A Comprehensive Guide to Antioxidant Capacity Assays: Comparison, Applications, and Best Practices for Biomedical Research

This article provides a systematic comparison of antioxidant capacity measurement assays for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals.

A Comprehensive Guide to Antioxidant Capacity Assays: Comparison, Applications, and Best Practices for Biomedical Research

Abstract

This article provides a systematic comparison of antioxidant capacity measurement assays for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals. It explores the fundamental mechanisms of common assays including DPPH, TEAC, FRAP, ORAC, and CUPRAC, detailing their reaction principles and appropriate applications. The content addresses methodological considerations for different sample types, troubleshooting for common limitations, and validation strategies through multi-assay correlation studies. By synthesizing current research trends and comparative data, this guide supports informed assay selection and interpretation for reliable antioxidant assessment in pharmaceutical development, functional food analysis, and clinical research.

Understanding Antioxidant Mechanisms: From Free Radical Chemistry to Assay Principles

Free radicals, characterized by the presence of unpaired electrons, are highly reactive molecules that play a significant dual role in human physiology and pathology [1]. These molecules, primarily comprising reactive oxygen species (ROS) and reactive nitrogen species (RNS), are generated through endogenous metabolic processes and exogenous environmental sources [2]. At moderate concentrations, free radicals function as crucial signaling molecules regulating vascular tone, immune function, and cellular homeostasis [3] [1]. However, excessive production overwhelms antioxidant defenses, leading to oxidative stress—a state of redox imbalance that damages lipids, proteins, and DNA [1]. This oxidative damage represents a common pathogenic mechanism in numerous diseases, including cancer, neurodegenerative disorders, cardiovascular conditions, and diabetes [2] [1]. The accurate assessment of antioxidant capacity through various biochemical assays is therefore critical for understanding oxidative stress pathology and developing therapeutic interventions [4] [5].

Fundamentals of Free Radicals and Oxidative Stress

Characteristics and Types of Free Radicals

Free radicals are atoms or molecules containing one or more unpaired electrons in their outermost valence shell, rendering them highly unstable and reactive [2] [1]. This unpaired electron drives free radicals to seek stability by donating or accepting electrons from other molecules, often initiating chain reactions that propagate cellular damage [1]. The most biologically significant free radicals include both ROS and RNS, which can be further classified as radical or non-radical species (Table 1) [2].

Table 1: Major Reactive Oxygen and Nitrogen Species

| Category | Species | Symbol | Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|

| ROS Radicals | Superoxide | O₂•⁻ | Precursor to most ROS; relatively low reactivity |

| Hydroxyl | •OH | Most reactive ROS; damages all biomolecules | |

| Peroxyl | ROO• | Initiates lipid peroxidation chains | |

| ROS Non-Radicals | Hydrogen Peroxide | H₂O₂ | Stable but generates •OH via Fenton reaction |

| Singlet Oxygen | ¹O₂ | Electrically excited oxygen molecule | |

| RNS Radicals | Nitric Oxide | NO• | Key signaling molecule; forms peroxynitrite |

| Nitrogen Dioxide | NO₂• | Potent oxidizing agent | |

| RNS Non-Radicals | Peroxynitrite | ONOO⁻ | Powerful oxidant from NO• and O₂•⁻ reaction |

Free radicals originate from both internal metabolic processes and external environmental exposures [3] [2]:

Mitochondrial Respiration: The electron transport chain represents the primary endogenous source, with complexes I and III being major sites of superoxide production due to electron leakage during oxidative phosphorylation [3]. Under physiological conditions, approximately 0.2-2% of electrons leak from the transport chain, generating O₂•⁻ [3].

Enzymatic Reactions: Various cellular enzymes produce free radicals as part of their normal catalytic cycles, including cytochrome P450 systems, xanthine oxidase, lipoxygenase, cyclooxygenase, and NADPH oxidases [2] [1].

Immune Cell Activation: Phagocytic cells such as macrophages and neutrophils generate superoxide and other ROS during the "respiratory burst" to destroy pathogens [1].

Exogenous Sources: Environmental factors including ultraviolet radiation, ionizing radiation, air pollutants, tobacco smoke, industrial chemicals, pesticides, and certain medications (e.g., paracetamol, halothane) significantly contribute to free radical load [2] [6].

Molecular Targets and Pathological Consequences

Oxidative stress occurs when ROS/RNS production exceeds the capacity of cellular antioxidant defenses, leading to damage of critical biological macromolecules [1]:

Lipid Peroxidation: Free radicals, particularly hydroxyl and peroxyl radicals, attack polyunsaturated fatty acids in cell membranes, initiating a chain reaction of lipid peroxidation [1]. This process compromises membrane integrity, fluidity, and function, while generating reactive aldehyde byproducts like malondialdehyde (MDA) and 4-hydroxynonenal (4-HNE) that can form protein adducts and propagate damage [1].

Protein Oxidation: Reactive species modify amino acid side chains (especially cysteine and methionine residues), cause protein-protein crosslinks, and fragment peptide backbones [1]. These modifications alter enzymatic activity, disrupt cellular signaling, and impair structural proteins, contributing to cellular dysfunction [1].

DNA Damage: The hydroxyl radical is particularly destructive to DNA, causing strand breaks, base modifications (e.g., 8-hydroxydeoxyguanosine), and DNA-crosslinks [1]. If unrepaired, these lesions promote mutations, genomic instability, and can initiate carcinogenesis [2] [1].

The cumulative damage to these biomolecules is implicated in the pathogenesis of numerous chronic conditions, including atherosclerosis, neurodegenerative diseases (Alzheimer's, Parkinson's), cancer, diabetes, rheumatoid arthritis, and the aging process itself [2] [1] [6].

Comparative Analysis of Antioxidant Capacity Assays

Understanding the methodology and limitations of antioxidant capacity assays is essential for interpreting experimental data and selecting appropriate assessment tools. These assays employ different mechanisms, including hydrogen atom transfer (HAT), single electron transfer (ET), and mixed approaches [7].

Table 2: Comparison of Major Antioxidant Capacity Assays

| Assay | Mechanism | Oxidant/Indicator | Redox Potential (E°') | Key Applications | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ABTS•+ Decolorization | ET (Primary) | ABTS•+ | 0.68 V [4] | Total antioxidant capacity of plant extracts, beverages, biological fluids [8] | Non-physiological radical; reaction pathways vary by antioxidant type [8] |

| DPPH | ET | DPPH• | 0.537 V [4] | Screening radical scavenging activity of pure compounds and extracts [9] | Limited solubility in aqueous systems; steric accessibility issues [9] |

| FRAP | ET | Fe³⁺-TPTZ | ~0.70 V [4] | Reducing capacity of antioxidants in acidic conditions [4] | Non-physiological pH; does not measure radical quenching capacity [4] |

| ORAC | HAT | Peroxyl radicals | 0.77-1.44 V [4] | Chain-breaking antioxidant capacity against peroxyl radicals [4] | More complex procedure; discontinued commercial kits affect standardization [4] |

| CUPRAC | ET | Cu²⁺-Nc | 0.59 V [4] | Wider pH applicability than FRAP; sensitive to thiols and peptides [4] | Limited correlation with some phenolic antioxidants [4] |

Thermodynamic and Kinetic Considerations in Assay Selection

The redox potential of the oxidant/indicator system fundamentally determines which antioxidants can participate in the reaction, as the thermodynamic condition requires that the oxidant must have a higher redox potential than the antioxidant [4]. However, recent research demonstrates that kinetic factors often play a more significant role in determining measured antioxidant activities than thermodynamic considerations alone [4]. For instance, a 2025 study found no regular dependence between measured total antioxidant capacity of garlic extract and the redox potential of oxidants/indicators across nine different assays, with the highest values observed in the ABTS•+ decolorization test despite its intermediate redox potential [4].

This complexity underscores the importance of selecting multiple complementary assays when evaluating antioxidant capacity, as no single method provides a comprehensive picture of antioxidant activity in complex biological systems or food matrices [5] [9]. The strong correlation between FRAP values and total polyphenol content (r = 0.913) compared to DPPH (r = 0.772) further highlights how assay selection influences results and their interpretation [9].

Experimental Protocols for Key Antioxidant Assays

ABTS Radical Cation Decolorization Assay

The ABTS assay is among the most widely used methods for determining total antioxidant capacity due to its simplicity, reproducibility, and applicability to both hydrophilic and lipophilic compounds [8].

Reagent Preparation:

- ABTS•+ Stock Solution: Dissolve ABTS in water or buffer to a final concentration of 7 mM.

- Oxidant Solution: Prepare potassium persulfate (K₂S₂O₈) at 2.45 mM final concentration.

- Radical Generation: Mix equal volumes of ABTS and potassium persulfate solutions and allow the reaction to proceed in darkness for 12-16 hours at room temperature to generate the ABTS•+ radical cation. The resulting solution exhibits an intense blue-green color with characteristic absorption maxima at 414, 645, 734, and 815 nm [8].

- Working Solution: Dilute the ABTS•+ stock solution with buffer (typically phosphate-buffered saline, pH 7.4) to an absorbance of 0.70 (±0.02) at 734 nm.

Procedure:

- Add appropriate aliquots of standard (typically Trolox) or sample to the ABTS•+ working solution.

- Incubate the reaction mixture for exactly 4-6 minutes at 30°C.

- Measure the absorbance decrease at 734 nm against a blank (buffer instead of sample).

- Calculate antioxidant capacity relative to Trolox standard curve and express as Trolox Equivalents (TE) [8].

Reaction Mechanism: The assay primarily follows an electron transfer mechanism where antioxidants reduce the colored ABTS•+ to its colorless neutral form. However, specific antioxidants, particularly phenolics, may also form coupling adducts with ABTS•+, leading to more complex reaction pathways than simple decolorization [8].

Ferric Reducing Antioxidant Power (FRAP) Assay

The FRAP assay measures the reducing capacity of antioxidants based on their ability to reduce ferric ions (Fe³⁺) to ferrous ions (Fe²⁺) [4].

Reagent Preparation:

- Acetate Buffer: 300 mM, pH 3.6.

- TPTZ Solution: 10 mM 2,4,6-tripyridyl-s-triazine in 40 mM HCl.

- Ferric Chloride: 20 mM FeCl₃·6H₂O solution.

- FRAP Working Solution: Mix acetate buffer, TPTZ solution, and FeCl₃ solution in a 10:1:1 ratio (v/v/v). This solution should be prepared fresh and warmed to 37°C before use.

Procedure:

- Add sample or standard to FRAP working solution.

- Incubate at 37°C for 4-10 minutes.

- Measure absorbance increase at 593 nm against a reagent blank.

- Calculate FRAP values using a FeSO₄·7H₂O or Trolox standard curve [4].

Oxygen Radical Absorbance Capacity (ORAC) Assay

The ORAC assay measures the ability of antioxidants to inhibit peroxyl radical-induced oxidation through a hydrogen atom transfer mechanism, more closely mimicking biological radical chain reactions [4].

Reagent Preparation:

- Fluorescein Solution: Prepare 70 nM fluorescein in phosphate buffer (75 mM, pH 7.4).

- AAPH Solution: Prepare 153 mM 2,2'-azobis(2-amidinopropane) dihydrochloride as peroxyl radical generator.

- Trolox Standards: Prepare fresh Trolox solutions in concentration range of 0-50 μM.

Procedure:

- Mix fluorescein solution with sample or standard in wells.

- Pre-incubate for 15 minutes at 37°C.

- Rapidly add AAPH solution to initiate reaction.

- Monitor fluorescence decay (excitation 485 nm, emission 520 nm) every 1-2 minutes for 60-90 minutes.

- Calculate area under curve (AUC) and compute ORAC values relative to Trolox standard curve [4].

Visualizing Free Radical Pathways and Antioxidant Mechanisms

Free Radical Formation and Cellular Impact

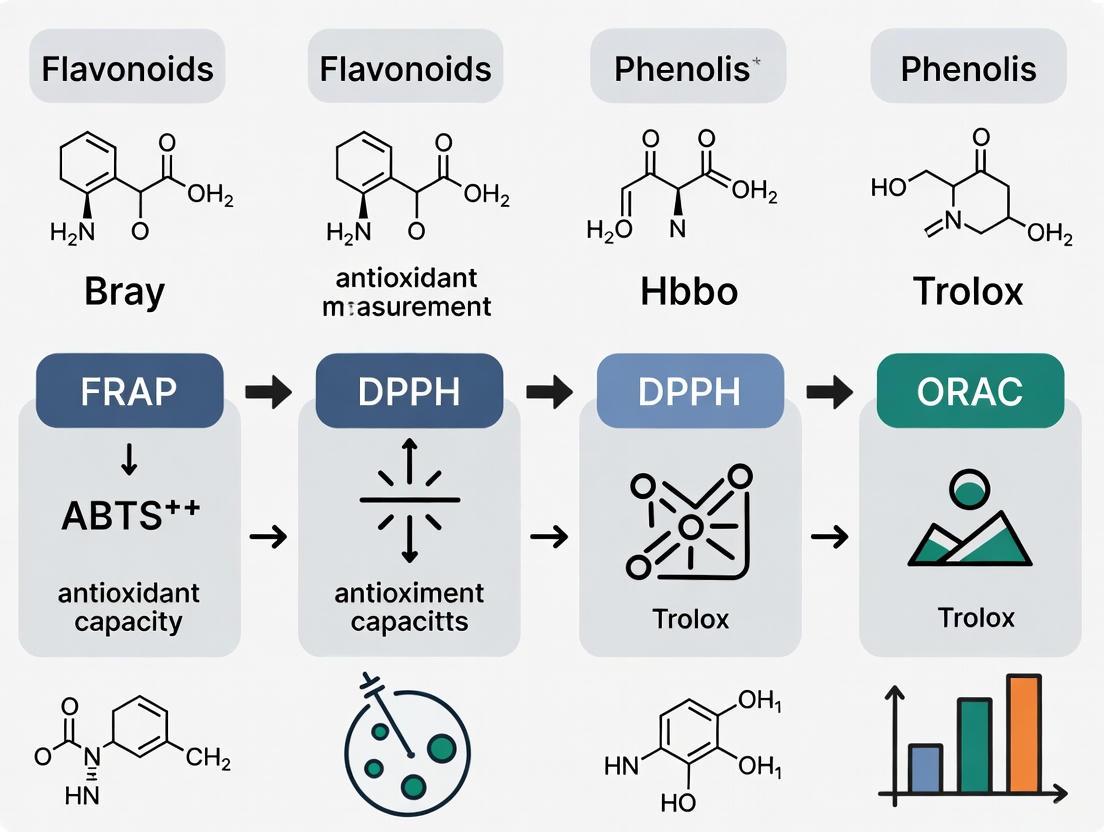

Antioxidant Capacity Assessment Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Reagents for Antioxidant Capacity Assessment

| Reagent | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| ABTS (2,2'-Azino-bis-3-ethylbenzthiazoline-6-sulfonic acid) | Chromogenic substrate oxidized to ABTS•+ radical cation | Stable radical with absorption maxima at 734 nm; works at physiological pH [8] |

| DPPH (2,2-Diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl) | Stable free radical dissolved in organic solvents | Deep purple color (λmax = 517 nm); limited use in aqueous systems [9] |

| TPTZ (2,4,6-Tripyridyl-s-triazine) | Chromogenic chelator for ferrous ions | Forms blue Fe²⁺-TPTZ complex (λmax = 593 nm) in FRAP assay [4] |

| Trolox (6-Hydroxy-2,5,7,8-tetramethylchroman-2-carboxylic acid) | Water-soluble vitamin E analog | Standard reference compound for TEAC expression [4] [8] |

| Fluorescein | Fluorescent probe in ORAC assay | Fluorescence decay monitored during peroxyl radical attack [4] |

| AAPH (2,2'-Azobis-2-amidinopropane dihydrochloride) | Peroxyl radical generator | Thermally decomposes to produce peroxyl radicals at constant rate [4] |

| Neocuproine (2,9-Dimethyl-1,10-phenanthroline) | Chelator for cuprous ions in CUPRAC assay | Forms yellow-orange Cu⁺-neocuproine complex (λmax = 450 nm) [4] |

| Potassium Persulfate | Oxidizing agent for ABTS•+ generation | Converts ABTS to ABTS•+ radical cation overnight [8] |

The biology of oxidative stress encompasses complex interactions between free radical generation, cellular damage pathways, and antioxidant defense mechanisms. The accurate assessment of antioxidant capacity through multiple complementary assays provides crucial insights into oxidative stress-related pathophysiology and potential therapeutic interventions. While ABTS, FRAP, DPPH, and ORAC represent the most widely employed methods, each approach possesses distinct mechanistic principles, advantages, and limitations that researchers must consider when designing experiments and interpreting results. The continued refinement of these assessment methods and their correlation with biological outcomes remains essential for advancing our understanding of oxidative stress in human health and disease.

Living organisms continuously produce reactive oxygen species (ROS) and reactive nitrogen species (RNS) as byproducts of normal cellular metabolism, particularly during processes such as mitochondrial respiration and immune cell activation [10] [1]. While these reactive species play crucial roles in cell signaling and pathogen defense, their overproduction leads to oxidative stress, a state characterized by an imbalance between oxidants and antioxidants that results in molecular damage [10] [1]. This damage includes lipid peroxidation of cell membranes, oxidation of proteins, and DNA mutation, which can ultimately lead to cellular dysfunction and is implicated in the pathogenesis of numerous chronic diseases including cancer, neurodegenerative disorders, cardiovascular diseases, and diabetes [11] [10] [1].

To counteract this threat, organisms have evolved sophisticated antioxidant defense systems comprising both enzymatic and non-enzymatic components that work synergistically to neutralize reactive species [12] [10] [13]. These systems provide a multi-layered defense strategy: the first line prevents radical formation, the second line scavenges and inactivates existing radicals, and the third line repairs resulting damage [14]. Understanding the classification, mechanisms, and interplay of these antioxidant systems is fundamental for research aimed at mitigating oxidative stress-related pathologies.

Classification of Antioxidants

Antioxidants can be broadly categorized based on their mode of action (enzymatic vs. non-enzymatic) and origin (endogenous vs. exogenous). This classification reflects the complex, multi-faceted defense network that organisms utilize to maintain redox homeostasis [12] [14] [13].

Table 1: Comprehensive Classification of Antioxidant Systems

| Category | Sub-category | Key Components | Primary Function/Location |

|---|---|---|---|

| Enzymatic Antioxidants | Primary Defense Enzymes | Superoxide Dismutase (SOD), Catalase (CAT), Glutathione Peroxidase (GPx) | Catalyze the conversion of ROS into less harmful molecules; various cellular compartments including cytosol, mitochondria, and peroxisomes [11] [12] [13] |

| Supportive Enzymes | Glutathione Reductase (GR), Dehydroascorbate Reductase (DHAR) | Regenerate reduced forms of other antioxidants (e.g., glutathione and ascorbate) to maintain antioxidant capacity [11] [12] | |

| Non-Enzymatic Antioxidants | Endogenous (Produced by the body) | Glutathione (GSH), Uric Acid, Melatonin, Bilirubin, Albumin, Metal-binding proteins (Ferritin, Transferrin, Ceruloplasmin) | Act as direct scavengers of free radicals, chelate pro-oxidant metal ions, and serve as crucial components of the plasma antioxidant capacity [14] |

| Exogenous (Obtained from diet) | Vitamin C (Ascorbate), Vitamin E (Tocopherols), Carotenoids (e.g., β-carotene), Polyphenols (e.g., Flavonoids, Phenolic acids) | Scavenge free radicals in aqueous and lipid phases, respectively; often work synergistically to regenerate other antioxidants [12] [15] |

Enzymatic Antioxidants

Enzymatic antioxidants constitute the body's primary defense mechanism, catalyzing the conversion of reactive species into less harmful products [12] [13].

- Superoxide Dismutase (SOD): SOD is the first line of defense against ROS, catalyzing the dismutation (or partitioning) of the superoxide anion (O₂•⁻) into hydrogen peroxide (H₂O₂) and molecular oxygen (O₂) [13] [1]. This reaction is crucial because it neutralizes the superoxide radical, which is a precursor to more damaging ROS.

- Catalase (CAT): This enzyme, predominantly located in cellular peroxisomes, catalyzes the conversion of hydrogen peroxide into water and molecular oxygen [13]. CAT has one of the highest turnover rates of all enzymes and is particularly effective at degrading high concentrations of H₂O₂ [13].

- Glutathione Peroxidase (GPx): GPx is a key enzyme that reduces hydrogen peroxide and lipid hydroperoxides to water and corresponding alcohols, respectively. This process oxidizes glutathione (GSH) to glutathione disulfide (GSSG) [11] [13]. The reaction is critical for protecting cell membranes from lipid peroxidation.

- Supportive Enzymes: Enzymes like Glutathione Reductase (GR) play an essential supporting role by recycling oxidized glutathione (GSSG) back to its reduced, active form (GSH) using NADPH as a cofactor, thereby maintaining the cellular redox balance [11] [13].

Non-Enzymatic Antioxidants

This category includes a diverse array of small molecules that function as direct scavengers of free radicals, metal chelators, or partners in regenerative cycles [14] [15].

Endogenous Non-Enzymatic Antioxidants: These are synthesized within the body.

- Glutathione (GSH): Often referred to as the "master antioxidant," GSH is a tripeptide thiol present in high concentrations in most cells. It directly neutralizes ROS, serves as a cofactor for GPx, and helps regenerate other antioxidants like vitamins C and E [11] [14].

- Uric Acid, Melatonin, and Bilirubin: Once considered mere waste products, these molecules are now recognized for their significant antioxidant properties, including scavenging various ROS and RNS [14].

- Metal-Binding Proteins (MBPs): Proteins such as albumin, ceruloplasmin, ferritin, and transferrin inhibit the formation of highly reactive hydroxyl radicals by sequestering free iron and copper ions, thereby preventing them from participating in Fenton reactions [14].

Exogenous Non-Enzymatic Antioxidants: These are obtained from the diet and are vital for maintaining and boosting the body's defense system.

- Vitamin C (Ascorbic Acid): A water-soluble vitamin that acts as a potent scavenger of a wide range of ROS in aqueous environments. It also plays a key role in regenerating vitamin E from its oxidized form in membranes [15].

- Vitamin E (α-Tocopherol): The major lipid-soluble antioxidant in cell membranes, it protects polyunsaturated fatty acids from lipid peroxidation by donating a hydrogen atom to lipid peroxyl radicals [15].

- Polyphenols and Carotenoids: A large class of plant-derived compounds with potent antioxidant and anti-inflammatory activities. They function primarily as free radical scavengers due to their favorable chemical structure [12] [15].

The synergistic relationship between these components is fundamental to an effective antioxidant network. For instance, the ascorbate-glutathione cycle is a key metabolic pathway in plants and animals for the detoxification of H₂O₂, demonstrating how non-enzymatic antioxidants and enzymes work in concert [11] [12].

Figure 1: Antioxidant Defense Network. This diagram illustrates the interplay between oxidative stress triggers, the major classes of enzymatic and non-enzymatic antioxidants, and the resulting cellular outcome of redox homeostasis.

Measurement of Antioxidant Capacity: A Comparison of Key Assays

Evaluating the antioxidant capacity of compounds and biological samples is a cornerstone of redox biology research. Multiple in vitro assays have been developed, each based on distinct principles and mechanisms. The choice of assay is critical, as different methods can yield varying results for the same sample due to differences in underlying reaction mechanisms, redox potentials, and kinetic factors [4] [16].

The most widely used assays can be grouped based on their primary mechanism of action:

- Electron Transfer (ET)-Based Assays: These methods measure the ability of an antioxidant to reduce an oxidant, which is accompanied by a color change. Examples include the Folin-Ciocalteu assay (for total phenolics), Ferric Reducing Antioxidant Power (FRAP), and Cupric Ion Reducing Antioxidant Capacity (CUPRAC) [4] [17].

- Hydrogen Atom Transfer (HAT)-Based Assays: These methods quantify the ability of an antioxidant to donate a hydrogen atom to quench a free radical. A key example is the Oxygen Radical Absorbance Capacity (ORAC) assay [4] [16].

- Mixed-Mode (ET/HAT) Assays: Some assays, like the Trolox Equivalent Antioxidant Capacity (TEAC) assay using the 2,2'-azinobis(3-ethylbenzothiazoline-6-sulfonate) radical (ABTS•), can involve both mechanisms [4].

- Cellular and In Vivo Assays: More complex models, including cell cultures and animal studies, measure the impact of antioxidants on biomarkers of oxidative stress such as malondialdehyde (MDA) for lipid peroxidation, 8-hydroxy-2'-deoxyguanosine (8-OHdG) for DNA damage, and the activity of endogenous antioxidant enzymes like SOD and CAT [16] [1].

Table 2: Comparison of Key In Vitro Antioxidant Capacity Assays

| Assay Name | Mechanism | Key Reagents & Reaction | Common Output | Advantages & Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ABTS•+ Decolorization Assay | Mixed (ET/HAT) | ABTS•+ radical (blue) is reduced to colorless ABTS by antioxidants [4]. | Trolox Equivalents (TE) | Advantage: Rapid, simple, applicable to both hydrophilic and lipophilic antioxidants [4].Limitation: Not biologically relevant [16]. |

| Oxygen Radical Absorbance Capacity (ORAC) | HAT | Antioxidant competes with a fluorescent probe to scavenge peroxyl radicals (ROO•) generated from AAPH [4] [16]. | Trolox Equivalents (TE) | Advantage: Biologically relevant radical source; accounts for reaction kinetics [16].Limitation: More time-consuming and complex than ET-based assays [16]. |

| Ferric Reducing Antioxidant Power (FRAP) | ET | Antioxidants reduce yellow Fe³⁺-TPTZ complex to blue Fe²⁺-TPTZ at low pH [4]. | Trolox or Fe²⁺ Equivalents | Advantage: Simple, rapid, and inexpensive [4].Limitation: Non-physiological pH; ignores HAT-based antioxidants [4]. |

| Cupric Ion Reducing Antioxidant Capacity (CUPRAC) | ET | Antioxidants reduce Cu²⁺ to Cu⁺, which forms a complex with neocuproine, producing a yellow color [4]. | Trolox Equivalents (TE) | Advantage: Works at physiological pH; applicable to many antioxidant types [4]. |

| Folin-Ciocalteu (FC) Assay | ET | Reduces phosphomolybdic/phosphotungstic acid complexes in the FC reagent, producing a blue color [17]. | Gallic Acid Equivalents (GAE) | Advantage: Standard for estimating total phenolic content [17].Limitation: Measures reducing capacity, not specific radical scavenging [17]. |

Experimental Protocol for Key Assays

To ensure reproducibility, standardized protocols must be followed. Below is a generalized workflow for two commonly used assays.

Protocol 1: ABTS Radical Cation (ABTS•+) Decolorization Assay [4]

- Stock Solution Preparation: Generate the ABTS•+ radical cation by reacting ABTS solution (e.g., 7 mM) with potassium persulfate (e.g., 2.45 mM final concentration). Allow the mixture to stand in the dark at room temperature for 12-16 hours before use.

- Working Solution Preparation: Dilute the stock ABTS•+ solution with a suitable buffer (e.g., phosphate buffered saline, PBS, pH 7.4) to an absorbance of 0.70 (±0.02) at 734 nm.

- Sample Analysis: Mix a known volume of the antioxidant sample (or standard, e.g., Trolox) with the ABTS•+ working solution.

- Incubation and Measurement: Allow the reaction to proceed for a fixed time (e.g., 6 minutes) in the dark.

- Data Calculation: Measure the decrease in absorbance at 734 nm. Plot a standard curve of the percentage inhibition of absorbance vs. Trolox concentration and express the results as micromoles of Trolox Equivalents (TE) per gram of sample or liter of fluid.

Protocol 2: Oxygen Radical Absorbance Capacity (ORAC) Assay [4] [16]

- Reagent Preparation: Prepare a fluorescein stock solution and a source of peroxyl radicals, commonly 2,2'-azobis(2-amidinopropane) dihydrochloride (AAPH).

- Plate Setup: In a microplate, combine fluorescein (as the target molecule), the antioxidant sample or Trolox standard, and AAPH (as the peroxyl radical generator).

- Kinetic Reading: Immediately place the plate in a fluorescence microplate reader preheated to 37°C. Monitor the fluorescence (excitation ~485 nm, emission ~520 nm) every 1-2 minutes until it decays to less than 5% of the initial reading.

- Data Analysis: Calculate the area under the fluorescence decay curve (AUC) for each well. The net AUC (AUCsample - AUCblank) is used to calculate the ORAC value, expressed as Trolox Equivalents, based on the linear regression of the standard curve.

Figure 2: Experimental Workflow for Antioxidant Capacity Assays. This flowchart outlines the general decision-making process and key steps involved in performing three major types of antioxidant capacity assays.

Comparative Data from Research Studies

The variability in results obtained from different assays for the same compound underscores the importance of method selection. Research has demonstrated that the measured antioxidant activity is highly dependent on the assay's specific reaction mechanism and conditions [4].

Table 3: Measured Antioxidant Activity of Selected Compounds Across Different Assays (in mol Trolox Equivalents/mol compound) [4]

| Antioxidant | ABTS•+ Decolorization | ORAC | FRAP | Fe(III)-Phenanthroline Reduction |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gallic Acid | 4.07 ± 0.23 | 1.05 ± 0.09 | 2.16 ± 0.14 | 3.11 ± 0.22 |

| Ascorbic Acid | 1.08 ± 0.09 | 0.50 ± 0.04 | 1.03 ± 0.12 | 0.81 ± 0.06 |

| Glutathione (GSH) | 1.30 ± 0.19 | 0.42 ± 0.05 | 0.03 ± 0.05 | 0.006 ± 0.011 |

| NADH | 0.77 ± 0.05 | 0.32 ± 0.02 | 1.51 ± 0.09 | 0.30 ± 0.04 |

Data adapted from a 2025 study comparing assays with oxidants/indicators of different redox potentials [4]. Note the high activity of Gallic Acid in ABTS and FRAP assays, and the relatively low activity of GSH in FRAP and Fe(III)-Phenanthroline assays compared to its performance in the ABTS assay.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents and Materials

Successful research in antioxidant defense systems relies on a well-equipped toolkit. The following table details essential reagents, materials, and instruments used in the field, particularly for the assays described in this guide.

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Antioxidant Studies

| Category | Item | Primary Function in Research |

|---|---|---|

| Chemical Reagents & Kits | ABTS (2,2'-azinobis(3-ethylbenzothiazoline-6-sulfonate)) | Generation of the stable radical cation (ABTS•+) for the TEAC antioxidant assay [4]. |

| Trolox (6-hydroxy-2,5,7,8-tetramethylchroman-2-carboxylic acid) | Water-soluble vitamin E analog used as a standard reference compound in many antioxidant capacity assays (ABTS, ORAC, etc.) [4]. | |

| AAPH (2,2'-azobis(2-amidinopropane) dihydrochloride) | A water-soluble azo compound used as a source of thermally generated peroxyl radicals in the ORAC assay [4] [16]. | |

| Folin-Ciocalteu Reagent | A mixture of phosphomolybdic and phosphotungstic acids used to quantify total phenolic content via a reduction reaction [17]. | |

| FRAP Reagent (Fe³⁺-TPTZ complex) | Pre-formed complex that changes color upon reduction by antioxidants, used in the FRAP assay [4]. | |

| Neocuproine (2,9-dimethyl-1,10-phenanthroline) | A specific chelator for Cu⁺ ions, used as a chromogenic oxidizing agent in the CUPRAC assay [4]. | |

| Biochemicals & Standards | Reduced Glutathione (GSH) | Key endogenous antioxidant; studied for its direct scavenging activity and as a component of the GPx enzyme system [11] [4]. |

| Enzymes (SOD, CAT, GPx) | Purified enzymes used as standards in activity assays or as targets in inhibition studies [11] [13]. | |

| Biomarker Assay Kits (e.g., for MDA, 8-OHdG) | Commercial kits for standardized colorimetric or fluorometric measurement of oxidative stress biomarkers like malondialdehyde (MDA) and 8-hydroxy-2'-deoxyguanosine (8-OHdG) [1]. | |

| Laboratory Equipment | UV-Vis Spectrophotometer / Microplate Reader | Essential instrument for measuring color changes or absorbance in assays like ABTS, FRAP, and Folin-Ciocalteu [4] [17]. |

| Fluorescence Microplate Reader | Required for kinetic assays that rely on fluorescence, such as the ORAC assay [4] [16]. | |

| Centrifuges and Sonicators | Used for sample preparation, including the extraction of antioxidants from tissues or complex matrices [17]. |

The intricate network of enzymatic and non-enzymatic antioxidants forms a vital defense system against the constant threat of oxidative damage. A clear understanding of their classification, individual mechanisms, and synergistic interactions is fundamental for researchers in biochemistry, pharmacology, and drug development. This guide has outlined the core components of this system, from primary enzymes like SOD and CAT to essential endogenous molecules like glutathione and key dietary antioxidants like vitamins C and E.

Furthermore, the comparison of antioxidant capacity measurement assays reveals a critical insight: no single method provides a complete picture. The choice of assay—whether ET-based (FRAP, CUPRAC), HAT-based (ORAC), or mixed-mode (ABTS)—profoundly influences the results and their biological interpretation [4] [16]. The scientific community increasingly recognizes the necessity of using multiple assay types to capture the diverse mechanisms of antioxidant action and to generate more physiologically relevant data. As research advances, the integration of these in vitro findings with in vivo and clinical studies will be paramount for developing effective antioxidant-based therapies to combat oxidative stress-related diseases.

Selecting and Implementing Antioxidant Assays: Protocols and Sample-Specific Applications

The measurement of antioxidant capacity is a fundamental practice in food science, pharmaceutical development, and nutritional research. Among the various methods developed to quantify this capacity, the 1,1-diphenyl-2-picrylhydrazyl (DPPH) radical scavenging assay stands as one of the most putative, popular, and commonly used techniques [18]. Its widespread adoption stems from its simplicity, cost-effectiveness, and reproducibility across diverse laboratory settings. This assay provides researchers with a straightforward approach to evaluate the free radical scavenging ability of compounds, extracts, and biological samples, making it an indispensable tool for initial antioxidant screening.

The significance of antioxidant assessment continues to grow parallel to increasing scientific understanding of oxidative stress—a physiological condition characterized by an imbalance between reactive oxygen species (ROS) and the body's antioxidant defenses [18] [16]. This imbalance contributes to the pathogenesis of numerous chronic diseases, including cancer, cardiovascular disorders, diabetes, and neurodegenerative conditions [16]. Additionally, in food and pharmaceutical systems, antioxidants play crucial roles in preventing oxidative deterioration during processing and storage, thereby extending product shelf life [18]. The DPPH assay offers researchers a valuable method to identify and quantify potential antioxidant sources, whether from synthetic or natural origins, with a growing preference toward natural antioxidants due to safety concerns regarding synthetic variants [18].

Fundamental Principles of the DPPH Assay

Chemical Properties of DPPH Radical

The DPPH radical (DPPH•) is a stable organic nitrogen radical characterized by its deep violet color in solution, which exhibits a strong absorption maximum at approximately 517 nm [19] [20]. This remarkable stability—uncommon among most free radicals—derives from the delocalization of the spare electron over the entire molecule through resonance stabilization, a phenomenon known as the "push-pull" effect exerted by the electron-donating diphenylamino group and electron-accepting picryl group [19] [20]. This resonance prevents the dimerization that typically occurs with most transient free radicals, allowing DPPH to maintain its radical character under standard laboratory conditions when protected from light [20].

The DPPH radical is soluble in various organic solvents, including methanol, ethanol, and acetone, but is nearly insoluble in water at room temperature [20]. The stability of DPPH solutions is maintained for extended periods when stored in the dark, though molecular oxygen can react slightly with DPPH in the presence of light [20]. From a chemical reactivity perspective, DPPH• selectively interacts with different chemical species: radicals typically attack the phenyl ring, while hydrogen atom donors react with the divalent nitrogen atom [20]. The steric hindrance around the nitrogen atom provided by the three aromatic rings limits the approach of bulky radicals to this reactive site, while smaller hydrogen donors can access the nitrogen to form the corresponding hydrazine (DPPH-H) [20].

Mechanism of Radical Scavenging

The core principle of the DPPH assay involves the spectrophotometric measurement of the radical's decolorization when it encounters a hydrogen-donating antioxidant substance. When an antioxidant molecule (AH) donates a hydrogen atom to DPPH•, the reduced form (DPPH-H) is produced, resulting in a loss of the characteristic violet color and a corresponding decrease in absorbance at 517 nm [19] [20]. The primary reaction can be represented as:

DPPH• + AH → DPPH-H + A•

The resulting antioxidant-derived radical (A•) may subsequently undergo further reactions that influence the overall stoichiometry [19]. The degree of discoloration directly correlates with the antioxidant's radical-scavenging efficiency and concentration [21].

The reaction mechanisms between antioxidants and DPPH radicals can proceed through different pathways, primarily influenced by the molecular structure of the antioxidant and the reaction conditions. For phenolic compounds—which constitute a major class of natural antioxidants—three potential mechanisms have been identified: hydrogen atom transfer (HAT), single-electron transfer followed by proton transfer (SET-PT), and sequential proton loss electron transfer (SPLET) [20]. The predominant mechanism depends on various factors including the chemical environment, solvent system, and structural properties of the antioxidant. The table below summarizes these key reaction mechanisms:

Table 1: Reaction Mechanisms in DPPH Radical Scavenging

| Mechanism | Process Description | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|

| Hydrogen Atom Transfer (HAT) | Antioxidant directly transfers a hydrogen atom to the DPPH radical. | Single-step process; preferred in non-polar environments; kinetic control. |

| Single-Electron Transfer Followed by Proton Transfer (SET-PT) | Antioxidant first transfers an electron, then a proton to DPPH. | Two-step process; favored in polar solvents; depends on ionization potential. |

| Sequential Proton Loss Electron Transfer (SPLET) | Antioxidant first dissociates to form an anion, which then transfers an electron to DPPH. | Prevalent for compounds with acidic protons; solvent-dependent. |

The following diagram illustrates the fundamental radical scavenging reaction between an antioxidant and the DPPH radical:

Figure 1: Fundamental DPPH Radical Scavenging Reaction

Experimental Protocol and Methodologies

Standard DPPH Assay Procedure

The basic DPPH assay protocol involves preparing a stable DPPH radical solution in an appropriate solvent (typically methanol or ethanol) and mixing it with the test compound or extract at specific concentrations [18] [19]. After a defined incubation period under controlled conditions, the absorbance is measured at 517 nm against a blank. The percentage of DPPH radical scavenging activity is calculated using the formula:

DPPH Scavenging Activity (%) = [(A₀ - A₁) / A₀] × 100

Where A₀ is the absorbance of the control (DPPH solution without antioxidant) and A₁ is the absorbance of the sample (DPPH solution with antioxidant) [21].

A modified protocol based on Brand-Williams et al. (1995) with minor adaptations commonly used in contemporary research is detailed below [19] [22]:

DPPH Solution Preparation: Prepare a 0.1 mM DPPH solution in methanol (or ethanol). For a 0.5 mM stock solution, accurately weigh 1.97 mg of DPPH and dissolve in 10 mL of methanol [19].

Sample Preparation: Prepare serial dilutions of the test compound or extract in the same solvent used for the DPPH solution.

Reaction Mixture: Combine 1 mL of DPPH solution with 0.2-1 mL of sample solution and adjust the total volume to 4 mL with solvent [22]. For initial screening, a single concentration may be used, while for IC₅₀ determination, a concentration series is recommended.

Incubation: Allow the reaction mixture to stand in the dark at room temperature for 30 minutes (variations between 10-60 minutes exist across protocols) [19] [22].

Absorbance Measurement: Measure the absorbance of the mixture at 517 nm against a blank consisting of the sample solution without DPPH.

Control Preparation: Prepare a control containing the same volume of DPPH solution and solvent without the test sample.

The following workflow diagram outlines the key steps in the DPPH assay protocol:

Figure 2: DPPH Assay Experimental Workflow

Data Interpretation and Expression of Results

Several parameters can be used to express DPPH assay results, each with distinct advantages:

IC₅₀ Value: The half-maximal inhibitory concentration represents the concentration of antioxidant required to scavenge 50% of DPPH radicals. Lower IC₅₀ values indicate higher antioxidant potency [19] [21].

Antiradical Power (ARP): Calculated as 1/IC₅₀, providing a direct positive correlation between value and antioxidant efficacy [19].

Trolox Equivalent Antioxidant Capacity (TEAC): Expresses antioxidant activity relative to the standard antioxidant Trolox (a water-soluble vitamin E analog) [4] [22] [9].

Antiradical Efficiency (AE): Incorporates both reaction kinetics and stoichiometry, calculated as AE = 1/(IC₅₀ × T₅₀), where T₅₀ is the time needed to reach the steady state at IC₅₀ [19].

For quantitative comparison, the results are often expressed as Trolox equivalents (TE) per mass of sample (e.g., mmol TE/kg or μmol TE/g), allowing standardized comparison across different studies and sample types [22] [9].

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Reagents for DPPH Assay

| Reagent/Material | Function/Role in Assay | Specifications & Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| DPPH Radical (1,1-diphenyl-2-picrylhydrazyl) | Stable free radical source; reaction substrate for antioxidants. | Purity >95%; store desiccated at -20°C; protect from light; prepare fresh solution in organic solvent. |

| Methanol or Ethanol | Solvent for DPPH radical and sample extracts. | HPLC or spectroscopic grade; anhydrous; may use aqueous mixtures (e.g., 80%) for polar compounds. |

| Trolox (6-hydroxy-2,5,7,8-tetramethylchroman-2-carboxylic acid) | Standard reference antioxidant for quantification. | Water-soluble vitamin E analog; prepare fresh stock solutions in solvent or buffer. |

| Antioxidant Samples | Test compounds for radical scavenging assessment. | Pure compounds or complex extracts; dissolve in same solvent as DPPH solution to avoid precipitation. |

| Spectrophotometer | Instrument for absorbance measurement at 517 nm. | UV-Vis instrument with 1 cm pathlength quartz or disposable plastic cuvettes. |

Comparative Analysis with Other Antioxidant Assays

Key Differences in Mechanism and Application

While the DPPH assay is valuable for initial antioxidant screening, it represents just one approach among many for assessing antioxidant capacity. Different assays measure distinct aspects of antioxidant activity, employing varied mechanisms and reaction conditions. Understanding these differences is crucial for selecting appropriate methods and interpreting results within a broader research context.

The DPPH assay primarily measures hydrogen-donating capacity through a mixed SET/HAT mechanism [20]. In contrast, other common assays like FRAP (Ferric Reducing Antioxidant Power) and TEAC (Trolox Equivalent Antioxidant Capacity) operate mainly through single-electron transfer (SET) mechanisms [9]. The ORAC (Oxygen Radical Absorbance Capacity) assay, meanwhile, evaluates the ability to quench peroxyl radicals through hydrogen atom transfer, more closely mimicking biological radical chain-breaking activity [4] [16].

Each assay varies in its applicability to different antioxidant types. The DPPH assay works well for both hydrophilic and lipophilic antioxidants, particularly phenolic compounds, though solvent choice significantly affects results [19] [20]. FRAP performs best for reducing antioxidants in acidic conditions, while TEAC is applicable to both hydrophilic and lipophilic systems and works at physiological pH [4] [9].

Inter-Assay Correlation and Comparative Data

Recent comparative studies reveal varying degrees of correlation between different antioxidant assays. A 2025 study investigating 15 plant-based spices, herbs, and food materials found that FRAP exhibited the strongest correlation with total polyphenol content (r = 0.913), followed by TEAC (r = 0.856) and DPPH (r = 0.772) [9]. This suggests that while these assays measure related properties, they capture different aspects of antioxidant capacity.

The redox potential of the oxidant/indicator system represents another critical differentiator between assays. The DPPH•/DPPH couple has a standard redox potential of 0.537 V, which is intermediate compared to other common assays [4]. This medium redox potential makes DPPH reactive with a broad range of antioxidants while excluding very weak reductants. The following table compares key technical aspects of major antioxidant capacity assays:

Table 3: Comparison of Major Antioxidant Capacity Assays

| Assay | Mechanism | Redox Potential (E°') | Key Applications | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DPPH | Mixed SET/HAT | 0.537 V [4] | Pure compounds, plant extracts, food samples. | Simple, rapid, inexpensive; no special equipment; suitable for hydrophilic/lipophilic antioxidants. | Solvent dependency; interference from pigments; not physiological. |

| ABTS/TEAC | Primarily SET | 0.68 V [4] | Biological fluids, plant extracts, beverages. | Fast reaction; works at physiological pH; applicable to hydrophilic/lipophilic systems. | Non-physiological radical; pre-generation of radical required. |

| FRAP | SET | 0.70 V [4] | Biological samples, plant extracts, food. | Simple, rapid, robust; does not require specialized equipment. | Non-physiological conditions (acidic pH); measures only reducing capacity. |

| ORAC | HAT | 0.77-1.44 V [4] | Biological samples, functional foods. | biologically relevant radical; applicable to both hydrophilic/lipophilic systems. | Requires fluorescent detection; more complex procedure; time-consuming. |

| FC (Folin-Ciocalteu) | SET | ~0.6-0.7 V (estimated) | Total phenolic content estimation. | Simple, well-established; high throughput capability. | Measures total reductants, not specifically antioxidants; interference from reducing sugars. |

A comprehensive 2025 study examining antioxidant activities of nine pure compounds using multiple assays demonstrated significant variability in results depending on the method employed [4]. For instance, gallic acid showed values ranging from 1.05 mol TE/mol in the ORAC assay to 4.07 mol TE/mol in the ABTS assay, highlighting how different mechanisms and reaction conditions yield different activity rankings [4]. This underscores the importance of using multiple complementary assays for comprehensive antioxidant profiling.

Applications and Case Studies

Appropriate Applications and Research Contexts

The DPPH assay finds appropriate application across multiple research domains:

Initial Screening of Natural Products: The method is extensively used for evaluating antioxidant potential in plant extracts, herbal medicines, and functional food ingredients [18] [23] [21]. For instance, studies on Ficus religiosa demonstrated significant DPPH radical scavenging activity, supporting its traditional medicinal use [23].

Food Science and Quality Control: The assay effectively monitors antioxidant changes during food processing and storage, assessing oxidative stability of lipids and oils [18] [9]. It successfully identifies potent antioxidant sources within spices and herbs, with Lamiaceae family members (rosemary, thyme, oregano) consistently showing high activity [9].

Structure-Activity Relationship Studies: Researchers utilize the DPPH assay to investigate how structural features influence antioxidant efficacy in phenolic compounds, flavonoids, and synthetic antioxidants [19] [20].

Nanotechnology and Material Science: Recent applications include evaluating antioxidant properties of biosynthesized nanoparticles, such as MgO nanoparticles using Ficus religiosa extracts [23].

Limitations and Inappropriate Applications

Despite its versatility, the DPPH assay demonstrates significant limitations in certain contexts:

Biological Relevance: The DPPH radical does not occur in biological systems, limiting direct extrapolation to in vivo conditions [16] [24]. The assay does not account for bioavailability, metabolism, or cellular uptake of antioxidants.

Kinetic Variability: Different antioxidants exhibit varying reaction kinetics with DPPH, with some reaching equilibrium rapidly while others require extended periods [19]. This complicates direct comparison between compounds with different reaction rates.

Interference Issues: Colored samples or those containing pigments can interfere with absorbance measurements at 517 nm [19]. Additionally, the assay is limited to solvents in which DPPH is soluble, primarily organic or aqueous-organic mixtures.

Plasma and Protein-Rich Samples: The assay is unsuitable for measuring antioxidant activity in plasma because proteins precipitate in the alcoholic reaction medium [19].

For these reasons, the DPPH assay should not serve as the sole method for claiming biological efficacy of antioxidants. Rather, it should form part of a comprehensive assessment strategy including cell-based assays, in vivo studies, and other complementary in vitro methods [16].

The DPPH radical scavenging assay remains a cornerstone methodology in antioxidant research due to its simplicity, reproducibility, and cost-effectiveness. Its continued popularity across diverse fields—from food science to natural product drug discovery—testifies to its utility as an initial screening tool. The assay provides valuable information about hydrogen-donating capacity, especially for phenolic compounds and plant extracts, making it particularly suitable for comparative studies of radical scavenging efficacy.

However, researchers must recognize the method's limitations, particularly its lack of direct biological relevance and potential for artifactual results. The future of antioxidant assessment lies in integrated approaches that combine DPPH screening with other in vitro methods measuring different mechanisms (SET, HAT, metal chelation), followed by cell-based assays and ultimately clinical validation [16]. Emerging trends include the development of standardized protocols to improve inter-laboratory reproducibility, miniaturized formats for high-throughput screening, and integration with advanced analytical techniques for compound identification.

As the field advances, the DPPH assay will likely maintain its position as an accessible entry point for antioxidant characterization while increasingly serving as one component in multifaceted assessment strategies. Its enduring value lies not in isolation, but as part of a complementary analytical framework that bridges chemical properties with biological activity in the ongoing quest to understand and utilize antioxidant compounds for health and preservation applications.

The quantification of antioxidant capacity is a fundamental practice in fields ranging from food science to pharmaceutical development. Among the numerous assays developed, the ABTS/TEAC (2,2'-azino-bis(3-ethylbenzothiazoline-6-sulfonic acid)/Trolox Equivalent Antioxidant Capacity) assay stands as one of the most widely cited and utilized methods in research laboratories globally [25]. According to citation metrics, ABTS-based assays rank among the three most popular antioxidant capacity methods, alongside DPPH (2,2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl) and FRAP (Ferric Reducing Antioxidant Power) assays [25]. The assay's prominence stems from its unique versatility in evaluating both hydrophilic and lipophilic antioxidants within complex samples [26], a capability that remains challenging for many alternative methods. This guide provides a comprehensive comparison of the ABTS/TEAC assay against other common antioxidant assessment methods, examining its fundamental principles, kinetic behavior, and practical advantages to inform researcher selection for specific applications.

Fundamental Principles and Reaction Mechanisms

Core Chemistry of the ABTS/TEAC Assay

The ABTS/TEAC assay operates on the principle of single electron transfer (SET) [27] [28]. The fundamental reaction involves the oxidation of the colorless ABTS molecule to form the stable radical cation ABTS•+, which displays a characteristic intense bluish-green color with absorption maxima at multiple wavelengths, most commonly monitored at 734 nm [25] [27]. This radical cation is generated prior to antioxidant interaction, typically through reaction with potassium persulfate, resulting in approximately 60% conversion of ABTS to ABTS•+ after 12-16 hours [25]. When antioxidants are introduced, they donate electrons to ABTS•+, resulting in a decolorization proportional to their concentration and antioxidant capacity [25].

The assay measures the total antioxidant capacity of a sample by comparing its radical quenching ability to that of Trolox (6-hydroxy-2,5,7,8-tetramethylchroman-2-carboxylic acid), a water-soluble vitamin E analog [29]. Results are expressed as Trolox equivalents, enabling standardized comparison across different samples and studies [29]. The dominant reaction mechanism can proceed via different pathways depending on solvent and pH conditions. In aqueous solutions, the reaction preferentially follows the SPLET (Sequential Proton Loss Electron Transfer) mechanism, while in ethanol and methanol, it may proceed via SET-PT (Single Electron Transfer Followed by Proton Transfer) [27].

Dual Solvent Capability: Hydrophilic and Lipophilic Assessment

A distinctive advantage of the ABTS/TEAC assay is its adaptability to both aqueous and organic solvent systems [26]. This dual capability enables the comprehensive assessment of antioxidant capacity across the full spectrum of polarity. The remarkable stability of the ABTS•+ radical cation in diverse media is the key characteristic that enables this versatility [26]. In buffered aqueous solutions, the assay effectively measures hydrophilic antioxidant activity (HAA), capturing the capacity of water-soluble antioxidants such as vitamin C, uric acid, and glutathione [26] [29]. When performed in organic solvents like ethanol or methanol, the assay determines lipophilic antioxidant activity (LAA), assessing fat-soluble antioxidants including vitamin E, carotenoids, and other non-polar phytochemicals [26]. This comprehensive scope makes the ABTS assay particularly valuable for evaluating complex biological samples and food extracts that contain diverse antioxidant compounds with varying solubilities.

Comparative Analysis of Major Antioxidant Capacity Assays

The landscape of antioxidant capacity assessment encompasses numerous methodologies, each with distinct mechanisms, advantages, and limitations. The ABTS/TEAC assay belongs to the SET-based methods, which measure the ability of antioxidants to transfer electrons to radical compounds [28]. This contrasts with HAT (Hydrogen Atom Transfer) based methods, such as ORAC (Oxygen Radical Absorbance Capacity), which quantify the ability of antioxidants to donate hydrogen atoms to peroxyl radicals [27] [28]. Understanding these fundamental differences is crucial for appropriate method selection and data interpretation.

Table 1: Comparison of Major Antioxidant Capacity Assays

| Assay | Reaction Mechanism | Primary Probe | Detection Wavelength | Measured Parameter | Key Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ABTS/TEAC | SET (primarily) [27] | ABTS•+ radical cation | 734 nm [25] | Decolorization extent | Both hydrophilic & lipophilic antioxidants [26] |

| DPPH | SET (primarily) [27] | DPPH radical | 517 nm [27] | Decolorization extent | Mainly lipophilic antioxidants |

| FRAP | SET exclusively [29] | Fe³⁺-TPTZ complex | 593 nm [29] | Color development | Reductive potential in acidic pH |

| ORAC | HAT [28] | AAPH-derived peroxyl radicals | Fluorescence (λex 495 nm) [29] | Fluorescence decay | Chain-breaking antioxidant activity |

| CUPRAC | SET [29] | Cu²⁺-neocuproine complex | 450 nm [29] | Color development | Reductive antioxidants |

Performance Metrics and Applicability

The practical utility of antioxidant assays varies significantly based on sample composition and research objectives. Recent comparative studies reveal that the ABTS assay demonstrates strong correlation with total polyphenol content (r = 0.856), positioned between FRAP (r = 0.913) and DPPH (r = 0.772) [9]. This intermediate correlation reflects the ABTS assay's broader reactivity with diverse antioxidant structures compared to the more selective DPPH assay. A critical distinction emerges when analyzing specific antioxidant subclasses: while some dihydrochalcones and flavanones show negligible reactivity in the DPPH assay, they demonstrate significant activity in the ABTS assay [27]. This makes ABTS particularly suitable for evaluating flavanone-rich samples such as citrus extracts. The ABTS assay also shows less dependency on the Bors criteria (structural features influencing antioxidant activity) compared to DPPH, making it more applicable to diverse phenolic structures [27].

Table 2: Quantitative Performance Comparison Across Food Matrices (Mean TEAC Values)

| Sample Category | ABTS/TEAC (μmol TE/g) | DPPH (μmol TE/g) | FRAP (μmol TE/g) | Relative Performance Pattern |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lamiaceae Herbs (Rosemary, Thyme) | High: 450-650 [9] | High: 420-600 [9] | High: 480-700 [9] | FRAP ≥ ABTS ≥ DPPH |

| Solanaceae (Tomato, Pepper) | Moderate: 120-250 [9] | Low-Moderate: 80-200 [9] | Moderate: 150-280 [9] | FRAP ≥ ABTS > DPPH |

| Zingiberaceae (Ginger, Turmeric) | Moderate-High: 200-400 [9] | Moderate: 180-350 [9] | Moderate-High: 250-450 [9] | FRAP ≥ ABTS ≥ DPPH |

| Amaranthaceae (Spinach, Beetroot) | Moderate: 150-300 [9] | Moderate: 140-280 [9] | Moderate: 160-320 [9] | FRAP ≥ ABTS ≥ DPPH |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Standardized ABTS/TEAC Assay Procedure

The following protocol details the optimized procedure for determining antioxidant capacity using the ABTS/TEAC assay, applicable to both hydrophilic and lipophilic samples [26] [27]:

- Radical Stock Solution Preparation: Dissolve 6.62 mg potassium persulfate and 38.4 mg ABTS diammonium salt in 10 mL demineralized water [27].

- Radical Generation: Incubate the solution in darkness for 12-16 hours to allow complete radical formation, characterized by the development of a persistent bluish-green color [25] [27].

- Working Solution Preparation: Dilute the stock solution with demineralized water (typically 1:100) to achieve an absorbance of 0.70 ± 0.02 at 734 nm [27].

- Sample Preparation: Prepare antioxidant samples in appropriate solvents (aqueous buffer for hydrophilic compounds, ethanol/methanol for lipophilic compounds) with serial dilutions (e.g., 0.075-1 mM) [27].

- Reaction Setup: Mix 10 μL of sample with 990 μL of ABTS•+ working solution [27].

- Incubation and Measurement: Allow the reaction to proceed for exactly 10 minutes at room temperature, then measure absorbance at 734 nm using a spectrophotometer [27].

- Calculation: Determine the percentage inhibition of absorbance relative to a blank and calculate Trolox equivalents from a standard curve.

HPLC-ABTS Coupled Method for Enhanced Specificity

For advanced applications requiring compound-specific antioxidant activity profiling, an online HPLC-ABTS method has been developed [26]. This technique utilizes two pumps—one for isocratic elution of separated compounds and another for delivery of preformed ABTS radical—coupled with a UV-VIS diode array detector [26]. This configuration enables dual analysis: conventional UV-VIS detection for compound identification simultaneous with ABTS-scavenging detection at 734 nm [26]. The method provides valuable information about the correspondence between specific compounds and their antioxidant activities, applicable to both hydrophilic and lipophilic antioxidants in complex samples like fruit juices [26].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Successful implementation of the ABTS/TEAC assay requires specific chemical reagents and instrumentation. The following table details essential components and their functions within the experimental workflow:

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Equipment for ABTS/TEAC Assay

| Item | Specification | Function/Role in Assay | Notes for Use |

|---|---|---|---|

| ABTS Diammonium Salt | High purity (>98%) | Source of radical cation precursor | Protect from light; store desiccated |

| Potassium Persulfate | Analytical grade | Oxidizing agent for radical generation | Fresh preparation recommended |

| Trolox Standard | Water-soluble vitamin E analog | Reference standard for quantification | Prepare fresh solutions daily |

| Spectrophotometer | UV-VIS with 734 nm capability | Absorbance measurement for quantification | Cuvette pathlength: 1 cm |

| Buffer Solutions | Phosphate buffer (pH 7.4) | Aqueous reaction medium for hydrophilic antioxidants | Adjust pH precisely |

| Organic Solvents | Ethanol, methanol (HPLC grade) | Reaction medium for lipophilic antioxidants | Use anhydrous for consistency |

| HPLC System | Binary pumps with diode array detector | Compound separation for advanced methods | Required for online ABTS profiling [26] |

Advantages and Limitations in Research Context

Key Advantages Over Alternative Methods

The ABTS/TEAC assay offers several distinctive advantages that explain its widespread adoption in research settings. Its most notable strength is the versatility to assess both hydrophilic and lipophilic antioxidants without methodological modification [26]. This dual capability eliminates the need for multiple assays when evaluating complex samples containing antioxidants of varying polarities. The rapid reaction kinetics of the ABTS assay compared to methods like DPPH enables faster data acquisition, with most reactions reaching completion within 10 minutes [27]. From a practical standpoint, the simplicity of implementation using common laboratory equipment makes the assay accessible to researchers across disciplines. The high reproducibility of results, when properly standardized, contributes to reliable inter-laboratory comparisons [25]. Furthermore, the pH flexibility of the ABTS system allows adaptation to various physiological or food-relevant conditions, unlike assays such as FRAP that require strongly acidic environments [29].

Limitations and Methodological Considerations

Despite its advantages, the ABTS/TEAC assay presents certain limitations that researchers must consider during experimental design and data interpretation. The biological relevance of the ABTS radical has been questioned, as it does not occur naturally in biological systems [25] [28]. This contrasts with methods like ORAC that use peroxyl radicals, which are physiologically relevant oxidants. Some phenolic antioxidants can form coupling adducts with ABTS•+, leading to potential overestimation of antioxidant capacity through non-stoichiometric reactions [25]. The solvent-dependent reaction mechanisms (SPLET in water vs. SET-PT in alcohols) can complicate direct comparisons between studies using different solvent systems [27]. Researchers should also note that the single-electron transfer mechanism primarily captured by ABTS may not fully represent hydrogen-donating capacity relevant to chain-breaking antioxidant activity in biological systems [27] [28].

The ABTS/TEAC assay represents a robust, versatile, and widely applicable method for comprehensive antioxidant capacity assessment. Its unique capability to evaluate both hydrophilic and lipophilic antioxidants within a unified framework makes it particularly valuable for analyzing complex biological samples, food extracts, and pharmaceutical formulations. While no single assay can fully capture the multifaceted nature of antioxidant activity, the ABTS method provides a balanced approach that complements other SET-based methods like FRAP and CUPRAC, as well as HAT-based methods like ORAC. The continued development of coupled techniques, such as HPLC-ABTS online systems, further enhances its utility by enabling compound-specific activity profiling [26]. For researchers investigating diverse antioxidant systems, the ABTS/TEAC assay offers an optimal combination of practicality, sensitivity, and breadth of application, particularly when used as part of a complementary assay strategy rather than a standalone measure of total antioxidant capacity.

The accurate assessment of antioxidant capacity is fundamental to research in food science, nutraceutical development, and pharmaceutical applications. Among the various methods developed, the Oxygen Radical Absorbance Capacity (ORAC) assay has distinguished itself through its unique mechanistic approach and biological relevance. Unlike methods based solely on electron transfer, the ORAC assay operates primarily via Hydrogen Atom Transfer (HAT), a mechanism that more closely mimics the radical chain-breaking activity of antioxidants in biological systems [30]. This physiological relevance makes ORAC particularly valuable for researchers investigating compounds that may mitigate oxidative stress, which is implicated in chronic diseases, food preservation, and cosmetic stability [31].

The fundamental challenge in antioxidant capacity assessment lies in the diversity of mechanisms through which antioxidants operate. No single assay can fully capture this complexity, necessitating the use of multiple complementary methods for comprehensive evaluation [31] [4]. Within this landscape, understanding the specific advantages, limitations, and appropriate applications of the ORAC assay is crucial for designing valid experiments and interpreting data in a biologically meaningful context, particularly when transitioning from in vitro findings to in vivo models and human clinical trials [32].

Fundamental Mechanisms: HAT vs. SET Assays

Antioxidant assays are broadly classified into two categories based on their underlying reaction mechanisms: Hydrogen Atom Transfer (HAT) and Single Electron Transfer (SET). These mechanisms dictate how an antioxidant neutralizes a free radical and are influenced by different structural and environmental factors.

- Hydrogen Atom Transfer (HAT) Mechanism: HAT-based methods measure the ability of an antioxidant to donate a hydrogen atom to a free radical, thereby stabilizing it [30]. A hydrogen atom consists of one proton and one electron; therefore, HAT simultaneously transfers both.

- Single Electron Transfer (SET) Mechanism: SET-based assays measure the ability of an antioxidant to transfer a single electron to reduce a metal ion, carbonyl, or radical [30]. This reaction is governed by the redox potential of the substrates involved [4].

The following diagram illustrates the key mechanistic differences between HAT and SET reactions in antioxidant assays.

The ORAC assay is predominantly a HAT-based method, which is significant because HAT is often the dominant mechanism for quenching peroxyl radicals in vivo [30]. This mechanistic fidelity is a primary reason for the assay's reputation for high biological relevance.

The ORAC assay is a standardized method for determining the antioxidant capacity of substances against peroxyl radicals, which are biologically relevant reactive oxygen species (ROS) [33]. The assay quantifies the ability of antioxidants to inhibit the peroxyl radical-induced oxidation of a fluorescent probe.

Key Principles and Reaction Workflow

The core principle of the ORAC assay involves thermal decomposition of 2,2'-azobis(2-methylpropionamidine) dihydrochloride (AAPH) to generate peroxyl radicals (ROO•) at a constant rate [33]. These radicals damage the fluorescent probe, fluorescein (FL), causing a loss of fluorescence. Antioxidants present in the sample compete with fluorescein for the peroxyl radicals, thereby protecting the probe and delaying the fluorescence decay. The extent of this protection, measured as the area under the fluorescence decay curve (AUC), is proportional to the antioxidant capacity of the sample [33].

The following diagram outlines the key stages of a standard ORAC experimental workflow.

Essential Research Reagents and Materials

A successful ORAC experiment requires specific, high-quality reagents. The table below details the essential components of the ORAC assay kit and their critical functions in the procedure.

Table 1: Key Research Reagent Solutions for the ORAC Assay

| Reagent/Material | Function in the Assay | Key Specifications |

|---|---|---|

| Fluorescein | Fluorescent probe whose signal decay is inhibited by antioxidants [33]. | Prepared as a 10 nM solution in phosphate buffer. |

| AAPH | Peroxyl radical generator via thermal decomposition [33]. | Typically used as a 240 mM solution; provides a constant radical flux. |

| Trolox | Water-soluble vitamin E analog used as a calibration standard [33]. | A series of concentrations (e.g., 12.5-200 µM) creates a standard curve. |

| Phosphate Buffer (pH 7.4) | Maintains a physiologically relevant reaction environment [33]. | 10 mM concentration, pH 7.4. |

| Black Opaque Microplate | Vessel for the reaction, preventing optical crosstalk between wells [33]. | 96-well plates are standard for high-throughput formats. |

Standardized Protocol and Data Calculation

A typical ORAC-FL protocol involves the following steps [33]:

- Preparation: Freshly prepare all reagent and sample solutions in phosphate buffer (10 mM, pH 7.4) daily.

- Plate Setup: In each well of a 96-well plate, pipette in triplicate:

- 150 µL of fluorescein (10 nM).

- 25 µL of Trolox standard, sample, or blank (phosphate buffer).

- Incubation: Seal the plate and incubate at 37°C for 30 minutes.

- Initiation: Rapidly add 25 µL of AAPH (240 mM) to each well using a multi-channel pipette or onboard injectors.

- Kinetic Measurement: Immediately commence fluorescence reading (Ex: 485 nm, Em: 520 nm) every 60-90 seconds for up to 120 minutes.

The data is calculated based on the net area under the fluorescence decay curve (AUC) for the sample and standards. The antioxidant capacity is expressed as Trolox Equivalents (TE), typically in micromoles of TE per gram or milliliter of sample (µmol TE/g or mL) [33]. The net AUC is derived from the sample AUC minus the blank AUC. The standard curve is constructed by plotting the net AUC of the Trolox standards against their concentration, enabling the interpolation of the sample's TE value.

Comparative Analysis of Major Antioxidant Capacity Assays

To fully appreciate the position of the ORAC assay, it must be compared with other common methods. The table below provides a structured comparison of ORAC with other frequently used assays, highlighting key methodological and interpretive differences.

Table 2: Comprehensive Comparison of Major Antioxidant Capacity Assays

| Assay | Primary Mechanism | Oxidant/Radical Used | Key Advantages | Key Limitations | Biological Relevance |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ORAC [30] [33] | HAT | Peroxyl Radical (ROO•) | - Uses biologically relevant radical.- Combines inhibition time & degree.- Suitable for hydrophilic/lipophilic fractions. | - Time-consuming.- Requires fluorescence detection.- Less suited for colored samples. | High – Measures inhibition of lipid peroxidation chain reaction. |

| FRAP [4] [30] | SET | Fe³⁺-TPTZ complex | - Simple, rapid, and cost-effective.- Highly reproducible. | - Non-physiological pH (3.6).- Does not involve a radical.- Inert to antioxidants that act via HAT. | Low – Measures reducing power under acidic conditions not found in vivo. |

| ABTS [4] [34] | SET (Primary) | ABTS•+ (Radical Cation) | - Fast reaction.- Can be used at physiological pH.- Applicable for both hydrophilic and lipophilic antioxidants. | - Uses a pre-formed, non-physiological radical.- Reactivity depends on redox potential. | Moderate – The radical is not common in biological systems, but the assay is comprehensive. |

| DPPH [9] [34] | SET (Primary) | DPPH• (Stable Radical) | - Simple procedure.- Does not require special equipment. | - Reaction can be slow.- Steric accessibility can limit reaction with large compounds.- Non-physiological radical. | Low – The stable, organic DPPH radical is not biologically relevant. |

| CUPRAC [30] | SET | Cu²⁺-Neocuproine | - Greater repeatability and reagent stability.- Operates at a more physiological pH than FRAP. | - Still an electron-transfer assay, not directly measuring radical quenching. | Moderate to High – Considered superior to FRAP/DPPH for its resemblance to in vivo conditions [30]. |

Correlation and Discrepancy Between Assays

Different assays often yield different results for the same sample because they measure different aspects of antioxidant activity [4]. For instance, the antioxidant activity of gallic acid has been reported to be 1.05 mol TE/mol in the ORAC assay, but ranges from 1.85 to 4.73 mol TE/mol in various SET-based assays like FRAP and ABTS [4]. These discrepancies arise because:

- Thermodynamic and Kinetic Factors: SET assays are influenced by the redox potential of the oxidant/antioxidant pair, while HAT assays are more influenced by bond dissociation energy and kinetic factors [4].

- Structural Dependence: The ABTS assay may be more useful than DPPH for detecting antioxidant capacity in a variety of foods, especially those with high-pigmented and hydrophilic antioxidants [34].

Assessing the Biological Relevance of the ORAC Assay

The transition from in vitro antioxidant measurements to proven health benefits in humans is a significant challenge. Regulatory bodies like the European Food Safety Authority (EFSA) emphasize that a statistically significant change in an in vitro assay does not automatically imply biological relevance for human health [32].

Strengths of the ORAC Assay in a Biological Context

The ORAC assay holds several advantages that contribute to its perceived biological relevance:

- Physiologically Relevant Radical Source: It uses peroxyl radicals (ROO•), which are common intermediates in lipid peroxidation and play a significant role in food spoilage and oxidative damage in vivo [31] [33].

- HAT Mechanism: The hydrogen atom transfer mechanism directly measures the radical chain-breaking activity of antioxidants, which is a key pathway for neutralizing radicals in biological systems [30].

- Quantification of Inhibition Kinetics: Unlike endpoint SET assays, ORAC combines the degree and time of inhibition into a single value (Area Under the Curve), capturing the kinetics of the antioxidant action, which can be critical for understanding efficacy over time [33].

Limitations and Regulatory Considerations

Despite its strengths, the ORAC assay has limitations that researchers must acknowledge:

- Indirect Measure: It is an in vitro chemical assay and does not account for bioavailability, metabolism, or tissue distribution in a living organism [31].

- Regulatory Scrutiny: EFSA guidance indicates that in vitro antioxidant capacity assays like ORAC, FRAP, and ABTS are not sufficient alone as predictors of human health benefit for health claim authorization, unless strongly linked to meaningful physiological outcomes in human trials [32].

- Need for Validation: To demonstrate true biological impact, ORAC data should be part of a larger evidence base that includes in vivo models, biomarker studies, and human clinical trials showing relevant health effects [31] [32].

The ORAC assay remains a powerful and widely used tool for ranking and comparing the antioxidant capacity of compounds, foods, and biological samples. Its foundation in the HAT mechanism and use of a biologically relevant peroxyl radical source make its results more translatable to complex biological systems compared to many SET-based assays.

However, the scientific community recognizes that no single in vitro assay can fully predict in vivo efficacy. The ORAC assay is most valuable when used as part of a complementary assay strategy—alongside methods like CUPRAC, ABTS, and cellular models—to provide a more holistic view of antioxidant behavior [31] [30]. Future research will continue to integrate these classical methods with advanced techniques, including high-throughput screening, omics technologies, and nanotechnology, to bridge the gap between laboratory measurements and real-world antioxidant therapies [31]. For researchers, the key is to apply the ORAC assay judiciously, interpret its results within the context of its mechanisms and limitations, and validate findings through rigorous in vivo and clinical studies to establish true biological relevance.

The accurate assessment of total antioxidant capacity (TAC) presents a significant challenge in biochemical and clinical research due to the diverse nature of antioxidants and the complex matrices in which they exist. Antioxidants function through multiple mechanisms, including hydrogen atom transfer (HAT), single electron transfer (SET), metal chelation, and enzyme inhibition [31] [35]. No single assay can comprehensively capture all these mechanisms, making method selection and adaptation critical for obtaining biologically relevant results.

The complexity of different sample matrices—from biological fluids like serum to complex plant extracts and food products—further complicates TAC assessment. Each matrix presents unique challenges including varying pH environments, solubility issues for lipophilic antioxidants, presence of interfering substances, and differences in antioxidant partitioning [36]. This guide provides a systematic comparison of antioxidant capacity assays and their adaptation for specific sample types, enabling researchers to select and validate appropriate methodologies for their specific applications.

Established Antioxidant Capacity Assays: Principles and Mechanisms

Fundamental Assay Classifications