Step Roadmap

Method development is a systematic process that transforms initial sample information into a optimized and robust analytical procedure.

Step 1: Define Method Objectives and Sample Analysis

The foundation of a successful method is a clear understanding of its purpose and the sample's nature.

- Method Scoping: Determine if the method is for potency testing (quantification of a major component) or purity determination (stability-indicating method for separating multiple analytes and impurities) [29]. This decision influences the choice of template (isocratic vs. gradient) and the required peak capacity [29].

- Sample Characterization: Identify the sample matrix (e.g., powdered drink, milk, yogurt) and its properties [30]. Understand the physicochemical properties of the target analytes, including chemical structure, molecular weight, pKa, log P, solubility, and chromophores [28] [29]. This information is critical for selecting the appropriate HPLC mode, column, and detector.

Step 2: Establish Initial Conditions

Begin with a set of standard, well-understood conditions to obtain the first chromatogram.

- HPLC Mode Selection: Reversed-phase chromatography is the starting point for most food analytes due to its broad applicability [28]. It is suitable for polar, semi-polar, and non-polar molecules.

- Column Selection: Start with a C18 bonded silica column (e.g., 150 mm or 100 mm length, 4.6 mm internal diameter, 3 or 5 µm particle size) for a good balance of efficiency, speed, and pressure [28] [31].

- Detector Selection: A Diode Array Detector (DAD) is preferred for method development as it provides spectral data for peak purity and identity confirmation [31]. For analytes without strong chromophores, consider Mass Spectrometry (MS) for superior selectivity and sensitivity [32].

- Mobile Phase and Scouting Gradient: Use a binary system: Mobile Phase A is a aqueous buffer (e.g., 10-50 mM phosphate or formate); Mobile Phase B is an organic modifier (acetonitrile or methanol) [28] [29]. Perform an initial broad scouting gradient (e.g., 5% to 100% B over 20-30 minutes) to determine the elution window and complexity of the sample [28] [29].

Table 1: Initial Method Scouting Conditions for Reversed-Phase HPLC

| Parameter | Recommended Starting Condition | Alternative Options |

|---|---|---|

| Column | C18 (150 x 4.6 mm, 5 µm) | C8, Phenyl, Cyano |

| Mobile Phase B | Acetonitrile | Methanol |

| Aqueous Buffer | Phosphate (pH 2.5-3.0) or Formate | Acetate, Trifluoroacetic Acid (TFA) |

| Flow Rate | 1.0 mL/min | 0.8 - 1.5 mL/min |

| Column Temperature | 30 °C | 25 - 40 °C |

| Detection | DAD (190-400 nm) | Fluorescence, MS, ELSD |

| Injection Volume | 10-20 µL | <5% of column void volume |

Step 3: Optimize Selectivity and Resolution

This is the most critical and iterative phase, aimed at achieving baseline resolution for all analytes of interest.

- Optimize Mobile Phase Composition: Adjust the pH of the aqueous buffer to manipulate the ionization state of acidic or basic analytes, significantly altering retention and selectivity [28] [31]. Vary the organic modifier ratio (isocratically or via a refined gradient program) to fine-tune elution strength [31].

- Systematic Optimization with DoE: Employ a Box-Behnken Design (BBD) to efficiently optimize multiple factors simultaneously. Key variables often include the initial and final percentage of organic modifier (%B) and the mobile phase pH [31]. Use Response Surface Methodology (RSM) and multi-response Desirability Functions to find the optimal conditions that maximize resolution (Rs > 1.5) and minimize analysis time [31].

- Column Chemistry Screening: If mobile phase optimization is insufficient, screen different column chemistries (e.g., C8, phenyl, cyano, polar-embedded) to exploit different selectivity mechanisms [30] [29].

Step 4: Finalize System Parameters

Once satisfactory selectivity is achieved, fine-tune the method for speed and practicality.

- Adjust Flow Rate and Temperature: Slight increases in flow rate or temperature can reduce analysis time and backpressure without compromising resolution [28].

- Scale to UHPLC: For higher throughput, transfer the method to an Ultra-High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (UHPLC) system using sub-2 µm particles and compatible hardware [33].

The following workflow diagram summarizes the method development process:

Experimental Protocol: Method Optimization Using a Box-Behnken Design

This protocol details the optimization of an HPLC-DAD method for separating seven food additives and caffeine in powdered drinks, as demonstrated in the literature [31].

Materials and Reagents

- Analytical Standards: Acesulfame potassium, benzoic acid, sorbic acid, sodium saccharin, tartrazine, caffeine, sunset yellow, aspartame.

- Solvents: HPLC-grade methanol, potassium dihydrogen phosphate, dipotassium hydrogen phosphate.

- Equipment: HPLC system with binary pump, autosampler, thermostatted column compartment, and DAD. Column: Shim-Pac GIST C18 (150 mm × 4.6 mm, 5 µm) or equivalent.

Experimental Design and Execution

- Factor Selection: Identify the critical factors significantly impacting separation. For this method:

- x1: %Methanol in phosphate buffer at the start of the gradient (e.g., 0-10%).

- x2: %Methanol in phosphate buffer at the end of the gradient (e.g., 60-100%).

- x3: pH of the mobile phase (e.g., 3-7).

- BBD Setup: Construct a BBD with the three factors at three levels each (-1, 0, +1), resulting in 15 experimental runs, including three center points for estimating error.

- Execution: Prepare the mobile phases and standard mixture according to the 15 conditions specified by the BBD. Perform the HPLC analyses, monitoring at 210 nm to observe all peaks.

- Response Measurement: For each chromatogram, record the critical resolution (Rs) between the least-resolved peak pair and the total analysis time.

Data Analysis and Multi-Response Optimization

- Model Fitting: Use RSM to fit a quadratic model for each response (resolution and analysis time).

- Desirability Function: Apply a desirability function (DF) to simultaneously optimize both responses. The goal is to maximize resolution (Rs > 1.5) and minimize analysis time.

- Prediction and Verification: The software will predict the optimal factor settings. Prepare the mobile phase at these predicted conditions (e.g., 8.5% methanol at start, 90% at end, pH 6.7) and perform a verification run to confirm the predicted chromatographic performance.

HPLC Method Validation Protocol

After development, the method must be validated to confirm it is fit for purpose, following ICH Q2(R1) guidelines [27] [12].

Validation Parameters and Acceptance Criteria

Table 2: Key HPLC Method Validation Parameters and Typical Acceptance Criteria for Food Analysis

| Validation Parameter | Definition | Experimental Procedure & Acceptance Criteria |

|---|---|---|

| Specificity/Selectivity | Ability to assess analyte unequivocally in the presence of matrix. | Inject blank matrix and standard. No interference at analyte retention time. Confirm with peak purity tools (DAD/MS) [27]. |

| Linearity & Range | Ability to obtain results proportional to analyte concentration. | Analyze ≥5 concentration levels. Correlation coefficient R² ≥ 0.999. Residuals randomly scattered [5] [12]. |

| Accuracy | Closeness between accepted reference value and found value. | Spike recovery at 80%, 100%, 120% of target level. Mean recovery 98–102% [32] [12]. |

| Precision | Closeness of agreement between a series of measurements. | Repeatability: 6 injections of one preparation, RSD < 1%. Intermediate Precision: Different day/analyst, RSD < 2% [5] [27]. |

| LOD / LOQ | Lowest detectable/quantifiable amount of analyte. | LOD = 3.3 × (SD of response/slope). LOQ = 10 × (SD of response/slope). Or S/N ≥ 3 for LOD, ≥10 for LOQ [27] [12]. |

| Robustness | Capacity to remain unaffected by small, deliberate parameter variations. | Deliberately vary flow rate (±0.1 mL/min), temp (±2°C), mobile phase pH (±0.1). System suitability criteria must still be met [27] [31]. |

System Suitability Testing

Prior to validation runs and daily use, perform system suitability testing to ensure the HPLC system is performing adequately. Parameters include plate count (N), tailing factor (T), repeatability (RSD of peak area), and resolution (Rs) between critical pairs, measured against predefined specifications [27].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Key Reagents and Materials for HPLC Method Development and Validation in Food Analysis

| Item | Function / Application | Notes for Selection |

|---|---|---|

| C18 Chromatographic Column | Reversed-phase separation of a wide range of food analytes. | The default choice; consider particle size (3-5 µm), pore size (80-120 Å), and endcapping for basic compounds [5] [28]. |

| Solid Phase Extraction (SPE) Cartridges (e.g., C18) | Sample clean-up and pre-concentration; reducing matrix effects in complex foods (yogurt, milk). | Critical for removing proteins and fats. C18 is common for medium to non-polar analytes [32] [7]. |

| Supported Liquid Extraction (SLE) Cartridges | Matrix removal for aqueous samples (e.g., milk, fruit juice). | Prevents emulsion formation, offers high reproducibility and efficient extraction of contaminants like alkylphenols [7]. |

| Acetonitrile & Methanol (HPLC Grade) | Organic modifiers in the mobile phase for reversed-phase HPLC. | Acetonitrile offers lower viscosity and UV cutoff; methanol offers different selectivity and is less expensive [28]. |

| Ammonium Formate/Acetate, Phosphate Salts | Preparation of buffered aqueous mobile phases to control pH and ionic strength. | Volatile buffers (formate/acetate) are required for LC-MS. Phosphate buffers offer wider pH range but are not MS-compatible [32] [31]. |

This application note provides a comprehensive roadmap for developing and validating reliable HPLC methods for food analysis. By adhering to this structured protocol—from careful planning and systematic optimization to rigorous validation—researchers can ensure the generation of accurate, precise, and defensible data. This structured approach is fundamental to advancing research in food safety, quality, and composition, ultimately supporting public health and regulatory compliance.